Digital humanities

Digital humanities

デジタルヒューマニティーズ (digital humanities, humanities computing)とは、人文学(古くは自由七科による教養科目)とICT(情報通信技術)との学際融合領域、ないしはその「対話」のことである。言い 方を変えると、デジタルヒューマニティーズ(デジタル・ヒューマニティーズ)とは、 ICTを通しての人文学の刷新(イノベーション)のことであり、また、技術偏重に傾いたICTを人間化(ヒューマナイズ)するプロジェクトのことで ある(→「CO*-DESIGN 用語集」)。

Digital

humanities (DH) is an area of scholarly activity at the

intersection of computing or digital technologies and the disciplines

of the humanities. It can be defined as new ways of doing scholarship

that involve collaborative, transdisciplinary, and computationally

engaged research, teaching, and publishing.[3] It brings digital tools

and methods to the study of the humanities with the recognition that

the printed word is no longer the main medium for knowledge production

and distribution. - digital

humanities

さて、ICTと人文学というのは犬猿の仲 にあるらしい。古くは、C.P.スノー(1961)の文系と理系の対立。そしてもう一方ではICT下に おける、人文社会系と技術工学系の対立である。野村一夫(2001)は、それをインフォアーツとインフォテックの対立と位置づけている。野村によるイン ターネットの歴史観は、幸福なインターネット大公開時代(=池田がパラフレイズす ると 「よいハッカーが公共圏を形成していた時代」)から、情報工学的転回を経て、情報教育が工学化さ れてゆく、不幸な時代へと転落してゆくことである。これが、野村のいうインフォテックの時代の招来であり、彼は真摯にその状況を危惧していた。

| Digital

humanities

(DH) is an area of scholarly activity at the intersection of computing

or digital technologies and the disciplines of the humanities. It

includes the systematic use of digital resources in the humanities, as

well as the analysis of their application.[1][2] DH can be defined as

new ways of doing scholarship that involve collaborative,

transdisciplinary, and computationally engaged research, teaching, and

publishing.[3] It brings digital tools and methods to the study of the

humanities with the recognition that the printed word is no longer the

main medium for knowledge production and distribution.[3] By producing and using new applications and techniques, DH makes new kinds of teaching possible, while at the same time studying and critiquing how these impact cultural heritage and digital culture.[2] DH is also applied in research. Thus, a distinctive feature of DH is its cultivation of a two-way relationship between the humanities and the digital: the field both employs technology in the pursuit of humanities research and subjects technology to humanistic questioning and interrogation, often simultaneously. |

デジタル・ヒューマニティーズ(DH)は、コンピューティングやデジタ

ル技術と人文科学の学問分野が交差する学術活動の領域である。人文科学におけるデジタルリソースの体系的な利用や、その応用に関する分析も含まれる。

[1][2] DHは、共同作業、学際的研究、コンピューターを駆使した研究、教育、出版を含む、新たな学術研究の方法と定義することができる。[3]

DHは、印刷された文字がもはや知識の生産と流通の主要な媒体ではないという認識のもと、デジタルツールと手法を人文科学の研究に導入する。[3] 新しいアプリケーションや技術を開発し、それらを活用することで、デジタル・ヒューマニティーズは新たな教育方法を可能にする。同時に、それらが文化遺産 やデジタル文化にどのような影響を与えるかを研究し、批評する。[2] デジタル・ヒューマニティーズは研究にも応用されている。このように、デジタル・ヒューマニティーズの特色は、人文科学とデジタルの双方向の関係を育むこ とである。すなわち、人文科学の研究にテクノロジーを活用する一方で、人文科学的な問いや調査をテクノロジーに課す。 |

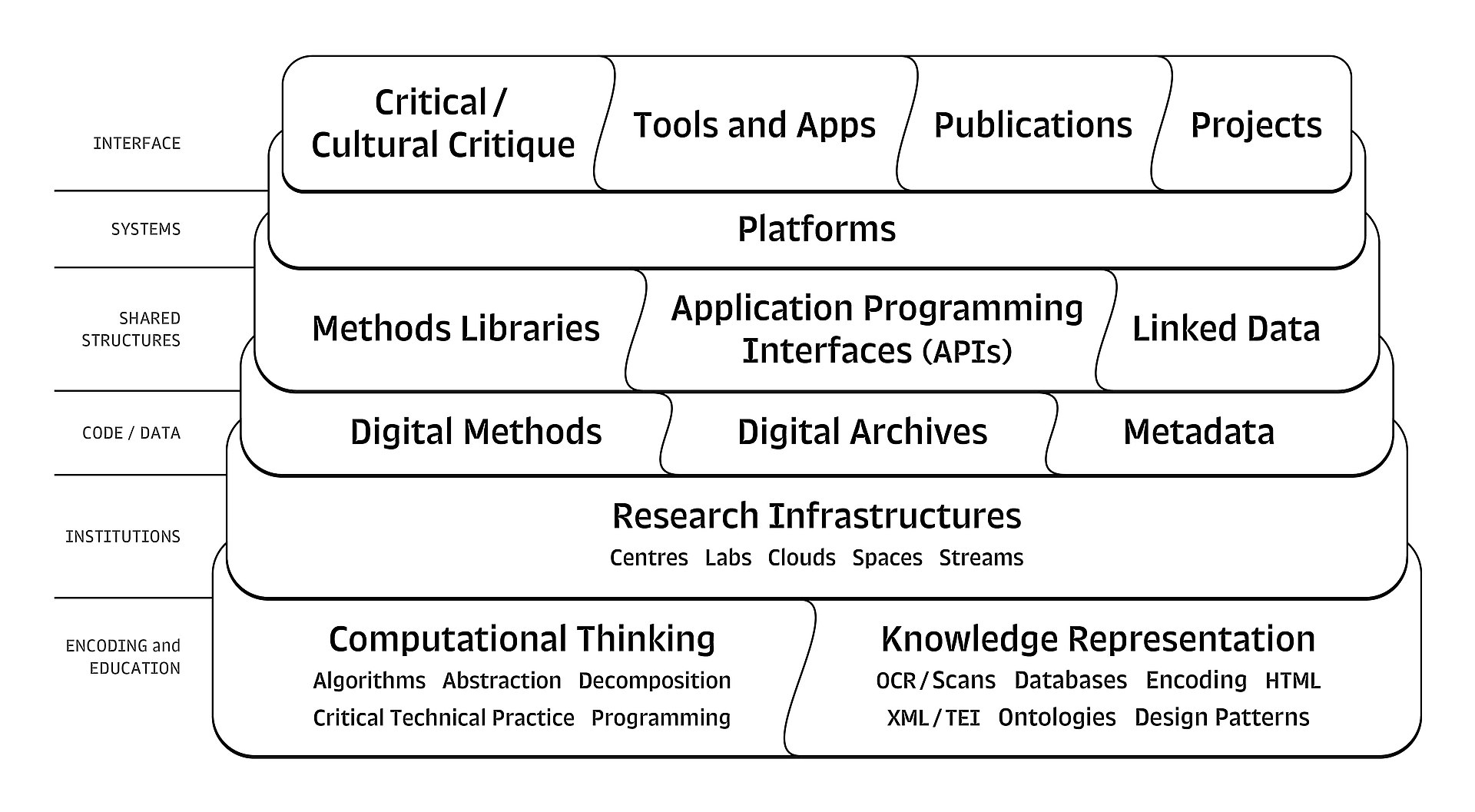

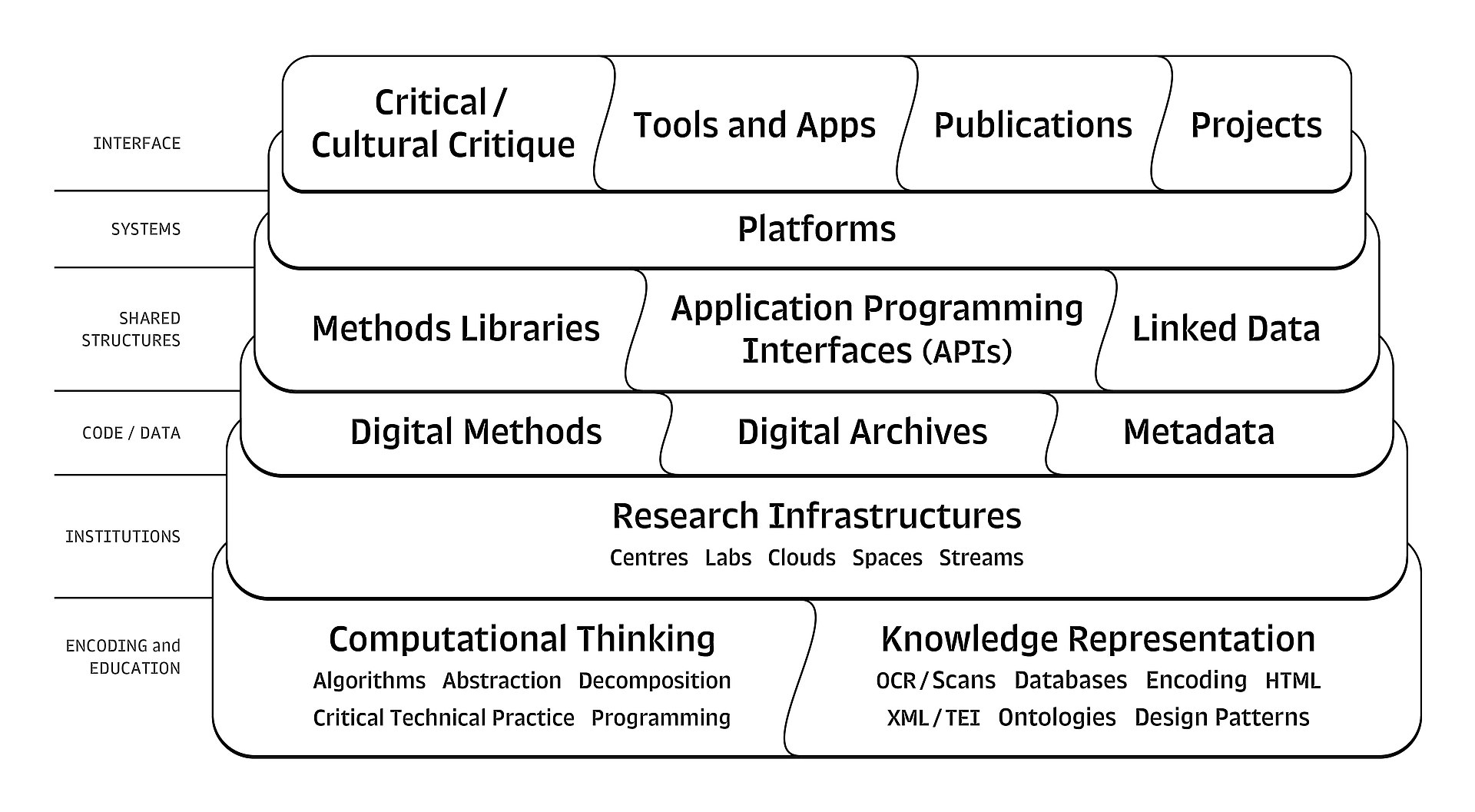

| Definition The definition of the digital humanities is being continually formulated by scholars and practitioners. Since the field is constantly growing and changing, specific definitions can quickly become outdated or unnecessarily limit future potential.[4] The second volume of Debates in the Digital Humanities (2016) acknowledges the difficulty in defining the field: "Along with the digital archives, quantitative analyses, and tool-building projects that once characterized the field, DH now encompasses a wide range of methods and practices: visualizations of large image sets, 3D modeling of historical artifacts, 'born digital' dissertations, hashtag activism and the analysis thereof, alternate reality games, mobile makerspaces, and more. In what has been called 'big tent' DH, it can at times be difficult to determine with any specificity what, precisely, digital humanities work entails."[5] Historically, the digital humanities developed out of humanities computing and has become associated with other fields, such as humanistic computing, social computing, and media studies. In concrete terms, the digital humanities embraces a variety of topics, from curating online collections of primary sources (primarily textual) to the data mining of large cultural data sets to topic modeling. Digital humanities incorporates both digitized (remediated) and born-digital materials and combines the methodologies from traditional humanities disciplines (such as rhetoric, history, philosophy, linguistics, literature, art, archaeology, music, and cultural studies) and social sciences,[6] with tools provided by computing (such as hypertext, hypermedia, data visualisation, information retrieval, data mining, statistics, text mining, digital mapping), and digital publishing. Related subfields of digital humanities have emerged like software studies, platform studies, and critical code studies. Fields that parallel the digital humanities include new media studies and information science as well as media theory of composition, game studies, particularly in areas related to digital humanities project design and production, and cultural analytics. Each disciplinary field and each country has its own unique history of digital humanities.[7]  The Digital Humanities Stack (from Berry and Fagerjord, Digital Humanities: Knowledge and Critique in a Digital Age) Berry and Fagerjord have suggested that a way to reconceptualise digital humanities could be through a "digital humanities stack". They argue that "this type of diagram is common in computation and computer science to show how technologies are 'stacked' on top of each other in increasing levels of abstraction. Here, [they] use the method in a more illustrative and creative sense of showing the range of activities, practices, skills, technologies and structures that could be said to make up the digital humanities, with the aim of providing a high-level map."[8] Indeed, the "diagram can be read as the bottom levels indicating some of the fundamental elements of the digital humanities stack, such as computational thinking and knowledge representation, and then other elements that later build on these."[9] In practical terms, a major distinction within digital humanities is the focus on the data being processed. For processing textual data, digital humanities builds on a long and extensive history of digital edition, computational linguistics and natural language processing and developed an independent and highly specialized technology stack (largely cumulating in the specifications of the Text Encoding Initiative). This part of the field is sometimes thus set apart from Digital Humanities in general as 'digital philology' or 'computational philology'. For the creation and analysis of digital editions of objects or artifacts, digital philologists have access to digital practices, methods, and technologies such as optical character recognition that are providing opportunities to adapt the field to the digital age.[10] |

定義 デジタル・ヒューマニティーズの定義は、研究者や実務者によって絶えず形成され続けている。この分野は常に成長と変化を続けているため、特定の定義はすぐ に時代遅れになったり、将来の可能性を不必要に制限したりする可能性がある。[4] 『デジタル・ヒューマニティーズにおける議論』第2巻(2016年)は、この分野の定義づけの難しさを認めている。「かつてこの分野を特徴づけていたデジ タルアーカイブ、数量的分析、ツール構築プロジェクトに加え、DHは現在、広範な手法と実践を包含している。大量の画像セットの視覚化、歴史的遺物の3D モデリング、『デジタルで生まれた』論文、ハッシュタグを用いた活動とその分析、代替現実ゲーム、モバイル・メイカースペースなどである。「ビッグ・テン ト」と呼ばれるDHでは、デジタル人文学の研究が具体的に何を意味するのかを特定することは時に困難である。」[5] 歴史的に見ると、デジタル人文学は人文科学コンピューティングから発展し、人文科学コンピューティング、ソーシャルコンピューティング、メディア研究など の他の分野と関連するようになった。具体的には、デジタル人文学は、一次資料(主にテキスト)のオンラインコレクションのキュレーションから、大規模な文 化データのデータマイニング、トピックモデリングまで、さまざまなトピックを取り入れている。デジタル・ヒューマニティーズは、デジタル化(修正)された 資料とデジタルで生まれた資料の両方を対象とし、従来の人文科学分野(修辞学、歴史学、哲学、言語学、文学、芸術、考古学、音楽、文化研究など)と社会科 学の方法論を、コンピューティング(ハイパーテキスト、ハイパーメディア、データ視覚化、情報検索、データマイニング、統計、テキストマイニング、デジタ ルマッピングなど)やデジタル出版のツールと組み合わせている。デジタル人文学の関連分野として、ソフトウェア研究、プラットフォーム研究、批判的コード 研究などが登場している。デジタル人文学と並行する分野には、ニューメディア研究や情報科学、および、特にデジタル人文学のプロジェクト設計や制作に関連 する分野におけるメディア理論、ゲーム研究、文化分析学などがある。各学問分野および各国には、独自のデジタル人文学の歴史がある。  デジタル・ヒューマニティーズ・スタック(Berry and Fagerjord, Digital Humanities: Knowledge and Critique in a Digital Ageより) BerryとFagerjordは、デジタル・ヒューマニティーズの再概念化の方法として「デジタル・ヒューマニティーズ・スタック」を提案している。彼 らは、「この種の図は、テクノロジーが抽象化のレベルを上げながら互いにどのように『積み重ねられている』かを表すために、計算やコンピュータサイエンス では一般的である」と主張している。ここでは、デジタル人文学を構成する活動、実践、スキル、テクノロジー、構造の広範な範囲を示すために、より説明的な 創造的な意味でこの手法が用いられている。高度なマップを提供することが目的である」[8] 実際、「この図は、デジタル人文学スタックの基本要素の一部、例えば計算思考や知識表現などを示す下層レベルとして読むことができ、さらにその上に構築さ れる他の要素も示している」[9] 実際問題として、デジタル人文学における主な区別は、処理されるデータに焦点が当てられている点である。テキストデータの処理に関しては、デジタル人文学 はデジタル版作成、計算言語学、自然言語処理の長い歴史の上に成り立っており、独自で高度に専門化された技術スタック(主にText Encoding Initiativeの仕様で蓄積されたもの)を開発している。この分野の一部は、デジタル人文学全般から「デジタル文献学」または「計算文献学」として 区別されることもある。デジタル版のオブジェクトやアーティファクトの作成や分析を行うデジタル文献学者は、デジタル技術、方法、および光学文字認識など のテクノロジーを利用することができ、それによりこの分野をデジタル時代に適応させる機会が提供されている。[10] |

| History Digital humanities descends from the field of humanities computing, whose origins reach back to 1940s and 50s, in the pioneering work of Jesuit scholar Roberto Busa, which began in 1946,[11] and of English professor Josephine Miles, beginning in the early 1950s.[12][13][14][15] In collaboration with IBM, Busa and his team created a computer-generated concordance to Thomas Aquinas' writings known as the Index Thomisticus.[3] Busa's works have been collected and translated by Julianne Nyhan and Marco Passarotti.[16] Other scholars began using mainframe computers to automate tasks like word-searching, sorting, and counting, which was much faster than processing information from texts with handwritten or typed index cards.[3] Similar first advances were made by Gerhard Sperl in Austria using computers by Zuse for Digital Assyriology.[17] In the decades which followed archaeologists, classicists, historians, literary scholars, and a broad array of humanities researchers in other disciplines applied emerging computational methods to transform humanities scholarship.[18][19] As Tara McPherson has pointed out, the digital humanities also inherit practices and perspectives developed through many artistic and theoretical engagements with electronic screen culture beginning the late 1960s and 1970s. These range from research developed by organizations such as SIGGRAPH to creations by artists such as Charles and Ray Eames and the members of E.A.T. (Experiments in Art and Technology). The Eames and E.A.T. explored nascent computer culture and intermediality in creative works that dovetailed technological innovation with art.[20] The first specialized journal in the digital humanities was Computers and the Humanities, which debuted in 1966. The Computer Applications and Quantitative Methods in Archaeology (CAA) association was founded in 1973. The Association for Literary and Linguistic Computing (ALLC) and the Association for Computers and the Humanities (ACH) were then founded in 1977 and 1978, respectively.[3] Soon, there was a need for a standardized protocol for tagging digital texts, and the Text Encoding Initiative (TEI) was developed.[3] The TEI project was launched in 1987 and published the first full version of the TEI Guidelines in May 1994.[14] TEI helped shape the field of electronic textual scholarship and led to Extensible Markup Language (XML), which is a tag scheme for digital editing. Researchers also began experimenting with databases and hypertextual editing, which are structured around links and nodes, as opposed to the standard linear convention of print.[3] In the nineties, major digital text and image archives emerged at centers of humanities computing in the U.S. (e.g. the Women Writers Project, the Rossetti Archive,[21] and The William Blake Archive[22]), which demonstrated the sophistication and robustness of text-encoding for literature.[23] The advent of personal computing and the World Wide Web meant that Digital Humanities work could become less centered on text and more on design. The multimedia nature of the internet has allowed Digital Humanities work to incorporate audio, video, and other components in addition to text.[3] The terminological change from "humanities computing" to "digital humanities" has been attributed to John Unsworth, Susan Schreibman, and Ray Siemens who, as editors of the anthology A Companion to Digital Humanities (2004), tried to prevent the field from being viewed as "mere digitization".[24] Consequently, the hybrid term has created an overlap between fields like rhetoric and composition, which use "the methods of contemporary humanities in studying digital objects",[24] and digital humanities, which uses "digital technology in studying traditional humanities objects".[24] The use of computational systems and the study of computational media within the humanities, arts and social sciences more generally has been termed the 'computational turn'.[25] In 2006 the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) launched the Digital Humanities Initiative (renamed Office of Digital Humanities in 2008), which made widespread adoption of the term "digital humanities" in the United States.[26] Digital humanities emerged from its former niche status and became "big news"[26] at the 2009 MLA convention in Philadelphia, where digital humanists made "some of the liveliest and most visible contributions"[27] and had their field hailed as "the first 'next big thing' in a long time."[28] |

歴史 デジタル・ヒューマニティーズは、人文科学コンピューティングの分野から派生したもので、その起源は1940年代から1950年代にまで遡り、イエズス会 の学者ロベルト・ブサの1946年からの先駆的な研究[11]や、1950年代初頭からの英語学教授ジョセフィン・マイルズの研究[12][13] [14][15]にまでさかのぼる。ブサと彼のチームは、IBMとの共同作業で、トマス・アクィナスによる著作のコンコーダンスをコンピュータで作成し た。これはトマス・アクィナス・インデックスとして知られている。[3] ブサの作品はジュリアン・ナイハンとマルコ・パッサロッティによって収集され、翻訳された。[16] 他の学者たちは、単語検索、分類、数え上げといった作業を自動化するためにメインフレームコンピュータを使い始めた。これは、 手書きやタイプしたインデックスカードでテキストから情報を処理するよりもはるかに高速であった。[3] 類似した最初の進歩は、オーストリアのゲルハルト・シュペールがツーゼのデジタル・アッシロロジー用コンピュータを使用して達成した。[17] その後数十年間、考古学者、古典学者、歴史家、文学者、およびその他の分野の幅広い人文科学の研究者が、新興の計算方法を使用して人文科学の研究を変革し た。[18][19] タラ・マクファーソンが指摘しているように、デジタル人文学は、1960年代後半から1970年代に始まった電子スクリーン文化との多くの芸術的・理論的 関わりを通じて発展した実践や視点も継承している。これには、SIGGRAPHなどの組織による研究から、チャールズ&レイ・イームズ夫妻やE.A.T. (芸術と技術の実験)のメンバーによる創作まで、幅広いものがある。イームズ夫妻やE.A.T.は、技術革新と芸術を融合させた創造的な作品を通じて、初 期のコンピュータ文化やメディア横断性を探究した。 デジタル人文学の専門誌としては、1966年に創刊された『Computers and the Humanities』が最初である。1973年には、コンピュータ応用と考古学における定量的方法(CAA)協会が設立された。その後、1977年に文 学・言語コンピューティング協会(ALLC)、1978年にコンピュータと人文学協会(ACH)がそれぞれ設立された。 やがて、デジタルテキストのタグ付けのための標準化されたプロトコルが必要となり、テキスト符号化イニシアティブ(TEI)が開発された。TEIプロジェ クトは1987年に開始され、1994年5月にTEIガイドラインの最初の完全版が発表された。TEIは電子テキスト研究分野の形成に貢献し、デジタル編 集用のタグスキームであるXML(拡張マークアップ言語)の開発につながった。また、研究者たちは、リンクとノードを中心に構成されたデータベースとハイ パーテキスト編集の実験も開始した。これは、印刷物の標準的な直線的な慣習とは対照的である。[3] 1990年代には、米国の人文科学コンピューティングの中心地で、主要なデジタルテキストおよび画像アーカイブが登場した(例えば、 Writers Project、the Rossetti Archive[21]、The William Blake Archive[22]など)が現れ、文学のテキストエンコーディングの洗練性と堅牢性を示した。[23] パーソナルコンピューティングとワールドワイドウェブの出現により、デジタル人文学の研究はテキスト中心からデザイン中心へと変化した。インターネットの マルチメディア性により、デジタル人文学の研究ではテキストに加えて、オーディオ、ビデオ、その他のコンポーネントを取り入れることができるようになっ た。[3] 「人文科学コンピューティング」から「デジタル・ヒューマニティーズ」への用語の変更は、アンソロジー『A Companion to Digital Humanities』(2004年)の編集者であるジョン・アンスワース、スーザン・シュライプマン、レイ・ジーメンスの功績である。彼らは、この分野 が「単なるデジタル化」として見られることを防ごうとしたのである。[24] その結果、このハイブリッドな用語は、 「デジタルオブジェクトの研究における現代人文科学の方法」を用いる修辞学や作文などの分野と、「伝統的な人文科学の研究におけるデジタル技術」を用いる デジタル人文学との間に重複が生じている。[24] 人文科学、芸術、社会科学における計算システムの利用や計算メディアの研究は、一般的に「計算論的転回」と呼ばれている。[25] 2006年には、全米人文科学基金(NEH)がデジタル・ヒューマニティーズ・イニシアティブ(2008年にデジタル・ヒューマニティーズ・オフィスに改 称)を立ち上げ、これにより「デジタル・ヒューマニティーズ」という用語が米国で広く普及することとなった。 デジタル・ヒューマニティーズは、それまでのニッチな地位から脱却し、2009年のフィラデルフィアでのMLA大会では「大きな話題」となった。[26] デジタル・ヒューマニストたちは「最も活気があり、最も目に見える貢献」を果たし、[27] 彼らの分野は「久しぶりの『次なる大きな話題』」として歓迎された。[28] |

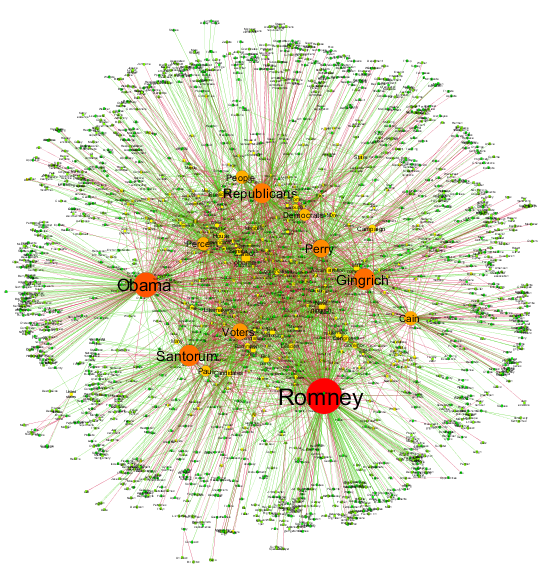

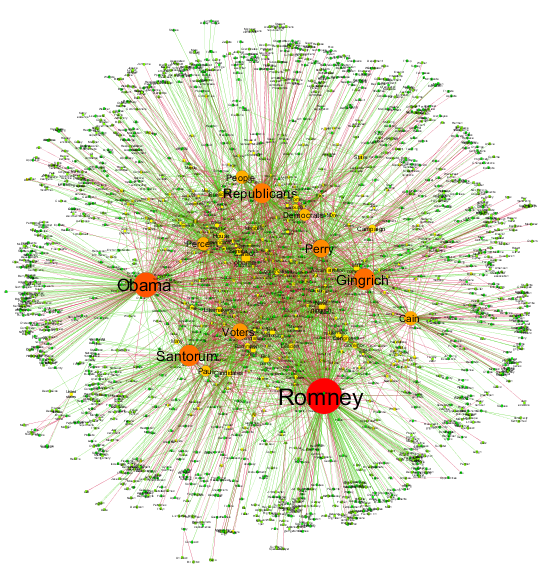

| Values and methods Although digital humanities projects and initiatives are diverse, they often reflect common values and methods.[29] These can help in understanding this hard-to-define field. Values[29] Critical and theoretical Iterative and experimental Collaborative and distributed Multimodal and performative Open and accessible Methods[29] Enhanced critical curation Augmented editions and fluid textuality Scale: the law of large numbers Distant/close, macro/micro, surface/depth Cultural analytics, aggregation, and data-mining Visualization and data design Locative investigation and thick mapping The animated archive Distributed knowledge production and performative access Humanities gaming Code, software, and platform studies Database documentaries Repurposable content and remix culture Pervasive infrastructure Ubiquitous scholarship In keeping with the value of being open and accessible, many digital humanities projects and journals are open access and/or under Creative Commons licensing, showing the field's "commitment to open standards and open source."[30] Open access is designed to enable anyone with an internet-enabled device and internet connection to view a website or read an article without having to pay, as well as share content with the appropriate permissions. Digital humanities scholars use computational methods either to answer existing research questions or to challenge existing theoretical paradigms, generating new questions and pioneering new approaches. One goal is to systematically integrate computer technology into the activities of humanities scholars,[31] as is done in contemporary empirical social sciences. Yet despite the significant trend in digital humanities towards networked and multimodal forms of knowledge, a substantial amount of digital humanities focuses on documents and text in ways that differentiate the field's work from digital research in media studies, information studies, communication studies, and sociology. Another goal of digital humanities is to create scholarship that transcends textual sources. This includes the integration of multimedia, metadata, and dynamic environments (see The Valley of the Shadow project at the University of Virginia, the Vectors Journal of Culture and Technology in a Dynamic Vernacular at University of Southern California, or Digital Pioneers projects at Harvard[32]). A growing number of researchers in digital humanities are using computational methods for the analysis of large cultural data sets such as the Google Books corpus.[33] Examples of such projects were highlighted by the Humanities High Performance Computing competition sponsored by the Office of Digital Humanities in 2008,[34] and also by the Digging Into Data challenge organized in 2009[35] and 2011[36] by NEH in collaboration with NSF,[37] and in partnership with JISC in the UK, and SSHRC in Canada.[38] In addition to books, historical newspapers can also be analyzed with big data methods. The analysis of vast quantities of historical newspaper content has showed how periodic structures can be automatically discovered, and a similar analysis was performed on social media.[39][40] As part of the big data revolution, gender bias, readability, content similarity, reader preferences, and even mood have been analyzed based on text mining methods over millions of documents[41][42][43][44][45] and historical documents written in literary Chinese.[46] Digital humanities is also involved in the creation of software, providing "environments and tools for producing, curating, and interacting with knowledge that is 'born digital' and lives in various digital contexts."[47] In this context, the field is sometimes known as computational humanities.  Narrative network of US Elections 2012[48] |

価値と方法 デジタル・ヒューマニティーズのプロジェクトやイニシアティブは多様であるが、共通の価値や方法が反映されていることが多い。[29] これらは、定義が難しいこの分野を理解する上で役立つ。 価値[29] 批判的かつ理論的 反復的かつ実験的 協働的かつ分散的 マルチモーダルかつパフォーマティビティ オープンかつアクセス可能 方法[29] 強化された批判的キュレーション 拡張版および流動的なテキスト性 規模:大数の法則 遠隔/近接、マクロ/ミクロ、表面/深層 文化分析、集約、データマイニング 視覚化およびデータ設計 位置情報調査および厚みのあるマッピング アニメーション化されたアーカイブ 分散型知識生産およびパフォーマティビティへのアクセス 人文科学ゲーム コード、ソフトウェア、プラットフォーム研究 データベース・ドキュメンタリー 再利用可能なコンテンツおよびリミックス文化 浸透するインフラ ユビキタス学問 オープンでアクセスしやすいという価値観に則り、多くのデジタル人文学プロジェクトや学術誌はオープンアクセスであり、また、クリエイティブ・コモンズ・ ライセンスの下にあるものもあり、この分野の「オープンスタンダードとオープンソースへのコミットメント」を示している。[30] オープンアクセスは、インターネットに接続できるデバイスとインターネット接続があれば、誰でも料金を支払うことなくウェブサイトを閲覧したり記事を読ん だりできるように設計されている。また、適切な許可を得た上でコンテンツを共有することも可能である。 デジタル人文学の研究者は、既存の研究課題への回答を得るため、あるいは既存の理論的パラダイムに異議を唱えるために、計算機的手法を用いる。これによ り、新たな疑問が生じ、新たなアプローチが切り開かれる。その目的の一つは、現代の実証的社会科学で行われているように、人文学者の活動にコンピュータ技 術を体系的に統合することである。しかし、デジタル人文学におけるネットワーク化やマルチモーダルな知識形態への大きな流れにもかかわらず、デジタル人文 学の大部分は、文書やテキストに重点を置いており、メディア研究、情報学、コミュニケーション学、社会学におけるデジタル研究とは分野が異なっている。デ ジタル人文学のもう一つの目標は、テキスト資料を超越する学問分野を創出することである。これには、マルチメディア、メタデータ、動的環境の統合が含まれ る(バージニア大学のThe Valley of the Shadowプロジェクト、南カリフォルニア大学のVectors Journal of Culture and Technology in a Dynamic Vernacular、ハーバード大学のDigital Pioneersプロジェクトを参照[32])。デジタル・ヒューマニティーズの研究者の間では、Googleブックス・コーパスなどの大規模な文化デー タセットの分析に計算機的手法を用いる研究者が増えている。[33] このようなプロジェクトの例は、2008年にデジタル・ヒューマニティーズ事務局が主催した「Humanities High Performance Computing」コンペティションで取り上げられ、脚光を浴びた。[34] また、 2009年[35]と2011年[36]にNEHがNSFと共同で主催し、英国のJISCおよびカナダのSSHRCと提携して実施された「Digging Into Data」チャレンジなどである。書籍に加えて、歴史的な新聞もビッグデータ手法で分析することができる。膨大な量の歴史的新聞記事のコンテンツの分析に より、周期的な構造が自動的に発見できることが示され、同様の分析がソーシャルメディアでも実施された。[39][40] ビッグデータ革命の一環として、性別による偏り、読みやすさ、コンテンツの類似性、読者の好み、さらには気分までもが、何百万もの文書[41][42] [43][44][45]や、文語中国語で書かれた歴史的文書[46]を対象に、テキストマイニング手法に基づいて分析されている。 デジタル・ヒューマニティーズはソフトウェアの作成にも関与しており、「デジタルで生まれ、さまざまなデジタル文脈で存在する知識を生成、管理、および相 互に作用するための環境とツール」を提供している[47]。この文脈において、この分野は「計算機ヒューマニティーズ」として知られることもある。  2012年米国大統領選挙の物語ネットワーク[48] |

| Tools Digital humanities scholars use a variety of digital tools for their research, which may take place in an environment as small as a mobile device or as large as a virtual reality lab. Environments for "creating, publishing and working with digital scholarship include everything from personal equipment to institutes and software to cyberspace."[49] Some scholars use advanced programming languages and databases, while others use less complex tools, depending on their needs. DiRT (Digital Research Tools Directory[50]) offers a registry of digital research tools for scholars. TAPoR (Text Analysis Portal for Research[51]) is a gateway to text analysis and retrieval tools. An accessible, free example of an online textual analysis program is Voyant Tools,[52] which only requires the user to copy and paste either a body of text or a URL and then click the 'reveal' button to run the program. There is also an online list[53] of online or downloadable Digital Humanities tools that are largely free, aimed toward helping students and others who lack access to funding or institutional servers. Free, open source web publishing platforms like WordPress and Omeka are also popular tools. |

ツール デジタル・ヒューマニティーズの研究者は、研究にさまざまなデジタルツールを使用している。モバイル機器のような小さな環境から、仮想現実ラボのような大 きな環境まで、さまざまな環境で研究が行われる可能性がある。「デジタル学術の作成、公開、作業」のための環境には、個人所有の機器から研究所、ソフト ウェアからサイバースペースまで、あらゆるものが含まれる。[49] 研究者のなかには、高度なプログラミング言語やデータベースを使用する者もいれば、ニーズに応じてより複雑性の低いツールを使用する者もいる。DiRT (Digital Research Tools Directory[50])は、研究者のためのデジタル研究ツールの登録を提供している。TAPoR(Text Analysis Portal for Research[51])は、テキスト分析および検索ツールへのゲートウェイである。オンラインのテキスト分析プログラムの例としては、アクセスが容易 で無料のVoyant Tools[52]がある。このプログラムは、ユーザーにテキストの本文またはURLをコピー&ペーストし、「reveal」ボタンをクリックするだけで 実行できる。また、オンラインまたはダウンロード可能なデジタル・ヒューマニティーズのツールのオンラインリスト[53]もあり、これらは主に無料で、資 金や機関サーバーへのアクセスが限られている学生やその他の人々を支援することを目的としている。WordPressやOmekaのような無料のオープン ソースのウェブ公開プラットフォームも人気のツールである。 |

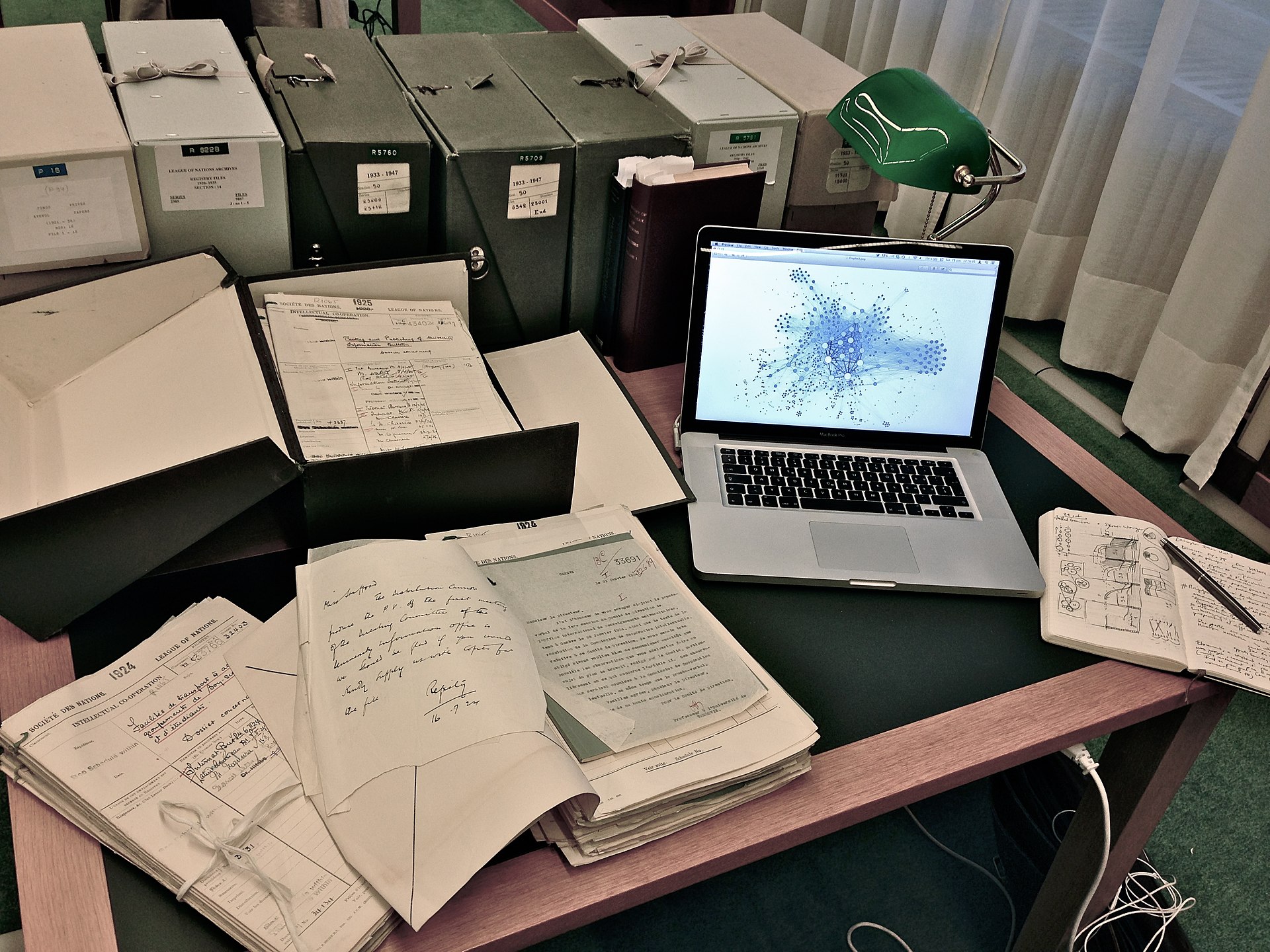

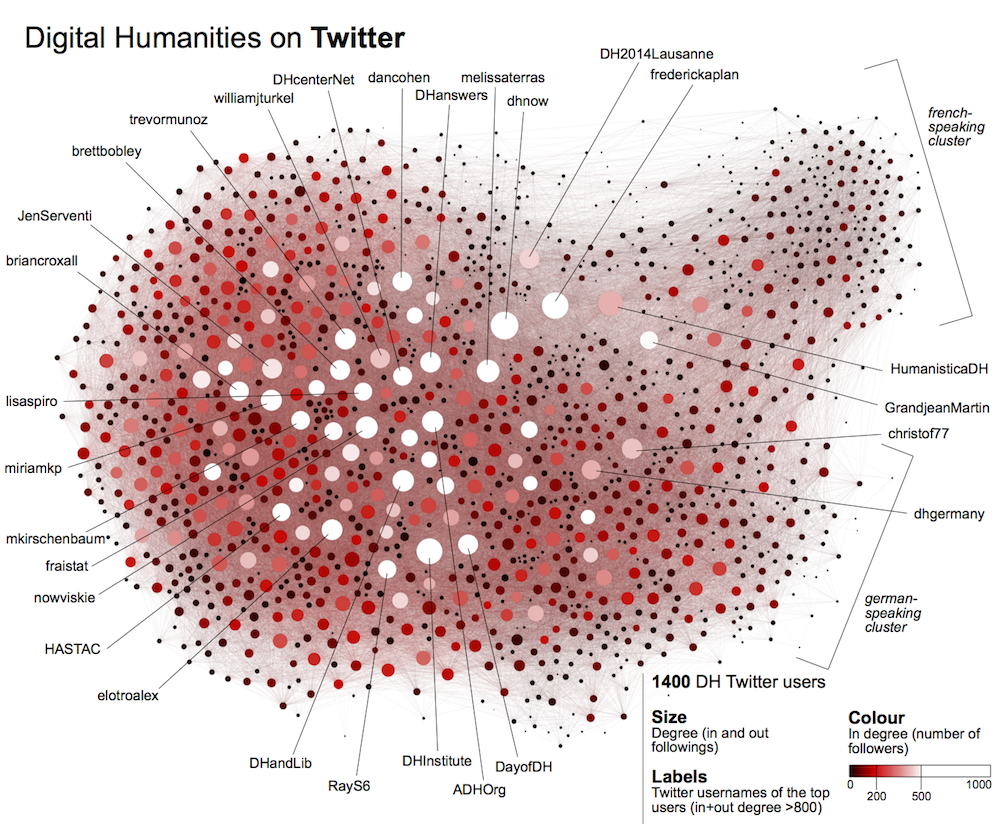

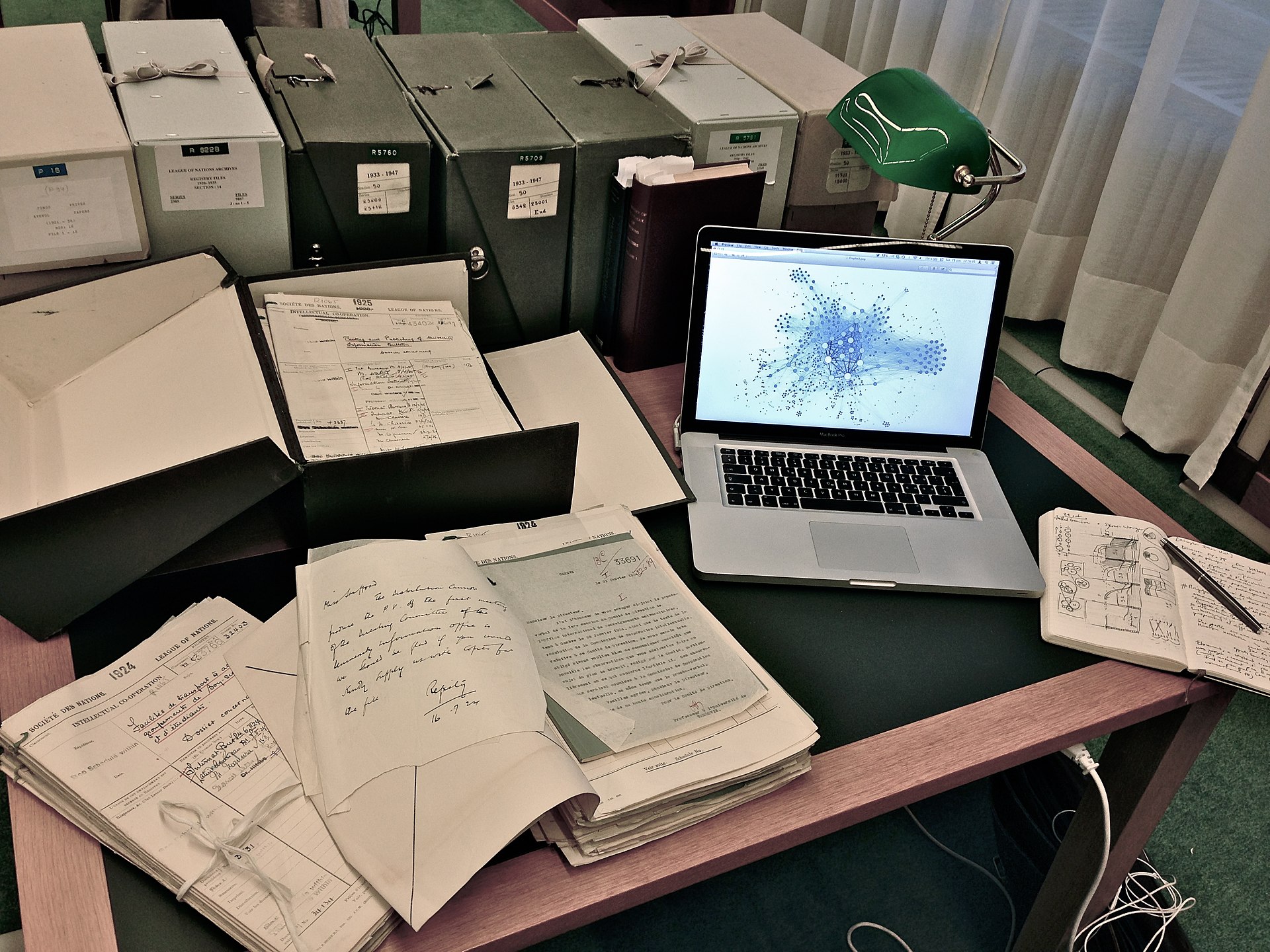

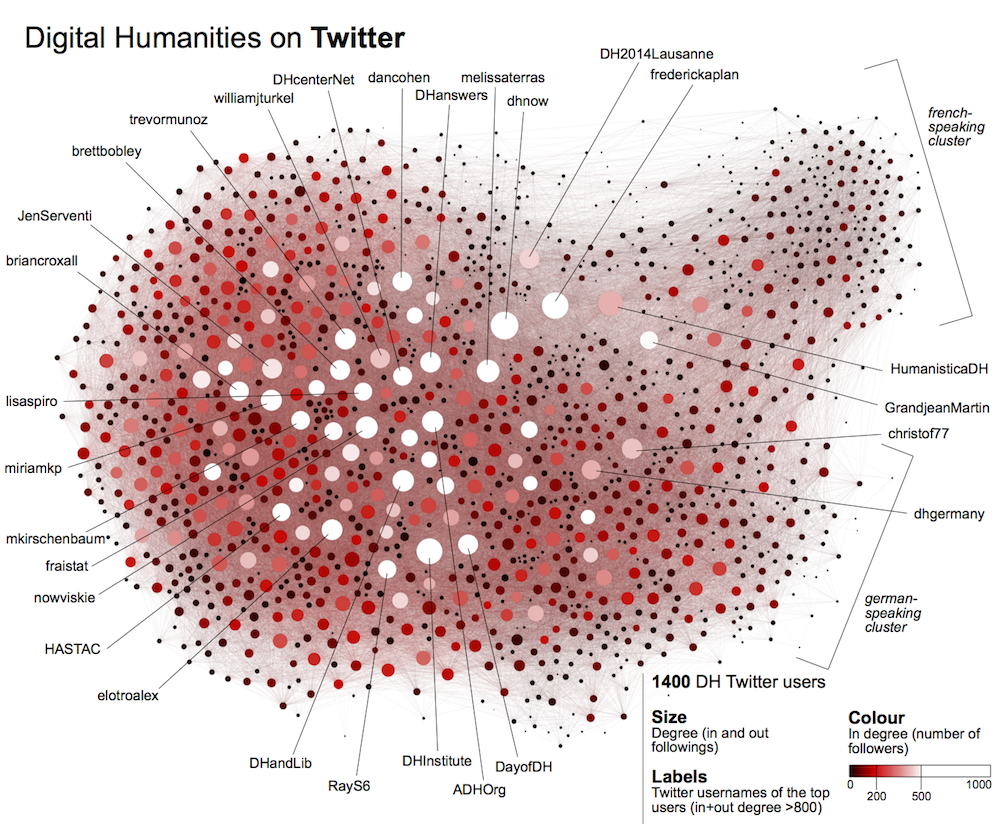

| Projects Digital humanities projects are more likely than traditional humanities work to involve a team or a lab, which may be composed of faculty, staff, graduate or undergraduate students, information technology specialists, and partners in galleries, libraries, archives, and museums. Credit and authorship are often given to multiple people to reflect this collaborative nature, which is different from the sole authorship model in the traditional humanities (and more like the natural sciences).[3] There are thousands of digital humanities projects, ranging from small-scale ones with limited or no funding to large-scale ones with multi-year financial support. Some are continually updated while others may not be due to loss of support or interest, though they may still remain online in either a beta version or a finished form. The following are a few examples of the variety of projects in the field:[54] Digital archives The Women Writers Project (begun in 1988) is a long-term research project to make pre-Victorian women writers more accessible through an electronic collection of rare texts. The Walt Whitman Archive[55] (begun in the 1990s) sought to create a hypertext and scholarly edition of Whitman's works and now includes photographs, sounds, and the only comprehensive current bibliography of Whitman criticism. The Emily Dickinson Archive (begun in 2013)[56] is a collection of high-resolution images of Dickinson's poetry manuscripts as well as a searchable lexicon of over 9,000 words that appear in the poems.  Example of network analysis as an archival tool at the League of Nations[57] The Slave Societies Digital Archive[58] (formerly Ecclesiastical and Secular Sources for Slave Societies), directed by Jane Landers[59] and hosted at Vanderbilt University, preserves endangered ecclesiastical and secular documents related to Africans and African-descended peoples in slave societies. This Digital Archive currently holds 500,000 unique images, dating from the 16th to the 20th centuries, and documents the history of between 6 and 8 million individuals. They are the most extensive serial records for the history of Africans in the Atlantic World and also include valuable information on the indigenous, European, and Asian populations who lived alongside them. Another example of a digital humanities projects focused on the Americas is at the National Autonomous University of Mexico, which has the digitization of 17th-century manuscripts, an electronic corpus of Mexican history from the 16th to 19th century, and the visualization of pre-Hispanic archaeological sites in 3-D.[60] A rare example of a digital humanities project focused on the cultural heritage of Africa is the Princeton Ethiopian, Eritrean, and Egyptian Miracles of Mary project, which documents African medieval stories, paintings, and manuscripts about the Virgin Mary from the 1300s into the 1900s.[61][62] The involvement of librarians and archivists plays an important part in digital humanities projects because of the recent expansion of their role so that it now covers digital curation, which is critical in the preservation, promotion, and access to digital collections, as well as the application of scholarly orientation to digital humanities projects.[63] A specific example involves the case of initiatives where archivists help scholars and academics build their projects through their experience in evaluating, implementing, and customizing metadata schemas for library collections.[64] Cultural analytics "Cultural analytics" refers to the use of computational method for exploration and analysis of large visual collections and also contemporary digital media. The concept was developed in 2005 by Lev Manovich who then established the Cultural Analytics Lab in 2007 at Qualcomm Institute at California Institute for Telecommunication and Information (Calit2). The lab has been using methods from the field of computer science called Computer Vision many types of both historical and contemporary visual media—for example, all covers of Time magazine published between 1923 and 2009,[65] 20,000 historical art photographs from the collection in Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York,[66] one million pages from Manga books,[67] and 16 million images shared on Instagram in 17 global cities.[68] Cultural analytics also includes using methods from media design and data visualization to create interactive visual interfaces for exploration of large visual collections e.g., Selfiecity and On Broadway. Cultural analytics research is also addressing a number of theoretical questions. How can we "observe" giant cultural universes of both user-generated and professional media content created today, without reducing them to averages, outliers, or pre-existing categories? How can work with large cultural data help us question our stereotypes and assumptions about cultures? What new theoretical cultural concepts and models are required for studying global digital culture with its new mega-scale, speed, and connectivity?[69] The term "cultural analytics" (or "culture analytics") is now used by many other researchers, as exemplified by two academic symposiums,[70] a four-month long research program at UCLA that brought together 120 leading researchers from university and industry labs,[71] an academic peer-review Journal of Cultural Analytics: CA established in 2016,[72] and academic job listings. Textual mining, analysis, and visualization WordHoard (begun in 2004) is a free application that enables scholarly but non-technical users to read and analyze, in new ways, deeply-tagged texts, including the canon of Early Greek epic, Chaucer, Shakespeare, and Spenser. The Republic of Letters (begun in 2008)[73] seeks to visualize the social network of Enlightenment writers through an interactive map and visualization tools. Network analysis and data visualization is also used for reflections on the field itself – researchers may produce network maps of social media interactions or infographics from data on digital humanities scholars and projects.  Network analysis: graph of Digital Humanities Twitter users[74] Document in Context of its Time (DICT) analysis style[75] and an online demo tool allow in an interactive way let users know whether the vocabulary used by an author of an input text was frequent at the time of text creation, whether the author used anachronisms or neologisms, and enables detecting terms in text that underwent considerable semantic change. Analysis of macroscopic trends in cultural change Culturomics is a form of computational lexicology that studies human behavior and cultural trends through the quantitative analysis of digitized texts.[76][77] Researchers data mine large digital archives to investigate cultural phenomena reflected in language and word usage.[78] The term is an American neologism first described in a 2010 Science article called Quantitative Analysis of Culture Using Millions of Digitized Books, co-authored by Harvard researchers Jean-Baptiste Michel and Erez Lieberman Aiden.[79] A 2017 study[45] published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America compared the trajectory of n-grams over time in both digitised books from the 2010 Science article[79] with those found in a large corpus of regional newspapers from the United Kingdom over the course of 150 years. The study further went on to use more advanced natural language processing techniques to discover macroscopic trends in history and culture, including gender bias, geographical focus, technology, and politics, along with accurate dates for specific events. The applications of digital humanities may be used along with other non humanities subject areas such as pure sciences, agriculture, management etc. to produce great variants of practical solutions to solve issues in industry as well as society.[80] Online publishing The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (begun in 1995) is a dynamic reference work of terms, concepts, and people from philosophy maintained by scholars in the field. MLA Commons[81] offers an open peer-review site (where anyone can comment) for their ongoing curated collection of teaching artifacts in Digital Pedagogy in the Humanities: Concepts, Models, and Experiments (2016).[82] The Debates in the Digital Humanities platform contains volumes of the open-access book of the same title (2012 and 2016 editions) and allows readers to interact with material by marking sentences as interesting or adding terms to a crowdsourced index. Wikimedia projects Some research institutions work with the Wikimedia Foundation or volunteers of the community, for example, to make freely licensed media files available via Wikimedia Commons or to link or load data sets with Wikidata. Text analysis has been performed on the contribution history of articles on Wikipedia or its sister projects.[83] DH-OER The 'South African Centre for Digital Language Resources' (SADiLaR ) was set up at a time when a global definition of Open Education Resources (OER) was being drafted and accepted by UNESCO [84] SADiLaR saw this an opportunity to stimulate activism and research around the use and creation of OERs for Digital Humanities. They initiated and launched the Digital Humanities OER ( DH-OER) project [85] to raise consciousness about the costs of materials, foster the adoption of open principles and practices and support the growth of open education resources and digital humanities in South African Higher education institutions. DH-OER began with 26 projects and an introduction to openness in April 2022.[86] It concluded in November 2023, when 16 projects showcased their efforts in a public event.[87] |

プロジェクト デジタル・ヒューマニティーズのプロジェクトは、従来の人文科学の研究よりも、教員、スタッフ、大学院生や学部生、情報技術の専門家、ギャラリー、図書 館、公文書館、博物館のパートナーなどから構成されるチームや研究室が関わる可能性が高い。 このような共同作業の性質を反映して、クレジットや著作者は複数の人物に与えられることが多く、これは従来の人文科学における単独著作者モデル(自然科学 に近い)とは異なる。[3] 人文科学のデジタルプロジェクトは数千件に上り、その規模も、資金が限定的または皆無の小規模なものから、複数年にわたる資金援助を受けている大規模なも のまで様々である。 継続的に更新されているものもあれば、支援や関心が失われたために更新が途絶えているものもあるが、ベータ版または完成版としてオンライン上に残っている 場合もある。 以下に、この分野におけるプロジェクトの多様性を示すいくつかの例を挙げる。[54] デジタルアーカイブ 女性作家プロジェクト(1988年開始)は、ビクトリア朝以前の女性作家の作品を、貴重なテキストの電子コレクションを通じてより入手しやすくするための 長期にわたる研究プロジェクトである。 ウォルト・ホイットマン・アーカイブ[55](1990年代開始)は、ホイットマンの作品のハイパーテキスト版および学術版を作成することを目的としてお り、現在では写真や音声、ホイットマン研究に関する唯一の包括的な現行書誌も含まれている。エミリー・ディキンソン・アーカイブ(2013年開始) [56]は、ディキンソンの詩の原稿の高解像度画像のコレクションであり、詩に登場する9,000語以上の検索可能な語彙集でもある。  国際連盟におけるアーカイブツールとしてのネットワーク分析の例[57] スレイブ・ソサイエティ・デジタル・アーカイブ[58](旧称:スレイブ・ソサイエティの教会および世俗資料)は、ジェーン・ランダース[59]が監督 し、ヴァンダービルト大学がホストを務める。このアーカイブは、奴隷社会におけるアフリカ人とアフリカ系の人々に関連する、絶滅の危機に瀕した教会および 世俗の文書を保存している。このデジタルアーカイブには現在、16世紀から20世紀までの50万点のユニークな画像が収められており、600万から800 万人の個人の歴史を記録している。これは大西洋世界におけるアフリカ人の歴史に関する最も広範な連続記録であり、また、彼らとともに暮らしていた先住民、 ヨーロッパ人、アジア人の貴重な情報も含まれている。アメリカ大陸に焦点を当てたデジタル人文学プロジェクトのもう一つの例として、メキシコ国立自治大学 では、17世紀の写本のデジタル化、16世紀から19世紀のメキシコの歴史に関する電子コーパス、先スペイン期の考古学遺跡の3D可視化を行っている。 アフリカの文化遺産に焦点を当てたデジタル人文学プロジェクトの珍しい例としては、1300年代から1900年代にかけてのアフリカの中世の聖母マリアに 関する物語、絵画、写本を記録するプリンストン大学エチオピア、エリトリア、エジプトの聖母マリアプロジェクトがある。 図書館員や記録管理者の関与は、デジタル・ヒューマニティーズのプロジェクトにおいて重要な役割を果たしている。というのも、彼らの役割は近年拡大してお り、デジタル・キュレーション(デジタルコレクションの保存、普及、アクセスにおいて重要な役割を果たす)もその対象となっているからだ。学術的な方向性 をデジタル・ヒューマニティーズのプロジェクトに適用することである。[63] 具体的な例としては、アーキビストが図書館のコレクションのメタデータ・スキーマの評価、実装、カスタマイズの経験を生かして、学者や研究者のプロジェク ト構築を支援する取り組みが挙げられる。[64] 文化分析 「文化分析」とは、膨大な視覚的コレクションや現代のデジタルメディアの調査と分析に計算方法を使用することを指す。この概念は2005年にレフ・マノ ヴィッチによって開発され、同氏は2007年にカリフォルニア情報通信研究所(Calit2)のクアルコム研究所に文化分析ラボを設立した。このラボで は、コンピュータビジョンと呼ばれるコンピュータサイエンスの分野の手法を、歴史的および現代的なさまざまな視覚メディアに適用している。例えば、 1923年から2009年までに発行されたタイム誌のすべての表紙[65]、ニューヨーク近代美術館(MoMA)のコレクションから2万点の歴史的な美術 写真[66]、 、マンガ本100万ページ分、[67] 17の世界都市でInstagramに投稿された1600万枚の画像などがある。[68] 文化分析には、メディアデザインやデータ視覚化の手法を活用して、大規模な視覚的コレクションの調査用にインタラクティブな視覚的インターフェースを作成 することも含まれる。例えば、SelfiecityやOn Broadwayなどである。 文化分析の研究では、多くの理論的な問題にも取り組んでいる。今日作成されるユーザー生成コンテンツとプロフェッショナルなメディアコンテンツの両方から 成る巨大な文化の宇宙を、平均値や外れ値、既存のカテゴリーに還元することなく、「観察」するにはどうすればよいのか? 文化に関する固定観念や思い込みを疑うのに、膨大な文化データはどのように役立つのか? 新たなメガスケール、スピード、接続性を持つグローバルなデジタル文化を研究するには、どのような新しい理論的な文化概念やモデルが必要なのか?[69] 「文化分析」(または「文化解析」)という用語は、現在では多くの他の研究者によって使用されている。その例として、2つの学術シンポジウム[70]、大 学および企業研究所から120人の主要研究者を集めたUCLAでの4か月間にわたる研究プログラム[71]、2016年に創刊された学術誌 『Journal of Cultural Analytics: CA』[72]、学術職の求人情報などがある。 テキストマイニング、分析、可視化 WordHoard(2004年に開始)は、学術的ではあるが専門的ではないユーザーが、初期ギリシャの叙事詩、チョーサー、シェイクスピア、スペンサー などの古典を含む、深くタグ付けされたテキストを新しい方法で読み、分析することを可能にする無料アプリケーションである。The Republic of Letters(2008年に開始)[73]は、啓蒙主義の作家たちの社会的ネットワークを、インタラクティブな地図や視覚化ツールを使って視覚化しよう とするものである。ネットワーク分析やデータの視覚化は、その分野自体の考察にも用いられている。研究者は、ソーシャルメディアの相互作用のネットワーク マップや、デジタル人文学の学者やプロジェクトに関するデータからインフォグラフィックを作成することができる。  ネットワーク分析:デジタル・ヒューマニティーズのTwitterユーザーのグラフ[74] Document in Context of its Time (DICT)分析スタイル[75]とオンラインのデモツールにより、入力テキストの著者が使用した語彙がテキスト作成当時頻繁に使用されていたものかどう か、著者が時代錯誤的な表現や新語を使用していたかどうか、テキスト内の用語で意味が大幅に変化したものを検出することができる。 文化変化の巨視的傾向の分析 Culturomicsは、デジタル化されたテキストの定量的分析を通じて人間の行動や文化の傾向を研究する計算言語学の一形態である。[76][77] 研究者は、言語や語法に反映される文化現象を調査するために、大規模なデジタルアーカイブをデータマイニングする。この用語は、2010年の 『Science』誌に掲載された「デジタル化された数百万冊の書籍を用いた文化の定量分析」という論文で初めて使用された米国の造語である。この論文 は、ハーバード大学の研究者ジャン=バティスト・ミシェルとエレス・リーバーマン・エイデンが共同執筆したものである。 2017年の研究[45]は、米国科学アカデミー紀要に掲載されたもので、2010年のScience誌の記事[79]で取り上げられた電子化書籍と、 150年間にわたる英国の地方新聞の大規模なコーパスで見つかったnグラムの軌跡を比較した。さらに研究は進み、より高度な自然言語処理技術を用いて、性 差別、地理的視点、テクノロジー、政治など、歴史や文化における巨視的な傾向を特定し、特定の出来事の正確な日付も特定した。 デジタル人文学の応用は、純粋科学、農業、経営など、人文学以外の分野と併用することで、産業や社会の問題を解決するための実用的なソリューションの多様 なバリエーションを生み出す可能性がある。 オンライン出版 スタンフォード哲学事典(1995年開始)は、哲学分野の学者によって維持されている、哲学の用語、概念、人物に関する動的な参考資料である。MLA Commons[81]は、Digital Pedagogy in the Humanities: Concepts, Models, and Experiments(2016年)の進行中のキュレーションされた教育アーティファクトのコレクションに対して、オープンピアレビューサイト(誰でも コメントを投稿できる)を提供している (2016年)[82]。「デジタル人文学における討論」プラットフォームには、同じタイトルのオープンアクセス書籍(2012年版および2016年版) が多数収録されており、読者は文章に興味深いとマークを付けたり、クラウドソースのインデックスに用語を追加したりすることで、資料と相互に作用すること ができる。 ウィキメディア・プロジェクト 一部の研究機関は、ウィキメディア財団やコミュニティのボランティアと協力し、例えば、ウィキメディア・コモンズを通じて自由にライセンスされたメディア ファイルを利用できるようにしたり、データセットをウィキデータにリンクしたりロードしたりしている。ウィキペディアや姉妹プロジェクトの記事への貢献履 歴については、テキスト分析が行われている。[83] DH-OER 「南アフリカデジタル言語資源センター」(SADiLaR)は、オープン教育リソース(OER)の世界的定義がUNESCOによって草案され、承認された 時期に設立された。SADiLaRは、これをデジタル人文学におけるOERの利用と作成に関する活動と研究を促進する好機と捉えた。彼らは、デジタル人文 学OER(DH-OER)プロジェクト[85]を立ち上げ、開始した。このプロジェクトは、教材のコストに関する意識を高め、オープンな原則と実践の採用 を促進し、南アフリカの高等教育機関におけるオープン教育リソースとデジタル人文学の成長を支援することを目的としている。DH-OERは2022年4月 に26のプロジェクトとオープン化の導入から始まった。[86] 16のプロジェクトが公開イベントで取り組みを紹介した2023年11月に終了した。[87] |

| Criticism In 2012, Matthew K. Gold identified a range of perceived criticisms of the field of digital humanities: "a lack of attention to issues of race, class, gender, and sexuality; a preference for research-driven projects over pedagogical ones; an absence of political commitment; an inadequate level of diversity among its practitioners; an inability to address texts under copyright; and an institutional concentration in well-funded research universities".[88] Similarly Berry and Fagerjord have argued that a digital humanities should "focus on the need to think critically about the implications of computational imaginaries, and raise some questions in this regard. This is also to foreground the importance of the politics and norms that are embedded in digital technology, algorithms and software. We need to explore how to negotiate between close and distant readings of texts and how micro-analysis and macro-analysis can be usefully reconciled in humanist work."[89] Alan Liu has argued, "while digital humanists develop tools, data, and metadata critically, therefore (e.g., debating the 'ordered hierarchy of content objects' principle; disputing whether computation is best used for truth finding or, as Lisa Samuels and Jerome McGann put it, 'deformance'; and so on) rarely do they extend their critique to the full register of society, economics, politics, or culture."[90] Some of these concerns have given rise to the emergent subfield of Critical Digital Humanities (CDH): Some key questions include: how do we make the invisible become visible in the study of software? How is knowledge transformed when mediated through code and software? What are the critical approaches to Big Data, visualization, digital methods, etc.? How does computation create new disciplinary boundaries and gate-keeping functions? What are the new hegemonic representations of the digital – 'geons', 'pixels', 'waves', visualization, visual rhetorics, etc.? How do media changes create epistemic changes, and how can we look behind the 'screen essentialism' of computational interfaces? Here we might also reflect on the way in which the practice of making-visible also entails the making-invisible – computation involves making choices about what is to be captured.[89] Negative publicity Lauren F. Klein and Gold note that many appearances of the digital humanities in public media are often in a critical fashion. Armand Leroi, writing in The New York Times, discusses the contrast between the algorithmic analysis of themes in literary texts and the work of Harold Bloom, who qualitatively and phenomenologically analyzes the themes of literature over time. Leroi questions whether or not the digital humanities can provide a truly robust analysis of literature and social phenomena or offer a novel alternative perspective on them. The literary theorist Stanley Fish claims that the digital humanities pursue a revolutionary agenda and thereby undermine the conventional standards of "pre-eminence, authority and disciplinary power".[91] However, digital humanities scholars note that "Digital Humanities is an extension of traditional knowledge skills and methods, not a replacement for them. Its distinctive contributions do not obliterate the insights of the past, but add and supplement the humanities' long-standing commitment to scholarly interpretation, informed research, structured argument, and dialogue within communities of practice".[3] Some have hailed the digital humanities as a solution to the apparent problems within the humanities, namely a decline in funding, a repeat of debates, and a fading set of theoretical claims and methodological arguments.[92] Adam Kirsch, writing in the New Republic, calls this the "False Promise" of the digital humanities.[93] While the rest of humanities and many social science departments are seeing a decline in funding or prestige, the digital humanities has been seeing increasing funding and prestige. Burdened with the problems of novelty, the digital humanities is discussed as either a revolutionary alternative to the humanities as it is usually conceived or as simply new wine in old bottles. Kirsch believes that digital humanities practitioners suffer from problems of being marketers rather than scholars, who attest to the grand capacity of their research more than actually performing new analysis and when they do so, only performing trivial parlor tricks of research. This form of criticism has been repeated by others, such as in Carl Staumshein, writing in Inside Higher Education, who calls it a "Digital Humanities Bubble".[94] Later in the same publication, Straumshein alleges that the digital humanities is a 'Corporatist Restructuring' of the Humanities.[95] Some see the alliance of the digital humanities with business to be a positive turn that causes the business world to pay more attention, thus bringing needed funding and attention to the humanities.[96] If it were not burdened by the title of digital humanities, it could escape the allegations that it is elitist and unfairly funded.[97] Black box There has also been critique of the use of digital humanities tools by scholars who do not fully understand what happens to the data they input and place too much trust in the "black box" of software that cannot be sufficiently examined for errors.[98] Johanna Drucker, a professor at UCLA Department of Information Studies, has criticized the "epistemological fallacies" prevalent in popular visualization tools and technologies (such as Google's n-gram graph) used by digital humanities scholars and the general public, calling some network diagramming and topic modeling tools "just too crude for humanistic work."[99] The lack of transparency in these programs obscures the subjective nature of the data and its processing, she argues, as these programs "generate standard diagrams based on conventional algorithms for screen display ... mak[ing] it very difficult for the semantics of the data processing to be made evident."[99] Similar problems can be seen at a lower level, with databases used for digital humanities analysis replicating the biases of the analogue systems of data.[100] As, essentially, "every database is a narrative"[100] visualisations or diagrams often obscure the underlying structures or omissions of data without acknowledging that they are incomplete or present only a particular angle. Diversity There has also been some recent controversy among practitioners of digital humanities around the role that race and/or identity politics plays. Tara McPherson attributes some of the lack of racial diversity in digital humanities to the modality of UNIX and computers themselves.[101] An open thread on DHpoco.org recently garnered well over 100 comments on the issue of race in digital humanities, with scholars arguing about the amount that racial (and other) biases affect the tools and texts available for digital humanities research.[102] McPherson posits that there needs to be an understanding and theorizing of the implications of digital technology and race, even when the subject for analysis appears not to be about race. Amy E. Earhart criticizes what has become the new digital humanities "canon" in the shift from websites using simple HTML to the usage of the TEI and visuals in textual recovery projects.[103] Works that have been previously lost or excluded were afforded a new home on the internet, but much of the same marginalizing practices found in traditional humanities also took place digitally. According to Earhart, there is a "need to examine the canon that we, as digital humanists, are constructing, a canon that skews toward traditional texts and excludes crucial work by women, people of color, and the LGBTQ community."[103] Issues of access Practitioners in digital humanities are also failing to meet the needs of users with disabilities. George H. Williams argues that universal design is imperative for practitioners to increase usability because "many of the otherwise most valuable digital resources are useless for people who are—for example—deaf or hard of hearing, as well as for people who are blind, have low vision, or have difficulty distinguishing particular colors."[104] In order to provide accessibility successfully, and productive universal design, it is important to understand why and how users with disabilities are using the digital resources while remembering that all users approach their informational needs differently.[104] Cultural criticism Digital humanities have been criticized for not only ignoring traditional questions of lineage and history in the humanities, but lacking the fundamental cultural criticism that defines the humanities. However, it remains to be seen whether or not the humanities have to be tied to cultural criticism, per se, in order to be the humanities.[90][19] The sciences[vague] might imagine the Digital Humanities as a welcome improvement over the non-quantitative methods of the humanities and social sciences.[105][106] Difficulty of evaluation As the field matures, there has been a recognition that the standard model of academic peer-review of work may not be adequate for digital humanities projects, which often involve website components, databases, and other non-print objects. Evaluation of quality and impact thus require a combination of old and new methods of peer review.[3] One response has been the creation of the DHCommons Journal. This accepts non-traditional submissions, especially mid-stage digital projects, and provides an innovative model of peer review more suited for the multimedia, transdisciplinary, and milestone-driven nature of Digital Humanities projects. Other professional humanities organizations, such as the American Historical Association and the Modern Language Association, have developed guidelines for evaluating academic digital scholarship.[107][108] Lack of focus on pedagogy The 2012 edition of Debates in the Digital Humanities recognized the fact that pedagogy was the "neglected 'stepchild' of DH" and included an entire section on teaching the digital humanities.[5] Part of the reason is that grants in the humanities are geared more toward research with quantifiable results rather than teaching innovations, which are harder to measure.[5] In recognition of a need for more scholarship on the area of teaching, the edited volume Digital Humanities Pedagogy was published and offered case studies and strategies to address how to teach digital humanities methods in various disciplines. |

批判 2012年、マシュー・K・ゴールドはデジタル人文学の分野に対する認識されている批判の数々を挙げている。「人種、階級、ジェンダー、セクシュアリティ の問題に対する関心の欠如、教育的なプロジェクトよりも研究主導のプロジェクトが好まれる傾向、政治的なコミットメントの欠如、実践者の多様性のレベルが 不十分、著作権のあるテキストを扱うことができない、 そして、資金力のある研究大学に機関が集中している」という問題がある。[88] 同様に、ベリーとフェイジャーヨッドは、デジタル人文学は「計算上の想像力の含意について批判的に考える必要性に焦点を当てるべきであり、この点について いくつかの疑問を提起すべきである」と主張している。これはまた、デジタル技術、アルゴリズム、ソフトウェアに埋め込まれた政治と規範の重要性を前面に押 し出すことでもある。テキストの密接な読みと遠い読みの間の折衷案を模索し、また、人文科学の研究において、ミクロ分析とマクロ分析をどのように有益に調 和させることができるかを探究する必要がある」[89] アラン・リューは、「デジタル・ヒューマニストがツール、データ、メタデータを批判的に開発する一方で、(例えば、「コンテンツ・オブジェクトの順序付き 階層」の原則を議論したり、 計算は真実の発見に最適なのか、それともリサ・サミュエルズとジェローム・マガンが言うように「脱構築」に最適なのか、など)めったに彼らの批判を社会、 経済、政治、文化のあらゆる領域にまで広げることはない」と主張している。[90] これらの懸念の一部が、批判的デジタル人文学(CDH)という新たな分野を生み出すきっかけとなった。 主な疑問点には以下のようなものがある。ソフトウェア研究において、不可視のものを可視化するにはどうすればよいのか? コードやソフトウェアを介することで、知識はどのように変化するのか? ビッグデータ、視覚化、デジタル手法などに対する批判的なアプローチとはどのようなものか? 計算はどのように新たな学問分野の境界と門番機能を創り出すのか?デジタルの新たな覇権的表現とは何か。「ジオンス」、「ピクセル」、「波」、「視覚 化」、「視覚修辞」などである。メディアの変化はどのように認識論の変化を生み出すのか。また、計算機インターフェースの「スクリーン本質論」の背後をど のように見ることができるのか。ここでは、可視化の実践が不可避的に不可視化をもたらすという点についても考察することができる。計算には、何を捉えるか についての選択が伴うのである。 否定的な報道 ローレン・F・クラインとゴールドは、公共メディアにおけるデジタル人文学の多くの登場は、批判的なものであることが多いと指摘している。ニューヨーク・ タイムズ紙に寄稿したアルマンド・レロイは、文学テキストのテーマをアルゴリズムで分析することと、文学のテーマを質的・現象学的に長期間にわたって分析 するハロルド・ブルームの研究との対比について論じている。レロワは、デジタル人文学が文学や社会現象について真に堅固な分析を提供できるのか、あるいは それらに対して新たな代替的な視点を提供できるのかを疑問視している。文学理論家のスタンリー・フィッシュは、デジタル人文学は革命的な課題を追求してお り、それによって「卓越性、権威、規律力」という従来の基準を損なうと主張している。[91] しかし、デジタル人文学の学者たちは、「デジタル人文学は、従来の知識、スキル、方法の延長であり、それらの代替ではない」と指摘している。その独特な貢 献は過去の洞察を消し去るものではなく、学術的な解釈、情報に基づく研究、体系的な議論、実践コミュニティ内での対話など、人文科学が長年取り組んできた ものを補完するものである」と指摘している。[3] デジタル・ヒューマニティーズは、ヒューマニティーズにおける明らかな問題、すなわち、資金援助の減少、議論の繰り返し、理論的主張や方法論的論争の衰退 に対する解決策として歓迎されている。[92] アダム・カーシュは『ザ・ニュー・リパブリック』誌で、これをデジタル・ヒューマニティーズの「偽りの約束」と呼んでいる。[93] その他のヒューマニティーズや多くの社会科学部が資金援助や名声の低下に直面する一方で、デジタル・ヒューマニティーズは資金援助と名声の増加を経験して いる。斬新さの問題を抱えるデジタル人文学は、通常考えられているような人文科学の革命的な代替案として、あるいは単に古い瓶に新しいワインを詰めたもの として論じられている。キルシュは、デジタル人文学の実践者は学者というよりもマーケティング担当者のような問題を抱えており、新しい分析を実際に行うよ りも、研究の大きな可能性を証明することに重点を置き、また、そうした分析を行う場合でも、研究における些細な手品のようなものに終始していると考える。 この種の批判は、インサイド・ハイヤー・エデュケーション誌に寄稿したカール・ストラウマシン(Carl Straumshein)のように、他の研究者によっても繰り返されている。ストラウマシンは、これを「デジタル人文学のバブル」と呼んでいる。[94] 同じ出版物の中で、ストラウマシンは、デジタル人文学は人文学の「コーポラティズム的再編」であると主張している。[95] 一部の デジタル人文学とビジネスの提携は、ビジネス界が人文学により関心を向けるきっかけとなり、必要な資金と注目を集めるという肯定的な展開であると見る者も いる。[96] デジタル人文学という肩書きがなければ、エリート主義的で不当に資金が提供されているという非難を免れることができるだろう。[97] ブラックボックス また、入力したデータがどう処理されるのかを十分に理解せず、エラーを十分に検証できないソフトウェアの「ブラックボックス」に過剰な信頼を置く研究者 が、デジタル人文学のツールを使用することに対する批判もある。[98] ジョアンナ・ドゥラッカー(UCLA情報学部教授)は、デジタル人文学の研究者や一般の人々が使用する一般的な視覚化ツールや技術(Googleのn 人文科学の研究者や一般の人々が使用する、Google の n-gram グラフのような視覚化ツールや技術に広く見られる「認識論的誤謬」を批判し、一部のネットワーク図やトピックモデリングツールを「人文科学の作業には粗雑 すぎる」と評している。[99] これらのプログラムの透明性の欠如は、データとその処理の主観性を不明瞭にする、と彼女は主張している。これらのプログラムは「画面表示用の従来のアルゴ リズムに基づく標準的な図を生成する。そのため、 。」[99] 類似の問題は、より低レベルでも見られ、デジタル人文学的分析に使用されるデータベースは、アナログのデータシステムの偏りを再現している。[100] 基本的に、「あらゆるデータベースは物語である」[100]ため、可視化やダイアグラムは、不完全であることや特定の観点のみを示していることを認めない まま、データの基礎構造や省略を不明瞭にすることが多い。 多様性 また、デジタル・ヒューマニティーズの実践者たちの間では、人種やアイデンティティ・ポリティクスが果たす役割をめぐって、最近いくつかの論争が起こって いる。Tara McPhersonは、デジタル・ヒューマニティーズにおける人種の多様性の欠如の一部を、UNIXやコンピュータ自体の性質に帰している。[101] DHpoco.orgの公開スレッドでは、最近、デジタル・ヒューマニティーズにおける人種の問題について100件を超えるコメントが集まった。学者たち は、 デジタル人文学の研究で利用可能なツールやテキストに、人種(およびその他の)偏見がどれほど影響しているかについて、学者たちが議論している。 [102] マクファーソンは、分析の対象が人種とは関係ないように見える場合でも、デジタル技術と人種との関連性を理解し理論化する必要があると主張している。 エイミー・E・エアハートは、単純なHTMLを使用したウェブサイトからTEIや視覚資料を使用したテキスト復元プロジェクトへの移行において、新たなデ ジタル人文学の「規範」となったものを批判している。[103] これまで失われたり排除されていた作品はインターネット上に新たな居場所を得たが、従来の人文科学に見られたのと同様の限定的な慣行の多くがデジタル上で も行われた。イーハートによると、「デジタル・ヒューマニストとして構築している正典を検証する必要がある。その正典は伝統的なテキストに偏り、女性、有 色人種、LGBTQコミュニティによる重要な作品を排除している」[103]。 アクセスの問題 デジタル・ヒューマニティーズの専門家も、障害を持つユーザーのニーズに応えられていない。ジョージ・H・ウィリアムズは、専門家がユーザビリティを高め るためにはユニバーサルデザインが不可欠であると主張している。「多くの場合、最も価値のあるデジタルリソースも、例えば耳が不自由な人や難聴の人、ある いは視覚障害者、弱視の人、 特定の色を識別することが困難な人々」もいるためである。[104] アクセシビリティを適切に提供し、生産的なユニバーサルデザインを実現するには、障害を持つユーザーがデジタルリソースをどのように利用しているのか、そ の理由と方法を理解することが重要である。ただし、すべてのユーザーが情報ニーズに異なるアプローチを取ることを念頭に置く必要がある。[104] 文化批評 デジタル人文学は、人文学における伝統的な系譜や歴史に関する問題を無視しているだけでなく、人文学を定義する基本的な文化批評を欠いているとして批判さ れてきた。しかし、人文科学が人文科学であるためには、文化批判と結びついている必要があるのかどうかはまだわからない。[90][19] 科学[曖昧]は、人文科学や社会科学の非定量的な手法を改善する歓迎すべきものとしてデジタル人文学を想像するかもしれない。[105][106] 評価の難しさ この分野が成熟するにつれ、ウェブサイトやデータベース、その他の印刷物以外の対象を含むことが多いデジタル人文学のプロジェクトには、学術的な査読の標 準モデルは適切ではないという認識が広まっている。そのため、質と影響力の評価には、新旧の査読方法を組み合わせる必要がある。[3] その一つの対応策として、DHCommons Journalが創刊された。これは、特に中間段階のデジタルプロジェクトなど、従来とは異なる投稿を受け入れ、デジタル人文学プロジェクトのマルチメ ディア性、学際性、マイルストーン重視の性質により適した革新的な査読モデルを提供している。 アメリカ歴史学会や現代語学会などの人文科学の専門機関は、学術的なデジタル研究を評価するためのガイドラインを策定している。[107][108] 教授法への焦点の欠如 2012年版『デジタル人文学における議論』は、教授法が「DHの顧みられない『厄介な隠し子』」であるという事実を認識し、デジタル人文学の教授法に関 するセクションを丸ごと1つ設けた。[5] その理由の一部は、人文科学分野における助成金は 測定が難しい教育の革新よりも、数値化できる結果を伴う研究に重点が置かれているためである。教育分野における研究の必要性が認識され、編著『デジタル・ ヒューマニティーズの教授法』が出版され、さまざまな分野におけるデジタル・ヒューマニティーズの教授法を教える方法について、ケーススタディや戦略が提 示された。 |

| Cyborg anthropology Digital anthropology |

サイボーグ人類学 デジタル人類学 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Digital_humanities |

|

リンク(コンピュータによる質的研究)

リンク

文献

その他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1997-2099

Do not paste, but

[Re]Think our message for all undergraduate

students!!!

Do not paste, but

[Re]Think our message for all undergraduate

students!!!

D5123 ( Type D51) photo 1936, from Wikicommons

++

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆