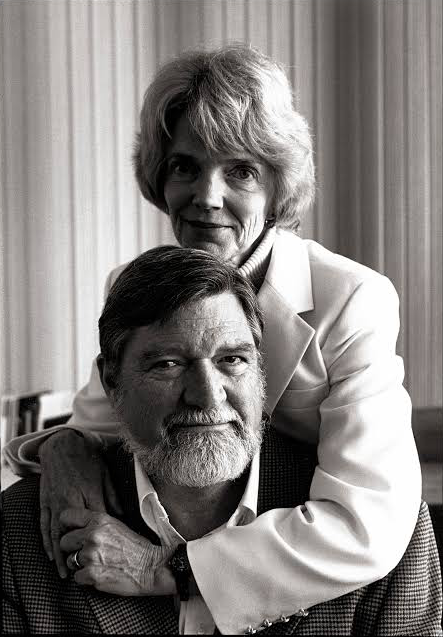

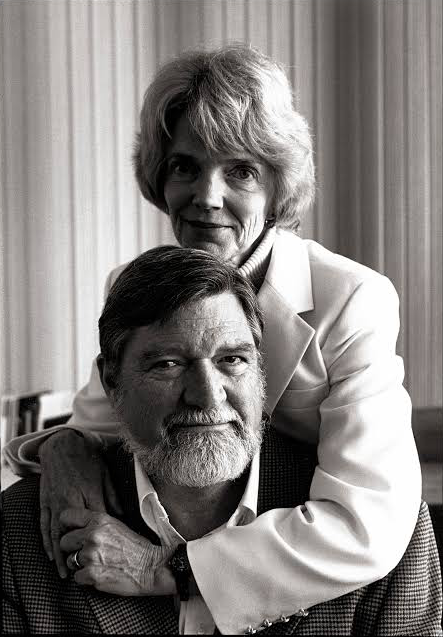

パトリシア&ポール・チャーチランド

Patricia and Paul Churchland, b.1943,1942

★パトリシア・スミス・チャーチランド(Patricia Smith Churchland、1943年7月16日生まれ)は、カナダ系アメリカ人の分析哲学者であり、神経哲学と心の哲学への貢献で知られている。彼女はカリ フォルニア大学サンディエゴ校(UCSD)の哲学名誉教授であり、1984年より同校で教鞭をとっている。また、1989年よりソーク生物学研究所の兼任 教授も務めている。[4] モスクワ大学哲学部のモスクワ意識研究センター理事会のメンバーでもある。[5] 2015年には、アメリカ芸術科学アカデミーのフェローに選出された。 ブリティッシュコロンビア大学、ピッツバーグ大学、オックスフォード大学ソマーヴィル・カレッジで教育を受け、1969年から1984年までマニトバ大学 で哲学を教え、哲学者のポール・チャーチランドと結婚している。[7] ニューヨーカー誌に寄稿したラリッサ・マクファーカーは、この哲学者夫婦について次のように述べている。「彼らの仕事はあまりにも似ているため、時折、雑 誌や書籍で、ひとりの人格として論じられることもある」[8]

☆ポール・モンゴメリ・チャーチランド(Paul Montgomery Churchland、1942年10月21日生まれ)は、神経哲学と心の哲学の研究で知られるカナダの哲学者である。ウィルフリッド・セラーズのもと ピッツバーグ大学で博士号を取得(1969年)した後、チャーチランドはマニトバ大学の正教授に昇進し、その後カリフォルニア大学サンディエゴ校 (UCSD)のヴァルツ・ファミリー哲学講座の教授に就任し、同校の神経計算研究所および認知科学学部の兼任教授にも就任した。 2017年2月現在、ChurchlandはUCSDの名誉教授であり、モスクワ大学意識研究センターの理事会メンバーでもある。Churchlandは 哲学者のパトリシア・チャーチランドの夫であり、彼女とは緊密に協力している(→ポール・チャーチランド)

| Patricia Smith Churchland

(born 16 July 1943)[3] is a Canadian-American analytic

philosopher[1][2] noted for her contributions to neurophilosophy and

the philosophy of mind. She is UC President's Professor of Philosophy

Emerita at the University of California, San Diego (UCSD), where she

has taught since 1984. She has also held an adjunct professorship at

the Salk Institute for Biological Studies since 1989.[4] She is a

member of the Board of Trustees Moscow Center for Consciousness Studies

of Philosophy Department, Moscow State University.[5] In 2015, she was

elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences.[6]

Educated at the University of British Columbia, the University of

Pittsburgh, and Somerville College, Oxford, she taught philosophy at

the University of Manitoba from 1969 to 1984 and is married to the

philosopher Paul Churchland.[7] Larissa MacFarquhar, writing for The

New Yorker, observed of the philosophical couple that: "Their work is

so similar that they are sometimes discussed, in journals and books, as

one person."[8] |

パトリシア・スミス・チャーチランド(Patricia Smith

Churchland、1943年7月16日生まれ)は、カナダ系アメリカ人の分析哲学者であり、神経哲学と心の哲学への貢献で知られている。彼女はカリ

フォルニア大学サンディエゴ校(UCSD)の哲学名誉教授であり、1984年より同校で教鞭をとっている。また、1989年よりソーク生物学研究所の兼任

教授も務めている。[4] モスクワ大学哲学部のモスクワ意識研究センター理事会のメンバーでもある。[5]

2015年には、アメリカ芸術科学アカデミーのフェローに選出された。

ブリティッシュコロンビア大学、ピッツバーグ大学、オックスフォード大学ソマーヴィル・カレッジで教育を受け、1969年から1984年までマニトバ大学

で哲学を教え、哲学者のポール・チャーチランドと結婚している。[7]

ニューヨーカー誌に寄稿したラリッサ・マクファーカーは、この哲学者夫婦について次のように述べている。「彼らの仕事はあまりにも似ているため、時折、雑

誌や書籍で、ひとりの人格として論じられることもある」[8] |

| Biography Early life and education Churchland was born Patricia Smith in Oliver, British Columbia,[3] and raised on a farm in the South Okanagan valley.[9][10] Both of her parents lacked a high-school education; her father and mother left school after grades 6 and 8 respectively. Her mother was a nurse and her father worked in newspaper publishing in addition to running the family farm. In spite of their limited education, Churchland has described her parents as interested in the sciences, and the worldview they instilled in her as a secular one. She has also described her parents as eager for her to attend college, and though many farmers in their community thought this "hilarious and a grotesque waste of money", they saw to it that she did so.[10] She took her undergraduate degree at the University of British Columbia, graduating with honors in 1965.[7] She received a Woodrow Wilson Fellowship to study at the University of Pittsburgh, where she took an M.A. in 1966.[7][11] Thereafter she studied at Somerville College, Oxford as a British Council and Canada Council Fellow, obtaining a B. Phil in 1969.[7] |

経歴 幼少期と教育 チャーチランドはブリティッシュコロンビア州オリバーでパトリシア・スミスとして生まれ、サウスオカナガンバレーの農場で育った。母親は看護師、父親は家 業の農場経営に加えて新聞出版の仕事に就いていた。 両親は学歴は高くないが、科学に関心があり、世俗的な世界観を娘に植えつけたと、チャーチランドは述べている。 また、両親は娘が大学に進学することを強く望み、地域社会の多くの農民がそれを「滑稽で、お金の無駄遣い」と考えていたにもかかわらず、娘が大学に進学で きるようにした。 彼女はブリティッシュコロンビア大学で学士号を取得し、1965年に優等で卒業した。[7] ウッドロー・ウィルソン奨学金を得てピッツバーグ大学で学び、1966年に修士号を取得した。[7][11] その後、ブリティッシュ・カウンシルおよびカナダ・カウンシルのフェローとしてオックスフォード大学ソマーヴィル・カレッジで学び、1969年に文学士号 を取得した。[7] |

| Academic career Churchland's first academic appointment was at the University of Manitoba, where she was an assistant professor from 1969 to 1977, an associate professor from 1977 to 1982, and promoted to a full professorship in 1983.[7] It was here that she began to make a formal study of neuroscience with the help and encouragement of Larry Jordan, a professor with a lab in the Department of Physiology there.[9][10][12] From 1982 to 1983 she was a Visiting Member in Social Science at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton.[13] In 1984, she was invited to take up a professorship in the department of philosophy at UCSD, and relocated there with her husband Paul, where both have remained since.[14] Since 1989, she has also held an adjunct professorship at the Salk Institute adjacent to UCSD's campus, where she became acquainted with Jonas Salk[4][9] whose name the Institute bears. Describing Salk, Churchland has said that he "liked the idea of neurophilosophy, and he gave me a tremendous amount of encouragement at a time when many other people thought that we were, frankly, out to lunch."[10] Another important supporter Churchland found at the Salk Institute was Francis Crick.[9][10] At the Salk Institute, Churchland has worked with Terrence Sejnowski's lab as a research collaborator.[15] Her collaboration with Sejnowski culminated in a book, The Computational Brain (MIT Press, 1993), co-authored with Sejnowski. Churchland was named the UC President's Professor of Philosophy in 1999, and served as Chair of the Philosophy Department at UCSD from 2000-2007.[7] She attended and was a speaker at the secularist Beyond Belief symposia in 2006, 2007, and 2008.[16][17][18] |

学術的な経歴 Churchlandの最初の学術職はマニトバ大学で、1969年から1977年までは助教授、1977年から1982年までは准教授、1983年には正 教授に昇進した。 [7] ここで彼女は、同校生理学部の研究室を持つ教授ラリー・ジョーダンの支援と励ましを受け、神経科学の正式な研究を始めた。[9][10][12] 1982年から1983年にかけては、プリンストン高等研究所の社会科学客員研究員を務めた。 [13] 1984年にはカリフォルニア大学サンディエゴ校(UCSD)の哲学部の教授職に招聘され、夫のポールとともに移住し、現在に至る。[14] 1989年からは、UCSDのキャンパスに隣接するソーク研究所でも兼任教授を務めている。同研究所の名称は、彼女が親交を深めたジョナス・ソークに由来 する。ソークについて、チャーチランドは「彼は神経哲学という考え方を好み、多くの人々が私たちの研究を正直言って的外れだと考えていた時期に、私に多大 な励ましを与えてくれた」と述べている。 [10] ソーク研究所でチャーチランドが発見したもう一人の重要な支援者は、フランシス・クリックであった。[9][10] ソーク研究所で、チャーチランドはテレンス・セジュノフスキの研究室と共同研究を行っていた。[15] セジュノフスキとの共同研究は、セジュノフスキとの共著『The Computational Brain』(MIT Press、1993年)という本に結実した。1999年にカリフォルニア大学総長哲学教授に任命され、2000年から2007年までカリフォルニア大学 サンディエゴ校哲学部の学部長を務めた。 2006年、2007年、2008年の世俗主義者によるシンポジウム「Beyond Belief」に参加し、講演を行った。 |

| Personal life Churchland first met her husband, the philosopher Paul Churchland, while they were both enrolled in a class on Plato at the University of Pittsburgh,[10] and they were married after she completed her B.Phil at Somerville College, Oxford.[9] Their children are Mark M. Churchland (born 1972) and Anne K. Churchland (born 1974), both of whom are neuroscientists.[19][20] Churchland is considered an atheist,[21] but she identified herself as pantheist in a 2012 interview.[22][23] |

人格 チャーチランドは、夫である哲学者のポール・チャーチランドと、ピッツバーグ大学でプラトンに関する授業を受講していた際に知り合った。[10] 2人は、彼女がオックスフォード大学ソマーヴィル・カレッジでB.Philを取得した後に結婚した。[9] 夫妻には、マーク・M・ マーク・M・チャーチランド(1972年生)とアン・K・チャーチランド(1974年生)の2人の子供がいる。2人とも神経科学者である。[19] [20] チャーチランドは無神論者とみなされているが[21]、2012年のインタビューでは汎神論者と自己規定している。[22][23] |

| Philosophical work Churchland is broadly allied to a view of philosophy as a kind of 'proto-science' - asking challenging but largely empirical questions. She advocates the scientific endeavour, and has dismissed significant swathes of professional philosophy as obsessed with what she regards as unnecessary.[24] Churchland's own work has focused on the interface between neuroscience and philosophy. According to her, philosophers are increasingly realizing that to understand the mind one must understand the brain. She applies findings from neuroscience to address traditional philosophical questions about knowledge, free will, consciousness and ethics. She is associated with a school of thought called eliminative materialism, which argues that common sense, immediately intuitive, or "folk psychological" concepts such as thought, free will, and consciousness will likely need to be revised in a physically reductionistic way as neuroscientists discover more about the nature of brain function.[25] 2014 saw a brief exchange of views on these topics with Colin McGinn in the pages of the New York Review Of Books.[26] |

哲学的な研究 チャーチランドは、哲学を「プロトサイエンス(原科学)」の一種と広く捉えており、挑戦的ではあるが、主に経験的な問いを投げかけている。彼女は科学的努力を提唱しており、専門的な哲学の大部分を、彼女が不必要とみなすものに執着しているとして退けている。 チャーチランド自身の研究は、神経科学と哲学の接点に焦点を当てている。彼女によると、哲学者たちは、心を理解するには脳を理解しなければならないとます ます認識するようになっている。彼女は神経科学の知見を応用し、知識、自由意志、意識、倫理に関する伝統的な哲学的な問いに取り組んでいる。彼女は、排除 的唯物論と呼ばれる学派に属しており、思考、自由意志、意識といった常識、直感的な、あるいは「フォークサイコロジー」の概念は、脳機能の性質について神 経科学者がより多くを発見するにつれ、物理的還元主義的な方法で修正する必要がある可能性が高いと主張している。[25] 2014年には、ニューヨーク・レビュー・オブ・ブックス誌上で、コリン・マギンとこれらのトピックについて短い意見交換が行われた。[26] |

| Awards and honors MacArthur Fellowship, 1991[7][27] Humanist Laureate, International Academy of Humanism, 1993[28] Honorary Doctor of Letters, University of Virginia, 1996[7] Honorary Doctor of Law, University of Alberta, 2007[9] Distinguished Cognitive Scientist, UC, Merced Cognitive and Information Sciences program, 2011[29] Fellow of the Cognitive Science Society, 2011[30] |

受賞および栄誉 マッカーサー・フェローシップ、1991年[7][27] 国際ヒューマニズム・アカデミーのヒューマニスト・ローレイト、1993年[28] 名誉文学博士号、バージニア大学、1996年[7] 名誉法学博士号、アルバータ大学、2007年[9] 2011年、カリフォルニア大学マーセド校認知情報科学プログラムの著名な認知科学者 2011年、認知科学学会フェロー |

| Works As sole author Neurophilosophy: Toward a Unified Science of the Mind-Brain. (1986) Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press. "The Hornswoggle Problem". (1996) San Diego, La Jolla, CA. Journal of Consciousness Studies. Brain-Wise: Studies in Neurophilosophy. (2002) Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press. Braintrust: What Neuroscience Tells Us about Morality. (2011) Princeton University Press. eBook ISBN 9781400838080[31] Touching A Nerve: The Self As Brain. (2013) W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0393058321 Conscience: The Origins of Moral Intuition. (2019) W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-1324000891 As co-author or editor The Computational Brain. (1992) Patricia S. Churchland and T. J. Sejnowski. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press. Neurophilosophy and Alzheimer's Disease. (1992) Edited by Y. Christen and Patricia S. Churchland. Berlin: Springer-Verlag. The Mind-Brain Continuum (1996). Edited by R.R. Llinás and Patricia S. Churchland: The MIT Press. On the Contrary: Critical Essays 1987-1997. (1998). Paul M. Churchland and Patricia S. Churchland. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press. |

作品 単著 『神経哲学:心と脳の統一科学に向けて』 (1986) マサチューセッツ州ケンブリッジ:MIT Press. 「The Hornswoggle Problem」 (1996) カリフォルニア州サンディエゴ、ラホーヤ。『意識研究ジャーナル』。 『脳に学ぶ:神経哲学研究』 (2002) マサチューセッツ州ケンブリッジ:MIT Press. Braintrust: What Neuroscience Tells Us about Morality. (2011) Princeton University Press. eBook ISBN 9781400838080[31] Touching A Nerve: The Self As Brain. (2013) W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0393058321 良心:道徳的直観の起源。 (2019) W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-1324000891 共著者または編者として 『計算脳』 (1992年) パトリシア・S・チャーチランド、T. J. セジュノフスキー著。マサチューセッツ州ケンブリッジ:MITプレス。 『神経哲学とアルツハイマー病』 (1992年) 編集:Y. クリステン、パトリシア・S・チャーチランド。ベルリン:シュプリンガー・フェアラーク。 『心と脳の連続体』(1996年)R.R. リナスとパトリシア・S・チャーチランド編:MIT Press 『On the Contrary: Critical Essays 1987-1997』(1998年)ポール・M・チャーチランドとパトリシア・S・チャーチランド著:マサチューセッツ州ケンブリッジ:MIT Press |

| Eliminative materialism Neurophilosophy Materialism Monism Philosophy of mind Reductionism Scientism |

消去法的唯物論 神経哲学 唯物論 一元論 心の哲学 還元主義 科学主義 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Patricia_Churchland |

☆ ポール・モンゴメリ・チャーチランド(Paul Montgomery Churchland、1942年10月21日生まれ)は、神経哲学と心の哲学の研究で知られるカナダの哲学者である。ウィルフリッド・セラーズのもと ピッツバーグ大学で博士号を取得(1969年)した後、チャーチランドはマニトバ大学の正教授に昇進し、その後カリフォルニア大学サンディエゴ校 (UCSD)のヴァルツ・ファミリー哲学講座の教授に就任し、同校の神経計算研究所および認知科学学部の兼任教授にも就任した。 2017年2月現在、ChurchlandはUCSDの名誉教授であり、モスクワ大学意識研究センターの理事会メンバーでもある。Churchlandは 哲学者のパトリシア・チャーチランドの夫であり、彼女とは緊密に協力している。

| Paul Montgomery

Churchland (born October 21, 1942) is a Canadian philosopher known for

his studies in neurophilosophy and the philosophy of mind. After

earning a Ph.D. from the University of Pittsburgh under Wilfrid Sellars

(1969), Churchland rose to the rank of full professor at the University

of Manitoba before accepting the Valtz Family Endowed Chair in

Philosophy at the University of California, San Diego (UCSD) and joint

appointments in that institution's Institute for Neural Computation and

on its Cognitive Science Faculty. As of February 2017, Churchland is recognised as Professor Emeritus at the UCSD, and is a member of the Board of Trustees of the Moscow Center for Consciousness Studies of Moscow State University. Churchland is the husband of philosopher Patricia Churchland, with whom he collaborates closely. |

ポール・モンゴメリ・チャーチランド(Paul

Montgomery

Churchland、1942年10月21日生まれ)は、神経哲学と心の哲学の研究で知られるカナダの哲学者である。ウィルフリッド・セラーズのもと

ピッツバーグ大学で博士号を取得(1969年)した後、チャーチランドはマニトバ大学の正教授に昇進し、その後カリフォルニア大学サンディエゴ校

(UCSD)のヴァルツ・ファミリー哲学講座の教授に就任し、同校の神経計算研究所および認知科学学部の兼任教授にも就任した。 2017年2月現在、ChurchlandはUCSDの名誉教授であり、モスクワ大学意識研究センターの理事会メンバーでもある。Churchlandは 哲学者のパトリシア・チャーチランドの夫であり、彼女とは緊密に協力している。 |

| Early life and education Paul Montgomery Churchland[2] was born in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada, on October 21, 1942.[3][4] Growing up in Vancouver, Churchland's father was a high school science teacher and his mother took in sewing. As a boy, he was obsessed with science fiction; he was particularly struck by the ideas in Robert A. Heinlein's Orphans of the Sky. Churchland liked building things in his father's woodworking and metal shop in their basement, and expected to become an aerodynamical engineer.[5] At the University of British Columbia, Churchland began with classes in math and physics, intending to pursue engineering. Conversations with fellow students in the summer before his sophomore year inspired him to begin taking philosophy classes.[5] He graduated with a Bachelor of Arts in 1964[3][4] He earned his Ph.D. from the University of Pittsburgh in 1969,[6] his dissertation entitled "Persons and P-Predicates" written with Wilfrid Sellars as his advisor.[2][3] |

幼少期と教育 ポール・モンゴメリー・チャーチランド[2]は1942年10月21日にカナダのブリティッシュコロンビア州バンクーバーで生まれた。[3][4]バン クーバーで育ったチャーチランドの父親は高校の科学教師であり、母親は裁縫をしていた。少年時代、彼はSFに夢中になり、特にロバート・A・ハインライン の『大空の孤児』のアイデアに感銘を受けた。チャーチランドは、自宅の地下室にある父親の木工・金工作業場で物を作るのが好きで、流体力学のエンジニアに なることを期待していた。 ブリティッシュコロンビア大学では、工学を専攻するつもりで数学と物理学のクラスから履修を始めた。2年生になる前の夏に、同級生たちとの会話から哲学の クラスを受講し始めた。1964年に文学士号を取得して卒業した。 1969年にピッツバーグ大学から博士号を取得し、論文のタイトルは「人格とP述語」で、ウィルフレッド・セラーズを指導教官として執筆した。[2] [3] |

| Career In 1969, Churchland took a position at the University of Manitoba,[3] where he would teach for fifteen years, becoming a full professor in 1979.[6][4] He spent a year at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton,[4] and joined the faculty at the University of California, San Diego in 1984.[3] There, he served as Department Chair from 1986–1990.[7] As of this February 2017, Churchland is recognised as Professor Emeritus at the University of California, San Diego,[8] where he earlier held the Valtz Family Endowed Chair in Philosophy (through 2011),[9][10] and continues to appear as a philosophy faculty member on the UCSD Interdisciplinary Ph.D. Program in Cognitive Science[11] and with the affiliated faculty of the UCSD Institute for Neural Computation.[12] As of February 2017, he is also a member of the Board of Trustees of the Center for Consciousness Studies of the Philosophy Department, Moscow State University.[13] |

経歴 1969年、Churchlandはマニトバ大学に職を得た。[3] そこで15年間教鞭をとり、1979年に正教授となった。 [6][4] その後、プリンストン高等研究所で1年間を過ごし、[4] 1984年にカリフォルニア大学サンディエゴ校の教授陣に加わった。[3] そこで、1986年から1990年まで学科長を務めた。[7] 2017年2月現在、チャーチランドはカリフォルニア大学サンディエゴ校の名誉教授とされているが[8]、同校では以前、ヴァルツ・ファミリー哲学講座の 教授職(2011年まで)を務めていた[9][10]。また、現在もUCSDの学際的認知科学博士課程プログラムの哲学教員[11] また、UCSD神経計算研究所の関連教員としても在籍している。[12] 2017年2月現在、モスクワ大学哲学部意識研究センターの評議員も務めている。[13] |

| Philosophical work Churchland's work is in the school of analytic philosophy in western philosophy, with interests in epistemology and the philosophy of science, and specific principal interests in the philosophy of mind and in neurophilosophy and artificial intelligence. His work has been described as being influenced by the work of W. V. O. Quine, Thomas Kuhn, Russell Hanson, Wilfrid Sellars, and Paul Feyerabend.[14] Along with his wife, Churchland is a major proponent of eliminative materialism,[15] the belief that everyday, common-sense, 'folk' psychology, which seeks to explain human behavior in terms of the beliefs and desires of agents, is actually a deeply flawed theory that must be eliminated in favor of a mature cognitive neuroscience.[6] where by folk psychology is meant everyday mental concepts such as beliefs, feelings, and desires, which are viewed as theoretical constructs without coherent definition, and thus destined to be obviated by a scientific understanding of human nature. From the perspective of Zawidzki, Churchland's concept of eliminativism is suggested as early as his book Scientific Realism and the Plasticity of Mind (1979), with its most explicit formulation appearing in a Journal of Philosophy essay, "Eliminative Materialism and the Propositional Attitudes" (1981).[6] Churchland believes that beliefs are not ontologically real; that is, that a future, fully matured neuroscience is likely to have no need for "beliefs" (see propositional attitudes), in the same manner that modern science discarded such notions as legends or witchcraft. According to Churchland, such concepts will not merely be reduced to more finely grained explanation and retained as useful proximate levels of description, but will be strictly eliminated as wholly lacking in correspondence to precise objective phenomena, such as activation patterns across neural networks. He points out that the history of science has seen many posits that were considered as real entities: such as phlogiston; caloric; the luminiferous ether; and vital forces that were thus eliminated.[citation needed] Moreover, in The Engine of Reason, The Seat of the Soul Churchland suggests that consciousness might be explained in terms of a recurrent neural network with its hub in the intralaminar nucleus of the thalamus, and feedback connections to all parts of the cortex. He acknowledges that this proposal will likely be found in error with regard to the neurological details, but states his belief that it is on the right track in its use of recurrent neural networks to account for consciousness. This has been described as a reductionist rather than eliminativist account of consciousness.[citation needed] |

哲学的な作品 チャーチランドの作品は、西洋哲学における分析哲学の学派に属し、認識論や科学哲学に関心を寄せており、特に心の哲学、神経哲学、人工知能に主な関心を抱 いている。彼の作品は、W. V. O. クワイン、トーマス・クーン、ラッセル・ハンソン、ウィルフレッド・セラーズ、ポール・フェイヤーアベントの作品に影響を受けていると評されている。 妻とともに、チャーチランドは消去的唯物論の主要な提唱者である。 人間の行動をエージェントの信念や欲求によって説明しようとする日常的で常識的な「フォーク」心理学は、実際には成熟した認知神経科学に取って代わられる べき、深刻な欠陥のある理論であるという信念である。 ここでフォークサイコロジーとは、信念、感情、欲求といった日常的な心的概念を意味し、これらは首尾一貫した定義のない理論的構築物と見なされ、したがっ て人間の本質に関する科学的理解によって不要になる運命にある。ザヴィツキの見解では、Churchlandの排除主義の概念は、早くも著書『科学的実在 論と心の可塑性』(1979年)で示唆されており、最も明確な定式化は『哲学ジャーナル』の論文「排除的唯物論と命題的態度」(1981年)に示されてい る。[6] チャーチランドは、信念は存在論的には現実のものではないと考えている。つまり、将来、神経科学が完全に成熟した暁には、「信念」(命題的態度を参照)は 不要になる可能性が高いと考えている。これは、現代科学が伝説や魔術といった概念を捨て去ったのと同じようなものである。チャーチランドによれば、そのよ うな概念は、より詳細な説明に還元され、有用な近似レベルの記述として残されるのではなく、神経ネットワーク全体の活性化パターンなどの厳密な客観的現象 との対応が全くないものとして厳密に排除されることになる。彼は、科学の歴史において、実体として考えられていた仮説が数多く存在したことを指摘してい る。例えば、フロギストン、熱力学、光輝エーテル、そして生命力が排除されたことなどである。 さらに、著書『The Engine of Reason, The Seat of the Soul』において、Churchlandは意識は視床の層内核をハブとする再帰型ニューラルネットワークと、大脳皮質全体へのフィードバック接続によっ て説明できる可能性を示唆している。彼は、この提案は神経学的詳細に関しては誤りである可能性が高いことを認めているが、意識を説明するために再帰型 ニューラルネットワークを使用するという点においては正しい方向性であると主張している。これは、意識の説明として還元論的であり、消去論的ではないとさ れている。[要出典] |

| Personal life Churchland is the husband of philosopher Patricia Churchland, and it has been noted that, "Their work is so similar that they are sometimes discussed, in journals and books, as one person."[16] The Churchlands are the parents of two children, Mark Churchland and Anne Churchland, both of whom are neuroscientists.[17] |

私生活 チャーチランドは哲学者のパトリシア・チャーチランドの夫であり、彼らの研究が非常に似ているため、論文や書籍で「1人の人格として論じられることもあ る」と指摘されている。 チャーチランド夫妻にはマーク・チャーチランドとアン・チャーチランドという2人の子供がいるが、2人とも神経科学者である。 |

| Written works Popular writing Churchland, Patricia Smith; Churchland, Paul (1990). "Could a Machine Think?". Scientific American. 262 (1, January): 32–37. Bibcode:1990SciAm.262a..32C. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0190-32. PMID 2294584. [Subtitle:] Classical AI is unlikely to yield conscious machines; systems that mimic the brain might.[subscription required] Scholarly work Books Professor Churchland has authored several books in philosophy, which have been translated into many languages.[3] His works are as follows: Churchland, Paul (1986) [1979]. Scientific Realism and the Plasticity of Mind. Cambridge Studies in Philosophy (1st paperback ed.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 157 pp. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511625435. ISBN 0-521-33827-1. ISSN 0950-6306. —— (1984). Matter and Consciousness. Cambridge, MA, USA: MIT Press. —— (1985). Images of Science: Scientific Realism versus Constructive Empiricism. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press. —— (1989). A Neurocomputational Perspective: The Nature of Mind and the Structure of Science. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-53106-2. —— (1995). The Engine of Reason, The Seat of the Soul: A Philosophical Journey into the Brain. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-53142-9. ——; Churchland, Patricia Smith (1998). On the Contrary: Critical Essays, 1987-1997. Cambridge, MA, USA: MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-53165-8. —— (2007). Neurophilosophy at Work. Cambridge, MA, USA: MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-521-86472-5. Churchland, Paul (2012). Plato's Camera: How the Physical Brain Captures a Landscape of Abstract Universals. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-01686-5. His book Matter and Consciousness has been frequently and extensively reprinted.[18] Both Scientific Realism and the Plasticity of Mind and A Neurocomputational Perspective have been reprinted.[19] Essays Professor Churchland has written a number of published articles, some of which have been translated into other languages, including several that have had a substantial impact in philosophy. Essays which have been reprinted include: Churchland, Paul (1981). "Eliminative Materialism and the Propositional Attitudes". Journal of Philosophy. 78 (2, February): 67–90. doi:10.2307/2025900. JSTOR 2025900. See also the PDF version at K. A. Akins' web pages at Simon Fraser University. —— (1981). "Functionalism, Qualia, and Intentionality". Philosophical Topics. 12: 121–145. doi:10.5840/philtopics198112146. —— (1985). "Reduction, Qualia and Direct Introspection of Brain States". Journal of Philosophy. 82 (1): 8–28. doi:10.2307/2026509. JSTOR 2026509. —— (1986). "Some Reductive Strategies in Cognitive Neurobiology". Mind. 95. —— (1988). "Folk Psychology and the Explanation of Human Behavior". Proceedings of the Aristotelean Society. Supp. Vol. LXII. —— (1990). "On the Nature of Theories: A Neurocomputational Perspective". Minnesota Studies in the Philosophy of Science. XIV. —— (1991). "Intertheoretic Reduction: A Neuroscientist's Field Guide". Seminars in Neuroscience. 2. —— (1995). "The Neural Representation of Social Reality". Mind and Morals. |

著作 人気のある著作 Churchland, Patricia Smith; Churchland, Paul (1990). 「Could a Machine Think?」. Scientific American. 262 (1, January): 32–37. Bibcode:1990SciAm.262a..32C. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0190-32. PMID 2294584. [字幕] 古典的なAIでは意識を持つ機械を作り出すことはできない。脳を模倣するシステムなら可能かもしれない。[購読が必要] 学術研究 書籍 チャーチランド教授は哲学に関する書籍を数冊執筆しており、それらは多くの言語に翻訳されている。[3] 彼の作品は以下の通りである。 Churchland, Paul (1986) [1979]. Scientific Realism and the Plasticity of Mind. Cambridge Studies in Philosophy (1st paperback ed.). ケンブリッジ、英国:ケンブリッジ大学出版局。157ページ。doi:10.1017/CBO9780511625435。ISBN 0-521-33827-1。ISSN 0950-6306。 —— (1984). Matter and Consciousness. ケンブリッジ、マサチューセッツ州、米国:MIT Press. —— (1985). Images of Science: Scientific Realism versus Constructive Empiricism. シカゴ、IL: シカゴ大学出版局。 —— (1989). A Neurocomputational Perspective: The Nature of Mind and the Structure of Science. マサチューセッツ州ケンブリッジ: MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-53106-2. —— (1995). 『理性のエンジン、魂の座:脳への哲学的旅』ケンブリッジ、マサチューセッツ州:MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-53142-9. ——; Churchland, Patricia Smith (1998). 『On the Contrary: Critical Essays, 1987-1997』ケンブリッジ、マサチューセッツ州、米国:MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-53165-8. —— (2007). 『仕事における神経哲学』。マサチューセッツ州ケンブリッジ、米国: MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-521-86472-5. ポール・チャーチランド (2012). 『プラトンのカメラ:物理的な脳が抽象的な普遍の風景を捉える仕組み』。マサチューセッツ州ケンブリッジ: MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-01686-5. 著書『物質と意識』は頻繁に、かつ広範囲に再版されている。[18] 『科学的実在論』と『心の可塑性』、『神経計算論的視点』も再版されている。[19] 論文 チャーチランド教授は多数の論文を発表しており、その中には他の言語に翻訳されたものもある。その中には哲学に多大な影響を与えたものもある。再版された 論文には以下のようなものがある。 Churchland, Paul (1981). 「Eliminative Materialism and the Propositional Attitudes」. Journal of Philosophy. 78 (2, February): 67–90. doi:10.2307/2025900. JSTOR 2025900. サイモン・フレーザー大学のK. A. AkinsのウェブページにあるPDF版も参照のこと。 —— (1981). 「Functionalism, Qualia, and Intentionality」. Philosophical Topics. 12: 121–145. doi:10.5840/philtopics198112146. —— (1985). 「Reduction, Qualia and Direct Introspection of Brain States」. Journal of Philosophy. 82 (1): 8–28. doi:10.2307/2026509. JSTOR 2026509. —— (1986). 「Some Reductive Strategies in Cognitive Neurobiology」. Mind. 95. —— (1988). 「フォークサイコロジーと人間行動の説明」。Proceedings of the Aristotelean Society. Supp. Vol. LXII. —— (1990). 「理論の本質について:神経計算論的視点」。ミネソタ科学哲学研究。XIV。 —— (1991). 「理論間の還元:神経科学者のフィールドガイド」。神経科学セミナー。2。 —— (1995). 「社会的現実の神経表現」。心と道徳。 |

| Further reading Churchland, Paul M. (2014) [1995]. "Neural Networks and Common Sense". In Baumgartner, Peter; Payr, Sabine (eds.). Speaking Minds: Interviews with Twenty Eminent Cognitive Scientists (interview). Princeton Legacy Library. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. pp. 33–46. ISBN 978-1-4008-6396-9. Retrieved 11 February 2017. McCauley, Robert, ed. (1996). The Churchlands and their Critics. Philosophers and their Critics. Cambridge, MA: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-631-18969-5. Retrieved 11 February 2017. The volume includes critical chapters from editor McCauley, Patricia Kitcher, Andy Clark, William G. Lycan, William Bechtel, Jerry Fodor and Ernie Lapore, Antonio R. Damasio and Hanna Damasio, John Marshall and Jennifer Gurd, and Owen Flanagan. These are then followed by a 94 pp. essay in response, by Paul Churchland and Patricia Churchland (hence the Churchlands are both the subject of and in part authors of this volume). Zawidzki, Tadeusz (May 2004). "Churchland, Paul". Dictionary of Philosophy of Mind. Retrieved 11 February 2017.[full citation needed] Keeley, Brian L. (2006). "Introduction: Becoming Paul M. Churchland (1942–) [Ch. 1]". In Keeley, Brian L. (ed.). Paul Churchland (PDF). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–31, esp. 1-2. ISBN 0-521-53715-0. Retrieved 11 February 2017. Ramsey, William (2013) [2003]. "Eliminative Materialism" (revision of 16 April 2013, based on 8 May 2003 original). In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 11 February 2017. |

さらに読む Churchland, Paul M. (2014) [1995]. 「Neural Networks and Common Sense」. In Baumgartner, Peter; Payr, Sabine (eds.). Speaking Minds: Interviews with Twenty Eminent Cognitive Scientists (interview). Princeton Legacy Library. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. pp. 33–46. ISBN 978-1-4008-6396-9. 2017年2月11日取得。 McCauley, Robert, ed. (1996). The Churchlands and their Critics. Philosophers and their Critics. Cambridge, MA: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-631-18969-5. 2017年2月11日取得。この巻には、編集者のマコーリー、パトリシア・キットチャー、アンディ・クラーク、ウィリアム・G・ライカン、ウィリアム・ ベッテル、ジェリー・フォドー、アーニー・ラポーレ、アントニオ・R・ダマシオ、ハンナ・ダマシオ、ジョン・マーシャル、ジェニファー・ガード、オーウェ ン・フラナガンによる重要な章が含まれている。これに続いて、ポール・チャーチランドとパトリシア・チャーチランドによる94ページの反論エッセイが続く (したがって、チャーチランド夫妻は、本巻の主題であり、また一部執筆者でもある)。 Zawidzki, Tadeusz (May 2004). 「Churchland, Paul」. Dictionary of Philosophy of Mind. Retrieved 11 February 2017.[full citation needed] キーリー、ブライアン・L. (2006). 「序文:ポール・M・チャーチランドになる(1942年~) [第1章]」. キーリー、ブライアン・L. (編). ポール・チャーチランド (PDF). イギリス、ケンブリッジ: ケンブリッジ大学出版局. pp. 1-31、特に1-2. ISBN 0-521-53715-0. 2017年2月11日取得。 Ramsey, William (2013) [2003]. 「Eliminative Materialism」 (revision of 16 April 2013, based on 8 May 2003 original). In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 11 February 2017. |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paul_Churchland |

|

| 脳がつくる倫理 : 科学と哲学から道徳の起源にせまる / パトリシア・S・チャーチランド著 ; 信原幸弘, 樫則章, 植原亮訳, 京都 : 化学同人 , 2013.8 | 第1章 序論 第2章 脳に基盤をもつ価値 第3章 気遣いと世話 第4章 協力することと信頼すること 第5章 ネットワーキング—遺伝子、脳、行動 第6章 社会生活のためのスキル 第7章 規則としてではなく 第8章 宗教と道徳 |

リ ンク

文 献(パトリシアを中心に)

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆