人種のステレオタイプ

What is so-called RACE stereotype ?

愛知県にあるオリエンタル食品のキャラクター(原図はLINE有料スタンプ

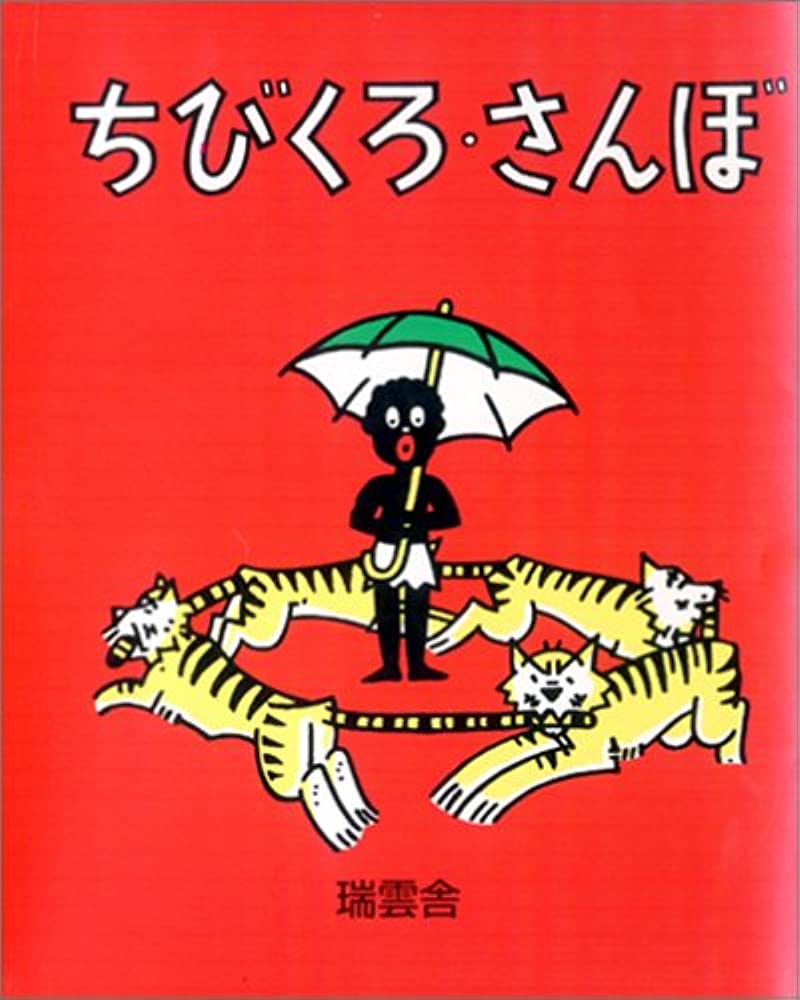

から2021年6月2日現在)文献:ジョン・ラッセル,1991『日本人の黒人観:問題は「ちびくろサンボ」だけではない』新評論。

人種のステレオタイプ

What is so-called RACE stereotype ?

愛知県にあるオリエンタル食品のキャラクター(原図はLINE有料スタンプ

から2021年6月2日現在)文献:ジョン・ラッセル,1991『日本人の黒人観:問題は「ちびくろサンボ」だけではない』新評論。

人種とは、科学的に証明することが絶対にでき ない人間を区分する分類概念です。つまり人種とはある考え方=見方であり事実ではない。しかしながら、人種主義(レイシズ ム)=人種差別思 想があるかぎり、人種の考え方がどのように生まれ、また「人種を信じて疑わない人」がどうしていなくならないのか?まだ人種差別という偏見がどのように維 持されているのかを知ることはとても重要になります!(→お子さまのページに もどります)

[ちゅうい!]これより以下を読むと20分以上かかりま す。

| Racial

stereotyping in advertising

refers to using assumptions about people based on characteristics

thought to be typical of their identifying racial group in marketing.[1] Advertising trends may adopt racially insensitive messages or comply with stereotypes that embrace the values of problematic racial ideologies. Commercials and other forms of media advertisements may be influenced by social stigma regarding race.[2] Racial stereotypes are mental frameworks that viewers use to process social information based on their cultural, racial, or ethnic group, which may not directly "carry negative or positive values."[3] Advertisers include racial stereotypes in their messaging to target a specific demographic, which can potentially impact viewers negatively through offensive language or concepts. A common rule of thumb for people working in advertising is to "be aware of the potential to cause serious or widespread offense when referring to different races, cultures, nationalities or ethnic groups."[4] |

広告における人種的ステレオタイプ化とは、マーケティングにおいて特定

の人種グループに典型的と考えられる特徴に基づいて人々についての仮定を使用することを指します。[1] 広告の傾向は、人種に配慮しないメッセージを採用したり、問題のある人種イデオロギーの価値観を受け入れる固定観念に準拠したりする可能性があります。コ マーシャルやその他の形式のメディア広告は、人種に関する社会的偏見の影響を受ける可能性があります。[2] 人種的な固定観念は、視聴者が文化、人種、民族グループに基づいて社会情報を処理するために使用する精神的な枠組みであり、直接的に「否定的または肯定的 な価値観を伝える」ものではない可能性があります。[3]広告主は、特定の層をターゲットにするためにメッセージに人種的な固定観念を含めますが、攻撃的 な言葉や概念を通じて視聴者に悪影響を与える可能性があります。広告業界に携わる人々の共通の経験則は、「異なる人種、文化、国籍、民族グループに言及す る場合は、深刻なまたは広範な攻撃を引き起こす可能性があることを認識する」ことです。[4] |

| Defining racism in advertising There is no universal definition of racism or standard for detecting it within the scope of advertisement.[5] Racial tropes are commonly used to target a particular demographic, which tends to lead to insult. The ambiguous nature of defining racism creates a debate about whether it is ethical to use stereotypes in advertisements. Those against racial stereotyping argue that using archetypes as representative of a population is an oversimplification of an entire race of people and further narrows the representation available of marginalized groups. This perspective argues that the media is especially harmful because commercial advertisements are one of the most prevalent and commonplace forms of media. Conversely, others believe that advertisements may use racial stereotypes as long as they do not cause intentional or lasting harm to a population.[6] Stereotypes are the inferred beliefs of roles, attributes, or positions assigned to different people based on factors like race, religion, sexual orientation, or gender.[7] Advertisers use stereotypes to provide familiarity to a viewer, but pose the risk of generalizing and misrepresenting groups of people to a large audience.[8] A debate has existed historically around using stereotypes in advertising, but can be simplified by the "mirror" vs. "mold" argument coined by Pollay in 1986.[9] This argument states that advertising "mirrors" society and does not present ideas to viewers that do not already exist as stereotypes. The "mirror" theory argues that advertising reflects the lifestyles and ideals of society and that it is this mirroring effect that drives familiarity with the product or service offered and the subsequent consumer engagement. However, the "mold" argument maintains that advertising influences society, and thus encourages stereotypes because of their ubiquity. The "mold" theory argues that sales are driven by society attempting to conform to the stereotypes and ideas communicated in advertising, as it shapes their own values and beliefs.[10] Stereotypes in advertising include creating caricatures based upon a perceived notion of a particular group. The limited amount of time given for a commercial advertisement leads to simplified characters who may employ archetypal traits.[11] Audiences use stereotypes to fill in holes in a general character's backstory. Within a thirty-second commercial, advertisers rely on audiences' preconceived notions to understand a character and situation based on the strict prioritization of their time. Stereotypes facilitate a collective but unspoken understanding of the meaning of the commercial, even if the stereotype is damaging to the affiliated group.[8] |

広告における人種差別の定義 人種差別の普遍的な定義や、広告の範囲内で人種差別を検出するための基 準はありません。[5]人種的な比喩は特定の層をターゲットにするためによく使用され、侮辱につながる傾向があります。人種差別の定義には曖昧な性質があ るため、広告でステレオタイプを使用することが倫理的かどうかについての議論が生じています。人種的なステレオタイプ化に反対する人々は、集団の代表とし て原型を使用することは、人類全体を過度に単純化しており、疎外されたグループの利用可能な表現をさらに狭めると主張しています。この観点は、商業広告が 最も普及している広告の 1 つであるため、メディアが特に有害であると主張します。そして一般的なメディア形式。逆に、国民に意図的または永続的な危害を与えない限り、広告は人種的 固定観念を使用してもよいと考える人もいます。[6] ステレオタイプとは、人種、宗教、性的指向、性別などの要素に基づいて、さまざまな人々に割り当てられる役割、属性、または立場についての推測される信念 です。[7]広告主は視聴者に親しみを与えるためにステレオタイプを使用しますが、人々のグループを一般化して多くの視聴者に誤って伝える危険がありま す。[8] 広告におけるステレオタイプの使用をめぐる議論は歴史的に存在していましたが、1986 年にポレーによって生み出された「鏡」対「型」の議論によって単純化できます。[9]この議論は、広告は社会を「映し出す」ものであり、ステレオタイプと してすでに存在しないアイデアを視聴者に提示するものではない、と述べています。「鏡」理論は、広告は社会のライフスタイルや理想を反映しており、提供さ れる製品やサービスへの親しみやすさとその後の消費者の関与を促進するのはこの鏡映効果であると主張します。しかし、「カビ」の議論は、広告は社会に影響 を与え、その遍在性ゆえに固定観念を助長すると主張する。「型」理論は、社会が広告で伝えられる固定観念や考え方に従おうとすることによって売上が促進さ れ、それが社会自身の価値観や信念を形作ると主張します。[10] 広告における固定観念には、特定のグループの認識された概念に基づいて風刺画を作成することが含まれます。商業広告に与えられる時間は限られているため、 典型的な特徴を使用する単純化されたキャラクターが作成されます。[11]視聴者は、一般的なキャラクターのバックストーリーの穴を埋めるためにステレオ タイプを使用します。32 秒のコマーシャル内で、広告主は視聴者の先入観に頼って、時間の厳密な優先順位に基づいて登場人物や状況を理解します。ステレオタイプは、たとえそれが所 属グループに損害を与える場合でも、コマーシャルの意味についての集団的ではあるが暗黙の理解を促進します。[8] |

| Targeting specific demographics Racial stereotyping has the potential to reap results for a company if it targets a particular demographic. Audiences have perceptual biases toward people or characters similar to themselves and within their in-group. An in-group consists of people whom individuals socially identify with through similarities in characteristics such as age, race, gender, and religion. Studies have shown that "the enhancement of in-group bias is more related to increased favoritism toward in-group members than increased hostility toward out-group members."[12] Advertisers use this knowledge when targeting a product or service to a particular market and may use demographics to inform the messages they present. Different countries and cultures speak different languages and understand symbols differently, so an advertiser must tactfully account for in-group bias. Viewers are more likely to cast favoritism toward people they can socially identify with. Advertisers, therefore, consider the audience heavily when figuring out how to present their characters. This thought process explains why advertisers use racial stereotyping they may not recognize as offensive. Advertisers argue that specific demographics can be used to simultaneously employ racial stereotypes and create a successful result for an audience. This argument suggests that a company can achieve successful marketing while creating a message which viewers can identify and connect with. Sociologist Stuart Hall argues that reading a particular image depends not only on the messages contained in it, but on the messages surrounding it and the situational, societal, and historical context.[13] He claims that society constructs stereotypes and it is not a company's responsibility to avoid them. |

特定の層をターゲットにする 企業が特定の層をターゲットにしている場合、人種的な固定観念は企業に利益をもたらす可能性があります。視聴者は、自分自身や同じグループ内の人々や登場 人物に対して、知覚的な偏見を持っています。内集団は、年齢、人種、性別、宗教などの特徴の類似性を通じて個人が社会的に同一視している人々で構成されま す。研究によると、「内集団バイアスの強化は、外集団メンバーに対する敵意の増加よりも、内集団メンバーに対する好意の増加に関連している」ことが示され ています。[12]広告主は、製品やサービスを特定の市場にターゲットを絞るときにこの知識を使用し、人口統計を使用して広告が提示するメッセージを知ら せることがあります。国や文化が異なれば、使用する言語も異なり、記号の理解も異なるため、広告主はグループ内バイアスを巧みに考慮する必要があります。 視聴者は、社会的に共感できる人に対して好意を抱く傾向があります。したがって、広告主はキャラクターをどのように表現するかを考えるとき、視聴者を非常 に考慮します。この思考プロセスは、広告主が攻撃的であると認識していない人種的なステレオタイプを使用する理由を説明しています。 広告主は、特定の人口動態を利用して、同時に人種的な固定観念を採用し、視聴者にとって成功する結果を生み出すことができると主張している。この議論は、 企業が視聴者が識別して共感できるメッセージを作成しながらマーケティングを成功させることができることを示唆しています。社会学者のスチュアート・ホー ルは、特定の画像を読むことは、そこに含まれるメッセージだけでなく、それを取り巻くメッセージや状況、社会、歴史的文脈にも依存すると主張します。 [13]彼は、社会が固定観念を構築しており、それを回避するのは企業の責任ではないと主張しています。 |

| Whitewashing Whitewashing is used in the advertising industry to show a preference for European traits. Whitewashing refers specifically to digitally altering the image of a model to make their appearance fairer. In a TEDx talk, Jean Kilbourne stated that standards of beauty for women are impossible, but especially so for "women of color, who are considered beautiful only insofar as they resemble the white ideal: light skin, straight hair, Caucasian features, round eyes."[14] Whitewashing is a technique used by advertisers to appeal to a perceived societal ideal. As an example, in 2008, beauty product company L'Oreal Paris was accused of whitewashing the singer Beyoncé's skin and hair color for their advertising campaign. The accusations suggested that they edited her to be light-complexioned and light-haired in their published images. L'Oreal received tremendous backlash for this incident, namely from the black community. Outraged individuals argued that the altered images diminished the Black community and sent a poor message to Beyoncé's young fans.[15] Other Black people in the media have experienced whitewashing, such as Lupita Nyong'o for Vanity Fair[16] or Kerry Washington for InStyle.[17] Many companies worry that racial stereotyping and whitewashing could lead to societal consequences, including anger toward the company or discrimination, as demonstrated by companies becoming more careful about their visual and textual choices for product advertising.[18] |

ホワイトウォッシング ホワイトウォッシュは広告業界でヨーロッパの特徴を好むことを示すために使用されます。ホワイトウォッシュとは、特にモデルの画像をデジタル的に変更し て、見た目をより美しくすることを指します。TEDxの講演でジーン・キルボーンは、女性の美しさの基準は不可能であるが、特に「有色人種の女性は、白い 肌、真っ直ぐな髪、白人の特徴、丸い目といった白人の理想に似ている場合にのみ美しいとみなされる」と述べた。 。」[14] ホワイトウォッシングは、社会の理想をアピールするために広告主が使用する手法です。 一例として、2008 年、美容製品会社ロレアル パリは、広告キャンペーンのために歌手ビヨンセの肌と髪の色を白塗りしたとして告発されました。告発は、公開された画像で彼女の肌の色が白く、髪が明るい ように編集したことを示唆している。ロレアルはこの事件で黒人コミュニティから多大な反発を受けた。これに激怒した人々は、改変された画像は黒人コミュニ ティを衰退させ、ビヨンセの若いファンに質の悪いメッセージを送ったと主張した。[15] Vanity Fair [16]のルピタ・ニョンゴや InStyle のケリー・ワシントンなど、メディアに登場する他の黒人もホワイトウォッシングを経験している。[17]多くの企業は、企業が製品広告のビジュアルおよび テキストの選択についてより慎重になっていることからもわかるように、人種的な固定観念やホワイトウォッシングが企業に対する怒りや差別などの社会的影響 につながる可能性があると懸念しています。[18] |

| Offending marginalized

populations One of the primary adverse effects of racial stereotyping in marketing is offending the population alluded to in an advertisement. Researcher Srividya Ramasubramanian discusses how stereotypes become harmful, explaining that there are two stages in the stereotyping process, where activation is more automatic and application is more deliberate. She means essentially that stereotypical thoughts about other groups exist for all people implicitly, even if not acted upon or outwardly expressed.[19] This argument suggests that all people believe in stereotypes to a certain degree, but only become offended when stereotypes are explicitly and openly stated. Because people naturally identify themselves socially, they assign qualities to themselves that they can also associate with other people. Creating connections within a particular group increases the likelihood of experiencing hurt by stereotypical messaging present in advertisements, which "has a significant impact on the way the individuals within the group self-identify."[20] Therefore, typical outcomes to offensive racial stereotypes are outrage at the producer of the advertisement or self-doubt within the group. Many believe that advertisements' archetypal representations of particular groups are unrealistic and distorted.[21] |

疎外された人々を攻撃する マーケティングにおける人種的固定観念の主な悪影響の 1 つは、広告でほのめかされた人々を不快にさせることです。 研究者のスリヴィディヤ・ラマスブラマニアン氏は、ステレオタイプがどのようにして有害になるのかについて議論し、ステレオタイプ化のプロセスには 2 つの段階があり、その活性化はより自動的に行われ、適用はより意図的に行われると説明しています。彼女が意味するのは、たとえ行動に移さなかったり、表向 きに表現されなかったとしても、他のグループについての固定観念が暗黙のうちにすべての人々に存在しているということです。[19]この議論は、すべての 人はある程度ステレオタイプを信じているが、それが明示的かつ公然と述べられた場合にのみ気分を害することを示唆しています。 人は自然に自分自身を社会的に認識するので、他の人にも関連付けることができる特質を自分自身に割り当てます。特定のグループ内でつながりを作ると、広告 に存在する紋切り型のメッセージによって傷つく可能性が高まり、これは「グループ内の個人の自己認識に重大な影響を与える」。[20]したがって、攻撃的 な人種的固定観念に対する典型的な結果は、広告の制作者に対する怒りや集団内の自信喪失です。多くの人は、広告における特定のグループの典型的な表現は非 現実的で歪んでいると信じています。[21] |

| Examples of racial stereotyping Stereotypes directed at people of Asian descent represent well-educated individuals with a high work ethic. Commercials with these stereotypes tend to exist within advertising that promotes technology and business more than other races.[11] Asian people were in ads that take place in the workplace or office setting in 50% of the print ads that they featured in, compared to other races that were featured in more leisure-oriented ads from 2003.[11] Ads that feature Asian American men often perpetuate a stereotype of success and sacrifice to achieve financial rewards, such as Paek and Shah's (2003) example of a print ad, in which an Asian man talking to his wife tells her he will have to work late, implying that his personal life is a secondary commitment to his work. Some argue that the stereotype of hard work and affluence may appear to be a positive one but is actually problematic.[22] Indeed, stereotypes related to the false "Model Minority" discourse have been proven to increase pressure on Asian people to be productive and successful.[23] Television and print advertising shape viewers' perceptions of minorities, and many Asian and Asian-American journalists argue that this representation of Asian people hegemonizes and inaccurately represents a vast and convoluted group.[24] Stereotypes of Black people common in advertisements are a connection to hip-hop music.[25] Black men in commercials also have exceptional physical and athletic ability, demonstrated by a young man playing basketball in a Kellogg's commercial or the variety of athletes in EA Sport's advertisements for basketball and soccer video games.[26] Similarly, a typical representation for Black women is the "angry black woman" stereotype, where the woman is portrayed as irrational and violent.[27] Other stereotypes may include the hypersexualization and dehumanization of Black people, as demonstrated through an ad by LINGsCARS[28] that received complaints about trivializing the Black Lives Matter movement and stereotyping by playing off the offensive phrase "Once you go black, you never go back."[29] The ad posted on Facebook read "Once you go black, you never go back" and "Black Cars Matter."[30] Latin American people are drastically underrepresented in the media, featured with speaking roles in only 1% of television ads[31] and in only 4.7% of television ads overall in the early 2000s time period.[32] In a study done by Mastro and Stern (2003) examining frequencies of different races in commercials, Latinx people advertise soap or hygiene products in 43% of ads they are featured in, closely followed by other non-occupational roles promoting clothing or footwear. Ads also more frequently sexualize Latinx populations.[31] Paek and Shah found Latinx populations to participate in advertisements that portrayed subservient and blue-collar labor roles.[11][33] Additionally, advertisements featuring Latinx people poke fun at accents, implement "Spanglish," and emphasize clichés.[34] |

人種的固定観念の例 アジア系の人々に対する固定観念は、高い教育を受け、高い労働倫理を持つ人々を表します。このようなステレオタイプのコマーシャルは、他の人種に比べてテ クノロジーやビジネスを促進する広告に存在する傾向があります。[11] 2003 年以降、よりレジャー志向の広告で特集された他の人種と比較して、アジア人が特集された印刷広告の 50% では、職場やオフィス環境で行われる広告にアジア人が出演していました。 [11 ]アジア系アメリカ人男性を特集した広告では、金銭的報酬を得るために成功と犠牲を払うというステレオタイプを永続させることがよくあります。たとえば、 Paek and Shah (2003) の印刷広告の例では、アジア系男性が妻と話していて、遅くまで働かなければならないと告げています。 、彼の私生活は仕事の二の次であることを暗示しています。勤勉で裕福であるという固定観念は肯定的なものに見えるかもしれないが、実際には問題があると主 張する人もいます。[22]実際、誤った「モデル・マイノリティ」言説に関連する固定観念が、アジア人に対して生産性と成功を求める圧力を増大させること が証明されている。[23]テレビや印刷広告は少数派に対する視聴者の認識を形成しており、多くのアジア人およびアジア系アメリカ人ジャーナリストは、こ のアジア人の表現が覇権を握っており、広大で複雑なグループを不正確に表していると主張している。[24] 広告でよく見られる黒人に対するステレオタイプは、ヒップホップ音楽と 結びついています。[25]コマーシャルに登場する黒人男性は、ケロッグのコマーシャルでバスケットボールをしている若い男性や、EA スポーツのバスケットボールやサッカーのビデオゲームの広告に登場するさまざまなアスリートによって証明されているように、並外れた身体能力と運動能力を 持っています。[26]同様に、黒人女性の典型的な表現は「怒っている黒人女性」というステレオタイプであり、女性は非合理的で暴力的なものとして描かれ ている。[27]他の固定観念には、黒人の命は重要であることを矮小化することに関する苦情を受けたLINGsCARS の広告[28]を通じて示されているように、黒人の過剰な性的差別と非人間化が含まれる可能性があります。「一度黒人になったら二度と戻れない」という攻 撃的なフレーズをもじって、運動と固定観念を表現しました。[29]フェイスブックに投稿された広告には「一度黒人になったら二度と戻れない」「黒い車は 重要だ」と書かれていた。[30] ラテンアメリカ人はメディアで大幅に過小評価されており、2000 年代初頭のテレビ広告のわずか 1% [31] 、テレビ広告全体のわずか 4.7% に講演者として出演していました。[32]コマーシャルにおけるさまざまな人種の頻度を調査したマストロとスターン (2003) の研究では、ラテン系人は自分たちが出演する広告の 43% で石鹸や衛生製品を宣伝しており、その次には衣料品や衛生製品を宣伝する他の非職業的な役割が続いています。履物。広告ではラテン系住民を性的に対象とす ることも頻繁に行われます。[31]ペクとシャーは、ラテン系住民が従属労働者やブルーカラーの労働者の役割を描写する広告に参加していることを発見し た。[11] [33]さらに、ラテン系の人々をフィーチャーした広告では、アクセントをからかい、「スパングリッシュ」を実装し、常套句を強調しています。[34] |

| Campaigns against stereotypes Some companies make efforts toward being culturally sensitive, but are not received well, such as Pepsi's advertisement featuring Kendall Jenner that was meant to highlight police brutality in the United States.[35] Pepsi and Kendall Jenner both later apologized for the insensitive ad and it was taken down.[36] Common complaints against the ad were that it was "co-opting protest movements for profit"[37] and demonstrated the "white savior" trope in a way that trivialized the movement against police brutality.[38] An effort that was more positively received by society was the transition of PepsiCo's Aunt Jemima to Pearl Milling Company in 2021.[39] Aunt Jemima was criticized for using stereotypical images and language to represent a Black woman as the "mammy" character.[40] Based on Nancy Green, Aunt Jemima was a stereotypical representation of this woman who created the original recipe and served as the face of the brand for years.[41] Dedicated to removing racial stereotypes, PepsiCo pledged a rebrand, a "$1 million commitment to empower and uplift Black girls and women," and a "five-year investment to uplift Black business and communities."[39] Another example of a commercial designed to combat racial stereotyping was the Proctor & Gamble "Widen the Screen" ad.[42] This ad was part of a "larger effort by the company to confront racial stereotypes in media and give opportunities to Black creators."[43] Proctor & Gamble created this campaign to emphasize statistics, including that "less than 6% of writers, directors, and producers of U.S.-produced films are Black," "only 8 of 1,447 directors identified as Black women" from 2007-2019, "black characters accounted for 15.7% of all film roles" in 2019, and "33% of the top 100 films in 2019 had no Black girls/women in any speaking or named roles."[44] According to Proctor & Gamble, their brand hopes to fight systemic racism and support Black creators.[44] |

固定観念に対するキャンペーン 一部の企業は文化的に配慮するよう努めていますが、米国での警察の残虐行為を強調することを目的としたケンダル・ジェンナーを起用したペプシの広告のよう に、評判は良くありません。[35]ペプシとケンダル・ジェンナーは後にこの無神経な広告について謝罪し、広告は削除された。[36]この広告に対する一 般的な苦情は、「抗議運動を利益のために利用している」というものであり[37]、警察の残虐行為に対する運動を矮小化する形で「白い救世主」という比喩 を誇示しているというものだった。[38] 社会によってより肯定的に受け入れられた取り組みは、2021年にペプシコ社のジェマイマおばさんがパール・ミル・カンパニーに移籍したことだった。 [39]ジェマイマおばさんは、黒人女性を「ママ」のキャラクターとして表現するためにステレオタイプのイメージと言語を使用したとして批判された。 [40]ナンシー・グリーンに基づいて、ジェマイマおばさんは、オリジナルのレシピを作成し、長年にわたってブランドの顔として機能したこの女性の典型的 な表現でした。[41]人種的な固定観念を取り除くことに専念するペプシコは、ブランド変更、「黒人の少女と女性に力を与え、高揚させるための100万ド ルのコミットメント」、そして「黒人のビジネスとコミュニティを高揚させるための5年間の投資」を約束した。[39] 人種的な固定観念に対抗するために設計されたコマーシャルのもう 1 つの例は、プロクター・アンド・ギャンブルの「ワイドン・ザ・スクリーン」広告です。[42]この広告は「メディアにおける人種的固定観念に立ち向かい、 黒人クリエイターに機会を与えるという同社による大規模な取り組み」の一環であった。[43]プロクター・アンド・ギャンブルは、2007年から「米国製 作映画の脚本家、監督、プロデューサーの6%未満が黒人である」、「1,447人の監督のうち黒人女性と認められるのはわずか8人」などの統計を強調する ためにこのキャンペーンを作成した。 2019年には「すべての映画の役柄の15.7%を黒人が演じた」とし、「2019年のトップ100映画のうち33%には、セリフや名前のある役で黒人の 少女/女性が登場しなかった」としている。[44]プロクター・アンド・ギャンブルによると、同社のブランドは体系的な人種差別と闘い、黒人クリエイター をサポートしたいと考えているという。[44] |

| See also Gender advertisement Representation of African Americans in media Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie |

ジェンダー広告 メディアにおけるアフリカ系アメリカ人の表現 チママンダ・ンゴジ・アディチェ |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Racial_stereotyping_in_advertising |

Google translator |

●民族的ステレオタイプ

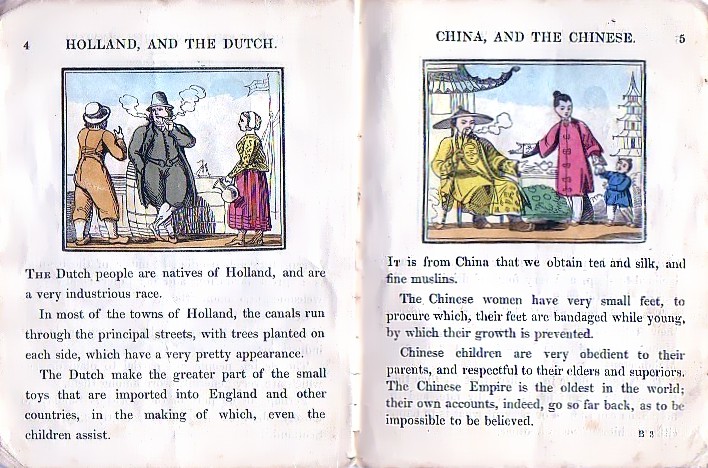

A 19th-century

British children's book informs its readers that the Dutch are a "very

industrious race", and that Chinese children are "very obedient to

their parents"

カルピスのこのマークは今はつかわれなくなりました

リンク

文献

その他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆