ウェウェテナンゴ歌曲集(16世紀)

The huehuetenango

songbook, music from 16th century guatemala

テノールのヨナタン・アルバラードとビウエラ奏者のアリエル・アブラモヴィッチ[Ariel Abramovich - YouTube] は、グアテマラ北部の多声音楽とグレゴリオ聖歌を収めた15巻からなる「ウ エウエテナンゴ歌曲写本」の楽譜を閲覧している。1582年から1635年の間に記録された350曲以上の作品の中から、この夢のデュオはミサ曲、モテッ ト、シャンソン、ビリャンシーコスを選び出した。それらはバロック前夜の大陸間音楽交流を垣間見せてくれる。ジョナタン[=ヨナタン]・アルバラドは、中 世やルネサンス期の 楽譜に記されたものから、ヨーロッパやアメリカ大陸の口承伝統に伝わるものまで、(非常に)古い歌を歌う歌手であり演奏者だ。音楽の第一歩は、ブエノスア イレス州メルセデスの音楽院ギタークラスと市立合唱団で踏み出した。その後、オーケストラ指揮、合唱指揮、作曲を学び、声楽とリュートで優等学位を取得し た。彼は、アンサンブル「セコンダ・プラティカ」の音楽監督であり共同創設者であり、「ダ・テンペラ・ヴェーリャ」および「ソラッツォ・アンサンブル」の メンバーでもある。作曲家ルイス・デ・ナルバエスの幻想曲に魅了されたアリエル・アブラモヴィッチは、10代の頃、16世紀のリュートとビウエラのレパー トリーに専念することを決意し、その決断を今日まで後悔することなく貫いている。1996年には、師でありメンターでもあるホプキンズ・スミスに師事する ため、スイスに移住し、スコラ・カントルム・バシリエンシスで学んだ。様々なミュージシャンと数枚のアルバムをリリースしており、中世およびルネサンス初 期のカスティーリャのレパートリーを専門とするアンサンブル、ダ・テンペラ・ヴェーリャのメンバーでもある。

ウエウエテナンゴ——途絶えた歌集からの歌

1932

年、アメリカの人類学者であり小説家でもあるオリバー・ラ・ファージは『サンタ・エウラリア:グアテマラのクチュマタン・先住民集落の宗教』を出版した。

この本は、6か月にわたる民族誌調査の成果であり、当時まだ道路が整備されていなかったグアテマラ北西部ウエウェテナンゴ県の僻地サンタ・エウラリアの住

民たちの文化と音楽生活の様々な側面を詳述した。彼の記述から、音楽がこれらの先住民コミュニティの日常生活や精神生活にどのように組み込まれ、カトリッ

クやその他の外部からの影響に対する抵抗と強制的な適応の象徴となっ

たかが明らかである。この融合的な遺産の豊かさと複雑さは、サン・

ミゲル・デ・アカタンのレパートリーに音楽的に反映されている。この用語は、1963年にグアテマラのこの町で収集された楽譜集を指すために、最初の研究

者ロバート・スティーブンソンによって造語されたものである。これらの楽譜は、中央アメリカ最高峰のクチュマタン山脈に位置する三つの小さな先住民集

落――サンタ・エウラリア、サン・マテオ・イシュタタン、サン・フアン・イシュコイ――に由来する。何世紀にもわたりこれらのコミュニティが大切に守って

き

たこのコレクションは、18冊の小型合唱譜で構成されている。そのうち15冊はインディアナ大学リリー図書館に所蔵され、1冊はプリンストン大学図書館、

1冊はチューレーン大学図書館、そしてもう1冊はハカルテナンゴの教区教会に保管されている。1960年代にこれらの楽譜をウエウェテナンゴから米国へ移

送

したメリノール宣教師会のアーカイブをクリスティン・ハーグが最近調査したところ、このコレクションは元々50冊で構成されていたことが明らかになっ

た。確かにこのコレクションには数多くのヨーロッパ作品(フランス歌曲、イタリアのマドリガル、カスティーリャのヴィリャンシーコ、ラテン語のミサ曲やモ

テット)の写本が含まれているが、同時に、ヨーロッパの音楽様式が先住民の知性、手、声を通じて変容し、独自の創造物へと昇華された複雑で神秘的な過程を

特権的に証言する資料でもある。これらの楽譜集の多機能性は、その雑多な内容に反映されている。一冊の本に、ラテン語のミサ曲、モテット、詩篇の完全版

と、ヴィリャンシーコや舞曲、短いフォーブルドン[Fauxbourdon]、グレゴリオ聖歌の対句、歌詞のない断片、様々な宗教的祝祭に対する多様な短い応答曲が混在しているのだ。

☆

曲

のリスト

1

Virgen Madre de Dios

2 Introito. Salve Sancta Parens

3 Kyrie Eleison

4 Pleni Sunt (De la 'Misa Sine Nomine')

5 Antiphona Ad Magnificat. 'Gloriose Virginis'

6 Magnificat 8 Toni

7 Benedicamus Domino / Deo Gratias

8 Content Est Riche-Paratum Cor Meum

9 Pater Noster

10 Hic Solus Dolores Nostros Tulit

11 Missa la Caça-Agnus Dei

12 O Bone Jesu

13 Clamabat Autem Mulier Cananea-Cananea

14 Amy Souffrez-Salamanca

15 Amor Che Mi Tormenti-Edmini

16 Con Qué la Lavaré?

17 Puse Mis Amores en Fernandino-Mulier Quit Ploras

18 Romance. de Antequera Sale El Moro

19 Dame Acojida en Tu Hato

★

| 1 Virgen

Madre

de Dios Associated Performer: Jonatan Alvarado Associated Performer: Ariel Abramovich Music Publisher: public domain Composer, Lyricist: Anonymous |

|

| 2 Introito.

Salve Sancta Parens Associated Performer: Jonatan Alvarado Associated Performer: Ariel Abramovich Music Publisher: public domain Composer, Lyricist: Anonymous |

|

| 3 Kyrie

Eleison Associated Performer: Jonatan Alvarado Associated Performer: Ariel Abramovich Music Publisher: public domain Composer, Lyricist: Anonymous |

|

| 4 Pleni

Sunt

(De la 'Misa Sine Nomine') Associated Performer: Jonatan Alvarado Associated Performer: Ariel Abramovich Music Publisher: public domain Composer, Lyricist: Anonymous |

|

| 5 Antiphona

Ad

Magnificat. 'Gloriose Virginis Associated Performer: Jonatan Alvarado Associated Performer: Ariel Abramovich Music Publisher: public domain Composer, Lyricist: Anonymous' |

|

| 6 Magnificat

8

Toni Associated Performer: Jonatan Alvarado Associated Performer: Ariel Abramovich Music Publisher: public domain Composer, Lyricist: Anonymous |

|

| 7 Benedicamus

Domino / Deo Gratias Associated Performer: Jonatan Alvarado Associated Performer: Ariel Abramovich Music Publisher: public domain Composer, Lyricist: Anonymous |

|

| 8 Content

Est

Riche-Paratum Cor Meum Associated Performer: Jonatan Alvarado Associated Performer: Ariel Abramovich Music Publisher: public domain Composer: Claudin de Sermisy - Claudin de Sermisy (ca. 1490-1562) Lyricist: Anonymous ++++++ - de Sermisy はイベリア半島の作曲家か?[フランス音楽小史][カ ンツォーネ] |

|

| 9 Pater

Noster Associated Performer: Jonatan Alvarado Associated Performer: Ariel Abramovich Music Publisher: public domain Composer, Lyricist: Anonymous |

|

| 10 Hic

Solus

Dolores Nostros Tulit Associated Performer: Jonatan Alvarado Associated Performer: Ariel Abramovich Music Publisher: public domain Composer, Lyricist: Anonymous |

|

| 11 Missa

la

Caça-Agnus Dei Associated Performer: Jonatan Alvarado Associated Performer: Ariel Abramovich Music Publisher: public domain Composer: Cristóbal de Morales - ルネサンス期のス ペイン人作曲家. Lyricist: Anonymous |

|

| 12 O

Bone Jesu Associated Performer: Jonatan Alvarado Associated Performer: Ariel Abramovich Music Publisher: public domain Composer: Juan de Anchieta Lyricist: Anonymous +++++++ Juan de Anchieta (c. 1450 - 1523), nacido en Azpeitia; compositor y clérigo; primo por vía materna de San Ignacio de Loyola. Vinculado a la casa de Isabel de Castilla; fue músico de la corte en 1489; además, en 1499, se desempeñó como canónigo de la catedral de Granada. Desde 1504 fue rector de la iglesia de su ciudad natal. Es autor de una extensa obra que comprende misas, motetes, canciones y piezas populares profanas. |

|

| 13 Clamabat

Autem Mulier Cananea-Cananea Associated Performer: Jonatan Alvarado Associated Performer: Ariel Abramovich Music Publisher: public domain Composer: Pedro de Escobar Lyricist: Anonymous +++ Pedro de Escobar (c. 1465 – after 1535), a.k.a. Pedro do Porto, was a Portuguese composer of the Renaissance, mostly active in Spain. He was one of the earliest and most skilled composers of polyphony in the Iberian Peninsula, whose music has survived. |

|

| 14 Amy

Souffrez-Salamanca Associated Performer: Jonatan Alvarado Associated Performer: Ariel Abramovich Music Publisher: public domain Composer: Pierre Moulu Lyricist: Anonymous ++++ Pierre Moulu (1484? – c. 1550) was a Franco-Flemish composer of the Renaissance who was active in France, probably in Paris. |

|

| 15 Amor

Che Mi

Tormenti-Edmini Associated Performer: Jonatan Alvarado Associated Performer: Ariel Abramovich Music Publisher: public domain Composer: Sebastiano Festa Lyricist: Anonymous +++++++++ Sebastiano Festa (ca. 1490–1495 – 31 July 1524) was an Italian composer of the Renaissance, active mainly in Rome. While his musical output was small, he was one of the earliest composers of madrigals, and was influential on other early composers of madrigals, such as Philippe Verdelot. He may have been related to his more famous contemporary Costanzo Festa, another early madrigal composer. |

|

| 16 Morraleos:

¿Con qué la lavaré? Associated Performer: Jonatan Alvarado Associated Performer: Ariel Abramovich Music Publisher: public domain Composer: Juan Vásquez Lyricist: Anonymous ++++ Juan Vásquez (or Vázquez, c. 1500 in Badajoz – c. 1560 in Seville) was a Spanish priest and composer of the Renaissance. He can be considered part of the School of Andalusia group of composers along with Francisco Guerrero, Cristóbal de Morales, Juan Navarro Hispalensis and others.[1][2][3] |

|

| 17 Puse

Mis

Amores en Fernandino-Mulier Quit Ploras Associated Performer: Jonatan Alvarado Associated Performer: Ariel Abramovich Music Publisher: public domain Composer: Juan Vásquez Lyricist: Anonymous |

|

| 18 Romance.

de

Antequera Sale El Moro Associated Performer: Jonatan Alvarado Associated Performer: Ariel Abramovich Music Publisher: public domain Composer, Lyricist: Anonymous |

|

| 19 Dame

Acojida en Tu Hato Associated Performer: Jonatan Alvarado Associated Performer: Ariel Abramovich Music Publisher: public domain Composer, Lyricist: Anonymous |

| Tenor Jonatan Alvarado and vihuelist Ariel Abramovich browse through the folios of the Huehuetenango song manuscript: 15 volumes of polyphony and Gregorian chants from Northern Guatemala. From the more than 350 works recorded between 1582 and 1635, the dream duo chose mass movements, motets, chansons and villancicos that offer a glimpse of the intercontinental musical traffic on the eve of the Baroque.? Jonatan Alvarado is a singer and player of (very) old songs, be them contained by Medieval and Renaissance manuscripts scattered all over the world, or found in the oral traditions of Europe and the Americas. He took his first musical steps in the guitar class at the conservatory and in the municipal choirs of Mercedes, Buenos Aires. He then studied orchestral conducting, choral conducting and composition, and later graduated with honours in singing and lute. He is musical director and co-founder of the ensemble Seconda Pratica and a member of Da Tempera Velha and Sollazzo Ensemble. Dazzled by a fantasy by composer Luys de Narvaez, Ariel Abramovich decided - being still a teenager - to dedicate exclusively to the lute and vihuela repertoire of the 16th century, a decision he has maintained to this day without any regrets. In 1996 he moved to Switzerland to study with his teacher and mentor, Hopkinson Smith, at the Schola Cantorum Basiliensis. He has released several albums with a variety of musicians and is member of the ensemble Da Tempera Velha, dedicated to Medieval and early Renaissance Castillian repertoire. | テノールのヨナタン・アルバラードとビウエラ奏者のアリエル・アブラモヴィッチは、グアテマラ北部の多声音楽とグレゴリオ聖歌を収めた15巻からなる「ウ エウエテナンゴ歌曲写本」の楽譜を閲覧している。1582年から1635年の間に記録された350曲以上の作品の中から、この夢のデュオはミサ曲、モテッ ト、シャンソン、ビリャンシーコスを選び出した。それらはバロック前夜の大陸間音楽交流を垣間見せてくれる。ジョナタン[=ヨナタン]・アルバラドは、中 世やルネサンス期の 楽譜に記されたものから、ヨーロッパやアメリカ大陸の口承伝統に伝わるものまで、(非常に)古い歌を歌う歌手であり演奏者だ。音楽の第一歩は、ブエノスア イレス州メルセデスの音楽院ギタークラスと市立合唱団で踏み出した。その後、オーケストラ指揮、合唱指揮、作曲を学び、声楽とリュートで優等学位を取得し た。彼は、アンサンブル「セコンダ・プラティカ」の音楽監督であり共同創設者であり、「ダ・テンペラ・ヴェーリャ」および「ソラッツォ・アンサンブル」の メンバーでもある。作曲家ルイス・デ・ナルバエスの幻想曲に魅了されたアリエル・アブラモヴィッチは、10代の頃、16世紀のリュートとビウエラのレパー トリーに専念することを決意し、その決断を今日まで後悔することなく貫いている。1996年には、師でありメンターでもあるホプキンズ・スミスに師事する ため、スイスに移住し、スコラ・カントルム・バシリエンシスで学んだ。様々なミュージシャンと数枚のアルバムをリリースしており、中世およびルネサンス初 期のカスティーリャのレパートリーを専門とするアンサンブル、ダ・テンペラ・ヴェーリャのメンバーでもある。 |

|

Huehuetenango Songs from an Interrupted Songbook In 1932, the American anthropologist and novelist Oliver La Farge published Santa Eulalia: The Religion of a Cuchumatan Indian Town (Guatemala). This book, the result of six months of ethnographic work, detailed various aspects of the cultural and musical life of the inhabitants of Santa Eulalia, a remote town in the Department of Huehuetenango, located in northwestern Guatemala, which at that time still lacked road access. Through his descriptions, it is evident how music was integrated into the daily and spiritual life of these indigenous communities, becoming a symbol of resistance and forced adaptation in the face of Catholicism and other external influences. The richness and complexity of this syncretic heritage are musically reflected in the repertoire of San Miguel de Acatán, a term coined by Robert Stevenson, its first scholar, to refer to a collection of musical manuscripts assembled in this Guatemalan town in 1963. These volumes originated from three small indigenous towns situated in the Chuchumatanes mountain range, the highest range in Central America: Santa Eulalia, San Mateo Ixtatán, and San Juan Ixcoi. The collection, treasured by these communities for centuries, comprises eighteen small-sized choir books. Fifteen of them are housed in the Lilly Library at Indiana University, one in the Princeton University Library, another in the Tulane University Library, and one more in the parish church of Jacaltenango. Recent research by Kristin Haag in the Archive of the Maryknoll Missionaries, who were responsible for transferring the volumes from Huehuetenango to the United States in the 1960s, reveals that the collection originally comprised fifty volumes. While it is true that the collection includes copies of numerous European pieces (French chansons, Italian madrigals, Castilian villancicos, Latin masses, and motets), it also serves as a privileged testimony to the complex and mysterious ways in which European modes were transformed through the minds, hands, and voices of the indigenous people, resulting in original creations. The multifunctional nature of these volumes is reflected in their miscellaneous content: a single book can contain complete masses, motets, and psalms in Latin, villancicos and dances alongside brief fabordones [Fauxbourdon??], Gregorian antiphons, untexted fragments, and a variety of brief responses to diverse religious celebrations. |

ウエウエテナンゴ 途絶えた歌集からの歌 1932年、アメリカの人類学者であり小説家でもあるオリバー・ラ・ファージは『サンタ・エウラリア:グアテマラのクチュマタン・先住民集落の宗教』を出 版した。この本は、6か月にわたる民族誌調査の成果であり、当時まだ道路が整備されていなかったグアテマラ北西部ウエウェテナンゴ県の僻地サンタ・エウラ リアの住民たちの文化と音楽生活の様々な側面を詳述した。彼の記述から、音楽がこれらの先住民コミュニティの日常生活や精神生活にどのように組み込まれ、 カトリックやその他の外部からの影響に対する抵抗と強制的な適応の象徴と なったかが明らかである。この融合的な遺産の豊かさと複雑さは、サン・ ミゲル・デ・アカタンのレパートリーに音楽的に反映されている。この用語は、1963年にグアテマラのこの町で収集された楽譜集を指すために、最初の研究 者ロバート・スティーブンソンによって造語されたものである。これらの楽譜は、中央アメリカ最高峰のクチュマタン山脈に位置する三つの小さな先住民集 落――サンタ・エウラリア、サン・マテオ・イシュタタン、サン・フアン・イシュコイ――に由来する。何世紀にもわたりこれらのコミュニティが大切に守って き たこのコレクションは、18冊の小型合唱譜で構成されている。そのうち15冊はインディアナ大学リリー図書館に所蔵され、1冊はプリンストン大学図書館、 1冊はチューレーン大学図書館、そしてもう1冊はハカルテナンゴの教区教会に保管されている。1960年代にこれらの楽譜をウエウェテナンゴから米国へ移 送 したメリノール宣教師会のアーカイブをクリスティン・ハーグが最近調査したところ、このコレクションは元々50冊で構成されていたことが明らかになっ た。確かにこのコレクションには数多くのヨーロッパ作品(フランス歌曲、イタリアのマドリガル、カスティーリャのヴィリャンシーコ、ラテン語のミサ曲やモ テット)の写本が含まれているが、同時に、ヨーロッパの音楽様式が先住民の知性、手、声を通じて変容し、独自の創造物へと昇華された複雑で神秘的な過程を 特権的に証言する資料でもある。これらの楽譜集の多機能性は、その雑多な内容に反映されている。一冊の本に、ラテン語のミサ曲、モテット、詩篇の完全版 と、ヴィリャンシーコや舞曲、短いフォーブルドン[Fauxbourdon]、グレゴリオ聖歌の対句、歌詞のない断片、様々な宗教的祝祭に対する多様な短い応答曲が混在しているのだ。 |

| The presence of marginalia and syllables with a possible mnemonic function suggests the pedagogical nature of these books, whose notation reflects highly original local practices. Additionally, the codices are noteworthy for offering a concept of an “open” work with traces of orality, as evidenced by ornamentation formulas and diminutions that were generally improvised and not written down. Similarly, there are phonetic alterations, linguistic archaisms, and non-standardized orthographies of the texts. Like the concept of the work, the concept of the composer did not hold the same relevance in the mindset of these indigenous communities as it did in the European world. For this reason, most of the repertoire copied in the books lacks attribution – with the exception of MS 8. Nonetheless, the identified concordances reveal the presence of Spanish composers (Juan de Anchieta, Cristóbal de Morales, Martín de Rivaflecha, Juan Vázquez, Johannes Urrede, Alonso de Ávila, Francisco de Peñalosa, Pedro de Escobar), Franco-Flemish composers (Josquin, Heinrich Isaac, Jean Mouton, Loyset Compère, Tilman Susato), French composers (Claudin de Sermisy), and Italian composers (Sebastiano Festa and Philippe Verdelot). This underlies the high degree of assimilation and the deep circulation of European music in Mesoamerica, both printed and manuscript,. Two local names also emerge in the books: Francisco de León, chapel master in Santa Eulalia, and Tomás Pascual, chapel master in San Juan Ixcoi. The latter has been attributed with the authorship of some villancicos by some researchers. What is beyond doubt is their role as copyists, compilers, and adapters – thus, creators – of a repertoire conceived under special missionary conditions. Due to its unique position in the context of New World musical collections, both for its monumentality – more than 350 works in the Lilly Library books alone – and its transcultural relevance, the repertoire of San Miguel Acatán has been the subject of various recordings since the 1990s. These recordings have tended to emphasize two aspects: the coplas and villancicos in Spanish and native languages (particularly the Mayan K’iche’ and Q’anjob’al dialects) and the use of musical instruments, considering that many of the works lack text (or only have a title or incipit) or have a dance rhythm, suggesting they were meant to be performed by groups of ministriles. The proposal devised by Jonathan Alvarado and Ariel Abramovich, based largely on their own transcriptions, represents an advancement by focusing primarily on works with Latin texts and arranging them for voice and vihuela, a characteristic ensemble of the 16th century not previously used in the interpretation of this Guatemalan repertoire. Furthermore, seven of the works included in this cd [1, 3, 4, 6, 7, 9] are premiere recordings, having never been recorded before, as far as we know. | 余白の注釈や記憶補助機能を持つ可能性のある音節の存在は、これらの書

籍が教育的な性質を持つことを示唆している。その表記法は極めて独創的な地域慣行を反映している。さらに、装飾定式や装飾音符など、一般的に即興で演奏さ

れ書き留められなかった痕跡から明らかなように、口承の痕跡を帯びた「開かれた」作品の概念を提供している点で、これらの写本は注目に値する。同様に、音

韻的変異、言語的古語、非標準的な綴りもテキストに見られる。作品の概念と同様に、作曲家の概念も、これらの先住民コミュニティの思考様式においては、

ヨーロッパ世界ほど重要視されていなかった。このため、写本に写されたレパートリーの大半は、MS

8を除き、作者不明である。それでも特定された一致点からは、スペイン人作曲家(フアン・デ・アンキエタ、クリストバル・デ・モラレス、マルティン・デ・

リバフレチャ、フアン・バスケス、ヨハネス・ウレデ、アロンソ・デ・アビラ、フランシスコ・デ・ペニャロサ、ペドロ・デ・エスコバル)、フランコ・フラン

ドル派作曲家(ジョスカーヌ、ハインリヒ・アイザック、ジャン・ムートン、ロワゼ・コンペール、ティルマン・ズーザート)、

フランス人作曲家(クロダン・ド・セルミジー)、イタリア人作曲家(セバスティアーノ・フェスタ、フィリップ・ヴェルデロット)の存在を明らかにしてい

る。これは、印刷物と写本の両方において、ヨーロッパ音楽がメソアメリカで高度に同化され、深く流通していたことを裏付けている。書物には二人の現地名も

登場する:サンタ・エウラリア礼拝堂の楽長フランシスコ・デ・レオンと、サン・フアン・イクソイ礼拝堂の楽長トマス・パスカルである。後者は一部の研究者

により、いくつかのヴィリャンシーコスの作者とされている。疑いの余地がないのは、彼らが写譜者、編纂者、編曲者――つまり創造者――としての役割を果た

した点だ。これは特別な宣教環境下で構想されたレパートリーにおいて顕著である。新世界音楽コレクションにおける特異な位置付け――リリー図書館所蔵の書

籍だけでも350曲以上という膨大な規模と、異文化間の関連性――ゆえに、サン・ミゲル・アカタンのレパートリーは1990年代以降、様々な録音の対象と

なってきた。これらの録音は主に二つの側面を強調する傾向にある。一つはスペイン語及び先住民言語(特にマヤ語キチェ方言とカンジョバル方言)によるコプ

ラとヴィリャンシーコ、もう一つは楽器の使用である。多くの作品が歌詞を欠く(あるいは題名や冒頭部のみ)か、舞踏リズムを持つことから、ミンストリル集

団による演奏を意図していたと推測されるからだ。ジョナサン・アルバラードとアリエル・アブラモヴィッチが提案した企画は、主に彼ら自身の転写に基づいて

おり、ラテン語の歌詞を持つ作品に焦点を当て、声楽とビウエラ(16世紀の特徴的なアンサンブル楽器)のための編曲を行うことで、グアテマラのレパート

リー解釈において新たな進展をもたらしている。さらに、このCDに収録された7作品[1、3、4、6、7、9]は、我々の知る限りこれまで録音されたこと

がない初録音である。 |

| The

program is structured into three imaginary

sections, with titles that mimic the style of vihuela and voice

publications released in Spain

between 1536 and 1576, many of which contain

repertoire that corresponds with the Guatemalan manuscripts. The idea

is to create an imaginary book for vihuela and voice in three parts,

modern but historically plausible, combining in

each section works taken from the actual manuscripts, listed alongside

the title of each piece.

As the doctrinal priests themselves did in the

16th and 17th centuries, the fragmentary nature

of some works has required various degrees of

adaptation, arrangement, and recreation of the

original material. This can be heard in pieces

such as Virgen, Madre de Dios [1], Deo gratias [7],

and Cananea [13], an anonymous copy of the famous motet Clamabat autem

mulier by Pedro de

Escobar (c. 1485 – after 1535).

The first imagined book includes parts of masses, magnificats, and

prayers for the entrance and

the end of the liturgical celebration. The second

book presents a selection of anonymous fourvoice motets, to which text

has been added that

is not found in the source. One of these, Paratum cor meum [8], is a

contrafactum of Le content

est riche, a very popular Parisian chanson by

Sermisy. The contrapuntal complexity of some

works reflects the interpretative level achieved

by the musicians of these communities, despite

not being professionals. The third book compiles various works in

vernacular languages,

some of which are contrafacta of recently identified European works:

Salamanca [14] is a concordance of the chanson Amy souffrez by Pierre

Moulu or Sermisy; Mulier quit ploras [17] corresponds to the

three-voice song Puse mis amores en

Fernandino by Juan Vázquez, while the Romance

[18] that opens ms 2 is, in reality, De Antequera

sale el moro, attributed to Cristóbal de Morales

by Miguel de Fuenllana in Orphénica Lyra (1554).

The musical collection of Huehuetenango is the

result of several interruptions: European colonization interrupted the

history of native communities, while the original artistic production

interrupted the European monopoly in Renaissance musical history. Over

time, the missionary

activity of these doctrines was also interrupted,

forever changing the place and function of these

manuscripts. Through the eclectic selection offered by this imagined

songbook, these invisible lines are revealed in which local production

and arrangement acquire the same relevance as

foreign works. This celebrates the sensitivity of

local composers and compilers and their ability

not only to receive and preserve knowledge –

which is no small feat – but also to contribute

creations of unique transcultural value within

the musical context of their time.

Javier Marín-López |

このプログラムは三つの架空のセクションで構成されている。各セクショ

ンのタイトルは、1536年から1576年の間にスペインで出版されたビウエラと声楽の楽譜の様式を模倣したもので、その多くはグアテマラ写本に対応する

レパートリーを含んでいる。現代的でありながら歴史的に妥当な、三部構成の架空のビウエラと声楽の楽譜集を創り出すという発想だ。各セクションでは実際の

写本から採った作品を組み合わせ、各曲のタイトルと共にリストアップしている。16世紀から17世紀にかけて教義学者たちが実際に行ったように、断片的な

性質を持つ作品については、様々な程度の適応、編曲、そして原資料の再構築が必要となった。このことは、例えば『聖母マリア、神の母』[1]、『神に感

謝』[7]、『カナネア』[13](ペドロ・デ・エスコバル(1485年頃 -

1535年以降)の有名なモテット『クラマバット・アウテム・ムリエール』の匿名写本)などの作品で聴き取れる。第一の想像上の書には、ミサ曲、マニフィ

カト、典礼の開始と終了のための祈りの一部が含まれている。第二の書は、匿名作の四声モテットの選集を提示しており、これには原典には見られない歌詞が追

加されている。その一つ『Paratum cor meum』[8]は、セルミシーの非常に人気のあるパリのシャンソン『Le content est

riche』のコントラファクトゥムである。一部作品の対位法的な複雑さは、プロではないにもかかわらず、これらの共同体の音楽家たちが到達した演奏水準

を反映している。第三の書は諸言語による様々な作品を収録しており、その中には最近特定されたヨーロッパ作品のコントラファクトゥムも含まれる:サラマン

カ[14]はピエール・ムルーあるいはセルミシーのシャンソン『Amy souffrez』のコンコルダンスである。『Mulier quit

ploras』[17]はフアン・バスケスの三声歌曲『Puse mis amores en

Fernandino』に対応し、写本2の冒頭を飾る『ロマンス』[18]は、実際にはミゲル・デ・フエンジャナが『オルフェニカ・リラ』(1554年)

でクリストバル・デ・モラレス作と記した『De Antequera sale el

moro』である。ウエウェテナンゴの音楽コレクションは幾度もの中断の産物である。ヨーロッパの植民地化は先住民コミュニティの歴史を断ち切り、一方、

固有の芸術的創造はルネサンス音楽史におけるヨーロッパの独占を断ち切った。時を経て、これらの教会の宣教活動もまた中断され、これらの写本の位置づけと

機能は永遠に変化した。この想像上の歌集が提示する折衷的な選曲を通じて、現地の制作と編曲が外国の作品と同等の重要性を獲得する、見えざる線が明らかに

なる。これは現地の作曲家や編纂者の感性を称えるものであり、彼らが知識を受け入れ保存する能力(これは決して小さな功績ではない)だけでなく、当時の音

楽的文脈において独自のトランスカルチュラルな価値を持つ創作を貢献する能力をも示している。 ハビエル・マリン=ロペス |

☆

| Jonatan Alvarado tenor Ariel Abramovich vihuela in G (Martin Haycock, 2011) vihuela in A (Francisco Hervás, 2021) |

Jonatan Alvarado tenor Ariel Abramovich vihuela in G (Martin Haycock, 2011) vihuela in A (Francisco Hervás, 2021) |

| Primer Libro En el qual se ponen algunas partes de misas, un magnificat y otras cosas para cantar tenor. In which are set certain parts of masses, a magnificat, and other things to sing the tenor. 1 Virgen Madre de Dios* 1:33 Ms. 7, f. 5r with tenor and superius voices recreated by Jonatan Alvarado 2 Introito: ‘Salve Sancta Parens’ 1:18 Kyriale Ms. 11 ff. 13v - 14r. 3 Kyrie eleison* 2:41 Ms. 8, ff. 8v - 9r 4 Pleni sunt [de la Misa sine nomine]* 1:47 Ms. 1, ff. 14v - 15r 5 Antiphona ad Magnificat: ‘Gloriose Virginis’ 1:07 Antifonario Ms. 13 f. 7v 6 Magnificat 8 toni* 6:47 Ms. 2, ff. 15v - 17r 7 Benedicamus Domino* 1:24 Ms. 3, ff. 33v - 34r / Ms. 5, f. 23v; ff. 31v - 32r Deo Gratias Ms. 8, ff. 27v - 28r, recreated by Jonatan Alvarado over the extant fabordón ‘Primeros Donos |

Segundo Libro El cual contiene motetes a cuatro de muy excelentes autores Which contains motets for four voices, by most excellent authors. 8 Paratum cor meum [Claudin de Sermisy ‘Le content est riche’] 2:01 Ms. 8, ff. 48v - 49r 9 Pater Noster* 3:55 Ms. 8, ff. 61v - 62r 10 Hic solus [dolores nostros] 3:23 Ms. 8, ff. 21v - 22r / Susato, ‘Ecclesiasticarum cantionum’, liber 2 f. ix 11 Agnus Dei [Cristobal de Morales from ‘Missa La Caça’] 1:16 Ms. 8, ff. 18v-20r 12 O bone Jesu [Juan de Anchieta] 2:33 Ms. 8, ff. 58v - 59r / ‘Cancioneiro de Lisboa’, ff. 14v - 16r 13 Cananea [Pedro de Escobar: ‘Clamabat autem mulier cananea’] 4:03 Ms. 8, ff. 18v - 19r; 56v - 57r / Ms. 9, ff. 12v - 13r / Biblioteca Geral da Universidade de Coimbra, MM 12, ff. 193v - 194r With a si placet line by Jonatan Alvarado. |

| Tercer Libro El cual contiene un estrambote y un romance viejo a cuatro; villancicos a tres y a cuatro en letra castellana, assi mismo una canción en lengua francesa para tañer Which contains a strambotto and an old romance, both for four voices; villancicos for three and four voices in the Castilian tongue, as well as a song in the French tongue, to be played. 14 Salamanca [Pierre Moulu (?) ‘Amy souffrez’] 1:27 Ms. 8, ff. 30v - 31r 15 Edmini [Sebastiano Festa ‘Amor che mi tormenti’] 2:26 Ms. 8, ff. 36v - 37r / Museo Internazionale e Biblioteca della Musica di Bologna, Ms. Q.21, ff. 35r - 35v. 16 ¿Con qué la lavaré? [Juan Vasquez ‘Morraleos’] 3:54 Ms. 8, ff. 51v - 52r / Juan Vásquez ‘Villancicos y Canciones a Cuatro Voces’, ff. 30v 17 Mulier quit ploras [Juan Vasquez ‘Puse mis amores en Fernandino’] 1:37 Ms. 8, ff. 21v - 22r / ‘Villancicos y Canciones de Juan Vasques a Tres y a Cuatro’, ff. Biii r-v 18 Romance [‘De Antequera sale el moro’] 3:01 Ms. 2, ff. 1v - 2r / Text from Martín Nucio; ‘Cancionero de Romances’ ff. 189v - 191r 19 Dame acojida en tu hato 2:11 Ms. 4, ff. 21v - 22r / ‘Cancioneiro de Belem’, ff. 66v / Esteban Daza ‘El Parnaso’, f. 96v - 97r * Premiere recordings Editions by Jonatan Alvarado except nos. 4 and 6, made by Richard O. Garven and Paul Borg respectively. Intabulations made by Ariel Abramovich except nr. 19, from “El Parnasso” by Esteban Daza. Assistance on historical Castillian pronunciation by Dra. Lola Pons. |

|

| 1 Virgen Madre de Dios Virgen Señora, vos Cosa soberana [estrella de la mañana Ruega por nos a Dios] Virgen Señora, vos. 2 Salve Sancta Parens, enixa puerpera regem. Qui caelum terramque regit in saecula saeculorum. 3 Kyrie eleison Christe eleison Kyrie eleison 5 Gloriose Virginis Mariae conceptionem; dignisimam recolamus que et genitris dignitatem obtinuit et virginalem pudicitiam nona misit. 6 Magnificat anima mea Dominum; Et exultavit spiritus meus in Deo salutari meo, Quia respexit humilitatem ancillae suae; ecce enim ex hoc beatam me dicent omnes generationes. Quia fecit mihi magna qui potens est, et sanctum nomen ejus, Et misericordia ejus a progenie in progenies timentibus eum. Virgin, Mother of God, Virgin and Lady you are. Sovereign thing Morning star. Pray for us to God, Virgin and Lady you are. Hail, Holy Mother, who in childbirth brought forth the King who rules heaven and earth forevermore. God have mercy Christ have mercy God have mercy Let’s commemorate the most dignified conception of the glorious Virgin Mary, who obtained the dignity of the procreator without losing her virginal purity. My soul doth magnify the Lord, and my spirit hath rejoiced in God my Saviour. For he hath regarded the low estate of his handmaiden: for, behold, from henceforth all generations shall call me blessed. For he that is mighty hath done to me great things; and holy is his name. And his mercy is on them that fear him from generation to generation. Fecit potentiam in bracchio suo; Dispersit superbos mente cordis sui. Deposuit potentes de sede, et exaltavit humiles. Esurientes implevit bonis, et divites dimisit inanes. Suscepit Israel, puerum suum, recordatus misericordiae suae, Sicut locutus est ad patres nostros, Abraham et semini ejus in saecula. Gloria Patri, et Filio, et Spiritui Sancto, sicut erat in principio, et nunc, et semper: et in Saecula saeculorum. Amen. 7 Benedicamus Dominum Deo gratias 8 Paratum cor meum, Deus Paratum cor meum. Exurge gloria mea, exurge psalterium et cithara, exurgam diluculo. 9 Pater Noster, qui es in caelis, sanctificetur nomen tuum. Adveniat regnum tuum. Fiat voluntas tua, sicut in caelo et in terra. Panem nostrum quotidianum da nobis hodie, et dimitte nobis debita nostra He hath shewed strength with his arm; he hath scattered the proud in the imagination of their hearts. He hath put down the mighty from their seats, and exalted them of low degree. He hath filled the hungry with good things; and the rich he hath sent empty away. He hath holpen his servant Israel, in remembrance of his mercy; As he spake to our fathers, to Abraham, and to his seed for ever. Glory be to the Father, and to the Son: and to the Holy Ghost; As it was in the beginning, is now, and ever shall be: world without end. Amen. Let us bless the Lord. Let us give thanks to God. My heart is ready, God, my heart is ready. Awake, my glory Awake, harp and lyre! I will awaken the dawn. Our Father, which art in heaven, hallowed be thy name; thy kingdom come; thy will be done, in earth as it is in heaven. Give us this day our daily bread. And forgive us our trespasses, |

sicut et nos dimittimus

debitoribus nostris. Et ne nos inducas in tentationem, sed libera nos a malo. Amen. 10 Hic solus dolores nostros tulit et languores hic solus portavit. Venite et videte coeli Rex Christus quare pependit in cruce, solus hic dolores nostros tulit. 12 O bone Jesu! Illumina oculos meos, nequando dicat inimicus meus praevalui adversus eum. In manus tuas, Domine, commendo spiritum meum; redemisti me, Domine, Deus veritatis. O Messias! Locutus sum in lingua mea, notum fac mihi domine finem meum. 13 Clamabat autem mulier channanea ad Dominum Jesum, dicens: Domine Jesu Christe, fili David, adiuva me; filia mea male a demonio vexatur. Respondens Jesus Christus Dominus dixit: Non sum missus nisi ad oves quae perierunt domus Israel. At illa venit et adoravit eum dicens: Domine, adiuva me. Respondens Jesus ait illi: Mulier, magna est fides tua, fiat tibi sicut vis. as we forgive them that trespass against us. And lead us not into temptation; but deliver us from evil. Amen. He alone bore our sorrows and our weaknesses. Come and see how Christ, the king of Heaven, hangs on the cross. He alone bore our sorrows. O good Jesus! Illuminate my eyes, lest my enemy say that I prevailed against him. O Lord! Into thy hands, Lord, do I commend my spirit; thou hast redeemed me, Lord, God of truth. O Messiah, I have spoken: let me know my end. But the Canaanite woman cried out to the Lord Jesus, saying: “Lord Jesus Christ, Son of David, help me; my daughter is badly tormented by a demon.” Jesus Christ the Lord answered and said: “I was not sent except to the lost sheep of the house of Israel. ” But she came and worshiped Him, saying: “Lord, help me. Jesus answered her and said: “Woman, great is your faith; let it be done for you as you wish.” 15 Amor che mi tormenti e m’appresenti il bel sguardo soave di quella che di me pietà non have. Perché non mostri a lei sì spesso il foco che mi consum’il core, com’a me mostri sua beltà infinita? Forse che saperria che cos’è amore e come si sottragge poco a poco un che lontan’ dalla speranza mia. Ah, dura sorte mia! Madonna non mi cura e certo vede che altro non regna in me ch’amore e fede. 16 ¿Con qué la lavaré la tez de la mi cara? ¿Con qué la lavaré que vivo mal penada...? Lávanse las casadas con agua de limones. Lávome yo, cuitada, con ansias y pasiones. Mi gran blancura y tez las tengo ya gastadas. ¿Con qué la lavaré, que vivo mal penada…? 17 Puse mis amores en Fernandillo ¡Ay, que era casado! ¡Mal me ha mentido! Love, you who torment me and present to me the sweet gaze of the one who has no pity for me. Why do you not show her as often the fire that consumes my heart, as you show me her infinite beauty? Perhaps she would know what love is and how little by little one withdraws far from my hope. Ah, my hard fate! My Lady does not care for me and surely sees that nothing else reigns in me but love and faith. With what shall I wash the complexion of my face? With what shall I wash it, as I live in deep sorrow...? Married women wash themselves with lemon water. I, wretched one, wash myself with anxieties and passions. My great fairness and complexion are already worn out. With what shall I wash it, as I live in deep sorrow...? I gave my love to Fernandillo. Alas! He was married! He has lied to me badly |

| Digas marinero del cuerpo garrido: ¿En cuál de aquellas naves pasa Fernadillo? ¡Ay, que era casado! ¡Mal me ha mentido! 18 De Antequera partió el moro De Antequera aquesa villa: con cartas en la su mano en que socorro pedía. Escritas iban con sangre, y no por falta de tinta. El moro que las llevaba Ciento y veinte años tenía. “Oh, gran Rey, si tú supieses mi triste mensajería, mesarías tus cabellos y la tu barba vellida”. 19 Dame acojida en tu hato, Buen pastor, que Dios te duela. Cata, que en el monte hiela. Esta noche en tu cabaña acoge al triste cuitado, que, de amores lastimado, sospira por la montaña. Mira que el tiempo se ensaña: duélete – Que Dios te duela. Cata, que en el monte hiela. Tell me, sailor with a strong body, in which of those ships goes Fernandillo? Alas! He was married! He has lied to me badly! From Antequera the Moor rode out, From Antequera, that town: with letters in his hand in which he asked for help. They were written with blood. and not for lack of ink. The Moor who carried them was a hundred and twenty years old. “Oh, great King, if you knew my sad message, you would tear your hair and your thick beard.” Give me shelter in your hut, good shepherd, may God have pity on you. Go away, that it is freezing in the mountain. Tonight, in your hut, welcome the sad and worried, that, wounded with love, sighs in the mountains. Look, the weather is enraging, take pity – may God have pity on you. Go away, that it is freezing in the mountain. Recording: Chiesa ed ex Convento di San Francesco, Orte (Italy), 30 March – 2 April 2024 Recording producer: Edoardo Lambertenghi Executive producer: Ariel Abramovich, Michael Sawall (note 1 music) Layout & booklet editor: Joachim Berenbold Translations: Mark Wiggins (English), Pierre Elie Mamou (français), Joachim Berenbold (deutsch) Design: Mónica Parra Artist photos: Albirú Muriel Photography π + © 2024 note 1 music gmbh, Heidelberg, Germany CD manufactured in the Netherlands Dedicated to Martina Zolezzi, for all her support and love Ariel Abramovich Dedicated to Nuno, for his presence as unconditional as it is essential, and the constant inspiration through the years. To Felipe, for his calm companionship, his warm smile and affectionate eyes. To Juan Pablo for his passion and his absolute dedication in both life and art. To Flor, Juan, Gabriel, and Emilio for their attentive listening. Jonatan Alvarado We would like to thank Nell Snaidas and Sebastian Zubieta, co-directors of the GEMAS series of the Gotham Early Music Scene and the Americas Society, for giving us the opportunity and providing us with the resources to create this program. To Beatriz Fontan, Samuel Diz, and the team of Música No Claustro for creating it with us and helping it to walk for the first time. Dr. Paul W. Borg for his invaluable study and catalog of the Huehu |

ウェウェテナンゴ・ソングブック~16世紀グアテマラからの音楽(アルヴァラド/アブラオヴィチ) HUEHUETENANGO SONGBOOK (THE) - Music from 16th Century Guatemala (Alvarado, Abramovich) このページのURLhttps://ml.naxos.jp/album/GCD923542 全トラック選択/解除 不詳 - Anonymous **:**ヴィルゲン・マドレ・デ・ディオス(ウェウェテナンゴ・ソングブック、グアテマラ北部、1582-1635)(J. アルバラドによる声とビウエラ編) Virgen Madre de Dios [Huehuetenango Songbook, Northern Guatemala, 1582-1635] (arr. J. Alvarado for voice and vihuela) 作詞 : 不詳 - Anonymous 編曲 : ジョナタン・アルヴァラド - Jonatan Alvarado ジョナタン・アルヴァラド - Jonatan Alvarado (テノール) アリエル・アブラモビチ - Ariel Abramovich (ビウエラ) 録音: 30 March - 2 April 2024, Chiesa ed ex Convento di San Francesco, Orte, Italy この作品のURLhttps://ml.naxos.jp/work/10793058 **:** » Virgen Madre de Dios [Huehuetenango Songbook, Northern Guatemala, 1582-1635] (arr. J. Alvarado for voice and vihuela) 1. - **:**めでたし、聖なる産みの母(入祭唱、ウェウェテナンゴ・ソングブック、グアテマラ北部、1582-1635)2. Salve Sancta Parens [Introit, Huehuetenango Songbook, Northern Guatemala, 1582-1635] 作詞 : 不詳 - Anonymous ジョナタン・アルヴァラド - Jonatan Alvarado (テノール) 録音: 30 March - 2 April 2024, Chiesa ed ex Convento di San Francesco, Orte, Italy この作品のURLhttps://ml.naxos.jp/work/10793059 **:**キリエ・エレイソン(ウェウェテナンゴ・ソングブック、グアテマラ北部、1582-1635)3. Kyrie eleison [Huehuetenango Songbook, Northern Guatemala, 1582-1635] 作詞 : ミサ典礼文 - Mass Text ジョナタン・アルヴァラド - Jonatan Alvarado (テノール) アリエル・アブラモビチ - Ariel Abramovich (ビウエラ) 録音: 30 March - 2 April 2024, Chiesa ed ex Convento di San Francesco, Orte, Italy この作品のURLhttps://ml.naxos.jp/work/10793060 **:**ミサ・シネ・ノミネ - 主の栄光は天地に満つ(ウェウェテナンゴ・ソングブック、グアテマラ北部、1582-1635)4. Misa sine nomine: Pleni sunt [Huehuetenango Songbook, Northern Guatemala, 1582-1635] アリエル・アブラモビチ - Ariel Abramovich (ビウエラ) 録音: 30 March - 2 April 2024, Chiesa ed ex Convento di San Francesco, Orte, Italy この作品のURLhttps://ml.naxos.jp/work/10793061 **:**栄光に満てる聖母(マニフィカトへのアンティフォナ、ウェウェテナンゴ・ソングブック、グアテマラ北部、1582-1635)5. Gloriose Virginis [Antiphona ad Magnificat, Huehuetenango Songbook, Northern Guatemala, 1582-1635] 作詞 : 不詳 - Anonymous ジョナタン・アルヴァラド - Jonatan Alvarado (テノール) 録音: 30 March - 2 April 2024, Chiesa ed ex Convento di San Francesco, Orte, Italy この作品のURLhttps://ml.naxos.jp/work/10793062 **:**8声のマニフィカト(マニフィカトへのアンティフォナ、ウェウェテナンゴ・ソングブック、グアテマラ北部、1582-1635)6. Magnificat 8 toni [Antiphona ad Magnificat, Huehuetenango Songbook, Northern Guatemala, 1582-1635] 作詞 : 新約聖書 - Bible - New Testament ジョナタン・アルヴァラド - Jonatan Alvarado (テノール) アリエル・アブラモビチ - Ariel Abramovich (ビウエラ) 録音: 30 March - 2 April 2024, Chiesa ed ex Convento di San Francesco, Orte, Italy この作品のURLhttps://ml.naxos.jp/work/10793063 **:**主を賛美せよ - 神に感謝せん(マニフィカトへのアンティフォナ、ウェウェテナンゴ・ソングブック、グアテマラ北部、1582-1635)(J. アルバラドによる声とビウエラ編) Benedicamus Domino - Deo Gratias [Antiphona ad Magnificat, Huehuetenango Songbook, Northern Guatemala, 1582-1635] (arr. J. Alvarado for voice and vihuela) 作詞 : 不詳 - Anonymous 編曲 : ジョナタン・アルヴァラド - Jonatan Alvarado ジョナタン・アルヴァラド - Jonatan Alvarado (テノール) アリエル・アブラモビチ - Ariel Abramovich (ビウエラ) 録音: 30 March - 2 April 2024, Chiesa ed ex Convento di San Francesco, Orte, Italy この作品のURLhttps://ml.naxos.jp/work/10793064 **:** » Benedicamus Domino - Deo Gratias [Antiphona ad Magnificat, Huehuetenango Songbook, Northern Guatemala, 1582-1635] (arr. J. Alvarado for voice and vihuela) 7. - **:**わが心は決意したり(C. ド・セルミジの「Le contente est riche」による)(ウェウェテナンゴ・ソングブック、グアテマラ北部、1582-1635) Paratum cor meum (after. C. de Sermisy's Le contente est riche) [Huehuetenango Songbook, Northern Guatemala, 1582-1635] 作詞 : 不詳 - Anonymous ジョナタン・アルヴァラド - Jonatan Alvarado (テノール) アリエル・アブラモビチ - Ariel Abramovich (ビウエラ) 録音: 30 March - 2 April 2024, Chiesa ed ex Convento di San Francesco, Orte, Italy この作品のURLhttps://ml.naxos.jp/work/10793065 **:** » Paratum cor meum (after. C. de Sermisy's Le contente est riche) [Huehuetenango Songbook, Northern Guatemala, 1582-1635] 8. - **:**天にましますわれらの父よ(マニフィカトへのアンティフォナ、ウェウェテナンゴ・ソングブック、グアテマラ北部、1582-1635)9. Pater Noster [Antiphona ad Magnificat, Huehuetenango Songbook, Northern Guatemala, 1582-1635] 作詞 : 新約聖書 - Bible - New Testament ジョナタン・アルヴァラド - Jonatan Alvarado (テノール) アリエル・アブラモビチ - Ariel Abramovich (ビウエラ) 録音: 30 March - 2 April 2024, Chiesa ed ex Convento di San Francesco, Orte, Italy この作品のURLhttps://ml.naxos.jp/work/10793066 **:**Hic solus (dolores nostros) [Huehuetenango Songbook, Northern Guatemala, 1582-1635] 作詞 : 不詳 - Anonymous ジョナタン・アルヴァラド - Jonatan Alvarado (テノール) アリエル・アブラモビチ - Ariel Abramovich (ビウエラ) 録音: 30 March - 2 April 2024, Chiesa ed ex Convento di San Francesco, Orte, Italy この作品のURLhttps://ml.naxos.jp/work/10793067 **:** » Hic solus (dolores nostros) [Huehuetenango Songbook, Northern Guatemala, 1582-1635] 10. - クリストバル・ド・モラレス - Cristóbal de Morales (1500-1553) **:**Missa La Caça: Agnus Dei (arr. for vihuela)11. 編曲 : 不詳 - Anonymous アリエル・アブラモビチ - Ariel Abramovich (ビウエラ) 録音: 30 March - 2 April 2024, Chiesa ed ex Convento di San Francesco, Orte, Italy この作品のURLhttps://ml.naxos.jp/work/10793068 フアン・デ・アンチエタ - Juan de Anchieta (1462-1523) **:**おお、慈悲深きイエス12. O bone Jesu 作詞 : 旧約聖書 - Bible - Old Testament ジョナタン・アルヴァラド - Jonatan Alvarado (テノール) アリエル・アブラモビチ - Ariel Abramovich (ビウエラ) 録音: 30 March - 2 April 2024, Chiesa ed ex Convento di San Francesco, Orte, Italy この作品のURLhttps://ml.naxos.jp/work/10793069 不詳 - Anonymous **:**カナネア(P. デ・エスコバルの「しかし彼女は神に向かって呼ぶ」による) Cananea (after. P. de Escobar's Clamabat autem mulier cananea) 作詞 : 新約聖書 - Bible - New Testament ジョナタン・アルヴァラド - Jonatan Alvarado (テノール) アリエル・アブラモビチ - Ariel Abramovich (ビウエラ) 録音: 30 March - 2 April 2024, Chiesa ed ex Convento di San Francesco, Orte, Italy この作品のURLhttps://ml.naxos.jp/work/10793070 **:** » Cananea (after. P. de Escobar's Clamabat autem mulier cananea) |

| https://ml.naxos.jp/album/GCD923542 |

|

★ ウェウェテナンゴ

| Huehuetenango

(Spanish pronunciation: [w̝e.we.t̪eˈnãŋ.ɡo]) is one of the 22

departments of Guatemala. It is located in the western highlands and

shares the borders with the Mexican state of Chiapas in the north and

west; with El Quiché in the east, and Totonicapán, Quetzaltenango and

San Marcos in the south. The capital is the city of Huehuetenango.[2] Huehuetenango's ethnic composition is one of the most diverse in Guatemala. While the Mam are predominant in the department, other Maya groups are the Q'anjob'al, Chuj, Jakaltek, Tektik, Awakatek, Chalchitek, Akatek and K'iche'. Each of these nine Maya ethnic groups speaks its own language.[3][4] |

ウエウェテナンゴ(スペイン語発音:

[w̝e.we.t̪eˈnãŋ.ɡo])はグアテマラの22の県の一つだ。西部の高地に位置し、北と西はメキシコのチアパス州と、東はエルキチェ県と、

南はトトニカパン県、ケツァルテナンゴ県、サンマルコス県と国境を接している。州都はウエウェテナンゴ市である。[2] ウエウェテナンゴの民族構成はグアテマラで最も多様である。マム族が州内で優勢だが、他のマヤ系民族としてカンホバル族、チュイ族、ハカルテク族、テクト ク族、アワカテク族、チャルチテク族、アカテク族、キチェ族が存在する。これら9つのマヤ系民族はそれぞれ独自の言語を話す。[3][4] |

| Name The department of Huehuetenango takes its name from the city of the same name which serves as the departmental capital. The name derives from the Nahuatl language of central Mexico, given by the indigenous allies of the Spanish conquistadors during the Spanish Conquest of Guatemala. It is usually said to mean "place of the elders", but it may also mean a "place of the ahuehuete trees".[5] |

名称 ウエウェテナンゴ県は、県都である同名の都市に由来する名称である。この名称は、グアテマラ征服時にスペイン征服者たちの同盟者であった先住民が用いた、 メキシコ中央部のナワトル語に由来する。一般に「長老たちの場所」を意味するとされるが、「アウエウエテの木々の場所」を意味する可能性もある。[5] |

| Geography Bridge over the San Juan River near its source which is one of the principal tourist attractions in the department. Huehuetenango covers an area of 7,403 square kilometres (2,858 sq mi) in western Guatemala and is bordered on the north and west by Mexico. On the east side it is bordered by the department of El Quiché and on the south by the departments of Totonicapán, Quetzaltenango and San Marcos.[6] The department encompasses almost the entire length of the Sierra de los Cuchumatanes mountain range, although there is a wide difference in altitude across the department, from heights of 3,352 metres (10,997 ft) above mean sea level to as low as 300 metres (980 ft) above sea level, encompassing an equally wide variation in local climate, ranging from mountain peaks where the temperature sometimes falls below freezing to tropical lowland rainforest.[7] The department possesses various rivers that flow into the Chixoy River, also known as the Río Negro, which flows into the system of rivers forming the drainage basin of the Usumacinta River, which empties into the Gulf of Mexico. The most important tributaries of the Chixoy in Huehuetenango are the Hondo and Xecunabaj rivers, which flow into the department from the neighbouring departments of El Quiché and Totonicapán.[8] The Cuilco River enters the department from neighbouring San Marcos and crosses into the Mexican state of Chiapas, where it joins with the Grijalva River, which empties into the Gulf of Mexico. Its most important tributaries in Huehuetenango are the Apal, Chomá and Coxtón rivers.[8] The Ixcán River has its source near Santa Cruz Barillas and flows northwards towards Mexico where it joins the Lacuntún River, a tributary of the Usumacinta.[9] The Nentón River is formed in the municipality of San Sebastián Coatán by the joining of the rivers Nupxuptenam and Jajaniguán. It flows westwards across the border into Mexico where it empties into the Presa de la Angostura reservoir.[10] The Selegua River has its source in the Sierra de los Cuchumatanes and flows northwards, crossing the border into Chiapas, where it joins the Cuilco River to form the Grijalva River, to flow onwards to the Gulf of Mexico. Its principal tributaries are the Pino, Sibilá, Ocubilá, Naranjo, Colorado, Torlón, Mapá and Chicol rivers.[11] The largest body of standing water in the department is Laguna Yolnabaj, in the extreme north, close to the border with Mexico. Smaller lakes include Laguna Maxbal, Laguna Yolhuitz, and Laguna Seca, all in the northeast of the department.[2] |

地理 サン・フアン川上流付近の橋は、この県を代表する観光名所の一つである。 ウエウェテナンゴ県はグアテマラ西部に位置し、面積は7,403平方キロメートル(2,858平方マイル)である。北と西はメキシコと国境を接する。東側 はエルキチェ県、南側はトトニカパン県、ケツァルテナンゴ県、サンマルコス県と接している。この県はシエラ・デ・ロス・クチュマタネス山脈のほぼ全域を包 含しているが、県内では標高に大きな差がある。平均海抜3,352メートル (10,997フィート)から海抜300メートル(980フィート)までの広範囲に及ぶ。これに伴い、気候も山岳地帯の氷点下から熱帯低地の熱帯雨林まで 多様に変化する。[7] この県にはチクソイ川(別名リオ・ネグロ)に注ぐ複数の河川が存在する。チクソイ川はウスマシンタ川流域を構成する河川系に流れ込み、メキシコ湾に注ぐ。 ウエウェテナンゴ県内でチクソイ川の主要な支流は、隣接するエルキチェ県およびトトニカパン県から県内へ流入するホンド川とセクナバハ川である。[8] クイルコ川は隣接するサンマルコス県から流入し、メキシコ・チアパス州へ流れ込む。同州でグリハルバ川と合流し、メキシコ湾へ注ぐ。ウエウェテナンゴ県内 の主要な支流はアパル川、チョマ川、コストン川である。[8] イクサン川はサンタ・クルス・バリジャス付近を源流とし、北へ流れメキシコへ向かう。そこでラクントゥン川と合流する。ラクントゥン川はウスマシンタ川の 支流である。[9] ネントン川はサン・セバスティアン・コアタン自治体でヌプシュプテナム川とハハニグアン川が合流して形成される。西へ流れ国境を越え、メキシコ国内でプレ サ・デ・ラ・アングストゥーラ貯水池に注ぐ。[10] セレグア川はシエラ・デ・ロス・クチュマタネス山脈を源流とし、北へ流れ国境を越えてチアパス州に入る。そこでクイコ川と合流しグリハルバ川を形成、メキ シコ湾へ注ぐ。主な支流はピノ川、シビラ川、オクビラ川、ナランホ川、コロラド川、トルロン川、マパ川、チコル川である。[11] この州で最大の停滞水域は、最北端のメキシコ国境近くにあるヨルナバジ湖である。小規模な湖としては、州北東部に位置するマックスバル湖、ヨルウィッツ 湖、セカ湖がある。[2] |

Population San Mateo Ixtatán. In 2018 the department was recorded as having 1,170,669 inhabitants.[1] Over 70% of the population are estimated to be living in poverty, with 22% living in extreme poverty and are unable to meet basic necessities.[12] The majority of the population (variously estimated at 64–75%) belongs to indigenous Maya groups with the remainder being Spanish-speaking Ladinos. The Ladinos tend to be concentrated in towns and villages including Huehuetenango, Cuilco, Chiantla, Malacatancito, La Libertad, San Antonio Huista and La Democracia, which have a relatively low indigenous population. In the rest of the department, the Maya groups make up the majority of the population as much in the towns as the countryside.[13] Huehuetenango has the greatest number of Mam Maya in Guatemala, although there are also Mam speakers in the departments of Quetzaltenango and San Marcos, and in the Mexican state of Chiapas.[14] In 2008, 58% of the population of the department was aged 19 years or younger.[15] |

人口 サン・マテオ・イスタタン。 2018年時点で、この県の人口は1,170,669人と記録されている。[1] 人口の70%以上が貧困状態にあると推定され、そのうち22%は極度の貧困状態にあり、基本的な生活必需品すら満たせない状況だ。[12] 人口の大半(推定64~75%)は先住民族マヤ系集団に属し、残りはスペイン語を話すラディーノである。ラディーノは、先住民人口が比較的少ないウエウェ テナンゴ、クイコ、チャンタ、マラカタンシト、ラ・リベルタ、サン・アントニオ・ウイスタ、ラ・デモクラシアなどの町や村に集中している傾向がある。州の その他の地域では、町でも田舎でも、マヤ系集団が人口の大半を占めている。[13] グアテマラ国内でマム・マヤ族が最も多く居住するのはウエウェテナンゴ県だが、ケツァルテナンゴ県やサンマルコス県、メキシコのチアパス州にもマム語話者 が存在する。[14] 2008年時点で、県内人口の58%が19歳以下であった。[15] |

| History Early history  The Maya ruins of Zaculeu, near Huehuetenango city The area had been occupied by the Maya civilization since at least the Mesoamerican Early Classic Period.[16] At the time of the Spanish Conquest, the Maya city of Zaculeu was the initial focus of Spanish attention in the region that would later become the department of Huehuetenango. The city was defended by the Mam king Kayb'il B'alam; in 1525 it was attacked by Gonzalo de Alvarado y Chávez, cousin of Conquistador Pedro de Alvarado.[17] After a siege lasting several months the Mam were reduced to starvation and Kayb'il B'alam finally surrendered the city to the Spanish.[18] Four years after the Spanish conquest of Huehuetenango, in 1529, San Mateo Ixtatán, Santa Eulalia and Jacaltenango were given in encomienda to the conquistador Gonzalo de Ovalle, a companion of Pedro de Alvarado.[19] In 1684, a council led by Enrique Enriquez de Guzmán, then governor of Guatemala, decided upon the reduction of San Mateo Ixtatán and nearby Santa Eulalia, both within the colonial administrative district of the Corregimiento of Huehuetenango.[20] On 2 February 1838, Huehuetenango joined with Quetzaltenango, El Quiché, Retalhuleu, San Marcos and Totonicapán to form the short-lived Central American state of Los Altos. The state was crushed in 1840 by general Rafael Carrera Turcios, at that time between periods in office as Guatemalan president.[21] Huehuetenango includes pre-Columbian Maya archaeological sites at Zaculeu, Chalchitán, Mojá and San Mateo Ixtatán.[22] |

歴史 初期の歴史  ウエウェテナンゴ市近郊のサクレウのマヤ遺跡 この地域は少なくともメソアメリカ古典前期からマヤ文明によって占領されていた。[16] スペイン征服の時代、マヤ都市サクレウは後にウエウェテナンゴ県となる地域におけるスペインの最初の注目点であった。この都市はマム族の王カイビル・バラ ムによって守られていたが、1525年に征服者ペドロ・デ・アルバラードの従兄弟であるゴンサロ・デ・アルバラード・イ・チャベスによって攻撃を受けた [17]。数ヶ月に及ぶ包囲戦の末、マム族は飢餓状態に追い込まれ、カイビル・バラムはついに都市をスペイン軍に降伏した。[18] スペインによるウエウェテナンゴ征服から4年後の1529年、サン・マテオ・イスタタン、サンタ・エウラリア、ハカルテナンゴは、ペドロ・デ・アルバラー ドの仲間である征服者ゴンサロ・デ・オバジェにエンコミエンダとして与えられた。[19] 1684年、当時グアテマラ総督であったエンリケ・エンリケス・デ・グスマンが率いる評議会は、サン・マテオ・イスタタンと近隣のサンタ・エウラリアの宗 教改革を決定した。両地は植民地行政区画であるウエウェテナンゴ管区内に属していた。[20] 1838年2月2日、ウエウェテナンゴはケツァルテナンゴ、エルキチェ、レタールレウ、サンマルコス、トトニカパンと連合し、短命に終わった中央アメリカ のロス・アルトス共和国を成立させた。この共和国は1840年、当時グアテマラ大統領職を離れていたラファエル・カレラ・トゥルシオス将軍によって鎮圧さ れた。[21] ウエウェテナンゴには、サクレウ、チャルチタン、モハ、サン・マテオ・イスタタンといった先コロンブス期のマヤ遺跡が含まれる。[22] |

| Departmental history The department of Huehuetenango was created by the presidential decree of Vicente Cerna Sandoval on 8 May 1866, although various attempts had been made to declare the district a department from 1826 onwards in order to better administer it.[23] By 1883, Huehuetenango had 248 coffee plantations and produced 7334 quintals (Imperial hundredweight) of coffee.[24] In 1887, a rebellion in Huehuetenango was put down by president Manuel Lisandro Barillas, who then suspended the constitutional guarantees of the department and redrafted its constitution.[25] |

県の歴史 ウエウェテナンゴ県は、1866年5月8日にビセンテ・セルナ・サンドバルの大統領令によって創設された。ただし、1826年以降、この地区をより良く管 理するために県に昇格させようとする試みが幾度か行われていた。[23] 1883年までに、ウエウェテナンゴには248のコーヒー農園があり、7334キンタル(インペリアル・クイントン)のコーヒーを生産していた。[24] 1887年、ウエウェテナンゴで起きた反乱はマヌエル・リサンドロ・バリージャス大統領によって鎮圧された。その後、大統領は同県の憲法上の保障を停止 し、憲法を再制定した。[25] |

| Economy and agriculture Huehuetenango has produced coffee since the 19th century During the 17th and 18th centuries, namely during the Spanish Colonial period, the main industries were mining and livestock production, which was run by Spaniards. In modern times agriculture is the most important industry, although mining continues on a small scale and handicraft production also contributes to the local economy.[26] Maize is cultivated across the whole department, without being limited by local climatic differences. The primary highland crops are wheat, potatoes, barley, alfalfa and beans. On the warmer lower slopes the primary crops are coffee, sugarcane, tobacco, chili, yuca, achiote and a wide range of fruits.[27] Although historically cattle and horse farming were important, the size of production is much reduced in modern times, with the rearing of sheep, which is now more widespread. Mines in Huehuetenango produce silver, lead, zinc and copper. Gold was once mined in the department but it is no longer extracted.[26] In 2000, the private mining company Minas de Guatemala S.A. was extracting antimony from underground mines near San Ildefonso Ixtahuacán.[28] Local handicraft production mainly consists of weaving traditional Maya textiles, mostly cotton but also wool, depending on the local climate.[26] In 2008 the most exported product was coffee.[29] |

経済と農業 ウエウェテナンゴでは19世紀からコーヒーが生産されている 17世紀から18世紀、すなわちスペイン植民地時代には、鉱業と畜産が主要産業であり、これらはスペイン人によって運営されていた。現代では農業が最重要 産業だが、小規模な鉱業も継続しており、手工芸品の生産も地域経済に貢献している[26]。トウモロコシは地域ごとの気候差に関係なく、県全域で栽培され ている。高地の主要作物は小麦、ジャガイモ、大麦、アルファルファ、豆類である。温暖な低地斜面では、コーヒー、サトウキビ、タバコ、唐辛子、キャッサ バ、アチオテ、そして多種多様な果物が主要作物だ。[27] 歴史的には牛や馬の飼育が重要だったが、現代では生産規模が大幅に縮小し、代わりに羊の飼育がより広く普及している。ウエウェテナンゴの鉱山では銀、鉛、 亜鉛、銅が産出される。かつては金も採掘されていたが、現在は採掘されていない。[26] 2000年には、民間鉱山会社ミナス・デ・グアテマラ社がサン・イルデフォンソ・イスタワカン近郊の地下鉱山からアンチモンを採掘していた。[28] 地元の工芸品生産は主に伝統的なマヤ織物の織物作りで、気候に応じて綿が中心だが羊毛も使われる。[26] 2008年、最も輸出された製品はコーヒーであった。[29] |

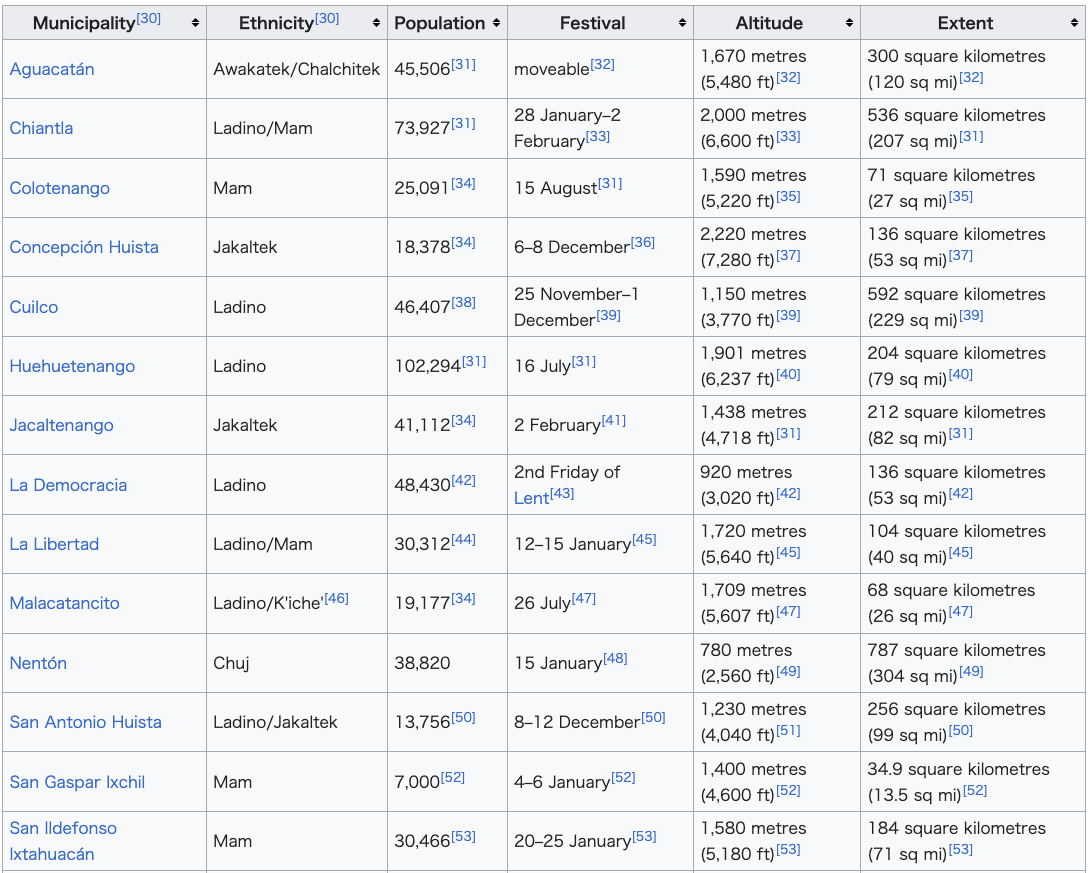

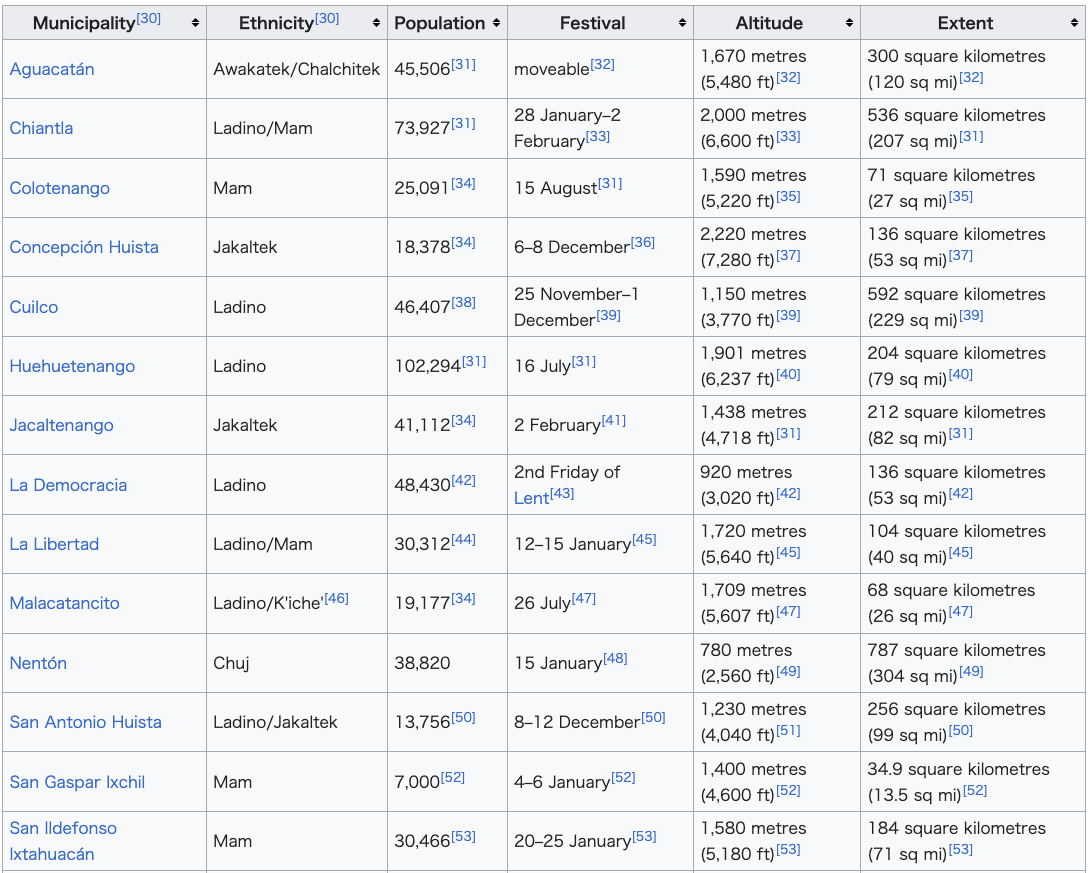

| Municipalities The department of Huehuetenango includes 31 municipalities:[30]   |

自治体 ウエウェテナンゴ県には31の自治体が含まれる。[30]   |

| People of note Former president of Guatemala Efraín Ríos Montt was born in Huehuetenango city on 16 June 1926.[80] Tourism   The image of Nuestra Señora de Chiantla The main tourist attractions in the department include the source of the San Juan River and the restored Maya ruins of Zaculeu.[81] The town of Chiantla is a centre for religious tourism, with the Catholic Church being a pilgrimage destination due to its image of the Virgin of Candelaria, known locally as Nuestra Señora de Chiantla ("Our Lady of Chiantla").[82] |

著名な人民 グアテマラの元大統領エフライン・リオス・モントは、1926年 6月16日にウエウェテナンゴ市で生まれた。[80] 観光   チアントラの聖母像 この州の主な観光名所には、サン・フアン川の源流と修復されたマヤ遺跡サクレウが含まれる。[81] チアントラの町は宗教観光の中心地であり、カトリック教会は巡礼地となっている。その理由は、地元で「チアントラの聖母(ヌエストラ・セニョーラ・デ・チ アントラ)」として知られるカンデラリアの聖母像が安置されているためである。[82] |

| References Arroyo, Bárbara (July–August 2001). "El Posclásico Tardío en los Altos de Guatemala". Arqueología Mexicana (in Spanish). IX (50). Mexico: Editorial Raíces: 38–43. ISSN 0188-8218. OCLC 29789840. Díaz Camposeco, Manrique; Megan Thomas; Wolfgang Krenmayr (2008). "Huehuetenango en Cifras" (PDF) (in Spanish). Huehuetenango, Guatemala.: Centro de Estudios y Documentación de la Frontera Occidental de Guatemala (CEDFOG). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-27. Retrieved 2010-02-09. Gaitán A., Héctor (c. 2004). Los Presidentes de Guatemala: Historia y Anécdotas (in Spanish). Guatemala City: Artemis & Edinter. ISBN 84-89452-25-3. OCLC 49591587. Hernández, Gonzalo; González, Miguel (2004). "Huehuetenango: Enclavado en la Sierra de los Cuchumatanes" (PDF) (in Spanish). Guatemala: Prensa Libre. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-15. Retrieved 2010-02-06. Guatemala (Map) (5th ed.). 1:470000. International Travel Maps. ITMB Publishing. 2005. ISBN 1-55341-230-3. MINEDUC (2001). Eleuterio Cahuec del Valle (ed.). Historia y Memorias de la Comunidad Étnica Chuj (PDF) (in Spanish). Vol. II (Versión escolar ed.). Guatemala: Universidad Rafael Landívar/UNICEF/FODIGUA. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-08-24. Retrieved 2010-02-06. Polo Sifontes, Francis. Zaculeu: Ciudadela Prehispánica Fortificada (in Spanish). Guatemala: IDAEH (Instituto de Antropología e Historia de Guatemala). Pons Sáez, Nuria (1997). La Conquista del Lacandón (in Spanish). Mexico: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. ISBN 968-36-6150-5. OCLC 40857165. Quintana Hernández, Francisca; Cecilio Luis Rosales (2006). Mames de Chiapas. Pueblos indígenas del México contemporáneo (in Spanish). Mexico: Comisión Nacional para el Desarrollo de los Pueblos Indígenas (CDI). ISBN 970-753-047-2. OCLC 254999882. Recinos, Adrian (1986). Pedro de Alvarado: Conquistador de México y Guatemala (in Spanish) (2nd ed.). Guatemala: CENALTEX Centro Nacional de Libros de Texto y Material Didáctico "José de Pineda Ibarra". OCLC 243309954. Rodríguez L., Carlos Antonio. "La Determinación Estadística de los Grupos Étnicos, el Indigenisma, la Situación de la Pobreza y la Exlusión Social. Los Censos Integrados del 2002 y la inclusión social de los grupos étnicos. Perfil nacional del desarrollo sociodemográfico" (PDF) (in Spanish). Retrieved 2010-02-07. Rodríguez Rouanet, Francisco; Fernando Seijas; Gerardo Townson Rincón (1992). Huehuetenango. Monografías de Guatemala, 2 (in Spanish). Guatemala: Banco Granai & Townson. OCLC 31405975. SEGEPLAN-USIGHUE (September 2002). "Caracterización del Municipio de Santiago Chimaltenango del Departamento de Huehuetenango" (PDF) (in Spanish). Huehuetenango, Guatemala: Secretaría Planificación y Programación/Unidad de Sistema de Información Geográfica de huehuetenango (SEGEPLAN-USIGHUE). Retrieved 2010-12-30. Tarax Herrera, Napoleón; Eulalio Argueta Calel; Víctor Manuel Larios Velásquez (September 2005). "Mitos, Cuentos y Leyendas Maya K'iche' en Malacatancito = Tzijonem B'anob'al Rech Kik'aslemal Ri K'iche'ab' Pa Ri Komon Malacatancito Ri K'o Nab'ajul" (PDF). Huehuetenango, Guatemala: helvetas Guatemala/Centro de Estudios y Documentación de la Frontera Occidental de Guatemala (CEDFOG). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-02-15. Retrieved 2010-02-08. (in Spanish and K'iche') Velasco, Pablo. "The Mineral Industries of Central America — Belize, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, and Panama" (PDF). U.S. Dept. of the Interior, Bureau of Mines. OCLC 21384999. Retrieved 2010-02-09. Wagner, Regina (2001). Historia del Café de Guatemala (in Spanish). Bogotá, Colombia: Benjamín Villegas & Asociados. ISBN 958-96982-8-X. OCLC 50391255. |

参考文献 アロヨ、バーバラ(2001年7月~8月)。「グアテマラ高地の後期ポストクラシック時代」。Arqueología Mexicana(スペイン語)。IX (50)。メキシコ:Editorial Raíces:38–43。ISSN 0188-8218。OCLC 29789840。 ディアス・カンポセコ、マンリケ、メーガン・トーマス、ヴォルフガング・クレンマイヤー(2008)。「数字で見るウエウェテナンゴ」(PDF)(スペイ ン語)。グアテマラ、ウエウェテナンゴ:グアテマラ西国境研究・文書センター(CEDFOG)。2011年7月27日にオリジナル(PDF)からアーカイ ブ。2010年2月9日取得。 ガイタン A.、ヘクター (c. 2004)。『グアテマラの大統領たち:歴史と逸話』 (スペイン語)。グアテマラシティ:アルテミス&エディンター。ISBN 84-89452-25-3。OCLC 49591587。 Hernández, Gonzalo; González, Miguel (2004). 「ウエウェテナンゴ:クチュマタン山脈に囲まれて」 (PDF) (スペイン語). グアテマラ: Prensa Libre. 2011年7月15日、オリジナル (PDF) からアーカイブ。2010年2月6日取得。 グアテマラ (地図) (第 5 版). 1:470000. インターナショナル・トラベル・マップス. ITMB パブリッシング. 2005. ISBN 1-55341-230-3. MINEDUC (2001). Eleuterio Cahuec del Valle (編). チュイ族の民族の歴史と記憶 (PDF) (スペイン語). 第 II 巻 (学校版). グアテマラ: ラファエル・ランディバル大学/ユニセフ/FODIGUA. 2009年8月24日にオリジナル (PDF) からアーカイブ。2010年2月6日取得。 ポロ・シフォンテス、フランシス。ザクレウ:要塞化された先スペイン時代の城塞(スペイン語)。グアテマラ:IDAEH(グアテマラ人類学歴史研究所)。 ポンス・サエス、ヌリア(1997)。ラカンダンの征服(スペイン語)。メキシコ:メキシコ国立自治大学。ISBN 968-36-6150-5。OCLC 40857165。 キンタナ・エルナンデス、フランシスカ;セシリオ・ルイス・ロサレス(2006)。『チアパス州のマメ族。現代メキシコの先住民(スペイン語)』。メキシ コ:先住民開発国家委員会(CDI)。ISBN 970-753-047-2。OCLC 254999882。 レシーノス、エイドリアン(1986)。『ペドロ・デ・アルバラド:メキシコとグアテマラの征服者』(スペイン語)(第2版)。グアテマラ: CENALTEX 国立教科書・教材センター「ホセ・デ・ピネダ・イバラ」。OCLC 243309954。 ロドリゲス L.、カルロス・アントニオ。「民族グループの統計的決定、先住民族主義、貧困と社会的排除の状況。2002 年の統合国勢調査と民族グループの社会的包摂。社会人口統計学的発展の全国プロファイル」 (PDF) (スペイン語)。2010年2月7日取得。 ロドリゲス・ルアネット、フランシスコ、フェルナンド・セイハス、ヘラルド・タウンソン・リンコン (1992)。ウエウェテナンゴ。グアテマラのモノグラフ、2 (スペイン語)。グアテマラ:バンコ・グラナイ&タウンソン。OCLC 31405975。 SEGEPLAN-USIGHUE (2002年9月). 「ウエウェテナンゴ県サンティアゴ・チマルテナンゴ市の特徴」 (PDF) (スペイン語). グアテマラ、ウエウェテナンゴ: 計画・プログラム事務局/ウエウェテナンゴ地理情報システムユニット (SEGEPLAN-USIGHUE). 2010年12月30日取得。 タラックス・エレーラ、ナポレオン、エウラリオ・アルゲタ・カレル、ビクトル・マヌエル・ラリオス・ベラスケス(2005年9月)。「マラカタンシトにお けるマヤ・キチェ族の神話、物語、伝説 = Tzijonem B『anob』al Rech Kik『aslemal Ri K』iche『ab』 Pa Ri Komon Malacatancito Ri K『o Nab』ajul」 (PDF). グアテマラ、ウエウェテナンゴ:ヘルベタス・グアテマラ/グアテマラ西国境研究・文書センター(CEDFOG)。2010年2月15日にオリジナル (PDF)からアーカイブ。2010年2月8日に取得。(スペイン語およびキチェ語) Velasco, Pablo. 「中米の鉱業 — ベリーズ、コスタリカ、エルサルバドル、グアテマラ、ホンジュラス、ニカラグア、パナマ」 (PDF). 米国内務省鉱山局。OCLC 21384999。2010年2月9日取得。 ワグナー、レジーナ (2001). 『グアテマラのコーヒーの歴史』 (スペイン語). コロンビア、ボゴタ: ベンハミン・ビジェガス&アソシアドス. ISBN 958-96982-8-X. OCLC 50391255. |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Huehuetenango_Department |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099