詩・ポエトリー

Poetry

☆ 詩(ギリシャ語の「作る」を意味する「ポイエーシス」に由来)は、言語の美的な、そしてしばしばリズミカルな[1][2][3]性質を利用して、文字通り の意味や表面的な意味に加えて、あるいはその代わりに意味を想起させる文学的芸術の一形態である。詩の特定の例は「詩」と呼ばれ、詩人によって書かれる。 詩人は、韻律、頭韻、音調、擬声語、韻律(韻律律による)、音象徴などの詩的技法と呼ばれるさまざまなテクニックを用いて、音楽的またはその他の芸術的効 果を生み出す。また、これらの効果を詩的な構造にまとめることも多いが、その構造は厳格な場合もあれば、自由な場合もあり、伝統的な場合もあれば、詩人に よって考案された場合もある。詩的な構造は言語や文化的な慣習によって劇的に異なるが、韻律(音節の強勢や音節(モーラ)の重みのパターン)を用いること が多い。また、音素、音素グループ、音調(声調言語に見られる音素ピッチシフト)、単語、またはフレーズ全体の反復パターンを用いることもある。これに は、子音韻(または単なる頭韻)、母音韻(dróttkvætt のように)、韻律(韻のパターン、音節群の一種)が含まれる。詩の構造は意味的である場合もある(例えば、Petrachan ソネットで必要とされる volta)。 ほとんどの詩は詩形にフォーマットされている。詩形とは、詩の構造に従う、ページ上の行の連続または積み重ねである。このため、詩は詩の同義語(換喩)と もなっている。[注1] 詩の種類の中には、特定の文化やジャンルに特有のものもあり、詩人が書く言語の特性に呼応する。ダンテ、ゲーテ、ミツキェヴィチ、ルーミーなどの詩を思い 浮かべる読者は、韻律や一定の韻律に基づく行で書かれた詩を思い浮かべるかもしれない。しかし、聖書詩や頭韻詩など、他の手段でリズムや韻律を生み出す伝 統もある。多くの現代詩は詩の伝統に対する批判を反映しており、[4] 韻律の原則そのものを検証したり、韻や一定のリズムを完全に無視したりしている。[5][6]

★オクタビオ・パスの審問(パス 2001:31)

1)他のいかなる表現にも形式にも帰しえない、詩的発話(詩)といったものがあるのか?

2)詩は何をいわんとしているのか?

3)詩的発話は、いかにして伝達されるのであろうか?

| In continental philosophy and semiotics, poiesis

(/pɔɪˈiːsɪs/; from Ancient Greek: ποίησις) is the process of emergence

of something that did not previously exist.[1] Forms of

poiesis—including autopoiesis, the process of sustenance through the

emergence of sustaining parts—are considered in philosophy and

semiotics to be the foundation of activity, alongside semiosis which is

considered the foundation of the production of meaning. |

大陸哲学および記号論において、ポイエーシス

(/pɔɪˈiːsɪs/、古代ギリシャ語:ποίησιςに由来)とは、それまで存在しなかった何らかのものが新たに生じるプロセスである。 [1]

オートポイエーシス(自己維持的な部分の創発による維持のプロセス)を含むポイエーシスの形態は、哲学や記号論において、意味の生産の基礎であるセミオシ

ス(意味作用)と並んで、活動の基礎であると考えられている。 |

| Etymology Poiesis is etymologically derived from the ancient Greek term ποιεῖν, which means "to make". It is related to the word poetry, which shares the same root. The word is also used as a suffix, as in the biological term hematopoiesis (the formation of blood cells). |

語源 ポイエーシス(Poiesis)という語は、語源的には古代ギリシャ語のποιεῖνに由来し、「作る」という意味である。詩(ポエム)という語も同じ語源であり、関連がある。この語は接尾辞としても使われ、生物学用語の「造血」(血球の形成)のように用いられる。 |

| Overview Heidegger referred to poiesis as a "bringing-forth", or physis as emergence. Examples of physis are the blooming of the blossom, the coming-out of a butterfly from a cocoon, and the plummeting of a waterfall when the snow begins to melt; the last two analogies underline Heidegger's example of a threshold occasion, a moment of ecstasis when something moves away from its standing as one thing to become another. These examples may also be understood as the unfolding of a thing out of itself; as being discloses or gathers from nothing, thus nothing is thought also as being. Plato's Symposium[2] and Timaeus[3] have been analyzed by modern scholars in this vein of interpretation. |

概要 ハイデガーは「ポイエーシス」を「産出」と、「フィシス」を「出現」と表現した。フィュシスの例としては、花の開花、蝶が繭から出てくること、雪が溶け始 めて滝が落下することなどが挙げられる。最後の2つの例えは、ハイデガーが挙げた「臨界の契機」を強調するものであり、あるものが一つの存在から別の存在 へと変化するエクスタシスの瞬間である。これらの例は、物事の展開として理解することもできる。つまり、存在が何もないところから開示され、集められるよ うに、存在もまた存在として考えられる。プラトンの『饗宴』[2]と『ティマイオス』[3]は、この解釈の観点から現代の学者によって分析されている。 |

| Meta-poiesis In their 2011 book, All Things Shining, Hubert Dreyfus and Sean Dorrance Kelly argue that embracing a "meta-poietic" mindset is the best, if not the only, method to authenticate meaning in the secular era: Meta-poiesis, as one might call it, steers between the twin dangers of the secular age: it resists nihilism by reappropriating the sacred phenomenon of physis, but cultivates the skill to resist physis in its abhorrent, fanatical form. Living well in our secular, nihilistic age, therefore, requires the higher-order skill of recognizing when to rise up as one with the ecstatic crowd and when to turn heel and walk rapidly away.[4] Furthermore, Dreyfus and Dorrance Kelly urge each person to become a sort of "craftsman" whose responsibility it is to refine their faculty for poiesis in order to achieve existential meaning in their lives and to reconcile their bodies with whatever transcendence there is to be had in life itself: "The task of the craftsman is not to generate the meaning, but rather to cultivate in himself the skill for discerning the meanings that are already there."[5] |

メタ・ポイエーシス 2011年の著書『All Things Shining』において、Hubert DreyfusとSean Dorrance Kellyは、世俗の時代における意味の認証には、「メタ・ポイエーシス」の考え方を採り入れることが最善の、そして唯一の方法であると論じている。 メタ・ポイエーシス(メタ・ポイエーシス)は、世俗時代の2つの危険の狭間をうまく操る。それは、神聖な現象であるフィュシスを再定義することでニヒリズ ムに抵抗するが、同時に、忌まわしい狂信的な形でのフィュシスに抵抗するスキルを培う。したがって、世俗的でニヒルな現代社会でうまく生きるためには、熱 狂的な群衆と一体となって立ち上がるべき時と、素早く後ずさりして立ち去るべき時を見分ける高度なスキルが必要となる。[4] さらに、ドレフュスとドランセ・ケリーは、各人格が「職人」のような存在になることを促している。職人の責任は、人生における実存的な意味を達成し、人生 そのものに存在する超越性と自身の身体を調和させるために、ポイエーシス能力を磨くことである。「職人の任務は、意味を生み出すことではなく、むしろすで に存在する意味を見極める能力を自らに培うことである」[5]。 |

| Allopoiesis, a process whereby a system can create something other than itself Esthesic and poietic – Terms used in the study of signs Self-organization – Process of creating order by local interactions Causa sui – Term that denotes something that is generated within itself Complex systems – System composed of many interacting components Always already – Philosophical term |

アロポイエーシス(Allopoiesis):システムがそれ自身以外の何かを作り出すプロセス エステーシス(Esthesic)とポイエーシス(Poietic):記号の研究で用いられる用語 自己組織化(Self-organization):局所的な相互作用によって秩序を作り出すプロセス カウザ・スイ(Causa sui):それ自身の中で生成されるものを示す用語 複雑系(Complex systems):多くの相互作用する構成要素から成るシステム 常にすでに(Always already):哲学用語 |

| Donald Polkinghorne,

Practice and the Human Sciences: The Case for a Judgment-Based Practice

of Care, SUNY Press, 2004, p. 115. Robert Cavalier, "The Nature of Eros," http://caae.phil.cmu.edu/Cavalier/80250/Plato/Symposium/Sym2.html Ludger Honnefelder, "Natur-Verhältnisse" in Nature als Gegenstand der Wissenschaften (Freiburg, 1992, pp. 11-16 Hubert Dreyfus and Sean Dorrance Kelly, "All Things Shining", 2011, Simon & Schuster, p. 212. Hubert Dreyfus and Sean Dorrance Kelly, "All Things Shining", 2011, Simon & Schuster, p. 209. |

ドナルド・ポルキンホーン著『実践と人間科学:判断に基づくケアの実践の必要性』SUNYプレス、2004年、115ページ。 ロバート・カヴァリエ、「エロスの本質」、http://caae.phil.cmu.edu/Cavalier/80250/Plato/Symposium/Sym2.html ルドガー・ホネフェルダー、「自然の関係性」、『自然を科学の対象として』(フライブルク、1992年、11-16ページ ヒューバート・ドレフュスとショーン・ドランシー・ケリー著『All Things Shining』2011年、サイモン&シュスター、212ページ。 ヒューバート・ドレフュスとショーン・ドランシー・ケリー著『All Things Shining』2011年、サイモン&シュスター、209ページ。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Poiesis |

**

| Poetry (from the

Greek word poiesis, "making") is a form of literary art that uses

aesthetic and often rhythmic[1][2][3] qualities of language to evoke

meanings in addition to, or in place of, literal or surface-level

meanings. Any particular instance of poetry is called a poem and is

written by a poet. Poets use a variety of techniques called poetic devices, such as assonance, alliteration, euphony and cacophony, onomatopoeia, rhythm (via metre), and sound symbolism, to produce musical or other artistic effects. They also frequently organize these effects into poetic structures, which may be strict or loose, conventional or invented by the poet. Poetic structures vary dramatically by language and cultural convention, but they often use rhythmic metre (patterns of syllable stress or syllable (mora) weight). They may also use repeating patterns of phonemes, phoneme groups, tones (phonemic pitch shifts found in tonal languages), words, or entire phrases. These include consonance (or just alliteration), assonance (as in the dróttkvætt), and rhyme schemes (patterns in rimes, a type of phoneme group). Poetic structures may even be semantic (e.g. the volta required in a Petrachan sonnet). Most written poems are formatted in verse: a series or stack of lines on a page, which follow the poetic structure. For this reason, verse has also become a synonym (a metonym) for poetry.[note 1] Some poetry types are unique to particular cultures and genres and respond to characteristics of the language in which the poet writes. Readers accustomed to identifying poetry with Dante, Goethe, Mickiewicz, or Rumi may think of it as written in lines based on rhyme and regular meter. There are, however, traditions, such as Biblical poetry and alliterative verse, that use other means to create rhythm and euphony. Much modern poetry reflects a critique of poetic tradition,[4] testing the principle of euphony itself or altogether forgoing rhyme or set rhythm.[5][6] Poetry has a long and varied history, evolving differentially across the globe. It dates back at least to prehistoric times with hunting poetry in Africa and to panegyric and elegiac court poetry of the empires of the Nile, Niger, and Volta River valleys.[7] Some of the earliest written poetry in Africa occurs among the Pyramid Texts written during the 25th century BCE. The earliest surviving Western Asian epic poem, the Epic of Gilgamesh, was written in the Sumerian language. Early poems in the Eurasian continent include folk songs such as the Chinese Shijing, religious hymns (such as the Sanskrit Rigveda, the Zoroastrian Gathas, the Hurrian songs, and the Hebrew Psalms); and retellings of oral epics (such as the Egyptian Story of Sinuhe, Indian epic poetry, and the Homeric epics, the Iliad and the Odyssey). Ancient Greek attempts to define poetry, such as Aristotle's Poetics, focused on the uses of speech in rhetoric, drama, song, and comedy. Later attempts concentrated on features such as repetition, verse form, and rhyme, and emphasized aesthetics which distinguish poetry from the format of more objectively-informative, academic, or typical writing, which is known as prose. Poetry uses forms and conventions to suggest differential interpretations of words, or to evoke emotive responses. The use of ambiguity, symbolism, irony, and other stylistic elements of poetic diction often leaves a poem open to multiple interpretations. Similarly, figures of speech such as metaphor, simile, and metonymy[8] establish a resonance between otherwise disparate images—a layering of meanings, forming connections previously not perceived. Kindred forms of resonance may exist, between individual verses, in their patterns of rhyme or rhythm. Poets – as, from the Greek, "makers" of language – have contributed to the evolution of the linguistic, expressive, and utilitarian qualities of their languages. In an increasingly globalized world, poets often adapt forms, styles, and techniques from diverse cultures and languages. A Western cultural tradition (extending at least from Homer to Rilke) associates the production of poetry with inspiration – often by a Muse (either classical or contemporary), or through other (often canonised) poets' work which sets some kind of example or challenge. In first-person poems, the lyrics are spoken by an "I", a character who may be termed the speaker, distinct from the poet (the author). Thus if, for example, a poem asserts, "I killed my enemy in Reno", it is the speaker, not the poet, who is the killer (unless this "confession" is a form of metaphor which needs to be considered in closer context – via close reading). |

詩(ギリシャ語の「作る」を意味する「ポイエーシス」に由来)は、言語

の美的な、そしてしばしばリズミカルな[1][2][3]性質を利用して、文字通りの意味や表面的な意味に加えて、あるいはその代わりに意味を想起させる

文学的芸術の一形態である。詩の特定の例は「詩」と呼ばれ、詩人によって書かれる。 詩人は、韻律、頭韻、音調、擬声語、韻律(韻律律による)、音象徴などの詩的技法と呼ばれるさまざまなテクニックを用いて、音楽的またはその他の芸術的効 果を生み出す。また、これらの効果を詩的な構造にまとめることも多いが、その構造は厳格な場合もあれば、自由な場合もあり、伝統的な場合もあれば、詩人に よって考案された場合もある。詩的な構造は言語や文化的な慣習によって劇的に異なるが、韻律(音節の強勢や音節(モーラ)の重みのパターン)を用いること が多い。また、音素、音素グループ、音調(声調言語に見られる音素ピッチシフト)、単語、またはフレーズ全体の反復パターンを用いることもある。これに は、子音韻(または単なる頭韻)、母音韻(dróttkvætt のように)、韻律(韻のパターン、音節群の一種)が含まれる。詩の構造は意味的である場合もある(例えば、Petrachan ソネットで必要とされる volta)。 ほとんどの詩は詩形にフォーマットされている。詩形とは、詩の構造に従う、ページ上の行の連続または積み重ねである。このため、詩は詩の同義語(換喩)と もなっている。[注1] 詩の種類の中には、特定の文化やジャンルに特有のものもあり、詩人が書く言語の特性に呼応する。ダンテ、ゲーテ、ミツキェヴィチ、ルーミーなどの詩を思い 浮かべる読者は、韻律や一定の韻律に基づく行で書かれた詩を思い浮かべるかもしれない。しかし、聖書詩や頭韻詩など、他の手段でリズムや韻律を生み出す伝 統もある。多くの現代詩は詩の伝統に対する批判を反映しており、[4] 韻律の原則そのものを検証したり、韻や一定のリズムを完全に無視したりしている。[5][6] 詩は長い歴史を持ち、世界中で多様な発展を遂げてきた。少なくとも、アフリカにおける狩猟を題材にした詩や、ナイル川、ニジェール川、ボルタ川流域の帝国 における賛美歌や哀歌の宮廷詩は、有史以前にまで遡る。[7] アフリカにおける最古の詩は、紀元前25世紀に書かれたピラミッドテキストの中に見られる。西アジア最古の叙事詩であるギルガメシュ叙事詩は、シュメール 語で書かれた。 ユーラシア大陸における初期の詩には、中国の詩経のような民謡、宗教的な賛美歌(サンスクリット語のリグヴェーダ、ゾロアスター教のガータ、フルリ人の 歌、ヘブライ語の詩篇など)、口承叙事詩の再話(エジプトのシヌヘの物語、インディアンの叙事詩、ホメロスの叙事詩『イーリアス』と『オデュッセイア』な ど)がある。 古代ギリシャでは、アリストテレスの『詩学』など、詩を定義しようとする試みが行われたが、その際には修辞学、演劇、歌、喜劇における言葉の用法に焦点が 当てられた。 その後、反復、韻文、韻といった特徴に注目が集まり、詩を、より客観的な情報伝達、学術的、または典型的な文章という形式から区別する美学が強調されるよ うになった。 詩は、言葉の解釈の違いを示唆したり、感情的な反応を引き起こしたりするために、形式や慣習を用いる。曖昧さ、象徴、皮肉、詩的な表現の他の様式的な要素 を用いることで、詩はしばしば複数の解釈が可能になる。同様に、隠喩、直喩、換喩などの修辞法は、それ以外では異質なイメージの間に共鳴を生み出す。つま り、意味の重層化であり、それまでは認識されていなかったつながりを形成する。類似した共鳴の形態は、個々の詩の韻やリズムのパターンにも存在するかもし れない。 ギリシャ語で「言葉の創造者」を意味する「詩人」は、言語の進化、表現力、実用性の向上に貢献してきた。グローバル化が進む世界において、詩人は多様な文 化や言語から形式、スタイル、テクニックを適応させることが多い。 西洋の文化伝統(少なくともホメーロスからリルケまで)では、詩の創作はインスピレーションと結び付けられており、ミューズ(古典的または現代的な)によ るもの、あるいは他の(しばしば聖典化された)詩人の作品を通じて、何らかの手本や挑戦となるものからインスピレーションを得る場合が多い。 一人称の詩では、歌詞は「私」という人格によって語られる。この「私」は、詩人(作者)とは別個の語り手と呼ばれることもある。したがって、例えば「私は リノで敵を殺した」という詩があった場合、殺人犯は詩人ではなく語り手である(ただし、この「告白」が比喩の一形態であり、より詳細な文脈を考慮する必要 がある場合を除く。つまり、精読によって)。 |

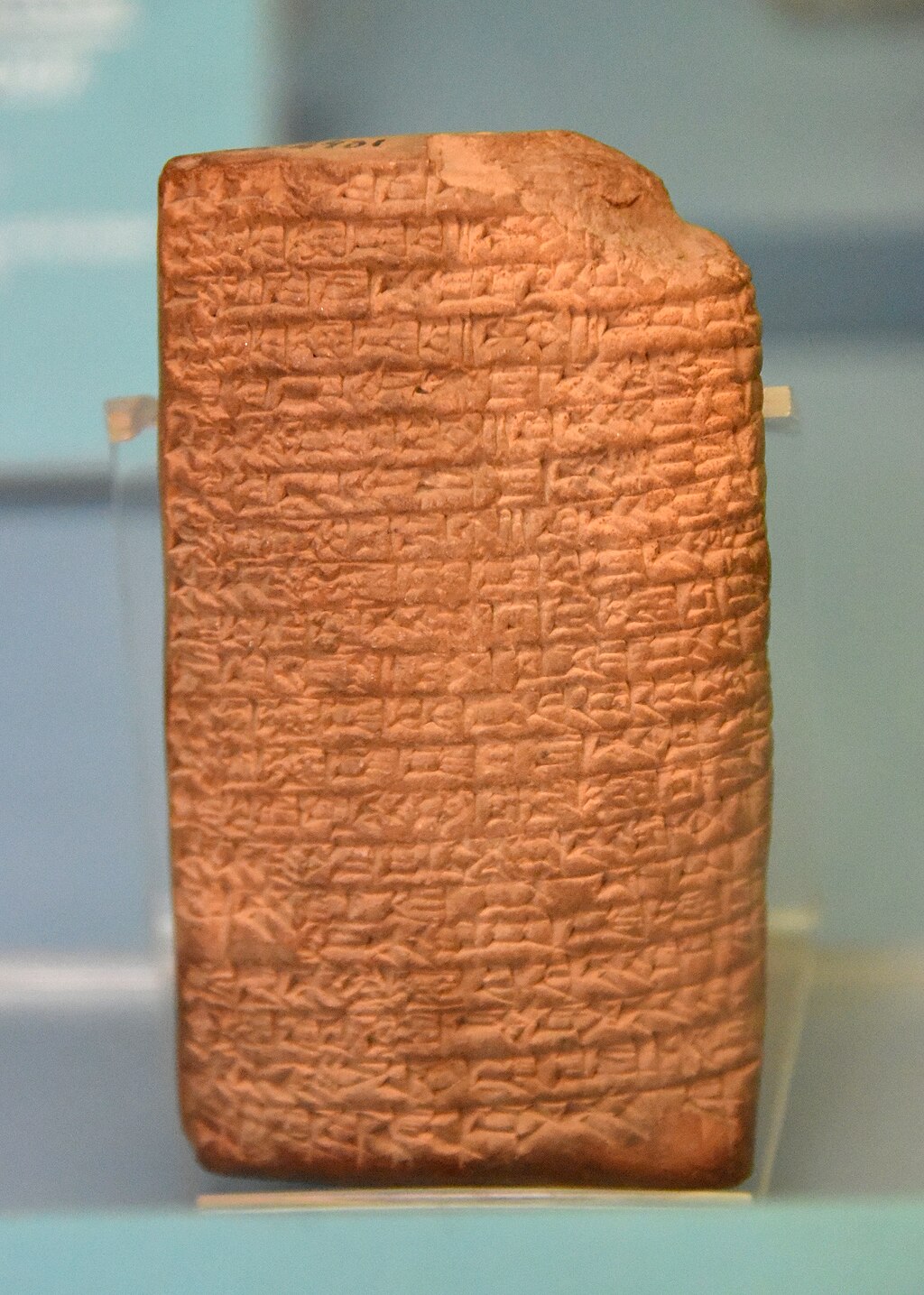

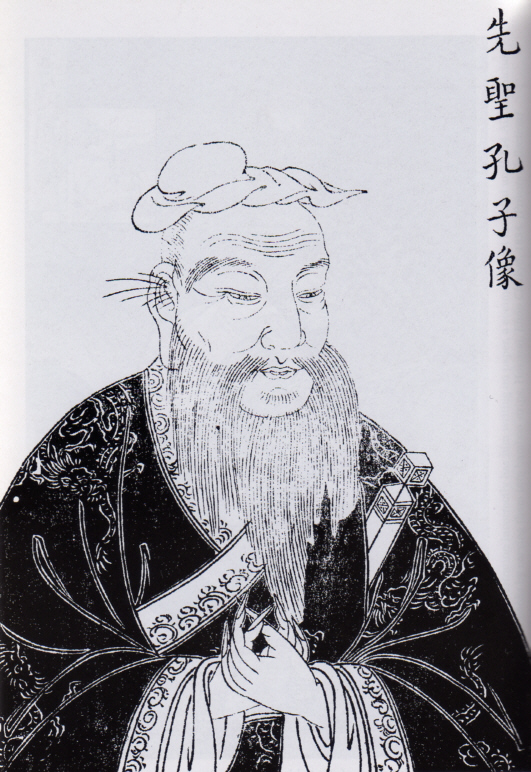

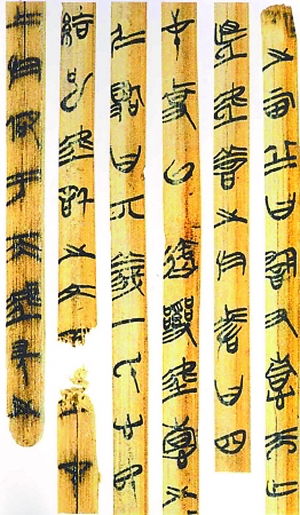

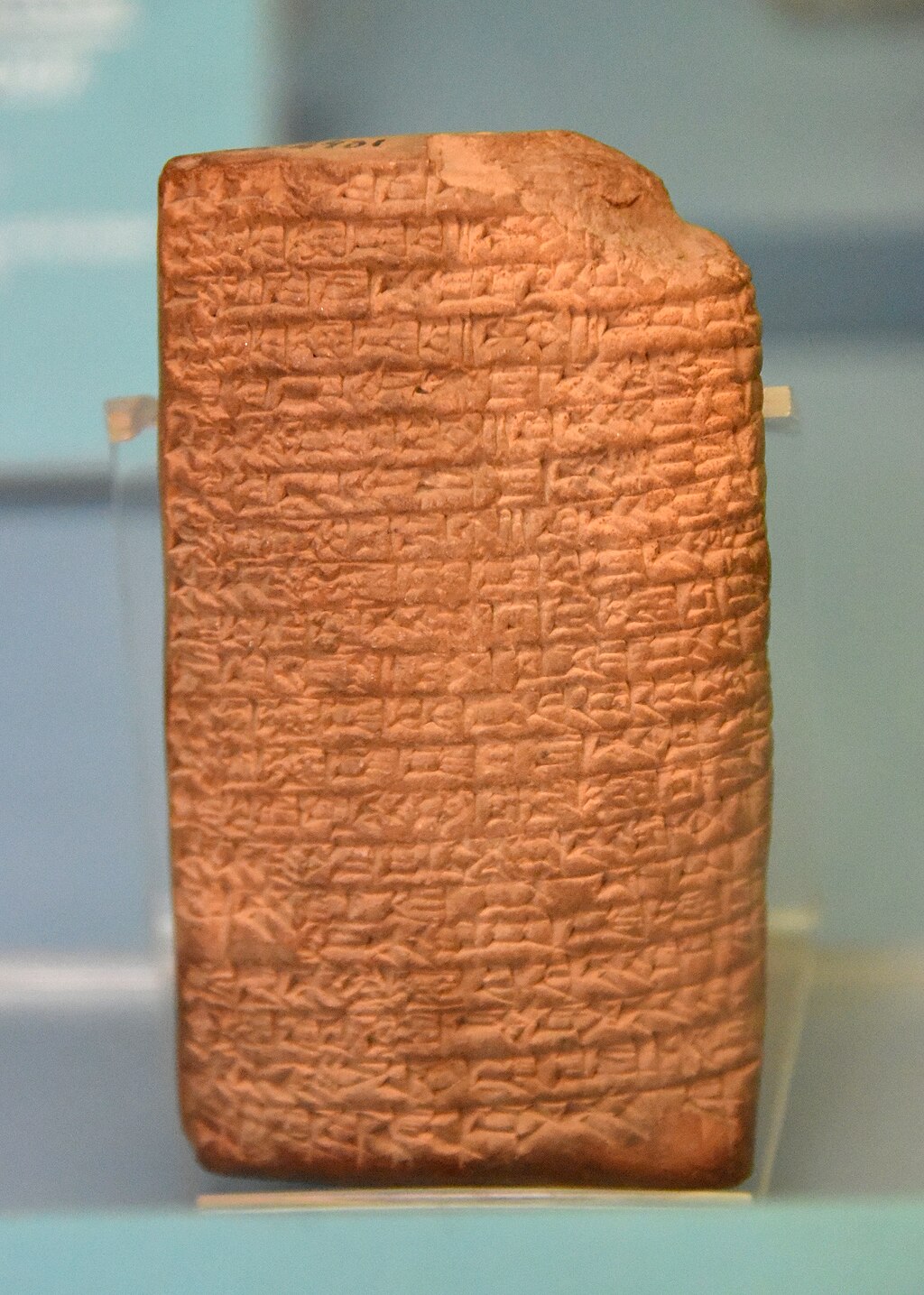

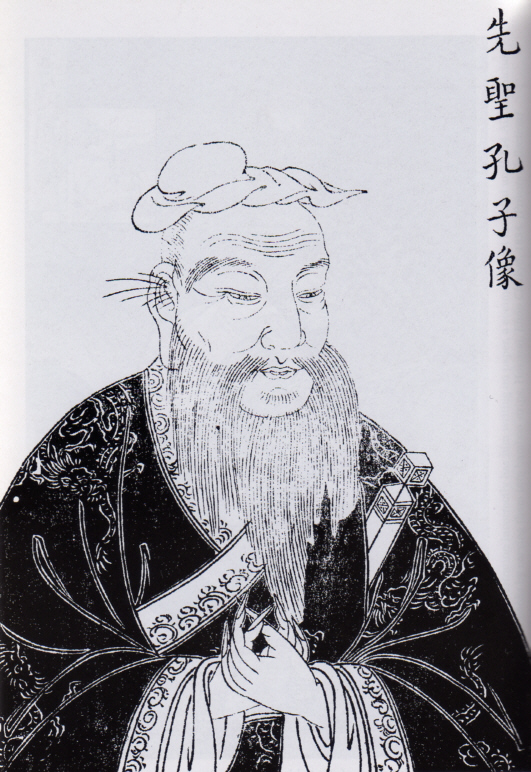

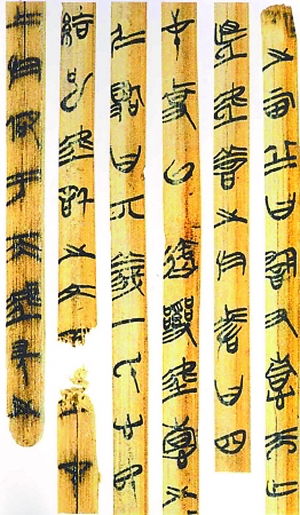

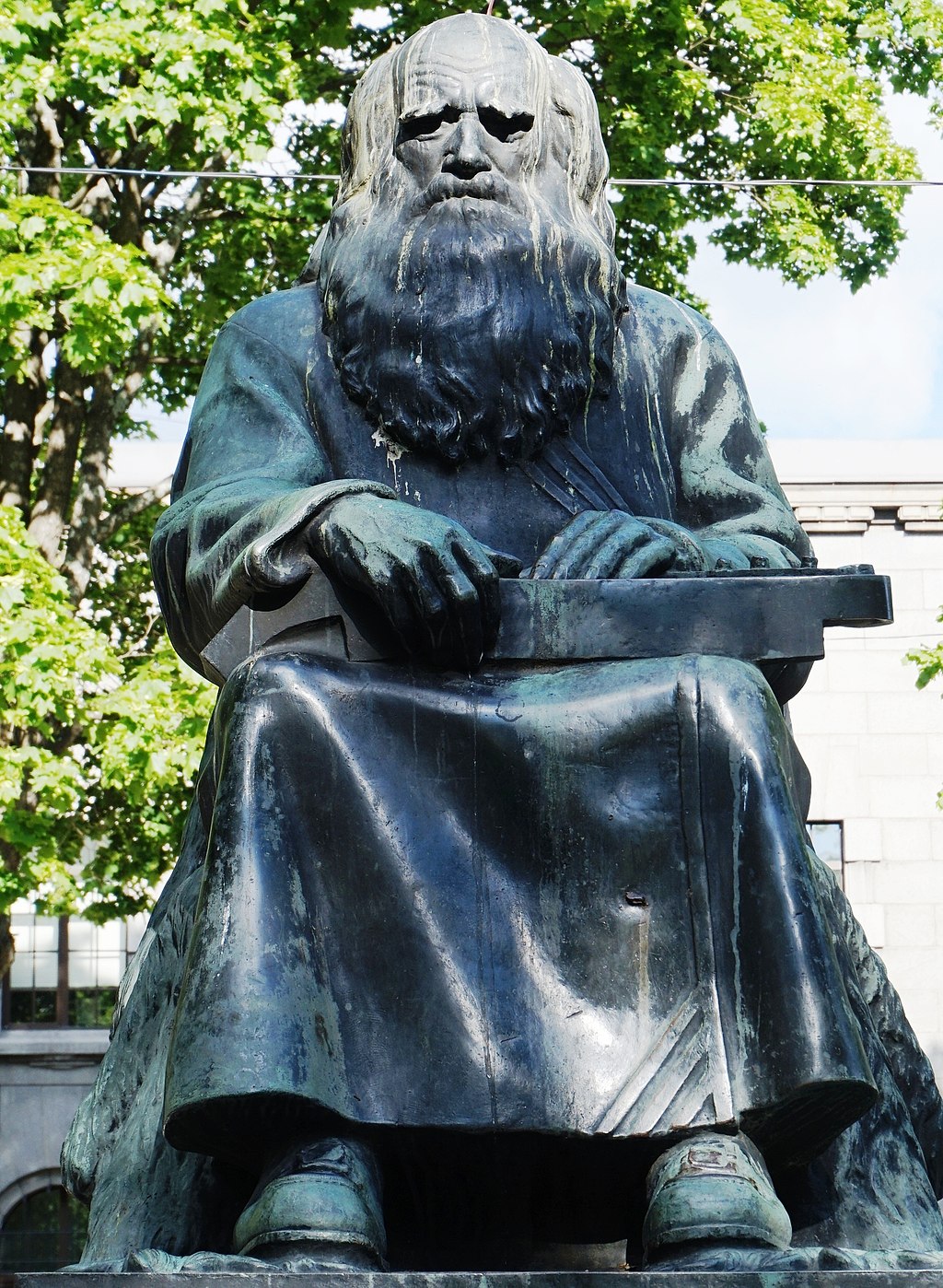

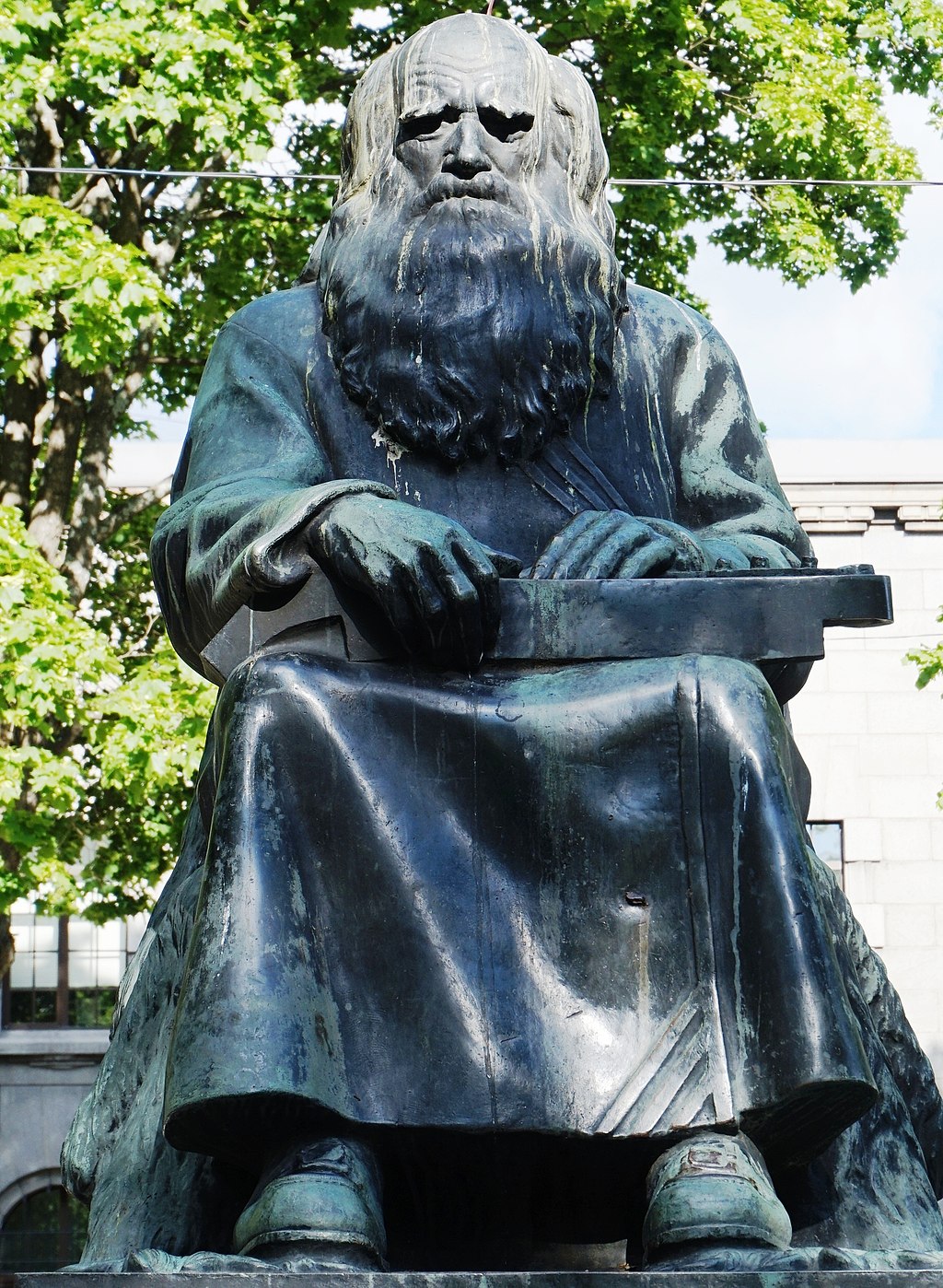

| History Main articles: History of poetry and Literary theory Early works Some scholars believe that the art of poetry may predate literacy, and developed from folk epics and other oral genres.[9][10] Others, however, suggest that poetry did not necessarily predate writing.[11] The oldest surviving epic poem, the Epic of Gilgamesh, dates from the 3rd millennium BCE in Sumer (in Mesopotamia, present-day Iraq), and was written in cuneiform script on clay tablets and, later, on papyrus.[12] The Istanbul tablet#2461, dating to c. 2000 BCE, describes an annual rite in which the king symbolically married and mated with the goddess Inanna to ensure fertility and prosperity; some have labelled it the world's oldest love poem.[13][14] An example of Egyptian epic poetry is The Story of Sinuhe (c. 1800 BCE).[15] Other ancient epics includes the Greek Iliad and the Odyssey; the Persian Avestan books (the Yasna); the Roman national epic, Virgil's Aeneid (written between 29 and 19 BCE); and the Indian epics, the Ramayana and the Mahabharata. Epic poetry appears to have been composed in poetic form as an aid to memorization and oral transmission in ancient societies.[11][16] Other forms of poetry, including such ancient collections of religious hymns as the Indian Sanskrit-language Rigveda, the Avestan Gathas, the Hurrian songs, and the Hebrew Psalms, possibly developed directly from folk songs. The earliest entries in the oldest extant collection of Chinese poetry, the Classic of Poetry (Shijing), were initially lyrics.[17] The Shijing, with its collection of poems and folk songs, was heavily valued by the philosopher Confucius and is considered to be one of the official Confucian classics. His remarks on the subject have become an invaluable source in ancient music theory.[18] The efforts of ancient thinkers to determine what makes poetry distinctive as a form, and what distinguishes good poetry from bad, resulted in "poetics"—the study of the aesthetics of poetry.[19] Some ancient societies, such as China's through the Shijing, developed canons of poetic works that had ritual as well as aesthetic importance.[20] More recently, thinkers have struggled to find a definition that could encompass formal differences as great as those between Chaucer's Canterbury Tales and Matsuo Bashō's Oku no Hosomichi, as well as differences in content spanning Tanakh religious poetry, love poetry, and rap.[21] Until recently, the earliest examples of stressed poetry had been thought to be works composed by Romanos the Melodist (fl. 6th century CE). However, Tim Whitmarsh writes that an inscribed Greek poem predated Romanos' stressed poetry.[22][23][24]  The oldest known love poem. Sumerian terracotta tablet#2461 from Nippur, Iraq. Ur III period, 2037–2029 BCE. Ancient Orient Museum, Istanbul The oldest known love poem. Sumerian terracotta tablet#2461 from Nippur, Iraq. Ur III period, 2037–2029 BCE. Ancient Orient Museum, Istanbul  The philosopher Confucius was influential in the developed approach to poetry and ancient music theory. The philosopher Confucius was influential in the developed approach to poetry and ancient music theory.  An early Chinese poetics, the Kǒngzǐ Shīlùn (孔子詩論), discussing the Shijing (Classic of Poetry) An early Chinese poetics, the Kǒngzǐ Shīlùn (孔子詩論), discussing the Shijing (Classic of Poetry) |

歴史 詳細は「詩の歴史」および「文学理論」を参照 初期の作品 一部の学者は、詩の芸術は文字の発明よりも古く、民衆の叙事詩やその他の口承のジャンルから発展したと信じている。[9][10] しかし、詩は必ずしも文字よりも古いものではないという意見もある。[11] 現存する最古の長編叙事詩『ギルガメシュ叙事詩』は、シュメール(現在のイラクのメソポタミア)で紀元前3千年紀に書かれたもので、粘土板に楔形文字で書 かれ、後にパピルスにも書かれた。 [12] 紀元前2000年頃のものとされるイスタンブールタブレット#2461には、王が豊饒と繁栄を確かなものにするために女神イナンナと象徴的に結婚し結ばれ るという、毎年恒例の儀式が描かれている。これを世界最古のラブソングとする説もある。[13][14] エジプトの叙事詩の例としては、『シヌヘの物語』(紀元前1800年頃)がある。[15] その他の古代の叙事詩には、ギリシャの『イーリアス』と『オデュッセイア』、ペルシアのアベスタ聖典(『ヤスナ』)、ローマの国民的叙事詩である『アエネ イス』(紀元前29年から19年の間に執筆)、そしてインディアンの叙事詩である『ラーマーヤナ』と『マハーバーラタ』などがある。叙事詩は、古代社会に おいて暗記や口頭伝承を助けるために詩の形式で作曲されたようである。 宗教的な賛美歌の古代のコレクションであるインディアンのサンスクリット語の『リグヴェーダ』、アヴェスタの『ガータ』、フルリ人の歌、ヘブライ語の『詩 篇』などの詩歌の他の形態は、民謡から直接発展した可能性がある。現存する最古の中国詩集『詩経』の最も古い作品は、当初は歌詞であった。[17] 詩と民謡を集めた『詩経』は、哲学者の孔子によって高く評価され、儒教の正典のひとつとされている。 孔子のこの主題に関する発言は、古代音楽理論における貴重な情報源となっている。[18] 詩という形式の特徴とは何か、優れた詩とそうでない詩の違いは何かを明らかにしようとする古代の思想家の努力は、「詩学」すなわち詩の美学の研究へとつな がった。[19] 古代の社会の中には、中国の『詩経』のように、儀式的な重要性と美的な重要性を兼ね備えた詩の規範を確立したものもある。 [20] さらに最近では、チョーサーの『カンタベリー物語』と松尾芭蕉の『奥の細道』ほどの形式上の違い、あるいは、聖書(タナハ)の宗教詩、恋愛詩、ラップ詩に わたる内容上の違いを包含する定義を見出すために、思想家たちが苦闘している。 最近まで、強勢詩の最も古い例は、6世紀に活躍したローマノス・メロディスト(Romanos the Melodist)の作品と考えられていた。しかし、ティム・ウィットマーシュ(Tim Whitmarsh)は、ギリシャの碑文詩がローマノスの強勢詩よりも古いと書いている。  最古の恋愛詩。イラクのニップルから出土したシュメールの粘土板#2461。ウル第三王朝時代、紀元前2037年から2029年。イスタンブール古代オリエント博物館 最古の愛の詩。シュメールの粘土板#2461、イラクのニップル出土。ウル第三王朝時代、紀元前2037年から2029年。イスタンブール古代オリエント博物館  哲学者の孔子は、詩と古代音楽理論の発展に影響を与えた。 哲学者の孔子は、詩や古代音楽理論の発展したアプローチに影響を与えた。  初期の中国詩学、詩経(Classic of Poetry)について論じた『孔子詩論(Kǒngzǐ Shīlùn)』 初期の中国詩学、詩経(Classic of Poetry)について論じた『孔子詩論(Kǒngzǐ Shīlùn)』 |

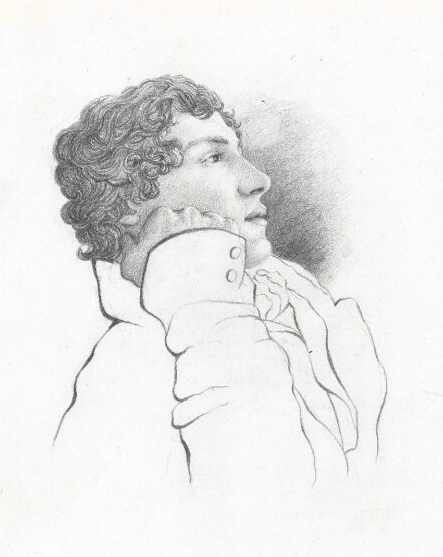

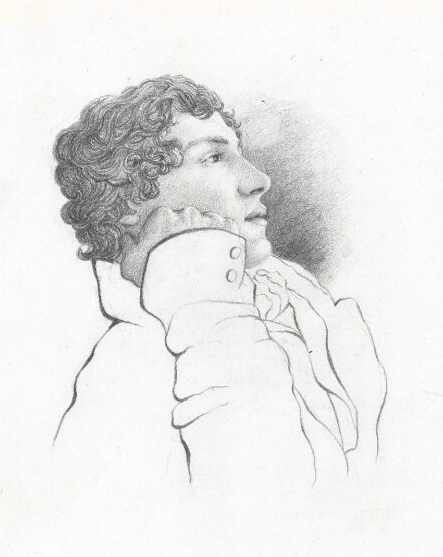

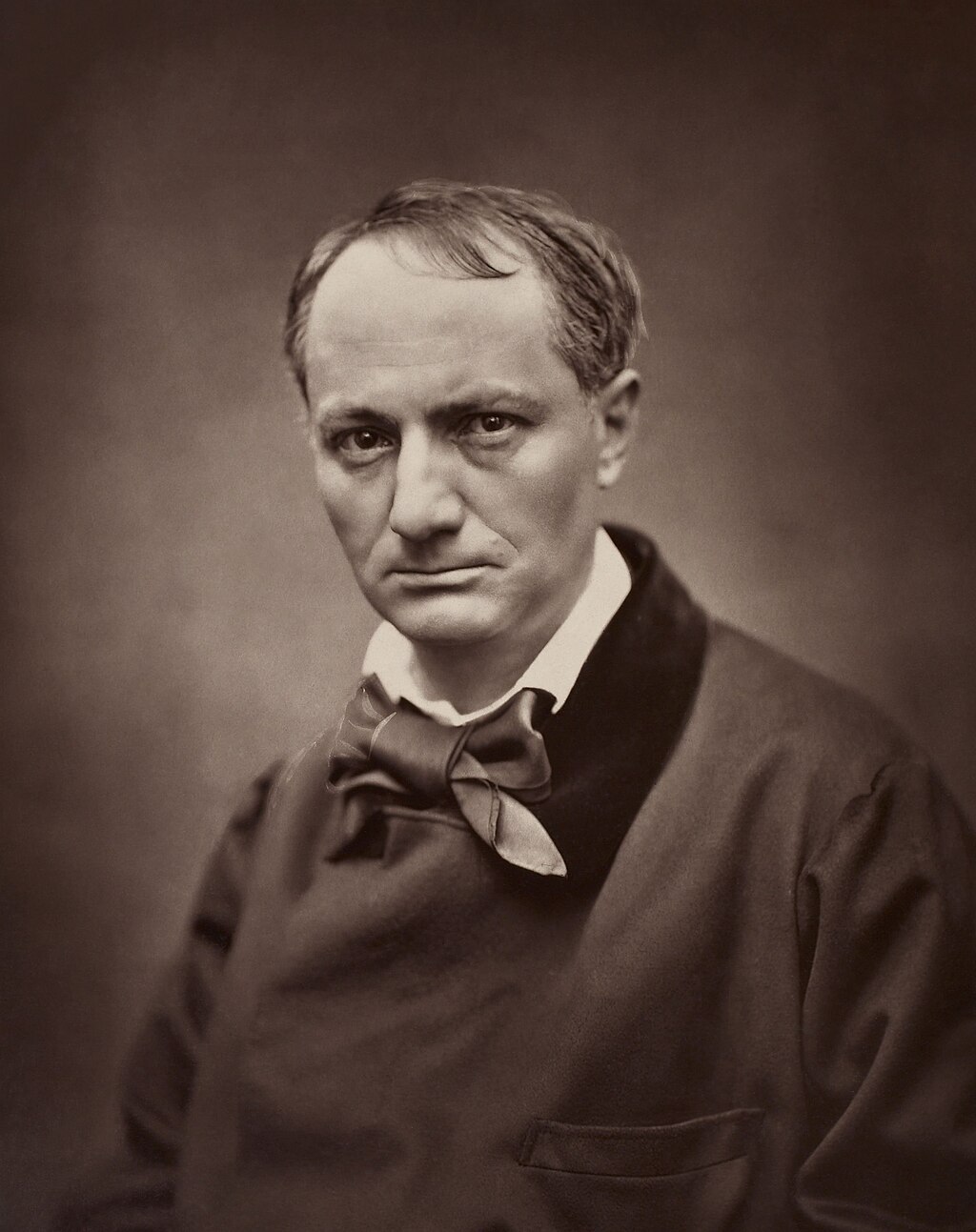

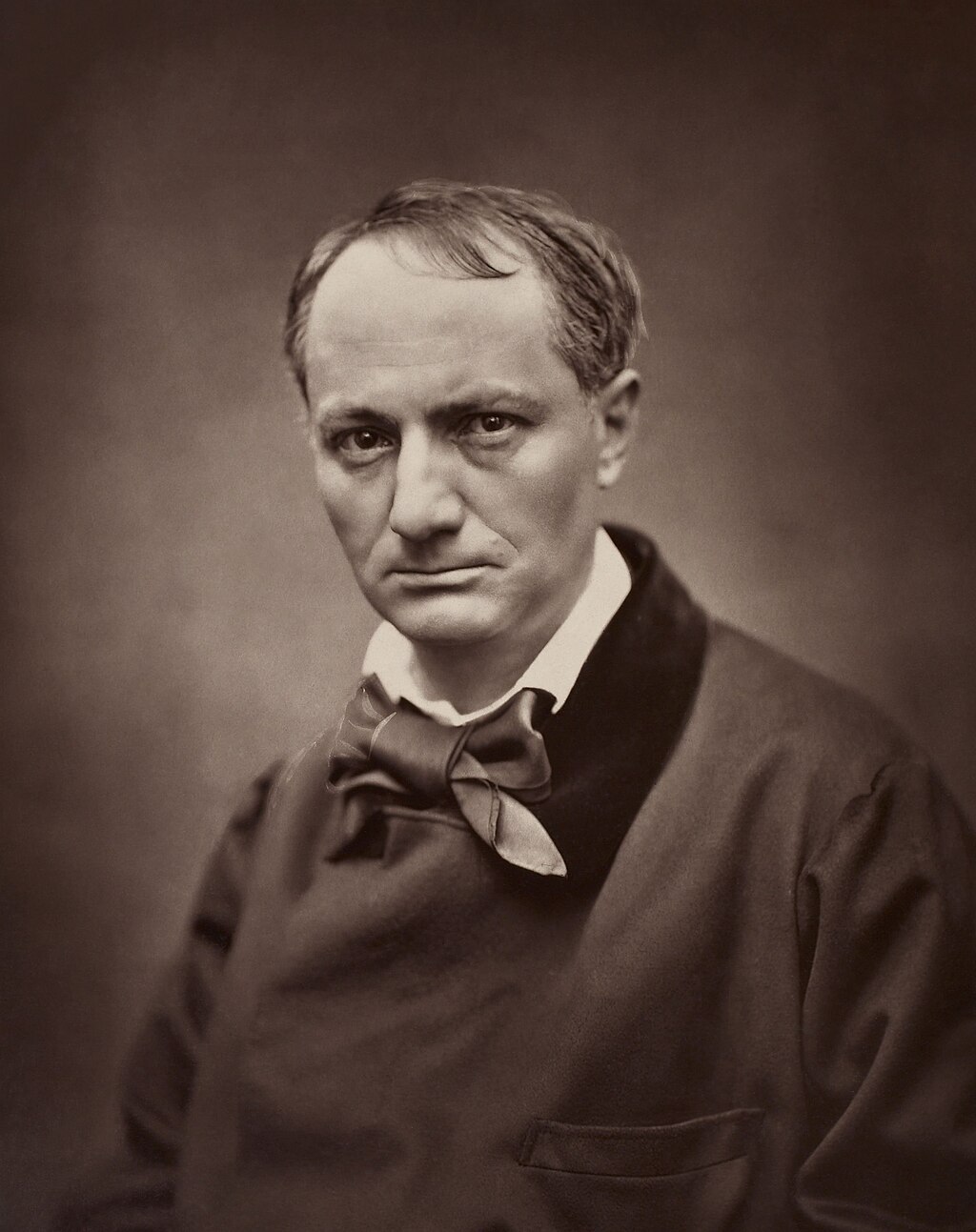

Western traditions Aristotle Classical thinkers in the West employed classification as a way to define and assess the quality of poetry. Notably, the existing fragments of Aristotle's Poetics describe three genres of poetry—the epic, the comic, and the tragic—and develop rules to distinguish the highest-quality poetry in each genre, based on the perceived underlying purposes of the genre.[25] Later aestheticians identified three major genres: epic poetry, lyric poetry, and dramatic poetry, treating comedy and tragedy as subgenres of dramatic poetry.[26]  John Keats Aristotle's work was influential throughout the Middle East during the Islamic Golden Age,[27] as well as in Europe during the Renaissance.[28] Later poets and aestheticians often distinguished poetry from, and defined it in opposition to prose, which they generally understood as writing with a proclivity to logical explication and a linear narrative structure.[29] This does not imply that poetry is illogical or lacks narration, but rather that poetry is an attempt to render the beautiful or sublime without the burden of engaging the logical or narrative thought-process. English Romantic poet John Keats termed this escape from logic "negative capability".[30] This "romantic" approach views form as a key element of successful poetry because form is abstract and distinct from the underlying notional logic. This approach remained influential into the 20th century.[31] During the 18th and 19th centuries, there was also substantially more interaction among the various poetic traditions, in part due to the spread of European colonialism and the attendant rise in global trade.[32] In addition to a boom in translation, during the Romantic period numerous ancient works were rediscovered.[33] |

西洋の伝統 アリストテレス 西洋の古典思想家たちは、詩の質を定義し評価する方法として分類法を採用していた。特に、アリストテレスの『詩学』の現存する断片では、叙事詩、喜劇詩、 悲劇詩という3つの詩のジャンルが説明されており、それぞれのジャンルの根底にあると認識される目的に基づいて、各ジャンルにおける最高品質の詩を区別す るためのルールが展開されている。[25] その後、美学の専門家たちは、叙事詩、抒情詩、劇詩という3つの主要なジャンルを特定し、喜劇と悲劇を劇詩の亜ジャンルとして扱った。[26]  ジョン・キーツ アリストテレスの著作は、イスラム黄金時代の中東全域で影響力を持ち[27]、またルネサンス期のヨーロッパでも影響力を持ち[28]、後の詩人や美学論 者は詩を散文と区別し、対立概念として定義することが多かった。彼らは一般的に、散文を論理的説明や直線的な物語構造に傾倒した文章と理解していた。 これは詩が非論理的であるとか、物語性に欠けるという意味ではなく、むしろ論理的思考や物語的思考プロセスを必要としない、美や崇高さを表現しようとする 試みであることを意味している。 英語のロマン派詩人ジョン・キーツは、この論理からの逃避を「ネガティブ・キャパビリティ」と呼んだ。[30] この「ロマン主義的」アプローチでは、形式が抽象的であり、その根底にある概念的論理とは異なるものであるため、形式が優れた詩の重要な要素であると見な している。このアプローチは20世紀まで影響力を持ち続けた。[31] 18世紀と19世紀には、ヨーロッパの植民地主義の拡大とそれに伴う世界貿易の増加も一因となり、さまざまな詩の伝統の間で、より活発な交流が行われた。[32] ロマン派の時代には、翻訳ブームに加え、多数の古代作品が再発見された。[33] |

20th-century and 21st-century disputes Archibald MacLeish Some 20th-century literary theorists rely less on the ostensible opposition of prose and poetry, instead focusing on the poet as simply one who creates using language, and poetry as what the poet creates.[34] The underlying concept of the poet as creator is not uncommon, and some modernist poets essentially do not distinguish between the creation of a poem with words, and creative acts in other media. Other modernists challenge the very attempt to define poetry as misguided.[35] The rejection of traditional forms and structures for poetry that began in the first half of the 20th century coincided with a questioning of the purpose and meaning of traditional definitions of poetry and of distinctions between poetry and prose, particularly given examples of poetic prose and prosaic poetry. Numerous modernist poets have written in non-traditional forms or in what traditionally would have been considered prose, although their writing was generally infused with poetic diction and often with rhythm and tone established by non-metrical means. While there was a substantial formalist reaction within the modernist schools to the breakdown of structure, this reaction focused as much on the development of new formal structures and syntheses as on the revival of older forms and structures.[36] Postmodernism goes beyond modernism's emphasis on the creative role of the poet, to emphasize the role of the reader of a text (hermeneutics), and to highlight the complex cultural web within which a poem is read.[37] Today, throughout the world, poetry often incorporates poetic form and diction from other cultures and from the past, further confounding attempts at definition and classification that once made sense within a tradition such as the Western canon.[38] The early 21st-century poetic tradition appears to continue to strongly orient itself to earlier precursor poetic traditions such as those initiated by Whitman, Emerson, and Wordsworth. The literary critic Geoffrey Hartman (1929–2016) used the phrase "the anxiety of demand" to describe the contemporary response to older poetic traditions as "being fearful that the fact no longer has a form",[39] building on a trope introduced by Emerson. Emerson had maintained that in the debate concerning poetic structure where either "form" or "fact" could predominate, that one need simply "Ask the fact for the form." This has been challenged at various levels by other literary scholars such as Harold Bloom (1930–2019), who has stated: "The generation of poets who stand together now, mature and ready to write the major American verse of the twenty-first century, may yet be seen as what Stevens called 'a great shadow's last embellishment,' the shadow being Emerson's."[40] In the 2020s, advances in artificial intelligence (AI), particularly large language models, enabled the generation of poetry in specific styles and formats.[41] A 2024 study found that AI-generated poems were rated by non-expert readers as more rhythmic, beautiful, and human-like than those written by well-known human authors. This preference may stem from the relative simplicity and accessibility of AI-generated poetry, which some participants found easier to understand.[42] |

20世紀と21世紀の論争 アーチボルド・マクリーシュ 20世紀の文学理論家の一部は、散文と詩の表面的な対立にあまり重点を置かず、詩人を単に言語を用いて創造する者と見なし、詩を詩人が創造するものとして 捉えている。[34] 詩人という創造者という基本概念は珍しいものではなく、モダニズム詩人の一部は、言葉による詩の創造と、他のメディアにおける創造的行為とを本質的に区別 していない。他のモダニストは、詩を定義しようとする試み自体を誤ったものだと批判している。 20世紀前半に始まった詩の伝統的な形式や構造の拒絶は、詩の伝統的な定義の目的や意味、詩と散文の区別に対する疑問と一致しており、特に詩的な散文や散 文的な詩の例が挙げられた。多くのモダニズム詩人は、伝統的な形式ではないものや、伝統的には散文と見なされていたものも書いており、彼らの作品は一般的 に詩的な表現が用いられ、しばしば非韻律的な手段によってリズムやトーンが確立されていた。構造の崩壊に対するモダニズム派内の形式主義的な反応は相当な ものだったが、この反応は、古い形式や構造の復活と同様に、新しい形式構造や総合的な発展にも焦点を当てていた。 ポストモダニズムは、詩人の創造的な役割を強調するモダニズムを超え、テキストの読者(解釈学)の役割を強調し、詩が読まれる複雑な文化的背景を浮き彫り にする。今日、世界中で、詩はしばしば他の文化や過去の詩の形式や表現を取り入れ、かつては西洋の正典のような伝統の中で意味をなしていた定義や分類の試 みをさらに混乱させている。 21世紀初頭の詩の伝統は、ホイットマン、エマーソン、ワーズワースなどが始めたような、それ以前の先駆的な詩の伝統に強く影響を受け続けているように見 える。文学評論家のジェフリー・ハートマン(1929年~2016年)は、古い詩の伝統に対する現代の反応を「もはや形が存在しないという事実を恐れる」 ものとして、「要求の不安」という表現を用いて説明している。[39] これは、エマーソンが導入した修辞法を基にしている。エマーソンは、詩の構造に関する議論において、「形」と「事実」のどちらが優勢になるかという問題に ついて、「事実から形を求める」だけでよいと主張していた。これは、ハロルド・ブルーム(1930年 - 2019年)などの他の文学研究者のさまざまなレベルで批判されており、ブルームは次のように述べている。「今、共に立つ詩人の世代は、成熟し、21世紀 の主要なアメリカ詩を書く準備ができているが、スティーヴンスが『偉大な影の最後の装飾』と呼んだもの、つまり影がエマーソンであると見なされる可能性が ある」[40] 2020年代には、人工知能(AI)の進歩、特に大規模言語モデルによって、特定のスタイルやフォーマットの詩の生成が可能になった。[41] 2024年の研究では、AIによって生成された詩は、専門家ではない読者から、著名な人間の作家によって書かれたものよりも、よりリズミカルで美しく、人 間らしいと評価されたことが分かった。この好みは、AIが生成した詩の相対的なシンプルさとアクセシビリティに起因する可能性があり、一部の参加者はそれ を理解しやすいと感じた。[42] |

| Elements Prosody Main article: Meter (poetry) Prosody is the study of the meter, rhythm, and intonation of a poem. Rhythm and meter are different, although closely related.[43] Meter is the definitive pattern established for a verse (such as iambic pentameter), while rhythm is the actual sound that results from a line of poetry. Prosody also may be used more specifically to refer to the scanning of poetic lines to show meter.[44] Rhythm Main articles: Timing (linguistics), tone (linguistics), and Pitch accent  Robinson Jeffers The methods for creating poetic rhythm vary across languages and between poetic traditions. Languages are often described as having timing set primarily by accents, syllables, or moras, depending on how rhythm is established, although a language can be influenced by multiple approaches. Japanese is a mora-timed language. Latin, Catalan, French, Leonese, Galician and Spanish are called syllable-timed languages. Stress-timed languages include English, Russian and, generally, German.[45] Varying intonation also affects how rhythm is perceived. Languages can rely on either pitch or tone. Some languages with a pitch accent are Vedic Sanskrit or Ancient Greek. Tonal languages include Chinese, Vietnamese and most Subsaharan languages.[46] Metrical rhythm generally involves precise arrangements of stresses or syllables into repeated patterns called feet within a line. In Modern English verse the pattern of stresses primarily differentiate feet, so rhythm based on meter in Modern English is most often founded on the pattern of stressed and unstressed syllables (alone or elided).[47] In the classical languages, on the other hand, while the metrical units are similar, vowel length rather than stresses define the meter.[48] Old English poetry used a metrical pattern involving varied numbers of syllables but a fixed number of strong stresses in each line.[49]  Marianne Moore The chief device of ancient Hebrew Biblical poetry, including many of the psalms, was parallelism, a rhetorical structure in which successive lines reflected each other in grammatical structure, sound structure, notional content, or all three. Parallelism lent itself to antiphonal or call-and-response performance, which could also be reinforced by intonation. Thus, Biblical poetry relies much less on metrical feet to create rhythm, but instead creates rhythm based on much larger sound units of lines, phrases and sentences.[50] Some classical poetry forms, such as Venpa of the Tamil language, had rigid grammars (to the point that they could be expressed as a context-free grammar) which ensured a rhythm.[51] Classical Chinese poetics, based on the tone system of Middle Chinese, recognized two kinds of tones: the level (平 píng) tone and the oblique (仄 zè) tones, a category consisting of the rising (上 sháng) tone, the departing (去 qù) tone and the entering (入 rù) tone. Certain forms of poetry placed constraints on which syllables were required to be level and which oblique. The formal patterns of meter used in Modern English verse to create rhythm no longer dominate contemporary English poetry. In the case of free verse, rhythm is often organized based on looser units of cadence rather than a regular meter. Robinson Jeffers, Marianne Moore, and William Carlos Williams are three notable poets who reject the idea that regular accentual meter is critical to English poetry.[52] Jeffers experimented with sprung rhythm as an alternative to accentual rhythm.[53] |

要素 韻律 詳細は「詩脚」を参照 韻律学は、詩の韻律、リズム、イントネーションの研究である。 リズムと韻律は異なるが、密接に関連している。[43] 韻律は、詩行(例えば、五歩格)に確立された決定的なパターンである。一方、リズムは詩行から生じる実際の音である。 韻律は、より具体的には、韻律を示すために詩行をスキャンすることを指す場合もある。[44] リズム 詳細は:タイミング(言語学)、トーン(言語学)、ピッチアクセント  ロビンソン・ジェファーズ 詩のリズムを生み出す方法は、言語によって、また詩の伝統によって異なる。言語は、アクセント、音節、モーラによって主にタイミングが設定されていると説 明されることが多いが、言語は複数のアプローチに影響される可能性もある。日本語はモーラタイミング言語である。ラテン語、カタルーニャ語、フランス語、 レオン語、ガリシア語、スペイン語は音節強勢言語と呼ばれる。 ストレス強勢言語には英語、ロシア語、一般的にドイツ語が含まれる。[45] リズムの知覚には、イントネーションの変化も影響する。 言語はピッチまたはトーンのいずれかに依存する。 ピッチアクセントを持つ言語にはヴェーダ・サンスクリット語や古代ギリシャ語がある。 トーン言語には中国語、ベトナム語、サハラ以南のほとんどの言語が含まれる。[46] 韻律のリズムは一般的に、強勢または音節を繰り返されるパターン(脚)に正確に配置する。現代英語の詩では、強勢のパターンが主に脚を区別するため、現代 英語の韻律は、強勢と非強勢の音節(単独または省略)のパターンに基づいている場合がほとんどである。[47] 一方、古典語では、韻律の単位は似ているが、強勢ではなく母音の長さが韻律を決定する。 [48] 古英語の詩では、各行に含まれる音節の数は様々だが、強勢は一定の数で置かれる韻律パターンが用いられていた。[49]  マリアン・ムーア 古代ヘブライ語の聖書詩(詩篇の多くを含む)の主な手法は、パラレリズム(平行主義)であった。これは修辞学上の構造で、連続する行が文法的構造、音韻構 造、概念的内容、またはその3つすべてにおいて互いに反映し合うものである。パラレリズムは、応答唱和やコール・アンド・レスポンスのパフォーマンスに適 しており、また、抑揚によっても強化される。したがって、聖書の詩は、韻律の脚をあまり用いることなく、代わりに、行、句、文といったより大きな音の単位 に基づいてリズムを生み出している。[50] 古典詩の形式の中には、タミル語のヴェンパのように、厳格な文法(文脈自由文法として表現できるほど)を持つものもあり、それによってリズムが確実なもの となっていた。[51] 古典中国詩学は、中世中国語の声調体系に基づいて、2種類の声調を認めていた。すなわち、平声(píng)と、上声(sháng)、去声(qù)、入声 (rù)からなる仄声(zè)である。詩の形式によっては、どの音節が平声で、どの音節が仄声でなければならないかという制約があった。 現代英語の詩でリズムを生み出すために使用される韻律の形式的なパターンは、もはや現代の英語詩を支配するものではなくなった。自由詩の場合、韻律は規則 正しい韻律よりも、緩やかな終止の単位に基づいて構成されることが多い。ロビンソン・ジェファース、マリアン・ムーア、ウィリアム・カルロス・ウィリアム ズは、規則正しいアクセント韻律が英語詩にとって不可欠であるという考えを否定した著名な詩人である。[52] ジェファースは、アクセント韻律の代替案として、跳躍リズムを試みた。[53] |

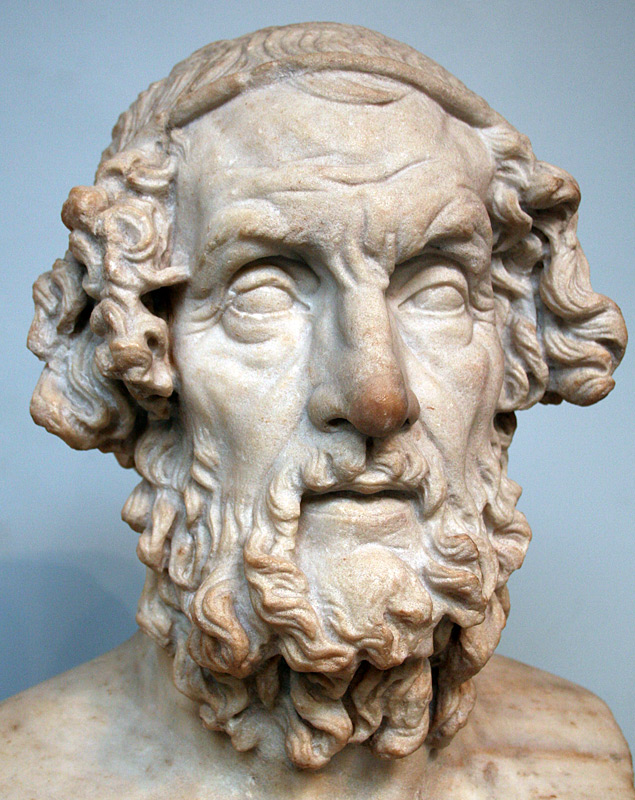

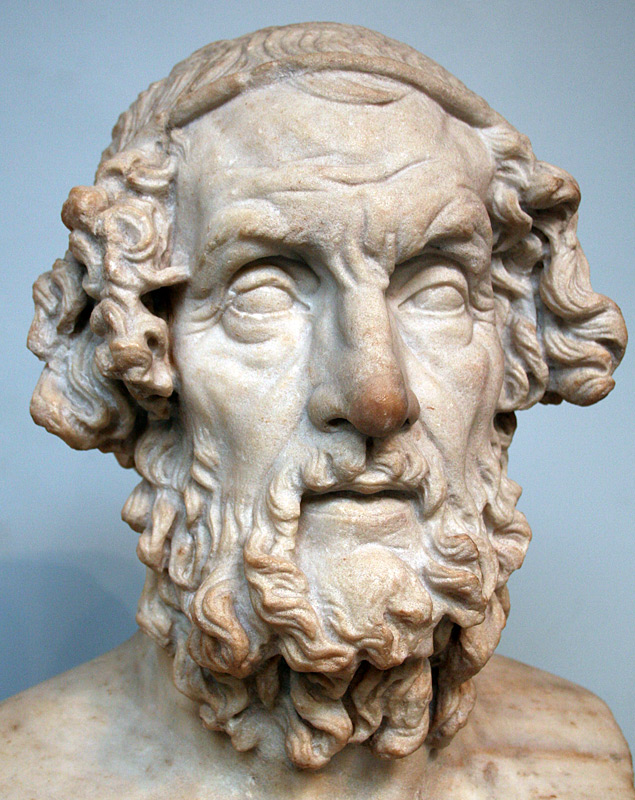

| Meter Main article: Scansion  Attic red-figure kathalos painting of Sappho from c. 470 BCE[54] In the Western poetic tradition, meters are customarily grouped according to a characteristic metrical foot and the number of feet per line.[55] The number of metrical feet in a line are described using Greek terminology: tetrameter for four feet and hexameter for six feet, for example.[56] Thus, "iambic pentameter" is a meter comprising five feet per line, in which the predominant kind of foot is the "iamb". This metric system originated in ancient Greek poetry, and was used by poets such as Pindar and Sappho, and by the great tragedians of Athens. Similarly, "dactylic hexameter", comprises six feet per line, of which the dominant kind of foot is the "dactyl". Dactylic hexameter was the traditional meter of Greek epic poetry, the earliest extant examples of which are the works of Homer and Hesiod.[57] Iambic pentameter and dactylic hexameter were later used by a number of poets, including William Shakespeare and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, respectively.[58] The most common metrical feet in English are:[59]  Homer: Roman bust, based on Greek original[60] iamb – one unstressed syllable followed by a stressed syllable (e.g. des-cribe, in-clude, re-tract) trochee—one stressed syllable followed by an unstressed syllable (e.g. pic-ture, flow-er) dactyl – one stressed syllable followed by two unstressed syllables (e.g. an-no-tate, sim-i-lar) anapaest—two unstressed syllables followed by one stressed syllable (e.g. com-pre-hend) spondee—two stressed syllables together (e.g. heart-beat, four-teen) pyrrhic—two unstressed syllables together (rare, usually used to end dactylic hexameter) There are a wide range of names for other types of feet, right up to a choriamb, a four syllable metric foot with a stressed syllable followed by two unstressed syllables and closing with a stressed syllable. The choriamb is derived from some ancient Greek and Latin poetry.[57] Languages which use vowel length or intonation rather than or in addition to syllabic accents in determining meter, such as Ottoman Turkish or Vedic, often have concepts similar to the iamb and dactyl to describe common combinations of long and short sounds.[61] Each of these types of feet has a certain "feel," whether alone or in combination with other feet. The iamb, for example, is the most natural form of rhythm in the English language, and generally produces a subtle but stable verse.[62] Scanning meter can often show the basic or fundamental pattern underlying a verse, but does not show the varying degrees of stress, as well as the differing pitches and lengths of syllables.[63] There is debate over how useful a multiplicity of different "feet" is in describing meter. For example, Robert Pinsky has argued that while dactyls are important in classical verse, English dactylic verse uses dactyls very irregularly and can be better described based on patterns of iambs and anapests, feet which he considers natural to the language.[64] Actual rhythm is significantly more complex than the basic scanned meter described above, and many scholars have sought to develop systems that would scan such complexity. Vladimir Nabokov noted that overlaid on top of the regular pattern of stressed and unstressed syllables in a line of verse was a separate pattern of accents resulting from the natural pitch of the spoken words, and suggested that the term "scud" be used to distinguish an unaccented stress from an accented stress.[65] Sanskrit poetry is organized according to chhandas, which are manifold and continue to influence several South Asian languages' poetry. |

韻律 詳細は「スキャン」を参照  紀元前470年頃のアッティカ赤像式カタロス絵画に描かれたサッフォーの肖像[54] 西洋の詩の伝統では、韻律は、特徴的な韻律の脚と1行あたりの脚の数によって分類されるのが一般的である。[55] 1行の韻律の脚の数は、ギリシャ語の専門用語で表記される。例えば、4つの脚の場合はテトラメーター、6つの脚の場合はヘクサメーターとなる。[56] したがって、「イアンビック・ペンタメーター」は、1行あたり5つの脚で構成される韻律であり、その中で優勢な脚は「イアンビ」である。この韻律は古代ギ リシャの詩から始まり、ピンダロスやサッフォー、アテナイの悲劇詩人たちによって用いられた。同様に、「ダクティク・ヘクサメーター」は1行あたり6つの 脚からなり、その主要な脚は「ダクティル」である。ダクティル・ヘクサメーターは、ギリシャの叙事詩の伝統的な韻律であり、現存する最古の例はホメーロス とヘシオドスの作品である。[57] ヤンビック・ペンタメーターとダクティル・ヘクサメーターは、その後、ウィリアム・シェイクスピアやヘンリー・ワズワース・ロングフェローを含む多くの詩 人によって使用された。[58] 英語で最も一般的な韻律の脚は以下の通りである。[59]  ホメロス:ギリシャ語原作に基づくローマの胸像[60] 強勢のない音節が1つ続き、その後に強勢のある音節が続く(例:des-cribe、in-clude、re-tract) 強勢のある音節が1つ続き、その後に強勢のない音節が続く(例:pic-ture、flow-er) ダクティル - 強勢のある音節の後に、非強勢の音節が2つ続く(例:an-no-tate、sim-i-lar) アナペスト - 非強勢の音節が2つ続き、その後に強勢のある音節が1つ続く(例:com-pre-hend) スポンディ - 強勢のある音節が2つ続く(例:heart-beat、four-teen) ピュリック(pyrrhic)— ストレスのない2つの音節が続く(rare、通常はダクティル六歩格の終わりに使用される) その他にも、強勢のある音節に続いてストレスのない音節が2つ続き、最後に強勢のある音節で終わる4音節の脚韻であるコリアム(choriamb)まで、 さまざまな脚韻の名称がある。コリャムは古代ギリシャやラテン詩から派生したものである。[57] オスマン・トルコ語やヴェーダ語のように、音節アクセントではなく母音の長さやイントネーションによって韻律を決定する言語では、長音と短音の一般的な組 み合わせを表現するために、イアンブやダクティルに類似した概念が用いられることが多い。[61] これらの韻律の種類は、単独で用いられる場合も他の韻律と組み合わされる場合も、それぞれ特有の「感覚」を持つ。例えば、イアンビュは英語において最も自 然なリズムの形であり、一般的に微妙ではあるが安定した詩を生み出す。[62] スキャニング・メーターは、詩の根底にある基本的な、あるいは根本的なパターンを示すことができるが、ストレスの度合いの変化や、音節の長さや高低の違い を示すことはできない。[63] 異なる「フィート」を複数用いて韻律を記述することの有用性については議論がある。例えば、ロバート・ピンスキーは、古典詩ではダクティルが重要である が、英語のダクティル韻律ではダクティルは非常に不規則に使用されており、むしろ、この言語に自然であると考えられる、イアンブやアナペストのパターンに 基づいて説明できると主張している。[64] 実際の韻律は、前述の基本的なスキャンメーターよりもはるかに複雑であり、多くの学者が、このような複雑性をスキャンするシステムの開発に取り組んでい る。ウラジーミル・ナボコフは、詩行における強勢と非強勢の音節の規則的なパターンに、話し言葉の自然な音高から生じるアクセントのパターンが重なってい ることに注目し、非アクセント強勢とアクセント強勢を区別するために「スキャッド」という用語を使用することを提案した。 サンスクリット詩はチャンドス(chhandas)に従って構成されており、チャンドスは多様であり、南アジアのいくつかの言語の詩に影響を与え続けている。 |

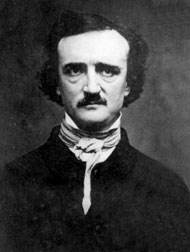

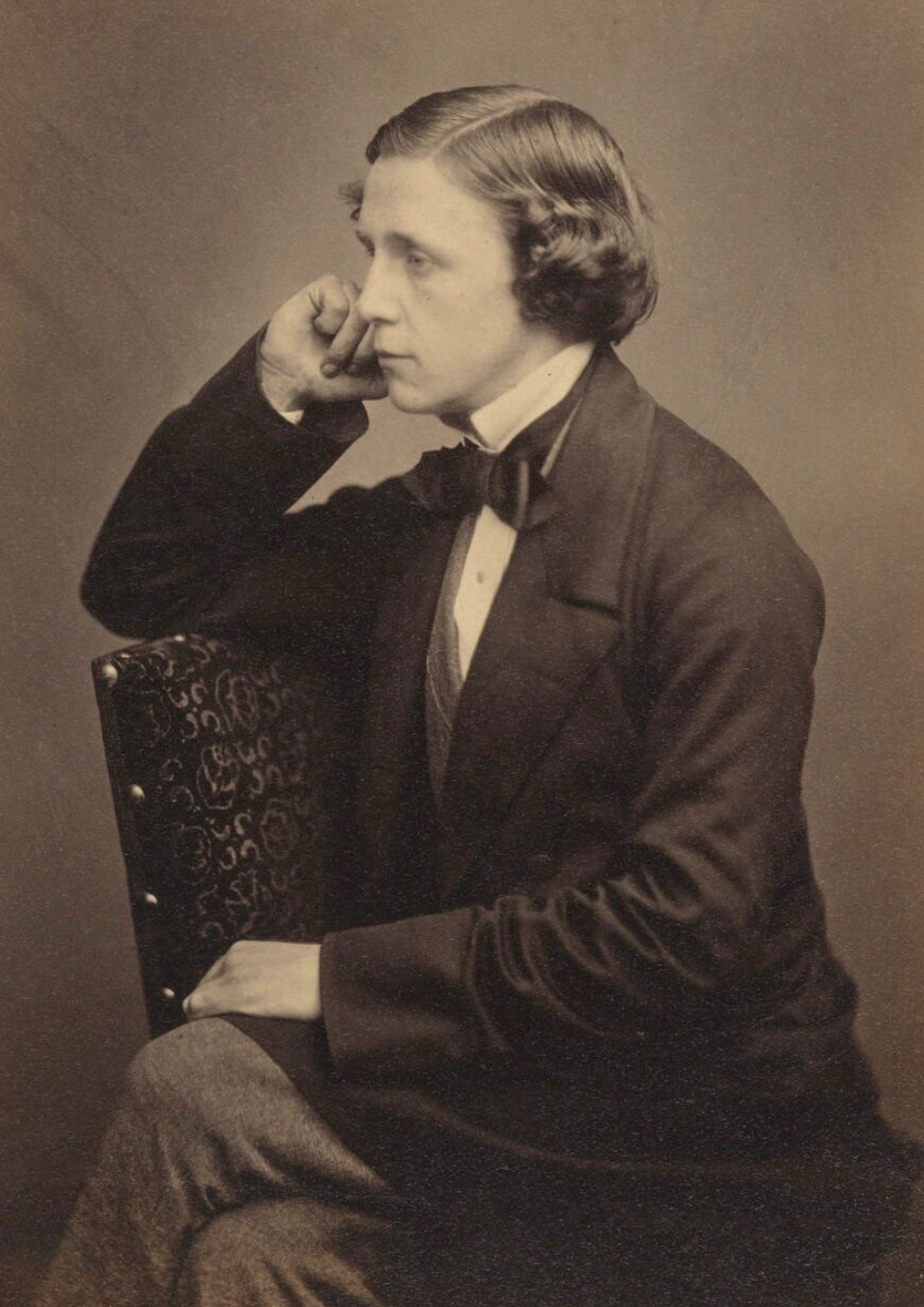

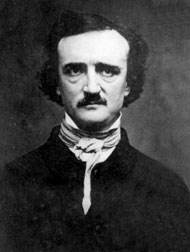

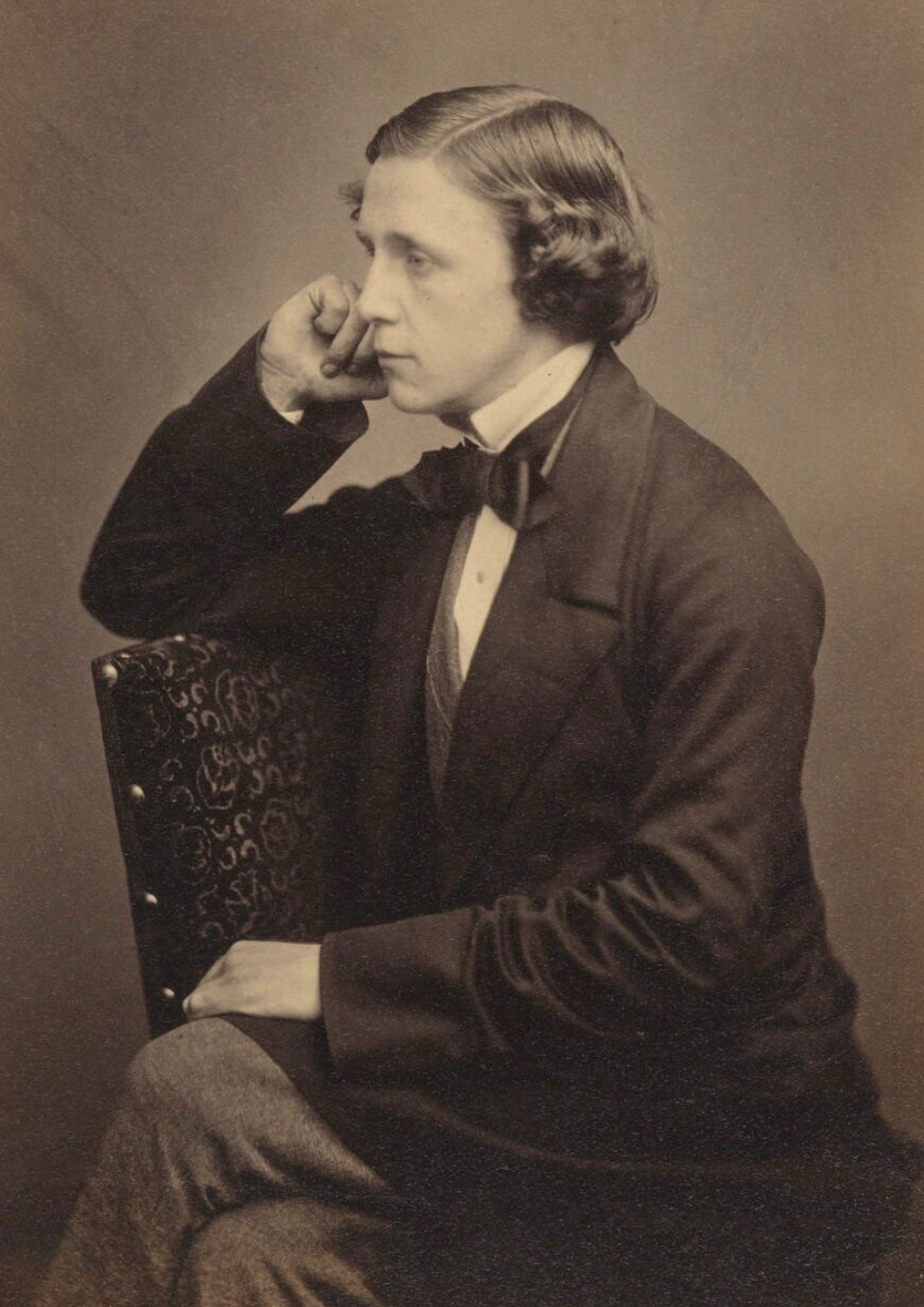

| Metrical patterns Main article: Meter (poetry)  Lewis Carroll's The Hunting of the Snark (1876) is mainly in anapestic tetrameter. Different traditions and genres of poetry tend to use different meters, ranging from the Shakespearean iambic pentameter and the Homeric dactylic hexameter to the anapestic tetrameter used in many nursery rhymes. However, a number of variations to the established meter are common, both to provide emphasis or attention to a given foot or line and to avoid boring repetition. For example, the stress in a foot may be inverted, a caesura (or pause) may be added (sometimes in place of a foot or stress), or the final foot in a line may be given a feminine ending to soften it or be replaced by a spondee to emphasize it and create a hard stop. Some patterns (such as iambic pentameter) tend to be fairly regular, while other patterns, such as dactylic hexameter, tend to be highly irregular.[66] Regularity can vary between language. In addition, different patterns often develop distinctively in different languages, so that, for example, iambic tetrameter in Russian will generally reflect a regularity in the use of accents to reinforce the meter, which does not occur, or occurs to a much lesser extent, in English.[67]  Alexander Pushkin Some common metrical patterns, with notable examples of poets and poems who use them, include: Iambic pentameter (John Milton, Paradise Lost; William Shakespeare, Sonnets)[68] Dactylic hexameter (Homer, Iliad; Virgil, Aeneid)[69] Iambic tetrameter (Andrew Marvell, "To His Coy Mistress"; Alexander Pushkin, Eugene Onegin; Robert Frost, Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening)[70] Trochaic octameter (Edgar Allan Poe, "The Raven")[71] Trochaic tetrameter (Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, The Song of Hiawatha; the Finnish national epic, The Kalevala, is also in trochaic tetrameter, the natural rhythm of Finnish and Estonian) Alexandrin (Jean Racine, Phèdre)[72] |

韻律パターン 詳細は「韻律 (詩)」を参照  ルイス・キャロルの『スナーク狩り』(1876年)は主にアナペーストテトラメーターで書かれている。 詩の伝統やジャンルによって異なる韻律が使われる傾向があり、シェイクスピアのイアンビックペンタメーターやホメーロスのダクティクヘクサメーターから、 多くの童謡で使われるアナペーストテトラメーターまで様々である。しかし、特定の脚や行に強調や注意を促したり、退屈な繰り返しを避けたりするために、確 立された韻律に多くのバリエーションが加えられることは一般的である。例えば、脚のストレスを反転させたり、中休止(またはポーズ)を追加したり(時には 脚やストレスの代わりに)、行の最後の脚を女性語的な語尾で柔らかくしたり、または強調するためにスポンディオで置き換え、強制的に停止させたりすること がある。いくつかのパターン(例えば、五歩格)はかなり規則的である傾向があるが、ダクティル六歩格のような他のパターンは、非常に不規則である傾向があ る。さらに、異なるパターンが異なる言語で際立って発達することもしばしばある。例えば、ロシア語の四歩格は、一般的に韻律を強調するアクセントの使用に 規則性が見られるが、英語では見られないか、見られるとしてもはるかに少ない程度である。  アレクサンドル・プーシキン 一般的な韻律パターンと、それを使用した詩人および詩の例を以下に示す。 イアンビック・ペンタメーター(ジョン・ミルトン『失楽園』、ウィリアム・シェイクスピア『ソネット』)[68] ダクティク・ヘクサメーター(ホメーロス『イーリアス』、ヴェルギリウス『アエネイス』)[69] イアンビック・テトラメーター(アンドリュー・マーヴェル「奥手な恋人に」、アレクサンドル・プーシキン『エフゲニー・オネーギン』、ロバート・フロスト『雪の降る日の夕暮れに森に立ち寄って』)[70] トロカイオス八歩格(エドガー・アラン・ポー、『大ガラス』)[71] トロカイオス四歩格(ヘンリー・ワズワース・ロングフェロー、『ハイアワサの歌』;フィンランドの国民叙事詩『カレワラ』もトロカイオス四歩格であり、フィンランド語やエストニア語の自然なリズムである) アレクサンドラン(ジャン・ラシーヌ、『フェードル』)[72] |

| Rhyme, alliteration, assonance Main articles: Rhyme, Alliterative verse, and Assonance The Old English epic poem Beowulf is in alliterative verse. Rhyme, alliteration, assonance and consonance are ways of creating repetitive patterns of sound. They may be used as an independent structural element in a poem, to reinforce rhythmic patterns, or as an ornamental element.[73] They can also carry a meaning separate from the repetitive sound patterns created. For example, Chaucer used heavy alliteration to mock Old English verse and to paint a character as archaic.[74] Rhyme consists of identical ("hard-rhyme") or similar ("soft-rhyme") sounds placed at the ends of lines or at locations within lines ("internal rhyme"). Languages vary in the richness of their rhyming structures; Italian, for example, has a rich rhyming structure permitting maintenance of a limited set of rhymes throughout a lengthy poem. The richness results from word endings that follow regular forms. English, with its irregular word endings adopted from other languages, is less rich in rhyme.[75] The degree of richness of a language's rhyming structures plays a substantial role in determining what poetic forms are commonly used in that language.[76] Alliteration is the repetition of letters or letter-sounds at the beginning of two or more words immediately succeeding each other, or at short intervals; or the recurrence of the same letter in accented parts of words. Alliteration and assonance played a key role in structuring early Germanic, Norse and Old English forms of poetry. The alliterative patterns of early Germanic poetry interweave meter and alliteration as a key part of their structure, so that the metrical pattern determines when the listener expects instances of alliteration to occur. This can be compared to an ornamental use of alliteration in most Modern European poetry, where alliterative patterns are not formal or carried through full stanzas. Alliteration is particularly useful in languages with less rich rhyming structures. Assonance, where the use of similar vowel sounds within a word rather than similar sounds at the beginning or end of a word, was widely used in skaldic poetry but goes back to the Homeric epic.[77] Because verbs carry much of the pitch in the English language, assonance can loosely evoke the tonal elements of Chinese poetry and so is useful in translating Chinese poetry.[78] Consonance occurs where a consonant sound is repeated throughout a sentence without putting the sound only at the front of a word. Consonance provokes a more subtle effect than alliteration and so is less useful as a structural element.[76] |

韻、頭韻、同韻 詳細は「韻」、「頭韻文」、「同韻」を参照 古英語の長編叙事詩『ベオウルフ』は頭韻文である。 韻、頭韻、母音韻、子音韻は、音の反復的なパターンを作り出す方法である。これらは詩において独立した構造的要素として、あるいはリズムパターンを強調す るものとして、あるいは装飾的な要素として用いられることがある。[73] また、これらは作り出された反復的な音のパターンとは別の意味を持つこともある。例えば、チョーサーは重厚な頭韻を用いて古英語の詩を揶揄し、登場人物を 古風に描いた。[74] 韻は、行末または行内の特定の位置(「内部韻」)に置かれる同一の音(「硬韻」)または類似の音(「軟韻」)で構成される。言語によって韻の構造の豊かさ は異なる。例えば、イタリア語は韻の構造が豊かであり、長編詩全体を通して限られた韻のセットを維持することができる。この豊かさは、規則的な形に従う語 尾に起因する。英語は他の言語から採用した不規則な語尾を持つため、韻の豊かさは劣る。[75] 言語の韻構造の豊かさは、その言語で一般的に使用される詩の形式を決定する上で重要な役割を果たす。[76] 頭韻とは、2語以上の単語の頭文字の文字または文字音が連続して繰り返されること、または短い間隔で繰り返されること、あるいは単語のアクセントのある部 分で同じ文字が繰り返されることを指す。頭韻と母音韻は、初期のゲルマン語、北欧語、古英語の詩の形式を構築する上で重要な役割を果たした。初期ゲルマン 詩の頭韻のパターンは、韻律と頭韻を構造の重要な部分として織り交ぜているため、韻律のパターンによって、聞き手が頭韻の例がいつ起こるかを予測できる。 これは、ほとんどの現代ヨーロッパ詩における装飾的な頭韻の使用と比較することができる。頭韻のパターンは形式的なものではなく、詩節全体にわたって継続 されるものではない。頭韻は、韻の構造がそれほど豊かではない言語では特に有用である。 同韻は、単語の語頭や語尾ではなく、単語内の類似した母音音の使用であり、スカルディック詩で広く使用されていたが、ホメーロスの叙事詩にまで遡る。 [77] 英語では動詞が抑揚の大部分を担うため、アソナンスは中国詩の音調的要素を大まかに想起させることができ、中国詩の翻訳に役立つ。[78] コンソナンスは、子音音が単語の語頭のみに置かれることなく、文全体を通して繰り返される場合に生じる。コンソナンスは頭韻よりも微妙な効果を引き起こす ため、構造的要素としてはあまり役立たない。[76] |

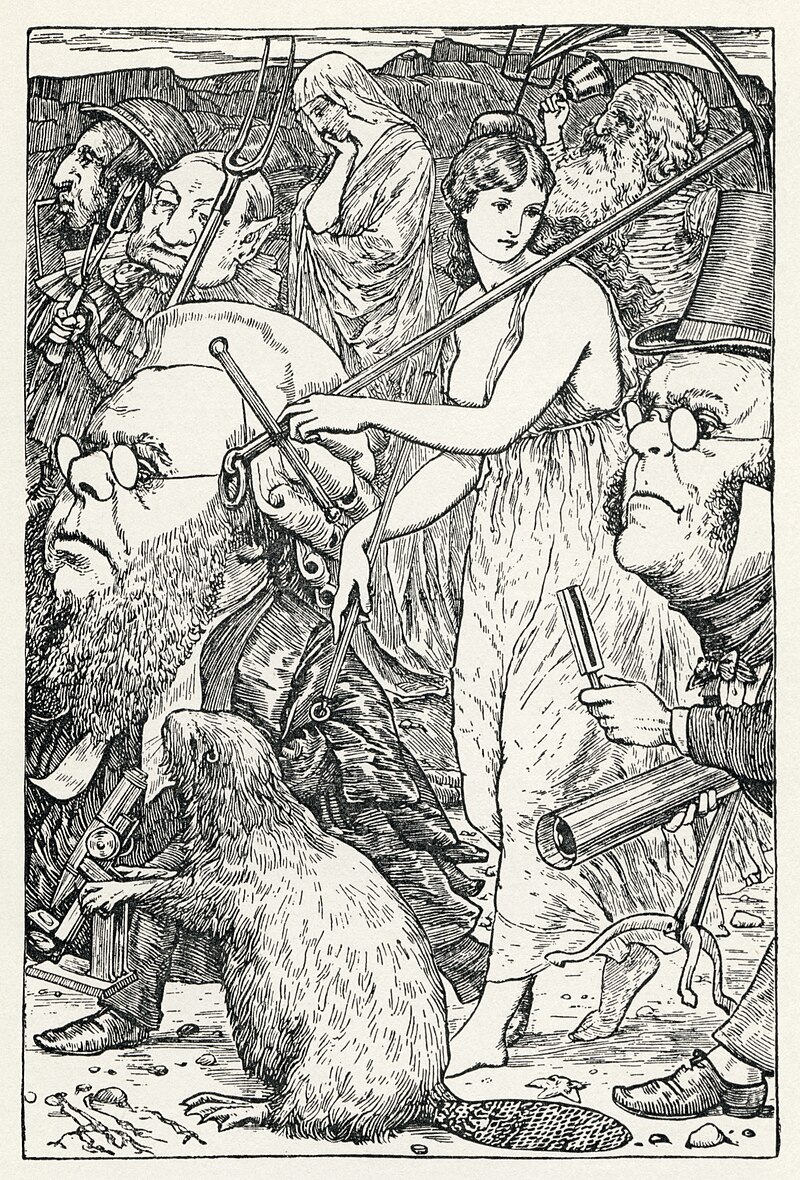

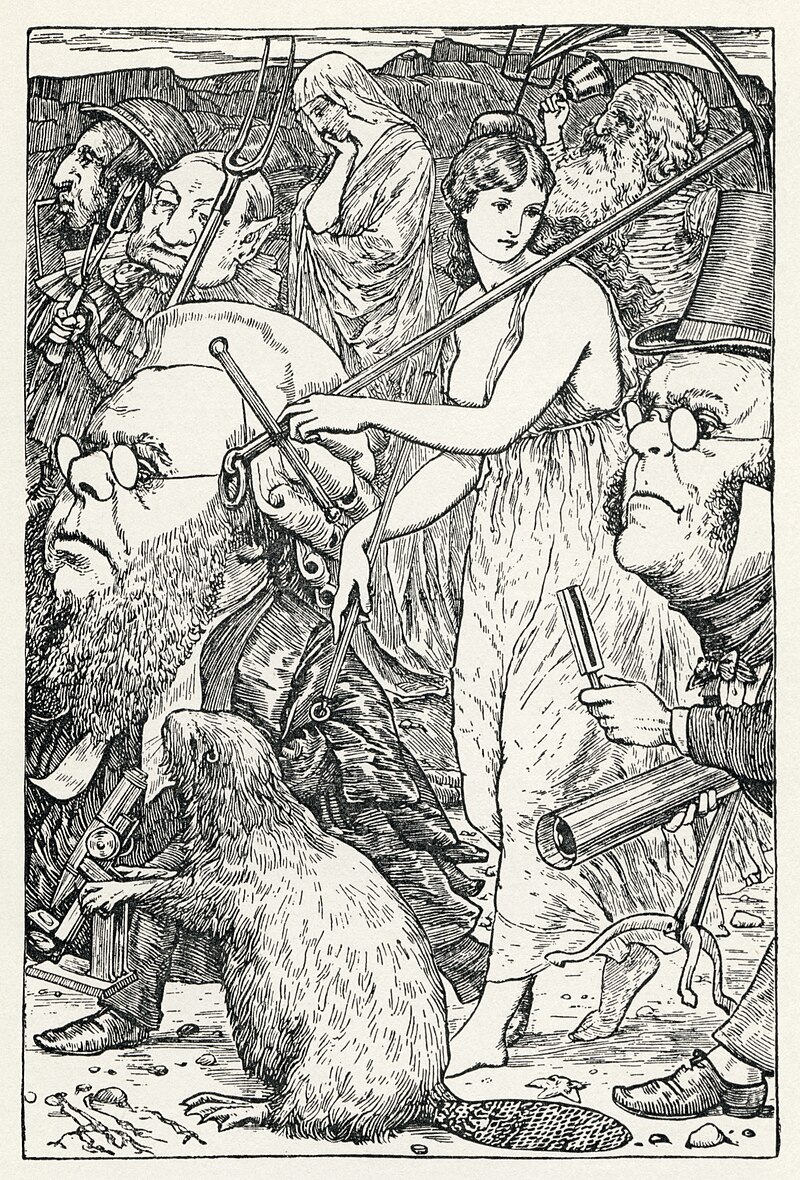

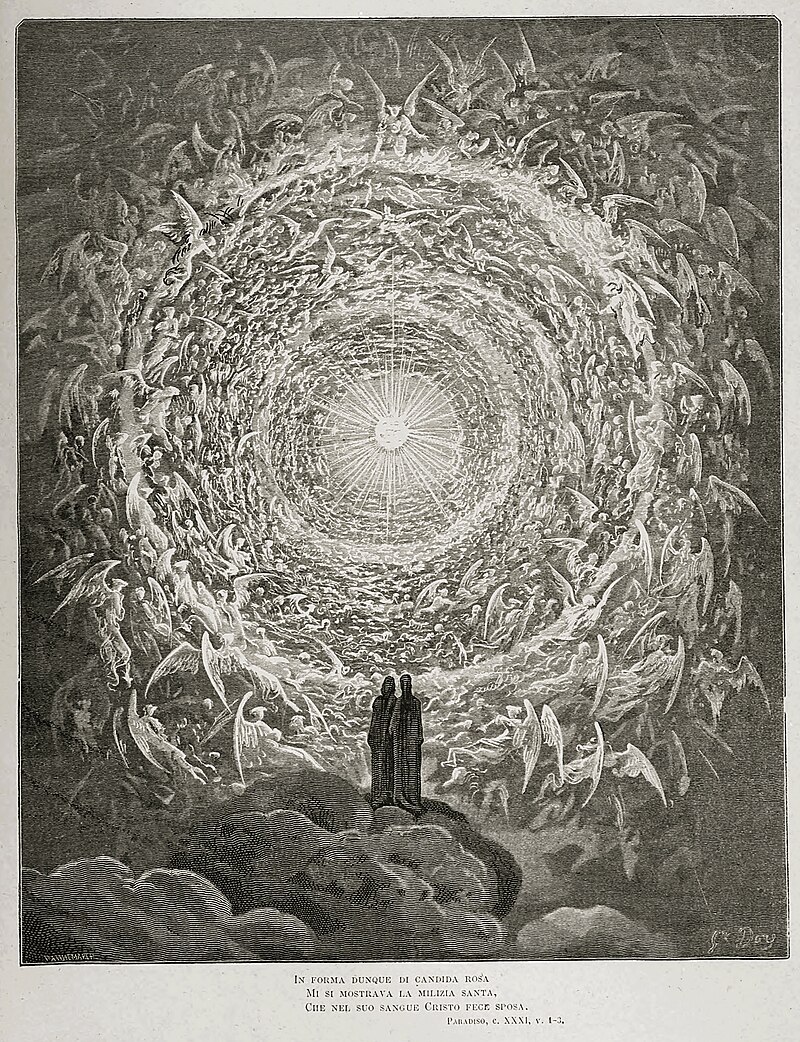

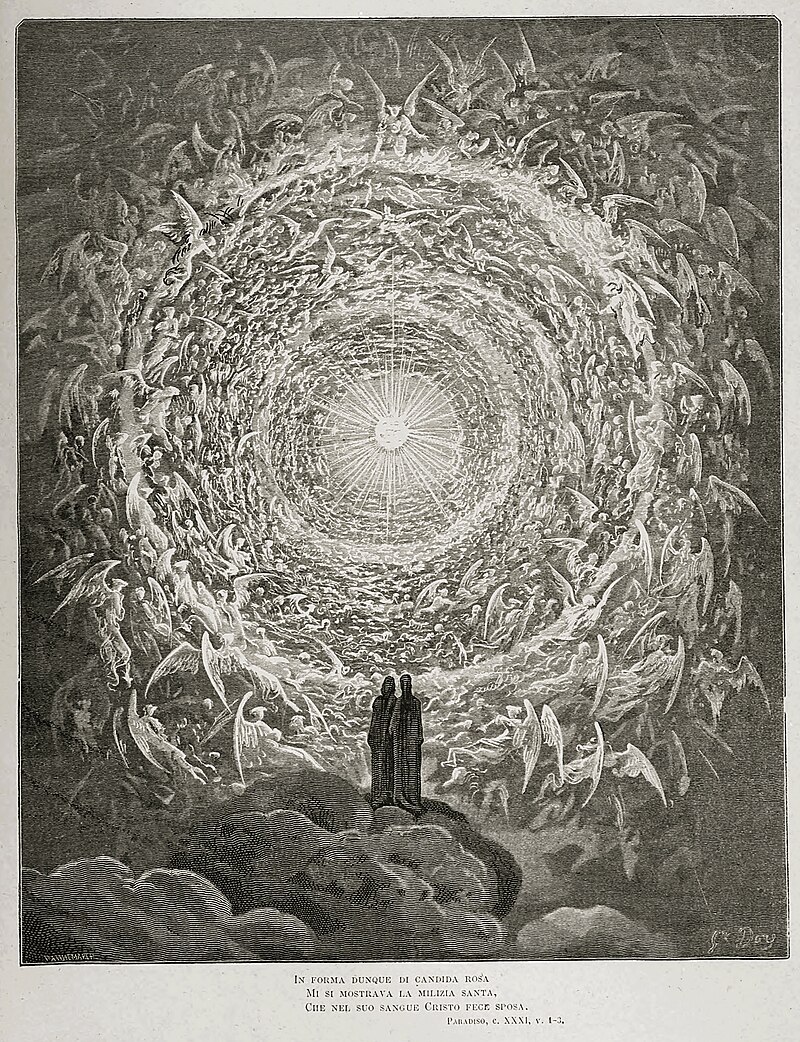

| Rhyming schemes Main article: Rhyme scheme  Divine Comedy: Dante and Beatrice see God as a point of light. In many languages, including Arabic and modern European languages, poets use rhyme in set patterns as a structural element for specific poetic forms, such as ballads, sonnets and rhyming couplets. However, the use of structural rhyme is not universal even within the European tradition. Much modern poetry avoids traditional rhyme schemes. Classical Greek and Latin poetry did not use rhyme.[79] Rhyme entered European poetry in the High Middle Ages, due to the influence of the Arabic language in Al Andalus.[80] Arabic language poets used rhyme extensively not only with the development of literary Arabic in the sixth century, but also with the much older oral poetry, as in their long, rhyming qasidas.[81] Some rhyming schemes have become associated with a specific language, culture or period, while other rhyming schemes have achieved use across languages, cultures or time periods. Some forms of poetry carry a consistent and well-defined rhyming scheme, such as the chant royal or the rubaiyat, while other poetic forms have variable rhyme schemes.[82] Most rhyme schemes are described using letters that correspond to sets of rhymes, so if the first, second and fourth lines of a quatrain rhyme with each other and the third line do not rhyme, the quatrain is said to have an AA BA rhyme scheme. This rhyme scheme is the one used, for example, in the rubaiyat form.[83] Similarly, an A BB A quatrain (what is known as "enclosed rhyme") is used in such forms as the Petrarchan sonnet.[84] Some types of more complicated rhyming schemes have developed names of their own, separate from the "a-bc" convention, such as the ottava rima and terza rima.[85] The types and use of differing rhyming schemes are discussed further in the main article. |

韻の体系 詳細は「韻の体系」を参照  神曲:ダンテとベアトリーチェは神を光の点として見る。 アラビア語や現代のヨーロッパの言語を含む多くの言語では、詩人はバラードやソネット、韻を踏んだ2行詩といった特定の詩の形式の構造要素として、一定の パターンで韻を踏む。しかし、構造的な韻の使用はヨーロッパの伝統の中でも普遍的なものではない。多くの現代詩は伝統的な韻律を避けている。古典ギリシャ 語やラテン語の詩では韻は用いられなかった。[79] 韻は、アル・アンダルスにおけるアラビア語の影響により、ヨーロッパの詩に中世盛期に登場した。[80] アラビア語の詩人たちは、6世紀に文学アラビア語が発展しただけでなく、はるかに古い口承詩とも、長い韻を踏むカシダのように、韻を広く用いた。 [81] 韻の踏み方には、特定の言語、文化、時代と関連付けられるものもあれば、言語、文化、時代を超えて用いられるものもある。詩の形式によっては、一貫した明 確な韻の踏み方を持つものもある(例えば、王の歌やルバイヤートなど)。一方、韻の踏み方が変化する詩の形式もある。[82] ほとんどの韻の仕組みは、韻のセットに対応する文字を使用して説明される。そのため、四行詩の1行目、2行目、4行目が互いに韻を踏んでおり、3行目が韻 を踏んでいない場合、その四行詩はAA BAの韻の仕組みを持つと言われる。この韻律は、例えばルバイヤート形式で用いられている。[83] 同様に、A BB Aの四行詩(「囲い韻」として知られる)は、ペトラルカのソネットのような形式で用いられている。 [84] さらに複雑な韻の規則には、「a-bc」の規則とは別に、独自の名称が付けられているものもある。例えば、オッターヴァ・リマやテルツァ・リマなどであ る。[85] 異なる韻の規則の種類や使用法については、本記事でさらに詳しく説明されている。 |

| Form in poetry Poetic form is more flexible in modernist and post-modernist poetry and continues to be less structured than in previous literary eras. Many modern poets eschew recognizable structures or forms and write in free verse. Free verse is, however, not "formless" but composed of a series of more subtle, more flexible prosodic elements.[86] Thus poetry remains, in all its styles, distinguished from prose by form;[87] some regard for basic formal structures of poetry will be found in all varieties of free verse, however much such structures may appear to have been ignored.[88] Similarly, in the best poetry written in classic styles there will be departures from strict form for emphasis or effect.[89] Among major structural elements used in poetry are the line, the stanza or verse paragraph, and larger combinations of stanzas or lines such as cantos. Also sometimes used are broader visual presentations of words and calligraphy. These basic units of poetic form are often combined into larger structures, called poetic forms or poetic modes (see the following section), as in the sonnet. |

詩における形式 詩の形式は、モダニズムやポストモダニズムの詩においてはより柔軟であり、過去の文学の時代よりも構造化されていない。多くの現代詩人は、認識できる構造 や形式を避け、自由詩で書く。しかし、自由詩は「形式のない」ものではなく、より繊細で柔軟な韻律の要素の連続で構成されている。 [86] したがって、詩はあらゆるスタイルにおいて、形式によって散文と区別される。[87] 詩の基本的な形式構造に対するある程度の配慮は、自由詩のあらゆる種類に見られる。しかし、そのような構造が度々無視されているように見えるとしてもであ る。[88] 同様に、古典的なスタイルで書かれた最良の詩には、強調や効果のために厳格な形式から逸脱する部分がある。[89] 詩で使用される主な構造要素には、行、スタンザまたは詩節、そしてスタンザや行をより大きく組み合わせたカントのようなものがある。また、言葉や書道を視 覚的により大きく表現することもある。これらの詩の基本単位は、ソネットのように、詩形または詩型(次のセクションを参照)と呼ばれるより大きな構造に組 み合わされることが多い。 |

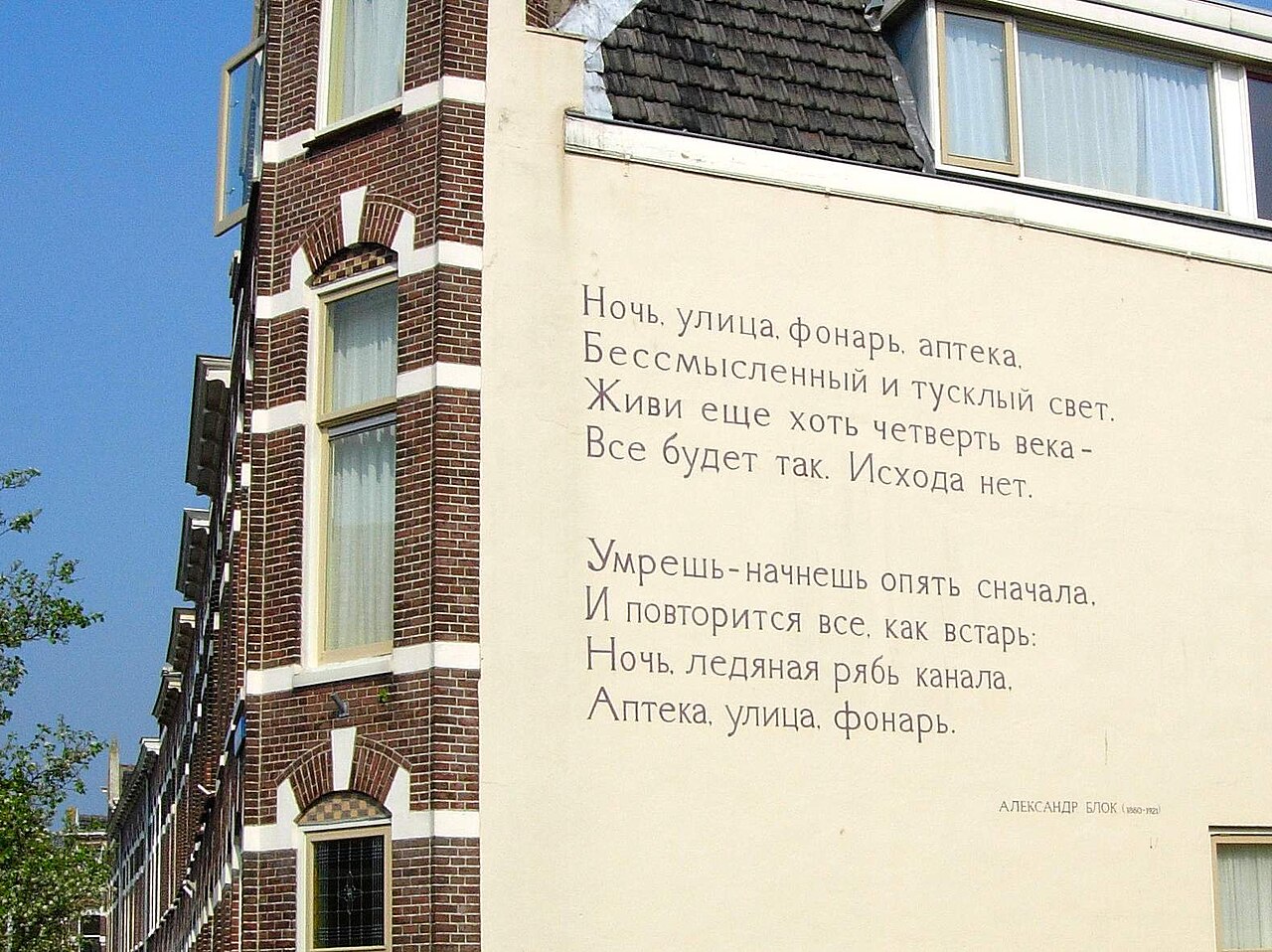

| Lines and stanzas Main articles: Line (poetry) and Stanza Poetry is often separated into lines on a page, in a process known as lineation. These lines may be based on the number of metrical feet or may emphasize a rhyming pattern at the ends of lines. Lines may serve other functions, particularly where the poem is not written in a formal metrical pattern. Lines can separate, compare or contrast thoughts expressed in different units, or can highlight a change in tone.[90] See the article on line breaks for information about the division between lines. Lines of poems are often organized into stanzas, which are denominated by the number of lines included. Thus a collection of two lines is a couplet (or distich), three lines a triplet (or tercet), four lines a quatrain, and so on. These lines may or may not relate to each other by rhyme or rhythm. For example, a couplet may be two lines with identical meters which rhyme or two lines held together by a common meter alone.[91]  Blok's Russian poem, "Noch, ulitsa, fonar, apteka" ("Night, street, lamp, drugstore"), on a wall in Leiden Other poems may be organized into verse paragraphs, in which regular rhymes with established rhythms are not used, but the poetic tone is instead established by a collection of rhythms, alliterations, and rhymes established in paragraph form.[92] Many medieval poems were written in verse paragraphs, even where regular rhymes and rhythms were used.[93] In many forms of poetry, stanzas are interlocking, so that the rhyming scheme or other structural elements of one stanza determine those of succeeding stanzas. Examples of such interlocking stanzas include, for example, the ghazal and the villanelle, where a refrain (or, in the case of the villanelle, refrains) is established in the first stanza which then repeats in subsequent stanzas. Related to the use of interlocking stanzas is their use to separate thematic parts of a poem. For example, the strophe, antistrophe and epode of the ode form are often separated into one or more stanzas.[94] In some cases, particularly lengthier formal poetry such as some forms of epic poetry, stanzas themselves are constructed according to strict rules and then combined. In skaldic poetry, the dróttkvætt stanza had eight lines, each having three "lifts" produced with alliteration or assonance. In addition to two or three alliterations, the odd-numbered lines had partial rhyme of consonants with dissimilar vowels, not necessarily at the beginning of the word; the even lines contained internal rhyme in set syllables (not necessarily at the end of the word). Each half-line had exactly six syllables, and each line ended in a trochee. The arrangement of dróttkvætts followed far less rigid rules than the construction of the individual dróttkvætts.[95] |

行と節 詳細は「行 (詩)」および「節」を参照 詩はしばしば、ページ上の行に分けられる。このプロセスは「行分け」として知られている。これらの行は、韻律の脚の数に基づいていたり、行末の韻を踏むパ ターンを強調している場合がある。行は、特に詩が定型韻律で書かれていない場合、他の機能を持つこともある。行は、異なる単位で表現された思考を区切った り、比較したり、対比させたり、あるいはトーンの変化を強調したりする。行の区切り方については、改行に関する記事を参照のこと。 詩の行はしばしばスタンザにまとめられ、その数は含まれる行の数で呼ばれる。したがって、2行の詩は対聯(または対句)、3行は三連(または三行詩)、4 行は四行詩、というように呼ばれる。これらの行は、韻やリズムによって互いに関連している場合も、そうでない場合もある。例えば、対聯は、韻を踏む同一の 韻律を持つ2行の場合もあれば、共通の韻律のみによって結びつけられた2行の場合もある。  ライデンにある壁に描かれたブロクのロシア詩「Noch, ulitsa, fonar, apteka」(「夜、通り、ランプ、薬局」) 他の詩は詩のパラグラフにまとめられる場合があり、その際には、定型の韻やリズムは用いられないが、代わりに、パラグラフ形式で確立された韻、頭韻、韻の 集合によって詩的なトーンが確立される。[92] 中世の詩の多くは、定型韻や定型リズムが用いられている場合でも、詩のパラグラフで書かれていた。[93] 多くの詩の形式では、スタンザは相互に連結しており、あるスタンザの韻の仕組みやその他の構造的要素が、その後のスタンザのそれらを決定する。このような 相互に連結したスタンザの例としては、例えば、リフレイン(ヴィラネルの場合はリフレイン)が最初のスタンザで確立され、その後のスタンザで繰り返され る、ガザルやヴィラネルが挙げられる。連節の使用に関連して、詩のテーマ部分を区切るために使用されることもある。例えば、オード形式のストローフェ、ア ンティストローフェ、エポデは、1つまたは複数の連節に分けられることが多い。 叙事詩などの特に長編の形式詩では、連節自体が厳格な規則に従って構成され、組み合わされることもある。スカルディック詩では、ドロットクヴェットのスタ ンザは8行からなり、各行には3つの「リフト」が頭韻または同韻で構成されていた。奇数行には、2つか3つの頭韻に加えて、必ずしも語頭でなくても、異な る母音を持つ子音の部分的韻が含まれていた。偶数行には、決まった音節の内部韻が含まれていた(必ずしも語尾でなくてもよい)。各行は6つの音節からな り、各行の末尾はトロチェで終わる。ドロットクヴェットの配列は、個々のドロットクヴェットの構成よりもはるかに厳格な規則に従っている。[95] |

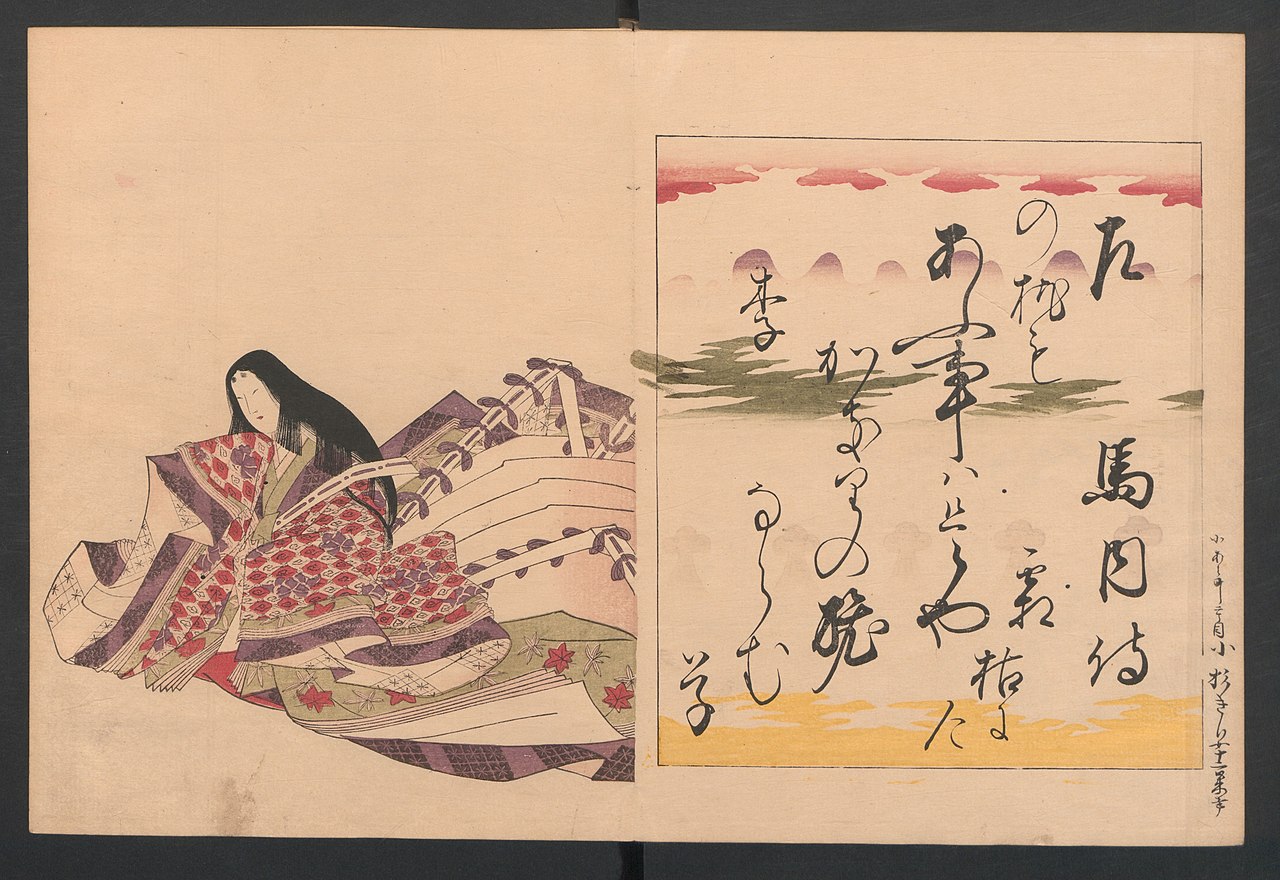

Visual presentation Poem from an anthology. Left team, Uma no naishi: "Au koto wa kore ya kagiri no tabi naramu kusa no makura mo shimogarenikeri": portrait of Ume no naishi Poetry is often written down in verse, writing structures that echo the poetic structure. This poem by Uma no Naishi is written in chirashigaki (scattered writing). The characters are deliberately written out of order. The first part of the poem is written in the third column from the right, while the second column from the right comes later in the poem.[96] Chirashigaki may also retain the order, but divide and space the characters unconventionally, with a column break partway through a poetic line or a word. This slows and delinearizes the reading process, changing the read rhythm.[97] It was also a convenient way of using expensive letter paper efficiently.[96] Main article: Visual poetry Even before the advent of printing, the visual appearance of poetry often added meaning or depth. Acrostic poems conveyed meanings in the initial letters of lines or in letters at other specific places in a poem.[98] In Arabic, Hebrew and Chinese poetry, the visual presentation of finely calligraphed poems has played an important part in the overall effect of many poems.[99] With the advent of printing, poets gained greater control over the mass-produced visual presentations of their work. Visual elements have become an important part of the poet's toolbox, and many poets have sought to use visual presentation for a wide range of purposes. Some Modernist poets have made the placement of individual lines or groups of lines on the page an integral part of the poem's composition. At times, this complements the poem's rhythm through visual caesuras of various lengths, or creates juxtapositions so as to accentuate meaning, ambiguity or irony, or simply to create an aesthetically pleasing form. In its most extreme form, this can lead to concrete poetry or asemic writing.[100][101] |

視覚的な表現 詩歌集からの詩。左陣、馬内侍「逢うことはこれや限りの旅なるかも草の枕も下がり寝」:梅乃内侍の肖像 詩歌はしばしば詩形に書き留められ、詩の構造を反映した文章構造が用いられる。この梅内氏の詩は散らし書き(ちらしがき)で書かれている。文字は意図的に 順序を無視して書かれている。詩の最初の部分は右から3番目の列に書かれており、右から2番目の列は詩の後半に書かれている。[96] 散らし書きは文字の順序を維持している場合もあるが、文字を分割し、型にはまらない方法で文字を配置し、詩行や単語の途中で改行する。これにより、読解プ ロセスが遅くなり、直線的ではなくなり、読解のリズムも変化する。[97] また、高価な便箋を効率的に使用する便利な方法でもあった。[96] 詳細は「視覚詩」を参照 印刷術が発明される以前から、詩の視覚的な外観は意味や深みを加えることが多かった。アクロスティック詩は、行頭文字や詩の特定の場所にある文字で意味を 伝えた。[98] アラビア語、ヘブライ語、中国語の詩では、精巧な書道で書かれた詩の視覚的な表現が、多くの詩の全体的な効果において重要な役割を果たしてきた。[99] 印刷術の登場により、詩人たちは自身の作品の視覚的表現を大量生産できるようになり、視覚的要素は詩人の道具箱の重要な一部となった。多くの詩人たちは視 覚的表現を幅広い目的で使用しようと試みてきた。モダニズム詩人の一部は、詩の構成において、個々の行や行のグループをページ上に配置することを不可欠な 要素とした。時には、さまざまな長さの視覚的な休止によって詩のリズムを補完したり、意味や曖昧さ、皮肉を強調したり、あるいは単に美的に美しい形を作り 出すために、行や行群を配置することもある。 極端な例としては、具体詩やアセムティック・ライティング(無意味文字)がある。[100][101] |

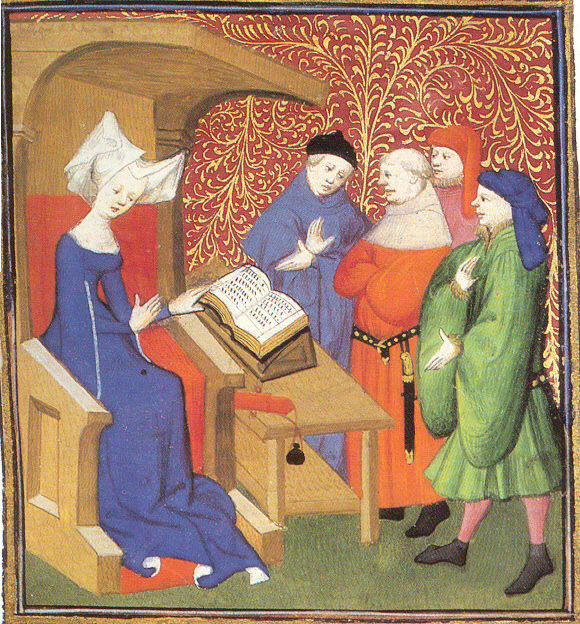

| Diction Main article: Poetic diction Poetic diction treats the manner in which language is used, and refers not only to the sound but also to the underlying meaning and its interaction with sound and form.[102] Many languages and poetic forms have very specific poetic dictions, to the point where distinct grammars and dialects are used specifically for poetry.[103][104] Registers in poetry can range from strict employment of ordinary speech patterns, as favoured in much late-20th-century prosody,[105] through to highly ornate uses of language, as in medieval and Renaissance poetry.[106] Poetic diction can include rhetorical devices such as simile and metaphor, as well as tones of voice, such as irony. Aristotle wrote in the Poetics that "the greatest thing by far is to be a master of metaphor."[107] Since the rise of Modernism, some poets have opted for a poetic diction that de-emphasizes rhetorical devices, attempting instead the direct presentation of things and experiences and the exploration of tone.[108] On the other hand, Surrealists have pushed rhetorical devices to their limits, making frequent use of catachresis.[109] Allegorical stories are central to the poetic diction of many cultures, and were prominent in the West during classical times, the late Middle Ages and the Renaissance. Aesop's Fables, repeatedly rendered in both verse and prose since first being recorded about 500 BCE, are perhaps the richest single source of allegorical poetry through the ages.[110] Other notables examples include the Roman de la Rose, a 13th-century French poem, William Langland's Piers Ploughman in the 14th century, and Jean de la Fontaine's Fables (influenced by Aesop's) in the 17th century. Rather than being fully allegorical, however, a poem may contain symbols or allusions that deepen the meaning or effect of its words without constructing a full allegory.[111] Another element of poetic diction can be the use of vivid imagery for effect. The juxtaposition of unexpected or impossible images is, for example, a particularly strong element in surrealist poetry and haiku.[112] Vivid images are often endowed with symbolism or metaphor. Many poetic dictions use repetitive phrases for effect, either a short phrase (such as Homer's "rosy-fingered dawn" or "the wine-dark sea") or a longer refrain. Such repetition can add a somber tone to a poem, or can be laced with irony as the context of the words changes.[113] |

言葉遣い 詳細は「詩的言葉遣い」を参照 詩的言葉遣いは、言語の使用法を扱うものであり、音だけでなく、その根底にある意味や音と形との相互作用にも言及する。 [102] 多くの言語や詩の形式には、非常に特異な詩的表現がある。詩のために、独特の文法や方言が使用されるほどである。[103][104] 詩における表現は、20世紀後半の韻律で好まれたように、通常の会話表現を厳密に用いるものから、中世やルネサンス期の詩のように、非常に装飾的な言語表 現まで、幅広いものがある。 詩的な表現には、修辞技法である類似や隠喩、あるいは皮肉などの声調が含まれる。 アリストテレスは『詩学』の中で、「比喩の達人になることが何よりも素晴らしい」と述べている。 [107] モダニズムの台頭以来、修辞技法を軽視し、物事や経験を直接的に表現し、トーンを探求する詩的表現を好む詩人もいる。[108] 一方、シュールレアリストたちは修辞技法を限界まで駆使し、カタクリシスを頻繁に使用した。[109] 寓話は多くの文化における詩的表現の中心であり、西洋では古典時代、中世後期、ルネサンス期に盛んに作られた。イソップ寓話は、紀元前500年頃に初めて 記録されて以来、詩や散文で繰り返し表現されてきたが、おそらくは時代を超えて最も豊かな寓話詩の源である。 [110] その他の著名な例としては、13世紀のフランス詩『バラのロマン』、14世紀のウィリアム・ラングランドの『ピエス・プロウマン』、17世紀のジャン・ ド・ラ・フォンテーヌの『寓話』(イソップの影響を受けた)などがある。しかし、詩は完全に寓話的であるというよりも、言葉の意味や効果を深める象徴や暗 示を含んでいる場合がある。 詩の表現のもう一つの要素は、効果を狙った鮮明なイメージの使用である。予期せぬ、あるいはありえないイメージの並置は、例えば、シュールレアリスム詩や 俳句において特に強い要素である。鮮明なイメージはしばしば象徴や隠喩を伴う。多くの詩的な表現では、効果を狙って短いフレーズ(ホメーロスの「バラ色の 指を持つ夜明け」や「ワインのように黒々とした海」など)や長いリフレインを繰り返し用いる。このような反復は詩に陰鬱なトーンを加えることもあれば、言 葉の文脈が変わることで皮肉が込められることもある。[113] |

| Forms See also: Category: Poetic forms  Statue of runic singer Petri Shemeikka at Kolmikulmanpuisto Park in Sortavala, Karelia Specific poetic forms have been developed by many cultures. In more developed, closed or "received" poetic forms, the rhyming scheme, meter and other elements of a poem are based on sets of rules, ranging from the relatively loose rules that govern the construction of an elegy to the highly formalized structure of the ghazal or villanelle.[114] Described below are some common forms of poetry widely used across a number of languages. Additional forms of poetry may be found in the discussions of the poetry of particular cultures or periods and in the glossary. |

フォーム 参照:カテゴリー:詩のフォーム  カレリア地方ソルタヴァラのKolmikulmanpuisto公園にあるルーン文字の歌手ペトリ・シェメイッカの像 特定の詩の形式は多くの文化によって発展してきた。より発展した、閉鎖的な、あるいは「受容された」詩の形式では、韻の踏み方、韻律、その他の詩の要素 は、エレジーの構築を司る比較的緩やかな規則から、ガザルやヴィラネルの高度に形式化された構造に至るまで、一連の規則に基づいている。[114] 以下では、多くの言語で広く使用されている詩の一般的な形式をいくつか説明する。その他の詩の形式については、特定の文化や時代の詩の議論や用語集を参照 のこと。 |

| Sonnet Main article: Sonnet  William Shakespeare Among the most common forms of poetry, popular from the Late Middle Ages on, is the sonnet, which by the 13th century had become standardized as fourteen lines following a set rhyme scheme and logical structure. By the 14th century and the Italian Renaissance, the form had further crystallized under the pen of Petrarch, whose sonnets were translated in the 16th century by Sir Thomas Wyatt, who is credited with introducing the sonnet form into English literature.[115] A traditional Italian or Petrarchan sonnet follows the rhyme scheme ABBA, ABBA, CDECDE, though some variation, perhaps the most common being CDCDCD, especially within the final six lines (or sestet), is common.[116] The English (or Shakespearean) sonnet follows the rhyme scheme ABAB CDCD EFEF GG, introducing a third quatrain (grouping of four lines), a final couplet, and a greater amount of variety in rhyme than is usually found in its Italian predecessors. By convention, sonnets in English typically use iambic pentameter, while in the Romance languages, the hendecasyllable and Alexandrine are the most widely used meters. Sonnets of all types often make use of a volta, or "turn," a point in the poem at which an idea is turned on its head, a question is answered (or introduced), or the subject matter is further complicated. This volta can often take the form of a "but" statement contradicting or complicating the content of the earlier lines. In the Petrarchan sonnet, the turn tends to fall around the division between the first two quatrains and the sestet, while English sonnets usually place it at or near the beginning of the closing couplet.  Carol Ann Duffy Sonnets are particularly associated with high poetic diction, vivid imagery, and romantic love, largely due to the influence of Petrarch as well as of early English practitioners such as Edmund Spenser (who gave his name to the Spenserian sonnet), Michael Drayton, and Shakespeare, whose sonnets are among the most famous in English poetry, with twenty being included in the Oxford Book of English Verse.[117] However, the twists and turns associated with the volta allow for a logical flexibility applicable to many subjects.[118] Poets from the earliest centuries of the sonnet to the present have used the form to address topics related to politics (John Milton, Percy Bysshe Shelley, Claude McKay), theology (John Donne, Gerard Manley Hopkins), war (Wilfred Owen, E. E. Cummings), and gender and sexuality (Carol Ann Duffy). Further, postmodern authors such as Ted Berrigan and John Berryman have challenged the traditional definitions of the sonnet form, rendering entire sequences of "sonnets" that often lack rhyme, a clear logical progression, or even a consistent count of fourteen lines. |

ソネット 詳細は「ソネット」を参照  ウィリアム・シェイクスピア 中世後期から人気のある最も一般的な詩の形式のひとつにソネットがある。13世紀までに定型化され、14行の韻律と論理構造を持つ詩となった。14世紀の イタリア・ルネサンス期には、ペトラルカの筆によって定型がさらに明確化され、ペトラルカのソネットは16世紀にサー・トマス・ワイアットによって英訳さ れ、ワイアットはソネット形式を英文学に導入した功績を認められている。 [115] 伝統的なイタリア風あるいはペトラルカ風のソネットは、韻律がABBA、ABBA、CDECDEとなっているが、特に最後の6行(またはセクステット)で は、CDCDCDという韻律が最も一般的であるが、多少のバリエーションがある。 [116] 英語(またはシェークスピアの)ソネットは、韻律はABAB CDCD EFEF GGで、3番目の四行連(4行のグループ)と最後の2行連、そしてイタリアの先行作品に通常見られるものよりも韻の変化に富んでいる。慣例として、英語の ソネットでは通常、五歩格が使用されるが、ロマンス諸語では、11音節韻とアレクサンドランが最も広く使用される韻律である。 あらゆるタイプのソネットでは、しばしば「ボルタ」または「ターン」と呼ばれる手法が用いられる。これは、詩の中で、ある考えがひっくり返ったり、質問に 答えが出たり(または質問が提示されたり)、主題がさらに複雑になったりするポイントである。この転換は、しばしば「しかし」という形で、前の行の内容を 否定したり、複雑にしたりする。ペトラルカのソネットでは、転換は最初の2つの四行詩と六行詩の区切りあたりに置かれる傾向があるが、英語のソネットで は、最後の2行の最初の行か、その近くに置かれることが多い。  キャロル・アン・ダフィー ソネットは、特に高度な詩的表現、鮮明なイメージ、そしてロマンチックな愛と関連付けられている。これは主にペトラルカの影響によるもので、また初期の英 国の実践者であるエドマンド・スペンサー(スペンサー流ソネットの名称の由来となった人物)、マイケル・ドレイトン、そしてシェイクスピアの影響によるも のである。シェイクスピアのソネットは、英語詩の中でも最も有名な作品のひとつであり、オックスフォード英語詩集には20編が収録されている。 [117] しかし、ボルタに関連する紆余曲折は、多くの主題に適用できる論理的な柔軟性を可能にする。[118] ソネットの初期の時代から現在に至るまでの詩人たちは、この形式を用いて、政治(ジョン・ミルトン、パーシー・ビッシュ・シェリー、クロード・マッケ イ)、神学(ジョン・ダン、ジェラルド・マンリー・ホプキンズ)、戦争(ウィルフレッド・オーウェン、E. E. )、ジェンダーやセクシュアリティ(キャロル・アン・ダフィー)など、さまざまなテーマを扱ってきた。さらに、テッド・ベリガンやジョン・ベリマンといっ たポストモダンの作家たちは、ソネットの伝統的な形式の定義に異議を唱え、韻を踏まず、明確な論理的展開を欠き、14行という一貫した行数でさえも守らな い「ソネット」の連作を数多く発表している。 |

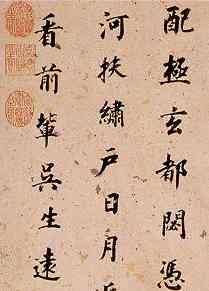

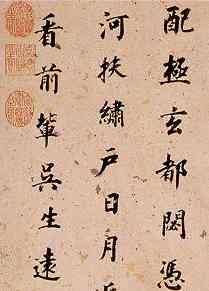

| Shi Main article: Shi (poetry)  Du Fu, "On Visiting the Temple of Laozi" Shi (simplified Chinese: 诗; traditional Chinese: 詩; pinyin: shī; Wade–Giles: shih) Is the main type of Classical Chinese poetry.[119] Within this form of poetry the most important variations are "folk song" styled verse (yuefu), "old style" verse (gushi), "modern style" verse (jintishi). In all cases, rhyming is obligatory. The Yuefu is a folk ballad or a poem written in the folk ballad style, and the number of lines and the length of the lines could be irregular. For the other variations of shi poetry, generally either a four line (quatrain, or jueju) or else an eight-line poem is normal; either way with the even numbered lines rhyming. The line length is scanned by an according number of characters (according to the convention that one character equals one syllable), and are predominantly either five or seven characters long, with a caesura before the final three syllables. The lines are generally end-stopped, considered as a series of couplets, and exhibit verbal parallelism as a key poetic device.[120] The "old style" verse (Gushi) is less formally strict than the jintishi, or regulated verse, which, despite the name "new style" verse actually had its theoretical basis laid as far back as Shen Yue (441–513 CE), although not considered to have reached its full development until the time of Chen Zi'ang (661–702 CE).[121] A good example of a poet known for his Gushi poems is Li Bai (701–762 CE). Among its other rules, the jintishi rules regulate the tonal variations within a poem, including the use of set patterns of the four tones of Middle Chinese. The basic form of jintishi (sushi) has eight lines in four couplets, with parallelism between the lines in the second and third couplets. The couplets with parallel lines contain contrasting content but an identical grammatical relationship between words. Jintishi often have a rich poetic diction, full of allusion, and can have a wide range of subject, including history and politics.[122][123] One of the masters of the form was Du Fu (712–770 CE), who wrote during the Tang Dynasty (8th century).[124] |

詩 詳細は「詩 (漢詩)」を参照  杜甫「尋訪老子廟」 詩(簡体字: 诗; 繁体字: 詩; 拼音: shī; ウェード式: shih)は、古典中国詩の主要な形式である。[119] この詩の形式の中で最も重要なバリエーションは、「民謡」スタイルの詩(越賦)、「古体」詩(古体)、「近体」詩(近体)である。いずれの場合も、韻を踏 むことが義務付けられている。「越府」は民謡または民謡スタイルの詩であり、行数や行の長さは不規則である。その他の詩のスタイルでは、通常は4行詩(四 言絶句)または8行詩が一般的であり、いずれの場合も偶数行で韻を踏む。行の長さは、文字の数(1文字が1音節に相当するという慣例に従う)によって決め られ、5文字か7文字の長さが一般的であり、最後の3音節の前に中休止がある。行は一般的に終止音で終わるが、連句の1つとして考えられており、詩の重要 な手法として言語の平行主義が用いられている。 [120] 「旧体」詩(Gushi)は「新体」詩(Jintishi)よりも形式的に厳格ではなく、新体詩という名称にもかかわらず、その理論的基礎は「旧体」詩と して遡るほど古く、実際には沈約(441年~513年)の時代に確立されたものであるが、陳子昂(661年~702年)の時代になってようやく完全に発展 したと考えられている。 [121] 律詩で知られる詩人の好例としては李白(701年-762年)が挙げられる。 そのほかの規則の中で、韻律規則は、中國中古音の四声の一定のパターンを使用することを含め、詩における声調のバリエーションを規定している。 韻律(律詩)の基本形は、4つの連が8行で構成され、第2連と第3連の行は平行になっている。対句は対照的な内容を含んでいるが、語の文法的な関係は同一 である。 ジンティシは、豊かな詩的表現や暗示に満ちていることが多く、歴史や政治など幅広い主題を取り扱うことができる。[122][123] この形式の達人の一人は、唐の時代(8世紀)に活躍した杜甫(712年-770年)である。[124] |

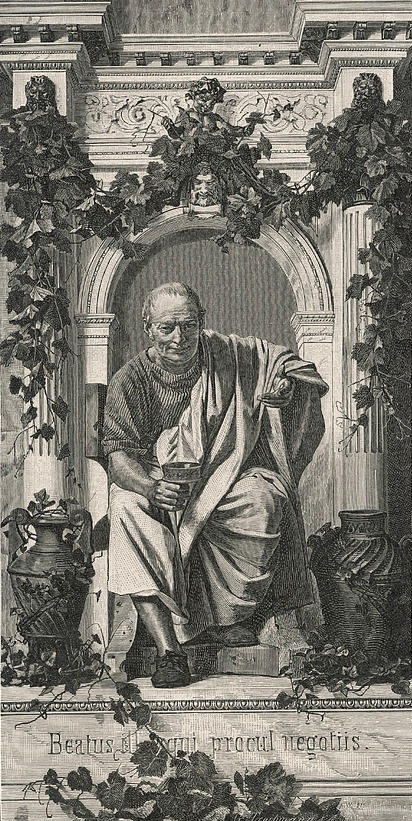

| Villanelle Main article: Villanelle  W. H. Auden The villanelle is a nineteen-line poem made up of five triplets with a closing quatrain; the poem is characterized by having two refrains, initially used in the first and third lines of the first stanza, and then alternately used at the close of each subsequent stanza until the final quatrain, which is concluded by the two refrains. The remaining lines of the poem have an AB alternating rhyme.[125] The villanelle has been used regularly in the English language since the late 19th century by such poets as Dylan Thomas,[126] W. H. Auden,[127] and Elizabeth Bishop.[128] Limerick Main article: Limerick (poetry) A limerick is a poem that consists of five lines and is often humorous. Rhythm is very important in limericks for the first, second and fifth lines must have seven to ten syllables. However, the third and fourth lines only need five to seven. Lines 1, 2 and 5 rhyme with each other, and lines 3 and 4 rhyme with each other. Practitioners of the limerick included Edward Lear, Lord Alfred Tennyson, Rudyard Kipling, Robert Louis Stevenson.[129] Tanka Main article: Tanka  Kakinomoto no Hitomaro Tanka is a form of unrhymed Japanese poetry, with five sections totalling 31 on (phonological units identical to morae), structured in a 5–7–5–7–7 pattern.[130] There is generally a shift in tone and subject matter between the upper 5–7–5 phrase and the lower 7–7 phrase. Tanka were written as early as the Asuka period by such poets as Kakinomoto no Hitomaro (fl. late 7th century), at a time when Japan was emerging from a period where much of its poetry followed Chinese form.[131] Tanka was originally the shorter form of Japanese formal poetry (which was generally referred to as "waka"), and was used more heavily to explore personal rather than public themes. By the tenth century, tanka had become the dominant form of Japanese poetry, to the point where the originally general term waka ("Japanese poetry") came to be used exclusively for tanka. Tanka are still widely written today.[132] Haiku Main article: Haiku Haiku is a popular form of unrhymed Japanese poetry, which evolved in the 17th century from the hokku, or opening verse of a renku.[133] Generally written in a single vertical line, the haiku contains three sections totalling 17 on (morae), structured in a 5–7–5 pattern. Traditionally, haiku contain a kireji, or cutting word, usually placed at the end of one of the poem's three sections, and a kigo, or season-word.[134] The most famous exponent of the haiku was Matsuo Bashō (1644–1694). An example of his writing:[135] 富士の風や扇にのせて江戸土産 fuji no kaze ya oogi ni nosete Edo miyage the wind of Mt. Fuji I've brought on my fan! a gift from Edo Khlong Main article: Thai poetry The khlong (โคลง, [kʰlōːŋ]) is among the oldest Thai poetic forms. This is reflected in its requirements on the tone markings of certain syllables, which must be marked with mai ek (ไม้เอก, Thai pronunciation: [máj èːk], ◌่) or mai tho (ไม้โท, [máj tʰōː], ◌้). This was likely derived from when the Thai language had three tones (as opposed to today's five, a split which occurred during the Ayutthaya Kingdom period), two of which corresponded directly to the aforementioned marks. It is usually regarded as an advanced and sophisticated poetic form.[136] In khlong, a stanza (bot, บท, Thai pronunciation: [bòt]) has a number of lines (bat, บาท, Thai pronunciation: [bàːt], from Pali and Sanskrit pāda), depending on the type. The bat are subdivided into two wak (วรรค, Thai pronunciation: [wák], from Sanskrit varga).[note 2] The first wak has five syllables, the second has a variable number, also depending on the type, and may be optional. The type of khlong is named by the number of bat in a stanza; it may also be divided into two main types: khlong suphap (โคลงสุภาพ, [kʰlōːŋ sù.pʰâːp]) and khlong dan (โคลงดั้น, [kʰlōːŋ dân]). The two differ in the number of syllables in the second wak of the final bat and inter-stanza rhyming rules.[136] Khlong si suphap The khlong si suphap (โคลงสี่สุภาพ, [kʰlōːŋ sìː sù.pʰâːp]) is the most common form still currently employed. It has four bat per stanza (si translates as four). The first wak of each bat has five syllables. The second wak has two or four syllables in the first and third bat, two syllables in the second, and four syllables in the fourth. Mai ek is required for seven syllables and Mai tho is required for four, as shown below. "Dead word" syllables are allowed in place of syllables which require mai ek, and changing the spelling of words to satisfy the criteria is usually acceptable. Ode Main article: Ode  Horace Odes were first developed by poets writing in ancient Greek, such as Pindar, and Latin, such as Horace. Forms of odes appear in many of the cultures that were influenced by the Greeks and Latins.[137] The ode generally has three parts: a strophe, an antistrophe, and an epode. The strophe and the antistrophe of the ode possess similar metrical structures and, depending on the tradition, similar rhyme structures. In contrast, the epode is written with a different scheme and structure. Odes have a formal poetic diction and generally deal with a serious subject. The strophe and antistrophe look at the subject from different, often conflicting, perspectives, with the epode moving to a higher level to either view or resolve the underlying issues. Odes are often intended to be recited or sung by two choruses (or individuals), with the first reciting the strophe, the second the antistrophe, and both together the epode.[138] Over time, differing forms for odes have developed with considerable variations in form and structure, but generally showing the original influence of the Pindaric or Horatian ode. One non-Western form which resembles the ode is the qasida in Arabic poetry.[139] Ghazal Main article: Ghazal The ghazal (also ghazel, gazel, gazal, or gozol) is a form of poetry common in Arabic, Bengali, Persian and Urdu. In classic form, the ghazal has from five to fifteen rhyming couplets that share a refrain at the end of the second line. This refrain may be of one or several syllables and is preceded by a rhyme. Each line has an identical meter and is of the same length.[140] The ghazal often reflects on a theme of unattainable love or divinity.[141] As with other forms with a long history in many languages, many variations have been developed, including forms with a quasi-musical poetic diction in Urdu.[142] Ghazals have a classical affinity with Sufism, and a number of major Sufi religious works are written in ghazal form. The relatively steady meter and the use of the refrain produce an incantatory effect, which complements Sufi mystical themes well.[143] Among the masters of the form are Rumi, the celebrated 13th-century Persian poet,[144] Attar, 12th century Iranian Sufi mystic poet who Rumi considered his master,[145] and their equally famous near-contemporary Hafez. Hafez uses the ghazal to expose hypocrisy and the pitfalls of worldliness, but also expertly exploits the form to express the divine depths and secular subtleties of love; creating translations that meaningfully capture such complexities of content and form is immensely challenging, but lauded attempts to do so in English include Gertrude Bell's Poems from the Divan of Hafiz[146] and Beloved: 81 poems from Hafez (Bloodaxe Books) whose Preface addresses in detail the problematic nature of translating ghazals and whose versions (according to Fatemeh Keshavarz, Roshan Institute for Persian Studies) preserve "that audacious and multilayered richness one finds in the originals".[147] Indeed, Hafez's ghazals have been the subject of much analysis, commentary and interpretation, influencing post-fourteenth century Persian writing more than any other author.[148][149] The West-östlicher Diwan of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, a collection of lyrical poems, is inspired by the Persian poet Hafez.[150][151][152] |

ヴィラネル 詳細は「ヴィラネル」を参照  W. H. オーデン ヴィラネルは、5つの3行連句と1つの4行連句からなる19行の詩である。この詩は、2つのリフレインを持つのが特徴であり、最初は第1連の第1行目と第 3行目で用いられ、その後は各連の末尾で交互に使用され、最後の4行連句で2つのリフレインが繰り返される。詩の残りの行は、AB交互韻を踏んでいる。 [125] ヴィラネルは、19世紀後半からディラン・トマス、W. H. オーデン、エリザベス・ビショップなどの詩人によって、英語で定期的に使用されてきた。[126][127][128] リメリック 詳細は「リメリック (詩)」を参照 リメリックは5行詩で、ユーモアのある詩であることが多い。 リメリックでは、1行目、2行目、5行目は7音節から10音節でなければならないため、韻律が非常に重要である。 しかし、3行目と4行目は5音節から7音節でよい。 1行目、2行目、5行目は互いに韻を踏んでおり、3行目と4行目も互いに韻を踏んでいる。リメリックの実践者には、エドワード・リア、アルフレッド・テニ スン、ラドヤード・キップリング、ロバート・ルイス・スティーブンソンなどがいる。 短歌 詳細は「短歌」を参照  柿本人麻呂 短歌は、5つのセクションからなり、それぞれが31音節(モーラと音韻単位が同一)で構成され、5-7-5-7-7のパターンで韻を踏まない日本語の詩で ある。一般的に、上部の5-7-5のフレーズと下部の7-7のフレーズの間には、トーンと主題の変化がある。短歌は、日本が中国風の詩の時代から脱却しつ つあった飛鳥時代に、柿本人麻呂(7世紀後半に活躍)などの詩人によってすでに作られていた。[131] 短歌は、もともと和歌(日本の形式的な詩)の短い形式であり、公的なテーマよりも個人的なテーマを追求するために多く使われていた。10世紀までに、短歌 は日本の詩の主流となり、当初は一般的な用語であった「和歌(「日本の詩」)」が、もっぱら短歌を指すようになった。今日でも短歌は広く詠まれている。 俳句 詳細は「俳句」を参照 俳句は、韻を踏まない日本語の詩の一般的な形式であり、17世紀に連句の冒頭の句である発句から発展したものである。通常は縦に1行で書かれ、5-7-5 のパターンで構成された合計17音(モーラ)の3つのセクションから成る。伝統的に、俳句には切れ字(句切り)が含まれ、通常は詩の3つのセクションのう ちの1つの最後に置かれる。また、季語(季節を表す言葉)も含まれる。[134] 俳句の最も有名な提唱者は松尾芭蕉(1644年-1694年)である。彼の作品の例:[135] 富士の風や扇にのせて江戸土産 fuji no kaze ya oogi ni nosete Edo miyage 富士の風や扇にのせて江戸土産 富士の風を 扇に載せて持って来たよ。 江戸土産だ 詳細は「タイの詩」を参照 クロン(タイ語:โคลง、[kʰlōːŋ])はタイの詩の最も古い形式のひとつである。これは、特定の音節の声調記号に関する要件に反映されており、 mai ek(ไม้เอก、タイ語発音:[máj èːk]、◌่)またはmai tho(ไม้โท、[máj tʰōː]、◌้)でマークする必要がある。これは、タイ語に3つのトーン(現在の5つとは対照的であり、アユタヤ王国時代に分岐した)があったことに由 来する可能性が高い。そのうちの2つは、前述の記号に直接対応している。通常、高度で洗練された詩の形式とみなされている。[136] クロンでは、スタンザ(タイ語発音:[bòt]、ボット)は種類によっていくつかの行(タイ語発音:[bàːt]、パーリ語およびサンスクリット語の pāda)に分かれる。バットはさらに2つのワック(วรรค、タイ語発音:[wák]、サンスクリット語のヴァルガに由来)に細分される。[注2] 最初のワックは5つの音節を持ち、2番目のワックは種類によって異なる可変の音節を持ち、省略されることもある。クロンの種類は、節に含まれるコウモリの 数によって名付けられる。また、大きく2つの種類に分けられる。クロンスーパップ(khlong suphap、[kʰlōːŋ sù.pʰâːp])とクロンダン(khlong dan、[kʰlōːŋ dân])である。この2つは、最後のバットの2番目のワックの音節数と、詩節間の韻の規則が異なる。[136] クロンスーパップ クロンスーサップ(khlong si suphap、[kʰlōːŋ sìː sù.pʰâːp])は現在でもっとも一般的に用いられている形式である。これは1つのスタンザにつき4つのバット(siは4と訳される)から成る。各 バットの最初のワックは5つの音節を持つ。2番目のワックは、最初のバットと3番目のバットでは2音節または4音節、2番目のバットでは2音節、4番目の バットでは4音節である。7音節の場合はMai ek、4音節の場合はMai thoが必要である。以下に例を示す。「死語」の音節は、Mai ekが必要な音節の代わりに使用することができ、基準を満たすように単語の綴りを変更することは通常認められている。 オード 詳細は「オード」を参照  ホラティウス オードは、ピンダロスなどの古代ギリシア語や、ホラティウスなどのラテン語で詩を書く詩人たちによって最初に発展した。オードの形式は、ギリシア人やラテ ン人に影響を受けた多くの文化に見られる。[137] オードは一般的に3つの部分から構成される。すなわち、ストロフェ、アンティストロフェ、エポデである。オードのストロフェとアンチストロフェは同様の韻 律構造を持ち、伝統によっては同様の韻構造を持つ。対照的に、エポデは異なる構成と構造で書かれる。オードは形式的な詩的表現を持ち、一般的に深刻な主題 を扱う。ストロフェとアンチストロフェは主題を異なる視点、しばしば相反する視点から捉え、エポデはより高いレベルに移動して、根底にある問題を観察また は解決する。オードは、2つのコーラス(または個人)によって朗読または歌唱されることが多い。最初のコーラスがストローフェを、2番目のコーラスがアン ティストローフェを朗読し、両者が一緒にエポデを朗読する。[138] 時が経つにつれ、オードの形式は、形式や構造にかなりのバリエーションがあるものの、一般的にピンダロスやホラティウスのオードの影響を受けている。西洋 以外の詩の形式で、odeに似たものとしては、アラビア詩のqasidaがある。[139] Ghazal 詳細は「Ghazal」を参照 Ghazal(ghazel、gazel、gazal、またはgozolとも)は、アラビア語、ベンガル語、ペルシア語、ウルドゥー語で一般的な詩の形式 である。古典的な形式では、ガザルは5から15の韻を踏む2行詩からなり、2行目の末尾にリフレインが繰り返される。このリフレインは1音節または複数音 節で構成され、韻を踏む。各行は同一の韻律で、同じ長さである。[140] ガザルはしばしば、叶わぬ愛や神性をテーマにしている。[141] 多くの言語で長い歴史を持つ他の形式と同様に、ウルドゥー語における音楽的な詩的表現を含む形式など、多くのバリエーションが発展してきた。[142] ガザルはスーフィズムと古典的な親和性があり、多くの主要なスーフィーの宗教的作品がガザル形式で書かれている。比較的安定した韻律とリフレインの使用 は、呪文のような効果を生み出し、スーフィーの神秘的なテーマをうまく補っている。[143] この形式の達人には、13世紀の著名なペルシア人詩人ルーミー[144]、ルーミーが師と仰いだ12世紀のイラン人スーフィー神秘主義詩人アタール [145]、そして彼らとほぼ同時代のハフェズがいる。ハーフェズは、偽善と俗世の落とし穴を暴くためにガザルを用いたが、同時に、神聖な愛の深さと世俗 的な愛の機微を表現するために、この形式を巧みに利用した。このような内容と形式の複雑さを意味深く捉えた翻訳を創作することは非常に困難であるが、英語 による試みとしては、ガートルード・ベルの『ハーフィズのディヴァンからの詩』[146]や『最愛の人: 81の詩(Bloodaxe Books)の序文では、ガザルの翻訳における問題の多い性質について詳細に論じられており、その版(ペルシア語研究ロシャン研究所のファテメ・ケシャ ヴァーズ氏によると)では、「オリジナルに見られる大胆かつ多層的な豊かさ」が保たれている。 [147] 実際、ハーフェズのガザルは多くの分析、論評、解釈の対象となっており、14世紀以降のペルシア語の著作に他のどの作家よりも大きな影響を与えている。 [148][149] ヨハン・ヴォルフガング・フォン・ゲーテの『西東のディヴァン』は、叙情詩のコレクションであり、ペルシアの詩人ハーフェズからインスピレーションを受け ている。[150][151][152] |