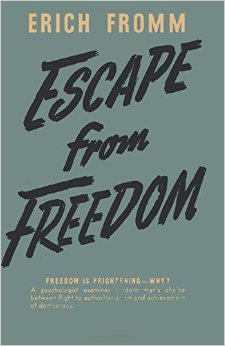

★Escape from Freedom: 『自由からの逃走』は精神分析学者エーリッヒ・フロムの著作で、 1941年にアメリカでファーラー&ラインハート社[1]からこのタイトルで出版され、その1年後にイギリスでラウトレッジ&ケーガン・ポール社から『自 由の恐怖』として出版された。この本はドイツ語に翻訳され、1952年に『自由の恐怖』というタイトルで出版された。この本の中でフロムは、人間の自由と の関係の移り変わり、個人の自由がいかに恐怖、不安、疎外を引き起こすか、そして多くの人民がいかに自由を放棄することで救いを求めるかを探求している。 ナチズムの台頭を可能にした心理社会的状況に特に重点を置きながら、権威主義がそのような人民の逃避のメカニズムになりうることを述べている。

| Escape from

Freedom is a book by psychoanalyst Erich Fromm, first published

under that title in the United States by Farrar & Rinehart[1] in

1941 and a year later as The Fear of Freedom in the UK by Routledge

& Kegan Paul. It was translated into German and first published in

1952 under the title Die Angst vor der Freiheit (The Fear of Freedom).

In the book, Fromm explores humanity's shifting relationship with

freedom, how individual freedom can cause fear, anxiety and alienation,

and how many people seek relief by relinquishing freedom. He describes

how authoritarianism can be a mechanism of escape for such people, with

special emphasis on the psychosocial conditions that enabled the rise

of Nazism. |

『自由からの逃走』は精神分析学者エーリッヒ・フロムの著作で、

1941年にアメリカでファーラー&ラインハート社[1]からこのタイトルで出版され、その1年後にイギリスでラウトレッジ&ケーガン・ポール社から『自

由の恐怖』として出版された。この本はドイツ語に翻訳され、1952年に『自由の恐怖』というタイトルで出版された。この本の中でフロムは、人間の自由と

の関係の移り変わり、個人の自由がいかに恐怖、不安、疎外を引き起こすか、そして多くの人民がいかに自由を放棄することで救いを求めるかを探求している。

ナチズムの台頭を可能にした心理社会的状況に特に重点を置きながら、権威主義がそのような人民の逃避のメカニズムになりうることを述べている。 |

| Summary Fromm's concept of freedom Fromm distinguishes between "freedom from" (negative freedom) and "freedom to" (positive freedom). The former refers to emancipation from restrictions such as social conventions placed on individuals by other people or institutions. This is the kind of freedom typified by the existentialism of Sartre, and has often been fought for historically but, according to Fromm, on its own it can be a destructive force unless accompanied by a creative element – 'freedom to' – the use of freedom to employ the total integrated personality in creative acts. This, he argues, necessarily implies a true connectedness with others that goes beyond the superficial bonds of conventional social intercourse: "...in the spontaneous realization of the self, man unites himself anew with the world..."[2] In the process of becoming freed from authority, Fromm says we are often left with feelings of hopelessness (he likens this process to the individuation of infants in the normal course of child development) that will not abate until we use our 'freedom to' and develop some form of replacement of the old order. However, a common substitute for exercising "freedom to" or authenticity is to submit to an authoritarian system that replaces the old order with another of different external appearance but identical function for the individual: to eliminate uncertainty by prescribing what to think and how to act. Fromm characterizes this as a dialectic historical process whereby the original situation is the thesis and the emancipation from it the antithesis. The synthesis is only reached when something has replaced the original order and provided humans with a new security. Fromm does not indicate that the new system will necessarily be an improvement. In fact, Fromm indicates this will only break the never-ending cycle of negative freedom that society submits to. |

まとめ フロムの自由の概念 フロムは「~からの自由」(消極的自由)と「~への自由」(積極的自由)を区別している。前者は、人民や制度によって個人に課せられた社会的慣習などの制 約からの解放を指す。これはサルトルの実存主義に代表されるような自由であり、歴史的にしばしば戦われてきたものであるが、フロムによれば、創造的な要 素、すなわち「〜する自由」、すなわち統合された人格全体を創造的行為に用いる自由が伴わなければ、それだけでは破壊的な力となりうる。このことは、従来 の社会的交流の表面的な結びつきを超えた、他者との真の結びつきを必然的に意味すると彼は主張する: 「...自己の自発的な実現において、人間は自らを世界と新たに一体化させる...」[2]。 フロムによれば、権威から解放される過程において、私たちはしばしば絶望的な感情を抱くことになる(彼はこの過程を、通常の子どもの発達過程における幼児 の個性化になぞらえている)。しかし、「~する自由」や真正性を行使するための一般的な代用品は、権威主義的なシステムに服従することである。権威主義的 なシステムは、古い秩序を、外見は異なるが、個人にとっては同じ機能を持つ別の秩序に置き換える。フロムはこれを弁証法的な歴史的過程として特徴づけてお り、元の状況がテーゼであり、そこからの解放がアンチテーゼである。統合に達するのは、何かが元の秩序に取って代わり、人間に新たな安心を与えたときであ る。フロムは、新しいシステムが必ずしも改善されるとは言っていない。むしろ、社会が服従する負の自由の終わりのない連鎖を断ち切るものでしかない。 |

| Freedom in history Freedom, argues Fromm, became an important issue in the 20th century, being seen as something to be fought for and defended. However, it has not always occupied such a prominent place in people's thinking and, as an experience, is not necessarily something that is unambiguously enjoyable. A major chapter in the book deals with the development of Protestant theology, with a discussion of the work of Calvin and Luther. The collapse of an old social order and the rise of capital led to a more developed awareness that people could be separate autonomous beings and direct their own future rather than simply fulfilling a socioeconomic role. This, in turn, fed into a new conception of God that had to account for the new freedom while still providing some moral authority. Luther painted a picture of man's relationship with God that was personal and individuated and free from the influence of the church, while Calvin's doctrine of predestination suggested that people could not work for salvation but have instead been chosen arbitrarily before they could make any difference. Both of these, argues Fromm, are responses to a freer economic situation. The first gives individuals more freedom to find holiness in the world around them without a complex church structure. The second, although superficially giving the appearance of a kind of determinism actually provided a way for people to work towards salvation. While people could not change their destinies, they could discover the extent of their holiness by committing themselves to hard work and frugality, both traits that were considered virtuous. In reality, this made people work harder to 'prove' to themselves that they were destined for God's kingdom. |

歴史における自由 フロムは、自由は20世紀に重要な課題となり、戦い、守るべきものとみなされるようになったと主張する。しかし、自由は常に人民の思考の中でそれほど重要 な位置を占めていたわけではないし、経験として、必ずしも明確に楽しめるものでもない。 本書の主要な章はプロテスタント神学の発展について扱っており、カルヴァンとルターの業績について論じている。古い社会秩序が崩壊し、資本が台頭したこと で、人民は単に社会経済的な役割を果たすだけでなく、独立した自律的な存在となり、自らの未来を切り開くことができるという認識がより発展した。そしてこ のことは、道徳的権威を与えながらも新しい自由を説明しなければならない神についての新しい概念に影響を与えた。ルターは、人格的で個性的であり、教会の 影響から自由である人間と神との関係を描き、カルヴァンの定命の教義は、人民は救いのために努力することはできず、その代わりに、何かを変える前に恣意的 に選ばれたと示唆した。フロムは、この二つはどちらも、より自由な経済状況に対する反応であると主張する。前者は、複雑な教会機構に頼らずとも、個人が周 囲の世界に聖性を見出す自由を与えるものである。もうひとつは、表面的には一種の決定論のように見えるが、実際には人民が救いに向かって努力する方法を提 供するものである。人民は自分の運命を変えることはできないが、美徳とされる勤勉さと倹約に身を投じることで、自分の神聖さの程度を知ることができた。現 実には、これによって人民は、自分が神の国へ行く運命にあることを自分自身に「証明」するために、より懸命に働くようになったのである。 |

| Escaping freedom As 'freedom from' is not an experience we enjoy in itself, Fromm suggests that many people, rather than using it successfully, attempt to minimise its negative effects by developing thoughts and behaviours that provide some form of security. These are as follows: Authoritarianism: Fromm characterises the authoritarian personality as containing both sadistic and masochistic elements. The authoritarian wishes to gain control over other people in a bid to impose some kind of order on the world, but also wishes to submit to the control of some superior force which may come in the guise of a person or an abstract idea. Destructiveness: Although this bears a similarity to sadism, Fromm argues that the sadist wishes to gain control over something. A destructive personality wishes to destroy something it cannot bring under its control. Conformity: This process is seen when people unconsciously incorporate the normative beliefs and thought processes of their society and experience them as their own. This allows them to avoid genuine free thinking, which is likely to provoke anxiety. |

自由から逃れる からの自由」は、それ自体を楽しむ経験ではないため、フロムは、多くの人民が、自由をうまく利用するのではなく、ある種の安心感を与える思考や行動を身に つけることによって、その否定的な影響を最小限に抑えようとすることを示唆している。それは以下のようなものである: 権威主義: フロムは権威主義的人格をサディスティックな要素とマゾヒスティックな要素の両方を含むものとして特徴づけている。権威主義者は、世界に何らかの秩序を押 し付けるために人民を支配したいと願うが、同時に人格や抽象的な観念を装った何らかの優れた力の支配に服従したいと願う。 破壊性: これはサディズムと似ているが、フロムはサディストは何かを支配したいと願うと主張する。破壊的人格は、自分の支配下に置けないものを破壊したいと望む。 適合性: このプロセスは、人民が無意識のうちに社会の規範的な信念や思考過程を取り込み、それを自分のものとして経験するときに見られる。これにより、純粋な自由 な思考を避けることができ、不安を引き起こす可能性が高い。 |

| Freedom in the 20th century Fromm analyzes the character of Nazi ideology and suggests that the psychological conditions of Germany after the first world war fed into a desire for some form of new order to restore the nation's pride. This came in the form of National Socialism and Fromm's interpretation of Mein Kampf suggests that Hitler had an authoritarian personality structure that not only made him want to rule over Germany in the name of a higher authority (the idea of a natural master race) but also made him an appealing prospect for an insecure middle class that needed some sense of pride and certainty. Fromm suggests there is a propensity to submit to authoritarian regimes when nations experience negative freedom but he sounds a positive note when he claims that the work of cultural evolution hitherto cannot be undone and Nazism does not provide a genuine union with the world. Fromm examines democracy and freedom. Modern democracy and the industrialised nation are models he praises but it is stressed that the kind of external freedom provided by this kind of society can never be utilised to the full without an equivalent inner freedom. Fromm suggests that though we are free from the totalitarian influence of any sort in this kind of society, we are still dominated by the advice of experts and the influence of advertising. The way to become free as an individual is to be spontaneous in our self-expression and in the way we behave. This is crystallised in his existential statement "There is only one meaning of life: the act of living it".[3] Fromm counters suggestions that this might lead to social chaos by claiming that being truly in touch with our humanity is to be truly in touch with the needs of those with whom we share the world. |

20世紀の自由 フロムはナチス・イデオロギーの性格を分析し、第一次世界大戦後のドイツの心理状況が、国民の誇りを回復するために何らかの形で新しい秩序を求めるように なったことを示唆している。フロムの『我が闘争』(Mein Kampf)の解釈では、ヒトラーは権威主義的な人格構造を持っており、より高い権威(自然的な支配者民族という考え)の名のもとにドイツを支配したいと 思わせただけでなく、誇りと確信を必要とする不安定な中産階級にとっても魅力的な人物であった。フロムは、国民が否定的な自由を経験すると、権威主義的な 体制に服従する傾向があることを示唆しているが、彼は、これまでの文化的進化の仕事は取り消すことはできず、ナショナリズムは世界との真の結合を提供する ものではないと主張し、肯定的な音を鳴らしている。 フロムは民主主義と自由について考察している。現代の民主主義と工業化国民は、彼が賞賛するモデルであるが、この種の社会が提供する外的な自由は、同等の 内的な自由なしには、決して十分に活用されることはないと強調する。フロムは、このような社会では全体主義的な影響から解放されているとはいえ、専門家の アドバイスや広告の影響に支配されていると指摘する。個人として自由になる方法は、自己表現と行動において自発的になることである。フロムは、人間性に真 に触れることは、世界を共有する人々のニーズに真に触れることだと主張することで、このことが社会の混乱につながるのではないかという指摘に反論している [3]。 |

| Critical theory Freudo-Marxism Life Against Death Psychohistory |

批評理論 フロイト=マルクス主義 死に対する生 精神史 |

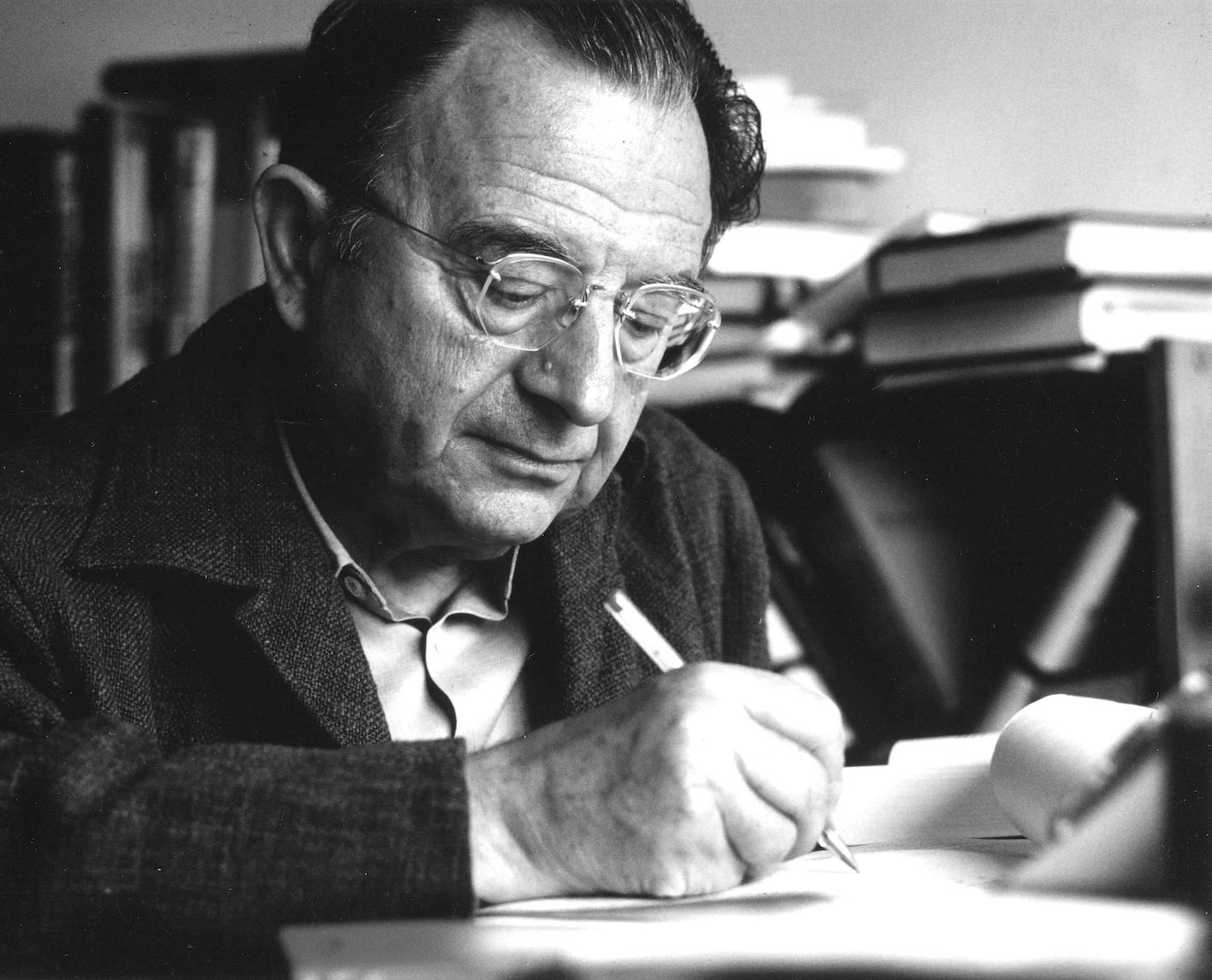

| 1. Funk, Rainer (2000). Erich

Fromm: His Life and Idea. New York: Continuum. pp. 169, 173. ISBN

0-8264-1224-6. 2. Fromm, Erich (1941). Escape From Freedom. Avon Books. p. 287. ISBN 0-380-47472-7. 3. Fromm, Erich (1941). Escape From Freedom. Avon Books. p. 289. ISBN 0-380-47472-7. |

1. Funk, Rainer (2000).

エーリッヒ・フロム: 彼の生涯と思想. ニューヨーク: 169, 173頁。ISBN 0-8264-1224-6. 2. Fromm, Erich (1941). 自由からの逃走. エイボン・ブックス. ISBN 0-380-47472-7. 3. Fromm, Erich (1941). 自由からの逃走. p. 289. ISBN 0-380-47472-7. |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Escape_from_Freedom |

Links

- ︎エーリッヒ・フロム▶︎︎▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎

リンク

- 5分でわかる『判断力批判』▶︎批判理性の鍛え方▶︎︎文化相対主義から政治的相対主義への危ない綱渡りについて▶︎愛の技法▶︎︎▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎

文献

- Rainer Funk, The Jewish Roots of Erich Fromm’s Humanistic Thinking. 1988.

- Fromm; E. (1922a): Das jüdische Gesetz. Ein Beitrag zur

Soziologie des Diasporajudentums, Heidelberg 1922, 227 S. (Manuskript).

その他の情報

☆

☆