偶然と偶発性

Contingency

☆ 論理学において偶発性(偶然, contingency) とは、ある文が必要でも不可能でもないことを意味する。様相論理学は、文が真である方法(様態)に関係する。偶発性は、必然性、可能性と並ぶ3つの基本的 なモードの1つである。様相論理学では、偶発的な文は、必要なものと不可能なものの間の様相領域に位置し、どちらの領域にも決して入らない。偶発的言明と 必要的言明は、可能的言明の完全な集合を形成する。この定義は広く受け入れられているが、偶発的なものと必然的なものの正確な区別(あるいはその欠如)に ついては、古代から疑問視されてきた。

・決定論▶︎自由意志▶文化決定論︎︎▶︎環境決定論▶非決定論▶︎▶

| In logic, contingency

is the feature of a statement making it neither necessary nor

impossible.[1][2] Contingency is a fundamental concept of modal logic.

Modal logic concerns the manner, or mode, in which statements are true.

Contingency is one of three basic modes alongside necessity and

possibility. In modal logic, a contingent statement stands in the modal

realm between what is necessary and what is impossible, never crossing

into the territory of either status. Contingent and necessary

statements form the complete set of possible statements. While this

definition is widely accepted, the precise distinction (or lack

thereof) between what is contingent and what is necessary has been

challenged since antiquity. |

論

理学において偶発性とは、ある文が必要でも不可能でもないことを意味する。様相論理学は、文が真である方法(様態)に関係する。偶発性は、必然性、可能性

と並ぶ3つの基本的なモードの1つである。様相論理学では、偶発的な文は、必要なものと不可能なものの間の様相領域に位置し、どちらの領域にも決して入ら

ない。偶発的言明と必要的言明は、可能的言明の完全な集合を形成する。この定義は広く受け入れられているが、偶発的なものと必然的なものの正確な区別(あ

るいはその欠如)については、古代から疑問視されてきた。 |

| Contingency and modal possibility In logic, a thing is considered to be possible when it is true in at least one possible world. This means there is a way to imagine a world in which a statement is true and in which its truth does not contradict any other truth in that world. If it were impossible, there would be no way to conceive such a world: the truth of any impossible statement must contradict some other fact in that world. Contingency is not impossible, so a contingent statement is therefore one which is true in at least one possible world. But contingency is also not necessary, so a contingent statement is false in at least one possible world.α While contingent statements are false in at least one possible world, possible statements are not also defined this way. Since necessary statements are a kind of possible statement (e.g. 2=2 is possible and necessary), then to define possible statements as 'false in some possible world' is to affect the definition of necessary statements. Since necessary statements are never false in any possible world, then some possible statements are never false in any possible world. So the idea that a statement might ever be false and yet remain an unrealized possibility is entirely reserved to contingent statements alone. While all contingent statements are possible, not all possible statements are contingent.[3] The truth of a contingent statement is consistent with all other truths in a given world, but not necessarily so. They are always possible in every imaginable world but not always trueβ in every imaginable world. This distinction begins to reveal the ordinary English meaning of the word "contingency," in which the truth of one thing depends on the truth of another. On the one hand, the mathematical idea that a sum of two and two is four is always possible and always true, which makes it necessary and therefore not contingent. This mathematical truth does not depend on any other truth, it is true by definition. On the other hand, since a contingent statement is always possible but not necessarily true, we can always conceive it to be false in a world in which it is also always logically achievable. In such a world, the contingent idea is never necessarily false since this would make it impossible in that world. But if it's false and yet still possible, this means the truths or facts in that world would have to change in order for the contingent truth to become actualized. When a statement's truth depends on this kind of change, it is contingent: possible but dependent on whatever facts are actually taking place in a given world. |

偶発性と様相的可能性 論理学では、あることが可能であると考えられるのは、それが少なくとも一つの可能な世界において真であるときである。これは、ある文が真であり、その真理 がその世界の他の真理と矛盾しないような世界を想像する方法があることを意味する。もし不可能であれば、そのような世界を想像する方法はない。不可能な文 の真理は、その世界における他の事実と矛盾しなければならない。偶発性は不可能ではないので、偶発的な言明とは、少なくとも一つの可能な世界において真で ある言明のことである。しかし、偶発性もまた必要ではないので、偶発的言明は少なくとも1つの可能な世界では偽である。必要的言明は可能的言明の一種であ るので(例えば、2=2は可能的かつ必要的である)、可能的言明を「ある可能的世界において偽である」と定義することは、必要的言明の定義に影響を与える ことになる。必要な言明はどのような可能性のある世界でも決して偽らないので、可能な言明の中にはどのような可能性のある世界でも決して偽らないものがあ る。だから、ある言明が偽である可能性があり、なおかつ未実現の可能性のままであるという考えは、偶発的言明だけに完全に留保されているのである。すべて の偶発的言明は可能であるが、すべての可能な言明が偶発的であるわけではない[3]。偶発的言明の真理は、与えられた世界における他のすべての真理と一致 するが、必ずしもそうではない。偶発的言明は、想像可能なあらゆる世界において常に可能であるが、想像可能なあらゆる世界において常に真βであるとは限ら ない。 この区別は、あることの真偽が別のことの真偽に依存するという「偶発性」という言葉の普通の英語の意味を明らかにし始める。一方では、2と2の和が4であ るという数学的な考えは常に可能であり、常に真である。この数学的真理は他の真理に依存せず、定義によって真である。一方、偶発的な記述は常に可能である が、必ずしも真ではないので、それが常に論理的に達成可能な世界では、我々は常にそれが偽であると考えることができる。そのような世界では、偶発的な考え は不可能になるので、必ずしも偽ではない。しかし、もしそれが偽であり、なおかつ可能であるならば、偶発的真理が現実化するためには、その世界の真理や事 実が変化しなければならないことになる。文の真理がこのような変化に依存している場合、それは偶発的なものである。 |

Contingency and modal necessity The statement "If all objects are physical, and A. N. Prior exists, then A. N. Prior is physical" may be logically true by form, but not necessarily true. Some philosophical distinctions are used to examine the line between contingent and necessary statements. These include analytic and epistemic distinctions as well as the modal distinctions already noted. But there is not always agreement about exactly what these distinctions mean or how they are used. Philosophers such as Jaakko Hintikka and Arthur Pap consider the concept of analytic truths, for example (as distinct from synthetic ones) to be ambiguous since in practice they are defined or used in different ways.[4][5] And while Saul Kripke stipulates that analytic statements are always necessary and a priori,[6] Edward Zalta claims that there are examples in which analytic statements are not necessary.[7] Kripke uses the example of a meter stick to support the idea that some a priori truths are contingent.[8] In Time and Modality, A. N. Prior argues that a cross-examination between the basic principles of modal logic and those of quantificational logic seems to require that "whatever exists exists necessarily." He says this threatens the definition of contingent statements as non-necessary things when one generically intuits that some of what exists does so contingently, rather than necessarily.[9] Harry Deutsch acknowledged Prior's concern and outlines rudimentary notes about a "Logic for Contingent Beings."[10] Deutsch believes that the solution to Prior's concern begins by removing the assumption that logical statements are necessary. He believes the statement format, "If all objects are physical, and ϕ exists, then ϕ is physical," is logically true by form but is not necessarily true if ϕ rigidly designates, for example, a specific person who is not alive.[11] |

偶発性と様相必然性 すべての物体が物理的であり、A.N.プライヤーが存在するならば、A.N.プライヤーは物理的である」という文は、形式的には論理的に正しいかもしれないが、必ずしも正しいとは限らない。 偶発的言明と必然的言明の境界線を検討するために、いくつかの哲学的区別が用いられる。これには、すでに述べた様相の区別だけでなく、分析的区別や認識論 的区別が含まれる。しかし、これらの区別が何を意味するのか、どのように使われるのかについては、必ずしも一致していない。例えばヤーッコ・ヒンティッカ やアーサー・パップなどの哲学者は、分析的真理(合成的真理とは異なる)という概念は曖昧であると考えている。 A. N. Priorは『Time and Modality』において、様相論理学の基本原理と数量論理学の基本原理との相互検証は、"存在するものはすべて必然的に存在する "ことを要求しているように見えると論じている。ハリー・ドイッチュはプライヤーの懸念を認め、「偶発的なもののための論理」[10]についての初歩的な メモを概説している。彼は、「すべての物体が物理的であり、φが存在するならば、φは物理的である」という文の形式は論理的には真であるが、φが例えば生 きていない特定の人物を厳密に指定する場合には必ずしも真ではないと考えている[11]。 |

Future contingency Aristotle's example of a sea battle as a future contingent demonstrates the paradox of the modal fallacy. Problem of future contingency Main article: Problem of future contingents In chapter 9 of De Interpretatione, Aristotle observes an apparent paradox in the nature of contingency. He considers that while the truth values of contingent past- and present-tense statements can be expressed in pairs of contradictions to represent their truth or falsity, this may not be the case of contingent future-tense statements. Aristotle asserts that if this were the case for future contingent statements as well, some of them would be necessarily true, a fact which seems to contradict their contingency.[12] Aristotle's intention with these claims breaks down into two primary readings of his work. The first view, considered notably by Boethius,[13] supposes that Aristotle's intentions were to argue against this logical determinism only by claiming future contingent statements are neither true nor false.[14][15][16] This reading of Aristotle regards future contingents as simply disqualified from possessing any truth value at all until they are actualized. The opposing view, with an early version from Cicero,[17] is that Aristotle was not attempting to disqualify assertoric statements about future contingents from being either true or false, but that their truth value was indeterminant.[18][19][20] This latter reading takes future contingents to possess a truth value, one which is necessary but which is unknown. This view understands Aristotle to be saying that while some event's occurrence at a specified time was necessary, a fact of necessity which could not have been known to us, its occurrence at simply any time was not necessary. Determinism and foreknowledge Medieval thinkers studied logical contingency as a way to analyze the relationship between Early Modern conceptions of God and the modal status of the world qua His creation.[21] Early Modern writers studied contingency against the freedom of the Christian Trinity not to create the universe or set in order a series of natural events. In the 16th century, European Reformed Scholasticism subscribed to John Duns Scotus' idea of synchronic contingency, which attempted to remove perceived contradictions between necessity, human freedom and the free will of God to create the world. In the 17th Century, Baruch Spinoza in his Ethics states that a thing is called contingent when "we do not know whether the essence does or does not involve a contradiction, or of which, knowing that it does not involve a contradiction, we are still in doubt concerning the existence, because the order of causes escape us."[22] Further, he states, "It is in the nature of reason to perceive things under a certain form of eternity as necessary and it is only through our imagination that we consider things, whether in respect to the future or the past, as contingent.[23] The eighteenth-century philosopher Jonathan Edwards in his work A Careful and Strict Enquiry into the Modern Prevailing Notions of that Freedom of Will which is supposed to be Essential to Moral Agency, Virtue and Vice, Reward and Punishment, Praise and Blame (1754), reviewed the relationships between action, determinism, and personal culpability. Edwards begins his argument by establishing the ways in which necessary statements are made in logic. He identifies three ways necessary statements can be made for which only the third kind can legitimately be used to make necessary claims about the future. This third way of making necessary statements involves conditional or consequential necessity, such that if a contingent outcome could be caused by something that was necessary, then this contingent outcome could be considered necessary itself "by a necessity of consequence".[24] Prior interprets[25] Edwards by supposing that any necessary consequence of any already necessary truth would "also 'always have existed,' so that it is only by a necessary connexion (sic) with 'what has already come to pass' that what is still merely future can be necessary."[26] Further, in Past, Present, and Future, Prior attributes an argument against the incompatibility of God's foreknowledge or foreordaining with future contingency to Edward's Enquiry.[27] |

未来の偶発性 未来の偶発性としての海戦というアリストテレスの例は、様相の誤謬のパラドックスを示している。 未来偶発性の問題 主な記事 未来の偶発性の問題 De Interpretatione』第9章で、アリストテレスは偶発性の本質における明白なパラドックスを観察している。アリストテレスは、過去時制と現在 時制の偶発的な言明の真理値は、その真偽を表す矛盾の組で表現できるが、未来時制の偶発的な言明の真偽値はそうではないと考える。アリストテレスは、もし これが未来の偶発的な陳述にも当てはまるのであれば、そのうちのいくつかは必然的に真となるはずであり、この事実はその偶発性と矛盾するように思われると 主張している[12]。第一の見解は、特にボエティウスによって考えられており[13]、アリストテレスの意図は、未来の偶発的な言明が真でも偽でもない と主張することによってのみ、この論理的決定論に反論することであったと仮定している[14][15][16]。アリストテレスのこの読み方は、未来の偶 発的な言明が現実化されるまで、真理的価値をまったく持たないものとして単に不適格であるとみなしている。キケロ[17]に初期のバージョンがある反対側 の見解は、アリストテレスは未来の偶発事象についての断定的な言明が真であるか偽であるかのどちらかであることを不問に付そうとしていたのではなく、その 真理値は不確定であるというものである[18][19][20]。この見解はアリストテレスが、ある事象が特定の時間に発生することは必要であり、それは われわれには知りえない必然の事実であるが、単に任意の時間に発生することは必要ではないと言っているのだと理解している。 決定論と予知 中世の思想家たちは、近世の神の概念と神の創造物としての世界の様相との関係を分析する方法として論理的偶発性を研究していた。16世紀、ヨーロッパの改 革派スコラ学は、ジョン・ドゥンス・スコトゥスの共時的偶有性の考えを支持し、必然性、人間の自由、そして世界を創造する神の自由意志の間に認識される矛 盾を取り除こうとした。17世紀、バルーク・スピノザは『倫理学』の中で、「本質が矛盾を伴うか伴わないか、あるいは、矛盾を伴わないことを知っていて も、原因の順序がわれわれから逃れられるために、その存在に関してわれわれがまだ疑念を抱いている」ときに、物事は偶発的と呼ばれると述べている [22]。 さらに彼は、「ある種の永遠性の下にある物事を必要なものとして認識するのは理性の本性であり、未来や過去に関してであれ、物事を偶発的なものとして考え るのは想像力を通じてのみである」と述べている[23]。 18世紀の哲学者であるジョナサン・エドワーズは、その著作『A Careful and Strict Enquiry into the Modern Prevailing Notions of that is supposed to be essential to Moral Agency, Virtue and Vice, Reward and Punishment, Praise and Blame』(1754年)の中で、行為、決定論、個人の過失責任の関係を再検討している。エドワーズはまず、論理学において必要な言明がなされる方法を 確立することから議論を始める。彼は、必要な言明がなされる3つの方法を特定し、そのうちの3番目の方法だけが、将来について必要な主張をするために合法 的に使用できる。この3つ目の必要的記述の方法は条件的必然性または結果的必然性を伴うものであり、偶発的な結果が必要な何かによって引き起こされる可能 性がある場合、この偶発的な結果は「結果的必然性によって」それ自体が必要であると考えられるというものである。 [24] プライアはエドワーズを、すでに必要な真理の必要な帰結は「『常に存在していた』のであり、『すでに実現したこと』との必然的な関連によってのみ、まだ単 に未来にあるものが必要でありうるのである」[26]と仮定することによって解釈している。 |

| Conceptual necessity Logical possibility Modal collapse Modal fallacy Modal logic Subjunctive possibility |

概念上の必然性 論理的可能性 様相の崩壊 様相の誤謬 様相論理 接続詞の可能性 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Contingency_(philosophy) |

|

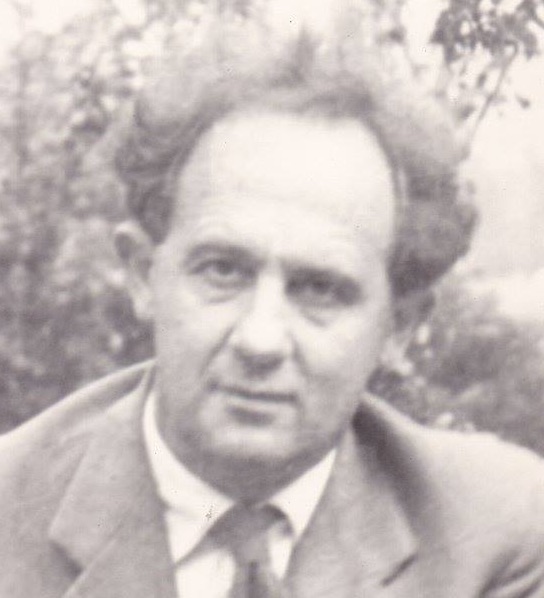

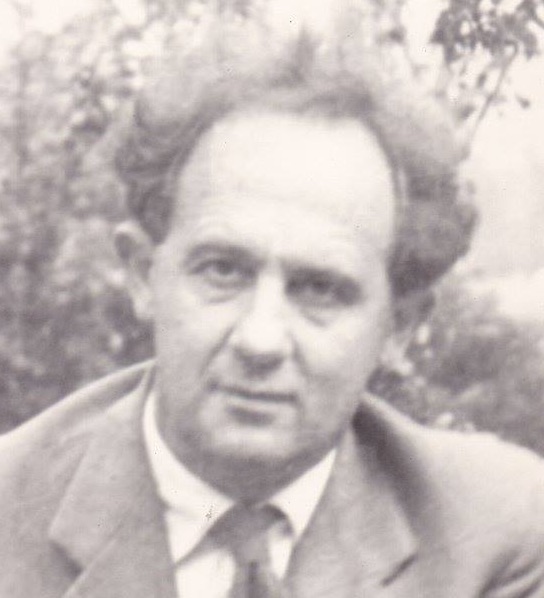

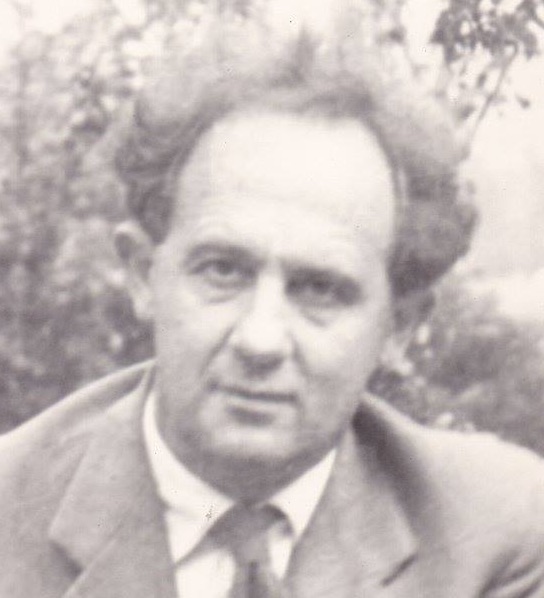

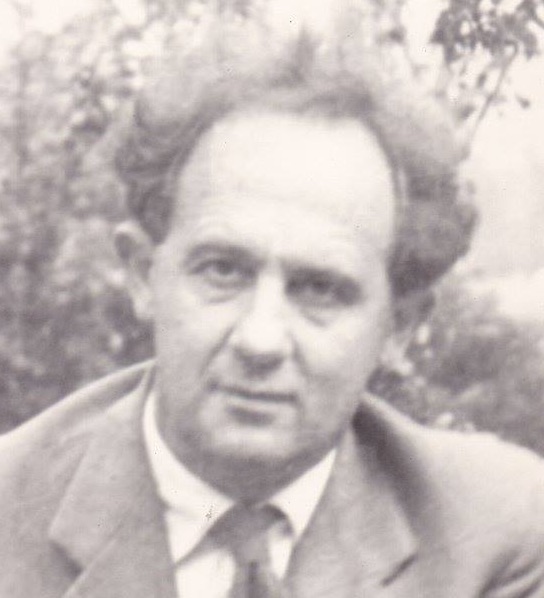

Arthur Norman Prior

(4 December 1914 – 6 October 1969), usually cited as A. N. Prior, was a

New Zealand–born logician and philosopher. Prior (1957) founded tense

logic, now also known as temporal logic, and made important

contributions to intensional logic, particularly in Prior (1971). Arthur Norman Prior

(4 December 1914 – 6 October 1969), usually cited as A. N. Prior, was a

New Zealand–born logician and philosopher. Prior (1957) founded tense

logic, now also known as temporal logic, and made important

contributions to intensional logic, particularly in Prior (1971).Biography Prior was born in Masterton, New Zealand, on 4 December 1914, the only child of Australian-born parents: Norman Henry Prior (1882–1967) and his wife born Elizabeth Munton Rothesay Teague (1889–1914). His mother died less than three weeks after his birth and he was cared for by his father's sister. His father, a medical practitioner in general practice, after war service at Gallipoli and in France—where he was awarded the Military Cross—remarried in 1920. There were three more children: Elaine, the epidemiologist Ian Prior, and Owen. Arthur Prior grew up in a prominent Methodist household. His two Wesleyan grandfathers, the Reverends Samuel Fowler Prior and Hugh Henwood Teague, were sent from England to South Australia as missionaries in 1875.[6] The Prior family first moved to New Zealand in 1893. As the son of a doctor, Prior at first considered becoming a biologist, but ended up focusing on theology and philosophy, graduating from the University of Otago in 1935 with a B.A. in philosophy. While studying for his B.A., Prior attended the seminary at Dunedin's Knox Theological Hall but decided against entering the Presbyterian ministry. John Findlay, Professor of Philosophy at Otago, first opened up the study of logic for Prior.[7] In 1936, Prior married Clare Hunter, a freelance journalist, and they spent several years in Europe, during which they tried to earn a living as writers. Daunted by the prospect of an invasion of Britain, he and Clare returned to New Zealand in 1940.[1] At this point in his life he was a devout Presbyterian, though he became an atheist later in life.[8][9] After divorce from his first wife, he remarried in 1943 to Mary Wilkinson, with whom he would have two children. He served in the Royal New Zealand Air Force from 1943 to 1945 before embarking on an academic career at Canterbury University College in February 1946. His first position was a lectureship which had become available when Karl Popper left the university.[10] After returning to New Zealand following a year at Oxford as a visiting lecturer he took up a professorship in 1959 at Manchester University where he remained until he was elected a Fellow of Balliol College, Oxford in 1966 and appointed a Reader. He continued his Manchester practice of accepting visiting professorships.[10] Arthur Prior went to give lectures at Norwegian universities in September 1969 and on 6 October 1969, the night before he was to deliver a lecture there, he died from a heart attack at Trondheim, Norway.[10] Professional life Prior was educated entirely in New Zealand, where he was fortunate to have come under the influence of J. N. Findlay,[1] under whom he wrote his M.A. thesis on 'The Nature of Logic'.[11] While Prior was very fond of the theology of Karl Barth, his early criticism of Barth's adherence to Philosophical Idealism, is a mark of Findlay's influence on Prior.[11] He began teaching philosophy and logic at Canterbury University College in February 1946, filling the vacancy created by Karl Popper's resignation. In 1951 Prior met J. J. C. Smart, also known as "Jack" Smart, at a philosophical conference in Australia and the two developed a life-long friendship. Their correspondence was influential on Prior's development of tense logic. Smart adhered to the tenseless theory of time and was never persuaded by Prior's arguments, though Prior was influential in making Smart skeptical about Wittgenstein's view on pseudo-relations.[12] He became Professor in 1953. Thanks to the good offices of Gilbert Ryle, who had met Prior in New Zealand in 1954, Prior spent the year 1956 on leave at the University of Oxford, where he gave the John Locke lectures in philosophy. These were subsequently published as Time and Modality (1957). This is a seminal contribution to the study of tense logic and the metaphysics of time, in which Prior championed the A-theorist view that the temporal modalities of past, present and future are basic ontological categories of fundamental importance for our understanding of time and the world. Prior was several times warned by J. J. C. Smart against making tense-logic the topic of his John Locke lectures. Smart feared that tense-logic would get Prior "involved in side issues, even straight philosophy, and not in the stuff that will do Oxford most good."[13] Prior was however convinced that tense-logic had the potential to benefit logic, as well as philosophy, and thus he considered his lectures an "expression of a conviction that formal logic and general philosophy have more to bring to one another than is sometimes supposed".[14] During his time at Oxford, Prior met Peter Geach and William Kneale, influenced John Lemmon, and corresponded with the adolescent Saul Kripke. Logic in the United Kingdom was then in a rather low state, being "deeply out of fashion and its practitioners were isolated and somewhat demoralized."[15] Prior arranged Logical a Colloquium which brought together such Logicians as John Lemmon, Peter Geach, Czesław Lejewski and more.[16] The colloquiums were a great success and, together with Prior's John Locke lecture and his visits around the country, he helped revitalize British logic.[16] From 1959 to 1966, he was Professor of Philosophy at the University of Manchester, having taught Osmund Lewry. From 1966 until his death he was Fellow and Tutor in philosophy at Balliol College, Oxford. His students include Max Cresswell, Kit Fine, and Robert Bull. Almost entirely self-taught in modern formal logic, Prior published four major papers on logic in 1952,[17] when he was 38 years of age, shortly after discovering the work of Józef Maria Bocheński and Jan Łukasiewicz,[18] despite very little of Łukasiewicz's work being translated into English.[19][20] He went so far as to read untranslated Polish texts without being able to speak Polish claiming "the symbols are so illuminating that the fact that the text is incomprehensible doesn’t much matter".[19] He went on to employ Polish notation throughout his career.[21] Prior (1955) distills much of his early teaching of logic in New Zealand. Prior's work on tense logic provides a systematic and extended defense of a tensed conception of reality in which propositional statements can change truth value over time.[22] Prior stood out by virtue of his strong interest in the history of logic. He was one of the first English-speaking logicians to appreciate the nature and scope of the logical work of Charles Sanders Peirce, and the distinction between de dicto and de re in modal logic. Prior taught and researched modal logic before Kripke proposed his possible worlds semantics for it, at a time when modality and intensionality commanded little interest in the English speaking world, and had even come under sharp attack by Willard Van Orman Quine. He is now said to be the precursor of hybrid logic.[23] Undertaking (in one section of his book Past, Present, and Future (1967)) the attempt to combine binary (e.g., "until") and unary (e.g., "will always be") temporal operators to one system of temporal logic, Prior—as an incidental result—builds a base for later hybrid languages. His work Time and Modality explored the use of a many-valued logic to explain the problem of non-referring names. Prior's work was both philosophical and formal and provides a productive synergy between formal innovation and linguistic analysis.[citation needed] Natural language, he remarked, can embody folly and confusion as well as the wisdom of our ancestors. He was scrupulous in setting out the views of his adversaries, and provided many constructive suggestions about the formal development of alternative views. Publications The following books were either written by Prior, or are posthumous collections of journal articles and unpublished papers that he wrote: 1949. Logic and the Basis of Ethics. Oxford University Press (ISBN 0-19-824157-7) 1955, 1962. Formal Logic. Oxford University Press. 1957. Time and Modality. Oxford University Press. Based on his 1956 John Locke lectures. 1962. "Changes in Events and Changes in Things". University of Kansas. 1967. Past, Present and Future. Oxford University Press. 1968. Papers on Time and Tense. Oxford University Press. 1971. Objects of Thought. Edited by P. T. Geach and A. J. P. Kenny. Oxford University Press. 1976. The Doctrine of Propositions and Terms. Edited by P. T. Geach and A. J. P. Kenny. London: Duckworth. 1976. Papers in Logic and Ethics. Edited by P. T. Geach and A. J. P. Kenny. London: Duckworth. 1977. Worlds, Times and Selves. Edited by Kit Fine. London: Duckworth. 2003. Papers on Time and Tense. Second expanded edition by Per Hasle, Peter Øhrstrøm, Torben Braüner & Jack Copeland. Oxford University Press. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arthur_Prior |

アー

サー・ノーマン・プライヤー(Arthur Norman Prior、1914年12月4日 -

1969年10月6日)はニュージーランド生まれの論理学者、哲学者。プライヤー(1957)は時制論理学(現在では時間論理学とも呼ばれる)を創始し、

特にプライヤー(1971)では強化論理学に重要な貢献をした。 アー

サー・ノーマン・プライヤー(Arthur Norman Prior、1914年12月4日 -

1969年10月6日)はニュージーランド生まれの論理学者、哲学者。プライヤー(1957)は時制論理学(現在では時間論理学とも呼ばれる)を創始し、

特にプライヤー(1971)では強化論理学に重要な貢献をした。略歴 1914年12月4日、ニュージーランドのマスタートン(Masterton)で、オーストラリア生まれの両親の間に生まれた: ノーマン・ヘンリー・プライヤー(1882-1967)とその妻エリザベス・マントン・ローセイ・ティーグ(1889-1914)の間に生まれた。生後3 週間足らずで母親が亡くなり、父親の妹に面倒を見てもらった。開業医であった父親は、ガリポリとフランスでの戦争従軍後、1920年に再婚した。さらに3 人の子供がいた: エレイン、疫学者のイアン・プライヤー、そしてオーウェンである。アーサー・プライヤーは著名なメソジストの家庭に育った。彼の2人のウェスレア派の祖 父、サミュエル・ファウラー・プライヤー牧師とヒュー・ヘンウッド・ティーグ牧師は、1875年に宣教師としてイングランドから南オーストラリアに派遣さ れた[6]。 医師の息子であったプライヤーは、当初生物学者になることを考えていたが、結局神学と哲学に専念することになり、1935年にオタゴ大学で哲学の学士号を 取得して卒業した。学士課程在学中、プライヤーはダニーデンのノックス神学館で神学校に通ったが、長老派の聖職に就くことは断念した。1936年、プライ ヤーはフリーランスのジャーナリストであったクレア・ハンターと結婚し、数年間をヨーロッパで過ごした。この時点で彼は敬虔な長老派であったが、後に無神 論者となる[8][9]。 最初の妻との離婚後、1943年にメアリー・ウィルキンソンと再婚し、2人の子供をもうける。1943年から1945年まで王立ニュージーランド空軍に勤 務した後、1946年2月にカンタベリー・ユニバーシティ・カレッジで学究生活に入る。最初の職は、カール・ポパーが同大学を去った際に空いた講師職で あった[10]。 オックスフォード大学での1年間の客員講師を経てニュージーランドに戻った後、1959年にマンチェスター大学で教授職に就き、1966年にオックス フォード大学バリオール・カレッジのフェローに選出され、リーダーに任命されるまで在籍した。彼は、客員教授職を引き受けるというマンチェスターでの慣行 を続けた[10]。 1969年9月、アーサー・プライアーはノルウェーの大学で講義を行うために赴いたが、その前夜の1969年10月6日、ノルウェーのトロンハイムで心臓発作により死去した[10]。 職業生活 プライヤーはニュージーランドで教育を受け、幸運なことにJ.N.フィンドレーの影響を受け、その下で「論理学の本質」に関する修士論文を執筆した[1]。 1946年2月、カール・ポパーの辞職に伴う空席を埋めるため、カンタベリー・ユニバーシティ・カレッジで哲学と論理学を教え始める。1951年、プライ ヤーはオーストラリアで開催された哲学会議で、「ジャック」スマートとしても知られるJ.J.C.スマートと出会い、2人は生涯にわたる友情を育む。二人 の手紙のやり取りは、プライヤーの時制論理学の発展に影響を与えた。スマートは無緊張時間理論に固執しており、プライヤーの議論に説得されることはなかっ たが、擬似関係に関するウィトゲンシュタインの見解に懐疑的にさせたのはプライヤーの影響であった[12]。1954年にニュージーランドでプライヤーに 会ったギルバート・ライルの好意により、プライヤーは1956年をオックスフォード大学で休暇を過ごし、そこでジョン・ロックの哲学講義を行った。その 後、『時間と様相』(1957年)として出版された。これは時制論理学と時間の形而上学の研究に対する画期的な貢献であり、過去、現在、未来という時間的 モダリティは、時間と世界を理解する上で基本的に重要な存在論的カテゴリーであるというA理論派の見解をプライアーは支持した。プライヤーはJ.J.C. スマートから、時制論理学をジョン・ロックの講義のテーマにしないよう何度か警告を受けた。しかしプライヤーは時制論理学が哲学だけでなく論理学にも利益 をもたらす可能性があると確信していたため、自分の講義を「形式論理学と一般哲学は時に考えられている以上に互いにもたらすものがあるという確信の表明」 であると考えていた[14]。 オックスフォード大学在学中、プライヤーはピーター・ギーチとウィリアム・ニールに会い、ジョン・レモンに影響を与え、青年期のソール・クリプキと文通を した。イギリスにおける論理学は当時かなり低迷しており、「流行から大きく外れており、その実践者は孤立し、いくぶん士気を失っていた」[15]。プライ ヤーは、ジョン・レモン、ピーター・ギアチ、チェスワフ・レジェフスキなどの論理学者を集めたLogical a Colloquiumを企画した。 [1959年から1966年まで、マンチェスター大学で哲学教授を務め、オズマンド・ルーリーを教えた。1966年から亡くなるまで、オックスフォード大 学バリオール・カレッジで哲学のフェロー兼チューターを務めた。教え子にはマックス・クレスウェル、キット・ファイン、ロバート・ブルらがいる。 ほとんど独学で現代形式論理学を学び、1952年、38歳のときに論理学に関する4つの主要な論文を発表した[17]。 [19][20]彼はポーランド語を話すことができなくても未翻訳のポーランドのテキストを読むほどで、「記号は非常に照明的であるため、テキストが理解 できないという事実はあまり重要ではない」と主張していた[19]。プライヤーの時制論理に関する研究は、命題文が時間の経過とともに真理値を変化させる ことができるという現実の時制概念について体系的かつ拡張された擁護を提供している[22]。 プライヤーは論理学の歴史に強い関心を持っていたことで際立っていた。彼はチャールズ・サンダース・パイアースの論理的研究の性質と範囲、そして様相論理 におけるde dictoとde reの区別を理解した最初の英語圏の論理学者の一人であった。クリプキが可能世界意味論を提唱する以前、英語圏ではモダリティや固有性がほとんど関心を持 たれておらず、ウィラード・ヴァン・オーマン・クワインによる鋭い攻撃を受けていた時代に、彼は様相論理学を教え、研究していた。 彼は現在ではハイブリッド論理の先駆者と言われている[23]。彼の著書Past, Present, and Future (1967)の一節で、二項演算子(例えば "until")と単項演算子(例えば "will always be")を1つの時間論理体系に結合する試みを行い、その付随的な結果としてPriorは後のハイブリッド言語の基礎を築いた。 彼の著作『時間とモダリティ』では、多値論理を用いて参照しない名前の問題を説明することを探求した。 プライヤーの研究は哲学的かつ形式的であり、形式的な革新と言語分析との間に生産的な相乗効果をもたらした[citation needed]。彼は、敵対する人々の見解を示すことに細心の注意を払い、代替的な見解の形式的発展について多くの建設的な示唆を与えた。 出版物 以下の書籍は、プライヤーが執筆したもの、あるいは彼が執筆した雑誌記事や未発表論文の遺稿集である: 1949. Logic and the Basis of Ethics. オックスフォード大学出版局 (ISBN 0-19-824157-7) 1955, 1962. 形式論理学. オックスフォード大学出版局 1957. 時間と様相. オックスフォード大学出版局。1956年のジョン・ロックの講義に基づく。 1962. 「出来事の変化と事物の変化」。カンザス大学。 1967. 過去、現在、未来」。オックスフォード大学出版局。 1968. 時間と時制に関する論文 オックスフォード大学出版局。 1971. 思考の対象 P.T.ギアチ、A.J.P.ケニー編。オックスフォード大学出版局。 1976. 命題と用語の教義。P.T.ギアチ、A.J.P.ケニー編。ロンドン: Duckworth. 1976. 論理学と倫理学の論文。P.T.ギーチ、A.J.P.ケニー編。ロンドン: ダックワース。 1977. 世界、時代、自己。キット・ファイン編集。ロンドン: ダックワース. 2003. 時間と時制に関する論文。Per Hasle, Peter Øhrstrøm, Torben Braüner & Jack Copeland 著. オックスフォード大学出版局。 |

| Probability theory or probability calculus

is the branch of mathematics concerned with probability. Although there

are several different probability interpretations, probability theory

treats the concept in a rigorous mathematical manner by expressing it

through a set of axioms. Typically these axioms formalise probability

in terms of a probability space, which assigns a measure taking values

between 0 and 1, termed the probability measure, to a set of outcomes

called the sample space. Any specified subset of the sample space is

called an event. Central subjects in probability theory include discrete and continuous random variables, probability distributions, and stochastic processes (which provide mathematical abstractions of non-deterministic or uncertain processes or measured quantities that may either be single occurrences or evolve over time in a random fashion). Although it is not possible to perfectly predict random events, much can be said about their behavior. Two major results in probability theory describing such behaviour are the law of large numbers and the central limit theorem. As a mathematical foundation for statistics, probability theory is essential to many human activities that involve quantitative analysis of data.[1] Methods of probability theory also apply to descriptions of complex systems given only partial knowledge of their state, as in statistical mechanics or sequential estimation. A great discovery of twentieth-century physics was the probabilistic nature of physical phenomena at atomic scales, described in quantum mechanics. [2] |

確

率論または確率微積分は、確率に関する数学の一分野である。確率の解釈にはさまざまなものがあるが、確率論はこの概念を公理の集合によって表現し、厳密な

数学的方法で扱う。一般に、これらの公理は確率を確率空間という観点から形式化したもので、標本空間と呼ばれる結果の集合に、確率尺度と呼ばれる0と1の

間の値をとる尺度を割り当てる。標本空間の任意の指定された部分集合は事象と呼ばれる。 確率論の中心的なテーマには、離散および連続の確率変数、確率分布、確率過程(非決定論的または不確実な過程や、単発的またはランダムな方法で時間と共に 発展する測定量を数学的に抽象化したもの)が含まれる。ランダムな事象を完全に予測することはできないが、その振る舞いについては多くのことが言える。こ のような振る舞いを記述する確率論における2つの主要な結果は、大数の法則と中心極限定理である。 統計学の数学的基礎として、確率論はデータの定量的分析を伴う多くの人間活動に不可欠である[1]。確率論の手法は、統計力学や逐次推定のように、状態の 部分的な知識しか与えられていない複雑系の記述にも適用される。20世紀物理学の大発見は、量子力学で説明される原子スケールでの物理現象の確率的性質で あった。[2] |

| History of probability Main article: History of probability The modern mathematical theory of probability has its roots in attempts to analyze games of chance by Gerolamo Cardano in the sixteenth century, and by Pierre de Fermat and Blaise Pascal in the seventeenth century (for example the "problem of points").[3] Christiaan Huygens published a book on the subject in 1657.[4] In the 19th century, what is considered the classical definition of probability was completed by Pierre Laplace.[5] Initially, probability theory mainly considered discrete events, and its methods were mainly combinatorial. Eventually, analytical considerations compelled the incorporation of continuous variables into the theory. This culminated in modern probability theory, on foundations laid by Andrey Nikolaevich Kolmogorov. Kolmogorov combined the notion of sample space, introduced by Richard von Mises, and measure theory and presented his axiom system for probability theory in 1933. This became the mostly undisputed axiomatic basis for modern probability theory; but, alternatives exist, such as the adoption of finite rather than countable additivity by Bruno de Finetti.[6] |

確率の歴史 主な記事 確率の歴史 現代の数学的確率論のルーツは、16世紀のジェロラモ・カルダーノ、17世紀のピエール・ド・フェルマーとブレーズ・パスカルによる偶然のゲームを分析する試み(例えば「点の問題」)にある[3]。 当初、確率論は主に離散事象を対象とし、その方法は主に組合せ論的であった。やがて、分析的な考察により、連続変数を理論に取り入れることを余儀なくされた。 これは、アンドレイ・ニコラエヴィチ・コルモゴロフが築いた基礎の上に、現代の確率論に結実した。コルモゴロフは、リヒャルト・フォン・ミーゼスが導入し た標本空間の概念と測度論を組み合わせ、1933年に確率論の公理系を発表した。これは現代の確率論の公理的基礎となったが、ブルーノ・デ・フィネッティ による可算加法性ではなく有限加法性の採用など、代替案も存在する[6]。 |

| Treatment Most introductions to probability theory treat discrete probability distributions and continuous probability distributions separately. The measure theory-based treatment of probability covers the discrete, continuous, a mix of the two, and more. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Probability_theory |

取り扱い 確率論の入門書の多くは、離散確率分布と連続確率分布を別々に扱っている。測度論に基づく確率の取り扱いは、離散、連続、両者の混合などをカバーしている。 (以下は数式を取り扱うので、英語のサイトを参照のこと) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Probability_theory |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆