「人種」と知性をめぐる論争史

History of the race and intelligence controversy

☆ 人種と知能論争の歴史は、人種と知能の研究において遭遇する集団間の差異を説明する可能性についての論争の歴史的展開に関わるものである。第一次世界大戦 の頃にIQテストが始まって以来、さまざまな集団の平均点の間に差があることが観察され、それが主に環境的・文化的要因によるものなのか、それともまだ発 見されていない遺伝的要因によるものなのか、あるいは環境的要因と遺伝的要因という二分法が議論の枠組みとして適切なのかどうかが議論されてきた。今日、 遺伝は人種間のIQテストの成績の差を説明しないというのが科学的コンセンサスである(→「知能指数(IQ)」)。

このページのより新しいヴァージョンがあります→race_and_intelligence02.html

★︎近年の注目すべき論争としては『ベルカーブ』をめぐるレイシストとアンチレイシストの攻防▶︎包括適応度▶︎︎▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎

| The history of the race and intelligence controversy

concerns the historical development of a debate about possible

explanations of group differences encountered in the study of race and

intelligence. Since the beginning of IQ testing around the time of

World War I, there have been observed differences between the average

scores of different population groups, and there have been debates over

whether this is mainly due to environmental and cultural factors, or

mainly due to some as yet undiscovered genetic factor, or whether such

a dichotomy between environmental and genetic factors is the

appropriate framing of the debate. Today, the scientific consensus is

that genetics does not explain differences in IQ test performance

between racial groups.[1][2][3] Pseudoscientific claims of inherent differences in intelligence between races have played a central role in the history of scientific racism. In the late 19th and early 20th century, group differences in intelligence were often assumed to be racial in nature.[4] ・Apart from intelligence tests, research relied on measurements such as brain size or reaction times. By the mid-1940s most psychologists had adopted the view that environmental and cultural factors predominated. ・In the mid-1960s, physicist William Shockley sparked controversy by claiming there might be genetic reasons that black people in the United States tended to score lower on IQ tests than white people. ・In 1969 the educational psychologist Arthur Jensen published a long article with the suggestion that compensatory education could have failed to that date because of genetic group differences. ・A similar debate among academics followed the publication in 1994 of The Bell Curve by Richard Herrnstein and Charles Murray. Their book prompted a renewal of debate on the issue and the publication of several interdisciplinary books on the issue. ・A 1995 report from the American Psychological Association responded to the controversy, finding no conclusive explanation for the observed differences between average IQ scores of racial groups. ・More recent work by James Flynn, William Dickens and Richard Nisbett has highlighted the narrowing gap between racial groups in IQ test performance, along with other corroborating evidence that environmental rather than genetic factors are the cause of these differences.[5][6][7][8] |

人種と知能論争の歴史は、人種と知能の研究において遭遇す

る集団間の差異を説明する可能性についての論争の歴史的展開に関わるものである。第一次世界大戦の頃にIQテストが始まって以来、さまざまな集団の平均点

の間に差があることが観察され、それが主に環境的・文化的要因によるものなのか、それともまだ発見されていない遺伝的要因によるものなのか、あるいは環境

的要因と遺伝的要因という二分法が議論の枠組みとして適切なのかどうかが議論されてきた。今日、遺伝は人種間のIQテストの成績の差を説明しないというのが科学的コンセンサスである[1][2][3]。 人種間に固有の知能の差があるという疑似科学的主張は、科学的人種差別の歴史において中心的な役割を果たしてきた。19世紀後半から20世紀初頭にかけ て、知能の集団差はしばしば人種的なものであると仮定された[4]。 ・1940年代半ばまでには、ほとんどの心理学者が環境的・文化的要因が優勢であるとい う見解を採用していた。 ・1960年代半ば、物理学者のウィリアム・ショックレーは、アメリカの黒人が白人よりもIQテストで低い点数を取る傾向があるのは、遺伝的な理由があるかもしれないと主張し、論争を巻き起こした。 ・1969 年には、教育心理学者のアーサー・ジェンセンが、遺伝的な集団差のために代償教育が今日まで失敗してきた可能性を示唆する長い論文を発表した。 ・1994 年、リチャード・ハーンシュタインとチャールズ・マーレイによる『ベル・カーブ』が出版されると、学者たちの間で同様の議論が起こった。彼らの本をきっか けに、この問題に関する議論が再燃し、この問題に関する学際的な本が何冊か出版された。 ・1995年のアメリカ心理学会の報告書は、この論争に反論し、人種間の平均IQスコアの差について決定的な説明がないことを明らかにした。 ・ ジェームス・フリン、ウィリアム・ディケンズ、リチャード・ニスベットによる最近の研究では、IQテストの成績における人種間の差が縮小していることが強 調され、遺伝的要因よりもむしろ環境的要因がこれらの差の原因であることを裏付ける証拠も示されている[5][6][7][8]。 |

| History Early history  Jean-Baptiste

Belley, an elected member of the National Convention and the Council of

Five Hundred during the French First Republic, advocated for racial

intellectual equality. Jean-Baptiste

Belley, an elected member of the National Convention and the Council of

Five Hundred during the French First Republic, advocated for racial

intellectual equality.In the 18th century, debates surrounding the institution of slavery in the Americas hinged on the question of whether innate differences in intellectual capacity existed between races, in particular between black people and white people.[9] Some European philosophers and scientists, such as Voltaire, David Hume, Immanuel Kant, and Carl Linnaeus, either argued or simply presupposed that white people were intellectually superior.[10] Others, such as Henri Gregoire and Constantin de Chasseboeuf, argued that ancient Egypt had been a black civilization, and that it was therefore black people who had "discovered the elements of science and art, at a time when all other men were barbarous."[11] During the French Revolution, Jean-Baptiste Belley, an elected member of the National Convention and the Council of Five Hundred who had been born in Senegal, became a leading proponent of the idea of racial intellectual equality.[12] In 1785, Thomas Jefferson wrote of his "suspicion" that black people were "inferior to... whites in endowments both of body and mind."[11] However, in 1791, after corresponding with the free African-American polymath Benjamin Banneker, Jefferson wrote that he hoped to see such "instances of moral eminence so multiplied as to prove that the want of talents observed in them is merely the effect of their degraded condition, and not proceeding from any difference in the structure of the parts on which intellect depends."[13]  Samuel Morton, an American physician, used the study of human skulls to argue for racial differences in intelligence. Samuel Morton, an American physician, used the study of human skulls to argue for racial differences in intelligence.During the 19th and early 20th centuries, the idea that there are differences in the brain structures and brain sizes of different races, and that this implied differences in intelligence, was a popular topic, inspiring numerous typological studies.[14][15][16] Samuel Morton's Crania Americana, published in 1839, was one such study, arguing that intelligence was correlated with brain size and that both of these metrics varied between racial groups.[17]  Francis Galton, an English eugenicist, argued that genius was unevenly distributed among racial groups. Through the publication of his book Hereditary Genius in 1869, polymath Francis Galton spurred interest in the study of mental abilities, particularly as they relate to heredity and eugenics.[18][19] Lacking the means to directly measure intellectual ability, Galton attempted to estimate the intelligence of various racial and ethnic groups. He based his estimations on observations from his and others' travels, the number and quality of intellectual achievements of different groups, and on the percentage of "eminent men" in each of these groups. Galton hypothesized that intelligence was normally distributed in all racial and ethnic groups, and that the means of these distributions varied between the groups. In Galton's estimation, ancient Attic Greeks had been the people with the highest incidence of genius intelligence, followed by contemporary Englishmen, with black Africans at a lower level, and Australian Aborigines lower still.[20] He did not specifically study Jews, but remarked that "they appear to be rich in families of high intellectual breeds".[20]  Autodidact and abolitionist Frederick Douglass served as a high-profile counterexample to myths of black intellectual inferiority. Meanwhile, the American abolitionist and escaped slave Frederick Douglass had gained fame for his oratory and incisive writings,[21] despite having learned to read as a child largely through surreptitious observation.[22] Accordingly, he had been described by abolitionists as a living counter-example to slaveholders' arguments that people of African descent lacked the intellectual capacity to function as independent American citizens.[23][24] His eloquence was so notable that some found it hard to believe he had once been a slave.[25] In the later years of his life, one newspaper described him as "a bright example of the capability of the colored race, even under the blighting influence of slavery, from which he emerged and became one of the distinguished citizens of the country."[26] Other abolitionists of the 19th century continued to advance the theme of ancient Egypt as a black civilization as an argument against racism. On this basis, scholar and diplomat Alexander Hill Everett argued in his 1927 book America: "With regard to the intellectual capabilities of the African race, it may be observed that Africa was once the nursery of science and literature, and it was from thence that they were disseminated among the Greeks and Romans."[27] Similarly, the philosopher John Stuart Mill posited in his 1849 essay "On the Negro Question" that "it was from Negroes, therefore, that the Greeks learnt their first lessons in civilization."[28][27] In 1895, R. Meade Bache of the University of Pennsylvania published an article in Psychological Review claiming that reaction time increases with evolution.[29] Bache supported this claim with data showing slower reaction times among White Americans when compared with those of Native Americans and African Americans, with Native Americans having the quickest reaction time. He hypothesized that the slow reaction time of White Americans was to be explained by their possessing more contemplative brains which did not function well on tasks requiring automatic responses. This was one of the first examples of modern "scientific racism", in which a veneer of science was used to bolster belief in the superiority of a particular race.[30][31] |

沿革 初期の歴史  フランス第一共和政時代、国民公会および五百人評議会の選出議員であったジャン=バティスト・ベルリーは、人種間の知的平等を提唱した。 フランス第一共和政時代、国民公会および五百人評議会の選出議員であったジャン=バティスト・ベルリーは、人種間の知的平等を提唱した。18世紀、アメリカ大陸における奴隷制度をめぐる議論は、人種間、特に黒人と白人の間に生まれつきの知的能力の差が存在するかどうかという問題に端を発し ていた[9]。ヴォルテール、デイヴィッド・ヒューム、イマヌエル・カント、カール・リンネのようなヨーロッパの哲学者や科学者の中には、白人の方が知的 能力が優れていると主張したり、単にそれを前提としたりする者もいた。 [10] アンリ・グレゴワールやコンスタンタン・ド・シャスブーフのように、古代エジプトは黒人文明であり、それゆえに「他のすべての人間が野蛮であった時代に、 科学と芸術の要素を発見した」のは黒人であったと主張する者もいた[11]。フランス革命期には、セネガル生まれの国民公会と五百人評議会の選出議員で あったジャン=バティスト・ベルレーが、人種的知的平等の思想の主要な支持者となった[12]。 1785年、トーマス・ジェファーソンは、黒人は「心身ともに白人より劣っている」という「疑念」を記した。 「しかし1791年、アフリカ系アメリカ人の自由主義者である博学者ベンジャミン・バネカーと文通をした後、ジェファーソンは「彼らに見られる才能の欠如 は、単に彼らの劣悪な状態の影響に過ぎず、知性が依存する部分の構造の違いから生じたものではないことを証明するような、道徳的に卓越した事例が増える」 ことを望んでいると書いている[13]。  アメリカの医師であるサミュエル・モートンは、人間の頭蓋骨の研究を用いて、知能における人種間の差異を主張した。 アメリカの医師であるサミュエル・モートンは、人間の頭蓋骨の研究を用いて、知能における人種間の差異を主張した。19世紀から20世紀初頭にかけて、人種によって脳の構造や脳の大きさに違いがあり、それが知能の違いを示唆しているという考え方が流行し、多くの類型論 的研究が行われた[14][15][16]。1839年に出版されたサミュエル・モートンの『クラニア・アメリカーナ』はそのような研究の一つであり、知 能は脳の大きさと相関関係にあり、これらの指標はどちらも人種によって異なると主張していた[17]。  イギリスの優生学者であるフランシス・ガルトン(ゴールトン)は、天才は人種間で不均等に分布していると主張した。 1869年に著書『Hereditary Genius(天才の遺伝)』を出版し、多神教徒フランシス・ガルトンは、特に遺伝や優生学に関連する精神能力の研究への関心を高めた[18][19]。 知的能力を直接測定する手段を欠いていたガルトンは、様々な人種や民族の知能を推定しようと試みた。彼は、彼や他の人々の旅行からの観察、異なる集団の知 的業績の数と質、そしてそれぞれの集団における「傑出した人物」の割合に基づいて推定を行った。ガルトンは、知能はすべての人種・民族集団で正規分布して おり、その平均値は集団によって異なると仮定した。ガルトンの推定では、古代のアッティカ・ギリシャ人が最も天才的な知能を持つ人々であり、次いで現代の イギリス人、アフリカ系黒人はより低いレベル、オーストラリアのアボリジニーはさらに低いレベルであった[20]。彼はユダヤ人については特に研究してい ないが、「彼らは高い知的品種を持つ家系に恵まれているようだ」と述べている[20]。  独学者であり奴隷廃止運動家であったフレデリック・ダグラスは、黒人の知的劣等性神話に対する有名な反例となった。 一方、アメリカの奴隷廃止論者であり逃亡奴隷であったフレデリック・ダグラスは、子供の頃に主に密かな観察によって文字を学んだにもかかわらず、その弁舌 と鋭い文章[21]で名声を博していた。 [23][24]彼の雄弁さは、彼がかつて奴隷であったとは信じがたいほど注目に値するものであった[25]。 晩年、ある新聞は彼を「奴隷制という殺伐とした影響下にあったとしても、有色人種の能力を示す輝かしい見本であり、そこから彼は立ち上がり、この国の傑出 した市民の一人となった」と評した[26]。 19世紀の他の奴隷廃止論者たちは、人種差別に反対する論拠として、古代エジプトが黒人文明であったというテーマを掲げ続けた。これに基づいて、学者で外 交官のアレクサンダー・ヒル・エヴェレットは1927年の著書『アメリカ』で次のように主張した。「アフリカ民族の知的能力に関しては、アフリカがかつて 科学と文学の苗床であったことが観察され、そこからギリシャ人とローマ人の間にそれらが広まったことが観察されよう。 「同様に、哲学者のジョン・スチュアート・ミルは1849年のエッセイ「黒人問題について」の中で、「それゆえ、ギリシャ人が文明の最初の教訓を学んだの は黒人からであった」と述べている[28][27]。 1895年、ペンシルバニア大学のR.ミード・バチェは『心理学評論』誌に反応時間は進化とともに長くなると主張する論文を発表した。彼は、白人アメリカ 人の反応時間が遅いのは、自動的な反応を必要とする作業ではうまく機能しない、より思索的な脳を持っているからだと仮説を立てた。これは現代の「科学的人 種差別」の最初の例のひとつであり、特定の人種の優越性に対する信念を強化するために科学の見かけが利用された[30][31]。 |

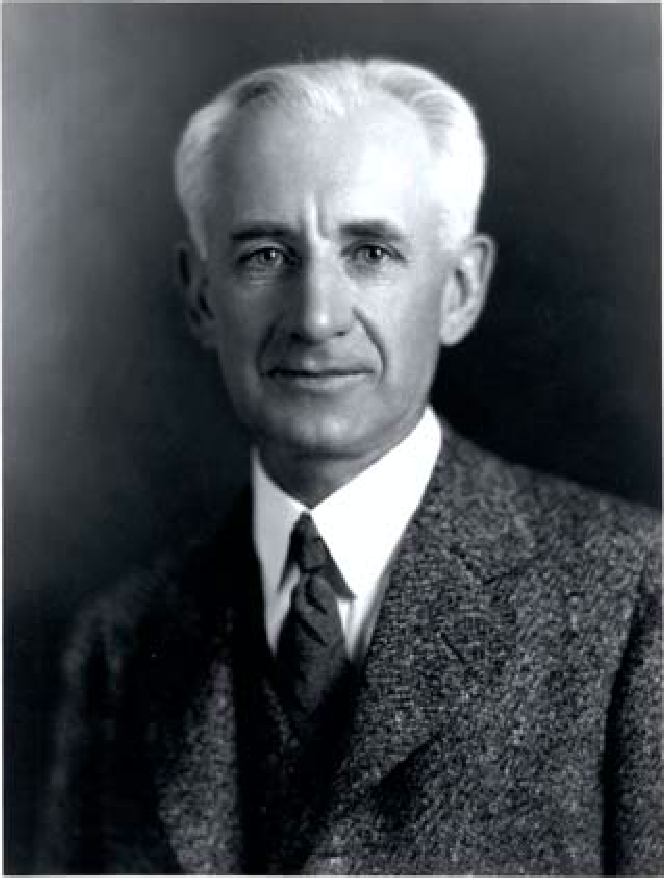

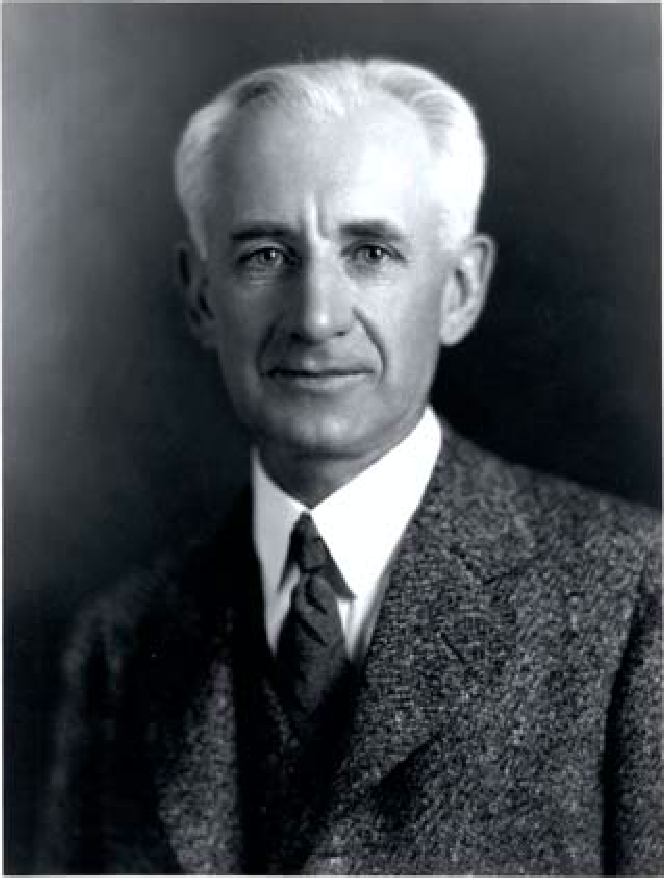

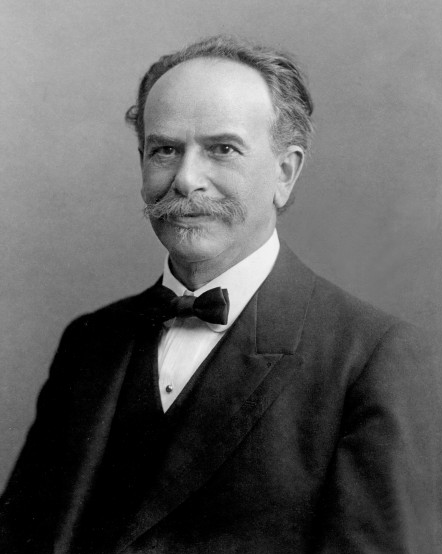

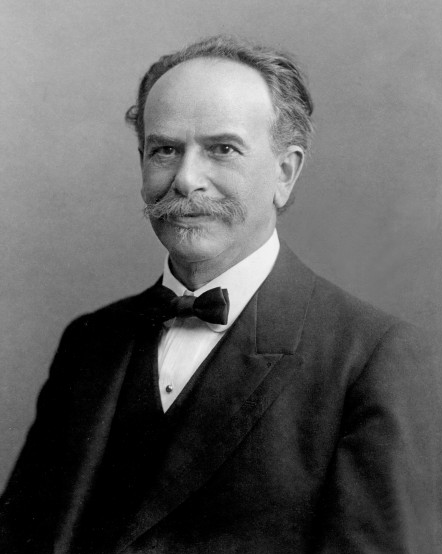

1900–1920 Sociologist W. E. B. Du Bois argued that black populations just as much as white ones naturally give rise to what he termed a "talented tenth" of intellectually gifted individuals. In 1903, the pioneering African-American sociologist W. E. B. Du Bois published his landmark collection of essays The Souls of Black Folk in defense of the inherent mental capacity and equal humanity of black people. According to Manning Marable, this book "helped to create the intellectual argument for the black freedom struggle in the twentieth century. 'Souls' justified the pursuit of higher education for Negroes and thus contributed to the rise of the black middle class."[32] In contrast to other civil rights leaders like Booker T. Washington, who advocated for incremental progress and vocational education as a way for black Americans to demonstrate the virtues of "industry, thrift, intelligence and property" to the white majority, Du Bois advocated for black schools to focus more on liberal arts and academic curriculum (including the classics, arts, and humanities), because liberal arts were required to develop a leadership elite.[33] Du Bois argued that black populations just as much as white ones naturally give rise to what he termed a "talented tenth" of intellectually gifted individuals.[34][35] At the same time, the discourse of scientific racism was accelerating.[36] In 1910 the sociologist Howard W. Odum published his book Mental and Social Traits of the Negro, which described African-American students as "lacking in filial affection, strong migratory instincts, and tendencies; little sense of veneration, integrity or honor; shiftless, indolent, untidy, improvident, extravagant, lazy, lacking in persistence and initiative and unwilling to work continuously at details. Indeed, experience with the Negro in classrooms indicates that it is impossible to get the child to do anything with continued accuracy, and similarly in industrial pursuits, the Negro shows a woeful lack of power of sustained activity and constructive conduct."[37][38] As the historian of psychology Ludy T. Benjamin explains, "with such prejudicial beliefs masquerading as facts," it was at this time that educational segregation on the basis of race was imposed in some states.[39][18]  Psychologist Lewis Terman, adapted the Stanford-Binet intelligence test and used it to argue for racial differences in intelligence. The first practical intelligence test was developed between 1905 and 1908 by Alfred Binet in France for school placement of children. Binet warned that results from his test should not be assumed to measure innate intelligence or used to label individuals permanently.[40] In 1916 Binet's test was translated into English and revised by Lewis Terman (who introduced IQ scoring for the test results) and published under the name Stanford–Binet Intelligence Scales. Terman wrote that Mexican-Americans, African-Americans, and Native Americans have a mental "dullness [that] seems to be racial, or at least inherent in the family stocks from which they come."[41] He also argued for a higher frequency of so-called "morons" among non-white American racial groups, and concluded that there were "enormously significant racial differences in general intelligence" which could not be remedied by education.[42]  Psychologist Robert Yerkes argued that immigration from Southern and Eastern Europe could decrease the average IQ of Americans. In 1916 a team of psychologists, led by Robert Yerkes and including Terman and Henry H. Goddard, adapted the Stanford-Binet tests as multiple-choice group tests for use by the US army. In 1919, Yerkes devised a version of this test for civilians, the National Intelligence Test, which was used in all levels of education and in business.[43] Like Terman, Goddard had argued in his book, Feeble-mindedness: Its Causes and Consequences (1914), that "feeble-mindedness" was hereditary; and in 1920 Yerkes in his book with Yoakum on the Army Mental Tests described how they "were originally intended, and are now definitely known, to measure native intellectual ability". Both Goddard and Terman argued that the feeble-minded should not be allowed to reproduce. In the US, however, independently and prior to the IQ tests, there had been political pressure for such eugenic policies, to be enforced by sterilization; in due course IQ tests were later used as justification for sterilizing the mentally retarded.[44][45] Early IQ tests were also used to argue for limits to immigration to the US. Already in 1917, Goddard reported on the low IQ scores of new arrivals at Ellis Island. Yerkes argued on the basis of his army test scores that there were consistently lower IQ levels among those from Southern and Eastern Europe, which he suggested could lead to a decline in the average IQ of Americans if immigration from these regions were not limited.[46][47] |

1900-1920 社会学者のW・E・B・デュボイスは、白人と同様に黒人の集団にも、彼が「才能ある10分の1」と呼ぶ知的才能のある人々が自然に生まれると主張した。 1903年、アフリカ系アメリカ人の先駆的社会学者W・E・B・デュボア(デュボイス)は、黒人固有の精神能力と平等な人間性を擁護する画期的なエッセイ集『黒人の魂』 を出版した。マニング・マラブルによれば、この本は「20世紀における黒人の自由闘争の知的論拠を生み出すのに貢献した」。『魂』は黒人の高等教育の追求 を正当化し、黒人の中産階級の台頭に貢献した」[32]。ブッカー・T・ワシントンのような他の公民権運動の指導者たちが、黒人アメリカ人が「産業、倹 約、知性、財産」の美徳を白人多数派に示す方法として、漸進的な進歩や職業教育を提唱したのとは対照的に、デュボワは、リベラルアーツが指導的なエリート を育成するために必要であるとして、黒人学校はリベラルアーツやアカデミックなカリキュラム(古典、芸術、人文学を含む)にもっと重点を置くべきだと提唱 した。 [33]デュボワは、黒人の集団は白人の集団と同様に、彼が「才能ある10分の1」と呼ぶ知的才能のある個人を自然に生み出すと主張した[34] [35]。 同時に、科学的人種差別の言説は加速していた[36]。 1910年、社会学者ハワード・W・オーダムは著書『黒人の精神的・社会的特質』を出版し、アフリカ系アメリカ人の学生を「親愛の情、強い移住本能、傾向 に欠け、尊敬の念、誠実さ、名誉の感覚に乏しく、移り気で、不摂生で、片付けができず、不謹慎で、浪費家で、怠け者で、粘り強さと自発性に欠け、細部にわ たって継続的に努力する気がない」と評した。実際、教室で黒人と接した経験によれば、この子どもに継続的に正確に何かをさせることは不可能であり、同様に 工業的な追求においても、黒人は持続的な活動や建設的な行動をする力がひどく欠けていることを示している」[37][38]。心理学の歴史家ルディ・T・ ベンジャミンが説明するように、「このような偏見に満ちた信念が事実の仮面をかぶって」、この時期にいくつかの州で人種による教育分離が行われたのである [39][18]。  心理学者のルイス・ターマンは、スタンフォード・ビネー式知能検査を応用し、それを使って知能の人種差を論じた。 最初の実用的な知能検査は、1905年から1908年にかけてフランスのアルフレッド・ビネによって、子供の学校への編入のために開発された。1916 年、ビネのテストは英語に翻訳され、ルイス・ターマン(テスト結果にIQスコアリングを導入した)によって改訂され、スタンフォード・ビネ知能検査 (Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scales)という名前で出版された。ターマンは、メキシコ系アメリカ人、アフリカ系アメリカ人、ネイティブ・アメリカンには、「人種的な、あるいは少 なくとも彼らの出自である家系に固有の(と思われる)鈍感さ」があると書いている[41]。彼はまた、いわゆる「白痴」の頻度が非白人アメリカ人種集団の 間で高いことを主張し、教育では改善できない「一般的な知能における非常に大きな人種差」があると結論づけた[42]。  心理学者のロバート・ヤークスは、南ヨーロッパや東ヨーロッパからの移民がアメリカ人の平均IQを低下させる可能性があると主張していた。 1916年、ロバート・ヤーキスが率い、ターマンやヘンリー・H・ゴダードを含む心理学者のチームが、スタンフォード・ビネテストを多肢選択式の集団テス トとして米軍で使用できるようにした。1919年、ヤーケスはこのテストの民間人向けバージョンである全米知能テストを考案し、あらゆる教育レベルやビジ ネスで使用されるようになった[43]: 1920年、ヤークスはヨーカムとの共著『陸軍精神試験』において、「もともと意図されていたものであり、現在では確実に知られていることだが、生来の知 的能力を測定するためのものである」と述べている。ゴダードもターマンも、精神薄弱者の繁殖を認めるべきではないと主張した。しかしアメリカでは、IQテ ストとは無関係に、またIQテスト以前から、不妊手術によって強制される優生政策を求める政治的圧力があった。やがてIQテストは、後に精神遅滞者を不妊 手術する正当な理由として使われるようになった[44][45]。 初期のIQテストは、アメリカへの移民の制限を主張するためにも使われた。1917年にはすでに、ゴダードがエリス島で新入国者のIQスコアが低いことを 報告していた。ヤーケスは陸軍のテストのスコアに基づいて、南ヨーロッパと東ヨーロッパからの移民のIQレベルが一貫して低いことを主張し、これらの地域 からの移民を制限しなければアメリカ人の平均IQの低下につながる可能性を示唆した[46][47]。 |

| 1920–1960 In the 1920s, psychologists started questioning underlying assumptions of racial differences in intelligence; although not discounting them, the possibility was considered that they were on a smaller scale than previously supposed and also due to factors other than heredity. In 1924, Floyd Allport wrote in his book Social Psychology[48] that the French sociologist Gustave Le Bon was incorrect in asserting "a gap between inferior and superior species", and pointed to "social inheritance" and "environmental factors" as accounting for differences. Nevertheless, he suggested that: "the intelligence of the white race is of a more versatile and complex order than that of the black race. It is probably superior to that of the red or yellow races."[42] In 1923, in his book A study of American intelligence, Carl Brigham wrote that on the basis of the Yerkes army tests: "The decline in intelligence is due to two factors, the change in races migrating to this country, and to the additional factor of sending lower and lower representatives of each race." He concluded that: "The steps that should be taken to preserve or increase our present mental capacity must, of course, be dictated by science and not by political expediency. Immigration should not only be restrictive, but highly selective."[46] The Immigration Act of 1924 put these recommendations into practice, introducing quotas based on the 1890 census, prior to the waves of immigration from Poland and Italy. While Gould and Kamin argued that the psychometric claims of Nordic superiority had a profound influence on the institutionalization of the 1924 immigration law, other scholars have argued that "the eventual passage of the 'racist' immigration law of 1924 was not crucially affected by the contributions of Yerkes or other psychologists".[49][50][51] In 1929, Robert Woodworth, in his textbook Psychology: A Study of Mental Life,[52] made no claims about innate differences in intelligence between races, pointing instead to environmental and cultural factors. He considered it advisable to "suspend judgment and keep our eyes open from year to year for fresh and more conclusive evidence that will probably be discovered".[53]  Raymond Cattell, known for psychometric research into intrapersonal psychological structure, advocated that supposedly inferior races should be euthanized. In the 1930s, the English psychologist Raymond Cattell wrote three tracts, Psychology and Social Progress (1933), The Fight for Our National Intelligence (1937) and Psychology and the Religious Quest (1938). The second was published by the Eugenics Society, of which he had been a research fellow; it predicted the disastrous consequences of not stopping the decline in the average intelligence in Britain by one point per decade. In 1933, Cattell wrote that, of all the European races, the "Nordic race was the most evolved in intelligence and stability of temperament". He argued for "no mixture of bloods between racial groups" because "the resulting re-shuffling of impulses and psychic units throws together in each individual a number of forces which may be incompatible". He rationalised the "hatred and abhorrence ... for the Jewish practice of living in other nations instead of forming an independent self-sustained group of their own", referring to them as "intruders" with a "crafty spirit of calculation". He recommended a rigid division of races, referring to those suggesting that individuals be judged on their merits, irrespective of racial background, as "race-slumpers". He wrote that in the past, "the backward branches of the tree of mankind" had been lopped off as "the American Indians, the Black Australians, the Mauris and the negroes had been driven by bloodshed from their lands", unaware of "the biological rationality of that destiny". He advocated what he saw as a more enlightened solution: by birth control, by sterilization, and by "life in adapted reserves and asylums", where the "races which have served their turn [should] be brought to euthanasia." He considered blacks to be naturally inferior, on account of their supposedly "small skull capacity". In 1937, he praised the Third Reich for their eugenic laws and for "being the first to adopt sterilization together with a policy of racial improvement". In 1938, after newspapers had reported on the segregation of Jews into ghettos and concentration camps, he commented that the rise of Germany "should be welcomed by the religious man as reassuring evidence that in spite of modern wealth and ease, we shall not be allowed ... to adopt foolish social practices in fatal detachment from the stream of evolution". In late 1937, Cattell moved to the US on the invitation of the psychologist Edward Thorndike of Columbia University, also involved in eugenics. He spent the rest of his life there as a research psychologist, devoting himself after retirement to devising and publicising a refined version of his ideology from the 1930s that he called beyondism.[54][55][56]  Franz Boas, regarded as the father of anthropology in the US,[57] had a lasting influence on the work of Otto Klineberg and his generation. In 1935, Otto Klineberg wrote two books, Negro Intelligence and Selective Migration and Race Differences, dismissing claims that African Americans in the northern states were more intelligent than those in the south. He argued that there was no scientific proof of racial differences in intelligence and that this should not therefore be used as a justification for policies in education or employment.[58][59] The hereditarian view began to change in the 1920s in reaction to excessive eugenicist claims regarding abilities and moral character, and also due to the development of convincing environmental arguments.[60] In the 1940s many psychologists, particularly social psychologists, began to argue that environmental and cultural factors, as well as discrimination and prejudice, provided a more probable explanation of disparities in intelligence. According to Franz Samelson, this change in attitude had become widespread by then,[61] with very few studies in race differences in intelligence, a change brought out by an increase in the number of psychologists not from a "lily-white ... Anglo-Saxon" background but from Jewish backgrounds. Other factors that influenced American psychologists were the economic changes brought about by the depression and the reluctance of psychologists to risk being associated with the Nazi claims of a master race.[62] The 1950 race statement of UNESCO, prepared in consultation with scientists including Klineberg, created a further taboo against conducting scientific research on issues related to race.[63] Adolf Hitler banned IQ testing for being "Jewish" as did Joseph Stalin for being "bourgeois".[64] |

1920-1960 1920年代になると、心理学者たちは知能における人種間の差の根底にある仮定に疑問を呈し始めた。それを否定するわけではないが、以前考えられていたよ りも規模が小さく、また遺伝以外の要因によるものである可能性が考えられた。1924年、フロイド・オールポートはその著書『社会心理学』[48]の中 で、フランスの社会学者ギュスターヴ・ル・ボンが「劣等種と優等種の間に隔たりがある」と主張したのは誤りであり、違いを説明するものとして「社会的遺 伝」と「環境要因」を指摘したと書いている。とはいえ、彼はこう示唆した: 「白人の知性は黒人の知性よりも多彩で複雑である。それはおそらく赤色人種や黄色人種よりも優れている」[42]。 1923年、カール・ブリガムはその著書『A study of American intelligence』の中で、ヤーキース陸軍のテストに基づいて次のように書いている: 「知能の低下は2つの要因によるもので、この国に移住してくる人種の変化と、各人種の代表者がどんどん低くなっているという付加的な要因によるものであ る」。彼はこう結論づけた: 「現在の精神能力を維持し、あるいは向上させるためにとるべき措置は、もちろん、政治的な都合ではなく、科学によって指示されなければならない。移民は制 限的であるだけでなく、高度に選択的であるべきである」[46]。1924年の移民法は、ポーランドとイタリアからの移民の波に先立ち、1890年の国勢 調査に基づく割当を導入し、これらの勧告を実践に移した。グールドとカミンは、北欧人の優位性に関する心理測定学的な主張が1924年の移民法の制度化に 大きな影響を与えたと主張したが、他の学者は「1924年の『人種差別的』移民法の最終的な成立は、ヤーキーズや他の心理学者の貢献によって決定的な影響 を受けたわけではない」と主張している[49][50][51]。 1929年、ロバート・ウッドワースはその教科書『心理学』において、次のように述べている: A Study of Mental Life][52]では、人種間の知能の生得的な差異については主張せず、代わりに環境的・文化的要因を指摘していた。彼は「判断を保留し、おそらく発見 されるであろう新鮮でより決定的な証拠を求めて、年ごとに目を見開いておく」ことが望ましいと考えていた[53]。  レイモンド・キャッテルは、個人内心理構造に関する心理測定学的研究で知られており、劣っていると思われる人種は安楽死させるべきだと提唱していた。 1930年代、イギリスの心理学者レイモンド・キャッテルは、『心理学と社会進歩』(1933年)、『われわれの国民的知性のための戦い』(1937 年)、『心理学と宗教的探求』(1938年)という3つの小冊子を書いた。2番目の小冊子は、彼が研究員を務めていた優生学協会が出版したもので、イギリ スの平均知能が10年に1ポイントずつ低下するのを止めなければ、悲惨な結果になると予言していた。1933年、キャッテルはヨーロッパのあらゆる人種の 中で、「北欧人種は知能と気質の安定性において最も進化している」と書いた。その結果、衝動や精神的な単位が入れ替わり、各個人の中に相容れない多くの力 が混在することになる」からである。彼は、「ユダヤ人が自分たちで独立した自立した集団を形成する代わりに、他国に住み着くという習慣に対する憎悪と嫌 悪」を合理化し、彼らを「狡猾な打算精神」を持つ「侵入者」と呼んだ。彼は人種を厳格に分けることを推奨し、人種的背景とは無関係に個人の能力で判断する ことを提案する人々を「人種差別主義者」と呼んだ。彼は、過去に「アメリカ・インディアン、オーストラリア黒人、モーリス人、黒人」が「その運命の生物学 的合理性」に気づかず、流血によって土地を追われたように、「人類の木の後方の枝」が切り落とされたと書いた。彼は、より賢明な解決法として、避妊手術、 「適応された保護区や精神病院での生活」を提唱した。彼は、黒人は「頭蓋骨の容量が小さい」という理由で、生まれつき劣っていると考えていた。1937 年、彼は第三帝国の優生保護法を賞賛し、「人種改良政策とともに不妊手術を最初に採用した」と述べた。1938年、ユダヤ人がゲットーや強制収容所に隔離 されたことが新聞で報道された後、彼はドイツの台頭を「宗教家は、近代的な富と安楽にもかかわらず、進化の流れから致命的に切り離された愚かな社会的慣習 を採用することは許されないという心強い証拠として歓迎すべきだ」とコメントした。1937年末、キャッテルは、同じく優生学に携わっていたコロンビア大 学の心理学者エドワード・ソーンダイクの招きで渡米した。彼はそこで研究心理学者として残りの人生を過ごし、引退後はビヨンドイズムと呼ばれる1930年 代からのイデオロギーの改良版の考案と公表に専念した[54][55][56]。  フランツ・ボアズはアメリカにおける人類学の父とみなされており[57]、オットー・クラインバーグとその世代の仕事に永続的な影響を与えた。 1935年、オットー・クラインバーグは『Negro Intelligence(黒人の知能)』と『Selective Migration and Race Differences(選択的移住と人種差)』という2冊の本を書き、北部の州のアフリカ系アメリカ人は南部の州のアフリカ系アメリカ人よりも知能が高 いという主張を退けた。彼は、知能に人種差があることを科学的に証明するものはなく、それゆえに教育や雇用における政策の正当化としてそれを用いるべきで はないと主張した[58][59]。 1940年代には、多くの心理学者、特に社会心理学者が、差別や偏見だけでなく環境や文化的要因も知能の格差を説明する要因であると主張し始めた。フラン ツ・サメルソンによれば、このような態度の変化はそのころには広まっており[61]、知能の人種差に関する研究はほとんど行われていなかった。アングロ・ サクソン系」ではなく、ユダヤ系の背景を持つ心理学者の増加によってもたらされた変化であった。アメリカの心理学者に影響を与えた他の要因は、恐慌によっ てもたらされた経済的な変化と、ナチスの支配者民族の主張と関連づけられる危険を冒すことを心理学者が嫌ったことであった[62]。クラインバーグを含む 科学者との協議によって作成された1950年のユネスコの人種声明は、人種に関連する問題について科学的研究を行うことに対するさらなるタブーを作り出し た[63]。 |

1960–1980 William Shockley, the Nobel laureate in physics, suggested that the decline in the average IQ in the US could be solved by eugenics.[65] In 1965 William Shockley, Nobel laureate in physics and professor at Stanford University, made a public statement at the Nobel conference on "Genetics and the Future of Man" about the problems of "genetic deterioration" in humans caused by "evolution in reverse". He claimed social support systems designed to help the disadvantaged had a regressive effect. Shockley subsequently claimed the most competent American population group were the descendants of original European settlers, because of the extreme selective pressures imposed by the harsh conditions of early colonialism.[66] Speaking of the "genetic enslavement" of African Americans, owing to an abnormally high birth rate, Shockley discouraged improved education as a remedy, suggesting instead sterilization and birth control. In the following ten years he continued to argue in favor of this position, claiming it was not based on prejudice but "on sound statistics". Shockley's outspoken public statements and lobbying brought him into contact with those running the Pioneer Fund who subsequently, through the intermediary Carleton Putnam, provided financial support for his extensive lobbying activities in this area, reported widely in the press. With the psychologist and segregationist R. Travis Osborne as adviser, he formed the Foundation for Research and Education on Eugenics and Dysgenics (FREED). Although its stated purpose was "solely for scientific and educational purposes related to human population and quality problems", FREED mostly acted as a lobbying agency for spreading Shockley's ideas on eugenics.[67][68]  Wickliffe Draper, founder of the Pioneer Fund The Pioneer Fund[69] had been set up by Wickliffe Draper in 1937 with one of its two charitable purposes being to provide aid for "study and research into the problems of heredity and eugenics in the human race" and "into the problems of race betterment with special reference to the people of the United States". From the late fifties onwards, following the 1954 Supreme Court decision on segregation in schools, it supported psychologists and other scientists in favour of segregation. All of these ultimately held academic positions in the Southern states, notably Henry E. Garrett (head of psychology at Columbia University until 1955), Wesley Critz George, Frank C.J. McGurk, R. Travis Osborne and Audrey Shuey, who in 1958 wrote The Testing of Negro Intelligence, demonstrating "the presence of native differences between Negroes and whites as determined by intelligence tests".[70][71][72] In 1959 Garrett helped to found the International Association for the Advancement of Ethnology and Eugenics, an organisation promoting segregation. In 1961 he blamed the shift away from hereditarianism, which he described as the "scientific hoax of the century", on the school of thought –the "Boas cult" – promoted by his former colleagues at Columbia, notably Franz Boas and Otto Klineberg, and more generally "Jewish organizations", most of whom "belligerently support the egalitarian dogma which they accept as having been 'scientifically' proved". He also pointed to Marxist origins in this shift, writing in a pamphlet, Desegregation: Fact and hokum, that: "It is certain that the Communists have aided in the acceptance and spread of egalitarianism although the extent and method of their help is difficult to assess. Egalitarianism is good Marxist doctrine, not likely to change with gyrations in the Kremlin line." In 1951 Garrett had even gone as far as reporting Klineberg to the FBI for advocating "many Communistic theories", including the idea that "there are no differences in the races of mankind".[73][74][75][76][77][78] One of Shockley's lobbying campaigns involved the educational psychologist, Arthur Jensen, of the University of California, Berkeley (UC Berkeley). Although earlier in his career Jensen had favored environmental rather than genetic factors as the explanation of race differences in intelligence, he had changed his mind during 1966-1967 when he was at the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences at Stanford. Here Jensen met Shockley and through him received support for his research from the Pioneer Fund.[70][79] Although Shockley and Jensen's names were later to become linked in the media,[70][80] Jensen does not mention Shockley as an important influence on his thought in his subsequent writings;[81][82] rather he describes as decisive his work with Hans Eysenck. He also mentions his interest in the behaviorist theories of Clark L. Hull which he says he abandoned largely because he found them to be incompatible with experimental findings during his years at Berkeley.[83]  Arthur Jensen, professor of educational psychology at UC Berkeley, wrote the 1969 article on intelligence that became one of the most controversial articles in the history of psychology. In a 1968 article published in Disadvantaged Child, Jensen questioned the effectiveness of child development and antipoverty programs, writing: "As a social policy, avoidance of the issue could be harmful to everyone in the long run, especially to future generations of Negroes, who could suffer the most from well-meaning but misguided and ineffective attempts to improve their lot."[84] In 1969 Jensen wrote a long article in the Harvard Educational Review, "How Much Can We Boost IQ and Scholastic Achievement?"[85] In his article, 123 pages long, Jensen insisted on the accuracy and lack of bias in intelligence tests, stating that the absolute quantity g that they measured, the general intelligence factor, first introduced by the English psychologist Charles Spearman in 1904, "stood like a Rock of Gibraltar in psychometrics". He stressed the importance of biological considerations in intelligence, commenting that "the belief in the almost infinite plasticity of intellect, the ostrich-like denial of biological factors in individual differences, and the slighting of the role of genetics in the study of intelligence can only hinder investigation and understanding of the conditions, processes, and limits through which the social environment influences human behavior." He argued at length that, contrary to environmentalist orthodoxy, intelligence was partly dependent on the same genetic factors that influence other physical attributes. More controversially, he briefly speculated that the difference in performance at school between blacks and whites might have a partly genetic explanation, commenting that there were "various lines of evidence, no one of which is definitive alone, but which, viewed all together, make it a not unreasonable hypothesis that genetic factors are strongly implicated in the average Negro-white intelligence difference. The preponderance of the evidence is, in my opinion, less consistent with a strictly environmental hypothesis than with a genetic hypothesis, which, of course, does not exclude the influence of environment or its interaction with genetic factors."[86][87] He advocated the allocation of educational resources according to merit and insisted on the close correlation between intelligence and occupational status, arguing that "in a society that values and rewards individual talent and merit, genetic factors inevitably take on considerable importance." Concerned that the average IQ in the US was inadequate to answer the increasing needs of an industrialised society, he predicted that people with lower IQs would become unemployable while at the same time there would be an insufficient number with higher IQs to fill professional posts. He felt that eugenic reform would prevent this more effectively than compensatory education, surmising that "the technique for raising intelligence per se in the sense of g, probably lie more in the province of biological science than in psychology or education". He pointed out that intelligence and family size were inversely correlated, particularly amongst the black population, so that the current trend in average national intelligence was dysgenic rather than eugenic. As he wrote, "Is there a danger that current welfare policies, unaided by eugenic foresight, could lead to the genetic enslavement of a substantial segment of our population? The fuller consequences of our failure seriously to study these questions may well be judged by future generations as our society's greatest injustice to Negro Americans." He concluded by emphasizing the importance of child-centered education. Although a tradition had developed for the exclusive use of cognitive learning in schools, Jensen argued that it was not suited to "these children's genetic and cultural heritage": although capable of associative learning and memorization ("Level I" ability), they had difficulties with abstract conceptual reasoning ("Level II" ability). He felt that in these circumstances the success of education depended on exploiting "the actual potential learning that is latent in these children's patterns of abilities". He suggested that, in order to ensure equality of opportunity, "schools and society must provide a range and diversity of educational methods, programs and goals, and of occupational opportunities, just as wide as the range of human abilities."[88][89][90] Later, writing about how the article came into being, Jensen said that the editors of the Review had specifically asked him to include his view on the heritability of race differences, which he had not previously published. He also maintains that only five percent of the article touched on the topic of race difference in IQ.[83] Cronbach (1975) also gave a detailed account of how the student editors of Harvard Educational Review commissioned and negotiated the content of Jensen's article.[91][92] Many academics have given commentaries on what they considered to be the main points of Jensen's article and the subsequent books in the early 1970s that expanded on its content. According to Jencks & Phillips (1998), in his article Jensen had argued "that educational programs for disadvantaged children initiated as the War on Poverty had failed, and the black-white race gap probably had a substantial genetic component." They summarised Jensen's argument as follows:[93] "Most of the variation in black-white scores is genetic" "No one has advanced a plausible environmental explanation for the black-white gap" "Therefore it is more reasonable to assume that part of the black-white gap is genetic in origin" According to Loehlin, Lindzey & Spuhler (1975), Jensen's article defended 3 claims:[94][page needed] IQ tests provide accurate measurements of a real human ability that is relevant in many aspects of life. Intelligence, as measured by IQ tests, is highly (about 80%) heritable and parents with low IQs are much more likely to have children with low IQs Educational programs have been unable to significantly change the intelligence of individuals or groups. According to Webster (1997), the article claimed "a correlation between intelligence, measured by IQ tests, and racial genes". He wrote that Jensen, based on empirical evidence, had concluded that "black intelligence was congenitally inferior to that of whites"; that "this partly explains unequal educational achievements"; and that, "because a certain level of underachievement was due to the inferior genetic attributes of blacks, compensatory and enrichment programs are bound to be ineffective in closing the racial gap in educational achievements."[95] Several commentators mention Jensen's recommendations for schooling:[96][page needed] according to Barry Nurcombe,[97] Jensen's own research suggests that IQ tests amalgamate two forms of thinking which are hierarchically related but which become differentially distributed in the population according to SES: level 1 and level 2, associative learning and abstract thinking (g), respectively. Blacks do as well as whites on tests of associative learning, but they fall behind on abstract thinking. The educational system should attend to this discrepancy and derive a more pluralistic approach. The current system puts minority groups at a marked disadvantage, since it overemphasizes g-type thinking. Jensen had already suggested in the article that initiatives like the Head Start Program were ineffective, writing in the opening sentence, "Compensatory education has been tried and it apparently has failed."[98] Other experts in psychometrics, such as Flynn (1980) and Mackintosh (1998), have given accounts of Jensen's theory of Level I and Level II abilities, which originated in this and earlier articles. As the historian of psychology William H. Tucker commented, Jensen's question is leading: "Is there a danger that current welfare policies, unaided by eugenic foresight, could lead to the genetic enslavement of a substantial segment of our population? The fuller consequences of our failure seriously to study these questions may well be judged by future generations as our society's greatest injustice to Negro Americans". Tucker noted that it repeats Shockley's phrase "genetic enslavement", which proved later to be one of the most inflammatory statements in the article.[89] Shockley conducted a widespread publicity campaign for Jensen's article, supported by the Pioneer Fund. Jensen's views became widely known in many spheres. As a result, there was renewed academic interest in the hereditarian viewpoint and in intelligence tests. Jensen's original article was widely circulated and often cited; the material was taught in university courses over a range of academic disciplines. In response to his critics, Jensen wrote a series of books on all aspects of psychometrics. There was also a widespread positive response from the popular press — with The New York Times Magazine dubbing the topic "Jensenism" — and amongst politicians and policy makers.[70][99] In 1971 Richard Herrnstein wrote a long article on intelligence tests in The Atlantic for a general readership. Undecided on the issues of race and intelligence, he discussed instead score differences between social classes. Like Jensen he took a firmly hereditarian point of view. He also commented that the policy of equal opportunity would result in making social classes more rigid, separated by biological differences, resulting in a downward trend in average intelligence that would conflict with the growing needs of a technological society.[100]  Hans Eysenck, professor of psychology at the Institute of Psychiatry and Jensen's mentor, whose work has been largely discredited.[101][102][103] Jensen and Herrnstein's articles were widely discussed. Hans Eysenck defended the hereditarian point of view and the use of intelligence tests in "Race, Intelligence and Education" (1971), a pamphlet presenting Jensenism to a popular audience, and "The Inequality of Man" (1973). He was severely critical of anti-hereditarians whose policies he blamed for many of the problems in society. In the first book he wrote that, "All the evidence to date suggests the strong and indeed overwhelming importance of genetic factors in producing the great variety of intellectual differences which [are] observed between certain racial groups", adding in the second, that "for anyone wishing to perpetuate class or caste differences, genetics is the real foe".[104] "Race, Intelligence and Education" was immediately criticized in strong terms by IQ researcher Sandra Scarr as an "uncritical popularization of Jensen's ideas without the nuances and qualifiers that make much of Jensen's writing credible or at least responsible."[105] Later scholars have identified errors and suspected data manipulation in Eysenck's work.[101] An inquiry on behalf of King's College London found 26 of his papers to be "incompatible with modern clinical science".[106][102][107] Rod Buchanan, a biographer of Eysenck, has argued that 87 publications by Eysenck should be retracted.[103][101] Student groups and faculty at Berkeley and Harvard protested Jensen and Herrnstein with charges of racism. Two weeks after the appearance of Jensen's article, Students for a Democratic Society staged protests against Arthur Jensen on the campus of the University of California, Berkeley, chanting "Fight racism. Fire Jensen!"[92][108] Jensen himself states that he even lost his employment at Berkeley because of the controversy.[83] Similar campaigns were waged in London against Eysenck and in Boston against sociobiologist Edward Wilson. The attacks on Wilson were orchestrated by the Sociobiology Study Group, part of the left wing organization Science for the People, formed of 35 scientists and students, including the Harvard biologists Stephen J. Gould and Richard Lewontin, who both became prominent critics of hereditarian research in race and intelligence.[109][110] In 1972 50 academics, including the psychologists Jensen, Eysenck, and Herrnstein as well as five Nobel laureates, signed a statement entitled "Resolution on Scientific Freedom Regarding Human Behavior and Heredity", criticizing the climate of "suppression, punishment and defamation of scientists who emphasized the role of heredity in human behavior". In October 1973 a half-page advertisement entitled "Resolution Against Racism" appeared in The New York Times. With over 1000 academic signatories, including Lewontin, it condemned "racist research", denouncing in particular Jensen, Shockley and Herrnstein.[111][112] This was accompanied by commentaries, criticisms and denouncements from the academic community. Two issues of the Harvard Educational Review were devoted to critiques of Jensen's work by psychologists, biologists and educationalists. As documented by Wooldridge (1995), the main commentaries involved: population genetics (Richard Lewontin, Luigi Cavalli-Sforza, Walter Bodmer); the heritability of intelligence (Christopher Jencks, Mary Jo Bane, Leon Kamin, David Layzer); the possible inaccuracy of IQ tests as measures of intelligence (summarised in Jensen 1980, pp. 20–21); and sociological assumptions about the relationship between intelligence and income (Jencks and Bane).[113] More specifically, the Harvard biologist Richard Lewontin commented on Jensen's use of population genetics, writing that, "The fundamental error of Jensen's argument is to confuse heritability of character within a population with heritability between two populations."[114] Jensen denied making such a claim, saying that his argument was that high within-group heritability increased the probability of non-zero between-group heritability.[115] The political scientists Christopher Jencks and Mary Jo Bane, also from Harvard, recalculated the heritability of intelligence as 45% instead of Jensen's estimate of 80%; and they calculated that only about 12% of variation in income was due to IQ, so that in their view the connections between IQ and occupation were less clear than Jensen had suggested.[116] Ideological differences also emerged in the controversy. The circle of scientists around Lewontin and Gould rejected the research of Jensen and Herrnstein as "bad science". While not objecting to research into intelligence per se, they felt that this research was politically motivated and objected to the reification of intelligence: the treatment of the numerical quantity g as a physical attribute like skin color that could be meaningfully averaged over a population group. They claimed that this was contrary to the scientific method, which required explanations at a molecular level, rather than the analysis of a statistical artifact in terms of undiscovered processes in biology or genetics. In response to this criticism, Jensen later wrote: "... what Gould has mistaken for 'reification' is neither more nor less than the common practice in every science of hypothesizing explanatory models to account for the observed relationships within a given domain. Well known examples include the heliocentric theory of planetary motion, the Bohr atom, the electromagnetic field, the kinetic theory of gases, gravitation, quarks, Mendelian genes, mass, velocity, etc. None of these constructs exists as a palpable entity occupying physical space." He asked why psychology should be denied "the common right of every science to the use of hypothetical constructs or any theoretical speculation concerning causal explanations of its observable phenomena".[63][117][118]  Cyril Burt, the English educationalist whose disputed twin studies were used as data by Jensen in some of his early articles and books The academic debate also became entangled with the so-called "Burt Affair", because Jensen's article had partially relied on the 1966 twin studies of the British educational psychologist Sir Cyril Burt: shortly after Burt's death in 1971, there were allegations, prompted by research of Leon Kamin, that Burt had fabricated parts of his data, charges which have never been fully resolved.[119] Franz Samelson documents how Jensen's views on Burt's work varied over the years: Jensen was Burt's main defender in the US during the 1970s.[120] In 1983, following the publication in 1978 of Leslie Hearnshaw's official biography of Burt, Jensen changed his mind, "fully accept[ing] as valid ... Hearnshaw's biography" and stating that "of course [Burt] will never be exonerated for his empirical deceptions".[121] However, in 1992, he wrote that "the essence of the Burt affair ... [was] a cabal of motivated opponents, avidly aided by the mass media, to bash [Burt's] reputation completely",[122] a view repeated in an invited address on Burt before the American Psychological Association,[123] when he called into question Hearnshaw's scholarship.[124]  Trofim Lysenko who, as director of Soviet research in biology under Joseph Stalin, blocked research into genetics for ideological reasons Similar charges of a politically motivated campaign to stifle scientific research on racial differences, later dubbed "Neo-Lysenkoism", were frequently repeated by Jensen and his supporters.[125] Jensen (1972) bemoaned the fact that "a block has been raised because of the obvious implications for the understanding of racial differences in ability and achievement. Serious considerations of whether genetic as well as environmental factors are involved has been taboo in academic circles", adding that: "In the bizarre racist theories of the Nazis and the disastrous Lysenkoism of the Soviet Union under Stalin, we have seen clear examples of what happens when science is corrupted by subservience to political dogma."[126][127] After the appearance of his 1969 article, Jensen was later more explicit about racial differences in intelligence, stating in 1973 "that something between one-half and three-fourths of the average IQ differences between American Negroes and whites is attributable to genetic factors." He even speculated that the underlying mechanism was a "biochemical connection between skin pigmentation and intelligence" linked to their joint development in the ectoderm of the embryo. Although Jensen avoided any personal involvement with segregationists in the US, he did not distance himself from the approaches of journals of the far right in Europe, many of whom viewed his research as justifying their political ends. In an interview with Nation Europa, he said that some human races differed from one another even more than some animal species, claiming that a measurement of "genetic distance" between blacks and whites showed that they had diverged over 46,000 years ago. He also granted interviews to Alain de Benoist's French journal Nouvelle École and Jürgen Rieger's German journal Neue Anthropologie of which he later became a regular contributor and editor, apparently unaware of its political orientation owing to his poor knowledge of German.[128][129][130][131] The debate was further exacerbated by issues of racial bias that had already intensified through the 1960s because of civil rights concerns and changes in the social climate. In 1968 the Association of Black Psychologists (ABP) had demanded a moratorium on IQ tests for children from minority groups. After a committee set up by the American Psychological Association drew up guidelines for assessing minority groups, failing to confirm the claims of racial bias, Jackson (1975) wrote the following as part of a response on behalf of the ABP:[132] Psychological testing historically has been a quasi-scientific tool in the perpetuation of racism on all levels of scientific objectivity, it [testing] has provided a cesspool of intrinsically and inferentially fallacious data which inflates the egos of whites by demeaning Black people and threatens to potentiate Black genocide. Other professional academic bodies reacted to the dispute differently. The Society for the Psychological Study of Social Issues, a division of the American Psychological Society, issued a public statement in 1969 criticizing Jensen's research, declaring that, "To construct questions about complex behavior in terms of heredity versus environment is to oversimplify the essence and nature of human development and behavior." The American Anthropological Association convened a panel discussion in 1969 at its annual general meeting, shortly after the appearance of Jensen's paper, where several participants labelled his research as "racist".[92] Subsequently, the association issued an official clarification, stating that, "The shabby misuse of IQ testing in the support of past American racist policies has created understandable anxiety over current research on the inheritance of human intelligence. But the resulting personal attacks on a few scientists with unpopular views has had a chilling effect on the entire field of behavioral genetics and clouds public discussion of its implications." In 1975 the Genetics Society of America made a similarly cautious statement: "The application of the techniques of quantitative genetics to the analysis of human behavior is fraught with human complications and potential biases, but well-designed research on the genetic and environmental components of human psychological traits may yield valid and socially useful results and should not be discouraged."[133][134] |

1960-1980 ノーベル物理学賞受賞者ウィリアム・ショックレーは、アメリカにおける平均IQの低下は優生学によって解決できると示唆した[65]。 1965年、ノーベル物理学賞受賞者でスタンフォード大学教授のウィリアム・ショックリーは、「遺伝学と人間の未来」に関するノーベル会議において、「逆 進化」によって引き起こされる人間の「遺伝的劣化」の問題について公に声明を発表した。彼は、不利な立場にある人々を助けるために作られた社会的支援制度 が、逆行的な効果をもたらしていると主張した。その後ショックレーは、最も有能なアメリカの人口集団は、初期の植民地主義の過酷な条件によって課せられた 極端な選択圧のため、ヨーロッパ人入植者の子孫であると主張した[66]。異常に高い出生率のためにアフリカ系アメリカ人の「遺伝的奴隷化」について語っ たショックレーは、救済策として教育の改善を奨励せず、代わりに不妊手術と避妊を提案した。その後10年間、彼はこの立場を支持する主張を続け、それは偏 見に基づくものではなく「健全な統計に基づくもの」であると主張した。ショックレーの率直な発言とロビー活動は、パイオニア基金を運営する人々との接触を もたらし、彼らはその後、カールトン・パットナムを仲介者として、この分野での彼の広範なロビー活動に資金援助を行い、マスコミで大きく報道された。心理 学者で隔離論者のR・トラビス・オズボーンを顧問に迎え、彼は優生学・異性学研究教育財団(FREED)を設立した。その目的は「人間の人口と質の問題に 関連する科学的・教育的目的のためだけ」であったが、FREEDはほとんど優生学に関するショックレーの考えを広めるためのロビー活動機関として機能して いた[67][68]。  パイオニア基金の創設者ウィクリフ・ドレイパー パイオニア基金[69]は1937年にウィクリフ・ドレイパーによって設立され、その2つの慈善目的のひとつは「人類における遺伝と優生学の問題について の研究と調査」、そして「アメリカ国民に特に言及した人種改良の問題」への援助を提供することであった。50年代後半からは、1954年の学校分離に関す る最高裁判決を受けて、分離を支持する心理学者やその他の科学者を支援した。これらの人たちは皆、最終的には南部諸州で学問的地位に就いていた。特にヘン リー・E・ギャレット(1955年までコロンビア大学心理学部長)、ウェズリー・クリッツ・ジョージ、フランク・C・J・マクガーク、R. トラヴィス・オズボーン、オードリー・シューイは1958年に『The Testing of Negro Intelligence』を執筆し、「知能テストによって判断される黒人と白人の間の生来の相違の存在」を実証した[70][71][72]。1959 年、ギャレットは隔離を推進する組織である国際民族学優生学振興協会の設立に協力した。1961年、ギャレットは「世紀の科学的デマ」と評した遺伝主義か らの脱却を、コロンビア大学でのかつての同僚、特にフランツ・ボアスやオットー・クラインベルグが推進した「ボアス・カルト」と、より一般的には「ユダヤ 人組織」、そのほとんどが「『科学的に』証明されたと受け入れている平等主義的教義を好戦的に支持している」と非難した。彼はまた、このシフトにマルクス 主義的な起源があることを指摘し、パンフレット『人種差別撤廃』の中でこう書いている: というパンフレットの中でこう書いている: 「共産主義者が平等主義の受容と普及に手を貸したことは確かだが、その程度と方法を評価するのは難しい。平等主義はマルクス主義者の優れた教義であり、ク レムリン路線の動揺によって変わることはないだろう」。1951年、ギャレットは「人類の人種に違いはない」という考えを含む「多くの共産主義的理論」を 提唱しているとして、クラインバーグをFBIに通報するまでに至っていた[73][74][75][76][77][78]。 ショックレーのロビー活動のひとつに、カリフォルニア大学バークレー校(UCバークレー)の教育心理学者アーサー・ジェンセンが関わっていた。ジェンセン はそのキャリアの初期には、知能の人種差の説明として遺伝的要因よりもむしろ環境的要因を支持していたが、スタンフォード大学の行動科学高等研究センター にいた1966年から1967年の間に考えを変えていた。ジェンセンはここでショックレーと出会い、彼を通じてパイオニア基金から研究への支援を受けるこ とになる。彼はまたクラーク・L・ハルの行動主義理論への関心についても言及しているが、それはバークレー校に在籍していた時代に実験的知見と相容れない ことがわかったために放棄したことが主な理由であると述べている[83]。  カリフォルニア大学バークレー校の教育心理学教授であるアーサー・ジェンセンは、1969年に心理学史上最も物議を醸す論文の一つとなった知能に関する論文を書いた。 1968年に『Disadvantaged Child』誌に掲載された論文で、ジェンセンは子どもの発達と反貧困プログラムの効果に疑問を投げかけ、こう書いている: 「社会政策として、この問題の回避は長期的には誰にとっても有害であり、特に将来の世代の黒人にとって有害である。 123ページに及ぶこの論文でジェンセンは、知能検査の正確さと偏りのなさを主張し、知能検査が測定する絶対量g、すなわち1904年にイギリスの心理学 者チャールズ・スピアマンによって初めて導入された一般知能因子は、「心理測定学においてジブラルタルの岩のように立っている」と述べている。彼は知能に おける生物学的考察の重要性を強調し、「知性のほとんど無限の可塑性を信じ、個人差における生物学的要因をダチョウのように否定し、知能研究における遺伝 学の役割を軽んじることは、社会環境が人間の行動に影響を与える条件、プロセス、限界の調査と理解を妨げるだけである」とコメントした。彼は、環境主義者 の正統性に反して、知能は他の身体的属性に影響を与えるのと同じ遺伝的要因に部分的に依存していると長々と主張した。さらに物議を醸したのは、黒人と白人 の学校での成績の差は、部分的には遺伝的な説明もあるのではないかと短時間推測したことである。「さまざまな証拠があり、そのどれもが単独では決定的なも のではないが、総合的に見れば、黒人と白人の平均的な知能の差には遺伝的要因が強く関与しているというのは、不合理ではない仮説である。もちろん、環境の 影響や遺伝的要因との相互作用を排除するものではない」[86][87] 。彼は、アメリカの平均IQが工業化社会の増大するニーズに応えるには不十分であることを懸念し、IQの低い人々が失業するようになると同時に、IQの高 い人々が専門職のポストに就くには数が足りなくなると予測した。彼は、優生学的改革が代償教育よりも効果的にこれを防ぐだろうと考え、「gという意味での 知能そのものを高める技術は、おそらく心理学や教育学よりも生物科学の領域にある」と推測した。彼は、特に黒人の間では、知能と家族の人数が逆相関してい ることを指摘し、国民の平均知能の現在の傾向は、優生的というよりはむしろ異質なものであるとした。現在の福祉政策が、優生学的な先見の明に助けられるこ となく、人口のかなりの部分を遺伝的に奴隷化することにつながる危険性はないだろうか?このような問題を真剣に研究しなかった結果、後世の人々は、私たち の社会が黒人アメリカ人に対して犯した最大の不公正と判断するかもしれない。彼は最後に、子供中心の教育の重要性を強調した。学校では伝統的に認知学習が 専ら用いられてきたが、ジェンセンは、それは「この子どもたちの遺伝的・文化的遺産」には適していないと主張した。連想学習や暗記(「レベルI」の能力) はできても、抽象的な概念推論(「レベルII」の能力)は苦手なのである。彼は、このような状況では、教育の成功は「これらの子供たちの能力のパターンに 潜在している実際の潜在的な学習」を利用することにかかっていると考えた。彼は、機会の平等を確保するためには、「学校と社会は、人間の能力の幅と同じよ うに、教育方法、プログラム、目標、職業機会の幅と多様性を提供しなければならない」と提案した[88][89][90]。 後に、この論文がどのようにして生まれたかについて書いたジェンセンは、『レビュー』の編集者から、それまで発表していなかった人種差の遺伝性についての 見解を含めるよう特別に求められたと述べている。クロンバック(1975年)もまた、ハーバード教育レヴューの学生編集者がどのようにジェンセンの論文の 内容を依頼し、交渉したかを詳細に説明している[91][92]。 多くの学者がジェンセンの論文の要点と思われる部分と、その内容を発展させた1970年代前半のその後の書籍について解説を行っている。Jencks & Phillips (1998)によれば、ジェンセンはその論文の中で「貧困戦争として始まった不利な立場にある子どもたちのための教育プログラムは失敗しており、白人と黒 人の人種格差はおそらく遺伝的な要素を多分に含んでいる」と主張していた。彼らはジェンセンの議論を次のように要約している[93]。 「黒人と白人の得点のばらつきのほとんどは遺伝的なものである。 "黒人と白人の格差について、もっともらしい環境的説明は誰もしていない" 「したがって、白人と黒人の格差の一部は遺伝的なものであると考える方が妥当である。 Loehlin, Lindzey & Spuhler (1975)によれば、ジェンセンの論文は以下の3つの主張を擁護している[94][要ページ]。 IQテストは人生の多くの局面で関連する人間の真の能力を正確に測定する。 IQテストによって測定される知能は遺伝性が高く(約80%)、IQの低い親はIQの低い子供を持つ可能性が高い。 教育プログラムでは、個人や集団の知能を大きく変えることはできない。 ウェブスター(1997)によれば、この論文は「IQテストで測定される知能と人種遺伝子の間に相関関係がある」と主張している。彼は、ジェンセンが経験 的証拠に基づいて、「黒人の知能は先天的に白人の知能よりも劣っている」、「このことが不平等な教育成果を部分的に説明している」、「一定レベルの学業不 振は黒人の劣った遺伝的属性によるものであるため、代償プログラムや強化プログラムは教育成果における人種間の格差を解消するには効果がないに違いない」 と結論づけたと書いている[95]。いくつかの論者はジェンセンの学校教育に対する提言に言及している。 ジェンセン自身の研究によれば、IQテストは、階層的に関連しながらも、SESに応じて集団の中で異なって分布する2つの思考形態、すなわちそれぞれレベ ル1とレベル2、すなわち連想学習と抽象的思考(g)を統合している。黒人は、連想学習のテストでは白人に劣らないが、抽象思考では遅れをとる。教育シス テムはこの矛盾に目を向け、より多元的なアプローチを導き出すべきである。現在のシステムでは、g型思考が過度に強調されているため、少数派グループは著 しく不利な立場に置かれている。 ジェンセンはすでにこの論文で、ヘッド・スタート・プログラムのような取り組みが効果的でないことを示唆しており、冒頭で「代償教育が試みられたが、明ら かに失敗した」と書いている[98]。フリン(1980)やマッキントッシュ(1998)といった他の心理測定学の専門家も、この論文やそれ以前の論文に 端を発するジェンセンのレベルI能力とレベルII能力の理論について説明している。心理学史家のウィリアム・H・タッカーがコメントしているように、ジェ ンセンの問いは先導的である: 「現在の福祉政策が、優生学的な先見性に助けられることなく、人口のかなりの部分を遺伝的に奴隷化することにつながる危険性はないだろうか?このような疑 問を真剣に研究することを私たちが怠った結果、後世の人々は、私たちの社会が黒人アメリカ人に対して犯した最大の不公正と判断するかもしれない」。タッ カーは、この記事がショックレーの「遺伝的奴隷化」というフレーズを繰り返していると指摘した。 ショックレーは、パイオニア基金の支援を受けて、ジェンセンの論文の広範な宣伝キャンペーンを行った。ジェンセンの見解は多くの分野で広く知られるように なった。その結果、遺伝論的視点と知能検査に対する学問的関心が再び高まった。ジェンセンの元の論文は広く流布し、しばしば引用された。その内容は、さま ざまな学問分野の大学の講義で教えられた。批評家に対する反論として、ジェンセンは心理測定のあらゆる側面に関する一連の本を書いた。また、ニューヨー ク・タイムズ誌がこのトピックを「ジェンセン主義」と呼ぶなど、大衆紙や政治家、政策立案者の間でも肯定的な反応が広まった[70][99]。 1971年、リチャード・ハーンシュタインは『アトランティック』誌に一般読者向けに知能検査に関する長い記事を書いた。人種と知能の問題については決め かねており、代わりに社会階層間の得点差について論じた。ジェンセンと同様、彼は強固な遺伝論的見解を示した。彼はまた、機会均等の政策は、生物学的な差 異によって分けられた社会階級をより硬直化させる結果となり、その結果、平均的な知能の低下傾向をもたらし、技術社会の増大するニーズと相反することにな るだろうとコメントしている[100]。  精神医学研究所の心理学教授であり、ジェンセンの師匠であったハンス・アイゼンクは、その研究はほとんど信用されていない[101][102][103]。 ジェンセンとハーンシュタインの論文は広く議論された。ハンス・アイゼンクは、イェンセン主義を大衆向けに紹介した小冊子である "Race, Intelligence and Education"(1971年)や "The Inequality of Man"(1973年)において、遺伝論的視点や知能検査の利用を擁護した。彼は反遺伝子主義者を厳しく批判し、その政策が社会における多くの問題の原因 であると非難した。最初の本で彼は、「現在までのすべての証拠は、ある特定の人種集団の間に観察される多種多様な知的差異を生み出す上で、遺伝的要因が強 く、実に圧倒的に重要であることを示唆している」と書き、2番目の本では、「階級やカーストによる差異を永続させたいと願う者にとって、遺伝学は真の敵で ある」と付け加えた。 [104] 『人種、知能、そして教育』は、IQ研究者のサンドラ・スカールによって、「ジェンセンの著作の多くを信頼できるものにしているニュアンスや、少なくとも 責任あるものにしている修飾語のない、ジェンセンのアイデアの無批判な大衆化」として、直ちに強い言葉で批判された。 「アイゼンクの伝記作家であるロッド・ブキャナンは、アイゼンクによる87の出版物は撤回されるべきだと主張している[103][101]。 バークレー校とハーバード大学の学生グループと教員は、人種差別の容疑でジェンセンとハーンシュタインに抗議した。ジェンセンの論文が掲載された2週間 後、「民主社会のための学生たち」はカリフォルニア大学バークレー校のキャンパスでアーサー・ジェンセンに対する抗議活動を行い、「人種差別と闘え。ジェ ンセンはクビにしろ!」[92][108]と叫び、ジェンセン自身もこの論争のためにバークレー校での職を失ったと述べている[83]。同様のキャンペー ンはロンドンではアイゼンクに対して、ボストンでは社会生物学者のエドワード・ウィルソンに対して行われた。ウィルソンに対する攻撃は、ハーバード大学の 生物学者スティーヴン・J・グールドとリチャード・ルウォンティンを含む35人の科学者と学生で構成された左翼団体「人々のための科学」の一部である社会 生物学研究グループによって組織された。 [1972年、心理学者のジェンセン、アイゼンク、ハーンシュタインや5人のノーベル賞受賞者を含む50人の学者が、「人間の行動と遺伝に関する科学の自 由に関する決議」と題する声明に署名し、「人間の行動における遺伝の役割を強調する科学者に対する弾圧、処罰、中傷」の風潮を批判した。1973年10 月、『ニューヨーク・タイムズ』紙に「人種差別反対決議」と題する半ページの広告が掲載された。レウォンティンを含む1000人以上の学者が署名し、「人 種差別研究」を非難し、特にジェンセン、ショックレー、ハーンシュタインを糾弾した[111][112]。 これには学界からの論評、批判、糾弾が添えられた。ハーバード・エデュケーショナル・レビュー』誌の2つの号は、心理学者、生物学者、教育学者によるジェ ンセンの研究に対する批評に費やされた。Wooldridge(1995)が記録しているように、主な論評は、集団遺伝学(Richard Lewontin、Luigi Cavalli-Sforza、Walter Bodmer)、知能の遺伝性(Christopher Jencks、Mary Jo Bane、Leon Kamin、David Layzer)、知能の尺度としてのIQテストの不正確さの可能性(Jensen 1980, pp. より具体的には、ハーバード大学の生物学者リチャード・ルウォンティンはジェンセンの集団遺伝学の利用についてコメントし、「ジェンセンの議論の根本的な 誤りは、集団内の性格の遺伝率と2つの集団間の遺伝率とを混同していることである。 「同じくハーバード大学の政治学者クリストファー・ジェンクスとメアリー・ジョー・ベインは、知能の遺伝率をジェンセンの推定値である80%ではなく 45%と再計算し、所得の変動の約12%のみがIQによるものであると計算した。 この論争では、イデオロギーの違いも浮上した。レウォンティンとグールドを中心とする科学者のサークルは、ジェンセンとハーンシュタインの研究を「悪い科 学」として否定した。知能の研究それ自体に異論があったわけではないが、彼らはこの研究が政治的な動機に基づくものであると感じ、知能の再定義、つまり数 値gを集団の平均値として意味を持つ肌の色のような身体的属性として扱うことに異論を唱えた。これは、生物学や遺伝学の未発見の過程から統計的な人工物を 分析するのではなく、分子レベルでの説明を必要とする科学的手法に反していると主張したのである。この批判に対し、ジェンセンは後に次のように書いてい る。「グールドが『再定義』と誤解しているのは、与えられた領域内で観察された関係を説明するために説明モデルを仮定するという、あらゆる科学における一 般的な慣行以上でも以下でもない。よく知られている例としては、惑星運動の天動説、ボーア原子、電磁場、気体の運動論、重力、クォーク、メンデルの遺伝 子、質量、速度などがある。これらの構成要素のどれもが、物理的空間を占める触知可能な実体として存在しない」。彼はなぜ心理学が「仮説的な構成要素の使 用や、観察可能な現象の因果的な説明に関する理論的な推測に対するあらゆる科学に共通の権利」を否定されなければならないのかと問うていた[63] [117][118]。  シリル・バートはイギリスの教育学者であり、その双子研究はジェンセンの初期の論文や著書でデータとして使用された。 1971年のバートの死の直後、レオン・カミンの研究によって、バートがデータの一部を捏造したという疑惑が持ち上がり、この疑惑は完全には解決されてい ない[119]。フランツ・サメルソンは、バートの研究に対するジェンセンの見解が長年にわたってどのように変化していったかを記録している: ジェンセンは1970年代にはアメリカにおけるバートの主な擁護者であった[120]。1983年、レスリー・ハーンショウによるバートの公式伝記が 1978年に出版された後、ジェンセンは考えを変え、「ハーンショウの伝記を有効なものとして完全に受け入れた」。しかし1992年、彼は「バート事件の 本質は......。[この見解は、アメリカ心理学会でのバートに関する招待講演[123]でも繰り返され、ハーンショーの学識に疑問を投げかけている [124]。  ヨシフ・スターリンのもとでソ連の生物学研究の責任者として、イデオロギー的な理由から遺伝学の研究を妨害したトロフィム・リセンコ。 後に「ネオ・ライセンコ主義」と呼ばれる、人種差に関する科学的研究を封じ込めようとする政治的動機に基づくキャンペーンに関する同様の告発は、ジェンセ ンと彼の支持者によって頻繁に繰り返された[125]。環境要因だけでなく遺伝的要因も関与しているかどうかを真剣に考察することは、学界ではタブー視さ れてきた」とし、次のように付け加えている: 「ナチスの奇妙な人種差別理論やスターリン政権下のソビエト連邦の悲惨なリセンコ主義において、科学が政治的ドグマへの従属によって腐敗したときに何が起 こるかを、私たちは明確な例として目の当たりにしてきた」[126][127]。 1969年の論文発表後、ジェンセンは後に知能の人種差についてより明確に述べ、1973年には「アメリカの黒人と白人の間の平均IQの差の2分の1から 4分の3は遺伝的要因に起因する」と述べている。さらに彼は、その根本的なメカニズムは、胚の外胚葉における皮膚の色素と知能の共同発達に関連する「皮膚 の色素と知能の生化学的関連」であるとさえ推測した。ジェンセンはアメリカでは人種隔離主義者との個人的な関わりを避けたが、ヨーロッパの極右雑誌のアプ ローチとは距離を置かなかった。ネーション・エウロパ』誌のインタビューで、彼は、ある種の人類はある種の動物以上に互いに異なっていると述べ、黒人と白 人の「遺伝的距離」を測定した結果、彼らが4万6000年以上前に分岐したことがわかったと主張した。彼はまた、アラン・ド・ブノワのフランスの雑誌 『ヌーヴェル・エコール』やユルゲン・リーガーのドイツの雑誌『ノイエ・アントロポロジー』にもインタビューに応じており、後に彼はこの雑誌の常連寄稿者 兼編集者となったが、ドイツ語の知識が乏しかったため、その政治的な方向性には気づいていなかったようである[128][129][130][131]。 この議論は、公民権問題や社会情勢の変化から1960年代を通じてすでに激化していた人種的偏見の問題によってさらに悪化した。1968年、黒人心理学者 協会(ABP)は、マイノリティ・グループの子どもに対するIQテストの一時停止を要求していた。アメリカ心理学会が設置した委員会がマイノリティ・グ ループを評価するためのガイドラインを作成したが、人種的偏見の主張を確認することができなかったため、ジャクソン(1975年)はABPを代表して回答 の一部として次のように書いている[132]。 心理テストは歴史的に、科学的客観性のあらゆるレベルにおいて人種差別を永続させるための準科学的な道具であり、それ(テスト)は、黒人を卑下することに よって白人の自尊心を膨らませ、黒人の大量虐殺を助長する恐れのある、本質的かつ推論的に誤ったデータの巣窟を提供してきた。 他の専門学術団体は、この論争に対して異なる反応を示した。アメリカ心理学会の一部門である社会問題心理学研究学会は、1969年にジェンセンの研究を批 判する声明を発表し、「複雑な行動に関する問題を遺伝か環境かという観点から構成することは、人間の発達と行動の本質と性質を単純化しすぎることである」 と宣言した。アメリカ人類学会は、ジェンセンの論文が発表された直後の1969年の年次総会でパネルディスカッションを行い、何人かの参加者がジェンセン の研究を「人種差別主義者」とレッテルを貼った[92] 。しかし、その結果、不人気な見解を持つ少数の科学者に対する個人攻撃が、行動遺伝学の分野全体に冷ややかな影響を及ぼし、その意味するところについての 公的な議論を曇らせている。1975年、アメリカ遺伝学会は同様に慎重な声明を出した: 「人間の行動の分析に量的遺伝学の技術を応用することは、人間的な複雑さと潜在的な偏りを伴うが、人間の心理的特徴の遺伝的・環境的要素に関するよく設計 された研究は、有効で社会的に有用な結果をもたらす可能性があり、これを抑制すべきではない」[133][134]。 |

1980–2000 James Flynn, the New Zealand political scientist who has studied changes in group-level IQ averages over time. In the 1980s, political scientist James Flynn compared the results of groups who took both older and newer versions of specific IQ tests. His research led him to the discovery of what is now called the Flynn effect: a substantial increase in average IQ scores over the years across all groups tested. His discovery was confirmed later by many other studies. While trying to understand these remarkable test score increases, Flynn had postulated in 1987 that "IQ tests do not measure intelligence but rather a correlate with a weak causal link to intelligence".[135][136] By 2009, however, Flynn felt that the IQ test score changes are real. He suggests that our fast-changing world has faced successive generations with new cognitive challenges that have considerably stimulated intellectual ability. "Our brains as presently constructed probably have much excess capacity ready to be used if needed. That was certainly the case in 1900."[137] Flynn notes that "Our ancestors in 1900 were not mentally retarded. Their intelligence was anchored in everyday reality. We differ from them in that we can use abstractions and logic and the hypothetical to attack the formal problems that arise when science liberates thought from concrete situations. Since 1950, we have become more ingenious in going beyond previously learned rules to solve problems on the spot."[138]  Richard Lynn, the controversial English psychologist who has argued for global group differences in intelligence. From the 1980s onwards, the Pioneer Fund continued to fund hereditarian research on race and intelligence, in particular the two English-born psychologists Richard Lynn of the University of Ulster and J. Philippe Rushton of the University of Western Ontario, who became president of the fund in 2002. Rushton returned to the cranial measurements of the 19th century, using brain size as an extra factor determining intelligence; in collaboration with Jensen, he most recently developed updated arguments for the genetic explanation of race differences in intelligence.[139] Lynn, longtime editor of and contributor to Mankind Quarterly, has concentrated his research in race and intelligence on gathering and tabulating data purporting to show race differences in intelligence across the world. He has also made suggestions about the political implications of his data, including the revival of older theories of eugenics.[140] Snyderman & Rothman (1987) announced the results of a survey conducted in 1984 on a sample of over a thousand psychologists, sociologists and educationalists in a multiple choice questionnaire, and expanded in 1988 into the book The IQ Controversy, the Media, and Public Policy. The book claimed to document a liberal bias in the media coverage of scientific findings regarding IQ. The survey included the question, "Which of the following best characterizes your opinion of the heritability of black-white differences in IQ?" 661 researchers returned the questionnaire, and of these, 14% declined to answer the question, 24% voted that there was insufficient evidence to give an answer, 1% voted that the gap was purely "due entirely to genetic variation", 15% voted that it "due entirely due to environmental variation" and 45% voted that it was a "product of genetic and environmental variation". Jencks & Phillips (1998) have pointed out that those who replied "both" did not have the opportunity to specify whether genetics played a large role. There has been no agreement amongst psychometricians on the significance of this particular answer.[141] Scientists supporting the hereditarian point of view have seen it as a vindication of their position.[142] In 1989, Rushton was placed under police investigation by the Attorney General of Ontario, after complaints that he had promoted racism in one of his publications on race differences. In the same year, Linda Gottfredson of the University of Delaware had an extended battle with her university over the legitimacy of grants from the Pioneer Fund, eventually settled in her favour.[70][143] Both later responded with an updated version of Henry E. Garrett's "egalitarian dogma", labelling the claim that all races were equal in cognitive ability as an "egalitarian fiction" and a "scientific hoax". Gottfredson (1994) spoke of a "great fraud", a "collective falsehood" and a "scientific lie", citing the findings of Snyderman and Rothman as justification. Rushton (1996) wrote that there was a "taboo on race" in scientific research that had "no parallel ... not the Inquisition, not Stalin, not Hitler".[144] In his 1998 book "The g Factor: The Science of Mental Ability", Jensen reiterated his earlier claims of Neo-Lysenkoism, writing that "The concept of human races [as] a fiction" has various "different sources, none of them scientific", one of them being "Neo-Marxist philosophy", which "excludes consideration of genetic or biological factors ... from any part in explaining behavioral differences amongst humans". In the same year, the evolutionary psychologist Kevin B. MacDonald went much further, reviving Garrett's claim of the "Boas cult" as a Jewish conspiracy, after which "research on racial differences ceased, and the profession completely excluded eugenicists like Madison Grant and Charles Davenport".[145] In 1994, the debate on race and intelligence was reignited by the publication of the book The Bell Curve: Intelligence and Class Structure in American Life by Richard Herrnstein and Charles Murray. The book was received positively by the media, with prominent coverage in Newsweek, Time, The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal. Although only two chapters of the book were devoted to race differences in intelligence, treated from the same hereditarian standpoint as Jensen's 1969 paper, it nevertheless caused a similar furore in the academic community to Jensen's article. Many critics, including Stephen J. Gould and Leon Kamin, asserted that the book contained unwarranted simplifications and flaws in its analysis; in particular there were criticisms of its reliance on Lynn's estimates of average IQ scores in South Africa, where data had been used selectively, and on Rushton's work on brain size and intelligence, which was controversial and disputed. These criticisms were subsequently presented in books, most notably The Bell Curve Debate (1995), Inequality by Design: Cracking the Bell Curve Myth (1996) and an expanded edition of Gould's The Mismeasure of Man (1996).[146] In 1994 a group of 52 scientists, including Rushton, Lynn, Jensen and Eysenck, were cosignatories of an op-ed article in The Wall Street Journal written by Linda Gottfredson entitled "Mainstream Science on Intelligence". The article, supporting the conclusions of The Bell Curve, was later republished in an expanded version in the journal Intelligence.[147][148][149] The editorial included the statements:[150][151] Genetics plays a bigger role than environment in creating IQ differences among individuals ... The bell curve for whites is centred roughly around IQ 100; the bell curve for American blacks roughly around 85 ... black 17-year olds perform, on the average, more like white 13-year olds in reading, math and science, with Hispanics in between. Another early criticism was that Herrnstein and Murray did not submit their work to academic peer review before publication.[152] There were also three books written from the hereditarian point of view: Why race matters: race differences and what they mean (1997) by Michael Levin; The g Factor: The Science of Mental Ability (1998) by Jensen; and Intelligence; a new look by Hans Eysenck. Various other books of collected contributions appeared at the same time, including The black-white test gap (1998) edited by Christopher Jencks and Meredith Phillips, Intelligence, heredity and environment (1997) edited by Robert Sternberg and Elena Grigorenko.[153] A section in IQ and human intelligence (1998) by Nicholas Mackintosh discussed ethnic groups and Race and intelligence: separating science from myth (2002) edited by Jefferson Fish presented further commentary on The Bell Curve by anthropologists, psychologists, sociologists, historians, biologists and statisticians.[154] In 1999 the same journal Intelligence reprinted as an invited editorial a long article by the attorney Harry F. Weyher Jr. defending the integrity of the Pioneer Fund, of which he was then president and of which several editors, including Gottfredson, Jensen, Lynn and Rushton, were grantees. In 1994 the Pioneer-financed journal Mankind Quarterly,[155] of which Roger Pearson was the manager and pseudonymous contributor, had been described by Charles Lane in a review of The Bell Curve in the New York Review of Books as "a notorious journal of 'racial history' founded, and funded, by men who believe in the genetic superiority of the white race"; he had called the fund and its journal "scientific racism's keepers of the flame." Gottfredson had previously defended the fund in 1989–1990, asserting that Mankind Quarterly was a "multicultural journal" dedicated to "diversity ... as an object of dispassionate study" and that Pearson did not approve of membership of the American Nazi Party. Pearson (1991) had himself defended the fund in his book Race, Intelligence and Bias in Academe.[156] In response to the debate on The Bell Curve, the American Psychological Association set up a ten-person taskforce, chaired by Ulrich Neisser, to report on the book and its findings. In its report, "Intelligence: Knowns and Unknowns", published in February 1996, the committee made the following comments on race differences in intelligence:[157] African American IQ scores have long averaged about 15 points below those of Whites, with correspondingly lower scores on academic achievement tests. In recent years the achievement-test gap has narrowed appreciably. It is possible that the IQ-score differential is narrowing as well, but this has not been clearly established. The cause of that differential is not known; it is apparently not due to any simple form of bias in the content or administration of the tests themselves. The Flynn effect shows that environmental factors can produce differences of at least this magnitude, but that effect is mysterious in its own right. Several culturally-based explanations of the Black/White IQ differential have been proposed; some are plausible, but so far none has been conclusively supported. There is even less empirical support for a genetic interpretation. In short, no adequate explanation of the differential between the IQ means of Blacks and Whites is presently available. Jensen commented: As I read the APA statement, [...] I didn't feel it was contradicting my position, but rather merely sidestepping it. It seems more evasive of my position than contradictory. The committee did acknowledge the factual status of what I have termed the Spearman Effect, the reality of g, the inadequacy of test bias and socioeconomic status as causal explanations, and many other conclusions that don't differ at all from my own position. [...] Considering that the report was commissioned by the APA, I was surprised it went as far as it did. Viewed in that light, I am not especially displeased by it.[158] Rushton found himself at the centre of another controversy in 1999 when unsolicited copies of a special abridged version of his 1995 book Race, Evolution and Behavior, aimed at a general readership, were mass mailed to psychologists, sociologists and anthropologists in North American universities. As a result, Transaction Publishers withdrew from publishing the pamphlet, financed by the Pioneer Fund, and issued an apology in the January 2000 edition of the journal Society. In the pamphlet Rushton recounted how black Africans had been seen by outside observers through the centuries as naked, insanitary, impoverished and unintelligent. In modern times he remarked that their average IQ of 70 "is the lowest ever recorded", due to smaller average brain size. He explained these differences in terms of evolutionary history: those that had migrated to colder climates in the north to evolve into whites and Asians had adapted genetically to have more self-control, lower levels of sex hormones, greater intelligence, more complex social structures, and more stable families. He concluded that whites and Asians are more disposed to "invest time and energy in their children rather than the pursuit of sexual thrills. They are 'dads' rather than 'cads.'" J. Philippe Rushton did not distance himself from groups on the far right in the US. He was a regular contributor to the newsletters of American Renaissance and spoke at many of their biennial conferences, in 2006 sharing the platform with Nick Griffin, leader of the British National Party.[70][159][160][161] |