Traditional focuses of sociology include social stratification, social class, social mobility, religion, secularization, law, sexuality, gender, and deviance. Recent studies have added socio-technical aspects of the digital divide as a new focus.[6] As all spheres of human activity are affected by the interplay between social structure and individual agency, sociology has gradually expanded its focus to other subjects and institutions, such as health and the institution of medicine; economy; military; punishment and systems of control; the Internet; sociology of education; social capital; and the role of social activity in the development of scientific knowledge.

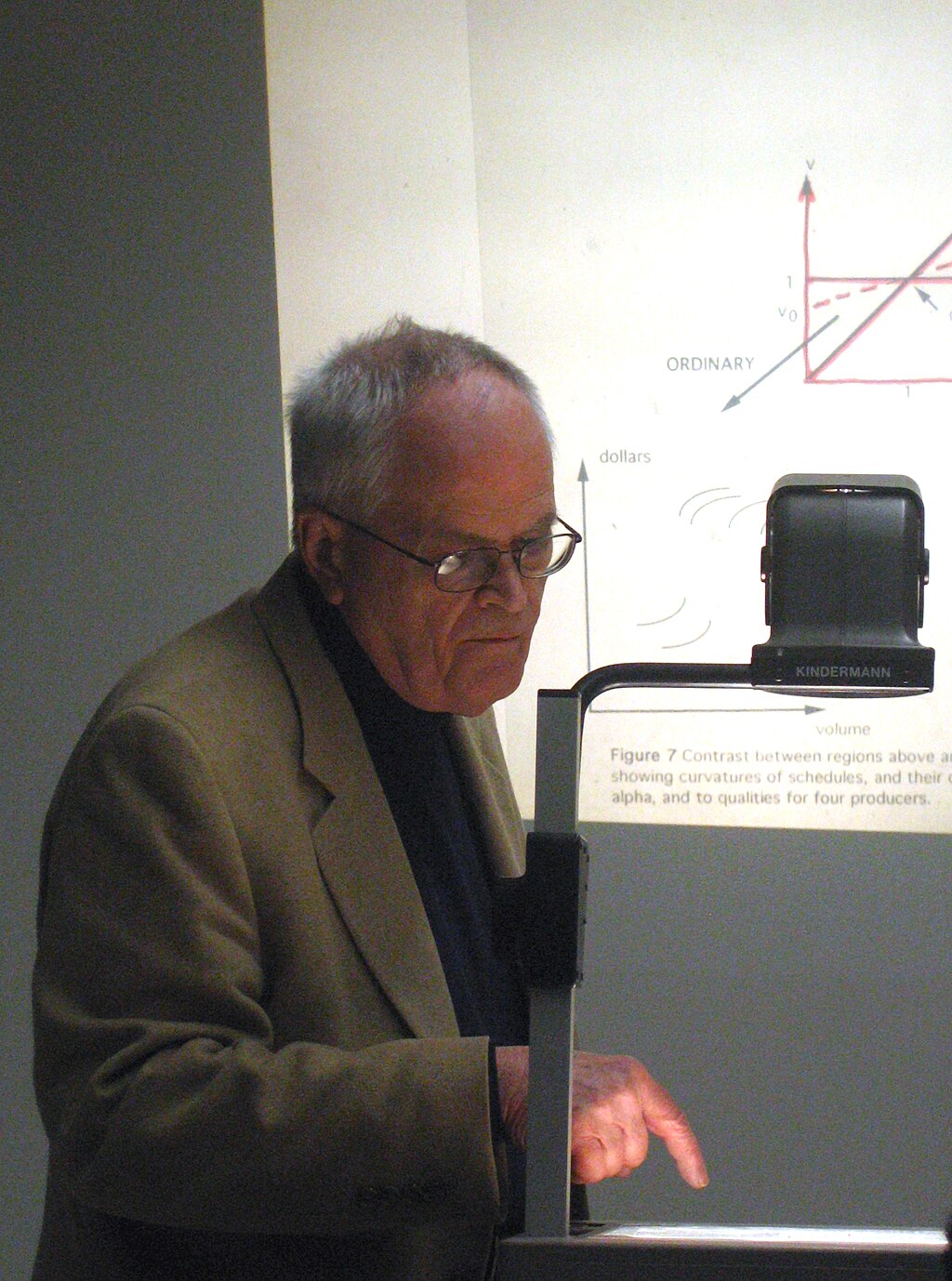

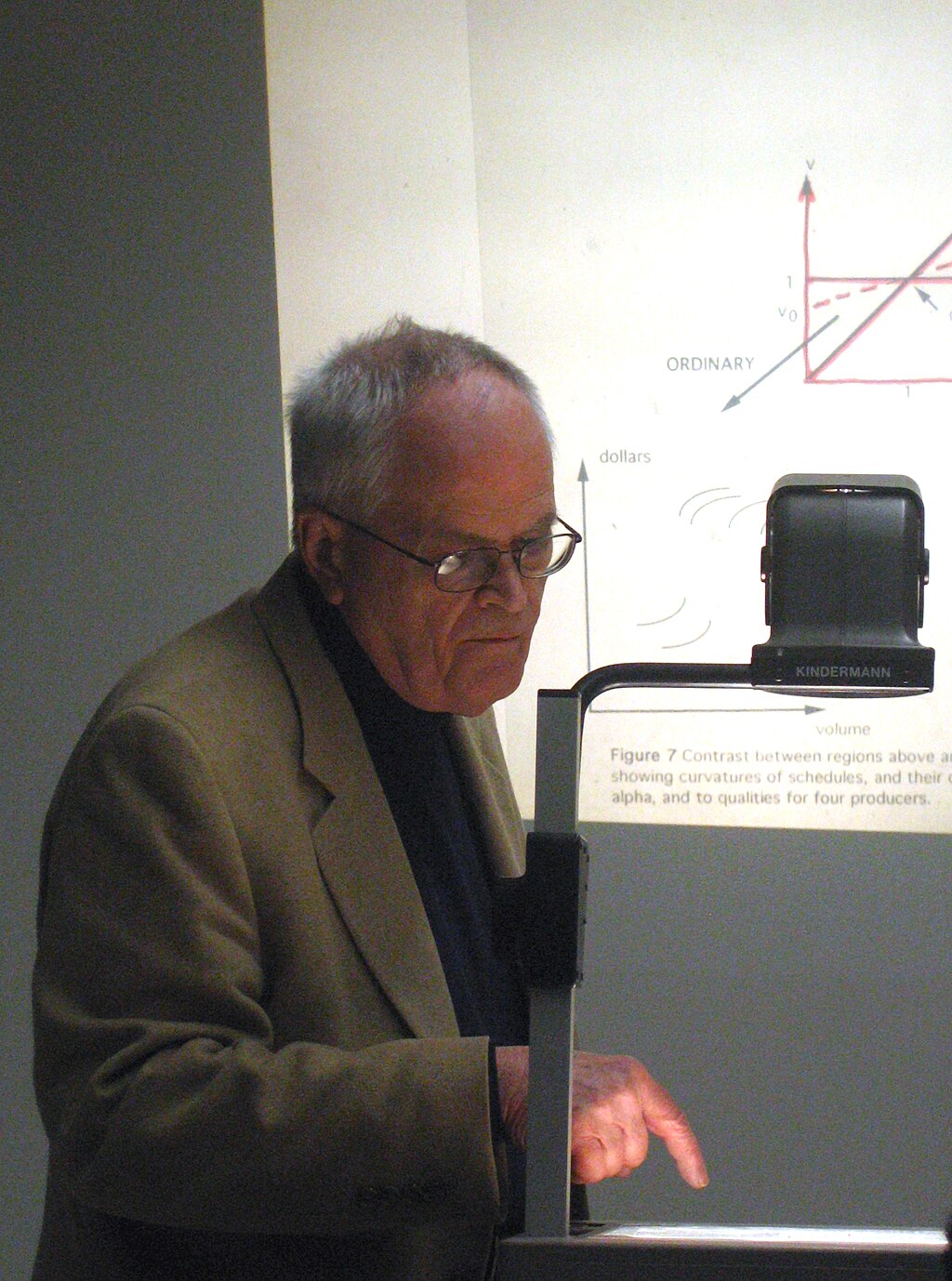

The range of social scientific methods has also expanded, as social researchers draw upon a variety of qualitative and quantitative techniques. The linguistic and cultural turns of the mid-20th century, especially, have led to increasingly interpretative, hermeneutic, and philosophical approaches towards the analysis of society. Conversely, the turn of the 21st century has seen the rise of new analytically, mathematically, and computationally rigorous techniques, such as agent-based modelling and social network analysis.[7][8]

Social research has influence throughout various industries and sectors of life, such as among politicians, policy makers, and legislators; educators; planners; administrators; developers; business magnates and managers; social workers; non-governmental organizations; and non-profit organizations, as well as individuals interested in resolving social issues in general.

社会学の伝統的な研究対象には、社会階層、社会階級、社会移動、宗教、世俗化、法、性、ジェンダー、逸脱などが含まれる。最近の研究では、デジタル・ディ バイドの社会技術的側面が新たな焦点として加わっている。[6] 人間の活動のあらゆる領域が社会構造と個人の行動の相互作用の影響を受けるため、社会学は徐々に保健や医学制度、経済、軍事、処罰と統制システム、イン ターネット、教育社会学、社会資本、科学的知識の発展における社会活動の役割など、他の主題や制度にも焦点を広げてきた。

社会科学の手法も拡大し、社会研究者はさまざまな定性的および定量的手法を活用している。特に20世紀半ばの言語学と文化論の転換は、社会分析に対する解 釈的、解釈学的、哲学的アプローチをますます増やす結果となった。逆に、21世紀に入ってからは、エージェント・ベース・モデリングやソーシャル・ネット ワーク分析など、分析、数学、計算の面で厳密な新しい手法が台頭している。

社会調査は、政治家、政策立案者、立法者、教育者、プランナー、行政官、開発者、実業家や経営者、ソーシャルワーカー、非政府組織、非営利団体など、生活のさまざまな産業や分野に影響を与えている。また、社会問題の解決に関心を持つ個人にも影響を与えている。

Main article: History of sociology

Further information: List of sociologists and Timeline of sociology

Ibn Khaldun statue in Tunis, Tunisia (1332–1406)

Sociological reasoning predates the foundation of the discipline itself. Social analysis has origins in the common stock of universal, global knowledge and philosophy, having been carried out as far back as the time of old comic poetry which features social and political criticism,[9] and ancient Greek philosophers Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle. For instance, the origin of the survey can be traced back to at least the Domesday Book in 1086,[10][11] while ancient philosophers such as Confucius wrote about the importance of social roles.[12][13]

Medieval Arabic writings encompass a rich tradition that unveils early insights into the field of sociology. Some sources consider Ibn Khaldun, a 14th-century Muslim scholar from Tunisia,[note 1] to have been the father of sociology, although there is no reference to his work in the writings of European contributors to modern sociology.[14][15][16][17] Khaldun's Muqaddimah was considered to be amongst the first works to advance social-scientific reasoning on social cohesion and social conflict.[18][19][20][21][22][23]

詳細は「社会学史」を参照

さらに詳しい情報: 社会学者の一覧、社会学の歴史年表

チュニスのイブン・ハルドゥーン像(1332年-1406年)

社会学的な推論は、その学問自体の成立よりも古い歴史を持つ。社会分析は、普遍的な世界的な知識や哲学の共通の蓄積に起源を持ち、社会や政治に対する批判 を特徴とする古い風刺詩の時代[9]や、古代ギリシアのソクラテス、プラトン、アリストテレスといった哲学者の時代まで遡ることができる。例えば、調査の 起源は少なくとも1086年のドームズデイ・ブックまで遡ることができるが、一方で、孔子などの古代の哲学者は社会的な役割の重要性を説いていた。

中世のアラビア語文献は、社会学の分野における初期の洞察を明らかにする豊かな伝統を包含している。一部の資料では、チュニジア出身の14世紀のイスラム学者イブン・ハルドゥーン(注 1)を社会学の父としているが、近代社会学に貢献したヨーロッパの文献には、彼の業績に関する言及はない。 [14][15][16][17] ハルドゥーンの『ムカッディマ』は、社会の結束と社会の対立に関する社会科学的な推論を前進させた最初の著作のひとつと考えられている。[18][19] [20][21][22][23]

The word sociology derives part of its name from the Latin word socius ('companion' or 'fellowship'[24]). The suffix -logy ('the study of') comes from that of the Greek -λογία, derived from λόγος (lógos, 'word' or 'knowledge').[citation needed]

The term sociology was first coined in 1780 by the French essayist Emmanuel-Joseph Sieyès in an unpublished manuscript.[25][note 2] Sociology was later defined independently by French philosopher of science Auguste Comte (1798–1857) in 1838[26] as a new way of looking at society.[27]: 10 Comte had earlier used the term social physics, but it had been subsequently appropriated by others, most notably the Belgian statistician Adolphe Quetelet.[28] Comte endeavored to unify history, psychology, and economics through the scientific understanding of social life. Writing shortly after the malaise of the French Revolution, he proposed that social ills could be remedied through sociological positivism, an epistemological approach outlined in the Course in Positive Philosophy (1830–1842), later included in A General View of Positivism (1848). Comte believed a positivist stage would mark the final era in the progression of human understanding, after conjectural theological and metaphysical phases.[29] In observing the circular dependence of theory and observation in science, and having classified the sciences, Comte may be regarded as the first philosopher of science in the modern sense of the term.[30][31]

Auguste Comte (1798–1857)

Comte gave a powerful impetus to the development of sociology, an impetus that bore fruit in the later decades of the nineteenth century. To say this is certainly not to claim that French sociologists such as Durkheim were devoted disciples of the high priest of positivism. But by insisting on the irreducibility of each of his basic sciences to the particular science of sciences which it presupposed in the hierarchy and by emphasizing the nature of sociology as the scientific study of social phenomena Comte put sociology on the map. To be sure, [its] beginnings can be traced back well beyond Montesquieu, for example, and to Condorcet, not to speak of Saint-Simon, Comte's immediate predecessor. But Comte's clear recognition of sociology as a particular science, with a character of its own, justified Durkheim in regarding him as the father or founder of this science, even though Durkheim did not accept the idea of the three states and criticized Comte's approach to sociology.

— Frederick Copleston, A History of Philosophy: IX Modern Philosophy (1974), p. 118

社会学という語は、その名称の一部をラテン語のsocius(「仲間」または「友情」)に由来する。接尾辞-logy(「~の研究」)は、ギリシャ語の-λογίαに由来し、λόγος(lógos、「言葉」または「知識」)から派生したものである。

社会学という用語は、1780年にフランスのエッセイスト、エマニュエル=ジョゼフ・シエイエスによって未発表の原稿で初めて作られた。[25][注2] 社会学はその後、フランスの科学哲学者オーギュスト・コント(1798年-1857年)によって1838年に、社会を観察する新しい方法として独自に定義 された。[26][注27]: 10 コンテは以前に「社会物理学」という用語を使用していたが、その後、特にベルギーの統計学者アドルフ・ケトレー(Adolphe Quetelet)によって流用されるようになった。[28] コンテは、社会生活の科学的理解を通じて、歴史、心理学、経済学を統合しようとした。フランス革命の動乱の直後に著述した彼は、社会病理は社会学的実証主 義によって改善できると提案した。これは、後に『一般実証主義概観』(1848年)に収録された『実証哲学講義』(1830年~1842年)で概説された 認識論的アプローチである。コントは、仮説的な神学や形而上学の段階を経て、実証主義の段階が人類の理解の進歩における最後の時代を画すると信じていた。 [29] 科学における理論と観察の循環的依存関係を観察し、科学を分類したコントは、現代的な意味での科学哲学の最初の哲学者とみなされるかもしれない。[30] [31]

オーギュスト・コント(1798年~1857年)

コントは社会学の発展に強力な弾みをつけたが、その弾みは19世紀後半に実を結んだ。 しかし、デュルケムのようなフランスの社会学者たちが、実証主義の最高司祭であるコントの熱心な信奉者であったと主張するつもりはない。しかし、彼は、各 々の基礎科学が、その階層において前提とされる諸科学の特定の科学に還元されないことを主張し、社会現象の科学的探究としての社会学の性質を強調すること で、社会学を世に知らしめた。確かに、その始まりは、例えばモンテスキューやコンドルセ、さらにはサン=シモン(コンドルセの直前の先駆者)よりもずっと 遡ることができる。しかし、社会学を独自の性格を持つ個別科学として明確に認識したコントは、デュルケムがコントをこの科学の父または創始者とみなすこと を正当化した。デュルケムは3つの状態の概念を受け入れず、コントの社会学へのアプローチを批判したが、それでもなお、である。

— フレデリック・コープストン、『哲学史:近代哲学(1974年)』、118ページ

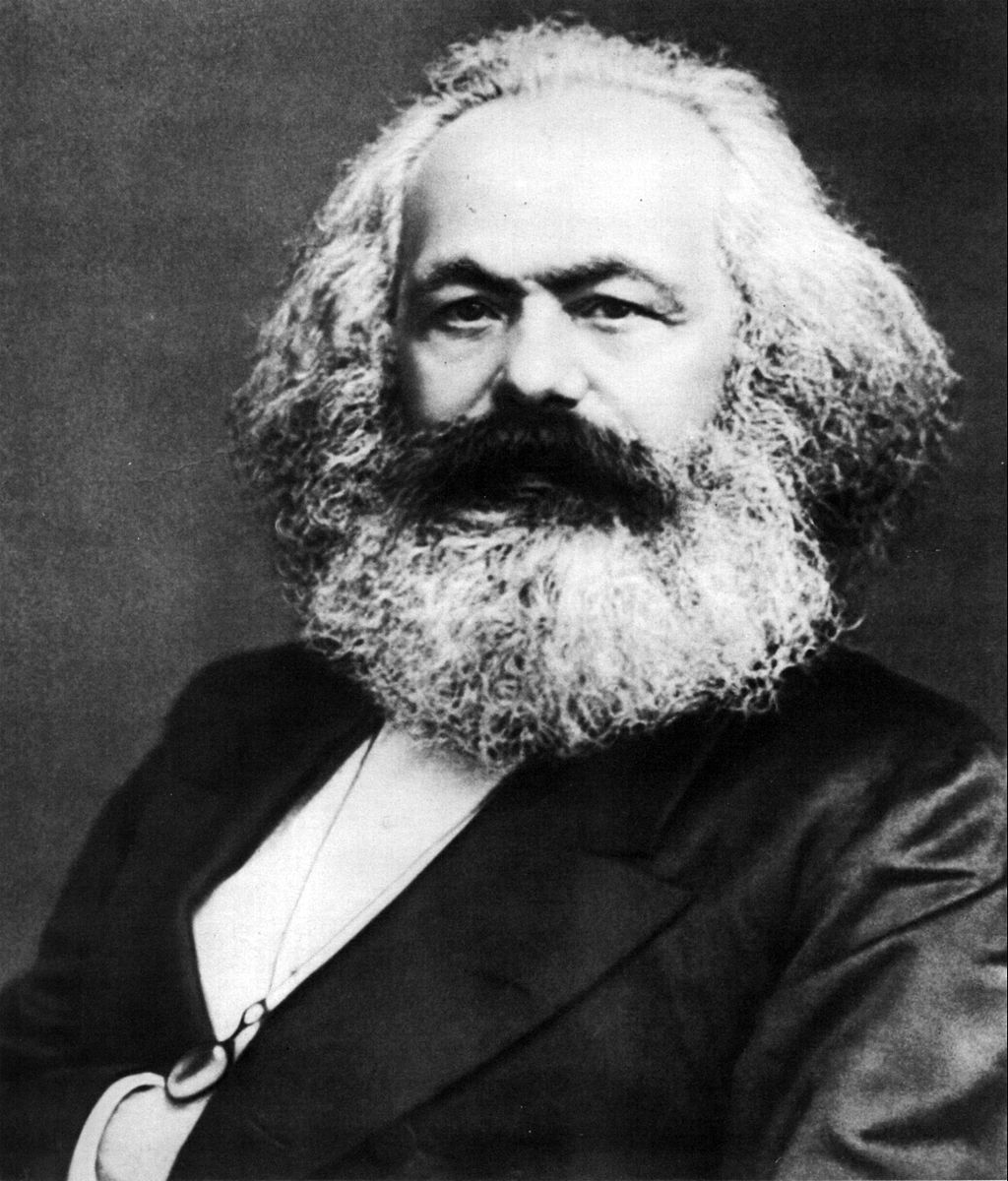

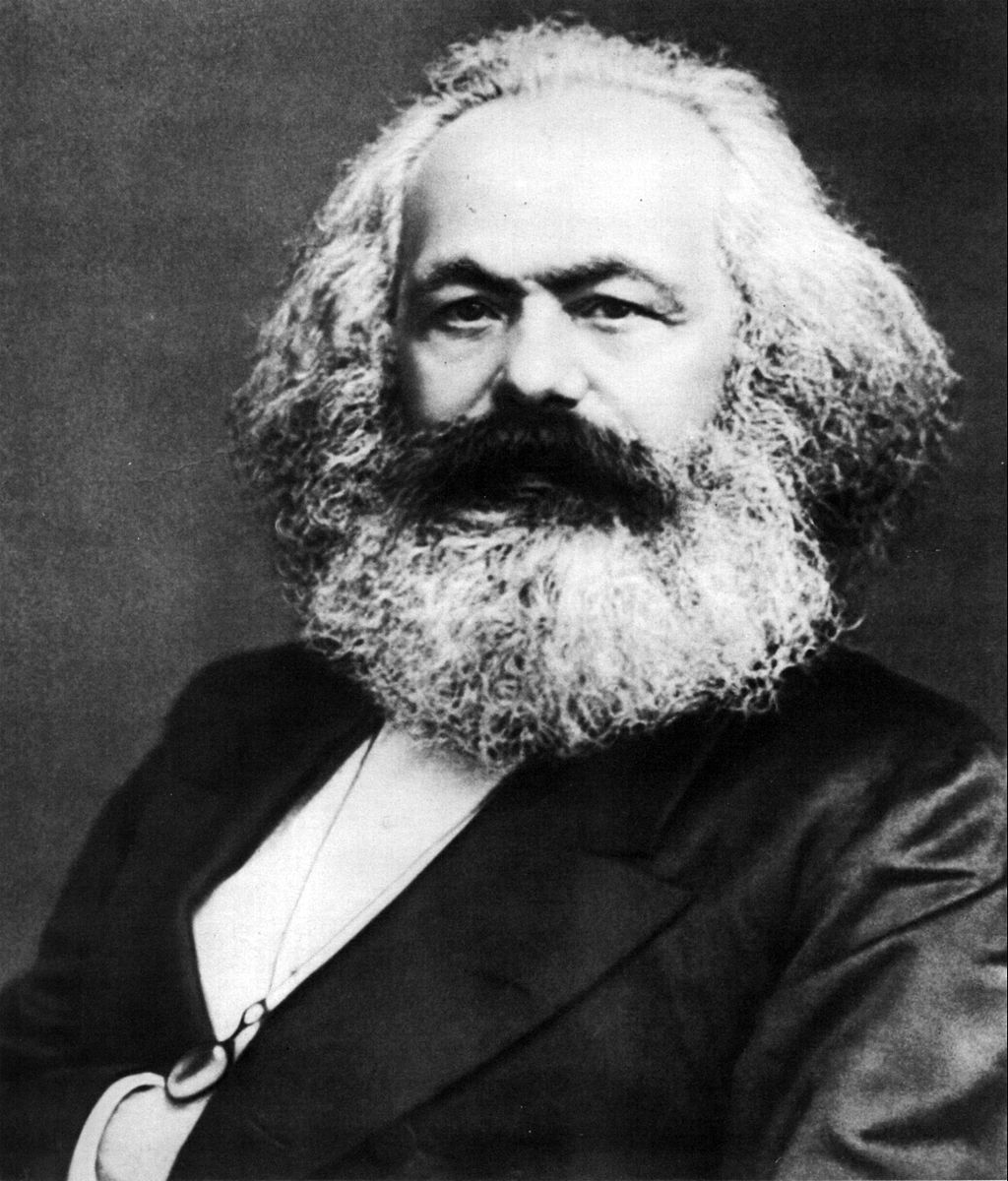

Karl Marx (1818–1883)

Marx

Both Comte and Karl Marx set out to develop scientifically justified systems in the wake of European industrialization and secularization, informed by various key movements in the philosophies of history and science. Marx rejected Comtean positivism[32] but in attempting to develop a "science of society" nevertheless came to be recognized as a founder of sociology as the word gained wider meaning. For Isaiah Berlin, even though Marx did not consider himself to be a sociologist, he may be regarded as the "true father" of modern sociology, "in so far as anyone can claim the title."[33]: 130

To have given clear and unified answers in familiar empirical terms to those theoretical questions which most occupied men's minds at the time, and to have deduced from them clear practical directives without creating obviously artificial links between the two, was the principal achievement of Marx's theory. The sociological treatment of historical and moral problems, which Comte and after him, Spencer and Taine, had discussed and mapped, became a precise and concrete study only when the attack of militant Marxism made its conclusions a burning issue, and so made the search for evidence more zealous and the attention to method more intense.[33]: 13–14

カール・マルクス(1818年-1883年)

マルクス

コンテとカール・マルクスは、ヨーロッパの産業化と世俗化の動きを受けて、歴史哲学と科学哲学におけるさまざまな主要な運動から得た知見を基に、科学的に 正当化された体系を構築しようとした。マルクスはコントの実証主義を否定したが[32]、それでも「社会の科学」を開発しようとしたことで、その言葉が広 義の意味を持つようになったため、社会学の創始者として認められるようになった。イザイア・バーリンは、マルクスは自らを社会学者だとは思っていなかった が、それでも「誰かがその肩書きを主張できる限りにおいて」現代社会学の「真の父」と見なされるかもしれないと述べている[33]:130

当時、人々の心を最も占領していた理論的な疑問に対して、馴染みのある経験的な用語で明確かつ統一的な答えを与え、その2つの間に明らかに人為的な関連性 を作り出すことなく、そこから明確な実践的な指針を導き出したことが、マルクスの理論の主な功績である。歴史的および道徳的問題の社会学的な考察は、コン テやその後継者であるスペンサーやテーヌによって議論され、体系化されていたが、マルクス主義の急進派による攻撃がその結論を喫緊の課題とし、それによっ て証拠の探索がより熱心になり、方法への注目がより強烈になったときに初めて、正確かつ具体的な研究となった。[33]:13-14

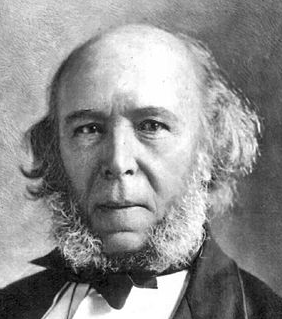

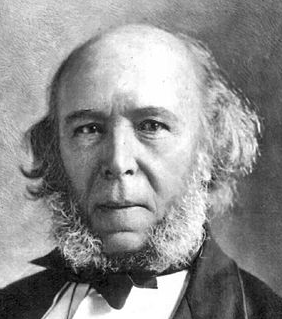

Herbert Spencer (1820–1903)

Herbert Spencer was one of the most popular and influential 19th-century sociologists. It is estimated that he sold one million books in his lifetime, far more than any other sociologist at the time.[34] So strong was his influence that many other 19th-century thinkers, including Émile Durkheim, defined their ideas in relation to his. Durkheim's Division of Labour in Society is to a large extent an extended debate with Spencer from whose sociology Durkheim borrowed extensively.[35]

Also a notable biologist, Spencer coined the term survival of the fittest.[36] While Marxian ideas defined one strand of sociology, Spencer was a critic of socialism, as well as a strong advocate for a laissez-faire style of government. His ideas were closely observed by conservative political circles, especially in the United States and England.[37]

ハーバート・スペンサー(1820年 - 1903年)

ハーバート・スペンサーは、19世紀で最も人気があり影響力のある社会学者の一人であった。生涯に100万冊の書籍を売り上げたといわれ、これは同時代の どの社会学者よりもはるかに多い数字である。[34] 彼の影響力は非常に強力であったため、エミール・デュルケムをはじめとする多くの19世紀の思想家たちは、自身の考えを彼の考えとの関連で定義した。デュ ルケムの『社会における労働の分割』は、その大部分がスペンサーとの議論を拡張したものであり、デュルケムはスペンサーの社会学から広範にわたって借用し ている。[35]

また著名な生物学者でもあったスペンサーは、「適者生存」という用語を造語した。[36] マルクス主義の考え方が社会学の一つの流れを定義づける一方で、スペンサーは社会主義の批判者であり、自由放任主義の強力な擁護者でもあった。彼の考え は、特にアメリカとイギリスの保守的な政治界で、注意深く観察されていた。[37]

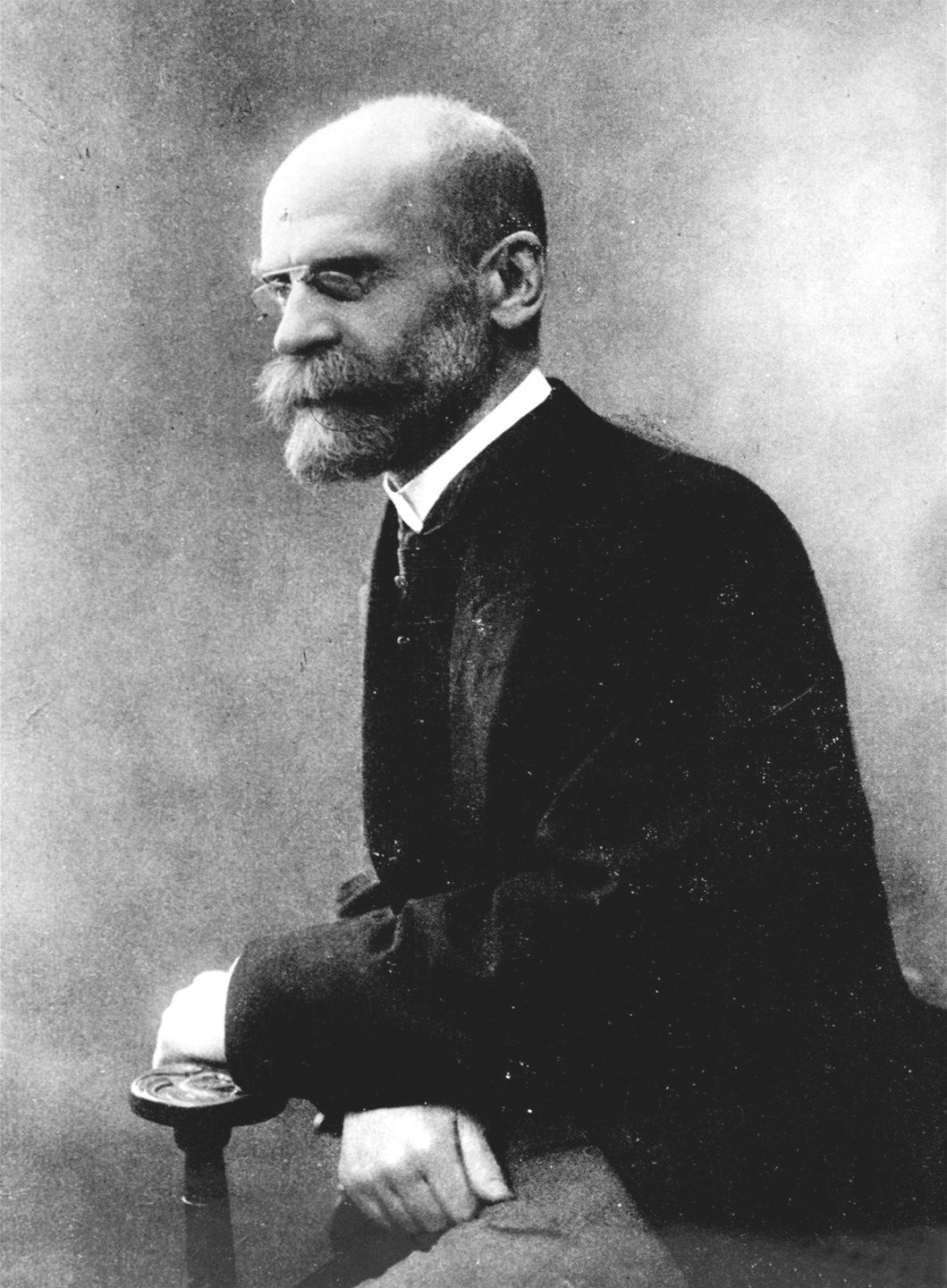

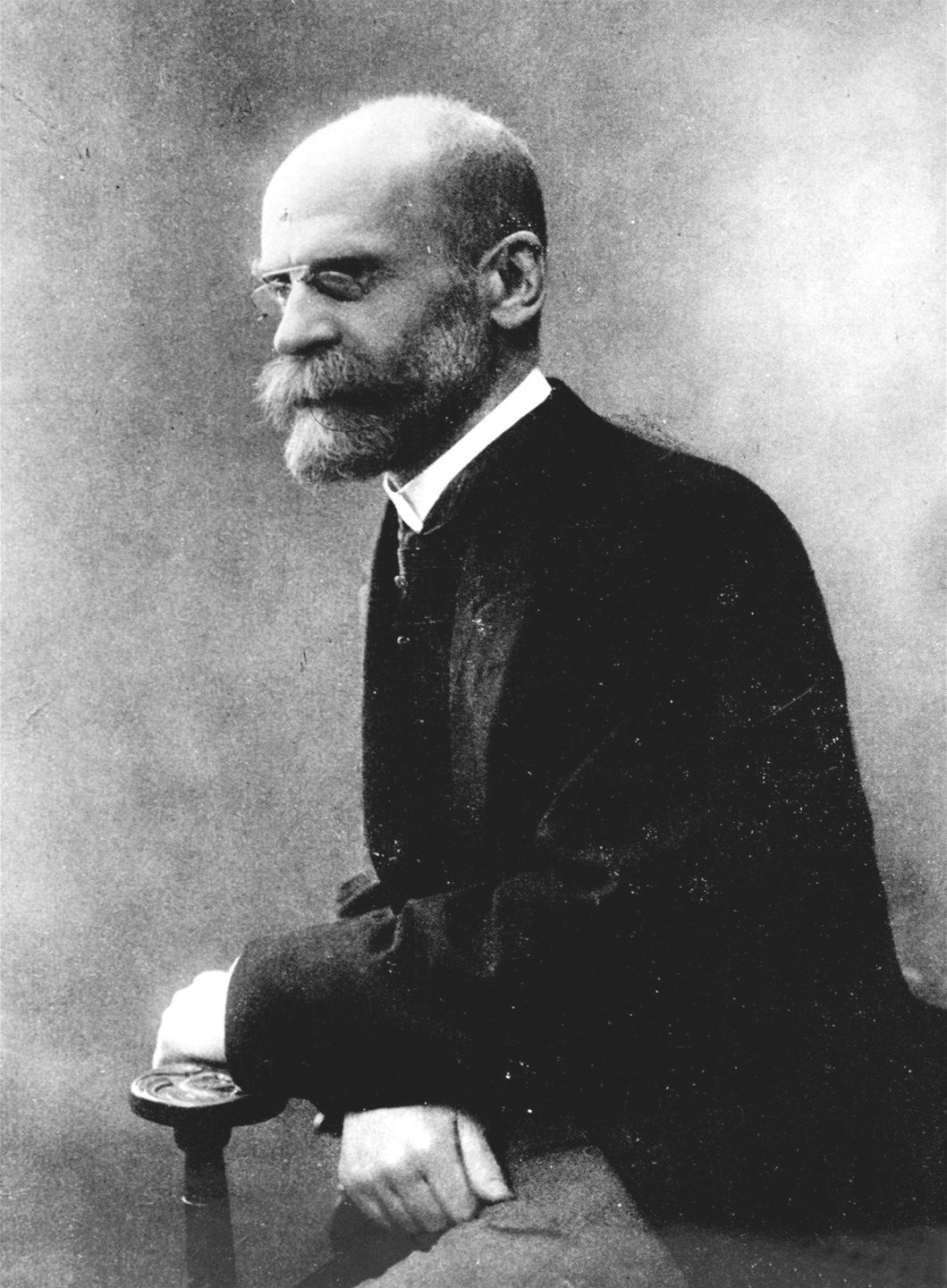

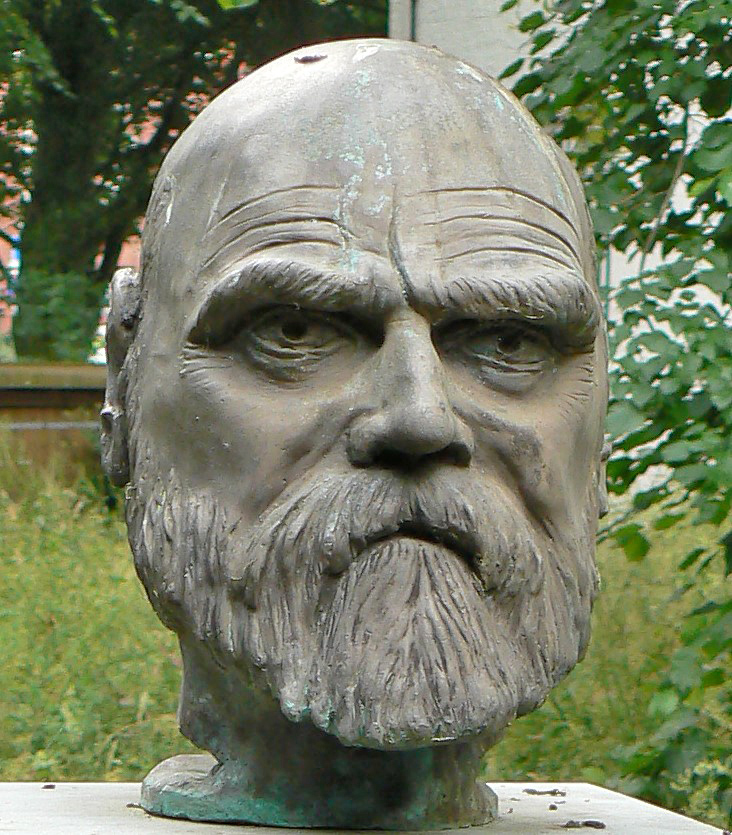

Main articles: Émile Durkheim and Social facts

Émile Durkheim

The first formal Department of Sociology in the world was established in 1892 by Albion Small—from the invitation of William Rainey Harper—at the University of Chicago. The American Journal of Sociology was founded shortly thereafter in 1895 by Small as well.[38]

The institutionalization of sociology as an academic discipline, however, was chiefly led by Émile Durkheim, who developed positivism as a foundation for practical social research. While Durkheim rejected much of the detail of Comte's philosophy, he retained and refined its method, maintaining that the social sciences are a logical continuation of the natural ones into the realm of human activity, and insisting that they may retain the same objectivity, rationalism, and approach to causality.[39] Durkheim set up the first European department of sociology at the University of Bordeaux in 1895, publishing his Rules of the Sociological Method (1895).[40] For Durkheim, sociology could be described as the "science of institutions, their genesis and their functioning."[41]

Durkheim's monograph Suicide (1897) is considered a seminal work in statistical analysis by contemporary sociologists. Suicide is a case study of variations in suicide rates among Catholic and Protestant populations, and served to distinguish sociological analysis from psychology or philosophy. It also marked a major contribution to the theoretical concept of structural functionalism. By carefully examining suicide statistics in different police districts, he attempted to demonstrate that Catholic communities have a lower suicide rate than that of Protestants, something he attributed to social (as opposed to individual or psychological) causes. He developed the notion of objective social facts to delineate a unique empirical object for the science of sociology to study.[39] Through such studies he posited that sociology would be able to determine whether any given society is healthy or pathological, and seek social reform to negate organic breakdown, or "social anomie".

Sociology quickly evolved as an academic response to the perceived challenges of modernity, such as industrialization, urbanization, secularization, and the process of rationalization.[42] The field predominated in continental Europe, with British anthropology and statistics generally following on a separate trajectory. By the turn of the 20th century, however, many theorists were active in the English-speaking world. Few early sociologists were confined strictly to the subject, interacting also with economics, jurisprudence, psychology and philosophy, with theories being appropriated in a variety of different fields. Since its inception, sociological epistemology, methods, and frames of inquiry, have significantly expanded and diverged.[5]

Durkheim, Marx, and the German theorist Max Weber are typically cited as the three principal architects of sociology.[43] Herbert Spencer, William Graham Sumner, Lester F. Ward, W. E. B. Du Bois, Vilfredo Pareto, Alexis de Tocqueville, Werner Sombart, Thorstein Veblen, Ferdinand Tönnies, Georg Simmel, Jane Addams and Karl Mannheim are often included on academic curricula as founding theorists. Curricula also may include Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Marianne Weber, Harriet Martineau, and Friedrich Engels as founders of the feminist tradition in sociology. Each key figure is associated with a particular theoretical perspective and orientation.[44]

Marx and Engels associated the emergence of modern society above all with the development of capitalism; for Durkheim it was connected in particular with industrialization and the new social division of labor which this brought about; for Weber it had to do with the emergence of a distinctive way of thinking, the rational calculation which he associated with the Protestant Ethic (more or less what Marx and Engels speak of in terms of those 'icy waves of egotistical calculation'). Together the works of these great classical sociologists suggest what Giddens has recently described as 'a multidimensional view of institutions of modernity' and which emphasises not only capitalism and industrialism as key institutions of modernity, but also 'surveillance' (meaning 'control of information and social supervision') and 'military power' (control of the means of violence in the context of the industrialisation of war).[44]

— John Harriss, The Second Great Transformation? Capitalism at the End of the Twentieth Century (1992)

主な記事:エミール・デュルケームと社会的事実

エミール・デュルケーム

世界で最初の正式な社会学の学科は、ウィリアム・レイニー・ハーパーの招聘により、1892年にアルビオン・スモールがシカゴ大学に設立した。その後まもなく、1895年にスモールによって『アメリカ社会学会誌』が創刊された。

しかし、学問分野としての社会学の制度化は、実証主義を実用的な社会調査の基礎として発展させたエミール・デュルケムが主導した。デュルケムはコンテの哲 学の多くを否定したが、その方法論は維持し、改良を加えた。社会科学は、人間活動の領域における自然の論理的継続であるとし、社会科学も同じ客観性、合理 主義、因果関係へのアプローチを維持できると主張した。 [39] デュルケムは1895年にボルドー大学でヨーロッパ初の社会学講座を開設し、『社会学的方法の規準』(1895年)を出版した。[40] デュルケムにとって社会学とは、「制度、その起源、その機能に関する科学」であった。[41]

デュルケムの単行本『自殺論』(1897年)は、現代の社会学者たちによって統計的分析の画期的な研究とみなされている。『自殺論』は、カトリック教徒と プロテスタント教徒の自殺率の相違に関する事例研究であり、社会学的な分析を心理学や哲学と区別する役割を果たした。また、構造機能主義の理論的概念への 大きな貢献となった。デュルケムは、異なる警察管区における自殺統計を慎重に調査し、カトリック教徒のコミュニティの自殺率はプロテスタント教徒よりも低 いことを証明しようとした。彼は、その原因を社会的(個人や心理とは対照的な)要因に帰した。彼は、社会学という科学が研究する独自の経験的対象を明確に するために、客観的社会的事実という概念を打ち出した。[39] このような研究を通じて、社会学は、任意の社会が健全であるか病的なものであるかを判断し、有機的な機能不全、すなわち「社会的アノミー」を否定するため の社会改革を求めることができると彼は主張した。

社会学は、近代化の課題として認識されていたもの、例えば産業化、都市化、世俗化、合理化のプロセスなどへの学術的な回答として急速に発展した。[42] この分野は主にヨーロッパ大陸で発展し、イギリスの人類学や統計学は概ね独自の発展を遂げた。しかし20世紀に入ると、多くの理論家が英語圏で活躍するよ うになった。初期の社会学者の多くは、社会学だけに厳密に専念するのではなく、経済学、法学、心理学、哲学などとも交流し、さまざまな異なる分野で理論が 応用されていた。社会学の始まり以来、社会学の認識論、方法、調査の枠組みは大幅に拡大し、多様化している。

デュルケーム、マルクス、ドイツの理論家マックス・ウェーバーは、社会学の3大創始者として一般的に引用されている。[43] ハーバート・スペンサー、ウィリアム・グラハム・サムナー、レスター・F・ウォード、W.E.B. ヴィルフレド・パレート、アレクシス・ド・トクヴィル、ヴェルナー・ゾンバルト、トースティン・ヴェブレン、フェルディナント・トニース、ゲオルク・ジン メル、ジェーン・アダムズ、カール・マンハイムは、学術的なカリキュラムでは創始理論家としてしばしば取り上げられる。また、社会学におけるフェミニスト の伝統の創始者として、シャーロット・パーキンス・ギルマン、マリアン・ウェーバー、ハリエット・マーティノー、フリードリヒ・エンゲルスが挙げられるこ ともある。各主要人物は、特定の理論的視点や方向性と関連している。

マルクスとエンゲルスは、近代社会の出現を何よりも資本主義の発展と関連づけた。デュルケムにとっては、それは特に産業化と、それがもたらした新たな社会 的分業と関連していた。ウェーバーにとっては、それは独特な思考様式、すなわちプロテスタンティズム的倫理(マルクスとエンゲルスが『利己的な計算の氷の ような波』という言葉で表現したもの)と関連する合理的な計算と関連していた。これらの偉大な古典的社会学者の作品を総合すると、ギデンズが最近「近代の 制度に関する多次元的な見方」と表現したものが示唆される。それは、近代の主要な制度として資本主義と産業主義だけでなく、「監視」(「情報管理と社会的 監督」を意味する)や「軍事力」(戦争の工業化という文脈における暴力手段の管理)も強調するものである。[44]

—ジョン・ハリスの『20世紀末の資本主義:第二の大きな変革?』(1992年)

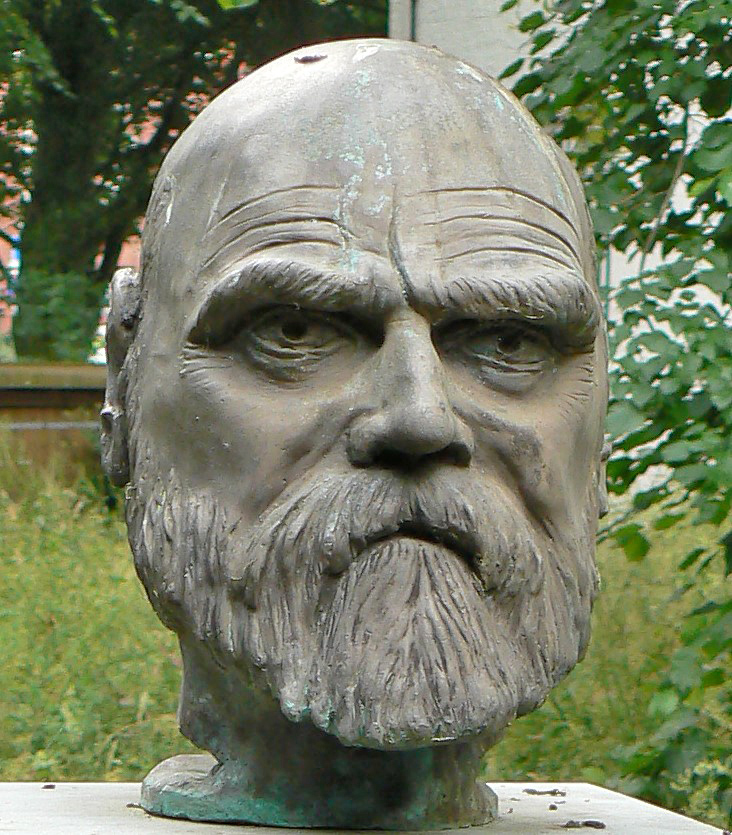

Bust of Ferdinand Tönnies in Husum, Germany

The first college course entitled "Sociology" was taught in the United States at Yale in 1875 by William Graham Sumner.[45] In 1883, Lester F. Ward, who later became the first president of the American Sociological Association (ASA), published Dynamic Sociology—Or Applied social science as based upon statical sociology and the less complex sciences, attacking the laissez-faire sociology of Herbert Spencer and Sumner.[37] Ward's 1,200-page book was used as core material in many early American sociology courses. In 1890, the oldest continuing American course in the modern tradition began at the University of Kansas, lectured by Frank W. Blackmar.[46] The Department of Sociology at the University of Chicago was established in 1892 by Albion Small, who also published the first sociology textbook: An introduction to the study of society.[47] George Herbert Mead and Charles Cooley, who had met at the University of Michigan in 1891 (along with John Dewey), moved to Chicago in 1894.[48] Their influence gave rise to social psychology and the symbolic interactionism of the modern Chicago School.[49] The American Journal of Sociology was founded in 1895, followed by the ASA in 1905.[47]

The sociological canon of classics with Durkheim and Max Weber at the top owes its existence in part to Talcott Parsons, who is largely credited with introducing both to American audiences.[50] Parsons consolidated the sociological tradition and set the agenda for American sociology at the point of its fastest disciplinary growth. Sociology in the United States was less historically influenced by Marxism than its European counterpart, and to this day broadly remains more statistical in its approach.[51]

The first sociology department established in the United Kingdom was at the London School of Economics and Political Science (home of the British Journal of Sociology) in 1904.[52] Leonard Trelawny Hobhouse and Edvard Westermarck became the lecturers in the discipline at the University of London in 1907.[53][54] Harriet Martineau, an English translator of Comte, has been cited as the first female sociologist.[55] In 1909, the German Sociological Association was founded by Ferdinand Tönnies, Max Weber, and Georg Simmel, among others.[56] Weber established the first department in Germany at the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich in 1919, having presented an influential new antipositivist sociology.[57] In 1920, Florian Znaniecki set up the first department in Poland. The Institute for Social Research at the University of Frankfurt (later to become the Frankfurt School of critical theory) was founded in 1923.[58] International co-operation in sociology began in 1893, when René Worms founded the Institut International de Sociologie, an institution later eclipsed by the much larger International Sociological Association (ISA), founded in 1949.[59]

ドイツのフーズムにあるフェルディナント・トイニースの胸像

「社会学」と題された最初の大学コースは、1875年にウィリアム・グラハム・サムナーによって米国のイェール大学で教えられた。1883年には、後に 後にアメリカ社会学会(ASA)の初代会長となるレスター・F・ウォードが『動態社会学――静態社会学と単純な科学を基礎とした応用社会科学』を出版し、 ハーバート・スペンサーとサムナーの自由放任主義的社会学を攻撃した。[37] ウォードの1,200ページに及ぶこの本は、初期の多くのアメリカ社会学コースで主要教材として使用された。1890年、フランク・W・ブラックマーが講 義を担当する、近代的な伝統に基づくアメリカ最古の継続的なコースがカンザス大学で始まった。[46] シカゴ大学社会学部の設立は1892年で、アルビオン・スモールが初代学部長を務めた。スモールは、社会学の最初の教科書『社会研究入門』の著者でもあ る。 [47] 1891年にミシガン大学で出会ったジョージ・ハーバート・ミードとチャールズ・コールヤー(ジョン・デューイも同席)は、1894年にシカゴに移った。 [48] 彼らの影響により、現代シカゴ学派の社会心理学と象徴的相互作用主義が生まれた。[49] 1895年に『アメリカ社会学ジャーナル』が創刊され、1905年にはASAが設立された。[47]

デュルケームとマックス・ウェーバーを頂点とする社会学の古典は、その存在の一部をタルコット・パ-ソンズに負っている。パ-ソンズは、両者をアメリカに 紹介したことで広く知られている。[50] パ-ソンズは社会学の伝統を確立し、アメリカ社会学が最も急速に発展した時期にその方向性を定めた。アメリカにおける社会学は、ヨーロッパの社会学よりも 歴史的にマルクス主義の影響をあまり受けておらず、今日に至るまで、そのアプローチは統計学的なものが多い。[51]

イギリスで最初に社会学の学科が設置されたのは、1904年のロンドン・スクール・オブ・エコノミクス・アンド・ポリティカル・サイエンス(『ブリティッ シュ・ジャーナル・オブ・ソシオロジー』の発行元)である。[52] 1907年には、レナード・トレルニー・ホブハウスとエドヴァルド・ヴェステルマルクがロンドン大学の講師となった。 [53][54] コンテの英訳者であるハリーエット・マーティノーは、最初の女性社会学者として挙げられている。[55] 1909年には、フェルディナント・トンネス、マックス・ヴェーバー、ゲオルク・ジンメルらによってドイツ社会学会が設立された。 [56] ウェーバーは1919年にミュンヘン大学にドイツ初の社会学講座を設立し、影響力のある反ポスト実証主義的社会学を提示した。[57] 1920年には、フロリアン・ザナシェツキがポーランド初の社会学講座を設立した。フランクフルト大学社会研究所(後に批判理論のフランクフルト学派とな る)は1923年に設立された。[58] 社会学における国際協力は1893年に始まり、ルネ・ウォームズが国際社会学協会(Institut International de Sociologie)を設立した。この機関は、1949年に設立されたはるかに大きな国際社会学会(ISA)によって後に吸収された。[59]

Main article: Sociological theory

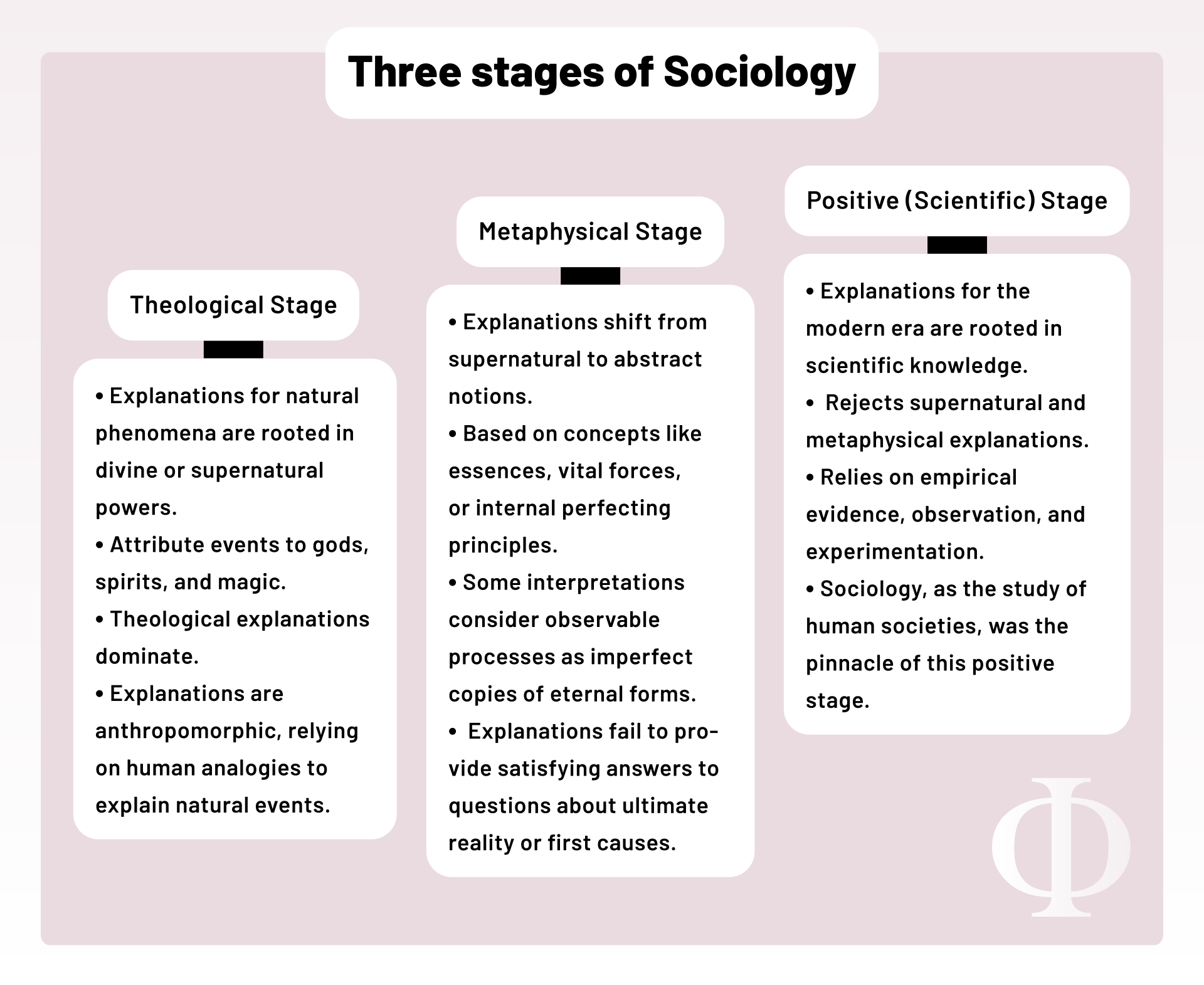

Three stages of Sociology

Positivism and anti-positivism

Positivism

Main article: Positivism

The overarching methodological principle of positivism is to conduct sociology in broadly the same manner as natural science. An emphasis on empiricism and the scientific method is sought to provide a tested foundation for sociological research based on the assumption that the only authentic knowledge is scientific knowledge, and that such knowledge can only arrive by positive affirmation through scientific methodology.[citation needed]

Our main goal is to extend scientific rationalism to human conduct.... What has been called our positivism is but a consequence of this rationalism.[60]

— Émile Durkheim, The Rules of Sociological Method (1895)

The term has long since ceased to carry this meaning; there are no fewer than twelve distinct epistemologies that are referred to as positivism.[39][61] Many of these approaches do not self-identify as "positivist", some because they themselves arose in opposition to older forms of positivism, and some because the label has over time become a pejorative term[39] by being mistakenly linked with a theoretical empiricism. The extent of antipositivist criticism has also diverged, with many rejecting the scientific method and others only seeking to amend it to reflect 20th-century developments in the philosophy of science. However, positivism (broadly understood as a scientific approach to the study of society) remains dominant in contemporary sociology, especially in the United States.[39]

Loïc Wacquant distinguishes three major strains of positivism: Durkheimian, Logical, and Instrumental.[39] None of these are the same as that set forth by Comte, who was unique in advocating such a rigid (and perhaps optimistic) version.[62][4]: 94–8, 100–4 While Émile Durkheim rejected much of the detail of Comte's philosophy, he retained and refined its method. Durkheim maintained that the social sciences are a logical continuation of the natural ones into the realm of human activity, and insisted that they should retain the same objectivity, rationalism, and approach to causality.[39] He developed the notion of objective sui generis "social facts" to serve as unique empirical objects for the science of sociology to study.[39]

The variety of positivism that remains dominant today is termed instrumental positivism. This approach eschews epistemological and metaphysical concerns (such as the nature of social facts) in favour of methodological clarity, replicability, reliability and validity.[63] This positivism is more or less synonymous with quantitative research, and so only resembles older positivism in practice. Since it carries no explicit philosophical commitment, its practitioners may not belong to any particular school of thought. Modern sociology of this type is often credited to Paul Lazarsfeld,[39] who pioneered large-scale survey studies and developed statistical techniques for analysing them. This approach lends itself to what Robert K. Merton called middle-range theory: abstract statements that generalize from segregated hypotheses and empirical regularities rather than starting with an abstract idea of a social whole.[64]

詳細は「社会学理論」を参照

社会学の3つの段階

実証主義と反実証主義

実証主義

詳細は「実証主義」を参照

実証主義の包括的な方法論の原則は、社会学を自然科学とほぼ同じ方法で実施することである。実証主義では、経験主義と科学的方法論を重視し、唯一の真正な 知識は科学的知識であり、そのような知識は科学的手段による肯定的な肯定によってのみ到達できるという前提に基づいて、社会学的研究のための検証済みの基 盤を提供しようとしている。

我々の主な目的は、科学的合理主義を人間の行動にまで拡大することである。我々の実証主義と呼ばれるものは、この合理主義の結果に過ぎない。

— エミール・デュルケム、『社会学的方法の規則』(1895年)

この用語は、この意味ではとっくに廃れている。実証主義と呼ばれる認識論は12種類以上ある。[39][61] これらのアプローチの多くは「実証主義」と自らを規定していない。その理由のいくつかは、それ自体が古い形の実証主義への反対として生まれたためであり、 また、そのレッテルが、理論的経験論と誤って関連付けられたことで、時代とともに軽蔑的な用語となったためである。反実証主義の批判の度合いも様々であ り、科学的手法を否定する者もいれば、20世紀の科学哲学の発展を反映させるために修正を求める者もいる。しかし、実証主義(広くは社会研究における科学 的アプローチとして理解されている)は、現代の社会学、特に米国では依然として支配的である。

ロイク・ワカンは、実証主義の3つの主要な流れを区別している。デュルケム流、論理主義、道具主義の3つである。[39] これらのいずれも、厳格な(おそらく楽観的な)バージョンを提唱した点でユニークなコントのそれとは異なる。[62][4]:94-8,100-4 エミール・デュルケムは、コントの哲学の多くの詳細を否定したが、その方法論は維持し、改良した。デュルケムは、社会科学は自然哲学の論理的延長として人 間の活動領域に存在するものであると主張し、自然科学と同じ客観性、合理主義、因果関係へのアプローチを維持すべきであると主張した。[39] 彼は、社会学という科学が研究する独自の経験的対象として、独自の「社会的事実」という概念を開発した。[39]

今日でも支配的な実証主義の多様性は、道具的実証主義と呼ばれる。このアプローチは、方法論の明確性、再現性、信頼性、妥当性を重視するあまり、認識論的 および形而上学的関心(社会的事実の性質など)を排除する。この実証主義は、多かれ少なかれ量的研究と同義であり、実質的には古い実証主義に似ている。明 確な哲学的コミットメントを持たないため、その実践者は特定の学派に属さない場合もある。このタイプの現代社会学は、大規模な調査研究の先駆者であり、そ の分析のための統計的手法を開発したポール・ラザーズフェルドに帰されることが多い。[39] このアプローチは、ロバート・K・マートンがミドルレンジ・セオリーと呼んだものに適している。すなわち、社会全体についての抽象的な考えから出発するの ではなく、分離された仮説と経験則から一般化する抽象的なステートメントである。[64]

Main article: Antipositivism

The German philosopher Hegel criticised traditional empiricist epistemology, which he rejected as uncritical, and determinism, which he viewed as overly mechanistic.[4]: 169 Karl Marx's methodology borrowed from Hegelian dialecticism but also a rejection of positivism in favour of critical analysis, seeking to supplement the empirical acquisition of "facts" with the elimination of illusions.[4]: 202–3 He maintained that appearances need to be critiqued rather than simply documented. Early hermeneuticians such as Wilhelm Dilthey pioneered the distinction between natural and social science ('Geisteswissenschaft'). Various neo-Kantian philosophers, phenomenologists and human scientists further theorized how the analysis of the social world differs to that of the natural world due to the irreducibly complex aspects of human society, culture, and being.[65][66]

In the Italian context of development of social sciences and of sociology in particular, there are oppositions to the first foundation of the discipline, sustained by speculative philosophy in accordance with the antiscientific tendencies matured by critique of positivism and evolutionism, so a tradition Progressist struggles to establish itself.[67]

At the turn of the 20th century, the first generation of German sociologists formally introduced methodological anti-positivism, proposing that research should concentrate on human cultural norms, values, symbols, and social processes viewed from a resolutely subjective perspective. Max Weber argued that sociology may be loosely described as a science as it is able to identify causal relationships of human "social action"—especially among "ideal types", or hypothetical simplifications of complex social phenomena.[4]: 239–40 As a non-positivist, however, Weber sought relationships that are not as "historical, invariant, or generalisable"[4]: 241 as those pursued by natural scientists. Fellow German sociologist, Ferdinand Tönnies, theorised on two crucial abstract concepts with his work on "gemeinschaft and gesellschaft" (lit. 'community' and 'society'). Tönnies marked a sharp line between the realm of concepts and the reality of social action: the first must be treated axiomatically and in a deductive way ("pure sociology"), whereas the second empirically and inductively ("applied sociology").[68]

詳細は「反実証主義」を参照

ドイツの哲学者ヘーゲルは、批判精神に欠けるとして伝統的な経験論的認識論を批判し、また、機械論的過ぎるとみなして決定論を否定した。[4]:169 カール・マルクスの方法論はヘーゲル弁証法から借りたものだが、批判的分析を支持する立場から実証主義を拒絶し、幻想の排除によって「事実」の経験的な獲 得を補完しようとした。[4]: 202–3 彼は、外見は単に記録するのではなく、批判的に検討する必要があると主張した。初期の解釈学者であるヴィルヘルム・ディルタイ(Wilhelm Dilthey)は、自然科学と社会科学(「精神科学」)の区別を先駆的に行った。さまざまな新カント派の哲学者、現象学者、人間科学者は、人間社会、文 化、存在の不可還元的に複雑な側面により、社会世界の分析が自然科学の世界の分析とどのように異なるかをさらに理論化した。

イタリアにおける社会科学、特に社会学の発展の文脈では、実証主義と進化論の批判によって熟成された反科学的な傾向に従う思弁哲学によって支えられた、この学問の最初の基礎に対する反対論がある。そのため、進歩主義の伝統は確立に苦戦している。

20世紀の変わり目に、ドイツの社会学者の第一世代が、方法論的反実証主義を正式に導入し、研究はあくまでも主観的な視点から、人間の文化的規範、価値、 象徴、社会過程に集中すべきであると提案した。マックス・ウェーバーは、社会学は人間の「社会的行為」の因果関係を特定できることから、大まかに言えば科 学であると主張した。特に「理想型」、すなわち複雑な社会現象の仮説的な単純化においてである。[4]: 239–40 しかし、非実証主義者であるウェーバーは、自然科学者が追求するような「歴史的、不変的、または一般化できる」[4]: 241 関係性を追求したわけではなかった。同じドイツの社会学者であるフェルディナント・トニースは、「ゲマインシャフトとゲゼルシャフト」(直訳すると「共同 体」と「社会」)に関する研究で、2つの重要な抽象概念を理論化した。トニースは、概念の領域と社会行動の現実の間に明確な線引きをした。前者は公理的に 演繹的に扱われなければならない(「純粋社会学」)が、後者は経験的に帰納的に扱われるべきである(「応用社会学」)。[68]

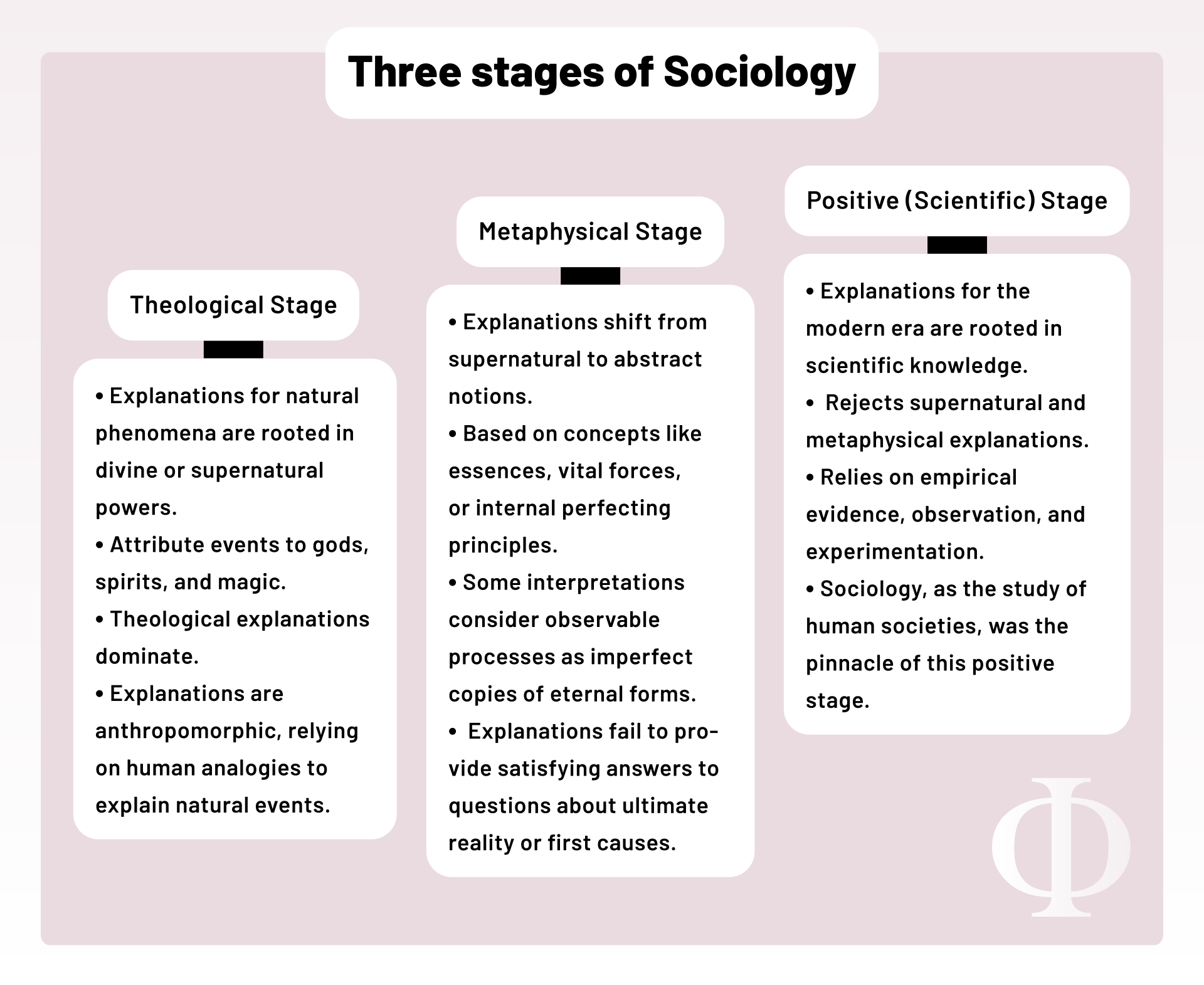

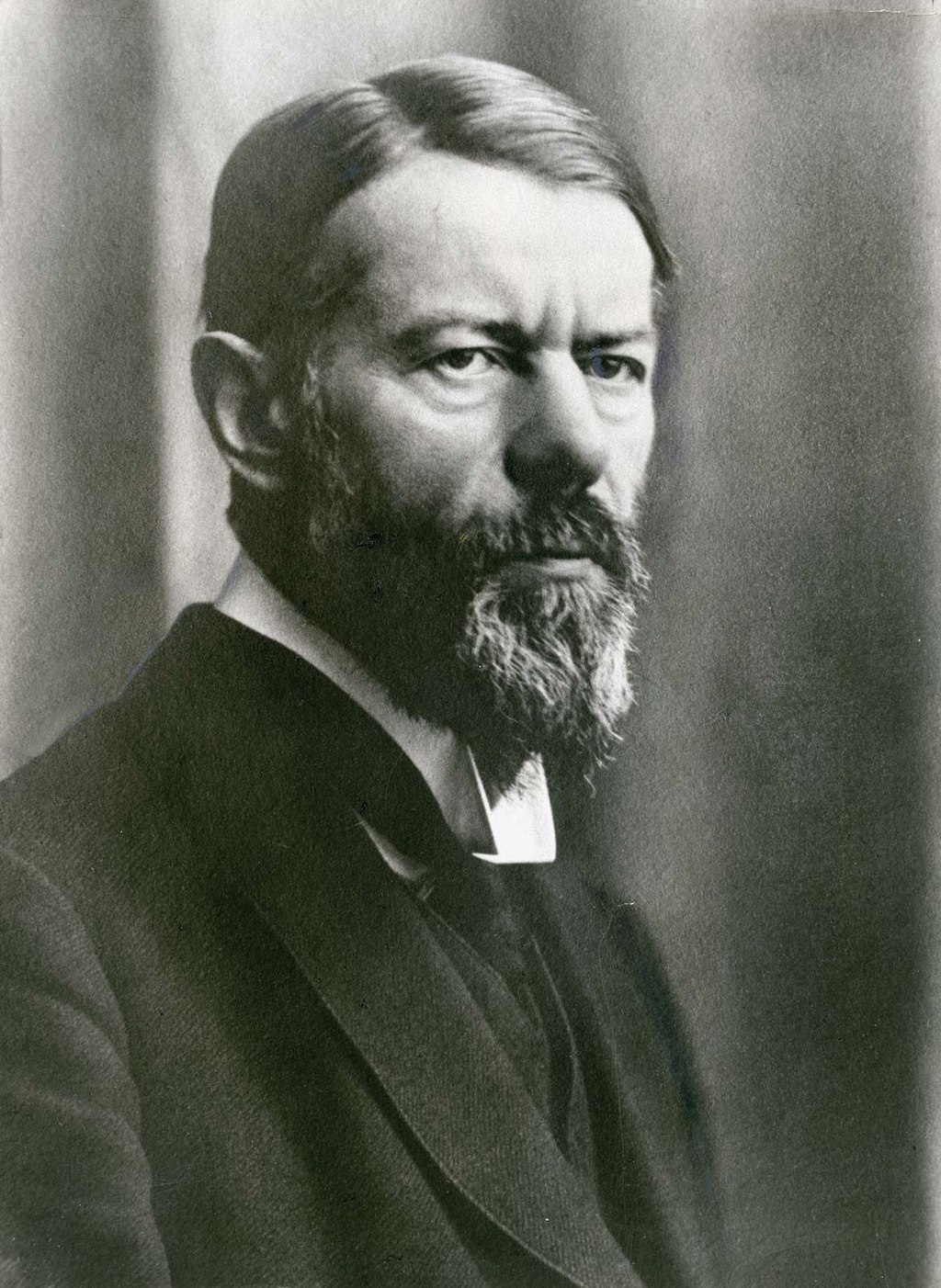

Max Weber in 1918, facing right and looking at the camera

Max Weber in 1918

[Sociology is] ... the science whose object is to interpret the meaning of social action and thereby give a causal explanation of the way in which the action proceeds and the effects which it produces. By 'action' in this definition is meant the human behaviour when and to the extent that the agent or agents see it as subjectively meaningful ... the meaning to which we refer may be either (a) the meaning actually intended either by an individual agent on a particular historical occasion or by a number of agents on an approximate average in a given set of cases, or (b) the meaning attributed to the agent or agents, as types, in a pure type constructed in the abstract. In neither case is the 'meaning' to be thought of as somehow objectively 'correct' or 'true' by some metaphysical criterion. This is the difference between the empirical sciences of action, such as sociology and history, and any kind of prior discipline, such as jurisprudence, logic, ethics, or aesthetics whose aim is to extract from their subject-matter 'correct' or 'valid' meaning.[69]

— Max Weber, The Nature of Social Action (1922), p. 7

Both Weber and Georg Simmel pioneered the "Verstehen" (or 'interpretative') method in social science; a systematic process by which an outside observer attempts to relate to a particular cultural group, or indigenous people, on their own terms and from their own point of view.[70] Through the work of Simmel, in particular, sociology acquired a possible character beyond positivist data-collection or grand, deterministic systems of structural law. Relatively isolated from the sociological academy throughout his lifetime, Simmel presented idiosyncratic analyses of modernity more reminiscent of the phenomenological and existential writers than of Comte or Durkheim, paying particular concern to the forms of, and possibilities for, social individuality.[71] His sociology engaged in a neo-Kantian inquiry into the limits of perception, asking 'What is society?' in a direct allusion to Kant's question 'What is nature?'[72]

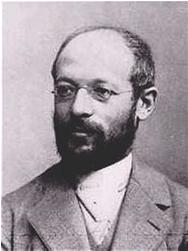

Georg Simmel

The deepest problems of modern life flow from the attempt of the individual to maintain the independence and individuality of his existence against the sovereign powers of society, against the weight of the historical heritage and the external culture and technique of life. The antagonism represents the most modern form of the conflict which primitive man must carry on with nature for his bodily existence. The eighteenth century may have called for liberation from all the ties which grew up historically in politics, in religion, in morality, and in economics to permit the original natural virtue of man, which is equal in everyone, to develop without inhibition; the nineteenth century may have sought to promote, in addition to man's freedom, his individuality (which is connected with the division of labor) and his achievements which make him unique and indispensable but which at the same time make him so much the more dependent on the complementary activity of others; Nietzsche may have seen the relentless struggle of the individual as the prerequisite for his full development, while socialism found the same thing in the suppression of all competition – but in each of these the same fundamental motive was at work, namely the resistance of the individual to being leveled, swallowed up in the social-technological mechanism.[73]

— Georg Simmel, The Metropolis and Mental Life (1903)

1918年のマックス・ウェーバー、右を向きカメラ目線

1918年のマックス・ウェーバー

社会学とは...社会行動の意味を解釈し、それによってその行動がどのように進展し、どのような影響が生じるのかを因果関係に基づいて説明する科学であ る。この定義における「行為」とは、行為者または行為者たちが主観的に意味のあるものとして認識する時点および範囲における人間の行動を意味する。ここで いう「意味」とは、(a) 特定の歴史的状況において個々の行為者が意図した意味、または、特定の事例群において概ね平均的な行為者たちが意図した意味、あるいは、(b) 抽象的に構築された純粋なタイプにおいて、タイプとして行為者または行為者たちに帰属された意味、のいずれかを指す。いずれの場合も、「意味」は、形而上 学的基準によって、何らかの客観的な「正しさ」や「真実性」を持つと考えるべきではない。これは、社会学や歴史学などの経験科学と、法学、論理学、倫理 学、美学など、対象から「正しい」または「妥当な」意味を抽出することを目的とする先行する学問との違いである。

— マックス・ヴェーバー、『社会行動の性質』(1922年)、7ページ

ヴェーバーとゲオルク・ジンメルは、社会科学における「理解(または解釈)」という方法の先駆者であった。これは、外部の観察者が特定の文化集団や先住民 と彼ら自身の言葉や視点で関わりを持つことを試みる体系的なプロセスである。[70] 特にジンメルの研究を通じて、社会学は実証主義的なデータ収集や壮大な決定論的構造法の枠を超えた可能性を獲得した。生涯を通じて社会学の学会から比較的 孤立していたシムメルは、現象学や実存主義の作家たちを思わせる独特な近代性の分析を提示し、特に社会的な個性の形態と可能性に注目した。 [71] 彼の社会学は、カントの「自然とは何か」という問いに直接言及しながら、「社会とは何か」という問いを投げかけ、知覚の限界について新カント主義的な探究 を行った。[72]

ゲオルク・ジンメル

現代生活の最も深い問題は、個人が社会の権力、歴史的遺産の重み、外部の文化や生活技術に抗して、自身の存在の独立性と独自性を維持しようとする試みから 生じている。この対立は、原始人が自身の肉体的な存在のために自然と戦わなければならなかった紛争の最も現代的な形を表している。18世紀は、政治、 政治、宗教、道徳、経済の分野で歴史的に生じたあらゆるしがらみから解放し、万人に等しく備わっている人間の本来の自然な美徳が抑制されることなく発達す ることを許容しようとしたのかもしれない。19世紀は、人間の自由に加えて、個性(これは分業と関連している)と、人間を唯一無二でかけがえのない存在に しながら、同時に他者の補完的な活動に大きく依存させるような功績を促進しようとしたのかもしれない。ニーチェは、個人の容赦ない闘争がその完全な発展の 前提条件であると見ていたかもしれない。一方、社会主義は、競争の抑制に同じものを見出した。しかし、これらのそれぞれにおいて、同じ根本的な動機が働い ていた。すなわち、個人が均一化され、社会技術的メカニズムに飲み込まれることへの抵抗である。[73]

— ゲオルク・ジンメル、『大都市と精神生活』(1903年)

The contemporary discipline of sociology is theoretically multi-paradigmatic[74] in line with the contentions of classical social theory. Randall Collins' well-cited survey of sociological theory[75] retroactively labels various theorists as belonging to four theoretical traditions: Functionalism, Conflict, Symbolic Interactionism, and Utilitarianism.[76]

Accordingly, modern sociological theory predominantly descends from functionalist (Durkheim) and conflict (Marx and Weber) approaches to social structure, as well as from symbolic-interactionist approaches to social interaction, such as micro-level structural (Simmel) and pragmatist (Mead, Cooley) perspectives. Utilitarianism (also known as rational choice or social exchange), although often associated with economics, is an established tradition within sociological theory.[77][78]

Lastly, as argued by Raewyn Connell, a tradition that is often forgotten is that of Social Darwinism, which applies the logic of Darwinian biological evolution to people and societies.[79] This tradition often aligns with classical functionalism, and was once the dominant theoretical stance in American sociology, from c. 1881 – c. 1915,[80] associated with several founders of sociology, primarily Herbert Spencer, Lester F. Ward, and William Graham Sumner.

Contemporary sociological theory retains traces of each of these traditions and they are by no means mutually exclusive.[citation needed]

現代の社会学は、古典的社会理論の論争に沿って、理論的には多パラダイム的である[74]。ランダル・コリンズによる社会学理論のよく引用される調査 [75]では、さまざまな理論家を遡及的に4つの理論的伝統、すなわち機能主義、葛藤、象徴的相互作用論、功利主義に分類している[76]。

したがって、現代の社会学理論は、社会構造に対する機能主義(デュルケム)や葛藤(マルクスやウェーバー)のアプローチ、および社会的な相互作用に対する 象徴的相互作用論のアプローチ、例えばミクロレベルの構造(ジンメル)やプラグマティズム(ミード、クーリー)の視点などから主に派生している。功利主義 (合理的選択や社会的交換とも呼ばれる)は、経済学と関連付けられることが多いが、社会学理論においては確立された伝統である。

最後に、レイウィン・コネルが主張するように、しばしば忘れられている伝統として、社会ダーウィニズムがある。これは、ダーウィンの生物進化論の論理を人 間や社会に適用するものである。 この伝統はしばしば古典的機能主義と一致し、1881年頃から1915年頃まではアメリカ社会学の支配的な理論的立場であった。[80] 主にハーバート・スペンサー、レスター・F・ウォード、ウィリアム・グラハム・サムナーといった社会学の創始者たちと関連している。

現代の社会学理論は、これらの伝統のそれぞれを継承しており、決して相互に排他的なものではない。[要出典]

Main article: Structural functionalism

A broad historical paradigm in both sociology and anthropology, functionalism addresses the social structure—referred to as "social organization" by the classical theorists—with respect to the whole as well as the necessary function of the whole's constituent elements. A common analogy (popularized by Herbert Spencer) is to regard norms and institutions as 'organs' that work towards the proper functioning of the entire 'body' of society.[81] The perspective was implicit in the original sociological positivism of Comte but was theorized in full by Durkheim, again with respect to observable, structural laws.

Functionalism also has an anthropological basis in the work of theorists such as Marcel Mauss, Bronisław Malinowski, and Radcliffe-Brown. It is in the latter's specific usage that the prefix "structural" emerged.[82] Classical functionalist theory is generally united by its tendency towards biological analogy and notions of social evolutionism, in that the basic form of society would increase in complexity and those forms of social organization that promoted solidarity would eventually overcome social disorganization. As Giddens states:[83]

Functionalist thought, from Comte onwards, has looked particularly towards biology as the science providing the closest and most compatible model for social science. Biology has been taken to provide a guide to conceptualizing the structure and the function of social systems and to analyzing processes of evolution via mechanisms of adaptation. Functionalism strongly emphasizes the pre-eminence of the social world over its individual parts (i.e. its constituent actors, human subjects).

詳細は「構造機能主義」を参照

社会学と人類学の両方における広範な歴史的パラダイムである機能主義は、古典理論家たちによって「社会組織」とも呼ばれる社会構造全体、およびその構成要 素の必要な機能について論じる。よく知られた類似例(ハーバート・スペンサーによって広められた)としては、社会という「身体」全体の適切な機能に向けて 働く「器官」として、規範や制度を捉えるというものがある。[81] この視点は、コントによる社会学実証主義の原初的なものには暗黙的に含まれていたが、デュルケムによって完全に理論化された。

機能主義は、マルセル・モース、ブロニスワフ・マリノフスキ、ラドクリフ=ブラウンといった理論家の研究にも人類学的な基礎がある。後者の特定の用法にお いて、「構造的」という接頭辞が生まれたのである。[82] 古典的な機能主義理論は、一般的に、社会の基本形態は複雑性を増し、連帯を促進する社会組織の形態が最終的に社会の混乱を克服するという、生物学的類似性 と社会進化論の概念という傾向によって結びつけられている。ギデンズが述べているように、[83]

機能主義は、コント以降、社会科学にとって最も近しく、最も適合性のあるモデルを提供する科学として生物学に特に注目してきた。生物学は、社会システムの 構造と機能の概念化、および適応のメカニズムを介した進化のプロセスの分析の指針を提供すると考えられてきた。機能主義は、社会世界がその個々の部分(す なわち、その構成員である人間)よりも優れていることを強く強調する。

Main article: Conflict theory

Functionalist theories emphasize "cohesive systems" and are often contrasted with "conflict theories", which critique the overarching socio-political system or emphasize the inequality between particular groups. The following quotes from Durkheim[84] and Marx[85] epitomize the political, as well as theoretical, disparities, between functionalist and conflict thought respectively:

To aim for a civilization beyond that made possible by the nexus of the surrounding environment will result in unloosing sickness into the very society we live in. Collective activity cannot be encouraged beyond the point set by the condition of the social organism without undermining health.

— Émile Durkheim, The Division of Labour in Society (1893)

The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles. Freeman and slave, patrician and plebeian, lord and serf, guild-master and journeyman, in a word, oppressor and oppressed, stood in constant opposition to one another, carried on an uninterrupted, now hidden, now open fight, a fight that each time ended, either in a revolutionary re-constitution of society at large, or in the common ruin of the contending classes.

— Karl Marx & Friedrich Engels, The Communist Manifesto (1848)

詳細は「葛藤理論」を参照

機能主義理論は「凝集システム」を強調し、包括的な社会政治システムを批判したり、特定の集団間の不平等を強調する「葛藤理論」と対比されることが多い。 デュルケム[84]とマルクス[85]の次の引用は、それぞれ機能主義と葛藤理論の政治的、理論的な相違を象徴している。

周囲の環境の結びつきによって可能となる文明を超えた文明を目指すことは、私たちが暮らす社会に病を解き放つ結果となる。社会組織の状態によって設定された限度を超えて集団活動を奨励することは、保健を損なうことなく行うことはできない。

— エミール・デュルケーム著『社会における分業』(1893年)

これまでに存在したすべての社会の歴史は、階級闘争の歴史である。自由民と奴隷、貴族と平民、領主と農奴、ギルドの親方と見習い職人、一言で言えば、抑圧 者と被抑圧者は、常に互いに敵対し、隠れたり現れたりする戦いを絶え間なく繰り広げた。その戦いは、社会全体が革命的に再編されるか、争う階級が共に滅び るかによって、その都度終結した。

— カール・マルクスとフリードリヒ・エンゲルス、『共産党宣言』(1848年)

Main articles: Symbolic interactionism, Dramaturgy (sociology), Interpretive sociology, and Phenomenological sociology

Symbolic interaction—often associated with interactionism, phenomenology, dramaturgy, interpretivism—is a sociological approach that places emphasis on subjective meanings and the empirical unfolding of social processes, generally accessed through micro-analysis.[86] This tradition emerged in the Chicago School of the 1920s and 1930s, which, prior to World War II, "had been the center of sociological research and graduate study."[87][page needed] The approach focuses on creating a framework for building a theory that sees society as the product of the everyday interactions of individuals. Society is nothing more than the shared reality that people construct as they interact with one another. This approach sees people interacting in countless settings using symbolic communications to accomplish the tasks at hand. Therefore, society is a complex, ever-changing mosaic of subjective meanings.[27]: 19 Some critics of this approach argue that it only looks at what is happening in a particular social situation, and disregards the effects that culture, race or gender (i.e. social-historical structures) may have in that situation.[27] Some important sociologists associated with this approach include Max Weber, George Herbert Mead, Erving Goffman, George Homans, and Peter Blau. It is also in this tradition that the radical-empirical approach of ethnomethodology emerges from the work of Harold Garfinkel.

主な記事:象徴的相互作用主義、ドラマツルギー(社会学)、解釈社会学、現象学的社会学

象徴的相互作用論は、相互作用論、現象学、ドラマツルギー、解釈主義と関連付けられることが多いが、主観的な意味と社会過程の実証的展開に重点を置く社会 学的なアプローチであり、通常はミクロ分析を通じてアクセスされる。[86] この伝統は、1920年代と1930年代のシカゴ学派で生まれた。第二次世界大戦前には、「社会学的研究と大学院教育の中心地であった」[ [87][要出典] このアプローチは、社会を個々人の日常的な相互作用の産物とみなす理論の構築に向けた枠組みの作成に重点を置いている。社会とは、人々が相互に作用し合う 中で構築する共有された現実以外の何者でもない。このアプローチでは、人々は無数の状況下で、目の前の課題を達成するために象徴的なコミュニケーションを 用いて相互に作用していると見なしている。したがって、社会とは主観的な意味の複雑かつ常に変化するモザイクである。[27]: 19 このアプローチに対する批判のいくつかでは、特定の社会的状況で起こっていることだけを観察し、文化、人種、性別(すなわち社会歴史的構造)がその状況に 与える影響を無視していると主張している。[27] このアプローチに関連する重要な社会学者には、マックス・ウェーバー、ジョージ・ハーバート・ミード、アーヴィング・ゴフマン、ジョージ・ホーマンス、 ピーター・ブラウなどがいる。また、ハロルド・ガフィンケルの研究からエスノメソドロジーの急進的経験主義的アプローチが生まれたのも、この伝統である。

Main articles: Utilitarianism, Rational choice theory, and Exchange theory

Utilitarianism is often referred to as exchange theory or rational choice theory in the context of sociology. This tradition tends to privilege the agency of individual rational actors and assumes that within interactions individuals always seek to maximize their own self-interest. As argued by Josh Whitford, rational actors are assumed to have four basic elements:[88]

"a knowledge of alternatives;"

"a knowledge of, or beliefs about the consequences of the various alternatives;"

"an ordering of preferences over outcomes;" and

"a decision rule, to select among the possible alternatives"

Exchange theory is specifically attributed to the work of George C. Homans, Peter Blau and Richard Emerson.[89] Organizational sociologists James G. March and Herbert A. Simon noted that an individual's rationality is bounded by the context or organizational setting. The utilitarian perspective in sociology was, most notably, revitalized in the late 20th century by the work of former ASA president James Coleman.[citation needed]

主な記事:功利主義、合理的選択理論、交換理論

功利主義は、社会学の文脈では交換理論や合理的選択理論と呼ばれることが多い。この伝統は、個々の合理的な行為者の行動を重視する傾向があり、相互作用の なかで個人は常に自己の利益を最大化しようとするという前提に立つ。ジョシュ・ホイットフォードが論じているように、合理的な行為者は4つの基本的要素を 持つと想定されている。

「代替案に関する知識」

「さまざまな選択肢の結果に関する知識または信念」、

「結果に対する優先順位付け」、そして

「可能な選択肢の中から選択するための決定規則」である

交換理論は、特にジョージ・C・ホーマンス、ピーター・ブラウ、リチャード・エマーソンの研究に起因するものである。[89] 組織社会学のジェームズ・G・マーチとハーバート・A・サイモンは、個人の合理性は文脈や組織の設定によって制限されると指摘した。社会学における功利主 義的視点は、とりわけ、元ASA会長のジェームズ・コールマンの研究によって20世紀後半に再活性化された。[要出典]

Following the decline of theories of sociocultural evolution in the United States, the interactionist thought of the Chicago School dominated American sociology. As Anselm Strauss describes, "we didn't think symbolic interaction was a perspective in sociology; we thought it was sociology."[87] Moreover, philosophical and psychological pragmatism grounded this tradition.[90] After World War II, mainstream sociology shifted to the survey-research of Paul Lazarsfeld at Columbia University and the general theorizing of Pitirim Sorokin, followed by Talcott Parsons at Harvard University. Ultimately, "the failure of the Chicago, Columbia, and Wisconsin [sociology] departments to produce a significant number of graduate students interested in and committed to general theory in the years 1936–45 was to the advantage of the Harvard department."[91] As Parsons began to dominate general theory, his work primarily referenced European sociology—almost entirely omitting citations of both the American tradition of sociocultural-evolution as well as pragmatism. In addition to Parsons' revision of the sociological canon (which included Marshall, Pareto, Weber and Durkheim), the lack of theoretical challenges from other departments nurtured the rise of the Parsonian structural-functionalist movement, which reached its crescendo in the 1950s, but by the 1960s was in rapid decline.[92]

By the 1980s, most functionalist perspectives in Europe had broadly been replaced by conflict-oriented approaches,[93] and to many in the discipline, functionalism was considered "as dead as a dodo:"[94] According to Giddens:[95]

The orthodox consensus terminated in the late 1960s and 1970s as the middle ground shared by otherwise competing perspectives gave way and was replaced by a baffling variety of competing perspectives. This third 'generation' of social theory includes phenomenologically inspired approaches, critical theory, ethnomethodology, symbolic interactionism, structuralism, post-structuralism, and theories written in the tradition of hermeneutics and ordinary language philosophy.

米国における社会文化進化論の衰退後、シカゴ学派の相互作用思想が米国社会学を支配した。アンセルム・ストラウスが述べているように、「私たちは象徴的相 互作用を社会学の視点とは考えず、社会学そのものであると考えていた」[87]。さらに、この伝統は哲学的・心理学的実用主義に根ざしていた[90]。第 二次世界大戦後、社会学の主流は、コロンビア大学のポール・ラザーズフェルドによる調査研究とピティリム・ソローキンによる一般的な理論化へと移行し、そ の後ハーバード大学のタルコット・パールソンが続いた。結局、「1936年から1945年の間、シカゴ大学、コロンビア大学、ウィスコンシン大学(社会 学)の各学部が、一般理論に関心を持ち、それに専心する大学院生を多数輩出できなかったことは、ハーバード大学にとって有利に働いた」のである。[91] パーソンズが一般理論を支配し始めたとき、彼の研究は主にヨーロッパの社会学を参照しており、アメリカにおける社会文化進化論の伝統やプラグマティズムの 引用はほとんど完全に省略されていた。パーソンズによる社会学の正典(マーシャル、パレート、ウェーバー、デュルケムなどを含む)の修正に加え、他の学部 の理論的挑戦の欠如がパーソンズ流の構造機能主義運動の高まりを助長し、それは1950年代に絶頂期を迎えたが、1960年代には急速に衰退した。

1980年代までに、ヨーロッパにおける機能主義的視点のほとんどは、対立を重視するアプローチに取って代わられた[93]。そして、多くの人々にとって、機能主義は「ドードー鳥のように死んだ」ものと考えられていた[94]。ギデンズによると、[95]

正統派のコンセンサスは、1960年代後半から1970年代にかけて終焉を迎えた。それまでは競合する見解が共有していた中間領域が消滅し、不可解なほど 多様な競合する見解が台頭したためである。この第三世代の社会理論には、現象学に影響を受けたアプローチ、批判理論、エスノメソドロジー、象徴相互作用 論、構造主義、ポスト構造主義、解釈学や日常言語哲学の伝統に則った理論などが含まれる。

While some conflict approaches also gained popularity in the United States, the mainstream of the discipline instead shifted to a variety of empirically oriented middle-range theories with no single overarching, or "grand", theoretical orientation. John Levi Martin refers to this "golden age of methodological unity and theoretical calm" as the Pax Wisconsana,[96] as it reflected the composition of the sociology department at the University of Wisconsin–Madison: numerous scholars working on separate projects with little contention.[97] Omar Lizardo describes the pax wisconsana as "a Midwestern flavored, Mertonian resolution of the theory/method wars in which [sociologists] all agreed on at least two working hypotheses: (1) grand theory is a waste of time; [and] (2) good theory has to be good to think with or goes in the trash bin."[98] Despite the aversion to grand theory in the latter half of the 20th century, several new traditions have emerged that propose various syntheses: structuralism, post-structuralism, cultural sociology and systems theory.[citation needed] Some sociologists have called for a return to 'grand theory' to combat the rise of scientific and pragmatist influences within the tradition of sociological thought (see Duane Rousselle).[99]

Anthony Giddens

Structuralism

The structuralist movement originated primarily from the work of Durkheim as interpreted by two European scholars: Anthony Giddens, a sociologist, whose theory of structuration draws on the linguistic theory of Ferdinand de Saussure; and Claude Lévi-Strauss, an anthropologist. In this context, 'structure' does not refer to 'social structure', but to the semiotic understanding of human culture as a system of signs. One may delineate four central tenets of structuralism:[100]

Structure is what determines the structure of a whole.

Structuralists believe that every system has a structure.

Structuralists are interested in 'structural' laws that deal with coexistence rather than changes.

Structures are the 'real things' beneath the surface or the appearance of meaning.

The second tradition of structuralist thought, contemporaneous with Giddens, emerges from the American School of social network analysis in the 1970s and 1980s,[101] spearheaded by the Harvard Department of Social Relations led by Harrison White and his students. This tradition of structuralist thought argues that, rather than semiotics, social structure is networks of patterned social relations. And, rather than Levi-Strauss, this school of thought draws on the notions of structure as theorized by Levi-Strauss' contemporary anthropologist, Radcliffe-Brown.[102] Some[103] refer to this as "network structuralism", and equate it to "British structuralism" as opposed to the "French structuralism" of Levi-Strauss.

米国では、いくつかの葛藤アプローチも人気を博したが、その代わりに、この学問分野の主流は、単一の包括的または「壮大な」理論的志向を持たない、さまざ まな経験主義的中間理論へとシフトした。ジョン・レヴィ・マーティンは、この「方法論の統一と理論の平穏の黄金時代」を「パックス・ウィスコンソナ」と呼 んだ。これはウィスコンシン大学マディソン校の社会学部の構成を反映したものであり、多数の学者が別々のプロジェクトに取り組んでいたが、ほとんど論争は なかった。 [97] オマール・リザルドは、この「ウィスコンシン学派の平和」を「中西部の風味を帯びた、マートン的な理論と方法論の戦争の解決」と表現し、その中で「(1) 大理論は時間の無駄、(2)優れた理論は思考に適したものでなければならない、さもなければゴミ箱行き」という2つの作業仮説に、すべての社会学者が同意 したと述べている。 [98] 20世紀後半には、大理論に対する嫌悪感があったにもかかわらず、さまざまな総合を提案するいくつかの新しい伝統が生まれた。構造主義、ポスト構造主義、 文化社会学、システム理論などである。[要出典] 科学とプラグマティズムの影響力が社会学思想の伝統の中で高まっていることを受け、一部の社会学者は「大理論」への回帰を呼びかけている(デュアン・ルセ ルを参照)。[99]

アンソニー・ギデンズ

構造主義

構造主義運動は、デュルケムの研究を解釈した2人のヨーロッパの学者、すなわち、フェルディナン・ド・ソーシュールの言語理論を参考にした構造化理論を提 唱した社会学者アンソニー・ギデンズと、人類学者クロード・レヴィ=ストロースの研究から始まった。この文脈における「構造」とは、「社会構造」ではな く、記号の体系としての人間文化の記号論的理解を指す。構造主義の4つの主要な原則を以下に挙げることができる。

構造とは、全体を構成するものである。

構造主義者は、あらゆるシステムには構造があると考えている。

構造主義者は、変化よりも共存を扱う「構造的」な法則に関心を持っている。

構造とは、意味の表面や外観の下にある「実体」である。

ギデンズと同時代の構造主義思想の第二の潮流は、1970年代から1980年代にかけてのアメリカにおける社会ネットワーク分析学派から生まれたものであ り、[101] ハーバード大学社会関係学部(Harrison Whiteと彼の学生たちによって主導された)が先導した。この構造主義思想の潮流は、記号論よりもむしろ、社会構造はパターン化された社会関係のネット ワークであると主張する。また、レヴィ=ストロースよりも、レヴィ=ストロースの同時代の文化人類学者ラドクリフ=ブラウンが理論化した構造の概念を重視 している。[102] これを「ネットワーク構造主義」と呼び、レヴィ=ストロースの「フランス構造主義」に対抗する「イギリス構造主義」と同一視する者もいる。

Post-structuralist thought has tended to reject 'humanist' assumptions in the construction of social theory.[104] Michel Foucault provides an important critique in his Archaeology of the Human Sciences, though Habermas (1986) and Rorty (1986) have both argued that Foucault merely replaces one such system of thought with another.[105][106] The dialogue between these intellectuals highlights a trend in recent years for certain schools of sociology and philosophy to intersect. The anti-humanist position has been associated with "postmodernism", a term used in specific contexts to describe an era or phenomena, but occasionally construed as a method.[citation needed]

ポスト構造主義思想は、社会理論の構築における「ヒューマニズム」的仮定を拒絶する傾向にある。[104] ミシェル・フーコーは著書『人間科学の考古学』で重要な批判を行っているが、ハーバーマス(1986年)とロルティ(1986年)は、フーコーは単に一つ の思考体系を別のものに置き換えているだけだと主張している。 [105][106] これらの知識人たちの対話は、近年、社会学や哲学の特定の学派が交差する傾向を浮き彫りにしている。反ヒューマニズムの立場は、「ポストモダニズム」とい う用語と関連付けられてきた。この用語は、特定の時代や現象を説明する際に使用されるが、時には方法論として解釈されることもある。[要出典]

Overall, there is a strong consensus regarding the central problems of sociological theory, which are largely inherited from the classical theoretical traditions. This consensus is: how to link, transcend or cope with the following "big three" dichotomies:[107]

subjectivity and objectivity, which deal with knowledge;

structure and agency, which deal with action;

and synchrony and diachrony, which deal with time.

Lastly, sociological theory often grapples with the problem of integrating or transcending the divide between micro, meso, and macro-scale social phenomena, which is a subset of all three central problems.[citation needed]

Subjectivity and objectivity

Main articles: Objectivity (science), Objectivity (philosophy), and Subjectivity

This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.

Find sources: "Sociology" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (March 2023) (Learn how and when to remove this message)

The problem of subjectivity and objectivity can be divided into two parts: a concern over the general possibilities of social actions, and the specific problem of social scientific knowledge. In the former, the subjective is often equated (though not necessarily) with the individual, and the individual's intentions and interpretations of the objective. The objective is often considered any public or external action or outcome, on up to society writ large. A primary question for social theorists, then, is how knowledge reproduces along the chain of subjective-objective-subjective, that is to say: how is intersubjectivity achieved? While, historically, qualitative methods have attempted to tease out subjective interpretations, quantitative survey methods also attempt to capture individual subjectivities. Qualitative methods take an approach to objective description known as in situ, meaning that descriptions must have appropriate contextual information to understand the information.[108]

The latter concern with scientific knowledge results from the fact that a sociologist is part of the very object they seek to explain, as Bourdieu explains:

How can the sociologist effect in practice this radical doubting which is indispensable for bracketing all the presuppositions inherent in the fact that she is a social being, that she is therefore socialised and led to feel "like a fish in water" within that social world whose structures she has internalised? How can she prevent the social world itself from carrying out the construction of the object, in a sense, through her, through these unself-conscious operations or operations unaware of themselves of which she is the apparent subject?

— Pierre Bourdieu, "The Problem of Reflexive Sociology", An Invitation to Reflexive Sociology (1992), p. 235

Structure and agency

Main article: Structure and agency

Structure and agency, sometimes referred to as determinism versus voluntarism,[109] form an enduring ontological debate in social theory: "Do social structures determine an individual's behaviour or does human agency?" In this context, agency refers to the capacity of individuals to act independently and make free choices, whereas structure relates to factors that limit or affect the choices and actions of individuals (e.g. social class, religion, gender, ethnicity, etc.). Discussions over the primacy of either structure or agency relate to the core of sociological epistemology (i.e. "what is the social world made of?", "what is a cause in the social world, and what is an effect?").[110] A perennial question within this debate is that of "social reproduction": how are structures (specifically, structures producing inequality) reproduced through the choices of individuals?

全体として、社会学理論の中心的な問題については、古典的な理論的伝統から受け継がれたものが多いが、強い合意がある。この合意とは、以下の「ビッグ3」の二分法をどのように関連づけるか、超越するか、あるいは対処するかというものである。

主観性と客観性(知識を扱う)、

構造と作用(行動を扱う)、

そして同時性と異時性(時間を扱う)である。

最後に、社会学理論は、ミクロ、メゾ、マクロの各スケールの社会現象の間の隔たりを統合または超越する問題にしばしば取り組むが、これは3つの中心的な問題のサブセットである。

主観性と客観性

詳細は「客観性 (科学)」、「客観性 (哲学)」、および「主観性」を参照

この節は検証可能な参考文献や出典が全く示されていないか、不十分です。出典を追加して記事の信頼性向上にご協力ください。出典の記載がない内容は、削除されることがあります。

出典: 「社会学」 – ニュース · 新聞 · 書籍 · 学者 · JSTOR (2023年3月) (Learn how and when to remove this message)

主観性と客観性の問題は、2つの部分に分けることができる。すなわち、社会行動の一般的な可能性に対する懸念と、社会科学的な知識の具体的な問題である。 前者の場合、主観はしばしば個人と同一視され(必ずしもそうとは限らないが)、個人の意図や客観の解釈とされる。客観はしばしば、社会全体にわたるあらゆ る公的または外部的な行動や結果とみなされる。したがって、社会理論家にとっての主要な問題は、主観-客観-主観の連鎖に沿って知識がどのように再生産さ れるか、つまり、いかにして相互主観性が達成されるかということである。歴史的に、定性的な方法は主観的な解釈を明らかにしようとしてきたが、定量的な調 査方法も個々の主観性を捉えようとしている。定性的な方法は、イン・シチュ(in situ)と呼ばれる客観的な記述のアプローチを取る。これは、記述には情報を理解するための適切な文脈情報が含まれていなければならないことを意味す る。

後者の科学的知識に関する懸念は、ブルデューが説明しているように、社会学者がまさに彼らが説明しようとする対象の一部であるという事実から生じる。

社会学者は、彼女が社会的な存在であり、したがって社会化され、彼女が内面化したその社会世界の構造の中で「水を得た魚のように」感じるように導かれると いう事実の本質的な前提条件をすべて排除するために不可欠な、この根本的な疑いを実際にどのようにして生じさせることができるだろうか?彼女は、社会世界 そのものが、ある意味で彼女を通して、彼女が表向きの主体であるこれらの無意識の操作や、自己を意識しない操作を通して、対象の構築を行うのをどのように して防ぐことができるのだろうか?

— ピエール・ブルデュー、『反省的社会学の問題』、『反省的社会学への招待』(1992年)、235ページ

構造と作用

詳細は「構造と作用」を参照

構造と行為は、決定論対意志論とも呼ばれることがあるが、社会理論における永続的な存在論的論争を形成している。「社会構造が個人の行動を決定するのか、 それとも人間の行為が決定するのか」という論争である。この文脈において、行為とは個人が独立して行動し、自由な選択を行う能力を指し、構造とは個人の選 択や行動を制限したり影響を与える要因(例えば、社会階級、宗教、性別、民族など)を指す。構造と行為のどちらが優先されるかについての議論は、社会学的 認識論の核心に関わるものである(すなわち、「社会世界は何でできているのか?」「社会世界における原因とは何か、そして結果とは何か?」)。[110] この議論における永遠の問いは、「社会的再生産」に関するものである。すなわち、構造(特に、不平等を生み出す構造)は、個人の選択を通じてどのように再 生産されるのか?

This section relies largely or entirely on a single source. Relevant discussion may be found on the talk page. Please help improve this article by introducing citations to additional sources.

Find sources: "Sociology" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (March 2023)

Synchrony and diachrony (or statics and dynamics) within social theory are terms that refer to a distinction that emerged through the work of Levi-Strauss who inherited it from the linguistics of Ferdinand de Saussure.[102] Synchrony slices moments of time for analysis, thus it is an analysis of static social reality. Diachrony, on the other hand, attempts to analyse dynamic sequences. Following Saussure, synchrony would refer to social phenomena as a static concept like a language, while diachrony would refer to unfolding processes like actual speech. In Anthony Giddens' introduction to Central Problems in Social Theory, he states that, "in order to show the interdependence of action and structure…we must grasp the time space relations inherent in the constitution of all social interaction." And like structure and agency, time is integral to discussion of social reproduction.

In terms of sociology, historical sociology is often better positioned to analyse social life as diachronic, while survey research takes a snapshot of social life and is thus better equipped to understand social life as synchronized. Some argue that the synchrony of social structure is a methodological perspective rather than an ontological claim.[102] Nonetheless, the problem for theory is how to integrate the two manners of recording and thinking about social data.

この節は主に、または完全に単一の出典に依拠している。関連する議論は、トークページで見つかる可能性がある。この記事を改善するために、追加の出典を導入することで、この記事の改善にご協力ください。

出典を見つける: 「社会学」 – ニュース · 新聞 · 書籍 · 学者 · JSTOR (2023年3月)

社会理論における共時性と通時性(または静態と動態)は、フェルディナン・ド・ソーシュールの言語学からレヴィ=ストロースが継承した区別を指す用語であ る。[102] 共時性は分析のために時間を切り取るため、静態的社会現実の分析となる。一方、通時性は動的な連続性を分析しようとする。ソシュールに従うなら、同期性は 言語のような静的な概念として社会現象を指し、一方、通時性は実際の会話のような展開プロセスを指すことになる。アンソニー・ギデンズは著書『社会理論に おける中心的問題』の序文で、「行為と構造の相互依存性を示すためには…あらゆる社会的相互作用の構成に内在する時間と空間の関係を把握しなければならな い」と述べている。そして、構造や行為と同様に、時間は社会再生産の議論に不可欠である。

社会学の観点では、歴史社会学は社会生活を縦断的に分析するのに適していることが多いが、調査研究は社会生活の瞬間を切り取るものであり、したがって社会 生活を同期して理解するのに適している。社会構造の同期性は存在論的な主張というよりも方法論的な視点であるという意見もある。[102] しかし、理論上の問題は、社会データを記録し、考える2つの方法論をどのように統合するかということである。

Main article: Social research

Sociological research methods may be divided into two broad, though often supplementary, categories:[111]

Qualitative designs emphasize understanding of social phenomena through direct observation, communication with participants, or analysis of texts, and may stress contextual and subjective accuracy over generality.

Quantitative designs approach social phenomena through quantifiable evidence, and often rely on statistical analysis of many cases (or across intentionally designed treatments in an experiment) to establish valid and reliable general claims.

Sociologists are often divided into camps of support for particular research techniques. These disputes relate to the epistemological debates at the historical core of social theory. While very different in many aspects, both qualitative and quantitative approaches involve a systematic interaction between theory and data.[112] Quantitative methodologies hold the dominant position in sociology, especially in the United States.[39] In the discipline's two most cited journals, quantitative articles have historically outnumbered qualitative ones by a factor of two.[113] (Most articles published in the largest British journal, on the other hand, are qualitative.) Most textbooks on the methodology of social research are written from the quantitative perspective,[114] and the very term "methodology" is often used synonymously with "statistics". Practically all sociology PhD programmes in the United States require training in statistical methods. The work produced by quantitative researchers is also deemed more 'trustworthy' and 'unbiased' by the general public,[115] though this judgment continues to be challenged by antipositivists.[115]

The choice of method often depends largely on what the researcher intends to investigate. For example, a researcher concerned with drawing a statistical generalization across an entire population may administer a survey questionnaire to a representative sample population. By contrast, a researcher who seeks full contextual understanding of an individual's social actions may choose ethnographic participant observation or open-ended interviews. Studies will commonly combine, or 'triangulate', quantitative and qualitative methods as part of a 'multi-strategy' design. For instance, a quantitative study may be performed to obtain statistical patterns on a target sample, and then combined with a qualitative interview to determine the play of agency.[112]

詳細は「社会調査」を参照

社会学的研究方法は、2つの大きなカテゴリーに分けられるが、しばしば相互補完的なものである。

質的デザインは、直接観察、参加者とのコミュニケーション、またはテキストの分析を通じて社会現象の理解を重視し、一般性よりも文脈や主観的な正確性を重視する。

量的研究は、定量化可能な証拠を通じて社会現象にアプローチし、多くの事例(または実験における意図的に設計された処置全体)の統計的分析に頼ることで、妥当で信頼性の高い一般的な主張を確立することが多い。

社会学者は、特定の研究手法を支持する陣営に分かれることが多い。こうした論争は、社会理論の歴史的な核心にある認識論の論争に関連している。多くの点で 大きく異なるものの、定性的・定量的アプローチの両方とも、理論とデータの体系的な相互作用を伴うものである。[112] 定量的な方法論は社会学、特にアメリカ合衆国において支配的な地位を占めている。[39] この学問分野で最も引用される2つの学術誌では、定量的な論文が歴史的に定性的な論文を2倍の数で上回っている。[113] (一方で、イギリス最大の学術誌に掲載される論文のほとんどは定性的なものである。) 社会調査の方法論に関する教科書のほとんどは量的な視点から書かれており[114]、「方法論」という用語は「統計」と同義語として使用されることが多 い。米国では、社会学の博士課程プログラムでは、ほぼ例外なく統計的手法のトレーニングが必須となっている。量的研究者の成果は、一般の人々からより「信 頼性」が高く「偏りのない」ものとみなされているが、この判断は反実証主義者たちによって引き続き疑問視されている。

調査方法の選択は、多くの場合、研究者が何を調査しようとしているかによって大きく左右される。例えば、母集団全体にわたる統計的一般化を導くことを目的 とする研究者は、代表的な標本母集団に対して調査アンケートを実施することがある。これに対し、個人の社会的行動の文脈を完全に理解しようとする研究者 は、エスノグラフィーの参与観察や自由回答式のインタビューを選択することがある。研究では通常、量的および質的方法を組み合わせる、つまり「多角化」す ることが、「多角化戦略」の一部として行われる。例えば、量的研究が標本における統計的パターンを把握するために実施され、その後、質的インタビューと組 み合わされて、行為主体の役割が決定されることがある。[112]

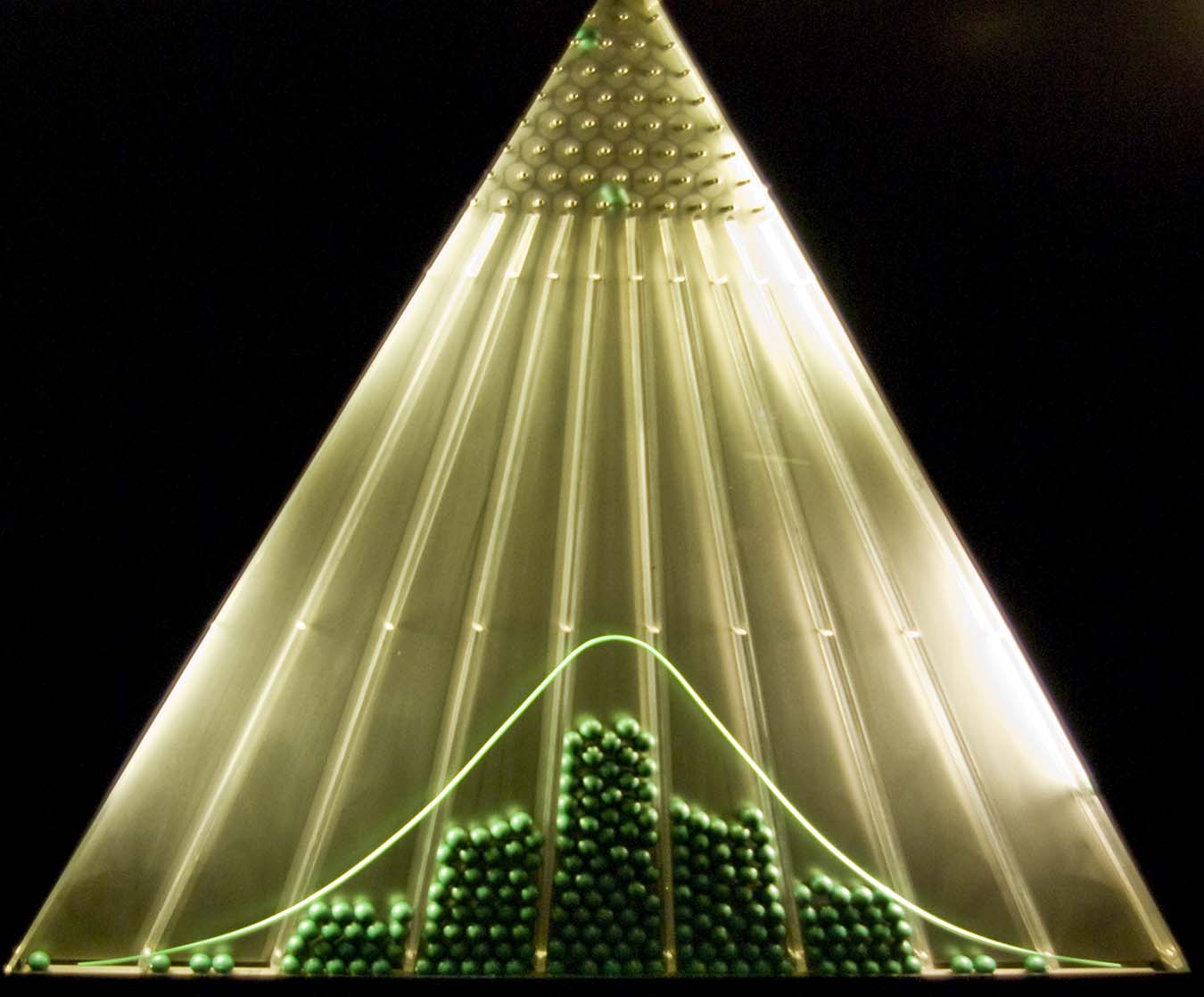

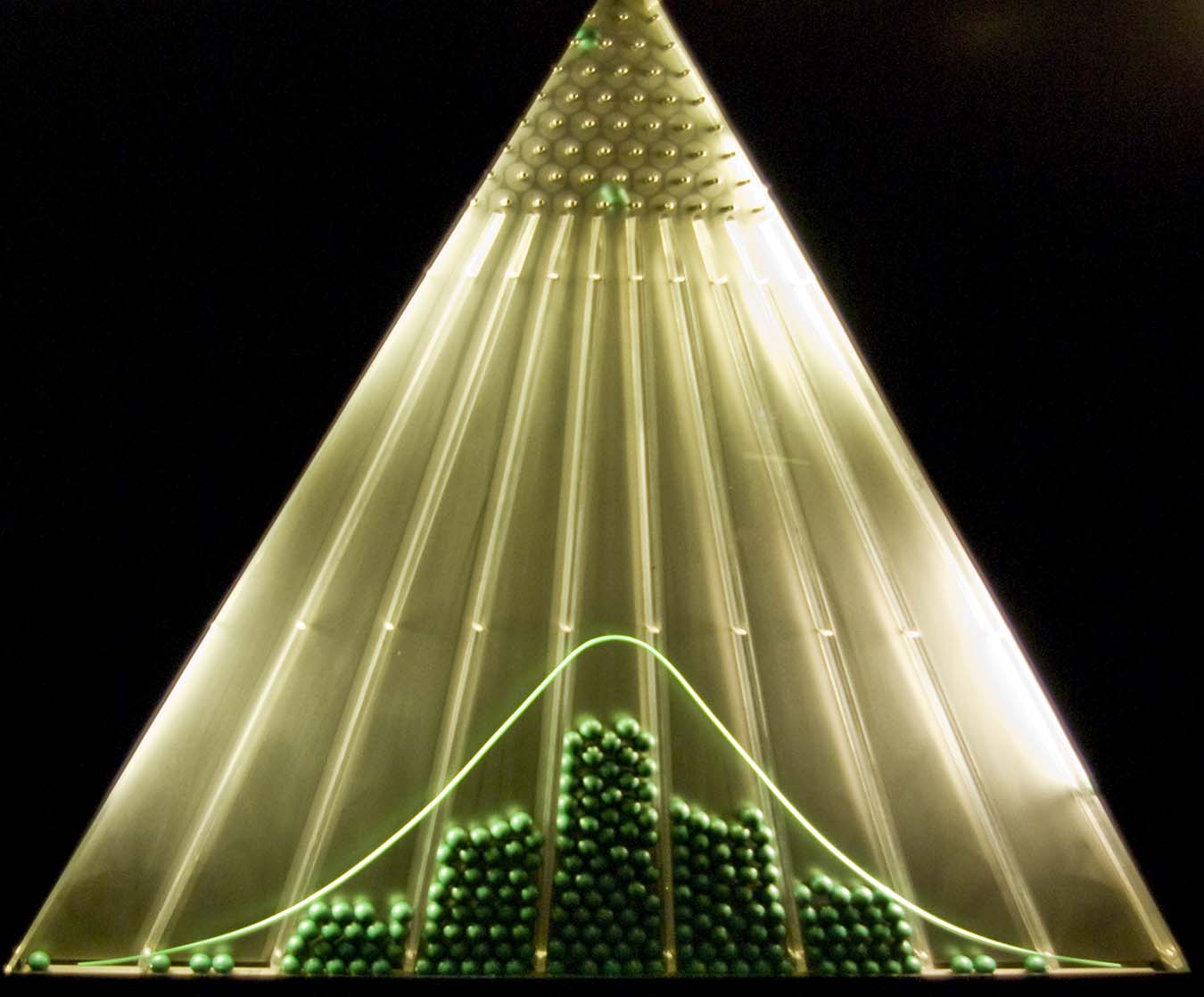

The bean machine, designed by early social research methodologist Sir Francis Galton to demonstrate the normal distribution, which is important to much quantitative hypothesis testing[a]

Quantitative methods are often used to ask questions about a population that is very large, making a census or a complete enumeration of all the members in that population infeasible. A 'sample' then forms a manageable subset of a population. In quantitative research, statistics are used to draw inferences from this sample regarding the population as a whole. The process of selecting a sample is referred to as 'sampling'. While it is usually best to sample randomly, concern with differences between specific subpopulations sometimes calls for stratified sampling. Conversely, the impossibility of random sampling sometimes necessitates nonprobability sampling, such as convenience sampling or snowball sampling.[112]

初期の社会調査法学者であるフランシス・ゴルトン卿が考案した「ビーン・マシン」は、多くの量的仮説検定において重要な正規分布を示すために使用される。

量的方法は、非常に大規模な母集団に関する質問を行うために使用されることが多く、その母集団の全構成員を対象とした国勢調査や完全な列挙は実行不可能で ある。 したがって、「サンプル」は母集団の管理可能な部分集合となる。量的調査では、このサンプルから母集団全体に関する推論を導くために統計が用いられる。サ ンプルを選択するプロセスは「サンプリング」と呼ばれる。通常はランダムサンプリングが望ましいが、特定のサブ・ポピュレーション間の相違を考慮する必要 がある場合には層化サンプリングが求められることもある。逆に、ランダムサンプリングが不可能な場合には、任意サンプリングやスノーボールサンプリングな どの非確率サンプリングが必要となることもある。[112]

The following list of research methods is neither exclusive nor exhaustive:

Archival research (or the Historical method): Draws upon the secondary data located in historical archives and records, such as biographies, memoirs, journals, and so on.

Content analysis: The content of interviews and other texts is systematically analysed. Often data is 'coded' as a part of the 'grounded theory' approach using qualitative data analysis (QDA) software, such as Atlas.ti, MAXQDA, NVivo,[116] or QDA Miner.

Experimental research: The researcher isolates a single social process and reproduces it in a laboratory (for example, by creating a situation where unconscious sexist judgements are possible), seeking to determine whether or not certain social variables can cause, or depend upon, other variables (for instance, seeing if people's feelings about traditional gender roles can be manipulated by the activation of contrasting gender stereotypes).[117] Participants are randomly assigned to different groups that either serve as controls—acting as reference points because they are tested with regard to the dependent variable, albeit without having been exposed to any independent variables of interest—or receive one or more treatments. Randomization allows the researcher to be sure that any resulting differences between groups are the result of the treatment.

Longitudinal study: An extensive examination of a specific person or group over a long period of time.[citation needed]

Observation: Using data from the senses, the researcher records information about social phenomenon or behaviour. Observation techniques may or may not feature participation. In participant observation, the researcher goes into the field (e.g. a community or a place of work), and participates in the activities of the field for a prolonged period of time in order to acquire a deep understanding of it.[27]: 42 Data acquired through these techniques may be analysed either quantitatively or qualitatively. In the observation research, a sociologist might study global warming in some part of the world that is less populated.

Program Evaluation is a systematic method for collecting, analyzing, and using information to answer questions about projects, policies and programs,[118] particularly about their effectiveness and efficiency. In both the public and private sectors, stakeholders often want to know whether the programs they are funding, implementing, voting for, or objecting to are producing the intended effect. While program evaluation first focuses on this definition, important considerations often include how much the program costs per participant, how the program could be improved, whether the program is worthwhile, whether there are better alternatives, if there are unintended outcomes, and whether the program goals are appropriate and useful.[119]

Survey research: The researcher gathers data using interviews, questionnaires, or similar feedback from a set of people sampled from a particular population of interest. Survey items from an interview or questionnaire may be open-ended or closed-ended.[27]: 40 Data from surveys is usually analysed statistically on a computer.

以下の研究方法は、排他的でも網羅的でもない。

アーカイブ調査(または歴史的方法):伝記、回顧録、日記など、歴史的アーカイブや記録に保管されている二次データを利用する。

内容分析:インタビューやその他のテキストの内容を系統的に分析する。多くの場合、Atlas.ti、MAXQDA、NVivo、QDA Minerなどの質的データ分析(QDA)ソフトウェアを使用した「グラウンデッド・セオリー」アプローチの一環としてデータを「コード化」する。

実験的研究:研究者は、ある特定の社会的変数が他の変数の原因となるか、あるいは他の変数に依存するかどうかを明らかにするために、単一の社会的プロセス を分離し、それを実験室で再現する(例えば、無意識の性差別的判断が可能な状況を作り出すなど)。 [117] 参加者は、ランダムに異なるグループに割り当てられ、そのグループは、コントロール(興味のある独立変数にさらされることはないが、従属変数に関してテス トされるため、参照点として機能する)となるか、1つ以上の処置を受ける。ランダム化により、研究者は、グループ間の結果として生じる差異が処置の結果で あることを確実にすることができる。

縦断的研究:特定の人格またはグループを長期間にわたって広範に調査する。

観察:感覚から得たデータを用いて、研究者は社会現象や行動に関する情報を記録する。観察手法には参加型と非参加型がある。参与観察では、研究者は現場 (例えば、コミュニティや職場)に入り、その現場での活動を長期間参加することで、その現場を深く理解する。[27]:42 これらの手法で得られたデータは、量的または質的に分析することができる。観察研究では、社会学者が人口密度の低い世界のどこかで地球温暖化を研究するか もしれない。

プログラム評価は、プロジェクト、政策、プログラムに関する質問に答えるために、情報を収集、分析、利用する体系的な方法である。特に、それらの有効性と 効率性についてである。[118] 公共部門でも民間部門でも、利害関係者は、資金提供、実施、投票、反対しているプログラムが意図した効果を生み出しているかどうかを知りたいと考えること が多い。プログラム評価では、まずこの定義に焦点を当てるが、重要な考慮事項には、参加1人当たりのプログラム費用、プログラムの改善方法、プログラムの 価値、より良い代替案の有無、予期せぬ結果の有無、プログラム目標の適切性と有用性などが含まれることが多い。[119]

調査研究:研究者は、関心のある特定の母集団から抽出した一群の人々を対象に、インタビュー、アンケート、または同様のフィードバックを用いてデータを収 集する。インタビューやアンケートにおける調査項目は、自由回答形式または選択回答形式である場合がある。[27]:40 調査データは通常、コンピュータ上で統計的に分析される。

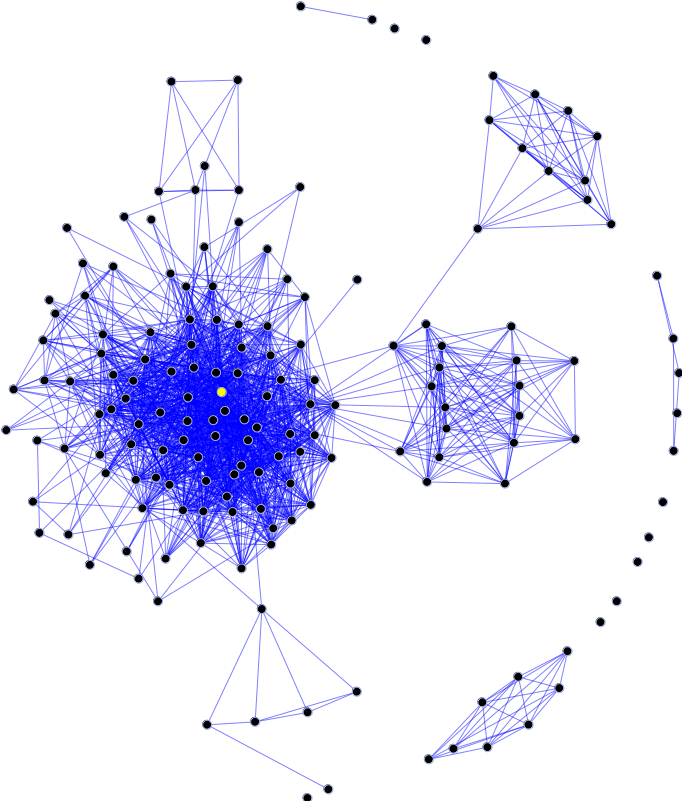

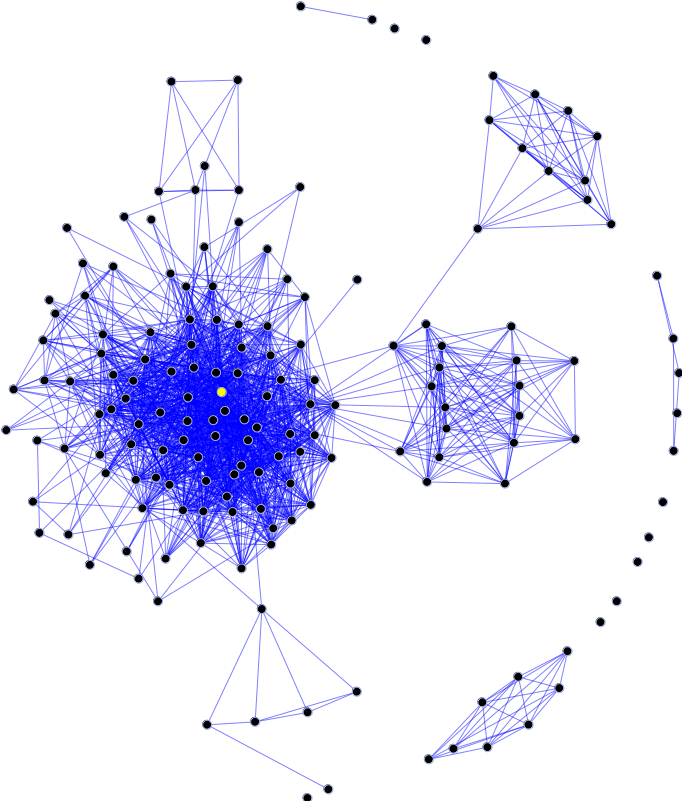

A social network diagram: individuals (or 'nodes') connected by relationships

Main article: Computational sociology

Sociologists increasingly draw upon computationally intensive methods to analyse and model social phenomena.[120] Using computer simulations, artificial intelligence, text mining, complex statistical methods, and new analytic approaches like social network analysis and social sequence analysis, computational sociology develops and tests theories of complex social processes through bottom-up modelling of social interactions.[7]

Although the subject matter and methodologies in social science differ from those in natural science or computer science, several of the approaches used in contemporary social simulation originated from fields such as physics and artificial intelligence.[121][122] By the same token, some of the approaches that originated in computational sociology have been imported into the natural sciences, such as measures of network centrality from the fields of social network analysis and network science. In relevant literature, computational sociology is often related to the study of social complexity.[123] Social complexity concepts such as complex systems, non-linear interconnection among macro and micro process, and emergence, have entered the vocabulary of computational sociology.[124] A practical and well-known example is the construction of a computational model in the form of an "artificial society", by which researchers can analyse the structure of a social system.[125][126]

社会ネットワーク図:関係によって結ばれた個人(または「ノード」)

詳細は「計算社会学」を参照

社会学者は、社会現象を分析しモデル化するために、計算集約的な手法をますます活用するようになっている。[120] 計算社会学では、コンピュータシミュレーション、人工知能、テキストマイニング、複雑な統計的手法、および社会ネットワーク分析や社会的順序分析のような 新しい分析アプローチを活用し、社会的な相互作用のボトムアップ・モデリングを通じて、複雑な社会過程の理論を開発し検証している。[7]

社会科学の主題や方法論は、自然科学やコンピュータサイエンスのそれらとは異なるが、現代の社会シミュレーションで用いられるアプローチのいくつかは、物 理学や人工知能などの分野から派生したものである。関連文献では、計算社会学はしばしば社会の複雑性の研究と関連付けられている。 [123] 複雑系、マクロとミクロのプロセス間の非線形相互接続、創発などの社会の複雑性に関する概念は、計算社会学の用語として取り入れられている。[124] 実用的でよく知られた例としては、「人工社会」という形式の計算モデルの構築が挙げられる。これにより、研究者は社会システムの構造を分析することができ る。[125][126]

For a topical guide, see Outline of sociology.

Culture

Max Horkheimer (left, front), Theodor Adorno (right, front), and Jürgen Habermas (right, back), 1965

Main articles: Sociology of culture, Cultural criminology, and Cultural studies

Sociologists' approach to culture can be divided into "sociology of culture" and "cultural sociology"—terms which are similar, though not entirely interchangeable. Sociology of culture is an older term, and considers some topics and objects as more or less "cultural" than others. Conversely, cultural sociology sees all social phenomena as inherently cultural.[127] Sociology of culture often attempts to explain certain cultural phenomena as a product of social processes, while cultural sociology sees culture as a potential explanation of social phenomena.[128]

For Simmel, culture referred to "the cultivation of individuals through the agency of external forms which have been objectified in the course of history."[71] While early theorists such as Durkheim and Mauss were influential in cultural anthropology, sociologists of culture are generally distinguished by their concern for modern (rather than primitive or ancient) society. Cultural sociology often involves the hermeneutic analysis of words, artefacts and symbols, or ethnographic interviews. However, some sociologists employ historical-comparative or quantitative techniques in the analysis of culture, Weber and Bourdieu for instance. The subfield is sometimes allied with critical theory in the vein of Theodor W. Adorno, Walter Benjamin, and other members of the Frankfurt School. Loosely distinct from the sociology of culture is the field of cultural studies. Birmingham School theorists such as Richard Hoggart and Stuart Hall questioned the division between "producers" and "consumers" evident in earlier theory, emphasizing the reciprocity in the production of texts. Cultural Studies aims to examine its subject matter in terms of cultural practices and their relation to power. For example, a study of a subculture (e.g. white working class youth in London) would consider the social practices of the group as they relate to the dominant class. The "cultural turn" of the 1960s ultimately placed culture much higher on the sociological agenda.[citation needed]

トピックガイドとして、社会学の概要を参照のこと。

文化

マックス・ホルクハイマー(左、前)、テオドール・アドルノ(右、前)、ユルゲン・ハーバーマス(右、後)、1965年

主な記事:文化社会学、文化犯罪学、カルチュラル・スタディーズ

社会学者の文化に対するアプローチは、「文化社会学」と「文化社会学」に分けられる。これらは似た用語であるが、完全に置き換えられるわけではない。文化 社会学はより古い用語であり、いくつかのトピックや対象を、他のものよりも多かれ少なかれ「文化的」であるとみなす。逆に、文化社会学では、あらゆる社会 現象は本質的に文化的であるとみなす。[127] 文化社会学では、文化を社会現象の潜在的な説明として捉える。文化社会学では、文化を社会現象の潜在的な説明として捉える。

シムメルにとって文化とは、「歴史の過程で客体化された外的な形態を通じて個人が育成されること」を意味した。[71] デュルケームやマウスといった初期の理論家は文化人類学に影響を与えたが、文化社会学の研究者たちは一般的に、現代社会(原始的または古代の社会ではな く)への関心によって区別される。文化社会学では、言葉、人工物、シンボルの解釈分析や、エスノグラファーによるインタビューがしばしば行われる。しか し、ウェーバーやブルデューのように、文化の分析に歴史比較法や量的手法を用いる社会学者もいる。この分野は、テオドール・W・アドルノやウォルター・ベ ンヤミン、フランクフルト学派の他のメンバーのような批判理論と関連していることもある。文化社会学とはやや異なる分野に、カルチュラル・スタディーズが ある。リチャード・ホガートやスチュアート・ホールといったバーミンガム学派の理論家たちは、初期の理論に見られる「生産者」と「消費者」の区分に疑問を 呈し、テキストの生産における相互性を強調した。カルチュラル・スタディーズは、その主題を文化的な実践と権力との関係という観点から調査することを目的 としている。例えば、サブカルチャー(例えばロンドンの白人労働者階級の若者)の研究では、支配的な階級との関連において、そのグループの社会的実践を考 察する。1960年代の「文化の転回」は、最終的に文化を社会学の議題としてより高い位置に置くこととなった。

Main articles: Sociology of literature, Sociology of art, Sociology of film, and Sociology of music

Sociology of literature, film, and art is a subset of the sociology of culture. This field studies the social production of artistic objects and its social implications. A notable example is Pierre Bourdieu's Les Règles de L'Art: Genèse et Structure du Champ Littéraire (1992).[129] None of the founding fathers of sociology produced a detailed study of art, but they did develop ideas that were subsequently applied to literature by others. Marx's theory of ideology was directed at literature by Pierre Macherey, Terry Eagleton and Fredric Jameson. Weber's theory of modernity as cultural rationalization, which he applied to music, was later applied to all the arts, literature included, by Frankfurt School writers such as Theodor Adorno and Jürgen Habermas. Durkheim's view of sociology as the study of externally defined social facts was redirected towards literature by Robert Escarpit. Bourdieu's own work is clearly indebted to Marx, Weber and Durkheim.[citation needed]

主な記事:文学社会学、芸術社会学、映画社会学、音楽社会学

文学、映画、芸術社会学は文化社会学の一部である。この分野では芸術的対象の社会的生産とその社会的影響を研究する。著名な例としては、ピエール・ブル デューの『芸術の規則:文学的場の生成と構造』(1992年)がある。[129] 社会学の創始者たちのうち、芸術に関する詳細な研究を行った者はいないが、彼らは後に他の人々によって文学に適用された考え方を発展させた。マルクスのイ デオロギー論は、ピエール・マシュレ、テリー・イーグルトン、フレドリック・ジェイムソンによって文学に向けられた。ヴェーバーの「文化の合理化としての 近代性」理論は、音楽に適用された後、アドルノやハーバーマスといったフランクフルト学派の作家たちによって、文学を含むすべての芸術に適用された。デュ ルケムの「社会学は外的に定義された社会的事実の研究である」という見解は、ロベール・エスカルピによって文学に向け直された。ブルデュー自身の研究は、 明らかにマルクス、ヴェーバー、デュルケムの影響を受けている。

Main articles: Criminology, Sociology of law, Sociology of punishment, Deviance, and Social disorganization theory

Criminologists analyse the nature, causes, and control of criminal activity, drawing upon methods across sociology, psychology, and the behavioural sciences. The sociology of deviance focuses on actions or behaviours that violate norms, including both infringements of formally enacted rules (e.g., crime) and informal violations of cultural norms. It is the remit of sociologists to study why these norms exist; how they change over time; and how they are enforced. The concept of social disorganization is when the broader social systems leads to violations of norms. For instance, Robert K. Merton produced a typology of deviance, which includes both individual and system level causal explanations of deviance.[130]

Sociology of law

The study of law played a significant role in the formation of classical sociology. Durkheim famously described law as the "visible symbol" of social solidarity.[131] The sociology of law refers to both a sub-discipline of sociology and an approach within the field of legal studies. Sociology of law is a diverse field of study that examines the interaction of law with other aspects of society, such as the development of legal institutions and the effect of laws on social change and vice versa. For example, an influential recent work in the field relies on statistical analyses to argue that the increase in incarceration in the US over the last 30 years is due to changes in law and policing and not to an increase in crime; and that this increase has significantly contributed to the persistence of racial stratification.[132]

主な記事:犯罪学、法社会学、刑罰社会学、逸脱、社会解体理論

犯罪学者は、犯罪活動の性質、原因、制御について、社会学、心理学、行動科学の手法を駆使して分析する。逸脱の社会学は、正式に制定された規則の侵害(例 えば犯罪)と、文化的な規範の非公式な違反の両方を含む、規範に違反する行動や振る舞いに焦点を当てる。これらの規範がなぜ存在するのか、どのようにして 時とともに変化するのか、そしてどのようにして強制されるのかを研究することは、社会学者の職務である。社会の混乱という概念は、より広範な社会システム が規範の違反につながることを指す。例えば、ロバート・K・マートンは逸脱の類型論を提示し、そこには逸脱の個人レベルおよびシステムレベルの原因説明が 含まれている。[130]

法社会学

法の研究は古典的社会学の形成において重要な役割を果たした。デュルケムは、法律を社会的な連帯の「目に見える象徴」として有名に描写した。[131] 法社会学は、社会学のサブディシプリンと法学研究分野におけるアプローチの両方を指す。法社会学は、法律制度の発展や、社会変化に対する法律の影響、その 逆の影響など、法律と社会の他の側面との相互作用を研究する多様な研究分野である。例えば、この分野における最近の有力な研究では、過去30年間に米国で 投獄者が増加しているのは、犯罪の増加ではなく、法律や警察の変化によるものであり、この増加が人種的階層化の持続に大きく寄与していると主張している。 [132]