ヒトの進化

Human

Evolution

解説:池田光穂

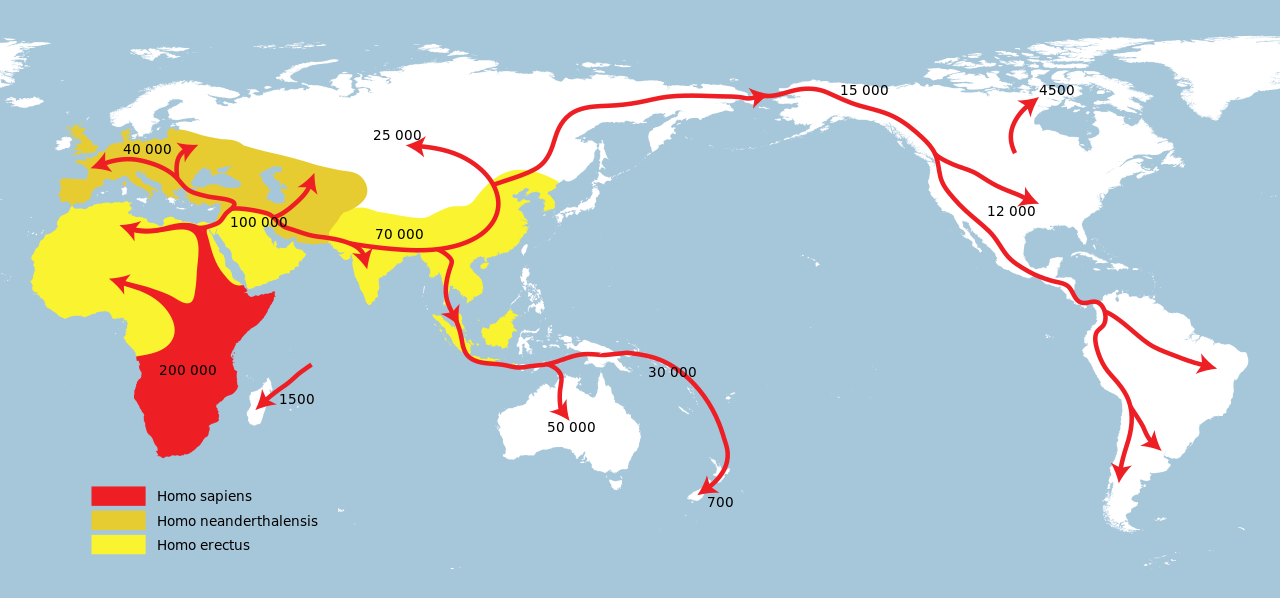

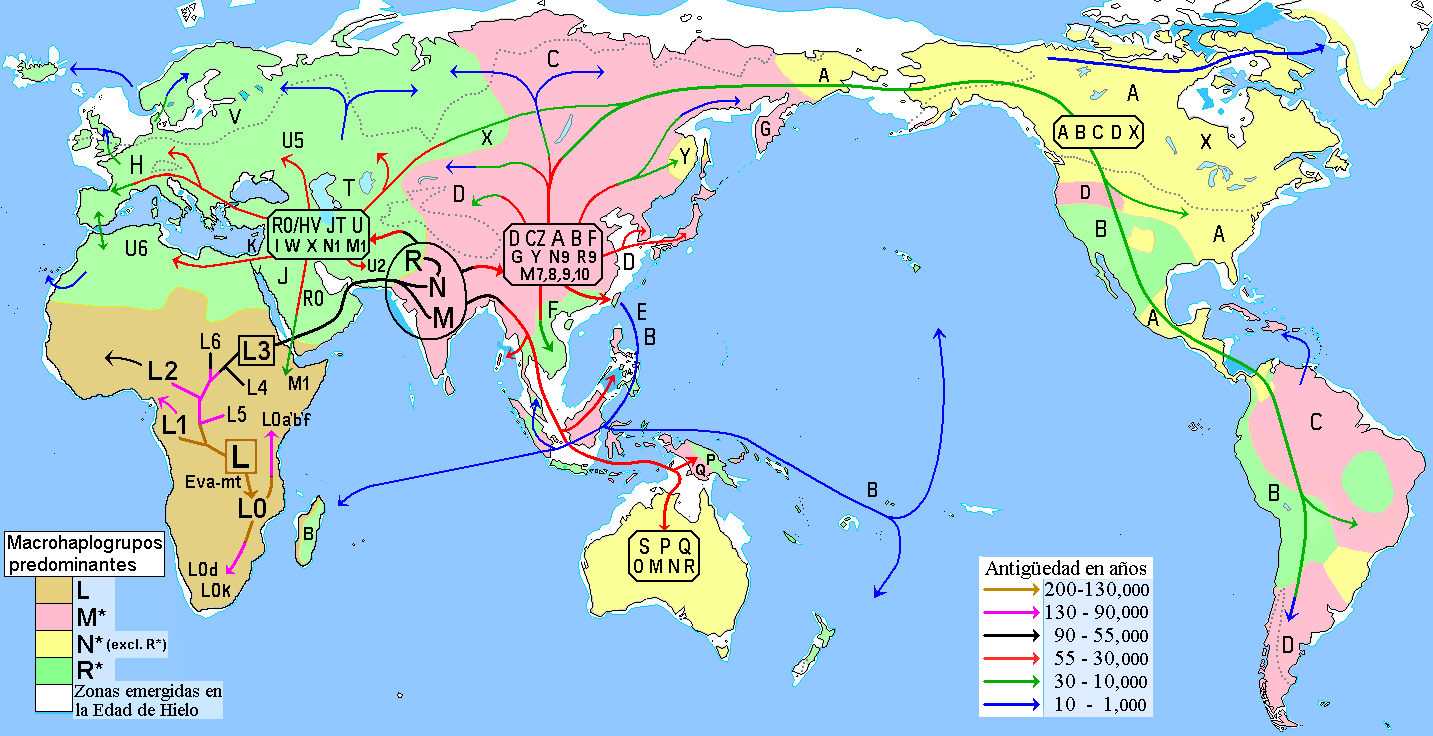

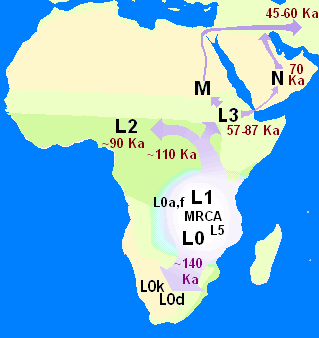

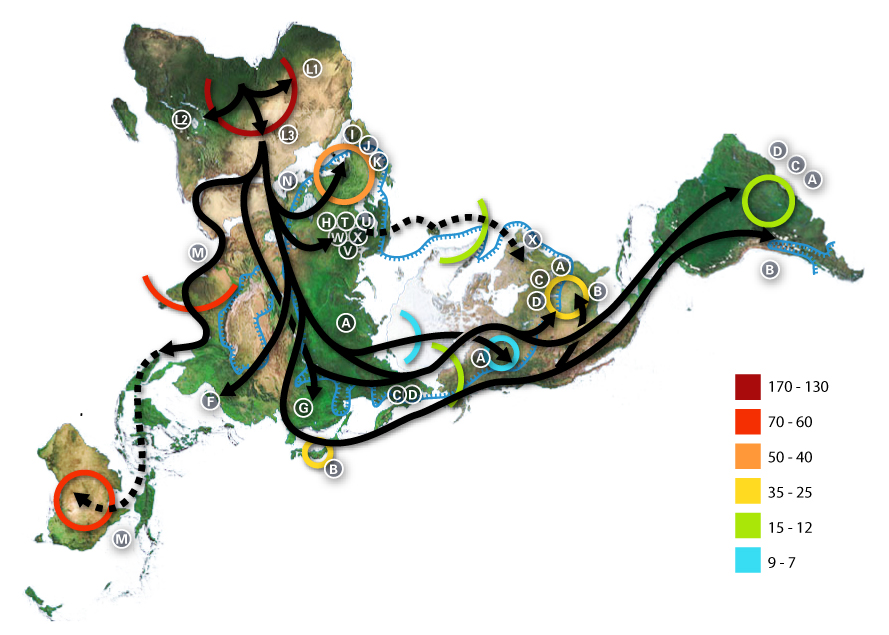

現 生人類(ホモ・サピエンス)は、約30万年前に、現在の北アフリカ、モロッコで進化したが、最古の遺跡は、アフリカ東部でみつかっている。私たちの祖先 は、アフリカ全域に生息する種だった。広大な大陸の各地に生息する多種多様な集団だった。初期の人類の一部は、最後の25万年前アジアとヨーロッパに移住 したが、アフリカを出たあとは長続きせず、子孫はおそらく残っていない。7万年前に別の集団がアフリカを出て、世界に根をおろしはじめた(ラザフォード 2022:9)

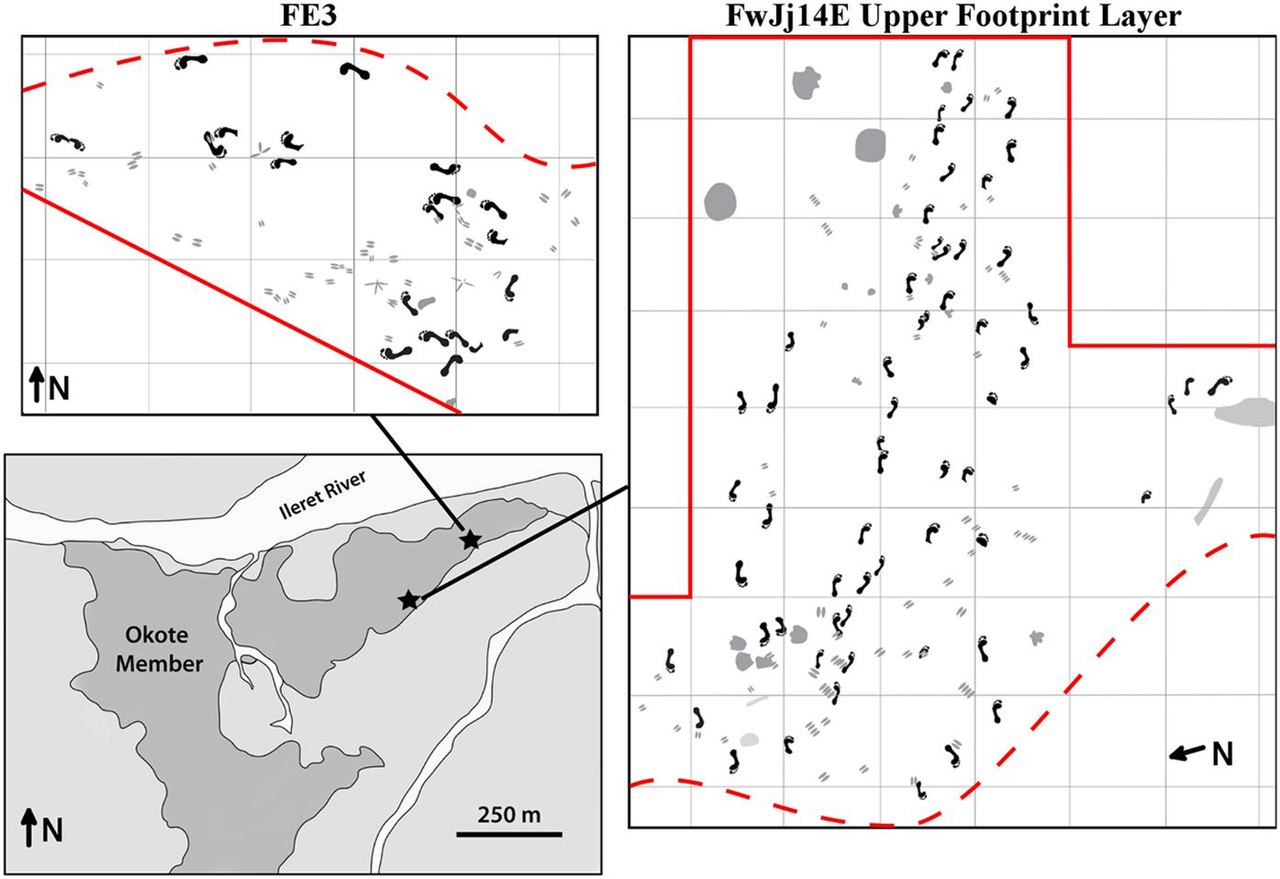

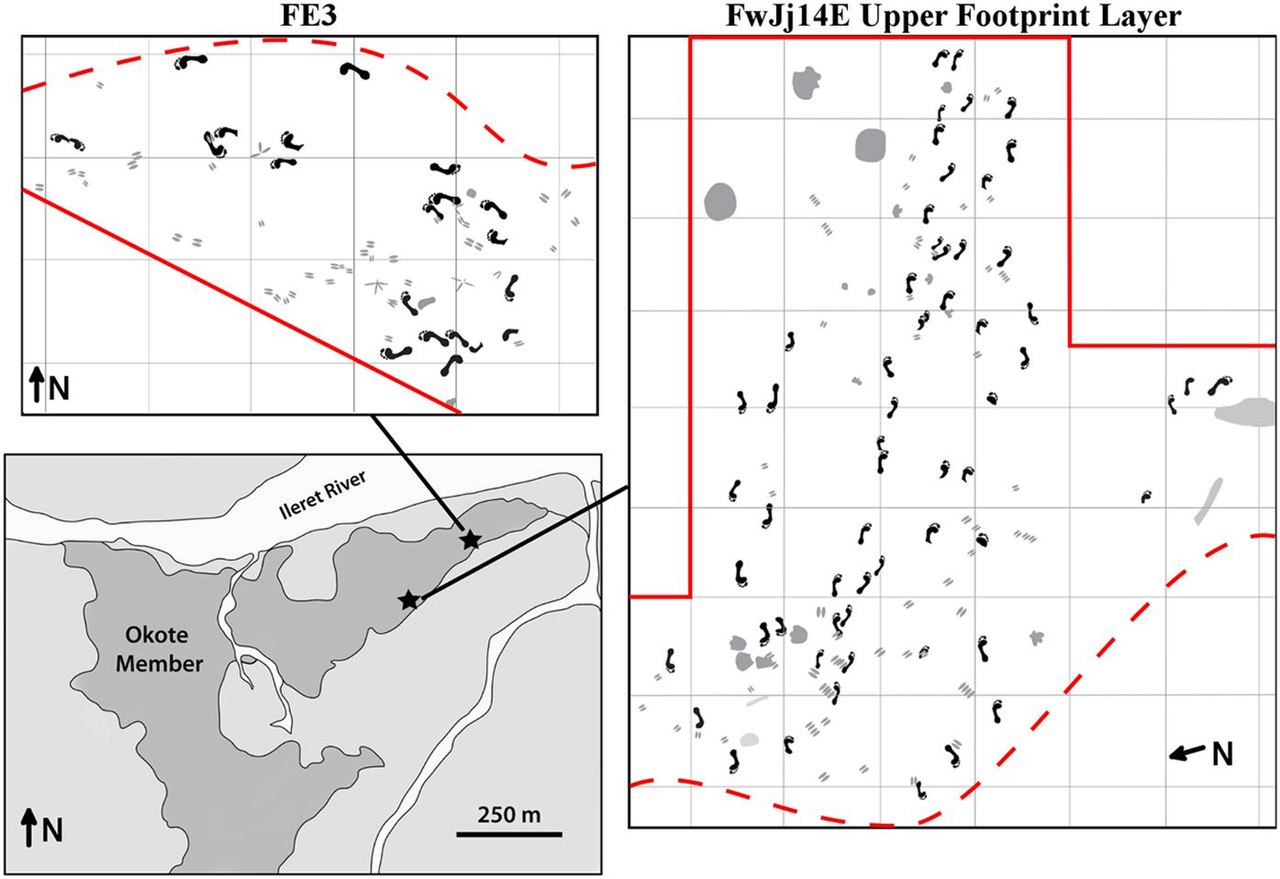

★ホモ・サピエンス以前の人類の進化の足跡

|

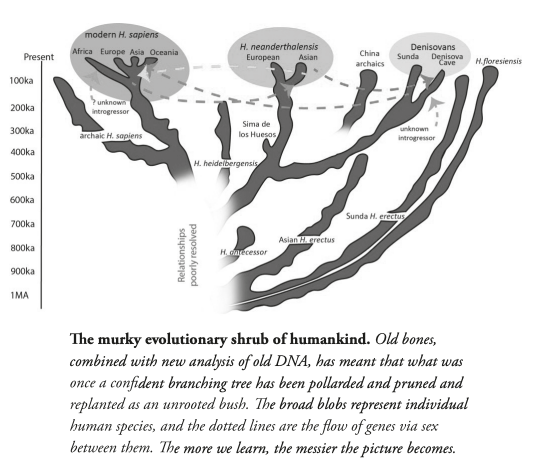

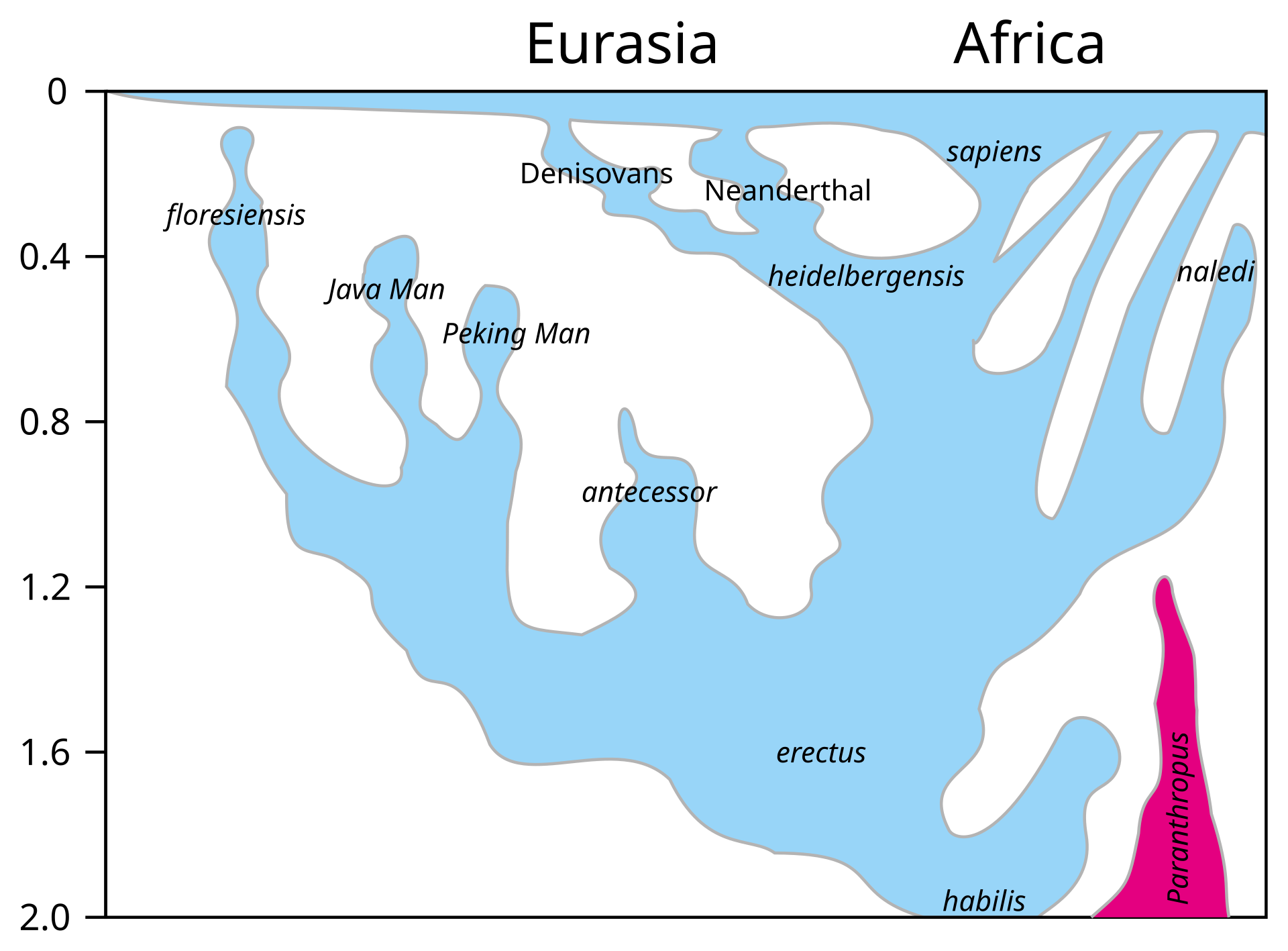

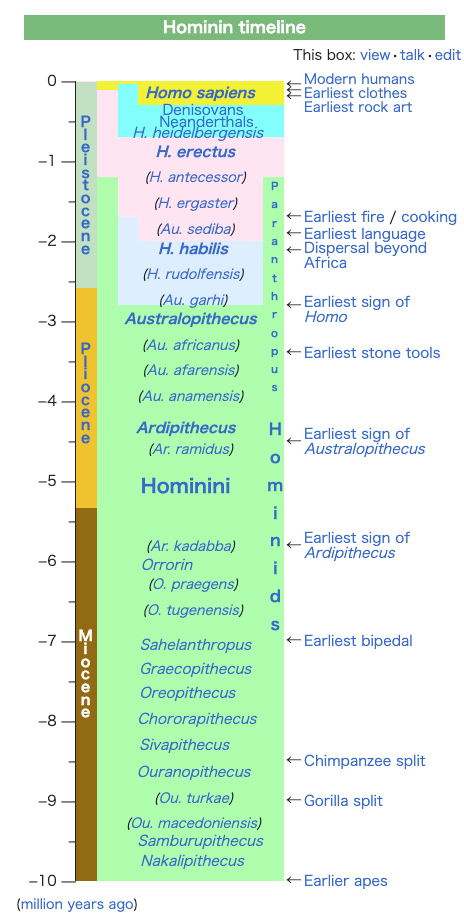

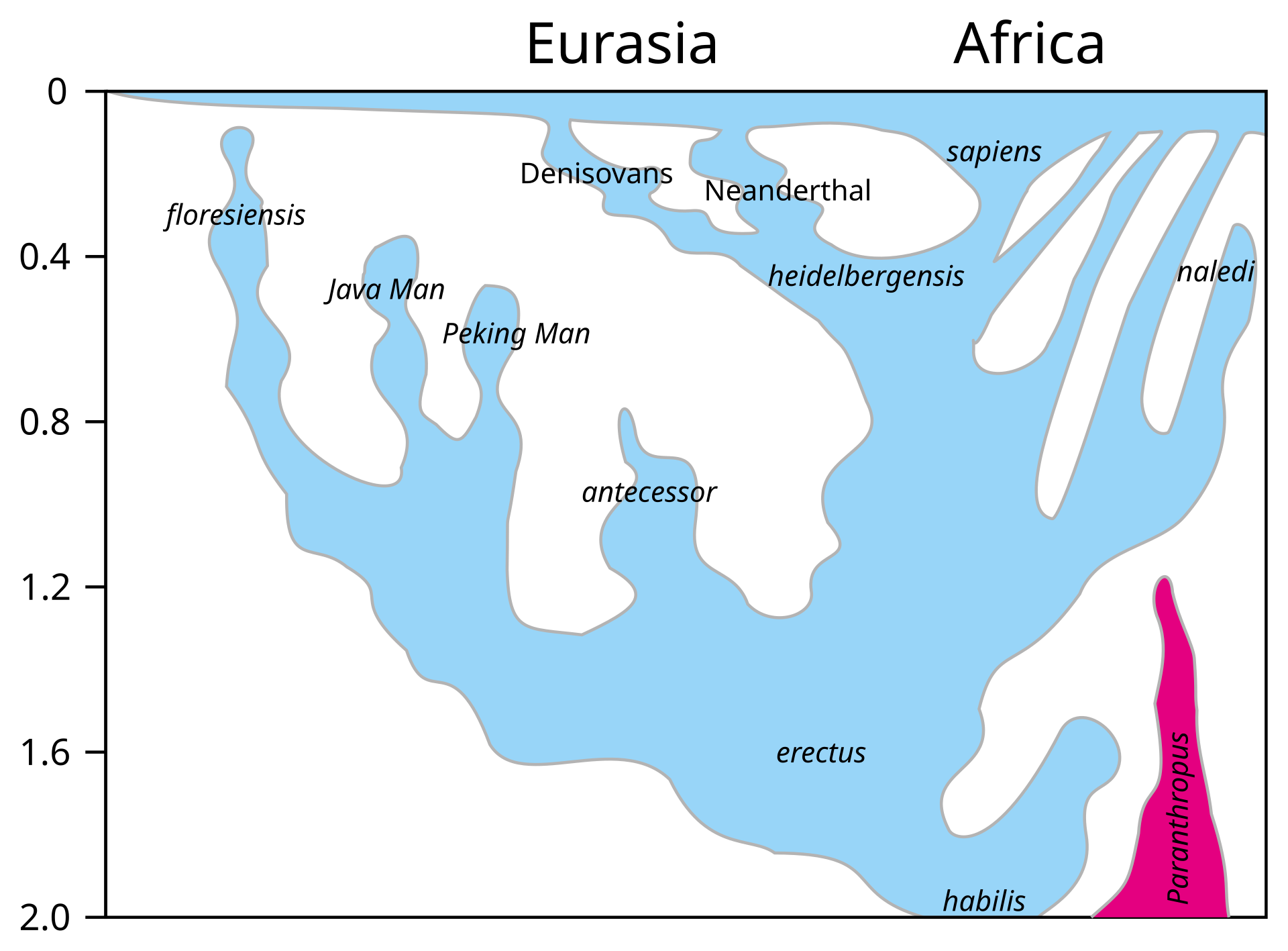

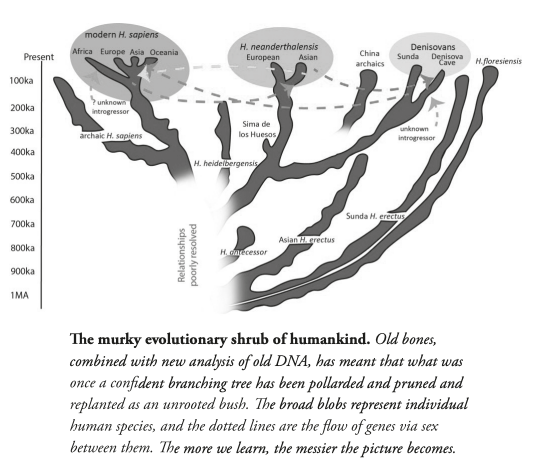

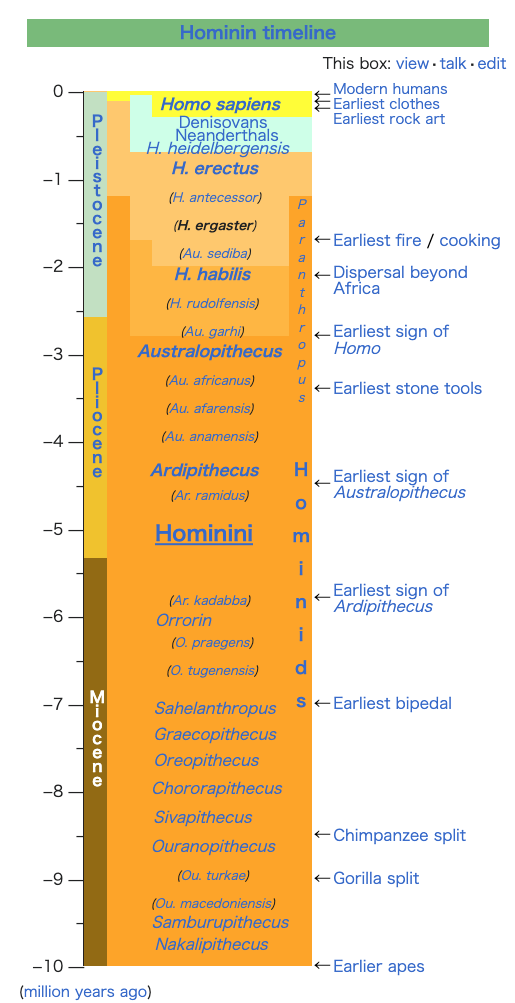

"Human evolution is the evolutionary process that led to the emergence of anatomically modern humans, beginning with the evolutionary history of primates—in particular genus Homo—and leading to the emergence of Homo sapiens as a distinct species of the hominid family, which includes the great apes. This process involved the gradual development of traits such as human bipedalism and language,[1] as well as interbreeding with other hominins, which indicate that human evolution was not linear but a web.[2][3][4][5] The study of human evolution involves several scientific disciplines, including physical anthropology, primatology, archaeology, paleontology, neurobiology, ethology, linguistics, evolutionary psychology, embryology and genetics.[6] Genetic studies show that primates diverged from other mammals about 85 million years ago, in the Late Cretaceous period(後期白亜紀), and the earliest fossils appear in the Paleocene(暁新世), around 55 million years ago.[7] Within the superfamily Hominoidea, the family Hominidae diverged from the family Hylobatidae(テナガザル科) some 15–20 million years ago; subfamily Homininae (African apes) diverged from Ponginae (orangutans[a]) about 14 million years ago; the tribe Hominini (including humans, Australopithecus, and chimpanzees) parted from the tribe Gorillini (gorillas) between 8–9 million years ago; and, in turn, the subtribes Hominina (humans and extinct biped ancestors) and Panina (chimpanzees) separated 4–7 million years ago.[8]" - Human evolution.

︎ |

「ヒ

トの進化とは、霊長類、特にホモ属の進化の歴史から始まり、ホモ・サピエンスが類人猿を含むヒト科の別種として出現するに至った、解剖学的に現生人類の出

現に至る進化の過程を指す。この過程では、ヒトの二足歩行や言語などの形質が徐々に発達し、他のヒト科の動物との交配も行われており、ヒトの進化は直線的

なものではなく、網の目のようなものであったことを示している。人類進化の研究には、人類学、霊長類学、考古学、古生物学、神経生物学、倫理学、言語学、

進化心理学、発生学、遺伝学など、いくつかの科学分野が関わっている。遺伝学的研究によると、霊長類は約8500万年前の白亜紀後期に他の哺乳類から分岐

し、最古の化石は約5500万年前の暁新世に発見されている。ヒト上科のうち、ヒト科は約1500万~2000万年前にヒヨケザル科から分岐し、ヒト亜科

(アフリカ類人猿)は約1400万年前にポンジナ科(オランウータン[a])から分岐した;

ヒト族(ヒト、アウストラロピテクス、チンパンジーを含む)は、800万~900万年前にゴリリーニ族(ゴリラ)と別れ、さらに400万~700万年前に

ホミニナ亜族(ヒトと絶滅した二足歩行の祖先)とパニナ亜族(チンパンジー)が分かれた」。 ▶︎ヒトゲノム・プロジェク ト▶︎︎▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎ |

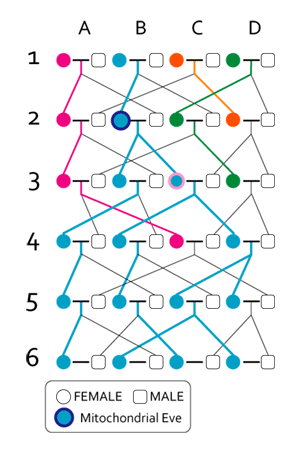

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/A_Brief_History_of_Everyone_Who_Ever_Lived A Brief History of Everyone Who Ever Lived: The Stories in Our Genes (published in the United States as A Brief History of Everyone Who Ever Lived: The Human Story Retold Through Our Genes) is a popular science book by British geneticist, author and broadcaster Adam Rutherford. It was first published in 2016 in the United Kingdom by Weidenfeld & Nicolson. An updated edition[a] was published in the United States in 2017, with a different subtitle, by The Experiment.[1] The book is about human genetics and what it reveals about human identity and their history. A Brief History of Everyone Who Ever Lived won gold at the 2017 Foreword INDIE Book Awards for Science,[2] and won the 2018 Thomas Bonner Book Prize.[3] The book was also a 2017 National Book Critics Circle Award non-fiction finalist,[4] featured on the 2017 Wellcome Book Prize longlist,[5] and appeared on National Geographic's top 12 books from 2017.[6] Table of contents Foreword by Siddhartha Mukherjee [*] Introduction Part One: How we came to be Horny and mobile The first European union These American lands [*] When we were kings The king lives on Richard III, Act VI The king is dead ... Part Two: Who we are now The end of race The most wonderous map ever produced by humankind Fate A short introduction to the future of humankind Epilogue [*] 2017 US edition  Synopsis A Brief History of Everyone Who Ever Lived explains the Out of Africa hypothesis that Homo sapiens originated in Africa about 200,000 years ago. They began slowly migrating to Europe around 100,000 years ago, where they encountered Neanderthals. DNA extracted from Neanderthal remains and compared to contemporary human DNA showed that Homo sapiens mated with Homo neanderthalensis. Today, about 2% of the sequence in European genomes is of Neanderthal origin. The book also investigates the lineage of European kings. DNA has enabled geneticists to construct their family trees going back to Charlemagne in the 8th century. Rutherford shows that family trees are not neat and tidy, but tangled webs. They often collapse in on themselves as a result of inbreeding. King Charles II's family tree was particularly bad as a result of incest in the family. Their rationale for this practice was to preserve their "royal blood", and this often had an adverse effect on their health; Charles himself was disabled, epileptic and mentally unstable. The book discusses the genes responsible for some human traits, including red hair, earwax and lactose intolerance/lactase persistence. Racial classification is shown to be a scientifically invalid concept. The genome encodes a huge number of characteristics that differ from person to person, which far outnumber the physical differences between black and white people. Rutherford concludes that genetics cannot be used to define race. Francis Galton and his contribution to the development of eugenics is also examined. The Human Genome Project revealed that humans only have about 20,000 genes, far fewer than scientists expected, and ended up posing more questions than it answered. The project also highlighted the limits of genetics and that it is no panacea for diseases. Rutherford criticises the popular press for their inaccurate reporting on genetics, and companies conducting DNA ancestry tests that produce impossibly accurate results. He says these companies and the press often overlook the fact that genetics is not an exact science – it is probabilistic. Successive migrations of Homo sapiens (red), starting about 200,000 years ago in Africa Reception In a review in The Guardian, Colin Grant described A Brief History of Everyone Who Ever Lived as an "effervescent work, brimming with tales and confounding ideas".[7] He called the author "an enthusiastic guide" who disentangles the maze of collapsed family trees and inbreeding. Grant felt that he was "especially illuminating" on the ill-defined notion of race, and "how it both does and doesn't exist". He said that Rutherford aims high: the rewriting human history, but called him "a commendable historian ... who is determined to illuminate the commonality of Homo sapiens".[7] Robin McKie described Rutherford's exposition of the Human Genome Project as "elegant". Writing in another review of the book in The Guardian, McKie noted how the author is careful to bring the project's "dreams of a medical revolution" down to earth, emphasising that its "greatest achievement ... was working out exactly how little we knew."[8] McKie praised Rutherford for highlighting modern genetics' limitations, that it is better at describing humans as a species than as individuals. He called the book "a polished, thoroughly entertaining history of Homo sapiens", adding that it is "popular science writing at its best".[8] In a review in The New York Times, Misha Angrist described A Brief History of Everyone Who Ever Lived as "nothing less than a tour de force".[1] Despite the book's ambitious tile, he felt that Rutherford "deliver[s] on its great promise". Angrist complimented the author on his "captivating storytelling" that is "entertaining and engaging" and "never feels pedantic".[1] He was impressed by the way Rutherford dealt with such sensitive topics as race and eugenics, and that he used examples like earwax and lactose intolerance, rather than Mendel's exhumed pea plants to demonstrate how genetics work. Angrist concluded his review by stating: "If genetics can ever offer us words to live by, I reckon these are probably the best it can do."[1] Nancy R. Curtis wrote in the Library Journal that A Brief History of Everyone Who Ever Lived should attract readers of both popular and technical science books. She said it is "amusing and provocative", and "may bruise the egos of a few genealogists".[9] Curtis did, however, complain that Rutherford gives too much attention to European and British issues, and from time to time "succumbs to editorializing on peripheral topics", for example creationism and genetic determinism.[9] In a review in The Wall Street Journal, Charles C. Mann was a little critical of the book's title, saying that it "is not particularly brief, not exactly a history and not concerned with everyone who ever lived".[10] But he was pleased that Rutherford did not fall into the trap of "hyping the science to sell the story" that popular science books often do. He said the author is "an enthusiastic guide and a good story-teller", although Mann did complain about Rutherford's many digressions that interrupt the flow of the text.[10] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/A_Brief_History_of_Everyone_Who_Ever_Lived |

ゲ

ノムが語る人類全史 / アダム・ラザフォード著 ; 垂水雄二訳, 東京 : 文藝春秋 , 2017. 『これまで生きたすべての人の略史: 米国では『A Brief History of Everyone Who Ever Lived』として出版されている: The Human Story Retold Through Our Genes)は、英国の遺伝学者、作家、放送作家のアダム・ラザフォードによるポピュラーな科学書である。2016年に英国でWeidenfeld & Nicolson社から初版が出版された。本書は、人間の遺伝学と、それが人間のアイデンティティとその歴史について明らかにすることについて書かれてい る。 A Brief History of Everyone Who Ever Lived』は2017年のForeword INDIE Book Awards for Scienceで金賞を受賞し[2]、2018年のThomas Bonner Book Prizeを受賞した[3]。 本書はまた、2017年のNational Book Critics Circle Awardのノンフィクション部門の最終選考に残り[4]、2017年のWellcome Book Prizeのロングリストに掲載され[5]、National Geographicの2017年のトップ12冊に登場した[6]。 目次 シッダールタ・ムカルジーによる序文 [*]. はじめに 第1部 私たちはいかにして生まれたか ムラムラとモバイル 最初のヨーロッパ連合 アメリカの土地 [*] 私たちが王様だった頃 王は生き続ける リチャード三世 第6幕 王は死んだ パート2:現在の私たち 人種の終わり 人類が生み出した最も不思議な地図 運命 人類の未来への短い序章 エピローグ [2017 米国版  あらすじ 本書は、ホモ・サピエンスは約20万年前にアフリカで誕生したという「アウト・オブ・アフリカ」仮説を説明する。ホモ・サピエンスはおよそ20万年前にア フリカで誕生し、10万年前にヨーロッパへゆっくりと移動し始め、そこでネアンデルタール人と遭遇した。ネアンデルタール人の遺体から抽出したDNAを現 代人のDNAと比較したところ、ホモ・サピエンスはホモ・ネアンデルターレンシスと交配したことがわかった。現在、ヨーロッパ人のゲノムの塩基配列の約 2%がネアンデルタール人由来である。本書はまた、ヨーロッパの王の血統についても調査している。DNAのおかげで、遺伝学者たちは8世紀のカール大帝に さかのぼる家系図を作ることができるようになった。ラザフォードは、家系図は整然としたものではなく、もつれた網の目のようなものであることを示してい る。近親交配の結果、家系はしばしば崩壊する。チャールズ2世の家系は近親相姦の結果、特にひどいものだった。この近親相姦の根拠は 「王家の血 」を維持するためであったが、それがしばしば健康に悪影響を及ぼし、チャールズ2世自身、身体障害、てんかん、精神不安定であった。 本書では、赤毛、耳垢、乳糖不耐症/ラクターゼ持続性など、人間の形質の原因となる遺伝子について論じている。人種分類は科学的に無効な概念であることが 示されている。ゲノムは人によって異なる膨大な数の特徴をコードしており、それは黒人と白人の身体的差異をはるかに凌駕している。ラザフォードは、遺伝学 で人種を定義することはできないと結論づけている。フランシス・ガルトンと優生学の発展への彼の貢献についても考察されている。ヒトゲノム・プロジェクト は、ヒトが持つ遺伝子が科学者の予想をはるかに下回る約2万個しかないことを明らかにし、答えよりも多くの疑問を投げかける結果となった。このプロジェク トはまた、遺伝学の限界と、それが病気に対する万能薬ではないことを浮き彫りにした。ラザフォードは、遺伝学に関する不正確な報道をする大衆紙や、あり得 ないほど正確な結果を出すDNA先祖鑑定を行う企業を批判する。これらの企業や報道機関は、遺伝学が厳密な科学ではなく、確率的なものであるという事実を しばしば見落としているという。 ホモ・サピエンス(赤)は、約20万年前のアフリカを起点に移動を繰り返した。 レセプション ガーディアン』紙の書評で、コリン・グラントは『A Brief History of Everyone Who Ever Lived』を「物語と混乱させるアイデアに溢れた、活気に満ちた作品」[7]と評し、著者を「崩壊した家系図と近親交配の迷路を解きほぐす、熱心なガイ ド」と呼んだ。グラントは、人種という定義づけの曖昧な概念について、そして「人種がどのように存在し、また存在しないか」について、彼が「特に示唆に富 んでいる」と感じた。彼は、ラザフォードは人類史の書き換えという高い目標を掲げているが、「ホモ・サピエンスの共通性に光を当てようと決意してい る......称賛に値する歴史家」だと述べている[7]。 ロビン・マッキーは、ラザフォードのヒトゲノム計画についての説明を「エレガント」と評した。ガーディアン』紙の別の書評でマッキーは、著者がいかにこの プロジェクトの「医療革命の夢」を現実のものにするために慎重であるかを指摘し、「最大の功績は......われわれがどれほど何も知らなかったかを正確 に解明したことだ」と強調した[8]。彼はこの本を「洗練された、徹底的に面白いホモ・サピエンスの歴史」と呼び、「最高のポピュラーサイエンス」だと付 け加えた[8]。 『ニューヨーク・タイムズ』紙の書評で、ミーシャ・アングリストは『A Brief History of Everyone Who Ever Lived』を「力作にほかならない」と評した[1]。この本の野心的なタイルにもかかわらず、彼はラザフォードが「その大きな約束を果たしている」と感 じた。ラザフォードが人種や優生学といったデリケートなトピックを扱い、遺伝学がどのように作用するかを示すために、メンデルの発掘したエンドウ豆ではな く、耳垢や乳糖不耐症のような例を用いたことに感銘を受けたという。アングリストは最後にこう述べた: 「遺伝学がわれわれに生きるための言葉を与えてくれるとしたら、おそらくこれが最善だろう」[1]。 ナンシー・R・カーティスは、『A Brief History of Everyone Who Ever Lived』について、ポピュラーな科学書と専門書の両方の読者を惹きつけるはずだと『Library Journal』誌に書いている。しかし、カーティスは、ラザフォードがヨーロッパとイギリスの問題に注意を向けすぎており、時折、創造論や遺伝的決定論 のような「周辺的な話題の論説に屈している」と不満を述べている[9]。 [ウォール・ストリート・ジャーナル』紙の書評で、チャールズ・C・マンはこの本のタイトルについて、「特に簡潔というわけでもなく、正確には歴史という わけでもなく、これまで生きてきたすべての人に関係しているわけでもない」と少々批判的であった[10]。 しかし彼は、ラザフォードが一般的な科学書にありがちな「物語を売るために科学を誇張する」という罠に陥っていないことを喜んだ。著者は「熱心なガイドで あり、優れたストーリーテラー」であると語ったが、マンはラザフォードの脱線が多く、文章の流れを妨げていると苦言を呈した[10]。 |

最 近の現生人類のアフリカ起源説によると、現生人類はアフリカでハイデルベルゲンシス、ローデシエンシス、またはアンテセサーから進化し、約5万年から 10万年前にアフリカ大陸から移動し、徐々に現地のH. エレクトゥス、デニソワ・ホミニン、フロレシエンシス、ルゾネンシス、ネアンデルタール人などの地域個体群に徐々に取って代わった。解剖学的に現生人類の 前身であるアルカイック・ホモ・サピエンスは、40万年から25万年前の中期旧石器時代に進化した。最近のDNAの証拠によると、ネアンデルタール人由来 のいくつかのハプロタイプがアフリカ以外のすべての集団に存在し、ネアンデ ルタール人やデニソワ人などの他のヒト科の動物はゲノムの最大6%を現生人類に寄与した可能性があり、これらの種間の交雑が限られていたことを示唆してい る。 [象徴文化、言語、特殊な石器技術の発達を伴う行動的近代性への移行は、一部の人類学者によれば約5万年前に起こったとされているが、もっと長い スパンで徐々に行動が変化したことを示唆する証拠を指摘する者もいる。

| 1 Anatomical changes -Human

evolution. 1.1 Bipedalism 1.2 Encephalization 1.3 Sexual dimorphism 1.4 Ulnar opposition 1.5 Other changes 2 History of study 2.1 Before Darwin 2.2 Darwin 2.3 First fossils 2.4 The East African fossils 2.5 The genetic revolution 2.6 The quest for the earliest hominin 2.7 Human dispersal 2.7.1 Dispersal of modern Homo sapiens 3 Evidence 3.1 Evidence from molecular biology 3.1.1 Genetics 3.2 Evidence from the fossil record 3.3 Inter-species breeding |

1 解剖学的変化 -ヒトの進化 1.1 二足歩行 1.2 脳化 1.3 性二型 1.4 尺骨対立 1.5 その他の変化 2 研究の歴史 2.1 ダーウィン以前 2.2 ダーウィン 2.3 最初の化石 2.4 東アフリカの化石 2.5 遺伝子革命 2.6 最初期のヒトの探求 2.7 ヒトの分散 2.7.1 現代ホモ・サピエンスの分散 3 証拠 3.1 分子生物学的証拠 3.1.1 遺伝学 3.2 化石記録からの証拠 3.3 種間交配 |

| 4

Before Homo 4.1 Early evolution of primates 4.2 Divergence of the human clade from other great apes 4.3 Genus Australopithecus 5 Evolution of genus Homo 5.1 H. habilis and H. gautengensis 5.2 H. rudolfensis and H. georgicus 5.3 H. ergaster and H. erectus 5.4 H. cepranensis and H. antecessor 5.5 H. heidelbergensis 5.6 H. rhodesiensis, and the Gawis cranium 5.7 Neanderthal and Denisovan 5.8 H. floresiensis 5.9 H. luzonensis 5.10 H. sapiens 6 Use of tools 6.1 Stone tools 7 Transition to behavioral modernity 8 Recent and ongoing human evolution *** 12 References 12.1 Sources 13 Further reading |

4 ホモ以前 4.1 霊長類の初期進化 4.2 ヒトと他の類人猿の分岐 4.3 アウストラロピテクス属 5 ホモ属の進化 5.1 H. habilisとH. gautengensis 5.2 ルドルフェンシスとゲオルギウス 5.3 エルガスターとエレクタス 5.4 H. cepranensisとH. antecessor 5.5 ハイデルベルク人 5.6 H. rhodesiensisとGawis頭蓋 5.7 ネアンデルタール人とデニソワ人 5.8 フロレシエンシス 5.9 ルゾネンシス 5.10 サピエンス 6 道具の使用 6.1 石器 7 行動近代化への移行 8 最近の人類進化と現在進行形 *** 12 参考文献 12.1 出典 13 参考文献 |

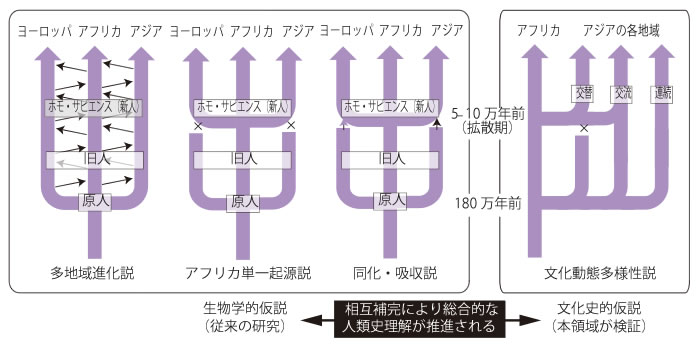

★新人の出現に関する「多地域進化説」「アフリカ単一起源説」「同化・吸収説」と「文化動態多様性説」

出典:「パレオアジア文化史学」https://paleoasia.jp/research_overview/

リンク

おばかさんのための人類 学︎▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎

| Human evolution is

the evolutionary process within the history of primates that led to the

emergence of Homo sapiens as a distinct species of the hominid family,

which includes all the great apes. This process involved the gradual

development of traits such as human bipedalism, dexterity and complex

language,[1] as well as interbreeding with other hominins (a tribe of

the African hominid subfamily),[2] indicating that human evolution was

not linear but weblike.[3][4][5][6] The study of human evolution

involves several scientific disciplines, including physical and

evolutionary anthropology, paleontology, and genetics.[7][8] Primates diverged from other mammals about 85 million years ago (mya), in the Late Cretaceous period, with their earliest fossils appearing over 55 mya, during the Paleocene.[9] Primates produced successive clades leading to the ape superfamily, which gave rise to the hominid and the gibbon families; these diverged some 15–20 mya. African and Asian hominids (including orangutans) diverged about 14 mya. Hominins (including the Australopithecine and Panina subtribes) parted from the Gorillini tribe (gorillas) between 8–9 mya; Australopithecine (including the extinct biped ancestors of humans) separated from the Pan genus (containing chimpanzees and bonobos) 4–7 mya.[10] The Homo genus is evidenced by the appearance of H. habilis over 2 mya,[a] while anatomically modern humans emerged in Africa approximately 300,000 years ago. |

ヒトの進化とは、霊長類の歴史の中で、すべての類人猿を含むヒト科の別

種としてホモ・サピエンスが出現するに至った進化の過程である。この過程では、ヒトの二足歩行、器用さ、複雑な言語などの形質が徐々に発達し[1]、他の

ホミニン(アフリカヒト亜科の一種)との交雑が行われ[2]、ヒトの進化が直線的ではなく、網の目のようなものであったことを示している[3][4]

[5][6]。 霊長類は約8,500万年前(mya)の白亜紀後期に他の哺乳類から分岐し、最古の化石は5,500万年以上前の暁新世に出現した[9]。アフリカとアジ アのヒト科(オランウータンを含む)は約1400万年前に分岐した。ヒト亜科(アウストラロピテクス亜科とパニナ亜科を含む)は8-9ミヤの間にゴリリー ニ族(ゴリラ)から別れ、アウストラロピテクス亜科(ヒトの絶滅した二足歩行の祖先を含む)は4-7ミヤの間にパン属(チンパンジーとボノボを含む)から 分かれた[10]。ホモ属は2ミヤ以上のハビリスの出現によって証明され[a]、解剖学的に現生人類は約30万年前にアフリカで出現した。 |

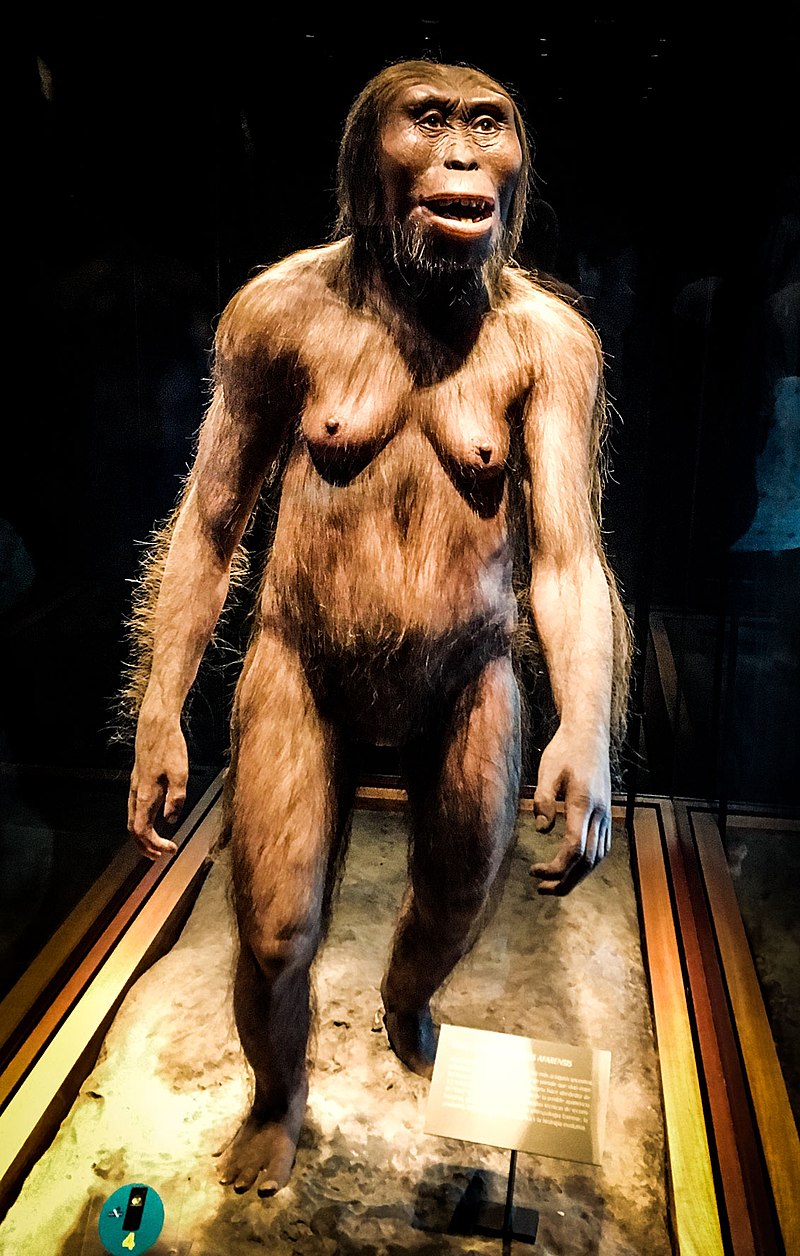

| Before Homo For evolutionary history before primates, see Evolution of mammals, History of life, and Timeline of human evolution. Early evolution of primates See also: Evolution of primates The evolutionary history of primates can be traced back 65 million years.[11][12][13][14][15] One of the oldest known primate-like mammal species, the Plesiadapis, came from North America;[16][17][18][19][20][21] another, Archicebus, came from China.[22] Other similar basal primates were widespread in Eurasia and Africa during the tropical conditions of the Paleocene and Eocene.  Notharctus tenebrosus, American Museum of Natural History, New York David R. Begun[23] concluded that early primates flourished in Eurasia and that a lineage leading to the African apes and humans, including to Dryopithecus, migrated south from Europe or Western Asia into Africa. The surviving tropical population of primates—which is seen most completely in the Upper Eocene and lowermost Oligocene fossil beds of the Faiyum depression southwest of Cairo—gave rise to all extant primate species, including the lemurs of Madagascar, lorises of Southeast Asia, galagos or "bush babies" of Africa, and to the anthropoids, which are the Platyrrhines or New World monkeys, the Catarrhines or Old World monkeys, and the great apes, including humans and other hominids. The earliest known catarrhine is Kamoyapithecus from the uppermost Oligocene at Eragaleit in the northern Great Rift Valley in Kenya, dated to 24 million years ago.[24] Its ancestry is thought to be species related to Aegyptopithecus, Propliopithecus, and Parapithecus from the Faiyum, at around 35 mya.[25] In 2010, Saadanius was described as a close relative of the last common ancestor of the crown catarrhines, and tentatively dated to 29–28 mya, helping to fill an 11-million-year gap in the fossil record.[26]  Reconstructed tailless Proconsul skeleton In the Early Miocene, about 22 million years ago, the many kinds of arboreally adapted primitive catarrhines from East Africa suggest a long history of prior diversification. Fossils at 20 million years ago include fragments attributed to Victoriapithecus, the earliest Old World monkey. Among the genera thought to be in the ape lineage leading up to 13 million years ago are Proconsul, Rangwapithecus, Dendropithecus, Limnopithecus, Nacholapithecus, Equatorius, Nyanzapithecus, Afropithecus, Heliopithecus, and Kenyapithecus, all from East Africa. The presence of other generalized non-cercopithecids of Middle Miocene from sites far distant—Otavipithecus from cave deposits in Namibia, and Pierolapithecus and Dryopithecus from France, Spain and Austria—is evidence of a wide diversity of forms across Africa and the Mediterranean basin during the relatively warm and equable climatic regimes of the Early and Middle Miocene. The youngest of the Miocene hominoids, Oreopithecus, is from coal beds in Italy that have been dated to 9 million years ago. Molecular evidence indicates that the lineage of gibbons diverged from the line of great apes some 18–12 mya, and that of orangutans (subfamily Ponginae)[b] diverged from the other great apes at about 12 million years; there are no fossils that clearly document the ancestry of gibbons, which may have originated in a so-far-unknown Southeast Asian hominoid population, but fossil proto-orangutans may be represented by Sivapithecus from India and Griphopithecus from Turkey, dated to around 10 mya.[27] Hominidae subfamily Homininae (African hominids) diverged from Ponginae (orangutans) about 14 mya. Hominins (including humans and the Australopithecine and Panina subtribes) parted from the Gorillini tribe (gorillas) between 8–9 mya; Australopithecine (including the extinct biped ancestors of humans) separated from the Pan genus (containing chimpanzees and bonobos) 4–7 mya.[10] The Homo genus is evidenced by the appearance of H. habilis over 2 mya,[a] while anatomically modern humans emerged in Africa approximately 300,000 years ago. Divergence of the human clade from other great apes Species close to the last common ancestor of gorillas, chimpanzees and humans may be represented by Nakalipithecus fossils found in Kenya and Ouranopithecus found in Greece. Molecular evidence suggests that between 8 and 4 million years ago, first the gorillas, and then the chimpanzees (genus Pan) split off from the line leading to the humans. Human DNA is approximately 98.4% identical to that of chimpanzees when comparing single nucleotide polymorphisms (see human evolutionary genetics). The fossil record, however, of gorillas and chimpanzees is limited; both poor preservation – rain forest soils tend to be acidic and dissolve bone – and sampling bias probably contribute to this problem. Other hominins probably adapted to the drier environments outside the equatorial belt; and there they encountered antelope, hyenas, dogs, pigs, elephants, horses, and others. The equatorial belt contracted after about 8 million years ago, and there is very little fossil evidence for the split—thought to have occurred around that time—of the hominin lineage from the lineages of gorillas and chimpanzees. The earliest fossils argued by some to belong to the human lineage are Sahelanthropus tchadensis (7 Ma) and Orrorin tugenensis (6 Ma), followed by Ardipithecus (5.5–4.4 Ma), with species Ar. kadabba and Ar. ramidus. It has been argued in a study of the life history of Ar. ramidus that the species provides evidence for a suite of anatomical and behavioral adaptations in very early hominins unlike any species of extant great ape.[28] This study demonstrated affinities between the skull morphology of Ar. ramidus and that of infant and juvenile chimpanzees, suggesting the species evolved a juvenalised or paedomorphic craniofacial morphology via heterochronic dissociation of growth trajectories. It was also argued that the species provides support for the notion that very early hominins, akin to bonobos (Pan paniscus) the less aggressive species of the genus Pan, may have evolved via the process of self-domestication. Consequently, arguing against the so-called "chimpanzee referential model"[29] the authors suggest it is no longer tenable to use chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes) social and mating behaviors in models of early hominin social evolution. When commenting on the absence of aggressive canine morphology in Ar. ramidus and the implications this has for the evolution of hominin social psychology, they wrote: Of course Ar. ramidus differs significantly from bonobos, bonobos having retained a functional canine honing complex. However, the fact that Ar. ramidus shares with bonobos reduced sexual dimorphism, and a more paedomorphic form relative to chimpanzees, suggests that the developmental and social adaptations evident in bonobos may be of assistance in future reconstructions of early hominin social and sexual psychology. In fact the trend towards increased maternal care, female mate selection and self-domestication may have been stronger and more refined in Ar. ramidus than what we see in bonobos.[28]: 128 The authors argue that many of the basic human adaptations evolved in the ancient forest and woodland ecosystems of late Miocene and early Pliocene Africa. Consequently, they argue that humans may not represent evolution from a chimpanzee-like ancestor as has traditionally been supposed. This suggests many modern human adaptations represent phylogenetically deep traits and that the behavior and morphology of chimpanzees may have evolved subsequent to the split with the common ancestor they share with humans. Genus Australopithecus Main article: Australopithecus  Reconstruction of "Lucy" The genus Australopithecus evolved in eastern Africa around 4 million years ago before spreading throughout the continent and eventually becoming extinct 2 million years ago. During this time period various forms of australopiths existed, including Australopithecus anamensis, Au. afarensis, Au. sediba, and Au. africanus. There is still some debate among academics whether certain African hominid species of this time, such as Au. robustus and Au. boisei, constitute members of the same genus; if so, they would be considered to be Au. robust australopiths whilst the others would be considered Au. gracile australopiths. However, if these species do indeed constitute their own genus, then they may be given their own name, Paranthropus. Australopithecus (4–1.8 Ma), with species Au. anamensis, Au. afarensis, Au. africanus, Au. bahrelghazali, Au. garhi, and Au. sediba; Kenyanthropus (3–2.7 Ma), with species K. platyops; Paranthropus (3–1.2 Ma), with species P. aethiopicus, P. boisei, and P. robustus A new proposed species Australopithecus deyiremeda is claimed to have been discovered living at the same time period of Au. afarensis. There is debate if Au. deyiremeda is a new species or is Au. afarensis.[30] Australopithecus prometheus, otherwise known as Little Foot has recently been dated at 3.67 million years old through a new dating technique, making the genus Australopithecus as old as afarensis.[31] Given the opposable big toe found on Little Foot, it seems that the specimen was a good climber. It is thought given the night predators of the region that he built a nesting platform at night in the trees in a similar fashion to chimpanzees and gorillas. |

ホモ以前 霊長類以前の進化の歴史については、哺乳類の進化、生命の歴史、人類進化の年表を参照のこと。 霊長類の初期進化 こちらも参照: 霊長類の進化 霊長類の進化の歴史は6,500万年前に遡ることができる[11][12][13][14][15]。最古の霊長類に似た哺乳類の1種であるプレシアダピ スは北アメリカから来た[16][17][18][19][20][21]。  Notharctus tenebrosus、アメリカ自然史博物館、ニューヨーク デヴィッド・R・ベガン[23]は、初期の霊長類はユーラシア大陸で繁栄し、ドライオピテクスを含むアフリカの類人猿とヒトにつながる系統がヨーロッパま たは西アジアからアフリカに南下したと結論づけた。現存する熱帯の霊長類の集団は、カイロの南西にあるファイユーム窪地の上部始新世と最下部の漸新世の化 石層で最も完全に見られ、マダガスカルのキツネザルを含む現存するすべての霊長類の種を生み出した、 マダガスカルのキツネザル、東南アジアのロリス、アフリカのガラゴ(ブッシュ・ベビー)、そして類人猿(プラティルヒネス、新世界ザル、カタールヒネス、 旧世界ザル、そしてヒトやその他のヒト科動物を含む類人猿)である。 最古のカタロヒ類として知られているのは、ケニアの大地溝帯北部にあるエラガレイトの漸新世の最上部に生息するカモヤピテクスで、その年代は2400万年 前である[24]。その祖先は、約3500万年前のファイユームのエイプトピテクス、プロプリオピテクス、パラピテクスと近縁種であると考えられている。 [25]2010年、サーダニウスはクラウンカタロニアの最後の共通祖先の近縁種とされ、化石記録における1,100万年の空白を埋めるのに役立つ29- 28ミヤと暫定的に年代測定された[26]。  復元された無尾のプロコンスルの骨格 およそ2,200万年前の前期中新世において、東アフリカに生息していた樹上適応型の原始カタユウレイボヤムシの多くの種類は、事前に多様化した長い歴史 を示唆している。2,000万年前の化石には、旧世界最古のサルであるビクトリアピテクス(Victoriapithecus)の断片が含まれている。 1300万年前までの類人猿の系統に属すると考えられている属には、プロコンスル、ラングワピテクス、デンドロピテクス、リムノピテクス、ナチョラピテク ス、エクアトリウス、ニャンザピテクス、アフロピテクス、ヘリオピテクス、ケニヤピテクスがあり、これらはすべて東アフリカ産である。 ナミビアの洞窟堆積物からはオタビピテクスが、フランス、スペイン、オーストリアからはピエロラピテクスとドライオピテクスが見つかっている。中新世のホ ミノイドの中で最も若いオレオピテクスは、900万年前のイタリアの炭層から発見された。 分子生物学的証拠によると、テナガザルの系統は類人猿の系統から約1800万年~1200万年前に分岐し、オランウータン(ポンジナータ亜科)[b]の系 統は他の類人猿から約1200万年前に分岐した; しかし、オランウータンの祖先の化石は、インド産のシバピテクスとトルコ産のグリフォピテクスに代表されるかもしれない。 [27] ヒト科ヒト亜科(アフリカヒト科)は、約1400万年前にポンジナ科(オランウータン)から分岐した。ヒト亜科(ヒト、アウストラロピテクス亜科、パニナ 亜科を含む)は8-9ミヤの間にゴリリーニ族(ゴリラ)から別れ、アウストラロピテクス亜科(ヒトの絶滅した二足歩行の祖先を含む)は4-7ミヤでパン属 (チンパンジーとボノボを含む)から分かれた。 [10]ホモ属は2ミヤ以上のハビリスの出現によって証明され[a]、解剖学的に現生人類は約30万年前にアフリカで出現した。 ヒトと他の類人猿の分岐 ゴリラ、チンパンジー、ヒトの最後の共通祖先に近い種は、ケニアで発見されたナカリピテクスやギリシャで発見されたオウラノピテクスに代表されるかもしれ ない。分子生物学的証拠によれば、800万年から400万年前の間に、まずゴリラ、次にチンパンジー(パン属)がヒトにつながる系統から分かれた。一塩基 多型を比較すると、ヒトのDNAはチンパンジーのDNAと約98.4%同一である(ヒトの進化遺伝学を参照)。しかし、ゴリラとチンパンジーの化石記録は 限られている。保存状態が悪いこと(熱帯雨林の土壌は酸性で骨が溶けやすい)とサンプリングの偏りの両方が、おそらくこの問題の一因だろう。 他のホミニンは、おそらく赤道帯の外側の乾燥した環境に適応し、そこでカモシカ、ハイエナ、イヌ、ブタ、ゾウ、ウマなどに遭遇した。赤道帯は約800万年 前以降に縮小し、その頃にゴリラやチンパンジーの系統からホミニンの系統が分かれたと考えられているが、それを示す化石はほとんどない。ヒトの系統に属す るとされる最古の化石は、サヘラントロプス・チャデンシス(7Ma)とオロリン・トゥゲネンシス(6Ma)であり、アルディピテクス(5.5- 4.4Ma)がそれに続く。 Ar.ramidusの生活史の研究では、この種は現存の類人猿のどの種とも異なり、非常に初期のヒトにおける一連の解剖学的および行動的適応の証拠を提 供していると主張されている[28]。この研究では、Ar.ramidusの頭蓋形態と幼児および幼若チンパンジーの頭蓋形態との間の親近性が示され、こ の種が成長軌道の異時的解離を介して幼若化または小児化した頭蓋顔面形態を進化させたことが示唆された。また、この種は、パン属の中でも攻撃性の低い種で あるボノボ(Pan paniscus)に似た、ごく初期のヒト科の動物が、自己家畜化の過程を経て進化したのではないかという考え方を支持するものであるとも主張された。そ の結果、著者らはいわゆる「チンパンジー参照モデル」[29]に反論し、ヒトの初期社会進化のモデルにチンパンジー(Pan troglodytes)の社会行動や交尾行動を用いることはもはや通用しないことを示唆している。Ar.ramidusに攻撃的な犬歯の形態がないこ と、そしてこのことがヒト科動物の社会心理学の進化に与える影響について、彼らは次のように書いている: もちろん、Ar. ramidusはボノボとは大きく異なり、ボノボは機能的な犬歯の研ぎ出し複合体を保持している。しかし、Ar. ramidusがボノボと共通するのは性的二型が減少していること、そしてチンパンジーと比べてより小柄であることで、ボノボに見られる発達的・社会的適 応が、初期のヒトの社会心理学や性心理学の復元に役立つ可能性があることを示唆している。実際、母性的ケアの増加、女性の交尾相手の選択、自己家畜化の傾 向は、ボノボに見られるものよりもAr: 128 著者らは、人間の基本的な適応の多くは、中新世後期から鮮新世初期のアフリカの古代の森林や森の生態系で進化したと主張している。その結果、ヒトは従来考 えられてきたようなチンパンジーのような祖先からの進化ではないかもしれないと論じている。また、チンパンジーの行動や形態は、ヒトと共通の祖先と分かれ た後に進化した可能性があるとしている。 アウストラロピテクス属 主な記事 アウストラロピテクス  ルーシー "の復元 アウストラロピテクス属は、約400万年前にアフリカ東部で進化した後、アフリカ大陸全体に広がり、最終的に200万年前に絶滅した。この時代には、アウ ストラロピテクス・アナメンシス、アウストラロピテクス・アファレンシス、アウストラロピテクス・セディバ、アウストラロピテクス・アフリカヌスなど、さ まざまな形態のアウストラロピスが存在した。もしそうであれば、これらの種はアウストラロピテクスとみなされ、その他の種はアウストラロピテクスとみなさ れることになる。もしそうであれば、これらの種はAu. アウストラロピテクス(4-1.8 Ma)。Au. anamensis、Au. afarensis、Au. africanus、Au. bahrelghazali、Au. garhi、Au. sedibaが含まれる; ケニアントロプス(3-2.7 Ma)、K. platyops種を含む; パラントロプス(3-1.2 Ma)、種P. aethiopicus、P. boisei、P. robustusを含む。 新種アウストラロピテクス・デイレメダ(Australopithecus deyiremeda)は、アウストラロピテクス・アファレンシス(Au. afarensis)と同時代に生息していたことが発見されたと主張されている。アウストラロピテクス・デイレメダが新種なのか、それともアウストラロピ テクス・アファレンシスなのかについては議論がある[30]。リトルフットとして知られるアウストラロピテクス・プロメテウスは、最近、新しい年代測定技 術によって367万年前のものとされ、アウストラロピテクス属はアファレンシスと同じくらい古いものとなった[31]。リトルフットに見られる反対趾を考 えると、この標本はクライミングが得意であったようだ。この地域の夜間捕食動物を考えると、チンパンジーやゴリラと同じような方法で、夜間に木の上に巣を 作ったのではないかと考えられている。 |

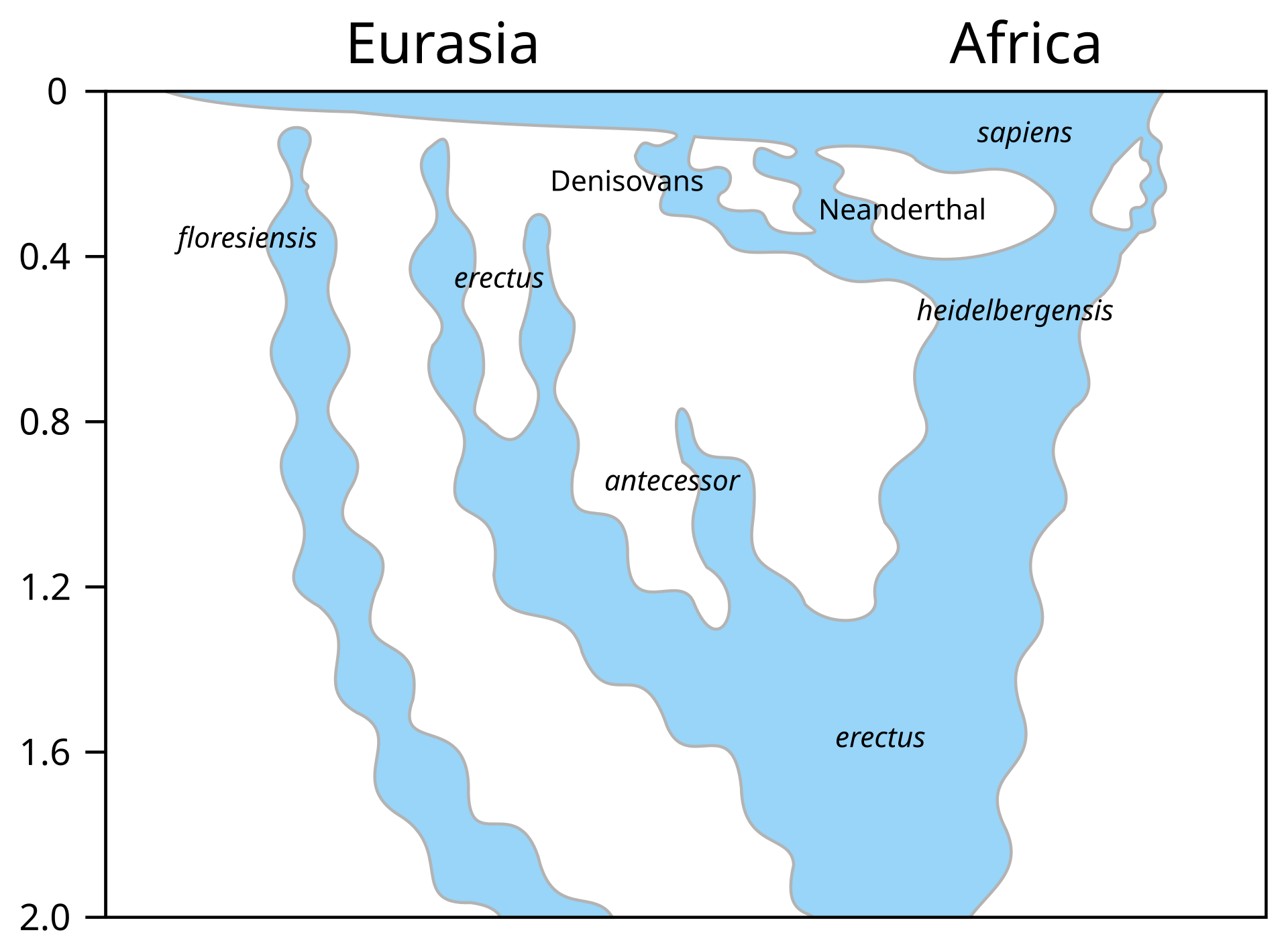

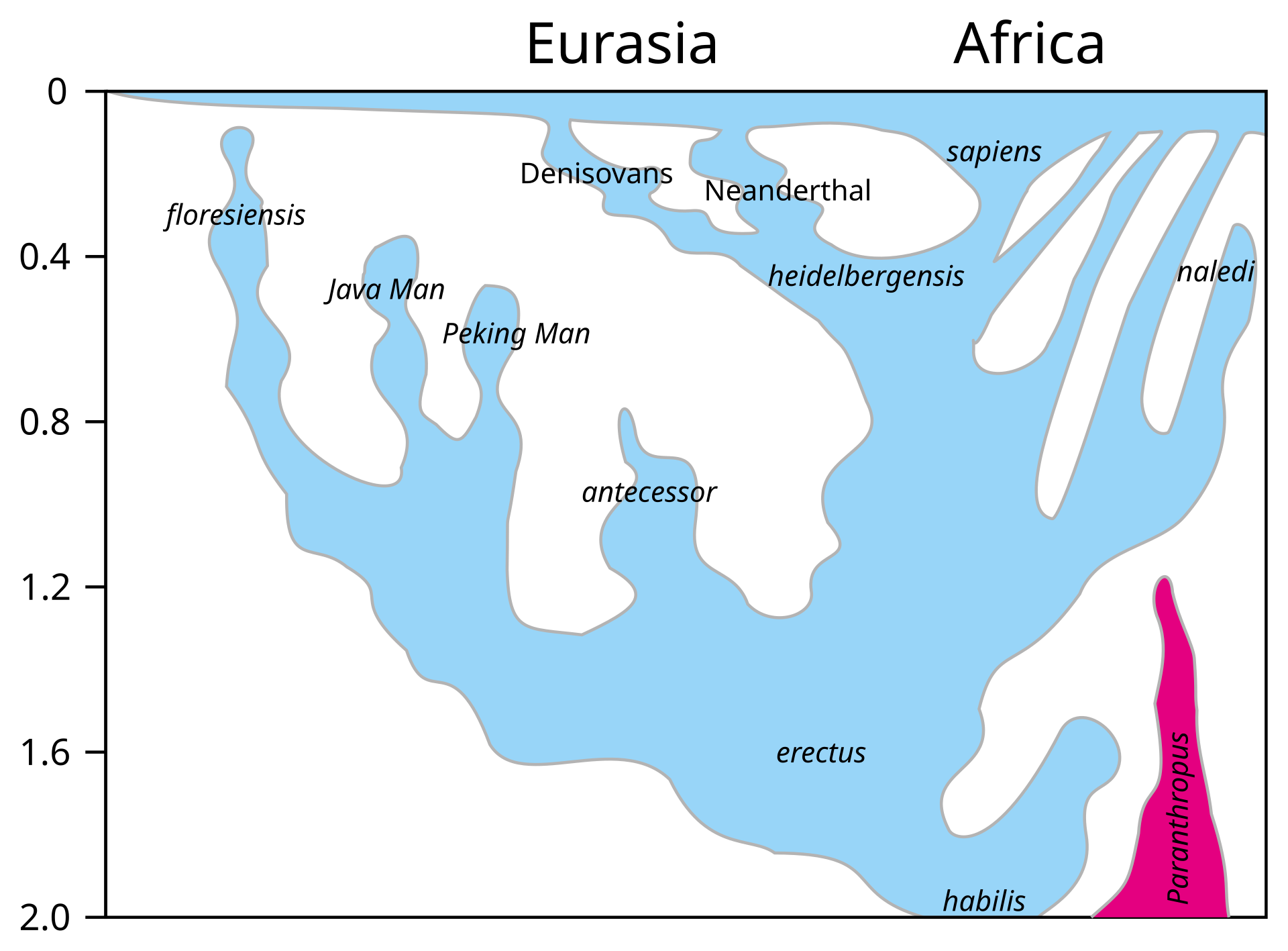

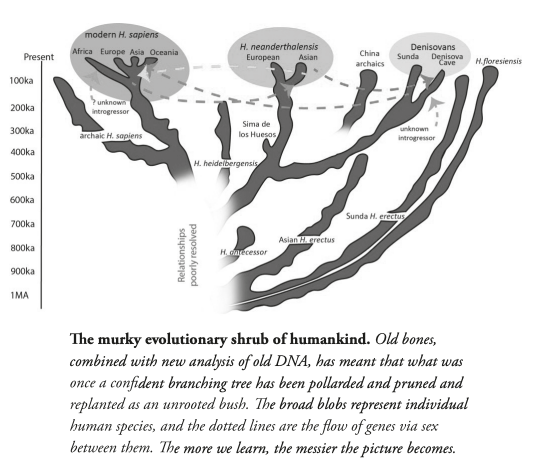

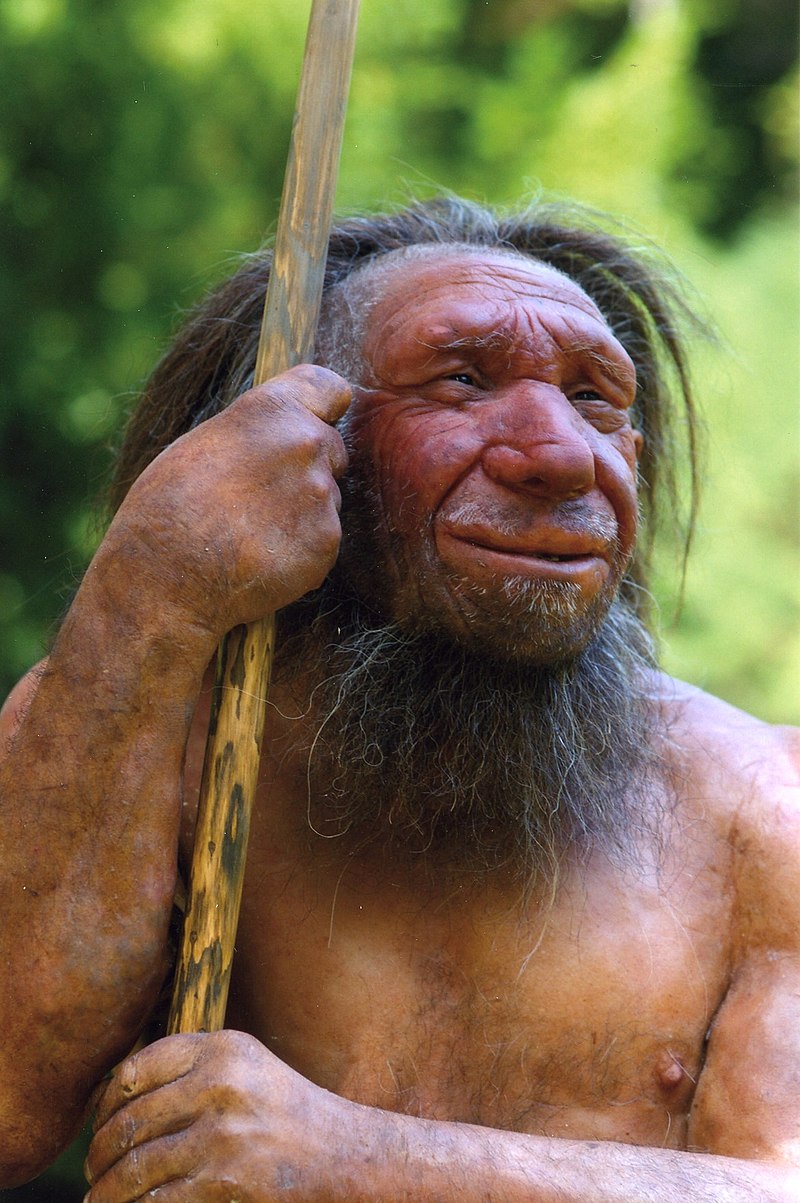

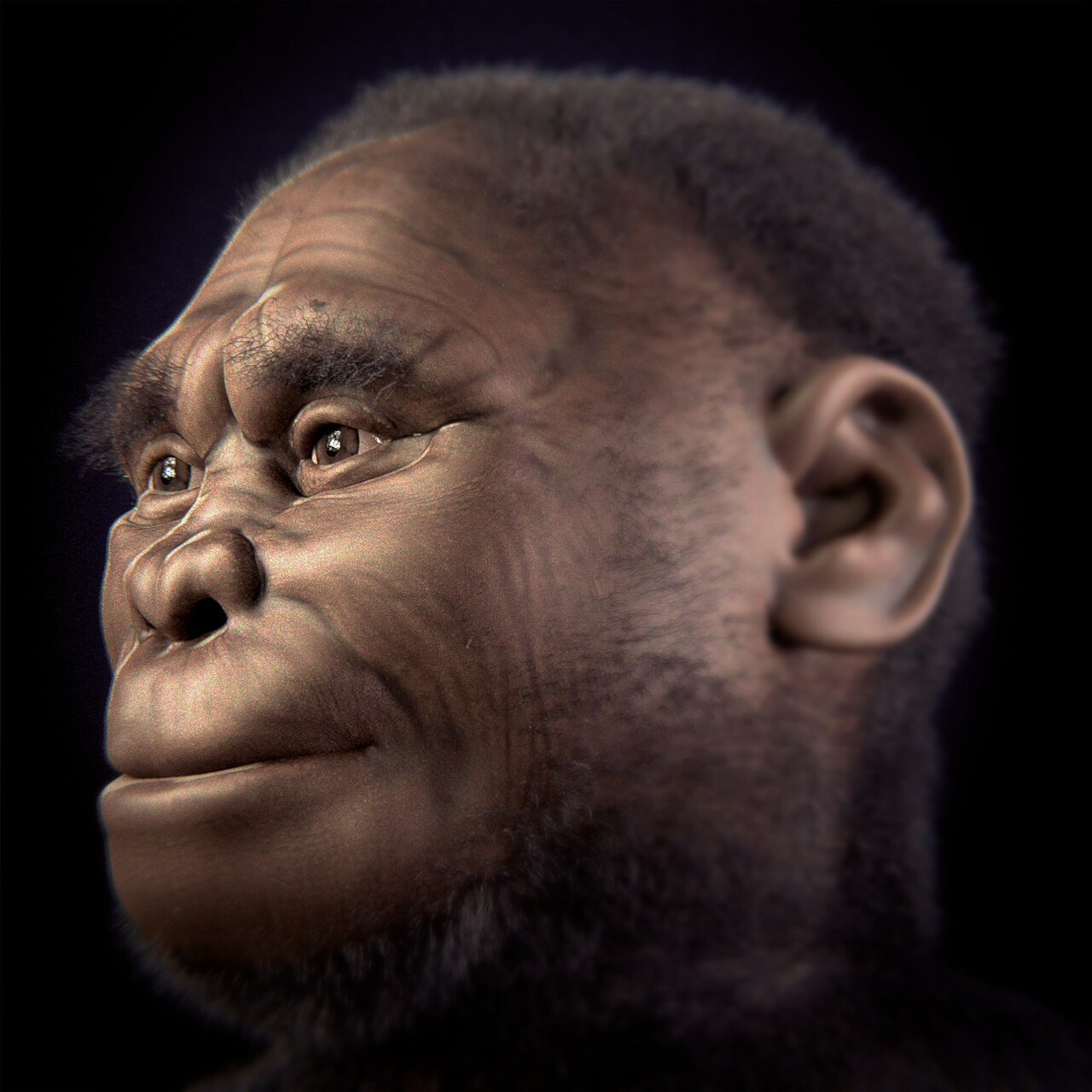

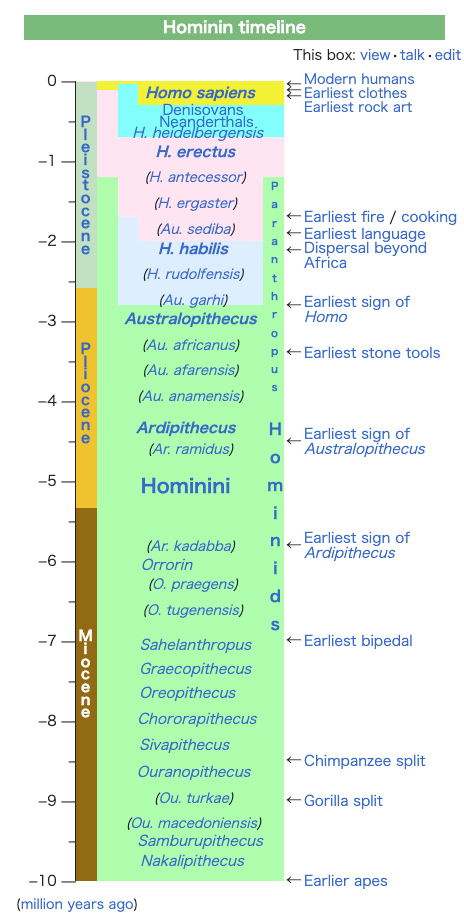

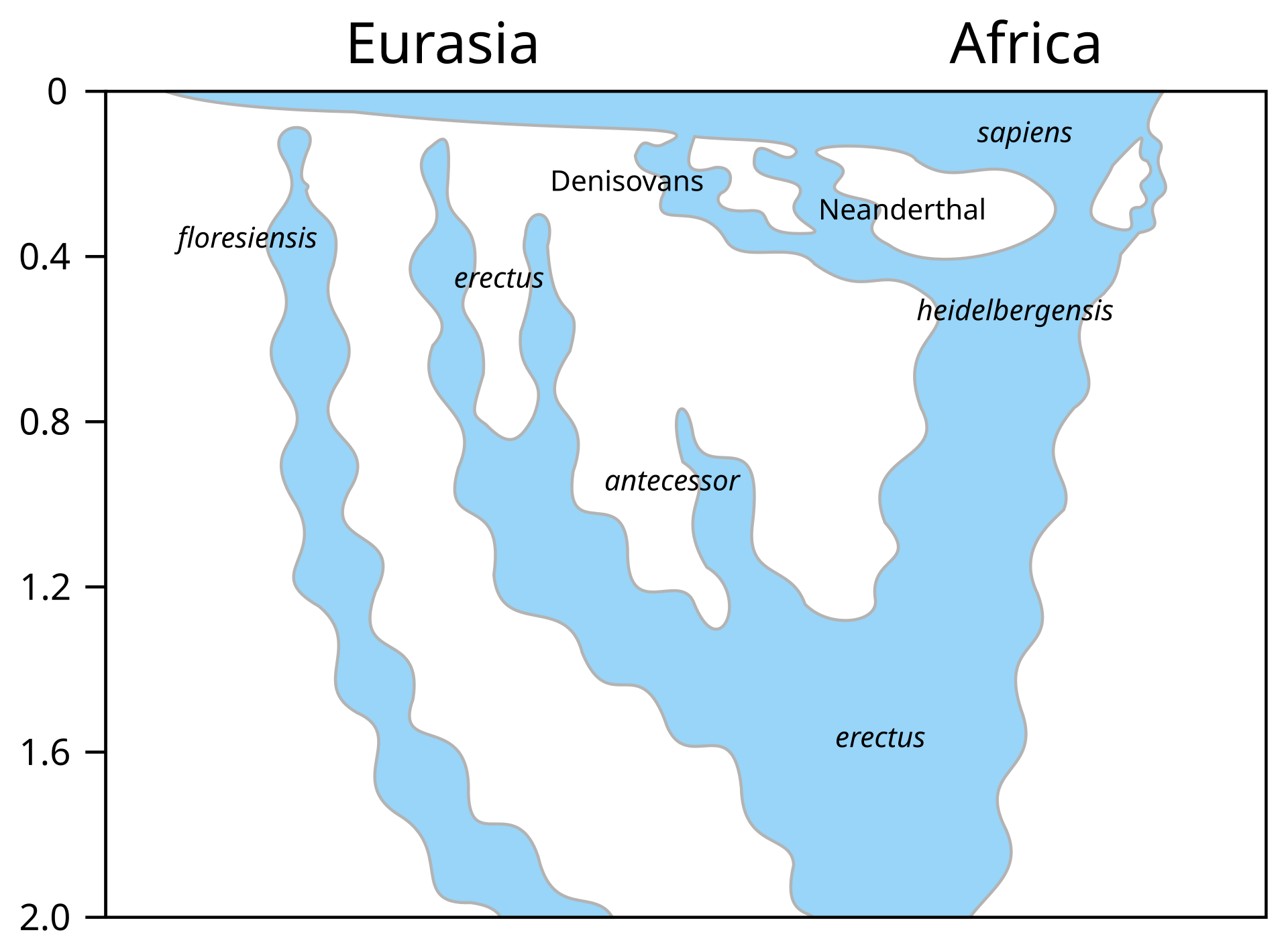

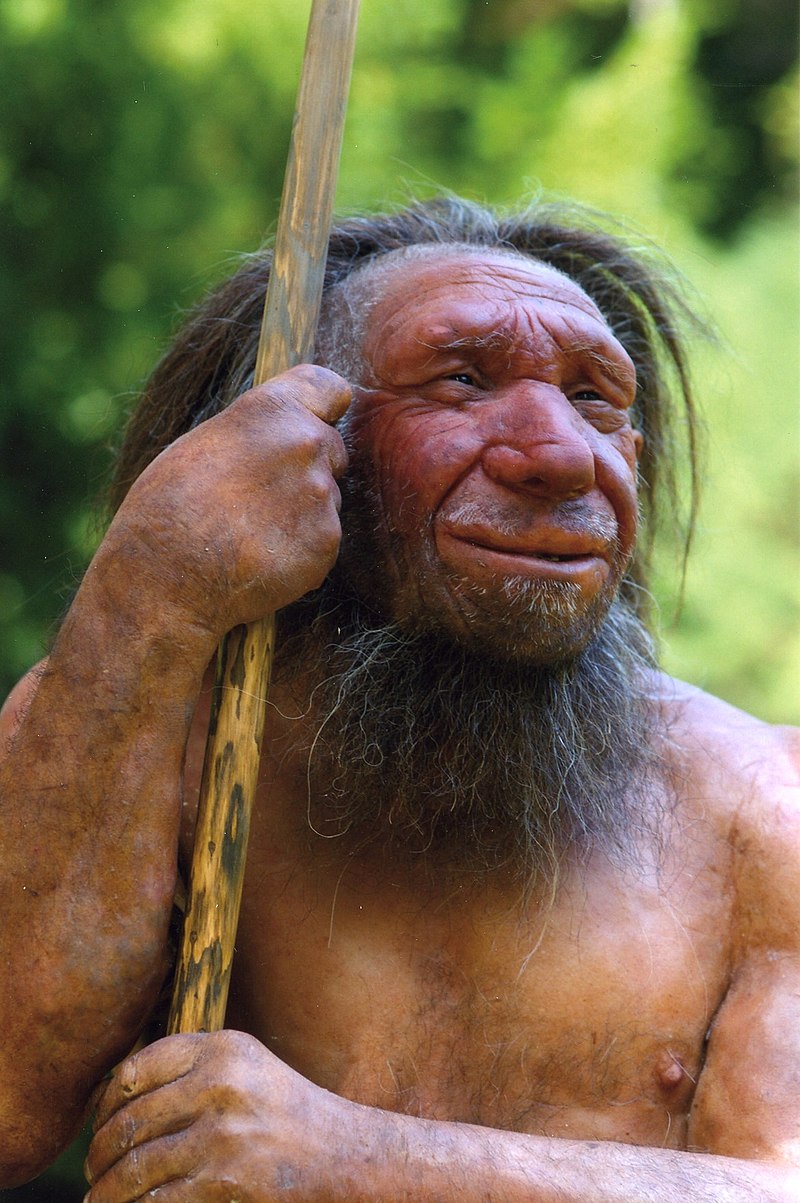

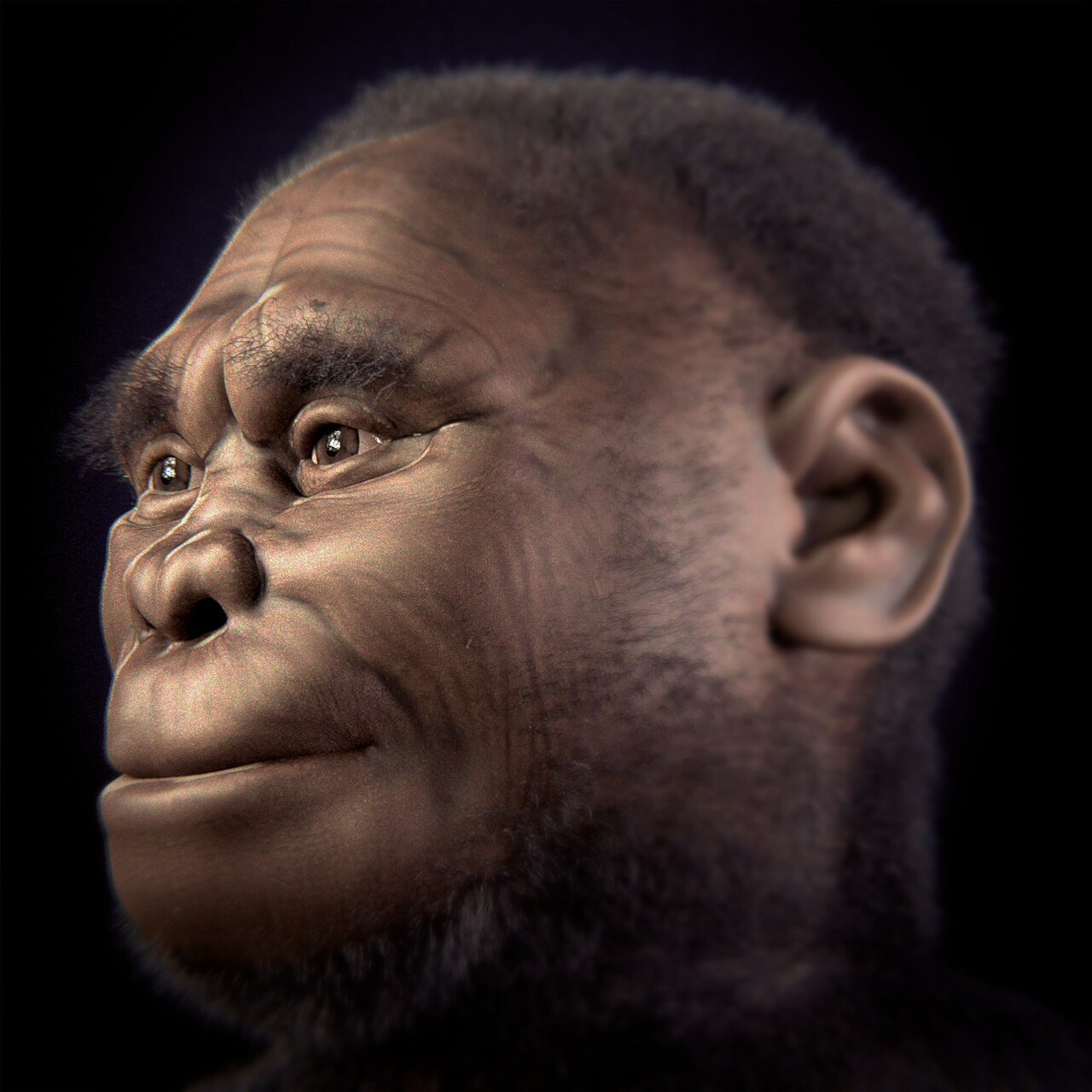

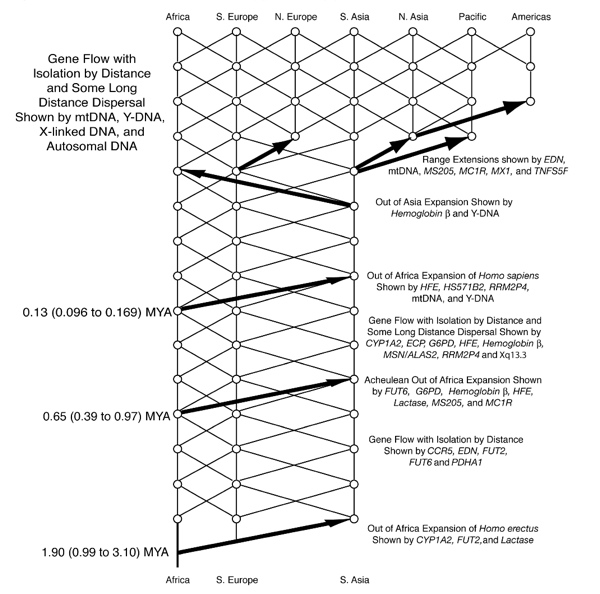

| Evolution of genus Homo Main article: Homo  The earliest documented representative of the genus Homo is Homo habilis, which evolved around 2.8 million years ago,[32] and is arguably the earliest species for which there is positive evidence of the use of stone tools. The brains of these early hominins were about the same size as that of a chimpanzee, although it has been suggested that this was the time in which the human SRGAP2 gene doubled, producing a more rapid wiring of the frontal cortex. During the next million years a process of rapid encephalization occurred, and with the arrival of Homo erectus and Homo ergaster in the fossil record, cranial capacity had doubled to 850 cm3.[33] (Such an increase in human brain size is equivalent to each generation having 125,000 more neurons than their parents.) It is believed that H. erectus and H. ergaster were the first to use fire and complex tools, and were the first of the hominin line to leave Africa, spreading throughout Africa, Asia, and Europe between 1.3 to 1.8 million years ago.  A model of the phylogeny of H. sapiens during the Middle Paleolithic. The horizontal axis represents geographic location; the vertical axis represents time in millions of years ago.[34] Homo heidelbergensis is shown as diverging into Neanderthals, Denisovans and H. sapiens. With the expansion of H. sapiens after 200 kya, Neanderthals, Denisovans and unspecified archaic African hominins are shown as again subsumed into the H. sapiens lineage. In addition, admixture events in modern African populations are indicated.  Hominin timeline  According to the recent African origin of modern humans theory, modern humans evolved in Africa possibly from H. heidelbergensis, H. rhodesiensis or H. antecessor and migrated out of the continent some 50,000 to 100,000 years ago, gradually replacing local populations of H. erectus, Denisova hominins, H. floresiensis, H. luzonensis and H. neanderthalensis.[35][36][37][38][39] Archaic Homo sapiens, the forerunner of anatomically modern humans, evolved in the Middle Paleolithic between 400,000 and 250,000 years ago.[40][41][42] Recent DNA evidence suggests that several haplotypes of Neanderthal origin are present among all non-African populations, and Neanderthals and other hominins, such as Denisovans, may have contributed up to 6% of their genome to present-day humans, suggestive of a limited interbreeding between these species.[43][44][45] The transition to behavioral modernity with the development of symbolic culture, language, and specialized lithic technology happened around 50,000 years ago, according to some anthropologists,[46] although others point to evidence that suggests that a gradual change in behavior took place over a longer time span.[47] Homo sapiens is the only extant species of its genus, Homo. While some (extinct) Homo species might have been ancestors of Homo sapiens, many, perhaps most, were likely "cousins", having speciated away from the ancestral hominin line.[48][49] There is yet no consensus as to which of these groups should be considered a separate species and which should be a subspecies; this may be due to the dearth of fossils or to the slight differences used to classify species in the genus Homo.[49] The Sahara pump theory (describing an occasionally passable "wet" Sahara desert) provides one possible explanation of the early variation in the genus Homo. Based on archaeological and paleontological evidence, it has been possible to infer, to some extent, the ancient dietary practices[50] of various Homo species and to study the role of diet in physical and behavioral evolution within Homo.[51][52][53][54][55] Some anthropologists and archaeologists subscribe to the Toba catastrophe theory, which posits that the supereruption of Lake Toba on Sumatran island in Indonesia some 70,000 years ago caused global consequences,[56] killing the majority of humans and creating a population bottleneck that affected the genetic inheritance of all humans today.[57] The genetic and archaeological evidence for this remains in question however.[58] Nonetheless, on 31 August 2023, researchers reported, based on genetic studies, that a human ancestor population bottleneck (from a possible 100,000 to 1000 individuals) occurred "around 930,000 and 813,000 years ago ... lasted for about 117,000 years and brought human ancestors close to extinction."[59][60] H. habilis and H. gautengensis Homo habilis lived from about 2.8[32] to 1.4 Ma. The species evolved in South and East Africa in the Late Pliocene or Early Pleistocene, 2.5–2 Ma, when it diverged from the australopithecines with the development of smaller molars and larger brains. One of the first known hominins, it made tools from stone and perhaps animal bones, leading to its name homo habilis (Latin 'handy man') bestowed by discoverer Louis Leakey. Some scientists have proposed moving this species from Homo into Australopithecus due to the morphology of its skeleton being more adapted to living in trees rather than walking on two legs like later hominins.[61] In May 2010, a new species, Homo gautengensis, was discovered in South Africa.[62] H. rudolfensis and H. georgicus These are proposed species names for fossils from about 1.9–1.6 Ma, whose relation to Homo habilis is not yet clear. Homo rudolfensis refers to a single, incomplete skull from Kenya. Scientists have suggested that this was a specimen of Homo habilis, but this has not been confirmed.[63] Homo georgicus, from Georgia, may be an intermediate form between Homo habilis and Homo erectus,[64] or a subspecies of Homo erectus.[65] H. ergaster and H. erectus  Reconstruction of Turkana boy who lived 1.5 to 1.6 million years ago The first fossils of Homo erectus were discovered by Dutch physician Eugene Dubois in 1891 on the Indonesian island of Java. He originally named the material Anthropopithecus erectus (1892–1893, considered at this point as a chimpanzee-like fossil primate) and Pithecanthropus erectus (1893–1894, changing his mind as of based on its morphology, which he considered to be intermediate between that of humans and apes).[66] Years later, in the 20th century, the German physician and paleoanthropologist Franz Weidenreich (1873–1948) compared in detail the characters of Dubois' Java Man, then named Pithecanthropus erectus, with the characters of the Peking Man, then named Sinanthropus pekinensis. Weidenreich concluded in 1940 that because of their anatomical similarity with modern humans it was necessary to gather all these specimens of Java and China in a single species of the genus Homo, the species H. erectus.[67][68] Homo erectus lived from about 1.8 Ma to about 70,000 years ago – which would indicate that they were probably wiped out by the Toba catastrophe; however, nearby H. floresiensis survived it. The early phase of H. erectus, from 1.8 to 1.25 Ma, is considered by some to be a separate species, H. ergaster, or as H. erectus ergaster, a subspecies of H. erectus. Many paleoanthropologists now use the term Homo ergaster for the non-Asian forms of this group, and reserve H. erectus only for those fossils that are found in Asia and meet certain skeletal and dental requirements which differ slightly from H. ergaster. In Africa in the Early Pleistocene, 1.5–1 Ma, some populations of Homo habilis are thought to have evolved larger brains and to have made more elaborate stone tools; these differences and others are sufficient for anthropologists to classify them as a new species, Homo erectus—in Africa.[69] The evolution of locking knees and the movement of the foramen magnum are thought to be likely drivers of the larger population changes. This species also may have used fire to cook meat. Richard Wrangham notes that Homo seems to have been ground dwelling, with reduced intestinal length, smaller dentition, and "brains [swollen] to their current, horrendously fuel-inefficient size",[70] and hypothesizes that control of fire and cooking, which released increased nutritional value, was the key adaptation that separated Homo from tree-sleeping Australopithecines.[71] See also: Control of fire by early humans H. cepranensis and H. antecessor These are proposed as species intermediate between H. erectus and H. heidelbergensis. H. antecessor is known from fossils from Spain and England that are dated 1.2 Ma–500 ka.[72][73] H. cepranensis refers to a single skull cap from Italy, estimated to be about 800,000 years old.[74] H. heidelbergensis Main article: Homo heidelbergensis H. heidelbergensis ("Heidelberg Man") lived from about 800,000 to about 300,000 years ago. Also proposed as Homo sapiens heidelbergensis or Homo sapiens paleohungaricus.[75] H. rhodesiensis, and the Gawis cranium H. rhodesiensis, estimated to be 300,000–125,000 years old. Most current researchers place Rhodesian Man within the group of Homo heidelbergensis, though other designations such as archaic Homo sapiens and Homo sapiens rhodesiensis have been proposed. In February 2006 a fossil, the Gawis cranium, was found which might possibly be a species intermediate between H. erectus and H. sapiens or one of many evolutionary dead ends. The skull from Gawis, Ethiopia, is believed to be 500,000–250,000 years old. Only summary details are known, and the finders have not yet released a peer-reviewed study. Gawis man's facial features suggest its being either an intermediate species or an example of a "Bodo man" female.[76] Neanderthal and Denisovan Main articles: Neanderthal and Denisovan  Reconstruction of an elderly Neanderthal man Homo neanderthalensis, alternatively designated as Homo sapiens neanderthalensis,[77] lived in Europe and Asia from 400,000[78] to about 28,000 years ago.[79] There are a number of clear anatomical differences between anatomically modern humans (AMH) and Neanderthal specimens, many relating to the superior Neanderthal adaptation to cold environments. Neanderthal surface to volume ratio was even lower than that among modern Inuit populations, indicating superior retention of body heat. Neanderthals also had significantly larger brains, as shown from brain endocasts, casting doubt on their intellectual inferiority to modern humans. However, the higher body mass of Neanderthals may have required larger brain mass for body control.[80] Also, recent research by Pearce, Stringer, and Dunbar has shown important differences in brain architecture. The larger size of the Neanderthal orbital chamber and occipital lobe suggests that they had a better visual acuity than modern humans, useful in the dimmer light of glacial Europe. Neanderthals may have had less brain capacity available for social functions. Inferring social group size from endocranial volume (minus occipital lobe size) suggests that Neanderthal groups may have been limited to 120 individuals, compared to 144 possible relationships for modern humans. Larger social groups could imply that modern humans had less risk of inbreeding within their clan, trade over larger areas (confirmed in the distribution of stone tools), and faster spread of social and technological innovations. All these may have all contributed to modern Homo sapiens replacing Neanderthal populations by 28,000 BP.[80] Earlier evidence from sequencing mitochondrial DNA suggested that no significant gene flow occurred between H. neanderthalensis and H. sapiens, and that the two were separate species that shared a common ancestor about 660,000 years ago.[81][82][83] However, a sequencing of the Neanderthal genome in 2010 indicated that Neanderthals did indeed interbreed with anatomically modern humans c. 45,000-80,000 years ago, around the time modern humans migrated out from Africa, but before they dispersed throughout Europe, Asia and elsewhere.[84] The genetic sequencing of a 40,000-year-old human skeleton from Romania showed that 11% of its genome was Neanderthal, implying the individual had a Neanderthal ancestor 4–6 generations previously,[85] in addition to a contribution from earlier interbreeding in the Middle East. Though this interbred Romanian population seems not to have been ancestral to modern humans, the finding indicates that interbreeding happened repeatedly.[86] All modern non-African humans have about 1% to 4% (or 1.5% to 2.6% by more recent data) of their DNA derived from Neanderthals.[87][84][88] This finding is consistent with recent studies indicating that the divergence of some human alleles dates to one Ma, although this interpretation has been questioned.[89][90] Neanderthals and AMH Homo sapiens could have co-existed in Europe for as long as 10,000 years, during which AMH populations exploded, vastly outnumbering Neanderthals, possibly outcompeting them by sheer numbers.[91] In 2008, archaeologists working at the site of Denisova Cave in the Altai Mountains of Siberia uncovered a small bone fragment from the fifth finger of a juvenile member of another human species, the Denisovans.[92] Artifacts, including a bracelet, excavated in the cave at the same level were carbon dated to around 40,000 BP. As DNA had survived in the fossil fragment due to the cool climate of the Denisova Cave, both mtDNA and nuclear DNA were sequenced.[43][93] While the divergence point of the mtDNA was unexpectedly deep in time,[94] the full genomic sequence suggested the Denisovans belonged to the same lineage as Neanderthals, with the two diverging shortly after their line split from the lineage that gave rise to modern humans.[43] Modern humans are known to have overlapped with Neanderthals in Europe and the Near East for possibly more than 40,000 years,[95] and the discovery raises the possibility that Neanderthals, Denisovans, and modern humans may have co-existed and interbred. The existence of this distant branch creates a much more complex picture of humankind during the Late Pleistocene than previously thought.[93][96] Evidence has also been found that as much as 6% of the DNA of some modern Melanesians derive from Denisovans, indicating limited interbreeding in Southeast Asia.[97][98] Alleles thought to have originated in Neanderthals and Denisovans have been identified at several genetic loci in the genomes of modern humans outside Africa. HLA haplotypes from Denisovans and Neanderthal represent more than half the HLA alleles of modern Eurasians,[45] indicating strong positive selection for these introgressed alleles. Corinne Simoneti at Vanderbilt University, in Nashville and her team have found from medical records of 28,000 people of European descent that the presence of Neanderthal DNA segments may be associated with a higher rate of depression.[99] The flow of genes from Neanderthal populations to modern humans was not all one way. Sergi Castellano of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology reported in 2016 that while Denisovan and Neanderthal genomes are more related to each other than they are to us, Siberian Neanderthal genomes show more similarity to modern human genes than do European Neanderthal populations. This suggests Neanderthal populations interbred with modern humans around 100,000 years ago, probably somewhere in the Near East.[100] Studies of a Neanderthal child at Gibraltar show from brain development and tooth eruption that Neanderthal children may have matured more rapidly than Homo sapiens.[101] H. floresiensis Main article: Homo floresiensis  A facial reconstruction of Homo floresiensis H. floresiensis, which lived from approximately 190,000 to 50,000 years before present (BP), has been nicknamed the hobbit for its small size, possibly a result of insular dwarfism.[102] H. floresiensis is intriguing both for its size and its age, being an example of a recent species of the genus Homo that exhibits derived traits not shared with modern humans. In other words, H. floresiensis shares a common ancestor with modern humans, but split from the modern human lineage and followed a distinct evolutionary path. The main find was a skeleton believed to be a woman of about 30 years of age. Found in 2003, it has been dated to approximately 18,000 years old. The living woman was estimated to be one meter in height, with a brain volume of just 380 cm3 (considered small for a chimpanzee and less than a third of the H. sapiens average of 1400 cm3).[102] However, there is an ongoing debate over whether H. floresiensis is indeed a separate species.[103] Some scientists hold that H. floresiensis was a modern H. sapiens with pathological dwarfism.[104] This hypothesis is supported in part, because some modern humans who live on Flores, the Indonesian island where the skeleton was found, are pygmies. This, coupled with pathological dwarfism, could have resulted in a significantly diminutive human. The other major attack on H. floresiensis as a separate species is that it was found with tools only associated with H. sapiens.[104] The hypothesis of pathological dwarfism, however, fails to explain additional anatomical features that are unlike those of modern humans (diseased or not) but much like those of ancient members of our genus. Aside from cranial features, these features include the form of bones in the wrist, forearm, shoulder, knees, and feet. Additionally, this hypothesis fails to explain the find of multiple examples of individuals with these same characteristics, indicating they were common to a large population, and not limited to one individual.[103] In 2016, fossil teeth and a partial jaw from hominins assumed to be ancestral to H. floresiensis were discovered[105] at Mata Menge, about 74 km (46 mi) from Liang Bua. They date to about 700,000 years ago[106] and are noted by Australian archaeologist Gerrit van den Bergh for being even smaller than the later fossils.[107] H. luzonensis Main article: Homo luzonensis A small number of specimens from the island of Luzon, dated 50,000 to 67,000 years ago, have recently been assigned by their discoverers, based on dental characteristics, to a novel human species, H. luzonensis.[108] H. sapiens Main articles: Archaic humans, Early modern human, Archaic human admixture with modern humans, and Human § Evolution  Reconstruction of early Homo sapiens from Jebel Irhoud, Morocco c. 315 000 years BP H. sapiens (the adjective sapiens is Latin for "wise" or "intelligent") emerged in Africa around 300,000 years ago, likely derived from H. heidelbergensis or a related lineage.[109][110] In September 2019, scientists reported the computerized determination, based on 260 CT scans, of a virtual skull shape of the last common human ancestor to modern humans/H. sapiens, representative of the earliest modern humans, and suggested that modern humans arose between 260,000 and 350,000 years ago through a merging of populations in East and South Africa.[111][112] Between 400,000 years ago and the second interglacial period in the Middle Pleistocene, around 250,000 years ago, the trend in intra-cranial volume expansion and the elaboration of stone tool technologies developed, providing evidence for a transition from H. erectus to H. sapiens. The direct evidence suggests there was a migration of H. erectus out of Africa, then a further speciation of H. sapiens from H. erectus in Africa. A subsequent migration (both within and out of Africa) eventually replaced the earlier dispersed H. erectus. This migration and origin theory is usually referred to as the "recent single-origin hypothesis" or "out of Africa" theory. H. sapiens interbred with archaic humans both in Africa and in Eurasia, in Eurasia notably with Neanderthals and Denisovans.[43][97] The Toba catastrophe theory, which postulates a population bottleneck for H. sapiens about 70,000 years ago,[113] was controversial from its first proposal in the 1990s and by the 2010s had very little support.[114] Distinctive human genetic variability has arisen as the result of the founder effect, by archaic admixture and by recent evolutionary pressures. |

ホモ属の進化 主な記事 ホモ属  ホモ属の最古の記録はホモ・ハビリス(Homo habilis)であり、約280万年前に進化した[32]。初期のホミニンの脳はチンパンジーとほぼ同じ大きさであったが、この時期にヒトの SRGAP2遺伝子が倍増し、前頭皮質の配線がより急速に進んだことが示唆されている。その後100万年の間に、急速な脳化のプロセスが起こり、化石記録 にホモ・エレクトスとホモ・エルガスターが登場する頃には、頭蓋の容量は2倍の850cm3になっていた[33](ヒトの脳サイズがこれほど大きくなると いうことは、各世代が親世代よりも12万5,000個多くのニューロンを持つことに相当する)。H.エレクタスとH.エルガスターは、火と複雑な道具を使 用した最初の人類であり、130万年から180万年前にアフリカ、アジア、ヨーロッパに広がった、アフリカを出た最初の人類であったと考えられている。  中期旧石器時代のサピエンス系統のモデル。横軸は地理的位置を表し、縦軸は数百万年前の時間を表す[34]。ホモ・ハイデルベルゲンシスはネアンデルター ル人、デニソワ人、サピエンスに分岐したことが示されている。200kya以降のサピエンス・ホモの拡大により、ネアンデルタール人、デニソワ人、そして 特定されていないアフリカの古人類が再びサピエンス・ホモの系統に組み込まれたことが示されている。さらに、現代のアフリカ人集団における混血事象が示さ れている。  ヒトの年表  最近の現生人類のアフリカ起源説によると、現生人類はアフリカでハイデルベルゲンシス、ローデシエンシス、またはアンテセサーから進化し、約5万年から 10万年前にアフリカ大陸から移動し、徐々に現地のH. エレクトゥス、デニソワ・ホミニン、フロレシエンシス、ルゾネンシス、ネアンデルタール人などの地域個体群に徐々に取って代わった。[35][36] [37][38][39] 解剖学的に現生人類の前身であるアルカイック・ホモ・サピエンスは、40万年から25万年前の中期旧石器時代に進化した。 [40][41][42]最近のDNAの証拠によると、ネアンデルタール人由来のいくつかのハプロタイプがアフリカ以外のすべての集団に存在し、ネアンデ ルタール人やデニソワ人などの他のヒト科の動物はゲノムの最大6%を現生人類に寄与した可能性があり、これらの種間の交雑が限られていたことを示唆してい る。 [象徴文化、言語、特殊な石器技術の発達を伴う行動的近代性への移行は、一部の人類学者によれば約5万年前に起こったとされているが[46]、もっと長い スパンで徐々に行動が変化したことを示唆する証拠を指摘する者もいる[47]。 ホモ・サピエンスは、ホモ属の現存する唯一の種である。いくつかの(絶滅した)ホモ属の種はホモ・サピエンスの祖先であったかもしれないが、多くの(おそ らくほとんどの)種は、祖先のヒトの系統から離れて種分化した「いとこ」であった可能性が高い。 [48][49]これらのグループのどれを別種と見なし、どれを亜種と見なすべきかについては、まだコンセンサスが得られていない。これは化石が少ないた めか、ホモ属の種を分類するために使用されるわずかな違いのためかもしれない[49]。サハラポンプ説(時折通行可能な「湿った」サハラ砂漠を説明する) は、ホモ属の初期の変異の1つの可能な説明を提供する。 考古学的・古生物学的証拠に基づいて、様々なホモ属の古代の食習慣[50]をある程度推測することが可能であり、ホモ属内の身体的・行動的進化における食 の役割を研究することが可能である[51][52][53][54][55]。 人類学者や考古学者の中には、約7万年前にインドネシアのスマトラ島で起きたトバ湖の大噴火が世界的な影響を引き起こし、人類の大多数が死亡し、今日の全 人類の遺伝的継承に影響を与える人口ボトルネックを作り出したとするトバ大災害説を支持する者もいる[56]。 [57]しかし、その遺伝学的・考古学的証拠には疑問が残る[58]。それにもかかわらず、2023年8月31日、研究者たちは遺伝学的研究に基づいて、 ヒトの祖先の集団ボトルネック(10万から1000個体の可能性から)が「約93万年前と81万3000年前に起こり......約11万7000年間続 き、ヒトの祖先を絶滅に近づけた」と報告した[59][60]。 ホモ・ハビリスとハウテンエンシス ホモ・ハビリスは約2.8[32]~1.4Maに生息していた。この種は鮮新世後期または更新世前期、2.5-2 Maに南アフリカと東アフリカで進化し、より小さな臼歯とより大きな脳の発達によってアウストラロピテクスから分岐した。発見者ルイス・リーキーがホモ・ ハビリス(ラテン語で「便利な人」)と命名した。一部の科学者は、この種の骨格の形態が後のホミニンのような二足歩行よりもむしろ樹上生活に適応している ことから、ホモからアウストラロピテクスに移すことを提案している[61]。 2010年5月、南アフリカで新種のホモ・ガウテンゲンシスが発見された[62]。 ホモ・ルドルフェンシス(H. rudolfensis)とホモ・ジオルギカス(H. georgicus これらは約1.9-1.6Maの化石の種名候補であり、ホモ・ハビリスとの関係はまだ明らかではない。 ホモ・ルドルフェンシスは、ケニアで発見された1つの不完全な頭蓋骨を指す。科学者たちは、これがホモ・ハビリスの標本であると示唆しているが、確認はさ れていない[63]。 グルジアから出土したホモ・ジオルギカスは、ホモ・ハビリスとホモ・エレクトスの中間型[64]、あるいはホモ・エレクトスの亜種である可能性がある [65]。 エルガスターとホモ・エレクタス  150万年から160万年前に生きていたトゥルカナの少年の復元像 ホモ・エレクトスの最初の化石は、1891年にオランダ人医師ユージン・デュボアによってインドネシアのジャワ島で発見された。彼は当初、この化石をチン パンジーのような霊長類の化石と考え、Anthropopithecus erectus(1892-1893)とPithecanthropus erectus(1893-1894)と命名した。 [66]数年後の20世紀、ドイツの医師で古人類学者のフランツ・ヴァイデンライヒ(1873-1948)は、当時ピテカントロプス・エレクトスと名付け られたデュボアのジャワ人と、当時シナントロプス・ペキネンシスと名付けられた北京人の特徴を詳細に比較した。ヴァイデンライヒは1940年に、現代人と の解剖学的類似性から、ジャワと中国のこれらの標本すべてをホモ属の単一種、H. erectusに集める必要があると結論づけた[67][68]。 ホモ・エレクトスは、約1.8 Maから約7万年前まで生息していた。これは、彼らがおそらくトバ大災害によって絶滅したことを示している。1.8Maから1.25MaまでのH.エレク タスの初期段階は、別種であるH.エルガスター、あるいはH.エレクタスの亜種であるH.エルガスターと考える人もいる。現在、多くの古人類学者は、この グループの非アジア型にホモ・エルガスターという用語を使い、アジアで発見され、エルガスターとはわずかに異なる骨格や歯列の条件を満たす化石にのみ、ホ モ・エレクトスを保留している。 アフリカの更新世前期、1.5-1 Maにおいて、ホモ・ハビリスのいくつかの集団は、より大きな脳を進化させ、より精巧な石器を作ったと考えられている。これらの違いや他の違いは、人類学 者がアフリカでホモ・エレクトスという新種に分類するのに十分なものである[69]。ロッキング膝の進化と大後頭孔の移動が、より大きな集団の変化の原動 力になったと考えられている。この種はまた、肉を調理するために火を使っていた可能性もある。リチャード・ウランガムは、ホモは地面に住んでいたようで、 腸の長さが短く、歯列が小さく、「脳が(現在の恐ろしいほど燃料効率の悪いサイズに)膨張していた」[70]と指摘し、栄養価を高める火と調理のコント ロールが、ホモと樹上で眠るアウストラロピテクスを分けた重要な適応であったと仮説を立てている[71]。 こちらも参照: 初期人類による火のコントロール H.セプラネンシスとH.アンテセソール これらはH. erectusとH. heidelbergensisの中間種として提唱されている。 H. antecessorはスペインとイングランドの化石から知られており、その年代は1.2 Ma-500 kaである[72][73]。 H.セプラネンシスはイタリアから産出した単一の頭蓋を指し、約80万年前のものと推定されている[74]。 ハイデルベルゲンシス 主な記事 ホモ・ハイデルベルゲンシス ハイデルベルク人(H. heidelbergensis)は、約80万年前から約30万年前まで生息していた。ホモ・サピエンス・ハイデルベルゲンシスまたはホモ・サピエンス・ パレオフンガリカスとしても提唱されている[75]。 H.ローデシエンシスとガウィス頭蓋 30万~125万年前のものと推定されるH. 現在の研究者の多くは、ローデシア人をホモ・ハイデルベルゲンシスのグループに分類しているが、古代のホモ・サピエンスやホモ・サピエンス・ローデシエン シスといった他の呼称も提案されている。 2006年2月、H.エレクトゥスとH.サピエンスの中間種、あるいは進化の行き詰まりのひとつである可能性のある化石、ガウィス頭蓋が発見された。エチ オピアのガウィスで発見された頭蓋骨は、50万年から25万年前のものと考えられている。詳細については概略しかわかっておらず、発見者はまだ査読付きの 研究を発表していない。ガウィス人の顔の特徴は、中間種か「ボド人」女性の一例であることを示唆している[76]。 ネアンデルタール人とデニソワ人 主な記事 ネアンデルタール人とデニソワ人  高齢のネアンデルタール人の復元 ホモ・サピエンス・ネアンデルターレンシスとも呼ばれるホモ・ネアンデルターレンシスは[77]、40万年[78]から約2万8千年前までヨーロッパとア ジアに住んでいた[79]。解剖学的に現生人類(AMH)とネアンデルタール人の標本の間には、多くの明確な解剖学的違いがあり、その多くはネアンデル タール人の寒冷環境への優れた適応に関連している。ネアンデルタール人の体表面容積比は、現代のイヌイット集団の体表面容積比よりもさらに低く、体温保持 に優れていることを示している。 ネアンデルタール人はまた、脳内鋳型から示されるように脳が著しく大きく、現代人より知的能力が劣っていたことに疑問を投げかけている。しかし、ネアンデ ルタール人の体格が大きかったため、体をコントロールするために脳の大きさが必要であった可能性がある[80]。また、ピアース、ストリンガー、ダンバー による最近の研究では、脳の構造における重要な違いが示されている。ネアンデルタール人の眼窩室と後頭葉の大きさは、彼らが現代人よりも優れた視力を持っ ていたことを示唆している。 ネアンデルタール人は社会的機能に使える脳の容量が少なかったのかもしれない。後頭葉の大きさを差し引いた頭蓋内容積から社会集団の大きさを推測すると、 ネアンデルタール人の集団は120人に限られていた可能性がある。より大きな社会集団は、現生人類が一族内での近親交配のリスクをより少なくし、より広い 地域で交易を行い(石器の分布で確認される)、社会的・技術的革新をより早く広めたことを意味する可能性がある。これらすべてが、28,000BPまでに ネアンデルタール人の集団を現代のホモ・サピエンスが置き換えることに貢献した可能性がある[80]。 ミトコンドリアDNAの塩基配列決定から得られた以前の証拠では、ネアンデルタール人とサピエンス人の間に有意な遺伝子流動は起こらず、両者は約66万年 前に共通の祖先を共有した別個の種であると示唆されていた[81][82][83]。しかし、2010年に行われたネアンデルタール人ゲノムの塩基配列決 定によって、ネアンデルタール人は解剖学的に現生人類と約45,000~80,000年前に実際に交雑していたことが示された。ルーマニアの4万年前の人 骨の遺伝子配列決定では、ゲノムの11%がネアンデルタール人であったことから、この個体には4~6世代前にネアンデルタール人の祖先がいたことが示唆さ れた[85]。この交雑したルーマニアの集団は現生人類の祖先ではないようだが、この発見は交雑が繰り返し起こったことを示している[86]。 アフリカ系以外の現生人類はすべて、ネアンデルタール人由来のDNAを約1%から4%(より最近のデータでは1.5%から2.6%)持っている[87] [84][88]。この発見は、いくつかのヒトの対立遺伝子の分岐が1Maまでさかのぼることを示す最近の研究と一致しているが、この解釈には疑問が投げ かけられている[89][90]。 [89][90] ネアンデルタール人とAMHホモ・サピエンスはヨーロッパで10,000年もの間共存していた可能性があり、その間にAMHの個体群が爆発的に増加し、ネ アンデルタール人を圧倒的に上回った。 2008年、シベリアのアルタイ山脈にあるデニソワ洞窟の遺跡で、考古学者が別の人類であるデニソワ人の第5指の小さな骨片を発見した。デニソワ洞窟の冷 涼な気候のため、化石の断片にDNAが残存していたため、mtDNAと核DNAの両方の塩基配列が決定された[43][93]。 mtDNAの分岐点は予想外に深い時期であったが[94]、全ゲノム配列はデニソワ人がネアンデルタール人と同じ系統に属し、両者は現生人類を生み出した 系統から分岐した直後に分岐したことを示唆した。 [この発見は、ネアンデルタール人、デニソワ人、現生人類が共存し、交雑していた可能性を提起している。この遠い支流の存在は、後期更新世における人類に ついて、これまで考えられていたよりもはるかに複雑な図式を作り出している[93][96]。現代のメラネシア人のDNAの6%もがデニソワ人に由来する という証拠も見つかっており、これは東南アジアにおける交雑が限定的であったことを示している[97][98]。 ネアンデルタール人やデニソワ人に由来すると考えられているアレルは、アフリカ以外の現生人類のゲノムのいくつかの遺伝子座で同定されている。デニソワ人 とネアンデルタール人由来のHLAハプロタイプは、現代ユーラシア人のHLA対立遺伝子の半分以上を占めており[45]、これらの移入対立遺伝子に対する 強い正の選択を示している。ナッシュビルにあるヴァンダービルト大学のコリン・シモネティとその研究チームは、ヨーロッパ系の28,000人の医療記録か ら、ネアンデルタール人のDNAセグメントが存在すると、うつ病の発症率が高くなる可能性があることを発見した[99]。 ネアンデルタール人から現生人類への遺伝子の流れは一方通行ではなかった。マックス・プランク進化人類学研究所のセルジ・カステラノが2016年に報告し たところによると、デニソワ人とネアンデルタール人のゲノムは我々よりも近縁であるが、シベリアのネアンデルタール人ゲノムはヨーロッパのネアンデルター ル人集団よりも現生人類の遺伝子との類似性を示している。このことは、ネアンデルタール人集団が10万年ほど前、おそらく近東のどこかで現生人類と交雑し たことを示唆している[100]。 ジブラルタルでのネアンデルタール人の子供の研究は、脳の発達と歯の萌出から、ネアンデルタール人の子供がホモ・サピエンスよりも急速に成熟した可能性を 示している[101]。 フロレシエンシス 主な記事 ホモ・フローレシエンシス  ホモ・フローレシエンシスの顔の復元図 ホモ・フローレシエンシスは、およそ19万年前から5万年前まで生息していたホモ属の一種で、その小ささからホビットというニックネームで呼ばれている。 言い換えれば、フロレシエンシスは現生人類と共通の祖先を持つが、現生人類の系統から分かれ、独自の進化の道をたどったということである。主な発見は、 30歳前後の女性と思われる骨格標本である。2003年に発見され、およそ18,000年前のものと推定されている。生きていた女性の身長は1メートル、 脳の容積はわずか380cm3(チンパンジーとしては小さく、H.サピエンスの平均1400cm3の3分の1以下と考えられている)と推定された [102]。 しかし、H.フローレシエンシスが本当に別種であるかどうかについては議論が続いている[103]。一部の科学者は、H.フローレシエンシスは病的な小人 症を持つ現代のH.サピエンスであると主張している[104]。この仮説は、骨格が発見されたインドネシアのフローレス島に住む現代人の一部がピグミーで あることから、一部支持されている。これは病的な小人症と相まって、著しく小柄な人類を生み出した可能性がある。H.フロレシエンシスを別種とするもう一 つの大きな攻撃は、それがH.サピエンスとしか結びつかない道具を持って発見されたことである[104]。 しかし、病的な小人症という仮説は、現代人(病気の有無にかかわらず)とは異なり、私たちの属の古代のメンバーとはよく似た、さらなる解剖学的特徴を説明 することができない。頭蓋の特徴は別として、手首、前腕、肩、膝、足の骨の形などである。加えて、この仮説は、これらの同じ特徴を持つ個体が複数発見され たことを説明することができず、それらが1つの個体に限定されたものではなく、大規模な集団に共通するものであったことを示している[103]。 2016年、リャン・ブアから約74km(46マイル)離れたマタ・メンゲで、フロレシエンシスの祖先と想定されるヒト科の動物の歯の化石と顎の一部が発 見された[105]。それらは約70万年前のものであり[106]、オーストラリアの考古学者Gerrit van den Berghによって、後の化石よりもさらに小さいことが指摘されている[107]。 ルソンエンシス 主な記事 ホモ・ルツォネンシス 50,000年から67,000年前にルソン島で発見された少数の標本は、発見者たちによって、歯の特徴から新種の人類であるH. サピエンス 主な記事 主な記事:古期人類、初期現生人類、古期人類と現生人類の混血、および人類§進化。  315,000年前、モロッコのジェベル・イルフードで発見された初期ホモ・サピエンスの復元。 ホモ・サピエンス(サピエンスという形容詞はラテン語で「賢明な」「知的な」を意味する)は、約30万年前にアフリカで出現し、おそらくH. ハイデルベルゲンシスまたはその近縁系統に由来する[109][110]。 2019年9月、科学者たちは、260のCTスキャンに基づいて、現生人類/H. サピエンスに共通する最後の人類の祖先の仮想的な頭蓋骨の形状をコンピューターで決定したことを報告した。sapiens、最古の現生人類の代表であり、 現生人類は東アフリカと南アフリカにおける集団の合併を通じて26万年前から35万年前の間に発生したことを示唆した[111][112]。 40万年前から更新世中期の第2間氷期、約25万年前までの間に、頭蓋内容積の拡大傾向と石器技術の精巧化が進み、H.エレクトゥスからH.サピエンスへ の移行の証拠となった。直接的な証拠は、アフリカからH.エレクトゥスが移動し、その後アフリカでH.エレクトゥスからH.サピエンスがさらに種分化した ことを示唆している。その後の移動(アフリカ内とアフリカ外の両方)が、最終的に先に分散したH.エレクタスに取って代わったのである。この移動・起源説 は通常、「最近の単一起源説」あるいは「アフリカ外起源説」と呼ばれている。H.サピエンスはアフリカとユーラシアの両方で古代の人類と交雑しており、 ユーラシアでは特にネアンデルタール人やデニソワ人と交雑していた[43][97]。 約7万年前にH.サピエンスが集団ボトルネックに陥ったとするトバ・カタストロフィー説[113]は、1990年代に初めて提唱されたときから物議を醸 し、2010年代にはほとんど支持されなくなっていた[114]。 ヒトの遺伝的多様性は、創始者効果、古代の混血、最近の進化圧力の結果として生じた。 |

| ダンバー『人類 進化の謎を解き明かす』 参考文献 | |

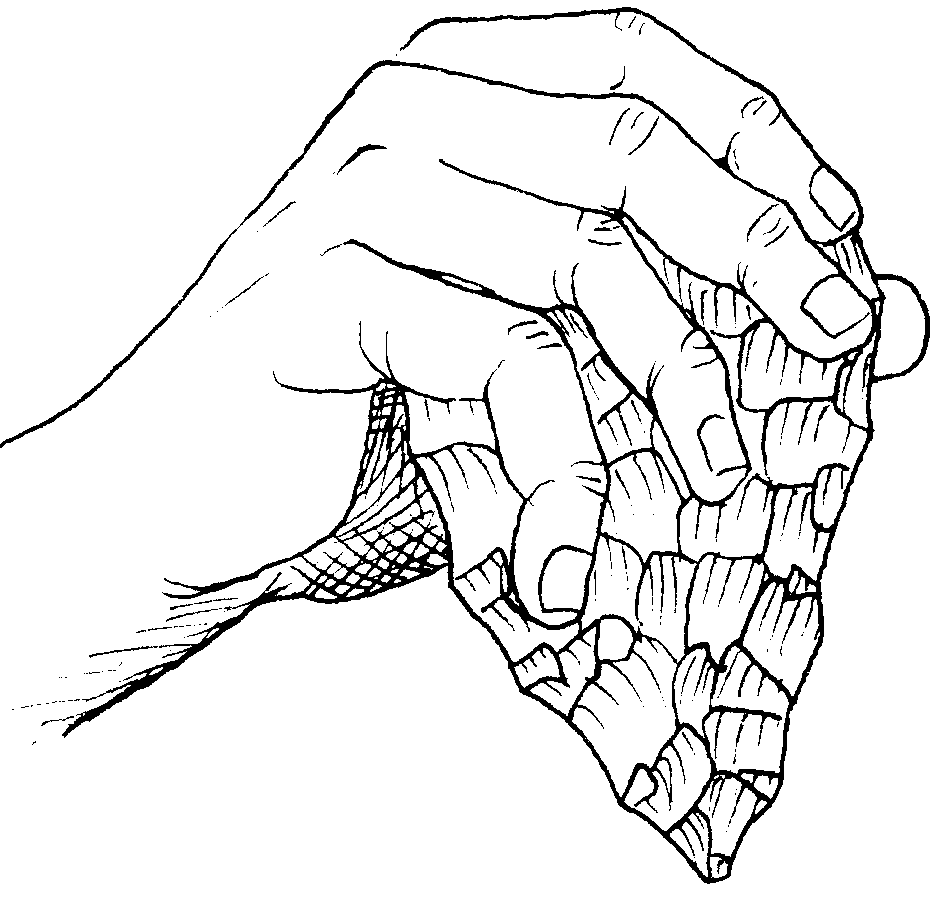

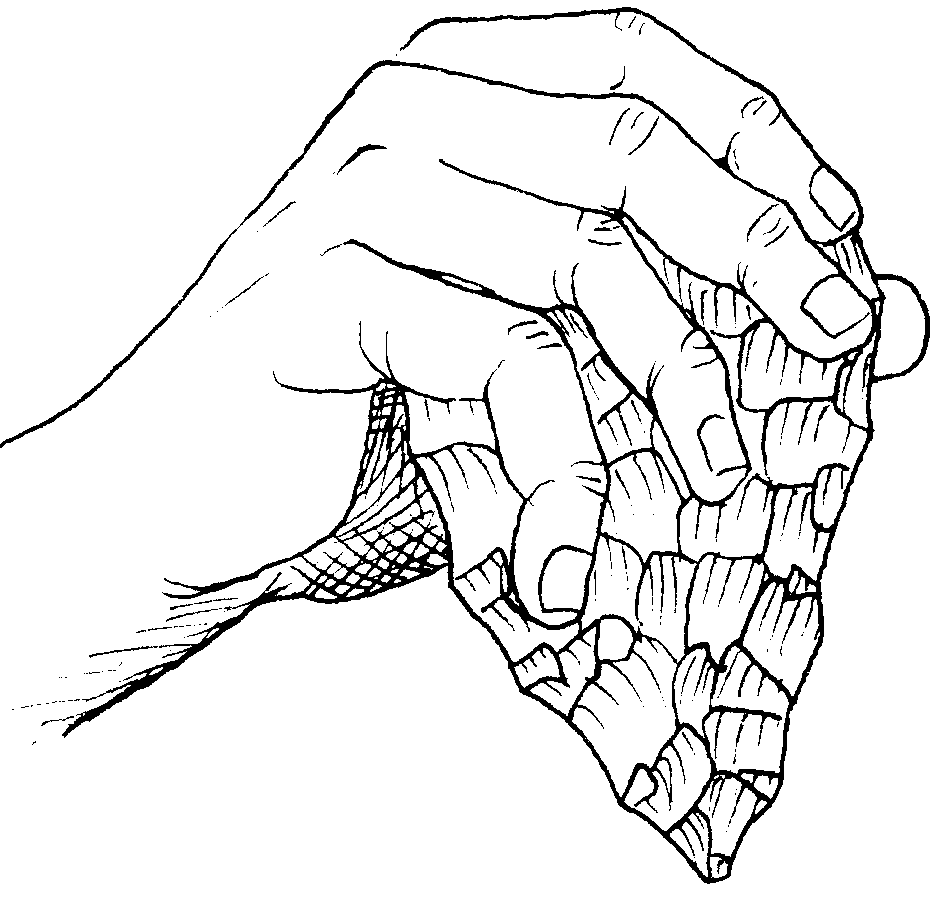

Homo ergaster

is an extinct species or subspecies of archaic humans who lived in

Africa in the Early Pleistocene. Whether H. ergaster constitutes a

species of its own or should be subsumed into H. erectus is an ongoing

and unresolved dispute within palaeoanthropology. Proponents of

synonymisation typically designate H. ergaster as "African Homo

erectus"[2] or "Homo erectus ergaster".[3] The name Homo ergaster

roughly translates to "working man", a reference to the more advanced

tools used by the species in comparison to those of their ancestors.

The fossil range of H. ergaster mainly covers the period of 1.7 to 1.4

million years ago, though a broader time range is possible.[4] Though

fossils are known from across East and Southern Africa, most H.

ergaster fossils have been found along the shores of Lake Turkana in

Kenya. There are later African fossils, some younger than 1 million

years ago, that indicate long-term anatomical continuity, though it is

unclear if they can be formally regarded as H. ergaster specimens. As a

chronospecies, H. ergaster may have persisted to as late as 600,000

years ago, when new lineages of Homo arose in Africa. Homo ergaster

is an extinct species or subspecies of archaic humans who lived in

Africa in the Early Pleistocene. Whether H. ergaster constitutes a

species of its own or should be subsumed into H. erectus is an ongoing

and unresolved dispute within palaeoanthropology. Proponents of

synonymisation typically designate H. ergaster as "African Homo

erectus"[2] or "Homo erectus ergaster".[3] The name Homo ergaster

roughly translates to "working man", a reference to the more advanced

tools used by the species in comparison to those of their ancestors.

The fossil range of H. ergaster mainly covers the period of 1.7 to 1.4

million years ago, though a broader time range is possible.[4] Though

fossils are known from across East and Southern Africa, most H.

ergaster fossils have been found along the shores of Lake Turkana in

Kenya. There are later African fossils, some younger than 1 million

years ago, that indicate long-term anatomical continuity, though it is

unclear if they can be formally regarded as H. ergaster specimens. As a

chronospecies, H. ergaster may have persisted to as late as 600,000

years ago, when new lineages of Homo arose in Africa.Those who believe H. ergaster should be subsumed into H. erectus consider there to be too little difference between the two to separate them into distinct species. Proponents of keeping the two species as distinct cite morphological differences between the African fossils and H. erectus fossils from Asia, as well as early Homo evolution being more complex than what is implied by subsuming species such as H. ergaster into H. erectus. Additionally, morphological differences between the specimens commonly seen as constituting H. ergaster might suggest that H. ergaster itself does not represent a cohesive species. Regardless of their most correct classification, H. ergaster exhibit primitive versions of traits later expressed in H. erectus and are thus likely the direct ancestors of later H. erectus populations in Asia. Additionally, H. ergaster is likely ancestral to later hominins in Europe and Africa, such as modern humans and Neanderthals. Several features distinguish H. ergaster from australopithecines as well as earlier and more basal species of Homo, such as H. habilis. Among these features are their larger body mass, relatively long legs, obligate bipedalism, relatively small jaws and teeth (indicating a major change in diet) as well as body proportions and inferred lifestyles more similar to modern humans than to earlier and contemporary hominins. With these features in mind, some researchers view H. ergaster as being the earliest true representative of the genus Homo. H. ergaster lived on the savannah in Africa, a unique environment with challenges that would have resulted in the need for many new and distinct behaviours. Earlier Homo probably used counter-attack tactics, like modern primates, to keep predators away. By the time of H. ergaster, this behaviour had probably resulted in the development of true hunter-gatherer behaviour, a first among primates. H. ergaster was an apex predator.[5] Further behaviours that might first have arisen in H. ergaster include male-female divisions of foraging and true monogamous pair bonds. H. ergaster also marks the appearance of more advanced tools of the Acheulean industry, including the earliest known hand axes. Though undisputed evidence is missing, H. ergaster might also have been the earliest hominin to master control of fire. |

ホモ・エ

ルガスターは、

前期更新世にアフリカに生息していた古人類の絶滅種または亜種である。エルガスターが独自の種を構成しているのか、それともホモ・エレクトスに包含される

べきなのかは、古人類学の中で現在も続いている未解決の論争である。同義語の支持者は通常、H.

ergasterを「アフリカのホモ・エレクトス」[2]または「ホモ・エレクトス・エルガスター」と呼んでいる[3]。ホモ・エルガスターという名前

は、彼らの祖先のものと比べてより高度な道具を使用する種であることを意味する「働く男」に大まかに翻訳される。ホモ・エルガスターの化石は、主に170

万年前から140万年前までの期間をカバーしているが、より広い範囲の化石が発見されている可能性もある。アフリカには100万年前より若い化石もあり、

長期的な解剖学的連続性を示しているが、正式にエルガスターの標本とみなすことができるかどうかは不明である。年代種としては、エルガスターはアフリカで

ホモの新系統が誕生した60万年前まで存続していた可能性がある。 ホモ・エ

ルガスターは、

前期更新世にアフリカに生息していた古人類の絶滅種または亜種である。エルガスターが独自の種を構成しているのか、それともホモ・エレクトスに包含される

べきなのかは、古人類学の中で現在も続いている未解決の論争である。同義語の支持者は通常、H.

ergasterを「アフリカのホモ・エレクトス」[2]または「ホモ・エレクトス・エルガスター」と呼んでいる[3]。ホモ・エルガスターという名前

は、彼らの祖先のものと比べてより高度な道具を使用する種であることを意味する「働く男」に大まかに翻訳される。ホモ・エルガスターの化石は、主に170

万年前から140万年前までの期間をカバーしているが、より広い範囲の化石が発見されている可能性もある。アフリカには100万年前より若い化石もあり、

長期的な解剖学的連続性を示しているが、正式にエルガスターの標本とみなすことができるかどうかは不明である。年代種としては、エルガスターはアフリカで

ホモの新系統が誕生した60万年前まで存続していた可能性がある。エルガスター種をエレクタス種に含めるべきだと考える人々は、両種を別個の種に分けるには、両者の間にあまりに違いがなさすぎると考えている。2つの種を 別個のものとして維持する賛成派は、アフリカの化石とアジアで産出したH.エレクタスの化石との間の形態学的な違いや、初期のホモの進化がH.エルガス ターのような種をH.エレクタスに包含することで暗示されるよりも複雑であったことを挙げている。さらに、エルガスターを構成する種と一般に考えられてい る標本間の形態学的相違は、エルガスター自体がまとまった種ではないことを示唆しているのかもしれない。最も正しい分類にかかわらず、エルガスターは後に H. erectusに発現する形質の原始版を示しており、したがってアジアにおける後のH. erectus個体群の直接の祖先である可能性が高い。さらにエルガスターは、ヨーロッパとアフリカの現生人類やネアンデルタール人など、後のホミニンの 祖先である可能性が高い。 エルガスターは、アウストラロピテクスや、ハビリスなど、より古く、より基底的なホモの一種と区別される特徴がいくつかある。これらの特徴の中には、体格 の大きさ、比較的長い脚、義務的な二足歩行、比較的小さな顎と歯(食生活が大きく変化したことを示す)、さらに体のプロポーションや推測される生活様式 が、それ以前のホモや現代のホモよりも現代人に近いことなどがある。これらの特徴を考慮し、エルガスターをホモ属最古の真の代表とみなす研究者もいる。 エルガスターはアフリカのサバンナで生活していたが、このような特殊な環境では、多くの新しく独特な行動が必要であっただろう。それ以前のホモはおそら く、現代の霊長類と同じように、捕食者を遠ざけるために反撃の戦術を使っていたのだろう。エルガスターの時代には、この行動はおそらく霊長類では初とな る、真の狩猟採集行動を発達させた。H. ergasterは頂点捕食者であった[5]。H. ergasterで初めて生じたと思われる行動には、オスとメスによる採食の分担や、真の一夫一婦制のペア結合などがある。H. ergasterはまた、最古の手斧を含む、より高度なアシュレアン産業の道具の出現を示す。議論の余地のない証拠は見つかっていないが、エルガスターは 火を操ることができる最古のヒト科動物であった可能性もある。 |

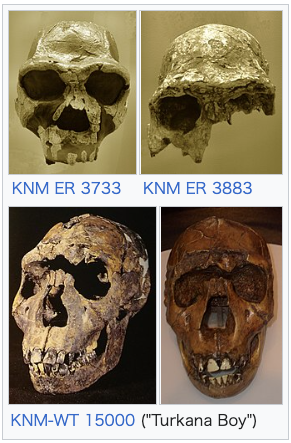

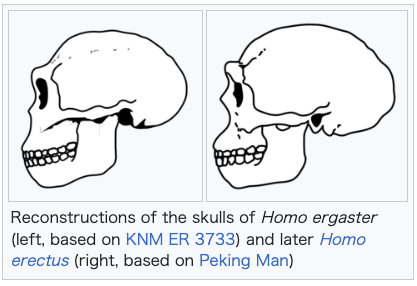

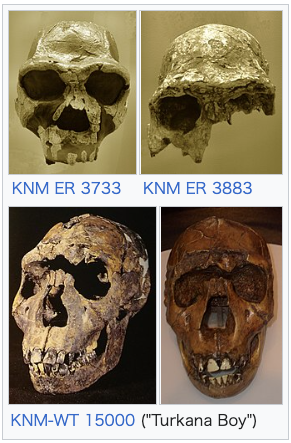

Research history Replica of KNM ER 992, the holotype specimen of Homo ergaster The systematics and taxonomy of Homo in the Early to Middle Pleistocene is one of the most disputed areas of palaeoanthropology.[6] In early palaeoanthropology and well into the twentieth century, it was generally assumed that Homo sapiens was the end result of gradual modifications within a single lineage of hominin evolution. As the perceived transitional form between early hominins and modern humans, H. erectus, originally assigned to contain archaic human fossils in Asia, came to encompass a wide range of fossils covering a large span of time (almost the entire temporal range of Homo). Since the late twentieth century, the diversity within H. erectus has led some to question what exactly defines the species and what it should encompass. Some researchers, such as palaeoanthropologist Ian Tattersall in 2013, have questioned H. erectus since it contains an "unwieldly" number of fossils with "substantially differing morphologies".[7] In the 1970s, palaeoanthropologists Richard Leakey and Alan Walker described a series of hominin fossils from Kenyan fossil localities on the eastern shore of Lake Turkana. The most notable finds were two partial skulls; KNM ER 3733 and KNM ER 3883, found at Koobi Fora. Leakey and Walker assigned these skulls to H. erectus, noting that their brain volumes (848 and 803 cc respectively) compared well to the far younger type specimen of H. erectus (950 cc). Another significant fossil was a fossil mandible recovered at Ileret and described by Leakey with the designation KNM ER 992 in 1972 as "Homo of indeterminate species".[8] In 1975, palaeoanthropologists Colin Groves and Vratislav Mazák designated KNM ER 992 as the holotype specimen of a distinct species, which they dubbed Homo ergaster.[9] The name (ergaster being derived from the Ancient Greek ἐργαστήρ, ergastḗr, 'workman') roughly translates to "working man"[10] or "workman".[11] Groves and Mazák also included many of the Koobi Fora fossils, such as KNM ER 803 (a partial skeleton and some isolated teeth) in their designation of the species, but did not provide any comparison with the Asian fossil record of H. erectus in their diagnosis, inadvertently causing some of the later taxonomic confusion in regards to the species.[12] A nearly complete fossil, interpreted as a young male (though the sex is actually undetermined), was discovered at the western shore of Lake Turkana in 1984 by Kenyan archaeologist Kamoya Kimeu.[11] The fossils were described by Leakey and Walker, alongside paleoanthropologists Frank Brown and John Harris, in 1985 as KNM-WT 15000 (nicknamed "Turkana Boy"). They interpreted the fossil, consisting of a nearly complete skeleton, as representing H. erectus.[13] Turkana Boy was the first discovered comprehensively preserved specimen of H. ergaster/erectus found and constitutes an important fossil in establishing the differences and similarities between early Homo and modern humans.[14] Turkana Boy was placed in H. ergaster by paleoanthropologist Bernard Wood in 1992,[11] and is today, alongside other fossils in Africa previously designated as H. erectus, commonly seen as a representative of H. ergaster by those who support H. ergaster as a distinct species.[15 |

研究の歴史 ホモ・エルガスターのホロタイプ標本KNM ER 992のレプリカ 前期更新世から中期更新世におけるホモの系統と分類学は、古人類学で最も論争が多い分野の一つである[6]。初期の古人類学から20世紀まで、ホモ・サピ エンスはヒトの進化の単一系統の中で徐々に変化した最終結果であると一般的に考えられていた。初期ホミニンと現生人類の過渡的な形態として認識されていた H.エレクタスは、当初アジアの古代のヒトの化石を含むとされていたが、大きなスパン(ホモのほぼ全時間的範囲)をカバーする幅広い化石を包含するように なった。20世紀後半以降、H. erectusの多様性から、種を定義するものは一体何なのか、何を包含すべきなのか、という疑問の声が上がっている。2013年の古人類学者イアン・ タッターソールのように、H. erectusには「実質的に異なる形態」を持つ「扱いにくい」数の化石が含まれていることから、H. erectusに疑問を呈する研究者もいる[7]。 1970年代、古人類学者のリチャード・リーキーとアラン・ウォーカーは、トゥルカナ湖の東岸にあるケニアの化石産地で発見された一連のヒト科の化石につ いて記述した。最も注目すべき発見は、Koobi Foraで発見されたKNM ER 3733とKNM ER 3883の2つの部分頭骨である。LeakeyとWalkerは、これらの頭蓋骨の脳容積(それぞれ848ccと803cc)が、H. erectusの遥かに若いタイプ標本(950cc)とよく比較されていることに注目し、H. erectusと断定した。もう一つの重要な化石は、イレレで発見された下顎骨の化石であり、1972年にリーキーによってKNM ER 992という名称で「種不詳のホモ」として記載された[8]。 1975年、古人類学者のコリン・グローブスとブラチスラフ・マザークは、KNM ER 992を別種のホロタイプ標本とし、ホモ・エルガスターと命名した[9]。この名前(エルガスターは古代ギリシャ語のἐργαστήρ, ergastė, 'workman'に由来する)は、大まかに訳すと「働く人」[10]または「労働者」となる。 [11] グローブスとマザークはまた、KNM ER 803(部分骨格といくつかの孤立した歯)のようなコオビ・フォラの化石の多くをこの種の呼称に含めたが、その診断においてH. erectusのアジアの化石記録との比較を示さなかったため、不注意にもこの種に関する後の分類学的混乱の原因となった[12]。 1984年にケニアの考古学者であるカモヤ・キメウによってトゥルカナ湖の西岸で若い男性(実際には性別は未確定)と解釈されるほぼ完全な化石が発見され た[11]。彼らは、ほぼ完全な骨格からなるこの化石をエルガスター・エレクトス(H. erectus)と解釈した[13]。トゥルカナ・ボーイは、エルガスター・エレクトスの完全な保存状態で発見された最初の標本であり、初期ホモと現生人 類の相違点と類似点を明らかにする上で重要な化石である。 [14]トゥルカナ・ボーイは1992年に古人類学者のバーナード・ウッドによってエルガスターに分類され[11]、現在ではエルガスターを別種として支 持する人々によって、以前はエルガスターとして指定されていたアフリカの他の化石と並んで、エルガスターの代表として一般的に見られている[15]。 |

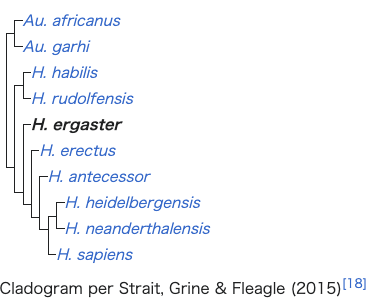

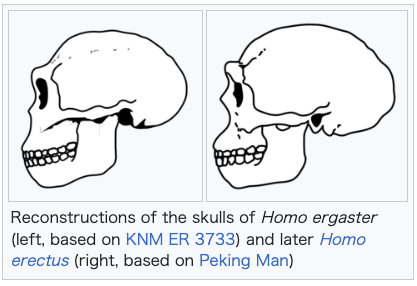

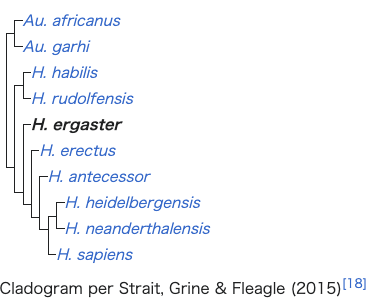

| Classification H. ergaster is easily distinguished from earlier and more basal species of Homo, notably H. habilis and H. rudolfensis, by a number of features that align them, and their inferred lifestyle, more closely to modern humans than to earlier and contemporary hominins. As compared to their relatives, H. ergaster had body proportions more similar to later members of the genus Homo, notably relatively long legs which would have made them obligately bipedal. The teeth and jaws of H. ergaster are also relatively smaller than those of H. habilis and H. rudolfensis, indicating a major change in diet.[16] In 1999, palaeoanthropologists Bernard Wood and Mark Collard argued that the conventional criteria for assigning species to the genus Homo were flawed and that early and basal species, such as H. habilis and H. rudolfensis, might appropriately be reclassified as ancestral australopithecines. In their view, the true earliest representative of Homo was H. ergaster.[17] Au. africanus Au. garhi H. habilis H. rudolfensis H. ergaster H. erectus H. antecessor H. heidelbergensis H. neanderthalensis H. sapiens ++++++++++++++++++  +++++++++++++++++++++++ Cladogram per Strait, Grine & Fleagle (2015)[18] Since its description as a separate species in 1975, the classification of the fossils referred to H. ergaster has been in dispute. H. ergaster was immediately dismissed by Leakey and Walker and many influential researchers, such as palaeoanthropologist G. Philip Rightmire, who wrote an extensive treatise on H. erectus in 1990, continued to prefer a more inclusive and comprehensive H. erectus. Overall, there is no doubt that the group of fossils composing H. erectus and H. ergaster represent the fossils of a more or less cohesive subset of closely related archaic humans. The question is instead whether these fossils represent a radiation of different species or the radiation of a single, highly variable and diverse, species over the course of almost two million years.[9] This long-running debate remains unresolved, with researchers typically using the terms H. erectus s.s. (sensu stricto) to refer to H. erectus fossils in Asia and the term H. erectus s.l. (sensu lato) to refer to fossils of other species that may or may not be included in H. erectus, such as H. ergaster, H. antecessor and H. heidelbergensis.[19]  Reconstructions of the skulls of Homo ergaster (left, based on KNM ER 3733) and later Homo erectus (right, based on Peking Man) For obvious reasons, H. ergaster shares many features with H. erectus, such as large forward-projecting jaws, large brow ridges and a receding forehead.[20] Many of the features of H. ergaster are clearly more primitive versions of features later expressed in H. erectus, which somewhat obscures the differences between the two.[21] There are subtle, potentially significant, differences between the East African and East Asian fossils. Among these are the somewhat higher-domed and thinner-walled skulls of H. ergaster, and the even more massive brow ridges and faces of Asian H. erectus.[20] The question is made more difficult since it regards how much intraspecific variation can be exhibited in a single species before it needs to be split into more, a question that in and of itself does not have a clear-cut answer. A 2008 analysis by anthropologist Karen L. Baab, examining fossils of various H. erectus subspecies, and including fossils attributed to H. ergaster, found that the intraspecific variation within H. erectus was greater than expected for a single species when compared to modern humans and chimpanzees, but fell well within the variation expected for a species when compared to gorillas, and even well within the range expected for a single subspecies when compared to orangutans (though this is partly due to the great sexual dimorphism exhibited in gorillas and orangutans).[22] Baab concluded that H. erectus s.l. was either a single but variable species, several subspecies divided by time and geography or several geographically dispersed but closely related species.[23] In 2015, paleoanthropologists David Strait, Frederick Grine and John Fleagle listed H. ergaster as one of the seven "widely recognized" species of Homo, alongside H. habilis, H. rudolfensis, H. erectus, H. heidelbergensis, H. neanderthalensis and H. sapiens, noting that other species, such as H. floresiensis and H. antecessor, were less widely recognised or more poorly known.[18] Variation in the fossil material  KNM ER 3733 KNM ER 3883 KNM-WT 15000 ("Turkana Boy") Comparing various African fossils attributed to H. erectus or H. ergaster to Asian fossils, notably the type specimen of H. erectus, in 2013, Ian Tattersall concluded that referring to the African material as H. ergaster rather than "African H. erectus" was a "considerable improvement" as there were many autapomorphies distinguishing the material of the two continents from one another.[24] Tattersall believes it to be appropriate to use the designation H. erectus only for eastern Asian fossils, disregarding its previous use as the name for an adaptive grade of human fossils from throughout Africa and Eurasia. Though Tattersall concluded that the H. ergaster material represents the fossils of a single clade of Homo, he also found there to be considerable diversity within this clade; the KNM ER 992 mandible accorded well with other fossil mandibles from the region, such as OH 22 from Olduvai and KNM ER 3724 from Koobi Fora, but did not necessarily match with cranial material, such as KNM ER 3733 and KNM ER 3883 (since neither preserves the jaw), nor with the mandible preserved in Turkana Boy, which has markedly different dentition.[24] The most "iconic" fossil of H. ergaster is the KNM ER 3733 skull, which is sharply distinguished from Asian H. erectus by a number of characteristics, including that the brow ridges project forward as well as upward and arc separately over each orbit and the braincase being quite tall compared to its width, with its side walls curving. KNM ER 3733 can be distinguished from KNM ER 3883 by a number of features as well, notably in that the margins of KNM ER 3883's brow ridges are very thickened and protrude outwards but slightly downwards rather than upwards.[25] Both skulls can be distinguished from the skull of Turkana Boy, which possesses only slightly substantial thickenings of the superior orbital margins, lacking the more vertical thickening of KNM ER 3883 and the aggressive protrusion of KNM ER 3733. In addition to this, the facial structure of Turkana Boy is narrower and longer than that of the other skulls, with a higher nasal aperture and likely a flatter profile of the upper face. It is possible that these differences can be accounted for through Turkana Boy being a subadult, 7 to 12 years old.[26] Furthermore, KNM ER 3733 is presumed to have been the skull of a female (whereas Turkana Boy is traditionally interpreted as male), which means that sexual dimorphism may account for some of the differences.[14] The differences between Turkana Boy's skull and KNM ER 3733 and KNM ER 3883, as well as the differences in dentition between Turkana Boy and KNM ER 992 have been interpreted by some, such as paleoanthropologist Jeffrey H. Schwartz, as suggesting that Turkana Boy and the rest of the H. ergaster material does not represent the same taxon. Schwartz also noted none of the fossils seemed to represent H. erectus either, which he believed was in need of significant revision.[27] In 2000, French palaeoanthropologist Valéry Zeitoun suggested that KNM ER 3733 and KNM ER 3883 should be referred to two separate species, which she dubbed H. kenyaensis (type specimen KNM ER 3733) and H. okotensis (type specimen KNM ER 3883), but these designations have found little acceptance.[28] |