human nature in Marx and Marxism

La Sagrada Familia Migrante (Kelly Latimore. 2017)

マルクスにおける人間の本性

human nature in Marx and Marxism

La Sagrada Familia Migrante (Kelly Latimore. 2017)

担当:池田光穂

ウィキペディア、Marx's theory of human nature、からの翻訳

| Marx's

theory of human nature Some Marxists posit what they deem to be Karl Marx's theory of human nature, which they accord an important place in his critique of capitalism, his conception of communism, and his 'materialist conception of history'. Marx, however, does not refer to human nature as such, but to Gattungswesen, which is generally translated as 'species-being' or 'species-essence'. According to a note from Marx in the Manuscripts of 1844, the term is derived from Ludwig Feuerbach's philosophy, in which it refers both to the nature of each human and of humanity as a whole.[1] However, in the sixth Theses on Feuerbach (1845), Marx criticizes the traditional conception of human nature as a species which incarnates itself in each individual, instead arguing that human nature is formed by the totality of social relations. Thus, the whole of human nature is not understood, as in classical idealist philosophy, as permanent and universal: the species-being is always determined in a specific social and historical formation, with some aspects being biological. According to Professor Emeritus David Ruccio, a transhistorical concept of "human nature" would be eschewed by Marx who wouldn't accept any transhistorical or transcultural "human nature." much in the same way as in Marxian critique of political economy.[2] |

人間本性(human

nature)についてのマルクスの諸説(総論) マルクス主義者の中には、カール・マルクスの人間性理論を、 彼の資本主義批判、共産主義概念、「歴史の唯物論的概念」において重要な位置を占めるとする者もいる。しかし、マルクスは人間本性に言及せず、 Gattungswesen(一般に「種-存在」または「種-本質」と訳されている)に言及している。1844年の『手稿』にあるマルクスの注によれば、 この言葉はルートヴィヒ・フォイエルバッハの哲学に由来し、そこでは人間一人一人の性質と人類全体の性質の両方を指している[1]。 しかし、マルクスは『フォイエルバッハに関するテーゼ』第6巻(1845年)において、人間性を各個人に化身する種として捉える従来の概念を批判し、代わ りに人間性は社会関係の総体によって形成されると主張している。つまり、人間性の全体は、古典的観念論哲学のように、永久的かつ普遍的なものとして理解さ れるのではなく、種としての存在は常に特定の社会的・歴史的形成の中で決定され、ある側面は生物学的であるとするのである。デヴィッド・ルキオ名誉教授に よれば、歴史的なものを超えた「人間性」概念は、マルクスによって敬遠され、マルクスによる政治経済批判と同じように、歴史的、文化的に超えた「人間性」 を認めないだろう[2]と述べている。 |

| The sixth thesis on

Feuerbach and the determination of human nature by social relations The sixth of the Theses on Feuerbach, written in 1845, provided an early discussion by Marx of the concept of human nature. It states: Feuerbach resolves the essence of religion into the essence of man [menschliches Wesen = ‘human nature’]. But the essence of man is no abstraction inherent in each single individual. In reality, it is the ensemble of the social relations. Feuerbach, who does not enter upon a criticism of this real essence is hence obliged: 1. To abstract from the historical process and to define the religious sentiment regarded by itself, and to presuppose an abstract — isolated - human individual. 2. The essence therefore can by him only be regarded as ‘species’, as an inner ‘dumb’ generality which unites many individuals only in a natural way.[3] Thus, Marx appears to say that human nature is no more than what is made by the "social relations". Norman Geras's Marx and Human Nature (1983), however, offers an argument against this position.[4] In outline, Geras shows that, while the social relations are held to "determine" the nature of people, they are not the only such determinant. However, Marx makes statements where he specifically refers to a human nature which is more than what is conditioned by the circumstances of one's life. In Capital, in a footnote critiquing utilitarianism, he says that utilitarians must reckon with "human nature in general, and then with human nature as modified in each historical epoch".[5] Marx is arguing against an abstract conception of human nature, offering instead an account rooted in sensuous life. While he is quite explicit that "[a]s individuals express their life, so they are. Hence what individuals are depends on the material conditions of their production",[6] he also believes that human nature will condition (against the background of the productive forces and relations of production) the way in which individuals express their life. History involves "a continuous transformation of human nature",[7] though this does not mean that every aspect of human nature is wholly variable; what is transformed need not be wholly transformed. Marx did criticise the tendency to "transform into eternal laws of nature and of reason, the social forms springing from your present mode of production and form of property".[8] For this reason, he would likely have wanted to criticise certain aspects of some accounts of human nature. Some people believe, for example, that humans are naturally selfish – Immanuel Kant and Thomas Hobbes, for example.[9][10][11] (Both Hobbes and Kant thought that it was necessary to constrain our human nature in order to achieve a good society – Kant thought we should use rationality, Hobbes thought we should use the force of the state – Marx, as we shall see, thought that the good society was one which allows our human nature its full expression.) Most Marxists will argue that this view is an ideological illusion and the effect of commodity fetishism: the fact that people act selfishly is held to be a product of scarcity and capitalism, not an immutable human characteristic. For confirmation of this view, we can see how, in The Holy Family Marx argues that capitalists are not motivated by any essential viciousness, but by the drive toward the bare "semblance of a human existence".[12] (Marx says "semblance" because he believes that capitalists are as alienated from their human nature under capitalism as the proletariat, even though their basic needs are better met.) |

フォイエルバッハに関する第6テーゼと社会関係による人間性

の決定 フォイエルバッハに関する第6論文は、1845年に書かれたもので、マルクスが人間性の概念について早くから論じたものである。それは次のように述べてい る。 フォイエルバッハは、宗教の本質を人間の本質(menschliches Wesen=「人間性」)に分解している。しかし、人間の本質とは、一人一人の個人に固有の抽象的なものではない。現実には、それは社会的関係のアンサン ブルである。この本質の批判に踏み込まないフォイエルバッハは、それゆえ、次のような義務を負っている。 1. 1.歴史的過程から抽象化し、それ自身と見なされる宗教的感情を定義し、抽象的な-孤立した-人間個人を前提とすること。 2. したがって本質とは、彼によって「種」として、自然な方法でのみ多くの個人を結合する内的な「間抜けな」一般性としてのみ見なすことができるのである [3]。 このように、マルクスは人間の本質が「社会的関係」によって作られるものにほかならないと言っているように見える。しかし、ノーマン・ゲラス『マルクスと 人間の本性』(1983年)は、このような立場に対する議論を提供する[4]。ゲラスは概略、社会関係が人間の本性を「決定」するとしながらも、それが唯 一の決定要因ではないことを示す。しかし、マルクスは人生の状況によって条件づけられる以上の人間の本性について具体的に言及する発言をしている。資本 論』では、功利主義を批判する脚注で、功利主義者は「一般的な人間性、そして各歴史的時代において修正された人間性」を考慮しなければならないと述べてい る[5]。マルクスは、人間性についての抽象概念に対して、代わりに感覚的生活に根ざした説明をしているのである。彼は「個人がその生を表現するように、 個人もまたそうである」と明確に述べている。それゆえ、個人が何であるかはその生産の物質的条件に依存する」[6]が、彼はまた、人間の本性が(生産力と 生産関係を背景にして)個人が自分の人生を表現する方法を条件付けると信じている。歴史は「人間性の連続的な変容」[7]を伴うが、これは人間性のあらゆ る側面が完全に変化するということではなく、変容されるものが完全に変容される必要はないのである。 マルクスは「現在の生産様式と財産形態から生じている社会的形態を自然や理性の永遠の法則に変換する」傾向を批判していた[8]。 そのため、彼は人間性についてのいくつかの説明のある側面を批判したかったのであろう。例えば、イマニュエル・カントやトマス・ホッブズなど、人間は生ま れつき利己的であると考える人々がいる[9][10][11](ホッブズとカントは共に良い社会を実現するために人間の性質を抑制することが必要であると 考え、カントは合理性を、ホッブズは国家の力を利用すべきと考えていたが、これから見るようにマルクスは良い社会とは人間の性質を完全に表現できる社会で あると考えていたのである]。ほとんどのマルクス主義者は、この見解はイデオロギー的な幻想であり、商品フェティシズムの影響であると主張するだろう。人 が利己的に行動するという事実は、欠乏と資本主義の産物であり、不変の人間の特性ではないと考えられている。この見解の確認のために、マルクスは『聖家 族』の中で、資本家が本質的な悪意によってではなく、むき出しの「人間的存在の似姿」に対するドライブによって動機づけられていることを論じることができ る[12](マルクスが「似姿」と言うのは、資本家が基本的なニーズはよりよく満たされているとしても、資本主義の下ではプロレ階級と同様に彼らの人間性 から疎外していると彼が考えているためである)。 |

| Needs and drives In the 1844 Manuscripts the young Marx wrote: Man is directly a natural being. As a natural being and as a living natural being he is on the one hand endowed with natural powers, vital powers – he is an active natural being. These forces exist in him as tendencies and abilities – as instincts. On the other hand, as a natural, corporeal, sensuous objective being he is a suffering, conditioned and limited creature, like animals and plants. That is to say, the objects of his instincts exist outside him, as objects independent of him; yet these objects are objects that he needs – essential objects, indispensable to the manifestation and confirmation of his essential powers.[13] In the Grundrisse Marx says his nature is a "totality of needs and drives".[14] In The German Ideology he uses the formulation: "their needs, consequently their nature".[15] We can see then, that from Marx's early writing to his later work, he conceives of human nature as composed of "tendencies", "drives", "essential powers", and "instincts" to act in order to satisfy "needs" for external objectives. For Marx then, an explanation of human nature is an explanation of the needs of humans, together with the assertion that they will act to fulfill those needs. (c.f. The German Ideology, chapter 3).[16] Norman Geras gives a schedule of some of the needs which Marx says are characteristic of humans: ...for other human beings, for sexual relations, for food, water, clothing, shelter, rest and, more generally, for circumstances that are conducive to health rather than disease. There is another one ... the need of people for a breadth and diversity of pursuit and hence of personal development, as Marx himself expresses these, 'all-round activity', 'all-round development of individuals', 'free development of individuals', 'the means of cultivating [one's] gifts in all directions', and so on.[17] Marx says "It is true that eating, drinking, and procreating, etc., are ... genuine human functions. However, when abstracted from other aspects of human activity, and turned into final and exclusive ends, they are animal."[18][19] |

ニーズとドライブ(=欲求と欲動) 1844年の『経済学・哲学草稿』 で、若き日のマルクスはこう書いている。 人間は、直接的には、自然な存在である。自然な存在として、生きている自然な存在として、彼は一方では自然な力、生命力を授かっている-彼は活動的な自然 な存在である。これらの力は、傾向や能力として、つまり本能として、彼の中に存在する。他方、自然の、肉体の、感覚的な客観的存在である彼は、動物や植物 のように、苦しみ、条件づけられ、制限された被造物である。すなわち、彼の本能の対象は、彼の外部に、彼とは独立した対象として存在する。しかし、これら の対象は、彼が必要とする対象、すなわち彼の本質的な力の発現と確認に欠くことのできない本質的な対象である[13]。 マルクスは『グルントリッセ(経済学批判要綱)』において彼 の性質が「欲求と衝動の総体」であると言っている[14]。 また『ドイツ・イデオロギー』において彼は定式化を用いている。「このようにマルクスの初期の著作から後期の著作まで、彼は人間の本性を外的な目的に対す る「欲求」を満たすために行動する「傾向」「衝動」「本質的な力」「本能」から構成されるものとして考えていることがわかる[15]。そして、マルクスに とって、人間性の説明とは、人間の欲求の説明であり、その欲求を満たすために人間が行動するという主張である。(ノーマン・ゲラスは、マルクスが人間の特 徴であるとする欲求のいくつかをあげている[16]。 他の人間に対する欲求、性的関係に対する欲求、食物、水、衣服、住居、休息に対する欲求、そしてより一般的には、病気よりもむしろ健康を助長する状況に対 する欲求である。もう一つ、...マルクス自身がこれらを表現しているように、「全方位的活動」、「個人の全方位的発展」、「個人の自由な発展」、「あら ゆる方向に(自分の)才能を培う手段」など、追求の幅と多様性、したがって個人的発展のための人々の必要性もある[17]。 マルクスは「食べること、飲むこと、子孫を残すことなどは、......正真正銘の人間の機能であることは事実である。しかし、人間の活動の他の側面から 抽象化され、最終的かつ排他的な目的に転化されるとき、それらは動物的である」[18][19]と述べている。 |

| Humans as free, purposive

producers In several passages throughout his work, Marx shows how he believes humans to be essentially different from other animals. "Men can be distinguished from animals by consciousness, by religion or anything else you like. They themselves begin to distinguish themselves from animals as soon as they begin to produce their means of subsistence, a step which is conditioned by their physical organisation."[6] In this passage from The German Ideology, Marx alludes to one difference: that humans produce their physical environments. But do not a few other animals also produce aspects of their environment as well? The previous year, Marx had already acknowledged: It is true that animals also produce. They build nests and dwellings, like the bee, the beaver, the ant, etc. But they produce only their own immediate needs or those of their young; they produce only when immediate physical need compels them to do so, while man produces even when he is free from physical need and truly produces only in freedom from such need; they produce only themselves, while man reproduces the whole of nature; their products belong immediately to their physical bodies, while man freely confronts his own product. Animals produce only according to the standards and needs of the species to which they belong, while man is capable of producing according to the standards of every species and of applying to each object its inherent standard; hence, man also produces in accordance with the laws of beauty.[20] In the same work, Marx writes: The animal is immediately one with its life activity. It is not distinct from that activity; it is that activity. Man makes his life activity itself an object of his will and consciousness. He has conscious life activity. It is not a determination with which he directly merges. Conscious life activity directly distinguishes man from animal life activity. Only because of that is he a species-being. Or, rather, he is a conscious being – i.e., his own life is an object for him, only because he is a species-being. Only because of that is his activity free activity. Estranged labour reverses the relationship so that man, just because he is a conscious being, makes his life activity, his essential being, a mere means for his existence.[21] Also in the segment on Estranged Labour: Man is a species-being, not only because he practically and theoretically makes the species – both his own and those of other things – his object, but also – and this is simply another way of saying the same thing – because he looks upon himself as the present, living species, because he looks upon himself as a universal and therefore free being.[22] More than twenty years later, in Capital, he came to muse on a similar subject: A spider conducts operations that resemble those of a weaver, and a bee puts to shame many an architect in the construction of her cells. But what distinguishes the worst architect from the best of bees is this, that the architect raises his structure in imagination before he erects it in reality. At the end of every labour-process, we get a result that already existed in the imagination of the labourer at its commencement. He not only effects a change of form in the material on which he works, but he also realises a purpose of his own that gives the law to his modus operandi, and to which he must subordinate his will. And this subordination is no mere momentary act.[23] From these passages we can observe something of Marx's beliefs about humans. That they characteristically produce their environments, and that they would do so, even were they not under the burden of "physical need" – indeed, they will produce the "whole of [their] nature", and may even create "in accordance with the laws of beauty". Perhaps most importantly, though, their creativity, their production is purposive and planned. Humans, then, make plans for their future activity, and attempt to exercise their production (even lives) according to them. Perhaps most importantly, and most cryptically, Marx says that humans make both their "life activity" and "species" the "object" of their will. They relate to their life activity, and are not simply identical with it. Michel Foucault's definition of biopolitics as the moment when "man begins to take itself as a conscious object of elaboration" may be compared to Marx's definition hereby exposed. |

自由で目的意識のある生産者としての人間 マルクスは、人間が他の動物とは本質的に異なると考えていることを、その著作のいくつかの箇所で示している。「人間は、意識によって、宗教によって、その 他何によってでも、動物から区別することができる。人間は意識によって動物から区別され、宗教によって、あるいは他のどんなものによっても区別される。人 間自身は、生計手段を生産し始めるとすぐに動物から区別され始め、そのステップは彼らの物理的組織によって条件付けられる」[6]『ドイツイデオロギー』 のこの文章で、マルクスは、人間が彼らの身体環境を生産するという一つの差異を暗示している。しかし、他のいくつかの動物も同様に環境の側面を作り出して はいないだろうか。その前年、マルクスはすでに認めていた。 動物もまた生産していることは事実である。彼らは、蜂、ビーバー、アリなどのように、巣や住居を作る。しかし、彼らは、自分自身の当面の必要、あるいは、 自分の子供の必要だけを生産する。彼らは、当面の肉体的必要からそうせざるを得ないときだけ生産するが、人間は、肉体的必要から自由なときでさえ生産し、 そのような必要から自由でこそ真に生産する。彼らは自分だけを生産するが、人間は自然の全体を再生産する。彼らの生産物は彼らの肉体に直ちに帰属するが、 人間は自分の生産物と自由に対峙する。動物は自分が属する種の基準と必要性に従ってのみ生産するが、人間はあらゆる種の基準に従って生産し、それぞれの対 象に固有の基準を適用することができる。それゆえ、人間は美の法則に従って生産することもできる[20]。 同じ著作の中で、マルクスはこう書いている。 動物はその生命活動と直ちに一体である。それはその活動から区別されるのではなく、その活動である。人間は、自分の生命活動そのものを自分の意志と意識の 対象とする。彼は意識的な生命活動を持っている。それは、彼が直接的に融合する決定ではない。意識的な生命活動は、人間を動物の生命活動から直接に区別す る。それゆえにのみ、彼は種的存在なのである。というより、彼は意識的存在である--すなわち、彼自身の生命が彼にとって対象であるのは、彼が種的存在で あるからにほかならない。それゆえにこそ、彼の活動は自由な活動なのである。疎外された労働はこの関係を逆転させ、人間は意識的存在であるという理由だけ で、自分の生命活動、つまり本質的存在を自分の存在のための単なる手段にしてしまうのである[21]。 また、Estranged Labourのセグメントで 人間は種的存在であり、それは彼が実際的かつ理論的に種を-彼自身と他のものの両方を-彼のオブジェクトにするからだけではなく、また-これは単に同じこ とを言う別の方法であるが-彼が自分自身を現在の、生きている種として見るから、彼が自分自身を普遍的でそれゆえ自由な存在として見るからである [22]」と述べている。 20年以上後の『資本論』において、彼は同様の主題について思索するようになった。 蜘蛛は機織り職人に似た作業を行い、蜂はその細胞の構築において多くの建築家を辱める。しかし、最悪の建築家と最良の蜂とを区別するものは、建築家が現実 に建てる前に、想像の中でその構造物を立ち上げるということである。あらゆる労働過程の終わりには、その開始時に労働者の想像の中にすでに存在していた結 果が得られる。彼は、自分が作業する材料に形の変化をもたらすだけでなく、自分のやり方に法則を与え、自分の意志をそれに従属させなければならない自分の 目的を実現するのである。そしてこの従属は単なる瞬間的な行為ではない[23]。 これらの文章から、人間についてのマルクスの信念のようなものを観察することができる。彼らは特徴的に自分の環境を生産し、「物理的な必要性」の負担がな いとしてもそうするだろうということ、実際、彼らは「(彼らの)自然の全体」を生産し、「美の法則にしたがって」創造さえするかもしれない。しかし、おそ らく最も重要なことは、彼らの創造性、生産は目的的であり、計画的であるということである。そして、人間は、将来の活動の計画を立て、それに従って生産 (生命さえも)を行使しようとするのである。おそらく最も重要で、最も不可解なことに、マルクスは、人間は自分の「生命活動」と「種」の両方を自分の意志 の「対象」にすると言っている。それらは彼らの生命活動に関係するものであり、単にそれと同一であるわけではない。ミシェル・フーコーの生政治の定義は、 「人間がそれ自体を精緻化の意識的対象として捉え始める」瞬間として、ここに露呈したマルクスの定義と比較することができるだろう。 |

| Life and the species as the

objects of humans To say that A is the object of some subject B, means that B (specified as an agent) acts upon A in some respect. Thus if "the proletariat smashes the state" then "the state" is the object of the proletariat (the subject), in respect of smashing. It is similar to saying that A is the objective of B, though A could be a whole sphere of concern and not a closely defined aim. In this context, what does it mean to say that humans make their "species" and their "lives" their "object"? It's worth noting that Marx's use of the word object can imply that these are things which humans produces, or makes, just as they might produce a material object. If this inference is correct, then those things that Marx says about human production above, also apply to the production of human life, by humans. And simultaneously, "As individuals express their life, so they are. What they are, therefore, coincides with their production, both with what they produce and with how they produce. The nature of individuals thus depends on the material conditions determining their production."[6] To make one's life one's object is therefore to treat one's life as something that is under one's control. To raise in imagination plans for one's future and present, and to have a stake in being able to fulfill those plans. To be able to live a life of this character is to achieve "self-activity" (actualisation), which Marx believes will only become possible after communism has replaced capitalism. "Only at this stage does self-activity coincide with material life, which corresponds to the development of individuals into complete individuals and the casting-off of all natural limitations. The transformation of labour into self-activity corresponds to the transformation of the earlier limited intercourse into the intercourse of individuals as such".[24] What is involved in making one's species one's object is more complicated (see Allen Wood 2004, pp. 16–21). In one sense, it emphasises the essentially social character of humans, and their need to live in a community of the species. In others, it seems to emphasise that we attempt to make our lives expressions of our species-essence; further that we have goals concerning what becomes of the species in general. The idea covers much of the same territory as "making one's life one's object": it concerns self-consciousness, purposive activity, and so forth. |

人間の対象としての生命と種 Aがある主体Bの客体であるということは、B(代理人として特定される)が何らかの点でAに作用することを意味する。したがって、もし「プロレタリアート が国家を粉砕する」なら、「国家」は粉砕に関して、プロレタリアート(主体)の客体である。これは、AはBの目的であると言うことに似ていますが、Aは密 接に定義された目的ではなく、関心領域全体である可能性があります。この文脈で、人間が自分の「種」や「命」を「目的」にするというのは、どういうことな のだろうか。マルクスが「対象」という言葉を使ったことは、ちょうど人間が物質的なものを生産するように、これらが人間が生産するもの、あるいは作るもの であることを暗示していることができることに注目すべきである。もしこの推論が正しければ、マルクスが人間の生産について述べたことは、人間による人間の 生命の生産にも当てはまることになる。そして同時に、「個人がその生命を表現するように、個人もまた存在する。したがって、彼らが何であるかは、彼らの生 産と一致し、彼らが何を生産するか、どのように生産するかの両方と一致する。したがって、個人の性質は、その生産を決定する物質的条件に依存する」 [6]。 自分の人生を自分の対象とすることは、それゆえ自分の人生を自分の支配下にあるものとして扱うことである。自分の将来と現在のために想像力を働かせて計画 を立て、その計画を実現することに利害関係を持つこと。このような性格の人生を送ることができるということは、「自己活動」(実現)を達成することであ り、マルクスは、共産主義が資本主義に取って代わった後でのみ可能になると考えている。「この段階になって初めて、自己活動が物質的生活と一致し、それ は、個人が完全な個人へと発展し、あらゆる自然的制約を捨て去ることに対応するのである。労働の自己活動への転換は、それまでの限定された交際をそのよう な個人の交際に転換することに対応する」[24]。 自分の種を自分の対象とすることに関わることはより複雑である(Allen Wood 2004, pp.16-21参照)。ある意味では、それは人間の本質的に社会的な性格と、種の共同体の中で生きる必要性を強調するものである。また、私たちが自らの 生活を種としての存在感を示すものにしようとすること、さらに、種が一般的にどうなっていくのかについて目標を持つことを強調しているようにも見える。こ の考え方は、「自分の人生を自分のものにする」ことと同じ領域を多く含んでいる。つまり、自己意識、目的意識的な活動などに関するものである。 |

| Humans as homo faber? It is often said that Marx conceived of humans as homo faber, referring to Benjamin Franklin's definition of "man as the tool-making animal" – that is, as "man, the maker",[25] though he never used the term himself. It is generally held that Marx's view was that productive activity is an essential human activity, and can be rewarding when pursued freely. Marx's use of the words work and labour in the section above may be unequivocally negative; but this was not always the case, and is most strongly found in his early writing. However, Marx was always clear that under capitalism, labour was something inhuman, and dehumanising. "labour is external to the worker – i.e., does not belong to his essential being; that he, therefore, does not confirm himself in his work, but denies himself, feels miserable and not happy, does not develop free mental and physical energy, but mortifies his flesh and ruins his mind".[26] While under communism, "In the individual expression of my life I would have directly created your expression of your life, and therefore in my individual activity I would have directly confirmed and realised my true nature, my human nature, my communal nature".[27] |

ホモ・ファーベル(工作人)としての人間? マルクスは、ベンジャミン・フランクリンが「道具を作る動物としての人間」、つまり「作り手である人間」として定義したことにちなんで、人間をホモ・ファ ベルとして考えたとよく言われるが、彼自身はこの言葉を使わなかった[25]。一般には、生産活動は人間の本質的な活動であり、自由に追求すれば報われる ものであるというのがマルクスの見解であるとされている。上の節でマルクスが仕事と労働という言葉を使ったのは、明らかに否定的であるかもしれない。しか し、マルクスは、資本主義のもとでは、労働は非人間的なものであり、人間性を奪うものであることを常に明確にしていた。「労働は労働者の外部にあり、すな わち労働者の本質的な存在に属しておらず、それゆえ彼は労働において自分自身を確認するのではなく、自分自身を否定し、惨めで幸せではないと感じ、自由な 心身のエネルギーを開発するのではなく、彼の肉を死滅させ、彼の心を破滅させる」26]。 一方共産主義の下では「私の人生の個々の表現において私は直接あなたの人生の表現を作っていたであろうし、したがって私の個々の活動において私は直接私の 本質、私の人間の本質、私の共同の本性を確認し実現していただろう」と述べている27][27]。 |

| Marx and race There are multiple examples of racism in Marx works, with adverse references to people of colour including those of Black African heritage, Indians, Slavs and Jews. For example;: “The Jewish n(word) Lassalle who, I’m glad to say, is leaving at the end of this week, has happily lost another 5,000 talers in an ill-judged speculation. The chap would sooner throw money down the drain than lend it to a ‘friend,’ even though his interest and capital were guaranteed. ... It is now quite plain to me—as the shape of his head and the way his hair grows also testify—that he is descended from the negroes who accompanied Moses’ flight from Egypt (unless his mother or paternal grandmother interbred with a n(word)). Now, this blend of Jewishness and Germanness, on the one hand, and basic negroid stock, on the other, must inevitably give rise to a peculiar product. The fellow’s importunity is also n(word)-like.” Karl Marx, “Marx to Friedrich Engels in Manchester,” 1862 Tremaux “proved that the common Negro type is the degenerate form of a much higher one ... a very significant advance over Darwin.” Karl Marx, letter to Friedrich Engels, August 7, 1866 “Without slavery, North America, the most progressive of countries, would be transformed into a patriarchal country. Wipe out North America from the map of the world and you will have anarchy— the complete decay of modern commerce and civilization. Abolish slavery and you will have wiped America off the map of nations.” Karl Marx, “The Poverty of Philosophy,” 1847 “Take Amsterdam, for instance, a city harboring many of the worst descendants of the Jews whom Ferdinand and Isabella drove out of Spain and who, after lingering a while in Portugal, were driven out of there too and eventually found a place of retreat in Holland. ... Here and there and everywhere that a little capital courts investment, there is ever one of these little Jews ready to make a little suggestion or place a little bit of a loan. The smartest highwayman in the Abruzzi is not better posted about the locale of the hard cash in a traveler’s valise or pocket than these little Jews about any loose capital in the hands of a trader ... These small Jewish agents draw their supplies from the big Jewish houses ... and practice great ostensible devotion to the religion of their race.” Karl Marx, “The Russian Loan,” 1856 |

マルクスと人種 マルクスの作品には人種差別の例が多数あり、アフリカ系黒人、インド人、スラブ人、ユダヤ人など有色人種に対する悪意ある言及がなされている。たとえば、 次のようなものである。 「ユダヤ人のラサールは、嬉しいことに今週末で退社することになったが、不謹慎な投機で5千タラも損をしてしまった。この男は、自分の利子と資本が保証さ れているにもかかわらず、『友人』に貸すよりも、すぐに金をどぶに捨てようとする。... 彼の頭の形や髪の生え方が証明しているように、彼がモーゼのエジプト脱出に同行した黒人の子孫であることはもう明白だ(彼の母親か父方の祖母が「ニグロ」と交配していなければの話だが)。さて、このようにユダヤ人とドイツ 人、そして基本的なネグロイドの血統が混ざり合うと、必然的に特異な産物が生まれ るに違いない。この仲間の輸入性もニグロ的である」。——カール・マルクス「マルクスからマンチェスターのフリードリヒ・エンゲルスへ」1862年 トレモーは、「一般的なニグロの型は、はるかに高いものの退化した形であることを証明した......ダーウィンに対する非常に大きな進歩である」。カー ル・マルクス、フリードリヒ・エンゲルスへの手紙、1866年8月7日 「奴隷制がなければ、最も進歩的な国である北アメリカは家父長制の国に変貌してしまうだろう。世界地図から北米を消し去れば、無政府状態になり、近代商業 と文明の完全な崩壊が起こるだろう。奴隷制を廃止すれば、アメリカという国を地図上から消し去ったことになる」。カール・マルクス「哲学の貧困」1847 年 「例えばアムステルダムは、フェルディナンドとイザベラがスペインから追い出し、しばらくポルトガルに滞在した後、そこからも追い出されて、結局オランダ に隠れ家を見つけたユダヤ人の最悪の子孫を多く受け入れている都市である。... このような小さなユダヤ人の一人が、ちょっとした提案をしたり、ちょっとした融資をしたりする準備ができているのだ。アブルッツィ地方で最も賢いハイウェ イマンは、旅行者の財布やポケットの中の現金のありかについて、これらの小さなユダヤ人ほど、貿易商の手にあるあらゆる緩い資本について、よく知らされて いない......。これらの小さなユダヤ人工作員は、大きなユダヤ人の家から物資を調達し......自分たちの民族の宗教に表向きの大きな献身を実践 する。" カール・マルクス「ロシアの貸金」1856年 |

“What is the worldly religion of the Jew? Huckstering. What is his worldly God? Money. ... Money is the jealous god of Israel, in face of which no other god may exist. Money degrades all the gods of man—and turns them into commodities. ... The bill of exchange is the real god of the Jew. His god is only an illusory bill of exchange. ... The chimerical nationality of the Jew is the nationality of the merchant, of the man of money in general.” Karl Marx, “On the Jewish Question,” 1844 “This splendid territory [the Balkans] has the misfortune to be inhabited by a conglomerate of different races and nationalities, of which it is hard to say which is the least fit for progress and civilization. Slavonians, Greeks, Wallachians, Arnauts, twelve millions of men, are all held in submission by one million of Turks, and up to a recent period, it appeared doubtful whether, of all these different races, the Turks were not the most competent to hold the supremacy which, in such a mixed population, could not but accrue to one of these nationalities.” Karl Marx, “The Russian Menace to Europe,” 1853 “Thus we find every tyrant backed by a Jew, as is every Pope by a Jesuit. In truth, the cravings of oppressors would be hopeless, and the practicability of war out of the question, if there were not an army of Jesuits to smother thought and a handful of Jews to ransack pockets. ... The fact that 1,855 years ago Christ drove the Jewish money-changers out of the temple, and that the money-changers of our age, enlisted on the side of tyranny, happen again to be Jews is perhaps no more than a historic coincidence.” Karl Marx, “The Russian Loan,” 1856 “The expulsion of a Leper people from Egypt, at the head of whom was an Egyptian priest named Moses. Lazarus, the leper, is also the basic type of the Jew.” Karl Marx, letter to Friedrich Engels, May 10, 1861 “Abraham, Isaac and Jacob were fantasy-mongers, that the Israelites were idolators ... that the tribe of Simeon (exiled under Saul) had moved to Mecca where they built a heathenish temple and worshipped stones.” Karl Marx, letter to Engels, June 16, 1864 “Indian society has no history at all, at least no known history. What we shall call its history is but the history of the successive invaders who founded their empires on the passive basis of that unresisting and unchanging society.” Karl Marx, New York Daily Tribune, August 8, 1853 “Russia is a name usurped by the Muscovites. They are not Slavs, do not belong at all to the Indo-German race, but are des intrus [intruders], who must again he hurled back beyond the Dnieper, etc.” Karl Marx, letter to Friedrich Engels, June 24, 1865[28][29][30][31] |

(人種論:つづき) "ユダヤ人の世俗的な宗教 "とは?ハックステーリングです。彼の世俗的な神は何であるか?金だ。... お金はイスラエルの嫉妬深い神であり、その前では他のいかなる神も存在することができない。金は人間のすべての神を堕落させ、商品に変えてしまう。... 為替手形は、ユダヤ人の本当の神である。彼の神は幻の為替手形に過ぎない。... ユダヤ人のキメラ的な国籍は、商人の国籍であり、一般に貨幣を扱う人間の国籍である」。カール・マルクス「ユダヤ人問題について」1844年 「この素晴らしい領土(バルカン半島)には、不幸にも、さまざまな人種と民族の集合体が住んでおり、そのうちのどれが進歩と文明に最も適していないかは、 言うのが難しい。スラヴォニア人、ギリシア人、ワラキア人、アルナウ人、1200万人の男が、100万人のトルコ人に服従している。つい最近までは、これ らすべての異なる人種の中で、トルコ人が最も有能でないかと疑われたが、このような混合集団では、これらの民族のいずれかに至らざるを得ないのだ"。カー ル・マルクス「ヨーロッパに対するロシアの脅威」1853年 「このように、すべての暴君がユダヤ人に支えられているように、すべてのローマ法王がイエズス会に支えられていることがわかる。実のところ、抑圧者の渇望 は絶望的であり、戦争を実行することは問題外である。もし、思想を抑圧するイエズス会の軍隊とポケットを物色する一握りのユダヤ人がいなければ。... 1855年前にキリストがユダヤ人の両替商を神殿から追い出し、現代の両替商が専制政治の側につき、再びユダヤ人であるという事実は、おそらく歴史的な偶 然の一致に過ぎない」。カール・マルクス「ロシアの貸金」1856年 "エジプトからハンセン病の民を追放したのは、モーゼというエジプトの祭司であった。らい病人のラザロは、ユダヤ人の基本型でもある。" カール・マルクス、フリードリヒ・エンゲルスへの手紙、1861年5月10日 "アブラハム、イサク、ヤコブは空想家であり、イスラエル人は偶像崇拝者であると・・・シメオン族(サウル時代に追放)はメッカに移住し、異教徒の神殿を 建てて石を拝んでいると。" カール・マルクス、エンゲルスへの手紙、1864年6月16日 「インド社会には歴史が全くない、少なくとも既知の歴史はない。われわれがその歴史と呼ぶものは、その無抵抗で不変の社会の受動的な基礎の上に彼らの帝国 を築いた歴代の侵略者の歴史にすぎない。" カール・マルクス、ニューヨーク・デイリー・トリビューン、1853年8月8日号 "ロシアというのは、ムスコヴィッツに簒奪された名前である。彼らはスラブ人ではなく、インド・ドイツ人種にはまったく属さず、デ・イントルス(侵入者) であり、ドニエプル川を越えて再び追い返さなければならない、などというのである。カール・マルクス、フリードリヒ・エンゲルス宛書簡、1865年6月 24日[28][29][30][31]。 |

| Human nature and historical

materialism Marx's theory of history attempts to describe the way in which humans change their environments and (in dialectical relation) their environments change them as well. That is: Not only do the objective conditions change in the act of reproduction, e.g. the village becomes a town, the wilderness a cleared field etc., but the producers change, too, in that they bring out new qualities in themselves, develop themselves in production, transform themselves, develop new powers and ideas, new modes of intercourse, new needs and new language.[32] Further Marx sets out his "materialist conception of history" in opposition to "idealist" conceptions of history; that of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, for instance. "The first premise of all human history is, of course, the existence of living human individuals. Thus the first fact to be established is the physical organisation of these individuals and their consequent relation to the rest of nature."[6] Thus: History does nothing, it "possesses no immense wealth", it "wages no battles". It is man, real, living man who does all that, who possesses and fights; "history" is not, as it were, a person apart, using man as a means to achieve its own aims; history is nothing but the activity of man pursuing his aims.[33] So we can see that, even before we begin to consider the precise character of human nature, "real, living" humans, "the activity of man pursuing his aims" is the very building block of Marx's theory of history. Humans act upon the world, changing it and themselves; and in doing so they "make history".[6] However, even beyond this, human nature plays two key roles. In the first place, it is part of the explanation for the growth of the productive forces, which Marx conceives of as the driving force of history. Secondly, the particular needs and drives of humans explain the class antagonism which is generated under capitalism. |

人間の本質と史的唯物論 マルクスの歴史論は、人間が環境を変え、その環境も人間を変える(弁証法的関係)様相を記述しようとするものである。つまり 例えば、村が町になり、荒野が耕作地になるなど、再生産の行為において客観的条件が変化するだけでなく、生産者もまた、彼ら自身の中に新しい性質を引き出 し、生産において彼ら自身を発展させ、彼らを変革し、新しい力とアイデア、新しい交際様式、新しいニーズと新しい言語を開発するという点で変化する [32]」と。 さらにマルクスは、例えばGeorg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegelのような「観念論的」な歴史概念に対抗して、彼の「唯物論的歴史概念」を示している。「すべての人間の歴史の最初の前提は、もちろん、生きてい る人間の個人の存在である。したがって、確立されるべき最初の事実は、これらの個人の物理的な組織と、その結果として生じる自然の他の部分との関係であ る」[6] このように。 歴史は何もせず、「莫大な富を持たず」、「戦いもしない」。歴史」とは、いわば、それ自身の目的を達成するために人間を手段として使用する分離した人間で はなく、歴史とは、自分の目的を追求する人間の活動にほかならないのである[33]。 だから私たちは、人間性、「現実の、生きている」人間の正確な性格を検討し始める前でさえ、「自分の目的を追求する人間の活動」がマルクスの歴史論のまさ に構成要素であることを見ることができる。人間は世界に対して行動し、世界と自分自身を変え、そうすることで「歴史を作る」[6]。しかし、それ以上に人 間の本性は二つの重要な役割を果たす。第一に、マルクスが歴史の原動力として考えている生産力の成長に対する説明の一部である。第二に、人間の特殊な欲求 と衝動は、資本主義のもとで発生する階級対立を説明する。 |

| Human nature and the

expansion of the productive forces It has been held by several writers that it is Marx's conception of human nature which explains the "development thesis" (Cohen, 1978) concerning the expansion of the productive forces, which according to Marx, is itself the fundamental driving force of history. If true, this would make his account of human nature perhaps the most fundamental aspect of his work. Geras writes, (1983, pp. 107–108, italics in original) "historical materialism itself, this whole distinctive approach to society that originates with Marx, rests squarely upon the idea of a human nature." It highlights that specific nexus of universal needs and capacities which explains the human productive process and man's organized transformation of the material environment; which process and transformation it treats in turn as the basis both of the social order and of historical change.' G.A. Cohen (1988, p. 84): "The tendency's autonomy is just its independence of social structure, its rootedness in fundamental material facts of human nature and the human situation." Allen Wood (2004, p. 75): "Historical progress consists fundamentally in the growth of people's abilities to shape and control the world about them. This is the most basic way in which they develop and express their human essence" (see also, the quotation from Allen Wood above). In his article Reconsidering Historical Materialism, however, Cohen gives an argument to the effect that human nature cannot be the premise on which the plausibility of the expansion of the productive forces is grounded: Production in the historical anthropology is not identical with production in the theory of history. According to the anthropology, people flourish in the cultivation and exercise of their manifold powers, and are especially productive - which in this instance means creative - in the condition of freedom conferred by material plenty. But, in the production of interest to the theory of history, people produce not freely but because they have to, since nature does not otherwise supply their wants; and the development in history of the productive power of man (that is, of man as such, of man as a species) occurs at the expense of the creative capacity of the men who are agents and victims of that development. (p. 166 in ed. Callinicos, 1989) The implication of this is that hence "one might ... imagine two kinds of creature, one whose essence it was to create and the other not, undergoing similarly toilsome histories because of similarly adverse circumstances. In one case, but not the other, the toil would be a self-alienating exercise of essential powers" (p. 170). Hence, "historical materialism and Marxist philosophical anthropology are independent of, though also consistent with, each other" (p. 174, see especially sections 10 and 11). The problem is this: it seems as though the motivation most people have for the work they do isn't the exercise of their creative capacity; on the contrary, labour is alienated by definition in the capitalist system based on salary, and people only do it because they have to. They go to work not to express their human nature but to find theirs means of subsistence. So in that case, why do the productive forces grow – does human nature have anything to do with it? The answer to this question is a difficult one, and a closer consideration of the arguments in the literature is necessary for a full answer than can be given in this article. However, it is worth bearing in mind that Cohen had previously been committed to the strict view that human nature (and other "asocial premises") were sufficient for the development of the productive forces – it could be that they are only one necessary constituent. It is also worth considering that by 1988 (see quotation above), he appears to consider that the problem is resolved. Some needs are far more important than others. In The German Ideology Marx writes that "life involves before everything else eating and drinking, a habitation, clothing and many other things". All those other aspects of human nature which he discusses (such as "self-activity") are therefore subordinate to the priority given to these. Marx makes explicit his view that humans develop new needs to replace old: "the satisfaction of the first need (the action of satisfying, and the instrument of satisfaction which has been acquired) leads to new needs".[34] |

人間性と生産力の拡大 生産力の拡大に関する「発展テーゼ」(Cohen, 1978)を説明するのは、マルクスの人間性の概念であり、それは、マルクスによれば、それ自体が歴史の基本的な推進力であるとする見解が、いくつかの作 家によって示されている。もし、それが本当なら、彼の人間性に関する説明は、おそらく彼の著作の最も基本的な側面となるであろう。ゲラスは、(1983, pp. 107-108, italics in original) "historical materialism itself, this whole distinctive approach to society that origates with Marx, restsely on the idea of a human nature "と書いている。それは、人間の生産過程と物質環境の人間の組織的変容を説明する普遍的なニーズと能力の特定の結びつきを強調し、その過程と変容は、社会 秩序と歴史的変化の両方の基礎として順番に扱われる」。G.A.コーエン(1988、p.84)。"傾向の自律性は、社会構造からの独立性であり、人間性 と人間状況の基本的な物質的事実に根ざしていることにほかならない。" アレン・ウッド(2004, p.75)。「歴史的進歩は、基本的に、自分たちを取り巻く世界を形成し、コントロールする人々の能力の成長から成っている。これは、彼らが人間の本質を 開発し、表現する最も基本的な方法である」(上記アレン・ウッドの引用も参照のこと)。 しかし、コーエンは、論文『史的唯物論の再検討』の中で、生産力の拡大の妥当性の根拠となる前提が人間性ではありえないという趣旨の議論を展開している。 歴史人類学における生産は、歴史理論における生産と同一ではない。歴史的人間学によれば、人々は、その多様な力の育成と行使において繁栄し、物質的な豊か さによって与えられる自由の状態において、とりわけ生産的である-この場合、創造的であることを意味する-のである。しかし、歴史学の理論にとっての利益 の生産では、人々は自由に生産するのではなく、自然が他に彼らの欲求を供給しないので、生産しなければならない。そして、歴史における人間の生産力(つま り、そのような人間、種としての人間の)の発展は、その発展の代理人であり犠牲者である人間の創造的能力を犠牲にして起こるのである。(カリニコス編、 1989年、166頁) このことが意味するところは、それゆえ、「人は......2種類の生き物を想像するかもしれない、一方は創造することを本質とし、他方はそうではなく、 同じように不利な状況のために同じように苦労する歴史を歩んでいる。一方では、労苦は本質的な力の自己疎外的な行使であるが、他方では、そうではない」 (170頁)。したがって、「史的唯物論とマルクス主義の哲学的人間学は、互いに矛盾しないが、独立している」(174頁、特に10、11節参照)のであ る。それどころか、給与に基づく資本主義体制では、労働は定義上疎外されたものであり、人々は、そうしなければならないからそうしているだけなのである。 人間らしさを表現するためではなく、生活の糧を得るために働きに出るのである。では、その場合、なぜ生産力は伸びるのでしょうか。人間性は関係するので しょうか。この問いに対する答えは難しいもので、この記事でできる以上の答えを出すには、文献にある議論をより詳しく検討する必要がある。しかし、コーエ ンが以前、生産力の発展には人間性(およびその他の「非社会的前提」)が十分であるという厳格な見解に傾倒していたことは心に留めておく価値がある-それ は、人間性が必要な構成要素の一つに過ぎないということかもしれない。また、1988年までに(上記の引用を参照)、彼はこの問題が解決されたと考えてい るようであることも考慮する価値がある。 ある種のニーズは、他のニーズよりもはるかに重要である。マルクスは、『ドイツ・イデオロギー』のなかで、「生活には、他の何よりもまず、食べること、飲 むこと、住むこと、着ること、その他多くのことが含まれる」と書いている。したがって、彼が論じている人間性の他のすべての側面(たとえば「自己活動」) は、これらに与えられた優先順位に従属するものである。マルクスは、人間が古い欲求に代わって新しい欲求を発達させるという見解を明らかにしている。「最 初の欲求の充足(充足する行為、獲得された充足の道具)は新しい欲求をもたらす」[34]。 |

| Human nature, Marx's

ethical thought and alienation Geras says of Marx's work that: "Whatever else it is, theory and socio-historical explanation, and scientific as it may be, that work is a moral indictment resting on the conception of essential human needs, an ethical standpoint, in other words, in which a view of human nature is involved" (1983, pp. 83–84). |

人間の本性、マルクスの倫理思想、疎外 ゲラスはマルクスの著作について次のように述べている。「理論や社会歴史的な説明、科学的なものであるにせよ、その仕事は人間の本質的な欲求の概念に立脚 した道徳的な告発であり、言い換えれば、人間の本性についての見解が関わっている倫理的立場である」(1983、83-84ページ)。 |

| Alienation Alienation, for Marx, is the estrangement of humans from aspects of their human nature. Since – as we have seen – human nature consists in a particular set of vital drives and tendencies, whose exercise constitutes flourishing, alienation is a condition wherein these drives and tendencies are stunted. For essential powers, alienation substitutes disempowerment; for making one's own life one's object, one's life becoming an object of capital. Marx believes that alienation will be a feature of all society before communism. The opposite of alienation is "actualisation" or "self-activity" – the activity of the self, controlled by and for the self.[citation needed] |

疎外 マルクスにとって、疎外とは、人間がその人間的本性の側面から疎外されることである。 これまで見てきたように、人間の本性は、特定の生命的な衝動と傾向の集合から成り、 その行使が繁栄を構成するので、疎外は、これらの衝動と傾向が阻害される状態である。 本質的な力の代わりに、疎外は、脱力、つまり、自分の人生を自分の対象とすること、自分の人生が資本の対象となることを代弁している。マルクスは、疎外が 共産主義以前のすべての社会の特徴になると考えている。疎外の反対は「実現」または「自己活動」であり、自己によって、自己のために制御される自己の活動 である[引用原文が必要]。 |

| Gerald Cohen's criticism One important criticism of Marx's "philosophical anthropology" (i.e. his conception of humans) is offered by Gerald Cohen, the leader of Analytical Marxism, in Reconsidering Historical Materialism (in ed. Callinicos, 1989). Cohen claims: "Marxist philosophical anthropology is one sided. Its conception of human nature and human good overlooks the need for self-identity than which nothing is more essentially human." (p. 173, see especially sections 6 and 7). The consequence of this is held to be that "Marx and his followers have underestimated the importance of phenomena, such as religion and nationalism, which satisfy the need for self-identity. (Section 8.)" (p. 173). Cohen describes what he sees as the origins of Marx's alleged neglect: "In his anti-Hegelian, Feuerbachian affirmation of the radical objectivity of matter, Marx focused on the relationship of the subject to an object which is in no way subject, and, as time went on, he came to neglect the subject's relationship to itself, and that aspect of the subject's relationship to others which is a mediated (that is, indirect), form of relationship to itself" (p. 155). Cohen believes that people are driven, typically, not to create identity, but to preserve that which they have in virtue, for example, of "nationality, or race, or religion, or some slice or amalgam thereof" (pp. 156–159). Cohen does not claim that "Marx denied that there is a need for self-definition, but [instead claims that] he failed to give the truth due emphasis" (p. 155). Nor does Cohen say that the sort of self-understanding that can be found through religion etc. is accurate (p. 158). Of nationalism, he says "identifications [can] take benign, harmless, and catastrophically malignant forms" (p. 157) and does not believe "that the state is a good medium for the embodiment of nationality" (p. 164). |

ジェラルド・コーエンの批判 マルクスの「哲学的人間学」(人間に関する概念)に対する重要な批判として、分析的マルクス主義のリーダーであるジェラルド・コーエンが、『史的唯物論の 再検討』(カリニコス編、1989)の中で述べていることがある。コーエンはこう主張する。「マルクス主義の哲学的人間学は一面的である。その人間性と人 間的善の概念は、自己同一性の必要性を見落としており、それ以上に本質的に人間的なものはない。(173頁、特に第6節、第7節参照)。その結果、「マル クスとその追随者たちは、宗教やナショナリズムなど、自己同一性の欲求を満たす現象の重要性を過小評価している」(第8節)とされる。(第8節) "とする。(p. 173). コーエンは、マルクスが無視したとされる原点と思われるものを述べている。「反ヘーゲル的、フォイエルバッハ的な物質の根本的客観性の肯定において、マル クスは、主体がいかなる形でもない対象との関係に焦点を当て、時が経つにつれて、主体の自分自身との関係、そして、主体の他者との関係の、媒介(つまり間 接)的形態であるその側面を軽視するようになった」(155ページ)。 コーエンは、人々は典型的に、アイデンティティを創造するのではなく、例えば「国籍、人種、宗教、あるいはそれらの断片やアマルガム」のおかげで持ってい るものを維持しようと駆り立てられると信じている(156-159頁)。コーエンは、「マルクスが自己定義の必要性を否定したのではなく、(その代わり に)真理を十分に強調することに失敗したと主張している」(155頁)。また、コーエンは、宗教などを通じて見出されるような自己理解が正確であるとも 言っていない(p.158)。ナショナリズムについては、「同一性は、良性、無害、そして破滅的に悪性の形態をとることができる」(157頁)とし、「国 家が民族性を体現するためのよい媒体であるとは考えていない」(164頁)とする。 |

| Karl Marx's theory of alienation Karl Marx's theory of alienation describes the estrangement (German: Entfremdung) of people from aspects of their human nature (Gattungswesen, 'species-essence') as a consequence of the division of labor and living in a society of stratified social classes. The alienation from the self is a consequence of being a mechanistic part of a social class, the condition of which estranges a person from their humanity.[1] The theoretical basis of alienation is that the worker invariably loses the ability to determine life and destiny when deprived of the right to think (conceive) of themselves as the director of their own actions; to determine the character of said actions; to define relationships with other people; and to own those items of value from goods and services, produced by their own labour. Although the worker is an autonomous, self-realized human being, as an economic entity this worker is directed to goals and diverted to activities that are dictated by the bourgeoisie—who own the means of production—in order to extract from the worker the maximum amount of surplus value in the course of business competition among industrialists. In the Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844 (1932), Karl Marx expressed the Entfremdung theory—of estrangement from the self. Philosophically, the theory of Entfremdung relies upon The Essence of Christianity (1841) by Ludwig Feuerbach, which states that the idea of a supernatural god has alienated the natural characteristics of the human being. Moreover, Max Stirner extended Feuerbach's analysis in The Ego and its Own (1845) that even the idea of 'humanity' is an alienating concept for individuals to intellectually consider in its full philosophic implication. Marx and Friedrich Engels responded to these philosophical propositions in The German Ideology (1845). |

カール・マルクスの疎外論 カール・マルクスの疎外論は、分業や階層化された社会での生 活の結果として、人が人間性(Gattungswesen、「種的本質」)の側面から疎外される(ドイツ語:Entfremdung)ことを述べている。 自己からの疎外は、社会階級の機械的な一部であることの結果であり、その状態は人をその人間性から疎外する[1]。 疎外の理論的根拠は、労働者が自分自身の行動の監督者として自分自身を考える(構想する)権利、その行動の性格を決める権利、他の人々との関係を定める権 利、そして自分自身の労働によって生産された財やサービスなどの価値のあるものを所有する権利を奪われると、人生と運命を決定する能力を必ず失ってしまう というものである。労働者は、自律的で自己実現された人間であるが、経済的実体として、この労働者は、生産手段を所有するブルジョアジーによって指示され た目標に向かい、活動に転用される。それは、産業人同士のビジネス競争の過程で、労働者から最大量の剰余価値を引き出すためである。 カール・マルクスは、1844年の『経済哲学手稿』(1932年)の中で、Entfremdung理論-自己からの疎外-を表明している。哲学的には、 フォイエルバッハの『キリスト教の本質』(1841)に依拠しており、超自然的な神の思想が人間の自然な特性を疎外していると述べている。さらにマック ス・シュティルナーは『自我と自己』(1845年)で、「人間性」という概念さえも、個人がその哲学的含意のすべてを知的に考察するには疎外された概念で あるというフォイエルバッハの分析を発展させたのである。マルクスとエンゲルスは、『ドイツ・イデオロギー』(1845年)でこれらの哲学的命題に応え た。 |

| From their Gattungswesen

(species-essence) The Gattungswesen ('species-essence' or 'human nature'), of individuals is not discrete (separate and apart) from their activity as a worker and as such species-essence also comprises all of innate human potential as a person. Conceptually, in the term species-essence, the word species describes the intrinsic human mental essence that is characterized by a "plurality of interests" and "psychological dynamism," whereby every individual has the desire and the tendency to engage in the many activities that promote mutual human survival and psychological well-being, by means of emotional connections with other people, with society. The psychic value of a human consists in being able to conceive (think) of the ends of their actions as purposeful ideas, which are distinct from the actions required to realize a given idea. That is, humans are able to objectify their intentions by means of an idea of themselves as "the subject" and an idea of the thing that they produce, "the object." Conversely, unlike a human being an animal does not objectify itself as "the subject" nor its products as ideas, "the object," because an animal engages in directly self-sustaining actions that have neither a future intention, nor a conscious intention. Whereas a person's Gattungswesen does not exist independently of specific, historically conditioned activities, the essential nature of a human being is actualized when an individual—within their given historical circumstance—is free to subordinate their will to the internal demands they have imposed upon themselves by their imagination and not the external demands imposed upon individuals by other people. |

彼らの「類的存在(Gattungswesen)」 個人の類的存在(Gattungswesen)は、労働者としての活動から切り離されたものではなく、種的本質は人間としての生得的な可能性のすべてを含 んでいるのである。 概念的には、類的存在(species-essence)という言葉は、すべての個人が他の人々、社会との感情的なつながりによって、人間の相互の生存と 心理的な幸福を促進する多くの活動に従事する欲求と傾向を持っている「複数の利益」と「心理的ダイナミズム」によって特徴づけられる人間の本質的精神的本 質を表している。人間の心理的価値は、自分の行動の目的を、ある考えを実現するために必要な行動とは異なる目的的な考えとして思い浮かべる(思考する)こ とができることにある。つまり、人間は、自分自身を「主体」とする観念と、自分が生み出すものを「客体」とする観念によって、自分の意図を客観化すること ができるのである。逆に、動物は、将来の意図も意識的な意図もない、直接的に自立した行動をとるので、人間と違って、自分を「主体」とし、その生産物を 「客体」という観念として対象化することはない。人間の「ガットゥング・ズウェッセン」が歴史的に条件付けられた特定の活動から独立して存在しないのに対 し、人間の本質的な性質は、個人が与えられた歴史的状況の中で、自分の意志を、他者から個人に課される外的要求ではなく、自分の想像によって自分に課した 内的要求に自由に従属させるときに実現されるのである。 |

| alienation (contin.) In a capitalist society, the worker's alienation from their humanity occurs because the worker can express labour—a fundamental social aspect of personal individuality—only through a private system of industrial production in which each worker is an instrument: i.e., a thing, not a person. In the "Comment on James Mill" (1844), Marx explained alienation thus: Let us suppose that we had carried out production as human beings. Each of us would have, in two ways, affirmed himself, and the other person. (i) In my production I would have objectified my individuality, its specific character, and, therefore, enjoyed not only an individual manifestation of my life during the activity, but also, when looking at the object, I would have the individual pleasure of knowing my personality to be objective, visible to the senses, and, hence, a power beyond all doubt. (ii) In your enjoyment, or use, of my product I would have the direct enjoyment both of being conscious of having satisfied a human need by my work, that is, of having objectified man's essential nature, and of having thus created an object corresponding to the need of another man's essential nature ... Our products would be so many mirrors in which we saw reflected our essential nature.[2] In the Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844 (1844/1932), Marx identified four types of alienation that occur to the worker labouring under a capitalist system of industrial production. They are alienation of the worker from their product, from the act of production, from their Gattungswesen ('species-essence') and from other workers.[3] |

疎外(続き) 資本主義社会では、労働者が人間性から疎外される。なぜな ら、労働者は、個人的個性の基本的社会的側面である労働を、各労働者が道具である私的な工業生産システムを通じてのみ表現できるからである。マルクスは、 「ジェームズ・ミルについてのコメント」(1844年)の中で、疎外について次のように説明している。 われわれが人間として生産を行ったと仮定してみよう。私たちはそれぞれ、二つの方法で、自分自身と他者とを肯定していただろう。(i)私は、自分の生産に おいて、自分の個性、その特異な性格を客観化し、したがって、活動の間、自分の生命の個別的な発現を楽しんだだけでなく、その対象を見るとき、自分の個性 が客観的で、感覚に見え、それゆえ、あらゆる疑いを越えた力であると知る個別的喜びを持っただろう。(ii) あなたが私の製品を楽しむ、あるいは使用するとき、私は、私の仕事によって人間の必要を満たしたこと、つまり人間の本質的な性質を客観化したことを意識す ることと、こうして別の人間の本質的な性質の必要に対応する対象を創造したことを直接楽しむことができるだろう............。私たちの製品 は、私たちの本質的な性質が映し出された多くの鏡のようなものであろう[2]。 1844年の『経済哲学手稿』(1844/1932)でマルクスは資本主義の工業生産システムの下で労働する労働者に生じる4つのタイプの疎外を特定し た。それらは労働者の生産物からの疎外、生産行為からの疎外、彼らのGattungswesen(「種-本質」)からの疎外、そして他の労働者からの疎外 である[3]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marx%27s_theory_of_human_nature |

https://www.deepl.com/ja/translator |

■余滴

真実か虚偽を問わず

「女性は与える存在」という命題の立て方が誤謬なのである。「与えることを通して人間は女性というものになる」というがより適切であるし、エージェンシー

化した肋骨と土からできたアダムとのジェンダー互酬性のはじまりなのだ(→「」)。

■リンク

■文 献

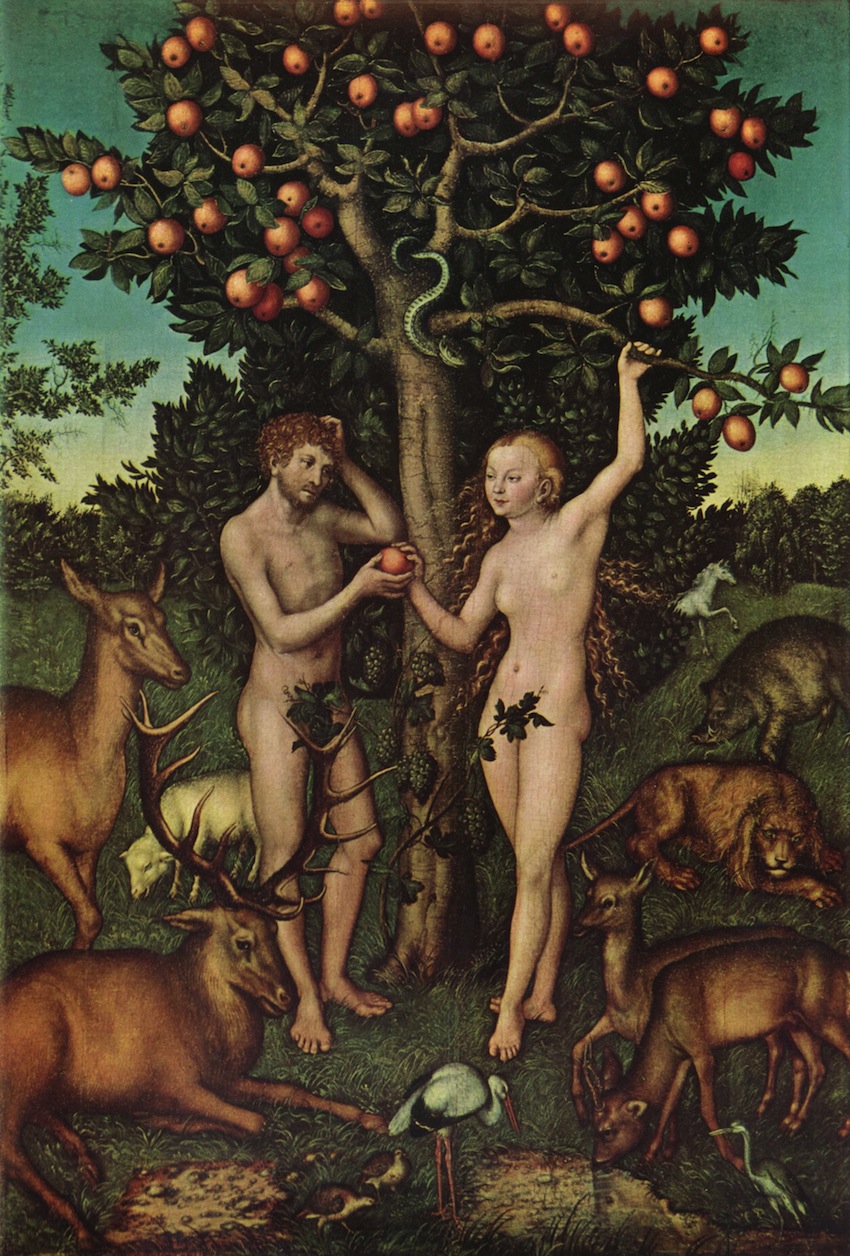

Lucas Cranach the Elder (1472–1553) , Adam and Eve, 1526

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099