オストラネーニエ

異化, 脱親密化, ostranenie, остранение

解説:池田光穂

日常言語は、自動化し無意識化した日常を 自然化する機能(=ドクサ化機能)をもつ。

しかし、日常言語による現前化したものだ けが「現実」ではないことは、我々が非日常的なことを出会ったり、事故にあったりすることで、その事実 は開裂するかのごとく出現する。

その日常性を破壊する、ないしは、ちょっ と傷つけることにより、日常性が開裂する機能をもつ言語あるいは言語機能をもつ実体が存在する。

それが詩的言語である。詩的言語は、ヴィ クトール・ボリソビッチ・シクロフスキー(Viktor Borisovich Shklovskii, 1893-1984)らによるロシア・フォルマリズムの運動のなかで、日常 言語との区別のなかで定式化された。オストラネーニエ(ostranenie) は、芸術の手法としての非日常化、あるいは異化(いか)として理論化されたものであり、詩的言語は、これにより日常言語により構築される世界を打破し、芸 術を我々の前に開示するのである。

| Defamiliarization or

ostranenie (Russian: остранение, IPA: [ɐstrɐˈnʲenʲɪjə]) is the artistic

technique of presenting to audiences common things in an unfamiliar or

strange way so they could gain new perspectives and see the world

differently. According to the Russian formalists who coined the term,

it is the central concept of art and poetry. The concept has influenced

20th-century art and theory, ranging over movements including Dada,

postmodernism, epic theatre, science fiction, and philosophy;

additionally, it is used as a tactic by recent movements such as

culture jamming. |

デファミリアリゼーション(脱親密化)またはオストラネニエ(ロシア

語: остранение、IPA:

[ɐstrɐˈnʲenʲɪjə])とは、観客にありふれたものを馴染みのない、あるいは奇妙な方法で提示し、新たな視点を得て世界を異なる視点から見る

ことを可能にする芸術的手法である。この用語を考案したロシア・フォルマリストによれば、これは芸術と詩の中心的な概念である。この概念は、ダダイズム、

ポストモダニズム、叙事詩的演劇、SF、哲学などの運動を含む20世紀の芸術と理論に影響を与えてきた。さらに、カルチャー・ジャミングなどの最近の運動

では戦術として用いられている。 |

| Coinage The term "defamiliarization" was first coined in 1917 by Russian formalist Viktor Shklovsky in his essay "Art as Device" (alternate translation: "Art as Technique").[1]: 209 Shklovsky invented the term as a means to "distinguish poetic from practical language on the basis of the former's perceptibility."[1]: 209 Essentially, he is stating that poetic language is fundamentally different than the language that we use every day because it is more difficult to understand: "Poetic speech is formed speech. Prose is ordinary speech – economical, easy, proper, the goddess of prose [dea prosae] is a goddess of the accurate, facile type, of the "direct" expression of a child."[2]: 20 This difference is the key to the creation of art and the prevention of "over-automatization," which causes an individual to "function as though by formula."[2]: 16 This distinction between artistic language and everyday language, for Shklovsky, applies to all artistic forms: The purpose of art is to impart the sensation of things as they are perceived and not as they are known. The technique of art is to make objects 'unfamiliar', to make forms difficult, to increase the difficulty and length of perception because the process of perception is an aesthetic end in itself and must be prolonged.[2]: 16 Thus, defamiliarization serves as a means to force individuals to recognize artistic language: In studying poetic speech in its phonetic and lexical structure as well as in its characteristic distribution of words and in the characteristic thought structures compounded from the words, we find everywhere the artistic trademark – that is, we find material obviously created to remove the automatism of perception; the author's purpose is to create the vision which results from that deautomatized perception. A work is created "artistically" so that its perception is impeded and the greatest possible effect is produced through the slowness of the perception.[2]: 19 This technique is meant to be especially useful in distinguishing poetry from prose, for, as Aristotle said, "poetic language must appear strange and wonderful."[2]: 19 As writer Anaïs Nin discussed in her 1968 book The Novel of the Future: It is the function of art to renew our perception. What we are familiar with we cease to see. The writer shakes up the familiar scene, and as if by magic, we see a new meaning in it.[3] According to literary theorist Uri Margolin: Defamiliarization of that which is or has become familiar or taken for granted, hence automatically perceived, is the basic function of all devices. And with defamiliarization come both the slowing down and the increased difficulty (impeding) of the process of reading and comprehending and an awareness of the artistic procedures (devices) causing them.[4] |

造語 「異化」という用語は、1917年にロシア・フォルマリストのヴィクトル・シクロフスキーが「芸術としての装置」(「芸術としての技術」という訳語もあ る)という論文で初めて使用したものである。[1]: 209 シクロフスキーは、「詩的な言語と実用的な言語を、前者の知覚可能性に基づいて区別する」手段として、この用語を考案した。 [1]: 209 基本的には、詩的な言語は理解するのがより難しいことから、私たちが日常的に使用する言語とは根本的に異なる、と彼は述べている。「詩的な言語は形成され た言語である。散文は日常的な話し言葉であり、簡潔で、容易で、適切で、散文の女神(ディー・プロサイ)は正確で、流暢なタイプの女神であり、子どもの 「直接的な」表現の女神である」[2]: 20 この違いこそが芸術の創造と、「まるで定式によって機能しているかのように」個人を機能させる「過剰な自動化」を防ぐための鍵となる[2]: 16 芸術的な言語と日常的な言語のこの区別は、シュクロフスキーにとって、あらゆる芸術形式に当てはまる。 芸術の目的は、物事を知られている通りにではなく、知覚された通りに感じさせることである。芸術のテクニックは、対象を「見慣れないもの」にし、形を難解 にし、知覚の難易度と時間を増やすことである。なぜなら、知覚のプロセス自体が美的な目的であり、延長されなければならないからだ。[2]:16 したがって、異化は芸術言語を認識させる手段として機能する。 詩的言語を音声構造や語彙構造、あるいは言葉の独特な配置や言葉から構成される独特な思考構造を研究する中で、私たちは至る所で芸術的な特徴を見出す。つ まり、私たちは明らかに知覚の自動性を排除するために作られた素材を見出す。著者の目的は、その自動性を排除した知覚から生じる視覚を作り出すことであ る。作品は「芸術的」に創作され、その知覚が妨げられ、知覚の遅さによって最大限の効果が生み出されるようにする。[2]:19 このテクニックは、詩と散文を区別する際に特に有用である。なぜなら、アリストテレスが「詩的な言語は奇妙で素晴らしいものでなければならない」と述べて いるからだ。[2]:19 作家のアナイス・ニンは、1968年の著書『未来の小説』で次のように述べている。 芸術の役割は、私たちの知覚を新たにするということである。見慣れたものは、見えなくなる。作家は見慣れた情景を揺さぶり、まるで呪術的であるかのよう に、その中に新たな意味を見出すのである。 文学理論家ウリ・マーゴリンは次のように述べている。 見慣れたものや当たり前だと思われているもの、自動的に認識されているものを「異化」することは、すべての手法の基本的な機能である。そして、「異化」に よって、読むことや理解することのプロセスが遅くなり、難しくなる(妨げられる)とともに、それらを引き起こす芸術的な手法(手段)に気づくようになる。 [4] |

| Usage In Romantic poetry The technique appears in English Romantic poetry, particularly in the poetry of Wordsworth, and was defined in the following way by Samuel Taylor Coleridge, in his Biographia Literaria: "To carry on the feelings of childhood into the powers of manhood; to combine the child's sense of wonder and novelty with the appearances which every day for perhaps forty years had rendered familiar ... this is the character and privilege of genius." Preceding Coleridge's formulation is that of the German Romantic poet and philosopher Novalis: "The art of estranging in a given way, making a subject strange and yet familiar and alluring, that is Romantic poetics."[5] In Russian literature To illustrate what he means by defamiliarization, Shklovsky uses examples from Tolstoy, whom he cites as using the technique throughout his works: "The narrator of 'Kholstomer,' for example, is a horse, and it is the horse's point of view (rather than a person's) that makes the content of the story seem unfamiliar."[2]: 16 As a Russian Formalist, many of Shklovsky's examples use Russian authors and Russian dialects: "And currently Maxim Gorky is changing his diction from the old literary language to the new literary colloquialism of Leskov. Ordinary speech and literary language have thereby changed places (see the work of Vyacheslav Ivanov and many others)."[2]: 19-20 Defamiliarization also includes the use of foreign languages within a work. At the time that Shklovsky was writing, there was a change in the use of language in both literature and everyday spoken Russian. As Shklovsky puts it: "Russian literary language, which was originally foreign to Russia, has so permeated the language of the people that it has blended with their conversation. On the other hand, literature has now begun to show a tendency towards the use of dialects and/or barbarisms."[2]: 19 Narrative plots can also be defamiliarized. The Russian formalists distinguished between the fabula or basic story stuff of a narrative and the syuzhet or the formation of the story stuff into a concrete plot. For Shklovsky, the syuzhet is the fabula defamiliarized. Shklovsky cites Lawrence Sterne's Tristram Shandy as an example of a story that is defamiliarized by unfamiliar plotting.[6] Sterne uses temporal displacements, digressions, and causal disruptions (e.g., placing the effects before their causes) to slow down the reader's ability to reassemble the (familiar) story. As a result, the syuzhet "makes strange" the fabula. |

用法 ロマン派詩において この手法は、特にワーズワースの詩に見られるように、英語のロマン派詩に現れる。サミュエル・テイラー・コールリッジは著書『文学小史』の中で、次のよう に定義している。「子供の頃の感情を、青年期の力へと昇華させること。子供の持つ驚きや新鮮さの感覚を、おそらく40年もの間毎日見慣れてきた外観と組み 合わせること。これこそが天才の特性であり特権である。」 コールリッジの定式化に先立つものとして、ドイツのロマン派の詩人であり哲学者でもあるノヴァーリスの次の言葉がある。「与えられた方法で疎外する芸術、主題を奇妙でありながら親しみやすく魅力的なものにする、それがロマン派の詩学である」[5] ロシア文学において 馴れ合いを断ち切るという意味を説明するために、シュクロフスキーはトルストイの作品を例に挙げている。シュクロフスキーはトルストイの作品全体にわたっ てこの手法が用いられていると述べている。例えば『ホレストマー』の語り手は馬であり、物語の内容が不慣れに感じられるのは、馬の視点(人格ではなく)に よるものである。」[2]:16 ロシア・フォルマリストとして、シュクロフスキーの例の多くはロシアの作家やロシアの方言を用いている。「そして現在、マクシム・ゴーリキーは、レフスコ フの新しい文学的俗語に、古い文学的言語から話し方を変えつつある。 日常会話と文学的言語は、それによって立場を入れ替えた(ヴィャチェスラフ・イワノフやその他多くの作品を参照)」[2]:19-20 異化には、作品内での外国語の使用も含まれる。シュクロフスキーが執筆していた当時、文学と日常会話におけるロシア語の両方で、言語の使用に変化が生じて いた。シュクロフスキーは次のように述べている。「もともとロシアには外国語であったロシアの文語は、民衆の言語に浸透し、民衆の会話と混ざり合ってい る。一方、文学では方言や野蛮な表現が使われる傾向が現れ始めている」[2]:19 物語のプロットもまた異化されうる。ロシア・フォルマリストは、物語の基本的な素材であるファブラと、その素材が具体的なプロットへと形成されるスジェッ トを区別した。シュクロフスキーにとって、スジェットとはファブラが異化されたものである。シュクロフスキーは、馴染みのないプロットによって異化された 物語の例として、ローレンス・スターンの『トリスタン・シャンドリ』を挙げている。[6] スターンは、時間的なずれ、脱線、因果関係の混乱(例えば、原因の前に結果を配置する)を用いて、読者が(馴染みのある)物語を再構成する能力を遅らせて いる。その結果、シユゼットはファブラを「奇妙なもの」にしている。 |

| Related concepts Différance Shklovsky's defamiliarization can also be compared to Jacques Derrida's concept of différance: What Shklovskij wants to show is that the operation of defamiliarization and its consequent perception in the literary system is like the winding of a watch (the introduction of energy into a physical system): both "originate" difference, change, value, motion, presence. Considered against the general and functional background of Derridian différance, what Shklovsky calls "perception" can be considered a matrix for production of difference.[1]: 212 Since the term différance refers to the dual meanings of the French word difference to mean both "to differ" and "to defer", defamiliarization draws attention to the use of common language in such a way as to alter one's perception of an easily understandable object or concept. The use of defamiliarization both differs and defers, since the use of the technique alters one's perception of a concept (to defer), and forces one to think about the concept in different, often more complex, terms (to differ). Shklovskij's formulations negate or cancel out the existence/possibility of a "real" perception: variously, by (1) the familiar Formalist denial of a link between literature and life, connoting their status as non-communicating vessels, (2) always, as if compulsively, referring to a real experience in terms of empty, dead, and automatized repetition and recognition, and (3) implicitly locating real perception at an unspecifiable temporally anterior and spatially other place, at a mythic "first time" of naïve experience, the loss of which to automatization is to be restored by aesthetic perceptual fullness.[1]: 218 |

関連概念 差延 シュクロフスキーの異化は、ジャック・デリダの差延の概念とも比較することができる。 シュクロフスキーが示そうとしたのは、文学システムにおける異化作用とその結果としての知覚は、時計のゼンマイを巻くこと(物理システムへのエネルギーの 導入)に似ており、どちらも「差異、変化、価値、運動、存在を『生み出す』」ということである。 デリダの「差延」の一般的な機能的背景に照らして考えると、シュクロフスキーが「知覚」と呼ぶものは、差異を生み出すためのマトリックスであると考えるこ とができる。[1]:212 差延という用語は、フランス語の「差異」という単語の二重の意味、すなわち「異なる」と「延期する」の両方を指すため、異化は、容易に理解できる対象や概 念に対する認識を変えるような方法で、日常的な言語の使用に注目を集める。デファミリアリゼーションの使用は、概念に対する認識を変える(defer)と 同時に、異なる、しばしばより複雑な用語で概念について考えさせる(to differ)ため、異なるものであり、また先延ばしでもある。 シュクロフスキーの理論は、「現実の」認識の存在/可能性を否定または相殺する。すなわち、(1) 文学と人生のつながりを否定する形式主義者の見解は、 文学と人生の間のつながりを否定し、両者がコミュニケーション不能な器であることを暗示する、(2) 常に、強迫的にでもするように、空虚で死んだ、自動化された反復と認識という観点から現実の経験に言及する、(3) 暗黙のうちに現実の知覚を特定不可能な時間的に以前の、空間的に他の場所、すなわち、自動化によって失われた素朴な経験の神話的な「最初」に位置づけ、美 的知覚の完全性によって回復させる。[1]: 218 |

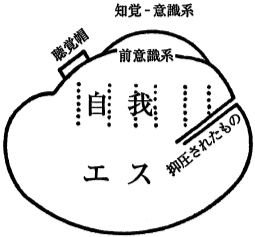

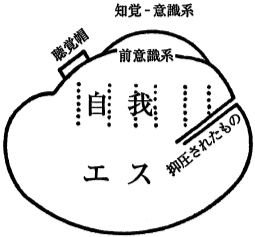

| The Uncanny The influence of Russian Formalism on twentieth-century art and culture is largely due to the literary technique of defamiliarization or 'making strange', and has also been linked to Freud's notion of the uncanny.[7] In Das Unheimliche ("The Uncanny"),[8] Freud states that "the uncanny is that class of the frightening which leads back to what is known of old and long familiar," however, this is not a fear of the unknown, but more of a feeling about something being both strange and familiar.[8]: 220 The connection between ostranenie and the uncanny can be seen where Freud muses on the technique of literary uncanniness: "It is true that the writer creates a kind of uncertainty in us in the beginning by not letting us know, no doubt purposely, whether he is taking us into the real world or into a purely fantastic one of his own creation."[8]: 230 When "the writer pretends to move in the world of common reality," they can situate supernatural events, such as the animation of inanimate objects, in the quotidian, day-to-day reality of the modern world, defamiliarizing the reader and provoking an uncanny feeling.[8]: 250 |

不気味なもの ロシア・フォルマリズムが20世紀の芸術と文化に与えた影響は、大きくは「異化」または「ストレンジ化」という文学的手法によるものであり、フロイトの 「不気味なもの」という概念とも関連している。 [7] 『不気味なものについて』(「Das Unheimliche」)[8] の中で、フロイトは「不気味なものは、古くから知られ、長い間親しまれてきたものへとつながる恐ろしさである」と述べている。しかし、これは未知のものに 対する恐怖ではなく、奇妙でありながら親しみのあるものに対する感覚である。[8]: 220 オストラネーニエとアンキャニーの関連性は、フロイトが文学的な不気味さのテクニックについて考察した箇所に見られる。「作家が、意図的に、読者に知らせ ないことによって、読者の中に一種の不確実性を生み出すのは確かである。それは、読者を現実の世界に導くのか、それとも、作家自身の創造による純粋な空想 の世界に導くのか、どちらなのかを知らせないことによってである。」 [8]: 230 作家が「現実の世界を舞台にしているのか、それとも自身の創作による純粋な空想の世界なのか、明らかに意図的に知らせないことで、読者の中に一種の不確実 性が生まれるのは事実である。」[8]: 230 作家が「現実の世界を舞台にしている」ように見せかける場合、無生物の物体が動き出すといった超自然的な出来事を、現代世界の日常的な日々の現実の中に位 置づけることができる。それは読者に既視感を与え、不気味な感覚を引き起こす。[8]: 250 |

| The Estrangement effect Defamiliarization has been associated with the poet and playwright Bertolt Brecht, whose Verfremdungseffekt ("estrangement effect") was a potent element of his approach to theatre. In fact, as Willett points out, Verfremdungseffekt is "a translation of the Russian critic Viktor Shklovskij's phrase 'Priem Ostranenija', or 'device for making strange'".[9] Brecht, in turn, has been highly influential for artists and film-makers including Jean-Luc Godard and Yvonne Rainer. Science fiction critic Simon Spiegel, who defines defamiliarization as "the formal-rhetorical act of making the familiar strange (in Shklovsky's sense)," distinguished it from Brecht's estrangement effect. To Spiegel, estrangement is the effect on the reader which can be caused by defamiliarization or through deliberate recontextualization of the familiar.[10] |

疎外効果 異化は、詩人であり劇作家でもあるベルトルト・ブレヒトと関連付けられており、彼の「疎外効果」は、演劇に対するアプローチの重要な要素であった。実際、 Willettが指摘しているように、Verfremdungseffektは「ロシアの批評家ヴィクトル・シクロフスキーの『プリエム・オストラネニ ヤ』、すなわち『奇妙にするための装置』という表現の翻訳」である。[9] ブレヒトは、ジャン=リュック・ゴダールやイボンヌ・レイナーを含むアーティストや映画製作者に多大な影響を与えた。 SF評論家のサイモン・シュピーゲルは、異化を「(シュクロフスキーの定義における)馴染みのあるものを奇妙なものにする形式・修辞的行為」と定義し、ブ レヒトの疎外効果と区別している。シュピーゲルにとって、疎外とは、異化によって、あるいは馴染みのあるものの意図的な再文脈化によって引き起こされる読 者への効果である。[10] |

| Verfremdungseffekt Problematization Distancing effect Nacirema Mooreeffoc Jamais vu Megalia |

異化効果 問題化 距離化効果 ナシレマ ムーア効果 ジャメイヴュー メガリア |

| Shklovsky, Viktor (2017).

Berlina, Alexandra (ed.). Viktor Shklovsky: A Reader. Translated by

Berlina, Alexandra. New York: Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN

978-1-5013-1036-2. OCLC 934676872. Shklovskij, Viktor. "Art as Technique". Literary Theory: An Anthology. Ed. Julie Rivkin and Michael Ryan. Malden: Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 1998. Basil Lvoff, "The Twists and Turns of Estrangement" [1]. Min Tian, The Poetics of Difference and Displacement: Twentieth-Century Chinese-Western Intercultural Theatre. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2008. Ostranenie Magazine |

シュクロフスキー、ヴィクトル (2017).

ベルリナ、アレクサンドラ (編). ヴィクトル・シュクロフスキー: リーディング. ベルリナ、アレクサンドラ訳. ニューヨーク:

ブルームズベリー・アカデミック. ISBN 978-1-5013-1036-2. OCLC 934676872. シュクロフスキー、ヴィクトル. 「芸術としてのテクニック」. 文学理論:アンソロジー。ジュリー・リブキン、マイケル・ライアン編。マールデン:Blackwell Publishing Ltd、1998年。 バジル・ルヴォフ、「疎外の紆余曲折」[1]。 ミン・ティエン、『異なることと変位の詩学:20世紀の中国と西洋の異文化演劇』。香港:香港大学出版、2008年。 Ostranenie Magazine |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Defamiliarization |

オストラネーニエ (ostranenie, ロシア語 остранение) は、英語の翻訳では「見慣れないようにすること=異化(Defamiliarization)」と紹介されている。

■ リンク

■ 文献

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆