Medical Ethics

医療倫理学

Medical Ethics

医療倫理学(いりょう・りんりがく; Medical ethics) とは、保健ケアとくに医療に関する倫理的事象(=医療倫理)をあつかう研究 分野である。医療のみならず、生物学、政治学、 社会学、文化人類学、法学、哲学などのさまざまな分野と関連性をもつ、学際的な研究分野である。生命倫理学(bioethics, バイオエシックス)と医療倫理学はテーマを共有することが多いので、「基本的に同じ」と判断しても間違いではない。私は、別項で生命倫理学を次のように定 義しています。つまり生命倫理とは「人間を対象にした治療および実験に関する倫理・道徳、ひいてはそれらに関する諸研究」(→ 出典「生命倫理学と医療人類学」)

★ここでは医療倫理のABCを(英語ウィ キペディアの"Medical ethics" にしたがって)説明します

| Definition and

Outline Medical ethics is an applied branch of ethics which analyzes the practice of clinical medicine and related scientific research.[1] Medical ethics is based on a set of values that professionals can refer to in the case of any confusion or conflict. These values include the respect for autonomy, non-maleficence, beneficence, and justice.[2] Such tenets may allow doctors, care providers, and families to create a treatment plan and work towards the same common goal.[3] These four values are not ranked in order of importance or relevance and they all encompass values pertaining to medical ethics.[4] However, a conflict may arise leading to the need for hierarchy in an ethical system, such that some moral elements overrule others with the purpose of applying the best moral judgement to a difficult medical situation.[5] Medical ethics is particularly relevant in decisions regarding involuntary treatment and involuntary commitment. There are several codes of conduct. The Hippocratic Oath discusses basic principles for medical professionals.[5] This document dates back to the fifth century BCE.[6] Both The Declaration of Helsinki (1964) and The Nuremberg Code (1947) are two well-known and well respected documents contributing to medical ethics. Other important markings in the history of medical ethics include Roe v. Wade[why?] in 1973 and the development of hemodialysis in the 1960s. With hemodialysis now available, but a limited number of dialysis machines to treat patients, an ethical question arose on which patients to treat and which ones not to treat, and which factors to use in making such a decision.[7] More recently, new techniques for gene editing aiming at treating, preventing and curing diseases utilizing gene editing, are raising important moral questions about their applications in medicine and treatments as well as societal impacts on future generations.[8][9] As this field continues to develop and change throughout history, the focus remains on fair, balanced, and moral thinking across all cultural and religious backgrounds around the world.[10][11] The field of medical ethics encompasses both practical application in clinical settings and scholarly work in philosophy, history, and sociology. Medical ethics encompasses beneficence, autonomy, and justice as they relate to conflicts such as euthanasia, patient confidentiality, informed consent, and conflicts of interest in healthcare.[12][13][14] In addition, medical ethics and culture are interconnected as different cultures implement ethical values differently, sometimes placing more emphasis on family values and downplaying the importance of autonomy. This leads to an increasing need for culturally sensitive physicians and ethical committees in hospitals and other healthcare settings.[10][11][15] |

定義と概要 医療倫理は、臨床医学および関連する科学研究の実践を分析する応用倫理 学の一分野である。[1] 医療倫理は、専門家が混乱や葛藤に直面した場合に参照できる一連の価値観に基づいている。これらの価値観には、自律性の尊重、非加害、恩恵、正義などが含 まれる。[2] このような原則により、医師、介護提供者、家族が治療計画を立て、同じ共通の目標に向かって取り組むことができる。[3] これら4つの価値観は重要度や関連性の順にランク付けされているわけではなく、すべてが 医療倫理に関する価値観をすべて包含している。[4] しかし、倫理システムに階層が必要となるような対立が生じる場合がある。その場合、困難な医療状況に最善の道徳的判断を適用することを目的として、一部の 道徳的要素が他の要素に優先されることになる。[5] 医療倫理は、非自発的治療および非自発的入院に関する決定において特に重要である。 幾つかの行動規範がある。ヒポクラテスの誓いは医療従事者の基本原則について述べている。[5] この文書は紀元前5世紀にさかのぼる。[6] ヘルシンキ宣言(1964年)とニュルンベルク綱領(1947年)は、医療倫理に貢献した2つの著名な文書として広く知られ、高く評価されている。医療倫 理の歴史におけるその他の重要な出来事としては、1973年のロー対ウェイド事件[なぜ?]や、1960年代の血液透析の開発が挙げられる。血液透析が利 用可能になったが、患者を治療する透析装置の数は限られていたため、どの患者を治療し、どの患者を治療しないか、また、そのような決定を行う際にどの要素 を用いるかという倫理的な問題が生じた。[7] さらに最近では、遺伝子編集を利用した病気の治療、予防、治癒を目的とした遺伝子編集の新しい技術が、医療や治療への応用、および将来の世代への社会的影 響に関する重要な道徳的問題を引き起こしている。[8][9] この分野が歴史の中で発展し変化し続ける中で、世界中のあらゆる文化や宗教的背景を踏まえた公正かつバランスの取れた道徳的思考に焦点が当てられている。 [10][11] 医療倫理の分野は、臨床現場での実用的な応用と、哲学、歴史、社会学における学術的な研究の両方を包含している。 医療倫理は、安楽死、患者の守秘義務、インフォームドコンセント、医療における利益相反などの問題に関連する、恩恵、自律性、正義を包含する。[12] [13][14] さらに、医療倫理と文化は相互に関連しており、異なる文化では倫理的な価値観が異なる形で実践されるため、時には家族の価値観がより重視され、自律性の重 要性が軽視されることもある。このため、病院やその他の医療現場では、文化的に敏感な医師や倫理委員会の必要性が高まっている。[10][11][15] |

| Medical ethics relationships Medical ethics defines relationships in the following directions: a medical worker — a patient; a medical worker — a healthy person (relatives); a medical worker — a medical worker. Medical ethics includes provisions on medical confidentiality, medical errors, iatrogenesis, duties of the doctor and the patient. Medical ethics is closely related to bioethics, but these are not identical concepts. Since the science of bioethics arose in an evolutionary way in the continuation of the development of medical ethics, it covers a wider range of issues.[16] Medical ethics is also related to the law. But ethics and law are not identical concepts. More often than not, ethics implies a higher standard of behavior than the law dictates.[17] |

医療倫理の関係 医療倫理は、以下の関係を定義する。 医療従事者と患者 医療従事者と健康な人([患者の?]親族) 医療従事者と医療従事者 医療倫理には、医療上の守秘義務、医療過誤、医原性、医師と患者の義務に関する規定が含まれる。 医療倫理は生命倫理と密接に関連しているが、両者は同一の概念ではない。生命倫理は医療倫理の発展の延長線上で進化してきたため、より幅広い問題を扱って いる。 医療倫理は法律とも関連している。しかし、倫理と法律は同一の概念ではない。多くの場合、倫理は法律が規定するよりも高い行動基準を意味する。 |

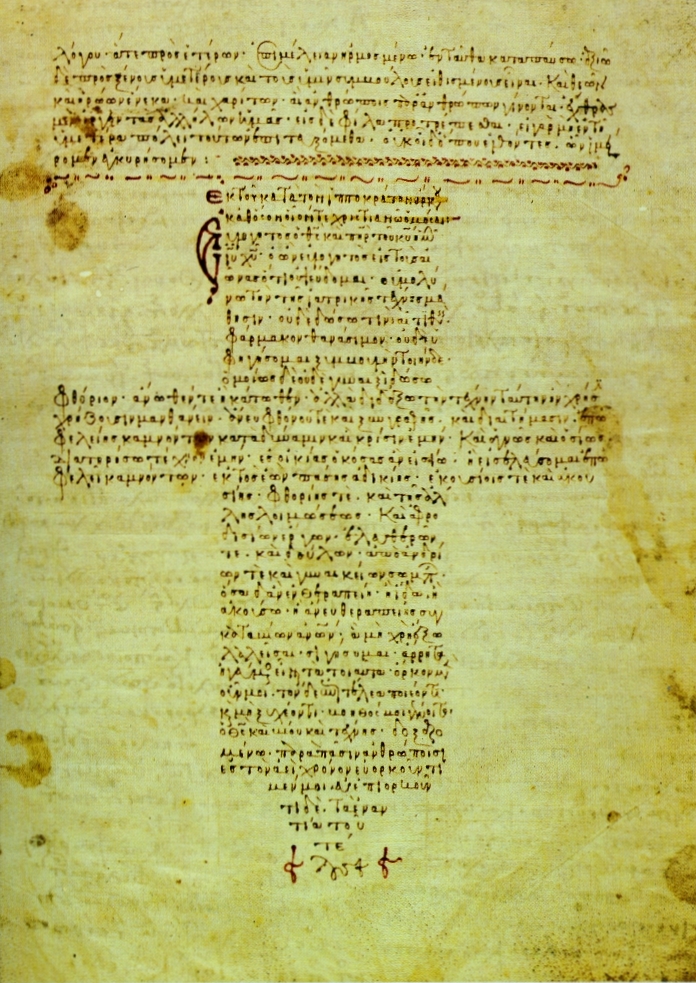

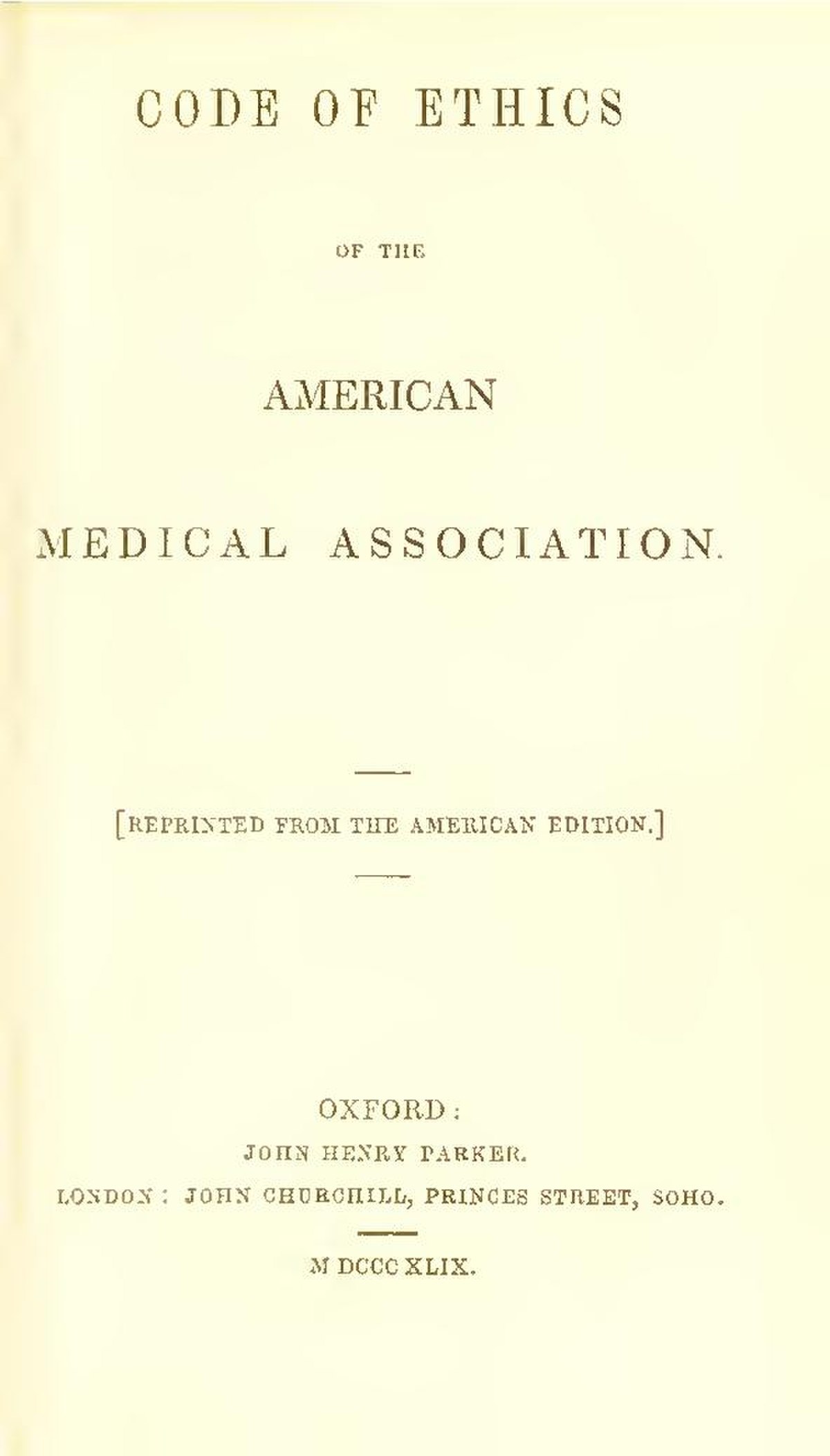

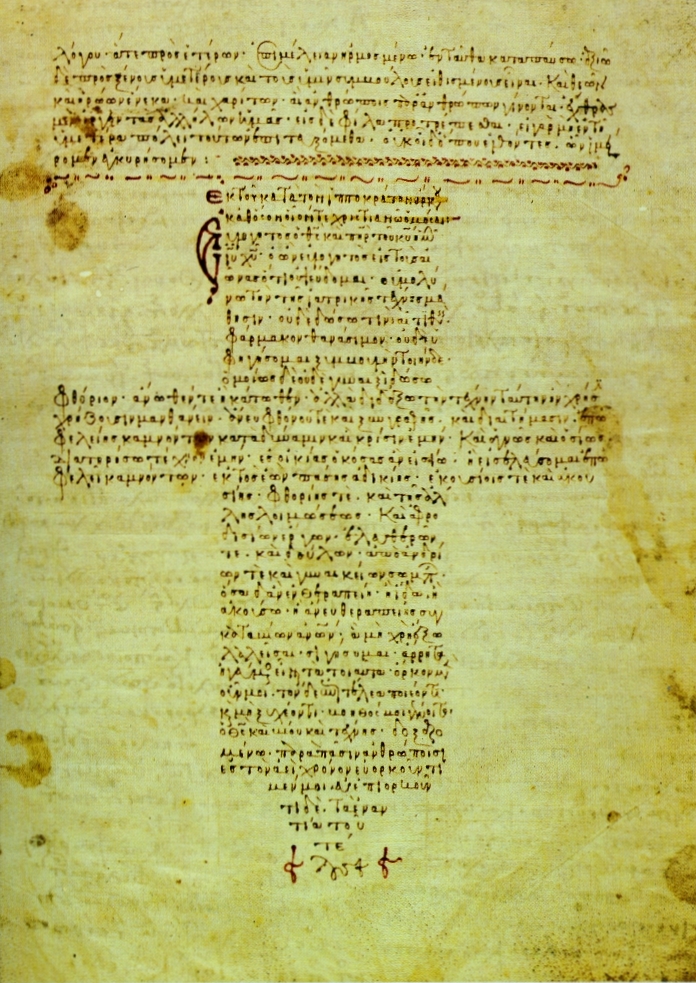

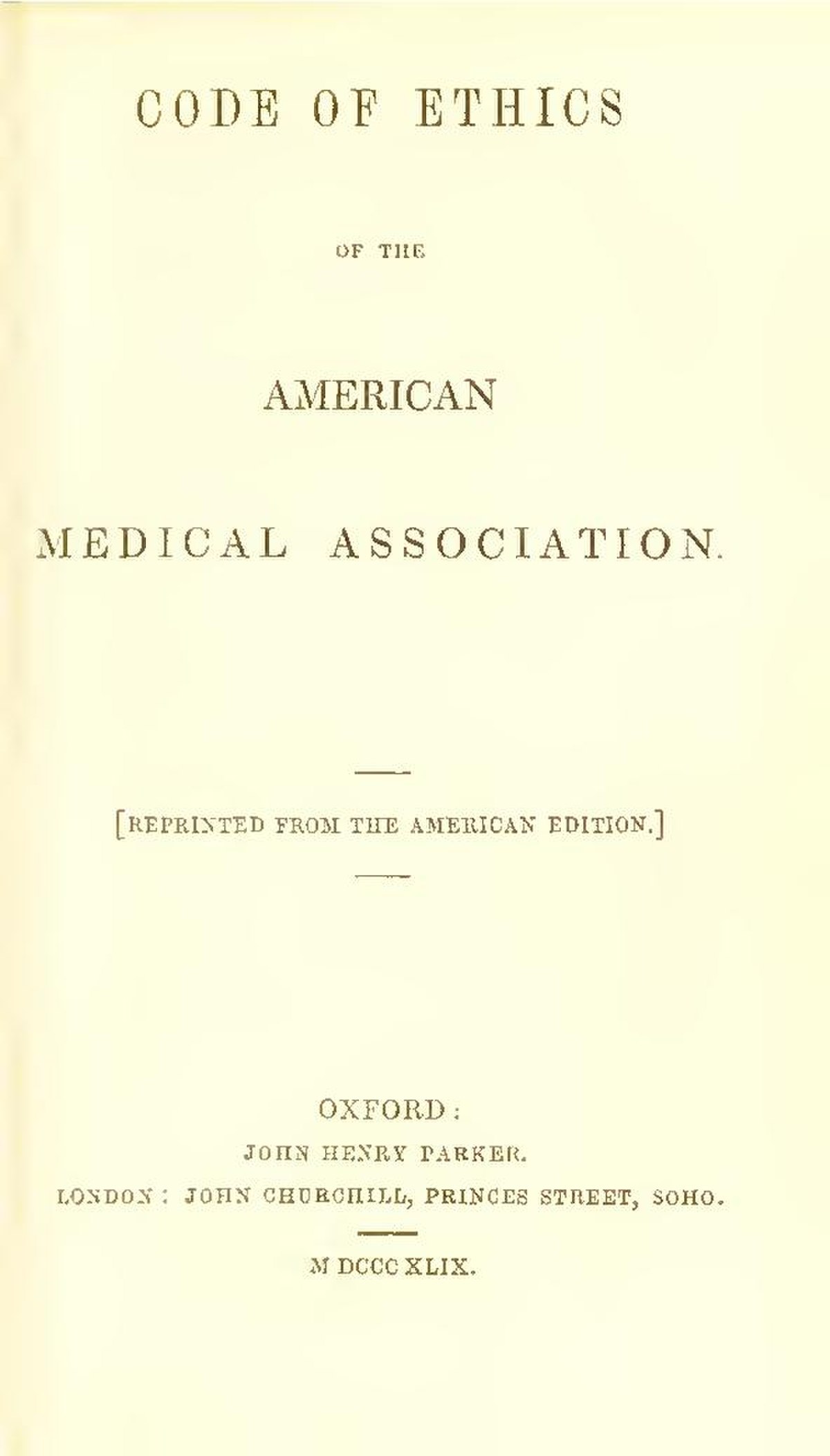

| History See also: List of medical ethics cases  A 12th-century Byzantine manuscript of the Hippocratic Oath  AMA Code of Medical Ethics The term medical ethics first dates back to 1803, when English author and physician Thomas Percival published a document describing the requirements and expectations of medical professionals within medical facilities. The Code of Ethics was then adapted in 1847, relying heavily on Percival's words.[18] Over the years in 1903, 1912, and 1947, revisions have been made to the original document.[18] The practice of medical ethics is widely accepted and practiced throughout the world.[4] Historically, Western medical ethics may be traced to guidelines on the duty of physicians in antiquity, such as the Hippocratic Oath, and early Christian teachings. The first code of medical ethics, Formula Comitis Archiatrorum, was published in the 5th century, during the reign of the Ostrogothic Christian king Theodoric the Great. In the medieval and early modern period, the field is indebted to Islamic scholarship such as Ishaq ibn Ali al-Ruhawi (who wrote the Conduct of a Physician, the first book dedicated to medical ethics), Avicenna's Canon of Medicine and Muhammad ibn Zakariya ar-Razi (known as Rhazes in the West), Jewish thinkers such as Maimonides, Roman Catholic scholastic thinkers such as Thomas Aquinas, and the case-oriented analysis (casuistry) of Catholic moral theology. These intellectual traditions continue in Catholic, Islamic and Jewish medical ethics. By the 18th and 19th centuries, medical ethics emerged as a more self-conscious discourse. In England, Thomas Percival, a physician and author, crafted the first modern code of medical ethics. He drew up a pamphlet with the code in 1794 and wrote an expanded version in 1803, in which he coined the expressions "medical ethics" and "medical jurisprudence".[19] However, there are some who see Percival's guidelines that relate to physician consultations as being excessively protective of the home physician's reputation. Jeffrey Berlant is one such critic who considers Percival's codes of physician consultations as being an early example of the anti-competitive, "guild"-like nature of the physician community.[20][21] In addition, since the mid 19th century up to the 20th century, physician-patient relationships that once were more familiar became less prominent and less intimate, sometimes leading to malpractice, which resulted in less public trust and a shift in decision-making power from the paternalistic physician model to today's emphasis on patient autonomy and self-determination.[22] In 1815, the Apothecaries Act was passed by the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It introduced compulsory apprenticeship and formal qualifications for the apothecaries of the day under the license of the Society of Apothecaries. This was the beginning of regulation of the medical profession in the UK. In 1847, the American Medical Association adopted its first code of ethics, with this being based in large part upon Percival's work.[23] While the secularized field borrowed largely from Catholic medical ethics, in the 20th century a distinctively liberal Protestant approach was articulated by thinkers such as Joseph Fletcher. In the 1960s and 1970s, building upon liberal theory and procedural justice, much of the discourse of medical ethics went through a dramatic shift and largely reconfigured itself into bioethics.[24] Well-known medical ethics cases include: Albert Kligman's dermatology experiments Deep sleep therapy Doctors' Trial Greenberg v. Miami Children's Hospital Research Institute Henrietta Lacks Chester M. Southam's Cancer Injection Study Human radiation experiments Jesse Gelsinger Moore v. Regents of the University of California Surgical removal of body parts to try to improve mental health Medical Experimentation on Black Americans Milgram experiment Radioactive iodine experiments The Monster Study Plutonium injections The David Reimer case The Stanford Prison Experiment Tuskegee syphilis experiment Willowbrook State School Yanomami blood sample collection Darkness in El Dorado Since the 1970s, the growing influence of ethics in contemporary medicine can be seen in the increasing use of Institutional Review Boards to evaluate experiments on human subjects, the establishment of hospital ethics committees, the expansion of the role of clinician ethicists, and the integration of ethics into many medical school curricula.[25] COVID-19 In December 2019, the virus COVID-19 emerged as a threat to worldwide public health and, over the following years, ignited novel inquiry into modern-age medical ethics. For example, since the first discovery of COVID-19 in Wuhan, China[26] and subsequent global spread by mid-2020, calls for the adoption of open science principles dominated research communities.[27] Some academics believed that open science principles — like constant communication between research groups, rapid translation of study results into public policy, and transparency of scientific processes to the public — represented the only solutions to halt the impact of the virus. Others, however, cautioned that these interventions may lead to side-stepping safety in favor of speed, wasteful use of research capital, and creation of public confusion.[27] Drawbacks of these practices include resource-wasting and public confusion surrounding the use of hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin as treatment for COVID-19 — a combination which was later shown to have no impact on COVID-19 survivorship and carried notable cardiotoxic side-effects[28] — as well as a type of vaccine hesitancy specifically due to the speed at which COVID-19 vaccines were created and made publicly available.[29] However, open science also allowed for the rapid implementation of life-saving public interventions like wearing masks and social distancing, the rapid development of multiple vaccines and monoclonal antibodies that have significantly lowered transmission and death rates, and increased public awareness about the severity of the pandemic as well as explanation of daily protective actions against COVID-19 infection, like hand washing.[27] Other notable areas of medicine impacted by COVID-19 ethics include: Resource rationing, especially in Intensive Care Units that did not have enough ventilators or beds to serve the influx of severely ill patients.[30] Lack of PPE for providers, putting them at increased risk of infection during patient care.[31] Heavy burden on healthcare providers and essential workers during entirety of pandemic[32] Closure of schools and increase in virtual schooling, which presented issues for families with limited internet access.[33] Magnification of disparities in health, causing the pandemic to impact BIPOC and disabled communities more so than other demographics worldwide.[34] Increase in hate crimes towards Asian-Americans, specifically Chinese-Americans related to COVID-19 related xenophobia.[35] Closure of businesses, offices, and restaurants resulted in increased unemployment and economic recession.[36] Vaccine hesitancy.[29] Refusal to mask or social distance, increasing transmission rates.[37] Cessation of non-essential medical procedures, delay of routine care, and conversion to telehealth as clinics and hospitals remained overwhelmed with COVID-19 patients.[38] The ethics of COVID-19 spans many more areas of medicine and society than represented in this paragraph — some of these principles will likely not be discovered until the end of the pandemic which, as of September 12, 2022, is still ongoing. |

歴史 参照:医療倫理事例一覧  12世紀のビザンチン写本によるヒポクラテスの誓い  AMA医療倫理規定 医療倫理という用語は、1803年にイギリスの作家であり医師でもあったトーマス・パーシバルが医療施設における医療従事者の要件と期待を記した文書を出 版したときに初めて使用された。その後、1847年に倫理規定が策定されたが、その際にはパーシバルの言葉が大きく影響した。[18] 1903年、1912年、1947年と、長年にわたって当初の文書は改訂されてきた。[18] 医療倫理の実践は世界中で広く受け入れられ、実践されている。[4] 歴史的には、西洋の医療倫理は古代の医師の義務に関する指針、例えばヒポクラテスの誓い、初期キリスト教の教えなどに遡ることができる。医療倫理の最初の 規範である『Formula Comitis Archiatrorum』は、ゴート族のキリスト教王テオドリック大王の治世下の5世紀に出版された。中世から近現代にかけては、イスラム教の学者であ るイサク・イブン・アリー・アル・ルハーウィ(『医師の心得』を著した最初の医療倫理の専門家)、アヴィセンナの『医学の規範』、ムハンマド・ イブン・ザカリヤ・アル・ラージー(西洋ではラゼスとして知られる)、マイモニデスなどのユダヤ人の思想家、トマス・アクィナスなどのローマ・カトリック のスコラ学派の思想家、そしてカトリックの道徳神学における事例志向分析(詭弁学)などである。これらの知的伝統は、カトリック、イスラム教、ユダヤ教の 医療倫理において受け継がれている。 18世紀から19世紀にかけて、医療倫理はより自覚的な議論として浮上した。英国では、医師であり作家でもあったトーマス・パーシヴァルが、最初の近代的 医療倫理規定を策定した。彼は1794年に規定を記載したパンフレットを作成し、1803年にはその拡大版を執筆し、その中で「医療倫理」と「医療法学」 という表現を考案した。[19] しかし、パーシヴァルの医師の診察に関するガイドラインは、ホームドクターの評判を過度に保護するものだと考える人もいる。ジェフリー・バーラントは、 パーシバルの医師相談規定を、医師社会の反競争的で「ギルド」的な性質を体現する初期の例であると考える批判者の一人である。[20][21] さらに、19世紀半ばから20世紀にかけて、 かつてはより身近であった医師と患者の関係は、20世紀までには目立たなくなり、親密さも薄れ、時には医療過誤につながることもあった。その結果、社会的 な信頼が低下し、意思決定の権限は温情主義的な医師モデルから、患者の自主性と自己決定を重視する現在のモデルへとシフトした。 1815年、英国議会は「薬剤師法」を可決した。この法律は、薬剤師会(Society of Apothecaries)の免許制のもと、当時の薬剤師に強制的な見習い期間と正式な資格を導入した。これが英国における医療専門職の規制の始まりで あった。 1847年には、米国医師会が初の倫理規定を採択したが、これはパーシバルの研究を大いに参考にしたものである。[23] 世俗化された医療分野はカトリックの医療倫理から多くを学んだが、20世紀には、ジョセフ・フレッチャーなどの思想家によって、プロテスタントの自由主義 的なアプローチが明確に示された。1960年代と1970年代には、リベラルな理論と手続き的正義を基盤として、医療倫理に関する議論の多くが劇的な変化 を遂げ、主に生命倫理へと再構成された。 よく知られた医療倫理の事例には以下のようなものがある。 アルバート・クリグマンの皮膚科実験 ディープスリープ療法 医師裁判 グリーンバーグ対マイアミ小児病院研究所 ヘンリエッタ・ラックス チェスター・M・サウザムのがん注射研究 人体放射線実験 ジェシー・ゲルシンガー ムーア対カリフォルニア大学理事会 精神衛生改善を目的とした身体部位の外科的切除 黒人アメリカ人に対する医療実験 ミルグラム実験 放射性ヨウ素実験 モンスター研究 プルトニウム注射 デビッド・ライマー事件 スタンフォード監獄実験 タスキギー梅毒実験 ウィローブルック州立学校 ヤノマミ族の血液サンプル採取 エルドラドの闇 1970年代以降、現代医学における倫理の重要性が高まり、被験者に対する実験を評価する機関審査委員会の利用増加、病院倫理委員会の設立、臨床倫理学者 の役割拡大、そして多くの医学部のカリキュラムに倫理が組み込まれるようになった。 COVID-19 2019年12月、新型コロナウイルス(COVID-19)が世界的な公衆衛生上の脅威として浮上し、その後の数年間で、現代の医療倫理に関する新たな研 究が活発化している。例えば、2019年12月に中国・武漢で初めて新型コロナウイルス(COVID-19)が発見され[26]、2020年半ばまでに世 界中に広がったことを受け、研究コミュニティではオープンサイエンスの原則の採用を求める声が主流となった[27]。一部の学者は、研究グループ間の継続 的なコミュニケーション、研究結果の迅速な公共政策への反映、一般市民への科学的プロセスの透明性など、オープンサイエンスの原則がウイルスの影響を食い 止める唯一の解決策であると信じていた。しかし、一部の専門家は、こうした介入策は、スピードを優先するあまり安全性を犠牲にしたり、研究資金の無駄遣い や、一般市民の混乱を招く可能性があると警告している。[27] こうした慣行の欠点としては、COVID-19の治療薬としてヒドロキシクロロキンとアジスロマイシンの併用が用いられたことによる資源の浪費や、一般市 民の混乱が挙げられる。 。この組み合わせは、後にCOVID-19の生存率に影響を与えないことが示され、顕著な心毒性副作用があることが判明した[28]。また、特に COVID-19ワクチンが作成され、一般に利用可能になるまでのスピードが速かったことによる、一種のワクチン忌避も挙げられる[29]。しかし、オー プンサイエンスは、 マスクの着用やソーシャル・ディスタンス(社会的距離)といった救命的な公的介入の迅速な実施、感染率と死亡率を大幅に低下させる複数のワクチンやモノク ローナル抗体の急速な開発、パンデミックの深刻さに対する国民の意識向上、そして手洗いなど、日常的なCOVID-19感染予防行動の説明も可能にした。 その他、COVID-19の倫理が影響を与えた医療の注目すべき分野には、 特に、重症患者の急増に対応できるだけの人工呼吸器やベッドが十分にない集中治療室におけるリソースの配分[30] 医療従事者に対する個人用保護具(PPE)の不足により、患者のケア中に感染リスクが高まる[31] パンデミック全体を通じて医療従事者や不可欠な労働者に大きな負担がかかる[32] 学校の閉鎖とオンライン教育の増加により、インターネットへのアクセスが限られている家庭に問題が生じた[33] 健康格差の拡大により、パンデミックが世界中の他の人口統計よりもBIPOCや障害者コミュニティに大きな影響を与えた。 アジア系アメリカ人、特にCOVID-19に関連する外国人嫌悪に関連する中国系アメリカ人に対するヘイトクライムの増加。 企業、オフィス、レストランの閉鎖により、失業率が上昇し、景気が後退した。 ワクチン接種への抵抗感。[29] マスク着用やソーシャル・ディスタンスの拒否により、感染率が上昇。[37] クリニックや病院が新型コロナウイルス感染症患者で溢れかえったため、必要不可欠ではない医療処置の中止、日常的なケアの遅延、遠隔医療への転換が行われ た。 新型コロナウイルス感染症の倫理は、この段落で示されているよりもはるかに多くの医療と社会の領域にまたがっている。これらの原則の一部は、2022年9 月12日現在も継続中のパンデミックが終息するまで発見されない可能性が高い。 |

| Values A common framework used when analysing medical ethics is the "four principles" approach postulated by Tom Beauchamp and James Childress in their textbook Principles of Biomedical Ethics. It recognizes four basic moral principles, which are to be judged and weighed against each other, with attention given to the scope of their application. The four principles are:[39] Respect for autonomy – the patient has the right to refuse or choose their treatment.[40] Beneficence – a practitioner should act in the best interest of the patient.[40] Non-maleficence – to not be the cause of harm. Also, "Utility" – to promote more good than harm.[40] Justice – concerns the distribution of scarce health resources, and the decision of who gets what treatment.[40] Autonomy The principle of autonomy, broken down into "autos" (self) and "nomos (rule), views the rights of an individual to self-determination.[22] This is rooted in society's respect for individuals' ability to make informed decisions about personal matters with freedom. Autonomy has become more important as social values have shifted to define medical quality in terms of outcomes that are important to the patient and their family rather than medical professionals.[22] The increasing importance of autonomy can be seen as a social reaction against the "paternalistic" tradition within healthcare.[22][41] Some have questioned whether the backlash against historically excessive paternalism in favor of patient autonomy has inhibited the proper use of soft paternalism to the detriment of outcomes for some patients.[42] The definition of autonomy is the ability of an individual to make a rational, uninfluenced decision. Therefore, it can be said that autonomy is a general indicator of a healthy mind and body. The progression of many terminal diseases are characterized by loss of autonomy, in various manners and extents. For example, dementia, a chronic and progressive disease that attacks the brain can induce memory loss and cause a decrease in rational thinking, almost always results in the loss of autonomy.[43] Psychiatrists and clinical psychologists are often asked to evaluate a patient's capacity for making life-and-death decisions at the end of life. Persons with a psychiatric condition such as delirium or clinical depression may lack capacity to make end-of-life decisions. For these persons, a request to refuse treatment may be taken in the context of their condition. Unless there is a clear advance directive to the contrary, persons lacking mental capacity are treated according to their best interests. This will involve an assessment involving people who know the person best to what decisions the person would have made had they not lost capacity.[44] Persons with the mental capacity to make end-of-life decisions may refuse treatment with the understanding that it may shorten their life. Psychiatrists and psychologists may be involved to support decision making.[45] Beneficence Main article: Beneficence (ethics) The term beneficence refers to actions that promote the well-being of others. In the medical context, this means taking actions that serve the best interests of patients and their families.[2] However, uncertainty surrounds the precise definition of which practices do in fact help patients. James Childress and Tom Beauchamp in Principles of Biomedical Ethics (1978) identify beneficence as one of the core values of healthcare ethics. Some scholars, such as Edmund Pellegrino, argue that beneficence is the only fundamental principle of medical ethics. They argue that healing should be the sole purpose of medicine, and that endeavors like cosmetic surgery and euthanasia are severely unethical and against the Hippocratic Oath.[citation needed] Non-maleficence Main article: Primum non nocere The concept of non-maleficence is embodied by the phrase, "first, do no harm," or the Latin, primum non nocere. Many consider that should be the main or primary consideration (hence primum): that it is more important not to harm your patient, than to do them good, which is part of the Hippocratic oath that doctors take.[46] This is partly because enthusiastic practitioners are prone to using treatments that they believe will do good, without first having evaluated them adequately to ensure they do no harm to the patient. Much harm has been done to patients as a result, as in the saying, "The treatment was a success, but the patient died." It is not only more important to do no harm than to do good; it is also important to know how likely it is that your treatment will harm a patient. So a physician should go further than not prescribing medications they know to be harmful—he or she should not prescribe medications (or otherwise treat the patient) unless s/he knows that the treatment is unlikely to be harmful; or at the very least, that patient understands the risks and benefits, and that the likely benefits outweigh the likely risks. In practice, however, many treatments carry some risk of harm. In some circumstances, e.g. in desperate situations where the outcome without treatment will be grave, risky treatments that stand a high chance of harming the patient will be justified, as the risk of not treating is also very likely to do harm. So the principle of non-maleficence is not absolute, and balances against the principle of beneficence (doing good), as the effects of the two principles together often give rise to a double effect (further described in next section). Even basic actions like taking a blood sample or an injection of a drug cause harm to the patient's body. Euthanasia also goes against the principle of beneficence because the patient dies as a result of the medical treatment by the doctor. Double effect Main article: Principle of double effect Double effect refers to two types of consequences that may be produced by a single action,[47] and in medical ethics it is usually regarded as the combined effect of beneficence and non-maleficence.[48] A commonly cited example of this phenomenon is the use of morphine or other analgesic in the dying patient. Such use of morphine can have the beneficial effect of easing the pain and suffering of the patient while simultaneously having the maleficent effect of shortening the life of the patient through the deactivation of the respiratory system.[49] Respect for human rights The human rights era started with the formation of the United Nations in 1945, which was charged with the promotion of human rights. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948) was the first major document to define human rights. Medical doctors have an ethical duty to protect the human rights and human dignity of the patient so the advent of a document that defines human rights has had its effect on medical ethics.[50] Most codes of medical ethics now require respect for the human rights of the patient. The Council of Europe promotes the rule of law and observance of human rights in Europe. The Council of Europe adopted the European Convention on Human Rights and Biomedicine (1997) to create a uniform code of medical ethics for its 47 member-states. The Convention applies international human rights law to medical ethics. It provides special protection of physical integrity for those who are unable to consent, which includes children. No organ or tissue removal may be carried out on a person who does not have the capacity to consent under Article 5.[51] As of December 2013, the convention had been ratified or acceded to by twenty-nine member-states of the Council of Europe.[52] The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) also promotes the protection of human rights and human dignity. According to UNESCO, "Declarations are another means of defining norms, which are not subject to ratification. Like recommendations, they set forth universal principles to which the community of States wished to attribute the greatest possible authority and to afford the broadest possible support." UNESCO adopted the Universal Declaration on Human Rights and Biomedicine (2005) to advance the application of international human rights law in medical ethics. The Declaration provides special protection of human rights for incompetent persons. In applying and advancing scientific knowledge, medical practice and associated technologies, human vulnerability should be taken into account. Individuals and groups of special vulnerability should be protected and the personal integrity of such individuals respected.[53] Solidarity Individualistic standards of autonomy and personal human rights as they relate to social justice seen in the Anglo-Saxon community, clash with and can also supplement the concept of solidarity, which stands closer to a European healthcare perspective focused on community, universal welfare, and the unselfish wish to provide healthcare equally for all.[54] In the United States individualistic and self-interested healthcare norms are upheld, whereas in other countries, including European countries, a sense of respect for the community and personal support is more greatly upheld in relation to free healthcare.[54] Acceptance of ambiguity in medicine  Ethical prayer for medical wisdom by Dr Edmond Fernandes The concept of normality, that there is a human physiological standard contrasting with conditions of illness, abnormality and pain, leads to assumptions and bias that negatively affects health care practice.[55] It is important to realize that normality is ambiguous and that ambiguity in healthcare and the acceptance of such ambiguity is necessary in order to practice humbler medicine and understand complex, sometimes unusual usual medical cases.[55] Thus, society's views on central concepts in philosophy and clinical beneficence must be questioned and revisited, adopting ambiguity as a central player in medical practice.[55] |

価値 医療倫理を分析する際に用いられる一般的な枠組みとして、トム・ビューチャンプとジェームズ・チルドレスが教科書『生命医学倫理の原則』で提唱した「四原 則」アプローチがある。これは、適用範囲に注意を払いつつ、互いに比較評価されるべき4つの基本的な道徳原則を認識するものであ る。4つの原則は以下の通 りである: 自律性の尊重 - 患者には治療を拒否または選択する権利がある。 [40] 善行 - 医療従事者は患者の最善の利益のために行動すべきである。 [40] 非加害 - 害の原因となってはならない。また、「有用性」 - 害よりも益を促進すること。 [40] 正義 - 希少な医療資源の分配、および誰がどのような治療を受けるかの決定に関するもの。 自律性 自律の原則は、「autos」(自己)と「nomos」(規則)に分解され、自己決定に対する個人の権利を捉えている。[22] これは、個人の自由に関する事項について、十分な情報を得た上で決定する個人の能力を社会が尊重することに根ざしている。医療の質を定義する際に、医療従 事者よりも患者とその家族にとって重要な結果を重視する方向に社会の価値観が変化したため、自律性はより重要性を増している。[22] 自律性の重要性の高まりは、 医療における「温情主義」の伝統に対する社会的な反応と見ることができる。[22][41] 患者の自主性を支持する歴史的に行き過ぎた温情主義に対する反動が、一部の患者の治療結果を損なう形で、ソフトな温情主義の適切な利用を妨げているのでは ないかという疑問も呈されている。[42] 自律性の定義は、個人が合理的な判断を、何の影響も受けずに下す能力である。したがって、自律性は健全な心身の一般的な指標であると言える。多くの終末期 疾患の進行は、さまざまな方法や程度で自律性の喪失を特徴とする。例えば、脳を侵す慢性進行性の疾患である認知症は、記憶喪失を誘発し、合理的な思考の低 下を引き起こすことがほとんどであり、その結果、自律性を失うことになる。 精神科医や臨床心理士は、終末期における患者の生死にかかわる意思決定能力の評価を求められることがよくある。せん妄や臨床うつ病などの精神疾患を抱える 人は、終末期の意思決定能力を欠く場合がある。このような人々に対しては、治療拒否の要請がその人の状態を考慮したものとして受け取られる可能性がある。 明確な事前指示がない限り、意思能力のない人は、最善の利益に基づいて扱われる。これには、その人が意思能力を失っていなかった場合、どのような決定を下 したかを最もよく知る人々による評価が含まれる。[44] 終末期の決定を行う意思能力のある人は、それが命を縮める可能性があることを理解した上で、治療を拒否することができる。意思決定を支援するために、精神 科医や心理学者が関与することもある。[45] 善行 詳細は「善行(倫理)」を参照 「善行」という用語は、他者の幸福を促進する行為を指す。医療の文脈では、患者とその家族の最善の利益となる行動を取ることを意味する。[2] しかし、実際にはどの行為が患者を助けることになるのか、その正確な定義については不確実性が残る。 ジェームズ・チャドレスとトム・ビューチャンプは『生命倫理の原則』(1978年)において、医療倫理の中核的価値観のひとつとして「恩恵」を挙げてい る。エドマンド・ペレグリーノなどの学者は、恩恵こそが医療倫理の唯一の根本原則であると主張している。彼らは、医療の唯一の目的は治療であるべきであ り、美容整形や安楽死のような試みは深刻な倫理違反であり、ヒポクラテスの誓いに反していると主張している。 非加害 詳細は「プリムム・ノン・ノケアレ」を参照 非加害の概念は、「まず、害を与えないこと」、またはラテン語の「プリムム・ノン・ノケアレ」という表現に体現されている。多くの人々は、患者に害を与え ないことが重要であると考える(したがって、primum)。患者に害を与えないことは、患者に良いことをするよりも重要である。これは、医師が誓うヒポ クラテスの誓いの一部である。[46] 熱心な医師は、患者に害を与えないことを十分に評価することなく、患者に良いと信じる治療法を使用しがちであることが、その理由の一部である。その結果、 患者に多くの害がもたらされてきた。「治療は成功したが、患者は死亡した」という諺にもあるように。害をなさないことよりも、善を行うことの方がより重要 であるだけでなく、自分の治療が患者に害を与える可能性を把握することも重要である。したがって、医師は有害であると分かっている薬を処方しないという以 上のことをすべきである。すなわち、その治療が有害である可能性が低いと分かっている場合を除いては、薬を処方すべきではない(あるいは、患者を治療すべ きではない)。あるいは、少なくとも、患者がリスクと利益を理解しており、見込まれる利益が見込まれるリスクを上回っている場合である。 しかし実際には、多くの治療には何らかの害のリスクが伴う。状況によっては、例えば治療を行わなければ深刻な結果になるような絶望的な状況では、患者に害 を与える可能性が高いリスクの高い治療が正当化される。なぜなら、治療を行わないことによるリスクも、患者に害を与える可能性が高いからだ。したがって、 非加害の原則は絶対的なものではなく、加害の原則(善行)とのバランスを取る。この2つの原則が同時に作用すると、しばしば二重の効果が生じる(次項でさ らに詳しく説明する)。採血や薬物の注射といった基本的な行為でも、患者の身体に害を与える。安楽死も、医師による医療行為の結果として患者が死亡するた め、加害の原則に反する。 二重の結果(→二重効果の教義) 詳細は「二重の結果の原則」を参照 二重の結果とは、単一の行為によって生じる可能性のある2つの結果を指す[47]。医療倫理においては、通常、恩恵と非加害性の複合的な効果とみなされる [48]。 この現象のよく引用される例としては、死にかけている患者へのモルヒネやその他の鎮痛剤の使用が挙げられる。モルヒネの使用は、患者の苦痛を和らげるとい う有益な効果をもたらす一方で、呼吸器系の不活性化を通じて患者の寿命を縮めるという有害な効果も同時に生じさせる可能性がある。 人権の尊重 人権の時代は、人権の促進を目的として1945年に設立された国際連合の誕生とともに始まった。世界人権宣言(1948年)は、人権を定義した最初の主要 文書である。医師には患者の人権と尊厳を守る倫理的義務があるため、人権を定義する文書の出現は医療倫理に影響を与えた。[50] 現在、ほとんどの医療倫理規定では患者の人権を尊重することが求められている。 欧州評議会は、欧州における法の支配と人権の遵守を推進している。欧州評議会は、47の加盟国に共通する医療倫理規定を策定するために、欧州人権・バイオ メディカル条約(1997年)を採択した。この条約は、医療倫理に国際人権法を適用するものである。この条約は、同意することができない人々(子供を含 む)に対して、身体の完全性に対する特別な保護を規定している。 第5条により、同意能力のない人に対しては、いかなる臓器や組織の摘出も行ってはならない。[51] 2013年12月現在、この条約は欧州評議会の29の加盟国によって批准または承認されている。[52] また、国連教育科学文化機関(UNESCO)も人権と人間の尊厳の保護を推進している。UNESCOによれば、「宣言は、批准の対象とはならない規範を定 めるもう一つの手段である。勧告と同様に、国家社会が最大限の権限を付与し、最大限の支援を提供したいと望む普遍的な原則を定めるものである」 ユネスコは、医療倫理における国際人権法の適用を推進するために、世界人権宣言と生命倫理(2005年)を採択した。この宣言では、無能力者に対する人権 の特別な保護が規定されている。 科学的知識、医療行為、関連技術の適用と推進にあたっては、人間の脆弱性を考慮すべきである。特別な脆弱性を持つ個人や集団は保護され、そのような個人の 人格は尊重されるべきである。 連帯 アングロサクソン社会に見られる社会正義に関連する個人主義的な自律性や個人の人権の基準は、連帯の概念と衝突するが、補完することもできる。連帯の概念 は、地域社会、普遍的な福祉、そして 。[54] 米国では個人主義的で利己的な医療の規範が支持されているが、欧州諸国を含む他の国々では、無料医療に関しては地域社会への敬意や個人的な支援の感覚がよ り強く支持されている。[54] 医療における曖昧さの受容  エドモンド・フェルナンデス博士による医療的知恵のための倫理的祈り 正常という概念、すなわち、病気、異常、苦痛の状態とは対照的な人間の生理学的標準という概念は、医療行為に悪影響を及ぼす思い込みや偏見につながる。 [55] 正常という概念が曖昧であること、そして医療における曖昧さ、およびそのような曖昧さの受容が 謙虚な医療を実践し、複雑で時に異常な通常の医療事例を理解するためには、必要であることを理解することが重要である。[55] したがって、哲学における中心概念と臨床的恩恵に関する社会の見解は、疑問視され、再検討されなければならない。医療行為における中心的な役割として曖昧 性を採用する。[55] |

| Conflicts Between beneficence and non-maleficence Beneficence can come into conflict with non-maleficence when healthcare professionals are deciding between a “first, do no harm” approach vs. a “first, do good” approach, such as when deciding whether or not to operate when the balance between the risk and benefit of the operation is not known and must be estimated. Healthcare professionals who place beneficence below other principles like non-maleficence may decide not to help a patient more than a limited amount if they feel they have met the standard of care and are not morally obligated to provide additional services. Young and Wagner argued that, in general, beneficence takes priority over non-maleficence (“first, do good,” not “first, do no harm”), both historically and philosophically.[1] Between autonomy and beneficence/non-maleficence Autonomy can come into conflict with beneficence when patients disagree with recommendations that healthcare professionals believe are in the patient's best interest. When the patient's interests conflict with the patient's welfare, different societies settle the conflict in a wide range of manners. In general, Western medicine defers to the wishes of a mentally competent patient to make their own decisions, even in cases where the medical team believes that they are not acting in their own best interests. However, many other societies prioritize beneficence over autonomy. People deemed to not be mentally competent or having a mental disorder may be treated involuntarily. Examples include when a patient does not want treatment because of, for example, religious or cultural views. In the case of euthanasia, the patient, or relatives of a patient, may want to end the life of the patient. Also, the patient may want an unnecessary treatment, as can be the case in hypochondria or with cosmetic surgery; here, the practitioner may be required to balance the desires of the patient for medically unnecessary potential risks against the patient's informed autonomy in the issue. A doctor may want to prefer autonomy because refusal to respect the patient's self-determination would harm the doctor-patient relationship. Organ donations can sometimes pose interesting scenarios, in which a patient is classified as a non-heart beating donor (NHBD), where life support fails to restore the heartbeat and is now considered futile but brain death has not occurred. Classifying a patient as a NHBD can qualify someone to be subject to non-therapeutic intensive care, in which treatment is only given to preserve the organs that will be donated and not to preserve the life of the donor. This can bring up ethical issues as some may see respect for the donors wishes to donate their healthy organs as respect for autonomy, while others may view the sustaining of futile treatment during vegetative state maleficence for the patient and the patient's family. Some are worried making this process a worldwide customary measure may dehumanize and take away from the natural process of dying and what it brings along with it. Individuals' capacity for informed decision-making may come into question during resolution of conflicts between autonomy and beneficence. The role of surrogate medical decision-makers is an extension of the principle of autonomy. On the other hand, autonomy and beneficence/non-maleficence may also overlap. For example, a breach of patients' autonomy may cause decreased confidence for medical services in the population and subsequently less willingness to seek help, which in turn may cause inability to perform beneficence. The principles of autonomy and beneficence/non-maleficence may also be expanded to include effects on the relatives of patients or even the medical practitioners, the overall population and economic issues when making medical decisions. Euthanasia Main articles: Euthanasia and Voluntary euthanasia There is disagreement among American physicians as to whether the non-maleficence principle excludes the practice of euthanasia. Euthanasia is currently legal in the states of Washington, DC, California, Colorado, Oregon, Vermont, and Washington.[56] Around the world, there are different organizations that campaign to change legislation about the issue of physician-assisted death, or PAD. Examples of such organizations are the Hemlock Society of the United States and the Dignity in Dying campaign in the United Kingdom.[57] These groups believe that doctors should be given the right to end a patient's life only if the patient is conscious enough to decide for themselves, is knowledgeable about the possibility of alternative care, and has willingly asked to end their life or requested access to the means to do so. This argument is disputed in other parts of the world. For example, in the state of Louisiana, giving advice or supplying the means to end a person's life is considered a criminal act and can be charged as a felony.[58] In state courts, this crime is comparable to manslaughter.[59] The same laws apply in the states of Mississippi and Nebraska.[60] |

コンフリクト 利益と非加害の間の対立 医療従事者が「まず害を与えない」アプローチと「まず善を行う」アプローチを比較検討する際に、利益と非加害の原則が対立することがある。例えば、手術の リスクと利益のバランスが不明で推定しなければならない場合、手術を行うかどうかを決定する際に、利益と非加害の原則が対立することがある。医療従事者 が、非加害性の原則よりも恩恵の原則を優先させる場合、標準的なケアを提供し、追加のサービスを提供する道徳的義務がないと判断すれば、患者を限られた期 間以上は助けないと判断する可能性がある。ヤングとワグナーは、一般的に恩恵の原則は非加害性の原則よりも優先されるべきであり(「まず善行を」であり、 「まず害をなさない」ではない)、これは歴史的にも哲学的にも正しいと主張している。 自律性と恩恵/非加害性との関係 医療従事者が患者にとって最善であると考える推奨事項に患者が同意しない場合、自律性と恩恵が対立する可能性がある。患者の利益と患者の福祉が対立する場 合には、さまざまな学会がさまざまな方法で対立を解決している。一般的に、西洋医学では、たとえ医療チームが患者が最善の利益を得ていないと判断した場合 でも、精神的に健全な患者が自ら決定を下すことを尊重する。しかし、他の多くの学会では、自律よりも善行を優先する。精神的に健全ではない、あるいは精神 障害があるとみなされた人々は、非自発的に治療される可能性がある。 例えば、患者が治療を望まない場合、その理由は宗教的または文化的見解によるものである。安楽死の場合、患者または患者の親族が患者の命を絶つことを望む 場合がある。また、患者が不必要な治療を望む場合もある。例えば、心気症や美容整形の場合がこれに該当する。この場合、医療上不要な潜在的なリスクに対す る患者の希望と、この問題における患者のインフォームド・コンセントに基づく自律性とのバランスを取ることが医療従事者に求められる。医師は、患者の自己 決定を尊重しないことは医師と患者の関係を損なうことになるため、自律性を優先したいと考えるかもしれない。 臓器提供は、時に興味深い状況を引き起こすことがある。患者は心拍動なしドナー(NHBD)として分類され、生命維持装置では心拍を回復できず、もはや無 駄とみなされるが、脳死には至っていない場合である。患者をNHBDと分類することで、非治療的集中治療の対象となる資格が与えられる。非治療的集中治療 では、提供される臓器を保存するためにのみ治療が行われ、ドナーの生命維持は目的とされない。これは倫理的な問題を引き起こす可能性がある。健康な臓器を 寄付するという意思表示を尊重することは、自律性の尊重と見なす人もいる一方で、植物状態の間、無益な治療を続けることは患者とその家族にとって有害であ ると考える人もいるからだ。このプロセスを世界的な慣例的な措置とすることは、人間性を奪い、自然な死のプロセスやそれに伴うものを奪うことになるのでは ないかと懸念する人もいる。 個人の情報に基づく意思決定能力は、自律性と善行の間の対立の解決の際に疑問視される可能性がある。代理医療意思決定者の役割は、自律性の原則の延長であ る。 一方、自律性と善行/非加害性は重複することもある。例えば、患者の自律性が侵害されると、その集団における医療サービスへの信頼が低下し、その結果、助 けを求める意欲が減退し、善行が実行できなくなる可能性がある。 また、医療上の決定を行う際には、患者の親族や医療従事者、さらには全住民や経済問題にまで影響が及ぶ可能性があるため、自律性と善行/非加害性の原則は 拡大解釈されるべきである。 安楽死 詳細は「安楽死」および「自発的安楽死」を参照 非加害の原則が安楽死の実践を排除するかどうかについては、米国の医師の間でも意見が分かれている。安楽死は現在、ワシントン州、コロンビア特別区、カリ フォルニア州、コロラド州、オレゴン州、バーモント州で合法である。[56] 世界中には、医師による死の援助(PAD)の問題に関する法律の改正を求めるキャンペーンを行うさまざまな団体がある。そのような団体の例としては、米国 のヘムロック協会や英国の尊厳死キャンペーンなどがある。[57] これらの団体は、患者が自分で決定できるだけの意識があり、代替治療の可能性について知識があり、自らの意思で人生の終結を望んだり、その手段へのアクセ スを要求したりした場合にのみ、医師に患者の命を絶つ権利を与えるべきだと考えている。 この主張は、世界の他の地域では異論がある。例えば、ルイジアナ州では、自殺幇助や自殺手段の提供は犯罪行為と見なされ、重罪として起訴される可能性があ る。[58] 州裁判所では、この犯罪は過失致死罪に相当する。[59] ミシシッピ州とネブラスカ州でも同様の法律が適用されている。[60] |

| Informed consent Main article: Informed consent Informed consent refers to a patient's right to receive information relevant to a recommended treatment, in order to be able to make a well-considered, voluntary decision about their care.[61] To give informed consent, a patient must be competent to make a decision regarding their treatment and be presented with relevant information regarding a treatment recommendation, including its nature and purpose, and the burdens, risks and potential benefits of all options and alternatives.[62] After receiving and understanding this information, the patient can then make a fully informed decision to either consent or refuse treatment.[63] In certain circumstances, there can be an exception to the need for informed consent, including, but not limited to, in cases of a medical emergency or patient incompetency.[64] The ethical concept of informed consent also applies in a clinical research setting; all human participants in research must voluntarily decide to participate in the study after being fully informed of all relevant aspects of the research trial necessary to decide whether to participate or not.[65] Informed consent is both an ethical and legal duty; if proper consent is not received prior to a procedure, treatment, or participation in research, providers can be held liable for battery and/or other torts.[66] In the United States, informed consent is governed by both federal and state law, and the specific requirements for obtaining informed consent vary state to state.[67] |

イ

ンフォームドコンセント 詳細は「インフォームドコンセント」を参照 インフォームド・コンセントとは、推奨された治療に関する情報を受け取り、治療についてよく考えた上で自発的に決定する患者の権利を指す。[61] インフォームド・コンセントを得るには、患者は自身の治療に関する決定能力があり、治療の推奨に関する関連情報(その性質や目的、負担、リスク、およびす べての選択肢や代替案の潜在的な利益を含む)が提示されていなければならない。[62] 情報を受け取り、 この情報を理解した上で、患者は治療に同意するか拒否するかを十分に理解した上で決定することができる。[63] 特定の状況下では、インフォームドコンセントの必要性を免除できる場合があり、これには医療上の緊急事態や患者の意思能力の欠如などが含まれるが、これら に限定されない。[64] インフォームドコンセントの倫理的概念は臨床研究の現場にも適用され、研究に参加するすべての人間は、 参加するかどうかを決定するために必要な研究試験のすべての関連側面について、十分に説明を受けなければならない。[65] インフォームド・コンセントは倫理的および法的義務である。手続き、治療、または研究への参加の前に適切な同意が得られていない場合、医療提供者は暴行お よび/またはその他の不法行為の責任を問われる可能性がある。[66] 米国では、インフォームド・コンセントは連邦法および州法の両方によって規定されており、インフォームド・コンセント取得の具体的な要件は州によって異な る。[67] |

| Confidentiality Confidentiality is commonly applied to conversations between doctors and patients.[68] This concept is commonly known as patient-physician privilege. Legal protections prevent physicians from revealing their discussions with patients, even under oath in court. Confidentiality is mandated in the United States by the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 known as HIPAA,[69] specifically the Privacy Rule, and various state laws, some more rigorous than HIPAA. However, numerous exceptions to the rules have been carved out over the years. For example, many states require physicians to report gunshot wounds to the police and impaired drivers to the Department of Motor Vehicles. Confidentiality is also challenged in cases involving the diagnosis of a sexually transmitted disease in a patient who refuses to reveal the diagnosis to a spouse, and in the termination of a pregnancy in an underage patient, without the knowledge of the patient's parents. Many states in the U.S. have laws governing parental notification in underage abortion.[70][71] Those working in mental health have a duty to warn those who they deem to be at risk from their patients in some countries.[72] Traditionally, medical ethics has viewed the duty of confidentiality as a relatively non-negotiable tenet of medical practice. More recently, critics like Jacob Appel have argued for a more nuanced approach to the duty that acknowledges the need for flexibility in many cases.[12] Confidentiality is an important issue in primary care ethics, where physicians care for many patients from the same family and community, and where third parties often request information from the considerable medical database typically gathered in primary health care. Privacy and the Internet In increasing frequency, medical researchers are researching activities in online environments such as discussion boards and bulletin boards, and there is concern that the requirements of informed consent and privacy are not applied, although some guidelines do exist.[73] One issue that has arisen, however, is the disclosure of information. While researchers wish to quote from the original source in order to argue a point, this can have repercussions when the identity of the patient is not kept confidential. The quotations and other information about the site can be used to identify the patient, and researchers have reported cases where members of the site, bloggers and others have used this information as 'clues' in a game in an attempt to identify the site.[74] Some researchers have employed various methods of "heavy disguise."[74] including discussing a different condition from that under study.[75][76] Healthcare institutions' websites have the responsibility to ensure that the private medical records of their online visitors are secure from being marketed and monetized into the hands of drug companies, occupation records, and insurance companies. The delivery of diagnosis online leads patients to believe that doctors in some parts of the country are at the direct service of drug companies, finding diagnosis as convenient as what drug still has patent rights on it.[77] Physicians and drug companies are found to be competing for top ten search engine ranks to lower costs of selling these drugs with little to no patient involvement.[78] With the expansion of internet healthcare platforms, online practitioner legitimacy and privacy accountability face unique challenges such as e-paparazzi, online information brokers, industrial spies, unlicensed information providers that work outside of traditional medical codes for profit. The American Medical Association (AMA) states that medical websites have the responsibility to ensure the health care privacy of online visitors and protect patient records from being marketed and monetized into the hands of insurance companies, employers, and marketers. [40] With the rapid unification of healthcare, business practices, computer science and e-commerce to create these online diagnostic websites, efforts to maintain health care system's ethical confidentiality standard need to keep up as well. Over the next few years, the Department of Health and Human Services has stated that they will be working towards lawfully protecting the online privacy and digital transfers of patient Electronic Medical Records (EMR) under The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). [41]. Looking forward, strong governance and accountability mechanisms will need to be considered with respect to digital health ecosystems, including potential metaverse healthcare platforms, to ensure the highest ethical standards are upheld relating to medical confidentiality and patient data.[79] |

守秘義務 守秘義務は、医師と患者間の会話に一般的に適用される。[68] この概念は、患者と医師の特権として一般的に知られている。法的な保護により、医師は患者との話し合いを明らかにすることはできない。たとえ法廷で宣誓し たとしてもである。 守秘義務は、米国では1996年の医療保険の相互運用性と説明責任に関する法律(HIPAA)[69]、特にプライバシー規則、およびさまざまな州法に よって義務付けられている。HIPAAよりも厳しい規定もある。しかし、長年にわたり、この規則には数多くの例外が設けられてきた。例えば、多くの州で は、医師は銃創の傷害を警察に報告し、運転能力に問題のある運転者を自動車管理局に報告することが義務付けられている。また、患者が配偶者に性感染症の診 断を明かさない場合や、未成年患者の妊娠中絶を患者の両親に知らせずに実施する場合にも、守秘義務が問われる。米国の多くの州では、未成年の人工妊娠中絶 における親への通知を規定する法律がある。[70][71] 精神保健に従事する者は、患者が危険な状態にあると判断した場合は、その旨を警告する義務がある国もある。[72] 伝統的に、医療倫理では守秘義務は医療行為の原則として比較的譲歩できないものと見なされてきた。しかし、最近では、ジェイコブ・アッペルなどの批判派 が、多くの場合において柔軟性が必要であることを認める、守秘義務に対するより繊細なアプローチを主張している。 プライバシーの保護は、プライマリケア倫理における重要な問題である。プライマリケアでは、医師が同じ家族や地域社会に属する多数の患者を診るため、ま た、通常、プライマリケアで収集される膨大な医療データベースに第三者から情報提供の要請が寄せられることが多いからである。 プライバシーとインターネット 医療研究者は、オンライン上のディスカッションボードや掲示板などの環境における活動を研究することが増えているが、インフォームドコンセントやプライバ シー保護の要件が適用されていないのではないかという懸念がある。ただし、いくつかのガイドラインは存在する。 しかし、生じた問題のひとつは情報の開示である。研究者は論点を主張するために元のソースからの引用を希望するが、患者の身元が守られない場合、これは悪 影響を及ぼす可能性がある。引用やその他のサイトに関する情報は患者の特定に利用される可能性があり、研究者は、サイトメンバーやブロガーなどがこの情報 を手がかりにゲームでサイトを特定しようとした事例を報告している。[74] 研究者の一部は、研究対象とは異なる症状について議論するなど、さまざまな「偽装」の手法を採用している。[74][75][76] 医療機関のウェブサイトには、オンライン訪問者の医療記録が製薬会社や職業記録、保険会社に販売され、収益化されることがないよう、その安全性を確保する 責任がある。オンラインでの診断の提供は、患者に、国内の一部の地域の医師は製薬会社の直接的なサービスに就いていると信じ込ませ、特許権が残っている医 薬品と同様に診断を都合よく見つけていると信じ込ませる。[77] 医師と製薬会社は、患者の関与をほとんど、あるいはまったく伴わずに、これらの医薬品の販売コストを下げるために、検索エンジンのトップ10のランクを 競っていることが分かっている。[78] インターネット医療プラットフォームの拡大に伴い、オンライン医療従事者の正当性やプライバシーの説明責任は、電子パパラッチ、オンライン情報ブロー カー、産業スパイ、利益追求のために従来の医療規定外で活動する無認可の情報プロバイダーなど、独特な課題に直面している。米国医師会(AMA)は、医療 ウェブサイトにはオンライン訪問者の医療プライバシーを確保し、患者の記録が保険会社、雇用主、マーケティング担当者の手に渡り、マーケティングや収益化 に利用されないように保護する責任があると述べている。[40] 医療、ビジネス慣行、コンピュータサイエンス、電子商取引が急速に統合され、オンライン診断ウェブサイトが誕生する中、医療システムの倫理的機密性基準を 維持するための取り組みも同様に進めていく必要がある。今後数年間で、保健社会福祉省は、医療保険の携行性と責任に関する法律(HIPAA)に基づき、患 者の電子カルテ(EMR)のオンラインプライバシーとデジタル転送を合法的に保護するための取り組みを進めていくと述べている。[41]。今後は、医療上 の機密性と患者データに関する最高水準の倫理基準を維持するために、潜在的なメタバース医療プラットフォームを含むデジタルヘルスエコシステムに関して、 強力なガバナンスと説明責任のメカニズムを検討する必要があるだろう。[79] |

| Control, resolution and

enforcement In the UK, medical ethics forms part of the training of physicians and surgeons[80] and disregard for ethical principles can result in doctors barred from medical practice after a decision by the Medical Practitioners Tribunal Service.[81]: 32 To ensure that appropriate ethical values are being applied within hospitals, effective hospital accreditation requires that ethical considerations are taken into account, for example with respect to physician integrity, conflict of interest, research ethics and organ transplantation ethics. Guidelines There is much documentation of the history and necessity of the Declaration of Helsinki. The first code of conduct for research including medical ethics was the Nuremberg Code. This document had large ties to Nazi war crimes, as it was introduced in 1997, so it didn't make much of a difference in terms of regulating practice. This issue called for the creation of the Declaration. There are some stark differences between the Nuremberg Code and the Declaration of Helsinki, including the way it is written. Nuremberg was written in a very concise manner, with a simple explanation. The Declaration of Helsinki is written with a thorough explanation in mind and including many specific commentaries.[82] In the United Kingdom, General Medical Council provides clear overall modern guidance in the form of its 'Good Medical Practice' statement.[83] Other organizations, such as the Medical Protection Society and a number of university departments, are often consulted by British doctors regarding issues relating to ethics. Ethics committees Often, simple communication is not enough to resolve a conflict, and a hospital ethics committee must convene to decide a complex matter. These bodies are composed primarily of healthcare professionals, but may also include philosophers, lay people, and clergy – indeed, in many parts of the world their presence is considered mandatory in order to provide balance. With respect to the expected composition of such bodies in the US, Europe and Australia, the following applies.[84] U.S. recommendations suggest that Research and Ethical Boards (REBs) should have five or more members, including at least one scientist, one non-scientist, and one person not affiliated with the institution.[85] The REB should include people knowledgeable in the law and standards of practice and professional conduct.[85] Special memberships are advocated for handicapped or disabled concerns, if required by the protocol under review. The European Forum for Good Clinical Practice (EFGCP) suggests that REBs include two practicing physicians who share experience in biomedical research and are independent from the institution where the research is conducted; one lay person; one lawyer; and one paramedical professional, e.g. nurse or pharmacist. They recommend that a quorum include both sexes from a wide age range and reflect the cultural make-up of the local community. The 1996 Australian Health Ethics Committee recommendations were entitled, "Membership Generally of Institutional Ethics Committees". They suggest a chairperson be preferably someone not employed or otherwise connected with the institution. Members should include a person with knowledge and experience in professional care, counseling or treatment of humans; a minister of religion or equivalent, e.g. Aboriginal elder; a layman; a laywoman; a lawyer and, in the case of a hospital-based ethics committee, a nurse. The assignment of philosophers or religious clerics will reflect the importance attached by the society to the basic values involved. An example from Sweden with Torbjörn Tännsjö on a couple of such committees indicates secular trends gaining influence. |

管理、解決、施行 英国では、医療倫理は医師や外科医の研修の一部となっており[80]、倫理原則を無視した場合には、医療従事者審議会サービスによる決定の後、医師が医療 行為から排除される可能性がある[81]:32。 病院内で適切な倫理観が適用されていることを保証するために、効果的な病院認定では、例えば医師の誠実さ、利益相反、研究倫理、臓器移植倫理などに関し て、倫理的配慮が考慮されることが求められる。 ガイドライン ヘルシンキ宣言の歴史と必要性については、多くの文献が存在する。医療倫理を含む研究のための最初の行動規範はニュルンベルク綱領であった。この文書は 1997年に導入されたもので、ナチスの戦争犯罪と密接な関係があったため、実際の業務を規制する上で大きな違いをもたらすものではなかった。この問題が 宣言の作成を必要としたのである。ニュルンベルク綱領とヘルシンキ宣言の間には、その記述方法を含め、いくつかの顕著な相違点がある。ニュルンベルク綱領 は簡潔に、簡素に記述されている。一方、ヘルシンキ宣言は、詳細な説明を念頭に置いて記述されており、多くの具体的な解説を含んでいる。 英国では、英国医師会(General Medical Council)が「良質な医療の実践(Good Medical Practice)」という声明の形で、明確な全体的な現代的な指針を提供している。[83] 医療保護協会(Medical Protection Society)や多数の大学学部など、他の組織も、倫理に関する問題について英国の医師からよく相談を受ける。 倫理委員会 しばしば、単純なコミュニケーションだけでは対立を解決するには不十分であり、複雑な問題を決定するために病院の� これらの委員会は主に医療従事者で構成されるが、哲学者、一般市民、聖職者も含まれることがある。実際、世界の多くの地域では、バランスを取るために彼ら の参加が必須とされている。 米国、欧州、オーストラリアにおけるこのような委員会の構成について、以下のことが当てはまる。[84] 米国の勧告では、研究倫理委員会(REB)は少なくとも科学者1名、非科学者1名、および当該機関に所属しない者1名を含む5名以上の委員で構成すべきで あるとしている。[85] REBには、法律および業務基準、専門職の行動規範に精通した人物を含めるべきである。[85] 審査中のプロトコルで必要とされる場合、障害者または身体障害者の懸念事項については特別の委員を置くことが推 欧州臨床試験実施に関するフォーラム(EFGCP)は、REBには生物医学研究の経験を共有し、研究実施施設から独立した2名の現役医師、1名の一般市 民、1名の弁護士、1名の医療従事者(看護師または薬剤師など)を含めることを推奨している。また、幅広い年齢層の男女両性で構成し、地域社会の文化的構 成を反映させることを推奨している。 1996年のオーストラリア保健倫理委員会の勧告は、「倫理委員会の構成員」と題されていた。 委員長は、その施設に雇用されている者や何らかの関係がある者以外が望ましいとされている。 委員には、人間の専門的ケア、カウンセリング、治療に関する知識と経験を持つ者、宗教家またはそれに相当する者(例えば、先住民の長老)、一般市民、一般 市民の女性、弁護士、そして病院を拠点とする倫理委員会 哲学者や宗教家が任命されることは、社会が基本的な価値観に重要性を置いていることを反映している。スウェーデンにおけるトルビョーン・タンネシェーが委 員を務めるいくつかの委員会の例は、世俗化の傾向が影響力を強めていることを示している。 |

| Cultural concerns Cultural differences can create difficult medical ethics problems. Some cultures have spiritual or magical theories about the origins and cause of disease, for example, and reconciling these beliefs with the tenets of Western medicine can be very difficult. As different cultures continue to intermingle and more cultures live alongside each other, the healthcare system, which tends to deal with important life events such as birth, death and suffering, increasingly experiences difficult dilemmas that can sometimes lead to cultural clashes and conflict. Efforts to respond in a culturally sensitive manner go hand in hand with a need to distinguish limits to cultural tolerance.[10] Culture and language As more people from different cultural and religious backgrounds move to other countries, among these, the United States, it is becoming increasingly important to be culturally sensitive to all communities in order to provide the best health care for all people.[11] Lack of cultural knowledge can lead to misunderstandings and even inadequate care, which can lead to ethical problems. A common complaint patients have is feeling like they are not being heard, or perhaps, understood.[11] Preventing escalating conflict can be accomplished by seeking interpreters, noticing body language and tone of both yourself and the patient as well as attempting to understand the patient's perspective in order to reach an acceptable option.[11] Some believe most medical practitioners in the future will have to be or greatly benefit from being bilingual. In addition to knowing the language, truly understanding culture is best for optimal care.[86] Recently, a practice called 'narrative medicine' has gained some interest as it has a potential for improving patient-physician communication and understanding of patient's perspective. Interpreting a patient's stories or day-to-day activities as opposed to standardizing and collecting patient data may help in acquiring a better sense of what each patient needs, individually, with respect to their illness. Without this background information, many physicians are unable to properly understand the cultural differences that may set two different patients apart, and thus, may diagnose or recommend treatments that are culturally insensitive or inappropriate. In short, patient narrative has the potential for uncovering patient information and preferences that may otherwise be overlooked. Medical humanitarianism In order to address the underserved, uneducated communities in need of nutrition, housing, and healthcare disparities seen in much of the world today, some argue that we must fall back on ethical values in order to create a foundation to move towards a reasonable understanding, which encourages commitment and motivation to improve factors causing premature death as a goal in a global community.[13] Such factors – such as poverty, environment and education – are said to be out of national or individual control and so this commitment is by default a social and communal responsibility placed on global communities that are able to aid others in need.[13] This is based on the framework of 'provincial globalism,' which seeks a world in which all people have the capability to be healthy.[13] One concern regarding the intersection of medical ethics and humanitarian medical aid is how medical assistance can be as harmful as it is helpful to the community being served. One such example being how political forces may control how foreign humanitarian aid can be utilized in the region it is meant to be provided in. This would be congruous in situations where political strife could lead such aid being used in favor of one group over another. Another example of how foreign humanitarian aid can be misused in its intended community includes the possibility of dissonance forming between a foreign humanitarian aid group and the community being served.[87] Examples of this could include the relationships being viewed between aid workers, style of dress, or the lack of education regarding local culture and customs.[88] Humanitarian practices in areas lacking optimum care can also pause other interesting and difficult ethical dilemmas in terms of beneficence and non-maleficence. Humanitarian practices are based upon providing better medical equipment and care for communities whose country does not provide adequate healthcare.[89] The issues with providing healthcare to communities in need may sometimes be religious or cultural backgrounds keeping people from performing certain procedures or taking certain drugs. On the other hand, wanting certain procedures done in a specific manner due to religious or cultural belief systems may also occur. The ethical dilemma stems from differences in culture between communities helping those with medical disparities and the societies receiving aid. Women's rights, informed consent and education about health become controversial, as some treatments needed are against societal law, while some cultural traditions involve procedures against humanitarian efforts.[89] Examples of this are female genital mutilation (FGM), aiding in reinfibulation, providing sterile equipment in order to perform procedures such as FGM, as well as informing patients of their HIV positive testing. The latter is controversial because certain communities have in the past outcast or killed HIV positive individuals.[89] Healthcare reform and lifestyle Leading causes of death in the United States and around the world are highly related to behavioral consequences over genetic or environmental factors.[90] This leads some to believe true healthcare reform begins with cultural reform, habit and overall lifestyle.[90] Lifestyle, then, becomes the cause of many illnesses and the illnesses themselves are the result or side-effect of a larger problem.[90] Some people believe this to be true and think that cultural change is needed in order for developing societies to cope and dodge the negative effects of drugs, food and conventional modes of transportation available to them.[90] In 1990, tobacco use, diet, and exercise alone accounted for close to 80 percent of all premature deaths and continue to lead in this way through the 21st century.[90] Heart disease, stroke, dementia, and diabetes are some of the diseases that may be affected by habit-forming patterns throughout our life.[90] Some believe that medical lifestyle counseling and building healthy habits around our daily lives is one way to tackle health care reform.[90] Other cultures and healthcare Buddhist medicine Buddhist ethics and medicine are based on religious teachings of compassion and understanding[91] of suffering and cause and effect and the idea that there is no beginning or end to life, but that instead there are only rebirths in an endless cycle.[10] In this way, death is merely a phase in an indefinitely lengthy process of life, not an end. However, Buddhist teachings support living one's life to the fullest so that through all the suffering which encompasses a large part of what is life, there are no regrets. Buddhism accepts suffering as an inescapable experience, but values happiness and thus values life.[10] Because of this, suicide and euthanasia, are prohibited. However, attempts to rid oneself of any physical or mental pain and suffering are seen as good acts. On the other hand, sedatives and drugs are thought to impair consciousness and awareness in the dying process, which is believed to be of great importance, as it is thought that one's dying consciousness remains and affects new life. Because of this, analgesics must not be part of the dying process, in order for the dying person to be present entirely and pass on their consciousness wholesomely. This can pose significant conflicts during end of life care in Western medical practice.[10]  Taoist symbol of Yin and Yang Chinese medicine In traditional Chinese philosophy, human life is believed to be connected to nature, which is thought of as the foundation and encompassing force sustaining all of life's phases.[10] Passing and coming of the seasons, life, birth and death are perceived as a cyclic and perpetual occurrences that are believed to be regulated by the principles of yin and yang.[10] When one dies, the life-giving material force referred to as ch'i, encompassing both body and spirit, rejoins the material force of the universe and cycles on with respect to the rhythms set forth by yin and yang.[10] Because many Chinese people believe that circulation of both physical and 'psychic energy' is important to stay healthy, procedures which require surgery, as well as donations and transplantations of organs, are seen as a loss of ch'i, resulting in the loss of someone's vital energy supporting their consciousness and purpose in their lives. Furthermore, a person is never seen as a single unit but rather as a source of relationship, interconnected in a social web.[10] Thus, it is believed that what makes a human one of us is relatedness and communication and family is seen as the basic unit of a community.[10][15] This can greatly affect the way medical decisions are made among family members, as diagnoses are not always expected to be announced to the dying or sick, the elderly are expected to be cared for and represented by their children and physicians are expected to act in a paternalistic way.[10][15] In short, informed consent as well as patient privacy can be difficult to enforce when dealing with Confucian families.[10] Furthermore, some Chinese people may be inclined to continue futile treatment in order to extend life and allow for fulfillment of the practice of benevolence and humanity.[10] In contrast, patients with strong Daoist beliefs may see death as an obstacle and dying as a reunion with nature that should be accepted, and are therefore less likely to ask for treatment of an irreversible condition.[10] Islamic culture and medicine Some believe Islamic medical ethics and framework remain poorly understood by many working in healthcare. It is important to recognize that for people of Islamic faith, Islam envelops and affects all aspects of life, not just medicine.[92] Because many believe it is faith and a supreme deity that hold the cure to illness, it is common that the physician is viewed merely as help or intermediary player during the process of healing or medical care.[92] In addition to Chinese culture's emphasis on family as the basic unit of a community intertwined and forming a greater social construct, Islamic traditional medicine also places importance on the values of family and the well-being of a community.[15][92] Many Islamic communities uphold paternalism as an acceptable part of medical care.[92] However, autonomy and self-rule is also valued and protected and, in Islamic medicine, it is particularly upheld in terms of providing and expecting privacy in the healthcare setting. An example of this is requesting same gender providers in order to retain modesty.[92] Overall, Beauchamp's principles of beneficence, non-maleficence and justice[2] are promoted and upheld in the medical sphere with as much importance as in Western culture.[92] In contrast, autonomy is important but more nuanced. Furthermore, Islam also brings forth the principles of jurisprudence, Islamic law and legal maxims, which also allow for Islam to adapt to an ever-changing medical ethics framework.[92] |

文化的な懸念 文化の違いは、医療倫理上の難しい問題を引き起こすことがある。例えば、病気の起源や原因について、精神的な、あるいは魔術的な理論を持つ文化もある。こ うした信念と西洋医学の原則を調和させることは非常に難しい。異なる文化が混ざり合い、より多くの文化が共存するにつれ、誕生、死、苦しみといった重要な 人生の出来事に対処する傾向にある医療制度は、時に文化的な衝突や対立につながることもある難しいジレンマを経験することが増えている。文化的に敏感な対 応を試みる努力は、文化的な寛容の限界を区別する必要性と表裏一体である。[10] 文化と言語 異なる文化や宗教的背景を持つ人々が他国に移住する中、その中には米国も含まれるが、すべての人々に最善の医療を提供するためには、あらゆるコミュニティ に対して文化的に敏感であることがますます重要になっている。[11] 文化的な知識の欠如は誤解につながり、不適切なケアさえ招く可能性があり、それは倫理的な問題につながる可能性がある。患者がよく訴える不満は、自分の意 見が聞いてもらえていない、あるいは理解されていないと感じることである。[11] 対立の悪化を防ぐには、通訳を求めたり、自分と患者の両者のボディランゲージや口調に注意を払ったり、患者の視点に立って理解しようと努めたりすること で、受け入れ可能な選択肢を見出すことができる。[11] 将来、ほとんどの医療従事者はバイリンガルであるか、あるいはバイリンガルであることが非常に有益であると考えられている。言語を理解するだけでなく、文 化を本当に理解することが、最適なケアにとって最善である。[86] 最近では、「ナラティブ・メディスン(物語医療)」と呼ばれる診療が、患者と医師のコミュニケーションや患者の視点の理解を改善する可能性があるとして、 関心を集めている。患者のデータ収集を標準化するのではなく、患者の物語や日々の活動を解釈することは、患者一人一人が病気に関して何を必要としているか をより深く理解するのに役立つかもしれない。この背景情報がなければ、多くの医師は、2人の異なる患者を隔てる文化の違いを適切に理解できず、その結果、 文化的に鈍感であったり不適切な診断や治療を推奨してしまう可能性がある。つまり、患者の語りは、見過ごされてしまう可能性のある患者の情報や好みを明ら かにする可能性を秘めているのだ。 医療人道主義 今日、世界の多くの地域で見られる栄養不足、住居不足、医療格差といった問題を抱える恵まれない地域や教育を受けていない地域に対応するためには、早死の 要因を改善するという目標に向かって、世界的なコミュニティが努力と意欲を傾けるよう、合理的な理解を促す基盤を構築するために、倫理的な価値観に立ち返 る必要があると主張する人もいる。[13] このような要因、例えば 貧困、環境、教育などの要因は、国民や個人の力ではどうにもならないものであるため、この取り組みは、必然的に、困っている人々を支援できる国際社会に課 せられた社会的責任、共同責任となる。[13] これは、「地域的グローバリズム」の枠組みに基づくもので、すべての人が健康になる能力を持つ世界を追求するものである。[13] 医療倫理と人道医療支援の交差に関する懸念事項のひとつは、医療支援が、支援対象の地域社会にとって有益であると同時に有害となる可能性があることであ る。その一例として、外国からの人道支援が、本来の提供対象地域においてどのように利用されるかを政治勢力がコントロールする可能性が挙げられる。これ は、政治的対立が原因で、あるグループを支援する目的で提供された人道支援が別のグループに有利に利用されるような状況に当てはまる。外国からの人道支援 が意図した地域で悪用されるもう一つの例としては、外国からの人道支援団体と支援対象地域との間に不和が生じる可能性がある。[87] その例としては、支援活動家間の関係、服装のスタイル、または現地の文化や習慣に関する教育の欠如などが挙げられる。[88] 最適なケアが欠如している地域における人道支援の実践は、恩恵と非加害性の観点から、興味深く困難な倫理的ジレンマを引き起こす可能性もある。人道支援の 実践は、自国で十分な医療ケアを提供できない地域社会に対して、より優れた医療機器やケアを提供することに基づいている。[89] 医療を必要とする地域社会への医療提供に関する問題は、時に人々を特定の手順の実行や特定の薬の服用から遠ざける宗教的または文化的背景である場合があ る。一方で、宗教や文化的な信念体系から特定の処置を特定の方法で実施することを望む場合もある。医療格差のある人々を支援するコミュニティと支援を受け る社会との文化の違いから、倫理的なジレンマが生じる。必要な治療法が社会の法律に反する場合や、文化的な伝統が人道的な取り組みに反する処置を含む場合 など、女性の権利、インフォームドコンセント、健康に関する教育は論争の的となる。[89] その例としては、女性性器切除(FGM)、再焼灼術の支援、FGMなどの処置を行うための滅菌器具の提供、および患者へのHIV陽性検査結果の通知などが ある。後者は論争の的となっている。なぜなら、特定のコミュニティでは過去にHIV陽性者を追放したり殺害したりしていたからである。[89] 医療改革とライフスタイル 米国および世界における主な死因は、遺伝的要因や環境的要因よりも行動の結果と強く関連している。[90] そのため、真の医療改革は文化改革、習慣、ライフスタイル全般から始まると考える人もいる。[90] ライフスタイルは、多くの病気の原因となり、病気そのものはより大きな問題の結果または副作用である。 90] これを真実と信じ、発展途上社会が薬物や食品、従来の交通手段の負の影響に対処し、回避するためには文化の変革が必要だと考える人もいる。[90] 1990年には、たばこの使用、食生活、運動だけで早死の80パーセント近くを占めており、 21世紀に入っても、この傾向は続いている。[90] 心臓病、脳卒中、認知症、糖尿病などは、生涯にわたる習慣形成パターンによって影響を受ける可能性がある病気である。[90] 医療生活相談や日常生活における健康的な習慣の形成が、医療改革に取り組む一つの方法であると考える人もいる。[90] 他の文化や医療 仏教医学 仏教の倫理と医学は、苦しみや因果応報に対する慈悲と理解の宗教的教え[91]、そして、人生には始まりも終わりもなく、代わりに無限のサイクルの中で生 まれ変わるだけだという考えに基づいている。[10] このように、死は単に終わりではなく、無限に長い人生の過程における一局面に過ぎない。しかし、仏教の教えでは、人生の大部分を占める苦しみを通して、後 悔のないよう全力で生きることが推奨されている。仏教では、苦しみは避けられない経験として受け入れられているが、幸福を重視し、それゆえに人生も重視し ている。[10] このため、自殺や安楽死は禁じられている。しかし、肉体的または精神的な痛みや苦しみを取り除く試みは、善行とみなされている。一方で、鎮静剤や薬物は、 死を迎える過程において意識や認識を損なうと考えられている。死を迎える意識が残り、新たな生命に影響を与えると考えられているため、これは非常に重要な ことである。このため、死を迎える人が完全に存在し、健全な意識を伝えるためには、鎮痛剤は死を迎える過程の一部であってはならない。これは、西洋医学の 終末期医療において、重大な対立を引き起こす可能性がある。  道教の陰陽のシンボル 中国医学 伝統的な中国哲学では、人間の生命は自然とつながっていると考えられており、自然は生命のあらゆる局面を支える基盤であり包括的な力であると考えられてい る。[10] 季節の移り変わりや生命、誕生と死は、循環的かつ永遠に繰り返される出来事であり、 。人が死ぬと、気と呼ばれる生命を与える物質的な力が、肉体と精神の両方を包み込み、宇宙の物質的な力と再び結びつき、陰と陽によって定められたリズムに 従って循環する。 多くの中国人は、肉体的にも「精神的なエネルギー」の循環が健康を維持するために重要であると信じているため、手術を必要とする処置や臓器の寄付や移植 は、その人の生命を支える活力の損失と見なされ、結果としてその人の意識や人生の目的を損なうことになると見なされる。さらに、人は決して単一の単位とし てではなく、むしろ社会的なつながりの中で相互に結びついた関係性の源として見られる。[10] したがって、人間を人間たらしめているのは関係性とコミュニケーションであり、家族はコミュニティの基本単位であると考えられている。[10][15] これは、家族の間で医療上の決定が下される際に大きな影響を与える可能性がある。というのも、病人の家族には病状が告知されないことが多く、高齢者は子供 たちに世話を任せる傾向があり、医師は温情主義的な対応を取ることが期待されているからである。[10][15] つまり、儒教的な家族を相手にする場合、インフォームドコンセントや患者のプライバシー保護を徹底させるのは難しいのである。[10] さらに、一部の中国人は、命を延ばすために無益な治療を続け、仁徳や人道の実践を全うしようとする傾向がある。[10] これとは対照的に、道教の信仰が強い患者は、死を障害と見なし、死ぬことは自然との再会であり、受け入れるべきことであると考えるため、不可逆的な病状に 対する治療を求める可能性は低い。[10] イスラム文化と医療 一部の人は、イスラムの医療倫理や枠組みは、医療に携わる多くの人々には依然として十分に理解されていないと考えている。イスラム教徒にとって、イスラム 教は医療だけでなく生活のあらゆる側面を包み込み、影響を及ぼしていることを認識することが重要である。[92] 多くの人々は、病気の治療は信仰と至高の神がもたらすものであると信じているため、医師は治療や医療ケアの過程において、単に手助けをする者、または仲介 者とみなされるのが一般的である。[92] また、中国では、家族を社会の基本単位として重視し、それが複雑に絡み合ってより大きな社会構造を形成しているが、イスラムの伝統医学でも、家族の価値と 社会の幸福が重視されている。多くのイスラム教社会では、医療ケアの一部としてパターナリズム(温情主義)が容認されている。[92] しかし、自律性や自己統治も尊重され保護されており、イスラム医学では、医療現場におけるプライバシーの提供と期待という観点で特に重視されている。その 一例として、慎み深さを保つために同性医療従事者を希望することが挙げられる。[92] 全体的には、ベーチャムの「善行」、「非加害」、「正義」の原則[2]が西洋文化と同様に医療分野でも重要視され、推進されている。[92] これに対し、自律性は重要ではあるが、より微妙なニュアンスを持つ。さらに、イスラム教は法の原則、イスラム法、法の格言ももたらしており、それらもま た、イスラム教が絶えず変化する医療倫理の枠組みに適応することを可能にしている。[92] |

Conflicts of interest "More Doctors Smoke Camels than Any Other Cigarette" advertisement for Camel cigarettes in the 1940s Physicians should not allow a conflict of interest to influence medical judgment. In some cases, conflicts are hard to avoid, and doctors have a responsibility to avoid entering such situations. Research has shown that conflicts of interests are very common among both academic physicians[93] and physicians in practice.[94][95] Referral Doctors who receive income from referring patients for medical tests have been shown to refer more patients for medical tests.[96] This practice is proscribed by the American College of Physicians Ethics Manual.[97] Fee splitting and the payments of commissions to attract referrals of patients is considered unethical and unacceptable in most parts of the world.[citation needed] Vendor relationships See also: Pharmaceutical marketing § To health care providers Studies show that doctors can be influenced by drug company inducements, including gifts and food.[14] Industry-sponsored Continuing Medical Education (CME) programs influence prescribing patterns.[98] Many patients surveyed in one study agreed that physician gifts from drug companies influence prescribing practices.[99] A growing movement among physicians is attempting to diminish the influence of pharmaceutical industry marketing upon medical practice, as evidenced by Stanford University's ban on drug company-sponsored lunches and gifts. Other academic institutions that have banned pharmaceutical industry-sponsored gifts and food include the Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions, University of Michigan, University of Pennsylvania, and Yale University.[100][101] Treatment of family members The American Medical Association (AMA) states that "Physicians generally should not treat themselves or members of their immediate family".[102] This code seeks to protect patients and physicians because professional objectivity can be compromised when the physician is treating a loved one. Studies from multiple health organizations have illustrated that physician-family member relationships may cause an increase in diagnostic testing and costs.[103] Many doctors still treat their family members. Doctors who do so must be vigilant not to create conflicts of interest or treat inappropriately.[104][105] Physicians that treat family members need to be conscious of conflicting expectations and dilemmas when treating relatives, as established medical ethical principles may not be morally imperative when family members are confronted with serious illness.[103][106] Sexual relationships Sexual relationships between doctors and patients can create ethical conflicts, since sexual consent may conflict with the fiduciary responsibility of the physician.[107] Out of the many disciplines in current medicine, there are studies that have been conducted in order to ascertain the occurrence of Doctor-Patient sexual misconduct. Results from those studies appear to indicate that certain disciplines are more likely to be offenders than others. Psychiatrists and obstetrician-gynecologists, for example, are two disciplines noted for having a higher rate of sexual misconduct.[108] The violation of ethical conduct between doctors and patients also has an association with the age and sex of doctor and patient. Male physicians aged 40–59 years have been found to be more likely to have been reported for sexual misconduct; women aged 20–39 have been found to make up a significant portion of reported victims of sexual misconduct.[109] Doctors who enter into sexual relationships with patients face the threats of losing their medical license and prosecution. In the early 1990s, it was estimated that 2–9% of doctors had violated this rule.[110] Sexual relationships between physicians and patients' relatives may also be prohibited in some jurisdictions, although this prohibition is highly controversial.[111] |

利益相反 1940年代のキャメル・タバコの広告「他のどのタバコよりも多くの医師がキャメルを吸っている」 医師は、利益相反が医療上の判断に影響を及ぼすことを許してはならない。場合によっては、利益相反を避けることが困難な場合もあり、医師にはそのような状 況に陥らないようにする責任がある。研究により、利益相反は学術的な医師[93]および実務医[94][95]の両者において非常に一般的であることが示 されている。 紹介 患者を医療検査に回すことで収入を得ている医師は、より多くの患者を医療検査に回す傾向にあることが示されている。[96] この慣行は、米国医師会の倫理マニュアルで禁じられている。[97] 料金の折半や患者紹介を誘引するための手数料の支払いは、世界の大半の地域では非倫理的かつ容認できないものと見なされている。[要出典] 業者との関係 参照:製薬マーケティング § 医療従事者向け 研究によると、医師は製薬会社からの贈り物や食事などの誘因に影響を受ける可能性があることが示されている。[14] 業界がスポンサーとなっている継続的医学教育(CME)プログラムは処方パターンに影響を与える。[98] ある研究で調査された多くの患者は、製薬会社からの医師への贈り物が処方方法に影響を与えることに同意した。[99] スタンフォード大学が製薬会社がスポンサーとなっている昼食や贈り物を禁止したことからも明らかなように、医療行為に対する製薬業界のマーケティングの影 響を減少させようとする動きが医師の間で高まっている。製薬業界がスポンサーとなっている贈り物や食事を禁止している他の学術機関には、ジョンズ・ホプキ ンス医療機関、ミシガン大学、ペンシルベニア大学、イェール大学などがある。[100][101] 家族の治療 米国医師会(AMA)は、「医師は通常、自分自身や肉親の治療を行なってはならない」と述べている。[102] この規範は、医師が愛する者を治療する場合、専門的な客観性が損なわれる可能性があるため、患者と医師を保護することを目的としている。複数の医療機関に よる研究では、医師と家族の関係が診断検査とコストの増加につながる可能性があることが示されている。[103] 多くの医師は依然として家族の治療を行なっている。そうした医師は、利益相反を生じさせたり、不適切な治療を行ったりしないよう、常に警戒していなければ ならない。[104][105] 家族を治療する医師は、家族が重病に直面している場合には確立された医療倫理原則が道徳的に必須ではない場合があるため、親族を治療する際には相反する期 待やジレンマを意識する必要がある。[103][106] 性的関係 医師と患者間の性的関係は、性的同意が医師の受託者責任と対立する可能性があるため、倫理的葛藤を生じさせる可能性がある。[107] 現在の医療における多くの分野のうち、医師と患者間の性的不祥事の発生を把握するために実施された研究がある。これらの研究結果によると、特定の分野が他 の分野よりも加害者となる可能性が高いことが示唆されている。例えば、精神科医と産婦人科医は、性的不祥事の発生率が高いことで知られている。[108] 医師と患者間の倫理規定違反は、医師と患者の年齢や性別とも関連がある。40歳から59歳の男性医師が性的不品行で報告される可能性が高いことが判明して いる。また、20歳から39歳の女性が性的不品行の被害者として報告されるケースの相当な割合を占めていることも判明している。[109] 患者と性的関係を持つ医師は、医師免許の剥奪や起訴の脅威に直面する。1990年代初頭には、医師の2~9%がこの規則に違反していると推定されていた。 [110] 医師と患者の親族との性的関係も、一部の管轄区域では禁止されている可能性があるが、この禁止については非常に議論の余地がある。[111] |

| Futility Further information: Futile medical care In some hospitals, medical futility is referred to as treatment that is unable to benefit the patient.[112] An important part of practicing good medical ethics is by attempting to avoid futility by practicing non-maleficence.[112] What should be done if there is no chance that a patient will survive or benefit from a potential treatment but the family members insist on advanced care?[112] Previously, some articles defined futility as the patient having less than a one percent chance of surviving. Some of these cases are examined in court. Advance directives include living wills and durable powers of attorney for health care. (See also Do Not Resuscitate and cardiopulmonary resuscitation) In many cases, the "expressed wishes" of the patient are documented in these directives, and this provides a framework to guide family members and health care professionals in the decision-making process when the patient is incapacitated. Undocumented expressed wishes can also help guide decisions in the absence of advance directives, as in the Quinlan case in Missouri. "Substituted judgment" is the concept that a family member can give consent for treatment if the patient is unable (or unwilling) to give consent themselves. The key question for the decision-making surrogate is not, "What would you like to do?", but instead, "What do you think the patient would want in this situation?". Courts have supported family's arbitrary definitions of futility to include simple biological survival, as in the Baby K case (in which the courts ordered a child born with only a brain stem instead of a complete brain to be kept on a ventilator based on the religious belief that all life must be preserved). Baby Doe Law establishes state protection for a disabled child's right to life, ensuring that this right is protected even over the wishes of parents or guardians in cases where they want to withhold treatment. |

無益 さらに詳しい情報:無益な医療 一部の病院では、医療の無益性とは患者に利益をもたらすことができない治療を指す。[112] 医療倫理を実践する上で重要なのは、非加害性の原則を実践することで無益性を回避しようとすることである。[112] 患者が治療によって回復する見込みがない場合、家族が積極的治療を強く希望している場合、どうすべきだろうか?[112] 以前は、患者が1パーセント未満の生存確率である場合を無益と定義する記事もあった。このようなケースの一部は法廷で審理される。 事前指示書にはリビング・ウィル(事前指示書)や医療に関する継続委任状が含まれる。(蘇生処置拒否や心肺蘇生法も参照)多くの場合、患者の「表明された 希望」はこれらの指示書に文書化されており、これにより患者が意思決定能力を失った場合の意思決定プロセスにおいて、家族や医療従事者が判断するための枠 組みが提供される。ミズーリ州のクインラン事件のように、文書化されていない表明された希望も、事前指示書がない場合の意思決定の指針となる。 「代理判断」とは、患者が同意を与えることができない(または同意を与えたくない)場合、家族が治療の同意を与えることができるという概念である。意思決 定の代理を務める人にとって重要な問いは、「あなたはどうしたいですか?」ではなく、「患者がこのような状況で何を望むと思いますか?」である。 裁判所は、ベビーKのケース(裁判所は、脳幹のみで完全な脳を持たずに生まれた子供に対して、生命はすべて維持されなければならないという宗教的信念に基 づき、人工呼吸器をつけるよう命じた)のように、単純な生物学的生存を無益性の恣意的な定義に含める家族の主張を支持してきた。 ベイビー・ドウ法は、障害を持つ子供の生存権を州が保護することを定めており、親や保護者が治療を拒否したいと考えた場合でも、この生存権が保護されるこ とを保証している。 |

| Applied ethics Bioethics The Citadel Clinical Ethics Clinical governance Do not resuscitate Empathy Ethical code Ethics of circumcision Euthanasia Evidence-based medical ethics Fee splitting Hastings Center Healthcare in India Hippocratic Oath Health insurance Human radiation experiments Islamic bioethics Jewish medical ethics Joint Commission International, JCI MacLean Center for Clinical Medical Ethics Medical Code of Ethics Medical Law International Medical law Medical torture Pharmacological torture Military medical ethics Nursing ethics Patient abuse Philosophy of Healthcare Political abuse of psychiatry Project MKULTRA Research ethics consultation Resources for clinical ethics consultation Right to health Seven Sins of Medicine U.S. patients' bill of rights UN Principles of Medical Ethics Unethical human experimentation World Medical Association Reproductive medicine Abortion / Abortion debate Eugenics Gene splicing Human cloning Human genetic engineering Human trafficking Medical research Animal testing Children in clinical research CIOMS Guidelines Clinical Equipoise Clinical research ethics Declaration of Geneva Declaration of Helsinki Declaration of Tokyo Ethical problems using children in clinical trials First-in-man study Good clinical practice Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act Institutional Review Board Nuremberg Code Research ethics consultation Universal Declaration of Human Rights |

応用倫理 生命倫理 シタデル 臨床倫理 臨床ガバナンス 蘇生措置を行わない 共感 倫理規定 割礼の倫理 安楽死 エビデンスに基づく医療倫理 報酬の分割 ヘイスティングスセンター インドの医療 ヒポクラテスの誓い 健康保険 人体放射線実験 イスラム生命倫理 ユダヤ医学倫理 国際合同委員会(JCI マクリーン臨床医療倫理センター 医療倫理規定 医療法国際 医療法 医療における拷問 薬理学的な拷問 軍事医療倫理 看護倫理 患者への虐待 ヘルスケアの哲学 政治による精神医学の悪用 MKULTRAプロジェクト 研究倫理コンサルテーション 臨床倫理コンサルテーションのためのリソース 健康に対する権利 医療における7つの罪 米国患者権利章典 国連医療倫理原則 非倫理的な人体実験 世界医師会 生殖医療 中絶/中絶に関する議論 優生学 遺伝子組み換え ヒトクローン ヒト遺伝子工学 人身売買 医学研究 動物実験 臨床研究における子ども CIOMSガイドライン 臨床試験用エキポイズ 臨床研究倫理 ジュネーブ宣言 ヘルシンキ宣言 東京宣言 臨床試験における子どもの倫理的問題 ファースト・イン・マン試験 医薬品の臨床試験の実施に関する基準 医療保険の相互運用性と説明責任に関する法律 治験審査委員会 ニュルンベルク綱領 研究倫理相談 世界人権宣言 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Medical_ethics |

|

★先例拘束の原則(stare decisis)の存在

医療倫理学は、医療倫理(リンク先はウィキペディア日本語)とい う歴史に先行する経験的事実と原則に依存する、すなわち先例拘束の原則(stare decisis)があるので、そのことを次に解説しよう(Weise, Mary Victoria, Medical Ethics Made Easy, 2016)。

「医療倫理の4原則」というものがもっとも有名である。すなわち、1)自己決 定(Autonomy)、2)善行(Benevolence)、3)無加害(Nonmaleficence)、そして、4)配分上の正義(Distributive Justice)

Weise (2016)の論文にしたがってその考え方を復習してみよう。

| 自己決定(Autonomy) | Patients' right to

self-determination emphasizes that patients are autonomous beings and

have the right to make their own choices about the care they prefer to

receive. This ethical principle is best exemplified in informed

consent, which is decision making that involves disclosure of risks and

benefits. ... |

Case 01: A 57-year-old man

suffers a massive stroke. The patient is in the intensive care unit, on

a ventilator, and remains unresponsive. Family and friends tell

hospital staff that he does not have an AD but would always say he does

not want aggressive measures. Patient has a slow recovery but still

suffers from dysphagia, so providers needed to make decisions on a

feeding tube. Who should they speak to? Who would be the surrogate

decision maker? With the patient not presenting with an AD, providers

could turn to the Surrogate Act and try to discern if the patient had a

spouse or adult children; if not, then ask about his parents. If

parents are not alive, or not able to participate, then turn to

siblings, and finally extended family or friends. This offers a way to

“sift through” the crowd who is offering answers and allows staff to

narrow down the correct decision maker. |

| Case 02: A 55-year-old man is