スペインの音楽

☆ スペインでは音楽の歴史は長い。西洋音楽の発展において重要な役割を果たし、ラテンアメリカ音楽にも大きな影響を与えた。スペイン音楽は、フラメンコやク ラシックギターなどの伝統的なスタイルと関連付けられることが多い。これらの音楽は一般的であるが、地域によってさまざまな伝統的な音楽やダンスのスタイ ルがある。例えば、北西部の音楽はバグパイプに大きく依存しており、ホタはスペインの中央部と北部に広く普及しており、フラメンコは南部で生まれた。スペ イン音楽は、15世紀から17世紀初頭にかけての西洋クラシック音楽の初期発展において、重要な役割を果たした。トマス・ルイス・デ・ビクトリアのような 作曲家、スペインオペラのサルスエラのような様式、マヌエル・デ・ファリャのバレエ、フランシスコ・タレガのクラシックギター音楽などに見られる音楽の革 新性は、幅広いものである。今日では、スペインでも他の国々でも、商業的なポピュラー音楽のさまざまなスタイルが主流となっている。

★ス

ペイン音楽 / ホセ・スビラ著 ; 浜田滋郎訳, 東京 : 白水社 , 1961.8. - (文庫クセジュ ; 306)/ La

musique espagnole, José Subirá ; traduit de l'espagnol par Marguerite

Jouve, Presses Universitaires de France 1959 Que sais-je? no. 823

| 0. まえがき |

5 |

・フランスにおけるスペイン音楽史に対する関心の高さ ・本書は、自著「スペインおよびイスパノアメリカの音楽史(1953)」と「音楽の歴史全4巻(1958)」の要約である。 |

| 1. 古代と中世 |

7 |

・地中海とアルプスという2つの起源 ・メリスマ的節回し ・スペインの歴史(→スペインの歴史01:先史時代からアルアンダルスからレコンキスタまで) ・スペインのローマ化(→モサラベ) ・10世紀11世紀の聖歌集(ネウマ記譜法)(17) ・ローマ聖歌の導入(アルフォンソ6世) ・さまざまな楽派(19) ・マドリード手稿本(20) ・多声作曲法(パリ、オックスフォード)(22) ・カンティガス・デ・サンタ・マリア(22) ・プロヴァンス起源のシャンソン(23) ・プロバンスのトルバドゥール[吟遊詩人](23) ・トロバーリオ(24) ・祈祷書(ブレビアーリオ)(24) ・(宗教劇起源の)シビーラの歌=クリスマス前後に、初期にはラテン語で、後には俗語で歌われた(24)→ビリャンシーコ(25) ・10世紀には、シビーラの歌は、リポルとコルドバの教会で歌われた(24) ・14世紀半ばになる、単旋律だったシビーラの歌は、4声の多声歌曲になる。(→ポリフォニー) ・15世紀、ファン・デル・エンシーナ「牧人劇」における「終わりのビリャンシーコ」(25) ・モンセラートの赤い本(26) ・スペイン印刷の最初の典礼音楽は、ドミニコ会派の行列賛美歌集(プロセシオナーリオ)、最初の音楽教本は、ドミンゴ・ドゥラン(Domingo Marcos Durán)の「美しき光(lux bella)」(28) |

| 2. 近代の黎明から16世紀末まで |

30 |

・スペインの歴史(→スペイン初期近代)は1492年からはじまる(30) ・「王宮の歌曲集」(1460-1510年までの459曲の多声音楽)——ビリャンシーコ、フロットラ、ロマンセを含む ・「メディナセーリの歌曲集」——ビリャンシーコ、ロマンセ、カンシオン、マドリガルを含む(32) ・「コロンブス図書館の歌曲集」(32) ・「ウプサラ歌曲集」には百曲のビリャンシーコ収録 ・「ファンバスケスのソネートとビリャンシーコ集成」(32) ・エンサラーダ:諸国の俗謡などをまぜこんだこっけいなマドリガル. ・ビリャネスカは、ビリャンシーコと区別ができないが、手が込んでおり、マドリガルに近い(33) ・アンダルシアの作曲家たちはビリャンシーコとトノ(歌謡・俗謡)を好み、カタルーニャ楽派はマドリガルに傾倒する、傾向(33) ・ビウエラ(書物ではビウエーラ)の流行(33)  ・歌曲集「エル・マエストロ」(34)——ビリャンシーコ等を多く含む ・「ビウエラのための楽譜集」(35) ・ビウエラからギターへ(35) ・最初のギター楽譜本は1586年(36) ・ファン・デル・エンシーナによる劇場音楽の隆盛(37) ・幕間劇のパソのなかに、ビリャンシーコが演奏されるようになる(38) ・アンダルシーア楽派のその後(42-) ・「霊的なビリャンシーコとカンシオン」(43) ・ファン・バスケス(43)[Juan Vásquez]→「マドリガル」 ・ペドロ・リモンテ「マドリガルとビリャンシーコのスペイン詩集」(44) ・鍵盤音楽の誕生(45)、トレド大聖堂「皇帝のオルガン」(45) ・賛美歌集の編纂(45-46) ・多数の音楽論、音楽学問論が出版される(46-47) |

| 3. 17世紀 |

48 |

・16世紀はスペイン音楽の絶頂期なら、17世紀は衰退期 ・多声音楽から単旋律音楽の勝利(48-49) ・世俗歌謡集のひとつ「ファン・ロメーロのビリャンシーコ集」(49) ・クラウディオ・デ・サブロナーラ(49) ・ロマンセとビリャンシーコはまだ優勢(50) ・16世紀のビウエラから17世紀のギター音楽へ(51) ・17世紀はハープ音楽の世紀でもある(52) ・職業的な劇団の形成(53) ・スペイン最初のオペラ「恋なき森」(53) ・オペラが世界的なら、サルスエーラはスペインのものだ(54) ・サルスエーラ=小歌劇(54) ・サルスエーラの王族から庶民への進出(55) ・サルスエーラ概念の拡張つまりさまざまな歌唱の形式がこのジャンルに盛り込まれる(56) ・聖餐神秘劇(acto sacramental )の拡大化(57) ・宗教的な歌曲にビリャンシーコやロマンセの(世俗歌謡が取り込まれていく)(57) ・ラ・メルセーのマエストロ・デ・カピージャのファン・ロメーロ(Juan Romero)が作曲にかかわる(58) ・しかしながら、この時期にもビリャンシーコの作曲家は対位法にこだわる(59) ・1601年バチカンはフェリペIII世のデスカサルス・レアーレス修道院の新条例を認可(59) ・聖歌隊指揮者の音楽教育の画一化、そのなかには対位法も含まれる(59) ・エンカルナシオン王立修道院での落成では、モテットとビリャンシーコが歌われる(59-61) ・作曲家の列伝が紹介(60-63) ・典礼書の出版多数(64) |

| 4. 18世紀 |

67 |

・1701年ブルボン王朝の登場(67)→「スペイン初期近代」 ・スペイン教会にイタリアのものがたくさん流入(67) ・音楽にもイタリアのものが多く導入される(68) ・17世紀後半から、貴族の邸宅のなかで器楽合奏がおこなわれるようになる(69) ・ギター復興運動がおこる(70) ・ホアキン・ニン「スペイン古典ピアノ集」(71) ・劇場音楽(73) ・オペラ音楽(73-) ・サルスエラは引き続き人気のあるジャンルに(77) ・コメディア・アルモニカ(78) ・トナディーリャという幕間音楽の流行(79) ・18世紀スペイン宗教音楽で、対位法が衰退しつつある(82):宗教音楽(82-) ・エンカルナシオン修道院のハイメ・バリウス( ;?-1822)のビリャンシーコ作曲、200曲(85) ・ビリャンシーコは「スペインのカンタータである」(85)——スペイン教会に普及——クリスマスと聖体祭に歌われる ・おびただしい数のビリャンシーコが作曲される ・(世俗歌のみならず)聖歌として歌われる(85) ・オラトリオの作曲(86) ・典礼本の印刷(86) ・音楽書の印刷(87) ・1767年イエズス会のスペインからの退去(→「スペイン帝国の他の地域と同様に、イエズス会は1767年にメキシコから追放された。彼らの大農園は売却され、バハ・カリフォルニアのコレヒオと伝道所は 他の修道会に引き継がれた」)(88) ・イエズス会士の音楽に関する起源書、理論書などの貢献(88-89) ・Tomás de Iriarte, La La Música, 1779 - ・教会音楽本など(90) |

| 5. 19世紀 |

92 |

・政治的騒乱の時代(92) ・サルスエラの再興が試みられる(102-103) ・宗教音楽(105) ・宗教音楽家(106-) |

| 6. 20世紀 |

113 |

・1943年、スペイン音楽学会創設(133) ・カンティガス・サンタ・マリアの現代語訳(133) |

| 7. 民族音楽にあらわれるスペインの魂 |

152 |

・民俗音楽の分析法(138) ・民衆的宗教歌:サンボンバと太鼓の伴奏のビリャンシーコ(140)- Zambomba 2022 - Jerez de la Frontera 17.12.2022 ・クリスマスに歌われるアギナルド(140) ・受難と死の歌(サエータ)(140) ・コプラ(→スタンザ)、セギディーリャ[セギディージャ]、ロマンセという詩の形式(140) ・コプラの事例:4連の詩句:8音節の4行、時に、折り返し句(estribillo)——chorus or refrain(141) ・セギディージャの事例:4連の詩句:4行だが、7音節と5音節が交代し、後に、5音節、7音節、5音節の三行の折り返し句がつく。後者は、一詩節7行になる。(141) ・ロマンセ:非常にながい物語歌で、不完全韻で書かれ、普通は一行8音節。対応するメロディは詩のはじめの4行にあてはまり、そのまま詩の終わりまで同じものがつづく。4行ごとに(メロディの一節が終わる毎に)飾りの折り返しが加えられることがある。(142) ・チリミーア[チリミア](144)など、楽器の説明がつづく |

| 8. 訳者あとがき |

||

| 9. 参考文献 |

||

| 10. 主要人物索引 |

楽曲リンク(YouYube)

***

| In Spain, music has

a long history. It has played an important role in the development of

Western music, and has greatly influenced Latin American music. Spanish

music is often associated with traditional styles such as flamenco and

classical guitar. While these forms of music are common, there are many

different traditional musical and dance styles across the regions. For

example, music from the north-west regions is heavily reliant on

bagpipes, the jota is widespread in the centre and north of the

country, and flamenco originated in the south. Spanish music played a

notable part in the early developments of western classical music, from

the 15th through the early 17th century. The breadth of musical

innovation can be seen in composers like Tomás Luis de Victoria, styles

like the zarzuela of Spanish opera, the ballet of Manuel de Falla, and

the classical guitar music of Francisco Tárrega. Nowadays, in Spain as

elsewhere, the different styles of commercial popular music are

dominant. |

スペインでは音楽の歴史は長い。西洋音楽の発展において重要な役割を果

たし、ラテンアメリカ音楽にも大きな影響を与えた。スペイン音楽は、フラメンコやクラシックギターなどの伝統的なスタイルと関連付けられることが多い。こ

れらの音楽は一般的であるが、地域によってさまざまな伝統的な音楽やダンスのスタイルがある。例えば、北西部の音楽はバグパイプに大きく依存しており、ホ

タはスペインの中央部と北部に広く普及しており、フラメンコは南部で生まれた。スペイン音楽は、15世紀から17世紀初頭にかけての西洋クラシック音楽の

初期発展において、重要な役割を果たした。トマス・ルイス・デ・ビクトリアのような作曲家、スペインオペラのサルスエラのような様式、マヌエル・デ・ファ

リャのバレエ、フランシスコ・タレガのクラシックギター音楽などに見られる音楽の革新性は、幅広いものである。今日では、スペインでも他の国々でも、商業

的なポピュラー音楽のさまざまなスタイルが主流となっている。 |

Origins of the music of Spain Musical instruments in the Diocesan Museum of Albarracín. The Iberian peninsula has had a history of receiving different musical influences from around the Mediterranean Sea and across Europe. In the two centuries before the Christian era, Roman rule brought with it the music and ideas of Ancient Greece; early Christians, who had their own differing versions of church music arrived during the height of the Roman Empire; the Visigoths, a Romanized Germanic people, who took control of the peninsula following the fall of the Roman Empire; the Moors and Jews in the Middle Ages. Hence, there have been more than two thousand years of internal and external influences and developments that have produced a large number of unique musical traditions. |

スペイン音楽の起源 アルバラシン教区博物館の楽器 イベリア半島は地中海沿岸やヨーロッパ各地からさまざまな音楽の影響を受けてきた歴史がある。キリスト教以前の2世紀の間、ローマの支配は古代ギリシャの 音楽と思想をもたらした(→スペインの歴史)。ローマ帝国全盛期には、独自の 教会音楽のバージョンを持った初期キリスト教徒が到来した。ローマ帝国崩壊後には半島を支配した、 ローマ化されたゲルマン民族である西ゴート族(→Visigothic art and architecture)。中世にはムーア人とユダヤ人がいた。そのため、2千年以上にわたって内外からの影響や発展が繰り返 され、数 多くの独特な音楽の伝統が生まれた。 |

Medieval period Cantigas de Santa maría, medieval Spain  Codex Las Huelgas, a medieval Spanish music manuscript, circa 1300 AD. Isidore of Seville wrote about the local music in the 6th century. His influences were predominantly Greek, and yet he was an original thinker, and recorded some of the first details about the early music of the Christian church. He perhaps is most famous in musical history for declaring that it was not possible to notate sounds, an assertion which revealed his ignorance of the notational system of ancient Greece, suggesting that this knowledge had been lost with the fall of the Roman Empire in the west.[citation needed] The Moors of Al-Andalus were usually relatively tolerant of Christianity and Judaism, especially during the first three centuries of their long presence in the Iberian peninsula, during which Christian and Jewish music continued to flourish. Music notation was developed in Spain as early as the 8th century (the so-called Visigothic neumes) to notate the chant and other sacred music of the Christian church, but this obscure notation has not yet been deciphered by scholars, and exists only in small fragments.[citation needed] The music of the early medieval Christian church in Spain is known, misleadingly, as the "Mozarabic Chant", which developed in isolation prior to the Islamic invasion and was not subject to the Papacy's enforcement of the Gregorian chant as the standard around the time of Charlemagne, by which time the Muslim armies had conquered most of the Iberian peninsula. As the Christian reconquista progressed, these chants were almost entirely replaced by the Gregorian standard, once Rome had regained control of the Iberian churches. The style of Spanish popular songs of the time is presumed to have been heavily influenced by the music of the Moors, especially in the south, but as much of the country still spoke various Latin dialects while under Moorish rule (known today as the Mozarabic) earlier musical folk styles from the pre-Islamic period continued in the countryside where most of the population lived, in the same way as the Mozarabic Chant continued to flourish in the churches. In the royal Christian courts of the reconquistors, music like the Cantigas de Santa Maria, also reflected Moorish influences. Other important medieval sources include the Codex Calixtinus collection from Santiago de Compostela and the Codex Las Huelgas from Burgos. The so-called Llibre Vermell de Montserrat (red book) is an important devotional collection from the 14th century.[citation needed]  Iberian Kingdoms in 1400 |

中世 カンティガス・デ・サンタ・マリア、中世スペイン  ラス・ウエルガス写本、中世スペインの音楽の写本、西暦1300年頃 セビリアのイシドールは6世紀に地元の音楽について著述した。彼の影響は主にギリシャに由来するが、彼は独創的な思想家であり、キリスト教教会の初期音楽 について、いくつかの最初の詳細を記録した。彼は、音符で音を記譜することは不可能であると宣言したことで、音楽史上最も有名かもしれない。この主張は、 古代ギリシャの記譜法に対する彼の無知を露呈しており、この知識は西ローマ帝国の崩壊とともに失われたことを示唆している。[要出典] アル・アンダルスに住んでいたムーア人は、キリスト教やユダヤ教に対して比較的寛容であり、特にイベリア半島に長く住んでいた最初の3世紀の間は、キリス ト教やユダヤ教の音楽が盛んに作られていた。スペインでは早くも8世紀には、キリスト教会の聖歌やその他の宗教音楽を記譜するための楽譜(いわゆる西ゴー ト・ネウマ)が開発されていたが、この不明瞭な楽譜は学者によって未だ解読されておらず、断片的な形でしか存在していない。[要出典] スペインにおける初期中世のキリスト教会の音楽は、 スペインの初期中世キリスト教会の音楽は、誤解を招くように「モサラベ聖歌」として知られている。これはイスラム教徒の侵入以前に孤立して発展したもので あり、イスラム教徒の軍隊がイベリア半島の大部分を征服したシャルルマーニュの時代には、教皇庁がグレゴリオ聖歌を標準として強制する対象ではなかった。 キリスト教徒によるレコンキスタが進むにつれ、ローマがイベリア半島の教会の支配を取り戻すと、これらの聖歌はほぼ完全にグレゴリオ聖歌に置き換えられ た。当時のスペインの民謡のスタイルは、特に南部においてムーア人の音楽から大きな影響を受けていたと推測されているが、ムーア人の支配下にあった時代に は、国内の多くの地域でさまざまなラテン語の方言が話されていた(今日ではモサラベ語として知られている)。イスラム教以前の時代に生まれた音楽の民族的 なスタイルは、人口のほとんどが暮らしていた田舎で生き続け、モサラベ聖歌が教会で盛んに歌われ続けたのと同じように、モサラベ聖歌も生き続けた。レコン キスタを遂行したキリスト教王家の宮廷では、カンティガス・デ・サンタ・マリアのような音楽もムーア人の影響を反映していた。その他の重要な中世の資料と しては、サンティアゴ・デ・コンポステーラの『カリクスティヌス写本』コレクションやブルゴスの『ラス・ウエルガス写本』などがある。いわゆる『モンセ ラート赤本』(Llibre Vermell de Montserrat)は、14世紀の重要な信仰のコレクションである。  1400年頃のイベリア半島の王国(→「国民国家」) |

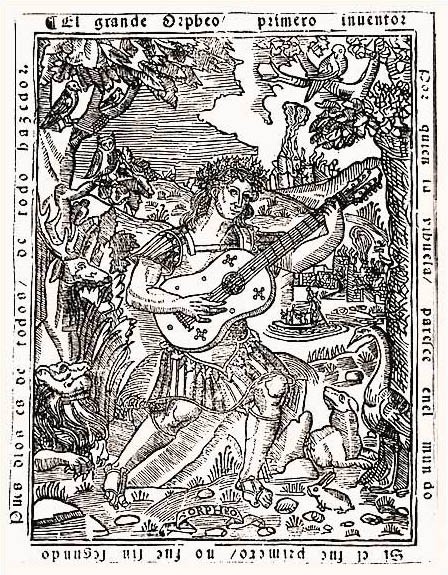

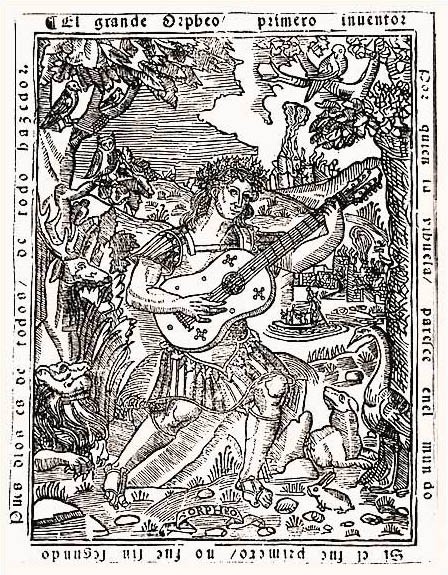

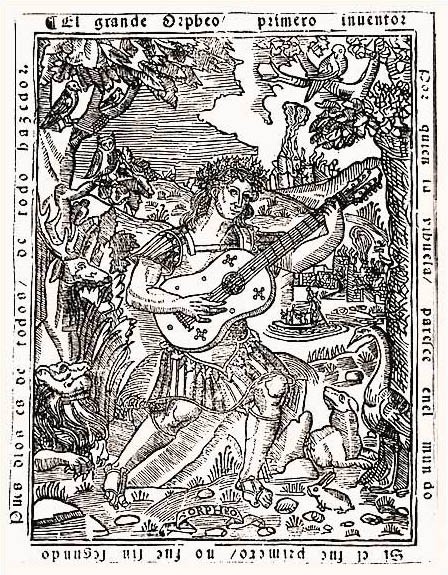

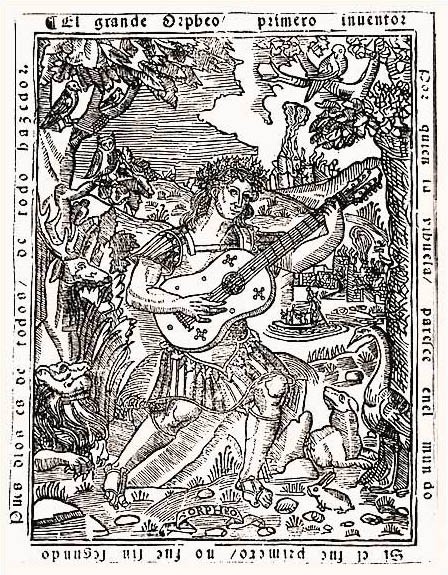

Renaissance and Baroque periods Orpheus playing the vihuela. Frontispiece from the famous work El maestro by Luis de Milán, 1536. In the early Renaissance, Mateo Flecha el Viejo and the Castilian dramatist Juan del Encina ranked among the main composers in the post-Ars Nova period. Renaissance song books included the Cancionero de Palacio, the Cancionero de Medinaceli, the Cancionero de Upsala (kept in Carolina Rediviva library), the Cancionero de la Colombina, and the later Cancionero de la Sablonara. The organist Antonio de Cabezón stands out for his keyboard compositions and mastery. An early 16th-century polyphonic vocal style developed in Spain was closely related to that of the Franco-Flemish composers. Merging of these styles occurred during the period when the Holy Roman Empire and the Burgundy were part of the dominions under Charles I (king of Spain from 1516 to 1556), since composers from the North of Europe visited Spain, and native Spaniards traveled within the empire, which extended to the Netherlands, Germany and Italy. Music composed for the vihuela by Luis de Milán, Alonso Mudarra and Luis de Narváez was one of the main achievements of the period. The Aragonese Gaspar Sanz authored the first learning method for guitar. Spanish composers of the Renaissance included Francisco Guerrero, Cristóbal de Morales, and Tomás Luis de Victoria (late Renaissance period), all of whom spent a significant portion of their careers in Rome. The latter was said to have reached a level of polyphonic perfection and expressive intensity equal or even superior to Palestrina and Lassus [citation needed]. Most Spanish composers returned home from travels abroad late in their careers to spread their musical knowledge in their native land, or in the late 16th century to serve at the Court of Philip II. |

ルネサンスとバロックの時代 ビウエラを演奏するオルフェウス。1536年、ルイス・デ・ミラン著の有名な作品『エル・マエストロ』の口絵。 初期ルネサンスでは、マテオ・フレチャ・エル・ビエホとカスティーリャの劇作家フアン・デル・エンシーナが、アルス・ノヴァ後の時代における主要な作曲家 の一人として数えられていた。ルネサンス期の歌集には、カンシオネロ・デ・パラシオ、カンシオネロ・デ・メディナセリ、カンシオネロ・デ・ウプサラ(カロ リナ・レティビバ図書館所蔵)、カンシオネロ・デ・ラ・コロンビーナ、そして後のカンシオネロ・デ・ラ・サブラノラなどがある。オルガニストのアントニ オ・デ・カベソンは、鍵盤楽器の作曲と演奏で際立った存在であった。 16世紀初頭にスペインで発展した多声音楽の歌唱スタイルは、フランドル・フランスの作曲家のスタイルと密接な関係があった。これらのスタイルの融合は、 神聖ローマ帝国とブルゴーニュがスペイン王カルロス1世(在位1516年~1556年)の領土の一部であった時代に起こった。北ヨーロッパの作曲家たちが スペインを訪れ、スペイン人がオランダ、ドイツ、イタリアにまで領土を広げていた神聖ローマ帝国の領土内を旅したためである。ルイス・デ・ミラン、アロン ソ・ムダーラ、ルイス・デ・ナルバエスがビウエラのために作曲した音楽は、この時代の主な成果のひとつである。アラゴン人のガスパール・サンツは、ギター の最初の学習方法を著した。ルネサンス期のスペイン人作曲家には、フランシスコ・ゲレロ、クリストバル・デ・モラレス、トマス・ルイス・デ・ビクトリア (後期ルネサンス期)などがおり、彼らは皆、キャリアの大部分をローマで過ごした。後者は、ポリフォニーの完成度と表現力の強さにおいて、パレストリーナ やラッススに匹敵する、あるいはそれ以上のレベルに達していたと言われている。[要出典] スペインの作曲家の多くは、晩年になって海外からの帰国を果たし、自国の音楽界に自らの音楽的知識を広めたり、16世紀後半にはフェリペ2世の宮廷で活躍 したりした。 |

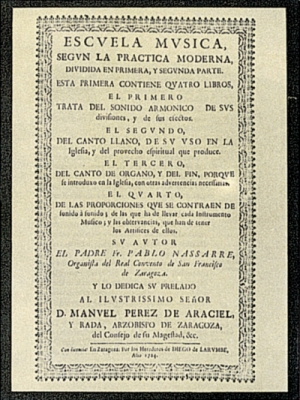

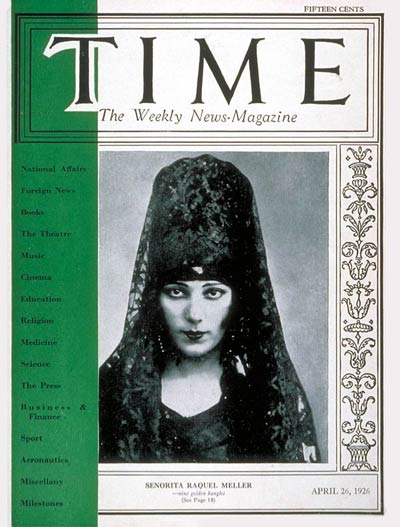

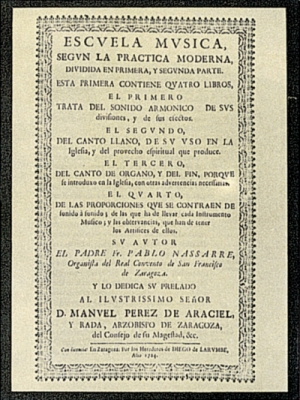

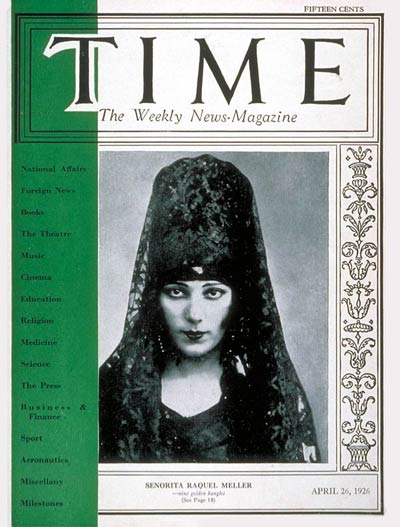

18th to 20th centuries Front cover of book: Escuela Música según la práctica moderna published in 1723–1724 Antonio Soler's Sonata No. 84, an example of Classical era music in Spain Duration: 8 minutes and 28 seconds.8:28 Problems playing this file? See media help. By the end of the 17th century the "classical" musical culture of Spain was in decline, and was to remain that way until the 19th century. Classicism in Spain, when it arrived, was inspired by Italian models, as in the works of Antonio Soler. Some outstanding Italian composers such as Domenico Scarlatti and Luigi Boccherini were appointed to the Madrid royal court. The short-lived Juan Crisóstomo Arriaga is credited as the main beginner of Romantic sinfonism in Spain. [citation needed]  Raquel Meller appeared on the 26 April 1926 cover of Time magazine. Although symphonic music was never too important in Spain, chamber, solo instrumental (mainly guitar and piano) vocal and opera (both traditional opera, and the Spanish version of the singspiel) music was written by local composers. Zarzuela, a native form of opera that includes spoken dialogue, is a secular musical genre which developed in the mid-17th century, flourishing most importantly in the century after 1850. Francisco Asenjo Barbieri was a key figure in the development of the romantic zarzuela; whilst later composers such as Ruperto Chapí, Federico Chueca and Tomás Bretón brought the genre to its late 19th-century apogee. Leading 20th-century zarzuela composers included Pablo Sorozábal and Federico Moreno Torroba. Fernando Sor, Dionisio Aguado, Francisco Tárrega and Miguel Llobet are known as composers of guitar music. Fine literature for violin was created by Pablo Sarasate and Jesús de Monasterio. Musical creativity mainly moved into areas of popular music until the nationalist revival of the late Romantic era. Spanish composers of this period included Felipe Pedrell, Isaac Albéniz, Enrique Granados, Joaquín Turina, Manuel de Falla, Jesús Guridi, Ernesto Halffter, Federico Mompou, Salvador Bacarisse, and Joaquín Rodrigo. In the 1930s, Spain's music scene was vibrant and diverse amidst significant social and political changes. Traditional Spanish music, particularly flamenco, continued to flourish, influenced by artists like Federico García Lorca and Manuel de Falla. |

18世紀から20世紀 書籍の表紙:1723年から1724年に出版された『Escuela Música según la práctica moderna』 スペ イン古典派音楽の代表例であるアントニオ・ソレルのソナタ第84番 演奏時間:8分28秒 このファイルの再生に問題がありますか? メディアヘルプをご覧ください。 17世紀末には、スペインの「古典派」音楽文化は衰退し、19世紀までその状態が続いた。スペインに古典主義が到来した際には、アントニオ・ソレールの作 品に見られるように、イタリアのモデルからインスピレーションを得ていた。ドメニコ・スカルラッティやルイジ・ボッケリーニといった傑出したイタリア人作 曲家がマドリードの王宮に召喚された。短命に終わったフアン・クリストバル・デ・アリアガは、スペインにおけるロマン派交響主義の主な開拓者として知られ ている。  1926年4月26日号の『タイム』誌の表紙を飾ったのはラケル・メラーであった。 スペインでは交響曲はあまり重要視されてこなかったが、室内楽、独奏楽器(主にギターとピアノ)、声楽、オペラ(伝統的なオペラとスペイン版ジングシュ ピール)の作曲は、地元の作曲家によって行われた。セリフのあるスペイン独自のオペラであるサルスエラは、17世紀半ばに発展した世俗音楽のジャンルであ り、1850年以降に最も盛んになった。フランシスコ・アセンホ・バルビエリはロマン派サルスエラの発展に重要な役割を果たし、その後、ルペルト・チャ ピ、フェデリコ・チュエカ、トマス・ブレットンといった作曲家が19世紀末にこのジャンルを絶頂期へと導いた。20世紀の主要なサルスエラ作曲家には、パ ブロ・ソロサバルやフェデリコ・モレノ・トロバなどがいる。 ギター音楽の作曲家としては、フェルナンド・ソル、ディオニシオ・アグアド、フランシスコ・タレガ、ミゲル・リョベートなどが知られている。ヴァイオリン のための優れた楽曲は、パブロ・サラサーテやヘスス・デ・モナステリオによって生み出された。 音楽の創造性は主にポピュラー音楽の分野へと移行し、ロマン派後期の民族復興期まで続いた。この時代のスペイン人作曲家には、フェリペ・ペドレル、イサー ク・アルベニス、エンリケ・グラナドス、ホアキン・トゥリーナ、マヌエル・デ・ファリャ、ヘスス・グリディ、エルネスト・ハルフテル、フェデリコ・モンポ ウ、サルバドール・バカライス、ホアキン・ロドリーゴなどがいる。 1930年代、スペインの音楽シーンは、社会や政治の大きな変化のなかで活気に満ち、多様性をみせていた。スペインの伝統音楽、特にフラメンコは、フェデ リコ・ガルシア・ロルカやマヌエル・デ・ファリャなどのアーティストの影響を受け、引き続き盛況であった。 |

| Performers Main articles: List of Spanish musicians and List of bands from Spain  Raphael recognized for being one of the forerunners of the romantic ballad. In the realm of classical music, Spain boasts a rich tradition of accomplished singers and performers who have made significant contributions to the global musical landscape. The country hosts a vibrant classical music scene, characterized by a multitude of professional orchestras and esteemed opera houses. With over forty professional orchestras spread across its regions, Spain serves as a hub for orchestral excellence. Among these ensembles, notable names include the Orquestra Simfònica de Barcelona, Orquesta Nacional de España, and the Orquesta Sinfónica de Madrid. These orchestras showcase the nation's commitment to fostering musical talent and nurturing classical repertoire. In addition to its orchestral prowess, Spain boasts a selection of distinguished opera houses that serve as pillars of the classical music community. Among these institutions, the Teatro Real, the Gran Teatre del Liceu, Teatro Arriaga, and the El Palau de les Arts Reina Sofía stand as esteemed venues renowned for their commitment to showcasing world-class opera productions. These opera houses provide platforms for both established and emerging singers to showcase their talents on a prestigious stage. During the 1940s, Spanish music was shaped by the aftermath of the Civil War and Francisco Franco's dictatorship. Traditional genres like flamenco and classical music continued to thrive, albeit under strict censorship. Popular music forms such as zarzuela and pasodoble celebrated Spanish identity. The era reflected a complex interplay of cultural resilience, political control, and the influence of broader European events like World War II. Overall, music in 1940s Spain mirrored a society in transition, navigating between tradition and the constraints of authoritarian rule. |

パフォーマー 詳細は:スペインの音楽家の一覧、スペインのバンドの一覧  ラファエルはロマンティック・バラードの先駆者の一人として認められている。 クラシック音楽の分野では、スペインは世界的な音楽の風景に多大な貢献をしてきた熟練した歌手や演奏家の豊かな伝統を誇っている。スペインには多数のプロ のオーケストラや著名なオペラハウスがあることで特徴づけられる活気のあるクラシック音楽のシーンがある。 スペインには40を超えるプロのオーケストラが国内各地に存在し、オーケストラの卓越性における中心地となっている。 これらのアンサンブルの中でも特に有名なのは、バルセロナ交響楽団、スペイン国立管弦楽団、マドリード交響楽団などである。 これらのオーケストラは、音楽の才能を育み、クラシックのレパートリーを育むという国民の取り組みを象徴している。 オーケストラの卓越した実力に加え、スペインにはクラシック音楽界の柱となる著名なオペラハウスがいくつもある。 その中でも、テアトロ・レアル、リセウ大劇場、テアトロ・アリアガ、パラウ・デ・ラ・ムジカは、世界クラスのオペラ作品の上演に力を入れていることで知ら れる由緒ある会場である。 これらのオペラハウスは、著名な歌手や新進の歌手がその才能を一流の舞台で披露する場を提供している。 1940年代、スペインの音楽は、内戦とフランシスコ・フランコの独裁政権の余波によって形作られた。厳しい検閲下に置かれていたにもかかわらず、フラメ ンコやクラシック音楽などの伝統的なジャンルは引き続き盛況であった。サルスエラやパソドブレなどの大衆音楽はスペインのアイデンティティを祝った。この 時代は、文化の回復力、政治的統制、第二次世界大戦のようなヨーロッパの広域にわたる出来事の影響が複雑に絡み合った時代であった。全体として、1940 年代のスペインの音楽は、伝統と権威主義的支配の制約の間を揺れ動きながら、変遷する社会を映し出していた。 |

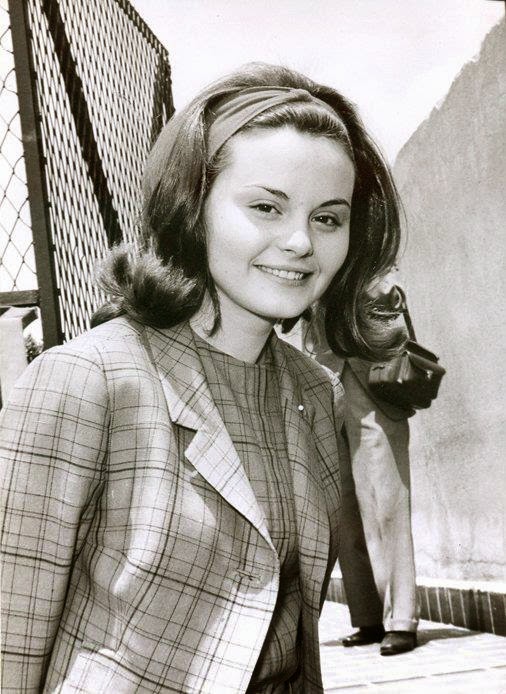

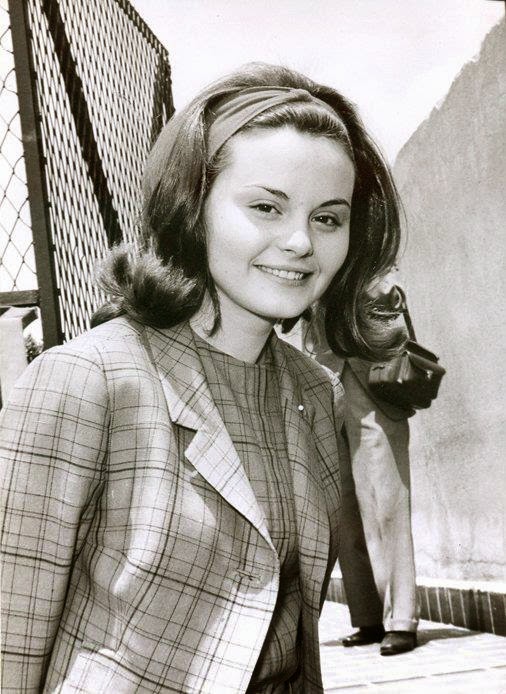

| Ye-yé Main article: Yé-yé  Massiel most successful Yé-yé singers in Spain. The Yé-yé movement, stemming from the English pop-refrain "yeah-yeah," took on a unique form in various cultural contexts, notably in France and Spain. Initially coined in France to describe a genre influenced by American rock and British beat music of the early 1960s, such as the twist, Yé-yé music quickly gained popularity for its lively and uplifting characteristics. In Spain, Concha Velasco is often credited as the catalyst for the Yé-yé scene with her 1965 hit "La Chica Ye-Yé." However, even before Velasco's breakthrough, artists like Karina had already begun making significant strides with their infectious tunes as early as 1963. These pioneering female singers not only popularized Yé-yé music but also set the stage for a vibrant cultural movement characterized by catchy melodies and youthful exuberance. Spanish Yé-yé music, much like its French counterpart, drew heavily from American and British influences but also incorporated elements of traditional Spanish music, particularly flamenco rhythms. This fusion of styles created a dynamic musical landscape that resonated with audiences not only in Spain but also across Spanish-speaking communities worldwide. The genre's ability to blend international pop trends with indigenous musical traditions contributed to its enduring appeal and cultural significance. In contemporary times, artists such as Rosalía have continued to explore and reinterpret this fusion of styles, blending modern pop sensibilities with traditional Spanish music elements. This ongoing evolution highlights the Yé-yé movement's lasting influence on Spanish pop culture, showcasing its adaptability and continued relevance in shaping the musical identity of Spain. As a result, Yé-yé music remains a vital chapter in the broader narrative of how global musical influences intersect with local cultural expressions. |

イエイエ 詳細は「イエイエ」を参照  マッシエルはスペインで最も成功したイエイエ歌手である。 イエイエは、英語のポップリフレイン「yeah-yeah」に由来するが、フランスやスペインなど、さまざまな文化的な文脈の中で独特な形を取った。当 初、1960年代初頭のアメリカン・ロックやブリティッシュ・ビート音楽の影響を受けたジャンルを指す言葉としてフランスで生まれた「イエイエ」という言 葉は、ツイストなどと同様、イエイエ音楽は活気があり、高揚感のある音楽として急速に人気を博した。スペインでは、1965年のヒット曲「La Chica Ye-Yé」で、コンチャ・ベラスコがイエイエ・シーンの立役者とされることが多い。しかし、ベラスコのブレイク以前の1963年には、カリナのような アーティストがすでに、その魅力的な楽曲で大きな躍進を遂げていた。こうした先駆的な女性歌手たちは、イェイェイェ音楽を広めただけでなく、キャッチーな メロディと若者の活気を特徴とする活気あふれる文化運動の舞台を整えた。 スペインのイェイイェ音楽は、フランス版と同様に、アメリカやイギリスの影響を強く受けているが、伝統的なスペイン音楽、特にフラメンコのリズムの要素も 取り入れている。このスタイルの融合は、ダイナミックな音楽の風景を生み出し、スペインだけでなく、世界中のスペイン語圏のコミュニティの聴衆の心にも響 いた。このジャンルの、国際的なポップのトレンドと土着の音楽の伝統を融合させる能力は、その永続的な魅力と文化的意義に貢献した。 現代では、ロサリアのようなアーティストたちが、現代のポップ感覚と伝統的なスペイン音楽の要素を融合させながら、このスタイルの融合を探究し、再解釈し 続けている。この進化は、イェイェイェ運動がスペインのポップカルチャーに与えた影響が今も続いていることを示しており、スペインの音楽的アイデンティ ティを形成する上で、その適応性と継続的な関連性を示している。その結果、イェイェイェ音楽は、グローバルな音楽的影響がローカルな文化的表現と交差す る、より広範な物語の重要な一章であり続けている。 |

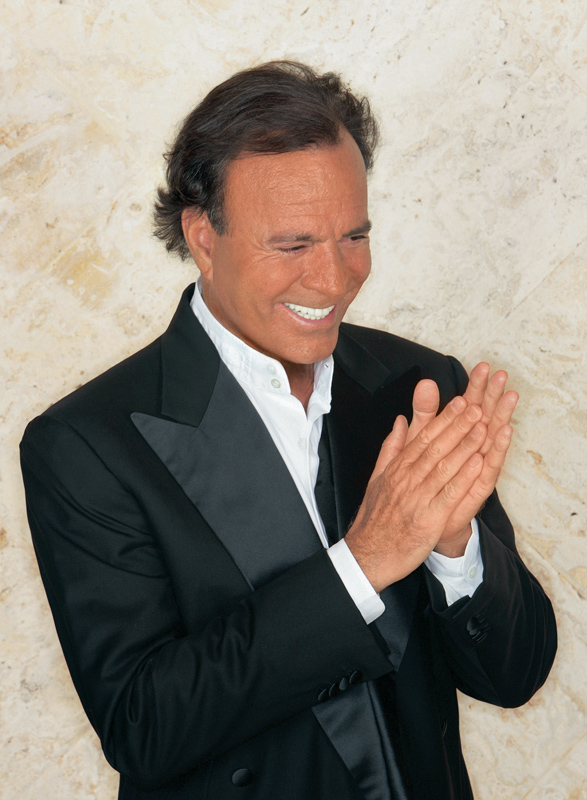

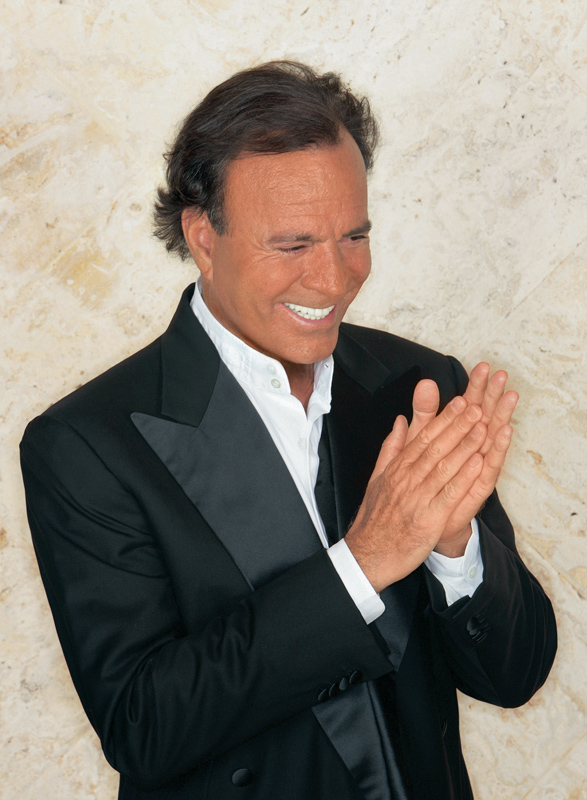

| Popular music in Spain This section is written like a personal reflection, personal essay, or argumentative essay that states a Wikipedia editor's personal feelings or presents an original argument about a topic. Please help improve it by rewriting it in an encyclopedic style. (September 2015) (Learn how and when to remove this message)  Rocío Dúrcal is one of the best-selling Spanish-speaking women in the industry. Spanish pop music's journey through the tumultuous years of Francisco Franco's regime was marked by resilience and adaptation. Despite strict censorship and limited outlets for contemporary music, the Benidorm International Song Festival emerged as a beacon of opportunity for Spanish musicians. Inspired by Italy's San Remo Music Festival, Benidorm provided a crucial platform for artists to showcase new musical styles to eager audiences. This festival not only introduced international influences but also nurtured local talent, laying the groundwork for future developments in Spanish pop. An injured Real Madrid football player-turned-singer, for example, became the world-famous Julio Iglesias. During the 1960s and early 1970s, tourism boomed, bringing yet more musical styles from the rest of the continent and abroad. During Franco's rule, which heavily restricted women's rights and roles in public life, female artists faced additional barriers in expressing themselves through music. However, some managed to break through these constraints, contributing to the vibrant underground music scene that emerged despite censorship. Artists like Marisol, who started as a child star in the 1960s, and Rocío Dúrcal, who became a prominent figure in Spanish music and film, navigated these challenges to become beloved icons of their time.  Julio Iglesias is the Latin artist who has sold the most albums in history. The 1980s ushered in a transformative era with La Movida Madrileña, a vibrant cultural movement centered in Madrid. This period was pivotal for Spain's pop music scene, fostering a spirit of experimentation and creativity across diverse genres such as electronica, Euro disco, rock, punk, and hip-hop. Spanish pop music began to carve out its own distinctive identity, moving beyond emulation of Anglo-American trends to embrace originality and diversity. La Movida not only revitalized artistic expression but also catalyzed the industry's growth, setting the stage for Spain's emergence as a powerhouse in global music. Female artists such as Alaska (of Alaska y los Pegamoides and later Fangoria) and Martirio emerged as influential figures, challenging traditional gender roles and exploring new sounds and styles.  Mónica Naranjo rose to fame in the 1990s with hits like "Sola" and "Sobreviviré" Julio Iglesias, Enrique Iglesias, and Alejandro Sanz stand as icons of Spanish pop music's international success. These artists not only captivated audiences within Spain but also resonated globally, showcasing the universal appeal of Spanish-language music. Julio Iglesias, in particular, achieved unprecedented success as the best-selling male Latin artist of all time, illustrating the enduring impact of Spanish pop on the global music landscape.[1] In Spain itself, the 1990s were characterized by a vibrant underground music scene that thrived in major cities like Madrid and Barcelona. Alternative rock bands such as Los Planetas and Dover gained prominence, bringing a fresh energy to Spanish pop with their indie rock influences and experimental sounds. This period also saw the emergence of electronic music and dance clubs, further diversifying the musical landscape and fostering a new generation of DJs and producers. The integration of Spanish and Latin American music markets further amplified this influence, fostering a dynamic cultural exchange that continues to shape trends and innovation in the industry. Mónica Naranjo, known for her powerful vocals and dramatic performances, and Ana Belén, whose sophisticated style and versatile voice made her a prominent figure. These artists contributed to a diverse and vibrant era in Spanish music, each leaving a lasting impact with their distinctive contributions to the genre.  Since their debut La Oreja de Van Gogh, they have sold more than 8 million albums worldwide. In contemporary times, Spanish female artists continue to thrive and innovate across various genres. Artists like Rosalía have garnered international acclaim for their unique blend of flamenco, pop, and urban music, pushing boundaries and redefining what it means to be a Spanish pop star in the global music scene. Aitana has risen to prominence through her participation in talent shows and subsequent chart-topping hits. These singers exemplify Spain's diverse musical landscape and its ability to blend traditional influences with contemporary trends in pop music. Male singers like Pablo Alborán, David Bisbal, Manuel Carrasco, and Melendi continue to captivate audiences with their distinct voices and memorable songs. Artists like Enrique Iglesias and Alejandro Sanz have become successful internationally winning major music awards such as the Grammy Award. As Spanish is commonly spoken in Spain and most of Latin America, music from both regions have been able to crossover with each other.[2] According to the Sociedad General de Autores y Editores (SGAE), Spain is the largest Latino music market in the world.[3] As a result, the Latin music industry encompasses Spanish-language music from Spain.[4][5] The Latin Academy of Recording Arts & Sciences, the organization responsible for the Latin Grammy Awards, includes music from Spain including a category for Best Flamenco Album with voting members living in the country.[6][7] |

スペインのポピュラー音楽 この節は、ウィキペディア編集者の個人的な感想や主観的な意見、独自の論点を提示する私論、または原論の体裁で書かれている。百科事典的な文体に書き直し て、改善にご協力ください。 (2015年9月) (メッセージの削除方法とタイミングについてはこちらをご覧ください)  ロシオ・デュルカルは、業界で最も売れたスペイン語を話す女性歌手の一人である。 フランシスコ・フランコ独裁政権下の激動の時代を通じて、スペインのポップミュージックは、回復力と適応力によって特徴づけられた。厳しい検閲と現代音楽 の限られた発表の場にもかかわらず、ベニドルム国際歌謡祭はスペインのミュージシャンにとってのチャンスの光として登場した。イタリアのサンレモ音楽祭に 触発されたベニドルムは、アーティストたちが新しい音楽スタイルを熱心な観客に披露する重要なプラットフォームとなった。このフェスティバルは、国際的な 影響を紹介するだけでなく、地元の才能を育み、スペインポップの将来の発展の基礎を築いた。例えば、負傷したレアル・マドリードのサッカー選手で、後に歌 手となったフリオ・イグレシアスは、世界的に有名な歌手となった。1960年代から1970年代前半にかけて、観光ブームが到来し、大陸や海外からさらに 多くの音楽スタイルがもたらされた。フランコ将軍が政権を握っていた時代には、女性の権利や社会での役割が厳しく制限されていたため、女性アーティストた ちは音楽を通して自己表現をする上で、さらなる障壁に直面した。しかし、一部のアーティストたちは、検閲にもかかわらず台頭した活気あるアンダーグラウン ド音楽シーンに貢献し、こうした制約を乗り越えることに成功した。1960年代に子役としてデビューしたマリソルや、スペインの音楽と映画界で著名な存在 となったロシオ・デュルカルのようなアーティストたちは、こうした困難を乗り越え、時代を象徴する愛される存在となった。  フリオ・イグレシアスは、ラテン系のアーティストとして史上最も多くのアルバムを売り上げた。 1980年代には、マドリードを中心に活気あふれる文化運動「ラ・モビーダ・マドリレーニャ」が巻き起こり、変革の時代が幕を開けた。この時期はスペイン のポップミュージック界にとって極めて重要な時期であり、エレクトロニカ、ユーロディスコ、ロック、パンク、ヒップホップなど、さまざまなジャンルの音楽 に実験精神と創造性が育まれた。スペインのポップミュージックは、英米のトレンドを模倣するだけでなく、独自性と多様性を追求する独自のアイデンティティ を確立し始めた。ラ・モビダは芸術表現を活性化させただけでなく、業界の成長を促進し、スペインが世界の音楽界で強国として台頭するための舞台を整えた。 アラスカ(Alaska y los Pegamoides、後にFangoria)やマルティリオ(Martirio)といった女性アーティストが影響力のある人物として登場し、伝統的な性 別役割に異議を唱え、新しいサウンドやスタイルを模索した。  モニカ・ナランホ(Mónica Naranjo)は1990年代に「Sola」や「Sobreviviré」などのヒット曲で有名になった。 フリオ・イグレシアス(Julio Iglesias)、エンリケ・イグレシアス(Enrique Iglesias)、アレハンドロ・サンス(Alejandro Sanz)は、スペインのポップミュージックの国際的な成功の象徴である。これらのアーティストはスペイン国内の観客を魅了しただけでなく、世界的な反響 を呼び、スペイン語の音楽の普遍的な魅力を示した。特にフリオ・イグレシアスは、ラテン系男性アーティストとして史上最高の売り上げを記録し、スペイン語 ポップスが世界の音楽界に与えた影響の持続性を示すこととなった。[1] スペイン国内では、1990年代はマドリッドやバルセロナなどの主要都市で活気のあるアンダーグラウンド音楽シーンが特徴的であった。 ロス・プラネタスやドーバーなどのオルタナティブ・ロックバンドが注目を集め、インディーズ・ロックの影響や実験的なサウンドでスペインポップに新たな活 力をもたらした。この時期には、エレクトロニックミュージックやダンスクラブも登場し、音楽の風景はさらに多様化し、新しい世代のDJやプロデューサーが 育っていった。スペインとラテンアメリカの音楽市場の統合は、この影響力をさらに強め、業界のトレンドやイノベーションを形成し続けるダイナミックな文化 交流を促進した。パワフルなボーカルとドラマチックなパフォーマンスで知られるモニカ・ナランホや、洗練されたスタイルと多彩な歌声で著名なアナ・ベレン などである。これらのアーティストは、スペイン音楽の多様で活気のある時代に貢献し、それぞれがそのジャンルに独特な貢献をしたことで、今もなお強い影響 力を残している。  デビュー以来、ラ・オレハ・デ・バン・ゴッホは全世界で800万枚以上のアルバムを売り上げている。 現代では、スペインの女性アーティストたちはさまざまなジャンルで活躍し、革新を続けている。ロサリアのようなアーティストは、フラメンコ、ポップ、アー バンミュージックを独自のスタイルで融合させ、国際的な評価を得ている。彼女たちは、グローバルな音楽シーンにおいて、スペインのポップスターとは何かと いう概念を再定義し、その境界線を押し広げている。アイターナは、タレントショーへの参加とそれに続くチャート首位のヒット曲で一躍有名になった。これら の歌手は、スペインの多様な音楽シーンと、ポップミュージックにおける伝統的な影響と現代的なトレンドを融合させる能力を体現している。パブロ・アルバラ ン、ダビッド・ビスバル、マヌエル・カラスコ、メレンディといった男性歌手は、独特な歌声と心に残る歌で聴衆を魅了し続けている。 エンリケ・イグレシアスやアレハンドロ・サンスといったアーティストは、グラミー賞などの主要な音楽賞を受賞し、国際的な成功を収めている。スペイン語は スペインおよびラテンアメリカの大半の国々で話されているため、両地域の音楽はクロスオーバーしている。[2] スペインはラテン音楽市場としては世界最大であり、[3] ラテン音楽業界はスペイン語のスペインの音楽も包含している。[4][5] ラテン・グラミー賞を主催するラテン・アカデミー・オブ・レコーディング・アーツ・アンド・サイエンシズには、スペイン在住の投票会員による最優秀フラメ ンコ・アルバム部門など、スペインの音楽も含まれている。[6][7] |

Music by region The regions of Spain have distinctive musical traditions. There is also a movement of singer-songwriters with politically active lyrics, paralleling similar developments in Latin America and Portugal. The singer and composer Eliseo Parra (b 1949) has recorded traditional folk music from the Basque country and Castile as well as his own compositions inspired from the musical styles of Spain and abroad. Andalusia Main article: Music of Andalusia  Flamenco dancing in Seville.  Panda de Verdiales in Málaga. Though Andalusia is best known for flamenco music, there is also a tradition of gaita rociera (tabor pipe) music in western Andalusia and a distinct violin and plucked-string type of band music known as panda de verdiales in Málaga. Sevillanas is related to flamenco and most flamenco performers have at least one classic sevillana in their repertoire. The style originated as a medieval Castilian dance, called the seguidilla, which was adopted with a flamenco style in the 19th century. Today, this lively couples' dance is popular in most parts of Spain, though the dance is often associated with the city of Seville's famous Easter feria. The region has also produced singer-songwriters like Javier Ruibal and Carlos Cano [es], who revived a traditional music called copla. Catalan Kiko Veneno and Joaquín Sabina are popular performers in a distinctly Spanish-style rock music, while Sephardic musicians like Aurora Moreno, Luís Delgado and Rosa Zaragoza keep Andalusian Sephardic music alive. Aragon Main article: Music of Aragon  Aragonese jota dancing. Jota, popular across Spain, might have its historical roots in the southern part of Aragon. Jota instruments include the castanets, guitar, bandurria, tambourines and sometimes the flute. The guitarro, a unique kind of small guitar also seen in Murcia, seems Aragonese in origin. Besides its music for stick-dances and dulzaina (shawm), Aragon has its own gaita de boto (bagpipes) and chiflo (tabor pipe). As in the Basque country, Aragonese chiflo can be played along to a chicotén string-drum (psaltery) rhythm. Asturias, Cantabria and Galicia Main article: Music of Galicia, Cantabria and Asturias  Asturian gaiteros (bagpipe players) Northwest Spain (Asturias, Galicia and Cantabria) is home to a distinct musical tradition extending back into the Middle Ages. The signature instrument of the region is the gaita (bagpipe). The gaita is often accompanied by a snare drum, called the tamboril, and is played in processional marches. Other instruments include the requinta, a kind of fife, as well as harps, fiddles, rebec and zanfona (hurdy-gurdy). The music itself runs the gamut from uptempo muiñeiras to stately marches. As in the Basque Country, Cantabrian music also features intricate arch and stick dances but the tabor pipe does not play as an important role as it does in Basque music. Traditionally, Galician music included a type of chanting song known as alalas. Alalas may include instrumental interludes, and were believed to have a very long history, based on legends. There are local festivals of which Ortigueira's Festival Internacional do Mundo Celta is especially important. Drum and bagpipe couples range among the most beloved kinds of Galician music, that also includes popular bands like Milladoiro. Pandereteiras are traditional groups of women that play tambourines and sing - bands like Tanxugueiras are directly influenced by this tradition. The bagpipe virtuosos Carlos Núñez and Susana Seivane are especially popular performers. Asturias is also home to popular musicians such as José Ángel Hevia (bagpiper) and the group Llan de cubel. Circular dances using a 6/8 tambourine rhythm are a hallmark of this area. Vocal asturianadas show melismatic ornamentations similar to those of other parts of the Iberian Peninsula. There are many festivals, such as "Folixa na Primavera" (April, in Mieres), "Intercelticu d'Avilés" (Interceltic festival of Avilés, in July), as well as many "Celtic nights" in Asturias. Balearic Islands Main article: Music of the Balearic Islands In the Balearic Islands, Xeremiers or colla de xeremiers are a traditional ensemble that consists of flabiol (a five-hole tabor pipe) and xeremias (bagpipes). Majorca's Maria del Mar Bonet was one of the most influential artists of nova canço, known for her political and social lyrics. Tomeu Penya, Biel Majoral, Cerebros Exprimidos and Joan Bibiloni are also popular. Basque Country Main article: Basque music  Ezpatadantza of the Basque Country. The most popular kind of Basque music is named after the dance trikitixa, which is based on the accordion and tambourine. Popular performers are Joseba Tapia and Kepa Junkera. Highly appreciated folk instruments are the txistu (a tabor pipe similar to Occitanian galoubet recorder), alboka (a double clarinet played in circular-breathing technique, similar to other Mediterranean instruments like launeddas) and txalaparta (a huge xylophone, similar to the Romanian toacă and played by two performers in a fascinating game-performance). As in many parts of the Iberian peninsula, there are ritual dances with sticks, swords and arches made from vegetation. Other popular dances are the fandango, jota and 5/8 zortziko. Basques on both sides of the Spanish-French border have been known for their singing since the Middle Ages, and a surge of Basque nationalism at the end of the 19th century led to the establishment of large Basque-language choirs that helped preserve their language and songs. Even during the persecution of the Francisco Franco era (1939–1975), when the Basque language was outlawed, traditional songs and dances were defiantly preserved in secret, and they continue to thrive despite the popularity of commercially marketed pop music. Canary Islands Main article: Music of the Canary Islands In the Canary Islands, Isa, a local kind of Jota, is now popular, and Latin American musical (Cuban) influences are quite widespread, especially with the charango (a kind of guitar). Timple, a local instrument which resembles ukulele / cavaquinho, is commonly seen in plucked-string bands. A popular set on El Hierro island consists of drums and wooden fifes (pito herreño). The tabor pipe is customary in some ritual dances on the island of Tenerife. Castile, Madrid and León Main article: Music of Castile, Madrid and León  Children in Castilian folk costume in Soria, Castile. A large inland region, Castile, Madrid and Leon were Celtiberian country before its annexation and cultural latinization by the Roman Empire but it is extremely doubtful that anything from the musical traditions of the Celtic era have survived. Ever since, the area has been a musical melting pot; including Roman, Visigothic, Jewish, Moorish, Italian, French and Roma influences, but the longstanding influences from the surrounding regions and Portugal continue to play an important role. Areas within Castile and León generally tend to have more musical affinity with neighboring regions than with more distant parts of the region. This has given the region diverse musical traditions. Jota is popular, but is uniquely slow in Castile and León, unlike its more energetic Aragonese version. Instrumentation also varies much from the one in Aragon. Northern León, that shares a language relationship with a region in northern Portugal and the Spanish regions of Asturias and Galicia, also shares their musical influences. Here, the gaita (bagpipe) and tabor pipe playing traditions are prominent. In most of Castile, there is a strong tradition of dance music for dulzaina (shawm) and rondalla groups. Popular rhythms include 5/8 charrada and circle dances, jota and habas verdes. As in many other parts of the Iberian peninsula, ritual dances include paloteos (stick dances). Salamanca is known as the home of tuna, a serenade played with guitars and tambourines, mostly by students dressed in medieval clothing. Madrid is known for its chotis music, a local variation to the 19th-century schottische dance. Flamenco, although not considered native, is popular among some urbanites but is mainly confined to Madrid. Catalonia Main article: Music of Catalonia Though Catalonia is best known for sardana music played by a cobla, there are other traditional styles of dance music like ball de bastons (stick-dances), galops, ball de gitanes. Music is at the forefront in cercaviles and celebrations similar to Patum in Berga. Flabiol (a five-hole tabor pipe), gralla or dolçaina (a shawm) and sac de gemecs (a local bagpipe) are traditional folk instruments that make part of some coblas. Catalan gipsies and Andalusian immigrants to Catalonia created their own style of rumba called rumba catalana which is a popular style that's similar to flamenco, but not technically part of the flamenco canon. The rumba catalana originated in Barcelona when the rumba and other Afro-Cuban styles arrived from Cuba in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Catalan performers adapted them to the flamenco format and made it their own. Though often dismissed by aficionados as "fake" flamenco, rumba catalana remains wildly popular to this day. The havaneres singers remain popular. Nowadays, young people cultivate Rock català popular music, as some years ago the Nova Cançó was relevant. Extremadura Main article: Music of Extremadura Having long been the poorest part of Spain, Extremadura is a largely rural region known for the Portuguese influence on its music. As in the northern regions of Spain, there is a rich repertoire for tabor pipe music. The zambomba friction-drum (similar to Portuguese sarronca or Brazilian cuica) is played by pulling on a rope which is inside the drum. It is found throughout Spain. The jota is common, here played with triangles, castanets, guitars, tambourines, accordions and zambombas. Murcia Main article: Music of Murcia Murcia is a region in the south-east of Spain which, historically, experienced considerable Moorish colonisation, is similar in many respects to its neighbour, Andalusia. The guitar-accompanied cante jondo Flamenco style is especially associated with Murcia as are rondallas, plucked-string bands. Christian songs, such as the polyphonic chant of the Auroro singers, are traditionally sung a cappella, sometimes accompanied by the sound of church bells, and cuadrillas are festive songs primarily played during holidays, like Christmas. Navarre and La Rioja  Ioaldunak dancers of Navarre. Navarre and La Rioja are small northern regions with diverse cultural elements. Bordered by Aragon and the Basque Autonomous Community, they also share much of the music found in those two regions. Northern Navarre is Basque in language, while the Southern section shares more Aragonese features. The jota genre is also known in both Navarre and La Rioja. Both regions have rich dance and dulzaina (shawm) traditions. Txistu (tabor pipe) and dulzaina ensembles are very popular in the public celebrations of Navarre. Valencia Main article: Music of Valencia Traditional music from Valencia is characteristically Mediterranean in origin. Valencia also has its local kind of Jota. Moreover, Valencia has a high reputation for musical innovation, and performing brass bands called bandes are common, with one appearing in almost every town. Dolçaina (shawm) is widely found. Valencia also shares some traditional dances with other Iberian areas, like for instance, the ball de bastons (stick-dances). The group Al Tall is also well-known, experimenting with the Berber band Muluk El Hwa, and revitalizing traditional Valencian music, following the Riproposta Italian musical movement. |

地域別の音楽 スペインの地域にはそれぞれ独特の音楽の伝統がある。ラテンアメリカやポルトガルでも同様の動きが見られるが、スペインでも政治的な主張を歌詞に盛り込ん だシンガーソングライターの活動が活発である。歌手であり作曲家でもあるエリセオ・パラ(1949年生まれ)は、バスク地方やカスティーリャ地方の伝統的 な民族音楽を録音しているほか、スペインや海外の音楽スタイルからインスピレーションを得た自身の作曲作品も録音している。 アンダルシア 詳細は「アンダルシアの音楽」を参照  セビリアのフラメンコダンス  マラガのパンダ・デ・ベルディアレス アンダルシアはフラメンコ音楽で最もよく知られているが、アンダルシア西部にはガイタ・ロシエラ(タボール・パイプ)音楽の伝統があり、マラガにはパン ダ・デ・ベルディアレスと呼ばれる独特のバイオリンと撥弦楽器のバンド音楽がある。 セビジャーナスはフラメンコと関連があり、ほとんどのフラメンコ・パフォーマーは、少なくとも1曲はクラシックなセビジャーナスをレパートリーに持ってい る。このスタイルは、セギディーリャと呼ばれる中世カスティーリャのダンスに由来し、19世紀にフラメンコのスタイルが取り入れられた。現在では、この活 気のあるカップルダンスはスペインのほとんどの地域で人気があるが、このダンスはセビリアの有名なイースター・フェリアと関連付けられることが多い。 この地方は、コプラと呼ばれる伝統音楽を復活させたハビエル・ルイバルやカルロス・カノのようなシンガーソングライターも輩出している。 カタロニア人のキコ・ベネノやホアキン・サビーナは、スペインらしいロック音楽の人気アーティストである。一方、アウロラ・モレノ、ルイス・デルガド、ロ サ・サラゴサといったセファルディの音楽家たちは、アンダルシアのセファルディ音楽を生き続けさせている。 アラゴン 詳細は「アラゴンの音楽」を参照  アラゴン地方のホタの踊り。 スペイン全土で人気のあるホタは、アラゴン南部にその歴史的ルーツがあるかもしれない。ホタの楽器にはカスタネット、ギター、バンドゥリア、タンバリン、 そして時にはフルートが含まれる。ムルシアでも見られる独特な小型ギターであるギターロは、アラゴンが起源であると思われる。 棒踊りの音楽やドルサイナ(ショーム)のほかにも、アラゴンには独自のガイタ・デ・ボト(バグパイプ)やチフロ(タボール・パイプ)がある。 バスク地方と同様に、アラゴン地方のチフロは、シコテンの弦ドラム(プサルテリー)のリズムに合わせて演奏される。 アストゥリアス、カンタブリア、ガリシア 詳細は「ガリシア、カンタブリア、アストゥリアスの音楽」を参照  アストゥリアスのバグパイプ奏者 スペイン北西部(アストゥリアス、ガリシア、カンタブリア)には、中世にまで遡る独特な音楽の伝統がある。この地方の代表的な楽器は、ガイタ(バグパイ プ)である。ガイタは、タンボリンと呼ばれるスネアドラムと共によく演奏され、行列の行進曲として演奏される。その他の楽器には、リコーダ(笛の一種)や ハープ、フィドル、レベック、ザンフォナ(ハーディガーディ)などがある。音楽は、アップテンポのムイニェイラスから厳かな行進曲まで幅広い。バスク地方 と同様に、カンタブリア地方の音楽も、複雑なアーチダンスやスティックダンスを特徴とするが、バスク音楽ほどタボールパイプは重要な役割を果たさない。伝 統的に、ガリシア音楽には「アララ」と呼ばれる歌が含まれていた。アララには楽器演奏の合間を挟むこともあり、伝説によると非常に長い歴史を持つと考えら れている。 オルティゲイラのセルタ・ムンド・セレタ国際フェスティバル(Festival Internacional do Mundo Celta)は特に重要な地元のフェスティバルである。 ガリシア音楽で最も愛されているのは、ドラムとバグパイプのデュオで、ミラドイロ(Milladoiro)のような人気バンドも含まれる。 パンデレテーラス(Pandereteiras)はタンバリンを叩きながら歌う伝統的な女性グループで、タンシュゲイラス(Tanxugueiras)の ようなバンドは、この伝統に直接影響を受けている。 バグパイプの名人カルロス・ヌニェス(Carlos Núñez)とスサーナ・セイバネ(Susana Seivane)は特に人気の高い演奏家である。 アストゥリアスは、ホセ・アンヘル・エビア(バグパイプ奏者)やグループ、Llan de cubelなどの人気ミュージシャンも輩出している。6/8のタンバリンのリズムを使った輪舞は、この地域の特色である。アストゥリアス地方の声楽は、イ ベリア半島の他の地域と同様に、旋律装飾が特徴的である。 多くのフェスティバルが開催されており、例えば「フォリクサ・ナ・プリマベーラ」(4月、ミエレス)、「インターセルティク・ダビレス」(アビレスのケル ト文化フェスティバル、7月)などがある。また、アストゥリアスでは「ケルトの夜」が数多く開催されている。 バレアレス諸島 詳細は「バレアレス諸島の音楽」を参照 バレアレス諸島では、シェレミエスまたはコラ・デ・シェレミエスと呼ばれる伝統的な合奏団があり、フラビオル(5つの穴を持つタブールパイプ)とシェレミ ア(バグパイプ)で構成されている。マヨルカ島のマリア・デル・マル・ボネットは、政治や社会を題材にした歌詞で知られるノヴァ・カンソの最も影響力のあ るアーティストの一人であった。トメウ・ペーニャ、ビエル・マジョラル、セレブロス・エクスプリミドス、ジョアン・ビビロニも人気がある。 バスク自治州 詳細は「バスク音楽」を参照  バスク自治州のエスパタダンツァ。 バスク音楽で最も人気のあるものは、アコーディオンとタンバリンをベースにしたトリキティシャというダンスにちなんで名付けられたものである。人気の高い 演奏家には、ジョセバ・タピアとケパ・フンケラがいる。高く評価されている民族楽器には、シストゥ(オック語のガルーベ・リコーダーに似たタボール・パイ プ)、アルボカ(ラウネッダなどの地中海の楽器に似た循環呼吸法で演奏されるダブル・クラリネット)、チャラパルタ(ルーマニアのトアカに似た巨大な木琴 で、2人の演奏者による魅惑的なゲームパフォーマンスで演奏される)などがある。イベリア半島の多くの地域と同様に、植物から作られた棒、剣、弓を使った 儀式の踊りがある。 その他の人気のある踊りには、ファンダンゴ、ホタ、5/8拍子のゾルツィコなどがある。 スペインとフランスの国境の両側に住むバスク人は、中世の時代から歌で知られており、19世紀末に高まったバスク民族主義の波は、バスク語の合唱団の設立 につながり、バスク語と歌の保存に貢献した。フランシスコ・フランコの独裁政権時代(1939年~1975年)にバスク語が非合法化されていた間も、伝統 的な歌や踊りは秘密裏に反抗的に守られ、商業的に販売されるポップミュージックが人気を博しているにもかかわらず、今も盛んである。 カナリア諸島 詳細は「カナリア諸島の音楽」を参照 カナリア諸島では、ホタの一種であるイサが現在人気があり、ラテンアメリカの音楽(特にキューバ)の影響が広く浸透している。特にチャランゴ(ギターの一 種)で顕著である。ティンブレというウクレレやカヴァキーニョに似た現地の楽器は、弦楽器のバンドでよく見られる。エル・イエロ島では、ドラムと木製の笛 (ピト・エレーニョ)のセットが人気である。テネリフェ島では、儀式の舞踊でタボールの笛が用いられる。 カスティーリャ、マドリード、レオン 詳細は「カスティーリャ、マドリード、レオンの音楽」を参照  カスティーリャのソリアで民族衣装を着た子供たち。 内陸部の広大な地域であるカスティーリャ、マドリード、レオンは、ローマ帝国による併合と文化的ラテン化以前はケルトイベリア人の土地であったが、ケルト 時代の音楽的伝統が生き残っているかどうかは極めて疑わしい。それ以来、この地域は音楽のるつぼであり、ローマ、西ゴート族、ユダヤ、ムーア、イタリア、 フランス、ロマなどの影響を受けているが、周辺地域やポルトガルからの長年にわたる影響は、今も重要な役割を果たしている。カスティーリャ・イ・レオン州 内の地域は、一般的に、近隣の地域との音楽的な親和性の方が、州内の遠隔地との親和性よりも強い傾向がある。このことが、この地域に多様な音楽的伝統をも たらしている。 ホタは人気があるが、カスティーリャ・イ・レオン州では独特にゆったりとしたテンポで演奏され、よりエネルギッシュなアラゴン地方のバージョンとは異なっ ている。楽器編成もアラゴン地方とは大きく異なる。レオン州北部は、ポルトガル北部の地域やスペインのアストゥリアス州、ガリシア州と言語的な関係があ り、音楽的にもこれらの地域からの影響を受けている。ここでは、バグパイプの一種であるガイタ(gaita)やタボール(tabor)の演奏が盛んであ る。カスティーリャ地方のほとんどの地域では、ドルセイナ(dulcaina)やロンダラ(rondalla)のグループによるダンス音楽の伝統が根強 い。ポピュラーなリズムには、5/8拍子のチャラダ(charrada)や輪舞、ホタ(jota)、ハバス・ベルデス(habas verdes)などがある。イベリア半島の他の多くの地域と同様に、儀式の舞踊にはパルテオ(棒を使った踊り)がある。サラマンカは、マグロの故郷として 知られている。これは、ギターとタンバリンで演奏されるセレナーデで、中世の衣装をまとった学生たちによって主に演奏される。マドリードは、19世紀のス コットランド舞踊の地方変種であるチョティス音楽で知られている。フラメンコは、土着の音楽とは見なされていないが、一部の都会の人々に人気があり、主に マドリードに限定されている。 カタルーニャ 詳細は「カタルーニャ音楽」を参照 カタルーニャは、コブラ(cobla)が演奏するサルダーナ(sardana)音楽で最もよく知られているが、他にも棒踊り(ball de bastons)、ギャロップ、ジプシー舞曲(ball de gitanes)などの伝統的な舞曲がある。セルカヴィエス(cercaviles)やパトゥム(Patum)のような祝祭では音楽が前面に押し出され る。フラビオル(Flabiol)(5つの穴を持つタボールパイプ)、グラッラ(gralla)またはドルセイナ(dolçaina)(ショーム)、サッ ク・デ・ヘメクス(sac de gemecs)(地元のバグパイプ)は、コブラの一部で使用される伝統的な民族楽器である。 カタルーニャのジプシーとアンダルシアからのカタルーニャ移民は、独自のルンバスタイルを生み出し、ルンバ・カタラナと呼ばれるようになった。これはフラ メンコに似た人気のあるスタイルだが、厳密にはフラメンコの正統なスタイルではない。ルンバ・カタラナは、19世紀から20世紀初頭にかけて、ルンバやそ の他のアフリカ系キューバ音楽がキューバからバルセロナに伝わったときに生まれた。カタルーニャの演奏家たちは、それらをフラメンコの形式に適応させ、独 自のスタイルを作り上げた。愛好家たちからは「偽物」のフラメンコとしてしばしば否定されるものの、ルンバ・カタラナは今日でも高い人気を保っている。 ハバネラの歌手たちは依然として人気がある。今日では、数年前にノヴァ・カンソが流行したように、若者たちはロック・カタラを好む。 エストレマドゥーラ 詳細は「エストレマドゥーラの音楽」を参照 スペインで最も貧しい地域であったエストレマドゥーラは、ポルトガルの影響を受けた音楽で知られる、大部分が農村地域である。スペイン北部と同様に、タ ボールと呼ばれるパイプ音楽のレパートリーが豊富である。ザンボンバ摩擦ドラム(ポルトガルのサロンカやブラジルのクイーカに似ている)は、ドラム内部の ロープを引っ張って演奏する。スペイン全土で見られる。ホタは一般的で、ここではトライアングル、カスタネット、ギター、タンバリン、アコーディオン、ザ ンボンバが使われている。 ムルシア 詳細は「ムルシアの音楽」を参照 ムルシアはスペイン南東部の地方で、歴史的にムーア人の入植が著しかった。多くの点で隣接するアンダルシア地方と類似している。特に、ギター伴奏のカン テ・ホンド(フラメンコ様式)やロンダラ(撥弦楽団)はムルシアと関連付けられている。 アウロロ歌手の多声音楽のようなキリスト教の歌は、伝統的にアカペラで歌われ、時には教会の鐘の音が伴奏として加わる。また、クドリリャスは主にクリスマ スなどの祝祭日に演奏される祝祭歌である。 ナバラとラ・リオハ  ナバラの踊り手たち。 ナバラとラ・リオハは、北部の小さな地域であり、多様な文化要素が混在している。アラゴンとバスク自治州に隣接しており、これらの2つの地域で見られる音 楽の多くを共有している。北部のナバラはバスク語圏であるが、南部はアラゴン語圏である。ホタのジャンルは、ナバラとラ・リオハの両方で知られている。両 地域とも、ダンスとドルサイナ(ショーム)の伝統が豊かである。シストゥ(タブール・パイプ)とドルサイナのアンサンブルは、ナバラの祝祭では非常に人気 がある。 バレンシア 詳細は「バレンシアの音楽」を参照 バレンシアの伝統音楽は、地中海の音楽に特徴付けられる。バレンシアにも独自のホタがある。さらに、バレンシアは音楽の革新性でも高い評価を得ており、バ ンドと呼ばれるブラスバンドの演奏は一般的で、ほとんどの町にひとつはある。ドルサイナ(ショーム)も広く見られる。バレンシアには、他のイベリア半島の 地域と共通する伝統舞踊もあり、例えば棒を使った棒踊り(ball de bastons)がある。また、Al Tallというグループも有名で、ベルベル人のバンドMuluk El Hwaと実験的な試みを行い、イタリアの音楽運動Ripropostaに倣ってバレンシアの伝統音楽を活性化させている。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Music_of_Spain |

|

The Codex Las Huelgas is a music manuscript or codex from c. 1300 which originated in and has remained in the Cistercian convent of Santa María la Real de Las Huelgas in Burgos, in northern Spain. The convent was a wealthy one which had connections with the royal family of Castile. The manuscript contains 45 monophonic pieces (20 sequences, 5 conductus, 10 Benedicamus tropes) and 141 polyphonic compositions. Most of the music dates from the late 13th century, with some music from the first half of the 13th century (Notre Dame repertory), and a few later additions from the first quarter of the 14th century. Many of the pieces are not found in any other manuscripts. It is written on parchment, with the staves written in red ink with Franconian notation. The bulk of material is written in one hand, although as many as 12 people contributed to it, including corrections and later additions. Johannes Roderici (Juan Rodríguez in modern Spanish) inscribed his name in a number of places in the manuscript. He may have composed a couple of the pieces in the manuscript, as well as being scribe, compiler, and corrector, according to his own inscriptions. The music was intended for use in performance, presumably within the monastery which had a choir of 100 women at one point in the 13th century. The manuscript raises questions regarding performance practice of the pieces it contains, especially the polyphonic repertory. It is believed that this choir of women performed the polyphonic works in the manuscript, despite Cistercian rules against the performance of polyphonic music.[1] Two-part polyphony appears to have been considered legitimate. In 1217, the General Chapter complained about two English abbeys which were said to sing in three or four parts in the manner of non-monastic churches; the implication is that two-part polyphony was then acceptable, and the manuscript contains two-part solfège exercises with notations on their use in the convent. However, there are also three-part pieces. Publication history The manuscript was rediscovered in 1904 by two Benedictine monks who were researching Gregorian chant. However, the music was not published until the 1930s. There is also a 1980s edition. Huelgas Ensemble The Huelgas Ensemble, a Belgian group specialising in polyphony, takes its name from the codex. It was founded in 1971. Recordings There have been many recordings of music from the Codex.[2] Notable recordings include those of: Sequentia (Ensemble Sequentia, Köln). Codex Las Huelgas: Music from the Royal Convent of Las Huelgas de Burgos, 13-14th C. on Deutsche Harmonia Mundi, 1992. Directed by Benjamin Bagby & Barbara Thornton. The Huelgas Ensemble, which was founded by Paul Van Nevel, has performed many important early Spanish and Portuguese works including much music from the Codex. Anonymous 4, founded in 1986. This women's a cappella group, released the album: "Secret Voices: Chant and Polyphony from the Las Huelgas Codex" in 2011.[2] Ars Combinatoria, founded in 1991 by Canco López. The concept behind the creation of the group was to be able to perform any type of music from any period, changing the composition of the ensemble accordingly. Ars Combinatoria released the album: "Mulier Misterio. El Códice de las Huelgas. Musaris" in 2017. Bibliography Higinio Anglès El Còdex Musical de Las Huelgas. Música a veus dels segles XIII-XIV, 3 vols., Institut d’Estudis Catalans, Barcelona, 1931; facsimile edition with commentary. Gordon Athol Anderson The Las Huelgas Manuscript, Burgos, Monasterio de Las Huelgas, 2 vols., Corpus Mensurabilis Musicæ 79, American Institute of Musicology, Hänssler Verlag, Neuhausen-Stuttgart, 1982; transcription into modern notation. References Goldberg by Juan Carlos Asensio. Translated by Yolanda Acker. Ernest H. Sanders; Peter M. Lefferts. "Sources, MS, §V: Early motet 2. Principal individual sources.", Grove Music Online, ed. L. Macy (accessed May 20, 2006), grovemusic.com (subscription access). Judith Tick. "Women in music, §II: Western classical traditions in Europe & the USA 2. 500–1500.", Grove Music Online, ed. L. Macy (accessed February 5, 2006), grovemusic.com (subscription access). |

ラス・ウエルガス聖歌集は、1300年頃に書かれた音楽の写本または古写本で、スペイン北部ブルゴスにあるシトー会修道院サンタ・マリア・ラ・レアル・ デ・ラス・ウエルガスに保管されている。この修道院はカスティーリャ王家とつながりのある裕福な修道院であった。 この写本には、単旋律の楽曲45曲(20のシーケンス、5つのコンダクトゥス、10のベネディクム・トロペ)と、141曲の多旋律の楽曲が収められてい る。 楽曲のほとんどは13世紀後半のものであるが、13世紀前半(ノートルダム楽派の楽曲)のものもいくつか含まれており、14世紀前半の楽曲も若干追加され ている。これらの楽曲の多くは、他の写本には見られないものである。 羊皮紙に書かれており、譜表は赤インクでフランケン音符表記で書かれている。大半の楽曲は片手で書かれているが、12人もの人々が貢献しており、その中に は修正や後からの追加も含まれる。ヨハネス・ロデリクス(スペイン語ではフアン・ロドリゲス)は、写本の数箇所に自らの名前を記している。 彼自身の記述によると、彼は写本の編纂者、編集者、訂正者であるだけでなく、いくつかの楽曲を作曲した可能性もある。 この音楽は演奏用に意図されたもので、おそらく13世紀のある時期には100人の女性聖歌隊がいた修道院内で使用されていたと考えられる。この写本は、そ の中に収められた楽曲の演奏慣習、特にポリフォニー作品の演奏慣習について疑問を投げかけている。シトー会の規則ではポリフォニー音楽の演奏は禁じられて いたにもかかわらず、この修道女たちの合唱団は写本に収められたポリフォニー作品を演奏していたと考えられている。[1] 2部構成のポリフォニーは正当なものとみなされていたようだ。1217年、総会は、修道院以外の教会のやり方で3部または4部合唱で歌っているとされる2 つの英国の修道院について苦言を呈した。このことから、2部ポリフォニーは当時受け入れられていたことが示唆される。写本には、修道院での使用法の注釈付 きの2部ソルフェージュ練習曲が含まれている。しかし、3部曲もある。 出版の歴史 写本は、グレゴリオ聖歌の研究をしていたベネディクト会の修道士2人によって1904年に再発見された。しかし、この音楽が出版されたのは1930年代に なってからである。1980年代の版もある。 Huelgas Ensemble Huelgas Ensembleは、多声音楽を専門とするベルギーのグループで、その名称は写本から取られたものである。1971年に結成された。 録音 この写本からの音楽の録音は数多くある。[2] 著名な録音には以下のようなものがある。 Sequentia (アンサンブル・セクエンティア、ケルン)。Codex Las Huelgas: Music from the Royal Convent of Las Huelgas de Burgos, 13-14th C. on Deutsche Harmonia Mundi, 1992. 監督:ベンジャミン・バグビー、バーバラ・ソーントン。 ポール・ヴァン・ネヴェルによって結成されたヒューエルガ・アンサンブルは、この写本に収められた多くの楽曲を含む、スペインおよびポルトガルの初期の重 要な作品を数多く演奏している。 1986年に結成された女性アカペラ・グループ、匿名4。2011年にはアルバム『シークレット・ヴォイシズ:ヒューエルガ写本からの聖歌とポリフォ ニー』をリリースした。 アルス・コンビナトリアは、カンコ・ロペスによって1991年に設立された。このグループの創設の背景には、あらゆる時代のあらゆるタイプの音楽を、編成 を適宜変更しながら演奏できるというコンセプトがあった。アルス・コンビナトリアは2017年にアルバム「Mulier Misterio. El Códice de las Huelgas. Musaris」をリリースした。 参考文献 Higinio Anglès 『ラス・ウエルガス写本音楽集。13世紀から14世紀の歌声。3巻、カタルーニャ研究所、バルセロナ、1931年;注釈付きファクシミリ版。 ゴードン・アソル・アンダーソン著『ラス・ウエルガス写本』ブルゴス、ラス・ウエルガス修道院、2巻、Corpus Mensurabilis Musicæ 79、アメリカ音楽学会、Hänssler Verlag、ノイハウゼン・シュトゥットガルト、1982年;現代の楽譜への転記。 参考文献 Juan Carlos Asensio著『Goldberg』。Yolanda Acker訳。 Ernest H. Sanders; Peter M. Lefferts. 「Sources, MS, §V: Early motet 2. Principal individual sources.」, Grove Music Online, ed. L. Macy (accessed May 20, 2006), grovemusic.com (subscription access). ジュディス・ティック「音楽における女性たち、§II:ヨーロッパと米国における西洋クラシック音楽の伝統 2. 500–1500年」、グローヴ・ミュージック・オンライン、L. マシー編(2006年2月5日アクセス)、grovemusic.com(購読アクセス)。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Las_Huelgas_Codex |

|

Jewish music in The International Sephardi Music Festival in Cordoba- Ancient Groove

Codex

Las Huelgas: Homo miserabilis (Motet) (Folio 127 verso - 128 recto)

☆まるごと1冊スペイン音楽の本 / 下山静香著, アルテスパブリッシング , 2023

0. 序章

0.1 スペイン音楽の特徴

0.2 スペイン音学史概観

1. 地理と歴史

1.1 スペインの主な地方

1.2 その他の地方

2. 作曲家と演奏家

2.1 主なクラシック作曲家たち

2.2 クラシック演奏家・歌手10選

3. 作品紹介

3.1 鉄板名曲10選

3.2 聴くべき名曲10選

4. 踊りと歌

4.1 スペインの舞踊10

4.2 スペインの歌10

5. 舞台芸術

5.1 スペインが舞台のオペラ10選

5.2 スペイン・オペラとサルスエラ10選

6. 文化と都市

6.1 芸術様式と時代

6.2 スペイン文学史概観

6.3 10都市音楽散歩

7. コラム

☆スペイン音楽 / ホセ・スビラ著 ; 浜田滋郎訳, 白水社 , 1961 . - (文庫クセジュ, 306)

0. まえがき

1. 古代と中世

2. 近代の黎明から16世紀末まで

3. 17世紀

4. 18世紀

5. 19世紀

6. 今世紀(20世紀)

7. 民族音楽にあらわれるスペイン魂

Comunidades autónomas de España

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆