ニッコロ・マキャベリ

Niccolò di Bernardo dei Machiavelli,

1469-1527

☆ ニッコロ・ディ・ベルナルド・デイ・マキャヴェリ[あるいはマキャベリ](Niccolò di Bernardo dei Machiavelli)[a](1469年5月3日 - 1527年6月21日)は、イタリア・ルネサンス期に生きたフィレンツェ出身の外交官、著述家、哲学者、歴史家である。彼は、1513年頃に執筆したもの の、死後5年経った1532年まで出版されなかった政治論『君主論』(伊: Il Principe)で最もよく知られている。彼はしばしば、近代政治哲学および政治学の父と呼ばれている。 長年にわたり、外交および軍事問題を担当するフィレンツェ共和国の高官を務めた。喜劇、謝肉祭の歌、詩を書いた。彼の個人的な書簡は、イタリアの書簡の歴 史家や学者にとっても重要である。[8] 1498年から1512年にかけて、メディチ家が政権を失った時期に、フィレンツェ共和国の第二書記官として働いた。 彼の死後、マキャベリの名前は、彼の代表作『君主論』で最も有名なように、不謹慎な行為を想起させるようになった。[9] 彼は、自身の経験と歴史の研究から、政治には常に欺瞞、裏切り、犯罪が伴うことを学んだと主張した。[10] と主張した。彼は支配者たちに、政治的に必要であれば悪事にも手を染めるべきだと助言し、国家の改革を成功させた指導者が、改革を妨げる可能性のある他の 指導者を殺害したとしても非難されるべきではないと主張した。政治の現実を率直に描写したものと考える者もいる。また、『君主論』を、権力を掌握し維持す る方法を独裁者候補に教えるマニュアルと見る者もいる。[14] 最近でも、レオ・シュトラウスなどの学者は、マキャベリは「悪の教師」であったという伝統的な見解を再提示している。[15] マキャベリは君主論で最も有名になったが、学者たちは彼の他の政治哲学の著作における勧告にも注目している。君主論ほどは知られていないが、『リヴィウス についての講話』(1517年頃執筆)は近代共和制への道を開いたとされている。[16] 彼の著作は、古典的共和制への関心を復活させた啓蒙主義の作家たち、 ジャン=ジャック・ルソーやジェイムズ・ハリントンなどがその例である。マキャベリの政治的リアリズムは、ハンナ・アレントをはじめとする学者や政治家た ちに影響を与え続けている。また、彼の手法は、オットー・フォン・ビスマルクなどの現実主義と比較されている。[18][19]

| Niccolò di Bernardo

dei Machiavelli[a] (3 May 1469 – 21 June 1527) was a Florentine[4][5]

diplomat, author, philosopher, and historian who lived during the

Italian Renaissance. He is best known for his political treatise The

Prince (Il Principe), written around 1513 but not published until 1532,

five years after his death.[6] He has often been called the father of

modern political philosophy and political science.[7] For many years he served as a senior official in the Florentine Republic with responsibilities in diplomatic and military affairs. He wrote comedies, carnival songs, and poetry. His personal correspondence is also important to historians and scholars of Italian correspondence.[8] He worked as secretary to the second chancery of the Republic of Florence from 1498 to 1512, when the Medici were out of power. After his death Machiavelli's name came to evoke unscrupulous acts of the sort he advised most famously in his work, The Prince.[9] He claimed that his experience and reading of history showed him that politics has always involved deception, treachery, and crime.[10] He advised rulers to engage in evil when political necessity requires it, and argued specifically that successful reformers of states should not be blamed for killing other leaders who could block change.[11][12][13] Machiavelli's Prince has been surrounded by controversy since it was published. Some consider it to be a straightforward description of political reality. Others view The Prince as a manual, teaching would-be tyrants how they should seize and maintain power.[14] Even into recent times, some scholars, such as Leo Strauss, have restated the traditional opinion that Machiavelli was a "teacher of evil".[15] Even though Machiavelli has become most famous for his work on principalities, scholars also give attention to the exhortations in his other works of political philosophy. While less well known than The Prince, the Discourses on Livy (composed c. 1517) has been said to have paved the way for modern republicanism.[16] His works were a major influence on Enlightenment authors who revived interest in classical republicanism, such as Jean-Jacques Rousseau and James Harrington.[17] Machiavelli's political realism has continued to influence generations of academics and politicians, including Hannah Arendt, and his approach has been compared to the Realpolitik of figures such as Otto von Bismarck.[18][19] |

ニッコロ・ディ・ベルナルド・デイ・マキャヴェリ(Niccolò

di Bernardo dei Machiavelli)[a](1469年5月3日 -

1527年6月21日)は、イタリア・ルネサンス期に生きたフィレンツェ出身の外交官、著述家、哲学者、歴史家である。彼は、1513年頃に執筆したもの

の、死後5年経った1532年まで出版されなかった政治論『君主論』(伊: Il

Principe)で最もよく知られている。彼はしばしば、近代政治哲学および政治学の父と呼ばれている。 長年にわたり、外交および軍事問題を担当するフィレンツェ共和国の高官を務めた。喜劇、謝肉祭の歌、詩を書いた。彼の個人的な書簡は、イタリアの書簡の歴 史家や学者にとっても重要である。[8] 1498年から1512年にかけて、メディチ家が政権を失った時期に、フィレンツェ共和国の第二書記官として働いた。 彼の死後、マキャベリの名前は、彼の代表作『君主論』で最も有名なように、不謹慎な行為を想起させるようになった。[9] 彼は、自身の経験と歴史の研究から、政治には常に欺瞞、裏切り、犯罪が伴うことを学んだと主張した。[10] と主張した。彼は支配者たちに、政治的に必要であれば悪事にも手を染めるべきだと助言し、国家の改革を成功させた指導者が、改革を妨げる可能性のある他の 指導者を殺害したとしても非難されるべきではないと主張した。政治の現実を率直に描写したものと考える者もいる。また、『君主論』を、権力を掌握し維持す る方法を独裁者候補に教えるマニュアルと見る者もいる。[14] 最近でも、レオ・シュトラウスなどの学者は、マキャベリは「悪の教師」であったという伝統的な見解を再提示している。[15] マキャベリは君主論で最も有名になったが、学者たちは彼の他の政治哲学の著作における勧告にも注目している。君主論ほどは知られていないが、『リヴィウス についての講話』(1517年頃執筆)は近代共和制への道を開いたとされている。[16] 彼の著作は、古典的共和制への関心を復活させた啓蒙主義の作家たち、 ジャン=ジャック・ルソーやジェイムズ・ハリントンなどがその例である。マキャベリの政治的リアリズムは、ハンナ・アレントをはじめとする学者や政治家た ちに影響を与え続けている。また、彼の手法は、オットー・フォン・ビスマルクなどの現実主義と比較されている。[18][19] |

| Life For a chronological guide, see Timeline of Niccolò Machiavelli.  Oil painting of Machiavelli by Cristofano dell'Altissimo Machiavelli was born in Florence, Italy, the third child and first son of attorney Bernardo di Niccolò Machiavelli and his wife, Bartolomea di Stefano Nelli, on 3 May 1469.[20] The Machiavelli family is believed to be descended from the old marquesses of Tuscany and to have produced thirteen Florentine Gonfalonieres of Justice,[21] one of the offices of a group of nine citizens selected by drawing lots every two months and who formed the government, or Signoria; he was never, though, a full citizen of Florence because of the nature of Florentine citizenship in that time even under the republican regime. Machiavelli married Marietta Corsini in 1501. They had seven children, five sons and two daughters: Primerana, Bernardo, Lodovico, Guido, Piero [it], Baccina and Totto.[22][23] Machiavelli was born in a tumultuous era. The Italian city-states, and the families and individuals who ran them could rise and fall suddenly, as popes and the kings of France, Spain, and the Holy Roman Empire waged acquisitive wars for regional influence and control. Political-military alliances continually changed, featuring condottieri (mercenary leaders), who changed sides without warning, and the rise and fall of many short-lived governments.[24] Machiavelli was taught grammar, rhetoric, and Latin by his teacher, Paolo da Ronciglione.[25] It is unknown whether Machiavelli knew Greek; Florence was at the time one of the centres of Greek scholarship in Europe.[26] In 1494 Florence restored the republic, expelling the Medici family that had ruled Florence for some sixty years. Shortly after the execution of Savonarola, Machiavelli was appointed to an office of the second chancery, a medieval writing office that put Machiavelli in charge of the production of official Florentine government documents.[27] Shortly thereafter, he was also made the secretary of the Dieci di Libertà e Pace. In the first decade of the sixteenth century, he carried out several diplomatic missions, most notably to the papacy in Rome. Florence sent him to Pistoia to pacify the leaders of two opposing factions which had broken into riots in 1501 and 1502; when this failed, the leaders were banished from the city, a strategy which Machiavelli had favoured from the outset.[28] From 1502 to 1503, he witnessed the brutal reality of the state-building methods of Cesare Borgia (1475–1507) and his father, Pope Alexander VI, who were then engaged in the process of trying to bring a large part of central Italy under their possession.[29] The pretext of defending Church interests was used as a partial justification by the Borgias. Other excursions to the court of Louis XII and the Spanish court influenced his writings such as The Prince. At the start of the 16th century, Machiavelli conceived of a militia for Florence, and he then began recruiting and creating it.[30] He distrusted mercenaries (a distrust that he explained in his official reports and then later in his theoretical works for their unpatriotic and uninvested nature in the war that makes their allegiance fickle and often unreliable when most needed),[31] and instead staffed his army with citizens, a policy that yielded some positive results. By February 1506 he was able to have four hundred farmers marching on parade, suited (including iron breastplates), and armed with lances and small firearms.[30] Under his command, Florentine citizen-soldiers conquered Pisa in 1509.[32]  Machiavelli's tomb in the Santa Croce Church in Florence Machiavelli's success was short-lived. In August 1512, the Medici, backed by Pope Julius II, used Spanish troops to defeat the Florentines at Prato.[33] In the wake of the siege, Piero Soderini resigned as Florentine head of state and fled into exile. The experience would, like Machiavelli's time in foreign courts and with the Borgia, heavily influence his political writings. The Florentine city-state and the republic were dissolved, with Machiavelli then being removed from office and banished from the city for a year.[34] In 1513, the Medici accused him of conspiracy against them and had him imprisoned.[35] Despite being subjected to torture[34] ("with the rope", in which the prisoner is hanged from his bound wrists from the back, forcing the arms to bear the body's weight and dislocating the shoulders), he denied involvement and was released after three weeks. Machiavelli then retired to his farm estate at Sant'Andrea in Percussina, near San Casciano in Val di Pesa, where he devoted himself to studying and writing political treatises. During this period, he represented the Florentine Republic on diplomatic visits to France, Germany, and elsewhere in Italy.[34] Despairing of the opportunity to remain directly involved in political matters, after a time he began to participate in intellectual groups in Florence and wrote several plays that (unlike his works on political theory) were both popular and widely known in his lifetime. Politics remained his main passion, and to satisfy this interest, he maintained a well-known correspondence with more politically connected friends, attempting to become involved once again in political life.[36] In a letter to Francesco Vettori, he described his experience: When evening comes, I go back home, and go to my study. On the threshold, I take off my work clothes, covered in mud and filth, and I put on the clothes an ambassador would wear. Decently dressed, I enter the ancient courts of rulers who have long since died. There, I am warmly welcomed, and I feed on the only food I find nourishing and was born to savour. I am not ashamed to talk to them and ask them to explain their actions and they, out of kindness, answer me. Four hours go by without my feeling any anxiety. I forget every worry. I am no longer afraid of poverty or frightened of death. I live entirely through them.[37] Machiavelli died on 21 June 1527 from a stomach ailment[38] at the age of 58 after receiving his last rites.[39][40] He was buried at the Church of Santa Croce in Florence. In 1789 George Nassau Clavering, and Pietro Leopoldo, Grand Duke of Tuscany, initiated the construction of a monument on Machiavelli's tomb. It was sculpted by Innocenzo Spinazzi, with an epitaph by Doctor Ferroni inscribed on it.[41][b] |

生涯 年代順の概略については、「ニッコロ・マキャヴェッリ年表」を参照のこと。  クリストファーノ・デッラルティッシモによるマキャベリの油彩画 マキャベリは1469年5月3日、イタリアのフィレンツェで、弁護士ベルナルド・ディ・ニコロ・マキャベリとその妻バルトロメア・ディ・ステファノ・ネッ リの三男として生まれた。マキャベリ家は、トスカーナの古い侯爵家の末裔であり、 フィレンツェ共和国の正義の旗手(ゴンファローニエーレ)を13人も輩出した家系である。[21] ゴンファローニエーレは、2ヶ月ごとにくじ引きで選ばれた9人の市民グループの役職のひとつであり、政府、すなわちシニョリーアを構成していた。しかし、 共和政下とはいえ、当時のフィレンツェの市民権の性質上、マキアヴェリはフィレンツェの完全な市民となることはなかった。マキアヴェリは1501年にマリ エッタ・コルシーニと結婚した。彼らの間には5人の息子と2人の娘、プリメラーナ、ベルナルド、ロドヴィーコ、グイード、ピエロ、バッキーナ、トットの7 人の子供がいた。 マキャベリは激動の時代に生まれた。イタリア都市国家とその統治者である一族や個人は、ローマ教皇やフランス、スペイン、神聖ローマ帝国の王たちが地域的 な影響力と支配権を巡って貪欲な戦争を繰り広げる中で、突然台頭したり没落したりすることがあった。政治と軍事の同盟関係は絶えず変化し、前触れもなく寝 返る傭兵のリーダーであるコンドッティエーリが特徴的であり、多くの短命な政府の興亡が繰り返された。 マキャベリは教師のパオロ・ダ・ロンキリオーネから文法、修辞学、ラテン語を学んだ。[25] マキャベリがギリシャ語を話せたかどうかは不明であるが、当時フィレンツェはヨーロッパにおけるギリシャ学問の中心地のひとつであった。[26] 1494年、フィレンツェは共和国を復活させ、60年近くフィレンツェを支配していたメディチ家を追放した。サヴォナローラが処刑された直後、マキアヴェ リは第2書記官に任命された。中世の書記官は、フィレンツェ政府の公式文書の作成を担当する役職であった。[27] その後まもなく、彼は「自由と平和の10人」の書記官にも任命された。 16世紀の最初の10年間、彼はいくつかの外交任務を遂行し、特にローマ教皇庁との外交が有名である。フィレンツェは彼をピストイアに派遣し、1501年 と1502年に暴動を起こした2つの対立派閥の指導者を鎮圧させた。これが失敗に終わると、指導者たちは街から追放された。これは当初からマキャベリが支 持していた戦略であった。[28] 1502年から1503年にかけて、 彼はチェーザレ・ボルジア(1475年-1507年)とその父であるアレクサンデル6世(教皇アレクサンデル6世)が、当時、イタリア中部の大部分を自ら の領土にしようとしていた過程で、国家建設の手法の残忍な現実を目撃した。[29] ボルジア家は、教会の利益を守るという口実を一部の正当化として用いた。ルイ12世の宮廷やスペイン宮廷への他の遠征は、『君主論』などの彼の著作に影響 を与えた。 16世紀の初頭、マキャベリはフィレンツェの民兵組織を構想し、その組織化と創設に着手した。[30] 彼は傭兵を信用していなかった(この不信感については、公式報告書や 彼らの忠誠心が気まぐれで、最も必要な時に信頼できないことが多いのは、戦争に非愛国的で無関心な性質があるからだと説明している)[31]。そして、代 わりに市民を軍に採用し、その政策はいくつかの肯定的な結果をもたらした。1506年2月までに、彼は400人の農民をパレード行進させ、鎧(鉄の胸当て を含む)を身にまとわせ、槍や小型の火器で武装させることができた。[30] 彼の指揮下で、フィレンツェの市民兵士たちは1509年にピサを征服した。[32]  フィレンツェのサンタ・クローチェ教会にあるマキャベリの墓 マキャベリの成功は長くは続かなかった。1512年8月、教皇ユリウス2世の支援を受けたメディチ家はスペイン軍を動員し、プラートでフィレンツェ軍を打 ち負かした。[33] この包囲戦の後、ピエロ・ソデリーニはフィレンツェの国家元首を辞任し、亡命した。この経験は、マキャベリが外国の宮廷やボルジア家で過ごした時期と同様 に、彼の政治的な著作に大きな影響を与えることとなった。フィレンツェの都市国家と共和国は解体され、マキャベリは職を解かれ、1年間国外追放となった。 [34] 1513年、メディチ家は彼を自分たちに対する陰謀の罪で告発し、投獄した。[35] 拷問(「縄」と呼ばれるもので、後ろから縛った手首を吊るし、腕に体重を支えさせ、肩を脱臼させる)にかけられたにもかかわらず、彼は関与を否定し、3週 間後に釈放された。 その後マキアヴェリは、サン・カシャーノ・イン・ヴァル・ディ・ペーザ近郊のサンタンドレア・イン・ペルクッシーナにある農場に隠棲し、政治論文の執筆と 研究に専念した。この期間中、彼はフィレンツェ共和国を代表してフランス、ドイツ、その他のイタリア諸国を外交訪問した。[34] 政治問題に直接関わる機会を失ったことに絶望し、しばらくしてからはフィレンツェの知識人グループに参加し、いくつかの戯曲を書いた。それらの作品は(政 治理論に関する作品とは異なり)人気を博し、彼の存命中に広く知られることとなった。政治への情熱は変わらず、その興味を満たすため、政治的によりコネの ある友人たちと有名な書簡のやりとりを続け、再び政治の世界に関わろうとしていた。[36] フランチェスコ・ヴェットーリへの手紙の中で、彼は自身の経験を次のように述べている。 夕方になると私は家に戻り、書斎に入る。敷居をまたぐ際に、泥と汚れにまみれた仕事着を脱ぎ、大使が着るような服を身にまとう。身なりを整え、とっくに亡 くなった支配者の古い宮廷に入る。そこで私は温かく迎え入れられ、栄養があり、味わうために生まれてきた唯一の食べ物を口にする。彼らに話しかけ、彼らの 行動について説明を求めることに恥ずかしさはない。彼らは親切心から、私の質問に答えてくれた。不安を感じることもなく、4時間が経過した。あらゆる心配 事を忘れていた。貧困を恐れることも、死を恐れることもなくなっていた。私は彼らを通して完全に生きているのだ。[37] マキアヴェッリは1527年6月21日、胃の病気により58歳で死去した。[38][39][40] 彼はフィレンツェのサンタ・クローチェ教会に埋葬された。1789年、ジョージ・ナッソー・クラヴァーリングとトスカーナ大公ピエトロ・レオポルドは、マ キアヴェッリの墓に記念碑を建設することを発案した。それはイノセンツォ・スピナッツィによって彫刻され、フェローニ博士による碑文が刻まれた。[41] [b] |

| Major works The Prince Main article: The Prince  Lorenzo di Piero de' Medici, to whom the final version of The Prince was dedicated Machiavelli's best-known book Il Principe contains several maxims concerning politics. Instead of the more traditional target audience of a hereditary prince, it concentrates on the possibility of a "new prince". To retain power, the hereditary prince must carefully balance the interests of a variety of institutions to which the people are accustomed.[42] By contrast, a new prince has the more difficult task in ruling: He must first stabilise his newfound power in order to build an enduring political structure. Machiavelli suggests that the political benefits of stability and security can be achieved in the face of moral corruption. Machiavelli believed that public and private morality had to be understood as two different things in order to rule well.[43] As a result, a ruler must be concerned not only with reputation, but also must be positively willing to act unscrupulously at the right times. Machiavelli believed that, for a ruler, it was better to be widely feared than to be greatly loved; a loved ruler retains authority by obligation, while a feared leader rules by fear of punishment.[44] As a political theorist, Machiavelli emphasized the "necessity" for the methodical exercise of brute force or deceit, including extermination of entire noble families, to head off any chance of a challenge to the prince's authority.[45] Scholars often note that Machiavelli glorifies instrumentality in state building, an approach embodied by the saying, often attributed to interpretations of The Prince, "The ends justify the means".[46] Fraud and deceit are held by Machiavelli as necessary for a prince to use.[47] Violence may be necessary for the successful stabilization of power and introduction of new political institutions. Force may be used to eliminate political rivals, destroy resistant populations, and purge the community of other men strong enough of a character to rule, who will inevitably attempt to replace the ruler.[48] In one passage, Machiavelli subverts the advice given by Cicero to avoid duplicity and violence, by saying that the prince should "be the fox to avoid the snares, and a lion to overwhelm the wolves". It would become one of Machiavelli's most famous maxims.[49] Machiavelli's view that acquiring a state and maintaining it requires evil means has been noted as the chief theme of the treatise.[50] Machiavelli has become infamous for such political advice, ensuring that he would be remembered in history through the adjective "Machiavellian".[51] Due to the treatise's controversial analysis on politics, in 1559, the Catholic Church banned The Prince, putting it on the Index Librorum Prohibitorum.[52][53] Humanists, including Erasmus (c. 1466 – 1536), also viewed the book negatively. As a treatise, its primary intellectual contribution to the history of political thought is the fundamental break between political realism and political idealism, due to it being a manual on acquiring and keeping political power. In contrast with Plato and Aristotle, Machiavelli insisted that an imaginary ideal society is not a model by which a prince should orient himself. Concerning the differences and similarities in Machiavelli's advice to ruthless and tyrannical princes in The Prince and his more republican exhortations in Discourses on Livy, a few commentators assert that The Prince, although written as advice for a monarchical prince, contains arguments for the superiority of republican regimes, similar to those found in the Discourses. In the 18th century, the work was even called a satire, for example by Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712–1778).[54][55] Scholars such as Leo Strauss (1899–1973) and Harvey Mansfield (b. 1932) have stated that sections of The Prince and his other works have deliberately esoteric statements throughout them.[56] However, Mansfield states that this is the result of Machiavelli's seeing grave and serious things as humorous because they are "manipulable by men", and sees them as grave because they "answer human necessities".[57] The Marxist theorist Antonio Gramsci (1891–1937) argued that Machiavelli's audience was the common people, as opposed to the ruling class, who were already made aware of the methods described through their education.[58] |

主要作品 君主論 詳細は「君主論」を参照  君主論の最終版は、ロレンツォ・ディ・ピエロ・デ・メディチに捧げられた マキアヴェッリの最も有名な著書『君主論』には、政治に関するいくつかの格律が含まれている。伝統的な読者層である世襲の君主ではなく、「新しい君主」の 可能性に焦点を当てている。世襲の君主が権力を維持するには、人々が慣れ親しんできたさまざまな機関の利害を慎重に調整しなければならない。[42] それに対して、新しい君主は統治においてより困難な課題を抱えている。まず、手に入れたばかりの権力を安定させ、永続する政治体制を築く必要がある。マ キャベリは、道徳の腐敗を前にしても、政治的な安定と安全の利益は達成できると示唆している。マキャベリは、政治をうまく行うためには、公的な道徳と私的 な道徳は異なるものとして理解されなければならないと考えていた。[43] その結果、統治者は評判を気にかけるだけでなく、適切なタイミングで悪事を働くことも積極的に望まなければならない。マキャベリは、統治者にとって、広く 恐れられることは、深く愛されることよりも望ましいと考えた。愛される統治者は義務によって権威を維持するが、恐れられる指導者は処罰への恐怖によって支 配する。[44] 政治理論家として、マキャベリは、王子の権威に対する挑戦の可能性を排除するために、貴族の一族を根絶やしにするなど、残忍な力や欺瞞を計画的に行使する 必要性を強調した。[45] 学者たちは、マキアヴェッリが国家建設における手段を美化していると指摘することが多い。この考え方は、しばしば『君主論』の解釈に帰せられる「目的は手 段を正当化する」という言葉に体現されている。[46] マキアヴェッリは、詐欺や欺瞞は君主が用いるべきものだと考えている。[47] 権力の安定化と新しい政治制度の導入を成功させるためには、暴力が必要な場合もある。政治的ライバルを排除し、抵抗勢力を壊滅し、支配者に取って代わろう とする者たちを排除するために、武力を行使することが必要となる場合もある。[48] マキャベリは、ある箇所で、キケロが「二枚舌と暴力を避けるべきである」と説くのを否定し、君主は「罠を避ける狐となり、狼を圧倒する獅子となるべきであ る」と述べている。これはマキャベリの格律の中でも最も有名なもののひとつとなった。[49] 国家を獲得し、それを維持するには悪を必要とするというマキャベリの考えは、この論文の主要テーマとして指摘されている。[50] マキャベリはこのような政治的助言によって悪名高い存在となり、形容詞「マキャベリ的」によって歴史に記憶されることとなった。[51] 政治に関する論争を呼ぶ分析を理由に、1559年にはカトリック教会が『君主論』を禁書とし、発禁図書表に載せた。[52][53] エラスムス(c. 1466年 - 1536年)を含む人文主義者たちも、この本を否定的に捉えていた。政治思想史におけるこの著作の主な知的貢献は、政治権力を獲得し維持するためのマニュ アルであるがゆえに、政治的リアリズムと政治的理想主義の根本的な断絶である。プラトンやアリストテレスとは対照的に、マキャベリは架空の理想社会は君主 が自らを方向付けるためのモデルではないと主張した。 『君主論』における冷酷で暴君的な君主へのマキャベリの助言と、『リヴィウスについて』における共和制への助言との相違点と類似点について、一部の論者 は、『君主論』は君主制の君主への助言として書かれたものだが、共和制の優位性を主張する議論が含まれており、『リヴィウスについて』にも見られるものと 同様であると主張している。18世紀には、例えばジャン=ジャック・ルソー(1712年-1778年)によって、この作品は風刺であるとさえ呼ばれた。 [54][55] レオ・シュトラウス(1899年-1973年)やハーヴェイ・マンチェスター(1932年生まれ)などの学者は、『君主論』やその他の作品のいくつかの部 分には、意図的に難解な表現が用いられていると述べている。[56] しかし、マンスフィールドは、これはマキャベリが深刻で重大な事柄を「人々によって操作可能」であるという理由でユーモアを交えて表現した結果であり、深 刻な事柄として捉えているのは、それらが「人間の必要性を満たす」からであると述べている。 マルクス主義理論家のアントニオ・グラムシ(1891年 - 1937年)は、マキャベリの読者層は支配階級ではなく、すでに教育を通じてその手法を知らされていた一般大衆であったと主張した。[58] |

| Discourses on Livy Main article: Discourses on Livy The Discourses on the First Ten Books of Titus Livius, written around 1517, and published in 1531, often referred to simply as the Discourses or Discorsi, is nominally a discussion regarding the classical history of early Ancient Rome, although it strays far from this subject matter and also uses contemporary political examples to illustrate points. Machiavelli presents it as a series of lessons on how a republic should be started and structured. It is a larger work than The Prince, and while it more openly explains the advantages of republics, it also contains many similar themes from his other works.[59] For example, Machiavelli has noted that to save a republic from corruption, it is necessary to return it to a "kingly state" using violent means.[60] He excuses Romulus for murdering his brother Remus and co-ruler Titus Tatius to gain absolute power for himself in that he established a "civil way of life".[61] Commentators disagree about how much the two works agree with each other, as Machiavelli frequently refers to leaders of republics as "princes".[62] Machiavelli even sometimes acts as an advisor to tyrants.[63][64] Other scholars have pointed out the aggrandizing and imperialistic features of Machiavelli's republic.[65] Nevertheless, it became one of the central texts of modern republicanism, and has often been argued to be a more comprehensive work than The Prince.[66] |

リウィウスについての論説 詳細は「リウィウスについての論説」を参照 ティトゥス・リウィウスによる『リウィウスについての論説』は、1517年頃に執筆され、1531年に出版された。この著作は、しばしば単に『論説』また は『論考』と呼ばれ、名目上は古代ローマ初期の古典史に関する議論であるが、この主題から大きく逸脱しており、また、論点を説明するために現代の政治的例 も使用されている。マキャベリは、共和国をどのようにして立ち上げ、組織化するかについての一連の教訓としてこれを提示している。『君主論』よりも大著で あり、共和国の利点をより率直に説明しているが、彼の他の著作にも類似したテーマが多く含まれている。例えば、マキャベリは、共和国を腐敗から救うために は、暴力的な手段を用いて「王政」に戻す必要があると指摘している。 弟レムスと共同統治者ティトゥス・タティウスを殺害して、自分自身に絶対的な権力を得るために、ロムルスを正当化した。なぜなら、彼は「市民的な生活様 式」を確立したからだ。[61] 解説者たちは、この2つの著作がどの程度一致しているかについて意見が分かれている。なぜなら、マキャベリは共和制の指導者を「君主」と呼ぶことが多いた めである。[62] マキャベ 時に暴君の顧問の役割も果たしている。[63][64] 他の学者は、マキアヴェリの共和国論には誇張や帝国主義的な特徴があると指摘している。[65] しかし、この著作は近代共和主義の中心的な文献のひとつとなり、君主論よりも包括的な著作であると主張されることも多い。[66] |

Originality Engraved portrait of Machiavelli, from the Peace Palace Library's Il Principe, published in 1769 Major commentary on Machiavelli's work has focused on two issues: how unified and philosophical his work is and how innovative or traditional it is.[67] Coherence There is some disagreement concerning how best to describe the unifying themes, if there are any, that can be found in Machiavelli's works, especially in the two major political works, The Prince and Discourses. Some commentators have described him as inconsistent, and perhaps as not even putting a high priority on consistency.[67][68] Others such as Hans Baron have argued that his ideas must have changed dramatically over time. Some have argued that his conclusions are best understood as a product of his times, experiences and education. Others, such as Leo Strauss and Harvey Mansfield, have argued strongly that there is a strong and deliberate consistency and distinctness, even arguing that this extends to all of Machiavelli's works including his comedies and letters.[67][69] Influences Commentators such as Leo Strauss have gone so far as to name Machiavelli as the deliberate originator of modernity itself. Others have argued that Machiavelli is only a particularly interesting example of trends which were happening around him. In any case, Machiavelli presented himself at various times as someone reminding Italians of the old virtues of the Romans and Greeks, and other times as someone promoting a completely new approach to politics.[67] That Machiavelli had a wide range of influences is in itself not controversial. Their relative importance is however a subject of ongoing discussion. It is possible to summarize some of the main influences emphasized by different commentators. The Mirror of Princes genre Gilbert (1938) summarized the similarities between The Prince and the genre it imitates, the so-called "Mirror of Princes" style. This was a classically influenced genre, with models at least as far back as Xenophon and Isocrates. While Gilbert emphasized the similarities, however, he agreed with all other commentators that Machiavelli was particularly novel in the way he used this genre, even when compared to his contemporaries such as Baldassare Castiglione and Erasmus. One of the major innovations Gilbert noted was that Machiavelli focused on the "deliberate purpose of dealing with a new ruler who will need to establish himself in defiance of custom". Normally, these types of works were addressed only to hereditary princes. (Xenophon is also an exception in this regard.) Classical republicanism Commentators such as Quentin Skinner and J.G.A. Pocock, in the so-called "Cambridge School" of interpretation, have asserted that some of the republican themes in Machiavelli's political works, particularly the Discourses on Livy, can be found in medieval Italian literature which was influenced by classical authors such as Sallust.[70][71] |

独創性 平和宮図書館の『君主論』に刻まれたマキャベリの肖像画(1769年出版) マキャベリの作品に関する主な論評は、その作品がどれほど統一性があり、かつ哲学的であるか、また、どれほど革新的であるか、あるいは伝統的であるかという2つの問題に焦点を当てている。 一貫性 マキャベリの著作、特に『君主論』と『論語』という2つの主要な政治的著作に見られる統一的なテーマについて、もしあるとすれば、それをどのように表現す るのが最善かについては、意見が分かれている。 一部の評論家は、マキャベリは一貫性を欠いており、おそらく一貫性を重視してもいなかったと評している。[67][68] ハンス・バロンなどの他の評論家は、彼の考えは時代とともに劇的に変化したに違いないと主張している。彼の結論は、彼の時代、経験、教育の産物として理解 するのが最も適切であると主張する者もいる。レオ・シュトラウスやハーヴェイ・マンチェスターなどの他の学者は、マキャベリの作品には喜劇や書簡も含め、 一貫性と独自性が強く意図的に存在していると強く主張し、この主張はマキャベリの全作品に及ぶと主張している。 影響 レオ・シュトラウスなどの論者は、マキャベリを近代の意図的な創始者であるとまで主張している。一方で、マキャベリは彼を取り巻く時代の流れの中で特に興 味深い例に過ぎないという意見もある。いずれにせよ、マキャベリは、ある時はイタリア人にローマ人やギリシア人の古い美徳を思い出させる人物として、また ある時は政治に対する全く新しいアプローチを推進する人物として、様々な場面で自らを表現した。 マキャベリが幅広い影響力を持っていたことは、それ自体は議論の余地がない。しかし、その相対的な重要性については現在も議論が続いている。異なる論者たちが強調した主な影響力のいくつかを要約することは可能である。 君主の鏡」というジャンル ギルバート(1938年)は、『君主論』とそれを模倣したジャンル、いわゆる「君主の鏡」スタイルとの類似点を要約している。これは古典に影響を受けた ジャンルであり、少なくともクセノフォンやイソクラテスにまで遡るモデルがあった。ギルバートは類似点を強調したが、マキャベリがこのジャンルを駆使した 方法が、同時代のバルダッサーレ・カスティリオーネやエラスムスと比較しても特に斬新であったという点については、他のすべての論者と同様の意見であっ た。ギルバートが指摘した主な革新のひとつは、マキアヴェッリが「慣習に逆らって自らを確立する必要がある新しい支配者に対処するための意図的な目的」に 焦点を当てたことである。通常、この種の作品は世襲の王子のみを対象としていた。(この点ではクセノフォンも例外である。) 古典共和主義 クエンティン・スミスや J.G.A. ポロックといった、いわゆる「ケンブリッジ学派」の解釈の論客たちは、マキャベリの政治作品、特に『リヴィウスについての講話』に見られる共和制のテーマ のいくつかは、サッルスなどの古典作家の影響を受けた中世イタリア文学にも見られると主張している。[70][71] |

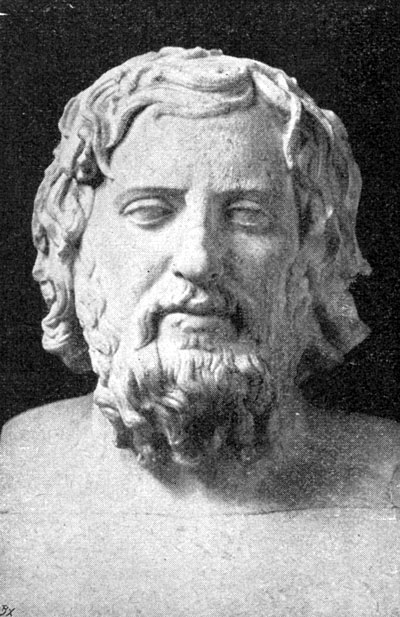

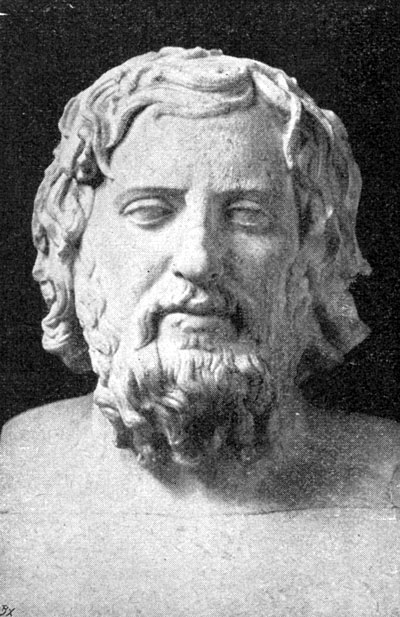

Classical political philosophy: Xenophon, Plato and Aristotle Xenophon, author of the Cyropedia The Socratic school of classical political philosophy, especially Aristotle, had become a major influence upon European political thinking in the late Middle Ages. It existed both in the Catholicised form presented by Thomas Aquinas, and in the more controversial "Averroist" form of authors like Marsilius of Padua. Machiavelli was critical of Catholic political thinking and may have been influenced by Averroism. But he rarely cites Plato and Aristotle, and most likely did not approve of them. Leo Strauss argued that the strong influence of Xenophon, a student of Socrates more known as a historian, rhetorician and soldier, was a major source of Socratic ideas for Machiavelli, sometimes not in line with Aristotle. While interest in Plato was increasing in Florence during Machiavelli's lifetime, Machiavelli does not show particular interest in him, but was indirectly influenced by his readings of authors such as Polybius, Plutarch and Cicero. The major difference between Machiavelli and the Socratics, according to Strauss, is Machiavelli's materialism, and therefore his rejection of both a teleological view of nature and of the view that philosophy is higher than politics. With their teleological understanding of things, Socratics argued that by nature, everything that acts, acts towards some end, as if nature desired them, but Machiavelli claimed that such things happen by blind chance or human action.[72] Classical materialism Strauss argued that Machiavelli may have seen himself as influenced by some ideas from classical materialists such as Democritus, Epicurus and Lucretius. Strauss however sees this also as a sign of major innovation in Machiavelli, because classical materialists did not share the Socratic regard for political life, while Machiavelli clearly did.[72] Thucydides Some scholars note the similarity between Machiavelli and the Greek historian Thucydides, since both emphasized power politics.[73][74] Strauss argued that Machiavelli may indeed have been influenced by pre-Socratic philosophers, but he felt it was a new combination: ...contemporary readers are reminded by Machiavelli's teaching of Thucydides; they find in both authors the same "realism", i.e., the same denial of the power of the gods or of justice and the same sensitivity to harsh necessity and elusive chance. Yet Thucydides never calls in question the intrinsic superiority of nobility to baseness, a superiority that shines forth particularly when the noble is destroyed by the base. Therefore Thucydides' History arouses in the reader a sadness which is never aroused by Machiavelli's books. In Machiavelli we find comedies, parodies, and satires but nothing reminding of tragedy. One half of humanity remains outside of his thought. There is no tragedy in Machiavelli because he has no sense of the sacredness of "the common". – Strauss (1958, p. 292) |

古典的政治哲学:クセノフォン、プラトン、アリストテレス クセノフォン著『キュロス年代記』 古典的政治哲学のソクラテス学派、特にアリストテレスは、中世後期のヨーロッパの政治思想に大きな影響を与えた。トマス・アクィナスが提示したカトリック 的な形と、パドヴァのマルシリウスなどの著者の論争の的となった「アヴェロエス」の形の両方で存在していた。マキャベリはカトリックの政治思想を批判して おり、アヴェロエスに影響を受けた可能性がある。しかし、彼はプラトンやアリストテレスをほとんど引用しておらず、おそらく彼らを認めていなかった。レ オ・シュトラウスは、ソクラテスの弟子であり、歴史家、修辞学者、軍人としてより知られるクセノフォンの強い影響が、アリストテレスとは一致しないことも あるマキアヴェッリにとってのソクラテス的思考の主要な源泉であったと論じた。マキアヴェッリ存命中、フィレンツェではプラトンへの関心が高まっていた が、マキアヴェッリはプラトンに特別な関心を示さず、ポリュビオス、プルタルコス、キケロなどの著述家を間接的に読んでいた。 シュトラウスによれば、マキャベリとソクラテス派の主な相違点は、マキャベリの唯物論であり、それゆえ、自然に対する目的論的見解と、哲学が政治よりも優 位にあるという見解の両方を否定していることである。目的論的な物の見方を持つソクラテス派は、自然はあたかもそれを望んでいるかのように、本質的に、作 用するものはすべて何らかの目的に向かって作用すると主張したが、マキャベリは、そのようなことは盲目の偶然や人間の行動によって起こると主張した。 古典的唯物論 シュトラウスは、マキャベリは自身がデモクリトス、エピクロス、ルクレティウスといった古典的唯物論者の考えに影響を受けていると見なしていた可能性があ ると論じた。しかし、シュトラウスは、古典的唯物論者はソクラテス的な政治生活への関心を持っていなかったが、マキャベリは明らかに持っていたため、これ もマキャベリにおける大きな革新の兆候であると見ている。 トゥキュディデス マキャベリとギリシャの歴史家トゥキュディデスには、両者とも権力政治を強調していたことから類似性があるとする学者もいる。[73][74] ストラウスは、マキャベリは確かにプレソクラテス時代の哲学者たちから影響を受けていたかもしれないが、それは新しい組み合わせであると主張した。 現代の読者はマキアヴェッリの教えからトゥキュディデスを思い出す。彼らは両者の著者に同じ「リアリズム」、すなわち神々や正義の力の否定、そして過酷な 必然性と捉えどころのない偶然に対する同じ感受性を見出す。しかし、トゥキュディデスは高貴なものと卑しいものとの本質的な優劣を疑問視することは決して ない。この優劣は、高貴なものが卑しいものによって滅ぼされるときに特に際立つ。それゆえ、トゥキュディデスの『歴史』は、マキアヴェリの著作では決して 呼び起こされない読者の悲しみを呼び起こす。マキアヴェリには喜劇、パロディ、風刺があるが、悲劇を思わせるものは何もない。人類の半分は彼の思想の外に ある。マキアヴェリには「一般大衆」の神聖さに対する感覚がないため、悲劇はない。-シュトラウス(1958年、292ページ) |

| Beliefs Amongst commentators, there are a few consistently made proposals concerning what was most new in Machiavelli's work. Empiricism and realism versus idealism Machiavelli is sometimes seen as the prototype of a modern empirical scientist, building generalizations from experience and historical facts, and emphasizing the uselessness of theorizing with the imagination.[67] He emancipated politics from theology and moral philosophy. He undertook to describe simply what rulers actually did and thus anticipated what was later called the scientific spirit in which questions of good and bad are ignored, and the observer attempts to discover only what really happens. — Joshua Kaplan, 2005[75] Machiavelli felt that his early schooling along the lines of traditional classical education was essentially useless for the purpose of understanding politics. Nevertheless, he advocated intensive study of the past, particularly regarding the founding of a city, which he felt was a key to understanding its later development.[75] Moreover, he studied the way people lived and aimed to inform leaders how they should rule and even how they themselves should live. Machiavelli denies the classical opinion that living virtuously always leads to happiness. For example, Machiavelli viewed misery as "one of the vices that enables a prince to rule."[76] Machiavelli stated that "it would be best to be both loved and feared. But since the two rarely come together, anyone compelled to choose will find greater security in being feared than in being loved."[77] In much of Machiavelli's work, he often states that the ruler must adopt unsavoury policies for the sake of the continuance of his regime. Because cruelty and fraud play such important roles in his politics, it is not unusual for certain issues (such as murder and betrayal) to be commonplace within his works.[78] A related and more controversial proposal often made is that he described how to do things in politics in a way which seemed neutral concerning who used the advice – tyrants or good rulers.[67] That Machiavelli strove for realism is not doubted, but for four centuries scholars have debated how best to describe his morality. The Prince made the word Machiavellian a byword for deceit, despotism, and political manipulation. Leo Strauss declared himself inclined toward the traditional view that Machiavelli was self-consciously a "teacher of evil", since he counsels the princes to avoid the values of justice, mercy, temperance, wisdom, and love of their people in preference to the use of cruelty, violence, fear, and deception.[79] Strauss takes up this opinion because he asserted that failure to accept the traditional opinion misses the "intrepidity of his thought" and "the graceful subtlety of his speech".[80] Italian anti-fascist philosopher Benedetto Croce (1925) concludes Machiavelli is simply a "realist" or "pragmatist" who accurately states that moral values, in reality, do not greatly affect the decisions that political leaders make.[81] German philosopher Ernst Cassirer (1946) held that Machiavelli simply adopts the stance of a political scientist – a Galileo of politics – in distinguishing between the "facts" of political life and the "values" of moral judgment.[82] On the other hand, Walter Russell Mead has argued that The Prince's advice presupposes the importance of ideas like legitimacy in making changes to the political system.[83] |

信念 評論家の間では、マキャベリの著作で最も新しいものとして、一貫して提案されているものがいくつかある。 経験論と現実主義対理想主義 マキャベリは、経験や歴史的事実から一般化を構築し、想像力による理論化の無益さを強調する、近代的な経験科学者の原型と見なされることがある。 彼は政治を神学や道徳哲学から解放した。彼は支配者が実際に行うことを簡潔に記述することを試み、これにより、後に「科学的」精神と呼ばれるようになる考え方を予見した。この精神では、善悪の問題は無視され、観察者は実際に起こることを発見しようとするだけである。 —ジョシュア・カプラン、2005年[75] マキャベリは、伝統的な古典教育に沿った初期の学校教育は、政治を理解する目的には本質的に役立たないと考えていた。しかし、彼は過去の徹底的な研究、特 に都市の建国について研究することを提唱し、建国こそがその後の発展を理解する鍵であると考えていた。[75] さらに、彼は人々の生活様式を研究し、指導者たちがどのように統治すべきか、さらには指導者自身がどのように生きるべきかを伝えることを目指した。マキア ヴェッリは、高潔に生きることが常に幸福につながるという古典的な意見を否定している。例えば、マキアヴェッリは「君主が統治を可能にする悪徳のひとつ」 として不幸を捉えている。[76] マキアヴェッリは「愛されることと恐れられることの両方を備えるのが最善である。しかし、この2つが同時に実現することはまれであるため、選択を迫られた 者は、恐れられることの方が愛されることよりも安心できると考えるだろう」[77] マキャベリの著作の多くで、彼は支配者は体制の継続のために好ましくない政策を採用しなければならないと述べている。 彼の政治思想において残虐行為や詐欺が重要な役割を果たしているため、彼の著作では殺人や裏切りといった特定の問題が一般的であることも珍しくない [78]。 関連して、しばしば議論の的となる提案として、マキャベリは、その助言を悪用する者が暴君であろうと善良な統治者であろうと、政治における物事の進め方を 中立的に描写したというものがある。[67] マキャベリが現実主義を追求していたことは疑いのないことであるが、4世紀にわたって学者たちは、彼の道徳観をどのように表現するのが最善であるかについ て議論を続けてきた。『君主論』は、マキャベリアン(Machiavellian)という言葉を欺瞞、専制、政治的操り人形の代名詞にした。レオ・シュト ラウスは、マキャベリが「悪の教師」であるという伝統的な見解に自らも傾倒していると宣言した。なぜなら、マキャベリは君主たちに、残酷さ、暴力、恐怖、 欺瞞を用いることを優先し、正義、慈悲、節制、知恵、民衆への愛といった価値観を避けるよう助言しているからだ。[79] シュトラウスがこの意見を取り上げたのは、伝統的な見解を受け入れないことは「 彼の思想の機敏さ」と「彼の言葉の優雅な巧妙さ」を見失うと主張したためである。[80] イタリアの反ファシズムの哲学者ベネデット・クローチェ(1925年)は、マキャベリは単に「現実主義者」または「実利主義者」であり、現実には道徳的価 値は政治指導者の決定に大きな影響を与えないと正確に述べていると結論づけている。[81] ドイツの哲学者エルンスト・カッシーラーは (1946年)は、マキアヴェリは政治学者の立場、すなわち政治におけるガリレオのような立場に立って、政治生活における「事実」と道徳的判断における 「価値」を区別しているに過ぎない、と主張している。[82] 一方、ウォルター・ラッセル・ミードは、『君主論』の助言は、政治体制に変更を加えるにあたって、正統性のような考え方が重要であることを前提としている と主張している。[83] |

| Fortune Machiavelli is generally seen as being critical of Christianity as it existed in his time, specifically its effect upon politics, and also everyday life.[84] In his opinion, Christianity, along with the teleological Aristotelianism that the Church had come to accept, allowed practical decisions to be guided too much by imaginary ideals and encouraged people to lazily leave events up to providence or, as he would put it, chance, luck or fortune. While Christianity sees modesty as a virtue and pride as sinful, Machiavelli took a more classical position, seeing ambition, spiritedness, and the pursuit of glory as good and natural things, and part of the virtue and prudence that good princes should have. Therefore, while it was traditional to say that leaders should have virtues, especially prudence, Machiavelli's use of the words virtù and prudenza was unusual for his time, implying a spirited and immodest ambition. Mansfield describes his usage of virtù as a "compromise with evil".[85] Famously, Machiavelli argued that virtue and prudence can help a man control more of his future, in the place of allowing fortune to do so. Najemy has argued that this same approach can be found in Machiavelli's approach to love and desire, as seen in his comedies and correspondence. Najemy shows how Machiavelli's friend Vettori argued against Machiavelli and cited a more traditional understanding of fortune.[86] On the other hand, humanism in Machiavelli's time meant that classical pre-Christian ideas about virtue and prudence, including the possibility of trying to control one's future, were not unique to him. But humanists did not go so far as to promote the extra glory of deliberately aiming to establish a new state, in defiance of traditions and laws. While Machiavelli's approach had classical precedents, it has been argued that it did more than just bring back old ideas and that Machiavelli was not a typical humanist. Strauss (1958) argues that the way Machiavelli combines classical ideas is new. While Xenophon and Plato also described realistic politics and were closer to Machiavelli than Aristotle was, they, like Aristotle, also saw philosophy as something higher than politics. Machiavelli was apparently a materialist who objected to explanations involving formal and final causation, or teleology. Machiavelli's promotion of ambition among leaders while denying any higher standard meant that he encouraged risk-taking, and innovation, most famously the founding of new modes and orders. His advice to princes was therefore certainly not limited to discussing how to maintain a state. It has been argued that Machiavelli's promotion of innovation led directly to the argument for progress as an aim of politics and civilization. But while a belief that humanity can control its own future, control nature, and "progress" has been long-lasting, Machiavelli's followers, starting with his own friend Guicciardini, have tended to prefer peaceful progress through economic development, and not warlike progress. As Harvey Mansfield (1995, p. 74) wrote: "In attempting other, more regular and scientific modes of overcoming fortune, Machiavelli's successors formalized and emasculated his notion of virtue." Machiavelli however, along with some of his classical predecessors, saw ambition and spiritedness, and therefore war, as inevitable and part of human nature. Strauss concludes his 1958 book Thoughts on Machiavelli by proposing that this promotion of progress leads directly to the advent of new technologies being invented in both good and bad governments. Strauss argued that the unavoidable nature of such arms races, which existed before modern times and led to the collapse of peaceful civilizations, show that classical-minded men "had to admit in other words that in an important respect the good city has to take its bearings by the practice of bad cities or that the bad impose their law on the good".Strauss (1958, pp. 298–299) |

フォーチュン マキャベリは、概して、彼が生きた時代のキリスト教、特に政治や日常生活への影響を批判的に見ていたと見られている。[84] 彼の意見では、キリスト教は教会が受け入れるようになった目的論的アリストテレス主義とともに、現実的な決定が想像上の理想に導かれ過ぎることを許し、人 々に怠惰に摂理、すなわち、彼が言うところの「偶然、運、幸運」に任せることを奨励していた。キリスト教では謙虚さを美徳とし、傲慢さを罪とみなすのに対 し、マキャベリはより古典的な立場をとっており、野心、気概、栄光の追求を善であり自然なこと、そして善良な君主が持つべき美徳や思慮深さの一部であると みなしていた。そのため、指導者には美徳、特に思慮深さが必要であると伝統的に言われていたが、マキャベリがvirtùとprudenzaという言葉を用 いたのは、当時の時代としては異例であり、活気があり、謙虚でない野心を意味していた。マンスフィールドは、virtùの用法を「悪との妥協」と表現して いる。[85] よく知られているように、マキャベリは、美徳と思慮深さがあれば、運命に身を任せるのではなく、自らの未来をより多くコントロールできると主張した。 ナジェミは、マキャベリの喜劇や書簡に見られる愛と欲望に対するアプローチにも、同じ考え方が見られると主張している。ナジェミは、マキャベリの友人ヴェットーリがマキャベリに対して異論を唱え、より伝統的な運命の理解を引用したことを示している。 一方で、マキャベリの時代のヒューマニズムは、美徳や思慮深さに関する古典的なキリスト教以前の考え方、すなわち、自らの未来をコントロールしようとする 可能性を含めて、彼独自のものではなかった。しかし、ヒューマニストたちは、伝統や法を無視して、意図的に新しい国家を樹立することを目指すことの余分な 栄光を宣伝するほどには踏み込もうとはしなかった。 マキャベリの手法には古典的な先例があるが、それは単に古い考えを復活させる以上のものだったし、マキャベリは典型的な人文主義者ではなかったという議論 もある。シュトラウス(1958年)は、マキャベリが古典的な考えを組み合わせた方法は新しいと主張している。クセノフォンやプラトンも現実的な政治につ いて記述しており、アリストテレスよりもマキャベリに近い存在であったが、彼らはアリストテレスと同様に、哲学を政治よりも高いものとして捉えていた。マ キアヴェッリは明らかに唯物論者であり、形式因や最終因、すなわち目的論を伴う説明に異議を唱えていた。 マキアヴェッリは、より高い基準を否定しながらも指導者たちの野心を煽り、リスクを冒すことや、最も有名な例としては新しい形態や秩序の創設といった革新 を奨励した。したがって、彼が君主たちに与えた助言は、国家を維持する方法を論じることに限定されるものではなかった。マキャベリの革新の推進は、政治と 文明の目的としての進歩の主張に直接つながったと主張されている。しかし、人類が自らの未来をコントロールし、自然をコントロールし、「進歩」できるとい う信念は長く続いているが、マキャベリの信奉者たちは、彼の友人であるギッチャーディニをはじめ、好戦的な進歩ではなく、経済発展による平和的な進歩を好 む傾向にある。ハーヴェイ・マンセフィールド(Harvey Mansfield)は1995年、74ページで次のように書いている。「マキアヴェッリの後継者たちは、運命を克服する他の、より規則的で科学的な方法 を試みる中で、彼の徳の概念を形式化し、骨抜きにした。 しかし、マキャベリは古典的な先人たちと同様に、野心や気概、そして戦争を避けられないもの、人間の本質の一部であると捉えていた。 シュトラウスは1958年の著書『マキャベリについての考察』の結論で、この進歩の促進が、善政にも悪政にも直結する新しいテクノロジーの発明につながる と提案している。ストラウスは、このような軍拡競争の不可避性は、近代以前から存在し、平和的な文明の崩壊につながったと主張し、古典的な考えを持つ人々 は「言い換えれば、重要な点において、善き都市は悪しき都市の実践によって方向性を定めなければならない、あるいは、悪しきものが善きものにその法を押し 付ける、ということを認めざるを得ない」と論じた。ストラウス(1958年、298~299ページ) |

| Religion Machiavelli shows repeatedly that he saw religion as man-made, and that the value of religion lies in its contribution to social order and the rules of morality must be dispensed with if security requires it.[87][88] In The Prince, the Discourses and in the Life of Castruccio Castracani he describes "prophets", as he calls them, like Moses, Romulus, Cyrus the Great and Theseus (he treated pagan and Christian patriarchs in the same way) as the greatest of new princes, the glorious and brutal founders of the most novel innovations in politics, and men whom Machiavelli assures us have always used a large amount of armed force and murder against their own people.[89] He estimated that these sects last from 1,666 to 3,000 years each time, which, as pointed out by Leo Strauss, would mean that Christianity became due to start finishing about 150 years after Machiavelli.[90] Machiavelli's concern with Christianity as a sect was that it makes men weak and inactive, delivering politics into the hands of cruel and wicked men without a fight.[91] While Machiavelli's own religious allegiance has been debated, it is assumed that he had a low regard of contemporary Christianity.[92] While fear of God can be replaced by fear of the prince, if there is a strong enough prince, Machiavelli felt that having a religion is in any case especially essential to keeping a republic in order.[93] For Machiavelli, a truly great prince can never be conventionally religious himself, but he should make his people religious if he can. According to Strauss (1958, pp. 226–227) he was not the first person to explain religion in this way, but his description of religion was novel because of the way he integrated this into his general account of princes. Machiavelli's judgment that governments need religion for practical political reasons was widespread among modern proponents of republics until approximately the time of the French Revolution. This, therefore, represents a point of disagreement between Machiavelli and late modernity.[94] |

宗教 マキャベリは繰り返し、宗教を人間が作り出したものと見なしていたことを示している。また、宗教の価値は社会秩序への貢献にあり、安全保障が必要であれば 道徳の規則は無視されなければならないと述べている。[87][88] 『君主論』、『君主論』、『カストルッチョ・カストラーニの生涯』において、マキャベリは「預言者」と称するモーゼ、ロムルス、キュロス大王、テーセウス ( 異教徒とキリスト教の家長たちを同じように扱った)を、新しい君主たちのうち最も偉大な者、政治における最も斬新な革新の輝かしい残忍な創始者、そしてマ キャベリが断言するように、自国民に対して常に大量の武力と殺人を駆使してきた者たちであると述べている。[89] 彼は、これらの宗派がそれぞれ1,666年から3,000年続くものと推定したが、レオ・シュトラウスが指摘しているように、 、キリスト教はマキャベリから約150年後に終焉を迎えることになるだろうと指摘している。[90] マキャベリが宗派としてのキリスト教を懸念していたのは、キリスト教が人間を弱く無気力にし、戦うことなく残酷で邪悪な人間の手中に政治を委ねてしまうこ とだった。[91] マキャベリ自身の宗教的忠誠心が議論の的となっているが、彼は現代のキリスト教を低く評価していたと考えられている。[92] 神への恐れは君主への恐れに置き換わる可能性があるが、もし強力な君主がいるならば、マキャベリは宗教を持つことは共和国を秩序ある状態に保つために特に 不可欠であると感じていた。[93] マキャベリにとって、真に偉大な君主は決して伝統的な宗教心を持つことはないが、もし可能であれば、国民を宗教心を持つようにすべきである。シュトラウス (1958年、226-227ページ)によると、マキャベリは宗教をこのように説明した最初の人物ではないが、宗教を君主論に統合したという点で、彼の宗 教観は斬新であった。 マキャベリが「政治的な現実的な理由から、政府には宗教が必要である」と判断したことは、フランス革命の頃まで、共和制を唱える近代の支持者たちの間で広く受け入れられていた。したがって、これはマキャベリと近代後期の間の意見の相違を示すものである。[94] |

| Positive side to factional and individual vice Despite the classical precedents, which Machiavelli was not the only one to promote in his time, Machiavelli's realism and willingness to argue that good ends justify bad things, is seen as a critical stimulus towards some of the most important theories of modern politics. Firstly, particularly in the Discourses on Livy, Machiavelli is unusual in the positive side to factionalism in republics which he sometimes seems to describe. For example, quite early in the Discourses, (in Book I, chapter 4), a chapter title announces that the disunion of the plebs and senate in Rome "kept Rome free". That a community has different components whose interests must be balanced in any good regime is an idea with classical precedents, but Machiavelli's particularly extreme presentation is seen as a critical step towards the later political ideas of both a division of powers or checks and balances, ideas which lay behind the US constitution, as well as many other modern state constitutions. Similarly, the modern economic argument for capitalism, and most modern forms of economics, was often stated in the form of "public virtue from private vices". Also in this case, even though there are classical precedents, Machiavelli's insistence on being both realistic and ambitious, not only admitting that vice exists but being willing to risk encouraging it, is a critical step on the path to this insight. Mansfield however argues that Machiavelli's own aims have not been shared by those he influenced. Machiavelli argued against seeing mere peace and economic growth as worthy aims on their own if they would lead to what Mansfield calls the "taming of the prince".[95] |

党派主義と個人の悪徳の肯定的な側面 マキアヴェリが当時推進していた古典的な先例は彼だけのものではなかったが、マキアヴェリの現実主義と、善の目的が悪いことを正当化するという主張への意欲は、現代政治における最も重要な理論のいくつかに対する重要な刺激として見られている。 まず、特に『リヴィウスについての論考』において、マキャベリは、彼が時折描写しているように見える共和制における党派主義の肯定的な側面において、異例 である。例えば、『論考』のかなり早い段階(第1巻、第4章)で、ローマにおける平民と元老院の分裂が「ローマを自由の身に保った」と章のタイトルで宣言 している。社会には異なる構成要素があり、その利益を均衡させることが優れた政治体制には必要であるという考え方は古典的な先例があるが、マキャベリの提 示した考え方は特に極端であり、後の政治思想である権力分立や牽制と均衡の考え方への重要な一歩となった。これらの考え方は、米国憲法やその他多くの近代 国家の憲法の背景にあるものである。 同様に、資本主義を擁護する現代の経済論や、ほとんどの現代の経済形態は、「私的な悪徳から公共の徳」という形でしばしば表現されている。この場合も、古 典的な先例があるとはいえ、マキャベリが現実的かつ野心的であることを主張し、悪徳の存在を認めるだけでなく、それを助長するリスクを厭わないことは、こ の洞察に至る重要なステップである。 しかし、マンスフィールドは、マキャベリが影響を与えた人々が、マキャベリ自身の目的を共有していないと主張している。マキャベリは、単なる平和と経済成 長をそれ自体の価値ある目的と見なすことに反対し、それらがマンスフィールドが「君主の飼い慣らし」と呼ぶものにつながるのであれば、と主張した。 [95] |

Influence Statue at the Uffizi To quote Robert Bireley:[96] ...there were in circulation approximately fifteen editions of the Prince and nineteen of the Discourses and French translations of each before they were placed on the Index of Paul IV in 1559, a measure which nearly stopped publication in Catholic areas except in France. Three principal writers took the field against Machiavelli between the publication of his works and their condemnation in 1559 and again by the Tridentine Index in 1564. These were the English cardinal Reginald Pole and the Portuguese bishop Jeronymo Osorio, both of whom lived for many years in Italy, and the Italian humanist and later bishop, Ambrogio Caterino Politi. Machiavelli's ideas had a profound impact on political leaders throughout the modern west, helped by the new technology of the printing press. During the first generations after Machiavelli, his main influence was in non-republican governments. Pole reported that The Prince was spoken of highly by Thomas Cromwell in England and had influenced Henry VIII in his turn towards Protestantism, and in his tactics, for example during the Pilgrimage of Grace.[97] A copy was also possessed by the Catholic king and emperor Charles V.[98] In France, after an initially mixed reaction, Machiavelli came to be associated with Catherine de' Medici and the St. Bartholomew's Day massacre. As Bireley (1990:17) reports, in the 16th century, Catholic writers "associated Machiavelli with the Protestants, whereas Protestant authors saw him as Italian and Catholic". In fact, he was apparently influencing both Catholic and Protestant kings.[99] One of the most important early works dedicated to criticism of Machiavelli, especially The Prince, was that of the Huguenot, Innocent Gentillet, whose work commonly referred to as Discourse against Machiavelli or Anti Machiavel was published in Geneva in 1576.[100] He accused Machiavelli of being an atheist and accused politicians of his time by saying that his works were the "Koran of the courtiers", that "he is of no reputation in the court of France which hath not Machiavel's writings at the fingers ends".[101] Another theme of Gentillet was more in the spirit of Machiavelli himself: he questioned the effectiveness of immoral strategies (just as Machiavelli had himself done, despite also explaining how they could sometimes work). This became the theme of much future political discourse in Europe during the 17th century. This includes the Catholic Counter Reformation writers summarised by Bireley: Giovanni Botero, Justus Lipsius, Carlo Scribani, Adam Contzen, Pedro de Ribadeneira, and Diego de Saavedra Fajardo.[102] These authors criticized Machiavelli, but also followed him in many ways. They accepted the need for a prince to be concerned with reputation, and even a need for cunning and deceit, but compared to Machiavelli, and like later modernist writers, they emphasized economic progress much more than the riskier ventures of war. These authors tended to cite Tacitus as their source for realist political advice, rather than Machiavelli, and this pretence came to be known as "Tacitism".[103] "Black tacitism" was in support of princely rule, but "red tacitism" arguing the case for republics, more in the original spirit of Machiavelli himself, became increasingly important. Cardinal Reginald Pole read The Prince while he was in Italy, and on which he gave his comments.[104] Frederick the Great, king of Prussia and patron of Voltaire, wrote Anti-Machiavel, with the aim of rebutting The Prince.[105] |

影響 ウフィツィ美術館の像 ロバート・ビリーを引用すると、[96] 1559年にパウルス4世のインデックスに掲載される前、プリンスの版はおよそ15種類、ディスカッションは19種類、それぞれフランス語訳が流通してい た。この措置により、フランスを除くカトリック圏では出版がほぼ停止された。マキアヴェリの著作が出版され、1559年に非難され、1564年にトリエン ト・インデックスによって再び非難されるまでの間、3人の主要な作家がマキアヴェリに反対した。彼らは、長年イタリアで暮らしたイングランドの枢機卿レジ ナルド・ポールとポルトガル司教ヘロニモ・オソリオ、そしてイタリアの人文主義者で後に司教となったアンブロージョ・カテリーノ・ポリティであった。 マキアヴェッリの思想は、印刷機という新しい技術の助けもあって、近代西欧の政治指導者たちに多大な影響を与えた。マキアヴェッリ以降の最初の世代では、 彼の影響力は共和制以外の政府において主に発揮された。ポールは、『君主論』がイギリスでトマス・クロムウェルによって高く評価され、プロテスタントへの 転向や、例えば恩赦巡礼の間の戦術においてヘンリー8世に影響を与えたと報告している。[97] また、カトリックの王であり皇帝でもあったカール5世もこの本を所有していた。[98] フランスでは、当初は反応がまちまちであったが、マキャベリは後にカトリーヌ・ド・メディシスとサン・バルテルミーの虐殺と結び付けられるようになった。 Bireley (1990:17) の報告によると、16世紀にはカトリックの著述家たちは「マキアヴェッリをプロテスタントと結びつけていたが、プロテスタントの著述家たちは彼をイタリア 人かつカトリックとして見ていた」という。実際、マキアヴェッリはカトリックとプロテスタントの両方の王たちに影響を与えていたようである。 マキャベリ批判の初期の最も重要な著作のひとつ、特に『君主論』に対する批判として、ユグノーのイノサン・ジャンティエの著作が挙げられる。彼の著作は一 般的に『マキャベリ論』または『アンチ・マキアヴェリ』と呼ばれ、1576年にジュネーヴで出版された。彼はマキャベリを無神論者と非難し、彼の著作を 『宮廷人のコーラン』であり、「フランス宮廷において、マキアヴェリの著作を熟知していない者はいない」と述べた。[101] ジャンティエのもう一つのテーマは、マキアヴェリ自身の精神により近いものであった。彼は不道徳な戦略の有効性を疑問視した(マキアヴェリ自身もそうで あったように、時にはそれが有効である可能性についても説明していたにもかかわらず)。これは、17世紀のヨーロッパにおける政治的言説のテーマとなっ た。これには、ビレリーがまとめたカトリックの対抗宗教改革の作家たち、すなわち、ジョヴァンニ・ボテロ、ユストゥス・リプシウス、カルロ・スクリヴァー ニ、アダム・コンツェン、ペドロ・デ・リバデネイラ、ディエゴ・デ・サアベドラ・ファハルドなどが含まれる。[102] これらの作家たちはマキアヴェッリを批判したが、同時に彼を追随する面も多々あった。彼らは君主が評判を気にかける必要性を認め、狡猾さや欺瞞さえも必要 であるとしたが、マキャベリと比較すると、また後の近代主義の作家たちと同様に、彼らは戦争というより危険性の高い事業よりも経済的進歩をより重視した。 これらの著者は、マキャベリよりもむしろタキトゥスを現実主義的政治的助言の源として引用する傾向があり、この傾向は「タキトゥス主義」として知られるよ うになった。[103] 「黒のタキトゥス主義」は君主制を支持するものであったが、「赤のタキトゥス主義」は共和制を主張するものであり、マキャベリ自身の本来の精神により近い ものであり、次第に重要性を増していった。枢機卿レジナルド・ポールはイタリア滞在中に『君主論』を読み、それについてコメントを残している。[104] プロイセン王でヴォルテールのパトロンでもあったフリードリヒ2世は、『君主論』に反論することを目的として『アンチ・マキアヴェリ』を著した。 [105] |

Francis Bacon argued the case for what would become modern science which would be based more upon real experience and experimentation, free from assumptions about metaphysics, and aimed at increasing control of nature. He named Machiavelli as a predecessor. Modern materialist philosophy developed in the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries, starting in the generations after Machiavelli. Modern political philosophy tended to be republican, but as with the Catholic authors, Machiavelli's realism and encouragement of innovation to try to control one's own fortune were more accepted than his emphasis upon war and factional violence. Not only was innovative economics and politics a result, but also modern science, leading some commentators to say that the 18th century Enlightenment involved a "humanitarian" moderating of Machiavellianism.[106] The importance of Machiavelli's influence is notable in many important figures in this endeavour, for example Bodin,[107] Francis Bacon,[108] Algernon Sidney,[109] Harrington, John Milton,[110] Spinoza,[111] Rousseau, Hume,[112] Edward Gibbon, and Adam Smith. Although he was not always mentioned by name as an inspiration, due to his controversy, he is also thought to have been an influence for other major philosophers, such as Montaigne,[113] Descartes,[114] Hobbes, Locke[115] and Montesquieu.[116][117] Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who is associated with very different political ideas, viewed Machiavelli's work as a satirical piece in which Machiavelli exposes the faults of a one-man rule rather than exalting amorality. In the seventeenth century it was in England that Machiavelli's ideas were most substantially developed and adapted, and that republicanism came once more to life; and out of seventeenth-century English republicanism there were to emerge in the next century not only a theme of English political and historical reflection – of the writings of the Bolingbroke circle and of Gibbon and of early parliamentary radicals – but a stimulus to the Enlightenment in Scotland, on the Continent, and in America.[118] |

フランシス・ベーコンは、形而上学的な仮定から自由で、より現実の経験と実験に基づく、自然の支配力を高めることを目的とした、現代科学となるべきものの論拠を主張した。彼はマキアヴェリを先駆者と位置づけた。 現代の唯物論哲学は、マキアヴェリ以降の世代から始まり、16世紀、17世紀、18世紀に発展した。近代の政治哲学は共和制を志向する傾向にあったが、カ トリックの著述家と同様に、マキャベリの現実主義や、自らの運命をコントロールしようとする革新の奨励は、彼の戦争や派閥間の暴力への重点よりも受け入れ られた。革新的な経済や政治だけでなく、近代科学も結果として生み出され、一部の論者は、18世紀の啓蒙主義はマキャベリズムを「人道主義」的に緩和した ものだったと主張している。 マキャベリの影響の重要性は、この試みにおける多くの重要な人物、例えばボダン[107]、フランシス・ベーコン[108]、アルジャーノン・シドニー [109]、ハリントン、ジョン・ミルトン[110]、スピノザ[111]、ルソー、ヒューム[112]、エドワード・ギボン、アダム・スミスなどにおい て顕著である。論争の的となったため、彼がインスピレーションの源として常に名前を挙げられるわけではなかったが、モンテーニュ、デカルト、ホッブズ、 ロック、モンテスキューといった他の主要な哲学者たちにも影響を与えたと考えられている 。ジャン=ジャック・ルソーは、政治思想が非常に異なる人物であるが、マキャベリの著作を、道徳の否定を称揚するのではなく、専制政治の欠点を暴く風刺作 品として捉えていた。 17世紀には、マキアヴェリの思想が最も本格的に発展し、適応されたのはイギリスであり、共和主義が再び息を吹き返した。そして、17世紀のイギリスの共 和主義から、次の世紀には、 ボリングブローク派やギボン、初期の議会急進派の著作に見られるように、英国の政治的・歴史的考察のテーマとなっただけでなく、スコットランド、大陸、ア メリカにおける啓蒙主義への刺激ともなった。[118] |

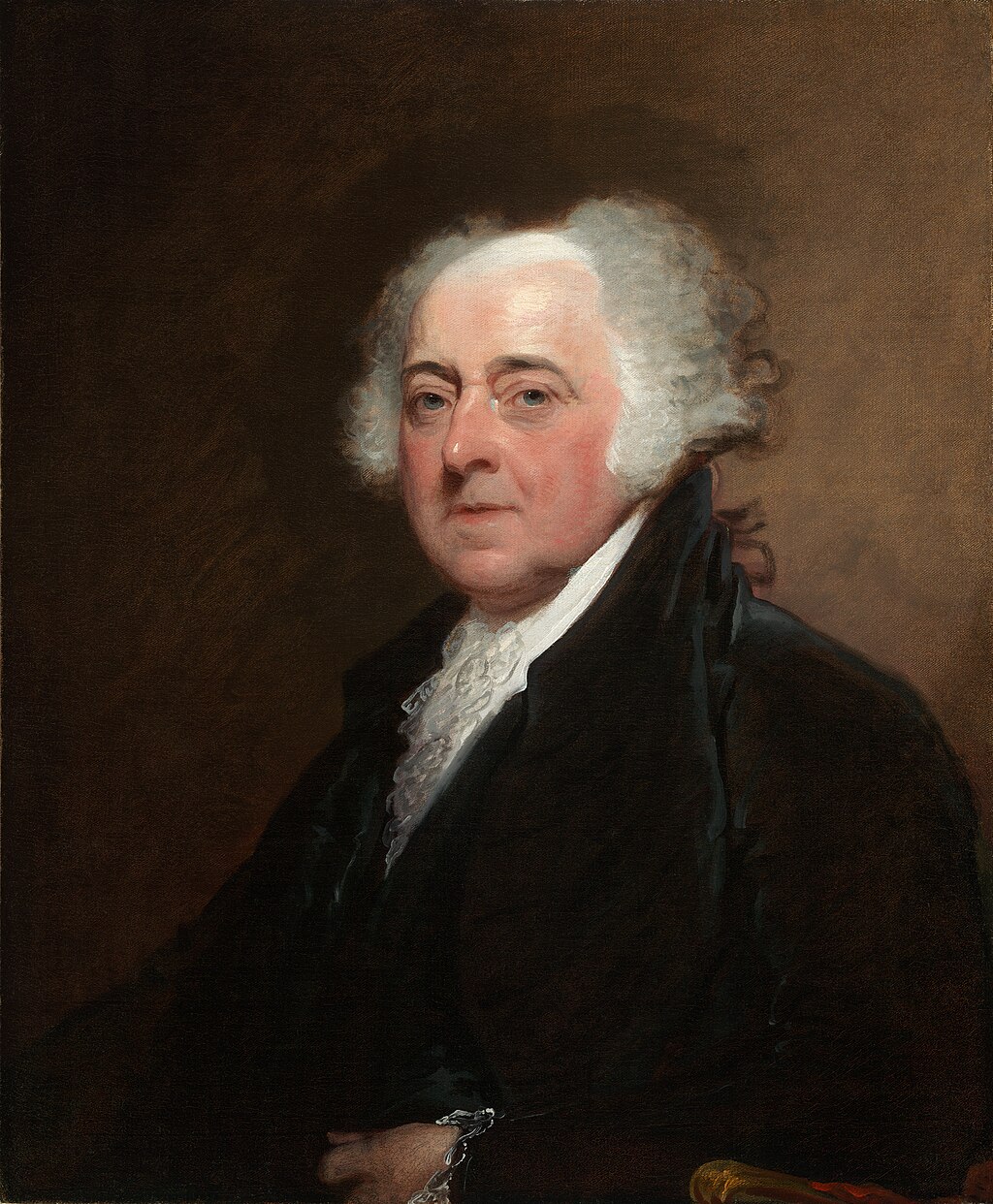

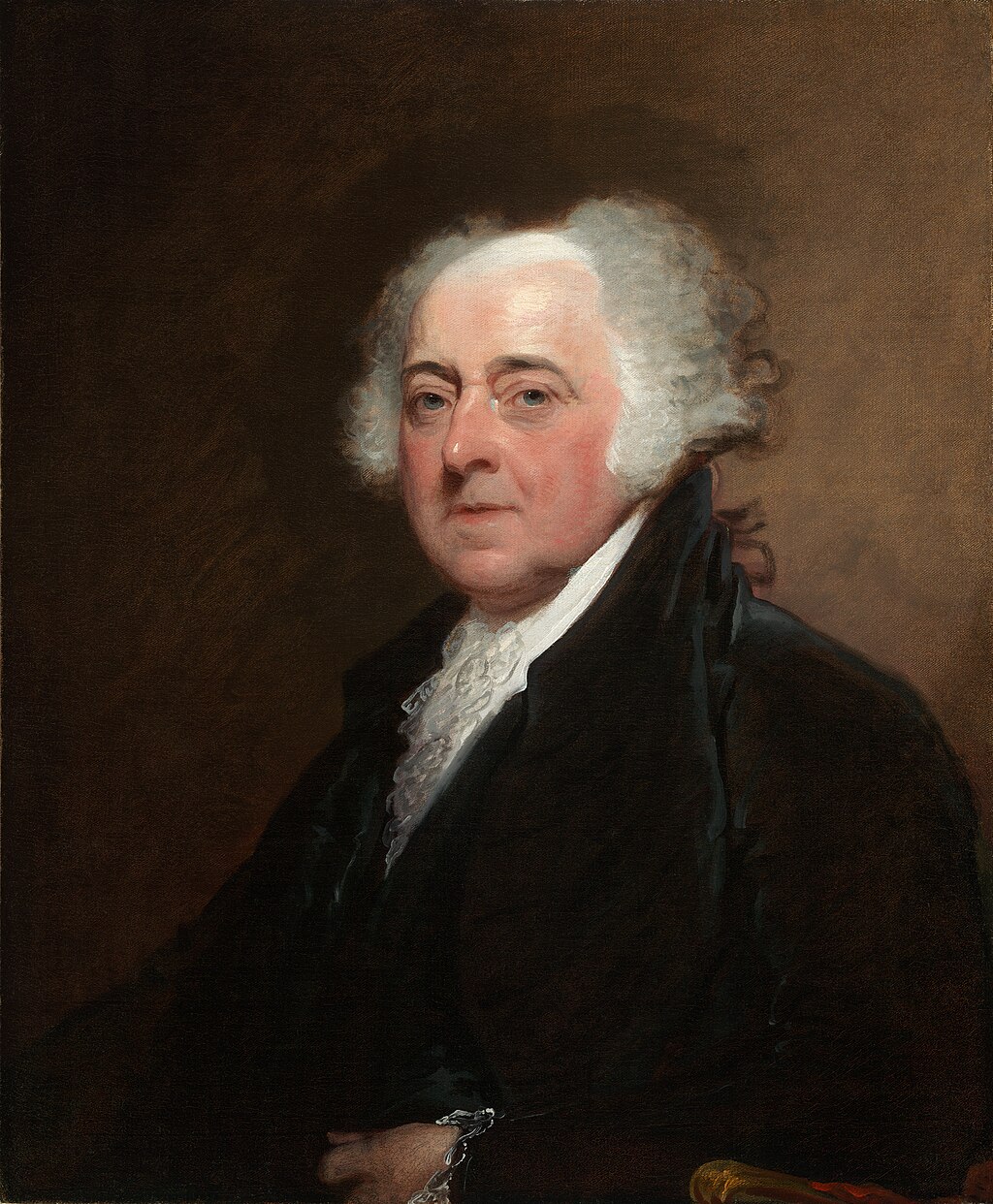

John Adams admired Machiavelli's rational description of the realities of statecraft. Adams used Machiavelli's works to argue for mixed government. Scholars have argued that Machiavelli was a major indirect and direct influence upon the political thinking of the Founding Fathers of the United States due to his overwhelming favouritism of republicanism and the republican type of government. According to John McCormick, it is still very much debatable whether or not Machiavelli was "an advisor of tyranny or partisan of liberty."[119] Benjamin Franklin, James Madison and Thomas Jefferson followed Machiavelli's republicanism when they opposed what they saw as the emerging aristocracy that they feared Alexander Hamilton was creating with the Federalist Party.[120] Hamilton learned from Machiavelli about the importance of foreign policy for domestic policy, but may have broken from him regarding how rapacious a republic needed to be in order to survive.[121][122] George Washington was less influenced by Machiavelli.[123] The Founding Father who perhaps most studied and valued Machiavelli as a political philosopher was John Adams, who profusely commented on the Italian's thought in his work, A Defence of the Constitutions of Government of the United States of America.[124] In this work, John Adams praised Machiavelli, with Algernon Sidney and Montesquieu, as a philosophic defender of mixed government. For Adams, Machiavelli restored empirical reason to politics, while his analysis of factions was commendable. Adams likewise agreed with the Florentine that human nature was immutable and driven by passions. He also accepted Machiavelli's belief that all societies were subject to cyclical periods of growth and decay. For Adams, Machiavelli lacked only a clear understanding of the institutions necessary for good government.[124] |

ジョン・アダムズは、マキアヴェリの政治の現実を理性的に描写した記述を賞賛した。アダムズはマキアヴェリの著作を引用して混合政府を主張した。 学者たちは、マキアヴェリが共和制と共和制の政府を圧倒的に支持していたため、米国建国の父たちの政治思想に間接的・直接的に大きな影響を与えたと論じて いる。ジョン・マコーミックによると、マキャベリが「専制の助言者か、自由の擁護者か」という点については、今でも議論が分かれているという。[119] ベンジャミン・フランクリン、ジェームズ・マディソン、トーマス・ジェファーソンは、アレクサンダー・ハミルトンが連邦党とともに作り上げようとしている と彼らが恐れた貴族政治の台頭に反対する際に、マキャベリの共和主義に従った。連邦党とともに作り上げようとしていると彼らが恐れた貴族政治に反対した。 [120] ハミルトンはマキアヴェリから、内政政策にとって外交政策がいかに重要であるかを学んだが、共和国が生き残るためにどれほど強欲である必要があるかについ ては、マキアヴェリと意見が分かれたかもしれない。[121][122] ジョージ・ワシントンはマキアヴェリからそれほど影響を受けていない。[123] おそらく最もマキアヴェリを研究し、政治哲学者として高く評価していた建国の父はジョン・アダムズであり、著書『アメリカ合衆国統治憲法の擁護』の中で、 イタリア人の思想について数多く言及している。[124] この著作の中でジョン・アダムズは、アルジャーノン・シドニーやモンテスキューとともに、混合政府の哲学的擁護者としてマキアヴェリを賞賛している。アダ ムスにとって、マキアヴェリは政治に経験則を取り戻した人物であり、派閥に関する彼の分析は称賛に値するものであった。アダムスは、人間の本質は不変であ り、情熱によって突き動かされるというマキアヴェリの考えにも同意していた。また、あらゆる社会は周期的に成長と衰退を繰り返すというマキアヴェリの信念 も受け入れていた。アダムスにとって、マキアヴェリに欠けていたのは、優れた政治に必要な制度に対する明確な理解だけだった。[124] |

| 20th century The 20th-century Italian Communist Antonio Gramsci drew great inspiration from Machiavelli's writings on ethics, morals, and how they relate to the State and revolution in his writings on Passive Revolution, and how a society can be manipulated by controlling popular notions of morality.[125] Joseph Stalin read The Prince and annotated his own copy.[126] In the 20th century there was also renewed interest in Machiavelli's play La Mandragola (1518), which received numerous stagings, including several in New York, at the New York Shakespeare Festival in 1976 and the Riverside Shakespeare Company in 1979, as a musical comedy by Peer Raben in Munich's Anti Theatre in 1971, and at London's National Theatre in 1984.[127] |

20世紀 20世紀のイタリア共産主義者アントニオ・グラムシは、倫理、道徳、そしてそれらが国家や革命とどのように関わるかについて、マキャベリの『受動的革命』 の著作から多大なインスピレーションを得た。また、社会が道徳に関する大衆の概念をコントロールすることで操作できるという考えも得た。[125] ヨシフ・スターリンは『君主論』を読み、自身の所有する本に注釈を付けた。 20世紀には、マキャベリの戯曲『ラ・マンドラゴラ』(1518年)への関心も再び高まった。この作品は、ニューヨーク・シェイクスピア・フェスティバル (1976年)やリバーサイド・シェイクスピア・カンパニー(1979年)など、ニューヨークで数回上演されたほか、 1976年のニューヨーク・シェイクスピア・フェスティバル、1979年のリバーサイド・シェイクスピア・カンパニー、1971年のミュンヘンのアンチ・ シアターでのペール・ラーベンによるミュージカル・コメディ、1984年のロンドンのナショナル・シアターなど、多数の上演が行われた。[127] |

"Machiavellian" Portrait of a Gentleman (Cesare Borgia), used as an example of a successful ruler in The Prince Machiavelli's works are sometimes even said to have contributed to the modern negative connotations of the words politics and politician,[128] and it is sometimes thought that it is because of him that Old Nick became an English term for the Devil.[129] The adjective Machiavellian became a term describing a form of politics that is "marked by cunning, duplicity, or bad faith".[130] Machiavellianism also remains a popular term used casually in political discussions, often as a byword for bare-knuckled political realism.[131][132] While Machiavellianism is notable in the works of Machiavelli, scholars generally agree that his works are complex and have equally influential themes within them. For example, J. G. A. Pocock (1975) saw him as a major source of the republicanism that spread throughout England and North America in the 17th and 18th centuries and Leo Strauss (1958), whose view of Machiavelli is quite different in many ways, had similar remarks about Machiavelli's influence on republicanism and argued that even though Machiavelli was a teacher of evil he had a "grandeur of vision" that led him to advocate immoral actions. Whatever his intentions, which are still debated today, he has become associated with any proposal where "the end justifies the means". For example, Leo Strauss (1987, p. 297) wrote: Machiavelli is the only political thinker whose name has come into common use for designating a kind of politics, which exists and will continue to exist independently of his influence, a politics guided exclusively by considerations of expediency, which uses all means, fair or foul, iron or poison, for achieving its ends – its end being the aggrandizement of one's country or fatherland – but also using the fatherland in the service of the self-aggrandizement of the politician or statesman or one's party. |

「マキャベリ的な」 紳士(チェーザレ・ボルジア)の肖像は、『君主論』の中で成功した統治者の例として用いられている。 マキャベリの著作は、政治や政治家という言葉の現代における否定的な意味合いにも影響を与えたとさえ言われることがある。[128] また、マキャベリが原因で「オールドニック」が英語で悪魔を意味するようになったと考えられていることもある。[129] 「マキャベリ的な」という形容詞は、 「ずる賢さ、二枚舌、不誠実さ」を特徴とする政治形態を指す用語となった。[130] マキャベリズムという言葉も、政治的な議論で頻繁に軽々しく使われる一般的な用語であり、しばしば、露骨な政治的リアリズムの代名詞として使われている。 [131][132] マキャベリズムはマキャベリの著作で注目に値するものであるが、彼の著作は複雑であり、同様に影響力のあるテーマが含まれているという点では学者たちの意 見は一致している。例えば、J. G. A. ポコック(1975年)は、17世紀と18世紀にイギリスと北アメリカに広まった共和主義の主要な源としてマキャベリを捉えており、レオ・シュトラウス (1958年)は、 マキアヴェッリに対する見解は多くの点でかなり異なっているが、レオ・シュトラウス(1958年)も共和主義に対するマキアヴェッリの影響について同様の 見解を示しており、マキアヴェッリが悪の教師であったとしても、非道徳的な行動を擁護するに至った「壮大なビジョン」を持っていたと主張している。彼の意 図が何であったかについては現在も議論が続いているが、彼は「目的が手段を正当化する」というあらゆる提案と関連付けられるようになった。例えば、レオ・ シュトラウス(1987年、297ページ)は次のように書いている。 マキャベリは、その名が政治の一種を指す一般的な用法として使われるようになった唯一の政治思想家である。その政治は、彼の影響とは無関係に存在し、今後 も存在し続けるだろう。その政治は、専ら便宜的な考慮に基づいて導かれるものであり、 鉄や毒物など、あらゆる手段を駆使して目的を達成する。その目的とは、自国や祖国の拡大である。しかし、政治家や国家、あるいは政党の自己拡大のために祖 国を利用することもある。 |

| In popular culture Main article: Machiavelli in popular culture Due to Machiavelli's popularity, he has been featured in various ways in cultural depictions. In English Renaissance theatre (Elizabethan and Jacobian), the term "Machiavel" (from 'Nicholas Machiavel', an "anglicization" of Machiavelli's name based on French) was used for a stock antagonist that resorted to ruthless means to preserve the power of the state, and is now considered a synonym of "Machiavellian".[133][134][135] Christopher Marlowe's play The Jew of Malta (ca. 1589) contains a prologue by a character called Machiavel, a Senecan ghost based on Machiavelli.[136] Machiavel expresses the cynical view that power is amoral, saying: "I count religion but a childish toy, And hold there is no sin but ignorance." Shakespeares titular character, Richard III, refers to Machiavelli in Henry VI, Part III, as the "murderous Machiavel".[137] |

大衆文化において 詳細は「大衆文化におけるマキャベリ」を参照 マキャベリの人気により、彼は文化的な描写において様々な形で取り上げられてきた。英語によるルネサンス演劇(エリザベス朝およびジェームズ朝)では、 「マキアヴェル」(「ニコラス・マキアヴェル」に由来する。マキアヴェリの名前をフランス語に基づいて「英語化した」もの)という用語が、国家の権力を維 持するために非情な手段に訴える典型的な敵役を表すために用いられ、現在では「マキアヴェリズム」の同義語とみなされている。[133][134] [135] クリストファー・マーロウの戯曲『マルタのユダヤ人』(1589年頃)には、マキャベリをモデルにしたセネカの亡霊であるマキャベルという登場人物によるプロローグがある。[136] マキャベルは、権力は非道徳的であるというシニカルな見解を次のように表現している。 「私は宗教を子供のおもちゃとみなす。 そして、罪は無知以外にはないと考えている」と述べている。 シェイクスピアの主人公リチャード3世は、ヘンリー6世第3部でマキャベリを「殺人者マキャベリ」と呼んでいる。[137] |

| Works See also: Category:Works by Niccolò Machiavelli Political and historical works Peter Withorne's 1573 translation of The Art of War Discorso sopra le cose di Pisa (1499) Del modo di trattare i popoli della Valdichiana ribellati (1502) Descrizione del modo tenuto dal Duca Valentino nello ammazzare Vitellozzo Vitelli, Oliverotto da Fermo, il Signor Pagolo e il duca di Gravina Orsini (1502) – A Description of the Methods Adopted by the Duke Valentino when Murdering Vitellozzo Vitelli, Oliverotto da Fermo, the Signor Pagolo, and the Duke di Gravina Orsini Discorso sopra la provisione del danaro (1502) – A discourse about the provision of money. Ritratti delle cose di Francia (1510) – Portrait of the affairs of France. Ritratto delle cose della Magna (1508–1512) – Portrait of the affairs of Germany. The Prince (1513) Discourses on Livy (1517) Dell'Arte della Guerra (1519–1520) – The Art of War, high military science. Discorso sopra il riformare lo stato di Firenze (1520) – A discourse about the reforming of Florence. Sommario delle cose della citta di Lucca (1520) – A summary of the affairs of the city of Lucca. The Life of Castruccio Castracani of Lucca (1520) – Vita di Castruccio Castracani da Lucca, a short biography. Istorie Fiorentine (1520–1525) – Florentine Histories, an eight-volume history of the city-state Florence, commissioned by Giulio de' Medici, later Pope Clement VII. |

作品 参照: Category:ニコロ・マキアヴェッリの作品 政治的・歴史的著作 ピーター・ウィソーンによる『兵法』(1573年翻訳 ピサの事物についての論考(1499年) ヴァルディキアーナの民衆をどう扱うか (1502) ヴァレンティーノ公爵がヴィテッロッツォ・ヴィテッリ、オリヴェロット・ダ・フェルモ、パゴロ・シニョール、グラヴィナ・オルシーニ公爵を殺害する際に採 用した方法についての記述 (1502) - ヴァレンティーノ公爵がヴィテッロッツォ・ヴィテッリ、オリヴェロット・ダ・フェルモ、パゴロ・シニョール、グラヴィナ・オルシーニ公爵を殺害する際に採 用した方法についての記述 Discorso sopra la provisione del danaro (1502) - お金の支給に関する談話。 Portrait of the affairs of France (1510) - フランスに関する肖像画。 マグナの肖像 (1508-1512) - ドイツの肖像。 王子(1513年) リヴィに関する言説(1517年) Dell'Arte della Guerra (1519-1520) - 戦争術、高等軍事学。 Discorso sopra il riformare lo stato di Firenze (1520) - フィレンツェの改革に関する言説。 Sommario delle cose della città di Lucca (1520) - ルッカ市の事務の要約。 The Life of Castruccio Castracani of Lucca (1520) - Castruccio Castracani da Luccaの略伝。 Istorie Fiorentine (1520-1525) - Florentine Histories, 8巻からなる都市国家フィレンツェの歴史書で、ジュリオ・デ・メディチ(後のローマ教皇クレメンス7世)の依頼によるものである。 |

| Besides being a statesman and

political scientist, Machiavelli also translated classical works, and

was a playwright (Clizia, Mandragola), a poet (Sonetti, Canzoni,

Ottave, Canti carnascialeschi), and a novelist (Belfagor arcidiavolo). Some of his other work: Decennale primo (1506) – a poem in terza rima. Decennale secondo (1509) – a poem. Andria or The Girl from Andros (1517) – a semi-autobiographical comedy, adapted from Terence.[138] Mandragola (1518) – The Mandrake – a five-act prose comedy, with a verse prologue. Clizia (1525) – a prose comedy. Belfagor arcidiavolo (1515) – a novella. Asino d'oro (1517) – The Golden Ass is a terza rima poem, a new version of the classic work by Apuleius. Frammenti storici (1525) – fragments of stories. Other works Della Lingua (Italian for "On the Language") (1514), a dialogue about Italy's language is normally attributed to Machiavelli. Machiavelli's literary executor, Giuliano de' Ricci, also reported having seen that Machiavelli, his grandfather, made a comedy in the style of Aristophanes which included living Florentines as characters, and to be titled Le Maschere. It has been suggested that due to such things as this and his style of writing to his superiors generally, there was very likely some animosity to Machiavelli even before the return of the Medici.[139] |

マキャベリは政治家、政治学者であるだけでなく、古典作品の翻訳も手がけ、劇作家(『クリツィア』、『マンドラゴラ』)、詩人(『ソネット』、『カンツォーナ』、『オッターヴェ』、『カルナスキ・スケリシの歌』)、小説家(『悪魔ベルファゴ』)としても活躍した。 その他の作品には以下のようなものがある。 デチェンナーレ・プリモ(1506年) - テルツァ・リーマの詩。 デチェンナーレ・セコンド(1509年) - 詩。 アンドリアまたはアンドロスからの少女(1517年) - テレンスを翻案した半自伝的喜劇。 マンドラゴラ(1518年) - マンデラゴラ - 5幕構成の散文喜劇で、詩のプロローグ付き。 『クリツィア』(1525年) - 散文喜劇。 『ベルファゴーレ』(1515年) - 短編小説。 『黄金のろば』(1517年) - 『黄金のろば』はテルツァ・リーマ詩で、アプレイウスの古典作品の改作。 『歴史的断片』(1525年) - 物語の断片。 その他の作品 Della Lingua(イタリア語で「言語について」の意)(1514年)は、イタリアの言語に関する対話であり、通常はマキャベリによるものとされている。 マキャベリの文学的執行人であるジュリアーノ・デ・リッチは、祖父であるマキャベリがアリストファネスのスタイルで喜劇を書き、フィレンツェの住人を登場 人物として登場させ、その作品は『仮面』と題されたと報告している。このようなことや、一般的に目上の人々に対して書く彼のスタイルから、メディチ家の復 帰以前からマキアヴェリに対する反感があった可能性が高いことが示唆されている。[139] |

| Florentine military reforms Historic recurrence Mayberry Machiavelli |

フィレンツェの軍事改革 歴史の繰り返し メイベリー・マキャベリ |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Niccol%C3%B2_Machiavelli |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆