オートポイエーシス

Autopoiesis

Raymond Savignac

1950

☆

オートポイエーシス(ギリシャ語のαὐτo-(auto)「自己」とποίησις(poiesis)「創造、生産」に由来する)という用語は、生命に関

する現在のいくつかの理論の1つであり、自己の構成要素を自ら作り出すことで自己を生産し維持できるシステムを指す。[1]

この用語は、1972年に出版された『オートポイエーシスと認知:

生体細胞の自己維持化学を定義するために、チリの生物学者であるウンベルト・マトゥラーナと

フランシスコ・ヴァレラによって発表された。

この概念は、それ以来、認知、神経生物学、システム理論、建築学、社会学などの分野に応用されている。ニクラス・ルーマンは、オートポイエーシスの概念を

組織論に簡単に導入した。[3]

| The term autopoiesis

(from Greek αὐτo- (auto) 'self' and ποίησις (poiesis) 'creation,

production'), one of several current theories of life, refers to a

system capable of producing and maintaining itself by creating its own

parts.[1] The term was introduced in the 1972 publication Autopoiesis

and Cognition: The Realization of the Living by Chilean biologists

Humberto Maturana and Francisco Varela to define the self-maintaining

chemistry of living cells.[2] The concept has since been applied to the fields of cognition, neurobiology, systems theory, architecture and sociology. Niklas Luhmann briefly introduced the concept of autopoiesis to organizational theory.[3] |

オートポイエーシス(ギリシャ語のαὐτo-(auto)「自己」と

ποίησις(poiesis)「創造、生産」に由来する)という用語は、生命に関する現在のいくつかの理論の1つであり、自己の構成要素を自ら作り出

すことで自己を生産し維持できるシステムを指す。[1] この用語は、1972年に出版された『オートポイエーシスと認知:

生体細胞の自己維持化学を定義するために、チリの生物学者であるウンベルト・マトゥラーナとフランシスコ・ヴァレラによって発表された。 この概念は、それ以来、認知、神経生物学、システム理論、建築学、社会学などの分野に応用されている。ニクラス・ルーマンは、オートポイエーシスの概念を 組織論に簡単に導入した。[3] |

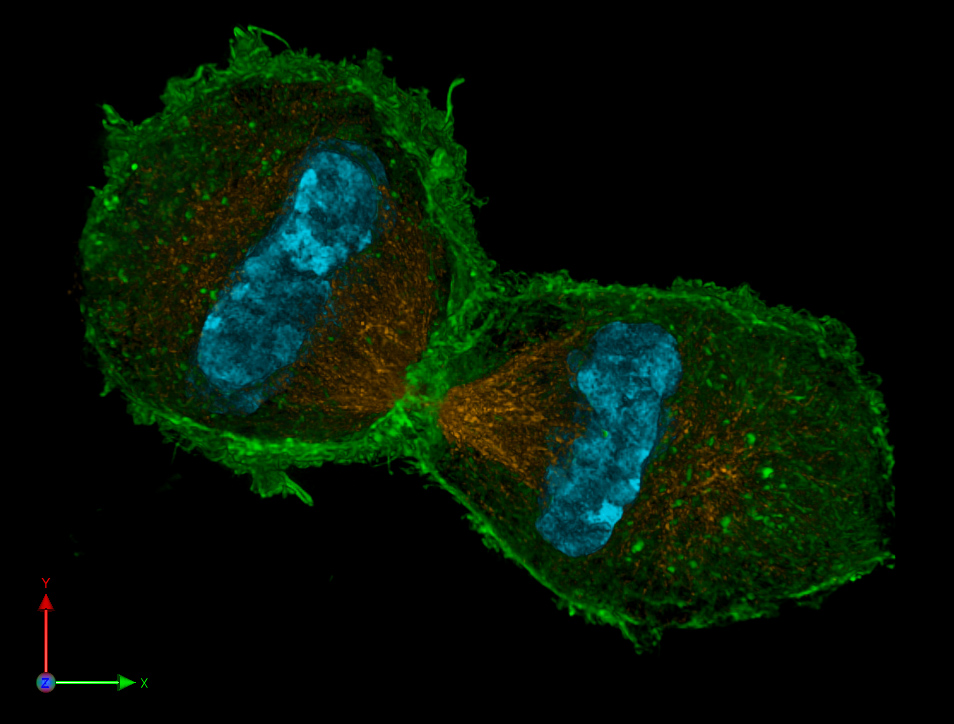

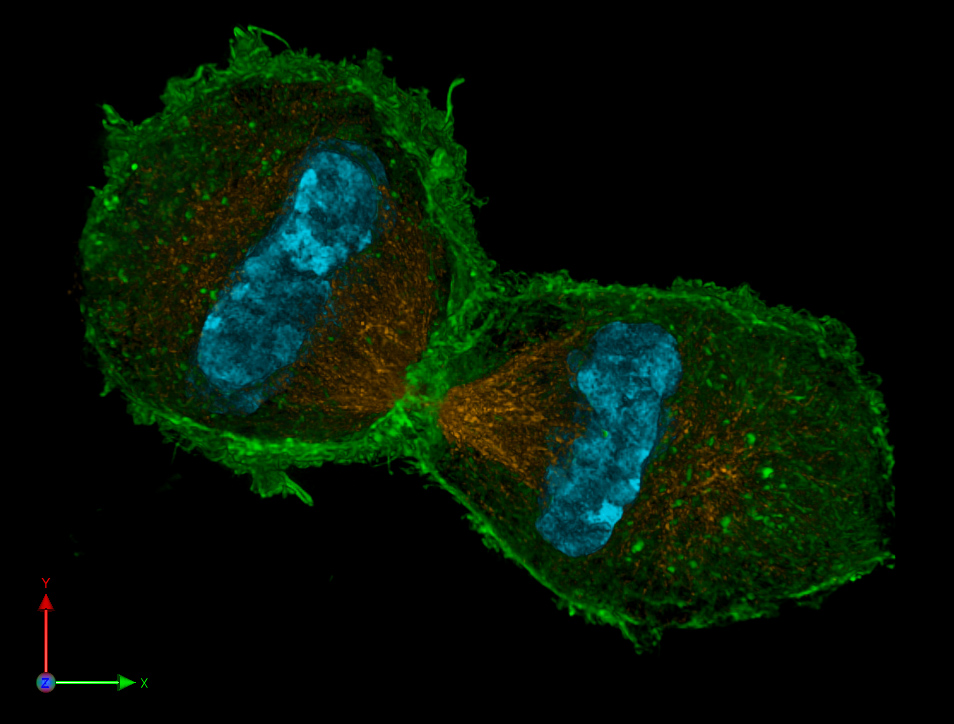

3D representation of a living cell during the process of mitosis, example of an autopoietic system |

有糸分裂中の生きた細胞の3D表現、オートポイエーシス(自己生成)システムの例 |

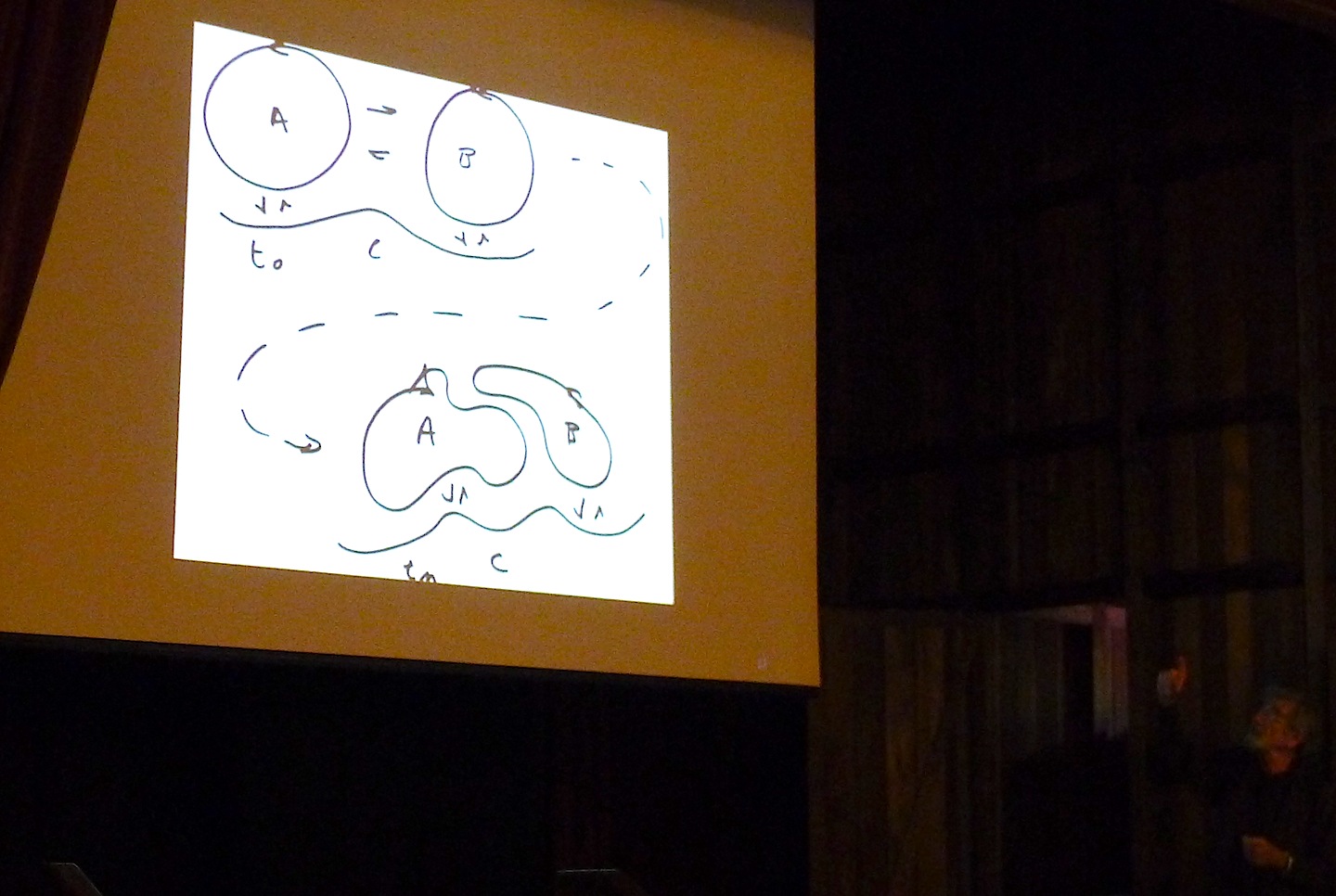

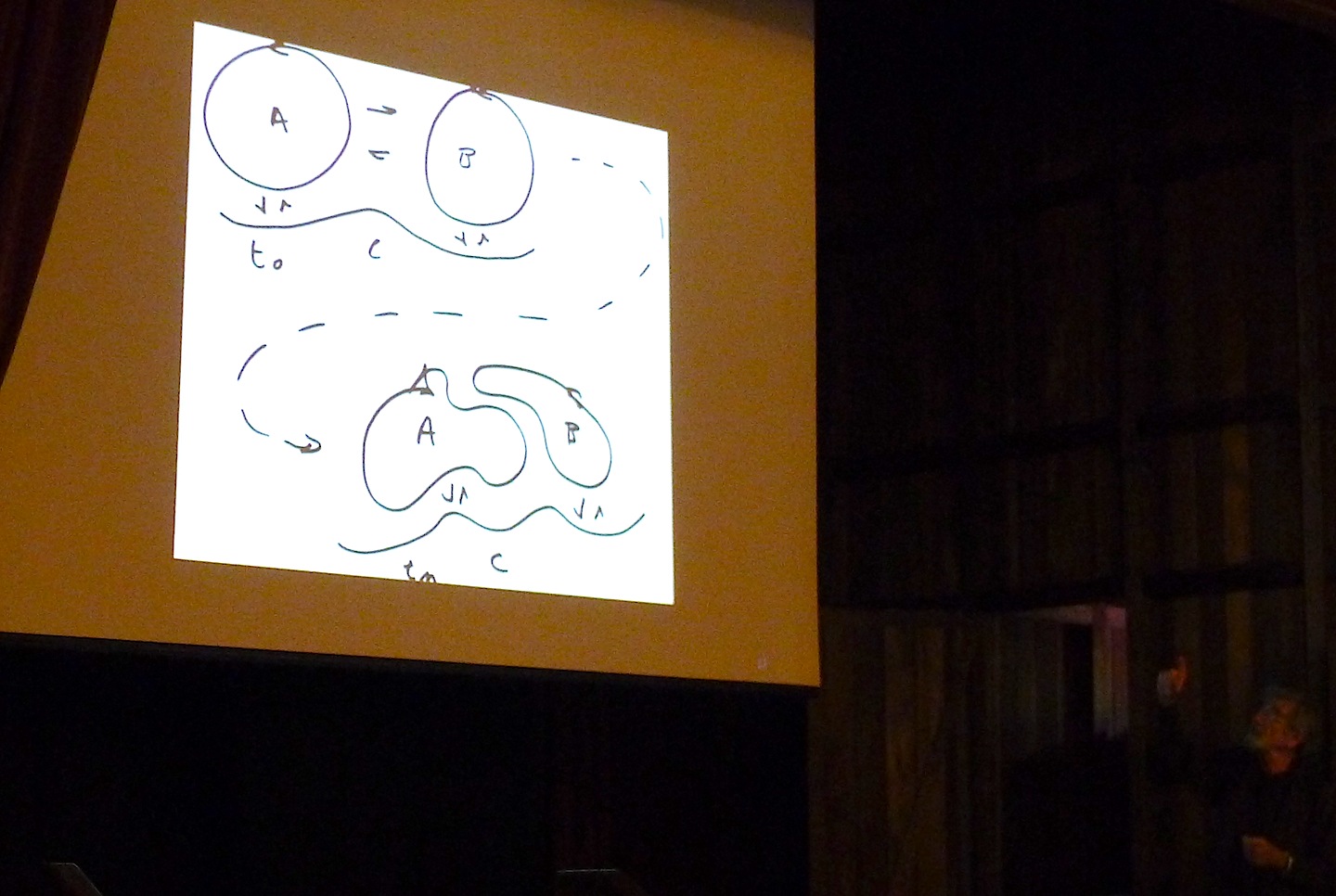

| Overview In their 1972 book Autopoiesis and Cognition, Chilean biologists Maturana and Varela described how they invented the word autopoiesis.[4]: 89 : 16 "It was in these circumstances ... in which he analyzed Don Quixote's dilemma of whether to follow the path of arms (praxis, action) or the path of letters (poiesis, creation, production), I understood for the first time the power of the word "poiesis" and invented the word that we needed: autopoiesis. This was a word without a history, a word that could directly mean what takes place in the dynamics of the autonomy proper to living systems." They explained that,[4]: 78 "An autopoietic machine is a machine organized (defined as a unity) as a network of processes of production (transformation and destruction) of components which: (i) through their interactions and transformations continuously regenerate and realize the network of processes (relations) that produced them; and (ii) constitute it (the machine) as a concrete unity in space in which they (the components) exist by specifying the topological domain of its realization as such a network." They described the "space defined by an autopoietic system" as "self-contained", a space that "cannot be described by using dimensions that define another space. When we refer to our interactions with a concrete autopoietic system, however, we project this system on the space of our manipulations and make a description of this projection."[4]: 89 |

概要 チリの生物学者であるマトゥラーナとヴァレラは、1972年の著書『オートポイエーシスと認知』で、オートポイエーシスという言葉の発明について説明して いる。 「それはこのような状況下でのことだった...。彼は、武器の道(Praxis、行動)に従うか、文字の道(Poiesis、創造、生産)に従うかという ドン・キホーテのジレンマを分析した。私はその時初めて「ポイエーシス」という言葉の力を理解し、私たちが必要とする「オートポイエーシス」という言葉を 発明した。これは歴史のない言葉であり、生命システムに固有の自律性の力学で起こることを直接的に意味する言葉であった。」 彼らは次のように説明している。[4]:78 「オートポイエーシス機械とは、構成要素の生産(変換と破壊)プロセスをネットワークとして組織化(統一体として定義)した機械である。(i)相互作用と 変換を通じて、それらを生産したプロセス(関係)のネットワークを継続的に再生し、実現する。(ii)それら(構成要素)が存在する空間において、その実 現の位相領域を特定することで、機械を具体的な統一体として構成する。」 彼らは「オートポイエーシスシステムによって定義された空間」を「自己完結的」な空間と表現し、それは「他の空間を定義する次元を用いては記述できない」 空間であると述べた。しかし、具体的なオートポイエーシスシステムとの相互作用について言及する際には、このシステムを操作する空間に投影し、その投影に ついて記述する。[4]:89 |

| Meaning Autopoiesis was originally presented as a system description that was said to define and explain the nature of living systems. A canonical example of an autopoietic system is the biological cell. The eukaryotic cell, for example, is made of various biochemical components such as nucleic acids and proteins, and is organized into bounded structures such as the cell nucleus, various organelles, a cell membrane and cytoskeleton. These structures, based on an internal flow of molecules and energy, produce the components which, in turn, continue to maintain the organized bounded structure that gives rise to these components. An autopoietic system is to be contrasted with an allopoietic system, such as a car factory, which uses raw materials (components) to generate a car (an organized structure) which is something other than itself (the factory). However, if the system is extended from the factory to include components in the factory's "environment", such as supply chains, plant / equipment, workers, dealerships, customers, contracts, competitors, cars, spare parts, and so on, then as a total viable system it could be considered to be autopoietic.[5] Of course, cells also require raw materials (nutrients), and produce numerous products -waste products, the extracellular matrix, intracellular messaging molecules, etc. Autopoiesis in biological systems can be viewed as a network of constraints that work to maintain themselves. This concept has been called organizational closure[6] or constraint closure[7] and is closely related to the study of autocatalytic chemical networks where constraints are reactions required to sustain life. Though others have often used the term as a synonym for self-organization, Maturana himself stated he would "[n]ever use the notion of self-organization ... Operationally it is impossible. That is, if the organization of a thing changes, the thing changes".[8] Moreover, an autopoietic system is autonomous and operationally closed, in the sense that there are sufficient processes within it to maintain the whole. Autopoietic systems are "structurally coupled" with their medium, embedded in a dynamic of changes that can be recalled as sensory-motor coupling.[9] This continuous dynamic is considered as a rudimentary form of knowledge or cognition and can be observed throughout life-forms. An application of the concept of autopoiesis to sociology can be found in Niklas Luhmann's Systems Theory, which was subsequently adapted by Bob Jessop in his studies of the capitalist state system. Marjatta Maula adapted the concept of autopoiesis in a business context.[10] The theory of autopoiesis has also been applied in the context of legal systems by not only Niklas Luhmann, but also Gunther Teubner.[11][12] Patrik Schumacher has applied the term to refer to the 'discursive self-referential making of architecture.' [13][14] Varela eventually further applied autopoesis to develop models of mind, brain, and behavior called non-representationalist, enactive, embodied cognitive neuroscience, culminating in neurophenomenology. In the context of textual studies, Jerome McGann argues that texts are "autopoietic mechanisms operating as self-generating feedback systems that cannot be separated from those who manipulate and use them".[15] Citing Maturana and Varela, he defines an autopoietic system as "a closed topological space that 'continuously generates and specifies its own organization through its operation as a system of production of its own components, and does this in an endless turnover of components'", concluding that "Autopoietic systems are thus distinguished from allopoietic systems, which are Cartesian and which 'have as the product of their functioning something different from themselves'". Coding and markup appear allopoietic", McGann argues, but are generative parts of the system they serve to maintain, and thus language and print or electronic technology are autopoietic systems.[16]: 200–1 The philosopher Slavoj Žižek, in his discussion of Hegel, argues: "Hegel is – to use today's terms – the ultimate thinker of autopoiesis, of the process of the emergence of necessary features out of chaotic contingency, the thinker of contingency's gradual self-organisation, of the gradual rise of order out of chaos."[17] [17] Žižek S (2012). Less Than Nothing. Verso. p. 467. |

意味 オートポイエーシスは、当初、生命システムの性質を定義し、説明するシステム記述として提示された。オートポイエーシスシステムの典型的な例は生物の細胞 である。例えば、真核細胞は核酸やタンパク質などの様々な生化学成分から構成され、細胞核、様々な細胞小器官、細胞膜、細胞骨格などの境界のある構造に組 織化されている。これらの構造は、分子とエネルギーの内部の流れに基づいて、構成要素を生成し、その構成要素が、それらを生み出す組織化された境界構造を 維持し続ける。 オートポイエーシスシステムは、原材料(構成要素)を使用して、それ自身(工場)とは異なるもの(自動車)である自動車(組織化された構造)を生成する、 自動車工場のようなアロポイエーシスシステムと対比される。しかし、そのシステムを工場からサプライチェーン、工場/設備、労働者、販売代理店、顧客、契 約、競合他社、自動車、スペアパーツなど、工場の「環境」に含まれる構成要素まで拡大して捉えると、全体として機能するシステムとしてオートポイエーシス 的であるとみなすことができる。 もちろん、細胞も原材料(栄養素)を必要とし、廃棄物、細胞外マトリックス、細胞内伝達分子など、多数の産物を生成する。 生物学的システムにおけるオートポイエーシスは、自己維持に働く制約のネットワークとして捉えることができる。この概念は、組織閉鎖[6]または制約閉鎖 [7]と呼ばれ、制約が生命維持に必要な反応である自己触媒化学ネットワークの研究と密接に関連している。 他の人々は、この用語を自己組織化と同義語として使用することが多いが、マチュラーナ自身は「自己組織化という概念は決して使用しない... 運用上、それは不可能である。つまり、もし対象の組織が変化すれば、その対象も変化する」と述べている。[8] さらに、オートポイエーティックシステムは自律的であり、運用上閉じている。つまり、全体を維持するのに十分なプロセスがその内部に存在するという意味で ある。オートポイエーティックなシステムは、感覚運動の結合として想起できる変化のダイナミクスに埋め込まれ、その媒体と「構造的に結合」している。 [9] この連続的なダイナミクスは、知識や認知の初歩的な形態と考えられており、生命体全体を通じて観察することができる。 オートポイエーシスの概念の社会学への応用は、ニクラス・ルーマンのシステム理論に見られ、その後ボブ・ジェサップが資本主義国家体制の研究に採用した。 マルヤッタ・マウラはオートポイエーシスの概念をビジネスに適用した。[10] オートポイエーシスの理論は、ニクラス・ルーマンだけでなくギュンター・テュブナーによっても法制度の文脈で応用されている。[11][12] パトリック・シューマッハーは、この用語を「建築の議論的自己言及的構築」を指すために応用している。[13][14] ヴァレラは最終的にオートポイエーシスをさらに応用し、非表象主義、エナクティブ、身体化認知神経科学と呼ばれる心、脳、行動のモデルを開発し、神経現象 学に集大成した。 テキスト研究の文脈では、ジェローム・マガンはテキストは「操作し使用する人々から切り離すことのできない自己生成フィードバックシステムとして機能する オートポイエーシス的メカニズム」であると主張している。[15] マチュラーナとヴァレラを引き合いに出し、彼はオートポイエーシス的システムを「 自身の構成要素を生産するシステムとして、その操作を通じて、自身の組織を継続的に生成し、特定する。そして、これは構成要素の無限の入れ替わりの中で行 われる」と定義し、「オートポイエーティックシステムは、デカルト主義であり、『その機能の産物として、それ自身とは異なる何かを持つ』アロポイエー ティックシステムとは区別される」と結論づけている。コーディングとマークアップはアロポイエーシス的である」とマクガンは主張するが、それらは維持する システムの生成的な部分であり、したがって言語や印刷、あるいは電子技術はオートポイエーシス的システムである。[16]: 200–1 哲学者のスラヴォイ・ジジェクは、ヘーゲルについての 議論の中で次のように主張している。 「ヘーゲルは、今日の用語で言えば、オートポイエーシスの究極の思想家である。すな わち、混沌とした偶然性の中から必要な特徴が現れるプロセス、偶然性が徐々に自己組織化するプロセス、混沌の中から徐々に秩序が生まれるプロセスの思想家 である」[17] [17] Žižek S (2012). Less Than Nothing. Verso. p. 467. |

| Relation to complexity Autopoiesis can be defined as the ratio between the complexity of a system and the complexity of its environment.[18] This generalized view of autopoiesis considers systems as self-producing not in terms of their physical components, but in terms of its organization, which can be measured in terms of information and complexity. In other words, we can describe autopoietic systems as those producing more of their own complexity than the one produced by their environment. — Carlos Gershenson, "Requisite Variety, Autopoiesis, and Self-organization" [19] Autopoiesis has been proposed as a potential mechanism of abiogenesis, by which molecules evolved into more complex cells that could support the development of life.[20] Comparison with other theories of life Autopoiesis is just one of several current theories of life, including the chemoton[21] of Tibor Gánti, the hypercycle of Manfred Eigen and Peter Schuster,[22] [23] [24] the (M,R) systems[25][26] of Robert Rosen, and the autocatalytic sets[27] of Stuart Kauffman, similar to an earlier proposal by Freeman Dyson.[28] All of these (including autopoiesis) found their original inspiration in Erwin Schrödinger's book What is Life?[29] but at first they appear to have little in common with one another, largely because the authors did not communicate with one another, and none of them made any reference in their principal publications to any of the other theories. Nonetheless, there are more similarities than may be obvious at first sight, for example between Gánti and Rosen.[30] Until recently[31][32][33] there have been almost no attempts to compare the different theories and discuss them together. |

複雑性との関係 オートポイエーシスは、システムの複雑性と環境の複雑性の比率として定義することができる。 このオートポイエーシスに関する一般的な見解では、システムを物理的な構成要素ではなく、情報や複雑性の観点から測定できるその組織という観点から自己生 産的であるとみなしている。言い換えれば、オートポイエーシスシステムとは、環境によって生産されるものよりも、自身の複雑性を多く生産するものであると 表現できる。 — カルロス・ガーシェンソン、「Requisite Variety, Autopoiesis, and Self-organization」[19] オートポイエーシスは、生命の起源の潜在的なメカニズムとして提案されており、それによって分子が生命の進化を支えるより複雑な細胞へと進化する可能性が ある。[20] 生命に関する他の理論との比較 オートポイエーシスは、生命に関する現在のいくつかの理論のうちの1つにすぎず、ティボール・ガーンティのケモトーン[21]、マンフレート・アイゲンと ピーター・シュスターのハイパーサイクル[22][23][24]、ロバート・ローゼンの(M,R)システム[25][26]、スチュアート・カウフマン の自己触媒セット[27]( フリーマン・ダイソンの初期の提案に類似している。[28] これらの理論(オートポイエーシスも含む)はすべて、アーウィン・シュレディンガーの著書『生命とは何か』に着想を得ているが[29]、当初は互いに共通 点がほとんどないように見えた。その主な理由は、著者同士が交流を持たなかったこと、また、いずれの理論も主要な出版物の中で他の理論に言及することがな かったことによる。しかし、例えばGántiとRosenの間には、一見しただけではわからないほど多くの類似点がある。最近まで[31][32] [33]、異なる理論を比較し、それらをまとめて議論しようとする試みはほとんど行われてこなかった。 |

| Relation to cognition An extensive discussion of the connection of autopoiesis to cognition is provided by Evan Thompson in his 2007 publication, Mind in Life.[34] The basic notion of autopoiesis as involving constructive interaction with the environment is extended to include cognition. Initially, Maturana defined cognition as behavior of an organism "with relevance to the maintenance of itself".[35]: 13 However, computer models that are self-maintaining but non-cognitive have been devised, so some additional restrictions are needed, and the suggestion is that the maintenance process, to be cognitive, involves readjustment of the internal workings of the system in some metabolic process. On this basis it is claimed that autopoiesis is a necessary but not a sufficient condition for cognition.[36] Thompson wrote that this distinction may or may not be fruitful, but what matters is that living systems involve autopoiesis and (if it is necessary to add this point) cognition as well.[37]: 127 It can be noted that this definition of 'cognition' is restricted, and does not necessarily entail any awareness or consciousness by the living system. With the publication of The Embodied Mind in 1991, Varela, Thompson and Rosch applied autopoesis to make non-representationalist, and enactive models of mind, brain and behavior, which further developed embodied cognitive neuroscience, later culminating in neurophenomenology. |

認知との関係 オートポイエーシスと認知の関係についての詳細な議論は、エヴァン・トンプソンが2007年に発表した著書『Mind in Life』で展開している。[34] 環境との建設的な相互作用を伴うというオートポイエーシスの基本概念は、認知を含めるように拡張されている。当初、マチュラーナは「自己の維持に関連す る」生物の行動として認知を定義した。[35]:13 しかし、自己維持はするが認知はしないコンピュータモデルが考案されているため、いくつかの追加の制限が必要であり、認知であるためには維持プロセスは代 謝プロセスの一部としてシステムの内部動作の再調整を伴うという提案がなされている。このことを踏まえて、オートポイエーシスは認知の必要条件ではあるが 十分条件ではないと主張されている。[36] トンプソンは、この区別が有益であるか否かはわからないが、重要なのは、生命システムにはオートポイエーシスと( この点を付け加える必要があるならば)認知も含まれる。[37]:127 この「認知」の定義は限定的であり、必ずしも生命システムによる意識や認識を意味するものではないことに留意すべきである。1991年に『The Embodied Mind』を出版したヴァレラ、トンプソン、ロッシュはオートポイエーシスを応用し、非表象論的かつ行為遂行的モデルとして心、脳、行動を説明した。これ により、身体化された認知神経科学がさらに発展し、後に神経現象学へと結実した。 |

| Relation to consciousness The connection of autopoiesis to cognition, or if necessary, of living systems to cognition, is an objective assessment ascertainable by observation of a living system. One question that arises is about the connection between cognition seen in this manner and consciousness. The separation of cognition and consciousness recognizes that the organism may be unaware of the substratum where decisions are made. What is the connection between these realms? Thompson refers to this issue as the "explanatory gap", and one aspect of it is the hard problem of consciousness, how and why we have qualia.[38] A second question is whether autopoiesis can provide a bridge between these concepts. Thompson discusses this issue from the standpoint of enactivism. An autopoietic cell actively relates to its environment. Its sensory responses trigger motor behavior governed by autopoiesis, and this behavior (it is claimed) is a simplified version of a nervous system behavior. The further claim is that real-time interactions like this require attention, and an implication of attention is awareness.[39] |

意識との関係 オートポイエーシスと認知の関係、あるいは必要であれば、生体システムと認知の関係は、生体システムの観察によって確認できる客観的な評価である。 ここで生じる疑問のひとつは、このようにして見られる認知と意識の関係である。認知と意識を分離することは、生物が意思決定の基盤について認識していない 可能性があることを認識している。これらの領域の関係とはどのようなものだろうか。トンプソンはこれを「説明のギャップ」と呼び、そのひとつの側面は、ク オリアがどのようにして、なぜ存在するのかという意識の難問である。 第二の疑問は、オートポイエーシスがこれらの概念の橋渡しとなり得るかという点である。トンプソンは、この問題をエナクティヴィズムの観点から論じてい る。オートポイエーシスを持つ細胞は、その環境と能動的に関わりを持つ。感覚の反応は、オートポイエーシスによって支配される運動行動を引き起こし、この 行動(と主張されている)は神経系の行動の単純化されたバージョンである。さらに主張されているのは、このようなリアルタイムの相互作用には注意が必要で あり、注意の含意は意識であるということである。[39] |

| Criticism There are multiple criticisms of the use of the term in both its original context, as an attempt to define and explain the living, and its various expanded usages, such as applying it to self-organizing systems in general or social systems in particular.[40] Critics have argued that the concept and its theory fail to define or explain living systems and that, because of the extreme language of self-referentiality it uses without any external reference, it is really an attempt to give substantiation to Maturana's radical constructivist or solipsistic epistemology,[41] or what Danilo Zolo[42][43] has called instead a "desolate theology". An example is the assertion by Maturana and Varela that "We do not see what we do not see and what we do not see does not exist".[44] According to Razeto-Barry, the influence of Autopoiesis and Cognition: The Realization of the Living in mainstream biology has proven to be limited. Razeto-Barry believes that autopoiesis is not commonly used as the criterion for life.[45] Zoologist and philosopher Donna Haraway also criticizes the usage of the term, arguing that "nothing makes itself; nothing is really autopoietic or self-organizing",[46] and suggests the use of sympoiesis, meaning "making-with", instead. |

批判 この用語の使用については、生命を定義し説明しようとする本来の文脈と、自己組織化システム一般や社会システムに特に適用するなど、さまざまな拡大された 用法の両方について、複数の批判がある。[40] 批判者たちは、この概念と理論は生命システムを定義したり説明したりできないと主張し、 また、外部参照を一切用いずに自己言及的な極端な表現を用いているため、実際にはマトゥラーナの急進的な構成主義的または独我論的な認識論を正当化しよう とする試みである、という批判もある。その例として、マトゥラーナとヴァレラによる「私たちは見えないものは見えず、見えないものは存在しない」という主 張がある。[44] ラゼト=バリーによると、『オートポイエーシスと認知:生命の実現』の生物学における主流への影響は限定的であることが証明されている。ラゼト=バリー は、オートポイエーシスが生命の基準として一般的に使用されていないと考えている。[45] 動物学者で哲学者のドナ・ハラウェイもまた、この用語の使用を批判しており、「自分自身で何かを作り出すものはなく、本当にオートポイエーシス的または自 己組織的なものは何もない」と主張している[46]。そして、代わりに「一緒に作り出す」という意味のシンポイエーシス(sympoiesis)という用 語の使用を提案している。 |

| Abiogenesis – Life arising from

non-living matter Adaptive system – System that can adapt to the environment Allopoiesis Autocatalytic set – collection of chemical entities Autonomous agency theory – viable system theory Biosemiotics – Biology interpreted as a sign system Dissipative system – Thermodynamically open system which is not in equilibrium Chemoton – Abstract model for the fundamental unit of life Dynamical system – Mathematical model of the time dependence of a point in space Enactivism – Philosophical concept Free energy principle – Hypothesis in neuroscience Hypercycle (chemistry) – Cyclic sequence of self-reproducing single cycles Information metabolism – Psychological theory of interaction between biological organisms and their environment Loschmidt's paradox – Conflict between known physical principles (time symmetry and entropy) Niklas Luhmann – German sociologist (1927–1998) Non-equilibrium thermodynamics – Branch of thermodynamics Poietic Generator – Social network game played on a two-dimensional matrix Polytely – Problem-solving technique Quine (computing) – Self-replicating program Relational order theories – Sociological theory Robert Rosen – American theoretical biologist Self-replication – Type of behavior of a dynamical system Self-replicating machine – Device able to make copies of itself Viable system theory – concerns cybernetic processes in relation to the development/evolution of dynamical systems |

非生物から生命が生まれること 環境に適応できるシステム アロポイエーシス 自己触媒集合体 自律的機関理論 生物学を記号システムとして解釈する生物学 熱力学的平衡にない開放系 生命の基本単位の抽象モデル 力学系 – 空間における点の時間依存性の数学モデル エナクティヴィズム – 哲学的概念 自由エネルギー原理 – 神経科学における仮説 ハイパーサイクル(化学) – 自己再生産する単一サイクルの周期的な順列 情報代謝 – 生物と環境の相互作用に関する心理学的理論 ロシュミットのパラドックス – 既知の物理原理(時間対称性とエントロピー)間の対立 ニクラス・ルーマン – ドイツの社会学者(1927年 - 1998年 非平衡熱力学 – 熱力学の一分野 ポエティック・ジェネレーター – 2次元マトリクス上でプレイするソーシャルネットワークゲーム ポリテリー – 問題解決テクニック クワイン(コンピューティング) - 自己複製プログラム 関係順序理論 - 社会学理論 ロバート・ローゼン - アメリカの理論生物学者 自己複製 - 力学系の一種 自己複製機械 - 自身を複製できる装置 実行可能システム理論 - 力学系の開発/進化に関連するサイバネティクスプロセスを扱う |

| Capra F (1997). The Web of Life.

Random House. ISBN 978-0-385-47676-8. – general introduction to the

ideas behind autopoiesis Goosseff KA (2010). "Autopoeisis and meaning: a biological approach to Bakhtin's superaddressee". Journal of Organizational Change Management. 23 (2): 145–151. doi:10.1108/09534811011031319. Dyke C (1988). The Evolutionary Dynamics of Complex Systems: A Study in Biosocial Complexity. New York: Oxford University Press. Livingston I (2006). Between Science and Literature: An Introduction to Autopoetics. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-07254-3. —an adaptation of autopoiesis to language. Luhmann, Niklas (1990). Essays on Self-Reference. Columbia University Press. —Luhmann's adaptation of autopoiesis to social systems Luisi PL (February 2003). "Autopoiesis: a review and a reappraisal". Die Naturwissenschaften. 90 (2): 49–59. Bibcode:2003NW.....90...49L. doi:10.1007/s00114-002-0389-9. PMID 12590297. S2CID 10611332. —biologist view of autopoiesis Maturana, Humberto R.; Varela, Francisco J. (1972). Autopoiesis and cognition: the realization of the living. Boston studies in the philosophy and history of science. Dordrecht: Reidel. p. 141. OCLC 989554341. Varela, Francisco G.; Maturana, Humberto R.; Uribe, R. (1974-05-01). "Autopoiesis: The organization of living systems, its characterization and a model". Biosystems. 5 (4): 187–196. Bibcode:1974BiSys...5..187V. doi:10.1016/0303-2647(74)90031-8. ISSN 0303-2647. PMID 4407425. Retrieved 2020-11-13. Maturana, Humberto; Varela, Francisco (1980). Autopoiesis and Cognition: The Realization of the Living (2nd ed.). Springer. ISBN 9789027710161. Cohen RS, Wartofsky MW, eds. (30 April 1980). Boston Studies in the Philosophy of Science. Vol. 42. Dordecht: D. Reidel Publishing Co. ISBN 978-90-277-1015-4. —the main published reference on autopoiesis Mingers J (1994). Self-Producing Systems. Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers. ISBN 978-0-306-44797-6. —a book on the autopoiesis concept in many different areas Robb FF (1991). "Accounting – A Virtual Autopoietic System?". Systems Practice. 4 (3): 215–235. doi:10.1007/BF01059566. S2CID 145281360. Tabbi J (2002). Cognitive Fictions. Vol. 2002. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 978-0-8166-3557-3. — draws on systems theory and cognitive science to introduce autopoiesis to literary studies Varela FJ, Maturana HR, Uribe R (1974). "Autopoiesis: the organization of living systems, its characterization and a model". Biosystems. 5 (4): 187–196. Bibcode:1974BiSys...5..187V. doi:10.1016/0303-2647(74)90031-8. PMID 4407425. —one of the original papers on the concept of autopoiesis. Bourgine P, Stewart J (2004). "Autopoiesis and cognition". Artificial Life. 10 (3): 327–45. doi:10.1162/1064546041255557. PMID 15245631. S2CID 11475918. Winograd T, Flores F (1990). Understanding Computers and Cognition: A New Foundation for Design. Ablex Pub. Corp. ISBN 9780893910501. —cognitive systems perspective on autopoiesis |

カプラ F (1997年). 『生命のウェブ』.

ランダムハウス. ISBN 978-0-385-47676-8. – オートポイエーシスの背景にある考え方についての一般的な紹介 Goosseff KA (2010年). 「オートポイエーシスと意味:バフチンのスーパーアドレッシーに対する生物学的アプローチ」. 『組織変革マネジメントジャーナル』. 23 (2): 145–151. doi:10.1108/09534811011031319. ダイク C (1988). 『複雑系の進化力学:生物社会の複雑性に関する研究』。ニューヨーク:オックスフォード大学出版。 リビングストン I (2006). 科学と文学の間:オートポイエーシス入門. イリノイ大学出版. ISBN 978-0-252-07254-3. —オートポイエーシスを言語に適応させたもの。 ルーマン、ニクラス (1990). 自己言及に関する試論. コロンビア大学出版. —ルーマンによるオートポイエーシスの社会システムへの適応 Luisi PL (February 2003). 「Autopoiesis: a review and a reappraisal」. Die Naturwissenschaften. 90 (2): 49–59. Bibcode:2003NW.....90...49L. doi:10.1007/s00114-002-0389-9. PMID 12590297. S2CID 10611332. —オートポイエーシスの生物学者による見解 マトゥラーナ、ウンベルト・R.; ヴァレラ、フランシスコ・J. (1972). オートポイエーシスと認知:生命の実現. 科学の哲学と歴史に関するボストン研究. ドルドレヒト: ライデル. p. 141. OCLC 989554341. Varela, Francisco G.; Maturana, Humberto R.; Uribe, R. (1974-05-01). 「Autopoiesis: The organization of living systems, its characterization and a model」. Biosystems. 5 (4): 187–196. Bibcode:1974BiSys...5..187V. doi:10.1016/0303-2647(74)90031-8. ISSN 0303-2647. PMID 4407425. 2020年11月13日閲覧。 マトゥラーナ、ウンベルト; ヴァレラ、フランシスコ (1980). オートポイエーシスと認知:生命の実現(第2版). シュプリンガー. ISBN 9789027710161. コーエンRS、ワートフスキーMW、編 (1980年4月30日). ボストン研究科学哲学. 第42巻. ドルデヒト: D. Reidel Publishing Co. ISBN 978-90-277-1015-4. —オートポイエーシスに関する主な参考文献 Mingers J (1994). Self-Producing Systems. Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers. ISBN 978-0-306-44797-6. —さまざまな分野におけるオートポイエーシス概念に関する書籍 Robb FF (1991). 「会計 - 仮想オートポイエーシスシステム?」. Systems Practice. 4 (3): 215–235. doi:10.1007/BF01059566. S2CID 145281360. Tabbi J (2002). Cognitive Fictions. Vol. 2002. ミネソタ大学出版。ISBN 978-0-8166-3557-3。— システム理論と認知科学を援用し、オートポイエーシスを文学研究に導入する Varela FJ, Maturana HR, Uribe R (1974). 「Autopoiesis: the organization of living systems, its characterization and a model」. Biosystems. 5 (4): 187–196. Bibcode:1974BiSys...5..187V. doi:10.1016/0303-2647(74)90031-8. PMID 4407425. —オートポイエーシス概念に関するオリジナル論文のひとつ。 Bourgine P, Stewart J (2004). 「Autopoiesis and cognition」. Artificial Life. 10 (3): 327–45. doi:10.1162/1064546041255557. PMID 15245631. S2CID 11475918. ウィノグラード、T、フローレス、F(1990年)。 コンピュータと認知の理解:設計のための新たな基礎。 Ablex Pub. Corp. ISBN 9780893910501。 —オートポイエーシスに関する認知システム的視点 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Autopoiesis |

☆

ウ

ンベルト・アウグスト・マトゥラーナ・ローメシン(スペイン語: Humberto Augusto Maturana

Romesín、1928年9月14日 - 2021年5月6日)は、チリの生物学者。 マツラナと表記されることもある。

人物

神経生物学 (neurobiology) の実験から得られた観察事実に基づいて、哲学や認知科学とも関係した領域の研究を行った。

特に、1970年代はじめに教え子のフランシスコ・バレーラとともにオートポイエーシスの概念を創出したことで有名である。

ハトの網膜の反応が外界の物理的刺激とは簡単には対応しないという観察事実がマトゥラーナがオートポイエーシスの概念にたどり着くきっかけとなった。

このことから、生命システムとは神経系を有していようといまいと認識を行うシステムであるとの考えに達し、徹底的構成主義 (radical

constructivism) や相対主義的認識論 (relativistic epistemology) を提唱した。

進化プロセスに対してもそれを適者生存としてではなくナチュラル・ドリフト (natural drift) として捉えることを主張した。

経歴

サンティアゴ出身。チリ大学で医学のちに生物学を学び、1954年よりロックフェラー財団の奨学金を得てロンドン大学ユニヴァーシティ・カレッジで解剖学

と神経生理学 (neurophysiology) を学び、1958年にハーヴァード大学で博士号を取得した。 チリ大学の

"Laboratorio de Neurobiología y Biología del Conocer" (知識の神経生物学・生物学研究所)

において神経科学を研究した。

主な著作

Maturana, H.R. and Varela, F.J. (1972) De máquinas y seres vivos,

Santiago:Editorial Universitaria.

English version: (1980) "Autopoiesis: the organization of the living"

in Autopoiesis and Cognition: the Ralization of the Living, Boston:D.

Reidel; (2001) Springer, ISBN 9027710163 (pbk).

河本英夫 訳 (1991) 『オートポイエーシス — 生命システムとは何か』 国文社, ISBN 4772003673.

Maturana, H.R. (1978) "Biology of language: the Epistemology of

Reality," in Miller, G.A., and Lenneberg, E. (eds.), Psychology and

Biology of Language and Thought: Essays in Honor of Eric Lenneberg,

Academic Press, pp. 27–63.

Maturana, H.R. and Varela, F.J. (1987) The Tree of Knowledge: the

Biological Roots of Human Understanding, Boston:New Science Library;

(1992) Rev. ed., Boston:Shambhala, ISBN 0877736421 (pbk).

管啓次郎 訳 (1987) 『知恵の樹 — 生きている世界はどのようにして生まれるのか』 朝日出版社, ISBN 4255870284;

(1997) ちくま学芸文庫, ISBN 4480083898.

Maturana, H.R. (1988) "Ontology of Observing: the Biological

Foundations of Self-consciousness and the Physical Domain of Existence"

in Conference Workbook: Texts in Cybernetics, American Society For

Cybernetics Conference, Felton, CA. pp. 18–23.

Maturana, H.R. (1988) "REALITY: the Search for Objectivity or the Quest

for a Compelling Argument" in The Irish Journal of Psychology, 9:25–82.

Maturana, H.R. (1999) "Autopoiesis, Structural Coupling and Cognition."

| Humberto

Maturana Romesín (September 14, 1928 – May 6, 2021) was a Chilean

biologist and philosopher. Some name him a second-order cybernetics

theoretician alongside the likes of Heinz von Foerster, Gordon Pask,

Herbert Brün and Ernst von Glasersfeld. Maturana, along with Francisco Varela and Ricardo B. Uribe, was known for creating the term "autopoiesis" about the self-generating, self-maintaining structure in living systems, and concepts such as structural determinism and structural coupling.[1] His work was influential in many fields, mainly the field of systems thinking and cybernetics. Overall, his work is concerned with the biology of cognition.[2] Maturana (2002) insisted that autopoiesis exists only in the molecular domain, and he did not agree with the extension into sociology and other fields: The molecular domain is the only domain of entities that through their interactions give rise to an open ended diversity of entities (with different dynamic architectures) of the same kind in a dynamic that can give rise to an open ended diversity of recursive processes that in their turn give rise to the composition of an open ended diversity of singular dynamic entities.[3] |

ウンベルト・マトゥラーナ・ロメシン(1928年9月14日 -

2021年5月6日)はチリの生物学者、哲学者である。ハインツ・フォン・フェルスター、ゴードン・パスク、ヘルベルト・ブリュン、エルンスト・フォン・

グレイザースフェルドらと並ぶ2次サイバネティクスの理論家である。 マトゥラーナは、フランシスコ・ヴァレラやリカルド・B・ウリベとともに、生命システムにおける自己生成・自己維持構造に関する「オートポイエーシス」と いう言葉や、構造決定論や構造結合といった概念を生み出したことで知られている。マトゥラーナ(2002)は、オートポイエーシスは分子領域にのみ存在す ると主張し、社会学や他の分野への拡張には同意しなかった: 分子領域は、それらの相互作用を通じて、同じ種類の(異なる動的アーキテクチャを持つ)実体のオープンエンドな多様性を生み出す実体の唯一の領域であり、 その実体は、再帰的プロセスのオープンエンドな多様性を生み出すことができる。 |

| Maturana was born in Santiago,

Chile. After completing secondary school at the Liceo Manuel de Salas

in 1947, he enrolled at the University of Chile, studying first

medicine in Santiago, then biology in London and Cambridge, Mass. |

マトゥラーナはチリのサンティアゴに生まれた。1947年にリセオ・マ

ヌエル・デ・サラスで中等教育を受けた後、チリ大学に入学し、まずサンティアゴで医学を、その後ロンドンとマサチューセッツ州ケンブリッジで生物学を学ん

だ。 |

| In 1954, he obtained a

scholarship from the Rockefeller Foundation to study anatomy and

neurophysiology with J. Z. Young (the “discoverer” of the squid giant

axon and who later wrote the foreword to The Tree of Knowledge) at

University College London. Maturana wrote that he was as an ”invisible”

student never officially accepted in University College, London.

Nonetheless, he did research and produced a paper(1) investigating the

possibility of the presence of efferent fibers running from the brain

to the retina. In this study, he unilaterally severed optic nerves of

toads who were maintained weeks to months post-surgery. Maturana then

examined the ocular and brain stumps of the cut nerves using the

conventional Weigert’s and Holmes’s nerve fiber staining methods and

although 'thin', concluded that efferent fibers existed. Amphibians,

unlike avian and reptile species, lacked a distinct isthmo-optic

nucleus located in the caudal part of the midbrain with direct

connections to the retina. Maturana then went to Harvard for his PhD work with George B Chapman as his advisor. Chapman’s speciality was cell biology and ultrastructure. Maturana produced a PhD thesis in 1958 and a research paper(2) on the amphibian optic nerve. Why he did this particular work is not clear? Chapman was a cytologist using ultrastructural methods. He never worked on frogs or optic nerves even during his later distinguished career at Georgetown University. However, at MIT, down the street from Harvard, Jerome Lettvin was electrophysiologically recording from the frog optic nerve. Maturana made contact with Lettvin through J.Z. Young (who knew Lettvin and colleagues from work they carried out at the Zoological Station in Naples, Italy). Maturana's thesis revealed the frog optic nerve contains thirty times more fibers than previously estimated (3). Most of the fibers are unmyelinated and collectively the number of optic nerve fibers is around 500,000. He found that the number of fibers in the optic nerve approximately matches the number of ganglion cells in the retina. Maturana formally joined Lettvin’s laboratory at MIT’s Research Laboratory of Electronics (RLE) as a post-doctoral fellow. The details from his thesis about the frog optic nerve were useful for subsequent physiological studies. Maturana and Lettvin recorded electrical activity in the frog optic nerve and in the midbrain optic tectum, the principal target of the retina. They found that the unmyelinated optic nerve fibers terminate in the most superficial layers of the tectum and the myelinated optic nerve fibers terminate in layers below. Several sets of optic nerve fibers form visuotopic maps of visual space in the tectum. They published the paper "What the Frog's Eye Tells the Frog's Brain" (4) with Warren McCulloch and Walter Pitts, also at MIT, that became extensively cited and may have been one of the earliest papers in the realm of neuroethology. Their work was distinguished from other similar studies at the time by using “natural” visual stimuli rather than spots of light of various sizes and durations. They discovered five physiological types of retinal ganglion cells. Four of these five types are restricted to an individual layer of the tectum. One of these types is insensitive to spots of light but are exquisitely sensitive to small, dark, convexly-shaped moving objects that they dubbed "bug detectors". Lettvin and Maturana carried out the physiological and anatomical experiments and McCulloch and Pitts, famed for earlier theoretical work modeling neurons and neural networks and for epistemological approaches to the recognition of universals, provided theoretical rigor. Maturana as first author, co-wrote a longer paper elaborating on the results of the Frog’s Eye paper(5). The MIT group also produced a brief but notable physiological paper on regeneration of cut frog optic nerve fibers and showed they grow back to their original tectal locations(6). They also produced a paper describing two classes of visually evoked tectal cells. One class responded primarily to novel visual stimuli (“newness” cells); the other class responded best to stimuli repeatedly presented (“sameness” cells)(7). Maturana followed his anuran studies with studies in pigeon vision(8, 9) and with Lettvin and Wall, one of the first electrophysiological studies in octopus(10). After a 2 year post-doctoral period at MIT, he returned to Chile in 1960. |

1954年、ロックフェラー財団から奨学金を得て、ロンドン大学でJ・

Z・ヤング(イカの巨大軸索の「発見者」であり、後に『知識の木』の序文を書いた人物)のもとで解剖学と神経生理学を学んだ。マトゥラーナは、自分が「透

明な」学生であったため、ユニバーシティ・カレッジ・ロンドンに正式に受け入れられることはなかったと書いている。それにもかかわらず、彼は研究を行い、

脳から網膜へと走る求心性線維の存在の可能性を調査する論文(1)を発表した。この研究では、術後数週間から数カ月を経過したヒキガエルの視神経を一方的

に切断した。そしてマトゥラーナは、切断した神経の眼球と脳の切り株を従来のワイガートとホームズの神経線維染色法で調べ、「細い」ものの、求心性線維が

存在すると結論づけた。両生類は鳥類や爬虫類と違って、網膜に直接つながっている中脳の尾部にある明瞭な視索核を欠いていた。 マトゥラーナはその後、ハーバード大学でジョージ・B・チャップマンを指導教官として博士号を取得した。チャップマンの専門は細胞生物学と超微細構造で あった。マトゥラーナは1958年に博士論文を発表し、両生類の視神経に関する研究論文(2)を発表した。なぜ彼がこのような個別主義的な研究を行ったの かは定かではない。チャップマンは超微細構造法を用いた細胞学者であった。後にジョージタウン大学で卓越したキャリアを積んだときでさえ、カエルや視神経 を研究したことはなかった。しかし、ハーバード大学から通りを隔てたマサチューセッツ工科大学(MIT)では、ジェローム・レトヴィンがカエルの視神経か ら電気生理学的な記録を行っていた。マトゥラーナは、J.Z.ヤング(イタリアのナポリの動物学研究所でレトヴィンとその同僚と知り合いだった)を通じて レトヴィンと知り合った。マトゥラーナの論文により、カエルの視神経には以前推定されていたよりも30倍も多くの線維があることが明らかになった(3)。 繊維のほとんどは無髄であり、視神経繊維の総数は約50万本である。彼は、視神経の線維の数が網膜の神経節細胞の数とほぼ一致することを発見した。 マトゥラーナはMITのエレクトロニクス研究所(RLE)のレトヴィンの研究室にポスドクとして正式に加わった。カエルの視神経に関する彼の論文の詳細 は、その後の生理学的研究に役立った。マトゥラーナとレトヴィンは、カエルの視神経と、網膜の主要な標的である中脳視蓋の電気活動を記録した。彼らは、無 髄の視神経線維は視蓋の最も表層で終端し、有髄の視神経線維はその下の層で終端することを発見した。視神経線維のいくつかのセットは、視蓋における視覚空 間の視床地図を形成している。彼らは、同じくマサチューセッツ工科大学のウォーレン・マッカロクとウォルター・ピッツとともに、「カエルの目がカエルの脳 に伝えること」(4)という論文を発表した。 彼らの研究は、様々な大きさと持続時間の光スポットではなく、「自然な」視覚刺激を用いることで、当時の他の類似研究とは一線を画していた。彼らは網膜神 経節細胞に5つの生理学的タイプを発見した。この5種類のうち4種類は、視蓋の個々の層に限定されている。そのうちの1種類は光の点には鈍感だが、小さく て暗い凸状の動く物体には非常に敏感で、彼らはこれを「虫検出器」と名付けた。レトヴィンとマトゥラーナは生理学的・解剖学的実験を行い、マッカロクと ピッツはニューロンや神経回路網をモデル化する理論的研究と普遍性の認識に対する認識論的アプローチで有名であり、理論的厳密性を提供した。 マトゥラーナは筆頭著者として、Frog's Eye論文の結果を詳しく説明した長い論文を共同執筆した(5)。MITのグループはまた、切断されたカエルの視神経線維の再生に関する短いながらも注目 すべき生理学的論文を発表し、視神経線維が元の視蓋の位置まで成長することを示した(6)。彼らはまた、視覚誘発性視蓋細胞の2つのクラスについて述べた 論文も発表した。一方は主に新しい視覚刺激に反応し(「新しさ」細胞)、もう一方は繰り返し提示される刺激に最もよく反応する(「同一性」細胞)(7)。 マトゥラーナはアヌラーナの研究の後、ハトの視覚の研究を行い(8, 9)、レトヴィンとウォールと共にタコにおける最初の電気生理学的研究を行った(10)。マサチューセッツ工科大学で2年間のポスドク期間を過ごした後、 1960年にチリに戻った。 |

| Academic career Maturana was appointed Assistant Prof in Dept of Biology of Medical School of University of Chile Santiago, at the age of 32. He worked in neuroscience at the University of Chile, in the Biología del Conocer (Biology of Knowing) research center. Maturana's work has been developed and integrated into the work on ontological coaching developed by Fernando Flores and Julio Olalla. In 1994, he received Chile's National Prize for Natural Sciences.[4] Maturana established his own reflection and research center, the Instituto de Formación Matriztica. In 2020, he was awarded an honorary fellowship by the Cybernetics Society. Maturana died in Santiago on May 6, 2021, at age 92, due to pneumonia.[5][6] |

学者としてのキャリア マトゥラーナは32歳でチリ大学サンティアゴ校医学部生物学科の助教授に任命された。チリ大学のBiología del Conocer(知ることの生物学)研究センターで神経科学に携わる。マトゥラーナの研究は、フェルナンド・フローレスとフリオ・オラージャが開発した存 在論的コーチングに関する研究に発展・統合された。 1994年にはチリの自然科学国民賞を受賞した[4]。 マトゥラーナは自身の内省と研究センターであるInstituto de Formación Matrizticaを設立した。2020年、サイバネティックス協会から名誉フェローシップを授与される。 2021年5月6日、肺炎のためサンティアゴで死去、享年92歳[5][6]。 |

Work Maturana, 2012  A drawing in zero time Maturana's research interests concern concepts like cognition, autopoiesis, languaging, zero time cybernetics and structurally determined systems. Maturana's work extends to philosophy, cognitive science and even family therapy. He was inspired by the work of the biologist Jakob von Uexküll. His inspiration for his work in cognition came while he was a medical student and became seriously ill with tuberculosis. Confined in a sanatorium with very little to read, he spent time reflecting on his condition and the nature of life. What he came to realize was "that what was peculiar to living systems was that they were discrete autonomous entities such that all the processes that they lived, they lived in reference to themselves ... whether a dog bites me or doesn't bite me, it is doing something that has to do with itself." This paradigm of autonomy formed the basis of his studies and work.[2] Maturana and his student Francisco Varela were the first to define and employ the concept of "autopoiesis", which was Maturana's original idea. Aside from making important contributions to the field of evolution, Maturana is associated with an epistemology built upon empirical findings in neurobiology. Maturana and Varela wrote "Living systems are cognitive systems, and living as a process is a process of cognition. This statement is valid for all organisms, with or without a nervous system."[7] Reflections on life and association with Francisco Varela In an article in Constructivist Foundations. Maturana described the origins of the concept of autopoiesis and his collaboration with Varela.[8] |

仕事 マトゥラーナ, 2012  ゼロ時間のドローイング マトゥラーナの研究対象は、認知、オートポイエーシス、言語化、ゼロ時間サイバネティクス、構造決定システムといった概念である。マトゥラーナの研究は、 哲学、認知科学、家族療法にまで及んでいる。彼は生物学者ヤコブ・フォン・ユクスキュルの研究に触発された。 彼が認知の研究を始めるきっかけとなったのは、医学生時代に結核で重い病気にかかったことだった。療養所に閉じ込められ、ほとんど本を読むこともできな かった彼は、自分の病状と人生の本質について考える時間を過ごした。犬が私を噛もうが噛まままなかろうが、それは自分自身と関係のあることをしているの だ」。この自律性のパラダイムは、彼の研究と仕事の基礎となった[2]。 マトゥラーナとその弟子フランシスコ・バレラは、マトゥラーナ独自の考えである「オートポイエーシス」という概念を初めて定義し、採用した。マトゥラーナ は、進化の分野に重要な貢献をした以外にも、神経生物学における経験的知見に基づいて構築された認識論に関連している。マトゥラーナとヴァレラは「生命シ ステムは認知システムであり、プロセスとしての生命は認知のプロセスである」と書いた。この言葉は、神経系の有無にかかわらず、すべての生物に有効であ る」[7]。 フランシスコ・ヴァレラの人生とその交友を振り返る マトゥラーナは『構成主義的基礎』誌に寄稿した。マトゥラーナはオートポイエーシスの概念の起源とヴァレラとのコラボレーションについて述べている [8]。 |

| Publications Articles on anatomy and physiology 1958 H.R. Maturana Efferent fibres in the optic nerve of the toad (Bufo bufo) J. Anat Jan 92 : 21-27. [ He thanked JZ Young “for always valuable criticism and friendly encouragement.” On the paper his institutional address is Dept. Anatomy University College, London. With present address Biological Laboratory, Harvard University, Cambridge Mass.] 1959 Humberto R Maturana The Fine Anatomy of the optic nerve of anurans – an electron microscope study. Journal of Biophysical and Biochemical Cytology 7 107-120 [Present address: Research Laboratory of Electronics, MIT “My appreciation to Professor G.B. Chapman under whom this work was done as a doctoral thesis”] 1959 Maturana, H.R. Number of Fibres in the Optic Nerve and the number of Ganglion Cells in the Retina of Anurans Nature 183 1400-1407. 1959 J.Y. Lettvin, H.R. Maturana, W. S. McCulloch. W.H. Pitts What the Frog’s Eye Tells The Frog’s Brain Proceedings of the IRE 47: 1940-1951. 1960 H.R. Maturana, J.Y. Lettvin, W. S. McCulloch. W.H. Pitts Anatomy and Physiology of Vision in the frog (Rana pipiens). J. General Physiology 43 129-175. 1959 H.R. Maturana, J.Y. Lettvin, W. S. McCulloch. W.H. Pitts Evidence that cut optic nerve fibers grow back to original location. Science 130: 1709-10. 1960 J. Y. Lettvin, H. R. Maturana, W. H. Pitts, W. S. McCulloch Two Remarks on the Visual System of the Frog [In MIT Press publication, 'Sensory Communications']. 1963 H.R. Maturana and S. Frenk Directional movement and horizontal edge detectors in the pigeon retina Science 142 977-979. 1965 H,R. Maturana and S. Frenk Synaptic connections of the centrifugal fibers in the pigeon retina. Science 150 359-361 1965. 1965 Boycott BB, Lettvin JY, Maturana HR, Wall PD Octopus optic responses Experimental Neurology, 12, 247-256. 1968 Maturana, H, G. Uribe, S. Frenk A biological theory of relativistic colour coding in the primate retina Arch Biol Med Exp. 1:1-30 1970 Varela, FG, Maturana, HR Time courses of excitation and inhibition in retinal ganglion cells. Experimental Neurology 1970 H.R. Maturana, F. Varela and S. Frenk Size Constancy and the Perception of Space Cognition I (I), pp. 97-104. 1972 Philosophy The initial paper which stands as a prelude to all that followed: Biology of Cognition Archived 2009-09-17 at the Wayback Machine. Humberto R. Maturana. Biological Computer Laboratory Research Report BCL 9.0. Urbana IL: University of Illinois, 1970. As Reprinted in: Autopoiesis and Cognition: The Realization of the Living. Dordecht: D. Reidel Publishing Co., 1980, pp. 5–58. Books 1979 Autopoiesis and Cognition: The Realization of the Living With Francisco Varela. (Boston Studies in the Philosophy of Science). ISBN 90-277-1015-5. 1984 The tree of knowledge. Biological basis of human understanding. With Francisco Varela Revised edition (92) The Tree of Knowledge: Biological Roots of Human Understanding. ISBN 978-0-87773-642-4 1990 Biology of Cognition and epistemology. Ed Universidad de la Frontera. Temuco, Chile. 1992 Conversations with Humberto Maturana: Questions to biologist Psychotherapist. With K. Ludewig. Ed Universidad de la Frontera. Temuco, Chile. 1992. 1994 Reflections and Conversations. With Kurt Ludewig. Collection Family Institute. FUPALI Ed. Cordova. 1994 1994 Democracy is a Work of Art. Collection Roundtable. Linotype Ed Bogota Bolivar y Cia. 1997 Objectivity - An argument to force. Santiago de Chile: Ed Dolmen. 1997 Machines and living things. Autopoiese to do Organização Vivo. With Francisco Varela Porto Alegre: Medical Arts, 1997. 2004 From Being to Doing, The Origins of the Biology of Cognition. With Bernhard Poerksen. Paperback, 2004 2009 The Origins of humanness in the Biology of Love. With Gerda Verden-Zoller and Pille Bunnell. 2004 From biology to psychology. Paperback. 2009 Sense of humanity. Paperback. 2008 Habitar humano en seis ensayos de biología-cultural. With Ximena Dávila. 2012 The Origin of Humanness in the Biology of Love. With Gerda Verden-Zöller. Edited by Pille Bunnell. Philosophy Document Center, Charlottesville VA; Exeter UK: Imprint Academic, Imprint Academic. 2015 El árbol del vivir. With Ximena Dávila. 2019 Historia de nuestro vivir cotidiano. With Ximena Dávila. |

出版物 解剖学と生理学に関する論文 1958 H.R.マトゥラーナ ヒキガエル(Bufo bufo)の視神経における遠心性線維 J. Anat Jan 92 : 21-27. [彼はJZ Youngに「いつも貴重な批評と友好的な励ましをありがとう」と感謝した。論文では、彼の所属機関はDepartment.Anatomy University College, Londonとなっている。現住所はハーバード大学生物学研究所(マサチューセッツ州ケンブリッジ)である。 1959 Humberto R Maturana The Fine Anatomy of the optic nerve of anurans - an electron microscope study. Journal of Biophysical and Biochemical Cytology 7 107-120 [現職: この研究が博士論文として行われたG.B.チャップマン教授に感謝する。] 1959 Maturana, H.R. 視神経の線維数と無尾動物の網膜における神経節細胞数 Nature 183 1400-1407. 1959 J.Y. Lettvin, H.R. Maturana, W. S. McCulloch. W.H.ピッツ カエルの目はカエルの脳に何を語るのか? 1960年 H.R.マトゥラーナ、J.Y.レトヴィン、W.S.マッカロク。W.H. Pitts Anatomy and Physiology of Vision in the frog (Rana pipiens). J. General Physiology 43 129-175. 1959 H.R.マトゥラーナ、J.Y.レトヴィン、W.S.マッカロク。W.H.ピッツ 切断された視神経線維が元の位置に成長する証拠。Science 130: 1709-10. 1960 J. Y. Lettvin, H. R. Maturana, W. H. Pitts, W. S. McCulloch カエルの視覚系に関する2つの指摘 [MIT Press出版, 『Sensory Communications』所収]. 1963 H.R. Maturana and S. Frenk 鳩の網膜における方向運動と水平エッジ検出器 Science 142 977-979. 1965 H,R. ハト網膜における遠心性線維のシナプス結合。サイエンス 150 359-361 1965年 1965 Boycott BB, Lettvin JY, Maturana HR, Wall PD Octopus optic responses Experimental Neurology, 12, 247-256. 1968 Maturana, H, G. Uribe, S. Frenk 霊長類の網膜における相対論的色彩コーディングの生物学的理論 Arch Biol Med Exp. 1970 Varela, FG, Maturana, HR 網膜神経節細胞における興奮と抑制の時間経過。実験神経学 1970 H.R. Maturana, F. Varela and S. Frenk Size Constancy and the Perception of Space Cognition I (I), pp.97-104. 1972 哲学 その後に続くすべての前奏曲となる最初の論文である: 認知の生物学 Archived 2009-09-17 at the Wayback Machine. ウンベルト・R・マトゥラーナ. Biological Computer Laboratory Research Report BCL 9.0. Urbana IL: University of Illinois, 1970. 再掲: オートポイエーシスと認知: The Realization of the Living. Dordecht: D. Reidel Publishing Co., 1980, pp. 著書 1979 オートポイエーシスと認知: フランシスコ・ヴァレラとの共著。(ボストン科学哲学研究)。ISBN 90-277-1015-5. 1984 知識の木。人間理解の生物学的基礎。フランシスコ・バレラとともに 改訂版(92) The Tree of Knowledge: 人間理解の生物学的根源. ISBN 978-0-87773-642-4 1990 認知の生物学と認識論。フロンテラ大学編。チリ、テムコ。 1992 フンベルト・マトゥラーナとの対話: 生物学者への質問 心理療法家。K.ルデヴィッヒと。Ed Universidad de la Frontera. チリ、テムコ。1992. 1994年 反省と対話。クルト・ルーデヴィッヒと。コレクション・ファミリー・インスティテュート。FUPALI編。コルドバ。1994 1994 民主主義は芸術作品である。コレクション・ラウンドテーブル。Linotype Ed Bogota Bolivar y Cia. 1997 客観性-強要する議論。サンティアゴ・デ・チリ: エド・ドルメン。 1997 機械と生物。オートポイエーゼから生体組織へ。フランシスコ・ヴァレラと共著 ポルト・アレグレ:メディカル・アート社 1997年 2004 「存在から行為へ、認知の生物学の起源」。ベルンハルト・ポークセンと共著。ペーパーバック、2004年 2009年 愛の生物学における人間性の起源。ゲルダ・フェルデン=ゾラー、ピレ・ブンネルと共著。 2004年 生物学から心理学へ。ペーパーバック。 2009年 センス・オブ・ヒューマニティー ペーパーバック。 2008 Habitar Humano en seis ensayos de biología-cultural. シメナ・ダビラとの共著。 2012 愛の生物学における人間性の起源。ゲルダ・フェルデン=ツェラーと共著。ピレ・ブンネル編集。Philosophy Document Center, Charlottesville VA; Exeter UK: Imprint Academic, インプリント・アカデミック。 2015 El árbol del vivir. シメナ・ダビラと共著。 2019 Historia de nuestro vivir cotidiano. シメナ・ダビラと。 |

| Autopoiesis Constructivism Ernst von Glasersfeld Francisco Varela Heinz von Foerster Molecular cellular cognition Neurobiology Neurophilosophy Second-order cybernetics Santiago theory of cognition Vittorio Guidano William Ross Ashby |

オートポイエーシス 構成主義 エルンスト・フォン・グレイザースフェルド フランシスコ・ヴァレラ ハインツ・フォン・フェルスター 分子細胞認知 神経生物学 神経哲学 二次サイバネティクス サンチャゴ認知理論 ヴィットリオ・グイダーノ ウィリアム・ロス・アシュビー |

| Letelier, Juan-Carlos; Marín,

Gonzalo; Mpodozis, Jorge (19 March 2008). "History: The Biology of

Cognition Laboratory of the Universidad de Chile (1960–2006)". Riegler, Alexander; Bunnell, Pille, eds. (2011). "The Work of Humberto Maturana and Its Application Across the Sciences". Constructivist Foundations (Special issue). 6 (3): 287–406. |

Letelier, Juan-Carlos; Marín,

Gonzalo; Mpodozis, Jorge (19 March 2008). "歴史:

チリ大学認知生物学研究室(1960-2006年)". Riegler, Alexander; Bunnell, Pille編 (2011). 「Humberto Maturanaの仕事と科学全体への応用」. Constructivist Foundations (Special issue). 6 (3): 287-406. |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Humberto_Maturana |

★

| 知恵の樹 / H. マトゥラーナ, F. バレーラ著 ; 管啓次郎訳, 東京 : 筑摩書房 , 1997.12. - (ちくま学芸文庫)/ El árbol del conocimiento.[pdf] | El árbol del conocimiento.[pdf] |

| Capítulo 1: Conocer el Conocer Capítulo 11: La Organización de lo Vivo Capítulo III: Historia: Reproducción y Herencia Capítulo IV: La Vida de los Metacelulares Capítulo V: La Deriva Natural de los Seres Vivos Capítulo VI: Dominios Conductuales Capítulo VII: Sistema Nervioso y Conocimiento Capítulo VIII: Los Fenómenos Sociales Capítulo IX: Dominios Lingüísticos y Conciencia Humana Capítulo X: El Arbol del Conocimiento Glosario Fuentes de las Ilustraciones |

第1章:知ることについて 第11章:生命の組織 第3章:歴史:生殖と遺伝 第4章:メタ細胞の生命 第5章:生物の自然漂流 第6章:行動領域 第7章:神経系と知識 第8章:社会現象 第9章:言語領域と人間の意識 第10章:知識の木 用語集 図版の出典 |

★サ イバネティックスの革命家たち : アジェンデ時代のチリにおける技術と政治 / エデン・メディーナ著 ; 大黒岳彦訳, 青土社 , 2022

テ クノロジーは社会主義の夢を描けたのか?1970年代前半、民主的選挙によって選ばれたチリの社会主義政権は、サイバネティックスを使って国家経済を統制 するという未知の挑戦に乗り出した。チリ独自の社会主義という政治的な理想と、「サイバーシン計画」という技術革新とが交差するところに、いったい何が生 じたのか。そして、米国の「見えざる封鎖」の中、どのような運命を辿ったのか。関係資料や関係者への聞き取り調査から、歴史の裏側で進行したテクノロジー の試みの全貌を引き出し、数々の学術賞を受賞した圧倒的労作。

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099