Action

Anthropology, アクションアンソロポロジー

アクション人類学

Action

Anthropology, アクションアンソロポロジー

Sol Tax (30 October 1907 – 4 January 1995)

解説:池田光穂

【定義】

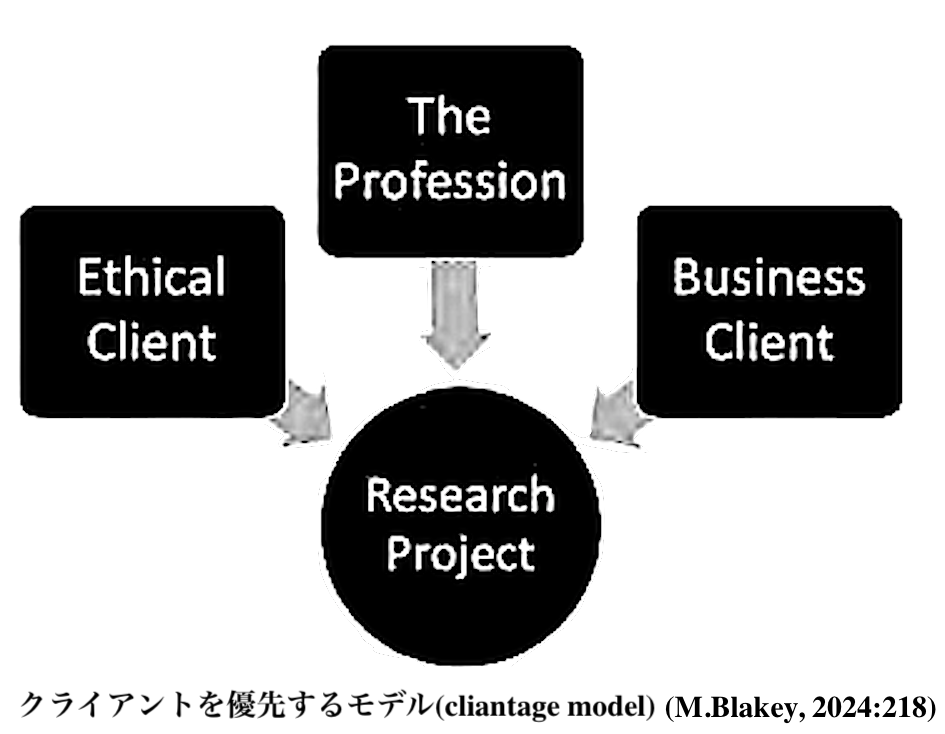

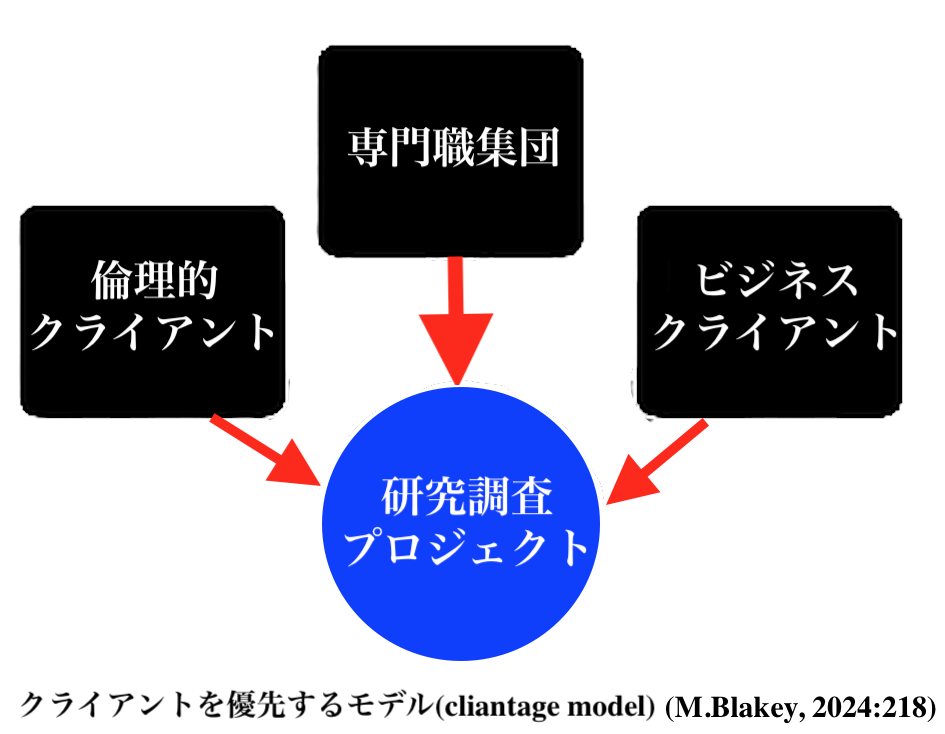

アクション人類学とは、人類学の具体的な検討を通して、たんに人類学の応用的活動における貢献を試みるだけでなく、人類学が研究対象となる 当事者と共に意思決定プロセスに関わる実践的学問である(→アクション・リ サーチ)。従って、アクション人類学とは、臨床的実践のことでもある("[A]ction anthropology is clinical" - R. C. Mitchell, Action anthropology, 1970)。

アクション人類学は、ソル・タックスによると「純粋な研究者とともに結びつくような知的および政治的相互依存性」というものを要求すること

になり、それ(=依存性)は「クライアントや政府の結びつき=コネクションよりも支援のための大学と基金の間のコネクションに依存する」という

Action anthropology requires the "intellectual and the political independence that one associates with the pure researcher; it depends on university and foundation connections for support rather than those of a client or government." (Tax 1964: 257) - 上掲のミッチェル論文からの引用

アクション人類学は、それの研究と実践の関係性を、生身の人間(および集団)に求めるので、当然のことながら研究上の倫理を、他の自然科学 や社会科学以上に負うことになる(→研究倫理)。

アクション人類学者が関わる研究と実践の関係性は、大きく分けて2つの特色がある:ひとつは(1)研究対象となるクライアントからの「要求 (demand)」であり、他のひとつは、(2)研究の遂行に関わる「(諸)リスク (risks)」である。

アクション人類学は、フォックス・インディアン(the Mesquakie)の居留地に、ソル・タックスが学生を引率して調査する研究から始まった。最初は、参与観察を通してフォックス・インディアンの社会や 文化を理解することから始まったが、彼らに対する周囲の「白人の視点」がもつ偏見や、彼ら自身が内面化しているように思われた、自己に対する偏見、とりわ け、開発から「遅れたインディアン」についての意識調査と、彼ら(=クライアント)自身がそれをどう考えているのかということに対する、人類学者とクライ アントの間の対話が始まるようになった。

アクション人類学は、現地社会に対する応用や「干渉」ないしは介入から入るのではない。まずは、純粋な研究から出発することが肝心である。 そして、対象になっている人たち(the people in question)が望まないような概念ないしは他者表象を放棄していくような、ある種の人類学がもっている表象化の減算主義を特色とする点で興味深い ——なぜなら民族誌研究は、データの解釈の上にさらにデータ収集をおこなうという加算主義的な表象戦略をとるからである。

「人類学における公共的関与」より

◆ 引用文 Tax, Sol, (1964) The Use of Anthropology, In Tax. Sol ed., 1964. Horizons of anthropology. Pp.248-258Chicago: Aldine.

【1】"Here then we come to the second answer to the question. It is as teachers of the lessons of the whole of anthropology that we put our science to use; and we teach not only in the classroom, important as that is to most of us, but wherever we work and live. Anthropology has become for us a way of life, a set of values to pass on to whomever we touch: our parents and our children; our colleagues at work or play; our fellow citizens wherever they are. " (Tax 1964:251)

「ここで、質問に対する2つ目の

答えにたどり着く。私たちは、人類学全体の教訓を教える教師として、私たちの科学を活用する。私たちにとって人類学は、親や子供たち、職場や遊びの仲間た

ち、そしてどこにいても同じ市民である仲間たちなど、誰に接するときにも伝えるべき価値観であり、生き方なのである」。

【2】"Let us accept the independence of the anthropologist. Supposing him to be a research scientist serving only the one master and responsible only to his conscience and to his colleagues, let us give him this problem: What are the circumstances in which a community of people achieves its own goals, or is on the contrary frustrated? Assuming that there is basic agreement on what is wanted, communities of people still fall short of their goals. This happens whether the community one has in mind is a modern city unable to keep itself clean and orderly; or a nation unable to control the growth of a strangling bureaucracy; or even the faculty of a University unable to protect its academic freedom. The problem is one for the tools as weB of political science, economics, and sociology; but it is the sort of general problem which anthropologists characteristically tackle, borrowing what tools we need. We would think of beginning the anthropological research in a small community of a culture different from our own, since this is our special method of objectifying the problem; but we would hope to end up with some general understanding of the processes involved. Should we succeed in learning how any community of people can better achieve its own goals, we would have put anthropology to important use." (Tax 1964:255-256).

「人類学者の独立性を認めよう。

彼をただ一人の主人に仕え、自分の良心と同僚にのみ責任を負う研究科学者と仮定して、彼にこの問題を与えてみよう。何が望まれているのかについて基本的な

合意があると仮定しても、人々の共同体はやはり目標を達成できない。これは、その共同体が、清潔で整然とした状態を保つことができない近代都市であろう

と、首を絞めるような官僚主義の成長を制御することができない国家であろうと、学問の自由を守ることができない大学の教授陣であろうと同じである。この問

題は、政治学、経済学、社会学といった道具の問題であるが、人類学者が特徴的に取り組む一般的な問題であり、どのような道具が必要かを借りつつ取り組むも

のである。問題を客観化するための特別な方法であるため、人類学的研究は、自分たちとは異なる文化の小さな共同体から始めることを考えるだろう。どのよう

な人々の共同体であれ、どのようにすれば自らの目標をよりよく達成できるかを学ぶことに成功すれば、人類学を重要な形で役立てることができるだろう。」

【3】"The method of research that is suited to this problem, however, appears to violate the canon that the anthropologist should not become involved in public affairs. In the three or four cases where the problem has been successfully pursued, the anthropologists found that they had to interfere quite deliberately in social processes. To study such a problem requires helping the people of the community to discover their goals; but since there are cOlppeting goals and wants and forces in the society, this cannot be a simple educational process. (If it were so simple, there would be no problem to begin with.) So the anthropologist takes a special position in the community and becomes an actor as well as an observer." (Tax 1964:256)

「しかし、この問題に適した調査

方法は、人類学者が公的な問題に関与すべきではないという規範に反するように思われる。この問題をうまく追究できた3、4件のケースでは、人類学者は社会

的プロセスにかなり意図的に干渉しなければならないことがわかった。このような問題を研究するには、コミュニティの人々が自分たちの目標を発見する手助け

をする必要があるが、社会には様々な目標や欲求や力が存在するため、これは単純な教育プロセスではありえない。(だから人類学者は共同体の中で特別な立場

をとり、観察者であると同時に行為者となるのである。」

【4】"The community responded remarkably; and Holmberg's experiment proved an important point not only for anthropology but also for the people of Vic os and Peru, for all others in similar circumstances, and for the policy-making powers in the world. Similarly the University of Chicago's experiment in helping a sman community of North American Indians to resolve its problems has led to understandings not only about American Indian problems in general, but about those of other population enclaves like the Maori of New Zealand or tribal peoples in India or Africa. The general lesson that they will adjust to the modern world when their identity and their own cultural values are not threatened is important because such threats may not really be necessary. The understandings gained by this method of research by the anthropologists of Cornell and Chicago could probably not have come In any other way. The results are proving themselves in an understanding of the problems of new nations, of North American cities, even of the organization of universities. Indeed, the unique community of anthropologists of the world that I mentioned as being now in existence was helped into being directly by what was learned from American Indians. The same understanding may some day help the peoples of the world to achieve the common goal of peace."(Tax 1964:256-257)

「ホルンベルクの実験は、人類学

にとってだけでなく、ビックオスとペルーの人々にとっても、同じような境遇にある他のすべての人々にとっても、そして世界の政策立案者にとっても、重要な

ポイントであることを証明した。同様に、北米インディアンのスマン・コミュニティが抱える問題の解決を支援したシカゴ大学の実験は、アメリカ・インディア

ンの問題全般についてだけでなく、ニュージーランドのマオリ族やインドやアフリカの部族民のような他の人口の飛び地の問題についても理解するきっかけと

なった。自分たちのアイデンティティや文化的価値が脅かされなければ、彼らは現代社会に適応していくという一般的な教訓は重要である。コーネルとシカゴの

人類学者によるこの調査方法で得られた理解は、おそらく他の方法では得られなかっただろう。その成果は、新しい国家の問題、北米の都市の問題、さらには大

学の組織の問題を理解する上で証明されつつある。実際、私が現在存在すると述べた世界の人類学者のユニークなコミュニティは、アメリカ・インディアンから

学んだことが直接その誕生を助けたのである。同じ理解が、いつの日か世界の人々が平和という共通の目標を達成する助けとなるかもしれない。」

【5】"This new method of research, which Paul Broca could not have predicted, is often called "action anthropology." It does not fit the distinction frequently made between pure and applied research. It requires the intellectual and the political independence that one associates with a pure researcher; it depends upon university and foundation connections and support rather than those of a client or government. But it also requires that the anthropologist leave his ivory tower and that without losing his objectivity he enter into some world of affairs which becomes for the time being his laboratory."(Tax 1964:257)

「ポール・ブローカが予測できな

かったこの新しい調査方法は、しばしば "行動人類学(=アクション人類学)

"と呼ばれる。純粋研究と応用研究という区別には当てはまらない。純粋な研究者としての知的独立性と政治的独立性を必要とし、クライアントや政府ではな

く、大学や財団のコネクションや支援に依存する。しかし、人類学者が象牙の塔を離れ、客観性を失うことなく、当分の間、自分の研究室となる世界に入り込む

ことも必要なのである。」

【出典】"The Documentary History of the Fox Project (Gearing, Netting, and Peattie 1960). For a discussion of the tenets of "Action Anthropology" which emerged from the Fox project, see especially articles in the latter volume by Tax (pp. 167-171), Diesing (pp. 182-197), and Peattie (pp. 300-304)."(Tax 1964:258)

◆ 関連リンク

◆ 文献

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099