Guatemalan Revolution, "Revolución, 1944-1954", 1944年革命

Edgar

Rice Burroughs, Land of Terror,

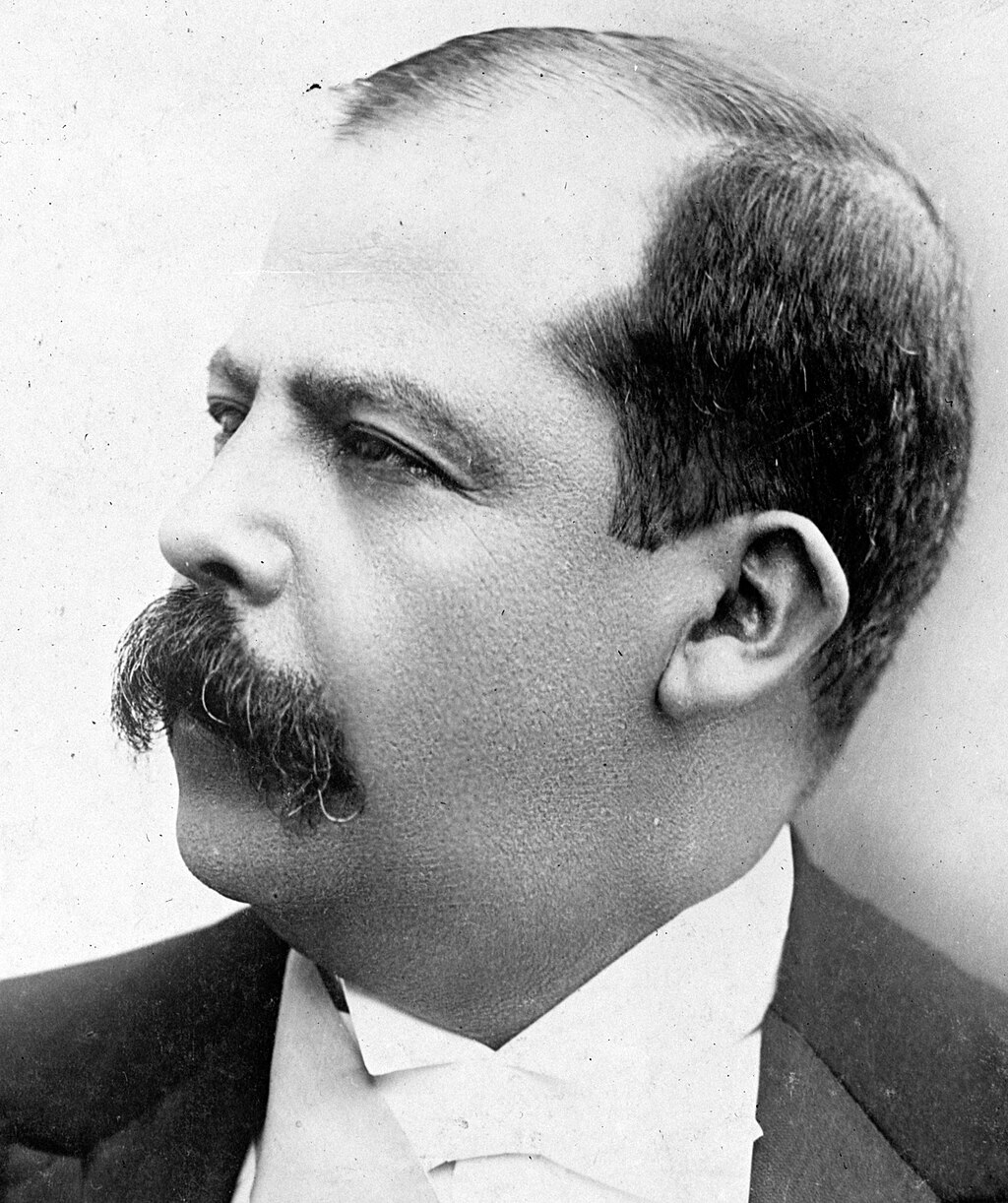

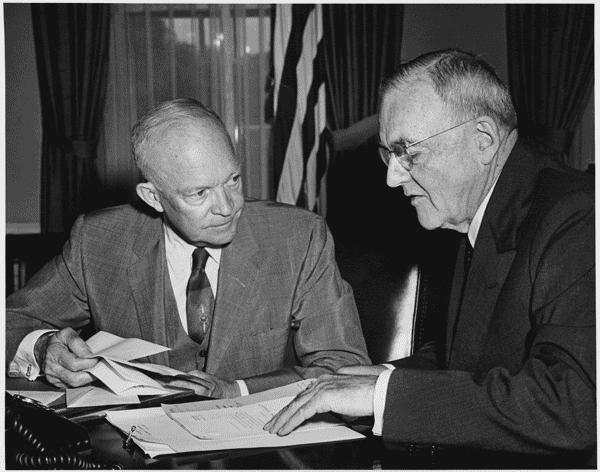

1944 - Project Gutenberg Australia./ Jacobo Árbenz, Jorge Toriello, and Francisco Arana, members of the military junta.1944

グアテマラ革命

Guatemalan Revolution, "Revolución, 1944-1954", 1944年革命

Edgar

Rice Burroughs, Land of Terror,

1944 - Project Gutenberg Australia./ Jacobo Árbenz, Jorge Toriello, and Francisco Arana, members of the military junta.1944

解説:池田光穂

☆グアテマラの歴史において、1944年のホルヘ・ウ

ビコに対するクーデターから1954年のハコボ・アルベンスに対するクーデターまでの期間は、現地では

「革命(スペイン語: La

Revolución)」(the Guatemalan Revolution)

として知られている。また「春の十年」とも呼ばれ、1944年から1996年の内戦終結まで、グアテマラにおける代表民主制の頂

点を強調する呼称である。この時期には、社会・政治、特に農地改革が実施され、ラテンアメリカ全域に影響を与えた。[1]

19世紀後半から1944年まで、グアテマラは一連の権威主義的な統治者によって支配された。彼らはコーヒー輸出を支援することで経済強化を図った。

1898年から1920年にかけて、マヌエル・エストラーダ・カブレラは熱帯果実を扱う米国企業ユナイテッド・フルーツ社に大規模な特権を付与し、多くの

先住民から共同所有地を奪った。1931年から1944年まで独裁者として統治したホルヘ・ウビコの下では、厳しい労働規制と警察国家の確立により、この

過程はさらに強化された。

1944年6月、大学生と労働団体が主導した民主化を求める民衆運動によりウビコは辞任を余儀なくされた。後任としてフェデリコ・ポンセ・バイデス率いる

3人格による軍事政権が樹立された。この政権はウビコの抑圧政策を継続したが、1944年10月にハコボ・アルベンス主導の軍事クーデターにより打倒され

た。この事件は「十月革命」としても知られる。クーデター指導者たちは軍事評議会を結成し、直ちに公選を実施した。この選挙では、進歩的な哲学教授であり

民衆運動の象徴となったフアン・ホセ・アレバロが圧勝した。彼は穏健な社会改革プログラムを実施し、広く成功した識字運動やほぼ自由な選挙プロセスを実現

した。ただし、文盲の女性には投票権が与えられず、共産党は禁止された。

1951年にアレバロの任期が終了すると、ハコボ・アルベンスが圧勝で大統領に選出された。アルベンスはアレバロの改革を継続し、野心的な土地改革プログ

ラム「法令900号」を開始した。これに基づき、大規模土地所有者の未耕作地は補償と引き換えに収用され、貧困に苦しむ農業労働者に再分配された。約50

万人がこの法令の恩恵を受けた。受益者の大半は先住民であり、その祖先はスペイン侵攻後に土地を奪われていた。アルベンスの政策はユナイテッド・フルーツ

社と対立した。同社は未耕作地の一部を失ったのである。同社はアルベンス政権打倒を米国政府に働きかけ、国務省はアルベンスが共産主義者であるとの口実で

クーデターを画策した。カルロス・カスティーヨ・アルマスが軍事政権の首班として権力を掌握し、グアテマラ内戦が始まった。この戦争は1960年から

1996年まで続き、軍は先住民マヤ族に対するジェノサイド(集団虐殺)や民間人への広範な人権侵害を行った。

++++

1523 スペインによる征服

1573 スペイン王領の総督領となる

1921 スペインから独立

1823 中米諸州連合結成

1838 中米諸州連合より分離独立

1931年〜 ホルヘ・ウビコ独裁政権

1939-1945 第二次世界大戦

===

1944年 7月 ウビコ大統領辞任、後任にフアン・フェデリコ・ポンセ・ヴァイデス将軍(Juan Federico Ponce Vaides, 1889-1956)が就任

1944年10月 10月反乱、フアン・フェデリコ・ポンセ・ヴァイデス将軍が辞任、大統領選挙がおこなわれること になる。

1944年の革命評議会。左からアルベンス、トリエージョ、アラナ

1944年12月 自由選挙でアレバロ(Juan Jose Arevalo Bermejo, 1904-1990)が大統領に当選

1945年3月 アレバロ政権に就く、1945年憲法の発 布

1947年2月 イギリスはギリシャとトルコに対する経済援助を停止することをアメ リカ合衆国に通知。トルーマンは翌月、議会でトルーマン・ドクトリンを表明。冷戦体制がはじまると言われる。

1949年 アルベンス派の人間によってアラナ(Francisco

Javier Arana, 1905-1949)が暗殺される

1951年 アルベンス(Jacobo Arbenz Guzman, 1913-1971:アレバロ政権期の国防大臣)大統領

1952年 農地改革法

チェ・ゲバラ(Ernesto Guevara, 1928-1967)、1952年4月にブエノスアイレス大学医学部卒業、その後、ラテンアメリカの国々を旅行する。1954年、イルダ・ガデア (Hilda Gadea, 1925-1974)とグアテマラで知りあう。ガデアは、ペルー・リマ生まれで、左翼政党(ARPA, Alianza Popular Revolucionaria Americana)のリーダーだった。ガデアは、チェの最初の妻となる。2人は、アルマスの軍事的制圧の混乱の中、メキシコに逃れる。55年に結婚。下 記の写真はウィキペディア(スペイン語)のガデアの項目からとったもので、1955年の新婚旅行で(メキシコの)ユカタン半島で撮られたものである。

1953年8月頃 アラン・ダレスCIA長官は、アルベンス排除の計画をするように

命令。

1954年3月 カラカスでの第10回米州会議で、アイゼンハワー政権は、グアテマ ラにおける共産主義化の懸念を批判する。

1954年5月 チェコ製の武器輸入が発覚し、米国のグアテマラへの単独介入を決意

したといわれる。

1954年6月

ホンジュラス領内より(CIAの支援を受けた)カスティーリョ・ア ルマス大佐による反革命軍のグアテマラ侵攻(6月18日)、首都制圧によりアルベンスは6月27日に辞任(CIA長官アレン・ウェルシュ・ダレス(Allen Dulles, 1893-1969)はこれに関与)

1954年 10月アルマス大統領に就任。1945年憲法の停止

1955年

1956年

1957年 アルマス暗殺。

1958年 ミゲル・イディゴラス・フエンテス(Miguel Ydígoras Fuentes, 1895-1982)独裁政権。

1960年11月(→グアテマラ 内戦関連年表)

イディゴラス・フエンテス大統領に対する 軍の反乱鎮圧(1960年11月)、武装反乱軍は山間部でゲリラ活動を開始(1962年年頭にゲリラ戦による抗戦を布告する)→これにより内戦期の開始を 1960/61年にするかで所説がある)

1962年2月 武装反乱軍グループは「MR13」(Movimiento Revolucionario, 13 de noviembre, Alejandro de Leo'n)結成(活動拠点をラス・ミナス山中にもとめ る)(→グアテマラ内戦関連年表)

===

*****グアテマラ革命とは以上の10年間の社会改 革(===で囲まれた部分)のことをさす****

ca. 1962年 左側勢力の武装闘争開始

1982年 グアテマラ国民革命連合(URNG)

1990年 革命連合と国民和解委員会(CNR)の和 平合意

1996年12月 URNGと政府の和平合意締結

=

☆グアテマラ革命(the Guatemalan Revolution)

| The period in the

history of Guatemala between the coups against Jorge Ubico in 1944 and

Jacobo Árbenz in 1954 is known locally as the Revolution (Spanish: La

Revolución). It has also been called the Ten Years of Spring,

highlighting the peak years of representative democracy in Guatemala

from 1944 until the end of the civil war in 1996. It saw the

implementation of social, political, and especially agrarian reforms

that were influential across Latin America.[1] From the late 19th century until 1944, Guatemala was governed by a series of authoritarian rulers who sought to strengthen the economy by supporting the export of coffee. Between 1898 and 1920, Manuel Estrada Cabrera granted significant concessions to the United Fruit Company, an American corporation that traded in tropical fruit, and dispossessed many indigenous people of their communal lands. Under Jorge Ubico, who ruled as a dictator between 1931 and 1944, this process was intensified, with the institution of harsh labor regulations and a police state.[2] In June 1944, a popular pro-democracy movement led by university students and labor organizations forced Ubico to resign. He appointed a three-person military junta to take his place, led by Federico Ponce Vaides. This junta continued Ubico's oppressive policies, until it was toppled in a military coup led by Jacobo Árbenz in October 1944, an event also known as the "October Revolution". The coup leaders formed a junta which swiftly called for open elections. These elections were won in a landslide by Juan José Arévalo, a progressive professor of philosophy who had become the face of the popular movement. He implemented a moderate program of social reform, including a widely successful literacy campaign and a largely free election process, although illiterate women were not given the vote and communist parties were banned. Following the end of Arévalo's presidency in 1951, Jacobo Árbenz was elected to the presidency in a landslide. Árbenz continued Arévalo's reforms, and began an ambitious land-reform program, known as Decree 900. Under it, the uncultivated portions of large land-holdings were expropriated in return for compensation, and redistributed to poverty-stricken agricultural laborers. Approximately 500,000 people benefited from the decree. The majority of them were indigenous people, whose forebears had been dispossessed after the Spanish invasion. Árbenz's policies ran afoul of the United Fruit Company, which lost some of its uncultivated land. The company lobbied the US government for the overthrow of Árbenz, and the US State Department responded by engineering a coup under the pretext that Árbenz was a communist. Carlos Castillo Armas took power at the head of a military junta, starting the Guatemalan Civil War. The war lasted from 1960 to 1996, and saw the military commit genocide against the indigenous Maya peoples and widespread human rights violations against civilians. |

グアテマラの歴史において、1944年のホルヘ・ウビコに対するクーデ

ターから1954年のハコボ・アルベンスに対するクーデターまでの期間は、現地では「革命(スペイン語: La

Revolución)」として知られている。また「春の十年」とも呼ばれ、1944年から1996年の内戦終結まで、グアテマラにおける代表民主制の頂

点を強調する呼称である。この時期には、社会・政治、特に農地改革が実施され、ラテンアメリカ全域に影響を与えた。[1] 19世紀後半から1944年まで、グアテマラは一連の権威主義的な統治者によって支配された。彼らはコーヒー輸出を支援することで経済強化を図った。 1898年から1920年にかけて、マヌエル・エストラーダ・カブレラは熱帯果実を扱う米国企業ユナイテッド・フルーツ社に大規模な特権を付与し、多くの 先住民から共同所有地を奪った。1931年から1944年まで独裁者として統治したホルヘ・ウビコの下では、厳しい労働規制と警察国家の確立により、この 過程はさらに強化された。 1944年6月、大学生と労働団体が主導した民主化を求める民衆運動によりウビコは辞任を余儀なくされた。後任としてフェデリコ・ポンセ・バイデス率いる 3人格による軍事政権が樹立された。この政権はウビコの抑圧政策を継続したが、1944年10月にハコボ・アルベンス主導の軍事クーデターにより打倒され た。この事件は「十月革命」としても知られる。クーデター指導者たちは軍事評議会を結成し、直ちに公選を実施した。この選挙では、進歩的な哲学教授であり 民衆運動の象徴となったフアン・ホセ・アレバロが圧勝した。彼は穏健な社会改革プログラムを実施し、広く成功した識字運動やほぼ自由な選挙プロセスを実現 した。ただし、文盲の女性には投票権が与えられず、共産党は禁止された。 1951年にアレバロの任期が終了すると、ハコボ・アルベンスが圧勝で大統領に選出された。アルベンスはアレバロの改革を継続し、野心的な土地改革プログ ラム「法令900号」を開始した。これに基づき、大規模土地所有者の未耕作地は補償と引き換えに収用され、貧困に苦しむ農業労働者に再分配された。約50 万人がこの法令の恩恵を受けた。受益者の大半は先住民であり、その祖先はスペイン侵攻後に土地を奪われていた。アルベンスの政策はユナイテッド・フルーツ 社と対立した。同社は未耕作地の一部を失ったのである。同社はアルベンス政権打倒を米国政府に働きかけ、国務省はアルベンスが共産主義者であるとの口実で クーデターを画策した。カルロス・カスティーヨ・アルマスが軍事政権の首班として権力を掌握し、グアテマラ内戦が始まった。この戦争は1960年から 1996年まで続き、軍は先住民マヤ族に対するジェノサイド(集団虐殺)や民間人への広範な人権侵害を行った。 |

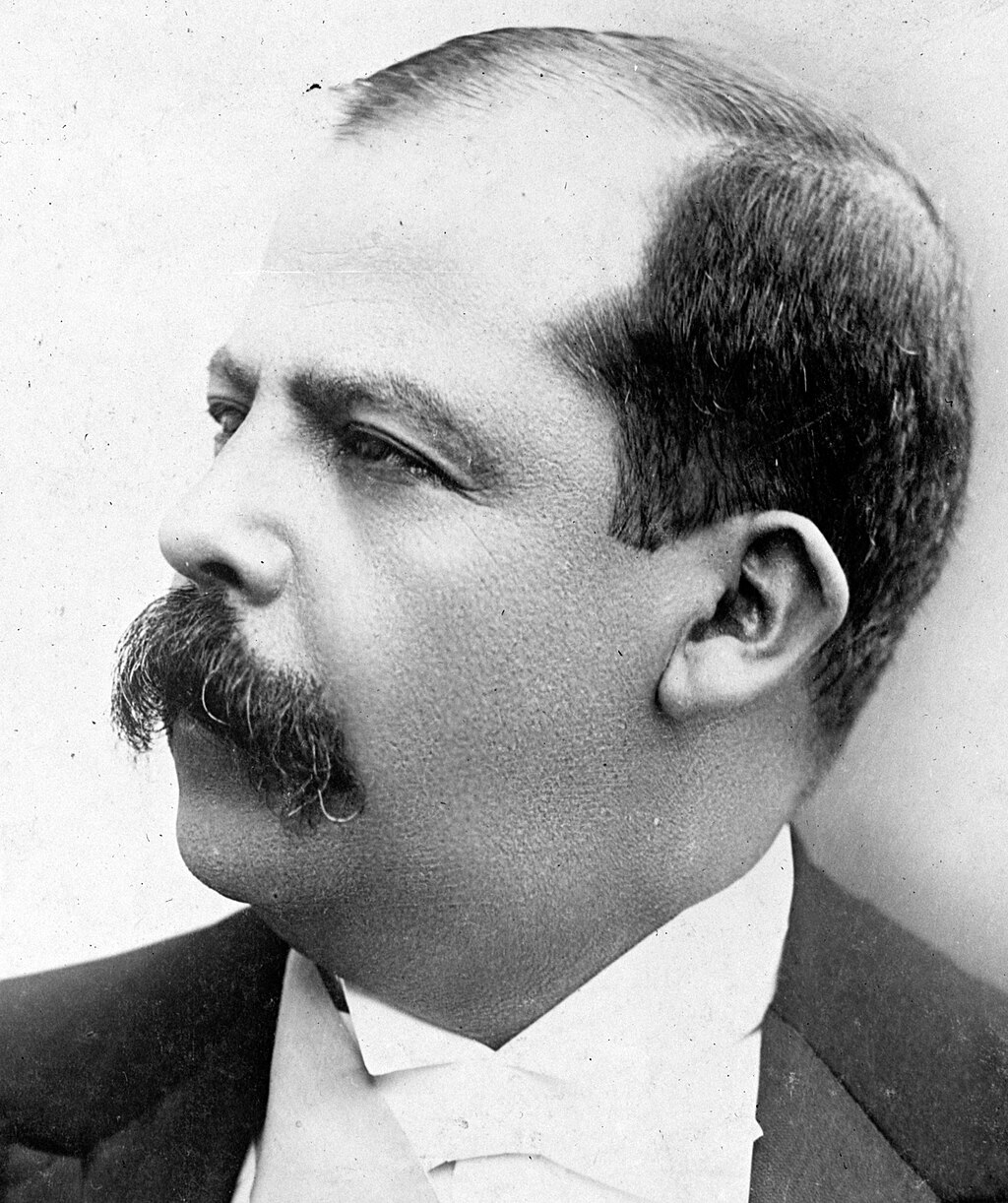

| Background Early 20th Century  Manuel Estrada Cabrera, President of Guatemala from 1898 to 1920. Cabrera granted large concessions to the American United Fruit Company Prior to the Spanish invasion in 1524, the population of Guatemala was almost exclusively Maya.[3] The Spanish conquest created a system of wealthy European landowners overseeing a labor force composed of slaves and bonded laborers. However, the community lands of the indigenous population remained in their control until the late 19th century.[3] At this point, rising global demand for coffee made its export a significant source of income for the government. As a result, the state supported the coffee growers by passing legislation that took land away from the Indian population, as well as relaxing labor laws so that bonded labor could be used on the plantations.[3][4] The US-based United Fruit Company (UFC) was one of many foreign companies that acquired large tracts of both state land and indigenous land.[4] Manuel Estrada Cabrera, who was president of Guatemala from 1898 to 1920, permitted limited unionization in rural Guatemala, but also made further concessions to the UFC.[3][5] In 1922, the Communist Party of Guatemala was created, and became a significant influence among urban laborers; however, it had little reach among the rural and Indian populations.[4] In 1929, the Great Depression led to the collapse of the economy and a rise in unemployment, leading to unrest among workers and labourers. Fearing the possibility of a revolution, the landed elite lent their support to Jorge Ubico y Castañeda, who had built a reputation for ruthlessness and efficiency as a provincial governor. Ubico won the election that followed in 1931, in which he was the only candidate.[3][4] |

背景 20世紀初頭  マヌエル・エストラーダ・カブレラは1898年から1920年までグアテマラの大統領を務めた。カブレラはアメリカのユナイテッド・フルーツ社に大規模な権益を認めた。 1524年のスペイン侵攻以前、グアテマラの人口はほぼマヤ族だけで構成されていた[3]。スペインによる征服は、奴隷や債務労働者からなる労働力を監督 する富裕なヨーロッパ人地主の体制を生み出した。しかし先住民の共同所有地は19世紀後半まで彼らの管理下に留まった[3]。この頃、世界的なコーヒー需 要の高まりにより、その輸出は政府の重要な収入源となった。結果として国家は、インディアンから土地を収用する法律を制定し、債務労働を農園で利用できる よう労働法を緩和することで、コーヒー生産者を支援した[3]。[4] 米国に本拠を置くユナイテッド・フルーツ・カンパニー(UFC)は、国有地と先住民の土地の両方を大規模に取得した数多の外国企業の一つであった。[4] 1898年から1920年までグアテマラ大統領を務めたマヌエル・エストラーダ・カブレラは、農村部での限定的な労働組合結成を認めた一方で、UFCへの さらなる譲歩も行っている。[3][5] 1922年にはグアテマラ共産党が結成され、都市部の労働者層に大きな影響力を持つようになったが、農村部やインディアン層への浸透はほとんど見られな かった。[4] 1929年、世界恐慌により経済が崩壊し失業率が上昇した。これにより労働者や農民の間で不安が広がった。革命の可能性を恐れた土地所有者層は、州知事と して冷酷さと効率性で名声を築いたホルヘ・ウビコ・イ・カスタニェダを支援した。ウビコは1931年の選挙で唯一の候補者として当選した。[3][4] |

Dictatorship of Jorge Ubico Jorge Ubico, the dictator of Guatemala from 1931 to 1944. He passed laws allowing landowners to use lethal force to defend their property Ubico had made statements supporting the labor movement when campaigning for the presidency, but after his election his policy quickly became authoritarian. He abolished the system of debt peonage, and replaced it with a vagrancy law, which required all men of working age who did not own land to perform a minimum of 100 days of hard labor.[6] In addition, the state made use of unpaid Indian labor to work on public infrastructure like roads and railroads. Ubico also froze wages at very low levels, and passed a law allowing land-owners complete immunity from prosecution for any action they took to defend their property,[6] an action described by historians as legalizing murder.[7] He greatly strengthened the police force, turning it into one of the most efficient and ruthless in Latin America.[8] The police were given greater authority to shoot and imprison people suspected of breaking the labor laws. The result of these laws was to create tremendous resentment against him among agricultural laborers.[2] Ubico was highly contemptuous of the country's indigenous people, once stating that they resembled donkeys.[9] Ubico had great admiration for the fascist leaders of Europe, such as Francisco Franco and Benito Mussolini.[10] However, he saw the United States as an ally against the supposed communist threat of Mexico. He made a concerted effort to gain American support; when the US declared war on Germany and Japan in 1941, Ubico followed suit, and acting on American instructions arrested all people of German descent in Guatemala.[11] He permitted the US to establish an air base in Guatemala, with the stated aim of protecting the Panama Canal.[12] Like his predecessors, he made large concessions to the United Fruit Company, granting it 200,000 hectares (490,000 acres) of public land in exchange for a promise to build a port. He later released the company from this obligation as well, citing the economic crisis.[13] Since its entry into Guatemala, the UFC had expanded its land holdings by displacing the peasantry and converting their farmland into banana plantations. This process accelerated under Ubico, whose government did nothing to stop it.[14] |

ホルヘ・ウビコ独裁政権 ホルヘ・ウビコは1931年から1944年までグアテマラの独裁者であった。彼は地主が財産を守るために致死的な武力行使を認める法律を制定した ウビコは大統領選挙運動中に労働運動を支持する発言をしていたが、当選後はすぐに権威主義的な政策に転じた。債務奴隷制度を廃止し、代わりに浮浪者法を制 定した。この法律では、土地を所有しない労働年齢の男性は全員、最低100日間の重労働を義務付けられた[6]。さらに国家は、道路や鉄道などの公共イン フラ建設に、無償のインディアン労働力を動員した。ウビコは賃金を極度に低い水準で凍結し、土地所有者が財産を守るために行ったあらゆる行為について完全 な免責を認める法律を制定した[6]。歴史家はこの措置を「殺人を合法化した」と評している[7]。彼は警察組織を大幅に強化し、ラテンアメリカで最も効 率的で冷酷な組織の一つへと変貌させた。[8] 警察は労働法違反の疑いがある人民を射殺・投獄する権限を大幅に拡大された。これらの法律の結果、農業労働者層に彼に対する強い反感を生んだ。[2] ウビコは国内の先住民を深く軽蔑しており、かつて「彼らはロバに似ている」と発言したことがある。[9] ウビコはフランシスコ・フランコやベニート・ムッソリーニといったヨーロッパのファシスト指導者に強い敬意を抱いていた。[10] しかし彼は、メキシコがもたらすとされる共産主義の脅威に対する同盟国としてアメリカ合衆国を見ていた。彼はアメリカの支持を得るために組織的な努力を行 い、1941年にアメリカがドイツと日本に宣戦布告すると、ウビコもそれに追随し、アメリカの指示に基づいてグアテマラ国内のドイツ系住民全員を逮捕し た。[11] 彼はパナマ運河保護を名目として、アメリカによるグアテマラ内空軍基地設置を許可した。[12] 前任者たちと同様、ユナイテッド・フルーツ社に大規模な譲歩を行い、港湾建設の約束と引き換えに公有地20万ヘクタール(49万エーカー)を付与した。後 に経済危機を理由に、同社をこの義務からも解放した。[13] グアテマラ進出以来、UFCは農民を追い出し農地をバナナ農園に転用することで土地所有を拡大してきた。この過程はウビコ政権下で加速したが、政府はこれ を阻止する措置を一切講じなかった。[14] |

| June 1944 general strike The onset of World War II increased economic unrest in Guatemala. Ubico responded by cracking down more fiercely on any form of protest or dissent.[15] In 1944, popular revolt broke out in neighboring El Salvador, which briefly toppled dictator Maximiliano Hernández Martínez. However, he quickly returned to power, leading to a flood of exiled El Salvadorian revolutionaries moving to Guatemala.[16] This coincided with a series of protests at the university in Guatemala City. Ubico responded by suspending the constitution on 22 June 1944.[15][16][17] The protesters, who by this point included many middle-class members in addition to students and workers, called for a general strike,[18] and presented an ultimatum to Ubico the next day, demanding the reinstatement of the constitution. They also presented him a petition signed by 311 of the most prominent Guatemalan citizens. Ubico sent the police to disrupt the protests by firing on them, and declared martial law.[19][20][17] |

1944年6月のゼネスト 第二次世界大戦の勃発はグアテマラの経済不安を増大させた。ウビコはあらゆる抗議や異議申し立てに対してより厳しい弾圧で応じた。[15] 1944年、隣国エルサルバドルで民衆蜂起が発生し、独裁者マクシミリアノ・エルナンデス・マルティネスを一時的に倒した。しかし彼はすぐに権力に復帰 し、その結果、亡命したエルサルバドル革命家たちがグアテマラに殺到した。[16] これと時を同じくして、グアテマラシティの大学で一連の抗議活動が発生した。ウビコはこれに対し、1944年6月22日に憲法を停止した。[15] [16][17] この時点で学生や労働者に加え多くの中産階級も参加していた抗議者たちは、ゼネストを呼びかけ[18]、翌日ウビコに憲法回復を要求する最後通告を突きつ けた。彼らはまた、グアテマラの著名な市民311名が署名した請願書をウビコに提出した。ウビコは警察を動員して抗議活動に発砲し、抗議活動を妨害した上 で戒厳令を宣言した。[19][20][17] |

| Ubico resigns and appoints an interim government Clashes between protesters and the military continued for a week, during which the revolt gained momentum. At the end of June, Ubico submitted his resignation to the National Assembly, leading to huge celebrations in the streets.[21] The resignation of Ubico did not restore democracy. Ubico appointed three generals, Federico Ponce Vaides, Eduardo Villagrán Ariza, and Buenaventura Pineda, to a junta which would lead the provisional government. A few days later, Ponce Vaides persuaded the congress to appoint him interim president.[22][23] Ponce pledged to hold free elections soon, while at the same time suppressing the protests.[24] Press freedom was suspended,[24] arbitrary detentions continued, and memorial services for slain revolutionaries were prohibited.[23] However, the protests had grown to the point where the government could not stamp them out, and rural areas also began organizing against the dictatorship. The government began using the police to intimidate the indigenous population to keep the junta in power through the forthcoming election. This resulted in growing support for an armed revolution among some sections of the populace.[23] By now, the army was disillusioned with the junta, and progressives within it had begun to plot a coup.[25] On 1 October 1944, Alejandro Cordova, the editor of El Imparcial, the main opposition newspaper, was assassinated. This led to the military coup plotters reaching out to the leaders of the protests, in an attempt to turn the coup into a popular uprising. Ponce Vaides announced elections, but the pro-democracy forces denounced them as a fraud, citing his attempts to rig them.[25] Ponce Vaides sought to stabilize his regime by playing on inter-racial tension within the Guatemalan population. The most vocal support for the revolution had come from the Ladinos, or people of mixed racial or Spanish descent. Ponce Vaides sought to exploit their fear of the Indians by paying thousands of indigenous peasants to march in Guatemala City in his support, and promising them land if they supported the Liberal party that Ubico had begun as a front for the dictatorship.[26] |

ウビコは辞任し、暫定政府を任命した 抗議者と軍隊の衝突は一週間続き、その間に反乱は勢いを増した。6月末、ウビコは国民議会に辞表を提出し、街では大々的な祝賀が行われた。[21] ウビコの辞任は民主主義を回復しなかった。ウビコはフェデリコ・ポンセ・バイデス、エドゥアルド・ビジャグラン・アリサ、ブエナベンチュラ・ピネダの3人 の将軍を暫定政府を率いる軍事評議会に任命した。数日後、ポンセ・バイデスは議会を説得し、自身を暫定大統領に任命させた。[22][23] ポンセは早期の自由選挙実施を約束すると同時に、抗議活動を弾圧した。[24] 報道の自由は停止され[24]、恣意的な拘束は続き、殺害された革命家たちの追悼式も禁止された[23]。しかし抗議活動は政府が鎮圧できないほど拡大 し、農村部でも独裁政権への抵抗運動が始まった。政府は警察を利用して先住民を威嚇し、迫る選挙を通じて軍事評議会の権力を維持しようとした。これによ り、一部民衆の間で武装革命への支持が高まった[23]。この頃には軍部も軍事政権に幻滅し、内部の進歩派がクーデターを画策し始めていた[25]。 1944年10月1日、主要野党紙エル・インパルシアルの編集長アレハンドロ・コルドバが暗殺された。これにより軍事クーデター計画者たちは抗議運動の指 導者たちに接触し、クーデターを民衆蜂起へと発展させようとした。ポンセ・バイデスが選挙を宣言したが、民主化派勢力は彼の選挙操作の試みを指摘し、これ を不正選挙と非難した[25]。ポンセ・バイデスはグアテマラ国内の人種間対立を利用することで政権安定を図ろうとした。革命への最も声高な支持は、ラ ディーノ(混血またはスペイン系住民)から寄せられていた。ポンセ・バイデスは、ウビコが独裁政権の隠れ蓑として設立した自由党を支持すれば土地を与える と約束し、数千人の先住民農民にグアテマラシティでの支持行進を金で買わせることで、彼らのインディアンへの恐怖心を利用しようとした[26]。 |

| October revolution By mid-October, several different plans to overthrow the junta had been set in motion by various factions of the pro-democracy movement, including teachers, students, and progressive factions of the army. On 19 October, the government learned of one of these conspiracies.[25] That same day, a small group of army officers launched a coup, led by Francisco Javier Arana and Jacobo Árbenz Guzmán.[27] Although the coup had initially been plotted by Árbenz and Major Aldana Sandoval, Sandoval had prevailed upon Arana to join them;[28] however, Sandoval himself did not participate in the coup attempt, and was described as having "lost his nerve".[28] They were joined the next day by other factions of the army and the civilian population. Initially, the battle went against the revolutionaries, but after an appeal for support their ranks were swelled by unionists and students, and they eventually subdued the police and army factions loyal to Ponce Vaides. On October 20, the next day, Ponce Vaides surrendered unconditionally.[25]  Jacobo Árbenz, Jorge Toriello, and Francisco Arana, who oversaw the transition to a civilian government after the October Revolution Ponce Vaides was allowed to leave the country safely, as was Ubico himself. The military junta was replaced by another three-person junta consisting of Árbenz, Arana, and an upper-class youth named Jorge Toriello, who had played a significant role in the protests. Although Arana had come to the military conspiracy relatively late, his defection had brought the powerful Guardia de Honor (Honor Guard) over to the revolutionaries, and for this crucial role he was rewarded with a place on the junta. The junta promised free and open elections to the presidency and the congress, as well as for a constituent assembly.[29] The resignation of Ponce Vaides and the creation of the junta has been considered by scholars to be the beginning of the Guatemalan Revolution.[29] However, the revolutionary junta did not immediately threaten the interests of the landed elite. Two days after Ponce Vaides' resignation, a violent protest erupted at Patzicía, a small Indian hamlet. The junta responded with swift brutality, silencing the protest. The dead civilians included women and children.[30] |

十月革命 10月中旬までに、民主化運動の様々な派閥――教師、学生、軍内の進歩派など――によって、軍事政権打倒に向けた異なる計画が動き出していた。10月19日、政府はそのうちの一つの陰謀を察知した[25]。 同日、フランシスコ・ハビエル・アラナとハコボ・アルベンス・グスマン率いる少数の軍将校がクーデターを起こした[27]。このクーデターは当初アルベン スとアルダナ・サンドバル少佐によって計画されたが、サンドバルはアラナを説得して参加させた[28]。しかしサンドバル自身はクーデター未遂に参加せ ず、「肝を据え損ねた」と評された。[28] 翌日には他の軍部勢力や市民層が加わった。当初は革命派が劣勢だったが、支援を呼びかけた結果、労働組合員や学生が加わり、最終的にポンセ・バイデスに忠 実な警察・軍部勢力を制圧した。翌10月20日、ポンセ・バイデスは無条件降伏した。[25]  10月革命後の文民政府移行を主導したハコボ・アルベンス、ホルヘ・トリエロ、フランシスコ・アラナ ポンセ・バイデスとウビコ自身は国外退去を許された。軍事政権はアルベンス、アラナ、そして抗議運動で重要な役割を果たした上流階級の青年ホルヘ・トリエ ロからなる新たな三人政権に取って代わられた。アラナは軍事陰謀に加わったのが比較的遅かったが、彼の離反によって強力な栄誉衛兵隊が革命派に味方した。 この決定的な役割が評価され、彼は軍事評議会の席を得たのである。評議会は大統領選挙、議会選挙、そして憲法制定議会選挙を自由かつ公正に行うことを約束 した[29]。 ポンセ・バイデスの辞任と軍事評議会の成立は、学者によってグアテマラ革命の始まりと見なされている[29]。しかし革命評議会は、当初は土地所有エリー トの利益を直接脅かすことはなかった。ポンセ・バイデスの辞任から2日後、小さなインディアン集落パツィシアで激しい抗議活動が発生した。評議会は即座に 残忍な弾圧で抗議を鎮圧した。犠牲となった民間人には女性や子供も含まれていた。[30] |

| Election of Arévalo Further information: Juan José Arévalo Juan José Arévalo Bermejo was born into a middle-class family in 1904. He became a primary school teacher for a brief while, and then earned a scholarship to a university in Argentina, where he earned a doctorate in the philosophy of education. He returned to Guatemala in 1934, and sought a position in the Ministry of Education.[31][32] However, he was denied the position he wished for, and felt uncomfortable under the dictatorship of Ubico. He left the country and held a faculty position in Argentina until 1944, when he returned to Guatemala.[31] In July 1944 the Renovación Nacional, the teachers' party, had been formed, and Arévalo was named its candidate. In an unexpected surge of support, his candidacy was endorsed by many of the leading organizations among the protesters, including the student federation. His lack of connection to the dictatorship and his academic background both worked in his favor among the students and teachers. At the same time, the fact that he had chosen to go into exile in conservative Argentina rather than revolutionary Mexico reassured landowners worried about socialist or communist reform.[33] The subsequent elections took place in December 1944, and were broadly considered free and fair,[34] although only literate men were given the vote.[35] Unlike in similar historical situations, none of the junta members stood for election.[34] Arévalo's closest challenger was Adrián Recinos, whose campaign included a number of individuals identified with the Ubico regime.[34] The ballots were tallied on 19 December 1944, and Arévalo won in a landslide, receiving more than four times as many ballots as the other candidates combined.[34] |

アレバロの選出 詳細情報:フアン・ホセ・アレバロ フアン・ホセ・アレバロ・ベルメホは1904年、中流家庭に生まれた。短期間小学校教師を務めた後、アルゼンチンの大学に奨学金を得て留学し、教育哲学の 博士号を取得した。1934年にグアテマラへ帰国し、教育省での職を求めた。[31][32] しかし希望の職は得られず、ウビコ独裁政権下での居心地の悪さを感じた。彼は国外へ出てアルゼンチンで教職に就き、1944年にグアテマラへ帰国した。 [31] 1944年7月、教師政党である国民刷新党が結成され、アレバロはその候補者に指名された。予想外の支持拡大により、彼の立候補は学生連盟を含む抗議運動 の主要組織の多くから支持された。独裁政権との繋がりのなさや学歴が、学生や教師層に好感を持たれたのである。同時に、革命的なメキシコではなく保守的な アルゼンチンに亡命を選んだ事実が、社会主義や共産主義改革を懸念する地主層を安心させた。[33] その後の選挙は1944年12月に実施され、広く自由かつ公正と評価された[34]。ただし投票権は識字能力のある男性に限られていた[35]。類似の歴 史的事例とは異なり、軍事評議会のメンバーは誰も立候補しなかった[34]。アレバロの最も有力な対抗馬はアドリアン・レシノスであり、その選挙運動には ウビコ政権と結びついた人物が多数参加していた。[34] 投票集計は1944年12月19日に行われ、アレバロは圧勝した。得票数は他の候補者全員の合計の4倍以上に達したのである。[34] |

| Presidency of Arévalo Arévalo took office on 15 March 1945, inheriting a country with numerous social and economic issues. Despite Ubico's policy of using unpaid labor to build public roads, internal transport was severely inadequate. 70% of the population was illiterate, and malnutrition and poor health were widespread. The wealthiest 2% of landowners owned nearly three quarters of agricultural land, and as a result less than 1% was cultivated. The indigenous peasants either had no land, or had far too little to sustain themselves. Three quarters of the labor force were in agriculture, and industry was essentially nonexistent.[36] Ideology  Juan José Arévalo in 1945 Arévalo identified his ideology as "spiritual socialism". He held the belief that the only way to alleviate the backwardness of most Guatemalans was through a paternalistic government. He was strongly opposed to classical Marxism, and believed in a capitalist society that was regulated to ensure that its benefits went to the entire population.[37] Arévalo's ideology was reflected in the new constitution that the Guatemalan assembly ratified soon after his inauguration, which was one of the most progressive in Latin America. It mandated suffrage for all but illiterate women, a decentralization of power, and provisions for a multiparty system. Communist parties were, however, forbidden.[37] The constitution and Arévalo's socialist ideology became the basis for much of the reform enacted under Arévalo and (later) Jacobo Árbenz. Although the US government would later portray the ideology of the revolution as radical communist, it did not in fact represent a major shift leftward, and was staunchly anti-communist.[37] Arévalo's economic vision for the country was centered around private enterprise.[38] |

アレバロ大統領 アレバロは1945年3月15日に大統領職に就いた。引き継いだ国は数多くの社会問題と経済問題を抱えていた。ウビコ政権が公共道路建設に無償労働力を動 員した政策にもかかわらず、国内の交通網は著しく不十分だった。人口の70%が文盲であり、栄養失調と健康不良が蔓延していた。最も裕福な2%の土地所有 者が農地の4分の3近くを所有していたため、耕作地は1%未満だった。先住民の小作農は土地を持たないか、自活するにはあまりにも少ない土地しか持ってい なかった。労働力の4分の3が農業に従事しており、産業は実質的に存在しなかった。[36] イデオロギー  1945年のフアン・ホセ・アレバロ アレバロは自らのイデオロギーを「精神的社会主義」と位置付けた。大多数のグアテマラ人の後進性を解消する唯一の道は、父権的な政府による統治にあると信 じていた。古典的マルクス主義には強く反対し、その恩恵が全人口に行き渡るよう規制された資本主義社会を支持した。[37] アレバロの思想は、就任直後にグアテマラ議会が批准した新憲法に反映された。この憲法はラテンアメリカで最も進歩的なもののひとつであり、文盲の女性を除 く全員の選挙権、権力の分散化、複数政党制の規定を定めていた。ただし共産党は禁止された。[37] この憲法とアレバロの社会主義思想は、アレバロ政権下(後にハコボ・アルベンス政権下)で実施された多くの改革の基盤となった。米国政府は後にこの革命の 思想を急進的な共産主義と描写したが、実際には左傾化の大転換を意味するものではなく、むしろ強固な反共主義であった。[37] アレバロの国家経済構想は民間企業を中心に据えていた。[38] |

| Labor movement The revolution in 1944 left many of the biggest opponents of organized labor unaffected, such as the landed elite and the United Fruit Company. The revolution, and election of Arévalo, nonetheless marked a significant shift in the fortunes of labor unions.[39] The protests of 1944 strengthened the labor movement to the point where Ponce Vaides stopped enforcing the repressive vagrancy law, which was abolished in the 1945 constitution. On 1 May 1945, Arévalo made a speech celebrating organized labor, to a tremendously positive reception. The freedom of press guaranteed in the new constitution also drew much attention to the brutal working conditions in Guatemala City.[39] From the beginning, the new unions that were formed fell into two camps, those that were communist and those that were not. The repressive policies of the Ubico government had driven both factions underground, but they re-emerged after the revolution.[40] The communist movement was also strengthened by the release of those of its leaders who had been imprisoned by Ubico. Among them were Miguel Mármol, Víctor Manuel Gutiérrez, and Graciela García, the latter unusual for being a woman in a movement that women were discouraged from participating in. The communists began to organize in the capital, and established a school for workers, known as the Escuela Claridad, or the Clarity School, which taught reading, writing, and also helped organize unions. Six months after the school was established, President Arévalo closed the school down, and deported all the leaders of the movement who were not Guatemalan. However, the communist movement survived, mostly by its dominance of the teachers' union.[41] Arévalo's response toward the non-communist unions was mixed. In 1945, he criminalized all rural labor unions in workplaces with fewer than 500 workers, which included most plantations.[41] One of the few unions big enough to survive this law was of the banana workers employed by the UFC. In 1946 this union organized a strike, which provoked Arévalo into outlawing all strikes until a new labor code was passed. This led to efforts on the part of employers to stall the labor code, as well as to exploit workers as far as possible before it was passed.[41] The unions were also damaged when the US government persuaded the American Federation of Labor to found the Organización Regional Internacional del Trabajo (ORIT), a union that took a strongly anti-communist stance.[41] Despite the powerful opposition, by 1947 the labor unions had managed to organize enough support to force the congress to pass a new labor code. This law was revolutionary in many ways; it forbade discrimination in salary levels on the basis of "age, race, sex, nationality, religious beliefs, or political affiliation".[42] It created a set of health and safety standards in the workplace, and standardized an eight-hour working day and a 45-hour working week, although the congress succumbed to pressure from the plantation lobby and exempted plantations from this provision. The code also required plantation owners to construct primary schools for the children of their workers, and expressed a general commitment to "dignifying" the position of workers.[42] Although many of these provisions were never enforced, the creation of administrative mechanisms for this law in 1948 allowed several of its provisions to be systematically enforced.[42] The law as a whole had a huge positive impact on worker rights in the country, including raising the average wages by a factor of three or more.[43][42] |

労働運動 1944年の革命は、土地所有者層やユナイテッド・フルーツ社など、組織化された労働運動の最大の反対勢力の多くに影響を与えなかった。それでも革命とア レバロの当選は、労働組合の運命に重大な転換をもたらした。[39] 1944年の抗議活動は労働運動を強化し、ポンセ・バイデス政権が抑圧的な浮浪者法を施行しなくなった。この法律は1945年憲法で廃止された。1945 年5月1日、アレバロは組織労働を称える演説を行い、非常に好意的な反応を得た。新憲法で保障された報道の自由も、グアテマラシティの過酷な労働環境に多 くの注目を集めた。[39] 結成当初から、新たな労働組合は共産主義系と非共産主義系の二つの陣営に分かれた。ウビコ政権の弾圧政策により両派は地下に潜ったが、革命後に再び姿を現 した。[40] 共産主義運動は、ウビコ政権下で投獄されていた指導者たちの釈放によっても強化された。その中にはミゲル・マルモル、ビクトル・マヌエル・グティエレス、 そして女性として異例の存在だったグラシエラ・ガルシアがいた。当時、女性の運動参加は推奨されていなかったのだ。共産主義者たちは首都で組織化を始め、 労働者向けの学校「エスクエラ・クラリダッド(明晰学校)」を設立した。ここでは読み書きを教え、組合結成の支援も行われた。学校設立から半年後、アレバ ロ大統領は学校を閉鎖し、グアテマラ人以外の運動指導者全員を追放した。しかし共産主義運動は、主に教師組合を掌握していたことで生き延びた。[41] アレバロの非共産主義組合に対する対応は混血のだった。1945年、彼は労働者500人未満の職場における全ての農村労働組合を非合法化した。これは大半 のプランテーションを対象とした。[41] この法律を生き延びた数少ない大規模組合の一つが、UFC(United Fruit Company)に雇用されたバナナ労働者の組合であった。1946年、この組合がストライキを組織したことで、アレバロは新たな労働法が成立するまで全 てのストライキを禁止する措置を取った。これにより、使用者側は労働法の成立を遅らせようとする動きを見せると同時に、成立前に労働者を可能な限り搾取し ようとした[41]。さらに米国政府がアメリカ労働総同盟(AFL)を説得し、強硬な反共産主義姿勢を取る労働組合「地域国際労働機構(ORIT)」を設 立させたことも、労働組合にとって打撃となった。[41] 強力な反対勢力にもかかわらず、1947年までに労働組合は十分な支持を集め、議会に新たな労働法の成立を迫ることに成功した。この法律は多くの点で画期 的であった。「年齢、人種、性別、国籍、宗教的信念、政治的所属」に基づく賃金差別を禁止した。[42] 職場における健康安全基準を定め、8時間労働制と週45時間労働を標準化した。ただし議会はプランテーション業界団体の圧力に屈し、プランテーションをこ の規定から除外した。同法はまた、プランテーション所有者に労働者子女のための小学校建設を義務付け、「労働者の地位を尊厳あるものとする」という一般的 な方針を表明した。[42] これらの規定の多くは実施されなかったものの、1948年にこの法律の行政機構が創設されたことで、いくつかの規定が体系的に施行されるようになった。 [42] この法律全体は、平均賃金を3倍以上に引き上げるなど、国内の労働者権利に多大な好影響を与えた。[43][42] |

| Foreign relations The Arévalo government attempted to support democratic ideals abroad as well. One of Arévalo's first actions was to break diplomatic relations with the government of Spain under dictator Francisco Franco. At two inter-American conferences in the year after his election, Arévalo recommended that the republics in Latin America not recognize and support authoritarian regimes. This initiative was defeated by the dictatorships supported by the United States, such as the Somoza regime in Nicaragua. In response, Arévalo broke off diplomatic ties with the Nicaraguan government and with the government of Rafael Trujillo in the Dominican Republic.[44] Frustrated by the lack of results from working with the other Latin American governments, Arévalo began to support the Caribbean Legion, which sought to replace dictatorships with democracies across Latin America, by force if necessary. This led to the administration being labelled as communist by the dictatorial governments in the region.[45] The Arévalo government also floated the idea of a Central American Federation, as being the only way that a democratic government could survive in the region. He approached several leaders of democratic Central American countries, but was rejected by all except Castañeda Castro, the president of El Salvador. The two leaders began talks to build a union, and set up several commissions to look into the issue. In late 1945 they announced the formation of the union, but the formalization of the process got delayed by internal troubles in both countries, and in 1948 the Castro government was toppled in a military coup led by Óscar Osorio.[46] |

外交関係 アレバロ政権は国外においても民主主義の理念を支援しようとした。アレバロの最初の行動の一つは、独裁者フランシスコ・フランコ率いるスペイン政府との外 交関係を断絶することだった。選挙後の1年間に開催された二つの米州会議で、アレバロはラテンアメリカの共和国に対し、権威主義体制を承認・支援しないよ う勧告した。この提案は、ニカラグアのソモサ政権など米国が支援する独裁政権によって否決された。これに対しアレバロは、ニカラグア政府およびドミニカ共 和国のラファエル・トルヒーヨ政権との外交関係を断絶した[44]。他のラテンアメリカ諸国との協力が成果を上げないことに苛立ったアレバロは、必要なら ば武力行使も辞さない姿勢でラテンアメリカ全域の独裁政権を民主主義に置き換えようとするカリブ海連隊を支援し始めた。このため同政権は、地域の独裁政権 から共産主義的とレッテルを貼られることとなった。[45] アレバロ政権はまた、民主主義政府がこの地域で存続する唯一の手段として、中央アメリカ連邦構想を打ち出した。彼は民主主義的な中央アメリカ諸国の指導者 数名に接触したが、エルサルバドルのカスタニェダ・カストロ大統領を除く全員が拒否した。両指導者は連合構築に向けた協議を開始し、この問題を検討する複 数の委員会を設置した。1945年末に両国は連合結成を発表したが、両国内部の混乱により正式な手続きは遅延した。1948年にはオスカル・オソリオ率い る軍事クーデターによりカストロ政権が倒された。[46] |

| 1949 coup attempt As the highest-ranking military officer in the October Revolution, Francisco Arana had led the three-man junta that formed the interim government after the coup. He was opposed to handing over power to a civilian government, first seeking to postpone the 1944 election, and then to annul it. In return for allowing Arévalo to become president, Arana was granted the newly created position of "chief of the armed forces", ranked above the minister of defense. The position had a six-year term, and controlled all military appointments. In December 1945, Arévalo was involved in a motoring accident which left him seriously injured. Fearing a military coup, the leaders of the Revolutionary Action Party (PAR) made a pact with Arana, in which the party agreed to support his candidacy in the 1950 elections in return for a promise to refrain from a coup.[47] Arana's support began to be solicited by the landed elite, who felt threatened by Arévalo's reforms. Arana, who was not initially inclined to get involved with politics, began to make occasional statements against the government. In the 1948 parliamentary election, he backed a number of opposition candidates, all of whom were defeated. By 1949 the National Renovation Party and the PAR were both openly hostile to Arana, while a small fragment of the Popular Liberation Front split off to support him. The leftist parties decided to back Árbenz instead, as they believed that only a military officer could defeat Arana.[48] On 16 July 1949, Arana delivered an ultimatum to Arévalo, demanding the expulsion of all of Árbenz's supporters from the cabinet and the military; he threatened a coup if his demands were not met. Arévalo informed Árbenz and other progressive leaders of the ultimatum, who all agreed that Arana should be exiled. Two days later, Arévalo and Arana had another meeting; on the way back, Arana's convoy was intercepted by a small force led by Árbenz. A shootout ensued, killing three men, including Arana. Arana's supporters in the military rose up in revolt, but they were leaderless, and by the next day the rebels asked for negotiations. The coup attempt left approximately 150 dead and 200 wounded. Many of Arana's supporters, including Carlos Castillo Armas, were exiled. The details of the incident were not made public.[49] |

1949年のクーデター未遂 10月革命における最高位の軍人として、フランシスコ・アラナはクーデター後に暫定政府を樹立した3人による軍事評議会の指導者であった。彼は文民政府へ の権力移譲に反対し、まず1944年の選挙延期を求め、その後その無効化を図った。アレバロが大統領になることを認める見返りとして、アラナは新設された 「軍最高司令官」の地位を与えられた。この地位は国防大臣より上位に位置し、任期は6年で、全ての軍人人事権を掌握していた。1945年12月、アレバロ は自動車事故に遭い重傷を負った。軍事クーデターを恐れた革命行動党(PAR)の指導者たちはアラナと協定を結んだ。党は1950年の選挙で彼の立候補を 支持する代わりに、クーデターを控えることを約束させたのだ。[47] アラナの支持は、アレバロの改革に脅威を感じた大地主層から求められ始めた。当初政治に関与する意思がなかったアラナは、政府に対する批判を時折表明し始 めた。1948年の議会選挙では複数の野党候補を支援したが、全員が落選した。1949年までに国民刷新党とPARは共にアラナに公然と敵対する一方、人 民解放戦線の一部が分裂して彼を支持した。左派政党は、軍人しかアラナを倒せないと考え、代わりにアルベンスを支援することを決めた。[48] 1949年7月16日、アラナはアレバロに最後通告を突きつけた。アルベンスの支持者を内閣と軍から全員追放するよう要求し、要求が受け入れられなければ クーデターを起こすと脅した。アレバロはアルベンスら進歩派指導者にこの最後通告を伝え、全員がアラナの国外追放に同意した。二日後、アレバロとアラナは 再び会談したが、帰途のアラナ護衛隊はアルベンス率いる小部隊に襲撃された。銃撃戦が発生し、アラナを含む3名が死亡した。軍内のアラナ支持派は反乱を起 こしたが、指導者を失っていたため、翌日には反乱軍が交渉を求めた。このクーデター未遂事件では約150名が死亡、200名が負傷した。カルロス・カス ティーヨ・アルマスを含む多くのアラナ支持派が国外追放された。事件の詳細は公表されなかった。[49] |

| Presidency of Árbenz Further information: Jacobo Árbenz Election Árbenz's role as defense minister had already made him a strong candidate for the presidency, and his firm support of the government during the 1949 uprising further increased his prestige. In 1950, the economically moderate Partido de Integridad Nacional (PIN) announced that Árbenz would be its presidential candidate in the upcoming election. This announcement was quickly followed by endorsements from most parties on the left, including the influential PAR, as well as from labor unions.[50] Árbenz had only a couple of significant challengers in the election, in a field of ten candidates.[50] One of these was Jorge García Granados, who was supported by some members of the upper-middle class who felt the revolution had gone too far. Another was Miguel Ydígoras Fuentes, who had been a general under Ubico, and who had the support of the hardline opponents of the revolution. During his campaign, Árbenz promised to continue and expand the reforms begun under Arévalo.[51] The election was held on 15 November 1950, and Árbenz won more than 60% of the vote, in elections that were free and fair with the exception of the disenfranchisement of illiterate female voters. Árbenz was inaugurated as president on 15 March 1951.[50] |

アルベンス大統領 詳細情報:ハコボ・アルベンス 選挙 アルベンスは国防相としての実績が既に大統領候補としての有力な地位を築いており、1949 年反乱時に政府を断固として支持したことでさらに威信を高めた。1950年、経済的に穏健な国民統合党(PIN)は、アルベンスを次期大統領選挙の党候補 に指名すると発表した。この発表後、影響力のあるPARを含む左派政党の大半や労働組合が相次いで支持を表明した[50]。10人の候補者が争った選挙 で、アルベンスに真正面から対抗したのはわずか数名だった[50]。その一人がホルヘ・ガルシア・グラナドスで、革命が行き過ぎたと考える上流中産階級の 一部から支持を得ていた。もう一人はミゲル・イディゴラス・フエンテスで、ウビコ政権下の将軍であり、革命の強硬な反対派の支持を得ていた。アルベンスは 選挙運動中、アレバロ政権下で始まった改革を継続・拡大することを約束した。[51] 選挙は1950年11月15日に実施され、アルベンスは60%以上の得票率で勝利した。この選挙は、文盲の女性有権者の選挙権剥奪を除けば、自由かつ公正 なものであった。アルベンスは1951年3月15日に大統領に就任した。[50] |

| Árbenz's personal background Main article: Jacobo Árbenz Árbenz was born in 1913 into a middle-class family of Swiss heritage.[52] In 1935 he had graduated from the Escuela Politécnica, Guatemala's national military academy, with excellent grades, and had subsequently become an officer in the Guatemalan army under Ubico.[53] As an officer, Árbenz himself had been required to escort chain-gangs of prisoners. This process had radicalized him, and he had begun to form links to the labor movement. In 1938 he had met and married María Villanova, who was also interested in social reform, and who became a significant influence on him and a national figure in her own right. Another strong influence on him was José Manuel Fortuny, a well-known Guatemalan communist, who was one of his main advisers during his government.[52][53] In 1944, disgusted with Ubico's authoritarian regime, he and his fellow officers had begun plotting against the government. When Ubico resigned in 1944, Árbenz had witnessed Ponce Vaides intimidate the congress into naming him president. Highly offended by this, Árbenz plotted against Ponce Vaides, and was one of the military leaders of the coup that toppled him, in addition to having been one of the few officers in the revolution who had formed and maintained connections to the popular civilian movement.[52] |

アルベンスの人格的な経歴 詳細記事: ハコボ・アルベンス アルベンスは1913年、スイス系の中流家庭に生まれた[52]。1935年にはグアテマラ国立軍事学校エスクエラ・ポリテクニカを優秀な成績で卒業し、 その後ウビコ政権下のグアテマラ軍将校となった。軍人として、アルベンス自身も囚人連行の護送任務を命じられた。この経験が彼を急進化させ、労働運動との 繋がりを築き始めた。1938年には社会改革に関心を持つマリア・ビジャノバと出会い結婚し、彼女は後に彼に大きな影響を与える存在となり、自身でも国民 的人物となった。彼に強く影響を与えたもう一人の人物は、著名なグアテマラ共産党員ホセ・マヌエル・フォルトゥーニであった。彼はアルベンス政権下で主要 な顧問の一人を務めた。[52][53] 1944年、ウビコ独裁政権に嫌気が差したアルベンスと将校仲間は政府転覆の謀議を開始した。同年ウビコが辞任した際、アルベンスはポンセ・バイデスが議 会を威圧して自身を大統領に指名させる場面を目撃している。これに強い憤りを感じたアルベンスはポンセ・バイデスに対する陰謀を企て、彼を倒したクーデ ターの軍事指導者の一人となった。さらに革命において、民衆的な市民運動とのつながりを形成し維持した数少ない将校の一人でもあったのである。[52] |

| Agrarian reform Main article: Decree 900 The biggest component of Árbenz's project of modernization was his agrarian reform bill.[54] Árbenz drafted the bill himself with the help of advisers that included some leaders of the communist party as well as non-communist economists.[55] He also sought advice from numerous economists from across Latin America.[54] The bill was passed by the National Assembly on 17 June 1952, and the program went into effect immediately. The focus of the program was on transferring uncultivated land from large landowners to their poverty stricken laborers, who would then be able to begin a viable farm of their own.[54] Árbenz was also motivated to pass the bill because he needed to generate capital for his public infrastructure projects within the country. At the behest of the United States, the World Bank had refused to grant Guatemala a loan in 1951, which made the shortage of capital more acute.[56] The official title of the agrarian reform bill was Decree 900. It expropriated all uncultivated land from landholdings that were larger than 673 acres (272 ha). If the estates were between 672 acres (272 ha) and 224 acres (91 ha) in size, uncultivated land was expropriated only if less than two-thirds of it was in use.[56] The owners were compensated with government bonds, the value of which was equal to that of the land expropriated. The value of the land itself was the value that the owners had declared in their tax returns in 1952.[56] The redistribution was organized by local committees that included representatives from the landowners, the laborers, and the government.[56] Of the nearly 350,000 private land-holdings, only 1710 were affected by expropriation. The law itself was cast in a moderate capitalist framework; however, it was implemented with great speed, which resulted in occasional arbitrary land seizures. There was also some violence, directed at land-owners, as well as at peasants that had minor landholdings of their own.[56] By June 1954, 1.4 million acres of land had been expropriated and distributed. Approximately 500,000 individuals, or one-sixth of the population, had received land by this point.[56] The decree also included provision of financial credit to the people who received the land. The National Agrarian Bank (Banco Nacional Agrario, or BNA) was created on 7 July 1953, and by June 1954 it had disbursed more than $9 million in small loans. 53,829 applicants received an average of 225 US dollars, which was twice as much as the Guatemalan per capita income.[56] The BNA developed a reputation for being a highly efficient government bureaucracy, and the United States government, Árbenz's biggest detractor, did not have anything negative to say about it.[56] The loans had a high repayment rate, and of the $3,371,185 handed out between March and November 1953, $3,049,092 had been repaid by June 1954.[56] The law also included provisions for nationalization of roads that passed through redistributed land, which greatly increased the connectivity of rural communities.[56] Contrary to the predictions made by the detractors of the government, the law resulted in a slight increase in Guatemalan agricultural productivity, and to an increase in cultivated area. Purchases of farm machinery also increased.[56] Overall, the law resulted in a significant improvement in living standards for many thousands of peasant families, the majority of whom were indigenous people.[56] Historian Piero Gleijeses stated that the injustices corrected by the law were far greater than the injustice of the relatively few arbitrary land seizures.[56] Historian Greg Grandin stated that the law was flawed in many respects; among other things, it was too cautious and deferential to the planters, and it created communal divisions among peasants. Nonetheless, it represented a fundamental power shift in favor of those that had been marginalized before then.[57] |

農地改革 詳細記事: 政令900号 アルベンスの近代化計画の最大の要素は、彼の農地改革法案であった。[54] アルベンスは、共産党の指導者や非共産主義の経済学者を含む助言者たちの助けを借りて、自らこの法案を起草した。[55] また、ラテンアメリカ各地の多くの経済学者からも助言を求めた。[54] この法案は1952年6月17日に国民議会で可決され、直ちに施行された。この政策の焦点は、未耕作地を大地主から貧困に苦しむ労働者へ移転させることに あった。これにより労働者は自立した農場経営を開始できるはずだった。[54] アルベンスがこの法案を成立させた動機には、国内の公共インフラ事業に必要な資金を調達する必要性も含まれていた。米国の要請により、世界銀行は1951 年にグアテマラへの融資を拒否しており、これが資本不足をさらに深刻化させていた。[56] 農地改革法案の正式名称は法令900号であった。この法令は、673エーカー(272ヘクタール)を超える土地所有権から、すべての未耕作地を収用した。 672エーカー(272ヘクタール)以上224エーカー(91ヘクタール)以下の土地所有者については、耕作地の3分の2未満しか利用されていない場合に 限り、未耕作地が収用された[56]。所有者には、収用された土地と同額の政府債券が補償として支払われた。土地の価値は、所有者が1952年の納税申告 書に記載した金額を基準とした。再分配は、地主・労働者・政府の代表者で構成される地方委員会が実施した。約35万件の私有地のうち、収用対象となったの はわずか1710件であった。この法律自体は穏健な資本主義的枠組みで制定されたが、その実施は極めて迅速に行われたため、時折恣意的な土地接収が発生し た。また、土地所有者や、わずかな土地を所有する農民たちに対する暴力行為も一部見られた。[56] 1954年6月までに、140万エーカーの土地が収用され分配された。この時点で約50万人の個人、つまり人口の6分の1が土地を受け取っていた [56]。法令には土地受領者への金融信用供与も規定されていた。国立農業銀行(Banco Nacional Agrario、略称BNA)は1953年7月7日に設立され、1954年6月までに900万ドル以上の小口融資を実行した。53,829人の申請者が平 均225米ドルを受け取ったが、これはグアテマラの一人当たり国民所得の2倍に相当した[56]。BNAは極めて効率的な政府機関として評価され、アルベ ンス政権の最大の批判者であった米国政府すら、これについて否定的な見解を示さなかった。[56] 融資の返済率は高く、1953年3月から11月にかけて支給された3,371,185ドルのうち、1954年6月までに3,049,092ドルが返済され た。[56] この法律には、再分配された土地を通る道路のナショナリズムに関する規定も含まれており、これにより農村地域の接続性が大幅に向上した。[56] 政府批判派の予測に反し、この法律はグアテマラの農業生産性をわずかに向上させ、耕作面積の増加をもたらした。農業機械の購入も増加した。[56] 全体として、この法律は数万の農民世帯(その大半が先住民)の生活水準を大幅に改善した。[56] 歴史家ピエロ・グレイヘセスは、この法律によって是正された不正は、比較的少数の恣意的な土地収用による不正よりもはるかに大きいと述べた。[56] 歴史家グレッグ・グランディンは、この法律には多くの点で欠陥があったと指摘した。とりわけ、プランター層に対して過度に慎重かつ恭順的であり、農民の間 に共同体の分裂を生んだ。しかしながら、それまでは境界化されていた者たちにとって、これは根本的な権力シフトを意味したのである。[57] |

| United Fruit Company Main article: United Fruit Company History The United Fruit Company had been formed in 1899 by the merger of two large American corporations.[58] The new company had major holdings of land and railroads across Central America, which it used to support its business of exporting bananas.[59] In 1900 it was already the world's largest exporter of bananas.[60] By 1930 it had an operating capital of US$215 million and had been the largest landowner and employer in Guatemala for several years.[61] Under Manuel Estrada Cabrera and other Guatemalan presidents, the company obtained a series of concessions in the country that allowed it to massively expand its business. These concessions frequently came at the cost of tax revenue for the Guatemalan government.[60] The company supported Jorge Ubico in the leadership struggle that occurred from 1930 to 1932, and upon assuming power, Ubico expressed willingness to create a new contract with it. This new contract was immensely favorable to the company. It included a 99-year lease to massive tracts of land, exemptions from virtually all taxes, and a guarantee that no other company would receive any competing contract. Under Ubico, the company paid virtually no taxes, which hurt the Guatemalan government's ability to deal with the effects of the Great Depression.[60] Ubico asked the company to pay its workers only 50 cents a day, to prevent other workers from demanding higher wages.[61] The company also virtually owned Puerto Barrios, Guatemala's only port to the Atlantic Ocean, allowing the company to make profits from the flow of goods through the port.[61] By 1950, the company's annual profits were US$65 million, twice the revenue of the Guatemalan government.[62] |

ユナイテッド・フルーツ・カンパニー メイン記事: ユナイテッド・フルーツ・カンパニー 歴史 ユナイテッド・フルーツ・カンパニーは1899年、二つのアメリカの大企業が合併して設立された。[58] 新会社は中米全域に広大な土地と鉄道網を所有し、バナナ輸出事業を支える基盤とした。[59] 1900年までに、同社はすでに世界最大のバナナ輸出業者となっていた。[60] 1930年までに運転資本は2億1500万米ドルに達し、数年にわたりグアテマラ最大の土地所有者かつ雇用主であった。[61] マヌエル・エストラーダ・カブレラをはじめとするグアテマラ大統領の下で、同社は同国において一連の特権を獲得し、事業を大幅に拡大した。これらの特権は しばしばグアテマラ政府の税収を犠牲にして得られた。[60] 同社は1930年から1932年にかけての権力闘争においてホルヘ・ウビコを支援し、ウビコが政権を掌握すると、同社との新たな契約締結に意欲を示した。 この新契約は同社に極めて有利な内容であった。広大な土地の99年間にわたる賃貸借権、事実上全ての税金の免除、他社が競合する契約を一切受けられないと いう保証が含まれていた。ウビコ政権下で同社は実質的に税金を支払わなかったため、グアテマラ政府は大恐慌の影響に対処する能力を損なった。[60] ウビコは他の労働者が賃上げを要求するのを防ぐため、同社に労働者への日給をわずか50セントに抑えるよう要求した。[61] 同社はまた、グアテマラ唯一の大西洋港であるプエルト・バリオスを実質的に所有し、港を通る貨物の流れから利益を得ていた。[61] 1950年までに、同社の年間利益は6500万米ドルに達し、グアテマラ政府の歳入の2倍となった。[62] |

| Impact of the revolution Due to its long association with Ubico's government, the United Fruit Company (UFC) was seen as an impediment to progress by Guatemalan revolutionaries after 1944. This image was worsened by the company's discriminatory policies towards its colored workers.[62][63] Thanks to its position as the country's largest landowner and employer, the reforms of Arévalo's government affected the UFC more than other companies. Among other things, the labor code passed by the government allowed its workers to strike when their demands for higher wages and job security were not met. The company saw itself as being specifically targeted by the reforms, and refused to negotiate with the numerous sets of strikers, despite frequently being in violation of the new laws.[64] The company's labor troubles were compounded in 1952 when Jacobo Árbenz passed Decree 900, the agrarian reform law. Of the 550,000 acres (220,000 ha) that the company owned, 15% were being cultivated; the rest of the land, which was idle, came under the scope of the agrarian reform law.[64] |

革命の影響 ユビコ政権との長年の関係ゆえに、ユナイテッド・フルーツ社(UFC)は1944年以降のグアテマラ革命家たちから進歩の妨げと見なされた。このイメージ は、同社が有色人種労働者に対して行った差別的政策によってさらに悪化した。[62][63] 国内最大の土地所有者かつ雇用主という立場ゆえ、アレバロ政権の改革はUFCに他企業以上の影響を与えた。政府が制定した労働法により、賃上げや雇用保障 の要求が受け入れられない場合、労働者はストライキを行えるようになった。同社は自らを改革の標的と見なし、新法を頻繁に違反しながらも、多数のストライ キ参加者との交渉を拒否した。[64] 1952年、ハコボ・アルベンスが農地改革法である法令900号を公布したことで、同社の労使問題はさらに深刻化した。同社が所有する55万エーカー (22万ヘクタール)の土地のうち、耕作されていたのは15%に過ぎず、残りの遊休地は農地改革法の適用対象となった。[64] |

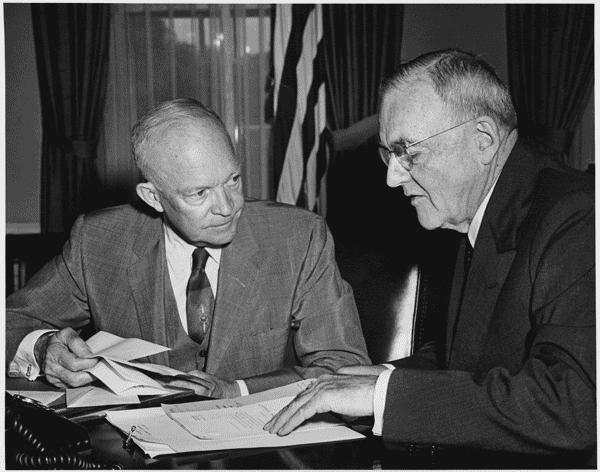

| Lobbying efforts The United Fruit Company responded with intensive lobbying of members of the United States government, leading many US congressmen and senators to criticize the Guatemalan government for not protecting the interests of the company.[65] The Guatemalan government responded by saying that the company was the main obstacle to progress in the country. American historians observed that "To the Guatemalans it appeared that their country was being mercilessly exploited by foreign interests which took huge profits without making any contributions to the nation's welfare."[65] In 1953, 200,000 acres (81,000 ha) of uncultivated land was expropriated by the government, which offered the company compensation at the rate of 2.99 US dollars to the acre, twice what the company had paid when it bought the property.[65] More expropriation occurred soon after, bringing the total to over 400,000 acres (160,000 ha); the government offered compensation to the company at the rate at which the UFC had valued its own property for tax purposes.[64] This resulted in further lobbying in Washington, particularly through Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, who had close ties to the company.[65] The company had begun a public relations campaign to discredit the Guatemalan government; it hired public relations expert Edward Bernays, who ran a concerted effort to portray the company as the victim of the Guatemalan government for several years.[66] The company stepped up its efforts after Dwight Eisenhower had been elected in 1952. These included commissioning a research study on Guatemala from a firm known to be hawkish, which produced a 235-page report that was highly critical of the Guatemalan government.[67] Historians have stated that the report was full of "exaggerations, scurrilous descriptions and bizarre historical theories".[67] The report nonetheless had a significant impact on the Congressmen that it was sent to. Overall, the company spent over a half-million dollars to influence both lawmakers and members of the public in the US that the Guatemalan government needed to be overthrown.[67] |

ロビー活動 ユナイテッド・フルーツ社は、アメリカ政府関係者への強力なロビー活動で応じた。これにより多くの米国下院議員や上院議員が、同社の利益を守らないグアテ マラ政府を批判するに至った。[65] グアテマラ政府はこれに対し、同社が国内発展の主要な障害であると反論した。アメリカの歴史家たちはこう指摘している。「グアテマラ人にとって、自国は外 国資本によって容赦なく搾取されているように見えた。彼らは莫大な利益を得ながら、国民の福祉には何の貢献もしていなかったのだ」[65] 1953年、政府は20万エーカー(81,000ヘクタール)の未開墾地を収用した。補償額は1エーカーあたり2.99米ドルで、同社が土地購入時に支 払った金額の2倍であった。[65] その後も収用は続き、総面積は40万エーカー(16万ヘクタール)を超えた。政府は、同社が税務目的で自社資産を評価した単価に基づき補償を提示した [64]。これによりワシントンでのロビー活動がさらに活発化し、特に同社と密接な関係にあったジョン・フォスター・ダレス国務長官を通じて行われた。 [65] 同社はグアテマラ政府の信用を傷つけるための広報キャンペーンを開始した。広報の専門家エドワード・バーネイズを雇い、数年にわたり同社をグアテマラ政府 の被害者として描く組織的な取り組みを実行した。[66] 同社は1952年にドワイト・アイゼンハワーが当選した後、活動を強化した。これには、強硬派として知られる企業にグアテマラに関する調査研究を委託する ことも含まれ、グアテマラ政府を強く批判する235ページに及ぶ報告書が作成された。[67] 歴史家たちは、この報告書が「誇張、中傷的な記述、奇妙な歴史理論」に満ちていたと述べている。[67] それでも報告書は送付先議員に重大な影響を与えた。総額50万ドル以上を投じ、グアテマラ政府打倒の必要性を米国内の議員と一般市民に働きかけたのであ る。[67] |

| CIA instigated coup d'état Main article: 1954 Guatemalan coup d'état Political motivations In addition to the lobbying of the United Fruit Company, several other factors also led the United States to launch the coup that toppled Árbenz in 1954. During the years of the Guatemalan Revolution, military coups occurred in several other Central American countries that brought firmly anti-communist governments to power. Army officer Major Oscar Osorio won staged elections in El Salvador in 1950, Cuban dictator Fulgencio Batista took power in 1952.[68] Honduras, where the land-holdings of the United Fruit Company were the most extensive, had been ruled by an anti-communist government sympathetic to the United States since 1932. These developments created tension between the other governments and Árbenz, which was exacerbated by Arévalo's support for the Caribbean Legion.[68] This support also worried the United States and the newly formed Central Intelligence Agency. According to US historian Richard Immerman, during the beginning of the Cold War, the US and the CIA tended to assume that everybody who opposed it was a communist. Thus, despite Arévalo's ban of the communist party, important figures in the US government were already predisposed to believe that the revolutionary government had been infiltrated by communists, and was a danger to the US.[69] During the years of the revolution, several reports and memoranda were circulated amongst US government agencies that furthered this belief.[69] |

CIAがクーデターを扇動した 主な記事: 1954年グアテマラクーデター 政治的動機 ユナイテッド・フルーツ社のロビー活動に加え、1954年にアルベンス政権を倒すクーデターを米国が実行に移した背景には、他にもいくつかの要因があっ た。グアテマラ革命の期間中、他のいくつかの中米諸国でも軍事クーデターが発生し、強硬な反共産主義政権が樹立された。エルサルバドルでは1950年に陸 軍将校オスカル・オソリオ少佐が偽装選挙で勝利し、キューバでは1952年にフルヘンシオ・バティスタ独裁政権が樹立された[68]。ユナイテッド・フ ルーツ社の土地所有が最も広範だったホンジュラスでは、1932年以降、米国に同調する反共政権が支配していた。こうした動きは、他の諸政府とアルベンス 政権との間に緊張を生み、アレバロがカリブ海連隊を支援したことでさらに悪化した[68]。この支援は米国と新設の中央情報局(CIA)も懸念させた。米 国の歴史家リチャード・イマーマンによれば、冷戦の初期段階において、米国とCIAは共産主義に反対する者は皆共産主義者であると見なす傾向があった。し たがって、アレバロが共産党を禁止したにもかかわらず、米国政府の重要人物たちは、革命政府が共産主義者に浸透されており、米国にとって危険であるという 見解を既に抱いていたのである[69]。革命の期間中、この見解をさらに強める複数の報告書や覚書が米国政府機関内で回覧された[69]。 |

| Operation PBFortune Further information: Operation PBFortune Although the administration of Harry Truman had become convinced that the Guatemalan government had been penetrated by communists, it relied on purely diplomatic and economic means to try and reduce the communist influence, at least until the end of its term.[70] The United States had refused to sell arms to the Guatemalan government after 1944; in 1951 it began to block weapons purchases by Guatemala from other countries. In 1952 Truman became sufficiently convinced of the threat posed by Árbenz to start planning a covert overthrow, titled Operation PBFortune.[71] The plan had originally been suggested by the US-supported dictator of Nicaragua, Anastasio Somoza García, who said that if he were given weapons, he could overthrow the Guatemalan government. Truman gave the CIA permission to go ahead with the plan, without informing the Department of State.[71] The CIA placed a shipment of weapons on a vessel owned by the United Fruit Company, and the operation was paid for by Rafael Trujillo and Marcos Pérez Jiménez, the right-wing anti-communist dictators of the Dominican Republic and Venezuela, respectively.[71][72] The operation was to be led by Carlos Castillo Armas.[72] However, the US Department of State discovered the conspiracy, and Secretary of State Dean Acheson persuaded Truman to abort the plan.[71][72] |

PBFortune作戦 詳細情報: PBFortune作戦 ハリー・トルーマン政権はグアテマラ政府が共産主義者に浸透されていると確信していたが、少なくとも任期終了までは純粋に外交的・経済的手段に頼って共産 主義の影響力を減らそうとした。[70] 米国は1944年以降グアテマラ政府への武器販売を拒否し、1951年には他国からの武器購入も阻止し始めた。1952年、トルーマンはアルベンスがもた らす脅威を十分に確信し、秘密裏の政権転覆計画「PBFortune作戦」の立案を開始した。[71] この計画は元々、米国が支援するニカラグアの独裁者アナスタシオ・ソモサ・ガルシアが提案したもので、武器を与えられればグアテマラ政府を打倒できると主 張していた。トルーマンは国務省に通知することなく、CIAに計画実行の許可を与えた。[71] CIAは武器をユナイテッド・フルーツ社の船舶に積み込み、作戦費用はドミニカ共和国のラファエル・トルヒーヨとベネズエラのマルコス・ペレス・ヒメネス という、それぞれ右派の反共独裁者から調達した。[71][72] この作戦はカルロス・カスティーヨ・アルマスが指揮する予定だった。[72] しかし米国務省がこの陰謀を発見し、ディーン・アチソン国務長官がトルーマンに計画の中止を説得した。[71][72] |

| Operation PBSuccess Further information: Operation PBSuccess  John Foster Dulles and US President Dwight Eisenhower In November 1952, Dwight Eisenhower was elected president of the US. Eisenhower's campaign had included a pledge for a more active anti-communist policy. Several figures in his administration, including Secretary of State John Foster Dulles and his brother and CIA director Allen Dulles had close ties to the United Fruit Company. Both of these factors made Eisenhower predisposed to supporting the overthrow of Árbenz.[73] The CIA operation to overthrow Jacobo Árbenz, code-named Operation PBSuccess, was authorized by Eisenhower in August 1953.[74] The operation was granted a budget of 2.7 million dollars for "psychological warfare and political action".[74] The total budget has been estimated at between 5 and 7 million dollars, and the planning employed over 100 CIA agents.[75] The CIA planning included drawing up lists of people within Árbenz's government to be assassinated if the coup were to be carried out. Manuals of assassination techniques were compiled, and lists were also made of people whom the junta would dispose of.[74] After considering several candidates to lead the coup, including Miguel Ydígoras Fuentes, the CIA settled on Carlos Castillo Armas.[75] The US state department also embarked on a campaign to ensure that other countries would not sympathize with the Guatemalan government, by linking it to communism and the Soviet Union.[76] By 1954 Árbenz had become desperate for weapons, and decided to acquire them secretly from Czechoslovakia, which would have been the first time that a Soviet bloc country shipped weapons to the Americas.[77][78] The shipment of these weapons acted as the final spur for the CIA to launch its coup.[78] |

オペレーション・ピービーサクセス 詳細情報:オペレーション・ピービーサクセス  ジョン・フォスター・ダレスとドワイト・アイゼンハワー米大統領 1952年11月、ドワイト・アイゼンハワーが米国大統領に選出された。アイゼンハワーの選挙運動には、より積極的な反共政策を掲げる公約が含まれてい た。彼の政権内の複数の人物、国務長官ジョン・フォスター・ダレスとその弟でCIA長官のアレン・ダレスは、ユナイテッド・フルーツ社と密接な関係を持っ ていた。これらの要因が相まって、アイゼンハワーはアルベンス政権の転覆を支持する傾向にあった。[73] CIAによるハコボ・アルベンツ政権転覆作戦(コードネーム:オペレーション・PBSuccess)は、1953年8月にアイゼンハワーによって承認され た。作戦には「心理戦および政治工作」として270万ドルの予算が割り当てられた。総予算は500万~700万ドルと推定され、計画立案には100人以上 のCIA工作員が動員された。CIAの計画には、クーデター実行時に暗殺対象とするアルベンス政権関係者のリスト作成も含まれていた。暗殺技術の手引書が 作成され、軍事政権が排除すべき人々リストも作成された。[74] ミゲル・イディゴラス・フエンテスを含む複数のクーデター指導者候補を検討した後、CIAはカルロス・カスティーヨ・アルマスを最終候補に決定した。 [75] 米国務省はまた、グアテマラ政府を共産主義やソ連と結びつけることで、他国がグアテマラ政府に同情しないよう工作を開始した。[76] 1954年までにアルベンスは武器の確保に追い詰められ、チェコスロバキアから密かに調達することを決断した。これはソ連圏の国がアメリカ大陸に武器を輸 送する初めての事例となるはずだった。[77][78] この武器輸送が、CIAにクーデターを実行させる最後の引き金となった。[78] |

| Invasion On 18 June 1954, Castillo Armas led a convoy of trucks carrying 480 men across the border from Honduras into Guatemala. The weapons had come from the CIA, which had also trained the men in camps in Nicaragua and Honduras.[79][80] Since his army was badly outnumbered by the Guatemalan army, the CIA plan required Castillo Armas to camp within the Guatemalan border, while it mounted a psychological campaign to convince the Guatemalan people and government that Castillo's victory was a fait accompli. This campaign included using Catholic priests to give anti-communist sermons, strafing several towns using CIA aircraft, and placing a naval blockade around the country.[79][80] It also involved dropping leaflets by airplane through the country, and carrying out a radio broadcast entitled "The Voice of Liberation" which announced that Guatemalan exiles led by Castillo Armas were shortly about to liberate the country.[79] The military force led by Castillo Armas attempted to make forays towards the towns of Zacapa and Puerto Barrios; however, these were beaten back by the Guatemalan army.[80] The propaganda broadcast by the CIA had far more effect; it succeeded in leading a Guatemalan pilot to defect, which led to Árbenz grounding the entire air force, fearing its defection.[79] The CIA also used its planes, flown by American pilots, to bomb Guatemalan towns for psychological effect.[79] When the old planes used by the invasion force were found to be inadequate, the CIA persuaded Eisenhower to authorize the use of two additional planes.[80] Guatemala made an appeal to the United Nations, but the US vetoed an investigation into the incident by the Security Council, stating that it was an internal matter in Guatemala.[81][82] On 25 June, a CIA plane bombed Guatemala City, destroying the government's main oil reserves. Frightened by this, Árbenz ordered the army to distribute weapons to local peasants and workers.[83] The army refused to do this, instead demanding that Árbenz either resign or come to terms with Castillo Armas.[83][82] Knowing that he could not fight on without the support of the army, Jacobo Árbenz resigned on 27 June 1954, handing over power to Colonel Carlos Enrique Diaz.[83][82] US ambassador John Peurifoy then mediated negotiations held in El Salvador between the army leadership and Castillo Armas which led to Castillo being included in the ruling military junta on 7 July 1954, and was named provisional president a few days later.[83] The US recognized the new government on 13 July.[84] Elections were held in early October, from which all political parties were barred from participating, and Castillo Armas was the only candidate, winning the election with 99% of the vote.[83][85] Among the outcomes of the meeting in El Salvador was a planned new constitution, which would roll back most of the progressive reform brought by the revolution.[82] |

侵攻 1954年6月18日、カスティーヨ・アルマスは480名の兵士を乗せたトラック隊を率い、ホンジュラス国境を越えてグアテマラへ侵入した。武器はCIA から提供されたもので、兵士たちはニカラグアとホンジュラスの訓練キャンプでCIAによって訓練されていた。[79][80] グアテマラ軍に兵力で大きく劣っていたため、CIAの計画ではカスティージョ・アルマスは国境内に陣を敷くことになっていた。その間、CIAは心理作戦を 展開し、グアテマラの人民と政府にカスティージョの勝利が既成事実であると信じ込ませようとした。この作戦には、カトリック司祭による反共産主義説教、 CIA航空機による複数の町への機銃掃射、そして国全体を包囲する海上封鎖が含まれていた。[79][80] さらに、飛行機によるビラ散布や「解放の声」と題したラジオ放送も実施された。この放送では、カスティージョ・アルマス率いる亡命グアテマラ人たちが間も なく祖国を解放すると宣言していた。[79] カスティージョ・アルマス率いる軍事部隊はザカパとプエルト・バリオスへの進撃を試みたが、グアテマラ軍に撃退された。[80] CIAの宣伝放送ははるかに大きな効果を発揮し、グアテマラ人パイロットの亡命を成功させた。これによりアルベンスは空軍全体の離脱を恐れ、全機を地上待 機させた。[79] CIAはまた、心理作戦としてグアテマラの町々を爆撃するため、アメリカ人パイロットが操縦する自局の航空機を使用した。[79] 侵攻部隊が使用した旧式機が不十分だと判明すると、CIAはアイゼンハワーに追加で2機の使用を許可するよう働きかけた。[80] グアテマラは国連に訴えたが、米国は安全保障理事会による事件調査を拒否権で阻止し、これはグアテマラの内政問題だと主張した。[81][82] 6月25日、CIAの航空機がグアテマラシティを爆撃し、政府の主要石油備蓄を破壊した。これに恐怖したアルベンスは、軍に地元の農民や労働者に武器を配 布するよう命じた。[83] 軍はこれを拒否し、代わりにアルベンスに辞任か、カスティージョ・アルマスとの和解のいずれかを要求した。[83][82] 軍の支持なしには戦えないと悟ったハコボ・アルベンスは1954年6月27日に辞任し、権力をカルロス・エンリケ・ディアス大佐に引き渡した。[83] [82] その後、米国大使ジョン・ピュリフォイが仲介役となり、エルサルバドルで軍指導部とカスティーヨ・アルマスとの交渉が行われた。その結果、1954年7月 7日にカスティーヨが軍事政権に組み入れられ、数日後に暫定大統領に任命された。[83] 米国は7月13日に新政府を承認した。[84] 10月初旬に選挙が実施されたが、全ての政党が参加を禁止され、カスティージョ・アルマスが唯一の候補者として立候補し、得票率99%で当選した。 [83][85] エルサルバドルでの会合の結果として、革命によってもたらされた進歩的な改革の大半を後退させる新憲法の制定が計画された。[82] |

| Aftermath Further information: Guatemalan Civil War  Ixil people carrying exhumed bodies Ixil Maya carrying exhumed bodies of their relatives killed in the Guatemalan Civil War Following the coup, hundreds of peasant leaders were rounded up and executed. Historian Greg Grandin has stated that "There is general consensus today among academics and Guatemalan intellectuals that 1954 signaled the beginning of what would become the most repressive state in the hemisphere".[86] Following the coup and the establishment of the military dictatorship, a series of leftist insurgencies began in the countryside, frequently with a large degree of popular support, which triggered the Guatemalan Civil War that lasted until 1996. The largest of these movements was led by the Guerrilla Army of the Poor, which at its largest point had 270,000 members.[87] Two-hundred thousand (200,000) civilians were killed in the war, and numerous human rights violations committed, including massacres of civilian populations, rape, aerial bombardment, and forced disappearances.[87] Historians estimate that 93% of these violations were committed by the United States-backed military,[87] which included a genocidal scorched-earth campaign against the indigenous Maya population in the 1980s.[87] |

余波 詳細情報:グアテマラ内戦  遺体を運び出すイシル族 グアテマラ内戦で殺害された親族の遺体を運び出すイシル・マヤの人民 クーデター後、数百人の農民指導者が一斉に逮捕され処刑された。歴史家グレッグ・グランディンは「1954年が、この地域で最も抑圧的な国家の始まりを告 げたという点で、今日の学者やグアテマラ知識人の間には概ね合意がある」と述べている。[86] クーデターと軍事独裁政権の樹立後、農村部で一連の左翼反乱が始まった。これらはしばしば広範な民衆の支持を得て、1996年まで続いたグアテマラ内戦を 引き起こした。このうち最大の運動は「貧者のゲリラ軍」が主導し、最盛期には27万人のメンバーを擁した[87]。戦争では20万人の民間人が殺害され、 民間人虐殺、強姦、空爆、強制失踪など数多くの人権侵害が行われた。[87] 歴史家らの推計によれば、これら侵害行為の93%は米国が支援する軍隊によって行われた[87]。これには1980年代における先住民族マヤに対するジェ ノサイド的な焦土作戦も含まれる[87]。 |

| Banana republic |

バナナ共和国 |

| Chapman, Peter (2007). Bananas:

How the United Fruit Company Shaped the World. New York, New York, USA:

Canongate. ISBN 978-1-84767-194-3. Cullather, Nicholas (23 May 1997) [1994], Kornbluh, Peter; Doyle, Kate (eds.), "CIA and Assassinations: The Guatemala 1954 Documents", National Security Archive Electronic Briefing Book No. 4, Washington, D.C., USA: National Security Archive Forster, Cindy (2001). The Time of Freedom: Campesino Workers in Guatemala's October Revolution. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA: University of Pittsburgh Press. ISBN 978-0-8229-4162-0. Gleijeses, Piero (1991). Shattered Hope: The Guatemalan Revolution and the United States, 1944–1954. Princeton, New Jersey, USA: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-02556-8. Grandin, Greg (2000). The Blood of Guatemala: a History of Race and Nation. Durham, North Carolina, USA: Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-2495-9. Immerman, Richard H. (1982). The CIA in Guatemala: The Foreign Policy of Intervention. Austin, Texas, USA: University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-71083-2. McAllister, Carlota (2010). "A Headlong Rush into the Future". In Grandin, Greg; Joseph, Gilbert (eds.). A Century of Revolution. Durham, North Carolina, USA: Duke University Press. pp. 276–309. ISBN 978-0-8223-9285-9. Retrieved 14 January 2014. Schlesinger, Stephen; Kinzer, Stephen (1999). Bitter Fruit: The Story of the American Coup in Guatemala. Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA: David Rockefeller Center series on Latin American studies, Harvard University. ISBN 978-0-674-01930-0. Voionmaa, Daniel Noemi (18 August 2022). Surveillance, the Cold War, and Latin American Literature. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-009-19122-7. |

チャップマン、ピーター(2007)。『バナナ:ユナイテッド・フルーツ社が世界を変えた方法』。ニューヨーク州ニューヨーク:キャノンゲート。ISBN 978-1-84767-194-3。 カラザー、ニコラス(1997年5月23日)[1994年]、コーンブルー、ピーター;ドイル、ケイト(編)、『CIAと暗殺:グアテマラ1954年文書』、国家安全保障アーカイブ電子ブリーフィングブック第4号、ワシントンD.C.、米国:国家安全保障アーカイブ フォスター、シンディ(2001年)。自由の時:グアテマラ十月革命における農民労働者たち。米国ペンシルベニア州ピッツバーグ:ピッツバーグ大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-8229-4162-0。 グレイジェセス、ピエロ(1991)。砕かれた希望:グアテマラ革命とアメリカ合衆国、1944–1954。米国ニュージャージー州プリンストン:プリンストン大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-691-02556-8。 グランディン、グレッグ(2000)。『グアテマラの血:人種と国民の歴史』。米国ノースカロライナ州ダーラム:デューク大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-8223-2495-9。 イマーマン、リチャード・H.(1982)。『グアテマラにおけるCIA:介入の外交政策』。米国テキサス州オースティン:テキサス大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-292-71083-2。 マカリスター、カルロタ(2010)。「未来への突進」。グレッグ・グランディン、ギルバート・ジョセフ(編)。『革命の世紀』所収。米国ノースカロライ ナ州ダーラム:デューク大学出版局。276–309頁。ISBN 978-0-8223-9285-9。2014年1月14日閲覧。 シュレジンジャー、スティーブン;キンザー、スティーブン(1999)。『苦い果実:グアテマラにおけるアメリカのクーデター物語』。米国マサチューセッ ツ州ケンブリッジ:ハーバード大学デイヴィッド・ロックフェラー・センター・ラテンアメリカ研究シリーズ。ISBN 978-0-674-01930-0。 ヴォイオンマー、ダニエル・ノエミ(2022年8月18日)。『監視、冷戦、そしてラテンアメリカ文学』。ケンブリッジ大学出版局。ISBN 978-1-009-19122-7。 |

| Cullather, Nicholas (2006).

Secret History: The CIA's Classified Account of its Operations in

Guatemala 1952–54 (2nd ed.). Stanford University Press. ISBN

978-0-8047-5468-2. Gleijeses, Piero (October 1989). "The Agrarian Reform of Jacobo Arbenz". Journal of Latin American Studies. 21 (3). Cambridge University Press: 453–480. doi:10.1017/S0022216X00018514. JSTOR 156959. S2CID 145201357. (subscription required) Handy, Jim (1994). Revolution in the Countryside: Rural Conflict and Agrarian Reform in Guatemala, 1944–1954. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-4438-0. Jonas, Susanne (1991). The Battle for Guatemala: Rebels, Death Squads, and U.S. Power (5th ed.). Westview Press. ISBN 978-0-8133-0614-8. Krehm, William (1999). Democracies and Tyrannies of the Caribbean in the 1940s. COMER Publications. ISBN 978-1-896266-81-7. Loveman, Brian; Davies, Thomas M. (1997). The Politics of Antipolitics: the Military in Latin America (3rd, revised ed.). Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-8420-2611-6. Rabe, Stephen G. (1988). Eisenhower and Latin America: The Foreign Policy of Anticommunism. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-4204-1. Streeter, Stephen M. (2000). Managing the Counterrevolution: the United States and Guatemala, 1954–1961. Ohio University Press. ISBN 978-0-89680-215-5. Striffler, Steve; Moberg, Mark (2003). Banana Wars: Power, Production, and History in the Americas. Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-3196-4. Trefzger, Douglas W. (2002). "Guatemala's 1952 Agrarian Reform Law: A Critical Reassessment". International Social Science Review. 77 (1/2). Pi Gamma Mu, International Honor Society in Social Sciences: 32–46. JSTOR 41887088. (subscription required) |

カラザー、ニコラス(2006年)。『秘密の歴史:CIAのグアテマラ作戦機密記録 1952-54』(第2版)。スタンフォード大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-8047-5468-2。 グレイジェセス、ピエロ(1989年10月)。「ハコボ・アルベンツの農地改革」。『ラテンアメリカ研究ジャーナル』。21巻3号。ケンブリッジ大学出版 局:453–480頁。doi:10.1017/S0022216X00018514。JSTOR 156959. S2CID 145201357. (購読が必要) ハンディ、ジム (1994). 『田舎の革命:グアテマラにおける農村紛争と農地改革、1944–1954年』. ノースカロライナ大学出版局. ISBN 978-0-8078-4438-0. ヨナス、スザンヌ(1991)。『グアテマラをめぐる戦い:反乱軍、死の部隊、そして米国の権力』(第5版)。ウェストビュー・プレス。ISBN 978-0-8133-0614-8。 クレーム、ウィリアム(1999)。『1940年代カリブ海の民主主義と専制政治』。COMER出版。ISBN 978-1-896266-81-7。 ラヴマン、ブライアン;デイヴィス、トーマス・M(1997)。『反政治の政治学:ラテンアメリカにおける軍隊』(第3版、改訂版)。ローマン&リトルフィールド。ISBN 978-0-8420-2611-6。 レーベ、スティーブン・G.(1988)。『アイゼンハワーとラテンアメリカ:反共主義の外交政策』。ノースカロライナ大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-8078-4204-1。 ストリーター、スティーブン・M.(2000)。『反革命の管理:アメリカ合衆国とグアテマラ、1954–1961』。オハイオ大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-89680-215-5。 ストリフラー、スティーブ;モーバーグ、マーク(2003)。『バナナ戦争:アメリカ大陸における権力、生産、そして歴史』。デューク大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-8223-3196-4。 トレフツガー、ダグラス・W.(2002)。「グアテマラの1952年農地改革法:批判的再評価」。『国際社会科学レビュー』。77巻(1/2)。社会科学国際栄誉学会Pi Gamma Mu:32–46頁。JSTOR 41887088。(購読が必要) |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Guatemalan_Revolution |

Queqchí

people carrying their loved one's remains after an exhumation in

Cambayal in Alta Verapaz department, Guatemala. Since 1997, the Centre

of Forensic Anthropology and Applied Sciences (CAFCA) has been helping

to heal the deep wounds caused by Guatemala’s internal conflict. The

impact of CAFCA’s forensic work is twofold: It helps families to find

their loved ones and come to terms with their loss and it gathers the

evidence needed to bring their murderers to justice. Photo: CAFCA

archive.

Land of Terror

"Land of Terror is a 1944 fantasy novel by American writer Edgar Rice Burroughs, the sixth in his series about the fictional "hollow earth" land of Pellucidar. It is the penultimate novel in the series and the last to be published during Burrough's lifetime. Unlike most of the other books in the Pellucidar series, this novel was never serially published in any magazine because it was rejected by all of Burroughs's usual publishers."

Edgar Rice

Burroughs, Land

of Terror, 1944 - Project Gutenberg Australia.

【関連リンク】

【文献】

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

++

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099