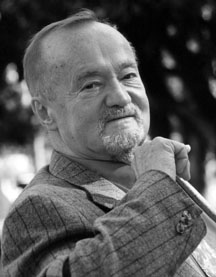

スティーヴン・トゥルーミン

Stephen Edelston Toulmin,

1922-2009

Stephen Toulmin, 1922-2009

☆ス ティーブン・エデルストン・トゥルーミン(/ˈtuːlmɪn/; 1922年3月25日 - 2009年12月4日)は、イギリスの哲学者、著述家、教育者であった。ルートヴィヒ・ウィトゲンシュタインの影響を受け、トゥルーミンは道徳的推論の分 析に著作を捧げた。彼の著作全体を通じて、道徳的問題の背後にある倫理を評価する際に効果的に使用できる実践的な議論を展開しようとした。彼の著作は後 に、修辞学の分野において修辞的議論を分析するのに有用であることが判明した。1958年の著書『議論の用途』で発表された、議論を分析するために用いら れる6つの相互に関連する要素を含む図式である「トゥルーミンの議論モデル」は、特に修辞学とコミュニケーションの分野、そしてコンピュータ科学におい て、彼の最も影響力のある業績と見なされている。

☆【医療倫理におけるトゥルーミンの業績】ア

ルバート・ジョンスンやスティーブン・トゥールミン(『決疑論の濫用』1988年)などの決疑論者は、応用倫理学の伝統的なパラダイムに異議を

唱えている。

決疑論者は、理論から出発して特定の事例に理論を適用するのではなく、特定の事例そのものから出発し、その事例について道徳的に重要な特徴(理論と実践の

両方の考慮事項を含む)を考慮すべきかを問う。

ジョンセンとトウルミンは、医療倫理委員会の観察から、特に問題のある道徳的な事例について、参加者がイデオロギーや理論ではなく、その事例の事実を重視

した場合には、しばしばコンセンサスが得られることに注目している。したがって、ラビ、カトリック司祭、不可知論者は、この特定の事例では、最善の策は特

別な医療措置を差し控えることであるという点では同意するかもしれないが、各自の立場を支持する理由については意見が分かれる可能性がある。理論ではなく

事例に焦点を当てることで、道徳的な議論を行う人々は合意の可能性を高めることができる。

| Stephen Edelston

Toulmin

(/ˈtuːlmɪn/; 25 March 1922 – 4 December 2009) was a British

philosopher, author, and educator. Influenced by Ludwig Wittgenstein,

Toulmin devoted his works to the analysis of moral reasoning.

Throughout his writings, he sought to develop practical arguments which

can be used effectively in evaluating the ethics behind moral issues.

His works were later found useful in the field of rhetoric for

analyzing rhetorical arguments. The Toulmin model of argumentation, a

diagram containing six interrelated components used for analyzing

arguments, and published in his 1958 book The Uses of Argument, was

considered his most influential work, particularly in the field of

rhetoric and communication, and in computer science. |

スティーブン・エデルストン・トゥルーミン(/ˈtuːlmɪn/;

1922年3月25日 -

2009年12月4日)は、イギリスの哲学者、著述家、教育者であった。ルートヴィヒ・ウィトゲンシュタインの影響を受け、トゥルーミンは道徳的推論の分

析に著作を捧げた。彼の著作全体を通じて、道徳的問題の背後にある倫理を評価する際に効果的に使用できる実践的な議論を展開しようとした。彼の著作は後

に、修辞学の分野において修辞的議論を分析するのに有用であることが判明した。1958年の著書『議論の用途』で発表された、議論を分析するために用いら

れる6つの相互に関連する要素を含む図式である「トゥルーミンの議論モデル」は、特に修辞学とコミュニケーションの分野、そしてコンピュータ科学におい

て、彼の最も影響力のある業績と見なされている。 |

| Biography Stephen Toulmin was born in London, UK, on 25 March 1922 to Geoffrey Edelson Toulmin and Doris Holman Toulmin.[1] He earned his Bachelor of Arts degree from King's College, Cambridge, in 1943, where he was a Cambridge Apostle. Soon after, Toulmin was hired by the Ministry of Aircraft Production as a junior scientific officer, first at the Malvern Radar Research and Development Station and later at the Supreme Headquarters of the Allied Expeditionary Force in Germany. At the end of World War II, he returned to England to earn a Master of Arts degree in 1947 and a PhD in philosophy from Cambridge University, subsequently publishing his dissertation as An Examination of the Place of Reason in Ethics (1950). While at Cambridge, Toulmin came into contact with the Austrian philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein, whose examination of the relationship between the uses and the meanings of language shaped much of Toulmin's own work. |

伝記 スティーブン・トゥルーミンは1922年3月25日、イギリス・ロンドンでジェフリー・エデルソン・トゥルーミンとドリス・ホルマン・トゥルーミンの子と して生まれた[1]。1943年にケンブリッジ大学キングズ・カレッジで文学士号を取得し、在学中はケンブリッジ・アポストリの会員であった。その後間も なく、トゥルーミンが航空機生産省に初級科学官として採用され、最初はマルバーン・レーダー研究開発ステーションで、後にドイツ駐留連合国遠征軍最高司令 部で勤務した。第二次世界大戦終結後、彼はイギリスに戻り、1947年にケンブリッジ大学で文学修士号、その後哲学博士号を取得した。博士論文は『倫理に おける理性の位置に関する考察』(1950年)として出版された。ケンブリッジ在学中、トゥルーミンはオーストリアの哲学者ルートヴィヒ・ウィトゲンシュ タインと接触した。ウィトゲンシュタインが言語の使用と意味の関係を考察したことは、トゥルーミンの研究の多くに影響を与えた。 |

| After graduating from Cambridge,

he was appointed University Lecturer in Philosophy of Science at Oxford

University from 1949 to 1954, during which period he wrote a second

book, The Philosophy of Science: an Introduction (1953). Soon after, he

was appointed to the position of Visiting Professor of History and

Philosophy of Science at Melbourne University in Australia from 1954 to

1955, after which he returned to England, and served as Professor and

Head of the Department of Philosophy at the University of Leeds from

1955 to 1959. While at Leeds, he published one of his most influential

books in the field of rhetoric, The Uses of Argument (1958)[pdf],

which

investigated the flaws of traditional logic. Although it was poorly

received in England and satirized as "Toulmin's anti-logic book" by

Toulmin's fellow philosophers at Leeds, the book was applauded by the

rhetoricians in the United States, where Toulmin served as a visiting

professor at New York, Stanford, and Columbia Universities in 1959.[2]

While in the States, Wayne Brockriede and Douglas Ehninger introduced

Toulmin's work to communication scholars, as they recognized that his

work provided a good structural model useful for the analysis and

criticism of rhetorical arguments. In 1960, Toulmin returned to London

to hold the position of director of the Unit for History of Ideas of

the Nuffield Foundation. |

ケンブリッジ大学卒業後、1949年から1954年までオックスフォー ド大学で科学哲学の大学講師を務めた。この期間に第二著書『科学哲学入門』(1953年)を執筆した。その後まもなく、1954年から1955年までオー ストラリアのメルボルン大学にて科学史・科学哲学の客員教授に任命された。その後イギリスに戻り、1955年から1959年までリーズ大学にて哲学教授お よび哲学部長を務めた。リーズ大学在職中、彼は修辞学分野で最も影響力のある著作の一つ『議論の用途』(1958年)を出版した。この著作は伝統的な論理 学の欠陥を検証したものである。この著作はイギリスでは不評で、リーズ大学の同僚哲学者たちから「トゥルーミンの反論理学書」と揶揄されたが、アメリカで は修辞学者たちから称賛された。トゥルーミンは1959年にニューヨーク大学、スタンフォード大学、コロンビア大学で客員教授を務めていた。[2] アメリカ滞在中、ウェイン・ブロックリードとダグラス・エニンガーは、トゥルーミンの研究が修辞的議論の分析と批判に有用な構造モデルを提供すると認識 し、コミュニケーション学者たちに彼の研究を紹介した。1960年、トゥルーミンはロンドンに戻り、ナフィールド財団の思想史研究ユニットのディレクター 職に就いた。 |

| In 1965, Toulmin returned to the

United States, where he held positions at various universities. In

1967, Toulmin served as literary executor for close friend N.R. Hanson,

helping in the posthumous publication of several volumes. While at the

University of California, Santa Cruz, Toulmin published Human

Understanding: The Collective Use and Evolution of Concepts

(1972),

which examines the causes and the processes of conceptual change. In

this book, Toulmin uses a novel comparison between conceptual change

and Charles Darwin's model of biological evolution to analyse the

process of conceptual change as an evolutionary process. The book

confronts major philosophical questions as well.[3] In 1973, while a

professor in the Committee on Social Thought at the University of

Chicago, he collaborated with Allan Janik, a philosophy professor at La

Salle University, on the book Wittgenstein's Vienna, which advanced a

thesis that underscores the significance of history to human reasoning:

Contrary to philosophers who believe the absolute truth advocated in

Plato's idealized formal logic, Toulmin argues that truth can be a

relative quality, dependent on historical and cultural contexts (what

other authors have termed "conceptual schemata"). |

1965年、トゥルーミンはアメリカに戻り、いくつかの大学で教職に就 いた。1967年には親友N・R・ハンソンの遺稿執行者として、数冊の著作の死後出版を手助けした。カリフォルニア大学サンタクルス校在職中、トゥルーミ ンは『人間の理解:概念の集合的使用と進化』(1972年)を出版した。この著作では概念変化の原因と過程を検証している。トゥルーミンは概念変化と チャールズ・ダーウィンの生物学的進化モデルとの斬新な比較を用い、概念変化の過程を進化的プロセスとして分析した。本書は主要な哲学的問題にも取り組ん でいる[3]。1973年、シカゴ大学社会思想委員会教授在任中に、ラ・サール大学哲学教授アラン・ジャニックと共著『ウィトゲンシュタインのウィーン』 を発表。この著作は、人間の推論における歴史の重要性を強調する論旨を展開した: プラトンの理想化された形式論理が主張する絶対的真理を信じる哲学者たちとは対照的に、トゥルーミンは真理が相対的な性質であり、歴史的・文化的文脈(他 の著者が「概念的枠組み」と呼んだもの)に依存し得ると論じる。 |

| From 1975 to 1978, he worked

with the National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of

Biomedical and Behavioral Research, established by the United States

Congress. During this time, he collaborated with Albert R. Jonsen to

write The Abuse

of Casuistry: A History of Moral Reasoning (1988),

which demonstrates the procedures for resolving moral cases. One of his

most recent works, Cosmopolis: The Hidden Agenda of Modernity (1990),

written while Toulmin held the position of the Avalon Foundation

Professor of the Humanities at Northwestern University, specifically

criticizes the practical use and the thinning morality underlying

modern science. |

1975年から1978年にかけて、彼は米国議会が設置した「生物医

学・行動研究における被験者保護のための国家委員会」で働いた。この期間、アルバート・R・ジョンセンと共同で『決疑論の濫用:道徳的推論の歴史』

(1988年)を執筆し、道徳的ケースを解決する手順を示した。彼の近著の一つである『コスモポリス:近代性の隠された意図』(1990年)は、ノース

ウェスタン大学アバロン財団人文科学教授職に就いていた時期に執筆されたもので、特に現代科学の実用主義的利用と、その根底にある薄っぺらい道徳観を批判

している。 |

| Toulmin held distinguished

professorships at a number of different universities, including

Columbia, Dartmouth College, Michigan State, Northwestern, Stanford,

the University of Chicago, and the University of Southern California

School of International Relations. In 1997 the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) selected Toulmin for the Jefferson Lecture, the U.S. federal government's highest honor for achievement in the humanities.[4][5] His lecture, "A Dissenter's Story" (alternatively entitled "A Dissenter's Life"), discussed the roots of modernity in rationalism and humanism, the "contrast of the reasonable and the rational", and warned of the "abstractions that may still tempt us back into the dogmatism, chauvinism and sectarianism our needs have outgrown".[6] The NEH report of the speech further quoted Toulmin on the need to "make the technical and the humanistic strands in modern thought work together more effectively than they have in the past".[7] On 2 March 2006 Toulmin received the Austrian Decoration for Science and Art.[8] He was married four times, once to June Goodfield,[9] with whom he collaborated on a series of books on the history of science. His children are Greg, of McLean, Va., Polly Macinnes of Skye, Scotland, Camilla Toulmin in the UK and Matthew Toulmin of Melbourne, Australia. On 4 December 2009 Toulmin died of a heart failure at the age of 87 in Los Angeles, California.[10] |

トゥルーミンはコロンビア大学、ダートマス大学、ミシガン州立大学、

ノースウェスタン大学、スタンフォード大学、シカゴ大学、南カリフォルニア大学国際関係学部など、異なる多くの大学で著名な教授職を務めた。 1997年、全米人文科学基金(NEH)はトゥルーミンをジェファーソン・レクチャーの講演者に選出した。これは米国連邦政府が人文科学分野の功績に対し て授与する最高の栄誉である。[4][5] 彼の講演「異議を唱える者の物語」(別題「異議を唱える者の生涯」)は、合理主義とヒューマニズムにおける近代性の根源、「合理的と理性的の対比」につい て論じ、我々の必要性がすでに超越した「独断主義、排外主義、宗派主義へ再び誘うかもしれない抽象概念」への警戒を促した。[6] NEHの講演報告書はさらに、トゥルーミンが「現代思想における技術的要素と人文的要素を、過去よりも効果的に連携させる必要性」について述べたことを引 用している。[7] 2006年3月2日、トゥルーミンはオーストリア科学芸術勲章を受章した。[8] 彼は4度の結婚歴があり、そのうち1度はジュン・グッドフィールド[9]とのもので、科学史に関する一連の著作を共同執筆した。子供はバージニア州マク リーン在住のグレッグ、スコットランド・スカイ島在住のポリー・マキネス、英国在住のカミラ・トゥルーミン、オーストラリア・メルボルン在住のマシュー・ トゥルーミンである。 2009年12月4日、トゥルーミンはカリフォルニア州ロサンゼルスにて心不全により87歳で死去した。[10] |

| Note |

脚注番号は上掲 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stephen_Toulmin |

ス

ティーヴン・トゥルーミンの哲学を、英語のウィキペディアのライターたちは"メタ哲学(Meta-philosophy)"と呼んでいる。トゥルーミンの

思考法を、哲学と呼ぼうがメタ哲学と呼ぼうが、どうでもいいのであるが、その思考法は傾聴に値する。

| Objection to

absolutism and relativism Throughout many of his works, Toulmin pointed out that absolutism (represented by theoretical or analytic arguments) has limited practical value. Absolutism is derived from Plato's idealized formal logic, which advocates universal truth; accordingly, absolutists believe that moral issues can be resolved by adhering to a standard set of moral principles, regardless of context. By contrast, Toulmin contends that many of these so-called standard principles are irrelevant to real situations encountered by human beings in daily life. To develop his contention, Toulmin introduced the concept of argument fields. In The Uses of Argument (1958), Toulmin claims that some aspects of arguments vary from field to field, and are hence called "field-dependent", while other aspects of argument are the same throughout all fields, and are hence called "field-invariant". The flaw of absolutism, Toulmin believes, lies in its unawareness of the field-dependent aspect of argument; absolutism assumes that all aspects of argument are field invariant. In Human Understanding (1972), Toulmin suggests that anthropologists have been tempted to side with relativists because they have noticed the influence of cultural variations on rational arguments. In other words, the anthropologist or relativist overemphasizes the importance of the "field-dependent" aspect of arguments, and neglects or is unaware of the "field-invariant" elements. In order to provide solutions to the problems of absolutism and relativism, Toulmin attempts throughout his work to develop standards that are neither absolutist nor relativist for assessing the worth of ideas. In Cosmopolis (1990), he traces philosophers' "quest for certainty" back to René Descartes and Thomas Hobbes, and lauds John Dewey, Wittgenstein, Martin Heidegger, and Richard Rorty for abandoning that tradition. |

絶対主義と相対主義への異議 トゥールミンは多くの著作で、絶対主義(理論的・分析的議論に代表される)の実用的な価値は限定的だと指摘した。絶対主義はプラトンの理想化された形式論 理に由来し、普遍的真理を主張する。したがって絶対主義者は、文脈に関わらず標準的な道徳原則に従うことで道徳的問題は解決できると信じる。これに対し トゥールミンは、こうしたいわゆる標準原則の多くは、人間が日常生活で直面する現実の状況とは無関係だと論じる。 この主張を展開するため、トゥールミンは議論の領域という概念を導入した。『議論の用途』(1958年)において、彼は議論のいくつかの側面は領域によっ て異なり「領域依存的」と呼ばれる一方、他の側面はあらゆる領域で共通であり「領域不変的」と呼ばれると主張している。トゥールミンは、絶対主義の欠陥 は、議論の分野依存的側面を認識していない点にあると考えている。絶対主義は、議論のあらゆる側面が分野不変であると仮定するのだ。 『人間の理解』(1972年)において、トゥールミンは人類学者が相対主義者に同調する誘惑に駆られてきたのは、文化的差異が合理的な議論に影響を与える ことに気づいたからだと示唆している。つまり、人類学者や相対主義者は、議論の「分野依存的」側面の重要性を過度に強調し、「分野不変的」要素を軽視、あ るいは認識していない。絶対主義と相対主義の問題に対する解決策を提供するため、トゥールミンは、その著作全体を通じて、アイデアの価値を評価するため の、絶対主義でも相対主義でもない基準の開発を試みている。 『コスモポリス』(1990年)では、哲学者の「確実性の追求」をルネ・デカルトとトマス・ホッブズにまで遡って考察し、その伝統を放棄したジョン・ デューイ、ウィトゲンシュタイン、マーティン・ハイデガー、リチャード・ローティを称賛している。 |

| Humanizing modernity In Cosmopolis Toulmin seeks the origins of the modern emphasis on universality (philosophers' "quest for certainty"), and criticizes both modern science and philosophers for having ignored practical issues in preference for abstract and theoretical issues. The pursuit of absolutism and theoretical arguments lacking practicality, for example, is, in his view, one of the main defects of modern philosophy. Similarly, Toulmin sensed a thinning of morality in the field of sciences, which has diverted its attention from practical issues concerning ecology to the production of the atomic bomb. To solve this problem, Toulmin advocated a return to humanism consisting of four returns: a return to oral communication and discourse, a plea which has been rejected by modern philosophers, whose scholarly focus is on the printed page; a return to the particular or individual cases that deal with practical moral issues occurring in daily life (as opposed to theoretical principles that have limited practicality); a return to the local, or to concrete cultural and historical contexts; and, finally, a return to the timely, from timeless problems to things whose rational significance depends on the time lines of our solutions. He follows up on this critique in Return to Reason (2001), where he seeks to illuminate the ills that, in his view, universalism has caused in the social sphere, discussing, among other things, the discrepancy between mainstream ethical theory and real-life ethical quandaries. |

近代の人間化 『コスモポリス』において、トゥルーミンは近代における普遍性への強調(哲学者の「確実性の追求」)の起源を探り、実践的問題を軽視して抽象的・理論的問 題を優先したとして、近代科学と哲学者の双方を批判している。例えば、絶対主義の追求や実践性を欠いた理論的議論は、彼の見解では近代哲学の主要な欠陥の 一つである。同様に、トゥルーミンは科学分野における道徳性の希薄化を察知した。それは生態学に関する実践的問題から原子爆弾の製造へと注意を逸らしたの である。この問題を解決するため、トゥルーミンは四つの回帰からなるヒューマニズムへの回帰を提唱した。第一に、口頭でのコミュニケーションと言説への回 帰である。これは印刷物に学術的焦点を置く現代哲学者たちによって拒絶されてきた主張だ。第二に、日常生活で生じる実践的な道徳的問題を扱う個別事例や個 別ケースへの回帰である(実用性が限られた理論的原則とは対照的に)。地域性、すなわち具体的文化的・歴史的文脈への回帰。そして最後に、永遠の問題か ら、その合理的意義が我々の解決策の時間軸に依存する事象への回帰である。彼はこの批判を『理性の回帰』(2001年)でさらに展開し、普遍主義が社会領 域にもたらした弊害を明らかにしようとする。そこでは、主流の倫理理論と現実の倫理的ジレンマとの乖離などが論じられている。 |

| Argumentation |

議論 |

Toulmin model of argument Toulmin argumentation can be diagrammed as a conclusion established, more or less, on the basis of a fact supported by a warrant (with backing), and a possible rebuttal. Further information: Practical arguments Arguing that absolutism lacks practical value, Toulmin aimed to develop a different type of argument, called practical arguments (also known as substantial arguments). In contrast to absolutists' theoretical arguments, Toulmin's practical argument is intended to focus on the justificatory function of argumentation, as opposed to the inferential function of theoretical arguments. Whereas theoretical arguments make inferences based on a set of principles to arrive at a claim, practical arguments first find a claim of interest, and then provide justification for it. Toulmin believed that reasoning is less an activity of inference, involving the discovering of new ideas, and more a process of testing and sifting already existing ideas—an act achievable through the process of justification. Toulmin believed that for a good argument to succeed, it needs to provide good justification for a claim. This, he believed, will ensure it stands up to criticism and earns a favourable verdict. In The Uses of Argument (1958), Toulmin proposed a layout containing six interrelated components for analyzing arguments: Claim (Conclusion) A conclusion whose merit must be established. In argumentative essays, it may be called the thesis.[11] For example, if a person tries to convince a listener that he is a British citizen, the claim would be "I am a British citizen" (1). Ground (Fact, Evidence, Data) A fact one appeals to as a foundation for the claim. For example, the person introduced in 1 can support his claim with the supporting data "I was born in Bermuda" (2). Warrant A statement authorizing movement from the ground to the claim. In order to move from the ground established in 2, "I was born in Bermuda", to the claim in 1, "I am a British citizen", the person must supply a warrant to bridge the gap between 1 and 2 with the statement "A man born in Bermuda will legally be a British citizen" (3). Backing Credentials designed to certify the statement expressed in the warrant; backing must be introduced when the warrant itself is not convincing enough to the readers or the listeners. For example, if the listener does not deem the warrant in 3 as credible, the speaker will supply the legal provisions: "I trained as a barrister in London, specialising in citizenship, so I know that a man born in Bermuda will legally be a British citizen". Rebuttal (Reservation) Statements recognizing the restrictions which may legitimately be applied to the claim. It is exemplified as follows: "A man born in Bermuda will legally be a British citizen, unless he has betrayed Britain and has become a spy for another country". Qualifier Words or phrases expressing the speaker's degree of force or certainty concerning the claim. Such words or phrases include "probably", "possible", "impossible", "certainly", "presumably", "as far as the evidence goes", and "necessarily". The claim "I am definitely a British citizen" has a greater degree of force than the claim "I am a British citizen, presumably". (See also: Defeasible reasoning.) |

トゥルーミンの議論モデル トゥルーミンの議論は、保証(裏付け)によって支持された事実と、反論の可能性に基づいて、多かれ少なかれ確立された結論として図式化できる。 詳細情報:実践的議論 絶対主義には実践的価値がないと主張するトゥルーミンは、実践的議論(実質的議論とも呼ばれる)と呼ばれる異なるタイプの議論を発展させることを目指し た。絶対主義者の理論的議論とは対照的に、トゥルーミンの実践的議論は、理論的議論の推論機能とは異なり、議論の正当化機能に焦点を当てることを意図して いる。理論的議論が一連の原則に基づいて推論を行い主張に到達するのに対し、実践的議論はまず関心のある主張を見つけ、その後それを正当化する。トゥルー ミンは、推論とは新しい考えを発見する推論活動というより、既存の考えを検証し選別するプロセスであり、それは正当化の過程を通じて達成可能だと考えた。 トゥルーミンは、優れた議論が成功するには、主張に対して十分な正当化を提供する必要があると考えた。これにより批判に耐え、好意的な評価を得られると彼 は信じていた。『議論の用途』(1958年)において、トゥルーミンは議論を分析するための相互に関連する6つの構成要素からなる枠組みを提案した: 主張(結論) その正当性を確立すべき結論。論説文では「テーゼ」と呼ばれることもある[11]。例えば、ある人格が聞き手に自分が英国市民であると説得しようとする場 合、主張は「私は英国市民である」(1)となる。 根拠(事実、証拠、データ) 主張の基盤として訴える事実。例えば、1で述べた人格は「私はバミューダで生まれた」という支持データ(2)で主張を裏付けられる。 保証 根拠から主張への移行を正当化する文言。2で確立した根拠「私はバミューダで生まれた」から、1の主張「私は英国市民である」へ移行するには、1と2の間 の隔たりを埋める保証文「バミューダ生まれの男性は法的に英国市民となる」を提示する必要がある(3)。 裏付け 保証文で表明された主張を証明するための証拠。保証文自体が読者や聴衆を十分に納得させられない場合に提示される。例えば、聴衆が3の保証文を信用しない 場合、発言者は法的根拠を提示する:「私はロンドンで弁護士として訓練を受け、市民権を専門とした。故に、バミューダ生まれの男性は法的に英国市民となる ことを知っている」。 反論(留保) 主張に対して正当に適用され得る制限を認める発言。例:「バミューダ生まれの男性は、英国を裏切り他国のスパイとなった場合を除き、法的に英国市民とな る」 限定語 主張に対する話者の確信度や力強さを示す語句。例:「おそらく」「可能性」「不可能」「確かに」「おそらく」「証拠の範囲内では」「必然的に」など。「私 は間違いなく英国市民だ」という主張は「おそらく英国市民だ」という主張より強い確信度を持つ。(参照:反駁可能な推論) |

| The

first three elements, claim, ground, and warrant, are considered as the

essential components of practical arguments, while the second triad,

qualifier, backing, and rebuttal, may not be needed in some arguments. |

最初の三要素である主張、根拠、保証は、実践的な議論の必須要素と見な

される。一方、二番目の三要素である限定条件、裏付け、反論は、一部の議論では必要とされない場合がある。 |

| When

Toulmin first proposed it, this layout of argumentation was based on

legal arguments and intended to be used to analyze the rationality of

arguments typically found in the courtroom. Toulmin did not realize

that this layout could be applicable to the field of rhetoric and

communication until his works were introduced to rhetoricians by Wayne

Brockriede and Douglas Ehninger. Their Decision by Debate (1963)

streamlined Toulmin's terminology and broadly introduced his model to

the field of debate.[12] Only after Toulmin published Introduction to

Reasoning (1979) were the rhetorical applications of this layout

mentioned in his works. One criticism of the Toulmin model is that it does not fully consider the use of questions in argumentation.[13] The Toulmin model assumes that an argument starts with a fact or claim and ends with a conclusion, but ignores an argument's underlying questions. In the example "Harry was born in Bermuda, so Harry must be a British subject", the question "Is Harry a British subject?" is ignored, which also neglects to analyze why particular questions are asked and others are not. (See Issue mapping for an example of an argument-mapping method that emphasizes questions.) Toulmin's argument model has inspired research on, for example, goal structuring notation (GSN), widely used for developing safety cases,[14] and argument maps and associated software.[15] |

トゥルーミンが最初にこの議論の枠

組みを提案した時、それは法廷における議論を分析するために考案されたもので、法廷で典型的に見られる議論の合理性を分析することを目的としていた。トゥ

ルーミン自身が、この枠組みが修辞学やコミュニケーションの分野にも適用可能であることに気づいたのは、ウェイン・ブロックリードとダグラス・エニング

アーによって彼の著作が修辞学者たちに紹介されてからのことだった。彼らの『ディベートによる決定』(1963年)は、トゥルーミンの用語体系を整理し、

そのモデルをディベート分野に広く紹介した[12]。トゥルーミン自身がこの枠組みの修辞学的応用について言及したのは、『推論入門』(1979年)を出

版してからのことである。 トゥルーミン・モデルの批判の一つは、議論における質問の使用を十分に考慮していない点だ。[13] トゥルーミンモデルは、議論が事実や主張から始まり結論で終わることを前提とするが、議論の根底にある質問を無視している。「ハリーはバミューダで生まれ たから、ハリーは英国国民に違いない」という例では、「ハリーは英国国民か?」という質問が無視され、なぜ特定の質問が投げかけられ、他の質問は投げかけ られないのかという分析も欠けている。(質問を重視する議論マッピング手法の例については、イシューマッピングを参照のこと。) トゥルーミンの議論モデルは、例えば安全ケース開発に広く用いられる目標構造化表記法(GSN)[14]や、議論マップ及び関連ソフトウェア[15]など の研究に影響を与えている。 |

| Ethics |

倫理(学) |

| Good reasons approach In Reason in Ethics (1950), his doctoral dissertation, Toulmin sets out a Good Reasons approach of ethics, and criticizes what he considers to be the subjectivism and emotivism of philosophers such as A. J. Ayer because, in his view, they fail to do justice to ethical reasoning. |

正当な理由のアプローチ トゥルーミンは博士論文『倫理における理由』(1950年)において、倫理学における正当な理由のアプローチを提唱し、A・J・エイヤーら哲学者たちの主 観主義や感情主義を批判した。彼の見解では、彼らは倫理的推論を正当に評価できていないからである。 |

| Revival of casuistry By reviving casuistry (also known as case ethics), Toulmin sought to find the middle ground between the extremes of absolutism and relativism. Casuistry was practiced widely during the Middle Ages and the Renaissance to resolve moral issues. Although casuistry largely fell silent during the modern period, in The Abuse of Casuistry: A History of Moral Reasoning (1988), Toulmin collaborated with Albert R. Jonsen to demonstrate the effectiveness of casuistry in practical argumentation during the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, effectively reviving it as a permissible method of argument. Casuistry employs absolutist principles, called "type cases" or "paradigm cases", without resorting to absolutism. It uses the standard principles (for example, sanctity of life) as referential markers in moral arguments. An individual case is then compared and contrasted with the type case. Given an individual case that is completely identical to the type case, moral judgments can be made immediately using the standard moral principles advocated in the type case. If the individual case differs from the type case, the differences will be critically assessed in order to arrive at a rational claim. Through the procedure of casuistry, Toulmin and Jonsen identified three problematic situations in moral reasoning: first, the type case fits the individual case only ambiguously; second, two type cases apply to the same individual case in conflicting ways; third, an unprecedented individual case occurs, which cannot be compared or contrasted to any type case. Through the use of casuistry, Toulmin demonstrated and reinforced his previous emphasis on the significance of comparison to moral arguments, a significance not addressed in theories of absolutism or relativism. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stephen_Toulmin +++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ Casuistry (/ˈkæzjuɪstri/ KAZ-ew-iss-tree) is a process of reasoning for resolving an ethical dilemma (moral problem) either by extracting or by extending abstract rules from a particular case of conscience, and reapplying those abstract rules to other, different ethical dilemmas.[1] Casuistry is a method of reasoning common to applied ethics and jurisprudence. Moreover, in philosophy, the term casuistry is a pejorative criticism of the use of clever, but unsound reasoning, especially in ethical questions, as in the case of sophistry.[2] As a method of reasoning, casuistry is both the: Study of cases of conscience and a method of solving conflicts of obligations by applying general principles of ethics, religion, and moral theology to particular and concrete cases of human conduct. This frequently demands an extensive knowledge of natural law and equity, civil law, ecclesiastical precepts, and an exceptional skill in interpreting these various norms of conduct. . . .[3] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Casuistry +++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ In ethics, casuistry (/ˈkæzjuɪstri/ KAZ-ew-iss-tree) is a process of reasoning that seeks to resolve moral problems by extracting or extending abstract rules from a particular case, and reapplying those rules to new instances. https://navymule9.sakura.ne.jp/Casuistry.html |

決疑論の

復活 決疑論(別名:決疑論)の復活により、トゥルーミンは絶対主義と相対主義という両極端の中間点を見出そうとした。決疑論は中世とルネサンス期に広く実践さ れ、道徳的問題を解決するために用いられた。近代において決疑論はほぼ廃れたが、トゥルーミンは『決疑論の濫用:道徳的推論の歴史』(1988年)におい てアルバート・R・ジョンセンと共同で、中世とルネサンス期における実践的議論における決疑論の有効性を示し、これを許容される議論方法として事実上復活 させた。 決疑論は絶対主義に陥ることなく、「類型事例」あるいは「パラダイム事例」と呼ばれる絶対主義的原理を用いる。道徳的議論において基準となる原理(例えば 生命の尊厳)を参照指標として使用する。個々の事例を類型事例と比較対照する。個々の事例が類型事例と完全に同一であれば、類型事例で提唱される標準的道 徳原理を用いて即座に道徳的判断を下せる。個別事例が類型事例と異なる場合、差異を批判的に評価し、合理的な主張を導き出すのである。 決疑論の過程を通じて、トゥルーミンとジョンセンは道徳的推論における三つの問題状況を特定した。第一に、類型事例が個別事例に曖昧にしか適合しない場 合。第二に、二つの類型事例が同一個別事例に矛盾する形で適用される場合。第三に、いかなる類型事例とも比較対照できない前例のない個別事例が発生する場 合である。決疑論の手法を用いることで、トゥルーミンは道徳的議論における比較の重要性を示し、その重要性を強調した。この重要性は、絶対主義や相対主義 の理論では扱われていなかったものである。 +++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ 決疑論あるいはカズイストリー(/ˈkæzjuɪstri/ KAZ-ew-iss-tree)とは、倫理的ジレンマ(道徳的問題)を解決するための推論過程である。具体的には、良心の特定の事例から抽象的な規則を 抽出し、あるいは拡張し、それらの抽象的な規則を他の異なる倫理的ジレンマに再適用する。[1] カズイストリーは応用倫理学と法学に共通する推論方法である。さらに哲学において、カズイストリーという用語は、特に倫理的問題において、ソフィストの論 法のように、巧妙だが不健全な推論を用いることに対する蔑称的な批判である。[2] 推論の方法として、カズイストリーは次の両方を指す: 良心の事例研究であると同時に、倫理・宗教・道徳神学の一般原則を具体的かつ個別の人的行為事例に適用することで義務の衝突を解決する手法である。これに は自然法・衡平法・民法・教会教義に関する広範な知識と、これらの多様な行動規範を解釈する卓越した技能が頻繁に求められる。……[3] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Casuistry +++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ 倫理学において決疑法(/ˈkæzjuɪstri/ KAZ-ew-iss-tree)とは、特定の事例から抽象的なルールを抽出または 拡張し、それらのルールを新たな事例に再適用することによって道徳的問 題を解決しようとする推論のプロセス https://navymule9.sakura.ne.jp/Casuistry.html |

| Philosophy of science |

科学哲学 |

| Evolutionary model In 1972, Toulmin published Human Understanding, in which he asserts that conceptual change is an evolutionary process. In this book, Toulmin attacks Thomas Kuhn's account of conceptual change in his seminal work The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (1962). Kuhn believed that conceptual change is a revolutionary process (as opposed to an evolutionary process), during which mutually exclusive paradigms compete to replace one another. Toulmin criticized the relativist elements in Kuhn's thesis, arguing that mutually exclusive paradigms provide no ground for comparison, and that Kuhn made the relativists' error of overemphasizing the "field variant" while ignoring the "field invariant" or commonality shared by all argumentation or scientific paradigms. In contrast to Kuhn's revolutionary model, Toulmin proposed an evolutionary model of conceptual change comparable to Darwin's model of biological evolution. Toulmin states that conceptual change involves the process of innovation and selection. Innovation accounts for the appearance of conceptual variations, while selection accounts for the survival and perpetuation of the soundest conceptions. Innovation occurs when the professionals of a particular discipline come to view things differently from their predecessors; selection subjects the innovative concepts to a process of debate and inquiry in what Toulmin considers as a "forum of competitions". The soundest concepts will survive the forum of competition as replacements or revisions of the traditional conceptions. From the absolutists' point of view, concepts are either valid or invalid regardless of contexts. From the relativists' perspective, one concept is neither better nor worse than a rival concept from a different cultural context. From Toulmin's perspective, the evaluation depends on a process of comparison, which determines whether or not one concept will improve explanatory power more than its rival concepts. |

進化モデル 1972年、トゥルーミンは『人間の理解』を出版した。この本で彼は、概念の変化は進化的なプロセスであると主張している。トゥルーミンはこの書物におい て、トーマス・クーンの画期的な著作『科学革命の構造』(1962年)における概念変化の説明を批判している。クーンは概念変化が革命的なプロセス(進化 的なプロセスとは対照的に)であり、その過程で互いに排他的なパラダイムが互いを置き換えるために競い合うと信じていた。トゥルーミンはクーンの主張に含 まれる相対主義的要素を批判し、互いに排他的なパラダイムは比較の基盤を提供せず、クーンが「分野変異」を過度に強調する一方で、全ての議論や科学的パラ ダイムに共通する「分野不変」要素を無視するという相対主義者の誤りを犯したと論じた。 クーンの革命的モデルとは対照的に、トゥルーミンはダーウィンの生物学的進化モデルに匹敵する概念変化の進化的モデルを提案した。トゥルーミンによれば、 概念変化には革新と選択のプロセスが伴う。革新は概念的変異の出現を説明し、選択は最も妥当な概念の存続と永続を説明する。革新は特定分野の専門家が先人 とは異なる見解を持つことで生じ、選択は革新的な概念をトゥルーミンが「競争の場」と称する議論と探究のプロセスに晒す。最も妥当な概念は、伝統的概念の 代替または修正として、競争の場の試練を生き残るのである。 絶対主義者の立場では、概念は文脈に関わらず有効か無効かのいずれかである。相対主義者の視点では、異なる文化的文脈に由来する競合概念と比べて、ある概 念が優れているとも劣っているとも言い切れない。トゥルーミンの視点では、評価は比較のプロセスに依存し、ある概念が競合概念よりも説明力を向上させるか どうかを決定するのである。 |

| Pantheon of skeptics At a meeting of the executive council of the Committee for Skeptical Inquiry (CSI) in Denver, Colorado in April 2011, Toulmin was selected for inclusion in CSI's Pantheon of Skeptics. The Pantheon of Skeptics was created by CSI to remember the legacy of deceased fellows of CSI and their contributions to the cause of scientific skepticism.[16] |

懐疑主義者の殿堂 2011年4月、コロラド州デンバーで開催された懐疑的探究委員会(CSI)の執行理事会において、トゥルーミンはCSIの「懐疑主義者の殿堂」への選出 が決定された。この殿堂は、CSIの故人となったフェローたちの功績と科学的懐疑主義への貢献を記念するためにCSIが創設したものである。[16] |

| Works An Examination of the Place of Reason in Ethics (1950) ISBN 0-226-80843-2 The Philosophy of Science: An Introduction (1953) The Uses of Argument (1958) 2nd edition 2003: ISBN 0-521-53483-6 Metaphysical Beliefs, Three Essays (1957) with Ronald W. Hepburn and Alasdair MacIntyre The Riviera (1961) Seventeenth century science and the arts (1961) Foresight and Understanding: An Enquiry into the Aims of Science (1961) ISBN 0-313-23345-4 The Fabric of the Heavens (The Ancestry of Science, volume 1) (1961) with June Goodfield ISBN 0-226-80848-3 The Architecture of Matter (The Ancestry of Science, volume 2) (1962) with June Goodfield ISBN 0-226-80840-8 Night Sky at Rhodes (1963) The Discovery of Time (The Ancestry of Science, volume 3) (1965) with June Goodfield ISBN 0-226-80842-4 Physical Reality (1970) Human Understanding: The Collective Use and Evolution of Concepts (1972) ISBN 0-691-01996-7 Wittgenstein's Vienna (1973) with Allan Janik On the Nature of the Physician's Understanding (1976)[17] Knowing and Acting: An Invitation to Philosophy (1976) ISBN 0-02-421020-X An Introduction to Reasoning with Allan Janik and Richard D. Rieke (1979), 2nd ed. 1984; 3rd edition 1997: ISBN 0-02-421160-5 The Return to Cosmology: Postmodern Science and the Theology of Nature (1985) ISBN 0-520-05465-2 The Abuse of Casuistry: A History of Moral Reasoning (1988) with Albert R. Jonsen ISBN 0-520-06960-9 Cosmopolis: The Hidden Agenda of Modernity (1990) ISBN 0-226-80838-6 Social Impact of AIDS in the United States (1993) with Albert R. Jonsen Beyond theory – changing organizations through participation (1996) with Björn Gustavsen (editors) Return to Reason (2001) ISBN 0-674-01235-6 |

著作 倫理学における理性の位置づけに関する考察(1950年) ISBN 0-226-80843-2 科学哲学入門(1953年) 議論の用法(1958年) 第2版2003年:ISBN 0-521-53483-6 形而上学的な信念、三つの論文(1957)ロナルド・W・ヘップバーン、アラスデア・マッキンタイアと共著 リヴィエラ(1961) 17世紀の科学と芸術(1961) 先見性と理解:科学の目的に関する考察(1961)ISBN 0-313-23345-4 『天の構造』(科学の祖先、第1巻)(1961年)ジューン・グッドフィールドと共著 ISBN 0-226-80848-3 『物質の構造』(科学の祖先、第2巻)(1962年)ジューン・グッドフィールドと共著 ISBN 0-226-80840-8 ロードス島の夜空(1963年) 時間の発見(科学の祖先、第3巻)(1965年)ジューン・グッドフィールドとの共著 ISBN 0-226-80842-4 物理的現実(1970年) 人間の理解:概念の集合的使用と進化(1972年) ISBN 0-691-01996-7 ウィトゲンシュタインのウィーン(1973)アラン・ジャニックと共著 医師の理解の本質について(1976)[17] 知ることと行動すること:哲学への招待(1976)ISBN 0-02-421020-X 『推論入門』アラン・ジャニック、リチャード・D・リーク共著(1979年)、第2版1984年、第3版1997年 ISBN 0-02-421160-5 『宇宙論への回帰:ポストモダン科学と自然の神学』(1985年) ISBN 0-520-05465-2 『決疑論の濫用:道徳的推論の歴史』(1988年)アルバート・R・ジョンセンとの共著 ISBN 0-520-06960-9 『コスモポリス:近代性の隠されたアジェンダ』(1990年) ISBN 0-226-80838-6 『米国におけるエイズの社会的影響』(1993年)アルバート・R・ジョンセンとの共著 『理論を超えて―参加による組織変革』(1996年)ビョルン・グスタフセンとの共著(編者) 『理性への回帰』(2001年)ISBN 0-674-01235-6 |

| Argumentation

theory Cambridge University Moral Sciences Club |

論証理論 ケンブリッジ大学道徳科学クラブ |

| Further reading Hitchcock, David; Verheij, Bart, eds. (2006). Arguing on the Toulmin Model: New Essays in Argument Analysis and Evaluation. Springer-Verlag Netherlands. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-4938-5_3. ISBN 978-1-4020-4937-8. OCLC 82229075. |

参考文献 ヒッチコック、デイヴィッド;フェルハイ、バート編(2006)。『トゥルーミン・モデルに基づく議論:議論分析と評価に関する新論集』。スプリンガー・ ヴェルラッグ・ネザーランズ。doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-4938-5_3。ISBN 978-1-4020-4937-8。OCLC 82229075。 |

| 1. "Toulmin, Stephen Edelston

(1922–2009), philosopher and historian of ideas". Oxford Dictionary of

National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. 2004.

doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/102307. ISBN 978-0-19-861411-1. Retrieved 8

January 2025. (Subscription, Wikipedia Library access or UK public

library membership required.) 2. Loui, Ronald P. (2006). "A Citation-Based Reflection on Toulmin and Argument". In Hitchcock, David; Verheij, Bart (eds.). Arguing on the Toulmin Model: New Essays in Argument Analysis and Evaluation. Springer Netherlands. pp. 31–38. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-4938-5_3. ISBN 978-1-4020-4937-8. Retrieved 25 June 2010. Toulmin's 1958 work is essential in the field of argumentation 3. Westfall, Richard. "Review: Toulmin and Human Understanding". The Journal of Modern History. 47 (4): 691–8. doi:10.1086/241374. S2CID 147375119. 4. Jefferson Lecturers Archived 20 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine at NEH Website (retrieved 22 January 2009). 5. "California Scholar Wins Government Honor", The New York Times, 12 February 1997. 6. Stephen Toulmin, "A Dissenter's Life" Archived 27 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine (text of Toulmin's Jefferson Lecture) at USC website. 7. "The Jefferson Lecture" Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, report on 1997 lecture, at NEH website. 8. "Reply to a parliamentary question" (PDF) (in German). p. 1761. Retrieved 24 November 2012. 9. The Discovery of Time. Penguin. 1967. 10. Grimes, William (11 December 2009). "Stephen Toulmin, a Philosopher and Educator, Dies at 87". The New York Times. 11. Wheeler, Kip (19 October 2010). "Toulmin Model of Argument" (PDF). cn.edu. Retrieved 12 October 2018. 12. Book description of Decision by Debate at Google Books: "The most lasting legacy of the work is its break with formal, deductive logic and its introduction of Stephen Toulmin's model of argument to undergraduate student debaters, which, since then, has become a mainstay of what many have called the Renaissance of argumentation studies. Without the work presented in Decision by Debate, contemporary interdisciplinary views of argumentation that now dominate many disciplines might have never have taken place or at least have been severely delayed." 13. Eruduran, Sibel; Aleixandre, Marilar, eds. (2007). Argumentation in Science Education: Perspectives from Classroom-Based Research. Science & Technology Education Library. Vol. 35. New York: Springer-Verlag. pp. 15–16. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-6670-2. ISBN 9781402066696. OCLC 171556540. 14. Spriggs, John (2012). GSN—The Goal Structuring Notation: A Structured Approach to Presenting Arguments. London; New York: Springer-Verlag. doi:10.1007/978-1-4471-2312-5. ISBN 9781447123118. OCLC 792775478. 15. Reed, Chris; Walton, Douglas N.; Macagno, Fabrizio (March 2007). "Argument diagramming in logic, law and artificial intelligence". The Knowledge Engineering Review. 22 (1): 87–109. doi:10.1017/S0269888907001051. S2CID 26294789. 16. "The Pantheon of Skeptics". CSI. Committee for Skeptical Inquiry. Archived from the original on 31 January 2017. Retrieved 30 April 2017. 17. The Journal of Medicine and Philosophy, 1976, vol. 1, no. 1 |

1.

「トゥルーミン、スティーブン・エデルストン(1922–2009)、哲学者・思想史家」。『オックスフォード国家人物事典』(オンライン版)。オックス

フォード大学出版局。2004年。doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/102307。ISBN

978-0-19-861411-1。2025年1月8日取得。(購読、Wikipedia

Libraryアクセス、または英国公共図書館会員資格が必要) 2. Loui, Ronald P. (2006). 「トゥルーミンと議論に関する引用に基づく考察」. Hitchcock, David; Verheij, Bart (編). 『トゥルーミンモデルに基づく議論:議論分析と評価の新論考』. Springer Netherlands. pp. 31–38. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-4938-5_3. ISBN 978-1-4020-4937-8. 2010年6月25日閲覧。 トゥルーミンの1958年の著作は論証の分野において不可欠である 3. ウェストフォール、リチャード。「書評: トゥルーミンと人間の理解」『現代史ジャーナル』47巻4号: 691–8頁. doi:10.1086/241374. S2CID 147375119. 4. ジェファーソン記念講演者 NEHウェブサイト(2011年10月20日ウェイバックマシンにアーカイブ)より(2009年1月22日取得). 5. 「カリフォルニアの学者が政府栄誉を受賞」『ニューヨーク・タイムズ』1997年2月12日付。 6. スティーブン・トゥルーミン「異論者の生涯」USCウェブサイト(トゥルーミンのジェファーソン講演テキスト、2009年2月27日ウェイバックマシンに アーカイブ)。 7. 「ジェファーソン講演」2016年3月3日ウェイバックマシンにアーカイブ、1997年講演の報告、NEHウェブサイト掲載。 8. 「議会質問への回答」(PDF)(ドイツ語)。p. 1761。2012年11月24日閲覧。 9. 『時間の発見』。ペンギン社。1967年。 10. グライムズ、ウィリアム(2009年12月11日)。「哲学者・教育者スティーブン・トゥルーミン、87歳で死去」。ニューヨーク・タイムズ。 11. ウィーラー、キップ(2010年10月19日)。「トゥルーミン論証モデル」(PDF)。cn.edu。2018年10月12日閲覧。 12. Google Booksにおける『ディシジョン・バイ・ディベート』の書籍説明:「この著作の最も永続的な遺産は、形式的演繹論理からの決別と、学部生ディベーターへ のスティーブン・トゥルーミンの議論モデルの提示である。これはその後、多くの者が議論研究のルネサンスと呼ぶものの基幹となった。『ディシジョン・バ イ・ディベート』で提示された研究がなければ、現在多くの分野で主流となっている現代的な学際的議論観は、おそらく生まれなかったか、少なくとも大幅に遅 れていたであろう。」 13. Eruduran, Sibel; Aleixandre, Marilar, 編 (2007). 『科学教育における議論:教室ベース研究からの視点』. 科学技術教育ライブラリー. 第35巻. ニューヨーク:シュプリンガー・フェルラッグ。pp. 15–16。doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-6670-2。ISBN 9781402066696。OCLC 171556540。 14. スプリッグス、ジョン(2012)。GSN—目標構造化表記法:議論を提示する構造化されたアプローチ。ロンドン;ニューヨーク:シュプリンガー・ヴェル ラッグ。doi:10.1007/978-1-4471-2312-5。ISBN 9781447123118。OCLC 792775478。 15. リード、クリス; ウォルトン、ダグラス N.; マカニョ、ファブリツィオ (2007年3月). 「論理学、法学、人工知能における議論の図式化」. 『ナレッジ・エンジニアリング・レビュー』. 22 (1): 87–109. doi:10.1017/S0269888907001051. S2CID 26294789. 16. 「懐疑主義者の殿堂」. CSI. 懐疑的調査委員会. 2017年1月31日にオリジナルからアーカイブ. 2017年4月30日に閲覧. 17. 『医学と哲学のジャーナル』, 1976年, 第1巻, 第1号 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stephen_Toulmin |

★ 伝記

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099