生成文法

Generative grammar

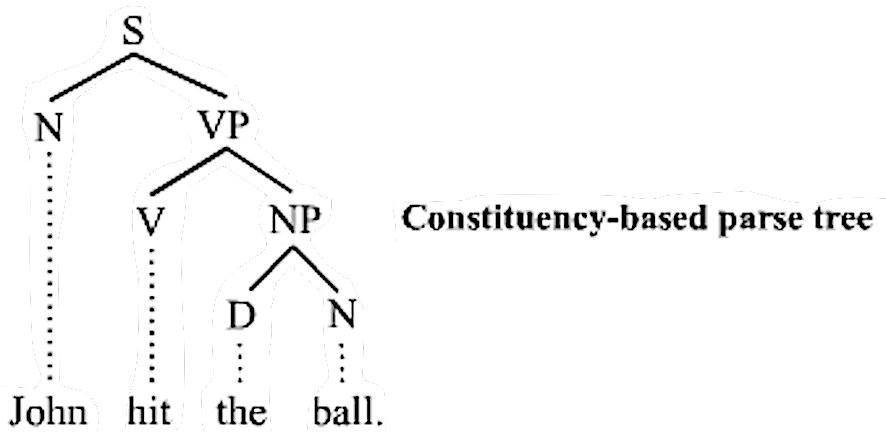

A generative parse tree: the sentence is divided into a noun phrase (subject), and a verb phrase which includes the object. This is in contrast to structural and functional grammar which consider the subject and object as equal constituents.[1][2]

☆ 生成文法(せいせいぶんぽう、英: generativism /ˈdərətʒɚɪvɪzəm/)[3]は、言語学を仮説上の生得的文法構造の研究とみなす言語理論である。 [4]論理統語論[7]や語彙論[8][9][a]から派生した、以前の構造主義的な言語学の理論を生物学的[5]あるいは生物学的[6]に修正したもの である。生成文法は、繰り返し適用することで、望めばいくらでも長くすることができる不定数の文を生成することができる明示的な規則の体系である。構造モ デルや機能モデルとの違いは、生成文法では目的語が動詞句の中で基本的に生成されることである[10][11]。この認知的構造と称されるものは、普遍文 法の一部であり、人間の遺伝子変異によって引き起こされる統語構造であると考えられている[12]。

|

Generative grammar Generative grammar, or generativism /ˈdʒɛnərətɪvɪzəm/,[3] is a linguistic theory that regards linguistics as the study of a hypothesised innate grammatical structure.[4] It is a biological[5] or biologistic[6] modification of earlier structuralist theories of linguistics, deriving from logical syntax[7] and glossematics.[8][9][a] Generative grammar considers grammar as a system of rules that generates exactly those combinations of words that form grammatical sentences in a given language. It is a system of explicit rules that may apply repeatedly to generate an indefinite number of sentences which can be as long as one wants them to be. The difference from structural and functional models is that the object is base-generated within the verb phrase in generative grammar.[10][11] This purportedly cognitive structure is thought of as being a part of a universal grammar, a syntactic structure which is caused by a genetic mutation in humans.[12] Generativists have created numerous theories to make the NP VP (NP) analysis work in natural language description. That is, the subject and the verb phrase appearing as independent constituents, and the object placed within the verb phrase. A main point of interest remains in how to appropriately analyse Wh-movement and other cases where the subject appears to separate the verb from the object.[13] Although claimed by generativists as a cognitively real structure, neuroscience has found no evidence for it.[14][15] In other words, generative grammar encompasses proposed models of linguistic cognition; but there is still no specific indication that these are quite correct. Recent arguments have been made that the success of large language models undermine key claims of generative syntax because they are based on markedly different assumptions, including gradient probability and memorized constructions, and out-perform generative theories both in syntactic structure and in integration with cognition and neuroscience.[16] |

生成文法(せいせいぶんぽう) 生成文法(せいせいぶんぽう、英: generativism /ˈdərətʒɚɪvɪzəm/)[3]は、言語学を仮説上の生得的文法構造の研究とみなす言語理論である。 [4]論理統語論[7]や語彙論[8][9][a]から派生した、以前の構造主義的な言語学の理論を生物学的[5]あるいは生物学的[6]に修正したもの である。生成文法は、繰り返し適用することで、望めばいくらでも長くすることができる不定数の文を生成することができる明示的な規則の体系である。構造モ デルや機能モデルとの違いは、生成文法では目的語が動詞句の中で基本的に生成されることである[10][11]。この認知的構造と称されるものは、普遍文 法の一部であり、人間の遺伝子変異によって引き起こされる統語構造であると考えられている[12]。 生成論者は自然言語記述においてNP VP(NP)分析を機能させるために数多くの理論を作り出してきた。つまり、主語と動詞句は独立した構成要素として現れ、目的語は動詞句の中に置かれる。 主語が動詞と目的語を分離しているように見えるWh-movementやその他のケースをどのように適切に分析するかが主な関心事項として残っている [13]。生成論者は認知的に実在する構造であると主張しているが、神経科学はその証拠を発見していない[14][15]。言い換えれば、生成文法は言語 認知の提案モデルを包含しているが、これらが完全に正しいという具体的な兆候はまだない。最近の議論では、大規模な言語モデルの成功は、勾配確率や記憶さ れた構文など、著しく異なる仮定に基づいており、統語構造においても、認知や神経科学との統合においても、生成論よりも優れているため、生成統語論の主要 な主張を損なうという主張がなされている[16]。 |

| There are a number of different

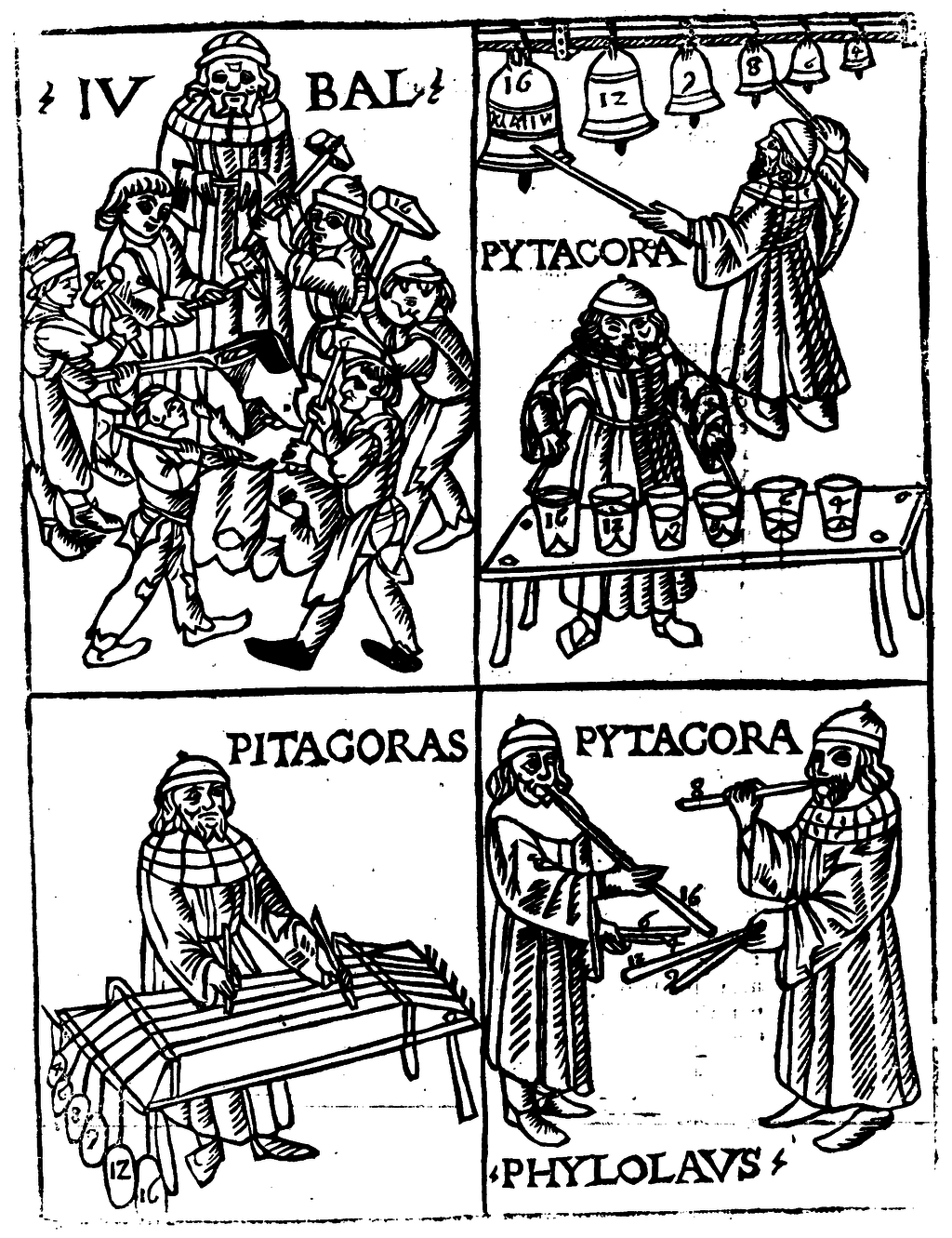

approaches to generative grammar. Common to all is the effort to come

up with a set of rules or principles that formally defines each and

every one of the members of the set of well-formed expressions of a

natural language. The term generative grammar has been associated with

at least the following schools of linguistics: Transformational grammar (TG) Standard theory (ST) Extended standard theory (EST) Revised extended standard theory (REST) Principles and parameters theory (P&P) Government and binding theory (GB) Minimalist program (MP) Monostratal (or non-transformational) grammars Relational grammar (RG) Lexical-functional grammar (LFG) Generalized phrase structure grammar (GPSG) Head-driven phrase structure grammar (HPSG) Categorial grammar Tree-adjoining grammar Optimality Theory (OT) Historical development of models of transformational grammar Main article: Transformational grammar Leonard Bloomfield, an influential linguist in the American Structuralist tradition, saw the ancient Indian grammarian Pāṇini as an antecedent of structuralism.[17][18] However, in Aspects of the Theory of Syntax, Chomsky writes that "even Panini's grammar can be interpreted as a fragment of such a 'generative grammar'",[19] a view that he reiterated in an award acceptance speech delivered in India in 2001, where he claimed that "the first 'generative grammar' in something like the modern sense is Panini's grammar of Sanskrit".[20] Military funding to generativist research was influential to its early success in the 1960s.[21] Generative grammar has been under development since the mid 1950s, and has undergone many changes in the types of rules and representations that are used to predict grammaticality. In tracing the historical development of ideas within generative grammar, it is useful to refer to the various stages in the development of the theory: Standard theory (1956–1965) The so-called standard theory corresponds to the original model of generative grammar laid out by Chomsky in 1965. A core aspect of standard theory is the distinction between two different representations of a sentence, called deep structure and surface structure. The two representations are linked to each other by transformational grammar. Extended standard theory (1965–1973) The so-called extended standard theory was formulated in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Features are: syntactic constraints generalized phrase structures (X-bar theory) Revised extended standard theory (1973–1976) The so-called revised extended standard theory was formulated between 1973 and 1976. It contains restrictions upon X-bar theory (Jackendoff (1977)). assumption of the complementizer position. Move α Relational grammar (ca. 1975–1990) Main article: Relational grammar An alternative model of syntax based on the idea that notions like subject, direct object, and indirect object play a primary role in grammar. Government and binding/principles and parameters theory (1981–1990) Main articles: Government and binding and Principles and parameters Chomsky's Lectures on Government and Binding (1981) and Barriers (1986). Minimalist program (1990–present) Main article: Minimalist program The minimalist program is a line of inquiry that hypothesizes that the human language faculty is optimal, containing only what is necessary to meet humans' physical and communicative needs, and seeks to identify the necessary properties of such a system. It was proposed by Chomsky in 1993.[22] |

生成文法にはさまざまなアプローチがある。すべてに共通するのは、自然

言語の整った表現の集合の一つひとつを正式に定義する規則や原理のセットを考え出す努力である。生成文法という用語は、少なくとも以下の言語学の学派と関

連している: 変形文法(TG) 標準理論(ST) 拡張標準理論(EST) 改訂拡張標準理論(REST) 原理とパラメータ理論 (P&P) ガバメント&バインディング理論(GB) 最小化プログラム (MP) 単変換(または非変換)文法 関係文法 (RG) 語彙機能文法 (LFG) 一般化句構造文法 (GPSG) 頭部駆動句構造文法 (HPSG) カテゴリー文法 木結合文法 最適性理論(OT) 変形文法モデルの歴史的発展 主な記事 変形文法 アメリカの構造主義の伝統の中で影響力のある言語学者であるレナード・ブルームフィールドは、古代インドの文法学者パーニニを構造主義の前身と見なしてい た。 [17][18]しかし、チョムスキーは『構文論の諸相』の中で、「パニーニの文法でさえも、そのような『生成文法』の断片として解釈することができる」 と書いており[19]、この見解は2001年にインドで行われた受賞スピーチの中でも繰り返し述べられており、「現代的な意味での最初の『生成文法』はパ ニーニのサンスクリット語の文法である」と主張している[20]。 1960年代の初期の成功には、生成論的研究に対する軍からの資金援助が影響していた[21]。 生成文法は1950年代半ばから開発されており、文法性を予測するために使用される規則や表現の種類に多くの変化があった。生成文法における考え方の歴史 的な発展をたどる上で、理論の発展における様々な段階を参照することは有益である: 標準理論(1956-1965) いわゆる標準理論は、1965年にチョムスキーが提唱した生成文法の原型に相当する。 標準理論の核となる側面は、深層構造と表層構造と呼ばれる文の2つの異なる表現間の区別である。この2つの表現は、変形文法によって互いにリンクされてい る。 拡張標準理論 (1965-1973) 1960年代後半から1970年代前半にかけて、いわゆる拡張標準理論が提唱された。特徴は 構文制約 一般化された句構造(Xバー理論) 改訂拡張標準理論 (1973-1976) 1973年から1976年にかけて改訂された拡張標準理論。この理論には X-bar理論(Jackendoff (1977))の制限 補語の位置の仮定 αを動かす 関係文法 (1975-1990年頃) 主な記事 関係文法 主語、直接目的語、間接目的語などの概念が文法において主要な役割を果たすという考えに基づく構文の代替モデル。 政府と束縛/原理とパラメータ理論(1981-1990年) 主な記事 政府と束縛、原理とパラメータ チョムスキーの「政府と束縛に関する講義」(1981年)と「障壁」(1986年)。 ミニマリスト・プログラム(1990年~現在) 主な記事 ミニマリスト・プログラム ミニマリスト・プログラムとは、人間の言語能力は最適であり、人間の身体的およびコミュニケーション上の必要を満たすのに必要なものだけを含んでいるとい う仮説を立て、そのようなシステムに必要な特性を特定しようとする研究路線である。1993年にチョムスキーによって提唱された[22]。 |

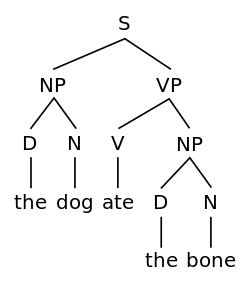

| Context-free grammars Main article: Context-free grammar Generative grammars can be described and compared with the aid of the Chomsky hierarchy (proposed by Chomsky in the 1950s). This sets out a series of types of formal grammars with increasing expressive power. Among the simplest types are the regular grammars (type 3); Chomsky argues that these are not adequate as models for human language, because of the allowance of the center-embedding of strings within strings, in all natural human languages. At a higher level of complexity are the context-free grammars (type 2). The derivation of a sentence by such a grammar can be depicted as a derivation tree. Linguists working within generative grammar often view such trees as a primary object of study. According to this view, a sentence is not merely a string of words. Instead, adjacent words are combined into constituents, which can then be further combined with other words or constituents to create a hierarchical tree-structure. The derivation of a simple tree-structure for the sentence "the dog ate the bone" proceeds as follows. The determiner the and noun dog combine to create the noun phrase the dog. A second noun phrase the bone is created with determiner the and noun bone. The verb ate combines with the second noun phrase, the bone, to create the verb phrase ate the bone. Finally, the first noun phrase, the dog, combines with the verb phrase, ate the bone, to complete the sentence: the dog ate the bone. The following tree diagram illustrates this derivation and the resulting structure:  Such a tree diagram is also called a phrase marker. They can be represented more conveniently in text form, (though the result is less easy to read); in this format the above sentence would be rendered as: [S [NP [D The ] [N dog ] ] [VP [V ate ] [NP [D the ] [N bone ] ] ] ] Chomsky has argued that phrase structure grammars are also inadequate for describing natural languages, and formulated the more complex system of transformational grammar.[23] |

文脈自由文法 主な記事 文脈自由文法 生成文法は、チョムスキー階層(1950年代にチョムスキーが提唱)を用いて記述・比較することができる。この階層は、表現力が増すにつれて、一連の形式 文法の種類を定めている。最も単純なものは正則文法(タイプ3)である。チョムスキーは、人間の自然言語には文字列の中に文字列を埋め込む中心埋め込みが 存在するため、人間の言語のモデルとしては適切ではないと主張している。 さらに複雑なのは文脈自由文法(タイプ2)である。このような文法による文の導出は、導出木として描くことができる。生成文法に携わる言語学者は、このよ うな木を主要な研究対象としてとらえることが多い。この考え方によれば、文は単なる単語の羅列ではない。その代わりに、隣接する単語が組み合わされて構成 要素となり、さらに他の単語や構成要素と組み合わされて階層的なツリー構造を作ることができる。 犬が骨を食べた」という文の単純な木構造の導出は次のように進む。決定子 the と名詞 dog が結合して名詞句 the dog が作成されます。第 2 の名詞句 the bone が、決定詞 the と名詞 bone で作成されます。動詞 ate は 2 番目の名詞句 the bone と結合して、動詞句 ate the bone を作ります。最後に、最初の名詞句 the dog が動詞句 ate the bone と結合して、the dog ate the bone という文が完成します。次の樹形図は、この導出とその結果の構造を示しています:  このような樹形図はフレーズ・マーカーとも呼ばれます。このような樹形図はフレーズ・マーカーとも呼ばれます。フレーズ・マーカーはテキスト形式でもより 簡単に表現することができます(ただし、結果は読みにくくなります): [S [NP [D The ] [N dog ] ]となります。[VP [V ate ] [NP [D the ] [N bone ] ] ]となります。] ] チョムスキーは、句構造文法も自然言語を記述するには不十分であると主張し、より複雑な変換文法の体系を定式化した[23]。 |

| Evidentiality Noam Chomsky, the main proponent of generative grammar, believed he had found linguistic evidence that syntactic structures are not learned but "acquired" by the child from universal grammar. This led to the establishment of the poverty of the stimulus argument in the 1980s. However, critics claimed Chomsky's linguistic analysis had been inadequate.[24] Linguistic studies had been made to prove that children have innate knowledge of grammar that they could not have learned. For example, it was shown that a child acquiring English knows how to differentiate between the place of the verb in main clauses from the place of the verb in relative clauses. In the experiment, children were asked to turn a declarative sentence with a relative clause into an interrogative sentence. Against the expectations of the researchers, the children did not move the verb in the relative clause to its sentence initial position, but to the main clause initial position, as is grammatical.[25] Critics however pointed out that this was not evidence for the poverty of the stimulus because the underlying structures that children were proved to be able to manipulate were actually highly common in children's literature and everyday language.[24] This led to a heated debate which resulted in the rejection of generative grammar from mainstream psycholinguistics and applied linguistics around 2000.[26][27] In the aftermath, some professionals argued that decades of research had been wasted due to generative grammar, an approach which has failed to make a lasting impact on the field.[27]  The sentence from the study which shows that it is not the verb in the relative clause, but the verb in the main clause that raises to the head C°.[28] There is no evidence that syntactic structures are innate. While some hopes were raised at the discovery of the FOXP2 gene,[29][30] there is not enough support for the idea that it is 'the grammar gene' or that it had much to do with the relatively recent emergence of syntactical speech.[31] Neuroscientific studies using ERPs have found no scientific evidence for the claim that human mind processes grammatical objects as if they were placed inside the verb phrase. Instead, brain research has shown that sentence processing is based on the interaction of semantic and syntactic processing.[14] However, since generative grammar is not a theory of neurology, but a theory of psychology, it is completely normal in the field of neurology to find no concreteness of the verb phrase in the brain. In fact, these rules do not exist in our brains, but they do model the external behaviour of the mind.[citation needed] This is why GG claims to be a theory of psychology and is considered to be real cognitively.[32] Generativists also claim that language is placed inside its own mind module and that there is no interaction between first-language processing and other types of information processing, such as mathematics.[33][b] This claim is not based on research or the general scientific understanding of how the brain works.[34][35] Chomsky has answered the criticism by emphasising that his theories are actually counter-evidential. He however believes it to be a case where the real value of the research is only understood later on, as it was with Galileo.[36] |

証拠性 生成文法の主唱者であるノーム・チョムスキーは、統語構造は学習されるものではなく、普遍文法から子供が「獲得」するものであるという言語学的証拠を発見 したと考えていた。これにより、1980年代に刺激の貧困論が確立された。しかし、批判者たちはチョムスキーの言語分析が不十分であったと主張した。例え ば、英語を習得する子供は、主節における動詞の位置と相対節における動詞の位置を区別する方法を知っていることが示された。実験では、子どもたちに相対節 を含む宣言文を疑問文に変えるよう求めた。研究者たちの予想に反して、子どもたちは相対節の動詞を文法どおりに文頭の位置に移動させず、主節の文頭の位置 に移動させた[25]。しかし批評家たちは、子どもたちが操作できると証明された基本構造は、実際には児童文学や日常的な言語において非常に一般的なもの であったため、これは刺激の貧困さの証拠にはならないと指摘した。 [24]このことは、2000年頃に主流の心理言語学や応用言語学から生成文法を否定する結果となる激しい論争を引き起こした[26][27]。その余波 として、一部の専門家は、生成文法、つまりこの分野に永続的なインパクトを与えることができなかったアプローチのために、何十年もの研究が無駄になったと 主張した[27]。  相対節の動詞ではなく、主節の動詞が頭C°に上がることを示した研究の文[28]。 構文構造が生得的であるという証拠はない。FOXP2遺伝子が発見されたことで期待が高まったが[29][30]、この遺伝子が「文法遺伝子」であると か、比較的最近になって構文音声が出現したことに大きく関係しているという考えには十分な裏付けがない[31]。 ERPを使った神経科学的研究では、人間の心が文法的な対象をあたかも動詞句の中に置くように処理するという主張に対する科学的な証拠は見つかっていな い。その代わり、脳研究によって、文の処理は意味処理と構文処理の相互作用に基づいていることが示されている[14]。しかし、生成文法は神経学の理論で はなく、心理学の理論であるため、脳内に動詞句の具体性が見つからないことは、神経学の分野ではまったく普通のことである。実際、これらの規則は脳には存 在しないが、心の外的な振る舞いをモデル化している。[要出典]これがGGが心理学の理論であると主張し、認知的に実在すると考えられている理由である [32]。 生成論者はまた、言語はそれ自身の心のモジュールの中に配置されており、第一言語処理と数学などの他のタイプの情報処理との間には相互作用がないと主張し ている[33][b]。この主張は研究や脳の働きに関する一般的な科学的理解に基づいていない[34][35]。 チョムスキーは自身の理論が実際には反明示的であることを強調することで批判に答えている。しかし彼は、ガリレオがそうであったように、研究の本当の価値 が後になって初めて理解されるケースであると考えている[36]。 |

| Music Generative grammar has been used in music theory and analysis since the 1980s.[37][38] The most well-known approaches were developed by Mark Steedman[39] as well as Fred Lerdahl and Ray Jackendoff,[40] who formalized and extended ideas from Schenkerian analysis.[41] More recently, such early generative approaches to music were further developed and extended by various scholars.[42] [43][44][45][46] French composer Philippe Manoury applied the systematic of generative grammar to the field of contemporary classical music.[citation needed]  |

音楽 生成文法は1980年代から音楽理論や分析に用いられてきた[37][38]。 最もよく知られたアプローチは、マーク・スティードマン[39]や、シェンカー分析からのアイデアを形式化し拡張したフレッド・ラーダールとレイ・ジャッ ケンドフ[40]によって開発された[41]。 [最近では、このような音楽に対する初期の生成的アプローチが様々な学者によってさらに発展・拡張された[42][43][44][45][46]。フラ ンスの作曲家フィリップ・マヌリーは、生成文法の体系を現代クラシック音楽の分野に応用した[要出典]。 |

| Cognitive linguistics Cognitive revolution Digital infinity Formal grammar Functional theories of grammar Generative lexicon Generative metrics Generative principle Generative semantics Generative systems Linguistic competence Parsing Phrase structure rules Syntactic Structures |

認知言語学 認知革命 デジタル無限大 形式文法 文法の機能理論 生成語彙 生成的測定基準 生成原理 生成的意味論 生成システム 言語能力 構文解析 句構造規則 構文構造 |

Aspects of the Theory of Syntax (known in linguistic circles simply as Aspects[1]) is a book on linguistics written by American linguist Noam Chomsky, first published in 1965. In Aspects, Chomsky presented a deeper, more extensive reformulation of transformational generative grammar (TGG), a new kind of syntactic theory that he had introduced in the 1950s with the publication of his first book, Syntactic Structures. Aspects is widely considered to be the foundational document and a proper book-length articulation of Chomskyan theoretical framework of linguistics.[2] It presented Chomsky's epistemological assumptions with a view to establishing linguistic theory-making as a formal (i.e. based on the manipulation of symbols and rules) discipline comparable to physical sciences, i.e. a domain of inquiry well-defined in its nature and scope. From a philosophical perspective, it directed mainstream linguistic research away from behaviorism, constructivism, empiricism and structuralism and towards mentalism, nativism, rationalism and generativism, respectively, taking as its main object of study the abstract, inner workings of the human mind related to language acquisition and production. |

『統語論の諸相』(Aspects of the Theory of Syntax)(言語学界では単に Aspects[1] として知られている)は、アメリカの言語学者ノーム・チョムスキーが著した言語学に関する本で、1965年に初めて出版された。『アスペクト』の中で、 チョムスキーは、1950年代に最初の著書『統語構造』を発表した際に紹介した、新しい種類の統語論である「変換生成文法(TGG)」について、より深 く、より広範囲にわたる再定義を行った。『アスペクト』は、チョムスキーの言語学理論的枠組みの基礎となる文書であり、適切な長さの本としてまとめられた ものであると広く考えられている[2]。この本は、言語理論構築を、その性質と範囲が明確に定義された研究領域である物理学などの自然科学と同等の形式 (すなわち、記号と規則の操作に基づく)の学問として確立することを目指して、チョムスキーの認識論的前提を提示している。哲学的な観点から見ると、この 本は、行動主義、構成主義、経験主義、構造主義といった言語研究の主流を離れ、それぞれ精神主義、自然主義、合理主義、生成主義へと方向付け、言語習得と 生成に関連する人間の心の抽象的な内面の働きを主な研究対象とした。 |

| Background After the publication of Chomsky's Syntactic Structures, the nature of linguistic research began to change, especially at MIT and elsewhere in the linguistic community where TGG had a favorable reception. Morris Halle, a student of Roman Jacobson and a colleague of Chomsky at MIT's Research Laboratory of Electronics (RLE), was a strong supporter of Chomsky's ideas of TGG. At first Halle worked on a generative phonology of Russian and published his work in 1959.[3] From 1956 until 1968, together with Chomsky (and also with Fred Lukoff initially), Halle developed a new theory of phonology called generative phonology. Their collaboration culminated with the publication of The Sound Pattern of English in 1968. Robert Lees, a linguist of the traditional structuralist school, went to MIT in 1956 to work in the mechanical translation project at RLE, but became convinced by Chomsky's TGG approach and went on to publish, in 1960, probably the very first book of a linguistic analysis based on TGG entitled The Grammar of English Nominalizations. This work was preceded by Lees's doctoral thesis on the same topic, for which he was given a Ph.D. in electrical engineering. Lees was technically the first student of the new TGG paradigm. Edward S. Klima, a graduate of the Masters program from Harvard and hired by Chomsky at RLE in 1957, produced pioneering TGG-based work on negation.[4] In 1959, Chomsky wrote a critical review of B. F. Skinner's Verbal Behavior (1957) in the journal Language, in which he emphasized on the fundamentally human characteristic of verbal creativity, which is present even in very young children, and rejected the behaviorist way of describing language in ambiguous terms such as "stimulus", "response", "habit", "conditioning", and "reinforcement".[5] With Morris Halle and others, Chomsky founded the graduate program in linguistics at MIT in 1961. The program immediately attracted some of the brightest young American linguists. Jerry Fodor and Jerrold Katz, both graduates of the Ph.D. program at Princeton, and Paul Postal, a Ph.D. from Yale, were some of the first students of this program. They made major contributions to the nascent field of TGG. John Viertel, a colleague of Chomsky at RLE in the 1950s, began working for a Ph.D. dissertation under Chomsky on the linguistic thoughts of Wilhelm von Humboldt, a nineteenth-century German linguist. Viertel's English translations of Humboldt's works influenced Chomsky at this time and made him abandon Saussurian views of linguistics.[6] Chomsky also collaborated with visiting French mathematician Marcel-Paul Schützenberger, and was able to formulate one of the most important theorems of formal linguistics, the Chomsky-Schützenberger hierarchy. Within the theoretical framework of TGG, G. H. Matthews, Chomsky's colleague at RLE, worked on the grammar of Hidatsa, a Native American language. J. R. Applegate worked on the German noun phrase. Lees and Klima looked into English pronominalization. Matthews and Lees worked on the German verb phrase.[7] On the nature of the linguistic research at MIT in those days, Jerry Fodor recalls that "...communication was very lively, and I guess we shared a general picture of the methodology for doing, not just linguistics, but behavioral science research. We were all more or less nativist, and all more or less mentalist. There was a lot of methodological conversation that one didn't need to have. One could get right to the substantive issues. So, from that point of view, it was extremely exciting."[8] In 1962, Chomsky gave a paper at the Ninth International Congress of Linguists entitled "The Logical Basis of Linguistic Theory", in which he outlined the transformational generative grammar approach to linguistics. In June 1964, he delivered a series of lectures at the Linguistic Institute of the Linguistic Society of America (these were later published in 1966 as Topics in the Theory of Generative Grammar). All of these activities aided to develop what is now known as the "Standard Theory" of TGG, in which the basic formulations of Syntactic Structures underwent considerable revision. In 1965, eight years after the publication of Syntactic Structures, Chomsky published Aspects partly as an acknowledgment of this development and partly as a guide for future directions for the field. |

背景 チョムスキーの『統語構造』が出版された後、言語研究のあり方は変化し始めた。特に、TGGが好意的に受け入れられたマサチューセッツ工科大学(MIT) やその他の言語研究コミュニティにおいて、その傾向は顕著であった。ローマン・ヤコブソンの教え子であり、MITの電子工学研究所(RLE)でチョムス キーの同僚でもあったモリス・ホールは、TGGに関するチョムスキーの考え方を強く支持していた。当初、ハレはロシア語の生成音韻論に取り組み、1959 年にその成果を発表した[3]。1956年から1968年にかけて、ハレはチョムスキー(当初はフレッド・ルコフも)とともに、生成音韻論と呼ばれる音韻 論の新理論を展開した。彼らの共同研究の集大成として、1968年に『The Sound Pattern of English』が刊行された。伝統的な構造主義言語学派の言語学者ロバート・リースは、1956年にマサチューセッツ工科大学(MIT)のRLE (Research Laboratory of English)の機械翻訳プロジェクトに参加したが、チョムスキーのTGGアプローチに感銘を受け、1960年にTGGに基づく言語分析の最初の著書と なる『The Grammar of English Nominalizations』を出版した。この研究は、リースの同じテーマの博士論文に先行するもので、この論文により彼は電気工学の博士号を取得し た。 リースは、技術的には新しい TGG パラダイムの最初の学生であった。ハーバード大学の修士課程を修了し、1957年にチョムスキーが率いるRLEに採用されたエドワード・S・クリマは、否 定に関するTGGに基づく先駆的な研究を行った[4]。1959年、チョムスキーは『Language』誌にB.F.スキナーの『Verbal Behavior』(1957)に関する批判的な書評を寄稿し、 彼は、言語創造性という人間にとって本質的な特性が非常に幼い子供たちにも備わっていることを強調し、言語を「刺激」「反応」「習慣」「条件付け」「強 化」といった曖昧な用語で表現する行動主義的な方法を否定した[5]。 モリス・ハレらとともに、チョムスキーは1961年にマサチューセッツ工科大学(MIT)の言語学大学院課程を設立した。このプログラムはたちまち、アメ リカで最も優秀な若手言語学者たちの注目を集めた。プリンストン大学の博士課程を修了したジェリー・フォダーとジェロルド・カッツ、そしてイェール大学の 博士課程を修了したポール・ポスタルは、このプログラムの最初の学生たちであった。彼らは、TGGという新しい分野に多大な貢献をした。1950年代に RLEでチョムスキーの同僚だったジョン・ヴィルヘルムは、19世紀のドイツ人言語学者ヴィルヘルム・フォン・フンボルトの言語思想に関する論文をチョム スキーの下で執筆し始めた。ヴィルテルによるフンボルトの著作の英訳は、この時期にチョムスキーに影響を与え、言語学におけるソシュール主義的見解を放棄 させることとなった[6]。また、チョムスキーはフランスから来た数学者マルセル=ポール・シュッツェンベルガーと共同研究を行い、形式言語学における最 も重要な定理のひとつであるチョムスキー=シュッツェンベルガーの階層構造を定式化することに成功した。TGGの理論的枠組みの中で、RLEのチョムス キーの同僚であるG. H. マシューズは、ネイティブアメリカンの言語であるヒダツァ語の文法に取り組んだ。J. R. アプルゲートはドイツ語の名詞句を研究し、リーズとクリマは英語の代名詞化を研究した。マシューズとリーズはドイツ語の動詞句の研究に取り組んだ[7]。 当時のマサチューセッツ工科大学における言語研究の本質について、ジェリー・フォダーは「...コミュニケーションは非常に活発で、言語学だけでなく行動 科学の研究を行うための方法論について、大まかな共通認識があったと思う。私たちは皆、多かれ少なかれ言語主義者であり、多かれ少なかれ精神主義者でも あった。必要のない方法論的な会話もたくさんあった。本質的な問題に直接取り組むことができた。その点では、非常に刺激的だった」[8]。1962年、 チョムスキーは「言語理論の論理的基礎」と題した論文を第9回国際言語学者会議で発表し、言語学における生成文法理論のアプローチの概要を説明した。 1964年6月、彼はアメリカ言語学会言語研究所で一連の講義を行った(これらは後に1966年に『生成文法理論の諸問題』として出版された)。 これらの活動すべてが、現在「標準理論」として知られるTGGの発展に貢献し、統語構造の基礎的な定式化が大幅に修正された。『統語構造』が出版されてか ら8年後の1965年、チョムスキーは『アスペクト』を出版した。これは、この発展を認める意味と、この分野における今後の方向性を示す意味を併せ持って いた。 |

| Overview of topics As British linguist Peter Hugoe Matthews noted in his review[9] of the book, the content of Aspects can be divided into two distinct parts: Chapter 1 is concerned with the psychological reality of language and the philosophy of language research, and the rest of the chapters deal with specific technical details within generative grammar. The goal of linguistic theory Competence vs. performance: descriptive adequacy See also: Linguistic competence and Levels of adequacy In Aspects, Chomsky lays down the abstract, idealized context in which a linguistic theorist is supposed to perform his research: "Linguistic theory is concerned primarily with an ideal speaker-listener, in a completely homogeneous speech-community, who knows its language perfectly and is unaffected by such grammatically irrelevant conditions as memory limitations, distractions, shifts of attention and interest, and errors (random or characteristic) in applying his knowledge of the language in actual performance." He makes a "fundamental distinction between competence (the speaker-hearer's knowledge of his language) and performance (the actual use of language in concrete situation)."[10] A "grammar of a language" is "a description of the ideal speaker-hearer's intrinsic competence", and this "underlying competence" is a "system of generative processes."[11] An "adequate grammar" should capture the basic regularities and the productive nature of a language.[12] Chomsky calls this "descriptive adequacy" of the linguistic theory, in the sense that "it correctly describes its object, namely the linguistic intuition—the tacit competence—of the native speaker. In this sense, the grammar is justified on external grounds, on grounds of correspondence to linguistic fact."[13] Language acquisition, universal grammar and explanatory adequacy See also: Language acquisition § Generativism, Universal grammar, and Levels of adequacy Additionally, Chomsky sets forth another ambitious goal for linguistic theory in Aspects: that it has to be "sufficiently rich to account for acquisition of language, yet not so rich as to be inconsistent with the known diversity of language." In other words, linguistic theory must be able to describe how any normal human child masters the complexities of his mother tongue at such a young age, and how children all over the world master languages which are enormously different from one another in terms of vocabulary, word order and morpho-syntactic constructions. In Chomsky's opinion, in order for a linguistic theory to be justified on "internal grounds" and to achieve "explanatory adequacy", it has to show how a child's brain, when exposed to primary linguistic data, uses special innate abilities or strategies (described as a set of principles called "Universal Grammar") and selects the correct grammar of the language over many other grammars compatible with the same data.[13] Grammaticality and acceptability See also: Grammaticality For Chomsky, "grammaticalness is ... a matter of degree."[14] When sentences are directly generated by the system of grammatical rules, they are called "perfectly" or "strictly well-formed" grammatical sentences.[15] When sentences are "derivatively generated" by "relaxing" some grammatical rules (such as "subcategorization rules" or "selectional rules"[15]), they deviate from strictly well-formedness.[16] Chomsky calls these grammatically "deviant".[17] The degree and manner of their deviation can be evaluated by comparing their structural description with that of the strictly well-formed sentences. In this way, a theory of "degree of grammaticalness" can eventually be developed.[15] According to Chomsky, an "acceptable" sentence is one that is "perfectly natural" and "immediately comprehensible" and "in no way bizarre or outlandish".[18] The notion of acceptability depends on various "dimensions" such as "rapidity, correctness, and uniformity of recall and recognition, normalcy of intonation".[18] Chomsky adds that "acceptability is a concept that belongs to the study of performance, whereas grammaticalness belongs to the study of competence."[14] So, there can be sentences that are grammatical but nevertheless unacceptable because of "memory limitations" or intonational and stylistic factors."[14] Emphasis on mentalism See also: Mentalism (psychology) § The new mentalism In Aspects Chomsky writes that "linguistic theory is mentalistic, since it is concerned with discovering a mental reality underlying actual behavior."[11] With this mentalist interpretation of linguistic theory, Chomsky elevated linguistics to a field that is part of a broader theory of human mind, i.e. the cognitive sciences. According to Chomsky, a human child's mind is equipped with a "language acquisition device" formed by inborn mental properties called "linguistic universals" which eventually constructs a mental theory of the child's mother tongue.[19] The linguist's main object of inquiry, as Chomsky sees it, is this underlying psychological reality of language. Instead of making catalogs and summaries of linguistic behavioral data demonstrated on the surface (i.e. behaviorism), a Chomsky-an linguist should be interested in using "introspective data" to ascertain the properties of a deeper mental system. The mentalist approach to linguistics proposed by Chomsky is also different from an investigation of the neurophysiological mechanisms underlying language. It is about abstractly determining the properties and functions of such mechanisms.[20] The structure of grammar: deep structure See also: Deep structure and surface structure, Phrase structure rules, Parse tree, and Transformational grammar The grammar model discussed in Noam Chomsky's Aspects of the Theory of Syntax (1965) In Aspects, Chomsky summarized his proposed structure of a grammar in the following way: "A grammar contains a syntactic component, a semantic component and a phonological component...The syntactic component consists of a base and a transformational component. The base, in turn, consists of a categorial subcomponent and a lexicon. The base generates deep structures. A deep structure enters the semantic component and receives a semantic interpretation; it is mapped by transformational rules into a surface structure, which is then given a phonetic interpretation by the rules of the phonological component."[21] In this grammar model, syntax is given a prominent, generative role, whereas phonology and semantics are assigned secondary, interpretive roles. This theory of grammar would later come to be known as the "Standard Theory" (ST). The base subcomponent The base in the syntactic component functions as follows: In the first step, a simple set of phrase structure rules generate tree diagrams (sometimes called Phrase Markers) consisting of nodes and branches, but with empty terminal nodes; these are called "pre-lexical structures". In the second step, the empty terminal nodes are filled with complex symbols consisting of morphemes accompanied by syntactic and semantic features, supplied from the lexicon via lexical insertion rules. The resulting tree diagram is called a "deep structure". Comparison with the Syntactic Structures model The Aspects model or ST differed from Syntactic Structures (1957) in a number of ways. Firstly, the notion of kernel sentences (a class of sentences produced by applying obligatory transformational rules) was abandoned and replaced by the notion of "deep structures", within which negative, interrogative markers, etc. are embedded. This simplified the generation of "surface" sentences, whereas in the previous model, a number of successive optional transformational rules had to be applied on the kernel sentences to arrive at the same result. Secondly, the addition of a semantic component to the grammar marked an important conceptual change since Syntactic Structures, where the role of meaning was effectively neglected and not considered part of the grammatical model.[22] Chomsky mentions that the semantic component is essentially the same as described in Katz and Postal (1964). Among the more technical innovations are the use of recursive phrase structure rules and the introduction of syntactic features in lexical entries to address the issue of subcategorization. Syntactic features In Chapter 2 of Aspects, Chomsky discusses the problem of subcategorization of lexical categories and how this information should be captured in a generalized manner in the grammar. He deems that rewriting rules are not the appropriate device in this regard. As a solution, he borrows the idea of features use in phonology. A lexical category such as noun, verb, etc. is represented by a symbol such as N, V. etc. A set of "subcategorization rules" then analyzes these symbols into "complex symbols", each complex symbol being a set of specified "syntactic features", grammatical properties with binary values. Syntactic feature is one of the most important technical innovations of the Aspects model. Most contemporary grammatical theories have preserved it. |

トピックの概要 英国の言語学者ピーター・ヒューゴ・マシューズは、この本の書評[9]の中で、Aspectsの内容は2つの部分に分けることができると指摘している。第1章は言語の心理学的現実と言語研究哲学について、残りの章は生成文法における具体的な技術的詳細について扱っている。 言語理論の目的 能力とパフォーマンス:記述の妥当性 参照:言語能力と妥当性のレベル 『アスペクト』の中で、チョムスキーは言語理論家が研究を行うべき抽象的で理想化された文脈を提示している。「言語理論は、主に、言語を完全に理解し、記 憶力の限界、注意散漫、興味の移り変わり、言語知識の実際の使用におけるエラー(ランダムまたは特徴的)といった文法的に無関係な条件の影響を受けない、 完全に均質な言語社会における理想的な話し手・聞き手を対象としている。彼は、「能力(話者・聞き手の言語知識)とパフォーマンス(具体的な状況における 言語の実際の使用)」を「根本的に区別」している[10]。「言語の文法」とは、「理想的な話者・聞き手の本質的な能力の記述」であり、この「基礎となる 能力」は、「生成プロセスの体系」である 生成過程の体系」である[11]。「適切な文法」とは、言語の基本的な規則性と生産的な性質を捉えるべきである[12]。チョムスキーは、言語理論の「記 述的妥当性」をこう呼んでいる。それは、「対象、すなわち言語的直観、すなわち母語話者の暗黙的な能力を正しく記述する」という意味でである。この意味 で、文法は言語的事実に一致するという外的な根拠によって正当化されるのである。」[13] 言語習得、普遍文法、説明的妥当性 参照:言語習得 § 生成主義、普遍文法、妥当性のレベル さらに、チョムスキーは『アスペクト』の中で言語理論に別の野心的な目標を掲げている。それは、「言語習得を説明できるほど十分に豊かであり、同時に、言 語の多様性という既知の事実と矛盾しないほど豊かではない」ものでなければならない、というものである。言い換えれば、言語理論は、ごく幼い子供たちがど のようにして母国語の複雑な構造を習得するのか、また世界中の子供たちが、語彙、語順、形態統語構造において互いに大きく異なる言語をどのようにして習得 するのかを説明できなければならない。 チョムスキーの考えでは、言語理論が「内部的な根拠」によって正当化され、「説明的妥当性」を達成するためには、子どもが言語の初期データにさらされた際 に、特別な生得的な能力や戦略(「普遍文法」と呼ばれる一連の原則として説明される)を用いて、同じデータと適合する他の多くの文法の中からその言語の正 しい文法を選択する方法を示す必要がある[13]。 文法性と受容性 参照: 文法性 チョムスキーにとって、「文法性は...程度の問題である」[14]。文法規則のシステムによって直接生成された文は、「完全に」または「厳密に正しく形 成された」文法的な文と呼ばれる[15]。文が、いくつかの文法規則を「緩和」することによって「派生的に生成」された場合(例えば、「下位分類化規則」 や「選択規則」[15]など)、厳密に正しく形成されたものから逸脱することになる[16]。(「下位分類化規則」や「選択規則」など)[15]、厳密に 正しい文法から逸脱している[16]。チョムスキーはこれらを文法的に「逸脱」と呼んでいる[17]。逸脱の程度や方法は、厳密に正しい文の構造記述と比 較することで評価できる。このようにして、「文法性の度合い」の理論が最終的に構築されることになる[15]。 チョムスキーによると、「受け入れられる」文とは、「完全に自然」で「すぐに理解できる」ものであり、「奇抜でも突飛でもない」ものである[18]。受け 入れられるという概念は、「想起と認識の速さ、正確さ、均一性 「想起と認識の速さ、正確さ、均一性、イントネーションの正常さ」などである[18]。チョムスキーはさらに、「受容性はパフォーマンスの研究に属する概 念であるのに対し、文法性は能力の研究に属する概念である」[14]と付け加えている。つまり、文法的には正しいが、「記憶力の限界」やイントネーション や文体の要因により受容できない文章が存在し得るということである[14]。 精神主義の強調 参照:メンタリズム(心理学) § 新しいメンタリズム 『アスペクト』の中で、チョムスキーは「言語理論はメンタリズム的である。なぜなら、実際の行動の根底にある心理的な現実を発見することに焦点を当ててい るからだ」と書いている[11]。言語理論をこのようにメンタリズム的に解釈することで、チョムスキーは言語学を、より広範な人間の心の理論の一部である 認知科学の分野へと高めた。チョムスキーによれば、人間の子供の心には「言語獲得装置」が備わっており、それは「言語普遍性」と呼ばれる生来の精神特性に よって形成され、最終的には子供の母国語の心理理論を構築する。チョムスキー学派の言語学者は、表面的に示される言語行動データのカタログや要約を作成す る(すなわち行動主義)のではなく、「内省的データ」を使用してより深い精神システムの特性を確認することに興味を持つべきである。 チョムスキーが提唱する言語学における心霊主義的アプローチは、言語の根底にある神経生理学的メカニズムの研究とも異なる。それは、そのようなメカニズムの性質と機能を抽象的に決定することに関するものである[20]。 文法の構造:深層構造 関連項目:深層構造と表層構造、句構造規則、構文解析木、変換文法 ノーム・チョムスキー著『統語論の諸相』(1965年)で論じられた文法モデル 『諸相』の中で、チョムスキーは自身が提唱する文法の構造を次のように要約している。「文法は、統語成分、意味成分、音韻成分から構成される...統語成 分は、基底成分と変換成分から構成される。ベースは、さらに、範疇のサブコンポーネントと語彙から構成される。ベースは深層構造を生成する。深層構造は意 味成分に入り、意味解釈を受ける。そして、変形規則によって表層構造に変換され、音韻規則によって音韻解釈を受ける。この文法理論は後に「標準理論」 (ST)として知られるようになる。 ベースサブコンポーネント 構文コンポーネントのベースは、以下の機能を持つ。まず、シンプルな句構造規則により、ノードと枝で構成され、末端ノードが空のツリー図(フレーズマー カーと呼ばれることもある)が生成される。これを「プレ語彙構造」と呼ぶ。次に、空だった末端ノードに、形態素と構文的・意味的特徴からなる複雑な記号が 挿入される。この記号は、語彙挿入規則により語彙から供給される。こうしてできたツリー図は「深層構造」と呼ばれる。 構文構造モデルとの比較 アスペクトモデルまたはSTは、統語構造(1957年)とは多くの点で異なっていた。まず、必須の変形規則を適用して生成される文のクラスである「核文」 の概念は放棄され、「深層構造」の概念に置き換えられた。これにより、「表面」文の生成が簡素化された。一方、従来のモデルでは、同じ結果を得るために は、核文に複数の連続したオプションの変換規則を適用する必要があった。 第二に、文法に意味論的要素を追加したことは、重要な概念上の変化を意味した。なぜなら、意味の役割は事実上無視され、文法モデルの一部とは考えられてい なかったからである[22]。チョムスキーは、意味論的要素は、Katz and Postal (1964)で説明されているものと同じであると述べている。 より技術的な革新としては、再帰的句構造規則の使用と、下位分類化の問題に対処するための語彙項目における統語的特徴の導入が挙げられる。 統語論的特徴 『アスペクト』の第2章で、チョムスキーは語彙範疇のサブカテゴリー化の問題と、この情報をどのようにして文法に一般化して取り込むべきかを論じている。 彼は、この点において書き換え規則は適切な手法ではないと考えている。解決策として、彼は音韻論で使用されている特徴の概念を借用している。名詞、動詞な どの語彙範疇は、N、Vなどの記号で表わされる。一連の「下位分類化規則」がこれらの記号を「複合記号」に分析し、各複合記号は指定された「統語的特徴」 の集合体となる。 統語的特徴は、アスペクトモデルの最も重要な技術革新の1つである。 ほとんどの現代文法理論はこれを継承している。 |

| Significance Linguistics UCLA linguist Tim Stowell considers Aspects to be "effectively the most important foundational document of the field" of transformational generative grammar (TGG), providing "the definitive exposition of the classical theory of TGG—the so-called Standard Theory".[2] University of Cambridge linguists Ian Roberts and Jeffrey Watumull maintain that Aspects ushered in the "Second Cognitive Revolution—the revival of rationalist philosophy first expounded in the Enlightenment", in particular by Leibniz.[23] Philosophy Moral philosopher John Rawls compared building a theory of morality to that of the generative grammar model found in Aspects. In A Theory of Justice (1971), he notes that just like Chomsky's grammar model assumes a set of finite underlying principles that are supposed to adequately explain the variety of sentences in linguistic performance, our sense of justice can be defined as a set of moral principles that give rise to everyday judgments.[24] Medicine In his Nobel Prize lecture titled "The Generative Grammar of the Immune System", the 1984 Nobel Prize laureate in Medicine and Physiology Niels K. Jerne used Chomsky's generative grammar model in Aspects to explain the human immune system, comparing "the variable region of a given antibody molecule" to "a sentence". "The immense repertoire of the immune system then becomes ... a lexicon of sentences which is capable of responding to any sentence expressed by the multitude of antigens which the immune system may encounter." Jerne called the DNA segments in chromosomes which encode the variable regions of antibody polypeptides a human's inheritable "deep structures", which can account for the innately complex yet miraculously effective fighting capacity of human antibodies against complex antigens. This is comparable to Chomsky's hypothesis that a child is born with innate language universals to acquire a complex human language in a very short time.[25] Artificial intelligence Neuroscientist David Marr wrote that the goal of artificial intelligence is to find and solve information processing problems. First, one must build a computational theory of the problem (i.e. the abstract formulation of the "what" and "why" of the problem). And then one must construct an algorithm that implements it (i.e. the "how" of the problem). Marr likened the computational theory of an information processing problem to the notion of "competence" mentioned in Aspects.[26] |

意義 言語学 UCLA の言語学者ティム・ストウェルは、『アスペクト』を「事実上、生成文法(TGG)の分野における最も重要な基礎文書」であり、「TGG の古典的理論、いわゆる標準理論の決定的な解説」を提供していると考える[2]。 ケンブリッジ大学の言語学者 イアン・ロバーツとジェフリー・ワトゥムルは、アスペクトが「第二認知革命、すなわち啓蒙思想で初めて説かれた合理主義哲学の復活」をもたらしたと主張している。 哲学 道徳哲学者のジョン・ロールズは、道徳の理論を構築することを『アスペクト』で述べられている生成文法モデルと比較した。『正義論』(1971年)の中 で、彼は、チョムスキーの文法モデルが言語表現における文の多様性を適切に説明するために、有限の根本原則の集合を仮定しているのと同様に、私たちの正義 感は日常的な判断を生み出す道徳的原則の集合として定義できると記している[24]。 医学 1984年のノーベル医学生理学賞受賞者、ニールス・K・イェルネは、 1984年にノーベル医学・生理学賞を受賞したニールス・K・イェルネは、ノーベル賞受賞講演「免疫系の生成文法」の中で、チョムスキーの生成文法モデル を『Aspects』で説明し、人間の免疫システムを「ある抗体分子の可変領域」と「文章」に例えて説明した。「免疫システムの膨大なレパートリーは、免 疫システムが遭遇する可能性のある多数の抗原によって表現されるあらゆる文に反応できる文の語彙となる」とジェーンは述べている。ジェーンは、抗体ポリペ プチドの可変領域をコードする染色体上の DNA セグメントを、人間が遺伝的に受け継ぐ「深層構造」と呼び、それが、複雑な抗原に対する人間の抗体の、生まれつき複雑でありながら奇跡的なほど効果的な戦 闘能力の説明になるとした。これは、子どもには複雑な言語を習得するための生得的な言語普遍性が備わっており、ごく短期間で複雑な言語を習得するという チョムスキーの仮説にも通じるものである[25]。 人工知能 神経科学者のデビッド・マーは、人工知能の目的は情報処理の問題を発見し、解決することであると述べている。まず、問題の計算理論を構築しなければならな い(すなわち、問題の「何」と「なぜ」を抽象的に定式化)。そして、それを実装するアルゴリズムを構築しなければならない(すなわち、問題の「方法」)。 Marrは、情報処理問題の計算理論を『アスペクト』で言及されている「能力」の概念に例えた[26]。 |

| Criticism Several of the theoretical constructs and principles of the generative grammar introduced in Aspects such as deep structures, transformations, autonomy and primacy of syntax, etc. were either abandoned or substantially revised after they were shown to be either inadequate or too complicated to account for, in a simple and elegant way, many idiosyncratic example sentences from different languages.[27] As a response to these problems encountered within the Standard Theory, a new approach called the generative semantics (as opposed to the interpretive semantics in Aspects) was invented in the early 1970s by some of Chomsky's collaborators (notably George Lakoff[28]), and was incorporated later in the late 1980s into what is now known as the school of cognitive linguistics, at odds with Chomskyan school of generative linguistics. Chomsky himself addressed these issues at around the same time (early 1970s) and updated the model to an "Extended Standard Theory", where syntax was less autonomous, the interaction between the syntactic and the semantic component was much more interactive and the transformations were cyclical.[29] |

批判 『アスペクト』で導入された生成文法の理論的構造や原理のいくつかは、深層構造、変換、文法の自律性と優位性など、さまざまな言語の独特な例文を、シンプ ルでエレガントな方法で説明するには不十分であったり複雑すぎたりすることが明らかになったため、放棄されたり大幅に修正されたりした[27]。標準理論 で生じたこれらの問題への対策として、 生成意味論と呼ばれる新しいアプローチ(『アスペクト』における解釈意味論とは対照的)が、1970年代初頭にチョムスキーの協力者たち(特にジョージ・ レイコフ[28])によって考案され、後に1980年代後半に認知言語学派として知られるようになった。これは、チョムスキーの生成言語学派とは対立する ものだった。チョムスキー自身もほぼ同時期(1970年代初頭)にこれらの問題を取り上げ、文法がそれほど自律的ではなく、文法と意味の要素間の相互作用 がより相互的で、変換が循環的である「拡張標準理論」にモデルを更新した[29]。 |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099