アート・アーカイブという思想

On

thinking Art Archives

(AA) in Japan

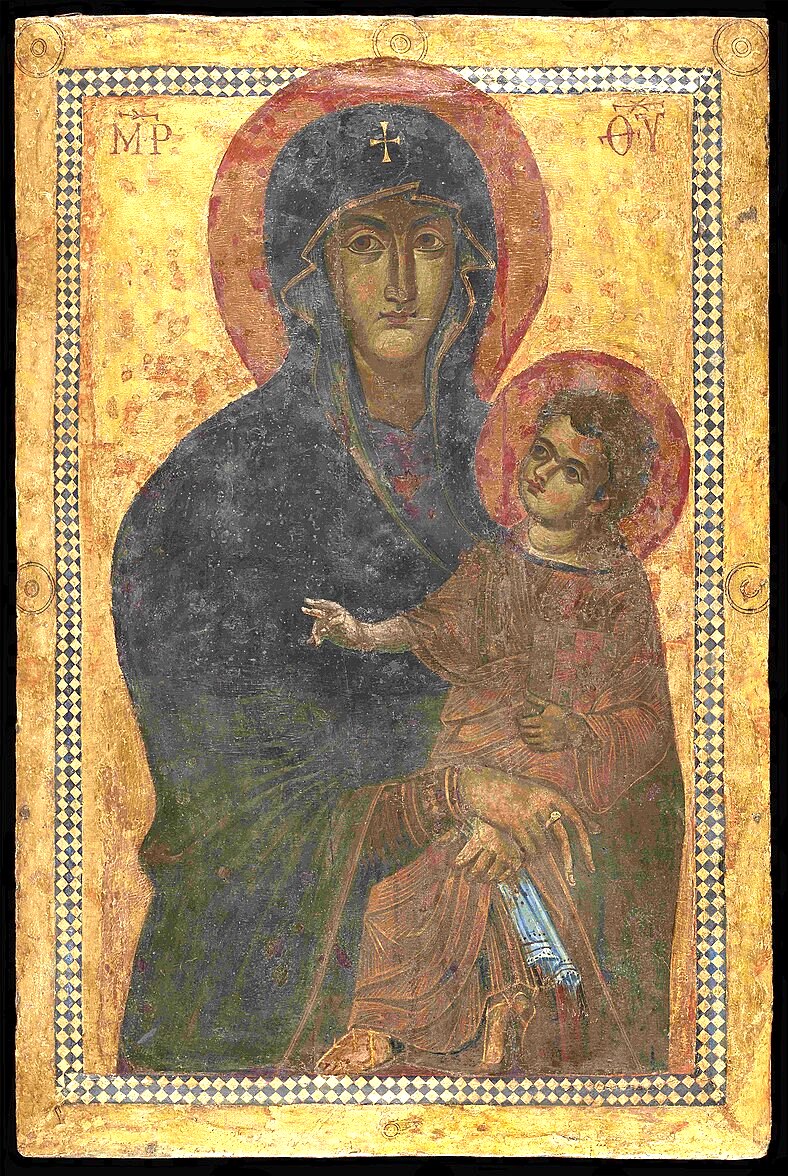

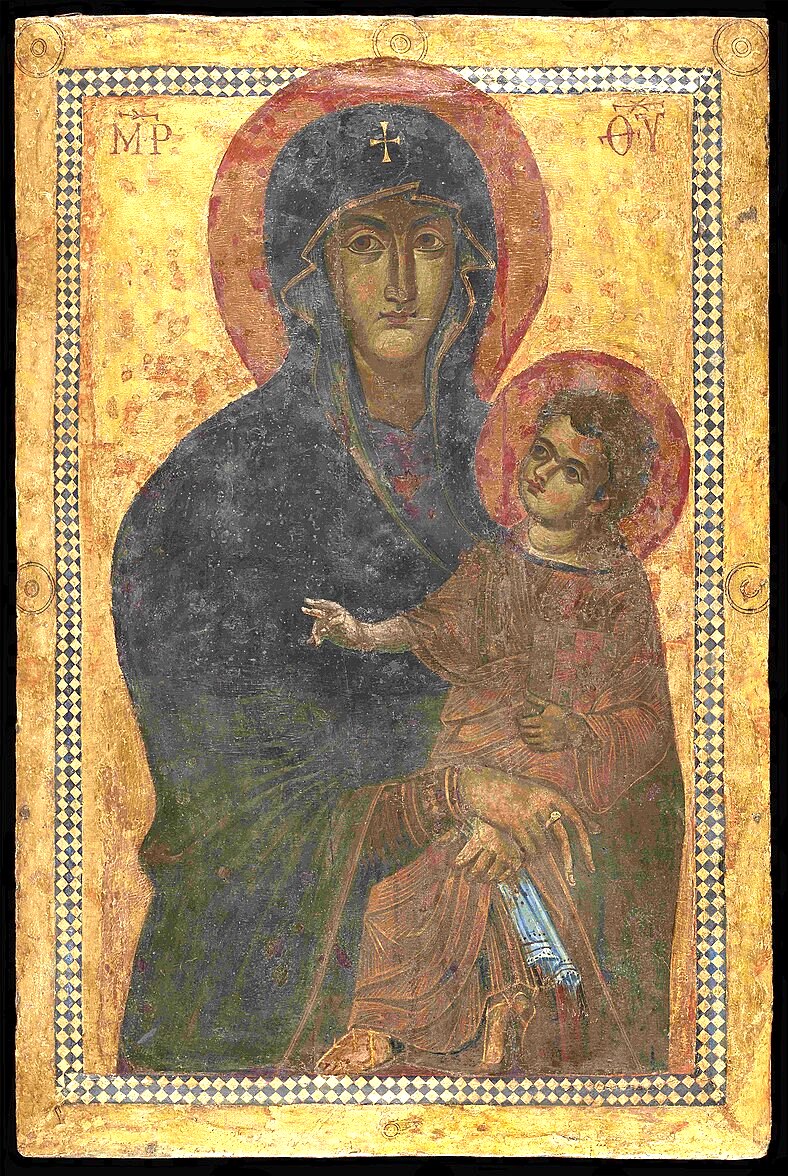

Icon Salus Populi Romani before restoration from 2018.

アート・アーカイブという思想

On

thinking Art Archives

(AA) in Japan

Icon Salus Populi Romani before restoration from 2018.

池田光穂

「記憶に対する強い関心は、現代美術、学術的な議論、そして世界中で見られる追悼、記念、慰 霊といった社会的慣習において、今もなお根強く残っている。アーカイブは、記憶の場であり、記憶の 触媒として、社会の記憶のあり方に中心的な役割を果たしている。過去数十年にわたり、アーカイブをソース、コンセプト、主題として扱うアーティストたちの 取り組みは、アーカイブの記憶の働きと伝達にスポットライトを当ててきた。」(Kathy Carbone, 2020)

「ウィキペディアは、知識の全体像に直接かつ自由にアクセスできるものです。アメリカでは

10年前から多くの生徒が、"すでに2日前に手に入れた情報にしか

アクセスできないのに、なぜ高いお金を払って勉強しなければならないのか?"と私に質問してきました。知識への即時アクセスです。また、仕事にも変化をも

たらしています。例を挙げましょう。例えば、あなたが病気になって医者に診てもらうとします。以前は、医師は有能で、あなたは何も知りませんでした。自分

の病気について何の情報も持っていなかったのです。今日、あなたは医者にかかる前に、ウィキペディアで自分の症状について情報を得ます。その結果、『プチ

プセ』の中でも言っていますが、資格の有無が推定され、無能であることが推定されるのです。医者と患者の関係、先生と生徒の関係などが変わってきているの

です。ウィキペディアは社会的関係、人間関係、教育的関係を大きく変えつつあるのです。」ミッシェル・セール

「文化記録の保管庫(アーカイブ)とは、海外領土に対する知的・芸術的投資がおこなわれた場であるということだ」(サイード 2025:19)

Kathy Carbone, Archival Art: Memory Practices, Interventions, and Productions, Curator: The Museum Journal. https://doi.org/10.1111/cura.12358

アート・アーカイブという用語は、日本語では、その言葉で検索すると各種の「アート・アーカ イブ」のプロジェクトが陸続とリンクされる。しかし、英語において、ウィキペディア(英語)では、Asia Art Archive (亚洲艺术文献库)ならびにArchives of American Art(スミソニアン)の2つのリンクが見つかるのみである。

そして、実際にヴァーチャルにそれぞれのアーカイブを「訪れて」みよう。まず、アジア・アー ト・アーカイブ(https://aaa.org.hk/en)である。それ ぞれのプロジェクトに誘う項目のビジュアルがとても野心的でかつ魅力的である。

●MICHEL SERRES, https://032c.com/magazine/michel-serresの

翻訳プロジェクト(→こちら)

そのような活動のなかで、文化人類学者としての私が一番関心のあるプロジェクトはアメリカ芸 術アーカイブにおける、オーラル・ヒストリー・プログラム(下記)である。アート作品は、ギャラリーに展示され、多くはコレクターや一般の人たちに買われ てゆく運命にあり、そのうち美術館や博物館に収蔵されるのは、歴史的な流れのなかに揉まれて、収蔵する価値が定着するまで、数年から数百年ぐらいの時間が かかるのが常である。

また、収集されるのは「巨匠」とよばれる作家や「大作(magnum opus, Masterpiece) が中心になる。このような、芸術の評価と市場価値が直結する時代における、アート・アーカイブというのは、美術館や博物館そのものであり、古く からキュレーションという領域で処理がおこなわれてきた。

しかし1970年や、それ以前から始まる前衛芸術やアクション芸術などが大衆に膾炙するにつ れて、社会は、アーティストの生きた活動や、社会史における位置付け、また、巨匠と呼ばれる作品における歴史的評価や、現在における「価値」の生成—— キース・ヘリング(Keith Haring, 1958-1990)やバンクシー(Banksy)のようにグラフィティから社会批判 から生まれれ、それが芸術性を獲得してゆくプロセス——に関心が生まれるようになり、ミッ シェル・フーコー流の「芸術作品の考古学」(=「知の考古学」の 捩り)が求められるようにまでなった。

そこでは、芸術家のオーラル・ヒストリーや社会経済史のなかに、それぞれの芸術家や芸術家集

団を位置付ける作業が進行中である。

| Asia Art Archive

(AAA) is a nonprofit organisation based in Hong Kong which focuses

on documenting the recent history of contemporary art in Asia within an

international context. AAA incorporates material that members of local

art communities find relevant to the field, and provides educational

and public programming. In 2016, AAA is one of the most comprehensive

publicly accessible collections of research materials in the field,[1]

and has initiated about 150 public, educational, and residential

programmes.[citation needed] AAA is a registered charity in Hong Kong and that is governed by a Board of Directors and guided by a rotating Advisory Board. The collection is accessible free of charge at AAA in Hong Kong’s Sheung Wan District at 233 Hollywood Road, and searchable via an online catalog. International locations are based in New York (Asia Art Archive in America) and New Delhi (Asia Art Archive in India).[2] |

アジア・アート・アーカイブ(AAA)は、香港を拠点とする非営利団体

で、国際的な文脈におけるアジアの現代美術の近現代史の記録に重点的に取り組んでいる。AAAは、地元のアートコミュニティのメンバーが関連性が高いと考

える資料を取り入れ、教育および公共プログラムを提供している。2016年現在、AAAは、この分野における最も包括的な一般公開の研究資料コレクション

の1つであり[1]、約150の公開、教育、および滞在型プログラムを開始している。 AAAは香港で登録された慈善団体であり、理事会によって運営され、持ち回り制の諮問委員会によって指導されている。コレクションは香港のションワン地区 にあるAAA(233 Hollywood Road)で無料で閲覧でき、オンラインカタログでも検索できる。 海外拠点はニューヨーク(アジア・アート・アーカイブ・イン・アメリカ)とニューデリー(アジア・アート・アーカイブ・イン・インディア)にある。[2] |

| History Asia Art Archive was founded in 2000 by Claire Hsu, Johnson Chang Tsong-zung and Ronald Arculli with a mandate to document and secure the multiple recent histories of contemporary art in the region.[3][4] Hsu became its first Executive Director. In 10 years, AAA has collected over 33,000 titles related to contemporary art. The Archive has organised more than 150 programmes and projects beyond its library and archival activities. These range from research-driven projects and discursive gatherings to residencies and youth and community projects. Speakers at public talks and symposia have included Ai Weiwei, Tobias Berger, David Elliott, Htein Lin, Huang Yongping, Yuko Hasegawa, Jun Nguyen-Hatsushiba, Xu Bing, and Mariko Mori.[5] In 2007, AAA launched a residency programme to encourage new readings of the physical material in the Archive, to offer individuals the chance to work with material outside their usual concentrations, and to support projects around the idea of the ‘archive’. International residents have included Raqs Media Collective and Young-hae Chang Heavy Industries; local residents have included art critic and curator Jasper Lau Kin Wah, and artists Cedric Maridet, Pak Sheung Chuen, and Wong Wai Yin. AAA has also initiated focused research projects that build areas of specialization in the collection. These include the recently completed four-year project ‘Materials of the Future: Documenting Contemporary Chinese Art 1980-1990’ which focused on performance art in the region, the digitisation of the personal archives of Geeta Kapur and Vivan Sundaram from Delhi, and the current digitisation of the archives of Ray Langenbach from Malaysia, Natasha Salon in Hanoi, and Blue Space in Ho Chi Minh City.[6] The chair of the board since 2003 is Jane DeBevoise.[7][8] |

歴史 アジア・アート・アーカイブ(Asia Art Archive)は、この地域の現代美術における複数の近現代史を記録し、保存することを目的として、2000年にクレア・スー、ジョンソン・チャン・ ツォンゾン、ロナルド・アルクーリによって設立された。[3][4] スーは初代エグゼクティブ・ディレクターに就任した。 10年間にわたり、AAAは現代美術に関する3万3千点以上のタイトルを収集した。アーカイブは、図書館やアーカイブ活動以外にも150以上のプログラム やプロジェクトを企画した。これらは、リサーチ主導のプロジェクトや討論会から、レジデンスや青少年・地域プロジェクトまで多岐にわたる。 公開講演やシンポジウムの講演者には、アイ・ウェイウェイ、トビアス・ベルガー、デイヴィッド・エリオット、テイン・リン、ホアン・ヨンピン、長谷川祐 子、ジュン・グエン=ハツシバ、シュ・ビン、そして森万里子がいる。 2007年には、アーカイブの物理的資料の新たな読み方を奨励し、個人が通常の専門分野以外の資料を扱う機会を提供し、「アーカイブ」という概念をめぐる プロジェクトを支援することを目的としたレジデンス・プログラムを開始した。これまでに、ラックス・メディア・コレクティブやヤンヘ・チャン・ヘビー・イ ンダストリーズなどの海外からのレジデント、美術評論家でキュレーターのジャスパー・ラウ・キンワ、アーティストのセドリック・マリデ、パク・シュン・ チュエン、ウォン・ワイ・インなどの地元出身のレジデントが滞在した。 AAAはまた、コレクションの専門分野を構築する集中的な研究プロジェクトも開始した。これには、最近完了した4年間のプロジェクト「Materials of the Future: Documenting Contemporary Chinese Art 1980-1990(未来の素材:1980年から1990年の中国現代美術の記録)」が含まれ、このプロジェクトでは、この地域のパフォーマンス・アート に焦点が当てられた。また、デリーのギータ・カプールとヴィヴァン・スンダラムの個人アーカイブのデジタル化、および現在マレーシアのレイ・ランゲンバッ ハ、ハノイのナターシャ・サロン、ホーチミン市のブルー・スペースのアーカイブのデジタル化も行われている。 2003年より理事長はジェーン・デボヴィースが務めている。[7][8] |

| Archive Acquisition The Archive's collection policy is designed to reflect the priorities of local and regional artists, art organizations, galleries, critics, and academics. In December 2017, there were more than 50,000 records available through the online library catalogue.[9] About 70% of AAA’s acquisitions are donations;[citation needed] some are unsolicited but many are gathered by AAA’s researchers, who are based in cities across Asia including Hong Kong, Beijing, Taipei, Seoul, Manila, Tokyo and New Delhi. AAA's Special Collections AAA’s Special Collections include primary source documents such as artists’ writings, sketches, and original visual documentation. As well as personal material donated by individuals, there are rare periodicals and publications. The archive keeps files of individuals, events, and organizations, and produces some of its own material, including images and audio-visual material. AAA’s Special Collections include original sketches and texts by artists, including Roberto Chabet (The Philippines), Ha Bik Chuen (China),[7] Lu Peng (China), Mao Xuhui (China), Wu Shanzhuan (China), and Zhang Xiaogang (China). The archive has an ongoing project in collaboration with ARTstor to digitize the collection, with plans to make the scans available online through the two organizations' websites.[10] |

アーカイブの収集 アーカイブの収集方針は、地元および地域のアーティスト、アート団体、ギャラリー、評論家、学術関係者の優先事項を反映するように策定されている。 2017年12月現在、オンライン図書館カタログを通じて50,000件以上の記録が利用可能となっている。[9] AAAの収集品の約70%は寄贈によるものであり、[要出典]一部は依頼なしで寄贈されたものもあるが、多くは香港、北京、台北、ソウル、マニラ、東京、 ニューデリーなどアジアの各都市に拠点を置くAAAの研究員によって収集されたものである。 AAAの特別コレクション AAAの特別コレクションには、アーティストの著作、スケッチ、オリジナルの視覚資料などの一次資料が含まれる。個人から寄贈された資料のほか、希少な定 期刊行物や出版物もある。このアーカイブは、個人、イベント、組織のファイルを保管し、画像やオーディオビジュアル資料を含む独自の資料も作成している。 AAAの特別コレクションには、ロベルト・チャベット(フィリピン)、ハ・ビク・チュエン(中国)、[7] ルー・ペン(中国)、マオ・シュエフイ(中国)、ウー・シャンチュアン(中国)、ジャン・シャオガン(中国)などのアーティストによるオリジナルスケッチ やテキストが含まれている。アーカイブは、ARTstorとの共同プロジェクトとしてコレクションのデジタル化を進めており、2つの組織のウェブサイトを 通じてスキャン画像をオンラインで公開する計画である。[10] |

| Selected projects https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Asia_Art_Archive#Selected_projects |

|

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Asia_Art_Archive |

https://www.deepl.com/ja/translator |

| The

Archives of American Art is the largest collection of primary

resources documenting the history of the visual arts in the United

States. More than 20 million items of original material[1] are housed

in the Archives' research centers in Washington, D.C. and New York City. As a research center within the Smithsonian Institution, the Archives houses materials related to a variety of American visual art and artists. All regions of the country and numerous eras and art movements are represented. Among the significant artists represented in its collection are Jackson Pollock, Lee Krasner, Marcel Breuer, Rockwell Kent, John Singer Sargent, Winslow Homer, John Trumbull, and Alexander Calder. In addition to the papers of artists, the Archives collects documentary material from art galleries, art dealers, and art collectors. It also houses a collection of over 2,000 art-related oral history interviews, and publishes a bi-yearly publication, the Archives of American Art Journal, which showcases collections within the Archives. |

アーカイブ・オブ・アメリカン・アートは、米国の視覚芸術の歴史を記録

した一次資料の最大のコレクションである。2000万点を超えるオリジナル資料[1]が、ワシントンD.C.とニューヨーク市のアーカイブの研究センター

に保管されている。 スミソニアン協会内の研究センターとして、アーカイブスはさまざまなアメリカの視覚芸術や芸術家に関する資料を収蔵している。 収蔵品には、全米のあらゆる地域、そして数多くの時代や芸術運動が含まれている。 収蔵品に含まれる著名な芸術家には、ジャクソン・ポロック、リー・クラズナー、マルセル・ブロイヤー、ロックウェル・ケント、ジョン・シンガー・サージェ ント、ウィンスロー・ホーマー、ジョン・トランブル、アレクサンダー・カルダーなどがいる。アーカイブでは、芸術家の資料に加え、美術館、美術商、美術収 集家からの資料も収集している。また、2,000件を超える美術関連のオーラル・ヒストリー・インタビューのコレクションも所蔵しており、アーカイブ内の コレクションを紹介する年2回発行の『Archives of American Art Journal』も発行している。 |

| History The Archives of American Art was founded in Detroit in 1954 by then Director of the Detroit Institute of Arts, Edgar Preston Richardson, and art collector Lawrence A. Fleischman. The first archivist was Arline Custer, the librarian of the Detroit Institute of Arts Research Library.[2] Concerned about the lack of material relating to American art, Richardson and Fleischman organized the Archives of American Art with the support of scholars and businessmen. Their intention was to collect materials related to American artists, art dealers, institutions and writers, and to allow scholars and writers to access the holdings.[3] In 1970 the Archives became part of the Smithsonian Institution, moving its processing center and storage facility from Detroit to the Old Patent Office Building in Washington, D.C.[4] Currently the collection and offices are located at the Victor Building, on 9th Street NW, only a few blocks away from the Old Patent Office Building.[5][page needed] Every year the Archives honors individual contributions to the American art community with the Archives of American Art Medal and art historians with the Lawrence A. Fleischman Award for Scholarly Excellence in the Field of American Art History. These awards are presented at the Archives' annual benefit and have been rewarded to Mark di Suvero, Chuck Close, John Wilmerding and others.[6] In 2011, the Archives of American Art became the first Smithsonian business unit to work directly with Wikipedia through the Wikipedia Galleries, Libraries, and Museums project, starting by appointing the first Smithsonian Wikipedian in Residence, Sarah Stierch.[7] |

歴史 アーカイブ・オブ・アメリカン・アートは、1954年にデトロイト美術館の当時の館長エドガー・プレストン・リチャードソンと美術収集家のローレンス・ A・フリッシュマンによってデトロイトで設立された。初代記録係は、デトロイト美術館研究図書館の司書であったアーライン・カスタ―であった。[2] リチャードソンとフリッシュマンは、アメリカ美術に関する資料の不足を懸念し、学者や実業家の支援を受けてアーカイブ・オブ・アメリカン・アートを設立し た。彼らの意図は、アメリカ人アーティスト、美術商、機関、作家に関する資料を収集し、学者や作家が所蔵品にアクセスできるようにすることだった。[3] 1970年、アーカイブはスミソニアン博物館の一部となり、処理センターと保管施設をデトロイトからワシントンD.C.の旧特許庁ビルに移転した。[4] 現在、コレクションとオフィスは、オールドパテントオフィスビルから数ブロックしか離れていない、ワシントンD.C.の9番街にあるビクタービルに置かれ ている。[5][要出典] 毎年、アーカイブスは、アメリカ美術界への貢献を称え、アーカイブス・オブ・アメリカン・アート・メダルを授与している。また、アメリカ美術史の分野にお ける学術的卓越性を称え、ローレンス・A・フリッシュマン賞を美術史家に授与している。これらの賞はアーカイブの年次募金活動で贈呈され、マーク・ディ・ スヴェーロ、チャック・クロース、ジョン・ウィルマーディングなどにも授与されている。 2011年には、アメリカ美術アーカイブはウィキペディア・ギャラリー、図書館、博物館プロジェクトを通じてウィキペディアと直接協力する最初のスミソニ アン事業部門となり、最初のスミソニアン・ウィキペディアン・イン・レジデンスであるサラ・スティアチを任命した。 |

| Collections Upon the founding of the Archives, all collections, whether loaned or donated to the Archives, were duplicated on microfilm, allowing the Archives to offer easy access to its collections nationwide and to establish archival databases in New York, Washington, D.C., Boston, Detroit, and at the DeYoung Museum in San Francisco.[8] Today's affiliates consist of the DeYoung, Boston Public Library, the Amon Carter Museum and The Huntington Library.[9] The Archives also offers microfilm for interlibrary loan at no charge.[8][10] Microfilm is no longer being produced at the Archives as it has been superseded by digitization. With funding from the Terra Foundation for American Art Digitization Program, the Archives has fully digitized numerous collections, which are accessible on their website.[11] In April, 2011, the Archives received a second Terra grant of $3 million to fund another five years of digitization and technological developments, which began in 2005 with a $3.6 million grant from Terra.[12] The Archives relies heavily on grants and private donations to fund the archival processing and care of collections. In 2009 the Archives received a $213,315 grant from the Leon Levy Foundation to process the André Emmerich Gallery records and a $100,000 gift from the Kress Foundation to complete the digitization of the Jacques Seligmann & Company records. In 2009 the Archives acquired 88 collections totaling 717 linear feet.[11] Notable collections The Archives holds a unique collection of material from notable artists, dealers, critics and collectors. While papers and documents make up a large portion of the Archives, more unique objects have been acquired over the years. These include a bird nest and a Kewpie doll from the collection of artist Joseph Cornell; painter George Luks' death mask; and a cast iron model car that belonged to Franz Kline.[13] The earliest letter in the collection was written by John Smibert in 1743, in which Smibert describes to his dealer his theories about the future of art in America.[14] |

コレクション アーカイブズの設立に際し、貸与または寄贈されたすべてのコレクションはマイクロフィルムに複製され、これにより、アーカイブズは全米でコレクションへの 容易なアクセスを提供し、ニューヨーク、ワシントンD.C.、ボストン、デトロイト、サンフランシスコのデ・ヤング美術館にアーカイブズのデータベースを 構築することが可能となった。 。現在の提携機関は、デ・ヤング美術館、ボストン公共図書館、アモン・カーター美術館、ハンティントン図書館である。[9] また、アーカイブスでは、図書館間相互貸借用のマイクロフィルムを無料で提供している。[8][10] マイクロフィルムは、デジタル化に取って代わられたため、アーカイブスでは現在では作成されていない。テラ財団のアメリカ美術デジタル化プログラムからの 資金提供により、アーカイブスは多数のコレクションを完全にデジタル化し、そのウェブサイト上でアクセス可能にした。[11] 2011年4月、アーカイブスは2005年にテラ財団から360万ドルの助成金を受けて開始したデジタル化と技術開発をさらに5年間継続するための2度目 の助成金として300万ドルを受け取った。 公文書館は、記録の処理やコレクションの保存に多額の助成金や民間からの寄付に頼っている。2009年には、レオン・レヴィ財団からアンドレ・エメリッ ヒ・ギャラリーの記録処理に213,315ドルの助成金を受け、またクレス財団からジャック・セリグマン・アンド・カンパニーの記録のデジタル化完了に 10万ドルの寄付を受けた。2009年には、総計717リニアフィート(1リニアフィートは約0.3048メートル)に及ぶ88のコレクションがアーカイ ブに加えられた。 注目すべきコレクション アーカイブには、著名な芸術家、ディーラー、評論家、コレクターによるユニークなコレクションが保管されている。書類や文書がアーカイブの大半を占めてい るが、さらにユニークな品々が長年にわたって収集されてきた。これには、芸術家ジョセフ・コーネルのコレクションから寄贈された鳥の巣やキューピー人形、 画家ジョージ・ラックスの死のマスク、フランツ・クラインの鋳鉄製モデルカーなどが含まれる。コレクションで最も古い手紙は、1743年にジョン・スミ バートが書いたもので、スミバートが自身の美術商に、アメリカの芸術の未来についての自身の理論を説明している。 |

| -The papers of African American

artists -The papers of Latino and Latin American artists Over 100 individuals and organizations are represented in the Archives' Latin American art collection. Topics range from Mexican muralism to Surrealism, New Deal art patronage and the Chicano Movement. Notable collections include the diary of Carlos Lopez, the sketchbooks of Emilio Sanchez, source material for Mel Ramos and research materials from Esther McCoy relating to Mexican architecture. They also maintain oral histories starting in 1964.[16] -The Boris Mirski Gallery -Leo Castelli Gallery -Rockwell Kent papers |

-アフリカ系アメリカ人アーティストの作品 -ラテン系およびラテンアメリカ人アーティストの作品 アーカイブのラテンアメリカ美術コレクションには、100人以上の個人および団体が含まれている。 メキシコ壁画運動からシュールレアリスム、ニューディール政策による芸術支援、チカーノ運動まで、さまざまなトピックが網羅されている。 注目すべきコレクションには、カルロス・ロペスの日記、エミリオ・サンチェスのスケッチブック、メル・ラモスの資料、メキシコ建築に関するエスター・マッ コイの研究資料などがある。また、1964年から始まったオーラル・ヒストリーも保管している。[16] -ボリス・ミルスキー・ギャラリー -レオ・キャステリ・ギャラリー -ロックウェル・ケント文書 |

| Oral histories In 1958, the Archives of American Art started an oral history program with base support from the Ford Foundation and continued with support from New York State Council on the Arts, Pew Charitable Trust, the Mark Rothko Foundation, and the Pasadena Art Alliance. Today the Archives houses nearly 2,000 oral history interviews relating to American art.[19] The program continues today with funding from the Terra Foundation of American Art, the Brown Foundation of Houston, the Widgeon Point Charitable Foundation, the Art Dealers Association of America.[20] Donor Nanette L. Laitman funded The Nanette L. Laitman Documentation Project for Craft and Decorative Arts in America enabling over 150 interviews with American craft artists.[21] In 2009, the Archives received two major grants to further their oral history program: a $75,000 grant from the A G Foundation which established the Elizabeth Murray Oral History of Women in the Visual Arts Project destined to fund oral history interviews with important women within the American art community),[11] and a $250,000 grant from Save America's Treasures to assist with the digitization of approximately 4,000 recordings and the preservation of 6,000 hours of sound.[19] |

オーラル・ヒストリー 1958年、フォード財団の支援により、アーカイブ・オブ・アメリカン・アートはオーラル・ヒストリー・プログラムを開始し、その後、ニューヨーク州芸術 協議会、ピュー・チャリタブル・トラスト、マーク・ロスコ財団、パサディナ・アート・アライアンスの支援を受け、活動を継続した。現在、アーカイブにはア メリカ美術に関する2,000件近いオーラル・ヒストリー・インタビューが収蔵されている。[19] このプログラムは現在も、テラ・アメリカ美術財団、ヒューストン・ブラウン財団、ウィジェット・ポイント慈善財団、アメリカ美術商協会からの資金援助によ り継続されている。アメリカ美術ディーラー協会などから資金援助を受けている。[20] 寄付者であるナンネット・L・レイトマンは、アメリカ工芸美術のナンネット・L・レイトマン・ドキュメンテーション・プロジェクトに資金を提供し、150 人以上のアメリカ工芸作家へのインタビューを可能にした。[21] 2009年には、オーラル・ヒストリー・プログラムのさらなる発展のために、アーカイブは2つの主要な助成金を受けた。A G Foundationから7万5千ドルの助成金を受け、アメリカ美術界で重要な女性たちとのオーラル・ヒストリー・インタビューの資金提供を目的とした 「エリザベス・マレーによる視覚芸術における女性たちのオーラル・ヒストリー・プロジェクト」を設立した 。また、アメリカ美術界の重要な女性たちとのオーラル・ヒストリー・インタビューの資金提供を目的とした「エリザベス・マレーによる視覚芸術界の女性たち のオーラル・ヒストリー・プロジェクト」を設立したA G 財団から7万5千ドルの助成金を受け取った。[11] さらに、約4,000件の録音のデジタル化と6,000時間分の音声の保存を支援するセーブ・アメリカズ・トレジャーズから25万ドルの助成金も受け取っ た。[19] |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Archives_of_American_Art |

|

| A masterpiece, magnum

opus

(Latin for 'great work'), or chef-d’œuvre (French: [ʃɛ.d‿œvʁ]; French

for 'master of work'; pl. chefs-d’œuvre) in modern use is a creation

that has been given much critical praise, especially one that is

considered the greatest work of a person's career or a work of

outstanding creativity, skill, profundity, or workmanship. Historically, a "masterpiece" was a work of a very high standard produced to obtain membership of a guild or academy in various areas of the visual arts and crafts. |

現代において「傑作」、「最高傑作」(ラテン語で「偉大な作品」)、ま

たは「最高傑作」(フランス語: [ʃɛ.d‿œvʁ]、「傑作」の意、複数形:

chefs-d’œuvre)と呼ばれるものは、特にその人のキャリアの中で最も偉大な作品、または創造性、技術、深み、または仕上がりが際立った作品と

して、多くの批評家から高い評価を得た作品である。 歴史的には、「傑作」とは、視覚芸術や工芸のさまざまな分野において、ギルドやアカデミーの会員資格を得るために制作された非常に高い水準の作品を指して いた。 |

| Etymology The form masterstik is recorded in English or Scots in a set of Aberdeen guild regulations dated to 1579, whereas "masterpiece" is first found in 1605, already outside a guild context, in a Ben Jonson play.[4] "Masterprize" was another early variant in English.[5] In English, the term rapidly became used in a variety of contexts for an exceptionally good piece of creative work, and was "in early use, often applied to man as the 'masterpiece' of God or Nature".[6] |

語源 masterstikは英語またはスコットランド語で1579年のアバディーンのギルド規則に記録されているが、「masterpiece」は1605 年、ギルドの文脈以外ではすでにベン・ジョンソンの劇で初めて見られる[4]。「masterprize」も英語の初期の変種であった[5]。 英語では、この言葉は様々な文脈で非常に優れた創作物のために急速に使われるようになり、「初期の使用では、しばしば神や自然の『傑作』として人間に適用 された」[6]。 |

| History Originally, the term masterpiece referred to a piece of work produced by an apprentice or journeyman aspiring to become a master craftsman in the old European guild system. His fitness to qualify for guild membership was judged partly by the masterpiece, and if he was successful, the piece was retained by the guild. Great care was therefore taken to produce a fine piece in whatever the craft was, whether confectionery, painting, goldsmithing, knifemaking, leatherworking, or many other trades. In London, in the 17th century, the Worshipful Company of Goldsmiths, for instance, required an apprentice to produce a masterpiece under their supervision at a "workhouse" in Goldsmiths' Hall. The workhouse had been set up as part of a tightening of standards after the company became concerned that the level of skill of goldsmithing was being diluted. The wardens of the company had complained in 1607 that the "true practise of the Art & Mystery of Goldsmithry is not only grown into great decays but also dispersed into many parts, so as now very few workmen are able to finish & perfect a piece of plate singularly with all the garnishings & parts thereof without the help of many & several hands...". The same goldsmithing organization still requires the production of a masterpiece but it is no longer produced under supervision.[7][8] In Nuremberg, Germany, between 1531 and 1572, apprentices who wished to become master goldsmith were required to produce columbine cups, dies for a steel seal, and gold rings set with precious stones before they could be admitted to the goldsmiths' guild. If they failed to be admitted, then they could continue to work for other goldsmiths but not as a master themselves. In some guilds, apprentices were not allowed to marry until they had obtained full membership.[9] In its original meaning, the term was generally restricted to tangible objects, but in some cases, where guilds covered the creators of intangible products, the same system was used. The best-known example today is Richard Wagner's opera Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg (1868), where much of the plot is concerned with the hero's composition and performance of a "masterpiece" song, to allow him to become a meistersinger in the (non-commercial) Nuremberg guild. This follows the surviving rulebook of the guild. The practice of producing a masterpiece has continued in some modern academies of art, where the general term for such works is now reception piece. The Royal Academy in London uses the term "diploma work" and it has acquired a fine collection of diploma works received as a condition of membership. |

歴史 元来、マスターピースとは、ヨーロッパの古いギルド制度において、職人を目指す見習いや職工が制作した作品を指す。ギルドの会員になるための資格は、この 作品によって判断され、成功すれば、その作品はギルドに残された。そのため、菓子、絵画、金細工、刃物、革細工など、どのような工芸品であっても、優れた 作品を作るために細心の注意が払われた。 例えば、17世紀のロンドンでは、金細工職人組合(Worshipful Company of Goldsmiths)が、金細工会館にある「ワークハウス」で、自分たちの監督のもとに傑作を生み出すことを弟子に要求していた。これは、金細工の技術 水準が低下していることに危機感を抱いた金細工会社が、基準を厳しくするために設置したものだった。金細工の芸術と神秘の真の実践は、大きく衰退している だけでなく、多くの部分に分散しており、今では多くの人の手を借りなければ、一枚の板をすべての装飾や部品とともに完成させることができる職人はほとんど いない...」と、1607年に会社の監視役から苦情が寄せられていました。同じ金細工の組織でも、傑作の制作が求められることは変わらないが、もはや監 督のもとで制作されることはない[7][8]。 ドイツのニュルンベルクでは、1531年から1572年にかけて、金細工師を目指す見習いは、金細工師のギルドに入る前に、コロンビアのカップ、鋼鉄印鑑 用の型、貴石をセットした金の指輪を製作することを要求されました。もし、入門できなければ、他の金細工職人の下で働くことはできても、自ら親方になるこ とはできない。ギルドによっては、徒弟は正式な会員になるまで結婚することが許されなかった[9]。 本来の意味では、一般に有形物に限定されていたが、ギルドが無形物の製作者を対象とする場合にも、同様の制度が用いられたことがある。今日最もよく知られ ている例は、リヒャルト・ワーグナーのオペラ『ニュルンベルクのマイスタージンガー』(1868)で、プロットの多くは、主人公が(非商業的な)ニュルン ベルクのギルドでマイスタージンガーになるために「名曲」を作曲し演奏することと関係している。これは、現存するギルドのルールブックに従ったものであ る。 傑作を生み出すという習慣は、現代の一部の美術アカデミーでも続いており、現在ではそのような作品の総称をレセプション・ピースと呼んでいる。ロンドンの ロイヤル・アカデミーでは「ディプロマ・ワーク」という言葉を使い、会員資格の条件として受け取ったディプロマ・ワークの素晴らしいコレクションを獲得し ている。 |

| Modern use In modern use, a masterpiece is a creation in any area of the arts that has been given much critical praise, especially one that is considered the greatest work of a person's career or to a work of outstanding creativity, skill, profundity, or workmanship. For example, the novel David Copperfield by Charles Dickens is generally considered a literary masterpiece.[10][11][12] The term is often used loosely, and some critics, such as Edward Douglas of The Tracking Board, feel it is overused in describing recent films.[13] |

現代的な用法 現代的な用法では、傑作とは芸術のあらゆる分野で多くの批評的賞賛を受けた創造物、特に個人の経歴の中で最も偉大な作品とみなされるもの、または卓越した 創造性、技術、深遠さ、または技量を持つ作品に与えられるものである。例えば、チャールズ・ディケンズの小説『デイヴィッド・カッパーフィールド』は一般 に文学的傑作とされている[10][11][12]。この言葉はしばしば緩く使われ、トラッキングボードのエドワード・ダグラスなど一部の評論家は最近の 映画を説明する際に使いすぎだと感じている[13]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Masterpiece |

https://www.deepl.com/ja/translator |

| About the Archives of American

Art Founded at the Detroit Institute of Arts in 1954, the Archives of American Art collects, preserves, and makes available primary sources documenting the history of the visual arts in the United States. History The Archives of American Art is the world’s preeminent and most widely used research center dedicated to collecting, preserving, and providing access to primary sources that document the history of the visual arts in America. Founded in Detroit in 1954 by Edgar P. Richardson, then Director of the Detroit Institute of Arts, and Lawrence A. Fleischman, a Detroit executive and active young collector, the initial goal of the Archives was to serve as microfilm repository; this mission expanded quickly to collecting and preserving original material and in 1970, the Archives joined the Smithsonian Institution, sharing its mandate: the increase and diffusion of knowledge. Resources Our resources serve as reference for countless dissertations, exhibitions, catalogs, articles, and books on American art and artists, and preserve the untold stories that—without a central repository such as the Archives—might have otherwise been lost. Our vast holdings are a vital resource to anyone interested in American culture over the past 200 years and consist of more than 20 million letters, diaries, scrapbooks, manuscripts, financial records, photographs, films, and audiovisual recordings of artists, dealers, collectors, critics, scholars, museums, galleries, associations, and other art world figures. The Archives also houses the largest collection of oral histories anywhere on the subject of art. Founded on the belief that the public needs free and open access to the most valuable research materials, our collections are available to all who wish to consult original papers at our research centers or use our reference services remotely every year, and to millions who visit us online to consult digitized collections. Future Growth The Archives is still growing! Each year, our collecting specialists travel the country seeking the papers of artists, dealers, and collectors, and once new collections are acquired, professional archivists preserve the materials and create easy-to-use guides. Through collecting, preserving, and providing access to our collections, the Archives inspires new ways of interpreting the visual arts in America and allows current and future generations to piece together the nation’s rich artistic and cultural heritage. Please consider a donation and help us ensure that significant records and untold stories documenting the history of American art are collected, preserved, and shared with the world. |

アメリカ美術アーカイブについて 1954年にデトロイト美術館で設立されたアメリカ美術アーカイブは、米国の視覚芸術の歴史を記録した一次資料の収集、保存、公開を行っている。 沿革 アメリカ美術アーカイブは、米国の視覚芸術の歴史を記録した一次資料の収集、保存、公開を行う世界屈指の研究センターであり、最も広く利用されている。 1954年にデトロイト美術館の館長であったエドガー・P・リチャードソン氏と、デトロイトの重役であり、熱心な若きコレクターでもあったローレンス・ A・フリッシュマン氏によってデトロイトで設立されたアーカイブの当初の目的は、マイクロフィルムの保管場所となることだった。この使命は、オリジナル資 料の収集と保存へと急速に拡大し、1970年にはスミソニアン協会に加盟し、知識の増大と普及という使命を共有することとなった。 リソース 当アーカイブのリソースは、アメリカ美術や芸術家に関する数えきれないほどの論文、展覧会、カタログ、記事、書籍の参考資料として利用されており、また、 アーカイブのような中央保管所がなければ失われていたかもしれない、語られることのなかった物語を保存している。 過去200年間のアメリカ文化に関心を持つ人々にとって、当アーカイブの膨大なコレクションは欠かせない貴重な資料であり、アーティスト、ディーラー、コ レクター、評論家、学者、美術館、ギャラリー、協会、その他のアート界の著名人による2000万通を超える手紙、日記、スクラップブック、原稿、財務記 録、写真、フィルム、視聴覚記録で構成されている。また、当アーカイブは、芸術に関するオーラル・ヒストリー(口述歴史)の最大のコレクションも所蔵して いる。 一般の人々が最も価値のある研究資料に自由にアクセスできる必要があるという信念に基づき、当アーカイブのコレクションは、毎年、研究センターで原本の書 類を閲覧したい方や遠隔地から参照サービスを利用したい方、またオンラインでデジタル化されたコレクションを閲覧する数百万人の方々に公開されている。 今後の成長 アーカイブは今も成長を続けています。毎年、収集の専門家が全国を巡り、アーティスト、ディーラー、コレクターの資料を収集しています。新しいコレクショ ンが入手されると、プロのアーキビストが資料を保存し、使いやすいガイドを作成します。 収集、保存、コレクションへのアクセス提供を通じて、アーカイブはアメリカ視覚芸術の新たな解釈を喚起し、現在および将来の世代がこの国の豊かな芸術的・ 文化的遺産を再構成することを可能にします。 アメリカ美術の歴史を記録する貴重な記録や語り継がれるべき物語を収集、保存し、世界と共有していくために、ぜひ寄付をご検討ください。 |

| https://www.aaa.si.edu/about |

https://www.deepl.com/ja/translator |

「Met“y”averse~メチャバース、それは あなたの世界~」(東京藝術大学藝大アートプラザ、2022年11月12月)における「みょうじなまえ」(TW @vent_invent)さんのプロジェクト——問題提起 として重要。

●日本におけるアート・アーカイブの「貧困」

アート・アーカイブという用語は、日本語では、その 言葉で検索すると各種の「アート・アーカ イブ」のプロジェクトが陸続とリンクされるが、それはメディア・アーカイブの一種で、かつ、単なる他の美術館や博物館への催し(イベント)へのリンクを貼 るだけの恥ずかしいものである。なぜなら、日本の美術館や博物館には、過去の展示をウェブでアーカイブ化して、それを未来に繋げていこうという発想が希薄 だからである。したがって、自ら「アート・アーカ イブ」と称してリンクを貼る「業者」はリンク仲介のフリーライダーにしかすぎず、リンクの消失にまったく無責任だからである。そのような日本の現今の 「アート・アーカ イブ」のプロジェクトに未来はない。

また、「メディア・アーカイブに接近しつつあること

は危険である」という危惧は、リアルとヴァーチャルの単純な二分法なので限界があると私は思う。ヴァーチャルなものをどのようにしてリアルな経験に接続さ

せようとするのが「良質」のアートアーカイブの発想なのではないでしょうか。

●Hans Ulrich Obristのこと

| Hans Ulrich

Obrist

(born 1968) is a Swiss art curator, critic, and historian of art. He is

artistic director at the Serpentine Galleries, London. Obrist is the

author of The Interview Project, an extensive ongoing project of

interviews. He is also co-editor of the Cahiers d'Art review. |

ハンス・ウルリッヒ・オブリスト(1968年生まれ)は、スイスのアー

ト・キュレーター、評論家、美術史家。ロンドンのサーペンタイン・ギャラリーズのアーティスティック・ディレクターを務める。現在進行中の大規模なインタ

ビュー・プロジェクト「The Interview Project」の著者。また、レビュー誌「カイエ・ダール」の共同編集者でもある。 |

| Obrist was born in Weinfelden,

Switzerland on May 24, 1968.[1] At the age 23, he organized an

exhibition of contemporary art in his kitchen.[2] Some of his early

projects Obrist curated for the art initiative museum in progress for

example the legendary exhibition museum in progress with Alighiero

Boetti on board of Austrian Airlines in 1993,[3] Interventions in the

daily newspaper Der Standard 1995 with artists like Christian Marclay,

Matt Mullican and Lawrence Weiner, and Travelling Eye in the magazine

Profil 1995/1996 with John Baldessari, Nan Goldin, Felix

Gonzalez-Torres and Gerhard Richter amongst others.[4] Obrist is also a jury member of the art project Safety Curtain, which museum in progress has been realizing at the Vienna State Opera with famous artists like Tauba Auerbach, David Hockney, Joan Jonas, Jeff Koons, Maria Lassnig, Rosemarie Trockel, Cy Twombly and Carrie Mae Weems since 1998.[5] In 1993, Obrist founded the Museum Robert Walser and began to run the Migrateurs program at the Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris where he served as a curator for contemporary art. In 1996, he co-curated Manifesta 1, the first edition of the roving European biennial of contemporary art. In the November 2009 issue of ArtReview, Obrist was ranked number one in the publication's annual list of the art world's one-hundred most powerful people and that same year he was made an Honorary Fellow of the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA).[6] Obrist first gained art world attention in 1991, when as a student in Politics and Economics in St. Gallen, Switzerland, he mounted an exhibition in the kitchen of his apartment entitled The Kitchen Show[7] It featured work by Christian Boltanski and Peter Fischli & David Weiss.[8] Obrist is an advocate and archivist for artists, and has said: "I really do think artists are the most important people on the planet, and if what I do is a utility and helps them, then that makes me happy. I want to be helpful."[7] Obrist is known for his lively pace and emphasis on inclusion in all cultural activities. While maintaining official curatorial positions, he is also the co-founder of the Brutally Early Club,[9] a discussion group open to all that meets at Starbucks in London, Berlin, New York and Paris at 6:30 a.m., and is a contributing editor of 032c magazine, Artforum and Paradis Magazine, among others. Obrist has lectured internationally at academic and art institutions including European Graduate School in Saas-Fee,[10] University of East Anglia,[11] Southbank Centre,[12] Institute of Historical Research,[13] and Architectural Association.[14] He lives and works in London. |

1968年5月24日、スイスのヴァインフェルデンに生まれる[1]。

[例えば、1993年にオーストリア航空の機内で行われたアリギエロ・ボエッティとの伝説的な展覧会「museum in

progress」[3]、1995年にクリスチャン・マークレー、マット・マリカン、ローレンス・ワイナーなどのアーティストと日刊紙『Der

Standard』で行った「Interventions」や1995/1996年の雑誌『Profile』でジョン・バルデサリ、ナン・ゴールディン、

フェリックス・ゴンザレス・トレス、ゲルハルト・リヒターらとの「Travelling Eye」などの初期のプロジェクトで企画を担当した [4]. また、1998年からウィーン国立オペラ座でタウバ・アウエルバッハ、デヴィッド・ホックニー、ジョーン・ジョナス、ジェフ・クーンズ、マリア・ラスニ グ、ロズマリー・トロッケル、サイ・トゥオンブリー、キャリー・メイ・ウィームスといった有名アーティストと実現したアートプロジェクト「セーフティ・ カーテン」の審査員も務めている[5]。 1993年、ロベール・ヴァルザー美術館を設立し、パリ市立近代美術館の「Migrateurs」プログラムを運営し始め、現代美術のキュレーターを務め る。1996年には、ヨーロッパを巡回する現代美術のビエンナーレ、マニフェスタ1の第1回を共同キュレーションした。2009年11月、 ArtReview誌の「アート界で最もパワフルな100人」の第1位に選ばれ、同年、王立英国建築家協会(RIBA)の名誉フェローに任命された [6]。 [1991年、スイスのザンクトガレンで政治・経済学を学んでいたオブリストが、自宅アパートのキッチンで「The Kitchen Show」展を開催し[7]、クリスチャン・ボルタンスキー、ピーター・フィッシュリ&ダヴィッド・ヴァイスの作品を展示。「アーティストが地球上で最も 重要な人々であり、私のすることが彼らの役に立つのであれば、それは私にとって幸せなことです。私は役に立ちたいのです」[7]。オブリストは、その活発 なペースと、あらゆる文化活動への関与を強調することで知られている。 キュレーターとしての公式な立場を維持する一方で、ロンドン、ベルリン、ニューヨーク、パリのスターバックスで朝6時半に開かれる誰でも参加できる討論会 「Brutally Early Club」[9]の共同設立者であり、032c誌、Artforum、Paradis Magazineなどの寄稿編集者でもある。サースフェーのヨーロッパ大学院[10]、イースト・アングリア大学[11]、サウスバンク・センター [12]、歴史研究所[13]、建築協会などの学術・芸術機関で国際的に講義を行っている[14] ロンドンに在住し制作活動を行っている。 |

| The Interview project Obrist's interest in interviews was first triggered by two very long conversations that he read when he was a student. One was between Pierre Cabanne and Marcel Duchamp, and the other between David Sylvester and Francis Bacon. "These books somehow brought me to art," he has said. "They were like oxygen, and were the first time that the idea of an interview with an artist as a medium became of interest to me. They also sparked my interest in the idea of sustained conversations—of interviews recorded over a period of time, perhaps over the course of many years; the Bacon/Sylvester interviews took place over three long sessions, for example."[15] So far, nearly 2000 hours of interviews have been recorded.[16] This fascinating archive is referred to by Obrist as "an endless conversation". He began publishing these interviews in Artforum in 1996 and in 2003 eleven of these interviews were released as Interviews Volume 1. Volume 2 was published in Summer 2010. With the release, a total of 69 artists, architects, writers, film-makers, scientists, philosophers, musicians and performers share their unique experiences and frank insights. The longer interviews in Obrist's archive are being published singly in ongoing series of books entitled "The Conversation Series". Thus far, 28 books have been published, each containing a lengthy interview with cultural figures including John Baldessari, Zaha Hadid, Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster, Yoko Ono, Robert Crumb and Rem Koolhaas. A number of Obrist's interviews have also appeared in the Berlin culture magazine 032c, including those with artists Elaine Sturtevant and Richard Hamilton, historian Eric Hobsbawm, and structural engineer Cecil Balmond of Arup.[17] |

インタビュー・プロジェクト オブリストのインタビューへの興味は、学生時代に読んだ2つの非常に長い会話に端を発している。ひとつはピエール・カバンヌとマルセル・デュシャン、もう ひとつはデヴィッド・シルヴェスターとフランシス・ベーコンの対談です。「これらの本が、どういうわけか私をアートに導いてくれたのです。「アーティスト へのインタビューというメディアを初めて意識したのは、酸素のようなものでした。また、持続的な対話という考え方に興味を持つようになりました。例えば、 ベーコンとシルヴェスターのインタビューは、3回にわたる長いセッションで録音されました」[15]。 この魅力的なアーカイブをオブリストは「終わりなき会話」と呼んでいる[16]。彼はこれらのインタビューを1996年にArtforumに掲載し始め、 2003年に11本のインタビューがInterviews Volume 1としてリリースされた。2010年夏には第2巻が刊行された。このリリースにより、合計69人のアーティスト、建築家、作家、映画制作者、科学者、哲学 者、ミュージシャン、パフォーマーが、それぞれのユニークな体験や率直な洞察を語っています。 オブリストのアーカイブにある長いインタビューは、「The Conversation Series」と名付けられた継続的な書籍のシリーズとして単行本化されている。これまでに28冊が出版され、ジョン・バルデッ サリ、ザハ・ハディッド、ドミニク・ゴンザレス=フェルスター、オノ・ヨーコ、ロバート・クラム、レム・コールハースといった文化人へのロングインタ ビューが収録されています。また、ベルリンのカルチャー誌『032c』には、アーティストのエレイン・スターテヴァントやリチャード・ハミルトン、歴史家 のエリック・ホブスバウム、Arupの構造エンジニアのセシル・バルモンドなど、オブリストのインタビューが多数掲載されている[17]。 |

| Curatorial activities Obrist's practice includes an ongoing exploration of the history of art institutions and curatorial practice. In his early 20s he began to research the topic. "At a certain moment, when I started doing my own shows, I felt it would be really interesting to know what is the history of my profession. I realized that there was no book, which was kind of a shock."[16] He has since helped to rectify this gap with exhibitions on curating and a book entitled A Brief History of Curating. This volume, which is part of Obrist's Interviews project (see above) compiles interviews from some of the leading curators of the 20th century. While the history of exhibitions has started, in this last decade, to be examined more in depth, what remains largely unexplored are the ties that interconnected manifestations have created among curators, institutions, and artists. For this reason, Obrist's conversations go beyond stressing the remarkable achievements of a few individuals...Obrist's collected volume pieces together "a patchwork of fragments," underlining a network of relationships within the art.[18] In keeping with his desire to explore the world of art and view it as an open system, Obrist has long advocated a participatory model for his activities. One early project, 1997's "do it", is an ongoing exhibition [19] that consists of instructions set out by artists for anyone to follow. In his introduction to the project, Obrist notes that "do it stems from an open exhibition model, and exhibition in progress. Individual instructions can open empty spaces for occupation and invoke possibilities for the interpretations and rephrasing of artworks in a totally free manner. do it effects interpretations based on location, and calls for a dovetailing of local structures with the artworks themselves. The diverse cities in which do it takes place actively construct the artwork context and endow it with their individual marks or distinctions."[19](sic) Obrist curated "Utopia Station", a section of the Venice Biennale, in 2003, and is briefly interviewed about the project in Sarah Thornton's Seven Days in the Art World.[20] In 2007, Obrist co-curated Il Tempo del Postino with Philippe Parreno for the Manchester International Festival, also presented at Art Basel, 2009, organised by Fondation Beyeler and Theater Basel. In the same year, the Van Alen Institute awarded him the New York Prize Senior Fellowship for 2007–2008. In 2008 he curated Everstill at the Lorca House in Granada. More recently, Obrist initiated a series of "marathons", a series of public events he conceived in Stuttgart in 2005. The first in the Serpentine series, the Interview Marathon in 2006, involved interviews with leading figures in contemporary culture over 24 hours, conducted by Obrist and architect Rem Koolhaas. This was followed by the Experiment Marathon, conceived by Obrist and artist Olafur Eliasson in 2007, which included 50 experiments by speakers across both arts and science, including Peter Cook, Neil Turok, Kim Gordon, Simone Forti, Fia Backstrom and Joseph Grigely. There was also the Manifesto Marathon in 2008 and the Poetry Marathon in 2009, which consisted of poems read aloud by artists and writers including Gilbert & George, Tracey Emin, Nick Laird, Geoffrey Hill, and James Fenton.[21] The 2014 Extinction Marathon: Visions of the Future[22] linked the humanities and the sciences to discussions of environmental and human impact on the world today. It was programmed with artist Gustav Metzger whose research addresses issues of extinction and climate change. Notable participants included artists Etel Adnan, Ed Atkins, Jesse Darling, Gilbert & George, Katja Novitskova, Yoko Ono, Susan Hiller, Marguerite Humeau, Trevor Paglen, Cornelia Parker amongst notable model and actor Lily Cole and founder of The Whole Earth Catalog and co-founder of The Long Now Foundation Stewart Brand. |

キュレーター活動 オブリストの活動には、美術機関の歴史とキュレーションの実践に関する継続的な探求が含まれている。20代前半にこのテーマを研究し始めた。「あるとき、 自分の展覧会を始めたとき、自分の職業の歴史を知ることはとても興味深いことだと感じました。その後、キュレーションに関する展覧会や『A Brief History of Curating』という本で、このギャップの是正に貢献している。この本は、オブリストのインタビュー・プロジェクト(上記参照)の一環で、20世紀を 代表するキュレーターたちからのインタビューをまとめたものである。 展覧会の歴史はこの10年でより深く検討されるようになったが、キュレーター、機関、アーティストの間で相互に関連する表現がどのような絆で結ばれている かは、まだほとんど解明されていない。このため、オブリストの対話は、少数の個人の顕著な業績を強調することにとどまらない...オブリストの収集された ボリュームは、芸術内の関係のネットワークを強調し、「断片のパッチワーク」をつなぎ合わせる[18]。 アートの世界を探求し、それを開かれたシステムとして捉えたいという彼の願望に沿って、オブリストは自身の活動において参加型モデルを長く提唱してきた。 初期のプロジェクトのひとつである1997年の「do it」は、アーティストによって設定された誰でも実行可能な指示書からなる継続的な展覧会である[19]。プロジェクトの紹介でオブリストは「do itは開かれた展覧会のモデル、そして進行中の展覧会に由来している」と述べている。個々の指示は、空いたスペースを占拠するために開かれ、全く自由に作 品の解釈や言い換えの可能性を呼び起こすことができる。do itは、場所に基づいた解釈をもたらし、地域の構造と作品そのものとの同調を求める。do itの舞台となる多様な都市は、作品の文脈を能動的に構築し、それぞれの痕跡や差異を付与する。 2003年、ヴェネツィア・ビエンナーレの一部である「ユートピア・ステーション」をキュレーションし、サラ・ソーントン著『Seven Days in the Art World』でこのプロジェクトについて短いインタビューを受ける[20]。2007年、マンチェスター国際フェスティバルでフィリップ・パレーノと共同 キュレーションし、バイエラー財団とシアターバーゼルが企画した2009年のアートバーゼルでも発表される。同年、ヴァン・アレン・インスティテュートよ り2007-2008年度ニューヨーク・プライズ・シニア・フェローシップを授与される。2008年にはグラナダのロルカハウスで「Everstill」 のキュレーションを行った。 最近では、2005年にシュトゥットガルトで発案した公開イベント「マラソン」シリーズを開始した。サーペンタイン・シリーズの第1弾として2006年に 開催された「インタビュー・マラソン」では、現代文化を代表する人物にオブリストと建築家レム・コールハースが24時間にわたってインタビューを行いまし た。ピーター・クック、ニール・トゥロック、キム・ゴードン、シモーネ・フォルティ、フィア・バックストローム、ジョセフ・グリゲリーなど、アートとサイ エンス両方の分野の講演者による50の実験が行われたのです。また、2008年にはマニフェスト・マラソン、2009年にはポエトリー・マラソンが開催さ れ、ギルバート&ジョージ、トレーシー・エミン、ニック・レアード、ジェフリー・ヒル、ジェームズ・フェントンなどのアーティストや作家による詩の朗読で 構成されている[21]。 2014年に開催された「Extinction Marathon」。Visions of the Future[22]は、人文科学と科学を結びつけ、今日の世界における環境と人間の影響について議論しました。絶滅と気候変動の問題を研究するアーティ スト、グスタフ・メッツガーを迎えてプログラムされたものです。注目すべき参加者は、アーティストのEtel Adnan、Ed Atkins、Jesse Darling、Gilbert & George、Katja Novitskova、Yoko Ono、Susan Hiller、Marguerite Humeau、Trevor Paglen、Cornelia Parker、モデルで俳優のLily Cole、The Whole Earth Catalog創設者およびThe Long Now Foundation共同創設者のStewart Brandなどである。 |

| Kino der Kunst Festival, member

of the board of trustees (since 2013)[23] Museum Berggruen, member of the international council[24] Thyssen-Bornemisza Art Contemporary, member of the advisory board[25] Ullens Center for Contemporary Art (UCCA), member of the advisory board (2014–2015)[26] Locarno Festival, member of the jury (2012) Manifesta, member of the supervisory board (1994–2002)[27] |

|

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hans_Ulrich_Obrist |

https://www.deepl.com/ja/translator |

| In an interview with Hans Ulrich Obrist, Michel Serres

(1930-2019) expressed interest in the emergence of a new political

philosophy that addresses the digital context of the 21st century, "I

think that out of this place of no law that is the Internet there will

soon emerge a new law, completely different from that which organized

our old metric space." |

ミシェル・セール(1930-2019)はハンス・ウルリッヒ・オブリ

ストとのインタビューの中で、「インターネットという法のない場所から、我々の古い計量空間を組織していたものとは全く異なる新しい法がすぐに現れると思

う」と21世紀のデジタル文脈に対応する新しい政治哲学の出現に関心を示している。 |

+++

MICHEL SERRES, https://032c.com/magazine/michel-serres

| MICHEL

SERRES is a French philosopher who specializes in the history of

science and whose work attempts to reclaim the art of thinking the

unthinkable. Born in 1930 in Lot-et-Garonne, Serres is a member

immortel of L’Académie française and has been a professor at Stanford

University, in the heart of Silicon Valley, since 1984. He’s authored

more than 60 volumes that range in topics from parasites to the “noise”

that lingers in the background of life and thought. Serres’ writing is

like a slow night of constant drinking, taking us irreversibly to

places we didn’t know we were heading towards. In 1985 he published Les cinq sens, a lament on the marginalization of the knowledge we gain from our fives senses through science and the scientific mind. So it came as somewhat of a surprise for his observers when Serres came out in unrestrained support of online culture, particularly Wikipedia, in the first years of the 2000s. “Wikipedia shows us the confidence we have in being human,” he said in 2007. Whether through technology or our own bodies, the world of information is only ever accessible through mediation (Serres often deploys the Greek god Hermes and angels in his writing). His most recent book, Petite Poucette (2012), or “Thumbelina,” is an optimistic work that discusses today’s revolution in communications and the cognitive and political transformations it’s brought about. “Army, nation, church, people, class, proletariat, family, market … these are abstractions, flying overhead like so many cardboard effigies,” Serres writes in Petite Poucette. It’s been on the French bestseller list since its release and has sold more than 100,000 copies. It’s a sort of love letter to the digital generation, and surprising in many ways. One of these is that almost no one in the English-speaking world has ever heard of it. In this conversation with 032c’s contributing editor Hans Ulrich Obrist, Serres muses on the dawn of our new era. |

ミシェル・セール(MICHEL

SERRES)は、フランスの哲学者であり、科学史を専門とする。1930年、ロット・エ・ガロンヌ県に生まれ、1984年からシリコンバレーの中心にあ

るスタンフォード大学の教授を務め、アカデミー・フランセーズの不滅のメンバーである。寄生虫から人生や思考の背景に潜む「ノイズ」に至るまで、60冊以

上の著作がある。セールの文章は、まるで飲み続けている夜のように、私たちを知らず知らずのうちに、取り返しのつかないところへ連れて行ってくれる。 1985年には、科学と科学的思考によって五感から得られる知識が疎外されていることを嘆いた『Les cinq sens』を発表している。そのため、2000年代初頭、セールがネット文化、特にウィキペディアを全面的に支持するようになったことは、彼を観察してい た人々にとっていささか驚きであったようだ。「ウィキペディアは、われわれが人間であることへの自信を示している」と彼は2007年に語っている。テクノ ロジーであれ、私たち自身の身体であれ、情報の世界は媒介を通してしかアクセスできない(セールはしばしばギリシャ神話のヘルメスや天使を登場させる)。 最新作『Petite Poucette』(2012年)、通称「おやゆび姫」は、今日のコミュニケーション革命と、それがもたらす認知的・政治的変容を論じた楽観的な作品であ る。軍隊、国家、教会、国民、階級、プロレタリアート、家族、市場...これらは抽象的なもので、たくさんの段ボールの塑像のように頭上を飛んでいる」 と、セールは『Petite Poucette』に書いている。この本は発売以来、フランスのベストセラーリストに載り、10万部以上売れた。デジタル世代へのラブレターのようなもの で、いろいろな意味で驚かされる。そのひとつが、英語圏ではほとんど誰も聞いたことがないということだ。032cの寄稿編集者ハンス・ウルリッヒ・オブリ ストとの対談で、セールスは新しい時代の幕開けについて考察している。 |

| HANS ULRICH OBRIST: I want to

start by talking about Petite Poucette. MICHEL SERRES: I’m all ears. The book is so optimistic about the 21st century. How did writing it come about? It came to me both slowly and quickly. First, it had been a long time since I had written books on communication, which is to say on Hermes, the god of communication, and on “the parasite” of, or the barriers to, communication. These are concepts I’ve been working on for a very long time. Second, I’ve been teaching for the past 35 years at Stanford, in the middle of Silicon Valley, and so I’m well informed about the field’s new technologies, industries, and startups. My background on these issues is both theoretical and practical. I spoke a lot about Hermes with Bruno Latour, at the time when you and him published Conversations on Science, Culture, and Time (1995). Even as early as the 1980s you talked about this era of communication in the journal Hermes. In a sense, you predicted it. It wasn’t exactly a prediction because the ideas were already in the air. And it was well before the 80s, since the first Hermes was published in the 60s. At that time we could already see that blue-collar work was being replaced by white-collar jobs. We could already see that industry was changing, that jobs in the service industry were starting to replace manufacturing jobs across the market. It was clear that communication was gaining on production and that our societies were already starting to shift. I was very sensitive to those changes as early as the 1960s and 70s, and of course they accelerated, and when computers and new technologies arrived they experienced a vertical growth. |

HANS ULRICH OBRIST:まずは「Petite

Poucette」の話から始めたいと思います。 ミッシェル・ゼール お聞きしたいことがあります。 この本は21世紀についてとても楽観的です。どのような経緯で書かれたのですか? この本は、ゆっくりと、そして素早く私のもとにやってきました。まず、コミュニケーション、つまりコミュニケーションの神であるヘルメスや、コミュニケー ションに寄生するもの、あるいはコミュニケーションを阻害するものについて本を書くのは久しぶりのことでした。これらは、私が長い間取り組んできたコンセ プトです。第二に、私は過去35年間、シリコンバレーのど真ん中にあるスタンフォード大学で教えてきたので、この分野の新しい技術や産業、スタートアップ についてよく知っているのです。これらの問題に対する私のバックグラウンドは、理論と実践の両方です。 エルメスについては、あなたとブルーノ・ラトゥールが『科学・文化・時間に関する対話』(1995年)を出版したときに、よく話をしました。1980年代 にも、あなたは『ヘルメス』誌上で、このコミュニケーションの時代について話していましたね。ある意味で、あなたはそれを予言していたのです。 すでにアイデアは出ていたので、予言というわけではありません。しかも、最初のヘルメスが出版されたのが60年代ですから、80年代よりかなり前のことで す。当時、ブルーカラーの仕事がホワイトカラーに取って代わられつつあることは、すでに目に見えていました。産業が変化し、市場全体で製造業の仕事がサー ビス業に取って代わられ始めていることも、すでに目に見えていた。コミュニケーションが生産に取って代わり、社会が変化し始めているのは明らかでした。私 は、1960年代から70年代にかけて、早くもそうした変化に敏感になっていました。もちろん、変化は加速し、コンピューターや新しいテクノロジーが登場 すると、垂直的な成長を遂げました。 |

| “We need a Tocqueville for the

21st century.” In Petite Poucette you talk about three distinct revolutions, and you say we’re in the middle of one, Can you talk about the revolution we’re currently experiencing and the consequences it brings? I’ve spoken of three revolutions from a historical perspective. The first was in the first millennium BC, when writing emerged in an oral world. The second was printing in the 15th century, with the advent of Gutenberg and the book. It seems to me that our revolution, the digital one, is the third. It’s a revolution that rests on the medium/message binary, in other words, on hard/soft. At the “oral stage,” the information medium was the human body and the message was oral. The medium later became paper and the message was written, or printed. And today the medium is hardware and the message is electronic – it’s the third revolution. Each of these revolutions – that of writing, that of printing, and ours – has transformed practically all aspects of society. Each brought about financial changes, industrial changes, new jobs, changes in language, in science, and even in religion. With writing emerged the religion of the book, and Christianity followed Judaism. When printing appeared it was the Protestant Reformation that surfaced in reaction to Catholicism. Each time there was a revolution in almost every field, and today we can also expect a crisis to affect all similar sectors. I recently spoke with Adam Curtis, the great British filmmaker who works for the BBC. He talked about institutional crises, and how there are practically no large institutions that aren’t experiencing a crisis today. In England, the crisis of the BBC is worth noting. Is this linked to what you’re describing? What might these institutions be replaced by? A diagnosis – in the medical sense of the term – of your first question would be to say, yes, all of our institutions are experiencing a crisis today. Of course this is particularly apparent in media organizations: the newspaper, the book, etc. But look at universities, too, for example. Today’s higher education is also facing a major crisis, because online courses are taking over. What will become of our universities, which used to be concentrated locally but today don’t really need to be as much. All these types of institutions are in a crisis, including the political ones. We can now look clearly at this from the diagnostic perspective and analyze the changes with lucidity. But your second question is about prognosis: Which society, or which institutions, will replace them? I don’t know how to answer that question yet. I believe that what we need most today is a great political philosopher capable of inventing new institutions. So for the time being, I don’t quite know how to answer your second question. |

"21世紀にはトクヴィルが必要だ" Petite Poucette』の中で、あなたは3つの異なる革命について話し、私たちはその1つの真っ只中にいると言っていますが、私たちが現在経験している革命と それがもたらす結果について話してもらえますか? 私はこれまで、歴史的な観点から3つの革命について話してきました。1つ目は紀元前1,000年頃、口承の世界に文字が登場した時です。2つ目は、15世 紀にグーテンベルクと本が登場した印刷革命です。今回のデジタル革命は、3番目の革命だと思います。メディアとメッセージの二元論、つまりハードとソフト の二元論に立脚した革命です。口承段階」では、情報媒体は人体であり、メッセージは口頭であった。その後、媒体は紙となり、メッセージは文字、つまり印刷 物となった。そして現在、媒体はハードウェア、メッセージは電子化され、3度目の革命が起きている。 文字の革命、印刷の革命、そして私たちの革命、これらの革命はそれぞれ社会のあらゆる側面を変えました。金融の変化、産業の変化、新しい仕事、言葉の変 化、科学の変化、そして宗教の変化さえも引き起こした。文字が登場すると、本の宗教が生まれ、ユダヤ教に続いてキリスト教が生まれた。印刷が登場すると、 カトリックへの反動からプロテスタントの宗教改革が表面化した。その都度、ほとんどすべての分野で革命が起こったが、今日もまた、同じようなすべての分野 に危機が訪れると予想される。 最近、BBCで働くイギリスの偉大な映画監督、アダム・カーティスと話をしました。彼は、制度的な危機について、そして今日危機を経験していない大きな機 関は実質的に存在しないことを話しました。イギリスでは、BBCの危機は注目に値します。これは、あなたがおっしゃることと関係があるのでしょうか?これ らの制度は何に取って代わられるのでしょうか? 最初の質問に対する診断-医学的な意味での-は、「はい、今日、すべての組織が危機を経験しています」と言うことでしょう。もちろん、これは新聞や本など のメディア組織に特に顕著に見られます。しかし、例えば、大学を見てください。今日の高等教育も大きな危機に直面しています。オンラインコースが主流に なっているからです。昔は地元に集中していたけれど、今はそれほど必要ない大学はどうなるのでしょう。政治的なものも含めて、この種の機関はすべて危機に 瀕しているのです。私たちは今、これを診断の観点から明確に見ることができ、その変化を明晰に分析することができます。しかし、2番目の質問は、予後につ いてです。どのような社会が、あるいはどのような制度が、彼らに取って代わるのでしょうか。この質問にはまだ答えようがありません。今、私たちが最も必要 としているのは、新しい制度を発明することのできる偉大な政治哲学者だと思うのです。ですから、当面は、2番目の質問にどう答えたらいいのか、よくわかり ません。 |

| “I would rather a well-made than

a well-filled head.” The other day on the radio you talked about how Tocqueville is your hero. You spoke about how extraordinary it is that even though he was only in the United States for a few months he really grasped it when he wrote Democracy in America (1835/1840). Is there a Tocqueville for the 21st century? We need a Tocqueville for the 21st century. Exactly. Who could be these political philosophers of the 21st century? Do you see any emerging? I would not like to die without having tried to answer that question. This is the question I would like to work on. That’s fantastic! Perhaps it could be the subject of an upcoming book. This is what I’m studying at the moment. In the 19th century there were many inventors of political philosophy: the Utopian Socialists, Marx, and many, many more. In the 20th century there was a great void in political philosophy, and we are still experiencing it today. Are new technologies giving birth to a new human being? That’s right. Already at the time that printing was invented Michel de Montaigne wrote in his Essays (1580), “I would rather a well-made than a well-filled head.” He had noticed this peculiar thing, which was that the head – as a thinking subject – was changing. The feeling at the time of the printing revolution was that a new way of thinking was emerging, and proof of this is that mathematical physics came about around this time. Today, too, a new way of thinking – and quite simply, a new head – is emerging. You can see it in the computer: It holds your memory and a lot of your operating system. As a result, there are many old brain functions that are being replaced by the computer, and thus the head is changing. That’s the new human being. The thinking subject is changing, but our way of being together is also shifting. When you take the subway in London or in Paris you see everyone on their phone, and they’re completely transforming the community that once was the subway’s. People are calling their neighbor – their virtual neighbor, that is – on the phone. Two things are changing: the thinking subject and the community as subject. |

"よく満たされた頭より よくできた頭を選ぶ" 先日ラジオで、トクヴィルが自分のヒーローだと話していましたね。彼がアメリカに数ヶ月しかいなかったにもかかわらず、『アメリカにおける民主主義』 (1835/1840)を書いたときに、それを本当に理解していたことがいかにすごいかということを話していましたね。21世紀のトクヴィルはいるので しょうか? 21世紀のトクヴィルは必要ですね。その通りです。 21世紀の政治哲学者は誰でしょうか?誰か出てきそうですか? その問いに答えられないまま死ぬのはもったいない。これこそ私が取り組みたい問題です。 素晴らしいですね。もしかしたら、今度出版される本の題材になるかもしれませんね。 今、私が研究しているのは、このようなことです。19世紀には、ユートピア社会主義者、マルクス、その他多くの政治哲学の発明者がいました。20世紀には 政治哲学に大きな空白があり、現在もそれを経験しています。 新しい技術が新しい人間を生んでいるのでしょうか? その通りである。すでに印刷が発明された頃、ミシェル・ド・モンテーニュは『エッセイ』(1580年)の中で、"私はよく満たされた頭よりも、よく作られ た頭を望む "と書いている。彼は、頭というものが--考える主体として--変化していく、この奇妙なことに気づいていたのです。印刷革命の頃、新しい考え方が生まれ つつあることを感じていたが、その証拠に、この頃、数理物理学が誕生している。今日でも、新しい考え方、簡単に言えば新しい頭が生まれつつある。それはコ ンピュータを見ればわかります。メモリやオペレーティングシステムの多くをコンピュータが担っています。その結果、多くの古い脳の機能がコンピューターに 取って代わられ、頭の中も変わってきています。それが新しい人間です。考える主体も変化していますが、一緒にいる方法も変化しているのです。ロンドンやパ リで地下鉄に乗ると、誰もが携帯電話を使っていますが、かつての地下鉄のコミュニティが完全に変容しているのです。人々は隣人-つまりバーチャルな隣人- に電話をかけているのです。考える主体」と「主体としてのコミュニティ」という2つのことが変化しているのです。 |

| “The Internet today is a space

of no law” You explain so pertinently that networks are of a previous era, and that we don’t have the same idea of references today. In fact, we’re in a topological space without any distances. What does this space mean for the future? Before, when you’d give me your address in London, it was a code that referred to a space on the map of London, or on the map of the British Isles. This map was drawn according to what we call metric geometry, which was used to define distances. With new technologies, distance disappears. Distance is not only shortened today, as it was with a horse or a plane, it’s eliminated altogether. As a result, your new address – which is the address of your mobile phone or your computer – functions regardless of where you are, and sends messages no matter where your correspondent resides. As a result of this kind of proximity we no longer live in the same space as our parents did. Our space has changed, and of course this change of space plays a decisive role in many things, particularly law. Do you remember the forest where Robin Hood lives? Robin Hood! Yes, it’s a place of no law. Exactly. I think that the Internet today is a space of no law. When travelers went into the forest, they suddenly realized that the thieves and criminals who were in the forest obeyed Robin Hood. And Robin Hood has an extraordinary name, because Robin means “he who wears the magistrate’s robe,” “he who wears the judge’s robe.” So Robin Hood – in French it’s Robin des Bois, or “Robin of the woods”) – means “he who makes law in a place of no law.” It’s extraordinary. I think that out of this place of no law that is the Internet there will soon emerge a new law, completely different from that which organized our old metric space. In this context the recent [Edward] Snowden case is fascinating. It’s caused such a ruckus in terms of legal detentions and the dynamics of what is free. What are Western democracies? How do you see the Snowden case? That’s exactly it. It’s precisely the sort of crash, or collision, between the former law and the new law, between the past place of no law and the new law. How do you see Wikileaks and [Julian] Assange in all this? It’s the same thing. Inside the space that is the Internet there exists a law that has nothing to do with the law that organizes the space we previously lived in, and as a result, there is a reciprocal ignorance and struggle between these two laws. From a certain point of view, those who inhabit the Internet, as I do and as you certainly do, are quite supportive of this freedom, of Wikileaks, for example. |

"今日のインターネットは、法則性のない空間" ネットワークは前の時代のもので、今の私たちにはリファレンスという考え方がないことを、とても的確に説明されていますね。実際、私たちは距離のないトポ ロジカルな空間にいるのです。この空間は、未来にとってどのような意味を持つのでしょうか。 以前は、ロンドンの住所を教えてもらうと、それはロンドンの地図上、あるいはイギリス諸島の地図上の空間を指すコードだったんです。この地図は、距離を定 義するために使われる、いわゆるメートル幾何学に基づいて描かれていました。新しいテクノロジーによって、距離は消滅します。馬や飛行機のように距離が縮 まるだけでなく、距離がまったくなくなってしまったのです。その結果、携帯電話やコンピュータのアドレスである新しいアドレスは、あなたがどこにいても機 能し、通信相手がどこにいてもメッセージを送ることができるようになりました。このような近さの結果、私たちはもはや両親と同じ空間に住んでいるわけでは ありません。私たちの空間は変わりました。もちろん、この空間の変化は多くのこと、特に法律において決定的な役割を担っています。皆さんはロビン・フッド の住む森を覚えていますか? ロビン・フッド!?そう、そこは法のない場所なのです。 その通りです。今のインターネットは、法のない空間だと思います。旅人が森に入ったとき、ふと気がつくと、森にいた泥棒や犯罪者たちはロビン・フッドに従 順になっていた。そして、ロビン・フッドというのはとんでもない名前で、ロビンは "判事の衣を着る者""裁判官の衣を着る者 "という意味なのです。つまり、ロビン・フッド(フランス語ではRobin des Bois、「森のロビン」)とは、"法のない場所で法を作る者 "という意味なのです。とんでもない話です。私は、インターネットという法のない場所から、私たちの古い計量空間を組織していたものとは全く異なる、新し い法が間もなく出現すると思います。 その意味で、最近のエドワード・スノーデンの事件は興味深いものです。法的拘束や、何が自由であるかの力学という点で、これほどの騒動を引き起こしたので す。西側民主主義とは何でしょうか?スノーデン事件をどう見るか? まさにその通りです。まさに、旧法と新法、過去の無法地帯と新法との衝突、あるいは衝突のようなものです。 ウィキリークスとジュリアン・アサンジをどう見ますか? 同じことです。インターネットという空間の中には、私たちが以前住んでいた空間を組織する法律とは何の関係もない法律が存在し、その結果、この二つの法律 の間に相互の無知と闘争が存在しているのです。ある観点から見ると、私がそうであるように、また皆さんが確かにそうであるように、インターネットに生息す る人々は、例えばウィキリークスなど、この自由をかなり支持しているのです。 |

| “Wikipedia is greatly changing

social relations, human relations, and pedagogical relations.” You’re passionate about Wikipedia because it’s a democracy of knowledge. You link it to Paul the Apostle. Wikipedia is the direct and free access to knowledge in its entirety. A lot of my students in America have been asking me for 10 years now, “Why should I pay so much for my studies when they only give me access to information that I’ve already had for two days?” It’s immediate access to knowledge. It’s also transforming jobs. Let me give you an example. Say, you’re ill and you go see your doctor. In the past the doctor was competent and you were clueless. You had no information about your illness. Before going to see the doctor today you go to Wikipedia to inform yourself about your symptoms. As a result, and I say it in Petite Poucette, there’s a presumption of qualifications, and a presumption of incompetence. The relationship between doctor and patient is changing, as is the relationship between teacher and student, and so on. Wikipedia is greatly changing social relations, human relations, and pedagogical relations. Your idea of the quasi-object is that it’s neither object nor subject. It’s a relation. The other day I had my Blackberry in my hand and wondered if it’s a quasi-object. Do you see the iPhone and the Blackberry as quasi-objects? They’re certainly quasi-objects, but they’re almost intelligent quasi-objects as well. Almost intelligent! It’s a relational object, which means that you and I are connected together right now because of it. How was the idea of the quasi-object born? I first read about it in The Parasite, which came out in 1980. Had it already appeared in Hermes? Well I’m a bit like the English. I was born in southwestern France and played rugby often growing up. I was very passionate about the ball, about what the ball represents. By analyzing the ball’s function in the game of rugby I came to the idea of the quasi-object, through sport, by watching and playing with the ball. That’s beautiful. So you had an epiphany through rugby? Exactly. And an object is also an object that would rather be an object and not a thing. I’ve been reading about the Gulf of Mexico, which is becoming a judicial entity that can defend itself. I’m curious about the idea of the judicial dimension of the object and the quasi-object. That’s the subject of another book I wrote, The Natural Contract (1990). In it I try to explain that the idea of the subject of law is starting to transform itself today, and that natural objects can become subjects of law. For example, Yellowstone Park could undertake legal action against someone who polluted it. This is starting to pass into law. I have news from several countries in which they are starting to think about this question, saying that certain natural objects can become subjects of law. It’s a very important idea in terms of environmental solutions. It’s decisive for the environment. A new step in Western law. I was speaking with the artist Philippe Parreno recently, and he spoke about how certain films, or forms, or artworks can behave in the way quasi-objects do when they’re put into circulation. Can art be a quasi-object? It always has been to a certain extent, because it’s enabled a relation to a given society. It’s created a society, even. Some quasi-objects are artworks, such as religious objects, and can bring a community together at once. In some sense, it has always been one of art’s functions. There’s no doubt about it. Philippe also wondered if the quasi-object can produce reality? Oh, of course! When a quasi-object unites a community, that community becomes real – that community is born. The quasi-object creates the community. Yes, yes, it creates. The virtual often creates the real, my friend! Us humans spend our lives making the virtual real. What is a coin? It’s a quasi-object. It’s virtual because it can be transformed into anything. Money is a “general equivalent,” and yet there is nothing more real than money today. There’s no doubt about it. And at the beginning it was a quasi-object. You’ve often collaborated with others, and conversation is an important practice in your philosophy. Do you believe that we can invent new forms through collaboration, or even through friendship? Yes. Certainly. I think it can be done. The key to inventing through conversation is to ensure that the conversation is not … a sort of fight to the death between two set opinions. Each participant in the conversation must be free and open. I’m curious whether the parasite engages in acts of resistance. How do you see notions of resistance in a world of new technologies, where the exterior no longer exists to a certain extent? I’m not sure I know how to answer that question, as it should be. The word “resistance” for us French is intricately linked to the Second World War. You remember the Résistance against the invader? And so from that point of view, of course. But the word “resistance” has several meanings as well. With regards to parasites, we have discovered that certain bacteria are resistant to antibiotics. In this case, the parasite has evolved and has become a symbiont. And so there’s a sort of evolution of the parasite, which is at first dangerous, and can kill, and then all of a sudden it becomes collaborator and then symbiont. In the end, perhaps resistance is a process that occurs between parasitism and symbiosis. That’s my answer. Do you think it’s possible to link art with ecologic justice? It could very well be today’s fundamental evolution of art, which means coming back to an inspiration that was quite a traditional one, but also anew – to open oneself up to living species, to open up to life and to nature. I was speaking recently with Doris Lessing, the writer from London, and she spoke about the idea that there are always unwritten books. Books that we didn’t dare write or that we didn’t have time to write, or maybe it was because of circumstances outside of the book. You’ve published over 60 books. What are your unrealized or utopian projects? Again, there’s still a problem that I’d like to solve: our political institutions. There’s no doubt that it’s the book that hasn’t been written and that I would like to write. Credits Interview HANS ULRICH OBRIST Portrait MANUEL COHEN |

"ウィキペディアは社会的関係、人間関係、教育的関係を大きく変えてい

る。" あなたがウィキペディアに情熱を注ぐのは、それが知識の民主主義だからです。使徒パウロにリンクしていますね。 ウィキペディアは、知識の全体像に直接かつ自由にアクセスできるものです。アメリカでは10年前から多くの生徒が、"すでに2日前に手に入れた情報にしか アクセスできないのに、なぜ高いお金を払って勉強しなければならないのか?"と私に質問してきました。知識への即時アクセスです。また、仕事にも変化をも たらしています。例を挙げましょう。例えば、あなたが病気になって医者に診てもらうとします。以前は、医師は有能で、あなたは何も知りませんでした。自分 の病気について何の情報も持っていなかったのです。今日、あなたは医者にかかる前に、ウィキペディアで自分の症状について情報を得ます。その結果、『プチ プセ』の中でも言っていますが、資格の有無が推定され、無能であることが推定されるのです。医者と患者の関係、先生と生徒の関係などが変わってきているの です。ウィキペディアは社会的関係、人間関係、教育的関係を大きく変えつつあるのです。 あなたの考える「準物質」は、物体でも主体でもない。関係性があるんです。先日、ブラックベリーを手にして、これは準物質なのだろうかと考えました。 iPhoneやBlackBerryを準オブジェクトと見なしますか? 確かに準オブジェクトですが、ほとんど知的な準オブジェクトでもあります。ほとんど知的!?関係性のある物体で、そのおかげであなたと私は今、つながって いるわけですから。 準物質というアイデアはどのようにして生まれたのですか?最初に読んだのは、1980年に出版された『パラサイト』です。エルメス』にはすでに登場してい たのですか? 私はイギリス人と少し似ているんです。私はフランス南西部の生まれで、幼少期はよくラグビーをやっていました。私はボールについて、ボールが象徴するもの について、とても情熱的でした。ラグビーのゲームにおけるボールの機能を分析することで、スポーツを通して、ボールを見たり、ボールで遊んだりすること で、準オブジェという考え方にたどり着いたのです。 それは美しいですね。では、ラグビーを通じて啓示を受けたのですね。 その通りです。 そして、モノはむしろモノであってモノでないことを望むモノでもある。メキシコ湾が自らを守ることができる司法的存在になりつつある、という記事を読んだ ことがあります。対象物や準対象物の司法的次元という考え方に興味があります。 これは、私が書いた別の本『自然契約』(1990年)の主題でもあります。この本で私は、法の主体という考え方が今日、変容し始めており、自然物が法の主 体になりうるということを説明しようとしています。例えば、イエローストーン公園は、そこを汚染した人に対して法的措置を取ることができます。これが法律 として成立し始めているのです。この問題について考え始めているいくつかの国からのニュースでは、ある種の自然物は法律の主体になり得ると言っています。 環境問題の解決という点では、非常に重要なアイデアです。 環境にとって決定的なことだ。欧米の法律における新たな一歩です。 最近、アーティストのフィリップ・パレノと話したのですが、彼は、ある種の映画や形態、あるいは芸術作品が、流通に乗せられたときに、準オブジェのような 振る舞いをすることがある、と話していました。アートは準オブジェになり得るか? ある社会との関係を可能にするものである以上、ある程度は常にそうであったでしょう。それは、ある社会との関係を可能にし、社会を作り上げるからです。準 オブジェの中には、宗教的なオブジェのように、あるコミュニティを一度にまとめることができるアートワークもあります。ある意味で、それは常にアートの機 能の一つであった。それは間違いない。 フィリップはまた、準オブジェクトは現実を生み出すことができるのか、と考えていた。 もちろんです。擬似オブジェクトがコミュニティをひとつにすると、そのコミュニティは現実のものとなる。擬似オブジェクトが共同体をつくるんだ。そうだ、 そうだ、創造するのだ。バーチャルがリアルを生み出すことはよくあることなのだ。私たち人間は、バーチャルをリアルにすることに人生を費やしているので す。コインとは何でしょう?準物質です。何にでも形を変えられるからバーチャルなのです。貨幣は「一般的な等価物」でありながら、今日、貨幣以上にリアル なものはない。それは間違いない。そして、はじめは準物質だった。 あなたはしばしば他者とコラボレーションしてきましたし、会話はあなたの哲学において重要な実践です。コラボレーションや友情を通じて、新しい形を生み出 すことができるとお考えですか? はい。もちろんです。それは可能だと思います。会話を通じて発明するための鍵は、会話が2つの決まった意見の間の死闘のようなものではないことを保証する ことです。会話に参加する一人ひとりが、自由でオープンでなければなりません。 寄生虫が抵抗行為をするのかどうか、気になります。新しいテクノロジーの世界では、外部はもはやある程度存在しないのですが、抵抗という概念をどのように 捉えていますか? その質問にどう答えたらいいのか、自分でもよくわからないんです。私たちフランス人にとっての「抵抗」という言葉は、第二次世界大戦と複雑にリンクしてい ます。侵略者に対するレジスタンス(Résistance)を覚えていますか?というように、その観点からも、もちろんそうです。しかし、「抵抗」という 言葉には、いくつかの意味もあります。寄生虫に関しては、ある種の細菌が抗生物質に対して耐性を持つことが分かっています。この場合、寄生虫が進化して共 生するようになったのです。最初は危険で、殺すこともできる寄生虫が、突然、協力者になり、共生者になるという、ある種の進化があるわけです。結局、抵抗 力というのは寄生と共生の間に生じるプロセスなのかもしれません。それが私の答えです。 アートとエコロジーの正義を結びつけることは可能だと思いますか? それは、今日のアートの根本的な進化であり、伝統的なインスピレーションに立ち戻ると同時に、新たなインスピレーション、つまり、生きている種や生命、自 然に対して自らを開放することを意味するのかもしれません。 最近、ロンドン出身の作家、ドリス・レッシングと話したのですが、彼女は「書かれていない本が常にある」という考えについて話していました。あえて書かな かった本、書く時間がなかった本、あるいは本以外の事情で書かなかった本があります。あなたは60冊以上の本を出版されています。未実現のプロジェクトや ユートピアのプロジェクトはありますか? 繰り返しになりますが、やはり解決したい問題があります。それは、私たちの政治制度です。それは、まだ書かれていない本であり、私が書きたいと思う本であ ることは間違いありません。 クレジット インタビュー ハンス・ウルリッヒ・オブリスト ポートレート マニュエル・コーエン |

| https://032c.com/magazine/michel-serres |

https://www.deepl.com/ja/translator |

+++

結論:アート&アーカイブ・プロジェクトは、アートを人類の記憶として、記録するプロジェクトとなるので、「アート・アクティヴィズム」の一種の活動領域にも入るだろう。

+++

Links

リンク(サイト内)

リンク(2022年12月6日訪問調査関連リンク)

文献

その他の情報

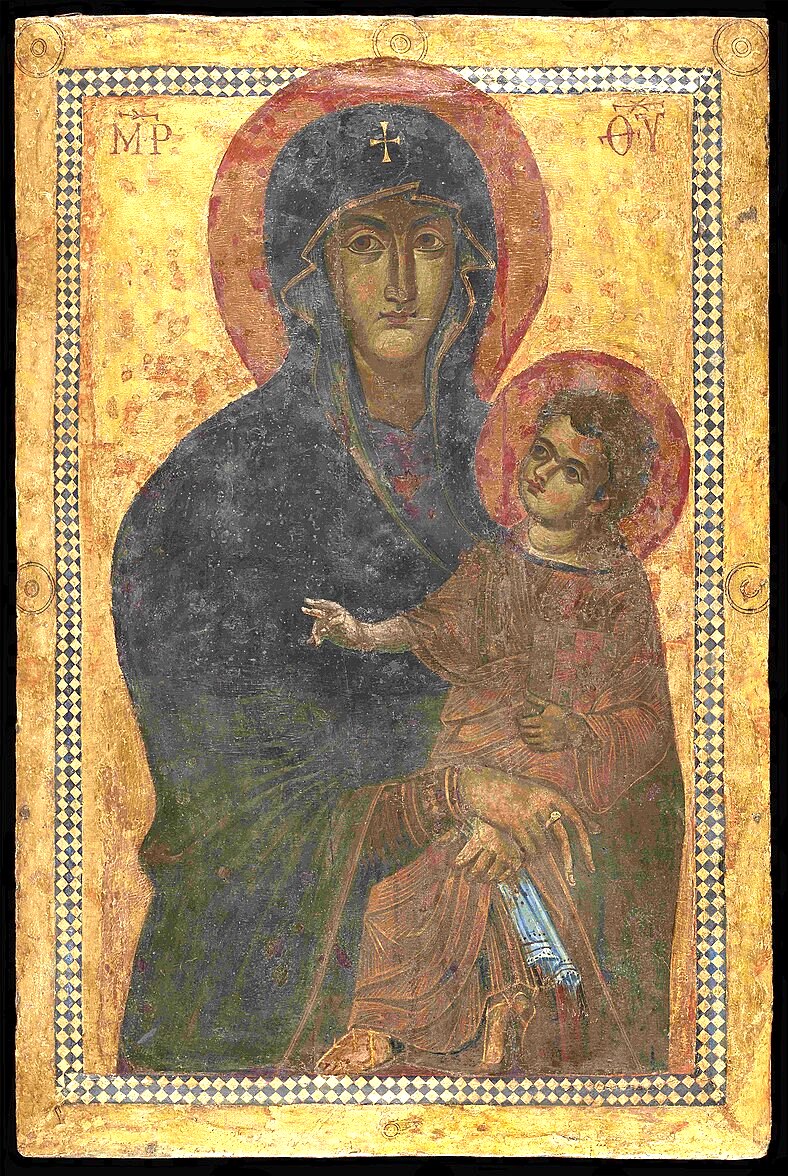

Icon Salus Populi Romani before restoration from 2018.

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆ ☆

☆