医療社会学

Medical Sociology

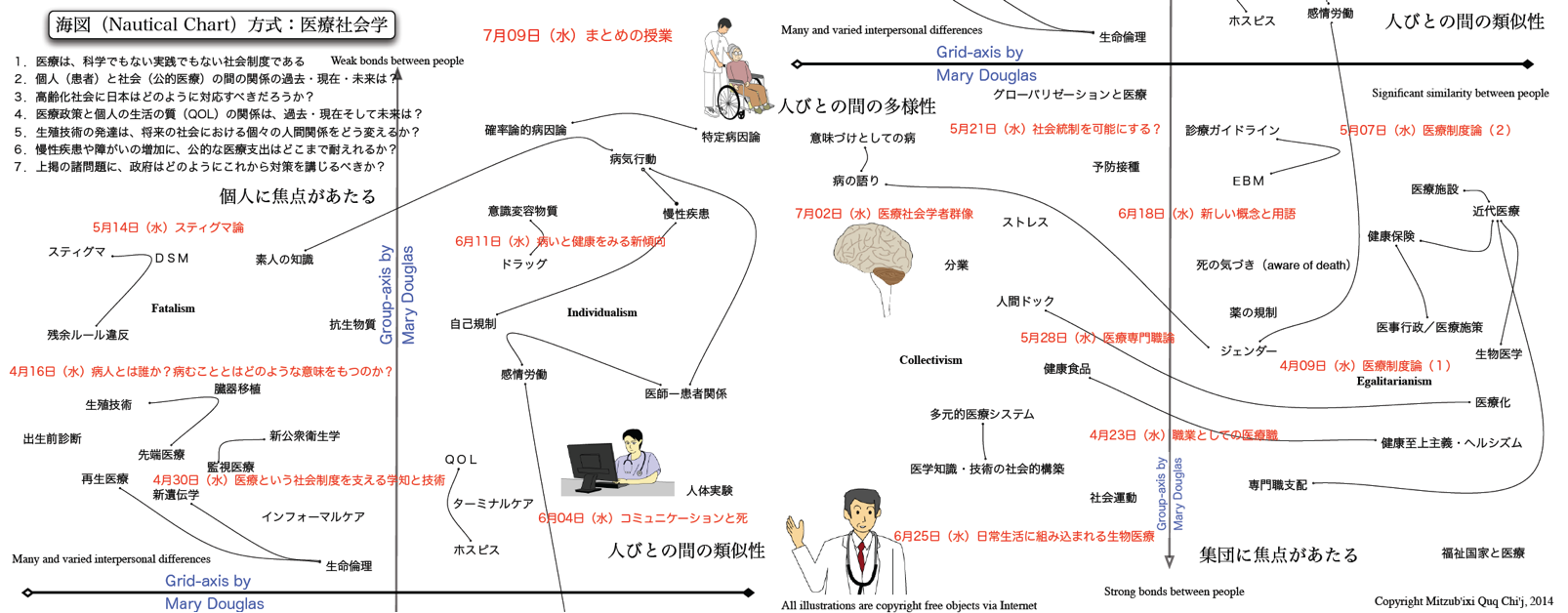

クリックすると拡大します!!(png) -- 縦ジョイント完全版はこちら(medical_sociology_chart.jpg)

☆ 医療社会学(Medical sociology) は、健康、病気、医療資源への差 別的アクセス、医療の社会的組織化、医療提供、医療 知識の生産、方法の選択、医療従事者の行動と相互作用 の研究、医療行為の(臨床的・身体的というよりは)社 会的・文化的影響の社会学的分析である。医療社会学者はまた、患者、医師、医学教育の質的経験にも関心があり、社会科学と臨床科学の交差点にある現象を探 求するために、公衆衛生学、ソーシャルワーク、人口学、老年学の境界で活動することが多い。保健医療格差は一般的に、階級、人種、民族、移民、ジェン ダー、セクシュアリティ、年齢といった典型的なカテゴリーに関連している。客観的な社会学的研究結果は、すぐに規範的で政治的な問題となる。 医療社会学の初期の研究は、ローレンス・J・ヘンダーソンによっ て行われた。彼はヴィルフレド・パレートの理論的関心に触発され、タルコッ ト・パーソンズの社会学的システム理論への関心に影響を与えた。パーソンズは医療社会学の創始者の一人であり、病人と他者との相互作用関係に社会的役割理 論を適用した。その後、エリオット・フリードソンのような他の社会学者は、医療専門職がどのように自らの利益を確保しているかに注目し、対立理論の視点を とっている。 医療社会学は通常、社会学、臨床心理学、保健学などの学位コースの一部として、あるいは修士課程専用のコースとして教えられ、医療倫理学や生命倫理学と組 み合わされることもある。イギリスでは、1944年のグッドノー報告を受けて、社会学が医学カリキュラムに導入された: 医学において、病気の病因に関する 「社会的説明 」は、一部の医師にとって、病気の純粋な臨床的・心理的基準から医学的思考の方向転換を意味した。医学的説明への 「社会的 」要因の導入は、地域社会と密接に関係する医学の分野、すなわち社会医学と、後の総合診療において最も強く証明された」[3](→「社会学」)。

目次

++++

| Medical

sociology is the sociological analysis of health, Illness, differential

access to medical resources, the social organization of medicine,

Health Care Delivery, the production of medical knowledge, selection of

methods, the study of actions and interactions of healthcare

professionals, and the social or cultural (rather than clinical or

bodily) effects of medical practice.[1] The field commonly interacts

with the sociology of knowledge, science and technology studies, and

social epistemology. Medical sociologists are also interested in the

qualitative experiences of patients, doctors, and medical education;

often working at the boundaries of public health, social work,

demography and gerontology to explore phenomena at the intersection of

the social and clinical sciences. Health disparities commonly relate to

typical categories such as class, race, ethnicity, immigration, gender,

sexuality, and age. Objective sociological research findings quickly

become a normative and political issue. Early work in medical sociology was conducted by Lawrence J Henderson whose theoretical interests in the work of Vilfredo Pareto inspired Talcott Parsons' interests in sociological systems theory. Parsons is one of the founding fathers of medical sociology, and applied social role theory to interactional relations between sick people and others. Later other sociologists such as Eliot Freidson have taken a conflict theory perspective, looking at how the medical profession secures its own interests.[2]: 291 Key contributors to medical sociology since the 1950s include Howard S. Becker, Mike Bury, Peter Conrad, Jack Douglas, Eliot Freidson, David Silverman, Phil Strong, Bernice Pescosolido, Carl May, Anne Rogers, Anselm Strauss, Renee Fox, and Joseph W. Schneider. The field of medical sociology is usually taught as part of a wider sociology, clinical psychology or health studies degree course, or on dedicated master's degree courses where it is sometimes combined with the study of medical ethics and bioethics. In Britain, sociology was introduced into the medical curriculum following the Goodenough report in 1944: "In medicine, 'social explanations' of the etiology of disease meant for some doctors a redirection of medical thought from the purely clinical and psychological criteria of illness. The introduction of 'social' factors into medical explanation was most strongly evidenced in branches of medicine closely related to the community — Social Medicine and, later, General Practice".[3] |

医療社会学は、健康、病気、医療資源への差

別的アクセス、医療の社会的組織化、医療提供、医療 知識の生産、方法の選択、医療従事者の行動と相互作用

の研究、医療行為の(臨床的・身体的というよりは)社

会的・文化的影響の社会学的分析である。医療社会学者はまた、患者、医師、医学教育の質的経験にも関心があり、社会科学と臨床科学の交差点にある現象を探

求するために、公衆衛生学、ソーシャルワーク、人口学、老年学の境界で活動することが多い。保健医療格差は一般的に、階級、人種、民族、移民、ジェン

ダー、セクシュアリティ、年齢といった典型的なカテゴリーに関連している。客観的な社会学的研究結果は、すぐに規範的で政治的な問題となる。 医療社会学の初期の研究は、ローレンス・J・ヘンダーソンによっ て行われた。彼はヴィルフレド・パレートの理論的関心に触発され、タルコッ ト・パーソンズの社会学的システム理論への関心に影響を与えた。パーソンズは医療社会学の創始者の一人であり、病人と他者との相互作用関係に社会的役割理 論を適用した。その後、エリオット・フリードソンのような他の社会学者は、医療専門職がどのように自らの利益を確保しているかに注目し、対立理論の視点を とっている。 医療社会学は通常、社会学、臨床心理学、保健学などの学位コースの一部として、あるいは修士課程専用のコースとして教えられ、医療倫理学や生命倫理学と組 み合わされることもある。イギリスでは、1944年のグッドノー報告を受けて、社会学が医学カリキュラムに導入された: 医学において、病気の病因に関する 「社会的説明 」は、一部の医師にとって、病気の純粋な臨床的・心理的基準から医学的思考の方向転換を意味した。医学的説明への 「社会的 」要因の導入は、地域社会と密接に関係する医学の分野、すなわち社会医学と、後の総合診療において最も強く証明された」[3]。 |

| History Samuel W. Bloom argues that the study of medical sociology has a long history but tended to be done as one of advocacy in response to social events rather than a field of study. He cites the 1842 publication of the sanitary conditions of the labouring population of Great Britain as a good example of such research. This medical sociology included an element of social science, studying social structures as a cause or mediating factor in disease, such as for public health or social medicine.[4]: 11 Bloom argues the development of medical sociology is linked to the development of sociology within American universities. He argues that the 1865 creation of the American Social Science Association (ASSA) was a key event in this development.[4]: 25 ASSA's initial aim was policy reform on the basis of science.[4]: 25 Bloom argues that over the next few decades the role of ASSA moved from advocacy to academic discipline, noting that a number of academic professional bodies broke away from the ASSA during this period, starting with the American Historical Association in 1884. The American Sociological Society formed in 1905.[4]: 26 The Russell Sage Foundation, formed in 1907, was a large philanthropic organization which worked closely with the American Sociological Society, which had medical sociology as a primary focus of its suggested policy reform.[4]: 36 Bloom argues that the presidency of Donald R Young, a professor of sociology, that started in 1947 was significant in the development of medical sociology.[4]: 182 Young motivated by a desire to legitimize sociology, encouraged Esther Lucile Brown, an anthropologist who studied the professions, to focus her work on the medical professions due to medicine's societal status.[4]: 183 Harry Stock Sullivan Harry Stack Sullivan was a psychiatrist who investigated the treatment of schizophrenia using approaches of interpersonal psychotherapy working with sociologists and social scientists including Lawrence K. Frank, W. I. Thomas, Ruth Benedict, Harold Lasswell and Edward Sapir.[4]: 76 Bloom argues that Sullivans work, and its focus on putative interpersonal causes and treatment of schizophrenia influenced ethnographic study of the hospital setting.[4]: 76 |

歴史 サミュエル・W・ブルームは、医療社会学の研究には長い歴史があるが、研究の一分野というよりは、社会的な出来事に対応した提唱の一つとして行われる傾向 があったと論じている。彼は、そのような研究の好例として、1842年に出版されたイギリスの労働人口の衛生状態を挙げている。この医学社会学には、公衆 衛生や社会医学のように、疾病の原因や媒介因子としての社会構造を研究する社会科学の要素も含まれていた[4]: 11 ブルームは、医療社会学の発展が、アメリ カの大学における社会学の発展と関連し ていると論じている。彼は、1865年のアメリカ社会科学協会(ASSA)の設立が、この発展における重要な出来事であったと論じている[4]:25 ASSAの当初の目的は、科学に基づく政策改革であった[4]:25 ブルームは、その後数十年にわたって、ASSAの役割は擁護から学問的規律へと移っていったと論じ、1884年のアメリカ歴史学会を皮切りに、この時期に 多くの学問的専門団体がASSAから離脱したことを指摘している。アメリカ社会学会は1905年に結成された[4]: 26。 1907年に結成されたラッセル・セージ財団は、医療社会学を政策改革提案の主要な焦点としていたアメリカ社会学会と緊密に協力した大規模な慈善団体で あった[4]: 36 ブルームは、1947年に始まったドナ ルド・ヤング社会学教授の会長職が、医 療社会学の発展において重要であった と論じている[4]: 182 ヤングは、社会学を正統化したいという願望に突き動かされ、専門職を研究していた人類学者エスター・ルシール・ブラウンに、医学の社会的地位のために、彼 女の研究を医療専門職に集中させるよう促した: 183 ハリー・ストック・サリヴァン ハリー・スタック・サリヴァンは精神科医であり、ローレンス・K・フランク、W・I・トーマス、ルース・ベネディクト、ハロルド・ラスウェル、エドワー ド・サピアら社会学者や社会科学者と協力し、対人関係心理療法のアプローチを用いて精神分裂病の治療について研究した[4]: 76。ブルームは、サリヴァンの研究、そしてその精神分裂病の推定上の対人関係の原因や治療への焦点は、病院環境のエスノグラファー研究に影響を与えたと 論じている[4]: 76。 |

| Medical profession The profession of medicine has been studied by sociologists. Talcott Parsons looked at the profession from a functionalist perspective, focusing on medics roles as experts, their altruism, and how they support communities. Other sociologists have taken a conflict theory perspective, looking at how the medical profession secures its own interests. Of these, Marxist conflict theory perspective considers how the ruling classes can enact power through medicine, while other theories propose a more structural pluralist approach, exemplified by Eliot Freidson, looking at how the professions themselves secure influence.[2]: 291 Medical education The study of medical education has been a central part of medical sociology since its emergence in the 1950s. The first publication on the topic was Robert Merton's The Student Physician. Other scholars who studied the field include Howard S. Becker, with his publication Boys in White.[5]: 1 The hidden curriculum is a concept in medical education that refers to a distinction between what is officially taught and what is learned by a medical student.[5]: 16 The concept was introduced by Philip W. Jackson in his book Life in the Classroom, but developed further by Benson Snyder. The concept has been criticised by Lakomski and there has been considerable debate on the concepts within the educational community.[5]: 17 Medical dominance Writing the 1970s, Eliot Freidson argued that medicine had reached a point of "professional dominance" over the content of their work, other health professions and their clients by convincing the public of medicine's effectiveness, gaining a legal monopoly over their work, and appropriating other "medical" knowledge through control of training.[6]: 433 This concept of dominance has been extended to professions as a whole in closure theory, where professions are seen as competing for scope of practice, for example in the work of Andrew Abbott.[6]: 434 Coburn argues that academic interest in medical dominance has decreased over time due to the increased role of capitalism in healthcare in the US,[6]: 436 challenges to the control of health policy by politicians, economists and planners, and increased agency of patients through access to the internet.[6]: 439 Sociologist nursing professor Kath M. Melia argues that so far as nurses are concerned, medical paternalistic attitudes have remained.[7][8] |

医療という職業 医療という職業は社会学者によって研究されてきた。タルコット・パーソンズは、専門家としての医学者の役割、利他主義、地域社会をどのように支えているか に焦点を当て、機能主義的な視点からこの職業を考察した。他の社会学者は、医療専門職がどのように自らの利益を確保しているかに注目し、対立理論の視点を とってきた。これらのうち、マルクス主義的な対立理論の視点は、支配階級が医療を通じてどのように権力を行使できるかを考察するものであり、他の理論は、 エリオット・フリードソンに代表されるように、より構造的な多元主義的アプローチを提案し、専門職自身がどのように影響力を確保するかを考察するものであ る[2]: 291。 医学教育 医学教育の研究は、1950年代に登場して以来、医学社会学の中心的な役割を担ってきた。このテーマに関する最初の出版物は、ロバート・マートンの 『The Student Physician』である。この分野を研究した他の学者としては、ハワード・S・ベッカー(Howard S. Becker)の『白衣の少年たち(Boys in White)』がある[5]: 1 隠れたカリキュラム(hidden curriculum)とは、医学教育における概念であり、医学生が公式に教えられることと学ぶことの区別を指す[5]: 16 この概念はフィリップ・W・ジャクソンが著書『Life in the Classroom』で紹介したが、ベンソン・スナイダーによってさらに発展させられた。この概念はラコムスキーによって批判されており、教育界ではこの 概念についてかなりの議論がなされている[5]: 17 医学的優位性(=医療的支配) 1970年代にエリオット・フリードソンは、医学は、医学の有効性を一般大衆に信じ込ませ、医学の仕事を法的に独占し、トレーニングの管理を通じて他の 「医学」知識を流用することで、自分たちの仕事の内容、他の保健専門職、顧客に対する「専門職支配」の域に達していると主張した[6]: 433 この支配の概念は、例えばアンドリュー・アボットの研究において、専門職が診療の範囲について競争していると見なされている閉鎖理論において、専門職全体 へと拡張されている[6]: 434コバーンは、アメリカにおける医療における資本主義の役割の増大により、医療支配に対する学問的関心は時代とともに低 下してきたと論じている[6]: 436 政治家、経済学者、プランナーによる保健政策の統制への挑戦、そしてインターネットへのアクセスによる患者の主体性の増大である[6]: 439 社会学者の看護学教授キャス・M・メリアは、看護師に関する限り、医療的パターナリスティックな態度が残っていると主張している[7][8]。 |

| Medicalization Medicalization describes the process whereby an ever-wider range of human experiences are defined, experienced and treated as a medical condition. Examples of medicalization can be seen in deviance, such as defining addiction or antisocial personality disorder as a medical condition. Feminist scholars have shown that the female body is prone to medicalization, arguing that the tendency of viewing the female body as the Other has been a factor in this.[9]: 151 Medicalization can obscure social factors by defining a condition as existing entirely within an individual and can be depoliticizing, suggesting than an intervention should be medical when the best intervention is political. Medicalization can give the profession of medicine undue influence.[9]: 152 |

医療化 医療化とは、人間のさまざまな経験が、医学的な状態として定義され、経験され、扱われるようになる過程を指す。医療化の例は、依存症や反社会性パーソナリ ティ障害を病状と定義するような逸脱行為に見られる。フェミニストの学者たちは、女性の身体が医学化されやすいことを示し、女性の身体を他者として見る傾 向がその要因であると論じている[9]: 151 医療化は、ある状態を完全に個人の中に存在するものとして定義することで社会的要因を曖昧にし、最良の介入は政治的なものであるにもかかわらず、介入は医 療的なものであるべきだと示唆し、非政治的になりかねない。医療化は医療という職業に不当な影響力を与える可能性がある: 152 |

| Social construction of illness See also: Social construction of disability Social constructionists study the relationships between ideas about illness and expression, perception and understanding of illness by individuals, institutions and society.[9]: 148 Social constructionists study why diseases exist in one place and not another, or disappear from a particular area. For example, premenstrual syndrome, anorexia nervosa and susto appear to exist in some cultures but not others. There are a broad range of social constructionist frameworks used in medical sociology that make different assumptions about the relationships between ideas, social processes and the material world.[9]: 149 Illnesses vary in the degree to which their definition is socially constructed; some illnesses are straightforwardly biological.[9]: 150 For straightforwardly biological diseases, it would not be meaningful to describe them as a social construction, though it might be meaningful to study the social processes that resulted in the discovery of the disease.[9]: 150 Some illnesses are contested when a patient complains about a disease despite the medical community being unable to find a biological mechanism for disease. Examples of contested diseases include myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS), fibromyalgia and Gulf War syndrome. Contested diseases can be studied as social constructs but there is no biomedical understanding. Some contested diseases, such as ME/CFS, are accepted by the institutions of biomedicine while others, such as environmental diseases, are not.[9]: 153 |

病気の社会的構築 こちらも参照のこと: 障害の社会的構築 社会構築主義者は、病気に関する考え方と、個人、制度、社会による病気の表現、認識、理解との関係を研究している[9]: 148 社会構築主義者は、なぜある場所に病気が存在し、別の場所には存在しないのか、あるいは特定の地域から病気が消えるのかを研究している。例えば、月経前症 候群、神経性食欲不振症、サストは、ある文化圏では存在するが、他の文化圏では存在しないように見える。 医療社会学で使用される社会構築主義の枠組みは広範に わたっており、観念、社会的プロセス、物質的世界の間の関 係について異なる前提を置いている[9]: 149 病気は、その定義が社会的に構築される度合いにおいて様々である: 150 まさしく生物学的な病気については、その病気を発見することになった社会的過程を研究することは意味があるかもしれないが、それを社会的構築として記述す ることは意味がないだろう[9]: 150 医学界が病気の生物学的メカニズムを発見できないにもかかわらず、患者が病気について訴えている場合、争われる病気もある。争病の例としては、筋痛性脳脊 髄炎/慢性疲労症候群(ME/CFS)、線維筋痛症、湾岸戦争症候群などがある。争議病は、社会科学として研究することはできるが、生物医学的な理解はな い。ME/CFSのような争議病は生物医学の制度に受け入れられているが、環境病のような争議病は受け入れられていない[9]: 153 |

| Sick role The study of the social construction of illness within medical sociology can be traced to Talcott Parsons' notion of the sick role.[9]: 148 Parsons introduced the notion of the sick role in his book The Social System.[10]: 211 Parsons argued that the sick role is a social role approved and enforced by social norms and institutional behaviours where an individual is viewed as showing certain behaviour because they are in need of support.[10]: 212 Parsons argues that defining properties are that the sick person is exempt from normal social roles, that they are not "responsible" for their condition, that they should try to get well, and that they should seek technically competent people to help them.[10]: 213 The concept of the sick role has been critiqued by sociologists from neo-marxist, phenomonological and social interactionist perspectives, as well as by those with anti-establishment viewpoints.[11]: 76 Burnham argues that part of this criticism is a rejection of functionalism due to its associations with conservatism. The sick role fell out of favour in the 1990s.[11] |

病気の役割 医療社会学における疾病の社会的構築の研究は、タルコット・パーソンズによる病者の役割の概念にまで遡ることができる: 10]: 211 パーソンズは、病者の役割とは、社会規範と制度的行動によって承認され、強制される社会的役割であると主張した。 パーソンズは、病人が通常の社会的役割から免除されていること、自分の状態に対して「責任」を負っていないこと、治るように努力すること、技術的に有能な人々に助けを求めること、が定義的な特性であると論じている[10]: 213。 病者の役割という概念は、新マルクス主義、表現論的、社会的相互作用論的な視点からの社会学者や、反体制的な視点を持つ人々によって批判されてきた。病的役割は1990年代に支持されなくなった[11]。 |

| Labelling theory Labelling theory is derived from the work of Howard S. Becker, who studied the sociology of marijuana use. He argued that norms and deviant behaviour are partly the result of the definitions applied by others. Eliot Freidson applied these concepts to illness.[10]: 226 Labelling theory separates the aspects of an individual's behaviour caused by an illness, and that which is caused by the application of a label. Freidson distinguished labels based on legitimacy and the degree to which to this legitimacy affected an individual's responsibilities.[10]: 227 Labelling theory has been criticized on the grounds that it does not explain which behaviours are labelled as deviant and why people engage in behaviours which are labelled as deviant: labelling theory is not a complete theory of deviant behaviour.[10]: 228 |

ラベリング理論 ラベリング理論は、マリファナ使用の社会学を研究したハワード・S・ベッカーの研究に由来する。彼は、規範や逸脱行動は部分的には他者によって適用された定義の結果であると主張した。エリオット・フライドソンはこれらの概念を疾病に応用した。 ラベリング理論は、病気によって引き起こされる個人の行動の側面と、ラベルの適用によって引き起こされる側面とを分離する。フレイドソンは正当性に基づくレッテルと、その正当性が個人の責任に及ぼす影響の度合いに基づくレッテルを区別した[10]: 227。 ラベリング理論は、どのような行動が逸脱行動としてラベリングされるのか、またなぜ人々が逸脱行動としてラベリングされる行動に関与するのかを説明していないという理由で批判されてきた。 |

| Mental health An illness framework is the dominant framework for disease in psychiatry and diagnosis is considered worthwhile.[12]: 2 Psychiatry has emphasized the biological when considering mental illness.[12]: 3 Some psychiatrists have criticized this model: some prefer biopsychosocial definitions, while others prefer social constructionist models, and still others have argued that madness is an intelligent response if all circumstances are understood (Laing and Esterson). Thomas Szasz, who trained as a psychiatrist, argued that mental health was a bad concept in his 1961 book The Myth of Mental Illness, arguing that minds can only be ill metaphorically.[12]: 3 |

精神保健 病気の枠組みは精神医学における支配的な病気の枠組みであり、診断には価値があると考えられている[12]: 2 精神医学は精神疾患を考える際に生物学的なものを重視してきた[12]: 3 このモデルを批判する精神科医もいる: 3 このモデルを批判する精神科医もいる:生物心理社会学的定義を好む者もいれば、社会構築主義的モデルを好む者もおり、また、すべての状況を理解すれば、狂 気は知的反応であると主張する者もいる(レイングとエスターソン)。精神科医としての訓練を受けたトーマス・サスは、1961年に出版した『精神病の神 話』の中で、精神保健は悪い概念であると主張し、心は比喩的にしか病むことができないと論じた[12]: 3 |

| Doctor–patient relationship The doctor–patient relationship, the social interactions between healthcare providers and those who interact with them, is studied by medical sociology. There are different models for the interaction between a patient and doctor, which may have been more or less prevalent at different times. One such model is medical consumerism, which has partly given way to patient consumerism. Medical paternalism Medical paternalism is the perspective that doctors want what is best for the patient and must take decisions on behalf of the patient because the patient is not competent to make their own decisions. Parsons argued that though there was an asymmetry of knowledge and power in the doctor–patient relationship, the medical system provided sufficient safeguards to protect the patient, justifying a paternalistic role by the doctor and medical system.[13]: 496 A system of medical paternalism was prominent following the second world war through to the mid-1960s. Writing in the 1970s, Eliot Freidson referred to medicine as having "professional dominance", determining its work and defining a conceptualization of the problems that are brought to it and the best solutions to them.[13]: 497 Professional dominance is defined by three characteristics: practitioners having power over clients, for example through dependency, knowledge, or location asymmetry; control over juniors in the field, requiring juniors' deference and submission; and control over other professions either by excluding them from practice, or placing them under control of the medical profession.[12]: 161 Yeyoung Oh Nelson argues that this system of paternalism was in part undermined by organizational change in the following decades in the US whereby insurance companies, managers and the pharmaceutical industry started competing for role of conceptualizing and delivering medical services, part of the motive being cost-saving.[13]: 498 |

医師と患者の関係 医療提供者とそれに関わる人々との社会科学的相互作用である医師と患者の関係は、医療社会学によって研究されている。患者と医師の相互作用には異なるモデ ルがあり、それは時代によって多かれ少なかれ広まっていたかもしれない。そのようなモデルのひとつが医療消費主義であり、一部は患者消費主義に取って代わ られた。 医療パターナリズム 医療パターナリズムとは、医師は患者にとって最善のことを望んでおり、患者は自分で決断する能力がないため、患者に代わって決断を下さなければならないと いう考え方である。パーソンズは、医師と患者の関係には知識と権力の非対称性が存在するが、医療制度は患者を保護するために十分なセーフガードを提供して おり、医師と医療制度によるパターナリスティックな役割を正当化すると主張した[13]: 496 医学的パターナリズムのシステムは、第二次世界大戦後から1960年代半ばまで顕著であった。1970年代に書かれたエリオット・フリードソンは、医学が 「専門家による支配」を持ち、その仕事を決定し、医学に持ち込まれる問題の概念化とそれに対する最善の解決策を定義していると述べている[13]: 497 専門家の優位性は、次の3つの特徴によって定義される:例えば、依存、知識、場所の非対称性などを通じて、実務家が顧客に対して権力を持つこと、後輩の恭 順と服従を必要とする、その分野の後輩に対する支配、そして、診療から排除するか、医療専門職の支配下に置くことによって、他の専門職を支配することであ る: 161 イェヨン・オー・ネルソンは、このパターナリズムのシステムは、その後数十年の米国における組織的変化によって、保険会社、経営者、製薬業界が医療サービスの概念化と提供の役割を競い合うようになり、その動機の一部はコスト削減であったと論じている[13]: 498 |

| Bioethics Main article: Bioethics § Medical sociology Bioethics studies ethical concern in medical treatment and research. Many scholars believe that bioethics arose due to a perceived lack of accountability of the medical profession, the field has been broadly adopted with most US hospitals offering some form of ethical consultation. The social effects of the field of bioethics have been studied by medical sociologists.[14]: 2 Informed consent, having its roots in bioethics, is the process by which a doctor and a patient agree to a particular intervention. Medical sociology studies the social processes that influence and at times limit consent.[15] |

生命倫理 主な記事 生命倫理 § 医療社会学 生命倫理学は、医療や研究における倫理的な問題を研究する学問である。多くの学者は、生命倫理は医療専門職の説明責任の欠如が認識されたために発生したと 考えており、この分野は広く採用され、米国のほとんどの病院が何らかの形で倫理相談を提供している。生命倫理の社会的影響は、医療社会学者によって研究さ れている[14]: 2 インフォームド・コンセントとは、生命倫理にルーツを持つもので、医師と患者が個別介入に同意するプロセスを指す。医療社会学では、同意に影響を与え、時 には同意を制限する社会科学が研究されている[15]。 |

| Related fields Social medicine Social medicine is a similar field to medical sociology in that it tries to conceptualize social interactions[16]: 241 in investigating how the study of social interactions can be used in medicine.[17]: 9 However, the two fields have different training, career paths, titles, funding and publication.[16]: 241 In the 2010s, Rose and Callard argued that this distinction may be arbitrary.[16]: 242 In the 1950s, Strauss argued that it was important to maintain the independence of medical sociology from medicine so that there was a different perspective on sociology separate from the aims of medicine.[16]: 242 Strauss feared that if medical sociology started to adopt the goals expected by medicine it risked losing its focus on analysing society. These fears that have been echoed since by Reid, Gold and Timmermans.[16]: 248 Rosenfeld argues that the study of sociology focused solely on making recommendations for medicine has limited use for theory building and its findings cease to apply in different social situations.[16]: 249 Richard Boulton argues that medical sociology and social medicine are "co-produced" in the sense that social medicine responds to the conceptualization of medical practices created by medical sociology and alters medical practice and medical understanding in response, and that the effects of these changes are then analyzed by medical sociology once again.[16]: 245 He argues that the tendency to view certain theories such as the scientific method (positivism) as the basis for all knowledge, and conversely the tendency to view all knowledge as associated with some activity both risk undermining the field of medical sociology.[16]: 250 |

関連分野 社会医学 社会医学は、社会的相互作用[16]: 241を概念化しようとする点で、社会的相互作用の 研究が医学においてどのように利用されうるか を研究するという点で、医療社会学と類似し た分野である[17]: 9 しかし、2つの分野は訓練、キャリアパス、 肩書き、資金調達、出版において異なって いる[16]: 241 2010年代、RoseとCallardは、この区別 は恣意的なものであるかもしれないと主張し た[16]: 242。 1950年代、シュトラウスは、医学社会学が医学の目 的から切り離された社会学という異なる視点を持 つために、医学社会学の医学からの独立性を維 持することが重要であると主張していた。このような危惧は、Reid、Gold、 Timmermansらも同じことを述べている。 [16]: 248 Rosenfeldは、医学のための提言を行うことだけに焦点をあてた 社会学研究は、理論構築のための用途が限られ、その知見は 異なる社会状況において適用されなくなると論じている。 リチャード・ボールトンは、医療社会学と社会医学は、社会医学が医療社会学によって創出された医療実践の概念化に反応し、それに応じて医療実践と医療理解 を変化させ、その変化の影響が再び医療社会学によって分析されるという意味で、「共同生産」されていると論じている。 [16]: 245 彼は、科学的方法(実証主義)のような特定の理論 をすべての知識の基礎とみなす傾向や、逆にすべての知 識を何らかの活動に関連するものとしてみなす傾向 は、いずれも医療社会学の領域を弱体化させる危険性があ ると論じている[16]: 250。 |

| Medical anthropology Peter Conrad notes that medical anthropology studies some of the same phenomena as medical sociology but argues that medical anthropology has different origins, originally studying medicine within non-western cultures and using different methodologies.[18]: 91–92 He argues that there was some convergence between the disciplines, as medical sociology started to adopt some of the methodologies of anthropology such as qualitative research and began to focus more on the patient, and medical anthropology started to focus on western medicine. He argues that more interdisciplinary communication could improve both disciplines.[18]: 97 |

医療人類学 ピーター・コンラッドは、医療人類学は医療社会学と同じ現象を研究しているが、医療人類学は異なる起源を持ち、もともとは非西洋文化における医学を研究 し、異なる方法論を使用していたと主張している。[18]: 91–92 彼は、医療社会学が質的研究などの人類学の方法論を採用し始め、患者により重点を置くようになったこと、また医療人類学が西洋医学に重点を置くようになっ たことから、両分野の間にはある程度の収束があったと主張している。彼は、学際的なコミュニケーションをより活発にすることで、両分野が改善される可能性 があると主張している。[18]: 97 |

| Epidemiological transition Gothenburg Study of Children with DAMP Health disparities Medicalization Sociology of health and illness Social medicine Stroke Belt |

疫学的転換 ヨーテボリ小児研究 保健格差 医療化 保健と疾病の社会学 社会医学 脳卒中(心臓血管疾病)ベルト地帯 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Medical_sociology |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

下図をクリックすると拡大します

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆