マルクスにおける疎外概念

alienation of Marx

and/or Marxism

☆

カール・マルクスの疎外理論は、人間が労働や広い世界、人間性、そして自己から切り離され疎遠になる状態を説明する。この疎外は資本主義社会における分業

の結果であり、人間の人生が社会階級の機械的な一部として生きられることを意味する。[1]

疎外の理論的根拠は、労働者が以下の権利を奪われると、必ずや人生と運命を決定する能力を失うという点にある。すなわち、自らを自らの行動の主体と考える

権利、その行動の性質を決定する権利、他者との関係を定義する権利、そして自らの労働によって生産された財やサービスから価値ある物品を所有する権利であ

る。労働者は自律的で自己実現した人間であるにもかかわらず、経済的主体として、生産手段を所有するブルジョアジーによって定められた目標へと導かれ、産

業資本家間の競争過程において労働者から最大限の剰余価値を搾取するために、ブルジョアジーが指示する活動へと逸らされるのである。

この理論はマルクスの著作全体に見られるが、特に初期の著作『1844年の経済哲学草稿』や、後年の『資本論』の草稿『Grundrisse』において最

も詳細に論じられている。マルクスの理論はゲオルク・ヴィルヘルム・フリードリヒ・ヘーゲルと、ルートヴィヒ・フォイエルバッハの『キリスト教の本質』

(1841年)に大きく依拠している。[3]

マックス・シュティルナーは『自我とその所有』(1845年)において、フェーエルバッハの分析をさらに発展させ、「人類」という概念そのものが疎外的な

概念であると主張した。マルクスとフリードリヒ・エンゲルスは『ドイツ・イデオロギー』(1845年)において、これらの哲学的主張に反論した。

| Karl Marx's theory

of alienation describes the separation and estrangement of people from

their work, their wider world, their human nature, and their selves.

Alienation is a consequence of the division of labour in a capitalist

society, wherein a human being's life is lived as a mechanistic part of

a social class.[1] The theoretical basis of alienation is that a worker invariably loses the ability to determine life and destiny when deprived of the right to think of themselves as the director of their own actions; to determine the character of these actions; to define relationships with other people; and to own those items of value from goods and services, produced by their own labour. Although the worker is an autonomous, self-realised human being, as an economic entity this worker is directed to goals and diverted to activities that are dictated by the bourgeoisie—who own the means of production—in order to extract from the worker the maximum amount of surplus value in the course of business competition among industrialists. The theory, while found throughout Marx's writings, is explored most extensively in his early works, particularly the Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844, and in his later working notes for Capital, the Grundrisse.[2] Marx's theory draws heavily from Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, and from The Essence of Christianity (1841) by Ludwig Feuerbach.[3] Max Stirner extended Feuerbach's analysis in The Ego and its Own (1845), claiming that even the idea of 'humanity' is itself an alienating concept. Marx and Friedrich Engels responded to these philosophical propositions in The German Ideology (1845). |

カール・マルクスの疎外理論は、人間が労働や広い世界、人間性、そして

自己から切り離され疎遠になる状態を説明する。この疎外は資本主義社会における分業の結果であり、人間の人生が社会階級の機械的な一部として生きられるこ

とを意味する。[1] 疎外の理論的根拠は、労働者が以下の権利を奪われると、必ずや人生と運命を決定する能力を失うという点にある。すなわち、自らを自らの行動の主体と考える 権利、その行動の性質を決定する権利、他者との関係を定義する権利、そして自らの労働によって生産された財やサービスから価値ある物品を所有する権利であ る。労働者は自律的で自己実現した人間であるにもかかわらず、経済的主体として、生産手段を所有するブルジョアジーによって定められた目標へと導かれ、産 業資本家間の競争過程において労働者から最大限の剰余価値を搾取するために、ブルジョアジーが指示する活動へと逸らされるのである。 この理論はマルクスの著作全体に見られるが、特に初期の著作『1844年の経済哲学草稿』や、後年の『資本論』の草稿『Grundrisse』において最 も詳細に論じられている。マルクスの理論はゲオルク・ヴィルヘルム・フリードリヒ・ヘーゲルと、ルートヴィヒ・フォイエルバッハの『キリスト教の本質』 (1841年)に大きく依拠している。[3] マックス・シュティルナーは『自我とその所有』(1845年)において、フェーエルバッハの分析をさらに発展させ、「人類」という概念そのものが疎外的な 概念であると主張した。マルクスとフリードリヒ・エンゲルスは『ドイツ・イデオロギー』(1845年)において、これらの哲学的主張に反論した。 |

| Two forms of alienation In his writings from the early 1840s, Karl Marx uses the German words Entfremdung ("alienation" or "estrangement", derived from 'fremd', which means "alien") and Entäusserung ("externalisation" or "alienation", which alludes to the idea of relinquishment or surrender) to suggest an unharmonious or hostile separation between entities that naturally belong together.[4] The concept of alienation has two forms: "subjective" and "objective".[5] Alienation is "subjective" when human individuals feel "estranged" or do not feel at home in the modern social world.[6] By this account, alienation consists in an individual's experience of his or her life as meaningless, or his/herself as worthless.[7] "Objective" alienation, by contrast, makes no reference to the beliefs or feelings of human beings. Rather, human beings are objectively alienated when they are hindered from developing their essential human capacities.[8] For Marx, objective alienation is the cause of subjective alienation: individuals experience their lives as lacking meaning or fulfilment because modern society does not promote the deployment of their human capacities.[8] Marx derives this concept from Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, whom he credits with significant insight into the basic structure of the modern social world, and how it is disfigured by alienation.[9] Hegel's view is that, in the modern social world, objective alienation has already been vanquished, as the institutions of the rational or modern state enable individuals to fulfill themselves. Hegel believes that the family, civil society, and the political state facilitate people's actualisation, both as individuals and members of a community. Nonetheless, there still exists widespread subjective alienation, where people feel estranged from the modern social world, or do not recognise modern society as a home. Hegel's project is not to reform or change the institutions of the modern social world, but to change the way in which society is understood by its members.[10] Marx shares Hegel's belief that subjective alienation is widespread, but denies that the modern state enables individuals to actualise themselves. Marx instead takes widespread subjective alienation to indicate that objective alienation has not yet been overcome.[11] |

疎外の二形態 1840年代初頭の著作において、 カール・マルクスはドイツ語のEntfremdung(「疎外」または「疎遠」、『fremd』(異質な)に由来)とEntäusserung(「外部 化」または「疎外」、放棄や譲渡の概念を暗示)という語を用いて、本来一体であるべき存在間の不調和あるいは敵対的な分離を暗示している。[4] 疎外という概念には「主観的」と「客観的」の二形態がある。[5] 人間個人が現代社会において「疎外感」を抱く、あるいは居心地の悪さを感じる場合、それは「主観的」疎外である。[6] この見解によれば、疎外とは個人が自らの生活を無意味に感じたり、自分自身を無価値に感じたりする経験から成る。[7] 対照的に「客観的」疎外は、人間の信念や感情には言及しない。むしろ人間が本質的な能力を発展させることを妨げられる時、客観的に疎外されるのである。 [8] マルクスにとって、客観的疎外は主観的疎外の原因である。現代社会が人間能力の展開を促進しないため、個人は自らの生活に意味や充足が欠けていると経験するのだ。[8] マルクスはこの概念をゲオルク・ヴィルヘルム・フリードリヒ・ヘーゲルから導き出している。マルクスはヘーゲルが現代社会の基本構造と、疎外によってそれ が歪められる過程について重要な洞察を与えたと評価している。[9] ヘーゲルの見解では、合理的な近代国家の制度が個人の自己実現を可能にするため、現代社会においては客観的疎外は既に克服されている。ヘーゲルは、家族、 市民社会、政治国家が、個人として、また共同体の成員としての人々の自己実現を促進すると考える。しかしながら、人々が近代社会から疎外されたと感じた り、近代社会を居場所として認識できなかったりする主観的疎外が依然として広く存在している。ヘーゲルの企ては、近代社会世界の制度を改革したり変えたり することではなく、社会がその成員によって理解される方法を変えることにある。[10] マルクスは主体的疎外が広範に存在するというヘーゲルの見解を共有するが、近代国家が個人の自己実現を可能にするという主張は否定する。マルクスはむしろ、主体的疎外の広範な存在を、客観的疎外が未だ克服されていない証拠と見なす。[11] |

| Dimensions of alienated labour Marx stated that in a capitalist society, workers are alienated from their labour - they cannot decide on their own productive activities, nor can they use or own the value of what they produce.[12]: 155 In the "Notes on James Mill" (1844), Marx explained alienation thus: Let us suppose that we had carried out production as human beings . . . In my production I would have objectified my individuality, its specific character, and, therefore, enjoyed not only an individual manifestation of my life during the activity, but also, when looking at the object, I would have the individual pleasure of knowing my personality to be objective, visible to the senses, and, hence, a power beyond all doubt. ... Our products would be so many mirrors in which we saw reflected our essential nature.[12]: 86 In the first manuscript of the Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844, Marx identifies four interrelated dimensions of alienated labour: alienated labour alienates the worker, first, from the product of his labour; second, from his own activity; third, from what Marx, following Feuerbach, calls species-being; and fourth, from other human beings.[13] |

疎外された労働の次元 マルクスは資本主義社会において、労働者は自らの労働から疎外されていると述べた。つまり労働者は自らの生産活動を決定できず、生産物の価値を利用したり 所有したりすることもできないのである[12]: 155 。1844年の『ジェームズ・ミルに関する覚書』において、マルクスは疎外を次のように説明し ている: 仮に我々が人間として生産を行っていたとしよう……私の生産において、私は自らの個性、その特質を客観化していたはずだ。したがって活動中に人生の個人的 表現を享受するだけでなく、対象を見つめる際には、自らの人格が客観的であり、感覚的に認識可能であり、疑いの余地のない力であることを知る個別の喜びを 得ていたはずだ。…我々の生産物は、我々自身の本質が映し出される鏡となるだろう。[12]: 86 1844年の『経済学・哲学草稿』初稿において、マルクスは疎外された労働の四つの相互関連する次元を特定している。疎外された労働は、第一に労働者をそ の労働の産物から、第二に自身の活動から、第三にマルクスがフォイエルバッハに倣って「種的存在」と呼ぶものから、そして第四に他の人間から疎外するの だ。[13] |

| From a worker's product Marx begins with an account of man's alienation from the products of his labour. In work, a worker objectifies his labour in the object that he produces.[14] The objectification of a worker's labour is simultaneously its alienation. The worker loses control of the product to the owner of the means of production, the capitalist. The product's sale by the capitalist further reinforces the capitalist's power of wealth over the worker.[15] The worker thus relates to the product as an alien object, which dominates and enslaves him. The products of his labour constitute a separate world of objects, which is alien to him.[14] The worker creates an object, which appears to be his property. However, he now becomes its property. Where in earlier historical epochs, one person ruled over another, now the thing rules over the person, the product over the producer.[16] The design of the product and how it is produced are determined, not by the producers who make it (the workers), nor by the consumers of the product (the buyers), but by the capitalist class who besides accommodating the worker's manual labour also accommodate the intellectual labour of the engineer and the industrial designer who create the product in order to shape the taste of the consumer to buy the goods and services at a price that yields a maximal profit. Aside from the workers having no control over the design-and-production protocol, alienation (Entfremdung) broadly describes the conversion of labour (work as an activity), which is performed to generate a use value (the product), into a commodity, which—like products—can be assigned an exchange value. That is, the capitalist gains control of the manual and intellectual workers and the benefits of their labour, with a system of industrial production that converts this labour into concrete products (goods and services) that benefit the consumer. Moreover, the capitalist production system also reifies labour into the "concrete" concept of "work" (a job), for which the worker is paid wages— at the lowest-possible rate— that maintain a maximum rate of return on the capitalist's investment capital; this is an aspect of exploitation. Furthermore, with such a reified system of industrial production, the profit (exchange value) generated by the sale of the goods and services (products) that could be paid to the workers is instead paid to the capitalist classes: the functional capitalist, who manages the means of production; and the rentier capitalist, who owns the means of production. |

労働者の生産物から マルクスは、人間が自らの労働の生産物から疎外される過程の記述から始める。労働において、労働者は自らの労働を生産物という対象に客観化する。[14] 労働者の労働の客観化は、同時にその疎外でもある。労働者は生産手段の所有者である資本家に対して、生産物に対する支配権を失う。資本家による生産物の販 売は、労働者に対する資本家の富の支配力をさらに強化する。[15] こうして労働者は、自分を支配し隷属させる異質な対象として生産物と関わる。彼の労働の産物は、彼にとって異質な、独立した物体の世界を構成する。 [14] 労働者は物を作り出すが、それは一見彼の所有物に見える。しかし今や彼はその物の所有物となる。過去の歴史的時代では人格が人格を支配したが、今や物が人 格を支配し、製品が生産者を支配するのだ。[16] 製品の設計と生産方法は、それを製造する生産者(労働者)や製品の消費者(買い手)によって決定されるのではない。資本家階級によって決定されるのだ。資 本家階級は労働者の肉体労働を吸収するだけでなく、製品の創造に携わる技術者や工業デザイナーの知的労働も吸収する。彼らは消費者の嗜好を形成し、格律利 益を生む価格で商品やサービスを購入させるために製品を創造するのだ。労働者が設計・生産プロトコルを支配できないことに加え、疎外 (Entfremdung)とは、使用価値(製品)を生み出すために遂行される労働(活動としての労働)が、商品(製品と同様に交換価値を付与され得るも の)へと変換される過程を広く指す。つまり資本家は、産業生産システムを通じて労働を具体的な製品(商品やサービス)に変換し、消費者を利する形で、肉体 労働者と知的労働者、そして彼らの労働の成果を支配するのだ。さらに資本主義的生産システムは、労働を「仕事」という「具体的」概念へと物象化する。労働 者はこの仕事に対して賃金(可能な限り最低水準の賃金)を受け取るが、これは資本家の投資資本に対する最大利回りを維持するためのものであり、搾取の一形 態である。さらに、こうした物象化された工業生産システムでは、商品やサービス(製品)の販売によって生み出された利益(交換価値)は、本来なら労働者に 支払われるべきものだが、代わりに資本家階級に支払われる。つまり、生産手段を管理する機能的資本家と、生産手段を所有するレント資本家である。 |

From a worker's productive activity Strikers confronted by soldiers during the 1912 textile factory strike in Lawrence, Massachusetts, United States, called when owners reduced wages after a state law reduced the work week from 56 to 54 hours In the capitalist mode of production, the generation of products (goods and services) is accomplished with an endless sequence of discrete, repetitive motions that offer the worker little psychological satisfaction for "a job well done." By means of commodification, the labour power of the worker is reduced to wages (an exchange value); the psychological estrangement (Entfremdung) of the worker results from the unmediated relation between his productive labour and the wages paid to him for the labour. The worker is alienated from the means of production via two forms: wage compulsion and the imposed production content. The worker is bound to unwanted labour as a means of survival, labour is not "voluntary but coerced" (forced labour). The worker is only able to reject wage compulsion at the expense of their life and that of their family. The distribution of private property in the hands of wealth owners, combined with government enforced taxes compel workers to labour. In a capitalist world, our means of survival is based on monetary exchange, therefore we have no other choice than to sell our labour power and consequently be bound to the demands of the capitalist. The worker "[d]oes not feel content but unhappy, does not develop freely his physical and mental energy but mortifies his body and ruins his mind. The worker therefore only feels himself outside his work, and in his work feels outside himself;" "[l]abor is external to the worker,"[17]: 74 it is not a part of their essential being. During work, the worker is miserable, unhappy and drained of their energy, work "mortifies his body and ruins his mind." The production content, direction and form are imposed by the capitalist. The worker is being controlled and told what to do since they do not own the means of production they have no say in production, "labour is external to the worker, i.e. it does not belong to his essential being.[17]: 74 A person's mind should be free and conscious, instead it is controlled and directed by the capitalist, "the external character of labour for the worker appears in the fact that it is not his own but someone else's, that it does not belong to him, that in it he belongs, not to himself, but to another."[17]: 74 This means he cannot freely and spontaneously create according to his own directive as labour's form and direction belong to someone else. |

労働者の生産活動から 1912年、アメリカ・マサチューセッツ州ローレンスで起きた繊維工場ストライキ。州法により週労働時間が56時間から54時間に短縮された後、経営者が賃金を引き下げたことに抗議して発生した。兵士と対峙するストライキ参加者たち 資本主義的生産様式において、製品(商品とサービス)の生成は、断続的で反復的な動作の無限の連鎖によって達成される。この動作は労働者に「仕事を成し遂 げた」という心理的満足をほとんど与えない。商品化によって、労働者の労働力は賃金(交換価値)に還元される。労働者の心理的疎外 (Entfremdung)は、生産的労働とそれに対する賃金との間に媒介が存在しない関係から生じる。労働者は二つの形態を通じて生産手段から疎外され る:賃金強制と強制された生産内容である。労働者は生存手段として望まぬ労働に縛られ、労働は「自発的ではなく強制されたもの」(強制労働)となる。労働 者が賃金強制を拒否できるのは、自らの命と家族の命を犠牲にする場合のみである。富の所有者による私有財産の分配と、政府が強制する税金が相まって、労働 者を労働へと駆り立てる。資本主義世界では、生存手段は貨幣交換に依存しているため、労働力を売り渡す以外に選択肢がなく、結果として資本家の要求に縛ら れるのである。 労働者は「満足ではなく不幸を感じ、身体的・精神的エネルギーを自由に発展させるのではなく、肉体を損ない精神を破壊する。ゆえに労働者は仕事の外でしか 自己を感じられず、仕事の中では自己の外にいると感じる」のである。「労働は労働者にとって外部的なものである」[17]:74、それは労働者自身の本質 的な存在の一部ではない。労働中、労働者は惨めで不幸であり、エネルギーを消耗する。労働は「肉体を萎縮させ、精神を破壊する」。生産内容・方向・形態は 資本家によって強制される。労働者は支配され、何をすべきか指示される。生産手段を所有しないため、生産において発言権を持たない。「労働は労働者にとっ て外部のものであり、すなわち彼の本質的存在に属さない」。[17]: 74 人格の精神は自由で自覚的であるべきなのに、資本家に支配され指示される。「労働の外部性は、労働者にとってそれが自分自身の労働ではなく他人の労働であ ること、自分には属さず、その中で自分が自分自身ではなく他人に属しているという事実において現れる」。[17]: 74 これは、労働の形態と方向性が 他者に属するため、労働者が自らの意思で自由に創造することができないことを意味する。 |

| From a worker's Gattungswesen (species-being) The Gattungswesen ('species-being' or 'human nature'), of individuals is not discrete (separate and apart) from their activity as a worker and as such species-essence also comprises all of innate human potential as a person. Conceptually, in the term species-essence, the word species describes the intrinsic human mental essence that is characterised by a "plurality of interests" and "psychological dynamism," whereby every individual has the desire and the tendency to engage in the many activities that promote mutual human survival and psychological well-being, by means of emotional connections with other people, with society. [citation needed] The psychic value of a human consists in being able to conceive (think) of the ends of their actions as purposeful ideas, which are distinct from the actions required to realise a given idea. That is, humans are able to objectify their intentions by means of an idea of themselves as "the subject" and an idea of the thing that they produce, "the object." Conversely, unlike a human being, an animal does not objectify itself as "the subject" nor its products as ideas, "the object," because an animal engages in directly self-sustaining actions that have neither a future intention, nor a conscious intention. Whereas a person's Gattungswesen does not exist independently of specific, historically conditioned activities, the essential nature of a human being is actualised when an individual— within their given historical circumstance— is free to subordinate their will to the internal demands they have imposed upon themselves by their imagination and not the external demands imposed upon individuals by other people. |

労働者のガットゥングスヴェーゼン(種的存在)から 個人のガットゥングスヴェーゼン(種的存在あるいは人間性)は、労働者としての活動から切り離されたものではない。したがってこの種の本質は、人格としての生来の潜在能力の全てをも包含する。 概念的に、種の本質という用語において、「種」という言葉は、「複数の関心」と「心理的ダイナミズム」によって特徴づけられる人間固有の精神的本質を記述 する。これにより、あらゆる個人は、他の人々や社会との感情的なつながりを通じて、相互の人間の生存と心理的幸福を促進する多くの活動に従事したいという 欲求と傾向を持つ。[出典必要] 人間の精神的価値は、自らの行動の目的を「目的的な観念」として構想(思考)できる点にある。これは特定の観念を実現するための行動とは区別される。つま り人間は、自らを「主体」とする観念と、自らが生み出すものを「客体」とする観念によって、自らの意図を客観化できるのだ。逆に、動物は人間とは異なり、 自らを「主体」として客観化せず、その産物を「客体」としての観念ともしない。なぜなら動物は、未来の意図も意識的な意図も伴わない、直接的な自己維持行 動に従事するだけだからだ。一方、人格のガッテンゲスヴェーゼン(種としての本質)は、特定の歴史的に条件づけられた活動から独立して存在するわけではな い。しかし、人間の本質は、個人が与えられた歴史的状況の中で、他者から課せられた外的な要求ではなく、自らの想像力によって自らに課した内的な要求に 従って意志を従属させる自由を持つときに実現される。 |

| Relations of production Whatever the character of a person's consciousness (will and imagination), societal existence is conditioned by their relationships with the people and things that facilitate survival, which is fundamentally dependent upon cooperation with others, thus, a person's consciousness is determined inter-subjectively (collectively), not subjectively (individually), because humans are a social animal. In the course of history, to ensure individual survival societies have organised themselves into groups who have different, basic relationships to the means of production. One societal group (class) owned and controlled the means of production while another societal class worked the means of production and in the relations of production of that status quo the goal of the owner-class was to economically benefit as much as possible from the labour of the working class. In the course of economic development when a new type of economy displaced an old type of economy—agrarian feudalism superseded by mercantilism, in turn superseded by the Industrial Revolution—the rearranged economic order of the social classes favoured the social class who controlled the technologies (the means of production) that made possible the change in the relations of production. Likewise, there occurred a corresponding rearrangement of the human nature (Gattungswesen) and the system of values of the owner-class and of the working-class, which allowed each group of people to accept and to function in the rearranged status quo of production-relations. Despite the ideological promise of industrialisation—that the mechanisation of industrial production would raise the mass of the workers from a brutish life of subsistence existence to honourable work—the division of labour inherent to the capitalist mode of production thwarted the human nature (Gattungswesen) of the worker and so rendered each individual into a mechanistic part of an industrialised system of production, from being a person capable of defining their value through direct, purposeful activity. Moreover, the near-total mechanisation and automation of the industrial production system would allow the (newly) dominant bourgeois capitalist social class to exploit the working class to the degree that the value obtained from their labour would diminish the ability of the worker to materially survive. As a result of this exploitation, when the proletarian working-class become a sufficiently developed political force, they will effect a revolution and re-orient the relations of production to the means of production—from a capitalist mode of production to a communist mode of production. In the resultant communist society, the fundamental relation of the workers to the means of production would be equal and non-conflictual because there would be no artificial distinctions about the value of a worker's labour; the worker's humanity (Gattungswesen) thus respected, men and women would not become alienated. In the communist socio-economic organisation, the relations of production would operate the mode of production and employ each worker according to their abilities and benefit each worker according to their needs. Hence, each worker could direct their labour to productive work suitable to their own innate abilities, rather than be forced into a narrowly defined, minimum-wage "job" meant to extract maximal profit from individual labour as determined by and dictated under the capitalist mode of production. In the classless, collectively-managed communist society, the exchange of value between the objectified productive labour of one worker and the consumption benefit derived from that production will not be determined by or directed to the narrow interests of a bourgeois capitalist class, but instead will be directed to meet the needs of each producer and consumer. Although production will be differentiated by the degree of each worker's abilities, the purpose of the communist system of industrial production will be determined by the collective requirements of society, not by the profit-oriented demands of a capitalist social class who live at the expense of the greater society. Under the collective ownership of the means of production, the relation of each worker to the mode of production will be identical and will assume the character that corresponds to the universal interests of the communist society. The direct distribution of the fruits of the labour of each worker to fulfil the interests of the working class—and thus to an individual's own interest and benefit— will constitute an un-alienated state of labour conditions, which restores to the worker the fullest exercise and determination of their human nature. |

生産関係 人格の意識(意志と想像力)がどのような性質であれ、社会的存在は生存を可能にする人々や物との関係によって規定される。生存は基本的に他者との協力に依 存しているため、人格の意識は主観的(個人的)にではなく、相互主観的(集団的)に決定される。なぜなら人間は社会的動物だからだ。歴史の過程において、 個体の生存を確保するため、社会は生産手段に対する基本的な関係が異なる集団へと組織化されてきた。ある社会集団(階級)が生産手段を所有・支配し、別の 社会階級が生産手段を操作する。この現状の生産関係において、所有者階級の目標は労働者階級の労働から可能な限り経済的利益を得ることだった。経済発展の 過程で、新しい経済形態が古い経済形態に取って代わるたびに——農業封建制が重商主義に、重商主義が産業革命に取って代わられるように——再編成された社 会階級の経済秩序は、生産関係の変化を可能にした技術(生産手段)を支配する社会階級に有利に働いた。同様に、所有者階級と労働者階級の人間性(ガトゥン グスヴェーゼン)と価値体系にも対応する再編成が生じ、各集団が再編成された生産関係における現状を受け入れ、機能することを可能にした。 産業化のイデオロギー的約束——工業生産の機械化が労働者大衆を生存のための野蛮な生活から尊厳ある労働へと引き上げるという約束——にもかかわらず、資 本主義的生産様式に内在する分業は労働者の人間性(ガットゥングスヴェーゼン)を阻害し、各個人を直接的で目的を持った活動を通じて自らの価値を定義でき る人格から、工業化された生産システムの機械的な一部へと変質させた。さらに、工業生産システムのほぼ完全な機械化と自動化は、(新たに)支配的となった ブルジョア資本家階級が労働者階級を搾取することを可能にし、その労働から得られる価値が労働者の物質的生存能力を低下させるほどに搾取を可能にした。こ の搾取の結果、プロレタリア労働者階級が十分に発達した政治的勢力となった時、彼らは革命を起こし、生産関係と生産手段の関係を再構築する。つまり資本主 義的生産様式から共産主義的生産様式へと転換するのだ。こうして成立する共産主義社会では、労働者の生産手段に対する基本的関係は平等かつ非対立的とな る。労働者の労働価値に人為的な差別が存在しないため、労働者としての尊厳(ガットゥングスヴェーゼン)が尊重され、男女は疎外されない。 共産主義的社会経済組織において、生産関係は生産様式を運営し、各労働者を能力に応じて雇用し、各労働者を必要に応じて利益を与える。したがって、各労働 者は自らの生来の能力に適した生産的労働に労力を向けられる。資本主義的生産様式によって決定され、強制される、個人の労働から最大限の格律を搾取するた めの狭く定義された最低賃金の「仕事」に強制されることはない。階級なき集団管理の共産主義社会では、ある労働者の客観化された生産的労働と、その生産か ら得られる消費的利益との価値交換は、ブルジョア資本家階級の狭隘な利益によって決定されたり導かれたりすることはない。代わりに、各生産者と消費者の必 要を満たすために導かれるのだ。生産は各労働者の能力の程度によって差別化されるが、共産主義的産業生産システムの目的は、社会全体の犠牲の上に生きる資 本家階級による利益指向の要求ではなく、社会の集団的要請によって決定される。生産手段の集団所有のもとでは、各労働者と生産様式との関係は同一となり、 共産主義社会の普遍的利益に対応する性格を帯びる。各労働者の労働の成果を直接分配し、労働者階級の利益を満たすこと——それゆえ個人の利益と福祉を満た すこと——は、労働条件の疎外されていない状態を構成する。これは労働者に人間性の完全な行使と決定権を回復させる。 |

| From other workers Capitalism reduces the labour of the worker to a commercial commodity that can be traded in the competitive labour-market, rather than as a constructive socio-economic activity that is part of the collective common effort performed for personal survival and the betterment of society. In a capitalist economy, the businesses who own the means of production establish a competitive labour-market meant to extract from the worker as much labour (value) as possible in the form of capital. The capitalist economy's arrangement of the relations of production provokes social conflict by pitting worker against worker in a competition for "higher wages", thereby alienating them from their mutual economic interests; the effect is a false consciousness, which is a form of ideological control exercised by the capitalist bourgeoisie through its cultural hegemony. Furthermore, in the capitalist mode of production Marx believed the philosophic collusion of religion in justifying the relations of production facilitates the realisation and then worsens the alienation (Entfremdung) of the worker from their humanity; it is a socio-economic role independent of religion being "the opiate of the masses".[18] |

他の労働者から 資本主義は労働者の労働を、個人的な生存と社会の向上に向けた集団的共同努力の一部である建設的な社会経済活動としてではなく、競争的な労働市場で取引可 能な商業的商品へと還元する。資本主義経済において、生産手段を所有する企業は、労働者から資本という形で可能な限り多くの労働(価値)を搾取することを 目的とした競争的な労働市場を確立する。資本主義経済における生産関係の手配は、労働者同士を「より高い賃金」をめぐる競争に駆り立てることで社会的対立 を引き起こし、それによって労働者同士が相互の経済的利益から疎外される。この効果は偽りの意識であり、資本家ブルジョワジーが文化的ヘゲモニーを通じて 行使するイデオロギー的支配の一形態である。さらにマルクスは、資本主義的生産様式において、生産関係を正当化するための宗教の哲学的共謀が、労働者の人 間性からの疎外(Entfremdung)の実現を促進し、その後悪化させると考えた。これは宗教が「大衆の麻薬」であるという概念とは独立した社会経済 的役割である。[18] |

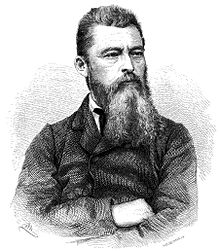

| Philosophical significance and influences The concept of alienation does not originate with Marx. Marx's two main influences in his use of the term are Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel and Ludwig Feuerbach.[19]  Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel Philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770–1831) postulated the idealism that Marx countered with dialectical materialism. For Hegel, alienation consists in an "unhappy consciousness". By this term, Hegel means a misunderstood form of Christianity, or a Christianity that hasn't been interpreted according to Hegel's own pantheism.[19] In The Phenomenology of Spirit (1807), Hegel described the stages in the development of the human Geist ('spirit'), by which men and women progress from ignorance to knowledge of the self and of the world. Developing Hegel's human-spirit proposition, Marx said that those poles of idealism— "spiritual ignorance" and "self-understanding"— are replaced with material categories, whereby "spiritual ignorance" becomes "alienation" and "self-understanding" becomes man's realisation of his Gattungswesen (species-essence). |

哲学的意義と影響 疎外という概念はマルクスが創始したものではない。マルクスがこの用語を用いる上で主に影響を受けたのは、ゲオルク・ヴィルヘルム・フリードリヒ・ヘーゲルとルートヴィヒ・フォイエルバッハである。[19]  ゲオルク・ヴィルヘルム・フリードリヒ・ヘーゲル 哲学者ゲオルク・ヴィルヘルム・フリードリヒ・ヘーゲル(1770–1831)は、マルクスが弁証法的唯物論で対抗した観念論を提唱した。 ヘーゲルにとって疎外とは「不幸な意識」である。この用語でヘーゲルが意味するのは、誤解されたキリスト教、あるいはヘーゲル自身の汎神論に従って解釈されていないキリスト教を指す。[19] 『精神現象学』(1807年)において、ヘーゲルは人間の「ガイスト」(精神)の発展段階を描き、男女が自己と世界に関する無知から知識へと進歩する過程 を論じた。ヘーゲルの人間精神論を発展させ、マルクスは、観念論の二極である「精神的無知」と「自己理解」が物質的カテゴリーに置き換わると述べた。すな わち「精神的無知」は「疎外」となり、「自己理解」は人間が自らのガッテンゲスヴェーゼン(種本質)を自覚することとなる。 |

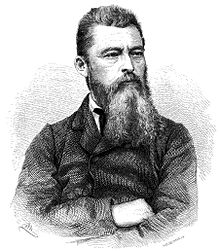

Ludwig Feuerbach Philosopher Ludwig Feuerbach (1804–1872) analysed religion from a psychological perspective in The Essence of Christianity (1841) and according to him divinity is humanity's projection of their human nature. The middle-period writings of Ludwig Feuerbach, where he critiques Christianity and philosophy, are pre-occupied with the problem of alienation.[20] In these works, Feuerbach argues that an inappropriate separation of individuals from their essential human nature is at the heart of Christianity.[21] Feuerbach believes the alienation of modern individuals consists in their holding false beliefs about God. God is not an objective being, but is instead a projection of man's own essential predicates.[21] Christian belief entails the sacrifice, the practical denial or repression, of essential human characteristics. Feuerbach characterises his own work as having a therapeutic goal – healing the painful separation at the heart of alienation.[22] |

ルートヴィヒ・フォイエルバッハ 哲学者ルートヴィヒ・フォイエルバッハ(1804–1872)は『キリスト教の本質』(1841年)において、宗教を心理学的観点から分析した。彼によれば、神性は人間が自らの本質を投影したものである。 ルードヴィヒ・フォイエルバッハの中期著作、すなわちキリスト教と哲学を批判した著作群は、疎外の問題に深く関わるものである[20]。これらの著作にお いてフォイエルバッハは、個人をその本質的な人間性から不適切に分離することがキリスト教の核心にあると論じる。[21] フォイエルバッハは、現代人の疎外は神に対する誤った信念に起因すると考える。神は客観的存在ではなく、人間自身の本質的属性から投影されたものに過ぎな い。[21] キリスト教信仰は、人間の本質的特徴を犠牲にし、実践的に否定または抑圧することを伴う。フォイエルバッハは自身の著作を治療的目標を持つものと位置づけ る——疎外の核心にある痛ましい分離を癒すことである。[22] |

| Entfremdung and the theory of history See also: Marx's theory of history and Dialectical materialism In Part I: "Feuerbach – Opposition of the Materialist and Idealist Outlook" of The German Ideology (1846), Karl Marx said the following: Things have now come to such a pass that the individuals must appropriate the existing totality of productive forces, not only to achieve self-activity, but also, merely, to safeguard their very existence.[23] That humans psychologically require the life activities that lead to their self-actualisation as persons remains a consideration of secondary historical relevance because the capitalist mode of production eventually will exploit and impoverish the proletariat until compelling them to social revolution for survival. Yet, social alienation remains a practical concern, especially among the contemporary philosophers of Marxist humanism. In The Marxist-Humanist Theory of State-Capitalism (1992), Raya Dunayevskaya discusses and describes the existence of the desire for self-activity and self-actualisation among wage-labour workers struggling to achieve the elementary goals of material life in a capitalist economy. |

疎外と歴史観 関連項目:マルクスの歴史観、弁証法的唯物論 『ドイツ・イデオロギー』(1846年)第一部「フォイエルバッハ-唯物論的見解と観念論的見解の対立」において、カール・マルクスは次のように述べている: 事態は今や、個人が自己活動を実現するためだけでなく、単に自らの生存を守るためにも、既存の生産力全体の掌握を余儀なくされる段階に至っている。[23] 人間が心理的に、自己実現につながる人格活動を必要とする点は、二次的な歴史的意義に留まる。なぜなら資本主義的生産様式は最終的にプロレタリアートを搾 取し貧困化させ、生存のための社会革命を迫るからだ。しかし社会的疎外は、特に現代のマルクス主義的人間主義哲学者にとって実践的な関心事であり続ける。 『国家資本主義のマルクス主義的人間主義理論』(1992年)において、ラヤ・ドゥナエフスカヤは、資本主義経済下で物質的生活の基本的目標達成に苦闘す る賃金労働者の中に、自己活動と自己実現への欲求が存在することを論じ、描写している。 |

| Entfremdung and social class In Chapter 4 of The Holy Family (1845), Marx said that capitalists and proletarians are equally alienated, but that each social class experiences alienation in a different form: The propertied class and the class of the proletariat present the same human self-estrangement. But the former class feels at ease and strengthened in this self-estrangement, it recognises estrangement as its own power, and has in it the semblance of a human existence. The class of the proletariat feels annihilated, this means that they cease to exist in estrangement; it sees in it its own powerlessness and in the reality of an inhuman existence. It is, to use an expression of Hegel, in its abasement, the indignation at that abasement, an indignation to which it is necessarily driven by the contradiction between its human nature and its condition of life, which is the outright, resolute and comprehensive negation of that nature. Within this antithesis, the private property-owner is therefore the conservative side, and the proletarian the destructive side. From the former arises the action of preserving the antithesis, from the latter the action of annihilating it.[24] |

疎外と社会階級 『聖家族』(1845年)第4章でマルクスは、資本家とプロレタリアートは等しく疎外されているが、それぞれの社会階級が異なる形で疎外を経験すると述べた: 所有階級とプロレタリアート階級は、同じ人間的自己疎外を呈している。しかし前者の階級はこの自己疎外の中で安堵と強化を感じ、疎外を自らの力として認識 し、そこに人間的存在の様相を見出す。プロレタリアート階級は疎外の中で消滅を感じ、これは彼らが疎外の中で存在しなくなることを意味する。彼らはそこに 自らの無力さと非人間的存在の現実を見るのだ。ヘーゲルの表現を用いれば、それは卑しめられつつある状態において、その卑しめられへの憤りであり、人間性 とその生活条件との矛盾によって必然的に駆り立てられる憤りである。その生活条件とは、人間性を断固として、徹底的に、包括的に否定するものである。この 対立関係において、私有財産所有者は保守的な側面であり、プロレタリアートは破壊的な側面である。前者からは対立を保存する行動が、後者からは対立を消滅 させる行動が生じるのである。[24] |

| Criticism In discussion of "aleatory materialism" (matérialisme aléatoire) or "materialism of the encounter," French philosopher Louis Althusser criticised a teleological (goal-oriented) interpretation of Marx's theory of alienation because it rendered the proletariat as the subject of history; an interpretation tainted with the absolute idealism of the "philosophy of the subject," which he criticised as the "bourgeois ideology of philosophy".[25] |

批判 「偶然的唯物論」(matérialisme aléatoire)あるいは「遭遇の唯物論」に関する議論において、 フランスの哲学者ルイ・アルチュセールは、マルクスの疎外理論に対する目的論的(目標指向的)解釈を批判した。その解釈はプロレタリアートを歴史の主体と して位置づけるものであり、「主体の哲学」という絶対的観念論に汚染された解釈であった。アルチュセールはこの解釈を「ブルジョア哲学のイデオロギー」と して批判した。[25] |

| Commodity fetishism – Concept in Marxist analysis Critique of political economy – Social critique Cultural evolution – Evolutionary theory of social change Theories of class consciousness and reification by György Lukács The Society of the Spectacle – 1967 book by Guy Debord Disenchantment – Cultural rationalization and devaluation of religion |

商品フェティシズム – マルクス主義分析における概念 政治経済批判 – 社会批判 文化進化論 – 社会変革の進化論的理論 ゲオルグ・ルカーチによる階級意識と物象化の理論 スペクタクル社会 – 1967年出版のギ・ドゥボール著書 脱魔術化 – 文化の合理化と宗教の価値低下 |

| Footnotes 1. "Karl Marx on alienated labour". 2009. 2. Ollman 1983, p. 271. 3. Schacht 1970, pp. 67–68. 4. Wood 2004, p. 3. 5. Leopold 2007, p. 68. 6. Leopold 2007, pp. 68–69. 7. Wood 2004, p. 8. 8. Leopold 2007, p. 69. 9. Leopold 2007, p. 74. 10. Leopold 2007, p. 76. 11. Leopold 2007, pp. 76–77. 12. Qian, Ying (2024). Revolutionary Becomings: Documentary Media in Twentieth-Century China. New York, NY: Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231204477. 13. Jaeggi 2014, p. 11. 14. Petrović 1967, p. 83. 15. Arthur 1986. 16. Leopold 2007, p. 230. 17. Marx, Karl. [1844] 1932. Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844. 18. Marx on Alienation 19. Wood 2004, p. 10. 20. Leopold 2007, pp. 205–206. 21. Leopold 2007, p. 206. 22. Leopold 2007, pp. 207–208. 23. Marx, Karl (1846). "Part I: Feuerbach. Opposition of the Materialist and Idealist Outlook". The German Ideology. 24. Chapter 4 of The Holy Family- see under Critical Comment No. 2 25. Bullock, Allan, and Stephen Trombley, eds. 1999. "Alienation." Pp. 22 in The New Fontana Dictionary of Modern Thought. |

脚注 1. 「カール・マルクスによる疎外された労働について」。2009年。 2. オルマン 1983年、271ページ。 3. シャクト 1970年、67–68ページ。 4. ウッド 2004年、3ページ。 5. レオポルド 2007, p. 68. 6. レオポルド 2007, pp. 68–69. 7. ウッド 2004, p. 8. 8. レオポルド 2007, p. 69. 9. レオポルド 2007, p. 74. 10. レオポルド 2007, p. 76. 11. レオポルド 2007, pp. 76–77. 12. 銭英 (2024). 『革命的生成:20世紀中国のドキュメンタリーメディア』. ニューヨーク: コロンビア大学出版局. ISBN 9780231204477. 13. ヤーギ 2014, p. 11. 14. ペトロヴィッチ 1967, p. 83. 15. アーサー 1986. 16. レオポルド 2007, p. 230. 17. マルクス, カール. [1844] 1932. 『1844年の経済哲学草稿』. 18. 疎外に関するマルクス 19. ウッド 2004, p. 10. 20. レオポルド 2007, pp. 205–206. 21. レオポルド 2007, p. 206. 22. レオポルド 2007, pp. 207–208. 23. マルクス, カール (1846). 「第一部:フォイエルバッハ。唯物論的見解と観念論的見解の対立」『ドイツ・イデオロギー』 24. 『聖家族』第4章 - 批判的注釈第2項参照 25. ブルロック、アラン、スティーブン・トロンブリー編 1999. 「疎外」『新フォンタナ現代思想辞典』22頁。 |

| References Althusser, Louis (2005) [1965]. For Marx. Translated by Brewster, Ben. London: Verso. ISBN 978-1-84467-052-9. Arthur, Christopher J. (1986). "Alienated Labour". Dialectics of Labour: Marx and his Relation to Hegel. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. Archived from the original on 7 December 2022. Retrieved 4 December 2024. Hook, Sidney (1962) [1950]. From Hegel To Marx: Studies in the Intellectual Development of Karl Marx. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press. Jaeggi, Rahel (2014). "Marx and Heidegger: Two Versions of Alienation Critique". In Neuhoser, Frederick (ed.). Alienation. Columbia University Press. pp. 11–21. ISBN 978-0-231-53759-9. Leopold, David (2007). The Young Karl Marx: German Philosophy, Modern Politics and Human Flourishing. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511490606. ISBN 978-0-511-28935-4. Marx, Karl (1992) [1844]. "Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts". Early Writings. Translated by Livingstone, Rodney; Benton, Gregory. London: Penguin Classics. pp. 279–400. ISBN 0-14-044574-9. Mészáros, Istvan (1970). Marx's Theory of Alienation. London: Merlin Press. ISBN 9780850361193. Ollman, Bertell (1983) [1971]. Alienation: Marx's Conception of Man in Capitalist Society (2nd ed.). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-09813-0. Petrović, Gajo (1967). Marx in the Mid-twentieth Century: A Yugoslav Philosopher Considers Karl Marx's Writings. Garden City, New York: Anchor Books. OCLC 1036708143. Retrieved 4 December 2024. Schacht, Richard (1970). Alienation. Garden City, New York: Doublkeday & Company, Inc. Wood, Allen W. (2004) [1985]. Karl Marx (2nd ed.). London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-203-34001-1. |

参考文献 アルチュセール、ルイ(2005年)[1965年]。『マルクスのために』。ベン・ブリュースター訳。ロンドン:ヴェルソ。ISBN 978-1-84467-052-9。 アーサー、クリストファー・J.(1986年)。「疎外された労働」『労働の弁証法:マルクスとヘーゲルとの関係』オックスフォード:バジル・ブラックウェル。2022年12月7日にオリジナルからアーカイブ。2024年12月4日に取得。 フック、シドニー(1962)[1950]。『ヘーゲルからマルクスへ:カール・マルクスの知的発展に関する研究』ミシガン州アナーバー:ミシガン大学出版局。 ヤーギ、ラーヘル (2014). 「マルクスとハイデガー:疎外批判の二つの形態」. ノイホーザー、フレデリック (編). 『疎外』. コロンビア大学出版局. pp. 11–21. ISBN 978-0-231-53759-9. レオポルド、デイヴィッド(2007)。『若きカール・マルクス:ドイツ哲学、近代政治、そして人間の繁栄』。イングランド、ケンブリッジ:ケンブリッジ 大学出版局。doi:10.1017/CBO9780511490606。ISBN 978-0-511-28935-4。 マルクス、カール(1992年)[1844年]。「経済学・哲学草稿」。『初期著作集』。ロドニー・リビングストン、グレゴリー・ベントン訳。ロンドン:ペンギン・クラシックス。279–400頁。ISBN 0-14-044574-9。 メサロシュ、イシュトヴァーン(1970年)。『マルクスの疎外理論』。ロンドン:マーリン・プレス。ISBN 9780850361193。 オルマン、バーテル(1983年)[1971年]。『疎外:資本主義社会におけるマルクスの人間観』(第2版)。イングランド、ケンブリッジ:ケンブリッジ大学出版局。ISBN 0-521-09813-0。 ペトロヴィッチ、ガヨ(1967)。『20世紀半ばのマルクス:ユーゴスラビアの哲学者がカール・マルクスの著作を考察する』。ニューヨーク州ガーデンシティ:アンカーブックス。OCLC 1036708143。2024年12月4日取得。 シャハト、リヒャルト(1970)。『疎外』。ニューヨーク州ガーデンシティ:ダブルデイ社。 ウッド、アレン・W.(2004)[1985]。『カール・マルクス』(第2版)。ロンドン:ラウトリッジ。ISBN 978-0-203-34001-1。 |

| Further reading Althusser, Louis. 1965. For Marx. Verso. Avineri, Shlomo. Hegel's Philosophy of Right and Hegel's Theory of the Modern State. Axelos, Kostas. Alienation and Techne in the Thought of Karl Marx. Blackledge, Paul. 2008. "Marxism and Ethics." International Socialism 120. Cohen, G. A. 1977. "Alienation and Fetishism." Ch. 5 in Karl Marx's Theory of History: A Defence. Dahms, Harry. 2006. "Does "Alienation" Have a Future? – Recapturing the Core of Critical Theory." In The Evolution of Alienation. Elster, Jon. 1985. Making Sense of Marx. Geras, Norman. Marx and Human Nature: Refutation of a Legend. — discusses alienation and the related concept of human nature. Gouldner, Alvin W. 1980. "Alienation: From Hegel to Marx." Pp. 177–98 in The Two Marxisms. New York: Oxford University Press. Langman, Lauren, and Devorah K. Fishman, eds. 2006. The Evolution of Alienation: Trauma, Promise, and the Millennium. Lanham. Mandel, Ernest. 1970. "The Causes of Alienation." International Socialist Review 31(3):19–23, 49–50. Mandel, Ernest, and George Novack. 1973. The Marxist Theory of Alienation (2nd ed.). Marcuse, Herbert. 1941. Reason and Revolution: Hegel and the Rise of Social Theory. Mészáros, István. 1970. Marx's Theory of Alienation. —— Lukács' The Young Hegel and Origins of the Concept of Alienation. Ollman, Bertell. 1976. Alienation: Marx's Conception of Man in Capitalist Society (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. Pappenheim, Fritz. 1964. "Alienation in American Society." Monthly Review 52(2). Plamenatz, John. 1975. Karl Marx's Philosophy of Man. Schacht, Richard. 1970. Alienation. Wolff, Jonathan. Why Read Marx Today? — an introduction to the concept and types of Entfremdung. Wood, Allen W. "Part I: Alienation of Karl Marx." In The Arguments of the Philosophers. "Alienation," Glossary of Terms. Encyclopaedia of Marxism. "Ludwig Feuerbach." Encyclopaedia of Marxism. |

追加文献(さらに読む) アルチュセール、ルイ。1965年。『マルクスのために』。ヴェルソ。 アヴィネリ、シュロモ。『ヘーゲルの『法の哲学』とヘーゲルの近代国家論』。 アクセロス、コスタス。『カール・マルクスの思想における疎外とテクネー』。 ブラックリッジ、ポール。2008年。「マルクス主義と倫理」。『インターナショナル・ソーシャルリズム』120号。 コーエン、G. A. 1977年。「疎外とフェティシズム」。カール・マルクスの歴史理論:擁護 第5章。 ダムス、ハリー。2006年。「疎外」には未来があるか?―批判理論の核心を再構築する。『疎外の進化』所収。 エルスター、ジョン。1985年。『マルクスを理解する』。 ゲラス、ノーマン。『マルクスと人間性:伝説の反駁』。疎外と、それに関連する人間性の概念について論じている。 グールドナー、アルビン・W。1980年。「疎外:ヘーゲルからマルクスへ」。『二つのマルクス主義』177-98ページ。ニューヨーク:オックスフォード大学出版局。 ラングマン、ローレン、デヴォラ・K・フィッシュマン編。2006年。『疎外感の進化:トラウマ、約束、そしてミレニアム』。ラナム。 マンデル、アーネスト。1970年。「疎外感の原因」。『国際社会主義レビュー』31(3):19-23、49-50。 マンデル、アーネスト、ジョージ・ノバック共著。1973年。『疎外に関するマルクス主義理論』(第2版)。 マルクーゼ、ヘルベルト。1941年。『理性と革命:ヘーゲルと社会理論の誕生』。 メザーロシュ、イシュトヴァーン。1970年。『マルクスの疎外理論』。 ——『ルカーチの「若いヘーゲル」と疎外概念の起源』。 オルマン、バーテル。1976年。『疎外:資本主義社会におけるマルクスの人間観』(第2版)。ケンブリッジ大学出版局。 パッペンハイム、フリッツ。1964年。「アメリカ社会における疎外」。『月刊レビュー』52(2)。 プラメナッツ、ジョン。1975年。『カール・マルクスの人間哲学』。 シャクト、リヒャルト。1970. 『疎外』. ウォルフ、ジョナサン. 『なぜ今日マルクスを読むのか?―エントフレムドゥングの概念と類型への序説』. ウッド、アレン・W. 「第一部:カール・マルクスの疎外」. 『哲学者たちの論争』所収. 「疎外」. 『用語集』. 『マルクス主義百科事典』. 「ルートヴィヒ・フォイエルバッハ」. 『マルクス主義百科事典』. |

| Warburton, Nigel. 19 January 2015. "Karl Marx on Alienation," narrated by Gillian Anderson. A History of Ideas. UK: BBC Radio 4. |

|

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marx%27s_theory_of_alienation |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099