合理主義・合理論

Rationalism

☆ 哲学において合理主義あるいは合理論(rationalism) とは(「合理性」の概念にもとづいて)「理性を知識の主要な源泉およびテストとみなす」 認識論的見解、または「知識や正当化の源泉として理性に訴えるあらゆる 見解」であり、しばしば信仰、伝統、感覚的経験といった他の可能な知識の源泉とは対照的である。より正式には、合理主義は「真理の基準が感覚的では なく、知的で演繹的である」方法論または理論として定義される。

| In philosophy, rationalism

is the epistemological view that "regards reason as the chief source

and test of knowledge"[1] or "any view appealing to reason as a source

of knowledge or justification",[2] often in contrast to other possible

sources of knowledge such as faith, tradition, or sensory experience.

More formally, rationalism is defined as a methodology or a theory "in

which the criterion of truth is not sensory but intellectual and

deductive".[3] In a major philosophical debate during the Enlightenment,[4] rationalism (sometimes here equated with innatism) was opposed to empiricism. On the one hand, the rationalists emphasized that knowledge is primarily innate and the intellect, the inner faculty of the human mind, can therefore directly grasp or derive logical truths; on the other hand, the empiricists emphasized that knowledge is not primarily innate and is best gained by careful observation of the physical world outside the mind, namely through sensory experiences. Rationalists asserted that certain principles exist in logic, mathematics, ethics, and metaphysics that are so fundamentally true that denying them causes one to fall into contradiction. The rationalists had such a high confidence in reason that empirical proof and physical evidence were regarded as unnecessary to ascertain certain truths – in other words, "there are significant ways in which our concepts and knowledge are gained independently of sense experience".[5] Different degrees of emphasis on this method or theory lead to a range of rationalist standpoints, from the moderate position "that reason has precedence over other ways of acquiring knowledge" to the more extreme position that reason is "the unique path to knowledge".[6] Given a pre-modern understanding of reason, rationalism is identical to philosophy, the Socratic life of inquiry, or the zetetic (skeptical) clear interpretation of authority (open to the underlying or essential cause of things as they appear to our sense of certainty). In recent decades, Leo Strauss sought to revive "Classical Political Rationalism" as a discipline that understands the task of reasoning, not as foundational, but as maieutic. |

哲学において合理主義(rationalism)

とは、「理性を知識の主要な源泉およびテストとみなす」[1]認識論的見解、または「知識や正当化の源泉として理性に訴えるあらゆる見解」[2]であり、

しばしば信仰、伝統、感覚的経験といった他の可能な知識の源泉とは対照的である。より正式には、合理主義は「真理の基準が感覚的ではなく、知的で演繹的で

ある」方法論または理論として定義される[3]。 啓蒙時代の主要な哲学論争[4]において、合理主義(ここでは生得主義と同一視されることもある)は経験主義と対立していた。一方、合理主義者たちは、知 識は主に生得的なものであり、人間の心の内なる能力である知性はそれゆえに論理的真理を直接的に把握したり導き出したりすることができると強調し、他方、 経験主義者たちは、知識は主に生得的なものではなく、心の外にある物理的世界を注意深く観察することによって、すなわち感覚的経験を通じて得るのが最善で あると強調した。合理主義者たちは、論理学、数学、倫理学、形而上学において、それを否定すれば矛盾に陥るほど根本的に真理である原理が存在すると主張し た。合理主義者たちは理性に高い自信を持っていたため、経験的証明や物理的証拠は特定の真理を確認するためには不要であるとみなされていた。言い換えれ ば、「我々の概念や知識が感覚的経験とは無関係に得られる重要な方法が存在する」ということである[5]。 この方法や理論に対する強調の度合いの違いによって、「理性が知識を得る他の方法よりも優先される」という穏健な立場から、理性が「知識への唯一無二の 道」であるという極端な立場まで、様々な合理主義の立場が生まれる[6]。理性に対する前近代的な理解を前提とすれば、合理主義は哲学、ソクラテスの探究 生活、または権威のゼテス的(懐疑的)な明確な解釈(私たちの確かな感覚に見える物事の根本的または本質的な原因に対して開かれたもの)と同一である。こ こ数十年、レオ・シュトラウスは「古典的政治的合理主義」を、推論の課題を基礎的なものとしてではなく、メユーティックなものとして理解する学問として復 活させようとした。 |

| Background Rationalism – as an appeal to human reason as a way of obtaining knowledge – has a philosophical history dating from antiquity. The analytical nature of much of philosophical enquiry, the awareness of apparently a priori domains of knowledge such as mathematics, combined with the emphasis of obtaining knowledge through the use of rational faculties (commonly rejecting, for example, direct revelation) have made rationalist themes very prevalent in the history of philosophy.    Since the Enlightenment, rationalism is usually associated with the introduction of mathematical methods into philosophy as seen in the works of Descartes, Leibniz, and Spinoza.[3] This is commonly called continental rationalism, because it was predominant in the continental schools of Europe, whereas in Britain empiricism dominated. Even then, the distinction between rationalists and empiricists was drawn at a later period and would not have been recognized by the philosophers involved. Also, the distinction between the two philosophies is not as clear-cut as is sometimes suggested; for example, Descartes and Locke have similar views about the nature of human ideas.[5] Proponents of some varieties of rationalism argue that, starting with foundational basic principles, like the axioms of geometry, one could deductively derive the rest of all possible knowledge. Notable philosophers who held this view most clearly were Baruch Spinoza and Gottfried Leibniz, whose attempts to grapple with the epistemological and metaphysical problems raised by Descartes led to a development of the fundamental approach of rationalism. Both Spinoza and Leibniz asserted that, in principle, all knowledge, including scientific knowledge, could be gained through the use of reason alone, though they both observed that this was not possible in practice for human beings except in specific areas such as mathematics. On the other hand, Leibniz admitted in his book Monadology that "we are all mere Empirics in three fourths of our actions."[6] Political usage In politics, rationalism, since the Enlightenment, historically emphasized a "politics of reason" centered upon rational choice, deontology, utilitarianism, secularism, and irreligion[7] – the latter aspect's antitheism was later softened by the adoption of pluralistic reasoning methods practicable regardless of religious or irreligious ideology.[8][9] In this regard, the philosopher John Cottingham[10] noted how rationalism, a methodology, became socially conflated with atheism, a worldview: In the past, particularly in the 17th and 18th centuries, the term 'rationalist' was often used to refer to free thinkers of an anti-clerical and anti-religious outlook, and for a time the word acquired a distinctly pejorative force (thus in 1670 Sanderson spoke disparagingly of 'a mere rationalist, that is to say in plain English an atheist of the late edition...'). The use of the label 'rationalist' to characterize a world outlook which has no place for the supernatural is becoming less popular today; terms like 'humanist' or 'materialist' seem largely to have taken its place. But the old usage still survives. |

背景 理性主義は、知識を得る方法として人間の理性に訴えるもので、古代から続く哲学の歴史を持っている。哲学的探求の多くが分析的であること、数学のような明 らかに先験的な知識領域を意識していること、理性的能力の使用を通じて知識を得ることを重視していること(一般に、例えば直接的な啓示を否定しているこ と)などが相まって、合理主義のテーマは哲学の歴史において非常に広く浸透している。

それでも、合理主義者と経験主義者の区別は後の時代になされたものであり、当事者である哲学者たちは認識していなかったであろう。また、この2つの哲学の 区別は時に示唆されるほど明確ではなく、例えばデカルトとロックは人間の観念の本質について同様の見解を持っている[5]。 ある種の合理主義の支持者は、幾何学の公理のような基礎的な基本原理から出発すれば、残りのすべての可能な知識を演繹的に導くことができると主張してい る。この考え方を最も明確に持っていた著名な哲学者はバルーク・スピノザとゴットフリート・ライプニッツであり、彼らはデカルトが提起した認識論的・形而 上学的問題に取り組もうとした結果、合理主義の基本的アプローチを発展させることになった。スピノザもライプニッツも、科学的知識を含むすべての知識は、 原理的には理性のみによって得られると主張したが、数学のような特定の分野を除いて、人間には実際には不可能であるとした。一方、ライプニッツは著書『モ ナドロジー』の中で、「われわれはすべて、われわれの行動の4分の3において、単なる経験者である」と認めている[6]。 政治的用法 政治においては、啓蒙主義以来、合理主義は歴史的に合理的選択、非論理主義、功利主義、世俗主義、無宗教[7]を中心とした「理性の政治」を強調してお り、後者の反神論的な側面は後に宗教的、無宗教的なイデオロギーに関係なく実践可能な多元的な推論方法の採用によって和らげられた[8][9]。この点に 関して、哲学者のジョン・コッティンガム[10]は、方法論である合理主義が世界観である無神論と社会的にどのように混同されるようになったかを指摘して いる: 過去、特に17世紀と18世紀において、「合理主義者」という言葉は反宗教的、反教徒的な考えを持つ自由な思想家を指す言葉としてしばしば使われ、一時期 この言葉は明らかに侮蔑的な力を持つようになった(そのため1670年にサンダーソンは「単なる合理主義者、つまり平たく言えば後期版の無神論者...」 と侮蔑的に語っている)。合理主義者」というレッテルは、超自然的なものの存在を認めない世界観を特徴づけるものとして、今日ではあまり使われなくなって いる。しかし、古い用法はまだ残っている。 |

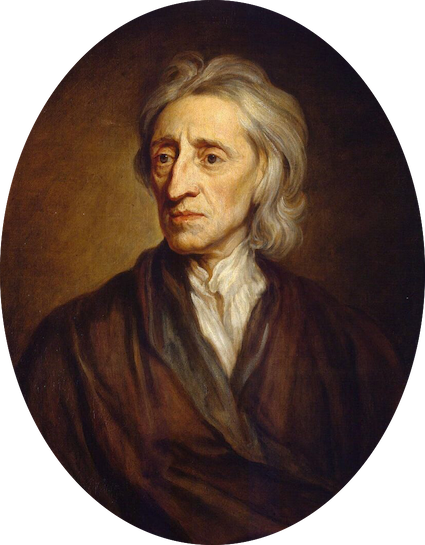

| Philosophical usage Rationalism is often contrasted with empiricism. Taken very broadly, these views are not mutually exclusive, since a philosopher can be both rationalist and empiricist.[2] Taken to extremes, the empiricist view holds that all ideas come to us a posteriori, that is to say, through experience; either through the external senses or through such inner sensations as pain and gratification. The empiricist essentially believes that knowledge is based on or derived directly from experience. The rationalist believes we come to knowledge a priori – through the use of logic – and is thus independent of sensory experience. In other words, as Galen Strawson once wrote, "you can see that it is true just lying on your couch. You don't have to get up off your couch and go outside and examine the way things are in the physical world. You don't have to do any science."[11] Between both philosophies, the issue at hand is the fundamental source of human knowledge and the proper techniques for verifying what we think we know. Whereas both philosophies are under the umbrella of epistemology, their argument lies in the understanding of the warrant, which is under the wider epistemic umbrella of the theory of justification. Part of epistemology, this theory attempts to understand the justification of propositions and beliefs. Epistemologists are concerned with various epistemic features of belief, which include the ideas of justification, warrant, rationality, and probability. Of these four terms, the term that has been most widely used and discussed by the early 21st century is "warrant". Loosely speaking, justification is the reason that someone (probably) holds a belief. If A makes a claim and then B casts doubt on it, A's next move would normally be to provide justification for the claim. The precise method one uses to provide justification is where the lines are drawn between rationalism and empiricism (among other philosophical views). Much of the debate in these fields are focused on analyzing the nature of knowledge and how it relates to connected notions such as truth, belief, and justification. At its core, rationalism consists of three basic claims. For people to consider themselves rationalists, they must adopt at least one of these three claims: the intuition/deduction thesis, the innate knowledge thesis, or the innate concept thesis. In addition, a rationalist can choose to adopt the claim of Indispensability of Reason and or the claim of Superiority of Reason, although one can be a rationalist without adopting either thesis.[citation needed] The indispensability of reason thesis: "The knowledge we gain in subject area, S, by intuition and deduction, as well as the ideas and instances of knowledge in S that are innate to us, could not have been gained by us through sense experience."[1] In short, this thesis claims that experience cannot provide what we gain from reason. The superiority of reason thesis: '"The knowledge we gain in subject area S by intuition and deduction or have innately is superior to any knowledge gained by sense experience".[1] In other words, this thesis claims reason is superior to experience as a source for knowledge. Rationalists often adopt similar stances on other aspects of philosophy. Most rationalists reject skepticism for the areas of knowledge they claim are knowable a priori. When you claim some truths are innately known to us, one must reject skepticism in relation to those truths. Especially for rationalists who adopt the Intuition/Deduction thesis, the idea of epistemic foundationalism tends to crop up. This is the view that we know some truths without basing our belief in them on any others and that we then use this foundational knowledge to know more truths.[1] Intuition/deduction thesis Main articles: Intuition (philosophy) and Deductive reasoning "Some propositions in a particular subject area, S, are knowable by us by intuition alone; still others are knowable by being deduced from intuited propositions."[12] Generally speaking, intuition is a priori knowledge or experiential belief characterized by its immediacy; a form of rational insight. We simply "see" something in such a way as to give us a warranted belief. Beyond that, the nature of intuition is hotly debated. In the same way, generally speaking, deduction is the process of reasoning from one or more general premises to reach a logically certain conclusion. Using valid arguments, we can deduce from intuited premises. For example, when we combine both concepts, we can intuit that the number three is prime and that it is greater than two. We then deduce from this knowledge that there is a prime number greater than two. Thus, it can be said that intuition and deduction combined to provide us with a priori knowledge – we gained this knowledge independently of sense experience.  To argue in favor of this thesis, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, a prominent German philosopher, says, The senses, although they are necessary for all our actual knowledge, are not sufficient to give us the whole of it, since the senses never give anything but instances, that is to say particular or individual truths. Now all the instances which confirm a general truth, however numerous they may be, are not sufficient to establish the universal necessity of this same truth, for it does not follow that what happened before will happen in the same way again. … From which it appears that necessary truths, such as we find in pure mathematics, and particularly in arithmetic and geometry, must have principles whose proof does not depend on instances, nor consequently on the testimony of the senses, although without the senses it would never have occurred to us to think of them…[13]  Empiricists such as David Hume have been willing to accept this thesis for describing the relationships among our own concepts.[12] In this sense, empiricists argue that we are allowed to intuit and deduce truths from knowledge that has been obtained a posteriori. By injecting different subjects into the Intuition/Deduction thesis, we are able to generate different arguments. Most rationalists agree mathematics is knowable by applying the intuition and deduction. Some go further to include ethical truths into the category of things knowable by intuition and deduction. Furthermore, some rationalists also claim metaphysics is knowable in this thesis. Naturally, the more subjects the rationalists claim to be knowable by the Intuition/Deduction thesis, the more certain they are of their warranted beliefs, and the more strictly they adhere to the infallibility of intuition, the more controversial their truths or claims and the more radical their rationalism.[12] In addition to different subjects, rationalists sometimes vary the strength of their claims by adjusting their understanding of the warrant. Some rationalists understand warranted beliefs to be beyond even the slightest doubt; others are more conservative and understand the warrant to be belief beyond a reasonable doubt. Rationalists also have different understanding and claims involving the connection between intuition and truth. Some rationalists claim that intuition is infallible and that anything we intuit to be true is as such. More contemporary rationalists accept that intuition is not always a source of certain knowledge – thus allowing for the possibility of a deceiver who might cause the rationalist to intuit a false proposition in the same way a third party could cause the rationalist to have perceptions of nonexistent objects. Innate knowledge thesis "We have knowledge of some truths in a particular subject area, S, as part of our rational nature."[14] The Innate Knowledge thesis is similar to the Intuition/Deduction thesis in the regard that both theses claim knowledge is gained a priori. The two theses go their separate ways when describing how that knowledge is gained. As the name, and the rationale, suggests, the Innate Knowledge thesis claims knowledge is simply part of our rational nature. Experiences can trigger a process that allows this knowledge to come into our consciousness, but the experiences do not provide us with the knowledge itself. The knowledge has been with us since the beginning and the experience simply brought into focus, in the same way a photographer can bring the background of a picture into focus by changing the aperture of the lens. The background was always there, just not in focus. This thesis targets a problem with the nature of inquiry originally postulated by Plato in Meno. Here, Plato asks about inquiry; how do we gain knowledge of a theorem in geometry? We inquire into the matter. Yet, knowledge by inquiry seems impossible.[15] In other words, "If we already have the knowledge, there is no place for inquiry. If we lack the knowledge, we don't know what we are seeking and cannot recognize it when we find it. Either way we cannot gain knowledge of the theorem by inquiry. Yet, we do know some theorems."[14] The Innate Knowledge thesis offers a solution to this paradox. By claiming that knowledge is already with us, either consciously or unconsciously, a rationalist claims we don't really learn things in the traditional usage of the word, but rather that we simply use words we know. Innate concept thesis "We have some of the concepts we employ in a particular subject area, S, as part of our rational nature."[16] Similar to the Innate Knowledge thesis, the Innate Concept thesis suggests that some concepts are simply part of our rational nature. These concepts are a priori in nature and sense experience is irrelevant to determining the nature of these concepts (though, sense experience can help bring the concepts to our conscious mind).  In his book Meditations on First Philosophy,[17] René Descartes postulates three classifications for our ideas when he says, "Among my ideas, some appear to be innate, some to be adventitious, and others to have been invented by me. My understanding of what a thing is, what truth is, and what thought is, seems to derive simply from my own nature. But my hearing a noise, as I do now, or seeing the sun, or feeling the fire, comes from things which are located outside me, or so I have hitherto judged. Lastly, sirens, hippogriffs and the like are my own invention."[18] Adventitious ideas are those concepts that we gain through sense experiences, ideas such as the sensation of heat, because they originate from outside sources; transmitting their own likeness rather than something else and something you simply cannot will away. Ideas invented by us, such as those found in mythology, legends and fairy tales, are created by us from other ideas we possess. Lastly, innate ideas, such as our ideas of perfection, are those ideas we have as a result of mental processes that are beyond what experience can directly or indirectly provide. Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz defends the idea of innate concepts by suggesting the mind plays a role in determining the nature of concepts, to explain this, he likens the mind to a block of marble in the New Essays on Human Understanding, This is why I have taken as an illustration a block of veined marble, rather than a wholly uniform block or blank tablets, that is to say what is called tabula rasa in the language of the philosophers. For if the soul were like those blank tablets, truths would be in us in the same way as the figure of Hercules is in a block of marble, when the marble is completely indifferent whether it receives this or some other figure. But if there were veins in the stone which marked out the figure of Hercules rather than other figures, this stone would be more determined thereto, and Hercules would be as it were in some manner innate in it, although labour would be needed to uncover the veins, and to clear them by polishing, and by cutting away what prevents them from appearing. It is in this way that ideas and truths are innate in us, like natural inclinations and dispositions, natural habits or potentialities, and not like activities, although these potentialities are always accompanied by some activities which correspond to them, though they are often imperceptible."[19]  Some philosophers, such as John Locke (who is considered one of the most influential thinkers of the Enlightenment and an empiricist), argue that the Innate Knowledge thesis and the Innate Concept thesis are the same.[20] Other philosophers, such as Peter Carruthers, argue that the two theses are distinct from one another. As with the other theses covered under the umbrella of rationalism, the more types and greater number of concepts a philosopher claims to be innate, the more controversial and radical their position; "the more a concept seems removed from experience and the mental operations we can perform on experience the more plausibly it may be claimed to be innate. Since we do not experience perfect triangles but do experience pains, our concept of the former is a more promising candidate for being innate than our concept of the latter.[16] |

哲学的用法 合理主義はしばしば経験主義と対比される。哲学者は合理主義者であると同時に経験主義者でもありうるので、非常に大雑把に考えれば、これらの見解は相互に 排他的なものではない。経験主義者は基本的に、知識は経験に基づいている、あるいは経験から直接得られると考えている。合理主義者は、私たちは先験的に、 つまり論理の使用を通じて知識を得るのであり、したがって感覚的経験とは無関係であると考える。つまり、ガレン・ストローソンがかつて書いたように、「ソ ファに横になっているだけで、それが真実であることがわかる。ソファから立ち上がって外に出て、物理的な世界のあり方を調べる必要はない。科学などする必 要はない」[11]。 両方の哲学の間で、目下の問題は、人間の知識の根本的な源と、私たちが知っていると思っていることを検証するための適切な技術である。両哲学が認識論の傘 下にあるのに対し、両者の議論は正当化論というより広い認識論の傘下にある保証の理解にある。認識論の一部であるこの理論は、命題や信念の正当性を理解し ようとするものである。認識論者は、正当化、保証、合理性、確率といった考えを含む、信念のさまざまな認識論的特徴に関心を抱いている。これら4つの用語 のうち、21世紀初頭までに最も広く使われ、議論されてきた用語は「正当性」である。大雑把に言えば、正当化とは誰かが(おそらく)信念を持つ理由のこと である。 Aがある主張をし、それにBが疑念を投げかけた場合、Aの次の行動は通常、その主張の正当性を示すことだろう。正当性を証明するためにどのような方法を使 うかは、合理主義 と経験主義(他の哲学的見解も含む)の境界線が引かれるところである。これらの分野での議論の多くは、知識の本質を分析し、それが真理、信念、正当化と いった関連概念とどのように関係しているかに焦点が当てられている。 合理主義の核心は、3つの基本的な主張から成り立っている。人々が合理主義者であると考えるには、これら3つの主張のうち少なくとも1つを採用しなければ ならない。直観/演繹テーゼ、生得的知識テーゼ、生得的概念テーゼである。さらに、合理主義者は理性の不可欠性の主張と理性の優越性の主張を採用すること ができるが、どちらの主張も採用せずに合理主義者になることもできる[要出典]。 理性の欠くことのできないテーゼ:「私たちが直観や演繹によって対象領域Sにおいて得る知識、また私たちに生得的に備わっているSにおける知識のアイデア や事例は、私たちが感覚的経験によって得ることはできなかった」[1]要するに、このテーゼは、私たちが理性から得るものを経験は提供できないと主張す る。 理性の優越性テーゼ:「我々が直感や演繹によって、あるいは生得的に持っている対象領域Sに関する知識は、感覚的経験によって得られるどのような知識より も優れている」[1]。言い換えれば、このテーゼは、理性が知識の源として経験よりも優れていると主張する。 合理主義者は哲学の他の側面においても同様の立場をとることが多い。合理主義者の多くは、先験的に知ることができると主張する知識の領域については懐疑主 義を否定する。ある真理が生まれながらにして私たちに知られていると主張する場合、それらの真理に関しては懐疑主義を否定しなければならない。特に、直観 /演繹テーゼを採用する合理主義者にとっては、認識論的基礎づけ主義という考え方が浮上しがちである。これは、私たちはいくつかの真理を、それ以外の真理 を根拠とすることなく知っており、さらに多くの真理を知るためにこの基礎的知識を用いるという考え方である[1]。 直観/演繹テーゼ 主な記事 直観(哲学)、演繹的推論 「ある特定の主題領域Sにおけるいくつかの命題は、直観のみによって知ることができる。 一般的に言えば、直観とは、即時性を特徴とする先験的な知識または経験的信念であり、合理的洞察の一形態である。理性的な洞察の一形態である。私たちは単 に、保証された信念を与えるような方法で何かを「見る」だけである。それ以上に、直観の本質については、熱い議論が交わされている。同じように、一般的に 言えば、演繹とは、論理的に確かな結論に到達するために、1つ以上の一般的な前提から推論するプロセスのことである。有効な論証を用いれば、直観した前提 から推論することができる。 例えば、両方の概念を組み合わせると、3という数が素数であり、2より大きいことを直感できる。そしてこの知識から、2より大きい素数が存在することを推 論する。このように、直観と演繹が組み合わさって、先験的な知識が得られると言える。  ドイツの著名な哲学者であるゴットフリート・ヴィルヘルム・ライプニッツは、このテーゼを支持するために次のように述べている、 感覚は、われわれの実際の知識のすべてにとって必要ではあるが、そのすべてを与えるには十分ではない。一般的な真理を確認するすべての事例は、それがどん なに多くても、この同じ真理の普遍的必然性を立証するには十分ではない。...このことから、純粋数学、特に算術や幾何学に見られるような必然的真理に は、その証明が実例に依存しない原理、ひいては感覚の証言に依存しない原理がなければならないことがわかる。  デイヴィッド・ヒュームなどの経験論者は、私たち自身の概念間の関係を説明するために、このテーゼを喜んで受け入れている[12]。この意味で、経験論者 は、私たちは事後的に得られた知識から真理を直観し、推論することが許されていると主張している。 直観/演繹のテーゼに異なる主題を注入することで、異なる議論を生み出すことができる。ほとんどの合理主義者は、数学が直観と演繹を適用することによって 知ることができることに同意する。さらに、倫理的真理を直観と演繹によって知りうるものの範疇に含める者もいる。さらに、形而上学もこのテーゼで知ること ができると主張する合理主義者もいる。当然のことながら、合理主義者が直観・演繹テーゼによって知りうると主張する対象が多ければ多いほど、彼らが保証す る信念がより確かなものであればあるほど、また直観の無謬性をより厳格に守れば守るほど、彼らの真理や主張が物議を醸し、彼らの合理主義がより急進的なも のになる[12]。 対象が異なるだけでなく、合理主義者は保証の理解を調整することで、その主張の強さを変えることがある。合理主義者の中には、保証された信念はわずかな疑 いをも超えるものであると理解する者もいれば、より保守的で、保証は合理的な疑いを超える信念であると理解する者もいる。 合理主義者はまた、直観と真理との結びつきに関しても異なる理解と主張を持っている。合理主義者の中には、直観は絶対的なものであり、私たちが真実である と直観するものはすべてそうであると主張する者もいる。より現代的な合理主義者たちは、直観は常に確かな知識の源であるとは限らないとし、第三者が合理主 義者に存在しないものを知覚させるのと同じように、合理主義者に誤った命題を直観させる欺瞞者の可能性を認めている。 生得的知識テーゼ "我々は、我々の合理的な性質の一部として、特定の主題領域Sにおけるいくつかの真理についての知識を持っている"[14]。 生得的知識テーゼは、知識が先験的に得られると主張する点で、直観/演繹テーゼと類似している。この2つのテーゼは、知識がどのように獲得されるかを説明 する際に、別々の道を歩む。生得的知識テーゼは、その名前と根拠が示すように、知識は単に人間の理性的な本性の一部であると主張する。経験は、知識が私た ちの意識の中に入ってくるプロセスを引き起こすが、経験によって知識そのものが得られるわけではない。写真家がレンズの絞りを変えることで、写真の背景に ピントを合わせることができるのと同じように、知識は最初から私たちとともにあり、体験によってピントが合うようになっただけなのだ。ピントが合っていな いだけで、背景は常にそこにあったのだ。 この論文は、もともとプラトンが『メノン』で提起した探究の本質に関する問題を対象としている。プラトンはここで、幾何学の定理についてどのように知識を 得るのか、と問うている。われわれはその問題を探究する。しかし、探究による知識は不可能であるように思われる[15]。言い換えれば、「もしわれわれが すでに知識を持っているならば、探究の余地はない。もし知識がなければ、私たちは自分が何を求めているのかわからず、それを見つけても認識することができ ない。いずれにせよ、探究によって定理の知識を得ることはできない。しかし、私たちはいくつかの定理を知っている。知識は意識的であれ無意識的であれ、す でに私たちの手元にあると主張することで、合理主義者は、伝統的な言葉の用法では、私たちは本当に物事を学んでいるのではなく、単に知っている言葉を使用 しているだけだと主張する。 生得的概念論 "私たちは、私たちの合理的な性質の一部として、特定の対象領域Sで用いる概念のいくつかを持っている"[16]。 生得的知識テーゼと同様に、生得的概念テーゼは、いくつかの概念は単に我々の理性的性質の一部であることを示唆している。これらの概念は先験的なものであ り、感覚経験はこれらの概念の性質を決定するのに無関係である(ただし、感覚経験は概念を意識にもたらすのに役立つ)。  ルネ・デカルトはその著書『第一哲学の瞑想』 [17]の中で、「私の観念の中には、生得的なもの、外来的なもの、私が発明したものがある。あるものが何であるか、真理が何であるか、思考が何であるか についての私の理解は、単に私自身の本性に由来するように思われる。しかし、私が今しているように音を聞いたり、太陽を見たり、炎を感じたりするのは、私 の外側にあるものからきている。最後に、サイレンやヒッポグリフなどは私自身の発明である」[18]。 熱の感覚のような観念は、外部に由来するものであり、他の何かではなく、自分自身の類似性を伝達するものであるため、単に自分の意志で取り除くことができ ないものである。神話や伝説、おとぎ話に見られるような、私たちが発明した観念は、私たちが持っている他の観念から私たちが創り出したものである。最後 に、生得的な観念とは、例えば完全性についての観念のように、経験によって直接的あるいは間接的にもたらされるものを超えた、精神的なプロセスの結果とし て私たちが持つ観念のことである。 ゴットフリート・ヴィルヘルム・ライプニッツは、『新・人間理解論』の中で心を大理石の塊に例えて、心が概念の性質を決定する役割を担っていることを示唆 し、生得的概念という考えを擁護している、 これが、私が大理石の塊を例として取り上げた理由である。むしろ、完全に均一な塊や空白の石版、つまり哲学者の言葉で言うところのタブラ・ラサと呼ばれる ものである。というのも、もし魂が白紙のタブレットのようなものだとしたら、大理石の塊の中にヘラクレスの像があるのと同じように、真理は私たちの中にあ るはずだからである。しかし、もし石の中に、他の図形よりもヘラクレスの図形を際立たせる鉱脈があるとすれば、この石はそのように決定され、ヘラクレスは あたかも生まれつきのようになるであろう。このように、観念や真理は、自然な傾向や性質、自然な習慣や潜在能力のように、われわれに生得的に備わっている のであって、活動のようなものではない。  ジョン・ロック(啓蒙主義において最も影響力のある思 想家の一人であり、経験主義者)のように、生得的知識論と生得的概念論は同じものであると主張する哲学者もいる[20]。合理主義の傘の下で扱われる他の テーゼと同様に、哲学者が生得的であると主張する概念の種類や数が多ければ多いほど、その立場は議論を呼び、過激になる。私たちは完全な三角形を経験する ことはないが、痛みを経験することはあるので、前者の概念は後者の概念よりも生得的である可能性が高い。 |

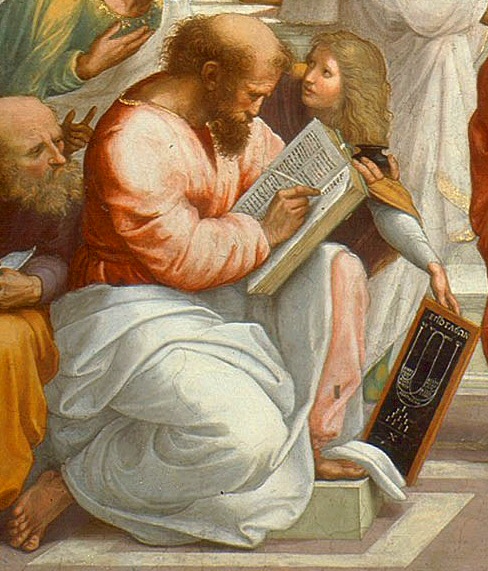

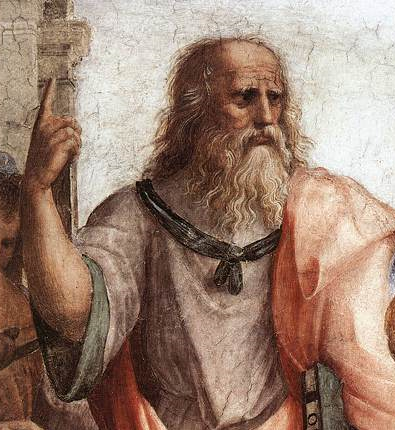

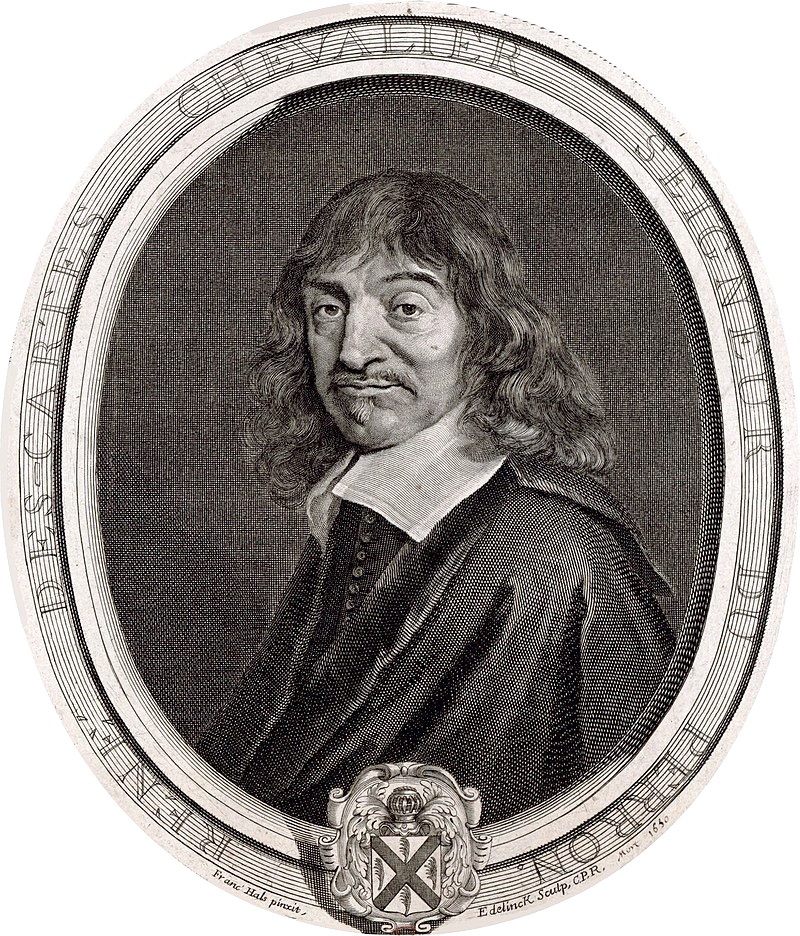

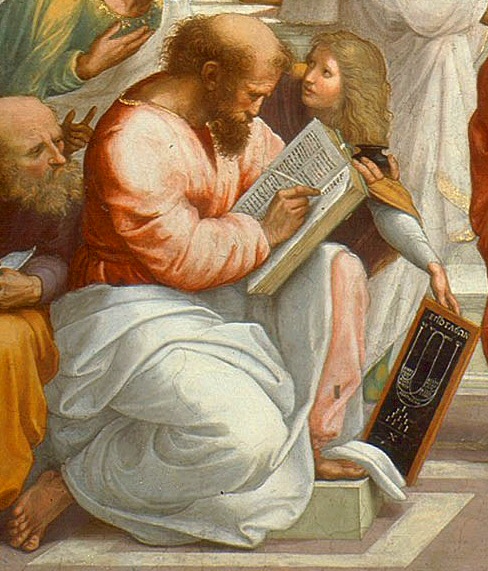

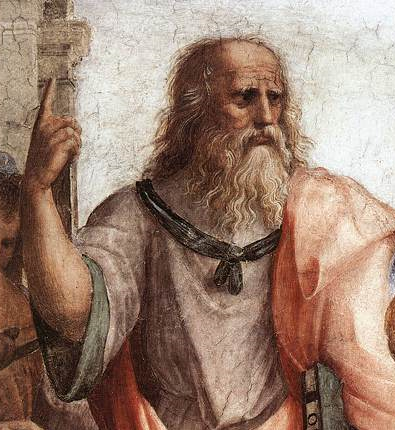

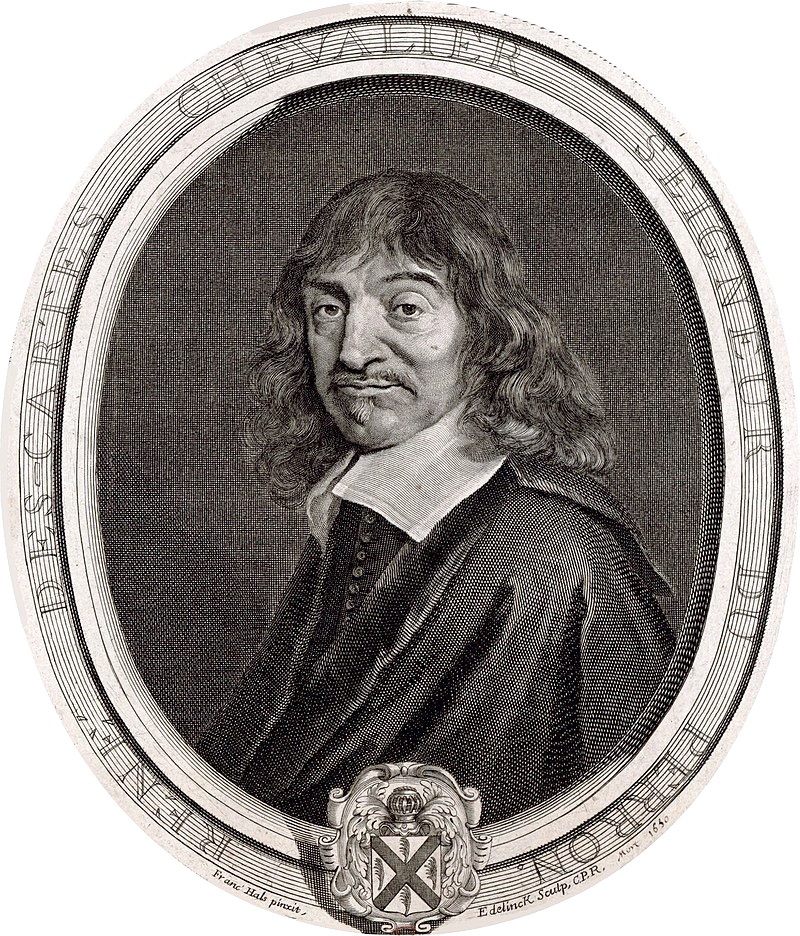

| History Rationalist philosophy in Western antiquity  Detail of Pythagoras with a tablet of ratios, numbers sacred to the Pythagoreans, from The School of Athens by Raphael. Vatican Palace, Vatican City Although rationalism in its modern form post-dates antiquity, philosophers from this time laid down the foundations of rationalism. In particular, the understanding that we may be aware of knowledge available only through the use of rational thought.[citation needed] Pythagoras (570–495 BCE) Main article: Pythagoras Pythagoras was one of the first Western philosophers to stress rationalist insight.[21] He is often revered as a great mathematician, mystic and scientist, but he is best known for the Pythagorean theorem, which bears his name, and for discovering the mathematical relationship between the length of strings on lute and the pitches of the notes. Pythagoras "believed these harmonies reflected the ultimate nature of reality. He summed up the implied metaphysical rationalism in the words 'All is number'. It is probable that he had caught the rationalist's vision, later seen by Galileo (1564–1642), of a world governed throughout by mathematically formulable laws".[22] It has been said that he was the first man to call himself a philosopher, or lover of wisdom.[23] Plato (427–347 BCE) Main article: Plato  Plato in The School of Athens, by Raphael Plato held rational insight to a very high standard, as is seen in his works such as Meno and The Republic. He taught on the Theory of Forms (or the Theory of Ideas)[24][25][26] which asserts that the highest and most fundamental kind of reality is not the material world of change known to us through sensation, but rather the abstract, non-material (but substantial) world of forms (or ideas).[27] For Plato, these forms were accessible only to reason and not to sense.[22] In fact, it is said that Plato admired reason, especially in geometry, so highly that he had the phrase "Let no one ignorant of geometry enter" inscribed over the door to his academy.[28] Aristotle (384–322 BCE) Main article: Aristotle Aristotle's main contribution to rationalist thinking was the use of syllogistic logic and its use in argument. Aristotle defines syllogism as "a discourse in which certain (specific) things having been supposed, something different from the things supposed results of necessity because these things are so."[29] Despite this very general definition, Aristotle limits himself to categorical syllogisms which consist of three categorical propositions in his work Prior Analytics.[30] These included categorical modal syllogisms.[31] Middle Ages  Ibn Sina Portrait on Silver Vase Although the three great Greek philosophers disagreed with one another on specific points, they all agreed that rational thought could bring to light knowledge that was self-evident – information that humans otherwise could not know without the use of reason. After Aristotle's death, Western rationalistic thought was generally characterized by its application to theology, such as in the works of Augustine, the Islamic philosopher Avicenna (Ibn Sina), Averroes (Ibn Rushd), and Jewish philosopher and theologian Maimonides. The Waldensians sect also incorporated rationalism into their movement.[32] One notable event in the Western timeline was the philosophy of Thomas Aquinas who attempted to merge Greek rationalism and Christian revelation in the thirteenth-century.[22][33] Generally, the Roman Catholic Church viewed Rationalists as a threat, labeling them as those who "while admitting revelation, reject from the word of God whatever, in their private judgment, is inconsistent with human reason."[34] Classical rationalism  René Descartes (1596–1650) Main article: René Descartes Descartes was the first of the modern rationalists and has been dubbed the 'Father of Modern Philosophy.' Much subsequent Western philosophy is a response to his writings,[35][36][37] which are studied closely to this day. Descartes thought that only knowledge of eternal truths – including the truths of mathematics, and the epistemological and metaphysical foundations of the sciences – could be attained by reason alone; other knowledge, the knowledge of physics, required experience of the world, aided by the scientific method. He also argued that although dreams appear as real as sense experience, these dreams cannot provide persons with knowledge. Also, since conscious sense experience can be the cause of illusions, then sense experience itself can be doubtable. As a result, Descartes deduced that a rational pursuit of truth should doubt every belief about sensory reality. He elaborated these beliefs in such works as Discourse on the Method, Meditations on First Philosophy, and Principles of Philosophy. Descartes developed a method to attain truths according to which nothing that cannot be recognised by the intellect (or reason) can be classified as knowledge. These truths are gained "without any sensory experience," according to Descartes. Truths that are attained by reason are broken down into elements that intuition can grasp, which, through a purely deductive process, will result in clear truths about reality. Descartes therefore argued, as a result of his method, that reason alone determined knowledge, and that this could be done independently of the senses. For instance, his famous dictum, cogito ergo sum or "I think, therefore I am", is a conclusion reached a priori i.e., prior to any kind of experience on the matter. The simple meaning is that doubting one's existence, in and of itself, proves that an "I" exists to do the thinking. In other words, doubting one's own doubting is absurd.[21] This was, for Descartes, an irrefutable principle upon which to ground all forms of other knowledge. Descartes posited a metaphysical dualism, distinguishing between the substances of the human body ("res extensa") and the mind or soul ("res cogitans"). This crucial distinction would be left unresolved and lead to what is known as the mind–body problem, since the two substances in the Cartesian system are independent of each other and irreducible. Baruch Spinoza (1632–1677) Main article: Philosophy of Spinoza The philosophy of Baruch Spinoza is a systematic, logical, rational philosophy developed in seventeenth-century Europe.[38][39][40] Spinoza's philosophy is a system of ideas constructed upon basic building blocks with an internal consistency with which he tried to answer life's major questions and in which he proposed that "God exists only philosophically."[40][41] He was heavily influenced by Descartes,[42] Euclid[41] and Thomas Hobbes,[42] as well as theologians in the Jewish philosophical tradition such as Maimonides.[42] But his work was in many respects a departure from the Judeo-Christian tradition. Many of Spinoza's ideas continue to vex thinkers today and many of his principles, particularly regarding the emotions, have implications for modern approaches to psychology. To this day, many important thinkers have found Spinoza's "geometrical method"[40] difficult to comprehend: Goethe admitted that he found this concept confusing.[citation needed] His magnum opus, Ethics, contains unresolved obscurities and has a forbidding mathematical structure modeled on Euclid's geometry.[41] Spinoza's philosophy attracted believers such as Albert Einstein[43] and much intellectual attention.[44][45][46][47][48] Gottfried Leibniz (1646–1716) Main article: Gottfried Leibniz Leibniz was the last major figure of seventeenth-century rationalism who contributed heavily to other fields such as metaphysics, epistemology, logic, mathematics, physics, jurisprudence, and the philosophy of religion; he is also considered to be one of the last "universal geniuses".[49] He did not develop his system, however, independently of these advances. Leibniz rejected Cartesian dualism and denied the existence of a material world. In Leibniz's view there are infinitely many simple substances, which he called "monads" (which he derived directly from Proclus). Leibniz developed his theory of monads in response to both Descartes and Spinoza, because the rejection of their visions forced him to arrive at his own solution. Monads are the fundamental unit of reality, according to Leibniz, constituting both inanimate and animate objects. These units of reality represent the universe, though they are not subject to the laws of causality or space (which he called "well-founded phenomena"). Leibniz, therefore, introduced his principle of pre-established harmony to account for apparent causality in the world. Immanuel Kant (1724–1804) Main article: Immanuel Kant Kant is one of the central figures of modern philosophy, and set the terms by which all subsequent thinkers have had to grapple. He argued that human perception structures natural laws, and that reason is the source of morality. His thought continues to hold a major influence in contemporary thought, especially in fields such as metaphysics, epistemology, ethics, political philosophy, and aesthetics.[50] Kant named his brand of epistemology "Transcendental Idealism", and he first laid out these views in his famous work The Critique of Pure Reason. In it he argued that there were fundamental problems with both rationalist and empiricist dogma. To the rationalists he argued, broadly, that pure reason is flawed when it goes beyond its limits and claims to know those things that are necessarily beyond the realm of every possible experience: the existence of God, free will, and the immortality of the human soul. Kant referred to these objects as "The Thing in Itself" and goes on to argue that their status as objects beyond all possible experience by definition means we cannot know them. To the empiricist, he argued that while it is correct that experience is fundamentally necessary for human knowledge, reason is necessary for processing that experience into coherent thought. He therefore concludes that both reason and experience are necessary for human knowledge. In the same way, Kant also argued that it was wrong to regard thought as mere analysis. "In Kant's views, a priori concepts do exist, but if they are to lead to the amplification of knowledge, they must be brought into relation with empirical data".[51] Contemporary rationalism Rationalism has become a rarer label of philosophers today; rather many different kinds of specialised rationalisms are identified. For example, Robert Brandom has appropriated the terms "rationalist expressivism" and "rationalist pragmatism" as labels for aspects of his programme in Articulating Reasons, and identified "linguistic rationalism", the claim that the contents of propositions "are essentially what can serve as both premises and conclusions of inferences", as a key thesis of Wilfred Sellars.[52] Outside of academic philosophy, some participants in the internet communities surrounding Less Wrong and Slate Star Codex have described themselves as "rationalists."[53][54][55] The term has also been used in this way by critics such as Timnit Gebru.[56] |

歴史 西洋古代における合理主義哲学  ラファエロ作『アテネの学校』より、ピタゴラスにとって神聖な数である比の石版を持つピタゴラスの詳細。バチカン宮殿、バチカン市国 合理主義の現代的な形は古代より後であるが、この時代の哲学者たちは合理主義の基礎を築いた。特に、合理的な思考を用いることによってのみ得られる知識に 気づくことができるという理解である[要出典]。 ピタゴラス(前570年-前495年) 主な記事 ピタゴラス ピタゴラスは、合理主義的洞察力を強調した最初の西洋哲学者の一人である[21]。彼は偉大な数学者、神秘主義者、科学者として尊敬されることが多いが、 彼の名を冠したピタゴラスの定理と、リュートの弦の長さと音の高さの数学的関係を発見したことで最もよく知られている。ピタゴラスは「これらの調和が現実 の究極的な性質を反映していると考えた」。彼は、暗黙の形而上学的合理主義を『すべては数である』という言葉に集約した。彼は、後にガリレオ(1564- 1642)が見た、数学的に定式化可能な法則によって全体が支配される世界という合理主義者のヴィジョンを捉えていた可能性が高い」[22]。 プラトン(前427年-前347年) 主な記事 プラトン  ラファエロ作『アテネの学堂』のプラトン プラトンは、『メノ』や『共和国』などの作品に見られるように、理性的な洞察力を非常に高い水準に置いていた。プラトンは形相論(あるいはイデア論) [24][25][26]を説いており、その中で最も高く最も根源的な現実は、感覚を通じて私たちに知られる変化の物質的世界ではなく、むしろ抽象的で非 物質的な(しかし実質的な)形相(あるいはイデア)の世界であると主張している。 [実際、プラトンは理性、特に幾何学を非常に賞賛しており、彼のアカデミーの扉に「幾何学を知らない者を入れるな」という言葉を刻ませたと言われている [28]。 アリストテレス(前384年-前322年) 主な記事 アリストテレス アリストテレスの合理主義的思考への主な貢献は、対義論理の使用と議論におけるその使用であった。この非常に一般的な定義にもかかわらず、アリストテレス はその著作『先行論理学』[30]において、3つの定言命題からなる定言命法に限定している。 中世  銀の壷に描かれたイブン・シーナの肖像画 ギリシアの三大哲学者は特定の点では互いに意見を異にしたが、理性的思考が自明な知識、つまり理性を用いなければ人間が知りえない情報を明るみに出すこと ができるという点では一致していた。アリストテレスの死後、西洋の合理主義思想は一般的に、アウグスティヌス、イスラム哲学者アヴィセンナ(イブン・シー ナ)、アヴェロエス(イブン・ルシュド)、ユダヤの哲学者・神学者マイモニデスなどの著作のように、神学への応用によって特徴づけられた。西洋の時系列に おける注目すべき出来事のひとつは、13世紀にギリシャの合理主義とキリスト教の啓示を融合させようとしたトマス・アクィナスの哲学であった[22] [33]。 一般的にローマ・カトリック教会は合理主義者を脅威とみなし、「啓示を認めながらも、その私的な判断において人間の理性と矛盾するものは神の言葉から拒絶 する」者たちとしてレッテルを貼っていた[34]。 古典的合理主義  ルネ・デカルト (1596-1650) 主な記事 ルネ・デカルト デカルトは近代合理主義者の第一人者であり、「近代哲学の父」と呼ばれている。その後の西洋哲学の多くは、デカルトの著作に対する反応であり[35] [36][37]、今日に至るまで綿密に研究されている。 デカルトは、数学の真理や科学の認識論的・形而上学的基礎を含む永遠の真理に関する知識のみが理性のみによって到達できると考え、それ以外の知識、すなわ ち物理学の知識は科学的方法によって助けられた世界の経験を必要とした。彼はまた、夢は感覚体験と同じように現実に見えるが、夢は人に知識を与えることは できないと主張した。また、意識的な感覚体験は錯覚の原因となりうるので、感覚体験そのものを疑うことができる。その結果、デカルトは、真理を合理的に追 求するためには、感覚的現実に関するあらゆる信念を疑うべきだと推論した。デカルトは、『方法論についての論考』、『第一哲学の瞑想』、『哲学の原理』な どの著作の中で、これらの信念を詳しく述べている。デカルトは、知性(理性)によって認識できないものは知識として分類できないという真理を獲得する方法 を開発した。デカルトによれば、これらの真理は「いかなる感覚的経験もなしに」得られる。理性によって得られる真理は、直観が把握できる要素に分解され、 純粋に演繹的なプロセスを経て、現実に関する明確な真理をもたらす。 したがってデカルトは、その方法の結果として、理性のみが知識を決定し、それは感覚とは無関係に行うことができると主張した。例えば、デカルトの有名な口 癖であるコギト・エルゴ・スム(「我思う、ゆえに我あり」)は、アプリオリに、つまりその事柄に関するあらゆる経験に先立って到達した結論である。単純な 意味は、自分の存在を疑うこと自体が、考えるために「私」が存在することを証明するということである。言い換えれば、自分自身を疑うことは不合理であると いうことである[21]。これはデカルトにとって、他のあらゆる形式の知識を基礎づけるための反論の余地のない原理であった。デカルトは形而上学的な二元 論を提唱し、人体の物質(「外延的なもの」)と心や魂(「コギタン的なもの」)を区別した。デカルト体系における2つの物質は互いに独立であり、還元不可 能であるため、この重要な区別は未解決のまま放置され、心身問題として知られるようになる。 バルーク・スピノザ(1632-1677) 主な記事 スピノザの哲学 スピノザの哲学は、17世紀のヨーロッパで発展した体系的、論理的、合理的な哲学である[38][39][40]。スピノザの哲学は、基本的な構成要素の 上に構築された思想の体系であり、人生の主要な問題に答えようとする内的一貫性を持ち、その中で「神は哲学的にのみ存在する」と提唱した。 「40][41]彼はデカルト[42]、ユークリッド[41]、トマス・ホッブズ[42]、そしてマイモニデス[42]のようなユダヤ哲学の伝統の神学者 たちから大きな影響を受けていた。スピノザの思想の多くは今日でも思想家たちを悩ませ続けており、特に感情に関する彼の原理の多くは、現代の心理学へのア プローチに影響を及ぼしている。今日に至るまで、多くの重要な思想家がスピノザの「幾何学的方法」[40]を理解することを困難だと感じている: ゲーテはこの概念を混乱させると認めていた[citation needed]。彼の大著である『倫理学』には未解決の不明瞭な部分が含まれており、ユークリッドの幾何学をモデルとした禁断的な数学的構造を持っている [41]。スピノザの哲学はアルベルト・アインシュタイン[43]のような信奉者を惹きつけ、多くの知的注目を集めた[44][45][46][47] [48]。 ゴットフリート・ライプニッツ(1646年-1716年) 主な記事 ゴットフリート・ライプニッツ ライプニッツは、形而上学、認識論、論理学、数学、物理学、法学、宗教哲学といった他の分野にも大きく貢献した17世紀合理主義の最後の中心人物であり、 最後の「普遍的天才」の一人とも考えられている[49]。ライプニッツはデカルトの二元論を否定し、物質世界の存在を否定した。ライプニッツの考えでは、 無限に多くの単純な物質が存在し、彼はそれを「モナド」と呼んだ(これはプロクロスに直接由来する)。 ライプニッツはデカルトとスピノザに対抗してモナドの理論を発展させた。ライプニッツによれば、モナドは現実の基本単位であり、無生物と生物を構成する。 ライプニッツによれば、モナドは現実の基本単位であり、無生物と生物を構成する。この現実の単位は宇宙を代表するが、因果律や空間の法則には従わない(ラ イプニッツはこれを「根拠のある現象」と呼んだ)。そこでライプニッツは、世界の見かけ上の因果関係を説明するために、あらかじめ確立された調和の原理を 導入した。 イマヌエル・カント(1724-1804) 主な記事 イマヌエル・カント カントは近代哲学の中心人物の一人であり、その後のすべての思想家が取り組まなければならない条件を設定した。彼は、人間の知覚が自然法則を構造化し、理 性が道徳の源泉であると主張した。彼の思想は、特に形而上学、認識論、倫理学、政治哲学、美学などの分野において、現代思想に大きな影響を与え続けている [50]。 カントは自身の認識論のブランドを「超越論的観念論」と名付け、有名な著作『純粋理性批判』の中でこれらの見解を初めて示した。その中で彼は、合理主義者 と経験主義者の両方のドグマには根本的な問題があると主張した。合理主義者に対しては、大まかに言えば、純粋理性がその限界を超えて、神の存在、自由意 志、人間の魂の不滅など、あらゆる可能な経験の領域を必然的に超えているものを知ろうとするとき、純粋理性には欠陥があると主張した。カントはこれらの対 象を「それ自体におけるもの」と呼び、定義上、あらゆる可能な経験を超えた対象であることは、私たちがそれらを知ることができないことを意味すると主張す る。経験主義者に対して、彼は、人間の知識には基本的に経験が必要であることは正しいが、その経験を首尾一貫した思考に処理するためには理性が必要である と主張した。したがって、人間の知識には理性と経験の両方が必要だと結論づけたのである。同じように、カントはまた、思考を単なる分析とみなすのは間違っ ていると主張した。「カントの見解では、アプリオリな概念は存在するが、それが知識の増幅につながるのであれば、経験的なデータとの関係を持たせなければ ならない」[51]。 現代の合理主義 合理主義は今日、哲学者のレッテルとしては稀なものとなっている。例えば、ロバート・ブランダムは『Articulating Reasons』における彼のプログラムの側面のラベルとして「合理主義的表現主義」や「合理主義的プラグマティズム」という用語を流用しており、ウィル フレッド・セラーズの重要なテーゼとして、命題の内容が「本質的に推論の前提としても結論としても機能するものである」という主張である「言語合理主義」 を特定している[52]。 アカデミックな哲学の外では、Less WrongやSlate Star Codexを取り巻くインターネット・コミュニティの参加者の一部が自らを「合理主義者」[53][54][55]と表現している。 |

| Criticism Rationalism was criticized by American psychologist William James for being out of touch with reality. James also criticized rationalism for representing the universe as a closed system, which contrasts with his view that the universe is an open system.[57] Proponents of emotional choice theory criticize rationalism by drawing on new findings from emotion research in psychology and neuroscience. They point out that the rationalist paradigm is generally based on the assumption that decision-making is a conscious and reflective process based on thoughts and beliefs. It presumes that people decide on the basis of calculation and deliberation. However, cumulative research in neuroscience suggests that only a small part of the brain's activities operate at the level of conscious reflection. The vast majority of its activities consist of unconscious appraisals and emotions.[58] The significance of emotions in decision-making has generally been ignored by rationalism, according to these critics. Moreover, emotional choice theorists contend that the rationalist paradigm has difficulty incorporating emotions into its models, because it cannot account for the social nature of emotions. Even though emotions are felt by individuals, psychologists and sociologists have shown that emotions cannot be isolated from the social environment in which they arise. Emotions are inextricably intertwined with people's social norms and identities, which are typically outside the scope of standard rationalist accounts.[59] Emotional choice theory seeks to capture not only the social but also the physiological and dynamic character of emotions. It represents a unitary action model to organize, explain, and predict the ways in which emotions shape decision-making.[60] |

批判 合理主義はアメリカの心理学者であるウィリアム・ジェームズによって、現実と乖離していると批判された。ジェームズはまた合理主義が宇宙を閉じたシステム として表現していることを批判しており、宇宙は開かれたシステムであるという彼の見解とは対照的である[57]。 感情選択理論の支持者たちは、心理学や神経科学における感情研究から得られた新たな知見をもとに合理主義を批判している。彼らは、合理主義のパラダイムは 一般的に意思決定が思考や信念に基づく意識的で反省的なプロセスであるという仮定に基づいていると指摘する。人は計算と熟慮に基づいて意思決定を行うと仮 定しているのだ。しかし、神経科学における研究の積み重ねは、意識的な反省のレベルで活動している脳の活動はごく一部に過ぎないことを示唆している。これ らの批判者によれば、意思決定における感情の重要性は、合理主義では一般的に無視されてきた。さらに、感情的選択の理論家は、合理主義のパラダイムは感情 の社会的性質を説明できないため、感情をモデルに組み込むことが困難であると主張している。たとえ感情が個人によって感じられるものであっても、心理学者 や社会学者は、感情が発生する社会的環境から感情を切り離すことはできないことを示してきた。感情は人々の社会的規範やアイデンティティと密接に絡み合っ ており、一般的に標準的な合理主義的説明の範囲外である[59]。感情選択理論は、社会性だけでなく、生理的で動的な感情の特徴も捉えようとしている。感 情が意思決定を形成する方法を組織化し、説明し、予測するための一元的な行動モデルを表している[60]。 |

| 17th-century philosophy Critical rationalism Emotional choice theory Historical criticism Humanism Idealism Innatism Irrationalism Logical truth Natural philosophy Nominalism Noology Objectivity (philosophy) Objectivity (science) Pancritical rationalism Panrationalism Phenomenology (philosophy) Philosophical realism Platonic realism Positivism Psychological nativism Rational choice theory Rational expectations Rational mysticism Rational realism Rationalist International Rationality and Power Realistic rationalism Pluralistic rationalism Theistic rationalism |

17世紀の哲学 批判的合理主義 感情的選択理論 歴史批評 ヒューマニズム 観念論 無邪気主義 非合理主義 論理的真理 自然哲学 名辞論 ノーロジー 客観性(哲学) 客観性(科学) 汎批判的合理主義 汎合理主義 現象学(哲学) 哲学的実在論 プラトン的実在論 実証主義 心理学的自然主義 合理的選択理論 合理的期待 合理的神秘主義 合理的実在論 合理主義インターナショナル 合理性と権力 現実的合理主義 多元的合理主義 神学的合理主義 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rationalism |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆