エドワード・バーネット・タイラー

Edward

Burnett Tylor, 1832-1917

エドワード・バーネット・タイラー

Edward

Burnett Tylor, 1832-1917

解説:池田光穂

「エドワード・バーネット・タイラー (Sir Edward Burnett Tylor FRAI、1832年10月2日〜1917年1月2日)は、文化人類学の創始者であるイギリスの人類学者である。タイラーの思想は、19世紀の文化進化論 を代表するものだ。『原始文化』(1871年)と『人類学』(1881年)では、チャールズ・ライエルの進化論に基づいて、人類学の科学的研究の文脈を定義 した。タイラーは、社会や宗教の発展には機能的な基盤があり、それは普遍的なものであると判断した。タイラーは、すべての社会は野蛮から野蛮を経て文明へ と発展するという3つの基本的な段階を経ると主張した。タイラーは社会人類学の創始者であり、彼の著作によって19世紀の人類学の学問体系が構築された。 彼は、「人間の歴史と前史の研究は、英国社会の改革のための基礎として利用できる」と考えていた。タイラーは、アニミズム(万物や自然界に存在する個々の 魂やアニマへの信仰)という言葉を再び一般的に使用するようになった。彼はアニミズムを宗教の発展の第一段階と考えていた」)

| Sir Edward Burnett Tylor FRAI (2 October 1832 – 2 January 1917) was an English anthropologist, and professor of anthropology.[1] Tylor's ideas typify 19th-century cultural evolutionism. In his works Primitive Culture (1871) and Anthropology (1881), he defined the context of the scientific study of anthropology, based on the evolutionary theories of Charles Lyell. He believed that there was a functional basis for the development of society and religion, which he determined was universal. Tylor maintained that all societies passed through three basic stages of development: from savagery, through barbarism to civilization.[2] Tylor is a founding figure of the science of social anthropology, and his scholarly works helped to build the discipline of anthropology in the nineteenth century.[3] He believed that "research into the history and prehistory of man [...] could be used as a basis for the reform of British society".[4] Tylor reintroduced the term animism (faith in the individual soul or anima of all things and natural manifestations) into common use.[5] He regarded animism as the first phase in the development of religions. |

サー・エドワード・バーネット・タイラー FRAI(1832年10月2日 - 1917年1月2日)は、イギリスの人類学者であり、人類学教授であった。[1] タイラーの思想は19世紀の文化進化論を典型的に示す。著書『原始文化』(1871年)および『人類学』(1881年)において、彼はチャールズ・ライエ ルの進化論に基づき、人類学の科学的探究の枠組みを定義した。彼は社会と宗教の発展には機能的な基盤があり、それが普遍的であると確信していた。タイラー は全ての社会が三つの基本段階を経ると主張した。すなわち野蛮から、未開を経て文明へと至る段階である。[2] タイラーは社会人類学の創始者であり、その学術的業績は19世紀における人類学という学問分野の構築に貢献した。[3] 彼は「人類の歴史と先史時代に関する研究は[...]英国社会改革の基盤として活用できる」と信じていた。[4] タイラーはアニミズム(万物や自然現象に個々の魂やアニマが宿るとの信仰)という用語を一般使用に再導入した。[5]彼はアニミズムを宗教発展の第一段階と見なした。 |

| Early life and education Tylor was born in 1832, in Camberwell, London, the son of Joseph Tylor and Harriet Skipper, part of a family of wealthy Quakers who owned a London brass factory. His elder brother, Alfred Tylor, became a geologist.[6] He was educated at Grove House School, Tottenham, but due to his Quaker faith and the death of his parents he left school at the age of 16 without obtaining a degree.[7] After leaving school, he prepared to help manage the family business. This plan was put aside when he developed tuberculosis at age 23. Following medical advice to spend time in warmer climes, Tylor left England in 1855, and travelled to the Americas. The experience proved to be an important and formative one, sparking his lifelong interest in studying unfamiliar cultures. During his travels, Tylor met Henry Christy, a fellow Quaker, ethnologist and archaeologist. Tylor's association with Christy greatly stimulated his awakening interest in anthropology, and helped broaden his inquiries to include prehistoric studies.[6] |

幼少期と教育 タイラーは1832年、ロンドンのキャンバーウェルで生まれた。父はジョセフ・タイラー、母はハリエット・スキッパーで、ロンドンの真鍮工場を所有する裕福なクエーカー教徒の一家であった。兄のアルフレッド・タイラーは地質学者となった[6]。 彼はトッテナムのグローブ・ハウス・スクールで教育を受けたが、クエーカー教徒としての信仰と両親の死により、16歳で学位を取得せずに学校を去った [7]。退学後、彼は家業の経営を手伝う準備をした。しかし23歳で結核を発症したため、この計画は棚上げとなった。温暖な気候で過ごすよう医師の助言を 受けたタイラーは、1855年にイングランドを離れ、アメリカ大陸へ旅立った。この経験は重要な形成期となり、未知の文化研究への生涯にわたる関心を呼び 起こした。 旅の途中、タイラーは同じクエーカー教徒で民族学者・考古学者であるヘンリー・クリスティと出会った。クリスティとの交流は、彼の人類学への目覚めた関心を大いに刺激し、先史研究を含む探求の幅を広げる助けとなった。[6] |

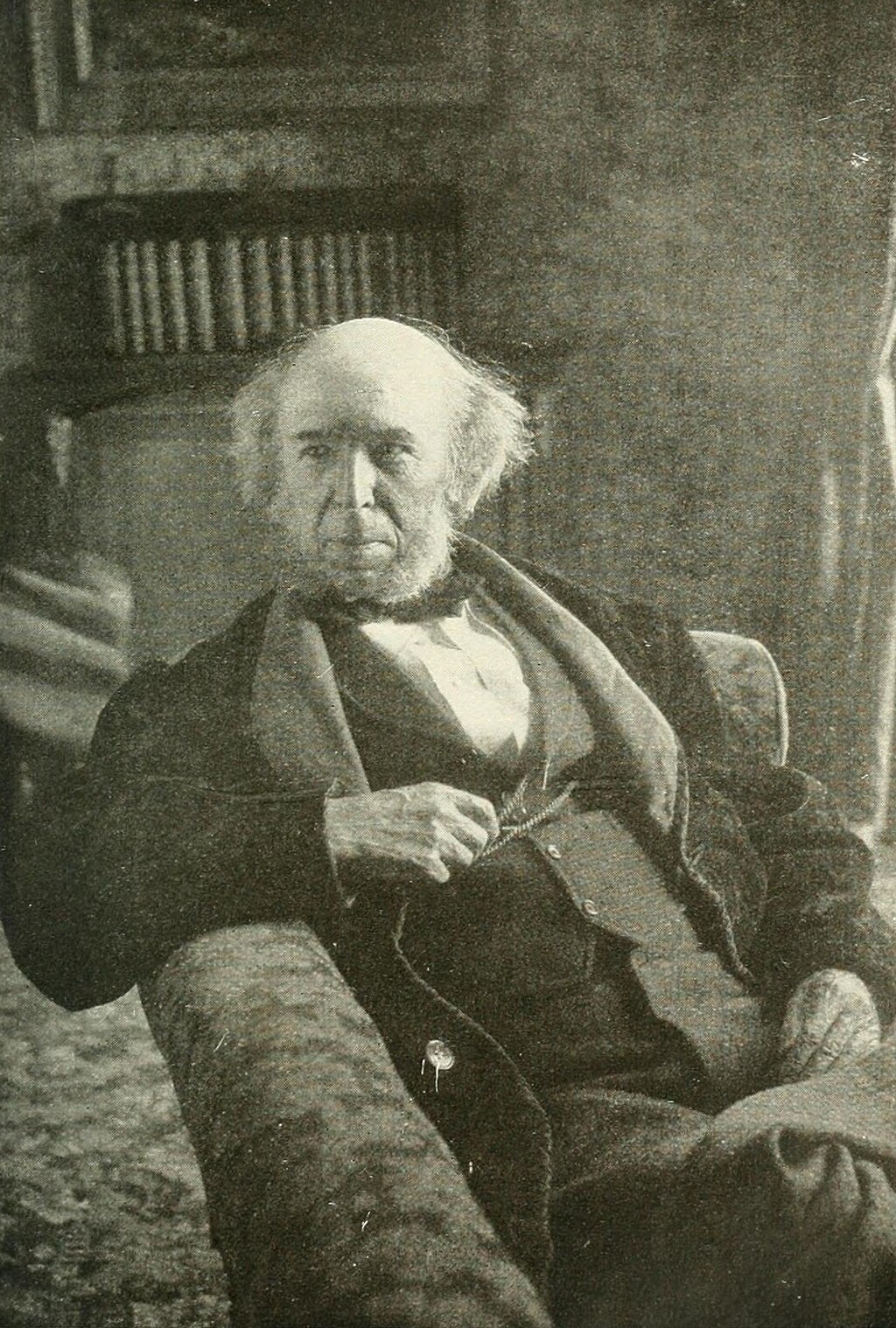

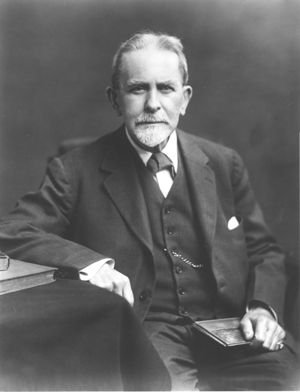

Professional career One of the last portraits of the aged Tylor; from Folk-Lore, 1917. Tylor's first publication was a result of his 1856 trip to Mexico with Christy. His notes on the beliefs and practices of the people he encountered were the basis of his work Anahuac: Or Mexico and the Mexicans, Ancient and Modern (1861), published after his return to England. Tylor continued to study the customs and beliefs of tribal communities, both existing and prehistoric (based on archaeological finds). He published his second work, Researches into the Early History of Mankind and the Development of Civilization, in 1865. Following this came his most influential work, Primitive Culture (1871). This was important not only for its thorough study of human civilisation and contributions to the emergent field of anthropology, but for its undeniable influence on a handful of young scholars, such as J. G. Frazer, who were to become Tylor's disciples and contribute greatly to the scientific study of anthropology in later years. Tylor was appointed Keeper of the University Museum at Oxford in 1883, and, as well as serving as a lecturer, held the title of the first "Reader in Anthropology" from 1884 to 1895. In 1896 he was appointed the first Professor of Anthropology at Oxford University.[6] He was also closely involved in the early history of the Pitt Rivers Museum, built adjacent to the University Museum.[8] Tylor acted as anthropological consultant on the first edition of the Oxford English Dictionary.[9] The 1907, festschrift Anthropological Essays presented to Edward Burnett Tylor, formally presented to Tylor on his 75th birthday, contains essays by 20 anthropologists, a 15-page appreciation of Tylor's work by Andrew Lang, and a comprehensive bibliography of Tylor's publications compiled by Barbara Freire-Marreco.[6][10][11] |

専門職としての経歴 老いたタイラーの最後の肖像画の一つ。1917年『フォークロア』誌より。 タイラーの最初の著作は、1856年にクリスティと共にメキシコへ行った旅の結果であった。彼が出会った人々の信仰や慣習に関する記録は、帰国後に刊行さ れた『アナワック:古代と現代のメキシコとメキシコ人』(1861年)の基礎となった。タイラーはその後も、現存する部族社会と先史時代の部族社会(考古 学的発見に基づく)の慣習や信仰を研究し続けた。1865年には第二作『人類の初期歴史と文明の発展に関する研究』を発表。これに続く1871年の『原始 文化』は彼の最も影響力ある著作となった。この著作は、人類文明の徹底的な研究と新興分野である人類学への貢献だけでなく、J・G・フレイザーら数名の若 手学者(後にタイラーの弟子となり、後年の人類学の科学的研究に大きく貢献する者たち)に与えた紛れもない影響という点でも重要であった。 タイラーは1883年にオックスフォード大学博物館の館長に任命され、講師を務める傍ら、1884年から1895年まで初代「人類学講師」の称号を保持し た。1896年にはオックスフォード大学初代人類学教授に任命された[6]。また大学博物館に隣接して建設されたピット・リバース博物館の初期運営にも深 く関わった[8]。タイラーは『オックスフォード英語辞典』初版の編集において人類学顧問を務めた[9]。 1907年、エドワード・バーネット・タイラーに贈られた記念論文集『Anthropological Essays』は、タイラーの75歳の誕生日に正式に贈呈されたもので、20人の人類学者による論文、アンドルー・ラングによる15ページにわたるタイ ラーの業績への賛辞、バーバラ・フレイレ・マレコが編集したタイラーの出版物の包括的な書誌が掲載されている。 |

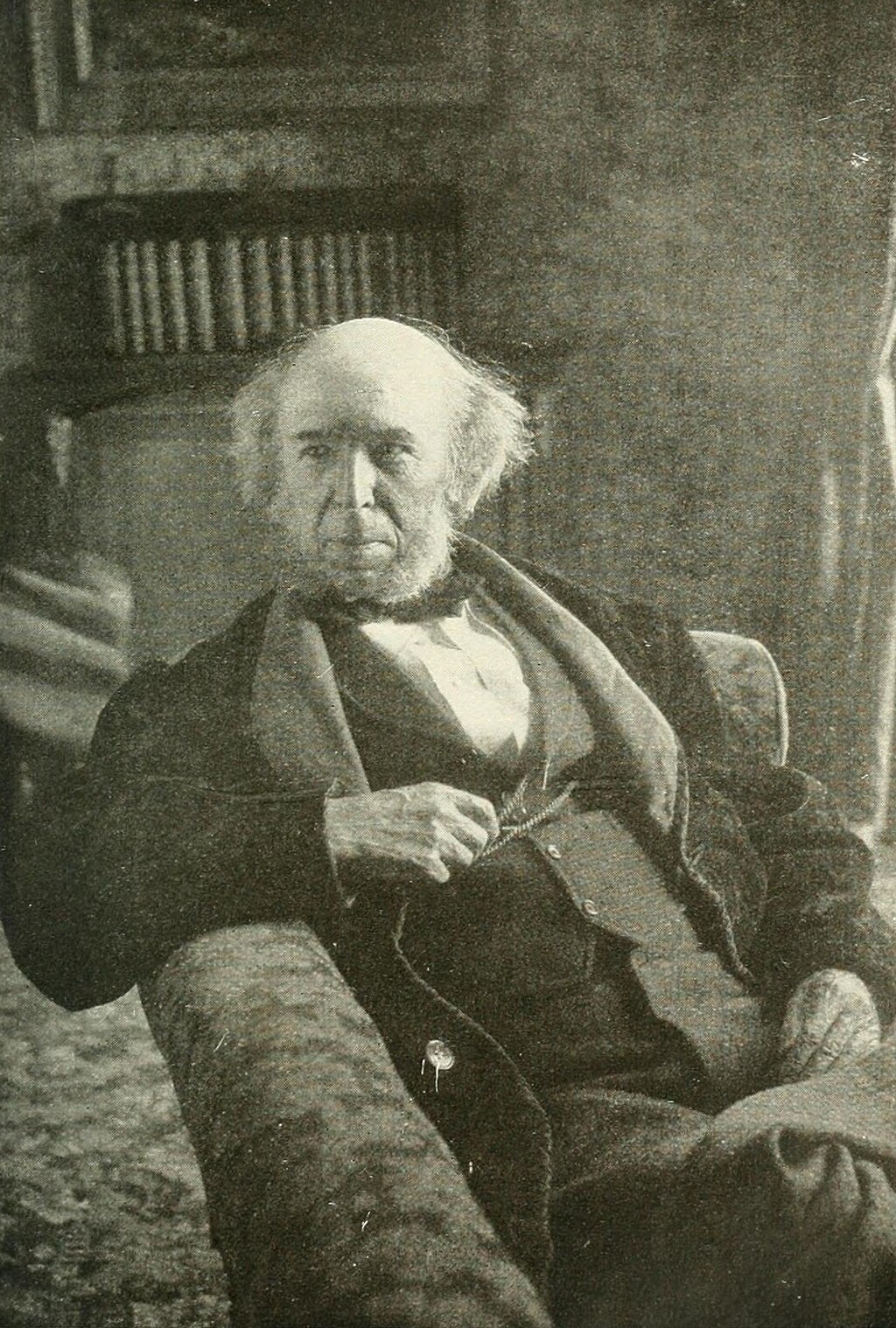

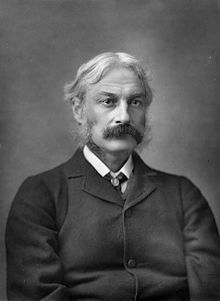

| Thought Classification and criticisms  Herbert Spencer The word evolution is forever associated in the popular mind with Charles Darwin's Theory of Evolution, which professes, among other things, that man as a species developed diachronically from some ancestor among the Primates who was also ancestor to the Great Apes, as they are popularly termed, and yet this term was not a neologism of Darwin's. He took it from the cultural milieu, where it meant etymologically "unfolding" of something heterogeneous and complex from something simpler and more homogeneous. Herbert Spencer, a contemporary of Darwin, applied the term to the universe, including philosophy and what Tylor would later call culture.[12] This view of the universe was generally termed evolutionism, while its exponents were evolutionists.[13] In 1871 Tylor published Primitive Culture, becoming the originator of cultural anthropology.[14] His methods were comparative and historical ethnography. He believed that a "uniformity" was manifest in culture, which was the result of "uniform action of uniform causes". He regarded his instances of parallel ethnographic concepts and practices as indicative of "laws of human thought and action". He was an evolutionist and therefore considered the task of cultural anthropology to discover "stages of development or evolution". Evolutionism was distinguished from another creed, diffusionism, postulating the spread of items of culture from regions of innovation. A given apparent parallelism thus had at least two explanations: the instances descend from an evolutionary ancestor, or they are alike because one diffused into the culture from elsewhere.[15] These two views are exactly parallel to the tree model and wave model of historical linguistics, which are instances of evolutionism and diffusionism, language features being instances of culture. Two other classifications were proposed in 1993 by Upadhyay and Pandey,[16] Classical Evolutionary School and Neo Evolutionary School, the Classical to be divided into British, American, and German. The Classical British Evolutionary School, primarily at Oxford University, divided society into two evolutionary stages, savagery and civilization, based on the archaeology of John Lubbock, 1st Baron Avebury. Upadhyay and Pandey list its adherents as Robert Ranulph Marett, Henry James Sumner Maine, John Ferguson McLennan, and James George Frazer, as well as Tylor.[17] Marett was the last man standing, dying in 1943. By the time of his death, Lubbock's archaeology had been updated. The American School, beginning with Lewis Henry Morgan,[18] was likewise superseded, both being replaced by the Neoevolutionist School, beginning with V. Gordon Childe. It brought the archaeology up-to-date and tended to omit the intervening society names, such as savagery; for example, Neolithic is both a tool tradition and a form of society. There are some other classifications. Theorists of each classification each have their own criticisms of the Classical/Neo Evolutionary lines, which despite them remains the dominant view. Some criticisms are in brief as follows.[19] There is really no universality; that is, the apparent parallels are accidental, on which the theorist has imposed a model that does not really fit. There is no uniform causality, but different causes might produce similar results. All cultural groups do not have the same stages of development. The theorists are arm-chair anthropologists; their data is insufficient to form realistic abstractions. They overlooked cultural diffusion. They overlooked cultural innovation. None of the critics claim definitive proof that their criticisms are less subjective or interpretive than the models they criticise. |

思考 分類と批判  ハーバート・スペンサー 進化という言葉は、一般の認識において永遠にチャールズ・ダーウィンの進化論と結びついている。この理論は、とりわけ、人類という種が、霊長類の中の祖先 から、いわゆる大型類人猿の祖先でもある存在へと、時間的に発展したと主張する。しかしこの用語はダーウィンの新造語ではなかった。彼はこの言葉を文化圏 から借用した。そこでは語源的に、より単純で均質な状態から異質で複雑なものが「展開」することを意味していた。ダーウィンの同時代人であるハーバート・ スペンサーは、この用語を宇宙全体、すなわち哲学や後にタイラーが「文化」と呼ぶものにも適用した[12]。この宇宙観は一般に進化論と呼ばれ、その提唱 者は進化論者と呼ばれた。[13] 1871年、タイラーは『原始文化』を出版し、文化人類学の創始者となった[14]。彼の方法は比較歴史民族誌学であった。彼は文化には「均一性」が顕著 に現れており、それは「均一な原因による均一な作用」の結果だと信じていた。彼は、民族誌的概念や慣行における並行事例を「人間の思考と行動の法則」を示 すものと見なした。進化論者であったため、文化人類学の任務は「発展または進化の段階」を発見することだと考えた。 進化論は、文化の要素が革新地域から拡散すると仮定する拡散説という別の信条と区別された。したがって、ある見かけ上の類似性には少なくとも二つの説明が あった:事例は進化的な祖先から派生したものか、あるいは一方が他方へ拡散したために類似しているかのいずれかである。[15] これらの二つの見解は、言語特徴が文化の事例であるという歴史言語学の樹形モデルと波動モデルに完全に並行する。これらは進化論と拡散説の事例である。 1993年にウパディヤイとパンディによって、さらに2つの分類が提案された[16]。古典的進化論学派と新進化論学派であり、古典的進化論学派は英国、 米国、ドイツに分けられる。主にオックスフォード大学を中心とした古典的英国進化論学派は、ジョン・ラバック、第1代アベベリー男爵の考古学に基づいて、 社会を2つの進化段階、すなわち野蛮と文明に分けました。ウパディヤイとパンディは、その支持者として、ロバート・ラナルフ・マレット、ヘンリー・ジェー ムズ・サムナー・メイン、ジョン・ファーガソン・マクレナン、ジェームズ・ジョージ・フレイザー、そしてタイラーを挙げている[17]。マレットは 1943年に亡くなり、この学派の最後の生き残りとなった。彼の死までに、ラバックの考古学は更新されていた。ルイス・ヘンリー・モーガン[18] に端を発するアメリカ学派も同様に取って代わられ、その両方が V. ゴードン・チャイルドに端を発する新進化論学派に取って代わられた。新進化論学派は考古学を最新の状態に更新し、野蛮社会などの中間的な社会名称を省略す る傾向があった。例えば、新石器時代は、道具の伝統であると同時に社会形態でもある。 他にもいくつかの分類法がある。各分類法の理論家たちは、古典的/新進化論的枠組みに対してそれぞれ独自の批判を持っているが、それにもかかわらず、この 枠組みは依然として主流の見解である。批判の要点は以下の通りだ[19]。真の普遍性は存在しない。つまり、見かけ上の類似性は偶然のものであり、理論家 がそれに当てはまらないモデルを無理に当てはめた結果である。統一的な因果関係は存在せず、異なる原因が類似の結果を生むことがある。全ての文化集団が同 じ発展段階にあるわけではない。理論家たちは机上の人類学者であり、現実的な抽象化を形成するにはデータが不十分だ。彼らは文化拡散を見落としている。文 化革新も見落としている。批判者たちの誰も、自らの批判が批判対象のモデルよりも主体的・解釈的でないという決定的な証拠を提示していない。 |

| Basic concepts Culture Tylor's notion is best described in his most famous work, the two-volume Primitive Culture. The first volume, The Origins of Culture, deals with ethnography including social evolution, linguistics, and myth. The second volume, Religion in Primitive Culture, deals mainly with his interpretation of animism. On the first page of Primitive Culture, Tylor provides a definition which is one of his most widely recognised contributions to anthropology and the study of religion:[20] Culture or Civilization, taken in its wide ethnographic sense, is that complex whole which includes knowledge, belief, art, morals, law, custom, and any other capabilities and habits acquired by man as a member of society. — Tylor[21] Also, the first chapter of the work gives an outline of a new discipline, science of culture, later known as culturology.[22] |

基本概念 文化 タイラーの概念は、彼の最も有名な著作である二巻本の『原始文化』に最もよく表れている。第一巻『文化の起源』は、社会進化論、言語学、神話を含む民族誌を扱っている。第二巻『原始文化における宗教』は、主にアニミズムに関する彼の解釈を扱っている。 『原始文化』の冒頭で、タイラーは人類学と宗教研究への最も広く認知された貢献の一つとなる定義を提示している:[20] 文化あるいは文明とは、広義の民族誌的意味において、知識、信念、芸術、道徳、法律、習慣、その他あらゆる能力や習慣を含む、人間が社会の一員として獲得した複雑な全体である。 — タイラー[21] また、同書の第一章では、後に文化学として知られる新たな学問分野「文化科学」の概要が示されている[22]。 |

| Universals Unlike many of his predecessors and contemporaries, Tylor asserts that the human mind and its capabilities are the same globally, despite a particular society's stage in social evolution.[23] This means that a hunter-gatherer society would possess the same amount of intelligence as an advanced industrial society. The difference, Tylor asserts, is education, which he considers the cumulative knowledge and methodology that takes thousands of years to acquire. Tylor often likens primitive cultures to "children", and sees culture and the mind of humans as progressive. His work was a refutation of the theory of social degeneration, which was popular at the time.[7] At the end of Primitive Culture, Tylor writes, "The science of culture is essentially a reformers' science".[24] |

普遍性 タイラーは、多くの先人や同時代人とは異なり、特定の社会の社会進化の段階にかかわらず、人間の精神とその能力は世界的に同じだと主張する[23]。これ は、狩猟採集社会も先進工業社会と同じ知性を備えていることを意味する。違いは教育にあるとタイラーは主張し、教育とは数千年の歳月をかけて蓄積される知 識と方法論だと考える。タイラーはしばしば原始文化を「子供」に例え、文化と人間の精神を進化的と見なした。彼の研究は当時流行していた社会退化論への反 論であった[7]。『原始文化』の結末でタイラーは「文化の科学は本質的に改革者の科学である」と記している[24]。 |

| Tylor's evolutionism In 1881 Tylor published a work he called Anthropology, one of the first under that name. In the first chapter he uttered what would become a sort of constitutional statement for the new field, which he could not know and did not intend at the time: "History, so far as it reaches back, shows arts, sciences, and political institutions beginning in ruder states, and becoming in the course of ages, more intelligent, more systematic, more perfectly arranged or organized, to answer their purposes". — Tylor 1881, p. 15 The view was a restatement of ideas first innovated in the early 1860s. The theorist perhaps most influential on Tylor was John Lubbock, 1st Baron Avebury, innovator of the terminology, "Paleolithic" and "Neolithic". A prominent banker and British liberal Parliamentarian, he was imbued with a passion for archaeology. The initial concepts of prehistory were his. Lubbock's works featured prominently in Tylor's lectures and in the Pitt Rivers Museum subsequently. |

タイラーの進化論 1881年、タイラーは『人類学』と題した著作を発表した。これは人類学という名称で出版された最初の著作の一つである。第一章で彼は、当時知る由もなく意図もしていなかったが、この新分野の憲法的宣言ともなるような言葉を記した: 「歴史が遡れる限り、芸術、科学、政治制度はより原始的な状態から始まり、時代を経て、その目的に応じてより知的で、より体系的で、より完璧に整えられたり組織化されたりするようになることを示している」 — タイラー 1881年、p. 15 この見解は、1860年代初頭に初めて提唱された思想の再表明であった。タイラーに最も影響を与えた理論家は、おそらくジョン・ラバック(初代アベベリー 男爵)であろう。彼は「旧石器時代」「新石器時代」という用語を考案した。著名な銀行家であり英国自由党の議員でもあった彼は、考古学への情熱に燃えてい た。先史時代の初期概念は彼によるものである。ラバックの著作は、タイラーの講義やその後のピット・リバース博物館において重要な位置を占めた。 |

| Survivals A term ascribed to Tylor was his theory of "survivals". His definition of survivals is processes, customs, and opinions, and so forth, which have been carried on by force of habit into a new state of society different from that in which they had their original home, and they thus remain as proofs and examples of an older condition of culture out of which a newer has been evolved. — Tylor[25] "Survivals" can include outdated practices, such as the European practice of bloodletting, which lasted long after the medical theories on which it was based had faded from use and been replaced by more modern techniques.[26] Critics argued that he identified the term but provided an insufficient reason as to why survivals continue. Tylor's meme-like concept of survivals explains the characteristics of a culture that are linked to earlier stages of human culture.[27] Studying survivals assists ethnographers in reconstructing earlier cultural characteristics and possibly reconstructing the evolution of culture.[28] |

遺存(サバイバル、残存) タイラーに帰せられる用語が「遺存」の理論である。彼の遺存の定義は次の通りだ 習慣の力によって、それらが生まれた元の社会状態とは異なる新しい社会状態へと引き継がれた過程、慣習、意見などであり、それらはこうして、より新しい文化が進化した古い文化状態の証拠や例として残っている。 —タイラー[25] 「サバイバルズ」には時代遅れの慣行も含まれる。例えばヨーロッパの瀉血療法は、その根拠となった医学理論が廃れ、より近代的な技術に取って代わられた後 も長く続いた[26]。批判者は、彼がこの用語を特定したものの、サバイバルズが継続する理由について不十分な説明しか提供していないと主張した。タイ ラーのミーム的なサバイバル概念は、人類文化の初期段階と結びついた文化の特徴を説明するものである。[27] サバイバルの研究は、エスノグラファーにとって初期の文化的特徴を再構築し、ひいては文化の進化を再構築する助けとなる。[28] |

| Evolution of religion Tylor argued that people had used religion to explain things that occurred in the world.[29] He saw that it was important for religions to have the ability to explain why and for what reason things occurred in the world.[30] For example, God (or the divine) gave us sun to keep us warm and give us light. Tylor argued that animism is the true natural religion that is the essence of religion; it answers the questions of which religion came first and which religion is essentially the most basic and foundation of all religions.[30] For him, animism is the best answer to those questions and so it must be the true foundation of all religions. Animism is described as the belief in spirits inhabiting and animating beings or souls existing in things.[30] To Tylor, the fact that modern religious practitioners continue to believe in spirits shows that such people were no more advanced than primitive societies.[31] For him, that implied that modern religious practitioners do not understand the ways of the universe and how life truly works because they have excluded science from their understanding of the world.[31] By excluding scientific explanation in their understanding of why and how things occur, he asserts modern religious practitioners are rudimentary. He perceived the modern religious belief in God as a "survival" of primitive ignorance.[31] However, Tylor believed that atheism was not the logical end of cultural and religious development but instead a highly-minimalist form of monotheist deism. He thus posited an anthropological description of "the gradual elimination of paganism" and disenchantment but not secularization.[32] |

宗教の進化 タイラーは、人民が宗教を用いて世界において起こる事象を説明してきたと主張した。[29] 彼は、宗教が世界において事象が起こる理由や目的を説明できる能力を持つことが重要だと見なした。[30] 例えば、神(あるいは神聖なる存在)は我々を温め、光を与えるために太陽を与えたのだ。タイラーはアニミズムこそが宗教の本質である真の自然宗教だと主張 した。それは「どの宗教が最初に生まれたのか」「どの宗教が本質的に最も基礎的で全ての宗教の基盤なのか」という問いに答えるものだ[30]。彼にとって アニミズムはそれらの問いに対する最良の答えであり、したがって全ての宗教の真の基盤でなければならない。アニミズムとは、物体に宿り生命を与える精霊 や、物の中に存在する魂を信じる思想と説明される[30]。 タイラーにとって、現代の宗教実践者が依然として精霊を信じ続けている事実は、そうした人民が原始社会と比べて進歩していないことを示している[31]。 彼によれば、それは現代の宗教実践者が世界の理解から科学を排除したため、宇宙の仕組みや生命の真の働きを理解していないことを意味する[31]。物事が なぜ、どのように起こるのかについての理解から科学的説明を排除している点で、現代の宗教実践者は未発達であると彼は主張する。彼は現代の宗教における神 への信仰を、原始的な無知の「残存」と見なした[31]。しかしタイラーは、無神論が文化的・宗教的発展の論理的帰結ではなく、むしろ一神教的自然神論の 極度に最小化された形態であると信じていた。したがって彼は「異教の漸進的排除」と脱魔術化(disenchantment)を人類学的に記述したが、世 俗化(secularization)ではないと位置付けた[32]。 |

| Awards and achievements 1871: Elected a Fellow of the Royal Society. 1875: Honorary degree of Doctor of Civil Laws from the University of Oxford. 1886: Honorary membership of the Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society[33] 1907: Huxley Memorial Medal 1912: Knighted for his contributions. |

受賞歴と功績 1871年:王立協会フェローに選出される。 1875年:オックスフォード大学より法学博士の名誉学位を授与される。 1886年:マンチェスター文学哲学協会名誉会員となる[33] 1907年:ハクスリー記念メダルを受賞する。 1912年:功績によりナイトの称号を授与される。 |

| List of important publications in anthropology Urmonotheismus Wilhelm Schmidt, 1868-1954 Andrew Lang |

人類学における重要な出版物のリスト 一神教 ヴィルヘルム・シュミット(1868-1954) アンドルー・ラング |

| 1. "Tylor, Edward Burnett". Who's Who. Vol. 59. 1907. p. 1785. 2. Long, Heather. "Social Evolutionism". University of Alabama Department of Anthropology. Archived from the original on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 6 March 2016. 3. Paul Bohannan, Social Anthropology (New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 1969) 4. Lewis, Herbert S (1998). "The Misrepresentation of Anthropology and its Consequences". American Anthropologist. 100 (3): 716–731. doi:10.1525/aa.1998.100.3.716. JSTOR 682051. 5. "Animism", Online Etymology Dictionary, accessed 2 October 2007. 6. Chisholm 1911. 7. Lowie, Robert H. (April–June 1917). "Edward B. Tylor". American Anthropologist. New Series. 19 (2): 262–268. doi:10.1525/aa.1917.19.2.02a00050. JSTOR 660758. 8. "Edward Burnett Tylor: biography", Pitt Rivers Museum 9. Ogilvie, Sarah (2012). Words of the World: A Global History of the Oxford English Dictionary. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107021839. 10. Anthropological Essays presented to Edward Burnett Tylor. Oxford at the Clarendon Press. 1907. 11. "Review of Anthropological Essays presented to Edward Burnett Tylor edited by W. H. R. Rivers, R. R. Marett, and N. W. Thomas". The Athenaeum (4174): 522–523. 26 October 1907. 12. Goldenweiser 1922, pp. 50–55 13. "Evolution". The American Educator. Vol. 3. 1897. 14. The first sentence of Chapter 1 states the founding definition of culture: "Culture, or Civilization, ... is that complex whole which includes knowledge, belief, art, morals, law, custom, and any other capabilities and habits acquired by man as a member of society". 15. Goldenweiser 1922, pp. 55–59 16. Upadhyay & Pandey 1993, p. 23 17. Upadhyay & Pandey 1993, pp. 33–53 18. Upadhyay & Pandey 1993, pp. 53–62 19. Upadhyay & Pandey 1993, pp. 65–68 20. Giulio Angioni, L'antropologia evoluzionistica di Edward B. Tylor in Tre saggi... cit. in Related Studies[when?] 21. Tylor 1871, p. 1, Vol. 1. 22. Leslie A. White (21 November 1958). "Culturology". Science. New Series. 128 (3334): 1246. Bibcode:1958Sci...128.1246W. doi:10.1126/science.128.3333.1246. JSTOR 1754562. PMID 17751354. S2CID 239772878. 23. Stringer, Martin D. (December 1999). "Rethinking Animism: Thoughts from the Infancy of Our Discipline". The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute. 5 (4): 541–555. doi:10.2307/2661147. JSTOR 2661147. 24. Tylor 1920, p. 410. 25. Tylor 1920, p. 16. 26. Braun, Willi and Russel T. McCutcheon, eds. 2000. Guide to the Study of Religion. London: Continuum. 160. 27. Moore 1997, p. 23. 28. Moore 1997, p. 24. 29. Strenski 2006, p. 93. 30. Strenski 2006, p. 94. 31. Strenski 2006, p. 99. 32. Josephson-Storm 2017, p. 99. 33. Memoirs and proceedings of the Manchester Literary & Philosophical Society FOURTH SERIES Eighth VOLUME |

1. 「タイラー、エドワード・バーネット」『フー・イズ・フー』第59巻、1907年、1785頁。 2. ロング、ヘザー「社会進化論」アラバマ大学人類学部。2016年3月7日時点のオリジナルからアーカイブ。2016年3月6日閲覧。 3. ポール・ボハナン『社会人類学』(ニューヨーク:ホルト・ラインハート・アンド・ウィンストン社、1969年) 4. ルイス、ハーバート・S(1998年)。「人類学の誤った表現とその結果」。『アメリカン・アンソロポロジスト』100巻3号:716–731頁。doi:10.1525/aa.1998.100.3.716. JSTOR 682051. 5. 「アニミズム」, オンライン語源辞典, 2007年10月2日アクセス. 6. チザム 1911. 7. ロバート・H・ローウィ (1917年4月–6月). 「エドワード・B・タイラー」. 『アメリカ人類学者』. 新シリーズ. 19 (2): 262–268. doi:10.1525/aa.1917.19.2.02a00050. JSTOR 660758. 8. 「エドワード・バーネット・タイラー:伝記」ピット・リバース博物館 9. オギルヴィー、サラ(2012)。『世界の言葉:オックスフォード英語辞典の世界史』。ケンブリッジ大学出版局。ISBN 9781107021839。 10. 『エドワード・バーネット・タイラーに捧げる人類学論文集』。オックスフォード、クラレンドン・プレス。1907年。 11. 「W・H・R・リヴァース、R・R・マレット、N・W・トーマス編『エドワード・バーネット・タイラーに捧げる人類学論集』書評」。『アテナエウム』第4174号:522–523頁。1907年10月26日。 12. ゴールデンワイザー 1922, pp. 50–55 13. 「進化論」『アメリカン・エデュケーター』第3巻、1897年。 14. 第1章の冒頭文は文化の定義を次のように述べる:「文化、あるいは文明とは…知識、信念、芸術、道徳、法律、習慣、その他社会の一員として人間が獲得したあらゆる能力や習慣を含む複合体である」。 15. ゴールデンワイザー 1922, pp. 55–59 16. ウパディヤイ&パンディ 1993, p. 23 17. ウパディヤイ&パンディ 1993, pp. 33–53 18. ウパディヤイ&パンディ 1993, pp. 53–62 19. ウパディヤイ&パンディ 1993, pp. 65–68 20. ジュリオ・アンジョニ, 『エドワード・B・タイラーの進化人類学』, 『三つの論文...』所収, 関連研究[時期不明]で引用 21. タイラー 1871, p. 1, 第1巻 22. レスリー・A・ホワイト (1958年11月21日). 「文化学」. 科学. 新シリーズ. 128 (3334): 1246. Bibcode:1958Sci...128.1246W. doi:10.1126/science.128.3333.1246. JSTOR 1754562。PMID 17751354。S2CID 239772878。 23. ストリンガー、マーティン D. (1999年12月)。「アニミズムの再考:我々の学問の黎明期からの考察」。王立人類学協会誌。5 (4): 541–555. doi:10.2307/2661147. JSTOR 2661147. 24. タイラー 1920, p. 410. 25. タイラー 1920, p. 16. 26. ブラウン、ウィリーとラッセル・T・マカッチョン編 2000. 『宗教研究ガイド』. ロンドン: コンティニュアム. 160. 27. ムーア 1997, p. 23. 28. ムーア 1997, p. 24. 29. ストレンスキー 2006, p. 93. 30. ストレンスキー 2006, p. 94. 31. ストレンスキー 2006, p. 99. 32. ジョセフソン=ストーム 2017, p. 99. 33. 『マンチェスター文学・哲学協会紀要 第四シリーズ 第八巻』 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edward_Burnett_Tylor |

1832

Edward Burnett Tylor was born in 1832, in Camberwell, London, and was the son of Joseph Tylor and Harriet Skipper, part of a family of wealthy Quakers who owned a London brass factory. His elder brother, Alfred Tylor, became a geologist.[6]

1855

"He was educated at Grove House School, Tottenham, but due to his Quaker faith and the death of his parents he left school at the age of 16 without obtaining a degree.[7] After leaving school, he prepared to help manage the family business. This plan was put aside when he developed tuberculosis at age 23. Following medical advice to spend time in warmer climes, Tylor left England in 1855, and travelled to the Americas. The experience proved to be an important and formative one, sparking his lifelong interest in studying unfamiliar cultures./ During his travels, Tylor met Henry Christy, a fellow Quaker, ethnologist and archaeologist. Tylor's association with Christy greatly stimulated his awakening interest in anthropology, and helped broaden his inquiries to include prehistoric studies.[6]"

1856

"Tylor's first publication was a result of his 1856 trip to

Mexico with Christy. His notes on the beliefs and practices of the

people he encountered were the basis of his work Anahuac: Or Mexico and

the Mexicans, Ancient and Modern (1861), published after his return to

England. Tylor continued to study the customs and beliefs of tribal

communities, both existing and prehistoric (based on archaeological

finds). He published his second work, Researches into the Early History

of Mankind and the Development of Civilization, in 1865. Following this

came his most influential work, Primitive Culture (1871). This was

important not only for its thorough study of human civilisation and

contributions to the emergent field of anthropology, but for its

undeniable influence on a handful of young scholars, such as J. G. Frazer,

who were to become Tylor's disciples and contribute greatly to the

scientific study of anthropology in later years."

1861 Anahuac: or, Mexico and the Mexicans, Ancient and Modern. London: Longman, Green, Longman and Roberts. 1861.

1865 Researches into the Early History of Mankind and the Development of Civilization. London: John Murray. 1865.

1867 Tylor, Edward B. (1867). "Phenomena of the Higher Civilisation: Traceable to a Rudimental Origin among Savage Tribes" (PDF). Anthropological Review. 5 (18/19): 303–314. doi:10.2307/3024922. JSTOR 3024922.

1871 Primitive Culture. 1 & 2. London: John Murray. 1871.

1877 Tylor, Edward B. (1877). "Remarks on Japanese Mythology" (PDF). The Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland. 6: 55–60. doi:10.2307/2841246. JSTOR 2841246./ Spencer, Herbert; Tylor, Edward B. (1877). With Herbert Spencer. "Review of The Principles of Sociology". Mind. 2 (7): 415–429. doi:10.1093/mind/os-2.7.415. JSTOR 2246921.

1880 Tylor, Edward B. (1880). "Remarks on the Geographical Distribution of Games" (PDF). The Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland. 9: 23–30. doi:10.2307/2841865. JSTOR 2841865.

1881 Tylor, E. B. (1881). "On the Origin of the Plough, and Wheel-Carriage". The Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland. 10: 74–84. doi:10.2307/2841649. JSTOR 2841649./Anthropology an introduction to the study of man and civilization. London: Macmillan and Co. 1881.

1882 Tylor, Edward

B. (1882). "Notes on the Asiatic Relations of

Polynesian Culture". The Journal of the Anthropological Institute of

Great Britain and Ireland. 11: 401–405. doi:10.2307/2841767. JSTOR

2841767.

1883

"Tylor was appointed Keeper of the University Museum at Oxford

in 1883, and, as well as serving as a lecturer, held the title of the

first "Reader in Anthropology" from 1884 to 1895. In 1896 he was

appointed the first Professor of Anthropology at Oxford University.[6]

He was involved in the early history of the Pitt Rivers Museum,

although to a debatable extent.[8] Tylor acted as anthropological

consultant on the first edition of the Oxford English Dictionary.[9]"

1884 Tylor, E. B. (1884). "Old Scandinavian Civilisation Among the Modern Esquimaux" (PDF). The Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland. 13: 348–357. doi:10.2307/2841897. JSTOR 2841897./ "Life of Dr. Rolleston". Scientific Papers and Addresses by George Rolleston. I. Oxford: Clarendon Press. 1884. pp. lx–lxv.

1889 ylor, Edward B. (1889). "On a Method of Investigating the Development of Institutions; applied to Laws of Marriage and Descent" (PDF). Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute. 18: 245–272. doi:10.2307/2842423. hdl:2027/hvd.32044097779680. JSTOR 2842423.

1890 Tylor, E. B. (1890). "Notes on the Modern Survival of Ancient Amulets Against the Evil Eye" (PDF). The Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland. 19: 54–56. doi:10.2307/2842533. JSTOR 2842533.

1896 "The Matriarchal Family System". Nineteenth Century. 40: 81–96. 1896./American Lot-Games as Evidence of Asiatic Intercourse Before the Time of Columbus. Leiden: E.J. Brill. 1896.

1898 Tylor, Edward B. (1899). "Remarks on Totemism, with Especial Reference to Some Modern Theories Respecting It" (PDF). The Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland. 28 (1/2): 138–148. doi:10.2307/2842940. JSTOR 2842940./Three Papers. London: Harrison and Sons.

1905 Tylor, Edward

B. (1905). "Professor Adolf Bastian: Born June

26, 1826; Died February 3, 1905" (PDF). Man. 5: 138–143. JSTOR 2788004.

1907

"The 1907 festschrift Anthropological Essays presented to Edward Burnett Tylor, formally presented to Tylor on his 75th birthday, contains essays by 20 anthropologists, a 15-page appreciation of Tylor's work by Andrew Lang, and a comprehensive bibliography of Tylor's publications compiled by Barbara Freire-Marreco.[6][10][11]"

1917

| Classification and

criticisms |

The word

evolution is forever associated in the popular mind with Charles

Darwin’s Theory of Evolution, which professes, among other things, that

man as a species developed diachronically from some ancestor among the

Primates who was also ancestor to the Great Apes, as they are popularly

termed, and yet this term was not a neologism of Darwin’s. He took it

from the cultural milieu, where it meant etymologically "unfolding" of

something heterogeneous and complex from something simpler and more

homogeneous. Herbert Spencer, a contemporary of Darwin, applied the

term to the universe, including philosophy and what Tylor would later

call culture.[12] This view of the universe was generally termed

evolutionism, while its exponents were evolutionists.[13] In 1871 Tylor published Primitive Culture, becoming the originator of cultural anthropology.[14] His methods were comparative and historical ethnography. He believed that a "uniformity" was manifest in culture, which was the result of "uniform action of uniform causes." He regarded his instances of parallel ethnographic concepts and practices as indicative of "laws of human thought and action." He was an evolutionist. The task of cultural anthropology therefore is to discover "stages of development or evolution." Evolutionism was distinguished from another creed, diffusionism, postulating the spread of items of culture from regions of innovation. A given apparent parallelism thus had at least two explanations: the instances descend from an evolutionary ancestor, or they are alike because one diffused into the culture from elsewhere.[15] These two views are exactly parallel to the tree model and wave model of historical linguistics, which are instances of evolutionism and diffusionism, language features being instances of culture. Two other classifications were proposed in 1993 by Upadhyay and Pandey,[16] Classical Evolutionary School and Neo Evolutionary School, the Classical to be divided into British, American, and German. The Classical British Evolutionary School, primarily at Oxford University, divided society into two evolutionary stages, savagery and civilization, based on the archaeology of John Lubbock, 1st Baron Avebury. Upadhyay and Pandey list its adherents as Robert Ranulph Marett, Henry James Sumner Maine, John Ferguson McLennan, and James George Frazer, as well as Tylor.[17] Marett was the last man standing, dying in 1943. By the time of his death, Lubbock's archaeology had been updated. The American School, beginning with Lewis Henry Morgan,[18] was likewise superseded, both being replaced by the Neoevolutionist School, beginning with V. Gordon Childe. It brought the archaeology up-to-date and tended to omit the intervening society names, such as savagery; for example, Neolithic is both a tool tradition and a form of society. There are some other classifications. Theorists of each classification each have their own criticisms of the Classical/Neo Evolutionary lines, which despite them remains the dominant view. Some criticisms are in brief as follows.[19] There is really no universality; that is, the apparent parallels are accidental, on which the theorist has imposed a model that does not really fit. There is no uniform causality, but different causes might produce similar results. All cultural groups do not have the same stages of development. The theorists are arm-chair anthropologists; their data is insufficient to form realistic abstractions. They overlooked cultural diffusion. They overlooked cultural innovation. None of the critics claim definitive proof that their criticisms are less subjective or interpretive than the models they criticise. |

進化という言葉は、一般の人々の心の中で、チャールズ・ダーウィンの進

化論と永遠に結びついている。進化論は、とりわけ、一般的に「大猿」と呼ばれる霊長類の祖先から、人類という種が非連続的に進化したと主張しているが、こ

の用語はダーウィンの新造語ではない。彼はそれを文化的な環境から取り入れたが、そこでは語源的には、より単純で均質なものから、異質で複雑なものが「展

開」することを意味していた。

ダーウィンの同時代人であるハーバート・スペンサーは、この用語を宇宙に適用し、哲学や、後にタイラーが文化と呼ぶものも含めた。[12]

この宇宙観は一般的に進化論と呼ばれ、その支持者たちは進化論者と呼ばれた。[13] 1871年、タイラーは『原始文化』を出版し、文化人類学の創始者となった。[14] 彼の方法は比較歴史民族誌学であった。彼は文化には「均一性」が現れると信じており、それは「均一な原因による均一な作用」の結果であると考えていた。彼 は、民族誌学上の概念や慣習の類似例を「人間の思考と行動の法則」を示すものとして捉えていた。彼は進化論者であった。したがって文化人類学の課題は、 「発展または進化の段階」を発見することである。 進化論は、文化の要素が革新の地域から広がっていくとする拡散説という別の信条と区別されていた。 このように一見したところ類似性が見られる場合、少なくとも2つの説明が可能である。すなわち、進化論の観点から見ると、類似性は進化の過程で生まれたも の、あるいは、拡散説の観点から見ると、ある文化が他の文化から広がったために類似している、という説明である。[15] これらの2つの見解は、歴史言語学におけるツリーモデルとウェーブモデルにまさに類似している。言語の特徴は文化の一例である。 1993年には、ウパディヤイとパンデイが、古典派進化論派と新進化論派という2つの分類を提案している。[16] 古典派進化論派は、イギリス、アメリカ、ドイツに分かれる。古典派イギリス進化論派は、主にオックスフォード大学で、ジョン・ラブロック初代アベブリー男 爵の考古学を基に、社会を「野蛮」と「文明」という2つの進化段階に分けた。UpadhyayとPandeyは、この学派の信奉者として、ロバート・ラナ ルフ・マレット、ヘンリー・ジェイムズ・サムナー・メーン、ジョン・ファーガソン・マクレナン、ジェイムズ・ジョージ・フレイザー、そしてタイラーを挙げ ている。[17] マレットは最後の生き残りであったが、1943年に死去した。彼の死の頃には、ラブックの考古学は更新されていた。アメリカ学派も、ルイス・ヘンリー・ モーガンに始まる[18]同様に取って代わられ、両者ともV.ゴードン・チャイルドに始まる新進化論派に取って代わられた。新進化論派は考古学を最新のも のとし、野蛮といった中間的な社会名を省略する傾向にあった。例えば、新石器時代は道具の伝統であり、社会形態でもある。 他の分類もある。各分類の理論家たちは、古典的/新進化論的見解に対してそれぞれ独自の批判を行っているが、それにもかかわらず、この見解は依然として支 配的な見解である。批判のいくつかを簡単にまとめると以下のようになる。[19] 普遍性は実際には存在しない。つまり、一見したところの類似性は偶然であり、理論家が無理やり当てはめたモデルが実際には適合しないということである。一 様な因果関係は存在せず、異なる原因が類似の結果を生み出す可能性もある。すべての文化集団が同じ発展段階にあるわけではない。理論家たちは机上の人類学 者であり、現実的な抽象概念を形成するにはデータが不十分である。彼らは文化の拡散を見落としている。彼らは文化の革新を見落としている。批判者の誰も、 彼らの批判が批判するモデルよりも主観的または解釈的ではないという決定的な証拠を主張していない。 |

| Culture |

Tylor's notion is

best described in his most famous work, the two-volume Primitive

Culture. The first volume, The Origins of Culture, deals with

ethnography including social evolution, linguistics, and myth. The

second volume, Religion in Primitive Culture, deals mainly with his

interpretation of animism. On the first page of Primitive Culture, Tylor provides a definition which is one of his most widely recognised contributions to anthropology and the study of religion:[20] Culture or Civilization, taken in its wide ethnographic sense, is that complex whole which includes knowledge, belief, art, morals, law, custom, and any other capabilities and habits acquired by man as a member of society. — Tylor[21] Also, the first chapter of the work gives an outline of a new discipline, science of culture, later known as culturology.[22] |

タイラーの考えは、彼の最も有名な著作である2巻本『原始文化』に最も

よく表れている。第1巻『文化の起源』では、社会進化、言語学、神話を含む民族誌が扱われている。第2巻『原始文化における宗教』では、主に彼のアニミズ

ムの解釈が扱われている。 『プリミティブ・カルチャー』の最初のページで、タイラーは人類学および宗教研究への最も広く認められた貢献のひとつである定義を提示している。 文化または文明とは、広義のエスノグラフィー的な意味で捉えれば、知識、信念、芸術、道徳、法、慣習、および社会の一員として人間が獲得したその他の能力 や習慣を含む、複雑な全体である。 — タイラー[21] また、この著作の第1章では、後にカルチュロロジーとして知られることになる新しい学問分野、文化科学の概要が示されている。[22] |

| Universals |

Unlike many of

his predecessors and contemporaries, Tylor asserts that the human mind

and its capabilities are the same globally, despite a particular

society's stage in social evolution.[23] This means that a

hunter-gatherer society would possess the same amount of intelligence

as an advanced industrial society. The difference, Tylor asserts, is

education, which he considers the cumulative knowledge and methodology

that takes thousands of years to acquire. Tylor often likens primitive

cultures to "children", and sees culture and the mind of humans as

progressive. His work was a refutation of the theory of social

degeneration, which was popular at the time.[7] At the end of Primitive

Culture, Tylor writes, "The science of culture is essentially a

reformers' science."[24] |

多くの先人や同時代人と異なり、タイラーは、特定の社会の社会進化の段

階に関わらず、人間の心とその能力は世界的に同じであると主張している。[23]

つまり、狩猟採集社会も高度な工業社会と同等の知性を備えているということである。タイラーは、その違いは教育にあると主張し、教育とは何千年もかけて蓄

積された知識と方法論であると考える。タイラーはしばしば原始文化を「子供」に例え、文化と人間の精神は進歩的であると考える。彼の研究は、当時流行して

いた社会退化論への反論であった。『原始文化』の末尾で、タイラーは「文化の科学は本質的に改革者の科学である」と書いている。 |

| Tylor's

evolutionism |

In 1881 Tylor

published a work he called Anthropology, one of the first under that

name. In the first chapter he uttered what would become a sort of

constitutional statement for the new field, which he could not know and

did not intend at the time: "History, so far as it reaches back, shows arts, sciences, and political institutions beginning in ruder states, and becoming in the course of ages, more intelligent, more systematic, more perfectly arranged or organized, to answer their purposes." — Tylor 1881, p. 15 The view was a restatement of ideas first innovated in the early 1860s. The theorist perhaps most influential on Tylor was John Lubbock, 1st Baron Avebury, innovator of the terminology, "Paleolithic" and "Neolithic." A prominent banker and British liberal Parliamentarian, he was imbued with a passion for archaeology. The initial concepts of prehistory were his. Lubbock's works featured prominently in Tylor's lectures and in the Pitt Rivers Museum subsequently. |

1881年、テイラーは『人類学』と名付けた著作を出版した。これは、

その名で出版された最初の著作のひとつである。その第1章で、彼は当時知る由もなかったし、意図もしていなかったが、この新しい分野における憲法のような

声明となるような言葉を口にしている。 「歴史を遡る限り、芸術、科学、政治制度は、より原始的な状態から始まり、長い年月を経て、より知的で、より体系的で、より完璧に配置または組織化され、 目的にかなうものになっていく」 — テイラー、1881年、15ページ この見解は、1860年代初頭に初めて提唱された考えの再表明であった。テイラーに最も影響を与えた理論家は、おそらく「旧石器時代」と「新石器時代」と いう用語を考案したジョン・ラブック(初代アヴベリー男爵)であろう。著名な銀行家であり自由党の国会議員でもあったラブックは、考古学に情熱を傾けてい た。先史時代の概念は、彼が最初に提唱したものである。ラブックの著作は、テイラーの講義や、その後ピット・リバーズ博物館で取り上げられた。 |

| Survivals |

A term ascribed to Tylor was his

theory of "survivals". His definition of survivals is processes, customs, and opinions, and so forth, which have been carried on by force of habit into a new state of society different from that in which they had their original home, and they thus remain as proofs and examples of an older condition of culture out of which a newer has been evolved. — Tylor[25] "Survivals" can include outdated practices, such as the European practice of bloodletting, which lasted long after the medical theories on which it was based had faded from use and been replaced by more modern techniques.[26] Critics argued that he identified the term but provided an insufficient reason as to why survivals continue. Tylor's meme-like concept of survivals explains the characteristics of a culture that are linked to earlier stages of human culture.[27] Studying survivals assists ethnographers in reconstructing earlier cultural characteristics and possibly reconstructing the evolution of culture.[28] |

テイラーに与えられた用語は「生存」の理論である。

テイラーの生存の定義は、 プロセス、習慣、意見などであり、それらは、元々存在していた社会とは異なる新しい社会において、習慣の力によって引き継がれてきた。そして、それらは、 新しい文化が発展する前の古い文化の状態の証拠や例として残っている。 — テイラー[25] 「遺存」には、ヨーロッパで行われていた瀉血のような時代遅れの慣習も含まれる。瀉血は、その基礎となった医学理論が使われなくなり、より近代的な技術に 取って代わられた後も、長い間続いた。[26] 批評家たちは、彼はその用語を特定したが、なぜ遺存が続くのかについての理由付けが不十分であると主張した。タイラーの遺存に関するミームのような概念 は、人類文化の初期段階と関連する文化の特徴を説明している。[27] サバイバルの研究は、エスノグラファーが以前の文化の特徴を再構築し、場合によっては文化の進化を再構築するのに役立つ。[28] |

| Evolution of religion |

Tylor argued that people had

used religion to explain things that occurred in the world.[29] He saw

that it was important for religions to have the ability to explain why

and for what reason things occurred in the world.[30] For example, God

(or the divine) gave us sun to keep us warm and give us light. Tylor

argued that animism is the true natural religion that is the essence of

religion; it answers the questions of which religion came first and

which religion is essentially the most basic and foundation of all

religions.[30] For him, animism was the best answer to these questions,

so it must be the true foundation of all religions. Animism is

described as the belief in spirits inhabiting and animating beings, or

souls existing in things.[30] To Tylor, the fact that modern religious

practitioners continued to believe in spirits showed that these people

were no more advanced than primitive societies.[31] For him, this

implied that modern religious practitioners do not understand the ways

of the universe and how life truly works because they have excluded

science from their understanding of the world.[31] By excluding

scientific explanation in their understanding of why and how things

occur, he asserts modern religious practitioners are rudimentary. Tylor

perceived the modern religious belief in God as a "survival" of

primitive ignorance.[31] However, Tylor did not believe that atheism

was the logical end of cultural and religious development, but instead

a highly minimalist form of monotheist deism. Tylor thus posited an

anthropological description of "the gradual elimination of paganism"

and disenchantment, but not secularization.[32] |

タイラーは、人々は世界で起こることを説明するために宗教を利用してき

たと主張した。[29] 彼は、宗教には世界で起こることを説明できる能力が重要であると認識していた。[30]

たとえば、神(または神聖なもの)は私たちを温め、光を与えるために太陽を与えた。タイラーは、アニミズムこそが宗教の本質であり、真の自然宗教であると

主張した。それは、どの宗教が最初に来たのか、どの宗教が本質的にすべての宗教の最も基本的な基盤であるのかという疑問に答えるものである。[30]

彼にとって、アニミズムはこれらの疑問に対する最善の答えであったため、すべての宗教の真の基盤であるに違いない。アニミズムとは、物体に宿り生命を吹き

込む精霊や、物に存在する魂を信じる信仰であると説明されている。[30]

タイラーにとって、現代の宗教実践者が精霊を信じ続けているという事実は、これらの人々が未開社会よりも進歩していないことを示している。[31]

彼にとって、

これは、現代の宗教実践者が世界の理解から科学を排除しているため、宇宙の仕組みや生命の真の働きを理解していないことを意味していると彼は考えた。

[31]

物事がなぜ、どのようにして起こるのかという理解において科学的説明を排除していることから、彼は現代の宗教実践者は初歩的であると主張している。タイ

ラーは、現代の神への信仰を原始的な無知の「生存」と捉えていた。[31]

しかし、タイラーは無神論が文化や宗教の発展の論理的な帰結であるとは考えておらず、むしろ一神教の神智論の極めてミニマリスト的な形態であると考えてい

た。タイラーは、こうして「異教の段階的排除」と「呪術の喪失」という人類学的な説明を提唱したが、世俗化ではないと主張した。[32] |

| アニミズム |

人類学におけるアニミズム

(animism)は、

一九世紀の文化進化主義人類学者エドワード・B・タイラーが名付けたものが標準となっている。しかし彼の著書『未開文化(Primitive

Culture)』においては、その語源は一七世紀のフロギストン派の化学者ゲオルグ・シュタールの生気論に由来すると述べている(Tylor

1903:425-426)。生気論は唯物論に対立する考え方で、あらゆる生命体はたんなる物質から成り立っているのではなく生命の「気(アニマ)」——

魂とも訳されるが物理的な気体というよりも物質的な根拠をもたない生気のような概念である——が不可欠だとする思想である。アリストテレスの古典『霊魂

論』のラテン語のタイトルは「デ・アニマ(De anima,

アニマ=魂について)」という。さてタイラーは、スピリチュアリズムがその代表だとしているが、アニミズムは——彼の言い方によると、いわゆるより古くか

らの「低級の人類」から文明人のあいだにも見られる——普遍的な人間的特質と考えているようだ。タイラーによると、宗教はこのようなアニミズムみられる自

然崇拝から死者崇拝や呪物崇拝(フェティシズム)を経て多神教になり、そして最後に一神教へ進化したのではないかと考えた。ここでのポイントは、アニミズ

ムは原始的な心性であるが、現代人にも共有するものだとしたことである。と言ってもタイラーが経験したのは一九世紀終わりから二〇世紀初頭が現代にほかな

らないので、彼がいう現代人は、現在の我々が知るICTのテクノロジーからおよそほど遠い今から百年前の人びとであり、アニミニズムは彼らの心性であるこ

とを押さえておこう。 |

| マナ |

マナは、もともと1891年にコドリントン(Robert

Henry Codrington, 1830-1922)により紹介されたメラネシアの宗

教概念を理解するための用語。コドリントンによると、死霊(=死人の幽霊)や死んだ人のたましい(魂)には、多くのマナが含まれる。その

ために(物理的な力以外で)生きている人を苦しめたり、場合によっては助けたりする。なぜなら、死霊や魂はちから、つまりマナをもっているからなのだと

説明される。 |

| マナイズム |

コドリントンよりも後進のマレット(Robert Ranulph

Marett, 1866-1943)は、アニミズム理論(animatist

theory)の特殊なものをマナイズム(マナ信仰,“Manaism”)と名づけようと提唱しました。なぜなら世界中の「原始的あるいは未開(ともに

primitive)」な人たちは、生きている=活力のあるようにみえるもの、あるいはそうでないものの全ての事物がもつ、個人を超えた(非人格的な)力

つまり物体化されていない超自然的な力を信じているからだと彼(=マレット)は考えました。それらの力は、結局のところ、物理的な力で表現される(例:モ

ノが壊れる、天災がおこる、飢饉になる、人が傷病する)のですが、それを起こすちから(力)は、物理的なものを超えている(=「超自然,

supernatural」の言葉の本来の意味)と「未開人」は考えているのではないか。マレットは、そのようにマナイズムの説明をするのに仮説をたてま

した。 |

| トー テミズム |

ある社会がいくつかの集団に分かれ、各々の集団とひとつないしは複数の

動物や植物、ときには人工的なものや動

物の一部などと特別な関連があるとする宗教形態がみられる時、それをトーテミズム(totemism)と呼ぶ。トーテミズムはフランス語の発音では濁

らずトーテミスムと呼ばれることがありますが、ともに同じものである。したがってトーテミズムは特定の宗教やイデオロギーをさすのではなく、あるパターン

をもつ宗教形態をさす分析 概念である。トーテミズムはスコットランドの法学者マクレナン(John Ferguson McLennan,

1827-1881)が19世紀の中ごろに、進化主

義の立場から結婚の原理を人類学的に説明するための概念として、はじめて定式化しました(→「法の人類学入門 」)。 |

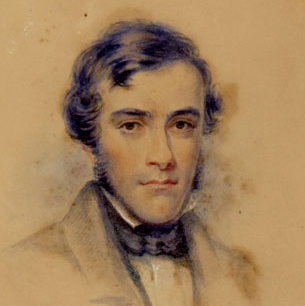

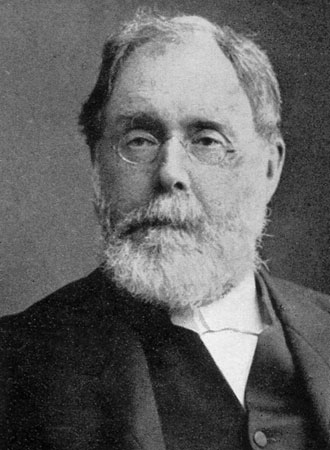

Sir James George

Frazer, 1854-1941 |

ジェームズ・ジョージ・フレーザー; |

Andrew Lang,

1844-1912 |

アンドルー・ラング; Andrew

Lang FBA (31 March 1844 – 20 July 1912) was a Scottish poet, novelist,

literary critic, and contributor to the field of anthropology. He is

best known as a collector of folk and fairy tales. The Andrew Lang

lectures at the University of St Andrews are named after him. |

Robert

Henry Codrington, 1830-1922 |

Robert Henry

Codrington (15 September 1830, Wroughton, Wiltshire – 11 September

1922)[1] was an Anglican priest and anthropologist who made the first

study of Melanesian society and culture. His work is still held as a

classic of ethnography. Codrington wrote, "One of the first duties of a

missionary is to try to understand the people among whom he works,"[2]

and he himself reflected a deep commitment to this value. Codrington

worked as headmaster of the Melanesian Mission school on Norfolk Island

from 1867 to 1887.[1] Over his many years with the Melanesian people,

he gained a deep knowledge of their society, languages, and customs

through a close association with them. He also intensively studied

"Melanesian languages", including the Mota language.[1] |

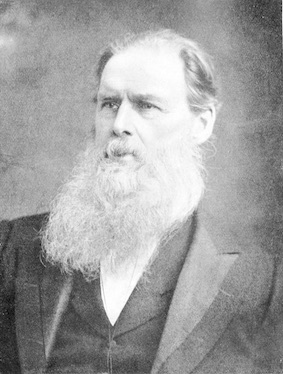

Robert Ranulph

Marett, 1866-1943 |

Robert Ranulph

Marett (13 June 1866 – 18 February 1943) was a British ethnologist and

a proponent of the British Evolutionary School of cultural

anthropology. Founded by Marett's older colleague, Edward Burnett

Tylor, it asserted that modern primitive societies provide evidence for

phases in the evolution of culture, which it attempted to recapture via

comparative and historical methods. Marett focused primarily on the

anthropology of religion. Studying the evolutionary origin of

religions, he modified Tylor's animistic theory to include the concept

of mana. Marett's anthropological teaching and writing career at Oxford

University spanned the early 20th century before World War Two. He

trained many notable anthropologists. He was a colleague of John Myres,

and through him, studied Aegean archaeology. |

| William

Robertson Smith, 1846-1894 |

++

年譜

・文化の「定義」(E・タイラー)E.B.Tylor(1832-1917)

「文化あるいは文明とは、そのひろい民族誌学上の意味で理解されているところでは、社会の成 員としての人間(man)によって獲得された知識、信条、芸術、法、道徳、慣習や、他のいろいろな能力や習性(habits)を含む複雑な総体である。」

【原文】

"Culture and Civilization, taken in its wide ethnographic sense, is that complex whole which includes knowledge, belief, art, morals, law, custom, and any other capabilities and habits acquired by man as a menmber of society."

Edward Burnett Tylor,Capter 1.of "Primitive Culture"(London: John Murray & Co.,1871, 2 vols.)pp.1-25.;E.B.Tylor(1832-1917)[ただし、引用は次の文献による。Fried, Morton H.,ed.1968, Readings in anthropology, 2nd ed.,vol.II: Cultural Anthropology, New York: Thomas Y.Crowell Company, p.2]

1871 タイラー『未開文化 』Primitive Culture: researches into the development of mythology, philosophy, religion, language, art and custom』

Taylor, Primitive Cultur(1920年版)の冒頭のパラグラフが有名な彼の「文化」の定義であり、以下のようになっている。

"CULTURE or Civilization, taken in its wide ethnographic sense, is that complex whole which includes knowledge, belief, art, morals, law, custom, and any other capabilities and habits acquired by, man as a member of society. The condition of culture among the various societies of mankind, in so far as it 'is c1.pable of being investigated on general principles, is a subject apt for the study of laws of human thought and action. On the one hand, the uniformity which so largely pervades civilization may be ascribed, in great measure, to the uniform action of uniform causes: while on the other hand its various grades may be regarded as stages of development or evolution, each the outcome of previous history, and about to do its proper part in shaping the history of the future. To the investigation of these two great principles in several departments of ethnography, with especial consideration of the civilization of the lower tribes as related to the Civilization of the higher nations, the present volumes are devoted" (Tylor 1920:1, Vol. 1).

1884 タイラー、オックスフォード大学人類学教授就任[→この時期のこと]

・タイラーの文化概念の利点と限界

タイラーの文化概念の便利なところは、人間のつくりあげたものは、具体から抽象、創造、伝 承、破壊にいたるまで、人間の活動のすべてを包括できるという点にあります。これは、(1)文化にはさまざまな要素があり、(2)それらの要素はお互いに 絡み合い、従って(3)文化はその総体から捉えるべきである、という視点を、当時の西洋世界に提示したことになります。

他方で、その欠点は、文化とは人間が作り上げ維持しているもの<すべて>を枚挙しないかぎり 理解できないことになります。しかし、これまでの文化についてのさまざまな記述がその社会の全体を枚挙的にあげたものではないし、その部分において全体を 表象することができるという経験的事実があります。また、異なった社会にも相違する部分と異なった部分があり、文化はそのどちらをさすのか不明瞭である点 など、理論的な精確さ欠いているということも指摘できます。

・タイラーの文化概念の継承者

タイラーの文化概念の継承をしたのは、英国においては『人類学におけるノートと質問(Notes and Queries on anthropology)』という 人類学調査ハンドブック(タイラーじしんも執筆者の一人です)や、アメリカ合州国のジョージ・ペーター・マードックと、彼に関連する一連の学派のプロジェ クト(HRAF, Human Relations Area Files:フラーフと呼ばれます)などです。

英国の機能主義の伝統においては、マリ ノフスキー(1922)は『人類学のノートと質問』に対しては懐疑的かつ批判的であったのに対して、ラドクリフ=ブラウンや彼がアメリカ合州国で教鞭(1931-37)をとってい たシカゴ大学社会学部では、その枚挙的な文化項目の情報の蓄積に関心をもつことを、学生に勧めており、この方法論が(どちらかというと)重視されていまし た。

リンク

文献

その他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆