World System Theory and Cultural Anthropology

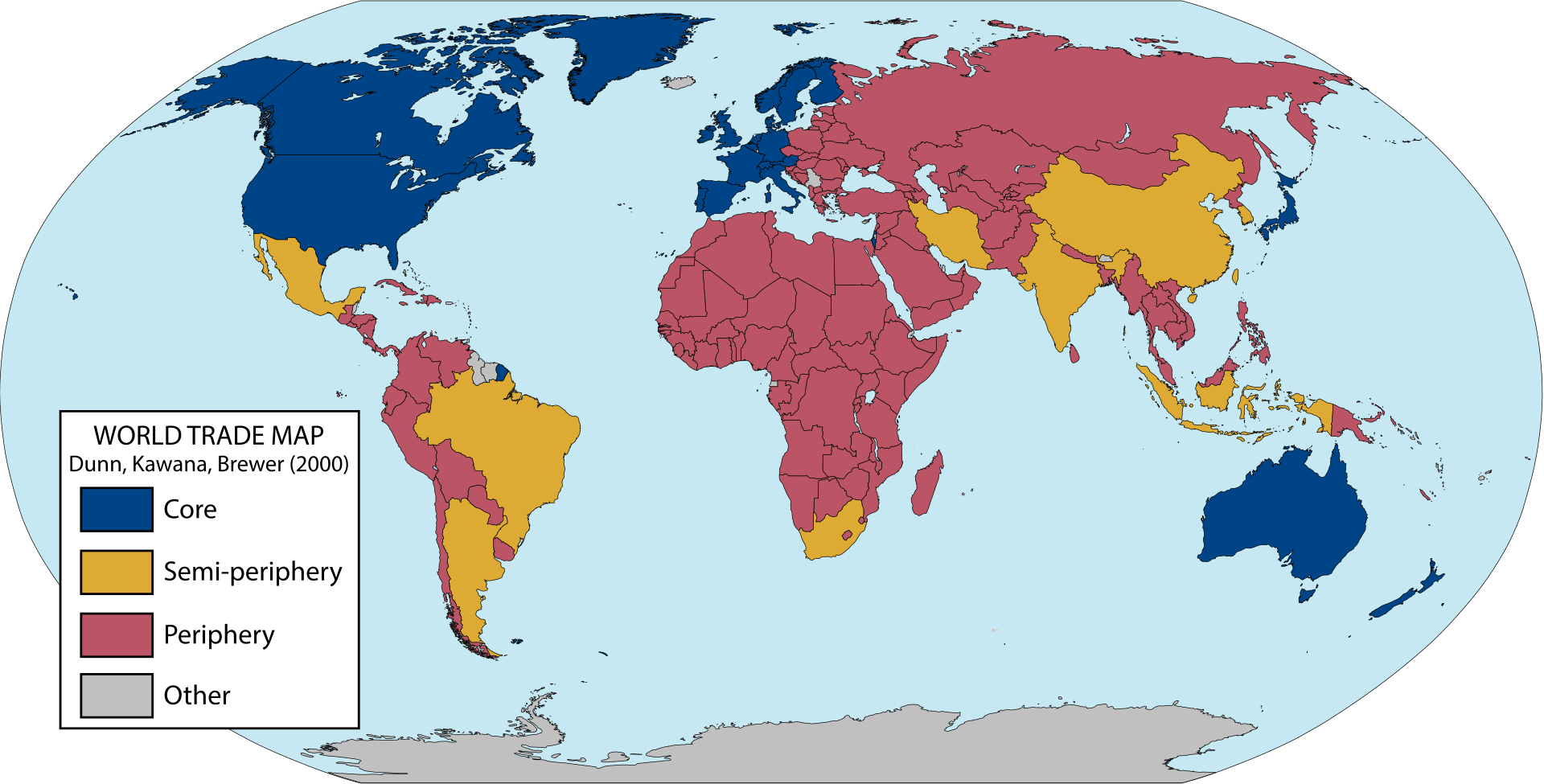

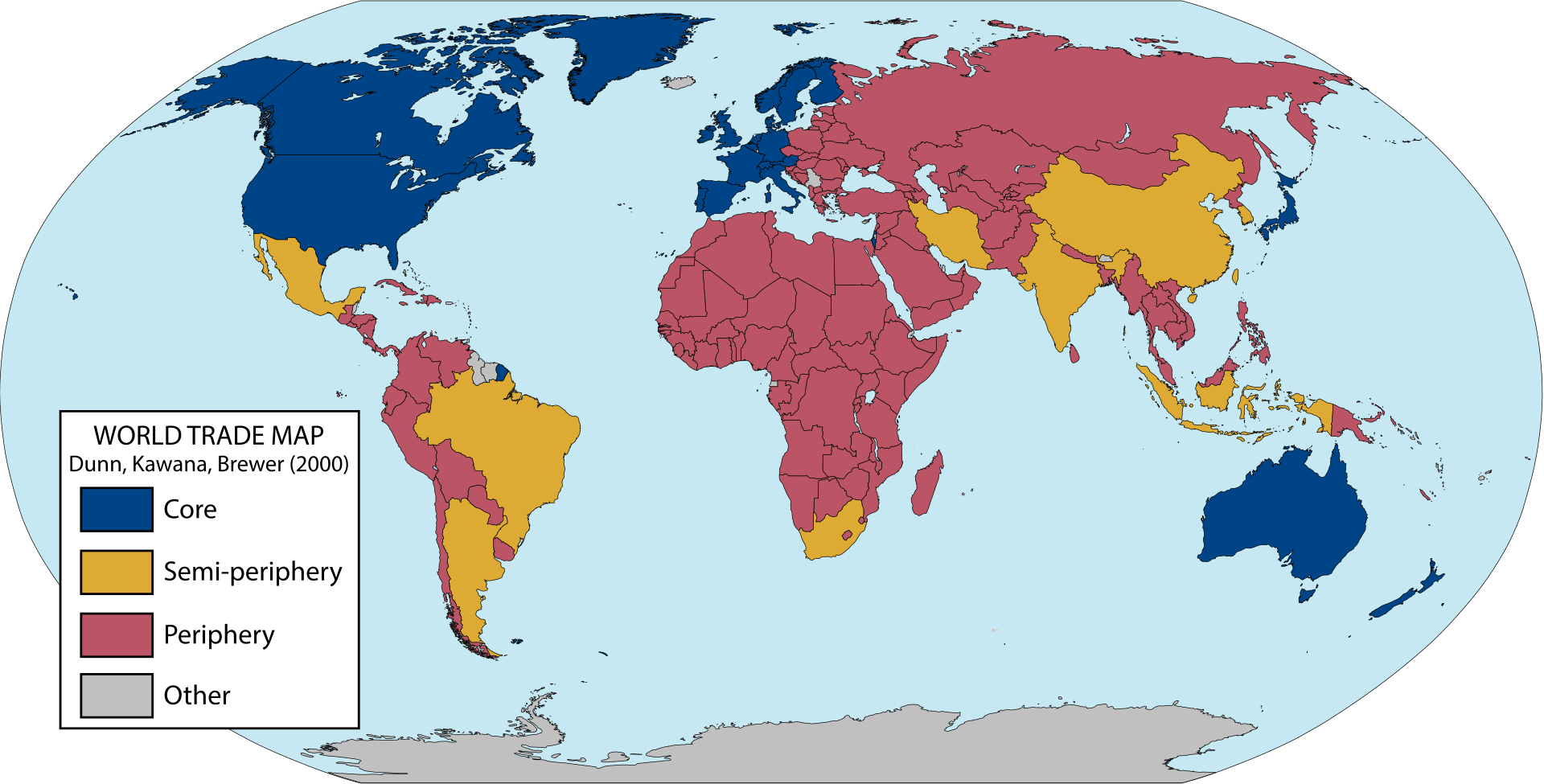

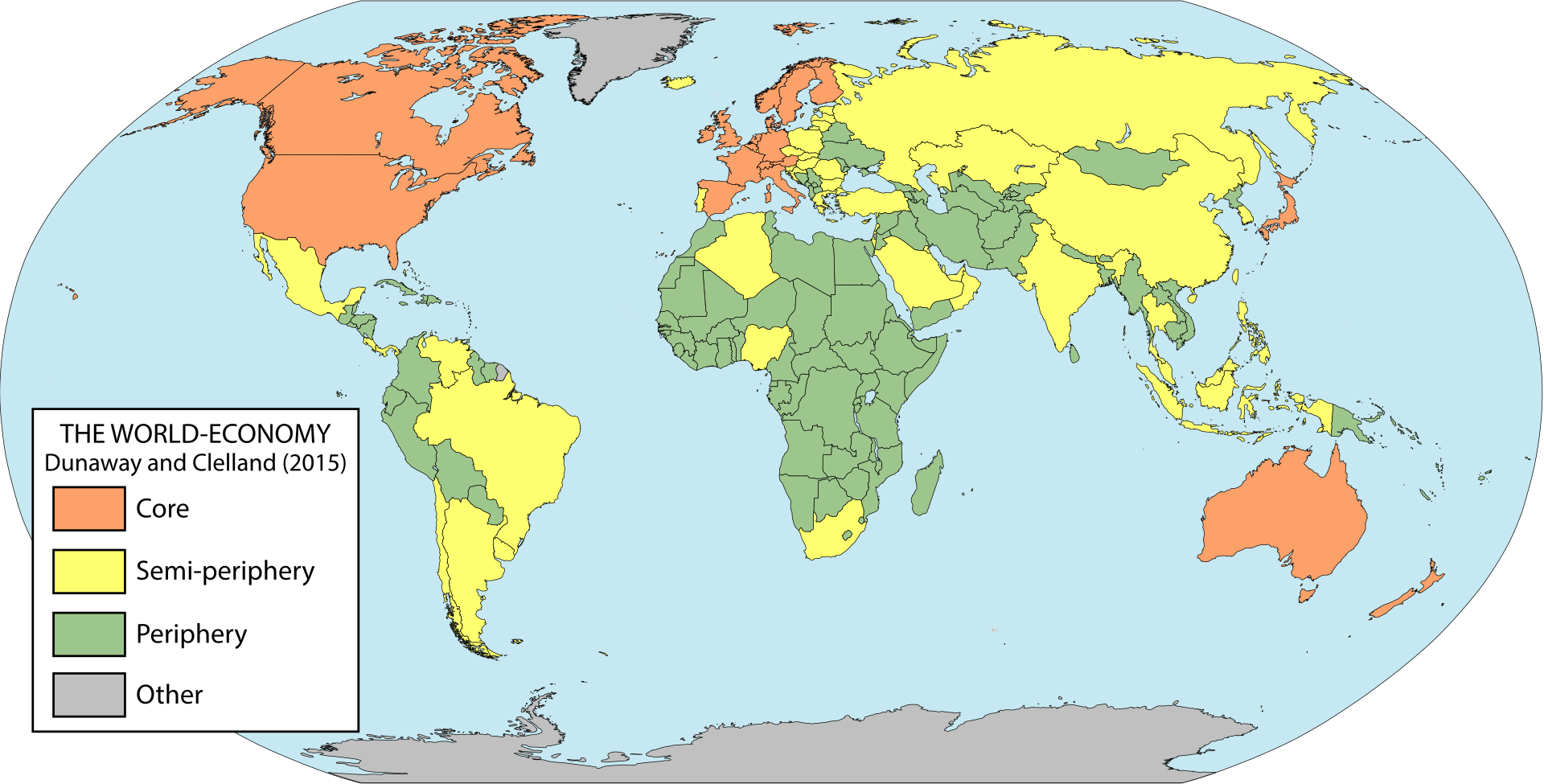

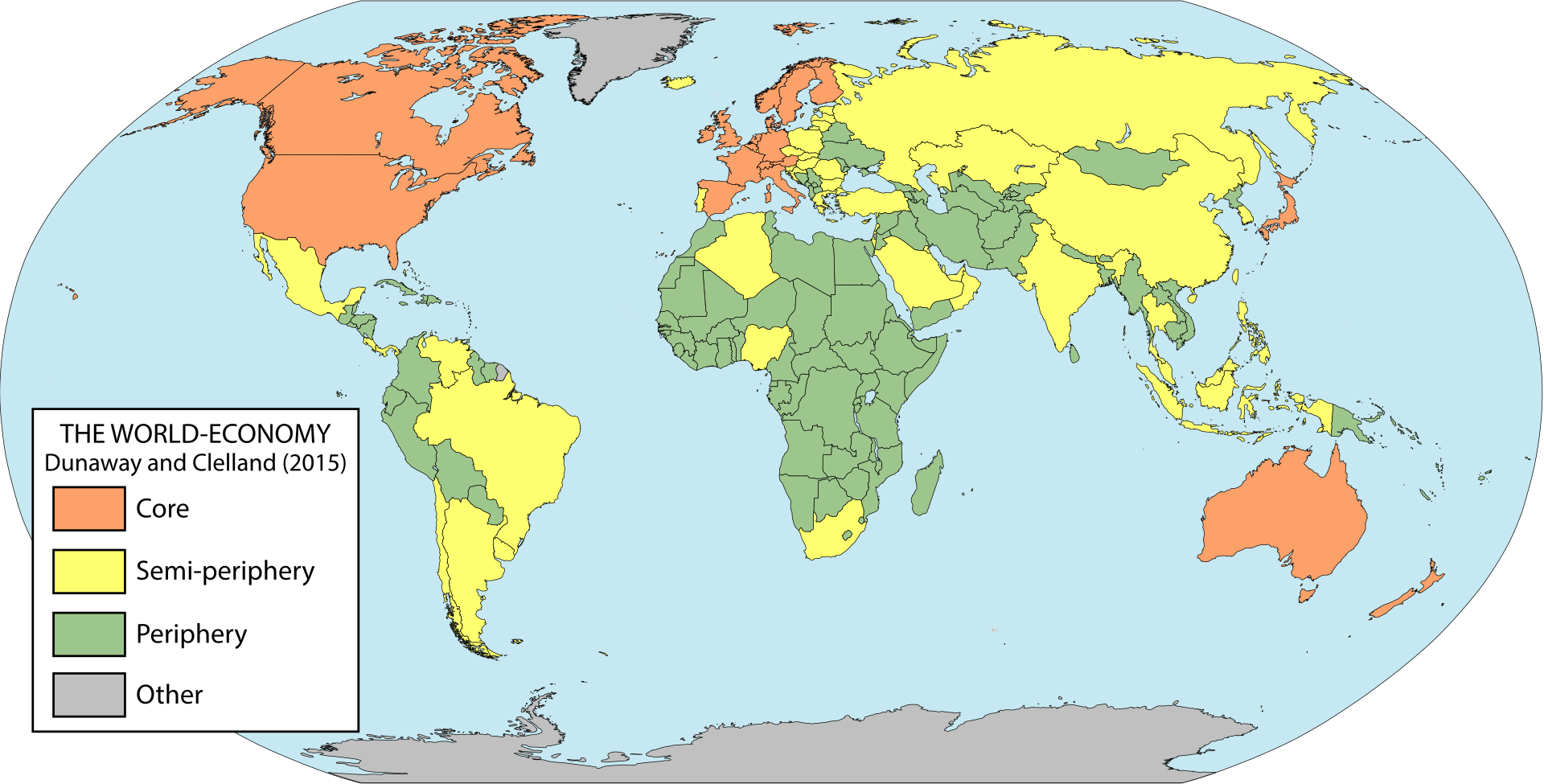

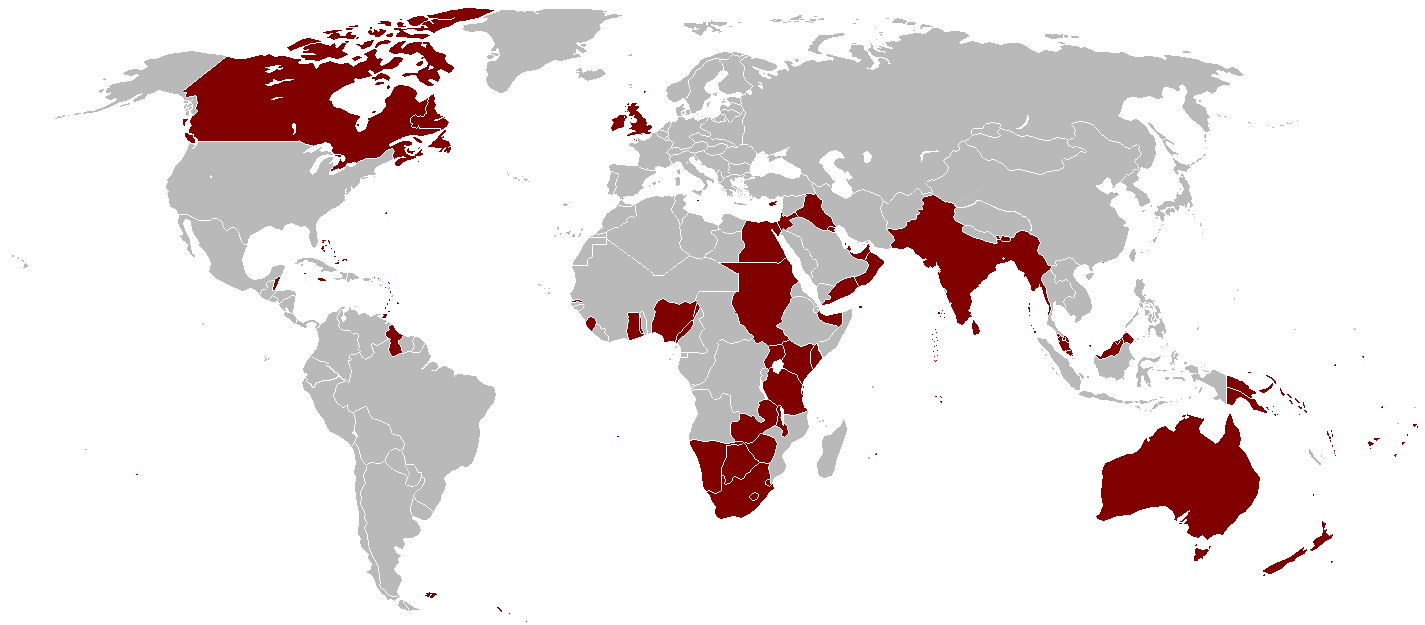

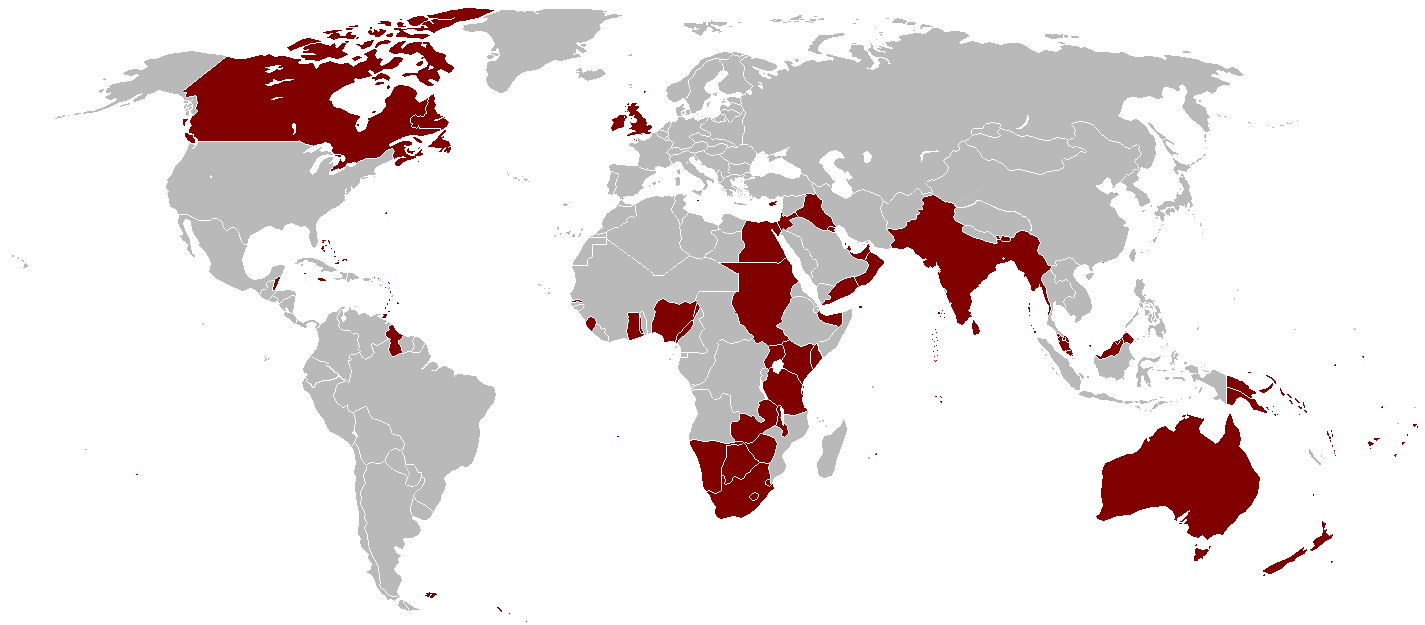

2000年時点における各国の想定貿易地位に基づく世界地図。世界システム論に基づく中核国(青)、準周辺国(黄)、周辺国(赤)の区分を用いている。チェイス=ダン、カワナ、ブリュワー(2000)のリストに基づく。

世界システム論と文化人類学

World System Theory and Cultural Anthropology

2000年時点における各国の想定貿易地位に基づく世界地図。世界システム論に基づく中核国(青)、準周辺国(黄)、周辺国(赤)の区分を用いている。チェイス=ダン、カワナ、ブリュワー(2000)のリストに基づく。

★世界システム論 World-systems theory (世界システム分析または世界システム視点とも呼ばれる)[3]は、世界史と社会変革に対する学際的アプローチであり、社会分析の主要な(ただし排他的な ものではない)単位として世界システム(国民ではなく)を重視する[3]。世界システム論者は、自らの理論が国家の興亡、所得格差、社会不安、帝国主義を 説明すると主張する。 「世界システム」とは、地域間・国家を超えた分業体制を指し、世界を中核国、準周辺国、周辺国に区分する。[4]中核国は高度技能・資本集約型産業を有 し、その他の地域は低技能・労働集約型産業と原材料採掘を担う。[5] この構造は分業によって統一され、資本主義経済に根差した世界経済を形成している[6]。特定の国々が世界覇権国となる現象は歴史的に繰り返され、過去数 世紀における世界システムの地理的拡大と経済的深化に伴い、その地位はオランダからイギリスへ、そして(最も最近では)アメリカへと移行してきた。[5] 世界システム論の主要な提唱者はイマニュエル・ウォーラスティンである。[7] 世界システム分析の構成要素には、フェルナン・ブルデルの「ロングデュール」、アンドレ・ギュンダー・フランクの「発展による未発達」、そして単一社会仮 説が含まれる。[8] ロングデュールとは、社会システムが日常的な活動を通じて漸進的に変化し、継続的に再生産されるという概念である。 [8]「発展の未発達」は、周辺部における経済プロセスを中核部における発展の対極として説明する。貧しい国々が貧困化されることで、少数の国々が豊かに なるのだ。[8]最後に、単一社会仮説は複数社会仮説に対立し、世界を全体として捉えることを含む。[8]。

| World-systems theory

(also known as world-systems analysis or the world-systems

perspective)[3] is a multidisciplinary approach to world history and

social change which emphasizes the world-system (and not nation states)

as the primary (but not exclusive) unit of social analysis.[3]

World-systems theorists argue that their theory explains the rise and

fall of states, income inequality, social unrest, and imperialism. The "world-system" refers to the inter-regional and transnational division of labor, which divides the world into core countries, semi-periphery countries, and periphery countries.[4] Core countries have higher-skill, capital-intensive industries, and the rest of the world has low-skill, labor-intensive industries and extraction of raw materials.[5] This constantly reinforces the dominance of the core countries.[5] This structure is unified by the division of labour. It is a world-economy rooted in a capitalist economy.[6] For a time, certain countries have become the world hegemon; during the last few centuries, as the world-system has extended geographically and intensified economically, this status has passed from the Netherlands, to the United Kingdom and (most recently) to the United States.[5] Immanuel Wallerstein is the main proponent of world systems theory.[7] Components of the world-systems analysis are longue durée by Fernand Braudel, "development of underdevelopment" by Andre Gunder Frank, and the single-society assumption.[8] Longue durée is the concept of the gradual change through the day-to-day activities by which social systems are continually reproduced.[8] "Development of underdevelopment" describes the economic processes in the periphery as the opposite of the development in the core. Poorer countries are impoverished to enable a few countries to get richer.[8] Lastly, the single-society assumption opposes the multiple-society assumption and includes looking at the world as a whole.[8] |

世界システム論(世界システム分析または世界システム視点とも呼ばれ

る)[3]は、世界史と社会変革に対する学際的アプローチであり、社会分析の主要な(ただし排他的なものではない)単位として世界システム(国民ではな

く)を重視する[3]。世界システム論者は、自らの理論が国家の興亡、所得格差、社会不安、帝国主義を説明すると主張する。 「世界システム」とは、地域間・国家を超えた分業体制を指し、世界を中核国、準周辺国、周辺国に区分する。[4]中核国は高度技能・資本集約型産業を有 し、その他の地域は低技能・労働集約型産業と原材料採掘を担う。[5] この構造は分業によって統一され、資本主義経済に根差した世界経済を形成している[6]。特定の国々が世界覇権国となる現象は歴史的に繰り返され、過去数 世紀における世界システムの地理的拡大と経済的深化に伴い、その地位はオランダからイギリスへ、そして(最も最近では)アメリカへと移行してきた。[5] 世界システム論の主要な提唱者はイマニュエル・ウォーラスティンである。[7] 世界システム分析の構成要素には、フェルナン・ブルデルの「ロングデュール」、アンドレ・ギュンダー・フランクの「発展による未発達」、そして単一社会仮 説が含まれる。[8] ロングデュールとは、社会システムが日常的な活動を通じて漸進的に変化し、継続的に再生産されるという概念である。 [8]「発展の未発達」は、周辺部における経済プロセスを中核部における発展の対極として説明する。貧しい国々が貧困化されることで、少数の国々が豊かに なるのだ。[8]最後に、単一社会仮説は複数社会仮説に対立し、世界を全体として捉えることを含む。[8]。 |

A world map of countries by their supposed trading status in 2000, using the world system differentiation into core countries (blue), semi-periphery countries (yellow) and periphery countries (red). Based on the list in Chase-Dunn, Kawana, and Brewer (2000).[1] |

2000年時点における各国の想定貿易地位に基づく世界地図。世界システム論に基づく中核国(青)、準周辺国(黄)、周辺国(赤)の区分を用いている。チェイス=ダン、カワナ、ブリュワー(2000)のリストに基づく。[1] |

| Background Immanuel Wallerstein has developed the best-known version of world-systems analysis, beginning in the 1970s.[9][10] Wallerstein traces the rise of the capitalist world-economy from the "long" 16th century (c. 1450–1640).[11] The rise of capitalism, in his view, was an accidental outcome of the protracted crisis of feudalism (c. 1290–1450).[12] Europe (the West) used its advantages and gained control over most of the world economy and presided over the development and spread of industrialization and capitalist economy, indirectly resulting in unequal development.[4][5][10] Though other commentators refer to Wallerstein's project as world-systems "theory," he consistently rejects that term.[13] For Wallerstein, world-systems analysis is a mode of analysis that aims to transcend the structures of knowledge inherited from the 19th century, especially the definition of capitalism, the divisions within the social sciences, and those between the social sciences and history.[14] For Wallerstein, then, world-systems analysis is a "knowledge movement"[15] that seeks to discern the "totality of what has been paraded under the labels of the... human sciences and indeed well beyond".[16] "We must invent a new language," Wallerstein insists, to transcend the illusions of the "three supposedly distinctive arenas" of society, economy and politics.[17] The trinitarian structure of knowledge is grounded in another, even grander, modernist architecture, the distinction of biophysical worlds (including those within bodies) from social ones: "One question, therefore, is whether we will be able to justify something called social science in the twenty-first century as a separate sphere of knowledge."[18][19] Many other scholars have contributed significant work in this "knowledge movement."[4] |

背景 イマニュエル・ウォーラスティンは1970年代から、世界システム分析の最も著名な理論を展開した[9][10]。ウォーラスティンは資本主義的世界経済 の台頭を「長い16世紀」(約1450年~1640年)に遡って考察する。[11] 彼の見解では、資本主義の台頭は封建制の長期危機(約1290年~1450年)の偶発的な結果であった。[12] ヨーロッパ(西洋)はその優位性を活用し、世界経済の大部分を支配下に置き、工業化と資本主義経済の発展・拡散を主導した。これが間接的に不平等な発展を もたらしたのである。[4][5][10] 他の論者がウォーラスティン のプロジェクトを世界システム「理論」と呼ぶのに対し、彼は一貫してこの用語を拒否している。[13] ウォーラスティンにとって世界システム分析とは、19世紀から継承された知識構造、特に資本主義の定義、社会科学内部の区分、そして社会科学と歴史学の間 の区分を超越しようとする分析手法である。[14] したがってウォーラスティンにとって、世界システム分析は「知識運動」[15]であり、「...人間科学のラベルの下で誇示されてきたものの総体、そして それをはるかに超えたもの」[16]を見極めようとするものである。「我々は新たな言語を発明しなければならない」とウォーラスティンは主張する。それは 社会・経済・政治という「三つの区別された領域」という幻想を超越するためである。[17] この三元的な知識構造は、さらに壮大な近代主義的枠組み、すなわち身体内を含む生物物理的世界と社会世界の区別に基づいている。「したがって一つの問題 は、21世紀において『社会科学』と呼ばれるものを独立した知識領域として正当化できるかどうかである」[18][19]。この「知識運動」には多くの研 究者が重要な貢献をしている。[4] |

| Origins Influences World-systems theory traces emerged in the 1970s.[3] Its roots can be found in sociology, but it has developed into a highly interdisciplinary field.[4] World-systems theory was aiming to replace modernization theory, which Wallerstein criticised for three reasons:[4] its focus on the nation state as the only unit of analysis its assumption that there is only a single path of evolutionary development for all countries its disregard of transnational structures that constrain local and national development. There are three major predecessors of world-systems theory: the Annales school, the Marxist tradition, and dependency theory.[4][20] The Annales School tradition, represented most notably by Fernand Braudel, influenced Wallerstein to focus on long-term processes and geo-ecological regions as units of analysis. Marxism added a stress on social conflict, a focus on the capital accumulation process and competitive class struggles, a focus on a relevant totality, the transitory nature of social forms and a dialectical sense of motion through conflict and contradiction. World-systems theory was also significantly influenced by dependency theory, a neo-Marxist explanation of development processes. Other influences on the world-systems theory come from scholars such as Karl Polanyi, Nikolai Kondratiev[21] and Joseph Schumpeter. These scholars researched business cycles and developed concepts of three basic modes of economic organization: reciprocal, redistributive, and market modes. Wallerstein reframed these concepts into a discussion of mini systems, world empires, and world economies. Wallerstein sees the development of the capitalist world economy as detrimental to a large proportion of the world's population.[22] Wallerstein views the period since the 1970s as an "age of transition" that will give way to a future world system (or world systems) whose configuration cannot be determined in advance.[23] Other world-systems thinkers include Oliver Cox, Samir Amin, Giovanni Arrighi, and Andre Gunder Frank, with major contributions by Christopher Chase-Dunn, Beverly Silver, Janet Abu Lughod, Li Minqi, Kunibert Raffer, and others.[4] In sociology, a primary alternative perspective is World Polity Theory, as formulated by John W. Meyer.[citation needed] |

起源 影響 世界システム論の萌芽は1970年代に現れた[3]。その根源は社会学にあるが、高度に学際的な分野へと発展した[4]。世界システム論は近代化理論に取って代わることを目指していた。ウォーラスティンが近代化理論を批判した理由は三つある[4]: 分析単位として国民のみに焦点を当てたこと 全ての国に単一の進化的発展経路しか存在しないという前提 地域的・国民的発展を制約する越境的構造を無視したこと 世界システム論には三つの主要な前身がある:アナル学派、マルクス主義の伝統、従属理論である。[4][20] 特にフェルナン・ブルデルに代表されるアナル学派の伝統は、ウォーラスティンに長期プロセスと地理生態学的地域を分析単位として重視するよう影響を与え た。マルクス主義は社会的対立の強調、資本蓄積過程と競争的階級闘争への焦点、関連する総体への注目、社会形態の過渡的性質、そして対立と矛盾を通じた弁 証法的運動感覚を加えた。 世界システム論はまた、発展過程を説明する新マルクス主義理論である従属理論からも大きな影響を受けた。 世界システム論へのその他の影響源としては、カール・ポラニー、ニコライ・コンドラチエフ[21]、ヨーゼフ・シュンペーターといった学者たちが挙げられ る。これらの学者たちは景気循環を研究し、経済組織の三つの基本形態——相互扶助的形態、再分配的形態、市場的形態——の概念を発展させた。ウォーラス ティンはこれらの概念を再構築し、ミニシステム、世界帝国、世界経済の議論へと発展させた。 ウォーラスティンは、資本主義的世界経済の発展が世界人口の大部分に有害であると見なしている[22]。彼は1970年代以降の時代を「過渡期」と位置づ け、その先には事前に決定できない構成を持つ未来の世界システム(あるいは世界システム群)が到来すると予測する。[23] その他の世界システム論者には、オリバー・コックス、サミール・アミン、ジョヴァンニ・アリッギ、アンドレ・ギュンダー・フランクらがおり、クリスト ファー・チェイス=ダン、ビバリー・シルバー、ジャネット・アブ・ルゴッド、李敏琪、クニベルト・ラッファーらが主要な貢献をしている。[4] 社会学における主要な代替的視点は、ジョン・W・マイヤーが提唱した世界政治理論である。[出典が必要] |

| Dependency theory Main article: Dependency theory World-systems analysis builds upon but also differs fundamentally from dependency theory. While accepting world inequality, the world market and imperialism as fundamental features of historical capitalism, Wallerstein broke with orthodox dependency theory's central proposition. For Wallerstein, core countries do not exploit poor countries for two basic reasons. Firstly, core capitalists exploit workers in all zones of the capitalist world economy (not just the periphery) and therefore, the crucial redistribution between core and periphery is surplus value, not "wealth" or "resources" abstractly conceived. Secondly, core states do not exploit poor states, as dependency theory proposes, because capitalism is organised around an inter-regional and transnational division of labor rather than an international division of labour. Thirdly, economically relevant structures such as metropolitan regions, international unions and bilateral agreements tend to weaken and blur out the economic importance of nation-states and their borders.[24] During the Industrial Revolution, for example, English capitalists exploited slaves (unfree workers) in the cotton zones of the American South, a peripheral region within a semiperipheral country, United States.[25] From a largely Weberian perspective, Fernando Henrique Cardoso described the main tenets of dependency theory as follows: There is a financial and technological penetration of the periphery and semi-periphery countries by the developed capitalist core countries. That produces an unbalanced economic structure within the peripheral societies and between them and the central countries. That leads to limitations upon self-sustained growth in the periphery. That helps the appearance of specific patterns of class relations. They require modifications in the role of the state to guarantee the functioning of the economy and the political articulation of a society, which contains, within itself, foci of inarticulateness and structural imbalance.[26] Dependency and world system theory propose that the poverty and backwardness of poor countries are caused by their peripheral position in the international division of labor. Since the capitalist world system evolved, the distinction between the central and the peripheral states has grown and diverged. In recognizing a tripartite pattern in the division of labor, world-systems analysis criticized dependency theory with its bimodal system of only cores and peripheries. |

従属理論 メイン記事: 従属理論 世界システム分析は従属理論を基盤としつつも、根本的に異なる。歴史的資本主義の基本的特徴として世界の不平等、世界市場、帝国主義を認めつつも、ウォー ラスティンはその正統派従属理論の中核的主張を否定した。ウォーラスティンによれば、中核諸国が貧しい国々を搾取しない理由は二つある。 第一に、中核資本家は資本主義世界経済の全領域(周辺部のみではない)で労働者を搾取するため、中核と周辺間の決定的な再分配は「富」や「資源」の抽象的 概念ではなく、剰余価値である。第二に、中核国家は従属理論が主張するように貧しい国家を搾取しない。なぜなら資本主義は国際分業ではなく、地域間・超国 家的分業を基盤として組織されているからだ。第三に、大都市圏、国際連合、二国間協定といった経済的に重要な構造は、国民とその国境の経済的重要性を弱 め、曖昧にする傾向がある。[24] 例えば産業革命期には、英国の資本家がアメリカ南部の綿花地帯で奴隷(不自由な労働者)を搾取した。この地域は半周辺国であるアメリカ合衆国内の周辺地域であった。[25] フェルナンド・エンリケ・カルドーゾは、主にウェーバー的視点から従属理論の主要な主張を次のように説明した: 先進資本主義中核国による周辺・準周辺国への金融的・技術的浸透が存在する。 これは周辺社会内部および周辺社会と中核国との間に不均衡な経済構造を生み出す。 これが周辺地域における自立的成長の制約につながる。 これにより特定の階級関係パターンが出現する。 これらは、経済の機能と、内部に不整合と構造的不均衡の焦点を含む社会の政治的結束を保証するため、国家の役割変更を必要とする。[26] 従属理論と世界システム理論は、貧しい国の貧困と後進性は、国際分業における周辺の位置によって引き起こされると主張する。資本主義世界システムが発展す るにつれ、中心国と周辺国の区別は拡大し、分化してきた。世界システム分析は、分業における三極構造を認識し、中心と周辺のみからなる二極構造の従属理論 を批判した。 |

| Immanuel Wallerstein The best-known version of the world-systems approach was developed by Immanuel Wallerstein.[7][10] Wallerstein notes that world-systems analysis calls for a unidisciplinary historical social science and contends that the modern disciplines, products of the 19th century, are deeply flawed because they are not separate logics, as is manifest for example in the de facto overlap of analysis among scholars of the disciplines.[3] Wallerstein offers several definitions of a world-system, defining it in 1974 briefly: a system is defined as a unit with a single division of labor and multiple cultural systems.[27] He also offered a longer definition: ...a social system, one that has boundaries, structures, member groups, rules of legitimation, and coherence. Its life is made up of the conflicting forces which hold it together by tension and tear it apart as each group seeks eternally to remold it to its advantage. It has the characteristics of an organism, in that it has a life-span over which its characteristics change in some respects and remain stable in others. One can define its structures as being at different times strong or weak in terms of the internal logic of its functioning.[28] In 1987, Wallerstein again defined it: ... not the system of the world, but a system that is a world and which can be, most often has been, located in an area less than the entire globe. World-systems analysis argues that the units of social reality within which we operate, whose rules constrain us, are for the most part such world-systems (other than the now extinct, small minisystems that once existed on the earth). World-systems analysis argues that there have been thus far only two varieties of world-systems: world-economies and world empires. A world-empire (examples, the Roman Empire, Han China) are large bureaucratic structures with a single political center and an axial division of labor, but multiple cultures. A world-economy is a large axial division of labor with multiple political centers and multiple cultures. In English, the hyphen is essential to indicate these concepts. "World system" without a hyphen suggests that there has been only one world-system in the history of the world. — [3] Wallerstein characterizes the world system as a set of mechanisms, which redistributes surplus value from the periphery to the core. In his terminology, the core is the developed, industrialized part of the world, and the periphery is the "underdeveloped", typically raw materials-exporting, poor part of the world; the market being the means by which the core exploits the periphery. Apart from them, Wallerstein defines four temporal features of the world system. Cyclical rhythms represent the short-term fluctuation of economy, and secular trends mean deeper long run tendencies, such as general economic growth or decline.[3][4] The term contradiction means a general controversy in the system, usually concerning some short term versus long term tradeoffs. For example, the problem of underconsumption, wherein the driving down of wages increases the profit for capitalists in the short term, but in the long term, the decreasing of wages may have a crucially harmful effect by reducing the demand for the product. The last temporal feature is the crisis: a crisis occurs if a constellation of circumstances brings about the end of the system. In Wallerstein's view, there have been three kinds of historical systems across human history: "mini-systems" or what anthropologists call bands, tribes, and small chiefdoms, and two types of world-systems, one that is politically unified and the other is not (single state world empires and multi-polity world economies).[3][4] World-systems are larger, and are ethnically diverse. The modern world-system, a capitalist world-economy, is unique in being the first and only world-system, which emerged around 1450 to 1550, to have geographically expanded across the entire planet, by about 1900. It is defined, as a world-economy, in having many political units tied together as an interstate system and through its division of labor based on capitalist enterprises.[29] |

イマニュエル・ウォーラスティン 世界システム論の最も著名な展開はイマニュエル・ウォーラスティンによってなされた。[7][10] ウォーラスティンは、世界システム分析には単一学問分野の歴史的社会科学が必要だと指摘し、19世紀の産物である現代の学問分野は、例えば各分野の研究者 間の分析が事実上重複していることから明らかなように、独立した論理体系ではないため根本的に欠陥があると主張する。[3] ウォーラスティンは世界システムについて複数の定義を提示し、1974年には簡潔にこう定義した: システムとは、単一の分業と複数の文化システムを有する単位として定義される。[27] 彼はより長い定義も提示している: ...境界、構造、構成集団、正当化のルール、そして結束性を持つ社会システムである。その生命は、緊張によって結びつけつつ引き裂く対立する力によって 成り立つ。各集団が永遠に自らの利益のために再構築しようとするからだ。それは有機体のような特徴を持つ。つまり、その特性が一部では変化し、他では安定 を保つ寿命を持つ。その構造は、機能の内部論理において、異なる時強くなったり弱くなったりすると定義できる。[28] 1987年、ウォーラスティンは再び次のように定義した: ...世界のシステムではなく、世界そのものであるシステムであり、それは地球全体よりも狭い地域に存在し得る(そして大抵は存在してきた)。世界システ ム分析によれば、我々が活動する社会的現実の単位、すなわち我々を制約する規則を持つ単位は、大部分がこうした世界システムである(かつて地球上に存在し た、現在は消滅した小規模なミニシステムを除く)。世界システム分析は、これまでに存在した世界システムは二種類のみだと主張する:世界経済と世界帝国で ある。世界帝国(例:ローマ帝国、漢王朝中国)は単一の政治中心と軸的な分業構造を持つ巨大な官僚機構であるが、複数の文化を有する。世界経済は複数の政 治中心と複数の文化を有する巨大な軸的分業構造である。英語ではこれらの概念を示すためにハイフンが不可欠である。「World system」とハイフンなしで表記すると、世界史上ただ一つの世界システムしか存在しなかったことを示唆してしまう。 — [3] ウォーラスティンは世界システムを、周辺部から中心部へ剰余価値を再分配する一連のメカニズムと特徴づける。彼の用語では、中心部とは世界の先進工業地域 を指し、周辺部とは「未発達」で典型的には原材料輸出に依存する貧困地域を指す。市場は中心部が周辺部を搾取する手段である。 これらに加え、ウォーラスティンは世界システムの四つの時間的特徴を定義する。循環的リズムは経済の短期変動を表し、世俗的傾向はより深い長期的傾向、例 えば一般的な経済成長や衰退を意味する[3][4]。矛盾という用語はシステム内の一般的な論争を指し、通常は短期と長期のトレードオフに関わる。例え ば、消費不足の問題では、賃金の引き下げは短期的に資本家の利益を増大させるが、長期的には賃金低下による製品需要の減少が致命的な悪影響を及ぼす可能性 がある。最後の時間的特徴は危機である。状況の複合がシステムの終焉をもたらす場合に危機が発生する。 ウォーラスティンの見解によれば、人類史には三種類の歴史的システムが存在した。「ミニシステム」、すなわち人類学者がバンド、部族、小規模首長制と呼ぶ もの、そして二種類の世界システムである。一つは政治的に統一された世界帝国、もう一つは統一されていない世界経済(単一国家世界帝国と多政体世界経済) である[3][4]。世界システムはより大規模で、民族的に多様である。現代世界システム、すなわち資本主義的世界経済は、1450年から1550年頃に 現れ、1900年頃までに地球全体に地理的拡大を遂げた、最初にして唯一の世界システムとして特異である。世界経済として定義されるのは、多くの政治単位 が国家間システムとして結びつき、資本主義企業に基づく分業を通じて機能している点にある。[29] |

| Importance World-Systems Theory can be useful in understanding world history and the core countries' motives for imperialization and other involvements like the US aid following natural disasters in developing Central American countries or imposing regimes on other core states.[30] With the interstate system as a system constant, the relative economic power of the three tiers points to the internal inequalities that are on the rise in states that appear to be developing.[31] Some argue that this theory, though, ignores local efforts of innovation that have nothing to do with the global economy, such as the labor patterns implemented in Caribbean sugar plantations.[32] Other modern global topics can be easily traced back to the world-systems theory. As global talk about climate change and the future of industrial corporations, the world systems theory can help to explain the creation of the G-77 group, a coalition of 77 peripheral and semi-peripheral states wanting a seat at the global climate discussion table. The group was formed in 1964, but it now has more than 130 members who advocate for multilateral decision making. Since its creation, G-77 members have collaborated with two main aims: 1) decreasing their vulnerability based on the relative size of economic influence, and 2) improving outcomes for national development.[33] World-systems theory has also been utilized to trace CO2 emissions’ damage to the ozone layer. The levels of world economic entrance and involvement can affect the damage a country does to the earth. In general, scientists can make assumptions about a country's CO2 emissions based on GDP. Higher exporting countries, countries with debt, and countries with social structure turmoil land in the upper-periphery tier. Though more research must be done in the arena, scientists can call core, semi-periphery, and periphery labels as indicators for CO2 intensity.[34] In a health realm, studies have shown the effect of less industrialized countries’, the periphery's, acceptance of packaged foods and beverages that are loaded with sugars and preservatives. While core states benefit from dumping large amounts of processed, fatty foods into poorer states, there has been a recorded increase in obesity and related chronic conditions such as diabetes and chronic heart disease. While some aspects of the modernization theory have been found to improve the global obesity crisis, a world systems theory approach identifies holes in the progress.[35] Knowledge economy and finance now dominate the industry in core states while manufacturing has shifted to semi-periphery and periphery ones.[36] Technology has become a defining factor in the placement of states into core or semi-periphery versus periphery.[37] Wallerstein's theory leaves room for poor countries to move into better economic development, but he also admits that there will always be a need for periphery countries as long as there are core states who derive resources from them.[38] As a final mark of modernity, Wallerstein admits that advocates are the heart of this world-system: “Exploitation and the refusal to accept exploitation as either inevitable or just constitute the continuing antinomy of the modern era”.[39] |

重要性 世界システム論は、世界史の理解や、中米の発展途上国における自然災害後の米国援助、あるいは他の中核国への体制押し付けといった帝国化やその他の関与に 対する中核国の動機を理解するのに有用である[30]。国家間システムをシステム定数とすると、三層の相対的経済力は、発展途上に見える国家内で増大しつ つある内部的不平等を指し示している。[31] しかしこの理論は、カリブ海の砂糖農園で実施された労働形態のように、世界経済とは無関係な地域的な革新努力を無視していると指摘する者もいる。[32] その他の現代的な世界的課題も、世界システム論に容易に遡及できる。 気候変動や産業企業の未来に関する国際的な議論の中で、世界システム理論はG-77グループの形成を説明するのに役立つ。これは77の周辺・準周辺国が結 束し、地球規模の気候議論の席を求める連合体だ。このグループは1964年に結成されたが、現在では130以上の加盟国が参加し、多国間意思決定を提唱し ている。創設以来、G-77加盟国は主に二つの目的で協力してきた:1) 経済的影響力の相対的な規模に基づく脆弱性の軽減、2) 国民の発展の成果向上である。[33] 世界システム論はまた、二酸化炭素排出がオゾン層に与える損害を追跡するためにも利用されてきた。世界経済への参入度と関与度は、一国が地球に与える損害 に影響する。一般的に科学者はGDPに基づき、一国のCO2排出量を推測できる。輸出量の多い国、債務を抱える国、社会構造が不安定な国は上位周辺層に位 置する。この分野ではさらなる研究が必要だが、科学者はCO2排出強度を示す指標として「中核」「準周辺」「周辺」という分類を用いることができる。 [34] 健康分野では、工業化が進んでいない周辺国が、糖分や保存料を多く含む加工食品・飲料を受け入れる影響が研究で明らかになっている。中核国が貧しい国々に 大量の加工食品や高脂肪食品を投棄する一方で、肥満や糖尿病・慢性心疾患などの関連慢性疾患の増加が記録されている。近代化理論のいくつかの側面は世界的 な肥満危機を改善すると見なされているが、世界システム理論的アプローチは進歩の欠陥を指摘している。[35] 知識経済と金融が現在、中核国の産業を支配している一方、製造業は準周辺部や周辺部へ移行している。[36] 技術は国家を中核・準周辺・周辺に分類する決定的要因となった。[37] ウォーラスティンの理論は貧しい国々がより良い経済発展へ移行する余地を残す一方、中核国家が周辺国家から資源を搾取する限り、周辺国家の存在が常に必要 となることも認めている。[38] 現代性の最終的特徴として、ウォーラスティンはこの世界システムの核心を擁護する者たちだと認めている。「搾取と、搾取を必然的あるいは正当なものとして 受け入れることを拒む姿勢こそが、現代の継続的な矛盾を構成している」と。[39] |

| Influence on International Law Third World Approaches to International Law (TWAIL), influenced by world-systems theory, critique the traditional view of international law (IL) as a horizontal system of equal sovereign states. This orthodox perspective, rooted in legal positivism, is challenged by the argument that global capitalism functions as a de facto sovereign power, shaping and enforcing international law in a hierarchical, top-down manner. Scholars like Antony Anghie have examined the historical role of international law in advancing colonial agendas, aligning this analysis with the Marxian concept of primitive accumulation. This concept situates colonialism within the broader framework of capital accumulation, demonstrating how IL has historically facilitated the exploitation and subordination of non-European states. From this perspective, international law is not a neutral framework of horizontal equality but a tool that mirrors and perpetuates the dominance of global capital. By doing so, it enforces a vertical hierarchy of power, subordinating states and communities to the interests of dominant economic and political forces.[40] |

国際法への影響 第三世界国際法論(TWAIL)は世界システム論の影響を受け、国際法(IL)を対等な主権国家の水平的システムとする従来の見解を批判する。法実証主義 に根ざしたこの正統的視点は、グローバル資本主義が事実上の主権的権力として機能し、国際法を階層的でトップダウンな方法で形成・強制するという主張に よって挑戦されている。 アントニー・アンギーら研究者は、国際法が植民地主義的アジェンダを推進した歴史的役割を検証し、この分析をマルクス主義の「原始的蓄積」概念と結びつけ た。この概念は植民地主義を資本蓄積の広範な枠組みに位置づけ、国際法が非ヨーロッパ諸国の搾取と従属を歴史的に促進してきたことを示す。この視点から国 際法は、水平的な平等を保障する中立的枠組みではなく、グローバル資本の支配を反映し永続させる道具である。それにより垂直的な権力階層を強制し、国家や 共同体を支配的な経済・政治勢力の利益に従属させるのである。[40] |

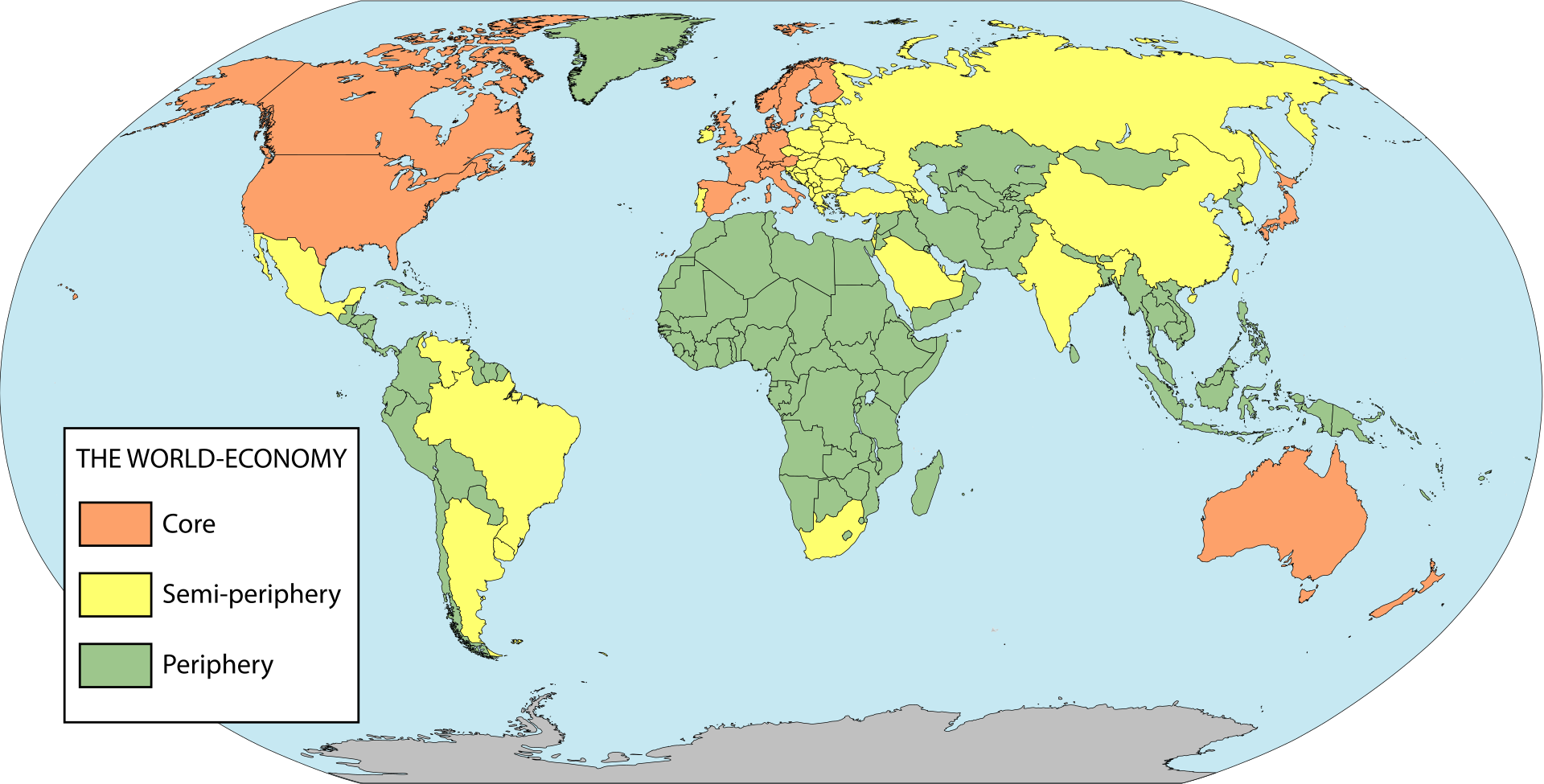

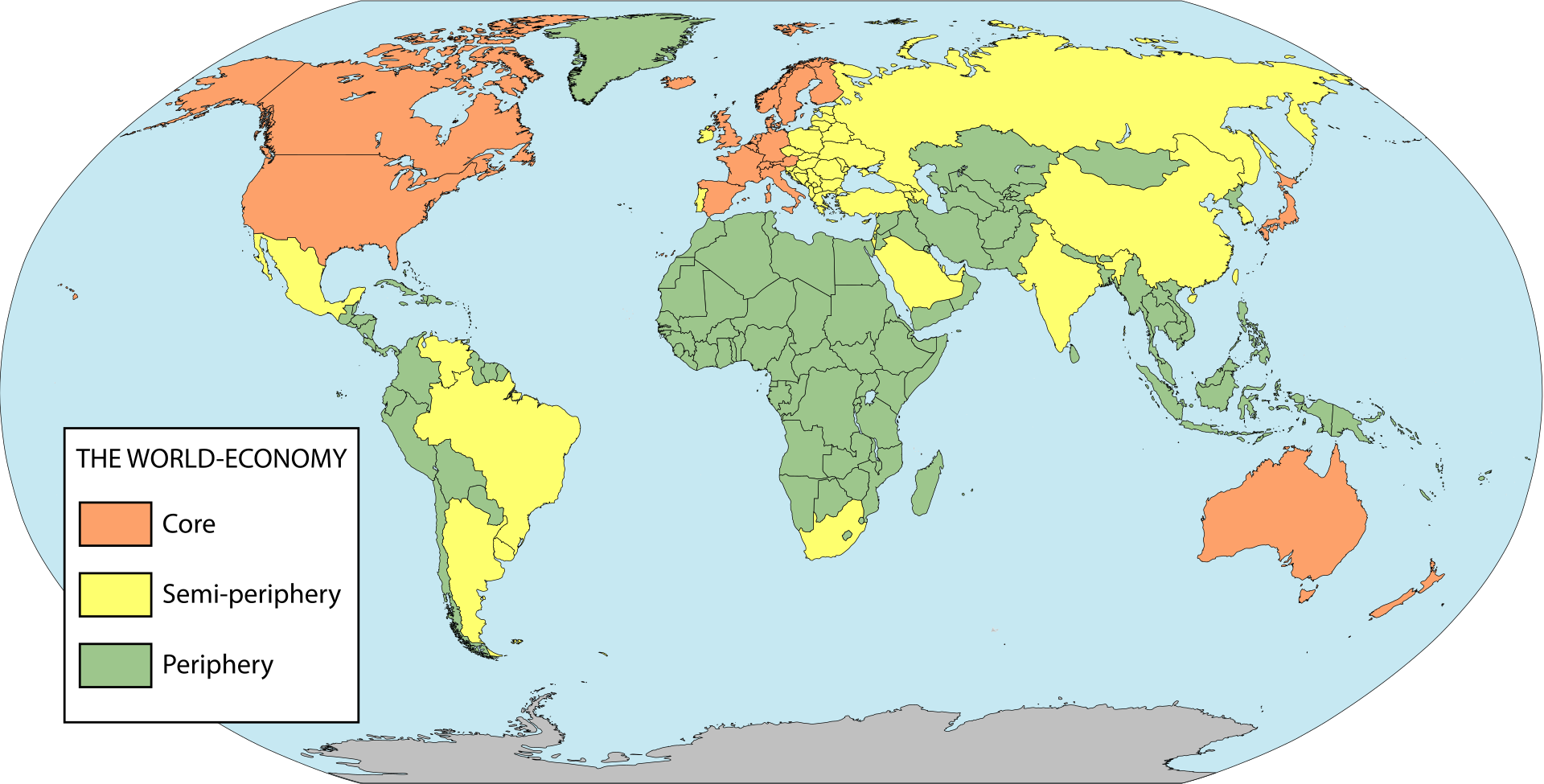

| Characteristics See also: Core-periphery This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "World-systems theory" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (March 2023) (Learn how and when to remove this message)  A model of a core-periphery system like that used in world-systems theory World-systems analysis argues that capitalism, as a historical system, has always integrated a variety of labor forms within a functioning division of labor (world economy). Countries do not have economies but are part of the world economy. Far from being separate societies or worlds, the world economy manifests a tripartite division of labor, with core, semiperipheral and peripheral zones. In the core zones, businesses, with the support of states they operate within, monopolise the most profitable activities of the division of labor. There are many ways to attribute a specific country to the core, semi-periphery, or periphery. Using an empirically based sharp formal definition of "domination" in a two-country relationship, Piana in 2004 defined the "core" as made up of "free countries" dominating others without being dominated, the "semi-periphery" as the countries that are dominated (usually, but not necessarily, by core countries) but at the same time dominating others (usually in the periphery) and "periphery" as the countries dominated. Based on 1998 data, the full list of countries in the three regions, together with a discussion of methodology, can be found. The late 18th and early 19th centuries marked a great turning point in the development of capitalism in that capitalists achieved state society power in the key states, which furthered the industrial revolution marking the rise of capitalism. World-systems analysis contends that capitalism as a historical system formed earlier and that countries do not "develop" in stages, but the system does, and events have a different meaning as a phase in the development of historical capitalism, the emergence of the three ideologies of the national developmental mythology (the idea that countries can develop through stages if they pursue the right set of policies): conservatism, liberalism, and radicalism. Classification of the countries according to the world-system analysis of I. Wallerstein: core, semi-periphery and periphery. Classification of the countries according to the world-system analysis of I. Wallerstein: core, semi-periphery and periphery. Proponents of world-systems analysis see the world stratification system the same way Karl Marx viewed class (ownership versus nonownership of the means of production) and Max Weber viewed class (which, in addition to ownership, stressed occupational skill level in the production process). The core states primarily own and control the major means of production in the world and perform the higher-level production tasks. The periphery nations own very little of the world's means of production (even when they are located in periphery states) and provide less-skilled labour. Like a class system within states, class positions in the world economy result in an unequal distribution of rewards or resources. The core states receive the greatest share of surplus production, and periphery states receive the smallest share. Furthermore, core states are usually able to purchase raw materials and other goods from non-core states at low prices and demand higher prices for their exports to non-core states. Chirot (1986) lists the five most important benefits coming to core states from their domination of the periphery: 1. Access to a large quantity of raw material 2. Cheap labour 3. Enormous profits from direct capital investments 4. A market for exports 5. Skilled professional labor through migration of these people from the non-core to the core.[41] According to Wallerstein, the unique qualities of the modern world system include its capitalistic nature, its truly global nature, and the fact that it is a world economy that has not become politically unified into a world empire.[4] |

特徴 関連項目: 中心・周辺 この記事は検証可能な情報源を必要としている。信頼できる情報源を追加して、この記事を改善してほしい。出典のない記述は削除される可能性がある。 出典を探す: 「世界システム論」 – ニュース · 新聞 · 書籍 · 学術文献 · JSTOR (2023年3月) (このメッセージの削除方法と時期について)  世界システム理論で用いられるような中核-周辺システムモデル 世界システム分析によれば、資本主義という歴史的システムは、常に機能する分業(世界経済)の中で多様な労働形態を統合してきた。国家は独自の経済を持つ のではなく、世界経済の一部である。世界経済は独立した社会や世界などではなく、中核、準周辺、周辺という三つの分業領域を顕在化させている。中核地域で は、企業が所在する国家の支援を得て、分業体系の中で最も収益性の高い活動を独占している。 特定の国を中核・準周辺・周辺に分類する方法は多数存在する。二国間関係における「支配」を実証的に厳密に定義した形式的アプローチを用いる場合、 2004年のピアーナは「中核」を「支配されずに他を支配する『自由な国々』」と定義し、「準周辺」を(通常は中核国によってだが必ずしもそうではない) 支配されつつも同時に他(通常は周辺国)を支配する国々とし、「周辺」を支配される国々とした。1998年のデータに基づく三地域に属する全国のリストと 方法論に関する議論は、以下のリンクで確認できる。 18世紀末から19世紀初頭は、資本主義発展における重大な転換点であった。主要国家において資本家が国家社会権力を掌握し、これが産業革命を促進して資 本主義の台頭を決定づけたのである。世界システム論は、資本主義という歴史的システムがより早期に形成されたと主張する。国民が段階的に「発展」するので はなく、システム自体が発展し、各事象は歴史的資本主義の発展段階として異なる意味を持つ。これに伴い、国民発展神話(適切な政策を追求すれば国民が段階 を経て発展できるという思想)の三つのイデオロギー——保守主義、自由主義、急進主義——が出現した。 I. ウォーラスティンの世界システム分析に基づく国家分類:中核、準周辺、周辺。 I. ウォーラスティンの世界システム分析に基づく国家分類:中核、準周辺、周辺。 世界システム分析の支持者たちは、世界の階層化システムを、カール・マルクスが階級(生産手段の所有と非所有)を捉えた方法や、マックス・ウェーバーが階 級(所有に加え、生産過程における職業的技能レベルを強調した)を捉えた方法と同様に見ている。中核国家は主に世界の主要な生産手段を所有・支配し、高次 生産任務を担う。周辺国民は世界の生産手段をほとんど所有せず(周辺地域に位置する場合でも)、低技能労働を提供する。国家内の階級制度と同様に、世界経 済における階級的位置は報酬や資源の不平等な分配をもたらす。中核国は生産余剰の最大の分け前を得て、周辺国は最小の分け前しか得られない。さらに中核国 は通常、非中核国から原材料やその他の商品を低価格で買い付け、非中核国への輸出には高値を要求できる。チロット(1986)は、中核国が周辺支配から得 る五つの主要な利益を列挙している: 1. 大量の原材料へのアクセス 2. 安価な労働力 3. 直接資本投資による莫大な利益 4. 輸出市場 5. 非中核地域から中核地域への移住による熟練専門労働力の獲得[41] ウォーラスティンによれば、現代世界システムの特質は、その資本主義的性質、真にグローバルな性質、そして政治的に世界帝国へと統合されていない世界経済であるという事実にある[4]。 |

| Core states Main article: Core countries In general, core states: Are the most economically diversified, wealthy, and powerful both economically and militarily[4][10] Have strong central governments controlling extensive bureaucracies and powerful militaries[4][10] Have stronger and more complex state institutions that help manage economic affairs internally and externally Have a sufficiently large tax base, such that state institutions can provide the infrastructure for a strong economy Are highly industrialised and produce manufactured goods for export instead of raw materials[4] Increasingly tend to specialise in the information, finance, and service industries Are more regularly at the forefront of new technologies and new industries. Contemporary examples include the electronics and biotechnology industries. The use of the assembly line is a historic example of this trend. Have strong bourgeois and working classes[4] Have significant means of influence over non-core states[4] Are relatively independent of outside control  World Systems Theory (Dunaway and Clelland 2015) Throughout the history of the modern world system, a group of core states has competed for access to the world's resources, economic dominance, and hegemony over periphery states. Occasionally, one core state possessed clear dominance over the others.[5] According to Immanuel Wallerstein, a core state is dominant over all the others when it has a lead in three forms of economic dominance: 1. Productivity dominance allows a country to develop higher-quality products at a cheaper price compared to other countries. 2. Productivity dominance may lead to trade dominance. In this case, there is a favorable balance of trade for the dominant state since other countries are buying more of its products than those of others. 3. Trade dominance may lead to financial dominance. At this point, more money is flowing into the country than is leaving it. Bankers from the dominant state tend to acquire greater control over the world's financial resources.[42] Military dominance is also likely once a state has reached this point. However, it has been posited that throughout the modern world system, no state has been able to use its military to gain economic dominance. Each of the past dominant states became dominant with fairly small levels of military spending and began to lose economic dominance with military expansion later on.[43] Historically, cores were located in northwestern Europe (England, France, Netherlands) but later appeared in other parts of the world such as the United States, Canada, and Australia.[5][10] |

中核国家 主な記事: 中核諸国 一般的に、中核国家は: 経済的にも軍事的にも最も多様化され、豊かで強力である[4][10] 広範な官僚機構と強力な軍隊を統制する強力な中央政府を持つ[4][10] 国内外の経済問題を管理するより強力で複雑な国家機関を持つ 国家機関が強力な経済基盤を提供できるほど十分な税収基盤を持つ 高度に工業化され、原材料ではなく輸出向け製造品を生産する[4] 情報・金融・サービス産業への特化傾向が強まっている 新技術・新産業の最先端を常に走る。現代の例として電子産業やバイオテクノロジー産業が挙げられる。組立ラインの採用はこの傾向の歴史的実例である 強固なブルジョワ階級と労働者階級を有する[4] 非中核国に対して重要な影響力を持つ[4] 外部からの支配に対して比較的独立している  世界システム論(Dunaway and Clelland 2015) 近代世界システムの歴史を通じて、中核国グループは世界の資源へのアクセス、経済的優位性、周辺国に対するヘゲモニーを争ってきた。時折、ある中核国が他 国に対して明らかな優位性を示すこともあった。[5] イマニュエル・ウォーラスティンによれば、中核国家が他の全ての国家に対して優位性を示すのは、以下の三つの経済的優位性において主導権を握っている場合 である: 1. 生産性優位性により、その国は他国と比較してより安価に高品質の製品を開発できる。 2. 生産性優位性は貿易優位性につながる可能性がある。この場合、他国がその国の製品を他国の製品よりも多く購入するため、優位性を持つ国家にとって有利な貿易収支が生じる。 3. 貿易支配は金融支配につながる可能性がある。この段階では、国外に流出する資金よりも流入する資金が多くなる。支配的国家の銀行家は、世界の金融資源に対する支配力を強める傾向がある。[42] 国家がこの段階に達すると、軍事的支配も生じやすくなる。しかし、近代世界システムにおいて、軍事力を用いて経済的支配を獲得できた国家は存在しないとい う見解が示されている。過去の支配的国家はいずれも、比較的少ない軍事支出で支配的地位を獲得し、その後軍事拡大に伴い経済的支配力を失い始めた。 [43] 歴史的に、中核地域は北西ヨーロッパ(イギリス、フランス、オランダ)に位置していたが、後にアメリカ、カナダ、オーストラリアなど世界の他の地域にも出 現した。[5][10] |

| Peripheral states Main article: Periphery countries Are the least economically diversified Have relatively weak governments[4][10] Have relatively weak institutions, with tax bases too small to support infrastructural development Tend to depend on one type of economic activity, often by extracting and exporting raw materials to core states[4][10] Tend to be the least industrialized[10] Are often targets for investments from multinational (or transnational) corporations from core states that come into the country to exploit cheap unskilled labor in order to export back to core states Have a small bourgeois and a large peasant classes[4] Tend to have populations with high percentages of poor and uneducated people Tend to have very high social inequality because of small upper classes that own most of the land and have profitable ties to multinational corporations Tend to be extensively influenced by core states and their multinational corporations and often forced to follow economic policies that help core states and harm the long-term economic prospects of peripheral states.[4] Historically, peripheries were found outside Europe, such as in Latin America and today in sub-Saharan Africa.[10] |

周辺国 主な記事: 周辺国 経済的多様性が最も低い 政府の力が比較的弱い[4][10] 制度が比較的脆弱で、税収基盤がインフラ整備を支えるには小さすぎる 単一の経済活動に依存する傾向があり、多くの場合、原料を採掘して中核国へ輸出する[4][10] 工業化が最も進んでいない傾向がある[10] 中核国からの多国籍(または越境)企業による投資対象となりやすい。これらの企業は安価な非熟練労働力を搾取し、中核国へ輸出するために進出する 小ブルジョア階級が小さく、農民階級が大きい[4] 貧困層や無学な人民の割合が高い人口構成を持つ傾向がある 土地の大半を所有し多国籍企業と利益関係を持つ少数の上流階級が存在するため、社会的不平等が極めて大きい傾向がある 中核国とその多国籍企業から広範な影響を受け、中核国に利益をもたらす一方で周辺国の長期的経済見通しを損なう経済政策を強制されることが多い[4] 歴史的に、周辺地域はヨーロッパの外、例えばラテンアメリカや現在のサハラ以南アフリカに存在した[10] |

| Semi-peripheral states Main article: Semiperiphery countries Semi-peripheral states are those that are midway between the core and periphery.[10] Thus, they have to keep themselves from falling into the category of peripheral states and at the same time, they strive to join the category of core states. Therefore, they tend to apply protectionist policies most aggressively among the three categories of states.[29] They tend to be countries moving towards industrialization and more diversified economies. These regions often have relatively developed and diversified economies but are not dominant in international trade.[10] They tend to export more to peripheral states and import more from core states in trade. According to some scholars, such as Chirot, they are not as subject to outside manipulation as peripheral societies; but according to others (Barfield), they have "periperial-like" relations to the core.[4][44] While in the sphere of influence of some cores, semiperipheries also tend to exert their own control over some peripheries.[10] Further, semi-peripheries act as buffers between cores and peripheries[10] and thus "...partially deflect the political pressures which groups primarily located in peripheral areas might otherwise direct against core-states" and stabilise the world system.[4][5] Semi-peripheries can come into existence from developing peripheries and declining cores.[10] Historically, two examples of semiperipheral states would be Spain and Portugal, which fell from their early core positions but still managed to retain influence in Latin America.[10] Those countries imported silver and gold from their American colonies but then had to use it to pay for manufactured goods from core countries such as England and France.[10] In the 20th century, states like the "settler colonies" of Australia, Canada and New Zealand had a semiperipheral status. In the 21st century, states like Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa (BRICS), and Israel are usually considered semiperipheral.[45] |

準周辺国 詳細な記事: 準周辺国 準周辺国とは、中核と周辺の中間に位置する国々である[10]。したがって、周辺国に分類されることを避けつつ、同時に中核国に仲間入りしようと努める。 したがって、三つの国家カテゴリーの中で最も積極的に保護主義政策を適用する傾向がある。[29] これらは工業化と経済の多様化に向かう国々であることが多い。これらの地域は比較的発展し多様化した経済を持つが、国際貿易において支配的ではない。 [10] 貿易では周辺国への輸出が多く、中核国からの輸入が多い傾向がある。チロットら一部の学者は、周辺社会ほど外部からの操作を受けにくい主体性を持っている と指摘する。しかしバーフィールドらによれば、中核国に対して「周辺的関係」を有しているという。[4][44] 一部の中心国の影響圏内にある一方で、半周辺地域は自らも周辺地域に対して支配力を行使する傾向がある[10]。さらに半周辺地域は中心と周辺の間で緩衝 地帯として機能し[10]、それゆえ「...主に周辺地域に所在する集団が中心国に対して向け得る政治的圧力を部分的にそらす」ことで世界システムを安定 化させる[4]。[5] 半周辺地域は、発展途上の周辺地域や衰退する中核地域から生まれることがある[10]。歴史的に見れば、スペインとポルトガルが半周辺国家の例だ。両国は 初期の中核的地位から転落したが、ラテンアメリカにおける影響力を維持することに成功した[10]。これらの国々はアメリカ植民地から銀や金を輸入した が、それをイギリスやフランスといった中核国からの工業製品の購入代金に充てざるを得なかった。[10] 20世紀には、オーストラリア、カナダ、ニュージーランドといった「入植地植民地」が半周辺的地位にあった。21世紀では、ブラジル、ロシア、インド、中 国、南アフリカ(BRICS)やイスラエルが通常、半周辺的と見なされている。[45] |

| Interstate system Main article: Interstate system (world-systems theory) Between the core, periphery and semi-periphery countries lies a system of interconnected state relationships, or the interstate system. The interstate system arose either as a concomitant process or as a consequence of the development of the capitalist world-system over the course of the “long” 16th century as states began to recognize each other's sovereignty and form agreements and rules between themselves.[46] Wallerstein wrote that there were no concrete rules about what exactly constitutes an individual state as various indicators of statehood (sovereignty, power, market control etc.) could range from total to nil. There were also no clear rules about which group controlled the state, as various groups located inside, outside, and across the states’ frontiers could seek to increase or decrease state power in order to better profit from a world-economy.[47] Nonetheless, the “relative power continuum of stronger and weaker states has remained relatively unchanged over 400-odd years” implying that while there is no universal state system, an interstate system had developed out of the sum of state actions, which existed to reinforce certain rules and preconditions of statehood. These rules included maintaining consistent relations of production, and regulating the flow of capital, commodities and labor across borders to maintain the price structures of the global market. If weak states attempt to rewrite these rules as they prefer them, strong states will typically intervene to rectify the situation.[48] The ideology of the interstate system is sovereign equality, and while the system generally presents a set of constraints on the power of individual states, within the system states are “neither sovereign nor equal.” Not only do strong states impose their will on weak states, strong states also impose limitations upon other strong states, and tend to seek strengthened international rules, since enforcing consequences for broken rules can be highly beneficial and confer comparative advantages.[49] External areas External areas are those that maintain socially necessary divisions of labor independent of the capitalist world economy.[10] |

国家間システム 詳細記事: 国家間システム (世界システム論) 中核国、周辺国、準周辺国の間には、相互に結びついた国家関係、すなわち国家間システムが存在する。国家間システムは、「長い16世紀」の過程で資本主義 的世界システムが発展するにつれ、国家が互いの主権を認め合い、相互に協定や規則を形成する過程で、付随的なプロセスとして、あるいは結果として生じたも のである。[46] ウォーラスティンは、国家を構成する具体的な要素(主権、権力、市場支配など)は完全なものから皆無なものまで様々であるため、個々の国家を定義する明確 な規則は存在しないと記した。また、国家を支配する集団についても明確な規則はなく、国家の境界の内側、外側、そして境界を越えた様々な集団が、世界経済 からより多くの利益を得るために国家の権力を増大させたり減少させたりしようと試みることがある。[47] しかしながら「強国と弱国の相対的な力関係は400年余りにわたりほぼ不変」であり、普遍的な国家体系は存在しないものの、国家行動の総和から国家間シス テムが発展し、国家性の特定のルールや前提条件を強化する役割を果たしてきたことを示唆している。これらの規則には、一貫した生産関係を維持すること、国 境を越えた資本・商品・労働力の流れを規制して世界市場の価格構造を維持することが含まれる。弱小国家が自らの都合でこれらの規則を書き換えようとすれ ば、強国は通常、状況を是正するために介入する。[48] 国家間システムのイデオロギーは主権平等である。このシステムは一般的に個々の国家の権力に制約を課すが、システム内では国家は「主権も平等も有さな い」。強国は弱国に自らの意志を押し付けるだけでなく、他の強国に対しても制限を課し、国際ルール強化を志向する傾向がある。なぜなら、ルール違反への制 裁を実行することは極めて有益であり、比較優位をもたらすからである。[49] 外部領域 外部領域とは、資本主義的世界経済とは独立して、社会的に必要な分業を維持している領域を指す。[10] |

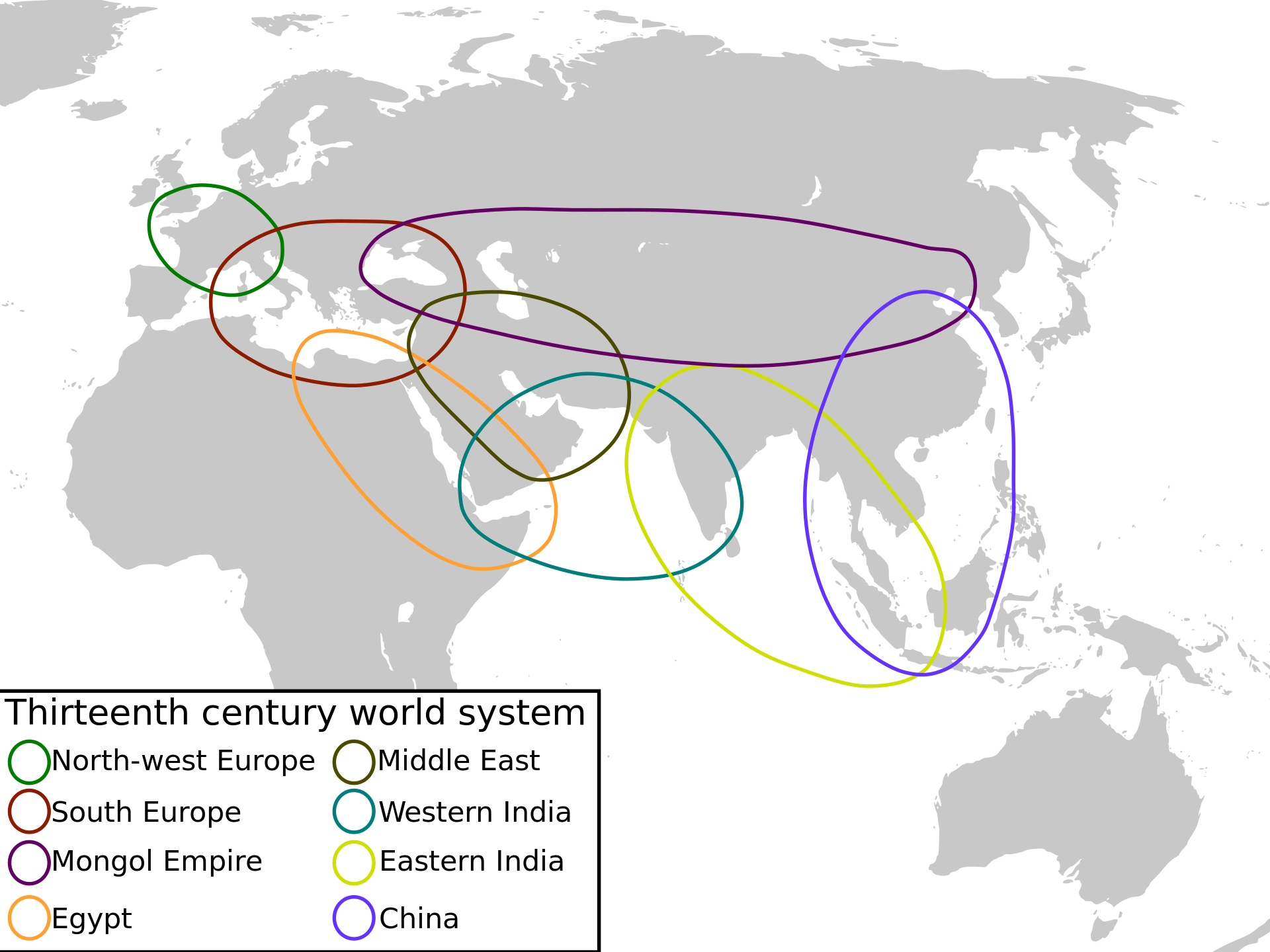

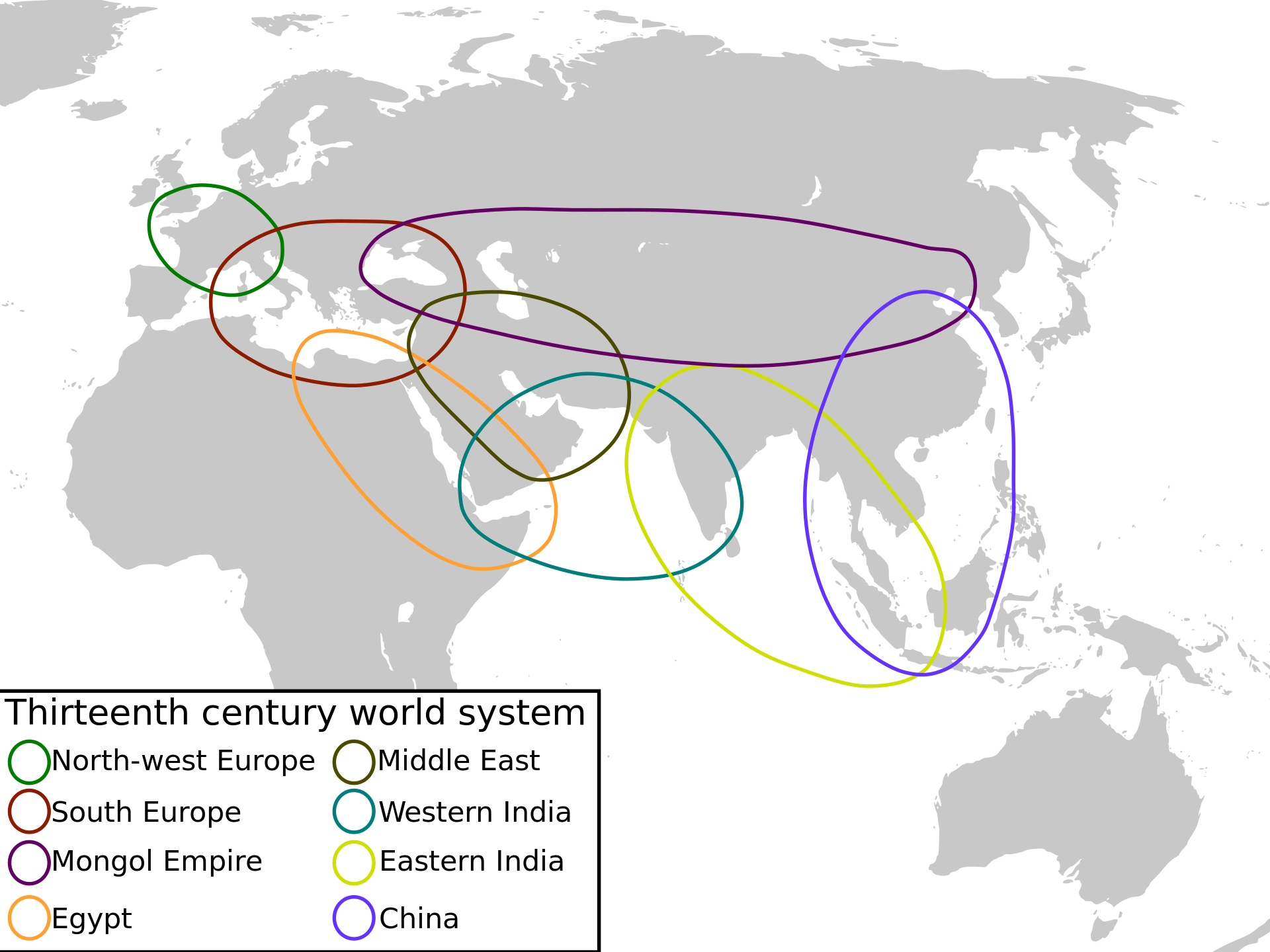

The interpretation of world history The 13th century world-system Wallerstein traces the origin of today's world-system to the "long 16th century" (a period that began with the discovery of the Americas by Western European sailors and ended with the English Revolution of 1640).[4][5][10] And, according to Wallerstein, globalization, or the becoming of the world's system, is a process coterminous with the spread and development of capitalism over the past 500 years. Janet Abu Lughod argues that a pre-modern world system extensive across Eurasia existed in the 13th century prior to the formation of the modern world-system identified by Wallerstein. She contends that the Mongol Empire played an important role in stitching together the Chinese, Indian, Muslim and European regions in the 13th century, before the rise of the modern world system.[50] In debates, Wallerstein contends that Lughod's system was not a "world-system" because it did not entail integrated production networks, but it was instead a vast trading network. |

世界史の解釈 13世紀の世界システム ウォーラスティンは、今日の世界システムの起源を「長い16世紀」(西ヨーロッパの船乗りによるアメリカ大陸の発見から始まり、1640年のイングランド 革命で終わる期間)に遡る。[4][5][10] そしてウォーラスティンによれば、グローバリゼーション、すなわち世界システムの形成は、過去500年にわたる資本主義の拡散と発展と同時進行する過程で ある。 ジャネット・アブ・ルゴッドは、ウォーラスティンが特定した近代世界システムの形成以前に、13世紀のユーラシア全域に広がる前近代的世界システムが存在 したと主張する。彼女は、現代世界システムが台頭する前の13世紀において、モンゴル帝国が中国、インディアン、イスラム、ヨーロッパの各地域を結びつけ る上で重要な役割を果たしたと主張している[50]。議論の中でウォーラスティンは、ルゴッドのシステムは統合された生産ネットワークを伴わなかったため 「世界システム」ではなく、広大な交易ネットワークであったと反論している。 |

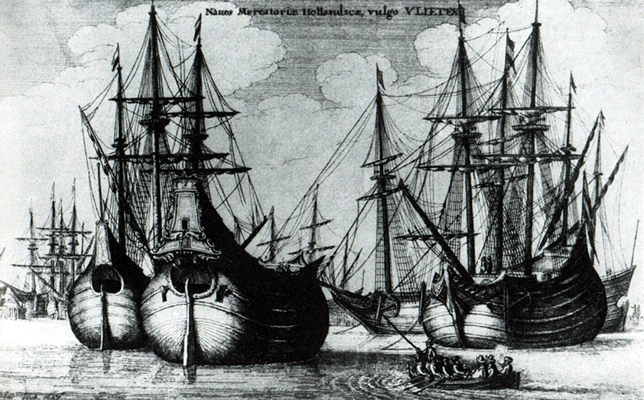

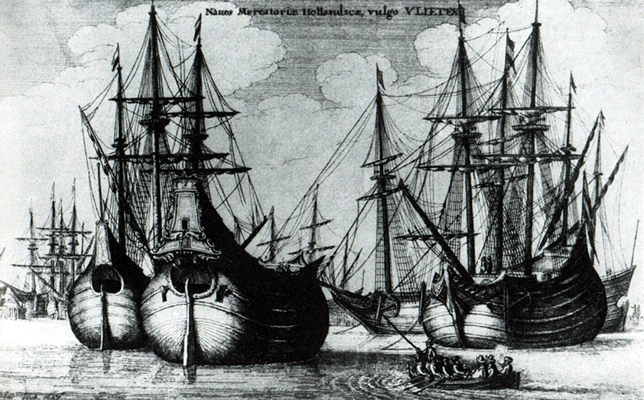

The 11th century world system Andre Gunder Frank goes further and claims that a global world system that includes Asia, Europe and Africa has existed since the 4th millennium BCE. The centre of this system was in Asia, specifically China.[51] Andrey Korotayev goes even further than Frank and dates the beginning of the world system formation to the 10th millennium BCE and connects it with the start of the Neolithic Revolution in the Middle East. According to him, the centre of this system was originally in Western Asia.[52] Before the 16th century, Europe was dominated by feudal economies.[10] European economies grew from mid-12th to 14th century but from 14th to mid 15th century, they suffered from a major crisis.[5][10] Wallerstein explains this crisis as caused by the following: 1. stagnation or even decline of agricultural production, increasing the burden of peasants, 2. decreased agricultural productivity caused by changing climatological conditions (Little Ice Age), 3. an increase in epidemics (Black Death), 4. optimum level of the feudal economy having been reached in its economic cycle; the economy moved beyond it and entered a depression period.[10] As a response to the failure of the feudal system, European society embraced the capitalist system.[10] Europeans were motivated to develop technology to explore and trade around the world, using their superior military to take control of the trade routes.[5] Europeans exploited their initial small advantages, which led to an accelerating process of accumulation of wealth and power in Europe.[5] Wallerstein notes that never before had an economic system encompassed that much of the world, with trade links crossing so many political boundaries.[10] In the past, geographically large economic systems existed but were mostly limited to spheres of domination of large empires (such as the Roman Empire); development of capitalism enabled the world economy to extend beyond individual states.[10] International division of labor was crucial in deciding what relationships exists between different regions, their labor conditions and political systems.[10] For classification and comparison purposes, Wallerstein introduced the categories of core, semi-periphery, periphery, and external countries.[10] Cores monopolized the capital-intensive production, and the rest of the world could provide only workforce and raw resources.[5] The resulting inequality reinforced existing unequal development.[5] According to Wallerstein there have only been three periods in which a core state dominated in the modern world-system, with each lasting less than one hundred years. In the initial centuries of the rise of European dominance, Northwestern Europe constituted the core, Mediterranean Europe the semiperiphery, and Eastern Europe and the Western hemisphere (and parts of Asia) the periphery.[5][10] Around 1450, Spain and Portugal took the early lead when conditions became right for a capitalist world-economy. They led the way in establishing overseas colonies. However, Portugal and Spain lost their lead, primarily by becoming overextended with empire-building. It became too expensive to dominate and protect so many colonial territories around the world.[43][44][53]  Dutch fluyts of the seventeenth century The first state to gain clear dominance was the Netherlands in the 17th century, after its revolution led to a new financial system that many historians consider revolutionary.[43] An impressive shipbuilding industry also contributed to their economic dominance through more exports to other countries.[41] Eventually, other countries began to copy the financial methods and efficient production created by the Dutch. After the Dutch gained their dominant status, the standard of living rose, pushing up production costs.[42] Dutch bankers began to go outside of the country seeking profitable investments, and the flow of capital moved, especially to England.[43] By the end of the 17th century, conflict among core states increased as a result of the economic decline of the Dutch. Dutch financial investment helped England gain productivity and trade dominance, and Dutch military support helped England to defeat France, the other country competing for dominance at the time. |

11世紀の世界システム アンドレ・ギュンダー・フランクはさらに踏み込み、アジア、ヨーロッパ、アフリカを含むグローバルな世界システムが紀元前4千年紀から存在していたと主張 する。このシステムの中枢はアジア、特に中国にあった[51]。アンドレイ・コロタエフはフランクよりもさらに遡り、世界システム形成の始まりを紀元前1 万年に設定し、中東における新石器革命の始まりと結びつける。彼によれば、このシステムの中枢は当初西アジアにあった。[52] 16世紀以前、ヨーロッパは封建経済が支配的であった。[10] ヨーロッパ経済は12世紀半ばから14世紀にかけて成長したが、14世紀から15世紀半ばにかけて苦悩に見舞われた。[5][10] ウォーラスティンはこの危機を以下の要因によるものと説明する: 1. 農業生産の停滞あるいは衰退により、農民の負担が増大したこと 2. 気候条件の変化(小氷期)による農業生産性の低下 3. 疫病(ペスト)の増加 4. 封建経済が経済サイクルにおいて最適水準に達し、それを超えて不況期に入ったこと[10] 封建制度の失敗への対応として、ヨーロッパ社会は資本主義体制を受け入れた。[10] ヨーロッパ人は、優れた軍事力を用いて交易路を掌握しつつ、世界を探検し交易するための技術開発に意欲的だった。[5] ヨーロッパ人は初期の小さな優位性を活用し、それがヨーロッパにおける富と権力の蓄積プロセスを加速させた。[5] ウォーラスティンは、これほど多くの地域を包含し、これほど多くの政治的境界を越える貿易ネットワークを持つ経済システムはかつて存在しなかったと指摘し ている。[10] 過去にも地理的に広大な経済システムは存在したが、それは主に大帝国(ローマ帝国など)の支配圏内に限定されていた。資本主義の発展により、世界経済は個 々の国家の枠を超えて拡大することが可能となった。[10] 国際分業は、異なる地域間の関係性、労働条件、政治体制を決定する上で決定的に重要であった。[10] 分類と比較のため、ウォーラスティンは中核、準周辺、周辺、外部諸国というカテゴリーを導入した。[10] 中核は資本集約的生産を独占し、世界の残りの地域は労働力と原材料しか提供できなかった。[5] その結果生じた不平等は、既存の不均衡な発展をさらに強化した。[5] ウォーラスティンによれば、近代世界システムにおいて中核国家が支配的だった時期は三度しかなく、いずれも百年に満たない。ヨーロッパ支配が台頭した初期 の数世紀には、北西ヨーロッパが中核、地中海ヨーロッパが準周辺、東ヨーロッパと西半球(及びアジアの一部)が周辺を形成した。[5][10] 1450年頃、資本主義的世界経済が成立する条件が整うと、スペインとポルトガルが先行した。両国は海外植民地開拓の先駆けとなった。しかし、帝国建設に よる過度の拡張が主因で、両国は主導権を失った。世界中に広がる植民地を支配・保護するコストが膨大になったのである。[43][44][53]  17世紀のオランダ・フルート船 17世紀、革命を経て多くの歴史家が画期的と評価する新たな金融システムを確立したオランダが、初めて明確な優位性を獲得した国家となった。[43] 優れた造船業も他国への輸出拡大を通じ、経済的優位性に貢献した。[41] 結局、他国もオランダが生み出した金融手法と効率的な生産方法を模倣し始めた。オランダが支配的地位を確立すると、生活水準が上昇し生産コストが押し上げ られた。[42] オランダの銀行家は国外へ出て利益を生む投資を求め始め、資本の流れは特にイングランドへと向かった。[43] 17世紀末までに、オランダの経済的衰退を背景に主要国間の対立は激化した。オランダの金融投資はイングランドの生産性向上と貿易支配を助け、オランダの 軍事支援は当時支配を争っていたフランスをイングランドが打ち負かすのに貢献した。 |

Map showing the British Empire in 1921 In the 19th century, Britain replaced the Netherlands as the hegemon.[5] As a result of the new British dominance, the world system became relatively stable again during the 19th century. The British began to expand globally, with many colonies in the New World, Africa, and Asia. The colonial system began to place a strain on the British military and, along with other factors, led to an economic decline. Again there was a great deal of core conflict after the British lost their clear dominance. This time it was Germany, and later Italy and Japan that provided the new threat. Industrialization was another ongoing process during British dominance, resulting in the diminishing importance of the agricultural sector.[10] In the 18th century, Britain was Europe's leading industrial and agricultural producer; by 1900, only 10% of England's population was working in the agricultural sector.[10] By 1900, the modern world system appeared very different from that of a century earlier in that most of the periphery societies had already been colonised by one of the older core states.[41] In 1800, the old European core claimed 35% of the world's territory, but by 1914, it claimed 85% of the world's territory, with the Scramble for Africa closing out the imperial era.[43] If a core state wanted periphery areas to exploit as had done the Dutch and British, these periphery areas had to be taken from another core state, which the US did by way of the Spanish–American War, and Germany, and then Japan and Italy, attempted to do in the leadup to World War II. The modern world system was thus geographically global, and even the most remote regions of the world had all been integrated into the global economy.[4][5] As countries vied for core status, so did the United States. The American Civil War led to more power for the Northern industrial elites, who were now better able to pressure the government for policies helping industrial expansion. Like the Dutch bankers, British bankers were putting more investment toward the United States. The US had a small military budget compared to other industrial states at the time.[43] The US began to take the place of the British as a new dominant state after World War I.[5] With Japan and Europe in ruins after World War II, the US was able to dominate the modern world system more than any other country in history, while the USSR and to a lesser extent China were viewed as primary threats.[5] At its height, US economic reach accounted for over half of the world's industrial production, owned two thirds of the gold reserves in the world and supplied one third of the world's exports.[43] However, since the end of the Cold War, the future of US hegemony has been questioned by some scholars, as its hegemonic position has been in decline for a few decades.[5] By the end of the 20th century, the core of the wealthy industrialized countries was composed of Western Europe, the United States, Japan and a rather limited selection of other countries.[5] The semiperiphery was typically composed of independent states that had not achieved Western levels of influence, while poor former colonies of the West formed most of the periphery.[5] |

1921年の大英帝国を示す地図 19世紀、イギリスはオランダに代わって覇権国となった[5]。新たなイギリスの支配により、19世紀の世界体制は再び比較的安定した。イギリスは新大 陸、アフリカ、アジアに多くの植民地を持ち、世界的に拡大を始めた。植民地体制は英国軍に負担をかけ始め、他の要因と相まって経済的衰退を招いた。英国が 明確な優位性を失った後、再び中核国間の深刻な対立が生じた。今度はドイツが新たな脅威となり、後にイタリアと日本が続いた。 工業化は英国優位時代にも進行し、農業部門の重要性を低下させた。18世紀、英国は欧州随一の工業・農業生産国であった。1900年までに、イングランドの人口のわずか10%が農業部門で働いていた。[10] 1900年までに、近代世界システムは1世紀前とは大きく異なる様変わりしていた。周辺社会の大半が、既存の中心国家のいずれかによって既に植民地化され ていたのである。[41] 1800年時点で旧ヨーロッパ中核地域が占める世界領土は35%だったが、1914年までに85%に達した。アフリカ分割競争が帝国主義時代の幕を閉じた のである。[43] オランダや英国のように周辺地域を搾取したい中核国家は、他の中核国家からその地域を奪わねばならなかった。米国は米西戦争によってこれを実行し、ドイ ツ、次いで日本とイタリアが第二次世界大戦前夜に同様の試みを行った。こうして近代世界システムは地理的に地球規模となり、世界の最も辺境の地域さえも全 て世界経済に組み込まれたのである。[4][5] 各国が中核国としての地位を争う中、米国もまたその一角を占めた。南北戦争は北部の産業エリート層の権力強化をもたらし、彼らは政府に対し産業拡大を助け る政策を強く要求できるようになった。オランダの銀行家たちと同様、英国の銀行家たちも米国への投資を増やしていた。当時の米国は他の工業国と比べて軍事 予算が少なかった。[43] 第一次世界大戦後、米国は英国の代わりに新たな支配的国家としての地位を確立し始めた。[5] 第二次世界大戦後、日本とヨーロッパが廃墟と化したことで、米国は歴史上いかなる国よりも現代世界システムを支配するに至った。一方、ソ連、そしてより小 規模ながら中国が主要な脅威と見なされていた。[5] 全盛期には、米国の経済的影響力は世界の工業生産高の半分以上を占め、世界の金準備の3分の2を所有し、世界の輸出の3分の1を供給していた。[43] しかし冷戦終結後、米国のヘゲモニーは数十年かけて衰退しており、一部の学者から米国のヘゲモニーが将来的に危ういとの指摘がある。[5] 20世紀末までに、富裕な工業国の核心は西ヨーロッパ、米国、日本、および比較的限られた他の国々で構成されていた。[5] 半周辺部には通常、西側諸国の影響力水準に達していない独立国家が位置し、貧しい旧西側植民地が周辺部の大部分を形成していた。[5] |

| Criticisms World-systems theory has attracted criticisms from its rivals; notably for being too focused on economy and not enough on culture and for being too core-centric and state-centric.[4] William I. Robinson has criticized world-systems theory for its nation-state centrism, state-structuralist approach, and its inability to conceptualize the rise of globalization.[54] Robinson suggests that world-systems theory does not account for emerging transnational social forces and the relationships forged between them and global institutions serving their interests.[54] These forces operate on a global, rather than state system and cannot be understood by Wallerstein's nation-centered approach.[54] According to Wallerstein himself, critique of the world-systems approach comes from four directions: the positivists, the orthodox Marxists, the state autonomists, and the culturalists.[3] The positivists criticise the approach as too prone to generalization, lacking quantitative data and failing to put forth a falsifiable proposition.[3] Orthodox Marxists find the world-systems approach deviating too far from orthodox Marxist principles, such as by not giving enough weight to the concept of social class.[3] It is worth noting, however, that "[d]ependency theorists argued that [the beneficiaries of class society, the bourgeoisie,] maintained a dependent relationship because their private interests coincided with the interest of the dominant states."[55] The state autonomists criticize the theory for blurring the boundaries between state and businesses.[3] Further, the positivists and the state autonomists argue that state should be the central unit of analysis.[3] Finally, the culturalists argue that world-systems theory puts too much importance on the economy and not enough on the culture.[3] In Wallerstein's own words: In short, most of the criticisms of world-systems analysis criticize it for what it explicitly proclaims as its perspective. World-systems analysis views these other modes of analysis as defective and/or limiting in scope and calls for unthinking them.[3] One of the fundamental conceptual problems of the world-system theory is that the assumptions that define its actual conceptual units are social systems. The assumptions, which define them, need to be examined as well as how they are related to each other and how one changes into another. The essential argument of the world-system theory is that in the 16th century a capitalist world economy developed, which could be described as a world system.[56] The following is a theoretical critique concerned with the basic claims of world-system theory: "There are today no socialist systems in the world-economy any more than there are feudal systems because there is only one world system. It is a world-economy and it is by definition capitalist in form."[56] Robert Brenner has pointed out that the prioritization of the world market means the neglect of local class structures and class struggles: "They fail to take into account either the way in which these class structures themselves emerge as the outcome of class struggles whose results are incomprehensible in terms merely of market forces."[56] Another criticism is that of reductionism made by Theda Skocpol: she believes the interstate system is far from being a simple superstructure of the capitalist world economy: "The international states system as a transnational structure of military competition was not originally created by capitalism. Throughout modern world history, it represents an analytically autonomous level [... of] world capitalism, but [is] not reducible to it."[56] A concept that we can perceive as critique and mostly as renewal is the concept of coloniality (Anibal Quijano, 2000, Nepantla, Coloniality of power, eurocentrism and Latin America).[57] Issued from the think tank of the group "modernity/coloniality" [es] in Latin America, it re-uses the concept of world working division and core/periphery system in its system of coloniality. But criticizing the "core-centric" origin of World-system and its only economical development, "coloniality" allows further conception of how power still processes in a colonial way over worldwide populations (Ramon Grosfogel, "the epistemic decolonial turn" 2007):[58] "by 'colonial situations' I mean the cultural, political, sexual, spiritual, epistemic and economic oppression/exploitation of subordinate racialized/ethnic groups by dominant racialized/ethnic groups with or without the existence of colonial administration". Coloniality covers, so far, several fields such as coloniality of gender (Maria Lugones),[59] coloniality of "being" (Maldonado Torres), coloniality of knowledge (Walter Mignolo) and Coloniality of power (Anibal Quijano). |

批判 世界システム論は、対立する学説から批判を受けている。特に経済に偏重し文化を軽視している点、そして中核地域中心主義・国家中心主義的である点が指摘さ れている。[4] ウィリアム・I・ロビンソンは、世界システム論が国民国家中心主義的であること、国家構造主義的アプローチを取っていること、そしてグローバリゼーション の台頭を概念化できない点を批判している。[54] ロビンソンは、世界システム理論が台頭する越境的社会勢力と、それらの勢力と利益を代表するグローバル機関との間に形成される関係を説明していないと指摘 する。[54] これらの勢力は国家システムではなくグローバルな次元で活動し、ウォーラスティンの国民中心アプローチでは理解できない。[54] ウォーラスティン自身によれば、世界システム論への批判は四つの方向から来ている。実証主義者、正統派マルクス主義者、国家自律論者、そして文化主義者で ある。[3] 実証主義者は、このアプローチが一般化に偏りすぎ、定量データに乏しく、反証可能な命題を提示していないと批判する。[3] 正統派マルクス主義者は、社会階級概念を十分に重視しないなど、世界システム論が正統派マルクス主義の原則から大きく逸脱していると見なす。[3] ただし「従属理論派は[階級社会の受益者であるブルジョアジーが]支配的国家の利益と私的利益が一致したため依存関係を維持した」と主張した点に留意すべ きである[55]。国家自律論者は国家と企業の境界を曖昧にしたと理論を批判する[3]。さらに実証主義者と国家自律論者は、分析の中心単位は国家である べきだと主張する。[3] 最後に、文化主義者は世界システム理論が経済を過度に重視し、文化を軽視していると主張する。[3] ウォーラスティン自身の言葉を借りれば: 要するに、世界システム分析に対する批判の大半は、同理論が自ら明言する視点そのものを非難している。世界システム分析は他の分析手法を欠陥がある、あるいは範囲が限定的だと見なし、それらを無思考に排除するよう求めるのだ。[3] 世界システム理論の根本的な概念的問題の一つは、その実体概念単位を定義する前提が社会システムである点だ。それらを定義する前提自体、相互の関係性、そ して一つが他へ移行する過程を検証する必要がある。世界システム理論の核心的主張は、16世紀に資本主義的世界経済が発展し、それが世界システムとして記 述可能だということだ。[56] 以下は世界システム論の基本的主張に関する理論的批判である:「今日の世界経済には、封建システムが存在しないのと同様に、社会主義システムは存在しな い。なぜなら世界システムは一つしかなく、それは世界経済であり、定義上資本主義的形式を有しているからだ。」[56] ロバート・ブレナーは、世界市場の優先化が地域の階級構造と階級闘争の軽視を意味すると指摘している: 「彼らは、これらの階級構造自体が、市場力学だけでは理解不能な結果をもたらす階級闘争の帰結として出現する過程を考慮に入れていない」[56]。別の批 判として、セダ・スコックポールによる還元主義への指摘がある。彼女は国家間システムが資本主義世界経済の単純な上部構造とは程遠いと考える:「軍事競争 の越境的構造としての国際国家システムは、資本主義によって創出されたものではない。近代世界史を通じて、それは世界資本主義の分析的に自律したレベルを 表しているが、それに還元されるものではない。」[56] 批判的であり、主に刷新として捉えられる概念が「コロニアル性」である(アニバル・キハノ、2000年、『ネパントラ』誌掲載「権力のコロニアル性、ヨー ロッパ中心主義、そしてラテンアメリカ」)。[57] ラテンアメリカの「現代性/コロニアリティ」[es] グループというシンクタンクから生まれたこの概念は、世界分業と中核/周辺システムという概念をコロニアリティのシステムに再利用している。しかし世界シ ステム論の「中心地本位」的起源と経済的発展のみに焦点を当てた点を批判しつつ、「植民性」は権力が依然として世界規模で植民地的な手法で作用する様相を さらに概念化することを可能にする(ラモン・グロスフォゲル『認識論的脱植民地化への転換』2007年):[58] 「『植民的状況』とは、植民地行政の有無にかかわらず、支配的な人種化/民族化された集団による、従属的な人種化/民族化された集団への文化的、政治的、 性的、精神的、認識論的、経済的抑圧/搾取を意味する」。コロニアル性はこれまでに、ジェンダーのコロニアル性(マリア・ルゴネス)、[59]「存在」の コロニアル性(マルドナド・トーレス)、知識のコロニアル性(ウォルター・ミニョーロ)、権力のコロニアル性(アニバル・キハノ)など、複数の領域を包含 している。 |

| Related journals Annales. Histoire, Sciences sociales Ecology and Society Journal of World-Systems Research |

関連雑誌 アナル。歴史、社会科学 生態学と社会 世界システム研究ジャーナル |

| Big History Dependency theory Structuralist economics Third Space Theory Third place Hybridity Post-colonial theory General systems theory Geography and cartography in medieval Islam Globalization International relations theory List of cycles Social cycle theory Sociocybernetics Systems philosophy Systems thinking Systemography War cycles Hierarchy theory |

ビッグ・ヒストリー 従属理論 構造主義経済学 第三空間理論 サードプレイス ハイブリッド性 ポストコロニアル理論 一般システム理論 中世イスラムの地理学と地図学 グローバリゼーション 国際関係論 循環のリスト 社会循環理論 社会サイバネティクス システム哲学 システム思考 システムグラフィ 戦争の循環 階層理論 |

| Further reading Works of Samir Amin; especially 'Empire of Chaos' (1991) and 'Le developpement inegal. Essai sur les formations sociales du capitalisme peripherique' (1973) Works of Giovanni Arrighi Volker Bornschier in libraries (WorldCat catalog) József Böröcz (2005), 'Redistributing Global Inequality: A Thought Experiment', Economic and Political Weekly Archived 2009-02-27 at the Wayback Machine, February 26:886-92. (1992) 'Dual Dependency and Property Vacuum: Social Change in the State Socialist Semiperiphery' Theory & Society, 21:74-104. Christopher K. Chase-Dunn in libraries (WorldCat catalog) Andre Gunder Frank in libraries (WorldCat catalog) Grinin, L., Korotayev, A. and Tausch A. (2016) Economic Cycles, Crises, and the Global Periphery. Springer International Publishing, Heidelberg, New York, Dordrecht, London, ISBN 978-3-319-17780-9. Kohler, Gernot; Emilio José Chaves, eds. (2003). Globalization: Critical Perspectives. Hauppauge, New York: Nova Science Publishers. ISBN 1-59033-346-2. With contributions by Samir Amin, Christopher Chase-Dunn, Andre Gunder Frank, Immanuel Wallerstein. Pre-publication download of Chapter 5: The European Union: global challenge or global governance? 14 world system hypotheses and two scenarios on the future of the Union, pages 93 - 196 Arno Tausch at http://edoc.vifapol.de/opus/volltexte/2012/3587/pdf/049.pdf. Gotts, Nicholas M. (2007). "Resilience, Panarchy, and World-Systems Analysis". Ecology and Society. 12 (1). doi:10.5751/ES-02017-120124. hdl:10535/3271. Korotayev A., Malkov A., Khaltourina D. Introduction to Social Macrodynamics: Compact Macromodels of the World System Growth. Moscow: URSS, 2006. ISBN 5-484-00414-4 . Lenin, Vladimir, 'Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism' Moore, Jason W. (2000). "Environmental Crises and the Metabolic Rift in World-Historical Perspective Archived 2017-03-09 at the Wayback Machine," Organization & Environment 13(2), 123–158. Raffer K. (1993), ‘Trade, transfers, and development: problems and prospects for the twenty-first century’ Aldershot, Hants, England; Brookfield, Vt., USA: E. Elgar Pub. Co. Raffer K. and Singer H.W. (1996), ‘The Foreign Aid Business. Economic Assistance and Development Cooperation’ Cheltenham and Borookfield: Edward Alger. Osvaldo Sunkel in libraries (WorldCat catalog) Tausch A. and Christian Ghymers (2006), 'From the "Washington" towards a "Vienna Consensus"? A quantitative analysis on globalization, development and global governance'. Hauppauge, New York: Nova Science. |

参考文献 サミール・アミンの著作。特に『混沌の帝国』(1991年)と『不均等な発展:周辺資本主義の社会形成に関する試論』(1973年) ジョヴァンニ・アリッギの著作 ヴォルカー・ボルンシアーの著作(WorldCatカタログ) ヨーゼフ・ボロチ (2005)「グローバルな不平等の再分配:思考実験」『経済と政治週刊』2月26日号886-92頁。 (1992)「二重依存と所有権の空白:国家社会主義的準周辺部における社会変革」『理論と社会』21号74-104頁。 クリストファー・K・チェイス=ダンを図書館で調べる(WorldCatカタログ) アンドレ・ギュンダー・フランクを図書館で調べる(WorldCatカタログ) グリニン, L., コロタエフ, A. と タウシュ, A. (2016) 『経済循環、危機、そしてグローバル周辺部』 スプリンガー・インターナショナル・パブリッシング, ハイデルベルク, ニューヨーク, ドルドレヒト, ロンドン, ISBN 978-3-319-17780-9. コーラー、ゲルノット;エミリオ・ホセ・チャベス編(2003)。『グローバリゼーション:批判的視点』。ニューヨーク州ホープポージ:ノヴァ・サイエン ス・パブリッシャーズ。ISBN 1-59033-346-2。サミル・アミン、クリストファー・チェイス=ダン、アンドレ・ギュンダー・フランク、イマニュエル・ウォーラスティンによる 寄稿を含む。第5章「欧州連合:グローバルな挑戦か、グローバルガバナンスか? 14の世界システム仮説と連合の未来に関する二つのシナリオ」93-196ページをhttp: //edoc.vifapol.de/opus/volltexte/2012/3587/pdf/049.pdfにてアーノ・タウシュが先行公開。 ゴッツ、ニコラス・M. (2007). 「レジリエンス、パナークシー、世界システム分析」. 『エコロジー・アンド・ソサエティ』. 12 (1). doi:10.5751/ES-02017-120124. hdl:10535/3271. コロターエフ A.、マルコフ A.、ハルトゥリーナ D. 『社会マクロダイナミクス入門:世界システム成長のコンパクト・マクロモデル』モスクワ:URSS、2006年。ISBN 5-484-00414-4。 レーニン, ウラジーミル, 『帝国主義、資本主義の最高段階』 ムーア, ジェイソン・W. (2000). 「環境危機と世界史的視点における代謝の断絶 Archived 2017-03-09 at the Wayback Machine」, 『組織と環境』13(2), 123–158. ラファー K. (1993), 『貿易、移転、開発:21世紀の問題と展望』 イングランド、ハンプシャー州アルダーショット; アメリカ、バーモント州ブルックフィールド: E. エルガー出版 ラファー K. と シンガー H.W. (1996), 『対外援助ビジネス。経済援助と開発協力」チェルトナムおよびブルックフィールド:エドワード・エルガー社。 オスバルド・スンケル所蔵図書館(WorldCat カタログ) タウシュ A. および クリスチャン・ガイマーズ (2006)、「『ワシントン・コンセンサス』から『ウィーン・コンセンサス』へ?グローバル化、開発、グローバル・ガバナンスに関する定量的分析」。ニューヨーク州ホープポージ:ノヴァ・サイエンス社。 |

| Fernand Braudel Center for the Study of Economies, Historical Systems and Civilizations closed as of June 2020 Review, A Journal of the Fernand Braudel Center Institute for Research on World-Systems (IROWS), University of California, Riverside World-Systems Archive Working Papers in the World Systems Archive World-Systems Archive Books World-Systems Electronic Seminars Preface to "ReOrient" by Andre Gunder Frank |

フェルナン・ブローデル経済・歴史システム・文明研究センターは2020年6月をもって閉鎖された レビュー、フェルナン・ブローデル研究センター誌 カリフォルニア大学リバーサイド校 世界システム研究所(IROWS) 世界システム・アーカイブ 世界システム・アーカイブ研究論文集 世界システム・アーカイブ書籍 世界システム電子セミナー アンドレ・ギュンダー・フランク著『ReOrient』序文 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/World-systems_theory |

「ウォーラスティンの世界システムの概念 について整理しておこう。世界システ ムとは、全地球的経済システムとして資本主義の起源と発展をとらえようとする見方で ある。世界システム論は以下の基本的命題に整理できる。

(1)現代の資本主義の発展の基 盤は国民国家にはなく、単一の分業体制にもとづく地 球全体におよぶ世界システムとよばれるものにある

(2)世界システムは、完全に孤立した自 給経済を除けば、人間の歴史の中で唯一存在 したシステムである。

(3)世界システムは、政治的にも経済的 にも支配的な「中核」と、中核に経済的に従 属する「辺境」からなり、その中間に中核と辺境の両方の経済的・政治的性格が混在す る「半辺境」があるという三つの構成要素を想定する

(4)中核は辺境より原料を供給されて工 業生産が可能になる。したがって辺境で産出 される原料供給は中核における価格設定に従属する。そこでは不均等交換が生じてい る。

(5)この世界経済システムは、15世紀 ヨーロッパの資本主義的農業、つまり「農業 資本主義」から発展が始まった。

ウォーラスティン理論の要諦は、世界の辺 境で見られる社会諸現象は中核で生起する 社会現象と深く連動し、それは地球規模で生起している経済現象とセットで考察する必 要があるということだ」。

★

| 世界システム論(せかいシステムろん、英語: world-systems

theory)は、アメリカの社会学者・歴史学者、イマニュエル・ウォーラステインが提唱した「巨視的歴史理論」[1]である。 各国を独立した単位として扱うのではなく、より広範な「世界」という視座から近代世界の歴史を考察する。 その理論の細部についての批判・反論はあるものの、世界を一体として把握する総合的な視座を打ち出した意義やその重要性については広く受け入れられてい る。 |

|

| 概要 世界システムとは、複数の文化体(帝国、都市国家、民族など)を含む広大な領域に展開する分業体制であり、周辺の経済的余剰を中心に移送する為の史的シス テムである。世界システムとは言うものの、必ずしも地球全域を覆う規模に達している必要はなく、一つの国・民族の枠組みを超えているという意味で「世界」 システムと呼ばれるのであり[2]、コロンブスによるアメリカ大陸の「発見」以前においても世界システムは存在した[3]とされる。中央(中核)・半周 辺・周辺(周縁)の三要素による分業であり、歴史上、政治的統合を伴う「世界帝国」か政治的統合を伴わない「世界経済」、どちらか二つの形態をとってきた [4]。 しかし過去において存在した世界システムと、16世紀に成立した「近代世界システム」が決定的に異なるのは、前者が世界経済から世界帝国へ移行したか、さ もなくば早期に消滅したのに対し[5]、後者は世界帝国となることなく政治的には分裂したまま存続している点である。ウォーラステインは近代世界システム のみが世界帝国となる事なく、そして衰退する事無く存在し続ける理由として世界的な資本主義の発展を挙げており、近代世界システムが多数の(言い換えれば 世界システムに比較し小規模の)政治システムにより成り立っていた為、経済的余剰を世界帝国特有の巨大官僚機構や広域防衛体制に蕩尽する[6]事無くシス テム全体の成長に寄与させる事ができ、また経済的要因の作用範囲が個々の政体の支配範囲を凌駕していた為、世界経済は政治的な掣肘を超えて発展する事が可 能となった、としている[7]。 上記のようにウォーラステインは近代世界システムの特徴に資本主義を挙げているが、彼の言う「資本主義」は一般に使用される場合とは若干定義が異なり、自 由意志に基づく労働契約を必ずしも必要とはしていない。彼によればシステムはただ一つの生産関係によって規定されるため、世界システムの中心諸国さえ「自 由な労働」に基づく資本主義的な生産様式に則っているのであれば、システム全体を資本主義的と称する事ができる。つまり資本主義的な中心諸国向けに生産さ れるのであれば、どんな生産形態を採っていようとも世界的な資本主義経済の一端に過ぎない、とウォーラステインは主張している[8]。 このように同じシステム内においても、中心・半周辺・周辺で役割と生産形態が異なるのが世界システムの国際的分業体制である[9]。ウォーラステインによ れば、近代世界システムにおいて世界経済のもたらす利潤分配は著しく中央に集中するが、統一的な政治機構が存在しないため、この経済的不均衡の是正が行わ れる可能性は極めて小さい。その為、近代世界システムは内部での地域間格差を拡大する傾向を持つ事になる[10]。単線的発展段階論によれば「後進」周辺 地域は「先進」西欧諸国と同じ道をたどり、やがて先進中央諸国に追い付く、少なくとも経済格差は縮まっていくはずであるが、この様な理由により、周辺は中 央に対する原料・食料などの一次産品供給地として単一産業化されており、開発前の「未開発」とも、開発途中の「発展途上」とも異なる「低開発」として固定 化されてしまっているのである。 |

|

| 重要概念 世界システム ひとつの分業体制に組み込まれた広大な領域のこと。国などのいかなる政治的単位をも超える規模を持つということから「世界」システムと呼ばれる。世界シス テムは世界経済と世界帝国に分類される。なお、ここで言う世界とは地球上すべてを覆う概念ではなく、より小さな地域的単位を含む。イスラム世界、地中海世 界、東アジア世界、新世界、旧世界といった概念を思い浮かべると分かりやすい。従って、時代によっては複数の世界システムが同時に地球上に存在することも あり得る。 世界経済 政治的統合を伴わない世界システムのこと。近代世界システム以外の世界経済は世界帝国へと変化するか、世界帝国への変化を待たず早期に消滅した。 世界帝国 政治的に統合された世界システムのこと。官僚制度や防衛・鎮圧のための軍事費によりやがて崩壊した。 近代世界システム いまだ世界帝国への変化も、消滅もしない特異な世界システム。とある世界システムが他の世界システムを包摂し成長することで成立した。16世紀以来拡大を 続け、現在、地球上に唯一存在する世界システムとされる。つまり、この世界の世界システム。 ヘゲモニー(覇権) 世界システム内において、ある中心国家が生産・流通・金融の全てにおいて他の中心国家を圧倒している場合、その国家は「ヘゲモニー国家(覇権国家)」と呼 ばれる。ウォーラステインによれば、ヘゲモニーはオランダ・イギリス・アメリカの順で推移したとされる。ただし、ヘゲモニーは常にどの国家が握っていると いうものではなく、上記三国の場合、オランダは17世紀中葉、イギリスは19世紀中葉、そしてアメリカは第二次世界大戦後からベトナム戦争までの時期にヘ ゲモニーを握っていたとされる。この内、イギリス・アメリカに関してはヘゲモニー国家であったことにほぼ異論はないが、しばしばオランダに関し、その優位 はヘゲモニーと呼べる程には至らなかったとも考えられている。 ヘゲモニーにおける優位は生産・流通・金融の順で確立され、失われる際も同じ順である[11]。実際、イギリスが「世界の工場」としての地位を失った後も シティはしばらく世界金融の中心として栄え、アメリカが巨額の貿易赤字をかかえるようになってもウォール街がいまだ世界経済の要として機能している [12]。 |

|

| 世界システム論からみたソ連 世界システム論者たちは、世界が資本主義の「世界」と社会主義の「世界」に分断されていると理解されてきた冷戦時代から、「世界経済の一体性」を強調して きた。ウォーラーステインは、ソヴィエト連邦が近代世界システムのなかでアメリカ合衆国と政治的には敵対することで、むしろ機能的には世界経済を安定化さ せていると論じている。 |

|

| 日本での受容 1981年に川北稔によって『近代世界システム』が翻訳される。川北自身が歴史学者であることに表れているように、いち早く世界システム論の可能性に気が ついたのは、一国史的な歴史認識に限界を感じ、交易を軸に産業革命などを世界史的な視野で研究を進めていた角山榮らを中心とした、歴史学者のグループで あった。 その後、ウォーラステインと世界システム論は研究者以外にも急速に知られるようになる。それは当時、アメリカ経済の冷え込みが見え始めた一方で、好調の日 本経済が留まることを知らないかのように思われ、「次のヘゲモニー国家は日本」という日本経済礼賛の文脈で用いられたためであった。しかしバブル崩壊とと もにこの種の言説は鳴りを潜めることとなった[13]。 |

|

| 批判 西洋中心主義 世界システム論の扱う範囲はあまりに広いため、個々の分野の専門家から詳細に関して多くの指摘がなされている。世界システム論に対して寄せられた批判の論 点には、西洋中心主義 (Eurocentric)、経済以外の要因が軽視されている事などがある。ウォーラステインの共同作業者でもあり批判者でもあるアンドレ・グンダー・フ ランクは著書『リオリエント』(1998) において、マルクスやブローデルなどと同様にウォーラステインは「世界経済」を近代西洋に限定しているが、近代以前あるいは以降においてすらも、世界経済 の基軸はアジアにあったとした。ウォーラステインはフランクが1800年以降の西欧諸国のヘゲモニーについて軽視しすぎていると応答した。 また、全四部作として計画されたにもかかわらず、いまだ第三部までしか出版されていない未完の理論であるという指摘もある。いずれにせよ、専門領域に特化 しがちな諸研究を統合する視座を提供しうる世界システム論の功績は否定できないとともに、相互批判の中で更なる理論的発展が期待されている。 |

|

| 唯物史観 従属理論 マルクス主義 世界の一体化 国際関係論 - 国際政治経済学 貿易史 クリストファー・チェイス=ダン |

|

| 参考文献 注:以下に挙げられていないウォーラステインの世界システム論関係の多数の著書・寄稿記事などは#著作と#外部リンクを参照のこと。 イマニュエル・ウォーラステイン 著、川北稔 訳『近代世界システム : 農業資本主義と「ヨーロッパ世界経済」の成立』岩波書店〈岩波現代選書, 63,64〉、1981年。ISBN 4000047329。 川北稔、山下範久、玉木俊明、平田雅博、脇村孝平ほか 著、川北稔 編『知の教科書 ウォーラーステイン』講談社〈講談社選書メチエ〉、2001年9月。ISBN 4-06-258222-8。 I.ウォーラステイン『近代世界システムI 農業資本主義と「ヨーロッパ世界経済」の成立』』川北稔訳、名古屋大学出版会、2013 I.ウォーラステイン『近代世界システムII 重商主義と「ヨーロッパ世界経済」の凝集 1600-1750』』川北稔訳、名古屋大学出版会、2013 I.ウォーラステイン『近代世界システムIII 「資本主義的世界経済」の再拡大 1730s-1840s』川北稔訳、名古屋大学出版会、2013 I.ウォーラステイン『近代世界システムIV 中道自由主義の勝利 1789-1914』川北稔訳、名古屋大学出版会、2013 I.ウォーラステイン『反システム運動』太田仁樹訳、大村書店、1992 I.ウォーラステイン『史的システムとしての資本主義』川北稔訳、岩波書店、1997(岩波文庫、2022) 田中明彦『現代政治学叢書19 世界システム』東京大学出版会、1989 |

|

| https://x.gd/cu3Wt |

★

● 従属論(dependency theory)

従属論とは「従来の帝国主義理論や一国単位での単線型発展モデ ルに対し、この理論は「先進国」の経済発展と「第三世界」の低開発をセットにして考えようとするものである。すなわち、第三世界の低開発は彼らを支配する 先進国に原因があり、第三世界の近代化(資本形成)は先進国の経済発展に従属する形において行なわれる(低開発の開発)、という主張である。この問題を解 決するには、前者の後者への従属を断ち切る必要があるというもの」

"Dependency theory is the notion that resources flow from a "periphery" of poor and underdeveloped states to a "core" of wealthy states, enriching the latter at the expense of the former. It is a central contention of dependency theory that poor states are impoverished and rich ones enriched by the way poor states are integrated into the "world system"./ The theory arose as a reaction to modernization theory, an earlier theory of development which held that all societies progress through similar stages of development, that today's underdeveloped areas are thus in a similar situation to that of today's developed areas at some time in the past, and that, therefore, the task of helping the underdeveloped areas out of poverty is to accelerate them along this supposed common path of development, by various means such as investment, technology transfers, and closer integration into the world market. Dependency theory rejected this view, arguing that underdeveloped countries are not merely primitive versions of developed countries, but have unique features and structures of their own; and, importantly, are in the situation of being the weaker members in a world market economy. / Dependency theory no longer has many proponents as an overall theory, though some writers have argued for its continuing relevance as a conceptual orientation to the global division of wealth"- Dependency theory.

従属理論(Dependency theory)とは、貧しく搾取された国家の「周縁」から、富裕な国家の「中心」へと資源が流れ、前者の犠牲のもとに後者が豊かになるという考え 方である。従属 理論の主な主張は、貧しい国家が「世界システム」に統合される方法によって、貧しい国家は貧しくなり、豊かな国家は豊かになるというものである。この理論 は、第二次世界大戦後の1960年代後半に、ラテンアメリカにおける開発の遅れの原因を追究する学者たちによって公式に発展したものである。 この理論は、近代化理論への反動として生まれた。近代化理論は、すべての社会は同様の発展段階を経て進歩するという、それ以前に提唱されていた発展理論で あり、今日の低開発地域は、過去のある時点で今日の先進地域と同じような状況にあった 、したがって、投資、技術移転、世界市場への統合など、さまざまな手段によって、この想定される共通の開発経路に沿って、低開発地域を貧困から救済する作 業を加速させることが必要である、というものであった。従属理論は、この見解を否定し、発展途上国は単に先進国の原始版ではなく、独自の特色と構造を有し ており、重要なのは、世界市場経済における弱者であるという立場であると主張した。[2] 一部の論者は、富のグローバルな分配に対する概念的な方向性として、その継続的な関連性を主張している。[3] 従属理論の論者は、一般的にリベラル改革派とネオ・マルクス主義者の2つのカテゴリーに分けられる。リベラル改革派は、通常、特定の政策介入を提唱する が、ネオ・マルクス主義者は計画経済を提案する。[4]

従属理論発展史

1957 Paul A. Baran, The Political Economy of Growth.

1967 Andre Gunder Frank, Capitalism and Underdevelopment in Latin America: Historical Studies of Chile and Brazil, Monthly Review Press.

1967 Theotônio dos Santos Júnior, El Nuevo Carácter de la Dependencia, Chile.

1969 Arghiri

Emmanuel, L’échange inégal: Essais sur les antagonismes dans les

rapports économiques internationaux. Paris: François Maspero.

1970 Samir Amin, L'accumulation

à l'échelle mondiale (translation: Accumulation on a world scale)

1972 Andre Gunder Frank, Lumpenbourgeoisie, Lumpendevelopment: Dependence, Class, and Politics in Latin America, Monthly Review Press.

1977 Ernesto Laclau, Politics and Ideology in Marxist Theory:

Capitalism, Fascism, Populism, Verso, 1977(従属論批判)

1978 Andre Gunder Frank, Dependent Accumulation and Underdevelopment, Macmillan

1998 Andre Gunder Frank, Reorient: Global Economy in the Asian Age, (University of California Press, 1998

リンク

文献

その他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

A stop sign ironically defaced with a plea not to deface stop signs

「停止看板を汚すな!」とスプレーで汚された停止看板Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆