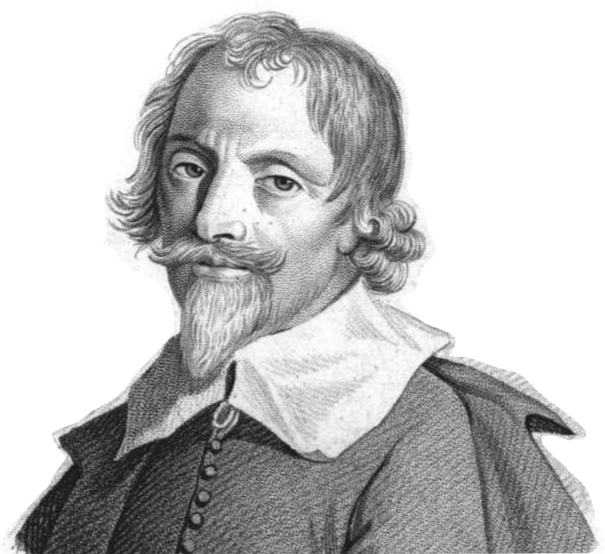

ガブリエル・ノーデ頌歌

Ode for Gabriel Naudé, 1600-1653

ガブリエル・ノーデ頌歌

Ode for Gabriel Naudé, 1600-1653

ガブリエル・ノーデは、まずなによりもリベルタンであった——伊藤敬(2022:108)

ガブリエル・ノーデは、フランスの司書。「1627 年の「図書館設立のための意見書」(Advis pour dresser une bibliothèque)は図書館論の嚆矢であり、後世に影響を与えている。その後、枢機卿・宰相ジュール・マザランの創設したマザラン図書館(Bibliothèque Mazarine)の司書としてこのことを実践した。この本の中で徹底した学術的価値のある図書の収集と利用者への公開を説いた。図書構成論としては 「古典とともに新しい科学の著作」「論争のある主題については、反論 書」「原書と翻訳書」の所蔵を求め、公平な選書、原書と2次的著作の系統的収集を唱え ている。利用者への公開とともに近代図書館の理論的基礎を与えた」

"Gabriel Naudé (2 February 1600 – 10 July 1653) was a French librarian and scholar. He was a prolific writer who produced works on many subjects including politics, religion, history and the supernatural. An influential work on library science was the 1627 book Advice on Establishing a Library. Naudé was later able to put into practice all the ideas he put forth in Advice, when he was given the opportunity to build and maintain the Bibliothèque Mazarine, the library of Cardinal Jules Mazarin./ Naudé is a precursor of Pierre Bayle and Fontenelle." - Gabriel Naudé.

| Naudé was born in

Paris in early 1600 to a family of modest means. His father was a lowly

official and his mother was a young illiterate woman.[1] He was

described by his teachers as tenacious and passionate about his

education. Naudé entered college at a young age where he studied

philosophy and grammar.[2] Later he studied medicine at Paris and Padua

(where he attended Cesare Cremonini's lessons), and became physician to

Louis XIII. At the age of twenty, Naudé published his first book Le Marfore ou Discours Contre les Lisbelles.[3] The work would bring him to the attention of Henri de Mesme, président à mortier of the Paris Parlement. Mesme offered Naudé the job of librarian to his personal collection. Mesmes had a large library for the period (about 8,000 volumes) and it was open to scholars who had the appropriate references.[4] Naudé's service in Mesme's library would give him experience which he would use later to write the book Advice on Establishing a Library. Naudé wrote Advice for Mesme as a guide for building and maintaining his library. In 1629 he became librarian to Cardinal Guidi di Bagno at Rome, and on Bagni's death in 1641 librarian to Cardinal Francesco Barberini. |

ノーデは1600年初頭、パリで質素な家庭に生まれた。父親は下級役

人、母親は文盲の若い女性であった[1] 。彼は教師から粘り強くて教育熱心だと言われていた。若くして大学に入り、哲学と文法を学んだ[2]

。その後、パリとパドヴァ(チェーザレ・クレモニーニのレッスンに参加)で医学を学び、ルイ13世の侍医となった。 20歳の時、最初の著作『Le Marfore ou Discours Contre les Lisbelles』を出版し[3]、この著作によってパリ議会の臼砲議長アンリ・ド・メスの目に留まることになる。メスメは、ナウデに自分の蔵書の司書 の仕事を依頼した。メスメは当時としては大規模な図書館(約8000冊)を持っており、適切な文献を持つ学者に開放されていた[4]。ナウデは、メスメの 図書館を建設し維持するための指針として、『メスメへの助言』を書いたのである。1629年にはローマのグイディ・ディ・バーニョ枢機卿の司書となり、 1641年にバーニが亡くなるとフランチェスコ・バルベリーニ枢機卿の司書となった。 |

| At the desire of Cardinal

Richelieu he began a controversy with the Benedictines, denying Jean

Gerson's authorship of De Imitatione Christi. Richelieu intended to

make Naudé his librarian, and on his death Naudé accepted a similar

offer from Cardinal Mazarin. For the next ten years he devoted himself

to bringing together from all parts of Europe the assemblage of books

known as the Bibliothèque Mazarine. Mazarin had brought with him to

Paris a collection numbering over 5,000 volumes.[5] Like Naudé, he

believed in an open library to be used by the public for the public

good. In 1642 he purchased a building to house his library and he

instructed Naudé to build up the finest collection possible. The fastest way was to absorb entire libraries into the collection, advice that Naudé included in his book. Naudé plundered second hand book sellers, and Mazarin instructed his ambassadors, government officials and generals to collect books for him. Naudé was able to travel Europe, and during one trip that lasted several months he collected over 14,000 volumes.[6] By 1648 the library had built up to an estimated at 40,000 volumes.[5][7]: 17 It was open on a regular basis and had built up a sizable number (almost 100) of regular patrons, and several staff members to keep it functioning properly. It became the first in France to be open for all, without references. |

リシュリュー枢機卿の意向でベネディクト派と論争を始め、ジャン・ジェ

ルソンの『キリストへの畏敬』の著作権を否定した。リシュリューはノーデを司書にしようと考え、ノーデはその死後、マザラン枢機卿から同様の申し出を受け

る。その後10年間、彼はヨーロッパ各地から「マザリーヌ図書館」と呼ばれる書籍の集合体を集めることに専念する。マザランは5,000冊以上の蔵書をパ

リに持ち込んだ[5]。ナウデと同様、彼は公共の利益のために公衆が利用する開かれた図書館を信じた。1642年、彼は図書館を収容するための建物を購入

し、ノーデに可能な限り最高のコレクションを構築するように指示した。 ノーデは、図書館を丸ごと吸収してしまうのが一番手っ取り早いというアドバイスを自著の中で述べている。ノーデは古本屋を襲い、マザランは大使や政府高 官、将軍に本を集めるように指示した。ノーデはヨーロッパを旅行することができ、数ヶ月にわたる旅行で14,000冊以上の本を集めた[6]。 1648年までに図書館は推定40,000冊まで蓄積された[5][7]。 17 定期的に開館し、かなりの数の常連客(ほぼ100人)と、図書館を適切に機能させるための数名のスタッフを擁していた。フランスで初めて、レファレンスな しで誰でも利用できるようになった。 |

| Mazarin's library was sold by

the parlement of Paris during the troubles of the Fronde, and Queen

Christina invited Naudé to Stockholm.[7]: 17 He was not happy in

Sweden, and on Mazarin's appeal that he should re-form his scattered

library Naudé returned at once. But his health was broken, and he died

on the journey in Abbeville on 10 July 1653. The friend of Gui Patin, of Pierre Gassendi and all the liberal thinkers of his time, Naudé was no mere bookworm; his books show traces of the critical spirit which made him a worthy colleague of the humorists and scholars who prepared the way for the better known writers of the siècle de Louis XIV. |

マザランの図書館はフロンドの乱でパリ高等法院に売却され、クリス

ティーナ王妃はナウデをストックホルムに招いた[7]。 17

彼はスウェーデンでは満足できず、マザランが散逸した図書館を再建するよう訴えたため、ナウデはすぐに帰国した。しかし、健康を害し、1653年7月10

日、アベヴィルで旅の途中で亡くなった。 ギ・パタンやピエール・ガッセンディをはじめ、当時の自由主義的な思想家たちの友人であったノーデは、単なる読書家ではなく、その著書には、ルイ14世の 時代に有名な作家たちへの道を開いたユーモア作家や学者の同僚としてふさわしい批判精神の跡が残っている。 |

| Naudé, in his career as a

librarian, “opposed censorship, and encouraged library owners to allow

others to use their books, a practice he considered a great honor for

the owner – an honor equal to that of having the opportunity to build a

fine library."[8] Naudé found it favorable to collect original format

of books and to keep the volumes collected intact. He was a true

believer of considering the needs of those that would access them and

felt strong consideration to be sought from the experts in each

particular field. He was adamant about collecting in all languages,

about all religions, subject matters, and literature. During his career in librarianship, Naudé helped instruct collectors and libraries in the selection and acquisition of their titles and how to create catalogs for their libraries. He was a major proponent of scouring secondhand bookshops and print shops for valuable and hard to find literary works. “When Naudé has been in town, the booksellers' shops seem devastated as by a whirlwind. Having bought up in every last one of them all the books, whether in manuscript or in print, dealing in any language whatever with any subject or division of learning no matter what, he has left the stores stripped and bare.”[9] |

ノーデは司書として、「検閲に反対し、図書館の所有者が自分の本を他人

に使わせることを奨励し、この行為は所有者にとって大きな名誉であり、立派な図書館

を建てる機会を得たことと同等の名誉だと考えた」[8]。また、利用する人のニーズを考え、各分野の専門家に強い配慮を求めることを信条とした。彼は、あ

らゆる言語、あらゆる宗教、主題、文学について収集することを固く決意していた。 図書館員としてのキャリアにおいて、ノーデはコレクターや図書館に対して、タイトルの選択と取得、図書館のカタログの作成方法について指導を行った。ま た、古書店や印刷所で貴重な文学作品や入手困難な作品を探し出すことを推奨していた。「ノーデが街にいると、書店はまるで旋風を巻き起こすかのように荒廃 する。原稿であれ印刷物であれ、どんな言語であれ、どんな学問の主題や部門であれ、あらゆる本を残らず買い占めた彼は、店を丸裸にしてしまったのだ」 [9]という。 |

| Works Including works edited by him, a list of ninety-two pieces is given in the Naudaeana. The principal ones are: Le Marfore, ou discours contre les libelles (Paris, 1620), very rare, reprinted 1868; Instruction à la France sur la vérité de l'histoire des Frères de la Roze-Croix (1623, 1624), displaying their impostures; Apologie pour tous les grands personages faussement soupçonnez de magie (1625, 1653, 1669, 1712), Pythagoras, Socrates, Thomas Aquinas Jerome Cardan and Solomon are among those defended; Advis pour dresser une bibliothèque (1627, 1644, 1676; translated by John Evelyn, 1661), full of sound and liberal views on librarianship and considered as a founding stone of library science; Addition à l'histoire de Louys XI (1630), this includes an account of the origin of printing; Bibliographia politica (Venice, 1633, etc.; in French, 1642); De studio liberali syntagma (1632, 1654), a practical treatise found in most collections of directions for studies; De studio militari syntagma (1637), esteemed in its day; Considérations politiques sur les coups d'état (1639). A disciple of Machiavelli, he considered that politics must be rendered "autonomous from morality, sovereign in relation to religion"[12] A Bibliotheca Pontificia was completed and seen into print by Louis Jacob.[13] |

|

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gabriel_Naud%C3%A9 |

https://www.deepl.com/ja/translator |

■サイドストーリー

1945年8月18日、渡辺一夫はそれまでフランス 語で日記備忘を書いていたが、「母国語で思ったことを書く喜び。はじめよう」とフランス語で記した。言いたいことを自由におっしゃればいいのです。

リンク(サイト内)

リンク(サイト外)

文献

その他の情報