「物語の構造分析序説」

Introduction à l'analyse strucuturale des récites, An Introduction to the Structural Analysis of Narrative

「物語の構造分析序説」

Introduction à l'analyse strucuturale des récites, An Introduction to the Structural Analysis of Narrative

「物 語の構造分析序説(Introduction à l'analyse strucuturale des récites)」は、ロラ ン・バルト(Barthes, Roland, 1915-1980)による1966年の論文(Communications, 8, 1-27, doi : 10.3406/comm.1966.1113)で ある。同年にすでに英訳で、An Introduction to the Structural Analysis of Narrative. で交換されている。

目次

含 意

『物

語の構造分析』では、作家の伝記的評論の「死」を宣言し、かつ作者の「意図」を拒否し、作品の理解を読者に委ねることになる。この場合のジレンマは、「作

品の真の解釈」の多元性について、従来の文芸批評という枠組みでは理解不能ないしは耐えきれないという問題を抱えることになる。

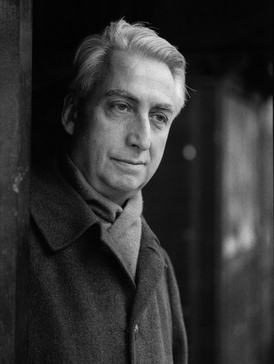

★ロラン・バルト先生について

| Roland Gérard Barthes

(/bɑːrt/;[2] French: [ʁɔlɑ̃ baʁt]; 12 November 1915 – 26 March 1980)[3]

was a French literary theorist, essayist, philosopher, critic, and

semiotician. His work engaged in the analysis of a variety of sign

systems, mainly derived from Western popular culture.[4] His ideas

explored a diverse range of fields and influenced the development of

many schools of theory, including structuralism, anthropology, literary

theory, and post-structuralism. Barthes is perhaps best known for his 1957 essay collection Mythologies, which contained reflections on popular culture, and the 1967/1968 essay "The Death of the Author", which critiqued traditional approaches in literary criticism. During his academic career he was primarily associated with the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales (EHESS) and the Collège de France. |

ロラン・バルト(Roland Gérard

Barthes、[2]フランス語発音: [ʁɔlɑ̃ baʁt]、1915年11月12日 -

1980年3月26日)は、フランスの文学理論家、エッセイスト、哲学者、批評家、記号学者である。彼の作品は、主に西洋のポピュラーカルチャーから派生

したさまざまな記号システムの分析に取り組んだものである。[4]

彼の思想は多様な分野を探求し、構造主義、人類学、文学理論、ポスト構造主義など、多くの学派の理論の発展に影響を与えた。 バルトは、1957年のエッセイ集『神話たち』で大衆文化に関する考察をまとめたこと、また1967年から1968年にかけて発表されたエッセイ「作者の 死」で文学批評における伝統的なアプローチを批判したことで、おそらく最もよく知られている。学術的な経歴においては、主に高等社会科学研究学院 (EHESS)とコレージュ・ド・フランスと関連していた。 |

| Biography Early life Roland Barthes was born on 12 November 1915 in the town of Cherbourg in Normandy.[5] His father, naval officer Louis Barthes, was killed in a battle during World War I in the North Sea before Barthes's first birthday. His mother, Henriette Barthes, and his aunt and grandmother raised him in the village of Urt and the city of Bayonne. In 1924, Barthes' family moved to Paris,[6] though his attachment to his provincial roots would remain strong throughout his life. Student years Barthes showed great promise as a student and spent the period from 1935 to 1939 at the Sorbonne, where he earned a licence in classical literature. He was plagued by ill health throughout this period, suffering from tuberculosis, which often had to be treated in the isolation of sanatoria.[7] His repeated physical breakdowns disrupted his academic career, affecting his studies and his ability to take qualifying examinations. They also exempted him from military service during World War II. His life from 1939 to 1948 was largely spent obtaining a licence in grammar and philology, publishing his first papers, taking part in a medical study, and continuing to struggle with his health. He received a diplôme d'études supérieures (roughly equivalent to an MA by thesis) from the University of Paris in 1941 for his work in Greek tragedy.[8] Early academic career In 1948, he returned to purely academic work, gaining numerous short-term positions at institutes in France, Romania, and Egypt. During this time, he contributed to the leftist Parisian paper Combat, out of which grew his first full-length work, Writing Degree Zero (1953). In 1952, Barthes settled at the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, where he studied lexicology and sociology. During his seven-year period there, he began to write a popular series of bi-monthly essays for the magazine Les Lettres Nouvelles, in which he dismantled myths of popular culture (gathered in the Mythologies collection that was published in 1957). Consisting of fifty-four short essays, mostly written between 1954 and 1956, Mythologies were acute reflections of French popular culture ranging from an analysis on soap detergents to a dissection of popular wrestling.[9] Knowing little English, Barthes taught at Middlebury College in 1957 and befriended the future English translator of much of his work, Richard Howard, that summer in New York City.[10] |

経歴 幼少期 ロラン・バルトは1915年11月12日、ノルマンディーのシェルブールで生まれた。[5] 父親のルイ・バルトは海軍将校であり、バルトが1歳の誕生日を迎える前に、第一次世界大戦中の北海での戦いで戦死した。母親のアンリエット・バルトと叔 母、祖母がウルとバイヨンヌで彼を育てた。1924年、バルトの家族はパリに移住したが、[6] 地方のルーツへの愛着は生涯を通じて強く残ることとなった。 学生時代 バルトは学生として大きな可能性を示し、1935年から1939年までソルボンヌ大学で過ごし、古典文学の学位を取得した。この期間、彼は結核に苦しみ、 療養所で隔離治療を受けることも多かった。[7] 繰り返される体調不良により学業に支障をきたし、学位取得に必要な試験を受ける能力にも影響が出た。また、第二次世界大戦中は兵役が免除されていた。 1939年から1948年にかけての彼の生活は、文法と文献学の学位取得、最初の論文の発表、医学研究への参加、そして健康問題との闘いに費やされた。 1941年には、ギリシャ悲劇に関する研究でパリ大学より上級研究課程修了証書(論文による修士号にほぼ相当)を授与された。 初期の学術的キャリア 1948年、彼は純粋な学術研究に復帰し、フランス、ルーマニア、エジプトの研究機関で短期の職を多数経験した。この時期、彼はパリ左派系紙「コンバット」に寄稿し、そこから最初の長編作品『零度の執筆』(1953年)が生まれた。 1952年、バルトはフランス国立科学研究センターに移り、語彙学と社会学を研究した。 7年間の在籍中、彼は雑誌『レ・レットル・ヌーヴェル』に隔月で人気コラムを書き始め、大衆文化の神話を解体した(1957年に出版された『神話学』にま とめられている)。54の短いエッセイから成る『神話学』は、主に1954年から1956年の間に書かれたもので、石鹸洗剤の分析からプロレスの分析ま で、フランスの大衆文化を鋭く考察したものだった。[9] 英語をほとんど話せなかったバルトは、1957年にミドルベリー大学で教鞭をとり、その夏、ニューヨークで、後に自身の作品の多くを英訳することになるリ チャード・ハワードと親交を結んだ。[10] |

| Rise to prominence Barthes spent the early 1960s exploring the fields of semiology and structuralism, chairing various faculty positions around France, and continuing to produce more full-length studies. Many of his works challenged traditional academic views of literary criticism and of renowned figures of literature. His unorthodox thinking led to a conflict with a well-known Sorbonne professor of literature, Raymond Picard, who attacked the French New Criticism (a label that he inaccurately applied to Barthes) for its obscurity and lack of respect towards France's literary roots. Barthes's rebuttal in Criticism and Truth (1966) accused the old, bourgeois criticism of a lack of concern with the finer points of language and of selective ignorance towards challenging theories, such as Marxism. By the late 1960s, Barthes had established a reputation for himself. He traveled to the US and Japan, delivering a presentation at Johns Hopkins University. During this time, he wrote his best-known work,[according to whom?] the 1967 essay "The Death of the Author," which, in light of the growing influence of Jacques Derrida's deconstruction, would prove to be a transitional piece in its investigation of the logical ends of structuralist thought. |

著名になる 1960年代初頭、バルトはフランス各地で教鞭をとりながら、記号論や構造主義の分野を探求し、より本格的な研究を続けた。彼の作品の多くは、文学批評や 著名な文学作品に対する伝統的な学術的見解に異議を唱えるものであった。彼の型破りな考え方は、ソルボンヌ大学の著名な文学教授レイモン・ピカールとの対 立を生んだ。ピカールは、フランス新批評(彼がバルトに不正確に適用した呼称)を難解でフランスの文学的ルーツを尊重していないとして攻撃した。バルトは 『批評と真理』(1966年)で、言語の細部に注意を払わない旧態依然としたブルジョワ批評や、マルクス主義などの挑戦的な理論に対する選択的な無視を非 難した。 1960年代後半には、バルトはすでに名声を確立していた。アメリカや日本を訪れ、ジョンズ・ホプキンス大学で講演を行った。この時期に、彼の最も有名な 作品である1967年のエッセイ「作者の死」を書いた。この作品は、ジャック・デリダの脱構築の影響が高まる中、構造主義思想の論理的帰結を調査する上 で、転換期を象徴する作品となる。 |

| Mature critical work Barthes continued to contribute with Philippe Sollers to the avant-garde literary magazine Tel Quel, which was developing similar kinds of theoretical inquiry to that pursued in Barthes's writings. In 1970, Barthes produced what many consider to be his most prodigious work,[who?] the dense, critical reading of Balzac's Sarrasine entitled S/Z. Throughout the 1970s, Barthes continued to develop his literary criticism; he developed new ideals of textuality and novelistic neutrality. In 1971, he served as visiting professor at the University of Geneva. In those same years he became primarily associated with the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales (EHESS). In 1975 he wrote an autobiography titled Roland Barthes and in 1977 he was elected to the chair of Sémiologie Littéraire at the Collège de France. In the same year, his mother, Henriette Barthes, to whom he had been devoted, died, aged 85. They had lived together for 60 years. The loss of the woman who had raised and cared for him was a serious blow to Barthes. His last major work, Camera Lucida, is partly an essay about the nature of photography and partly a meditation on photographs of his mother. The book contains many reproductions of photographs, though none of them are of Henriette. |

成熟した批評的作品 バルトはフィリップ・ソラーズとともに前衛的な文学雑誌『テル・ケル』に寄稿し続けた。この雑誌は、バルトの著作で追求されたものと同様の理論的探究を展 開していた。1970年、バルトは、多くの人々から最も偉大な作品とみなされている[誰?]、バルザックの『サラジーヌ』の濃密な批評的読解である 『S/Z』を制作した。1970年代を通じて、バルトは文学批評を発展させ続けた。テキスト性と小説の中立性に関する新たな理想を打ち立てた。1971年 にはジュネーヴ大学の客員教授を務めた。この時期、主に高等社会科学研究学院(EHESS)と関わりを持つようになった。 1975年には『ロラン・バルト』と題する自伝を著し、1977年にはコレージュ・ド・フランスの文学記号論講座の教授に選出された。同じ年、彼が献身的 に尽くしてきた母親のアンリエット・バルトが85歳で死去した。2人は60年間一緒に暮らしていた。彼を育て、世話をした女性を失ったことは、バルトに とって深刻な打撃となった。彼の最後の主要な作品『明るい部屋』は、写真の本質についてのエッセイであり、同時に、母親の写真についての考察でもある。こ の本には多くの写真の複製が掲載されているが、そのどれもがアンリエットのものではない。 |

| Death On 25 February 1980, Roland Barthes was knocked down by the driver of a laundry van while walking home through the streets of Paris. One month later, on 26 March,[11] he died from the chest injuries he had sustained in the crash.[12] |

死 1980年2月25日、ローラン・バルトはパリの街を歩いて帰宅中に、クリーニング店のドライバーにひかれた。その1か月後の3月26日、[11] 彼は事故による胸部の負傷が原因で死亡した。[12] |

| Writings and ideas Early thought Barthes's earliest ideas reacted to the trend of existentialist philosophy that was prominent in France during the 1940s, specifically to the figurehead of existentialism, Jean-Paul Sartre. Sartre's What Is Literature? (1947) expresses a disenchantment both with established forms of writing and more experimental, avant-garde forms, which he feels alienate readers. Barthes's response was to try to discover that which may be considered unique and original in writing. In Writing Degree Zero (1953), Barthes argues that conventions inform both language and style, rendering neither purely creative. Instead, form, or what Barthes calls "writing" (the specific way an individual chooses to manipulate conventions of style for a desired effect), is the unique and creative act. However, a writer's form is vulnerable to becoming a convention once it has been made available to the public. This means that creativity is an ongoing process of continual change and reaction. In Michelet, a critical analysis of the French historian Jules Michelet, Barthes developed these notions, applying them to a broader range of fields. He argued that Michelet's views of history and society are obviously flawed. In studying his writings, he continued, one should not seek to learn from Michelet's claims; rather, one should maintain a critical distance and learn from his errors, since understanding how and why his thinking is flawed will show more about his period of history than his own observations. Similarly, Barthes felt that avant-garde writing should be praised for its maintenance of just such a distance between its audience and itself. In presenting an obvious artificiality rather than making claims to great subjective truths, Barthes argued, avant-garde writers ensure that their audiences maintain an objective perspective. In this sense, Barthes believed that art should be critical and should interrogate the world, rather than seek to explain it, as Michelet had done. |

著作と思想 初期の思想 バルトの初期の思想は、1940年代にフランスで隆盛を極めた実存主義哲学の潮流、特に実存主義の旗手ジャン=ポール・サルトルに反応したものであった。 サルトルの著書『文学とは何か』(1947年)は、確立された文学の形式と、より実験的で前衛的な形式の両方に幻滅を感じていることを表現しており、それ らは読者を疎外していると感じていた。バルトは、文学においてユニークで独創的とみなされるものを発見しようとした。著書『零度の執筆』(1953年)の 中で、バルトは、慣例が言語とスタイルの両方に影響を与え、どちらも純粋な創造性を欠くものになると主張している。その代わりに、形式、つまりバルトが 「執筆」(個人が特定の効果を狙ってスタイルの慣例を操作する方法)と呼ぶものが、ユニークで創造的な行為である。しかし、作家の形式は、いったん公衆に 公開されると、慣例になりやすい。つまり、創造性とは、絶え間なく変化し、反応し合う継続的なプロセスである。 フランスの歴史家ジュール・ミシュレの批判的分析である『ミシュレ』において、バルトはこれらの概念をさらに発展させ、より幅広い分野に適用した。彼は、 ミシュレの歴史観や社会観には明らかな欠陥があると論じた。ミシュレの著作を研究する際には、彼の主張から学ぶのではなく、むしろ批判的な距離を保ち、彼 の誤りから学ぶべきである。なぜなら、彼の思考がどのように、なぜ欠陥があるのかを理解することは、彼自身の観察よりも、その時代の歴史についてより多く を明らかにするからだ。同様に、バルトは、前衛的な文章は、読者と作品との間にまさにそのような距離を維持している点で賞賛されるべきだと感じていた。バ ルトは、主観的な真実を主張するのではなく、明らかな作為性を提示することで、前衛的な作家は読者が客観的な視点を持ち続けることを保証していると主張し た。この意味において、バルトは、ミシュレがそうしたように芸術が世界を説明しようとするのではなく、批判的であり、世界を問い質すべきだと考えていた。 |

| Semiotics and myth Barthes's many monthly contributions, collected in his Mythologies (1957), frequently interrogated specific cultural materials in order to expose how bourgeois society asserted its values through them. For example, Barthes cited the portrayal of wine in French society. Its description as a robust and healthy habit is a bourgeois ideal that is contradicted by certain realities (i.e., that wine can be unhealthy and inebriating). He found semiotics, the study of signs, useful in these interrogations. He developed a theory of signs to demonstrate this perceived deception. He suggested that the construction of myths results in two levels of signification: the "language-object", a first order linguistic system; and the "metalanguage", the second-order system transmitting the myth.[13] The former pertains to the literal or explicit meaning of things while the latter is composed of the language used to speak about the first order.[13] Barthes explained that these bourgeois cultural myths were "second-order signs," or "connotations." A picture of a full, dark bottle is a signifier that relates to a specific "signified": a fermented, alcoholic beverage. However, the bourgeoisie relate it to a new signified: the idea of healthy, robust, relaxing experience. Motivations for such manipulations vary, from a desire to sell products to a simple desire to maintain the status quo. These insights brought Barthes in line with similar Marxist theory. Barthes used the term "myth" while analyzing the popular, consumer culture of post-war France in order to reveal that "objects were organized into meaningful relationships via narratives that expressed collective cultural values."[9] In The Fashion System Barthes showed how this adulteration of signs could easily be translated into words. In this work he explained how in the fashion world any word could be loaded with idealistic bourgeois emphasis. Thus, if popular fashion says that a 'blouse' is ideal for a certain situation or ensemble, this idea is immediately naturalized and accepted as truth, even though the actual sign could just as easily be interchangeable with 'skirt', 'vest' or any number of combinations. In the end Barthes's Mythologies became absorbed into bourgeois culture, as he found many third parties asking him to comment on a certain cultural phenomenon, being interested in his control over his readership. This turn of events caused him to question the overall utility of demystifying culture for the masses, thinking it might be a fruitless attempt, and drove him deeper in his search for individualistic meaning in art. |

記号論と神話 バルトは『神話体系』(1957年)にまとめた毎月の寄稿のなかで、ブルジョワ社会がそれらを通して自らの価値を主張する方法を明らかにするために、特定 の文化的な素材を頻繁に検証した。例えば、バルトはフランス社会におけるワインの描写を引用した。ワインがたくましく健康的な習慣であるという描写は、ブ ルジョワの理想であり、現実(すなわち、ワインは不健康で酩酊を引き起こす可能性がある)によって否定されている。彼は記号論、すなわち記号の研究がこう した疑問の解明に役立つと考えた。彼は記号の理論を展開し、この認識された欺瞞を証明した。彼は、神話の構築は2つのレベルの記号化をもたらす、と示唆し た。「言語-対象」という第一言語体系と、「メタ言語」という神話を伝える第二言語体系である。 [13] 前者は物事の文字通りの、または明白な意味に関係し、後者は第一級について語る際に使用される言語で構成される。[13] バルトは、こうしたブルジョワ文化の神話は「第二級の記号」、つまり「含蓄」であると説明した。満ちた暗い瓶の写真は、特定の「シニフィエ」、すなわち発 酵したアルコール飲料を意味するシニフィアンである。しかし、ブルジョワ階級は、それを新たなシニフィエ、すなわち健康でたくましくリラックスできる体験 という概念に関連付ける。このような操作の動機はさまざまで、商品を売りたいという欲望から、現状を維持したいという単純な欲望まである。こうした洞察に より、バルトはマルクス主義の類似理論と一致することとなった。バルトは、戦後のフランスの大衆消費文化を分析する際に「神話」という用語を使用し、「物 事は、集団的文化価値を表現する物語を通じて、意味のある関係性へと組織化されている」ことを明らかにした。 『ファッションシステム』の中で、バルトは、この記号の混淆がどのように簡単に言葉に置き換えられるかを示した。この作品の中で、ファッションの世界で は、どのような言葉も理想主義的なブルジョワの強調を伴う可能性があると説明している。したがって、一般に流行しているファッションが「ブラウス」を特定 の状況や服装に最適であると主張すれば、その考えはすぐに自然なものとして受け入れられ、真実として受け止められる。実際の記号は「スカート」、「ベス ト」、またはその他の組み合わせと容易に置き換えられる可能性があるにもかかわらず、である。結局、バルトの『神話学』はブルジョワ文化に吸収されていっ た。バルトは、多くの第三者が特定の文化現象についてコメントを求め、読者に対する彼の影響力に関心を示していることに気づいた。この出来事をきっかけ に、彼は大衆のための文化の神秘性を解き明かすことの全体的な有用性を疑問視するようになり、それは無駄な試みかもしれないと考え、芸術における個人主義 的な意味の探求にさらに深くのめり込んでいった。 |

| Structuralism and its limits As Barthes's work with structuralism began to flourish around the time of his debates with Picard, his investigation of structure focused on revealing the importance of language in writing, which he felt was overlooked by old criticism. Barthes's "Introduction to the Structural Analysis of Narrative"[14] is concerned with examining the correspondence between the structure of a sentence and that of a larger narrative, thus allowing narrative to be viewed along linguistic lines. Barthes split this work into three hierarchical levels: 'functions', 'actions' and 'narrative'. 'Functions' are the elementary pieces of a work, such as a single descriptive word that can be used to identify a character. That character would be an 'action', and consequently one of the elements that make up the narrative. Barthes was able to use these distinctions to evaluate how certain key 'functions' work in forming characters. For example, key words like 'dark', 'mysterious' and 'odd', when integrated together, formulate a specific kind of character or 'action'. By breaking down the work into such fundamental distinctions Barthes was able to judge the degree of realism given functions have in forming their actions and consequently with what authenticity a narrative can be said to reflect on reality. Thus, his structuralist theorizing became another exercise in his ongoing attempts to dissect and expose the misleading mechanisms of bourgeois culture. While Barthes found structuralism to be a useful tool and believed that discourse of literature could be formalized, he did not believe it could become a strict scientific endeavour. In the late 1960s, radical movements were taking place in literary criticism. The post-structuralist movement and the deconstructionism of Jacques Derrida were testing the bounds of the structuralist theory that Barthes's work exemplified. Derrida identified the flaw of structuralism as its reliance on a transcendental signifier; a symbol of constant, universal meaning would be essential as an orienting point in such a closed off system. This is to say that without some regular standard of measurement, a system of criticism that references nothing outside of the actual work itself could never prove useful. But since there are no symbols of constant and universal significance, the entire premise of structuralism as a means of evaluating writing (or anything) is hollow.[citation needed] |

構造主義とその限界 バルトの構造主義的研究がピカールとの論争の頃に盛んになり始めたように、彼の構造の調査は、古い批評が看過していると感じていた、文章における言語の重 要性を明らかにすることに焦点を当てていた。バルトの「物語の構造分析序説」[14]は、文章の構造とより大きな物語の構造との対応関係を調査することに 関心があり、それによって物語を言語の観点から見ることができる。バルトは、この作品を「機能」、「行為」、「物語」という3つの階層レベルに分類した。 「機能」とは、作品の最も基本的な要素であり、例えば、登場人物を特定するのに使用される単語の描写などである。その登場人物は「行為」であり、結果的に 物語を構成する要素の1つとなる。バルトは、これらの区別を用いて、特定の重要な「機能」がどのようにして登場人物を形成するかを評価することができた。 例えば、「暗い」、「神秘的な」、「奇妙な」といったキーワードは、統合されることで特定のキャラクターまたは「行動」を形作る。作品をこのような基本的 な区別に分解することで、バルトは、機能がその行動を形成する上でどの程度のリアリズムが与えられているかを判断し、その結果、物語が現実を反映している とどの程度真実味があるかを判断することができた。こうして、彼の構造主義理論は、ブルジョワ文化の誤解を招くメカニズムを分析し、暴露しようとする彼の 継続的な試みにおける、もう一つの取り組みとなった。 バルトは構造主義を有用なツールと見なし、文学の言説は形式化できると考えていたが、厳密な科学的取り組みになるとは考えていなかった。1960年代後半 には、文学批評において急進的な動きが起こっていた。ポスト構造主義運動とジャック・デリダの脱構築主義は、バルトの作品が体現した構造主義理論の限界を 試すものであった。デリダは、超越的な記号に依存していることを構造主義の欠陥として指摘した。閉鎖的なシステムにおいては、一定かつ普遍的な意味を持つ シンボルが、方向性を示すものとして不可欠である。つまり、何らかの測定基準がなければ、作品そのもの以外の何ものにも言及しない批評の体系は決して有益 なものにはなりえないということである。しかし、恒常的かつ普遍的な意味を持つ記号など存在しないため、文章(またはその他のもの)を評価する手段として の構造主義の前提はすべて空虚である。 |

| Transition Such thought led Barthes to consider the limitations not just of signs and symbols, but also of Western culture's dependency on beliefs of constancy and ultimate standards. He travelled to Japan in 1966 where he wrote Empire of Signs (published in 1970), a meditation on Japanese culture's contentment in the absence of a search for a transcendental signifier. He notes that in Japan there is no emphasis on a great focus point by which to judge all other standards, describing the centre of Tokyo, the Emperor's Palace, as not a great overbearing entity, but a silent and nondescript presence, avoided and unconsidered. As such, Barthes reflects on the ability of signs in Japan to exist for their own merit, retaining only the significance naturally imbued by their signifiers. Such a society contrasts greatly to the one he dissected in Mythologies, which was revealed to be always asserting a greater, more complex significance on top of the natural one. In the wake of this trip Barthes wrote what is largely considered to be his best-known work, the essay "The Death of the Author" (1967). Barthes saw the notion of the author, or authorial authority, in the criticism of literary text as the forced projection of an ultimate meaning of the text. By imagining an ultimate intended meaning of a piece of literature one could infer an ultimate explanation for it. But Barthes points out that the great proliferation of meaning in language and the unknowable state of the author's mind makes any such ultimate realization impossible. As such, the whole notion of the 'knowable text' acts as little more than another delusion of Western bourgeois culture. Indeed, the idea of giving a book or poem an ultimate end coincides with the notion of making it consumable, something that can be used up and replaced in a capitalist market. "The Death of the Author" is considered to be a post-structuralist work,[15] since it moves past the conventions of trying to quantify literature, but others see it as more of a transitional phase for Barthes in his continuing effort to find significance in culture outside of the bourgeois norms [citation needed]. Indeed, the notion of the author being irrelevant was already a factor of structuralist thinking. |

移行 このような考えから、バルトは記号やシンボルの限界だけでなく、不変性や究極の基準という信念に依存する西洋文化の限界についても考察するようになった。 1966年に日本を訪れた彼は、超越的な記号を求めることのない日本文化の満足感について考察した『記号の帝国』(1970年出版)を著した。彼は、日本 では他のあらゆる基準を判断するような中心となる重要なポイントが強調されていないと指摘し、東京の中心である皇居を、威圧的な存在ではなく、無言で目立 たない存在であり、避けられ、顧みられない存在であると描写している。このように、バルトは、日本における記号が、それ自体の価値のために存在し、シニ フィアンが自然に与える意味のみを保持する能力について考察している。このような社会は、バルトが『神話論』で分析した社会とは大きく対照的であり、後者 は常に自然な意味の上に、より大きく、より複雑な意味を主張していることが明らかになった。 この旅の後、バルトは最も有名な作品とされるエッセイ「作者の死」(1967年)を著した。バルトは、文学的テクストの批評における作者、すなわち作者の 権威という概念を、テクストの究極的な意味の強制的な投影と捉えた。文学作品の究極的な意図された意味を想像することで、その作品の究極的な説明を推論す ることができる。しかし、バルトは、言語における意味の著しい拡散と著者の心の不可知の状態により、そのような究極の理解は不可能であると指摘している。 そのため、「理解可能なテキスト」という概念全体は、西洋のブルジョワ文化のもう一つの妄想にすぎない。実際、本や詩に究極の目的を与えるという考えは、 それを消費可能なもの、つまり資本主義市場で使い捨てられ、交換可能なものにするという考えと一致する。「作者の死」は、文学を数値化しようとする慣習を 乗り越えた作品であるため、ポスト構造主義的な作品であると考えられているが[15]、一方で、ブルジョワの規範以外の文化に意義を見出そうとするバルト の継続的な努力の過渡期の作品であると見る向きもある[要出典]。実際、著者は無関係であるという概念は、すでに構造主義的な思考の要因であった。 |

| Textuality and S/Z Since Barthes contends that there can be no originating anchor of meaning in the possible intentions of the author, he considers what other sources of meaning or significance can be found in literature. He concludes that since meaning can't come from the author, it must be actively created by the reader through a process of textual analysis. In his S/Z (1970), Barthes applies this notion in an analysis of Sarrasine, a Balzac novella. The result was a reading that established five major codes for determining various kinds of significance, with numerous lexias throughout the text – a "lexia" here being defined as a unit of the text chosen arbitrarily (to remain methodologically unbiased as possible) for further analysis.[16] The codes led him to define the story as having a capacity for plurality of meaning, limited by its dependence upon strictly sequential elements (such as a definite timeline that has to be followed by the reader and thus restricts their freedom of analysis). From this project Barthes concludes that an ideal text is one that is reversible, or open to the greatest variety of independent interpretations and not restrictive in meaning. A text can be reversible by avoiding the restrictive devices that Sarrasine suffered from, such as strict timelines and exact definitions of events. He describes this as the difference between the writerly text, in which the reader is active in a creative process, and a readerly text in which they are restricted to just reading. The project helped Barthes identify what it was he sought in literature: an openness for interpretation. |

テクスト性とS/Z バルトは、作者の意図に意味の起源となる拠り所はないと主張しているため、文学において意味や意義の他の源泉となり得るものは何かを考察している。彼は、 意味が作者から生じることはありえないため、テクスト分析のプロセスを通じて、読者が能動的に意味を創り出す必要があると結論づけている。バルトは著書 『S/Z』(1970年)で、この概念をバルザックの短編小説『サラザン』の分析に適用した。その結果、さまざまな種類の意義を決定するための5つの主要 なコードを確立する読み取りが行われ、テキスト全体に多数のレクシアが存在することが明らかになった。ここで「レクシア」とは、さらなる分析のために(で きる限り方法論的に偏りのないように)任意に選択されたテキストの単位と定義される。 [16] これらのコードにより、彼は物語には厳密な順序に依存する要素(例えば、読者が従わなければならない明確な時間軸など)によって制限されるものの、複数の 意味を持つ可能性があると定義した。 バルトは、このプロジェクトから、理想的なテキストとは可逆的、つまり、多様な独立した解釈を可能にし、意味を限定しないものであると結論づけている。テ キストは、サラスティンが苦しんだような、厳格な時間軸や出来事の正確な定義といった制限的な手法を避けることで、可逆的なものとなる。彼はこれを、読者 が創造的なプロセスに能動的に関わる「作家的なテキスト」と、読者が読書だけに制限される「読者的なテキスト」の違いとして説明している。このプロジェク トは、バルトが文学に求めるもの、すなわち解釈の余地を明確にするのに役立った。 |

| Neutral and novelistic writing This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (March 2018) (Learn how and when to remove this message) In the late 1970s, Barthes was increasingly concerned with the conflict of two types of language: that of popular culture, which he saw as limiting and pigeonholing in its titles and descriptions, and neutral, which he saw as open and noncommittal.[17] He called these two conflicting modes the Doxa (the official and unacknowledged systems of meaning through which culture is absorbed)[18]) and the Para-doxa. While Barthes had sympathized with Marxist thought in the past (or at least parallel criticisms), he felt that, despite its anti-ideological stance, Marxist theory was just as guilty of using violent language with assertive meanings, as was bourgeois literature. In this way they were both Doxa and both culturally assimilating. As a reaction to this, he wrote The Pleasure of the Text (1975), a study that focused on a subject matter he felt was equally outside the realm of both conservative society and militant leftist thinking: hedonism. By writing about a subject that was rejected by both social extremes of thought, Barthes felt he could avoid the dangers of the limiting language of the Doxa. The theory he developed out of this focus claimed that, while reading for pleasure is a kind of social act, through which the reader exposes him/herself to the ideas of the writer, the final cathartic climax of this pleasurable reading, which he termed the bliss in reading or jouissance, is a point in which one becomes lost within the text. This loss of self within the text or immersion in the text, signifies a final impact of reading that is experienced outside the social realm and free from the influence of culturally associative language and is thus neutral with regard to social progress. Despite this newest theory of reading, Barthes remained concerned with the difficulty of achieving truly neutral writing, which required an avoidance of any labels that might carry an implied meaning or identity towards a given object. Even carefully crafted neutral writing could be taken in an assertive context through the incidental use of a word with a loaded social context. Barthes felt his past works, like Mythologies, had suffered from this. He became interested in finding the best method for creating neutral writing, and he decided to try to create a novelistic form of rhetoric that would not seek to impose its meaning on the reader. One product of this endeavor was A Lover's Discourse: Fragments in 1977, in which he presents the fictionalized reflections of a lover seeking to identify and be identified by an anonymous amorous other. The unrequited lover's search for signs by which to show and receive love makes evident illusory myths involved in such a pursuit. The lover's attempts to assert himself into a false, ideal reality is involved in a delusion that exposes the contradictory logic inherent in such a search. Yet at the same time the novelistic character is a sympathetic one, and is thus open not just to criticism but also understanding from the reader. The result is one that challenges the reader's views of social constructs of love, without trying to assert any definitive theory of meaning. |

中立で小説的な文章 この節には検証可能な参考文献や出典が全く示されていないか、不十分である。出典を追加して記事の信頼性向上にご協力ください。 出典の無い内容は疑問視され、削除される可能性がある。 (2018年3月) (Learn how and when to remove this message) 1970年代後半、バルトは2種類の言語の対立にますます関心を抱くようになった。すなわち、タイトルや説明において限定的で型にはまったものとして彼が 捉えた大衆文化の言語と、開放的で無責任なものとして彼が捉えた中立的な言語である。彼は、この2つの対立する様式を「ドクサ(文化が吸収される公式で認 知されていない意味の体系)」[18]と「パラドクサ」と呼んだ。バルトは過去にマルクス主義思想に共感していた(あるいは少なくとも批判を並列的に捉え ていた)が、反イデオロギー的立場にもかかわらず、マルクス主義理論はブルジョワ文学と同様に、断定的な意味を持つ暴力的な言語を使用していると感じてい た。このように、両者はドクサであり、文化的に同化されていた。これに対する反応として、彼は『テクストの快楽』(1975年)を著した。この研究では、 保守的な社会と過激な左派の思考の両方の領域から等しく排除されていると感じていた主題、すなわち快楽主義に焦点を当てた。両極端な思想を持つ社会から拒 絶された主題について書くことで、バルトはドクサの限定的な言語の危険性を回避できると考えた。この観点から彼が展開した理論は、読書は一種の社会的行為 であり、読者はその行為を通じて作家の思想に触れるが、この快楽的な読書の最終的なカタルシス的なクライマックス、すなわち彼が「読書における至福」また は「快楽享受」と呼ぶものは、読者がテキストの中に没入する瞬間であると主張した。テキスト内での自己喪失やテキストへの没入は、社会的領域の外で経験さ れ、文化的に関連付けられた言語の影響を受けない、読書による最終的な衝撃を意味する。 この最新の読書理論にもかかわらず、バルトは、特定の対象に対して暗示的な意味や同一性を伴う可能性のあるラベル付けを避ける必要がある、真に中立的な文 章を書くことの難しさに依然として関心を抱いていた。慎重に作られた中立的な文章でさえ、社会的背景に含蓄のある言葉が偶発的に使われることで、断定的な 文脈として受け取られる可能性がある。バルトは、これまでの著作『神話体系』などがこの問題に苦しめられてきたと感じていた。彼は、中立的な文章を書くた めの最善の方法を見つけ出すことに興味を抱くようになり、読者に意味を押し付けようとしない小説的な修辞の形を創り出そうと試みることにした。この試みの 成果の一つが、1977年の『恋人たちの談話:断片』である。この作品では、匿名の愛する相手を見つけ、見つけてもらおうとする恋人の架空の考察が提示さ れている。片思いの恋人が愛を示し、受け取るための兆候を模索する姿は、その追求にまつわる幻想的な神話を明らかにしている。虚偽の理想の現実の中に自己 を主張しようとする恋人の試みは、そのような探求に内在する矛盾した論理を露わにする妄想と関わっている。しかし同時に、小説の性格は共感できるものであ り、読者からの批判だけでなく理解も受け入れる余地がある。その結果、意味の決定的な理論を主張しようとすることなく、愛の社会的構築物に対する読者の見 方を問う作品となっている。 |

| Mind and body Barthes also attempted to reinterpret the mind–body dualism theory.[19] Like Friedrich Nietzsche and Emmanuel Levinas, he also drew from Eastern philosophical traditions in his critique of European culture as "infected" by Western metaphysics. His body theory emphasized the formation of the self through bodily cultivation.[19] The theory, which is also described as ethico-political entity, considers the idea of the body as one that functions as a "fashion word" that provides the illusion of a grounded discourse.[20] This theory has influenced the work of other thinkers such as Jerome Bel.[21] |

心と身体 バルトは、心身二元論の再解釈も試みた。[19] フリードリヒ・ニーチェやエマニュエル・レヴィナスと同様に、バルトも西洋形而上学に「感染」されたヨーロッパ文化を批判するにあたり、東洋の哲学伝統か ら着想を得た。彼の身体理論は、身体の鍛錬を通じて自己を形成することを強調している。[19] この理論は、倫理的・政治的な存在とも表現され、身体の概念を、現実的な議論の幻想を提供する「流行語」として機能するものとして捉えている。[20] この理論は、ジェローム・ベル(Jerome Bel)などの他の思想家の作品にも影響を与えている。[21] |

| Photography and Henriette Barthes Throughout his career, Barthes had an interest in photography and its potential to communicate actual events. Many of his monthly myth articles in the 1950s had attempted to show how a photographic image could represent implied meanings and thus be used by bourgeois culture to infer 'naturalistic truths'. But he still considered the photograph to have a unique potential for presenting a completely real representation of the world. When his mother, Henriette Barthes, died in 1977 he began writing Camera Lucida as an attempt to explain the unique significance a picture of her as a child carried for him. Reflecting on the relationship between the obvious symbolic meaning of a photograph (which he called the studium) and that which is purely personal and dependent on the individual, that which 'pierces the viewer' (which he called the punctum),[22] Barthes was troubled by the fact that such distinctions collapse when personal significance is communicated to others and can have its symbolic logic rationalized. Barthes found the solution to this fine line of personal meaning in the form of his mother's picture. Barthes explained that a picture creates a falseness in the illusion of 'what is', where 'what was' would be a more accurate description. As had been made physical through Henriette Barthes's death, her childhood photograph is evidence of 'what has ceased to be'. Instead of making reality solid, it serves as a reminder of the world's ever changing nature. Because of this there is something uniquely personal contained in the photograph of Barthes's mother that cannot be removed from his subjective state: the recurrent feeling of loss experienced whenever he looks at it. As one of his final works before his death, Camera Lucida was both an ongoing reflection on the complicated relations between subjectivity, meaning and cultural society as well as a touching dedication to his mother and description of the depth of his grief. |

写真とアンリエット・バルト バルトは生涯を通じて写真と、実際の出来事を伝える写真の可能性に関心を抱いていた。1950年代に毎月発表された神話に関する記事の多くは、写真が暗示 的な意味を表現し、ブルジョワ文化が「自然主義的真実」を推論するために利用できることを示そうとしていた。しかし、バルトは依然として、写真には世界を 完全にリアルに表現する独自の可能性があると考えていた。1977年に彼の母親であるアンリエット・バルトが亡くなったとき、彼は母親の幼少期の写真が彼 にとって持つ特別な意味を説明しようとして『カメラ・ルシダ』の執筆を始めた。 写真の明白な象徴的な意味(バルトはこれを「スタディウム」と呼んだ)と、純粋に個人的で個人の人格に依存する意味、つまり「見る者を突き刺す」もの(バ ルトはこれを「プンクトゥム」と呼んだ)[22]との関係について考察する中で、バルトは、個人的な意味が他者に伝えられ、象徴論が合理化されると、こう した区別が崩壊してしまうという事実を問題視した。バルトは、この人格的な意味の微妙な境界線に対する解決策を、母親の写真という形で見出した。バルト は、写真が「あるもの」という幻想に偽りを生み出し、より正確な表現は「あったもの」であると説明した。アンリエット・バルトの死によって物理的なものと なった彼女の幼少期の写真は、「なくなったもの」の証拠である。現実を確固たるものにするのではなく、それは、常に変化し続ける世界の性質を思い出させる ものとなる。だからこそ、バルトの母親の写真には、彼の主観的な状態から取り除くことのできない独特な個性が宿っている。彼がその写真を見るたびに、繰り 返し喪失感を味わうのだ。『カメラ・ルシダ』は、バルトが亡くなる直前に完成させた作品のひとつであり、主観性、意味、文化社会の複雑な関係についての考 察を続けつつ、母親への感動的な献辞であり、深い悲しみの描写でもあった。 |

| Posthumous publications A posthumous collection of essays was published in 1987 by François Wahl, Incidents.[23] It contains fragments from his journals: his Soirées de Paris (a 1979 extract from his erotic diary of life in Paris); an earlier diary he kept which explicitly detailed his paying for sex with men and boys in Morocco; and Light of the Sud Ouest (his childhood memories of rural French life). In November 2007, Yale University Press published a new translation into English (by Richard Howard) of Barthes's little known work What is Sport. This work bears a considerable resemblance to Mythologies and was originally commissioned by the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation as the text for a documentary film directed by Hubert Aquin. In February 2009, Éditions du Seuil published Journal de deuil (Journal of Mourning), based on Barthes's files written from 26 November 1977 (the day following his mother's death) up to 15 September 1979, intimate notes on his terrible loss: The (awesome but not painful) idea that she had not been everything to me. Otherwise I would never have written a work. Since my taking care of her for six months long, she actually had become everything for me, and I totally forgot of ever have written anything at all. I was nothing more than hopelessly hers. Before that she had made herself transparent so that I could write.... Mixing-up of roles. For months long I had been her mother. I felt like I had lost a daughter. He grieved his mother's death for the rest of his life: "Do not say mourning. It's too psychoanalytic. I'm not in mourning. I'm suffering." and "In the corner of my room where she had been bedridden, where she had died and where I now sleep, in the wall where her headboard had stood against I hung an icon—not out of faith. And I always put some flowers on a table. I do not wish to travel anymore so that I may stay here and prevent the flowers from withering away." In 2012 the book Travels in China was published. It consists of his notes from a three-week trip to China he undertook with a group from the literary journal Tel Quel in 1974. The experience left him somewhat disappointed, as he found China "not at all exotic, not at all disorienting".[24] |

死後の出版 1987年には、フランソワ・ワール社から死後のエッセイ集『インシデント』が出版された。[23] そこには、彼のジャーナルからの抜粋が含まれている。パリでの生活を綴ったエロティックな日記からの抜粋である『パリでの夜』(1979年)、モロッコで 男性や少年と性行為の対価を支払ったことを詳細に記した初期の日記、そして『南西の光』(フランスの田舎での幼少期の思い出)などである。2007年11 月、イェール大学出版局は、あまり知られていないバルトの作品『What is Sport』の英訳(リチャード・ハワード訳)を出版した。この作品は『神話体系』とかなり類似しており、もともとはカナダ放送協会がユベール・アカン監 督によるドキュメンタリー映画のテキストとして依頼したものだった。 2009年2月には、Éditions du Seuil社より、1977年11月26日(彼の母親の死の翌日)から1979年9月15日までのバルトが書いたファイルを基にした『Journal de deuil(喪の日記)』が出版された。これは、彼の母親の死という大きな喪失についての親密なメモであり、その中には次のような記述がある。 彼女は私のすべてではなかったという考え(それは畏怖すべきものではあるが、苦痛ではない)。そうでなければ、作品を書くことは決してなかっただろう。 6ヶ月間彼女の世話をしたので、実際には彼女が私のすべてになっていた。そして、私は自分が何かを書いたことなどまったく忘れていた。私は彼女に絶望的に 愛されていた。それ以前は、彼女は透明になってくれていたので、私は書くことができた。役割の混乱。数ヶ月間、私は彼女の母親だった。私は娘を失ったよう な気持ちだった。 彼は生涯にわたって母親の死を嘆き悲しんだ。「喪に服すなどと言ってはいけない。そんな言葉は精神分析的すぎる。私は喪に服しているわけではない。苦しん でいるのだ」そして、「彼女が寝たきりになり、死に、そして私が今眠っている部屋の片隅で、彼女の枕元にあった壁に、信仰心からではなく、私はイコンを掛 けた。そして、私はいつもテーブルに花を置いている。もう旅行はしたくない。ここに留まって花が枯れないようにしたい。」 2012年には『中国旅行』が出版された。これは、1974年に文学雑誌『Tel Quel』のグループと3週間の中国旅行に出かけた際の彼のメモから構成されている。その経験は彼にとってやや失望の残るものとなり、中国を「まったくエ キゾチックでもなく、まったく方向感覚を失わせるものでもない」と感じた。[24] |

| Influence Roland Barthes's criticism contributed to the development of theoretical schools such as structuralism, semiotics, and post-structuralism. While his influence is mainly found in these theoretical fields with which his work brought him into contact, it is also felt in every field concerned with the representation of information and models of communication, including computers, photography, music, and literature.[citation needed] One consequence of Barthes's breadth of focus is that his legacy includes no following of thinkers dedicated to modeling themselves after him. The fact that Barthes's work was ever adapting and refuting notions of stability and constancy means there is no canon of thought within his theory to model one's thoughts upon, and thus no "Barthesism".[citation needed] |

影響 ロラン・バルトの批評は、構造主義、記号論、ポスト構造主義などの理論学派の発展に貢献した。彼の影響力は主に、彼の作品が彼を接触させたこれらの理論分 野に見られるが、コンピュータ、写真、音楽、文学など、情報の表現やコミュニケーションのモデルに関わるあらゆる分野でも感じられる。[要出典] バルトの幅広い関心の結果の一つは、彼を模範とする思想家の追随者がいないことである。バルトの作品が安定性と恒常性の概念を適応させ、反論してきたとい う事実から、彼の理論には自身の考え方を模範とするような思想の規範が存在せず、したがって「バルト主義」も存在しないことがわかる。[要出典] |

| Key terms Readerly and writerly are terms Barthes employs both to delineate one type of literature from another and to implicitly interrogate ways of reading, like positive or negative habits the modern reader brings into one's experience with the text itself. These terms are most explicitly fleshed out in S/Z, while the essay "From Work to Text", from Image—Music—Text (1977), provides an analogous parallel look at the active–passive and postmodern–modern ways of interacting with a text. |

キーワード 読み手」と「書き手」という用語は、バルトが文学の一種を別の文学から区別するために用いたものであり、また、現代の読者がテキストそのものとの経験に持 ち込む肯定的な、あるいは否定的な習慣のような、読み方について暗に問いかけるものでもある。これらの用語は『S/Z』で最も明確に説明されているが、一 方で、1977年の『映像-音楽-テキスト』に収録されたエッセイ「作品からテクストへ」では、テクストとの能動的・受動的な関わり方、ポストモダンとモ ダンの関わり方について、同様の観点から考察している。 |

| Readerly text A text that makes no requirement of the reader to "write" or "produce" their own meanings. The reader may passively locate "ready-made" meaning. Barthes writes that these sorts of texts are "controlled by the principle of non-contradiction" (156), that is, they do not disturb the "common sense," or "Doxa," of the surrounding culture. The "readerly texts," moreover, "are products [that] make up the enormous mass of our literature" (5). Within this category, there is a spectrum of "replete literature," which comprises "any classic (readerly) texts" that work "like a cupboard where meanings are shelved, stacked, [and] safeguarded" (200).[25] |

読み手本位のテキスト 読み手に「書く」ことや「生み出す」ことを要求しないテキスト。読み手は受動的に「既製の」意味を見つける。バルトは、この種のテキストは「非矛盾律の原 則によって制御されている」(156)と記している。つまり、それらは周囲の文化の「常識」や「ドクサ」を乱さないということである。さらに、「読み手向 けのテキスト」は「文学の膨大な量を作り上げる製品」である(5)。このカテゴリーには、「意味が保管され、積み重ねられ、[そして]保護される食器棚の ように機能する」あらゆる古典的な(読み手向けの)テキストで構成される「充実した文学」のスペクトルがある(200)。[25] |

| Writerly text A text that aspires to the proper goal of literature and criticism: "... to make the reader no longer a consumer but a producer of the text" (4). Writerly texts and ways of reading constitute, in short, an active rather than passive way of interacting with a culture and its texts. A culture and its texts, Barthes writes, should never be accepted in their given forms and traditions. As opposed to the "readerly texts" as "product," the "writerly text is ourselves writing, before the infinite play of the world is traversed, intersected, stopped, plasticized by some singular system (Ideology, Genus, Criticism) which reduces the plurality of entrances, the opening of networks, the infinity of languages" (5). Thus reading becomes for Barthes "not a parasitical act, the reactive complement of a writing", but rather a "form of work" (10). |

作家的なテクスト(書き手本位のテキスト) 文学や批評の正しい目標を志向するテクスト:「... 読者をテキストの消費者ではなく生産者にする」(4)。作家的なテクストと読み方は、簡単に言えば、文化やそのテクストと相互作用する受動的ではなく能動 的な方法である。バルトは、文化とそのテキストは、その与えられた形や伝統のままに受け入れるべきではないと書いている。「読み手としてのテキスト」とい う「製品」とは対照的に、「書き手としてのテキスト」とは、「世界の無限の遊びが、いくつかの特異なシステム(イデオロギー、ジャンル、批評)によって横 断、交差、停止、可塑化される前に、私たちが書くことである。そのシステムは、入り口の多様性、ネットワークの開口部、言語の無限性を削減するものであ る」(5)。したがって、バルトにとって読書とは「寄生的な行為、書かれたものの反応的な補完」ではなく、「労働の形態」である(10)。 |

| The Author and the scriptor Author and scriptor are terms Barthes uses to describe different ways of thinking about the creators of texts. "The author" is the traditional concept of the lone genius creating a work of literature or other piece of writing by the powers of his/her original imagination. For Barthes, such a figure is no longer viable. The insights offered by an array of modern thought, including the insights of Surrealism, have rendered the term obsolete. In place of the author, the modern world offers a figure Barthes calls the "scriptor," whose only power is to combine pre-existing texts in new ways. Barthes believes that all writing draws on previous texts, norms, and conventions, and that these are the things to which the reader must turn to understand a text. As a way of asserting the relative unimportance of the writer's biography compared to these textual and generic conventions, Barthes says that the scriptor has no past, but is born with the text. He also argues that, in the absence of the idea of an "author-God" to control the meaning of a work, interpretive horizons are opened up considerably for the active reader. As Barthes puts it, "the death of the author is the birth of the reader."[26] |

作者と執筆者 作者と執筆者とは、テクストの作者について異なる考え方を表すためにバルトが用いた用語である。「作者」とは、文学やその他の文章を独創的な想像力によっ て創造する孤高の天才という伝統的な概念である。バルトにとって、そのような人物はもはや存在しえない。シュールレアリスムの洞察力を含む、現代思想の洞 察力が、この用語を時代遅れのものにしてしまった。 現代社会では、著者の代わりに、バルトが「スクリプター」と呼ぶ人物が登場する。スクリプターの唯一の力は、既存のテキストを新しい方法で組み合わせるこ とだけである。バルトは、すべての文章は過去のテキスト、規範、慣習から着想を得ており、読者は文章を理解するために、これらのものに目を向ける必要があ ると信じている。こうしたテクストやジャンルの慣例に比べれば、作家の伝記はさほど重要ではないことを主張する手段として、バルトは「スクリプター」には 過去がなく、テクストとともに生まれると述べている。また、作品の意味を支配する「神のような作者」という概念が存在しない場合、能動的な読者にとって解 釈の地平は大幅に開かれると主張している。バルトの言葉を借りれば、「作者の死は読者の誕生である」[26]。 |

| Criticism In 1964, Barthes wrote "The Last Happy Writer" ("Le dernier des écrivains heureux" in Essais critiques), the title of which refers to Voltaire. In the essay he commented on the problems of the modern thinker after discovering the relativism in thought and philosophy, discrediting previous philosophers who avoided this difficulty. Disagreeing roundly with Barthes's description of Voltaire, Daniel Gordon, the translator and editor of Candide (The Bedford Series in History and Culture), wrote that "never has one brilliant writer so thoroughly misunderstood another."[27] The sinologist Simon Leys, in a review of Barthes's diary of a trip to China during the Cultural Revolution, disparages Barthes for his seeming indifference to the situation of the Chinese people, and says that Barthes "has contrived—amazingly—to bestow an entirely new dignity upon the age-old activity, so long unjustly disparaged, of saying nothing at great length."[28] |

批判 1964年、バルトは「最後の幸福な作家」(「Le dernier des écrivains heureux」、『批評的試み』所収)を著した。このタイトルはヴォルテールを指している。このエッセイで彼は、相対主義的な思考や哲学を発見した後の 現代思想家の問題について論じ、この困難を避けてきた過去の哲学者たちを否定した。ボルテールの評を書いたバルトの記述に強く反対するダニエル・ゴードン は、『カンディード』(『ベッドフォード・シリーズ』歴史と文化)の翻訳者兼編集者であり、「これほど見事に誤解された偉大な作家は他にいない」と書いて いる。 中国研究家のサイモン・リースは、文化大革命中の中国を訪れたバルトの日記の書評で、バルトが中国の民衆の状況に対して無関心であるかのように見えたこと を批判し、バルトは「驚くべきことに、長い間不当に軽視されてきた、長々と何も言わないという古くからの行為に、まったく新しい尊厳を与えた」と述べてい る。[28] |

| In popular culture Barthes's A Lover's Discourse: Fragments was the inspiration for the name of 1980s new wave duo The Lover Speaks. Jeffrey Eugenides' The Marriage Plot draws out excerpts from Barthes's A Lover's Discourse: Fragments as a way to depict the unique intricacies of love that one of the main characters, Madeleine Hanna, experiences throughout the novel.[29] In the film Birdman (2014) by Alejandro González Iñárritu, a journalist quotes to the protagonist Riggan Thompson an extract from Mythologies: "The cultural work done in the past by gods and epic sagas is now done by laundry-detergent commercials and comic-strip characters".[30] In the film The Truth About Cats & Dogs (1996) by Michael Lehmann, Brian is reading an extract from Camera Lucida over the phone to someone he thinks to be a beautiful woman but is actually her more intellectual and less physically desirable friend.[31] In the film Elegy, based on Philip Roth's novel The Dying Animal, the character of Consuela (played by Penélope Cruz) is first depicted in the film carrying a copy of Barthes's The Pleasure of the Text on the campus of the university where she is a student.[32] Laurent Binet's novel The 7th Function of Language is based on the premise that Barthes was not merely accidentally hit by a van driver but that he was instead murdered, as part of a conspiracy to acquire a document known as the "Seventh Function of Language".[33] |

大衆文化において、 バルトの『恋人たちのディスクール:断片』は、1980年代のニューウェーブデュオ「ザ・ラヴァーズ・スピークス」のバンド名のインスピレーションとなった。 ジェフリー・ユージェニデスの小説『結婚の条件』では、小説の主要人物の一人であるマデリン・ハンナが小説全体を通して経験する独特な愛の複雑さを描写する方法として、バルトの『恋人たちのディスクール:断片』からの抜粋が引用されている。 アレハンドロ・ゴンサレス・イニャリトゥ監督の映画『バードマン』(2014年)では、主人公のリーガン・トンプソンに、ジャーナリストが『神話』からの 抜粋を引用する。「神々や叙事詩の英雄たちによって過去に行われた文化的な仕事は、今では洗濯洗剤のCMや漫画のキャラクターたちによって行われている」 [30]。 マイケル・レマンの映画『猫と犬の真実』(1996年)では、ブライアンが美しい女性と思われる人物に電話で『カメラ・ルシダ』からの抜粋を読んでいるが、実際にはその女性は彼女の友人で、より知的で肉体的に魅力的ではない人物であった。 フィリップ・ロスの小説『死の動物』を原作とする映画『エレジー』では、ペネロペ・クルス演じるコンスエラというキャラクターが、学生として通う大学のキャンパスで、最初にバルトの『テクストの快楽』を携えている場面が描かれている。 ロラン・ビネの小説『言語の第7の機能』は、バルトが単に偶然に轢かれたのではなく、むしろ「言語の第7の機能」として知られる文書を入手するための陰謀の一環として殺害されたという前提に基づいている。[33] |

| Bibliography Works (1953) Le degré zéro de l'écriture (1954) Michelet par lui-même (1957) Mythologies, Seuil: Paris. (1963) Sur Racine, Editions du Seuil: Paris (1964) Éléments de sémiologie, Communications 4, Seuil: Paris. (1970) L'Empire des signes, Skira: Geneve. (1970) S/Z, Seuil: Paris. (1971) Sade, Fourier, Loyola, Editions du Seuil: Paris. (1972) Le Degré zéro de l'écriture suivi de Nouveaux essais critiques, Editions du Seuil: Paris. (1973) Le plaisir du texte, Editions du Seuil: Paris. (1975) Roland Barthes, Éditions du Seuil: Paris (1977) Poétique du récit, Editions du Seuil: Paris. (1977) Fragments d'un discours amoureux, Paris (1978) Préface, La Parole Intermédiaire, F. Flahault, Seuil: Paris (1980) Recherche de Proust, Editions du Seuil: Paris. (1980) La chambre claire: note sur la photographie. [Paris]: Cahiers du cinéma: Gallimard: Le Seuil, 1980. (1981) Essais critiques, Editions du Seuil: Paris. (1982) Littérature et réalité, Editions du Seuil: Paris. (1988) Michelet, Editions du Seuil: Paris. (1993) Œuvres complètes, Editions du Seuil: Paris. (2009) Carnets du voyage en Chine, Christian Bourgeois: Paris.[34] (2009) Journal de deuil, Editions du Seuil/IMEC: Paris.[34] Translations to English The Fashion System (1967), University of California Press: Berkeley. Writing Degree Zero (1968), Hill and Wang: New York. ISBN 0-374-52139-5 Elements of Semiology (1968), Hill and Wang: New York. Mythologies (1972), Hill and Wang: New York. The Pleasure of the Text (1975), Hill and Wang: New York. S/Z: An Essay (1975), Hill and Wang: New York. ISBN 0-374-52167-0 Sade, Fourier, Loyola (1976), Farrar, Straus and Giroux: New York. Image—Music—Text (1977), Hill and Wang: New York. Roland Barthes by Roland Barthes (1977) (In this so-called autobiography, Barthes interrogates himself as a text.) The Eiffel Tower and other Mythologies (1979), University of California Press: Berkeley. Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography (1981), Hill and Wang: New York. Critical Essays (1972), Northwestern University Press A Barthes Reader (1982), Hill and Wang: New York. Empire of Signs (1983), Hill and Wang: New York. The Grain of the Voice: Interviews 1962–1980 (1985), Jonathan Cape: London. The Responsibility of Forms: Critical Essays on Music, Art, and Representation (1985), Basil Blackwell: Oxford. The Rustle of Language (1986), B. Blackwell: Oxford. Criticism and Truth (1987), The Athlone Pr.: London. Michelet (1987), B.Blackwell: Oxford. Writer Sollers (1987), University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis. Roland Barthes (1988), Macmillan Pr.: London. A Lover's Discourse: Fragments (1990), Penguin Books: London. New Critical Essays (1990), University of California Press: Berkeley. Incidents (1992), University of California Press: Berkeley. On Racine (1992), University of California Press: Berkeley The Semiotic Challenge (1994), University of California Press: Berkeley. The Neutral: Lecture Course at the Collège de France (1977–1978) (2005), Columbia University Press: New York. The Language of Fashion (2006), Power Publications: Sydney. What Is Sport? (2007), Yale University Press: London and New Haven. ISBN 978-0-300-11604-5 Mourning Diary (2010), Hill and Wang: New York. ISBN 978-0-8090-6233-1[35] The Preparation of the Novel: Lecture Courses and Seminars at the Collège de France (1978–1979 and 1979–1980) (2011), Columbia University Press: New York. How to Live Together: Notes for a Lecture Course and Seminar at the Collège de France (1976–1977) (2013), Columbia University Press: New York. |

参考文献 著作 (1953) 『文字の零度 (1954) 『ミシュレ自身によるミシュレ (1957) 『神話』、Seuil: Paris. (1963) 『ラシーヌについて』、Editions du Seuil: Paris (1964) 『記号論の諸要素』、Communications 4、Seuil: Paris. (1970) 『記号の帝国』、Skira: ジュネーブ。 (1970) 『S/Z』、Seuil: パリ。 (1971) 『サド、フーリエ、ロヨラ』、Seuil: パリ。 (1972) 『エクリチュールの零度』、Seuil: パリ。 (1973) 『テクストの快楽』、Éditions du Seuil: Paris. (1975) 『ロラン・バルト』、Éditions du Seuil: Paris (1977) 『物語の詩学』、Éditions du Seuil: Paris. (1977) 『愛の断片』、パリ (1978) 『序文』、La Parole Intermédiaire、F. Flahault、Seuil: Paris (1980) 『プルーストの追憶』、Seuil: Paris. (1980) 『明るい部屋――写真についての覚書』、[Paris]: Cahiers du cinéma: Gallimard: Le Seuil, 1980. (1981) 『評論集』、Seuil: Paris. (1982) 『文学と現実』、Seuil: Paris. (1988) ミシュレ、エディシオン・デュ・スーユ:パリ。 (1993) 全集、エディシオン・デュ・スーユ:パリ。 (2009) 中国旅行記、クリスチャン・ブルジョワ:パリ。[34] (2009) 喪の日記、エディシオン・デュ・スーユ/IMEC:パリ。[34] 英語への翻訳 『ファッション・システム』(1967年)、カリフォルニア大学出版:バークレー。 『ディグリー・ゼロの書き方』(1968年)、ヒル・アンド・ワング:ニューヨーク。ISBN 0-374-52139-5 『記号論の要素』(1968年)、ヒル・アンド・ワング:ニューヨーク。 『神話学』(1972年)、ヒル・アンド・ワング:ニューヨーク。 『テクストの快楽』(1975年)、ヒル・アンド・ワング社:ニューヨーク。 『S/Z:エッセイ』(1975年)、ヒル・アンド・ワング社:ニューヨーク。ISBN 0-374-52167-0 『サド・フーリエ・ロヨラ』(1976年)、ファラ・ストラウス・アンド・ジルー社:ニューヨーク。 『イメージ=音楽=テクスト』(1977年)、ヒル・アンド・ワング:ニューヨーク。 『ロラン・バルトによるロラン・バルト』(1977年)(このいわゆる自伝の中で、バルトは自らをテキストとして問い詰める。 『エッフェル塔とその他の神話』(1979年)、カリフォルニア大学出版:バークレー。 『カメラ・ルシダ:写真についての省察』(1981年)、ヒル・アンド・ワング:ニューヨーク。 Critical Essays (1972), Northwestern University Press A Barthes Reader (1982), Hill and Wang: New York. Empire of Signs (1983), Hill and Wang: New York. The Grain of the Voice: Interviews 1962–1980 (1985), Jonathan Cape: London. 『形式の責任:音楽、芸術、表現に関する評論』(1985年、Basil Blackwell:オックスフォード) 『言語のざわめき』(1986年、B. Blackwell:オックスフォード) 『批評と真実』(1987年、The Athlone Pr.:ロンドン) ミシュレ(1987年)、B.Blackwell: Oxford. 作家ソラー(1987年)、ミネアポリス大学出版:ミネアポリス。 ロラン・バルト(1988年)、マクミラン出版:ロンドン。 恋人たちの言説:断片(1990年)、ペンギンブックス:ロンドン。 新しい批評論文(1990年)、カリフォルニア大学出版:バークレー。 Incidents (1992), カリフォルニア大学出版局: バークレー。 On Racine (1992), カリフォルニア大学出版局: バークレー The Semiotic Challenge (1994), カリフォルニア大学出版局: バークレー。 The Neutral: Lecture Course at the Collège de France (1977–1978) (2005), コロンビア大学出版局: ニューヨーク。 The Language of Fashion (2006), Power Publications: Sydney. What Is Sport? (2007), Yale University Press: London and New Haven. ISBN 978-0-300-11604-5 Mourning Diary (2010), Hill and Wang: New York. ISBN 978-0-8090-6233-1[35] 小説の準備:コレージュ・ド・フランスにおける講義コースとセミナー(1978年~1979年および1979年~1980年)(2011年)、コロンビア大学出版局:ニューヨーク。 いかに共に生きるか:コレージュ・ド・フランスにおける講義コースとセミナーのためのノート(1976年~1977年)(2013年)、コロンビア大学出版局:ニューヨーク。 |

| Sources Allen, Graham (2003). Roland Barthes. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-13450-340-7. Calvet, Louis-Jean (1994). Roland Barthes: A Biography. Translated by Wykes, Sarah. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-34987-7.. Culler, Jonathan (2001). Roland Barthes: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. |

出典 アレン、グラハム(2003年)。ロラン・バルト。ロンドン:ルートレッジ。ISBN 978-1-13450-340-7。 カルヴェ、ルイ=ジャン(1994年)。ロラン・バルト:伝記。ワイクス、サラ訳。ブルーミントン:インディアナ大学出版。ISBN 0-253-34987-7。 Culler, Jonathan (2001). Roland Barthes: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. |

| Further reading Réda Bensmaïa, The Barthes Effect: The Essay as Reflective Text, trans. Pat Fedkiew, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987. Paul de Man, "Roland Barthes and the Limits of Structuralism", in Romanticism and Contemporary Criticism, ed. E.S. Burt, Kevin Newmark, and Andrzej Warminski, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1993. Jacques Derrida, "The Deaths of Roland Barthes," in Psyche: Inventions of the Other, Vol. 1, ed. Peggy Kamuf and Elizabeth G. Rottenberg, Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2007. D.A. Miller, Bringing Out Roland Barthes, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992. (A highly personal collection of fragments, aimed at both mourning Barthes and illuminating his work in terms of a "gay writing position.") Marie Gil, Roland Barthes: Au lieu de la vie, Paris: Flammarion, 2012. (The first major academic biography [562 p.]) Michael Moriarty, Roland Barthes, Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1991. (Explains various works of Roland Barthes) Jean-Michel Rabate, ed., Writing the Image After Roland Barthes, Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1997. Jean-Louis de Rambures, Interview with Roland Barthes in: Comment travaillent les écrivains, Paris: Flammarion, 1978 Mireille Ribiere, Roland Barthes, Ulverston: Humanities E-Books, 2008. Susan Sontag, "Remembering Barthes", in Under the Sign of Saturn, New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1980. Susan Sontag, "Writing Itself: On Roland Barthes", introduction to Roland Barthes, A Barthes Reader, ed. Susan Sontag, New York: Hill and Wang, 1982. Steven Ungar. Roland Barthes: Professor of Desire. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1983. ISBN 9780803245518 George R. Wasserman. Roland Barthes. Boston: Twayne Publishers, 1981. |

さらに読む レダ・ベンサマイア著『バルト効果:反射的テクストとしてのエッセイ』、パット・フェドキエフ訳、ミネアポリス:ミネソタ大学出版、1987年。 ポール・ド・マン著「ロラン・バルトと構造主義の限界」、E.S.バート、ケビン・ニューマーク、アンドジェイ・ヴァルミンスキ編『ロマン主義と現代批評』、ボルチモア: ジョンズ・ホプキンス大学出版、1993年。 ジャック・デリダ、「ロラン・バルトの死」、『プシュケ:他者の発明』第1巻、ペギー・カムフ、エリザベス・G・ロッテンバーグ編、スタンフォード大学出版、2007年。 D.A. Miller, Bringing Out Roland Barthes, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992. (きわめて個人的な断片のコレクション。バルトを追悼するとともに、「ゲイの執筆姿勢」という観点から彼の作品を解明することを目的としている。) Marie Gil, Roland Barthes: Au lieu de la vie, Paris: Flammarion, 2012. (初の主要な学術的伝記 [562ページ]) マイケル・モリアーティ著『ロラン・バルト』スタンフォード大学出版局、1991年。(ロラン・バルトのさまざまな作品を解説) ジャン=ミシェル・ラバテ編『ロラン・バルト以降のイメージの記述』ペンシルベニア大学出版局、フィラデルフィア、1997年。 ジャン=ルイ・ド・ランブール著『作家の仕事ぶり』フラマリオン、パリ、1978年 ミレイユ・リビエール著『ロラン・バルト』、ウルヴァーストーン:人文科学電子書籍、2008年。 スーザン・ソンタグ著『バルトを偲んで』、ニューヨーク:ファラ・ストラウス・アンド・ジルー、1980年。 スーザン・ソンタグ著『書くことそれ自体:ロラン・バルトについて』、ロラン・バルト著『バルト読本』序文、 スーザン・ソンタグ、ニューヨーク:ヒル・アンド・ワング、1982年。 スティーブン・アンガー著『ロラン・バルト:欲望の教授』リンカーン:ネブラスカ大学出版、1983年。ISBN 9780803245518 ジョージ・R・ワッシャーマン著『ロラン・バルト』ボストン:トウェイン・パブリッシャーズ、1981年。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roland_Barthes |

リ ンク

文 献

その他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆