うんこな哲学

On Bullshit Philisophy

☆ On Bullshit(デタラメについて)は、アメリカの哲学者ハリー・G・フランクファート( Harry G. Frankfurt, 1929-2023)による2005年の著書(元々は1986年の論文)で、デタラメ の概念を定義し、コミュニケーションの文脈におけるデタラメの適用を分析するデタラメ理論を提示している。フランクファートは、デタラメとは真実を無視し て説得しようとする発言であると定義している。嘘つきは真実を気にかけ、それを隠そうとするが、大ぼら吹きは自分が言うことが真実であろうと嘘であろうと 気にしない[。フランクファートによる大ぼら吹きの哲学的分析は、出版以来、学者によって分析、批判、採用されてきた。

★ フランクファートは、1986年に『Raritan Quarterly Review』誌に「On Bullshit」というエッセイを最初に発表した。19年後、このエッセイは『On Bullshit』(2005年)として出版され、一般読者にも人気を博した。同書は『ニューヨーク・タイムズ』紙のベストセラーリストに27週間ランク インし、テレビ番組『ザ・デイリー・ショー・ウィズ・ジョン・スチュワート』や、出版社プリンストン大学出版局の代表とのインタビュー でも取り上げられた。デイリー・ショー・ウィズ・ジョン・スチュワート』で取り上げられ、またプリンストン大学出版局の代表との インタビューでも話題となった。『On Bullshit』はフランクファートの続編『On Truth』(2006年)のベースとなった。

★

『On Truth』は、ハリー・フランクファートによる2006年の著書であり、2005年の著書『On

Bullshit』の続編である。この本では、真実を語るという意図の有無に関わらず、人は真実を気にかけるべきであるという主張が展開されている。この

本では、一般的に受け入れられている概念を超えて「真実」を定義することを明確に避けている。これは、現実のところ実際に対応するものでもあった。

| On Bullshit

is a 2005 book (originally a 1986 essay) by American philosopher Harry

G. Frankfurt which presents a theory of bullshit that defines the

concept and analyzes the applications of bullshit in the context of

communication. Frankfurt determines that bullshit is speech intended to

persuade without regard for truth. The liar cares about the truth and

attempts to hide it; the bullshitter doesn't care whether what they say

is true or false.[1] Frankfurt's philosophical analysis of bullshit has

been analyzed, criticized and adopted by academics since its

publication.[2] |

On

Bullshit(デタラメについて)は、アメリカの哲学者ハリー・G・フランクファートによる2005年の著書(元々は1986年の論文)で、デタラメ

の概念を定義し、コミュニケーションの文脈におけるデタラメの適用を分析するデタラメ理論を提示している。フランクファートは、デタラメとは真実を無視し

て説得しようとする発言であると定義している。嘘つきは真実を気にかけ、それを隠そうとするが、大ぼら吹きは自分が言うことが真実であろうと嘘であろうと

気にしない[1]。フランクファートによる大ぼら吹きの哲学的分析は、出版以来、学者によって分析、批判、採用されてきた[2]。 |

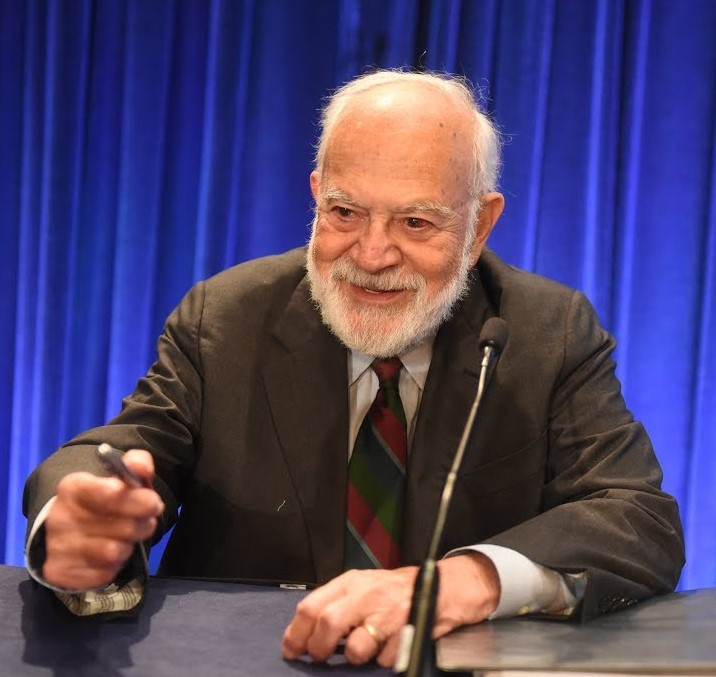

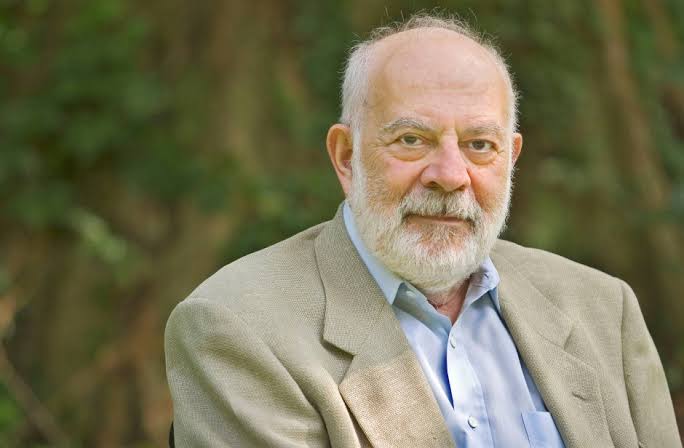

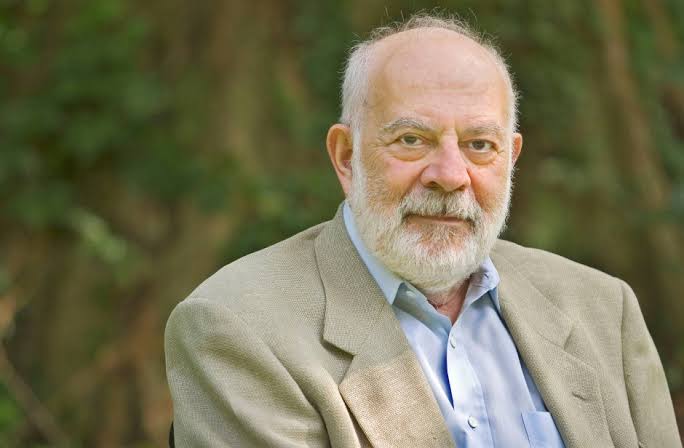

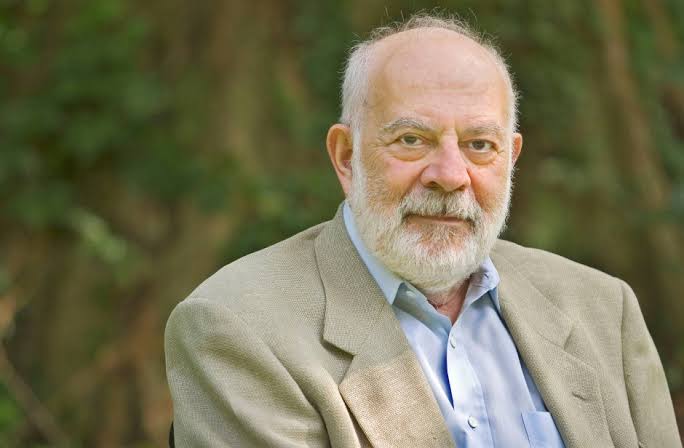

Harry G. Frankfurt, 1929-2023 History Frankfurt originally published the essay "On Bullshit" in the Raritan Quarterly Review journal in 1986. Nineteen years later, the essay was published as the book On Bullshit (2005), which proved popular among lay readers; the book appeared for 27 weeks on The New York Times Best Seller list[3] and was discussed on the television show The Daily Show With Jon Stewart,[4][5] as well as in an interview with a representative of the publisher, Princeton University Press.[6][7] On Bullshit served as the basis for Frankfurt's follow-up book On Truth (2006). |

ハリー・G・フランクファート(Harry G. Frankfurt, 1929-2023) 歴史 フランクファートは、1986年に『Raritan Quarterly Review』誌に「On Bullshit」というエッセイを最初に発表した。19年後、このエッセイは『On Bullshit』(2005年)として出版され、一般読者にも人気を博した。同書は『ニューヨーク・タイムズ』紙のベストセラーリストに27週間ランク インし[3]、テレビ番組『ザ・デイリー・ショー・ウィズ・ジョン・スチュワート』[4][5]や、出版社プリンストン大学出版局の代表とのインタビュー [6][7]でも取り上げられた。デイリー・ショー・ウィズ・ジョン・スチュワート』[4][5]で取り上げられ、またプリンストン大学出版局の代表との インタビューでも話題となった[6][7]。『On Bullshit』はフランクファートの続編『On Truth』(2006年)のベースとなった。 |

| Summary Frankfurt was a professional philosopher, trained in analytical philosophy. When asked why he decided to focus on bullshit, he explained: Respect for the truth and a concern for the truth are among the foundations for civilization. I was for a long time disturbed by the lack of respect for the truth that I observed... bullshit is one of the deformities of these values.[8] His book On Bullshit addresses his concern and makes a distinction between "bullshitters" and liars. He concludes that bullshitters are more insidious: they are more of a threat against the truth than are liars.[8] Humbug and bullshit Frankfurt begins his work on bullshit by presenting an explanation and examination of Max Black's concept of humbug.[9] Black's essay on humbug and Frankfurt's book on bullshit are similar. Both focus on understanding, defining and explaining their respective concepts and using examples. Frankfurt focuses on humbug, as he believes that it is similar to bullshit but is the more respectful term.[10] Frankfurt uses Black's work on humbug to break down the description of humbug into defining factors: "deceptive misrepresentation",[11] "short of lying”[12] "misrepresentation... of somebody's own thoughts, feelings, or attitudes",[13] and "especially by pretentious word or deed".[14] Frankfurt's analysis enables him to distinguish between humbug and lying. The main distinction is the intent that motivates them. The intent behind humbug is misrepresentation, whereas the intent behind lying is more extreme, intending to cover the truth. To Frankfurt, people tend to bullshit due to another motive that could hide something.[15] The comparison of humbug to lying acts as an initial introduction to bullshit. Humbug is closely related to bullshit, but Frankfurt believes that it is inadequate to explain bullshit and its characteristics.[16] Lying and bullshit Frankfurt's book focuses heavily on defining and discussing the difference between lying and bullshit. The main difference between the two is intent and deception. Both people who are lying and people who are telling the truth are focused on the truth. The liar wants to steer people away from discovering the truth, and the person telling the truth wants to present the truth. The bullshitter differs from both liars and people presenting the truth with their disregard of the truth. Frankfurt explains how bullshitters or people who are bullshitting are distinct, as they are not focused on the truth. A person who communicates bullshit is not interested in whether what they say is true or false, only in its suitability for their purpose.[17] In his book,[16] Frankfurt defines "shit", "bull session" and "bull". This is done in a lexicographical manner which breaks down the word bullshit and examines each component. The components of the word bullshit highlights the corresponding terms that encompass the overall meaning of the word bullshit: useless, insignificance and nonsense.[16] Next, Frankfurt focuses on the complete word and its implications and acceptance. He presents an example of advice provided to a child from his father which encourages choosing bullshit over lying when possible.[18] Frankfurt gives two reasons for the different levels of consequences between bullshit and lying. First, the liar is viewed as being purposefully deceitful or harmful because of the accompanying intent behind the act. Second, the person who bullshits lacks the kind of intention characteristic of the liar. Producing bullshit requires no knowledge of the truth. The liar is intentionally avoiding the truth, and the bullshitter may potentially be telling the truth or providing elements of the truth without the intention of doing so.[19] Frankfurt believes that bullshitters and the growing acceptance of bullshit are more harmful to society than liars and lying. This is because liars actively consider the truth when they conceal it, whereas bullshitters completely disregard the truth. "Bullshit is a greater enemy of the truth than lies are."[1] Frankfurt believes that while bullshit may be tolerated more, it is much more harmful. Rise of bullshit Frankfurt concludes his book by discussing the rise of bullshit.[16] He does not argue that there is more bullshit in society now[when?] than there was in the past. He explains that all forms of communications have increased, leading to more bullshit being seen, read and heard. He states that the social expectation for individuals to have and express their opinions on all matters requires more bullshit.[20] Despite a lack of knowledge on a subject matter, for example, politics, religion or art, there is an expectation to participate in the conversation and provide an opinion. This opinion is likely to be bullshit at times, as it is not based on fact and research. The opinion is motivated by a disregard of the truth with a desire to appear knowledgeable or adequately opinionated. Frankfurt acknowledges that bullshitting may not always be intentional but believes that ultimately it is performed with a disregard and carelessness of the truth.[21] Frankfurt argues that this rise in bullshit is dangerous, as it accepts and enables a growing disregard of the truth.[clarification needed] |

要約 フランクファートは分析哲学を学んだプロの哲学者であった。なぜデタラメに焦点を当てることにしたのか尋ねられたとき、彼は次のように説明した。 真実に対する敬意と真実への関心は、文明の基礎の一部である。私は長い間、自分が目撃した真実に対する敬意の欠如に悩まされていた...デタラメはこれら の価値観の変形の一つである[8]。 彼の著書『On Bullshit』は、彼の懸念を取り上げ、「デタラメ屋」と嘘つきを区別している。彼は、うそつきよりもうそつきの方がより陰湿であると結論付けてい る。 ハンプグとデタラメ フランクファートは、マックス・ブラックのハンプグの概念についての説明と考察を提示することで、デタラメについての著作を始めている[9]。ブラックの ハンプグに関するエッセイとフランクファートのデタラメに関する本は、類似している。どちらも、それぞれの概念を理解し、定義し、説明することと、例を用 いることに重点を置いている。フランクファートは、ハンプグはデタラメと似ているが、より丁寧な言葉であると考えているため、ハンプグに焦点を当てている [10]。フランクファートは、ハンプグの定義要素を明らかにするために、ハンプグに関するブラックの研究を利用している。「欺瞞的な虚偽表示」 [11]、「嘘とは言えない」[12]、「誰かの考え、感情、態度を偽って表現すること」[13]、「特に気取った言動によって」[14]。フランク ファートの分析により、ハンプと嘘を見分けることができる。主な違いは、それらを動機付ける意図である。ハンプガンの背後にある意図は虚偽の陳述であるの に対し、嘘をつく意図はもっと極端で、真実を隠蔽しようとするものである。フランクファートによれば、人々は何かを隠蔽しようとする別の動機から、でたら めを言う傾向がある[15]。 ハンプガンと嘘の比較は、でたらめを説明する最初の導入部として機能する。ハンプグはデタラメと密接な関係にあるが、フランクファートは、デタラメとその 特徴を説明するには不十分だと考えている[16]。 嘘とデタラメ フランクファートの本は、嘘とデタラメの違いを定義し、議論することに重点を置いている。この2つの主な違いは、意図と欺瞞である。嘘をつく人も真実を語 る人も、真実を重視している。嘘をつく人は、真実を発見されないように人々を誘導したがり、真実を語る人は真実を提示したがる。嘘つきと真実を語る人々と 異なるのは、嘘つきが真実を無視しているという点である。フランクファートは、嘘つきや嘘を語る人々が真実に関心がない点で異なることを説明している。嘘 を語る人は、自分の発言が真実か嘘かには興味がなく、自分の目的に合っているかどうかだけに関心がある[17]。これは辞書的な方法で、bullshit という単語を分解し、それぞれの構成要素を検証するものである。 bullshitという単語の構成要素は、bullshitという単語の全体的な意味を包含する、無用、無意味、ばかばかしいといった用語を浮き彫りにし ている[16]。 次にフランクファートは、単語全体とその含意や受容に焦点を当てている。彼は、父親が子供に与えたアドバイスを例に挙げている。そのアドバイスとは、嘘を つくよりも、可能な場合はうそをつくことを選ぶように促すものである[18]。フランクファートは、うそと嘘の異なる結果のレベルについて、2つの理由を 挙げている。まず、嘘をつく人は、その行為の背後にある意図があるため、意図的に人を欺いたり、害を与えたりしているとみなされる。次に、うそをつく人 は、嘘をつく人の特徴である意図を持たない。うそをつくには、真実の知識は必要ない。嘘つきは意図的に真実を避けているが、でたらめ屋はそうするつもりは ないが、真実を述べている可能性もあるし、真実の要素を提供している可能性もある[19]。フランクファートは、でたらめ屋とでたらめが受け入れられるよ うになったことは、嘘つきと嘘よ りも社会にとって有害だと考えている。なぜなら、嘘つきは真実を隠す際に積極的に真実を考慮するが、でたらめ屋は真実を完全に無視するからだ。「デタラメ は、嘘よりも真実の敵である」[1フランクファートは、デタラメはより容認されるかもしれないが、はるかに有害であると信じている。 デタラメ(bullshit)の台頭 フランクファートは、デタラメの台頭について論じて本書を締めくくっている[16]。彼は、社会におけるデタラメが過去よりも増えていると主張しているわ けではない[いつ?]。彼は、あらゆる形態のコミュニケーションが増加し、その結果、より多くのデタラメを目にしたり、読んだり、聞いたりするようになっ ていると説明している。彼は、あらゆる事柄について意見をもち、それを表明することが個人に社会的に期待されていることが、より多くのデタラメを必要とし ていると述べる[20]。例えば、政治、宗教、芸術といったテーマについて知識がないにもかかわらず、会話に参加し、意見を述べることを期待されている。 この意見は、事実や調査に基づかないため、デタラメである可能性が高い。この意見は、知識があるように見せかけたり、十分に意見を述べたりしたいという願 望から、真実を無視して動機づけられている。フランクファートは、デタラメを言うことが必ずしも意図的ではないことを認めているが、最終的には真実を無視 し、無頓着に行うものであると考えている[21]。フランクファートは、デタラメが増加することは危険であると主張している。なぜなら、真実を無視する傾向 が強まり、それが助長される可能性があるからだ[注釈が必要]。 |

| Reception and criticisms The responses to Frankfurt's work have varied greatly. Since the publication, it has been discussed, adapted, praised and criticized.[22] It has received a positive reception by many academics,[23] is considered remarkable by some,[24] and its popularity amongst the public is evident with its status as a best seller for many weeks.[25] His work has also received criticisms. One of the main criticisms has been that the work is overly simplistic[23] and too narrow:[26] that the book does not acknowledge the many dynamic factors involved in communication, or the dynamic nature of truth.[23] This criticism also explains that the work is limited in its analysis of other motives and forms of bullshit aside from one stemming from a lack of concern for the truth.[26] One critic notes that the book does not mention, or dismisses, the audience's ability to detect bullshit:[22] that Frankfurt's explanation of bullshit presents a narrative where bullshit goes unnoticed or is easily excusable by its audience.[27] Another critic points to the book's failure to rewrite the original essay to include an acknowledgement or discussion of criticism and accounting for any of the new developments and ideas within psychology and philosophy for the publication of his book.[28] Despite all these criticisms, as previously mentioned, the work is popular and has received a positive reception. Anthropologist and anarchist David Graeber refers to Frankfurt's text in his 2018 book Bullshit Jobs. |

評価と批判 フランクファートの著作に対する反応は様々である。出版以来、議論され、脚色され、賞賛され、批判されてきた[22]。多くの学者から好意的に受け入れら れ[23]、一部からは注目に値すると考えられ[24]、一般読者からの人気は、何週間にもわたってベストセラーの地位を維持したことでも明らかである [25]。彼の著作には批判もある。主な批判のひとつは、この作品が単純化しすぎている[23]、視野が狭すぎることである[26]。つまり、コミュニ ケーションに関わる多くの動的な要因や、真実の動的な性質について、この本は言及していないという批判である[23]。この批判はまた、この作品が、真実 に対する関心の欠如から生じるもの以外の、他の動機やデマの形態についての分析が限られていることも説明している 真実に対する関心の欠如から生じるもの以外については、分析が限定的であることも、この批判が指摘している。ある批評家は、この本では、聴衆がデマを見抜 く能力について言及されていない、あるいは無視されていると指摘している。 ] 別の批評家は、心理学や哲学における新たな発展やアイデアを本書の出版のために考慮し、批判に対する認識や議論を盛り込むために、元のエッセイを書き直す ことを怠ったことを指摘している[28]。 これらの批判にもかかわらず、前述の通り、この作品は人気があり、好意的に受け入れられている。人類学者でアナキストのデイヴィッド・グレーバーは、 2018年の著書『Bullshit Jobs』でフランクファートのテキストについて言及している。 |

| Truthiness Post-truth politics Rhetoric "On the Decay of the Art of Lying" by Mark Twain Bullshit Jobs by David Graeber "You Know What's Bullshit?" by James Rolfe |

真実らしさ ポスト真実の政治 レトリック 「嘘をつく技術の衰退について」マーク・トウェイン著 デヴィッド・グレーバーの『Bullshit Jobs』 「何がデタラメか分かるか?」ジェームズ・ロルフ著 うんこの哲学 |

| "On Bullshit". Raritan Quarterly Review. 6 (2): 81–100. Fall 1986. "On Bullshit". The Importance of What We Care About: Philosophical Essays. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 1988. pp. 117–133. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511818172.011. ISBN 0521333245. (hardback), ISBN 0521336112 (paperback). On Bullshit. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. 2005. ISBN 978-0691122946. |

|

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/On_Bullshit |

|

| Truthiness Truthiness is the belief or assertion that a particular statement is true based on the intuition or perceptions of some individual or individuals, without regard to evidence, logic, intellectual examination, or facts.[1][2] Truthiness can range from ignorant assertions of falsehoods to deliberate duplicity or propaganda intended to sway opinions.[3][4] The concept of truthiness has emerged as a major subject of discussion surrounding U.S. politics during the late 20th and early 21st centuries because of the perception among some observers of a rise in propaganda and a growing hostility toward factual reporting and fact-based discussion.[3] American television comedian Stephen Colbert coined the term truthiness in this meaning[5] as the subject of a segment called "The Wørd" during the pilot episode of his political satire program The Colbert Report on October 17, 2005. By using this as part of his routine, Colbert satirized the misuse of appeal to emotion and "gut feeling" as a rhetorical device in contemporaneous socio-political discourse.[6] He particularly applied it to U.S. President George W. Bush's nomination of Harriet Miers to the Supreme Court and the decision to invade Iraq in 2003.[7] Colbert later ascribed truthiness to other institutions and organizations, including Wikipedia.[8] Colbert has sometimes used a Dog Latin version of the term, "Veritasiness".[9] For example, in Colbert's "Operation Iraqi Stephen: Going Commando" the word "Veritasiness" can be seen on the banner above the eagle on the operation's seal. Truthiness was named Word of the Year for 2005 by the American Dialect Society and for 2006 by Merriam-Webster.[10][11] Linguist and OED consultant Benjamin Zimmer[5][12] pointed out that the word truthiness[13] already had a history in literature and appears in the Oxford English Dictionary (OED), as a derivation of truthy, and The Century Dictionary, both of which indicate it as rare or dialectal, and to be defined more straightforwardly as "truthfulness, faithfulness".[5] Responding to claims by Michael Adams that the word already existed with a different meaning, Colbert, presumably exploiting his definition of the word, said, "Truthiness is a word I pulled right out of my keister".[14] |

Truthiness(トゥルースネス=真実性) Truthiness(トゥルースネス)とは、証拠や論理、知的な考察、事実を考慮することなく、ある個人または複数の個人の直感や認識に基づいて特定の主張が真実であると信じたり主張したりすることである[1][2]。 トゥルースネスという概念は、20世紀後半から21世紀初頭にかけて、一部の観察者によるプロパガンダの増加や事実に基づく報道や議論に対する敵意の高ま りという認識から、米国政治をめぐる主要な議論のテーマとして浮上した[3]。 20世紀後半から21世紀初頭にかけて、一部の観測筋の間で、プロパガンダが増加し、事実に基づく報道や事実に基づく議論に対する敵意が高まっているとい う認識があったため、トゥルースネスという概念は、米国政治をめぐる主要な議論のテーマとして浮上した[3]。 米国のテレビコメディアン、スティーブン・コルベアは、2005年10月17日に放送された政治風刺番組『The Colbert Report』のパイロット版で、「The Wørd」というタイトルのコーナーのテーマとして、この用語を造語した[5]。これを彼の日常的な会話の一部として使用することで、コルベアは、感情に 訴えることや直感的な判断を、同時代の社会政治的な議論における修辞的な手法として誤用していることを風刺した[6]。彼は特に、ジョージ・W・ブッシュ 大統領によるハリエット・マイヤーズの最高裁判所への指名と、2003年のイラク侵攻の決定にこの言葉を当てはめた[7]。その後、コルベールはウィキペ ディアを含む他の機関や組織にも「真実らしさ」があると主張した[8]。コルベールは、この言葉を「Veritasiness」というラテン語風の言葉で 表すこともある[9]。例えば、コルベールの「Operation Iraqi Stephen: Going Commando」では、作戦の紋章のワシの上のバナーに「Veritasiness」という文字が見える。 「Truthiness」は、2005年にアメリカ方言学会、2006年にメリアム・ウェブスター社によって「今年の単語」に選ばれた[10][11]。 言語学者でありOEDのコンサルタントでもあるベンジャミン・ジンマー[5][12]は、この「Truthiness」という単語はすでに文学史に登場し ており、オックスフォード英語辞典(OED)では「truthiness」の派生語として掲載されていると指摘した。 また、『センチュリー辞書』では、どちらも「真実性、誠実さ」とより直接的に定義されている。[5]マイケル・アダムスが、この言葉はすでに別の意味で存 在していたと主張したことに対し、コルベールは、おそらくこの言葉の定義を利用し、「トゥルースィネスは、私が尻から引っ張り出した言葉だ」と述べた [14]。 |

| Use by Stephen Colbert Stephen Colbert, portraying his character Dr. Stephen T. Colbert, chose the word truthiness just moments before taping the premiere episode of The Colbert Report on October 17, 2005, after deciding the originally scripted word – "truth" – was not absolutely ridiculous enough: "We're not talking about truth, we're talking about something that seems like truth – the truth we want to exist", he explained.[15][16] He introduced his definition in the first segment of the episode, saying: "Now I'm sure some of the 'word police', the 'wordinistas' over at Webster's are gonna say, 'Hey, that's not a word'. Well, anybody who knows me knows I'm no fan of dictionaries or reference books. They're elitist. Constantly telling us what is or isn't true. Or what did or didn't happen."[7] When asked in an out-of-character interview with The Onion's A.V. Club for his views on "the 'truthiness' imbroglio that's tearing our country apart", Colbert elaborated on the critique he intended to convey with the word:[6] Truthiness is tearing apart our country, and I don't mean the argument over who came up with the word ... It used to be, everyone was entitled to their own opinion, but not their own facts. But that's not the case anymore. Facts matter not at all. Perception is everything. It's certainty. People love the President [George W. Bush] because he's certain of his choices as a leader, even if the facts that back him up don't seem to exist. It's the fact that he's certain that is very appealing to a certain section of the country. I really feel a dichotomy in the American populace. What is important? What you want to be true, or what is true? ... Truthiness is 'What I say is right, and [nothing] anyone else says could possibly be true.' It's not only that I feel it to be true, but that I feel it to be true. There's not only an emotional quality, but there's a selfish quality. During an interview on December 8, 2006, with Charlie Rose,[17] Colbert stated: I was thinking of the idea of passion and emotion and certainty over information. And what you feel in your gut, as I said in the first Wørd we did, which was sort of a thesis statement of the whole show – however long it lasts – is that sentence, that one word, that's more important to, I think, the public at large, and not just the people who provide it in prime-time cable, than information. At the 2006 White House Correspondents' Association Dinner, Colbert, the featured guest, described President Bush's thought processes using the definition of truthiness. Editor and Publisher used "truthiness" to describe Colbert's criticism of Bush, in an article published the same day titled "Colbert Lampoons Bush at White House Correspondents Dinner – President Not Amused?" E&P reported that the "blistering comedy 'tribute' to President Bush ... left George and Laura Bush unsmiling at its close" and that many people at the dinner "looked a little uncomfortable at times, perhaps feeling the material was a little too biting – or too much speaking 'truthiness' to power".[18] E&P reported a few days later that its coverage of Colbert at the dinner drew "possibly its highest one-day traffic total ever", and published a letter to the editor asserting that "Colbert brought truth wrapped in truthiness".[19] On the same weekend, The Washington Post and others also reported on the event.[20][21][22] Six months later, in a column titled "Throw The Truthiness Bums Out", The New York Times columnist Frank Rich called Colbert's after-dinner speech a "cultural primary" and christened it the "defining moment" of the United States' 2006 midterm elections.[23][24] Colbert refreshed "truthiness" in an episode of The Late Show with Stephen Colbert on July 18, 2016, using the neologism "Trumpiness" regarding statements made by Donald Trump during his 2016 presidential campaign.[25] According to Colbert, while truthiness refers to statements that feel true but are actually false, "Trumpiness" does not even have to feel true, much less be true. As evidence that Trump's remarks exhibit this quality, he cited a Washington Post column stating that many Trump supporters did not believe his "wildest promises" but supported him anyway.[26][27][28] |

スティーブン・コルベールによる使用 スティーブン・コルベールは、2005年10月17日に『The Colbert Report』の初回エピソードを収録する直前に、自身が演じるスティーブン・T・コルベール博士のキャラクターとして「truthiness」という単 語を選んだ。当初台本に書かれていた「truth(真実)」では不十分だと判断したのだ。 「真実」という言葉は、あまりにもばかばかしくて使えないと判断したのだ。彼は、「真実について話しているのではなく、真実のように思えること、つまり、 存在してほしい真実について話しているのだ」と説明した[15][16]。彼は、その定義を番組の最初の部分で次のように紹介した。「ウェブスターの『言 葉の警察』や『言葉の専門家』の一部が、『それは言葉じゃない』と言うだろうね。でも、僕を知っている人なら、僕が辞書や参考書のファンじゃないことは 知っている。それらはエリート主義で、何が真実で何が真実でないかを常に教えてくれる。あるいは、何が起こったのか、起こらなかったのか。 「私たちの国を分裂させている『真実らしさ』の混乱」について、The Onion の A.V. Club との普段とは違ったインタビューで意見を求められた際、コルベアは、この言葉を使って伝えたかった批判について詳しく説明しました:[6] 真実らしさが私たちの国を分裂させている。私が言いたいのは、この言葉を最初に使ったのが誰かという議論のことではない。 かつては、誰もが自分の意見を持つ権利があったが、自分の事実を持つ権利はなかった。しかし、今はそうではない。事実はまったく重要ではない。認識がすべ てだ。確信なのだ。人々は大統領(ジョージ・W・ブッシュ)を愛している。なぜなら、たとえ彼を裏付ける事実が存在しないように思えても、彼がリーダーと して選択したことに確信を持っているからだ。彼が確信を持っているという事実が、ある特定の層の人々にとって非常に魅力的だ。私はアメリカ国民の間に二分 法があると感じている。何が重要なのか?真実でありたいと思うのか、それとも真実なのか? 真実らしさとは、「私が正しいと思うことは正しいし、他の誰も言うことは真実であるはずがない」ということだ。私が真実だと思うだけでなく、真実だと思うように感じるのだ。そこには感情的な要素だけでなく、利己的な要素もある。 2006年12月8日、チャーリー・ローズとのインタビュー[17]で、コルベアは次のように述べた。 情熱や感情、そして情報に対する確信について考えていた。そして、私が最初に言ったように、番組全体に関する論文の要約のようなもので、それがどれほど長 く続くかは別として、視聴者の大半にとって、ゴールデンタイムのケーブル番組でそれを提供する人々だけでなく、情報よりも、その文章、その1つの単語の方 がより重要だと思う。 2006年のホワイトハウス記者協会晩餐会では、特別ゲストとして登場したコルトがブッシュ大統領の思考プロセスを「真実らしさ」の定義を用いて表現し た。 編集者兼発行人は、同日付けで「コルト、ホワイトハウス記者協会晩餐会でブッシュ大統領を風刺 - 大統領は面白くない?E&P は、「ブッシュ大統領に対する痛烈なコメディ『オマージュ』は、ジョージとローラ・ブッシュ夫妻を最後まで笑顔にさせなかった」と報じ、晩餐会に出席した 多くの人々が「このネタが辛辣すぎる、あるいは権力に対して『真実らしさ』を語りすぎていると感じたのか、時に少し居心地悪そうに見えた」と伝えた [18]。E&P は、その数日後に 数日後、E&Pは、ディナーでのコルベアの報道が「おそらく過去最高の1日のアクセス数を記録した」と報道し、「コルベアは真実を真実らしく包み 込んだ」と主張する編集者への手紙を掲載した[19]。同じ週末には、ワシントン・ポスト紙などもこのイベントについて報道した[20][21] [22]。6か月後、ニューヨーク・タイムズのコラムニスト、フランク・リッチは、「Throw The Truthiness Bums Out(真実らしさをぶちまけろ)」と題したコラムで、コルベアのディナー後のスピーチを「文化的プライマリー」と呼び、2006年の中間選挙における 「決定的瞬間」と評した[23][24]。コルベアは、『ザ・レイト・ショー・ウィズ・ 「Throw The Truthiness Bums Out」と題されたニューヨーク・タイムズのコラムニスト、フランク・リッチは、コルベアの食後のスピーチを「文化的プライマリー」と呼び、2006年の 米国中間選挙の「決定的瞬間」と評した[23][24]。 コルベアは、2016年7月18日放送の「The Late Show with Stephen Colbert」のエピソードで、「truthiness」を刷新した。2016年7月18日放送の『ザ・レイト・ショー・ウィズ・スティーブン・コルベ ア』で、ドナルド・トランプが2016年の大統領選挙キャンペーン中に発した発言について、「トランプらしさ」という新語を用いて「トゥルースらしさ」を 刷新した[25]。コルベアによると、「トゥルースらしさ」とは真実のように感じさせるが実際には偽りの発言を指すが、「トランプらしさ」は真実のように 感じさせる必要すらなく、まして真実である必要もない。トランプの発言がこの性質を持っている証拠として、彼は、多くのトランプ支持者は彼の「荒唐無稽な 公約」を信じていないが、それでも彼を支持していると述べたワシントン・ポストのコラムを引用した[26][27][28]。 |

| Coverage by news media After Colbert's introduction of truthiness, it quickly became widely used and recognized. Six days after, CNN's Reliable Sources featured a discussion of The Colbert Report by host Howard Kurtz, who played a clip of Colbert's definition.[29] On the same day, ABC's Nightline also reported on truthiness, prompting Colbert to respond by saying: "You know what was missing from that piece? Me. Stephen Colbert. But I'm not surprised. Nightline's on opposite me ..."[30] Within a few months of its introduction by Colbert, truthiness was discussed in The New York Times, The Washington Post, USA Weekly, the San Francisco Chronicle, the Chicago Tribune, Newsweek, CNN, MSNBC, Fox News, the Associated Press, Editor & Publisher, Salon, The Huffington Post, Chicago Reader, CNET, and on ABC's Nightline, CBS's 60 Minutes, and The Oprah Winfrey Show. The February 13, 2006 issue of Newsweek featured an article on The Colbert Report titled "The Truthiness Teller", recounting the career of the word truthiness since its popularization by Colbert.[13] The New York Times coverage and usage In its issue of October 25, 2005, eight days after the premiere episode of the Report, The New York Times ran its third article on The Colbert Report, "Bringing Out the Absurdity of the News".[31] The article specifically discussed the segment on "truthiness", although the Times misreported the word as "trustiness". In its November 1, 2005 issue, the Times ran a correction. On the next episode of the Report, Colbert took the Times to task for the error, pointing out, ironically, that "trustiness" is "not even a word".[32] The New York Times again discussed "truthiness" in its issue of December 25, 2005, this time as one of nine words that had captured the year's zeitgeist, in an article titled "2005: In a Word; Truthiness" by Jacques Steinberg. In crediting truthiness, Steinberg said, "the pundit who probably drew the most attention in 2005 was only playing one on TV: Stephen Colbert".[33] In the January 22, 2006 issue, columnist Frank Rich used the term seven times, with credit to Colbert, in a column titled "Truthiness 101: From Frey to Alito",[34] to discuss Republican portrayals of several issues (including the Samuel Alito nomination, the Bush administration's response to Hurricane Katrina, and Jack Murtha's Vietnam War record). Rich emphasized the extent to which the word had quickly become a cultural fixture, writing, "The mock Comedy Central pundit Stephen Colbert's slinging of the word 'truthiness' caught on instantaneously last year precisely because we live in the age of truthiness." Editor & Publisher reported on Rich's use of "truthiness" in his column, saying he "tackled the growing trend to 'truthiness,' as opposed to truth, in the U.S."[35] The New York Times published two letters on the 2006 White House Correspondents' Dinner, where Stephen Colbert was the featured guest, in its May 3, 2006 edition, under the headline "Truthiness and Power".[36] Frank Rich referenced truthiness again in The New York Times in 2008, describing the strategy of John McCain's presidential campaign as being "to envelop the entire presidential race in a thick fog of truthiness",[37] Rich explained that the campaign was based on truthiness because "McCain, Sarah Palin and their surrogates keep repeating the same lies over and over not just to smear their opponents and not just to mask their own record. Their larger aim is to construct a bogus alternative reality so relentless it can overwhelm any haphazard journalistic stabs at puncturing it."[37] Rich also noted, "You know the press is impotent at unmasking this truthiness when the hardest-hitting interrogation McCain has yet faced on television came on 'The View'. Barbara Walters and Joy Behar called him on several falsehoods, including his endlessly repeated fantasy that Palin opposed earmarks for Alaska. Behar used the word 'lies' to his face."[37] |

ニュースメディアによる報道 コルベールがトゥルースィーを紹介してから、この言葉は瞬く間に広まり、認知されるようになった。その6日後、CNNの「Reliable Sources」では、番組の司会者ハワード・カーツがコルベールの定義を引用しながら、「ザ・コルベール・レポート」について議論した。しかし、私は驚 いていない。「ナイトライン」が私の向かいに放送されている...」[30] コルバートが「トゥルースィー」を紹介してから数か月以内に、「トゥルースィー」は『ニューヨーク・タイムズ』、『ワシントン・ポスト』、『USAウィー クリー』、『サンフランシスコ・クロニクル』、『シカゴ・トリビューン』、『ニューズウィーク』、『 CNN、MSNBC、Fox News、AP通信、Editor & Publisher、Salon、The Huffington Post、Chicago Reader、CNET、ABCの「ナイトライン」、CBSの「60ミニッツ」、オプラ・ウィンフリー・ショーでも取り上げられた。 2006年2月13日号のニューズウィーク誌は、「The Truthiness Teller(真実味のある話し手)」と題した『The Colbert Report』の記事を掲載し、コバートによって広まった「truthiness」という言葉のキャリアについて振り返った[13]。 ニューヨーク・タイムズの報道と用法 2005年10月25日号では、 2005年10月25日、レポートの初回放送から8日後、ニューヨーク・タイムズは「ニュースのばかばかしさを引き出す」と題した、コルベア・レポートに 関する3つ目の記事を掲載した[31]。この記事では「真実らしさ」のコーナーについて特に論じられていたが、タイムズは「信頼性」と誤って報じていた。 2005年11月1日号のタイムズ紙は訂正記事を掲載した。『ザ・レポート』の次のエピソードで、コルトはタイムズ紙をこの誤りに責任追及し、皮肉にも 「信頼性」は「言葉ですらない」と指摘した[32]。 ニューヨーク・タイムズ紙は2005年12月25日号で再び「真実らしさ」を取り上げ、今回はその年の世相を象徴する9つの言葉のひとつとして、ジャッ ク・スタインバーグによる「2005年: ジャック・スタインバーグ著「2005年:一言で表現する、真実らしさ」では、スタインバーグは「2005年に最も注目を集めた評論家は、テレビでただ一 人、スティーブン・コルベアだけだった」と述べて、真実らしさを評価している[33]。 2006年1月22日号では、コラムニストのフランク・リッチが「真実らしさ入門:フレイからアリートへ」と題したコラムで、コルベアを引用しながらこの 言葉を7回使用し、共和党によるいくつかの問題(サミュエル・アリートの指名、ブッシュ政権のハリケーン・カトリーナへの対応、ジャック・マーサのベトナ ム戦争での経歴など)の描写について論じている[34]。フレイからアリートへ」と題したコラムで、共和党によるいくつかの問題(サミュエル・アリートの 指名、ブッシュ政権のハリケーン・カトリーナへの対応、ジャック・マーサのベトナム戦争での記録など)の描写について論じた。リッチは、この言葉が急速に 文化的な定着を遂げた度合いを強調し、「コメディ・セントラルのコメンテーター、スティーブン・コルベアの『真実らしさ』という言葉が瞬く間に広まったの は、まさに私たちが真実らしさの時代を生きているからなのだ」と書いている。「Editor & Publisher」誌は、リッチがコラムの中で「truthiness」という言葉を使用したことについて、「米国で真実ではなく『真実らしさ』を求め る傾向が高まっていることについて、彼は取り組んだ」と報じた[35]。 ニューヨーク・タイムズ紙は、2006年5月3日付の紙面に、スティーブン・コルベアがゲストとして登場した2006年のホワイトハウス記者晩餐会に関する2つの手紙を、「Truthiness and Power(真実らしさと権力)」の見出しで掲載した。 [36] フランク・リッチは2008年に再びニューヨーク・タイムズ紙で「真実らしさ」について言及し、ジョン・マケイン大統領選挙キャンペーンの戦略を「大統領 選全体を真実らしさの厚い霧で包み込む」ものだと評した[37]。リッチは、このキャンペーンが「真実らしさ」に基づいている理由について、「マケイン、 サラ・ペイリン、そして彼らの代理人は、ただ単に相手を中傷するためや、自分たちの実績を隠すためだけでなく、同じ嘘を何度も何度も繰り返している。彼ら の真の狙いは、偽りの現実を構築することであり、それは執拗で、ジャーナリストが突っこんでくるどんな突拍子もない質問も圧倒してしまうほどだ」 [37]。リッチはさらに、「マケインがテレビで受けた最も厳しい尋問が『The View』で放送されたとき、マスコミがこの真実らしさを暴くのに無力であることがわかった。バーバラ・ウォルターズとジョイ・ベアールは、マケインがア ラスカ州への予算措置に反対しているという彼の絶え間なく繰り返される空想を含む、いくつかの虚偽について彼を非難した。ベアールは彼の顔に向かって 「嘘」という言葉を使った。 |

Recognition A church sign stating, "Truthiness and Consequences", taken March 10, 2007, in Cape Coral, Florida Usage of "truthiness" continued to proliferate in media, politics, and public consciousness. On January 5, 2006, etymology professor Anatoly Liberman began an hour-long program on public radio by discussing truthiness and predicting it would be included in dictionaries in the next year or two.[38] His prediction seemed to be on track when, the next day, the American Dialect Society announced that "truthiness" was its 2005 Word of the Year, and the website of the Macmillan English Dictionary featured truthiness as its Word of the Week a few weeks later.[39] Truthiness was also selected by The New York Times as one of nine words that captured the spirit of 2005. Global Language Monitor,[40] which tracks trends in languages, named truthiness the top television buzzword of 2006, and another term Colbert coined with reference to truthiness, wikiality, as another of the top ten television buzzwords of 2006, the first time two words from the same show have made the list. [41] [42] The word was listed in the annual "Banished Word List" released by a committee at Lake Superior State University in Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan, in 2007. The list included "truthiness" among other overused terms, such as "awesome" celebrity couple portmanteaus such as "Brangelina", and "pwn".[43] In response, on January 8, 2007, Colbert said Lake Superior State University was an "attention-seeking second-tier state university".[44][non-primary source needed] The 2008 List of Banished Words restored "truthiness" to formal usage, in response to the 2007–2008 Writers Guild of America strike.[45] American Dialect Society's Word of the Year On January 6, 2006, the American Dialect Society announced that "truthiness" was selected as its 2005 Word of the Year. The Society described its rationale as follows: In its 16th annual words of the year vote, the American Dialect Society voted truthiness as the word of the year. First heard on The Colbert Report, a satirical mock news show on the Comedy Central television channel, truthiness refers to the quality of preferring concepts or facts one wishes or believes to be true, rather than concepts or facts known to be true. As Stephen Colbert put it, "I don't trust books. They're all fact, no heart."[10] Merriam-Webster's Word of the Year On December 10, 2006, the Merriam-Webster Dictionary announced that "truthiness" was selected as its 2006 Word of the Year on Merriam-Webster's Words of the Year, based on a reader poll, by a 5–1 margin over the second-place word google.[11] "We're at a point where what constitutes truth is a question on a lot of people's minds, and truth has become up for grabs", said Merriam-Webster president John Morse. "'Truthiness' is a playful way for us to think about a very important issue."[46] However, despite winning Word of the Year, the word does not appear in the 2006 edition of the Merriam-Webster English Dictionary. In response to this omission, during "The Wørd" segment on December 12, 2006, Colbert issued a new page 1344 for the tenth edition of the Merriam Webster dictionary that featured "truthiness". To make room for the definition of "truthiness", including a portrait of Colbert, the definition for the word "try" was removed with Colbert stating "Sorry, try. Maybe you should have tried harder." He also sarcastically told viewers to "not" download the new page and "not" glue it in the new dictionary in libraries and schools.[47][non-primary source needed] The New York Times crossword puzzle In the June 14, 2008 edition of The New York Times, the word was featured as 1-across in the crossword puzzle.[48] Colbert mentioned this during the last segment on the June 18 episode of The Daily Show with Jon Stewart, and declared himself the "King of the Crossword".[49][non-primary source needed] BBC "portrait of the decade" In December 2009, the BBC online magazine asked its readers to nominate suggestions of things to be included on a poster which would represent important events in the 2000s (decade), divided into five different categories: "People", "Words", "News", "Objects" and "Culture". Suggestions were sent in and a panel of five independent experts shortened each category to what they saw as the 20 most important. The selection in the "Words" category included "Truthiness".[50] Research There is a growing amount of research on how the truthiness of a claim is inflated by the accompanying nonprobative information. In particular, in 2012, a study examining truthiness was published by a group of students from three universities in the paper "Nonprobative photographs (or words) inflate truthiness".[51] The experiments showed that people are more likely to believe a claim is true regardless of evidence when a decorative photograph or irrelevant verbosity appears alongside the claim. [52][53] Also in 2012, Harvard University's Berkman Center hosted a two-day symposium at Harvard and MIT, "Truthiness in Digital Media", exploring "concerns about misinformation and disinformation" in new media.[54][55] The Truthiness Collaborative is a project at USC's Annenberg School "to advance research and engagement around the misinformation, disinformation, propaganda and other challenges to discourse fueled by our evolving media and technology ecosystem".[56][57] |

認知 「Truthiness and Consequences(真実らしさと結果)」と書かれた教会の看板。2007年3月10日、フロリダ州ケープコーラルにて撮影 「truthiness」という言葉は、メディア、政治、そして人々の意識の中でますます広まっていった。2006年1月5日、語源学者のアナトリー・ リーバーマンは、公共ラジオで1時間の番組を開始し、「トゥルースィー」について議論し、1~2年以内に辞書に掲載されるだろうと予測した[38]。彼の 予測は的中したかに思われた。翌日、アメリカ方言学会が 「truthiness」が2005年の年間単語に選ばれたことを発表し、数週間後にはマクミラン英語辞典のウェブサイトが「truthiness」を今 週の単語として取り上げた[39]。また、「truthiness」はニューヨーク・タイムズ紙が2005年の世相を象徴する9つの単語の1つとして選ん だ。言語のトレンドを追跡する Global Language Monitor は、2006年のテレビ界で最も話題になった流行語として「truthiness」を挙げている。また、コバートが「truthiness」にちなんで作 り出した「wikiality」という語も、2006年のテレビ界で最も話題になった流行語トップ10に選ばれ、同じ番組から2つの語が同時にリスト入り したのは初めてのこととなった。[41] [42] この言葉は、2007年にミシガン州スー・セント・マリーにあるレイク・スペリオル州立大学の委員会が発表した「禁止語リスト」に挙げられた。このリスト には、「truthiness」のほか、「awesome」のような使い古された言葉や、「Brangelina」のようなセレブカップルの合成語、 「pwn」などが含まれていた[43]。これに対し、2007年1月8日、コルベアは、スーペリア州立大学は「注目を浴びたい二流の州立大学」だと述べた [44][非一次情報源が必要]。 2008年の「禁句リスト」では、「truthiness」が正式な用語として復活した。これは、2007年から2008年にかけて全米脚本家組合がスト ライキを行ったことへの対応である[45]。 アメリカ方言学会の年間単語 2006年1月6日、アメリカ方言学会は「truthiness」を2005年の年間単語に選出したと発表した。同協会は、その理由について次のように説明している。 アメリカン・ダイアレクト・ソサエティは、第16回となる今年の言葉の投票で、「truthiness」を今年の言葉として選出した。 コメディ・セントラルの風刺的ニュース番組『The Colbert Report』で初めて使われた「truthiness」は、真実であると知られている概念や事実よりも、自分が真実であると望む、あるいは信じている概 念や事実を好むという性質を指す。スティーブン・コルベアは、「私は本を信用しない。それらはすべて事実であり、心がない」[10]。 メリアム・ウェブスターの年間単語 2006年12月10日、メリアム・ウェブスター辞典は、読者投票により「truthiness」が2006年の年間単語に選ばれたと発表した。読者投票 の結果、2位の「google」に5対1の差をつけて選ばれた。メリアム・ウェブスター社の社長ジョン・モースは、「真実とは何かが多くの人の関心事と なっている今、真実とは誰にでも主張できるものとなっている」と述べた。「トゥルースネス」は、非常に重要な問題について考えるための遊び心のある表現 だ」[46]。しかし、「今年の単語」に選ばれたにもかかわらず、この言葉は2006年版のMerriam-Webster English Dictionaryには掲載されていない。この省略に対して、2006年12月12日の「The Wørd」のコーナーで、コルベールはメリアム・ウェブスター辞典第10版の1344ページに「truthiness」を掲載した。コルベールの肖像画を 含む「truthiness」の定義のスペースを確保するため、「try」の定義は削除され、コルベールは「残念だ。もっと努力すべきだったかもしれな い」と述べた。また、視聴者に対して、新しいページをダウンロードしたり、図書館や学校の新しい辞書に貼り付けたりしないようにと皮肉った。 ニューヨーク・タイムズのクロスワードパズル 2008年6月14日付のニューヨーク・タイムズ紙で、この単語がクロスワードパズルの1マス目に登場した。6月18日放送の『デイリー・ショー with ジョン・スチュワート』の最後のコーナーで、これを話題にし、自らを「クロスワードの王様」と宣言した[49][非一次情報源が必要]。 BBC「10年間の肖像 2009年12月、BBCのオンラインマガジンは、2000年代(10年間)の重要な出来事を象徴するポスターに載せたいものを、5つのカテゴリー(「人 物」、「言葉」、「ニュース」、「物」、「文化」)に分けて、読者に推薦してもらう企画を実施した。「人物」、「言葉」、「ニュース」、「物」、「文化」 の5つである。提案が寄せられ、5人の独立した専門家からなるパネルが、各カテゴリーを最も重要と思われる20個に絞り込んだ。 「言葉」カテゴリーに選ばれたのは、「真実らしさ」であった[50]。 研究 主張の真実らしさが、根拠のない情報によって誇張される仕組みについて、研究が進められている。特に2012年には、3つの大学の学生グループによる真実 性の研究が「Nonprobative photographs (or words) inflate truthiness」という論文で発表された[51]。この実験では、主張に装飾的な写真や無関係な冗長な表現が添えられていると、証拠の有無に関わら ず人々は主張を真実だと信じやすくなることが示された。[52][53] また、2012年にはハーバード大学のバークマンセンターがハーバード大学とマサチューセッツ工科大学で2日間にわたるシンポジウム「デジタルメディアにおける真実性」を開催し、新メディアにおける「誤報や偽情報への懸念」について探求した[54][55]。 Truthiness Collaborativeは、USCのアネンバーグ・スクールにおけるプロジェクトで、「進化するメディアとテクノロジーのエコシステムによって煽られ る誤報、デマ、プロパガンダ、その他の言論への挑戦に関する研究と取り組みを推進する」ことを目的としている[56][57]。 |

| Alternative facts Bellyfeel Big lie – Propaganda technique Cognitive dissonance Confabulation Disinformation Doublethink Factoid Fake news De facto Illusory truth effect Mathiness Misinformation Newspeak Noble lie On Bullshit – an essay by Harry Frankfurt, originally written in 1986 but published as a book on January 10, 2005, nine months before Colbert coined truthiness Political correctness Processing fluency – a statement is more likely to be considered true if it is easier to process. Post-truth politics Selective exposure theory Solipsism Trumpism Truth sandwich Verisimilitude Wikiality – another word coined by Colbert |

Alternative facts Bellyfeel Big lie – Propaganda technique Cognitive dissonance Confabulation Disinformation Doublethink Factoid Fake news De facto Illusory truth effect Mathiness Misinformation Newspeak Noble lie On Bullshit – an essay by Harry Frankfurt, originally written in 1986 but published as a book on January 10, 2005, nine months before Colbert coined truthiness Political correctness Processing fluency – a statement is more likely to be considered true if it is easier to process. Post-truth politics Selective exposure theory Solipsism Trumpism Truth sandwich Verisimilitude Wikiality – another word coined by Colbert |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Truthiness |

|

Harry Gordon Frankfurt (May 29, 1929 – July 16, 2023) was an American philosopher. He was a professor emeritus of philosophy at Princeton University, where he taught from 1990 until 2002. Frankfurt also taught at Yale University, Rockefeller University, and Ohio State University. Frankfurt made significant contributions to fields like ethics and philosophy of mind. The attitude of caring played a central role in his philosophy. To care about something means to see it as important and reflects the person's character. According to Frankfurt, a person is someone who has second-order volitions or who cares about what desires he or she has. He contrasts persons with wantons. Wantons are beings that have desires but do not care about which of their desires is translated into action. In the field of ethics, Frankfurt gave various influential counterexamples, so-called Frankfurt cases, against the principle that moral responsibility depends on the ability to do otherwise. His most popular book is On Bullshit, which discusses the distinction between bullshitting and lying. Biography Early life Frankfurt was born David Bernard Stern at a home for unwed mothers in Langhorne, Pennsylvania, on May 29, 1929, and did not know his biological parents. Shortly after his birth, he was adopted by a middle-class Jewish family and given a new name, Harry Gordon Frankfurt. His adoptive parents, Bertha (née Gordon) and Nathan Frankfurt, a piano teacher and a bookkeeper, respectively, raised him in Brooklyn and Baltimore. He attended Johns Hopkins University, where he obtained his Bachelor of Arts in 1949 and Doctor of Philosophy in 1954, both in philosophy.[1] Career Frankfurt was professor emeritus of philosophy at Princeton University.[2] He previously taught at Ohio State University (1956–1962), SUNY Binghamton (1962–1963),[3] Rockefeller University (from 1963 until the philosophy department was closed in 1976),[4] Yale University (from 1976, where he served as chair of the philosophy department 1978–1987),[5] and then Princeton University (1990–2002).[2] His major areas of interest included moral philosophy, philosophy of mind and action, and 17th-century rationalism. His 2005 book On Bullshit, originally published in 1986 as a paper on the concept of "bullshit", unexpectedly became a bestseller, which led to his making media appearances such as on Jon Stewart's late-night television program, The Daily Show.[6] In this work he explains how bullshitting is different from lying, in that it is an act that has no regard for the truth. He argues that "It is impossible for someone to lie unless he thinks he knows the truth. Producing bullshit requires no such conviction." In 2006, he followed up with On Truth, a companion book in which he explored the dwindling appreciation in society for truth.[7] Among philosophers, he was for a time best known for his interpretation of Descartes's rationalism. His most influential work, however, has been on freedom of the will (on which he has written numerous important papers[8]) based on his concept of higher-order volitions and for developing "Frankfurt cases" (also known as "Frankfurt counter-examples", which are thought experiments designed to demonstrate the possibility of situations in which a person could not have done other than he/she did, but in which our intuition is to say nonetheless that this feature of the situation does not prevent that person from being morally responsible).[9] Frankfurt's view of compatibilism is perhaps the most influential version of compatibilism, developing the view that to be free is to have one's actions conform to one's more reflective desires. Frankfurt's version of compatibilism is the subject of a substantial number of citations.[10] More recently, he wrote on love and caring in The Reasons of Love.[11] Frankfurt was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1995.[12] He was a Visiting Fellow of All Souls College, Oxford University;[13] he served as president, Eastern Division, American Philosophical Association;[14] and he has received grants and fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation, the Andrew Mellon Foundation and the National Endowment for the Humanities.[13] |

ハリー・ゴードン・フランクファート(1929年5月29日 - 2023年7月16日)は、アメリカの哲学者である。1990年から2002年までプリンストン大学で哲学の教授を務めた。フランクファートは、イェール大 学、ロックフェラー大学、オハイオ州立大学でも教鞭をとった。 フランクファートは、倫理学や心の哲学などの分野に多大な貢献をした。彼の哲学において、思いやりという態度が中心的な役割を果たしている。何かを思いや る とは、それを重要と見なすことであり、その人の性格を反映している。フランクファートによれば、人は二次的意志を持つ者、すなわち自分が持つ欲望について 思 いやる者である。彼は、人を放縦な者と対比させる。放縦な者は、欲望を持つが、その欲望がどの欲望が行動に結びつくかについて思いやらない存在である。倫 理学の分野では、フランクファートは、道徳的責任は別の行動を取る能力に依存するという原則に対して、さまざまな影響力のある反例、いわゆるフランク ファート・ケースを提示した。彼の最も有名な著書は『虚偽について』であり、これは、でたらめを言うことと嘘をつくことの違いについて論じている。 経歴 幼少期 フランクファートは1929年5月29日、ペンシルベニア州ラングホーンの未婚の母のための施設でデイヴィッド・バーナード・スターンとして生まれ、実の両 親を知らない。生後まもなく、彼は中流階級のユダヤ人家庭に養子として迎えられ、ハリー・ゴードン・フランクファートという新しい名前を与えられた。養父母 のバーサ(旧姓ゴードン)とネイサン・フランクファートは、それぞれピアノ教師と簿記係であり、彼をブルックリンとボルチモアで育てた。彼はジョンズ・ホプ キンス大学に進学し、1949年に学士号、1954年に博士号を哲学で取得した。 経歴 フランクファートはプリンストン大学名誉教授(哲学)であった。[2] それ以前には、オハイオ州立大学(1956年から1962年)、ニューヨーク州立大学ビンガムトン校(1962年から1963年)、[3] ロックフェラー大学(1963年から哲学部が閉鎖された1976年まで)[4] 1976年に閉鎖されるまで)[4]、イエール大学(1976年より、1978年から1987年までは哲学部の学部長を務めた)[5]、そしてプリンスト ン大学(1990年から2002年)で教鞭をとった。[2] 彼の主な研究分野は、道徳哲学、心の哲学、行動哲学、17世紀の合理主義であった。2005年に出版された著書『On Bullshit』は、1986年に「bullshit」という概念に関する論文として発表されたもので、予想外のベストセラーとなった。これにより、彼 は深夜のテレビ番組『The Daily Show』など、メディアへの出演を果たした。[6] この著作で彼は、真実を考慮しない行為であるという点で、うそをつくこととデタラメを言うことは異なることを説明している。「真実を知っていると考えるの でなければ、誰かが嘘をつくことは不可能である。でたらめをでっちあげるには、そのような確信は必要ない」と彼は主張している。2006年には、社会にお ける真実への評価が低下していることを探求した『On Truth』を出版した。 哲学者の間では、彼は一時期、デカルトの合理主義の解釈で最もよく知られていた。しかし、彼の最も影響力のある作品は、高次意志の概念に基づく自由意志に 関するものであり(これについては、多数の重要な論文を執筆している[8])、「フランクファートの事例」(「フランクファートの反例」とも呼ばれる。これ は、人が特定の行動を取らざるを得なかった状況を実証するための思考実験であり、 しかし、それでもなお、その状況の特徴がその人物の道徳的責任を妨げるものではないと直観的に言えるような状況の可能性を実証するために考案された思考実 験である。[9] フランクファートのコンパティビリズムの考え方は、おそらくコンパティビリズムの最も影響力のあるバージョンであり、自由であるということは、自分の行動を より熟考した願望に適合させることであるという考え方を発展させたものである。フランクファートのコンパティビリズムの考え方は、数多くの引用の対象となっ ている。[10] 最近では、『愛の理由』で愛と思いやりについて書いている。[11] フランクファートは1995年にアメリカ芸術科学アカデミーのフェローに選出された。[12] オックスフォード大学オール・ソウルズ・カレッジの客員研究員でもあった。[13] アメリカ哲学協会東部会長も務めた。[14] また、グッゲンハイム財団、アンドリュー・メロン財団、全米人文科学基金から助成金やフェローシップを受けている。[13] |

| Philosophy Caring and importance According to Frankfurt, a lot of the philosophical discourse concerns either the domain of epistemology, which asks what we should believe, or ethics, which asks how we should act. He argues that there is another branch of inquiry that has received less attention, namely the question of what has importance or what we should care about.[15] An agent cares about something if he/she has a certain attitude of the will: He/she sees the entity in question as important to them. For Frankfurt, what we care about reflects our personal character or who we are. This also affects the person on the practical level concerning how he/she acts and leads his/her life.[16][17] In the academic literature, caring is often understood as a subjective attitude in contrast to importance as an objective factor. On this view, the importance of something determines whether it is appropriate to care about it: people should care about important things but not about unimportant ones.[18][19][20] Frankfurt defends a different perspective on this issue by arguing that caring about something makes this thing important. So when a person starts caring about something, this thing becomes important to them even if it was unimportant to them before. Frankfurt explains this in terms of needs: the caring attitude brings with it a need. Because of this need, the cared-for thing can affect the person's well-being and has thereby become important to them.[15][20] Yitzhak Benbaji terms this relation between caring and importance "Frankfurt's Care-Importance Principle". He rejects it based on the claim that at least some cases of the caring attitude are misguided. This usually involves situations in which the agent has a wrong belief that the object of their caring would affect their well-being. In one example, the agent follows a charlatan's health advice to avoid a certain type of food. Benbaji argues that this constitutes a counterexample because the person cares about avoiding this food even though it has no impact on their health or their well-being.[20] Personhood Persons are characterized by certain attributes or capacities, like reason, moral responsibility, and self-consciousness.[21][22] However, there is wide disagreement, both within the academic discourse and between different cultures about what the essential features of personhood are.[23] One influential and precisely formulated account of personhood is given by Frankfurt in his "Freedom of the Will and the Concept of a Person". He holds that persons are beings that have second-order volitions.[24][25] A volition is an effective desire, i.e. a desire that the agent is committed to realizing.[26][27] Not all desires become volitions: humans usually have many desires but put only some of them into action. For example, the agent may have one desire to eat an unhealthy cake but follows their other desire to have a healthy salad instead. In this case, eating the cake is a mere desire while eating the salad is a volition. Frankfurt places great importance on the difference between first- and second-order desires. Most regular desires, like the desire to eat healthy food or to buy a car, are first-order desires. Second-order desires are desires about desires.[26][24][25] So the desire to have a desire to eat healthy food is a second-order desire. Entities with first-order desires care about what the world around them is like, for example, whether they own a car or not. Entities with second-order desires care also about themselves, i.e. what they themselves are like and what mental states they possess. A second-order desire becomes a second-order volition if it is effective, i.e. if the agent is committed to realizing it by fostering the corresponding first-order desire. Frankfurt sees this as the mark of personhood because entities with second-order volitions do not just have desires but care about which desires they have. So persons are committed to the desires they have.[27][24] According to Frankfurt, not every entity with a mind is a person. He refers to such entities as "wantons". Wantons have desires and follow them but do not care about their own will. In this regard, they are indifferent to which of their desires become effective and are translated into action. Frankfurt holds that personhood is an important feature of humans but not of other animals. However, even some humans may be wantons at times. Various of Frankfurt's examples of such cases involve some forms of akrasia in which a person acts according to a first-order desire that he/she does not want to have on the second order. For example, a struggling drug addict may follow his/her first-order desire to take drugs despite having a second-order desire to stop wanting drugs.[26][24][25] Moral responsibility and principle of alternative possibilities The term "moral responsibility" refers to the forward-looking moral obligation to perform certain actions and to the backward-looking status of being worthy of blame or praise for having done something or having failed to do so.[28][29] An important principle in this regard is the principle of alternative possibilities. It states that "a person is morally responsible for what she has done only if she could have done otherwise".[30] Having this ability to do otherwise is usually associated with having free will.[31][32] So under normal circumstances, a person is morally responsible for stealing someone's lunch at the cafeteria. However, this may not be the case under special circumstances, for example, if a neurological disorder compelled them to do it. Frankfurt has rejected the principle of alternative possibilities based on a series of counterexamples, the so-called "Frankfurt cases". In one example, Allison's father has implanted a computer chip in Allison's head without her knowing. This chip would force Allison to walk her dog. However, Allison freely decides to do so and the chip is thus not activated. Frankfurt argues that, in this case, Allison is morally responsible for walking her dog even though she lacked the ability to do otherwise. The crux of this and similar cases is that the agent is morally responsible because he/she acted in accordance with his/her own will. This is so despite the fact that, usually unbeknownst to the agent, there was no real alternative.[30][33] This line of thought has led Frankfurt to advocate a form of compatibilism: If free will and moral responsibility do not depend on the ability to do otherwise, then they could even exist in a fully deterministic world.[34] Frankfurt cases have provoked a significant discussion of the principle of alternative possibilities. However, not everyone agrees that they are successful at disproving it.[30] |

哲学 思いやりと重要性 フランクファートによると、哲学的な議論の多くは、何を信じるべきかを問う認識論の領域、あるいは、どのように行動すべきかを問う倫理学の領域に関するもの である。彼は、あまり注目されていないもう一つの研究分野、すなわち、何が重要であるか、あるいは、何を気にかけるべきかという問題があると主張してい る。[15] あるエージェントが何かを気にかけるのは、その人が特定の意志の態度を持っている場合である。その対象を自分にとって重要であると見なす。フランクファート にとって、私たちが何に気を配るかは、私たちの個性や、私たちが何者であるかを反映している。また、それは、その人がどのように行動し、人生を歩むかとい う実践的なレベルにも影響を与える。[16][17] 学術文献では、思いやりはしばしば、客観的な要因としての重要性の対義語として、主観的な態度として理解されている。この見解では、何かを気にかけること が適切かどうかは、そのものの重要度によって決まる。人々は重要なことについては気にかけるべきだが、重要でないことについては気にかける必要はない。 [18][19][20] フランクファートは、何かを気にかけることでそのものが重要になるという主張によって、この問題に対する異なる見解を擁護している。つまり、人が何かを気に かけるようになったとき、そのものはその人にとって重要になる。たとえそれまで重要でなかったものであっても。フランクファートはこれをニーズの観点から説 明している。思いやりを持つという態度は、ニーズを伴う。このニーズがあるため、思いやりを持たれた対象は、その人の幸福に影響を与える可能性があり、そ れによってその人にとって重要になる。[15][20] イッツハク・ベンバジは、思いやりと重要性のこの関係を「フランクファートのケア・インポータンス原理」と呼んでいる。彼は、少なくとも思いやりを持つ態度 のいくつかのケースは誤ったものであるという主張に基づいて、この原理を否定している。これは通常、行為者が、世話の対象が自身の幸福に影響を与えるとい う誤った信念を持っている状況を伴う。一例として、ある種の食べ物を避けるために、詐欺師の健康アドバイスに従う場合が挙げられる。ベンバジは、この食べ 物が健康や幸福に影響を与えないにもかかわらず、その食べ物を避けることを気にかけているため、これは反例を構成すると主張している。[20] 人格 人間は、理性、道徳的責任、自己意識といった特定の属性や能力によって特徴づけられる。[21][22] しかし、学術的な議論においても、また異なる文化の間でも、人格の本質的な特徴が何であるかについては、大きな意見の相違がある。[23] 人格に関する影響力のある正確に定式化された説明のひとつは、フランクファートによる「意志の自由と人格の概念」である。彼は、人間とは第二級の意志を持つ 存在であると主張している。[24][25] 意志とは、効果的な欲望、すなわち、行為者が実現しようと決意する欲望である。[26][27] すべての欲望が意志になるわけではない。人間は通常、多くの欲望を抱えているが、そのうちのいくつかだけを行動に移す。例えば、ある行為者は、不健康な ケーキを食べたいという欲望を抱えているかもしれないが、代わりに健康的なサラダを食べたいという別の欲望に従う。この場合、ケーキを食べることは単なる 欲求であるが、サラダを食べることは意志である。フランクファートは、第一の欲求と第二の欲求の違いを非常に重視している。健康的な食事をしたいという欲求 や、車を買い求めるという欲求のような、ほとんどの通常の欲求は第一の欲求である。第二の欲求は、欲求に関する欲求である。[26][24][25] したがって、健康的な食事をしたいという欲求は第二の欲求である。第一級の欲求を持つ存在は、例えば車を持っているかどうかなど、自分を取り巻く世界がど のようなものであるかを気にかける。第二級の欲求を持つ存在は、自分自身、すなわち自分自身がどのような存在であるか、どのような心的状態を持っているか についても気にかける。第二級の欲求は、それが効果的である場合、すなわち、行為者が対応する第一級の欲求を育むことによってそれを実現することに専念す る場合、第二級の意志となる。フランクファートは、これを人格の証であると見なしている。なぜなら、第二級の意志を持つ存在は、ただ単に欲求を持っているだ けではなく、自分がどのような欲求を持っているかを気にしているからである。したがって、人は自分が持つ欲求に忠実である。[27][24] フランクファートによれば、心を持つ存在すべてが人間であるわけではない。彼はそのような存在を「放縦者」と呼ぶ。放縦者は欲望を持ち、それに従うが、自身 の意志については気にかけない。この点において、放縦者は、自身の欲望のうち、どの欲望が現実のものとなり、行動へと移されるかということには無関心であ る。フランクファートは、人間性は人間にとって重要な特徴であるが、他の動物には当てはまらないと主張している。しかし、人間であっても時にワントンとなる 場合がある。 フランクファートが挙げた例には、ある種の無力症(アクラシア)が関わっている。 無力症とは、ある人が第2の欲求として望まない第1の欲求に従って行動する状態である。 たとえば、薬物依存症で苦しむ人が、薬物を欲しがる気持ちをなくしたいという第2の欲求を抱えていながらも、薬物を摂取するという第1の欲求に従って行動 することがある。[26][24][25] 道徳的責任と代替可能性の原則 「道徳的責任」という用語は、特定の行動を実行するという未来志向の道徳的義務と、何かを実行したか、あるいは実行しなかったことに対して非難や賞賛に値 する状態であるという過去志向の状況を指す。[28][29] この点において重要な原則は、代替可能性の原則である。「人は、別の行動を取ることが可能であった場合にのみ、自分の行動に対して道徳的責任を負う」と述 べている。[30] 別の行動を取ることが可能であるという能力は、通常、自由意志を持つことと関連付けられている。[31][32] したがって、通常の状況下では、人はカフェテリアで他人の昼食を盗むことに対して道徳的責任を負う。しかし、特別な状況下ではそうとは限らない。例えば、 神経疾患によりそうせざるを得ない場合などである。フランクファートは、いわゆる「フランクファートの事例」と呼ばれる一連の反例に基づいて、代替可能性の原 則を否定している。一例として、アリソンの父親がアリソンの頭にコンピューターチップを埋め込んだが、アリソンはそれを知らなかった。このチップは、アリ ソンに犬の散歩を強制する。しかし、アリソンは自由にそうすることを決め、チップは作動しない。フランクファートは、この場合、アリソンは犬の散歩をすると いう道徳的責任があるが、それ以外の行動を取る能力が欠如していたと主張している。この事例や類似の事例の要点は、本人が自身の意思に従って行動したた め、本人が道徳的責任を負うということである。これは、通常、本人が気づいていない場合でも、実際には他に選択肢がないという事実にもかかわらず、そうで ある。[30][33] この考え方により、フランクファートは、両立説の一形態を提唱するに至った。すなわち、自由意志と道徳的責任が、他に選択肢があるかどうかという能力に依存 しないのであれば、それらは完全に決定論的な世界にも存在しうる、というものである。[34] フランクファートの事例は、代替可能性の原則に関する重要な議論を引き起こした。しかし、誰もがそれを否定することに成功していることに同意しているわけで はない。[30] |

| Personal life and death Harry Frankfurt was first married to Marilyn Rothman. They had two daughters. The marriage ended in divorce. He then married Joan Gilbert.[1] Frankfurt was an amateur classical pianist. He starting taking piano lessons from an early age, initially from his mother who hoped that he might pursue a career as a concert pianist. Frankfurt continued to play piano and receive lessons throughout his life, alongside his philosophical career. According to Frankfurt, becoming a professor of philosophy was acceptable to his mother, seeing as it was "close enough" to her other ambition for him, which was to become a rabbi.[35] Frankfurt died of congestive heart failure in Santa Monica, California, on July 16, 2023, at age 94.[1][36] |

私生活と死 ハリー・フランクファートは、最初にマリリン・ロスマンと結婚した。2人の娘がいた。この結婚は離婚で終わった。その後、ジョアン・ギルバートと再婚した。 フランクファートはアマチュアのクラシック・ピアニストであった。幼い頃からピアノを習い始め、当初はコンサート・ピアニストとしてのキャリアを望む母親か ら習っていた。フランクファートは哲学のキャリアを築きながらも、生涯にわたってピアノを演奏し、レッスンも受け続けた。フランクファートによると、哲学の教 授になることは、母親が息子のラビになるという他の野望に「十分に近しい」ものとして受け入れられることだったという。 フランクファートは2023年7月16日、カリフォルニア州サンタモニカでうっ血性心不全により94歳で死去した。[1][36] |

| Bibliography Demons, Dreamers and Madmen: The Defense of Reason in Descartes's Meditations. Princeton University Press. 2007 [1970]. ISBN 978-0691134161. The Importance of What We Care About: Philosophical Essays. Cambridge University Press. 1988. ISBN 978-0521336116. Necessity, Volition, and Love. Cambridge University Press. 1999. ISBN 978-0521633956. The Reasons of Love. Princeton University Press. 2004. ISBN 978-0691126241. On Bullshit. Princeton University Press. 2005. ISBN 0-691-12294-6. On Truth. Random House. 2006. ISBN 0-307-26422-X. Taking Ourselves Seriously & Getting It Right. Stanford University Press. 2006. ISBN 0-8047-5298-2. On Inequality. Princeton University Press. 2015. ISBN 978-0691167145. "Donald Trump Is BS, Says Expert in BS". Time. May 12, 2016. |

参考文献 『悪魔、夢想家、狂人:デカルトの『省察』における理性の擁護』プリンストン大学出版。2007年 [1970年]。ISBN 978-0691134161。 『私たちが大切に思うことの重要性:哲学エッセイ』ケンブリッジ大学出版。1988年。ISBN 978-0521336116。 『必要、意志、愛』ケンブリッジ大学出版局、1999年、ISBN 978-0521633956 『愛の理由』プリンストン大学出版局、2004年、ISBN 978-0691126241 『虚偽について』プリンストン大学出版。2005年。ISBN 0-691-12294-6。 『真実について』ランダムハウス。2006年。ISBN 0-307-26422-X。 『自分自身を真剣に考え、正しく理解する』スタンフォード大学出版。2006年。ISBN 0-8047-5298-2。 不平等について。プリンストン大学出版。2015年。ISBN 978-0691167145。 「ドナルド・トランプはBS(ブルシット)だ、とBSの専門家が語る」。タイム。2016年5月12日。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harry_Frankfurt |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆