神話学

Mythology

★本来、神聖なものであるにせよ宗教的なものであるにせよ、神話というものは、

個人的や逸話的というよりも、社会的な語りである。そして、自然、超自然、社

会文化なものであれ、神話は、事象の起源や創造について言及がある。神話は、特定の儀礼を表出するのだ。神話と儀礼は、共通の象徴的要素を共有し、創造的

かつ宗教的表現をするために両者は相補的な関係にある。

神話学(mythology)とは、神話 (mytho[s]-logy)を研究する学問。神話(myth)とは、読んで字のごとく、神や仏などの超自然的存在(supernatural beings)や、ものすごく昔(つまり神話的時代)の先祖や祖先、あるいは、人間のみならず動植物(→アニミズム)や事物の霊的存在が主人公になる物語 のことである。神話は、どのような社会において語られる時にも、そこには存在しないものについて話すので、語り手は聞き手とともにいる(=共在する)時空 間とは異なる話であることを強調する。また、語り終わったときには、そのような内容を過去のものや、伝聞推定のように表現して、「今まさにここに」という 時空間とは別物であることを強調する。

そのため、神話は、説話、民話、おとぎ話などの、い わゆる「法螺話」や「子供向けの話」などとも揶揄されたり、混同されたりする。また儀礼文や祝詞のような呪文のような中にも現出するが、こちらは「誰も信 じないが、厳粛に聞かなけれならない」中での形式化された物語でもある。

そのため、神話という言葉の現代的用語の中に、先にいった、「法 螺話」という意味が付与されるようになった。たとえば「現代の神話」や「都市伝説」は、形をかえた、荒唐無稽の話だが、聞くに値する話で、人々は半信半疑 で聞く。聞くに値する話ということは、神話は、人々の関心を引く「面白いもの」が多い。その面白さの原因は、偉大な文学研究者であったロラン・バルトなどによると、何らかの構造をもつということあるら しい。これは、啓蒙主義時代には、神話というものを反理性(=「理性」 概念に反するもの)の塊として考えて、我々の世界を理性的なものとすべし考え方(=カントの思想がその典型)の産物であった。ヘーゲルの時代になると、も う少しずる賢く(=狡知(こうち)と言う)なって、世界の中にある神話や民話は、人々に世界のあり方を考えさせる教訓や比喩(ないしは皮肉)となって、そ れらの神話の別の意味(=メタ階層理論という)を考えよと、啓蒙主義の教師は教え子たちに言うようになった。

さて、元の本流に戻ろう。構造をもつことから、文化的な広がりの中での普及と、人間がもつ物 語構造への没入という普遍的一般的性格から、神話の構造と、人間の理解の構造的一致について、多角的に洞察した、クロード・レヴィ=ストロースという、偉大な構造人類学者もいる(→「神話の構造的研究」)。

| The Elementary

Structures of Kinship was published in 1949 and quickly came to be

regarded as one of the most important anthropological works on kinship.

It was even reviewed favorably by Simone de Beauvoir, who saw it as an

important statement of the position of women in non-Western cultures. A

play on the title of Durkheim's famous Elementary Forms of the

Religious Life, Lévi-Strauss' Elementary Structures re-examined how

people organized their families by examining the logical structures

that underlay relationships rather than their contents. While British

anthropologists such as Alfred Reginald Radcliffe-Brown argued that

kinship was based on descent from a common ancestor, Lévi-Strauss

argued that kinship was based on the alliance between two families that

formed when women from one group married men from another.[28] Throughout the late 1940s and early 1950s, Lévi-Strauss continued to publish and experienced considerable professional success. On his return to France, he became involved with the administration of the CNRS and the Musée de l'Homme before finally becoming a professor (directeur d'études) of the fifth section of the École Pratique des Hautes Études, the 'Religious Sciences' section where Marcel Mauss was previously professor, the title of which chair he renamed "Comparative Religion of Non-Literate Peoples". While Lévi-Strauss was well known in academic circles, in 1955 he became one of France's best-known intellectuals by publishing Tristes Tropiques in Paris that year by Plon (best-known translated into English in 1973, published by Penguin). Essentially, this book was a memoir detailing his time as a French expatriate throughout the 1930s and his travels. Lévi-Strauss combined exquisitely beautiful prose, dazzling philosophical meditation, and ethnographic analysis of the Amazonian peoples to produce a masterpiece. The organizers of the Prix Goncourt, for instance, lamented that they were not able to award Lévi-Strauss the prize because Tristes Tropiques was nonfiction.[citation needed] Lévi-Strauss was named to a chair in social anthropology at the Collège de France in 1959. At roughly the same time he published Structural Anthropology, a collection of his essays that provided both examples and programmatic statements about structuralism. At the same time as he was laying the groundwork for an intellectual program, he began a series of institutions to establish anthropology as a discipline in France, including the Laboratory for Social Anthropology where new students could be trained, and a new journal, l'Homme, for publishing the results of their research. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Claude_L%C3%A9vi-Strauss |

『親族関係の基本構造』は1949年に出版され、すぐに親族関係に関す

る人類学的著作の中で最も重要なもののひとつとみなされるようになった。シモーヌ・ド・ボーヴォワールも、非西洋文化圏における女性の立場を示す重要な書

物として好意的に受け止めている。デュルケムの有名な『宗教生活の初歩的形態』のタイトルをもじったレヴィ=ストロースの『初歩的構造』は、人間関係の内

容ではなく、人間関係の根底にある論理的構造を考察することで、人々がどのように家族を組織しているかを再検討した。アルフレッド・レジナルド・ラドクリ

フ=ブラウンのようなイギリスの人類学者が、親族関係は共通の祖先からの子孫に基づいていると主張したのに対し、レヴィ=ストロースは、親族関係は、ある

集団の女性が別の集団の男性と結婚したときに形成される2つの家族の間の同盟に基づいていると主張した[28]。 1940年代後半から1950年代前半にかけて、レヴィ=ストロースは出版活動を続け、仕事上かなりの成功を収めた。フランスに戻ると、CNRSと人間博 物館の運営に携わるようになり、最終的に高等師範学校(École Pratique des Hautes Études)の第5部「宗教科学」の教授(directeur d'études)となった。 レヴィ=ストロースは学界ではよく知られていたが、1955年、パリで『Tristes Tropiques』を出版し、フランスで最もよく知られた知識人の一人となった(英語への翻訳は1973年にペンギン社から出版された『Tristes Tropiques』が最もよく知られている)。本書は基本的に、1930年代を通じてのフランス人駐在員としての生活と旅の詳細を記した回想録であっ た。レヴィ=ストロースは、絶妙に美しい散文、めくるめく哲学的瞑想、アマゾン民族の民族誌的分析を組み合わせ、傑作を生み出した。例えば、ゴンクール賞 の主催者は、『Tristes Tropiques』がノンフィクションであったため、レヴィ=ストロースに賞を与えることができなかったと嘆いた[要出典]。 レヴィ=ストロースは1959年にコレージュ・ド・フランスの社会人類学の講座に任命された。ほぼ同時期に、彼は構造主義についての実例と綱領的な声明を 提供したエッセイ集『構造人類学』を出版した。知的プログラムの基礎を固めると同時に、彼はフランスで人類学を学問として確立するために、新しい学生を養 成するための社会人類学研究室や、研究成果を発表するための新しい雑誌『l'Homme』など、一連の制度を開始した。 |

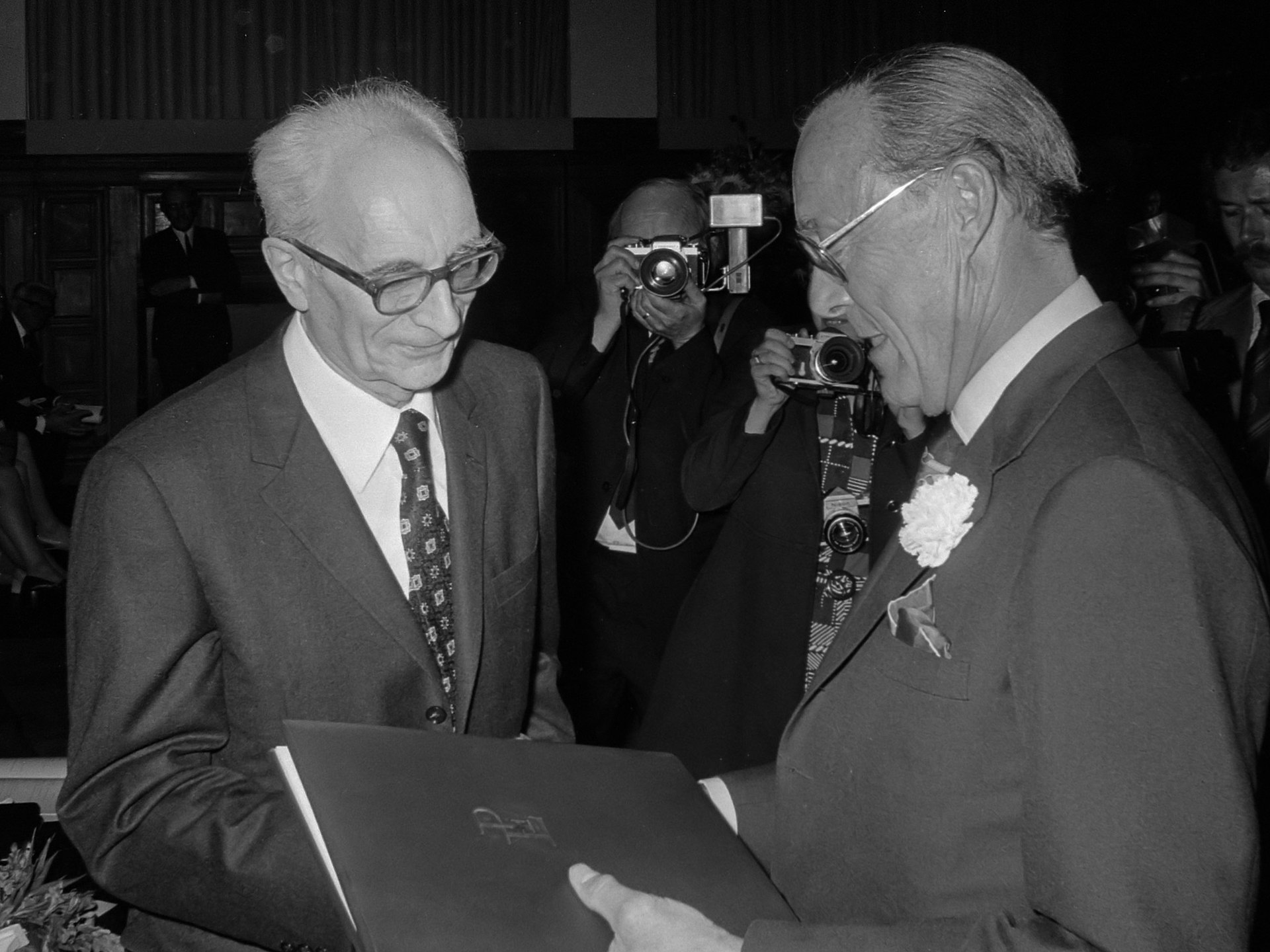

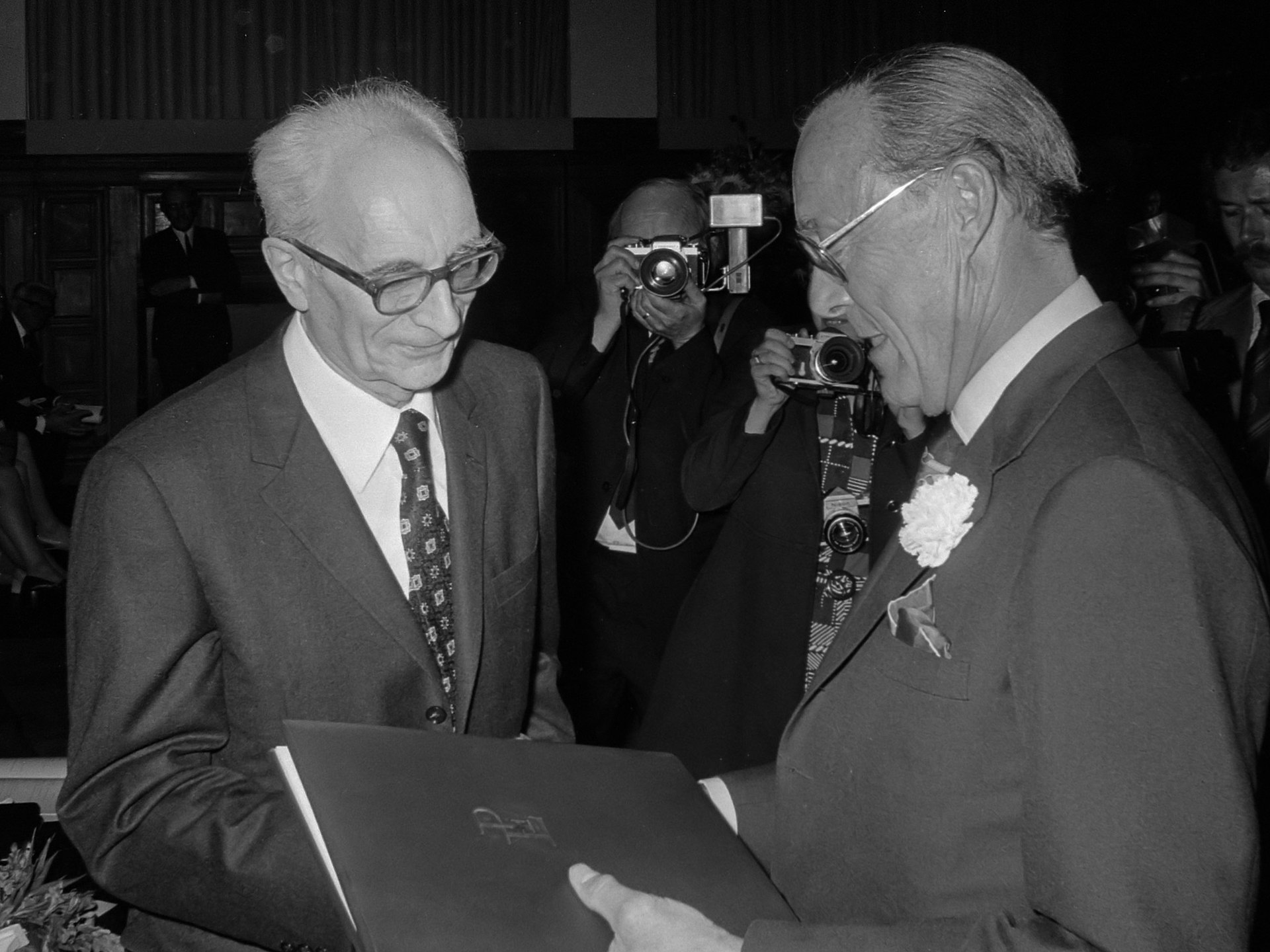

| Mythologiques Now a worldwide celebrity, Lévi-Strauss spent the second half of the 1960s working on his master project, a four-volume study called Mythologiques. In it, he followed a single myth from the tip of South America and all of its variations from group to group north through Central America and eventually into the Arctic Circle, thus tracing the myth's cultural evolution from one end of the Western Hemisphere to the other. He accomplished this in a typically structuralist way, examining the underlying structure of relationships among the elements of the story rather than focusing on the content of the story itself. While Pensée Sauvage was a statement of Lévi-Strauss's big-picture theory, Mythologiques was an extended, four-volume example of analysis. Richly detailed and extremely long, it is less widely read than the much shorter and more accessible Pensée Sauvage, despite its position as Lévi-Strauss's masterwork.  Claude Lévi-Strauss, receiving the Erasmus Prize (1973) Lévi-Strauss completed the final volume of Mythologiques in 1971. On 14 May 1973, he was elected to the Académie française, France's highest honour for a writer.[29] He was a member of other notable academies worldwide, including the American Academy of Arts and Letters. In 1956, he became foreign member of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences.[30] He then became a member of the American Philosophical Society in 1960 and the United States National Academy of Sciences in 1967.[31] He received the Erasmus Prize in 1973, the Meister-Eckhart-Prize for philosophy in 2003, and several honorary doctorates from universities such as Oxford, Harvard, Yale, and Columbia. He also was the recipient of the Grand-croix de la Légion d'honneur, was a Commandeur de l'ordre national du Mérite, and Commandeur des Arts et des Lettres. In 2005, he received the XVII Premi Internacional Catalunya (Generalitat of Catalonia). After his retirement, he continued to publish occasional meditations on art, music, philosophy, and poetry. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Claude_L%C3%A9vi-Strauss |

神話学 今や世界的な有名人となったレヴィ=ストロースは、1960年代後半、『Mythologiques(神話学)』と呼ばれる4巻からなる研究書の執筆に没 頭した。その中でレヴィ=ストロースは、ひとつの神話を南米の先端から、そのすべての変種を集団から集団へと追いかけ、中米を北上し、最終的には北極圏に 至るまで、西半球の端から端まで神話の文化的進化をたどった。彼は典型的な構造主義的手法でこれを成し遂げ、物語の内容そのものに焦点を当てるのではな く、物語の要素間の関係の根底にある構造を考察した。Pensée Sauvage』がレヴィ=ストロースの大局的な理論の表明であったのに対し、『Mythologiques』は4巻からなる拡大された分析例であった。 レヴィ=ストロースの代表作であるにもかかわらず、『Mythologiques』は『Pensée Sauvage』よりもはるかに短く、親しみやすい。  エラスムス賞を受賞したクロード・レヴィ=ストロース(1973年) レヴィ=ストロースは1971年に『神話学』の最終巻を完成させた。1973年5月14日、作家としてフランス最高の栄誉であるアカデミー・フランセーズ に選出される[29]。1973年にエラスムス賞、2003年にマイスター・エックハート賞(哲学部門)、オックスフォード大学、ハーバード大学、イェー ル大学、コロンビア大学などから名誉博士号を授与された。また、レジオンドヌール勲章を受章し、国家勲章コマンドゥール、芸術文化勲章コマンドゥールも受 章している。2005年には第17回カタルーニャ国際賞を受賞した。引退後も、芸術、音楽、哲学、詩についての瞑想を時折発表している。 |

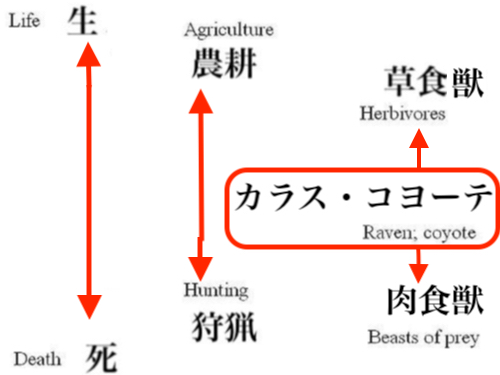

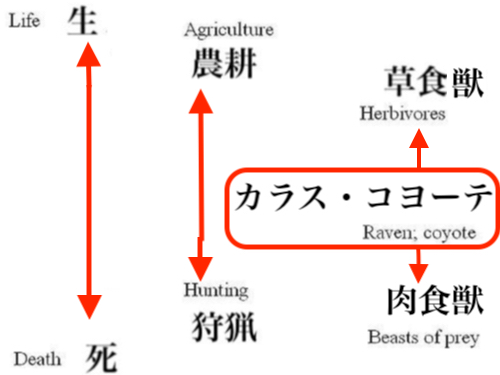

| Structuralist approach to myth Main article: Structuralist theory of mythology Similar to his anthropological theories, Lévi-Strauss identified myths as a type of speech through which a language could be discovered. His work is a structuralist theory of mythology which attempted to explain how seemingly fantastical and arbitrary tales could be so similar across cultures. Because he had the believe that there was no one "authentic" version of a myth, rather that they were all manifestations of the same language, he sought to find the fundamental units of myth, namely, the mytheme. Lévi-Strauss broke each of the versions of a myth down into a series of sentences, consisting of a relation between a function and a subject. Sentences with the same function were given the same number and bundled together. These are mythemes.[37] What Lévi-Strauss believed he had discovered when he examined the relations between mythemes was that a myth consists of juxtaposed binary oppositions. Oedipus, for example, consists of the overrating of blood relations and the underrating of blood relations, the autochthonous origin of humans, and the denial of their autochthonous origin. Influenced by Hegel, Lévi-Strauss believed that the human mind thinks fundamentally in these binary oppositions and their unification (the thesis, antithesis, synthesis triad), and that these are what makes meaning possible.[38] Furthermore, he considered the job of myth to be a sleight of hand, an association of an irreconcilable binary opposition with a reconcilable binary opposition, creating the illusion, or belief, that the former had been resolved.[37] Lévi-Strauss sees a basic paradox in the study of myth. On one hand, mythical stories are fantastic and unpredictable: the content of myth seems completely arbitrary. On the other hand, the myths of different cultures are surprisingly similar:[35]: 208 On the one hand it would seem that in the course of a myth anything is likely to happen. ... But on the other hand, this apparent arbitrariness is belied by the astounding similarity between myths collected in widely different regions. Therefore the problem: If the content of myth is contingent [i.e., arbitrary], how are we to explain the fact that myths throughout the world are so similar? Lévi-Strauss proposed that universal laws must govern mythical thought and resolve this seeming paradox, producing similar myths in different cultures. Each myth may seem unique, but he proposed it is just one particular instance of a universal law of human thought. In studying myth, Lévi-Strauss tries "to reduce apparently arbitrary data to some kind of order, and to attain a level at which a kind of necessity becomes apparent, underlying the illusions of liberty."[39] Laurie suggests that for Levi-Strauss, "operations embedded within animal myths provide opportunities to resolve collective problems of classification and hierarchy, marking lines between the inside and the outside, the Law and its exceptions, those who belong and those who do not."[40] According to Lévi-Strauss, "mythical thought always progresses from the awareness of oppositions toward their resolution."[35]: 224 In other words, myths consist of: elements that oppose or contradict each other and other elements that "mediate", or resolve, those oppositions. For example, Lévi-Strauss thinks the trickster of many Native American mythologies acts as a "mediator". Lévi-Strauss's argument hinges on two facts about the Native American trickster:  the trickster has a contradictory and unpredictable personality; the trickster is almost always a raven or a coyote. Lévi-Strauss argues that the raven and coyote "mediate" the opposition between life and death. The relationship between agriculture and hunting is analogous to the opposition between life and death: agriculture is solely concerned with producing life (at least up until harvest time); hunting is concerned with producing death. Furthermore, the relationship between herbivores and beasts of prey is analogous to the relationship between agriculture and hunting: like agriculture, herbivores are concerned with plants; like hunting, beasts of prey are concerned with catching meat. Lévi-Strauss points out that the raven and coyote eat carrion and are therefore halfway between herbivores and beasts of prey: like beasts of prey, they eat meat; like herbivores, they do not catch their food. Thus, he argues, "we have a mediating structure of the following type":[35]: 224 By uniting herbivore traits with traits of beasts of prey, the raven and coyote somewhat reconcile herbivores and beasts of prey: in other words, they mediate the opposition between herbivores and beasts of prey. As we have seen, this opposition ultimately is analogous to the opposition between life and death. Therefore, the raven and coyote ultimately mediate the opposition between life and death. This, Lévi-Strauss believes, explains why the coyote and raven have contradictory personalities when they appear as the mythical trickster: The trickster is a mediator. Since his mediating function occupies a position halfway between two polar terms, he must retain something of that duality—namely an ambiguous and equivocal character.[35]: 226 Because the raven and coyote reconcile profoundly opposed concepts (i.e., life and death), their own mythical personalities must reflect this duality or contradiction: in other words, they must have a contradictory, "tricky" personality. This theory about the structure of myth helps support Lévi-Strauss's more basic theory about human thought. According to this more basic theory, universal laws govern all areas of human thought: If it were possible to prove in this instance, too, that the apparent arbitrariness of the mind, its supposedly spontaneous flow of inspiration, and its seemingly uncontrolled inventiveness [are ruled by] laws operating at a deeper level...if the human mind appears determined even in the realm of mythology, a fortiori it must also be determined in all its spheres of activity.[39] Out of all the products of culture, myths seem the most fantastic and unpredictable. Therefore, Lévi-Strauss claims, that if even mythical thought obeys universal laws, then all human thought must obey universal laws. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Claude_L%C3%A9vi-Strauss |

神話への構造主義的アプローチ 主な記事 神話の構造主義理論 レヴィ=ストロースは、人類学的理論と同様に、神話を言語を発見するための一種の音声としてとらえた。彼の研究は神話の構造主義理論であり、一見空想的で 恣意的な物語が文化圏を越えてなぜこれほど似ているのかを説明しようとした。レヴィ=ストロースは、神話にはひとつの「真正な」バージョンは存在せず、む しろそれらはすべて同じ言語の現れであると考え、神話の基本的な単位、すなわち神話を見出そうとした。レヴィ=ストロースは神話の各バージョンを、機能と 主語の関係からなる一連の文に分解した。同じ機能を持つ文には同じ番号が与えられ、ひとまとめにされた。これが神話主題である[37]。 レヴィ=ストロースが神話主題間の関係を検討したときに発見したと考えたのは、神話は並置された二項対立から構成されているということであった。たとえば オイディプスは、血縁関係の過大評価と過小評価、人間の自生的起源とその自生的起源の否定から構成されている。ヘーゲルの影響を受けたレヴィ=ストロース は、人間の心は基本的にこのような二項対立とその統一(テーゼ、アンチテーゼ、シンセシスの三項対立)において思考しており、これらが意味を可能にしてい ると考えていた[38]。さらに、彼は神話の仕事を手品のようなもの、つまり和解不可能な二項対立と和解可能な二項対立の関連付けであり、前者が解決され たかのような錯覚、あるいは信念を生み出すものだと考えていた[37]。 レヴィ=ストロースは神話の研究において基本的なパラドックスを見ている。一方では、神話的な物語は幻想的で予測不可能であり、神話の内容は完全に恣意的 であるように思われる。他方で、異なる文化の神話は驚くほど類似している。 一方では、神話の過程では何でも起こりそうだと思われる。... しかし他方では、この見かけの恣意性は、広く異なる地域で収集された神話間の驚くべき類似性によって裏付けられる。神話の内容が偶発的[=恣意的]である ならば、世界中の神話がこれほど似ているという事実をどう説明すればいいのだろうか? レヴィ=ストロースは、普遍的な法則が神話的思考を支配し、この一見パラドックスを解決して、異なる文化圏に類似した神話を生み出すに違いないと提唱し た。それぞれの神話はユニークに見えるかもしれないが、それは人間の思考における普遍的な法則の特殊な一例に過ぎないと彼は提唱したのである。神話を研究 する際、レヴィ=ストロースは「明らかに恣意的なデータをある種の秩序に還元し、自由の幻想の根底にある、ある種の必然性が明らかになる水準に到達しよう とする」[39]。 レヴィ=ストロースによれば、「神話的思考は常に対立の認識からその解決に向かって進んでいく」[35]: 互いに対立したり矛盾したりする要素と それらの対立を「媒介」する、つまり解決する他の要素である。 例えば、レヴィ=ストロースは、多くのアメリカ先住民の神話に登場するトリックスターが「媒介者」として機能すると考えている。レヴィ=ストロースの議論 は、ネイティブ・アメリカンのトリックスターに関する2つの事実に基づいている:  トリックスターは矛盾した予測不可能な性格である; トリックスターはほとんどの場合、カラスかコヨーテである。 レヴィ=ストロースは、カラスとコヨーテが生と死の対立を「媒介」していると主張する。農業と狩猟の関係は、生と死の対立に類似している。農業は(少なく とも収穫期までは)生命を生み出すことだけに関心があり、狩猟は死を生み出すことに関心がある。さらに、草食動物と猛獣の関係は、農業と狩猟の関係に類似 している。農業のように草食動物は植物に関係し、狩猟のように猛獣は肉を捕らえることに関係する。レヴィ=ストロースは、カラスやコヨーテは腐肉を食べる ので、草食動物と猛獣の中間に位置すると指摘する。したがって、彼は「次のような仲介構造を持っている」と主張する[35]: 224。 草食動物の形質を猛獣の形質と一体化させることで、カラスとコヨーテは草食動物と猛獣をいくらか和解させる:言い換えれば、草食動物と猛獣の対立を調停す る。これまで見てきたように、この対立は究極的には生と死の対立に類似している。したがって、カラスとコヨーテは究極的には生と死の対立を媒介する。レ ヴィ=ストロースは、コヨーテとカラスが神話のトリックスターとして登場するとき、なぜ矛盾した人格を持つのか、このことが説明できると考えている: トリックスターは調停者である。トリックスターは媒介者であり、その媒介機能は二つの極論の中間の位置を占めているため、その二元性のようなもの、つまり 曖昧であいまいな性格を保持しなければならない。 カラスとコヨーテは深く対立する概念(すなわち生と死)を和解させるので、彼ら自身の神話的人格はこの二重性や矛盾を反映したものでなければならない。 神話の構造に関するこの理論は、人間の思考に関するレヴィ=ストロースのより基本的な理論を支持するのに役立つ。このより基本的な理論によれば、普遍的な 法則が人間の思考のあらゆる領域を支配している: もしこの例においても、心の見かけの恣意性、その自然発生的と思われるひらめきの流れ、そして一見制御不能に見えるその独創性が、[より深いレベルで作用 する]法則によって支配されていることを証明することが可能であれば......人間の心が神話の領域においてさえ決定されているように見えるのであれ ば、必然的にそれはその活動のすべての領域においても決定されているに違いない[39]。 文化のあらゆる産物の中で、神話は最も幻想的で予測不可能なものに見える。したがってレヴィ=ストロースは、神話的思考でさえ普遍的法則に従うのであれ ば、人間の思考はすべて普遍的法則に従わなければならないと主張する。 |

| Structuralist

theory of mythology In structural anthropology, Claude Lévi-Strauss, a French anthropologist, makes the claim that "myth is language". Through approaching mythology as language, Lévi-Strauss suggests that it can be approached the same way as language can be approached by the same structuralist methods used to address language. Thus, Lévi-Strauss offers a structuralist theory of mythology;[1] he clarifies, "Myth is language, functioning on an especially high level where meaning succeeds practically at 'taking off' from the linguistic ground on which it keeps rolling."[2] Overview Lévi-Strauss breaks down his argument into three main parts. Meaning is not isolated within the specific fundamental parts of the myth, but rather within the composition of these parts. Although myth and language are of similar categories, language functions differently in myth. Language in myth exhibits more complex functions than in any other linguistic expression. From these suggestions, he draws the conclusion that myth can be broken down into constituent units, and these units are different from the constituents of language. Finally, unlike the constituents of language, the constituents of a myth, which he labels “mythemes,” function as "bundles of relations."[3] This approach is a break from the “symbolists”, such as Carl Jung, who dedicate themselves to find meaning solely within the constituents rather than their relations.[4] For instance, Lévi-Strauss uses the example of the Oedipus myth and breaks it down to its component parts: Reading it in sequence from left to right, top to bottom, the myth is categorized sequentially and by similarities. Through analyzing the commonalities between the “mythemes” of the Oedipus story, understandings can be wrought from its categories. Thus, a structural approach towards myths is to address all of these constituents. Furthermore, a structural approach should account for all versions of a myth, as all versions are relevant to the function of the myth as a whole. This leads to what Lévi-Strauss calls a spiral growth of the myth that is continuous while the structure itself is not. The growth of the myth only ends when the “intellectual impulse which has produced it is exhausted.”[5] From mythology to literary criticism Myths are primarily acknowledged as oral traditions, while literature is in the form of written text. Still, anthropologists and literary critics both acknowledge the links between myths and relatively more contemporary literature. Therefore, many literary critics take the same Lévi-Straussian structuralist, as it is coined, approach to literature. This approach is, again, similar to Symbolist critics’ approach to literature. There is a search for the lowest constituent of the story. But as with the myth, Lévi-Straussian structuralism then analyzes the relations between these constituent parts in order to compare even greater relations between versions of stories as well as among stories themselves.[6] Furthermore, Lévi-Strauss suggests that the structural approach and mental processes dedicated towards analyzing the myth are similar in nature to those in science. This connection between myth and science is further elaborated in his books, Myth and Meaning and The Savage Mind. He suggests that the foundation of structuralism is based upon an innate understanding of the scientific process, which seeks to break down complex phenomena into its component parts and then analyze the relations between them. The structuralist approach to myth is precisely the same method, and as a method this can be readily applied to literature.[7] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Structuralist_theory_of_mythology |

神話学における構造理論 構造人類学の中で、フランスの人類学者クロード・レヴィ=ストロースは「神話は言語である」という主張をしている。レヴィ=ストロースは、神話を言語とし てとらえることで、言語を扱うのと同じ構造主義的手法によって、言語と同じように神話にアプローチできることを示唆している。このように、レヴィ=スト ロースは神話について構造主義的な理論を提供している[1]。彼は「神話は言語であり、意味が転がり続ける言語的な地面から実質的に『離陸』することに成 功する、とりわけ高いレベルで機能している」と明らかにしている[2]。 概要 レヴィ=ストロースは彼の議論を3つの主要な部分に分けている。意味は神話の特定の基本的部分の中に孤立しているのではなく、むしろこれらの部分の構成の 中にある。神話と言語は類似のカテゴリーに属するが、神話における言語の機能は異なる。神話における言語は、他のどの言語表現よりも複雑な機能を示す。こ れらの示唆から、彼は、神話は構成単位に分解することができ、これらの単位は言語の構成単位とは異なるという結論を導き出す。最後に、言語の構成要素とは 異なり、神話の構成要素は「神話主題」と名付けられ、「関係の束」として機能する[3]。このアプローチは、カール・ユングのような「象徴主義者」とは一 線を画すものであり、彼らは構成要素の関係ではなく、構成要素の中にのみ意味を見出すことに専念する[4]。例えば、レヴィ=ストロースはオイディプス神 話を例に挙げ、それを構成要素に分解する: 神話を左から右へ、上から下へと順番に読むことで、神話は順次、類似性によって分類される。オイディプス物語の「神話テーマ」間の共通点を分析すること で、そのカテゴリーから理解を導き出すことができる。したがって、神話に対する構造的アプローチとは、これらの構成要素すべてに取り組むことである。さら に、構造的アプローチは、神話のすべてのヴァージョンを説明しなければならない。このことは、レヴィ=ストロースが言うところの、神話の螺旋的な成長をも たらす。神話の成長は、「神話を生み出した知的衝動が尽きる」ときにのみ終わる[5]。 神話から文学批評へ 神話は主に口承伝承として認められているのに対し、文学は書かれたテキストの形をとっている。しかし、人類学者も文学批評家も、神話と比較的現代的な文学 とのつながりを認めている。そのため、多くの文芸批評家は、レヴィ=ストロース構造主義という造語と同じアプローチで文学を研究している。このアプローチ は、やはり象徴主義批評家の文学へのアプローチに似ている。そこには物語の最低の構成要素の探求がある。しかし、神話と同様に、レヴィ=ストロース構造主 義は、物語のバージョン間や物語そのもの間のより大きな関係を比較するために、これらの構成部分間の関係を分析する[6]。 さらにレヴィ=ストロースは、神話を分析するために捧げられる構造的なアプローチと精神的なプロセスは、科学におけるものと性質が似ていることを示唆して いる。神話と科学の間のこの結びつきは、彼の著書『神話と意味』や『未開の心』でさらに詳しく述べられている。構造主義の基礎は、複雑な現象を構成要素に 分解し、それらの関係を分析しようとする科学的プロセスに対する生得的な理解に基づいている。神話に対する構造主義のアプローチはまさに同じ方法であり、 方法としてこれは文学に容易に適用することができる[7]。 |

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Claude_L%C3%A9vi-Strauss

神話には、永劫回帰のモチーフがみられるということなど、シャーマニズムや伝統的社会の比較 神話学に多大なる貢献をしたミルチャ・エリアーデ(下記に紹介)という神話学者・宗教学者もいる。

神話学、あるいは神話研究は、このように、文学研究、文化人類学研究、宗教学研究を中心に発

達してきたと言うことができる。

Mircea Eliade (Bucarest, Rumania, 9 de marzo 1907 - Chicago, Estados Unidos, 22 de abril 1986) fue un filósofo, historiador de las religiones y novelista rumano. Hablaba y escribía con corrección rumano, francés, alemán, italiano e inglés, y podía también leer hebreo, persa y sánscrito. La mayor parte de su obra la escribió en rumano, francés e inglés. Formó parte del Círculo Eranos.

年譜は日本語(ウィキペディア)を中心にテキトーに編纂した

1907 3月13日 ブカレスト生まれ

1928 サンスクリット語と哲学をスレンドラナート・ダスグプタ(Surendranath Dasgupta, 1887-1952)(インドの哲学者、1885年 - 1952年)の下で研究するために、カルカッタまで船に乗る

1931 3月までヒマラヤの山小屋に籠もる、12月、ルーマニアに帰国。

1932 ブカレスト大学でナエ・イオネスクの助手を務め、講義・著作活動を行う。

1932 Solilocvii

1932 ブカレスト大学でエミール・シオラン(Emil Mihai Cioran, 1911-1995)やウジェーヌ・イヨネスコ(Eugène Ionesco, 1909-1994)に出会い、3人は途中短い中断はあるものの、生涯の友人となる

1933 小説『マイトレイ』は大評判に;Maitreyi, Ed. Cultura Naţională

1934 Oceanografie

1937 Cosmologie și alchimie babiloniană

1938 7月、政治的理由により逮捕され、ナエ・イオネスクとともにミエルクレア=チュク の収容所に送られるが、年内に釈放さる。

1939 Fragmentarium, Editura Vremea

1940 ルーマニア政府によりロンドンに文化担当の大使館職員として派遣

1941 1944年までリスボンでルーマニア大使館に勤める

1943 Insula lui

Euthanasius, Fundația Regală pentru Literatuă și Artă. Comentarii la

legenda meșterului Manole, Bucharest: Editura Publicom,

1945 パリに移住し、フランスで活動する。戦後にドイツの作家エルンスト・ユンガーと 『アンタイオス』誌を共同編集・発行している。

1945 ヨアヒム・ワッハ、シカゴ大学に赴任。

1949 Traité d’histoire des religions, Paris: Payot;Le Mythe de l'éternel retour, Paris: Gallimard

1951 La Chamanisme et les Techniques archaïques de l'extase, Paris: Payot,

1952 Images et symboles. Essais sur le symbolisme magico-religieux, Paris: Gallimard

1954 La Yoga: Immortalité et Liberté, Paris: Payot

1956 Forgerons et alchimistes, Paris:

Flammarion

1957 ヨアヒム・ワッハ(Joachim Wach, 1898-1955)の呼びかけに応じシカゴ大学に赴任。

宗教学者としてのエリアーデの才能はここで発揮され

る:「エリアーデの思想(学問的な流れ)は、ルドルフ・オットー(Rudolf Otto,

1869-1937)、ヘラルドゥス・ファン・デル・レーウ(Gerardus van

der Leeuw,

1890-1950)、ナエ・イオネスク、伝統主義派(Traditionalist

School)の業績に部分的な影響を受けている。エリアーデは、ヨアン・ペトル・クリアーヌなど多くの学者たちに決定的な影響を与えた。宗教史に関する

業績では、シャーマニズム、ヨーガ、宇宙論的神話に関する著作においてもっとも評価されている。シャーマニズムにおいては、憑依ではなく、脱魂(エクスタ

シー)を本質と説いた」

1958 Joachim Wach, The Comparative Study of Religions.(→宗 教の比較研究 / ヨアヒム・ヴァッハ著);Birth and Rebirth

1959 Initiation rites société secrètesNa issances mystiques Essai sur quelques types d'initiation

1962 Méphistophélès et l'androgyne, Paris: Gallimard,

1963 Aspects du mythe, Paris: Gallimard,

1967 Das Heilige und das Profane, Reinbeck: Rowohlt Taschenbuch,;Primitives to Zen: A Thematic Sourcebook on the History of Religions, London, New York; Harper & Row, 1967

1969 The Quest: History and Meaning in

Religion, Chicago: University of Chicago Press

1970年代以降、自分が戦前鉄衛団(Garda de Fier、極右政治組織)に対して共感を抱いていたことを自己批判する。

1970 De Zalmoxis à Gengis-Khan. Études comparatives sur les religions et le folklore de la Dacie et de l'Europe orientale, Paris: Payot

1976 Occultism, Witchcraft and Cultural Fashions, Chicago: University of Chicago Press

1976-1983 Histoire des croyances et des

idees religieuses, Paris: Payot

1986 4月22日 イリノイ州シカゴで死去

1999

●用語解説

Numinous (/ˈnjuːmɪnəs/) is a term derived from the Latin numen, meaning "arousing spiritual or religious emotion; mysterious or awe-inspiring."[1] The term was given its present sense by the German theologian and philosopher Rudolf Otto in his influential 1917 German book The Idea of the Holy. He also used the phrase mysterium tremendum as another description for the phenomenon. Otto's concept of the numinous influenced thinkers including Carl Jung, Mircea Eliade, and C. S. Lewis. It has been applied to theology, psychology, religious studies, literary analysis, and descriptions of psychedelic experiences.-Numinous.

◎余滴:18世紀から20世紀の神話思想

1)ヴァルター・ベンヤミンの神話(→神的暴力と神話的暴力)

2)18世紀の啓蒙主義の神話概念

3)19世紀のロマン派の神話概念(啓蒙主義に対抗 する神話概念)

4)ヘルマン・コーエンの宗教哲学における神話概念

5)フロイト理論における精神分析の神話概念

6)カール・グスタフ・ユングの原型としての神話

7)ルイ・アラゴンのシュールレアリスムにおける神 話概念

8)クロード・レヴィ=ストロースの構造主義神話概

念(=非歴史的で形式記号学的な神話概念)

リンク

文献

その他の情報

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099