アルゼンチンにおける先住民

Indigenous peoples in Argentina

The Tolaba family, proprietors of a roadside cafe en route from Salta to Cachi, northwest Argentina. December 2003.

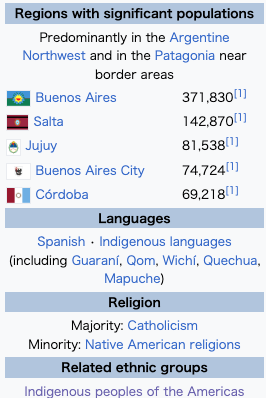

☆先住民系アルゼンチン人[Indigenous Argentines]

(スペイン語: Argentinos nativos)は、先住民アルゼンチン人(スペイン語: Argentinos

indígenas)とも呼ばれ、国民政府が公式に認定する39の先住民集団のいずれかからの祖先を主に、あるいは完全に持つアルゼンチン人を指す。

[2]

2022年の国勢調査[INDEC]によると、約1,306,730人(国内人口の2.83%)が先住民または先住民の第一世代の子孫として自己申告して

いる。[3]

最も人口の多い先住民グループは、アオニケンク族、コッラ族、コム族、ウィチ族、ディアグイタ族、モコビ族、ワルペ族、マプチェ族、グアラニ族であった。

[2]

多くのアルゼンチン人は、少なくとも1人の先住民の祖先を持つとも自認している。2011年にブエノスアイレス大学が実施した遺伝子調査では、調査対象と

なった320人のアルゼンチン人のうち、56%以上が片方の親系に少なくとも1人の先住民の祖先を持ち、約11%が両親の系譜に先住民の祖先を持つことが

示された。[4]

アルゼンチン北西部のフフイ州は先住民比率が最も高く10.07%である。次いでサルタ州が9.96%、チュブト州が7.92%である。[1]

Native Argentines

(Spanish: Argentinos nativos), also known as Indigenous Argentines

(Spanish: Argentinos indígenas), are Argentines who have predominant or

total ancestry from one of the 39 groups of Indigenous peoples

officially recognized by the national government.[2] As of the 2022

census [INDEC], some 1,306,730 Argentines (2.83% of the country's

population) self-identify as Indigenous or first-generation descendants

of Indigenous peoples.[3] The most populous Indigenous groups were the Aonikenk, Kolla, Qom, Wichí, Diaguita, Mocoví, Huarpes, Mapuche and Guarani.[2] Many Argentines also identify as having at least one Indigenous ancestor; a genetic study conducted by the University of Buenos Aires in 2011 showed that more than 56% of the 320 Argentines sampled were shown to have at least one Indigenous ancestor in one parental lineage and around 11% had Indigenous ancestors in both parental lineages.[4] The Jujuy Province, in the Argentine Northwest, is home to the highest percentage of Indigenous people with 10.07%, followed by Salta with 9.96% and Chubut with 7.92%.[1]  |

先住民系アルゼンチン人(スペイン語: Argentinos

nativos)は、先住民アルゼンチン人(スペイン語: Argentinos

indígenas)とも呼ばれ、国民政府が公式に認定する39の先住民集団のいずれかからの祖先を主に、あるいは完全に持つアルゼンチン人を指す。

[2]

2022年の国勢調査[INDEC]によると、約1,306,730人(国内人口の2.83%)が先住民または先住民の第一世代の子孫として自己申告して

いる。[3] 最も人口の多い先住民グループは、アオニケンク族、コッラ族、コム族、ウィチ族、ディアグイタ族、モコビ族、ワルペ族、マプチェ族、グアラニ族であった。 [2] 多くのアルゼンチン人は、少なくとも1人の先住民の祖先を持つとも自認している。2011年にブエノスアイレス大学が実施した遺伝子調査では、調査対象と なった320人のアルゼンチン人のうち、56%以上が片方の親系に少なくとも1人の先住民の祖先を持ち、約11%が両親の系譜に先住民の祖先を持つことが 示された。[4] アルゼンチン北西部のフフイ州は先住民比率が最も高く10.07%である。次いでサルタ州が9.96%、チュブト州が7.92%である。[1]  |

History Artifacts at the Pío Pablo Díaz Museum in Cachi, Salta Province. One of several in Argentina devoted to the ethnology of Indigenous peoples. Pre-Columbian history The earliest known evidence of Indigenous peoples in Argentina is dated 11,000 BC[5] and was discovered in what is now known as the Piedra Museo archaeological site in Santa Cruz Province. The Cueva de las Manos, also in Santa Cruz, is over 10,000 years old.[6] Both are among the oldest evidence of Indigenous culture in the Americas, and have, with several similarly ancient sites on other parts of the Southern Hemisphere, challenged the "Clovis First" hypothesis on the settlement of the Americas (the assumption, based on lacking evidence to the contrary, that the Clovis culture was the first in the Western Hemisphere).[7] |

歴史 サルタ州カチにあるピオ・パブロ・ディアス博物館の展示品。アルゼンチン国内に複数存在する先住民の民族学を専門とする博物館の一つだ。 コロンブス以前の歴史 アルゼンチンにおける先住民の存在を証明する最古の証拠は、紀元前 11,000 年のものであり[5]、現在のサンタクルス州にあるピエドラ博物館遺跡で発見された。同じくサンタクルス州にあるメンディア・デ・ラス・マノス遺跡は、 10,000 年以上の歴史を持つ。[6] どちらもアメリカ大陸における先住民文化の最古の証拠の一つであり、南半球の他の地域にある同様の古代遺跡とともに、アメリカ大陸の定住に関する「クロ ヴィス・ファースト」仮説(反対の証拠がないことを基に、クロヴィス文化が西半球で最初の文化であったとする仮説)に異議を唱えている。[7] |

| Indigenous peoples after European invasion By the year 1500, many different Indigenous communities lived in what is now modern Argentina. They were not a unified group but many independent ones, with distinct languages, societies, and relations with each other. As a result, they did not face the arrival of the Spanish colonization as a single block and had varied reactions toward the Europeans. The Spanish people looked down on the Indigenous population, considering them inferior to themselves.[8] For this reason, they kept very little historical information about them.[9]  Tehuelche Cacique Casimiro Biguá, c. 1864 In the 19th century major population movements altered the original Patagonian demography. Between 1820 and 1850 the original Aonikenk people were conquered and expelled from their territories by invading Mapuche (that called them Tehuelches) armies. By 1870 most of northern Patagonia and the south east Pampas were Araucanized.[10] During the Generation of 1880, European immigration was strongly encouraged as a way of occupying an empty territory, configuring the national population and, through their colonizing effort, gradually incorporating the nation into the world market. These changes were perhaps best summarized by the anthropological metaphor which states that "Argentines descend from ships."[11] The strength of the immigration and its contribution to the Argentine ethnography is evident by observing that Argentina became the country in the world that received the second highest number of immigrants, with 6.6 million, second only to the United States with 27 million, and ahead of countries such as Canada, Brazil, Australia, etc.[12][13] The expansion of European immigrant communities and the railways westward into the Pampas and south into Patagonia was met with Malón raids by displaced tribes. This led to the Conquest of the Desert in the 1870s, which resulted in over 1,300 Indigenous dead.[14][15] Indigenous cultures in Argentina were consequently affected by a process of invisibilization, promoted by the government during the second half of the 19th century and the early 20th.[16] The extensive explorations, research and writing by Juan Bautista Ambrosetti and other ethnographers during the 20th century, which followed earlier pioneer studies by anthropologists such as Robert Lehmann-Nitsche,[17] encouraged wider interest in Indigenous people in Argentina, and their contributions to the nation's culture were further underscored during the administration of President Juan Perón in the 1940s and 1950s as part of the rustic criollo culture and values exalted by Perón during that era.[18] Discriminatory policies toward these people and other minorities officially ended, moreover, with the August 3, 1988, enactment of the Antidiscrimination Law (Law 23.592) by President Raúl Alfonsín,[19] and were countered further with the establishment of a government bureau, the National Institute Against Discrimination, Xenophobia, and Racism (INADI), in 1995.[20] Corrientes Province, in 2004, became the first in the nation to award an Indigenous language (Guaraní) with co-official status,[21] and all 35 Native peoples were recognized by both the 2004 Indigenous Peoples Census and by their inclusion as self-descriptive categories in the 2010 census; Indigenous communities and Afro-Argentines thus became the only groups accorded any recognition as ethnic categories by the 2010 census.[22] |

ヨーロッパ人による侵略後の先住民 1500年までに、現在のアルゼンチンにあたる地域には多くの異なる先住民コミュニティが暮らしていた。彼らは統一された集団ではなく、それぞれ独立した 集団であり、異なる言語、社会、相互関係を持っていた。その結果、スペイン人による植民地化の到来を単一の集団として迎えることはなく、ヨーロッパ人に対 して様々な反応を示した。スペイン人は先住民を見下し、自分たちより劣った存在と考えていた[8]。このため、彼らに関する歴史的記録はほとんど残されて いない。[9]  テウェルチェ族の首長カシミロ・ビグア、1864年頃 19世紀、大規模な人口移動がパタゴニアの本来の人口構成を変えた。1820年から1850年にかけて、先住のアオニケンク族は侵入してきたマプチェ族 (彼らをテウェルチェと呼んだ)の軍隊に征服され、自らの領土から追放された。1870年までに、パタゴニア北部と南東パンパスの大部分はアラウカ化され ていた[10]。1880年代の世代において、空虚な領土を占有し、国民構成を形成し、植民地化の努力を通じて国民を世界市場に徐々に組み込む手段とし て、ヨーロッパ移民が強く奨励された。これらの変化は、おそらく「アルゼンチン人は船から降りてきた」という人類学的隠喩によって最もよく要約されてい る。[11] 移民の規模とそのアルゼンチン民族誌への貢献は、同国が世界第2位の移民受け入れ国(660万人)となった事実から明らかである。これは米国(2700万 人)に次ぎ、カナダ、ブラジル、オーストラリアなどを上回る数値だ。[12] [13] ヨーロッパ系移民コミュニティの拡大と、パンパス地方への西進、パタゴニア地方への南進に伴う鉄道建設は、追いやられた部族によるマロン襲撃に直面した。 これが1870年代の「砂漠征服」につながり、1,300人以上の先住民が死亡した。[14][15] その結果、アルゼンチンの先住民文化は、19 世紀後半から 20 世紀初頭にかけて政府によって推進された「不可視化」の過程の影響を受けた。[16] 20 世紀、ロベルト・レーマン・ニッチェなどの人類学者による先駆的な研究に続き、フアン・バウティスタ・アンブロセッティや他のエスノグラファーたちによる 広範な探検、研究、執筆活動が行われた。[17] これらは、アルゼンチンの先住民に対する幅広い関心を促し、1940年代から1950年代にかけてのフアン・ペロン大統領の政権下では、ペロンが当時称賛 した田舎のクリオージョ文化と価値観の一部として、先住民が国民の文化に果たした貢献がさらに強調された。[18] さらに、1988年8月3日にラウル・アルフォンシン大統領が反差別法(法律第23.592号)を制定したことで、これらの人々やその他のマイノリティに 対する差別的な政策は公式に終了した[19]。1995年には、政府機関である国家反差別・外国人嫌悪・人種主義対策機関(INADI)が設立され、差別 対策がさらに推進された。[20] 2004年、コリエンテス州は国民で初めて先住民言語(グアラニー語)を共同公用語として認定した[21]。また、2004年の先住民国勢調査と2010 年の国勢調査における自己申告カテゴリーへの組み入れにより、35の先住民集団全てが認められた。したがって、先住民コミュニティとアフリカ系アルゼンチ ン人は、2010年国勢調査において民族カテゴリーとして何らかの認識を与えられた唯一の集団となった[22]。 |

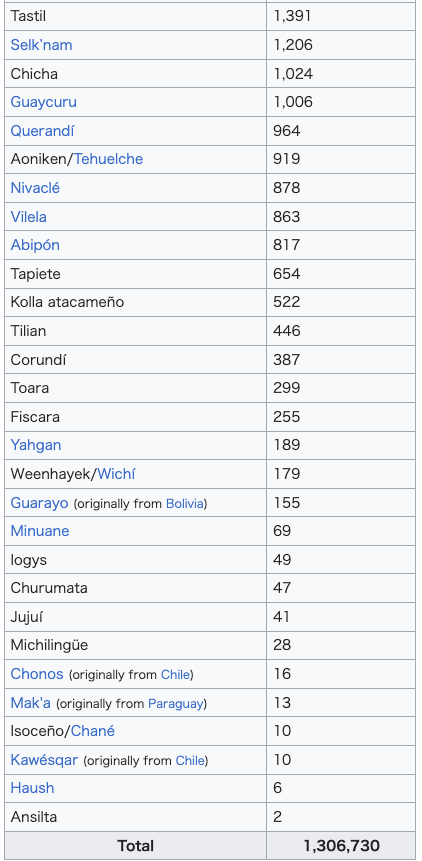

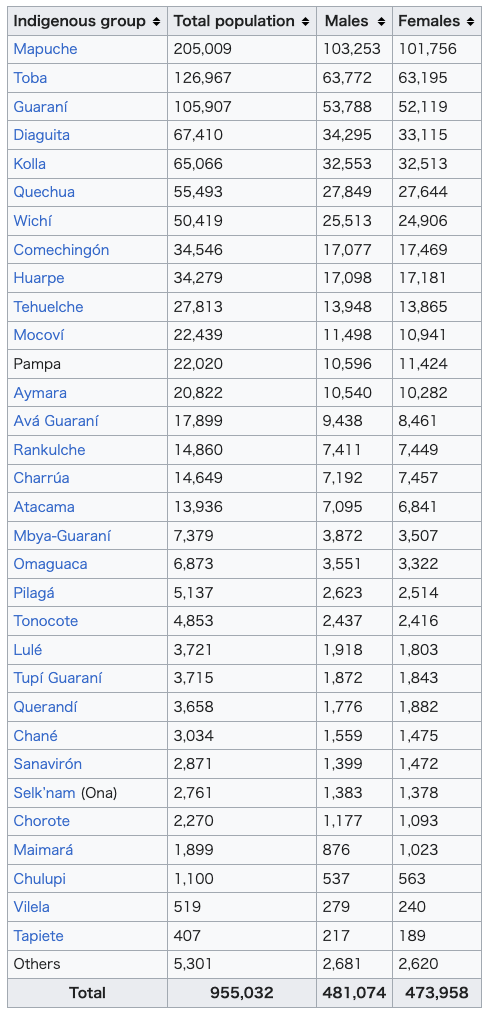

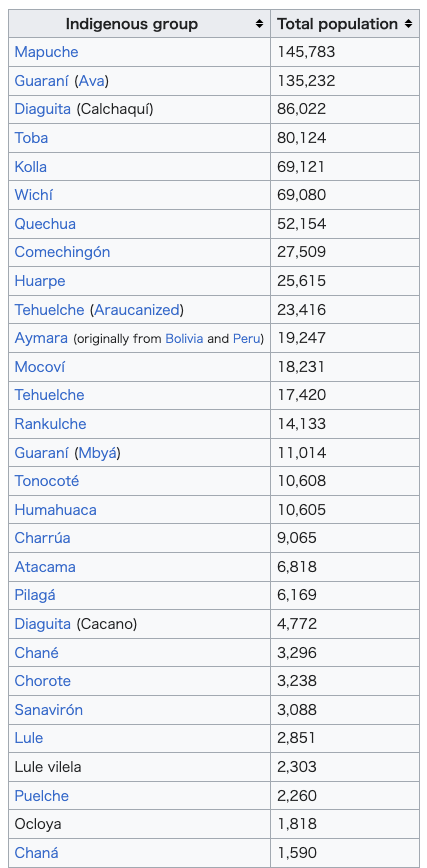

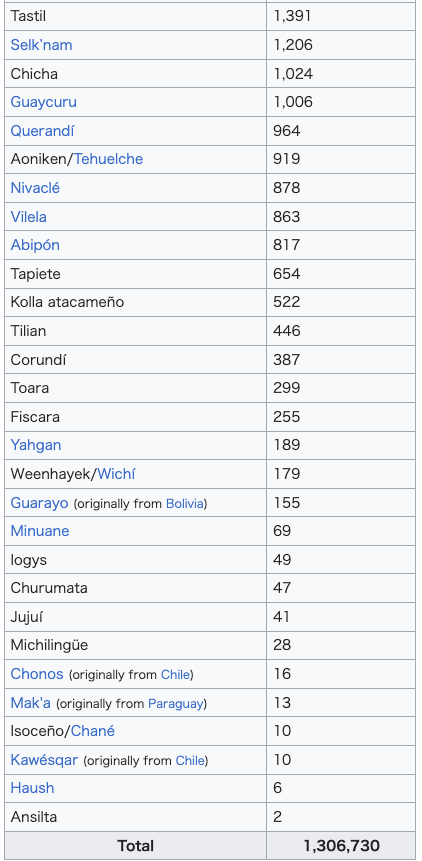

| Demographics Indigenous communities today Native Argentines 1778-2022 Year Population % of Argentina 1778 41,517 Steady 22.33% 2001 600,329 Decrease 1.66% 2010 955,032 Increase 2.38% 2022 1,306,730 Increase 2.83% Source: Argentina census INDEC.[23][24][1] Population pyramid of Indigenous Argentines in 2022. Population of Indigenous people in Greater Buenos Aires according to the 2022 census. As of the 2010 census [INDEC], some 955,032 Argentines (2.38% of the country's population) self-identify as Indigenous or first-generation descendants of Indigenous peoples.[3] The first government-led effort to produce accurate statistical data on the country's Indigenous peoples was the 2001 national census, which included a question on self-identification with Indigenous nations.[25] A more in-depth statistical survey came in 2004, with the Complimentary Survey on Indigenous Populations carried out by the National Institute for Indigenous Affairs (INAI). The 2004 survey which accounted for 600,329 people who see themselves as descending from or belonging to Indigenous people.[26] Indigenous organisations have questioned the factual accuracy of the 2004 survey: First, the methodology used in the survey was considered inadequate, as a large number of Indigenous people live in urban areas where the survey was not fully conducted. Second, many Indigenous people in the country hide their identity for fear of discrimination. Moreover, when the survey was designed in 2001, it was based on the existence of 18 known peoples in the country, opposed to the more than 31 groups recognized by the INAI today. This increase reflects a growing awareness amongst Indigenous people in terms of their ethnic belonging.[26] Guaraní girl in Yrapú, Misiones Province. As many Argentines either believe that the majority of the Indigenous have died out or are on the verge of doing so, or 'their descendants' assimilated into Western civilisation many years ago, they wrongly hold the idea that there are no Indigenous people in their country. The use of pejorative terms likening the Indigenous to lazy, idle, dirty, ignorant and savage are part of the everyday language in Argentina. Due to these incorrect stereotypes many Indigenous have over the years been forced to hide their identity in order to avoid being subjected to racial discrimination.[26] As of 2011, many Native people were still being denied land and human rights. Many of the Qom Native community had been struggling to protect the land they claim as ancestral territory and even the lives of its members. Qom community leader Félix Díaz claimed that his people were being denied medical assistance, did not have access to drinking water, and were subject to arbitrary rises on food prices by non-Indigenous businesses. He also claimed the local justice system refused to hear the local community's complaints.[27] The INAI, which reports to the Argentine Ministry of Justice and Human Rights, is tasked with overseeing the government's Indigenous policy and maintaining track of Argentina's Indigenous communities and their rights to their ancestral lands.[28] As of 2018, the INAI kept register of 1,653 communities, of which 1,456 held legal ownership over various territories.[29] |

人口統計 現代の先住民コミュニティ アルゼンチン先住民 1778-2022 年 人口 割合 アルゼンチン 1778 41,517 安定 22.33% 2001 600,329 減少 1.66% 2010年 955,032人 増加 2.38% 2022年 1,306,730人 増加 2.83% 出典:アルゼンチン国勢調査 INDEC。[23][24][1] 2022年におけるアルゼンチン先住民の人口ピラミッド。 2022年国勢調査に基づくブエノスアイレス大都市圏の先住民人口。 2010年国勢調査[INDEC]によると、約955,032人のアルゼンチン人(国内人口の2.38%)が自らを先住民または先住民の第一世代の子孫と認識している。[3] 政府主導で国内先住民に関する正確な統計データを作成した最初の試みは、2001年の国勢調査であった。この調査では、先住民国民への自己認識に関する質 問が含まれていた。[25] より詳細な統計調査は2004年に行われ、国立先住民問題研究所(INAI)が実施した「先住民人口補足調査」であった。2004年の調査では、自らを先 住民の末裔または所属者と見なす600,329人が計上された[26]。先住民組織は2004年調査の事実的正確性に疑問を呈している。第一に、調査手法 が不十分とされた。多くの先住民が都市部に居住しているが、調査は都市部で十分に実施されなかったためである。次に、国内の多くの先住民は差別を恐れて自 らのアイデンティティを隠している。さらに、2001年に調査が設計された時点では、国内に18の既知の民族が存在するとされていたが、これは現在の INAIが認める31以上の集団とは対照的である。この増加は、先住民の間で自らの民族的帰属意識が高まっていることを反映している。[26] ミシオネス州イラプのグアラニー族の少女。 多くのアルゼンチン人は、先住民の大半がすでに死滅したか、死滅寸前である、あるいは「その子孫」がはるか昔に西洋文明に同化したと信じているため、自国 に先住民は存在しないという誤った認識を抱いている。先住民を怠惰で、無気力で、不潔で、無知で、野蛮だと比喩する蔑称は、アルゼンチンでは日常語の一部 となっている。こうした誤った固定観念のため、多くの先住民は長年、人種差別の対象となるのを避けるために自らのアイデンティティを隠すことを余儀なくさ れてきた。[26] 2011年時点で、多くの先住民は依然として土地と人権を否定されていた。コム先住民コミュニティの多くは、祖先の土地と主張する土地の保護、さらにはコ ミュニティメンバーの命を守るために苦闘してきた。コムコミュニティの指導者フェリックス・ディアスは、自らが属する民族が医療支援を拒否され、飲料水へ のアクセスがなく、非先住民企業による食料価格の恣意的な値上げに晒されていると訴えた。また、地元の司法制度が地域コミュニティの苦情を聞くことを拒否 していると主張した。[27] アルゼンチン司法人権省傘下のINAIは、政府の先住民政策を監督し、アルゼンチンの先住民コミュニティとその祖先の土地に対する権利を追跡する任務を 負っている。[28] 2018年時点で、INAIは1,653のコミュニティを登録しており、そのうち1,456が様々な領土の法的所有権を保持していた。[29] |

| Genetic contribution in Argentine society Genetic ancestry of the average Argentinian gene pool according to Caputo et al. (2021) using X-DIPs (matrilineal).[30] European and West Asian Contribution (77.8%) Amerindian Contribution (18.0%) Sub-Saharan Contribution (4.20%) In addition to the Indigenous population in Argentina, most Argentines are descendants of Indigenous peoples or have some Indigenous ancestry.[4] Many genetic studies have shown that Argentina's genetic footprint is primarily, but not overwhelmingly, European. In a genetic study involving 441 Argentines from across the North East, North West, Southern, and Central provinces (especially the urban conglomeration of Buenos Aires) of the country, it was observed that 65% of the Argentine population was of European descent, followed by 31% of Indigenous descent, and 4% of African descent.[31] The same study also found there were great differences in the ancestry amongst Argentines as one traveled across the country. For example, the population in the North West provinces of Argentina (including the province of Salta) were on average of 66% Indigenous, 33% European, and 1% of African ancestry.[31] The European immigration to this North West part of the country was limited and the original Indigenous population largely thrived after their initial decline owing to the introduction of European diseases and colonization. Similarly, the study also showed that the population in the North Eastern provinces of Argentina (for example, Misiones, Chaco, Corrientes, and Formosa) were on average 43% of Indigenous, 54% European, and 3% of African ancestry.[31] The population of the Southern provinces of Argentina, such as Río Negro and Neuquén, were on average 40% of Indigenous, 54% European, and 6% of African ancestry.[31] Finally, only in areas of massive historical European immigration in Argentina, namely the Central provinces (Buenos Aires and the surrounding urban areas), Argentines were of overwhelmingly European ancestry, with the average person having 17% Indigenous, 76% European, and 7% of African ancestry.[31] In another study, that was titled the Regional pattern of genetic admixture in South America, the researchers included results from the genetic study of several hundreds of Argentines from all across the country. The study indicated that Argentines were as a whole made up of 38% indogenous, 58.9% of European, and 3.1% of African ancestry. Again, there were huge difference in the genetic ancestry from across the various regions of the country.[32] For example, Argentines who hailed from Patagonia were 45% Indigenous and 55% of European ancestry.[32] The population in the North West part of the country were made up of 69% of Indigenous, 23% of European, and 8% of African ancestry.[32] The population in the Gran Chaco part of the country were 38% of Indigenous, 53% of European, and 9% of African ancestry.[32] The population in the Mesopotamian part of the country were 31% of Indigenous, 63% of European, and 6.4% of African ancestry.[32] Finally, the population in the Pampa region of the country were 22% of Indigenous, 68% of European, and 10% of African ancestry.[32] Finally, in another study published in 2005 involving the North Western provinces of the country, the genetic structure of 1293 individuals from Jujuy, Salta, Tucumán, Santiago del Estero, Catamarca and La Rioja was analysed.[33] This study showed that the Spanish contribution (50%) predominated in Argentina's North West, followed by the Amerindian (40%) and African (10%) contributions.[33] According to this study, Argentines from Jujuy were 53% Indigenous, 47% European, and 0.1% African ancestry.[33] Argentines from Salta were 41% of Indigenous, 56% of European, and 3.1% of African ancestry.[33] Those from Catamarca were 37% of Indigenous, 53% of European, and 10% of African ancestry.[33] Those from La Rioja were on average 31% Indigenous, 50% European, and 19% African ancestry.[33] The inhabitants of Santiago del Estero were on average 30% Indigenous, 46% European, and 24% African ancestry.[33] The inhabitants of Tucumán were on average 24% Indigenous, 67% European, and 9% African ancestry.[33] |

アルゼンチン社会における遺伝的構成 カプトら(2021)によるX-DIPs(母系)を用いた平均的なアルゼンチン人遺伝子プールの遺伝的祖先構成。[30] ヨーロッパおよび西アジアの寄与(77.8%) アメリカ先住民の寄与(18.0%) サブサハラアフリカの寄与(4.20%) アルゼンチンの先住民に加え、大多数のアルゼンチン人は先住民の子孫であるか、何らかの先住民の祖先を持つ。[4] 多くの遺伝学的研究は、アルゼンチンの遺伝的足跡が主に、しかし圧倒的ではない、ヨーロッパ由来であることを示している。アルゼンチン北東部、北西部、南 部、中央部の各州(特にブエノスアイレス都市圏)から441名のアルゼンチン人を対象とした遺伝学研究では、アルゼンチン人口の65%がヨーロッパ系、 31%が先住民系、4%がアフリカ系であることが確認された。[31] 同じ研究では、国内を移動するにつれてアルゼンチン人の祖先構成に大きな差異があることも判明した。例えばアルゼンチン北西部州(サルタ州を含む)の人口 は平均で先住民66%、ヨーロッパ系33%、アフリカ系1%であった。[31] この北西部地域へのヨーロッパ移民は限定的であり、先住民人口はヨーロッパの伝染病や植民地化による初期の減少後、大きく回復した。同様に、アルゼンチン 北東部州(ミシオネス州、チャコ州、コリエンテス州、フォルモサ州など)では、平均して先住民系43%、ヨーロッパ系54%、アフリカ系3%であった。 [31] リオネグロ州やヌエケン州といったアルゼンチン南部州の人口は、平均して先住民40%、ヨーロッパ系54%、アフリカ系6%であった。[31] 最後に、アルゼンチンにおいて大規模な歴史的欧州移民が集中した地域、すなわち中央州(ブエノスアイレス及び周辺都市部)では、アルゼンチン人の祖先は圧 倒的に欧州系であり、平均的な人格は先住民17%、欧州系76%、アフリカ系7%の祖先構成を示した。[31] 別の研究「南米における遺伝的混血の地域パターン」では、研究者らは全国から数百人のアルゼンチン人を対象とした遺伝子研究の結果をまとめた。この研究に よれば、アルゼンチン人全体の祖先構成は先住民38%、ヨーロッパ系58.9%、アフリカ系3.1%であった。ここでも、国内の地域によって遺伝的祖先構 成に大きな差異が見られた[32]。例えばパタゴニア出身のアルゼンチン人は先住民45%、ヨーロッパ系55%であった。[32] 北西部の人口構成は先住民69%、ヨーロッパ系23%、アフリカ系8%であった。[32] グラン・チャコ地域では先住民38%、ヨーロッパ系53%、アフリカ系9%だった。[32] メソポタミア地域の人口構成は、先住民系31%、ヨーロッパ系63%、アフリカ系6.4%であった。[32] 最後に、パンパ地域の人口構成は、先住民系22%、ヨーロッパ系68%、アフリカ系10%であった。[32] さらに、2005年に発表された別の研究では、同国北西部州を対象に、フフイ州、サルタ州、トゥクマン州、サンティアゴ・デル・エステロ州、カタマルカ 州、ラ・リオハ州の1293名の遺伝的構造を分析した。[33] この研究では、アルゼンチン北西部ではスペイン系(50%)の遺伝的寄与が最も大きく、次いでアメリカ先住民系(40%)、アフリカ系(10%)の順で あった。[33] この研究によれば、フフイ州のアルゼンチン人は先住民系53%、ヨーロッパ系47%、アフリカ系0.1%の祖先構成であった。[33] サルタ州の住民は先住民系41%、ヨーロッパ系56%、アフリカ系3.1%であった。[33] カタマルカ州の住民は先住民系37%、ヨーロッパ系53%、アフリカ系10%であった。[33] ラ・リオハ州の住民は平均で先住民系31%、ヨーロッパ系50%、アフリカ系19%であった。[33] サンティアゴ・デル・エステロ州の住民は平均で先住民30%、ヨーロッパ系46%、アフリカ系24%の祖先構成であった。[33] トゥクマン州の住民は平均で先住民24%、ヨーロッパ系67%、アフリカ系9%の祖先構成であった。[33] |

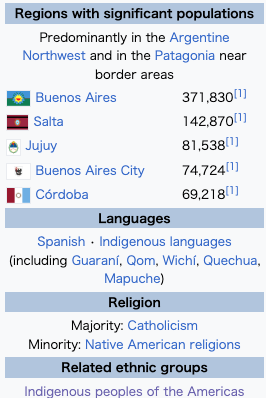

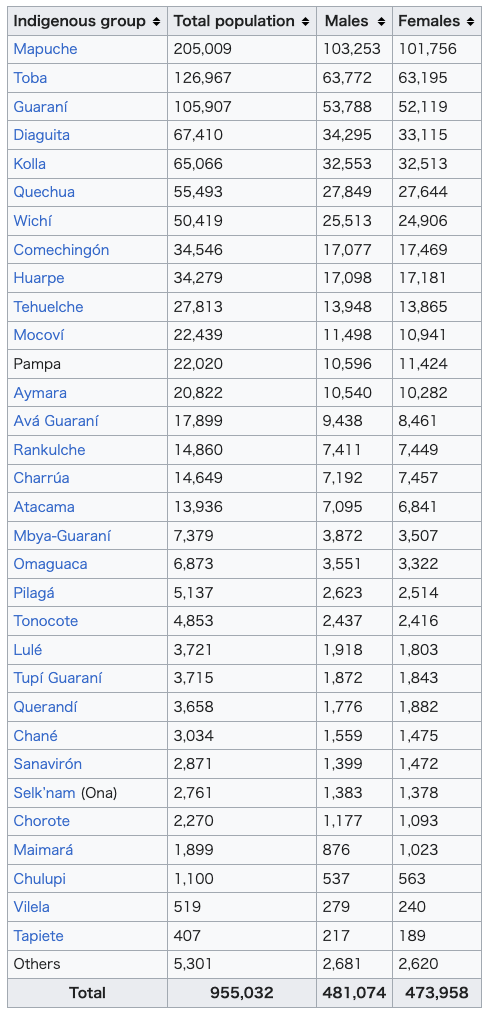

| Indigenous groups by population According to the 2010 census there are the following Indigenous groups:[3]  According to the 2022 census there are the following Indigenous groups:[1]   |

人口による先住民族グループ 2010年の国勢調査によれば、以下の先住民族グループが存在する。[3]  2022年の国勢調査によると、以下の先住民族グループが存在する。[1]   |

Indigenous groups by region |

地域ごとの先住民 |

| Indigenous peoples of South America Araucanization of Patagonia Bolivian Argentines Languages of Argentina Argentine people Abipón people Amaicha Calchaquí Capayán Poya people Guaraní people Selkʼnam genocide |

南米の先住民 パタゴニアのアラウカ化 ボリビア系アルゼンチン人 アルゼンチンの言語 アルゼンチン人 アビポン族 アマイチャ カルチャキ カパヤン ポヤ族 グアラニー族 セルクナム虐殺 |

| Notes 1. "Censo 2022". INDEC. Retrieved 8 March 2024. 2. "Encuesta Complementaria de Pueblos Indígenas". Archived from the original on 2008-06-11. Retrieved 2008-06-18. 3. "Censo Nacional de Población, Hogares y Viviendas 2010: Pueblos Originarios: Región Noroeste Argentino: Serie D No 1" (PDF) (in Spanish). INDEC. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 April 2016. Retrieved 5 December 2015. 4. "Estructura genética de la Argentina, Impacto de contribuciones genéticas". Ministerio de Educación de Ciencia y Tecnología de la Nación (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 20 August 2011. 5. Welcome Argentina: Expediciones Arqueológicas en Los Toldos y en Piedra Museo Archived 2012-03-10 at the Wayback Machine (in Spanish) 6. "Cueva de las Manos. UNESCO WHC website". Archived from the original on 2020-04-08. Retrieved 2019-12-26. 7. "Smithsonian: Paleoamerican Origins". Archived from the original on 2020-04-08. Retrieved 2011-04-29. 8. Bello, Alvaro; Rangel, Marta (April 2002). "La equidad y la exclusión de los pueblos indígenas y afrodescendientes en América Latina y el Caribe" (PDF). Revista de la CEPAL (in Spanish). 76: 41. ISSN 0252-0257. Retrieved 16 January 2023. 9. Galasso 111-112 10. Neuquén: Los pueblos originarios y los posteriores part I Archived 2015-05-01 at the Wayback Machine, part II Archived 2020-04-08 at the Wayback Machine 11. Trinchero, Héctor Hugo (2006). "The genocide of Indigenous peoples in the formation of the Argentine Nation-State". Journal of Genocide Research. 8 (2): 121–35. doi:10.1080/14623520600703008. S2CID 71409403. 12. "Archived copy" (PDF). www.cels.org.ar. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 June 2007. Retrieved 15 January 2022. 13. "Archived copy" (PDF). docentes.fe.unl.pt. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 August 2011. Retrieved 15 January 2022. 14. "Argentina Desert War 1879–1880". Onwar.com. 2003. Archived from the original on 2011-01-12. Retrieved 2011-04-29. 15. Jens Andermann. "Argentine Literature and the 'Conquest of the Desert', 1872–1896". Birkbeck, University of London. Archived from the original on 2006-10-28. Retrieved 2009-09-02. 16. Bartolomé, Miguel Alberto (2003). "Los pobladores del 'desierto' Genocidio, etnocidio y etnogénesis en la Argentina" [The inhabitants of the 'desert' genocide, ethnocide and ethnogenesis in Argentina]. Cuadernos de Antropología Social (in Spanish). 17 (1): 162–89. Archived from the original on 2020-04-01. Retrieved 2013-06-09. 17. Ballestero, Diego (2013). Los espacios de la antropología en la obra de Robert Lehmann-Nitsche, 1894-1938 (PhD). Universidad Nacional de La Plata. 18. Karush, Matthew; Chamosa, Oscar (2010). The New Cultural History of Peronism: Power and Identity in Mid-Twentieth Century. Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-9286-6. Archived from the original on 2022-04-07. Retrieved 2020-11-01. 19. Ley 23.592 Antidiscriminatoria Archived 2014-08-14 at the Wayback Machine (in Spanish) 20. Sitio oficial del instituto Nacional contra la Discriminación (INADI) Archived 2011-03-14 at the Wayback Machine (in Spanish) 21. Ley Provincial Nº 5.598, Corrientes Archived 2012-02-29 at the Wayback Machine (in Spanish) 22. INDEC. Censo 2010. Archived 2011-06-15 at the Wayback Machine (in Spanish) 23. "Censo 1778" (PDF). Retrieved 18 April 2024. 24. "Censo 2001–2010" [Table P1. Total population and intercensus absolute and relative variation by province or jurisdiction, 2001–2010]. INDEC (in Spanish). Archived from the original (XLS) on 2 September 2011. 25. "La identificación étnica en los registros de salud: experiencias y percepciones en el pueblo Mapuche de Chile y Argentina" (in Spanish). Pan American Health Organization. p. 21. Retrieved 16 January 2023. 26. "Indigenous Peoples in Argentina". International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs. Archived from the original on April 27, 2015. Retrieved June 9, 2013. 27. "Félix Diaz volvió a acampar para que lo reconozcan como representante de los pueblos originarios ante el Estado". Télam (in Spanish). 15 March 2016. Archived from the original on 16 January 2023. Retrieved 16 January 2023. 28. "Programas del Instituto Nacional de Asuntos Indígenas". CEPAL (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 2 January 2023. Retrieved 2 January 2023. 29. "Los Pueblos Originarios en Argentina, hoy". Secretaría de Cultura (in Spanish). 11 October 2018. Archived from the original on 2 January 2023. Retrieved 2 January 2023. 30. Caputo, M.; Amador, M. A.; Sala, A.; Riveiro Dos Santos, A.; Santos, S.; Corach, D. (2021). "Ancestral genetic legacy of the extant population of Argentina as predicted by autosomal and X-chromosomal DIPs". Molecular Genetics and Genomics. 296 (3): 581–590. doi:10.1007/s00438-020-01755-w. PMID 33580820. S2CID 231911367. Retrieved 13 February 2021. 31. Avena, Sergio; Via, Marc; Ziv, Elad; Pérez-Stable, Eliseo J.; Gignoux, Christopher R.; Dejean, Cristina; Huntsman, Scott; Torres-Mejía, Gabriela; et al. (2012). Kivisild, Toomas (ed.). "Heterogeneity in Genetic Admixture across Different Regions of Argentina". PLOS ONE. 7 (4) e34695. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...734695A. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0034695. PMC 3323559. PMID 22506044. 32. Godinho, N.M.O.; Gontijo, C.C.; Diniz, M.E.C.G.; Falcão-Alencar, G.; Dalton, G.C.; Amorim, C.E.G.; Barcelos, R.S.S.; Klautau-Guimarães, M.N.; Oliveira, S.F. (2008). "Regional patterns of genetic admixture in South America". Forensic Science International: Genetics Supplement Series. 1 (1): 329–30. doi:10.1016/j.fsigss.2007.10.069. 33. Alfaro, E. L.; Dipierri, J. E.; Gutiérrez, N. I.; Vullo, C. M. (2005). "Genetic structure and admixture in urban populations of the Argentine North-West". Annals of Human Biology. 32 (6): 724–37. doi:10.1080/03014460500287861. PMID 16418046. S2CID 22121799. |

注記 1. 「2022年国勢調査」。INDEC。2024年3月8日閲覧。 2. 「先住民族補足調査」。2008年6月11日にオリジナルからアーカイブ。2008年6月18日閲覧。 3. 「2010年国民・世帯・住宅国勢調査:先住民族:アルゼンチン北西部地域:シリーズD第1号」 (PDF) (スペイン語). INDEC. 2016年4月9日にオリジナル (PDF) からアーカイブ. 2015年12月5日に閲覧. 4. 「アルゼンチンの遺伝的構造、遺伝的貢献の影響」。国立科学技術教育省(スペイン語)。2011年8月20日にオリジナルからアーカイブ。 5. ウェルカム・アルゼンチン:ロス・トルドスおよびピエドラ・ムセオにおける考古学的調査 2012年3月10日にウェイバックマシンでアーカイブ(スペイン語) 6. 「メンディア・デ・ラス・マノス。ユネスコ世界遺産委員会ウェブサイト」。2020年4月8日にオリジナルからアーカイブ。2019年12月26日に取得。 7. 「スミソニアン:古アメリカ人の起源」。2020年4月8日にオリジナルからアーカイブ。2011年4月29日に取得。 8. Bello, Alvaro; Rangel, Marta (2002年4月). 「ラテンアメリカおよびカリブ海地域における先住民およびアフリカ系住民に対する公平性と排除」 (PDF). Revista de la CEPAL (スペイン語). 76: 41. ISSN 0252-0257. 2023年1月16日取得。 9. ガッラッソ 111-112 10. ヌエケン:先住民族とその後者たち 第1部 2015年5月1日時点のアーカイブ, 第2部 2020年4月8日時点のアーカイブ 11. トリンチェロ、ヘクター・ウーゴ (2006). 「アルゼンチン国民国家形成における先住民のジェノサイド」. Journal of Genocide Research. 8 (2): 121–35. doi:10.1080/14623520600703008. S2CID 71409403. 12. 「アーカイブされたコピー」 (PDF). www.cels.org.ar。2007年6月10日にオリジナル(PDF)からアーカイブ。2022年1月15日に取得。 13. 「アーカイブされたコピー」 (PDF)。docentes.fe.unl.pt。2011年8月14日にオリジナル(PDF)からアーカイブ。2022年1月15日に取得。 14. 「アルゼンチン砂漠戦争 1879–1880」. Onwar.com. 2003年. 2011年1月12日にオリジナルからアーカイブ. 2011年4月29日に閲覧. 15. イェンス・アンデルマン. 「アルゼンチン文学と『砂漠の征服』1872–1896」. ロンドン大学バークベック校. 2006年10月28日にオリジナルからアーカイブ. 2009年9月2日に閲覧. 16. バルトロメ、ミゲル・アルベルト (2003). 「『砂漠』の住民たち:アルゼンチンにおけるジェノサイド、エスノサイド、エスノジェネシス」. 『社会人類学ノート』 (スペイン語). 17 (1): 162–89. 2020年4月1日にオリジナルからアーカイブ。2013年6月9日に取得。 17. バレステロ、ディエゴ (2013)。ロベルト・レーマン・ニッチェの著作における人類学の空間、1894-1938 (博士論文)。ラプラタ国立大学。 18. Karush, Matthew; Chamosa, Oscar (2010). 『ペロン主義の新しい文化史:20 世紀半ばの権力とアイデンティティ』. デューク大学出版局. ISBN 978-0-8223-9286-6. 2022-04-07 のオリジナルからアーカイブ。2020-11-01 に取得。 19. 反差別法23.592号(スペイン語) 20. 国立差別対策研究所(INADI)公式サイト(スペイン語) 21. コリエンテス州法第5598号 Archived 2012-02-29 at the Wayback Machine (スペイン語) 22. INDEC. 2010年国勢調査 Archived 2011-06-15 at the Wayback Machine (スペイン語) 23. 「1778年国勢調査」 (PDF). 2024年4月18日閲覧。 24. 「2001年~2010年国勢調査」[表P1. 州または管轄区域別の総人口および国勢調査間の絶対的・相対的変動、2001年~2010年]。INDEC(スペイン語)。2011年9月2日にオリジナル(XLS)からアーカイブ。 25. 「医療記録における民族的識別:チリとアルゼンチンのマプチェ族における経験と認識」(スペイン語)。パンアメリカン保健機構。p. 21。2023年1月16日閲覧。 26. 「アルゼンチンの先住民」。「国際先住民族問題作業部会」が2015年4月27日にオリジナルからアーカイブ。2013年6月9日閲覧。 27. 「フェリックス・ディアスが先住民族の国家代表としての承認を求めて再びキャンプを張った」. Télam(スペイン語). 2016年3月15日. 2023年1月16日時点のオリジナルからアーカイブ. 2023年1月16日閲覧。 28. 「国立先住民問題研究所のプログラム」。CEPAL(スペイン語)。2023年1月2日にオリジナルからアーカイブ。2023年1月2日に取得。 29. 「今日のアルゼンチンの先住民族」。文化省(スペイン語)。2018年10月11日。2023年1月2日にオリジナルからアーカイブ。2023年1月2日に閲覧。 30. Caputo, M.; Amador, M. A.; Sala, A.; Riveiro Dos Santos, A.; Santos, S.; Corach, D. (2021). 「常染色体およびX染色体DIPsによって予測されるアルゼンチン現存人口の祖先遺伝的遺産」. 分子遺伝学およびゲノミクス。296 (3): 581–590. doi:10.1007/s00438-020-01755-w. PMID 33580820. S2CID 231911367. 2021年2月13日に取得。 31. Avena, Sergio; ビア、マーク; ジブ、エラド; ペレス=スタブル、エリセオ・J.; ジニュ、クリストファー・R.; デジャン、クリスティーナ; ハンツマン、スコット; トルレス=メヒア、ガブリエラ; 他 (2012). キヴィシルド、トーマス (編). 「アルゼンチンにおける異なる地域における遺伝的混血の異質性」. PLOS ONE. 7 (4) e34695. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...734695A. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0034695. PMC 3323559. PMID 22506044. 32. Godinho, N.M.O.; Gontijo, C.C.; Diniz, M.E.C.G.; Falcão-Alencar, G.; Dalton, G.C.; Amorim, C.E.G.; Barcelos, R.S.S.; Klautau-Guimarães, M.N.; Oliveira, S.F. (2008). 「南米における遺伝的混血の地域的パターン」. 法科学国際誌:遺伝学補遺シリーズ。1 (1): 329–30. doi:10.1016/j.fsigss.2007.10.069. 33. Alfaro, E. L.; Dipierri, J. E.; Gutiérrez, N. I.; Vullo, C. M. (2005). 「アルゼンチン北西部都市部住民の遺伝的構造と混血」. Annals of Human Biology. 32 (6): 724–37. doi:10.1080/03014460500287861. PMID 16418046. S2CID 22121799. |

| References Galasso, Norberto (2011). Historia de la Argentina. Argentina: Colihue. ISBN 978-950-563-478-1. |

参考文献 ガッラッソ、ノルベルト(2011)。『アルゼンチンの歴史』。アルゼンチン:コリウエ。ISBN 978-950-563-478-1。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indigenous_peoples_in_Argentina |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099