Perspektivismus,

Perspectivism: 観点主義、遠近法、遠近法主義

案内人:池田光穂:君は、アンナ・カレーニナを轢いた機関車の運転手の気持ちになったことがあるのか?

『パースペクティヴィズム問題集』より

パースペクティヴィズム

Perspektivismus,

Perspectivism: 観点主義、遠近法、遠近法主義

案内人:池田光穂:君は、アンナ・カレーニナを轢いた機関車の運転手の気持ちになったことがあるのか?

『パースペクティヴィズム問題集』より

ここでのパースペクティヴィズムとは、絵画技法における遠近法のことではない。ニーチェのパースペクティヴィズムとは、あらゆ る主体は自分自身から視点や視座(=パースペクティヴィズム)を取らざるをえなく、その自己中心主義から逃れて、見られるものからの視点や視座から、自己 の主体やその他もろもろのものに眼差しを向けることを、感じたり、理解することの困難さを自覚する、思想上のアポリア(難問)のことを示している。つま り、ニーチェのパースペクティヴィズムとは、見られるものからの視点や視座から、見 ているものを捉える見方であると、ここでは暫定的に定義できる。しかし、視点や視座を管理し、自分の自らのものにしていると考える意識は、 ニーチェによると「共同体的かつ群畜的な本性」に属しているので、いかに個人が視座を我が物としているように考えようとも「共同体的かつ群畜的な本性」の ことに無自覚になっていることを「知る」ことも重要になる。

★パースペクティヴィズム(Perspectivism)(ド イツ語: Perspektivismus、パースペクティヴァリズムとも呼ばれる)とは、何かの知覚や知識は、それを観察する人々の解釈的視点に常に拘束されると いう認識論的原則である。パースペクティヴィズムは、すべての視点や解釈が等しい真理や価値を持っているとはみなさないが、遠近法から切り離された絶対的 な世界観にアクセスできる者はいないとする[1]。そのため、パースペクティヴィズムはどのような視点の外側にあるものにも対応することによって真理を決 定しようとするのではなく、一般的には視点同士を比較し評価することによって真理を決定しようとする[1]。 パースペクティヴィズムは認識論的多元主義の初期の形態とみなすことができるが[2]、価値論、[3]道徳心理学、[4]実在論的形而上学を扱うこともあ る[5]。

★ニーチェの逆説.

「ニー

チェは「悦ばしき知識」や「権力への意志」で、他者のパースペクティヴ[このページ]をとることは極め

て難しいから、見解が多様であるという認識に到達することすら困難だと言っている。正しい解釈など存在しない。だけど、そのような多様な解釈の存在すら想

像だにできないわけであるから、正しい解釈など存在しないという認識に到達するには、多様な解釈があるという認識に(困難であるがどうしても)到達するこ

とが必要である。それすら困難なのに、どうやってその奥の院の「正しい解釈などない」と大見得を切れるのか、彼(=ニーチェ)の議論は逆説に満ちている」(→「ニーチェの逆説」)。

■ニーチェの遠近法/遠近法主義ノート[→オリジナ

ル出典は「人間機械論・再考」]

遠近法とは、パースペクティビズム・パースペクティヴィズム (Perspektivismus, Perspectivism)のことである。

「現存在の遠近法的性格はどこまで及ぶのか、あるいはまた、現存在は何かそれとは別な性格をも有っているのか、解釈もなく、「意味(ジン)」もない現存在

はまさに「愚にもつかぬもの(ウンジン)」となりはしないか、他面、一切の現存在は本質的に解釈する現存在ではないのか。こうしたことがらは、当然なが

ら、知性のこのうえなく勤勉な・極めて几帳面で良心的な分析や自己検討をもってしても解決されえないものである。それというのも、こうした分析をおこなう

際に人間の知性は、自己自身を自分の遠近法的形式のもとに見るほかなく、しかもその形式の内でのみ見るほかはないからである。わわわれは自

分の存在する片

隅の周囲を見ることができない。そのほかにもどんな種類の知性や遠近法がありうるのかを知ろうとすることなどは、徒な好奇心でしかない」——ニーチェ『悦

ばしき知識』信太正三訳、374節、p.442.、1993

「意識は、もともと、人間の個的実存に属するものではなく、むし

ろ人間における共同体的かつ群畜的な本性に属している。従って理の当然として、意識はま

た、共同体的かつ群畜的な効用に関する点でだけ、精妙な発達を

とげてきた。……われわれの行為は、根本において一つ一つみな比類のない仕方で個人的であ

り、唯一的であり、あくまでも個性的である、それには疑いの余地がない。それなのに、われわれがそれらを意識に翻訳するやいなや、それらはもうそう

見えな

くなる。……これこそが私の解する真の現象論であり遠近法論である」——ニーチェ『悦ばしき知識』信太正三訳、354節、p.394.、

1993

■ 遠近法、遠近法主義、Perspektive, Perspektivismus

●技法としての「遠近法」-- Perspective (graphical)はこちらです.

■マッハ

木田元に言わせれば、ニーチェの「遠近法的展望」 は、マッハの「現象」と同じであるという。

★哲学的パースペクティヴィズム(視点主義・観点主義)

| Perspectivism

(German: Perspektivismus; also called perspectivalism) is the

epistemological principle that perception of and knowledge of something

are always bound to the interpretive perspectives of those observing

it. While perspectivism does not regard all perspectives and

interpretations as being of equal truth or value, it holds that no one

has access to an absolute view of the world cut off from

perspective.[1] Instead, all such viewing occurs from some point of

view which in turn affects how things are perceived. Rather than

attempt to determine truth by correspondence to things outside any

perspective, perspectivism thus generally seeks to determine truth by

comparing and evaluating perspectives among themselves.[1]

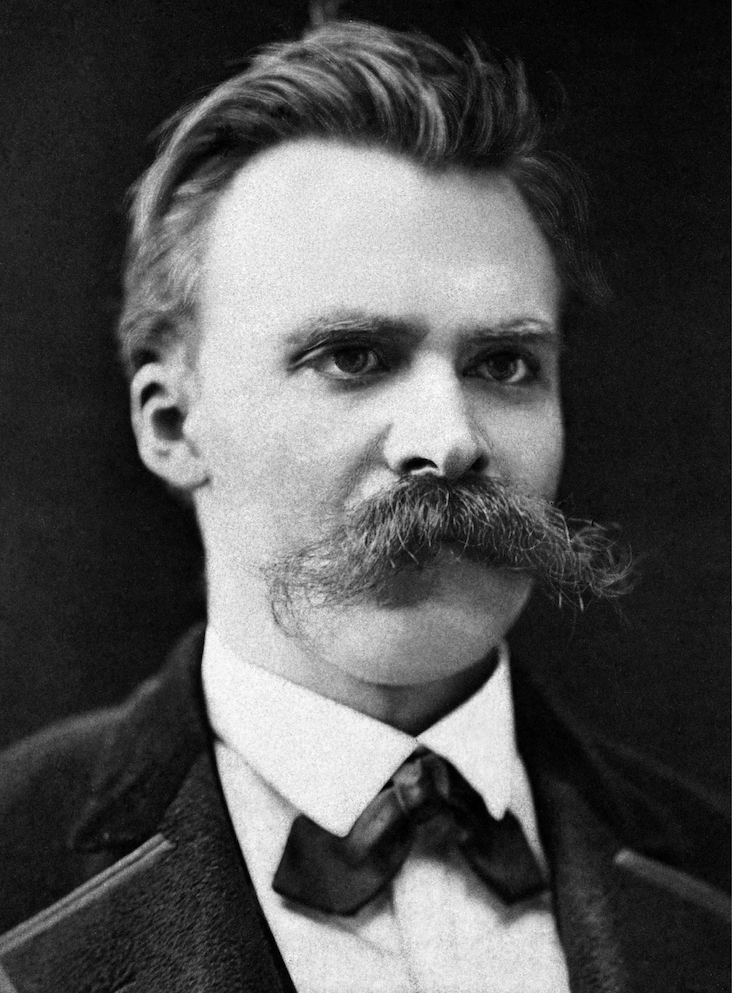

Perspectivism may be regarded as an early form of epistemological

pluralism,[2] though in some accounts includes treatment of value

theory,[3] moral psychology,[4] and realist metaphysics.[5] Early forms of perspectivism have been identified in the philosophies of Protagoras, Michel de Montaigne, and Gottfried Leibniz. However, its first major statement is considered to be Friedrich Nietzsche's development of the concept in the 19th century,[2][4] influenced by Gustav Teichmüller's use of the term some years prior.[6] For Nietzsche, perspectivism takes the form of a realist antimetaphysics[7] while rejecting both the correspondence theory of truth and the notion that the truth-value of a belief always constitutes its ultimate worth-value.[3] The perspectival conception of objectivity used by Nietzsche sees the deficiencies of each perspective as remediable by an asymptotic study of the differences between them. This stands in contrast to Platonic notions in which objective truth is seen to reside in a wholly non-perspectival domain.[4] Despite this, perspectivism is often misinterpreted[3] as a form of relativism or as a rejection of objectivity entirely.[8] Though it is often mistaken to imply that no way of seeing the world can be taken as definitively true, perspectivism can instead be interpreted as holding certain interpretations (such as that of perspectivism itself) to be definitively true.[3] During the 21st century, perspectivism has led a number of developments within analytic philosophy[9] and philosophy of science,[10] particularly under the early influence of Ronald Giere, Jay Rosenberg, Ernest Sosa, and others.[11] This contemporary form of perspectivism, also known as scientific perspectivism, is more narrowly focused than prior forms—centering on the perspectival limitations of scientific models, theories, observations, and focused interest, while remaining more compatible for example with Kantian philosophy and correspondence theories of truth.[11][12] Furthermore, scientific perspecitivism has come to address a number of scientific fields such as physics, biology, cognitive neuroscience, and medicine, as well as interdisciplinarity and philosophy of time.[11] Studies of perspectivism have also been introduced into contemporary anthropology, initially through the influence of Eduardo Viveiros de Castro and his research into indigenous cultures of South America.[13] The basic principle that things are perceived differently from different perspectives (or that perspective determines one's limited and unprivileged access to knowledge) has sometimes been accounted as a rudimentary, uncontentious form of perspectivism.[14] The basic practice of comparing contradictory perspectives to one another may also be considered one such form of perspectivism (See also: Intersubjectivity),[15] as may the entire philosophical problem of how true knowledge is to penetrate one's perspectival limitations.[16] |

パー

スペクティヴィズム(ドイツ語:Perspektivismus、

ペルスペクティヴァリズムとも)とは、あるものに対する知覚や知識は、それを観察する人々の解釈の視点に常に縛られるという認識論の原則である。パースペ

クティヴィズムは、すべての視点や解釈が等しく真実や価値を持つとは考えていないが、視点から切り離された絶対的な世界観にアクセスできる者はいないと主

張している。[1]

その代わり、そのような視点はすべて、物事の知覚に影響を与える何らかの視点から生じる。したがって、視点主義は一般的に、視点間の比較と評価によって真

実を決定しようとする。[1]

視点主義は、認識論的多元主義の初期の形であるとみなされることもあるが、価値理論[3]、道徳心理学[4]、現実主義的形而上学[5]の扱いを含むもの

もある。 初期の視点主義は、プロタゴラス、ミシェル・ド・モンテーニュ、ゴットフリート・ライプニッツの哲学に見られる。しかし、その最初の主要な声明は、19世 紀にフリードリヒ・ニーチェが概念を発展させたものと見なされており、[2][4] その数年前にグスタフ・ティヒミュラーが用いた用語の影響を受けている。[6] ニーチェにとって、視点主義は現実主義的反形而上学の形を取る [7] 一方で、真理の対応説と信念の真理値が常に究極的な価値を構成するという概念の両方を否定している。[3] ニーチェが用いた客観性の視点は、それぞれの視点の欠陥を、それらの間の差異を漸近的に研究することで改善できると見ている。これは、客観的真理が完全に 非視点的な領域に存在するとされるプラトニックな概念とは対照的である。[4] にもかかわらず、視点主義は相対主義の一形態であるとか、客観性を完全に否定するものとして誤解されることが多い。[3][8] 。世界の見方には、決定的に真実であると見なされるものはないと暗示していると誤解されることが多いが、むしろ、ある解釈(例えば、視点主義そのものの解 釈)を真実であると見なすという解釈も可能である。 21世紀には、特にロナルド・ギア、ジェイ・ローゼンバーグ、アーネスト・ソーサなどの初期の影響のもとで、分析哲学[9]および科学哲学[10]の分野 において、視点主義は多くの発展を導いてきた。[11] この視点主義の現代的な形態は、科学的視点主義とも呼ばれ、以前の形よりもより狭い範囲に焦点を当てている。科学的モデル、理論、観察、および関心の視点 的な限界を中心としつつ、 例えばカント哲学や真理の対応説などとの相性は良い。[11][12] さらに、科学的観点主義は物理学、生物学、認知神経科学、医学などの多くの科学分野、および学際領域や時間哲学にも適用されるようになった。[11] 観点主義の研究は、当初はエドゥアルド・ビヴェイロス・デ・カストロの影響と、彼の南米の先住民文化の研究を通じて、現代の文化人類学にも導入された。 [13] 物事は異なる視点から異なるように知覚される(あるいは、視点は知識への限定的で特権的ではないアクセスを決定する)という基本原則は、時には、議論の余 地のない初歩的な視点主義の形として説明されてきた。相矛盾する見解を互いに比較する基本的な手法も、そうした形の視点主義のひとつとみなすことができる (「相互主観性」も参照)[15]。また、真の知識が個人の視点の限界をどのようにして乗り越えるかという哲学上の問題全体も、そうした形の視点主義のひ とつとみなすことができる[16]。 |

| Precursors and early developments In Western languages, scholars have found perspectivism in the philosophies of Heraclitus (c. 540 – c. 480 BCE), Protagoras (c. 490 – c. 420 BCE), Michel de Montaigne[3][17] (1533 – 1592 CE), and Gottfried Leibniz[2] (1646 – 1716 CE). The origins of perspectivism have also been found to lie also within Renaissance developments in philosophy of art and its artistic notion of perspective.[18] In Asian languages, scholars have found perspectivism in Buddhist,[19] Jain,[20] and Daoist texts.[21] Anthropologists have found a kind of perspectivism in the thinking of some indigenous peoples.[13] Some theologians believe John Calvin interpreted various scriptures in a perspectivist manner.[22] Ancient Greek philosophy The Western origins of perspectivism can be found in the pre-Socratic philosophies of Heraclitus[23] and Protagoras.[2] In fact, a major cornerstone of Plato's philosophy is his rejection and opposition to perspectivism—this forming a principal element of his aesthetics, ethics, epistemology, and theology.[24] The antiperspectivism of Plato made him a central target of critique for later perspectival philosophers such as Nietzsche.[25] Montaigne Montaigne's philosophy presents in itself a perspectivism less as a doctrinaire position than as a core philosophical approach put into practice. Inasmuch as no one can occupy a God's-eye view, Montaigne holds that no one has access to a view which is totally unbiased, which does not interpret according to its own perspective. It is instead only the underlying psychological biases which view one's own perspective as unbiased.[17] In a passage from his "Of Cannibals", he writes: Men of intelligence notice more things and view them more carefully, but they [interpret] them; and to establish and substantiate their interpretation, they cannot refrain from altering the facts a little. They never present things just as they are but twist and disguise them to conform to the point of view from which they have seen them; and to gain credence for their opinion and make it attractive, they do not mind adding something of their own, or extending and amplifying.[26] — Michel de Montaigne, "Of Cannibals", Essais (1595), trans. J. M. Cohen |

先行者と初期の発展 西洋の言語では、ヘラクレイトス(紀元前540年頃 - 紀元前480年頃)、プロタゴラス(紀元前490年頃 - 紀元前420年頃)、ミシェル・ド・モンテーニュ(1533年 - 1592年)、ゴットフリート・ライプニッツ(1646年 - 1716年)の哲学に、学者たちはペルスペクティヴィズムを見出している。また、遠近法主義の起源は、ルネサンス期における芸術哲学の発展と、その芸術的 遠近法概念の中にも見出されている。[18] アジアの言語では、学者たちは仏教[19]、ジャイナ教[20]、道教の文献に遠近法主義を見出している。[21] 人類学者は、一部の先住民の考え方の中に遠近法主義の一種を見出している。[13] 一部の神学者は、ジョン・カルヴァンが様々な聖典を遠近法主義的に解釈したと考えている。[22] 古代ギリシャ哲学 西洋における視点主義の起源は、ヘラクレイトス[23]やプロタゴラス[2]のソクラテス以前の哲学に見られる。実際、プラトンの哲学の主要な礎石は、視 点主義への拒絶と反対であり、これは彼の美学、倫理、認識論、神学の主要な要素を形成している。[24] プラトンの反視点主義は、ニーチェなどの後の視点主義の哲学者たちから批判の的となった。[25] モンテーニュ モンテーニュの哲学は、教義的な立場というよりも、実践的な哲学の中心的なアプローチとして、それ自体が相対主義を示している。神の視点に立つことは誰に もできないため、モンテーニュは、完全に偏りのない視点、すなわち、自身の視点に立って解釈しない視点に立つことは誰にもできないと主張している。むし ろ、自分の視点が偏っていないと考えるのは、根底にある心理的な偏見だけである。[17] 著書『人食い人種について』の一節で、彼は次のように書いている。 知性のある人間はより多くのことに気づき、より注意深くそれらを観察するが、彼らはそれらを解釈する。そして、彼らの解釈を確立し裏付けるために、彼らは 事実を少し変えることをためらわない。彼らは物事をありのままに提示することは決してなく、自分が見た視点に合うように歪めたり偽装したりする。そして、 自分の意見に信憑性を持たせ、魅力的なものにするために、自分自身の考えを加えたり、内容を拡張したり、誇張したりすることを厭わない。 — ミシェル・ド・モンテーニュ、『人食い人種について』、『エセー』(1595年)、J. M. Cohen 訳 |

| Nietzsche In his works, Nietzsche makes a number of statements on perspective which at times contrast each other throughout the development of his philosophy. Nietzsche's perspectivism begins by challenging the underlying notions of 'viewing from nowhere', 'viewing from everywhere', and 'viewing without interpreting' as being absurdities.[25] Instead, all viewing is attached to some perspective, and all viewers are limited in some sense to the perspectives at their command.[27] In The Genealogy of Morals he writes: Let us be on guard against the dangerous old conceptual fiction that posited a 'pure, will-less, painless, timeless knowing subject'; let us guard against the snares of such contradictory concepts as 'pure reason', 'absolute spirituality', 'knowledge in itself': these always demand that we should think of an eye that is completely unthinkable, an eye turned in no particular direction, in which the active and interpreting forces, through which alone seeing becomes seeing something, are supposed to be lacking; these always demand of the eye an absurdity and a nonsense. There is only a perspective seeing, only a perspective knowing; and the more affects we allow to speak about one thing, the more eyes, different eyes, we can use to observe one thing, the more complete will our 'concept' of this thing, our 'objectivity' be.[28] — Friedrich Nietzsche, The Genealogy of Morals (1887; III:12), transl. Walter Kaufmann In this, Nietzsche takes a contextualist approach which rejects any God's-eye view of the world.[29] This has been further linked to his notion of the death of God and the dangers of a resulting relativism. However, Nietzsche's perspectivism itself stands in sharp contrast to any such relativism.[3] In outlining his perspectivism, Nietzsche rejects those who claim everything to be subjective, by disassembling the notion of the subject as itself a mere invention and interpretation.[30] He further states that, since the two are mutually dependent on each other, the collapse of the God's-eye view causes also the notion of the thing-in-itself to fall apart with it. Nietzsche views this collapse to reveal, through his genealogical project, that all that has been considered non-perspectival knowledge, the entire tradition of Western metaphysics, has itself been only a perspective.[27][29] His perspectivism and genealogical project are further integrated into each other in addressing the psychological drives that underlie various philosophical programs and perspectives, as a form of critique.[4] Here, contemporary scholar Ken Gemes views Nietzsche's perspectivism to above all be a principle of moral psychology, rejecting interpretations of it as an epistemological thesis outrightly.[4] It is through this method of critique that the deficiencies of various perspectives can be alleviated—through a critical mediation of the differences between them rather than any appeals to the non-perspectival.[4][17] In a posthumously published aphorism from The Will to Power, Nietzsche writes: "Everything is subjective," you say; but even this is interpretation. The "subject" is not something given, it is something added and invented and projected behind what there is.—Finally, is it necessary to posit an interpreter behind the interpretation? Even this is invention, hypothesis. In so far as the word "knowledge" has any meaning, the world is knowable; but it is interpretable otherwise, it has no meaning behind it, but countless meanings.—"Perspectivism." It is our needs that interpret the world; our drives and their For and Against. Every drive is a kind of lust to rule; each one has its perspective that it would like to compel all the other drives to accept as a norm.[30] — Friedrich Nietzsche, The Will to Power, §481 (1883–1888), transl. Walter Kaufmann and R. J. Hollingdale While Nietzsche does not plainly reject truth and objectivity, he does reject the notions of absolute truth, external facts, and non-perspectival objectivity.[4][25] Truth theory and the value of truth Despite receiving much attention within contemporary philosophy, there is no academic consensus on Nietzsche's conception of truth.[31] While his perspectivism presents a number of challenges regarding the nature of truth, its more controversial element lies in its questioning of the value of truth.[3] Contemporary scholars Steven D. Hales and Robert C. Welshon write that: Nietzsche's writings on truth are among the most elusive and difficult ones in his corpus. One indication of their obscurity is that on an initial reading he appears either blatantly inconsistent in his use of the words 'true' and 'truth', or subject to inexplicable vacillations on the value of truth.[32] |

ニーチェ ニーチェは、その著作の中で、哲学の発展の過程で時に相反する視点に関する多くの主張を行っている。ニーチェの視点主義は、まず「どこからも見ない」、 「どこからでも見る」、「解釈せずに見る」という根本的な概念を不合理であると批判することから始まる。[25] その代わりに、すべての視覚は、ある視点に結び付けられ、すべての視聴者は、ある意味で、自分たちの視点に制限されている。[27] 『道徳の系譜』の中で、彼は次のように書いている。 「純粋で、意志を持たず、苦痛もなく、時間にとらわれない認識主体」という危険な古い概念的虚構に対して警戒しよう。「純粋理性」、「絶対的精神」、「そ れ自体としての知識」といった矛盾した概念の罠に陥らないようにしよう。これらは常に、 考えられないような眼、特定の方向を向いていない眼、見ることを見るものにする唯一の能動的かつ解釈的な力が欠けていると想定される眼について考えること を常に要求する。あるものについて語らせる影響が増えれば増えるほど、また、あるものについて観察する目が増えれば増えるほど、異なる目が増えれば増える ほど、そのものについての我々の「概念」、我々の「客観性」はより完全なものとなる。 —フリードリヒ・ニーチェ、『道徳の系譜』(1887年、第3巻、第12章)、訳者ウォルター・カウフマン この点において、ニーチェは世界を神の視点から見ることを拒否する文脈主義的アプローチを取っている。[29] これはさらに、神の死と、その結果生じる相対主義の危険性というニーチェの概念と結びついている。しかし、ニーチェの相対主義自体は、そうした相対主義と は鋭い対照をなしている。[3] 相対主義の概略を説明する際、ニーチェは、主観的なものすべてを主張する人々を否定し、主観という概念自体が単なる発明であり解釈であると主張している。 [30] さらに、ニーチェは、両者は相互に依存しているため、神の視点の崩壊は、物自体の概念も一緒に崩壊させる、と述べている。ニーチェは、この崩壊によって、 彼の系譜学プロジェクトを通じて、これまで非視点的知識と考えられてきたもの、すなわち西洋形而上学の伝統全体が、それ自体が視点にすぎなかったことが明 らかになると考えている。[27][29] 彼の視点主義と系譜学プロジェクトは、批判の一形態として、さまざまな哲学プログラムや視点の根底にある心理的動機を扱うことで、さらに互いに統合されて いる。[4] ここで、現代の学者ケン・ゲイムズは、ニーチェの ニーチェの相対主義は、何よりもまず道徳心理学の原理であると見なし、それを認識論上の命題として解釈することを真っ向から否定している。[4] さまざまな視点の欠陥を緩和できるのは、この批判の方法を通じてである。すなわち、相対主義以外のものに訴えるのではなく、それらの相違を批判的に調停す ることによってである。[4][17] 『力への意志』の死後に発表された格言の中で、ニーチェは次のように書いている。 「すべては主観的だ」と君は言う。しかし、それさえも解釈なのだ。「主 観」とは与えられたものではなく、何かが付け加えられ、発明され、そこに存在するも のの背後に投影されたものなのだ。最後に、解釈の背後に解釈者を想定する必要があるだろうか? それさえも発明であり、仮説なのだ。 「知識」という言葉が意味を持つ限りにおいて、世界は知ることができ る。しかし、それ以外にも解釈は可能であり、その背後には意味はなく、無数の意味があ る。「視点主義(観点主義)」 世界を解釈するのは、私たちのニーズであり、私たちの衝動であり、それ に対する賛成と反対である。あらゆる衝動は支配欲の一種であり、それぞれが、他のす べての衝動に強制的に受け入れさせたい視点を持っている。 —フリードリヒ・ニーチェ、『力への意志』第481項(1883年-1888年)、訳:ウォルター・カウフマン、R. J. ホリングデール ニーチェは、真実や客観性を明確に否定しているわけではないが、絶対的な真理、外部の事実、非視点的客観性という概念は否定している。[4][25] 真理論と真理の価値 現代哲学において多くの注目を集めているにもかかわらず、ニーチェの真理観については学術的なコンセンサスは得られていない。[31] 彼の視点主義は真理の本質に関する多くの課題を提示しているが、より論争を呼んでいるのは、真理の価値を疑問視している点である。[3] 現代の学者であるスティーブン・D・ヘイルズとロバート・C・ウェルションは次のように書いている。 ニーチェの真理に関する著作は、彼の著作の中でも最も捉えどころがなく、理解が難しいものの一つである。その難解さを示す一つの例として、最初の読解で は、彼は「真実」と「真理」という言葉の使い方に露骨な矛盾があるか、あるいは真理の価値について説明できないほど揺れ動いているように見える。[32] |

| Later developments This section may need to be rewritten to comply with Wikipedia's quality standards. You can help. The talk page may contain suggestions. (April 2021) In the 20th century, perspectivism was discussed separately by José Ortega y Gasset[33] and Karl Jaspers.[34] Ortega Ortega's perspectivism, replaced his previous position that "man is completely social". His reversal is prominent in his work Verdad y perspectiva ("Truth and perspective"), where he explained that "each man has a mission of truth" and that what he sees of reality no other eye sees.[35] He explained: From different positions two people see the same surroundings. However, they do not see the same thing. Their different positions mean that the surroundings are organized in a different way: what is in the foreground for one may be in the background for another. Furthermore, as things are hidden one behind another, each person will see something that the other may not.[36] Ortega also maintained that perspective is perfected by the multiplication of its viewpoints.[37] He noted that war transpires due to the lack of perspective and failure to see the larger contexts of the actions among nations.[37] Ortega also cited the importance of phenomenology in perspectivism as he argued against speculation and the importance of concrete evidence in understanding truth and reality.[38] In this discourse, he highlighted the role of "circumstance" in finding out the truth since it allows us to understand realities beyond ourselves.[38] |

その後の展開 この節は、ウィキペディアの品質基準に適合させるために書き換えが必要となる可能性がある。あなたも手伝ってみませんか?トークページに提案が掲載されて いる可能性がある。(2021年4月) 20世紀には、オルテガ・イ・ガセット[33]とカール・ヤスパース[34]がそれぞれ個別にペルスペクティヴィズムについて論じている。 オルテガは、 それまでの「人間は完全に社会的存在である」という立場を、視点主義に置き換えた。この立場転換は、著書『真理と視点』(Verdad y perspectiva)で顕著であり、そこでは「人間にはそれぞれ真理の使命がある」こと、また「現実についてある人間が見ているものは、他の人間の目 には映らない」ことを説明している。 異なる位置から、2人の人間は同じ周囲を見ている。しかし、彼らは同じものを見ているわけではない。彼らの異なる位置は、周囲が異なる方法で組織されてい ることを意味する。ある人にとって前景にあるものが、他の人にとっては背景にあるかもしれない。さらに、物事が次から次へと隠されていくため、各人は他の 人が見えないものを見ることになる。 オルテガはまた、視点の多様化によって遠近法は完成するとも主張した。[37] 彼は、戦争は遠近法の欠如と、国民間の行動のより大きな文脈を見失うことによって引き起こされると指摘した。[37] オルテガはまた、 観念論における現象学の重要性を指摘し、憶測に反対し、真実と現実を理解する上で具体的な証拠の重要性を主張した。[38] この論説において、彼は真実を見出す上で「状況」が果たす役割を強調した。なぜなら、それは私たち自身を超えた現実を理解することを可能にするからだ。 [38] |

| Types of Perspectivism Contemporary types of perspectivism include: Individualist perspectivism Collectivist perspectivism Transcendental perspectivism Theological perspectivism |

パースペクティヴィズムのタイプ 現代のパースペクティヴィズムのタイプには以下のようなものがある。 個人主義的パースペクティヴィズム 集団主義的パースペクティヴィズム 超越論的パースペクティヴィズム 神学的パースペクティヴィズム |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Perspectivism |

|

| 群畜の道徳——ニーチェ『道徳の彼岸』(201) |

|

| As long as the utility which

determines moral estimates is only gregarious utility, as long as the

preservation of the community is only kept in view, and the immoral is

sought precisely and exclusively in what seems dangerous to the

maintenance of the community, there can be no “morality of love to

one’s neighbour.” Granted even that there is already a little constant

exercise of consideration, sympathy, fairness, gentleness, and mutual

assistance, granted that even in this condition of society all those

instincts are already active which are latterly distinguished by

honourable names as “virtues,” and eventually almost coincide with the

conception “morality”: in that period they do not as yet belong to the

domain of moral valuations—they are still ultra-moral. A sympathetic

action, for instance, is neither called good nor bad, moral nor

immoral, in the best period of the Romans; and should it be praised, a

sort of resentful disdain is compatible with this praise, even at the

best, directly the sympathetic action is compared with one which

contributes to the welfare of the whole, to the res publica. After all,

“love to our neighbour” is always a secondary matter, partly

conventional and arbitrarily manifested in relation to our fear of our

neighbour. After the fabric of society seems on the whole established

and secured against external dangers, it is this fear of our neighbour

which again creates new perspectives of moral valuation. Certain strong

and dangerous instincts, such as the love of enterprise, foolhardiness,

revengefulness, astuteness, rapacity, and love of power, which up till

then had not only to be honoured from the point of view of general

utility—under other names, of course, than those here given—but had

to be fostered and cultivated (because they were perpetually required

in the common danger against the common enemies), are now felt in their

dangerousness to be doubly strong—when the outlets for them are

lacking—and are gradually branded as immoral and given over to

calumny. The contrary instincts and inclinations now attain to moral

honour, the gregarious instinct gradually draws its conclusions. How

much or how little dangerousness to the community or to equality is

contained in an opinion, a condition, an emotion, a disposition, or an

endowment—that is now the moral perspective, here again fear is the

mother of morals. It is by the loftiest and strongest instincts, when

they break out passionately and carry the individual far above and

beyond the average, and the low level of the gregarious conscience,

that the self-reliance of the community is destroyed; its belief in

itself, its backbone, as it were, breaks; consequently these very

instincts will be most branded and defamed. The lofty independent

spirituality, the will to stand alone, and even the cogent reason, are

felt to be dangers; everything that elevates the individual above the

herd, and is a source of fear to the neighbour, is henceforth called

evil; the tolerant, unassuming, self-adapting, self-equalizing

disposition, the mediocrity of desires, attains to moral distinction

and honour. Finally, under very peaceful circumstances, there is always

less opportunity and necessity for training the feelings to severity

and rigour, and now every form of severity, even in justice, begins to

disturb the conscience, a lofty and rigorous nobleness and

self-responsibility almost offends, and awakens distrust, “the lamb,”

and still more “the sheep,” wins respect. There is a point of diseased

mellowness and effeminacy in the history of society, at which society

itself takes the part of him who injures it, the part of the criminal,

and does so, in fact, seriously and honestly. To punish, appears to it

to be somehow unfair—it is certain that the idea of “punishment” and

“the obligation to punish” are then painful and alarming to people. “Is

it not sufficient if the criminal be rendered harmless? Why should we

still punish? Punishment itself is terrible!”—with these questions

gregarious morality, the morality of fear, draws its ultimate

conclusion. If one could at all do away with danger, the cause of fear,

one would have done away with this morality at the same time, it would

no longer be necessary, it would not consider itself any longer

necessary!—Whoever examines the conscience of the present-day

European, will always elicit the same imperative from its thousand

moral folds and hidden recesses, the imperative of the timidity of the

herd: “we wish that some time or other there may be nothing more to

fear!” Some time or other—the will and the way thereto is nowadays

called “progress” all over Europe. |

道徳的評価を決定する公益が社交的な公益のみであり、共同体の維持が唯

一の目的とされ、共同体維持にとって危険と思われるものにのみ、不道徳さが求められる限り、「隣人愛の道徳」は存在しえない。配慮、同情、公平、優しさ、

相互扶助といったものがすでに少しずつ常に行われていると仮定しよう。また、この社会の状態においても、最近になって「美徳」という立派な名称で区別され

るようになった本能がすでに活動しており、最終的には「道徳」という概念とほぼ一致する。しかし、この時期においては、それらはまだ道徳的評価の領域に属

するものではない。たとえば、共感的な行動は、ローマ人の最良の時代においては、良いとも悪いとも、道徳的とも非道徳的とも呼ばれていなかった。そして、

もしそれが賞賛されるべきものだとしても、ある種の憤慨した軽蔑が、たとえ最良の状況であっても、この賞賛と両立する。結局のところ、「隣人愛」は常に二

次的な問題であり、隣人に対する恐怖心との関連において、部分的に慣習的かつ恣意的に表明されるものである。社会の組織が概ね確立され、外部の危険から守

られているように見えるようになった後、再び道徳的価値観の新たな展望を生み出すのは、隣人に対するこの恐怖である。企業家精神、向こう見ず、執念深さ、

抜け目なさ、強欲、権力への愛といった、ある種の強力で危険な本能は、それまでは一般の公益の観点から称賛されるべきものであり(もちろん、ここで挙げた

ものとは別の名称で)、

、それらを助長し、育成しなければならなかった(なぜなら、共通の敵に対する共通の危険においては、それらが常に必要とされたからだ)。しかし、それらの

発散先が欠如している今、それらの持つ危険性は倍増していると感じられ、徐々に不道徳として烙印を押され、中傷の対象となっている。今では、それとは反対

の本能や傾向が道徳的な名誉を得るようになり、社交的な本能は徐々に結論を導き出す。ある意見、状態、感情、気質、あるいは才能に、社会や平等にとってど

れほどの、あるいはどれほどの危険性が含まれているのか。それが今では道徳的な観点であり、ここでもまた、恐怖が道徳の母である。最も崇高で強力な本能が

情熱的に爆発し、個人が平均的なレベルをはるかに超えて集団的な良心の低レベルをはるかに超えるときに、社会の自立は破壊される。社会が自らを信じるとい

う信念、いわば社会の背骨が折れるのだ。その結果、まさにこれらの本能が最も強く非難され、中傷されることになる。崇高な独立精神、単独で立ち向かう意

志、そして説得力のある理性さえも危険視される。群れよりも個を高めるものすべて、そして隣人にとっての恐怖の源となるものは、今後は悪と呼ばれ、寛容で

控えめ、自己適応性があり、自己を平均化する性質、平凡な欲望は、道徳的な卓越性と名誉を獲得する。最後に、非常に平和な状況下では、感情を厳格に鍛える

機会や必要性は常に少なくなる。そして今、あらゆる厳格さは、正義においても良心を乱し始め、高潔で厳格な高潔さや自己責任はほとんど不快であり、不信感

を呼び覚ます。「子羊」は、さらに「羊」は尊敬を集める。社会の歴史には、病的な円熟と女々しさの兆しがあり、社会自体が社会を傷つけた者の味方となり、

犯罪者の味方となり、実際、真剣かつ誠実にそうする。罰することは、何となく不公平に思える。「罰する」という考えや「罰さなければならない」という義務

は、人々にとって苦痛であり、不安を覚えるものである。「犯罪者を無害にすれば十分ではないのか? なぜまだ罰しなければならないのか?

罰すること自体が恐ろしい!」――社交的な道徳、すなわち恐怖の道徳は、このような疑問から最終的な結論を導き出す。もし恐怖の原因である危険を完全に排

除できるのであれば、同時にこの道徳も排除されるだろう。もはや必要ではなく、もはや必要だとは思われなくなるのだ!

現代のヨーロッパ人の良心を吟味する者は誰でも、その道徳の千の折り目や隠れた奥底から、常に同じ命令を引き出すだろう。それは、群れをなす臆病者の命令

である。「いつか、もう何も恐れることがなくなることを願う!」 いつか、いつか、その意志と方法が、今日ではヨーロッパ全土で「進歩」と呼ばれている。 |

| 群畜の道徳——ニーチェ『道徳の彼岸』(202) | |

| Let us at once say again what we

have already said a hundred times, for people’s ears nowadays are

unwilling to hear such truths—our truths. We know well enough how

offensive it sounds when anyone plainly, and without metaphor, counts

man among the animals, but it will be accounted to us almost a crime,

that it is precisely in respect to men of “modern ideas” that we have

constantly applied the terms “herd,” “herd-instincts,” and suchlike

expressions. What avail is it? We cannot do otherwise, for it is

precisely here that our new insight is. We have found that in all the

principal moral judgments, Europe has become unanimous, including

likewise the countries where European influence prevails: in Europe

people evidently know what Socrates thought he did not know, and what

the famous serpent of old once promised to teach—they “know” today

what is good and evil. It must then sound hard and be distasteful to

the ear, when we always insist that that which here thinks it knows,

that which here glorifies itself with praise and blame, and calls

itself good, is the instinct of the herding human animal, the instinct

which has come and is ever coming more and more to the front, to

preponderance and supremacy over other instincts, according to the

increasing physiological approximation and resemblance of which it is

the symptom. Morality in Europe at present is herding-animal morality,

and therefore, as we understand the matter, only one kind of human

morality, beside which, before which, and after which many other

moralities, and above all higher moralities, are or should be possible.

Against such a “possibility,” against such a “should be,” however, this

morality defends itself with all its strength, it says obstinately and

inexorably “I am morality itself and nothing else is morality!” Indeed,

with the help of a religion which has humoured and flattered the

sublimest desires of the herding-animal, things have reached such a

point that we always find a more visible expression of this morality

even in political and social arrangements: the democratic movement is

the inheritance of the Christian movement. That its tempo, however, is

much too slow and sleepy for the more impatient ones, for those who are

sick and distracted by the herding-instinct, is indicated by the

increasingly furious howling, and always less disguised teeth-gnashing

of the anarchist dogs, who are now roving through the highways of

European culture. Apparently in opposition to the peacefully

industrious democrats and Revolution-ideologues, and still more so to

the awkward philosophasters and fraternity-visionaries who call

themselves Socialists and want a “free society,” those are really at

one with them all in their thorough and instinctive hostility to every

form of society other than that of the autonomous herd (to the extent

even of repudiating the notions “master” and “servant”—ni dieu ni

maître, says a socialist formula); at one in their tenacious opposition

to every special claim, every special right and privilege (this means

ultimately opposition to every right, for when all are equal, no one

needs “rights” any longer); at one in their distrust of punitive

justice (as though it were a violation of the weak, unfair to the

necessary consequences of all former society); but equally at one in

their religion of sympathy, in their compassion for all that feels,

lives, and suffers (down to the very animals, up even to “God”—the

extravagance of “sympathy for God” belongs to a democratic age);

altogether at one in the cry and impatience of their sympathy, in their

deadly hatred of suffering generally, in their almost feminine

incapacity for witnessing it or allowing it; at one in their

involuntary beglooming and heart-softening, under the spell of which

Europe seems to be threatened with a new Buddhism; at one in their

belief in the morality of mutual sympathy, as though it were morality

in itself, the climax, the attained climax of mankind, the sole hope of

the future, the consolation of the present, the great discharge from

all the obligations of the past; altogether at one in their belief in

the community as the deliverer, in the herd, and therefore in

“themselves.” |

今一度、すでに100回も言ってきたことを繰り返そう。なぜなら、現代

人の耳は、そのような真実(私たちの真実)を聞くことを拒んでいるからだ。誰かが比喩を用いずに、人間を動物の一種として単純に数えると、いかにも不快に

聞こえることは十分に承知しているが、しかし、まさに「現代的な考え方」を持つ人間に関して、私たちが「群れ」、「群れ本能」、そして同様の表現を常に用

いてきたことは、ほとんど犯罪とみなされるだろう。それが何の役に立つのか?

それ以外に方法はない。なぜなら、まさにこの点にこそ、私たちの新しい洞察があるからだ。ヨーロッパでは、ヨーロッパの影響力が及ぶ国々も含め、主要な道

徳的判断のすべてにおいて意見が一致していることが分かった。ヨーロッパの人々は、ソクラテスが自分が知らないと思っていたこと、そして昔の有名な蛇が教

えると約束したことについて、明らかに知っている。彼らは今日、善と悪が何であるかを知っているのだ。それゆえ、私たちが常に主張しているように、ここで

「知っている」と思い込み、賞賛や非難によって自らを誇示し、自らを「善」と呼ぶものは、群れをなす人間という動物が持つ本能であり、その本能は、他の本

能に対する優位性と支配性をますます前面に押し出し、優勢になってきている。現在のヨーロッパの道徳は家畜の道徳であり、したがって、我々の理解では、そ

れは人間としての道徳の一形態にすぎず、それ以前にも以後にも、そしてそれ以外にも、より高度な道徳を含め、多くの道徳が存在し、あるいは存在しうるはず

である。しかし、このような「可能性」や「あるべき姿」に対して、この道徳は全力で自己防衛し、頑固かつ容赦なく「私は道徳そのものであり、それ以外に道

徳などありえない!」と主張する。実際、家畜的な本能を持つ人間たちの最も崇高な欲望を満足させ、おだててきた宗教の助けを借りて、物事は、政治や社会の

仕組みにおいても、この道徳のより明白な表現が常にみられるような段階にまで達している。民主化運動はキリスト教運動の遺産である。しかし、そのテンポ

は、よりせっかちな者たちにとってはあまりにも遅く、眠気を誘うものだ。群れをなす本能に病みつきになり、気が散っている者たちにとっては、そのテンポは

あまりにも遅く、眠気を誘うものだ。そのことは、ますます激しく吠え、歯を食いしばる様子を隠そうともしなくなった無政府主義者の犬たちによって示されて

いる。彼らは今、ヨーロッパ文化の王道をさまよっている。平和的で勤勉な民主主義者や革命イデオローグ、そしてさらに厄介な哲学者や友愛団体に属する社会

主義者たち、そして「自由な社会」を望む彼らに対して、明らかに反対の立場を取っている。彼らは、自律的な群れ以外のあらゆる社会形態に対して、本能的な

徹底的な敵意を抱いている(「主人」と「使用人」という概念を否定するほどである。 u ni

maître、社会主義の公式が言うように)あらゆる特別な主張、あらゆる特別な権利や特権に対する粘り強い反対意見で一致している(これは究極的にはあ

らゆる権利に対する反対意見を意味する。なぜなら、すべてが平等であるとき、もはや「権利」は必要ないからだ)。また、懲罰的な正義に対する不信感でも一

致している(それはまるで、弱者に対する侵害であり、これまでの社会の必然的な帰結に対する不公平であるかのように)。しかし、同時に、共感という宗教、

感じ、生き、苦しむものすべてに対する同情心(動物にまで及び、さらには「神」にまで及ぶ。「神への同情」という贅沢さは民主主義の時代に属する)に完全

に共感し、同情の叫びと焦燥感、苦しみに対する死を覚悟するほどの憎悪、苦しみを目撃したり、苦しみを許容したりすることに対するほとんど女性的な無力感

に完全に共感し、

ヨーロッパが新たな仏教の脅威にさらされているかのように思える。相互の同情の道徳性を信じるという点で一致している。それはあたかもそれ自体が道徳であ

るかのように、人類の絶頂、達成された絶頂、未来への唯一の希望、現在の慰め、過去のすべての義務からの大きな解放である。全体として、共同体を解放者、

群れ、そして「自分自身」として信じるという点で一致している。 |

| Sourse: |

|

| HERD MORALITY Nietzsche objects to herd morality because it values what does not have value. It is in the interests of lower, not higher men. If each person’s values help establish favourable conditions for themselves, then the triumph of herd morality will lead to the continuation of herd-like people. It is therefore not something for the human race as a whole to live by. Herd morality is a development of the original slave morality which inherits most of its content, including a reinterpretation of various traits: impotence becomes goodness of heart, craven fear becomes humility, submission becomes ‘obedience’, cowardice and being forced to wait become patience, the inability to take revenge becomes forgiveness, the desire for revenge becomes a desire for justice, a hatred of one’s enemy becomes a hatred of injustice (Genealogy of Morals I §14). Happiness is opposed to suffering; pity v. indifference to suffering; peacefulness v. danger; altruism v. self-love; equality v. inequality; communal utility v. endangering such utility; ridding oneself of instincts v. enjoyment of instinctual satisfaction; well-being of the soul v. well-being of the body. This morality values what has no intrinsic value, and very often endangers what is of much greater value, viz. human greatness. Greatness requires suffering, danger, self-love, inequality, it goes against what is in the interests of people in general and is an expression of instinctual energy. ‘Well-being’ in herd morality limits human beings, promoting people who are modest, submissive and conforming. And so it opposes the development of higher people, it slanders their will to power and labels them evil. Belief in its values limits people who could become higher people, leading them to self-doubt and selfloathing (§269). Nietzsche calls this morality both clever (or shrewd) and stupid (§198). It contains and controls powerful instinctual emotions and drives. This is shrewd because these are dangerous to a herd person, who does not have a strong enough will to control their own emotions or stand up to others’. But it is stupid, because it is based on misunderstanding and fear and opposes the development of higher people. The deep fear of other people also undermines herd morality’s own values. Fear means then there can be no genuine neighbourly love (§201). We do not and cannot practice altruism, but our moral values require us to believe in it. As herd morality as developed, it seems to have lost that element that belonged to the ascetic ideal. It becomes a form of utilitarianism, aimed at happiness in this world, rather than redemption in the next. But with the loss of the ascetic ideal, there is nothing to inspire people to try to become better, greater, by overcoming their weaknesses or finding a creative, powerful responses to their ressentiment. Nietzsche praises Christianity for the greatness in art and architecture, for the depths of the soul, it produced. Without the ascetic ideal, we lose this, and morality is no longer a form of selfovercoming, and people become ‘smaller’, less great. Above all, herd morality has led to the degeneration of the human race (§62). We are not a species of animal that has fully developed into what it can be, because we keep alive ‘a surplus of deformed, sick, degenerating, frail’ people, which ‘ought to perish’. Christianity has bred a mediocre, sickly, good-natured animal. |

群畜道徳 ニーチェは、群畜道徳に異議を唱える。なぜなら、それは価値のないものを価値あるものとして評価するからだ。それは、上位の人間ではなく下位の人間の利益 となる。もし各人の価値観が、自分にとって好ましい条件を確立するのに役立つのであれば、群畜道徳の勝利は群畜のような人間を継続させることになる。した がって、それは人類全体が生きるために従うべきものではない。 群畜道徳は、その内容のほとんどを継承した元々の奴隷道徳の発展であり、さまざまな特徴の再解釈を含んでいる。無力は心の善良さとなり、臆病な恐怖は謙虚 さとなり、服従は「従順」となり、臆病と待たされることは忍耐となり、復讐できないことは許しとなり、復讐の欲望は正義の欲望となり、敵への憎悪は不正へ の憎悪となる(『道徳の系譜学』第1部 §14)。幸福は苦痛と対立する。苦痛に対する同情または無関心。平和と危険。利他主義と自己愛。平等と不平等。共同体の利益と、その利益を危険にさらす こと。本能から解放されることと、本能的な満足感を享受すること。魂の幸福と、肉体の幸福。この道徳は、本質的な価値を持たないものを重視し、はるかに大 きな価値を持つもの、すなわち人間の偉大さを危険にさらすことが非常に多い。偉大さには苦しみ、危険、自己愛、不平等が必要であり、それは一般の人々の利 益に反するものであり、本能的なエネルギーの表現である。群畜道徳における「幸福」は人間を制限し、謙虚で従順で順応的な人間を推奨する。そして、より高 い人間の発展を妨げ、彼らの権力への意志を中傷し、彼らを悪とみなす。その価値観を信奉することは、より高潔な人格者となる可能性のある人々を制限し、彼 らを自己不信と自己嫌悪へと導く(§269)。ニーチェは、この道徳を賢明(または抜け目ない)かつ愚かであると評している(§198)。この道徳は、強 力な本能的な感情や衝動を抑制し、制御する。これは抜け目ない。なぜなら、群畜的な人間にとって、自分の感情を制御したり、他者に対抗するだけの強い意志 を持たないことは危険だからだ。しかし、それは誤解と恐怖に基づいており、より高次の人間の発展に逆行するものであるため、愚かである。他者に対する深い 恐怖は、群畜道徳の価値そのものを損なう。恐怖は、真の隣人愛が存在し得ないことを意味する(§201)。私たちは利他主義を実践していないし、実践する こともできないが、私たちの道徳的価値観は、それを信じることを私たちに求めている。 群畜道徳が発達するにつれ、禁欲主義の理想に属する要素が失われたように思われる。それは、来世での救済よりも現世での幸福を目的とする功利主義の一形態 となる。しかし、禁欲主義の理想が失われたことで、人々を鼓舞して、弱さを克服したり、ルサンチマンに対する創造的で力強い反応を見出すことで、より良 く、より偉大になろうとする意欲をかき立てるものは何もなくなった。ニーチェは、キリスト教が芸術や建築の偉大さ、そして魂の深みを生み出したことを称賛 している。禁欲的な理想がなければ、私たちはこれらを失い、道徳はもはや自己克服の形ではなくなり、人々は「小さく」なり、偉大さを失う。 何よりも、群畜道徳が人類の退廃を招いたのである(§62)。私たちは、本来あるべき姿に完全に成長した動物の一種ではない。なぜなら、私たちは「滅びる べき」奇形、病気、退化、虚弱な人々を「余剰」として生かし続けているからだ。キリスト教は、平凡で病弱な、お人好しの動物を生み出した。 |

| https://x.gd/oTeL2 |

|

■リンク集

【文献】

ニーチェ年譜(http: //keikoyamamoto.com/nietzsche1-1.htm およびウィキペディア(日本語)による)

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099