理性

Reason

☆理性(Reason) とは、真実を求めることを目的として、新しい情報や既存の情報をもとに結論を導き出す、意識的な論理の適用能力である。哲学、宗教、科学、言語、数学、芸 術など、人間特有の活動と関連しており、通常、人間にのみ備わっている能力と考えられている。理性は、合理性と呼ばれることもある(→「要約『理性』」)。

| Reason

is the capacity of applying logic consciously by drawing conclusions

from new or existing information, with the aim of seeking the truth.[1]

It is associated with such characteristically human activities as

philosophy, religion, science, language, mathematics, and art, and is

normally considered to be a distinguishing ability possessed by

humans.[2][3] Reason is sometimes referred to as rationality.[4] Reasoning involves using more-or-less rational processes of thinking and cognition to extrapolate from one's existing knowledge to generate new knowledge, and involves the use of one's intellect. The field of logic studies the ways in which humans can use formal reasoning to produce logically valid arguments and true conclusions.[5] Reasoning may be subdivided into forms of logical reasoning, such as deductive reasoning, inductive reasoning, and abductive reasoning. Aristotle drew a distinction between logical discursive reasoning (reason proper), and intuitive reasoning,[6]: VI.7 in which the reasoning process through intuition—however valid—may tend toward the personal and the subjectively opaque. In some social and political settings logical and intuitive modes of reasoning may clash, while in other contexts intuition and formal reason are seen as complementary rather than adversarial. For example, in mathematics, intuition is often necessary for the creative processes involved with arriving at a formal proof, arguably the most difficult of formal reasoning tasks. Reasoning, like habit or intuition, is one of the ways by which thinking moves from one idea to a related idea. For example, reasoning is the means by which rational individuals understand the significance of sensory information from their environments, or conceptualize abstract dichotomies such as cause and effect, truth and falsehood, or good and evil. Reasoning, as a part of executive decision making, is also closely identified with the ability to self-consciously change, in terms of goals, beliefs, attitudes, traditions, and institutions, and therefore with the capacity for freedom and self-determination.[7] In contrast to the use of "reason" as an abstract noun, a reason is a consideration that either explains or justifies events, phenomena, or behavior.[8] Reasons justify decisions, reasons support explanations of natural phenomena, and reasons can be given to explain the actions (conduct) of individuals. The words are connected in this way: Using reason, or reasoning, means providing good reasons. For example, when evaluating a moral decision, "morality is, at the very least, the effort to guide one's conduct by reason—that is, doing what there are the best reasons for doing—while giving equal [and impartial] weight to the interests of all those affected by what one does."[9] Psychologists and cognitive scientists have attempted to study and explain how people reason, e.g. which cognitive and neural processes are engaged, and how cultural factors affect the inferences that people draw. The field of automated reasoning studies how reasoning may or may not be modeled computationally. Animal psychology considers the question of whether animals other than humans can reason. |

理性とは、真実を求めることを目的

として、新しい情報や既存の情報をもとに結論を導き出す、意識的な論理の適用能力である。[1]

哲学、宗教、科学、言語、数学、芸術など、人間特有の活動と関連しており、通常、人間にのみ備わっている能力と考えられている。[2][3]

理性は、合理性と呼ばれることもある。[4] 推論=リーズニング=理性づける(reasoning)とは、自分の既存の知識から新しい知識を生成するために、ある程度合理的な思考や認知のプロセスを 用いることを指し、知性の使用を伴う。論理学の分野では、人間が形式的な推論(reasoning)を用いて論理的に妥当な論拠と真の結論を導く方法を研 究している。[5] 推論(reasoning)は、演繹的推論(reasoning)、帰納的推論(reasoning)、仮説演繹的推論(reasoning)などの論理 的推論(reasoning)の形式に細分化される場合がある。 アリストテレスは、論理的演繹推論(reasoning)(理性)と直観的推論(reasoning)を区別した。直観による推論(reasoning) プロセスは、それがいかに妥当であっても、主観的で不透明になりがちである。社会的、政治的な状況によっては、論理的推論(reasoning)と直観的 推論(reasoning)が衝突することがあるが、他の状況では直観と形式的な推論(reasoning)は対立するものではなく、補完的なものと見な される。例えば、数学では、形式的な証明に到達する創造的なプロセスには直観がしばしば必要であり、おそらく形式的な推論(reasoning)の作業の 中で最も難しいものである。 推論(reasoning)は、習慣や直観と同様に、思考がひとつの考えから関連する考えへと移行する手段のひとつである。例えば、理性的な個人が環境か らの感覚情報の重要性を理解したり、因果関係や真偽、善悪といった抽象的な二項対立を概念化したりする手段が推論(reasoning)である。 また、意思決定の一環である推論(reasoning)は、目標、信念、態度、伝統、制度などの観点から、自己認識的に変化する能力、すなわち自由と自己 決定の能力と密接に関連している。 抽象名詞としての「reason」の用法とは対照的に、「reason」は出来事、現象、行動を説明または正当化する考察を意味する。[8] 理由によって決定が正当化され、自然現象の説明が裏付けられ、個人の行動(行為)を説明するために理由が与えられる。 この言葉は次のように関連している。理性を用いる、または推論(reasoning)するということは、正当な理由を提示することを意味する。例えば、道 徳的な判断を評価する際、「道徳とは、少なくとも、自分の行動を理性によって導く努力、つまり、最善の理由があることを行うことである。また、自分の行動 によって影響を受けるすべての人々の利益に等しく(公平に)重きを置くことである」[9]。 心理学者や認知科学者は、人がどのように推論(reasoning)するのか、例えば、どのような認知や神経プロセスが関与するのか、また、文化的な要因 が人々の推論(reasoning)にどのような影響を与えるのかを研究し、説明しようとしてきた。自動推論(reasoning)の分野では、推論 (reasoning)を計算機的にモデル化できるかどうかを研究している。動物心理学では、人間以外の動物が推論(reasoning)できるかどうか を研究している。 |

| Etymology and related words In the English language and other modern European languages, "reason", and related words, represent words which have always been used to translate Latin and classical Greek terms in their philosophical sense. The original Greek term was "λόγος" logos, the root of the modern English word "logic" but also a word that could mean for example "speech" or "explanation" or an "account" (of money handled).[10] As a philosophical term logos was translated in its non-linguistic senses in Latin as ratio. This was originally not just a translation used for philosophy, but was also commonly a translation for logos in the sense of an account of money.[11] French raison is derived directly from Latin, and this is the direct source of the English word "reason".[8] The earliest major philosophers to publish in English, such as Francis Bacon, Thomas Hobbes, and John Locke also routinely wrote in Latin and French, and compared their terms to Greek, treating the words "logos", "ratio", "raison" and "reason" as interchangeable. The meaning of the word "reason" in senses such as "human reason" also overlaps to a large extent with "rationality" and the adjective of "reason" in philosophical contexts is normally "rational", rather than "reasoned" or "reasonable".[12] Some philosophers, Thomas Hobbes for example, also used the word ratiocination as a synonym for "reasoning". |

語源と関連語 英語やその他の近代ヨーロッパの言語では、「reason」や関連語は、ラテン語や古典ギリシャ語の用語を哲学的な意味で翻訳するために常に使用されてきた言葉である。 ギリシャ語の原語は「λόγος」ロゴスであり、これは現代英語の「logic」の語源であるが、例えば「speech」や「explanation」、「account」(金銭の取り扱いに関する)を意味する言葉でもある。 哲学用語としてのロゴスは、ラテン語では言語学的な意味ではない「理性」と訳された。これはもともと哲学にのみ用いられた訳語ではなく、金銭の会計報告の意味でロゴスを訳す際にも一般的に用いられた。 フランス語の「raison」はラテン語から直接派生したものであり、これが英語の「reason」の直接的な語源である。 英語で著作を出版した最も初期の主要な哲学者であるフランシス・ベーコン、トマス・ホッブズ、ジョン・ロックらは、日常的にラテン語やフランス語でも著作 を残しており、ギリシャ語と比較しながら「ロゴス」、「ラティオ」、「レゾン」、「リーズン」といった言葉を互換的に使用していた。「理性」という言葉の 意味は、「人間の理性」などの感覚において、「合理性」とかなり重複しており、哲学的な文脈における「理性」の形容詞は通常、「推論 (reasoning)された」や「妥当な」ではなく、「合理的」である。[12] 例えばトマス・ホッブズのような一部の哲学者は、「推論(reasoning)」という言葉を「ratiocination」の同義語として使用してい た。 |

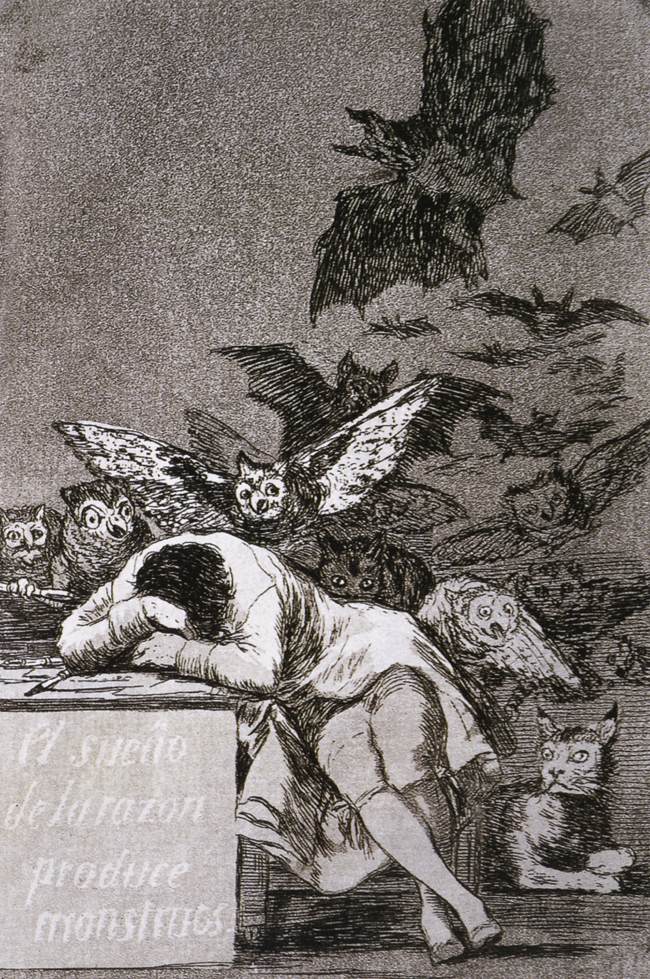

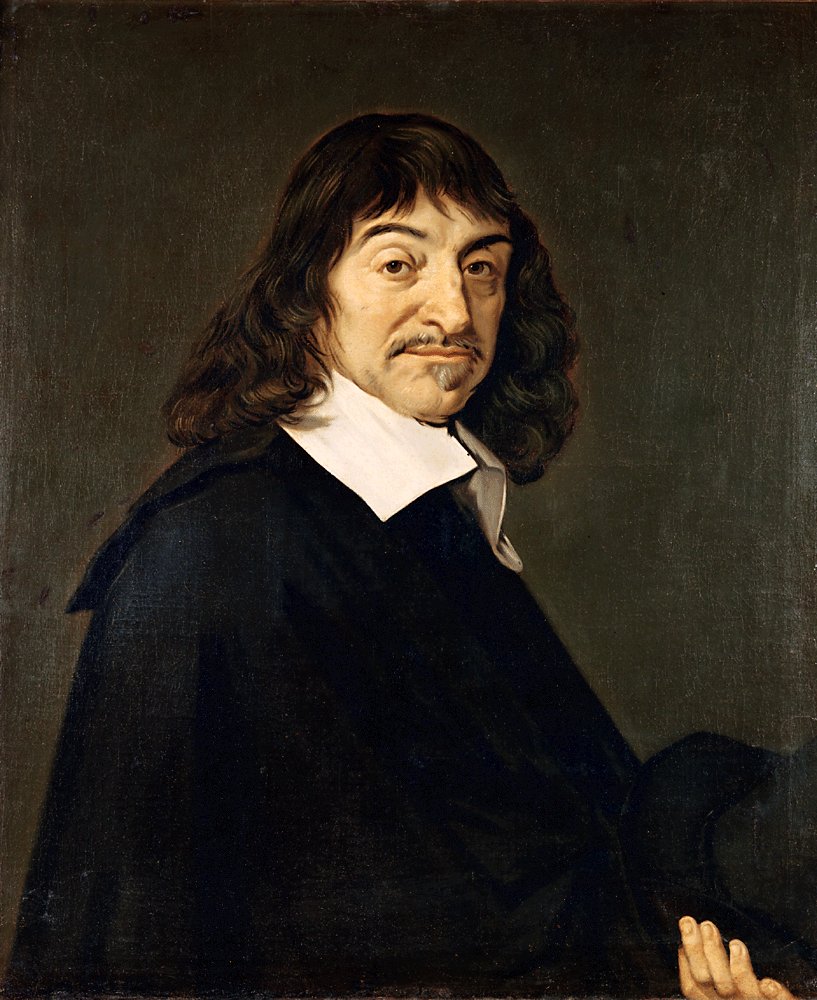

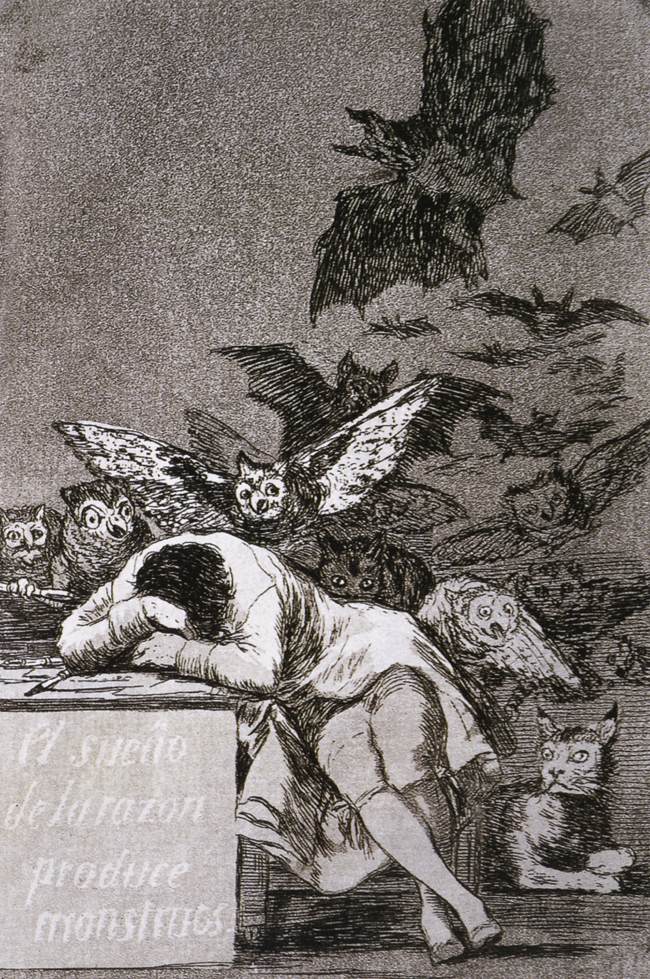

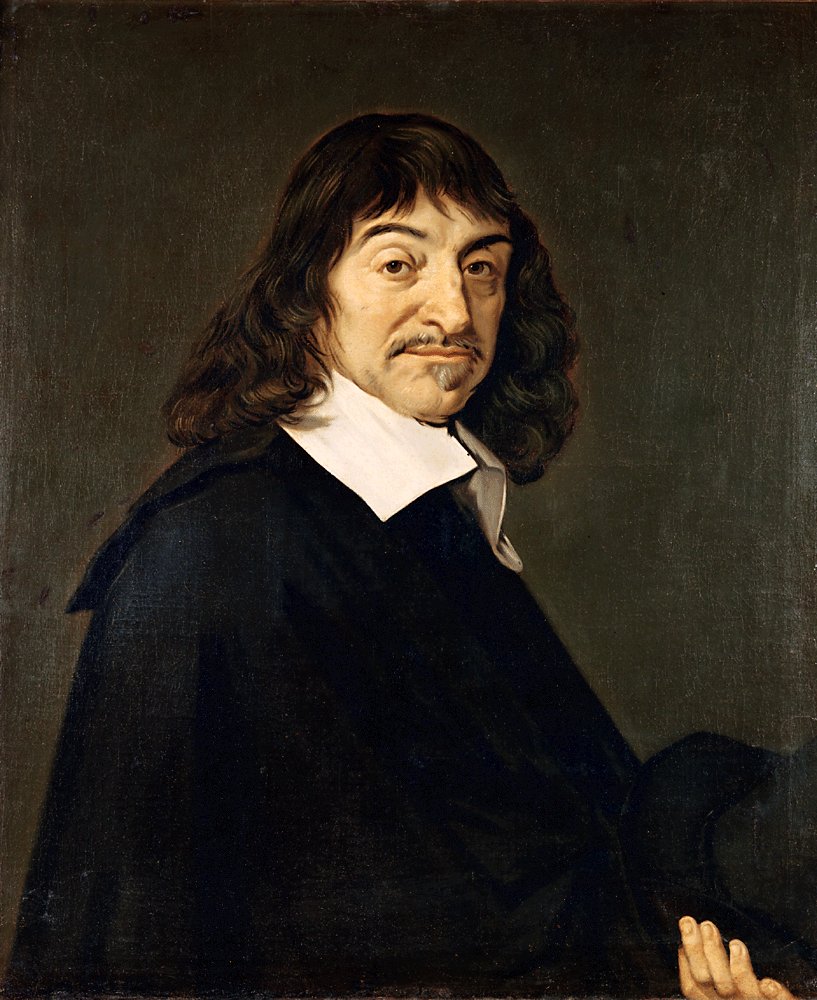

Philosophical history Francisco de Goya, The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters (El sueño de la razón produce monstruos), c. 1797 The proposal that reason gives humanity a special position in nature has been argued[citation needed] to be a defining characteristic of western philosophy and later western science, starting with classical Greece. Philosophy can be described as a way of life based upon reason, while reason has been among the major subjects of philosophical discussion since ancient times. Reason is often said to be reflexive, or "self-correcting", and the critique of reason has been a persistent theme in philosophy.[13] Classical philosophy For many classical philosophers, nature was understood teleologically, meaning that every type of thing had a definitive purpose that fit within a natural order that was itself understood to have aims. Perhaps starting with Pythagoras or Heraclitus, the cosmos was even said to have reason.[14] Reason, by this account, is not just a characteristic that people happen to have. Reason was considered of higher stature than other characteristics of human nature, because it is something people share with nature itself, linking an apparently immortal part of the human mind with the divine order of the cosmos. Within the human mind or soul (psyche), reason was described by Plato as being the natural monarch which should rule over the other parts, such as spiritedness (thumos) and the passions. Aristotle, Plato's student, defined human beings as rational animals, emphasizing reason as a characteristic of human nature. He described the highest human happiness or well being (eudaimonia) as a life which is lived consistently, excellently, and completely in accordance with reason.[6]: I The conclusions to be drawn from the discussions of Aristotle and Plato on this matter are amongst the most debated in the history of philosophy.[15] But teleological accounts such as Aristotle's were highly influential for those who attempt to explain reason in a way that is consistent with monotheism and the immortality and divinity of the human soul. For example, in the neoplatonist account of Plotinus, the cosmos has one soul, which is the seat of all reason, and the souls of all people are part of this soul. Reason is for Plotinus both the provider of form to material things, and the light which brings people's souls back into line with their source.[16] Christian and Islamic philosophy The classical view of reason, like many important Neoplatonic and Stoic ideas, was readily adopted by the early Church[17] as the Church Fathers saw Greek Philosophy as an indispensable instrument given to mankind so that we may understand revelation.[18][verification needed] For example, the greatest among the early Church Fathers and Doctors of the Church such as Augustine of Hippo, Basil of Caesarea, and Gregory of Nyssa were as much Neoplatonic philosophers as they were Christian theologians, and they adopted the Neoplatonic view of human reason and its implications for our relationship to creation, to ourselves, and to God. The Neoplatonic conception of the rational aspect of the human soul was widely adopted by medieval Islamic philosophers and continues to hold significance in Iranian philosophy.[15] As European intellectual life reemerged from the Dark Ages, the Christian Patristic tradition and the influence of esteemed Islamic scholars like Averroes and Avicenna contributed to the development of the Scholastic view of reason, which laid the foundation for our modern understanding of this concept.[19] Among the Scholastics who relied on the classical concept of reason for the development of their doctrines, none were more influential than Saint Thomas Aquinas, who put this concept at the heart of his Natural Law. In this doctrine, Thomas concludes that because humans have reason and because reason is a spark of the divine, every single human life is invaluable, all humans are equal, and every human is born with an intrinsic and permanent set of basic rights.[20] On this foundation, the idea of human rights would later be constructed by Spanish theologians at the School of Salamanca. Other Scholastics, such as Roger Bacon and Albertus Magnus, following the example of Islamic scholars such as Alhazen, emphasised reason an intrinsic human ability to decode the created order and the structures that underlie our experienced physical reality. This interpretation of reason was instrumental to the development of the scientific method in the early Universities of the high Middle Ages.[21] Subject-centred reason in early modern philosophy The early modern era was marked by a number of significant changes in the understanding of reason, starting in Europe. One of the most important of these changes involved a change in the metaphysical understanding of human beings. Scientists and philosophers began to question the teleological understanding of the world.[22] Nature was no longer assumed to be human-like, with its own aims or reason, and human nature was no longer assumed to work according to anything other than the same "laws of nature" which affect inanimate things. This new understanding eventually displaced the previous world view that derived from a spiritual understanding of the universe.  René Descartes Accordingly, in the 17th century, René Descartes explicitly rejected the traditional notion of humans as "rational animals", suggesting instead that they are nothing more than "thinking things" along the lines of other "things" in nature. Any grounds of knowledge outside that understanding was, therefore, subject to doubt. In his search for a foundation of all possible knowledge, Descartes decided to throw into doubt all knowledge—except that of the mind itself in the process of thinking: At this time I admit nothing that is not necessarily true. I am therefore precisely nothing but a thinking thing; that is a mind, or intellect, or understanding, or reason—words of whose meanings I was previously ignorant.[23] This eventually became known as epistemological or "subject-centred" reason, because it is based on the knowing subject, who perceives the rest of the world and itself as a set of objects to be studied, and successfully mastered, by applying the knowledge accumulated through such study. Breaking with tradition and with many thinkers after him, Descartes explicitly did not divide the incorporeal soul into parts, such as reason and intellect, describing them instead as one indivisible incorporeal entity. A contemporary of Descartes, Thomas Hobbes described reason as a broader version of "addition and subtraction" which is not limited to numbers.[24] This understanding of reason is sometimes termed "calculative" reason. Similar to Descartes, Hobbes asserted that "No discourse whatsoever, can end in absolute knowledge of fact, past, or to come" but that "sense and memory" is absolute knowledge.[25] In the late 17th century through the 18th century, John Locke and David Hume developed Descartes's line of thought still further. Hume took it in an especially skeptical direction, proposing that there could be no possibility of deducing relationships of cause and effect, and therefore no knowledge is based on reasoning alone, even if it seems otherwise.[26] Hume famously remarked that, "We speak not strictly and philosophically when we talk of the combat of passion and of reason. Reason is, and ought only to be the slave of the passions, and can never pretend to any other office than to serve and obey them."[27] Hume also took his definition of reason to unorthodox extremes by arguing, unlike his predecessors, that human reason is not qualitatively different from either simply conceiving individual ideas, or from judgments associating two ideas,[28] and that "reason is nothing but a wonderful and unintelligible instinct in our souls, which carries us along a certain train of ideas, and endows them with particular qualities, according to their particular situations and relations."[29] It followed from this that animals have reason, only much less complex than human reason. In the 18th century, Immanuel Kant attempted to show that Hume was wrong by demonstrating that a "transcendental" self, or "I", was a necessary condition of all experience. Therefore, suggested Kant, on the basis of such a self, it is in fact possible to reason both about the conditions and limits of human knowledge. And so long as these limits are respected, reason can be the vehicle of morality, justice, aesthetics, theories of knowledge (epistemology), and understanding.[citation needed][30] Substantive and formal reason In the formulation of Kant, who wrote some of the most influential modern treatises on the subject, the great achievement of reason (German: Vernunft) is that it is able to exercise a kind of universal law-making. Kant was able therefore to reformulate the basis of moral-practical, theoretical, and aesthetic reasoning on "universal" laws. Here, practical reasoning is the self-legislating or self-governing formulation of universal norms, and theoretical reasoning is the way humans posit universal laws of nature.[31] Under practical reason, the moral autonomy or freedom of people depends on their ability, by the proper exercise of that reason, to behave according to laws that are given to them. This contrasted with earlier forms of morality, which depended on religious understanding and interpretation, or on nature, for their substance.[32] According to Kant, in a free society each individual must be able to pursue their goals however they see fit, as long as their actions conform to principles given by reason. He formulated such a principle, called the "categorical imperative", which would justify an action only if it could be universalized: Act only according to that maxim whereby you can, at the same time, will that it should become a universal law.[33] In contrast to Hume, Kant insisted that reason itself (German Vernunft) could be used to find solutions to metaphysical problems, especially the discovery of the foundations of morality. Kant claimed that these solutions could be found with his "transcendental logic", which unlike normal logic is not just an instrument that can be used indifferently, as it was for Aristotle, but a theoretical science in its own right and the basis of all the others.[34] According to Jürgen Habermas, the "substantive unity" of reason has dissolved in modern times, such that it can no longer answer the question "How should I live?" Instead, the unity of reason has to be strictly formal, or "procedural". He thus described reason as a group of three autonomous spheres (on the model of Kant's three critiques): Cognitive–instrumental reason the kind of reason employed by the sciences; used to observe events, to predict and control outcomes, and to intervene in the world on the basis of its hypotheses Moral–practical reason what we use to deliberate and discuss issues in the moral and political realm, according to universalizable procedures (similar to Kant's categorical imperative) Aesthetic reason typically found in works of art and literature, and encompasses the novel ways of seeing the world and interpreting things that those practices embody For Habermas, these three spheres are the domain of experts, and therefore need to be mediated with the "lifeworld" by philosophers. In drawing such a picture of reason, Habermas hoped to demonstrate that the substantive unity of reason, which in pre-modern societies had been able to answer questions about the good life, could be made up for by the unity of reason's formalizable procedures.[35] The critique of reason Hamann, Herder, Kant, Hegel, Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, Heidegger, Foucault, Rorty, and many other philosophers have contributed to a debate about what reason means, or ought to mean. Some, like Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, and Rorty, are skeptical about subject-centred, universal, or instrumental reason, and even skeptical toward reason as a whole. Others, including Hegel, believe that it has obscured the importance of intersubjectivity, or "spirit" in human life, and they attempt to reconstruct a model of what reason should be. Some thinkers, e.g. Foucault, believe there are other forms of reason, neglected but essential to modern life, and to our understanding of what it means to live a life according to reason.[13] Others suggest that there is not just one reason or rationality, but multiple possible systems of reason or rationality which may conflict (in which case there is no super-rational system one can appeal to in order to resolve the conflict).[36] In the last several decades, a number of proposals have been made to "re-orient" this critique of reason, or to recognize the "other voices" or "new departments" of reason: For example, in opposition to subject-centred reason, Habermas has proposed a model of communicative reason that sees it as an essentially cooperative activity, based on the fact of linguistic intersubjectivity.[37] Nikolas Kompridis proposed a widely encompassing view of reason as "that ensemble of practices that contributes to the opening and preserving of openness" in human affairs, and a focus on reason's possibilities for social change.[38] The philosopher Charles Taylor, influenced by the 20th century German philosopher Martin Heidegger, proposed that reason ought to include the faculty of disclosure, which is tied to the way we make sense of things in everyday life, as a new "department" of reason.[39] In the essay "What is Enlightenment?", Michel Foucault proposed a critique based on Kant's distinction between "private" and "public" uses of reason:[40] Private reason the reason that is used when an individual is "a cog in a machine" or when one "has a role to play in society and jobs to do: to be a soldier, to have taxes to pay, to be in charge of a parish, to be a civil servant" Public reason the reason used "when one is reasoning as a reasonable being (and not as a cog in a machine), when one is reasoning as a member of reasonable humanity"; in these circumstances, "the use of reason must be free and public" |

哲学史 フランシスコ・デ・ゴヤ、『理性の眠りは怪物を生む』(El sueño de la razón produce monstruos)、1797年頃 理性が人間に自然界における特別な地位を与えるという提案は、西洋哲学、そして後に西洋科学の定義的な特徴であると主張されてきたが、これは古典ギリシア から始まったものである。哲学は理性に基づく生き方であると表現できるが、理性は古代から哲学的な議論の主要なテーマのひとつであった。理性はしばしば反 射的、すなわち「自己修正的」であると言われ、理性の批判は哲学における永続的なテーマであった。 古典哲学 多くの古典哲学者にとって、自然は目的論的に理解されていた。つまり、あらゆる事物には、それ自体が目的を持つと理解されていた自然の秩序に適合する明確 な目的があるということである。おそらくピタゴラスやヘラクレイトスから始まったように、宇宙には理性があるとも考えられていた。[14] この説明によると、理性は人間がたまたま持つ特性ではない。理性は、人間の本質的な特徴の中でも、より高い地位にあると考えられていた。なぜなら、それは 人間が自然そのものと共有するものであり、人間の精神の不死と思われる部分を宇宙の神聖な秩序と結びつけるものだからである。人間の精神または魂(プシュ ケ)において、理性はプラトンによって、気質(トュモス)や情念などの他の部分を支配すべき自然の君主であると描写された。プラトンの弟子であるアリスト テレスは、人間を理性的な動物と定義し、理性を人間の本質的な特徴として強調した。彼は、人間の最高の幸福または幸福(eudaimonia)とは、理性 に従って一貫して、卓越して、完全に生きることであると述べた。[6]:I この問題に関するアリストテレスとプラトンの議論から導かれる結論は、哲学史上最も議論されてきたもののひとつである。[15] しかし、アリストテレスのような目的論的な説明は、一神教や人間の魂の不死性や神性と矛盾しない形で理性を説明しようとする人々にとって、非常に大きな影 響力を持っていた。例えば、プロティノスの新プラトン主義的説明では、宇宙には一つの魂があり、それがすべての理性の座である。そして、すべての人間の魂 はこの魂の一部である。プロティノスにとって理性とは、物質的なものに形を与えるものであり、また、人々の魂をその源に立ち返らせる光でもある。 キリスト教とイスラム哲学 理性に関する古典的な見解は、多くの重要な新プラトン主義やストア主義の考え方と同様に、初期の教会によって容易に受け入れられた。[17] なぜなら、教会の父祖たちはギリシャ哲学を、神の啓示を理解するために人類に不可欠な手段として見ていたからである。[18][検証必要] 例えば、初期の教会の父祖たちや ヒッポのアウグスティヌス、カイサリアのバジル、ニッサのグレゴリウスといった初期の教会の父や教会博士たちは、キリスト教神学者であると同時に新プラト ン主義の哲学者でもあり、新プラトン主義の人間理性の考え方や、人間と創造物、人間同士、そして人間と神との関係性に対するその含意を採用した。 人間の魂の理性的側面に関する新プラトン主義の概念は、中世イスラムの哲学者たちによって広く受け入れられ、イラン哲学においても依然として重要な意味を 持っている。[15] ヨーロッパの知的活動が暗黒時代から復活すると、キリスト教の教父学の伝統と、アヴェロエスやアヴィセンナといった尊敬を集めたイスラムの学者たちの影響 が、スコラ学の理性観の発展に貢献した。この概念に対する現代の理解の基礎は、このスコラ学の理性観によって築かれた。[19] 古典的な理性の概念を自らの教義の展開に活用したスコラ学派の学者の中でも、トマス・アクィナスほど大きな影響力を持った人物はいない。トマスは、この概 念を自然法の中心に据えた。トマスは、人間には理性があり、理性は神聖なものの火花であるため、人間の生命はすべてかけがえのないものであり、人間はみな 平等であり、人間はすべて本質的かつ恒久的な一連の基本的な権利を持って生まれてくる、と結論づけている。[20] この考え方を基盤として、後にサラマンカ学派のスペイン人神学者たちによって人権の概念が構築されることになる。 ロジャー・ベーコンやアルベルトゥス・マグヌスといった他のスコラ学者たちは、アルハゼンのようなイスラム学者の例にならって、人間が持つ本質的な能力で ある理性を強調し、創造された秩序と、私たちが経験する物理的現実の根底にある構造を解読する能力を強調した。この理性の解釈は、初期の中世大学における 科学的方法の発展に役立った。 近現代哲学における主題=主体中心の理性 近現代は、ヨーロッパを起点として、理性の理解に多くの重要な変化が起こった時代であった。これらの変化の中でも最も重要なもののひとつは、人間に対する 形而上学的な理解の変化であった。科学者や哲学者たちは、目的論的な世界観に疑問を投げかけ始めた。[22] 自然はもはや人間のようなものではなく、独自の目的や理性を持つものではないとされ、人間の本性も、無生物に影響を与えるのと同じ「自然の法則」以外のも のに従って作用するものではないとされた。この新しい理解は、最終的に、宇宙の精神的な理解から導き出されたそれまでの世界観に取って代わった。  ルネ・デカルト それゆえ、17世紀のルネ・デカルトは、人間を「理性的な動物」とする伝統的な概念を明確に否定し、人間は自然界の他の「もの」と同様に「考えるもの」にすぎないとした。したがって、その理解の範疇を超えた知識の根拠は疑わしいものとなる。 あらゆる知識の基盤を模索する中で、デカルトは思考の過程における精神そのものを除き、あらゆる知識を疑うことにした。 現時点では、真実であるとは限らないものは何も認めない。したがって、私はまさに思考するもの以外の何者でもない。つまり、心、知性、理解、理性である。これらの言葉の意味については、以前は知らなかった。 これは、やがて認識論的または「主体中心」の理性として知られるようになった。なぜなら、それは、世界と自己を研究対象の集合体として認識する知覚主体を 基盤としており、そうした研究を通じて蓄積された知識を適用することで、その対象を習得し、成功裏に支配することを目指すものであるからだ。デカルトは、 伝統や彼以降の多くの思想家たちとは一線を画し、形のない魂を理性や知性といった部分に分割することは明確にせず、それらを分割不可能な形のない一つの実 体として表現した。 デカルトと同時代のトマス・ホッブズは、理性を「足し算と引き算」のより広範なバージョンと表現し、それは数字に限定されないものだと述べた。[24] この理性の理解は、時に「打算的」理性と呼ばれる。デカルトと同様に、ホッブズは「いかなる議論も、過去や未来の事実に関する絶対的な知識に到達すること はできない」が、「感覚と記憶」は絶対的な知識であると主張した。[25] 17世紀後半から18世紀にかけて、ジョン・ロックとデイヴィッド・ヒュームは、デカルトの思想をさらに発展させた。ヒュームは特に懐疑的な方向へと展開 させ、因果関係を推論(reasoning)する可能性はないと主張し、たとえそう見えるとしても、推論(reasoning)のみに基づいた知識は存在 しないとした。 ヒュームは「情念と理性の戦いについて語る際には、厳密かつ哲学的に語るわけではない。理性は、そして本来そうあるべきなのは、情念の奴隷であるのみであり、それらに奉仕し服従すること以外の役割を担うことは決してない」 と述べたことで有名である。[27] ヒュームはまた、理性の定義を異例なほど極端に捉え、先人たちとは異なり、人間の理性は個々の観念を単純に思い浮かべること、あるいは2つの観念を関連付 ける判断と質的に異なるものではないと主張した 「理性とは、私たちの魂に備わる素晴らしいが理解不能な本能にほかならず、特定の状況や関係に応じて、特定の性質を備えた一連の観念を私たちにもたらすも のにすぎない」[29]と主張した。このことから、動物にも理性はあるが、それは人間の理性よりもはるかに単純なものであるという結論が導かれる。 18世紀には、イマニュエル・カントが、超越論的な自己、すなわち「我」がすべての経験の必要条件であることを証明することで、ヒュームが誤っていたこと を示そうとした。したがって、カントは、そのような自己を前提とすれば、人間の知識の条件と限界の両方について論理的に考えることが実際可能であると示唆 した。そして、これらの限界が尊重される限り、理性は道徳、正義、美学、認識論(認識論)および理解の手段となり得る。[要出典][30] 実質的および形式的理性 この主題に関する最も影響力のある近代的な論文をいくつか著したカントの定式化において、理性(ドイツ語:Vernunft)の偉大な功績は、一種の普遍 的な法則制定を行う能力である。したがってカントは、「普遍的」法則に関する道徳的実践的、理論的、そして審美的な推論(reasoning)の基礎を再 定式化することができた。 ここで、実践的推論(reasoning)とは普遍的規範の自己制定または自治的定式化であり、理論的推論(reasoning)とは人間が自然界の普遍的法則を仮定する方法である。 実践的な理性の下では、人々の道徳的な自律性や自由は、その理性を適切に用いることによって、与えられた法則に従って行動する能力に依存する。これは、宗教的な理解や解釈、あるいは自然に依存していたそれ以前の道徳観とは対照的である。 カントによれば、自由な社会では、各個人が自分の目標を、理性によって与えられた原則に従う限り、各自の判断で追求できることが必要である。彼は「普遍的命題」と呼ばれる原則を定式化し、普遍化できる場合にのみ、その行動を正当化できるとした。 「汝の意志するところに従って行動せよ。同時に、それが普遍法となることを汝は望むであろう。」[33] ヒュームとは対照的に、カントは理性そのもの(ドイツ語でVernunft)が形而上学的問題、特に道徳の基礎の発見に対する解決策を見出すのに役立つと 主張した。カントは、これらの解決策は通常の論理とは異なり、アリストテレスのように無差別に使用できる道具ではなく、それ自体が理論科学であり、他のす べてのものの基礎である「超越論的論理学」によって見出すことができると主張した。 ユルゲン・ハーバーマスによると、理性の「実質的な統一性」は現代において失われ、「私はどう生きるべきか」という問いに答えられなくなっている。その代 わり、理性の統一性は厳密に形式的なもの、すなわち「手続き的なもの」でなければならない。彼は、理性を3つの自律的な領域の集合体(カントの3批判哲学 のモデル)として次のように説明している。 認識的・道具的理性 科学が用いる種類の理性であり、出来事を観察し、結果を予測・制御し、仮説に基づいて世界に介入するために用いられる 道徳的実践的理性 道徳的・政治的領域における問題を熟考し、議論するために用いられるもので、普遍化可能な手続き(カントの「定言的命法」に類似)に従う 美的理性 芸術作品や文学作品に典型的に見られるもので、それらの実践が体現する、世界を新たな視点で捉えたり、物事を新たな方法で解釈したりする能力を包含する ハーバーマスにとって、これら3つの領域は専門家の領域であり、したがって哲学者が「生活世界」と仲介する必要がある。ハーバーマスは、理性をこのように 描くことで、近代以前の社会では「善き生」に関する問いに答えられる可能性があった理性の実質的な統一性を、形式化できる手続きの統一性によって補うこと ができることを示そうとしたのである。 理性の批判 ハーマン、ヘルダー、カント、ヘーゲル、キルケゴール、ニーチェ、ハイデッガー、フーコー、ロートなど、多くの哲学者たちが、理性とは何か、あるいは、理 性とは何を意味すべきかという議論に貢献してきた。キルケゴール、ニーチェ、ロートなど、主体中心主義的、普遍主義的、あるいは道具主義的な理性に懐疑的 な者もおり、理性全体に対してさえも懐疑的である。一方、ヘーゲルなど、主観性や人間生活における「精神」の重要性を覆い隠してきたと考える者もおり、彼 らは理性のあるべき姿のモデルを再構築しようとしている。 例えばフーコーのような思想家は、無視されてはいるが現代生活には不可欠であり、理性に従って生きるとはどういうことかを理解する上でも重要な、理性の別 の形態があると主張している。[13] また、理性や合理性の体系は一つだけではなく、複数の体系が存在し、それらが衝突する可能性もある(その場合、衝突を解決するために訴えることのできる超 理性的な体系は存在しない)と主張する者もいる。[36] ここ数十年の間、理性に対するこうした批判を「再方向づけ」したり、理性の「他の声」や「新たな部門」を認識したりするための提案が数多くなされてきた。 例えば、主観中心の理性に反対して、ハーバーマスは、言語的間主観性の事実を基盤として、本質的に協調的な活動とみなすコミュニケーション的理性のモデルを提案している。 ニコラス・コンプリディスは、人間関係における「開放性への貢献と開放性の維持に寄与する実践の集合体」として、広く包括的な理性の概念を提案し、社会変革における理性の可能性に焦点を当てた。 20世紀のドイツの哲学者、マルティン・ハイデッガーの影響を受けた哲学者チャールズ・テイラーは、理性には、日常生活における物事の理解の仕方と結びついた「開示」の能力も含まれるべきであると提案し、それを理性の新たな「部門」として位置づけた。[39] ミシェル・フーコーは、エッセイ「啓蒙とは何か」の中で、カントによる理性の「私的」な使用と「公共的」な使用の区別に基づく批判を提案した。[40] 私的理由 個人が「機械の歯車」である場合、あるいは「社会で果たすべき役割があり、やるべき仕事がある場合:兵士になること、納税すること、教区の責任者になること、公務員になること」に用いられる理由 公共的理由 「一人の人間が、機械の歯車としてではなく、理性的な存在として、あるいは、良識ある人間として考えを巡らせている場合」に使用される理由。このような状況では、「理性の使用は自由かつ公開されていなければならない」 |

| Reason compared to related concepts Reason compared to logic See also: Logic The terms logic or logical are sometimes used as if they were identical with reason or rational, or sometimes logic is seen as the most pure or the defining form of reason: "Logic is about reasoning—about going from premises to a conclusion. ... When you do logic, you try to clarify reasoning and separate good from bad reasoning."[41] In modern economics, rational choice is assumed to equate to logically consistent choice.[42] However, reason and logic can be thought of as distinct—although logic is one important aspect of reason. Author Douglas Hofstadter, in Gödel, Escher, Bach, characterizes the distinction in this way: Logic is done inside a system while reason is done outside the system by such methods as skipping steps, working backward, drawing diagrams, looking at examples, or seeing what happens if you change the rules of the system.[43] Psychologists Mark H. Bickard and Robert L. Campbell argue that "rationality cannot be simply assimilated to logicality"; they note that "human knowledge of logic and logical systems has developed" over time through reasoning, and logical systems "can't construct new logical systems more powerful than themselves", so reasoning and rationality must involve more than a system of logic.[44][45] Psychologist David Moshman, citing Bickhard and Campbell, argues for a "metacognitive conception of rationality" in which a person's development of reason "involves increasing consciousness and control of logical and other inferences".[45][46] Reason is a type of thought, and logic involves the attempt to describe a system of formal rules or norms of appropriate reasoning.[45] The oldest surviving writing to explicitly consider the rules by which reason operates are the works of the Greek philosopher Aristotle, especially Prior Analytics and Posterior Analytics.[47][non-primary source needed] Although the Ancient Greeks had no separate word for logic as distinct from language and reason, Aristotle's newly coined word "syllogism" (syllogismos) identified logic clearly for the first time as a distinct field of study.[48] When Aristotle referred to "the logical" (hē logikē), he was referring more broadly to rational thought.[49] Reason compared to cause-and-effect thinking, and symbolic thinking Main articles: Causality and Symbols As pointed out by philosophers such as Hobbes, Locke, and Hume, some animals are also clearly capable of a type of "associative thinking", even to the extent of associating causes and effects. A dog once kicked, can learn how to recognize the warning signs and avoid being kicked in the future, but this does not mean the dog has reason in any strict sense of the word. It also does not mean that humans acting on the basis of experience or habit are using their reason.[29] Human reason requires more than being able to associate two ideas—even if those two ideas might be described by a reasoning human as a cause and an effect—perceptions of smoke, for example, and memories of fire. For reason to be involved, the association of smoke and the fire would have to be thought through in a way that can be explained, for example as cause and effect. In the explanation of Locke, for example, reason requires the mental use of a third idea in order to make this comparison by use of syllogism.[50] More generally, according to Charles Sanders Peirce, reason in the strict sense requires the ability to create and manipulate a system of symbols, as well as indices and icons, the symbols having only a nominal, though habitual, connection to either (for example) smoke or fire.[51] One example of such a system of symbols and signs is language. The connection of reason to symbolic thinking has been expressed in different ways by philosophers. Thomas Hobbes described the creation of "Markes, or Notes of remembrance" as speech.[52] He used the word speech as an English version of the Greek word logos so that speech did not need to be communicated.[53] When communicated, such speech becomes language, and the marks or notes or remembrance are called "Signes" by Hobbes. Going further back, although Aristotle is a source of the idea that only humans have reason (logos), he does mention that animals with imagination, for whom sense perceptions can persist, come closest to having something like reasoning and nous, and even uses the word "logos" in one place to describe the distinctions which animals can perceive in such cases.[54] Reason, imagination, mimesis, and memory Main articles: Imagination, Mimesis, Memory, and Recollection Reason and imagination rely on similar mental processes.[55] Imagination is not only found in humans. Aristotle asserted that phantasia (imagination: that which can hold images or phantasmata) and phronein (a type of thinking that can judge and understand in some sense) also exist in some animals.[56] According to him, both are related to the primary perceptive ability of animals, which gathers the perceptions of different senses and defines the order of the things that are perceived without distinguishing universals, and without deliberation or logos. But this is not yet reason, because human imagination is different. Terrence Deacon and Merlin Donald, writing about the origin of language, connect reason not only to language, but also mimesis.[57] They describe the ability to create language as part of an internal modeling of reality, and specific to humankind. Other results are consciousness, and imagination or fantasy. In contrast, modern proponents of a genetic predisposition to language itself include Noam Chomsky and Steven Pinker.[clarification needed] If reason is symbolic thinking, and peculiarly human, then this implies that humans have a special ability to maintain a clear consciousness of the distinctness of "icons" or images and the real things they represent. Merlin Donald writes:[58]: 172 A dog might perceive the "meaning" of a fight that was realistically play-acted by humans, but it could not reconstruct the message or distinguish the representation from its referent (a real fight).... Trained apes are able to make this distinction; young children make this distinction early—hence, their effortless distinction between play-acting an event and the event itself In classical descriptions, an equivalent description of this mental faculty is eikasia, in the philosophy of Plato.[59]: Ch.5 This is the ability to perceive whether a perception is an image of something else, related somehow but not the same, and therefore allows humans to perceive that a dream or memory or a reflection in a mirror is not reality as such. What Klein refers to as dianoetic eikasia is the eikasia concerned specifically with thinking and mental images, such as those mental symbols, icons, signes, and marks discussed above as definitive of reason. Explaining reason from this direction: human thinking is special in that we often understand visible things as if they were themselves images of our intelligible "objects of thought" as "foundations" (hypothēses in Ancient Greek). This thinking (dianoia) is "...an activity which consists in making the vast and diffuse jungle of the visible world depend on a plurality of more 'precise' noēta".[59]: 122 Both Merlin Donald and the Socratic authors such as Plato and Aristotle emphasize the importance of mimēsis, often translated as imitation or representation. Donald writes:[58]: 169 Imitation is found especially in monkeys and apes [...but...] Mimesis is fundamentally different from imitation and mimicry in that it involves the invention of intentional representations.... Mimesis is not absolutely tied to external communication. Mimēsis is a concept, now popular again in academic discussion, that was particularly prevalent in Plato's works. In Aristotle, it is discussed mainly in the Poetics. In Michael Davis's account of the theory of man in that work:[60] It is the distinctive feature of human action, that whenever we choose what we do, we imagine an action for ourselves as though we were inspecting it from the outside. Intentions are nothing more than imagined actions, internalizings of the external. All action is therefore imitation of action; it is poetic...[61] Donald, like Plato (and Aristotle, especially in On Memory and Recollection), emphasizes the peculiarity in humans of voluntary initiation of a search through one's mental world. The ancient Greek anamnēsis, normally translated as "recollection" was opposed to mneme or "memory". Memory, shared with some animals,[62] requires a consciousness not only of what happened in the past, but also that something happened in the past, which is in other words a kind of eikasia[59]: 109 "...but nothing except man is able to recollect."[63] Recollection is a deliberate effort to search for and recapture something once known. Klein writes that, "To become aware of our having forgotten something means to begin recollecting."[59]: 112 Donald calls the same thing autocueing, which he explains as follows:[58]: 173 [64] "Mimetic acts are reproducible on the basis of internal, self-generated cues. This permits voluntary recall of mimetic representations, without the aid of external cues—probably the earliest form of representational thinking." In a celebrated paper, the fantasy author and philologist J.R.R. Tolkien wrote in his essay "On Fairy Stories" that the terms "fantasy" and "enchantment" are connected to not only "the satisfaction of certain primordial human desires" but also "the origin of language and of the mind".[This quote needs a citation] Logical reasoning methods and argumentation Main article: Logical reasoning A subdivision of philosophy and a variety of reasoning is logic. The traditional main division made in philosophy is between deductive reasoning and inductive reasoning. Formal logic has been described as the science of deduction.[65] The study of inductive reasoning is generally carried out within the field known as informal logic or critical thinking. Deductive reasoning Main article: Deductive reasoning Deduction is a form of reasoning in which a conclusion follows necessarily from the stated premises. A deduction is also the name for the conclusion reached by a deductive reasoning process. A classic example of deductive reasoning is evident in syllogisms like the following: Premise 1 All humans are mortal. Premise 2 Socrates is a human. Conclusion Socrates is mortal. The reasoning in this argument is deductively valid because there is no way in which both premises could be true and the conclusion be false. Inductive reasoning Main article: Inductive reasoning Induction is a form of inference that produces properties or relations about unobserved objects or types based on previous observations or experiences, or that formulates general statements or laws based on limited observations of recurring phenomenal patterns. Inductive reasoning contrasts with deductive reasoning in that, even in the strongest cases of inductive reasoning, the truth of the premises does not guarantee the truth of the conclusion. Instead, the conclusion of an inductive argument follows with some degree of probability. For this reason also, the conclusion of an inductive argument contains more information than is already contained in the premises. Thus, this method of reasoning is ampliative. A classic example of inductive reasoning comes from the empiricist David Hume: Premise The sun has risen in the east every morning up until now. Conclusion The sun will also rise in the east tomorrow. Analogical reasoning Main article: Analogical reasoning Analogical reasoning is a form of inductive reasoning from a particular to a particular. It is often used in case-based reasoning, especially legal reasoning.[66] An example follows: Premise 1 Socrates is human and mortal. Premise 2 Plato is human. Conclusion Plato is mortal. Analogical reasoning is a weaker form of inductive reasoning from a single example, because inductive reasoning typically uses a large number of examples to reason from the particular to the general.[67] Analogical reasoning often leads to wrong conclusions. For example: Premise 1 Socrates is human and male. Premise 2 Ada Lovelace is human. Conclusion Ada Lovelace is male. Abductive reasoning Main article: Abductive reasoning Abductive reasoning, or argument to the best explanation, is a form of reasoning that does not fit in either the deductive or inductive categories, since it starts with incomplete set of observations and proceeds with likely possible explanations. The conclusion in an abductive argument does not follow with certainty from its premises and concerns something unobserved. What distinguishes abduction from the other forms of reasoning is an attempt to favour one conclusion above others, by subjective judgement or by attempting to falsify alternative explanations or by demonstrating the likelihood of the favoured conclusion, given a set of more or less disputable assumptions. For example, when a patient displays certain symptoms, there might be various possible causes, but one of these is preferred above others as being more probable. Fallacious reasoning Main articles: Fallacy, Formal fallacy, and Informal fallacy Flawed reasoning in arguments is known as fallacious reasoning. Bad reasoning within arguments can result from either a formal fallacy or an informal fallacy. Formal fallacies occur when there is a problem with the form, or structure, of the argument. The word "formal" refers to this link to the form of the argument. An argument that contains a formal fallacy will always be invalid. An informal fallacy is an error in reasoning that occurs due to a problem with the content, rather than the form or structure, of the argument. Unreasonable decisions and actions In law relating to the actions of an employer or a public body, a decision or action which falls outside the range of actions or decision available when acting in good faith can be described as "unreasonable". Use of the term is considered in the English law cases of Short v Poole Corporation (1926), Associated Provincial Picture Houses Ltd v Wednesbury Corporation (1947) and Braganza v BP Shipping Limited (2015).[68] Traditional problems raised concerning reason Philosophy is often characterized as a pursuit of rational understanding, entailing a more rigorous and dedicated application of human reasoning than commonly employed. Philosophers have long debated two fundamental questions regarding reason, essentially examining reasoning itself as a human endeavor, or philosophizing about philosophizing. The first question delves into whether we can place our trust in reason's ability to attain knowledge and truth more effectively than alternative methods. The second question explores whether a life guided by reason, a life that aims to be guided by reason, can be expected to lead to greater happiness compared to other approaches to life. Reason versus truth, and "first principles" See also: Truth, First principle, and Nous Since classical antiquity a question has remained constant in philosophical debate (sometimes seen as a conflict between Platonism and Aristotelianism) concerning the role of reason in confirming truth. People use logic, deduction, and induction to reach conclusions they think are true. Conclusions reached in this way are considered, according to Aristotle, more certain than sense perceptions on their own.[69] On the other hand, if such reasoned conclusions are only built originally upon a foundation of sense perceptions, then our most logical conclusions can never be said to be certain because they are built upon the very same fallible perceptions they seek to better.[70] This leads to the question of what types of first principles, or starting points of reasoning, are available for someone seeking to come to true conclusions. In Greek, "first principles" are archai, "starting points",[71] and the faculty used to perceive them is sometimes referred to in Aristotle[72] and Plato[73] as nous which was close in meaning to awareness or consciousness.[74] Empiricism (sometimes associated with Aristotle[75] but more correctly associated with British philosophers such as John Locke and David Hume, as well as their ancient equivalents such as Democritus) asserts that sensory impressions are the only available starting points for reasoning and attempting to attain truth. This approach always leads to the controversial conclusion that absolute knowledge is not attainable. Idealism, (associated with Plato and his school), claims that there is a "higher" reality, within which certain people can directly discover truth without needing to rely only upon the senses, and that this higher reality is therefore the primary source of truth. Philosophers such as Plato, Aristotle, Al-Farabi, Avicenna, Averroes, Maimonides, Aquinas, and Hegel are sometimes said[by whom?] to have argued that reason must be fixed and discoverable—perhaps by dialectic, analysis, or study. In the vision of these thinkers, reason is divine or at least has divine attributes. Such an approach allowed religious philosophers such as Thomas Aquinas and Étienne Gilson to try to show that reason and revelation are compatible. According to Hegel, "...the only thought which Philosophy brings with it to the contemplation of History, is the simple conception of reason; that reason is the Sovereign of the World; that the history of the world, therefore, presents us with a rational process."[76] Since the 17th century rationalists, reason has often been taken to be a subjective faculty, or rather the unaided ability (pure reason) to form concepts. For Descartes, Spinoza, and Leibniz, this was associated with mathematics. Kant attempted to show that pure reason could form concepts (time and space) that are the conditions of experience. Kant made his argument in opposition to Hume, who denied that reason had any role to play in experience. Reason versus emotion or passion See also: Emotion and Passion (emotion) After Plato and Aristotle, western literature often treated reason as being the faculty that trained the passions and appetites.[citation needed] Stoic philosophy, by contrast, claimed most emotions were merely false judgements.[77][78] According to the Stoics the only good is virtue, and the only evil is vice, therefore emotions that judged things other than vice to be bad (such as fear or distress), or things other than virtue to be good (such as greed) were simply false judgements and should be discarded (though positive emotions based on true judgements, such as kindness, were acceptable).[77][78][79] After the critiques of reason in the early Enlightenment the appetites were rarely discussed or were conflated with the passions.[citation needed] Some Enlightenment camps took after the Stoics to say reason should oppose passion rather than order it, while others like the Romantics believed that passion displaces reason, as in the maxim "follow your heart".[citation needed] Reason has been seen as cold, an "enemy of mystery and ambiguity",[80] a slave, or judge, of the passions, notably in the work of David Hume, and more recently of Freud.[citation needed] Reasoning that claims the object of a desire is demanded by logic alone is called rationalization.[citation needed] Rousseau first proposed, in his second Discourse, that reason and political life is not natural and is possibly harmful to mankind.[81] He asked what really can be said about what is natural to mankind. What, other than reason and civil society, "best suits his constitution"? Rousseau saw "two principles prior to reason" in human nature. First we hold an intense interest in our own well-being. Secondly we object to the suffering or death of any sentient being, especially one like ourselves.[82] These two passions lead us to desire more than we could achieve. We become dependent upon each other, and on relationships of authority and obedience. This effectively puts the human race into slavery. Rousseau says that he almost dares to assert that nature does not destine men to be healthy. According to Richard Velkley, "Rousseau outlines certain programs of rational self-correction, most notably the political legislation of the Contrat Social and the moral education in Émile. All the same, Rousseau understands such corrections to be only ameliorations of an essentially unsatisfactory condition, that of socially and intellectually corrupted humanity."[This quote needs a citation] This quandary presented by Rousseau led to Kant's new way of justifying reason as freedom to create good and evil. These therefore are not to be blamed on nature or God. In various ways, German Idealism after Kant, and major later figures such Nietzsche, Bergson, Husserl, Scheler, and Heidegger, remain preoccupied with problems coming from the metaphysical demands or urges of reason.[83] Rousseau and these later writers also exerted a large influence on art and politics. Many writers (such as Nikos Kazantzakis) extol passion and disparage reason. In politics modern nationalism comes from Rousseau's argument that rationalist cosmopolitanism brings man ever further from his natural state.[84] In Descartes' Error, Antonio Damasio presents the "Somatic Marker Hypothesis" which states that emotions guide behavior and decision-making. Damasio argues that these somatic markers (known collectively as "gut feelings") are "intuitive signals" that direct our decision making processes in a certain way that cannot be solved with rationality alone. Damasio further argues that rationality requires emotional input in order to function. Reason versus faith or tradition Main articles: Faith, Religion, and Tradition There are many religious traditions, some of which are explicitly fideist and others of which claim varying degrees of rationalism. Secular critics sometimes accuse all religious adherents of irrationality; they claim such adherents are guilty of ignoring, suppressing, or forbidding some kinds of reasoning concerning some subjects (such as religious dogmas, moral taboos, etc.).[85] Though theologies and religions such as classical monotheism typically do not admit to being irrational, there is often a perceived conflict or tension between faith and tradition on the one hand, and reason on the other, as potentially competing sources of wisdom, law, and truth.[74][86] Religious adherents sometimes respond by arguing that faith and reason can be reconciled, or have different non-overlapping domains, or that critics engage in a similar kind of irrationalism: Reconciliation Philosopher Alvin Plantinga argues that there is no real conflict between reason and classical theism because classical theism explains (among other things) why the universe is intelligible and why reason can successfully grasp it.[87] Non-overlapping magisteria Evolutionary biologist Stephen Jay Gould argues that there need not be conflict between reason and religious belief because they are each authoritative in their own domain (or "magisterium").[88] If so, reason can work on those problems over which it has authority while other sources of knowledge or opinion can have authority on the big questions.[89] Tu quoque Philosophers Alasdair MacIntyre and Charles Taylor argue that those critics of traditional religion who are adherents of secular liberalism are also sometimes guilty of ignoring, suppressing, and forbidding some kinds of reasoning about subjects.[90] Similarly, philosophers of science such as Paul Feyarabend argue that scientists sometimes ignore or suppress evidence contrary to the dominant paradigm. Unification Theologian Joseph Ratzinger, later Benedict XVI, asserted that "Christianity has understood itself as the religion of the Logos, as the religion according to reason," referring to John 1 Ἐν ἀρχῇ ἦν ὁ λόγος, usually translated as "In the beginning was the Word (Logos)." Thus, he said that the Christian faith is "open to all that is truly rational", and that the rationality of Western Enlightenment "is of Christian origin".[91] Some commentators have claimed that Western civilization can be almost defined by its serious testing of the limits of tension between "unaided" reason and faith in "revealed" truths—figuratively summarized as Athens and Jerusalem, respectively.[92] Leo Strauss spoke of a "Greater West" that included all areas under the influence of the tension between Greek rationalism and Abrahamic revelation, including the Muslim lands. He was particularly influenced by the Muslim philosopher Al-Farabi. To consider to what extent Eastern philosophy might have partaken of these important tensions, Strauss thought it best to consider whether dharma or tao may be equivalent to Nature (physis in Greek). According to Strauss the beginning of philosophy involved the "discovery or invention of nature" and the "pre-philosophical equivalent of nature" was supplied by "such notions as 'custom' or 'ways'", which appear to be really universal in all times and places. The philosophical concept of nature or natures as a way of understanding archai (first principles of knowledge) brought about a peculiar tension between reasoning on the one hand, and tradition or faith on the other.[74] |

関連概念と比較した理由 論理と比較した理由 参照:論理 論理または論理的という用語は、理性または理性的と同一であるかのように使用されることもある。また、論理は理性の最も純粋な、または定義する形態である とみなされることもある。「論理とは推論(reasoning)、すなわち前提から結論を導くことである。... 論理を行う際には、推論(reasoning)を明確にし、良い推論(reasoning)と悪い推論(reasoning)を区別しようとする。」 [41] 現代の経済学では、合理的選択は論理的に一貫した選択と同一であると想定されている。[42] しかし、理性と論理は別物であると考えられる。論理は理性の重要な側面ではあるが。作家ダグラス・ホフスタッターは著書『ゲーデル、エッシャー、バッハ』 の中で、この違いを次のように説明している。論理はシステム内部で行われるが、理性はシステム外部で、手順の省略、逆戻り、図の作成、例の参照、システム のルールを変更した場合に何が起こるかの確認などの方法によって行われる。[43]心理学者のマーク・H・ビッカードとロバート・L・キャンベルは、「合 理性は単純に論理性に同化されるものではない」と主張している。彼らは、「論理と論理システムに関する人間の知識は、推論(reasoning)を通じて 時間をかけて発展してきた」と指摘し、 論理システムは「それ自身よりも強力な新しい論理システムを構築することはできない」ため、推論(reasoning)と合理性は論理システム以上のもの を含まなければならないと主張している。[44][45] 心理学者のデビッド・モスマンは、ビックハードとキャンベルを引き合いに出し、人の理性の発達には「論理的およびその他の推論(reasoning)に対 する意識と制御の増加が伴う」という「メタ認知的な合理性の概念」を主張している。[45][46] 理性は思考の一種であり、論理は適切な推論(reasoning)の形式的な規則や規範の体系を記述しようとする試みを含む。[45] 理性が作用する規則を明確に考察した最古の現存する著作は、ギリシアの哲学者アリストテレスの著作、特に『前分析学』と『後分析学』である。[47][非 一次資料が必要] 古代ギリシア人には 古代ギリシア人には、言語や理性とは区別された論理学という独立した語は存在しなかったが、アリストテレスが新たに作った「三段論法」 (syllogismos)という語によって、論理学は初めて独立した学問分野として明確に定義された。[48] アリストテレスが「論理的なもの」(hē logikē)について言及した際には、より広義の理性的思考について言及していた。[49] 原因と結果の思考や象徴的思考と比較される理性 詳細は因果関係と象徴を参照 ホッブズ、ロック、ヒュームなどの哲学者が指摘しているように、一部の動物は原因と結果を関連付けることのできる「連想思考」の能力を明らかに有してい る。かつて蹴られた犬は、警告の兆候を認識する方法を学び、今後は蹴られないようにすることができるが、これはその犬が厳密な意味で理性を有していること を意味するものではない。また、経験や習慣に基づいて行動する人間が理性を用いているというわけでもない。[29] 人間の理性は、2つの考えを関連付ける能力以上のものを必要とする。たとえ、それらの2つの考えが、理性のある人間によって因果関係として説明される可能 性があるとしても、例えば煙の知覚と火の記憶などである。理性が関与するためには、煙と火の関連性が因果関係として説明できるような形で考えられなければ ならない。例えばロックの説明では、理性は三段論法を用いてこの比較を行うために、第三の観念を精神的に使用する必要がある。 より一般的に、チャールズ・サンダース・ピアスによれば、厳密な意味での理性は、記号、インデックス、アイコンからなる体系を創造し操作する能力を必要と する。記号は、名目上、習慣的に(例えば)煙や火のいずれかと結びついているにすぎない。[51] このような記号や符号の体系の例としては、言語がある。 理性と象徴的思考のつながりは、哲学者たちによってさまざまな方法で表現されてきた。トマス・ホッブズは、「マークス、または記憶のメモ」の作成を「ス ピーチ」と表現した。[52] 彼は「スピーチ」という言葉をギリシャ語の「ロゴス」の英語版として使用したため、スピーチは伝達される必要がなかった。[53] 伝達されると、このようなスピーチは言語となり、マーク、メモ、または記憶はホッブズによって「サイン」と呼ばれる。さらに遡れば、人間のみが理性(ロゴ ス)を持つという考えの源流はアリストテレスにあるが、彼は想像力があり、感覚知覚が持続する動物は、推論(reasoning)やヌースのようなものに 最も近いと述べている。また、動物がそのような場合に知覚できる区別を説明するのに「ロゴス」という言葉を使用している箇所もある。 理性、想像力、模倣、記憶 主な記事:想像力、模倣、記憶、想起 理性と想像力は、同様の精神過程に依存している。[55] 想像力は人間だけに存在するものではない。アリストテレスは、ファンタジア(想像力:イメージや幻影を保持できるもの)とフロネイン(ある意味で判断し理 解できる思考の一種)もまた、一部の動物に存在すると主張した。[56] 彼によると、両者は動物の持つ一次知覚能力に関連しており、それは異なる感覚の知覚を集め、普遍的なものを区別することなく、熟考や論理なしに知覚される 事物の順序を定義する。しかし、これはまだ理性ではない。なぜなら、人間の想像力は異なるからだ。 テレンス・ディーコンとマーリン・ドナルドは、言語の起源について論じ、理性を言語だけでなく模倣にも結びつけている。[57] 彼らは、言語を生み出す能力を現実の内的なモデリングの一部であり、人間特有のものとして説明している。その他の結果として、意識、想像力や空想が生まれ る。これに対して、言語そのものに対する遺伝的素因を唱える現代の論者には、ノーム・チョムスキーやスティーヴン・ピンカーがいる。[要出典] 理性が象徴的思考であり、人間特有のものであるとすれば、人間には「アイコン」すなわちイメージとそれが表象する実体との区別を明確に意識し続ける特別な能力があることを意味する。マーリン・ドナルドは次のように書いている。[58]:172 人間が現実的に演じている「戦い」という「意味」を犬は理解できるかもしれないが、そのメッセージを再構築したり、その表現と参照対象(現実の戦い)を区 別したりすることはできない。訓練されたサルは、この区別ができる。幼い子供は、この区別を早い時期に習得する。そのため、子供は、ある出来事を演じるこ とと、その出来事そのものを、何の苦労もなく区別することができる 古典的な記述では、この精神機能の同等の記述は、プラトンの哲学におけるエイクアシアである。[59]: これは、知覚が何かのイメージであるかどうか、 何らかの関連性はあるが同一ではないかどうかを認識する能力であり、それゆえ人間は夢や記憶、鏡に映った像が現実そのものではないことを認識できる。クラ インが「ディアノエーティック・エイカシア」と呼ぶものは、思考や心象、すなわち理性の定義として前述したような精神的なシンボル、アイコン、記号、マー クなど、特に思考や心象に関わるエイカシアである。この観点から理性を説明すると、人間の思考は、目に見えるものをあたかもそれ自体が理解可能な「思考の 対象」のイメージであるかのように理解することが多いという点で特殊である。この思考(ディアノイア)は、「...目に見える世界の広大で拡散したジャン グルを、より『正確な』ノエータの複数性に依存させる活動である」[59]: 122 マーリン・ドナルドと、プラトンやアリストテレスといったソクラテス派の著述家は、ミメーシス(模倣や表現と訳されることが多い)の重要性を強調している。ドナルドは次のように書いている。[58]: 169 模倣は特にサルや類人猿に見られるが[...しかし...]ミメーシスは模倣や擬態とは根本的に異なり、意図的な表現の発明を伴う。ミメーシスは外部とのコミュニケーションに絶対的に結びついているわけではない。 ミメーシスは、現在学術的な議論で再び注目されている概念であり、特にプラトンの作品で広く取り上げられている。アリストテレスでは、主に『詩学』で論じられている。マイケル・デイヴィスの人間論によると、[60] 人間が行動を選択する際に、あたかも外部からそれを観察しているかのように、自分自身のために行動を想像するというのが、人間の行動の特徴である。意図とは、想像上の行動、外部の内在化に他ならない。したがって、すべての行動は行動の模倣であり、詩的である。 ドナルドはプラトン(特に『記憶と想起について』におけるアリストテレス)と同様に、人間の精神世界における自発的な探求の開始という特異性を強調してい る。通常「想起」と訳される古代ギリシア語のanamnēsisは、「記憶」を意味するmnēmeと対立する概念である。記憶は、一部の動物と共有されて いるが[62]、過去に何が起こったかだけでなく、過去に何かが起こったという意識も必要であり、これは言い換えれば、ある種のエカイアである[59]: 109「...しかし、人間以外に思い出すことができるものは何もない」[63] 回想とは、かつて知っていた何かを探し出し、再び思い出すための意図的な努力である。クラインは、「何かを忘れたことに気づくことは、思い出すことを始め ることを意味する」と書いている。[59]:112 ドナルドは同じことを「オートキューイング」と呼び、次のように説明している。[58]:173[64]「模倣行為は、内発的な自己生成の合図に基づいて 再現可能である。これにより、外部からの合図を必要とせずに模倣表現を自発的に想起することが可能になる。おそらく、これは表象的思考の最も初期の形であ る。 著名な論文の中で、ファンタジー作家であり言語学者でもあるJ.R.R.トールキンは、「おとぎ話について」という論文の中で、「ファンタジー」と「魅 了」という言葉は、「特定の原始的な人間の欲求の充足」だけでなく、「言語と心の起源」にも関係していると述べている。[この引用には出典が必要] 論理的推論(reasoning)の方法と論証 詳細は「論理的推論(reasoning)」を参照 哲学の分野のひとつであり、推論(reasoning)のさまざまな形態のひとつが論理学である。哲学における伝統的な主な区分は演繹推論 (reasoning)と帰納推論(reasoning)である。形式論理学は演繹の科学として説明されてきた。[65] 帰納推論(reasoning)の研究は一般的に非公式論理学または批判的思考として知られる分野で行われている。 演繹推論(reasoning) 詳細は「演繹推論(reasoning)」を参照 演繹とは、前提から必然的に結論が導かれる推論(reasoning)の一形態である。演繹はまた、演繹的推論(reasoning)のプロセスによって導かれる結論の名称でもある。演繹的推論(reasoning)の典型的な例は、次の三段論法に見られる。 前提1 すべての人間は死すべき存在である。 前提2 ソクラテスは人間である。 結論 ソクラテスは死すべき存在である。 この論証の推論(reasoning)は演繹的に妥当である。なぜなら、両方の前提が真であり、結論が偽であるということはありえないからである。 帰納的推論(reasoning) 詳細は「帰納的推論(reasoning)」を参照 帰納法は、過去の観察や経験に基づいて、未観察の対象や種類に関する性質や関係を導き出す推論(reasoning)の一形態である。あるいは、繰り返される現象パターンの限定的な観察に基づいて、一般的な記述や法則を導き出す。 帰納的推論(reasoning)は演繹的推論(reasoning)とは対照的に、帰納的推論(reasoning)の最も強いケースにおいても、前提 の真実が結論の真実を保証するわけではない。その代わりに、帰納的論証の結論はある程度の確率で導かれる。この理由により、帰納的論証の結論には、前提に すでに含まれている以上の情報が含まれる。したがって、この推論(reasoning)方法は増幅的である。 帰納的推論(reasoning)の古典的な例として、経験論者デイヴィッド・ヒュームの次のものがある。 前提:今まで毎朝太陽は東から昇っていた。 結論:明日も太陽は東から昇るだろう。 類推的推論(reasoning) 詳細は「類推的推論(reasoning)」を参照 類推推論(reasoning)は、特定から特定への帰納推論(reasoning)の一形態である。 類推推論(reasoning)は、事例に基づく推論(reasoning)、特に法的推論(reasoning)においてよく用いられる。[66] 例を以下に示す。 前提1 ソクラテスは人間であり、死すべき存在である。 前提2 プラトンは人間である。 結論 プラトンは死すべき存在である。 類推推論(reasoning)は、単一の例から行う帰納推論(reasoning)の弱い形態である。なぜなら、帰納推論(reasoning)は通 常、多数の例を用いて特定から一般へと推論(reasoning)を行うからである。類推推論(reasoning)はしばしば誤った結論を導く。例え ば、 前提1 ソクラテスは人間であり、男性である。 前提2 アダ・ラブレスは人間である。 結論 アダ・ラブレスは男性である。 アブダクション 詳細は「帰納的推論(reasoning)」を参照 帰納的推論(reasoning)、または最善の説明への論証は、不完全な観察結果から出発し、可能性の高い説明を推し進めることから、演繹的推論 (reasoning)にも帰納的推論(reasoning)にも当てはまらない推論(reasoning)の一形態である。帰納的推論 (reasoning)の結論は、その前提から確実に導かれるものではなく、観察されていない事柄に関するものである。帰納法を他の推論 (reasoning)形式と区別するものは、主観的な判断、あるいは代替となる説明を否定しようとする試み、あるいは、ある程度論争の余地のある仮定を 前提として、支持する結論の可能性を示そうとする試みによって、ある結論を他の結論よりも支持しようとする点である。例えば、患者がある症状を示している 場合、さまざまな原因が考えられるが、そのうちの1つが他の原因よりも可能性が高いとして支持される。 誤った推論(reasoning) 詳細は「誤謬」、「形式誤謬」、および「非公式誤謬」を参照 議論における誤った推論(reasoning)は、誤った推論(reasoning)として知られている。議論における誤った推論(reasoning)は、形式誤謬または非公式誤謬のいずれかによって生じる可能性がある。 形式誤謬は、議論の形式や構造に問題がある場合に発生する。「形式」という語は、議論の形式との関連性を指している。形式誤謬を含む議論は常に無効である。 非公式誤謬は、議論の形式や構造ではなく、内容に問題があるために発生する推論(reasoning)の誤りである。 不合理な決定や行動 雇用主や公的機関の行動に関する法律において、誠実に行動する際に許容される行動や決定の範囲外にある決定や行動は、「不当」と表現される。この用語の使 用は、英国の訴訟事例であるShort v Poole Corporation (1926年)、Associated Provincial Picture Houses Ltd v Wednesbury Corporation (1947年)、Braganza v BP Shipping Limited (2015年)で検討されている。[68] 理性に関する伝統的な問題提起 哲学はしばしば、合理的な理解の追求として特徴づけられ、一般的に用いられるよりも厳密で献身的な人間の推論(reasoning)の適用を伴う。哲学者 たちは長い間、理性に関する2つの根本的な問題について議論してきた。本質的には、人間の努力としての推論(reasoning)そのものを検証したり、 哲学することについて哲学したりしてきた。最初の問いは、知識や真理を達成する上で、理性の能力を他の方法よりも効果的に信頼できるかどうかを掘り下げて いる。2つ目の問いは、理性によって導かれる人生、あるいは理性によって導かれることを目指す人生が、他の人生へのアプローチと比較して、より大きな幸福 につながることを期待できるかどうかを探求するものである。 理性対真理、そして「第一原理」 参照:真理、第一原理、ヌース 古典古代以来、真理を確証する理性の役割に関する問いは、哲学的な議論において常に存在し続けている(時にはプラトン主義とアリストテレス主義の対立と見 なされることもある)。人々は、論理、演繹、帰納法を用いて、真実であると考える結論に達する。アリストテレスによれば、このようにして導き出された結論 は、感覚知覚のみに基づくものよりも確実であると考えられている。[69] 一方、もしそのような推論(reasoning)による結論が、もともと感覚知覚のみに基づいて構築されているのであれば、最も論理的な結論であっても、 決して確実であるとは言えない。なぜなら、それらは、より優れたものを目指しているにもかかわらず、まさに同じ誤りを犯しやすい知覚に基づいて構築されて いるからである。[70] このことは、真の結論を導こうとする人にとって、どのような種類の第一原理、すなわち推論(reasoning)の出発点が利用可能であるかという疑問に つながる。ギリシャ語では、「第一原理」は「archai」であり、「出発点」である[71]。そして、それらを認識する能力は、アリストテレス[72] やプラトン[73]において、意識や認識に近い意味を持つ「nous」として言及されることがある。 経験論(アリストテレスと関連付けられることもあるが[75]、より正確にはジョン・ロックやデイヴィッド・ヒュームなどのイギリスの哲学者、およびデモ クリトスなどの古代の哲学者と関連付けられる)は、感覚による印象が推論(reasoning)および真理の探求の出発点として唯一利用できるものである と主張する。このアプローチは、絶対的な知識は獲得できないという物議を醸す結論に常に至る。観念論(プラトンとその学派に関連)は、「より高い」現実が 存在し、その中では感覚だけに頼る必要なく、一部の人間が直接的に真理を発見できると主張する。そして、このより高い現実が、したがって真理の第一の源泉 であると主張する。 プラトン、アリストテレス、アル・ファラビー、アヴィセンナ、アヴェロエス、マイモニデス、アクィナス、ヘーゲルといった哲学者たちは、理性は固定され、 発見可能であるべきだと主張したと言われている[誰によって?]。おそらく弁証法、分析、研究によって。これらの思想家の考えでは、理性は神聖なものであ り、少なくとも神聖な属性を持っている。このようなアプローチにより、トマス・アクィナスやエティエンヌ・ギルソンといった宗教哲学者たちは、理性と啓示 は両立しうることを示そうとした。ヘーゲルによれば、「哲学が歴史の思索に持ち込む唯一の思考は、理性の単純な概念である。すなわち、理性は世界の支配者 であり、世界の歴史は、したがって、私たちに理性的なプロセスを示すものである」[76]。 17世紀の合理主義者以来、理性はしばしば主観的な能力、あるいはむしろ概念を形成する無補助能力(純粋理性)とみなされてきた。デカルト、スピノザ、ラ イプニッツにとって、これは数学と関連していた。カントは、純粋理性が経験の条件である概念(時間と空間)を形成できることを示そうとした。カントは、理 性が経験において果たす役割を否定したヒュームに反対して、その主張を行った。 理性対感情または情熱 参照:感情と情熱(感情) プラトンとアリストテレス以降、西洋の文学では、理性はしばしば情熱や欲望を抑制する能力として扱われてきた。[要出典] それに対してストア哲学では、ほとんどの感情は単なる誤った判断であると主張した。[77][78] ストア派によれば、唯一の善は美徳であり、唯一の悪は悪徳である。したがって、 悪徳以外のものを悪と判断する感情(恐怖や苦痛など)や、美徳以外のものを善と判断する感情(貪欲など)は、単なる誤った判断であり、捨て去られるべきで ある(ただし、親切心など、真の判断に基づく肯定的な感情は受け入れられる)。初期の啓蒙主義における理性批判の後、情欲はほとんど議論されることがな く、情念と混同されるようになった。[要出典] 啓蒙主義のいくつかの派閥は、理性は情念を統制するのではなく、それに抵抗すべきであると主張し、ストア派にならった。一方、ロマン派のような他の派閥 は、情念が理性を置き換えると信じており、「心の赴くままに」という格言に表れている。[要出典] 理性は冷たく、「神秘と曖昧さの敵」であり[80]、情念の奴隷または審判者であると見なされてきた。特にデイヴィッド・ヒュームの著作において、また最近ではフロイトの著作においてそうである。[要出典] 欲望の対象は論理のみによって要求されると主張する推論(reasoning)は合理化と呼ばれる。[要出典] ルソーは、第二著『社会契約論』において、理性と政治生活は自然のものではなく、人類にとって有害である可能性があると初めて主張した。[81] 彼は、人類にとって自然なことについて、本当に何が言えるのかと問いかけた。理性と市民社会以外に、「人間の体質に最も適している」ものは何か? ルソーは人間の本性の中に「理性に先立つ二つの原理」を見出した。 まず、私たちは自身の幸福に強い関心を持つ。 第二に、私たちは知覚を持つあらゆる生物の苦しみや死に反対する。特に自分自身のような存在に対してはそうである。[82] これら二つの情熱は、私たちが達成できる以上のものを望むようにさせる。私たちは互いに依存し、権威と服従の関係に依存するようになる。これは事実上、人 類を奴隷状態に置くことになる。ルソーは、人間が健康であるように自然が人間を運命づけているわけではないと断言する勇気さえあったと述べている。リ チャード・ヴェルクレイによると、「ルソーは、合理的な自己修正のプログラムをいくつか概説しており、最も顕著なものは『社会契約論』の政治立法と『エ ミール』の道徳教育である。しかし、ルソーは、そうした修正は、社会的に、また知的に堕落した人間という本質的に不満足な状態を改善するものにすぎないと 理解していた」[この引用には出典が必要] ルソーが提示したこのジレンマは、善と悪を創造する自由としての理性を正当化するカントの新しい方法につながった。したがって、それらは自然や神のせいで はない。カント以降のドイツ観念論や、ニーチェ、ベルクソン、フッサール、シェーラー、ハイデッガーといった主要な後世の人物は、さまざまな形で、理性の 形而上学的要請や衝動から生じる問題にこだわり続けた。[83] ルソーやこれらの後世の作家は、芸術や政治にも大きな影響を与えた。多くの作家(ニコス・カザンザキスなど)は情熱を称賛し、理性を軽蔑する。政治におい ては、近代ナショナリズムは、合理主義的コスモポリタニズムが人間を自然な状態からますます遠ざけるというルソーの主張に由来する。 アントニオ・ダマシオは著書『デカルトの誤り』の中で、「ソマティック・マーカー仮説」を提示している。この仮説は、感情が人間の行動や意思決定を導くと いうものである。ダマシオは、これらのソマティック・マーカー(「直感」として総称される)は、理性だけでは解決できない意思決定プロセスをある特定の方 向に導く「直感的なシグナル」であると主張している。さらにダマシオは、理性が機能するためには感情のインプットが必要であると主張している。 理性対信仰または伝統 詳細は「信仰」、「宗教」、「伝統」を参照 多くの宗教的伝統があり、その中には明らかに唯信論的なものもあれば、さまざまな程度の合理性を主張するものもある。世俗的な批評家は、すべての宗教的信 奉者を非合理であると非難することがある。彼らは、そのような信奉者は、特定の主題(宗教的教義、道徳的タブーなど)に関する特定の種類の推論 (reasoning)を無視、抑制、禁止していると主張する。古典的単神教のような神学や宗教は、通常、非合理であることを認めないが、知恵、法、真理 の潜在的な競合する源泉として、信仰と伝統の一方と理性の他方との間にしばしば認識される対立や緊張がある。[74][86] 宗教的信奉者は、信仰と理性は調和しうる、あるいは重複しない異なる領域を持つ、あるいは批判者も同様の非合理主義に従事している、と反論することがある。 和解 哲学者のアルヴィン・プラントィンガは、古典的単神教は(他の事柄とともに)宇宙が理解可能である理由、そして理性がそれをうまく把握できる理由を説明しているため、理性と古典的単神教との間に真の対立はないと主張している。[87] 重複しない教義 進化生物学者のスティーブン・ジェイ・グールドは、理性と宗教的信念の間には対立は存在し得ない、なぜなら、それらはそれぞれ独自の領域(または「教導 権」)において権威を有しているからだ、と主張している。[88] もしそうであるならば、理性は、それが権威を有する問題について取り組むことができ、一方で、大きな問題については、他の知識や意見が権威を有することが できる。[89] 汝もまた 哲学者のアラスデア・マッキンタイアとチャールズ・テイラーは、世俗的自由主義の信奉者である伝統的宗教の批判者たちも、ある主題に関するある種の推論 (reasoning)を無視したり、抑制したり、禁じたりすることがあると主張している。[90] 同様に、ポール・フェイヤーアベンドなどの科学哲学者は、科学者たちが支配的なパラダイムに反する証拠を無視したり、抑制したりすることがあると主張して いる。 統一 神学者のヨゼフ・ラツィンガー(後のベネディクト16世)は、「キリスト教は、ロゴスの宗教、理性に基づく宗教として自らを理解してきた」と主張し、ヨハ ネによる福音書第1章「初めにロゴス(ことば)があった」を引用した。したがって、キリスト教信仰は「真に理性的なすべてに対して開かれている」とし、西 洋啓蒙主義の合理性は「キリスト教に由来する」と述べた。[91] 西洋文明は、「無助の」理性と「啓示された」真理への信仰との間の緊張の限界を真剣に試すことによって、ほぼ定義できると主張する論者もいる。この2つ は、それぞれアテネとエルサレムに比喩的にまとめられている。[92] レオ・シュトラウスは、ギリシャの合理主義とアブラハムの啓示との間の緊張の影響下にあるすべての地域、すなわちイスラム教徒の土地も含む「より大きな西 洋」について語った。彼は特にイスラム教徒の哲学者アル・ファラビーの影響を受けていた。東洋哲学がこれらの重要な緊張関係にどの程度関与しているかを考 察するために、シュトラウスは、ダルマやタオが自然(ギリシャ語ではフィュシス)と同義であるかどうかを考えるのが最善であると考えた。シュトラウスによ れば、哲学の始まりは「自然の発見または発明」であり、「哲学以前の自然」は「『慣習』や『方法』といった概念」によって供給されていた。これらの概念 は、あらゆる時代や場所において、本当に普遍的なものであるように見える。アルカイ(知識の第一原理)を理解する方法としての自然または複数の自然という 哲学的概念は、一方では推論(reasoning)、他方では伝統または信仰との間に独特の緊張関係をもたらした。[74] |

| Reason in particular fields of study Psychology and cognitive science See also: Psychology of reasoning Scientific research into reasoning is carried out within the fields of psychology and cognitive science. Psychologists attempt to determine whether or not people are capable of rational thought in a number of different circumstances. Assessing how well someone engages in reasoning is the project of determining the extent to which the person is rational or acts rationally. It is a key research question in the psychology of reasoning and cognitive science of reasoning. Rationality is often divided into its respective theoretical and practical counterparts. Behavioral experiments on human reasoning Experimental cognitive psychologists carry out research on reasoning behaviour. Such research may focus, for example, on how people perform on tests of reasoning such as intelligence or IQ tests, or on how well people's reasoning matches ideals set by logic (see, for example, the Wason test).[93] Experiments examine how people make inferences from conditionals like if A then B and how they make inferences about alternatives like A or else B.[94] They test whether people can make valid deductions about spatial and temporal relations like A is to the left of B or A happens after B, and about quantified assertions like all the A are B.[95] Experiments investigate how people make inferences about factual situations, hypothetical possibilities, probabilities, and counterfactual situations.[96] Developmental studies of children's reasoning Developmental psychologists investigate the development of reasoning from birth to adulthood. Piaget's theory of cognitive development was the first complete theory of reasoning development. Subsequently, several alternative theories were proposed, including the neo-Piagetian theories of cognitive development.[97] Neuroscience of reasoning This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (September 2023) (Learn how and when to remove this message) The biological functioning of the brain is studied by neurophysiologists, cognitive neuroscientists, and neuropsychologists. This includes research into the structure and function of normally functioning brains, and of damaged or otherwise unusual brains. In addition to carrying out research into reasoning, some psychologists—for example clinical psychologists and psychotherapists—work to alter people's reasoning habits when those habits are unhelpful. Computer science Automated reasoning Main articles: Automated reasoning and Computational logic See also: Reasoning system, Case-based reasoning, Semantic reasoner, and Knowledge reasoning In artificial intelligence and computer science, scientists study and use automated reasoning for diverse applications including automated theorem proving the formal semantics of programming languages, and formal specification in software engineering. Meta-reasoning See also: Metacognition Meta-reasoning is reasoning about reasoning. In computer science, a system performs meta-reasoning when it is reasoning about its own operation.[98] This requires a programming language capable of reflection, the ability to observe and modify its own structure and behaviour. Evolution of reason  Dan Sperber believes that reasoning in groups is more effective and promotes their evolutionary fitness. A species could benefit greatly from better abilities to reason about, predict, and understand the world. French social and cognitive scientists Dan Sperber and Hugo Mercier argue that, aside from these benefits, there could have been other forces driving the evolution of reason. They point out that reasoning is very difficult for humans to do effectively, and that it is hard for individuals to doubt their own beliefs (confirmation bias). Reasoning is most effective when it is done as a collective—as demonstrated by the success of projects like science. They suggest that there are not just individual, but group selection pressures at play. Any group that managed to find ways of reasoning effectively would reap benefits for all its members, increasing their fitness. This could also help explain why humans, according to Sperber, are not optimized to reason effectively alone. Sperber's & Mercier's argumentative theory of reasoning claims that reason may have more to do with winning arguments than with the search for the truth.[99] Reason in political philosophy and ethics Main articles: Political Philosophy, Ethics, and The Good Aristotle famously described reason (with language) as a part of human nature, because of which it is best for humans to live "politically" meaning in communities of about the size and type of a small city state (polis in Greek). For example: It is clear, then, that a human being is more of a political politikon = of the polis] animal [zōion] than is any bee or than any of those animals that live in herds. For nature, as we say, makes nothing in vain, and humans are the only animals who possess reasoned speech [logos]. Voice, of course, serves to indicate what is painful and pleasant; that is why it is also found in other animals, because their nature has reached the point where they can perceive what is painful and pleasant and express these to each other. But speech [logos] serves to make plain what is advantageous and harmful and so also what is just and unjust. For it is a peculiarity of humans, in contrast to the other animals, to have perception of good and bad, just and unjust, and the like; and the community in these things makes a household or city [polis].... By nature, then, the drive for such a community exists in everyone, but the first to set one up is responsible for things of very great goodness. For as humans are the best of all animals when perfected, so they are the worst when divorced from law and right. The reason is that injustice is most difficult to deal with when furnished with weapons, and the weapons a human being has are meant by nature to go along with prudence and virtue, but it is only too possible to turn them to contrary uses. Consequently, if a human being lacks virtue, he is the most unholy and savage thing, and when it comes to sex and food, the worst. But justice is something political [to do with the polis], for right is the arrangement of the political community, and right is discrimination of what is just.[100]: I.2, 1253a If human nature is fixed in this way, we can define what type of community is always best for people. This argument has remained a central argument in all political, ethical, and moral thinking since then, and has become especially controversial since firstly Rousseau's Second Discourse, and secondly, the Theory of Evolution. Already in Aristotle there was an awareness that the polis had not always existed and had to be invented or developed by humans themselves. The household came first, and the first villages and cities were just extensions of that, with the first cities being run as if they were still families with Kings acting like fathers.[100]: I.2, 1252b15 Friendship seems to prevail in man and woman according to nature [kata phusin]; for people are by nature [tēi phusei] pairing more than political [politikon], in as much as the household [oikos] is prior and more necessary than the polis and making children is more common [koinoteron] with the animals. In the other animals, community [koinōnia] goes no further than this, but people live together [sumoikousin] not only for the sake of making children, but also for the things for life; for from the start the functions [erga] are divided, and are different for man and woman. Thus they supply each other, putting their own into the common [eis to koinon]. It is for these reasons that both utility and pleasure seem to be found in this kind of friendship.[6]: VIII.12 Rousseau in his Second Discourse finally took the shocking step of claiming that this traditional account has things in reverse: with reason, language, and rationally organized communities all having developed over a long period of time merely as a result of the fact that some habits of cooperation were found to solve certain types of problems, and that once such cooperation became more important, it forced people to develop increasingly complex cooperation—often only to defend themselves from each other. In other words, according to Rousseau, reason, language, and rational community did not arise because of any conscious decision or plan by humans or gods, nor because of any pre-existing human nature. As a result, he claimed, living together in rationally organized communities like modern humans is a development with many negative aspects compared to the original state of man as an ape. If anything is specifically human in this theory, it is the flexibility and adaptability of humans. This view of the animal origins of distinctive human characteristics later received support from Charles Darwin's Theory of Evolution. The two competing theories concerning the origins of reason are relevant to political and ethical thought because, according to the Aristotelian theory, a best way of living together exists independently of historical circumstances. According to Rousseau, we should even doubt that reason, language, and politics are a good thing, as opposed to being simply the best option given the particular course of events that led to today. Rousseau's theory, that human nature is malleable rather than fixed, is often taken to imply (for example by Karl Marx) a wider range of possible ways of living together than traditionally known. However, while Rousseau's initial impact encouraged bloody revolutions against traditional politics, including both the French Revolution and the Russian Revolution, his own conclusions about the best forms of community seem to have been remarkably classical, in favor of city-states such as Geneva, and rural living. |

特定の研究分野における理由 心理学と認知科学 関連情報: 推論(reasoning)の心理学 推論(reasoning)に関する科学的研究は、心理学と認知科学の分野で行われている。心理学者は、さまざまな状況において、人が合理的な思考を行う能力があるかどうかを判断しようとしている。 ある人物がどの程度推論(reasoning)を行っているかを評価することは、その人物がどの程度合理的であるか、または合理的に行動しているかを判断 するプロジェクトである。これは、推論(reasoning)心理学および推論(reasoning)認知科学における重要な研究課題である。合理性は、 理論的合理性と実践的合理性のそれぞれに分けられることが多い。 人間の推論(reasoning)に関する行動実験 実験的認知心理学者は推論(reasoning)行動の研究を行っている。 このような研究では、例えば、知能テストやIQテストなどの推論(reasoning)テストにおける人間のパフォーマンスや、人間の推論 (reasoning)が論理によって設定された理想にどの程度一致しているか(例えば、ワソンテストを参照)に焦点を当てる場合がある。[93] 実験では、人々が「もしAならばB」のような条件文からどのように推論(reasoning)を行うか、また、「AまたはB」のような選択肢についてどの ように推論(reasoning)を行うかを検証する。。また、AはBの左にある、AはBの後に起こる、といった空間的・時間的関係や、すべてのAはBで あるといった数量化された主張について、妥当な推論(reasoning)ができるかどうかを検証する。実験では、事実状況、仮説的可能性、確率、反事実 状況について、人がどのように推論(reasoning)を行うかを調査する。 子どもの推論(reasoning)能力の発達に関する研究 発達心理学者は、出生から成人期までの推論(reasoning)能力の発達を研究している。ピアジェの認知発達理論は、推論(reasoning)能力 の発達に関する最初の完全な理論であった。その後、認知発達に関する新ピアジェ学派の理論など、いくつかの代替理論が提案された。 推論(reasoning)能力の神経科学 この節には出典が全く示されていない。出典を追加して記事の信頼性向上にご協力ください。出典の無い項目は、異議申し立てを受けて削除される場合があります。 (2023年9月) (Learn how and when to remove this message) 脳の生物学的機能は神経生理学者、認知神経科学者、神経心理学者によって研究されている。これには、正常に機能している脳の構造と機能、および損傷した脳 やその他の異常な脳の構造と機能に関する研究が含まれる。推論(reasoning)に関する研究を行うだけでなく、臨床心理学者や心理療法士などの一部 の心理学者は、その習慣が役に立たない場合、人々の推論(reasoning)の習慣を変えるために働いている。 コンピュータサイエンス 自動推論(reasoning) 詳細は「自動推論(reasoning)」および「計算論理」を参照 関連項目:推論(reasoning)システム、事例ベース推論(reasoning)、意味推論(reasoning)、知識推論(reasoning) 人工知能および計算機科学では、科学者たちは自動推論(reasoning)を研究し、プログラミング言語の形式意味論の自動定理証明、ソフトウェア工学における形式仕様など、さまざまな用途に利用している。 メタ推論(reasoning) 関連項目:メタ認知 メタ推論(reasoning)とは、推論(reasoning)に関する推論(reasoning)である。コンピュータサイエンスでは、システムが自 身の動作について推論(reasoning)を行う際にメタ推論(reasoning)を行う。[98] これには、自身の構造や動作を観察し修正する能力であるリフレクションが可能なプログラミング言語が必要である。 理性の進化  ダン・スペルバーは、集団での推論(reasoning)はより効果的であり、進化上の適応性を促進すると考えている。 種は、世界について推論(reasoning)し、予測し、理解する能力が向上することで、大きな利益を得ることができる。フランスの社会学者および認知 科学者であるダン・スペルバーとユーゴ・メルシエは、これらの利点とは別に、理性の進化を促す他の要因があった可能性があると主張している。彼らは、人間 が効果的に推論(reasoning)を行うのは非常に難しいことであると指摘し、個人が自身の信念を疑うことは難しい(確証バイアス)と述べている。推 論(reasoning)は、科学のようなプロジェクトの成功が示すように、集団で行うことで最も効果的になる。彼らは、個々人だけでなく集団にも選択圧 力が働いていると示唆している。効果的な推論(reasoning)の方法を見つけ出すことに成功した集団は、その集団のメンバー全員に利益をもたらし、 適応度を高めることになる。このことは、なぜ人間は単独で効果的に推論(reasoning)を行うようには最適化されていないのかという、 Sperberの主張を説明する助けにもなる。SperberとMercierの論争的な推論(reasoning)理論は、理性は真理の探究よりも議論 に勝つこととより関係が深いかもしれないと主張している。 政治哲学と倫理における理性 主な記事:政治哲学、倫理、善 アリストテレスは、理性(言語)を人間の本性の一部として有名に描写した。それゆえ、人間は「政治的に」生きることが最善であり、それはギリシャ語でポリスと呼ばれる小都市国家の規模と類型のコミュニティで意味を持つ。例えば: 人間は、ミツバチや群れで生活する他の動物よりも、ポリス(polis)の政治的な動物(politeikon)であることが明らかである。自然は、無駄 に何かを創造することはない。人間は、論理的な言語(ロゴス)を所有する唯一の動物である。もちろん、声は苦痛や快楽を伝えるためにある。だからこそ、他 の動物にも声がある。なぜなら、彼らの本性は、苦痛や快楽を認識し、それを互いに表現できるところまで達しているからだ。しかし、言葉(ロゴス)は、何が 有益で有害か、そして何が正義で不正義かを明らかにするためにある。なぜなら、善悪や正義不正などを認識できるのは、人間特有の能力であり、他の動物には ないからだ。そして、これらの認識を共有する共同体が、家庭や都市(ポリス)を形成する。本来、このような共同体の形成を求める欲求は誰の心にも存在する が、最初に共同体を設立した者は、非常に大きな善行を成し遂げたことになる。なぜなら、人間は完成されたとき、動物の中で最も優れた存在となるが、法と正 義から離れたとき、最も劣った存在となるからだ。 不正は武器を手にすると最も対処が難しくなる。人間が持つ武器は、本来、慎重さと徳と共にあるべきだが、それらを逆の用途に使うことも十分に可能だ。した がって、人間が徳を欠く場合、その人間は最も不道徳で野蛮な存在であり、性や食に関して言えば、最悪の存在である。しかし、正義とは政治的なものであり [ポリスに関係するもの]、正義とは政治共同体の秩序であり、正義とは正当なものの識別である。[100]: I.2, 1253a 人間の本性がこのように固定されているとすれば、どのような共同体が常に人々にとって最善であるかを定義することができる。この議論はそれ以来、政治、倫 理、道徳に関するあらゆる思考の中心的な議論であり続け、特にルソーの『第二談話』と進化論の登場以来、論争の的となっている。アリストテレスの時代には すでに、ポリスは常に存在していたわけではなく、人間自身の手で発明または開発されなければならないという認識があった。家庭が最初であり、最初の村や都 市は、その延長線上にあった。最初の都市は、王が父親のように振る舞う家族のようなものとして運営されていた。[100]: I.2, 1252b15 友情は、自然(カタ・フュシン)に従って男女の間にも存在しているように思われる。なぜなら、人間は本質的に(テイ・フュセイ)政治的(ポリティコン)な 関係よりも多くのペアを組み、家庭(オイコス)はポリスよりも優先され、必要とされるものであり、子供をもうけることは動物と共通しているからだ。他の動 物では、共同生活(koinōnia)はこれ以上のものではないが、人間は子供を作るためだけでなく、生活のためにも一緒に暮らす (sumoikousin)。なぜなら、人間には最初から機能(erga)が分かれており、男女で異なるからだ。こうして彼らは互いに補い合い、自分のも のを共有のものに注ぎ込む。このような理由から、この種の友情においては、実用性と快楽の両方が得られるように思われる。[6]: VIII.12 ルソーは『第二談話』で、ついに衝撃的な主張に踏み切った。すなわち、この伝統的な説明は事態を逆さまに捉えているというのだ。理性、言語、合理的に組織 化された社会はすべて、ある種の協力関係が特定の問題を解決できることが分かった結果として、長い時間をかけて発展してきたにすぎず、そのような協力関係 が重要性を増すと、人々はますます複雑な協力関係を発展させることを余儀なくされた。 つまり、ルソーによれば、理性、言語、合理的な社会は、人間や神々による意識的な決定や計画、あるいは人間の本性の先天的な性質によって生じたものではな い。その結果、人間が現代人のように合理的に組織された社会で暮らすことは、猿としての人間本来の状態と比較すると、多くの否定的な側面を持つ発展である と彼は主張した。この理論で人間特有のものがあるとすれば、それは人間の柔軟性と適応性である。この、人間の特徴の動物起源に関する見解は、後にチャール ズ・ダーウィンの進化論によって支持された。 理性の起源に関する2つの対立する理論は、政治思想や倫理思想にも関連している。なぜなら、アリストテレスの理論によると、歴史的状況とは無関係に、共存 の最善の方法が存在するからだ。ルソーによれば、理性、言語、政治が善であると考えることさえ疑うべきであり、今日に至る特定の経過を踏まえた単なる最善 の選択肢であると考えるべきではない。ルソーの理論、すなわち人間の本性は固定されたものではなく、変化しうるものであるという理論は、しばしば(例えば カール・マルクスによって)伝統的に知られていたものよりも幅広い共存のあり方を暗示していると解釈される。 しかし、ルソーの当初の影響は、フランス革命やロシア革命を含む伝統的な政治に対する血なまぐさい革命を促したが、彼自身の共同体における最善の形についての結論は、ジュネーブのような都市国家や田舎での生活を支持する、驚くほど古典的なものだったようだ。 |

| Argument – Attempt to persuade or to determine the truth of a conclusion Argumentation theory – Academic field of logic and rhetoric Common sense – Sound practical judgement in everyday matters Confirmation bias – Bias confirming existing attitudes Conformity – Matching opinions and behaviors to group norms Critical thinking – Analysis of facts to form a judgment Logic and rationality – Fundamental concepts in philosophy Outline of thought – Topic tree that identifies many types of thoughts/thinking, types of reasoning, aspects of thought, related fields, and more Outline of human intelligence – Topic tree presenting the traits, capacities, models, and research fields of human intelligence, and more Transduction (psychology) – generalization of attributes from specific examples of a category to the whole category |