スタンザ

stanza, Estancia

☆ スタンザ(伊: stanza, 連または節;スペイン語ではエスタンシア)は詩節とも呼ばれ、文学や音楽の歌詞において、定型詩(ていけいし)を構成する数行を、1つのまとまりとしてと らえるための単位である[1]。以下は日本語ウィキペディア「スタンザ」の説明。

ス タンザはイタリア語で「部屋」を意味する "stanza" が語源である[2]。日本では連(れん)と訳されることもある。さらに複数の連をまとめたものを節(せつ)や詩節(しせつ)ともいう。歌詞の中の節は、通 常「番」と呼ばれ、「この歌の歌詞は3番まである。」などという。英語などの言語では、言語が内包するシラブルから生まれるリズム、つまり韻律(いんり つ)を活用して作られる韻文(いんぶん)に対する用語である[3]。通説としては、「韻を踏む(いんをふむ)」語句、すなわち押韻(おういん)を含んだ、 4行以上からなる詩に対して使う[2]。行と行のあいだに空白やインデントが置かれている場合は、その前後のまとまりはそれぞれ別のスタンザであるととら える[3]。空白の行か句読点でスタンザを区切るのが印刷上の慣習なので、現代詩のほとんどは、印刷されたページ上でスタンザを恣意的に表すことが可能で ある。

※ロバート・ヘリック(Robert Herrick (poet))の詩 "To Anthea, Who May Command Him Any Thing" のスタンザでは、ABABでスタンザが構成されている。

Bid me to weep, and I will weep, - "A"

While I have eyes to see; - "B"

And having none, and yet I will keep - "A"

A heart to weep for thee. - "B"

★ 文学に使われるスタンザ

14

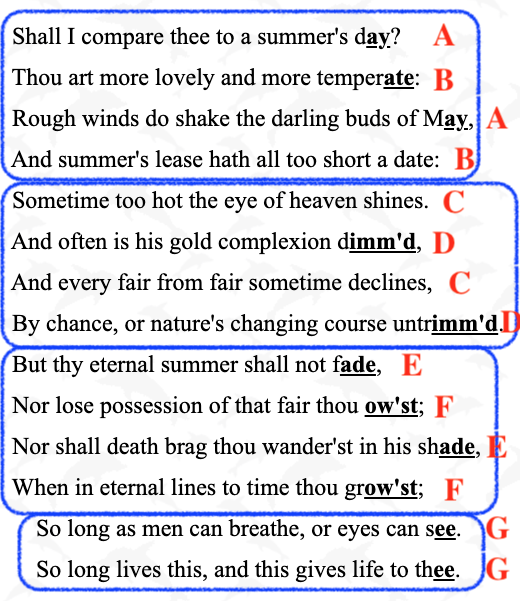

行で構成されたソネットのように、必ずしもスタンザとスタンザのあいだに空白やインデントがあるとは限らない。イングランド王国の詩人、シェイクスピアの

『ソネット集』から「ソネット18番」より(原典はウィキソースを参照:「ソネット18番」)。

Shall I compare thee to a summer's day?

Thou art more lovely and more temperate:

Rough winds do shake the darling buds of May,

And summer's lease hath all too short a date:

Sometime too hot the eye of heaven shines.

And often is his gold complexion dimm'd,

And every fair from fair sometime declines,

By chance, or nature's changing course untrimm'd.

But thy eternal summer shall not fade,

Nor lose possession of that fair thou ow'st;

Nor shall death brag thou wander'st in his shade,

When in eternal lines to time thou grow'st;

So long as men can breathe, or eyes can see.

So long lives this, and this gives life to thee.

押韻部分をみると、四行連による3つのスタンザ、つまりABAB形式の連続(ABAB CDCD

EFEF)と、二行連による1つのスタンザ(GG)を組み合わせた、合計4つのスタンザからなるソネットで

ある[3]。

★音楽に使われるスタンザ

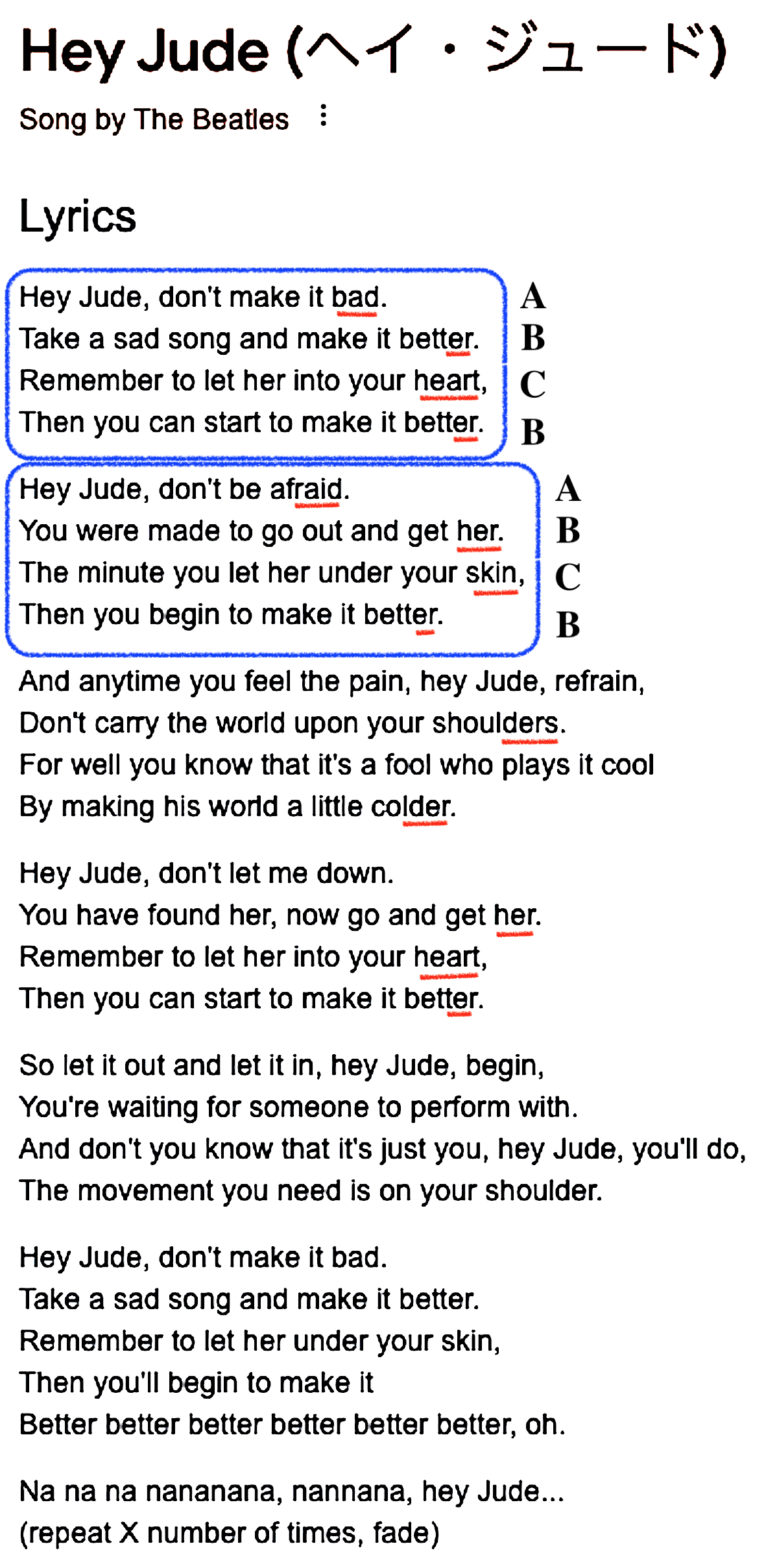

ス タンザは歌の歌詞においても成立することがある。イギリスのロックバンド、ザ・ビートルズの楽曲「ヘイ・ジュード」より。

ヴァー ス1とヴァース2をスタンザとしてとらえると、どちらも押韻構成がABCB形式に一致している[3]。

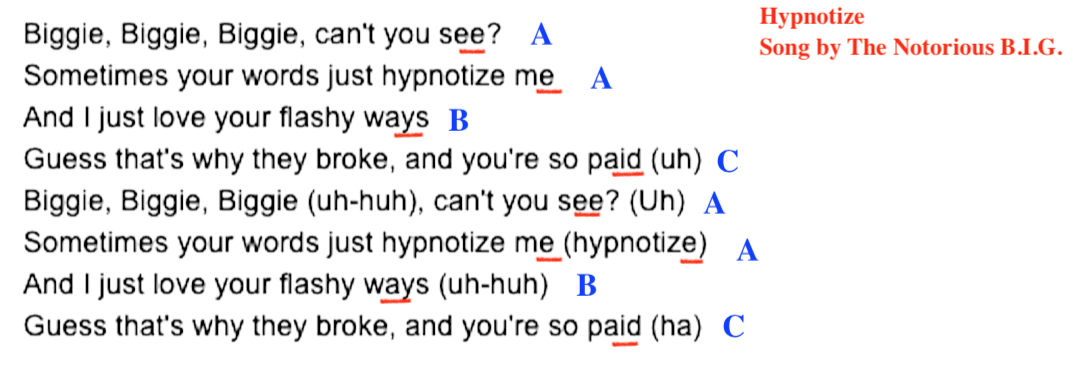

The Notorious B.I.G.の"Hypnotize" のある詩節では、AABC + AABC と押韻構成になっていることがわかる。

| La estancia

o estanza (del italiano stanza) es una estrofa formada por más de

seis versos endecasílabos y heptasílabos con rima consonante al

arbitrio del poeta, y cuya estructura se repite a lo largo de un mismo

poema.1 |

スタンザ(イタリア語のstanzaに由来)とは、詩人の裁量で子音韻

を踏んだ6行以上のエンデカシラバ(Endecasílabo)

とヘプタシラバ(Heptasílabo)

で構成され、その構造が同じ詩全体で繰り返されるスタンザのことである1。 |

| Características Tan solo se requiere que en las composiciones formadas por estancias, ora canción (lírica), ora oda, ora égloga, las restantes estrofas sigan el mismo esquema de la primera. Cada estrofa suele contener entre doce y catorce versos (o más, como en La canción real a una mudanza). La estancia difiere de la silva en que esta última no se divide en estrofas, no repite ninguna estructura de rimas y puede incluir versos sueltos, esto es, sin rima. |

特徴 歌(抒情詩)、頌歌(オード)、頌歌(エクローグ)のいずれかのスタンザで構成される楽曲では、残りのスタンザが最初のスタンザと同じパターンに従うこと だけが要求される。各スタンザは通常12行から14行(La canción real a una mudanzaのようにそれ以上)で構成される。エスタンシアがシラ(Sylla)と異なるのは、エスタンシアがスタンザに分かれていないこと、韻律構造 を繰り返さないこと、単行、つまり韻を踏んでいない行を含むことがあることである。 |

| Historia De origen provenzal, la cultivaron para sus canciones de tema amoroso los poetas florentinos del dolce stil nuovo, en particular Dante Alighieri y Francesco Petrarca. Este último incluyó varias en su Cancionero para romper la monotonía del soneto dominante. En España introdujeron la canción en estancias en el primer tercio del siglo xvi los poetas Garcilaso de la Vega y Juan Boscán, asentándola definitivamente en la literatura española sobre todo para géneros literarios líricos como la canción amorosa, la oda o la égloga. El poeta barroco inglés Edmund Spenser creó una variante en sus poemas Prothalamion y Epithalamion; en Italia, Leopardi creó estrofas más cortas y con rimas más libres; en Francia la cultivó con especial fortuna el simbolista Jean Moréas (Stances, 1899), creando otra variante: estrofas cortas de alejandrinos y heptasílabos que se van alternando. |

歴史 ダンテ・アリギエーリやフランチェスコ・ペトラルカをはじめとするフィレンツェのドルチェ・スティル・ヌーヴォの詩人たちが、恋の歌として愛唱した。特に ダンテ・アリギエーリやフランチェスコ・ペトラルカは、単調なソネットに風穴を開けるため、『カンキオネーロ』(Cancionero)に数編を収めた。 スペインでは、16世紀前半に詩人ガルシラソ・デ・ラ・ベガとフアン・ボスカンによってエスタンシアの歌が導入され、スペイン文学、特に愛の歌、頌歌、エ クローグなどの叙情的な文学ジャンルに決定的な地位を確立した。 イタリアでは、レオパルディがより自由な韻を踏んだ短いスタンザを創作した。フランスでは、象徴主義のジャン・モレアス(Stances, 1899)が特に成功し、アレクサンドリンとヘプタシラブルを交互に並べた短いスタンザを創作した。 |

| Estructura Posee una distribución repetida de rimas en varias estrofas sucesivas con el mismo esquema métrico, cada una de las cuales se divide en dos partes (la fronte, formada por dos pies de unos tres versos cada uno, y la sírima o coda,2 también formada por dos pies de unos tres versos) engarzadas ambas por un verso de enlace. La serie métrica se concluye con un envío o vuelta final de cuatro versos. Cada estancia puede tener a veces un último verso que sirva de estribillo o bordón. |

構造 この詩は、同じ拍子で韻が繰り返されるいくつかの連続したスタンザを持ち、それぞれのスタンザは2つの部分(それぞれ約3行の2つのフィートからなるフロ ンテと、同じく約3行の2つのフィートからなるシリーマまたはコーダ2)に分けられ、両者はリンキング・ラインで結ばれている。この一連の詩は、4行から なる最後のenvíoまたはreturnで締めくくられる。各スタンザは、リフレインとして機能する最終行を持つことがある。 |

| Clases En el género literario lírico denominado canción, el poema en estancias está formado por un número variable de estrofas iguales (generalmente entre cinco y siete), denominadas estancias, que combinan versos consonantados de siete y once sílabas. Generalmente se remata con un envío (llamado congedo en lengua italiana) que trasmite la canción a su destinatario. Cada estanza está constituida por dos partes: la frente (fronte) y la cola (coda o sirma). Dependiendo de cómo sean se distingue la canción siciliana de la canción petrarquista. Canción siciliana La fronte ("frente") está constituida por dos pies (piedi), que deben contener el mismo número de versos, pero cuyo esquema rítmico puede ser distinto. La coda ("cola"), del mismo modo, debe descomponerse en dos vueltas (volte) con idéntico esquema métrico. Canción petrarquista Ya ensayada su estructura por Dante Alighieri, es sancionada definitivamente por Francesco Petrarca. Consta de una frente de dos pies y una cola, generalmente, indivisa. Además entre frente y cola debe existir un verso de enlace (chiave) que rime con el último verso de la frente. El envío, por su parte, toma su estructura de la cola. A veces es una cola completa, a veces una de sus vueltas; y a veces tan solo sus últimos versos. |

クラス 歌曲として知られる抒情詩のジャンルでは、スタンザ詩は、7音節と11音節の子音行を組み合わせたスタンザと呼ばれる、可変数の等しいスタンザ(一般に 5~7)で構成される。一般的に、この詩は「envío」(イタリア語では「congedo」と呼ばれる)で結ばれ、その歌を宛先に伝える。 それぞれのスタンザは、前部(frontte)と後部(codaまたはsirma)の2つの部分から成る。シチリアの歌とペトラルカの歌は、その構成に よって区別される。 シチリアの歌 フロンテ(「前部」)は2つの足(ピエディ)で構成され、同じ行数の詩を含まなければならないが、韻律は異なっていてもよい。 コーダ(尾部)も同様に、同じ韻律を持つ2つの転回(volte)に分けられなければならない。 ペトラルカの歌 その構造は、ダンテ・アリギエーリによってすでに検証されていたが、フランチェスコ・ペトラルカによって決定的に認可された。 ペトラルカの歌は、2本足の前部と尾部で構成され、通常は分割されていない。さらに、前部と尾部の間には、前部の最後の行と韻を踏む連結行(キアーヴェ) がなければならない。 一方、デリバリーはテールからその構造を得ている。あるときは完全なテール、あるときはターンの1つ、またあるときは最後の行のみである。 |

| Funciones La estancia se usa sobre todo para expresar el los géneros literarios líricos de la canción amorosa, la oda y la égloga. |

|

| Ejemplo de estancia Perteneciente a la Égloga I de Garcilaso de la Vega: Divina Elisa, pues agora el cielo, con inmortales pies pisas y mides, y su mudanza ves estando queda, ¿por qué de mí te olvidas y no pides que se apresure el tiempo en que este velo rompa del cuerpo, y verme libre pueda, en la tercera rueda contigo mano a mano busquemos otro llano, busquemos otros montes y otros ríos, otros valles floridos y sombríos, donde descanse, y siempre pueda verte ante los ojos míos, sin miedo y sobresalto de perderte? Nunca pusieran fin al triste lloro los pastores, ni fueran acabadas las canciones que sólo el monte oía, si, mirando las nubes coloradas, al trasmontar del sol bordadas de oro, no vieran que era ya pasado el día. La sombra se veía venir corriendo apriesa ya por la falda espesa del altísimo monte, y recordando ambos como de sueño, y acabando el fugitivo sol, de luz escaso, su ganado llevando, se fueron recogiendo paso a paso. |

エスタンシアの例 ガルシラソ・デ・ラ・ベガの「エクローグI」より: 神聖なるエリサよ、アゴラの空のために、 不滅の足で踏み、測る、 そして、その変化を見るのだ、 なぜ私を忘れ、求めないのか。 このヴェールが私の体から引き剥がされるときが来るのを急ごうとしないのか。 私は自分自身を自由に見ることができる、 三輪車に乗って あなたと手を取り合って 別の平原を探そう、 他の山を、他の川を探そう、 花の咲き乱れる谷間を探そう、 私が休んでいて、いつも目の前にあなたがいる 目の前にいる、 あなたを失うことを恐れず、怯えずに。 羊飼いたちは、悲しい泣き声に終止符を打つことはなかった。 羊飼いたちは、その歌に終止符を打つことはなかった。 山だけに聞こえる歌だった、 もし、色づいた雲を見ていたら、 金で刺繍された太陽の昇るのを見ていた、 その日は過ぎ去った。 影が 疾走する 厚い裾の上を その影はすでに高い山の厚いすそを速く走っているのが見えた。 まるで夢の中のように、逃亡中の太陽を思い出した。 遁走する太陽、乏しい光、 彼らは家畜を運んでいた、 彼らは一歩一歩集まっていった。 |

| https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Estancia_(poes%C3%ADa) |

|

| In poetry, a stanza

(/ˈstænzə/; from Italian stanza, Italian: [ˈstantsa]; lit. 'room') is a

group of lines within a poem, usually set off from others by a blank

line or indentation.[1] Stanzas can have regular rhyme and metrical

schemes, but they are not required to have either. There are many

different forms of stanzas. Some stanzaic forms are simple, such as

four-line quatrains. Other forms are more complex, such as the

Spenserian stanza. Fixed verse poems, such as sestinas, can be defined

by the number and form of their stanzas. The stanza has also been known by terms such as batch, fit, and stave.[2] The term stanza has a similar meaning to strophe, though strophe sometimes refers to an irregular set of lines, as opposed to regular, rhymed stanzas.[3] Even though the term "stanza" is taken from Italian, in the Italian language the word "strofa" is more commonly used. In music, groups of lines are typically referred to as verses. The stanza in poetry is analogous with the paragraph in prose: related thoughts are grouped into units.[4] |

詩

において、スタンザ(/ˈstænzə/;イタリア語のstanza、イタリア語:

[ˈstantsa]から派生;文字通り「部屋」)とは、詩の中の行のグループであり、通常は空行または字下げによって他の部分と区別される。[1]

スタンザは規則正しい韻や韻律の体系を持つことができるが、必ずしもそうである必要はない。スタンザにはさまざまな形式がある。スタンザの形式には、4行

の四行詩のようにシンプルな形式もある。また、スペンサー・スタンザのように複雑な形式もある。セスティナのような定型詩は、スタンザの数と形式によって

定義できる。 スタンザは、バッチ、フィット、ステーブなどの用語でも知られている。 「スタンザ」という用語は「ストローフ」と類似した意味を持つが、「ストローフ」は、韻を踏んだ定型詩のスタンザとは対照的に、不規則な行の集合を指すこともある。 「スタンザ」という用語はイタリア語に由来するが、イタリア語では「ストローフ」という用語の方がより一般的に使用されている。 音楽では、行のグループは通常、節と呼ばれる。詩における節は、散文における段落に類似しており、関連する思考は単位としてグループ化される。[4] |

| Example 1 This short poem by Emily Dickinson has two stanzas of four lines each: I had no time to hate, because The grave would hinder me, And life was not so ample I Could finish enmity. Nor had I time to love; but since Some industry must be, The little toil of love, I thought, was large enough for me.[5] |

例1 エミリー・ディキンソンのこの短い詩は、4行の2つの節からなる。 憎む時間などなかった。なぜなら、 墓が私を妨げるからだ。 そして、人生はそれほど長くはない。 敵意を終わらせるには十分ではない。 愛する時間もなかった。しかし、 何かしらの産業が必要だ。 愛の小さな苦労は、 私には十分だと思った。[5] |

| Example 2 This poem by Andrew John Young has three stanzas of six lines each: Frost called to the water Halt And crusted the moist snow with sparkling salt; Brooks, their one bridges, stop, And icicles in long stalactites drop. And tench in water-holes Lurk under gluey glass-like fish in bowls. In the hard-rutted lane At every footstep breaks a brittle pane, And tinkling trees ice-bound, Changed into weeping willows, sweep the ground; Dead boughs take root in ponds And ferns on windows shoot their ghostly fronds. But vainly the fierce frost Interns poor fish, ranks trees in an armed host, Hangs daggers from house-eaves And on the windows ferny am bush weaves; In the long war grown warmer The sun will strike him dead and strip his armour.[6] |

例2 アンドリュー・ジョン・ヤングのこの詩は、6行からなる3つの節から成る。 霜が水に呼びかけた。 そして、湿った雪をきらめく塩で覆った。小川、その一本橋は止まり、 つらら状の氷柱が垂れ下がる。 そして、水たまりに潜むテナガミズテングは ボウルの中のネバネバしたガラスのような魚の下に潜む。 踏み固められた小道では 一歩歩くごとに脆い窓ガラスが割れ、 氷に覆われた木々が 枝垂れ柳に姿を変え、地面を掃き清める。 枯れ枝は池に根を下ろし 窓辺のシダは幽霊のような葉を伸ばす。 しかし、激しい霜はむなしく 哀れな魚を捕らえ、木々を武装した軍勢のように並べ、 家の軒から短剣を垂らし 窓にはシダが生い茂る。 長い戦いの間に温められた 太陽が彼を打ち倒し、鎧を剥ぎ取るだろう。[6] |

****

| STANZA |

スタンザ |

(Low Lat. stantia,

Ital. stantia or stanza), properly an apartment or storey in a house,

the term being hence adopted for literary purposes to denote a complete

section, of recurrent form, in a poem. A stanza is a strophe of two or

more lines, usually rhyming, but always recurring, the idea of fixed

repetition of form being essential to it. At the close of the 16th

century the word stanza began to be used with an adjective to designate

a particular species, as the "Spenserian stanza," because Spenser had

invented that nine-lined form for his Faerie Queen; or "Ariosto's

stanza" as Drayton described what is now known as ottava rima, because

Ariosto had written prominently in it. By "stanzaic law" is meant the

law which regulates the form and succession of stanzas. The stanza is a

modern development of the strophe of the ancients, modified by the

requirements of rhyme. |

(低Lat.

stantia、イタリア語stantiaまたはstanza)、正しくは家屋内のアパートまたは階、この用語は詩における反復形式の完全なセクションを

示すために、文学的な目的で採用されている。スタンザは2行以上のストロフェであり、通常は韻を踏むが、常に反復される。形式の固定された反復という考え

方が、スタンザには不可欠である。16世紀末には、スペンサーが『妖精女王』のために9行詩の形式を考案したことから、「スペンサーのスタンザ」というよ

うに、特定の種を指すために形容詞とともに「スタンザ」という語が使われ始めた。また、アリオストがこの形式で著名な作品を書いたことから、ドレイトンが

「アリオストのスタンザ」として、現在ではオッターヴァ・リーマとして知られるものを表現した。スタンザの法則」とは、スタンザの形式と連続性を規定する

法則を意味する。スタンザは、韻を踏むという要件によって修正された、古代のストローフェの現代的な発展形である。 |

| STROPHE |

ストロフェ |

(Gr. στροφή, from στρέφειν, to

turn), a term in versification which properly means a turn, as from one

foot to another, or from one side of a chorus to the other. In its

precise choral significance a strophe was a definite section in the

structure of an ode, when, as in Milton’s famous phrase in the preface

to Samson Agonistes, “strophe, antistrophe and epode were a kind of

stanzas framed only for the music.” In a more general sense the strophe

is a collection of various prosodical periods combined into a

structural unit. In modern poetry the strophe usually becomes identical

with the stanza, and it is the arrangement and the recurrence of the

rhymes which give it its character. But the ancients called a

combination of verse-periods a system, and gave the name strophe to

such a system only when it was repeated once or more in unmodified

form. It is said that Archilochus first created the strophe by binding

together systems of two or three lines. But it was the Greek

ode-writers who introduced the practice of strophe-writing on a large

scale, and the art was attributed to Stesichorus, although it is

probable that earlier poets were acquainted with it. The arrangement of

an ode in a splendid and consistent artifice of strophe, antistrophe

and epode was carried to its height by Pindar (see Ode). With the

development of Greek prosody, various peculiar strophe-forms came into

general acceptance, and were made celebrated by the frequency with

which leading poets employed them. Among these were the Sapphic, the

Elegiac, the Alcaic and the Asclepiadean strophe, all of them prominent

in Greek and Latin verse. The briefest and the most ancient strophe is

the dactylic distich, which consists of two verses of the same class of

rhythm, the second producing a melodic counterpart to the first. The

forms in modern English verse which reproduce most exactly the

impression aimed at by the ancient ode-strophe are the elaborate rhymed

stanzas of such poems as the “Nightingale” of Keats or the

“Scholar-Gypsy” of Matthew Arnold |

(Gr. στροφή、from στρέφειν、to

turn)、韻文における用語で、本来は「ターン」を意味し、1つの脚韻から別の脚韻へ、あるいはコーラスの一方の側から他方へという意味である。厳密な

合唱の意義において、ストローフェはオードの構造における明確なセクションであり、ミルトンの『サムソン・アゴニステス』の序文における有名な表現のよう

に、「ストローフェ、アンティストローフェ、エポデは音楽のみのために作られた一種のスタンザであった。」より一般的な意味では、ストローフェはさまざま

な韻律の期間を構造単位に組み合わせた集合体である。現代詩では、通常、ストローフェはスタンザと同一のものとなり、韻の配列と反復がその特徴となる。し

かし、古代人は詩行の組み合わせを「システム」と呼び、そのシステムがそのままの形で1回以上繰り返される場合にのみ、そのシステムに「ストローフェ」と

いう名称を与えた。アルキロコスが最初に2行または3行のシステムを組み合わせることでストローフェを創作したと言われている。しかし、大規模なストロー

フェの執筆を導入したのはギリシャのオード作家たちであり、その技術はステシコロスに帰せられるが、それ以前の詩人たちもすでにその技術を知っていた可能

性が高い。

オードを、見事な一貫した技巧であるストローフェ、アンティストローフェ、エポデで構成するという手法は、ピンダロスによって最高潮に達した(「オード」

を参照)。ギリシャの韻律の発展に伴い、さまざまな独特なストローフェ形式が一般に受け入れられるようになり、一流の詩人たちが頻繁に用いたことで有名に

なった。その中にはサッフォー、エレジー、アルカイック、アスクレピオスなどのストローフェがあり、いずれもギリシャやラテン語の詩で顕著である。最も短

く、最も古い韻文はダクティル・ディスティクで、同じリズムの2つの詩節からなり、2番目の詩節は1番目の詩節のメロディに呼応する。古代のオードの韻文

が意図した印象を最も正確に再現している現代英語の詩の形式は、キーツの「ナイチンゲール」やマシュー・アーノルドの「学者ジプシー」のような詩の精巧な

韻文の連である。 |

| VERSE |

ヴァース |

(from Lat. versus, literally a

line or furrow drawn by turning the plough, from vertere, and

afterwards signifying an arrangement of syllables into feet), the name

given to an assemblage of words so placed together as to produce a

metrical effect. The art of making, and the science of analysing, such

verses is known as Versification. According to Max Müller, there is an

analogy between versus and the Sanskrit term, vritta, which is the name

given by the ancient grammarians of India to the rule determining the

value of the quantity in vedic poetry. In modern speech, verse is

directly contrasted with prose, as being essentially the result of an

attention to determined rules of form. In English we speak of “a verse”

or “verses,” with reference to specific instances, or of “verse,” as

the general science or art of metrical expression, with its regulations

and phenomena. A verse, which is a series of rhythmical syllables,

divided by pauses, is destined in script to occupy a single line, and

was so understood by the ancients (the στίχος of the Greeks). The

Alexandrian scholiast Hephaestion speaks distinctly of verses that

ceased to be verses because they were too long; he stigmatizes a

pentameter line of Callimachus as στίχον ύπέρμετρον. There is no

danger, therefore, in our emphasizing this rule, and in saying that,

even in Mr Swinburne’s most extended experiments the theory is that a

verse fills but one line in a supposititious piece of writing. |

(ラテン語のversusに由来する。文字通りには、鋤を回して描く線

または溝を意味するが、後に音節を脚に配置することを意味するようになった)、韻律効果を生み出すように配置された単語の集合体に与えられる名称。このよ

うな詩を作る技術、および分析する科学は、韻文法として知られている。マックス・ミュラーによると、対とサンスクリット語の用語であるvrittaとの間

には類似性があり、vrittaはヴェーダ詩の音価を決定する規則を指すインドの古代文法学者による名称である。現代の話し言葉では、詩は散文と直接対比

され、本質的には定められた形式の規則に注意を払う結果である。英語では、特定の例を指して「詩」または「詩句」と言ったり、韻律表現の一般的な科学また

は芸術として、その規則や現象を指して「詩」と言う。詩は、休止で区切られたリズミカルな音節の連続であり、文字上は1行を占めるように定められており、

古代の人々もそう理解していた(ギリシア語の「スティコス」)。アレクサンドリアの注釈者ヘファイスティオンは、長すぎるために詩ではなくなった詩行につ

いて明確に述べている。彼はカリマコスの五歩格の行を「長すぎる詩行」と非難している。したがって、この規則を強調し、スウィンバーン氏の最も拡張された

実験においても、仮の作品では詩は1行しか占めないという理論であると述べることに危険はない。 |

| https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/1911_Encyclop%C3%A6dia_Britannica/ |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆