感情の社会学

Sociology of emotions

☆感

情社会学[Sociology

of emotions]は、感情という主題に社会学的な視点をもたらす。社会科学の一分野である社会学は、心と社会の両方を理解することに焦点

を当て、自己、相互作用、社会構造、文化の力学を研究する。[1]

感情の主題は古典的な社会学理論の初期にも見られるが、社会学者たちが感情の体系的な研究を始めたのは1970年代である。当時、この分野の研究者たちは

特に、感情が自己に与える影響、相互作用の流れを形作る方法、人々が社会構造や文化的象徴に対して感情的な愛着を育む過程、そして社会構造や文化的象徴が

感情の経験と表現をいかに制約するかに強い関心を抱いていた。[1]

社会学者たちは、感情が社会構造や文化的象徴体系の形成にどのように関与するか、また社会構造の解体や文化的伝統への挑戦において感情が果たす役割に注目

してきた。この場合、人間の動機付けは規範・価値観・信念への感情的コミットメントといった非合理的要因にも見出されるため、精神を理解するには情動と合

理的思考の両方を考慮する必要がある。[2][3][4][5]

社会学において、感情は人間同士の相互作用と協働によって構築される社会的産物と見なせる。感情は人間体験の一部であり、その意味は特定の社会の知識形態

から得られるものである。[6](→「感情/情動」)

| The Sociology

of emotions applies a sociological lens to the topic of emotions. The

discipline of Sociology, which falls within the social sciences, is

focused on understanding both the mind and society, studying the

dynamics of the self, interaction, social structure, and culture.[1]

While the topic of emotions can be found in early classic sociological

theories, sociologists began a more systematic study of emotions in the

1970s when scholars in the discipline were particularly interested in

how emotions influenced the self, how they shaped the flow of

interactions, how people developed emotional attachments to social

structures and cultural symbols, and how social structures and cultural

symbols constrained the experience and expression of emotions.[1]

Sociologists have focused on how emotions are present in the creation

of social structures and systems of cultural symbols, and how they can

also play a role in deconstructing social structures and challenging

cultural traditions. In this case, in order to understand the mind,

affect and rational thought must be considered since humans find

motivation among non-rational factors such as levels of emotional

commitment to norms, values, and beliefs.[2][3][4][5] Within sociology,

emotions can be seen as social constructs that are fabricated by

interaction and collaboration between human beings. Emotions are a part

of the human experience, and they gain their meaning from a given

society's forms of knowledge.[6] |

感情社会学は、感情という主題に社会学的な視点をもたらす。社会科学の

一分野である社会学は、心と社会の両方を理解することに焦点を当て、自己、相互作用、社会構造、文化の力学を研究する。[1]

感情の主題は古典的な社会学理論の初期にも見られるが、社会学者たちが感情の体系的な研究を始めたのは1970年代である。当時、この分野の研究者たちは

特に、感情が自己に与える影響、相互作用の流れを形作る方法、人々が社会構造や文化的象徴に対して感情的な愛着を育む過程、そして社会構造や文化的象徴が

感情の経験と表現をいかに制約するかに強い関心を抱いていた。[1]

社会学者たちは、感情が社会構造や文化的象徴体系の形成にどのように関与するか、また社会構造の解体や文化的伝統への挑戦において感情が果たす役割に注目

してきた。この場合、人間の動機付けは規範・価値観・信念への感情的コミットメントといった非合理的要因にも見出されるため、精神を理解するには情動と合

理的思考の両方を考慮する必要がある。[2][3][4][5]

社会学において、感情は人間同士の相互作用と協働によって構築される社会的産物と見なせる。感情は人間体験の一部であり、その意味は特定の社会の知識形態

から得られるものである。[6] |

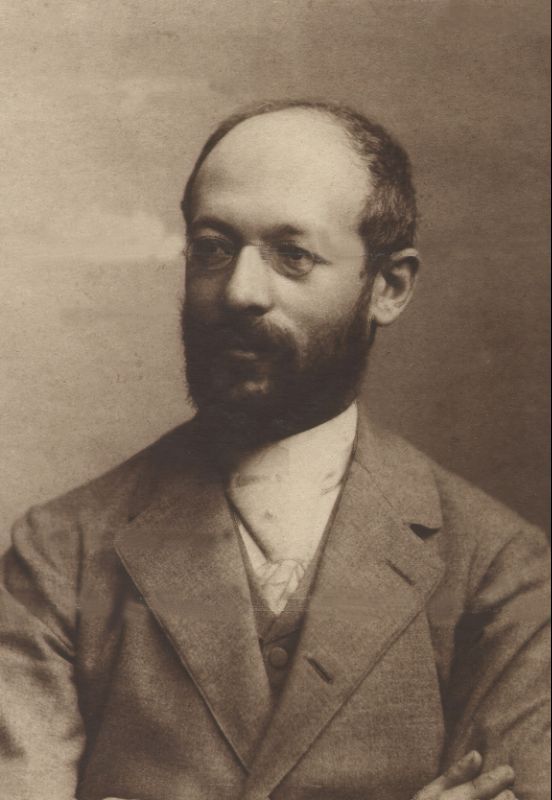

| A Sociological Approach to Emotions While disciplines such as psychology focus on individual processes that bring about emotions, sociology takes a closer look at contexts that humans find themselves in and examine how social structures and culture influence emotions within people.[1] Among the many possible disciplines that can approach the topic of emotions, there are specific aspects of Sociology that lend themselves to studying emotions. For example, the discipline of Sociology allows scholars to focus on the impact that factors such as social group (gender, class, race, and so on), culture, time, interactions, and situations may shape or influence human emotion.[6] Sociology of emotions covers a variety of topics and questions as they relate to emotions, such as how emotions emerge within human interaction, how social norms regulate emotional expression and feeling, emotional differences between social groups, classes, and cultures, and so on.[6] Within the discipline of Sociology, there are two specific fields that are particularly primed to approach the study of emotions: social psychology and the sociology of knowledge. In each of these fields, social factors are essential to studying mental structures and mentality.[6] Some researchers describe these patterned expectations through the idea of an "emotion regime," a term that highlights how social settings define which feelings may be expressed and how they should be managed.[7] This perspective emphasizes that emotions are shaped not only by interpersonal interaction but also by broader arrangements of power, cultural meaning, and institutional norms that authorize certain expressions and discourage others.[8]  George Herbert Mead According to George Herbert Mead, the human mind and the social self emerge in conduct with other people in social situations. The mind and self are social objects just like other physical objects, and the human perception of things involves taking a social attitude toward them.[9] All human products are socially constructed and they exist in relation to the social world; what people think of a given object, person, living creature, and so on is determined within and through the process of interaction with others and within social institutions.[10] Therefore, Mead placed mind and self "outside" of the human body in the sense that an individual's own mind and self exist only in relation to other minds and selves through social processes. Mead argued that "mind" is a combination, or structure, of relationships within a social world, and human consciousness functions within this relationship, but is not necessarily contained within a single human body.[11][12][6] The discipline sees human feeling and emotions as something that is experienced and constantly coming into existence in the context of cultural and historical variation; in other words, they shift and change depending on the social situation. Emotions are collective and they are determined by a given culture, community, or society.[6][13][14] According to Mead, feelings are related to ideas and develop in relation to the forms of knowledge that shape social factors such as class, generations, and so on.[9][10] Through the lens of sociology, emotions can be seen as social emergents in the way that they form part of the experience of a particular social group and its age, its experiences, and its responses.[6]  Just as emotions may emerge from social experiences, Sociology is also interested in exploring how institutions and individuals disseminate expert knowledge about emotions. For example, there are many institutional roles such as counselors, therapists, psychologists, and others who practice and disseminate "social knowledge".[6] Thus, emotions can be seen as social objects of human knowledge, efforts, and activities that are formed by social processes and generated by actors and social groups who have placed social significance on feelings and emotions. As social objects, emotions and feelings exist within specific social relationships and within a system of language. For example, discourse within the setting of therapy may assist in the dissemination of psychological knowledge within everyday life. This knowledge, which often includes knowledge about emotions, exists because of the social relationships, and the languages, in which they are discussed.[6] Some sociologists, especially those within the constructionist perspective, have made the claim that emotions primarily originate in culture. In this instance, members of a society learn emotional vocabulary, expressive behaviors, and shared meanings of every emotion from social relationships with others.[15][1] Gordon posits that it is only through the socialization process that individuals learn emotion vocabulary that allows them to name internal sensations connected to the objects, events, and relationships that they encounter. While this view recognizes how emotions are influences and constrained by cultural norms, values, and beliefs, evidence from other disciplines and evidence supporting cross-cultural universality of many emotions weaken the claim that all emotions are socially constructed.[16][17] The social constructionist perspective fails connect the activation, experience, and expressions of emotions to the human body.[1] Despite the fact that emotions are often constrained and fueled by sociocultural contexts, the nature and intensity of an emotion are driven by biological processes. Furthermore, there is a neurology of emotions that can't be ignored within the context of social science. Therefore, many behavioral capacities, including emotions, can't be solely explained by socialization and the constraints of social structures. While the social constructionist argument is not wholly wrong, it fails to recognize the neurological wiring for the production of emotions.[1] More recent studies within sociology have worked to better recognize the reciprocal relationship between biology and sociocultural processes.[18][19][20] Scholars have identified certain elements among emotions that connect to the sociological perspective. According to Turner and Stets,[1] five points include: 1. The biological activation of key body systems 2. Socially constructed cultural definitions and constraints on what emotions should be experienced and expressed in a situation 3. The application of linguistic labels provided by culture to internal sensations 4. The overt expression of emotions through facial, voice, and paralinguistic moves 5. Perceptions and appraisals of situational objects or events. Thus, according to this view, emotions are aroused by the activation of body systems. But once activated, emotions will be constrained by cognitive processes and culture. |

感情への社会学的アプローチ 心理学などの学問が感情を生み出す個人のプロセスに焦点を当てる一方で、社会学は人間が置かれる状況に目を向け、社会構造や文化が人々の感情にどう影響するかを検証する。 感情という主題にアプローチできる学問分野は数多く存在するが、社会学には感情研究に適した特異な側面がある。例えば社会学という学問領域は、社会的集団 (ジェンダー、階級、人種など)、文化、時間、相互作用、状況といった要因が人間の感情を形作り、あるいは影響を与える可能性に焦点を当てることを研究者 に許す。[6] 感情社会学は、感情に関連する多様な主題や問いを扱う。例えば、感情が人間相互作用の中でいかに生じるか、社会的規範が感情表現や感情をいかに規制する か、社会的集団・階級・文化間の感情的差異などである。[6] 社会学の分野内では、感情研究に特に適した二つの専門領域がある。社会心理学と知識社会学である。これらの分野のいずれにおいても、精神的構造やメンタリ ティを研究する上で社会的要因は不可欠である。[6] 一部の研究者は、こうしたパターン化された期待を「感情体制」という概念で説明する。この用語は、社会的状況がどの感情が表現され得るか、またそれらがど のように管理されるべきかを定義する点を強調するものである。[7] この視点は、感情が対人的相互作用だけでなく、特定の表現を許容し他の表現を抑制する、より広範な権力構造、文化的意味、制度的規範によっても形成される ことを強調する。[8]  ジョージ・ハーバート・ミード ジョージ・ハーバート・ミードによれば、人間の精神と社会的自己は、社会状況における他者との関わりの中で現れる。精神と自己は他の物理的対象と同様に社 会的対象であり、人間が物事を認識する過程には、それらに対する社会的態度が伴う。[9] あらゆる人間の産物は社会的に構築され、社会世界との関係性の中で存在する。特定の対象、人格、生物などに対する人々の認識は、他者との相互作用や社会制 度の過程の中で、そしてそれを通じて決定される。[10] したがってミードは、個人の心や自己を、社会的な過程を通じて他の心や自己との関係性の中でのみ存在するという意味で、人体の「外側」に位置づけた。ミー ドは「精神」とは社会世界における関係性の集合体、あるいは構造体であり、人間の意識はこの関係性の中で機能するが、必ずしも単一の人体内に閉じ込められ ているわけではないと主張した。[11][12] [6] この学問は、人間の感情や情動を、文化的・歴史的変異の文脈において経験され、絶えず生じているものと見なす。言い換えれば、それらは社会的状況に応じて 移り変わり変化する。感情は集合的なものであり、特定の文化、共同体、社会によって決定される。[6][13][14] ミードによれば、感情は観念と関連し、階級や世代といった社会的要因を形成する知識形態との関係の中で発展する。[9][10] 社会学の視点では、感情は特定の社会集団とその時代、経験、反応の一部を形成する点で、社会的創発現象と見なせる。[6]  感情が社会的経験から生じるのと同様に、社会学は制度や個人が感情に関する専門知識をいかに普及させるかを探求することにも関心を持つ。例えばカウンセ ラー、セラピスト、心理学者など「社会的知識」を実践し普及させる多くの制度的役割が存在する。[6] したがって感情は、社会的プロセスによって形成され、感情や情動に社会的意義を付与した主体や集団によって生み出される、人間の知識・努力・活動の社会的 対象と見なせる。社会的対象として、感情や情動は特定の社会的関係性と言語体系の中に存在する。例えば治療の場面における言説は、日常生活における心理学 的知識の普及を助けることがある。この知識、すなわち感情に関する知識は、それが議論される社会的関係と言語によって存在しているのだ。[6] 一部の社会学者、特に構成主義的視点に立つ者たちは、感情は主に文化に起源を持つと主張している。この場合、社会の成員は感情の語彙、表現行動、そしてあ らゆる感情の共有された意味を、他者との社会的関係から学ぶのだ。[15][1] ゴードンは、個人が遭遇する対象・出来事・関係性に関連する内的な感覚に名前を付けるための感情語彙を習得するのは、社会化プロセスを通じてのみだと主張 する。この見解は感情が文化的規範・価値観・信念によって影響を受け制約される点を認めるが、他分野からの証拠や多くの感情の文化横断的普遍性を支持する 証拠は、「全ての感情が社会的に構築される」という主張を弱める。[16] [17] 社会構築主義的視点は、感情の活性化・経験・表現を人体と結びつけることに失敗している。[1] 感情が社会文化的文脈によって制約され促進されることは事実だが、感情の本質と強度は生物学的プロセスによって駆動される。さらに、社会科学の文脈におい て無視できない感情の神経学が存在するのである。したがって、感情を含む多くの行動能力は、社会化や社会構造の制約だけで説明することはできない。社会構 築主義の主張は完全に間違っているわけではないが、感情の生成に関する神経学的仕組みを認識していない。[1] 社会学における最近の研究は、生物学と社会文化的プロセスの相互関係をよりよく認識しようと努めている。[18][19][20] 学者たちは、感情の中で社会学的視点につながる特定の要素を特定している。ターナーとステッツによれば[1]、その5つの要素は次のとおりである。 1. 主要な身体システムの生物学的活性化 2. 状況においてどのような感情を経験し表現すべきかに関する、社会的に構築された文化的定義と制約 3. 内的な感覚に対する、文化によって提供された言語的ラベルの適用 4. 顔、声、および言語以外の動きによる感情の明白な表現 5. 状況的な対象物や出来事に対する認識と評価 したがって、この見解によれば、感情は身体システムの活性化によって喚起される。しかし、一度活性化されると、感情は認知プロセスや文化によって制約されることになる。 |

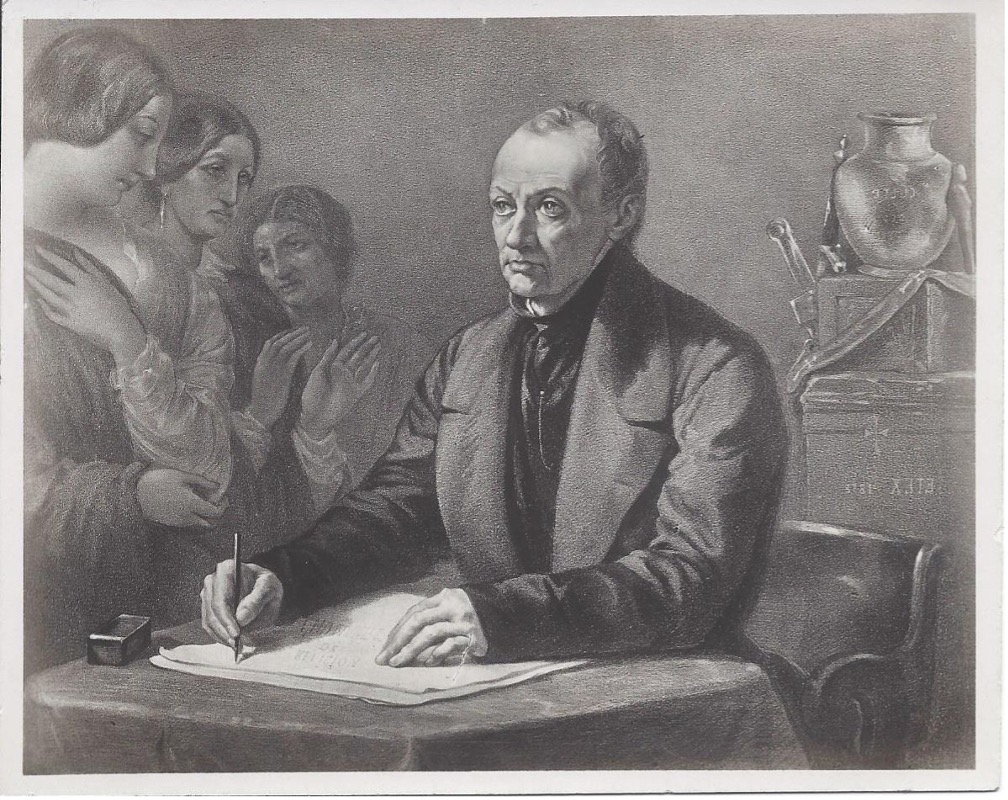

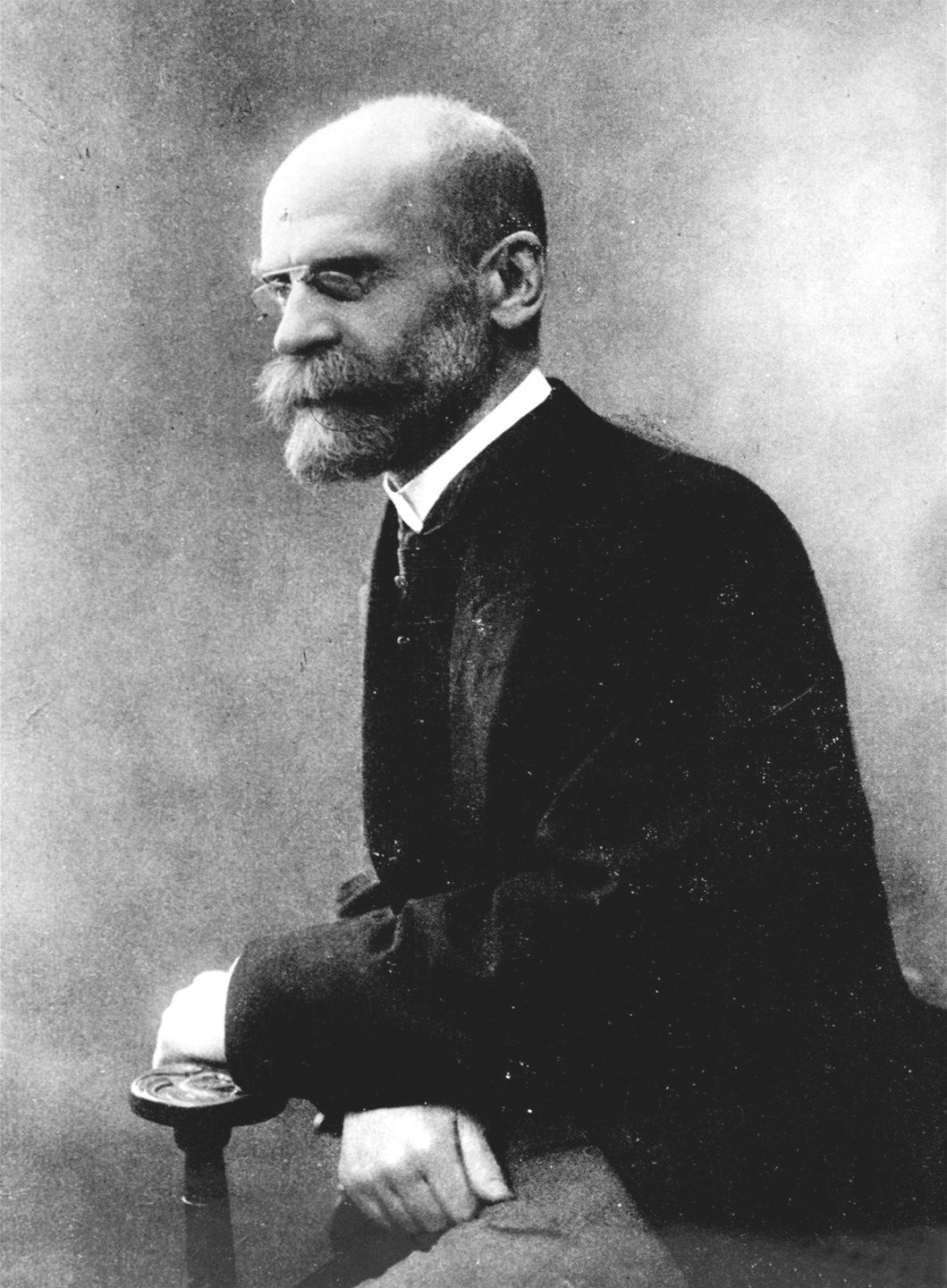

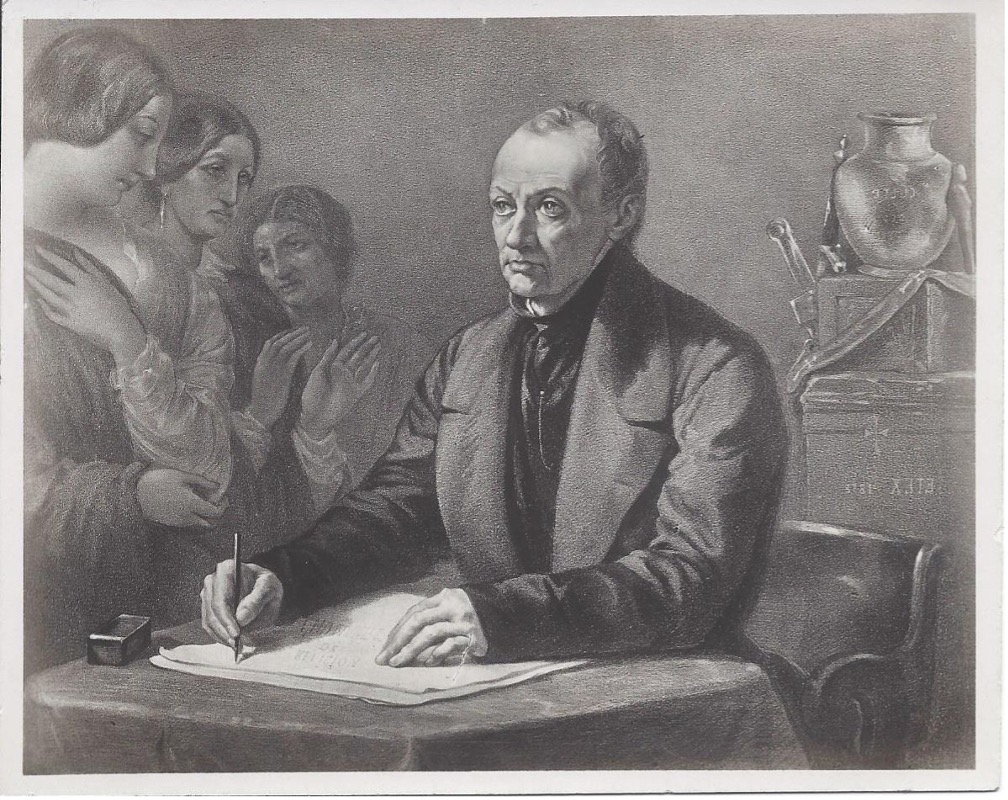

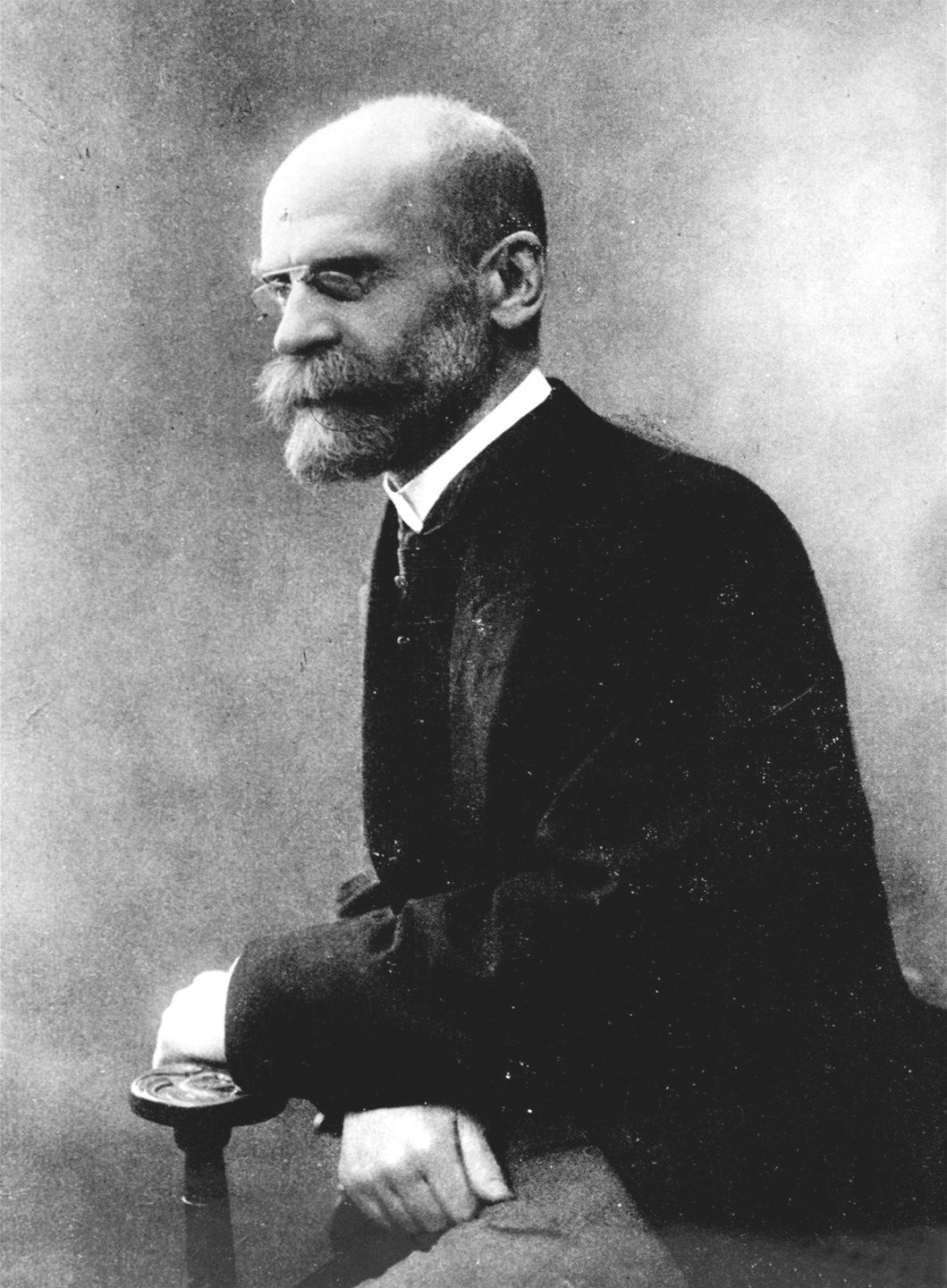

| Emotions Through the Lens of Sociological Theory The relationship between the sociology of emotions and mainstream sociology has not necessarily been seen as straightforward or a strong bond. Some sociologists who focus on emotions have claimed that some of the disciplines founding schools of thought neglect emotional issues, and thus classical theorists are not always included in the discussion of the sociology of emotions.[21][4] Chris Schilling claims[21] that the major traditions of sociological theory developed a particular interest in the social and moral dimensions of emotions, although the subject itself often came through the discussion of other disparate concepts within classical sociology. While interpretations of the sociological tradition vary in significant ways, it can be helpful to understand two distinct ways that the subject has been separated. According to Alan Dawe,[22][21] sociology can be split into a sociology of order and a sociology of action. Through this lens, the role of the study of emotions becomes more evident. While Sociology does not have a discipline-specific definition for emotions, there is evidence within classic analyses that emotions were a phenomenon that were concerned with how people experienced and expressed their contact and experiences within the social and natural worlds.[21][23] Out of the many classical sociological theorists, Auguste Comte, Emile Durkheim, Georg Simmel, and Max Weber played a particularly significant role in addressing the discipline of Sociology's concerns with order and action, both of which the topic of emotions is prominent.[21]  Auguste Comte Order and Emotions  Emile Durkheim Within a given society, there are institutions - such as the family, education, religion, and so on - that serve as a guiding source of moral sentiments and thoughts which influence the individuals within the society. Within classical sociological texts, a tension can be found within the description of individual humans: a duality between asocial impulses and social capacities.[21] For classical theorists such as Jean-Jacques Rousseau, the "natural man" is motivated by instinct and impulse, but within the context of civil society, these "animalistic" traits transform into morals such justice or duty.[21] This type of idea influenced Comte, and later his successor, Durkheim, both scholars of the French tradition who believed that society possessed the "status of a moral absolute." In this way, they viewed Society like a human body or organism, where there were different "parts" that each worked to fulfill the needs of the social whole. Both Comte and Durkheim pointed to the idea that it was the social collective that stimulated and directed emotions in a way that supported a broader societal moral order.[21] |

社会学理論のレンズを通して見た感情 感情社会学と主流社会学の関係は、必ずしも単純明快なものではなく、強固な結びつきとも見なされてこなかった。感情を研究対象とする社会学者の中には、学 問分野の創始的学派が感情問題を軽視しているとし、古典的理論家が感情社会学の議論に常に含まれるわけではないと主張する者もいる[21][4]。 クリス・シリングは[21]、社会学理論の主要な伝統が感情の社会的・道徳的側面に特に関心を寄せたと主張する。ただし感情という主題自体は、古典社会学 において他の多様な概念の議論を通じて扱われることが多かった。社会学伝統の解釈には重要な差異があるが、この主題が二つの異なる方法で分離されてきたこ とを理解することは有益である。アラン・ドウェによれば、社会学は秩序の社会学と行動の社会学に分けられる。この観点から、感情の研究の役割はより明らか になる。社会学には感情に関する学問分野特有の定義はないが、古典的な分析には、感情とは、人々が社会や自然界の中で接触や経験をどのように体験し、表現 するかという現象に関するものであるという証拠がある。[21][23] 多くの古典的な社会学理論家の中で、オーギュスト・コント、エミール・デュルケーム、ゲオルク・ジンメル、マックス・ヴェーバーは、感情というトピックが 顕著である秩序と行動に関する社会学の関心事に対処する上で、特に重要な役割を果たした。[21]  オーギュスト・コント 秩序と感情  エミール・デュルケーム 特定の社会には、家族、教育、宗教などの制度があり、それらは社会内の個人に影響を与える道徳的感情や思考の指針となる源として機能している。古典的な社 会学の文献では、個人に関する記述の中に、反社会的な衝動と社会的能力という二面性という緊張関係が見られる。[21] ジャン=ジャック・ルソーのような古典的理論家にとって、「自然人」は本能と衝動に駆られるが、市民社会という文脈では、こうした「動物的」特性が正義や 義務といった道徳へと変容する。[21] この種の思想はコントに影響を与え、後にその後継者であるデュルケームにも受け継がれた。両者ともフランス学派の学者であり、社会が「道徳的絶対者の地 位」を有すると信じていた。このように彼らは社会を人体や有機体のように捉え、それぞれが社会全体の必要を満たすために機能する異なる「部分」が存在する と考えた。コントもデュルケームも、より広範な社会的道徳秩序を支える形で感情を刺激し方向付けるのは社会的集団であるという考えを示した。[21] |

Action and Emotions Georg Simmel While Comte and Durkheim's theories stemmed from the idea of a social whole, there was another school of thought - the German tradition - that believed that it was the creative and ethical abilities within an individual that led humans to construct their own social and moral environment.[24][21] Within this context, two main views of emotions emerged: 1) emotions were seen as an impediment to self-determining actions, and 2) emotional capacities allowed people to transcend their limitations and become their "true selves."[21] German sociologist and philosopher Georg Simmel introduce the concept of the "moral soul," which views the soul as an individual possession and stimulates the need for an individually unique personality that contains emotions and intellect within the overall identity.[21][25] Simmel believed that the soul helps resolve internal conflicts between a person's individual, pre-social emotions and abilities and their social capacities. In Simmel's view, it is interaction alone that shapes the development o the soul, but the form of the interactions lead to a rigid development.[21] Simmel believed that interactions develop through the creation of shared mental orientations and social emotions that stem from human associations.[21]  Max Weber German sociologist Max Weber also looped emotions in with action. Instead of seeing emotion as a motivator of action, Weber suggested that individuals should channel their emotional selves in an effort to freely choose rational actions.[21] Weber saw rationalization as a way that humans increase their knowledge of how to pursue goals in the realm of science and technology, but in turn detracted from emotions that can come with experience, such as charisma.[21] |

行動と感情 ゲオルク・ジンメル コントとデュルケームの理論が社会全体の概念に由来する一方で、別の学派――ドイツの伝統――は、個人が持つ創造的・倫理的能力こそが、人間が自らの社会 的・道徳的環境を構築する原動力だと考えた。この文脈において、感情に関する二つの主要な見解が生まれた。1)感情は自律的行動の妨げと見なされる、2) 感情的能力は人々が自らの限界を超越し「真の自己」となることを可能にする、というものである。[21] ドイツの社会学者・哲学者ゲオルク・ジンメルは「道徳的魂」の概念を導入した。これは魂を個人の所有物と捉え、感情と知性を包括する全体的アイデンティ ティの中に、個々に固有の人格を必要とする考え方を促すものである。[21][25] ジンメルは、魂が個人の社会的形成以前の感情や能力と、社会的資質との間の内的葛藤を解決する助けとなると信じていた。ジンメルの見解では、魂の発達を形 作るのは相互作用だけであるが、その相互作用の形態が硬直的な発達につながる。[21] ジンメルは、相互作用は、人間の関係から生じる共有された精神的指向や社会的感情の創出を通じて発展すると考えていた。[21]  マックス・ヴェーバー ドイツの社会学者マックス・ヴェーバーも、感情と行動を結びつけた。ヴェーバーは、感情を行動の動機とみなすのではなく、個人が感情的な自己を、合理的な 行動を自由に選択するための努力に注ぐべきだと提案した。ヴェーバーは、合理化を、人間が科学技術の分野で目標を追求する方法に関する知識を増やす方法と みなしたが、その一方で、カリスマ性など、経験から得られる感情を損なうものともみなした。 |

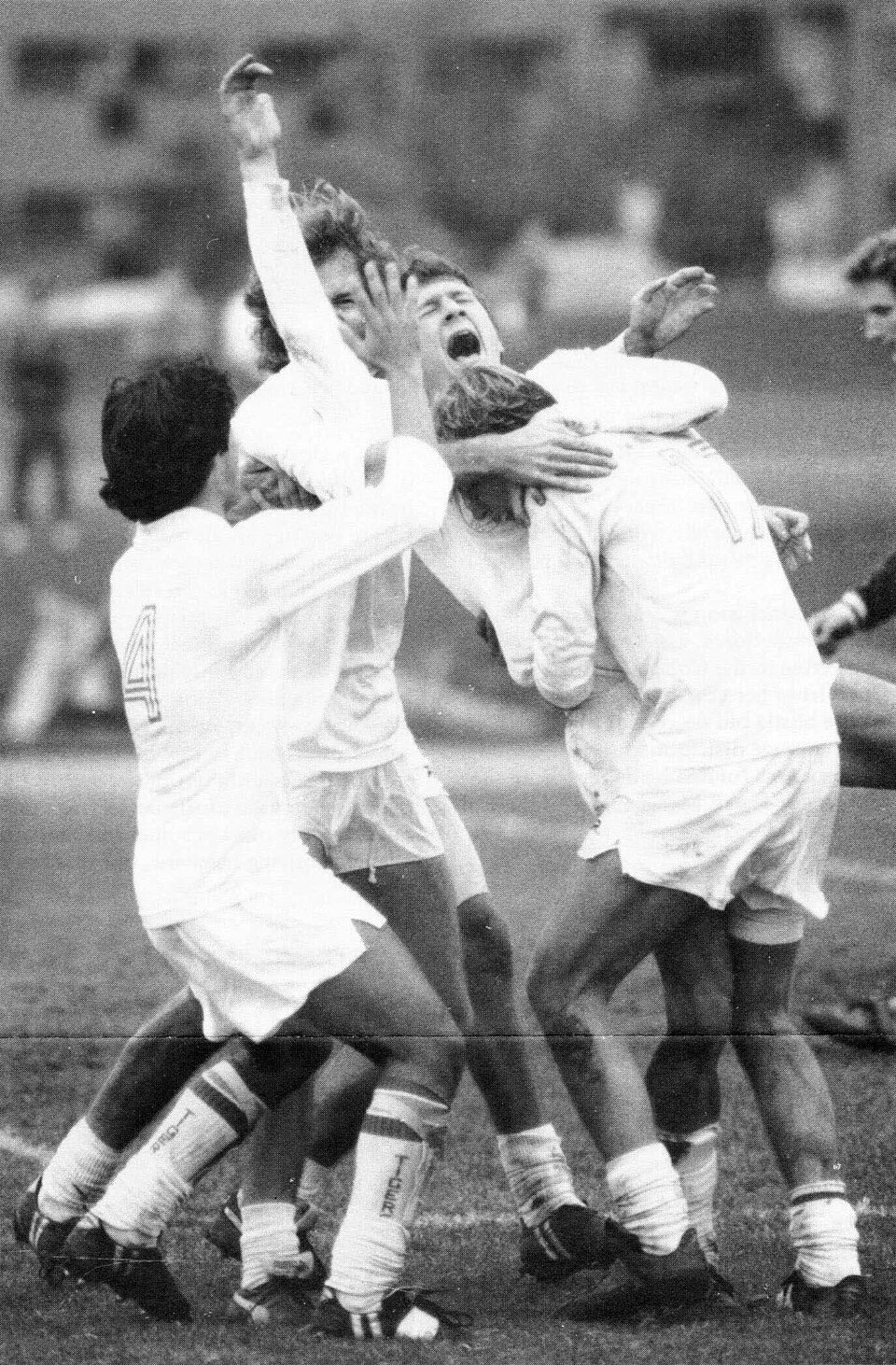

| Social Relations and Emotions Through a sociological lens, emotions can be seen as instigated by the social relationships that humans find themselves in. Emotions serve as responses to events within the social environment, and often other people, groups of people, or categories of people serve as objects of emotions.[26][5] Even when the self is the object of emotions, it is still thought of in terms of social relationships. From feeling joy after hearing a loved one's good news, to feeling nostalgia while talking to an old friend, to feeling sadness after being insulted, there are a variety of emotions that stem in consequence of what one interaction partner may do to the other.[27]  Sports wins serve as one of many examples of emotional expression, where athletes often present specific facial expressions that indicate feelings of joy, relief, excitement, and so on. Emotional Expressions Within face-to-face and video conversations, humans perceive emotions through facial expressions. Starting at infancy, the human brain begins to learn how to perceive faces through social exposure and experiences. Faces serve as a rich source of information within social contexts and can help people navigate the social world: facial expressions help people express their own emotions and the emotions of others, identify potential mates, discern who to trust, who may need help, and they even play a role in determining levels of innocence or guilt.[28][29][30][31][32][33] Facial expressions may vary slightly depending on a given culture or society, but there exists a common - or classical - view where certain emotion categories are reliably signaled by certain facial configurations.[32][34] Extending beyond face-to-face human interaction, electronic messages now contain emojis and emoticons that represent facial expressions for various emotion categories.[32][35] |

社会関係と感情 社会学的な視点から見ると、感情は人間が置かれている社会関係によって引き起こされるものと言える。感情は社会環境内の出来事に対する反応として機能し、 しばしば他の人々、集団、あるいは人々のカテゴリーが感情の対象となる。[26][5] たとえ自己が感情の対象であっても、それは依然として社会関係という観点から捉えられる。愛する人の良い知らせを聞いて喜びを感じることもあれば、旧友と 話すうちに懐かしさを感じることもある。侮辱されて悲しむこともある。相互の関わりの中で生じる様々な感情が存在するのだ。[27]  スポーツでの勝利は感情表現の一例だ。選手たちは喜び、安堵、興奮といった感情を示す特定の表情をしばしば見せる。 感情表現 対面やビデオ通話において、人間は表情を通じて感情を認識する。乳児期から、人間の脳は社会的接触や経験を通じて顔の認識方法を学び始める。顔は社会的文 脈において豊富な情報源となり、人々が社会世界をナビゲートする助けとなる。表情は自身の感情や他者の感情を表現し、潜在的な配偶者を識別し、信頼すべき 相手や助けを必要とする相手を見極め、さらには無罪か有罪かの判断にも関与する。[28][29][30] [31][32][33] 表情は特定の文化や社会によってわずかに異なる場合があるが、特定の感情カテゴリーが特定の顔の構成によって確実に示されるという共通の、あるいは古典的 な見解が存在する。[32][34] 対面の人間交流を超えて、電子メッセージには現在、様々な感情カテゴリーを表す顔の表情を表現する絵文字や顔文字が含まれている。[32][35] |

| References 1. Turner, Jonathan H.; Stets, Jan E. (2009). The sociology of emotions (Repr ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-84745-2. 2. Durkheim, Emile; Halls, W. D. (1984). The division of labor in society (in English and French). New York: Free Press. ISBN 978-0-02-907950-8. 3. Hochschild, Arlie Russell (April 1975). "The Sociology of Feeling and Emotion: Selected Possibilities". Sociological Inquiry. 45 (2–3): 280–307. doi:10.1111/j.1475-682X.1975.tb00339.x. ISSN 0038-0245. 4. Thoits, Peggy A. (August 1989). "The Sociology of Emotions". Annual Review of Sociology. 15 (1): 317–342. doi:10.1146/annurev.so.15.080189.001533. ISSN 0360-0572. 5. TenHouten, Warren D. (2006-11-22). A General Theory of Emotions and Social Life (0 ed.). Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203013441. ISBN 978-1-134-22908-6. 6. Franks, David D.; McCarthy, E. Doyle, eds. (1989). The sociology of emotions: original essays and research papers. Contemporary studies in sociology. Greenwich/Conn.: JAI Press. ISBN 978-1-55938-052-2. 7. Reddy, William M. (2001). The Navigation of Feeling: A Framework for the History of Emotions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 126. 8. Reddy, William M. (2001). The Navigation of Feeling: A Framework for the History of Emotions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 126. 9. Mead, George Herbert (2002). The philosophy of the present. Great books in philosophy. Amherst, N.Y: Prometheus Books. ISBN 978-1-57392-948-6. 10. Mead, George Herbert; Miller, David L. (1982). The individual and the social self: unpublished work of George Herbert Mead. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-51673-8. 11. Mead, George Herbert; Morris, Charles William; Huebner, Daniel R.; Joas, Hans (2015). Mind, self, and society (The definitive ed.). Chicago (Ill.): University of Chicago press. ISBN 978-0-226-11273-2. 12. Mead, George Herbert (1972). Morris, Charles W. (ed.). The philosophy of the act (7. impr ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-51666-0. 13. Rorty, Amélie, ed. (1980). Explaining emotions. Topics in philosophy ; 5. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-03775-5. 14. Rosenberg, Morris; Turner, Ralph H., eds. (1990). Social psychology: sociological perspectives. New Brunswick, U.S.A: Transaction Publishers. ISBN 978-0-88738-854-5. 15. Kemper, Theodore D. (1990). Research agendas in the sociology of emotions. SUNY series in the sociology of emotions. American sociological association. Albany (N.Y.): State University of New York press. ISBN 978-0-7914-0269-6. 16. Ekman, Paul; Friesen, Wallace V. (1971). "Constants across cultures in the face and emotion". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 17 (2): 124–129. doi:10.1037/h0030377. ISSN 1939-1315. PMID 5542557. 17. Kemper, Theodore D. (September 1981). "Social Constructionist and Positivist Approaches to the Sociology of Emotions". American Journal of Sociology. 87 (2): 336–362. doi:10.1086/227461. ISSN 0002-9602. 18. Kemper, Theodore D. (1990). Social structure and testosterone: explorations of the socio-bio-social chain. New Brunswick: Rutgers Univ. Pr. ISBN 978-0-8135-1551-9. 19. Franks, David D.; Smith, Thomas Spence (1999). Mind, brain, and society: toward a neurosociology of emotion. Social perspectives on emotion. Stamford (Conn.): JAI press. ISBN 978-0-7623-0411-0. 20. Turner, Jonathan H. (2000). On the origins of human emotions: a sociological inquiry into the evolution of human affect (Orig. print ed.). Stanford, Calif: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-3720-3. 21. Shilling, Chris (October 2002). "The Two Traditions in the Sociology of Emotions". The Sociological Review. 50 (2_suppl): 10–32. doi:10.1111/j.1467-954X.2002.tb03589.x. ISSN 0038-0261. 22. Dawe, Alan (June 1970). "The Two Sociologies". The British Journal of Sociology. 21 (2): 207–218. doi:10.2307/588409. JSTOR 588409. 23. Shilling, Chris (August 2001). "Embodiment, Experience and Theory: In Defence of the Sociological Tradition". The Sociological Review. 49 (3): 327–344. doi:10.1111/1467-954X.00335. ISSN 0038-0261. 24. Levine, Donald Nathan (1995). Visions of the sociological tradition. Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-47547-9. 25. Simmel, Georg; Helle, Horst Jürgen; Nieder, Ludwig (1997). Essays on religion. Monograph series / Society for the Scientific Study of Religion. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-06110-9. 26. Kemper, Theodore D. (1978). A social interactional theory of emotions. New York: Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-01405-8. 27. Kemper, Theodore D.; American Psychological Association, eds. (1990). Research agendas in the sociology of emotions. SUNY series in the sociology of emotions. Albany: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-0269-6. 28. Todorov, Alexander B. (2017). Face value: the irresistible influence of first impressions. Princeton, NJ Oxford: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-16749-7. 29. Mattarozzi, Katia; Colonnello, Valentina; De Gioia, Francesco; Todorov, Alexander (June 2017). "I care, even after the first impression: Facial appearance-based evaluations in healthcare context". Social Science & Medicine. 182: 68–72. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.04.011. PMID 28419891. 30. Zebrowitz, Leslie A. (1997). Reading faces: window to the soul?. New directions in social psychology. Boulder, Colo: Westview Press. ISBN 978-0-8133-2746-4. 31. Kramer, Robin S.S.; Young, Andrew W.; Burton, A. Mike (March 2018). "Understanding face familiarity". Cognition. 172: 46–58. doi:10.1016/j.cognition.2017.12.005. PMID 29232594. 32. Barrett, Lisa Feldman; Adolphs, Ralph; Marsella, Stacy; Martinez, Aleix M.; Pollak, Seth D. (July 2019). "Emotional Expressions Reconsidered: Challenges to Inferring Emotion From Human Facial Movements". Psychological Science in the Public Interest. 20 (1): 1–68. doi:10.1177/1529100619832930. ISSN 1529-1006. PMC 6640856. PMID 31313636. 33. Vrij, Aldert; Hartwig, Maria (September 2021). "Deception and lie detection in the courtroom: The effect of defendants wearing medical face masks". Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition. 10 (3): 392–399. doi:10.1016/j.jarmac.2021.06.002. ISSN 2211-369X. PMC 9902031. PMID 36778029. 34. Barrett, Lisa Feldman (2018). How emotions are made: the secret life of the brain (First Mariner Books ed.). Boston New York: Mariner Books. ISBN 978-0-544-12996-2. 35. Pfeifer, Valeria A.; Armstrong, Emma L.; Lai, Vicky Tzuyin (January 2022). "Do all facial emojis communicate emotion? The impact of facial emojis on perceived sender emotion and text processing". Computers in Human Behavior. 126 107016. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2021.107016. |

参考文献 1. ターナー、ジョナサン H.、ステッツ、ジャン E. (2009). 『感情の社会学』 (再版). ケンブリッジ: ケンブリッジ大学出版局. ISBN 978-0-521-84745-2. 2. ドルクハイム、エミール; ホールズ、W. D. (1984). 『社会における分業』(英語およびフランス語)。ニューヨーク:フリープレス。ISBN 978-0-02-907950-8。 3. ホックシールド、アーリー・ラッセル (1975年4月)。「感情と情動の社会学:選択された可能性」『社会学研究』45巻2-3号、280-307頁。doi:10.1111/j.1475 -682X.1975.tb00339.x。ISSN 0038-0245。 4. トイッツ、ペギー・A.(1989年8月)。「感情の社会学」。『社会学年次レビュー』。15巻1号:317–342頁。doi:10.1146/annurev.so.15.080189.001533。ISSN 0360-0572。 5. テンハウテン、ウォーレン・D. (2006-11-22). 『感情と社会生活に関する一般理論』 (0版). ラウトレッジ. doi:10.4324/9780203013441. ISBN 978-1-134-22908-6. 6. Franks, David D.; McCarthy, E. Doyle, 編 (1989). 『感情の社会学:原論と研究論文集』. 現代社会学研究. グリニッジ/コネチカット州: JAI Press. ISBN 978-1-55938-052-2. 7. Reddy, William M. (2001). 感情の航海:感情史の枠組み。ケンブリッジ:ケンブリッジ大学出版局。p. 126。 8. レディ、ウィリアム・M. (2001). 感情の航海:感情史の枠組み。ケンブリッジ:ケンブリッジ大学出版局。p. 126。 9. ミード、ジョージ・ハーバート (2002). 現在の哲学。哲学の偉大な書物。ニューヨーク州アマースト:プロメテウス・ブックス。ISBN 978-1-57392-948-6。 10. ミード、ジョージ・ハーバート;ミラー、デイヴィッド・L.(1982)。『個人と社会的自我:ジョージ・ハーバート・ミード未発表論文集』。シカゴ:シカゴ大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-226-51673-8。 11. ミード, ジョージ・ハーバート; モリス, チャールズ・ウィリアム; ヒューブナー, ダニエル・R.; ヨアス, ハンス (2015). 『心、自己、社会』(決定版). シカゴ (イリノイ州): シカゴ大学出版局. ISBN 978-0-226-11273-2. 12. ミード, ジョージ・ハーバート (1972). モリス、チャールズ W. (編). 行為の哲学 (第 7 版). シカゴ: シカゴ大学出版局. ISBN 978-0-226-51666-0. 13. ロールティ、アメリー、編 (1980). 感情の説明. 哲学のトピック ; 5. バークレー: カリフォルニア大学出版局. ISBN 978-0-520-03775-5。 14. ローゼンバーグ、モリス、ターナー、ラルフ H. 編 (1990)。社会心理学:社会学的視点。米国ニューブランズウィック:トランザクション出版社。ISBN 978-0-88738-854-5。 15. ケンパー、セオドア D. (1990)。感情社会学の研究課題。感情社会学に関する SUNY シリーズ。アメリカ社会学会。オールバニ(ニューヨーク州):ニューヨーク州立大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-7914-0269-6。 16. エックマン, ポール; フライゼン, ウォレス・V. (1971). 「顔と感情における文化横断的な共通点」. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 17 (2): 124–129. doi:10.1037/h0030377. ISSN 1939-1315. PMID 5542557. 17. ケンパー、セオドア・D. (1981年9月). 「感情社会学への社会構成主義的アプローチと実証主義的アプローチ」. アメリカ社会学雑誌. 87 (2): 336–362. doi:10.1086/227461. ISSN 0002-9602. 18. ケンパー、セオドア・D. (1990). 『社会構造とテストステロン:社会-生物-社会連鎖の探求』. ニューブランズウィック:ラトガース大学出版局. ISBN 978-0-8135-1551-9. 19. フランク、デイヴィッド・D.;スミス、トーマス・スペンス (1999). 心、脳、社会:感情の神経社会学に向けて。感情に関する社会的視点。スタンフォード(コネチカット州):JAI プレス。ISBN 978-0-7623-0411-0。 20. ターナー、ジョナサン H. (2000)。人間の感情の起源について:人間の感情の進化に関する社会学的調査(原版印刷版)。スタンフォード、カリフォルニア州:スタンフォード大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-8047-3720-3。 21. シリング、クリス(2002年10月)。「感情社会学における2つの伝統」。社会学レビュー。50 (2_suppl): 10–32。doi:10.1111/j.1467-954X.2002.tb03589.x. ISSN 0038-0261. 22. ドー、アラン(1970年6月)。「二つの社会学」。『英国社会学雑誌』。21巻2号:207–218頁。doi:10.2307/588409. JSTOR 588409. 23. クリストファー・シリング(2001年8月)。「身体化、経験、理論:社会学的伝統の擁護」。『社会学評論』49巻3号:327–344頁。doi:10.1111/1467-954X.00335. ISSN 0038-0261. 24. レバイン, ドナルド・ネイサン (1995). 『社会学伝統の諸相』. シカゴ: シカゴ大学出版局. ISBN 978-0-226-47547-9. 25. Simmel, Georg; Helle, Horst Jürgen; Nieder, Ludwig (1997). Essays on religion. Monograph series / Society for the Scientific Study of Religion. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-06110-9. 26. Kemper, Theodore D. (1978). A social interactional theory of emotions. New York: Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-01405-8。 27. ケンパー、セオドア D.、アメリカ心理学会編 (1990)。感情社会学の研究課題。感情社会学に関する SUNY シリーズ。オールバニ:ニューヨーク州立大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-7914-0269-6。 28. トドロフ、アレクサンダー B. (2017). 顔の価値:第一印象の抗いがたい影響力。ニュージャージー州プリンストン、オックスフォード:プリンストン大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-691-16749-7。 29. マタロッツィ、カティア;コロネッロ、ヴァレンティーナ;デ・ジョイア、フランチェスコ;トドロフ、アレクサンダー (2017年6月)。「第一印象の後も気にかける:医療現場における顔の外見に基づく評価」『Social Science & Medicine』182: 68–72. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.04.011. PMID 28419891. 30. Zebrowitz, Leslie A. (1997). 顔を読む:魂の窓?. 社会心理学の新たな方向性. コロラド州ボルダー:Westview Press. ISBN 978-0-8133-2746-4. 31. Kramer, Robin S.S.; Young, Andrew W.; Burton, A. Mike (2018年3月). 「顔の親しみやすさを理解する」. Cognition. 172: 46–58. doi:10.1016/j.cognition.2017.12.005. PMID 29232594. 32. バレット、リサ・フェルドマン、アドルフス、ラルフ、マルセラ、ステイシー、マルティネス、アレックス M.、ポラック、セス D. (2019年7月)。「感情表現の再考:人間の顔の動きから感情を推測することの難しさ」。公益のための心理学。20 (1): 1–68. doi:10.1177/1529100619832930。ISSN 1529-1006。PMC 6640856。PMID 31313636。 33. Vrij, Aldert; Hartwig, Maria (2021年9月)。「法廷における欺瞞と嘘の検知:医療用マスクを着用した被告人の影響」『Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition』10 (3): 392–399. doi:10.1016/j.jarmac.2021.06.002. ISSN 2211-369X. PMC 9902031. PMID 36778029。 34. バレット、リサ・フェルドマン (2018)。感情の成り立ち:脳の秘密の生活 (First Mariner Books ed.)。ボストン、ニューヨーク:Mariner Books。ISBN 978-0-544-12996-2。 35. ファイファー、ヴァレリア A.、 アームストロング、エマ L.、ライ、ヴィッキー・ツィイン (2022年1月)。「すべての顔文字は感情を伝えるのか?顔文字が送信者の感情の認識とテキスト処理に与える影響」。Computers in Human Behavior. 126 107016. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2021.107016. |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sociology_of_emotions |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099