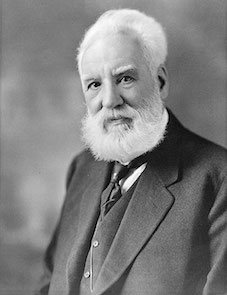

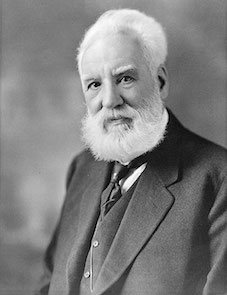

アレクサンダー・グラハム・ベル

Alexander Graham Bell

アレクサンダー・グラハム・ベル

Alexander Graham Bell

アレクサンダー・グラ ハム・ベル(Alexander Graham Bell、1847年3月3日 - 1922年8月2日)は、スコットランド生まれの科学者、発明家、工学者。世界初の実用的電話の発明で知られている。ベルの祖父、父、兄弟は弁論術とス ピーチに関連した仕事をし、母と妻は聾だった。このことはベルのライフワークに深く影響している[3]。聴覚とスピーチに関する研究から聴覚機器の実験を 行い、ついに最初のアメリカ合衆国の特許を取得した電話の発明(1876年)として結実した[注釈 2]。のちにベルは彼のもっとも有名な発明が科学者としての本当の仕事には余計なものだったと考え、書斎に電話機を置くことを断わった。その後もさまざま な発明をしており、光無線通信・水中翼船・航空工学などの分野で重要な業績を残した。1888年にはナショナルジオグラフィック協会創設に関わった [7]。その生涯を通じて科学振興および聾者教育に尽力し、人類の歴史上もっとも影響を及ぼした人物の1人とされることもある[8]。デシベル (decibel; dB)などに使われる相対単位「ベル」などにその名を残す。

| Alexander

Graham Bell

(/ˈɡreɪ.əm/, born Alexander Bell; March 3, 1847 – August 2, 1922)[4]

was a Scottish-born[N 1] inventor, scientist and engineer who is

credited with patenting the first practical telephone. He also

co-founded the American Telephone and Telegraph Company (AT&T) in

1885.[7] Bell's father, grandfather, and brother had all been associated with work on elocution and speech, and both his mother and wife were deaf; profoundly influencing Bell's life's work.[8] His research on hearing and speech further led him to experiment with hearing devices which eventually culminated in Bell being awarded the first U.S. patent for the telephone, on March 7, 1876.[N 2] Bell considered his invention an intrusion on his real work as a scientist and refused to have a telephone in his study.[9][N 3] Many other inventions marked Bell's later life, including groundbreaking work in optical telecommunications, hydrofoils, and aeronautics. Bell also had a strong influence on the National Geographic Society[11] and its magazine while serving as the second president from January 7, 1898, until 1903. Beyond his work in engineering, Bell had a deep interest in the emerging science of heredity.[12] |

アレクサンダー・グラハム・ベル(Alexander

Graham Bell、/ˈɡ, born Alexander Bell; March 3, 1847 - August 2,

1922)[4] はスコットランド生まれ[N 1]

の発明家、科学者でエンジニアであり、最初の実用電話の特許を取得したとされている人物。また、1885年にアメリカ電話電信会社(AT&T)を

共同設立した[7]。 ベルの父、祖父、兄はすべて発声と音声の研究に携わっており、彼の母親と妻はともに聴覚障害者であったため、ベルのライフワークに大きな影響を与えた [8]。聴覚と音声に関する彼の研究はさらに聴覚装置の実験につながり、最終的には1876年3月7日に電話に関する最初の米国特許をベルに授与された [N 2] ベルは自分の発明が科学者としての彼の本業の邪魔になると考え、自分の研究室に電話があるのを拒否している[9][N 3]。 その他にも、光通信、水中翼船、航空学など、多くの発明がベルの後半生を特徴づけた。また、1898年1月7日から1903年まで第2代会長を務め、ナ ショナルジオグラフィック協会[11]とその雑誌に強い影響力を与えた。 工学の仕事以外にも、ベルは遺伝という新しい科学に深い関心を抱いていた[12]。 |

| Early life Bell was born in Edinburgh, Scotland, on March 3, 1847.[13] The family home was at South Charlotte Street, and has a stone inscription marking it as Bell's birthplace. He had two brothers: Melville James Bell (1845–1870) and Edward Charles Bell (1848–1867), both of whom would die of tuberculosis.[14] His father was Alexander Melville Bell, a phonetician, and his mother was Eliza Grace Bell (née Symonds).[15] Born as just "Alexander Bell", at age 10, he made a plea to his father to have a middle name like his two brothers.[16][N 4] For his 11th birthday, his father acquiesced and allowed him to adopt the name "Graham", chosen out of respect for Alexander Graham, a Canadian being treated by his father who had become a family friend.[17] To close relatives and friends he remained "Aleck".[18] Bell and his siblings attended a Presbyterian Church in their youth.[19] First invention As a child, Bell displayed a curiosity about his world; he gathered botanical specimens and ran experiments at an early age. His best friend was Ben Herdman, a neighbour whose family operated a flour mill. At the age of 12, Bell built a homemade device that combined rotating paddles with sets of nail brushes, creating a simple dehusking machine that was put into operation at the mill and used steadily for a number of years.[20] In return, Ben's father John Herdman gave both boys the run of a small workshop in which to "invent".[20] From his early years, Bell showed a sensitive nature and a talent for art, poetry, and music that was encouraged by his mother. With no formal training, he mastered the piano and became the family's pianist.[21] Despite being normally quiet and introspective, he revelled in mimicry and "voice tricks" akin to ventriloquism that continually entertained family guests during their occasional visits.[21] Bell was also deeply affected by his mother's gradual deafness (she began to lose her hearing when he was 12), and learned a manual finger language so he could sit at her side and tap out silently the conversations swirling around the family parlour.[22] He also developed a technique of speaking in clear, modulated tones directly into his mother's forehead wherein she would hear him with reasonable clarity.[23] Bell's preoccupation with his mother's deafness led him to study acoustics. His family was long associated with the teaching of elocution: his grandfather, Alexander Bell, in London, his uncle in Dublin, and his father, in Edinburgh, were all elocutionists. His father published a variety of works on the subject, several of which are still well known, especially his The Standard Elocutionist (1860),[21] which appeared in Edinburgh in 1868. The Standard Elocutionist appeared in 168 British editions and sold over a quarter of a million copies in the United States alone. In this treatise, his father explains his methods of how to instruct deaf-mutes (as they were then known) to articulate words and read other people's lip movements to decipher meaning. Bell's father taught him and his brothers not only to write Visible Speech but to identify any symbol and its accompanying sound.[24] Bell became so proficient that he became a part of his father's public demonstrations and astounded audiences with his abilities. He could decipher Visible Speech representing virtually every language, including Latin, Scottish Gaelic, and even Sanskrit, accurately reciting written tracts without any prior knowledge of their pronunciation.[24] Education As a young child, Bell, like his brothers, received his early schooling at home from his father. At an early age, he was enrolled at the Royal High School, Edinburgh, Scotland, which he left at the age of 15, having completed only the first four forms.[25] His school record was undistinguished, marked by absenteeism and lacklustre grades. His main interest remained in the sciences, especially biology, while he treated other school subjects with indifference, to the dismay of his father.[26] Upon leaving school, Bell travelled to London to live with his grandfather, Alexander Bell, on Harrington Square. During the year he spent with his grandfather, a love of learning was born, with long hours spent in serious discussion and study. The elder Bell took great efforts to have his young pupil learn to speak clearly and with conviction, the attributes that his pupil would need to become a teacher himself.[27] At the age of 16, Bell secured a position as a "pupil-teacher" of elocution and music, in Weston House Academy at Elgin, Moray, Scotland. Although he was enrolled as a student in Latin and Greek, he instructed classes himself in return for board and £10 per session.[28] The following year, he attended the University of Edinburgh, joining his older brother Melville who had enrolled there the previous year. In 1868, not long before he departed for Canada with his family, Bell completed his matriculation exams and was accepted for admission to University College London.[29][failed verification] First experiments with sound His father encouraged Bell's interest in speech and, in 1863, took his sons to see a unique automaton developed by Sir Charles Wheatstone based on the earlier work of Baron Wolfgang von Kempelen.[30] The rudimentary "mechanical man" simulated a human voice. Bell was fascinated by the machine and after he obtained a copy of von Kempelen's book, published in German, and had laboriously translated it, he and his older brother Melville built their own automaton head. Their father, highly interested in their project, offered to pay for any supplies and spurred the boys on with the enticement of a "big prize" if they were successful.[30] While his brother constructed the throat and larynx, Bell tackled the more difficult task of recreating a realistic skull. His efforts resulted in a remarkably lifelike head that could "speak", albeit only a few words.[30] The boys would carefully adjust the "lips" and when a bellows forced air through the windpipe, a very recognizable Mama ensued, to the delight of neighbours who came to see the Bell invention.[31] Intrigued by the results of the automaton, Bell continued to experiment with a live subject, the family's Skye Terrier, Trouve.[32] After he taught it to growl continuously, Bell would reach into its mouth and manipulate the dog's lips and vocal cords to produce a crude-sounding "Ow ah oo ga ma ma". With little convincing, visitors believed his dog could articulate "How are you, grandmama?[33]" Indicative of his playful nature, his experiments convinced onlookers that they saw a "talking dog".[34] These initial forays into experimentation with sound led Bell to undertake his first serious work on the transmission of sound, using tuning forks to explore resonance. At age 19, Bell wrote a report on his work and sent it to philologist Alexander Ellis, a colleague of his father.[34] Ellis immediately wrote back indicating that the experiments were similar to existing work in Germany, and also lent Bell a copy of Hermann von Helmholtz's work, The Sensations of Tone as a Physiological Basis for the Theory of Music.[35] Dismayed to find that groundbreaking work had already been undertaken by Helmholtz who had conveyed vowel sounds by means of a similar tuning fork "contraption", Bell pored over the German scientist's book. Working from his own erroneous mistranslation of a French edition,[36] Bell fortuitously then made a deduction that would be the underpinning of all his future work on transmitting sound, reporting: "Without knowing much about the subject, it seemed to me that if vowel sounds could be produced by electrical means, so could consonants, so could articulate speech." He also later remarked: "I thought that Helmholtz had done it ... and that my failure was due only to my ignorance of electricity. It was a valuable blunder ... If I had been able to read German in those days, I might never have commenced my experiments!"[37][38][39][N 5] Family tragedy In 1865, when the Bell family moved to London,[40] Bell returned to Weston House as an assistant master and, in his spare hours, continued experiments on sound using a minimum of laboratory equipment. Bell concentrated on experimenting with electricity to convey sound and later installed a telegraph wire from his room in Somerset College to that of a friend.[41] Throughout late 1867, his health faltered mainly through exhaustion. His younger brother, Edward "Ted," was similarly affected by tuberculosis. While Bell recovered (by then referring to himself in correspondence as "A. G. Bell") and served the next year as an instructor at Somerset College, Bath, England, his brother's condition deteriorated. Edward would never recover. Upon his brother's death, Bell returned home in 1867. His older brother Melville had married and moved out. With aspirations to obtain a degree at University College London, Bell considered his next years as preparation for the degree examinations, devoting his spare time at his family's residence to studying. Helping his father in Visible Speech demonstrations and lectures brought Bell to Susanna E. Hull's private school for the deaf in South Kensington, London. His first two pupils were deaf-mute girls who made remarkable progress under his tutelage. While his older brother seemed to achieve success on many fronts including opening his own elocution school, applying for a patent on an invention, and starting a family, Bell continued as a teacher. However, in May 1870, Melville died from complications due to tuberculosis, causing a family crisis. His father had also experienced a debilitating illness earlier in life and had been restored to health by a convalescence in Newfoundland. Bell's parents embarked upon a long-planned move when they realized that their remaining son was also sickly. Acting decisively, Alexander Melville Bell asked Bell to arrange for the sale of all the family property,[42][N 6] conclude all of his brother's affairs (Bell took over his last student, curing a pronounced lisp),[43] and join his father and mother in setting out for the "New World". Reluctantly, Bell also had to conclude a relationship with Marie Eccleston, who, as he had surmised, was not prepared to leave England with him.[44] |

幼少期 ベルは1847年3月3日にスコットランドのエディンバラで生まれた[13]。実家はサウスシャーロットストリートにあり、ベルの生家と記された石碑があ る。彼には2人の兄弟がいた。父は音声学者のアレクサンダー・メルヴィル・ベル、母はエリザ・グレース・ベル(旧姓シモンズ)であった[15]。 [16][N 4] 11歳の誕生日に父親が承諾し、家族の友人となった父親が治療していたカナダ人のアレクサンダー・グラハムに敬意を表して選んだ「グラハム」という名前を 採用することを許した[17] 近親者や友人には「アレック」のままだった[18] ベルと彼の兄弟たちは少年時代に長老派教会に通った[19] 。 最初の発明 ベルは幼い頃から自分の世界に対する好奇心が旺盛で、植物の標本を集めたり、実験をしていた。親友は、製粉所を営む隣家のベン・ハードマンであった。12 歳の時、ベルは回転するパドルと爪ブラシを組み合わせた自家製の装置を作り、簡単な除草機を作った。その装置は製粉所で稼働し、何年もの間、安定して使わ れた[20] その代わり、ベンの父ジョン・ハードマンは2人の少年に小さな工房を与え、そこで「発明」する機会を与えた[20]。 ................. 家族の悲劇 1865年、ベル一家がロンドンに引っ越すと、ベルはアシスタントマスターとしてウェストンハウスに戻り、空き時間に最小限の実験装置を使って音の実験を 続けていた[40]。ベルは音を伝えるための電気の実験に集中し、後にサマセット・カレッジの自分の部屋から友人の部屋に電信線を設置した[41]。 1867年後半にかけて、主に疲労のために健康状態が悪くなった。弟のエドワード・テッドも同様に結核に冒されていた。ベルは回復し、翌年にはイギリスの バースにあるサマーセット・カレッジで教官を務めるが、弟の病状は悪化した。エドワードが回復することはなかった。兄の死を受けて、ベルは1867年に帰 国した。兄のメルヴィルは結婚して家を出ていた。ベルは、ロンドン大学(University College London)の学位取得を目指し、次の数年間は学位試験の準備期間と考え、実家で暇を見つけては勉強に励んだ。 父親がやっていたVisible Speechのデモンストレーションや講義を手伝ううちに、ベルはロンドンのサウスケンジントンにあるスザンナ・E・ハルの私立聾学校へ行くことになっ た。最初の生徒2人は、聾唖の少女で、彼の指導の下、目覚しい成長を遂げた。兄が聾学校の開校、発明の特許申請、家庭の確立など、さまざまな面で成功を収 めているように見える中、ベルは教師を続けていた。しかし、1870年5月、メルヴィルが結核の合併症で亡くなり、一家の危機が訪れる。しかし、1870 年5月、メルビルが結核を併発して亡くなり、一家は危機に陥った。父親も早くに病気で衰弱し、ニューファンドランドで療養して健康を回復していた。ベルの 両親は、残された息子も病弱であることを知り、長い間計画していた引っ越しに踏み切った。アレクサンダー・メルヴィル・ベルは断固として行動し、ベルに家 財の売却を手配し[42][N 6]、兄のすべての事務を終了し(ベルが最後の生徒を引き受け、顕著な舌打ちを治した)[43]、父と母と共に「新世界」に向けて出発するよう依頼した。 不本意ながら、ベルはマリー・エクルストンとの関係も終結させなければならなかったが、彼の推測通り、彼女は彼と共にイギリスを離れる用意はなかった [44]。 |

| Canada... Bell

Homestead National Historic Site. Melville House, the Bells' first home in North America, now a National Historic Site of Canada In 1870, 23-year-old Bell travelled with his parents and his brother's widow, Caroline Margaret Ottaway,[45] to Paris, Ontario,[46] to stay with Thomas Henderson, a Baptist minister and family friend.[47] The Bell family soon purchased a farm of 10.5 acres (42,000 m2) at Tutelo Heights (now called Tutela Heights), near Brantford, Ontario. The property consisted of an orchard, large farmhouse, stable, pigsty, hen-house, and a carriage house, which bordered the Grand River.[48][N 7] At the homestead, Bell set up his own workshop in the converted carriage house near to what he called his "dreaming place",[50] a large hollow nestled in trees at the back of the property above the river.[51] Despite his frail condition upon arriving in Canada, Bell found the climate and environs to his liking, and rapidly improved.[52][N 8] He continued his interest in the study of the human voice and when he discovered the Six Nations Reserve across the river at Onondaga, he learned the Mohawk language and translated its unwritten vocabulary into Visible Speech symbols. For his work, Bell was awarded the title of Honorary Chief and participated in a ceremony where he donned a Mohawk headdress and danced traditional dances.[53][N 9] After setting up his workshop, Bell continued experiments based on Helmholtz's work with electricity and sound.[54] He also modified a melodeon (a type of pump organ) so that it could transmit its music electrically over a distance.[55] Once the family was settled in, both Bell and his father made plans to establish a teaching practice and in 1871, he accompanied his father to Montreal, where Melville was offered a position to teach his System of Visible Speech. Work with the deaf Bell's father was invited by Sarah Fuller, principal of the Boston School for Deaf Mutes (later to become the public Horace Mann School for the Deaf)[56] to introduce the Visible Speech System by providing training for Fuller's instructors, but he declined the post in favour of his son. Travelling to Boston in April 1871, Bell proved successful in training the school's instructors.[57] He was subsequently asked to repeat the programme at the American Asylum for Deaf-mutes in Hartford, Connecticut, and the Clarke School for the Deaf in Northampton, Massachusetts. Returning home to Brantford after six months abroad, Bell continued his experiments with his "harmonic telegraph".[58][N 10] The basic concept behind his device was that messages could be sent through a single wire if each message was transmitted at a different pitch, but work on both the transmitter and receiver was needed.[59] Unsure of his future, he contemplated returning to London to complete his studies, but decided to return to Boston as a teacher.[60] His father helped him set up his private practice by contacting Gardiner Greene Hubbard, the president of the Clarke School for the Deaf for a recommendation. Teaching his father's system, in October 1872, Alexander Bell opened his "School of Vocal Physiology and Mechanics of Speech" in Boston, which attracted a large number of deaf pupils, with his first class numbering 30 students.[61][62] While he was working as a private tutor, one of his pupils was Helen Keller, who came to him as a young child unable to see, hear, or speak. She was later to say that Bell dedicated his life to the penetration of that "inhuman silence which separates and estranges".[63] In 1893, Keller performed the sod-breaking ceremony for the construction of Bell's new Volta Bureau, dedicated to "the increase and diffusion of knowledge relating to the deaf".[64][65] Throughout his lifetime, Bell sought to integrate the deaf and hard of hearing with the hearing world. Bell encouraged speech therapy and lip reading over sign language. He outlined this in a 1898 paper[66] detailing his belief that with resources and effort, the deaf could be taught to read lips and speak (known as oralism)[67] thus enabling their integration within the wider society.[68] Bell has been criticised by members of the Deaf community for supporting ideas that could cause the closure of dozens of deaf schools, and what some consider eugenicist ideas.[69] Bell did not support a ban on deaf people marrying each other, an idea articulated by the National Association of the Deaf (United States).[70] Although, in his memoir Memoir upon the Formation of a Deaf Variety of the Human Race, Bell observed that if deaf people tended to marry other deaf people, this could result in the emergence of a "deaf race".[71] Ultimately, in 1880, the Second International Congress on Education of the Deaf passed a resolution preferring the teaching of oral communication rather than signing in schools. Bell, top right, providing pedagogical instruction to teachers at the Boston School for Deaf Mutes, 1871. Throughout his life, he referred to himself as "a teacher of the deaf". |

カナダ時代 ベル夫妻が北米で最初に住んだメルヴィル・ハウスは、現在カナダ国定史跡に指定されている。 1870年、23歳のベルは両親と兄の未亡人であるキャロライン・マーガレット・オッタウェイ[45]とともにオンタリオ州パリに行き、バプティスト派の 牧師で家族の友人であるトーマス・ヘンダーソンの家に滞在した[47]。ベル一家はすぐにオンタリオ州ブラントフォード近くのトゥテロ・ハイツ(現在の トゥテラ・ハイツ)に10.5エーカー(42000m2)の農地を購入することになる。その敷地は果樹園、大きな農家、馬小屋、豚小屋、鶏小屋、馬車小屋 からなり、グランド川に面していた[48][N 7] 。 ベルはホームステッドで、彼が「夢の場所」と呼ぶ、川の上の敷地の奥にある木々に囲まれた大きなくぼみの近くにある改造された馬車小屋に自分の工房を設置 した[51]。カナダに到着したときには体が弱かったものの、ベルは気候と環境が彼の好みに合っていると感じ、急速に上達していった[52][N 8]。 [52][N 8] 彼は人間の声の研究に興味を持ち続け、川の向こうのオノンダガにあるシックスネイションズ保護区を発見すると、モホーク語を学び、その書かれていない語彙 を可視音声の記号に翻訳することに成功した。その功績により、ベルは名誉酋長の称号を与えられ、モホークの頭飾りをつけて伝統舞踊を踊る式典に参加した [53][N 9]。 また、メロディオン(ポンプ式オルガンの一種)を改造し、音楽を電気的に遠くまで伝えることができるようにした[55]。 家族が落ち着くと、ベルと彼の父親は教える仕事を確立する計画を立て、1871年に彼は父親とモントリオールに行き、メルヴィルは彼の可視音声のシステム を教えるポジションを提供されることになった。 ろう者との共同作業 ベルの父親は、ボストン聾唖学校(後に公立のホレス・マン聾学校)の校長サラ・フラーから、フラーの教官を訓練して可視音声システムを導入するように誘わ れたが[56]、息子に代わってその任を辞退した。その後、コネチカット州ハートフォードのアメリカンアサイラムやマサチューセッツ州ノーサンプトンのク ラーク聾学校でも同様のプログラムを行うよう要請された[57]。 6ヶ月の海外生活を終えてブラントフォードに戻ったベルは、「調和電信」の実験を続けた[58][N 10] 彼の装置の基本コンセプトは、それぞれのメッセージを異なるピッチで送信すれば1本のワイヤーでメッセージを送ることができるというものだったが、送信機 と受信機の両方に細工が必要だった[59]。 父親がクラークろう学校校長のガーディナー・グリーン・ハバードに連絡を取り、推薦を受けることで個人事業を立ち上げることができた[60]。父のシステ ムを教え、1872年10月、アレクサンダー・ベルはボストンで「発声生理学と発声力学の学校」を開校し、多くのろう者の生徒を集め、最初のクラスの生徒 数は30人だった[61][62]。 彼が家庭教師として働いていたとき、生徒の一人にヘレン・ケラーがいた。彼女は見ることも聞くことも話すこともできない幼少期に彼のもとに来たのである。 彼女は後に、ベルが「分離し疎遠にする非人間的な沈黙」の浸透に人生を捧げたと語っている[63]。 1893年、ケラーは「聾に関する知識の増大と普及」に捧げられたベルの新しいボルタ局建設のための起工式を行った[64][65]。 ベルは生涯を通じて、聴覚障害者を健聴者の世界に統合することを目指した。ベルは手話よりも言語療法と読唇術を奨励した。彼はこのことを1898年の論文 [66]で概説し、資源と努力さえあれば、ろう者は唇を読み、話すことを教えられる(オーラリズムとして知られる)[67]という信念を詳述し、それに よってより広い社会の中での彼らの統合を可能にした。 ベルは、何十ものろう学校の閉鎖を引き起こすようなアイデアや、優生学的アイデアと考えられるものを支持したために、ろう者のコミュニティのメンバーに よって批判されてきた[68]。 [69] ベルは、全米ろう者協会が提唱するろう者同士の結婚の禁止を支持しなかった[70]。しかし、ベルは、「人類のろう者種の形成に関する回想録」の中で、ろ う者が他のろう者と結婚する傾向があれば、それは「ろう者種」の出現をもたらすかもしれないと述べている。 [最終的に、1880年の第2回国際ろう者教育会議で、学校では手話ではなく、口頭でのコミュニケーションを教えることが望ましいという決議がなされた。 |

| Continuing experimentation In 1872, Bell became professor of Vocal Physiology and Elocution at the Boston University School of Oratory. During this period, he alternated between Boston and Brantford, spending summers in his Canadian home. At Boston University, Bell was "swept up" by the excitement engendered by the many scientists and inventors residing in the city. He continued his research in sound and endeavored to find a way to transmit musical notes and articulate speech, but although absorbed by his experiments, he found it difficult to devote enough time to experimentation. While days and evenings were occupied by his teaching and private classes, Bell began to stay awake late into the night, running experiment after experiment in rented facilities at his boarding house. Keeping "night owl" hours, he worried that his work would be discovered and took great pains to lock up his notebooks and laboratory equipment. Bell had a specially made table where he could place his notes and equipment inside a locking cover.[72] Worse still, his health deteriorated as he had severe headaches.[59] Returning to Boston in fall 1873, Bell made a far-reaching decision to concentrate on his experiments in sound. Deciding to give up his lucrative private Boston practice, Bell retained only two students, six-year-old "Georgie" Sanders, deaf from birth, and 15-year-old Mabel Hubbard. Each pupil would play an important role in the next developments. George's father, Thomas Sanders, a wealthy businessman, offered Bell a place to stay in nearby Salem with Georgie's grandmother, complete with a room to "experiment". Although the offer was made by George's mother and followed the year-long arrangement in 1872 where her son and his nurse had moved to quarters next to Bell's boarding house, it was clear that Mr. Sanders was backing the proposal. The arrangement was for teacher and student to continue their work together, with free room and board thrown in.[73] Mabel was a bright, attractive girl who was ten years Bell's junior but became the object of his affection. Having lost her hearing after a near-fatal bout of scarlet fever close to her fifth birthday,[74][75][N 11] she had learned to read lips but her father, Gardiner Greene Hubbard, Bell's benefactor and personal friend, wanted her to work directly with her teacher.[76] |

継続的な実験 1872年、ベルはボストン大学弁論部の発声生理学と雄弁術の教授に就任した。この間、彼はボストンとブラントフォードを交互に訪れ、夏にはカナダの自宅 で過ごした。ボストン大学でベルは、この街に住む多くの科学者や発明家たちが巻き起こす興奮に巻き込まれた。音の研究を続け、音符の伝達や発声の方法を見 つけようとしたが、実験に没頭する一方で、十分な時間を割くことができなかった。日夜、教育や個人授業に追われる中、ベルは夜遅くまで起きて、下宿の施設 を借りて実験に次ぐ実験を行うようになった。夜更かしが続くと、自分の研究がばれるのではないかと心配になり、ノートや実験器具に鍵をかけたりして、細心 の注意を払った。1873年秋にボストンに戻ったベルは、音の実験に専念することを決意する[59]。 ボストンでの儲かる個人診療所をあきらめ、ベルは、生まれつき耳が聞こえない6歳の「ジョージー」サンダースと15歳のメイベル・ハバードという2人の生 徒だけを残した。この2人の生徒が、その後の発展で重要な役割を果たすことになる。ジョージの父で裕福な実業家のトーマス・サンダースは、ベルにセーラム の近くにあるジョージーの祖母の家に滞在する場所を提供し、「実験」のための部屋も用意してくれた。この申し出はジョージの母親が行ったもので、1872 年に息子と看護師がベルの下宿の隣の宿舎に移り住んだ1年間の取り決めに続くものだったが、サンダース氏がこの提案を後押ししていることは明らかだった。 これは、教師と生徒が一緒に仕事を続け、部屋代と食事代は無料というものであった[73]。メイベルは明るく魅力的な少女で、ベルの10歳年下だったが、 彼の愛情の対象になっていた。5歳の誕生日間近に猩紅熱にかかり、聴力を失った彼女は、唇を読むことを学んでいたが、彼女の父親でベルの後援者であり個人 的な友人でもあるガーディナー・グリーン・ハバードが、彼女に直接先生と仕事をして欲しいと願っていた[76]。 |

| The

telephone. By 1874, Bell's initial work on the harmonic telegraph had entered a formative stage, with progress made both at his new Boston "laboratory" (a rented facility) and at his family home in Canada a big success.[N 12] While working that summer in Brantford, Bell experimented with a "phonautograph", a pen-like machine that could draw shapes of sound waves on smoked glass by tracing their vibrations. Bell thought it might be possible to generate undulating electrical currents that corresponded to sound waves.[78] Bell also thought that multiple metal reeds tuned to different frequencies like a harp would be able to convert the undulating currents back into sound. But he had no working model to demonstrate the feasibility of these ideas.[79] In 1874, telegraph message traffic was rapidly expanding and in the words of Western Union President William Orton, had become "the nervous system of commerce". Orton had contracted with inventors Thomas Edison and Elisha Gray to find a way to send multiple telegraph messages on each telegraph line to avoid the great cost of constructing new lines.[80] When Bell mentioned to Gardiner Hubbard and Thomas Sanders that he was working on a method of sending multiple tones on a telegraph wire using a multi-reed device, the two wealthy patrons began to financially support Bell's experiments.[81] Patent matters would be handled by Hubbard's patent attorney, Anthony Pollok.[82] In March 1875, Bell and Pollok visited the scientist Joseph Henry, who was then director of the Smithsonian Institution, and asked Henry's advice on the electrical multi-reed apparatus that Bell hoped would transmit the human voice by telegraph. Henry replied that Bell had "the germ of a great invention". When Bell said that he did not have the necessary knowledge, Henry replied, "Get it!" That declaration greatly encouraged Bell to keep trying, even though he did not have the equipment needed to continue his experiments, nor the ability to create a working model of his ideas. However, a chance meeting in 1874 between Bell and Thomas A. Watson, an experienced electrical designer and mechanic at the electrical machine shop of Charles Williams, changed all that. With financial support from Sanders and Hubbard, Bell hired Thomas Watson as his assistant,[N 13] and the two of them experimented with acoustic telegraphy. On June 2, 1875, Watson accidentally plucked one of the reeds and Bell, at the receiving end of the wire, heard the overtones of the reed; overtones that would be necessary for transmitting speech. That demonstrated to Bell that only one reed or armature was necessary, not multiple reeds. This led to the "gallows" sound-powered telephone, which could transmit indistinct, voice-like sounds, but not clear speech. |

電話 1874年までに、ベルの調和電信に関する初期の研究は形成段階に入り、ボストンの新しい「研究所」(借用施設)とカナダの実家の両方での進展は大きな成 功を収めていた[N 12] その夏、Brantfordで仕事をしていたベルは、「フォノトグラフ」という、音波の振動をなぞってスモークガラスにその形を描けるペン状の機械で実験 を行っている。ベルは、音波に対応するうねるような電流を発生させることができるかもしれないと考えた[78]。またベルは、ハープのように異なる周波数 に調律された複数の金属のリードが、うねる電流を再び音に変換することができるかもしれないと考えた。しかし、彼はこれらのアイデアの実現可能性を実証す るための実用的なモデルを持っていなかった[79]。 1874年、電信メッセージのトラフィックは急速に拡大し、ウエスタンユニオン社長のウィリアム・オートンの言葉を借りれば、「商業の神経系」となってい た。ベルがガーディナー・ハバードとトーマス・サンダースに、マルチリード装置を使って電信線に複数のトーンを送る方法を研究していると話したところ、2 人の裕福な後援者はベルの実験を財政的に支援し始めた[81]。 特許に関することは、ハバードの特許弁護士アンソニー・ポロックが扱うことになる[82]。 1875年3月、ベルとポロックは、当時スミソニアン博物館の館長だった科学者ジョセフ・ヘンリーを訪ね、ベルが人間の声を電信で伝えることを望んでいた 電気マルチリード装置について、ヘンリーの助言を仰いだ。ヘンリーは、ベルは「偉大な発明の芽を持っている」と答えた。必要な知識がないと言うベルに、ヘ ンリーは "Get it!"と答えた。この宣言は、実験を続けるための設備も、自分のアイデアの実用的なモデルを作る能力もなかったベルを大いに勇気づけた。しかし、 1874年、ベルと、チャールズ・ウィリアムズの電気機械工場で電気設計と整備に携わっていたトーマス・A・ワトソンとの偶然の出会いが、すべてを変えて しまったのだ。 サンダースとハバードからの資金援助を受けて、ベルはワトソンを助手として雇い[N 13]、二人は音響電信の実験を行った。1875年6月2日、ワトソンは誤ってリードの1本を弾いてしまい、電線の受信側にいたベルは、音声の伝送に必要 なリードの倍音を聞いてしまったのである。その結果、ベルは、複数のリードではなく、1本のリード(アーマチュア)が必要であることを証明した。この結 果、「ギャローズ」と呼ばれる音で動く電話機が誕生したのである。 |

| The race to the patent office In 1875, Bell developed an acoustic telegraph and drew up a patent application for it. Since he had agreed to share U.S. profits with his investors Gardiner Hubbard and Thomas Sanders, Bell requested that an associate in Ontario, George Brown, attempt to patent it in Britain, instructing his lawyers to apply for a patent in the U.S. only after they received word from Britain (Britain would issue patents only for discoveries not previously patented elsewhere).[84] Meanwhile, Elisha Gray was also experimenting with acoustic telegraphy and thought of a way to transmit speech using a water transmitter. On February 14, 1876, Gray filed a caveat with the U.S. Patent Office for a telephone design that used a water transmitter. That same morning, Bell's lawyer filed Bell's application with the patent office. There is considerable debate about who arrived first and Gray later challenged the primacy of Bell's patent. Bell was in Boston on February 14 and did not arrive in Washington until February 26.[citation needed] Bell's patent 174,465, was issued to Bell on March 7, 1876, by the U.S. Patent Office. Bell's patent covered "the method of, and apparatus for, transmitting vocal or other sounds telegraphically ... by causing electrical undulations, similar in form to the vibrations of the air accompanying the said vocal or other sound"[86][N 14] Bell returned to Boston the same day and the next day resumed work, drawing in his notebook a diagram similar to that in Gray's patent caveat.[citation needed] On March 10, 1876, three days after his patent was issued, Bell succeeded in getting his telephone to work, using a liquid transmitter similar to Gray's design. Vibration of the diaphragm caused a needle to vibrate in the water, varying the electrical resistance in the circuit. When Bell spoke the sentence "Mr. Watson—Come here—I want to see you" into the liquid transmitter,[87] Watson, listening at the receiving end in an adjoining room, heard the words clearly.[88] Although Bell was, and still is, accused of stealing the telephone from Gray,[89] Bell used Gray's water transmitter design only after Bell's patent had been granted, and only as a proof of concept scientific experiment,[90] to prove to his own satisfaction that intelligible "articulate speech" (Bell's words) could be electrically transmitted.[91] After March 1876, Bell focused on improving the electromagnetic telephone and never used Gray's liquid transmitter in public demonstrations or commercial use.[92] The question of priority for the variable resistance feature of the telephone was raised by the examiner before he approved Bell's patent application. He told Bell that his claim for the variable resistance feature was also described in Gray's caveat. Bell pointed to a variable resistance device in his previous application in which he described a cup of mercury, not water. He had filed the mercury application at the patent office a year earlier on February 25, 1875, long before Elisha Gray described the water device. In addition, Gray abandoned his caveat, and because he did not contest Bell's priority, the examiner approved Bell's patent on March 3, 1876. Gray had reinvented the variable resistance telephone, but Bell was the first to write down the idea and the first to test it in a telephone.[93] The patent examiner, Zenas Fisk Wilber, later stated in an affidavit that he was an alcoholic who was much in debt to Bell's lawyer, Marcellus Bailey, with whom he had served in the Civil War. He claimed he showed Gray's patent caveat to Bailey. Wilber also claimed (after Bell arrived in Washington D.C. from Boston) that he showed Gray's caveat to Bell and that Bell paid him $100 (equivalent to $2,500 in 2021). Bell claimed they discussed the patent only in general terms, although in a letter to Gray, Bell admitted that he learned some of the technical details. Bell denied in an affidavit that he ever gave Wilber any money.[94] |

特許庁との競争 1875年、ベルは音響電信機を開発し、特許申請書を作成した。ベルは、アメリカでの利益を出資者のガーディナー・ハバードとトーマス・サンダースに分配 することに合意していたので、オンタリオ州の同僚であるジョージ・ブラウンに、イギリスで特許を試みることを依頼し、弁護士にはイギリスから連絡が来てか らアメリカでの特許を申請するように指示した(イギリスは、他の場所で既に特許を取得していない発見のみ特許を発行する)[84]。 一方、エリシャ・グレイも音響電信の実験を行っており、水上送信機を使って音声を送信する方法を考えていた。1876年2月14日、グレイは水上送信機を 使った電話機の設計を米国特許庁に申請した。同じ日の朝、ベルの弁護士がベルの出願書類を特許庁に提出した。どちらが先に到着したかについてはかなりの議 論があり、グレイは後にベルの特許の優位性に異議を唱えた。ベルは2月14日にボストンにいて、ワシントンに到着したのは2月26日であった [citation needed]。 ベルの特許174,465は、1876年3月7日に米国特許庁からベルに発行された。ベルの特許は「声音またはその他の音を電信的に伝達する方法およびそ のための装置...前記声音またはその他の音に伴う空気の振動に似た形の電気的起伏を引き起こすことによって」を対象とした[86][N 14] ベルは同日にボストンに戻り、翌日に仕事を再開、グレーの特許警告に似た図を彼のノートに描き[citation needed]、この図が「グレーの特許警告」[notification]に記載された。 特許が発行されてから3日後の1876年3月10日、ベルはグレイの設計と同じような液体発信器を使い、電話を作動させることに成功した。これは、グレイ が考案したものと同じもので、振動板を振動させると、水中で針が振動し、回路の電気抵抗が変化する仕組みになっていた。ベルが「Mr. Watson-Come here-I want to see you」という文章を液体送信機に話しかけると、隣室で受信側を聞いていたワトソンにはその言葉がはっきりと聞こえた[88]。 ベルは、グレイから電話を盗んだと非難されたが[89]、グレイの水送機の設計を使ったのは、ベルの特許が認められた後であり、コンセプトの証明の科学実 験としてのみであり、理解しやすい「明瞭な音声」(ベルの言葉)を電気的に送信できることを彼自身が満足するように証明した[91]。 1876年3月以降、ベルは電磁電話の改善に注力し、グレイの水送機は公共のデモンストレーションにも商業利用にも決して使われることはなかった [92]。 電話の可変抵抗機能に対する優先権の問題は、審査官がベルの特許出願を承認する前に提起された。彼はベルに、可変抵抗機能に関する彼のクレームはグレイの 注意書きにも記載されていると言った。ベルは、以前の出願で、水ではなく、水銀の入ったカップを記載した可変抵抗装置を指摘した。ベルは、水銀を使った装 置を1年前の1875年2月25日に特許庁に出願しており、エリシャ・グレイが水の装置を説明するずっと前に、この水銀を使った装置を出願していたのであ る。さらに、グレイは注意書きを放棄し、ベルの優先権に異議を唱えなかったため、審査官は1876年3月3日、ベルの特許を承認している。グレイは可変抵 抗電話を再発明していたが、ベルはそのアイデアを最初に書き留め、最初に電話でテストしたのである[93]。 特許審査官のゼナス・フィスク・ウィルバーは、アルコール依存症で、南北戦争で共に戦ったベルの弁護士マーセラス・ベイリーに多額の借金があったと後に宣 誓供述している。彼は、グレイの特許の但し書きをベイリーに見せたと主張している。また、ウィルバーは、(ベルがボストンからワシントンD.C.に到着し た後)グレイの但し書きをベルに見せ、ベルは彼に100ドル(2021年の2500ドルに相当)を支払ったと主張している。ベルは、二人は特許について一 般論だけを議論したと主張したが、グレイへの手紙の中で、ベルは技術的な詳細の一部を知ったことを認めている。ベルは宣誓供述書でウィルバーに金銭を渡し たことを否定している[94]。 |

| Later developments On March 10, 1876, Bell used "the instrument" in Boston to call Thomas Watson who was in another room but out of earshot. He said, "Mr. Watson, come here – I want to see you" and Watson soon appeared at his side.[95] Continuing his experiments in Brantford, Bell brought home a working model of his telephone. On August 3, 1876, from the telegraph office in Brantford, Ontario, Bell sent a tentative telegram to the village of Mount Pleasant four miles (six kilometres) distant, indicating that he was ready. He made a telephone call via telegraph wires and faint voices were heard replying. The following night, he amazed guests as well as his family with a call between the Bell Homestead and the office of the Dominion Telegraph Company in Brantford along an improvised wire strung up along telegraph lines and fences, and laid through a tunnel. This time, guests at the household distinctly heard people in Brantford reading and singing. The third test on August 10, 1876, was made via the telegraph line between Brantford and Paris, Ontario, eight miles (thirteen kilometres) distant. This test was said by many sources to be the "world's first long-distance call".[96][97] The final test certainly proved that the telephone could work over long distances, at least as a one-way call. [98] The first two-way (reciprocal) conversation over a line occurred between Cambridge and Boston (roughly 2.5 miles) on October 9, 1876.[99] During that conversation, Bell was on Kilby Street in Boston and Watson was at the offices of the Walworth Manufacturing Company.[100] Bell and his partners, Hubbard and Sanders, offered to sell the patent outright to Western Union for $100,000, equal to $2,544,688 today. The president of Western Union balked, countering that the telephone was nothing but a toy. Two years later, he told colleagues that if he could get the patent for $25 million (equal to $701,982,759 today), he would consider it a bargain. By then, the Bell company no longer wanted to sell the patent.[101] Bell's investors would become millionaires while he fared well from residuals and at one point had assets of nearly one million dollars.[102] Bell began a series of public demonstrations and lectures to introduce the new invention to the scientific community as well as the general public. A short time later, his demonstration of an early telephone prototype at the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia brought the telephone to international attention.[103] Influential visitors to the exhibition included Emperor Pedro II of Brazil. One of the judges at the Exhibition, Sir William Thomson (later, Lord Kelvin), a renowned Scottish scientist, described the telephone as "the greatest by far of all the marvels of the electric telegraph".[104] On January 14, 1878, at Osborne House, on the Isle of Wight, Bell demonstrated the device to Queen Victoria,[105] placing calls to Cowes, Southampton and London. These were the first publicly witnessed long-distance telephone calls in the UK. The queen considered the process to be "quite extraordinary" although the sound was "rather faint".[106] She later asked to buy the equipment that was used, but Bell offered to make "a set of telephones" specifically for her.[107][108] The Bell Telephone Company was created in 1877, and by 1886, more than 150,000 people in the U.S. owned telephones. Bell Company engineers made numerous other improvements to the telephone, which emerged as one of the most successful products ever. In 1879, the Bell company acquired Edison's patents for the carbon microphone from Western Union. This made the telephone practical for longer distances, and it was no longer necessary to shout to be heard at the receiving telephone.[citation needed] Emperor Pedro II of Brazil was the first person to buy stock in Bell's company, the Bell Telephone Company. One of the first telephones in a private residence was installed in his palace in Petrópolis, his summer retreat forty miles (sixty-four kilometres) from Rio de Janeiro.[109] In January 1915, Bell made the first ceremonial transcontinental telephone call. Calling from the AT&T head office at 15 Dey Street in New York City, Bell was heard by Thomas Watson at 333 Grant Avenue in San Francisco. The New York Times reported: On October 9, 1876, Alexander Graham Bell and Thomas A. Watson talked by telephone to each other over a two-mile wire stretched between Cambridge and Boston. It was the first wire conversation ever held. Yesterday afternoon [on January 25, 1915], the same two men talked by telephone to each other over a 3,400-mile wire between New York and San Francisco. Dr. Bell, the veteran inventor of the telephone, was in New York, and Mr. Watson, his former associate, was on the other side of the continent.[11 |

その後の展開 1876年3月10日、ベルはボストンで「装置」を使って、別の部屋にいて聞こえないところにいたトーマス・ワトソンを呼び出した。彼は「ワトソンさん、 こっちへ来てください-あなたに会いたいのです」と言うと、ワトソンはすぐに彼のそばに現れた[95]。 ベルはブラントフォードで実験を続け、電話の実用的なモデルを持ち帰った。1876年8月3日、ベルはオンタリオ州ブラントフォードの電信局から、4マイ ル(6キロメートル)離れたマウントプレザントの村に仮の電報を送り、準備ができたことを知らせた。そして、電信線を使って電話をかけると、かすかな声が 返ってきた。翌日の夜、ベル・ホームステッドとブラントフォードのドミニオン電信会社の事務所を、電信線とフェンスに張り巡らされた即席の電線とトンネル を通して通話し、来客と家族を驚かせた。この時は、ブラントフォードの人たちが本を読んだり、歌を歌ったりしているのがはっきりと聞こえた。1876年8 月10日の3回目のテストは、ブラントフォードと8マイル(13キロメートル)離れたオンタリオ州パリスの間の電信線を使って行われた。このテストは、多 くの情報源から「世界初の長距離通話」であると言われていた[96][97]。最後のテストは、少なくとも片方向通話として、電話が長距離で機能すること を確実に証明した[98]。[98] 1876年10月9日にケンブリッジとボストンの間(およそ2.5マイル)で、回線を介した最初の双方向(相互)会話が行われた[99]。その会話中、ベ ルはボストンのKilby Streetに、ワトソンはWalworth Manufacturing Companyの事務所にいた[100]。 ... |

| Competitors As is sometimes common in scientific discoveries, simultaneous developments can occur, as evidenced by a number of inventors who were at work on the telephone.[111] Over a period of 18 years, the Bell Telephone Company faced 587 court challenges to its patents, including five that went to the U.S. Supreme Court,[112] but none was successful in establishing priority over the original Bell patent[113][114] and the Bell Telephone Company never lost a case that had proceeded to a final trial stage.[113] Bell's laboratory notes and family letters were the key to establishing a long lineage to his experiments.[113] The Bell company lawyers successfully fought off myriad lawsuits generated initially around the challenges by Elisha Gray and Amos Dolbear. In personal correspondence to Bell, both Gray and Dolbear had acknowledged his prior work, which considerably weakened their later claims.[115] On January 13, 1887, the U.S. Government moved to annul the patent issued to Bell on the grounds of fraud and misrepresentation. After a series of decisions and reversals, the Bell company won a decision in the Supreme Court, though a couple of the original claims from the lower court cases were left undecided.[116][117] By the time that the trial wound its way through nine years of legal battles, the U.S. prosecuting attorney had died and the two Bell patents (No. 174,465 dated March 7, 1876, and No. 186,787 dated January 30, 1877) were no longer in effect, although the presiding judges agreed to continue the proceedings due to the case's importance as a precedent. With a change in administration and charges of conflict of interest (on both sides) arising from the original trial, the US Attorney General dropped the lawsuit on November 30, 1897, leaving several issues undecided on the merits.[118] During a deposition filed for the 1887 trial, Italian inventor Antonio Meucci also claimed to have created the first working model of a telephone in Italy in 1834. In 1886, in the first of three cases in which he was involved,[N 15] Meucci took the stand as a witness in the hope of establishing his invention's priority. Meucci's testimony in this case was disputed due to a lack of material evidence for his inventions, as his working models were purportedly lost at the laboratory of American District Telegraph (ADT) of New York, which was later incorporated as a subsidiary of Western Union in 1901.[119][120] Meucci's work, like many other inventors of the period, was based on earlier acoustic principles and despite evidence of earlier experiments, the final case involving Meucci was eventually dropped upon Meucci's death.[121] However, due to the efforts of Congressman Vito Fossella, the U.S. House of Representatives on June 11, 2002, stated that Meucci's "work in the invention of the telephone should be acknowledged".[122][123][124] This did not put an end to the still-contentious issue.[125] Some modern scholars do not agree with the claims that Bell's work on the telephone was influenced by Meucci's inventions.[126][N 16] The value of the Bell patent was acknowledged throughout the world, and patent applications were made in most major countries, but when Bell delayed the German patent application, the electrical firm of Siemens & Halske set up a rival manufacturer of Bell telephones under their own patent. The Siemens company produced near-identical copies of the Bell telephone without having to pay royalties.[127] The establishment of the International Bell Telephone Company in Brussels, Belgium in 1880, as well as a series of agreements in other countries eventually consolidated a global telephone operation. The strain put on Bell by his constant appearances in court, necessitated by the legal battles, eventually resulted in his resignation from the company.[128][N 17] |

競合他社 科学的発見でよくあるように、同時進行の開発が行われることがあり、それは電話の研究に取り組んでいた多くの発明者たちによって証明されている [111]。 18年の間に、ベル電話会社はその特許に対して587件の法廷闘争に直面し、そのうちの5件は米国連邦裁判所に持ち込まれた[112]。ベル社の弁護士 は、当初エリシャ・グレイとアモス・ドルベアによる挑戦の周囲で発生した無数の訴訟をうまく撃退した。ベルへの個人的な手紙の中で、グレイとドルベアの両 方が彼の以前の研究を認めていたため、彼らの後の主張をかなり弱めることができた[115]。 1887年1月13日、米国政府は詐欺と不実表示を理由にベルに発行された特許を無効にするよう求めた。一連の決定と逆転の後、ベル社は最高裁で判決を勝 ち取ったが、下級審での元々の主張のうちのいくつかは未決定のままであった[116][117]。 しかし、判例としての重要性から、裁判長は裁判を継続することに同意した。政権交代と、原審から生じた(双方の)利益相反の告発により、米国司法長官は 1897年11月30日に訴訟を取り下げ、いくつかの問題が本案で未決定となった[118]。 .... |

| Alexander Graham Bell

Association for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing Alexander Graham Bell National Historic Site Bell Boatyard Bell Homestead National Historic Site Bell Telephone Memorial Berliner, Emile Bourseul, Charles IEEE Alexander Graham Bell Medal John Peirce, submitted telephone ideas to Bell Manzetti, Innocenzo Meucci, Antonio Oriental Telephone Company People on Scottish banknotes Pioneers, a Volunteer Network Reis, Philipp The Story of Alexander Graham Bell, a 1939 movie of his life The Telephone Cases Volta Laboratory and Bureau William Francis Channing, submitted telephone ideas to Bell |

|

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alexander_Graham_Bell |

https://www.deepl.com/ja/translator |

++

(decibel; dB)などに使われる相対単位「ベル」などにその名を残す。

| 1865年、ベル一

家はロンドンに引っ越したが[33]、アレック本人はウェストンハウス学院に助手として戻り、空いた時間で最小限の実験器具を使って音響についての実験を

続けた。おもに電気で音声を伝送する実験を行い、のちに自分の部屋から友人の部屋まで電信線を引いた[34]。1867年後半には極度の疲労で健康を害し

ている。弟エドワードも結核にかかり、同様に寝たきりとなった。アレックは翌年には回復し、イングランドのバースにあるサマーセット大学(英語版)で講師

を務めたが、弟の病状は悪化した。結局エドワードはそのまま亡くなり、アレックはロンドンに戻っている。兄メルヴィルは結婚して実家を出ている。ユニ

ヴァーシティ・カレッジ・ロンドンで学位を得るという目標を定め、学位試験のための勉強をし、空いた時間も実家での勉強に充てた。父の視話法のデモンスト

レーションと講義も手伝い、ロンドンのサウス・ケンジントンにあったスザンナ・E・ハルの私立聾学校を知るようになる。彼が最初に教えたのはそこの2人の

聾唖の少女で、2人は彼の指導でみるみる上達した。兄は弁論術の学校を開校し特許も取得するなど、ある程度の成功を収めていた。しかし1870年5月、兄

が結核をこじらせて亡くなり、一家の危機が訪れた。父も若いころかかった病気がぶりかえしたため、ニューファンドランド島(カナダ)で療養することにし

た。唯一生き残った息子であるアレックも病弱だと気付いた両親は、長期的移住の計画を立て始めた。父は断固として計画を推し進め、ベルに一家の財産の処分

をさせ[35][注釈

6]、兄の残した仕事の後始末をさせ(アレックは兄の学校の最後の生徒の面倒を見て、発音の矯正を行った)[36]、両親とともに「新世界」へ移住した

[37]。当時ベルはマリー・エクレストンという娘に恋心を抱いていたが、彼女はイングランドを離れることに同意しなかったため、しぶしぶ別れた

[37]。 |

ベルの父はマサチューセッツ州ボストンの

ボストン聾学校(現在の Horace Mann School for the

Deaf)[46]校長サラ・フラーに同校のインストラクターに視話法を教えてほしいと頼まれたが、彼はそれを辞退して代わりに息子を推薦した。1871

年4月、ボストンに出向いたベルは首尾よくインストラクターへの視話法伝授を成功させた[47]。続いてコネチカット州ハートフォードにある

American Asylum for Deaf-mutes、マサチューセッツ州ノーサンプトンの Clarke School for the

Deaf

でも同様の仕事をした。当時、猩紅熱(しょうこうねつ)の後遺症で聾者教育が深刻な問題となっていた。6か月後にブラントフォードに戻ると、

"harmonic telegraph" と名付けたものの実験を続けた[48][注釈

10]。彼の意匠の根底にある概念は、1つの導線で複数のメッセージをそれぞれ異なるピッチで送るというものだが、そのための送信機と受信機が新たに必要

だった[49]。将来に確信がないまま彼はロンドンに戻って研究を完成させることも考えたが、結局ボストンに戻って教師をすることにした[50]。父の紹

介で Clarke School for the Deaf

の校長ガーディナー・グリーン・ハバードが彼の開業を支援することになった。1872年10月、ボストンで視話法を教える学校 "School of

Vocal Physiology and Mechanics of Speech"

を開校。多くの若い聾者の注目を集め、開校当初に30人が入学した[51][52]。のちに、当時まだ幼かったヘレン・ケラーと知り合っている。1887

年、ベルはケラーに家庭教師アン・サリヴァンを紹介している。後年ケラーはベルについて、「隔離され隔絶された非人間的な静けさ」に風穴を開けてくれた人

と評した[53]。ベルも含めた当時の影響力のある人々の一部には、聴覚障害を克服すべきものとする見方があり、金と時間をかけ聾者に話し方を教え手話を

使わずに済むようにすることで、それまで閉ざされていた広い世界への道が拓けると信じていた[54]。しかし、当時の学校ではしゃべることを強制的に訓練

するために、手話ができないように手を後ろで縛るといった虐待も行われていた。ベルは手話教育に反対していたため、ろう文化に肯定的な人々はベルを否定的

に評価することがある[55]。 |

| ベ

ルはアメリカでの優生学運動とも関わりがある。1883年11月13日、米国科学アカデミーで Memoir upon the formation

of a deaf variety of the human race

と題した講演を行い、その中で両親が先天的に聾者だった場合に聾者の子が生まれる可能性が高いため、そのような婚姻は避けるべきだと提唱した[138]。

それとは別に家畜の繁殖を趣味として行っており、それが昂じて American

Breeders Association(アメリカ遺伝学会の前身) の保護下にあった生物学者デイビッド・スター・ジョーダン(David Starr Jordan,

1851-1931)の優生学委員会の委員に任命された。この委員会は明らかに優生学をヒトにも拡張適用した[139]。1912年から1918年まで、ニューヨークのコールド・スプリング・ハーバー研究所の優生記

録所の科学諮問委員会委員長を務め、定期会合に出席していた。1921

年、アメリカ自然史博物館が後援した第2回国際優

生学会議(The Second International Eugenics

Congress)の名誉議長を務めた。これらの組織はベルが「不完全な人種」と呼んだ人々の断種を法律化することを提案した(一部の州では実際に法律に

なった)。1930年代後半にはアメリカの半分の州が優生学的な法律を持っており、カリフォルニア州のそれはナチス・ドイツが手本にしたほ

どだった[140]。 |

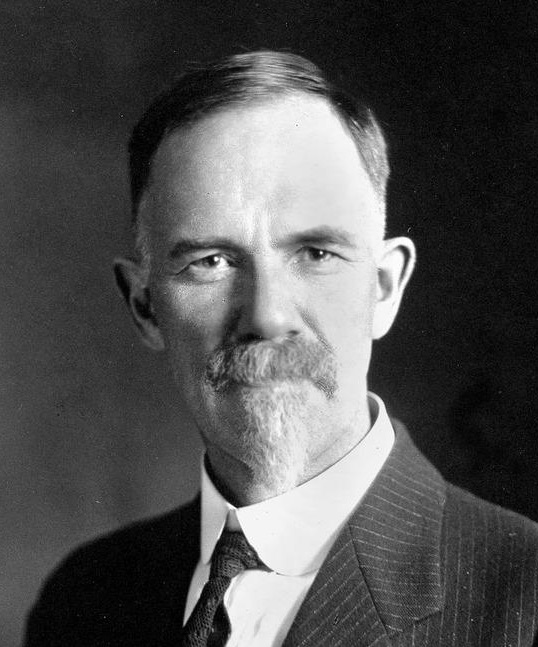

Charles

Benedict Davenport, ca. 1929. Charles

Benedict Davenport, ca. 1929. |

| The

American Genetic Association (AGA) is a USA-based professional

scientific organization dedicated to the study of genetics and genomics

which was founded as the American Breeders' Association in 1903.[1] The

association has published the Journal of Heredity since 1914, which

disseminates peer-reviewed organismal research in areas of general

interest to the genetics and genomics community. Recent articles have

focused on conservation genetics of endangered species and biodiversity

discovery,[2][3] phylogenomics, molecular adaptation and speciation,[4]

and genotype to phenotype associations. The American Breeders Association held its first meeting in 1903 to discuss the “new” science of genetics that arose from Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution and Gregor Mendel’s discoveries of the laws of inheritance.[clarification needed] The organization was established “to study the laws of breeding and to promote the improvement of plants and animals by the development of expert methods of breeding.” [1] In 1914, the American Breeders Association broadened its scope and became the American Genetic Association. Today, the AGA’s interests encompass evolutionary diversity and genomics across taxa and subject areas, including conservation genetics, phylogenetics, phylogeography, gene function, and the genetics of domestication. In 1965 it received a bequest from Wilhelmine Key to support a lecture series which bears her name.[5][6][7] The AGA disseminates progress in these fields through its publication, Journal of Heredity. It supports research and scholarship through sponsorship of an annual President’s Symposium, special events awards, the Stephen J. O’Brien Award, and the Evolutionary, Ecological, or Conservation Genomics Research Awards. The AGA is a 501(c)(3) corporation. |

米

国遺伝学会(AGA)は、1903年に米国育種家協会として設立された、遺伝学とゲノミクスの研究を専門とする米国に本拠を置く学術団体である[1]。

1914年以来、遺伝学とゲノミクスのコミュニティにとって一般的に興味深い分野の生物学的研究についての査読付きジャーナルを発行してきた。最近の論文

は、絶滅危惧種の保全遺伝学や生物多様性の発見、[2][3] 系統遺伝学、分子適応と種分化、[4]

遺伝子型と表現型の関連性などに焦点が当てられている。 アメリカ育種家協会は、チャールズ・ダーウィンの進化論とグレゴール・メンデルの遺伝の法則の発見から生まれた「新しい」遺伝学の科学について議論するた めに1903年に最初の会議を開いた[要確認]。この組織は「育種の法則を研究し、育種の専門的方法の開発によって植物や動物の改善を促進する」ために設 立されたものである[1][要確認]。[1] 1914年、アメリカ育種家協会はその範囲を広げ、アメリカ遺伝学協会となった。今日、AGAの関心は、保全遺伝学、系統学、系統地理学、遺伝子機能、家 畜化の遺伝学など、分類群や対象領域にわたる進化の多様性とゲノミクスに及んでいる。1965年には、ウィルヘルミン・キーから、彼女の名を冠したレク チャーシリーズを支援するための遺贈を受けた[5][6][7]。 AGAは、出版物であるJournal of Heredityを通じて、これらの分野の進歩を広めている。毎年開催される会長シンポジウム、特別イベント賞、スティーブン J. オブライエン賞、進化・生態・保全ゲノミクス研究賞のスポンサーシップを通じて、研究および奨学金を支援している。 AGAは、501(c)(3)法人である。 |

| Heredity

and genetics. Bell, along with many members of the scientific community at the time, took an interest in the popular science of heredity which grew out of the publication of Charles Darwin's book On the Origin of Species in 1859.[173] On his estate in Nova Scotia, Bell conducted meticulously recorded breeding experiments with rams and ewes. Over the course of more than 30 years, Bell sought to produce a breed of sheep with multiple nipples that would bear twins.[174] He specifically wanted to see if selective breeding could produce sheep with four functional nipples with enough milk for twin lambs.[175] This interest in animal breeding caught the attention of scientists focused on the study of heredity and genetics in humans.[176] In November 1883, Bell presented a paper at a meeting of the National Academy of Sciences titled "Upon the Formation of a Deaf Variety of the Human Race".[177] The paper is a compilation of data on the hereditary aspects of deafness. Bell's research indicated that a hereditary tendency toward deafness, as indicated by the possession of deaf relatives, was an important element in determining the production of deaf offspring. He noted that the proportion of deaf children born to deaf parents was many times greater than the proportion of deaf children born to the general population.[178] In the paper, Bell delved into social commentary and discussed hypothetical public policies to bring an end to deafness. He also criticized educational practices that segregated deaf children rather than integrated them fulling into mainstream classrooms. The paper did not propose sterilization of deaf people or prohibition on intermarriage,[179] noting that "We cannot dictate to men and women whom they should marry and natural selection no longer influences mankind to any great extent."[177] A review of Bell's "Memoir upon the Formation of a Deaf Variety of the Human Race" appearing in an 1885 issue of the "American Annals of the Deaf and Dumb" states that "Dr. Bell does not advocate legislative interference with the marriages of the deaf for several reasons one of which is that the results of such marriages have not yet been sufficiently investigated." The article goes on to say that "the editorial remarks based thereon did injustice to the author."[180] The paper's author concludes by saying "A wiser way to prevent the extension of hereditary deafness, it seems to us, would be to continue the investigations which Dr. Bell has so admirable begun until the laws of the transmission of the tendency to deafness are fully understood, and then by explaining those laws to the pupils of our schools to lead them to choose their partners in marriage in such a way that deaf-mute offspring will not be the result."[180] Historians have noted that Bell explicitly opposed laws regulating marriage, and never mentioned sterilization in any of his writings. Even after Bell agreed to engage with scientists conducting eugenic research, he consistently refused to support public policy that limited the rights or privileges of the deaf.[181] Bell's interest and research on heredity attracted the interest of Charles Davenport, a Harvard professor and head of the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory. In 1906, Davenport, who was also the founder of the American Breeder's Association, approached Bell about joining a new committee on eugenics chaired by David Starr Jordan. In 1910, Davenport opened the Eugenics Records office at Cold Spring Harbor. To give the organization scientific credibility, Davenport set up a Board of Scientific Directors naming Bell as chairman.[182] Other members of the board included Luther Burbank, Roswell H. Johnson, Vernon L. Kellogg, and William E. Castle.[182] In 1921, a Second International Congress of Eugenics was held in New York at the Museum of Natural History and chaired by Davenport. Although Bell did not present any research or speak as part of the proceedings, he was named as honorary president as a means to attract other scientists to attend the event.[183] A summary of the event notes that Bell was a "pioneering investigator in the field of human heredity".[183] |

遺伝と遺伝学 ベルは、当時の多くの科学者たちとともに、1859年に出版されたチャールズ・ダーウィンの著書『種の起源』から発展した一般的な遺伝の科学に興味を持っ た[173]。ノ バスコシア州の自分の土地で、ベルは雄羊と雌羊を使って綿密な記録をもとに交配実験を行っていた。30年以上にわたって、ベルは双子を産む複数の乳首を持 つ羊の品種を作ろうとした[174]。 彼は特に、選択的繁殖によって、双子の子羊に十分なミルクを与える4つの機能的乳首を持つ羊を作り出すことができるかどうかを確認したかった[175]。 動物繁殖におけるこの関心は、ヒトにおける遺伝と遺伝学の研究に焦点を当てていた科学者の目に留まった[176]。 1883年11月、ベルは全米科学アカデミーの会合で「人間の聴覚障害 者の変種の形成について」と題する論文を発表した[177]。この論文は聴覚障害の遺伝的側面に関するデータをまとめたものであった。ベルの研究は、聴覚 障害者の親族を持つことで示される聴覚障害への遺伝的傾向が、聴覚障害者の子孫の生産を決定する重要な要素であることを示した。彼は、聴覚障害者の両親か ら生まれた聴覚障害児の割合が、一般集団から生まれた聴覚障害児の割合の何倍もあることを指摘した[178]。論文の中でベルは社会批判を 掘り下げ、聴覚障害をなくすための公共政策の仮定を論じた。彼はまた、聴覚障害児を主流の教室に完全に統合するのではなく、隔離する教育実践を批判した。この論文は、聴覚障害者の不妊手術や異種婚姻の禁止を提案しておらず[179]、「我々は男女 が誰と結婚すべきかを指示することはできず、自然選択はもはや人類に大きな影響を及ぼさない」と指摘している[177]。 1885年の「アメリカ聾唖者年報」に掲載されたベルの「人類の聴覚障 害者の変種の形成に関する覚書」のレビューでは、「ベル博士は、いくつかの理由から聴覚障害者の結婚に対する立法的干渉を提唱していない、その一つはその ような結婚の結果がまだ十分に調査されていないことである。この論文の著者は最後に、「遺伝性難聴の拡大を防ぐより賢明な方法は、ベル博士が立派に始めた 調査を、まだ十分に調査されていない段階まで継続することだと思われる」と述べている[180]。そして、その法則を学校の生徒に説明することによって、 聾唖者の子供が生まれないような結婚相手を選ぶように導くことである」と結んでいる[180]。 歴史家は、ベルが結婚を規制する法律に明確に反対し、どの著作でも不妊手術に言及したことがないことを指摘している。ベルは優生学的な研究を行う科学者と 関わることに同意した後も、一貫して聴覚障害者の権利や特権を制限するような公共政策の支持を拒否していた[181]。 ベルの遺伝に関する関心と研究は、ハーバード大学教授でコールドスプリングハーバー研究所の所長であったチャールズ・ダベンポートの関心を集めた。 1906年、アメリカ育種家協会の創設者でもあるダベンポートは、デイヴィッド・スター・ジョーダンが委員長を務める優生学の新しい委員会に参加すること をベルに持ち掛けた。1910年、ダベンポートはコールド・スプリング・ハーバーに優生学記録局を開設した。この組織に科学的な信頼性を与えるために、ダ ベンポートはベルを委員長とする科学理事会を設立した[182]。理事会の他のメンバーには、ルーサー・バーバンク、ロスウェル・H・ジョンソン、ヴァー ノン・L・ケロッグ、ウィリアム・E・キャッスルが含まれていた[182]。 1921年、第2回国際優生学会議が、ニューヨークの自然史博物館で開催され、ダベンポートが議長を務めた。ベルは研究発表や講演を行わなかったが、他の 科学者をイベントに参加させる手段として名誉会長に指名された[183]。 イベントの概要には、ベルが「人間の遺伝の分野における先駆的な研究者」であったと記されている[183]。 |

| History

of the Cold

Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) The institution took root as The Biological Laboratory in 1890, a summer program for the education of college and high school teachers studying zoology, botany, comparative anatomy and nature. The program began as an initiative of Eugene G. Blackford and Franklin Hooper, director of the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences, the founding institution of The Brooklyn Museum.[21] In 1904, the Carnegie Institution of Washington established the Station for Experimental Evolution at Cold Spring Harbor on an adjacent parcel. In 1921, the station was reorganized as the Carnegie Institution Department of Genetics.[citation needed] the Eugenics Record Office (ERO) , 1910-1939 Between 1910 and 1939, the laboratory was the base of the Eugenics Record Office (ERO) of biologist Charles B. Davenport and his assistant Harry H. Laughlin, two prominent American eugenicists of the period. Davenport was director of the Carnegie Station from its inception until his retirement in 1934. In 1935 the Carnegie Institution sent a team to review the ERO's work, and as a result the ERO was ordered to stop all work. In 1939 the Institution withdrew funding for the ERO entirely, leading to its closure. The ERO's reports, articles, charts, and pedigrees were considered scientific facts in their day, but have since been discredited. Its closure came 15 years after its findings were incorporated into the National Origins Act (Immigration Act of 1924), which severely reduced the number of immigrants to America from southern and eastern Europe who, Harry Laughlin testified, were racially inferior to the Nordic immigrants from England and Germany. Charles Davenport was also the founder and the first director of the International Federation of Eugenics Organizations in 1925. Today, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory maintains the full historical records, communications and artifacts of the ERO for historical,[22] teaching and research purposes. The documents are housed in a campus archive and can be accessed online[23] and in a series of multimedia websites.[24] Carnegie Institution scientists at Cold Spring Harbor made many contributions to genetics and medicine. In 1908 George H. Shull discovered hybrid corn and the genetic principle behind it called heterosis, or "hybrid vigor."[25][26] This would become the foundation of modern agricultural genetics. In 1916, Clarence C. Little[27] was among the first scientists to demonstrate a genetic component of cancer. E. Carleton MacDowell in 1928 discovered a strain of mouse called C58 that developed spontaneous leukemia – an early mouse model of cancer.[28] In 1933, Oscar Riddle isolated prolactin, the milk secretion hormone[29] and Wilbur Swingle participated in the discovery of adrenocortical hormone, used to treat Addison's disease.[citation needed] Milislav Demerec was named director of the Laboratory in 1941. Demerec shifted the Laboratory's research focus to the genetics of microbes, thus setting investigators on a course to study the biochemical function of the gene. During World War Two, Demerec directed efforts at Cold Spring Harbor that resulted in major increases in penicillin production.[30] Beginning in 1941, and annually from 1945, three of the seminal figures of molecular genetics convened summer meetings at Cold Spring Harbor of what they called the Phage Group. Salvador Luria, of Indiana University; Max Delbrück, then of Vanderbilt University; and Alfred Hershey, then of Washington University in St. Louis, sought to discover the nature of genes through study of viruses called bacteriophages that infect bacteria.[citation needed] In 1945, Delbrück's famous Phage Course was taught for the first time, inspiring, among others, a young James D. Watson; it was repeated for many years after. CSH Symposia important in the cross-fertilization of ideas among molecular biology's pioneers were held in 1951, 1953, 1956, 1961, 1963, and 1966.[31] At the CSH Symposium in summer 1953, Watson made the first public presentation of DNA's double-helix structure.[citation needed] |

コー

ルドスプリングハーバー研究所(CSHL)の歴史 1890年、動物学、植物学、比較解剖学、自然学を学ぶ大学および高校の教師のための夏季教育プログラム「The Biological Laboratory」として発足した。このプログラムは、ユージン・G・ブラックフォードと、ブルックリン美術館の創設機関であるブルックリン芸術科学 研究所のディレクター、フランクリン・フーパーのイニシアティブで始まった[21]。1904年には、カーネギーワシントン研究所が隣接する区画に「コー ルド・スプリング・ハーバー進化実験ステーション」を設立した。1921年、同ステーションはカーネギー研究所遺伝学部門に改組された[要出典]。 優生学記録室(ERO), 1910-1939 1910年から1939年にかけて、この研究所は生物学者チャールズ・ B・ダベンポートとその助手ハリー・H・ラフリンの優生学記録室(ERO)の拠点であった。ダベンポートは、カーネギーステーションの設立から1934年 の退任まで所長を務めた。1935年、カーネギー研究所はEROの仕事を見直すためのチームを送り、その結果EROはすべての仕事を停止するよう命じられ た。1939年、カーネギー研究所はEROへの資金援助を打ち切り、EROは閉鎖された。EROの報告書、論文、図表、血統書は、当時は科学的事実とみな されていたが、その後、信用を失墜させることになった。この法律は、南ヨーロッパと東ヨーロッパからのアメリカへの移民を厳しく制限するもので、ハリー・ ラフリンは、イギリスとドイツからの北欧系移民より人種的に劣っていると証言している。また、チャールズ・ダベンポートは、1925年に優生学国際連盟機関(IFEO) を設立し、初代理事長に就任した。現在、コールドスプリングハーバー研究所は、歴史的、教育的、研究的目的のために、EROの歴史的記録、通信、遺物をす べて維持している[22]。これらの文書はキャンパス内のアーカイブに保管されており、オンライン[23]や一連のマルチメディアウェブサイトでアクセス することができる[24]。 コールドスプリングハーバーのカーネギー研究所の科学者は、遺伝学と医学に多くの貢献をしている。1908年、ジョージ・H・シャルはハイブリッドコーン を発見し、その背後にあるヘテロシス、つまり「雑種強勢」と呼ばれる遺伝原理を発見しました[25][26]。これは現代の農業遺伝学の基礎となるもので した。1916年、クラレンス・C・リトル[27]は、癌の遺伝的要素を証明した最初の科学者の一人です。1933年には、オスカー・リドルが乳汁分泌ホ ルモンであるプロラクティンを単離し[29]、ウィルバー・スウィングルはアジソン病の治療に用いられる副腎皮質ホルモンの発見に参加した[30]。 1941年、ミリスラフ・デメレツが研究所の所長に就任した。デメレックは、研究所の研究対象を微生物の遺伝学に移し、遺伝子の生化学的機能を研究する道 を開いた。第二次世界大戦中、デメレックはコールド・スプリング・ハーバーでの活動を指揮し、ペニシリンの生産量を大幅に増加させることに成功した [30]。 1941年に始まり、1945年からは毎年、分子遺伝学の重要人物3人が、コールドスプリングハーバーでファージグループと呼ばれる夏期会合を開いてい た。インディアナ大学のサルバドール・ルリア、ヴァンダービルト大学のマックス・デルブリュック、ワシントン大学セントルイス校のアルフレッド・ハーシー は、バクテリアに感染するバクテリオファージというウイルスの研究を通じて遺伝子の性質を明らかにしようとした[citation needed]。 1945年、デルブリュックの有名な「ファージ講座」が初めて開かれ、若き日のジェームズ・D・ワトソンらにインスピレーションを与え、その後何年にもわ たって繰り返された。分子生物学のパイオニアたちのアイデアの相互交流に重要な CSH シンポジウムは、1951 年、1953 年、1956 年、1961 年、1963 年、1966 年に開催された[31]。 1953年夏のCSHシンポジウムで、ワトソンはDNAの二重らせん構造について初めて公に発表した[citation needed]。 |

Links

リンク

文献

その他の情報