記憶

human memory

「記憶はある贖罪の行為を暗示する」

(ジョン・バージャー 2005:79)

私は歴史的事象を[自分の議論にとって]それほど本質化していな いので、歴史的事実がどうであるというよりも、そのような歴史的状況の中で人 は、自分の知識をどのように操作して生きているのか、あるいは、どう感じることができるのかについて焦点化したい。

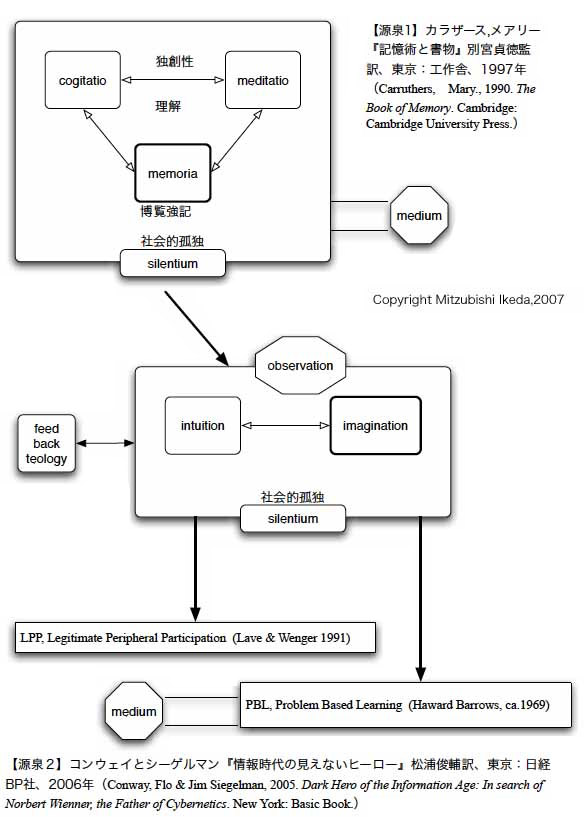

ヨーロッパの古代・中世には、人間の能力 における記憶の能力に 高い価値がおかれていたという。

ものごとを理解していることは、ものごとについてどれ だけ知っているということで計られる世界(→メリトクラシー)があるということである。もちろん、我々にも、記 憶の能力が卓越した者に羨望のまなざしが向けられることもある。しかし、我々は記憶よりも、思考においてより評価されるのは、創造性においてである。

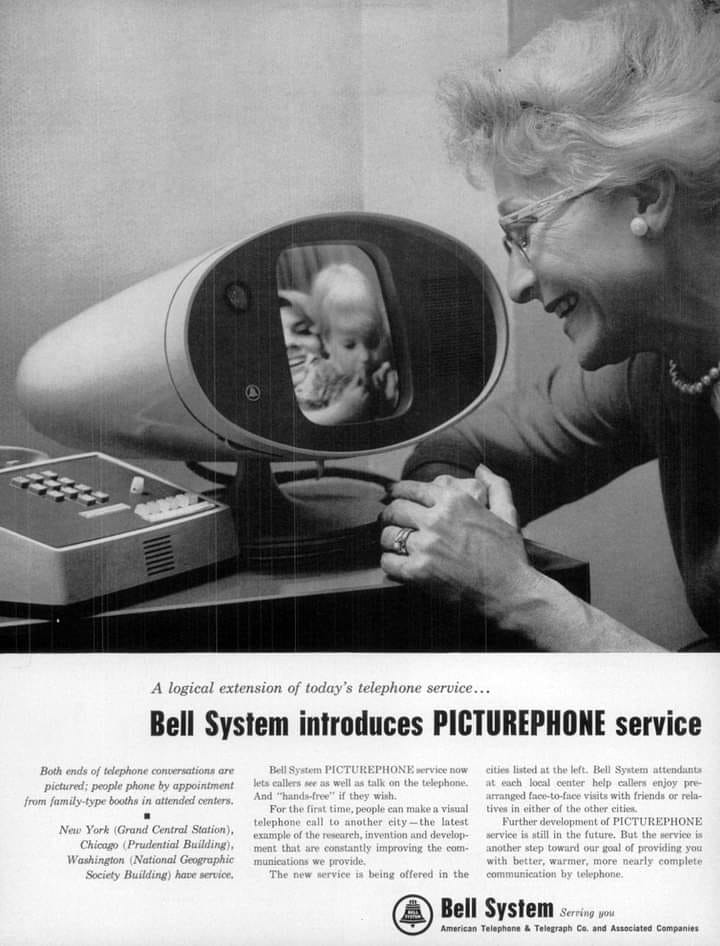

創造性が評価されるようになった背景に は、記憶の外部化という社会的技術の成功とその開発というものがある。マクルーハンでは ないが、印刷術で あり、印刷物をプールしておくコンピュータ(→「クラウド」) であり、電話・テレビ・ラジオメディアであり、今日ではデジタル送受信技術に支えられたネットワークコンピュー タシステム(machine)である。

| Memory is the

faculty of the mind by which data or information is encoded, stored,

and retrieved when needed. It is the retention of information over time

for the purpose of influencing future action.[1] If past events could

not be remembered, it would be impossible for language, relationships,

or personal identity to develop.[2] Memory loss is usually described as

forgetfulness or amnesia.[3][4][5][6][7][8] Memory is often understood as an informational processing system with explicit and implicit functioning that is made up of a sensory processor, short-term (or working) memory, and long-term memory.[9] This can be related to the neuron. The sensory processor allows information from the outside world to be sensed in the form of chemical and physical stimuli and attended to various levels of focus and intent. Working memory serves as an encoding and retrieval processor. Information in the form of stimuli is encoded in accordance with explicit or implicit functions by the working memory processor. The working memory also retrieves information from previously stored material. Finally, the function of long-term memory is to store through various categorical models or systems.[9] Declarative, or explicit memory, is the conscious storage and recollection of data.[10] Under declarative memory resides semantic and episodic memory. Semantic memory refers to memory that is encoded with specific meaning.[2] Meanwhile, episodic memory refers to information that is encoded along a spatial and temporal plane.[11][12][13] Declarative memory is usually the primary process thought of when referencing memory.[2] Non-declarative, or implicit, memory is the unconscious storage and recollection of information.[14] An example of a non-declarative process would be the unconscious learning or retrieval of information by way of procedural memory, or a priming phenomenon.[2][14][15] Priming is the process of subliminally arousing specific responses from memory and shows that not all memory is consciously activated,[15] whereas procedural memory is the slow and gradual learning of skills that often occurs without conscious attention to learning.[2][14] Memory is not a perfect processor and is affected by many factors. The ways by which information is encoded, stored, and retrieved can all be corrupted. Pain, for example, has been identified as a physical condition that impairs memory, and has been noted in animal models as well as chronic pain patients.[16][17][18][19] The amount of attention given new stimuli can diminish the amount of information that becomes encoded for storage.[2] Also, the storage process can become corrupted by physical damage to areas of the brain that are associated with memory storage, such as the hippocampus.[20][21] Finally, the retrieval of information from long-term memory can be disrupted because of decay within long-term memory.[2] Normal functioning, decay over time, and brain damage all affect the accuracy and capacity of the memory.[22][23] |

記憶とは、データや情報が符号化され、保存され、必要に応じて取り出さ

れる心の機能である。それは、将来の行動に影響を与える目的で、時間をかけて情報を保持することである。[1]

過去の出来事を記憶できなければ、言語、人間関係、あるいは個人のアイデンティティを発達させることは不可能である。[2]

記憶喪失は通常、物忘れや健忘症として説明される。[3][4][5][6][7][8] 記憶は、感覚プロセッサ、短期(または作業)記憶、長期記憶から構成される、明示的および暗示的な機能を持つ情報処理システムとして理解されることが多 い。[9] これは神経細胞に関連付けることができる。感覚プロセッサは、外界からの情報を化学的および物理的な刺激として感知し、さまざまなレベルの集中と意図を可 能にする。作業記憶は、符号化および検索プロセッサとして機能する。刺激の形態の情報は、作業記憶プロセッサによって明示的または暗示的な機能に従って符 号化される。作業記憶はまた、以前に保存された素材から情報を検索する。最後に、長期記憶の機能は、さまざまなカテゴリーモデルまたはシステムを通じて保 存することである。 宣言的または明示的記憶は、データの意識的な保存および想起である。宣言的記憶の下には、意味記憶およびエピソード記憶が存在する。意味記憶とは、特定の 意味で符号化された記憶を指す。[2] 一方、エピソード記憶とは、空間的および時間的な面で符号化された情報を指す。[11][12][13] 宣言的記憶は通常、記憶を参照する際に考えられる主要なプロセスである。[2] 非宣言的、または潜在的な記憶は、無意識の情報保存および想起である。[14] 非宣言的プロセスとしては、手続き記憶やプライミング現象による無意識の学習や情報の検索が挙げられる。[2][14][15] プライミングとは、記憶から特定の反応を潜在的に引き出すプロセスであり、すべての記憶が意識的に活性化されるわけではないことを示している。[15] 一方、手続き記憶とは、学習に対する意識的な注意を必要としないことが多い、ゆっくりとした段階的なスキルの学習である。[2][14] 記憶は完璧な処理能力を持っているわけではなく、多くの要因の影響を受ける。情報の符号化、保存、検索の方法はいずれも破損する可能性がある。例えば、痛 みは記憶を損なう身体的状態であることが確認されており、動物モデルや慢性痛患者でも指摘されている。[16][17][18][19] 新しい刺激に対する注意の度合いによって、記憶として保存される情報の量が減少する可能性がある。[2] また、 海馬など、記憶の保存に関連する脳の領域に物理的な損傷が生じることによって、保存プロセスが破損する可能性もある。[20][21] 最終的には、長期記憶の減退により、長期記憶からの情報の検索が妨げられる可能性もある。[2] 通常の機能、時間の経過による減退、脳の損傷はすべて、記憶の正確性と容量に影響を与える。[22][23] |

| Overview of the forms and functions of memory |

|

| Sensory memory Main article: Sensory memory Sensory memory holds information, derived from the senses, less than one second after an item is perceived. The ability to look at an item and remember what it looked like with just a split second of observation, or memorization, is an example of sensory memory. It is out of cognitive control and is an automatic response. With very short presentations, participants often report that they seem to "see" more than they can actually report. The first precise experiments exploring this form of sensory memory were conducted by George Sperling (1963)[24] using the "partial report paradigm." Subjects were presented with a grid of 12 letters, arranged into three rows of four. After a brief presentation, subjects were then played either a high, medium or low tone, cuing them which of the rows to report. Based on these partial report experiments, Sperling was able to show that the capacity of sensory memory was approximately 12 items, but that it degraded very quickly (within a few hundred milliseconds). Because this form of memory degrades so quickly, participants would see the display but be unable to report all of the items (12 in the "whole report" procedure) before they decayed. This type of memory cannot be prolonged via rehearsal. Three types of sensory memories exist. Iconic memory is a fast decaying store of visual information, a type of sensory memory that briefly stores an image that has been perceived for a small duration. Echoic memory is a fast decaying store of auditory information, also a sensory memory that briefly stores sounds that have been perceived for short durations.[25][26] Haptic memory is a type of sensory memory that represents a database for touch stimuli. |

感覚記憶 詳細は感覚記憶を参照 感覚記憶とは、知覚された対象について、感覚から得られた情報を1秒未満で保持することである。対象を一瞬見ただけで、その対象がどのような外観であった かを記憶する能力は、感覚記憶の一例である。これは認知制御の対象外であり、自動的な反応である。非常に短いプレゼンテーションでは、参加者はしばしば、 実際に報告できる以上のことを「見た」ように感じると報告する。この感覚記憶の形式を初めて正確に実験したのは、ジョージ・スペリング(1963年) [24]で、「部分報告パラダイム」を用いた。被験者には、4文字×3行の12文字のグリッドが提示された。短い提示の後、被験者には高い音、中程度の 音、低い音のいずれかが流され、どの行を報告するかを指示した。これらの部分報告の実験に基づいて、Sperlingは感覚記憶の容量はおよそ12項目で あるが、それは非常に速く(数百ミリ秒以内に)劣化することを示すことができた。この種の記憶は劣化が速いため、参加者はディスプレイを見ることはできて も、その記憶が消える前にすべての項目(「全体報告」手順では12項目)を報告することはできない。この種の記憶は、反復練習によって延長することはでき ない。 感覚記憶には3つの種類がある。 アイコニック記憶は、視覚情報の急速に減衰する貯蔵であり、知覚された画像を短時間だけ記憶する感覚記憶の一種である。 エコー記憶は、聴覚情報の急速に減衰する貯蔵であり、知覚された音を短時間だけ記憶する感覚記憶でもある。[25][26] ハプティック記憶は、触覚刺激のデータベースを表す感覚記憶の一種である。 |

| Short-term memory Main article: Short-term memory Short-term memory, not to be confused with working memory, allows recall for a period of several seconds to a minute without rehearsal. Its capacity, however, is very limited. In 1956, George A. Miller (1920–2012), when working at Bell Laboratories, conducted experiments showing that the store of short-term memory was 7±2 items. (Hence, the title of his famous paper, "The Magical Number 7±2.") Modern perspectives estimate the capacity of short-term memory to be lower, typically on the order of 4–5 items,[27] or argue for a more flexible limit based on information instead of items.[28] Memory capacity can be increased through a process called chunking.[29] For example, in recalling a ten-digit telephone number, a person could chunk the digits into three groups: first, the area code (such as 123), then a three-digit chunk (456), and, last, a four-digit chunk (7890). This method of remembering telephone numbers is far more effective than attempting to remember a string of 10 digits; this is because we are able to chunk the information into meaningful groups of numbers. This is reflected in some countries' tendencies to display telephone numbers as several chunks of two to four numbers. Short-term memory is believed to rely mostly on an acoustic code for storing information, and to a lesser extent on a visual code. Conrad (1964)[30] found that test subjects had more difficulty recalling collections of letters that were acoustically similar, e.g., E, P, D. Confusion with recalling acoustically similar letters rather than visually similar letters implies that the letters were encoded acoustically. Conrad's (1964) study, however, deals with the encoding of written text. Thus, while the memory of written language may rely on acoustic components, generalizations to all forms of memory cannot be made. |

短期記憶 詳細は「短期記憶」を参照 短期記憶は作業記憶と混同されるべきではないが、復習なしで数秒から1分間想起することができる。しかし、その容量は非常に限られている。1956年、 ジョージ・A・ミラー(1920年 - 2012年)はベル研究所に勤務していた際に、短期記憶の蓄積は7±2項目であることを示す実験を行った。(そのため、彼の有名な論文のタイトルは 「The Magical Number 7±2(呪術的数値7±2)」となった。)現代の見解では、短期記憶の容量はより少なく、通常は4~5項目程度であると推定されている[27]。あるい は、項目ではなく情報に基づいて、より柔軟な限界を主張する意見もある[28]。記憶容量は、 チャンキングと呼ばれるプロセスを通じて、記憶容量を増やすことができる。[29] たとえば、10桁の電話番号を思い出す場合、人は数字を3つのグループに分けることができる。まず、市外局番(123など)、次に3桁のグループ (456)、最後に4桁のグループ(7890)である。この電話番号の記憶方法は、10桁の数字列を記憶しようとするよりもはるかに効果的である。なぜな ら、情報を意味のある数字のグループに分割できるからだ。このことは、いくつかの国で電話番号を2~4桁の数字のグループに分けて表示する傾向があること にも反映されている。 短期記憶は、情報を保存する際に音響コードを主に使用し、視覚コードは補助的に使用すると考えられている。Conrad (1964)[30]は、被験者が音響的に類似した文字、例えばE、P、Dなどの集合を思い出すのに苦労していることを発見した。視覚的に類似した文字で はなく、音響的に類似した文字を思い出す際に混乱が生じることは、その文字が音響的にエンコードされていることを意味する。しかし、コンラッド(1964 年)の研究は、書かれたテキストのエンコーディングを扱っている。そのため、書かれた言語の記憶は音響成分に依存している可能性はあるが、あらゆる記憶形 態に一般化することはできない。 |

| Long-term memory Main article: Long-term memory  Olin Levi Warner's 1896 illustration, Memory, now housed in the Thomas Jefferson Building at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. The storage in sensory memory and short-term memory generally has a strictly limited capacity and duration. This means that information is not retained indefinitely. By contrast, while the total capacity of long-term memory has yet to be established, it can store much larger quantities of information. Furthermore, it can store this information for a much longer duration, potentially for a whole life span. For example, given a random seven-digit number, one may remember it for only a few seconds before forgetting, suggesting it was stored in short-term memory. On the other hand, one can remember telephone numbers for many years through repetition; this information is said to be stored in long-term memory. While short-term memory encodes information acoustically, long-term memory encodes it semantically: Baddeley (1966)[31] discovered that, after 20 minutes, test subjects had the most difficulty recalling a collection of words that had similar meanings (e.g. big, large, great, huge) long-term. Another part of long-term memory is episodic memory, "which attempts to capture information such as 'what', 'when' and 'where'".[32] With episodic memory, individuals are able to recall specific events such as birthday parties and weddings. Short-term memory is supported by transient patterns of neuronal communication, dependent on regions of the frontal lobe (especially dorsolateral prefrontal cortex) and the parietal lobe. Long-term memory, on the other hand, is maintained by more stable and permanent changes in neural connections widely spread throughout the brain. The hippocampus is essential (for learning new information) to the consolidation of information from short-term to long-term memory, although it does not seem to store information itself. It was thought that without the hippocampus new memories were unable to be stored into long-term memory and that there would be a very short attention span, as first gleaned from patient Henry Molaison[33][34] after what was thought to be the full removal of both his hippocampi. More recent examination of his brain, post-mortem, shows that the hippocampus was more intact than first thought, throwing theories drawn from the initial data into question. The hippocampus may be involved in changing neural connections for a period of three months or more after the initial learning. Research has suggested that long-term memory storage in humans may be maintained by DNA methylation,[35] and the 'prion' gene.[36][37] Further research investigated the molecular basis for long-term memory. By 2015 it had become clear that long-term memory requires gene transcription activation and de novo protein synthesis.[38] Long-term memory formation depends on both the activation of memory promoting genes and the inhibition of memory suppressor genes, and DNA methylation/DNA demethylation was found to be a major mechanism for achieving this dual regulation.[39] Rats with a new, strong long-term memory due to contextual fear conditioning have reduced expression of about 1,000 genes and increased expression of about 500 genes in the hippocampus 24 hours after training, thus exhibiting modified expression of 9.17% of the rat hippocampal genome. Reduced gene expressions were associated with methylations of those genes.[40] Considerable further research into long-term memory has illuminated the molecular mechanisms by which methylations are established or removed, as reviewed in 2022.[41] These mechanisms include, for instance, signal-responsive TOP2B-induced double-strand breaks in immediate early genes. Also the messenger RNAs of many genes that had been subjected to methylation-controlled increases or decreases are transported by neural granules (messenger RNP) to the dendritic spines. At these locations the messenger RNAs can be translated into the proteins that control signaling at neuronal synapses.[41] |

長期記憶 詳細は「長期記憶」を参照  ワシントンD.C.の米国議会図書館トーマス・ジェファーソン・ビルに収蔵されている、1896年のオーリン・レビ・ワーナーによるイラスト「記憶」。 感覚記憶や短期記憶の保存容量や保存期間は一般的に厳しく制限されている。つまり、情報は無限に保持されるわけではない。これに対して、長期記憶の総容量 はまだ確定されていないが、はるかに大量の情報を保存できる。さらに、長期記憶は、より長い期間、場合によっては一生の間、情報を保存することができる。 例えば、ランダムな7桁の数字を提示された場合、人はそれを数秒間だけ記憶し、その後忘れてしまう。これは短期記憶に保存されたことを示している。一方、 電話番号は繰り返し練習することで何年も記憶することができる。この情報は長期記憶に保存されていると考えられる。 短期記憶は音韻的に情報を符号化するのに対し、長期記憶は意味的に符号化する。Baddeley(1966年)[31]は、被験者が20分後に最も思い出 しにくかったのは、類似した意味を持つ単語の集合(big、large、great、hugeなど)であったことを発見した。長期記憶の別の部分はエピ ソード記憶であり、「いつ」「どこで」「何」といった情報を捉えようとするものである。[32] エピソード記憶により、個人は誕生日パーティーや結婚式といった特定の出来事を思い出すことができる。 短期記憶は、前頭葉(特に背外側前頭前皮質)と頭頂葉の領域に依存する、一過性の神経細胞の通信パターンによって支えられている。一方、長期記憶は、脳全 体に広く広がる神経接続のより安定した恒久的な変化によって維持されている。海馬は、新しい情報を学習する上で、短期記憶から長期記憶への情報の統合に不 可欠であるが、それ自体は情報を保存しないようである。海馬がなければ新しい記憶を長期記憶に保存することができず、ヘンリー・モレソンという患者 [33][34]から最初に得られた知見によると、両方の海馬が完全に除去されたと考えられていたため、非常に短い注意力しか持てないと考えられていた。 死後に行われた彼の脳のより最近の検査では、海馬は当初考えられていたよりも損傷を受けていなかったことが示され、初期のデータから導き出された理論に疑 問が投げかけられている。海馬は、最初の学習後3か月間以上、神経接続の変化に関与している可能性がある。 研究により、人間の長期記憶の保存は、DNAのメチル化[35]や「プリオン」遺伝子[36][37]によって維持されている可能性が示唆されている。 さらに研究が進み、長期記憶の分子基盤が調査された。2015年までに、長期記憶には遺伝子転写の活性化と新規タンパク質の合成が必要であることが明らか になった。[38] 長期記憶の形成は、記憶促進遺伝子の活性化と記憶抑制遺伝子の抑制の両方に依存しており、DNAメチル化/DNA脱メチル化が、この二重の制御を達成する ための主要なメカニズムであることが判明した。[39] 文脈恐怖条件付けによる新しい強力な長期記憶を持つラットでは、訓練後24時間で海馬において約1,000の遺伝子の発現が低下し、約500の遺伝子の発 現が増加しており、ラット海馬ゲノムの9.17%で発現の変化が認められた。遺伝子発現の低下は、それらの遺伝子のメチル化と関連していた。 長期記憶に関するさらなる研究により、2022年にレビューされたように、メチル化が確立または除去される分子メカニズムが解明された。[41] これらのメカニズムには、例えば、即時型遺伝子におけるシグナル応答性TOP2B誘発性二重鎖切断が含まれる。また、メチル化制御による増減の影響を受け た多くの遺伝子のメッセンジャーRNAは、神経顆粒(メッセンジャーRNP)によって樹状突起棘に輸送される。これらの場所でメッセンジャーRNAは、神 経シナプスにおけるシグナル伝達を制御するタンパク質に翻訳される可能性がある。[41] |

| Memory consolidation Main article: Memory consolidation The transition of a memory from short term to long term is called memory consolidation. Little is known about the physiological processes involved. Two propositions of how the brain achieves this task are backpropagation or backprop and positive feedback from the endocrine system. Backprop has been proposed as a mechanism the brain uses to achieve memory consolidation and has been used, for example by Geoffrey E. Hinton, Nobel Prize laureate for Physics in 2024, to build AI software. It implies a feedback to neurons consolidating a given memory to erase that information when the brain learns that that information is misleading or wrong. However, empirical evidence of its existence is not available.[42] On the contrary, positive feedback for consolidating a certain short term memory registered in neurons, and considered by the neuro-endocrine systems to be useful, will make that short term memory to consolidate into a permanent one. This has been shown to be true experimentally first in insects,[43][44][45][46][47] which use arginine and nitric oxide levels in their brains and endorphin receptors for this task. The involvement of arginine and nitric oxide in memory consolidation has been confirmed in birds, mammals and other creatures, including humans.[48] Glial cells have also an important role in memory formation, although how they do their work remains to be unveiled.[49][50] Other mechanisms for memory consolidation can not be discarded. |

記憶の固定 詳細は「記憶の固定」を参照 短期記憶から長期記憶への移行は、記憶の固定と呼ばれる。この過程に関わる生理学的プロセスについては、ほとんどわかっていない。脳がこの作業を達成する 方法に関する2つの仮説は、バックプロパゲーションまたはバックプロップと、内分泌系からの正のフィードバックである。バックプロパゲーションは、脳が記 憶の固定化を達成するために用いるメカニズムとして提案されており、2024年のノーベル物理学賞受賞者であるジェフリー・E・ヒントン氏などによって、 AIソフトウェアの構築に利用されている。これは、脳が特定の記憶を固定化するニューロンにフィードバックを行い、その情報が誤解を招くもの、あるいは誤 りであると学習した際に、その情報を消去することを意味する。しかし、その存在を示す実証的な証拠は得られていない。[42] それどころか、神経細胞に記録されたある短期記憶を固定化し、神経内分泌系が有用であるとみなす正のフィードバックは、その短期記憶を恒久的な記憶に固定 化する。これは、まず昆虫で実験的に証明されている。[43][44][45][46][47] 昆虫は、この作業のために脳内のアルギニンと一酸化窒素のレベル、およびエンドルフィン受容体を使用している。アルギニンと一酸化窒素が記憶の固定に関与 していることは、鳥類、哺乳類、そして人間を含むその他の生物でも確認されている。[48] グリア細胞もまた記憶形成において重要な役割を果たしているが、その仕組みはまだ解明されていない。[49][50] 記憶の固定に関するその他のメカニズムも無視することはできない。 |

Multi-store model Multi-store model The multi-store model (also known as Atkinson–Shiffrin memory model) was first described in 1968 by Atkinson and Shiffrin. The multi-store model has been criticised for being too simplistic. For instance, long-term memory is believed to be actually made up of multiple subcomponents, such as episodic and procedural memory. It also proposes that rehearsal is the only mechanism by which information eventually reaches long-term storage, but evidence shows us capable of remembering things without rehearsal. The model also shows all the memory stores as being a single unit whereas research into this shows differently. For example, short-term memory can be broken up into different units such as visual information and acoustic information. In a study by Zlonoga and Gerber (1986), patient 'KF' demonstrated certain deviations from the Atkinson–Shiffrin model. Patient KF was brain damaged, displaying difficulties regarding short-term memory. Recognition of sounds such as spoken numbers, letters, words, and easily identifiable noises (such as doorbells and cats meowing) were all impacted. Visual short-term memory was unaffected, suggesting a dichotomy between visual and audial memory.[51] |

マルチストアモデル マルチストアモデル マルチストアモデル(アトキンソン・シフリン記憶モデルとも呼ばれる)は、1968年にアトキンソンとシフリンによって初めて説明された。 マルチストアモデルは単純化しすぎているという批判がある。例えば、長期記憶は実際にはエピソード記憶や手続き記憶など複数のサブコンポーネントで構成さ れていると考えられている。また、リハーサルが唯一の情報が最終的に長期記憶に到達するメカニズムであると提案しているが、リハーサルなしでも物事を記憶 できることが証明されている。 また、このモデルではすべての記憶が単一のユニットとして示されているが、この点については異なる研究結果も示されている。例えば、短期記憶は視覚情報や 音響情報など、異なるユニットに分割することができる。ZlonogaとGerber(1986年)による研究では、患者「KF」がアトキンソン=シフリ ンモデルから逸脱した行動を示した。患者KFは脳に損傷があり、短期記憶に問題があった。数字、文字、単語、そして容易に識別できる騒音(ドアベルや猫の 鳴き声など)の音声認識に影響が見られた。視覚短期記憶には影響がなく、視覚と聴覚の記憶の間に二分法が存在することを示唆している。[51] |

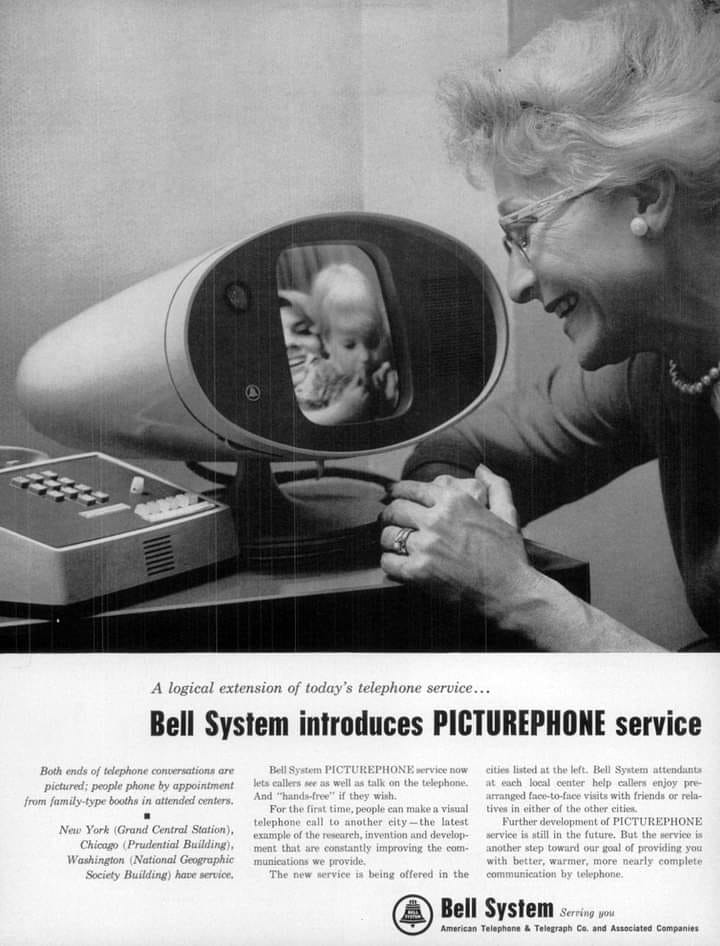

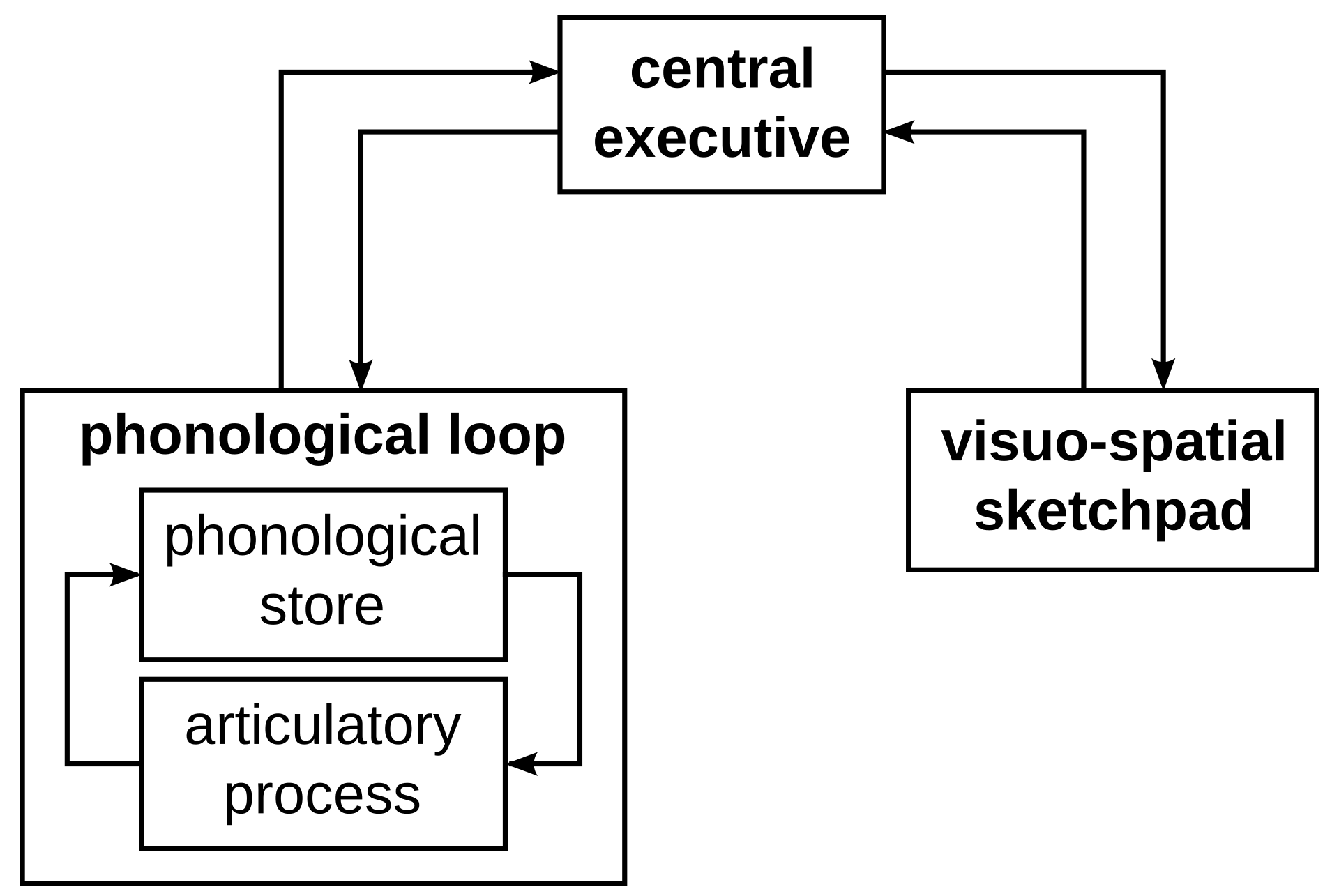

| Working memory Main article: Working memory  The working memory model In 1974 Baddeley and Hitch proposed a "working memory model" that replaced the general concept of short-term memory with active maintenance of information in short-term storage. In this model, working memory consists of three basic stores: the central executive, the phonological loop, and the visuo-spatial sketchpad. In 2000 this model was expanded with the multimodal episodic buffer (Baddeley's model of working memory).[52] The central executive essentially acts as an attention sensory store. It channels information to the three component processes: the phonological loop, the visuospatial sketchpad, and the episodic buffer. The phonological loop stores auditory information by silently rehearsing sounds or words in a continuous loop: the articulatory process (for example the repetition of a telephone number over and over again). A short list of data is easier to remember. The phonological loop is occasionally disrupted. Irrelevant speech or background noise can impede the phonological loop. Articulatory suppression can also confuse encoding and words that sound similar can be switched or misremembered through the phonological similarity effect. the phonological loop also has a limit to how much it can hold at once which means that it is easier to remember a lot of short words rather than a lot of long words, according to the word length effect. The visuospatial sketchpad stores visual and spatial information. It is engaged when performing spatial tasks (such as judging distances) or visual ones (such as counting the windows on a house or imagining images). Those with aphantasia will not be able to engage the visuospatial sketchpad. The episodic buffer is dedicated to linking information across domains to form integrated units of visual, spatial, and verbal information and chronological ordering (e.g., the memory of a story or a movie scene). The episodic buffer is also assumed to have links to long-term memory and semantic meaning. The working memory model explains many practical observations, such as why it is easier to do two different tasks, one verbal and one visual, than two similar tasks, and the aforementioned word-length effect. Working memory is also the premise for what allows us to do everyday activities involving thought. It is the section of memory where we carry out thought processes and use them to learn and reason about topics.[52] |

ワーキングメモリ 詳細は「ワーキングメモリ」を参照  ワーキングメモリモデル 1974年、バドリーとヒッチは、短期記憶の一般的な概念を、短期記憶装置内の情報の能動的な維持に置き換える「ワーキングメモリモデル」を提唱した。こ のモデルでは、ワーキングメモリは3つの基本的な記憶装置、すなわち、中央実行部、音韻ループ、視覚・空間的スケッチパッドから構成される。2000年に は、このモデルがマルチモーダルエピソードバッファー(ワーキングメモリーのBaddeleyモデル)によって拡張された。[52] 中央実行機能は、基本的に注意の感覚的ストアとして機能する。 情報を3つの構成プロセス、すなわち音韻ループ、視空間スケットパッド、エピソードバッファーに流す。 音韻ループは、音や単語を無言で反復練習することで、聴覚情報を記憶する。反復練習の例としては、電話番号を何度も繰り返し言うなどがある。 短いリストの方が記憶しやすい。音韻ループは時折中断される。無関係な音声や背景雑音は音韻ループを妨害する可能性がある。調音抑制は、エンコーディング を混乱させる可能性もある。また、音韻ループは一度に保持できる情報量に限界がある。つまり、語長効果によると、長い単語よりも短い単語を多く記憶する方 が容易である。 視空間ス ケッチパッドは視覚的および空間的な情報を保存する。これは、空間的なタスク(距離の判断など)や視覚的なタスク(家の窓の数を数えたり、イメージを想像したりするなど)を実行する際に使用される。失体感症の患者は視空間ス ケッチパッドを使用できない。 エピソードバッファーは、視覚、空間、言語の統合された情報単位や時系列の順序(例えば、物語や映画のシーンの記憶)を形成するために、さまざまな領域に わたる情報のリンクに専念している。エピソードバッファーはまた、長期記憶や意味的意味ともリンクしていると考えられている。 作業記憶モデルは、口頭と視覚による2つの異なる作業を行う方が、類似した2つの作業を行うよりも容易である理由や、前述の語長効果など、多くの実用的な 観察結果を説明している。作業記憶は、思考を伴う日常的な活動を可能にする前提でもある。作業記憶は、思考プロセスを実行し、学習やテーマに関する推論に それらを使用する記憶の一部である。[52] |

| Types Researchers distinguish between recognition and recall memory. Recognition memory tasks require individuals to indicate whether they have encountered a stimulus (such as a picture or a word) before. Recall memory tasks require participants to retrieve previously learned information. For example, individuals might be asked to produce a series of actions they have seen before or to say a list of words they have heard before. By information type Topographical memory involves the ability to orient oneself in space, to recognize and follow an itinerary, or to recognize familiar places.[53] Getting lost when traveling alone is an example of the failure of topographic memory.[54] Flashbulb memories are clear episodic memories of unique and highly emotional events.[55] People remembering where they were or what they were doing when they first heard the news of President Kennedy's assassination,[56] the Sydney Siege or of 9/11 are examples of flashbulb memories. Long-term Anderson (1976)[57] divides long-term memory into declarative (explicit) and procedural (implicit) memories. Declarative Main article: Declarative memory Declarative memory requires conscious recall, in that some conscious process must call back the information. It is sometimes called explicit memory, since it consists of information that is explicitly stored and retrieved. Declarative memory can be further sub-divided into semantic memory, concerning principles and facts taken independent of context; and episodic memory, concerning information specific to a particular context, such as a time and place. Semantic memory allows the encoding of abstract knowledge about the world, such as "Paris is the capital of France". Episodic memory, on the other hand, is used for more personal memories, such as the sensations, emotions, and personal associations of a particular place or time. Episodic memories often reflect the "firsts" in life such as a first kiss, first day of school or first time winning a championship. These are key events in one's life that can be remembered clearly. Research suggests that declarative memory is supported by several functions of the medial temporal lobe system which includes the hippocampus.[58] Autobiographical memory – memory for particular events within one's own life – is generally viewed as either equivalent to, or a subset of, episodic memory. Visual memory is part of memory preserving some characteristics of our senses pertaining to visual experience. One is able to place in memory information that resembles objects, places, animals or people in sort of a mental image. Visual memory can result in priming and it is assumed some kind of perceptual representational system underlies this phenomenon.[58] Procedural In contrast, procedural memory (or implicit memory) is not based on the conscious recall of information, but on implicit learning. It can best be summarized as remembering how to do something. Procedural memory is primarily used in learning motor skills and can be considered a subset of implicit memory. It is revealed when one does better in a given task due only to repetition – no new explicit memories have been formed, but one is unconsciously accessing aspects of those previous experiences. Procedural memory involved in motor learning depends on the cerebellum and basal ganglia.[59] A characteristic of procedural memory is that the things remembered are automatically translated into actions, and thus sometimes difficult to describe. Some examples of procedural memory include the ability to ride a bike or tie shoelaces.[60] |

種類 研究者たちは、認識記憶と想起記憶を区別している。認識記憶の課題では、個人が刺激(絵や言葉など)に以前に出くわしたことがあるかどうかを示すことが求 められる。想起記憶の課題では、参加者が以前に学んだ情報を取り出すことが求められる。例えば、個人は以前に見た一連の行動を再現したり、以前に聞いたこ とのある言葉のリストを言ったりすることが求められる。 情報の種類によって 空間記憶は、空間における自己の位置を把握する能力、旅程を認識しそれに従う能力、または見慣れた場所を認識する能力を伴う。[53] 単独で旅行中に道に迷うことは、空間記憶の失敗の例である。[54] フラッシュバルブ記憶とは、独特で感情的な出来事の鮮明なエピソード記憶である。[55] ケネディ大統領暗殺のニュースを最初に聞いたとき、自分がどこにいたか、何をしていただかを覚えている人々、[56] シドニーの立てこもり事件や9.11の事件を覚えている人々は、フラッシュバルブ記憶の例である。 長期 アンダーソン(1976年)[57]は、長期記憶を宣言的(明示的)記憶と手続き的(暗示的)記憶に分けている。 宣言的 詳細は「宣言的記憶」を参照 宣言的記憶は、意識的な想起を必要とする。つまり、意識的なプロセスによって情報を呼び戻さなければならない。明示的に保存され、取り出される情報から構 成されるため、明示的記憶と呼ばれることもある。宣言的記憶はさらに、文脈から独立した原則や事実に関する意味記憶と、時間や場所など特定の文脈に特有な 情報に関するエピソード記憶に細分化できる。意味記憶は、「パリはフランスの首都である」といった、世界に関する抽象的な知識のエンコードを可能にする。 一方、エピソード記憶は、特定の場所や時間に関する感覚、感情、個人的な連想など、より個人的な記憶に使用される。エピソード記憶は、ファーストキス、学 校初日、優勝初体験など、人生における「初めて」の出来事を反映することが多い。これらは、はっきりと記憶できる人生の重要な出来事である。 研究によると、宣言的記憶は海馬を含む内側側頭葉システムのいくつかの機能によって支えられていることが示唆されている。[58] 自伝的記憶(自分の人生における特定の出来事に関する記憶)は、一般的に、エピソード記憶と同等であるか、またはその一部であると見なされている。視覚記 憶は、視覚体験に関する感覚の特性を保持する記憶の一部である。人は、物体、場所、動物、人物などを、ある種の心象イメージとして記憶に留めることができ る。視覚記憶はプライミングを引き起こす可能性があり、この現象の根底には何らかの知覚表現システムがあると考えられている。 手続き的 これに対し、手続き的記憶(または潜在的記憶)は、意識的な情報の想起ではなく、潜在的な学習に基づいている。手続き記憶は、主に運動技能の習得に用いら れ、潜在記憶のサブセットと考えることができる。反復練習のみによって特定の課題をより上手にこなせるようになったときに、手続き記憶が明らかになる。新 しい顕在記憶が形成されたわけではないが、無意識のうちに以前の経験の一部にアクセスしている。運動学習に関わる手続き記憶は小脳と大脳基底核に依存して いる。 手続き記憶の特徴は、記憶されたことが自動的に行動に変換されるため、説明が難しい場合があることである。手続き記憶の例としては、自転車に乗る能力や靴ひもを結ぶ能力などがある。[60] |

| By temporal direction Another major way to distinguish different memory functions is whether the content to be remembered is in the past, retrospective memory, or in the future, prospective memory. John Meacham introduced this distinction in a paper presented at the 1975 American Psychological Association annual meeting and subsequently included by Ulric Neisser in his 1982 edited volume, Memory Observed: Remembering in Natural Contexts.[61][62] Thus, retrospective memory as a category includes semantic, episodic and autobiographical memory. In contrast, prospective memory is memory for future intentions, or remembering to remember (Winograd, 1988). Prospective memory can be further broken down into event- and time-based prospective remembering. Time-based prospective memories are triggered by a time-cue, such as going to the doctor (action) at 4pm (cue). Event-based prospective memories are intentions triggered by cues, such as remembering to post a letter (action) after seeing a mailbox (cue). Cues do not need to be related to the action (as the mailbox/letter example), and lists, sticky-notes, knotted handkerchiefs, or string around the finger all exemplify cues that people use as strategies to enhance prospective memory. |

時間的順序による 異なる記憶機能を区別するもう一つの主な方法は、記憶される内容が過去のものであるか、回顧的記憶であるか、あるいは未来のものであるか、予測的記憶であ るかである。ジョン・ミッチェムは、1975年の米国心理学会の年次総会で発表した論文でこの区別を導入し、その後、1982年にウルリック・ニーサーが 編集した『観察された記憶:自然な文脈における想起』に収録された。自然な文脈における記憶)に収録された。したがって、カテゴリーとしての回顧的記憶に は、意味記憶、エピソード記憶、および自伝的記憶が含まれる。これに対し、プロスペクティブ・メモリーは、将来の意図に関する記憶、すなわち「覚えるため に覚える」記憶である(Winograd, 1988)。プロスペクティブ・メモリーはさらに、出来事ベースのプロスペクティブ・リメンバー(将来の出来事を思い出すこと)と時間ベースのプロスペク ティブ・リメンバー(将来の予定を思い出すこと)に分類できる。時間ベースのプロスペクティブ・リメンバーは、午後4時に医者に診察に行く(行動)という 時間的な手がかり(キュー)によって引き起こされる。出来事ベースのプロスペクティブ・リメンバーは、郵便受けを見た後に手紙を投函する(行動)という キューによって引き起こされる意図である。キューは行動に関連している必要はない(郵便受けと手紙の例のように)。リスト、付箋、結び目をつけたハンカ チ、指に巻いた紐などは、すべて、将来記憶力を高めるための戦略として人々が用いるキューの例である。 |

| Study techniques To assess infants Infants do not have the language ability to report on their memories and so verbal reports cannot be used to assess very young children's memory. Throughout the years, however, researchers have adapted and developed a number of measures for assessing both infants' recognition memory and their recall memory. Habituation and operant conditioning techniques have been used to assess infants' recognition memory and the deferred and elicited imitation techniques have been used to assess infants' recall memory. Techniques used to assess infants' recognition memory include the following: Visual paired comparison procedure (relies on habituation): infants are first presented with pairs of visual stimuli, such as two black-and-white photos of human faces, for a fixed amount of time; then, after being familiarized with the two photos, they are presented with the "familiar" photo and a new photo. The time spent looking at each photo is recorded. Looking longer at the new photo indicates that they remember the "familiar" one. Studies using this procedure have found that 5- to 6-month-olds can retain information for as long as fourteen days.[63] Operant conditioning technique: infants are placed in a crib and a ribbon that is connected to a mobile overhead is tied to one of their feet. Infants notice that when they kick their foot the mobile moves – the rate of kicking increases dramatically within minutes. Studies using this technique have revealed that infants' memory substantially improves over the first 18-months. Whereas 2- to 3-month-olds can retain an operant response (such as activating the mobile by kicking their foot) for a week, 6-month-olds can retain it for two weeks, and 18-month-olds can retain a similar operant response for as long as 13 weeks.[64][65][66] Techniques used to assess infants' recall memory include the following: Deferred imitation technique: an experimenter shows infants a unique sequence of actions (such as using a stick to push a button on a box) and then, after a delay, asks the infants to imitate the actions. Studies using deferred imitation have shown that 14-month-olds' memories for the sequence of actions can last for as long as four months.[67] Elicited imitation technique: is very similar to the deferred imitation technique; the difference is that infants are allowed to imitate the actions before the delay. Studies using the elicited imitation technique have shown that 20-month-olds can recall the action sequences twelve months later.[68][69] |

研究手法 乳幼児の評価 乳幼児は、自分の記憶を報告する言語能力を持っていないため、幼い子どもの記憶を評価する際に言語による報告は使用できない。しかし、長年にわたり、研究 者たちは乳幼児の認識記憶と想起記憶の両方を評価するためのさまざまな手法を適応させ、開発してきた。乳幼児の認識記憶を評価するために慣れとオペラント 条件付けの手法が使用され、乳幼児の想起記憶を評価するために遅延再生と誘発模倣の手法が使用されてきた。 乳児の認識記憶を評価する手法には、以下のようなものがある。 視覚ペア比較手順(馴化に依存):まず乳児に、2枚の白黒写真(例えば、人間の顔写真)などの視覚刺激のペアを一定時間提示する。次に、2枚の写真に慣れ させた後、「見慣れた」写真と新しい写真を見せる。各写真を見ている時間を記録する。新しい写真を見つめる時間が長いということは、「見慣れた」写真を覚 えていることを示す。この手順を用いた研究では、生後5~6か月の乳児でも14日間も情報を保持できることが分かっている。 オペラント条件付けのテクニック:乳児をベビーベッドに寝かせ、天井から吊るしたモビールに繋がれたリボンを乳児の足に結びつける。乳児は、足を蹴るとモ ビールが動くことに気づき、数分以内に蹴る回数が劇的に増える。この手法を用いた研究により、乳児の記憶力は最初の18か月間で大幅に向上することが明ら かになっている。生後2~3か月の乳児は、足で床を蹴ってモビールを動かすなどのオペラント反応を1週間維持できるが、生後6か月の乳児は2週間、生後 18か月の乳児は13週間も同様のオペラント反応を維持できる。[64][65][66] 乳幼児の想起記憶を評価する際に用いられる手法には、以下のようなものがある。 遅延模倣法:実験者が乳幼児に一連の独特な行動(例えば、棒を使って箱のボタンを押す)を見せ、しばらく時間を置いてから、乳幼児にその行動を模倣するように求める。遅延模倣法を用いた研究では、14ヶ月児の一連の行動の記憶は4ヶ月間持続することが示されている。 誘発模倣法:遅延模倣法と非常に類似しているが、異なるのは、乳児が遅延前に行動を模倣することが許可される点である。誘発模倣法を用いた研究では、20ヶ月児が12ヶ月後に行動の順序を思い出すことができることが示されている。[68][69] |

| To assess children and older adults Researchers use a variety of tasks to assess older children and adults' memory. Some examples are: Paired associate learning – when one learns to associate one specific word with another. For example, when given a word such as "safe" one must learn to say another specific word, such as "green". This is stimulus and response.[70][71] Free recall – during this task a subject would be asked to study a list of words and then later they will be asked to recall or write down as many words that they can remember, similar to free response questions.[72] Earlier items are affected by retroactive interference (RI), which means the longer the list, the greater the interference, and the less likelihood that they are recalled. On the other hand, items that have been presented lastly suffer little RI, but suffer a great deal from proactive interference (PI), which means the longer the delay in recall, the more likely that the items will be lost.[73] Cued recall – one is given a significant hints to help retrieve information that has been previously encoded into the person's memory; typically this can involve a word relating to the information being asked to remember.[74] This is similar to fill in the blank assessments used in classrooms. Recognition – subjects are asked to remember a list of words or pictures, after which point they are asked to identify the previously presented words or pictures from among a list of alternatives that were not presented in the original list.[75] This is similar to multiple choice assessments. Detection paradigm – individuals are shown a number of objects and color samples during a certain period of time. They are then tested on their visual ability to remember as much as they can by looking at testers and pointing out whether the testers are similar to the sample, or if any change is present. Savings method – compares the speed of originally learning to the speed of relearning it. The amount of time saved measures memory.[76] Implicit-memory tasks – information is drawn from memory without conscious realization. |

子供や高齢者の評価 研究者たちは、高齢の子供や大人の記憶力を評価するために、さまざまな課題を用いる。 例としては以下のようなものがある。 ペアード・アソシエイト・ラーニング(ペアード連想学習) - ある特定の単語を別の単語と関連付けることを学習する。例えば、「金庫」という単語が与えられた場合、「緑」という別の特定の単語を言うことを学習する。これは刺激と反応である。[70][71] 自由再生 – この課題では、被験者は単語のリストを学習し、その後、記憶している単語をできるだけ多く思い出すか書き出すよう求められる。これは自由回答形式の質問に 似ている。[72] リストの項目は、より長いほど干渉が大きくなり、想起される可能性が低くなることを意味する。一方、最後に提示された項目は、逆向干渉の影響はほとんど受 けないが、先行干渉の影響を大きく受ける。先行干渉とは、想起の遅延が長くなるほど、項目が失われる可能性が高くなることを意味する。 手がかり再生(Cued recall) - 個人の記憶に以前にエンコードされた情報を取り出すのを助けるために、重要なヒントが与えられる。通常、これは記憶するよう求められている情報に関連する 言葉を含むことができる。[74] これは、教室で使用される穴埋めテストに類似している。 認識 – 被験者は単語や画像のリストを記憶するように求められ、その後、元のリストには含まれていなかった選択肢のリストの中から、以前に提示された単語や画像を特定するように求められる。[75] これは多肢選択式の評価に似ている。 検出パラダイム – 個人は一定の時間内に、多数の物体や色見本を見せられる。その後、被験者は、できるだけ多くのものを覚えるために、テスターを見ながら、そのテスターがサンプルと類似しているかどうか、あるいは何か変化があるかどうかを指摘する視覚能力を試される。 貯蓄法 – 最初に学習する速度と、それを再学習する速度を比較する。 節約された時間量は記憶力を測定する。[76] 潜在記憶作業 – 意識的に認識することなく、記憶から情報が引き出される。 |

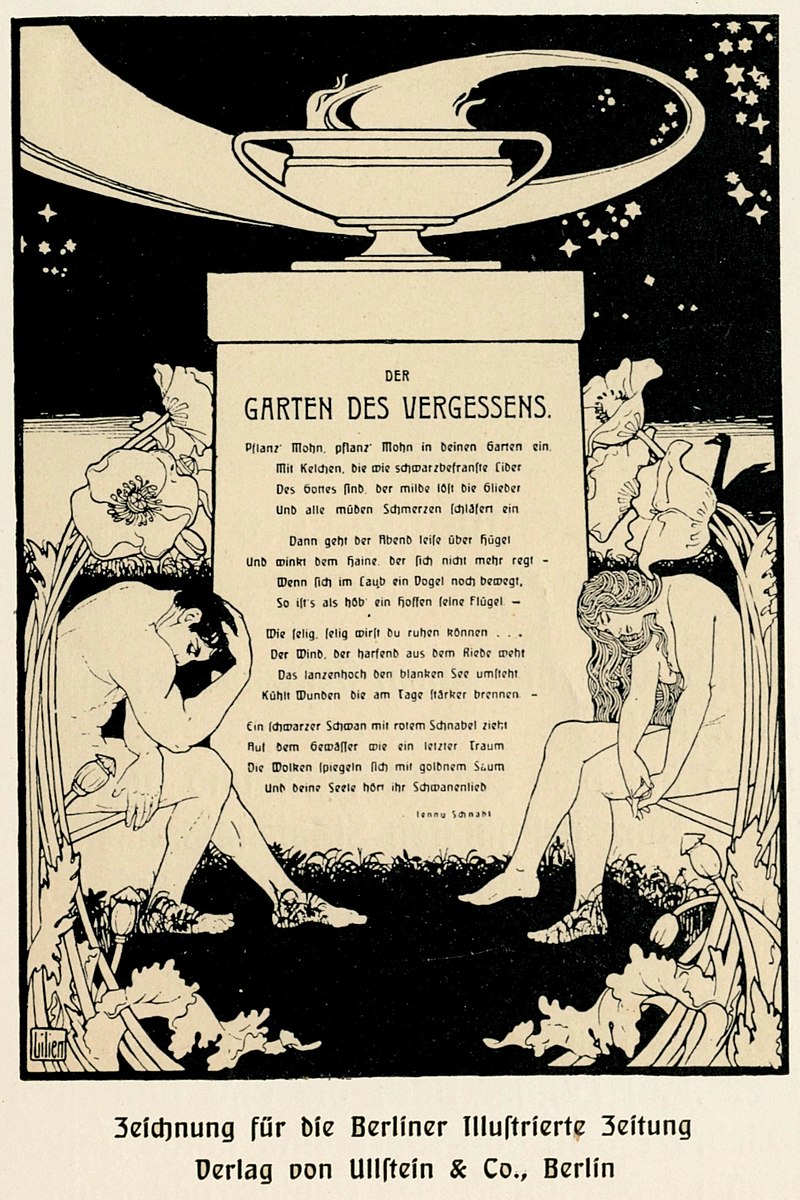

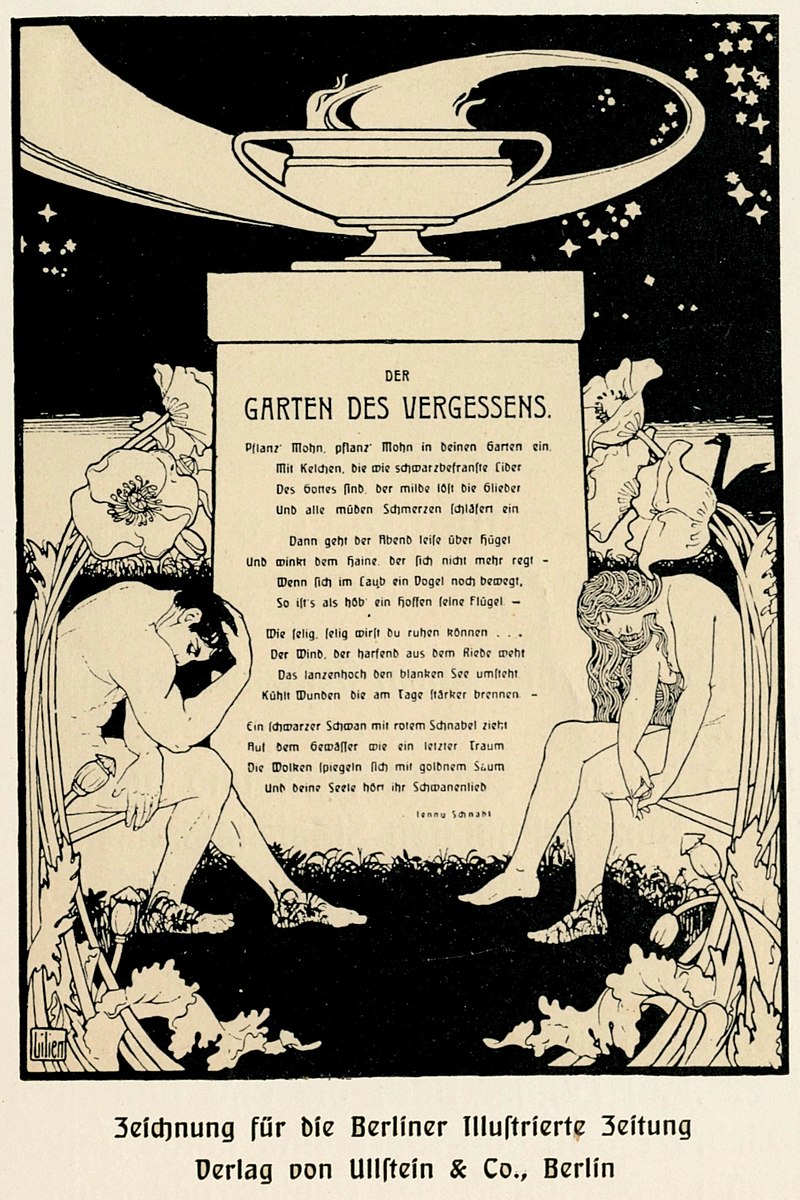

| Failures See also: Eyewitness memory  The garden of oblivion, illustration by Ephraim Moses Lilien Transience – memories degrade with the passing of time. This occurs in the storage stage of memory, after the information has been stored and before it is retrieved. This can happen in sensory, short-term, and long-term storage. It follows a general pattern where the information is rapidly forgotten during the first couple of days or years, followed by small losses in later days or years. Absent-mindedness – Memory failure due to the lack of attention. Attention plays a key role in storing information into long-term memory; without proper attention, the information might not be stored, making it impossible to be retrieved later. |

失敗 参照:目撃者の記憶  忘却の庭、エフライム・モーゼス・リリアンによるイラスト 儚さ - 記憶は時間の経過とともに劣化する。これは、情報が記憶された後、取り出される前の記憶の保管段階で起こる。感覚、短期、長期の保管で起こりうる。一般的 に、最初の数日または数年で急速に情報が忘れられ、その後、数年または数年の間に少しずつ失われていくというパターンがある。 うっかりミス – 注意不足による記憶障害。注意は長期記憶に情報を保存する上で重要な役割を果たしている。適切な注意が払われないと、情報が保存されず、後で取り出すことができなくなる可能性がある。 |

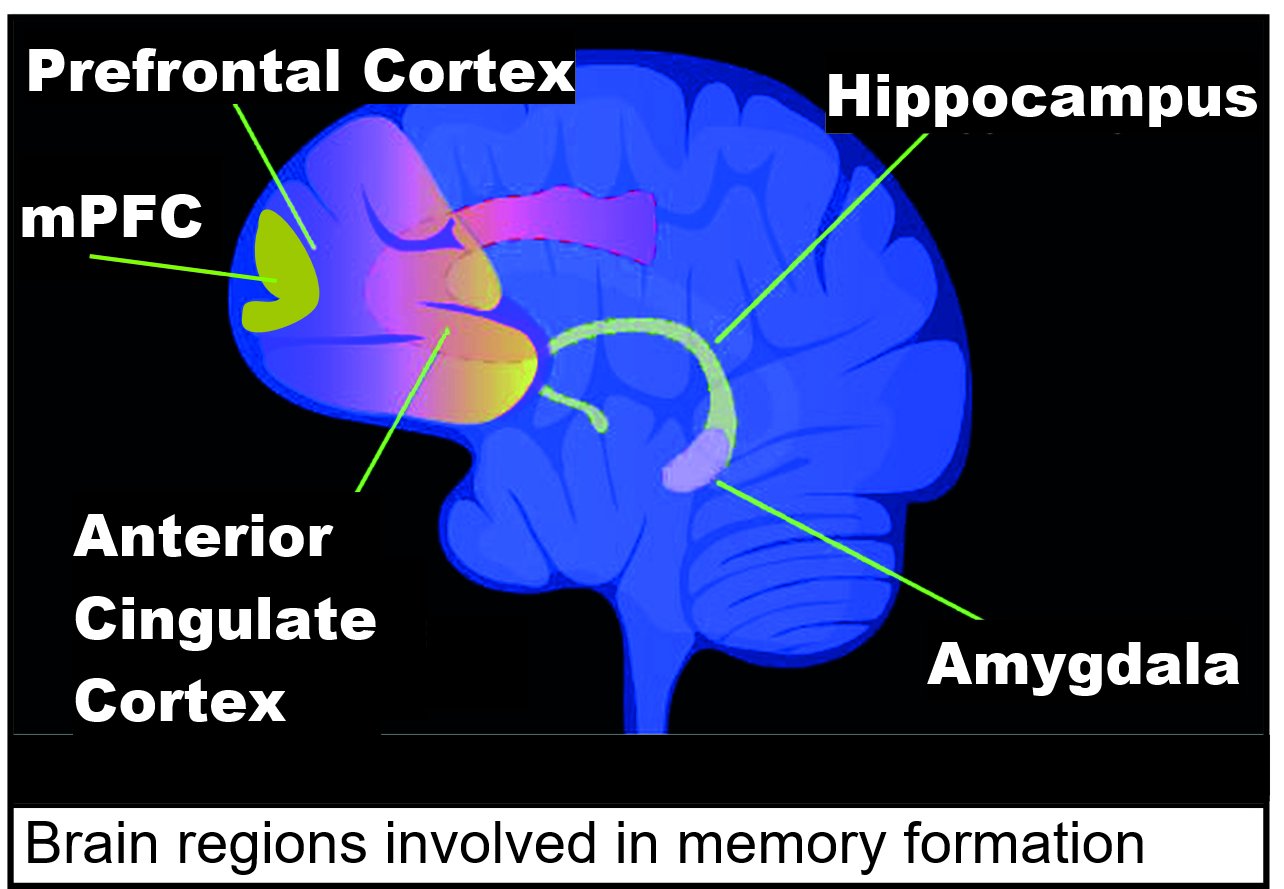

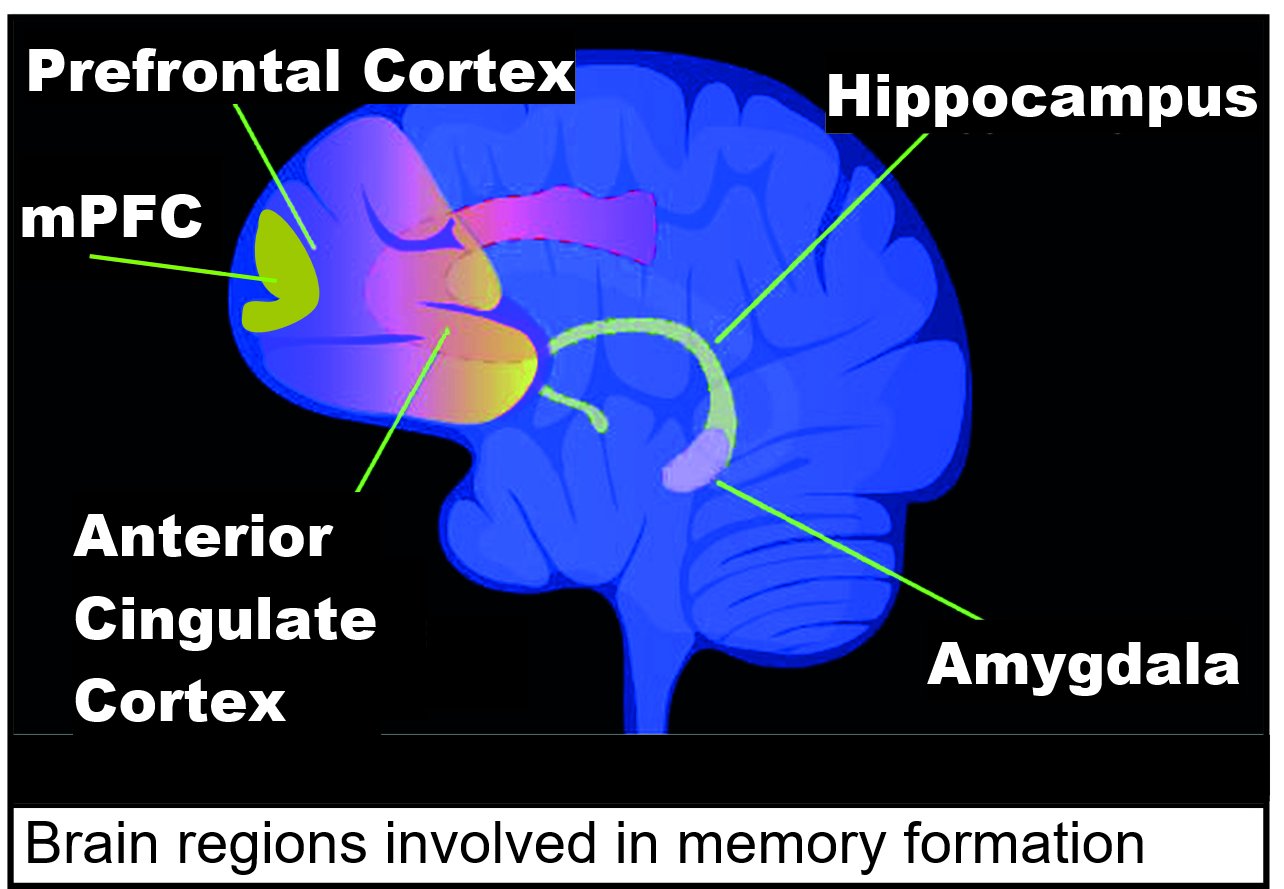

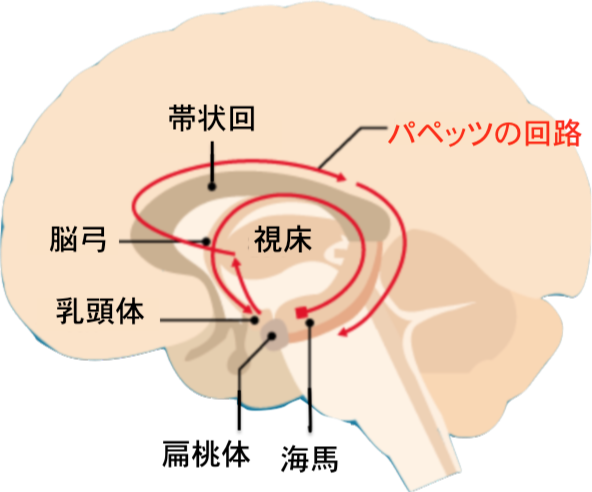

| Physiology Brain areas involved in the neuroanatomy of memory such as the hippocampus, the amygdala, the striatum, or the mammillary bodies are thought to be involved in specific types of memory. For example, the hippocampus is believed to be involved in spatial learning and declarative learning, while the amygdala is thought to be involved in emotional memory.[77] Damage to certain areas in patients and animal models and subsequent memory deficits is a primary source of information. However, rather than implicating a specific area, it could be that damage to adjacent areas, or to a pathway traveling through the area is actually responsible for the observed deficit. Further, it is not sufficient to describe memory, and its counterpart, learning, as solely dependent on specific brain regions. Learning and memory are usually attributed to changes in neuronal synapses, thought to be mediated by long-term potentiation and long-term depression. In general, the more emotionally charged an event or experience is, the better it is remembered; this phenomenon is known as the memory enhancement effect. Patients with amygdala damage, however, do not show a memory enhancement effect.[78][79] Hebb distinguished between short-term and long-term memory. He postulated that any memory that stayed in short-term storage for a long enough time would be consolidated into a long-term memory. Later research showed this to be false. Research has shown that direct injections of cortisol or epinephrine help the storage of recent experiences. This is also true for stimulation of the amygdala. This proves that excitement enhances memory by the stimulation of hormones that affect the amygdala. Excessive or prolonged stress (with prolonged cortisol) may hurt memory storage. Patients with amygdalar damage are no more likely to remember emotionally charged words than nonemotionally charged ones. The hippocampus is important for explicit memory. The hippocampus is also important for memory consolidation. The hippocampus receives input from different parts of the cortex and sends its output out to different parts of the brain also. The input comes from secondary and tertiary sensory areas that have processed the information a lot already. Hippocampal damage may also cause memory loss and problems with memory storage.[80] This memory loss includes retrograde amnesia which is the loss of memory for events that occurred shortly before the time of brain damage.[76] |

生理学 記憶の神経解剖学に関与する脳領域、例えば海馬、扁桃体、線条体、または乳頭体は、特定の種類の記憶に関与していると考えられている。例えば、海馬は空間学習や宣言的学習に関与していると考えられているが、扁桃体は情動記憶に関与していると考えられている。 患者や動物モデルの特定の部位が損傷を受け、その後に記憶障害が現れることは、主な情報源となっている。しかし、特定の部位が関係しているというよりも、 隣接する部位、あるいはその部位を通る経路が損傷を受けることが、実際に観察された障害の原因となっている可能性もある。さらに、記憶とその関連事項であ る学習を、特定の脳の部位のみに依存していると表現することは不十分である。学習と記憶は通常、神経シナプスの変化に起因すると考えられており、それは長 期増強と長期抑圧によって媒介されていると考えられている。 一般的に、感情を強く揺さぶられるような出来事や経験は、よりよく記憶される。この現象は記憶増強効果として知られている。しかし、扁桃体に損傷のある患者には記憶増強効果が見られない。[78][79] ヘッブは短期記憶と長期記憶を区別した。彼は、短期記憶に十分な長期間留まった記憶は、長期記憶に統合されると仮定した。しかし、その後の研究により、こ れは誤りであることが判明した。研究により、コルチゾールまたはエピネフリンの直接注入が最近の経験の保存に役立つことが示されている。これは扁桃体の刺 激についても同様である。これは、興奮が扁桃体に影響を与えるホルモンの刺激によって記憶力を高めることを証明している。過剰なストレスや長期間にわたる ストレス(コルチゾールが長期間にわたって分泌される)は、記憶の保存に悪影響を及ぼす可能性がある。扁桃体に損傷のある患者は、感情を伴う言葉と感情を 伴わない言葉のどちらを記憶する可能性も変わらない。海馬は明示的記憶にとって重要である。海馬は記憶の固定にも重要である。海馬は大脳皮質の異なる部分 から入力を受け、その出力を脳の異なる部分に送り出す。入力は、すでに多くの情報を処理した二次および三次感覚領域から送られてくる。海馬の損傷は、記憶 喪失や記憶の保存に関する問題を引き起こす可能性もある。[80] この記憶喪失には逆行性健忘が含まれ、これは脳損傷の直前に起こった出来事の記憶を失うものである。[76] |

| Cognitive neuroscience Main article: Cognitive neuroscience Cognitive neuroscientists consider memory as the retention, reactivation, and reconstruction of the experience-independent internal representation. The term of internal representation implies that such a definition of memory contains two components: the expression of memory at the behavioral or conscious level, and the underpinning physical neural changes (Dudai 2007). The latter component is also called engram or memory traces (Semon 1904). Some neuroscientists and psychologists mistakenly equate the concept of engram and memory, broadly conceiving all persisting after-effects of experiences as memory; others argue against this notion that memory does not exist until it is revealed in behavior or thought (Moscovitch 2007). One question that is crucial in cognitive neuroscience is how information and mental experiences are coded and represented in the brain. Scientists have gained much knowledge about the neuronal codes from the studies of plasticity, but most of such research has been focused on simple learning in simple neuronal circuits; it is considerably less clear about the neuronal changes involved in more complex examples of memory, particularly declarative memory that requires the storage of facts and events (Byrne 2007). Convergence-divergence zones might be the neural networks where memories are stored and retrieved. Considering that there are several kinds of memory, depending on types of represented knowledge, underlying mechanisms, processes functions and modes of acquisition, it is likely that different brain areas support different memory systems and that they are in mutual relationships in neuronal networks: "components of memory representation are distributed widely across different parts of the brain as mediated by multiple neocortical circuits".[81] Encoding. Encoding of working memory involves the spiking of individual neurons induced by sensory input, which persists even after the sensory input disappears (Jensen and Lisman 2005; Fransen et al. 2002). Encoding of episodic memory involves persistent changes in molecular structures that alter synaptic transmission between neurons. Examples of such structural changes include long-term potentiation (LTP) or spike-timing-dependent plasticity (STDP). The persistent spiking in working memory can enhance the synaptic and cellular changes in the encoding of episodic memory (Jensen and Lisman 2005). Working memory. Recent functional imaging studies detected working memory signals in both medial temporal lobe (MTL), a brain area strongly associated with long-term memory, and prefrontal cortex (Ranganath et al. 2005), suggesting a strong relationship between working memory and long-term memory. However, the substantially more working memory signals seen in the prefrontal lobe suggest that this area plays a more important role in working memory than MTL (Suzuki 2007). Consolidation and reconsolidation. Short-term memory (STM) is temporary and subject to disruption, while long-term memory (LTM), once consolidated, is persistent and stable. Consolidation of STM into LTM at the molecular level presumably involves two processes: synaptic consolidation and system consolidation. The former involves a protein synthesis process in the medial temporal lobe (MTL), whereas the latter transforms the MTL-dependent memory into an MTL-independent memory over months to years (Ledoux 2007). In recent years, such traditional consolidation dogma has been re-evaluated as a result of the studies on reconsolidation. These studies showed that prevention after retrieval affects subsequent retrieval of the memory (Sara 2000). New studies have shown that post-retrieval treatment with protein synthesis inhibitors and many other compounds can lead to an amnestic state (Nadel et al. 2000b; Alberini 2005; Dudai 2006). These findings on reconsolidation fit with the behavioral evidence that retrieved memory is not a carbon copy of the initial experiences, and memories are updated during retrieval. |

認知神経科学 詳細は「認知神経科学」を参照 認知神経科学者は、記憶を経験に依存しない内的表現の保持、再活性化、再構成とみなしている。内的表現という用語は、記憶の定義には2つの要素が含まれる ことを示唆している。すなわち、行動または意識レベルにおける記憶の表現と、それを支える物理的な神経変化である(Dudai 2007)。後者の要素は、エングラムまたは記憶痕跡とも呼ばれる(Semon 1904)。一部の神経科学者や心理学者は、経験の後に残る持続的な影響をすべて記憶と広く捉え、誤ってエングラムと記憶の概念を同一視している。また、 記憶は行動や思考に表れるまでは存在しないという考え方もある(Moscovitch 2007)。 認知神経科学において重要な問題のひとつは、脳内で情報や精神体験がどのように符号化され、表現されるかということである。科学者たちは可塑性に関する研 究からニューロンコードに関する多くの知識を得ているが、そのような研究のほとんどは単純なニューロン回路における単純な学習に焦点を当てたものであり、 事実や出来事の記憶を必要とする宣言的記憶(declarative memory)のような、より複雑な記憶の例に関わるニューロン変化については、かなり不明瞭である(Byrne 2007)。収束・発散領域は、記憶が保存され、呼び出される神経ネットワークである可能性がある。表象される知識の種類、基礎となるメカニズム、プロセ ス、機能、獲得の様式によって、いくつかの種類の記憶が存在することを考慮すると、異なる脳領域が異なる記憶システムを支え、それらが神経ネットワークに おいて相互関係にある可能性が高い。「記憶表象の構成要素は、複数の新皮質回路によって媒介されるように、脳の異なる部分に広く分布している」[81]。 エンコーディング。作業記憶のエンコーディングには、感覚入力によって引き起こされる個々のニューロンのスパイクが関与しており、感覚入力が消滅した後も 持続する(Jensen and Lisman 2005; Fransen et al. 2002)。エピソード記憶のエンコーディングには、ニューロン間のシナプス伝達を変化させる分子構造の持続的な変化が関与している。このような構造変化 の例としては、長期増強(LTP)やスパイクタイミング依存性可塑性(STDP)などがある。作業記憶における持続的なスパイクは、エピソード記憶のエン コーディングにおけるシナプスおよび細胞の変化を促進する可能性がある(Jensen and Lisman 2005)。 作業記憶。最近の機能画像研究では、長期記憶と強い関連性を持つ脳領域である内側側頭葉(MTL)と前頭前野の両方で作業記憶の信号が検出され (Ranganath et al. 2005)、作業記憶と長期記憶の間に強い関連性があることが示唆された。しかし、前頭前野で検出された作業記憶の信号ははるかに多く、この領域はMTL よりも作業記憶においてより重要な役割を果たしていることが示唆された(Suzuki 2007)。 固定化と再固定化。短期記憶(STM)は一時的なものであり、混乱しやすいが、長期記憶(LTM)は一度固定化されると持続性があり安定している。STM をLTMに分子レベルで固定化するプロセスには、おそらくシナプス固定化とシステム固定化という2つのプロセスが関与している。前者は内側側頭葉 (MTL)におけるタンパク質合成プロセスに関与し、後者は数か月から数年をかけてMTL依存性の記憶をMTL非依存性の記憶へと変化させる (Ledoux 2007)。近年、再固定化に関する研究の結果、このような従来の固定化の教義が再評価されるようになった。これらの研究では、想起後の予防がその後の記 憶の想起に影響を与えることが示された(Sara 2000)。新たな研究では、タンパク質合成阻害剤やその他の多くの化合物を用いた想起後の処理が健忘状態を引き起こす可能性があることが示されている (Nadel et al. 2000b; Alberini 2005; Dudai 2006)。再固定化に関するこれらの知見は、想起された記憶が最初の経験の単なる複製ではなく、想起中に記憶が更新されるという行動上の証拠と一致す る。 |

| Genetics See also: Long-term potentiation and Eric Kandel Study of the genetics of human memory is in its infancy though many genes have been investigated for their association to memory in humans and non-human animals. A notable initial success was the association of APOE with memory dysfunction in Alzheimer's disease. The search for genes associated with normally varying memory continues. One of the first candidates for normal variation in memory is the protein KIBRA,[82][medical citation needed] which appears to be associated with the rate at which material is forgotten over a delay period. There has been some evidence that memories are stored in the nucleus of neurons.[83][84] Genetic underpinnings Several genes, proteins and enzymes have been extensively researched for their association with memory. Long-term memory, unlike short-term memory, is dependent upon the synthesis of new proteins.[85] This occurs within the cellular body, and concerns the particular transmitters, receptors, and new synapse pathways that reinforce the communicative strength between neurons. The production of new proteins devoted to synapse reinforcement is triggered after the release of certain signaling substances (such as calcium within hippocampal neurons) in the cell. In the case of hippocampal cells, this release is dependent upon the expulsion of magnesium (a binding molecule) that is expelled after significant and repetitive synaptic signaling. The temporary expulsion of magnesium frees NMDA receptors to release calcium in the cell, a signal that leads to gene transcription and the construction of reinforcing proteins.[86] For more information, see long-term potentiation (LTP). One of the newly synthesized proteins in LTP is also critical for maintaining long-term memory. This protein is an autonomously active form of the enzyme protein kinase C (PKC), known as PKMζ. PKMζ maintains the activity-dependent enhancement of synaptic strength and inhibiting PKMζ erases established long-term memories, without affecting short-term memory or, once the inhibitor is eliminated, the ability to encode and store new long-term memories is restored. Also, BDNF is important for the persistence of long-term memories.[87] The long-term stabilization of synaptic changes is also determined by a parallel increase of pre- and postsynaptic structures such as axonal bouton, dendritic spine and postsynaptic density.[88] On the molecular level, an increase of the postsynaptic scaffolding proteins PSD-95 and HOMER1c has been shown to correlate with the stabilization of synaptic enlargement.[88] The cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB) is a transcription factor which is believed to be important in consolidating short-term to long-term memories, and which is believed to be downregulated in Alzheimer's disease.[89] |

遺伝学 関連情報:長期増強、エリック・カンデル 人間の記憶の遺伝学的研究はまだ始まったばかりであるが、人間や人間以外の動物において、多くの遺伝子が記憶との関連性について調査されている。 注目すべき初期の成功例としては、アルツハイマー病における記憶機能障害とAPOEとの関連性が挙げられる。 正常な記憶の変動に関連する遺伝子の探索は現在も続けられている。記憶の正常な変動の最初の候補のひとつは、タンパク質KIBRAである。[82][医学 的引用が必要]これは、遅延期間における材料の忘却率に関連しているようである。記憶がニューロンの核に保存されているという証拠がいくつかある。 [83][84] 遺伝的基礎 いくつかの遺伝子、タンパク質、および酵素が、記憶との関連性について広範囲に研究されている。長期記憶は短期記憶とは異なり、新しいタンパク質の合成に 依存している。[85] この合成は細胞体内で起こり、ニューロン間の伝達能力を強化する特定の伝達物質、受容体、新しいシナプス経路に関係している。シナプス強化に専念する新し いタンパク質の生産は、細胞内の特定の信号物質(海馬ニューロン内のカルシウムなど)が放出された後に引き起こされる。海馬細胞の場合、この放出は、重要 なシナプス信号伝達が繰り返された後に排出されるマグネシウム(結合分子)に依存している。マグネシウムの一時的な排出により、NMDA受容体が解放さ れ、細胞内のカルシウムが放出される。この信号は、遺伝子転写と強化タンパク質の構築につながる。[86] 詳細については、長期増強(LTP)を参照のこと。 LTPで新たに合成されたタンパク質のひとつは、長期記憶の維持にも不可欠である。このタンパク質は、PKMζとして知られる酵素タンパク質キナーゼC (PKC)の自律的に活性化された形態である。PKMζは、活動依存的なシナプス伝達強度の増強を維持し、PKMζを阻害すると、短期記憶には影響を与え ずに、あるいは阻害剤が排除されれば、新たな長期記憶の符号化と保存能力が回復する。また、BDNFは長期記憶の持続にも重要である。[87] シナプス変化の長期的安定化は、軸索小体、樹状突起棘、シナプス後密度などのシナプス前およびシナプス後構造の並行した増加によっても決定される。 [88] 分子レベルでは、シナプス後足場タンパク質PSD-95およびHOMER1cの増加は、 シナプス拡大の安定化と相関することが示されている。[88] cAMP応答エレメント結合タンパク質(CREB)は、短期記憶から長期記憶への固定化に重要な役割を果たすと考えられている転写因子であり、アルツハイ マー病では発現が低下すると考えられている。[89] |

| DNA methylation and demethylation Rats exposed to an intense learning event may retain a life-long memory of the event, even after a single training session. The long-term memory of such an event appears to be initially stored in the hippocampus, but this storage is transient. Much of the long-term storage of the memory seems to take place in the anterior cingulate cortex.[90] When such an exposure was experimentally applied, more than 5,000 differently methylated DNA regions appeared in the hippocampus neuronal genome of the rats at one and at 24 hours after training.[91] These alterations in methylation pattern occurred at many genes that were downregulated, often due to the formation of new 5-methylcytosine sites in CpG rich regions of the genome. Furthermore, many other genes were upregulated, likely often due to hypomethylation. Hypomethylation often results from the removal of methyl groups from previously existing 5-methylcytosines in DNA. Demethylation is carried out by several proteins acting in concert, including the TET enzymes as well as enzymes of the DNA base excision repair pathway (see Epigenetics in learning and memory). The pattern of induced and repressed genes in brain neurons subsequent to an intense learning event likely provides the molecular basis for a long-term memory of the event. Epigenetics Main article: Epigenetics in learning and memory Studies of the molecular basis for memory formation indicate that epigenetic mechanisms operating in neurons in the brain play a central role in determining this capability. Key epigenetic mechanisms involved in memory include the methylation and demethylation of neuronal DNA, as well as modifications of histone proteins including methylations, acetylations and deacetylations. Stimulation of brain activity in memory formation is often accompanied by the generation of damage in neuronal DNA that is followed by repair associated with persistent epigenetic alterations. In particular the DNA repair processes of non-homologous end joining and base excision repair are employed in memory formation.[92] |

DNAのメチル化と脱メチル化 激しい学習体験にさらされたラットは、たった一度のトレーニングセッションの後でも、その出来事の生涯記憶を保持することがある。このような出来事の長期 記憶は、当初は海馬に保存されるようだが、この保存は一時的なものである。記憶の長期保存の多くは、前帯状皮質で行われるようである。[90] このような曝露が実験的に適用された場合、5,000を超える異なるメチル化DNA領域が、 訓練後1時間後と24時間後のラットの海馬ニューロンゲノムで確認された。[91] これらのメチル化パターンの変化は、多くの遺伝子で起こり、その多くはゲノムのCpGリッチ領域における新たな5-メチルシトシンの部位の形成によるもの である。さらに、多くの他の遺伝子は、おそらくは低メチル化によるものであると考えられるが、アップレギュレーションされた。低メチル化は、しばしば DNAに以前から存在する5-メチルシトシンのメチル基が除去されることによって起こる。脱メチル化は、TET酵素やDNA塩基除去修復経路の酵素など、 いくつかのタンパク質が協調して行う。(学習と記憶におけるエピジェネティクスを参照)激しい学習の後に脳神経細胞で誘導された遺伝子と抑制された遺伝子 のパターンは、その出来事の長期記憶の分子基盤を提供している可能性が高い。 エピジェネティクス 詳細は「学習と記憶におけるエピジェネティクス」を参照 記憶形成の分子基盤の研究により、脳のニューロンで作用するエピジェネティックなメカニズムが、この能力を決定する上で中心的な役割を果たしていることが 示されている。記憶に関与する主なエピジェネティックなメカニズムには、ニューロンのDNAのメチル化と脱メチル化、およびメチル化、アセチル化、脱アセ チル化などのヒストンタンパク質の修飾が含まれる。 記憶形成における脳の活動の刺激は、神経細胞のDNAに損傷が生じることが多く、それに続いて持続的なエピジェネティックな変化に関連した修復が行われる。特に、非相同末端結合と塩基除去修復というDNA修復プロセスが記憶形成に用いられる。[92] |

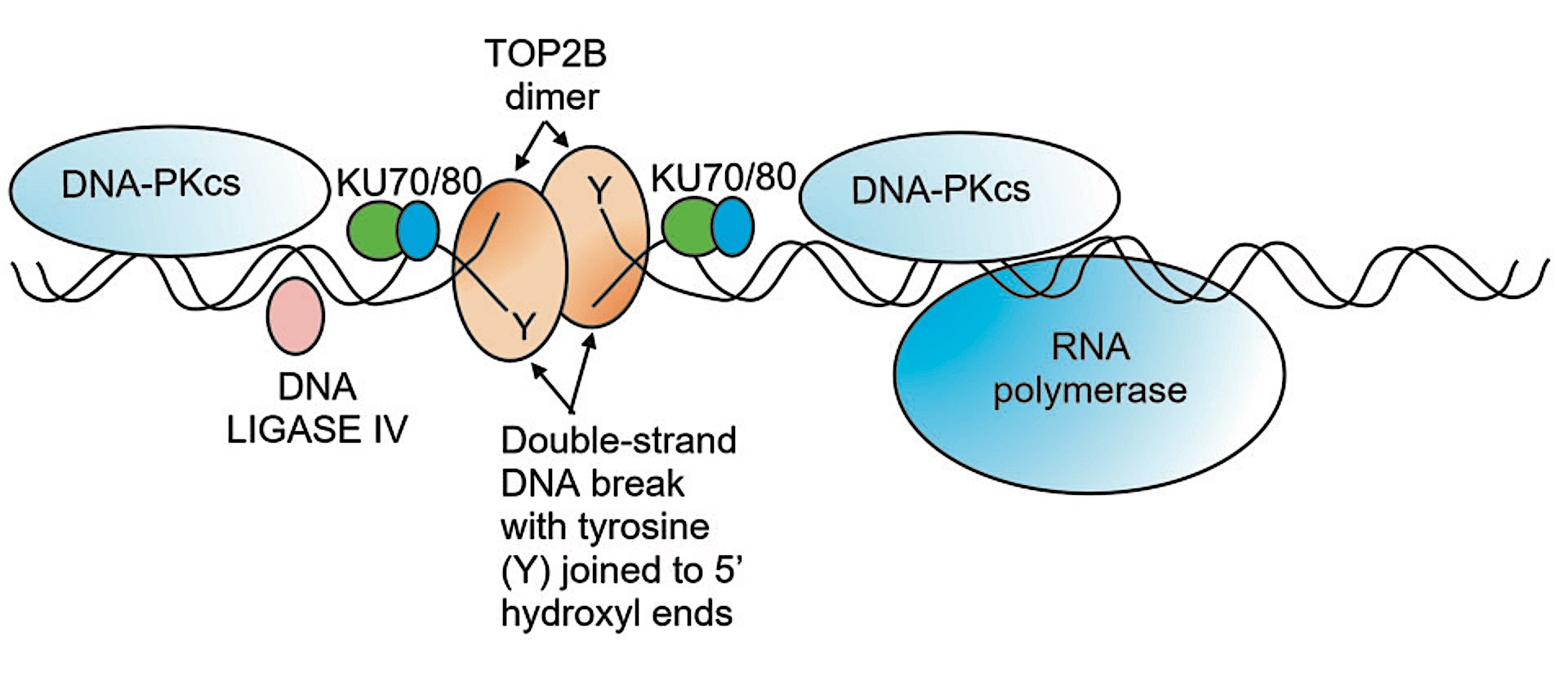

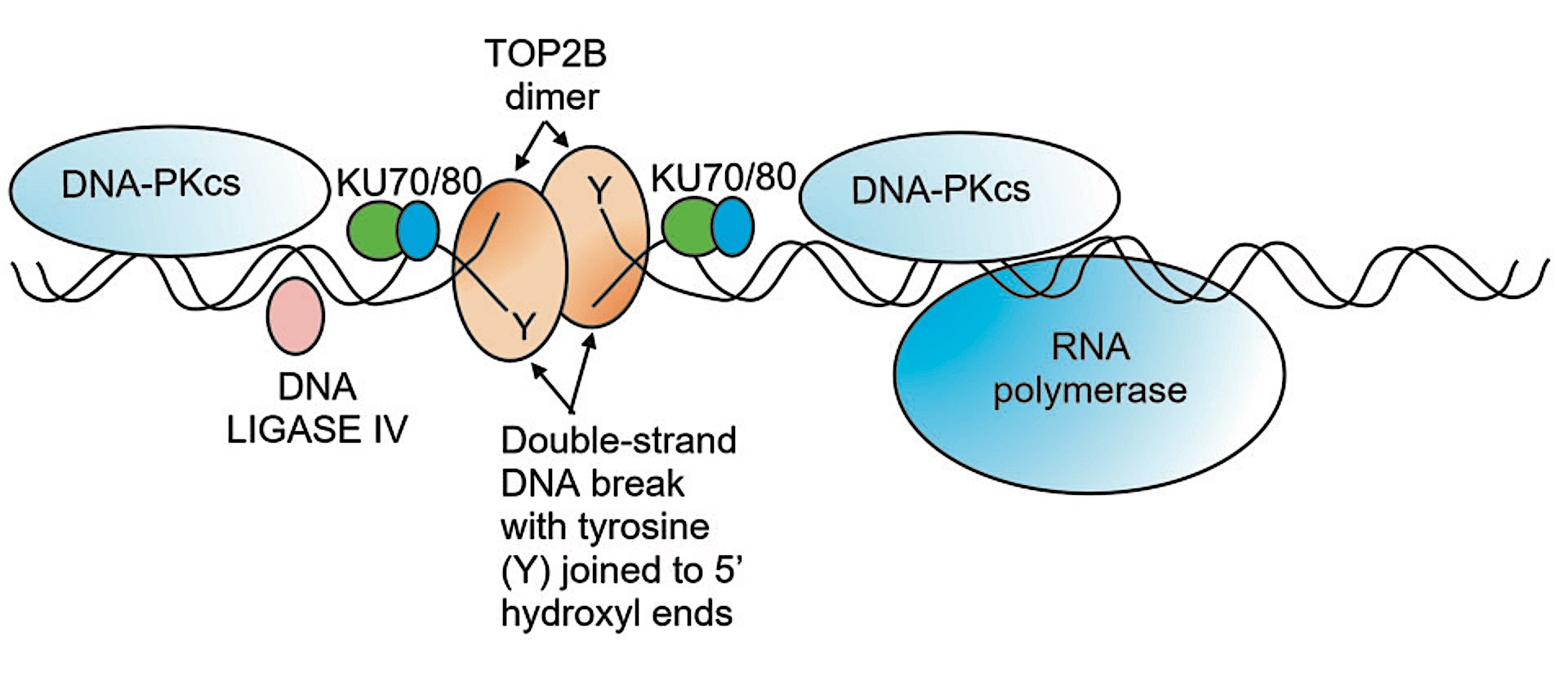

| DNA topoisomerase 2-beta in learning and memory During a new learning experience, a set of genes is rapidly expressed in the brain. This induced gene expression is considered to be essential for processing the information being learned. Such genes are referred to as immediate early genes (IEGs). DNA topoisomerase 2-beta (TOP2B) activity is essential for the expression of IEGs in a type of learning experience in mice termed associative fear memory.[93] Such a learning experience appears to rapidly trigger TOP2B to induce double-strand breaks in the promoter DNA of IEG genes that function in neuroplasticity. Repair of these induced breaks is associated with DNA demethylation of IEG gene promoters allowing immediate expression of these IEG genes.[93]  Regulatory sequence in a promoter at a transcription start site with a paused RNA polymerase and a TOP2B-induced double-strand break The double-strand breaks that are induced during a learning experience are not immediately repaired. About 600 regulatory sequences in promoters and about 800 regulatory sequences in enhancers appear to depend on double strand breaks initiated by topoisomerase 2-beta (TOP2B) for activation.[94][95] The induction of particular double-strand breaks are specific with respect to their inducing signal. When neurons are activated in vitro, just 22 of TOP2B-induced double-strand breaks occur in their genomes.[96] Such TOP2B-induced double-strand breaks are accompanied by at least four enzymes of the non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) DNA repair pathway (DNA-PKcs, KU70, KU80, and DNA LIGASE IV) (see Figure). These enzymes repair the double-strand breaks within about 15 minutes to two hours.[96][97] The double-strand breaks in the promoter are thus associated with TOP2B and at least these four repair enzymes. These proteins are present simultaneously on a single promoter nucleosome (there are about 147 nucleotides in the DNA sequence wrapped around a single nucleosome) located near the transcription start site of their target gene.[97]  Brain regions involved in memory formation including medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) The double-strand break introduced by TOP2B apparently frees the part of the promoter at an RNA polymerase-bound transcription start site to physically move to its associated enhancer (see regulatory sequence). This allows the enhancer, with its bound transcription factors and mediator proteins, to directly interact with the RNA polymerase paused at the transcription start site to start transcription.[96][98] Contextual fear conditioning in the mouse causes the mouse to have a long-term memory and fear of the location in which it occurred. Contextual fear conditioning causes hundreds of DSBs in mouse brain medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) and hippocampus neurons (see Figure: Brain regions involved in memory formation). These DSBs predominately activate genes involved in synaptic processes, that are important for learning and memory.[99] |

学習と記憶におけるDNAトポイソメラーゼ2-β 新しい学習体験の最中には、一連の遺伝子が脳内で急速に発現する。この誘導遺伝子発現は、学習中の情報の処理に不可欠であると考えられている。このような 遺伝子は、即時型遺伝子(IEG)と呼ばれる。DNAトポイソメラーゼ2-β(TOP2B)の活性は、マウスにおける一種の学習体験である連想性恐怖記憶 において、IEGの発現に不可欠である。[93] このような学習体験は、神経可塑性において機能するIEG遺伝子のプロモーターDNAにおける二重鎖切断を誘発するTOP2Bを急速に引き起こすようであ る。これらの誘発された切断の修復は、IEG遺伝子プロモーターのDNA脱メチル化と関連しており、これらのIEG遺伝子の即時発現を可能にする。 [93]  一時停止したRNAポリメラーゼとTOP2B誘発の二本鎖切断がある転写開始部位のプロモーターの制御配列 学習体験中に誘発された二本鎖切断は、直ちに修復されるわけではない。プロモーター領域の約600の調節配列とエンハンサー領域の約800の調節配列は、 トポイソメラーゼ2β(TOP2B)によって開始される二重鎖切断に依存して活性化されるようである。[94][95] 特定の二重鎖切断の誘導は、その誘導シグナルに関して特異的である。ニューロンがin vitroで活性化されると、TOP2Bによって誘導された二重鎖切断のうち、ゲノムに生じるのはわずか22個である。[96] このような TOP2B によって誘発された二本鎖切断には、非相同末端結合(NHEJ)DNA 修復経路の少なくとも 4 種類の酵素(DNA-PKcs、KU70、KU80、DNA LIGASE IV)が関与している(図を参照)。これらの酵素は、約15分から2時間以内に二重鎖切断を修復する。[96][97] プロモーターにおける二重鎖切断は、このようにTOP2Bおよび少なくともこれら4つの修復酵素と関連している。これらのタンパク質は、標的遺伝子の転写 開始部位付近にある単一のプロモーターヌクレオソーム(単一のヌクレオソームに巻き付いているDNA配列は約147ヌクレオチド)上に同時に存在する。 [97]  記憶形成に関与する脳領域には、内側前頭前皮質(mPFC)などがある。 TOP2Bによって引き起こされた2本鎖切断は、RNAポリメラーゼが結合した転写開始部位のプロモーターの一部を物理的に解放し、関連するエンハンサー (調節配列を参照)に移動させる。これにより、転写因子とメディエータータンパク質が結合したエンハンサーが、転写開始部位で一時停止しているRNAポリ メラーゼと直接相互作用し、転写を開始することができる。 マウスにおける文脈恐怖条件付けは、マウスに長期記憶と、その条件付けが行われた場所に対する恐怖心をもたらす。文脈恐怖条件付けは、マウスの脳内側前頭 前皮質(mPFC)と海馬のニューロンに数百ものDNA損傷を引き起こす(図:記憶形成に関与する脳領域を参照)。これらのDNA損傷は主に、学習と記憶 に重要なシナプスプロセスに関与する遺伝子を活性化する。[99] |

| In infancy Main article: Memory development For the inability of adults to retrieve early memories, see Childhood amnesia. Up until the mid-1980s it was assumed that infants could not encode, retain, and retrieve information.[100] A growing body of research now indicates that infants as young as 6-months can recall information after a 24-hour delay.[101] Furthermore, research has revealed that as infants grow older they can store information for longer periods of time; 6-month-olds can recall information after a 24-hour period, 9-month-olds after up to five weeks, and 20-month-olds after as long as twelve months.[102] In addition, studies have shown that with age, infants can store information faster. Whereas 14-month-olds can recall a three-step sequence after being exposed to it once, 6-month-olds need approximately six exposures in order to be able to remember it.[67][101] Although 6-month-olds can recall information over the short-term, they have difficulty recalling the temporal order of information. It is only by 9 months of age that infants can recall the actions of a two-step sequence in the correct temporal order – that is, recalling step 1 and then step 2.[103][104] In other words, when asked to imitate a two-step action sequence (such as putting a toy car in the base and pushing in the plunger to make the toy roll to the other end), 9-month-olds tend to imitate the actions of the sequence in the correct order (step 1 and then step 2). Younger infants (6-month-olds) can only recall one step of a two-step sequence.[101] Researchers have suggested that these age differences are probably due to the fact that the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus and the frontal components of the neural network are not fully developed at the age of 6-months.[68][105][106] In fact, the term 'infantile amnesia' refers to the phenomenon of accelerated forgetting during infancy. Importantly, infantile amnesia is not unique to humans, and preclinical research (using rodent models) provides insight into the precise neurobiology of this phenomenon. A review of the literature from behavioral neuroscientist Jee Hyun Kim suggests that accelerated forgetting during early life is at least partly due to rapid growth of the brain during this period.[107] |

乳児期 詳細は「記憶の発達」を参照 大人に初期の記憶を思い出すことができないことについては、「小児健忘症」を参照のこと。 1980年代半ばまでは、乳児は情報を符号化、保持、想起することができないと考えられていた。[100] しかし、現在では、生後6か月の乳児でも24時間遅れで情報を想起できることが、多くの研究によって示されている。[101] さらに、研究によって、乳児が成長するにつれて、 情報をより長い期間記憶できるようになる。生後6ヶ月の乳児は24時間後、9ヶ月の乳児は最長5週間後、20ヶ月の乳児は最長12ヶ月後でも情報を思い出 すことができる。[102] さらに、年齢とともに乳児はより速く情報を記憶できるようになることが研究で示されている。14ヶ月の乳児は3段階の順序を一度見せられただけで思い出す ことができるが、6ヶ月の乳児はそれを記憶するには約6回の提示が必要である。 6ヶ月児は短期間の記憶はできるが、情報の時間的順序を思い出すのは難しい。つまり、ステップ1を思い出した後にステップ2を思い出すことである。言い換 えれば、2段階の行動シーケンス(例えば、おもちゃの車を土台に置き、プランジャーを押しておもちゃを反対側の端まで転がす)を模倣するように指示された 場合、 2段階の動作シーケンス(例えば、おもちゃの車を土台に置き、プランジャーを押して反対側の端まで転がす)を模倣するように求められた場合、9ヶ月の乳児 は、そのシーケンスの動作を正しい順序(ステップ1、次にステップ2)で模倣する傾向がある。それより月齢の低い乳児(生後6ヶ月)は、2段階のシーケン スのうち1段階しか想起できない。[101] 研究者らは、こうした年齢による違いは、おそらく生後6ヶ月の時点では海馬の歯状回や神経ネットワークの前頭葉部分が十分に発達していないことが原因であ ると指摘している。[68][105][106] 実際、「幼児健忘」という用語は、乳児期に加速的に忘却が起こる現象を指している。重要なのは、幼児健忘は人間特有のものではなく、前臨床研究(齧歯類モ デルを使用)では、この現象の正確な神経生物学に関する洞察が得られていることである。行動神経科学者Jee Hyun Kimによる文献のレビューでは、乳児期の加速的な忘却は、少なくともこの時期の脳の急速な成長に起因する部分があることが示唆されている。[107] |

| Aging Main article: Memory and aging One of the key concerns of older adults is the experience of memory loss, especially as it is one of the hallmark symptoms of Alzheimer's disease. However, memory loss is qualitatively different in normal aging from the kind of memory loss associated with a diagnosis of Alzheimer's (Budson & Price, 2005). Research has revealed that individuals' performance on memory tasks that rely on frontal regions declines with age. Older adults tend to exhibit deficits on tasks that involve knowing the temporal order in which they learned information,[108] source memory tasks that require them to remember the specific circumstances or context in which they learned information,[109] and prospective memory tasks that involve remembering to perform an act at a future time. Older adults can manage their problems with prospective memory by using appointment books, for example. Gene transcription profiles were determined for the human frontal cortex of individuals from age 26 to 106 years. Numerous genes were identified with reduced expression after age 40, and especially after age 70.[110] Genes that play central roles in memory and learning were among those showing the most significant reduction with age. There was also a marked increase in DNA damage, likely oxidative damage, in the promoters of those genes with reduced expression. It was suggested that DNA damage may reduce the expression of selectively vulnerable genes involved in memory and learning.[110] |

加齢 詳細は「記憶と加齢」を参照 高齢者の主な関心事のひとつは記憶喪失の経験であり、特にアルツハイマー病の代表的な症状のひとつであることから、その関心は高い。しかし、記憶喪失は、 アルツハイマー病の診断に関連する記憶喪失とは質的に異なるものである(Budson & Price, 2005)。研究により、前頭葉に依存する記憶課題における個人のパフォーマンスは加齢とともに低下することが明らかになっている。高齢者は、情報を学習 した時間的な順序を知る必要がある課題[108]、情報を学習した特定の状況や文脈を記憶する必要があるソースメモリー課題[109]、将来のある時点で 行為を行うことを思い出す必要があるプロスペクティブメモリー課題において、欠損を示す傾向がある。高齢者は、例えば予定表を使用することで、プロスペク ティブメモリーに関する問題に対処することができる。 26歳から106歳までのヒトの前頭皮質における遺伝子転写プロファイルが決定された。多数の遺伝子が、40歳以降、特に70歳以降に発現が減少すること が確認された。[110] 記憶と学習に中心的な役割を果たす遺伝子は、加齢に伴い最も著しく減少する遺伝子の中に含まれていた。また、発現が低下したこれらの遺伝子のプロモーター では、DNA損傷、おそらく酸化損傷が著しく増加していた。DNA損傷は、記憶や学習に関与する選択的に脆弱な遺伝子の発現を低下させる可能性があること が示唆された。[110] |

| Disorders Main article: Memory disorder Much of the current knowledge of memory has come from studying memory disorders, particularly loss of memory, known as amnesia. Amnesia can result from extensive damage to: (a) the regions of the medial temporal lobe, such as the hippocampus, dentate gyrus, subiculum, amygdala, the parahippocampal, entorhinal, and perirhinal cortices[111] or the (b) midline diencephalic region, specifically the dorsomedial nucleus of the thalamus and the mammillary bodies of the hypothalamus.[112] There are many sorts of amnesia, and by studying their different forms, it has become possible to observe apparent defects in individual sub-systems of the brain's memory systems, and thus hypothesize their function in the normally working brain. Other neurological disorders such as Alzheimer's disease and Parkinson's disease[113][114] can also affect memory and cognition.[115] Hyperthymesia, or hyperthymesic syndrome, is a disorder that affects an individual's autobiographical memory, essentially meaning that they cannot forget small details that otherwise would not be stored.[116][117][118] Korsakoff's syndrome, also known as Korsakoff's psychosis, amnesic-confabulatory syndrome, is an organic brain disease that adversely affects memory by widespread loss or shrinkage of neurons within the prefrontal cortex.[76] While not a disorder, a common temporary failure of word retrieval from memory is the tip-of-the-tongue phenomenon. Those with anomic aphasia (also called nominal aphasia or Anomia), however, do experience the tip-of-the-tongue phenomenon on an ongoing basis due to damage to the frontal and parietal lobes of the brain. Memory dysfunction can also occur after viral infections.[119] Many patients recovering from COVID-19 experience memory lapses. Other viruses can also elicit memory dysfunction, including SARS-CoV-1, MERS-CoV, Ebola virus and even influenza virus.[119][120] |

障害 詳細は「記憶障害」を参照 記憶に関する現在の知識の多くは、記憶障害、特に記憶喪失、すなわち健忘症の研究から得られたものである。健忘症は、以下のような広範囲にわたる損傷に よって生じる可能性がある (a) 海馬、歯状回、錐体、扁桃体、海馬傍回、嗅内野、嗅周皮質など内側側頭葉の領域[111]、または (b) 中線間脳領域、特に 視床の背内側核と視床下部の乳頭体が挙げられる。[112] 健忘症には多くの種類があり、その異なる形態を研究することで、脳の記憶システムの個々のサブシステムにおける明らかな欠陥を観察することが可能となり、 正常に機能している脳におけるその機能について仮説を立てることができる。アルツハイマー病やパーキンソン病などの他の神経疾患もまた、記憶や認知に影響 を与える可能性がある。[115] ハイパサイミア、またはハイパサイミア症候群は、個人の自伝的記憶に影響を与える障害であり、本質的には、通常であれば記憶されないような些細な詳細を忘 れることができないことを意味する [116][117][118] コルサコフ症候群(コルサコフ精神病、健忘性譫妄症候群とも呼ばれる)は、前頭前皮質内の神経細胞の広範囲な損失または縮小により記憶に悪影響を及ぼす器 質性脳疾患である。 障害ではないが、記憶から単語を引き出す一時的な一般的な障害として、言葉が舌の先にある現象がある。しかし、語彙性失語症(呼称性失語症またはアノミアとも呼ばれる)の患者は、脳の前頭葉と頭頂葉の損傷により、継続的に言葉が舌の先にある現象を経験する。 また、ウイルス感染後にも記憶機能障害が起こりうる。[119]COVID-19から回復した患者の多くが記憶障害を経験している。SARS-CoV- 1、MERS-CoV、エボラウイルス、さらにはインフルエンザウイルスなど、他のウイルスも記憶機能障害を引き起こす可能性がある。[119] [120] |

| Influencing factors Interference Interference can hamper memorization and retrieval. There is retroactive interference, when learning new information makes it harder to recall old information[121] and proactive interference, where prior learning disrupts recall of new information. Although interference can lead to forgetting, it is important to keep in mind that there are situations when old information can facilitate learning of new information. Knowing Latin, for instance, can help an individual learn a related language such as French – this phenomenon is known as positive transfer.[122] Stress Main article: Effects of stress on memory Stress has a significant effect on memory formation and learning. In response to stressful situations, the brain releases hormones and neurotransmitters (ex. glucocorticoids and catecholamines) which affect memory encoding processes in the hippocampus. Behavioural research on animals shows that chronic stress produces adrenal hormones which impact the hippocampal structure in the brains of rats.[123] An experimental study by German cognitive psychologists L. Schwabe and O. Wolf demonstrates how learning under stress also decreases memory recall in humans.[124] In this study, 48 healthy female and male university students participated in either a stress test or a control group. Those randomly assigned to the stress test group had a hand immersed in ice cold water (the reputable SECPT or 'Socially Evaluated Cold Pressor Test') for up to three minutes, while being monitored and videotaped. Both the stress and control groups were then presented with 32 words to memorize. Twenty-four hours later, both groups were tested to see how many words they could remember (free recall) as well as how many they could recognize from a larger list of words (recognition performance). The results showed a clear impairment of memory performance in the stress test group, who recalled 30% fewer words than the control group. The researchers suggest that stress experienced during learning distracts people by diverting their attention during the memory encoding process. However, memory performance can be enhanced when material is linked to the learning context, even when learning occurs under stress. A separate study by cognitive psychologists Schwabe and Wolf shows that when retention testing is done in a context similar to or congruent with the original learning task (i.e., in the same room), memory impairment and the detrimental effects of stress on learning can be attenuated.[125] Seventy-two healthy female and male university students, randomly assigned to the SECPT stress test or to a control group, were asked to remember the locations of 15 pairs of picture cards – a computerized version of the card game "Concentration" or "Memory". The room in which the experiment took place was infused with the scent of vanilla, as odour is a strong cue for memory. Retention testing took place the following day, either in the same room with the vanilla scent again present, or in a different room without the fragrance. The memory performance of subjects who experienced stress during the object-location task decreased significantly when they were tested in an unfamiliar room without the vanilla scent (an incongruent context); however, the memory performance of stressed subjects showed no impairment when they were tested in the original room with the vanilla scent (a congruent context). All participants in the experiment, both stressed and unstressed, performed faster when the learning and retrieval contexts were similar.[126] This research on the effects of stress on memory may have practical implications for education, for eyewitness testimony and for psychotherapy: students may perform better when tested in their regular classroom rather than an exam room, eyewitnesses may recall details better at the scene of an event than in a courtroom, and persons with post-traumatic stress may improve when helped to situate their memories of a traumatic event in an appropriate context. Stressful life experiences may be a cause of memory loss as a person ages. Glucocorticoids that are released during stress cause damage to neurons that are located in the hippocampal region of the brain. Therefore, the more stressful situations that someone encounters, the more susceptible they are to memory loss later on. The CA1 neurons found in the hippocampus are destroyed due to glucocorticoids decreasing the release of glucose and the reuptake of glutamate. This high level of extracellular glutamate allows calcium to enter NMDA receptors which in return kills neurons. Stressful life experiences can also cause repression of memories where a person moves an unbearable memory to the unconscious mind.[76] This directly relates to traumatic events in one's past such as kidnappings, being prisoners of war or sexual abuse as a child. The more long term the exposure to stress is, the more impact it may have. However, short term exposure to stress also causes impairment in memory by interfering with the function of the hippocampus. Research shows that subjects placed in a stressful situation for a short amount of time still have blood glucocorticoid levels that have increased drastically when measured after the exposure is completed. When subjects are asked to complete a learning task after short term exposure they often have difficulties. Prenatal stress also hinders the ability to learn and memorize by disrupting the development of the hippocampus and can lead to unestablished long term potentiation in the offspring of severely stressed parents. Although the stress is applied prenatally, the offspring show increased levels of glucocorticoids when they are subjected to stress later on in life.[127] One explanation for why children from lower socioeconomic backgrounds tend to display poorer memory performance than their higher-income peers is the effects of stress accumulated over the course of the lifetime.[128] The effects of low income on the developing hippocampus is also thought be mediated by chronic stress responses which may explain why children from lower and higher-income backgrounds differ in terms of memory performance.[128] |

影響因子 干渉 干渉は記憶や想起を妨げる可能性がある。新しい情報を学習すると古い情報を思い出しにくくなる「逆向性干渉」[121]や、以前の学習が新しい情報の想起 を妨げる「順向性干渉」がある。干渉は忘却につながる可能性があるが、古い情報が新しい情報の学習を促進する状況もあることを念頭に置くことが重要であ る。例えば、ラテン語を知っていると、フランス語などの関連言語の学習に役立つ。この現象は「正の転移」として知られている。 ストレス 詳細は「ストレスが記憶に及ぼす影響」を参照 ストレスは記憶の形成と学習に大きな影響を及ぼす。ストレスの多い状況に反応して、脳はホルモンや神経伝達物質(グルココルチコイドやカテコールアミンな ど)を放出するが、これらは海馬における記憶の符号化プロセスに影響を与える。動物を用いた行動研究では、慢性的なストレスは副腎ホルモンを生成し、ラッ トの脳の海馬構造に影響を与えることが示されている。[123] ドイツの認知心理学者L. SchwabeとO. Wolfによる実験的研究では、ストレス下での学習が人間の記憶想起能力を低下させることが示されている。[124] この研究では、健康な女子大学生と男子大学生48名がストレス試験群と対照群に分かれて参加した。無作為にストレス試験グループに割り当てられた被験者 は、最大3分間、氷のように冷たい水に手を浸し(SECPTまたは「社会的に評価された寒冷プレッシャー試験」として知られる)、その様子は監視され、ビ デオ撮影された。ストレスグループとコントロールグループの両方に、32個の単語を暗記するよう指示した。24時間後、両グループにいくつ単語を記憶(自 由再生)できるか、また、より長い単語リストからいくつ認識できるか(認識パフォーマンス)をテストした。その結果、ストレステストグループでは、コント ロールグループよりも30%少ない単語しか思い出せず、記憶パフォーマンスに明らかな障害があることが示された。研究者は、学習中のストレスが記憶のエン コーディングプロセス中の注意をそらすことで、人々の集中力を乱す可能性があると示唆している。 しかし、学習内容が学習の文脈に関連している場合、ストレス下での学習であっても記憶力は向上する。認知心理学者のシュワブとウォルフによる別の研究で は、記憶保持テストが元の学習課題と類似または一致した文脈(すなわち、同じ部屋)で行われる場合、記憶力の低下やストレスが学習に及ぼす悪影響は軽減さ れることが示されている。 72人の健康な女子大学生と男子大学生を無作為にSECPTストレス試験群と対照群に割り当て、カードゲーム「神経衰弱」または「記憶」のコンピュータ版 である15組の絵カードの位置を覚えるよう求めた。実験が行われた部屋にはバニラの香りが充満していた。匂いは記憶の強い手がかりとなるためである。翌 日、バニラの香りが漂う同じ部屋、または異なる部屋で、記憶保持テストが行われた。物体の位置課題中にストレスを経験した被験者の記憶力は、バニラの香り のない見慣れない部屋でテストされた場合(不整合文脈)には著しく低下したが、バニラの香りのある元の部屋でテストされた場合(整合文脈)には、ストレス を経験した被験者の記憶力に障害は見られなかった。実験に参加したすべての被験者は、ストレスの有無に関わらず、学習と想起の文脈が類似している場合の方 が、より速く作業をこなすことができた。 ストレスが記憶に及ぼす影響に関するこの研究は、教育や目撃証言、心理療法などにも実用的な意味を持つ可能性がある。学生は試験室ではなく普段の教室でテ ストを受けた方が良い成績を収める可能性がある。また、目撃者は法廷よりも事件現場の方が詳細を思い出しやすい。心的外傷後ストレス障害を持つ人は、トラ ウマとなる出来事の記憶を適切な文脈に位置づける手助けをすることで改善する可能性がある。 ストレスの多い人生経験は、加齢による記憶喪失の原因となる可能性がある。ストレス時に放出されるグルココルチコイドは、脳の海馬領域にあるニューロンに 損傷を与える。そのため、ストレスの多い状況に遭遇するほど、後に記憶喪失になりやすくなる。グルココルチコイドはグルコースの放出とグルタミン酸の再吸 収を減少させるため、海馬にあるCA1ニューロンが破壊される。この細胞外グルタミン酸の大量発生により、カルシウムがNMDA受容体に入り込み、結果と してニューロンが死滅する。ストレスの多い生活体験は、耐え難い記憶を無意識の領域へと追いやる記憶の抑制を引き起こすこともある。[76] これは、誘拐、捕虜、幼少期の性的虐待など、過去のトラウマとなる出来事と直接関係している。 ストレスにさらされる期間が長ければ長いほど、その影響は大きくなる可能性がある。しかし、短期間のストレスでも、海馬の機能に支障をきたすことで記憶障 害を引き起こす。研究によると、ストレスの多い状況に短期間置かれた被験者でも、ストレスの多い状況を終えた後に測定すると、血中のグルココルチコイド値 が大幅に上昇していることが分かっている。短期間のストレスの後に学習課題を課すと、被験者はしばしば困難に直面する。また、出生前のストレスは海馬の発 達を妨げることで学習や記憶の能力を妨げ、ひどいストレスを受けた親を持つ子供に長期増強が確立されない原因となる可能性もある。ストレスは出生前に加え られたものであるが、子供が後にストレスを受けると、グルココルチコイドのレベルが上昇する。[127] 低所得層に属する子供が、高所得層の子供よりも記憶能力が劣る傾向にある理由のひとつとして、 生涯にわたって蓄積されたストレスの影響である。[128] 低所得が発達中の海馬に及ぼす影響も、慢性的なストレス反応によって媒介されると考えられている。このことが、低所得層と高所得層の子供たちの記憶力パ フォーマンスが異なる理由を説明している可能性がある。[128] |

| Sleep Main article: Sleep and memory Making memories occurs through a three-step process, which can be enhanced by sleep. The three steps are as follows: 1. Acquisition which is the process of storage and retrieval of new information in memory 2. Consolidation 3. Recall Sleep affects memory consolidation. During sleep, the neural connections in the brain are strengthened. This enhances the brain's abilities to stabilize and retain memories. There have been several studies which show that sleep improves the retention of memory, as memories are enhanced through active consolidation. System consolidation takes place during slow-wave sleep (SWS).[129][130] This process implicates that memories are reactivated during sleep, but that the process does not enhance every memory. It also implicates that qualitative changes are made to the memories when they are transferred to long-term store during sleep. During sleep, the hippocampus replays the events of the day for the neocortex. The neocortex then reviews and processes memories, which moves them into long-term memory. When one does not get enough sleep it makes it more difficult to learn as these neural connections are not as strong, resulting in a lower retention rate of memories. Sleep deprivation makes it harder to focus, resulting in inefficient learning.[129] Furthermore, some studies have shown that sleep deprivation can lead to false memories as the memories are not properly transferred to long-term memory. One of the primary functions of sleep is thought to be the improvement of the consolidation of information, as several studies have demonstrated that memory depends on getting sufficient sleep between training and test.[131] Additionally, data obtained from neuroimaging studies have shown activation patterns in the sleeping brain that mirror those recorded during the learning of tasks from the previous day,[131] suggesting that new memories may be solidified through such rehearsal.[132] |

睡眠 詳細は「睡眠と記憶」を参照 記憶の形成は3段階のプロセスを経て行われるが、睡眠によってそのプロセスを強化することができる。3つのステップは以下の通りである。 1. 獲得(記憶への新しい情報の蓄積と検索のプロセス) 2. 固定 3. 回想 睡眠は記憶の固定に影響を与える。睡眠中は、脳内の神経接続が強化される。これにより、記憶を安定させ保持する脳の能力が高まる。睡眠が記憶の保持力を向 上させることを示す研究はいくつかある。記憶は、活発な固定化によって強化されるためである。システム統合は徐波睡眠(SWS)中に起こる。[129] [130] このプロセスは、睡眠中に記憶が再活性化されることを示唆しているが、このプロセスがすべての記憶を強化するわけではない。また、睡眠中に記憶が長期保存 用に転送される際に、記憶に質的な変化が起こることも示唆している。睡眠中、海馬は大脳新皮質に対してその日の出来事を再生する。大脳皮質は記憶を再検討 し処理し、長期記憶へと移行させる。睡眠不足になると、神経接続が弱くなるため、学習が難しくなり、記憶の保持率が低下する。睡眠不足は集中力を低下さ せ、非効率的な学習につながる。[129] さらに、記憶が長期記憶に適切に移行しないため、睡眠不足は偽記憶につながる可能性があることが、いくつかの研究で示されている。睡眠の主な機能のひとつ は、情報の固定化を改善することであると考えられている。いくつかの研究が、記憶はトレーニングとテストの間に十分な睡眠をとることに依存していることを 実証しているためである。[131] さらに、神経画像研究から得られたデータは、前日のタスクの学習中に記録されたものと類似した、睡眠中の脳の活性化パターンを示している。[131] これは、新しい記憶はこのようなリハーサルを通じて固定化される可能性があることを示唆している。[132] |