Existentialism

Tsimshian Eagle Dance Headress ca.1870.

実存主義

Existentialism

Tsimshian Eagle Dance Headress ca.1870.

| Existentialism

is a

form of philosophical inquiry that explores the issue of human

existence.[1][2] Existentialist philosophers explore questions related

to the meaning, purpose, and value of human existence. Common concepts

in existentialist thought include existential crisis, dread, and

anxiety in the face of an absurd world and free will, as well as

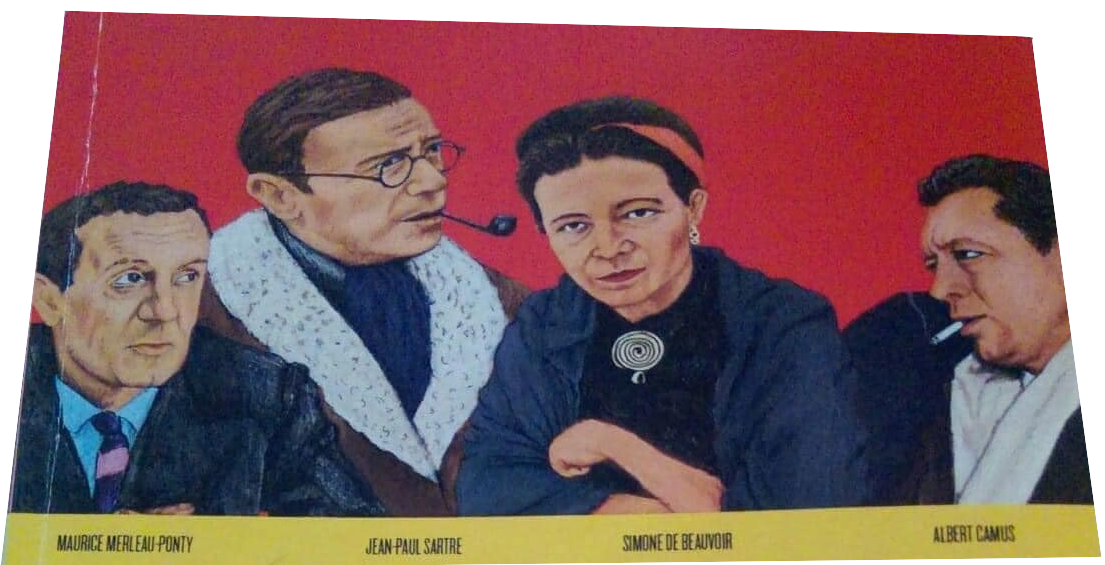

authenticity, courage, and virtue.[3] Existentialism is associated with several 19th- and 20th-century European philosophers who shared an emphasis on the human subject, despite often profound differences in thought.[4][2][5] Among the earliest figures associated with existentialism are philosophers Søren Kierkegaard, Friedrich Nietzsche and novelist Fyodor Dostoevsky, all of whom critiqued rationalism and concerned themselves with the problem of meaning. In the 20th century, prominent existentialist thinkers included Jean-Paul Sartre, Albert Camus, Martin Heidegger, Simone de Beauvoir, Karl Jaspers, Gabriel Marcel, and Paul Tillich. Many existentialists considered traditional systematic or academic philosophies, in style and content, to be too abstract and removed from concrete human experience.[6][7] A primary virtue in existentialist thought is authenticity.[8] Existentialism would influence many disciplines outside of philosophy, including theology, drama, art, literature, and psychology.[9] Existentialist philosophy encompasses a range of perspectives, but it shares certain underlying concepts. Among these, a central tenet of existentialism is that personal freedom, individual responsibility, and deliberate choice ar |

実存主義とは、人間存在の問題を探求する哲学的探究の一形態である

[1][2]。実存主義の哲学者たちは、人間存在の意味、目的、価値に関する問題を探求する。実存主義思想に共通する概念として、不条理な世界や自由意志

を前にした実存的危機、恐怖、不安、また真正性、勇気、美徳などがある[3]。 実存主義は19世紀から20世紀にかけてのヨーロッパの哲学者たちと関連しており、彼らはしばしば思想に大きな違いがあるにもかかわらず、人間の主体に対 する強調を共有していた[4][2][5]。20世紀には、ジャン=ポール・サルトル、アルベール・カミュ、マルティン・ハイデガー、シモーヌ・ド・ボー ヴォワール、カール・ヤスパース、ガブリエル・マルセル、パウル・ティリッヒといった著名な実存主義思想家がいた。 実存主義思想における第一の美徳は真正性である[8]。実存主義は神学、演劇、芸術、文学、心理学など、哲学以外の多くの分野に影響を与えることになる [9]。 実存主義哲学は様々な視点を包含しているが、その根底にある概念は共通している。その中でも実存主義の中心的な信条は、個人の自由、個人の責任、意図的な 選択が、自己発見の追求と人生の意味の決定に不可欠であるというものである[10]。 |

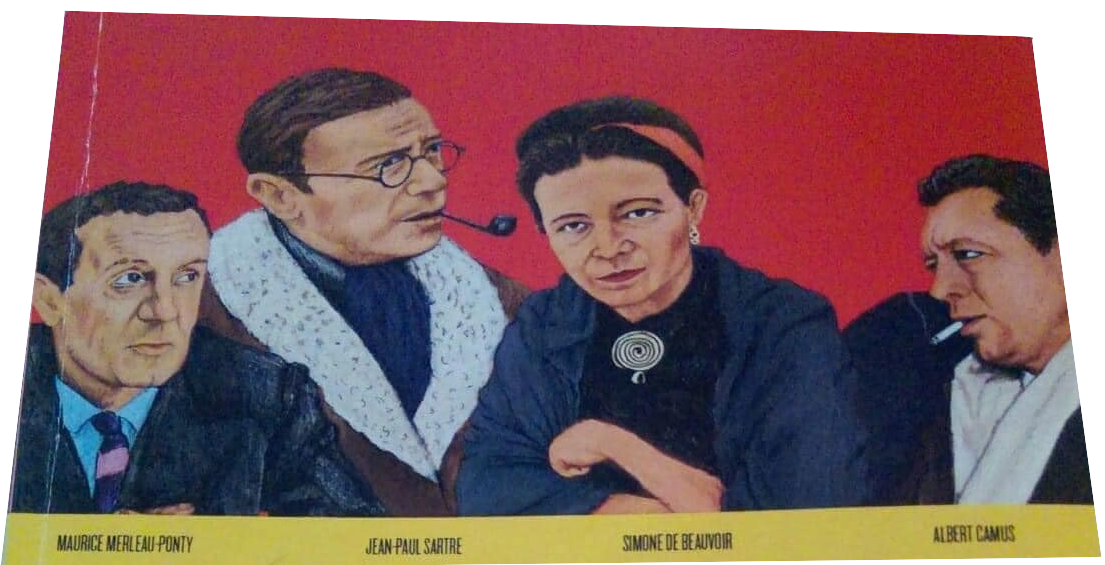

| Etymology The term existentialism (French: L'existentialisme) was coined by the French Catholic philosopher Gabriel Marcel in the mid-1940s.[11][12][13] When Marcel first applied the term to Jean-Paul Sartre, at a colloquium in 1945, Sartre rejected it.[14] Sartre subsequently changed his mind and, on October 29, 1945, publicly adopted the existentialist label in a lecture to the Club Maintenant in Paris, published as L'existentialisme est un humanisme (Existentialism Is a Humanism), a short book that helped popularize existentialist thought.[15] Marcel later came to reject the label himself in favour of Neo-Socratic, in honor of Kierkegaard's essay "On the Concept of Irony".  Some scholars argue that the term should be used to refer only to the cultural movement in Europe in the 1940s and 1950s associated with the works of the philosophers Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir, Maurice Merleau-Ponty, and Albert Camus.[4] Others extend the term to Kierkegaard, and yet others extend it as far back as Socrates.[16] However, it is often identified with the philosophical views of Sartre.[4] |

語源[編集] 実存主義(フランス語:L'existentialisme)という用語は、1940年代半ばにフランスのカトリック哲学者ガブリエル・マルセルによって 作られた。 [その後、サルトルは考えを改め、1945年10月29日にパリのクラブ・マントナンで行われた講演で、実存主義のラベルを公に採用し、実存主義思想の普 及に貢献した短編集『実存主義はヒューマニズムである』(L'existentialisme est un humanisme)として出版された[15]。  サルトル、シモーヌ・ド・ボーヴォワール、モーリス・メルロ=ポンティ、アルベール・カミュといった哲学者の著作に関連する1940年代から1950年代 のヨーロッパにおける文化運動のみを指す言葉として使用されるべきであると主張する学者もいる。 |

| Definitional issues and

background The labels existentialism and existentialist are often seen as historical conveniences in as much as they were first applied to many philosophers long after they had died. While existentialism is generally considered to have originated with Kierkegaard, the first prominent existentialist philosopher to adopt the term as a self-description was Sartre. Sartre posits the idea that "what all existentialists have in common is the fundamental doctrine that existence precedes essence", as the philosopher Frederick Copleston explains.[17] According to philosopher Steven Crowell, defining existentialism has been relatively difficult, and he argues that it is better understood as a general approach used to reject certain systematic philosophies rather than as a systematic philosophy itself.[4] In a lecture delivered in 1945, Sartre described existentialism as "the attempt to draw all the consequences from a position of consistent atheism".[18] For others, existentialism need not involve the rejection of God, but rather "examines mortal man's search for meaning in a meaningless universe", considering less "What is the good life?" (to feel, be, or do, good), instead asking "What is life good for?".[19] Although many outside Scandinavia consider the term existentialism to have originated from Kierkegaard, it is more likely that Kierkegaard adopted this term (or at least the term "existential" as a description of his philosophy) from the Norwegian poet and literary critic Johan Sebastian Cammermeyer Welhaven.[20] This assertion comes from two sources: The Norwegian philosopher Erik Lundestad refers to the Danish philosopher Fredrik Christian Sibbern. Sibbern is supposed to have had two conversations in 1841, the first with Welhaven and the second with Kierkegaard. It is in the first conversation that it is believed that Welhaven came up with "a word that he said covered a certain thinking, which had a close and positive attitude to life, a relationship he described as existential".[21] This was then brought to Kierkegaard by Sibbern. The second claim comes from the Norwegian historian Rune Slagstad, who claimed to prove that Kierkegaard himself said the term existential was borrowed from the poet. He strongly believes that it was Kierkegaard himself who said that "Hegelians do not study philosophy 'existentially;' to use a phrase by Welhaven from one time when I spoke with him about philosophy."[22] |

定義の問題と背景[編集] 実存主義と実存主義者というレッテルは、多くの哲学者が亡くなってから長い年月を経て初めて適用されたという点で、しばしば歴史的な便宜とみなされる。実 存主義は一般的にキルケゴールに端を発すると考えられているが、この言葉を自己記述として採用した最初の著名な実存主義哲学者はサルトルである。哲学者の フレデリック・コプルストンが説明するように、サルトルは「すべての実存主義者に共通するのは、実存が本質に先立つという基本的な教義である」という考え を提唱している[17]。哲学者のスティーヴン・クロウウェルによれば、実存主義の定義は比較的困難であり、体系的な哲学そのものというよりも、ある体系 的な哲学を否定するために用いられる一般的なアプローチとして理解されるのがよいと主張している。 [サルトルは1945年の講演で、実存主義を「一貫した無神論の立場からあらゆる結果を導き出そうとする試み」であると述べている。(いい人生とは何か」 (いい人生だと感じること、いい人生であること、いい人生であること)を考えるのではなく、「人生は何のためにあるのか」を問うのである[19]。 スカンジナビア国外では、実存主義という用語はキルケゴールから生まれたと考えている人が多いが、キルケゴールがこの用語(あるいは少なくとも彼の哲学を 説明する用語としての「実存主義」)をノルウェーの詩人であり文芸批評家であったヨハン・セバスティアン・カンマイヤー・ウェルハーフェンから採用した可 能性の方が高い[20]。 この主張は2つの情報源からきている: ノルウェーの哲学者エリック・ルンデスタッドは、デンマークの哲学者フレドリック・クリスチャン・シバーンに言及している。シッベルンは1841年に2 回、最初の会話をウェルハーヴェンと、2回目の会話をキルケゴールと交わしたとされている。最初の会話で、ウェルヘーヴェンは「人生に対して緊密で肯定的 な態度をとり、実存的な関係であると表現した、ある考え方をカバーする言葉」を思いついたとされている。 2つ目の主張はノルウェーの歴史家ルーン・スラグスタッドによるもので、彼はキルケゴール自身が実存的という言葉は詩人から借用したものだと言ったことを 証明すると主張した。彼は、「ヘーゲル主義者は哲学を『実存的』には研究しない。私が彼と哲学について話したあるときのウェルハーヴェンの言葉を使えば」 と言ったのはキルケゴール自身だと強く信じている[22]。 |

| Concepts Existence precedes essence Main article: Existence precedes essence Sartre argued that a central proposition of existentialism is that existence precedes essence, which is to say that individuals shape themselves by existing and cannot be perceived through preconceived and a priori categories, an "essence". The actual life of the individual is what constitutes what could be called their "true essence" instead of an arbitrarily attributed essence others use to define them. Human beings, through their own consciousness, create their own values and determine a meaning to their life.[23] This view is in contradiction to Aristotle and Aquinas, who taught that essence precedes individual existence.[24] Although it was Sartre who explicitly coined the phrase, similar notions can be found in the thought of existentialist philosophers such as Heidegger, and Kierkegaard: The subjective thinker's form, the form of his communication, is his style. His form must be just as manifold as are the opposites that he holds together. The systematic eins, zwei, drei is an abstract form that also must inevitably run into trouble whenever it is to be applied to the concrete. To the same degree as the subjective thinker is concrete, to that same degree his form must also be concretely dialectical. But just as he himself is not a poet, not an ethicist, not a dialectician, so also his form is none of these directly. His form must first and last be related to existence, and in this regard he must have at his disposal the poetic, the ethical, the dialectical, the religious. Subordinate character, setting, etc., which belong to the well-balanced character of the esthetic production, are in themselves breadth; the subjective thinker has only one setting—existence—and has nothing to do with localities and such things. The setting is not the fairyland of the imagination, where poetry produces consummation, nor is the setting laid in England, and historical accuracy is not a concern. The setting is inwardness in existing as a human being; the concretion is the relation of the existence-categories to one another. Historical accuracy and historical actuality are breadth. — Søren Kierkegaard (Concluding Postscript, Hong pp. 357–358.) Some interpret the imperative to define oneself as meaning that anyone can wish to be anything. However, an existentialist philosopher would say such a wish constitutes an inauthentic existence – what Sartre would call "bad faith". Instead, the phrase should be taken to say that people are defined only insofar as they act and that they are responsible for their actions. Someone who acts cruelly towards other people is, by that act, defined as a cruel person. Such persons are themselves responsible for their new identity (cruel persons). This is opposed to their genes, or human nature, bearing the blame. As Sartre said in his lecture Existentialism is a Humanism: "Man first of all exists, encounters himself, surges up in the world—and defines himself afterwards." The more positive, therapeutic aspect of this is also implied: a person can choose to act in a different way, and to be a good person instead of a cruel person.[25] Jonathan Webber interprets Sartre's usage of the term essence not in a modal fashion, i.e. as necessary features, but in a teleological fashion: "an essence is the relational property of having a set of parts ordered in such a way as to collectively perform some activity".[26]: 3 [4] For example, it belongs to the essence of a house to keep the bad weather out, which is why it has walls and a roof. Humans are different from houses because—unlike houses—they do not have an inbuilt purpose: they are free to choose their own purpose and thereby shape their essence; thus, their existence precedes their essence.[26]: 1–4 Sartre is committed to a radical conception of freedom: nothing fixes our purpose but we ourselves, our projects have no weight or inertia except for our endorsement of them.[27][28] Simone de Beauvoir, on the other hand, holds that there are various factors, grouped together under the term sedimentation, that offer resistance to attempts to change our direction in life. Sedimentations are themselves products of past choices and can be changed by choosing differently in the present, but such changes happen slowly. They are a force of inertia that shapes the agent's evaluative outlook on the world until the transition is complete.[26]: 5, 9, 66 Sartre's definition of existentialism was based on Heidegger's magnum opus Being and Time (1927). In the correspondence with Jean Beaufret later published as the Letter on Humanism, Heidegger implied that Sartre misunderstood him for his own purposes of subjectivism, and that he did not mean that actions take precedence over being so long as those actions were not reflected upon.[29] Heidegger commented that "the reversal of a metaphysical statement remains a metaphysical statement", meaning that he thought Sartre had simply switched the roles traditionally attributed to essence and existence without interrogating these concepts and their history.[30] The absurd Main article: Absurdism Sisyphus, the symbol of the absurdity of existence, painting by Franz Stuck (1920) The notion of the absurd contains the idea that there is no meaning in the world beyond what meaning we give it. This meaninglessness also encompasses the amorality or "unfairness" of the world. This can be highlighted in the way it opposes the traditional Abrahamic religious perspective, which establishes that life's purpose is the fulfillment of God's commandments.[31] This is what gives meaning to people's lives. To live the life of the absurd means rejecting a life that finds or pursues specific meaning for man's existence since there is nothing to be discovered. According to Albert Camus, the world or the human being is not in itself absurd. The concept only emerges through the juxtaposition of the two; life becomes absurd due to the incompatibility between human beings and the world they inhabit.[31] This view constitutes one of the two interpretations of the absurd in existentialist literature. The second view, first elaborated by Søren Kierkegaard, holds that absurdity is limited to actions and choices of human beings. These are considered absurd since they issue from human freedom, undermining their foundation outside of themselves.[32] The absurd contrasts with the claim that "bad things don't happen to good people"; to the world, metaphorically speaking, there is no such thing as a good person or a bad person; what happens happens, and it may just as well happen to a "good" person as to a "bad" person.[33] Because of the world's absurdity, anything can happen to anyone at any time and a tragic event could plummet someone into direct confrontation with the absurd. Many of the literary works of Kierkegaard, Beckett, Kafka, Dostoevsky, Ionesco, Miguel de Unamuno, Luigi Pirandello,[34][35][36][37] Sartre, Joseph Heller, and Camus contain descriptions of people who encounter the absurdity of the world. It is because of the devastating awareness of meaninglessness that Camus claimed in The Myth of Sisyphus that "There is only one truly serious philosophical problem, and that is suicide." Although "prescriptions" against the possible deleterious consequences of these kinds of encounters vary, from Kierkegaard's religious "stage" to Camus' insistence on persevering in spite of absurdity, the concern with helping people avoid living their lives in ways that put them in the perpetual danger of having everything meaningful break down is common to most existentialist philosophers. The possibility of having everything meaningful break down poses a threat of quietism, which is inherently against the existentialist philosophy.[38] It has been said that the possibility of suicide makes all humans existentialists. The ultimate hero of absurdism lives without meaning and faces suicide without succumbing to it.[39] Facticity Main article: Facticity This section may be too technical for most readers to understand. Please help improve it to make it understandable to non-experts, without removing the technical details. (November 2020) (Learn how and when to remove this message) Facticity is defined by Sartre in Being and Nothingness (1943) as the in-itself, which for humans takes the form of being and not being. It is the facts of one's personal life and as per Heidegger, it is "the way in which we are thrown into the world." This can be more easily understood when considering facticity in relation to the temporal dimension of our past: one's past is what one is, meaning that it is what has formed the person who exists in the present. However, to say that one is only one's past would ignore the change a person undergoes in the present and future, while saying that one's past is only what one was, would entirely detach it from the present self. A denial of one's concrete past constitutes an inauthentic lifestyle, and also applies to other kinds of facticity (having a human body—e.g., one that does not allow a person to run faster than the speed of sound—identity, values, etc.).[40] Facticity is a limitation and a condition of freedom. It is a limitation in that a large part of one's facticity consists of things one did not choose (birthplace, etc.), but a condition of freedom in the sense that one's values most likely depend on it. However, even though one's facticity is "set in stone" (as being past, for instance), it cannot determine a person: the value ascribed to one's facticity is still ascribed to it freely by that person. As an example, consider two men, one of whom has no memory of his past and the other who remembers everything. Both have committed many crimes, but the first man, remembering nothing, leads a rather normal life while the second man, feeling trapped by his own past, continues a life of crime, blaming his own past for "trapping" him in this life. There is nothing essential about his committing crimes, but he ascribes this meaning to his past. However, to disregard one's facticity during the continual process of self-making, projecting oneself into the future, would be to put oneself in denial of the conditions shaping the present self and would be inauthentic. The origin of one's projection must still be one's facticity, though in the mode of not being it (essentially). An example of one focusing solely on possible projects without reflecting on one's current facticity:[40] would be someone who continually thinks about future possibilities related to being rich (e.g. a better car, bigger house, better quality of life, etc.) without acknowledging the facticity of not currently having the financial means to do so. In this example, considering both facticity and transcendence, an authentic mode of being would be considering future projects that might improve one's current finances (e.g. putting in extra hours, or investing savings) in order to arrive at a future-facticity of a modest pay rise, further leading to purchase of an affordable car. Another aspect of facticity is that it entails angst. Freedom "produces" angst when limited by facticity and the lack of the possibility of having facticity to "step in" and take responsibility for something one has done also produces angst. Another aspect of existential freedom is that one can change one's values. One is responsible for one's values, regardless of society's values. The focus on freedom in existentialism is related to the limits of responsibility one bears, as a result of one's freedom. The relationship between freedom and responsibility is one of interdependency and a clarification of freedom also clarifies that for which one is responsible.[41][42] Authenticity Main article: Authenticity Many noted existentialists consider the theme of authentic existence important. Authenticity involves the idea that one has to "create oneself" and live in accordance with this self. For an authentic existence, one should act as oneself, not as "one's acts" or as "one's genes" or as any other essence requires. The authentic act is one in accordance with one's freedom. A component of freedom is facticity, but not to the degree that this facticity determines one's transcendent choices (one could then blame one's background for making the choice one made [chosen project, from one's transcendence]). Facticity, in relation to authenticity, involves acting on one's actual values when making a choice (instead of, like Kierkegaard's Aesthete, "choosing" randomly), so that one takes responsibility for the act instead of choosing either-or without allowing the options to have different values.[43] In contrast, the inauthentic is the denial to live[clarification needed] in accordance with one's freedom. This can take many forms, from pretending choices are meaningless or random, convincing oneself that some form of determinism is true, or "mimicry" where one acts as "one should".[citation needed] How one "should" act is often determined by an image one has, of how one in such a role (bank manager, lion tamer, sex worker, etc.) acts. In Being and Nothingness, Sartre uses the example of a waiter in "bad faith". He merely takes part in the "act" of being a typical waiter, albeit very convincingly.[44] This image usually corresponds to a social norm, but this does not mean that all acting in accordance with social norms is inauthentic. The main point is the attitude one takes to one's own freedom and responsibility and the extent to which one acts in accordance with this freedom.[45] The Other and the Look Main article: Other (philosophy) The Other (written with a capital "O") is a concept more properly belonging to phenomenology and its account of intersubjectivity. However, it has seen widespread use in existentialist writings, and the conclusions drawn differ slightly from the phenomenological accounts. The Other is the experience of another free subject who inhabits the same world as a person does. In its most basic form, it is this experience of the Other that constitutes intersubjectivity and objectivity. To clarify, when one experiences someone else, and this Other person experiences the world (the same world that a person experiences)—only from "over there"—the world is constituted as objective in that it is something that is "there" as identical for both of the subjects; a person experiences the other person as experiencing the same things. This experience of the Other's look is what is termed the Look (sometimes the Gaze).[46] While this experience, in its basic phenomenological sense, constitutes the world as objective and oneself as objectively existing subjectivity (one experiences oneself as seen in the Other's Look in precisely the same way that one experiences the Other as seen by him, as subjectivity), in existentialism, it also acts as a kind of limitation of freedom. This is because the Look tends to objectify what it sees. When one experiences oneself in the Look, one does not experience oneself as nothing (no thing), but as something (some thing). In Sartre's example of a man peeping at someone through a keyhole, the man is entirely caught up in the situation he is in. He is in a pre-reflexive state where his entire consciousness is directed at what goes on in the room. Suddenly, he hears a creaking floorboard behind him and he becomes aware of himself as seen by the Other. He is then filled with shame for he perceives himself as he would perceive someone else doing what he was doing—as a Peeping Tom. For Sartre, this phenomenological experience of shame establishes proof for the existence of other minds and defeats the problem of solipsism. For the conscious state of shame to be experienced, one has to become aware of oneself as an object of another look, proving a priori, that other minds exist.[47] The Look is then co-constitutive of one's facticity. Another characteristic feature of the Look is that no Other really needs to have been there: It is possible that the creaking floorboard was simply the movement of an old house; the Look is not some kind of mystical telepathic experience of the actual way the Other sees one (there may have been someone there, but he could have not noticed that person). It is only one's perception of the way another might perceive him.[48] Angst and dread Main article: Angst "Existential angst", sometimes called existential dread, anxiety, or anguish, is a term common to many existentialist thinkers. It is generally held to be a negative feeling arising from the experience of human freedom and responsibility.[49][50] The archetypal example is the experience one has when standing on a cliff where one not only fears falling off it, but also dreads the possibility of throwing oneself off. In this experience that "nothing is holding me back", one senses the lack of anything that predetermines one to either throw oneself off or to stand still, and one experiences one's own freedom.[51] It can also be seen in relation to the previous point how angst is before nothing, and this is what sets it apart from fear that has an object. While one can take measures to remove an object of fear, for angst no such "constructive" measures are possible. The use of the word "nothing" in this context relates to the inherent insecurity about the consequences of one's actions and to the fact that, in experiencing freedom as angst, one also realizes that one is fully responsible for these consequences. There is nothing in people (genetically, for instance) that acts in their stead—that they can blame if something goes wrong. Therefore, not every choice is perceived as having dreadful possible consequences (and, it can be claimed, human lives would be unbearable if every choice facilitated dread). However, this does not change the fact that freedom remains a condition of every action. Despair Main article: Despair See also: Existential crisis Despair is generally defined as a loss of hope.[52] In existentialism, it is more specifically a loss of hope in reaction to a breakdown in one or more of the defining qualities of one's self or identity. If a person is invested in being a particular thing, such as a bus driver or an upstanding citizen, and then finds their being-thing compromised, they would normally be found in a state of despair—a hopeless state. For example, a singer who loses the ability to sing may despair if they have nothing else to fall back on—nothing to rely on for their identity. They find themselves unable to be what defined their being. What sets the existentialist notion of despair apart from the conventional definition is that existentialist despair is a state one is in even when they are not overtly in despair. So long as a person's identity depends on qualities that can crumble, they are in perpetual despair—and as there is, in Sartrean terms, no human essence found in conventional reality on which to constitute the individual's sense of identity, despair is a universal human condition. As Kierkegaard defines it in Either/Or: "Let each one learn what he can; both of us can learn that a person's unhappiness never lies in his lack of control over external conditions, since this would only make him completely unhappy."[53] In Works of Love, he says: When the God-forsaken worldliness of earthly life shuts itself in complacency, the confined air develops poison, the moment gets stuck and stands still, the prospect is lost, a need is felt for a refreshing, enlivening breeze to cleanse the air and dispel the poisonous vapors lest we suffocate in worldliness. ... Lovingly to hope all things is the opposite of despairingly to hope nothing at all. Love hopes all things—yet is never put to shame. To relate oneself expectantly to the possibility of the good is to hope. To relate oneself expectantly to the possibility of evil is to fear. By the decision to choose hope one decides infinitely more than it seems, because it is an eternal decision. — Søren Kierkegaard, Works of Love |

概念[編集] 存在は本質に先立つ[編集] 主な記事 実存は本質に先立つ サルトルは、実存主義の中心的命題は「実存は本質に先立つ」ことであると主張した。つまり、個人は存在することによって自らを形成するのであり、先入観や アプリオリなカテゴリー、すなわち「本質」を通して認識することはできないということである。他者が恣意的に定義した本質ではなく、個人の実際の生活こそ が「真の本質」と呼べるものなのだ。この見解は、本質が個人の存在に先立つと説いたアリストテレスや アクィナスとは矛盾する[24]。この言葉を明確に作り出したのはサルトルであるが、ハイデガーやキルケゴールといった実存主義の哲学者の思想にも同様の 考え方が見られる: 主体的な思想家の形式、コミュニケーションの形式は、彼のスタイルである。主体的な思想家の形式、コミュニケーションの形式は、彼のスタイルである。彼の 形式は、彼が一緒に保持する対立物のように多様でなければならない。体系化されたeins, zwei, dreiは抽象的な形式であるが、それを具体的なものに適用しようとすれば、必ず問題にぶつかる。主体的な思想家が具体的であるのと同じ程度に、彼の形式 もまた具体的な弁証法的でなければならない。しかし、彼自身が詩人でもなく、倫理学者でもなく、弁証法学者でもないように、彼の形式もまた、直接にはこれ らのどれでもない。彼の形式は、最初で最後には存在と関係しなければならず、この点で、彼は詩的なもの、倫理的なもの、弁証法的なもの、宗教的なものを自 由に使わなければならない。従属的な性格、設定などは、美学的作品のバランスのとれた性格に属するものであるが、それ自体は幅のあるものである。主体的な 思想家は、ただ一つの設定-実存-しか持たず、地域性などとは何の関係もない。舞台は、詩が完成を生み出す想像のおとぎの国でもなければ、イギリスにある わけでもない。設定とは、人間として存在することの内面性であり、具体性とは、存在カテゴリーの相互関係である。歴史的正確さと歴史的実在性は幅がある。 - セーレン・キェルケゴール(『結びの言葉』ホン 357-358ページ) 自らを定義せよという命令は、誰でも何にでもなりたいと望むことができるという意味だと解釈する人もいる。しかし、実存主義の哲学者であれば、そのような 願いは不真面目な存在であり、サルトルが「悪意」と呼ぶようなものだと言うだろう。そうではなく、この言葉は、人は行動する限りにおいてのみ定義され、そ の行動には責任があると言うべきだろう。他人に対して残酷な行為をする人は、その行為によって残酷な人間として定義される。そのような人は、自分自身の新 しいアイデンティティ(残酷な人)に責任がある。これは、遺伝子や人間の本性が責任を負うのとは対照的である。 サルトルが『実存主義はヒューマニズムである』という講演の中で述べたように、「人間はまず存在し、自分自身に出会い、世界に湧き上がり、その後に自分自 身を定義する」のである。より肯定的で治療的な側面も暗示されている。人は別の方法で行動し、残酷な人間ではなく善良な人間になることを選択できるのだ [25]。 ジョナサン・ウェバーは、サルトルの本質という用語の用法を、モード的な方法、すなわち必要な特徴としてではなく、目的論的な方法で解釈している: 「本質とは、集合的に何らかの活動を行うように秩序づけられた部分の集合を持つという関係的特性である」[26]: 3[4]例えば、悪天候を防ぐことは 家の本質であり、そのために壁と屋根がある。人間は家とは異なり、家とは異なり、内蔵された目的を持っていない: 1-4 サルトルは自由の急進的な概念にコミットしている。私たちの目的を確定するものは私たち自身以外にはなく、私たちのプロジェクトは私たちがそれを支持する 以外には何の重みも慣性も持たない。[27][28]一方、シモーヌ・ド・ボーヴォワールは、人生の方向性を変えようとする試みに抵抗を与える様々な要因 が存在し、それは堆積という言葉でまとめられているとする。堆積はそれ自体、過去の選択の産物であり、現在において異なる選択をすることによって変えるこ とができるが、そのような変化はゆっくりと起こる。沈殿は、移行が完了するまで、世界に対するエージェントの評価的見通しを形成する慣性の力である [26]: 5, 9, 66 サルトルの実存主義の定義は、ハイデガーの大著『存在と時間』(1927年)に基づいていた。後に『ヒューマニズムに関する書簡』として出版されたジャ ン・ボーフレとの往復書簡の中で、ハイデガーはサルトルが自身の主観主義の目的のために彼を誤解しており、それらの行為が反省されない限り、行為が存在に 優先するという意味ではないことを暗示していた[29]。ハイデガーは「形而上学的な発言の逆転は形而上学的な発言のままである」とコメントしており、つ まり彼はサルトルがこれらの概念とその歴史を問うことなく、本質と存在に伝統的に帰属してきた役割を単にすり替えただけだと考えていた[30]。 不条理[編集] 主な記事 不条理 存在の不条理の象徴であるシジフォス、フランツ・シュトゥックによる絵画(1920年) 不条理という概念には、私たちが世界に与える意味を超えて、世界には意味がないという考えが含まれている。この無意味さはまた、世界の不道徳さや「不公平 さ」をも包含している。このことは、人生の目的は神の戒めを成就することであるとする伝統的なアブラハム教の宗教的観点と対立する形で強調することができ る[31]。不条理の人生を生きるということは、発見されるべきものが何もない以上、人間の存在に特定の意味を見出したり追求したりする人生を拒否するこ とを意味する。アルベール・カミュによれば、世界や人間それ自体は不条理ではない。実存主義文学における不条理の2つの解釈のうちの1つがこの見解であ る。二つ目の見解は、セーレン・キェルケゴールによって最初に提唱されたもので、不条理は人間の行為や選択に限定されるとするものである。不条理は人間の 自由から生じるものであり、人間自身の外側にある基盤を損なうものであるため、これらは不条理であると考えられている[32]。 不条理は、「善人には悪いことは起こらない」という主張とは対照的である。世界にとって、比喩的に言えば、善人や悪人というものは存在しない。キルケゴー ル、ベケット、カフカ、ドストエフスキー、イヨネスコ、ミゲル・デ・ウナムーノ、ルイジ・ピランデッロ、[34][35][36][37] サルトル、ジョセフ・ヘラー、カミュの文学作品の多くには、世界の不条理に遭遇する人々の描写がある。 カミュが『シジフォスの神話』の中で「真に深刻な哲学的問題はただ一つ、それは自殺である」と主張したのは、無意味さを痛感したからである。キルケゴール の宗教的「段階」からカミュの不条理にもかかわらず忍耐することの主張まで、この種の出会いがもたらしうる有害な結果に対する「処方箋」はさまざまだが、 意味のあるものすべてが壊れてしまうという絶え間ない危険にさらされるような生き方を避ける手助けをしようという関心は、ほとんどの実存主義哲学者に共通 している。意味のあるものすべてが壊れてしまう可能性は、静寂主義の脅威をもたらすが、それは本質的に実存主義哲学に反するものである。不条理主義の究極 のヒーローは意味なく生き、それに屈することなく自殺に直面する[39]。 事実性[編集] 主な記事 ファクトシティ このセクションは、ほとんどの読者には専門的すぎて理解できないかもしれない。技術的な詳細を削除することなく、非専門家にも理解できるように改善するこ とにご協力を。(2020年11月)(このメッセージを削除する方法とタイミングを学ぶ) 事実性とは、サルトルが『存在と無』(1943年)の中で定義した「内なる自己」であり、人間にとっては「存在すること」と「存在しないこと」という形を とる。ハイデガーに言わせれば、それは"私たちが世界に投げ込まれる方法"である。このことは、事実性を過去の時間的次元との関係で考えると、より容易に 理解できる。つまり、過去こそが、現在存在する人間を形成しているのである。しかし、自分の過去だけが自分であると言うことは、現在と未来において人が受 ける変化を無視することになるし、自分の過去だけが自分であると言うことは、現在の自分から完全に切り離すことになる。自分の具体的な過去を否定すること は、不真面目なライフスタイルを構成し、他の種類の事実性(人間の身体を持つこと、例えば音速よりも速く走ることができないもの、アイデンティティ、価値 観など)にも当てはまる[40]。 事実性は制限であり、自由の条件でもある。自分の事実性の大部分は、自分が選んだのではないもの(出生地など)で構成されているという意味で制限である が、自分の価値観がそれに依存している可能性が高いという意味で自由の条件である。しかし、自分の事実性が(例えば過去のものとして)「決まっている」と しても、それがその人を決定することはできない。自分の事実性に帰属する価値は、やはりその人が自由に帰属させるものなのだ。例えば、2人の男がいて、1 人は過去の記憶がなく、もう1人はすべてを覚えている。どちらも多くの犯罪を犯しているが、何も覚えていない一人目の男は、ごく普通の生活を送っている。 一方、二人目の男は、自分の過去に囚われていると感じ、自分の過去が現世に「囚われている」ことを責めながら、犯罪の生活を続けている。彼が犯罪を犯すこ とに本質的な意味は何もないが、彼はその意味を自分の過去に帰している。 しかし、未来に自己を投影するという自己形成の継続的なプロセスにおいて、自己の事実性を無視することは、現在の自己を形成している状況を否定することで あり、真正性を欠くことになる。自分の投影の原点は、(本質的に)そうではないというモードではあるが、やはり自分の事実性でなければならない。自分の現 在の事実性を省みることなく、可能性のあるプロジェクトにのみ集中する例としては、[40]金持ちになることに関連する将来の可能性(例えば、より良い 車、より大きな家、より良い生活の質など)について、現在そのための経済的手段を持たないという事実性を認めることなく考え続ける人が挙げられる。この例 では、事実性と超越性の両方を考慮すると、正真正銘の存在様式とは、将来の事実性である適度な昇給に到達するために、現在の財政を改善する可能性のある将 来のプロジェクト(労働時間を増やす、貯蓄を投資するなど)を検討し、さらに手頃な価格の車を購入することだろう。 事実性のもう一つの側面は、それが怒りを伴うということである。事実性によって制限されると、自由は怒りを「生む」。また、自分のしたことに「踏み込ん で」責任を取る事実性を持つ可能性がないことも、怒りを生む。 実存的自由のもう一つの側面は、人は自分の価値観を変えることができるということである。社会の価値観に関係なく、自分の価値観には責任がある。実存主義 における自由の焦点は、自由の結果として人が負う責任の限界と関連している。自由と責任の関係は相互依存の関係であり、自由を明確にすることは、自分が責 任を負うことを明確にすることでもある[41][42]。 真正性[編集] 主な記事 真正性 多くの著名な実存主義者は、本物の存在というテーマを重要視している。真正性とは、人は「自分自身を創造」し、その自分自身に従って生きなければならない という考えを含む。真正な存在のためには、人は自分自身として行動すべきであり、「自分の行為」としてではなく、「自分の遺伝子」としてでもなく、他の本 質が要求するものでもない。本物の行為とは、自分の自由に従って行う行為である。自由の構成要素は事実性であるが、この事実性が自分の超越的な選択を決定 してしまうほどではない(その場合、自分のした選択[自分の超越性から選択されたプロジェクト]をした背景を非難することができる)。真正性との関係にお ける事実性とは、選択をする際に(キルケゴールの『麻酔医』のように無作為に「選択」するのではなく)自分の実際の価値観に基づいて行動することであり、 その結果、異なる価値を持つ選択肢を許容することなくどちらか一方を選択するのではなく、その行為に責任を持つことになる[43]。 対照的に、不真面目とは、自分の自由に従って生きること[要明記]を否定することである。これは、選択肢が無意味であったりランダムであったりするふりを したり、ある種の決定論が真実であると自分自身を納得させたり、あるいは「あるべき」ように行動する「模倣」など、さまざまな形をとることができる[要出 典]。 どのように「行動すべきか」は、そのような役割(銀行の支店長、ライオンのテイマー、風俗嬢など)に就いている人がどのように行動するかという、人が持つ イメージによって決定されることが多い。サルトルは『存在と無』の中で、「悪意」を持ったウェイターの例を用いている。彼は、非常に説得力があるとはい え、典型的なウェイターであるという「演技」に参加しているにすぎない[44]。このイメージは通常、社会規範に対応しているが、だからといって、社会規 範に従った演技がすべて不真面目だというわけではない。重要なのは、自分自身の自由と責任に対してとる態度であり、この自由に従ってどの程度行動するかで ある[45]。 他者と視線[編集] 主な記事 他者(哲学) 他者(大文字の "O "で表記される)は、現象学とその相互主観性の説明により適切に属する概念である。しかし、この概念は実存主義者の著作で広く使われており、引き出された 結論は現象学的な説明とは若干異なっている。他者とは、ある人と同じ世界に住む、別の自由な主体の経験である。最も基本的な形では、間主観性と客観性を構 成するのは、この他者の経験である。明確にしておくと、人が他者を経験し、その他者が世界(人が経験するのと同じ世界)を-ただ「あちら」から-経験する とき、その世界は、両主体にとって同一のものとして「そこにある」ものであるという点で、客観的なものとして構成される。この他者の視線の経験は、「視 線」(時に「まなざし」)と呼ばれるものである[46]。 この経験は、その基本的な現象学的な意味において、世界を客観的なものとして構成し、自分自身を客観的に存在する主観性として構成する(人は他者の視線の 中に見られる自分自身を、まさにその人から見られる他者を主観性として経験するのと同じように経験する)一方で、実存主義においては、それは一種の自由の 制限としても作用する。というのも、「視線」は見るものを客観化する傾向があるからである。人は「視線」の中で自分を経験するとき、自分を無(ないもの) として経験するのではなく、有(あるもの)として経験するのである。サルトルの、鍵穴から誰かを覗き見る男の例では、男は自分が置かれている状況に完全に とらわれている。彼の意識はすべて、部屋の中で起こっていることに向けられている。突然、背後で床板がきしむ音が聞こえ、彼は他者から見られている自分に 気づく。そのとき彼は、自分がしていることを他人がしていると認識するように、自分自身を認識することになり、恥ずかしさでいっぱいになる。サルトルに とって、この羞恥の現象学的体験は、他者の心の存在を証明し、独我論の問題を打ち砕くものである。羞恥心という意識的な状態を経験するためには、自分が他 の視線の対象であることを自覚しなければならず、それによって他の心が存在することが先験的に証明される[47]。 視線のもう一つの特徴は、他者がそこにいたことを本当に必要としないことである: 床板がきしむのは単に古い家屋の動きである可能性もある。「視線」は、他者 が実際に自分を見ている様子の、ある種の神秘的なテレパシー体験ではない(そこに誰か がいたかもしれないが、その人に気づかなかったかもしれない)。それは他者が自分を知覚する方法についての自分の知覚に過ぎない[48]。 怒りと恐怖[編集] 主な記事 怒り 実存的恐怖、不安、苦悩と呼ばれることもある「実存的苦悩」は、多くの実存主義思想家に共通する用語である。一般的に、人間の自由と責任の経験から生じる 否定的な感情であるとされている[49][50]。典型的な例は、崖の上に立っているときに経験することであり、崖から落ちることを恐れるだけでなく、自 分自身を投げ落とす可能性にも恐怖を感じる。この「何も私を引き留めるものはない」という経験において、人は身を投げ出すか立ち止まるかを決定するものが 何もないことを感じ取り、自分自身の自由を体験する[51]。 また、前の点との関連で見ることができるのは、怒りがいかに無の前にあるかということであり、これが対象を持つ恐怖と異なる点である。人は恐怖の対象を取 り除くための手段を講じることができるが、怒りにはそのような「建設的」な手段は不可能である。この文脈で「無」という言葉が使われているのは、自分の行 動の結果に対する本質的な不安と、アングストとして自由を経験することで、その結果に対する全責任が自分にあることにも気づくという事実に関連している。 人の中には(例えば遺伝的に)自分の代わりに行動してくれるもの、つまり何か問題が起きたときに非難できるものはない。したがって、すべての選択が恐ろし い結果をもたらす可能性があると認識されるわけではない(そして、すべての選択が恐怖を助長するならば、人間の生活は耐え難いものになるだろうと主張する こともできる)。しかし、自由があらゆる行動の条件であることに変わりはない。 絶望[編集] 主な記事 絶望 以下も参照のこと: 実存的危機 絶望は一般的に希望の喪失と定義される[52]。 実存主義においては、より具体的には、自己やアイデンティティを定義する一つ以上の特質が崩れたことに対する希望の喪失である。ある人が、バスの運転手や 立派な市民といった特定のものであることに投資しており、その後、その存在であることが損なわれていることに気づいた場合、その人は通常、絶望の状態、つ まり絶望的な状態に置かれることになる。例えば、歌唱力を失った歌手が絶望するのは、他に頼れるものがない、つまり自分のアイデンティティを確立できない からだ。自分の存在を定義していたものになりきれない自分に気づくのだ。 実存主義的な絶望の概念が従来の定義と異なるのは、実存主義的な絶望は、あからさまに絶望していないときでもその人が置かれている状態だということだ。サ ルトルの言葉を借りれば、従来の現実には個人のアイデンティティを構成する人間の本質が存在しないため、絶望は普遍的な人間の状態なのである。キルケゴー ルは『 どちらか/あるいは』の中で次のように定義している。「各自ができることを学ぼう。私たちはともに、人の不幸は決して外的条件を制御できないことにあるの ではないことを学ぶことができる: 神に見捨てられた地上生活の世俗性が自己満足に閉じこもり、閉ざされた空気が毒を発生させ、瞬間が動けなくなり、立ち止まり、展望が失われるとき、私たち が世俗性の中で窒息しないように、空気を浄化し、毒の蒸気を吹き飛ばす、さわやかで活気づける風が必要と感じられる。... 愛情をもってすべてを望むことは、絶望して何も望まないこととは正反対である。愛はあらゆることを望むが、決して恥じることはない。良いことの可能性に期 待して身を投じることは、希望を抱くことである。悪の可能性に期待することは恐れることである。希望を選ぶという決断は、永遠の決断であるため、見かけ以 上に無限に多くのことを決断する。 - セーレン・キルケゴール『愛の著作集 |

| Opposition to positivism and

rationalism See also: Positivism and Rationalism Existentialists oppose defining human beings as primarily rational, and, therefore, oppose both positivism and rationalism. Existentialism asserts that people make decisions based on subjective meaning rather than pure rationality. The rejection of reason as the source of meaning is a common theme of existentialist thought, as is the focus on the anxiety and dread that we feel in the face of our own radical free will and our awareness of death. Kierkegaard advocated rationality as a means to interact with the objective world (e.g., in the natural sciences), but when it comes to existential problems, reason is insufficient: "Human reason has boundaries".[54] Like Kierkegaard, Sartre saw problems with rationality, calling it a form of "bad faith", an attempt by the self to impose structure on a world of phenomena—"the Other"—that is fundamentally irrational and random. According to Sartre, rationality and other forms of bad faith hinder people from finding meaning in freedom. To try to suppress feelings of anxiety and dread, people confine themselves within everyday experience, Sartre asserted, thereby relinquishing their freedom and acquiescing to being possessed in one form or another by "the Look" of "the Other" (i.e., possessed by another person—or at least one's idea of that other person).[55] |

実証主義と合理主義への反対[編集]。 以下も参照のこと: 実証主義と合理主義 実存主義者は、人間を主として合理的であると定義することに反対し、したがって実証主義と合理主義の両方に反対する。実存主義は、人は純粋な合理性よりも 主観的な意味に基づいて意思決定を行うと主張する。意味の源泉としての理性の否定は、実存主義思想の共通テーマであり、自分自身の根本的な自由意志や死を 意識することで感じる不安や 恐怖に焦点を当てている。キルケゴールは、(自然科学など)客観的世界と対話する手段として合理性を提唱したが、実存的問題となると、理性では不十分であ る: 「人間の理性には限界がある」[54]。 キルケゴールのように、サルトルは合理性に問題があると考え、それを「悪意」の一形態であり、根本的に非合理的でランダムである現象世界-「他者」-に構 造を押し付けようとする自己の試みであると呼んだ。サルトルによれば、合理性や他の形態の悪意は、人々が自由の意味を見出すのを妨げる。不安や恐怖の感情 を抑えようとするために、人々は日常的な経験の中に自らを閉じ込め、それによって自由を放棄し、「他者」の「視線」(すなわち、他者によって、あるいは少 なくともその他者についての自分の考え)によって何らかの形で憑依されることを承諾するのだとサルトルは主張した[55]。 |

| Religion See also: Atheistic existentialism, Christian existentialism, and Jewish existentialism An existentialist reading of the Bible would demand that the reader recognize that they are an existing subject studying the words more as a recollection of events. This is in contrast to looking at a collection of "truths" that are outside and unrelated to the reader, but may develop a sense of reality/God. Such a reader is not obligated to follow the commandments as if an external agent is forcing these commandments upon them, but as though they are inside them and guiding them from inside. This is the task Kierkegaard takes up when he asks: "Who has the more difficult task: the teacher who lectures on earnest things a meteor's distance from everyday life—or the learner who should put it to use?"[56] Philosophers such as Hans Jonas and Rudolph Bultmann introduced the concept of existentialist demythologization into the field of Early Christianity and Christian Theology, respectively.[57] |

宗教[編集] 以下も参照のこと: 無神論的実存主義、キリスト教的実存主義、ユダヤ教的実存主義 実存主義的な聖書の読み方は、読者に対して、自分自身が現存する主体であることを認識し、その言葉を出来事の回想として研究することを要求する。これは、 読者の外側にあり、読者とは無関係であるが、現実/神の感覚を発展させるかもしれない「真理」の集まりを見るのとは対照的である。そのような読者は、あた かも外部の存在が戒律を強制しているかのように戒律に従う義務を負うのではなく、あたかも戒律が読者の内側にあり、内側から導いているかのように戒律に従 うのである。これが、キルケゴールが問いかける課題である: 「日常生活から流星のような距離を置いて切実なことを講義する教師と、それを活用すべき学習者の、どちらがより困難な任務を負っているのだろうか」 [56] ハンス・ヨナスや ルドルフ・ブルトマンといった哲学者は、実存主義的な脱神話化の概念を、それぞれ初期キリスト教と キリスト教神学の分野に導入した[57]。 |

| Confusion with nihilism See also: Existential nihilism Although nihilism and existentialism are distinct philosophies, they are often confused with one another since both are rooted in the human experience of anguish and confusion that stems from the apparent meaninglessness of a world in which humans are compelled to find or create meaning.[58] A primary cause of confusion is that Friedrich Nietzsche was an important philosopher in both fields. Existentialist philosophers often stress the importance of angst as signifying the absolute lack of any objective ground for action, a move that is often reduced to moral or existential nihilism. A pervasive theme in existentialist philosophy, however, is to persist through encounters with the absurd, as seen in Albert Camus's philosophical essay The Myth of Sisyphus (1942): "One must imagine Sisyphus happy".[59] and it is only very rarely that existentialist philosophers dismiss morality or one's self-created meaning: Søren Kierkegaard regained a sort of morality in the religious (although he would not agree that it was ethical; the religious suspends the ethical), and Jean-Paul Sartre's final words in Being and Nothingness (1943): "All these questions, which refer us to a pure and not an accessory (or impure) reflection, can find their reply only on the ethical plane. We shall devote to them a future work."[44] |

ニヒリズムとの混同[編集]。 以下も参照のこと: 実存的ニヒリズム ニヒリズムと実存主義は別個の哲学であるが、どちらも人間が意味を見出したり創造したりせざるを得ない世界の明白な無意味さから生じる苦悩や混乱という人 間の経験に根ざしているため、しばしば混同される。 実存主義の哲学者たちは、行動に対する客観的根拠の絶対的な欠如を意味するものとして、しばしば怒りの重要性を強調するが、この動きはしばしば道徳的 ニヒリズムや実存的ニヒリズムに還元される。しかし、実存主義哲学に蔓延するテーマは、アルベール・カミュの哲学的エッセイ『シジフォスの神話』 (1942年)に見られるように、不条理との出会いを耐え抜くことである: 「人はシジフォスの幸福を想像しなければならない」[59]。実存主義の哲学者が道徳や自分で作り出した意味を否定することはごく稀である: セーレン・キルケゴールは宗教的なものの中にある種の道徳性を取り戻し(彼はそれが倫理的なものだとは認めないだろうが;宗教的なものは倫理的なものを保 留する)、ジャン=ポール・サルトルは『存在と無』(1943年)の中で最後の言葉を残した: 「付属的な(あるいは不純な)反省ではなく、純粋な反省に私たちを導くこれらの問いはすべて、倫理的な面においてのみ答えを見出すことができる。われわれ は将来、この問題に取り組むことになるだろう」[44]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Existentialism |

| History Precursors Some have argued that existentialism has long been an element of European religious thought, even before the term came into use. William Barrett identified Blaise Pascal and Søren Kierkegaard as two specific examples.[60] Jean Wahl also identified William Shakespeare's Prince Hamlet ("To be, or not to be"), Jules Lequier, Thomas Carlyle, and William James as existentialists. According to Wahl, "the origins of most great philosophies, like those of Plato, Descartes, and Kant, are to be found in existential reflections."[61] Precursors to existentialism can also be identified in the works of Iranian Muslim philosopher Mulla Sadra (c. 1571–1635), who would posit that "existence precedes essence" becoming the principle expositor of the School of Isfahan, which is described as "alive and active".[according to whom?] 19th century Kierkegaard and Nietzsche Main article: Søren Kierkegaard and Friedrich Nietzsche Kierkegaard is generally considered to have been the first existentialist philosopher.[4][62][63] He proposed that each individual—not reason, society, or religious orthodoxy—is solely tasked with giving meaning to life and living it sincerely, or "authentically".[64][65] Kierkegaard and Nietzsche were two of the first philosophers considered fundamental to the existentialist movement, though neither used the term "existentialism" and it is unclear whether they would have supported the existentialism of the 20th century. They focused on subjective human experience rather than the objective truths of mathematics and science, which they believed were too detached or observational to truly get at the human experience. Like Pascal, they were interested in people's quiet struggle with the apparent meaninglessness of life and the use of diversion to escape from boredom. Unlike Pascal, Kierkegaard and Nietzsche also considered the role of making free choices, particularly regarding fundamental values and beliefs, and how such choices change the nature and identity of the chooser.[66] Kierkegaard's knight of faith and Nietzsche's Übermensch are representative of people who exhibit freedom, in that they define the nature of their own existence. Nietzsche's idealized individual invents his own values and creates the very terms they excel under. By contrast, Kierkegaard, opposed to the level of abstraction in Hegel, and not nearly as hostile (actually welcoming) to Christianity as Nietzsche, argues through a pseudonym that the objective certainty of religious truths (specifically Christian) is not only impossible, but even founded on logical paradoxes. Yet he continues to imply that a leap of faith is a possible means for an individual to reach a higher stage of existence that transcends and contains both an aesthetic and ethical value of life. Kierkegaard and Nietzsche were also precursors to other intellectual movements, including postmodernism, and various strands of psychotherapy.[citation needed] However, Kierkegaard believed that individuals should live in accordance with their thinking.[67] In Twilight of the Idols, Nietzsche's sentiments resonate the idea of "existence precedes essence." He writes, "no one gives man his qualities-- neither God, nor society, nor his parents and ancestors, nor he himself...No one is responsible for man's being there at all, for his being such-and-such, or for his being in these circumstances or in this environment...Man is not the effect of some special purpose of a will, and end..."[68] Within this view, Nietzsche ties in his rejection of the existence of God, which he sees as a means to "redeem the world." By rejecting the existence of God, Nietzsche also rejects beliefs that claim humans have a predestined purpose according to what God has instructed. Dostoyevsky The first important literary author also important to existentialism was the Russian, Dostoyevsky.[69] Dostoyevsky's Notes from Underground portrays a man unable to fit into society and unhappy with the identities he creates for himself. Sartre, in his book on existentialism Existentialism is a Humanism, quoted Dostoyevsky's The Brothers Karamazov as an example of existential crisis. Other Dostoyevsky novels covered issues raised in existentialist philosophy while presenting story lines divergent from secular existentialism: for example, in Crime and Punishment, the protagonist Raskolnikov experiences an existential crisis and then moves toward a Christian Orthodox worldview similar to that advocated by Dostoyevsky himself.[70] Early 20th century See also: Martin Heidegger In the first decades of the 20th century, a number of philosophers and writers explored existentialist ideas. The Spanish philosopher Miguel de Unamuno y Jugo, in his 1913 book The Tragic Sense of Life in Men and Nations, emphasized the life of "flesh and bone" as opposed to that of abstract rationalism. Unamuno rejected systematic philosophy in favor of the individual's quest for faith. He retained a sense of the tragic, even absurd nature of the quest, symbolized by his enduring interest in the eponymous character from the Miguel de Cervantes novel Don Quixote. A novelist, poet and dramatist as well as philosophy professor at the University of Salamanca, Unamuno wrote a short story about a priest's crisis of faith, Saint Manuel the Good, Martyr, which has been collected in anthologies of existentialist fiction. Another Spanish thinker, José Ortega y Gasset, writing in 1914, held that human existence must always be defined as the individual person combined with the concrete circumstances of his life: "Yo soy yo y mi circunstancia" ("I am myself and my circumstances"). Sartre likewise believed that human existence is not an abstract matter, but is always situated ("en situation").[citation needed] Although Martin Buber wrote his major philosophical works in German, and studied and taught at the Universities of Berlin and Frankfurt, he stands apart from the mainstream of German philosophy. Born into a Jewish family in Vienna in 1878, he was also a scholar of Jewish culture and involved at various times in Zionism and Hasidism. In 1938, he moved permanently to Jerusalem. His best-known philosophical work was the short book I and Thou, published in 1922.[71] For Buber, the fundamental fact of human existence, too readily overlooked by scientific rationalism and abstract philosophical thought, is "man with man", a dialogue that takes place in the so-called "sphere of between" ("das Zwischenmenschliche").[72] Two Russian philosophers, Lev Shestov and Nikolai Berdyaev, became well known as existentialist thinkers during their post-Revolutionary exiles in Paris. Shestov had launched an attack on rationalism and systematization in philosophy as early as 1905 in his book of aphorisms All Things Are Possible. Berdyaev drew a radical distinction between the world of spirit and the everyday world of objects. Human freedom, for Berdyaev, is rooted in the realm of spirit, a realm independent of scientific notions of causation. To the extent the individual human being lives in the objective world, he is estranged from authentic spiritual freedom. "Man" is not to be interpreted naturalistically, but as a being created in God's image, an originator of free, creative acts.[73] He published a major work on these themes, The Destiny of Man, in 1931. Gabriel Marcel, long before coining the term "existentialism", introduced important existentialist themes to a French audience in his early essay "Existence and Objectivity" (1925) and in his Metaphysical Journal (1927).[74] A dramatist as well as a philosopher, Marcel found his philosophical starting point in a condition of metaphysical alienation: the human individual searching for harmony in a transient life. Harmony, for Marcel, was to be sought through "secondary reflection", a "dialogical" rather than "dialectical" approach to the world, characterized by "wonder and astonishment" and open to the "presence" of other people and of God rather than merely to "information" about them. For Marcel, such presence implied more than simply being there (as one thing might be in the presence of another thing); it connoted "extravagant" availability, and the willingness to put oneself at the disposal of the other.[75] Marcel contrasted secondary reflection with abstract, scientific-technical primary reflection, which he associated with the activity of the abstract Cartesian ego. For Marcel, philosophy was a concrete activity undertaken by a sensing, feeling human being incarnate—embodied—in a concrete world.[74][76] Although Sartre adopted the term "existentialism" for his own philosophy in the 1940s, Marcel's thought has been described as "almost diametrically opposed" to that of Sartre.[74] Unlike Sartre, Marcel was a Christian, and became a Catholic convert in 1929. In Germany, the psychologist and philosopher Karl Jaspers—who later described existentialism as a "phantom" created by the public[77]—called his own thought, heavily influenced by Kierkegaard and Nietzsche, Existenzphilosophie. For Jaspers, "Existenz-philosophy is the way of thought by means of which man seeks to become himself...This way of thought does not cognize objects, but elucidates and makes actual the being of the thinker".[78] Jaspers, a professor at the university of Heidelberg, was acquainted with Heidegger, who held a professorship at Marburg before acceding to Husserl's chair at Freiburg in 1928. They held many philosophical discussions, but later became estranged over Heidegger's support of National Socialism. They shared an admiration for Kierkegaard,[79] and in the 1930s, Heidegger lectured extensively on Nietzsche. Nevertheless, the extent to which Heidegger should be considered an existentialist is debatable. In Being and Time he presented a method of rooting philosophical explanations in human existence (Dasein) to be analysed in terms of existential categories (existentiale); and this has led many commentators to treat him as an important figure in the existentialist movement. After the Second World War Following the Second World War, existentialism became a well-known and significant philosophical and cultural movement, mainly through the public prominence of two French writers, Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus, who wrote best-selling novels, plays and widely read journalism as well as theoretical texts.[80] These years also saw the growing reputation of Being and Time outside Germany. French philosophers Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir Sartre dealt with existentialist themes in his 1938 novel Nausea and the short stories in his 1939 collection The Wall, and had published his treatise on existentialism, Being and Nothingness, in 1943, but it was in the two years following the liberation of Paris from the German occupying forces that he and his close associates—Camus, Simone de Beauvoir, Maurice Merleau-Ponty, and others—became internationally famous as the leading figures of a movement known as existentialism.[81] In a very short period of time, Camus and Sartre in particular became the leading public intellectuals of post-war France, achieving by the end of 1945 "a fame that reached across all audiences."[82] Camus was an editor of the most popular leftist (former French Resistance) newspaper Combat; Sartre launched his journal of leftist thought, Les Temps Modernes, and two weeks later gave the widely reported lecture on existentialism and secular humanism to a packed meeting of the Club Maintenant. Beauvoir wrote that "not a week passed without the newspapers discussing us";[83] existentialism became "the first media craze of the postwar era."[84] By the end of 1947, Camus' earlier fiction and plays had been reprinted, his new play Caligula had been performed and his novel The Plague published; the first two novels of Sartre's The Roads to Freedom trilogy had appeared, as had Beauvoir's novel The Blood of Others. Works by Camus and Sartre were already appearing in foreign editions. The Paris-based existentialists had become famous.[81] Sartre had traveled to Germany in 1930 to study the phenomenology of Edmund Husserl and Martin Heidegger,[85] and he included critical comments on their work in his major treatise Being and Nothingness. Heidegger's thought had also become known in French philosophical circles through its use by Alexandre Kojève in explicating Hegel in a series of lectures given in Paris in the 1930s.[86] The lectures were highly influential; members of the audience included not only Sartre and Merleau-Ponty, but Raymond Queneau, Georges Bataille, Louis Althusser, André Breton, and Jacques Lacan.[87] A selection from Being and Time was published in French in 1938, and his essays began to appear in French philosophy journals. French philosopher, novelist, and playwright Albert Camus Heidegger read Sartre's work and was initially impressed, commenting: "Here for the first time I encountered an independent thinker who, from the foundations up, has experienced the area out of which I think. Your work shows such an immediate comprehension of my philosophy as I have never before encountered."[88] Later, however, in response to a question posed by his French follower Jean Beaufret,[89] Heidegger distanced himself from Sartre's position and existentialism in general in his Letter on Humanism.[90] Heidegger's reputation continued to grow in France during the 1950s and 1960s. In the 1960s, Sartre attempted to reconcile existentialism and Marxism in his work Critique of Dialectical Reason. A major theme throughout his writings was freedom and responsibility. Camus was a friend of Sartre, until their falling-out, and wrote several works with existential themes including The Rebel, Summer in Algiers, The Myth of Sisyphus, and The Stranger, the latter being "considered—to what would have been Camus's irritation—the exemplary existentialist novel."[91] Camus, like many others, rejected the existentialist label, and considered his works concerned with facing the absurd. In the titular book, Camus uses the analogy of the Greek myth of Sisyphus to demonstrate the futility of existence. In the myth, Sisyphus is condemned for eternity to roll a rock up a hill, but when he reaches the summit, the rock will roll to the bottom again. Camus believes that this existence is pointless but that Sisyphus ultimately finds meaning and purpose in his task, simply by continually applying himself to it. The first half of the book contains an extended rebuttal of what Camus took to be existentialist philosophy in the works of Kierkegaard, Shestov, Heidegger, and Jaspers. Simone de Beauvoir, an important existentialist who spent much of her life as Sartre's partner, wrote about feminist and existentialist ethics in her works, including The Second Sex and The Ethics of Ambiguity. Although often overlooked due to her relationship with Sartre,[92] de Beauvoir integrated existentialism with other forms of thinking such as feminism, unheard of at the time, resulting in alienation from fellow writers such as Camus.[70] Paul Tillich, an important existentialist theologian following Kierkegaard and Karl Barth, applied existentialist concepts to Christian theology, and helped introduce existential theology to the general public. His seminal work The Courage to Be follows Kierkegaard's analysis of anxiety and life's absurdity, but puts forward the thesis that modern humans must, via God, achieve selfhood in spite of life's absurdity. Rudolf Bultmann used Kierkegaard's and Heidegger's philosophy of existence to demythologize Christianity by interpreting Christian mythical concepts into existentialist concepts. Maurice Merleau-Ponty, an existential phenomenologist, was for a time a companion of Sartre. Merleau-Ponty's Phenomenology of Perception (1945) was recognized as a major statement of French existentialism.[93] It has been said that Merleau-Ponty's work Humanism and Terror greatly influenced Sartre. However, in later years they were to disagree irreparably, dividing many existentialists such as de Beauvoir,[70] who sided with Sartre. Colin Wilson, an English writer, published his study The Outsider in 1956, initially to critical acclaim. In this book and others (e.g. Introduction to the New Existentialism), he attempted to reinvigorate what he perceived as a pessimistic philosophy and bring it to a wider audience. He was not, however, academically trained, and his work was attacked by professional philosophers for lack of rigor and critical standards.[94] |

歴史[編集] 前身[編集] 実存主義という言葉が使われるようになる以前から、実存主義はヨーロッパの宗教思想の要素であったと主張する者もいる。ウィリアム・バレットは ブレーズ・パスカルと セーレン・キェルケゴールを2つの具体例として挙げている[60]。ジャン・ウォールも ウィリアム・シェイクスピアの ハムレット王子(「To be, or not to be」)、ジュール・レキエ、トマス・カーライル、ウィリアム・ジェームズを実存主義者として挙げている。ワールによれば、「プラトン、デカルト、カント のようなほとんどの偉大な哲学の起源は、実存的考察の中に見出すことができる」[61]。実存主義の前身は、イランのイスラム哲学者であるムラ・サドラ (1571年頃~1635年)の著作にも見出すことができ、彼は「実存は本質に先行する」と唱え、「生き生きと活動している」と評されるイスファハン学派 の主要な論者となった。 19世紀[編集] キルケゴールとニーチェ[編集]。 主な記事 セーレン・キルケゴールとフリードリヒ・ニーチェ キルケゴールは一般的に最初の実存主義の哲学者であると考えられている[4][62][63]。 彼は、理性でも社会でも宗教の正統性でもなく、各個人が人生に意味を与え、それを誠実に生きること、すなわち「真正に」生きることだけが唯一の使命である と提唱した[64][65]。 キルケゴールとニーチェは実存主義運動の根幹をなすと考えられている最初の哲学者の2人であったが、どちらも「実存主義」という言葉は使っておらず、彼ら が20世紀の実存主義を支持していたかどうかは不明である。彼らは、数学や科学の客観的真理よりも、主観的な人間の経験に焦点を当てた。パスカルと同様、 彼らは、人生の無意味さとの静かな葛藤や、退屈から逃れるための気晴らしに関心を寄せていた。パスカルとは異なり、キルケゴールやニーチェはまた、特に基 本的な価値観や信念に関して、自由な選択をすることの役割や、そのような選択が選択者の性質やアイデンティティをどのように変化させるかについて考えてい た[66]。ニーチェの理想化された個人は、自分自身の価値観を発明し、その価値観が卓越する条件そのものを作り出している。対照的に、キルケゴールは、 ヘーゲルの抽象化のレベルに反対し、ニーチェほどキリスト教に敵対していない(実際には歓迎している)が、仮名を通して、宗教的真理(特にキリスト教)の 客観的確実性は不可能であるだけでなく、論理的逆説の上に成り立っているとさえ主張している。しかし彼は、個人が美的価値と倫理的価値の両方を超越した、 より高次の存在段階に到達するためには、信仰の飛躍が可能な手段であるとほのめかし続けている。キルケゴールとニーチェはまた、ポストモダニズムや様々な 心理療法など、他の知的運動の先駆者でもあった。 ニーチェは『偶像の黄昏』の中で、"存在は本質に先立つ "という考え方に共鳴している。神も、社会も、彼の両親や先祖も、彼自身も...人間がそこにいること、彼がそのような存在であること、彼がこのような状 況や環境にいることについては、誰も責任を負っていない...人間は、意志や目的といった特別な目的の結果ではない...」[68]。この見解の中で、 ニーチェは神の存在に対する拒絶を結びつけている。神の存在を否定することで、ニーチェは、神が指示したことに従って人間が定められた目的を持っていると 主張する信仰も否定している。 ドストエフスキー[編集] 実存主義にとっても重要な最初の文学者は、ロシアのドストエフスキーである[69]。ドストエフスキーの『地下からの覚書』は、社会に適合することができ ず、自ら作り出したアイデンティティに不満を抱く男を描いている。サルトルは実存主義に関する著書『実存主義はヒューマニズムである』の中で、実存的危機 の例としてドストエフスキーの『カラマーゾフの兄弟』を引用している。例えば、『罪と罰』では、主人公のラスコーリニコフが実存的危機を経験した後、ドス トエフスキー自身が提唱したのと同じようなキリスト教正統派の世界観へと向かっていく[70]。 20世紀初頭[編集] 以下も参照のこと: マルティン・ハイデガー 20世紀の最初の数十年間、多くの哲学者や作家が実存主義の思想を探求した。スペインの哲学者であるミゲル・デ・ウナムーノ・イ・ジュゴは、1913年に 出版した『人間と国家における生の悲劇的感覚』の中で、抽象的な合理主義とは対照的に「肉と骨」の生を強調した。ウナムーノは体系的な哲学を否定し、個人 の信仰の探求を支持した。彼は、ミゲル・デ・セルバンテスの小説『ドン・キホーテ』の登場人物への永続的な関心に象徴されるように、探求の悲劇的で不条理 ですらある本質を感じ続けていた。小説家、詩人、劇作家であり、サラマンカ大学の哲学教授でもあったウナムーノは、司祭の信仰の危機を描いた短編小説『殉 教者聖マヌエル』を書き、実存主義小説のアンソロジーに収められている。もう一人のスペインの思想家、ホセ・オルテガ・イ・ガセットは1914年に、人間 の存在とは常に、個人と人生の具体的な状況との組み合わせとして定義されなければならないとした。サルトルも同様に、人間の存在は抽象的な問題ではなく、 常に状況に置かれていると考えていた。 マルティン・ブーバーは主要な哲学的著作をドイツ語で執筆し、ベルリン大学とフランクフルト大学で学び、教えていたが、ドイツ哲学の主流からは離れてい た。1878年にウィーンのユダヤ人家庭に生まれたブーバーは、ユダヤ文化の研究者でもあり、シオニズムや ハシディズムにさまざまな形で関わった。1938年にはエルサレムに永住した。ブーバーにとって、人間存在の根本的な事実は、科学的合理主義や抽象的な哲 学的思考によってあまりにも簡単に見過ごされてしまうが、「人間と人間」であり、いわゆる「間の領域」(「das Zwischenmenschliche」)で行われる対話である[72]。 レフ・シェストフと ニコライ・ベルジャエフという二人のロシア人哲学者は、革命後のパリ亡命中に実存主義思想家としてよく知られるようになった。シェストフは1905年、 『万物は可能である』という格言集で、早くも哲学における合理主義と体系化への攻撃を開始した。ベルジャエフは、精神の世界と日常的な物の世界とを根本的 に区別した。ベルニャエフにとって人間の自由とは、科学的な因果関係の概念から独立した精神の領域に根ざしている。個々の人間が客観的な世界に生きている 限り、彼は本物の精神的自由から遠ざかっている。「人間」は自然主義的に解釈されるべきものではなく、神に似せて創造された存在であり、自由で創造的な行 為の創始者である[73]。 ガブリエル・マルセル(Gabriel Marcel)は、「実存主義」という言葉を作るずっと前に、初期のエッセイ『実存と客観性』(1925年)や『形而上学雑誌』(1927年)の中で、フ ランスの聴衆に実存主義の重要なテーマを紹介している[74]。マルセルにとっての調和とは、「弁証法的」ではなく「対話的」な世界に対するアプローチで あり、「驚きと驚愕」を特徴とし、他者や神についての単なる「情報」ではなく、その「存在」に開かれた「二次的反省」によって求められるものであった。マ ルセルにとって、このような「プレゼンス」は、単にそこに存在する(あるものが別のものの前に存在するように)以上のことを意味し、「贅沢な」利用可能 性、そして他者の自由に身を委ねる意思を含意していた[75]。 マルセルは二次的な内省を抽象的で科学技術的な一次的な内省と対比させ、抽象的なデカルト的自我の活動と結びつけていた。サルトルは1940年代に自身の 哲学に「実存主義」という言葉を採用したが、マルセルの思想はサルトルのそれとは「ほとんど正反対」と評されている[74]。サルトルとは異なり、マルセ ルはキリスト教徒であり、1929年にカトリックに改宗した。 ドイツでは、心理学者であり哲学者であったカール・ヤスパースが、後に実存主義を大衆によって作り出された「幻影」であると評し[77]、キルケゴールと ニーチェの影響を強く受けた自身の思想を「実存哲学」と呼んでいた。ヤスパースにとって、「実存哲学とは、人間が自分自身になろうとする思考の方法であ る......この思考の方法は対象を認識するのではなく、思考者の存在を解明し、現実化するものである」[78]。 ハイデルベルク大学の教授であったヤスパースは、ハイデガーと面識があった。ハイデガーはマールブルクで教授職を務めた後、1928年にフライブルクで フッサールの講座に就任した。二人は多くの哲学的議論を交わしたが、ハイデガーが国家社会主義を支持していたことから、後に疎遠になった。二人はキルケ ゴールに対する尊敬の念を共有しており[79]、1930年代にはハイデガーはニーチェについて広く講義を行っていた。とはいえ、ハイデガーをどこまで実 存主義者とみなすべきかは議論の余地がある。ハイデガーは『存在と時間』において、哲学的説明を人間の存在(Dasein)に根付かせ、実存的カテゴリー (existentiale)の観点から分析するという方法を提示した。 第二次世界大戦後[編集] 第二次世界大戦後、実存主義は、主にジャン=ポール・サルトルと アルベール・カミュという二人のフランス人作家の活躍によって、よく知られた重要な哲学的・文化的運動となり、彼らは理論的なテキストだけでなく、ベスト セラーの小説や戯曲、広く読まれるジャーナリズムを書いた[80]。 フランスの哲学者ジャン=ポール・サルトルと シモーヌ・ド・ボーヴォワールは、『存在と時間』を実存主義的な思想として扱った。 サルトルは1938年の小説『吐き気』や1939年の作品集『壁』の短編で実存主義のテーマを扱い、1943年には実存主義に関する論考『存在と無』を出 版していたが、彼と彼の側近であるカミュ、シモーヌ・ド・ボーヴォワール、モーリス・メルロ=ポンティらが実存主義として知られる運動の中心人物として国 際的に有名になったのは、ドイツ占領軍からのパリ解放後の2年間であった。 [カミュとサルトルは特に短期間のうちに戦後フランスを代表する知識人となり、1945年末には「あらゆる聴衆に届く名声」を獲得した[82]。サルトル は左翼思想の雑誌『レ・タン・モダン』を創刊し、その2週間後にはクラブ・マントナンの満員の会合で実存主義と世俗的ヒューマニズムに関する講演を行い、 広く報道された。ボーヴォワールは「新聞が私たちのことを論じない週はなかった」と書いている[83]。実存主義は「戦後最初のメディア・ブーム」となっ た[84]。 1947年末までに、カミュの初期の小説と戯曲は再版され、新作の戯曲『カリギュラ』は上演され、小説『ペスト』は出版された。サルトルの『自由への道』 三部作の最初の二作が発表され、ボーヴォワールの小説『他人の血』も発表された。カミュとサルトルの作品はすでに海外版で出版されていた。パリを拠点とす る実存主義者たちは有名になっていた[81]。 サルトルは1930年にドイツに渡り、エドムント・フッサールと マルティン・ハイデガーの 現象学を学んでおり[85]、彼の主要な論考である『存在と無』には彼らの仕事に対する批判的なコメントが含まれていた。ハイデガーの思想はまた、アレク サンドル・コジェーヴが1930年代にパリで行った一連の講義でヘーゲルを説明する際に用いたことで、フランスの哲学界でも知られるようになっていた [86]。この講義は大きな影響力を持ち、聴衆のメンバーにはサルトルやメルロ=ポンティだけでなく、レイモン・クノー、ジョルジュ・バタイユ、ルイ・ア ルチュセール、アンドレ・ブルトン、ジャック・ラカンなどが含まれていた[87]。1938年には『存在と時間』からの抜粋がフランス語で出版され、彼の エッセイがフランスの哲学雑誌に掲載され始めた。 フランスの哲学者、小説家、劇作家であるアルベール・カミュは、サルトルのエッセイを読んでいた。 ハイデガーはサルトルの著作を読み、最初に感銘を受け、こうコメントした: 「私はここで初めて、私が考える領域を基礎から経験した独立した思想家に出会った。ハイデガーの評価は1950年代から1960年代にかけてフランスで高 まり続けた。1960年代、サルトルは『弁証法的理性批判』の中で実存主義とマルクス主義の融和を試みた。彼の著作の主要なテーマは自由と責任であった。 カミュはサルトルの友人であり、『反逆者』、『アルジェの夏』、『シジフォスの神話』、『ストレンジャー』など、実存主義をテーマにした作品を書いた。表 題作の中でカミュは、存在の無益さを示すためにギリシャ神話のシジフォスのアナロジーを用いている。神話では、シジフォスは永遠に石を転がして丘を登るこ とを宣告されるが、頂上に到達しても、石は再び下まで転がっていく。カミュは、このような存在は無意味だが、シジフォスは最終的に、ただひたすらその仕事 に打ち込むことによって、その仕事に意味と目的を見出すのだと考えている。本書の前半には、カミュがキルケゴール、シェストフ、ハイデガー、ヤスパースの 作品から実存主義哲学とみなしたものに対する反論が延々と書かれている。 シモーヌ・ド・ボーヴォワールは、サルトルのパートナーとして人生の大半を過ごした重要な実存主義者であり、『第二の性』や『曖昧さの倫理学』などの著作 の中で、フェミニズムと実存主義の倫理について書いている。サルトルとの関係から見過ごされがちであるが[92]、ド・ボーヴォワールは実存主義をフェミ ニズムなどの他の思考形態と統合した。 キルケゴールやカール・バルトに続く重要な実存主義神学者であるパウル・ティリッヒは、キリスト教神学に実存主義の概念を適用し、実存主義神学を一般大衆 に紹介するのに貢献した。彼の代表的な著作『存在する勇気』は、キルケゴールの不安と人生の不条理についての分析を踏襲しつつも、現代人は人生の不条理に もかかわらず、神を介して自我を獲得しなければならないというテーゼを提唱している。ルドルフ・ブルルトマンは、キルケゴールとハイデガーの実存哲学を用 いて、キリスト教の神話的概念を実存主義的概念に解釈することで、キリスト教を脱神話化した。 実存現象学者であるモーリス・メルロ=ポンティは、一時期サルトルの仲間だった。メルロ=ポンティの『知覚の現象学』(1945年)はフランス実存主義の 主要な声明として認識されている。しかし後年、両者は修復不可能なほど意見が対立し、サルトルに味方したド・ボーヴォワール[70]など多くの実存主義者 を分裂させることになる。 イギリスの作家であるコリン・ウィルソンは、1956年に『アウトサイダー』という研究書を出版し、当初は批評家の称賛を浴びた。この本や他の本(『新実 存主義入門』など)において、彼は厭世的な哲学として認識されていたものを再活性化し、より多くの読者に届けようとした。しかし、彼はアカデミックな訓練 を受けておらず、彼の著作は厳密さや批評的基準が欠けているとして、プロの哲学者たちから攻撃された[94]。 |

| Influence outside philosophy Art Film and television Adolphe Menjou (left) and Kirk Douglas (right) in Paths of Glory (1957) Stanley Kubrick's 1957 anti-war film Paths of Glory "illustrates, and even illuminates...existentialism" by examining the "necessary absurdity of the human condition" and the "horror of war".[95] The film tells the story of a fictional World War I French army regiment ordered to attack an impregnable German stronghold; when the attack fails, three soldiers are chosen at random, court-martialed by a "kangaroo court", and executed by firing squad. The film examines existentialist ethics, such as the issue of whether objectivity is possible and the "problem of authenticity".[95] Orson Welles's 1962 film The Trial, based upon Franz Kafka's book of the same name (Der Prozeß), is characteristic of both existentialist and absurdist themes in its depiction of a man (Joseph K.) arrested for a crime for which the charges are neither revealed to him nor to the reader. Neon Genesis Evangelion is a Japanese science fiction animation series created by the anime studio Gainax and was both directed and written by Hideaki Anno. Existential themes of individuality, consciousness, freedom, choice, and responsibility are heavily relied upon throughout the entire series, particularly through the philosophies of Jean-Paul Sartre and Søren Kierkegaard. Episode 16's title, "The Sickness Unto Death, And..." (死に至る病、そして, Shi ni itaru yamai, soshite) is a reference to Kierkegaard's book, The Sickness Unto Death. Some contemporary films dealing with existentialist issues include Melancholia, Fight Club, I Heart Huckabees, Waking Life, The Matrix, Ordinary People, Life in a Day, Barbie, and Everything Everywhere All at Once.[96] Likewise, films throughout the 20th century such as The Seventh Seal, Ikiru, Taxi Driver, the Toy Story films, The Great Silence, Ghost in the Shell, Harold and Maude, High Noon, Easy Rider, One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest, A Clockwork Orange, Groundhog Day, Apocalypse Now, Badlands, and Blade Runner also have existentialist qualities.[97] Notable directors known for their existentialist films include Ingmar Bergman, Bela Tarr, Robert Bresson, Jean-Pierre Melville, François Truffaut, Jean-Luc Godard, Michelangelo Antonioni, Akira Kurosawa, Terrence Malick, Stanley Kubrick, Andrei Tarkovsky, Éric Rohmer, Wes Anderson, Woody Allen, and Christopher Nolan.[98] Charlie Kaufman's Synecdoche, New York focuses on the protagonist's desire to find existential meaning.[99] Similarly, in Kurosawa's Red Beard, the protagonist's experiences as an intern in a rural health clinic in Japan lead him to an existential crisis whereby he questions his reason for being. This, in turn, leads him to a better understanding of humanity. The French film, Mood Indigo (directed by Michel Gondry) embraced various elements of existentialism.[citation needed] The film The Shawshank Redemption, released in 1994, depicts life in a prison in Maine, United States to explore several existentialist concepts.[100] Literature A simple book cover in green displays the name of the author and the book First edition of The Trial by Franz Kafka (1925) Existential perspectives are also found in modern literature to varying degrees, especially since the 1920s. Louis-Ferdinand Céline's Journey to the End of the Night (Voyage au bout de la nuit, 1932) celebrated by both Sartre and Beauvoir, contained many of the themes that would be found in later existential literature, and is in some ways, the proto-existential novel. Jean-Paul Sartre's 1938 novel Nausea[101] was "steeped in Existential ideas", and is considered an accessible way of grasping his philosophical stance.[102] Between 1900 and 1960, other authors such as Albert Camus, Franz Kafka, Rainer Maria Rilke, T. S. Eliot, Yukio Mishima, Hermann Hesse, Luigi Pirandello,[34][35][37][103][104][105] Ralph Ellison,[106][107][108][109] and Jack Kerouac composed literature or poetry that contained, to varying degrees, elements of existential or proto-existential thought. The philosophy's influence even reached pulp literature shortly after the turn of the 20th century, as seen in the existential disparity witnessed in Man's lack of control of his fate in the works of H. P. Lovecraft.[110] Theatre Sartre wrote No Exit in 1944, an existentialist play originally published in French as Huis Clos (meaning In Camera or "behind closed doors"), which is the source of the popular quote, "Hell is other people." (In French, "L'enfer, c'est les autres"). The play begins with a Valet leading a man into a room that the audience soon realizes is in hell. Eventually he is joined by two women. After their entry, the Valet leaves and the door is shut and locked. All three expect to be tortured, but no torturer arrives. Instead, they realize they are there to torture each other, which they do effectively by probing each other's sins, desires, and unpleasant memories. Existentialist themes are displayed in the Theatre of the Absurd, notably in Samuel Beckett's Waiting for Godot, in which two men divert themselves while they wait expectantly for someone (or something) named Godot who never arrives. They claim Godot is an acquaintance, but in fact, hardly know him, admitting they would not recognize him if they saw him. Samuel Beckett, once asked who or what Godot is, replied, "If I knew, I would have said so in the play." To occupy themselves, the men eat, sleep, talk, argue, sing, play games, exercise, swap hats, and contemplate suicide—anything "to hold the terrible silence at bay".[111] The play "exploits several archetypal forms and situations, all of which lend themselves to both comedy and pathos."[112] The play also illustrates an attitude toward human experience on earth: the poignancy, oppression, camaraderie, hope, corruption, and bewilderment of human experience that can be reconciled only in the mind and art of the absurdist. The play examines questions such as death, the meaning of human existence and the place of God in human existence. Tom Stoppard's Rosencrantz & Guildenstern Are Dead is an absurdist tragicomedy first staged at the Edinburgh Festival Fringe in 1966.[113] The play expands upon the exploits of two minor characters from Shakespeare's Hamlet. Comparisons have also been drawn to Samuel Beckett's Waiting for Godot, for the presence of two central characters who appear almost as two halves of a single character. Many plot features are similar as well: the characters pass time by playing Questions, impersonating other characters, and interrupting each other or remaining silent for long periods of time. The two characters are portrayed as two clowns or fools in a world beyond their understanding. They stumble through philosophical arguments while not realizing the implications, and muse on the irrationality and randomness of the world. Jean Anouilh's Antigone also presents arguments founded on existentialist ideas.[114] It is a tragedy inspired by Greek mythology and the play of the same name (Antigone, by Sophocles) from the fifth century BC. In English, it is often distinguished from its antecedent by being pronounced in its original French form, approximately "Ante-GŌN." The play was first performed in Paris on 6 February 1944, during the Nazi occupation of France. Produced under Nazi censorship, the play is purposefully ambiguous with regards to the rejection of authority (represented by Antigone) and the acceptance of it (represented by Creon). The parallels to the French Resistance and the Nazi occupation have been drawn. Antigone rejects life as desperately meaningless but without affirmatively choosing a noble death. The crux of the play is the lengthy dialogue concerning the nature of power, fate, and choice, during which Antigone says that she is, "... disgusted with [the]...promise of a humdrum happiness." She states that she would rather die than live a mediocre existence. Critic Martin Esslin in his book Theatre of the Absurd pointed out how many contemporary playwrights such as Samuel Beckett, Eugène Ionesco, Jean Genet, and Arthur Adamov wove into their plays the existentialist belief that we are absurd beings loose in a universe empty of real meaning. Esslin noted that many of these playwrights demonstrated the philosophy better than did the plays by Sartre and Camus. Though most of such playwrights, subsequently labeled "Absurdist" (based on Esslin's book), denied affiliations with existentialism and were often staunchly anti-philosophical (for example Ionesco often claimed he identified more with 'Pataphysics or with Surrealism than with existentialism), the playwrights are often linked to existentialism based on Esslin's observation.[115] Activism Black existentialism explores the existence and experiences of Black people in the world.[116] Classical and contemporary thinkers include C.L.R James, Frederick Douglass, W.E.B DuBois, Frantz Fanon, Angela Davis, Cornel West, Naomi Zack, bell hooks, Stuart Hall, Lewis Gordon, and Audre Lorde.[117] Psychoanalysis and psychotherapy Main article: Existential therapy A major offshoot of existentialism as a philosophy is existentialist psychology and psychoanalysis, which first crystallized in the work of Otto Rank, Freud's closest associate for 20 years. Without awareness of the writings of Rank, Ludwig Binswanger was influenced by Freud, Edmund Husserl, Heidegger, and Sartre. A later figure was Viktor Frankl, who briefly met Freud as a young man.[118] His logotherapy can be regarded as a form of existentialist therapy. The existentialists would also influence social psychology, antipositivist micro-sociology, symbolic interactionism, and post-structuralism, with the work of thinkers such as Georg Simmel[119] and Michel Foucault. Foucault was a great reader of Kierkegaard even though he almost never refers to this author, who nonetheless had for him an importance as secret as it was decisive.[120] An early contributor to existentialist psychology in the United States was Rollo May, who was strongly influenced by Kierkegaard and Otto Rank. One of the most prolific writers on techniques and theory of existentialist psychology in the US is Irvin D. Yalom. Yalom states that Aside from their reaction against Freud's mechanistic, deterministic model of the mind and their assumption of a phenomenological approach in therapy, the existentialist analysts have little in common and have never been regarded as a cohesive ideological school. These thinkers—who include Ludwig Binswanger, Medard Boss, Eugène Minkowski, V. E. Gebsattel, Roland Kuhn, G. Caruso, F. T. Buytendijk, G. Bally, and Victor Frankl—were almost entirely unknown to the American psychotherapeutic community until Rollo May's highly influential 1958 book Existence—and especially his introductory essay—introduced their work into this country.[121] A more recent contributor to the development of a European version of existentialist psychotherapy is the British-based Emmy van Deurzen.[122] Anxiety's importance in existentialism makes it a popular topic in psychotherapy. Therapists often offer existentialist philosophy as an explanation for anxiety. The assertion is that anxiety is manifested of an individual's complete freedom to decide, and complete responsibility for the outcome of such decisions. Psychotherapists using an existentialist approach believe that a patient can harness his anxiety and use it constructively. Instead of suppressing anxiety, patients are advised to use it as grounds for change. By embracing anxiety as inevitable, a person can use it to achieve his full potential in life. Humanistic psychology also had major impetus from existentialist psychology and shares many of the fundamental tenets. Terror management theory, based on the writings of Ernest Becker and Otto Rank, is a developing area of study within the academic study of psychology. It looks at what researchers claim are implicit emotional reactions of people confronted with the knowledge that they will eventually die.[123] Also, Gerd B. Achenbach has refreshed the Socratic tradition with his own blend of philosophical counseling; as did Michel Weber with his Chromatiques Center in Belgium.[citation needed] |