ルネサンス期の音楽

Renaissance music

Gerard

van Honthorst, The Concert (1623), National Gallery of Art, Washington

D.C.

☆ アウトライン:「ルネサンス初期、現代的な楽譜は「古い複雑な記譜法を大幅に簡略化することで発展し、そのきっかけと促進要因として活版印刷が大きな役割 を果たした」とされている。[91] ルネサンス初期は、フランコ・フランドル音楽が主流だったが、16 世紀半ばからは、イタリア、特にフィレンツェのカメラタ、ローマ派、ヴェネツィア派などの作曲家たちによって、大きな影響が及んだ。1570年代以降、 フィレンツェのジロラモ・メイやフランスのジャン・アントワーヌ・ド・ベイフなど、古代ギリシャの音楽を復活させようとする試みがなされた。メイは、資料 調査の結果、ドリス式、フリギア式、リディア式のスタイルの違いを指摘した。彼は他の者たちとともに、多声音楽に批判的であり、カント・フェルモと呼ばれ るホモフォニー[=和音を伴う1つの主旋律を持つ音楽]を支持した。[92] ルネサンス音楽の特徴や表現手法としては、次のようなものが挙げられる。 音楽は(もはや匿名ではない)作曲家の作品として認識されるようになった。音楽は、社交的な娯楽(例えば、恋愛歌、酒歌、季節歌など)のために使用され、もはや神を賛美するためだけのものではなくなった。教会音楽では豊かなポリフォニー(多声部)が、世俗音楽ではホモフォニーで扱われる民謡のメロディーが流行した。 楽器は、ヴァイオリン、リコーダー、ガンバ、さまざまな管楽器、リュートなど、家族全員で製作された。声楽と器楽のパートは交換可能になり、固定の楽器編 成は一般的ではなくなった。中世の音楽とは対照的に、和声の感覚も変化し、ルネサンス以降、3度と6度は調和のとれた音程と認識されるようになった。 高ルネサンスの音楽の特徴は、ポリフォニーと和声の構造、そして多声と歌詞の理解との調和の追求であり、その代表はジョヴァンニ・ピエルルイジ・ダ・パレ ストリーナだ。[93] ルネサンスの音楽的アイデアの実現の頂点は、1600年頃にフィレンツェのサークルを中心に誕生したオペラだ。ヤコポ・ペリは、1600年に初演された音 楽劇「エウリディーチェ」を作曲し、これは今日、現存する最古のオペラとされている。クラウディオ・モンテヴェルディは、彼が「セコンダ・プラティカ」と 呼んだ、言葉よりも音楽が優先される新しいスタイルで、オペラ『オルフェオ』(1607年)と『アリアドネ』(1608年)を作曲した。」

| Musik → Hauptartikel: Musik der Renaissance In der Frühphase der Renaissance entwickelte sich die moderne Notenschreibung „durch eine radikale Vereinfachung der alten komplizierten Notationssysteme, wobei der Buchdruck als Initiator und Beschleuniger eine erhebliche Rolle gespielt hat.“[91] Zunächst war in der Renaissance die franko-flämische Musik stilbestimmend, ab der Mitte des 16. Jahrhunderts kamen die wesentlichen Impulse dann aus Italien, besonders durch Komponistenströmungen, die als Florentiner Camerata, Römische Schule und Venezianische Schule bezeichnet werden. Seit den 1570er Jahren gab es Versuche beispielsweise des Florentiners Girolamo Mei und des Franzosen Jean-Antoine de Baïf, die antike griechische Musik wiederzubeleben. Mei beschrieb als Ergebnis seiner Quellenforschung Unterschiede zwischen dorischem, phrygischem und lydischem Stil. Er kritisierte mit anderen die polyphone Musik und befürwortete die Homophonie unter der Bezeichnung canto fermo.[92] Als Eigenschaften und Stilmittel der Renaissancemusik lassen sich anführen: Die Musik wird als Werk von (nicht mehr anonymen) Komponisten begriffen. Sie dient zur geselligen Unterhaltung (z. B. Liebes-, Trink- und Jahreszeitenlieder) und nicht mehr nur zum Gotteslob. Es kommt zu einer reichen Polyphonie (Mehrstimmigkeit) in der Kirchenmusik und zu homophon behandelten Volkslied-Melodien im weltlichen Bereich. Der Instrumentenbau erfolgt in ganzen Familien, etwa Violinen, Blockflöten, Gamben, verschiedenen Blasinstrumenten sowie Lauten. Vokal- und Instrumentalpartien werden austauschbar, eine feste Instrumentierung ist nicht mehr generell üblich. Gegenüber der Musik des Mittelalters ändert sich das Harmonie-Empfinden: Terzen und Sexten werden seit der Renaissance als konsonant empfunden. Kennzeichnend für die Musik der Hochrenaissance ist das Bemühen zur Herstellung einer harmonischen Einheit zwischen polyphoner und akkordischer Struktur – am energischsten vertreten durch Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina – sowie zwischen Mehrstimmigkeit und Textverständlichkeit.[93] Einen Höhepunkt der musikalischen Verwirklichung von Ideen der Renaissance bildet die Entstehung der Oper um 1600, betrieben vor allem durch Florentiner Kreise. Jacopo Peri komponierte das im Jahr 1600 uraufgeführte Musikdrama Euridice, das heute als erste erhalten gebliebene Oper gilt. Claudio Monteverdi komponierte in dem von ihm als seconda prattica bezeichneten neuen Stil, bei dem eher die Worte die Musik bestimmten als umgekehrt,[94] die Opern Orfeo (1607) und Ariadne (1608). Siehe auch: Liste von Komponisten der Renaissance |

音楽 → 主な記事:ルネサンスの音楽 ルネサンス初期、現代的な楽譜は「古い複雑な記譜法を大幅に簡略化することで発展し、そのきっかけと促進要因として活版印刷が大きな役割を果たした」とさ れている。[91] ルネサンス初期は、フランコ・フランドル音楽が主流だったが、16 世紀半ばからは、イタリア、特にフィレンツェのカメラタ、ローマ派、ヴェネツィア派などの作曲家たちによって、大きな影響が及んだ。1570年代以降、 フィレンツェのジロラモ・メイやフランスのジャン・アントワーヌ・ド・ベイフなど、古代ギリシャの音楽を復活させようとする試みがなされた。メイは、資料 調査の結果、ドリス式、フリギア式、リディア式のスタイルの違いを指摘した。彼は他の者たちとともに、多声音楽に批判的であり、カント・フェルモと呼ばれ るホモフォニーを支持した。[92] ルネサンス音楽の特徴や表現手法としては、次のようなものが挙げられる。 音楽は(もはや匿名ではない)作曲家の作品として認識されるようになった。音楽は、社交的な娯楽(例えば、恋愛歌、酒歌、季節歌など)のために使用され、 もはや神を賛美するためだけのものではなくなった。教会音楽では豊かなポリフォニー(多声部)が、世俗音楽ではホモフォニーで扱われる民謡のメロディーが 流行した。 楽器は、ヴァイオリン、リコーダー、ガンバ、さまざまな管楽器、リュートなど、家族全員で製作された。声楽と器楽のパートは交換可能になり、固定の楽器編 成は一般的ではなくなった。中世の音楽とは対照的に、和声の感覚も変化し、ルネサンス以降、3度と6度は調和のとれた音程と認識されるようになった。 高ルネサンスの音楽の特徴は、ポリフォニーと和声の構造、そして多声と歌詞の理解との調和の追求であり、その代表はジョヴァンニ・ピエルルイジ・ダ・パレ ストリーナだ。[93] ルネサンスの音楽的アイデアの実現の頂点は、1600年頃にフィレンツェのサークルを中心に誕生したオペラだ。ヤコポ・ペリは、1600年に初演された音 楽劇「エウリディーチェ」を作曲し、これは今日、現存する最古のオペラとされている。クラウディオ・モンテヴェルディは、彼が「セコンダ・プラティカ」と 呼んだ、言葉よりも音楽が優先される新しいスタイルで、オペラ『オルフェオ』(1607年)と『アリアドネ』(1608年)を作曲した。 参照:ルネサンスの作曲家一覧 |

| https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Renaissance |

ルネサンス |

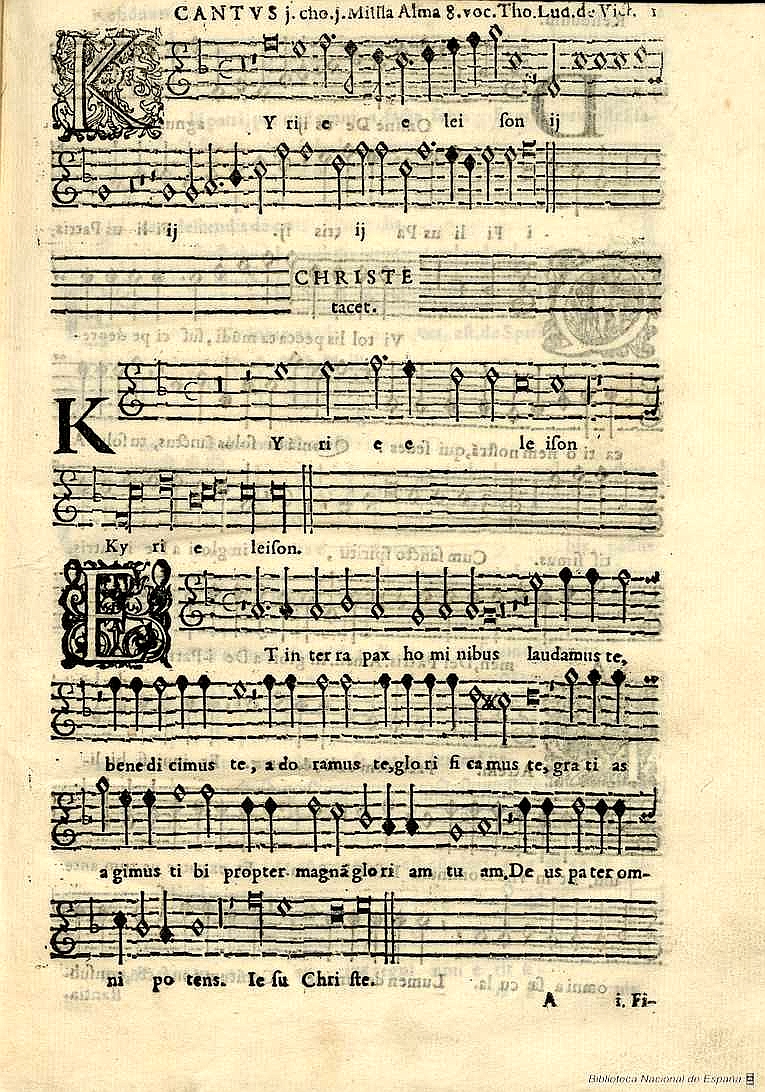

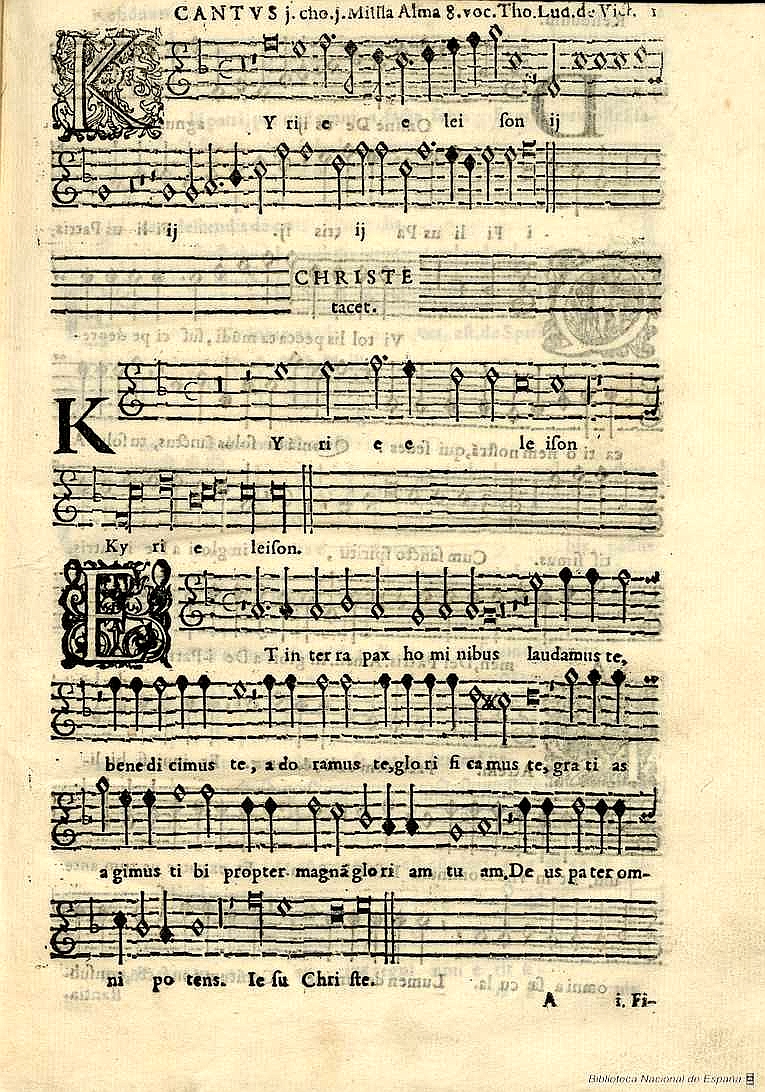

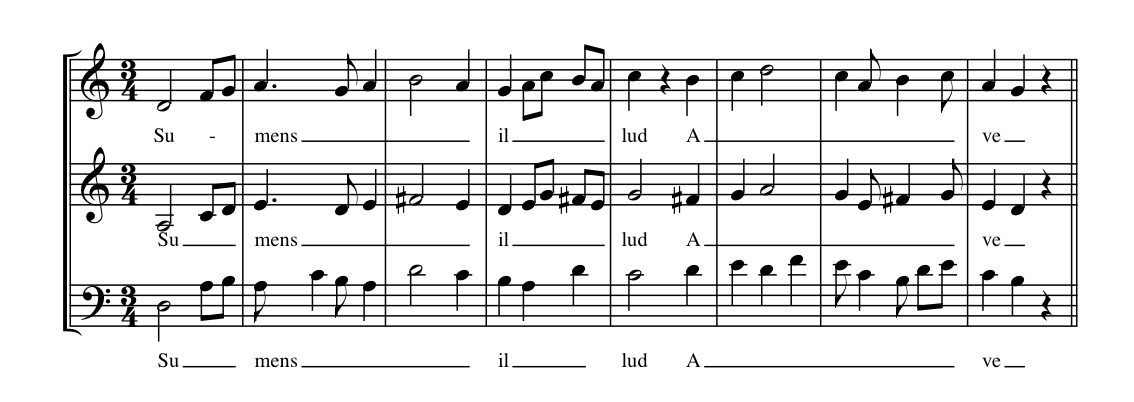

«Missa alma redemptoris» de Tomás Luis de Victoria, en Misas, magníficat, motetes, salmos y otras varias composiciones, Madrid, tipografía regia, 1600. |

トマス・ルイス・デ・ビクトリアの「ミサ・アルマ・レデンプトリス」、『ミサ曲、マグニフィカト、モテット、詩篇、その他様々な作曲』所収、マドリード、王立印刷所、1600年。 |

Teoría y notación Orlando di Lasso. Las composiciones del Renacimiento estaban escritas únicamente en partichelas; las partituras generales eran muy raras, y las barras de compás no se usaban. Las figuras eran generalmente más largas que las usadas en nuestros días; la unidad de pulso era la semibreve, o redonda. Como ocurría desde el Ars Nova cada breve (cuadrada) podía equivaler a dos o tres semibreves, que podría ser considerada como equivalente al compás moderno, aunque era un valor de nota y no un compás. Se puede resumir de esta forma: igual que en la actualidad, una negra puede equivaler a dos corcheas o tres que se escribirían como un tresillo. En la misma lógica se puede tener dos o tres valores más cortos de la siguiente figura, la mínima (equivalente a la moderna blanca) de cada semibreve. Estas diferentes permutaciones se denominan tempus perfecto/imperfecto según la relación de breve-semibreve y prolación perfecta/imperfecta en el caso de la relación semibreve-mínima, existiendo todas las combinaciones posibles entre uno y otro. La relación tres-uno se llamó perfecta y la dos-uno imperfecta. Para las figuras aisladas existían reglas que reducían a la mitad o doblaban el valor ("imperfeccionaban" o "alteraban" respectivamente) cuando estaban precedidas o seguidas de determinadas figuras. Las figuras con la cabeza negra (como las negras) eran menos habituales. Este desarrollo de la notación mensural blanca es el resultado de la popularización del uso (sustituyendo al pergamino) del papel, más débil y que no permitía el rasgado de la pluma para rellenar las notas. La notación de la época precedente, escrita en pergamino, era negra. Otros colores, y más tarde, el relleno de las notas (ennegrecimiento) fueron usados para indicar imperfecciones o alteraciones, etc. |

理論と記譜法 オルランド・ディ・ラッソ(Orlando di Lasso)。 ルネサンス期の作曲は、パート譜のみで記譜されていた。総譜はごく稀であり、小節線も使用されなかった。音符の長さは、現代で使用されているものよりも一 般的に長く、拍子の単位は全音符(丸音符)であった。アルス・ノヴァ以来、各ブリーヴ(四分音符)は 2 つまたは 3 つの全音符に相当し、現代の拍子に相当すると考えられていたが、それは音価であり、拍子ではなかった。これは次のように要約できる。現代と同じように、4 分音符は 2 つの 8 分音符、または 3 つの 8 分音符に相当し、3 連符として書かれる。 同じ論理で、次の図のように、各全音符の最小音符(現代の白音符に相当)の2つまたは3つのより短い音価を持つことができる。これらの異なる順列は、全音 符と全音符の関係に応じて「完全/不完全テンポ」、全音符と最小音符の関係に応じて「完全/不完全プロレーション」と呼ばれ、両者の間で考えられるすべて の組み合わせが存在する。3対1の関係はパーフェクト、2対1はインパーフェクトと呼ばれた。孤立した音符については、特定の音符が前後に続く場合に、そ の価値を半分にする、あるいは2倍にする(「不完全化」あるいは「変更」する)という規則があった。頭部が黒い音符(4分音符など)は、あまり一般的では なかった。この白の計量記譜法の発展は、羊皮紙に代わって、より弱く、ペンで音符を塗りつぶすことができない紙の使用が普及した結果である。それ以前の時 代、羊皮紙に書かれた記譜法は黒色だった。他の色、そして後に音符の塗りつぶし(黒化)が、不完全さや変更などを示すために用いられた。 |

| https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/M%C3%BAsica_del_Renacimiento |

★

詳細説明(Renaissance

music)

| Renaissance

music

is traditionally understood to cover European music of the 15th and

16th centuries, later than the Renaissance era as it is understood in

other disciplines. Rather than starting from the early 14th-century ars

nova, the Trecento music was treated by musicology as a coda to

medieval music and the new era dated from the rise of triadic harmony

and the spread of the contenance angloise style from the British Isles

to the Burgundian School. A convenient watershed for its end is the

adoption of basso continuo at the beginning of the Baroque period. The period may be roughly subdivided, with an early period corresponding to the career of Guillaume Du Fay (c. 1397–1474) and the cultivation of cantilena style, a middle dominated by Franco-Flemish School and the four-part textures favored by Johannes Ockeghem (1410s or '20s–1497) and Josquin des Prez (late 1450s–1521), and culminating during the Counter-Reformation in the florid counterpoint of Palestrina (c. 1525–1594) and the Roman School. Music was increasingly freed from medieval constraints, and more variety was permitted in range, rhythm, harmony, form, and notation. On the other hand, rules of counterpoint became more constrained, particularly with regard to treatment of dissonances. In the Renaissance, music became a vehicle for personal expression. Composers found ways to make vocal music more expressive of the texts they were setting. Secular music absorbed techniques from sacred music, and vice versa. Popular secular forms such as the chanson and madrigal spread throughout Europe. Courts employed virtuoso performers, both singers and instrumentalists. Music also became more self-sufficient with its availability in printed form, existing for its own sake. Precursor versions of many familiar modern instruments (including the violin, guitar, lute and keyboard instruments) developed into new forms during the Renaissance. These instruments were modified to respond to the evolution of musical ideas, and they presented new possibilities for composers and musicians to explore. Early forms of modern woodwind and brass instruments like the bassoon and trombone also appeared, extending the range of sonic color and increasing the sound of instrumental ensembles. During the 15th century, the sound of full triads became common, and towards the end of the 16th century the system of church modes began to break down entirely, giving way to functional tonality (the system in which songs and pieces are based on musical "keys"), which would dominate Western art music for the next three centuries. From the Renaissance era, notated secular and sacred music survives in quantity, including vocal and instrumental works and mixed vocal/instrumental works. A wide range of musical styles and genres flourished during the Renaissance, including masses, motets, madrigals, chansons, accompanied songs, instrumental dances, and many others. Beginning in the late 20th century, numerous early music ensembles were formed. Ensembles specializing in music of the Renaissance era give concert tours and make recordings, using modern reproductions of historical instruments and using singing and performing styles which musicologists believe were used during the era. |

ルネサンス音楽は、伝統的に

15~16世紀のヨーロッパ音楽を指すと理解されており、他の学問分野で理解されているルネサンス時代よりも後である。トレチェント音楽は、14世紀初頭

のアルス・ノーヴァから始まるのではなく、音楽学では中世音楽のコーダとして扱われ、新しい時代は、三和音の台頭と、イギリス諸島からブルゴーニュ派への

コンテナンス・アングロワーズ様式の広がりから始まった。バロック時代の始まりに通奏低音(バッソ・コンティヌオ)が採用されたことが、この時代の終わり

を示す便利な分水嶺である。 この時代は大まかに分けると、初期はギヨーム・デュ・フェイ(1397~1474年頃)とカンティレーナ様式の育成、中期はフランコ・フランドル派とヨハ ネス・オッケヘム(1410~1497年頃)とジョスカン・デ・プレ(1450年代後半~1521年頃)が好んだ4部形式、そして反宗教改革期にはパレス トリーナ(1525~1594年頃)とローマ派の華麗な対位法で最高潮に達する。 音楽はますます中世の制約から解放され、音域、リズム、和声、形式、記譜法においてより多様なものが許されるようになった。一方、対位法の規則は、特に不 協和音の扱いに関して、より制約されるようになった。ルネサンスでは、音楽は人格表現の手段となった。作曲家たちは、声楽曲のテキストをより表現豊かにす る方法を見出した。世俗音楽は聖楽から技法を吸収し、またその逆もあった。シャンソンやマドリガルといった人気のある世俗音楽の形式がヨーロッパ中に広 まった。宮廷では、歌手も器楽奏者もヴィルトゥオーゾ的な演奏家が起用された。音楽はまた、印刷された形で利用できるようになり、それ自体が存在すること で自給自足するようになった。 ルネサンス期には、ヴァイオリン、ギター、リュート、鍵盤楽器など、現代で親しまれている多くの楽器の前身となる楽器が新しい形に発展した。これらの楽器 は、音楽的アイデアの進化に対応するために改良され、作曲家や音楽家たちに新たな可能性を提示した。ファゴットやトロンボーンのような近代的な木管楽器や 金管楽器の初期形態も登場し、音の色彩の幅を広げ、器楽アンサンブルの響きを増大させた。15世紀には、完全な三和音の響きが一般的になり、16世紀末に は、教会モードのシステムが完全に崩壊し始め、機能調性(楽曲や小品が音楽の「調」に基づいているシステム)に道を譲り、その後3世紀にわたって西洋の芸 術音楽を支配することになる。 ルネサンス時代から、声楽と器楽の作品、声楽と器楽の混血の作品など、楽譜化された世俗音楽と聖楽が大量に残っている。ルネサンス期には、ミサ曲、モテッ ト、マドリガル、シャンソン、伴奏付き歌曲、器楽舞曲など、幅広い音楽スタイルやジャンルが花開いた。20世紀後半から、数多くの古楽アンサンブルが結成 された。ルネサンス時代の音楽を専門とするアンサンブルは、コンサートツアーやレコーディングを行っており、歴史的楽器の現代的な複製を使い、音楽学者が その時代に使われていたと考える歌唱法や演奏法を用いている。 |

| Overview The main characteristics of Renaissance music are:[1] Music based on modes. Rich texture, with four or more independent melodic parts being performed simultaneously. These interweaving melodic lines, a style called polyphony, is one of the defining features of Renaissance music. Blending, rather than contrasting, melodic lines in the musical texture. Harmony that placed a greater concern on the smooth flow of the music and its progression of chords. The development of polyphony produced the notable changes in musical instruments that mark the Renaissance musically from the Middle Ages. Its use encouraged the development of larger ensembles and demanded sets of instruments that would blend together across the whole vocal range.[2] One of the most pronounced features of early Renaissance European art music was the increasing reliance on the interval of the third and its inversion, the sixth. (In the Middle Ages, thirds and sixths had been considered dissonances; and consonances were derived only of the perfect intervals: the perfect fourth, the perfect fifth, the octave, and the unison). Polyphony—the use of multiple, independent melodic lines played simultaneously—became increasingly elaborate throughout the 14th century, with highly independent voices in both vocal music and instrumental music. The beginning of the 15th century showed simplification, with the composers often striving for smoothness in the melodic parts. This was possible because of a greatly increased vocal range in music. Previously, in the Middle Ages, the narrow vocal range necessitated frequent crossing of parts, thus requiring a greater contrast between them to distinguish the different parts. The modal character of Renaissance music—later replaced by the tonal approach developing in the subsequent Baroque music era—began to break down towards the end of the (Renaissance) period with the increased use of root motions of fifths or fourths; (see Circle of fifths for details). An example of a chord progression in which the chord roots move by the interval of a fourth is the chord progression in the key of C Major: "D minor/G Major/C Major"—these are all triads; three-note chords. The movement from the D minor chord to the G Major chord is an interval of a perfect fourth. The movement from the G Major chord to the C Major chord is also an interval of a perfect fourth. This later developed into one of the defining characteristics of tonality during the Baroque era.[citation needed] |

概要 ルネサンス音楽の主な特徴は以下の通りである[1]。 モードに基づく音楽。 豊かなパフォーマティビティ。4つ以上の独立した旋律パートが同時に演奏される。ポリフォニーと呼ばれるスタイルは、ルネサンス音楽の特徴のひとつであ る。 音楽のテクスチュアの中で、旋律線は対照的ではなく、むしろ混ざり合っている。 和声は、音楽のスムーズな流れや和音の進行をより重視した。 ポリフォニーの発展は、ルネサンスを音楽的に中世から特徴づける顕著な楽器の変化を生み出した。ポリフォニーの使用は、より大規模なアンサンブルの発展を 促し、声域全体にわたって調和する楽器のセットを要求した[2]。 初期ルネサンス期のヨーロッパの芸術音楽で最も顕著な特徴のひとつは、第3音とその逆数の第6音への依存が高まったことである。(中世では、第3音と第6 音は不協和音とみなされ、協和音は完全音程(完全第4音、完全第5音、オクターヴ、ユニゾン)のみに由来していた)。ポリフォニー(複数の独立した旋律線 を同時に演奏すること)は、14世紀を通じてますます精巧になり、声楽でも器楽でも独立性の高い声部が用いられるようになった。15世紀初頭には単純化が 進み、作曲家たちはしばしば旋律部分の滑らかさを追求した。これが可能になったのは、音楽における声域が大幅に広がったからである。それ以前の中世では、 声域が狭かったため、パートを頻繁に交差させる必要があり、異なるパートを区別するために、パート間のコントラストを大きくする必要があった。 ルネサンス音楽のモーダルな特徴は、その後のバロック音楽の時代に発展した調性的アプローチに取って代わられたが、(ルネサンス)時代の終わりには、5分 の5拍子や4分の4拍子のルート楽章の使用が増え、崩れ始めた(詳細は5分の5拍子の輪を参照)。コード・ルートが4分の1ずつ動くコード進行の例とし て、ハ長調のコード進行がある: 「ニ短調/ト長調/ハ長調"-これらはすべて3和音である。ニ短調のコードからト長調のコードへの移動は、完全4分の1音程である。ト長調の和音からハ長 調の和音への移動もまた、完全4分の1音程である。これは後に、バロック時代に調性を定義する特徴の1つに発展した[要出典]。 |

| Background As in the other arts, the music of the period was significantly influenced by the developments which define the Early Modern period: the rise of humanistic thought; the recovery of the literary and artistic heritage of Ancient Greece and Ancient Rome; increased innovation and discovery; the growth of commercial enterprises; the rise of a bourgeois class; and the Protestant Reformation. From this changing society emerged a common, unifying musical language, in particular, the polyphonic style of the Franco-Flemish school. The invention of the printing press in 1439 made it cheaper and easier to distribute music and music theory texts on a wider geographic scale and to more people. Prior to the invention of printing, written music and music theory texts had to be hand-copied, a time-consuming and expensive process. Demand for music as entertainment and as a leisure activity for educated amateurs increased with the emergence of a bourgeois class. Dissemination of chansons, motets, and masses throughout Europe coincided with the unification of polyphonic practice into the fluid style which culminated in the second half of the sixteenth century in the work of composers such as Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina, Orlande de Lassus, Thomas Tallis, William Byrd and Tomás Luis de Victoria. Relative political stability and prosperity in the Low Countries, along with a flourishing system of music education in the area's many churches and cathedrals allowed the training of large numbers of singers, instrumentalists, and composers. These musicians were highly sought throughout Europe, particularly in Italy, where churches and aristocratic courts hired them as composers, performers, and teachers. Since the printing press made it easier to disseminate printed music, by the end of the 16th century, Italy had absorbed the northern musical influences with Venice, Rome, and other cities becoming centers of musical activity. This reversed the situation from a hundred years earlier. Opera, a dramatic staged genre in which singers are accompanied by instruments, arose at this time in Florence. Opera was developed as a deliberate attempt to resurrect the music of ancient Greece.[3] |

背景 人文主義思想の台頭、古代ギリシャと古代ローマの文学的・芸術的遺産の回復、技術革新と発見の増加、商業企業の成長、ブルジョア階級の台頭、プロテスタン ト宗教改革などである。このような社会の変化から、共通で統一された音楽言語、特にフランコ・フランドル楽派のポリフォニー様式が生まれた。 1439年に印刷機が発明されたことで、音楽と音楽理論のテキストを、より広い地理的規模で、より多くの人々に、より安く、より簡単に配布できるように なった。印刷が発明される以前は、書かれた音楽や音楽理論のテキストは手書きでコピーしなければならず、時間も費用もかかる作業だった。娯楽としての音 楽、教養あるアマチュアの余暇活動としての音楽の需要は、ブルジョワ階級の出現とともに高まった。シャンソン、モテット、ミサ曲がヨーロッパ中に広まった のは、16世紀後半にジョヴァンニ・ピエルルイジ・ダ・パレストリーナ、オルランド・ド・ラッスス、トマス・タリス、ウィリアム・バード、トマス・ルイ ス・デ・ヴィクトリアといった作曲家たちの作品に結実した、ポリフォニックな様式が流動的な様式に統一された時期と重なる。低地諸国で政治が比較的安定し 繁栄していたことに加え、この地域の多くの教会や大聖堂で音楽教育が盛んに行われていたため、多数の歌手、器楽奏者、作曲家が育成された。これらの音楽家 はヨーロッパ中、特にイタリアで引っ張りだこで、教会や貴族の宮廷では作曲家、演奏家、教師として雇われた。印刷機によって印刷された音楽の普及が容易に なったため、16世紀末にはイタリアは北方音楽の影響を吸収し、ヴェネツィアやローマなどの都市が音楽活動の中心地となった。これは100年前の状況を逆 転させた。フィレンツェではこの時期に、歌手に楽器を伴奏させるドラマチックな演出のジャンルであるオペラが生まれた。オペラは、古代ギリシャの音楽を復 活させる意図的な試みとして発展した[3]。 |

| Genres Principal liturgical (church-based) musical forms, which remained in use throughout the Renaissance period, were masses and motets, with some other developments towards the end of the era, especially as composers of sacred music began to adopt secular (non-religious) musical forms (such as the madrigal) for religious use. The 15th and 16th century masses had two kinds of sources that were used: monophonic (a single melody line) and polyphonic (multiple, independent melodic lines), with two main forms of elaboration, based on cantus firmus practice or, beginning some time around 1500, the new style of "pervasive imitation", in which composers would write music in which the different voices or parts would imitate the melodic and/or rhythmic motifs performed by other voices or parts. Several main types of masses were used: Cyclic mass (tenor mass) Paraphrase mass Imitation mass Masses were normally titled by the source from which they borrowed. Cantus firmus mass uses the same monophonic melody, usually drawn from chant and usually in the tenor and most often in longer note values than the other voices.[4] Other sacred genres were the madrigale spirituale and the laude. During the period, secular (non-religious) music had an increasing distribution, with a wide variety of forms, but one must be cautious about assuming an explosion in variety: since printing made music more widely available, much more has survived from this era than from the preceding medieval era, and probably a rich store of popular music of the late Middle Ages is lost. Secular music was music that was independent of churches. The main types were the German Lied, Italian frottola, the French chanson, the Italian madrigal, and the Spanish villancico.[1] Other secular vocal genres included the caccia, rondeau, virelai, bergerette, ballade, musique mesurée, canzonetta, villanella, villotta, and the lute song. Mixed forms such as the motet-chanson and the secular motet also appeared. Purely instrumental music included consort music for recorders or viols and other instruments, and dances for various ensembles. Common instrumental genres were the toccata, prelude, ricercar, and canzona. Dances played by instrumental ensembles (or sometimes sung) included the basse danse (It. bassadanza), tourdion, saltarello, pavane, galliard, allemande, courante, bransle, canarie, piva, and lavolta. Music of many genres could be arranged for a solo instrument such as the lute, vihuela, harp, or keyboard. Such arrangements were called intabulations (It. intavolatura, Ger. Intabulierung). Towards the end of the period, the early dramatic precursors of opera such as monody, the madrigal comedy, and the intermedio are heard. |

ジャンル ルネサンス期を通じて使用された主な典礼音楽(教会音楽)の形式は、ミサ曲とモテットである。15~16世紀のミサ曲には、モノフォニック(単一の旋律 線)とポリフォニック(複数の独立した旋律線)の2種類の音源が使用され、カントゥス・ファルムの実践に基づくものと、1500年頃から作曲家が他の声部 やパートが演奏する旋律やリズムのモチーフを異なる声部やパートが模倣する音楽を書く「広範模倣」という新しいスタイルの、2つの主な推敲の形式があっ た。ミサ曲には主にいくつかの種類がある: 循環ミサ(テノール・ミサ) パラフレーズ・ミサ 模倣ミサ ミサ曲には通常、引用元のタイトルが付けられていた。カントゥス・フォルムス(Cantus firmus)ミサは、通常、聖歌から引用された同じ単旋律を用い、通常はテノールで、他の声部よりも長い音価で歌われることが多かった[4]。 この時代、世俗音楽(非宗教音楽)の流通は増加し、その形式も多種多様になったが、爆発的に多様化したと考えるのは慎重でなければならない。印刷によって 音楽がより広く入手できるようになったため、この時代には、それ以前の中世時代よりもはるかに多くの音楽が残っており、おそらく中世後期のポピュラー音楽 の豊かな蓄積が失われている。世俗音楽とは、教会から独立した音楽である。主なものとしては、ドイツのリート、イタリアのフロットラ、フランスのシャンソ ン、イタリアのマドリガル、スペインのヴィリャンシーコなどがある[1]。その他の世俗声楽のジャンルとしては、カッチャ、ロンドー、ヴィレライ、ベル ジュレット、バラード、ムジーク・メシュレ、カンツォネッタ、ヴィラネッラ、ヴィロッタ、リュートソングなどがあった。モテ・シャンソンや世俗モテットの ような混血の形式も登場した。 純粋な器楽曲には、リコーダーやヴィオールなどのためのコンソート音楽、さまざまなアンサンブルのための舞曲などがあった。一般的な器楽曲のジャンルは、 トッカータ、プレリュード、リチェルカーレ、カンツォーナであった。器楽アンサンブルで演奏される(あるいは歌われることもある)舞曲には、バス・ダンス (バッサダンツァ)、トゥールディオン、サルタレッロ、パヴァーヌ、ガリアール、アレマンデ、クーラント、ブランスル、カナリエ、ピヴァ、ラヴォルタなど があった。多くのジャンルの音楽は、リュート、ヴィウエラ、ハープ、キーボードなどの独奏楽器のために編曲することができた。このような編曲はインタビュ レーション(It. intavolatura, Ger. Intabulierung)と呼ばれた。 この時代の終わりには、モノディー、マドリガル・コメディー、インテルメディオといったオペラの初期の劇的な先駆けが聞かれるようになる。 |

Theory and notation Ockeghem, Kyrie "Au travail suis," excerpt, showing white mensural notation. According to Margaret Bent: "Renaissance notation is under-prescriptive by our [modern] standards; when translated into modern form it acquires a prescriptive weight that overspecifies and distorts its original openness".[5] Renaissance compositions were notated only in individual parts; scores were extremely rare, and barlines were not used. Note values were generally larger than are in use today; the primary unit of beat was the semibreve, or whole note. As had been the case since the Ars Nova (see Medieval music), there could be either two or three of these for each breve (a double-whole note), which may be looked on as equivalent to the modern "measure," though it was itself a note value and a measure is not. The situation can be considered this way: it is the same as the rule by which in modern music a quarter-note may equal either two eighth-notes or three, which would be written as a "triplet." By the same reckoning, there could be two or three of the next smallest note, the "minim," (equivalent to the modern "half note") to each semibreve. These different permutations were called "perfect/imperfect tempus" at the level of the breve–semibreve relationship, "perfect/imperfect prolation" at the level of the semibreve–minim, and existed in all possible combinations with each other. Three-to-one was called "perfect," and two-to-one "imperfect." Rules existed also whereby single notes could be halved or doubled in value ("imperfected" or "altered," respectively) when preceded or followed by other certain notes. Notes with black noteheads (such as quarter notes) occurred less often. This development of white mensural notation may be a result of the increased use of paper (rather than vellum), as the weaker paper was less able to withstand the scratching required to fill in solid noteheads; notation of previous times, written on vellum, had been black. Other colors, and later, filled-in notes, were used routinely as well, mainly to enforce the aforementioned imperfections or alterations and to call for other temporary rhythmical changes. Accidentals (e.g. added sharps, flats and naturals that change the notes) were not always specified, somewhat as in certain fingering notations for guitar-family instruments (tablatures) today. However, Renaissance musicians would have been highly trained in dyadic counterpoint and thus possessed this and other information necessary to read a score correctly, even if the accidentals were not written in. As such, "what modern notation requires [accidentals] would then have been perfectly apparent without notation to a singer versed in counterpoint." (See musica ficta.) A singer would interpret his or her part by figuring cadential formulas with other parts in mind, and when singing together, musicians would avoid parallel octaves and parallel fifths or alter their cadential parts in light of decisions by other musicians.[5] It is through contemporary tablatures for various plucked instruments that we have gained much information about which accidentals were performed by the original practitioners. For information on specific theorists, see Johannes Tinctoris, Franchinus Gaffurius, Heinrich Glarean, Pietro Aron, Nicola Vicentino, Tomás de Santa María, Gioseffo Zarlino, Vicente Lusitano, Vincenzo Galilei, Giovanni Artusi, Johannes Nucius, and Pietro Cerone. |

理論と記譜法 Ockeghem、Kyrie 「Au travail suis」、抜粋、白の記譜法を示す。 マーガレット・ベントによれば 「ルネサンスの記譜法は、私たち(現代人)の基準からすると過小な規定であり、現代的な形式に翻訳されると、その本来の開放性を過剰に規定し、歪める規定 的な重みを獲得する」[5]。ルネサンスの楽曲は個々のパート譜でのみ記譜され、楽譜は極めてまれで、小節線は使用されなかった。音価は一般的に今日使わ れているものよりも大きく、拍子の主な単位はセミブレーブ(全音符)であった。これは現代の「小節」に相当するが、それ自体が音価であり、小節は音価では ない。現代の音楽で、4分音符が2つの8分音符に相当するか、3つの8分音符に相当するかは、「3連符 」と表記されるルールと同じである。同じ計算で、次の最小音符である「ミニム」(現代の「2分音符」に相当)は、半音ごとに2つまたは3つになる。 これらの異なる順列は、ブレーベとセミブレーベの関係では「完全/不完全テンポス」、セミブレーベとミニムの関係では「完全/不完全プロレーション」と呼 ばれ、互いにあらゆる可能な組み合わせで存在した。3対1は 「完全」、2対1は 「不完全 」と呼ばれた。また、ある音符の前後に他の音符が続くと、その音符の価値が半分になったり2倍になったりする(それぞれ 「不完全 」または 「変化」)というルールも存在した。4分音符のような)黒い音符記号のある音符は、あまり見かけなくなった。このような白い記譜法の発達は、(ヴェラムで はなく)紙を使うようになった結果かもしれない。他の色や、後に塗りつぶされた音符も日常的に使われるようになったが、これは主に前述のような欠陥や変更 を強制したり、その他の一時的なリズムの変更を呼びかけたりするためであった。 アクシデンタル(音を変化させるシャープ、フラット、ナチュラルの追加など)は、今日のギター系楽器の運指譜(タブ譜)のように、必ずしも指定されること はなかった。しかし、ルネサンス期の音楽家たちは、ダイアド的対位法の高度な訓練を受けていたため、たとえ臨時記号が書かれていなかったとしても、楽譜を 正しく読むために必要な情報やその他の情報を持っていただろう。そのため、「現代の記譜法が要求するもの(臨時記号)は、対位法に精通した歌い手にとって は、記譜がなくても完全に明らかであっただろう。」(ムジカ・フィクタ参照)。(歌い手は、他のパートを念頭に置いてカデンシャルの定式を計算することに よって自分のパートを解釈し、一緒に歌うときには、演奏者は平行オクターヴや平行5度を避けたり、他の演奏者の決定を考慮してカデンシャル・パートを変更 したりした[5]。 特定の理論家については、ヨハネス・ティンクトリス、フランキヌス・ガフリウス、ハインリヒ・グラリアン、ピエトロ・アロン、ニコラ・ヴィチェンティー ノ、トマス・デ・サンタ・マリア、ジョセフ・ザルリーノ、ヴィセンテ・ルシターノ、ヴィンチェンツォ・ガリレイ、ジョヴァンニ・アルトゥージ、ヨハネス・ ヌシウス、ピエトロ・チェローネを参照のこと。 |

|

下に再掲 |

| Early period (1400–1470) The key composers from the early Renaissance era also wrote in a late medieval style, and as such, they are transitional figures. Leonel Power (c. 1370s or 1380s–1445) was an English composer of the late medieval and early Renaissance music eras. Along with John Dunstaple, he was one of the major figures in English music in the early 15th century.[6][7] Power is the composer best represented in the Old Hall Manuscript, one of the only undamaged sources of English music from the early 15th century. He was one of the first composers to set separate movements of the ordinary of the mass which were thematically unified and intended for contiguous performance. The Old Hall Manuscript contains his mass based on the Marian antiphon, Alma Redemptoris Mater, in which the antiphon is stated literally in the tenor voice in each movement, without melodic ornaments. This is the only cyclic setting of the mass ordinary which can be attributed to him.[8] He wrote mass cycles, fragments, and single movements and a variety of other sacred works. John Dunstaple (c. 1390–1453) was an English composer of polyphonic music of the late medieval era and early Renaissance periods. He was one of the most famous composers active in the early 15th century, a near-contemporary of Power, and was widely influential, not only in England but on the continent, especially in the developing style of the Burgundian School. Dunstaple's influence on the continent's musical vocabulary was enormous, particularly considering the relative paucity of his (attributable) works. He was recognized for possessing something never heard before in music of the Burgundian School: la contenance angloise ("the English countenance"), a term used by the poet Martin le Franc in his Le Champion des Dames. Le Franc added that the style influenced Dufay and Binchois. Writing a few decades later in about 1476, the Flemish composer and music theorist Tinctoris reaffirmed the powerful influence Dunstaple had, stressing the "new art" that Dunstaple had inspired. Tinctoris hailed Dunstaple as the fons et origo of the style, its "wellspring and origin."[This quote needs a citation] The contenance angloise, while not defined by Martin le Franc, was probably a reference to Dunstaple's stylistic trait of using full triadic harmony (three note chords), along with a liking for the interval of the third. Assuming that he had been on the continent with the Duke of Bedford, Dunstaple would have been introduced to French fauxbourdon; borrowing some of the sonorities, he created elegant harmonies in his own music using thirds and sixths (an example of a third interval is the notes C and E; an example of a sixth interval is the notes C and A). Taken together, these are seen as defining characteristics of early Renaissance music. Many of these traits may have originated in England, taking root in the Burgundian School around the middle of the century. Because numerous copies of Dunstaple's works have been found in Italian and German manuscripts, his fame across Europe must have been widespread. Of the works attributed to him only about fifty survive, among which are two complete masses, three connected mass sections, fourteen individual mass sections, twelve complete isorhythmic motets and seven settings of Marian antiphons, such as Alma redemptoris Mater and Salve Regina, Mater misericordiae. Dunstaple was one of the first to compose masses using a single melody as cantus firmus. A good example of this technique is his Missa Rex seculorum. He is believed to have written secular (non-religious) music, but no songs in the vernacular can be attributed to him with any degree of certainty. Oswald von Wolkenstein (c. 1376–1445) is one of the most important composers of the early German Renaissance. He is best known for his well-written melodies, and for his use of three themes: travel, God and sex.[9] Gilles Binchois (c. 1400–1460) was a Dutch composer, one of the earliest members of the Burgundian school and one of the three most famous composers of the early 15th century. While often ranked behind his contemporaries Guillaume Dufay and John Dunstaple by contemporary scholars, his works were still cited, borrowed and used as source material after his death. Binchois is considered[by whom?] to be a fine melodist, writing carefully shaped lines which are easy to sing and memorable. His tunes appeared in copies decades after his death and were often used as sources for mass composition by later composers. Most of his music, even his sacred music, is simple and clear in outline, sometimes even ascetic (monk-like). A greater contrast between Binchois and the extreme complexity of the ars subtilior of the prior (fourteenth) century would be hard to imagine. Most of his secular songs are rondeaux, which became the most common song form during the century. He rarely wrote in strophic form, and his melodies are generally independent of the rhyme scheme of the verses they are set to. Binchois wrote music for the court, secular songs of love and chivalry that met the expectations and satisfied the taste of the Dukes of Burgundy who employed him, and evidently loved his music accordingly. About half of his extant secular music is found in the Oxford Bodleian Library. Guillaume Du Fay (c. 1397–1474) was a Franco-Flemish composer of the early Renaissance. The central figure in the Burgundian School, he was regarded by his contemporaries as the leading composer in Europe in the mid-15th century.[10] Du Fay composed in most of the common forms of the day, including masses, motets, Magnificats, hymns, simple chant settings in fauxbourdon, and antiphons within the area of sacred music, and rondeaux, ballades, virelais and a few other chanson types within the realm of secular music. None of his surviving music is specifically instrumental, although instruments were certainly used for some of his secular music, especially for the lower parts; all of his sacred music is vocal. Instruments may have been used to reinforce the voices in actual performance for almost any of his works.[citation needed] Seven complete masses, 28 individual mass movements, 15 settings of chant used in mass propers, three Magnificats, two Benedicamus Domino settings, 15 antiphon settings (six of them Marian antiphons), 27 hymns, 22 motets (13 of these isorhythmic in the more angular, austere 14th-century style which gave way to more melodic, sensuous treble-dominated part-writing with phrases ending in the "under-third" cadence in Du Fay's youth) and 87 chansons definitely by him have survived.[citation needed]  Portion of Du Fay's setting of Ave maris stella, in fauxbourdon. The top line is a paraphrase of the chant; the middle line, designated "fauxbourdon", (not written) follows the top line but exactly a perfect fourth below. The bottom line is often, but not always, a sixth below the top line; it is embellished, and reaches cadences on the octave.Playⓘ Many of Du Fay's compositions were simple settings of chant, obviously designed for liturgical use, probably as substitutes for the unadorned chant, and can be seen as chant harmonizations. Often the harmonization used a technique of parallel writing known as fauxbourdon, as in the following example, a setting of the Marian antiphon Ave maris stella. Du Fay may have been the first composer to use the term "fauxbourdon" for this simpler compositional style, prominent in 15th-century liturgical music in general and that of the Burgundian school in particular. Most of Du Fay's secular (non-religious) songs follow the formes fixes (rondeau, ballade, and virelai), which dominated secular European music of the 14th and 15th centuries. He also wrote a handful of Italian ballate, almost certainly while he was in Italy. As is the case with his motets, many of the songs were written for specific occasions, and many are datable, thus supplying useful biographical information. Most of his songs are for three voices, using a texture dominated by the highest voice; the other two voices, unsupplied with text, were probably played by instruments.[citation needed] Du Fay was one of the last composers to make use of late-medieval polyphonic structural techniques such as isorhythm,[11] and one of the first to employ the more mellifluous harmonies, phrasing and melodies characteristic of the early Renaissance.[12] His compositions within the larger genres (masses, motets and chansons) are mostly similar to each other; his renown is largely due to what was perceived as his perfect control of the forms in which he worked, as well as his gift for memorable and singable melody. During the 15th century, he was universally regarded as the greatest composer of his time, an opinion that has largely survived to the present day.[13][14] |

初期(1400-1470年) 初期ルネサンス時代の主要な作曲家たちもまた、後期中世のスタイルで作曲しており、過渡期の人物といえる。レオネル・パワー(1370年代または1380 年代~1445年)は、中世後期からルネサンス初期にかけてのイギリスの作曲家である。ジョン・ダンステープルと並び、15世紀初頭のイギリス音楽界を代 表する作曲家である[6][7]。15世紀初頭のイギリス音楽で唯一破損していない資料のひとつであるオールド・ホール写本に最もよく表れている作曲家で ある。彼は、テーマ的に統一され、連続した演奏を意図したミサ曲の普通楽章を別々に作曲した最初の作曲家の一人である。オールド・ホール写本には、マリア 賛歌Alma Redemptoris Materに基づくミサ曲が収められている。ミサ曲の連作、断片、単一楽章のほか、さまざまな神聖な作品を作曲した[8]。 ジョン・ダンステープル(1390頃-1453)は、中世後期からルネサンス初期にかけてのイギリスのポリフォニック音楽の作曲家である。15世紀初頭に 活躍した最も有名な作曲家の一人で、パワーとほぼ同時代の作曲家であり、特にブルゴーニュ楽派の発展した様式において、イギリスのみならず大陸にも広く影 響を与えた。特に彼の(帰属する)作品が比較的少ないことを考慮すると、大陸の音楽用語に与えたダンスタプルの影響は甚大であった。詩人マルタン・ル・フ ランが『Le Champion des Dames』の中で用いた「la contenance angloise(英国的な表情)」という言葉である。ル・フランは、この様式がデュファイやビンチョワに影響を与えたと付け加えている。数十年後の 1476年頃、フランドルの作曲家で音楽理論家のティンクトリスは、ドゥンステープルが与えた強い影響力を再確認し、ドゥンステープルが触発した「新しい 芸術」を強調している。ティンクトリスは、ダンスタプルをこの様式のfons et origo、つまり「源泉であり起源」であると称賛した[この引用には引用が必要である]。 マルタン・ル・フランによって定義されたわけではないが、アングロワーズの内容は、おそらく、3分の1の音程を好むとともに、完全な3和音(3つの音の和 音)を用いるというダンスタプルの様式的特徴に言及したものであろう。彼がベッドフォード公爵と共に大陸に滞在していたと仮定すると、ダンスタプルはフラ ンスのフェイクブールドンに触れたはずで、そのソノリティの一部を借りて、彼は自身の音楽に3度音程と6度音程を使ったエレガントなハーモニーを創作した (3度音程の例はCとEの音、6度音程の例はCとAの音)。これらを総合すると、初期ルネサンス音楽を特徴づけるものと考えられる。これらの特徴の多く は、世紀半ば頃のブルゴーニュ楽派に根付いて、イギリスで生まれたと考えられる。 イタリアやドイツの写本からダンスタプルの作品のコピーが多数見つかっていることから、彼の名声はヨーロッパ中に広まっていたに違いない。彼の作品とされ るもののうち、現存しているのは約50曲のみで、その中には2曲のミサ曲全曲、3曲のミサ曲の連結部分、14曲のミサ曲の個別部分、12曲の等リズムのモ テット全曲、Alma redemptoris MaterやSalve Regina, Mater misericordiaeといったマリア賛歌の7曲の設定がある。ダンスタプルは、単一の旋律をカントゥス・フォルムスとして用いたミサ曲を最初に作曲 した一人である。この技法の好例が、彼のミサ・レクス・セクロルムである。彼は世俗曲(非宗教曲)を作曲したと考えられているが、彼の作品と断定できる俗 謡はない。 オズワルド・フォン・ヴォルケンシュタイン(1376-1445年頃)は、初期ドイツ・ルネサンスの最も重要な作曲家の一人である。彼はよく書かれた旋律 と、旅、神、性という3つのテーマを用いたことで最もよく知られている[9]。 ジル・ビンチョイス(1400年頃-1460年)はオランダの作曲家で、ブルゴーニュ楽派の初期のメンバーの一人であり、15世紀初頭の最も有名な3人の 作曲家の一人である。同時代のギョーム・デュファイやジョン・ダンステープルの後塵を拝することが多かったが、彼の作品は彼の死後も引用され、借用され、 原典として使用された。ビンチョワは[誰が?]優れたメロディストであり、歌いやすく覚えやすい、注意深く形作られた線を書くと考えられている。彼の曲 は、彼の死後何十年も経ってからコピーされ、後世の作曲家たちがミサ曲を作曲する際にしばしば素材として使われた。彼の音楽のほとんどは、聖楽でさえも、 シンプルで明快な輪郭を持ち、時には禁欲的(修道士的)ですらある。ビンチョワと、それ以前(14世紀)の極度に複雑なアルス・スブティリオールとの間 に、これ以上のコントラストがあることは想像に難くないだろう。彼の世俗歌曲のほとんどはロンドーで、これはこの世紀に最も一般的な歌曲形式となった。ス トロフ形式はほとんどなく、旋律は詩の韻律とは無関係である。ビンショワは宮廷のための音楽、愛と騎士道の世俗歌曲を書いたが、それは彼を雇ったブルゴー ニュ公爵家の期待に応え、その趣味を満足させるものであり、それに応じて彼の音楽を愛したことは明らかである。現存する彼の世俗音楽の約半分は、オックス フォード・ボドリアン図書館に所蔵されている。 ギョーム・デュ・フェイ(1397年頃-1474年)は、ルネサンス初期のフランコ・フランドルの作曲家である。ブルゴーニュ楽派の中心人物であり、同時 代の作曲家たちからは15世紀半ばのヨーロッパを代表する作曲家とみなされていた[10]。デュ・フェイは、聖楽の分野ではミサ曲、モテット、マニフィカ ト、賛美歌、フェイクブールドンによる簡単な聖歌の設定、アンティフォンを、世俗音楽の分野ではロンドー、バラード、ヴィレレー、その他いくつかのシャン ソンなど、当時一般的だった形式のほとんどを作曲した。現存する音楽には器楽曲はないが、世俗音楽の一部、特に低音部に楽器が使われていたのは確かで、聖 楽曲はすべて声楽曲である。聖曲はすべて声楽曲である。実際の演奏では、ほとんどの作品で声楽を補強するために楽器が使われた可能性がある。[7つのミサ 曲全曲、28のミサ曲の楽章、ミサ曲のプロパーに使われた聖歌の15の設定、3つのマニフィカト、2つのベネディカムス・ドミノの設定、15のアンティ フォンの設定(うち6つはマリア賛歌)、27の賛美歌、 22曲のモテット(このうち13曲は、より角ばった厳かな14世紀のスタイルによるアイソリズミックなもので、デュフェイの若い頃には、「3分の下」のカ デンツで終わるフレーズを持つ、よりメロディアスで官能的な高音部主体のパートライティングへと移行していった)、そして87曲のシャンソンが、間違いな くデュフェイによって書かれたものとして現存している。[要出典]。  デュ・フェイがフェイク・ブールドンで作曲した「Ave maris stella」の一部。上行は聖歌のパラフレーズで、「フェイク・ブールドン」と呼ばれる中行(書かれていない)は上行に続くが、ちょうど完全4分の1下 にある。最下行は、常にではないが、多くの場合、最上行の6分の1下であり、装飾が施され、オクターブ上のカデンツに達する。 デュフェイの曲の多くは聖歌の単純な設定であり、明らかに典礼用に作られたもので、おそらく装飾のない聖歌の代用として作られたもので、聖歌の和声化と見 ることができる。多くの場合、和声化にはフェイク・ブールドンと呼ばれる平行調の技法が用いられており、次の例はマリア賛歌Ave maris stellaの和声化である。デュ・フェイは、15世紀の典礼音楽全般、特にブルゴーニュ楽派の音楽で顕著だったこの単純な作曲様式に対して、 「fauxbourdon 」という言葉を使った最初の作曲家であったかもしれない。デュ・フェイの世俗(非宗教)歌曲のほとんどは、14~15世紀のヨーロッパの世俗音楽を支配し たフォルム・フィクス(ロンドー、バラード、ヴィレライ)に従っている。また、イタリアに滞在していた時期に、イタリア語のバラードもいくつか書いてい る。モテットの場合と同様、歌曲の多くは特定の機会に書かれたもので、その多くは年代を特定できるため、伝記的な情報として有用である。彼の歌曲のほとん どは3声のためのもので、最高声部を中心としたテクスチュアを用いている。 デュフェイは、アイソリズムのような中世後期のポリフォニックな構造的技法を用いた最後の作曲家の一人であり[11]、初期ルネサンスに特徴的な、より芳 醇なハーモニー、フレージング、メロディーを用いた最初の作曲家の一人である[12]。15世紀中、彼は同時代の最も偉大な作曲家として普遍的に評価さ れ、その意見は今日までほぼ存続している[13][14]。 |

Middle period (1470–1530) 1611 woodcut of Josquin des Prez, copied from a now-lost oil painting done during his lifetime [icon] ++++++++++++++++++++ This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (April 2020) ++++++++++++++++++++ During the 16th century, Josquin des Prez (c. 1450/1455 – 27 August 1521) gradually acquired the reputation as the greatest composer of the age, his mastery of technique and expression universally imitated and admired. Writers as diverse as Baldassare Castiglione and Martin Luther wrote about his reputation and fame. In England, the intense Marian tradition led to the Tudor votive style of polyphony, characterised by high treble lines and long solo verses with melisma. Antiphons were usually performed at the end of the liturgical day after compline.[15] The largest collection of the style is the late-15th-century Eton Choirbook.[16] By 1500, canticles, antiphons and Lady Masses were composed with up to nine parts in the texture, and vocal ranges and melodic complexity increased; Erasmus noted the powerful basses of the English choirs of the time, but criticised the excessively-virtuosic treble verses and he did not believe English music to be spiritually edifying as a result.[17][18] "In churches everywhere, there is a great deal of organ music and much singing; but the style of this music seems designed more to delight the ears than to inspire piety. [...] Boys, exercising their little voices, break out into shouts, with tremulous tones and undulating inflections up and down, doing nothing but distort the words so that you cannot understand what is being sung." - letter to Ulrich von Hutten (1519) Characteristics of the votive style, such as elaborate voice lines and melisma, began to be supplanted by more succinct continental traditions by the 1530s.[19] Apart from a brief but strong revival in the 1550s with the reign of Queen Mary,[20] the votive style died out due to its complexity, scale and devotional subject coming to odds with the ideals of the Edwardian and Elizabethan reformations. Former late proponents such as John Sheppard, Robert White and Thomas Tallis began composing in a more modern, imitative style of polyphony closer to that of the late period, such as in the Roman School.[21] Nevertheless, the Tudor votive style had enduring influence in the Anglican church: choristers and lay clerks often face each other antiphonally, placed in the quire's Decani and Cantoris, just as they did in the late Plantagenet and early Tudor periods.[22] |

中期(1470-1530年) 1611年、ジョスカン・デ・プレの木版画、生前に描かれた油絵の模写である。 [アイコン] ++++++++++++++++++++ このセクションは拡張が必要である。ぜひ追加してほしい。(2020年4月) ++++++++++++++++++++ 16世紀、ジョスカン・デ・プレ(1450/1455頃-1521年8月27日)は、時代最高の作曲家としての名声を徐々に獲得し、その卓越した技巧と表 現は広く模倣され、賞賛された。バルダッサーレ・カスティリオーネやマルティン・ルターなど様々な作家が、彼の名声と評判について書いている。 イギリスでは、激しいマリア会の伝統により、チューダー朝の奉納的なポリフォニー様式が生まれた。アンティフォンは通常、典礼日の終わりのコンプラインの 後に演奏された[15]。この様式の最大のコレクションは、15世紀後半のイートン聖歌集である[16]。[エラスムスは、当時のイギリスの合唱団の力強 い低音部に注目したが、過度にヴィルトゥオーゾ的な高音部を批判し、その結果、イギリスの音楽が霊的に啓発的なものだとは考えなかった[17][18]。 「どこの教会でも、多くのオルガン音楽と多くの歌がある。[......)少年たちは、小さな声で、震えるような調子で、上下に抑揚をつけながら、叫び声 を上げる。- ウルリッヒ・フォン・ハッテンへの手紙(1519年) 精巧な声部やメリスマといった奉納様式の特徴は、1530年代には、より簡潔な大陸の伝統に取って代わられ始めた[19]。1550年代にメアリー女王の 治世下で短期間ながら力強く復活した以外は[20]、奉納様式は、その複雑さ、規模、献身的な主題が、エドワード朝やエリザベス朝の改革の理想と対立した ために廃れた。ジョン・シェパード、ロバート・ホワイト、トマス・タリスといった後期の支持者たちは、ローマ楽派のような後期のポリフォニーに近い、より 近代的で模倣的なスタイルで作曲を始めた[21]。それでも、テューダー朝の奉納様式は英国国教会の教会において永続的な影響力を持っていた。 |

Late period (1530 –1600) San Marco in the evening. The spacious, resonant interior was one of the inspirations for the music of the Venetian School. In Venice, from about 1530 until around 1600, an impressive polychoral style developed, which gave Europe some of the grandest, most sonorous music composed up until that time, with multiple choirs of singers, brass and strings in different spatial locations in the Basilica San Marco di Venezia (see Venetian School). These multiple revolutions spread over Europe in the next several decades, beginning in Germany and then moving to Spain, France, and England somewhat later, demarcating the beginning of what we now know as the Baroque musical era. The Roman School was a group of composers of predominantly church music in Rome, spanning the late Renaissance and early Baroque eras. Many of the composers had a direct connection to the Vatican and the papal chapel, though they worked at several churches; stylistically they are often contrasted with the Venetian School of composers, a concurrent movement which was much more progressive. By far the most famous composer of the Roman School is Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina. While best known as a prolific composer of masses and motets, he was also an important madrigalist. His ability to bring together the functional needs of the Catholic Church with the prevailing musical styles during the Counter-Reformation period gave him his enduring fame.[23] The brief but intense flowering of the musical madrigal in England, mostly from 1588 to 1627, along with the composers who produced them, is known as the English Madrigal School. The English madrigals were a cappella, predominantly light in style, and generally began as either copies or direct translations of Italian models. Most were for three to six voices. Musica reservata is either a style or a performance practice in a cappella vocal music of the latter half of the 16th century, mainly in Italy and southern Germany, involving refinement, exclusivity, and intense emotional expression of sung text.[24] The cultivation of European music in the Americas began in the 16th century soon after the arrival of the Spanish, and the conquest of Mexico. Although fashioned in European style, uniquely Mexican hybrid works based on native Mexican language and European musical practice appeared very early. Musical practices in New Spain continually coincided with European tendencies throughout the subsequent Baroque and Classical music periods. Among these New World composers were Hernando Franco, Antonio de Salazar, and Manuel de Zumaya.[citation needed] In addition, writers since 1932 have observed what they call a seconda prattica (an innovative practice involving monodic style and freedom in treatment of dissonance, both justified by the expressive setting of texts) during the late 16th and early 17th centuries.[25] Mannerism In the late 16th century, as the Renaissance era closed, an extremely manneristic style developed. In secular music, especially in the madrigal, there was a trend towards complexity and even extreme chromaticism (as exemplified in madrigals of Luzzaschi, Marenzio, and Gesualdo). The term mannerism derives from art history. Transition to the Baroque See also: Transition from Renaissance to Baroque in instrumental music Beginning in Florence, there was an attempt to revive the dramatic and musical forms of Ancient Greece, through the means of monody, a form of declaimed music over a simple accompaniment; a more extreme contrast with the preceding polyphonic style would be hard to find; this was also, at least at the outset, a secular trend. These musicians were known as the Florentine Camerata. We have already noted some of the musical developments that helped to usher in the Baroque, but for further explanation of this transition, see antiphon, concertato, monody, madrigal, and opera, as well as the works given under "Sources and further reading." |

後期(1530年-1600年) 夕暮れのサン・マルコ。広々とした響きのある内部は、ヴェネツィア楽派の音楽のインスピレーションのひとつとなった。 ヴェネツィアでは、1530年頃から1600年頃まで、印象的な多声合唱様式が発展し、ヴェネチア・サンマルコ寺院の異なる空間的位置に複数の歌手、金管 楽器、弦楽器からなる合唱団を配置し、それまで作曲された音楽の中で最も壮大で最も響きのある音楽をヨーロッパに与えた(ヴェネツィア派を参照)。こうし た複数の革命は、その後数十年の間にヨーロッパ全土に広がり、ドイツに始まり、やや遅れてスペイン、フランス、イギリスへと移り、現在私たちがバロック音 楽時代と呼ぶものの始まりを画した。 ローマ楽派は、ルネサンス後期からバロック初期にかけて、ローマで主に教会音楽を作曲した作曲家のグループである。作曲家の多くはバチカンや法王庁礼拝堂 と直接のつながりがあったが、いくつかの教会で活動していた。様式的には、より進歩的だった同時代の運動であるヴェネツィア派の作曲家と対比されることが 多い。ローマ楽派の作曲家で最も有名なのは、ジョヴァンニ・ピエルルイージ・ダ・パレストリーナである。ミサ曲やモテットの作曲家として最もよく知られて いるが、マドリガルの作曲家としても重要な存在であった。カトリック教会の機能的なニーズと、反宗教改革期の一般的な音楽様式を結びつける彼の能力は、彼 に不朽の名声を与えた[23]。 主に1588年から1627年にかけて、イギリスにおけるマドリガルの短期間ではあるが激しい開花は、それらを生み出した作曲家たちとともに、イギリス・ マドリガル派として知られている。イギリスのマドリガルはアカペラで、軽快なスタイルが主流で、一般的にはイタリア語の模倣か直訳から始まった。ほとんど が3声から6声のためのものだった。 ムジカ・レゼルヴァータ(Musica reservata)とは、主にイタリアと南ドイツにおける16世紀後半のアカペラ声楽曲の様式またはパフォーマビティであり、洗練、排他性、歌われたテ キストの激しい感情表現を伴う[24]。 アメリカ大陸におけるヨーロッパ音楽の育成は、スペイン人が到着し、メキシコを征服した直後の16世紀に始まった。ヨーロッパの様式で作られたとはいえ、 メキシコ固有の言語とヨーロッパの音楽的慣習に基づいたメキシコ独自のハイブリッドな作品は、非常に早い時期に登場した。ニュー・スペインにおける音楽的 実践は、その後のバロック音楽と古典派音楽の時代を通じて、絶えずヨーロッパの傾向と一致していた。これらの新世界の作曲家の中には、エルナンド・フラン コ、アントニオ・デ・サラサール、マヌエル・デ・ズマヤがいる[要出典]。 さらに、1932年以降の著述家たちは、16世紀後半から17世紀初頭にかけて、彼らがセコンダ・プラッティカ(単旋律様式と不協和音の扱いにおける自由 を含む革新的な実践であり、いずれもテキストの表現的設定によって正当化される)と呼ぶものを観察している[25]。 マニエリスム 16世紀後半、ルネサンスの時代が終わると、極めてマンネリスティックな様式が発展した。世俗音楽、特にマドリガルでは、複雑さや極端な半音階主義(ルッ ツァスキ、マレンツィオ、ゲズアルドのマドリガルに代表される)を目指す傾向が見られた。マンネリズムという言葉は美術史に由来する。 バロックへの移行 こちらも参照のこと: 器楽におけるルネサンスからバロックへの移行 フィレンツェを皮切りに、古代ギリシャの演劇や音楽の形式を、単純な伴奏に乗せて宣言するモノディーという形式によって復活させようとする試みが始まっ た。これらの音楽家はフィレンツェ・カメラータとして知られていた。 バロックの先駆けとなった音楽の発展についてはすでに述べたが、この変遷については、アンティフォン、コンチェルタート、モノディ、マドリガル、オペラ、 そして 「資料と参考文献 」に挙げた作品を参照されたい。 |

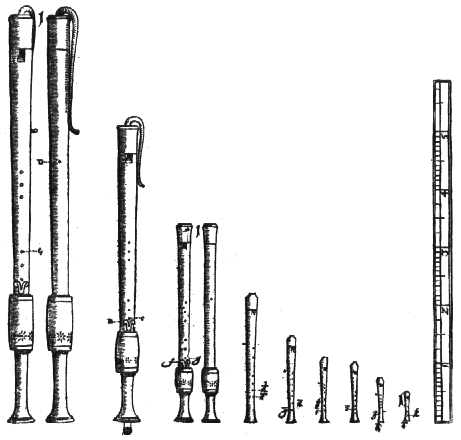

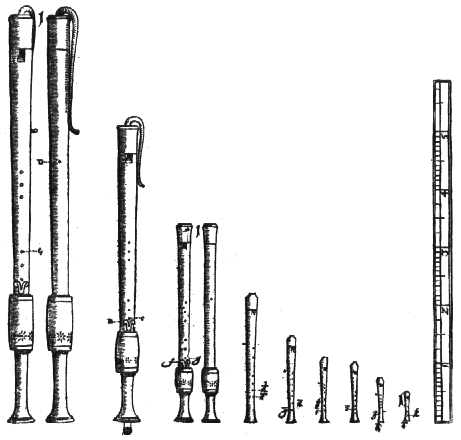

| Instruments See also: List of European medieval musical instruments, many of which overlap with Renaissance  Selection of Renaissance instruments Many instruments originated during the Renaissance; others were variations of, or improvements upon, instruments that had existed previously. Some have survived to the present day; others have disappeared, only to be recreated in order to perform music of the period on authentic instruments. As in the modern day, instruments may be classified as brass, strings, percussion, and woodwind. Medieval instruments in Europe had most commonly been used singly, often self-accompanied with a drone, or occasionally in parts. From at least as early as the 13th century through the 15th century there was a division of instruments into haut (loud, shrill, outdoor instruments) and bas (quieter, more intimate instruments).[26] Only two groups of instruments could play freely in both types of ensembles: the cornett and sackbut, and the tabor and tambourine.[4] At the beginning of the 16th century, instruments were considered to be less important than voices. They were used for dances and to accompany vocal music.[1] Instrumental music remained subordinated to vocal music, and much of its repertory was in varying ways derived from or dependent on vocal models.[3] |

楽器 こちらも参照のこと: ヨーロッパ中世楽器リスト(ルネサンスと重複するものも多い  ルネサンス楽器のセレクション ルネサンス期に誕生した楽器は数多く、それ以前から存在した楽器のバリエーションや改良型もある。現代まで残っているものもあれば、姿を消してしまったも のの、当時の音楽を本物の楽器で演奏するために再現されたものもある。現代と同じように、楽器は金管楽器、弦楽器、打楽器、木管楽器に分類される。 中世ヨーロッパでは、楽器は単独で使用されるのが一般的で、ドローンと伴奏することも多かった。少なくとも13世紀初頭から15世紀にかけては、楽器を オート(大音量の、けたたましい、屋外の楽器)とバス(より静かな、より親密な楽器)に分けていた[26]。両方のタイプのアンサンブルで自由に演奏でき る楽器は、コルネットとサックバット、タボールとタンバリンの2つのグループだけであった[4]。 16世紀初頭、楽器は声楽よりも重要でないと考えられていた。楽器は舞曲や声楽の伴奏に使用された[1]。器楽は声楽に従属したままであり、そのレパート リーの多くは様々な形で声楽のモデルから派生したり、声楽のモデルに依存していた[3]。 |

| Organs Various kinds of organs were commonly used in the Renaissance, from large church organs to small portatives and reed organs called regals. |

オルガン ルネサンス期には、大型の教会オルガンから小型のポルタティブ、レガルスと呼ばれるリードオルガンまで、さまざまな種類のオルガンが一般的に使われた。 |

| Brass Brass instruments in the Renaissance were traditionally played by professionals. Some of the more common brass instruments that were played: Slide trumpet: Similar to the trombone of today except that instead of a section of the body sliding, only a small part of the body near the mouthpiece and the mouthpiece itself is stationary. Also, the body was an S-shape so it was rather unwieldy, but was suitable for the slow dance music which it was most commonly used for. Cornett: Made of wood and played like the recorder (by blowing in one end and moving the fingers up and down the outside) but using a cup mouthpiece like a trumpet. Trumpet: Early trumpets had no valves, and were limited to the tones present in the overtone series. They were also made in different sizes. Sackbut (sometimes sackbutt or sagbutt): A different name for the trombone,[27] which replaced the slide trumpet by the middle of the 15th century.[28] |

金管楽器 ルネサンス時代の金管楽器は、伝統的に専門家によって演奏されていた。一般的に演奏されていた金管楽器をいくつか紹介しよう: スライド・トランペット: 今日のトロンボーンに似ているが、ボディの一部がスライドするのではなく、マウスピースとマウスピース近くのボディの一部だけが固定されている。また、胴 体がS字型なので扱いにくいが、最もよく使われたスローなダンス音楽に適していた。 コルネット:木製で、リコーダーのように(片方の端から息を吹き込み、指を上下に動かして)演奏するが、トランペットのようにカップ・マウスピースを使 う。 トランペット: 初期のトランペットにはバルブがなく、倍音列の音色に限られていた。サイズも異なる。 サックバット(sackbutt、sagbuttのこともある): トロンボーンの異なる呼称[27]で、15世紀半ばまでにスライドトランペットに取って代わられた[28]。 |

Strings Modern French hurdy-gurdy As a family, strings were used in many circumstances, both sacred and secular. A few members of this family include: Viol: This instrument, developed in the 15th century, commonly has six strings. It was usually played with a bow. It has structural qualities similar to the Spanish plucked vihuela (called viola da mano in Italy); its main separating trait is its larger size. This changed the posture of the musician in order to rest it against the floor or between the legs in a manner similar to the cello. Its similarities to the vihuela were sharp waist-cuts, similar frets, a flat back, thin ribs, and identical tuning. When played in this fashion, it was sometimes referred to as "viola da gamba", in order to distinguish it from viols played "on the arm": viole da braccio, which evolved into the violin family. Lyre: Its construction is similar to a small harp, although instead of being plucked, it is strummed with a plectrum. Its strings varied in quantity from four, seven, and ten, depending on the era. It was played with the right hand, while the left hand silenced the notes that were not desired. Newer lyres were modified to be played with a bow. Irish Harp: Also called the Clàrsach in Scottish Gaelic, or the Cláirseach in Irish, during the Middle Ages it was the most popular instrument of Ireland and Scotland. Due to its significance in Irish history, it is seen even on the Guinness label and is Ireland's national symbol even to this day. To be played it is usually plucked.[clarification needed] Its size can vary greatly from a harp that can be played in one's lap to a full-size harp that is placed on the floor Hurdy-gurdy: (Also known as the wheel fiddle), in which the strings are sounded by a wheel which the strings pass over. Its functionality can be compared to that of a mechanical violin, in that its bow (wheel) is turned by a crank. Its distinctive sound is mainly because of its "drone strings" which provide a constant pitch similar in their sound to that of bagpipes. Gittern and mandore: these instruments were used throughout Europe. Forerunners of modern instruments including the mandolin and guitar. Lira da braccio Bandora Cittern Lute Orpharion Vihuela Clavichord Harpsichord Virginal |

弦楽器 現代フランスのハーディ・ガーディ 弦楽器ファミリーは、聖俗を問わず様々な場面で使用された。弦楽器の仲間には以下のようなものがある: ヴィオール: 15世紀に開発されたこの楽器は、一般的に6本の弦を持つ。通常は弓で演奏する。スペインの撥弦楽器ヴィウエラ(イタリアではヴィオラ・ダ・マーノと呼ば れる)に似た構造的特質を持つが、主な特徴はサイズが大きいことである。そのため、チェロと同じように床に置いたり、足の間に挟んだりするように演奏者の 姿勢が変化した。ヴィウエラとの類似点は、鋭いウエストカット、似たようなフレット、平らな背中、薄い肋骨、同じチューニングである。このように演奏され る場合、「腕に乗せて」演奏するヴァイオリン(ヴァイオリン・ダ・ブラッチョ)と区別するため、「ヴィオラ・ダ・ガンバ」と呼ばれることもあった。 竪琴:構造は小型のハープに似ているが、弾くのではなく撥で叩く。弦の数は4本、7本、10本と時代によって異なる。右手で弾き、左手で不要な音を消す。 新しいライアーは弓で弾くように改良された。 アイリッシュ・ハープ スコットランド・ゲール語ではClàrsach、アイルランド語ではCláirseachとも呼ばれ、中世にはアイルランドとスコットランドで最もポピュ ラーな楽器だった。アイルランドの歴史におけるその重要性から、ギネスのラベルにも描かれており、今日に至るまでアイルランドの国民的シンボルとなってい る。膝の上で演奏できるハープから、床に置いて演奏するフルサイズのハープまで、その大きさは様々である。 ハーディ・ガーディ:(車輪バイオリンとしても知られる)弦が車輪の上を通ることで弦を鳴らす。その機能は、弓(車輪)をクランクで回すという点で、機械 式バイオリンと比較することができる。その特徴的な音は、主にバグパイプの音に似た一定の音程を提供する「ドローン弦」によるものである。 ギッテルンとマンドール:これらの楽器はヨーロッパ中で使われた。マンドリンやギターなどの現代楽器の先駆けである。 リラ・ダ・ブラッチョ バンドーラ シターン リュート オルファリオン ビウエラ クラヴィコード チェンバロ ヴァージナル |

| Percussion Some Renaissance percussion instruments include the triangle, the Jew's harp, the tambourine, the bells, cymbals, the rumble-pot, and various kinds of drums. Tambourine: The tambourine is a frame drum. The skin that surrounds the frame is called the vellum and produces the beat by striking the surface with the knuckles, fingertips, or hand. It could also be played by shaking the instrument, allowing the tambourine's jingles or pellet bells (if it has either) to "clank" and "jingle". Jew's harp: An instrument that produces sound using shapes of the mouth and attempting to pronounce different vowels with one's mouth. The loop at the bent end of the tongue of the instrument is plucked in different scales of vibration creating different tones. |

打楽器 ルネサンス期の打楽器には、トライアングル、ジュウ・ハープ、タンバリン、ベル、シンバル、ランブル・ポット、各種ドラムなどがある。 タンバリン タンバリンは枠太鼓である。枠を包む皮はベラムと呼ばれ、指の腹、指先、または手で表面を叩くことでビートを出す。また、楽器を振って、タンバリンのジン グルやペレットベル(どちらか一方があれば)を「カラン」「ジングル」と鳴らして演奏することもできる。 ジュウ・ハープ 口の形を使って音を出す楽器で、口でさまざまな母音を発音しようとする。この楽器の舌の曲がった先にある輪を、異なる振動の音階で弾くことで、異なる音色 を作り出す。 |

Woodwinds (aerophones) Musicians from 'Procession in honour of Our Lady of Sablon in Brussels.' Early 17th-century Flemish alta cappella. From left to right: bass dulcian, alto shawm, treble cornett, soprano shawm, alto shawm, tenor sackbut. Woodwind instruments (aerophones) produce sound by means of a vibrating column of air within the pipe. Holes along the pipe allow the player to control the length of the column of air, and hence the pitch. There are several ways of making the air column vibrate, which ways define the subcategories of woodwind instruments. A player may blow across a mouth hole, as in a transverse flute, or into a whistle mouthpiece, as in a recorder (a duct flute); into a single-reed mouthpiece, as in a modern-day clarinet or saxophone; or into a double-reed mouthpiece, as in an oboe or bassoon. All three methods of tone production can be found in Renaissance woodwinds. Shawm: A typical oriental[clarification needed] shawm is keyless and is about a foot long with seven finger holes and a thumb hole. The pipes were also most commonly made of wood and many of them had carvings and decorations on them. It was the most popular double reed instrument of the Renaissance period; it was commonly used in the streets with drums and trumpets because of its brilliant, piercing, and often deafening sound. To play the shawm a person puts the entire reed in their mouth, puffs out their cheeks, and blows into the pipe whilst breathing through their nose.  Renaissance recorders Reedpipe:[29] Made from a single short length of cane with a mouthpiece, four or five finger holes, and reed fashioned from it. The reed is made by cutting out a small tongue, but leaving the base attached. It is the predecessor of the saxophone and the clarinet. Hornpipe: Same as reed pipe but with a bell at the end. Bagpipe/Bladderpipe: Believed by the faithful to have been invented by herdsmen who thought using a bag made out of sheep or goat skin would provide continuing air pressure so that when its player is obliged to take a breath, the player need only squeeze the bag tucked underneath their arm to continue the tone. The mouth pipe has a simple round piece of leather hinged on to the bag end of the pipe and acts like a non-return valve. The reed is located inside the long mouthpiece, which would have been known as a bocal, had it been made of metal and had the reed been on the outside instead of the inside. Panpipe: Employs a number of wooden tubes with a stopper at one end and open on the other. Each tube is a different size (thereby producing a different tone), giving it a range of an octave and a half. The player can then place their lips against the desired tube and blow across it. Transverse flute: The transverse flute is similar to the modern flute with a mouth hole near the stoppered end and finger holes along the body. The player blows across the mouth hole and holds the flute to either the right or left side. Recorder: The recorder was a common instrument during the Renaissance period. Rather than a reed, it uses a whistle mouthpiece as its main source of sound production. It is usually made with seven finger holes and a thumb hole. |

木管楽器(エアロフォン) ブリュッセルのサブロンの聖母を讃える行列」の音楽隊。17世紀初頭のフランドルのアルタ・カペラ。左からバス・ダルシャン、アルト・ショーム、トレブ ル・コルネット、ソプラノ・ショーム、アルト・ショーム、テノール・サックバット。 木管楽器(エアロフォン)は、パイプ内の空気の柱が振動することで音を出す。パイプに沿って穴が開いているため、演奏者は空気柱の長さ、つまり音程をコン トロールすることができる。空気柱を振動させる方法はいくつかあり、木管楽器のサブカテゴリーを定義している。 奏者は、横笛のようにマウス・ホールを横切って吹くこともあれば、リコーダー(ダクト・フルート)のようにホイッスル・マウスピースに吹き込むこともあ る。現代のクラリネットやサクソフォンのようにシングルリードのマウスピースに吹き込むこともあれば、オーボエやファゴットのようにダブルリードのマウス ピースに吹き込むこともある。ルネサンス期の木管楽器には、この3つの音色生成方法がすべて見られる。 ショーム 典型的な東洋の[clarification needed]ショームはキーレスで、長さ約1フィート、7つの指穴と親指穴がある。また、パイプは木製が最も一般的で、その多くに彫刻や装飾が施されて いた。ルネサンス期には最もポピュラーなダブルリード楽器であり、その華麗で突き刺すような、しばしば耳をつんざくような音色のため、ドラムやトランペッ トとともに街頭でよく使われた。ショームを演奏するには、人格がリード全体を口にくわえ、頬を膨らませ、鼻から息を吹き込みながらパイプに息を吹き込む。  ルネサンス期のリコーダー リードパイプ:[29]1本の短い杖から作られ、マウスピース、4~5個の指孔、リードがある。リードは小さな舌を切り取って作られるが、根元はそのまま である。サクソフォーンやクラリネットの前身である。 ホーンパイプ: リードパイプと同じだが、先端にベルが付いている。 バグパイプ/ブラダーパイプ: 羊やヤギの皮で作った袋を使うことで、空気圧を持続させることができ、演奏者が息を吸うとき、腕の下に挟んだ袋を絞るだけで音色を続けることができると考 えた牧童が発明したと、信奉者たちによって信じられている。口パイプには、パイプの袋の端に蝶番で留められたシンプルな丸い革の部分があり、逆流防止弁の ような役割を果たす。リードは長いマウスピースの内側にあり、これが金属製でリードが内側ではなく外側にあれば、ボーカルと呼ばれていただろう。 パンパイプ: 一端にストッパーがあり、もう一方が開いている木製の管を何本も使う。管はそれぞれ大きさが異なり(それによって音色が異なる)、1オクターブ半の音域を 持つ。奏者は唇を目的の管に当て、管の向こう側を吹くことができる。 横笛:横笛は現代のフルートに似ており、止められた端の近くに口穴があり、胴に沿って指穴がある。奏者は口穴を横切るように吹き、フルートを左右どちらか に構える。 リコーダー リコーダーはルネサンス時代によく使われた楽器である。リードではなく、笛のマウスピースを主な音源として使用する。通常7つの指穴と親指穴がある。 |

| History of music List of Renaissance composers Music of the French Renaissance Music in the Elizabethan era |

音楽の歴史 ルネサンスの作曲家リスト フランス・ルネサンスの音楽 エリザベス朝時代の音楽 |

| Anon. "Seconda prattica".

Merriam-Webster.com, 2017 (accessed 13 September 2017). Anon. "What's with the Name?". Sackbut.com website, n.d. (accessed 14 October 2014). Atlas, Allan W. Renaissance Music. New York: W.W. Norton, 1998. ISBN 0-393-97169-4 Baines, Anthony, ed. Musical Instruments Through the Ages. New York: Walker and Company, 1975. Bent, Margaret. "The Grammar of Early Music: Preconditions for Analysis". In Tonal Structures of Early Music, [second edition], edited by Cristle Collins Judd.[page needed] Criticism and Analysis of Early Music 1. New York and London: Garland, 2000. ISBN 978-0-8153-3638-9, 978-0815323884 Reissued as ebook 2014. ISBN 978-1-135-70462-9 Bent, Margaret. "Power, Leonel". Grove Music Online, edited by Deane Root. S.l.: Oxford Music Online, n.d. (accessed June 23, 2015). Bessaraboff, Nicholas. Ancient European Musical Instruments, first edition. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1941. Besseler, Heinrich. 1950. "Die Entstehung der Posaune". Acta Musicologica, 22, fasc. 1–2 (January–June): 8–35. Bowles, Edmund A. 1954. "Haut and Bas: The Grouping of Musical Instruments in the Middle Ages". Musica Disciplina 8:115–40. Brown, Howard M. Music in the Renaissance. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1976. ISBN 0-13-608497-4 J. Peter Burkholder. "Borrowing." Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online, n.d. Retrieved September 30, 2011. Classen, Albrecht. "The Irrepressibility of Sex Yesterday and Today". In Sexuality in the Middle Ages and Early Modern Times, edited by Albrecht Classen, 44–47. S.l.: Walter de Gruyter, 2008. ISBN 978-3-11-020940-2 Emmerson, Richard Kenneth, and Sandra Clayton-Emmerson. Key Figures in Medieval Europe: An Encyclopedia. [New York?]: Routledge, 2006. ISBN 978-0-415-97385-4 Fenlon, Iain, ed. (1989). The Renaissance: from the 1470s to the End of the 16th Century. Man & Music. Vol. 2. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-773417-7. Fuller, Richard. 2010. Renaissance Music (1450–1600). GCSE Music Notes, at rpfuller.com (14 January, accessed 14 October 2014). Gleason, Harold and Becker, Warren. Music in the Middle Ages and Renaissance (Music Literature Outlines Series I). Bloomington, IN: Frangipani Press, 1986. ISBN 0-89917-034-X Judd, Cristle Collins, ed. Tonal Structures of Early Music. New York: Garland Publishing, 1998. ISBN 0-8153-2388-3 Lockwood, Lewis, Noel O’Regan, and Jessie Ann Owens. "Palestrina, Giovanni Pierluigi da." Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online, n.d. Retrieved September 30, 2011. Montagu, Jeremy. "Renaissance instruments". The Oxford Companion to Music, edited by Alison Latham. Oxford Music Online. Retrieved September 30, 2011. Munrow, David. Notes for the recording of Dufay: Misss "Se la face ay pale". Early Music Consort of London. (1974)[full citation needed] Munrow, David. Instruments of the Middle Ages and Renaissance. London: Oxford University Press, 1976. OED. "Renaissance". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.) Ongaro, Giulio. Music of the Renaissance. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 2003. Planchart, Alejandro Enrique (2001). "Du Fay [Dufay; Du Fayt], Guillaume". Grove Music Online. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.08268. ISBN 978-1-56159-263-0. (subscription, Wikilibrary access, or UK public library membership required) Pryer A. 1983. "Dufay". In The New Oxford Companion to Music, edited by Arnold[full citation needed]. Reese, Gustave (1959). Music in the Renaissance (revised ed.). New York City: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-09530-2. Stolba, Marie (1990). The Development of Western Music: A History. Dubuque: W.C. Brown. ISBN 978-0-697-00182-5. Leonel Power (c. 1375–1445) was one of the two leading composers of English music between 1410 and 1445. The other was John Dunstaple. Strunk, Oliver. Source Readings in Music History. New York: W.W. Norton, 1950. Orpheon Foundation, Vienna, Austria |

アノン 「Seconda prattica」.

Merriam-Webster.com, 2017 (accessed 13 September 2017). Anon. 「What's with the Name?」. Sackbut.comウェブサイト、n.d. (2014年10月14日アクセス). Atlas, Allan W. Renaissance Music. New York: W.W. Norton, 1998. ISBN 0-393-97169-4 Baines, Anthony, ed. Musical Instruments Through the Ages. ニューヨーク: Walker and Company, 1975. Bent, Margaret. 「The Grammar of Early Music: The Grammar of Early Music: Preconditions for Analysis". [ページが必要です] Criticism and Analysis of Early Music 1. New York and London: Garland, 2000. ISBN 978-0-8153-3638-9, 978-0815323884 2014年に電子書籍として再発行された。ISBN 978-1-135-70462-9 ベント、マーガレット. 「Power, Leonel」. Grove Music Online, edited by Deane Root. S.l: Oxford Music Online, n.d. (accessed June 23, 2015). Bessaraboff, Nicholas. Ancient European Musical Instruments, first edition. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1941. Besseler, Heinrich. 1950. 「Die Entstehung der Posaune". Acta Musicologica, 22, fasc. 1-2 (January-June): 8-35. Bowles, Edmund A. 1954. 「Haut and Bas: The Grouping of Musical Instruments in the Middle Ages". Musica Disciplina 8:115-40. Brown, Howard M. Music in the Renaissance. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1976. ISBN 0-13-608497-4 J. Peter Burkholder. 「Borrowing」. Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online, n.d. 2011年9月30日取得。 Classen, Albrecht. 「The Irrepressibility of Sex Yesterday and Today」. In Sexuality in the Middle Ages and Early Modern Times, edited by Albrecht Classen, 44-47. S.l: Walter de Gruyter, 2008. ISBN 978-3-11-020940-2 Emmerson, Richard Kenneth, and Sandra Clayton-Emmerson. An Encyclopedia: An Encyclopedia. [New York?] Routledge, 2006. ISBN 978-0-415-97385-4 Fenlon, Iain, ed. (1989). ルネサンス:1470年代から16世紀末まで. Man & Music. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-773417-7. Fuller, Richard. 2010. Renaissance Music (1450-1600). GCSE Music Notes, at rpfuller.com (14 January, accessed 14 October 2014). Gleason, Harold and Becker, Warren. Music in the Middle Ages and Renaissance (Music Literature Outlines Series I). Bloomington, IN: Frangipani Press, 1986. ISBN 0-89917-034-x Judd, Cristle Collins, ed. 初期音楽の調性構造. New York: Garland Publishing, 1998. ISBN 0-8153-2388-3 Lockwood, Lewis, Noel O'Regan, and Jessie Ann Owens. 「Palestrina, Giovanni Pierluigi da.」. Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online, n.d. Retrieved September 30, 2011. Montagu, Jeremy. 「Renaissance instruments」. The Oxford Companion to Music, edited by Alison Latham. Oxford Music Online. 2011年9月30日取得。 Munrow, David. デュフェイの録音のためのノート: Misss 「Se la face ay pale」. Early Music Consort of London. (1974)[full citation needed]. Munrow, David. Instruments of the Middle Ages and Renaissance. London: Oxford University Press, 1976. OED. 「Renaissance」. オックスフォード英語辞典(オンライン版). オックスフォード大学出版局。(購読または参加機関の会員登録が必要) オンガロ、ジュリオ. ルネサンスの音楽. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 2003. Planchart, Alejandro Enrique (2001). 「Du Fay [Dufay; Du Fayt], Guillaume」. Grove Music Online. Oxford, England: doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.08268. ISBN 978-1-56159-263-0. (定期購読、ウィキライブラリーへのアクセス、または英国公共図書館の会員登録が必要)。 Pryer A. 1983年。「Dufay". The New Oxford Companion to Music』(アーノルド編)所収[full citation needed]。 Reese, Gustave (1959). Music in the Renaissance (revised ed.). New York City: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-09530-2. Stolba, Marie (1990). 西洋音楽の発展: A History. Dubuque: W.C. Brown. ISBN 978-0-697-00182-5. レオネル・パワー(1375-1445年頃)は、1410年から1445年にかけてのイギリス音楽を代表する二人の作曲家の一人である。もう一人はジョ ン・ダンスタプルである。 Strunk, Oliver. Source Readings in Music History. New York: W.W. Norton, 1950. オルフェオン財団、ウィーン、オーストリア |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Renaissance_music |

|

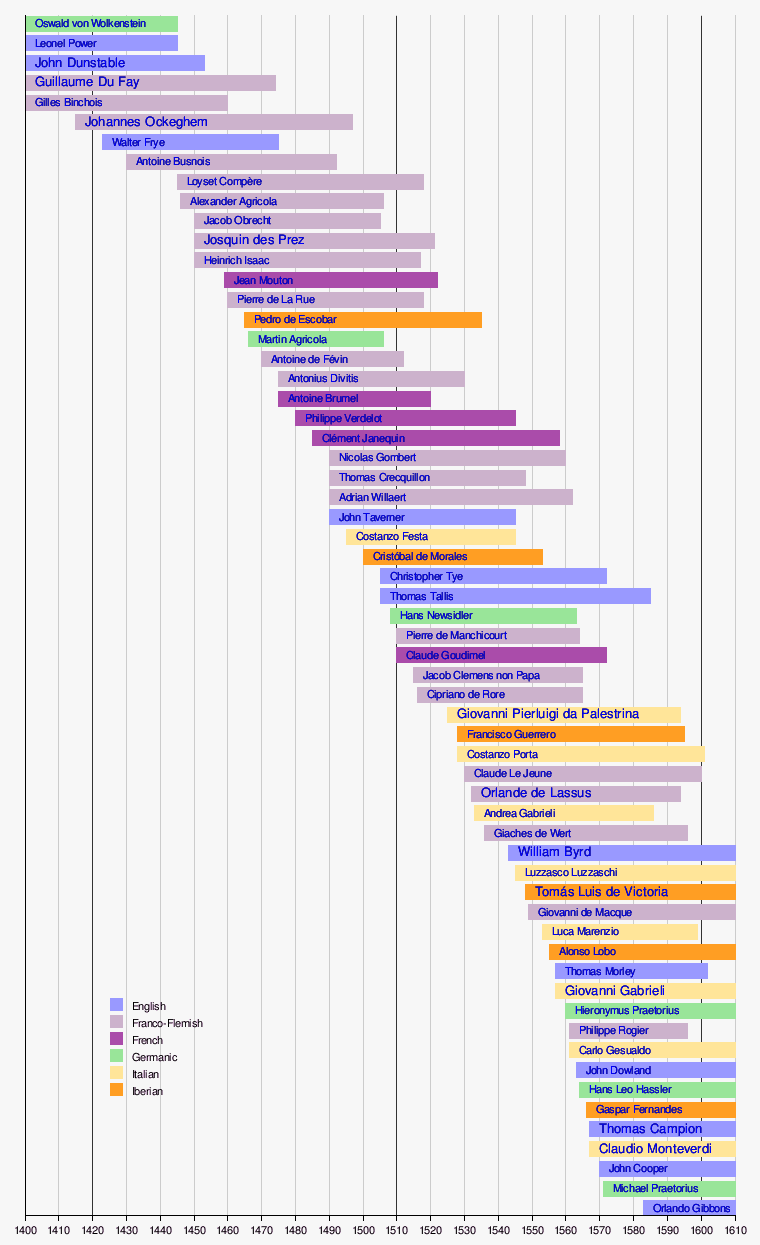

★Composers – timeline 作曲家の生涯の時系列

★ルネサンス期の作曲家リスト(List of Renaissance composers)

| Early (1400–1470) |

Alexander AgricolaGilles

BinchoisAntoine BusnoisLoyset CompèreGuillaume Du FayJohn

DunstapleWalter FryeHeinrich IsaacJean JapartJohannes MartiniJohannes

OckeghemLeonel PowerJohannes TinctorisGaspar van WeerbekeOswald von

Wolkenstein |

| Middle (1470–1530) |

Martin AgricolaAntoine

BrumelThomas CrecquillonAntonius DivitisCostanzo FestaAntoine de

FévinClément JanequinCristóbal de MoralesJean MoutonJacob

ObrechtJosquin des PrezPierre de la RueJohn TavernerPhilippe

VerdelotAdrian Willaert |

| Late (1530) |

Jacques ArcadeltWilliam

ByrdAntonio de CabezónJacobus ClemensAndrea GabrieliNicolas

GombertClaude GoudimelFrancisco GuerreroClaude Le JeuneOrlando di

LassoVicente LusitanoPierre de ManchicourtHans NeusidlerGiovanni

Pierluigi da PalestrinaCostanzo PortaCipriano de RoreThomas

TallisChristopher TyeTomás Luis de VictoriaGiaches de Wert |

| Mannerism and Transition to Baroque c.1600 |

Gregorio AllegriThomas

CampionJohn CooperJohn DowlandGirolamo FrescobaldiAlfonso

FontanelliGiovanni GabrieliCarlo GesualdoOrlando GibbonsHans Leo

HasslerAlonso LoboLuzzasco LuzzaschiGiovanni de MacqueLuca

MarenzioClaudio MonteverdiThomas MorleyJacopo PeriMichael

PraetoriusPhilippe RogierHeinrich SchützJan Pieterszoon Sweelinck |

| Musical forms |

CarolIntermedioMadrigalMagnificatMassOffertoryPavane |

| Traditions |

BritishCyprusElizabethanFranceGermanyItalyNetherlandsPolandPortugalSpain |

| Music publishing |

Hieronymus AndreaeAndrea

AnticoPierre AttaingnantVittorio BaldiniJacob BathenValerio

DoricoAntonio GardanoOttaviano PetrucciPetrus Phalesius the

ElderGirolamo ScottoTielman SusatoThomas Vautrollier |

| Background |

Early musicRenaissance ArtArchitectureDanceLiteraturePhilosophy |

リ ンク

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099