ミッシェル・フーコー 『古典時代における狂人の歴史』

Michel Foucault,

Histoire de la folie à l'âge classique, 1972.

ミッシェル・フーコー 『古典時代における狂人の歴史』

Michel Foucault,

Histoire de la folie à l'âge classique, 1972.

★哲学者ミシェル・フーコーは、 心理学の分野での先行研究、個人的な心 理的困難、精神病院での勤務経験などから、1961年に『狂気と非理性:古典主義時代における狂気の歴史(Histoire de la folie à l'âge classique)』(第1版)を書き上げた。1955年から1959年にかけて、ポーランドとドイツで文化外交と教育のポスト に就き、スウェーデンではウプサラ大学のフランス文化センターのディレクターを務めていた時に、この本を執筆したのである。

| Madness and

Civilization: A History of Insanity in the Age of Reason (French: Folie

et Déraison: Histoire de la folie à l'âge classique, 1961) is an

examination by Michel Foucault of the evolution of the meaning of

madness in the cultures and laws, politics, philosophy, and medicine of

Europe—from the Middle Ages until the end of the 18th century—and a

critique of the idea of history and of the historical method. Although

he uses the language of phenomenology to describe the influence of

social structures in the history of the Othering of insane people from

society, Madness and Civilization is Foucault's philosophic progress

from phenomenology toward something like structuralism (a label

Foucault himself always adamantly rejected). |

狂気と文明:理性の時代におけるひとつの歴史(Folie et

Déraison: Histoire de la folie à l'âge classique,

1961=狂気と錯乱-古典主義時代の狂気の歴史)は、中世から18世紀末までのヨーロッパの文化や法律、政治、哲学、医学における狂気の意味の変遷をミ

シェル・フーコーが考察し、歴史の概念と歴史的方法に対する批判を展開したものである。狂気の人たちが社会から他者化された歴史における社会構造の影響に

ついて、現象学の言葉を用いて説明しているが、『狂気と文明』は現象学から構造主義のようなもの(フーコー自身は常にこのレッテルを断固として拒否してい

る)へと向かうフーコーの哲学的な進歩であるといえるだろう。 |

★『狂気と文明』において、フーコーは狂気

(狂気)という概念の文化的進化を3つの段階に分けて追っている。

【中世】 中世では、社会はハンセン病患者を自分たちから遠ざけていた。一方、「古典時代」には、社会的に隔離される対象はハンセン病患者から狂人へと移ったが、そ の方法は異なっていた。中世のハンセン病患者は確かに危険視されていたが、社会から徹底的に拒絶されていたわけではなかった。ハンセン病患者のための病院 は、ほとんどの場合、都市の門の近くに位置しており、社会から離れてはいるものの、見えない場所にあるわけではなかった。ハンセン病患者の存在は、キリス ト教の慈善の義務を人々に思い出させ、社会に肯定的な役割を果たしていたのである。

【ルネサンス】 ルネサンス期の芸術作品では、狂気の人々は知恵(世界の限界に関する知識)を持つ存在として描かれ、文学では、狂気の人々は、人間が本質的に持つものと、 人間が装うものとの違いを明らかにする存在として描かれた。ルネサンス期の芸術作品や文学作品では、狂気の人々は、宇宙的な悲劇の神秘的な力を象徴する存 在として、理性的な人々と知的に関わり合う存在として描かれた。[2] フーコーは、愚か者の船というルネサンス期のイメージと、その後の監禁という概念とを対比させている。ルネサンスは狂人を閉じ込めるのではなく、彼らの循 環を確保した。そのため、「乗客」であり「通り過ぎる存在」である狂人は、人間の条件の象徴となった。「狂気とは死の予兆である」。 しかし、ルネサンスの知性主義は、中世の狂気に関する主観的な記述と比較して、理性と非理性について客観的に考え、記述する方法を開発し始めた。

【古典時代】 17世紀の理性の時代の幕開けに、ヨーロッパ諸国では「大監禁」と呼ばれる精神異常者の監禁が行われた。当初、精神異常者の管理は社会の周縁に隔離するこ とから始まり、その後、監禁によって社会から物理的に隔離された。 反社会的人物(娼婦、浮浪者、冒涜者など)とともに、パリ総合病院のような新しい施設に隔離した。フーコーによると、「総合病院」の設立はデカルトの『省 察』に対応し、哲学的な言説から非合理的なものを排除しようとする欲望を反映している。「古典的理性」は狂気という歴史に「断絶」をもたらしたのである。 さらに、キリスト教社会では、売春、浮浪、冒涜、不合理などの生き方を自ら選択した反社会的人間は道徳的に誤っているとみなされた。このような道徳的過ち を正すために、社会から追放された人々を収容する新しい制度では、受刑者に生活様式を改めることを強制するための、罰と報酬からなるプログラムで構成され た生活様式の体制が採用された。 このような施設収容を推進した社会経済的な要因としては、社会的に望ましくない人々を主流社会から物理的に隔離する法的権限を持つ、法外な社会的メカニズ ムの必要性、および、ワークハウスに住む貧困層の賃金と雇用を管理する必要性があった。ワークハウスに住む人々がいることで、自由民の労働者の賃金が低下 していたのである。[8] 精神異常者と精神正常者の概念上の区別は、自由社会から施設収容へと人間を法外に隔離する慣行によって生み出された社会的な構築物であった。また、施設収 容は、狂気というものを、自然の研究対象として、そして治療すべき病気として捉え始めた当時の医師たちにとって、狂気の人々を都合よく利用できるものにし た。

【近代】 近代は18世紀末に始まり、医師の監督下で精神異常者を収容する医療機関が設立された。これらの施設は、2つの文化的動機から生まれた。すなわち、(i) 貧困家庭から精神異常者を隔離して治療するという新たな目標、および、(ii) 社会的に望ましくない人々を隔離して社会を守るという古い目的である。この2つの明確な社会的目的はすぐに忘れ去られ、医療施設は狂気に対する治療的処置 を行う唯一の場所となった。名目上は科学的見地や診断の観点においてより進歩し、狂気の人々に対する臨床治療に思いやりがあるとはいえ、現代の医療施設は 中世の狂気に対する治療と同様に残酷な管理下に置かれたままであった。 1961年の『狂気と文明』の序文で、フーコーは次のように述べている。 現代人はもはや狂人とコミュニケーションをとることはない。共通の言語など存在しない、いや、もはや存在しえないのだ。18世紀末に狂気が精神疾患として 定義されたことは、対話の断絶を証明し、すでに実行された分離を意味し、狂気と理性との間で交わされた、不明瞭な構文の不完全な言葉のすべてを記憶から排 除する。精神医学の言語は、理性による狂気についての独白であり、このような沈黙の中でしか生まれることはなかった。

| 『狂気の歴史』

(Histoire de la folie à l'âge classique)とは、西欧の歴史において狂気を扱った文化と法律、政治、哲

学、思想、制度、芸術そして医学などにおける、狂気の意味の展開の考察であり―そして歴史の理念及び歴史学研究法の理念の批判である、ミシェル・フーコー

の1961年の著作である。 社会から正気でない人々を排除する歴史における社会構造の影響の記述のために現象学の言語を彼は用いるけれども、『狂気の歴史』は現象学から幾らか(彼自 身が断固として拒絶した彼へのラベルの)構造主義へのフーコーの哲学的進歩である[1]。 フランス語の教師をしていたスウェーデンのウプサラで第一稿が書かれた が(ウプサラ大学図書館の医学文庫が重要な役割を果たした)、スウェーデンにおける博士論文提出を拒否され、その後ワルシャワ、パリで完成された。『狂 気の歴史』はソルボンヌ大学に博士論文として提出され(審査員はジョルジュ・カンギレム、ダニエル・ラガーシュ(英語版、フランス語版))、同時に『狂気 と非理性、古典主義時代における狂気の歴史』というタイトルで1961年にプロン社(英語版、フランス語版)から出版された。出版された本書に対して、 フェルナン・ブローデル、モーリス・ブランショは熱烈な賛辞を送っている。その後、1972年、初版の序文を削除した現在の版『古典主義時代における狂気 の歴史』が、ガリマール社「歴史学叢書」から再刊された[2]。 |

|

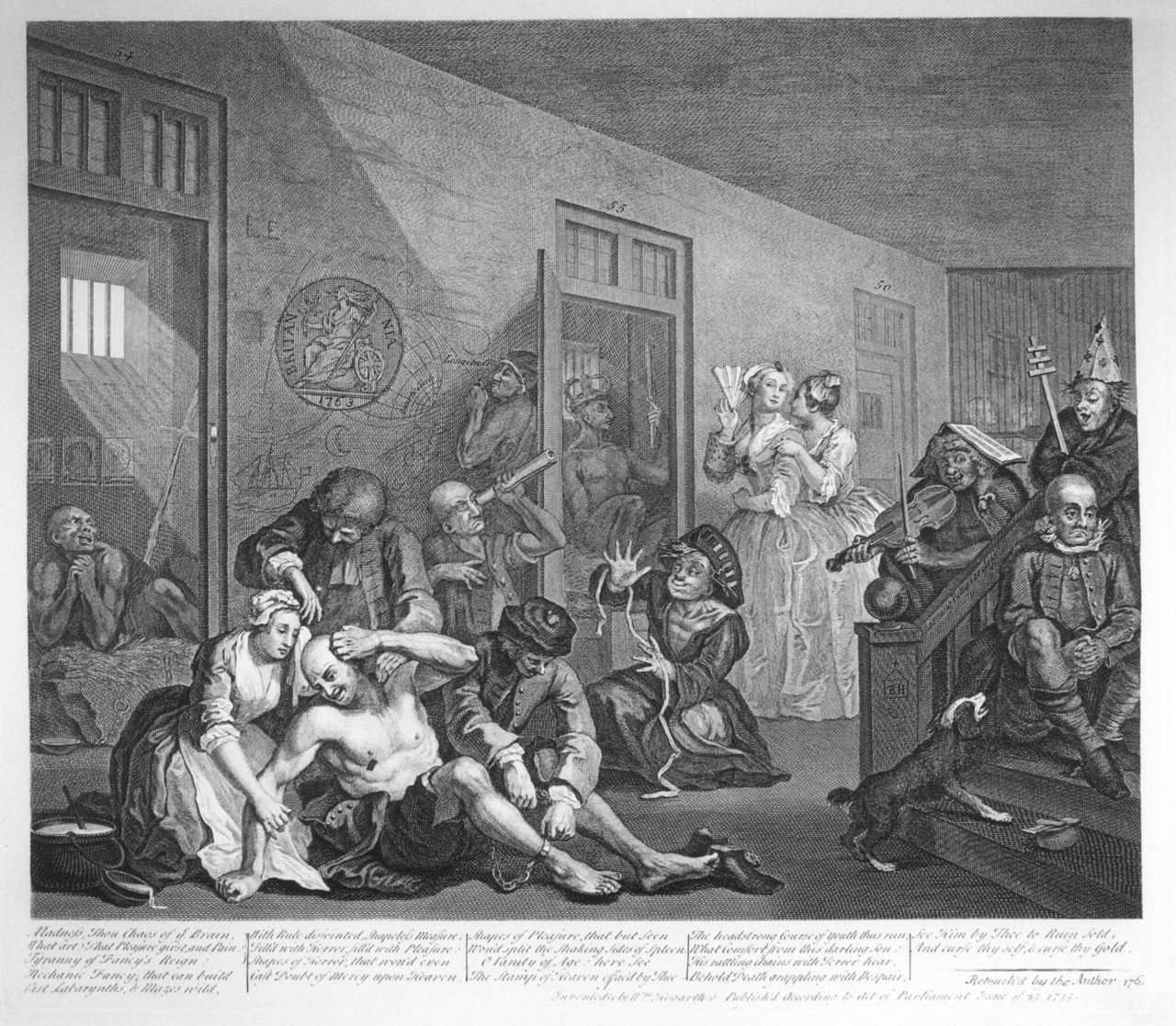

| 理論 「狂気の歴史」というタイトルは、決して自明のものではない。なぜなら、フーコーの目的は、精神疾患を医学的カテゴリーにおいて説明することではなく、西 欧において変容してきた狂気の内実を歴史的な次元においてとらえることにあったからである。それは、彼以前の人間科学が歴史的実践をなおざりにしてきたこ とへの批判でもあった[3]。フーコーは、その「歴史」を癩病患者が社会的にも物理的にも排除されていた中世まで遡る。そして、癩病は次第に姿を消してい き、狂気がそれに代わって排除されるべきものとなったと彼は言う。狂った人間を舟に乗せて送り出したという15世紀の「阿呆船」は、文字通りその排除が一 つの形をとったものであった。しかし、ルネサンス期には、狂気がきわめて豊饒なる現象として扱われるようになる。なぜなら、狂人とは、「人は神の理性 (Reason of God)には近づきえない」という思想の体現だったからである。セルバンテスの『ドン・キホーテ』にみられるように、あらゆる人間は欲望と異物に弱いもの だ。したがって、正常でない人間を神の理性に接近しすぎた存在と見なす考えは、中世社会で広く受け入れられていた。ボッシュやブリューゲルの絵画に表象さ れているものこそ「狂気」である。それは、死の不安であり、宇宙の混沌である。しかし、ルネサンス以降、この狂気は、それまでのイメージ(画像)から、エ ラスムスの「痴愚神礼賛」がその典型であるように言語のレベルに移される。そしてこのとき、狂気は、夢想的・宇宙的な強迫観念を離れ、理性との関係におい てとらえられるようになった。あるいは、より人間的なものに限定されたとも言える[4]。 17世紀になってはじめて、フーコーが「大監禁時代」と表現したことで 知られる潮流が起る。「理解不能な」人間たちが、システマティックに監禁され、収容されていった。18世紀には、狂気は、理性そのものを観察するかのよう に扱われるようになった。つまり、狂人は彼らを人間足らしめていたはずの何かを失い、動物じみた存在になってしまったと考えられ、そしてまた実際彼らは動 物のように扱われた。19世紀にはいると、たとえばピネルやフロイトが登場することで、はじめて狂気が精神の不調であり、治療することのできるものと考え られるようになる。大規模な監禁が行われたのは、17世紀ではなく、この19世紀だと主張する歴史家もわずかに存在するほどだ[5] 。また、こういった事実は、フーコーの理論の土台を揺るがせる批判でもある。つまり、啓蒙時代と狂人の抑圧との歴史的つながりが、危うくなってしまうの だ。 In the 17th-century Age of Reason, insane and socially undesirable people would end at The Madhouse. (Francisco Goya, 1812-1819)  フーコーは『狂気と文明』の中で、狂気(マッドネス)の概念の文化的変遷を、ルネサンス、古典期、近代の3つの段階を経て辿っている。  Hieronymous Bosch (Flemish, c. 1450-1516) Extraction of the Stone of Madness (c. 1490) |

|

| しかし、フーコーが示したのは、狂人のために特化した医療施設ではな

く、社会的なアウトサイダーを監禁するための施設が造られたということである。そこに

は、狂人だけでなく、浮浪者、失業者、虚弱者、孤児なども含まれていた。そういった人間たちみなを監禁するための施設が、西欧社会における狂人と狂気の概

念にどのような影響を与えたのか。フーコーは、そのことを問題にしていたのである。そこでは、「貧困」にあったはずの聖なる意味(貧者としてのキリスト)

が失われ、「狂気」もまた想像力と切り離されて、公共性の問題に結び

つけられたのだ[6]。 フーコーの考察の射程は、それに留まらない。彼が示してみせたのは、社会から締め出された人間をこのように「監禁」することが、ヨーロッパではごく一般的 だったということである。フランスでも、ドイツやイギリスなど他の国々でも、それぞれ独自にこの監禁は行われ、その仕組みは発達していった。このことは、 フーコーが西欧における狂気の歴史を一般化するためにフランスでの事象を取り上げたという批判が当たらないことを示している。ロイ・ポーター(英語版)の ような史家のなかにも、そのような反論を退け、フーコーの著作のもつ革新的な本質を認めようとしなかった過去の批判を撤回する者もではじめている[7]。 ルネサンス期における狂気は、社会的秩序の限界を示し、より深いところにある真実を照らし出す力を持っていた、ともフーコーは主張している。それは啓蒙の 光の前に沈黙させられていたものだ。近代における、フィリップ・ピネルやサミュエル・チューク(英語版)の手になる狂人の科学的、「人間学的」な扱いの登 場についてもフーコーは考察している。彼の主張によれば、そういった近代的な扱い方は、それまでの手法と何らかわるところがない。チュークの国では、狂人 とされた人間は、その狂気を手放さないあいだは、罰を与えられるところまで後退していた。同じように、ピネルの狂人の処置もまた嫌悪療法の延長であった。 凍えるような水を浴びせたり、拘束衣を用いたりして刺激を与えるのである。フーコーから見れば、このような扱いは、罪と罰の定型が患者のうちで内面化され るまで繰り返される蛮行に等しかった。 A Rake's Progress no.viii: the inmates at Beedlam Asylum, by William Hogarth.  |

|

| 意義 「狂気の歴史」は、精神医学への批判として広く読まれ、反精神医学の文脈のなかでしばしば引用された。フーコー自身は、特に回顧録のなかで「狂気のロマン 主義」を批判している。「狂気のロマン主義」とは、狂気を近代医学が抑圧した「天才」がかたちをまとったものとしがちな見方のことである。また、フーコー の読者がときに結論づけるような精神疾患の実体について論じたフーコーというのも正しくない。そうではなく、フーコーが探ったのはいかにして「狂気」が知 の対象として制度化されていくのか、また一方である種の権力が介入する先となるのかということであった。精神病院という矯正施設にこそ[8]、この暗黙裡 に築かれた知と権力の共犯関係がみてとれるのである。さらにまたフーコーは「狂気の歴史」とは「心理学の出現を可能にしたものの歴史」だと述べている。そ れは狂気が「人間の顔」を持ち、人間そのものを真理ととらえ科学的対象とするにいたった歴史なのだ[9]。 |

|

| 受容 批判的な分厚い本のFoucault (1985) の中で、哲学者のジョゼ・ギレーム・メルキュー(英語: José Guilherme Merquior)は、知の営みについての歴史としての『狂気の歴史』の価値は―社会的な力がどのように非正常の意味を決定するのか、そして人の心理的異 常についての社会の反応というフーコーの定立を侵す事実の誤りと解釈の誤りによって減少されたことを言った。彼のデータの恣意的な選択は、フーコーの言う 社会が狂人を賢人として認めた社会―制度的な慣習が罪よりも狂気の方が悪いと考えるキリスト教ヨーロッパ人の文化によって許された社会―であった歴史的な 時代の中で、矛盾するもの、刑務所に入らないことを妨げる歴史的証拠、及び非正常の人々に対する肉体的残忍性を無視した。それでもなお、メルキオールは、 ノーマン・O・ブラウン(英語: Norman O. Brown)のLife Against Death(英語版)(1959)のような、フーコーの『狂気の歴史』はディオニソス的な(英語版)原我(英語版)の解放のひとつの召還であり;そして哲 学者ジル・ドゥルーズと精神分析医のフェリックス・ガタリのアンチ・オイディプス(1972)についての着想を与えたことを言った[10]。 1994年のエッセーのPhänomenologie des Krankengeistes('Phenomenology of the Sick Spirit')の中で、哲学者ガリー・ガッティング(Gary Michael Gutting, 1942-2019)はこう述べた[11]。 The reactions of professional historians to Foucault's Histoire de la folie [1961] seem, at first reading, ambivalent, not to say polarized. There are many acknowledgements of its seminal role, beginning with Robert Mandrou's early review in [the Annales d'Histoire Economique et Sociale], characterizing it as a 'beautiful book' that will be 'of central importance for our understanding of the Classical period.' Twenty years later, Michael MacDonald confirmed Mandrou's prophecy: 'Anyone who writes about the history of insanity in early modern Europe must travel in the spreading wake of Michael Foucault's famous book, Madness and Civilization.’ (=フーコーの『Histoire de la folie』(1961年)に対するプロの歴史家の反応は、一読して両極端とまでは言わないまでもかなり両義的なもののように思われる。ロベール・マンド ロウが[Annales d'Histoire Economique et Sociale]に寄せた初期の書評で、「古典派時代の理解にとって中心的重要性を持つ」「美しい本」と評しているのをはじめ、その決定的な役割を認める ものが多い。20年後、マイケル・マクドナルドはマンドロウの予言を確認した:『近世ヨーロッパにおける狂気の歴史について書く者は、ミッシェル・フー コーの名著『狂気と文明』の広がる跡を旅しなければならない』。) もっと遅くの裏づけは、「経験主義的な内容とそれらの強力な理論的視野の両方をもって、ミッシェル・フーコーのその仕事は史学史において特別で中心的な位 置を占める、」と言うジャン・ゴールドスタイン(英語: Jan Goldstein)そして「時間は『狂気の歴史』をこれまでに書かれた狂気の歴史において最も洞察力のある仕事として証明した」というロイ・ポーター (英語: Roy Porter)を含む。しかしながら、フーコーは「文化の新しい歴史」の先駆者になったにもかかわらず、多くの批判がある[11]。 ケネス・ルイス(Kenneth Lewes)はPsychoanalysis and Male Homosexuality(1995)の中で、『狂気の歴史』は「1960年代の価値観の全般の大転換」の一部として起きたものである「精神医療と精神 分析の制度の批判」の一例であることを言った。『狂気の歴史』でフーコーが提示した歴史のことも同様である、しかしトーマス・サズ(英語: Thomas Szasz)のThe Myth of Mental Illness(英語版)よりも意味深い[12]。 |

|

| 『狂気の歴史』 (Histoire de la folie à l'âge classique) | |

| ある排除が別の排除に取って代わる フーコーはまず中世の分析から始め、特にハンセン病患者が社会から隔離されたことを指摘している。キリスト教世界には、おそらく19,000ものハンセン 病療養所があったとされており、この数字はマシュー・パリスの記述に基づいている。この問題から、ハンセン病が消滅した後、ハンセン病療養所はどうなった のかという疑問が生じる。「[...] これらの施設は残った。同じ場所で、2、3世紀後には、奇妙なほどよく似た排除のゲームが再び行われることになるだろう。」[3] そこから、フーコーは15世紀における精神疾患の概念の歴史と、17世紀のフランスにおける投獄への関心の高まりを辿る。一つの目安となるのは、1656 年の勅令による精神病院の創設である。a73> 世紀における投獄への関心の高まりについて概説している。一つの指標となるのが、1656年に法令によって設立された「総合病院」である。この病院は、狂 人だけでなく、貧者や犯罪者も収容する場所として機能した。この場所は、抑圧と慈善の両方の手段となった。こうした「混乱」は、すべて疑問を投げかけるも のである。 |

|

| 狂人、異端者、犯罪者、放蕩者の収容 狂人専用の施設は確かに存在した。オテル・デューは精神異常者のみを受け入れ、 ベスレムはロンドンの「気狂い」のみを受け入れていた。しかし、「狂人」や「凶暴者」は、他の収容者たち、さらには刑務所に収監されている者たちとも混ざり合い、区別されていなかった。 では、この2つの場所の違いについて考えてみよう。狂人だけが収容される場合、それは医療上の判断によるものであり、他の場所ではそうではない。さらに、 フーコーは、私たちが収容に感じる混乱は「公正」ではない見方であると示唆している。それは、古典時代を現代の視点で見ているためであり、したがって、古 典時代の誤りを理解することよりも、むしろ、排除という「均質な経験」、 「肯定的な兆候」や「肯定的な意識」といった「均質な経験」を理解することである。 さらに踏み込んで、フーコーは、狂人専用の収容施設が古典時代には新しいものではないと指摘している。この時代に新しく登場したのは、狂人とその他の人 々、慈善と抑圧が混在する場所である。実際、フーコーは狂人専用の病院の存在を指摘している。それは、フェズの7世紀、 a4>世紀、バグダッドでは12世紀、そして次の世紀にはカイロで… |

|

| 魂の病 最後に、狂気は魂の病気として認識され、その後フロイトによって精神疾患として認識されるようになった。 フーコーは、狂人の地位が、社会秩序の中で受け入れられ、あるいは認められた立場を占める存在から、四つの壁に閉じ込められ、隔離された排除された存在へと変化した過程に大きな関心を寄せている。 フーコーは、狂人に対するさまざまな治療方法や試み、特にフィリップ・ピネルとウィリアム・トゥークの研究を研究している。フーコーは、この2人が行った 治療は、彼らの先人たちによる治療と何ら変わらない権威主義的なものだったと明確に述べている。したがって、チュークの精神病院と治療法は、主に、狂人と 認められた個人たちが正常に行動することを学ぶまで彼らを罰し、事実上、完全に服従し、認められた規則に従う人間のように振る舞うことを強いるものであっ た。同様に、ピネルによる狂人への治療は、氷水シャワーや拘束衣の使用などの治療法を含む、嫌悪療法の拡張版に過ぎなかったようだ。フーコーにとって、こ の種の治療は、患者が判断と罰の構造を内面化するまで、繰り返し患者を虐待することに他ならない。 |

|

| 第一部 第I章 - Stultifera navis 第II章 - 大いなる閉じ込め 第3章 - 矯正の世界 第4章 - 狂気の体験 第5章 - 狂人たち 第二部 はじめに 第I章 - 種の園の狂人 第II章 - 妄想の超越 第III章 - 狂気の姿 第IV章 - 医師と患者 第三部 はじめに 第1章 - 大いなる恐怖 第2章 - 新たな分配 第3章 - 自由の正しい使い方 第4章 - 精神病院の誕生 第5章 - 人類学の輪 |

|

| https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Histoire_de_la_folie_%C3%A0_l%27%C3%A2ge_classique |

★英語版ウィキペディア

| Madness and Civilization: A History of Insanity in the Age of Reason (French: Folie et Déraison: Histoire de la folie à l'âge classique, 1961) is an examination by Michel Foucault of the evolution of the meaning of madness in the cultures and laws, politics, philosophy, and medicine of Europe—from the Middle Ages until the end of the 18th century—and a critique of the idea of history and of the historical method. Although he uses the language of phenomenology to describe the influence of social structures in the history of the Othering of insane people from society, Madness and Civilization is Foucault's philosophic progress from phenomenology toward something like structuralism (a label Foucault himself always adamantly rejected). | 狂気と文明:理性の時代におけるひとつの歴史(Folie et Déraison: Histoire de la folie à l'âge classique, 1961=狂気と錯乱-古典主義時代の狂気の歴史)は、中世から18世紀末までのヨーロッパの文化や法律、政治、哲学、医学における狂気の意味の変遷をミ シェル・フーコーが考察し、歴史の概念と歴史的方法に対する批判を展開したものである。狂気の人たちが社会から他者化された歴史における社会構造の影響に ついて、現象学の言葉を用いて説明しているが、『狂気と文明』は現象学から構造主義のようなもの(フーコー自身は常にこのレッテルを断固として拒否してい る)へと向かうフーコーの哲学的な進歩であるといえるだろう。 |

| In Madness and Civilization, Foucault traces the cultural evolution of the concept of insanity (madness) in three phases: the Renaissance; the Classical Age; and the Modern era. | フーコーは『狂気と文明』の中で、狂気(マッドネス)の概念の文化的変 遷を、ルネサンス、古典期、近代の3つの段階を経て辿っている。 |

| Renaissance In the Renaissance, art portrayed insane people as possessing wisdom (knowledge of the limits of the world), whilst literature portrayed the insane as people who reveal the distinction between what men are and what men pretend to be. Renaissance art and literature further depicted insane people as intellectually engaged with reasonable people, because their madness represented the mysterious forces of cosmic tragedy. Yet Renaissance intellectualism began to develop an objective way of thinking about and describing reason and unreason, compared with the subjective descriptions of madness from the Middle Ages. |

ルネサンス ルネサンス期の美術は、狂気の人物を知恵(世界の限界を知る知識)のある人物として描き、文学は、狂気の人物を、人間の本質と見せかけの区別を明らかにす る人物として描いている。さらにルネサンス期の美術や文学は、狂気が宇宙の悲劇の神秘的な力を表しているとして、狂気の人々を理性的な人々と知的に交わら せるように描いている。しかし、ルネサンス期の知識人は、中世の主観的な狂気の描写に対して、理性と理不尽について客観的に考え、描写する方法を開発し始 めたのである。 |

| Classical Age At the dawn of the Age of Reason in the 17th century, there occurred "the Great Confinement" of insane people in the countries of Europe; the initial management of insane people was to segregate them to the margins of society, and then to physically separate them from society by confinement, with other anti-social people (prostitutes, vagrants, blasphemers, et al.) into new institutions, such as the General Hospital of Paris. Christian European society perceived such anti-social people as being in moral error, for having freely chosen lives of prostitution, vagrancy, blasphemy, unreason, etc. To revert such moral errors, society's new institutions to confine outcast people featured way-of-life regimes composed of punishment-and-reward programs meant to compel the inmates to choose to reverse their choices of lifestyle. The socio-economic forces that promoted this institutional confinement included the legalistic need for an extrajudicial social mechanism with the legal authority to physically separate socially undesirable people from mainstream society; and for controlling the wages and employment of poor people living in workhouses, whose availability lowered the wages of freeman workers. The conceptual distinction, between the mentally insane and the mentally sane, was a social construct produced by the practices of the extrajudicial separation of a human being from free society to institutional confinement. In turn, institutional confinement conveniently made insane people available to medical doctors then beginning to view madness as a natural object of study, and then as an illness to be cured. |

古典時代 17世紀、理性の時代の幕開けとともに、ヨーロッパ諸国では精神異常者の「大収容」が行われた。精神異常者の管理は、まず社会の片隅に隔離し、次に他の反 社会的な人々(売春婦、浮浪者、冒涜者等)とともにパリの総合病院などの新しい施設に閉じ込め、社会から物理的に分離することであった。キリスト教ヨー ロッパ社会は、このような反社会的な人々を、売春、浮浪、冒涜、理不尽などの人生を自由に選択したことから、道徳的な過ちを犯したと認識したのである。こ のような道徳的な過ちを改めるために、社会は追放された人々を収容する新しい施設として、罰と報酬からなる生活様式制度を導入し、収容者にその生活様式の 選択を改めることを強要したのである。 このような施設収容を推進した社会経済的な力には、社会的に好ましくない人々を主流の社会から物理的に分離するための法的権限を持った超法規的な社会メカ ニズムへのニーズと、労働施設に住む貧しい人々の賃金と雇用を管理し、その利用が自由労働者の賃金を引き下げることへのニーズがあった。精神異常者と正気 者との間の概念的な区別は、人間を自由社会から施設収容へと超法規的に分離する慣行によって生み出された社会構築物であった。そして、施設収容は、当時、 狂気を自然な研究対象として、さらには治療すべき病気として捉え始めていた医学者たちにとって、狂気の人々を便利に利用できるようにした。 |

| Modern era The Modern era began at the end of the 18th century, with the creation of medical institutions for confining mentally insane people under the supervision of medical doctors. Those institutions were product of two cultural motives: (i) the new goal of curing the insane away from poor families; and (ii) the old purpose of confining socially undesirable people to protect society. Those two, distinct social purposes soon were forgotten, and the medical institution became the only place for the administration of therapeutic treatments for madness. Although nominally more enlightened in scientific and diagnostic perspective, and compassionate in the clinical treatment of insane people, the modern medical institution remained as cruelly controlling as were mediaeval treatments for madness. In the preface to the 1961 edition of Madness and Civilization, Foucault said that: Modern man no longer communicates with the madman . . . There is no common language, or rather, it no longer exists; the constitution of madness as mental illness, at the end of the eighteenth century, bears witness to a rupture in a dialogue, gives the separation as already enacted, and expels from the memory all those imperfect words, of no fixed syntax, spoken falteringly, in which the exchange, between madness and reason, was carried out. The language of psychiatry, which is a monologue by reason about madness, could only have come into existence in such a silence. |

近現代 近代は、18世紀末に精神異常者を医師の監督のもとに収容する医療機関が作られたことに始まる。この施設は、貧しい家庭から精神障害者を救い出すという新 しい目的と、社会を守るために社会的に好ましくない人々を閉じ込めるという古い目的という、二つの文化的動機の産物であった。この2つの明確な社会的目的 はすぐに忘れ去られ、医療機関が狂気の治療を行う唯一の場所となった。科学的診断の観点からは名目上、より啓蒙され、精神異常者の臨床的治療には思いやり があるが、現代の医療機関は、中世の狂気の治療と同様に残酷な支配のままであった。1961年版の『狂気と文明』の序文で、フーコーは次のように述べてい る。 現代人はもはや狂人とコミュニケーションすることはない... 18世紀末の精神疾患としての狂気の構成は、対話の断絶を証言し、すでに成立した分離を与え、狂気と理性の間で交わされていた、決まった構文のない、ため らいながら話す不完全な言葉すべてを記憶から追い出してしまうのだ。精神医学の言葉は、狂気についての理性による独白であるが、このような沈黙の中でしか 存在し得なかった。 |

| Anti-psychiatry and Michel Foucaut | |

| The decentralized movement has been active in various forms for two centuries. In the 1960s, there were many challenges to psychoanalysis and mainstream psychiatry, where the very basis of psychiatric practice was characterized as repressive and controlling. Psychiatrists identified with the movement included Thomas Szasz, Timothy Leary, Giorgio Antonucci, R. D. Laing, Franco Basaglia, Theodore Lidz, Silvano Arieti, and David Cooper. Others involved were Michel Foucault, Gilles Deleuze, Félix Guattari, and Erving Goffman. Cooper coined the term "anti-psychiatry" in 1967, and wrote the book Psychiatry and Anti-psychiatry in 1971.Thomas Szasz introduced the definition of mental illness as a myth in the book The Myth of Mental Illness (1961), Giorgio Antonucci introduced the definition of psychiatry as a prejudice in the book I pregiudizi e la conoscenza critica alla psichiatria (1986). | 分散型運動は、2世紀にわたってさまざまな形で活動を続けてきた。 1960年代には、精神分析および主流の精神医学に対する多くの挑戦がありました。そこでは、精神医学の実践のまさに基盤が抑圧的で支配的であると特徴付 けられました。この運動に参加した精神科医には、トーマス・サズ、ティモシー・リアリー、ジョルジオ・アントヌッチ、R・D・レイン、フランコ・バザーリ ア、セオドア・リッズ、シルヴァーノ・アリエッティ、デヴィッド・クーパーなどがいます。その他、ミシェル・フーコー、ジル・ドゥルーズ、フェリックス・ ガタリ、アーヴィング・ゴフマンなどが関わっていた。クーパーは1967年に「反精神医学」という言葉を作り、1971年に『精神医学と反精神医学』を書 いた。トマス・サズは『精神病の神話』(1961年)で精神病を神話として定義し、ジョルジョ・アントヌッチは『I pregiudizi e la conoscenza critica alla psichiatria』(1986年)で精神医学を偏見として定義していることを紹介した。 |

| According to Michel Foucault, there was a shift in the perception of madness, whereby it came to be seen as less about delusion, i.e. disturbed judgment about the truth, than about a disorder of regular, normal behaviour or will. Foucault argued that, prior to this, doctors could often prescribe travel, rest, walking, retirement and generally engaging with nature, seen as the visible form of truth, as a means to break with artificialities of the world (and therefore delusions). Another form of treatment involved nature's opposite, the theatre, where the patient's madness was acted out for him or her in such a way that the delusion would reveal itself to the patient. | ミシェル・フーコーによれば、狂気の認識には変化があり、それは妄想、 すなわち真理についての判断の乱れというよりも、規則的で正常な行動や意志の乱れとみなされるようになったのである。フーコーは、それ以前は、医師は、世 界の人工物(したがって妄想)と決別する手段として、旅行、休息、散歩、引退、そして一般に真実の目に見える形として見られる自然との関わりをしばしば処 方することができたと論じている。また、自然とは対極にある劇場では、患者の狂気が演じられ、妄想が患者の前に姿を現すという治療法もあった。 |

| Thus the most prominent therapeutic technique became to confront patients with a healthy sound will and orthodox passions, ideally embodied by the physician[citation needed]. The "cure" involved a process of opposition, of struggle and domination, of the patient's troubled will by the healthy will of the physician. It was thought the confrontation would lead not only to bring the illness into broad daylight by its resistance, but also to the victory of the sound will and the renunciation of the disturbed will. We must apply a perturbing method, to break the spasm by means of the spasm.... We must subjugate the whole character of some patients, subdue their transports, break their pride, while we must stimulate and encourage the others (Esquirol, J.E.D., 1816). Foucault also argued that the increasing internment of the "mentally ill" (the development of more and bigger asylums) had become necessary not just for diagnosis and classification but because an enclosed place became a requirement for a treatment that was now understood as primarily the contest of wills, a question of submission and victory. The techniques and procedures of the asylums at this time included "isolation, private or public interrogations, punishment techniques such as cold showers, moral talks (encouragements or reprimands), strict discipline, compulsory work, rewards, preferential relations between the physician and his patients, relations of vassalage, of possession, of domesticity, even of servitude between patient and physician at times". Foucault summarised these as "designed to make the medical personage the 'master of madness'" through the power the physician's will exerts on the patient. The effect of this shift then served to inflate the power of the physician relative to the patient, correlated with the rapid rise of internment (asylums and forced detention). | こうして、最も顕著な治療技法は、医師が理想的に体現する健全な意志と 正統な情熱をもって患者と対峙するようになった[citation needed]。治療」には、患者の悩める意志と医師の健全な意志との対立、闘争、支配のプロセスが含まれていた。この対立は、その抵抗によって病気を白 日の下にさらすだけでなく、健全な意志の勝利と、乱れた意志の放棄につながると考えられたのである。私たちは、痙攣の手段によって痙攣を断ち切るために、 動揺させる方法を適用しなければならない......。ある患者の全人格を服従させ、その興奮を抑え、そのプライドを打ち砕く一方で、他の患者を刺激し励 まさなければならない(Esquirol, J.E.D., 1816)」。フーコーはまた、「精神障害者」の収容の増加(より多くの、より大きな精神病院の開発)は、診断と分類のためだけでなく、今や主に意志の競 争、服従と勝利の問題として理解されている治療のために、閉じた場所が必要条件となったからである、と主張した。この時代の精神病院の技術や手続きには、 「隔離、私的または公的な尋問、冷水シャワーなどの懲罰技術、道徳的な話(励ましや叱責)、厳しい規律、強制労働、報酬、医師と患者の間の優遇関係、患者 と医師の間の家臣、所有、家事、時には隷属関係さえも」が含まれていた。フーコーはこれらを、医師の意志が患者に及ぼす力によって、「医学的人格を『狂気 の支配者』にするために設計された」と要約している。そして、この転換の効果は、患者に対する医師の力を増大させ、抑留(精神病院や強制収容)の急増と相 関しているのである。 |

| Three authors came to personify the movement against psychiatry, and two of these were practising psychiatrists. The initial and most influential of these was Thomas Szasz who rose to fame with his book The Myth of Mental Illness, although Szasz himself did not identify as an anti-psychiatrist. The well-respected R D Laing wrote a series of best-selling books, including The Divided Self. Intellectual philosopher Michel Foucault challenged the very basis of psychiatric practice and cast it as repressive and controlling. The term "anti-psychiatry" was coined by David Cooper in 1967. In parallel with the theoretical production of the mentioned authors, the Italian physician Giorgio Antonucci questioned the basis themselves of psychiatry through the dismantling of the psychiatric hospitals Osservanza and Luigi Lolli and the liberation – and restitution to life – of the people there secluded. | 3人の著者が精神医学に反対する運動を象徴するようになり、そのうちの 2人は現役の精神科医であった。このうち最初に登場し、最も影響力を持ったのはトーマス・サズで、「精神病の神話」という本で一躍有名になったが、サズ自 身は反精神科医とは認めていなかった。(もっと)尊敬されていたR・D・レインは、『分裂した自己』を含む一連のベストセラーを書いた。哲学者のミシェ ル・フーコーは、精神医学の実践の根幹に疑問を投げかけ、それを抑圧的で支配的なものとして投げかけた。反精神医学」という言葉は、1967年にデイ ヴィッド・クーパーによって作られた。上記の作家たちの理論的な生産と並行して、イタリアの医師ジョルジョ・アントヌッチは、精神病院オッセルヴァンツァ とルイジ・ロッリを解体し、そこに隔離されていた人々を解放し、生活に復帰させることを通じて、精神医療の基盤そのものに疑問を呈した。 |

| It has been argued by philosophers like Foucault that characterizations of "mental illness" are indeterminate and reflect the hierarchical structures of the societies from which they emerge rather than any precisely defined qualities that distinguish a "healthy" mind from a "sick" one. Furthermore, if a tendency toward self-harm is taken as an elementary symptom of mental illness, then humans, as a species, are arguably insane in that they have tended throughout recorded history to destroy their own environments, to make war with one another, etc. | フーコーのような哲学者は「精神病」の特徴は不確定で、「健康な」心と 「病気の」心を区別するような正確に定義された特質ではなく、むしろそれが出現する社会の階層的構造を反映していると主張してきた。さらに、自傷行為への 傾向が精神疾患の基本的な症状であるとするならば、記録された歴史を通じて、人間は自らの環境を破壊し、互いに戦争をする傾向があるという点で、種として 間違いなく狂気であると言えると、述べた。 |

| Madness and Civilization: A

History of Insanity in the Age of Reason (French: Folie et Déraison:

Histoire de la folie à l'âge classique, 1961)[i] is an examination by

Michel Foucault of the evolution of the meaning of madness in the

cultures and laws, politics, philosophy, and medicine of Europe—from

the Middle Ages until the end of the 18th century—and a critique of the

idea of history and of the historical method. Although he uses the language of phenomenology to describe the influence of social structures in the history of the Othering of insane people from society, Madness and Civilization is Foucault's philosophic progress from phenomenology toward something like structuralism (a label Foucault himself always adamantly rejected).[1] |

『狂気と文明: 理性の時代の狂気についての歴史』(フランス語:

Folie et Déraison: Histoire de la folie à l'âge classique,

1961)[i]は、ミシェル・フーコーによる、中世から18世紀末までのヨーロッパの文化や法律、政治、哲学、医学における狂気の意味の変遷についての

考察であり、歴史観や歴史的アプローチについての批判である。 彼は社会から精神異常者を排除する歴史における社会構造の影響を説明するのに現象学の用語を使用しているが、『狂気と文明』は現象学から構造主義(フー コー自身は常に断固として拒否していた呼称)のようなものへと向かうフーコーの哲学的進歩である。 |

| Background Philosopher Michel Foucault developed Madness and Civilization from his earlier works in the field of psychology,[ii] his personal psychological difficulties, and his professional experiences working in a mental hospital. He wrote the book between 1955 and 1959, when he worked cultural-diplomatic and educational posts in Poland and Germany,[2] as well as in Sweden as director of a French cultural centre at the University of Uppsala.[3] |

背景 哲学者ミシェル・フーコーは、心理学の分野における初期の著作[ii]、個人的な心理的困難、精神病院での勤務経験を基に『狂気と文明』を執筆した。同書 は、1955年から1959年の間に執筆されたもので、この間、フーコーはポーランドとドイツで文化外交および教育関連の職務に就いていたほか[2]、ス ウェーデンではウプサラ大学のフランス文化センター所長も務めていた[3]。 |

| Summary In the 17th-century Age of Reason, insane and socially undesirable people would end at The Madhouse. (Francisco Goya, 1812–1819) In Madness and Civilization, Foucault traces the cultural evolution of the concept of insanity (madness) in three phases: |

要約 17世紀の啓蒙時代には、狂気や社会的に望ましくない人々は精神病院で終わる。(フランシスコ・ゴヤ、1812年~1819年) 『狂気と文明』において、フーコーは狂気(狂気)という概念の文化的進化を3つの段階に分けて追っている。 |

| the Renaissance; the Classical Age;[4] and the Modern era Middle Ages In the Middle Ages, society distanced lepers from itself, while in the "Classical Age" the object of social segregation was moved from lepers to madmen, but in a different way. The lepers of the Middle Ages were certainly considered dangerous, but they were not the object of a radical rejection, as would be demonstrated by the fact that leper hospitals were almost always located near the city gates, far but not invisible from the community. The relative presence of the leper reminded everyone of the duty of Christian charity, and therefore played a positive role in society.[5] Renaissance In the Renaissance, art portrayed insane people as possessing wisdom (knowledge of the limits of the world), whilst literature portrayed the insane as people who reveal the distinction between what men are and what men pretend to be. Renaissance art and literature further depicted insane people as intellectually engaged with reasonable people, because their madness represented the mysterious forces of cosmic tragedy.[2] Foucault contrasts the Renaissance image of the ship of fools with later conceptions of confinement. The Renaissance, rather than locking up madmen, ensured their circulation, so that the madman as a "passenger" and "passing being" became the symbol of the human condition: "Madness is the anticipation of death".[6] Yet Renaissance intellectualism began to develop an objective way of thinking about and describing reason and unreason, compared with the subjective descriptions of madness from the Middle Ages.[1] |

ルネサンス、 古典時代、[4] 近代 中世 中世では、社会はハンセン病患者を自分たちから遠ざけていたが、「古典時代」では、社会的に隔離される対象はハンセン病患者から狂人へと移ったが、その方 法は異なっていた。中世のハンセン病患者は確かに危険視されていたが、社会から徹底的に拒絶されていたわけではなかった。ハンセン病患者のための病院は、 ほとんどの場合、都市の門の近くに位置しており、社会から離れているとはいえ、見えない場所にあるわけではなかった。ハンセン病患者の存在は、キリスト教 の慈善の義務を人々に思い出させ、社会に肯定的な役割を果たしていたのである。 ルネサンス ルネサンス期の芸術作品では、狂気の人々は知恵(世界の限界に関する知識)を持つ存在として描かれ、文学では、狂気の人々は、人間が本質的に持つものと、 人間が装うものとの違いを明らかにする存在として描かれた。ルネサンス期の芸術作品や文学作品では、狂気の人々は、宇宙的な悲劇の神秘的な力を象徴する存 在として、理性的な人々と知的に関わり合う存在として描かれた。[2] フーコーは、愚か者の船というルネサンス期のイメージと、その後の監禁という概念とを対比させている。ルネサンスは狂人を閉じ込めるのではなく、彼らの循 環を確保した。そのため、「乗客」であり「通り過ぎる存在」である狂人は、人間の条件の象徴となった。「狂気とは死の予兆である」[6]。 しかし、ルネサンスの知性主義は、中世の狂気に関する主観的な記述と比較して、理性と非理性について客観的に考え、記述する方法を開発し始めた。[1] |

| Classical Age At the dawn of the Age of Reason in the 17th century, there occurred "the Great Confinement" of insane people in the countries of Europe; the initial management of insane people was to segregate them to the margins of society, and then to physically separate them from society by confinement, with other anti-social people (prostitutes, vagrants, blasphemers, et al.) into new institutions, such as the General Hospital of Paris.[1] According to Foucault, the creation of the "general hospital" corresponds to Descartes's Meditations, and the desire to eliminate the irrational from philosophical discourse. "Classical reason" would have produced a "fracture" in the history of madness.[7] Moreover, Christian European society perceived such anti-social people as being in moral error, for having freely chosen lives of prostitution, vagrancy, blasphemy, unreason, etc. To revert such moral errors, society's new institutions to confine outcast people featured way-of-life regimes composed of punishment-and-reward programs meant to compel the inmates to choose to reverse their choices of lifestyle.[1] The socio-economic forces that promoted this institutional confinement included the legalistic need for an extrajudicial social mechanism with the legal authority to physically separate socially undesirable people from mainstream society; and for controlling the wages and employment of poor people living in workhouses, whose availability lowered the wages of freeman workers.[8] The conceptual distinction, between the mentally insane and the mentally sane, was a social construct produced by the practices of the extrajudicial separation of a human being from free society to institutional confinement. In turn, institutional confinement conveniently made insane people available to medical doctors then beginning to view madness as a natural object of study, and then as an illness to be cured.[1][2] |

古典時代 17世紀の理性の時代の幕開けに、ヨーロッパ諸国では「大監禁」と呼ばれる精神異常者の監禁が行われた。当初、精神異常者の管理は社会の周縁に隔離するこ とから始まり、その後、監禁によって社会から物理的に隔離された。 反社会的人物(娼婦、浮浪者、冒涜者など)とともに、パリ総合病院のような新しい施設に隔離した。[1] フーコーによると、「総合病院」の設立はデカルトの『省察』に対応し、哲学的な言説から非合理的なものを排除しようとする欲望を反映している。「古典的理 性」は狂気という歴史に「断絶」をもたらしたのである。[7] さらに、キリスト教社会では、売春、浮浪、冒涜、不合理などの生き方を自ら選択した反社会的人間は道徳的に誤っているとみなされた。このような道徳的過ち を正すために、社会から追放された人々を収容する新しい制度では、受刑者に生活様式を改めることを強制するための、罰と報酬からなるプログラムで構成され た生活様式の体制が採用された。 このような施設収容を推進した社会経済的な要因としては、社会的に望ましくない人々を主流社会から物理的に隔離する法的権限を持つ、法外な社会的メカニズ ムの必要性、および、ワークハウスに住む貧困層の賃金と雇用を管理する必要性があった。ワークハウスに住む人々がいることで、自由民の労働者の賃金が低下 していたのである。[8] 精神異常者と精神正常者の概念上の区別は、自由社会から施設収容へと人間を法外に隔離する慣行によって生み出された社会的な構築物であった。また、施設収 容は、狂気というものを、自然の研究対象として、そして治療すべき病気として捉え始めた当時の医師たちにとって、狂気の人々を都合よく利用できるものにし た。[1][2] |

| Modern era The Modern era began at the end of the 18th century, with the creation of medical institutions for confining mentally insane people under the supervision of medical doctors. Those institutions were product of two cultural motives: (i) the new goal of curing the insane away from poor families; and (ii) the old purpose of confining socially undesirable people to protect society. Those two, distinct social purposes soon were forgotten, and the medical institution became the only place for the administration of therapeutic treatments for madness. Although nominally more enlightened in scientific and diagnostic perspective, and compassionate in the clinical treatment of insane people, the modern medical institution remained as cruelly controlling as were mediaeval treatments for madness.[1] In the preface to the 1961 edition of Madness and Civilization, Foucault said that: Modern man no longer communicates with the madman ... There is no common language, or rather, it no longer exists; the constitution of madness as mental illness, at the end of the eighteenth century, bears witness to a rupture in a dialogue, gives the separation as already enacted, and expels from the memory all those imperfect words, of no fixed syntax, spoken falteringly, in which the exchange, between madness and reason, was carried out. The language of psychiatry, which is a monologue by reason about madness, could only have come into existence in such a silence.[9] |

近代 近代は18世紀末に始まり、医師の監督下で精神異常者を収容する医療機関が設立された。これらの施設は、2つの文化的動機から生まれた。すなわち、(i) 貧困家庭から精神異常者を隔離して治療するという新たな目標、および、(ii) 社会的に望ましくない人々を隔離して社会を守るという古い目的である。この2つの明確な社会的目的はすぐに忘れ去られ、医療施設は狂気に対する治療的処置 を行う唯一の場所となった。名目上は科学的見地や診断の観点においてより進歩し、狂気の人々に対する臨床治療に思いやりがあるとはいえ、現代の医療施設は 中世の狂気に対する治療と同様に残酷な管理下に置かれたままであった。[1] 1961年の『狂気と文明』の序文で、フーコーは次のように述べている。 現代人はもはや狂人とコミュニケーションをとることはない。共通の言語など存在しない、いや、もはや存在しえないのだ。18世紀末に狂気が精神疾患として 定義されたことは、対話の断絶を証明し、すでに実行された分離を意味し、狂気と理性との間で交わされた、不明瞭な構文の不完全な言葉のすべてを記憶から排 除する。精神医学の言語は、理性による狂気についての独白であり、このような沈黙の中でしか生まれることはなかった。[9] |

| Reception A Rake's Progress no. viii: the inmates at Bedlam Asylum, by William Hogarth In the critical volume, Foucault (1985), the philosopher José Guilherme Merquior said that the value of Madness and Civilization as intellectual history was diminished by errors of fact and of interpretation that undermine Foucault's thesis—how social forces determine the meanings of madness and society's responses to the mental disorder of the person. Specifically problematic was his selective citation of data, which ignored contradictory historical evidence of preventive imprisonment and physical cruelty towards insane people during the historical periods when Foucault said society perceived the mad as wise people—institutional behaviors allowed by the culture of Christian Europeans who considered madness worse than sin. Nonetheless, Merquior said that, like the book Life Against Death (1959), by Norman O. Brown, Foucault's book about Madness and Civilization is "a call for the liberation of the Dionysian id"; and gave inspiration for Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia (1972), by the philosopher Gilles Deleuze and the psychoanalyst Félix Guattari.[10] In his 1994 essay "Phänomenologie des Krankengeistes" ('Phenomenology of the Sick Spirit'), philosopher Gary Gutting said:[11] [T]he reactions of professional historians to Foucault's Histoire de la folie [1961] seem, at first reading, ambivalent, not to say polarized. There are many acknowledgements of its seminal role, beginning with Robert Mandrou's early review in [the Annales d'Histoire Economique et Sociale], characterizing it as a "beautiful book" that will be "of central importance for our understanding of the Classical period." Twenty years later, Michael MacDonald confirmed Mandrou's prophecy: "Anyone who writes about the history of insanity in early modern Europe must travel in the spreading wake of Michael Foucault's famous book, Madness and Civilization." Later endorsements included Jan Goldstein, who said: "For both their empirical content and their powerful theoretical perspectives, the works of Michel Foucault occupy a special and central place in the historiography of psychiatry;" and Roy Porter: "Time has proved Madness and Civilization [to be by] far the most penetrating work ever written on the history of madness." However, despite Foucault being herald of "the new cultural history", there was much criticism.[11] In Psychoanalysis and Male Homosexuality (1995), Kenneth Lewes said that Madness and Civilization is an example of the "critique of the institutions of psychiatry and psychoanalysis" that occurred as part of the "general upheaval of values in the 1960s." That the history Foucault presents in Madness and Civilization is similar to, but more profound than The Myth of Mental Illness (1961) by Thomas Szasz.[12] |

レセプション 放蕩息子の遍歴 第8図:ベドラム精神病院の収容者たち、ウィリアム・ホガース作 重要な著作『狂気と文明』(1985年)の中で、哲学者ホセ・ジルベルト・メルキオールは、狂気と文明の知的歴史としての価値は、事実と解釈の誤りによっ て損なわれていると述べている。その誤りとは、社会的な力が狂気と精神障害に対する社会の反応の意味をどのように決定するかという、フーコーのテーゼを損 なうものである。特に問題となったのは、彼がデータを選択的に引用したことで、これは、社会が狂気を賢者として認識していたとフーコーが述べた歴史的時代 における、狂人に対する予防拘禁や肉体的虐待という矛盾する歴史的証拠を無視するものだった。狂気は罪よりも悪いと考えるキリスト教ヨーロッパの文化に よって許容された制度上の行動である。それでも、メルキオールは、ノーマン・O・ブラウン著『生命対死』(1959年)と同様に、フーコーの『狂気と文 明』は「ディオニュソス的イドの解放を求めるもの」であると述べ、哲学者のジル・ドゥルーズと精神分析家のフェリックス・ガタリによる『アンチ・オイディ プス:資本主義と分裂症』(1972年)にインスピレーションを与えたと述べた。 1994年のエッセイ「Phänomenologie des Krankengeistes」(『病める精神の現象学』)において、哲学者のゲイリー・ガッティングは次のように述べている。 専門の歴史家のフーコーの『狂気の歴史』[1961年]に対する反応は、一読したところでは、相反するものであり、極端に分かれているとさえ言える。その 先駆的な役割を認める意見は多く、ロベール・マンデュロが『経済社会史年報』に書いた初期の批評では、この本を「古典時代を理解する上で中心的な重要性を 持つ」「美しい本」と評している。20年後、マイケル・マクドナルドはマンデュの予言を裏付けるように、「近現代ヨーロッパの狂気について書く者は、ミ シェル・フーコーの名著『狂気と文明』の広がり続ける影響の跡を辿らなければならない」と述べた。 その後、ヤン・ゴールドスタインは「ミシェル・フーコーの著作は、その実証的内容と強力な理論的視点の両面において、精神医学史において特別な中心的な位 置を占めている」と述べ、ロイ・ポーターは「『狂気と文明』は、狂気の歴史について書かれた著作の中で、最も洞察力に富んだ著作であることが、時が証明し ている」と述べた。しかし、フーコーが「新しい文化史」の先駆者であったにもかかわらず、多くの批判があった。 ケネス・ルイスは著書『精神分析と男性同性愛』(1995年)の中で、『狂気と文明』は「1960年代の価値観の激変」の一部として起こった「精神医学と 精神分析の制度批判」の例であると述べている。また、フーコーが『狂気と文明』で提示する歴史は、トーマス・サズの『精神病という神話』(1961年)に 類似しているが、より深遠であるとも述べている。[12] |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Madness_and_Civilization | https://www.deepl.com/ja/translator |

★初版の序文(デリダの批判(『エクリチュールと差異』収載論文)の後にこの序文は撤回)

| Pascal : « Les

hommes sont si nécessairement

fous que ce serait être fou par un autre tour de

folie de n'être pas fou. » Et cet autre texte, de

Dostoïewski, dans le Journal d'un écrivain : « Ce

n'est pas en enfermant son voisin qu'on se convainc

de son propre bon sens. » |

パスカル:「人間が狂気じみているのは避けがたいため、狂っていないということ

は、別の狂気によればやはり狂っているということになる。」そして、ドストエフスキーの『作家の日記』にある別の文章:「隣人を閉じ込めてみても、自分の正気(良識)を確信

することはできない。」 |

| Il faut faire l'histoire de cet

autre tour de folie.

- de cet autre tour par lequel les hommes, datlS

le geste de raison souveraine qui enferme leur

voisin, communiquent et se reconnaissent à travers

le langage sans merci de la non-folie ; retrouver

le moment de cette conj11ration, avant qu'elle

n'ait été définitivement établie dans le règne de

la vérité, avant qu'elle n'ait été ranimée par le

lyrisme de la protestation. Tâcher de rejoindre,

dans l'histoire, ce degré zéro de l'histoire de 1a

folie, où elle est expérience indifférenciée, expérience

non encore partagée du partage lui-'même.

Décrire, dès l'origine de sa courbure, cet « autre

tour», qui, de part et d'autre de son geste, laisse

retomber, choses désormais extérieures, sourdes

à tout échange, et comme mortes l'une à rautre,

la Raison et la Folie . |

この別の狂気の輪の歴史を記さねばならない。この別の輪によって、人々

は、隣人を閉じ込める至高の理性の行為から、非狂気の容赦ない言語を通じて意思疎通を図り、互いを認識するのだ。真実の支配が確立される前、抗議の叙情性

によって再燃する前に、この共謀の瞬間を見つけ出さなければならない。歴史の中で、狂気の歴史のゼロ地点、つまり、それがまだ区別されていない経験、共有

そのものの経験として共有されていない段階に、再び到達しようと試みるのだ。その曲がり始めから、この「もうひとつの曲がり」を描写すること。その動きの

両側で、もはや外部に存在し、あらゆる交流に無反応で、互いに死んでいるかのように見える、理性と狂気が落下していく様子を描写すること。 |

| C'est là sans doute une région

incommode. Il

faut pour la parcourir renoncer au confort • des

vérités terminales, et ne jamais se laisser guider

par ce que nous pouvons savoir de la folie. Aucun

des· concepts de la psycho-pathologie ne devra,

même et surtout dans le jeu implicite des rétrospections,

exercer de rôle organisateur .. Est constitutif

le geste qui partage la folie,. et non la science

qui s'établit, ce partage tille fois fait, dans le calme

revenu. Est originaire la césure qui établit la dis'."

tance entre raison et non-raison ; . quant à . la

prise que la raison exerce sur la non-rais01;1 pour

lui arracher sa vérité de folie, de faute ou de maladie,

elle en dérive, et de loin. Il va donc falloir

parler de ce primitif débat sans supposer de •victoire,

ni de droit à la victoire ; parler de ces gestes

ressassés dans l'histoire, en laissant en suspens

tout ce qui peut faire figure d'achèvement, de

repos dans la vérité ; parler de ce geste de coupure,

de cette distance prise, de ce vide instauré

entre la raison et ce qui n'est pas elle, sans jamais

prendre appui sur la plénitude de ce qu'elle prétend

être. |

それは確かに厄介な領域だ。そこを旅するには、終末的な真実という安楽

を捨て、狂気について我々が知りうることに決して導かれてはならない。精神病理学の概念は、たとえ、そしてとりわけ、暗黙の回顧のゲームにおいても、組織

的な役割を果たしてはならない。狂気を分断する行為こそが本質であり、その分断がなされた後、平穏が戻ったときに確立される科学ではない。理性と非理性の

距離を確立する断絶が原初的なものである。理性は非理性に対して、狂気や過ち、病気という真実を剥ぎ取るために影響力を行使するが、それは非理性から遠く

離れたところにある。したがって、この原始的な議論について、勝利や勝利の権利を前提とせずに語らなければならない。歴史の中で繰り返されてきたこれらの

行為について、完成や真実における安息とみなされるものはすべて保留にして語らなければならない。理性とそれ以外のものとの間に生じた断絶、距離、空白に

ついて語らなければならないが、理性が主張する完全性には決して依拠してはならない。 |

| Alors, et alors seulement,

pourra apparaître

le domaine où l'homme de folie et l'homme de

raison, se séparant, ne sont pas encore séparés,

et dans un langage très originaire, très fruste,

bien plus matinal que celui de la science, entament

le dialogue de leur rupture, qui témoigne d'une

façon fugitive qu'ils se parlent encore. Là, folie·

et non-folie, raison et non-raison sont confusément

impliquées : inséparables du moment qu'elles

n'existent pas encore, et existant l'une pour l'autre,

J'une par rapport à l'autre, dans l'échange qui.

les sépare. |

そうして、そしてそのときにのみ、狂気の人と理性の人とが分離しながら

もまだ分離していない領域が現れ、科学の言語よりもはるかに原始的で、粗野で、より朝早い言語で、彼らの断絶についての対話を始める。それは、彼らがまだ

互いに話しているということを、つかの間ながら証明している。そこでは、狂気と非狂気、理性と非理性は混ざり合って関わっている。それらはまだ存在してい

ないため分離不可能であり、互いに存在し合い、互いに関連し合い、両者を隔てる交流の中で存在しているのだ。 |

| Au milieu du nionde serein de la

maladie mentale,

l'homme moderne ne communique plus avec

le fou : il y à d'une part l'homme de raison qui

délègue vers la folie le médecin, n'autorisant ainsi

de, rapport qu'à travers l'universalité abstraite

de la maladie; il y a d'autre part l'homme de folié

qui ne communique avec l'autre que par l'intermédiaire

d'une raison tout aussi abstraite, qui est

ordre, contrainte physique et morale, pression

• anonyme dü groupe, exigence de conformité. De

langage commun, il n'y en a pas ; ou plutôt il

n'y en a plus ; la constitution de la folie comme

maladie mentale, à la fin du XVIII 8 siècle, dresse

le constat d'un dialogue rompu, donne la sêparation

comme déjà acquise, et enfonce dans l'oubli

tous ces mots imparfaits, sans syntaxe fixe, un

peu balbutiants, dans lesquels se faisait l'échange

de la folie et de la raison. Le langage de la psychiatrie,

qui est monologue de la raison sur la folie,

n'a pu s'établir que sur un tel silence. •

Je n'ai pas voulu faire l'histoire de c~ langage;

plutôt l'archéologie de ce silence. |

精神疾患の静寂な世界の中で、現代人はもはや狂人とコミュニケーション

をとらない。一方には、医師を狂気の世界に委ね、抽象的な疾患という普遍性を通じてのみ関係を認める理性の人間がいる。他方では、狂人である人間は、同様

に抽象的な理性、すなわち秩序、物理的・道徳的強制、集団による匿名的な圧力、順応の要求を通じてのみ他者とコミュニケーションを取る。共通の言語は存在

しない、あるいはもはや存在しない。18世紀末、精神疾患としての狂気が確立されたことで、対話は断絶し、分離は当然のこととみなされ、狂気と理性の交流

の手段であった、不完全で固定された構文も持たず、少しどもったような言葉たちは、すべて忘れ去られてしまった。精神医学の言語、すなわち狂気に対する理

性の独白は、このような沈黙の上にのみ確立されたのである。私はこの言語の歴史を綴ろうとしたのではなく、むしろこの沈黙の考古学を綴ろうとしたのだ。 |

| Les Grecs avaient rapport à

quelque chose qu'ils

appelaient u~ptc;. Ce rapport n'était pas seulement

de condamnation ; 1' existence de Thrasymaque

ou celle de Calliclès suffit à le montrer, même si

leur discours nous est transmis, enveloppé déjà

dans la dialectique rassurante de Socrate. Mais

Je Logos grec n'avait pas de contraire. |

ギリシャ人は、彼らが「ウプティク」と呼んだものとの関連を持ってい

た。この関連は、単に非難だけのものではなかった。トラシュマコスやカリクレスの存在がそれを十分に示している。彼らの議論は、すでにソクラテスの安心さ

せる弁証法に包まれて伝えられているものの、そうである。しかし、ギリシャのロゴスには反対概念は存在しなかった。 |

| L'homme européen depuis le fond

du Moyen

Age a rapport à quelque• chose qu'il appelle cohfusément

: Folie; Démence, Déraison. • C'est peut- •

être à cette présence obscure que la ;Raison occidentale

doit quelque chose de sa profondeur,comme à 1a menace de l'XXXX la MMM

des

discoureurs socratiques. En tout cas le rapport

Raison-Déraison constitue pour 1a culture occidentale

une des dimensions de son originalité ;

il l'accompagnait déjà bien avant Jérôme Bosch,.

et la suivra bien après Nietzsche et Artaud. |

中世の終わり頃から、ヨーロッパ人は、彼らが混乱して「狂気」「正気の

喪失」「理性の喪失」と呼んでいるものに関わってきた。おそらく、西洋の理性はその深みを、この曖昧な存在、つまりソクラテスの議論者たちのXXXXや

MMMの脅威に負っているのだろう。いずれにせよ、理性と非理性の関係は、西洋文化の独自性の側面の一つであり、ヒエロニムス・ボスよりずっと前から存在

し、ニーチェやアルトーのずっと後まで続くだろう。 |

| Qu'est-ce donc que cet

affrontement au.,.dessoüs

du langage de la raison ? Vers quoi pourrait nous

conduire une interrogation qui ne suivrait . pas

la raison dans son devenir horizontal, mais chercherait

à retracer dans le temps, cette verticalité

constante, qui, tout au long de la culture européenne,

la confronte à ce qu'elle n'est pas, la mesure

à sa propre démesure ? Vers quelle région irionsnous,

qui n'est ni l'histoire de la connaissance, ni

l'histoire tout court, qui n'est commandée ni

par 1-até. léologie de la vérité, ni par l'enchaînement

rationnel des causes, lesquels-n'ont valeur et sens

qu'au delà du partage? Une région, sans doute,

où. il serait question plutôt des limites que de

l'identité d'une culture. |

理性という言語の根底にあるこの対立とは一体何なのか?理性の水平的な

発展を追うのではなく、その歴史の中で、ヨーロッパ文化全体を通して、理性とは異なるもの、つまり理性自身の度を超えた部分と対峙する、この絶え間ない垂

直性を辿ろうとする問いは、私たちをどこへ導くだろうか?それは、知識の歴史でも、単なる歴史でもなく、真実の哲学や、共有を超えて初めて価値と意味を持

つ合理的な因果関係にも支配されない、どのような領域へと私たちを導くだろうか?それはおそらく、文化のアイデンティティよりも、その限界について問う領

域であるに違いない。 |

| L'âge classique - de Willis à Pinel, des fureurs

d'Oreste à la Maison du Sourd et à]uliettè-couvre

justement cette période où l'échange entre la folie

et la raison modifie son langage, et de manière

radicale. Dans l'histoire de la. folie, deux événements

signalent cette altération avèc une singulière

netteté: 1657, la création de l'Hôpital général,

et le « grand renfermement » des pauvres ; r794,

libération des· enchaînés de Bicêtre. Entre ces

deux événements singuliers et symétriques, quelque

chose se passe, dont l'ambiguïté a laissé dans

l'embarras les historiens de la médecine: répression

aveugle dans un régime absolutiste, selon les 'uns,

et, selon les autres, . découverte progressive, par

~ la science et la philanthropie, de la folie dans sa

vérité positive. En fait, au-dessous de ces_ signifi.cations réversibles, une structüre se forme, qui

ne dénoue pas cette ambiguïté, mais qui en décide. •

C'est cette structure qui rend compte du passage

de l'expérience médiévale et humaniste de la folie

à cette expérience qui est la nôtre, et qui confine

la folie dans la maladie mentale. Au Moyen

Age et jusqu'à la Renaissance le débat de l'homme

avec la démence était un débat dramatique • qui

• l'affrontait aux puissances sourdes du monde ;

et l'expérience de la folie s'obnubilait alors dans

des images où il était question de la Chute et de

l' Accomplissement, de la Bête, de la Métamorphose,

et de tous les secrets merveilleux du Savoir. A

notre époque l'.e xpérience de la folie se tait dans

1e calme d'un savoir qui, de la trop connaître,

l' ublie. Mais de l'une à l'autre de ces expériences,

le. passage s'est fait par un monde sans images ni

positivité, dans une sorte de transparence silen-cieuse

qui laisse apparaître, comme institution

muette, geste sans commentaire, savoir immédiat,

une grande structüre immobile ; celle-ci n'est ni

• du drame ni de la connaissance ; elle est le point

où l'histoire s'immobilise dans le tragique qui à

la fois la fonde et la récuse. |

古

典時代―ウィリスからピネル、オレステスの狂乱から聾者の家、そしてジュリエットまで―は、まさに狂気と理性の間の交流がその言語を根本的に変化させた時

期をカバーしている。狂気の歴史において、この変化を特異なほど明確に示している二つの出来事がある。1657年の総合病院の創設と貧しい人々の「大規模

な収容」、そして1794年のビセートル病院の鎖につながれた者たちの解放だ。この2つの特異で対称的な出来事の間に、何かが起こった。その曖昧さは、医

学史家たちを困惑させてきた。ある者は、絶対主義体制下での盲目的な弾圧だと言い、またある者は、科学と博愛主義によって、狂気がその肯定的な真実として

徐々に発見されていったのだと言う。実際、これらの逆転可能な意味合いの下には、この曖昧さを解消するわけではないが、それを決定づける構造が形成されて

いる。この構造こそが、中世や人文主義者による狂気の経験から、狂気を精神疾患として限定する我々の経験への移行を説明しているのだ。中世からルネサンス

期にかけて、人間と狂気の対話は、人間を世界の無言の力と対峙させる劇的な対話だった。そして狂気の経験は、堕落と成就、獣、変容、そして知識のあらゆる

素晴らしい秘密に関するイメージに固執していた。現代では、狂気の経験は、それを知りすぎるあまり忘れてしまう知識の静けさの中に沈黙している。しかし、

これらの経験の間には、イメージも積極性も存在しない世界、一種の静寂な透明性という世界が介在している。そこでは、無言の制度、無言のジェスチャー、即

座の知識、そして大きな不動の構造が、沈黙のうちに現れている。この構造は、ドラマでも知識でもない。それは、歴史が、その基礎であり、同時に否定でもあ

る悲劇の中で静止する点である。 |

章立て

1.Première partie

2.Deuxième partie

3.Troisième partie

リンク

文献

その他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

++

☆

☆

☆