ウィリアム・ロバートソン・スミス

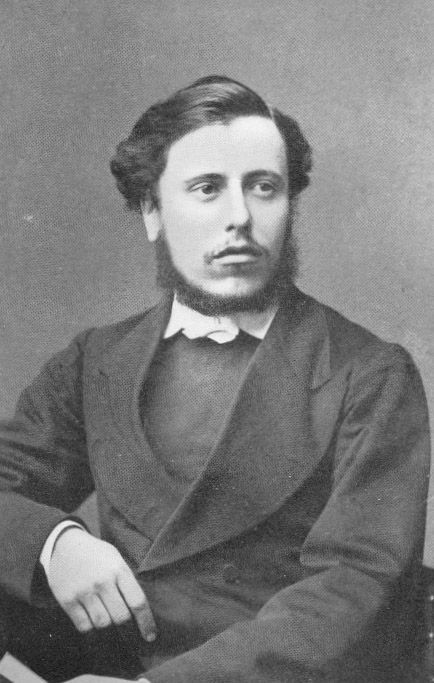

William Robertson

Smith, 1846-1894

☆ウィ

リアム・ロバートソン・スミス FRSE(1846年11月8日 -

1894年3月31日)は、スコットランドの東洋学者、旧約聖書学者、神学教授、スコットランド自由教会の牧師であった。彼はブリタニカ百科事典の編集者

であり、エンサイクロペディア・ビブリカにも寄稿した。また、宗教比較研究の基礎的な文献とされる著書『セム族の宗教』でも知られている。

| William Robertson

Smith FRSE (8 November 1846 – 31 March 1894) was a Scottish

orientalist, Old Testament scholar, professor of divinity, and minister

of the Free Church of Scotland. He was an editor of the Encyclopædia

Britannica and contributor to the Encyclopaedia Biblica. He is also

known for his book Religion of the Semites, which is considered a

foundational text in the comparative study of religion. |

ウィリアム・ロバートソン・スミス FRSE(1846年11月8日 - 1894年3月31日)は、スコットランドの東洋学者、旧約聖書学者、神学教授、スコットランド自由教会の牧師であった。彼はブリタニカ百科事典の編集者 であり、エンサイクロペディア・ビブリカにも寄稿した。また、宗教比較研究の基礎的な文献とされる著書『セム族の宗教』でも知られている。 |

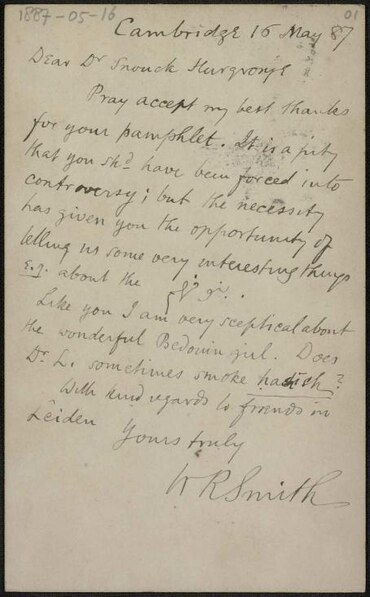

Life and career William Robertson Smith with a large volume Smith was born in Keig in Aberdeenshire the eldest son of Rev Dr William Pirie Smith DD (1811–1890), minister of the recently created Free Church of Scotland for the parishes of Keig and Tough, and of his wife, Jane Robertson. His brother was Charles Michie Smith.[1] He demonstrated a quick intellect at an early age. He entered Aberdeen University at fifteen, before transferring to New College, Edinburgh, to train for the ministry, in 1866. After graduation he took up a chair in Hebrew at the Aberdeen Free Church College in 1870, succeeding Prof Marcus Sachs.[2] In 1875, he wrote a number of important articles on religious topics in the ninth edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica. He became popularly known because of his trial for heresy in the 1870s, following the publication of an article in Britannica.  Letter by Smith (1887) In 1871 he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh; his proposer was Peter Guthrie Tait.[3] Smith's articles approached religious topics without endorsing the Bible as literally true. The result was a furore in the Free Church of Scotland, of which he was a member[4] as well as criticism from conservative parts of America.[5] As a result of the heresy trial, he lost his position at the Aberdeen Free Church College in 1881 and took up a position as a reader in Arabic at the University of Cambridge, where he eventually rose to the position of University Librarian, Professor of Arabic and a fellow of Christ's College.[6] It was during this time that he wrote The Old Testament in the Jewish Church (1881) and The Prophets of Israel (1882), which were intended to be theological treatises for the lay audience. In 1887 Smith became the editor of the Encyclopædia Britannica after the death of his employer Thomas Spencer Baynes left the position vacant. In 1889 he wrote his most important work, Religion of the Semites, an account of ancient Jewish religious life which pioneered the use of sociology in the analysis of religious phenomena. He was Professor of Arabic there with the full title 'Sir Thomas Adams Professor of Arabic' (1889–1894). He died of tuberculosis at Christ's College, Cambridge on 31 March 1894. He is buried with his parents at Keig churchyard. |

生涯と経歴 ウィリアム・ロバートソン・スミスと分厚い本 スミスは、アバディーンシャーのケイグで、当時創設されたばかりのスコットランド自由教会のケイグとタフの教区牧師であるウィリアム・ピリー・スミス博士 (1811年~1890年)とその妻ジェーン・ロバートソンの長男として生まれた。弟はチャールズ・ミチー・スミスである。[1] 彼は幼い頃から頭の回転が速いことを示していた。15歳でアバディーン大学に入学し、1866年に牧師になるための訓練を受けるため、エディンバラの ニューカレッジに転校した。卒業後は、1870年にアバディーン自由教会大学でヘブライ語の教授職に就き、マーカス・サックス教授の後継者となった。 [2] 1875年には、大英百科事典第9版に宗教に関する重要な記事を数多く執筆した。1870年代、大英百科事典への記事掲載後に異端審問にかけられたことで、広く知られるようになった。  スミス書簡(1887年) 1871年、エディンバラ王立協会のフェローに選出された。推薦者はピーター・ガスリー・テイトであった[3]。 スミスの記事は、聖書を文字通りの真実として支持することなく宗教的テーマに接近した。その結果、彼が所属していたスコットランド自由教会[4]で騒動が 起き、アメリカの保守派からも批判を受けた。異端審問の結果、1881年にアバディーン自由教会大学の職を失い、ケンブリッジ大学でアラビア語講師の職に 就いた。その後、大学図書館長、アラビア語教授、そしてクライスト・カレッジのフェローへと昇進した。[6] この時期に彼は『ユダヤ教会における旧約聖書』(1881年)と『イスラエルの預言者たち』(1882年)を執筆した。これらは一般信徒向けの神学論考を 意図したものであった。 1887年、雇い主トマス・スペンサー・ベインズの死により空席となったブリタニカ百科事典の編集長職にスミスが就任した。1889年には最も重要な著作 『セム族の宗教』を執筆した。古代ユダヤ人の宗教生活を記したこの書は、宗教現象の分析に社会学的手法を用いる先駆けとなった。彼は同大学でアラビア語教 授を務め、正式称号は「サー・トーマス・アダムズ記念アラビア語教授」(1889年~1894年)であった。 1894年3月31日、ケンブリッジ大学クライスト・カレッジにて結核により死去した。両親と共にキーグ教会の墓地に埋葬されている。 |

| Approach His views on the historical method of criticism can be illustrated in the following quote: Ancient books coming down to us from a period many centuries before the invention of printing have necessarily undergone many vicissitudes. Some of them are preserved only in imperfect copies made by an ignorant scribe of the dark ages. Others have been disfigured by editors, who mixed up foreign matter with the original text. Very often an important book fell altogether out of sight for a long time, and when it came to light again all knowledge of its origin was gone; for old books did not generally have title-pages and prefaces. And, when such a nameless roll was again brought into notice, some half-informed reader or transcriber was not unlikely to give it a new title of his own devising, which was handed down thereafter as if it had been original. Or again, the true meaning and purpose of a book often became obscure in the lapse of centuries, and led to false interpretations. Once more, antiquity has handed down to us many writings which are sheer forgeries, like some of the Apocryphal books, or the Sibylline oracles, or those famous Epistles of Phalaris which formed the subject of Bentley's great critical essay. In all such cases the historical critic must destroy the received view, in order to establish the truth. He must review doubtful titles, purge out interpolations, expose forgeries; but he does so only to manifest the truth, and exhibit the genuine remains of antiquity in their real character. A book that is really old and really valuable has nothing to fear from the critic, whose labours can only put its worth in a clearer light, and establish its authority on a surer basis.[7] |

アプローチ 彼の歴史的批評法に関する見解は、次の引用文で説明できる: 印刷技術が発明される何世紀も前の時代に遡る古書は、必然的に多くの変遷を経験してきた。その一部は、暗黒時代の無学な写本者が作成した不完全な写本とし てのみ保存されている。他のものは、編集者によって原典に異物を混入されることで歪められた。重要な書物が長期間完全に忘れ去られ、再び発見された時には その起源に関する知識が失われていることも頻繁にあった。古書には通常、表紙や序文が存在しなかったからだ。そして、こうした無名の巻物が再び注目を浴び ると、中途半端な知識を持つ読者や写本者が、自ら考案した新たな題名を付けることが少なくなかった。その題名はその後、あたかも本来のもののかのように受 け継がれていったのである。あるいは、書物の真の意味や目的が数世紀の経過で不明瞭になり、誤った解釈を招くこともあった。さらに古代は、外典書やシビュ ラの予言、あるいはベントレーの偉大な批評論文の主題となったファラリスの有名な書簡のような、完全な偽書も数多く我々に伝えている。こうした全ての事例 において、歴史的批評家は真実を確立するために、従来の通説を破壊しなければならない。疑わしい題名を再検討し、挿入部分を排除し、偽造を暴く必要があ る。しかしそれは真実を明らかにし、古代の真正な遺物をその真の姿で示すためだけに為される。真に古く真に価値ある書物は、批評家から何も恐れることはな い。批評家の労苦は、その価値をより明瞭に照らし出し、その権威をより確かな基盤に確立するだけだからだ。[7] |

| Published works Among his writings are the following. Books: annotated The Old Testament in the Jewish Church English Wikisource has original text related to this article: The Old Testament in the Jewish Church The Old Testament in the Jewish Church. A course of lectures on biblical criticism (Edinburgh: A. & C. Black 1881); second edition (London: A. & C. Black 1892). The author addresses the Christian believer who opposes higher criticism of the Old Testament, considering that it will reduce the Bible to rational historical terms and omit the supernatural [cf. 3–5]. He replies that the Bible's purpose is to give its readers entry into the experience of lived faith, to put them in touch with God working in history, which a true understanding of the text will better provide [8–9]. Critical Bible study, in fact, follows in the spirit of the Protestant Reformation [18–19]. Prior Catholic study of the Bible is faulted for being primarily interested in drawing out consistent doctrines [7, 25]. Instead Protestants initially turned to Jewish scholars who could better teach them Hebrew. However, the chief purpose of Jewish learning was legal: the Bible being a source of Jewish law, derived to settle their current disputes and issues of practice [52]. As Protestant bible study continued, the nature of the text began to reveal itself as complex and many layered. For example, especially in the earlier books, two different, redundant, and sometimes inconsistent versions appeared to co-exist [133]. This would imply that an editor had woven several pre-existing narratives together to form a composite text [cf. 90–91]. The Psalms are shown to reflect the life of the entire Hebrew people, rather than that of a single traditional author, King David [224]. Prior understanding was that all ritual and civil law in the Pentateuch (Books of Moses) had originated at Mount Sinai; Bible history being the story of how the Hebrews would follow or not a comprehensive moral order [231–232]. Yet from the Bible text, the author demonstrates how ritual law was initially ignored after Moses [254–256, 259]; only much later, following the return from exile, was the ritual system established under Ezra [226–227]. The Pentateuch contains laws and history [321]. Its history "does not profess to be written by Moses" as "he himself is habitually spoken of in the third person" [323–324]. From internal evidence found in the Bible, Pentateuch history was "written in the land of Canaan" after the death of Moses (c. 13th century BC), probably as late as "the period of kings", perhaps written under Saul or under David (c. 1010–970) [325]. The laws found in the Book of Deuteronomy [xii-xxvi] are also demonstrated to date to a time long after Moses [318–320]. In fact, everything in the reforms under King Josiah (r.640-609) are found written in the Deuteronomic code. His Book of the Covenant probably is none other than "the law of Deuteronomy, which, in its very form, appears to have once been a separate volume" [258]. Internal evidence found in the bible is discussed [e.g., 353–355]. In the centuries immediately following Moses, the Pentateuch was not the primary rule; rather Divine spiritual guidance was provided to the ancient Hebrew nation by their prophets [334–345]. Smith's lectures were originally given in Edinburgh and Glasgow during early 1881. "It is of the first importance for the reader to realize that Biblical Criticism is not the invention of modern scholars, but the legitimate interpretation of historical facts." The result is that "the history of Israel... [makes]... one of the strongest evidences of Christianity." (Author's Preface, 1881). Doctrinal opposition against Smith first arose after his 1875 encyclopaedia article "Bible" which covered similar ground. In 1878 Church heresy charges had been filed, "the chief of which concerned the authorship of Deuteronomy." These 1881 lectures followed his removal as professor at the Free Church College in Aberdeen.[8] Smith's 1881 edition "was a landmark in the history of biblical criticism in Britain, in particular because it laid before the general public the critical view to which Wellhausen had given classical expression in his Geschichte Israels which had appeared less than three years earlier, in 1878."[9][10] Yet "Smith did not merely repeat the arguments of Wellhausen, or anyone else; he approached the subject in a quite original way."[11] |

出版作品 彼の著作には以下のものがある。 書籍:注釈付き ユダヤ教会における旧約聖書 英語版ウィキソースには、この記事に関連する原文がある: ユダヤ教会における旧約聖書 ユダヤ教会における旧約聖書。聖書批評に関する講義集(エディンバラ:A. & C. Black 1881年);第二版(ロンドン:A. & C. Black 1892年)。 著者は、旧約聖書に対する高等批評に反対するキリスト教信者に向けて論じている。高等批評は聖書を合理的な歴史的用語に還元し、超自然的な要素を排除する と考えるからだ[cf. 3–5]。著者は反論する。聖書の目的は読者に生きた信仰の体験への入り口を与え、歴史の中で働く神との接触をもたらすことだ。真のテキスト理解こそがこ れをより良く実現するのだと[8-9頁]。批判的聖書研究は、実のところプロテスタント宗教改革の精神に則っている[18-19頁]。 カトリックによる従来の聖書研究は、一貫した教義の抽出に主眼を置いた点で欠陥があると批判される[7, 25]。これに対しプロテスタントは当初、ヘブライ語を教えられるユダヤ人学者たちに学んだ。しかしユダヤ人学者たちの主な目的は法的なものであった。聖 書はユダヤ教の律法の源泉であり、当時の論争や実践上の問題を解決するために解釈されていたのだ[52]。 プロテスタントの聖書研究が進むにつれ、テキストの本質は複雑で多層的であることが明らかになった。例えば、特に初期の書物では、二つの異なる、重複し た、時に矛盾するバージョンが共存しているように見えた[133]。これは編集者が複数の既存の物語を織り交ぜて複合テキストを形成したことを示唆してい る[cf. 90–91]。 詩篇は、単一の伝統的著者であるダビデ王の生涯ではなく、ヘブライ人民全体の生活を反映していることが示されている[224]。 従来の理解では、モーセ五書(モーセの書)における全ての儀礼・市民法はシナイ山で起源を持ち、聖書の歴史とはヘブライ人が包括的な道徳秩序に従うか否か の物語であった[231–232]。しかし聖書本文から、著者はモーセの死後、儀礼法が当初無視されていたことを示す[254-256, 259]。はるか後世、捕囚からの帰還を経て、エズラの下で儀礼体系が確立されたのである[226-227]。 モーセ五書には律法と歴史が含まれている[321]。その歴史部分は「モーセ自身によって書かれたとは主張していない」とされ、「モーセ自身は常に三人称 の人格で語られている」[323–324]。聖書内部の証拠から、五書の歴史部分はモーセの死後(紀元前13世紀頃)に「カナンの地で書かれた」とされ、 おそらく「王の時代」という遅い時期、サウルまたはダビデの治世下(紀元前1010–970年頃)に執筆された可能性が高い[325]。 申命記[xii-xxvi]に記された律法も、モーセの死後かなり経った時代に遡ることを示している[318–320]。実際、ヨシヤ王(在位640- 609)の改革で実施された全ての事項は、申命記的法典に記述されている。彼の『契約の書』は、おそらく「その形式から見て、かつては独立した巻物であっ たと思われる『申命記の律法』」に他ならない[258]。聖書内に存在する内部証拠について論じられている[例:353–355]。 モーセの死後数世紀の間、五書は主要な規範ではなかった。むしろ古代ヘブライ国民への神の霊的導きは、預言者たちによって提供されていたのだ[334–345]。 スミスの講義は1881年初頭、エディンバラとグラスゴーで最初に発表された。「読者が理解すべき最重要事項は、聖書批評が現代学者の発明ではなく、歴史 的事実の正当な解釈であるということだ」。その結果、「イスラエルの歴史は…キリスト教の最も強力な証拠の一つを構成する」のである(著者序文、1881 年)。 スミスに対する教義上の反対は、1875年に彼が百科事典に寄稿した「聖書」の項で同様の論点を扱った後に初めて生じた。1878年には教会による異端告 発が提出され、「その主たるものは申命記の作者問題に関するものだった」。これらの1881年の講義は、彼がアバディーン自由教会大学の教授職を解任され た後に続いたものである。[8] スミスの1881年版は「英国における聖書批評史の画期的な出来事であった。特に、ウェルハウゼンが1878年(わずか3年前)に発表した『イスラエルの 歴史』で古典的に表現した批判的見解を一般大衆に提示した点で顕著である」。[9][10] しかし「スミスはウェルハウゼンや他の誰かの議論を単に繰り返したわけではない。彼はこの主題に全く独創的な方法でアプローチした」[11]。 |

| The Prophets of Israel The Prophets of Israel and their place in history, to the close of the 8th century B.C. (Edinburgh: A. & C. Black 1882), reprinted with introduction and notes by T. K. Cheney (London: A. & C. Black 1895). The Hebrew prophets are presented in context with the ancient religious practice by neighboring nations. Instead of divination, elsewhere often used for political convenience or emotional release (however earnest), here the prophets of Israel witness to the God of justice, i.e., to their God's true nature [85–87, 107–108]. In announcing ethical guidance, these ancient prophets declared to the Jewish people the will of their God acting in history [70–75]. The opening chapters introduce the nature of Jehovah in Jewish history after Moses [33–41, {110–112, 116–118}] discussing neighboring religions [26–27, 38–40, 49–51, 66–68], regional theocracy [47–53], henotheism [53–60], national survival [32–39] and righteousness [34–36, 70–74], as well as Judges [30–31, 39, 42–45], and the prophet Elijah [76–87]. Then follows chapters on the prophets Amos [III], Hosea [IV], and Isaiah [V-VII], wherein Smith seeks to demonstrate how the Hebrew religion grew through each prophet's message.[12] The work concludes with the secular and religious history of the period preceding the exile [VIII]. In his Preface [xlix-lviii, at lvi–lvii], the author acknowledges reliance on critical biblical studies, specifically that established by Ewald, developed by Graf, and furthered by Kuenen referencing his Godsdienst, by Duhm per his Theologie der Propheten, and by Wellhausen, citing his Geschichte (1878). The author confidently rests the case for biblical religion on "ordinary methods of historical investigation" [17] and on the "general law of human history that truth is consistent, progressive, and imperishable, while every falsehood is self-contradictory, and ultimately falls to pieces. A religion which has endured every possible trial... declares itself by irresistible evidence to be a thing of reality and power." [16]. Yet, despite his heresy trial, current modern scholarship appraises W. R. Smith as too beholden to nineteenth-century Protestant doctrine, so that he fails in his Prophets of Israel book to achieve his avowed aim of historical inquiry. However flawed, "he will be remembered as a pioneer."[13] |

イスラエルの預言者たち イスラエルの預言者たちとその歴史的立場、紀元前8世紀末まで(エディンバラ:A. & C. ブラック社 1882年)、T. K. チェニーによる序文と注釈付きで再版(ロンドン:A. & C. ブラック社 1895年)。 ヘブライの預言者たちは、近隣国民の古代宗教的慣行との文脈の中で提示される。他の地域で政治的便宜や感情解放(いかに真剣であろうとも)のために用いら れることが多い占いの代わりに、イスラエルの預言者たちは正義の神、すなわち彼らの神の真の本質を証言するのだ[85–87, 107–108]。倫理的指針を告げるにあたり、これらの古代預言者たちはユダヤ人民に対し、歴史の中で作用する彼らの神の意志を宣言したのである [70–75]。 冒頭の数章は、モーセ以降のユダヤ史におけるエホバの神性を紹介し[33–41, {110–112, 116–118}]、近隣諸宗教について論じている[26–27, 38–40, 49–51, 66–68]、地域的神政政治[47–53]、一神教[53–60]、国民の存続[32–39]、正義[34–36, 70–74]、さらに士師記[30–31, 39, 42–45]、預言者エリヤ[76–87]について論じている。続いて預言者アモス[III]、ホセア[IV]、イザヤ[V-VII]に関する章が続き、 スミスは各預言者のメッセージを通じてヘブライ宗教が如何に発展したかを示そうとしている[12]。本書は流刑以前の世俗的・宗教的歴史[VIII]を もって結ぶ。 序文[xlix-lviii、lvi–lvii]において、著者は批判的聖書学、特にエーヴァルトが確立し、グラフが発展させ、クネーネンが『宗教論』 で、ドゥームが『預言者の神学』で、ウェルハウゼンが『歴史』(1878年)でそれぞれ推進した学説に依拠していることを認めている。 著者は聖書的宗教の立証を「通常の歴史的調査方法」[17]と「真実とは一貫性・漸進性・不滅性を備え、あらゆる虚偽は自己矛盾に陥り最終的に崩壊すると いう人類史の普遍法則」[16]に確信を持って依拠する。あらゆる試練に耐え抜いた宗教は…圧倒的証拠によって現実性と力を持つ存在であることを自ら証明 するのだ。 しかし異端審問を受けたにもかかわらず、現代の学界はW・R・スミスを19世紀プロテスタント教義に過度に拘束された人物と評価している。そのため彼の著 書『イスラエルの預言者たち』は、公言した歴史的探究という目的を達成できていない。欠陥はあるものの、「彼は先駆者として記憶されるだろう」[13]。 |

| Kinship and Marriage in Early Arabia Kinship and Marriage in Early Arabia (Cambridge University 1885); second edition, with additional notes by the Author and by Professor Ignaz Goldziher, Budapest, and edited with an introduction by Stanley A. Cook (London: A. & C. Black 1903); reprint 1963 Beacon Press, Boston, with a new Preface by E. L. Peters. This book in particular, among many others, drew the broad-brush criticism of Prof. Said as swimming in the narrow blinkered sea of 19th-century European Orientalism.[14][15] This work traces, from an earlier totemist matriarchy that practiced exogamy, the further development of a "system of male kinship, with corresponding laws of marriage and tribal organization, which prevailed in Arabia at the time of Mohammed." (Author's Preface). Chapters: 1. The Theory of the Genealogists as to the Origin of Arabic Tribal Groups. E.g., Bakr and Taghlib (proper names of ancestors), fictitious ancestors, unity of the tribal blood, female eponyms; 2. The Kindred Group [hayy] and its Dependents and Allies. E.g., adoption, blood covenant, property, tribe and family; 3. The Homogeneity of the Kindred Group in relation to the Law of Marriage and Descent. E.g., exogamy, types of marriage (e.g., capture, contract, purchase), inheritance, divorce, women's property; 4. Paternity. E.g., original sense of fatherhood, polyandry, infanticide; 5. Paternity, Polyandry with Male Kinship, and with Kinship through Women. E.g., evidence of Strabo, conjugal fidelity, chastity, milk brotherhood, two (female, and male) systems of kinship, decay of tribal feeling; 6. Female Kinship and Marriage Bars. E.g. forbidden degrees, the tent (bed) in marriage, matronymic families, beena marriages, ba'al marriage, totemism and heterogeneous groups; 7. Totemism. E.g., tribes named from animals, jinn, tribal marks or wasm; 8. Conclusion. E.g., origin of the tribal system, migrations of the Semites. Conceived at the frontier of academic study on early culture, Smith's work relied on a current anthropology proposed by the late John Ferguson McLennan, in his Primitive Marriage (Edinburgh 1865). (Author's Preface).[16] Smith also employed recent material by A. G. Wilken, Het Matriarchaat bij de oude Arabieren (1884) and by E. B. Tylor, Arabian Matriarchate (1884), and received suggestions from Theodor Nöldeke and from Ignaz Goldziher. (Author's Preface). Although still admired on several counts, the scholarly consensus now disfavors many of its conclusions. Smith here "forced the facts to fit McLennan's evolutionary schema, which was entirely defective."[17] Professor Edward Evans-Pritchard, while praising Smith for his discussion of the tribe [hayy], finds his theories about an early matriarchy wanting. Smith conceived feminine names for tribes as "survivals" of matriarchy, but they may merely reflect grammar, i.e., "collective terms in Arabic are constantly feminine", or lineage practice, i.e., "in a polygamous society the children of one father may be distinguished into groups by use of their mothers' names". Evans-Pritchard also concludes that "Smith makes out no case for the ancient Bedouin being totemic" but only for their "interest in nature". He faults Smith for his "blind acceptance of McLennan's formulations".[18] Smith was part of a general movement by historians, anthropologists, and others, that both theorized a matriarchy present in early civilizations and discovered traces of it. In the 19th century it included eminent scholars and well-known authors such as J.J. Bachofen, James George Frazer, Frederick Engels, and in the 20th century Robert Graves, Carl Jung, Joseph Campbell, Marija Gimbutas. Smith's conclusions were based on the then prevailing notion that matrifocal and matrilineal societies were the norm in Europe and western Asia, at least prior to the invasion of the Indo-Europeans from central Asia. Subsequent findings have not been kind to that thread of Smith's work which offers a prehistoric matriarchy to schematize the Semites. It is certainly recognized that a large number of prehistoric hunter-gatherer cultures practiced matrilinear or cognatic succession, as do many hunter-gatherer cultures today. Yet it is no longer widely accepted by scholars that the earliest Semites had a matrilineal system. This is due largely to the unearthing of thousands of Safaitic inscriptions in pre-Islamic Arabia, which appear to indicate that, on the issues of inheritance, succession, and political power, the Arabs of the pre-Islamic period were little different from the Arabs today.[citation needed] Evidence from both Arab and Amorite sources discloses the early Semitic family as being mainly patriarchal and patrilineal,[citation needed] as are the Bedouin today, while the early Indo-European family may have been matrilineal, or at least allotting high social status to women. Robert G. Hoyland a scholar of the Arabs and Islam writes, "While descent through the male line would seem to have been the norm in pre-Islamic Arabia, we are occasionally given hints of matrilineal arrangements."[19] |

初期アラビアにおける親族関係と婚姻 『初期アラビアにおける親族関係と婚姻』(ケンブリッジ大学出版、1885年);第二版は著者及びブダペストのイグナツ・ゴルツィーヘル教授による追加注 釈を加え、スタンリー・A・クックによる序文付きで編集(ロンドン:A. & C. ブラック、1903年);1963年再版(ビーコン・プレス、ボストン)、E. L. ピーターズによる新たな序文付き。この本は、他の多くの本の中でも特に、19世紀のヨーロッパのオリエンタリズムという狭い視野の海に溺れているという、 サイード教授による大まかな批判を受けた[14][15]。 この著作は、外婚制を実践していた初期のトーテミズム的な母系社会から、モハメッドの時代にアラビアで普及していた「男性親族制度と、それに対応する結婚法および部族組織」のさらなる発展を辿っている。(著者序文)。 章立て: 1. アラブ部族集団の起源に関する系図学者の理論。例:バクルとタグリブ(祖先の固有名詞)、架空の祖先、部族の血の統一、女性の地名由来。 2. 親族集団 [hayy] とその依存者および同盟者。例:養子縁組、血の誓約、財産、部族および家族。 3. 婚姻および血統の法則に関する親族集団の均質性。例:外婚制、婚姻の種類(例:略奪、契約、購入)、相続、離婚、女性の財産。 4. 父権。例:父性の本来の意味、一妻多夫制、幼児殺害; 5. 父権、男性親族関係に基づく一妻多夫制、女性親族関係に基づく一妻多夫制。例:ストラボンの証拠、夫婦の貞節、貞操、乳兄弟関係、二つの(女性系と男性系の)親族制度、部族感情の衰退; 6. 女性の親族関係と結婚の障壁。例:禁忌の程度、結婚におけるテント(ベッド)、母系家族、ビーナ結婚、バアル結婚、トーテミズム、異質な集団。 7. トーテミズム。例:動物に由来する部族名、ジン、部族の印、ワスム。 8. 結論。例:部族制度の起源、セム族の移住。 初期文化に関する学術研究の最前線で構想されたスミスの研究は、故ジョン・ファーガソン・マクレナンが『原始結婚』(エディンバラ、1865年)で提唱し た当時の人類学に依拠していた。(著者による序文)。[16] スミスはまた、A. G. ウィルケンによる『古代アラブ人の母系社会』(1884年)や E. B. タイラーによる『アラビアの母系社会』(1884年)といった最新の資料も活用し、テオドール・ネルデケやイグナツ・ゴルツィーアから提案を受けた。(著 者による序文)。 いくつかの点では今でも高く評価されているものの、学界のコンセンサスは現在、この著作の結論の多くを否定している。スミスはここで、「完全に欠陥のある マクレナンによる進化論的枠組みに事実を当てはめようとした」[17]。エドワード・エヴァンズ=プリチャード教授は、スミスによる部族 [hayy] に関する議論を称賛する一方で、初期の母系社会に関する彼の理論には不十分な点があると考えている。スミスは、部族の女性的な名称を母系社会の「残滓」と 捉えたが、それは単に文法、すなわち「アラビア語の集合用語は常に女性形である」ことや、血統の慣習、すなわち「一夫多妻制の社会では、同じ父親を持つ子 供たちは、母親の名前によってグループ分けされる」ことを反映しているだけかもしれない。エヴァンズ=プリチャードはまた、「スミスは古代ベドウィンが トーテム信仰を持っていたことを立証していない」と結論づけており、彼らが「自然に関心を持っていた」ことしか立証していないと結論づけている。彼は、ス ミスが「マクレナンによる定式化を盲目的に受け入れた」ことを批判している。[18] スミスは、歴史学者、人類学者、その他の人々による一般的な運動の一部であり、その運動は、初期文明に母系社会が存在したことを理論化し、その痕跡を発見 した。19 世紀には、J.J. バコフェン、ジェームズ・ジョージ・フレイザー、フリードリッヒ・エンゲルスなどの著名な学者や有名な作家が、20 世紀にはロバート・グレイブス、カール・ユング、ジョセフ・キャンベル、マリヤ・ギンブタスなどがこの運動に参加した。スミスの結論は、少なくとも中央ア ジアからのインド・ヨーロッパ人による侵略以前は、母系社会と母系社会がヨーロッパと西アジアでは標準的であったという、当時主流だった考えに基づいてい た。その後の発見は、セム族を概説するために先史時代の母系社会を提示したスミスの研究には厳しいものとなった。確かに、多くの先史時代の狩猟採集文化 が、今日の多くの狩猟採集文化と同様に、母系または同族の継承を実践していたことは認められている。しかし、最古のセム人が母系制を持っていたという見解 は、もはや学界で広く受け入れられていない。これは主に、イスラム以前のアラビアで発掘された数千のサファイティック碑文による。それらは、相続、継承、 政治権力といった問題において、イスラム以前のアラブ人が現代のアラブ人とほとんど異なることがなかったことを示唆している。[出典が必要] アラブとアモリ人の双方の資料から、初期セム族の家族は主に家長制かつ父系であったことが明らかになっている[出典が必要]。これは現代のベドウィンと同 様である。一方、初期インド・ヨーロッパ族の家族は母系であったか、少なくとも女性に高い社会的地位を与えていた可能性がある。アラブとイスラム研究者ロ バート・G・ホイルランドはこう記している。「イスラム以前のアラビアでは父系による血統継承が規範であったように思われるが、母系制の痕跡が時折見受け られる」[19] |

| The Religion of the Semites (1st) Lectures on the Religion of the Semites. Fundamental Institutions. First Series (London: Adam & Charles Black 1889); second edition [posthumous], edited by J. S. Black (1894), reprint 1956 by Meridian Library, New York; third edition, introduced and additional notes by S. A. Cook (1927), reprint 1969 by Ktav, New York, with prolegomenon by James Muilenberg. This well-known work seeks to reconstruct from scattered documents the several common religious practices and associated social behavior of the ancient Semitic peoples, i.e., of Mesopotamia, Syria, Phoenicia, Israel, Arabia [1, 9–10]. The book thus provides the contemporary historical context for the earlier Biblical writings. In two introductory lectures the author discusses primal religion and its evolution, which now seem too often to over generalize (perhaps inevitable in a pioneer work). In the first, Smith notes with caution the cuneiform records of Babylon, and the influence of ancient Egypt, then mentions pre-Islamic Arabia and the Hebrew Bible [13–14]; he discounts any possibility of "a complete comparative religion of Semitic religions" [15]. In the second lecture, Smith's comments range widely on various facets of primal religion in Semitic society, e.g., on the protected strangers (Heb: gērīm, sing. gēr; Arab: jīrān, sing. jār) who were "personally free but had no political rights". Smith continues, that as the tribe protects the gēr, so does the God protect the tribe as "clients" who obey and so are righteous; hence the tribal God may develop into a universal Deity whose worshippers follow ethical precepts [75–81]. Of the eleven lectures, Holy Places are discussed in lectures III to V. In the third lecture, nature gods of the land are discussed [84–113]; later jinn and their haunts are investigated [118–137], wherein the nature of totems are introduced [124–126]; then totem animals are linked to jinn [128–130], and the totem to the tribal god [137–139]. The fourth lecture discusses, e.g., the holiness and the taboos of the sanctuary. The fifth: holy waters, trees, caves, and stones. Sacrifices are addressed in lectures VI to XI. The sixth contains Smith's controversial theory of communal sacrifice regarding the totem, wherein the tribe, at a collective meal of the totem animal, come to realize together a social bond together with their totem-linked tribal god [226–231]. This communion theory, shared in some regard with Wellhausen, now enjoys little strong support.[20][21] On the cutting edge of biblical scholarship, this work builds on a narrower study by his friend professor Julius Wellhausen, Reste Arabischen Heidentums (Berlin 1887), and on other works on the religious history of the region and in general. (Smith's Preface).[22] The author also employs analogies drawn from James George Frazer,[23] to apply where insufficient data existed for the ancient Semites. (Smith's Preface). Hence Smith's methodology was soon criticized by Theodor Nöldeke.[24] Generally, the book was well received by contemporaries. It won Wellhausen's praise.[25] Later it would influence Émile Durkheim,[26][27] Mircea Eliade,[28] James George Frazer,[29][30] Sigmund Freud,[31] and Bronisław Malinowski.[32] After 75 years Evans-Pritchard, although noting his wide influence, summarized criticism of Smith's totemism, "Bluntly, all Robertson Smith really does is to guess about a period of Semitic history about which we know almost nothing."[33] |

セム人の宗教(第1版) 『セム人の宗教に関する講義。基本制度。第一シリーズ』(ロンドン:アダム&チャールズ・ブラック社、1889年); 第二版[遺稿]、J・S・ブラック編(1894年)、1956年メリディアン・ライブラリー(ニューヨーク)復刻版;第三版、S・A・クックによる序文と 追加注釈付き(1927年)、1969年クタブ(ニューヨーク)復刻版、ジェームズ・ミューレンバーグによる序論付き。 この著名な著作は、散逸した文献から古代セム系民族、すなわちメソポタミア、シリア、フェニキア、イスラエル、アラビアの諸民族に共通した宗教的慣行と関 連する社会的行動を再構築しようとするものである[1, 9–10]。本書はこうして、より古い聖書文献の当時の歴史的背景を提供する。 二つの導入講義で著者は原始宗教とその進化について論じるが、これは現在では過度に一般化しているように見える(先駆的な著作では避けられないかもしれな い)。最初の講義でスミスはバビロンの楔形文字記録と古代エジプトの影響に慎重に触れた後、イスラム以前のアラビアとヘブライ聖書に言及する [13–14]。彼は「セム諸宗教の完全な比較宗教」の可能性を否定する[15]。 第二講では、スミスはセム社会における原始宗教の諸相について広く論じている。例えば「人格は自由だが政治的権利を持たない」保護された異邦人(ヘブライ 語: gērīm、単数形 gēr;アラビア語: jīrān、単数形 jār)について言及する。スミスはさらに、部族がgērを保護するように、神もまた従順で従順な「被保護民」としての部族を保護すると述べる。したがっ て部族の神は、倫理的戒律に従う崇拝者を持つ普遍的な神へと発展しうるのである[75–81]。 全11講のうち、聖地については第III講から第V講で論じられる。第III講では土地の自然神が論じられる[84–113]。続く第4講では聖域の聖性と禁忌が論じられる。第五講:聖なる水、樹木、洞窟、石。 第六講から第十一講では犠牲が扱われる。第六講にはスミスの論争を呼んだ共同体犠牲理論が含まれ、部族がトーテム動物の共同食を通じてトーテムと結びつい た部族神との社会的絆を共に認識するという内容である[226–231]。この聖餐理論はウェルハウゼンと一部共通する点があるが、現在では強い支持を得 ていない[20][21] 。聖書学の最先端において、この著作は彼の友人であるユリウス・ウェルハウゼン教授のより限定的な研究『アラビア異教の残滓』(ベルリン、1887年) や、同地域および一般的な宗教史に関する他の著作を基盤としている。(スミスの序文)。[22] 著者はまた、古代セム人に関するデータが不十分な場合に適用するため、ジェームズ・ジョージ・フレイザー[23]からの類推も用いている(スミスの序 文)。したがって、スミスの方法論はすぐにテオドール・ノエルケによって批判された。[24] 一般的に、この本は同時代の人々に好評だった。ウェルハウゼンの称賛も得た。[25] 後に、エミール・デュルケーム[26][27]、ミルチャ・エリアーデ[28]、ジェームズ・ジョージ・フレイザー[29][30]、ジークムント・フロ イト[31]、ブロニスワフ・マリノフスキーに影響を与えた。[32] 75年後、エヴァンズ=プリチャードは、スミスの広範な影響力に言及しつつも、スミスのトーテミズムに対する批判を次のように要約している。「率直に言え ば、ロバートソン・スミスが実際にしていることは、私たちがほとんど何も知らないセム族の歴史の時代について推測しているだけだ」[33] |

| The Religion of the Semites (2nd, 3rd) Lectures on the Religion of the Semites. Second and Third Series, edited with an introduction by John Day (Sheffield Academic 1995). Based on the 'newly discovered' original lecture notes of William Robertson Smith; only the first series had been prepared for publication (1889, 2d ed. 1894) by the author. (Editor's Introduction at 11–13). Smith earlier had written that "three courses of lectures" were planned: the first regarding "practical religious institutions", the second on "the gods of Semitic heathenism", with the third focusing on the influence of Semitic monotheism. Yet because the first course of lectures (ending with sacrifice) did not finish, it left coverage of feasts and the priesthood "to run over into the second course".[34] Second Series [33–58]: I. Feasts; II. Priests and the Priestly Oracles; III. Diviners and Prophets. Third Series [59–112]: I. Semitic Polytheism (1); II. Semitic Polytheism (2); III. The Gods and the World: Cosmogony. An Appendix [113–142] contains contemporary press reports describing the lectures, including reports of extemporaneous comments made by Robertson Smith, which appear in neither of the two published texts derived from his lecture notes. |

セム人の宗教(第 2 巻、第 3 巻 セム人の宗教に関する講義。第 2 巻および第 3 巻、ジョン・デイによる序文付き(シェフィールド・アカデミック、1995 年)。 ウィリアム・ロバートソン・スミスの「新たに発見された」講義ノートに基づく。著者自身は第 1 巻のみを出版準備していた(1889 年、第 2 版 1894 年)。(編集者による序文 11-13 ページ)。スミスは以前、「3 つの講義コース」が計画されていたと書いていた。1 つ目は「実践的な宗教制度」について、2 つ目は「セム族の異教の神々」について、3 つ目はセム族の一神教の影響に焦点を当てたものだった。しかし、最初の講義(犠牲で終わる)は完了しなかったため、祝宴と聖職者に関する内容は「第 2 講義に持ち越された」[34]。 第 2 シリーズ [33–58]: I. 祝宴; II. 司祭と司祭の神託; III. 占い師と預言者。 第三シリーズ [59–112]: I. セミティック多神教 (1); II. セミティック多神教 (2); III. 神々と世界: 宇宙生成論。 付録 [113–142] には、講義に関する当時の報道記事が掲載されている。これには、ロバートソン・スミスの講義ノートから出版された 2 冊のテキストにはいずれも掲載されていない、彼の即興のコメントに関する記事も含まれている。 |

| Other Writings Articles in the Encyclopædia Britannica (9th edition, 1875–1889) XXIV volumes, which include: "Angel" II (1875), "Bible" III (1875), "Chronicles, Books of" V (1886), "David" VI (1887), "Decalogue" VII (1877), "Hebrew Language and Literature" XI (1880), "Hosea" XII (1881), "Jerusalem" XIII (1881), "Mecca" & "Medina" XV (1883), "Messiah" XVI (1883), "Paradise" XVIII (1885), "Priest" & "Prophet" XIX (1885), "Psalms, Book of" XX (1886), "Sacrifice" XXI (1886), "Temple" & "Tithes" XXIII (1888). Lectures and Essays, edited by J. S. Black and G. W. Chrystal (London: Adam & Charles Black 1912). I. Scientific Papers (1869–1873), 5 papers including: "On the flow of Electricity in Conducting Surfaces" (1870); II. Early Theological essays (1868–1870), 4 essays including: "Christianity and the supernatural" (1869), and, "The question of prophecy in the critical schools of the continent" (1870); III. Early Aberdeen lectures (1870–1874), 5 lectures including: "What history teaches us to seek in the Bible" (1870); and, "The fulfilment of Prophecy" (1871). IV. Later Aberdeen lectures (1874–1877), 4 lectures including: "On the study of the Old Testament in 1876" (1877); and, "On the poetry of the Old Testament" (1877). V. Arabian studies (1880–1881), 2 studies: "Animal tribes in the Old Testament" (1880); "A journey in the Hejâz" (1881).[35][36] VI. Reviews of Books, 2 reviews: Wellhausen's Geschichte Israels [1878] (1879); Renan's Histoire du Peuple d'Israël [1887] (1887). "Preface" to Julius Wellhausen, Prolegomena to the History of Israel, transl. by J.S.Black & A.Menzies (Edinburgh: Black 1885) at v–x. "Review" of Rudolf Kittel, Geschichte der Hebräer, II (1892) in the English Historical Review 8:314–316 (1893). |

その他の著作 ブリタニカ百科事典(第9版、1875–1889年)掲載記事 計24巻。収録項目:「天使」II巻(1875年)「聖書」III巻(1875年)「歴代誌」V巻(1886年)「ダビデ」VI巻(1887年) 「十戒」第7巻(1877年)、「ヘブライ語とヘブライ文学」第11巻(1880年)、「ホセア書」第12巻(1881年)、「エルサレム」第13巻 (1881年)、「メッカ」及び「メディナ」第15巻(1883年)、 「メシア」第16巻(1883年)、「楽園」第18巻(1885年)、「祭司」及び「預言者」第19巻(1885年)、「詩篇」第20巻(1886年)、 「犠牲」第21巻(1886年)、「神殿」及び「十分の一税」第23巻 (1888)。 講演と論文集、J. S. ブラックとG. W. クリスタル編(ロンドン:アダム&チャールズ・ブラック社 1912年)。 I. 科学論文(1869–1873)、5編を含む: 「導体表面における電気の流れについて」(1870年); II. 初期神学論考(1868–1870年)、4編の論考を含む:「キリスト教と超自然現象」(1869年)、「大陸批評学派における預言問題」(1870年); III. 初期アバディーン講義(1870–1874)、5講義を含む:「歴史が聖書に求めるものを教える」(1870年);「預言の成就」(1871年)。 IV. 後期アバディーン講義(1874–1877)、4講義を含む:「1876年の旧約聖書研究について」(1877年);「旧約聖書の詩学について」(1877年)。 「1876年の旧約聖書研究について」(1877年);「旧約聖書の詩について」(1877年)。 V. アラビア研究(1880–1881年)、2研究:「旧約聖書における動物部族」(1880年); 「ヘジャーズ地方の旅」(1881年)。[35][36] VI. 書評、2編:ウェルハウゼンの『イスラエル史』[1878](1879年);ルナンの『イスラエル民族史』[1887](1887年)。 ユリウス・ウェルハウゼン著『イスラエル史序説』J.S.ブラック&A.メンジーズ訳(エディンバラ:ブラック社1885年)への「序文」v–x頁。 ルドルフ・キッテル著『ヘブライ人史』第II巻(1892年)に対する「書評」『英国歴史評論』8巻314–316頁(1893年)。 |

| Heresy Trial documents The Presbytery's prosecution. Free Church of Scotland, Presbytery of Aberdeen, The Libel against Professor William Robertson Smith (1878). Smith's answers, and letter (published as pamphlets). "Answer to the form of libel" (Edinburgh: Douglas 1878). "Additional answer to the libel" (Edinburgh: Douglas 1878). "Answer to the amended libel" (Edinburgh: Douglas 1879). "An open letter to principal Rainy" (Edinburgh: Douglas 1880). |

異端審問の文書 長老会による起訴。 スコットランド自由教会、アバディーン長老会、ウィリアム・ロバートソン・スミス教授に対する誹謗中傷(1878年)。 スミスの回答と手紙(パンフレットとして出版)。 「誹謗中傷に対する回答」(エディンバラ:ダグラス、1878年)。 「誹謗中傷に対する追加回答」(エディンバラ:ダグラス、1878年)。 「修正された誹謗中傷に対する回答」(エディンバラ:ダグラス、1879年)。 「レイニー校長への公開書簡」(エディンバラ:ダグラス、1880年)。 |

| Commentary on Smith E. G. Brown, Obituary Notice. Prof. William Robertson Smith (London: Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, July 1894), 12 pages. Patrick Carnegie Simpson, The Life of Principal Rainy (London: Hodder and Stoughton 1909). Vol 2, pp. 306–403. John Sutherland Black & George Chrystal, The Life of William Robertson Smith (London: Adam & Charles Black 1912). A. R. Hope Moncreiff "Bonnie Scotland" (1922) or Scotland from Black's Popular Series of Colour Books.[37] John Buchan, The Kirk in Scotland (Edinburgh: Hodder and Stoughton Ltd. 1930). Ronald Roy Nelson, The Life and Thought of William Robertson Smith, 1846–1894 (dissertation, University of Michigan 1969). T. O. Beidelman, W. Robertson Smith and the Sociological Study of Religion (Chicago 1974). Edward Evans-Pritchard, A History of Anthropological Thought (NY: Basic Books 1981), Chap. 8 "Robertson Smith" at 69–81. Richard Allan Riesen, Criticism & Faith in late Victorian Scotland: A. B. Davidson, William Robertson Smith, George Adam Smith (University Press of America 1985) William Johnstone, editor, William Robertson Smith: Essays in reassessment (Sheffield Academic 1995). Gillian M. Bediako, Primal Religion and the Bible: William Robertson Smith and his heritage (Sheffield Academic 1997). John William Rogerson, The Bible and Criticism in Victorian Britain: Profiles of F. D. Maurice and William Robertson Smith (Sheffield Academic 1997). Aleksandar Bošković, "Anthropological Perspectives on Myth", Anuário Antropológico (Rio de Janeiro 2002) 99, pp. 103–144. [1] Archived 26 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine Alice Thiele Smith, Children of the Manse. Growing up in Victorian Aberdeenshire (Edinburgh: The Bellfield Press, 2004) Edited by Gordon Booth and Astrid Hess. Bernhard Maier, William Robertson Smith. His life, his work, and his times (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck 2009). [Forschungen zum Alten Testament]. |

スミスに関する解説 E. G. ブラウン、死亡記事。ウィリアム・ロバートソン・スミス教授(ロンドン:王立アジア協会誌、1894年7月)、12ページ。 パトリック・カーネギー・シンプソン、レイニー校長の生涯(ロンドン:ホッダー・アンド・ストートン、1909年)。第2巻、306~403ページ。 ジョン・サザーランド・ブラック&ジョージ・クリスタル著『ウィリアム・ロバートソン・スミスの生涯』(ロンドン:アダム&チャールズ・ブラック社、1912年)。 A. R. ホープ・モンクリフ著『ボニー・スコットランド』(1922年)、あるいはブラック社の人気シリーズ『カラーブック』のスコットランド編。[37] ジョン・ブキャン『スコットランドの教会』(エディンバラ:ホッダー・アンド・ストートン社 1930年)。 ロナルド・ロイ・ネルソン『ウィリアム・ロバートソン・スミスの生涯と思想、1846-1894』(ミシガン大学博士論文 1969年)。 T. O. バイデルマン『W. ロバートソン・スミスと宗教の社会学的研究』(シカゴ 1974年)。 エドワード・エヴァンズ=プリチャード『人類学的思想の歴史』(ニューヨーク:ベーシック・ブックス、1981年)、第8章「ロバートソン・スミス」69-81ページ。 リチャード・アラン・リーゼン『ビクトリア朝後期スコットランドの批評と信仰:A. B. デイヴィッドソン、ウィリアム・ロバートソン・スミス、ジョージ・アダム・スミス』(ユニバーシティ・プレス・オブ・アメリカ、1985年) ウィリアム・ジョンストン編『ウィリアム・ロバートソン・スミス:再評価のためのエッセイ』(シェフィールド・アカデミック、1995年)。 ジリアン・M・ベディアコ『原始宗教と聖書:ウィリアム・ロバートソン・スミスとその遺産』(シェフィールド・アカデミック、1997年)。 ジョン・ウィリアム・ロジャーソン『ビクトリア朝時代の英国における聖書と批評:F・D・モーリスとウィリアム・ロバートソン・スミスの人物像 (シェフィールド・アカデミック、1997年)。 アレクサンダル・ボスコヴィッチ、「神話に関する人類学的視点」、Anuário Antropológico(リオデジャネイロ、2002年)99、103-144ページ。[1] 2016年10月26日、ウェイバックマシンにアーカイブ。 アリス・ティーレ・スミス、『牧師館の子供たち。ビクトリア朝のアバディーンシャーで育つ』(エディンバラ:ベルフィールド・プレス、2004年)ゴードン・ブース、アストリッド・ヘス編。 ベルンハルト・マイヤー、『ウィリアム・ロバートソン・スミス。その生涯、その仕事、そしてその時代』(テュービンゲン:モーア・ジーベック、2009年)。[旧約聖書研究]。 |

| In popular culture Hiphop artist Astronautalis wrote a song about Smith entitled "The Case of William Smith". |

大衆文化において ヒップホップアーティストのアストロナウタリスは、スミスについて「ウィリアム・スミスの事件」という曲を書いた。 |

| Family His younger brother was the astronomer Charles Michie Smith FRSE.[38] |

家族 彼の弟は天文学者チャールズ・ミチー・スミスFRSEであった。[38] |

| 1. Biographical Index of Former

Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh 1783–2002 (PDF). The Royal

Society of Edinburgh. July 2006. ISBN 0-902-198-84-X. Archived from the

original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 16 July 2018. 2. Ewing, William Annals of the Free Church 3. Biographical Index of Former Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh 1783–2002 (PDF). The Royal Society of Edinburgh. July 2006. ISBN 0-902-198-84-X. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 16 July 2018. 4. Walker, Norman (1895). Chapters from the history of the Free church of Scotland. Edinburgh; London: Oliphant, Anderson & Ferrier. pp. 271–297. Retrieved 1 May 2017. 5. Dabney, Robert Lewis. Discussions of Robert Lewis Dabney Vol. 1: Evangelical and Theological. pp. 399–439. Retrieved 1 May 2017. 6. John Sutherland Black & George Chrystal, The Life of William Robertson Smith (London: Adam & Charles Black 1912) chs. xi & xii 7. The Old Testament in the Jewish Church (1892), p. 17. Also cited in the Preface to Encyclopedia Biblica. 8. Johnstone, "Introduction" 15–22, at 19, 20, in his edited William Robertson Smith. Essays in reassessment (Sheffield Academic 1995). 9. John W. Rogerson, "W. R. Smith's The Old Testament in the Jewish Church: Its antecedents, its influence, and its abiding value" in Johnstone, editor, William Robertson Smith. Essays in reassessment (Sheffield Academic 1995), 132–147, at 132. Here [132–136] Rogerson reviews briefly the reception of continental (German and Dutch) higher criticism, mentioning de Witte, Ewald, and Kuenen. 10. Cf. John Rogerson, Old Testament Criticism in the Nineteenth Century. England and Germany (Philadelphia: Fortress Press 1984), at Chapter 19, "Germany from 1860: the Path to Wellhausen" [257–272]; and, at Chapter 20, "England from 1880: the Triumph of Wellhausen" [273–289]. 11. Rogerson, "W. R. Smith's The Old Testament in the Jewish Church" in Johnstone, William Robertson Smith (1995), 132–147, at 136. Smith's "great contemporaries Kuenen and Wellhausen were historians and not theologians." But "for Smith, the God whose history of grace was disclosed by the historical criticism of the Old Testament was the God whose grace was still offered to the human race." Rogerson (1995) at 144, 145. 12. Bediako, Primal Religion and the Bible (1997) at 273, 276, 278. 13. Robert P. Carroll, "The Biblical Prophets as apologists for the Christian religion: reading William Robertson Smith's The Prophets of Israel today" in Johnstone, editor, William Robertson Smith. Essays in reassessment (1995), pp. 148–157, 149 ("anti-intellectual churches in the nineteenth century"), 152 ("an extremely Christian reading of the prophets"), 157 (quote). 14. Edward Said, Orientalism (New York: Random House 1978, reprint Vintage Books 1979), pp. 234–237, Kinship and Marriage quoted at 235 (per 344–345). 15. Cf., Jonathan Skinner, "Orientalists and Orientalisms: Robertson Smith and Edward W. Said" at pp. 376–382, in Johnstone, editor, William Robertson Smith. Essays in reassessment (1995). 16. McLennan is quoted that six social conditions form a mutually necessary totality: exogamy, totemism, blood feud, religious obligation of vengeance, female infanticide, and female kindship. McLennan, Studies in Ancient History (second series, 1896) at 28, as quoted by Evans-Pritchard, Social Anthropology (Oxford Univ. 1948), chap.2, at 34–35, reprint by The Free Press, Glencoe, 1962. 17. Peter Revière, "William Robertson Smith and John Ferguson McLennan: The Aberdeen roots of British social anthropology", 293–302, at 300, in Johnstone, editor, William Robertson Smith (1995). 18. Evans-Pritchard, A History of Anthropological Thought (1981) at 72 (hayy); at 72–74 (matriarchy), 73 (quotes re feminine names as grammar or lineage practice); at 74–76 (totems), 76 (quote "no case"); at 76–77 (quote re McLennan). 19. Robert G. Hoyland, Arabia and the Arabs. From the bronze age to the coming of Islam (London: Routledge 2001) at 129. Hoyland (at 64–65) discusses the Safaitic texts (20,000 graffiti) of '330 BC – 240 AD' but without focusing on male political power. 20. Cf., R. J. Thompson, Penitence and Sacrifice in Early Israel outside Levitical Law: An examination of the Fellowship Theory of early Israelite sacrifice (Leiden: Brill 1963), cited by Bediako (1997) at 306, n.4. 21. Evans-Pritchard writes, "The evidence for this theory... is negligiable." While not impossible, he infers other interpretations, concluding, "In this manner Robertson Smith misled both Durkeim and Freud." E. E. Evans-Pritchard, Theories of Primitive Religion (Oxford University 1965) at 51–52. Here Evans-Pritchard claims that between the first edition and second posthumous edition, certain passages were deleted "which might be thought to discredit the New Testament." Evans-Pritchard (1965) at 52, citing J. G. Frazer, The Gorgon's Head (1927) at 289. 22. Not mentioned by Smith are prior publications concerning the nascent anthropology, for example: J. J. Bachofen, Das Mutterrecht (1861); Fustel de Coulanges, Le Cité antique (1864); and, Edward Tylor, Researches into the Early History of Mankind (1865). 23. Frazer soon would publish his The Golden Bough (1890). 24 Also on account of method Smith was criticized by other contemporaries: Archibald Sayce, and Marie-Joseph Lagrange. Bediako, Primal Religion and the Bible (1997) at 305, n.3. 25. Rudolf Smend, "William Robertson Smith and Julius Wellhausen" in Johnston, William Robertson Smith (1995) at 226–242, 238–240. 26.Harriet Lutzky, "Deity and the Social Bond: Robertson Smith and the Psychoanalytic Theory of Religion" in Johnstone, editor, William Robertson Smith (1995) at 320–330, 322–323. 27. Gillian M. Bediako, Primal Religion and the Bible (1997) at 306–307. 28. William Johnstone, "Introduction" in his edited William Robertson Smith. Essays in reassessment (1995) at 15, n3. 29. Bediako, Primal Religion and the Bible (1997) at 307–308. 30. See discussion by Hushang Philosoph, "A Reconsideration of Frazer's relationship with Robertson Smith: The myth and the facts" in Johnstone, editor, William Robertson Smith (1995), 331–342, i.e., at 332. 31. Lutzky, "Deity and the Social Bond: Robertson Smith and the psychoanalytic theory of religion" in Johnstone, editor, William Robertson Smith (1995) at 320–330, 324–326. 32. Bediako, Primal Religion and the Bible (1997) at 307. 33. E. E. Evans-Pritchard, Theories of Primitive Religion (Oxford University 1965) at 51–53 & 56, quote at 52. "The evidence for these suppositions is exiguous." Evans-Pritchard (1965) at 51. 34. Smith, The Religion of the Semites (1889, 2d ed. 1894) at 26–27. 35. Edward W. Said, in his well-known book Orientalism (New York 1978), at 234–237, criticizes William Robertson Smith. Said twice quotes at length from Smith's 1881 Arabian study of his travels (at 491–492 [mistakenly by Said as 492–493], and at 498–499). "Smith the antiquarian scholar would not have had half the authority without his additional and direct experience of 'the Arabian facts'. It was the combination in Smith of the 'grasp' of primitive categories with the ability to see general truths behind the empirical vagarities of contemporary Oriental behavior that gave weight to his writing." Said (1979) at 235. Said calls Smith "a crucial link in the intellectual chain connecting the White-Man-as-expert to the modern Orient." Such link later enabled "Lawrence, Bell, and Philby" to construct reputations for expertise. Said (1979) at 235, 277. Of course, Said mocks such "Orientalist expertise, which is based on an irrefutable collective verity entirely within the Orientalist's philosophical and rhetorical grasp." Said (1979) at 236. 36. Cf., Jonathan Skinner, "Orientalists and Orientalisms. Robertson Smith and Edward W. Said" at 376–382, in Johnstone, editor, William Robertson Smith. Essays in reassessment (1995). 37. Moncrieff, A. R. Hope (1922). Bonnie Scotland (2nd ed.). London: A. & C. Black. p. 242. Retrieved 27 April 2017. 38. Biographical Index of Former Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh 1783–2002 (PDF). The Royal Society of Edinburgh. July 2006. ISBN 0-902-198-84-X. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 16 July 2018. |

1. エディンバラ王立協会元フェロー伝記索引 1783–2002 (PDF). エディンバラ王立協会. 2006年7月. ISBN 0-902-198-84-X. 2016年3月4日にオリジナル (PDF) からアーカイブ. 2018年7月16日に閲覧. 2. ユーイング、ウィリアム『自由教 会年鑑』 3. エディンバラ王立協会元フェローの伝記索引 1783–2002 (PDF). エディンバラ王立協会. 2006年7月. ISBN 0-902-198-84-X. 2016年3月4日、オリジナル (PDF) からアーカイブ。2018年7月16日取得。 4. ウォーカー、ノーマン (1895)。スコットランド自由教会の歴史からの章。エディンバラ、ロンドン:オリファント、アンダーソン&フェリア。271~297 ページ。2017年5月1日取得。 5. ダブニー、ロバート・ルイス。ロバート・ルイス・ダブニーに関する議論 第 1 巻:福音主義と神学。pp. 399–439. 2017年5月1日取得。 6. ジョン・サザーランド・ブラック&ジョージ・クリスタル、『ウィリアム・ロバートソン・スミスの生涯』(ロンドン:アダム&チャールズ・ブラック 1912年)chs. xi & xii 7. 『ユダヤ教会における旧約聖書』(1892年)、p. 17。また『聖書百科事典』の序文でも引用されている。 8. ジョンストーン、「序文」15-22、19、20、彼の編集によるウィリアム・ロバートソン・スミス。再評価のエッセイ(シェフィールド・アカデミック 1995)。 9. ジョン・W・ロジャーソン、「W・R・スミスの『ユダヤ教会における旧約聖書:その前史、影響、そして不変の価値』」ジョンストーン編、ウィリアム・ロ バートソン・スミス。再評価のエッセイ(シェフィールド・アカデミック、1995年)、132-147、132ページ。ここで[132-136]、ロ ジャーソンは、デ・ウィッテ、エヴァルト、クエネンに言及しながら、大陸(ドイツおよびオランダ)の高等批評の受容について簡潔に考察している。 10. ジョン・ロジャーソン、19世紀の旧約聖書批評。10. ジョン・ロジャーソン著『19 世紀の旧約聖書批評。 11. ロジャーソン、「W. R. スミスの『ユダヤ教会における旧約聖書』」ジョンストーン、ウィリアム・ロバートソン・スミス(1995)、132-147、136 ページ。スミスの「偉大な同時代人であるクーンとウェルハウゼンは、神学者ではなく歴史家であった」。しかし、「スミスにとって、旧約聖書の歴史的批判に よってその恵みの歴史が明らかにされた神は、依然として人類に恵みを与える神であった」とロジャーソン(1995)は 144、145 ページで述べている。 12. ベディアコ『原始宗教と聖書』(1997)273、276、278 ページ。 13. ロバート・P・キャロル、「キリスト教の擁護者としての聖書の預言者たち:ウィリアム・ロバートソン・スミスの『イスラエルの預言者たち』を今日読む」 ジョンストーン編、ウィリアム・ロバートソン・スミス。再評価のエッセイ(1995年)、 pp. 148–157, 149(「19世紀の反知性主義的な教会」)、152(「預言者たちに対する極めてキリスト教的な解釈」)、157(引用)。 14. エドワード・サイード、『オリエンタリズム』(ニューヨーク:ランダムハウス 1978年、復刻版 ヴィンテージブックス 1979年)、 pp. 234–237、235 ページで引用された「親族関係と結婚」(344–345 ページ)。 15. 参照、ジョナサン・スキナー、「オリエンタリストとオリエンタリズム:ロバートソン・スミスとエドワード・W・サイード」、pp. 376–382、ジョンストーン編、ウィリアム・ロバートソン・スミス。再評価のエッセイ(1995)。 16. マクレナンは、6つの社会的条件が相互に必要不可欠な全体を形成すると述べている。それは、外婚制、トーテミズム、血の復讐、復讐の宗教的義務、女児殺 し、女性の親族関係である。エヴァンズ=プリチャード『社会人類学』(オックスフォード大学出版、1948年)第2章34-35ページで引用された、マク レナン『古代史研究』(第2シリーズ、1896年)28ページ。 17. ピーター・レヴィエール、「ウィリアム・ロバートソン・スミスとジョン・ファーガソン・マクレナン:英国社会人類学のアバディーンにおけるルーツ」、293-302、300、ジョンストーン編、ウィリアム・ロバートソン・スミス(1995)。 18. エヴァンズ=プリチャード『人類学的思想の歴史』(1981年)72ページ(hayy)、72~74ページ(母系社会)、73ページ(文法または血統の慣 習としての女性名に関する引用)、74~76ページ(トーテム)、76ページ(「例がない」という引用)、76~77ページ (マクレナンに関する引用)。 19. ロバート・G・ホイルランド『アラビアとアラブ人。青銅器時代からイスラムの到来まで』(ロンドン:ラウトレッジ、2001年)129ページ。ホイルラン ド(64-65ページ)は、「紀元前330年から西暦240年」のサファイティック文書(2万の落書き)について論じているが、男性の政治権力には焦点を 当てていない。 20. R. J. トンプソン著『レビ記以外の初期イスラエルにおける悔い改めと犠牲:初期イスラエルの犠牲に関するフェローシップ理論の検証』(ライデン:ブリル社 1963年)を参照。ベディアコ(1997年)306、注4で引用。 21. エヴァンズ=プリチャードは、「この理論の証拠は...無視できるほどわずかである」と書いている。不可能ではないものの、彼は他の解釈を推測し、「この ようにして、ロバートソン・スミスはデュルケームとフロイトの両方を誤解させた」と結論づけている。E. E. エヴァンズ=プリチャード、『原始宗教の理論』(オックスフォード大学 1965年)51-52 ページ。ここでエヴァンズ=プリチャードは、初版と死後の第 2 版の間で、「新約聖書の信用を損なうと思われる」特定の文章が削除されたと主張している。エヴァンズ=プリチャード (1965) 52 ページ、J. G. フレイザー『ゴルゴンの頭』 (1927) 289 ページを引用。 22. スミスは、初期の人類学に関する先行出版物については言及していない。例えば、J. J. バコフェン『母権制』(1861年)、フステル・ド・クーランジュ『古代都市』(1864年)、エドワード・タイラー『人類の初期の歴史に関する研究』 (1865年)などである。 23. フレイザーはまもなく『黄金の枝』(1890年)を出版する。。 24 また、その方法論について、スミスは他の同時代の人々、アーチボルド・セイスやマリー=ジョセフ・ラグランジュからも批判を受けた。ベディアコ『原始宗教と聖書』(1997年)305、n.3。 25. ルドルフ・スメンド「ウィリアム・ロバートソン・スミスとユリウス・ウェルハウゼン」ジョンストン編『ウィリアム・ロバートソン・スミス』(1995年)226-242、 238–240。 26.ハリエット・ルツキー、「神と社会的絆:ロバートソン・スミスと精神分析的宗教理論」ジョンストン編、ウィリアム・ロバートソン・スミス(1995)320–330、322–323。 27. ギリアン・M・ベディアコ『原始宗教と聖書』(1997年)306-307ページ。 28. ウィリアム・ジョンストン『ウィリアム・ロバートソン・スミス:再評価のためのエッセイ』(1995年)15ページ、注3「序文」。 29. ベディアコ『原始宗教と聖書』(1997年)307-308ページ。 30. ハシャン・フィロソフによる議論を参照のこと。「フレイザーとロバートソン・スミスの関係の再考:神話と事実」ジョンストン編『ウィリアム・ロバートソン・スミス』(1995年)331-342ページ、すなわち332ページ。 31. Lutzky, 「神と社会的絆:ロバートソン・スミスと精神分析的宗教理論」 Johnstone 編, William Robertson Smith (1995) 320–330, 324–326 ページ。 32. Bediako, Primal Religion and the Bible (1997) 307 ページ。 33. E. E. エヴァンズ=プリチャード『原始宗教の理論』(オックスフォード大学 1965)51-53 ページおよび 56 ページ、52 ページからの引用。「これらの仮定を裏付ける証拠は乏しい」。エヴァンズ=プリチャード(1965)51 ページ。 34. スミス『セム族の宗教』(1889年、第2版1894年)26-27ページ。 35. エドワード・W・サイードは、その有名な著書『オリエンタリズム』(ニューヨーク、1978年)234-237ページで、ウィリアム・ロバートソン・スミ スを批判している。サイードは、スミスの 1881 年の旅行記『アラビア研究』から 2 回にわたって長文を引用している(491-492 ページ[サイードは 492-493 ページと誤って記載]、および 498-499 ページ)。 「古物研究家であるスミスは、『アラビアの事実』に関する追加的かつ直接的な経験がなければ、その権威の半分も得られなかっただろう。スミスの著作に重み を与えたのは、原始的なカテゴリーを「把握」する能力と、現代の東洋人の行動の経験的な変動の背後にある一般的な真実を見る能力とが組み合わさったこと だった。」(サイード、1979年、235ページ)。 サイードは、スミスを「専門家としての白人と現代の東洋とを結ぶ知的連鎖における重要なリンク」と呼んでいる。この連鎖は後に、「ローレンス、ベル、フィ ルビー」が専門知識の評判を築くことを可能にした。サイード(1979)235、277 ページ。もちろん、サイードは、このような「オリエンタリストの哲学的、修辞的把握の枠内に完全に収まる、反駁不可能な集合的真実に基づくオリエンタリス トの専門知識」を嘲笑している。サイード(1979)236 ページ。 36. ジョナサン・スキナー「オリエンタリストとオリエンタリズム。ロバートソン・スミスとエドワード・W・サイード」376-382 ページ、ジョンストーン編『ウィリアム・ロバートソン・スミス再評価論集』(1995 年)を参照。 37. モンクリフ、A. R. ホープ (1922)。『ボニー・スコットランド』 (第 2 版)。ロンドン:A. & C. ブラック。242 ページ。2017年4月27日取得。 38. エディンバラ王立協会元フェローの伝記索引 1783–2002 (PDF). エディンバラ王立協会. 2006年7月. ISBN 0-902-198-84-X. 2016年3月4日にオリジナル (PDF) からアーカイブ. 2018年7月16日取得. |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Robertson_Smith |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099