プロレゴメナ

学として現れるであろうあらゆる将来の形而上学のためのプロレゴメナ

Prolegomena zu einer jeden künftigen Metaphysik, die als Wissenschaft wird auftreten können

☆『学(Wissenshaft)として現れることのできるあらゆる将来の形而上学のための序説』(独: Prolegomena zu einer jeden künftigen Metaphysik, die als Wissenschaft wird auftreten können)は、ドイツの哲学者イマヌエル・カントによる著作である。1783年に出版され、『純粋理性批判』初版から2年後のことである。カントの比 較的短い著作の一つであり、『純粋理性批判』の主要な結論を要約している。その中には『批判』では用いられなかった論証も含まれる。カントはここで、より 理解しやすいアプローチを「分析的」と特徴づけ、『批判』における「合成的」な方法、すなわち精神の諸能力とその原理を順次検討する手法と対比させてい る。[1]本書は論争を意図したものでもある。カントは『純粋理性批判』の受けが思わしくなかったことに失望しており、ここでは批判的プロジェクトが形而 上学という 科学の存在そのものにとって重要だと繰り返し強調している。末尾の付録には『純粋理性批判』に対する否定的な書評への反論が収められている(→カント『プロレゴメナ(全文)』)。

Prolegomena to any future metaphysics that will be able to come forward as science : with selections from the Critique of pure reason / Immanuel Kant ; translated and edited by Gary Hatfield, Cambridge ; New York : Cambridge University Press , 2004. - (Cambridge texts in the history of philosophy)[pdf]

| Prolegomena

to Any Future Metaphysics That Will Be Able to Present Itself as a

Science [pdf](German: Prolegomena zu einer jeden künftigen Metaphysik,

die als Wissenschaft wird auftreten können) is a book by the German

philosopher Immanuel Kant, published in 1783, two years after the first

edition of his Critique of Pure Reason. One of Kant's shorter works, it

contains a summary of the Critique‘s main conclusions, sometimes by

arguments Kant had not used in the Critique. Kant characterizes his

more accessible approach here as an "analytic" one, as opposed to the

Critique‘s "synthetic" examination of successive faculties of the mind

and their principles.[1] The book is also intended as a polemic. Kant was disappointed by the poor reception of the Critique of Pure Reason, and here he repeatedly emphasizes the importance of its critical project for the very existence of metaphysics as a science. The final appendix contains a response to an unfavorable review of the Critique. |

『科学(Science)として現れることのできるあらゆる将来の形而上学のための序説』

(独: Prolegomena zu einer jeden künftigen Metaphysik, die als

Wissenschaft wird auftreten

können)は、ドイツの哲学者イマヌエル・カントによる著作である。1783年に出版され、『純粋理性批判』初版から2年後のことである。カントの比

較的短い著作の一つであり、『純粋理性批判』の主要な結論を要約している。その中には『批判』では用いられなかった論証も含まれる。カントはここで、より

理解しやすいアプローチを「分析的」と特徴づけ、『批判』における「合成的」な方法、すなわち精神の諸能力とその原理を順次検討する手法と対比させてい

る。[1] 本書は論争を意図したものでもある。カントは『純粋理性批判』の受けが思わしくなかったことに失望しており、ここでは批判的プロジェクトが形而上学という 科学の存在そのものにとって重要だと繰り返し強調している。末尾の付録には『純粋理性批判』に対する否定的な書評への反論が収められている。 |

| Contents Introduction Kant declared that the Prolegomena are for the use of both learners and teachers as an heuristic way to discover a science of metaphysics. Unlike other sciences, metaphysics has not yet attained universal and permanent knowledge. There are no standards to distinguish truth from error. Kant asked, "Can metaphysics even be possible?" David Hume investigated the problem of the origin of the concept of causality. Is the concept of causality truly independent of experience or is it learned from experience? Hume mistakenly attempted to derive the concept of causality from experience. He thought that causality was really based on seeing two objects that were always together in past experience. If causality is not dependent on experience, however, then it may be applied to metaphysical objects, such as an omnipotent God or an immortal soul. Kant claimed to have logically deduced how causality and other pure concepts originate from human understanding itself, not from experiencing the external world. Unlike the Critique of Pure Reason, which was written in the synthetic style, Kant wrote the Prolegomena using the analytical method. He divided the question regarding the possibility of metaphysics as a science into three parts. In so doing, he investigated the three problems of the possibility of pure mathematics, pure natural science, and metaphysics in general. His result allowed him to determine the bounds of pure reason and to answer the question regarding the possibility of metaphysics as a science. |

目次 序論 カントは『形而上学序説』が、形而上学という学問を発見するための発見的手法として、学習者と教師双方のためにあると宣言した。他の学問とは異なり、形而 上学は未だ普遍的かつ恒久的な知識に到達していない。真偽を区別する基準は存在しない。カントは問うた。「形而上学はそもそも可能なのか?」 デイヴィッド・ヒュームは因果性の概念の起源の問題を調査した。因果性の概念は経験から独立しているのか、それとも経験から学ぶものなのか?ヒュームは 誤って因果性の概念を経験から導こうとした。彼は因果性が実際には過去の経験において常に共存する二つの対象を観察することに基づくと考えた。しかし因果 性が経験に依存しないならば、それは全能の神や不滅の魂といった形而上学的対象にも適用できる。カントは因果性や他の純粋概念が外部世界の経験からではな く、人間の理解力そのものからいかに論理的に導かれるかを示したと主張した。 『純粋理性批判』が総合的な様式で書かれたのとは異なり、カントは『プロレゴメナ』を分析的方法を用いて執筆した。彼は形而上学が科学として成立しうる可 能性に関する問題を三つの部分に分けた。そうすることで、純粋数学、純粋自然科学、そして形而上学一般の三つの可能性に関する問題を調査したのである。そ の結果、彼は純粋理性の限界を決定し、形而上学が科学として成立しうる可能性に関する問題に答えることができた。 |

| Preamble on the peculiarities of

all metaphysical knowledge § 1. On the sources of metaphysics Metaphysical principles are a priori in that they are not derived from external or internal experience. Metaphysical knowledge is philosophical cognition that comes from pure understanding and pure reason. § 2. Concerning the kind of knowledge which can alone be called metaphysical a. On the distinction between analytical and synthetical judgments in general Analytical judgments are explicative. They express nothing in the predicate but what has already been actually thought in the concept of the subject. Synthetical judgments are expansive. The predicate contains something that is not actually thought in the concept of the subject. It amplifies knowledge by adding something to the subject's concept. b. The common principle of all analytical judgments is the law of contradiction The predicate of an affirmative analytical judgment is already contained in the concept of the subject, of which it cannot be denied without contradiction. All analytical judgments are a priori. c. Synthetical judgments require a principle that is different from the law of contradiction. 1. Judgments of experience are always synthetical. Analytical judgments are not based on experience. They are based merely on the subject's concept. 2. Mathematical judgments are all synthetical. Pure mathematical knowledge is different from all other a priori knowledge. It is synthetical and cannot be known from mere conceptual analysis. Mathematics require the intuitive construction of concepts. This intuitive construction implies an a priori view of the concept constructed in the mind. In the Critique of Pure Reason, Kant elaborates on this, explaining that "to construct a concept means to exhibit a priori the intuition corresponding to it.”[2] Arithmetical sums are the result of the addition of intuited counters. Geometrical concepts, such as "shortest distance," are known only through exhibiting the concept in pure intuition. 3. Metaphysical judgments, properly so called, are all synthetical. Concepts and judgments pertaining to metaphysics may be analytical. These may not be metaphysical but can be combined to make a priori, synthetical, metaphysical judgments. For example, the analytical judgment "substance only exists as subject" can be used to make the judgment "all substance is permanent," which is a synthetical and properly metaphysical judgment. |

形而上学的知識の特異性に関する序説 § 1. 形而上学の源泉について 形而上学的原理は、外的あるいは内的経験から導かれるものではないという点で、ア・プリオリに属する。形而上学的知識とは、純粋な理解力と純粋な理性から 生じる哲学的認識である。 § 2. 形而上学と呼べる唯一の知識の種類について a. 分析的判断と総合的判断の一般的な区別について 分析的判断は説明的である。それは主語の概念において既に実際に考えられているものを、述語において何も表現しない。総合的判断は拡張的である。述語は主 語の概念において実際に考えられていない何かを含む。それは主語の概念に何かを加えることで知識を拡大する。 b. すべての分析的判断に共通する原理は矛盾律である 肯定的分析的判断の述語は、主語の概念に既に含まれており、矛盾なくして否定することはできない。すべての分析的判断はア・プリオリに。 c. 合成的判断には、矛盾律とは異なる原理が必要である。 1. 経験的判断は常に合成的である。 分析的判断は経験に基づかない。単に主体の概念に基づいている。 2. 数学的判断は全て総合的である。 純粋数学的知識は他のあらゆるア・プリオリに知識とは異なる。それは総合的であり、単なる概念分析からは知り得ない。数学は概念の直観的構築を必要とす る。この直観的構築は、心の中で構築される概念に対するア・プリオリな見解を意味する。『純粋理性批判』においてカントはこれを詳述し、「概念を構築する とは、それに対応する直観をア・プリオリに提示することを意味する」と説明している[2]。算術的和は直観された算用単位の加算の結果である。「最短距 離」のような幾何学的概念は、純粋直観において概念を提示することによってのみ知られる。 3. 真に形而上学的と呼ばれる判断は全て合成的である。 形而上学に属する概念や判断は分析的である場合がある。これらは形而上学的ではないが、組み合わせてア・プリオリに・総合的・形而上学的な判断を形成し得 る。例えば「実体は主観としてのみ存在する」という分析的判断は、「全ての物質は永続的である」という判断を形成するのに用いられ得る。これは総合的かつ 真に形而上学的な判断である。 |

| § 3. A remark on the general

division of judgment into analytical and synthetical. This division is critical but has not been properly recognized by previous philosophers. § 4. The general question of the Prolegomena: Is metaphysics at all possible? The Critique of Pure Reason investigates this question synthetically. In it, an abstract examination of the concepts of the sources of pure reason results in knowledge of the actual science of metaphysics. The Prolegomena, on the other hand, starts with the known fact that there is actual synthetic a priori metaphysical knowledge of pure mathematics and pure natural science. From this knowledge, analytically, we arrive at the sources of the possibility of metaphysics. § 5. The general problem: How is knowledge from pure reason possible? By using the analytical method, we start from the fact that there are actual synthetic a priori propositions and then inquire into the conditions of their possibility. In so doing, we learn the limits of pure reason. |

§ 3.

判断を分析的判断と総合的判断に一般に分けることについての所見。 この区分は重要であるが、過去の哲学者たちによって適切に認識されてこなかった。 § 4. 『序説』の根本的な問い:形而上学はそもそも可能なのか? 『純粋理性批判』はこの問題を総合的に検討する。そこでは、純粋理性の源泉となる概念の抽象的考察が、形而上学という実在する科学の知識へと至る。一方 『プロレゴメナ』は、純粋数学と純粋自然科学において実在する総合的ア・プリオリ形而上学的知識が存在するという既知の事実から出発する。この知識から、 分析的に形而上学の可能性の源泉へと到達するのである。 § 5. 一般的課題:純粋理性による知識は如何にして可能か? 分析的方法を用いることで、我々は現実の総合的ア・プリオリな命題が存在するという事実から出発し、その可能性の条件を探求する。そうすることで、純粋理 性の限界を学ぶのである。 |

| Part one of the main

transcendental problem. How is pure mathematics possible? § 6. Mathematics consists of synthetic a priori knowledge. How was it possible for human reason to produce such a priori knowledge? If we understand the origins of mathematics, we might know the basis of all knowledge that is not derived from experience. § 7. All mathematical knowledge consists of concepts that are derived from intuitions. These intuitions, however, are not based on experience. § 8. How is it possible to intuit anything a priori? How can the intuition of the object occur before the experience of the object? § 9. My intuition of an object can occur before I experience an object if my intuition contains only the mere form of sensory experience. § 10. We can intuit things a priori only through the mere form of sensuous intuition. In so doing, we can only know objects as they appear to us, not as they are in themselves, apart from our sensations. Mathematics is not an analysis of concepts. Mathematical concepts are constructed from a synthesis of intuitions. Geometry is based on the pure intuition of space. The arithmetical concept of number is constructed from the successive addition of units in time. Pure mechanics uses time to construct motion. Space and time are pure a priori intuitions. They are the mere forms of our sensations and exist in us prior to all of our intuitions of objects. Space and time are a priori knowledge of a sensed object as it appears to an observer. § 11. The problem of a priori intuition is solved. The pure a priori intuition of space and time is the basis of empirical a posteriori intuition. Synthetic a priori mathematical knowledge refers to empirically sensed objects. A priori intuition relates to the mere form of sensibility; it makes the appearance of objects possible. The a priori form of a phenomenal object is space and time. The a posteriori matter of a phenomenal object is sensation, which is not affected by pure, a priori intuition. The subjective a priori pure forms of sensation, namely space and time, are the basis of mathematics and of all of the objective a posteriori phenomena to which mathematics refers. § 12. The concept of pure, a priori intuition can be illustrated by geometrical congruence, the three–dimensionality of space, and the boundlessness of infinity. These cannot be shown or inferred from concepts. They can only be known through pure intuition. Pure mathematics is possible because we intuit space and time as the mere form of phenomena. |

超越論の問題の第一部。純粋数学は如何にして可能か? § 6. 数学は合成的ア・プリオリに知識から成る。人間の理性が如何にしてこのようなア・プリオリに知識を生み出せたのか?数学の起源を理解すれば、経験に由来し ない全ての知識の基盤を知ることができるかもしれない。 § 7. あらゆる数学的知識は直観から派生した概念から成る。しかしこれらの直観は経験に基づかない。 § 8. 事物をア・プリオリに直観することはどうして可能なのか?対象の直観が対象の経験に先立って生じうるのか? § 9. 対象の直観が対象の経験に先立って生じうる場合、その直観が感覚的経験の単なる形式のみを含む場合に限られる。 § 10. 我々は感覚的直観の単なる形式を通じてのみ、事物をア・プリオリに直観しうる。そうすることで、我々は対象を、感覚から切り離された「それ自体」としてで はなく、我々に現れるままにしか知ることができない。数学は概念の分析ではない。数学的概念は直観の総合から構築される。幾何学は空間の純粋直観に基づ く。算術的概念である数は、時間における単位の連続的加算から構築される。純粋力学は時間を用いて運動を構築する。空間と時間は、ア・プリオリに純粋な先 天的直観である。それらは我々の感覚の単なる形式であり、あらゆる対象の直観に先立って我々に存在する。空間と時間は、観察者に現れる感覚対象の先天的認 識である。 § 11. 先天的直観の問題は解決された。空間と時間の純粋なア・プリオリな先天的直観は、経験的ア・ポステリオリな直観の基盤である。合成的先天的数学的認識は、 経験的に感覚される対象を指す。ア・プリオリに直観は単なる感覚の形式に関わる。それは対象の出現を可能にする。現象的対象の先天的形式は空間と時間であ る。現象的対象のア・ポステリオリな内容は感覚であり、これは純粋なア・プリオリな直観の影響を受けない。感覚の主観的ア・プリオリな純粋形式、すなわち 空間と時間は、数学および数学が指し示す全ての客観的ア・ポステリオリな現象の基礎である。 § 12. 純粋ア・プリオリな直観の概念は、幾何学的合同、空間の三次元性、無限の無限性によって説明できる。これらは概念から示したり推論したりすることはできな い。純粋直観によってのみ知ることができる。純粋数学が可能であるのは、我々が現象の単なる形式として空間と時間を直観するからである。 |

| § 13. The difference between

similar things which are not congruent cannot be made intelligible by

understanding and thinking about any concept. They can only be made

intelligible by being intuited or perceived. For example, the

difference of chirality is of this nature. So, also, is the difference

seen in mirror images. Right hands and ears are similar to left hands

and ears. They are not, however, congruent. These objects are not

things as they are apart from their appearance. They are known only

through sensuous intuition. The form of external sensible intuition is

space. Time is the form of internal sense. Time and space are mere

forms of our sense intuition and are not qualities of things in

themselves apart from our sensuous intuition. Remark I. Pure mathematics, including pure geometry, has objective reality when it refers to objects of sense. Pure mathematical propositions are not creations of imagination. They are necessarily valid of space and all of its phenomenal objects because a priori mathematical space is the foundational form of all a posteriori external appearance. Remark II. Berkeleian Idealism denies the existence of things in themselves. The Critique of Pure Reason, however, asserts that it is uncertain whether or not external objects are given, and we can only know their existence as a mere appearance. Unlike Locke's view, space is also known as a mere appearance, not as a thing existing in itself.[3] Remark III. Sensuous knowledge represents things only in the way that they affect our senses. Appearances, not things as they exist in themselves, are known through the senses. Space, time, and all appearances in general are mere modes of representation. Space and time are ideal, subjective, and exist a priori in all of our representations. They apply to all of the objects of the sensible world because these objects exist as mere appearances. Such objects are not dreams or illusions, though. The difference between truth and dreaming or illusion depends on the connection of representations according to rules of true experience. A false judgment can be made if we take a subjective representation as being objective. All the propositions of geometry are true of space and all of the objects that are in space. Therefore, they are true of all possible experience. If space is considered to be the mere form of sensibility, the propositions of geometry can be known a priori concerning all objects of external intuition. |

§ 13.

互いに一致しない類似物間の差異は、いかなる概念を理解し思考することによっても明瞭にすることはできない。それらは直観され、あるいは知覚されることに

よってのみ明瞭にできる。例えば、キラル性の差異はこの性質を持つ。同様に、鏡像に見られる差異もそうだ。右手と耳は左手と耳に類似している。しかしそれ

らは合同ではない。これらの対象は、その外観から切り離されたものとして存在するものではない。それらは感覚的直観によってのみ知られる。外的な感覚的直

観の形式は空間である。時間は内的な感覚の形式である。時間と空間は、我々の感覚的直観の単なる形式であり、感覚的直観から切り離されたものとしての物自

体の性質ではない。 備考I. 純粋数学(純粋幾何学を含む)は、感覚の対象を指す場合に客観的現実性を持つ。純粋数学的命題は想像の産物ではない。それらは空間及びその現象的対象全て に対して必然的に有効である。なぜなら、ア・プリオリな数学的空間は、あらゆるア・ポステリオリな外部現象の基礎的形式だからだ。 備考II.バークリー的観念論は物自体(ものそのもの)の存在を否定する。しかし『純粋理性批判』は、外部対象が与えられているか否かは不確かであり、我 々はそれらの存在を単なる現象としてしか知ることができないと主張する。ロックの見解とは異なり、空間もまた単なる現象として知られ、物自体として存在す るものではない。[3] 備考III. 感覚的認識は、物事が我々の感覚に作用する仕方においてのみそれを表象する。知覚されるのは物自体ではなく現象である。空間、時間、そしてあらゆる現象は 表象の単なる様態に過ぎない。空間と時間は観念的・主観的であり、我々のあらゆる表象にア・プリオリに存在する。それらは感覚世界の全ての対象に適用され る。なぜならこれらの対象は単なる現象として存在するからだ。ただし、そうした対象は夢や幻想ではない。真実と夢や幻想との違いは、真の経験の規則に従っ て表象が結びつくかどうかにかかっている。主観的な表象を客観的なものと見なせば、誤った判断がなされる。幾何学の命題はすべて、空間と空間にあるすべて の対象について真実である。したがって、それらはあらゆる可能な経験について真実だ。空間が単なる感覚の形式と見なされるならば、幾何学の命題は外部直観 の対象すべてに関してア・プリオリに知ることができる。 |

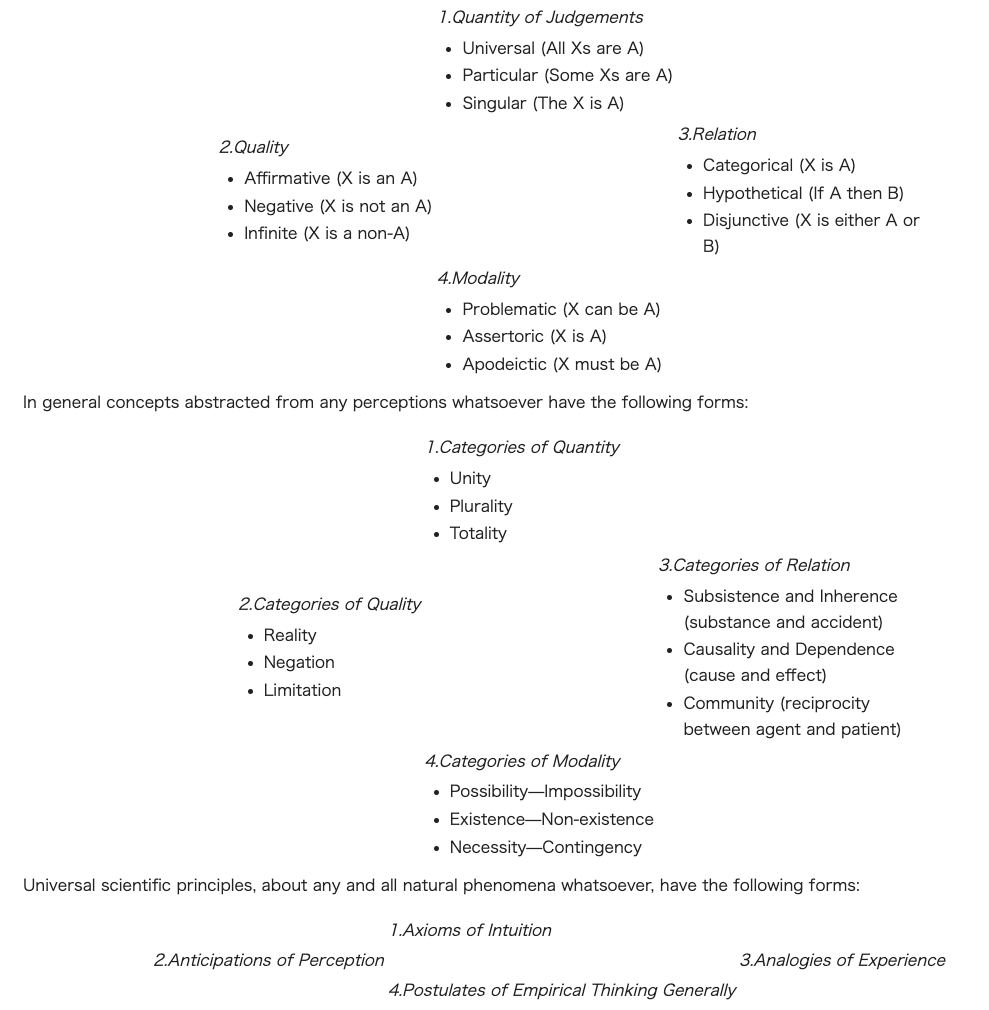

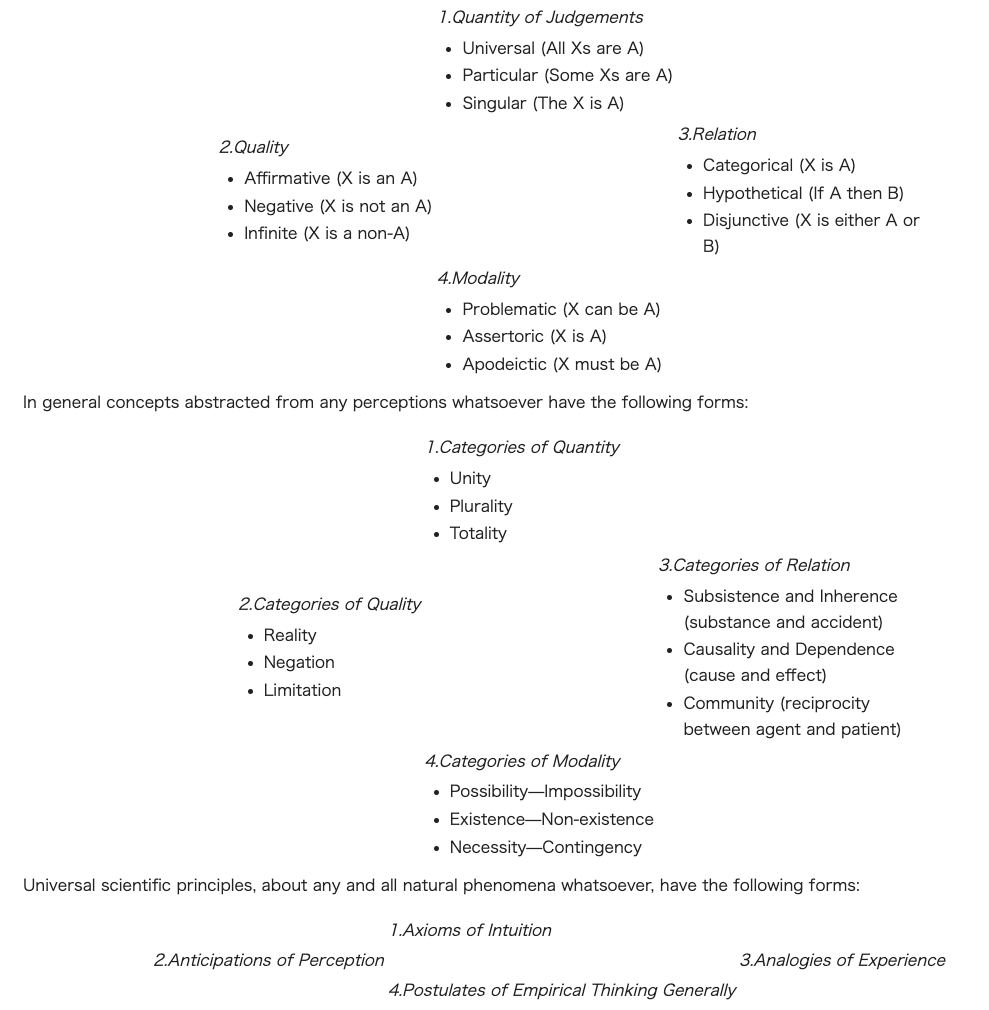

| Part two of the main

transcendental problem. How is pure natural science possible? § 14. An observer can't know anything about objects that exist in themselves, apart from being observed. Things in themselves cannot be known a priori because this would be a mere analysis of concepts. Neither can the nature of things in themselves be known a posteriori. Experience can never give laws of nature that describe how things in themselves must necessarily exist completely apart from an observer's experience. § 15. The universal science of nature contains a pure science of nature, as well as an empirical science of nature. The pure science of nature is a priori and expresses laws to which nature must necessarily conform. Two of its principles are "substance is permanent" and "every event has a cause." How is it possible that there are such a priori universal laws of nature? § 16. There is a priori knowledge of nature that precedes all experience. This pure knowledge is actual and can be confirmed by natural experience. We are not concerned with any so–called knowledge that cannot be verified by experience. § 17. The a priori conditions that make experience possible are also the sources of the universal laws of nature. How is this possible? § 18. Judgments of experience are empirical judgments that are valid for external objects. They require special pure concepts which have originated in the pure understanding. All judging subjects will agree on their experience of the object. When a perception is subsumed under these pure concepts, it is changed into objective experience. On the other hand, all empirical judgments that are only valid for the one judging subject are judgments of mere perception. These judgments of perception are not subsumed under a pure concept of the understanding. § 19. We cannot immediately and directly know an object as it is apart from the way that it appears. However, if we say that a judgment must be valid for all observers, then we are making a valid statement about an object. Judgments of experience are valid judgments about an object because they necessarily connect everyone's perceptions of the object through the use of a pure concept of the understanding. § 20. A judgment of perception is a connection of perceptions in a subject's mind. For example, "When the sun shines on a stone, the stone becomes warm." A judgment of perception has no necessary universality and therefore no objective validity. A judgment of perception can become a judgment of experience, as in "The sun warms the stone." This occurs when the subject's perceptions are connected according to the form of a pure concept of the understanding. These pure concepts of the understanding are the general forms that any object must assume in order to be experienced. § 21. In general, judgments about any perception whatsoever have the following forms:  |

超越論の問題の第二部。純粋自然科学は如何にして可能か? § 14. 観察者は、観察されることとは別に、それ自体として存在する物体について何も知り得ない。物自体はその概念の分析に過ぎないため、ア・プリオリに知り得な い。また物自体の本質はア・ポステリオリにも知り得ない。経験は、観察者の経験とは完全に独立して物自体が必然的に如何に存在しなければならないかを記述 する自然法則を決して与え得ない。 § 15. 自然の普遍的科学は、純粋自然科学と経験的自然科学を含む。純粋自然科学はア・プリオリにあり、自然が必然的に従わねばならない法則を表現する。その二つ の原理は「物質は永続する」と「あらゆる事象には原因がある」である。このようなア・プリオリな普遍的自然法則が存在する可能性はどのようにして生じるの か? § 16. あらゆる経験に先行する、自然に関するア・プリオリな知識が存在する。この純粋な知識は現実のものであり、自然経験によって確認され得る。我々は経験に よって検証できない、いわゆる知識には関心を寄せない。 § 17. 経験を可能にするア・プリオリな条件は、同時に自然の普遍的法則の源泉でもある。これはどうして可能なのか? § 18. 経験的判断とは、外部対象に対して有効な経験的判断である。これには純粋理解から生じた特別な純粋概念が必要だ。全ての判断主体は対象の経験について一致 する。知覚がこれらの純粋概念に帰属されると、それは客観的経験へと変容する。一方、判断する主体のみに有効な経験的判断は、単なる知覚の判断である。こ れらの知覚判断は、純粋な理解の概念の下に帰属しない。 § 19. 対象がどのように現れるかとは別に、対象そのものを直接的に知ることはできない。しかし、判断が全ての観察者にとって有効でなければならないと言うなら ば、それは対象についての有効な主張となる。経験的判断は、純粋な理解の概念を用いて、対象に対するあらゆる者の知覚を必然的に結びつけるため、対象につ いての有効な判断である。 § 20. 知覚的判断とは、主体の心における知覚の結びつきである。例えば「太陽が石に照りつけると、石は温かくなる」といったものである。知覚的判断には必然的な 普遍性がなく、したがって客観的有効性もない。知覚的判断は「太陽は石を温める」のように経験的判断となり得る。これは主体の知覚が純粋概念の形式に従っ て結びつけられた時に起こる。これらの純粋概念は、あらゆる対象が経験されるために必ず取り得る一般的形式である。 § 21. 一般に、あらゆる知覚に関する判断は次の形式を持つ:  |

| § 21a. This Prolegomena is a

critique of the understanding and it discusses the form and content of

experience. It is not an empirical psychology that is concerned with

the origin of experience. Experience consists of sense perceptions,

judgments of perception, and judgments of experience. A judgment of

experience includes what experience in general contains. This kind of

judgment results when a sense perception and a judgment of perception

are unified by a concept that makes the judgment necessary and valid

for all perceivers. § 22. The senses intuit. The understanding thinks, or judges. Experience is generated when a concept of the understanding is added[4][5] to a sense perception. The pure concepts of the understanding are concepts under which all sense perceptions must be subsumed [subsumirt] before they can be used in judgments of experience. A synthesis of perception then becomes necessary, universally valid, and representative of an experienced object. § 23. Pure a priori principles of possible experience bring mere phenomenal appearances under pure concepts of the understanding. This makes the empirical judgment valid in reference to an external object. These principles are universal laws of nature which are known before any experience. This solves the second question "How is the pure science of nature possible?". A logical system consists of the forms of all judgments in general. A transcendental system is made up of the pure concepts which are the conditions of all synthetical, necessary judgments. A physical system, which is a universal and pure science of nature, contains pure principles of all possible experience. § 24. The first physical principle of pure understanding subsumes all spatial and temporal phenomenal appearances under the concept of quantity. All appearances are extensive magnitudes. It is the principle of the axioms of intuition. The second physical principle subsumes sensation under the concept of quality. All sensations exhibit a degree, or intensive magnitude, of sensed reality. This is the principle of the anticipations of perception. § 25. In order for a relationship between appearances to be valid as an objective experience, it must be formulated in accordance with an a priori concept. The concepts of substance/accident, cause/effect, and action/reaction (community) constitute a priori principles that turn subjective appearances into objective experiences. The concept of substance relates appearances to existence. The concepts of cause and community relate appearances to other appearances. The principles that are made of these concepts are the real, dynamical [Newtonian] laws of nature. Appearances are related to experience in general as being possible, actual, or necessary. Judgments of experience, that are thought or spoken, are formulated by using these modes of expression. |

§ 21a.

この序説は理解力の批判であり、経験の形式と内容について論じる。経験の起源を扱う経験的心理学ではない。経験は感覚知覚、知覚判断、経験判断から成る。

経験判断には経験一般が含むものが含まれる。この種の判断は、感覚知覚と知覚判断が、その判断を全ての知覚者にとって必要かつ有効とする概念によって統一

された時に生じる。 § 22. 感覚は直観する。理解は思考し、あるいは判断する。経験は、感覚知覚に理解の概念が加えられる[4][5]ときに生成される。理解の純粋概念とは、経験の 判断に用いられる前に、全ての感覚知覚が包含されなければならない[subsumirt]概念である。こうして知覚の総合は、必要かつ普遍的に有効とな り、経験された対象を代表するようになる。 § 23. 可能な経験の純粋ア・プリオリ原理は、単なる現象的表象を純粋な理解の概念の下に収める。これにより経験的判断は外部対象に関して有効となる。これらの原 理は経験以前に知られる普遍的自然法則である。これは第二の問い「純粋自然科学はいかにして可能か?」を解決する。論理体系は一般のあらゆる判断の形式か ら成る。超越論的体系は、あらゆる総合的必然的判断の条件である純粋概念から構成される。物理体系、すなわち普遍的かつ純粋な自然科学は、あらゆる可能経 験の純粋原理を含む。 § 24. 純粋理解の第一物理原理は、全ての空間的・時間的現象的表象を量という概念の下に包含する。全ての表象は広延的量である。これは直観の公理の原理である。 第二物理原理は、感覚を質という概念の下に包含する。あらゆる感覚は、知覚された現実性の程度、すなわち強度的量を示す。これは知覚の予見の原理である。 § 25. 現象間の関係が客観的経験として有効であるためには、ア・プリオリに定式化されなければならない。実体/偶性、原因/結果、作用/反作用(共同性)の概念 は、主観的現象を客観的経験へと転換するア・プリオリの原理を構成する。実体の概念は現象を存在と結びつける。原因と共同体の概念は現象を他の現象と結び つける。これらの概念から成る原理こそが、現実の動的な[ニュートン的]自然法則である。 現象は一般に、可能・現実・必然のいずれかの形で経験と関連する。思考され、あるいは語られる経験の判断は、これらの表現様式を用いて形成される。 |

| § 26. The table of the Universal

Principles of Natural Science is perfect and complete. Its principles

are limited only to possible experience. The principle of the axioms of

intuition states that appearances in space and time are thought of as

quantitative, having extensive magnitude. The principle of the

anticipations of perception states that an appearance's sensed reality

has degree, or intensive magnitude. The principles of the analogies of

experience state that perceptual appearances, not things in themselves,

are thought of as experienced objects, in accordance with a priori

rules of the understanding. § 27. Hume wrote that we cannot rationally comprehend cause and effect (causality). Kant added that we also cannot rationally comprehend substance and accident (subsistence) or action and reaction (community). Yet he denied that these concepts are derived from experience. He also denied that their necessity was false and merely an illusion resulting from habit. These concepts and the principles that they constitute are known before experience and are valid when they are applied to the experience of objects. § 28. We cannot know anything about the relations of things in themselves or of mere appearances. When we speak or think about objects of experience, however, they must necessarily have the relations of subsistence, causality, and community. These concepts constitute the principles of the possibility of our experience. § 29. With regard to causality, we start with the logical form of a hypothetical judgment. We can make a subjective judgment of perception and say, "If the sun shines long enough on a body, then the body will become warm." This, however, is an empirical rule that is valid merely of appearances in one consciousness. If I want to make an objective, universally valid hypothetical judgment, however, I must make it in the form of causality. As such, I say, "The sun is the cause of heat." This is a universal and necessary law that is valid for the possibility of objective experience. Experience is the valid knowledge of the way that appearances succeed each other as objects. This knowledge is expressed in the form of a hypothetical [if/then] judgment. The concept of causality refers to thoughts and statements about the way that successive appearances and perceptions are universally and necessarily experienced as objects, in any consciousness. § 30. The principles that contain the reference of the pure concepts of the understanding to the sensed world can only be used to think or speak of experienced objects, not things in themselves. These pure concepts are not derived from experience. Experience is derived from these pure concepts. This solves Hume's problem regarding the pure concept of causality. Pure mathematics and pure natural science can never refer to anything other than mere appearances. They can only represent either (1) that which makes experience in general possible, or (2) that which must always be capable of being represented in some possible particular experience. § 31. By this method, we have gained definite knowledge with reference to metaphysics. Unscientific researchers could also say that we can never reach, with our reason, beyond experience. They, however, have no grounds for their assertion. § 32. Former philosophers claimed that the sensible world was an illusion. The intelligible world, they said, was real and actual. Critical philosophy, however, acknowledges that objects of sense are mere appearances, but they are usually not illusions. They are appearances of a thing in itself, which cannot be directly known. Our pure concepts [causality, subsistence, etc.] and pure intuitions [space, time] refer only to objects of possible sense experience. They are meaningless when referred to objects that cannot be experienced. § 33. Our pure concepts of the understanding are not derived from experience and they also contain strict necessity, which experience never attains. As a result, we are tempted to use them to think and speak about objects of thought that transcend experience. This is a transcendent and illegitimate use. § 34. Unlike empirical concepts, which are grounded on sense perceptions, the pure concepts of the understanding are based on schemata. This is explained in the Critique of Pure Reason, A 137 ff. The objects thus produced occur only in experience. In the Critique, A 236 ff., it is explained that nothing that is beyond experience can be meaningfully thought by using the pure concepts without sense perception. |

§ 26.

自然科学の普遍原理の体系は完全かつ完結している。その原理は可能な経験のみに限定される。直観の公理の原理は、時空間における表象が量的、すなわち広大

性を持つものとして考えられると述べる。知覚の予見の原理は、表象の知覚された現実性が強度、すなわち集約性を持つと述べる。経験の類推の原理は、知性の

ア・プリオリな規則に従い、知覚される現象こそが、物自体ではなく、経験された対象として考えられることを述べる。 § 27. ヒュームは、我々が原因と結果(因果性)を理性的に理解できないと記した。カントはさらに、実体と偶有性(実存)、作用と反作用(共同性)も理性的に理解 できないと付け加えた。しかし彼は、これらの概念が経験から派生したものではないと否定した。またそれらの必然性が虚偽であり、単なる習慣に起因する錯覚 であるという主張も否定した。これらの概念と、それらが構成する原理は経験以前に知られており、対象の経験に適用される際には有効である。 § 28. 我々は物自体や単なる表象の関係について何も知り得ない。しかし経験の対象について語ったり考えたりする際、それらは必然的に実在性・因果性・共存性の関 係を持たねばならない。これらの概念こそが我々の経験の可能性の原理を構成する。 § 29. 因果性に関しては、仮説的判断の論理形式から出発する。知覚の主観的判断として「太陽が物体に十分に長く照り続ければ、その物体は温かくなる」と言い得 る。しかしこれは、一つの意識における現象にのみ有効な経験則に過ぎない。客観的で普遍的に有効な仮説的判断を下そうとするなら、因果関係の形式で述べね ばならない。すなわち「太陽は熱の原因である」と言うのである。これは客観的経験の可能性において有効な、普遍的かつ必然的な法則だ。経験とは、現象が対 象として互いに続く様相についての有効な知識である。この知識は仮説的[もし~なら~]判断の形で表現される。因果性の概念とは、いかなる意識において も、連続する現象や知覚が普遍的かつ必然的に対象として経験される方法に関する思考や言明を指す。 § 30. 純粋な理解の概念が知覚された世界を参照する原理は、経験された対象について思考したり語ったりするためにのみ用いられ、物自体については用いられない。 これらの純粋な概念は経験から導かれるものではない。経験はこれらの純粋概念から派生する。これによりヒュームの因果性純粋概念に関する問題は解決され る。 純粋数学と純粋自然科学は、単なる表象以外の何物にも言及し得ない。それらが表象し得るのは、(1) 経験一般を可能にするもの、あるいは (2) 常に何らかの可能な個別経験において表象され得るものでなければならない。 § 31. この方法によって、我々は形而上学に関して確かな知識を得た。非科学的な研究者たちは、我々の理性は経験を超越することは決してできないとも主張できる。 しかし、彼らの主張には根拠がない。 § 32. 過去の哲学者たちは、感覚的世界は幻想だと主張した。知性的世界こそが現実的かつ実在的だと彼らは言った。しかし批判哲学は、感覚対象は単なる表象に過ぎ ないが、通常は幻影ではないと認める。それらは直接知ることのできない物自体(ものそのもの)の表象である。我々の純粋概念[因果性、実在性など]と純粋 直観[空間、時間]は、可能な感覚経験の対象にのみ関わる。それらは経験できない対象に適用すれば無意味となる。 § 33. 私たちの純粋な理解の概念は経験から導かれたものではなく、経験が決して到達しない厳密な必然性も含んでいる。その結果、私たちはそれらを用いて経験を超 越した思考の対象について考え、語ろうとする誘惑に駆られる。これは超越的で不正な使用である。 § 34. 感覚知覚に基づく経験的概念とは異なり、純粋理解概念は図式に基づく。これは『純粋理性批判』A 137以降で説明される。こうして生み出される対象は経験の中にのみ現れる。『批判』A 236以降では、感覚知覚なしに純粋概念を用いて経験を超えたものを意味ある形で思考することは不可能だと説明される。 |

| § 35. The understanding, which

thinks, should never wander beyond the bounds of experience. It keeps

the imagination in check. The impossibility of thinking about unnatural

beings should be demonstrated with scientific certainty. § 36. The constitution of our five senses and the way that they provide data makes nature possible materially, as a totality of appearances in space and time. The constitution of our understanding makes nature possible formally, as a totality of rules that regulate appearances in order for them to be thought of as connected in experience. We derive the laws of nature from the conditions of their necessary unity in one consciousness. We can know, before any experience, the universal laws of nature because they are derived from our sensibility and understanding. Nature and the possibility of experience in general are the same. The understanding does not derive its a priori laws from nature. The understanding prescribes laws to nature. § 37. The necessary laws of nature that we seem to discover in perceived objects have actually been derived from our own understanding. § 38. According to natural law, gravitation decreases inversely as the square of the surfaces, over which this force spreads, increases. Is this law found in space itself? No, it is found in the way that the understanding knows space. The understanding is the origin of the universal order of nature. It comprehends all appearances under its own laws. In so doing, it produces the form by which all experienced objects that appear to us are necessarily subject to its laws. § 39. Appendix to pure natural science. On the system of the categories. The Kantian categories constitute a complete, necessary system of concepts and thus lead to comprehension. These concepts constitute the form of connection between the concepts that occur in all empirical knowledge. To make a table of pure concepts, a distinction was made between the pure elementary concepts of the sensibility and those of the understanding. The former are space and time. The latter are the pure concepts or categories. The list is complete, necessary, and certain because it is based on a principle or rule. This principle is that thinking in general is judging. A table of the functions of judgments, when applied to objects in general, becomes a table of pure concepts of the understanding. These concepts, and only these, are our whole knowledge of things by pure understanding. These pure concepts are logical functions and do not, by themselves, produce a concept of an object. To do so, they need to be based on sensuous intuition. Their use is limited to experience. The systematic table of categories is used as a clue in the investigation of complete metaphysical knowledge. It was used in the Critique as a pattern for research on, among other things, the soul (A 344), the universe (A 415), and nothingness (A 292). |

§ 35.

思考する理解力は、決して経験の境界を越えてはならない。それは想像力を抑制する。不自然な存在について考えることの不可能性は、科学的な確実性をもって

示されるべきである。 § 36. 我々の五感の構成と、それらがデータを提供する方法は、自然を物質的に可能にする。すなわち、時空間における現象の総体として可能にする。我々の理解力の 構造は、自然を形式的に可能とする。つまり、経験において相互に関連付けられるように現象を規制する規則の総体として自然を可能とするのだ。我々は、一つ の意識における必然的統一の条件から自然法則を導き出す。経験以前に自然の普遍法則を知ることができるのは、それらが我々の感覚性と理解力から導かれるか らである。自然と経験の可能性は本質的に同一である。理解力は自然からそのア・プリオリな法則を導き出さない。理解は自然に法則を規定する。 § 37. 知覚された対象の中に発見されたように見える自然の必然的法則は、実際には我々自身の理解から導かれたものである。 § 38. 自然法則によれば、重力は、この力が広がる表面積の二乗に反比例して減少する。この法則は空間そのものに見出されるのか? 否、それは理解が空間を知る方法の中に見出される。理解は自然の普遍的秩序の起源である。それはあらゆる現象を自らの法則の下に把握する。そうすること で、我々に現れるあらゆる経験的対象が必然的にその法則に従属する形式を生み出すのである。 § 39. 純粋自然科学の補遺。範疇体系について。 カントの範疇は、完全かつ必然的な概念体系を構成し、それゆえ理解へと導く。これらの概念は、あらゆる経験的知識において現れる概念間の接続形式を成す。 純粋概念の表を作成するため、純粋な感覚の初歩的概念と理解の初歩的概念とが区別された。前者は空間と時間である。後者は純粋概念、すなわち範疇である。 この一覧は、原理または規則に基づいているため、完全かつ必然的であり、確実である。この原理とは、思考一般が判断であるということだ。判断の機能を、対 象一般に適用した表は、純粋な理解の概念の表となる。これらの概念、そしてこれらのみが、純粋な理解による我々の事物に関する全知識である。 これらの純粋な概念は論理的機能であり、それ自体では対象の概念を生み出さない。そのためには、感覚的直観に基づく必要がある。その使用は経験に限定され る。 体系化された範疇表は、完全な形而上学的知識の探究における手がかりとして用いられる。『批判』においては、とりわけ魂(A 344)、宇宙(A 415)、無(A 292)などの研究の枠組みとして用いられた。 |

| Part three of the main

transcendental problem. How is metaphysics in general possible? § 40. The truth or the objective reality of the concepts that are used in metaphysics cannot be discovered or confirmed by experience. Metaphysics is subjectively actual because its problems occur to everyone as a result of the nature of their reason. How, however, is metaphysics objectively possible? The concepts of reason are transcendent because they are concerned with the absolute totality of all possible experience. Reason doesn't know when to stop asking, "why?." Such an absolute totality cannot be experienced. The corresponding objects of the necessary Ideas of reason cannot be given in experience and are misleading illusions. Only through self–knowledge can reason prevent the consideration of the immanent, subjective, guiding Ideas as being transcendent objects. § 41. In order to establish metaphysics as a science, a clear distinction must be made between the categories (pure concepts of the understanding) and the Ideas (pure concepts of reason). § 42. The concepts of the understanding appear in experience. They are confirmed by experience. On the other hand, the transcendent concepts of reason cannot be confirmed or refuted by experience because they don't appear in experience. Reason must introspectively investigate itself in order to avoid errors, illusions, and dialectical problems. § 43. The origin of the transcendental Ideas is the three forms of syllogism that reason uses in its activity. The first Idea is based on the categorical syllogism. It is the psychological Idea of the complete substantial subject. This Idea results in a paralogism, or unwittingly false dialectical reasoning. The second Idea is based on the hypothetical syllogism. It is the cosmological Idea of the complete series of conditions. This Idea results in an antinomy, or contradiction. The third Idea is based on the disjunctive syllogism. It is the theological Idea of the complete complex of everything that is possible. This Idea results in the dialectical problem of the Ideal. In this way, reason and its claims are completely and systematically considered. § 44. The Ideas of reason are useless, and even detrimental, to the understanding of nature. Is the soul a simple substance? Did the world have a beginning or did it always exist? Did a Supreme Being design nature? Reason, however, can help to make understanding complete. To do this, reason's Ideas are thought of as though they are known objects. § 45. Prefatory Remark to the Dialectic of Pure Reason. Reason continues to ask "why?" and will not be satisfied until a final thing in itself is experienced and understood. This, however, is a deceitful illusion. This transcendent and unbounded abuse of knowledge must be restrained by toilsome, laborious scientific instruction. |

超越論の問題の第三部。形而上学は一般にどうして可能なのか? § 40. 形而上学で使用される概念の真理性や客観的実在性は、経験によって発見も確認もできない。形而上学は主観的に現実的である。なぜならその問題は、理性の性 質ゆえに誰にでも生じるからだ。しかし形而上学は客観的にどうして可能なのか?理性の概念は超越的である。なぜならそれらはあらゆる可能な経験の絶対的総 体に関わるからだ。理性は「なぜ?」と問い続けることを止められない。そのような絶対的総体は経験され得ない。理性の必然的観念に対応する対象は経験にお いて与えられず、誤った幻想である。自己認識を通じてのみ、理性は内在的・主体性・導きとなる観念を超越的対象として考察することを防げる。 § 41. 形而上学を科学として確立するためには、範疇(純粋な理解の概念)と観念(純粋な理性の概念)を明確に区別しなければならない。 § 42. 理解の概念は経験の中に現れる。それらは経験によって確認される。一方、理性の超越的概念は経験の中に現れないため、経験によって確認も反証もできない。 誤謬、錯覚、弁証法的問題を回避するため、理性は内省的に自らを調査しなければならない。 § 43. 超越的観念の起源は、理性がその活動において用いる三つの三段論法の形式である。第一の観念は、カテゴリー的三段論法に基づく。これは完全な実体的主体の 心理的観念である。この観念は、パラロジズム、すなわち無意識の誤った弁証法的推論をもたらす。第二の観念は仮言三段論法に基づく。完全な条件系列の宇宙 論的観念である。この観念は反論、すなわち矛盾をもたらす。第三の観念は選択三段論法に基づく。あらゆる可能性の完全な複合体の神学的観念である。この観 念は観念の弁証法的問題をもたらす。このようにして、理性とその主張は完全かつ体系的に考察される。 § 44. 理性の観念は、自然の理解にとって無益であり、むしろ有害である。魂は単純な実体か?世界には始まりがあったのか、それとも常に存在していたのか?至高の 存在が自然を設計したのか?しかし理性は、理解を完全にする助けとなり得る。そのために、理性の観念は既知の対象であるかのように考えられる。 § 45. 純粋理性弁証法への序説 理性は「なぜ?」と問い続け、最終的な物自体を経験し理解するまで満足しない。しかしこれは欺瞞的な幻想である。この超越的で無制限な知識の濫用は、労苦 を伴う勤勉な科学的指導によって抑制されねばならない。 |

| I. The Psychological Ideas

(wrongly use Reason beyond experience) § 46. Substance (subject) cannot be known. Only accidents (predicates) can be known. Substance is a mere Idea, not an object. Pure reason, however, wrongly wants to know the subject of every predicate. Every subject, however, is a predicate for yet another subject, and so on as far as our knowledge of predicates extends. We can never know an ultimate subject or absolute substance. We seem to have an ego, though, which is a thinking subject for our thoughts. The ego, however, is not known. It is only a conceptless feeling of an existence and a representation of something that is related to all thinking. § 47. We can call this thinking self, or soul, a substance. We can say that is an ultimate subject that is not the predicate of yet another subject. Substances, though, are permanent. If we cannot prove that the soul is permanent, then it is an empty, insignificant concept. The synthetical a priori proposition "the thinking subject is permanent" can only be proved if it is an object of experience. § 48. Substances can be said to be permanent only if we are going to associate them with possible or actual experience. We can never think of substances as independent of all experience. The soul, or thinking substance, cannot be proved to be permanent and immortal, because death is the end of experience. Only living beings can have experiences. We cannot prove anything about a person's thinking substance (soul) after the person dies. §49. We know only appearances, not things in themselves. Actual bodies are external appearances in space. My soul, self, or ego is an internal appearance in time. Bodies, as appearances of my outer sense, do not exist apart from my thoughts. I myself, as an appearance of my inner sense, do not exist apart from being my representation in time and cannot be known to be immortal. Space and time are forms of my sensibility and whatever exists in them is a real appearance that I experience. These appearances are connected in space and time according to universal laws of experience. Anything that cannot be experienced in space or time is nothing to us and does not exist for us. |

I. 心理学的観念(経験を超えた理性を誤用する) § 46. 実体(主体)は知ることができない。知ることができるのは偶有性(述語)のみである。実体は単なる観念であって、対象ではない。しかし純粋理性は誤って、 あらゆる述語の主語を知ろうとする。しかしあらゆる主語は、さらに別の主語の述語であり、述語に関する我々の知識が及ぶ限り、この連鎖は続く。究極の主体 や絶対的な実体を知ることは決してできない。しかし我々には自我があるように思える。それは思考の主体である。だが自我は知られない。それは概念のない存 在の感覚であり、あらゆる思考に関連する何かの表象に過ぎない。 § 47. この思考する自己、あるいは魂を実体と呼べる。それは別の主語の述語ではない究極の主語だと言える。だが実体は永続的である。魂が永続的だと証明できなけ れば、それは空虚で無意味な概念に過ぎない。「思考する主語は永続的である」というア・プリオリな総合命題は、経験の対象である場合にのみ証明可能だ。 § 48. 実体は、可能あるいは実際の経験と結びつける場合にのみ永続的と言える。実体をあらゆる経験から独立して考えることは決してできない。魂、すなわち思考す る実体が永続的で不死であることを証明することは不可能だ。なぜなら死は経験の終焉だからである。経験を持つことができるのは生きている存在だけだ。人格 が死んだ後のその人格の思考する実体(魂)について、我々は何も証明できない。 §49. 我々が知るものは現象のみであり、物自体ではない。実在する物体は空間における外的現象である。私の魂、自我、あるいは自我は時間における内的現象であ る。物体は私の外的感覚の現象として、私の思考から切り離して存在しない。私自身は、内的な感覚の表象として、時間における私の表象として存在している以 外には存在せず、不滅であるとは知ることができない。空間と時間は私の感覚性の形式であり、それらの中に存在するものはすべて、私が経験する現実的な表象 である。これらの表象は、経験の普遍的な法則に従って空間と時間の中で結びついている。空間や時間の中で経験できないものは、私たちにとって何ものでもな く、私たちにとって存在しない。 |

| II. The Cosmological Ideas

(wrongly use Reason beyond experience) §50. The Cosmological Idea is cosmological because it is concerned with sensually experienced objects and it is an Idea because the ultimate condition which it seeks can never be experienced. Because its objects can be sensed, the Cosmological Idea wouldn't usually be considered to be a mere Idea. However, it outruns experience when it seeks the ultimate condition for all conditioned objects. In so doing, it is a mere Idea. § 51. There are four Cosmological Ideas. They mistakenly refer to the completeness, which can never be experienced, of a series of conditions. Pure reason makes four kinds of contradictory assertions about these Ideas. These antinomies result from the nature of human reason and cannot be avoided. 1. Thesis: The world has a temporal and spatial beginning or limit. Antithesis: The world does not have a temporal and spatial beginning or limit . 2. Thesis: Everything in the world consists of something that is simple. Antithesis: Everything in the world does not consist of something that is simple. 3. Thesis: There are causes in the world that are, themselves, free and uncaused. Antithesis: There are no causes in the world that are, themselves, free and uncaused. 4. Thesis: In the series of causes in the world, there is a necessary, uncaused being. Antithesis: In the series of causes in the world, there is not a necessary, uncaused being. § 52a. This conflict between thesis and antithesis cannot be resolved dogmatically. Both are supported by proofs. The conflict results when an observer considers a phenomenon (an observed occurrence) to be a thing in itself (an observed occurrence without an observer). § 52b. The falsehood of mere Ideas, which cannot be experienced, cannot be discovered by reference to experience. The hidden dialectic of the four natural Ideas of pure reason, however, reveals their false dogmatism. Reason's assertions are based on universally admitted principles while contrary assertions are deduced from other universally acknowledged principles. Contradictory assertions are both false when they are based on a self–contradictory concept. There is no middle between the two false contradictory assertions and therefore nothing is thought by the self–contradictory concept on which they are based. § 52c. Experienced objects exist, in the way that they appear, only in experience. They do not exist, in the way that they appear, apart from a spectator's thoughts. In the first two antinomies, both the thesis and the antithesis are false because they are founded on a contradictory concept. With regard to the first antinomy, I cannot say that the world is infinite or finite. Infinite or finite space and time are mere Ideas and can never be experienced. With regard to the second antinomy, I cannot say that a body consists of an infinite or a finite number of simple parts. The division, into simple parts, of an experienced body reaches only as far as the possible experience reaches. § 53. The first two antinomies were false because they considered an appearance to be a thing–in–itself (a thing as it is apart from being an appearance). In the last two antinomies, due to a misunderstanding, an appearance was mistakenly opposed to a thing–in–itself. The theses are true of the world of things–in–themselves, or the intelligible world. The antitheses are true of the world of appearances, or the phenomenal world. In the third antinomy, the contradiction is resolved if we realize that natural necessity is a property of things only as mere appearances, while freedom is attributed to things–in–themselves. An action of a rational being has two aspects or states of being: (1) as an appearance, it is an effect of some previous cause and is a cause of some subsequent effect, and (2) as a thing–in–itself it is free or spontaneous. Necessity and freedom can both be predicated of reason. In the world of appearances, motives necessarily cause actions. On the other hand, rational Ideas and maxims, or principles of conduct, command what a reasonable being ought to do. All actions of rational beings, as appearances, are strictly determined by causality. The same actions are free when the rational being acts as a thing–in– itself in accordance with mere practical reason. The fourth antinomy is solved in the same way as the third. Nowhere in the world of sense experiences and appearances is there an absolutely necessary being. The whole world of sense experiences and appearances, however, is the effect of an absolutely necessary being which can be thought of as a thing–in–itself which is not in the world of appearances. § 54. This antinomy or self–conflict of reason results when reason applies its principles to the sensible world. The antinomy cannot be prevented as long as objects (mere appearances) of the sensible world are considered to be things–in–themselves (objects apart from the way that they appear). This exposition of the antinomy will allow the reader to combat the dialectical illusions that result from the nature of pure reason. |

II. 宇宙論的観念(経験を超えた理性を誤用する) §50. 宇宙論的観念が宇宙論的であるのは、感覚的に経験される対象を扱うからであり、観念であるのは、それが求める究極的条件が決して経験され得ないからであ る。その対象が感覚可能であるため、宇宙論的観念は通常、単なる観念とは見なされない。しかし、あらゆる条件付けられた対象の究極的条件を求める時、それ は経験を凌駕する。そうすることで、それは単なる観念となる。 § 51. 四つの宇宙論的観念が存在する。それらは誤って、経験されることのない一連の条件の完全性を指し示す。純粋理性はこれらの観念について四種類の矛盾した主 張を行う。これらの反論は人間理性の本質から生じ、避けられないものである。 1. 命題:世界には時間的・空間的な始まりまたは限界がある。反命題:世界には時間的・空間的な始まりまたは限界がない。 2. 命題:世界にあるすべてのものは単純なもので構成されている。反命題:世界にあるすべてのものは単純なもので構成されていない。 3. 命題:世界には、それ自体が自由で原因を持たない原因が存在する。反命題:世界には、それ自体が自由で原因を持たない原因は存在しない。 4. 命題:世界の原因の系列には、必然的で原因を持たない存在が存在する。反命題:世界の原因の系列には、必然的で原因を持たない存在は存在しない。 § 52a. 命題と反命題のこの対立は、独断的に解決できない。双方とも証明によって支えられている。この対立は、観察者が現象(観察された出来事)を物自体(観察者 なしの観察された出来事)と見なすときに生じる。 § 52b. 経験され得ない単なる観念の虚偽性は、経験に照らして発見することはできない。しかし純粋理性の四つの自然観念に内在する弁証法は、それらの誤った独断主 義を明らかにする。理性の主張は普遍的に認められた原理に基づく一方、反対の主張は他の普遍的に認められた原理から導かれる。矛盾する主張は、自己矛盾す る概念に基づく場合、双方とも虚偽である。二つの偽りの矛盾した主張の間に中間は存在せず、したがってそれらが基づく自己矛盾的概念によって何も考えられ ない。 § 52c. 経験された対象は、それらが現れる形で、経験の中でのみ存在する。それらは、観察者の思考から離れて、現れる形で存在しない。最初の二つの反論において、 正命題も反命題も、矛盾した概念に基づいているため、どちらも偽である。 最初の反論に関して言えば、世界が無限であるとも有限であるとも言えない。無限あるいは有限の空間と時間は単なる観念であり、決して経験されることはな い。 第二の反論に関しては、物体が無限または有限の単純部分から成るとは言えない。経験された物体の単純部分への分割は、可能な経験が及ぶ範囲までしか達しな い。 § 53. 最初の二つの反論が誤りだったのは、現象を物自体(現象としてではなくそれ自体として存在するもの)と見なしたためである。最後の二つの反論では、誤解に より現象が物自体と誤って対立させられた。命題は物自体の世界、すなわち知性界において真である。反命題は現象界において真である。 第三の反論では、自然的必然性は単なる現象としての事物にのみ属する性質であり、自由は物自体に帰属すると理解すれば矛盾は解消される。理性的な存在者の 行為には二つの側面、すなわち二つの存在状態がある:(1) 現象として、それは先行する何らかの原因の結果であり、後続する何らかの結果の原因である。(2) 物自体として、それは自由あるいは自発的である。必然性と自由はともに理性に対して言える。現象世界では、動機が必然的に行為を引き起こす。一方、理性的 な観念や格律、行動原理は、合理的な存在がすべきことを命じる。現象としての理性的な存在の行為はすべて、厳密に因果律によって決定される。同じ行為も、 理性的な存在が単なる実践理性に従って物自体として行動する時には自由となる。 第四の反論は第三と同様に解決される。感覚経験と表象の世界には、絶対的に必然的な存在はどこにも存在しない。しかし感覚経験と表象の世界全体は、表象の 世界に存在しない物自体として考え得る絶対的に必然的な存在の結果である。 § 54. この矛盾、すなわち理性の自己矛盾は、理性がその原理を感覚世界に適用する際に生じる。感覚世界の対象(単なる表象)を物自体(表象の仕方とは無関係な対 象)と見なす限り、この矛盾は避けられない。この矛盾の解説は、読者が純粋理性の性質から生じる弁証法的錯覚に対抗することを可能にするだろう。 |

| III. The Theological Idea § 55. This Idea is that of a highest, most perfect, primeval, original Being. From this Idea of pure reason, the possibility and actuality of all other things is determined. The Idea of this Being is conceived in order for all experience to be comprehended in an orderly, united connection. It is, however, a dialectical illusion that results when we assume that the subjective conditions of our thinking are the objective conditions of objects in the world. The theological Idea is an hypothesis that was made in order to satisfy reason. It mistakenly became a dogma. § 56. General Remark on the Transcendental Ideas The psychological, cosmological, and theological Ideas are nothing but pure concepts of reason. They cannot be experienced. All questions about them must be answerable because they are only principles that reason has originated from itself in order to achieve complete and unified understanding of experience. The Idea of a whole of knowledge according to principles gives knowledge a systematic unity. The unity of reason's transcendental Ideas has nothing to do with the object of knowledge. The Ideas are merely for regulative use. If we try to use these Ideas beyond experience, a confusing dialectic results. |

III. 神学的観念 § 55. この観念は、最高にして最も完全な、原初的・根源的な存在の観念である。純粋理性によるこの観念から、他のあらゆるものの可能性と現実性が決定される。こ の存在の観念は、あらゆる経験が秩序立った統一的な関連性の中で把握されるために構想される。しかし、我々の思考の主観的条件が世界の対象の客観的条件で あると仮定した結果生じる弁証法的錯覚である。神学的観念は、理性を満足させるために作られた仮説である。それは誤って教義となった。 § 56. 超越論的観念に関する一般的考察 心理的観念、宇宙論的観念、神学的観念は、純粋な理性の概念に過ぎない。それらは経験されることはできない。それらに関するあらゆる疑問は答えられるはず だ。なぜなら、それらは経験の完全かつ統一的な理解を達成するために、理性が自ら生み出した原理に過ぎないからである。原理に基づく知識全体の理念は、知 識に体系的な統一性をもたらす。理性の超越的理念の統一性は、知識の対象とは何の関係もない。理念は単なる規範的用途に過ぎない。もし経験を超えてこれら の理念を使おうとすれば、混乱した弁証法が生じる。 |

| Conclusion. On the determination

of the bounds of pure reason § 57. We cannot know things in themselves, that is, things as they are apart from being experienced. However, things in themselves may exist and there may be other ways of knowing them, apart from our experience. We must guard against assuming that the limits of our reason are the limits of the possibility of things in themselves. To do this, we must determine the boundary of the use of our reason. We want to know about the soul. We want to know about the size and origin of the world, and whether we have free will. We want to know about a Supreme Being. Our reason must stay within the boundary of appearances but it assumes that there can be knowledge of the things–in–themselves that exist beyond that boundary. Mathematics and natural science stay within the boundary of appearances and have no need to go beyond. The nature of reason is that it wants to go beyond appearances and wants to know the basis of appearances. Reason never stops asking "why?." Reason won't rest until it knows the complete condition for the whole series of conditions. Complete conditions are thought of as being the transcendental Ideas of the immaterial Soul, the whole world, and the Supreme Being. In order to think about these beings of mere thought, we symbolically attribute sensuous properties to them. In this way, the Ideas mark the bounds of human reason. They exist at the boundary because we speak and think about them as if they possess the properties of both appearances and things–in–themselves. Why is reason predisposed to metaphysical, dialectical inferences? In order to strengthen morality, reason has a tendency to be unsatisfied with physical explanations that relate only to nature and the sensible world. Reason uses Ideas that are beyond the sensible world as analogies of sensible objects. The psychological Idea of the Soul is a deterrent from materialism. The cosmological Ideas of freedom and natural necessity, as well as the magnitude and duration of the world, serve to oppose naturalism, which asserts that mere physical explanations are sufficient. The theological Idea of God frees reason from fatalism. § 58. We cannot know the Supreme Being absolutely or as it is in itself. We can know it as it relates to us and to the world. By means of analogy, we can know the relationship between God and us. The relationship can be like the love of a parent for a child, or of a clock–maker for his clock. We know, by analogy, only the relationship, not the unknown things that are related. In this way, we think of the world as if it was made by a Supreme Rational Being. |

結論。純粋理性の限界の決定について § 57. 我々は物自体、すなわち経験とは無関係に存在する物そのものを知ることはできない。しかし物自体は存在し得るし、我々の経験とは別の方法でそれを知る道が あるかもしれない。我々は、我々の理性の限界が物自体の可能性の限界であると仮定することを警戒しなければならない。そのためには、我々の理性の使用の境 界を決定しなければならない。 我々は魂について知りたい。世界の大きさや起源、自由意志の有無を知りたい。至高の存在について知りたい。我々の理性は現象の境界内に留まらねばならない が、その境界の彼方に存在する物自体についての知識が得られうると仮定する。数学や自然科学は現象の境界内に留まり、それを超える必要はない。理性の本質 は、現象を超越しようとし、現象の基盤を知ろうとする点にある。理性は「なぜ?」と問い続けることを決して止めない。一連の条件の完全な条件を知るまで、 理性は休むことはない。完全な条件とは、非物質的な魂、世界全体、そして至高の存在という超越的な観念と考えられる。こうした思考上の存在について考える ため、我々は象徴的に感覚的性質をそれらに帰属させる。このように、観念は人間の理性の限界を示す。それらが境界に存在する理由は、我々がそれらについ て、現象と物自体(ものそのもの)の両方の性質を兼ね備えているかのように語り、考えるからだ。 なぜ理性は形而上学的・弁証法的推論に傾くのか。道徳を強化するため、理性は自然や感覚世界のみに関わる物理的説明に満足しない傾向がある。理性は感覚世 界を超えた観念を、感覚対象の類推として用いる。魂という心理的観念は唯物論への抑止力となる。自由や自然的必然性といった宇宙論的観念、また世界の広大 さや永続性は、単なる物理的説明で十分だと主張する自然主義に対抗する役割を果たす。神という神学的観念は、理性を宿命論から解放する。 § 58. 我々は至高の存在を絶対的に、あるいはそれ自体のありのままに知ることはできない。我々は、それが我々や世界とどう関わるかを知ることはできる。類推に よって、神と我々の関係を知ることができる。その関係は、親が子を愛するように、あるいは時計職人が自分の時計を愛するように、といった関係に例えられ る。類推によって知るのは関係だけで、関係する未知の事物そのものではない。このようにして、我々は世界を、あたかも至高の理性的な存在によって作られた かのように考えるのである。 |

| Solution of the general question

of the Prolegomena. How is metaphysics possible as a science? Metaphysics, as a natural disposition of reason, is actual. Yet metaphysics itself leads to illusion and dialectical argument. In order for metaphysics to become a science, a critique of pure reason must systematically investigate the role of a priori concepts in understanding. The mere analysis of these concepts does nothing to advance metaphysics as a science. A critique is needed that will show how these concepts relate to sensibility, understanding, and reason. A complete table must be provided, as well as an explanation of how they result in synthetic a priori knowledge. This critique must strictly demarcate the bounds of reason. Reliance on common sense or statements about probability will not lead to a scientific metaphysics. Only a critique of pure reason can show how reason investigates itself and can be the foundation of metaphysics as a complete, universal, and certain science. |

プロレゴメナの一般的課題の解決。形而上学は如何にして科学となり得る

か? 形而上学は、理性の自然な傾向として実在する。しかし形而上学そのものは錯覚と弁証法的議論へと導く。形而上学が科学となるためには、純粋理性批判が理解 におけるア・プリオリな概念の役割を体系的に調査しなければならない。これらの概念を単に分析するだけでは、形而上学を科学として前進させることはできな い。これらの概念が感覚、理解、理性とどのように関連するかを示す批判が必要である。完全な表を提供するとともに、それらが如何にして合成的ア・プリオリ な認識をもたらすかを説明しなければならない。この批判は理性の境界を厳密に画定するものである。常識や確率に関する主張に依拠しても、科学的な形而上学 には至らない。純粋理性批判のみが、理性が如何に自己を考察するかを示し、完全かつ普遍的で確かな科学としての形而上学の基礎となり得るのである。 |

| Appendix How to make metaphysics as a science actual An accurate and careful examination of the one existing critique of pure reason is needed. Otherwise, all pretensions to metaphysics must be abandoned. The existing critique of pure reason can be evaluated only after it has been investigated. The reader must ignore for a while the consequences of the critical researches. The critique's researches may be opposed to the reader's metaphysics, but the grounds from which the consequences derive can be examined. Several metaphysical propositions mutually conflict with each other. There is no certain criterion of the truth of these metaphysical propositions. This results in a situation that requires that the present critique of pure reason must be investigated before it can be judged as to its value in making metaphysics an actual science. |

付録 形而上学を科学として実現する方法 現存する純粋理性批判を正確かつ慎重に検討する必要がある。さもなければ、形而上学へのあらゆる主張は放棄されねばならない。現存する純粋理性批判は、調 査を経た後にのみ評価可能である。読者は批判的研究の結果を一時的に無視せねばならない。批判の研究は読者の形而上学に反するかもしれないが、結果が導か れる根拠は検証可能である。いくつかの形而上学的命題は互いに矛盾している。これらの形而上学的命題の真偽を判断する確かな基準は存在しない。この状況 は、形而上学を現実の科学とする上で『純粋理性批判』の価値を判断する前に、まずこの批判自体を調査する必要性を示している。 |

| Pre-judging the Critique of Pure

Reason Kant was motivated to write this Prolegomena after reading what he judged to be a shallow and ignorant review of his Critique of Pure Reason. The review was published anonymously in a journal and was written by Garve with many edits and deletions by Feder. Kant's Critique was dismissed as "a system of transcendental or higher idealism." This made it seem as though it was an account of things that exist beyond all experience. Kant, however, insisted that his intent was to restrict his investigation to experience and the knowledge that makes it possible. Among other mistakes, the review claimed that Kant's table and deduction of the categories were "common well–known axioms of logic and ontology, expressed in an idealistic manner." Kant believed that his Critique was a major statement regarding the possibility of metaphysics. He tried to show in the Prolegomena that all writing about metaphysics must stop until his Critique was studied and accepted or else replaced by a better critique. Any future metaphysics that claims to be a science must account for the existence of synthetic a priori propositions and the dialectical antinomies of pure reason. |

『純粋理性批判』への先入観 カントがこの序説を書いた動機は、自身の『純粋理性批判』に対する浅薄で無知な書評を読んだことにある。その書評は匿名で雑誌に掲載され、ガーヴェが執筆 しフェーデルが大幅な修正と削除を加えたものだ。カントの批判は「超越論的あるいは高次の観念論体系」と一蹴された。これにより、経験を超越した事物の記 述であるかのように思われた。しかしカントは、自らの研究を経験とそれを可能にする知識に限定する意図を主張した。他の誤りの中でも、この書評はカントの 表と範疇の演繹を「理想主義的な方法で表現された、論理学と存在論の一般的な既知の公理」と主張した。カントは自身の『批判』が形而上学の可能性に関する 主要な声明であると信じていた。『プロレゴメナ』において、彼は『批判』が研究され受け入れられるか、あるいはより優れた批判に取って代わられるまで、形 而上学に関するあらゆる著作は停止されねばならないことを示そうとした。科学を自称する将来の形而上学は、合成的ア・プリオリ命題と純粋理性の弁証法的二 律背反の存在を説明せねばならない。 |

| Proposals as to an investigation

of the Critique of Pure Reason upon which a judgment may follow Kant proposed that his work be tested in small increments, beginning with the basic assertions. The Prolegomena can be used as a general outline to be compared to the Critique. He was not satisfied with certain parts of the Critique and suggested that the discussions in the Prolegomena be used to clarify those sections. The unsatisfactory parts were the deduction of the categories and the paralogisms of pure reason in the Critique. If the Critique and the Prolegomena are studied and revised by a united effort by thinking people, then metaphysics may finally become scientific. In this way, metaphysical knowledge can be distinguished from false knowledge. Theology will also be benefited because it will become independent of mysticism and dogmatic speculation. |

『純粋理性批判』の検討に関する提案、それに続く判断のために カントは自身の著作を、基本的な主張から始めて段階的に検証することを提案した。『序説』は『批判』と比較するための概略として利用できる。彼は『批判』 の特定の部分に満足しておらず、『序説』の議論を用いてそれらの箇所を明確化することを示唆した。不満足な部分は、批判における範疇の演繹と純粋理性の謬 論であった。批判とプロレゴメナを思考する人々による共同努力によって研究・修正されれば、形而上学はついに科学的となり得る。こうして形而上学的知識は 誤った知識と区別される。神学もまた、神秘主義や教条的思索から独立することで恩恵を受けるだろう。 |

| Reception Lewis White Beck claimed that the chief interest of the Prolegomena to the student of philosophy is "the way in which it goes beyond and against the views of contemporary positivism".[6] He wrote: "The Prolegomena is, moreover, the best of all introductions to that vast and obscure masterpiece, the Critique of Pure Reason. ... It has an exemplary lucidity and wit, making it unique among Kant's greater works and uniquely suitable as a textbook of the Kantian philosophy."[6] Ernst Cassirer asserted that "the Prolegomena inaugurates a new form of truly philosophical popularity, unrivaled for clarity and keenness".[7] Schopenhauer, in 1819, declared that the Prolegomena was "the finest and most comprehensible of Kant's principal works, which is far too little read, for it immensely facilitates the study of his philosophy".[8] As a teenager Ernst Mach read and was inspired by the Prolegomena, before later reaching the conclusion that the 'thing-in-itself' was "just an illusion".[9] |

レセプション ルイス・ホワイト・ベックは、『プロレゴメナ』が哲学の学生にとって最も興味深い点は「当時の実証主義の見解を超越し、それに反するその方法」だと主張し た。[6] 彼はこう書いている:「さらに『プロレゴメナ』は、広大で難解な傑作『純粋理性批判』への最良の入門書である。...その模範的な明快さと機知は、カント の主要著作の中でも特異であり、カント哲学の教科書として他に類を見ない適性を備えている。」[6]エルンスト・カッシラーは「『序説』は真に哲学的な大 衆性の新たな形式を開拓し、その明晰さと鋭さにおいて比類のないものである」と断言した。[7] ショーペンハウアーは1819年、『序説』を「カントの主要著作の中で最も優れ、最も理解しやすい作品であり、彼の哲学研究を大いに容易にするにもかかわ らず、あまりにも読まれていない」と宣言した。[8] エルンスト・マッハは青年期に『序説』を読み感銘を受けたが、後に「物自体」は「単なる幻想に過ぎない」という結論に達した。[9] |

| 1. Analytic and synthetic

methods are not the same as analytic and synthetic judgments. The

analytic method proceeds from the known to the unknown. The synthetic

method proceeds from the unknown to the known. In §§ 4 and 5, Kant

asserted that the analytic method assumes that cognitions from pure

reason are known to actually exist. We start from this trusted

knowledge and proceed to its sources which are unknown. Conversely, the

synthetic method starts from the unknown and penetrates by degrees

until it reaches a system of knowledge that is based on reason. 2. Kant 1999, p. A713, B741. 3. "Descartes has demonstrated the subjectivity of the secondary qualities of perceptible objects, but Kant has also demonstrated that of the primary qualities." Schopenhauer, Manuscript Remains, I, § 716. 4. How pure concepts of the understanding are added to perceptions is explained in the Critique of Pure Reason 5. Kant 1999, p. A137. 6. Prolegomena to any future metaphysics, "Editor's Introduction," The Library of Liberal Arts, 1950 7. Kant's life and thought, Chapter IV, Yale University Press, 1981, ISBN 0-300-02982-9 8. The World as Will and Representation, Volume I, Appendix, Dover Publications, 1969, ISBN 0-486-21761-2 9. Blackmore, John, ed. (1992). Ernst Mach: A Deeper Look. Springer. p. 115. |

1.

分析的方法と総合的方法は、分析的判断と総合的判断とは異なる。分析的方法は既知から未知へと進む。総合的方法は未知から既知へと進む。第4節と第5節で

カントは、分析的方法は純粋理性による認識が実際に存在することを前提としていると主張した。我々はこの確かな知識から出発し、その源である未知へと進む

のである。逆に、合成的方法は未知から出発し、段階的に探求を進め、最終的に理性に根差した知識体系に到達する。 2. カント 1999, p. A713, B741. 3. 「デカルトは知覚可能対象の二次的性質の主体性を証明したが、カントは一次的性質の主体性も証明した」ショーペンハウアー『遺稿』I, § 716. 4. 純粋理解概念が知覚にどのように付加されるかは『純粋理性批判』で説明されている 5. カント 1999, p. A137. 6. 『あらゆる将来の形而上学のための序説』「編集者序文」, The Library of Liberal Arts, 1950 7. カントの生涯と思想, 第IV章, イエール大学出版局, 1981, ISBN 0-300-02982-9 8. 『意志と表象としての世界』第1巻、付録、ドーバー出版、1969年、ISBN 0-486-21761-2 9. ブラックモア、ジョン編(1992)。『エルンスト・マッハ:より深い考察』。スプリンガー。p. 115。 |

| Sources Kant, Immanuel (1999). Critique of Pure Reason (The Cambridge Edition of the Works of Immanuel Kant). Translated and edited by Paul Guyer and Allen W. Wood. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-5216-5729-7. |

出典 カント、イマヌエル(1999)。『純粋理性批判』(ケンブリッジ版イマヌエル・カント著作集)。ポール・ガイヤーとアレン・W・ウッドによる翻訳・編 集。ケンブリッジ大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-5216-5729-7。 |

| Prolegomena

to Any Future Metaphysics, English translation by Gary Hatfield[pdf] Contains the Prolegomena, English translation by Jonathan Bennett Original German text Prolegomena to Any Future Metaphysics public domain audiobook at LibriVox |

『あらゆる将来の形而上学のための序説』、ゲイリー・ハットフィールド

英訳 『序説』を収録、ジョナサン・ベネット英訳 原著ドイツ語テキスト 『あらゆる将来の形而上学のための序説』パブリックドメイン音声書籍(LibriVox) |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099