系譜論・系譜学

Genealogy

A

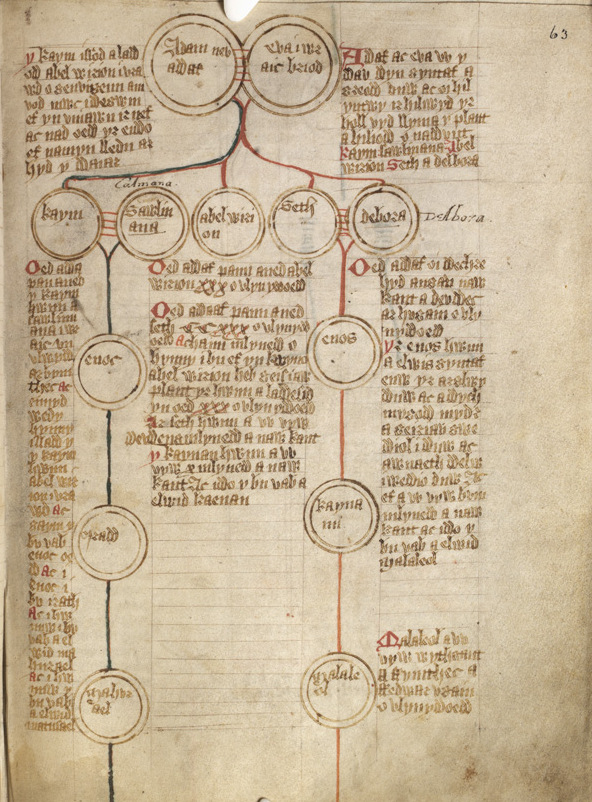

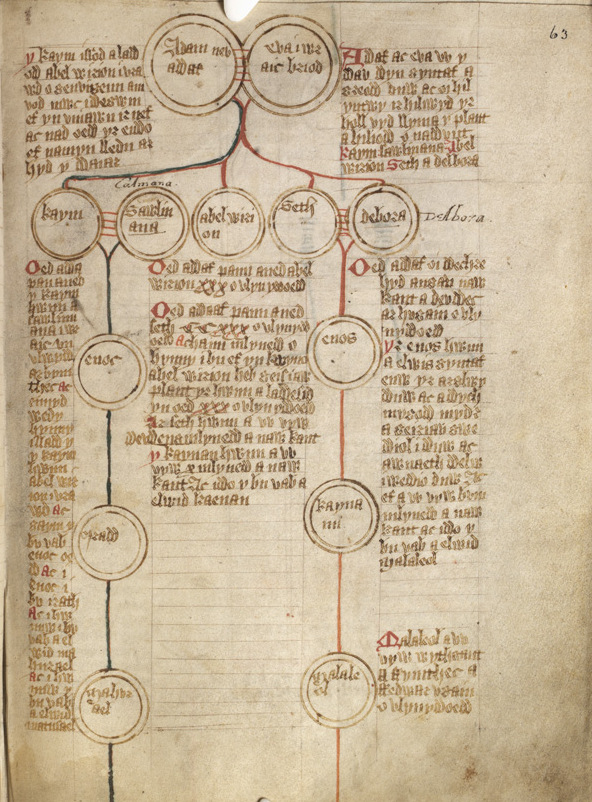

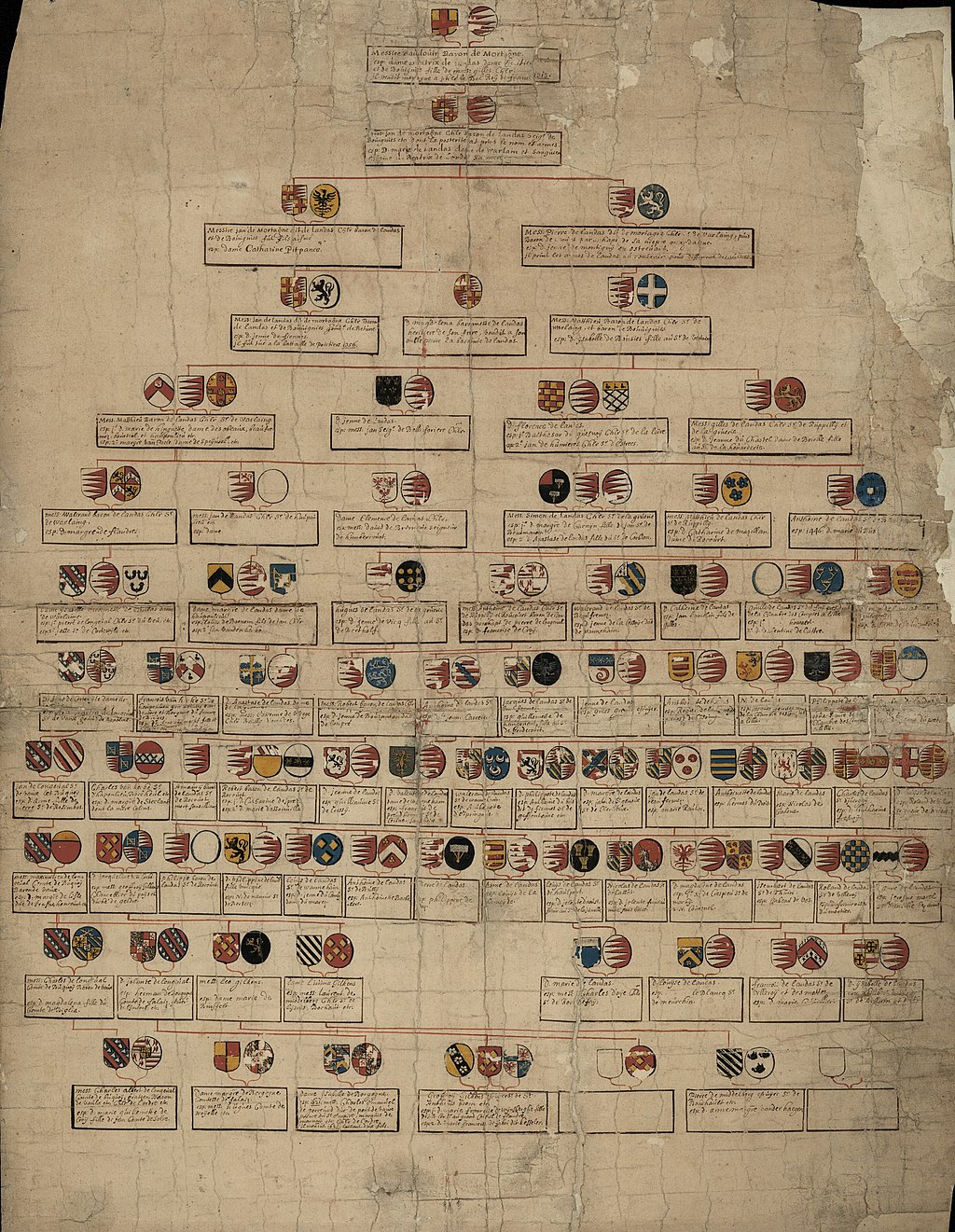

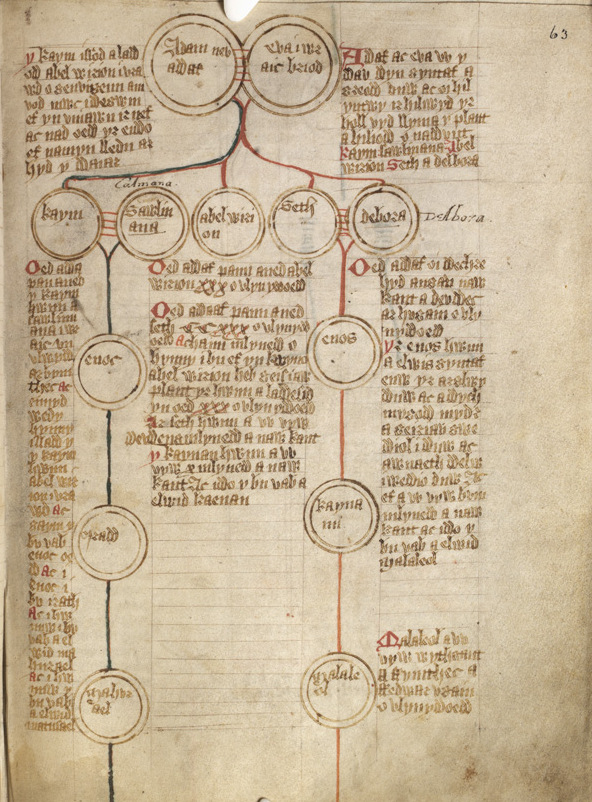

Medieval genealogy traced from Adam and Eve / The diagram shows the

pseudoscientific racial division, according to the Nuremberg Laws

☆

この記事(哲学の系譜論の説明の後の部分)は、家系、歴史、血統の研究についてのものである。ニーチェやフーコーが発展させた哲学的手法については、系譜学(哲学)を参照のこと。親族関係

の社会文化的進化については、家族の歴史を参照のこと。指導関係による学者の家系図については、学問の系譜を参照のこと。

その他の用法については、「系図 (曖昧さ回避)」を参照のこと。

「家族史」はここからリダイレクトされる。医学的な家族史については、家族史(医学)を参照のこと。その他の用法については、家族史

(曖昧さ回避)を参照のこと。

★

哲学において

系譜学とは、言説の範囲や広がり、あるいは全体性を説明しようとすることで、一般に理解されている様々な哲学的・社会的信念の出現に疑問を投げかけ、分析

の可能性を広げる歴史的手法である。さらに系譜学はしばしば、問題となっている言説を越えて、その可能性の条件へと目を向けようとする(特にミシェル・

フーコーの系譜学において)。それは、フリードリヒ・ニーチェの著作を引き継ぐものとして発展してきた。系譜学は、マルクス主義が

イデオロギーを用いて、特異な、あるいは支配的な言説(イデオロギー)に焦点を当てることで、当該時代における歴史的言説の全体性を説明しようとするのと

は対照的である。

例えば、「グローバリゼーション」のような概念の系譜を追跡することは、その概念が変化する構成的設定の中に位置づけられる限りにおいて、「系譜学」と呼

ぶことができる[1]。このことは、単にその意味の変化(語源)を記録するだけでなく、その意味の変化の社会的基礎を記録することを伴う。

| philosophical Genealogy |

哲学における系譜学 |

| Genealogy in general Genealogy (from Ancient Greek γενεαλογία (genealogía) 'the making of a pedigree')[2] is the study of families, family history, and the tracing of their lineages. Genealogists use oral interviews, historical records, genetic analysis, and other records to obtain information about a family and to demonstrate kinship and pedigrees of its members. The results are often displayed in charts or written as narratives. The field of family history is broader than genealogy, and covers not just lineage but also family and community history and biography.[3] The record of genealogical work may be presented as a "genealogy", a "family history", or a "family tree". In the narrow sense, a "genealogy" or a "family tree" traces the descendants of one person, whereas a "family history" traces the ancestors of one person,[4][5][6] but the terms are often used interchangeably.[7] A family history may include additional biographical information, family traditions, and the like.[3] The pursuit of family history and origins tends to be shaped by several motives, including the desire to carve out a place for one's family in the larger historical picture, a sense of responsibility to preserve the past for future generations, and self-satisfaction in accurate storytelling.[8] Genealogy research is also performed for scholarly or forensic purposes, or to trace legal next of kin to inherit under intestacy laws. |

系譜論(一般) 系図学(けいずがく、古代ギリシア語 γενεαλογία (genealogía)「血統を作ること」から)[2]とは、家族、家族の歴史、血統をたどる学問である。系図学者は、口頭での聞き取り調査、歴史的記 録、遺伝子分析、その他の記録を用いて、家族に関する情報を入手し、その構成員の血縁関係や 血統を示す。その結果は、しばしば図表で表示されたり、物語として書かれたりする。ファミリー・ヒストリーの分野は系図学よりも広く、家系だけでなく家族 やコミュニティの歴史や伝記も含む[3]。 系図の記録は「系図」、「家系図」、「家系図」として提示されることがある。狭い意味では、「系図」や「家系図」は一人の人物の子孫をたどるものであり、 「家系図」は一人の人物の祖先をたどるものであるが[4][5][6]、これらの用語はしばしば互換的に使用される[7]。 家族の歴史や出自を追求することは、より大きな歴史像の中に自分の家族の居場所を作りたいという願望、後世のために過去を保存するという責任感、正確な物 語を語ることによる自己満足など、いくつかの動機によって形成される傾向がある[8]。系図研究はまた、学術的または法医学的な目的のために、あるいは遺 留分法の下で相続する法的な近親者を追跡するために行われる。 |

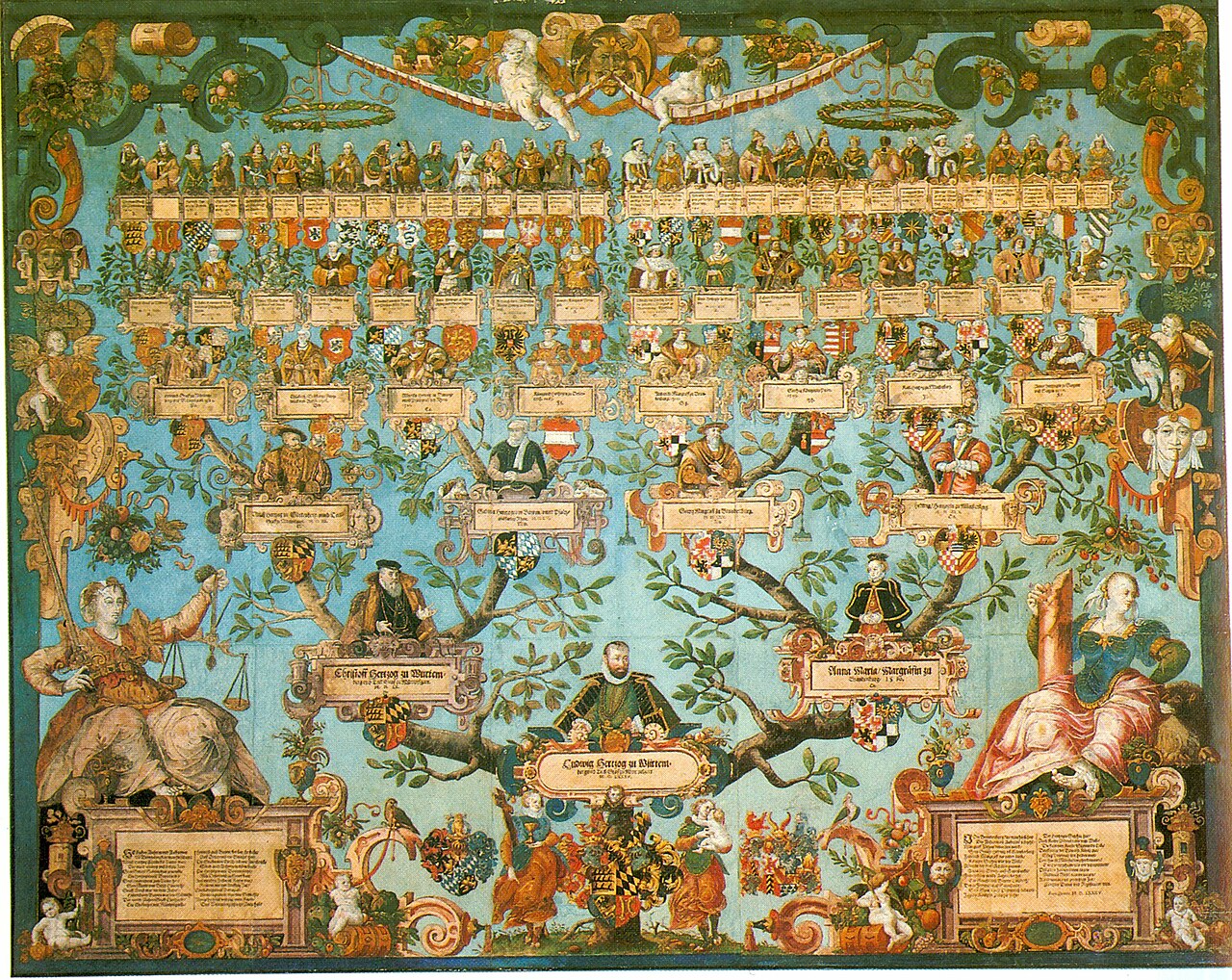

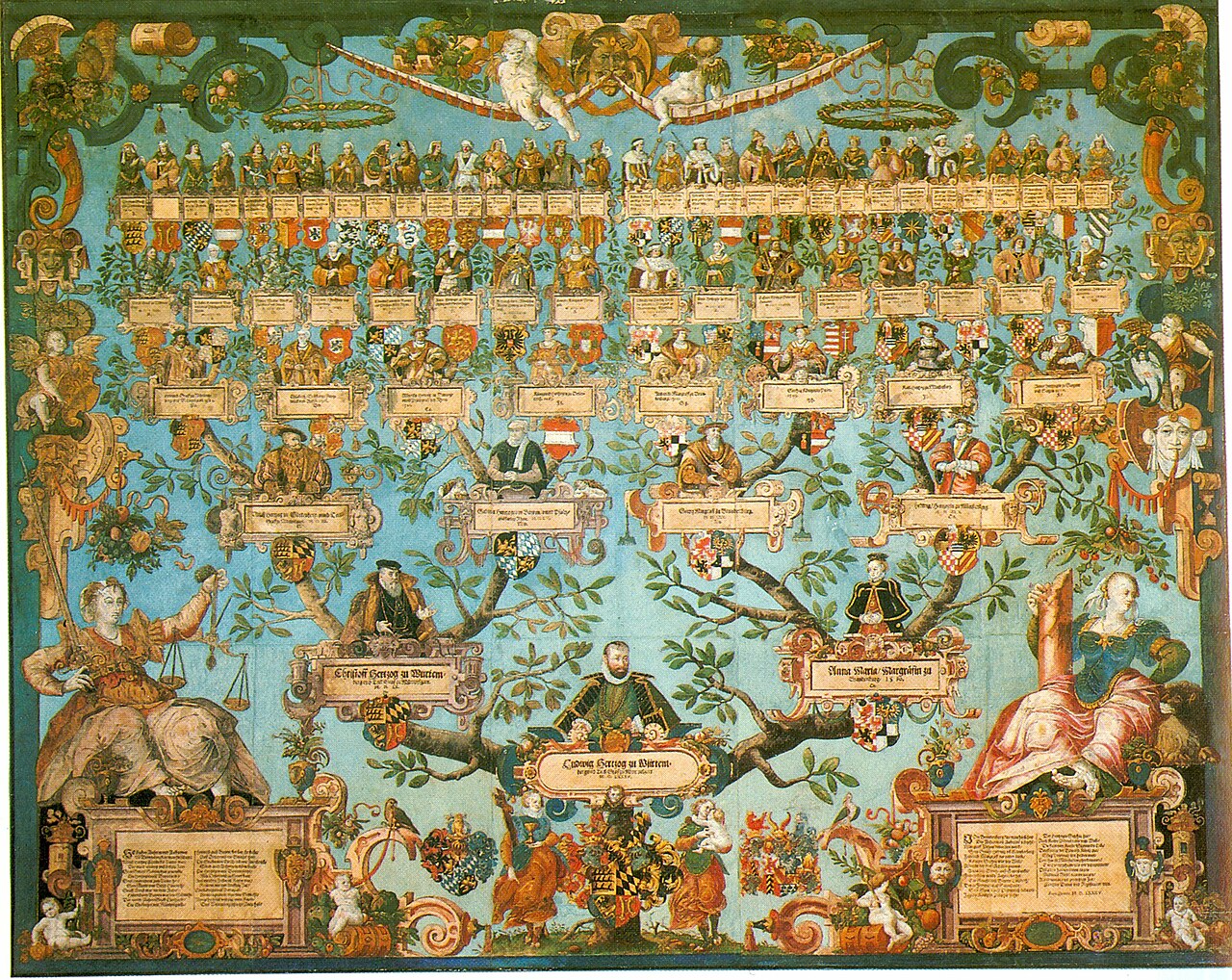

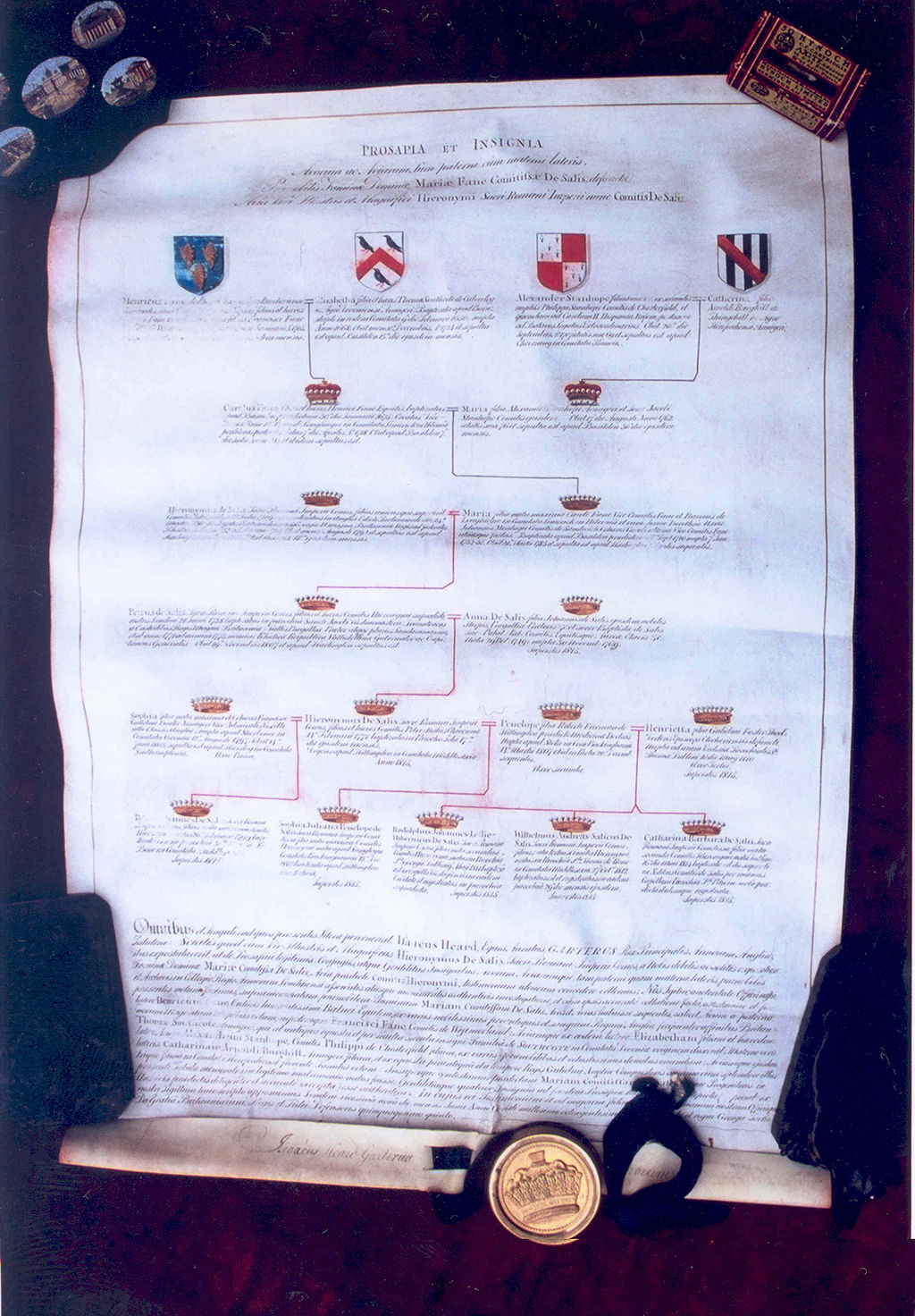

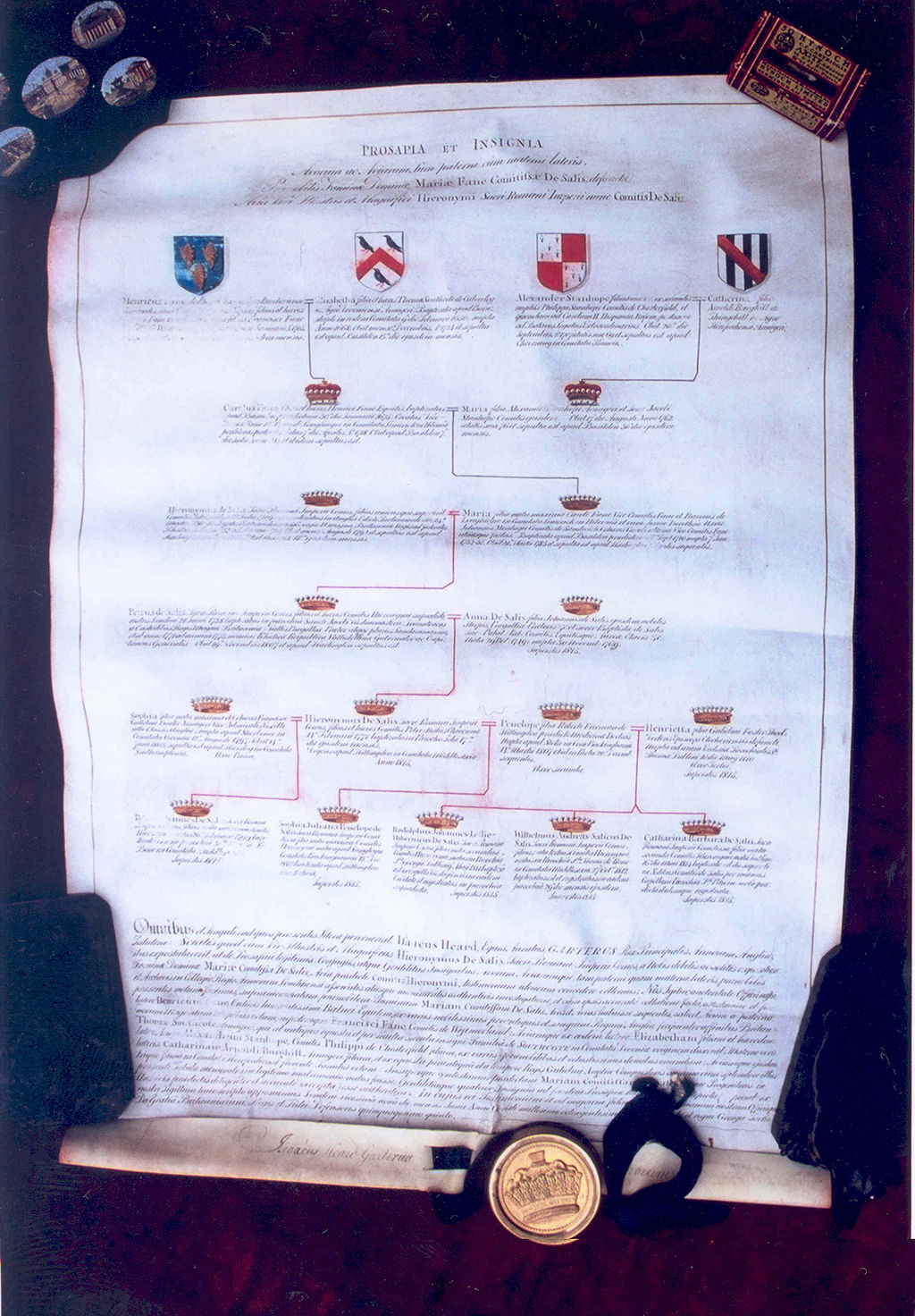

The family tree of Louis III, Duke of Württemberg (ruled 1568–1593) |

The family tree of Louis III, Duke of Württemberg (ruled 1568–1593) |

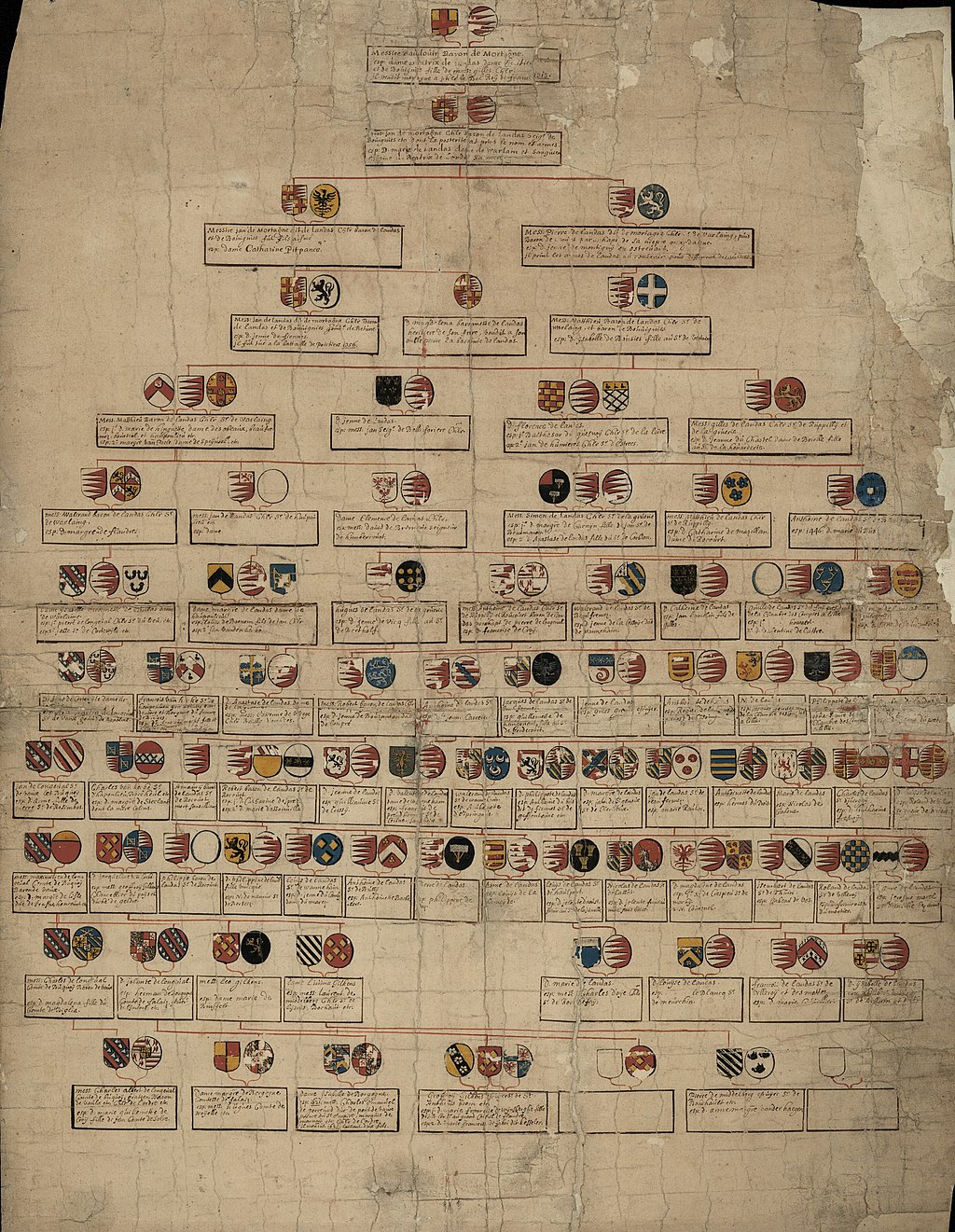

The family tree of "the Landas", a 17th-century family[1] |

The family tree of "the Landas", a 17th-century family[1] |

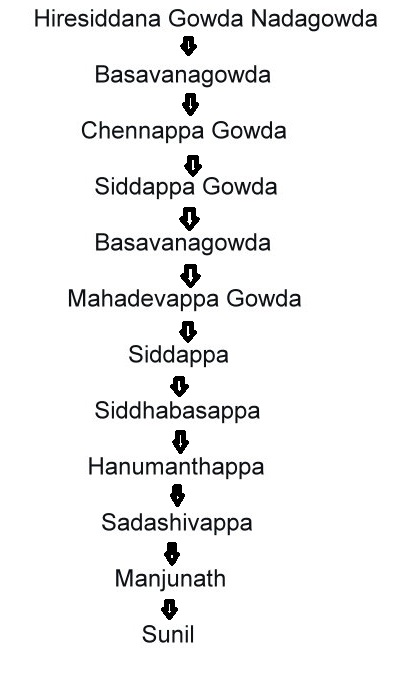

Twelve generations patrilineage of a Hindu Lingayat male from central Karnataka spanning over 275 years, depicted in descending order |

カルナータカ中部出身のヒンドゥー教徒リンガヤート男性の12代にわたる家系図(275年以上にわたる)。 |

| Overview Amateur genealogists typically pursue their own ancestry and that of their spouses. Professional genealogists may also conduct research for others, publish books on genealogical methods, teach, or produce their own databases. They may work for companies that provide software or produce materials of use to other professionals and to amateurs. Both try to understand not just where and when people lived but also their lifestyles, biographies, and motivations. This often requires—or leads to—knowledge of antiquated laws, old political boundaries, migration trends, and historical socioeconomic or religious conditions. Genealogists sometimes specialize in a particular group, e.g., a Scottish clan; a particular surname, such as in a one-name study; a small community, e.g., a single village or parish, such as in a one-place study; or a particular, often famous, person. Bloodlines of Salem is an example of a specialized family-history group. It welcomes members who can prove descent from a participant of the Salem Witch Trials or who simply choose to support the group. Genealogists and family historians often join family history societies, where novices can learn from more experienced researchers. Such societies generally serve a specific geographical area. Their members may also index records to make them more accessible or engage in advocacy and other efforts to preserve public records and cemeteries. Some schools engage students in such projects as a means to reinforce lessons regarding immigration and history.[9] Other benefits include family medical histories for families with serious medical conditions that are hereditary. The terms "genealogy" and "family history" are often used synonymously, but some entities offer a slight difference in definition. The Society of Genealogists, while also using the terms interchangeably, describes genealogy as the "establishment of a pedigree by extracting evidence, from valid sources, of how one generation is connected to the next" and family history as "a biographical study of a genealogically proven family and of the community and country in which they lived".[3] |

概要[編集] アマチュアの系図学者は通常、自分自身と配偶者の家系を調査する。プロの系図学者は、他人のために調査を行ったり、系図の方法に関する本を出版したり、教 えたり、独自のデータベースを作成したりすることもある。他の専門家やアマチュアに役立つソフトウェアを提供したり、資料を作成したりする会社に勤めるこ ともある。両者とも、人々がいつどこに住んでいたかということだけでなく、彼らのライフスタイル、伝記、動機を理解しようと努めている。そのためには、古 くからの法律、古い政治的境界線、移住の傾向、歴史的な社会経済的・宗教的状況についての知識が必要とされる、あるいはそれにつながることが多い。 系図学者は、特定のグループ、例えばスコットランドの氏族、ワンネーム研究のような特定の姓、小さなコミュニティ、例えばワンプレイス研究のような一つの 村や教区、あるいは特定の、しばしば有名な人物を専門とすることがある。セーラムの血統』は、家族史に特化したグループの一例である。セイラム魔女裁判の 参加者の子孫であることを証明できる会員や、単にこのグループを支援することを選んだ会員を歓迎している。 系図学者や家族史研究者は、初心者が経験豊富な研究者から学べる家族史学会に入会することが多い。このような学会は一般に特定の地域を対象としている。ま た、会員が記録にアクセスしやすくするために索引を作ったり、公的記録や墓地を保護するためのアドボカシー活動やその他の取り組みに参加したりすることも ある。学校によっては、移民や歴史に関する授業を強化する手段として、このようなプロジェクトに生徒を参加させるところもある[9]。その他の利点として は、遺伝性の重篤な病状を持つ家族のための家族病歴などがある。 系図」と「ファミリーヒストリー」は同義語として使われることが多いが、定義に若干の違いがある団体もある。系図学会(Society of Genealogists)は、この2つの用語を同じ意味で使用しているが、系図を「ある世代が次の世代にどのようにつながっているかの証拠を、有効な情 報源から抽出することによって、血統を確立すること」とし、家族史を「系図上証明された家族の伝記的研究、および彼らが住んでいた地域社会や国の研究」と 説明している[3]。 |

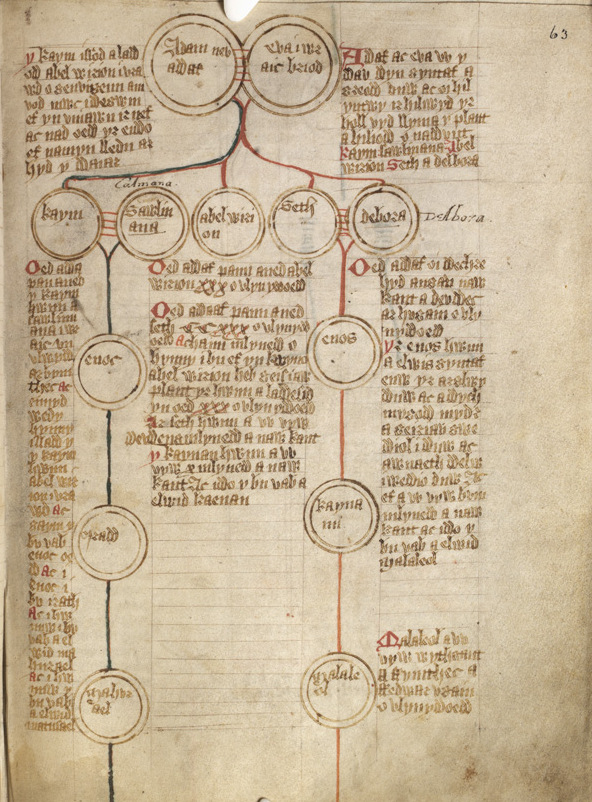

| Motivation Individuals conduct genealogical research for a number of reasons. Personal or medical interest Private individuals research genealogy out of curiosity about their heritage. This curiosity can be particularly strong among those whose family histories were lost or unknown due to, for example, adoption or separation from family through divorce, death, or other situations.[10] In addition to simply wanting to know more about who they are and where they came from, individuals may research their genealogy to learn about any hereditary diseases in their family history.[11] There is a growing interest in family history in the media as a result of advertising and television shows sponsored by large genealogy companies, such as Ancestry.com. This, coupled with easier access to online records and the affordability of DNA tests, has both inspired curiosity and allowed those who are curious to easily start investigating their ancestry.[12][13] Community or religious obligation In communitarian societies, one's identity is defined as much by one's kin network as by individual achievement, and the question "Who are you?" would be answered by a description of father, mother, and tribe. New Zealand Māori, for example, learn whakapapa (genealogies) to discover who they are.[14][15][16][17] Family history plays a part in the practice of some religious belief systems. For example, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) has a doctrine of baptism for the dead, which necessitates that members of that faith engage in family history research.[18][19][20] In East Asian countries that were historically shaped by Confucianism, many people follow a practice of ancestor worship as well as genealogical record-keeping. Ancestors' names are inscribed on tablets and placed in shrines, where rituals are performed. Genealogies are also recorded in genealogy books. This practice is rooted in the belief that respect for one's family is a foundation for a healthy society.[21] Establishing identity Royal families, both historically and in modern times, keep records of their genealogies in order to establish their right to rule and determine who will be the next sovereign. For centuries in various cultures, one's genealogy has been a source of political and social status.[22][23] Some countries and indigenous tribes allow individuals to obtain citizenship based on their genealogy. In Ireland and in Greece, for example, an individual can become a citizen if one of their grandparents was born in that country, regardless of their own or their parents' birthplace. In societies such as Australia or the United States, by the 20th century, there was growing pride in the pioneers and nation-builders. Establishing descent from these was, and is, important to lineage societies, such as the Daughters of the American Revolution and The General Society of Mayflower Descendants.[24] Modern family history explores new sources of status, such as celebrating the resilience of families that survived generations of poverty or slavery, or the success of families in integrating across racial or national boundaries. Some family histories even emphasize links to celebrity criminals, such as the bushranger Ned Kelly in Australia.[25] Legal and forensic research Main article: Investigative genetic genealogy Lawyers involved in probate cases do genealogy to locate heirs of property.[26][27] Detectives may perform genealogical research using DNA evidence to identify victims of homicides or perpetrators of crimes.[28][29][30][31][32] Scholarly research Historians and geneticists may carry out genealogical research to gain a greater understanding of specific topics in their respective fields, and some may employ professional genealogists in connection with specific aspects of their research. They also publish their research in peer-reviewed journals.[33] The introduction of postgraduate courses in genealogy in recent years has given genealogy more of an academic focus, with the emergence of peer-reviewed journals in this area. Scholarly genealogy is beginning to emerge as a discipline in its own right, with an increasing number of individuals who have obtained genealogical qualifications carrying out research on a diverse range of topics related to genealogy, both within academic institutions and independently.[34] Discrimination and persecution In the US, the "one-drop rule" asserted that any person with even one ancestor of black ancestry ("one drop" of "black blood") was considered black. It was codified into the law of some States (e.g. the Racial Integrity Act of 1924) to reinforce racial segregation. Genealogy was also used in Nazi Germany to determine whether a person was considered a "Jew" or a "Mischling" (Mischling Test), and whether a person was considered as "Aryan" (Ahnenpass). |

動機[編集] 個人が系図研究を行う理由は様々である。 個人的または医学的興味[編集]。 個人で系図を研究する人は、自分の遺産に対する好奇心からである。このような好奇心は、例えば養子縁組や離婚、死、その他の状況による家族との離別などに よって家族の歴史が失われたり、不明であったりした人々の間で特に強くなることがある[10]。単に自分が誰であり、どこから来たのかをもっと知りたいと いうだけでなく、家系に遺伝性の病気がないかどうかを知るために系図を調査する場合もある[11]。 Ancestry.comのような大手系図会社がスポンサーとなっている広告やテレビ番組の結果、メディアにおける家族史への関心が高まっている。これ は、オンライン記録へのアクセスが容易になり、DNA検査が手ごろな価格で受けられるようになったことと相まって、好奇心を刺激し、好奇心のある人々が簡 単に先祖の調査を始めることを可能にしている[12][13]。 共同体や宗教上の義務[編集]。 共同体主義的な社会では、自分のアイデンティティは個人の業績と同様に親族ネットワークによって定義され、「あなたは誰ですか」という質問には、父、母、 部族の記述によって答えられる。たとえばニュージーランドのマオリ族は、自分が何者であるかを発見するためにワカパパ(系図)を学ぶ[14][15] [16][17]。 家族の歴史は、いくつかの宗教的な信仰体系の実践に一役買っている。例えば、末日聖徒イエス・キリスト教会(末日聖徒教会)には死者のためのバプテスマという教義があり、その信徒は家族史の調査に従事する必要がある[18][19][20]。 歴史的に儒教によって形成された東アジアの国々では、多くの人々が系図を記録するだけでなく、祖先崇拝の習慣に従っている。先祖の名前は位牌に刻まれ、神 社に安置され、そこで儀式が行われる。また、系図は系図帳に記録される。この習慣は、家族を尊重することが健全な社会の基盤であるという信念に根ざしてい る[21]。 アイデンティティの確立[編集] 王家は、歴史的にも現代においても、その統治権を確立し、誰が次の君主になるかを決定するために、系図の記録を残す。様々な文化において何世紀もの間、系図は政治的・社会的地位の源泉となってきた[22][23]。 一部の国や先住民族は、系譜に基づいて市民権を取得することを認めている。例えばアイルランドや ギリシャでは、自分や両親の出生地に関係なく、祖父母のどちらかがその国で生まれていれば市民権を得ることができる。オーストラリアやアメリカのような社 会では、20世紀になると、開拓者や国家建設者に対する誇りが高まった。アメリカ独立革命の娘たち(Daughters of the American Revolution)やメイフラワー末裔協会(The General Society of Mayflower Descendants)のような血統協会にとって、こうした人々の子孫を証明することは重要であり、現在もそうである[24]。現代の家族史は、貧困や 奴隷の時代を何世代にもわたって生き抜いてきた家族の回復力を称えたり、人種や国境を越えて統合した家族の成功を称えたりするなど、新たな地位の源泉を探 求している。オーストラリアのブッシュレンジャー、ネッド・ケリーのように、有名な犯罪者とのつながりを強調する家族史もある[25]。 法的・法医学的研究[編集] 主な記事 遺伝子系図調査 遺言検認事件に携わる弁護士は、財産の相続人を探すために系図を作成する[26][27]。 刑事は、殺人事件の被害者や犯罪の加害者を特定するためにDNA証拠を用いた系図調査を行うことがある[28][29][30][31][32]。 学術研究[編集] 歴史学者や 遺伝学者は、それぞれの分野における特定のトピックについて理解を深めるために系図研究を行うことがあり、研究の特定の側面に関連して専門の系図学者を雇用する場合もある。また、研究内容を査読付き学術誌に発表することもある[33]。 近年、系図学の大学院コースが導入されたことで、系図学はより学術的な焦点を持つようになり、この分野の査読付き学術誌が出現した。学術的な系図学は、そ れ自体が学問分野として台頭し始めており、系図学の資格を取得した個人が、学術機関内や個人的に、系図学に関連する多様なトピックについて研究を行うこと が増えている[34]。 差別と迫害[編集] アメリカでは、黒人の先祖を一人でも持つ者(「黒人の血」を「一滴」でも持つ者)は黒人とみなすという「一滴ルール」があった。これは人種隔離を強化する ために、いくつかの州の法律に成文化された(1924年の人種統合法(Racial Integrity Act of 1924)など)。 系図はまた、ナチス・ドイツにおいて、その人が「ユダヤ人」とみなされるか「ミシュリング」(ミシュリング・テスト)とみなされるか、また「アーリア人」(アーネンパス)とみなされるかを判断するためにも使われた。 |

| History Pre-modern genealogy  A Medieval genealogy traced from Adam and Eve Hereditary emperors, kings and chiefs in several areas have long claimed descent from gods (thus establishing divine legitimacy). Court genealogists have preserved or invented appropriate genealogical pretensions - for example) in Japan,[35] Polynesia,[36] and the Indo-European world from from Scandinavia through ancient Greece to India.[37] Historically, in Western societies, genealogy focused on the kinship and descent of rulers and nobles, often arguing or demonstrating the legitimacy of claims to wealth and power. Genealogy often overlapped with heraldry, which reflected the ancestry of noble houses in their coats of arms. Modern scholars regard many claimed noble ancestries as fabrications, such as the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle's tracing of the ancestry of several English kings to the god Woden.[38] With the coming of Christianity to northern Europe, Anglo-Saxon royal genealogies extended the kings' lines of ancestry from Woden back to reach the line of Biblical patriarchs: Noah[39] and Adam. (This extension offered the side-benefit of connecting pretentious rulers with the prestigious genealogy of Jesus.)[40] Modern historians and genealogists may regard manufactured pseudo-genealogies with a degree of scepticism. However, the desire to find ancestral links with prominent figures from a legendary or distant past has persisted. In the United States, for example, it does no harm to establish one's links to ancestors who boarded the Mayflower. And the popularity of the genealogical hypothesis of The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail (1982) demonstrates popular interest in ancient bloodlines, however dubious. Some family trees have been maintained for considerable periods. The family tree of Confucius has been maintained for over 2,500 years and is listed in the Guinness Book of World Records as the largest extant family tree. The fifth edition of the Confucius Genealogy was printed in 2009 by the Confucius Genealogy Compilation Committee (CGCC).[41][42] Modern times In modern times, genealogy has become more widespread, with commoners as well as nobility researching and maintaining their family trees.[43] Genealogy received a boost in the late 1970s with the television broadcast of Roots: The Saga of an American Family by Alex Haley. His account of his family's descent from the African tribesman Kunta Kinte inspired many others to study their own lines.[44] With the advent of the Internet, the number of resources readily accessible to genealogists has vastly increased, fostering an explosion of interest in the topic.[45] Genealogy on the internet became increasingly popular starting in the early 2000s.[46] The Internet has become a major source not only of data for genealogists but also of education and communication. India Some notable places where traditional genealogy records are kept include Hindu genealogy registers at Haridwar (Uttarakhand), Varanasi and Allahabad (Uttar Pradesh), Kurukshetra (Haryana), Trimbakeshwar (Maharashtra), and Chintpurni (Himachal Pradesh).[47] United States Genealogical research in the United States was first systematized in the early 19th century, especially by John Farmer (1789–1838).[48] Before Farmer's efforts, tracing one's genealogy was seen as an attempt by the American colonists to secure a measure of social standing, an aim that was counter to the new republic's egalitarian, future-oriented ideals (as outlined in the Constitution).[48] As Fourth of July celebrations commemorating the Founding Fathers and the heroes of the Revolutionary War became increasingly popular, however, the pursuit of "antiquarianism", which focused on local history, became acceptable as a way to honor the achievements of early Americans.[citation needed] Farmer capitalized on the acceptability of antiquarianism to frame genealogy within the early republic's ideological framework of pride in one's American ancestors. He corresponded with other antiquarians in New England, where antiquarianism and genealogy were well established, and became a coordinator, booster, and contributor to the growing movement. In the 1820s, he and fellow antiquarians began to produce genealogical and antiquarian tracts in earnest, slowly gaining a devoted audience among the American people. Though Farmer died in 1838, his efforts led to the founding in 1845 of the New England Historic Genealogical Society (NEHGS), one of New England's oldest and most prominent organizations dedicated to the preservation of public records.[49] NEHGS publishes the New England Historical and Genealogical Register. The Genealogical Society of Utah, founded in 1894, later became the Family History Department of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. The department's research facility, the Family History Library, which Utah.com claims as "the largest genealogical library in the world",[50] was established to assist in tracing family lineages for special religious ceremonies which Latter-day Saints believe will seal family units together for eternity. Latter-day Saints believe that this fulfilled a biblical prophecy stating that the prophet Elijah would return to "turn the heart of the fathers to the children, and the heart of the children to their fathers."[51] There is a network of church-operated Family History Centers all over the United States and around the world, where volunteers assist the public with tracing their ancestors.[52] Brigham Young University offers bachelor's degree, minor, and concentration programs in Family History and is the only school in North America to offer this.[53] The American Society of Genealogists is the scholarly honorary society of the U.S. genealogical field. Founded by John Insley Coddington, Arthur Adams, and Meredith B. Colket, Jr., in December 1940, its membership is limited to 50 living fellows. ASG has semi-annually published The Genealogist, a scholarly journal of genealogical research, since 1980. Fellows of the American Society of Genealogists, who bear the post-nominal acronym "FASG", have written some of the most notable genealogical materials of the last half-century.[54] Some of the most notable scholarly American genealogical journals include The American Genealogist, National Genealogical Society Quarterly, The New England Historical and Genealogical Register, The New York Genealogical and Biographical Record, and The Genealogist.[55][56] |

歴史[編集] 前近代の系図[編集]  アダムとイブから辿る中世の系図 いくつかの地域の世襲的な天皇、王、首長は、長い間、神々の子孫であると主張してきた(したがって、神の正統性を確立してきた)。例えば)日本、[35] ポリネシア、[36]スカンディナヴィアから古代ギリシアを経てインドに至るインド・ヨーロッパ世界では、宮廷の系図作成者たちが適切な系図を保存した り、作り出したりしてきた[37]。 歴史的に西洋社会では、系図は支配者や貴族の親族関係や子孫に焦点を当て、しばしば富や権力に対する主張の正当性を主張したり証明したりした。系図はしば しば紋章学と重なり、貴族の家系を紋章に反映させた。現代の学者たちは、アングロサクソン年代記が数人のイングランド王の祖先をヴォーデン神になぞらえた ように、主張される貴族の祖先の多くは捏造であるとみなしている[38]。 [38]北欧にキリスト教が伝わると、アングロサクソン王家の系図は、王の先祖をヴォーデンから聖書の家長であるノア[39]とアダムにまで遡らせた(こ の延長は、気取った支配者をイエスの格調高い系図に結びつけるという副次的な利点をもたらした)[40]。 現代の歴史家や系図学者は、作られた偽系図を懐疑的に見るかもしれない。しかし、伝説的な、あるいは遠い過去の著名人との祖先のつながりを見つけたいとい う願望は根強く残っている。例えばアメリカでは、メイフラワー号に乗船した先祖とのつながりを証明することは、何の害もない。また、『聖なる血と聖杯』 (1982年)の系図仮説の人気は、たとえ疑わしいものであっても、古代の血統に対する大衆の関心を示している。 家系図の中には、かなりの期間にわたって維持されてきたものもある。孔子の家系図は2500年以上も維持されており、現存する最大の家系図としてギネス ブックに登録されている。孔子系図第5版は、孔子系図編纂委員会(CGCC)によって2009年に印刷された[41][42]。 現代[編集]。 現代では、系図はより広く普及しており、貴族だけでなく庶民も家系図を研究・管理している[43]。系図は1970年代後半、アレックス・ヘイリーによる 『ルーツ』のテレビ放映によって盛り上がりを見せた: アレックス・ヘイリーによる『あるアメリカの家族の物語』である。アフリカの部族長クンタ・キンテから続く彼の一族の子孫についての説明は、他の多くの人 々に自分の家系を研究するよう促した[44]。 インターネットの出現により、系図学者が容易にアクセスできる資料の数が大幅に増加し、このテーマへの関心が爆発的に高まった[45]。インターネット上 の系図学は2000年代初頭からますます人気を集めるようになった[46]。インターネットは系図学者にとってデータの主要な供給源となっただけでなく、 教育やコミュニケーションの場ともなっている。 インド[編集] 伝統的な系図記録が保管されている有名な場所には、ハリドワール(ウッタラーカンド州)、ヴァラナシと アラハバード(ウッタル・プラデーシュ州)、クルクシェトラ(ハリヤナ州)、トリンバケシュワル(マハラシュトラ州)、チントプルニ(ヒマーチャル・プラ デーシュ州)のヒンドゥー系図登録簿がある[47]。 アメリカ合衆国[編集] アメリカにおける系図研究は、19世紀初頭、特にジョン・ファーマー(1789-1838)によって初めて体系化された[48]。ファーマーの努力以前 は、系図をたどることは、アメリカの植民地主義者が社会的地位を確保しようとする試みとみなされており、(憲法に概説されている)新共和国の平等主義的で 未来志向の理想に反する目的であった。 [しかし、建国の父たちや独立戦争の英雄たちを記念する7月4日の祝賀行事がますます盛んになるにつれて、地元の歴史に焦点を当てた「古文書主義」の追求 が、初期アメリカ人の功績を称える方法として受け入れられるようになった[citation needed]。ファーマーは、古文書主義が受け入れられることを利用し、アメリカ人の祖先を誇りに思うという初期共和国のイデオロギーの枠組みの中で系 図学を組み立てた。彼は、古文書学と系図学が確立していたニューイングランドで他の古文書学者と連絡を取り合い、この運動が成長するための調整役、推進 役、貢献者となった。1820年代には、彼と仲間の古文書学者が本格的に系図や古文書に関する小冊子を作成し始め、徐々にアメリカ国民の熱心な読者を獲得 していった。ファーマーは1838年に亡くなったが、彼の努力によって1845年にニューイングランド歴史 系図 協会(New England Historic Genealogical Society、NEHGS)が設立された。 1894年に設立されたユタ系図協会は、後に末日聖徒イエス・キリスト教会の家族歴史部となった。同部門の研究施設である家族歴史図書館は、 Utah.comによると「世界最大の系図図書館」[50]であり、末日聖徒が信じている特別な宗教儀式のために家系をたどるのを助けるために設立され た。末日聖徒は、預言者エリヤが「父の心を子に向けさせ、子の心を父に向けさせる」ために戻ってくるという聖書の預言が成就したと信じている。 「51]教会が運営する家族歴史センターのネットワークが全米および世界中にあり、ボランティアが一般の人々の先祖をたどる手助けをしている[52] 。 アメリカ系図学会(American Society of Genealogists)は、米国の系図分野の学術的名誉学会である。1940年12月、ジョン・インスレイ・コディントン、アーサー・アダムス、メレ ディス・B・コルケット・ジュニアによって設立され、会員は存命中のフェロー50名に限定されている。ASGは1980年以来、系図研究の学術誌「The Genealogist」を年2回発行している。アメリカ系図学会のフェローは、「FASG」の略称を持ち、過去半世紀で最も注目すべき系図学資料を執筆 している[54]。 最も著名なアメリカの系図学学術誌には、『The American Genealogist』、『National Genealogical Society Quarterly』、『The New England Historical and Genealogical Register』、『The New York Genealogical and Biographical Record』、『The Genealogist』などがある[55][56]。 |

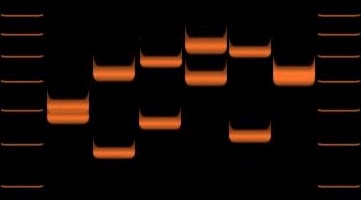

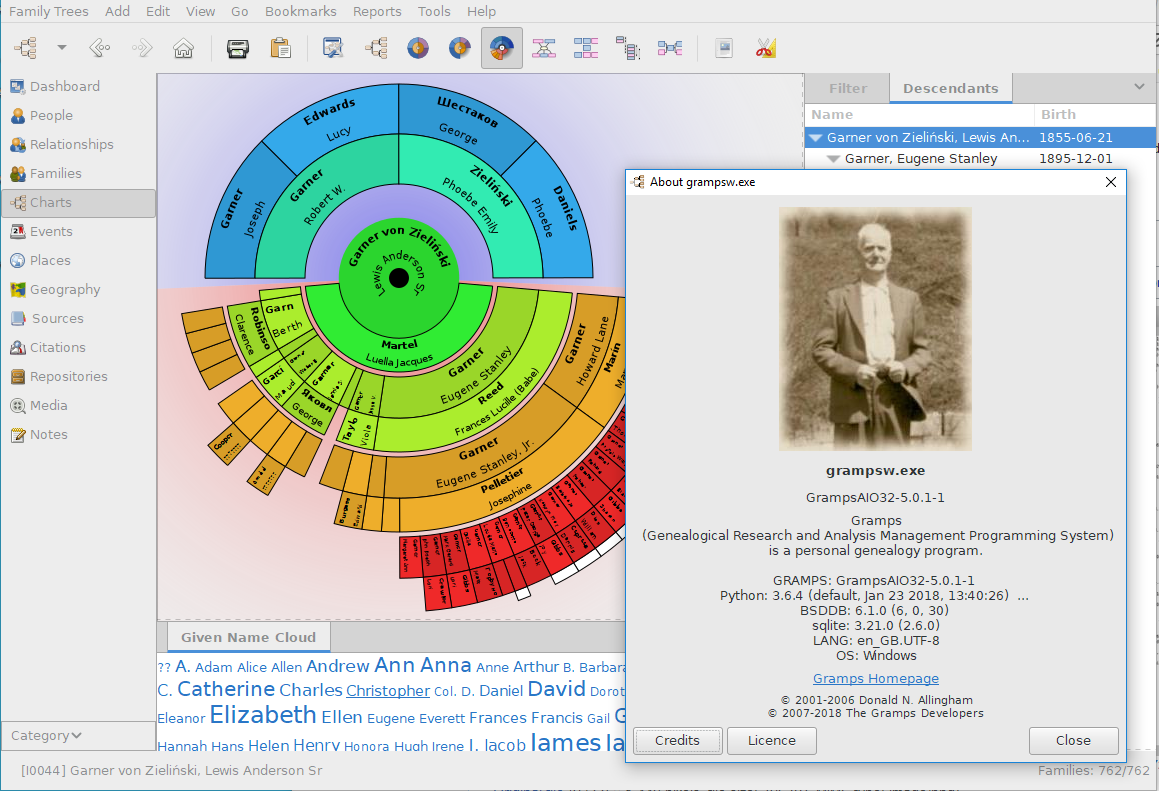

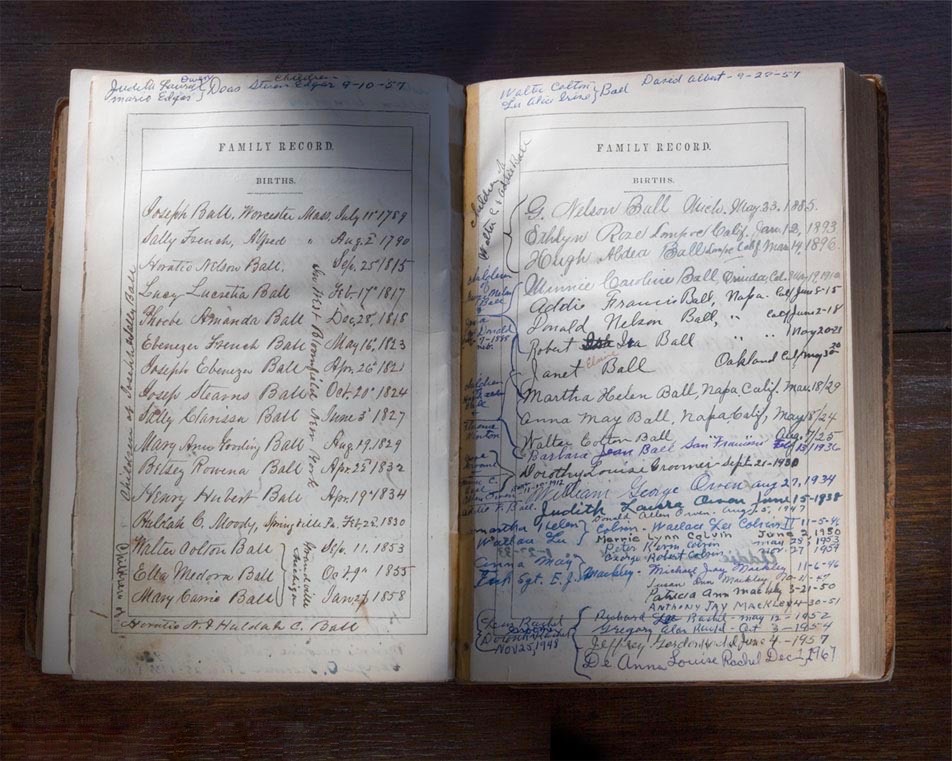

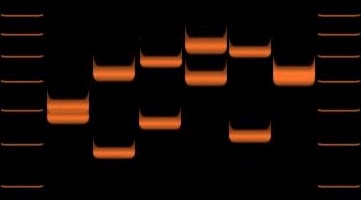

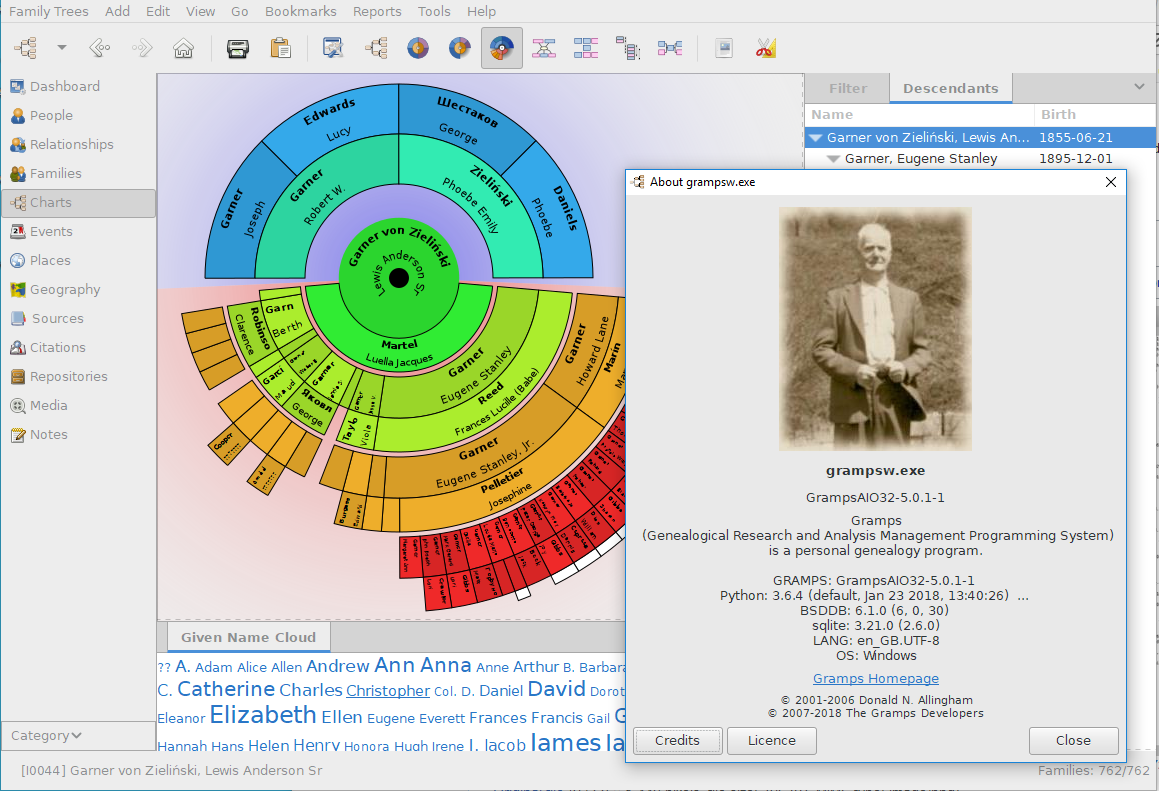

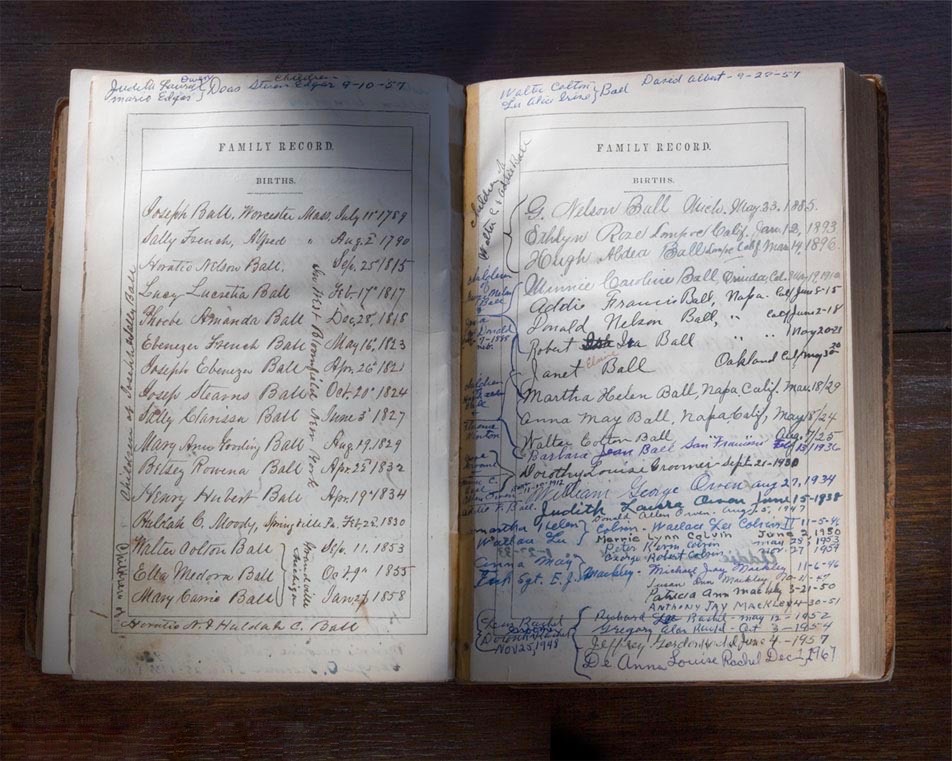

Research process 30 years of image research[57] arranged genealogically on a kitchen wall in Sweden 2019 Genealogical research is a complex process that uses historical records and sometimes genetic analysis to demonstrate kinship. Reliable conclusions are based on the quality of sources (ideally, original records), the information within those sources, (ideally, primary or firsthand information), and the evidence that can be drawn (directly or indirectly), from that information. In many instances, genealogists must skillfully assemble indirect or circumstantial evidence to build a case for identity and kinship. All evidence and conclusions, together with the documentation that supports them, is then assembled to create a cohesive genealogy or family history.[58] Genealogists begin their research by collecting family documents and stories. This creates a foundation for documentary research, which involves examining and evaluating historical records for evidence about ancestors and other relatives, their kinship ties, and the events that occurred in their lives. As a rule, genealogists begin with the present and work backwards in time. Historical, social, and family context is essential to achieving correct identification of individuals and relationships. Source citation is also important when conducting genealogical research.[59][60] To keep track of collected material, family group sheets and pedigree charts are used. Formerly handwritten, these can now be generated by genealogical software.[61] Genetic analysis Main article: Genetic genealogy  Variations of VNTR allele lengths in six individuals Because a person's DNA contains information that has been passed down relatively unchanged from early ancestors, analysis of DNA is sometimes used for genealogical research. Three DNA types are of particular interest. Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) is contained in the mitochondria of the egg cell and is passed down from a mother to all of her children, both male and female; however, only females pass it on to their children. Y-DNA is present only in males and is passed down from a father to his sons (direct male line) with only minor mutations occurring over time. Autosomal DNA (atDNA), is found in the 22 non-sex chromosomes (autosomes) and is inherited from both parents; thus, it can uncover relatives from any branch of the family. A genealogical DNA test allows two individuals to find the probability that they are, or are not, related within an estimated number of generations. Individual genetic test results are collected in databases to match people descended from a relatively recent common ancestor. See, for example, the Molecular Genealogy Research Project. Some tests are limited to either the patrilineal or the matrilineal line.[62] Collaboration Most genealogy software programs can export information about persons and their relationships in a standardized format called a GEDCOM. In that format, it can be shared with other genealogists, added to databases, or converted into family web sites. Social networking service (SNS) websites allow genealogists to share data and build their family trees online. Members can upload their family trees and contact other family historians to fill in gaps in their research. In addition to the (SNS) websites, there are other resources that encourage genealogists to connect and share information, such as rootsweb.ancestry.com[63] and rsl.rootsweb.ancestry.com.[64] Volunteerism Volunteer efforts figure prominently in genealogy.[65] These range from the extremely informal to the highly organized. On the informal side are the many popular and useful message boards such as Rootschat and mailing lists on particular surnames, regions, and other topics. These forums can be used to try to find relatives, request record lookups, obtain research advice, and much more. Many genealogists participate in loosely organized projects, both online and off. These collaborations take numerous forms. Some projects prepare name indexes for records, such as probate cases, and publish the indexes, either online or off. These indexes can be used as finding aids to locate original records. Other projects transcribe or abstract records. Offering record lookups for particular geographic areas is another common service. Volunteers do record lookups or take photos in their home areas for researchers who are unable to travel.[66] Those looking for a structured volunteer environment can join one of thousands of genealogical societies worldwide. Most societies have a unique area of focus, such as a particular surname, ethnicity, geographic area, or descendancy from participants in a given historical event. Genealogical societies are almost exclusively staffed by volunteers and may offer a broad range of services, including maintaining libraries for members' use, publishing newsletters, providing research assistance to the public, offering classes or seminars, and organizing record preservation or transcription projects.[67] Software  Gramps is an example of genealogy software. Main article: Genealogy software Genealogy software is used to collect, store, sort, and display genealogical data. At a minimum, genealogy software accommodates basic information about individuals, including births, marriages, and deaths. Many programs allow for additional biographical information, including occupation, residence, and notes, and most also offer a method for keeping track of the sources for each piece of evidence.[68] Most programs can generate basic kinship charts and reports, allow for the import of digital photographs and the export of data in the GEDCOM format (short for GEnealogical Data COMmunication) so that data can be shared with those using other genealogy software. More advanced features include the ability to restrict the information that is shared, usually by removing information about living people out of privacy concerns; the import of sound files; the generation of family history books, web pages and other publications; the ability to handle same-sex marriages and children born out of wedlock; searching the Internet for data; and the provision of research guidance. Programs may be geared toward a specific religion, with fields relevant to that religion, or to specific nationalities or ethnic groups, with source types relevant for those groups. Online resources involve complex programming and large data bases, such as censuses.[69] Records and documentation A family history page from an antebellum era family Bible Genealogists use a wide variety of records in their research. To effectively conduct genealogical research, it is important to understand how the records were created, what information is included in them, and how and where to access them.[70][71] List of record types  Records that are used in genealogy research include: Vital records Birth records Death records Marriage and divorce records Adoption records Biographies and biographical profiles (e.g. Who's Who) Cemetery lists Census records Church and Religious records Baptism or christening Brit milah or Baby naming certificates Confirmation Bar or bat mitzvah Marriage Funeral or death Membership City directories[72] and telephone directories Coroner's reports Court records Criminal records Civil records Diaries, personal letters and family Bibles DNA tests[73] Emigration, immigration and naturalization records Hereditary & lineage organization records, e.g. Daughters of the American Revolution records Land and property records, deeds Medical records Military and conscription records Newspaper articles Obituaries Occupational records Oral histories Passports Photographs Poorhouse, workhouse, almshouse, and asylum records School and alumni association records Ship passenger lists Social Security (within the US) and pension records Tax records Tombstones, cemetery records, and funeral home records Voter registration records Wills and probate records To keep track of their citizens, governments began keeping records of persons who were neither royalty nor nobility. In England and Germany, for example, such record keeping started with parish registers in the 16th century.[74] As more of the population was recorded, there were sufficient records to follow a family. Major life events, such as births, marriages, and deaths, were often documented with a license, permit, or report. Genealogists locate these records in local, regional or national offices or archives and extract information about family relationships and recreate timelines of persons' lives. In China, India and other Asian countries, genealogy books are used to record the names, occupations, and other information about family members, with some books dating back hundreds or even thousands of years. In the eastern Indian state of Bihar, there is a written tradition of genealogical records among Maithil Brahmins and Karna Kayasthas called "Panjis", dating to the 12th century CE. Even today these records are consulted prior to marriages.[75][76][77] In Ireland, genealogical records were recorded by professional families of senchaidh (historians) until as late as the mid-17th century. Perhaps the most outstanding example of this genre is Leabhar na nGenealach/The Great Book of Irish Genealogies, by Dubhaltach MacFhirbhisigh (d. 1671), published in 2004. FamilySearch collections  The Family History Library, operated by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, is the world's largest library dedicated to genealogical research. The LDS Church has engaged in large-scale microfilming of records of genealogical value. Its Family History Library in Salt Lake City, Utah, houses over 2 million microfiche and microfilms of genealogically relevant material, which are also available for on-site research at over 4,500 Family History Centers worldwide.[78] FamilySearch's website includes many resources for genealogists: a FamilyTree database, historical records,[79] digitized family history books,[80] resources and indexing for African American genealogy such as slave and bank records,[81] and a Family History Research Wiki containing research guidance articles.[82] Indexing ancestral information Indexing is the process of transcribing parish records, city vital records, and other reports, to a digital database for searching. Volunteers and professionals participate in the indexing process. Since 2006, the microfilm in the FamilySearch granite mountain vault is in the process of being digitally scanned, available online, and eventually indexed.[83][84] For example, after the 72-year legal limit for releasing personal information for the United States Census was reached in 2012, genealogical groups cooperated to index the 132 million residents registered in the 1940 United States Census.[85] Between 2006 and 2012, the FamilySearch indexing effort produced more than 1 billion searchable records.[86] In 2022, FamilySearch and Ancestry partnered to use Artificial Intelligence (AI) technology to help the process of indexing more records. The process first began with the public release of the 1950 United States Census. The index of the census would at first be created by an AI trained on handwriting in old documents and then reviewed by thousands of volunteers using FamilySearch. Record loss and preservation Sometimes genealogical records are destroyed, whether accidentally or on purpose. In order to do thorough research, genealogists keep track of which records have been destroyed so they know when information they need may be missing. Of particular note for North American genealogy is the 1890 United States Census, which was destroyed in a fire in 1921. Although fragments survive, most of the 1890 census no longer exists. Those looking for genealogical information for families that lived in the United States in 1890 must rely on other information to fill that gap.[87] War is another cause of record destruction. During World War II, many European records were destroyed.[88] Communists in China during the Cultural Revolution and in Korea during the Korean War destroyed genealogy books kept by families.[89][90] Often records are destroyed due to accident or neglect. Since genealogical records are often kept on paper and stacked in high-density storage, they are prone to fire, mold, insect damage, and eventual disintegration. Sometimes records of genealogical value are deliberately destroyed by governments or organizations because the records are considered to be unimportant or a privacy risk. Because of this, genealogists often organize efforts to preserve records that are at risk of destruction. FamilySearch has an ongoing program that assesses what useful genealogical records have the most risk of being destroyed, and sends volunteers to digitize such records.[88] In 2017, the government of Sierra Leone asked FamilySearch for help preserving their rapidly deteriorating vital records. FamilySearch has begun digitizing the records and making them available online.[91] The Federation of Genealogical Societies also organized an effort to preserve and digitize United States War of 1812 pension records. In 2010, they began raising funds, which were contribute by genealogists around the United States and matched by Ancestry.com. Their goal was achieved and the process of digitization was able to begin. The digitized records are available for free online.[92] |

研究のプロセス[編集] 30年にわたる画像調査[57]をスウェーデンの台所の壁に系図的に並べたもの 2019年 系図研究は、親族関係を証明するために歴史的記録と、時には遺伝子分析を用いる複雑なプロセスである。信頼できる結論は、情報源の質(理想的にはオリジナ ルの記録)、それらの情報源に含まれる情報(理想的には一次情報または直接の情報)、そしてその情報から(直接的または間接的に)導き出される証拠に基づ いている。多くの場合、系図学者は間接証拠や状況証拠を巧みに組み立てて、身元や血縁関係を立証しなければならない。すべての証拠と結論は、それらを裏付 ける文書とともに、まとまった系図または家族史を作成するために組み立てられる[58]。 系図学者は、家族の文書や物語を収集することから調査を開始する。これは、先祖やその他の親族、その親族関係、彼らの人生で起こった出来事についての証拠 を探すために、歴史的記録を調査・評価することを含む文書調査の基礎を作るものである。原則として、系図学者は現在から始め、時間をさかのぼって調査す る。歴史的、社会的、家族的背景は、個人と関係を正しく特定するために不可欠である。系図研究を行う際には、出典の引用も重要である[59][60]。収 集した資料を管理するために、家族グループシートや血統図が使用される。以前は手書きであったが、現在では系図作成ソフトウェアによって作成することがで きる[61]。 遺伝子解析[編集] 主な記事 遺伝子系図  6人におけるVNTR対立遺伝子の長さの変化 人のDNAには、初期の祖先から比較的変わらずに受け継がれてきた情報が含まれているため、DNAの解析が系図研究に用いられることがある。特に興味深い のは3種類のDNAである。ミトコンドリアDNA(mtDNA)は卵細胞のミトコンドリアに含まれ、男女を問わず母親からすべての子供に受け継がれるが、 子供に受け継がれるのは女性だけである。Y-DNAは男性にのみ存在し、父親からその息子(男性直系)に受け継がれるが、時間の経過とともにわずかな突然 変異が起こるだけである。常染色体DNA(atDNA)は、22本の非性染色体(常染色体)に存在し、両親から受け継がれる。系図DNA検査では、2人の 個人が推定何世代以内に血縁関係にあるか、ないかを調べることができる。個々の遺伝子検査結果はデータベースに集められ、比較的最近の共通の祖先の子孫で ある人々を照合する。例えば、Molecular Genealogy Research Projectを参照のこと。父系または母系に限定された検査もある[62]。 共同研究[編集] ほとんどの系図ソフトは、人物とその関係に関する情報をGEDCOMと呼ばれる標準化された形式でエクスポートすることができる。このフォーマットでは、 他の系図学者と共有したり、データベースに追加したり、家族のウェブサイトに変換したりすることができる。ソーシャル・ネットワーキング・サービス (SNS)のウェブサイトでは、系図作成者がオンラインでデータを共有し、家系図を作成することができる。メンバーは自分の家系図をアップロードし、他の 家系図作成者と連絡を取り、研究のギャップを埋めることができる。SNS)ウェブサイト以外にも、rootsweb.ancestry.com[63]や rsl.rootsweb.ancestry.com[64]など、系図研究者がつながり、情報を共有することを奨励するリソースがある。 ボランティア活動[編集] ボランティア活動は系図学において重要な位置を占める[65]。これらは極めて非公式なものから高度に組織化されたものまで様々である。 非公式なものとしては、Rootschatのような多くの人気があり有用な掲示板や、特定の姓や地域、その他のトピックに関するメーリングリストがある。 これらのフォーラムは、親戚を探したり、記録の検索を依頼したり、研究のアドバイスを得たり、その他多くのことに利用できる。多くの系図学者は、オンライ ンでもオフラインでも、緩やかに組織されたプロジェクトに参加している。このような共同作業には様々な形態がある。検認事件などの記録の人名索引を作成 し、オンラインまたはオフラインで公開するプロジェクトもある。これらの索引は、オリジナルの記録を探すためのファインディング・エイドとして利用するこ とができる。また、記録の転写や抄録を行う事業もある。特定の地理的地域の記録検索を提供することも、一般的なサービスである。ボランティアは、旅行がで きない研究者のために、地元で記録の検索や写真撮影を行う[66]。 体系化されたボランティア環境を求める人は、世界中に何千とある系図学会に参加することができる。ほとんどの学会は、特定の姓、民族、地理的地域、ある歴 史的出来事の参加者の子孫など、独自の分野に焦点を当てている。系図学会はほとんどボランティアによって運営されており、会員が利用できるライブラリーの 管理、ニュースレターの発行、一般市民への調査支援、クラスやセミナーの提供、記録の保存や転写プロジェクトの開催など、幅広いサービスを提供している [67]。 ソフトウェア[編集]  Grampsは系図ソフトウェアの一例である。 主な記事 系図ソフトウェア 系図ソフトウェアは、系図データを収集、保存、分類、表示するために使用される。最低限、系図ソフトウェアは、出生、結婚、死亡など、個人に関する基本的 な情報に対応している。多くのプログラムでは、職業、居住地、メモなどの伝記情報を追加することができ、ほとんどのプログラムでは、各証拠の出典を追跡す る方法も提供している[68]。ほとんどのプログラムでは、基本的な親族関係図やレポートを作成することができ、デジタル写真のインポートや、 GEDCOM形式(GEnealogical Data COMmunicationの略)でのデータのエクスポートが可能であるため、他の系図ソフトウェアを使用している人とデータを共有することができる。よ り高度な機能としては、共有する情報を制限する機能(通常はプライバシー保護の観点から生存している人物の情報を削除する)、音声ファイルのインポート、 家族歴史書、ウェブページ、その他の出版物の作成、同性婚や婚外子への対応、インターネットでのデータ検索、調査ガイダンスの提供などがある。特定の宗教 を対象としたプログラムでは、その宗教に関連した分野、特定の国籍や民族を対象としたプログラムでは、その民族に関連した出典の種類が用意されている。オ ンライン・リソースには、複雑なプログラミングや、国勢調査などの大規模なデータベースが含まれる[69]。 記録と文書[編集]  アンティベラム時代の家族聖書の家族史ページ 系図学者は調査において様々な記録を使用する。系図研究を効果的に行うためには、記録がどのように作成されたのか、どのような情報が含まれているのか、どこにどのようにアクセスすればよいのかを理解することが重要である[70][71]。 記録の種類の一覧[編集] 系図研究に使用される記録には以下のものがある: 出生記録 出生記録 死亡記録 結婚と 離婚の記録 養子縁組の記録 伝記および略歴(Who's Whoなど) 墓地リスト 国勢調査記録 教会と宗教の記録 洗礼または洗礼式 ブリット・ミラーまたは赤ちゃんの命名証明書 確認 バル・ミツヴァーまたはバット・ミツヴァー 結婚 葬儀または死亡 メンバーシップ 都市名鑑[72]と電話帳 検視報告書 裁判所記録 犯罪記録 民事記録 日記、個人的な手紙、家族の聖書 DNA検査[73] 移住、移民、帰化の記録 世襲・血統組織の記録(米国革命家の娘たちの記録など 土地と財産の記録、証書 医療記録 軍事および徴兵記録 新聞記事 死亡記事 職業記録 オーラルヒストリー パスポート 写真 貧民院、作業所、保養所、精神病院の記録 学校および同窓会の記録 船の乗客名簿 社会保障(米国内)および年金の記録 納税記録 墓石、墓地、葬儀場の記録 有権者登録記録 遺言書と 検認の記録 国民を把握するために、政府は王族でも 貴族でもない人の記録を取り始めた。例えば、イギリスやドイツでは、16世紀の教区台帳から記録が始まった[74]。出生、結婚、死亡といった人生の主要 な出来事は、免許証、許可証、報告書によって記録されることが多かった。系図学者は、これらの記録を地方、地域、国立の役所や公文書館で探し出し、家族関 係に関する情報を抽出し、その人の人生のタイムラインを再現する。 中国、インド、その他のアジア諸国では、系図帳が家族の名前、職業、その他の情報を記録するために使われており、数百年から数千年前のものもある。インド 東部のビハール州では、マイティル・ブラーミンやカルナ・カヤスタの間で「パンジ」と呼ばれる系図記録の文字による伝統があり、その歴史は紀元12世紀に までさかのぼる。今日でも、これらの記録は結婚の前に参照される[75][76][77]。 アイルランドでは、系図記録は17世紀半ばの終わり頃まで、センチャイド(歴史家)の専門家一族によって記録されていた。このジャンルの最も優れた例は、 2004年に出版されたDubhaltach MacFhirbhisigh(1671年没)のLeabhar na nGenealach/TheGreat Book of Genealogiesであろう。 ファミリーサーチのコレクション[編集]  末日聖徒イエス・キリスト教会が運営する家族歴史図書館は、系図研究に特化した世界最大の図書館である。 末日聖徒教会は、系図的に価値のある記録の大規模なマイクロフィルミングを行っている。ユタ州ソルトレイクシティにあるファミリー・ヒストリー・ライブラ リーには、系図に関連する資料のマイクロフィッシュとマイクロフィルムが200万点以上所蔵されており、世界4,500以上のファミリー・ヒストリー・セ ンターで現地調査も可能である[78]。 FamilySearchのウェブサイトには、FamilyTreeデータベース、歴史的記録、[79]デジタル化された家族歴史書、[80]奴隷や銀行 の記録などアフリカ系アメリカ人の系図に関するリソースや索引[81]、研究ガイダンス記事を含むFamily History Research Wiki[82]など、系図研究者のための多くのリソースが含まれている。 先祖情報の索引付け[編集] 索引作成とは、教区の記録、市のバイタル記録、その他の報告書などを、検索のためにデジタルデータベースに書き写す作業のことである。索引作成にはボラン ティアや専門家が参加している。2006年以降、ファミリーサーチの花崗岩の山の保管庫にあるマイクロフィルムは、デジタルスキャンされ、オンラインで利 用できるようになり、最終的には索引付けされる過程にある[83][84]。 例えば、2012年にアメリカ合衆国国勢調査のための個人情報の公開が72年間の法的制限に達した後、系図グループが協力して1940年のアメリカ合衆国国勢調査に登録された1億3,200万人の住民のインデックスを作成した[85]。 2006年から2012年にかけて、ファミリーサーチの索引作成作業は10億件以上の検索可能な記録を生み出した[86]。 2022年、FamilySearchとAncestryは人工知能(AI)技術を利用して、より多くの記録のインデックス作成プロセスを支援するために 提携した。このプロセスは、1950年のアメリカ合衆国国勢調査の一般公開から始まった。国勢調査の索引はまず、古い文書の筆跡を訓練したAIによって作 成され、その後ファミリーサーチを利用する何千人ものボランティアによって見直される。 記録の消失と保存[編集] 系図記録は、偶発的であれ意図的であれ、破棄されることがある。徹底的な調査を行うために、系図学者はどの記録が破棄されたかを記録しておき、必要な情報 がいつ欠落するかを把握しておく。北米の系図学で特に注目すべきは、1921年に火災で焼失した1890年合衆国国勢調査である。断片は残っているが、 1890年の国勢調査の大部分はもはや存在しない。1890年に米国に住んでいた家族の系図情報を探す人は、そのギャップを埋めるために他の情報に頼らな ければならない[87]。 戦争も記録破壊の原因の一つである。第二次世界大戦中、ヨーロッパの多くの記録が破壊された[88]。文化大革命中の中国や朝鮮戦争中の韓国では、共産主義者が家族が保管していた系図帳を破壊した[89][90]。 事故や放置によって記録が破壊されることも多い。系図記録は紙で保管され、高密度の保管庫に積み上げられていることが多いため、火災やカビ、虫害に遭いや すく、最終的には崩壊してしまう。また、系図学的に価値のある記録が、重要でない、あるいはプライバシーの危険性があるという理由で、政府や組織によって 意図的に破棄されることもある。このような理由から、系図学者はしばしば、破壊の危機に瀕した記録を保存する活動を組織する。ファミリーサーチは、どのよ うな有用な系図記録が破棄される危険性が最も高いかを評価し、そのような記録をデジタル化するためにボランティアを派遣する継続的なプログラムを持ってい る[88]。2017年、シエラレオネ政府はファミリーサーチに、急速に劣化している重要記録の保存への協力を要請した。ファミリーサーチは記録をデジタ ル化し、オンラインで利用できるようにし始めた[91] 。2010年、彼らは資金調達を開始し、アメリカ中の系図学者から寄付が集まり、Ancestry.comがそれに応じた。目標は達成され、デジタル化の プロセスを開始することができた。デジタル化された記録はオンラインで無料公開されている[92]。 |

| Types of information[edit] Genealogists who seek to reconstruct the lives of each ancestor consider all historical information to be "genealogical" information. Traditionally, the basic information needed to ensure correct identification of each person are place names, occupations, family names, first names, and dates. However, modern genealogists greatly expand this list, recognizing the need to place this information in its historical context in order to properly evaluate genealogical evidence and distinguish between same-name individuals. A great deal of information is available for British ancestry[93] with growing resources for other ethnic groups.[94] Family names[edit]  Lineage of a family, c. 1809 Family names are simultaneously one of the most important pieces of genealogical information, and a source of significant confusion for researchers.[95] In many cultures, the name of a person refers to the family to which they belongs. This is called the family name, surname, or last name. Patronymics are names that identify an individual based on the father's name. For example, Marga Olafsdottir is Marga, daughter of Olaf, and Olaf Thorsson is Olaf, son of Thor. Many cultures used patronymics before surnames were adopted or came into use. The Dutch in New York, for example, used the patronymic system of names until 1687 when the advent of English rule mandated surname usage.[96] In Iceland, patronymics are used by a majority of the population.[97] In Denmark and Norway patronymics and farm names were generally in use through the 19th century and beyond, though surnames began to come into fashion toward the end of the 19th century in some parts of the country. Not until 1856 in Denmark[98] and 1923 in Norway[99] were there laws requiring surnames. The transmission of names across generations, marriages and other relationships, and immigration may cause difficulty in genealogical research. For instance, women in many cultures have routinely used their spouse's surnames. When a woman remarried, she may have changed her name and the names of her children; only her name; or changed no names. Her birth name (maiden name) may be reflected in her children's middle names; her own middle name; or dropped entirely.[100] Children may sometimes assume stepparent, foster parent, or adoptive parent names. Because official records may reflect many kinds of surname change, without explaining the underlying reason for the change, the correct identification of a person recorded identified with more than one name is challenging. Immigrants to America often Americanized their names.[101] Surname data may be found in trade directories, census returns, birth, death, and marriage records. Given names[edit] This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (April 2015) (Learn how and when to remove this message) Genealogical data regarding given names (first names) is subject to many of the same problems as are family names and place names. Additionally, the use of nicknames is very common. For example, Beth, Lizzie or Betty are all common for Elizabeth, and Jack, John and Jonathan may be interchanged. Middle names provide additional information. Middle names may be inherited, follow naming customs, or be treated as part of the family name. For instance, in some Latin cultures, both the mother's family name and the father's family name are used by the children. Historically, naming traditions existed in some places and cultures. Even in areas that tended to use naming conventions, however, they were by no means universal. Families may have used them some of the time, among some of their children, or not at all. A pattern might also be broken to name a newborn after a recently deceased sibling, aunt or uncle. An example of a naming tradition from England, Scotland and Ireland: Child Namesake 1st son paternal grandfather 2nd son maternal grandfather 3rd son father 4th son father's oldest brother 1st daughter maternal grandmother 2nd daughter paternal grandmother 3rd daughter mother 4th daughter mother's oldest sister Another example is in some areas of Germany, where siblings were given the same first name, often of a favourite saint or local nobility, but different second names by which they were known (Rufname). If a child died, the next child of the same gender that was born may have been given the same name. It is not uncommon that a list of a particular couple's children will show one or two names repeated. Personal names have periods of popularity, so it is not uncommon to find many similarly named people in a generation, and even similarly named families; e.g., "William and Mary and their children David, Mary, and John". Many names may be identified strongly with a particular gender; e.g., William for boys, and Mary for girls. Others may be ambiguous, e.g., Lee, or have only slightly variant spellings based on gender, e.g., Frances (usually female) and Francis (usually male). Place names[edit] While the locations of ancestors' residences and life events are core elements of the genealogist's quest, they can often be confusing. Place names may be subject to variant spellings by partially literate scribes. Locations may have identical or very similar names. For example, the village name Brockton occurs six times in the border area between the English counties of Shropshire and Staffordshire. Shifts in political borders must also be understood. Parish, county, and national borders have frequently been modified. Old records may contain references to farms and villages that have ceased to exist. When working with older records from Poland, where borders and place names have changed frequently in past centuries, a source with maps and sample records such as A Translation Guide to 19th-Century Polish-Language Civil-Registration Documents can be invaluable. Available sources may include vital records (civil or church registration), censuses, and tax assessments. Oral tradition is also an important source, although it must be used with caution. When no source information is available for a location, circumstantial evidence may provide a probable answer based on a person's or a family's place of residence at the time of the event. Maps and gazetteers are important sources for understanding the places researched. They show the relationship of an area to neighboring communities and may be of help in understanding migration patterns. Family tree mapping using online mapping tools such as Google Earth (particularly when used with Historical Map overlays such as those from the David Rumsey Historical Map Collection) assist in the process of understanding the significance of geographical locations. Dates[edit] It is wise to exercise extreme caution with dates. Dates are more difficult to recall years after an event, and are more easily mistranscribed than other types of genealogical data.[102] Therefore, one should determine whether the date was recorded at the time of the event or at a later date. Dates of birth in vital records or civil registrations and in church records at baptism are generally accurate because they were usually recorded near the time of the event. Family Bibles are often a source for dates, but can be written from memory long after the event. When the same ink and handwriting is used for all entries, the dates were probably written at the same time and therefore will be less reliable since the earlier dates were probably recorded well after the event. The publication date of the Bible also provides a clue about when the dates were recorded since they could not have been recorded at any earlier date. People sometimes reduce their age on marriage, and those under "full age" may increase their age in order to marry or to join the armed forces. Census returns are notoriously unreliable for ages or for assuming an approximate death date. Ages over 15 in the 1841 census in the UK are rounded down to the next lower multiple of five years. Although baptismal dates are often used to approximate birth dates, some families waited years before baptizing children, and adult baptisms are the norm in some religions. Both birth and marriage dates may have been adjusted to cover for pre-wedding pregnancies. Calendar changes must also be considered. In 1752, England and her American colonies changed from the Julian to the Gregorian calendar. In the same year, the date the new year began was changed. Prior to 1752 it was 25 March; this was changed to 1 January. Many other European countries had already made the calendar changes before England had, sometimes centuries earlier. By 1751 there was an 11-day discrepancy between the date in England and the date in other European countries. For further detail on the changes involved in moving from the Julian to the Gregorian calendar, see: Gregorian calendar. The French Republican Calendar or French Revolutionary Calendar was a calendar proposed during the French Revolution, and used by the French government for about 12 years from late 1793 to 1805, and for 18 days in 1871 in Paris. Dates in official records at this time use the revolutionary calendar and need "translating" into the Gregorian calendar for calculating ages etc. There are various websites which do this.[103] Occupations[edit] Occupational information may be important to understanding an ancestor's life and for distinguishing two people with the same name. A person's occupation may have been related to his or her social status, political interest, and migration pattern. Since skilled trades are often passed from father to son, occupation may also be indirect evidence of a family relationship. It is important to remember that a person may change occupations, and that titles change over time as well. Some workers no longer fit for their primary trade often took less prestigious jobs later in life, while others moved upwards in prestige.[104] Many unskilled ancestors had a variety of jobs depending on the season and local trade requirements. Census returns may contain some embellishment; e.g., from labourer to mason, or from journeyman to master craftsman. Names for old or unfamiliar local occupations may cause confusion if poorly legible. For example, an ostler (a keeper of horses) and a hostler (an innkeeper) could easily be confused for one another. Likewise, descriptions of such occupations may also be problematic. The perplexing description "ironer of rabbit burrows" may turn out to describe an ironer (profession) in the Bristol district named Rabbit Burrows. Several trades have regionally preferred terms. For example, "shoemaker" and "cordwainer" have the same meaning. Finally, many apparently obscure jobs are part of a larger trade community, such as watchmaking, framework knitting or gunmaking. Occupational data may be reported in occupational licences, tax assessments, membership records of professional organizations, trade directories, census returns, and vital records (civil registration). Occupational dictionaries are available to explain many obscure and archaic trades.[105] |

情報の種類[編集] 各先祖の生涯を復元しようとする系図学者は、すべての歴史的情報を「系図」情報とみなしている。伝統的には、各人物を正しく特定するために必要な基本情報 は、地名、職業、姓、名、日付であった。しかし、現代の系図学者は、系図上の証拠を適切に評価し、同姓同名の個人を区別するためには、これらの情報を歴史 的文脈の中に位置づける必要があることを認識し、このリストを大幅に拡張している。イギリス人の祖先については多くの情報が入手可能であり[93]、他の エスニック・グループについてのリソースも増えつつある[94]。 姓[編集]  1809年頃の家系図 姓は同時に系図の最も重要な情報の一つであり、研究者にとっては大きな混乱の元でもある[95]。 多くの文化において、人の名前はその人が属する家族を指す。これは姓、苗字、名字と呼ばれる。パトロニミックは、父親の名前に基づいて個人を特定する名前 である。例えば、Marga OlafsdottirはOlafの娘Margaであり、Olaf ThorssonはThorの息子Olafである。多くの文化では、姓が採用されたり使われるようになったりする前に、守護霊呼称が使われていた。例え ば、ニューヨークのオランダ人は、1687年にイギリスの支配が始まり、姓の使用が義務付けられるまで、姓のシステムを使用していた[96]。 アイスランドでは、人口の大多数が姓を使用している[97]。 デンマークとノルウェーでは、姓が19世紀末に流行し始めた地域もあったが、姓と農場の名前は19世紀以降も一般的に使用されていた。デンマークでは 1856年まで[98]、ノルウェーでは1923年まで[99]、姓を義務付ける法律が制定されなかった。 世代を超えた名前の伝達、結婚その他の関係、移民は、系図研究を困難にすることがある。例えば、多くの文化において女性は配偶者の姓を日常的に使用してき た。女性が再婚した場合、自分の名前と子供の名前を変えることもあれば、自分の名前だけを変えることもあれば、名前を変えないこともある。彼女の出生名 (旧姓)は、子供のミドルネームに反映されたり、彼女自身のミドルネームに反映されたり、あるいは完全に削除されたりすることもある[100]。子供は、 継父母、里親、養父母の名前を名乗ることもある。公式記録には、変更の根本的な理由を説明することなく、多くの種類の姓の変更が反映されていることがある ため、複数の名前で記録されている人物を正しく識別することは困難である。アメリカへの移民はしばしば名前をアメリカナイズした[101]。 姓のデータは、貿易ディレクトリ、国勢調査の報告、出生、死亡、結婚の記録で見つけることができる。 姓[編集] このセクションでは出典を引用して いない 。信頼できる情報源への引用を追加することで、このセクションの改善にご協力いただきたい。ソースのないものは異議申し立てされ、削除されることがある。(2015年4月)(このメッセージを削除する方法とタイミングを学ぶ) 姓(ファーストネーム)に関する系図データは、姓や地名と同じような多くの問題を抱えている。さらに、ニックネームの使用は非常に一般的である。例えば、 エリザベスにはBeth、Lizzie、Bettyが一般的であり、Jack、John、Jonathanが入れ替わることもある。 ミドルネームは付加的な情報となる。ミドルネームは受け継がれることもあれば、命名の習慣に従ったもの、姓の一部として扱われることもある。例えば、ラテン文化圏では、母親の姓と父親の姓の両方を子供が使う場合もある。 歴史的に見ても、命名の習慣が存在する地域や文化はある。しかし、命名規則を使う傾向のある地域でも、決して普遍的なものではなかった。家族は、ある時 期、ある子供たちの間でそれらを使っていたかもしれないし、まったく使っていなかったかもしれない。また、最近亡くなった兄弟や叔父、叔母の名前を新生児 につけるというパターンも崩れるかもしれない。 イングランド、スコットランド、アイルランドの名づけの伝統の一例: 子供の名前 長男 父方の祖父 二男 母方の祖父 三男 父 四男 父の長兄 長女 母方の祖母 次女 父方の祖母 三女 母 四女 母の長姉 別の例として、ドイツの一部の地域では、兄弟姉妹に同じファーストネームが与えられ、多くの場合、好きな聖人や地元の貴族の名前が付けられたが、知られて いるセカンドネームは異なっていた(ルフネーム)。子供が亡くなった場合、次に生まれた同性の子供にも同じ名前が与えられたかもしれない。特定の夫婦の子 供のリストには、1人か2人の名前が繰り返されていることが珍しくない。 個人名には人気の時期があるため、一世代に同じような名前の人が何人もいたり、「ウィリアムとメアリーとその子供たちデビッド、メアリー、ジョン」のように同じような名前の家族がいたりすることも珍しくない。 例えば、「ウィリアムとメアリーとその子供たちデビッド、メアリー、ジョン」のようにである。また、リー(Lee)のように曖昧であったり、フランシス (Frances)(通常は女性)とフランシス(Francis)(通常は男性)のように性別によって綴りが若干異なるだけのものもある。 地名[編集] 先祖の居住地や生涯の出来事は系図探求の中心的要素であるが、しばしば混乱を招くことがある。地名は、部分的に識字能力のある書記によって綴りが変えられ ることがある。地名が同一または非常に類似している場合もある。例えば、ブロックトンという村名は、英国のシュロップシャー郡とスタフォードシャー郡の境 界地域に6回出現する。政治的な境界の変化も理解しなければならない。教区、郡、国の境界は頻繁に変更されている。古い記録には、存在しなくなった農場や 村が記されていることもある。国境や地名が過去何世紀にもわたって頻繁に変更されてきたポーランドの古い記録を扱う場合、『A Translation Guide to 19th-Century Polish-Language Civil-Registration Documents』のような、地図や記録例が掲載された資料が貴重なものとなる。 利用可能な情報源には、バイタル・レコード(市民登録または教会登録)、国勢調査、税評価などがある。口伝も重要な情報源であるが、その利用には注意が必 要である。ある場所について出典となる情報がない場合、状況証拠から、その出来事が起こったときのその人または家族の居住地に基づく答えが導き出されるこ とがある。 地図や官報は、調査した場所を理解するための重要な資料である。地図や官報は、その地域と近隣の地域との関係を示し、移住のパターンを理解するのに役立 つ。Google Earthなどのオンライン地図ツールを使った家系図作成は(特にDavid Rumsey Historical Map Collectionのような歴史地図オーバーレイと併用すると)、地理的位置の重要性を理解する過程で役立つ。 日付[編集] 日付には細心の注意を払うことが賢明である。日付は他のタイプの系図データよりも、出来事から数年後に思い出すことが難しく、誤記されやすい[102]。 したがって、その日付が出来事当時に記録されたものなのか、後日記録されたものなのかを判断する必要がある。バイタルレコードや市民登録、洗礼時の教会記 録における生年月日は、通常、その出来事の時近くに記録されたものであるため、一般的に正確である。家族の聖書はしばしば日付の情報源となるが、出来事の ずっと後に記憶に基づいて書かれたものである可能性がある。すべての記述に同じインクと筆跡が使われている場合、日付はおそらく同時に書かれたものであ り、それ以前の日付はおそらくその出来事のかなり後に記録されたものであるため、信頼性は低くなる。聖書の出版日も、その日付がいつ記録されたかを知る手 がかりとなる。 結婚すると年齢が下がることもあるし、「満年齢」未満の人が結婚したり軍隊に入ったりするために年齢が上がることもある。国勢調査の報告書は、年齢やおお よその死亡推定日については信頼できないことで有名である。イギリスの1841年の国勢調査では、15歳以上は5歳の倍数で切り捨てられている。 バプテスマの日付は、おおよその生年月日を推定するためによく使われるが、子供にバプテスマを授けるまで何年も待つ家庭もあり、宗教によっては成人のバプテスマが普通である。結婚前の妊娠をカバーするために、誕生日と結婚日の両方が調整されている場合もある。 暦の変化も考慮しなければならない。1752年、イギリスとアメリカの植民地はユリウス 暦からグレゴリオ暦に変更した。同年、新年の始まりの日が変更された。1752年以前は3月25日だったが、1月1日に変更された。他の多くのヨーロッパ 諸国は、イングランドより先に、時には何世紀も前に、すでに暦の変更を行っていた。1751年までには、イングランドの日付と他のヨーロッパ諸国の日付に は11日のずれがあった。 ユリウス暦からグレゴリオ暦への移行に伴う変更の詳細については、以下を参照のこと: グレゴリオ暦を参照のこと。 フランス共和暦またはフランス革命暦は、フランス革命時に提唱された暦で、フランス政府によって1793年後半から1805年までの約12年間、および 1871年の18日間、パリで使用された。この時期の公式記録の日付は革命暦を使用しており、年齢などを計算するためにグレゴリオ暦に「翻訳」する必要が ある。これを行う様々なウェブサイトがある[103]。 職業[編集] 職業情報は、先祖の生涯を理解したり、同姓同名の2人を区別したりするのに重要な場合がある。ある人物の職業は、その人物の社会的地位、政治的関心、移住 形態に関係している可能性がある。熟練した職業は父から子へと受け継がれることが多いため、職業は家族関係を示す間接的な証拠となることもある。 人は職業を変える可能性があり、肩書きも時代とともに変化することを忘れてはならない。主な職業に適さなくなった労働者の中には、後年あまり名声のない職 業に就く者もいれば、名声のある職業に就く者もいる[104]。国勢調査の報告書には、労働者から石工へ、職工から 名工へといったように、多少の装飾が含まれていることがある。古い、あるいは馴染みのない地域の職業名は、読みにくいと混乱を招くことがある。たとえば、 オストラー(馬の番人)とホストラー(宿屋の主人)は混同されやすい。同様に、このような職業に関する記述にも問題がある。ウサギの巣のアイロン職人」と いう不可解な記述は、ウサギの巣という名のブリストル地区のアイロン職人(職業)を表していることが判明するかもしれない。いくつかの職業には、地域的に 好まれる用語がある。例えば、"shoemaker "と "cordwainer "は同じ意味である。最後に、時計製造、骨組み編み、銃製造など、一見無名に見える仕事の多くは、より大きな貿易共同体の一部である。 職業データは、職業免許証、税評価、専門職団体の会員記録、業界名簿、国勢調査報告、バイタル記録(市民登録)などで報告されることがある。職業辞典は、多くの不明瞭で古めかしい職業を説明するために利用できる[105]。 |

| Reliability of sources Information found in historical or genealogical sources can be unreliable and it is good practice to evaluate all sources with a critical eye. Factors influencing the reliability of genealogical information include: the knowledge of the informant (or writer); the bias and mental state of the informant (or writer); the passage of time and the potential for copying and compiling errors. The quality of census data has been of special interest to historians, who have investigated reliability issues.[102][106] Knowledge of the informant The informant is the individual who provided the recorded information. Genealogists must carefully consider who provided the information and what they knew. In many cases the informant is identified in the record itself. For example, a death certificate usually has two informants: a physician who provides information about the time and cause of death and a family member who provides the birth date, names of parents, etc. When the informant is not identified, one can sometimes deduce information about the identity of the person by careful examination of the source. One should first consider who was alive (and nearby) when the record was created. When the informant is also the person recording the information, the handwriting can be compared to other handwriting samples. When a source does not provide clues about the informant, genealogists should treat the source with caution. These sources can be useful if they can be compared with independent sources. For example, a census record by itself cannot be given much weight because the informant is unknown. However, when censuses for several years concur on a piece of information that would not likely be guessed by a neighbor, it is likely that the information in these censuses was provided by a family member or other informed person. On the other hand, information in a single census cannot be confirmed by information in an undocumented compiled genealogy since the genealogy may have used the census record as its source and might therefore be dependent on the same misinformed individual. Motivation of the informant Even individuals who had knowledge of the fact, sometimes intentionally or unintentionally provided false or misleading information. A person may have lied in order to obtain a government benefit (such as a military pension), avoid taxation, or cover up an embarrassing situation (such as the existence of a non-marital child). A person with a distressed state of mind may not be able to accurately recall information. Many genealogical records were recorded at the time of a loved one's death, and so genealogists should consider the effect that grief may have had on the informant of these records. The effect of time The passage of time often affects a person's ability to recall information. Therefore, as a general rule, data recorded soon after the event are usually more reliable than data recorded many years later. However, some types of data are more difficult to recall after many years than others. One type especially prone to recollection errors is dates. Also the ability to recall is affected by the significance that the event had to the individual. These values may have been affected by cultural or individual preferences. Copying and compiling errors Genealogists must consider the effects that copying and compiling errors may have had on the information in a source. For this reason, sources are generally categorized in two categories: original and derivative. An original source is one that is not based on another source. A derivative source is information taken from another source. This distinction is important because each time a source is copied, information about the record may be lost and errors may result from the copyist misreading, mistyping, or miswriting the information. Genealogists should consider the number of times information has been copied and the types of derivation a piece of information has undergone. The types of derivatives include: photocopies, transcriptions, abstracts, translations, extractions, and compilations. In addition to copying errors, compiled sources (such as published genealogies and online pedigree databases) are susceptible to misidentification errors and incorrect conclusions based on circumstantial evidence. Identity errors usually occur when two or more individuals are assumed to be the same person. Circumstantial or indirect evidence does not explicitly answer a genealogical question, but either may be used with other sources to answer the question, suggest a probable answer, or eliminate certain possibilities. Compilers sometimes draw hasty conclusions from circumstantial evidence without sufficiently examining all available sources, without properly understanding the evidence, and without appropriately indicating the level of uncertainty. Primary and secondary sources In genealogical research, information can be obtained from primary or secondary sources. Primary sources are records that were made at the time of the event, for example a death certificate would be a primary source for a person's death date and place. Secondary sources are records that are made days, weeks, months, or even years after an event. |

情報源の信頼性[編集] 歴史的または系図的な情報源に見られる情報は信頼できないことがあり、すべての情報源を批判的な目で評価することは良い習慣である。系図情報の信頼性に影 響を与える要因には、情報提供者(または執筆者)の知識、情報提供者(または執筆者)の偏見や精神状態、時間の経過、複写や編集の誤りの可能性などがあ る。 国勢調査データの質は歴史家にとって特別な関心事であり、信頼性の問題を調査してきた[102][106]。 情報提供者の知識[編集] 情報提供者とは、記録された情報を提供した個人のことである。系図作成者は、誰が情報を提供し、彼らが何を知っていたかを慎重に検討しなければならない。 多くの場合、情報提供者は記録自体に明記されている。例えば、死亡診断書には通常2人の情報提供者がいる。死亡時刻や死因に関する情報を提供する医師と、 生年月日や両親の名前などを提供する家族である。 情報提供者が特定されていない場合、情報源を注意深く調べることによって、その人物の身元に関する情報を推測できることがある。まず、その記録が作成され たときに誰が生きていたか(近くにいたか)を考慮する必要がある。情報提供者が情報を記録した人物でもある場合、筆跡を他の筆跡サンプルと比較することが できる。 情報源から情報提供者に関する手がかりが得られない場合、系図学者はその情報源を慎重に扱うべきである。これらの情報源は、独立した情報源と比較すること ができれば有用である。例えば、国勢調査の記録は、それ自体では情報提供者が不明であるため、あまり重要視されない。しかし、数年分の国勢調査が、隣人に は推測できないような情報の一部で一致している場合、これらの国勢調査の情報は、家族またはその他の情報提供者によって提供されたものである可能性が高 い。一方、単一の国勢調査の情報は、文書化されていない系図の情報によって確認することはできない。 情報提供者の動機[編集]。 事実を知っていた個人であっても、意図的あるいは無意識に虚偽の情報を提供したり、誤解を招くような情報を提供したりすることがある。ある人は、政府から の恩恵(軍人年金など)を得たり、課税を避けたり、恥ずかしい状況(婚姻関係にない子どもの存在など)を隠蔽するために嘘をついたかもしれない。精神状態 が不安定な人は、情報を正確に思い出すことができないかもしれない。系図記録の多くは、愛する人の死亡時に記録されたものであるため、系図研究者は、悲し みがこれらの記録の情報提供者に与えた影響を考慮すべきである。 時間の影響[編集] 時間の経過はしばしば人の情報を思い出す能力に影響を与える。したがって、一般的なルールとして、事件後すぐに記録されたデータは、何年も経ってから記録 されたデータよりも信頼できることが多い。しかし、データの種類によっては、何年経っても思い出すのが難しいものもある。特に想起エラーを起こしやすいの は日付である。また、思い出す能力は、その出来事が個人にとってどのような意味を持っていたかに影響される。これらの価値観は文化や個人の嗜好に影響され ている可能性がある。 複写と編集の誤り[編集] 系図作成者は、コピーミスやコンパイルミスが資料の情報に与えた影響を考慮しなければならない。このため、出典は一般的に原典と派生元の2つに分類され る。原典とは、他の典拠に基づかないものである。派生的情報源とは、他の情報源から引用された情報である。この区別は重要である。というのも、資料が複写 されるたびに、その記録に関する情報が失われる可能性があり、複写者が情報を誤読、誤タイプ、誤記することによって誤りが生じる可能性があるからである。 系図作成者は、情報がコピーされた回数と、情報の一部が受けた派生物の種類を考慮すべきである。派生物の種類には、複写、転写、抄録、翻訳、抽出、編集な どがある。 複写ミスに加え、編集された情報源(出版された系図やオンライン血統データベースなど)は、誤認エラーや状況証拠に基づく誤った結論の影響を受けやすい。 同一性の誤りは通常、2人以上の個人が同一人物であると仮定された場合に発生する。状況証拠や間接証拠は、系図上の質問に明確に答えるものではないが、他 の情報源と併用することで、質問に答えたり、答えの可能性を示唆したり、特定の可能性を排除したりすることができる。編纂者は時に、入手可能なすべての資 料を十分に調べることなく、証拠を適切に理解することなく、不確実性のレベルを適切に示すことなく、状況証拠から性急に結論を導き出すことがある。 一次資料と二次資料[編集] 系図研究において、情報は一次資料または二次資料から得ることができる。一次情報源とは、その出来事が起こった当時に作成された記録であり、例えば死亡診 断書はその人の死亡日と死亡場所の一次情報源となる。二次情報源は、ある出来事の数日後、数週間後、数ヶ月後、あるいは数年後に作成された記録である。 |

| Standards and ethics Organizations that educate and certify genealogists have established standards and ethical guidelines they instruct genealogists to follow. Research standards Genealogy research requires analyzing documents and drawing conclusions based on the evidence provided in the available documents. Genealogists need standards to determine whether or not their evaluation of the evidence is accurate. In the past, genealogists in the United States borrowed terms from judicial law to examine evidence found in documents and how they relate to the researcher's conclusions. However, the differences between the two disciplines created a need for genealogists to develop their own standards. In 2000, the Board for Certification of Genealogists published their first manual of standards. The Genealogical Proof Standard created by the Board for Certification of Genealogists is widely distributed in seminars, workshops, and educational materials for genealogists in the United States. Other genealogical organizations around the world have created similar standards they invite genealogists to follow. Such standards provide guidelines for genealogists to evaluate their own research as well as the research of others. Standards for genealogical research include:[107][108][109] Clearly document and organize findings. Cite all sources in a specific manner so that others can locate them and properly evaluate them. Locate all available sources that may contain information relevant to the research question. Analyze findings thoroughly, without ignoring conflicts in records or negative evidence. Rely on original, rather than derivative sources, wherever possible. Use logical reasoning based on reliable sources to reach conclusions. Acknowledge when a specific conclusion is only "possible" or "probable" rather than "proven". Acknowledge that other records that have not yet been discovered may overturn a conclusion. Ethical guidelines Genealogists often handle sensitive information and share and publish such information. Because of this, there is a need for ethical standards and boundaries for when information is too sensitive to be published. Historically, some genealogists have fabricated information or have otherwise been untrustworthy. Genealogical organizations around the world have outlined ethical standards as an attempt to eliminate such problems. Ethical standards adopted by various genealogical organizations include:[110][111][109][108][112] Respect copyright laws Acknowledge where one consulted another's work and do not plagiarize the work of other researchers. Treat original records with respect and avoid causing damage to them or removing them from repositories. Treat archives and archive staff with respect. Protect the privacy of living individuals by not publishing or otherwise disclosing information about them without their permission. Disclose any conflicts of interest to clients. When doing paid research, be clear with the client about scope of research and fees involved. Do not fabricate information or publish false or unproven information as proven. Be sensitive about information found through genealogical research that may make the client or family members uncomfortable. In 2015, a committee presented standards for genetic genealogy at the Salt Lake Institute of Genealogy. The standards emphasize that genealogists and testing companies should respect the privacy of clients and recognize the limits of DNA tests. It also discusses how genealogists should thoroughly document conclusions made using DNA evidence.[113] In 2019, the Board for the Certification of Genealogists officially updated their standards and code of ethics to include standards for genetic genealogy.[107] |

基準と倫理[編集] 系図学者を教育・認定する組織は、系図学者に従うよう指導する基準や倫理指針を定めている。 研究基準[編集] 系図研究は、文書を分析し、利用可能な文書に記載されている証拠に基づいて結論を導き出す必要がある。系図学者は、その証拠の評価が正確かどうかを判断す るための基準を必要としている。かつて米国の系図学者は、文書に記載された証拠と研究者の結論との関連性を検討するために、司法法の用語を借用していた。 しかし、この2つの分野の違いから、系図学者が独自の基準を作成する必要性が生じた。2000年、系図学者認定委員会は最初の基準マニュアルを発表した。 系図学者認定委員会が作成した系図証明基準は、米国内の系図学者向けのセミナー、ワークショップ、教材などで広く配布されている。世界中の他の系図学団体 も同様の基準を作成し、系図学者に従うよう呼びかけている。このような基準は、系図学者が自分自身の調査や他人の調査を評価するためのガイドラインとな る。 系図研究の基準には以下が含まれる[107][108][109]。 調査結果を明確に文書化し、整理すること。 他の人が所在を確認し、適切に評価できるように、すべての出典を具体的な方法で引用する。 研究課題に関連する情報が含まれている可能性のある入手可能なすべての情報源を探す。 記録の矛盾や否定的な証拠を無視することなく、調査結果を徹底的に分析する。 可能な限り、派生的な情報源ではなく、オリジナルの情報源に頼る。 信頼できる情報源に基づいた論理的推論を用い、結論に達する。 特定の結論が「証明された」のではなく、「可能性がある」または「可能性が高い」だけであることを認識する。 まだ発見されていない他の記録が結論を覆す可能性があることを認める。 倫理的ガイドライン[編集] 系図学者はしばしば機密情報を扱い、そのような情報を共有したり公開したりする。そのため、公開するには微妙な情報である場合の倫理基準や境界線が必要で ある。歴史的に、系図研究者の中には情報を捏造したり、信用できない者もいる。このような問題を排除する試みとして、世界中の系図団体が倫理基準の概要を 定めている。様々な系図団体が採用している倫理基準には以下のようなものがある[110][111][109][108][112]。 著作権法を尊重する 他の研究者の研究を参考にした箇所を認め、他の研究者の研究を盗用しない。 オリジナルの記録を敬意を持って扱い、それらに損傷を与えたり、リポジトリから削除したりすることは避ける。 公文書館や公文書館の職員には敬意をもって接する。 生存している個人のプライバシーを保護するため、その個人に関する情報を、本人の許可なく出版またはその他の方法で開示しない。 利益相反がある場合は、クライアントに開示する。 有償の調査を行う場合は、調査範囲や料金について依頼者と 明確にする。 情報を捏造したり、嘘の情報や証明されていない情報を証明されたものとして公表しない。 系図調査を通じて判明した情報のうち、依頼者や家族を不快にさせる可能性のあるものには配慮すること。 2015年、委員会はソルトレイク系図研究所で遺伝系図の基準を発表した。この基準では、系図学者と検査会社は依頼者のプライバシーを尊重し、DNA検査 の限界を認識すべきであることが強調されている。また、系図学者がDNAの証拠を用いて下した結論をどのように徹底的に文書化すべきかについても論じてい る[113]。 2019年、系図学者認定委員会は、遺伝子系図学の基準を含むように、その基準と倫理規定を正式に更新した[107]。 |

| Ahnentafel Cluster genealogy Descent from antiquity Genealogical numbering systems Genealogy tourism International Museum for Family History List of genealogy databases List of Mormon family organizations List of national archives |

アーネンタフェル クラスターの系譜 古代からの系譜 系図番号システム 系図ツーリズム 国際家族歴史博物館 系図データベースのリスト モルモンの家族組織のリスト 国立公文書館のリスト |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Genealogy |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆