いくたびもミッシェル

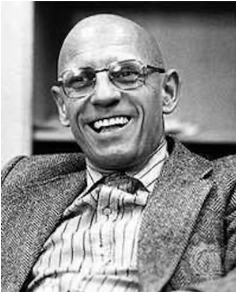

Memento Michel, 1926-1984

いくたびもミッシェル

Memento Michel, 1926-1984

■ 年譜:ウィキペディア(日本語・英語)「ミッシェル・フーコー」「Michel Foucault」 などにより作成。これと類似のサイト内ファイルに「ミッシェル・フーコー」があ ります。

1926年10月15日 ポワティエにて生まれる

1938 フッサール『ヨーロッパ諸学の危機と超越

論的現象学』死後公刊(1936〜1938年までハンガリーのベオグラードの哲学雑誌『フィロソフィア』で発表)

1943年6月 バカロレア(大学入学資格試験)に 合格

1945年 高等師範学校(Ecole Normale Supérieure)の試験を受けるも不合格

1946 高等師範学校合格(エコール・ノルマル〜 1951)

1948 自殺未遂事件

1950 大学教員資格試験に失敗

1950 6月17日再度、自殺未遂事件

1951 大学教員資格試験に合格。リール大学の助 手

1954 『精神疾患とパーソナリティ』(中山元・ 訳、筑摩書房[文庫])Maladie mentale et Personnalit・ Paris: PUF, 1954.

1955-1958

スウェーデン・ウプサラでフラ ンス会館館長就任。ウプサラ大学でフランス語を教え るかたわら、ウプサラ大学図書館(「ヴァレール文庫」と呼ばれる近代医学史関係の重要書を網羅したコレクションがある)に通いつめ、博士論文である『狂気 の歴史』を著す。

1958 10月〜1959年 ポーランド滞在。

「監視されていることを知っているポーランド人は、 親しくない人の受託には、いたるところに隠しマイクがとりつけられていることを知っているので、そうし た人に何かを話そうとするときは、街路で待っているものです。そのときの沈黙と、ごくありふれた身振り(みぶり)のうちに、レストランで声を小さくして語 る話しかたのうちに、手紙を燃やす身振りのうちに、息詰まるようなあらゆる種類の身振りのうちに、そして大学のキャンパスを襲うチュニジアの警察のむき出 しで野蛮な暴力のうちに、わたしは権力がもたらすある種の身体的な経験を、そして身体と権力との関係の経験を味わったのです」(フーコー2008 [June, 1975]:37)。出典:フーコー,ミッシェル『私は花火師です』中山元訳、筑摩書房、2008年

1961

『狂気の歴史』(Histoire

de la folie à l'âge

classique)とは、西欧の歴史において狂気を扱った文化と法律、政治、哲学、思想、制度、芸術そして医学などにおける、狂気の意味の展開の考察で

あり―そして歴史の理念及び歴史学研究法の理念の批判である、ミシェル・フーコーの1961年の著作である。フランス語の教師をしていたスウェーデンのウ

プサラで第一稿が書かれたが(ウプサラ大学図書館の医学文庫が重要な役割を果たした)、スウェーデンにおける博士論文提出を拒否され、その後ワルシャワ、

パリで完成された。『狂

気の歴史』はソルボンヌ大学に博士論文として提出され(審査員はジョルジュ・カンギレム、ダニエル・ラガーシュ(英語版、フランス語版))、同時に『狂気

と非理性、古典主義時代における狂気の歴史』というタイトルで1961年にプロン社(英語版、フランス語版)から出版された。出版された本書に対して、

フェルナン・ブローデル、モーリス・ブランショは熱烈な賛辞を送っている。その後、1972年、初版の序文を削除した現在の版『古典主義時代における狂気

の歴史』が、ガリマール社「歴史学叢書」から再刊された。

1962 『精神疾患と心理学』(神谷美恵子・訳、 みすず書房)Maladie mentale et Psychologie (Paris: PUF, 1962). = second and extensively revised edition of Maladie mentale et Personnalte

1963 『臨床医学の誕生』(神谷美恵子・訳、み すず書房)Naissance de la clinique: une archaologie du regard m仕ical (Paris: PUF, 1963).

1963 『レーモン・ルーセル』(豊崎光一・訳、 法政大学出版局)Raymond Roussel. (Paris: Gallimard, 1963), date of issue May 1963.

1966 『言葉と物』(渡辺一民ほか訳、新潮社) Les Mots et les Choses. Une archaologie des sciences humaines. Paris 1966.

1966-1968 チュニジアに滞在

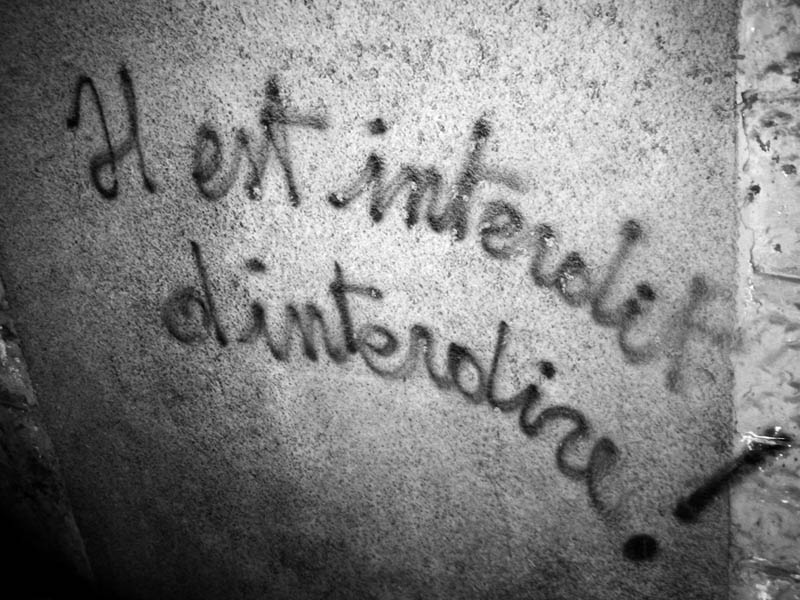

1968 5月10日パリで「68年5月」は じまる(5月2日〜6月23日:Mai 68)。 その2ヶ月前にチュニジアで流血の学生でもをフーコーは体験する。チュニジアでも学生ストライキ。

Il est interdit d'interdire !- "it is forbidden to forbid"

1968

モーリス・パンゲ(Maurice Pinguet, 1929-1991)が東京大学での教職を辞 した際に、フーコーはその後任を務めたいと申し出たが実現には至らなかった。この逸話の典拠は、『フーコー・コレクション1 狂気・理性』405頁 ちくま学芸文庫、2006年。

1968-1969

(冬)パリ・ヴァンセンヌ(パ リ第8大学)で教える。「誰にも聞こえるように『わたしはマルクス主義者ではない』と広言したことは、現実にはきわめてこんなことでした」(フーコー 2008 [June, 1975]:39)上掲書。

1969 『知の考古学』(中村雄一郎訳、河出書房 新社)L'Archaologie du savoir (Paris: Gallimard, March 1969).

1970 コレージュ・ド・フランス教授:講義『知 への意志』(コレージュ・ド・フランス講義 1970-71)

1971

『言説表現の秩序』(中村雄一郎訳、河出 書房新社)L'ordre du discours (Paris, Gallimard, 1971)

刑罰の理論と制度 (コレージュ・ド・フランス講義 1971-72)

Chomsky-Foucault Debate

on Power vs Justice (1971)

1972

処罰社会 (コレージュ・ド・フランス講義

1972-73)

『狂気の歴史:古典主義時代における』 (田村俶訳、新潮社)Histoire de la folie a l'age classique. Gallimard, 1972

1973

精神医学の権力 (コレージュ・ド・フランス講義

1973-74)

1974

異常者たち (コレージュ・ド・フランス講義

1974-75)

1975

『監獄の誕生』Surveiller et punir, naissance de la prison (Paris: Gallimard, February 1975).

コレージュドフランス講義『異常者たち』でカトリッ ク神秘主義に言及

社会は防衛しなければならない (コレージュ・ド・フランス講義

1975-76)

1976

『性の歴史 1権力への意志』 Histoire de la sexualit・1. La volonte de savoir (Paris: Gallimard, 1976).——この時の予告:2『肉と身体』、3『少年十字軍』、4『女性、母、ヒステリー患者』、5『倒錯者たち』、6『人口と人種』

1977

安全・領土・人口

(コレージュ・ド・フランス講義 1977-78)

1978

年頭(1月)よりイラン革命はじまる(→「アーヤトッラー・ルーホッラー・ホメイニーとイラン革命」)。

1-4月。コレージュドフランス講義『安全・領土・ 人口』にて、生権力の問題から授業をはじめる。権力はいくつもの手続きを経るプロ セスであり、(その中で)原因と結果が循環する構成体になる。それが授業内容の「安全」装置の説明(装置概念は1970年代後半のフーコーがよく使った用 語)。そこから「統治性」概念の検討に入る。司牧制、内政、外交と軍事。しかし2月8 日の5回目からは司牧制に絞られてゆく。8回目(3月1日)魂の統治技術に傾注される。ギリシア教父に対して「魂のオイコノミア」という用語を使う。

【フーコーとイラン革命, 1978-1979】秋 に2度イランを訪問する。フーコーとイラン革命については、ヘーゲルとフランス革命(あるいはハイチ革命)のような関係かどうかということである。フー コーにとって、ホメイニのイラン革命は、ある種の、思想的起爆剤ないしは「躓きの石」になり、後の彼の思考経験にどのように反映したか/反映されなかった のか?という問題である。

+++

| "In 1976, Gallimard published Foucault's Histoire de la sexualité: la volonté de savoir (The History of Sexuality: The Will to Knowledge), a short book exploring what Foucault called the "repressive hypothesis". It revolved largely around the concept of power, rejecting both Marxist and Freudian theory. Foucault intended it as the first in a seven-volume exploration of the subject.[132] Histoire de la sexualité was a best-seller in France and gained positive press, but lukewarm intellectual interest, something that upset Foucault, who felt that many misunderstood his hypothesis.[133] He soon became dissatisfied with Gallimard after being offended by senior staff member Pierre Nora.[134] Along with Paul Veyne and François Wahl, Foucault launched a new series of academic books, known as Des travaux (Some Works), through the company Seuil, which he hoped would improve the state of academic research in France.[135] He also produced introductions for the memoirs of Herculine Barbin and My Secret Life.[136]/ Foucault remained a political activist, focusing on protesting government abuses of human rights around the world. He was a key player in the 1975 protests against the Spanish government to execute 11 militants sentenced to death without fair trial. It was his idea to travel to Madrid with 6 others to give their press conference there; they were subsequently arrested and deported back to Paris.[138] In 1977, he protested the extradition of Klaus Croissant to West Germany, and his rib was fractured during clashes with riot police.[139] In July that year, he organised an assembly of Eastern Bloc dissidents to mark the visit of Soviet Premier Leonid Brezhnev to Paris.[140] In 1979, he campaigned for Vietnamese political dissidents to be granted asylum in France.[141]/ In 1977, Italian newspaper Corriere della sera asked Foucault to write a column for them. In doing so, in 1978 he travelled to Tehran in Iran, days after the Black Friday massacre. Documenting the developing Iranian Revolution, he met with opposition leaders such as Mohammad Kazem Shariatmadari and Mehdi Bazargan, and discovered the popular support for Islamism.[142] Returning to France, he was one of the journalists who visited the Ayatollah Khomeini, before visiting Tehran. His articles expressed awe of Khomeini's Islamist movement, for which he was widely criticised in the French press, including by Iranian expatriates. Foucault's response was that Islamism was to become a major political force in the region, and that the West must treat it with respect rather than hostility.[143] In April 1978, Foucault traveled to Japan, where he studied Zen Buddhism under Omori Sogen at the Seionji temple in Uenohara.[120]"︎ | 1976年、ガリマール社はフーコーの『性の歴史:知識への意志』

(Histoire de la sexualité: la volonté de

savoir)を出版した。これはフーコーが「抑圧仮説」と呼ぶものを探求した短編集であった。マルクス主義やフロイトの理論を否定し、権力の概念に大き

く関わるものであった。フーコーはこの本を、7巻からなるこのテーマの探求の最初の一冊とするつもりだった。フランスではベストセラーとなり、好意的な報

道がなされたが、知的関心は低く、フーコーは自分の仮説を多くの人が誤解していると感じ、憤慨した。ガリマール社では、先輩のピエール・ノラに怒られ、す

ぐに不満を募らせた。フーコーは、ポール・ヴェイヌ、フランソワ・ワールらとともに、フランスの学術研究の状況を改善するために、スイル社から新しい学術

書シリーズ「Des

travaux(いくつかの作品)」を創刊した。また、エルキュリーヌ・バルバンの回顧録『私の秘密の生活』の序文も執筆した。フーコーは政治活動家とし

て、世界各地で政府による人権侵害に抗議することに力を注いでいた。1975年、スペイン政府が死刑判決を受けた11人の過激派を公正な裁判を経ずに処刑

したことに対する抗議デモでは、中心的な役割を担った。その際、6人の仲間とともにマドリードで記者会見を行ったが、逮捕され、パリに送還された。

1977年、クラウス・クロワッサンの西ドイツへの引き渡しに抗議し、機動隊と衝突して肋骨を骨折した。同年7月、ソ連のブレジネフ首相のパリ訪問を記念

して、東欧諸国の反体制者たちの集会を組織した。1977年、イタリアの新聞社コリエール・デラ・セラはフーコーにコラムの執筆を依頼する。その際、

1978年にイランのテヘランを訪れ、「黒い金曜日」の大虐殺の数日後にイラン革命を記録した。発展途上のイラン革命を記録し、モハマド・カゼム・シャリ

アトマダーリやメフディ・バザルガンといった野党指導者と会い、イスラム主義への民衆の支持を発見したのである。フランスに戻り、テヘランを訪れる前にホ

メイニ師を訪ねたジャーナリストの一人である。彼の記事は、ホメイニのイスラム主義運動に対する畏敬の念を表現しており、イラン人駐在員を含むフランスの

新聞で広く批判された。フーコーの回答は、イスラム主義がこの地域の主要な政治勢力になること、そして西洋はそれを敵対視するのではなく、敬意をもって扱

うべきであるというものであった。1978年4月、フーコーは日本を訪れ、上野原市の西園寺で大森曹玄に禅を学んだ︎。 |

+++

▶︎Foucault and the Iranian Revolution : gender and the seductions of Islamism / Janet Afary and Kevin B. Anderson, University of Chicago Press , 2005.▶︎︎Tetz Hakoda, Bodies and Pleasures in the Happy Limbo of a Non-identity: Foucault against Butler on Herculine Barbin, ZINBUN No. 45 2014▶Thinking the Unthinkable: Foucault and the Islamic Revolution, Talk by Professor Behrooz Ghamari-Tabrizi at Stanford University on May 3, 2018︎▶︎︎ジジェク、スラヴォイ「ミッシェル・フーコーとイランの出来事」(Pp.166-181)「3章ラディカルな知識人たち、あるいは……」 『大義を忘れるな』中山徹・鈴木英明訳、青土社、2010年▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎

生政治の誕生 (コレージュ・ド・フランス講義

1978-79)[→「研究ノート:バイオポリティクス」「バイオポリティクス」]

1979

2月アーヤトッラー・ルーホッラー・ホメイニー帰国。

11月アメリカ大使館人質事件

生者たちの統治 (コレージュ・ド・フランス講義

1979-80)

1980

4月にアメリカ合衆国はイランに対して国交断絶。

主体性と真理 (コレージュ・ド・フランス講義

1980-81)

1981

「主体の解釈学 (コレージュ・ド・フランス講義 1981-82)

1982

Le Désordre des familles. Lettres de cachet des Archives de la Bastille. Présenté par Arlette Farge et Michel Foucault, («Collection Archives », 91) 1982

自己と他者の統治

(コレージュ・ド・フランス講義 1982-83)

1983

真理の勇気

(コレージュ・ド・フランス講義 1983-84)

1984

『性の歴史 2快楽の活用』 Histoire de la sexualite II, L'usage des plaisirs (Paris: Gallimard, 1984)

『性の歴史 3自己への配慮』 Histoire de la sexualite III, Le souci de soi (Paris: Gallimard, 1984)

CFでの「生政治装置」という講義アイディアは捨て られる(グロ 2020:7-8)

『肉の告白』の予告「キリスト教の最初の数世紀にお ける肉の経験と、欲望の解釈学および清めのための欲望の解読がそこではたす役割とを扱う」(グロ 2020:8-9)

エイズで死去

1989

2月ホメイニは、サルマン・ラシュディに対して死刑

のファトゥア(勅諭)を示す。6月にはこの判断は覆らせないと宣言される。

1991

7月11日ラシュディ『悪魔の詩』翻訳者であった筑

波大学助教授・五十嵐一(いがらし・ひとし, Hitoshi IGARASHI,

1947-1991)が大学構内にて首を切られて殺害(→「悪魔の詩訳者殺人事件」)

1994

Dits et écrits, 1954-1988 / Michel Foucault ; édition établie sous la direction de Daniel Defert et François Ewald ; avec la collaboration de Jacques Lagrange, 1 - 4. - [Paris] : Gallimard , c1994. - (Bibliothèque des sciences humaines)

1997

"Il faut défendre la société" : cours au Collège de France (1975-1976) / Michel Foucault ; édition établie, dans le cadre de l'Association pour le Centre Michel Foucault, sous la direction de François Ewald et Alessandro Fontana par Mauro Bertani et Alessandro Fontana: pbk. - [Paris] : Gallimard : Seuil , c1997. - (Hautes études)

1999 Les anormaux : cours au Collège de France (1974-1975) / Michel Foucault ; édition établie sous la direction de François Ewald et Alessandro Fontana, par Valerio Marchetti et Antonella Salomoni: pbk. - [Paris] : Gallimard : Seuil , c1999. - (Hautes études)

2001 L'herméneutique du sujet : cours au Collège de France (1981-1982) / Michel Foucault ; édition établie sous la direction de François Ewald et Alessandro Fontana, par Frédéric Gros: pbk. - [Paris] : Gallimard : Seuil , c2001. - (Hautes études)

2003 Le pouvoir psychiatrique : cours au Collège de France (1973-1974) / Michel Foucault ; édition établie sous la direction de François Ewald et Alessandro Fontana, par Jacques Lagrange: pbk. - [Paris] : Gallimard : Seuil , c2003. - (Hautes études)

2004 Sécurité, territoire, population : cours au Collège de France (1977-1978) / Michel Foucault ; édition établie sous la direction de François Ewald et Alessandro Fontana, par Michel Senellart : pbk. - [Paris] : Gallimard : Seuil , c2004. - (Hautes études)

2004 Naissance de la

biopolitique : cours au collège de France (1978-1979) / Michel Foucault

; édition établie sous la direction de François Ewald et Alessandro

Fontana, par Michel Senellart : pbk. - [Paris] : Gallimard : Seuil ,

c2004. - (Hautes études)

2008 Le gouvernement de soi et des autres : cours au Collège de France (1982-1983) / Michel Foucault ; édition établie sous la direction de François Ewald et Alessandro Fontana, par Frédéric Gros [Paris] : Gallimard : Seuil , c2008. - (Hautes études)

2009

Le courage de la vérité : cours au Collège de France (1983-1984) / Michel Foucault [Paris] : Seuil : Gallimard , c2009. - (Hautes études ; . { Le gouvernement de soi et des autres / Michel Foucault ; édition établie sous la direction de François Ewald et Alessandro Fontana par Frédéric Gros } ; v. 2)

2011 Leçons sur la

volonté de savoir : cours au collège de France, 1970-1971 suivi de Le

savoir d'Œdipe / Michel Foucault ; édition établie sous la direction de

François Ewald et Alessandro Fontana, par Daniel Defert : pbk. -

[Paris] : Gallimard : Seuil , c2011. - (Hautes études)

2018 Les Aveux de la Chair (肉の告白) Histoire de la sexualite IV, (solo se puede observar su Advertencia en PDF con clave, Frederic Gros: MFoucault_avertisse_Aveux_Chair_2018.pdf)

2020 肉の告白 / ミシェル・フーコー

[著] ; フレデリック・グロ編 : 槙改康之訳、新潮社 , 2020 . - (性の歴史 / ミシェル・フーコー著 ; 4)

****

+++

★英語版ウィキペディア"Paul-Michel

Foucault"からの翻訳:

| Paul-Michel

Foucault

(UK: /ˈfuːkoʊ/, US: /fuːˈkoʊ/;[9] French: [pɔl miʃɛl fuko]; 15 October

1926 – 25 June 1984) was a French philosopher, historian of ideas,

writer, political activist, and literary critic. Foucault's theories

primarily address the relationships between power and knowledge, and

how they are used as a form of social control through societal

institutions. Though often cited as a structuralist and postmodernist,

Foucault rejected these labels.[10] His thought has influenced

academics, especially those working in communication studies,

anthropology, psychology, sociology, criminology, cultural studies,

literary theory, feminism, Marxism and critical theory. Born in Poitiers, France, into an upper-middle-class family, Foucault was educated at the Lycée Henri-IV, at the École Normale Supérieure, where he developed an interest in philosophy and came under the influence of his tutors Jean Hyppolite and Louis Althusser, and at the University of Paris (Sorbonne), where he earned degrees in philosophy and psychology. After several years as a cultural diplomat abroad, he returned to France and published his first major book, The History of Madness (1961). After obtaining work between 1960 and 1966 at the University of Clermont-Ferrand, he produced The Birth of the Clinic (1963) and The Order of Things (1966), publications that displayed his increasing involvement with structuralism, from which he later distanced himself. These first three histories exemplified a historiographical technique Foucault was developing called "archaeology". From 1966 to 1968, Foucault lectured at the University of Tunis before returning to France, where he became head of the philosophy department at the new experimental university of Paris VIII. Foucault subsequently published The Archaeology of Knowledge (1969). In 1970, Foucault was admitted to the Collège de France, a membership he retained until his death. He also became active in several left-wing groups involved in campaigns against racism and human rights abuses and for penal reform. Foucault later published Discipline and Punish (1975) and The History of Sexuality (1976), in which he developed archaeological and genealogical methods that emphasized the role that power plays in society. Foucault died in Paris from complications of HIV/AIDS; he became the first public figure in France to die from complications of the disease. His partner Daniel Defert founded the AIDES charity in his memory. |

ポール=ミシェル・フーコー(イギリス: (イギリス:

/ˈfu(, アメリカ: /fuːko(; [9] French: [pɔl mi((]) /1926年10月15日 -

1984年6月25日)は、フランスの哲学者、思想史家、作家、政治活動家、文芸評論家。フーコーの理論は主に、権力と知識の関係、そしてそれらが社会制

度を通じて社会統制の一形態としてどのように利用されているかを扱っている。フーコーの思想は、特にコミュニケーション研究、人類学、心理学、社会学、犯

罪学、カルチュラル・スタディーズ、文学理論、フェミニズム、マルクス主義、批評理論などの研究者に影響を与えている。 フランスのポワチエで上流中産階級の家庭に生まれたフーコーは、アンリ4世リセ、高等師範学校(École Normale Supérieure)、パリ大学(ソルボンヌ大学)で教育を受け、哲学と心理学の学位を取得。海外で文化外交官を数年務めた後、フランスに戻り、最初の 主著『狂気の歴史』(1961年)を出版。1960年から1966年にかけてクレルモンフェラン大学で仕事を得た後、『診療所の誕生』(1963年)と 『物事の秩序』(1966年)を出版した。これらの最初の3つの歴史は、フーコーが開発しつつあった「考古学」と呼ばれる歴史学的技法を例証するもので あった。 1966年から1968年まで、フーコーはチュニス大学で教鞭をとった後、フランスに戻り、パリ第8大学の新しい実験大学の哲学部長となった。その後、 『知の考古学』(1969年)を出版。1970年、フーコーはコレージュ・ド・フランスの教員となり、この会員資格は亡くなるまで保持された。フーコーは また、人種差別や人権侵害に反対し、刑罰改革を求めるキャンペーンを展開するいくつかの左翼グループで活動するようになる。その後、『規律と罰』 (1975年)と『セクシュアリティの歴史』(1976年)を出版し、社会で権力が果たす役割を強調する考古学的・系図学的手法を開発した。 フーコーはHIV/AIDSの合併症によりパリで死去。HIV/AIDSの合併症で死亡したフランス初の公人となった。フーコーのパートナーであったダニ エル・デフェールは、フーコーを偲んで慈善団体AIDESを設立した。 |

| Early life Early years: 1926–1938 Paul-Michel Foucault was born on 15 October 1926 in the city of Poitiers, west-central France, as the second of three children in a prosperous, socially conservative, upper-middle-class family.[11] Family tradition prescribed naming him after his father, Paul Foucault (1893–1959), but his mother insisted on the addition of Michel; referred to as Paul at school, he expressed a preference for "Michel" throughout his life.[12] His father, a successful local surgeon born in Fontainebleau, moved to Poitiers, where he set up his own practice.[13] He married Anne Malapert, the daughter of prosperous surgeon Dr. Prosper Malapert, who owned a private practice and taught anatomy at the University of Poitiers' School of Medicine.[14] Paul Foucault eventually took over his father-in-law's medical practice, while Anne took charge of their large mid-19th-century house, Le Piroir, in the village of Vendeuvre-du-Poitou.[15] Together the couple had three children—a girl named Francine and two boys, Paul-Michel and Denys—who all shared the same fair hair and bright blue eyes.[16] The children were raised to be nominal Catholics, attending mass at the Church of Saint-Porchair, and while Michel briefly became an altar boy, none of the family was devout.[17] Michel is not related to the physicist Léon Foucault. In later life, Foucault revealed very little about his childhood.[18] Describing himself as a "juvenile delinquent", he said his father was a "bully" who sternly punished him.[19] In 1930, two years early, Foucault began his schooling at the local Lycée Henry-IV. There he undertook two years of elementary education before entering the main lycée, where he stayed until 1936. Afterwards, he took his first four years of secondary education at the same establishment, excelling in French, Greek, Latin, and history, though doing poorly at mathematics, including arithmetic.[20] Teens to young adulthood: 1939–1945 In 1939, the Second World War began, followed by Nazi Germany's occupation of France in 1940. Foucault's parents opposed the occupation and the Vichy regime, but did not join the Resistance.[21] That year, Foucault's mother enrolled him in the Collège Saint-Stanislas, a strict Catholic institution run by the Jesuits. Although he later described his years there as an "ordeal", Foucault excelled academically, particularly in philosophy, history, and literature.[22] In 1942 he entered his final year, the terminale, where he focused on the study of philosophy, earning his baccalauréat in 1943.[23] Returning to the local Lycée Henry-IV, he studied history and philosophy for a year,[24] aided by a personal tutor, the philosopher Louis Girard [fr].[25] Rejecting his father's wishes that he become a surgeon, in 1945 Foucault went to Paris, where he enrolled in one of the country's most prestigious secondary schools, which was also known as the Lycée Henri-IV. Here he studied under the philosopher Jean Hyppolite, an existentialist and expert on the work of 19th-century German philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel. Hyppolite had devoted himself to uniting existentialist theories with the dialectical theories of Hegel and Karl Marx. These ideas influenced Foucault, who adopted Hyppolite's conviction that philosophy must develop through a study of history.[26] University studies: 1946–1951 I wasn't always smart, I was actually very stupid in school ... [T]here was a boy who was very attractive who was even stupider than I was. And to ingratiate myself with this boy who was very beautiful, I began to do his homework for him—and that's how I became smart, I had to do all this work to just keep ahead of him a little bit, to help him. In a sense, all the rest of my life I've been trying to do intellectual things that would attract beautiful boys. — Michel Foucault, 1983[27] In autumn 1946, attaining excellent results, Foucault was admitted to the élite École Normale Supérieure (ENS), for which he undertook exams and an oral interrogation by Georges Canguilhem and Pierre-Maxime Schuhl to gain entry. Of the hundred students entering the ENS, Foucault ranked fourth based on his entry results, and encountered the highly competitive nature of the institution. Like most of his classmates, he lived in the school's communal dormitories on the Parisian Rue d'Ulm.[28] He remained largely unpopular, spending much time alone, reading voraciously. His fellow students noted his love of violence and the macabre; he decorated his bedroom with images of torture and war drawn during the Napoleonic Wars by Spanish artist Francisco Goya, and on one occasion chased a classmate with a dagger.[29] Prone to self-harm, in 1948 Foucault allegedly attempted suicide; his father sent him to see the psychiatrist Jean Delay at the Sainte-Anne Hospital Center. Obsessed with the idea of self-mutilation and suicide, Foucault attempted the latter several times in ensuing years, praising suicide in later writings.[30] The ENS's doctor examined Foucault's state of mind, suggesting that his suicidal tendencies emerged from the distress surrounding his homosexuality, because same-sex sexual activity was socially taboo in France.[31] At the time, Foucault engaged in homosexual activity with men whom he encountered in the underground Parisian gay scene, also indulging in drug use; according to biographer James Miller, he enjoyed the thrill and sense of danger that these activities offered him.[32] Although studying various subjects, Foucault soon gravitated towards philosophy, reading not only Hegel and Marx but also Immanuel Kant, Edmund Husserl and most significantly, Martin Heidegger.[33] He began reading the publications of philosopher Gaston Bachelard, taking a particular interest in his work exploring the history of science.[34] He graduated from the ENS with a B.A. (licence) in Philosophy in 1948[2] and a DES (diplôme d'études supérieures [fr], roughly equivalent to an M.A.) in Philosophy in 1949.[2] His DES thesis under the direction of Hyppolite was titled La Constitution d'un transcendental dans La Phénoménologie de l'esprit de Hegel (The Constitution of a Historical Transcendental in Hegel's Phenomenology of Spirit).[2] In 1948, the philosopher Louis Althusser became a tutor at the ENS. A Marxist, he influenced both Foucault and a number of other students, encouraging them to join the French Communist Party. Foucault did so in 1950, but never became particularly active in its activities, and never adopted an orthodox Marxist viewpoint, rejecting core Marxist tenets such as class struggle.[35] He soon became dissatisfied with the bigotry that he experienced within the party's ranks; he personally faced homophobia and was appalled by the anti-semitism exhibited during the 1952–53 "Doctors' plot" in the Soviet Union. He left the Communist Party in 1953, but remained Althusser's friend and defender for the rest of his life.[36] Although failing at the first attempt in 1950, he passed his agrégation in philosophy on the second try, in 1951.[37] Excused from national service on medical grounds, he decided to start a doctorate at the Fondation Thiers in 1951, focusing on the philosophy of psychology,[38] but he relinquished it after only one year in 1952.[39] Foucault was also interested in psychology and he attended Daniel Lagache's lectures at the University of Paris, where he obtained a B.A. (licence) in psychology in 1949 and a Diploma in Psychopathology (Diplôme de psychopathologie) from the university's institute of psychology (now Institut de psychologie de l'université Paris Descartes [fr]) in June 1952.[2] |

幼少期 若い頃 1926-1938 ポール=ミッシェル・フーコーは1926年10月15日、フランス中西部のポワチエ市で、裕福で社会的に保守的な上流中産階級の家庭に3人兄弟の2番目と して生まれた[11]。家訓では父ポール・フーコー(1893-1959)にちなんでフーコーと名付けることになっていたが、母はミシェルをつけることを 主張した。 父はフォンテーヌブロー生まれの外科医で、ポワチエに移り住み、開業医となった[13]。 [14] ポール・フーコーは義父の診療所を引き継ぎ、アンヌはヴァンドゥーブル・デュ・ポワトゥー村にある19世紀半ばに建てられた大きな家、ル・ピロワールを管 理した。 [15]夫妻の間には、フランシーヌという名の女の子と、ポール=ミッシェルとドゥニーという2人の男の子という3人の子供が生まれた。 1930年、フーコーは2年早く地元のリセ・アンリ4世で学び始める。そこで2年間の初等教育を受けた後、本科のリセに入学し、1936年まで在籍した。 その後、同校で最初の4年間の中等教育を受け、フランス語、ギリシャ語、ラテン語、歴史に秀でたが、算数を含む数学は苦手だった[20]。 10代から青年期:1939-1945年 1939年、第二次世界大戦が始まり、1940年にはナチス・ドイツがフランスを占領。フーコーの両親は占領とヴィシー政権に反対していたが、レジスタン スには参加しなかった[21]。後にフーコーはそこでの学生時代を「試練」であったと語るが、フーコーは学業、特に哲学、歴史、文学に秀でていた [22]。1942年、彼は最終学年であるターミナールに入り、そこで哲学の研究に専念し、1943年にバカロレアを取得した[23]。 地元のリセ・アンリ=Ⅳに戻り、哲学者ルイ・ジラールの個人指導を受けながら、歴史と哲学を1年間学んだ[24][25]。外科医になることを望んだ父の 反対を押し切り、1945年、フーコーはパリに渡り、リセ・アンリ=Ⅳとして知られるパリで最も権威のある中等学校に入学。ここで彼は、実存主義者であ り、19世紀ドイツの哲学者ゲオルク・ヴィルヘルム・フリードリヒ・ヘーゲルの研究の専門家であった哲学者ジャン・ヒュポリットに師事した。ヒュポリット は、実存主義の理論をヘーゲルやカール・マルクスの弁証法的理論と結びつけることに力を注いでいた。これらの思想はフーコーに影響を与え、哲学は歴史の研 究を通じて発展していかなければならないというハイポライトの信念を採用した[26]。 大学での研究 1946-1951 私はいつも頭が良かったわけではなく、実は学校ではとても頭が悪かった.[とても魅力的な男の子がいて、その子は私よりもっとバカだった。そうやって私は 賢くなったんだ。ある意味、私は残りの人生ずっと、美少年を惹きつけるような知的なことをしようとしてきた。 - ミシェル・フーコー、1983年[27]。 1946年秋、優秀な成績を収めたフーコーは、エリート校である高等師範学校(ENS)に入学を許可され、ジョルジュ・カンギレムとピエール=マクシム・ シュールによる試験と口頭試問を受け、入学を果たした。ENSに入学した100人の学生のうち、フーコーは成績で4位にランクされ、ENSの競争の激しさ に直面した。ほとんどの同級生と同様、彼はパリのウルム通りにある学校の共同寮に住んでいた[28]。 彼はほとんど人気がなく、多くの時間を一人で過ごし、熱心に読書をしていた。寝室にはスペインの画家フランシスコ・ゴヤがナポレオン戦争中に描いた拷問や 戦争の絵が飾られ、短剣を持って同級生を追いかけたこともあった[29]。自傷癖のあったフーコーは、1948年に自殺未遂を図ったとされ、父親は彼をサ ント・アンヌ病院センターの精神科医ジャン・ドレイに診せた。自傷行為と自殺のアイデアに取りつかれたフーコーは、その後何度も自殺を試み、後の著作では 自殺を賞賛している[30] 。 [31] 当時、フーコーはパリのアンダーグラウンドなゲイ・シーンで出会った男たちと同性愛の営みを行い、薬物使用にも耽っていた。伝記作家のジェームズ・ミラー によれば、彼はこれらの営みが彼に与えるスリルと危機感を楽しんでいた[32]。 様々な学問を学んだが、フーコーはすぐに哲学に傾倒し、ヘーゲルやマルクスだけでなく、イマヌエル・カント、エドムント・フッサール、そして最も重要なマ ルティン・ハイデガーも読んだ[33]。 1948年に哲学のA(免許)を取得し[2]、1949年に哲学のDES(diplôme d'études supérieures [fr]、修士にほぼ相当)を取得した[2]。ハイポライトの指導の下でのDESの論文のタイトルは『La Constitution d'un transcendental dans La Phénoménologie de l'esprit de Hegel(ヘーゲルの精神現象学における歴史的超越論者の構成)』であった[2]。 1948年、哲学者ルイ・アルチュセールがENSの講師となる。マルクス主義者であったアルチュセールは、フーコーや他の学生たちに影響を与え、フランス 共産党への入党を勧めた。フーコーは1950年に共産党に入党したが、共産党の活動に特に積極的に参加することはなく、階級闘争のようなマルクス主義の中 核的な考え方を否定し、正統的なマルクス主義の視点を採用することはなかった[35]。彼はすぐに党内で経験した偏見に不満を抱くようになり、個人的に同 性愛嫌悪に直面し、1952年から53年にかけてソビエト連邦で起こった「医師たちの陰謀」の際に示された反ユダヤ主義に愕然とした。彼は1953年に共 産党を離党したが、アルチュセールの友人であり擁護者であり続けた[36]。1950年の最初の受験では失敗したものの、1951年の2回目の受験で哲学 のアグレガシオン試験に合格した[37]。 フーコーは心理学にも興味を持っており、パリ大学でダニエル・ラガシュの講義を受け、1949年に心理学の学士号(免許)を取得し、1952年6月に同大 学の心理学研究所(現在のパリ・デカルト大学心理学研究所[fr])で精神病理学のディプロマ(Diplôme de psychopathologie)を取得した[2]。 |

| Early career (1951–1960) In the early 1950s, Foucault came under the influence of German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, who remained a core influence on his work throughout his life. France: 1951–1955 Over the following few years, Foucault embarked on a variety of research and teaching jobs.[40] From 1951 to 1955, he worked as a psychology instructor at the ENS at Althusser's invitation.[41] In Paris, he shared a flat with his brother, who was training to become a surgeon, but for three days in the week commuted to the northern town of Lille, teaching psychology at the Université de Lille from 1953 to 1954.[42] Many of his students liked his lecturing style.[43] Meanwhile, he continued working on his thesis, visiting the Bibliothèque Nationale every day to read the work of psychologists like Ivan Pavlov, Jean Piaget and Karl Jaspers.[44] Undertaking research at the psychiatric institute of the Sainte-Anne Hospital, he became an unofficial intern, studying the relationship between doctor and patient and aiding experiments in the electroencephalographic laboratory.[45] Foucault adopted many of the theories of the psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud, undertaking psychoanalytical interpretation of his dreams and making friends undergo Rorschach tests.[46] Embracing the Parisian avant-garde, Foucault entered into a romantic relationship with the serialist composer Jean Barraqué. Together, they tried to produce their greatest work, heavily used recreational drugs and engaged in sado-masochistic sexual activity.[47] In August 1953, Foucault and Barraqué holidayed in Italy, where the philosopher immersed himself in Untimely Meditations (1873–1876), a set of four essays by the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche. Later describing Nietzsche's work as "a revelation", he felt that reading the book deeply affected him, being a watershed moment in his life.[48] Foucault subsequently experienced another groundbreaking self-revelation when watching a Parisian performance of Samuel Beckett's new play, Waiting for Godot, in 1953.[49] Interested in literature, Foucault was an avid reader of the philosopher Maurice Blanchot's book reviews published in Nouvelle Revue Française. Enamoured of Blanchot's literary style and critical theories, in later works he adopted Blanchot's technique of "interviewing" himself.[50] Foucault also came across Hermann Broch's 1945 novel The Death of Virgil, a work that obsessed both him and Barraqué. While the latter attempted to convert the work into an epic opera, Foucault admired Broch's text for its portrayal of death as an affirmation of life.[51] The couple took a mutual interest in the work of such authors as the Marquis de Sade, Fyodor Dostoyevsky, Franz Kafka and Jean Genet, all of whose works explored the themes of sex and violence.[52] I belong to that generation who, as students, had before their eyes, and were limited by, a horizon consisting of Marxism, phenomenology and existentialism. For me the break was first Beckett's Waiting for Godot, a breathtaking performance. — Michel Foucault, 1983[53] Interested in the work of Swiss psychologist Ludwig Binswanger, Foucault aided family friend Jacqueline Verdeaux in translating his works into French. Foucault was particularly interested in Binswanger's studies of Ellen West who, like himself, had a deep obsession with suicide, eventually killing herself.[54] In 1954, Foucault authored an introduction to Binswanger's paper "Dream and Existence", in which he argued that dreams constituted "the birth of the world" or "the heart laid bare", expressing the mind's deepest desires.[55] That same year, Foucault published his first book, Maladie mentale et personalité (Mental Illness and Personality), in which he exhibited his influence from both Marxist and Heideggerian thought, covering a wide range of subject matter from the reflex psychology of Pavlov to the classic psychoanalysis of Freud. Referencing the work of sociologists and anthropologists such as Émile Durkheim and Margaret Mead, he presented his theory that illness was culturally relative.[56] Biographer James Miller noted that while the book exhibited "erudition and evident intelligence", it lacked the "kind of fire and flair" which Foucault exhibited in subsequent works.[57] It was largely critically ignored, receiving only one review at the time.[58] Foucault grew to despise it, unsuccessfully attempting to prevent its republication and translation into English.[59] Sweden, Poland, and West Germany: 1955–1960 Foucault spent the next five years abroad, first in Sweden, working as cultural diplomat at the University of Uppsala, a job obtained through his acquaintance with historian of religion Georges Dumézil.[60] At Uppsala he was appointed a Reader in French language and literature, while simultaneously working as director of the Maison de France, thus opening the possibility of a cultural-diplomatic career.[61] Although finding it difficult to adjust to the "Nordic gloom" and long winters, he developed close friendships with two Frenchmen, biochemist Jean-François Miquel and physicist Jacques Papet-Lépine, and entered into romantic and sexual relationships with various men. In Uppsala he became known for his heavy alcohol consumption and reckless driving in his new Jaguar car.[62] In spring 1956 Barraqué broke from his relationship with Foucault, announcing that he wanted to leave the "vertigo of madness".[63] In Uppsala, Foucault spent much of his spare time in the university's Carolina Rediviva library, making use of their Bibliotheca Walleriana collection of texts on the history of medicine for his ongoing research.[64] Finishing his doctoral thesis, Foucault hoped that Uppsala University would accept it, but Sten Lindroth, a positivistic historian of science there, remained unimpressed, asserting that it was full of speculative generalisations and was a poor work of history; he refused to allow Foucault to be awarded a doctorate at Uppsala. In part because of this rejection, Foucault left Sweden.[65] Later, Foucault admitted that the work was a first draft with certain lack of quality.[66] Again at Dumézil's behest, in October 1958 Foucault arrived in the capital of the Polish People's Republic, Warsaw and took charge of the University of Warsaw's Centre Français.[67] Foucault found life in Poland difficult due to the lack of material goods and services following the destruction of the Second World War. Witnessing the aftermath of the Polish October of 1956, when students had protested against the governing communist Polish United Workers' Party, he felt that most Poles despised their government as a puppet regime of the Soviet Union, and thought that the system ran "badly".[68] Considering the university a liberal enclave, he traveled the country giving lectures; proving popular, he adopted the position of de facto cultural attaché.[69] Like France and Sweden, Poland legally tolerated but socially frowned on homosexual activity, and Foucault undertook relationships with a number of men; one was with a Polish security agent who hoped to trap Foucault in an embarrassing situation, which therefore would reflect badly on the French embassy. Wracked in diplomatic scandal, he was ordered to leave Poland for a new destination.[70] Various positions were available in West Germany, and so Foucault relocated to the Institut français Hamburg [de] (where he served as director in 1958–1960), teaching the same courses he had given in Uppsala and Warsaw.[71][72] Spending much time in the Reeperbahn red light district, he entered into a relationship with a transvestite.[73] |

初期のキャリア(1951-1960) 1950年代初頭、フーコーはドイツの哲学者フリードリヒ・ニーチェの影響を受ける。 フランス:1951年~1955年 1951年から1955年まで、彼はアルチュセールの招きでENSで心理学の講師として働いていた。 [サント=アンヌ病院の精神医学研究所で研究を行うため、彼は非公式なインターンとなり、医師と患者の関係を研究したり、脳波実験室で実験を手伝ったりし た[44]。 [フーコーは精神分析家ジークムント・フロイトの理論の多くを取り入れ、夢の精神分析的解釈を引き受け、友人たちにロールシャッハ・テストを受けさせた [46]。 パリのアヴァンギャルドを受け入れたフーコーは、シリアル派の作曲家ジャン・バラケと恋愛関係に入る。1953年8月、フーコーとバラケはイタリアで休暇 を過ごし、哲学者は哲学者フリードリヒ・ニーチェの4つのエッセイから成る『時ならぬ瞑想』(1873-1876)に没頭した。後にニーチェの著作を「啓 示」と表現したフーコーは、この本を読んだことが自分の人生に深い影響を与え、分岐点となったと感じていた[48]。フーコーはその後、1953年にサ ミュエル・ベケットの新作戯曲『ゴドーを待ちながら』のパリ公演を観劇した際にも、画期的な自己啓示を経験している[49]。 文学に興味を持ったフーコーは、哲学者モーリス・ブランショの『ヌーヴェル・ルヴュ・フランセーズ』誌に掲載された書評の熱心な読者であった。ブランショ の文学的スタイルと批評理論に魅了されたフーコーは、後年、ブランショの「自分自身にインタビューする」という手法を取り入れた[50]。後者がこの作品 を叙事詩的なオペラに改作しようとしたのに対し、フーコーは生を肯定するものとして死を描いたブロッホのテキストを賞賛した[51]。夫婦はサド侯爵、 フョードル・ドストエフスキー、フランツ・カフカ、ジャン・ジュネといった作家の作品に相互に関心を持ち、その作品はすべて性と暴力のテーマを探求してい た[52]。 私は、学生時代にマルクス主義、現象学、実存主義からなる地平を目の前にし、それによって制限されていた世代に属する。私にとっての区切りは、まずベケッ トの『ゴドーを待ちながら』であり、息をのむようなパフォーマンスだった。 - ミシェル・フーコー、1983年[53]。 スイスの心理学者ルートヴィヒ・ビンスワンガーの著作に興味を持ったフーコーは、家族の友人であるジャクリーヌ・ヴェルドーに彼の著作のフランス語への翻 訳を手伝わせた。1954年、フーコーはビンスワンガーの論文「夢と実存」の序論を執筆し、その中で夢は「世界の誕生」あるいは「むき出しにされた心」で あり、心の最も深い欲望を表現していると主張した[55]。 [55]同年、フーコーは最初の著書『精神病と人格』(Maladie mentale et personalité)を出版し、パブロフの反射心理学からフロイトの古典的な精神分析まで幅広い題材を扱いながら、マルクス主義思想とハイデガー思想 の両方から影響を受けていることを示した。エミール・デュルケームやマーガレット・ミードといった社会学者や人類学者の研究を参照しながら、病気は文化的 に相対的なものであるという持論を展開した[56]。伝記作家のジェームズ・ミラーは、本書は「博識と明らかな知性」を示しているものの、フーコーがその 後の著作で示したような「火とセンス」に欠けていると指摘した[57]。 [フーコーはこの本を軽蔑するようになり、再出版や英語への翻訳を阻止しようとして失敗した[59]。 スウェーデン、ポーランド、西ドイツ:1955年-1960年 フーコーはその後5年間を海外で過ごし、最初はスウェーデンで、宗教史家ジョルジュ・デュメジルと知り合ったことで得たウプサラ大学の文化外交官として働 く。 [61] 「北欧の憂鬱」と長い冬に慣れることは難しかったが、2人のフランス人、生化学者のジャン=フランソワ・ミケルと物理学者のジャック・パペ=レピーヌと親 交を深め、さまざまな男性と恋愛や性的関係を結んだ。1956年春、バラケはフーコーとの関係を断ち切り、「狂気の眩暈」から抜け出したいと発表した [63]。ウプサラでは、フーコーは余暇の多くを大学のカロリナ・レディヴィヴァ図書館で過ごし、医学史に関する蔵書を利用して研究を続けた。 [博士論文を書き上げたフーコーは、ウプサラ大学がその論文を受理してくれることを期待したが、同大学の実証主義的な科学史家であるステン・リンドロス は、その論文が推測に基づく一般論に満ちており、歴史学としては稚拙であると主張し、フーコーにウプサラ大学で博士号を授与することを認めなかった。この 拒絶のせいもあり、フーコーはスウェーデンを去った[65]。後にフーコーは、この著作が初稿であり、一定の質を欠いていたことを認めている[66]。 1958年10月、フーコーは再びデュメジルの要請を受け、ポーランド人民共和国の首都ワルシャワに到着し、ワルシャワ大学のセンター・フランセの責任者 となった。1956年の「ポーランドの十月」の余波を目の当たりにしたフーコーは、学生たちが共産主義政権であるポーランド労働者党に抗議したことから、 ほとんどのポーランド人が自分たちの政権をソビエト連邦の傀儡政権として軽蔑しており、体制が「ひどく」機能していると感じていた。 [69]フランスやスウェーデンと同様、ポーランドは法的には同性愛を容認していたが、社会的には顰蹙を買っており、フーコーは多くの男性と関係を持っ た。外交上のスキャンダルに悩まされたフーコーは、ポーランドを去り、新たな目的地へと向かうことを命じられる[70]。西ドイツで様々な職を得ることが できたため、フーコーはアンスティチュ・フランセ・ハンブルク(1958年から1960年にかけて院長を務めた)に移り、ウプサラやワルシャワで行ってい たのと同じ講義を担当する[71][72]。レーパーバーンの歓楽街で多くの時間を過ごし、女装子と関係を持つ[73]。 |

| Growing career (1960–1970) Madness and Civilization: 1960 Histoire de la folie is not an easy text to read, and it defies attempts to summarise its contents. Foucault refers to a bewildering variety of sources, ranging from well-known authors such as Erasmus and Molière to archival documents and forgotten figures in the history of medicine and psychiatry. His erudition derives from years pondering, to cite Poe, 'over many a quaint and curious volume of forgotten lore', and his learning is not always worn lightly. — Foucault biographer David Macey, 1993[74] In West Germany, Foucault completed in 1960 his primary thesis (thèse principale) for his State doctorate, titled Folie et déraison: Histoire de la folie à l'âge classique (trans. "Madness and Insanity: History of Madness in the Classical Age"), a philosophical work based upon his studies into the history of medicine. The book discussed how West European society had dealt with madness, arguing that it was a social construct distinct from mental illness. Foucault traces the evolution of the concept of madness through three phases: the Renaissance, the later 17th and 18th centuries, and the modern experience. The work alludes to the work of French poet and playwright Antonin Artaud, who exerted a strong influence over Foucault's thought at the time.[75] Histoire de la folie was an expansive work, consisting of 943 pages of text, followed by appendices and a bibliography.[76] Foucault submitted it at the University of Paris, although the university's regulations for awarding a State doctorate required the submission of both his main thesis and a shorter complementary thesis.[77] Obtaining a doctorate in France at the period was a multi-step process. The first step was to obtain a rapporteur, or "sponsor" for the work: Foucault chose Georges Canguilhem.[78] The second was to find a publisher, and as a result Folie et déraison was published in French in May 1961 by the company Plon, whom Foucault chose over Presses Universitaires de France after being rejected by Gallimard.[79] In 1964, a heavily abridged version was published as a mass market paperback, then translated into English for publication the following year as Madness and Civilization: A History of Insanity in the Age of Reason.[80] Folie et déraison received a mixed reception in France and in foreign journals focusing on French affairs. Although it was critically acclaimed by Maurice Blanchot, Michel Serres, Roland Barthes, Gaston Bachelard, and Fernand Braudel, it was largely ignored by the leftist press, much to Foucault's disappointment.[81] It was notably criticised for advocating metaphysics by young philosopher Jacques Derrida in a March 1963 lecture at the University of Paris. Responding with a vicious retort, Foucault criticised Derrida's interpretation of René Descartes. The two remained bitter rivals until reconciling in 1981.[82] In the English-speaking world, the work became a significant influence on the anti-psychiatry movement during the 1960s; Foucault took a mixed approach to this, associating with a number of anti-psychiatrists but arguing that most of them misunderstood his work.[83] Foucault's secondary thesis (thèse complémentaire), written in Hamburg between 1959 and 1960, was a translation and commentary on German philosopher Immanuel Kant's Anthropology from a Pragmatic Point of View (1798);[72] the thesis was titled Introduction à l'Anthropologie.[84] Largely consisting of Foucault's discussion of textual dating—an "archaeology of the Kantian text"—he rounded off the thesis with an evocation of Nietzsche, his biggest philosophical influence.[85] This work's rapporteur was Foucault's old tutor and then-director of the ENS, Hyppolite, who was well acquainted with German philosophy.[76] After both theses were championed and reviewed, he underwent his public defense of his doctoral thesis (soutenance de thèse) on 20 May 1961.[86] The academics responsible for reviewing his work were concerned about the unconventional nature of his major thesis; reviewer Henri Gouhier noted that it was not a conventional work of history, making sweeping generalisations without sufficient particular argument, and that Foucault clearly "thinks in allegories".[87] They all agreed however that the overall project was of merit, awarding Foucault his doctorate "despite reservations".[88] University of Clermont-Ferrand, The Birth of the Clinic, and The Order of Things: 1960–1966 In October 1960, Foucault took a tenured post in philosophy at the University of Clermont-Ferrand, commuting to the city every week from Paris,[89] where he lived in a high-rise block on the rue du Dr Finlay.[90] Responsible for teaching psychology, which was subsumed within the philosophy department, he was considered a "fascinating" but "rather traditional" teacher at Clermont.[91] The department was run by Jules Vuillemin, who soon developed a friendship with Foucault.[92] Foucault then took Vuillemin's job when the latter was elected to the Collège de France in 1962.[93] In this position, Foucault took a dislike to another staff member whom he considered stupid: Roger Garaudy, a senior figure in the Communist Party. Foucault made life at the university difficult for Garaudy, leading the latter to transfer to Poitiers.[94] Foucault also caused controversy by securing a university job for his lover, the philosopher Daniel Defert, with whom he retained a non-monogamous relationship for the rest of his life.[95] Foucault adored the work of Raymond Roussel and wrote a literary study of it. Foucault maintained a keen interest in literature, publishing reviews in literary journals, including Tel Quel and Nouvelle Revue Française, and sitting on the editorial board of Critique.[96] In May 1963, he published a book devoted to poet, novelist, and playwright Raymond Roussel. It was written in under two months, published by Gallimard, and was described by biographer David Macey as "a very personal book" that resulted from a "love affair" with Roussel's work. It was published in English in 1983 as Death and the Labyrinth: The World of Raymond Roussel.[97] Receiving few reviews, it was largely ignored.[98] That same year he published a sequel to Folie et déraison, titled Naissance de la Clinique, subsequently translated as The Birth of the Clinic: An Archaeology of Medical Perception. Shorter than its predecessor, it focused on the changes that the medical establishment underwent in the late 18th and early 19th centuries.[99] Like his preceding work, Naissance de la Clinique was largely critically ignored, but later gained a cult following.[98] It was of interest within the field of medical ethics, as it considered the ways in which the history of medicine and hospitals, and the training that those working within them receive, bring about a particular way of looking at the body: the 'medical gaze'.[100] Foucault was also selected to be among the "Eighteen Man Commission" that assembled between November 1963 and March 1964 to discuss university reforms that were to be implemented by Christian Fouchet, the Gaullist Minister of National Education. Implemented in 1967, they brought staff strikes and student protests.[101] In April 1966, Gallimard published Foucault's Les Mots et les choses ('Words and Things'), later translated as The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences.[102] Exploring how man came to be an object of knowledge, it argued that all periods of history have possessed certain underlying conditions of truth that constituted what was acceptable as scientific discourse. Foucault argues that these conditions of discourse have changed over time, from one period's épistémè to another.[103] Although designed for a specialist audience, the work gained media attention, becoming a surprise bestseller in France.[104] Appearing at the height of interest in structuralism, Foucault was quickly grouped with scholars such as Jacques Lacan, Claude Lévi-Strauss, and Roland Barthes, as the latest wave of thinkers set to topple the existentialism popularized by Jean-Paul Sartre. Although initially accepting this description, Foucault soon vehemently rejected it.[105] Foucault and Sartre regularly criticised one another in the press. Both Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir attacked Foucault's ideas as "bourgeois", while Foucault retaliated against their Marxist beliefs by proclaiming that "Marxism exists in nineteenth-century thought as a fish exists in water; that is, it ceases to breathe anywhere else."[106] University of Tunis and Vincennes: 1966–1970 I lived [in Tunisia] for two and a half years. It made a real impression. I was present for large, violent student riots that preceded by several weeks what happened in May in France. This was March 1968. The unrest lasted a whole year: strikes, courses suspended, arrests. And in March, a general strike by the students. The police came into the university, beat up the students, wounded several of them seriously, and started making arrests ... I have to say that I was tremendously impressed by those young men and women who took terrible risks by writing or distributing tracts or calling for strikes, the ones who really risked losing their freedom! It was a political experience for me. — Michel Foucault, 1983[107] In September 1966, Foucault took a position teaching psychology at the University of Tunis in Tunisia. His decision to do so was largely because his lover, Defert, had been posted to the country as part of his national service. Foucault moved a few kilometres from Tunis, to the village of Sidi Bou Saïd, where fellow academic Gérard Deledalle lived with his wife. Soon after his arrival, Foucault announced that Tunisia was "blessed by history", a nation which "deserves to live forever because it was where Hannibal and St. Augustine lived".[108] His lectures at the university proved very popular, and were well attended. Although many young students were enthusiastic about his teaching, they were critical of what they believed to be his right-wing political views, viewing him as a "representative of Gaullist technocracy", even though he considered himself a leftist.[109] Foucault was in Tunis during the anti-government and pro-Palestinian riots that rocked the city in June 1967, and which continued for a year. Although highly critical of the violent, ultra-nationalistic and anti-semitic nature of many protesters, he used his status to try to prevent some of his militant leftist students from being arrested and tortured for their role in the agitation. He hid their printing press in his garden, and tried to testify on their behalf at their trials, but was prevented when the trials became closed-door events.[110] While in Tunis, Foucault continued to write. Inspired by a correspondence with the surrealist artist René Magritte, Foucault started to write a book about the impressionist artist Édouard Manet, but never completed it.[111] In 1968, Foucault returned to Paris, moving into an apartment on the Rue de Vaugirard.[112] After the May 1968 student protests, Minister of Education Edgar Faure responded by founding new universities with greater autonomy. Most prominent of these was the Centre Expérimental de Vincennes in Vincennes on the outskirts of Paris. A group of prominent academics were asked to select teachers to run the centre's departments, and Canguilheim recommended Foucault as head of the Philosophy Department.[113] Becoming a tenured professor of Vincennes, Foucault's desire was to obtain "the best in French philosophy today" for his department, employing Michel Serres, Judith Miller, Alain Badiou, Jacques Rancière, François Regnault, Henri Weber, Étienne Balibar, and François Châtelet; most of them were Marxists or ultra-left activists.[114] Lectures began at the university in January 1969, and straight away its students and staff, including Foucault, were involved in occupations and clashes with police, resulting in arrests.[115] In February, Foucault gave a speech denouncing police provocation to protesters at the Maison de la Mutualité.[116] Such actions marked Foucault's embrace of the ultra-left,[117] undoubtedly influenced by Defert, who had gained a job at Vincennes' sociology department and who had become a Maoist.[118] Most of the courses at Foucault's philosophy department were Marxist–Leninist oriented, although Foucault himself gave courses on Nietzsche, "The end of Metaphysics", and "The Discourse of Sexuality", which were highly popular and over-subscribed.[119] While the right-wing press was heavily critical of this new institution, new Minister of Education Olivier Guichard was angered by its ideological bent and the lack of exams, with students being awarded degrees in a haphazard manner. He refused national accreditation of the department's degrees, resulting in a public rebuttal from Foucault.[120] |

成長期のキャリア(1960-1970) 狂気と文明 1960 Histoire de la folie』は読みやすいテキストではない。フーコーは、エラスムスやモリエールといった有名な作家から、古文書や医学・精神医学史の忘れられた人物に至 るまで、困惑するほど多様な資料に言及している。彼の博識は、ポーの言葉を借りれば「忘れ去られた言い伝えの多くの古風で好奇心をそそる書物の上で」何年 も思索にふけったことに由来するものであり、その学識は必ずしも軽々しく身につけられているわけではない。 - フーコーの伝記作家デイヴィッド・メイシー、1993年[74]。 西ドイツにおいて、フーコーは1960年に『Folie et déraison』というタイトルの博士論文を完成させた: 同書は医学史の研究に基づいた哲学的著作である。この本は、西ヨーロッパ社会が狂気をどのように扱ってきたかを論じ、狂気は精神病とは異なる社会的構成物 であると主張した。フーコーは、ルネサンス、17世紀後半と18世紀、そして近代の経験という3つの段階を通して、狂気の概念の変遷をたどっている。この 作品は、当時のフーコーの思想に強い影響を与えたフランスの詩人であり劇作家であったアントナン・アルトーの作品を暗示している[75]。 フーコーはこの論文をパリ大学に提出したが、パリ大学の博士号授与の規定では、主論文とそれを補完する短い論文の両方を提出する必要があった[77]。最 初のステップは、ラポルトゥール、つまり研究の「スポンサー」を得ることであった: フーコーが選んだのはジョルジュ・カンギレムであった[78]。第二のステップは出版社を見つけることであり、その結果『Folie et déraison』は1961年5月にガリマールに断られた後、フーコーがPresses Universitaires de Franceよりも選んだプロン社からフランス語で出版された[79]: A History of Insanity in the Age of Reason』として出版された[80]。 この『Folie et déraison』はフランス国内でも、またフランス問題に焦点を当てた海外の雑誌でも、さまざまな評価を受けた。モーリス・ブランショ、ミシェル・セレ ス、ロラン・バルト、ガストン・バシュラール、フェルナン・ブローデルらによって批評的に絶賛されたものの、左派のマスコミからはほとんど無視され、フー コーを失望させた。1963年3月にパリ大学で行われた講義で、若手の哲学者ジャック・デリダによって形而上学を提唱していると批判されたことは記憶に新 しい。それに対してフーコーは、ルネ・デカルトに対するデリダの解釈を批判した。英語圏では、この著作は1960年代の反精神医学運動に大きな影響を与え た。フーコーはこれに対して複雑なアプローチをとり、多くの反精神医学者と付き合ったが、彼らのほとんどは自分の著作を誤解していると主張した[83]。 1959年から1960年にかけてハンブルクで書かれたフーコーの副論文(thèse complémentaire)は、ドイツの哲学者であるイマニュエル・カントの『プラグマティックな視点からの人間学』(1798年)の翻訳と解説で あった[72]。 [この論文の報告者はフーコーの古くからの家庭教師であり、当時ENSの所長であったヒポライトであり、彼はドイツ哲学に精通していた。 [76] 両論文が支持され、審査された後、彼は1961年5月20日に博士論文の公開弁論(soutenance de thèse)を行った。 [86]査読を担当した学者たちは、彼の主要な論文の型破りな性質に懸念を抱いていた。査読者のアンリ・グヒエは、それが従来の歴史学の著作ではなく、十 分な特定の議論なしに大雑把な一般化をしており、フーコーは明らかに「寓話で考えている」と指摘した[87]。しかし、彼らは全員、全体的なプロジェクト が有益であることに同意し、「留保はあったが」フーコーに博士号を授与した[88]。 クレルモンフェラン大学、『診療所の誕生』、『物事の秩序』: 1960-1966 1960年10月、フーコーはクレルモンフェラン大学で哲学の終身ポストを得て、毎週パリからクレルモンフェランに通い[89]、フィンレー通りにある高 層ビルに住んでいた[90]。哲学科の中に含まれていた心理学を教える責任を負っていた彼は、クレルモンでは「魅力的」だが「どちらかといえば伝統的」な 教師だと考えられていた[91]。 [1962年にヴュイユマンがコレージュ・ド・フランスに選出されると、フーコーはヴュイユマンの職を引き継ぐ: 共産党幹部のロジェ・ガロディである。フーコーは、ガロディに大学での生活を困難にさせ、ガロディをポワチエに移籍させた[94]。フーコーはまた、恋人 である哲学者ダニエル・ドフェールのために大学の職を確保し、論争を引き起こした。 フーコーはレイモン・ルーセルの作品を崇拝し、その文学的研究を書いた。 1963年5月、詩人、小説家、劇作家であるレイモン・ルーセルに捧げた本を出版。この本はガリマール社から出版され、伝記作家のデイヴィッド・メイシー によれば、ルーセルの作品への「恋情」から生まれた「非常に個人的な本」であった。この本は1983年に『死と迷宮』として英語で出版された: 同年、『Folie et déraison』の続編『Naissance de la Clinique』(後に『クリニックの誕生』と訳される)を出版: An Archaeology of Medical Perception』と訳された。前作よりも短い本書は、18世紀後半から19世紀初頭にかけての医学界の変化に焦点を当てたものであった[99]。 [フーコーはまた、1963年11月から1964年3月にかけて、ガウリスト派の国民教育大臣であったクリスチャン・フーシェによって実施される予定で あった大学改革を議論するために集められた「18人委員会」の一員にも選ばれていた。1967年に実施されたこの改革は、職員のストライキと学生の抗議行 動を引き起こした[101]。 1966年4月、ガリマール社からフーコーの『言葉と物』(Les Mots et les choses)が出版される: 人間がいかにして知の対象となったかを探求するこの本は、歴史のあらゆる時代において、科学的な言説として受け入れられるものを構成する、ある種の真理の 基礎的な条件を持っていたと論じている[102]。フーコーは、こうした言説の条件は時代とともに変化し、ある時代のエピステーメーから別の時代のエピス テーメーへと変化してきたと論じている[103]。専門家向けに作られたものの、この著作はメディアの注目を集め、フランスでは驚きのベストセラーとなっ た。フーコーとサルトルは定期的に新聞でお互いを批判していた。サルトルとシモーヌ・ド・ボーヴォワールはともにフーコーの思想を「ブルジョワ」として攻 撃し、フーコーは「マルクス主義は魚が水の中に存在するように、19世紀の思想の中に存在する。 チュニス大学とヴァンセンヌ大学:1966-1970年 チュニジアに)2年半住んだ。それは実に印象的だった。私は、フランスで5月に起こったことに数週間先行して起こった、大規模で暴力的な学生暴動に立ち 会った。これは1968年3月のことだった。暴動は1年間続いた。ストライキ、授業停止、逮捕。そして3月、学生によるゼネストが起こった。警察が大学に 入ってきて、学生を殴り、何人かに重傷を負わせ、逮捕を始めた......。小冊子を書いたり、配布したり、ストライキを呼びかけたりして、本当に自由を 失う危険を冒した若者たちに、私はとてつもない感銘を受けた!それは私にとって政治的な経験だった - ミシェル・フーコー、1983年[107]。 1966年9月、フーコーはチュニジアのチュニス大学で心理学を教える職に就く。そうすることにしたのは、恋人のデフェールが国家公務の一環としてチュニ ジアに赴任することになったからである。フーコーはチュニスから数キロ離れたシディ・ブ・サイード村に移り住み、そこには学者仲間のジェラール・デレダル が妻と住んでいた。到着後すぐにフーコーは、チュニジアは「歴史に祝福された」国であり、「ハンニバルと聖アウグスティヌスが住んでいた場所であるため、 永遠に生きるに値する」国であると発表した[108]。大学での彼の講義は非常に人気があり、多くの聴講者があった。多くの若い学生たちはフーコーの講義 に熱狂的であったが、彼の右翼的な政治的見解には批判的で、彼自身は左翼主義者であったにもかかわらず、彼を「ガウリスト・テクノクラシーの代表」とみな していた[109]。 フーコーは、1967年6月にチュニスを揺るがした反政府・親パレスチナ暴動の間、チュニスにいた。多くのデモ参加者の暴力的、超国家主義的、反ユダヤ主 義的な性質を強く批判しながらも、彼は自分の地位を利用して、過激な左翼の学生たちが、この扇動に参加したために逮捕され、拷問されるのを防ごうとした。 チュニスにいる間、フーコーは執筆活動を続けた。シュルレアリスムの芸術家ルネ・マグリットとの往復書簡に触発され、フーコーは印象派の芸術家エドゥアー ル・マネについての本を書き始めたが、完成することはなかった[111]。 1968年、フーコーはパリに戻り、ヴォジラール通りのアパートに引っ越した[112]。1968年5月の学生運動の後、エドガー・フォール教育大臣は、 より大きな自治権を持つ新しい大学を設立することで対応した。その中で最も顕著だったのは、パリ郊外のヴァンセンヌにあるヴァンセンヌ・エクスペリメンタ ル・センターであった。著名な学者のグループが、センターの学科を運営する教師を選ぶよう依頼され、カンギルハイムはフーコーを哲学科の学科長に推薦した [113]。 [113]ヴァンセンヌの終身教授となったフーコーの望みは、「今日のフランス哲学の最高峰」を自分の学部で獲得することであり、ミシェル・セレス、ジュ ディス・ミラー、アラン・バディウ、ジャック・ランシエール、フランソワ・ルノー、アンリ・ウェーバー、エティエンヌ・バリバール、フランソワ・シャトレ を採用し、彼らのほとんどはマルクス主義者や極左活動家であった[114]。 講義は1969年1月に同大学で開始され、フーコーを含む学生や職員はすぐに占拠や警察との衝突に巻き込まれ、逮捕者を出した。 [2月には、フーコーはメゾン・ド・ラ・ミュチュアリテで抗議者たちに対して警察の挑発行為を糾弾する演説を行った[116]。こうした行動は、フーコー が極左を受け入れたことを示すものであり[117]、ヴァンセンヌの社会学部で職を得、毛沢東主義者となったデフェールの影響を受けたことは間違いない。 [118] フーコーの哲学科のコースのほとんどはマルクス・レーニン主義を志向するものであったが、フーコー自身はニーチェ、「形而上学の終焉」、「セクシュアリ ティの言説」に関するコースを開講し、非常に人気が高く、定員を超える申し込みがあった[119]。右派の報道機関がこの新しい教育機関を激しく批判する 一方で、新しい教育大臣オリヴィエ・ギシャールは、そのイデオロギー的な傾向と、学生が行き当たりばったりで学位を授与される試験の欠如に怒りを覚えた。 彼は同学科の学位の国家認定を拒否し、フーコーは公の場で反論する結果となった[120]。 |

| Later life (1970–1984) Collège de France and Discipline and Punish: 1970–1975 Foucault desired to leave Vincennes and become a fellow of the prestigious Collège de France. He requested to join, taking up a chair in what he called the "history of systems of thought", and his request was championed by members Dumézil, Hyppolite, and Vuillemin. In November 1969, when an opening became available, Foucault was elected to the Collège, though with opposition by a large minority.[121] He gave his inaugural lecture in December 1970, which was subsequently published as L'Ordre du discours (The Discourse of Language).[122] He was obliged to give 12 weekly lectures a year—and did so for the rest of his life—covering the topics that he was researching at the time; these became "one of the events of Parisian intellectual life" and were repeatedly packed out events.[123] On Mondays, he also gave seminars to a group of students; many of them became a "Foulcauldian tribe" who worked with him on his research. He enjoyed this teamwork and collective research, and together they published a number of short books.[124] Working at the Collège allowed him to travel widely, giving lectures in Brazil, Japan, Canada, and the United States over the next 14 years.[125] In 1970 and 1972, Foucault served as a professor in the French Department of the University at Buffalo in Buffalo, New York.[126] In May 1971, Foucault co-founded the Groupe d'Information sur les Prisons (GIP) along with historian Pierre Vidal-Naquet and journalist Jean-Marie Domenach. The GIP aimed to investigate and expose poor conditions in prisons and give prisoners and ex-prisoners a voice in French society. It was highly critical of the penal system, believing that it converted petty criminals into hardened delinquents.[127] The GIP gave press conferences and staged protests surrounding the events of the Toul prison riot in December 1971, alongside other prison riots that it sparked off; in doing so it faced a police crackdown and repeated arrests.[128] The group became active across France, with 2,000 to 3,000, members, but disbanded before 1974.[129] Also campaigning against the death penalty, Foucault co-authored a short book on the case of the convicted murderer Pierre Rivière.[130] After his research into the penal system, Foucault published Surveiller et punir: Naissance de la prison (Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison) in 1975, offering a history of the system in western Europe. In it, Foucault examines the penal evolution away from corporal and capital punishment to the penitentiary system that began in Europe and the United States around the end of the 18th century.[131] Biographer Didier Eribon described it as "perhaps the finest" of Foucault's works, and it was well received.[132] Foucault was also active in anti-racist campaigns; in November 1971, he was a leading figure in protests following the perceived racist killing of Arab migrant Djellali Ben Ali.[citation needed] In this he worked alongside his old rival Sartre, the journalist Claude Mauriac, and one of his literary heroes, Jean Genet. This campaign was formalised as the Committee for the Defence of the Rights of Immigrants, but there was tension at their meetings as Foucault opposed the anti-Israeli sentiment of many Arab workers and Maoist activists.[133] At a December 1972 protest against the police killing of Algerian worker Mohammad Diab, both Foucault and Genet were arrested, resulting in widespread publicity.[134] Foucault was also involved in founding the Agence de Press-Libération (APL), a group of leftist journalists who intended to cover news stories neglected by the mainstream press. In 1973, they established the daily newspaper Libération, and Foucault suggested that they establish committees across France to collect news and distribute the paper, and advocated a column known as the "Chronicle of the Workers' Memory" to allow workers to express their opinions. Foucault wanted an active journalistic role in the paper, but this proved untenable, and he soon became disillusioned with Libération, believing that it distorted the facts; he did not publish in it until 1980.[135] In 1975 he had an LSD experience with Simeon Wade and Michael Stoneman in Death Valley, California and later wrote "it was the greatest experience of his life, and that it profoundly changed his life and his work". In front of Zabriskie Point they took LSD while listening to a well-prepared music program: Richard Strauss's Four Last Songs, followed by Charles Ives's Three Places in New England, ending with a few avant-garde pieces by Stockhausen.[136][137] According to Wade, as soon as he came back to Paris, Foucault scrapped the second History of Sexuality's manuscript, and totally rethought the whole project.[138] The History of Sexuality and Iranian Revolution: 1976–1979 In 1976, Gallimard published Foucault's Histoire de la sexualité: la volonté de savoir (The History of Sexuality: The Will to Knowledge), a short book exploring what Foucault called the "repressive hypothesis". It revolved largely around the concept of power, rejecting both Marxist and Freudian theory. Foucault intended it as the first in a seven-volume exploration of the subject.[139] Histoire de la sexualité was a best-seller in France and gained positive press, but lukewarm intellectual interest, something that upset Foucault, who felt that many misunderstood his hypothesis.[140] He soon became dissatisfied with Gallimard after being offended by senior staff member Pierre Nora.[141] Along with Paul Veyne and François Wahl, Foucault launched a new series of academic books, known as Des travaux (Some Works), through the company Seuil, which he hoped would improve the state of academic research in France.[142] He also produced introductions for the memoirs of Herculine Barbin and My Secret Life.[143] Foucault's Histoire de la sexualité concentrates on the relation between truth and sex.[144] He defines truth as a system of ordered procedures for the production, distribution, regulation, circulation, and operation of statements.[145] Through this system of truth, power structures are created and enforced. Though Foucault's definition of truth may differ from other sociologists before and after him, his work with truth in relation to power structures, such as sexuality, has left a profound mark on social science theory. In his work, he examines the heightened curiosity regarding sexuality that induced a "world of perversion" during the elite, capitalist 18th and 19th century in the western world. According to Foucault in History of Sexuality, society of the modern age is symbolized by the conception of sexual discourses and their union with the system of truth.[144] In the "world of perversion", including extramarital affairs, homosexual behavior, and other such sexual promiscuities, Foucault concludes that sexual relations of the kind are constructed around producing the truth.[146] Sex became not only a means of pleasure, but an issue of truth.[146] Sex is what confines one to darkness, but also what brings one to light.[147] Similarly, in The History of Sexuality, society validates and approves people based on how closely they fit the discursive mold of sexual truth.[148] As Foucault reminds us, in the 18th and 19th centuries, the Church was the epitome of power structure within society. Thus, many aligned their personal virtues with those of the Church, further internalizing their beliefs on the meaning of sex.[148] However, those who unify their sexual relation to the truth become decreasingly obliged to share their internal views with those of the Church. They will no longer see the arrangement of societal norms as an effect of the Church's deep-seated power structure. There exists an international citizenry that has its rights, and has its duties, and that is committed to rise up against every abuse of power, no matter who the author, no matter who the victims. After all, we are all ruled, and as such, we are in solidarity. — Michel Foucault, 1981[149] Foucault remained a political activist, focusing on protesting government abuses of human rights around the world. He was a key player in the 1975 protests against the Spanish government who were set to execute 11 militants sentenced to death without fair trial. It was his idea to travel to Madrid with six others to give a press conference there; they were subsequently arrested and deported back to Paris.[150] In 1977, he protested the extradition of Klaus Croissant to West Germany, and his rib was fractured during clashes with riot police.[151] In July that year, he organised an assembly of Eastern Bloc dissidents to mark the visit of Soviet general secretary Leonid Brezhnev to Paris.[152] In 1979, he campaigned for Vietnamese political dissidents to be granted asylum in France.[153] In 1977, Italian newspaper Corriere della sera asked Foucault to write a column for them. In doing so, in 1978 he travelled to Tehran in Iran, days after the Black Friday massacre. Documenting the developing Iranian Revolution, he met with opposition leaders such as Mohammad Kazem Shariatmadari and Mehdi Bazargan, and discovered the popular support for Islamism.[154] Returning to France, he was one of the journalists who visited the Ayatollah Khomeini, before visiting Tehran. His articles expressed awe of Khomeini's Islamist movement, for which he was widely criticised in the French press, including by Iranian expatriates. Foucault's response was that Islamism was to become a major political force in the region, and that the West must treat it with respect rather than hostility.[155] In April 1978, Foucault traveled to Japan, where he studied Zen Buddhism under Omori Sogen at the Seionji temple in Uenohara.[125] |

その後の人生(1970-1984) コレージュ・ド・フランスと『規律と罰』:1970-1975年 フーコーはヴァンセンヌを離れ、名門コレージュ・ド・フランスのフェローになることを望んだ。彼は「思想システム史」と呼ばれる講座に参加することを希望 し、デュメジル、ヒュポリット、ヴュイユマンの3人の会員が彼の希望を支持した。1969年11月、空席ができたため、フーコーは少数派の反対を押し切っ てコレージュに選出された[121]。1970年12月、彼は就任講演を行い、その講演は後に『言語の言説』(L'Ordre du discours)として出版された。 [この講義は「パリの知的生活のイベントのひとつ」となり、何度も満員御礼となった[123]。月曜日には、彼はまた学生のグループに対してセミナーを 行った。フーコーはこのチームワークと集団的な研究を楽しんでおり、彼らは一緒に数多くの短い本を出版した[124]。コレージュで働くことで、彼は広く 旅することができ、その後14年間にわたってブラジル、日本、カナダ、アメリカで講義を行った[125]。 1971年5月、フーコーは歴史家のピエール・ヴィダル=ナケ、ジャーナリストのジャン=マリー・ドメナックとともにGIP(Groupe d'Information sur les Prisons)を共同設立。GIPは、刑務所の劣悪な状況を調査・暴露し、囚人や元囚人にフランス社会での発言権を与えることを目的としていた。GIP は1971年12月にトゥール刑務所で起こった暴動をめぐって記者会見を開き、抗議活動を行った。 [128]このグループはフランス全土で活動するようになり、2,000人から3,000人のメンバーを擁したが、1974年以前に解散した[129]。 また、死刑反対運動を展開し、フーコーは有罪判決を受けた殺人者ピエール・リヴィエールの事件に関する短い本を共著した[130]: 1975年に『規律と罰:刑務所の誕生』を出版し、西ヨーロッパにおける刑罰制度の歴史を提示した。その中でフーコーは、18世紀末頃にヨーロッパとアメ リカで始まった、体罰と死刑から刑務所制度への刑罰の進化を検証している[131]。伝記作家のディディエ・エリボンは、この著作をフーコーの著作の中で 「おそらく最高傑作」と評し、好評を博した[132]。 1971年11月、アラブからの移民であるジェラリ・ベン・アリが人種差別によって殺害されたと認識されたことを受けて、フーコーは抗議活動の中心人物と なった。このキャンペーンは「移民の権利擁護委員会」として正式に発足したが、フーコーは多くのアラブ人労働者や毛沢東主義活動家の反イスラエル感情に反 対していたため、彼らの会合には緊張感があった。 [1972年12月、警察によるアルジェリア人労働者モハマド・ディアブの殺害に対する抗議活動で、フーコーとジュネは逮捕され、広く世間に知られること になった[134]。フーコーはまた、主流紙によって無視されたニュースを報道することを目的とした左派ジャーナリストのグループ、Agence de Press-Libération(APL)の設立にも関わった。1973年、彼らは日刊紙『リベラシオン』を創刊し、フーコーはフランス全土に委員会を 設置してニュースを収集し、紙面を配布することを提案し、労働者が意見を表明できるように「労働者の記憶のクロニクル」と呼ばれるコラムを提唱した。 1975年、カリフォルニア州デスバレーでシメオン・ウェイドとマイケル・ストーンマンとLSD体験をし、後に「人生最大の体験であり、彼の人生と仕事を 大きく変えた」と記している[135]。ザブリスキー・ポイントの前で、彼らは用意周到な音楽プログラムを聴きながらLSDを摂取した: リヒャルト・シュトラウスの『4つの最後の歌』、チャールズ・アイヴズの『ニューイングランドの3つの場所』と続き、シュトックハウゼンの前衛的な小品で 終わる[136][137]。ウェイドによれば、パリに戻るとすぐにフーコーは『セクシュアリティの歴史』第2版の原稿を破棄し、プロジェクト全体を全面 的に考え直したという。 セクシュアリティの歴史』とイラン革命: 1976-1979 1976年、ガリマールはフーコーの『性の歴史:知識への意志』(Histoire de la sexualité: la volonté de savoir)を出版した。この本は、マルクス主義とフロイトの理論を否定し、権力の概念を中心に展開された。フーコーはこの本を7巻からなる主題の探求 の最初の一冊とするつもりであった[139]。Histoire de la sexualitéはフランスでベストセラーとなり、好意的な報道を得たが、知的関心は薄く、多くの人が自分の仮説を誤解していると感じていたフーコーを 動揺させた[140]。 フーコーは上級スタッフのピエール・ノラに腹を立て、すぐにガリマールに不満を抱くようになる。 [141]ポール・ヴェイヌとフランソワ・ヴァールとともに、フーコーはフランスの学術研究の状況を改善することを期待し、セイユ社を通じて『Des travaux(いくつかの作品)』として知られる学術書の新シリーズを立ち上げた[142]。 フーコーのHistoire de la sexualitéは真理と性の関係に集中している[144]。彼は真理を陳述の生産、分配、規制、流通、運用のための秩序だった手続きのシステムとして 定義している[145]。フーコーの真理の定義は彼の前後の社会学者とは異なるかもしれないが、セクシュアリティのような権力構造との関係における真理に 関する彼の仕事は、社会科学理論に深い足跡を残している。フーコーの著作では、18世紀から19世紀にかけての西欧世界におけるエリート、資本主義の時代 に、「倒錯の世界」を誘発したセクシュアリティに対する好奇心の高まりを検証している。セクシュアリティの歴史』におけるフーコーによれば、近代の社会 は、性的言説の観念と真理の体系との結合によって象徴されている。 [144]婚外交渉、同性愛行動、その他のそのような性的乱交を含む「倒錯の世界」において、フーコーは、その種の性的関係は真実を生み出すことを中心に 構築されていると結論付けている[146]。 セックスは快楽の手段であるだけでなく、真実の問題となった[146]。 同様に、『セクシュアリティの歴史』においては、社会は、彼らがどれだけ性的真実の言説的型に忠実であるかに基づいて人々を正当化し、承認する [148]。フーコーが思い起こさせるように、18世紀から19世紀にかけて、教会は社会における権力構造の典型であった。148]しかし、自分の性的関 係を真理に統一する者は、自分の内的見解を教会の見解と共有する義務が減少していく。彼らはもはや、社会規範の取り決めを、教会の根深い権力構造の影響と みなすことはないだろう。 国際的な市民が存在し、その市民には権利があり、義務があり、誰が作者であろうと、誰が被害者であろうと、あらゆる権力の乱用に対して立ち上がることを約 束する。結局のところ、私たちはみな支配されているのであり、連帯しているのである。 - ミシェル・フーコー、1981年[149]。 フーコーは政治活動家であり続け、世界各地で政府による人権侵害に抗議することに力を注いだ。彼は、公正な裁判を経ずに死刑判決を受けた11人の過激派を 処刑しようとしていたスペイン政府に対する1975年の抗議活動の中心人物であった。1977年には、クラウス・クロワッサンの西ドイツへの引き渡しに抗 議し、機動隊と衝突して肋骨を骨折した[151]。同年7月には、ソ連のレオニード・ブレジネフ書記長のパリ訪問を記念して、東欧圏の反体制派の集会を組 織した[152]。1979年には、ベトナムの政治的反体制派にフランスへの亡命を認めるよう運動した[153]。 1977年、イタリアのコリエレ・デラ・セラ紙がフーコーにコラムの執筆を依頼。その際、1978年にイランのテヘランを訪れた。発展途上のイラン革命を 記録し、モハマド・カゼム・シャリアートマダーリやメフディ・バザルガンといった反対派の指導者たちと会い、イスラム主義に対する民衆の支持を知った [154]。フランスに戻り、テヘランを訪れる前にホメイニ師を訪問したジャーナリストの一人となる。彼の記事は、ホメイニのイスラム主義運動に対する畏 敬の念を表現したもので、イラン人駐在員を含め、フランスの新聞で広く批判された。1978年4月、フーコーは日本を訪れ、上野原にある清音寺で大森曹玄 に禅宗を学んだ[125]。 |

| Final years: 1980–1984 Although remaining critical of power relations, Foucault expressed cautious support for the Socialist Party government of François Mitterrand following its electoral victory in 1981.[156] But his support soon deteriorated when that party refused to condemn the Polish government's crackdown on the 1982 demonstrations in Poland orchestrated by the Solidarity trade union. He and sociologist Pierre Bourdieu authored a document condemning Mitterrand's inaction that was published in Libération, and they also took part in large public protests on the issue.[157] Foucault continued to support Solidarity, and with his friend Simone Signoret traveled to Poland as part of a Médecins du Monde expedition, taking time out to visit the Auschwitz concentration camp.[158] He continued his academic research, and in June 1984 Gallimard published the second and third volumes of Histoire de la sexualité. Volume two, L'Usage des plaisirs, dealt with the "techniques of self" prescribed by ancient Greek pagan morality in relation to sexual ethics, while volume three, Le Souci de soi, explored the same theme in the Greek and Latin texts of the first two centuries CE. A fourth volume, Les Aveux de la chair, was to examine sexuality in early Christianity, but it was not finished.[159] In October 1980, Foucault became a visiting professor at the University of California, Berkeley, giving the Howison Lectures on "Truth and Subjectivity", while in November he lectured at the Humanities Institute at New York University. His growing popularity in American intellectual circles was noted by Time magazine, while Foucault went on to lecture at UCLA in 1981, the University of Vermont in 1982, and Berkeley again in 1983, where his lectures drew huge crowds.[160] Foucault spent many evenings in the San Francisco gay scene, frequenting sado-masochistic bathhouses, engaging in unprotected sex. He praised sado-masochistic activity in interviews with the gay press, describing it as "the real creation of new possibilities of pleasure, which people had no idea about previously".[161] Foucault contracted HIV and eventually developed AIDS. Little was known of the virus at the time; the first cases had only been identified in 1980.[162] Foucault initially referred to AIDS as a "dreamed-up disease".[163] In summer 1983, he developed a persistent dry cough, which concerned friends in Paris, but Foucault insisted it was just a pulmonary infection.[164] Only when hospitalized was Foucault correctly diagnosed as being HIV-positive; treated with antibiotics, he delivered a final set of lectures at the Collège de France.[165] Foucault entered Paris' Hôpital de la Salpêtrière—the same institution that he had studied in Madness and Civilisation—on 10 June 1984, with neurological symptoms complicated by sepsis. He died in the hospital on 25 June.[166] Death On 26 June 1984, Libération announced Foucault's death, mentioning the rumour that it had been brought on by AIDS. The following day, Le Monde issued a medical bulletin cleared by his family that made no reference to HIV/AIDS.[167] On 29 June, Foucault's la levée du corps ceremony was held, in which the coffin was carried from the hospital morgue. Hundreds attended, including activists and academic friends, while Gilles Deleuze gave a speech using excerpts from The History of Sexuality.[168] His body was then buried at Vendeuvre-du-Poitou in a small ceremony.[169] Soon after his death, Foucault's partner Daniel Defert founded the first national HIV/AIDS organisation in France, AIDES; a play on the French word for "help" (aide) and the English- language acronym for the disease.[170] On the second anniversary of Foucault's death, Defert publicly revealed in The Advocate that Foucault's death was AIDS-related.[171] |

晩年 1980-1984 フーコーは権力関係に批判的であり続けたが、1981年の選挙での勝利後、フランソワ・ミッテラン社会党政権への慎重な支持を表明した[156]。しか し、同党が1982年にポーランドで連帯労働組合が組織したデモに対するポーランド政府の弾圧を非難することを拒否したため、彼の支持はすぐに悪化した。 社会学者ピエール・ブルデューとともにミッテランの無策を非難する文書を執筆し、『リベラシオン』誌に掲載され、この問題に関する大規模な抗議行動にも参 加した[157]。第2巻『L'Usage des plaisirs』では、古代ギリシャの異教道徳が性的倫理に関連して規定した「自己の技法」を扱い、第3巻『Le Souci de soi』では、紀元後2世紀のギリシャ語とラテン語のテキストにおける同じテーマを探求した。第4巻『Les Aveux de la chair』は初期キリスト教におけるセクシュアリティを考察する予定だったが、未完に終わった[159]。 1980年10月、フーコーはカリフォルニア大学バークレー校の客員教授となり、「真理と主観性」に関するハウソン講義を行い、11月にはニューヨーク大 学の人文科学研究所で講義を行った。フーコーは1981年にはUCLA、1982年にはバーモント大学、1983年にはバークレーで講義を行い、彼の講義 は多くの聴衆を集めた[160]。フーコーはサンフランシスコのゲイ・シーンで多くの夜を過ごし、サド・マゾ的な浴場に足繁く通い、無防備なセックスに興 じた。彼はゲイプレスとのインタビューでサド・マゾヒスティックな行為を賞賛し、それを「人々が以前は考えもしなかった新しい快楽の可能性の真の創造」と 表現した[161]。フーコーは当初、エイズを「夢物語のような病気」と呼んでいた[163]。1983年夏、乾いた咳が続くようになり、パリの友人たち は心配したが、フーコーはただの肺感染症だと主張した[164]。 [164] 入院して初めてフーコーはHIV陽性であると正しく診断され、抗生物質による治療を受け、コレージュ・ド・フランスで最後の講義を行った[165] 。6月25日に病院で死去した[166]。 死 1984年6月26日、リベラシオンはフーコーの死を発表し、エイズによるものだという噂に触れた。翌日、ル・モンド紙は遺族が確認した医学的速報を発表 し、HIV/AIDSについては言及しなかった[167]。6月29日、フーコーの死体安置所から棺を運ぶ儀式が行われた。ジル・ドゥルーズが『セクシュ アリティの歴史』からの抜粋を用いたスピーチを行い、彼の遺体はヴァンドゥヴル=デュ=ポワトゥーに埋葬された。 [169]フーコーのパートナーであったダニエル・ドフェールは、彼の死後すぐにフランス初のHIV/AIDSの全国組織であるAIDESを設立した。 フーコーの2回目の命日に、ドフェールは『アドヴォケイト』誌でフーコーの死がAIDSに関連したものであったことを公にした[171]。 |