イザベラ・バード『日本奥地紀行』にみる「臭い」の記述

Isabella

Bird's description of

"smell" in "Travels in the Interior of Japan

★The word smell in "Unbeaten

Tracks in Japan, by Isabella L. Bird," 1911.

| Blithely, at a merry

trot, the coolies hurried us away from the kindly group in the Legation

porch, across the inner moat and along the inner drive of the castle,

past gateways and retaining walls of Cyclopean masonry, across the

second moat, along miles of streets of sheds and shops, all grey,

thronged with foot-passengers and kurumas, with pack-horses loaded two

or three feet above their backs, the arches of their saddles red and

gilded lacquer, their frontlets of red leather, their “shoes” straw

sandals, their heads tied tightly to the saddle-girth on p. 36either

side, great white cloths figured with mythical beasts in blue hanging

down loosely under their bodies; with coolies dragging heavy loads to

the guttural cry of Hai! huida! with children whose heads were shaved

in hideous patterns; and now and then, as if to point a moral lesson in

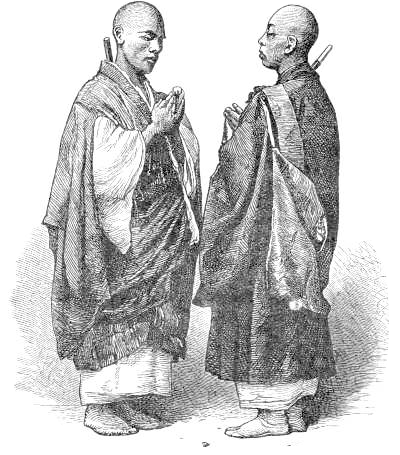

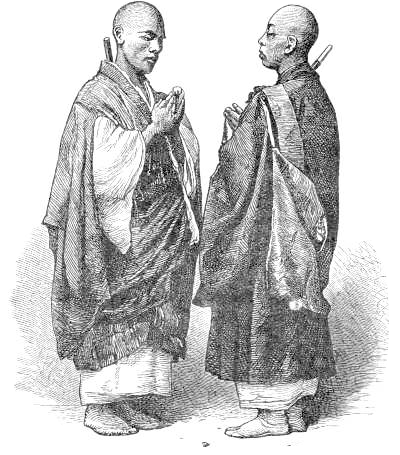

the midst of the whirling diorama, a funeral passed through the throng,

with a priest in rich robes, mumbling prayers, a covered barrel

containing the corpse, and a train of mourners in blue dresses with

white wings. Then we came to the fringe of Yedo, where the houses

cease to be continuous, but all that day there was little interval

between them. All had open fronts, so that the occupations of the

inmates, the “domestic life” in fact, were perfectly visible.

Many of these houses were road-side chayas, or tea-houses, and nearly

all sold sweet-meats, dried fish, pickles, mochi, or uncooked cakes of

rice dough, dried persimmons, rain hats, or straw shoes for man or

beast. The road, though wide enough for two carriages (of which

we saw none), was not good, and the ditches on both sides were

frequently neither clean nor sweet. Must I write it? The

houses were mean, poor, shabby, often even squalid, the smells were

bad, and the people looked ugly, shabby, and poor, though all were

working at something or other. p.36 |

公使館のポーチにいる親切な一団から、内堀を渡り、城の内通りに沿っ

て、キュクロペンの石造りの門や擁壁を過ぎ、二番目の堀を越え、小屋や店のある何マイルもの通りに沿って、陽気に、小走りに、クーリーたちは私たちを急が

せた。鞍のアーチは赤くて金色の漆、前立ては赤い革、靴はわらじ、頭は鞍の胴にしっかりと縛られている。また、「ハイ!ハイダ!」という小声の叫び声とと

もに重い荷物を引きずるクーリーもいた。そして時折、渦巻くジオラマの中で道徳的教訓を示すかのように、葬儀が群衆の中を通り過ぎ、豊かなローブを着た司

祭が祈りをつぶやき、死体の入った樽が置かれ、白い羽のついた青いドレスを着た弔問客の列が続いた。

そして、私たちは、家々が連続しなくなる江戸の端に来たが、その日はずっと、家々の間にほとんど隙間がなかった。

どの家も前面が開いていて、住人の職業、つまり「家庭生活」が完全に見えるようになっていた。

これらの家の多くは道端の茶屋であり、ほとんどすべての家で、甘い肉、干物、漬物、餅、干し柿、雨笠、藁ぐつなどが売られていた。

道路は馬車2台が通れるほど広いのだが(私たちは1台も見かけませんでした)、整備されておらず、両側の溝は清潔でも甘くもないことがしばしばでした。

書かなければならないのだろうか。

家々は意地悪く、貧しく、みすぼらしく、しばしば汚らしくさえあり、臭いはひどく、人々は醜く、みすぼらしく、貧しく見えたが、みな何かしらの仕事をして

いたのである。 |

| All day we travelled through

rice swamps, along a much-frequented road, as far as Kasukabé, a

good-sized but miserable-looking town, with its main street like one of

the poorest streets in Tôkiyô, and halted for the night at a large

yadoya, with downstairs and upstairs rooms, crowds of travellers, and

many evil smells. On

entering, the house-master or landlord, the

teishi, folded his hands and prostrated himself, touching the floor

with his forehead three times. It is a large, rambling old house,

and fully thirty servants were bustling about in the daidokoro, or

great open kitchen. I took a room upstairs (i.e. up a steep

step-ladder of dark, polished wood), with a balcony under the deep

eaves. The front of the house upstairs was one long room with

only sides and a front, but it was immediately divided into four by

drawing sliding screens or panels, covered with opaque wall papers,

into their proper grooves. A back was also improvised, but this

was formed of frames with panes of translucent paper, like our tissue

paper, with sundry holes and rents. This p. 40being done, I found

myself the possessor of a room about sixteen feet square, without hook,

shelf, rail, or anything on which to put anything—nothing, in short,

but a matted floor. Do not be misled by the use of this word

matting. Japanese house-mats, tatami, are as neat, refined, and

soft a covering for the floor as the finest Axminster carpet.

They are 5 feet 9 inches long, 3 feet broad, and 2½ inches thick.

The frame is solidly made of coarse straw, and this is covered with

very fine woven matting, as nearly white as possible, and each mat is

usually bound with dark blue cloth. Temples and rooms are

measured by the number of mats they contain, and rooms must be built

for the mats, as they are never cut to the rooms. They are always

level with the polished grooves or ledges which surround the

floor. They are soft and elastic, and the finer qualities are

very beautiful. They are as expensive as the best Brussels

carpet, and the Japanese take great pride in them, and are much

aggrieved by the way in which some thoughtless foreigners stamp over

them with dirty boots. Unfortunately they harbour myriads of

fleas. p.40 |

一日中、田んぼの中を、よく通る道を通って、春日部まで行った。春

日部は、それなりの大きさであるが、みすぼらしい町で、大通りは、東京の最も貧しい通りのひとつに似ていた。 大きな宿屋で一夜を明かしたが、そこには階下と階上の部屋があり、旅人たちが大勢いて、悪臭が

漂っていた。

入ってすぐ、家の主人や家主である定石が手を組み、額で床を三度触りながらひれ伏した。

大きな古民家で、30人ほどの使用人が大床で忙しく働いていた。

私は二階の部屋(つまり、黒く磨き上げられた木の急な脚立の上)を取ったが、深い軒下にはバルコニーがあった。

二階の家の正面は、側面と正面だけの長い一室だったが、不透明な壁紙で覆われた襖やパネルを適当な溝に引き込んで、すぐに四つに分けた。

裏も即席で作ったが、これはティッシュペーパーのような半透明の紙でできた枠に、いろいろな穴や裂け目を入れて作ったものだ。

これが終わると、私は約16フィート四方の部屋を所有することになったのだが、フックも棚もレールも、何も置くものがない、要するにマットな床があるだけ

である。 この「マット」という言葉に惑わされてはいけない。

日本の家庭用畳は、最高級のアキスミンスター絨毯と同じくらいきちんとした、洗練された、柔らかい床材である。

長さは5フィート9インチ、幅は3フィート、厚さは2.5インチです。

枠は粗い藁でしっかり作られており、これをできるだけ白に近い非常に細かい織物のマットで覆い、各マットは通常、紺色の布で縛られている。

寺院や部屋は、それらが含まれているマットの数で測定され、部屋は、彼らが部屋にカットされることはないので、マットのために構築する必要がある。

マットは、常に床を囲む磨かれた溝や棚と水平である。 柔らかく、弾力性があり、上質なものは非常に美しい。

ブリュッセルの最高級カーペットと同じくらい高価なもので、日本人はそれを非常に誇りにしており、一部の心ない外国人が汚れたブーツで踏みつけることに非

常に腹を立てている。 残念なことに、この絨毯には無数のノミが生息している。 |

| Outside my room an open balcony

with many similiar rooms ran round a forlorn aggregate of dilapidated

shingle roofs and water-butts. These rooms were all full.

Ito asked me for instructions once for all, put up my stretcher under a

large mosquito net of coarse green canvas with a fusty smell, filled my

bath, brought me some tea, rice, and eggs, took my passport to be

copied by the house-master, and departed, I know not whither. I

tried to write to you, but fleas and mosquitoes prevented it, and

besides, the fusuma were frequently noiselessly drawn apart, and

several pairs of dark, elongated eyes surveyed me through the cracks;

for there were two Japanese families in the room to the right, and five

men in that to the left. I closed the sliding windows, with

translucent paper for window panes, called shôji, and went to bed, but

the lack of privacy was fearful, and I have not yet sufficient trust in

my fellow-creatures to be comfortable without locks, walls, or

doors! Eyes were constantly applied to the sides of the room, a

girl twice drew aside the shôji between it and the corridor; a man, who

I afterwards found was a blind man, offering his services as a

shampooer, came in and said some (of course) unintelligible words, and

the new noises were p. 41perfectly bewildering. On one side a man

recited Buddhist prayers in a high key; on the other a girl was

twanging a samisen, a species of guitar; the house was full of talking

and splashing, drums and tom-toms were beaten outside; there were

street cries innumerable, and the whistling of the blind shampooers,

and the resonant clap of the fire-watchman who perambulates all

Japanese villages, and beats two pieces of wood together in token of

his vigilance, were intolerable. It was a life of which I knew

nothing, and the mystery was more alarming than attractive; my money

was lying about, and nothing seemed easier than to slide a hand through

the fusuma and appropriate it. Ito told me that the well was

badly contaminated, the odours were fearful; illness was to be feared

as well as robbery! So unreasonably I reasoned! [41] p.41 |

私の部屋の外には、同じような部屋がたくさんあるオープンバルコニー

が、荒廃した板葺き屋根と水桶の寂れた集合体を取り囲むように広がっていました。 これらの部屋はすべて満室だった。

伊藤は私に一通りの指示を求め、埃臭い粗い緑色の帆布でできた大きな蚊帳の

下に私の担架を置き、風呂を満たし、お茶と米と卵を持って来て、ハウスマスター

に私のパスポートをコピーしてもらい、私はどこへともなく出発した。

私はあなたに手紙を書こうとしたが、ノミや蚊に阻まれ、しかも襖は音もなく頻繁に引き離され、その隙間から何組もの黒くて細長い目が私を覗き込んでいた。

私は障子と呼ばれる半透明の紙を窓ガラス代わりにした引き違い窓を閉めて寝たが、プライバシーがないのは恐ろしく、鍵や壁や戸がなくても快適に過ごせるほ

ど、私はまだ同胞に対する信頼がないのだ

部屋の両側には常に視線が注がれ、少女は廊下との間にある障子を二度ほど脇に寄せた。後で知ったことだが、シャンプー屋としてサービスを提供する盲目の男

がやってきて、(もちろん)理解できない言葉を発し、新しい雑音は完璧に困惑させられた。

一方では男が高らかに念仏を唱え、他方では少女がギターの一種である三味線を鳴らしていた。家の中は話し声と水しぶきであふれ、外では太鼓とタムタムが鳴

らされ、無数の街頭演説があり、盲目のシャンプー屋の口笛や、日本のすべての村を巡回し、警戒の証として2本の木片を叩き合わせる火の見やぐらの響き渡る

拍手は、堪えがたくなるほどであった。

私のお金はそこら中に転がっていて、ふすまの隙間から手を入れて、それを拾い集めることほど簡単なことはないように思われました。

伊藤は、井戸はひどく汚染されており、匂いも恐ろしいと言った。 だから、私は理不尽な推理をしたのだ [41] |

| Already I can laugh at my fears

and misfortunes, as I hope you will. A traveller must buy his own

experience, and success or failure depends mainly on personal

idiosyncrasies. Many matters will be remedied by experience as I

go on, and I shall acquire the habit of feeling secure; but lack of

privacy, bad smells, and the torments of fleas and mosquitoes are, I

fear, irremediable evils. p.42 |

すでに私は自分の恐怖や不運を笑い飛ばすことができるようになった。

旅人は自分の経験を買わなければならないし、成功か失敗かは主に個人の特質によって決まる。

しかし、プライバシーの欠如、悪臭、ノミや蚊の被害は、取り返しのつかないものであ

ると思う。 |

| I don’t wonder that the Japanese

rise early, for their evenings are cheerless, owing to the dismal

illumination. In this and other houses the lamp consists of a

square or circular lacquer stand, with four uprights, 2½ feet high, and

panes of white paper. A flatted iron dish is suspended in this

full of oil, with the pith of a rush with a weight in the centre laid

across it, and one of the projecting ends is lighted. This

wretched apparatus is called an andon, and round its wretched “darkness

visible” the family huddles—the children to play games and learn

lessons, and the women to sew; for the Japanese daylight is short and

the houses are dark. Almost more deplorable is a candlestick of

the same height as the andon, with a spike at the top which fits into a

hole at the bottom of a “farthing candle” of vegetable wax, with a

thick wick made of rolled paper, which requires constant snuffing, and,

after giving for a short time a dim and jerky light, expires with a bad

smell. Lamps, burning mineral oils, native and imported, are

being manufactured on a large scale, but, apart from the peril

connected with them, the carriage of oil into country districts is very

expensive. No Japanese would think of sleeping without having an

andon burning all night in his room. - LETTER X.—(Continued.) p.73 |

日本人が早起きするのも無理はない。夜が暗いのは、この照明のせいなの

だから。 この家でも他の家でも、ランプは正方形か円形の漆の台で、高さ2フィート半の4本の直立した部分と、白い紙の窓ガラスで構成されている。

この中に油の入った平らな鉄の皿を吊るし、中央に錘をつけた藺草の髄を横たえて、突き出た端の一つを点灯させる。

この惨めな装置は行燈と呼ばれ、その惨めな「闇が見える」場所に家族が集まり、子供はゲームや習い事をし、女は裁縫をする。日本の日照時間は短く、家は暗

いからだ。

もっと悲惨なのは、行燈と同じ高さの燭台で、上部の突起を下部の穴にはめ込んで、植物性の蝋でできた「ファージング・キャンドル」、丸めた紙でできた太い

芯、これは常に嗅ぐ必要があり、短時間ぼんやりとぎこちない光を発した後、悪臭とともに消えてしまうのである。

国産や輸入の鉱物油を燃やすランプが盛んに製造されているが、危険な上に、田舎に油を運ぶのは非常に高価である。

日本人なら、自分の部屋で一晩中行燈を燃やさずに眠ろうとは思わないだろう。 |

| I saw everything out of doors

with Ito—the patient industry, the exquisitely situated village, the

evening avocations, the quiet dulness—and then contemplated it all from

my balcony and read the sentence (from a paper in the Transactions of

the Asiatic Society) which had led me to devise this journey, p.

86“There is a most exquisitely picturesque, but difficult, route up the

course of the Kinugawa, which seems almost as unknown to Japanese as to

foreigners.” There was a pure lemon-coloured sky above, and slush

a foot deep below. A road, at this time a quagmire, intersected

by a rapid stream, crossed in many places by planks, runs through the

village. This stream is at once “lavatory” and “drinking

fountain.” People come back from their work, sit on the planks,

take off their muddy clothes and wring them out, and bathe their feet

in the current. On either side are the dwellings, in front of

which are much-decayed manure heaps, and the women were engaged in

breaking them up and treading them into a pulp with their bare

feet. All wear the vest and trousers at their work, but only the

short petticoats in their houses, and I saw several respectable mothers

of families cross the road and pay visits in this garment only, without

any sense of impropriety. The younger children wear nothing but a

string and an amulet. The persons, clothing, and houses are alive

with vermin, and if the word squalor can be applied to independent and

industrious people, they were squalid. Beetles, spiders, and

wood-lice held a carnival in my room after dark, and the presence of

horses in the same house brought a number of horseflies. I

sprinkled my stretcher with insect powder, but my blanket had been on

the floor for one minute, and fleas rendered sleep impossible.

The night was very long. The

andon went out, leaving a strong

smell of rancid oil. The primitive Japanese dog—a

cream-coloured

wolfish-looking animal, the size of a collie, very noisy and

aggressive, but as cowardly as bullies usually are—was in great force

in Fujihara, and the barking, growling, and quarrelling of these

useless curs continued at intervals until daylight; and when they were

not quarrelling, they were howling. Torrents of rain fell,

obliging me to move my bed from place to place to get out of the

drip. At five Ito came and entreated me to leave, whimpering,

“I’ve had no sleep; there are thousands and thousands of fleas!”

He has travelled by another route to the Tsugaru Strait through the

interior, and says that he would not have believed that there was such

a place in Japan, and that people in Yokohama will not believe it when

he tells them of it and of the costume of the women. He is

“ashamed for a foreigner p. 87to see such a place,” he says. His

cleverness in travelling and his singular intelligence surprise me

daily. He is very anxious to speak good English, as distinguished

from “common” English, and to get new words, with their correct

pronunciation and spelling. Each day he puts down in his

note-book all the words that I use that he does not quite understand,

and in the evening brings them to me and puts down their meaning and

spelling with their Japanese equivalents. He speaks English

already far better than many professional interpreters, but would be

more pleasing if he had not picked up some American vulgarisms and

free-and-easy ways. It is so important to me to have a good

interpreter, or I should not have engaged so young and inexperienced a

servant; but he is so clever that he is now able to be cook,

laundryman, and general attendant, as well as courier and interpreter,

and I think it is far easier for me than if he were an older man.

I am trying to manage him, because I saw that he meant to manage me,

specially in the matter of “squeezes.” He is intensely Japanese,

his patriotism has all the weakness and strength of personal vanity,

and he thinks everything inferior that is foreign. Our manners,

eyes, and modes of eating appear simply odious to him. He

delights in retailing stories of the bad manners of Englishmen,

describes them as “roaring out ohio to every one on the road,”

frightening the tea-house nymphs, kicking or slapping their coolies,

stamping over white mats in muddy boots, acting generally like ill-bred

Satyrs, exciting an ill-concealed hatred in simple country districts,

and bringing themselves and their country into contempt and ridicule.

[87] He is very anxious about my good behaviour, and as I am

equally anxious to be courteous everywhere in Japanese fashion, and not

to violate the general rules of Japanese etiquette, I take his

suggestions as to what I ought to do and avoid in very good part, and

my bows are growing more profound every day! The people are so

kind and courteous, that it is truly brutal in foreigners not to be

kind and courteous to them. You will observe that I am entirely

dependent on Ito, not only for travelling arrangements, but for making

inquiries, gaining information, and even for companionship, such as it

is; and our being mutually embarked p. 88on a hard and adventurous

journey will, I hope, make us mutually kind and considerate.

Nominally, he is a Shintôist, which means nothing. At Nikkô I

read to him the earlier chapters of St. Luke, and when I came to the

story of the Prodigal Son I was interrupted by a somewhat scornful

laugh and the remark, “Why, all this is our Buddha over again!” pp.86-88 |

私は伊藤と一緒に戸外ですべてを見た。忍耐強い産業、絶妙な位置にある

村、夜の娯楽、静かな退屈、それからバルコニーからすべてを眺め、私がこの旅を思いついたきっかけである(アジア学会紀要の論文から)86ページの文章を

読んだ。「鬼怒川のコースには非常に絵になる、しかし難しい道があり、日本人も外国人もほとんど知らないようだ」。

上空にはレモン色の空が広がり、下界には1フィートの深さの泥があった。

このころは泥沼のような道と、所々に板を渡した急流が交差して、村を貫いている。

この小川は「便所」であり「水飲み場」でもある。

人々は仕事から戻ると、板の上に座り、泥まみれの服を脱いで絞り、流れに足を浸して水浴びをする。

両側には住居があり、その前にはかなり腐敗した肥溜めがあり、女性たちはそれを崩し、素足で踏みつぶす作業に従事していた。

仕事場ではベストとズボンを着用するが、家では短いペチコートのみで、立派な家庭の母親がこの衣服のみで道を渡り、訪問するのを何度か見たが、何の違和感

もない。 幼い子供たちは紐とお守りの他には何も身に着けていない。

人、衣服、家屋は害虫で生き生きとしており、独立した勤勉な人々に汚部屋という言葉が当てはまるなら、彼らは汚部屋であった。

日没後、私の部屋ではカブトムシ、クモ、シラミがカーニバルを開き、同じ家に馬がいたため、多数のアブが発生した。

私は担架に殺虫剤をまいたが、毛布は1分も床に置いたままだし、ノミのせいで眠れない。 夜が長い。 行燈が消えて、油の腐ったような臭いがする。

藤原では、原始的な日本犬、つまりコリーほどの大きさのクリーム色の狼のような動物が大勢いて、非常に騒がしく攻撃的だが、通常のいじめっ子と同じように

臆病である。 雨も激しく降って、水滴を避けるために寝床をあちこちに移さなければならない。

5時に伊藤がやってきて、「眠れない、ノミが何千匹も何万匹もいる」と泣きながら、私に帰るようにとせがんだ。

彼は別のルートで内陸を通って津軽海峡まで行ったが、日本にこんな場所があるなんて信じられなかったと言い、横浜の人がそのことや女性の衣装のことを話し

ても信じないだろうと言う。 彼は「外国人がそのような場所を見るのは恥ずかしいことだ」と言う。

彼の旅の巧みさと特異な知性には毎日驚かされている。

彼は、「一般的な」英語とは異なる「良い」英語を話し、新しい単語を正しい発音と綴りで覚えることに非常に神経を尖らせている。

毎日、私が使う言葉のうち、よく理解できないものをすべてノートに書き留め、夕方には私のところに持ってきて、その意味と綴りを日本語の相当語句と一緒に

書き留めておくのだ。

彼は、すでに多くのプロの通訳者よりはるかに英語が上手だが、アメリカの下品な言葉や自由で簡単な言い回しさえ覚えていなければ、もっと喜ばれることだろ

う。しかし、彼はとても賢いので、料理人、洗濯人、一般的な付き添い、そして宅配便や通訳もこなすことができ、年配の男性よりもはるかに楽だと思う。

私は彼を管理しようとしている。彼が私を管理しようとしているのがわかったからで、特に "絞り "の問題では。

彼は極めて日本人的で、愛国心には個人的な虚栄心の弱さと強さがあり、外国にあるものはすべて劣っていると考えている。

私たちのマナーや目、食事の仕方などは、彼にとっては単に不愉快なものにしか見えない。

彼はイギリス人の行儀の悪さを小売することに喜びを感じ、彼らを「道行く人に大声で叫ぶ」、茶店の仙女を怖がらせる、クーリーを蹴ったり叩いたりして、泥

だらけのブーツで白いマットを踏みつけ、概して育ちの悪いサテュロスみたいに振る舞い、単純な田舎町で隠しきれない憎悪を刺激し、自分と自分の国を軽蔑と

嘲笑に巻き込む、と表現している[87]。87]

彼は私の良い振る舞いをとても心配しており、私も同様に、日本流にどこでも礼儀正しく、日本のエチケットの一般的な規則に違反しないようにしたいと思って

いるので、私がすべきこと、避けるべきことについての彼の提案をとても良く受け取り、私のお辞儀は日に日に深くなっている![87]。

人々はとても親切で礼儀正しいので、外国人が彼らに親切で礼儀正しい態度を取らないのは本当に残酷なことです。

私は旅の手配だけでなく、問い合わせや情報収集、さらには交友関係においても、完全に伊藤に頼っていることがおわかりいただけると思う。

彼は名目上、神道家であるが、それは何の意味もない。

日航で私は聖ルカの序章を読み聞かせたが、放蕩息子の話になると、やや軽蔑した笑いを浮かべて、「これはすべて我々のブッダの再来だ!」と言ったので、私

はそれを中断した。 |

| Since shingle has given place to

thatch there is much to admire in the villages, with their steep roofs,

deep eaves and balconies, the warm russet of roofs and walls, the

quaint confusion of the farmhouses, the hedges of camellia and

pomegranate, the bamboo clumps and persimmon orchards, and (in spite of

dirt and bad smells) the generally satisfied look of the peasant

proprietors. p.91 |

急勾配の屋根、深い軒とバルコニー、屋根と壁の暖かい赤褐色、趣のある

農家の混在、ツバキとザクロの生垣、竹の塊と柿の果樹園、(汚れや悪臭にもかかわら

ず)農家の所有者の概ね満足した表情、茅葺きに取って代わって以来、村

には賞賛すべきことがたくさんあります。 |

| After a rapid run of twelve

miles through this enchanting scenery, the remaining course of the

Tsugawa is that of a broad, full stream winding marvellously through a

wooded and tolerably level country, partially surrounded by snowy

mountains. The river life was very pretty. Canoes abounded,

some loaded with vegetables, some with wheat, others with boys and

girls returning from school. Sampans with their white puckered

sails in flotillas of a dozen at a time crawled up the deep water, or

were towed through the shallows by crews frolicking and shouting.

Then the scene changed to a broad and deep river, with a peculiar

alluvial smell from the quantity of vegetable matter held in

suspension, flowing calmly between densely wooded, bamboo-fringed

banks, just high enough to conceal the surrounding country. No

houses, or p. 111nearly none, are to be seen, but signs of a continuity

of population abound. Every hundred yards almost there is a

narrow path to the river through the jungle, with a canoe moored at its

foot. Erections like gallows, with a swinging bamboo, with a

bucket at one end and a stone at the other, occurring continually, show

the vicinity of households dependent upon the river for their water

supply. Wherever the banks admitted of it, horses were being

washed by having water poured over their backs with a dipper, naked

children were rolling in the mud, and cackling of poultry, human

voices, and sounds of industry, were ever floating towards us from the

dense greenery of the shores, making one feel without seeing that the

margin was very populous. Except the boatmen and myself, no one

was awake during the hot, silent afternoon—it was dreamy and

delicious. Occasionally, as we floated down, vineyards were

visible with the vines trained on horizontal trellises, or bamboo

rails, often forty feet long, nailed horizontally on cryptomeria to a

height of twenty feet, on which small sheaves of barley were placed

astride to dry till the frame was full. p.111 |

この魅惑的な風景の中を12マイルほど急流で走った後、津川の残りの

コースは、部分的に雪山に囲まれた森林と比較的平坦な国の中を驚くほど曲がりくねった広く充実した流れになっている。

川での生活はとてもきれいだった。 カヌーは、野菜を積んだもの、小麦を積んだもの、学校から帰ってきた少年少女を乗せたものなど、たくさんある。

白い帆を張ったサンパンは、一度に十数隻の船団を組んで深い水を這い上がり、浅瀬では乗組員が戯れたり叫んだりして曳航している。

そして場面は広く深い川へと変わり、浮遊する植物質の量から沖積地特有の臭いがして、周囲の国を隠すのに十分な高さの、密生した森と竹に囲まれた土手の間

を静かに流れている。 家屋は見当たらないか、あるいはほとんど見当たらないが、人口が継続していることを示す痕跡が多く見られる。

ほぼ100ヤードごとに、ジャングルを抜けて川に出る細い道があり、その足元にカヌーが停泊している。

竹が揺れ、片方の端にバケツ、もう片方に石が置かれた絞首台のようなものが絶えず設置されており、水源を川に頼っている世帯が近くにあることを示してい

る。

土手の許す限り、馬は桶で背中に水をかけられて洗われ、裸の子供は泥の中で転がり、家禽の鳴き声、人の声、産業の音が、海岸の濃い緑から絶えずこちらに

漂っていて、この辺りが非常に人口が多いことを見ずに感じさせます。 船頭と私を除いては、暑くて静かな午後の間、誰も目を覚ましていなかった。

時折、葡萄畑が見え、葡萄の木が水平の棚に植えられているのが見えた。長さ40フィートの竹の柵が、20フィートの高さの杉の木に水平に釘付けされ、その

上に小さな麦束がまたがって、枠がいっぱいになるまで干されていた。 |

| A

severe day of mountain travelling brought us into another region.

We left Ichinono early on a fine morning, with three pack-cows, one of

which I rode [and their calves], very comely kine, with small noses,

short horns, straight spines, and deep bodies. I thought that I

might get some fresh milk, but the idea of anything but a calf milking

a cow was so new to the people that there was a universal laugh, and

Ito told me that they thought it “most disgusting,” and that the

Japanese think it “most disgusting” in foreigners to put anything “with

such a strong smell and taste” into their tea! All the cows had

cotton cloths, printed with blue dragons, suspended under their bodies

to keep them from mud and insects, and they wear straw shoes and cords

through the cartilages of their noses. The day being fine, a

great deal of rice and saké was on the move, and we met hundreds of

pack-cows, all of the same comely breed, in strings of four. LETTER

XVIII. p.128 |

一日がかりの厳しい山旅で、私たちは別の地方に入った。 晴

れた日の早朝に市野を出発し、3頭の牛(うち1頭は私が乗った)とその子牛を連れたが、小さな鼻、短い角、まっすぐな背骨、深い体、とても美しい子牛だっ

た。

私は新鮮な牛乳が手に入るかもしれないと思ったが、子牛以外のものが牛から乳を搾るという発想は人々にとってあまりに新鮮だったため、一同の笑いが起こっ

た。伊藤は私に、彼らは「最も嫌なこと」だと思い、日本人は外国人がお茶に「そのような強い匂いと味のする」ものを入れるのは「最も嫌なこと」だと思うと

言った! 牛はすべて綿の布を持っていた。

すべての牛は、泥や虫から身を守るために、青い龍がプリントされた綿布を体の下に吊るし、わら靴を履き、鼻の軟骨に紐を通している。

その日は天気が良かったので、大量の米と酒が移動しており、何百頭もの同じ品種の美しい牛が、4頭ずつ連なっているのに出会った。 |

| Yokote,

a town of 10,000 people, in which the best yadoyas are all

non-respectable, is an ill-favoured, ill-smelling, forlorn, dirty,

damp, miserable place, with a large trade in cottons. As I rode

through on my temporary biped the people rushed out from the baths to

see me, men and women alike without a particle of clothing. The

house-master was very polite, but I had a dark and dirty room, up a

bamboo ladder, and it swarmed with fleas and mosquitoes to an

exasperating extent. p. 148On the way I heard that a bullock was

killed every Thursday in Yokote, and had decided on having a broiled

steak for supper and taking another with me, but when I arrived it was

all sold, there were no eggs, and I made a miserable meal of rice and

bean curd, feeling somewhat starved, as the condensed milk I bought at

Yamagata had to be thrown away. I was somewhat wretched from

fatigue and inflamed ant bites, but in the early morning, hot and misty

as all the mornings have been, I went to see a Shintô temple, or miya,

and, though I went alone, escaped a throng. p.148 |

横

手は人口1万人の町で、最高の宿屋とはいえすべて非正規のもので、不遇で悪臭を放ち、寂しく、汚く、湿った、惨めな場所で、木綿の取引が盛んである。

私が仮の二足歩行で通り抜けると、人々は風呂場から駆け出して私を見に来た。男も女も一片の衣服もない。

家の主人はとても礼儀正しかったが、私の部屋は竹の梯子を登った暗い汚い部屋で、苛立たしいほどノミと蚊に群がっていた。148途中、横手では毎週木曜日

に牛が一頭殺されると聞き、夕食に焼き肉を食べて、もう一頭持っていこうと思ったが、到着するとすべて売られていて、卵もなく、山形で買った練乳も捨てな

ければならず、なんだか飢えた気分で米と豆腐の悲惨な食事を作ってしまった。

疲労と蟻に噛まれた炎症とで、いささか惨めな気分であったが、早朝、このところずっと暑くて霧のかかった日に、新東京の宮を見に行き、一人で行ったが、人

ごみを免れることができた。 |

| On

reaching Shingoji, being too tired to go farther, I was dismayed to

find nothing but a low, dark, foul-smelling room, enclosed only by

dirty shôji, in which to spend Sunday. One side looked into a

little mildewed court, with a slimy growth of Protococcus viridis, and

into which the people of another house constantly came to stare.

The other side opened on the earthen passage into the street, where

travellers wash their feet, the third into the kitchen, and the fourth

into the front room. Even before dark it was alive with

mosquitoes, and the fleas hopped on the mats like sand-flies.

There were no eggs, nothing but rice and cucumbers. At five on

Sunday morning I saw three faces pressed against the outer lattice, and

before evening the shôji were riddled with finger-holes, at each of

which a dark eye appeared. There was a still, fine rain all day,

with the mercury at 82°, and the heat, darkness, and smells were

difficult to endure. In the afternoon a small procession passed

the house, consisting of a decorated palanquin, carried and followed by

priests, with capes and stoles over crimson chasubles and white

cassocks. This ark, they said, contained papers inscribed with

the names of people and the evils they feared, and the priests were

carrying the papers to throw them into the river. p.153. -LETTER

XX.—(Concluded.) |

真

行寺に着くと、あまりに疲れていたので、遠くまで行くことはできなかったが、日曜日を過ごすには、汚い障子で囲まれた、低くて暗い、悪臭のする部屋しかな

いことに呆然とした。

片側は小さなカビの生えた中庭に面していて、そこにはプロトコッカス・ビリジスがヌルヌルと繁殖しており、他の家の人が絶えず覗き込んでくるのであった。

もう一方は、旅人が足を洗う土の通路に面しており、3番目は台所に、4番目は前室に通じていた。

暗くなる前から蚊が多く、蚤は砂蝿のように筵の上を飛び跳ねている。 卵はなく、米とキュウリだけだった。

日曜の朝五時、外格子には三つの顔が押しつけられ、夕方前には障子に指穴があき、その一つ一つに黒い眼が見えた。

一日中冷たい雨が降り続き、水銀は82度、暑さ、暗さ、匂いに耐えられませんでした。

午後、この家を小さな行列が通り過ぎた。装飾を施した輿を、深紅の肩章と白い胴衣の上にマントとストールを羽織った神官が担ぎ、その後に続いた。

この箱舟には、人々の名前と彼らが恐れている災いが刻まれた紙が入っていて、神官達はその紙を川に投げ入れるために運んでいるのだという。 |

| It

was pretty country, even in the downpour, when white mists parted and

fir-crowned heights looked out for a moment, or we slid down into a

deep glen with mossy boulders, lichen-covered stumps, ferny carpet, and

damp, balsamy smell of pyramidal cryptomeria, and a tawny torrent

dashing through it in gusts of passion. Then there were low

hills, much scrub, immense rice-fields, and violent inundations.

But it is not pleasant, even in the prettiest country, to cling on to a

pack-saddle with a saturated quilt below you and the water slowly

soaking down through your wet clothes into your boots, knowing all the

time that when you halt you must sleep on a wet bed, and change into

damp clothes, and put on the wet ones again the next morning. The

villages were poor, and most of the houses were of boards rudely nailed

together for ends, and for sides straw rudely tied on; they had no

windows, and smoke came out of every crack. They were as unlike

the houses which travellers see in southern Japan as a “black hut” in

Uist is like a cottage in a trim village in Kent. These peasant

proprietors have much to learn of the art of living. At

Tsuguriko, the next stage, where the Transport Office was so dirty that

I was obliged to sit in the street in the rain, they told us that we

could only get on a ri farther, because the bridges were all carried

away and the fords were impassable; but I engaged horses, and, by dint

of British doggedness and the willingness of the mago, I got the horses

singly and without their loads in small punts across the swollen waters

of the Hayakuchi, the Yuwasé, and the Mochida, and finally forded three

branches of my old friend the Yonetsurugawa, with the foam of its

hurrying waters whitening the men’s shoulders and the horses’ packs,

and with a hundred Japanese looking on at the “folly” of the foreigner.

p.180 |

土

砂降りの雨の中でも、白い霧が立ちこめ、モミの冠をかぶった高台が一瞬見えたかと思うと、深い渓谷に滑り落ち、苔むした岩、地衣に覆われた切り株、シダの

カーペット、ピラミッド型のスギナの湿ったバルサムの匂い、その中を激流が駆け抜けていく、美しい国であった。

そして、低い丘、多くの低木、広大な水田、激しい氾濫があった。

しかし、どんなに美しい国でも、荷台にしがみつき、下には飽和状態の掛け布団があり、濡れた服からブーツにゆっくりと水が染み込み、止まれば濡れたベッド

で寝なければならず、湿った服に着替え、翌朝にはまた濡れた服を着なければならないと常にわかっていることは、楽しいことではない。

村は貧しく、ほとんどの家は板の端を無骨に釘で打ち付け、側面は藁を無骨に縛ったもので、窓もなく、隙間からは煙が出ていた。

窓はなく、隙間からは煙が出ていた。旅人が南日本で見る家屋と同じように、ウイストの「黒い小屋」はケントの小ぎれいな村のコテージに似ていた。

このような農民の経営者は、生活技術について学ぶべきことがたくさんある。

次の津久井湖では、交通事務所があまりにも汚かったので、雨の中で路上に座らざるを得なかったが、橋はすべて流され、浅瀬は通れないので、あと一里しか進

めないと言われた。しかし、私は馬を雇い、英国の執念とマゴの意欲によって、馬を単独で、荷を載せずに小さなパントで早口、ユワゼ、持田の増水を渡り、つ

いに旧友米鶴川の三支流を渡った。急ぐ水の泡が男の肩と馬の荷を白くし、百人の日本人が外国人の「愚行」を見守っている。 |

| I

had a good meal seated in my chair on the top of the guest-seat to

avoid the fleas, which are truly legion. At dusk Shinondi

returned, and soon people began to drop in, till eighteen were

assembled, including the sub-chief and several very grand-looking old

men, with full, grey, wavy beards. Age is held in much reverence,

and it is etiquette for these old men to do honour to a guest in the

chief’s absence. As each entered he saluted me several times, and

after sitting down turned towards me and saluted again, going through

the same ceremony with every other person. They said they had

come “to bid me welcome.” They took their places in rigid order

at each side of the fireplace, which is six feet long, Benri’s mother

in the place of honour at the right, then Shinondi, then the sub-chief,

and on the other side the old men. Besides these, seven women sat

in a row in the background splitting bark. A large iron pan hung

over the fire from a blackened arrangement above, and Benri’s principal

wife cut wild roots, green beans, and seaweed, and shred dried fish and

venison among them, adding millet, water, and some strong-smelling

fish-oil, and set the whole on to stew for three hours, stirring the

“mess” now and then with a wooden spoon. p.240 |

私

はノミの大群を避けるため、客席の上座に座ったまま食事をした。

夕暮れ時にシノンディが戻ると、すぐに人が集まり始め、副酋長と、白髪で波打つひげを蓄えた、とても偉そうな老人数人を含む18人が集まりました。

老人は年齢を重んじるので、酋長が不在のときは客人に敬意を表すのが礼儀である。

入ってくるなり私に何度も敬礼し、座ってからも私の方を向いてまた敬礼し、他の人にも同じ儀式をした。 彼らは「私を歓迎するために来た」と言った。

彼らは長さ6尺の暖炉の両脇に整然と陣取り、右側にベンリ[ウク]の母、次にシノンディ、副長、そして反対側に老人たちが座りました。

このほか、後方には7人の女性が並んで座り、樹皮を割っている。

大きな鉄鍋が黒々と火にかけられ、ベンリ[ウク]の主夫が根菜やインゲン、海藻を切り、その中に干し魚や鹿肉を細切りにして、アワと水と香りの強い魚油を

加えて3時間ほど煮込み、時々木べらでかき混ぜながら「雑煮」を作っていた。 |

| Looking

inland, the volcano of Tarumai, with a bare grey top and a blasted

forest on its sides, occupies the right of the picture. To the

left and inland are mountains within mountains, tumbled together in

most picturesque confusion, densely covered with forest and cleft by

magnificent ravines, here and there opening out into narrow

valleys. The whole of the interior is jungle penetrable for a few

miles by shallow and rapid rivers, and by nearly smothered trails made

by the Ainos in search of game. The general lie of the country

made me very anxious to find out whether a much-broken ridge lying

among the mountains is or is not a series of tufa cones of ancient

date; and, applying for a good horse and Aino guide on horseback, I

left Ito to amuse himself, and spent much of a most splendid day in

investigations and in attempting to get round the back of the volcano

and up its inland side. There is a great deal to see and learn

there. Oh that I had strength! After hours of most tedious

and exhausting work I reached a point where there were several great

fissures emitting smoke and steam, with occasional subterranean

detonations. These were on the side of a small, flank crack which

was smoking heavily. There was light pumice everywhere, but

nothing like recent lava or scoriæ. One fissure was completely

lined with exquisite, acicular crystals of sulphur, which perished with

a touch. Lower down there were two hot springs with a deposit of

sulphur round their margins, and bubbles of gas, p. 291which, from its

strong, garlicky smell, I suppose to be sulphuretted hydrogen.

Farther progress in that direction was impossible without a force of

pioneers. I put my arm down several deep crevices which were at

an altitude of only about 500 feet, and had to withdraw it at once,

owing to the great heat, in which some beautiful specimens of tropical

ferns were growing. At the same height I came to a hot spring—hot

enough to burst one of my thermometers, which was graduated above the

boiling point of Fahrenheit; and tying up an egg in a

pocket-handkerchief and holding it by a stick in the water, it was hard

boiled in 8½ minutes. The water evaporated without leaving a

trace of deposit on the handkerchief, and there was no crust round its

margin. It boiled and bubbled with great force. p.291 |

内

陸を見ると、タルマイ火山が、灰色の頂をむき出しにし、その両側には吹きさらしの森があり、写真の右側を占めている。

左側と内陸部には、山の中に山があり、絵に描いたような混乱状態にあり、森で密に覆われ、壮大な渓谷があちこちにあり、狭い谷に口を開けている。

内陸部はすべてジャングルで、浅く急流な川が数キロメートルにわたって流れ、アイヌ人(=アイヌ民族)が狩猟のために作った小道はほとんど窒息している状

態である。

この国の全体的な様子から、私は山々の間に横たわる大きく崩れた尾根が、太古の時代に作られた一連のトゥファコーンであるかどうかを知りたくなり、良い馬

と馬に乗ったアイノ(アイヌ)のガイドを申し込んで、伊藤を楽しませてやり、最も素晴らしい日の大半を調査や火山の裏側とその内陸を回ろうとするために過

ごした。 そこには見るべきもの、学ぶべきものがたくさんある。 ああ、私に力があれば

何時間にもわたる退屈で疲れる作業の後、私は煙と蒸気を出し、時折地下で爆発を起こすいくつかの大きな亀裂のある地点にたどり着いた。

これらは、激しく煙を吐いている小さな脇腹の割れ目の側にありました。

いたるところに軽い軽石がありましたが、最近の溶岩や珪藻土のようなものはありませんでした。

ある裂け目は、硫黄の精巧な尖頭状の結晶で完全に覆われており、触ると消えてしまいました。

下には2つの温泉があり、その縁には硫黄の沈殿物があり、ガスの泡があった。p.291 その強いニンニク臭から、硫化水素と思われる。

その方向へさらに進むことは、開拓者たちの力なしには不可能だった。

私は、標高わずか500フィートほどの深い裂け目に何度か腕を下ろしたが、非常に暑かったため、すぐに腕を下ろさなければならなかった。

同じ高さのところに温泉があり、華氏の沸点より高い温度計が破裂するほど熱かった。ポケットチーフで卵を結び、棒で水の中に持っていくと、8分半で固ゆで

になった。 水分はハンカチに跡形もなく蒸発し、その縁には地肌がなかった。 沸騰して勢いよく泡が出た。 |

| Shiraôi

consists of a large old Honjin, or yadoya, where the daimiyô and his

train used to lodge in the old days, and about eleven Japanese houses,

most of which are saké shops—a fact which supplies an explanation of

the squalor of the Aino village of fifty-two houses, which is on the

shore at a respectful distance. There is no cultivation, in which

it is like all the fishing villages on this part of the coast, but

fish-oil and fish-manure are made in immense quantities, and, though it

is not the season here, the place is pervaded by “an ancient and

fish-like smell. p.294 |

白老は、昔、大名とその一行が宿泊した大きな古い本陣(やどや)と、

11軒ほどの日本家屋からなり、そのほとんどが酒屋である。この事実は、尊敬すべき距離の海岸にある52軒の相野村の汚さを説明するのに役立つ。 耕作(地?)はなく、この辺の漁村と同じだが、魚油と魚肥が大量に作られ、季節はずれだが「古

風な魚臭い」が充満している。 |

| The

Aino houses are much smaller, poorer, and dirtier than those of

Biratori. I went into a number of them, and conversed with the

people, many of whom understand Japanese. Some of the houses

looked like dens, and, as it was raining, husband, wife, and five or

six naked children, all as dirty as they could be, with unkempt,

elf-like locks, were huddled round the fires. Still, bad as it

looked and smelt, the fire was the hearth, and the hearth was

inviolate, and each smoked and dirt-stained group was a family, and it

was an advance upon the social life of, for instance, Salt Lake

City. The roofs are much flatter than those of the mountain

Ainos, and, as there are few store-houses, quantities of fish, “green”

skins, and venison, hang from the rafters, and the smell of these and

the stinging of the smoke were most trying. Few of the houses had

any guest-seats, but in the very poorest, when I asked shelter from the

rain, they put their best mat upon the ground, and insisted, much to my

distress, on my walking over it in muddy boots, saying, “It is Aino

custom.” Ever, p. 295in those squalid homes the broad shelf, with

its rows of Japanese curios, always has a place. I mentioned that

it is customary for a chief to appoint a successor when he becomes

infirm, and I came upon a case in point, through a mistaken direction,

which took us to the house of the former chief, with a great empty bear

cage at its door. On addressing him as the chief, he said, “I am

old and blind, I cannot go out, I am of no more good,” and directed us

to the house of his successor. Altogether it is obvious, from

many evidences in this village, that Japanese contiguity is hurtful,

and that the Ainos have reaped abundantly of the disadvantages without

the advantages of contact with Japanese civilisation. p.295 |

ア

イノ(=アイヌ)の家屋は、ビラトリの家屋よりもずっと小さく、貧しく、汚い。

私はそのうちのいくつかに入り、日本語を理解する多くの人々と会話を交わした。

中には巣窟のような家もあり、雨が降っていたので、夫、妻、そして5、6人の裸の子供たちが、みんな思い切り汚れていて、手入れされていない妖精のような

髪をして、火の周りに身を寄せ合っていました。

しかし、見た目や臭いは悪いが、火は囲炉裏であり、囲炉裏は不可侵であり、煙と汚れにまみれた集団はそれぞれ家族であり、例えばソルトレイクシティの社会

生活より進んでいた。 屋根は山のアイノスよりもずっと平らで、倉庫がほとんどな

いため、大量の魚や「グリーン」スキン、鹿肉が垂木に吊るされており、これらの匂いと煙の刺し込みは最も試練を与えるものであった。

客席のある家はほとんどなかったが、最も貧しい家では、私が雨宿りを頼むと、最高のマットを地面に敷き、「アイノの習慣だ」と言って、泥だらけのブーツで

その上を歩けと、私を苦しめるのである。 このような粗末な家では、日本の珍品を並べた広い棚がいつも場所を占めている。

酋長が病気になったとき、後継者を指名する習慣があると述べたが、私はその実例に出くわした。方向を間違えて、玄関に大きな空の熊の檻がある前の酋長の家

に連れて行かれた。 酋長と呼ぶと、彼は「私は年老いて目が見えないので、外に出ることができません。

この村にある多くの証拠から、日本人の隣接は有害であり、アイノス人は日本文明との接触による利点のない欠点を十分に享受していることが明らかである。 |

| Another

glorious day favoured my ride to Mori, but I was unfortunate in my

horse at each stage, and the Japanese guide was grumpy and

ill-natured—a most unusual thing. Otoshibé and a few other small

villages of grey houses, with “an ancient and fish-like smell,” lie

along the coast, busy enough doubtless in the season, but now looking

deserted and decayed, and houses are rather plentifully sprinkled along

many parts of the shore, with a wonderful profusion of vegetables and

flowers p. 317about them, raised from seeds liberally supplied by the

Kaitakushi Department from its Nanai experimental farm and

nurseries. For a considerable part of the way to Mori there is no

track at all, though there is a good deal of travel. One makes

one’s way fatiguingly along soft sea sand or coarse shingle close to

the sea, or absolutely in it, under cliffs of hardened clay or yellow

conglomerate, fording many small streams, several of which have cut

their way deeply through a stratum of black volcanic sand. I have

crossed about 100 rivers and streams on the Yezo coast, and all the

larger ones are marked by a most noticeable peculiarity, i.e. that on

nearing the sea they turn south, and run for some distance parallel

with it, before they succeed in finding an exit through the bank of

sand and shingle which forms the beach and blocks their progress. p.317 |

この日も晴天に恵まれ、森まで馬で行ったが、各段階で馬に恵まれず、日

本人ガイドは不機嫌で不機嫌で、とても珍しいことだった。 海岸沿いには、オトシ

ベをはじめ、「古代の魚のようなにおい」のする灰色の家々の小さな村がいくつかあり、季節には間違いなく賑やかだが、今はさびれ、朽ちているように見える。

海岸の多くの場所に家が散在し、その周りには開拓使が七井試験農場と苗床から豊富に提供した種を使った野菜や花が驚くほどたくさんある p. 317。

森への道のりは、かなりの距離を移動するにもかかわらず、まったく道がない。

海辺の柔らかい海砂や粗い礫岩、あるいは海中にある固まった粘土や黄色い礫岩の崖の下を疲労しながら進み、多くの小川を渡るが、そのうちのいくつかは黒い

火山性の砂の地層を深く切り開いて流れている。

私は蝦夷地の海岸で約100の川や小川を横断したが、大きな川はすべて、海に近づくと南に曲がり、海辺を形成して進行を阻む砂や礫の堤防に出口を見つける

まで、海と平行にしばらく流れるという顕著な特徴を持っている。 |

| https://gutenberg.org/cache/epub/2184/pg2184-images.html |

https://www.deepl.com/ja/translator |

Isabella Lucy Bird, married name Bishop FRGS (15 October 1831 – 7 October 1904), was a nineteenth-century British explorer, writer,[1] photographer,[2] and naturalist.[3] With Fanny Jane Butler she founded the John Bishop Memorial Hospital in Srinagar in today’s Kashmir.[4] She was the first woman to be elected Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society.[5]

イザベラ・ルーシー・バード、結婚名ビショップ

FRGS(1831年10月15日 - 1904年10月7日)は、19世紀のイギリスの探検家、作家[1]、写真家[2]、博物学者。 [3]

Fanny Jane Butlerとともに現在のカシミール地方のスリナガルにジョン・ビショップ記念病院を設立した。 [4]

女性で初めて王立地理学会会員になった[5].

+++

Links

リンク

文献

その他の情報

++

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099