ルース・ベイダー・ギンズバーグ

Ruth Bader Ginsburg, 1933-2020

☆ ジョーン・ルース・バーダー・ギンズバーグ( Joan Ruth Bader Ginsburg ;1933年3月15日 - 2020年9月18日) は、1993年から2020年に亡くなるまで連邦最高裁判事補を務めたアメリカの弁護士・法学者である。 退任するバイロン・ホワイト判事の後任としてビル・クリントン大統領に指名され、当時は穏健な合意形成者と見なされていた。ギンズバーグは初 のユダヤ系女性であり、サンドラ・デイ・オコナーに次いで2人目の女性判事であった。在任中、ギンズバーグはアメリカ合衆国対バージニア州(1996 年)、オルムステッド対L.C.州(1999年)、フレンズ・オブ・ジ・アース対レイドロー・エンバイロメンタル・サービス社(2000年)、シェリル市 対ニューヨーク州オナイダ・インディアン・ネーション(2005年)などの事件で多数意見を執筆した。在任後、ギンズバーグはリベラルな法律観を反映した 情熱的な反対意見で注目を集めた。彼女は「悪名高きR.B.G.」(「ザ・ノトーリアス・ビッグ(Notorious B.I.G. )」のパロディ)と呼ばれ、後にその呼び名を受け入れた。

| Joan Ruth Bader Ginsburg

(/ˈbeɪdər ˈɡɪnzbɜːrɡ/ BAY-dər GHINZ-burg; née Bader; March 15, 1933 –

September 18, 2020)[2] was an American lawyer and jurist who served as

an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from

1993 until her death in 2020.[3] She was nominated by President Bill

Clinton to replace retiring justice Byron White, and at the time was

viewed as a moderate consensus-builder.[4] Ginsburg was the first

Jewish woman and the second woman to serve on the Court, after Sandra

Day O'Connor. During her tenure, Ginsburg authored the majority

opinions in cases such as United States v. Virginia (1996), Olmstead v.

L.C. (1999), Friends of the Earth, Inc. v. Laidlaw Environmental

Services, Inc. (2000), and City of Sherrill v. Oneida Indian Nation of

New York (2005). Later in her tenure, Ginsburg received attention for

passionate dissents that reflected liberal views of the law. She was

popularly dubbed "the Notorious R.B.G.",[a] a moniker she later

embraced.[5] Ginsburg was born and grew up in Brooklyn, New York. Her older sister, Marilyn, died of meningitis at the age of six, when Joan was a baby, and her mother died shortly before she graduated from high school.[6] She earned her bachelor's degree at Cornell University and married Martin D. Ginsburg, becoming a mother before starting law school at Harvard, where she was one of the few women in her class. Ginsburg transferred to Columbia Law School, where she graduated joint first in her class. During the early 1960s she worked with the Columbia Law School Project on International Procedure, learned Swedish, and co-authored a book with Swedish jurist Anders Bruzelius; her work in Sweden profoundly influenced her thinking on gender equality. She then became a professor at Rutgers Law School and Columbia Law School, teaching civil procedure as one of the few women in her field. Ginsburg spent much of her legal career as an advocate for gender equality and women's rights, winning many arguments before the Supreme Court. She advocated as a volunteer attorney for the American Civil Liberties Union and was a member of its board of directors and one of its general counsel in the 1970s. In 1980, President Jimmy Carter appointed her to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit, where she served until her appointment to the Supreme Court in 1993. Between O'Connor's retirement in 2006 and the appointment of Sonia Sotomayor in 2009, she was the only female justice on the Supreme Court. During that time, Ginsburg became more forceful with her dissents, such as with Ledbetter v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co. (2007). Despite two bouts with cancer and public pleas from liberal law scholars, she decided not to retire in 2013 or 2014 when President Barack Obama and a Democratic-controlled Senate could appoint and confirm her successor.[7][8][9] Ginsburg died at her home in Washington, D.C., in September 2020, at the age of 87, from complications of metastatic pancreatic cancer. The vacancy created by her death was filled 39 days later by Amy Coney Barrett. The result was one of three major rightward shifts in the Court since 1953, following the appointment of Clarence Thomas to replace Thurgood Marshall in 1991 and the appointment of Warren Burger to replace Earl Warren in 1969.[10] |

ジョーン・ルース・バーダー・ギンズバーグ(Joan Ruth Bader Ginsburg /ˈbe↪Lm_l_26↩

ɡ ɪ nzbɡ / BAY-dər GHINZ-burg; 旧姓バーダー、1933年3月15日 - 2020年9月18日)[2]

は、1993年から2020年に亡くなるまで連邦最高裁判事補を務めたアメリカの弁護士・法学者である。

[3]退任するバイロン・ホワイト判事の後任としてビル・クリントン大統領に指名され、当時は穏健な合意形成者と見なされていた。[4]ギンズバーグは初

のユダヤ系女性であり、サンドラ・デイ・オコナーに次いで2人目の女性判事であった。在任中、ギンズバーグはアメリカ合衆国対バージニア州(1996

年)、オルムステッド対L.C.州(1999年)、フレンズ・オブ・ジ・アース対レイドロー・エンバイロメンタル・サービス社(2000年)、シェリル市

対ニューヨーク州オナイダ・インディアン・ネーション(2005年)などの事件で多数意見を執筆した。在任後、ギンズバーグはリベラルな法律観を反映した

情熱的な反対意見で注目を集めた。彼女は「悪名高きR.B.G.」と呼ばれ[a]、後にその呼び名を受け入れた[5]。 ギンズバーグはニューヨークのブルックリンで生まれ育った。コーネル大学で学士号を取得し、マーティン・D・ギンズバーグと結婚して母親になった後、ハー バード大学のロースクールに入学。ギンズバーグはコロンビア大学ロースクールに編入し、同校を首席で卒業した。1960年代初頭、コロンビア大学ロース クールの国際訴訟プロジェクトに参加し、スウェーデン語を学び、スウェーデンの法学者アンダース・ブルゼリウスと共著で本を出版した。その後、ラトガーズ 大学ロースクールとコロンビア大学ロースクールの教授となり、この分野では数少ない女性の一人として民事訴訟法を教えた。 ギンズバーグは弁護士としてのキャリアの大半を男女平等と女性の権利の擁護者として過ごし、最高裁判所で多くの弁論に勝利した。1970年代にはアメリカ 自由人権協会のボランティア弁護士として活動し、同協会の理事や顧問弁護士を務めた。1980年、ジミー・カーター大統領からコロンビア特別区巡回控訴裁 判所に任命され、1993年に最高裁判事に任命されるまで同裁判所を務めた。2006年にオコナーが引退してから2009年にソニア・ソトマイヨールが任 命されるまでの間、彼女は最高裁で唯一の女性判事だった。この間、ギンズバーグは、レドベター対グッドイヤー・タイヤ&ラバー社事件(2007年)など、 より力強い反対意見を述べるようになった。 2度のがん闘病とリベラル派の法学者たちからの公的な嘆願にもかかわらず、彼女はバラク・オバマ大統領と民主党が支配する上院が彼女の後継者を任命・承認 できる2013年または2014年に引退しないことを決めた[7][8][9]。ギンズバーグは2020年9月、転移性膵臓がんの合併症によりワシントン D.C.の自宅で87歳で死去した。彼女の死によって生じた空席は、39日後にエイミー・コニー・バレットが埋めることになった。この結果は、1991年 にサーグッド・マーシャルの後任としてクラレンス・トーマスが任命され、1969年にアール・ウォーレンの後任としてウォーレン・バーガーが任命されたこ とに続き、1953年以来、法廷が大きく右傾化した3つのうちの1つであった[10]。 |

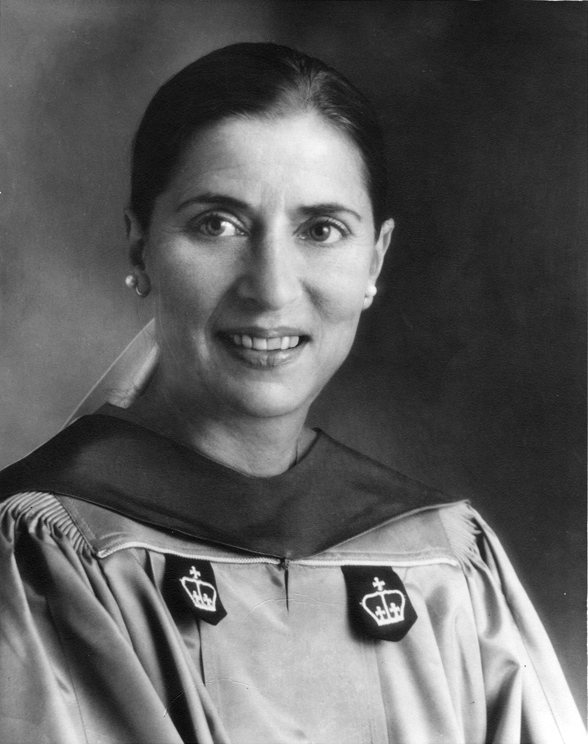

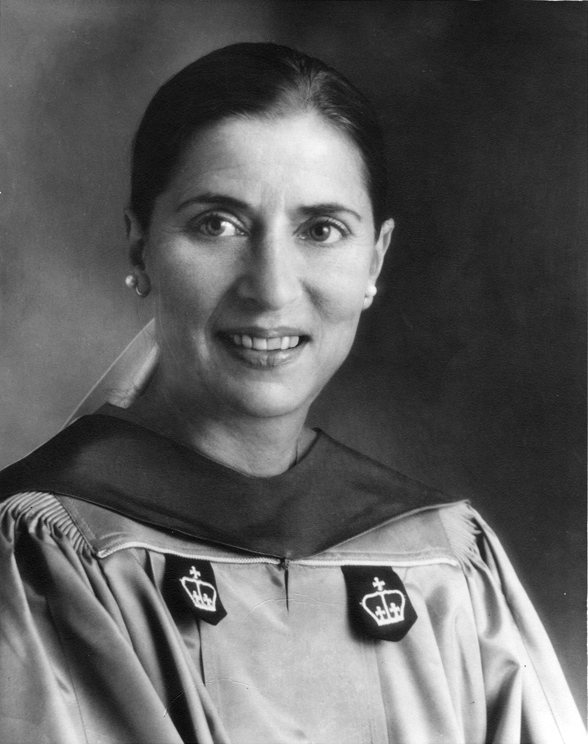

Early life and education Ginsburg in 1959, wearing her Columbia Law School academic regalia Joan Ruth Bader was born on March 15, 1933, at Beth Moses Hospital in the Brooklyn borough of New York City, the second daughter of Celia (née Amster) and Nathan Bader, who lived in Brooklyn's Flatbush neighborhood. Her father was a Jewish emigrant from Odesa, Ukraine, at that time part of the Russian Empire, and her mother was born in New York to Jewish parents who came from Kraków, Poland, at that time part of Austria-Hungary.[11] The Baders' elder daughter Marylin died of meningitis at age six. Joan, who was 14 months old when Marylin died, was known to the family as "Kiki", a nickname Marylin had given her for being "a kicky baby". When Joan started school, Celia discovered that her daughter's class had several other girls named Joan, so Celia suggested the teacher call her daughter by her second name, Ruth, to avoid confusion.[12]: 3–4 Although not devout, the Bader family belonged to East Midwood Jewish Center, a Conservative synagogue, where Ruth learned tenets of the Jewish faith and gained familiarity with the Hebrew language.[12]: 14–15 Ruth was not allowed to have a bat mitzvah ceremony because of Orthodox restrictions on women reading from the Torah, which upset her.[13] Starting as a camper from the age of four, she attended Camp Che-Na-Wah, a Jewish summer program at Lake Balfour near Minerva, New York, where she was later a camp counselor until the age of eighteen.[14] Celia took an active role in her daughter's education, often taking her to the library.[15] Celia had been a good student in her youth, graduating from high school at age 15, yet she could not further her own education because her family instead chose to send her brother to college. Celia wanted her daughter to get more education, which she thought would allow Ruth to become a high school history teacher.[16] Ruth attended James Madison High School, whose law program later dedicated a courtroom in her honor. Celia struggled with cancer throughout Ruth's high school years and died the day before Ruth's high school graduation.[15] Ruth Bader attended Cornell University in Ithaca, New York, where she was a member of Alpha Epsilon Phi sorority.[17]: 118 While at Cornell, she met Martin D. Ginsburg at age 17.[16] She graduated from Cornell with a Bachelor of Arts degree in government on June 23, 1954. While at Cornell, Bader studied under Russian-American novelist Vladimir Nabokov, and she later identified Nabokov as a major influence on her development as a writer.[18][19] She was a member of Phi Beta Kappa and the highest-ranking female student in her graduating class.[17][20] Bader married Ginsburg a month after her graduation from Cornell. The couple moved to Fort Sill, Oklahoma, where Martin Ginsburg, a Reserve Officers' Training Corps graduate, was stationed as a called-up active duty United States Army Reserve officer during the Korean War.[16][21][20] At age 21, Ruth Bader Ginsburg worked for the Social Security Administration office in Oklahoma, where she was demoted after becoming pregnant with her first child. She gave birth to a daughter in 1955.[22] In the fall of 1956, Ruth Bader Ginsburg enrolled at Harvard Law School, where she was one of only 9 women in a class of about 500 men.[23][24] The dean of Harvard Law, Erwin Griswold, reportedly invited all the female law students to dinner at his family home and asked the female law students, including Ginsburg, "Why are you at Harvard Law School, taking the place of a man?"[b][16][25][26] When her husband took a job in New York City, that same dean denied Ginsburg's request to complete her third year towards a Harvard law degree at Columbia Law School,[27] so Ginsburg transferred to Columbia and became the first woman to be on two major law reviews: the Harvard Law Review and Columbia Law Review. In 1959, she earned her law degree at Columbia and tied for first in her class.[15][28] |

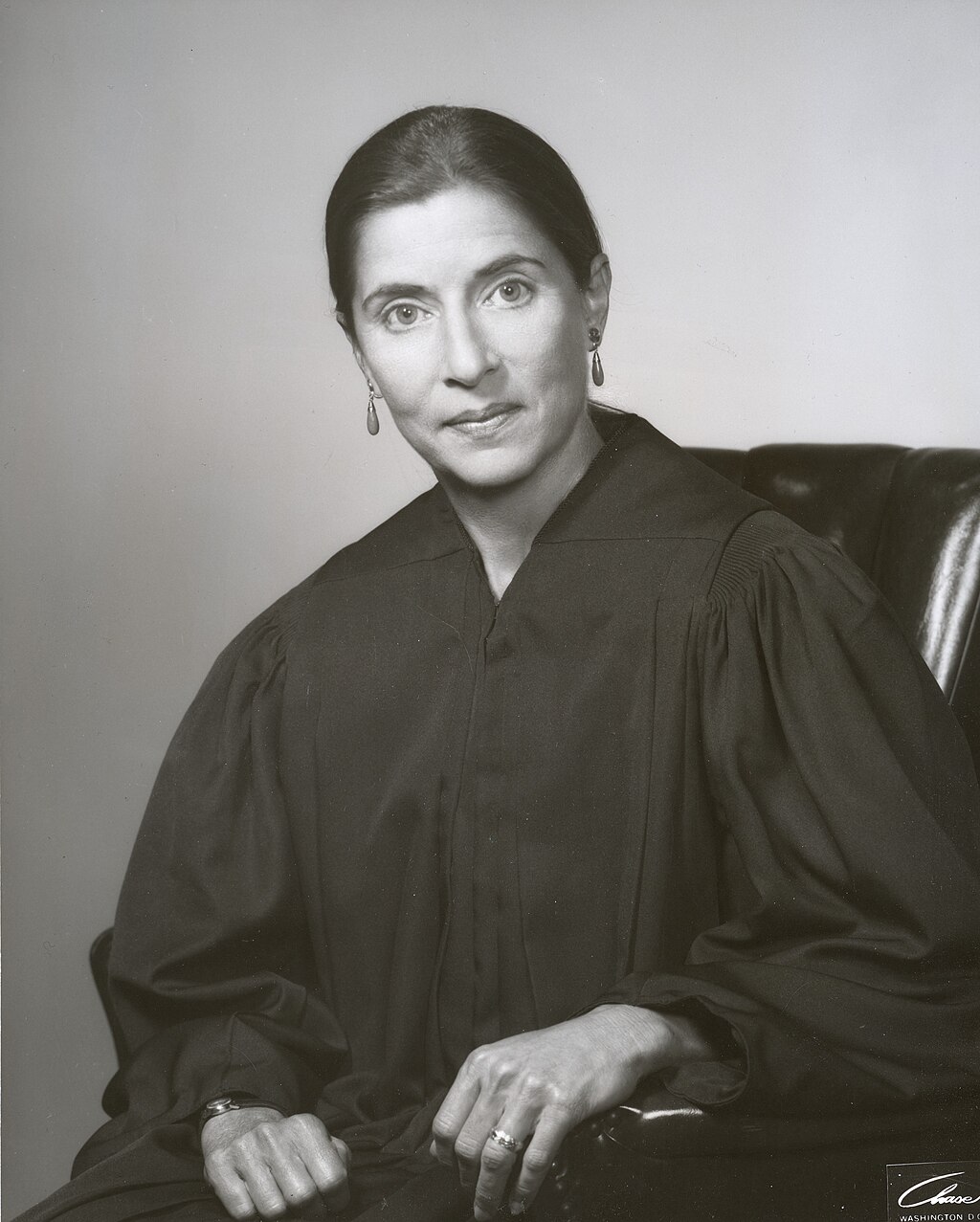

生い立ちと教育 1959年、コロンビア大学ロースクールの学制服に身を包んだギンズバーグ。 ジョーン・ルース・ベイダーは1933年3月15日、ニューヨーク市ブルックリン区のベス・モーゼス病院で、ブルックリンのフラットブッシュ地区に住むセ リア(旧姓アムスター)とネイサン・ベイダーの次女として生まれた。父親は当時ロシア帝国の一部であったウクライナのオデサから移住してきたユダヤ人で、 母親は当時オーストリア・ハンガリーの一部であったポーランドのクラクフから来たユダヤ人の両親のもと、ニューヨークで生まれた[11]。ベイダー家の長 女メアリンは6歳で髄膜炎で亡くなった。メアリンが亡くなったとき生後14ヶ月だったジョーンは、家族から「キキ」という愛称で呼ばれていた。ジョーンが 学校に通い始めたとき、セリアは娘のクラスにジョーンという名前の女の子が他にも何人かいることを知り、混乱を避けるために、セリアは先生に娘をセカンド ネームのルースで呼ぶよう提案した[12]: 3-4 敬虔ではなかったが、ベイダー家は保守派のシナゴーグであるイースト・ミッドウッド・ジューイッシュ・センターに所属し、ルースはそこでユダヤ教の教義を 学び、ヘブライ語に親しんだ[12]: 14-15 ルースはバット・ミツバの儀式を行うことを許されなかったが、それは女性がトーラーを朗読するという正統派の制約があったためで、彼女は動揺していた [13]。4歳からキャンパーとして参加した彼女は、ニューヨーク州ミネルヴァ近郊のバルフォア湖で行われるユダヤ教のサマープログラム、キャンプ・ チェ・ナ・ワに参加し、その後18歳までキャンプ・カウンセラーを務めた[14]。 セリアは娘の教育に積極的で、しばしば図書館に連れて行った[15]。セリアは若い頃は成績優秀で、15歳で高校を卒業したが、家族が代わりに兄を大学に 行かせることを選んだため、自分自身の教育を深めることができなかった。セリアは娘にもっと教育を受けさせたいと考え、そうすればルースが高校の歴史の教 師になれると考えた[16]。ルースはジェームズ・マディソン高校に通い、同校の法学科は後にルースにちなんで法廷を捧げた。セリアはルースの高校時代を 通じてがんと闘い、ルースの高校卒業式の前日に亡くなった[15]。 ルース・ベイダーはニューヨーク州イサカのコーネル大学に通い、アルファ・イプシロン・ファイ女子学生社交クラブに所属していた[17]: 118 コーネル大学在学中、17歳のときにマーティン・D・ギンズバーグと知り合った[16]。1954年6月23日、コーネル大学を卒業し、行政学の学士号を 取得。コーネル大学在学中、ベイダーはロシア系アメリカ人の小説家ウラジーミル・ナボコフに師事し、後にナボコフは彼女の作家としての成長に大きな影響を 与えたと語っている[18][19]。21歳のとき、ルース・ベイダー・ギンズバーグはオクラホマ州の社会保障局で働いたが、第一子を妊娠したため降格さ せられた。1955年に娘を出産した[22]。 1956年の秋、ルース・ベイダー・ギンズバーグはハーバード・ロー・スクールに入学し、約500人の男性から成るクラスでたった9人の女性の一人となっ た[23][24]。ハーバード・ローの学部長であるアーウィン・グリスウォルドは、女子法学生全員を彼の実家での夕食に招待し、ギンズバーグを含む女子 法学生に「なぜあなたはハーバード・ロー・スクールで男性の身代わりをしているのですか? 「[b][16][25][26]夫がニューヨークで職を得ると、同じ学部長がコロンビア大学ロースクールでハーバード大学法学部の学位取得に向けた3年 目を修了したいというギンズバーグの要求を拒否した[27]ため、ギンズバーグはコロンビア大学に編入し、ハーバード・ロー・レビューとコロンビア・ ロー・レビューという2つの主要なロー・レビューに在籍した最初の女性となった。1959年、コロンビア大学で法学位を取得し、クラスで1位タイとなった [15][28]。 |

| Early career At the start of her legal career, Ginsburg encountered difficulty in finding employment.[29][30][31] In 1960, Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter rejected Ginsburg for a clerkship because of her gender. He did so despite a strong recommendation from Albert Martin Sacks, who was a professor and later dean of Harvard Law School.[32][33][c] Columbia law professor Gerald Gunther also pushed for Judge Edmund L. Palmieri of the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York to hire Ginsburg as a law clerk, threatening to never recommend another Columbia student to Palmieri if he did not give Ginsburg the opportunity and guaranteeing to provide the judge with a replacement clerk should Ginsburg not succeed.[22][15][34] Later that year, Ginsburg began her clerkship for Judge Palmieri, and she held the position for two years.[22][15] Academia From 1961 to 1963, Ginsburg was a research associate and then an associate director of the Columbia Law School Project on International Procedure, working alongside director Hans Smit;[35][36] she learned Swedish to co-author a book with Anders Bruzelius on civil procedure in Sweden.[37][38] Ginsburg conducted extensive research for her book at Lund University in Sweden.[39] Ginsburg's time in Sweden and her association with the Swedish Bruzelius family of jurists also influenced her thinking on gender equality. She was inspired when she observed the changes in Sweden, where women were 20 to 25 percent of all law students; one of the judges whom Ginsburg observed for her research was eight months pregnant and still working.[16] Bruzelius' daughter, Norwegian supreme court justice and president of the Norwegian Association for Women's Rights, Karin M. Bruzelius, herself a law student when Ginsburg worked with her father, said that "by getting close to my family, Ruth realized that one could live in a completely different way, that women could have a different lifestyle and legal position than what they had in the United States."[40][41] Ginsburg's first position as a professor was at Rutgers Law School in 1963.[42] She was paid less than her male colleagues because, she was told, "your husband has a very good job."[31] At the time Ginsburg entered academia, she was one of fewer than twenty female law professors in the United States.[42] She was a professor of law at Rutgers from 1963 to 1972, teaching mainly civil procedure and receiving tenure in 1969.[43][44] In 1970, she co-founded the Women's Rights Law Reporter, the first law journal in the U.S. to focus exclusively on women's rights.[45] From 1972 to 1980, she taught at Columbia Law School, where she became the first tenured woman and co-authored the first law school casebook on sex discrimination.[44] She also spent a year as a fellow of the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences at Stanford University from 1977 to 1978.[46] Litigation and advocacy  Ginsburg standing by a window Ginsburg in 1977, photographed by Lynn Gilbert In 1972, Ginsburg co-founded the Women's Rights Project at the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), and in 1973, she became the Project's general counsel.[20] The Women's Rights Project and related ACLU projects participated in more than 300 gender discrimination cases by 1974. As the director of the ACLU's Women's Rights Project, she argued six gender discrimination cases before the Supreme Court between 1973 and 1976, winning five.[32] Rather than asking the Court to end all gender discrimination at once, Ginsburg charted a strategic course, taking aim at specific discriminatory statutes and building on each successive victory. She chose plaintiffs carefully, at times picking male plaintiffs to demonstrate that gender discrimination was harmful to both men and women.[32][44] The laws Ginsburg targeted included those that on the surface appeared beneficial to women, but in fact reinforced the notion that women needed to be dependent on men.[32] Her strategic advocacy extended to word choice, favoring the use of "gender" instead of "sex", after her secretary suggested the word "sex" would serve as a distraction to judges.[44] She attained a reputation as a skilled oral advocate, and her work led directly to the end of gender discrimination in many areas of the law.[47] Ginsburg volunteered to write the brief for Reed v. Reed, 404 U.S. 71 (1971), in which the Supreme Court extended the protections of the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to women.[44][48][d] In 1972, she argued before the 10th Circuit in Moritz v. Commissioner on behalf of a man who had been denied a caregiver deduction because of his gender. As amicus she argued in Frontiero v. Richardson, 411 U.S. 677 (1973), which challenged a statute making it more difficult for a female service member (Frontiero) to claim an increased housing allowance for her husband than for a male service member seeking the same allowance for his wife. Ginsburg argued that the statute treated women as inferior, and the Supreme Court ruled 8–1 in Frontiero's favor.[32] The court again ruled in Ginsburg's favor in Weinberger v. Wiesenfeld, 420 U.S. 636 (1975), where Ginsburg represented a widower denied survivor benefits under Social Security, which permitted widows but not widowers to collect special benefits while caring for minor children. She argued that the statute discriminated against male survivors of workers by denying them the same protection as their female counterparts.[50] In 1973, the same year Roe v. Wade was decided, Ginsburg filed a federal case to challenge involuntary sterilization, suing members of the Eugenics Board of North Carolina on behalf of Nial Ruth Cox, a mother who had been coercively sterilized under North Carolina's Sterilization of Persons Mentally Defective program on penalty of her family losing welfare benefits.[51][52][53] During a 2009 interview with Emily Bazelon of The New York Times, Ginsburg stated: "I had thought that at the time Roe was decided, there was concern about population growth and particularly growth in populations that we don't want to have too many of."[54] Bazelon conducted a follow-up interview with Ginsburg in 2012 at a joint appearance at Yale University, where Ginsburg claimed her 2009 quote was vastly misinterpreted and clarified her stance.[55][56] Ginsburg filed an amicus brief and sat with counsel at oral argument for Craig v. Boren, 429 U.S. 190 (1976), which challenged an Oklahoma statute that set different minimum drinking ages for men and women.[32][50] For the first time, the court imposed what is known as intermediate scrutiny on laws discriminating based on gender, a heightened standard of Constitutional review.[32][50][57] Her last case as an attorney before the Supreme Court was Duren v. Missouri, 439 U.S. 357 (1979), which challenged the validity of voluntary jury duty for women, on the ground that participation in jury duty was a citizen's vital governmental service and therefore should not be optional for women. At the end of Ginsburg's oral argument, then-Associate Justice William Rehnquist asked Ginsburg, "You won't settle for putting Susan B. Anthony on the new dollar, then?"[58] Ginsburg said she considered responding, "We won't settle for tokens," but instead opted not to answer the question.[58] Legal scholars and advocates credit Ginsburg's body of work with making significant legal advances for women under the Equal Protection Clause of the Constitution.[44][32] Taken together, Ginsburg's legal victories discouraged legislatures from treating women and men differently under the law.[44][32][50] She continued to work on the ACLU's Women's Rights Project until her appointment to the Federal Bench in 1980.[44] Later, colleague Antonin Scalia praised Ginsburg's skills as an advocate. "She became the leading (and very successful) litigator on behalf of women's rights—the Thurgood Marshall of that cause, so to speak." This was a comparison that had first been made by former solicitor general Erwin Griswold who was also her former professor and dean at Harvard Law School, in a speech given in 1985.[59][60][e] |

初期のキャリア 1960年、最高裁判事のフェリックス・フランクファーターは、ギンズバーグの性別を理由に事務職を拒否した[29][30][31]。彼は、ハーバード 大学ロースクールの教授であり後に学部長を務めたアルバート・マーティン・サックスの強い推薦にもかかわらず、そうした[32][33][c] 。その年の暮れ、ギンズバーグはパルミエリ判事の下でクラークシップを始め、2年間その職を務めた[22][15][34]。 学界 1961年から1963年にかけて、ギンズバーグはコロンビア大学ロースクールの国際訴訟プロジェクトでリサーチ・アソシエイト、その後アソシエイト・ ディレクターを務め、ディレクターのハンス・スミットとともに働いていた[35][36]。ギンズバーグはスウェーデンの民事訴訟手続に関する本をアン ダース・ブルゼリウスと共著するためにスウェーデン語を学んだ[37][38]。研究のためにギンズバーグが観察した裁判官の一人は、妊娠8カ月でありな がらまだ働いていた。[16] ブルゼリウスの娘であるノルウェーの最高裁判所判事であり、ノルウェー女性の権利協会の会長であるカリン・M. ブルゼリウスは、ギンズバーグが父親と一緒に働いていたとき、彼女自身は法学部の学生であったが、「私の家族と親しくなることによって、ルースは、人は まったく異なる生き方ができること、女性は米国で持っていたものとは異なるライフスタイルや法的地位を持つことができることに気づいた」と語っている [40][41]。 ギンズバーグの教授としての最初の職は1963年のラトガース・ロースクールであった[42]。「あなたの夫はとても良い仕事をしている」と言われたた め、彼女は男性の同僚よりも低い給料であった[31]。ギンズバーグが学界に入った当時、彼女はアメリカで20人以下の女性法学教授の一人であった [42]。1963年から1972年までラトガース大学の法学教授を務め、主に民事訴訟法を教え、1969年に終身在職権を得た[43][44]。 1972年から1980年までコロンビア大学ロースクールで教鞭をとり、女性初の終身在職者となり、性差別に関する初のロースクール判例集を共同執筆した [44]。また1977年から1978年までスタンフォード大学行動科学高等研究センターのフェローを1年間務めた[46]。 訴訟と弁護活動  窓際に立つギンズバーグ 1977年のギンズバーグ、リン・ギルバート撮影 1972年、ギンズバーグはアメリカ自由人権協会(ACLU)に女性の権利プロジェクトを共同設立し、1973年にはプロジェクトの顧問弁護士となった [20]。ACLUの女性の権利プロジェクトのディレクターとして、彼女は1973年から1976年の間に6件の男女差別訴訟を最高裁で論じ、5勝を挙げ た[32]。裁判所にすべての男女差別を一度に終わらせるよう求めるのではなく、ギンズバーグは戦略的なコースを描き、特定の差別的な法令に狙いを定め、 勝利を積み重ねた。彼女は慎重に原告を選び、時には男女差別が男女双方に有害であることを示すために男性の原告を選んだ[32][44]。ギンズバーグが 標的とした法律には、表面的には女性に有益に見えるが、実際には女性が男性に依存する必要があるという考え方を強化するものも含まれていた。 [32]彼女の戦略的擁護は言葉の選択にも及び、秘書が「セックス」という言葉が裁判官の注意をそらすと示唆した後、「セックス」の代わりに「ジェン ダー」の使用を支持した[44]。彼女は熟練した口頭弁論家としての評判を獲得し、彼女の活動は法律の多くの分野における男女差別の撤廃に直接つながった [47]。 ギンズバーグは、最高裁が憲法修正第14条の平等保護条項の保護を女性にも拡大したリード対リード事件(404 U.S. 71、1971年)の準備書面の執筆を自ら志願した[44][48][d] 1972年には、第10巡回区において、性別を理由に介護者控除を拒否された男性に代わって、モリッツ対コミッショナー事件で弁論を行った。アミカスとし て、フロンティエロ対リチャードソン事件(Frontiero v. Richardson, 411 U.S. 677 (1973))に異議を唱えた。この事件では、女性軍人(フロンティエロ)が夫のために住宅手当の増額を請求することは、妻のために同じ手当を求める男性 軍人よりも困難であるという法令が争われた。ギンズバーグは、この法令が女性を劣ったものとして扱っていると主張し、最高裁は8対1でフロンティエロ側に 有利な判決を下した[32]。ギンズバーグは、社会保障制度の下で遺族給付を拒否された寡婦の代理人を務めたが、寡婦は未成年の子供を養育しながら特別給 付金を受け取ることはできなかった。彼女は、この法律は男性の労働者の遺族に対して、女性の遺族と同じ保護を否定することで差別していると主張した [50]。 1973年、ロー対ウェイド裁判が判決されたのと同じ年に、ギンズバーグは、強制不妊手術に異議を唱える連邦裁判を起こし、ノースカロライナ州の優生学委 員会のメンバーを、ノースカロライナ州の精神障害者不妊手術プログラムの下で強制不妊手術を受けた母親、ニアル・ルース・コックスに代わって訴えた: 「私は、ローが決定された当時、人口増加、特に私たちがあまり多く持ちたくない人口の増加について懸念があったと思っていた」[54][54] バゼロンは、2012年にイェール大学での合同登壇でギンズバーグに再インタビューを行い、ギンズバーグは2009年の引用が大きく誤解されていると主張 し、自身の姿勢を明らかにした[55][56]。 ギンズバーグは、男女で異なる最低飲酒年齢を定めたオクラホマ州法に異議を唱えたクレイグ対ボーレン事件(429 U.S. 190、1976年)の法廷弁論で、アミカスブリーフを提出し、弁護人とともに傍聴した[32][50]。 [32][50][57]彼女が弁護士として最高裁で争った最後の裁判は、デュレン対ミズーリ裁判、439 U.S. 357 (1979)であった。この裁判では、陪審義務への参加は市民の重要な行政サービスであり、したがって女性の任意参加であってはならないとして、女性の自 発的な陪審義務の有効性が争われた。ギンズバーグの口頭弁論の最後に、ウィリアム・レンキスト判事(当時)はギンズバーグに、「それでは、スーザン・B・ アンソニーを新しいドルに載せることでは決着がつかないのですね?」[58]と質問した[58]。ギンズバーグは、「トークンでは決着がつきません 」と答えることも考えたが、その代わりにその質問には答えないことにした、と述べた[58]。 法学者や擁護者たちは、ギンズバーグの一連の活動が、憲法の平等保護条項の下で、女性のための重要な法的進歩をもたらしたと評価している[44] [32]。 ギンズバーグの法的勝利は、総合すると、立法府が法の下で女性と男性を異なるものとして扱うことを思いとどまらせた[44][32][50]。 彼女は、1980年に連邦判事に任命されるまで、ACLUの女性の権利プロジェクトで働き続けた[44]。後に、同僚のアントニン・スカリアは、擁護者と してのギンズバーグの能力を賞賛した。「彼女は女性の権利のための代表的な(そして非常に成功した)訴訟代理人となった。これは、彼女のハーバード・ ロー・スクールの元教授であり学部長でもあったアーウィン・グリスウォルド元事務総長が、1985年に行ったスピーチで初めて述べた比較であった[59] [60][e]。 |

| U.S. Court of Appeals In light of the mounting backlog in the federal judiciary, Congress passed the Omnibus Judgeship Act of 1978 increasing the number of federal judges by 117 in district courts and another 35 to be added to the circuit courts. The law placed an emphasis on ensuring that the judges included women and minority groups, a matter that was important to President Jimmy Carter who had been elected two years before. The bill also required that the nomination process consider the character and experience of the candidates.[61][62][63] Ginsburg was considering a change in career as soon as Carter was elected. She was interviewed by the Department of Justice to become Solicitor General, the position she most desired, but knew that she and the African-American candidate who was interviewed the same day had little chance of being appointed by Attorney General Griffin Bell.[64]  Ginsburg shaking hands with Carter as the two smile Ginsburg with President Jimmy Carter in 1980 At the time, Ginsburg was a fellow at Stanford University where she was working on a written account of her work in litigation and advocacy for equal rights. Her husband was a visiting professor at Stanford Law School and was ready to leave his firm, Weil, Gotshal & Manges, for a tenured position. He was at the same time working hard to promote a possible judgeship for his wife. In January 1979, she filled out the questionnaire for possible nominees to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, and another for the District of Columbia Circuit.[64] Ginsburg was nominated by President Carter on April 14, 1980, to a seat on the DC Circuit vacated by Judge Harold Leventhal upon his death. She was confirmed by the United States Senate on June 18, 1980, and received her commission later that day.[43][65]  Ginsburg in 1981 During her time as a judge on the DC Circuit, Ginsburg often found consensus with her colleagues including conservatives Robert H. Bork and Antonin Scalia.[66][67] Her time on the court earned her a reputation as a "cautious jurist" and a moderate.[4] Her service ended on August 9, 1993, due to her elevation to the United States Supreme Court,[43][68][69] and she was replaced by Judge David S. Tatel.[70] |

連邦控訴裁判所 連邦司法の人員不足が深刻化する中、連邦議会は1978年に連邦裁判官全権法を可決し、連邦裁判官の数を地方裁判所に117人、巡回裁判所にさらに35人 増員した。この法律は、裁判官の中に女性やマイノリティが含まれるようにすることに重点を置いており、これは2年前に当選したジミー・カーター大統領に とっても重要な問題であった。法案はまた、候補者の人柄と経験を考慮した指名プロセスを要求した[61][62][63]。ギンズバーグは、カーターが当 選するとすぐに転職を考えていた。彼女は最も希望していた法務事務総長になるために司法省の面接を受けたが、彼女と同じ日に面接を受けたアフリカ系アメリ カ人の候補者がグリフィン・ベル司法長官によって任命される可能性はほとんどないことを知っていた[64]。  カーターと笑顔で握手するギンズバーグ 1980年、ジミー・カーター大統領とギンズバーグ 当時、ギンズバーグはスタンフォード大学の研究員で、権利平等のための訴訟やアドボカシー活動に関する自分の仕事について、文章にまとめていた。彼女の夫 はスタンフォード大学ロースクールの客員教授であり、終身雇用の職を得るために所属していたワイル・ゴツハル法律事務所を辞めようとしていた。夫は同時 に、妻の裁判官就任の可能性を懸命にアピールしていた。ギンズバーグは1980年4月14日、カーター大統領によって、ハロルド・レヴェンタール判事の死 去によって空席となったワシントンDC巡回区に指名された。彼女は1980年6月18日に合衆国上院で承認され、その日のうちに辞令を受けた[43] [65]。  1981年のギンズバーグ ギンズバーグは、DC巡回区の判事として勤務していた間、保守派のロバート・H・ボークやアントニン・スカリアを含む同僚としばしば意見の一致を見た [66][67]。 彼女の法廷での勤務は、「慎重な法学者」「穏健派」という評判を得た[4]。1993年8月9日、連邦最高裁判所への昇格に伴い、彼女の勤務は終了し [43][68][69]、後任としてデビッド・S・タテル判事が任命された[70]。 |

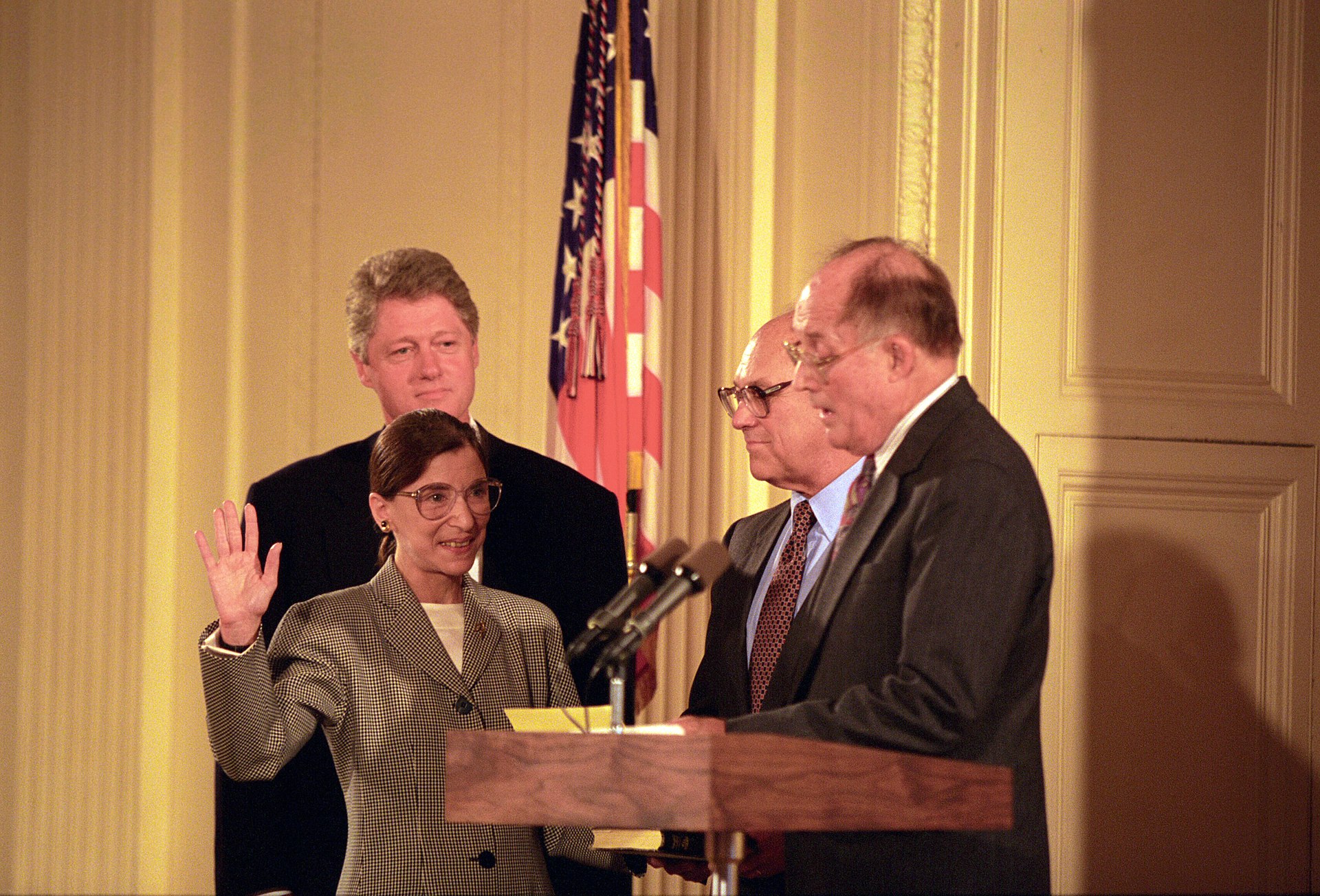

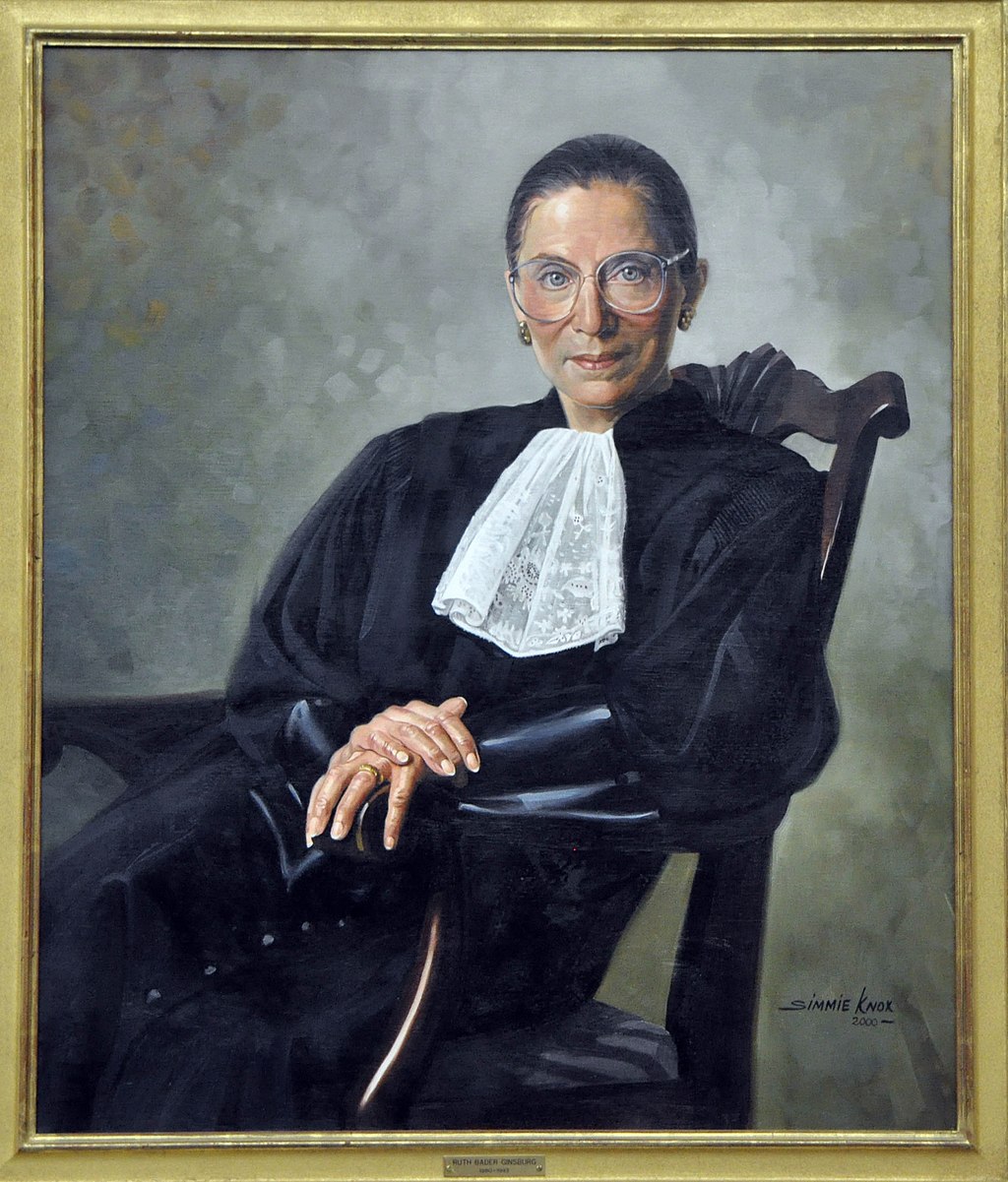

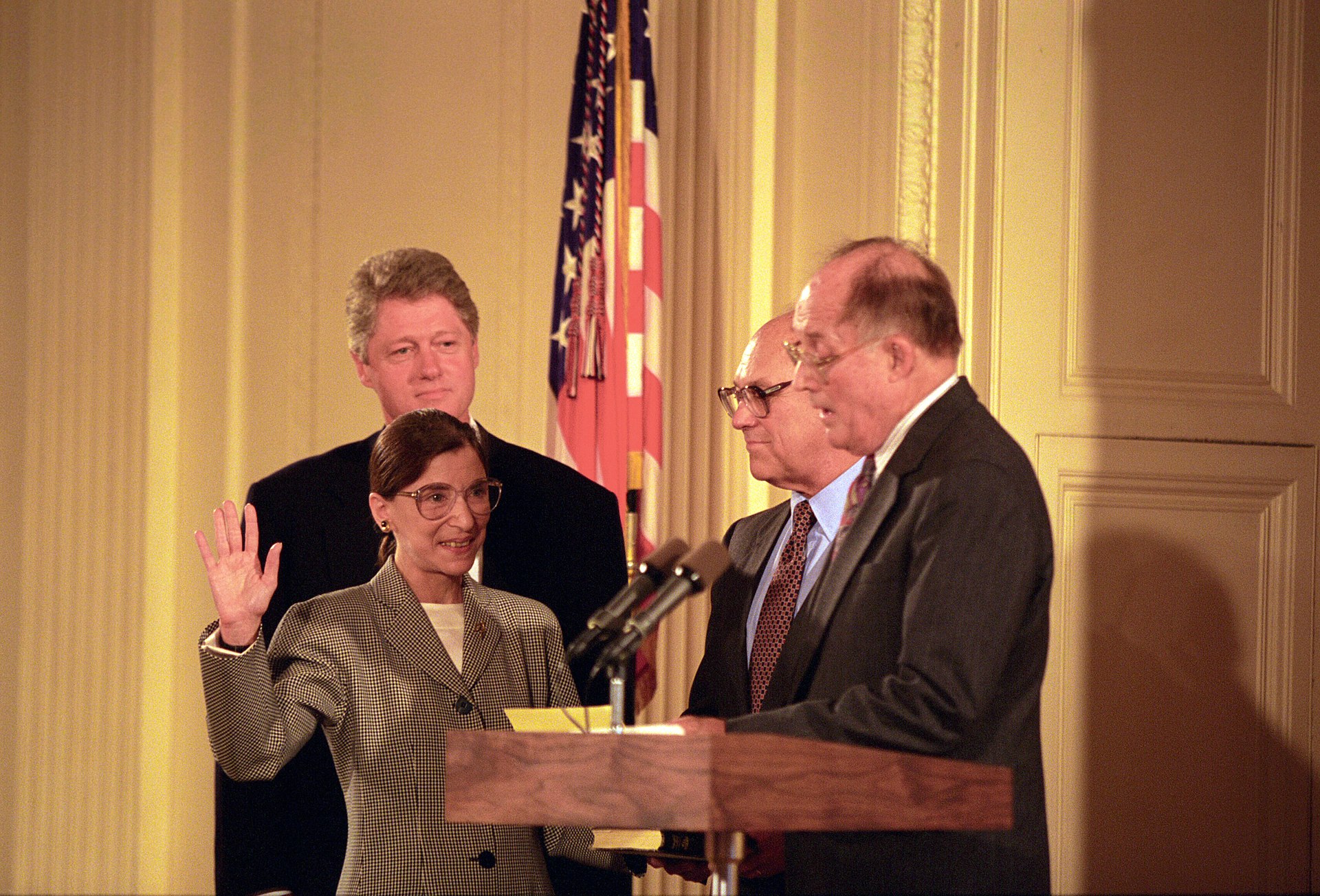

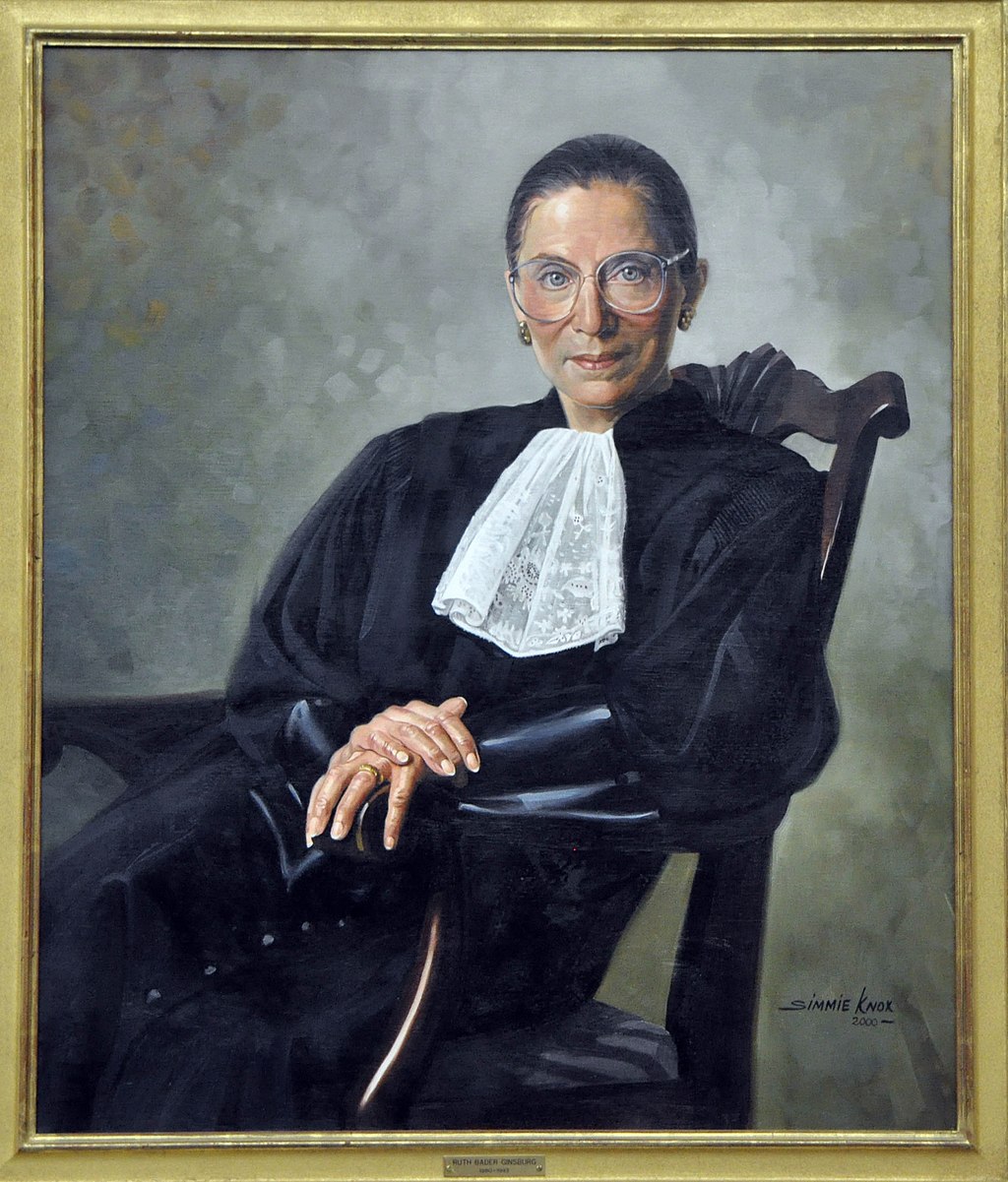

| Supreme Court Nomination and confirmation  Ginsburg speaking at a lectern Ginsburg officially accepting the nomination from President Bill Clinton on June 14, 1993 President Bill Clinton nominated Ginsburg as an associate justice of the Supreme Court on June 22, 1993, to fill the seat vacated by retiring justice Byron White.[71] She was recommended to Clinton by then–U.S. attorney general Janet Reno,[28] after a suggestion by Utah Republican senator Orrin Hatch.[72] At the time of her nomination, Ginsburg was viewed as having been a moderate and a consensus-builder in her time on the appeals court.[4][73] Clinton was reportedly looking to increase the Court's diversity, which Ginsburg did as the first Jewish justice since the 1969 resignation of Justice Abe Fortas. She was the second female and the first Jewish female justice of the Supreme Court.[4][74][75] She eventually became the longest-serving Jewish justice.[76] The American Bar Association's Standing Committee on the Federal Judiciary rated Ginsburg as "well qualified", its highest rating for a prospective justice.[77]  Ginsburg speaking into microphone at Senate confirmation hearing on her for her Supreme Court appointment Ginsburg giving testimony before the Senate Judiciary Committee during the hearings on her nomination to be an associate justice During her testimony before the Senate Judiciary Committee as part of the confirmation hearings, Ginsburg refused to answer questions about her view on the constitutionality of some issues such as the death penalty as it was an issue she might have to vote on if it came before the Court.[78] At the same time, Ginsburg did answer questions about some potentially controversial issues. For instance, she affirmed her belief in a constitutional right to privacy and explained at some length her personal judicial philosophy and thoughts regarding gender equality.[79]: 15–16 Ginsburg was more forthright in discussing her views on topics about which she had previously written.[78] The United States Senate confirmed her by a 96–3 vote on August 3, 1993.[f][43] She received her commission on August 5, 1993[43] and took her judicial oath on August 10, 1993.[81] Ginsburg's name was later invoked during the confirmation process of John Roberts. Ginsburg was not the first nominee to avoid answering certain specific questions before Congress,[g] and as a young attorney in 1981 Roberts had advised against Supreme Court nominees' giving specific responses.[82] Nevertheless, some conservative commentators and senators invoked the phrase "Ginsburg precedent" to defend his demurrers.[77][82] In a September 28, 2005, speech at Wake Forest University, Ginsburg said Roberts's refusal to answer questions during his Senate confirmation hearings on some cases was "unquestionably right".[83] Supreme Court tenure  Ginsburg being sworn in and smiling Chief Justice William Rehnquist swearing in Ginsburg as an associate justice of the Supreme Court, as her husband Martin Ginsburg and President Clinton watch Ginsburg characterized her performance on the Court as a cautious approach to adjudication.[84] She argued in a speech shortly before her nomination to the Court that "[m]easured motions seem to me right, in the main, for constitutional as well as common law adjudication. Doctrinal limbs too swiftly shaped, experience teaches, may prove unstable."[85] Legal scholar Cass Sunstein characterized Ginsburg as a "rational minimalist", a jurist who seeks to build cautiously on precedent rather than pushing the Constitution towards her own vision.[86]: 10–11 The retirement of Justice Sandra Day O'Connor in 2006 left Ginsburg as the only woman on the Court.[87][h] Linda Greenhouse of The New York Times referred to the subsequent 2006–2007 term of the Court as "the time when Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg found her voice, and used it".[89] The term also marked the first time in Ginsburg's history with the Court where she read multiple dissents from the bench, a tactic employed to signal more intense disagreement with the majority.[89]  The justices standing side-by-side, smiling Sandra Day O'Connor, Sonia Sotomayor, Ginsburg, and Elena Kagan, 2010. O'Connor is not wearing a robe because she was retired from the court when the picture was taken. With the retirement of Justice John Paul Stevens, Ginsburg became the senior member of what was sometimes referred to as the Court's "liberal wing".[44][90][91] When the Court split 5–4 along ideological lines and the liberal justices were in the minority, Ginsburg often had the authority to assign authorship of the dissenting opinion because of her seniority.[90][i] Ginsburg was a proponent of the liberal dissenters speaking "with one voice" and, where practicable, presenting a unified approach to which all the dissenting justices can agree.[44][90] During Ginsburg's entire Supreme Court tenure from 1993 to 2020, she only hired one African-American clerk (Paul J. Watford).[93][94] During her 13 years on the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit, she never hired an African-American clerk, intern, or secretary. The lack of diversity was briefly an issue during her 1993 confirmation hearing.[95] When this issue was raised by the Senate Judiciary Committee, Ginsburg stated that "If you confirm me for this job, my attractiveness to black candidates is going to improve."[96] This issue received renewed attention after more than a hundred of her former legal clerks served as pallbearers during her funeral.[97][98] Gender discrimination Ginsburg authored the Court's opinion in United States v. Virginia, 518 U.S. 515 (1996), which struck down the Virginia Military Institute's (VMI) male-only admissions policy as violating the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. For Ginsburg, a state actor could not use gender to deny women equal protection; therefore VMI must allow women the opportunity to attend VMI with its unique educational methods.[99] Ginsburg emphasized that the government must show an "exceedingly persuasive justification" to use a classification based on sex.[100] VMI proposed a separate institute for women, but Ginsburg found this solution reminiscent of the effort by Texas decades earlier to preserve the University of Texas Law School for Whites by establishing a separate school for Blacks.[101] Ginsburg dissented in the Court's decision on Ledbetter v. Goodyear, 550 U.S. 618 (2007), in which plaintiff Lilly Ledbetter sued her employer, claiming pay discrimination based on her gender, in violation of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. In a 5–4 decision, the majority interpreted the statute of limitations as starting to run at the time of every pay period, even if a woman did not know she was being paid less than her male colleague until later. Ginsburg found the result absurd, pointing out that women often do not know they are being paid less, and therefore it was unfair to expect them to act at the time of each paycheck. She also called attention to the reluctance women may have in male-dominated fields to making waves by filing lawsuits over small amounts, choosing instead to wait until the disparity accumulates.[102] As part of her dissent, Ginsburg called on Congress to amend Title VII to undo the Court's decision with legislation.[103] Following the election of President Barack Obama in 2008, the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act, making it easier for employees to win pay discrimination claims, became law.[104][105] Ginsburg was credited with helping to inspire the law.[103][105] Abortion rights Ginsburg discussed her views on abortion and gender equality in a 2009 New York Times interview, in which she said, "[t]he basic thing is that the government has no business making that choice for a woman."[106] Although Ginsburg consistently supported abortion rights and joined in the Court's opinion striking down Nebraska's partial-birth abortion law in Stenberg v. Carhart, 530 U.S. 914 (2000), on the 40th anniversary of the Court's ruling in Roe v. Wade, 410 U.S. 113 (1973), she criticized the decision in Roe as terminating a nascent democratic movement to liberalize abortion laws which might have built a more durable consensus in support of abortion rights.[107] Ginsburg was in the minority for Gonzales v. Carhart, 550 U.S. 124 (2007), a 5–4 decision upholding restrictions on partial birth abortion. In her dissent, Ginsburg opposed the majority's decision to defer to legislative findings that the procedure was not safe for women. Ginsburg focused her ire on the way Congress reached its findings and with their veracity.[108] Joining the majority for Whole Woman's Health v. Hellerstedt, 579 U.S. 582 (2016), a case which struck down parts of a 2013 Texas law regulating abortion providers, Ginsburg also authored a short concurring opinion which was even more critical of the legislation at issue.[109] She asserted the legislation was not aimed at protecting women's health, as Texas had said, but rather to impede women's access to abortions.[108][109] Search and seizure  A painting of Ginsburg in her robe, smiling and leaning in a chair Commissioned portrait by Simmie Knox, 2000 Although Ginsburg did not author the majority opinion, she was credited with influencing her colleagues on Safford Unified School District v. Redding, 557 U.S. 364 (2009),[110] which held that a school went too far in ordering a 13-year-old female student to strip to her bra and underpants so female officials could search for drugs.[110] In an interview published prior to the Court's decision, Ginsburg shared her view that some of her colleagues did not fully appreciate the effect of a strip search on a 13-year-old girl. As she said, "They have never been a 13-year-old girl."[111] In an 8–1 decision, the Court agreed that the school's search violated the Fourth Amendment and allowed the student's lawsuit against the school to go forward. Only Ginsburg and Stevens would have allowed the student to sue individual school officials as well.[110] In Herring v. United States, 555 U.S. 135 (2009), Ginsburg dissented from the Court's decision not to suppress evidence due to a police officer's failure to update a computer system. In contrast to Roberts's emphasis on suppression as a means to deter police misconduct, Ginsburg took a more robust view on the use of suppression as a remedy for a violation of a defendant's Fourth Amendment rights. Ginsburg viewed suppression as a way to prevent the government from profiting from mistakes, and therefore as a remedy to preserve judicial integrity and respect civil rights.[112]: 308 She also rejected Roberts's assertion that suppression would not deter mistakes, contending making police pay a high price for mistakes would encourage them to take greater care.[112]: 309 International law Ginsburg advocated the use of foreign law and norms to shape U.S. law in judicial opinions, a view rejected by some of her conservative colleagues. Ginsburg supported using foreign interpretations of law for persuasive value and possible wisdom, not as binding precedent.[113] Ginsburg expressed the view that consulting international law is a well-ingrained tradition in American law, counting John Henry Wigmore and President John Adams as internationalists.[114] Ginsburg's own reliance on international law dated back to her time as an attorney; in her first argument before the Court, Reed v. Reed, 404 U.S. 71 (1971), she cited two German cases.[115] In her concurring opinion in Grutter v. Bollinger, 539 U.S. 306 (2003), a decision upholding Michigan Law School's affirmative action admissions policy, Ginsburg noted there was accord between the notion that affirmative action admissions policies would have an end point and agrees with international treaties designed to combat racial and gender-based discrimination.[114] Voting rights and affirmative action In 2013, Ginsburg dissented in Shelby County v. Holder, in which the Court held unconstitutional the part of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 requiring federal preclearance before changing voting practices. Ginsburg wrote, "Throwing out preclearance when it has worked and is continuing to work to stop discriminatory changes is like throwing away your umbrella in a rainstorm because you are not getting wet."[116] Besides Grutter, Ginsburg wrote in favor of affirmative action in her dissent in Gratz v. Bollinger (2003), in which the Court ruled an affirmative action policy unconstitutional because it was not narrowly tailored to the state's interest in diversity. She argued that "government decisionmakers may properly distinguish between policies of exclusion and inclusion...Actions designed to burden groups long denied full citizenship stature are not sensibly ranked with measures taken to hasten the day when entrenched discrimination and its after effects have been extirpated."[117] Native Americans In 1997, Ginsburg wrote the majority opinion in Strate v. A-1 Contractors against tribal jurisdiction over tribal-owned land in a reservation.[118] The case involved a nonmember who caused a car crash in the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara Nation. Ginsburg reasoned that the state right-of-way on which the crash occurred rendered the tribal-owned land equivalent to non-Indian land. She then considered the rule set in Montana v. United States, which allows tribes to regulate the activities of nonmembers who have a relationship with the tribe. Ginsburg noted that the driver's employer did have a relationship with the tribe, but she reasoned that the tribe could not regulate their activities because the victim had no relationship to the tribe. Ginsburg concluded that although "those who drive carelessly on a public highway running through a reservation endanger all in the vicinity, and surely jeopardize the safety of tribal members", having a nonmember go before an "unfamiliar court" was "not crucial to the political integrity, the economic security, or the health or welfare of the Three Affiliated Tribes" (internal quotations and brackets omitted). The decision, by a unanimous Court, was generally criticized by scholars of Indian law, such as David Getches and Frank Pommersheim.[119]: 1024–5 Later in 2005, Ginsburg cited the doctrine of discovery in the majority opinion of City of Sherrill v. Oneida Indian Nation of New York and concluded that the Oneida Indian Nation could not revive its ancient sovereignty over its historic land.[120][121] The discovery doctrine has been used to grant ownership of Native American lands to colonial governments. The Oneida had lived in towns, grew extensive crops, and maintained trade routes to the Gulf of Mexico. In her opinion for the Court, Ginsburg reasoned that the historic Oneida land had been "converted from wilderness" ever since it was dislodged from the Oneidas' possession.[122] She also reasoned that "the longstanding, distinctly non-Indian character of the area and its inhabitants" and "the regulatory authority constantly exercised by New York State and its counties and towns" justified the ruling. Ginsburg also invoked, sua sponte, the doctrine of laches, reasoning that the Oneidas took a "long delay in seeking judicial relief". She also reasoned that the dispossession of the Oneidas' land was "ancient". Lower courts later relied on Sherrill as precedent to extinguish Native American land claims, including in Cayuga Indian Nation of New York v. Pataki.[119]: 1030–1 Less than a year after Sherrill, Ginsburg offered a starkly contrasting approach to Native American law. In December 2005, Ginsburg dissented in Wagnon v. Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation, arguing that a state tax on fuel sold to Potawatomi retailers would impermissibly nullify the Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation's own tax authority.[119]: 1032 In 2008, when Ginsburg's precedent in Strate was used in Plains Commerce Bank v. Long Family Land & Cattle Co., she dissented in part and argued that the tribal court of the Cheyenne River Lakota Nation had jurisdiction over the case.[119]: 1034–5 In 2020, Ginsburg joined the ruling of McGirt v. Oklahoma, which affirmed Native American jurisdictions over reservations in much of Oklahoma.[123] Other majority opinions In 1999, Ginsburg wrote the majority opinion in Olmstead v. L.C., in which the Court ruled that mental illness is a form of disability covered under the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990.[124] In 2000, Ginsburg wrote the majority opinion in Friends of the Earth, Inc. v. Laidlaw Environmental Services, Inc., in which the Court held that residents have standing to seek fines for an industrial polluter that affected their interests and that is able to continue doing so.[125][126] Decision not to retire under Obama When John Paul Stevens retired in 2010, Ginsburg became the oldest justice on the court at age 77.[127] Despite rumors that she would retire because of advancing age, poor health, and the death of her husband,[128][129] she denied she was planning to step down. In an interview in August 2010, Ginsburg said her work on the Court was helping her cope with the death of her husband.[127] She also expressed a wish to emulate Justice Louis Brandeis's service of nearly 23 years, which she achieved in April 2016.[127] Several times during the presidency of Barack Obama, progressive attorneys and activists called for Ginsburg to retire so that Obama could appoint a like-minded successor,[130][131][132] particularly while the Democratic Party held control of the U.S. Senate.[133][131] Ginsburg reaffirmed her wish to remain a justice as long as she was mentally sharp enough to perform her duties.[90] In 2013, Obama invited her to the White House when it seemed likely that Democrats would lose control of the Senate, but she again refused to step down.[8] She opined that Republicans would use the judicial filibuster to prevent Obama from appointing a jurist like herself.[134] She stated that she had a new model to emulate in her former colleague, Justice John Paul Stevens, who retired at the age of 90 after nearly 35 years on the bench.[135] Some[who?] believed that, in the lead-up to the 2016 U.S. presidential election, Ginsburg was waiting for candidate Hillary Clinton to beat candidate Donald Trump before retiring, because Clinton would nominate a more liberal successor for her than Obama would, or so that her successor could be nominated by the first female president.[136] After Trump's victory in 2016 and the election of a Republican Senate, she would have had to wait until 2021 for a Democrat to be president, but died in office in September 2020 at age 87.[137] |

最高裁判所 指名と承認  演説するギンズバーグ 1993年6月14日、ビル・クリントン大統領から正式に指名を受けるギンズバーグ ビル・クリントン大統領は1993年6月22日、退任するバイロン・ホワイト判事の後任として、ギンズバーグを最高裁判所準判事に指名した[71]。 [72]指名当時、ギンズバーグは控訴裁判所時代には穏健派で合意形成に努めたと見られていた[4][73]。クリントンは裁判所の多様性を高めようとし ていたと伝えられており、1969年にエイブ・フォータス判事が辞任して以来、初のユダヤ系判事としてギンズバーグはそれを実現した。彼女は女性としては 2人目、ユダヤ系女性としては初の最高裁判事となった[4][74][75]。最終的に彼女はユダヤ系判事として最も長く在任することになった[76]。 米国法曹協会の連邦司法常任委員会は、ギンズバーグを判事候補として最高の評価である「十分な資質がある」と評価した[77]。  ギンズバーグ最高裁判事任命のための上院承認公聴会でマイクに向かって話すギンズバーグ氏 上院司法委員会の判事候補指名公聴会で証言するギンズバーグ氏 ギンズバーグは、上院司法委員会の承認公聴会での証言の中で、死刑制度のようないくつかの問題の合憲性に関する見解について、もしそれが法廷に持ち込まれた場合、投票しなければならないかもしれない問題であるとして、質問に答えることを拒否した[78]。 その一方で、ギンズバーグは議論を呼びそうないくつかの問題については質問に答えた。例えば、彼女はプライバシーに対する憲法上の権利に対する信念を肯定 し、個人的な司法哲学と男女平等に関する考えを少し長く説明した[79]: 1993年8月3日、合衆国上院は96対3の賛成多数でギンズバーグを承認し た[f][43]。 ギンズバーグの名前は、後にジョン・ロバーツの承認プロセスで引き合いに出された。ギンズバーグは、議会で特定の質問に答えることを避けた最初の候補者で はなく[g]、1981年に若い弁護士であったロバーツは、最高裁判事候補者が具体的な回答をすることに反対するよう助言していた。 [82]にもかかわらず、保守派の論客や上院議員の中には、「ギンズバーグの先例」という言葉を持ち出して、彼の答弁拒否を擁護する者もいた[77] [82]。2005年9月28日にウェイクフォレスト大学で行われた演説で、ギンズバーグは、ロバーツが上院の承認公聴会でいくつかの事件についての質問 に答えることを拒否したことは「疑いなく正しい」と述べた[83]。 最高裁判所在任期間  笑顔で宣誓するギンズバーグ判事 夫のマーティン・ギンズバーグとクリントン大統領が見守る中、ウィリアム・レンキスト最高裁判事がギンズバーグの最高裁判事補就任を宣誓した。 ギンズバーグは法廷での実績を、裁決に対する慎重なアプローチとして特徴づけている[84]。 彼女は法廷に指名される直前の演説で、「憲法やコモンローの裁決には、基本的に緩和された運動が正しいと私には思える」と主張した。あまりに迅速に形成さ れた学説の手足は、不安定であることを証明するかもしれないと経験が教えている」[85]。法学者のキャス・サンステインは、ギンズバーグを「合理的ミニ マリスト」、つまり、憲法を自身のビジョンに押しつけるのではなく、判例に基づき慎重に構築しようとする法学者であると評している[86]: 10-11 2006年のサンドラ・デイ・オコナー判事の退任により、ギンズバーグが唯一の女性判事となった[87][h]。ニューヨーク・タイムズ紙のリンダ・グ リーンハウスは、その後の2006年から2007年にかけての任期を「ルース・ベイダー・ギンズバーグ判事が自分の声を見つけ、それを使った」期間と呼ん だ[89]。  並んで微笑む判事たち 2010年、サンドラ・デイ・オコナー、ソニア・ソトマイヨール、ギンズバーグ、エレナ・ケイガン。オコナーがローブを着ていないのは、この写真が撮影されたとき、彼女は法廷を引退していたからである。 ジョン・ポール・スティーブンス判事の退任に伴い、ギンズバーグは法廷の「リベラル翼」と呼ばれることのある上級判事となった[44][90][91]。 法廷がイデオロギーに沿って5対4に分裂し、リベラル派の判事が少数派となった場合、ギンズバーグは年功序列のため、反対意見の執筆権限を持つことが多 かった。 [90][i]ギンズバーグは、リベラル派の反対派が「声を一つにして」発言し、可能であれば反対派の判事全員が同意できるような統一的なアプローチを提 示することを支持した[44][90]。 1993年から2020年までのギンズバーグの最高裁在任期間中、彼女はアフリカ系アメリカ人の書記官を1人(ポール・J・ワトフォード)しか採用しな かった[93][94]。コロンビア特別区巡回区控訴裁判所での13年間、彼女はアフリカ系アメリカ人の書記官、インターン、秘書を一度も採用しなかっ た。多様性の欠如は、1993年に行われた彼女の承認公聴会でも一時問題となった[95]。 この問題が上院司法委員会から提起された際、ギンズバーグは「この仕事に私を承認すれば、黒人候補者に対する私の魅力は向上する」と述べた[96]。彼女 の葬儀の際、100人以上の元弁護士が喪主を務めたことで、この問題は再び注目を集めた[97][98]。 ジェンダー差別 ギンズバーグは、ヴァージニア陸軍士官学校(VMI)の男性のみの入学者受入政策を憲法修正第14条の平等保護条項に違反するとして取り消した、アメリカ 合衆国対ヴァージニア州裁判(United States v. Virginia, 518 U.S. 515 (1996))における裁判所の意見を執筆した。ギンズバーグによれば、国家権力がジェンダーを利用して女性の平等な保護を否定することはできず、した がってVMIは、そのユニークな教育方法を持つVMIに女性が入学する機会を認めなければならない[99]。ギンズバーグは、政府がジェンダーに基づく分 類を用いるには、「極めて説得力のある正当な理由」を示さなければならないと強調した[100]。 この裁判では、原告のリリー・レッドベッターが、1964年公民権法第7編に違反して、性別による賃金差別を受けたとして雇用主を訴えた。5対4の判決 で、多数派は、たとえ女性が男性より低い賃金しか支払われていないことを後になって知ったとしても、時効は賃金支払期間ごとに進行すると解釈した。ギンズ バーグ判事は、女性は自分の給与が低いことを知らないことが多いので、給与支給のたびに行動することを期待するのは不当であると指摘し、この結果を不合理 であるとした。彼女はまた、男性優位の分野で女性が少額の訴訟を起こして波風を立てることに消極的で、代わりに格差が累積するまで待つことを選ぶかもしれ ないことに注意を喚起した[102]。反対意見の一部として、ギンズバーグは連邦議会に対し、法律で裁判所の判決を取り消すためにタイトルVIIを改正す るよう求めた。 [103] 2008年にバラク・オバマ大統領が選出された後、リリー・レッドベター公正賃金法が制定され、従業員が賃金差別の訴えを勝訴しやすくなった[104] [105]。ギンズバーグは、この法律の発案に貢献したと評価されている[103][105]。 妊娠中絶の権利 ギンズバーグは2009年のニューヨーク・タイムズ紙のインタビューで、中絶と男女平等に関する自身の見解について語り、「基本的なことは、政府が女性の ためにその選択をする必要はないということです」と述べた[106]。914 (2000)、ロー対ウェイド裁判の判決410 U.S. 113 (1973)の40周年に、彼女はローの判決は、中絶の権利を支持する、より永続的なコンセンサスを築いたかもしれない、中絶法を自由化する初期の民主的 な運動を終了させたと批判した[107] ギンズバーグは、5対4で中絶の部分分娩の制限を支持する判決、ゴンザレス対カーハート裁判550 U.S. 124 (2007)では少数派だった。ギンズバーグは反対意見の中で、この手術が女性にとって安全ではないという立法府の所見に従うという多数派の決定に反対し た。ギンズバーグは、議会がその所見に到達した方法とその真実性に怒りを集中させた[108]。582 (2016)は、中絶提供者を規制する2013年のテキサス州法の一部を取り下げた事件であるが、ギンズバーグは、問題となった法律に対してさらに批判的 な短い同意意見も執筆している[109]。彼女は、テキサス州が言っていたように、この法律は女性の健康を守ることが目的ではなく、むしろ女性の中絶への アクセスを妨げることが目的であると主張した[108][109]。 捜索と押収  ローブ姿で微笑みながら椅子にもたれているギンズバーグの絵。 2000年、シミー・ノックスによる依頼肖像画。 ギンズバーグは多数意見を提出したわけではないが、サフォード統一学区対レディング事件(557 U.S. 364 (2009))[110]において同僚に影響を与えたと評価されている。この判決は、13歳の女子生徒にブラジャーとパンツ一丁になるまで裸になるよう学 校が命じたのは行き過ぎであり、女性職員が薬物捜査を行えるようにしたものである[110]。ギンズバーグは、判決前に発表されたインタビューで、同僚の 中には13歳の少女に対するストリップ・サーチの影響を十分に理解していない者もいるという見解を述べた。彼女が言ったように、「彼らは13歳の少女に なったことがない」[111]。8対1の判決で、裁判所は学校の捜索が憲法修正第4条に違反していることに同意し、生徒の学校に対する訴訟の進行を認め た。ギンズバーグとスティーブンスだけが、生徒が個々の学校関係者も訴えることを認めた[110]。 Herring v. United States, 555 U.S. 135 (2009)では、ギンズバーグは、警察官がコンピューターシステムのアップデートを怠ったことによる証拠の抑圧を認めなかった裁判所の判決に反対した。 ロバーツが警察の不正行為を抑止する手段としての弾圧を強調したのとは対照的に、ギンズバーグは、被告人の憲法修正第4条の権利侵害に対する救済措置とし ての弾圧の使用について、より強固な見解を示した。ギンズバーグは、抑圧を、政府が過ちから利益を得ることを防ぐための方法であり、したがって、司法の完 全性を維持し、市民の権利を尊重するための救済措置であると考えた[112]: 308 また彼女は、弾圧はミスを抑止しないというロバーツの主張を否定し、ミスのために警察に高い代償を支払わせることは、警察がより注意深くなることを促すと 主張した[112]: 309 国際法 ギンズバーグは、司法意見において米国法を形成するために外国の法律や規範を利用することを提唱したが、保守的な同僚の中にはこれを否定する者もいた。ギ ンズバーグは、拘束力のある判例としてではなく、説得力や可能性のある知恵として外国の法解釈を用いることを支持した[113]。ギンズバーグは、国際法 を参考にすることはアメリカ法においてよく染みついた伝統であるという見解を表明し、ジョン・ヘンリー・ウィグモアやジョン・アダムズ大統領を国際主義者 として数えている[114]。ギンズバーグ自身が国際法を頼りにしていたのは弁護士時代まで遡る。ミシガン大学ロースクールのアファーマティブ・アクショ ン入試方針を支持した判決であるGrutter v. Bollinger, 539 U.S. 306 (2003)における同調意見の中で、ギンズバーグは、アファーマティブ・アクション入試方針には終着点があるという考え方と、人種やジェンダーに基づく 差別と闘うために設計された国際条約との間に一致点があると指摘している[114]。 選挙権とアファーマティブ・アクション 2013年、ギンズバーグはシェルビー郡対ホルダー裁判において反対意見を述べ、投票慣行を変更する前に連邦政府の事前審査を必要とする1965年の投票 権法の一部を違憲とした。ギンズバーグは、「差別的な変更を阻止するためにプレクリアランスが機能し、機能し続けているにもかかわらず、それを投げ捨てる のは、暴風雨の中、濡れないからといって傘を捨てるようなものだ」と書いた[116]。 グラッターの他にも、ギンズバーグは、アファーマティブ・アクション政策が多様性という州の関心事に対して狭く調整されていないという理由で違憲とされた グラッツ対ボリンジャー裁判(2003年)において、反対意見としてアファーマティブ・アクションを支持する意見を書いている。彼女は、「政府の意思決定 者は、排除の政策と包摂の政策を適切に区別することができる......長い間市民としての地位を完全に否定されてきた集団に負担を強いるように設計され た行動は、定着した差別とその後遺症が根絶される日を早めるためにとられた措置と、分別のあるランク付けはできない」と主張した[117]。 アメリカ先住民 1997年、ギンズバーグはStrate対A-1 Contractors事件で、居留地内の部族所有地に対する部族管轄権に反対する多数意見を書いた[118]。この事件は、マンダン、ヒダツァ、アリカ ラ民族で自動車事故を起こした非会員に関するものであった。ギンズバーグは、事故が発生した州の道路は部族所有の土地を非インディアンの土地と同等にする と推論した。そして、モンタナ州対合衆国で定められた、部族が部族と関係のある非部族の活動を規制することを認める規則を検討した。ギンズバーグ氏は、運 転手の雇用主は部族と関係があると指摘したが、被害者は部族と関係がないため、部族は彼らの活動を規制できないとした。ギンズバーグは、「居留地内を走る 公道を不注意に運転する者は、周辺のすべての人を危険にさらし、確実に部族員の安全を脅かす」ものの、「見慣れない裁判所」に非部族員を出廷させること は、「3部族の政治的完全性、経済的安全性、または健康や福祉にとって極めて重要なことではない」と結論づけた(内部引用と括弧は省略)。全会一致による この判決は、David GetchesやFrank Pommersheimなどのインディアン法研究者により一般的に批判された[119]: 1024-5 その後2005年、ギンズバーグはCity of Sherrill v. Oneida Indian Nation of New Yorkの多数意見において発見のドクトリンを引用し、オナイダ・インディアン民族はその歴史的土地に対する古代の主権を復活させることはできないと結論 づけた[120][121]。発見のドクトリンは、アメリカ先住民の土地の所有権を植民地政府に認めるために使用されてきた。オナイダ族は町に住み、広範 な作物を栽培し、メキシコ湾への交易路を維持していた。ギンズバーグは法廷意見書の中で、歴史的なオナイダの土地はオナイダの所有から外れて以来、「原生 地域から転換」してきたと推論した[122]。また、「この地域とその住民の長年にわたる、明らかに非インディアン的な性格」と「ニューヨーク州とその郡 と町が絶えず行使してきた規制権限」が判決を正当化したと推論した。ギンズバーグはまた、オナイダ族が「司法救済を求めるのに長い時間を要した」ことを理 由に、無過失責任の原則を訴えた。また、オナイダ族の土地の剥奪は「古くから」行われていたとした。後に下級裁判所は、Cayuga Indian Nation of New York v. Patakiを含め、アメリカ先住民の土地請求権を消滅させる判例としてSherrillに依拠した[119]: 1030-1 シェリルから1年も経たないうちに、ギンズバーグはネイティブ・アメリカン法に対して対照的なアプローチを提示した。2005年12月、ギンズバーグは、 ワグノン対プレーリー・バンド・ポタワトミ・ネーションの裁判において、ポタワトミ族の小売業者に販売される燃料に対する州税は、プレーリー・バンド・ポ タワトミ・ネーション自身の課税権限を無効とするものであり、許されないと主張し、反対意見を述べた[119]: 1032 2008年、Plains Commerce Bank v. Long Family Land & Cattle Co.事件でギンズバーグのStrate事件の判例が使われたとき、彼女は一部で反対し、シャイアン・リバー・ラコタ・ネーションの部族裁判所に管轄権が あると主張した[119]: 1034-5 2020年、ギンズバーグはマクガート対オクラホマ裁判の判決に参加し、オクラホマ州の多くの居留地におけるネイティブ・アメリカンの管轄権を肯定した [123]。 その他の多数意見 1999年、ギンズバーグはオルムステッド対L.C.裁判の多数意見を執筆し、精神疾患は1990年障害者法の対象となる障害の一形態であるとの判決を下した[124]。 2000年、ギンズバーグはフレンズ・オブ・ジ・アース対レイドロー・エンバイロメンタル・サービシズ事件で多数意見を書き、同裁判所は、住民の利益に影 響を及ぼし、それを継続することができる産業汚染業者に対して罰金を求める原告適格が住民にあると判示した[125][126]。 オバマ政権下で引退しないことを決定 ジョン・ポール・スティーブンスが2010年に退任すると、ギンズバーグは77歳で法廷最年長判事となった[127]。高齢化、健康状態の悪化、夫の死な どを理由に退任するという噂があったが[128][129]、彼女は退任の計画を否定した。2010年8月のインタビューで、ギンズバーグは、法廷での仕 事が夫の死への対処に役立っていると語った[127]。また、ルイ・ブランディス判事の約23年にわたる勤続を見習いたいと表明し、2016年4月にそれ を達成した[127]。 バラク・オバマの大統領在任中に何度か、進歩的な弁護士や活動家たちは、オバマが志を同じくする後継者を任命できるよう、ギンズバーグに引退するよう求め た[130][131][132]が、特に民主党が連邦上院の支配権を握っている間はそうであった[133][131]。 ギンズバーグは、職務を遂行できるほど精神的に鋭敏である限り、判事であり続けたいという希望を再確認した。 [90]2013年、民主党が上院の主導権を失いそうになったとき、オバマ大統領は彼女をホワイトハウスに招いたが、彼女は再び退任を拒否した[8]。彼 女は、共和党はオバマ大統領が自分のような法学者を任命するのを阻止するために、司法議事妨害を利用するだろうとの見解を示した[134]。彼女は、35 年近く法廷に立ち、90歳で引退した元同僚のジョン・ポール・スティーブンス判事に、見習うべき新しいモデルがいると述べた[135]。 一部の[誰?]は、2016年の米大統領選を前に、ギンズバーグは引退する前にヒラリー・クリントン候補がドナルド・トランプ候補に勝つのを待っていたと 考えていた。クリントン候補はオバマ候補よりもリベラルな後継者を指名するだろうから、あるいは彼女の後継者を初の女性大統領が指名できるようにするため だった[136]。2016年にトランプが勝利し、共和党の上院議員が選出された後、彼女は民主党が大統領になる2021年まで待たなければならなかった が、2020年9月に87歳で在職中に死去した[137]。 |

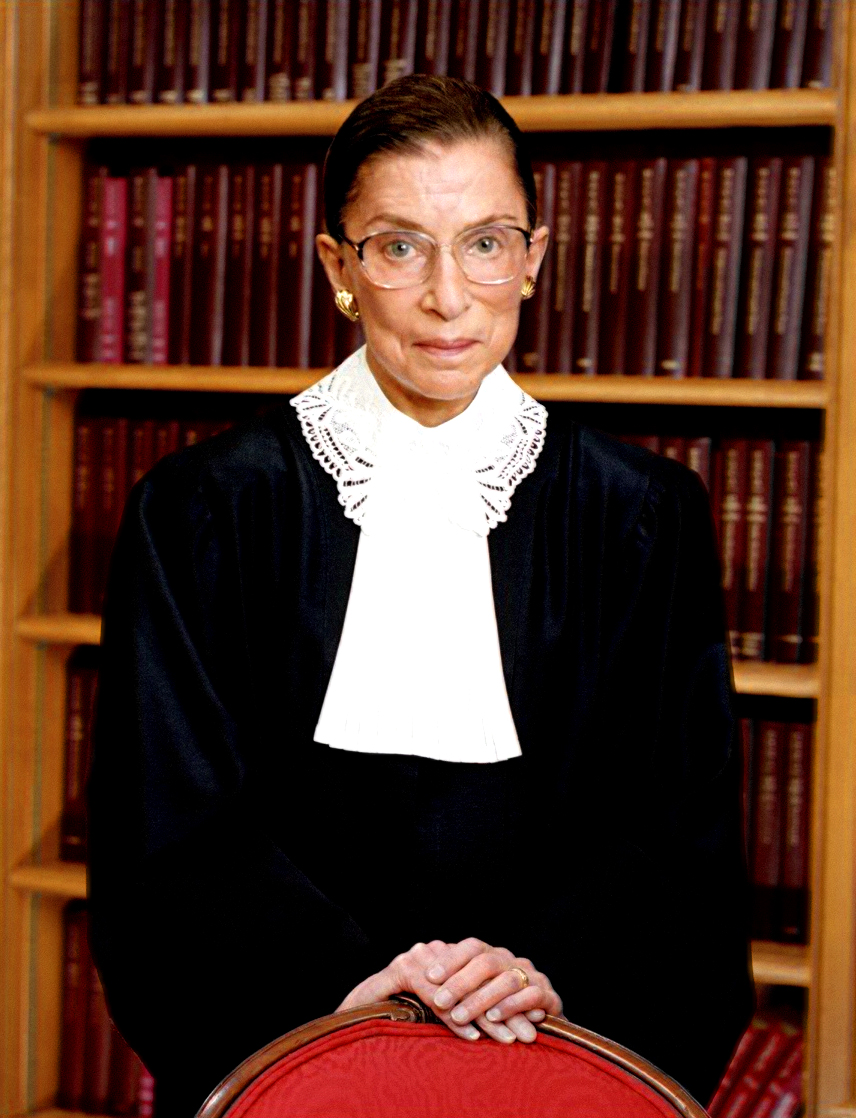

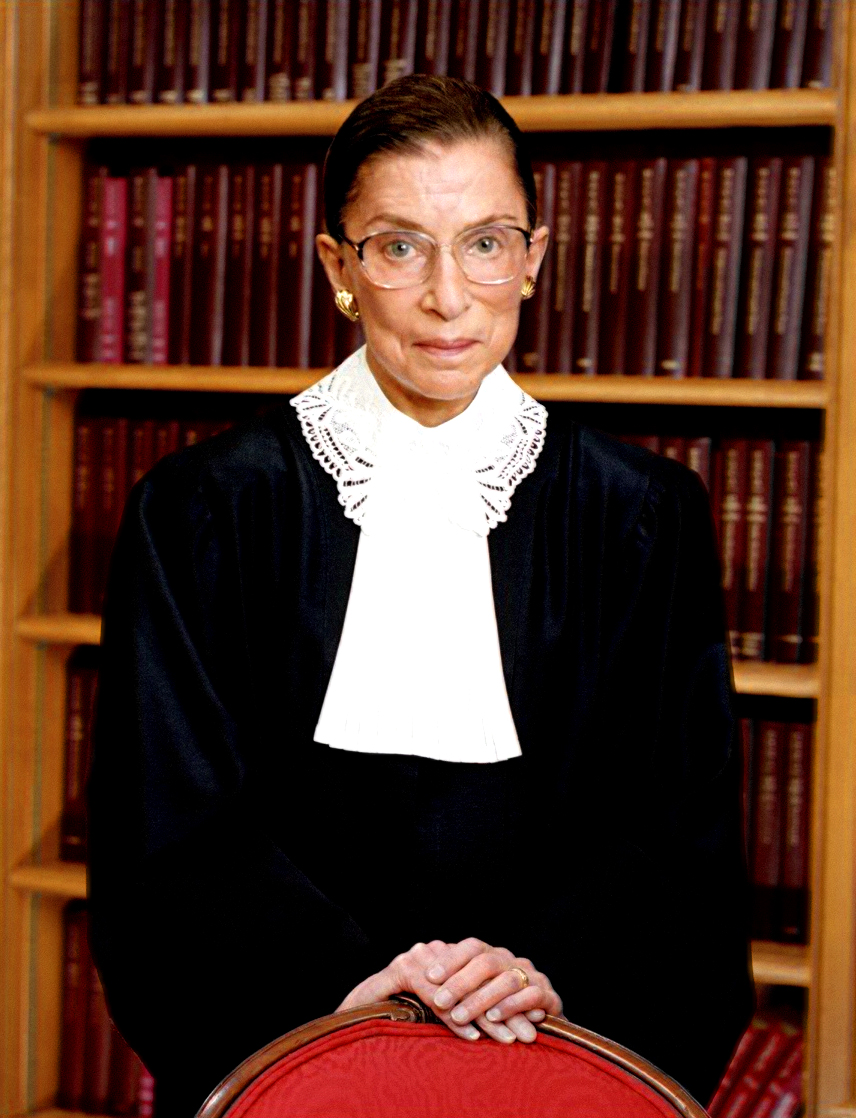

Other activities Ginsburg standing in front of a bookshelf Official portrait, c. 2006 At his request, Ginsburg administered the oath of office to Vice President Al Gore for a second term during the second inauguration of Bill Clinton on January 20, 1997.[138] She was the third woman to administer an inaugural oath of office.[139] Ginsburg is believed to have been the first Supreme Court justice to officiate at a same-sex wedding, performing the August 31, 2013, ceremony of Kennedy Center president Michael Kaiser and John Roberts, a government economist.[140] Earlier that summer, the Court had bolstered same-sex marriage rights in two separate cases.[141][142] Ginsburg believed the issue being settled led same-sex couples to ask her to officiate as there was no longer the fear of compromising rulings on the issue.[141] The Supreme Court bar formerly inscribed its certificates "in the year of our Lord", which some Orthodox Jews opposed, and asked Ginsburg to object to. She did so, and due to her objection, Supreme Court bar members have since been given other choices of how to inscribe the year on their certificates.[143] Despite their ideological differences, Ginsburg considered Antonin Scalia her closest colleague on the Court.[144] The two justices often dined together and attended the opera.[145] In addition to befriending modern composers, including Tobias Picker,[146][147] in her spare time, Ginsburg appeared in several operas in non-speaking supernumerary roles such as Die Fledermaus (2003) and Ariadne auf Naxos (1994 and 2009 with Scalia),[148] and spoke lines penned by herself in The Daughter of the Regiment (2016).[149] In January 2012, Ginsburg went to Egypt for four days of discussions with judges, law school faculty, law school students, and legal experts.[150][151] In an interview with Al Hayat TV, she said the first requirement of a new constitution should be that it would "safeguard basic fundamental human rights like our First Amendment". Asked if Egypt should model its new constitution on those of other nations, she said Egypt should be "aided by all Constitution-writing that has gone on since the end of World War II", and cited the United States Constitution and Constitution of South Africa as documents she might look to if drafting a new constitution. She said the U.S. was fortunate to have a constitution authored by "very wise" men but said that in the 1780s, no women were able to participate directly in the process, and slavery still existed in the U.S.[152]  Ginsburg speaking at a podium Ginsburg speaking at a naturalization ceremony at the National Archives in 2018 During three interviews in July 2016, Ginsburg criticized presumptive Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump, telling The New York Times and the Associated Press that she did not want to think about the possibility of a Trump presidency. She joked that she might consider moving to New Zealand.[153][154] She later apologized for commenting on the presumptive Republican nominee, calling her remarks "ill advised".[155] Ginsburg's first book, My Own Words, was published by Simon & Schuster on October 4, 2016.[12] The book debuted on The New York Times Best Seller List for hardcover nonfiction at No. 12.[156] While promoting her book in October 2016 during an interview with Katie Couric, Ginsburg responded to a question about Colin Kaepernick choosing not to stand for the national anthem at sporting events by calling the protest "really dumb". She later apologized for her criticism calling her earlier comments "inappropriately dismissive and harsh" and noting she had not been familiar with the incident and should have declined to respond to the question.[157][158][159] In 2021, Couric revealed that she had edited out some statements by Ginsburg in their interview; Ginsburg said that athletes who protested by not standing were showing "contempt for a government that has made it possible for their parents and grandparents to live a decent life ... which they probably could not have lived in the places they came from."[160][161] In 2017, Ginsburg gave the keynote address to a Georgetown University symposium on governmental reform. She spoke on the need for improving the confirmation process, "recall[ing] the 'collegiality' and 'civility' of her own nomination and confirmation..."[162] In 2018, Ginsburg expressed her support for the MeToo movement, which encourages women to speak up about their experiences with sexual harassment.[163] She told an audience, "It's about time. For so long women were silent, thinking there was nothing you could do about it, but now the law is on the side of women, or men, who encounter harassment and that's a good thing."[163] She also reflected on her own experiences with gender discrimination and sexual harassment, including a time when a chemistry professor at Cornell unsuccessfully attempted to trade her exam answers for sex |

その他の活動 本棚の前に立つギンズバーグ 公式ポートレート、2006年頃 1997年1月20日のビル・クリントン第2代大統領就任式では、アル・ゴア副大統領の要請を受け、2期目の宣誓を行った[138]。就任宣誓を行った女 性としては3人目[139]。2013年8月31日には、ケネディ・センター会長のマイケル・カイザーと政府エコノミストのジョン・ロバーツの挙式を執り 行い、最高裁判事として初めて同性婚の司式を行ったとされる[140]。 [141][142]ギンズバーグは、この問題に決着がついたことで、同性カップルがこの問題に関する妥協的な判決を下す恐れがなくなったため、彼女に司 式を依頼するようになったと考えた[141]。 最高裁の法廷では以前、「われらの主の年に」と証書を刻んでいたが、一部の正統派ユダヤ教徒はこれに反対し、ギンズバーグに異議を唱えるよう求めた。彼女の反対により、それ以降、最高裁判所の法廷弁護士は、年号の刻み方を他の選択肢から選べるようになった[143]。 イデオロギーの違いこそあれ、ギンズバーグはアントニン・スカリアを裁判所内で最も親しい同僚と考えていた[144]。 [145] 余暇にはトビアス・ピッカーを含む現代作曲家と親交を深めるほか[146][147]、ギンズバーグは『こうもり』(2003年)、『ナクソス島のアリア ドネ』(1994年、2009年、スカリアと共演)など、いくつかのオペラに喋らない上役で出演し[148]、『連隊の娘』(2016年)では自ら書いた セリフを喋った[149]。 2012年1月、ギンズバーグはエジプトを訪れ、裁判官、ロースクールの教員、ロースクールの学生、法律の専門家らと4日間にわたって議論を行った [150][151]。アル・ハヤトTVとのインタビューで、彼女は新憲法の第一要件は「憲法修正第1条のような基本的人権を守る」ことであるべきだと述 べた。エジプトは新憲法を他国の憲法を手本にするべきかとの質問に対し、彼女はエジプトは「第二次世界大戦の終結以来続いてきたすべての憲法制定に助けら れる」べきだと述べ、新憲法を起草する際に参考にする文書としてアメリカ合衆国憲法と南アフリカ共和国憲法を挙げた。彼女は、米国は「非常に賢明な」男性 たちによって憲法が制定された幸運な国だとしながらも、1780年代には女性がそのプロセスに直接参加することはできず、米国にはまだ奴隷制度が存在して いたと述べた[152]。  演壇でスピーチするギンズバーグ 2018年、国立公文書館での帰化式典でスピーチするギンズバーグ 2016年7月の3回のインタビューで、ギンズバーグは共和党大統領候補のドナルド・トランプを批判し、ニューヨーク・タイムズ紙とAP通信に対し、トラ ンプ大統領の可能性については考えたくないと語った。彼女は、ニュージーランドへの移住を考えるかもしれないと冗談を言った[153][154]。後に彼 女は、共和党の推定候補者についてコメントしたことを謝罪し、自分の発言は「不用意だった」と述べた[155]。 ギンズバーグの最初の著書『My Own Words』は、2016年10月4日にサイモン&シュスター社から出版された[12]。同書はニューヨーク・タイムズ紙のハードカバー・ノンフィクショ ンのベストセラー・リストで12位にランクインした[156]。2016年10月にケイティ・クーリックとのインタビューで同書のプロモーションを行って いた際、ギンズバーグはスポーツ・イベントで国歌斉唱に起立しないことを選択したコリン・キャパニックに関する質問に対して、その抗議を「本当に間抜け」 と答えた。彼女は後に、以前の自分の発言は「不適切に人を見下すような厳しいものだった」と批判したことを謝罪し、この事件をよく知らなかったので質問へ の回答を控えるべきだったと指摘した。 [157][158][159]2021年、クーリックはインタビューにおけるギンズバーグの発言の一部を編集していたことを明らかにした。ギンズバーグ は、起立しないことで抗議したアスリートたちは「彼らの両親や祖父母がまともな生活を送れるようにした政府を侮蔑している......おそらく彼らの出身 地では生活できなかっただろう」と述べた[160][161]。 2017年、ギンズバーグは政府改革に関するジョージタウン大学のシンポジウムで基調講演を行った。彼女は確認プロセスを改善する必要性について語り、「彼女自身の指名と確認における『合議性』と『礼節』を思い起こさせる......」[162]。 2018年、ギンズバーグは、女性たちがセクハラ経験を話すことを奨励するMeToo運動への支持を表明した[163]。長い間、女性は何もできないと 思って沈黙していたが、今や法律はハラスメントに遭遇した女性や男性の味方であり、それは良いことだ」[163] また彼女は、コーネル大学の化学教授が彼女の試験の答案をセックスと交換しようとして失敗したことなど、男女差別やセクハラに遭った自身の経験を振り返っ た。 |

Personal life The Ginsburgs smiling at the front of a crowd Martin and Ruth Bader Ginsburg at a White House event, 2009 A few days after Ruth Bader graduated from Cornell, she married Martin D. Ginsburg, who later became an internationally prominent tax attorney practicing at Weil, Gotshal & Manges. Upon Ruth Bader Ginsburg's accession to the D.C. Circuit, the couple moved from New York City to Washington, D.C., where Martin became a professor of law at Georgetown University Law Center. The couple's daughter, Jane C. Ginsburg (born 1955), is a professor at Columbia Law School. Their son, James Steven Ginsburg (born 1965), is the founder and president of Cedille Records, a classical music recording company based in Chicago, Illinois. Martin and Ruth had four grandchildren.[164] After the birth of their daughter, Martin was diagnosed with testicular cancer. During this period, Ruth attended class and took notes for both of them, typing her husband's dictated papers and caring for their daughter and her sick husband. During this period, she also was selected be a member of the Harvard Law Review. Martin died of complications from metastatic cancer on June 27, 2010, four days after their 56th wedding anniversary.[165] They spoke publicly of being in a shared earning/shared parenting marriage including in a speech Martin wrote and had intended to give before his death that Ruth delivered posthumously.[166] Ruth Bader Ginsburg was a non-observant Jew, attributing this to gender inequality in Jewish prayer ritual and relating it to her mother's death. However, she said she might have felt differently if she were younger, and she was pleased that Reform and Conservative Judaism were becoming more egalitarian in this regard.[167][168] In March 2015, Ginsburg and Rabbi Lauren Holtzblatt released "The Heroic and Visionary Women of Passover", an essay highlighting the roles of five key women in the saga. The text states, "These women had a vision leading out of the darkness shrouding their world. They were women of action, prepared to defy authority to make their vision a reality bathed in the light of the day ..."[169] In addition, she decorated her chambers with an artist's rendering of the Hebrew phrase from Deuteronomy, "Zedek, zedek, tirdof," ("Justice, justice shall you pursue") as a reminder of her heritage and professional responsibility.[170] Ginsburg had a collection of lace jabots from around the world.[171][172] She said in 2014 she had a particular jabot she wore when issuing her dissents (black with gold embroidery and faceted stones) as well as another she wore when issuing majority opinions (crocheted yellow and cream with crystals), which was a gift from her law clerks.[171][172] Her favorite jabot (woven with white beads) was from Cape Town, South Africa.[171] Health In 1999, Ginsburg was diagnosed with colon cancer, the first of her five[173] bouts with cancer. She underwent surgery followed by chemotherapy and radiation therapy. During the process, she did not miss a day on the bench.[174] Ginsburg was physically weakened by the cancer treatment, and she began working with a personal trainer. Bryant Johnson, a former Army reservist attached to the U.S. Army Special Forces, trained Ginsburg twice weekly in the justices-only gym at the Supreme Court.[175][176] Ginsburg saw her physical fitness improve after her first bout with cancer; she was able to complete twenty push-ups in a session before her 80th birthday.[175][177] Nearly a decade after her first bout with cancer, Ginsburg again underwent surgery on February 5, 2009, this time for pancreatic cancer.[178][179] She had a tumor that was discovered at an early stage.[178] She was released from a New York City hospital on February 13, 2009, and returned to the bench when the Supreme Court went back into session on February 23, 2009.[180][181][182] After experiencing discomfort while exercising in the Supreme Court gym in November 2014, she had a stent placed in her right coronary artery.[183][184] Ginsburg's next hospitalization helped her detect another round of cancer.[185] On November 8, 2018, Ginsburg fell in her office at the Supreme Court, fracturing three ribs, for which she was hospitalized.[186] An outpouring of public support followed.[187][188] Although the day after her fall, Ginsburg's nephew revealed she had already returned to official judicial work after a day of observation,[189] a CT scan of her ribs following her fall showed cancerous nodules in her lungs.[185] On December 21, Ginsburg underwent a left-lung lobectomy at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center to remove the nodules.[185] For the first time since joining the Court more than 25 years earlier, Ginsburg missed oral argument on January 7, 2019, while she recuperated.[190] She returned to the Supreme Court on February 15, 2019, to participate in a private conference with other justices in her first appearance at the Court since her cancer surgery in December 2018.[191] Months later in August 2019, the Supreme Court announced that Ginsburg had recently completed three weeks of focused radiation treatment to ablate a tumor found in her pancreas over the summer.[192] By January 2020, Ginsburg was cancer-free. By February 2020, the cancer had returned but this news was not released to the public.[173] However, by May 2020, Ginsburg was once again receiving treatment for a recurrence of cancer.[193] She reiterated her position that she "would remain a member of the Court as long as I can do the job full steam", adding that she remained fully able to do so.[194][195] |

私生活 群衆の前で微笑むギンズバーグ夫妻 マーティンとルース・ベイダー・ギンズバーグ(2009年、ホワイトハウスのイベントにて ルース・ベイダーはコーネル大学を卒業した数日後、マーティン・D・ギンズバーグと結婚した。彼は後にワイル・ゴツハル&マンジス法律事務所で活躍する国 際的に著名な税理士となった。ルース・ベイダー・ギンズバーグがD.C.巡回控訴院に就任すると、夫妻はニューヨークからワシントンD.C.に移り住み、 マーティンはジョージタウン大学法センターの教授となった。夫妻の娘ジェーン・C・ギンズバーグ(1955年生まれ)はコロンビア大学ロースクールの教授 である。息子のジェームス・スティーブン・ギンズバーグ(1965年生まれ)は、イリノイ州シカゴに本社を置くクラシック音楽のレコーディング会社、セ ディル・レコードの創設者兼社長である。マーティンとルースには4人の孫がいた[164]。 娘の誕生後、マーティンは精巣がんと診断された。この時期、ルースは授業に出席し、2人のためにノートを取り、夫が口述した論文をタイプし、娘と病気の夫 の世話をした。この間、彼女はハーバード・ロー・レビューのメンバーにも選ばれた。マーティンは2010年6月27日、56回目の結婚記念日の4日後に転 移性癌の合併症で亡くなった[165]。マーティンが生前に書き、ルースが死後に行うつもりだったスピーチを含め、二人は共稼ぎ・共育婚であることを公に 語った[166]。 ルース・ベイダー・ギンズバーグは、ユダヤ教の礼拝儀礼における男女不平等が原因であり、それを母親の死と関連付けるなど、非修道なユダヤ教徒であった。 2015年3月、ギンズバーグとローレン・ホルツブラット師は、「過ぎ越しの祭りの英雄的で先見の明のある女性たち」というエッセイを発表した。彼女たち は、自分たちの世界を覆っている暗闇から抜け出すビジョンを持っていた。彼女たちは行動する女性であり、そのビジョンを日の光を浴びながら現実のものとす るために、権威に逆らう用意ができていた......」[169]。さらに彼女は、自分の遺産と職業上の責任を思い起こさせるものとして、申命記のヘブラ イ語のフレーズ「ゼデク、ゼデク、ティルドフ」(「正義よ、正義を追求せよ」)を芸術家が描いたもので寝室を飾った[170]。 ギンズバーグは世界中のレースのジャボットのコレクションを持っていた[171][172]。 彼女は2014年に、反対意見を発表するときに着用する特別なジャボット(金の刺繍と切子石をあしらった黒)と、多数意見を発表するときに着用する別の ジャボット(かぎ針編みの黄色とクリーム色にクリスタルをあしらったもの)があると語ったが、これはロー・クラークからの贈り物であった[171] [172]。 健康 1999年、ギンズバーグは大腸がんと診断された。手術を受け、化学療法と放射線療法を受けた。この間、彼女は1日もベンチを休まなかった[174]。ギ ンズバーグはがん治療で肉体的に弱り、パーソナル・トレーナーと仕事を始めた。米陸軍特殊部隊に所属する元陸軍予備役、ブライアント・ジョンソンは、最高 裁判所の判事専用のジムで毎週2回、ギンズバーグのトレーニングを行った[175][176]。ギンズバーグは最初のがん闘病後、体力が向上するのを目の 当たりにし、80歳の誕生日を迎える前に、1回のセッションで20回の腕立て伏せをこなすことができた[175][177]。 最初の癌の闘病からほぼ10年後、ギンズバーグは2009年2月5日に再び手術を受けた。 [178]彼女は2009年2月13日にニューヨーク市の病院から退院し、2009年2月23日に最高裁判所が会期を再開した際にベンチに戻った [180][181][182]。2014年11月に最高裁判所のジムで運動中に不快感を覚えた後、彼女は右冠動脈にステントを留置した[183] [184]。 ギンズバーグの次の入院は、彼女が別の癌を発見するのに役立った[185]。 2018年11月8日、ギンズバーグは最高裁判所の執務室で転倒し、3本の肋骨を骨折し、入院した[186]。 国民からの支援の殺到が続いた[187][188]。 転倒の翌日、ギンズバーグの甥は、彼女が1日の観察の後、すでに司法の公務に復帰したことを明らかにしたが[189]、転倒後の肋骨のCTスキャンは、彼 女の肺に癌性の結節を示した。 [185]12月21日、ギンズバーグは結節を除去するためにメモリアル・スローン・ケタリングがんセンターで左肺葉切除術を受けた[185]。25年以 上前に裁判所に入所して以来初めて、ギンズバーグは療養中の2019年1月7日の口頭弁論を欠席した[190]。 2019年2月15日に最高裁判所に戻り、2018年12月のがん手術以来初めて裁判所に出廷し、他の判事たちとの非公開の会議に参加した[191]。 数カ月後の2019年8月、最高裁は、ギンズバーグが夏に膵臓に見つかった腫瘍を切除するための3週間の集中放射線治療を最近終えたと発表した [192]。 2020年1月までに、ギンズバーグは癌ではなかった。2020年2月までに、がんは再発したが、このニュースは公表されなかった[173]。 しかし、2020年5月までに、ギンズバーグは再びがんの再発の治療を受けていた[193]。 彼女は、「仕事をフルにこなせる限り、裁判所のメンバーであり続ける」という立場を改めて表明し、そうすることが完全に可能な状態にあることを付け加えた [194][195]。 |

| Death and succession Main articles: Death and state funeral of Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Amy Coney Barrett Supreme Court nomination § Death of Ruth Bader Ginsburg  Ginsburg was honored in a ceremony in Statuary Hall, and she became the first woman to lie in state at the Capitol on September 25, 2020, in the United States Capitol. Ginsburg was honored in a ceremony in Statuary Hall, and she became the first woman to lie in state at the Capitol, September 25, 2020. Ginsburg died from complications of pancreatic cancer on September 18, 2020, at age 87.[196][197] She died on the eve of Rosh Hashanah, and according to Rabbi Richard Jacobs, "One of the themes of Rosh Hashanah suggest that very righteous people would die at the very end of the year because they were needed until the very end".[198] After the announcement of her death, thousands of people gathered in front of the Supreme Court building to lay flowers, light candles, and leave messages.[199][200] Five days after her death, the eight Supreme Court justices, Ginsburg's children, and other family members held a private ceremony for Ginsburg in the Court's great hall. Following the private ceremony, due to COVID-19 pandemic conditions prohibiting the usual lying in repose in the great hall, Ginsburg's casket was moved outdoors to the Court's west portico so the public could pay respects. Thousands of mourners lined up to walk past the casket over the course of two days.[201] After the two days in repose at the Court, Ginsburg lay in state at the Capitol. She was the first woman and first Jew to lie in state therein.[j][202][203][204] On September 29, Ginsburg was buried beside her husband in Arlington National Cemetery.[205] Ginsburg's death opened a vacancy on the Supreme Court about six weeks before the 2020 presidential election, initiating controversies regarding the nomination and confirmation of her successor.[206][207][208] Days before her death, Ginsburg dictated a statement to her granddaughter Clara Spera, as heard by Ginsburg's doctor and others in the room at the time: "My most fervent wish is that I will not be replaced until a new president is installed."[209] President Trump's pick to replace her, Amy Coney Barrett, was confirmed by the Senate on October 27. |

死と継承 主な記事 ルース・ベイダー・ギンズバーグの死去と国葬、エイミー・コニー・バレット最高裁判事指名 § ルース・ベイダー・ギンズバーグの死去  ギンズバーグは、2020年9月25日、米国連邦議会議事堂の彫像ホールでの式典で表彰され、女性として初めて議事堂に安置された。 2020年9月25日、ギンズバーグ氏はスタチュアリーホールでの式典で表彰され、女性として初めて国会議事堂に眠ることになった。 ギンズバーグは2020年9月18日、膵臓癌の合併症により87歳で死去した[196][197]。彼女はロッシュ・ハッシャナーの前夜に亡くなり、ラ ビ・リチャード・ジェイコブスによれば、「ロッシュ・ハッシャナーのテーマのひとつは、非常に正しい人々が、最後まで必要とされたために、年の最後の最後 に死ぬことを示唆している」。 [198]彼女の死が発表された後、何千人もの人々が最高裁の建物の前に集まり、花を供え、ろうそくを灯し、メッセージを残した[199][200]。 彼女の死から5日後、8人の最高裁判事、ギンズバーグの子供たち、その他の家族が、裁判所の大広間でギンズバーグのための私的な式典を行った。COVID -19のパンデミック(世界的流行病)により、通常の大広間での安置が禁止されたため、非公開の儀式の後、ギンズバーグさんの棺は、一般市民が弔問できる よう、裁判所の西のポルティコへと屋外に移された。数千人の弔問客が2日間にわたって棺の前を列をなして通り過ぎた[201]。裁判所での2日間の安置の 後、ギンズバーグは国会議事堂に安置された。9月29日、ギンズバーグはアーリントン国立墓地に夫の傍らに埋葬された[205]。 ギンズバーグの死によって、2020年の大統領選の約6週間前に最高裁に空席が生じ、後任の指名と承認に関する論争が始まった[206][207] [208]。 ギンズバーグは死の数日前、孫娘のクララ・スペラに口述筆記をした: 「私の最も切なる願いは、新大統領が就任するまで私が後任にならないことです」[209] トランプ大統領が後任に指名したエイミー・コニー・バレットは、10月27日に上院で承認された。 |

Recognition Three women gripping a bust and smiling Ginsburg receiving the LBJ Liberty & Justice for All Award from Lynda Johnson Robb and Luci Baines Johnson at the Library of Congress in January 2020 In 2002, Ginsburg was inducted into the National Women's Hall of Fame.[210] Ginsburg was named one of 100 Most Powerful Women (2009),[211] one of Glamour magazine's Women of the Year 2012,[212] and one of Time magazine's 100 most influential people (2015).[213] She was awarded honorary degrees by Lund University (1969),[214] American University Law School (1981),[215] Vermont Law School (1984),[216] Georgetown University (1985),[215] DePaul University (1985), Brooklyn Law School (1987), Hebrew Union College (1988), Rutgers University (1990), Amherst College (1990),[215] Lewis & Clark College (1992),[217] Columbia University (1994),[218] Long Island University (1994),[219] NYU (1994),[220] Smith College (1994),[221] The University of Illinois (1994),[222] Brandeis University (1996),[223] George Washington University (1997),[224] Jewish Theological Seminary of America (1997),[220] Wheaton College (Massachusetts) (1997),[225] Northwestern University (1998),[226] University of Michigan (2001),[227] Brown University (2002),[228] Yale University (2003),[229] John Jay College of Criminal Justice (2004),[220] Johns Hopkins University (2004),[230] University of Pennsylvania (2007),[231] Willamette University (2009),[232] Princeton University (2010),[233] Harvard University (2011),[234] and the State University of New York (2019).[235] In 2009, Ginsburg received a Lifetime Achievement Award from Scribes—The American Society of Legal Writers.[236] In 2013, a painting featuring the four female justices to have served as justices on the Supreme Court (Ginsburg, Sandra Day O'Connor, Sonia Sotomayor, and Elena Kagan) was unveiled at the Smithsonian's National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C.[237][238] Researchers at the Cleveland Museum of Natural History gave a species of praying mantis the name Ilomantis ginsburgae after Ginsburg. The name was given because the neck plate of the Ilomantis ginsburgae bears a resemblance to a jabot, which Ginsburg was known for wearing. Moreover, the new species was identified based upon the female insect's genitalia instead of based upon the male of the species. The researchers noted that the name was a nod to Ginsburg's fight for gender equality.[239][240] Ginsburg was the recipient of the 2019 $1 million Berggruen Prize for Philosophy and Culture.[241][242] Awarded annually, the Berggruen Institute stated it recognizes "thinkers whose ideas have profoundly shaped human self-understanding and advancement in a rapidly changing world",[243] noting Ginsburg as "a lifelong trailblazer for human rights and gender equality".[244] Ginsburg donated the entirety of the prize money to charitable and non-profit organizations, including the Malala Fund, Hand in Hand: Center for Jewish-Arab Education in Israel, the American Bar Foundation, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, and the Washington Concert Opera.[245] Ginsburg received numerous additional awards, including the LBJ Foundation's Liberty & Justice for All Award, the World Peace & Liberty Award from international legal groups, a lifetime achievement award from Diane von Furstenberg's foundation, and the 2020 Liberty Medal by the National Constitution Center all in 2020 alone.[246][247] In February 2020, she received the World Peace & Liberty Award from the World Jurist Association and the World Law Foundation.[248] In 2019, the Skirball Cultural Center in Los Angeles created Notorious RBG: The Life and Times of Ruth Bader Ginsburg,[249] a large-scale exhibition focusing on Ginsburg's life and career.[250][251] In 2019 Ginsburg and the Dwight D. Opperman Foundation established the Ruth Bader Ginsburg Woman of Leadership Award.[252] Ginsburg presented the first award in February 2020 to arts patron and philanthropist Agnes Gund.[253] In March 2024, the organization had changed its award guidelines, with four of the five awards going to men. Notably, the list included Elon Musk and Rupert Murdoch, whose views are seen as incompatible with the liberal justice's; her family distanced itself from the award and asked for her name to be removed from it.[252][254][255] On March 18, 2024, chairperson Julie Opperman announced that the year's awards would not be given out and that the foundation would "reconsider its mission and make a judgment about how or whether to proceed in the future."[256]  Ruth Bader Ginsburg Hall at Cornell University The U.S. Navy announced on March 31, 2022, that it will name one of its John Lewis-class replenishment oilers the USNS Ruth Bader Ginsburg.[257] In August 2022, Ruth Bader Ginsburg Hall, a 162,849 sq ft residence hall at Cornell University, opened its doors to the Class of 2026.[258][259] In March 2023, a special session and bar memorial was held by the Supreme Court honoring Ginsburg's legacy.[260] Also in 2023, Ginsburg was featured on a USPS Forever stamp. The stamp was designed by art director Ethel Kessler, using an oil painting by Michael J. Deas based on a photograph by Philip Bermingham.[261] |

|