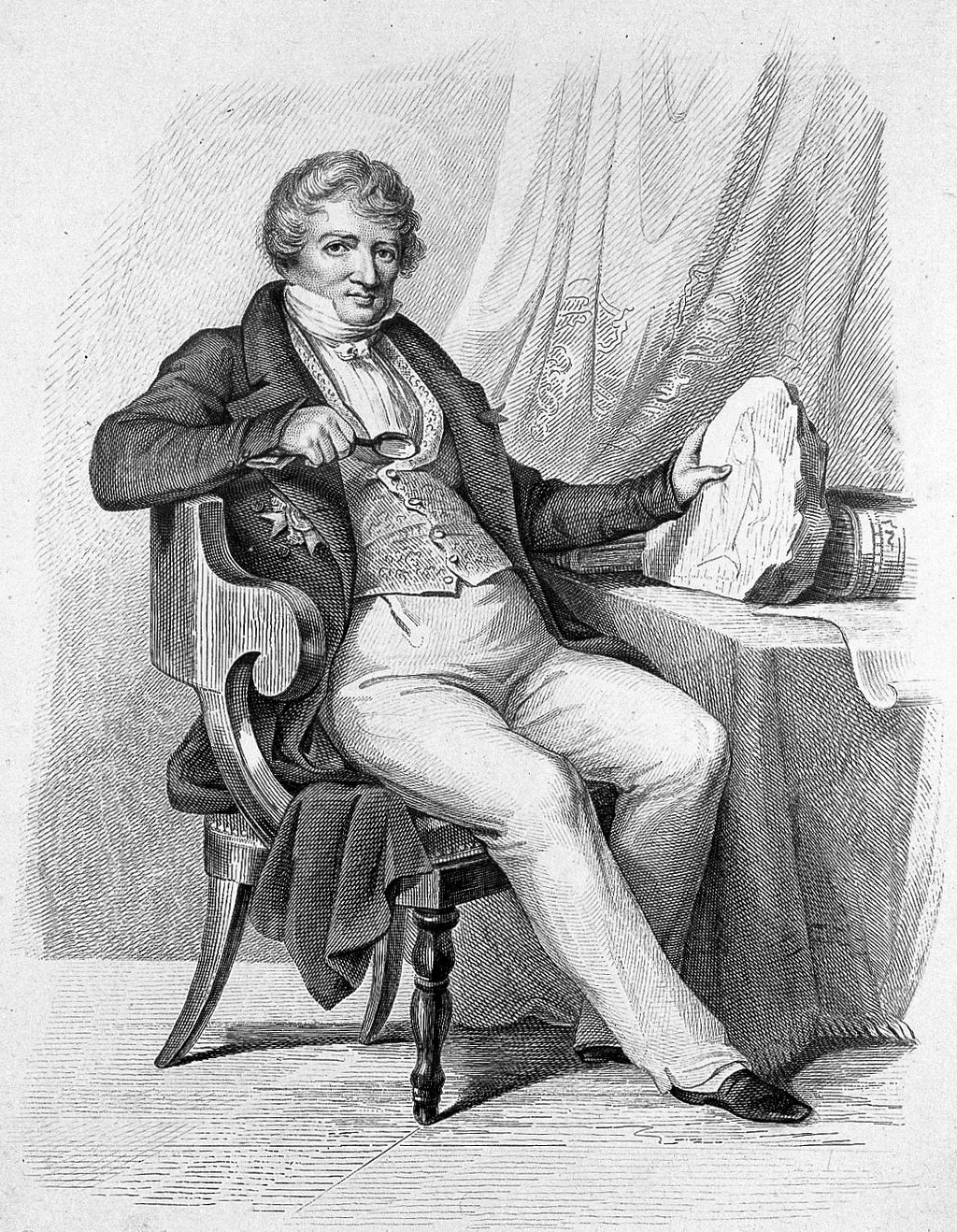

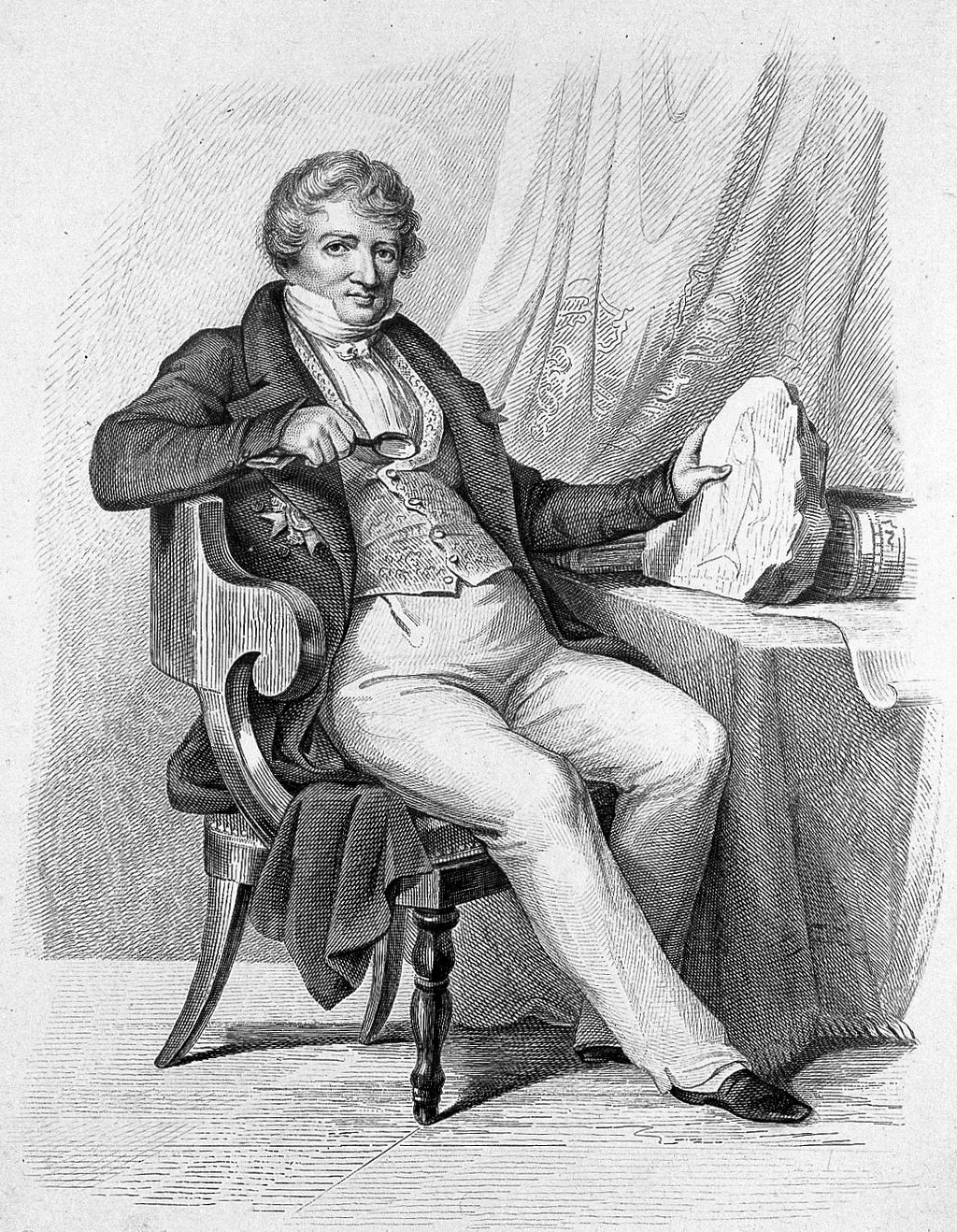

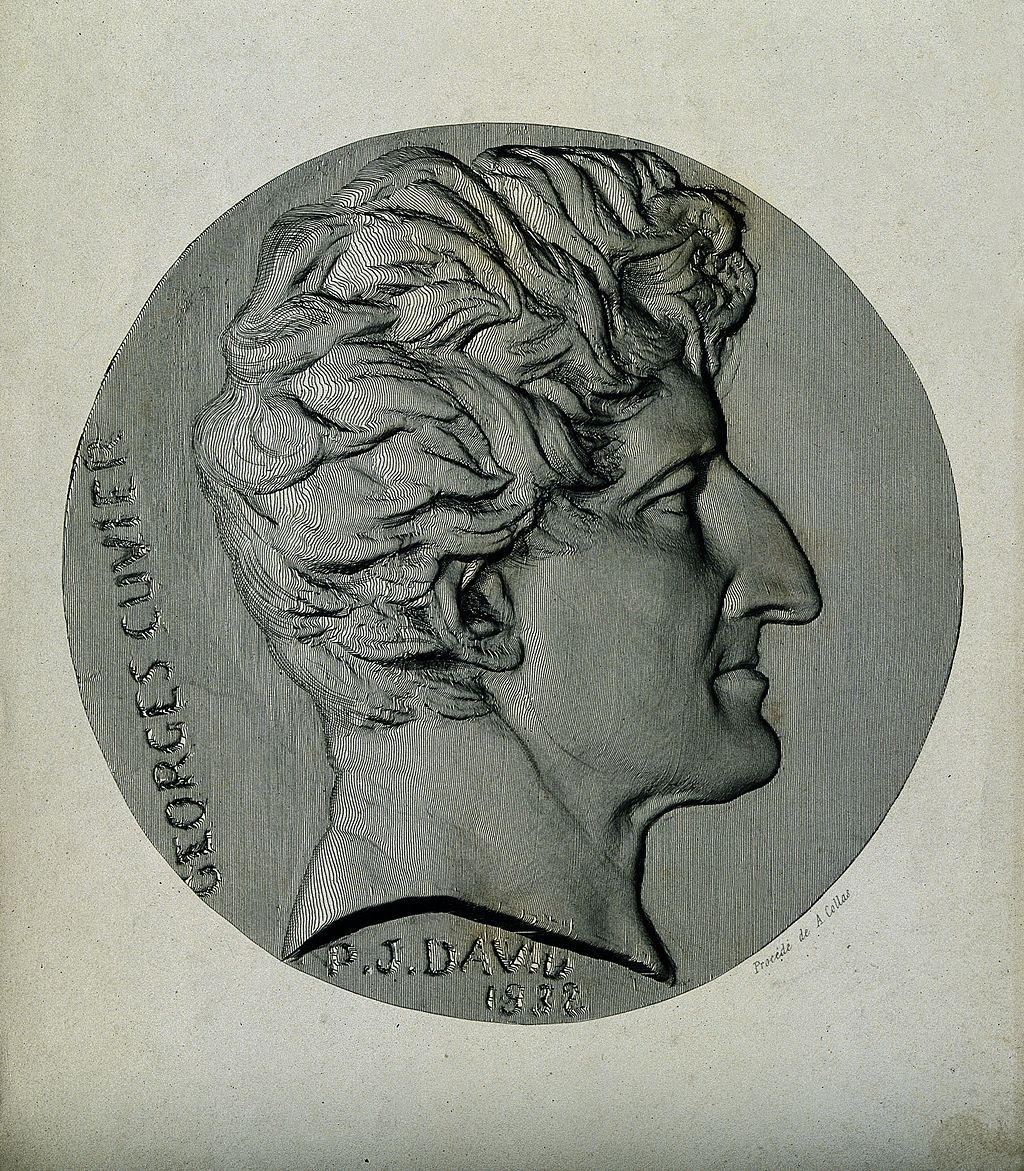

ジョルジュ・キュヴィエ

Georges Cuvier, 1769-1832

Engraving

by James

Thomson

☆ ジャン・レオポルド・ニコラ・フレデリック・キュヴィエ男爵(Jean Léopold Nicolas Frédéric, baron Cuvier, 1769年8月23日 - 1832年5月13日)は、ジョルジュ・キュヴィエ(Georges Cuvier, /ˈkju-ɪ; [1] French: [ʒɔ(ə) kyvje])として知られるフランスの自然科学者・動物学者であり、「古生物学の創始者」と呼ばれることもある。キュヴィエは19世紀初頭の自然科学研 究の中心人物であり、生きた動物と化石を比較する仕事を通じて、比較解剖学と古生物学の分野の確立に貢献した。 キュヴィエの研究は脊椎動物の古生物学の基礎と考えられており、彼は分類を系統にグループ分けし、化石と現生種の両方を分類に組み込むことによってリンネ の分類学を拡大した。キュヴィエは『地球論』(1813年)の中で、現在絶滅している種は、周期的に起こる大洪水によって絶滅したと提唱した。このように してキュヴィエは、19世紀初頭の地質学において、最も影響力のあるカタストロフィ主義の提唱者となった。 アレクサンドル・ブロンニャールとのパリ盆地の地層に関する研究により、生物層序学の基本原理が確立された。 その他の業績としては、北アメリカで発見された象のような骨が、後に彼が「マストドン」と命名することになる絶滅動物のものであること、現在のアルゼンチ ンで発掘された大きな骨格が、先史時代の巨大なナマケモノのものであることを立証し、これをメガテリウムと命名した。また、後に完全な遺骨が発見されたも のの、断片的な遺骨のみに基づいて、パリ盆地からパラオテリウム属とアノプロテリウム属という2つの偶蹄類属を確立した。彼は翼竜をプテロダクティルスと 命名し、水生爬虫類のモササウルスを記述し(発見も命名もしなかった)、太古の地球は哺乳類ではなく爬虫類が支配していたと示唆した最初の人物の一人であ る。 キュヴィエはまた、当時(ダーウィンの理論以前)主にジャン=バティスト・ド・ラマルクとジェフロワ・サン・ヒレールが提唱していた進化論に強く反対した ことでも知られている。キュヴィエは、進化の証拠はなく、むしろ大洪水などの地球規模の絶滅現象によって生命体が周期的に誕生し、滅亡している証拠だと考 えていた。1830年、キュヴィエとジョフロワは有名な論争を繰り広げたが、これは当時の生物学的思考における2つの大きな逸脱を例証するものであったと 言われている。 キュヴィエはまた、科学人種主義の基礎の一部となる人種研究を行い、人種間の身体的特性や精神的能力の違いとされる研究を発表した。キュヴィエはサラ・バートマンが亡くなる直前に検査を行い、彼女の死後に解剖を行い、彼女の身体的特徴をサルのそれと比較して蔑視した。 キュヴィエの最も有名な著作は『動物の王国』(1817年)である。1819年、キュヴィエはその科学的貢献を称えられ、終身貴族となった。コレラの流行中にパリで死去。キュヴィエの最も影響力のある信奉者には、大陸とアメリカのルイ・アガシズ、イギリスのリチャード・オーウェンがいる。キュヴィエの名前は、エッフェル塔に刻まれている72の名前のひとつである。

| Jean Léopold Nicolas

Frédéric, baron Cuvier (23 August 1769 – 13 May 1832), known as Georges

Cuvier (/ˈkjuːvieɪ/;[1] French: [ʒɔʁʒ(ə) kyvje]), was a French

naturalist and zoologist, sometimes referred to as the "founding father

of paleontology".[2] Cuvier was a major figure in natural sciences

research in the early 19th century and was instrumental in establishing

the fields of comparative anatomy and paleontology through his work in

comparing living animals with fossils. Cuvier's work is considered the foundation of vertebrate paleontology, and he expanded Linnaean taxonomy by grouping classes into phyla and incorporating both fossils and living species into the classification.[3] Cuvier is also known for establishing extinction as a fact—at the time, extinction was considered by many of Cuvier's contemporaries to be merely controversial speculation. In his Essay on the Theory of the Earth (1813) Cuvier proposed that now-extinct species had been wiped out by periodic catastrophic flooding events. In this way, Cuvier became the most influential proponent of catastrophism in geology in the early 19th century.[4] His study of the strata of the Paris basin with Alexandre Brongniart established the basic principles of biostratigraphy.[5] Among his other accomplishments, Cuvier established that elephant-like bones found in North America belonged to an extinct animal he later would name as a "mastodon", and that a large skeleton dug up in present-day Argentina was of a giant, prehistoric ground sloth, which he named Megatherium.[6] He also established two ungulate genera from the Paris Basin named Palaeotherium and Anoplotherium based on fragmentary remains alone, although more complete remains were later uncovered. He named the pterosaur Pterodactylus, described (but did not discover or name) the aquatic reptile Mosasaurus, and was one of the first people to suggest the earth had been dominated by reptiles, rather than mammals, in prehistoric times. Cuvier is also remembered for strongly opposing theories of evolution, which at the time (before Darwin's theory) were mainly proposed by Jean-Baptiste de Lamarck and Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire. Cuvier believed there was no evidence for evolution, but rather evidence for cyclical creations and destructions of life forms by global extinction events such as deluges. In 1830, Cuvier and Geoffroy engaged in a famous debate, which is said to exemplify the two major deviations in biological thinking at the time – whether animal structure was due to function or (evolutionary) morphology.[7] Cuvier supported function and rejected Lamarck's thinking. Cuvier also conducted racial studies which provided part of the foundation for scientific racism, and published work on the supposed differences between racial groups' physical properties and mental abilities.[8] Cuvier subjected Sarah Baartman to examinations alongside other French naturalists during a period in which she was held captive in a state of neglect. Cuvier examined Baartman shortly before her death, and conducted a dissection following her death that disparagingly compared her physical features to those of monkeys.[9] Cuvier's most famous work is Le Règne Animal (1817; English: The Animal Kingdom). In 1819, he was created a peer for life in honour of his scientific contributions.[10] Thereafter, he was known as Baron Cuvier. He died in Paris during an epidemic of cholera. Some of Cuvier's most influential followers were Louis Agassiz on the continent and in the United States, and Richard Owen in Britain. His name is one of the 72 names inscribed on the Eiffel Tower. |

ジャン・レオポルド・ニコラ・フレデリック・キュヴィエ男爵(Jean

Léopold Nicolas Frédéric, baron Cuvier, 1769年8月23日 -

1832年5月13日)は、ジョルジュ・キュヴィエ(Georges Cuvier, /ˈkju-ɪ; [1] French: [ʒɔ(ə)

kyvje])として知られるフランスの自然科学者・動物学者であり、「古生物学の創始者」と呼ばれることもある。

[2]キュヴィエは19世紀初頭の自然科学研究の中心人物であり、生きた動物と化石を比較する仕事を通じて、比較解剖学と古生物学の分野の確立に貢献し

た。 キュヴィエの研究は脊椎動物の古生物学の基礎と考えられており、彼は分類を系統にグループ分けし、化石と現生種の両方を分類に組み込むことによってリンネ の分類学を拡大した[3]。キュヴィエは『地球論』(1813年)の中で、現在絶滅している種は、周期的に起こる大洪水によって絶滅したと提唱した。この ようにしてキュヴィエは、19世紀初頭の地質学において、最も影響力のあるカタストロフィ主義の提唱者となった[4]。 アレクサンドル・ブロンニャールとのパリ盆地の地層に関する研究により、生物層序学の基本原理が確立された[5]。 その他の業績としては、北アメリカで発見された象のような骨が、後に彼が「マストドン」と命名することになる絶滅動物のものであること、現在のアルゼンチ ンで発掘された大きな骨格が、先史時代の巨大なナマケモノのものであることを立証し、これをメガテリウムと命名した[6]。また、後に完全な遺骨が発見さ れたものの、断片的な遺骨のみに基づいて、パリ盆地からパラオテリウム属とアノプロテリウム属という2つの偶蹄類属を確立した。彼は翼竜をプテロダクティ ルスと命名し、水生爬虫類のモササウルスを記述し(発見も命名もしなかった)、太古の地球は哺乳類ではなく爬虫類が支配していたと示唆した最初の人物の一 人である。 キュヴィエはまた、当時(ダーウィンの理論以前)主にジャン=バティスト・ド・ラマルクとジェフロワ・サン・ヒレールが提唱していた進化論に強く反対した ことでも知られている。キュヴィエは、進化の証拠はなく、むしろ大洪水などの地球規模の絶滅現象によって生命体が周期的に誕生し、滅亡している証拠だと考 えていた。1830年、キュヴィエとジョフロワは有名な論争を繰り広げたが、これは当時の生物学的思考における2つの大きな逸脱を例証するものであったと 言われている。 キュヴィエはまた、科学的人種差別の基礎の一部となる人種研究を行い、人種間の身体的特性や精神的能力の違いとされる研究を発表した[8]。キュヴィエは バートマンが亡くなる直前に検査を行い、彼女の死後に解剖を行い、彼女の身体的特徴をサルのそれと比較して蔑視した[9]。 キュヴィエの最も有名な著作は『動物の王国』(1817年)である。1819年、キュヴィエはその科学的貢献を称えられ、終身貴族となった[10]。コレ ラの流行中にパリで死去。キュヴィエの最も影響力のある信奉者には、大陸とアメリカのルイ・アガシズ、イギリスのリチャード・オーウェンがいる。キュヴィ エの名前は、エッフェル塔に刻まれている72の名前のひとつである。 |

Biography Portrait by François-André Vincent, 1795 Jean Léopold Nicolas Frédéric Cuvier was born in Montbéliard, where his Protestant ancestors had lived since the time of the Reformation.[11] His mother was Anne Clémence Chatel; his father, Jean-Georges Cuvier, was a lieutenant in the Swiss Guards and a bourgeois of the town of Montbéliard.[12] At the time, the town, which would be annexed to France on 10 October 1793, belonged to the Duchy of Württemberg. His mother, who was much younger than his father, tutored him diligently throughout his early years, so he easily surpassed the other children at school.[11] During his gymnasium years, he had little trouble acquiring Latin and Greek, and was always at the head of his class in mathematics, history, and geography.[13] According to Lee,[13] "The history of mankind was, from the earliest period of his life, a subject of the most indefatigable application; and long lists of sovereigns, princes, and the driest chronological facts, once arranged in his memory, were never forgotten."  Birthplace of Georges Cuvier in Montbéliard[14] At the age of 10, soon after entering the gymnasium, he encountered a copy of Conrad Gessner's Historiae Animalium, the work that first sparked his interest in natural history. He then began frequent visits to the home of a relative, where he could borrow volumes of the Comte de Buffon's massive Histoire Naturelle. All of these he read and reread, retaining so much of the information, that by the age of 12, "he was as familiar with quadrupeds and birds as a first-rate naturalist."[13] He remained at the gymnasium for four years. Cuvier spent an additional four years at the Caroline Academy in Stuttgart, where he excelled in all of his coursework. Although he knew no German on his arrival, after only nine months of study, he managed to win the school prize for that language. Cuvier's German education exposed him to the work of the geologist Abraham Gottlob Werner (1750–1817), whose Neptunism and emphasis on the importance of rigorous, direct observation of three-dimensional, structural relationships of rock formations to geological understanding provided models for Cuvier's scientific theories and methods.[15] Upon graduation, he had no money on which to live as he awaited an appointment to an academic office. So in July 1788, he took a job at Fiquainville chateau in Normandy as tutor to the only son of the Comte d'Héricy, a Protestant noble. There, during the early 1790s, he began his comparisons of fossils with extant forms. Cuvier regularly attended meetings held at the nearby town of Valmont for the discussion of agricultural topics. There, he became acquainted with Henri Alexandre Tessier (1741–1837), who had assumed a false identity. Previously, he had been a physician and well-known agronomist, who had fled the Terror in Paris. After hearing Tessier speak on agricultural matters, Cuvier recognized him as the author of certain articles on agriculture in the Encyclopédie Méthodique and addressed him as M. Tessier. Tessier replied in dismay, "I am known, then, and consequently lost."—"Lost!" replied M. Cuvier, "no; you are henceforth the object of our most anxious care."[16] They soon became intimate and Tessier introduced Cuvier to his colleagues in Paris"I have just found a pearl in the dunghill of Normandy", he wrote his friend Antoine-Augustin Parmentier.[17] As a result, Cuvier entered into correspondence with several leading naturalists of the day and was invited to Paris. Arriving in the spring of 1795, at the age of 26, he soon became the assistant of Jean-Claude Mertrud (1728–1802), who had been appointed to the chair of Animal Anatomy at the Jardin des Plantes. When Mertrud died in 1802, Cuvier replaced him in office and the Chair changed its name to Chair of Comparative Anatomy.[18] The Institut de France was founded in the same year, and he was elected a member of its Academy of Sciences. On 4 April 1796 he began to lecture at the École Centrale du Pantheon and, at the opening of the National Institute in April, he read his first paleontological paper, which subsequently was published in 1800 under the title Mémoires sur les espèces d'éléphants vivants et fossiles.[19] In this paper, he analyzed skeletal remains of Indian and African elephants, as well as mammoth fossils, and a fossil skeleton known at that time as the "Ohio animal". In his second paper in 1796, he described and analyzed a large skeleton found in Paraguay, which he would name Megatherium.[6] He concluded this skeleton represented yet another extinct animal and, by comparing its skull with living species of tree-dwelling sloths, that it was a kind of ground-dwelling giant sloth. Together, these two 1796 papers were a seminal or landmark event, becoming a turning point in the history of paleontology, and in the development of comparative anatomy, as well. They also greatly enhanced Cuvier's personal reputation and they essentially ended what had been a long-running debate about the reality of extinction. In 1799, he succeeded Daubenton as professor of natural history in the Collège de France. In 1802, he became titular professor at the Jardin des Plantes; and in the same year, he was appointed commissary of the institute to accompany the inspectors general of public instruction. In this latter capacity, he visited the south of France, but in the early part of 1803, he was chosen permanent secretary of the department of physical sciences of the Academy, and he consequently abandoned the earlier appointment and returned to Paris.[19] In 1806, he became a foreign member of the Royal Society, and in 1812, a foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences. In 1812, he became a correspondent for the Royal Institute of the Netherlands, and became a member in 1827.[20] Cuvier was elected a Foreign Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1822.[21]  Cuvier's tomb in the Père Lachaise Cemetery, Paris Cuvier then devoted himself more especially to three lines of inquiry: (i) the structure and classification of the Mollusca; (ii) the comparative anatomy and systematic arrangement of the fishes; (iii) fossil mammals and reptiles and, secondarily, the osteology of living forms belonging to the same groups.[19] In 1812, Cuvier made what the cryptozoologist Bernard Heuvelmans called his "Rash dictum": he remarked that it was unlikely that any large animal remained undiscovered. Ten years after his death, the word "dinosaur" would be coined by Richard Owen in 1842. During his lifetime, Cuvier served as an imperial councillor under Napoleon, president of the Council of Public Instruction and chancellor of the university under the restored Bourbons, Grand Officer of the Legion of Honour, a Peer of France, Minister of the Interior, and president of the Council of State under Louis Philippe. He was eminent in all these capacities, and yet the dignity given by such high administrative positions was as nothing compared to his leadership in natural science.[22] Cuvier was by birth, education, and conviction a devout Lutheran,[23] and remained Protestant throughout his life while regularly attending church services. Despite this, he regarded his personal faith as a private matter; he evidently identified himself with his confessional minority group when he supervised governmental educational programs for Protestants. He also was very active in founding the Parisian Biblical Society in 1818, where he later served as a vice president.[24] From 1822 until his death in 1832, Cuvier was Grand Master of the Protestant Faculties of Theology of the French University.[25] |

バイオグラフィー フランソワ=アンドレ・ヴァンサンによる肖像画、1795年 ジャン・レオポルド・ニコラ・フレデリック・キュヴィエは、宗教改革の時代からプロテスタントの先祖が住んでいたモンベリアールで生まれた[11]。母は アンヌ・クレマンス・シャテル、父はスイス衛兵中尉でモンベリアールの町のブルジョワだったジャン・ジョルジュ・キュヴィエ[12]。当時、1793年 10月10日にフランスに併合されることになるモンベリアールはヴュルテンベルク公国に属していた。幼少期は、父親よりずっと年下の母親から熱心に手ほど きを受けたため、学校では他の子供たちよりも抜きん出ていた[11]。 [リーによると、[13] 「人類の歴史は、彼の人生の最も早い時期から、最も不屈の努力の対象であった。」 "君主、王子、最も乾燥した年表の長いリストは、一度彼の記憶に整理されると、決して忘れられなかった。」  モンベリアールにあるジョルジュ・キュヴィエの生家[14]。 ギムナジウムに入学して間もない10歳の時、コンラッド・ゲスナーの『動物誌』(Historiae Animalium)に出会い、自然史に興味を持つようになる。その後、親戚の家に頻繁に通うようになり、そこでビュフォン伯爵の膨大な『自然史』を借り た。これらの本を何度も読み返し、多くの情報を得たキュヴィエは、12歳の頃には「一流の博物学者と同じように四足獣や鳥類に精通していた」[13]。 さらに4年間、シュトゥットガルトのカロライン・アカデミーで学んだキュヴィエは、すべての科目で優秀な成績を収めた。入学当初はドイツ語を全く知らな かったが、わずか9ヶ月でドイツ語の学校賞を受賞した。キュヴィエはドイツで教育を受け、地質学者アブラハム・ゴットローブ・ヴェルナー(1750- 1817)の研究に触れた。彼のネプチューン主義や、地質学的理解における岩層の三次元的、構造的関係の厳密で直接的な観察の重要性の強調は、キュヴィエ の科学的理論と方法のモデルとなった[15]。 卒業後、学問的な役職に任命されるのを待つ間、彼には生活費がなかった。そこで1788年7月、プロテスタントの貴族であったエリシー伯爵の一人息子の家 庭教師として、ノルマンディー地方のフィカンヴィル城で働くことになった。1790年代初頭、彼はそこで化石と現生生物の比較を始めた。キュヴィエは、近 くの町ヴァルモンで開かれる農業に関する会合に定期的に出席した。そこで、身分を偽っていたアンリ・アレクサンドル・テシエ(1741-1837)と知り 合う。以前は医師であり、有名な農学者であったが、パリのテロルから逃れていた。テシエの農業に関する講演を聞いたキュヴィエは、彼が『百科全書』 (Encyclopédie Méthodique)の農業に関する論文の著者であることを知り、テシエと名乗った。 テシエは狼狽して、「私は知られており、その結果迷子になってしまった」と答えた。 「その結果、キュヴィエは当時の一流の博物学者数人と文通を始め、パリに招かれた[17]。1795年春、26歳でパリに到着したキュヴィエは、すぐに植 物園の動物解剖学講座に任命されていたジャン=クロード・メルトルー(1728-1802)の助手となった。1802年にメルトルーが亡くなると、キュ ヴィエが後任となり、講座は比較解剖学講座と改称された[18]。 同年、フランス学士院が設立され、キュヴィエはその科学アカデミーの会員に選ばれた。1796年4月4日、パンテオン中央大学で講義を開始し、4月の国民 研究所の開所式で最初の古生物学的論文を読み、その後1800年に『Mémoires sur les espèces d'éléphants vivants et fossiles』というタイトルで出版された[19]。1796年の2本目の論文では、パラグアイで発見された大型の骨格標本について記述・分析し、メ ガテリウムと命名した[6]。彼はこの骨格標本がまた別の絶滅動物であり、その頭蓋骨を現生種の樹上生活動物であるナマケモノと比較することで、地上生活 動物である巨大ナマケモノの一種であると結論づけた。 1796年に発表されたこの2つの論文は、古生物学の歴史において、また比較解剖学の発展においても、画期的あるいは画期的な出来事であり、ターニングポ イントとなった。また、キュヴィエの個人的な名声も大いに高め、絶滅の現実について長く続いた論争に実質的な終止符を打った。 1799年、彼はドーバントンの後任としてコレージュ・ド・フランスの博物学教授に就任した。1802年には植物園の主任教授となり、同年、教育総監に随 行する研究所の使者に任命された。1806年には王立協会の外国人会員となり、1812年にはスウェーデン王立科学アカデミーの外国人会員となった。 1812年にはオランダ王立研究所の特派員となり、1827年には会員となった[20]。1822年にはアメリカ芸術科学アカデミーの外国名誉会員に選出 された[21]。  パリのペール・ラシェーズ墓地にあるキュヴィエの墓 (i)軟体動物の構造と分類、(ii)魚類の比較解剖学と系統的配列、(iii)哺乳類と爬虫類の化石、そして次に同じグループに属する現生生物の骨学である[19]。 1812年、キュヴィエは、暗号動物学者ベルナール・ヒューベルマンズが「無謀な独断」と呼ぶ発言をした。彼の死から10年後の1842年、リチャード・オーウェンによって「恐竜」という言葉が作られた。 キュヴィエは存命中、ナポレオン政権下で帝室参事官、ブルボン政権下で教令評議会議長と大学総長、ルイ・フィリップ政権下でレジオン・ドヌール勲章大官、 フランス貴族、内務大臣、国務院議長を歴任した。キュヴィエはこれらすべての地位において卓越した人物であったが、そのような行政上の高い地位から与えら れる威厳は、自然科学における彼の指導力に比べれば些細なものであった[22]。 キュヴィエは生まれも教育も信念も敬虔なルター派であり[23]、生涯プロテスタントを貫き、定期的に教会の礼拝に出席した。にもかかわらず、彼は自分の 個人的な信仰を私的な問題とみなしていた。プロテスタントのための政府の教育プログラムを監督していたとき、彼は明らかに自分の告白的少数派と自分を同一 視していた。1822年から1832年に亡くなるまで、キュヴィエはフランス大学のプロテスタント神学部のグランド・マスターを務めた[25]。 キュヴィエは、解剖学者が化石の骨格を復元するのに役立つだけでなく、彼の原理には膨大な予測力があると考えた。例えば、モンマルトルの石膏採石場で有袋 類に似た化石を発見したとき、彼はその化石の骨盤にも有袋類によく見られる骨が含まれていることを正しく予測した[59]。 |

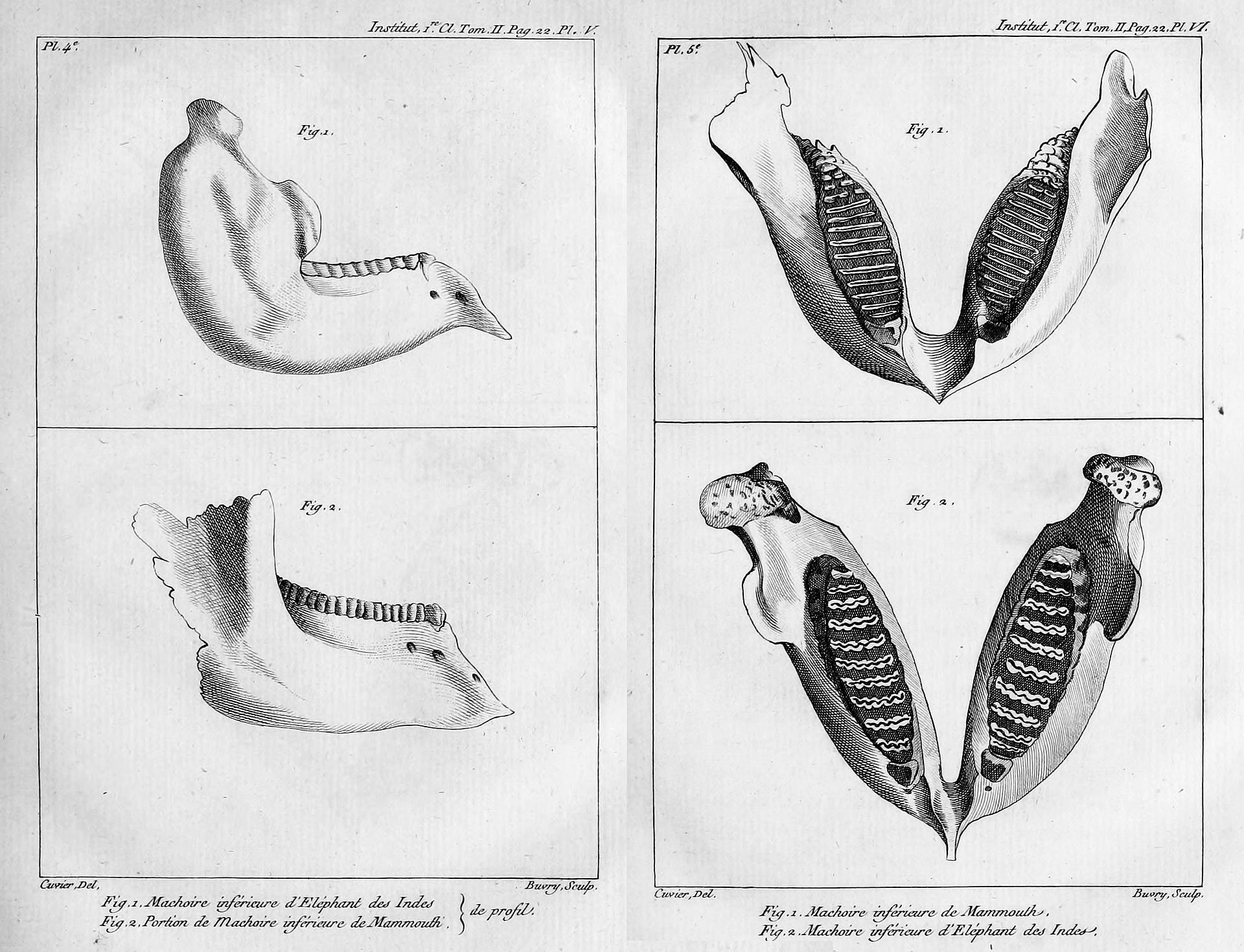

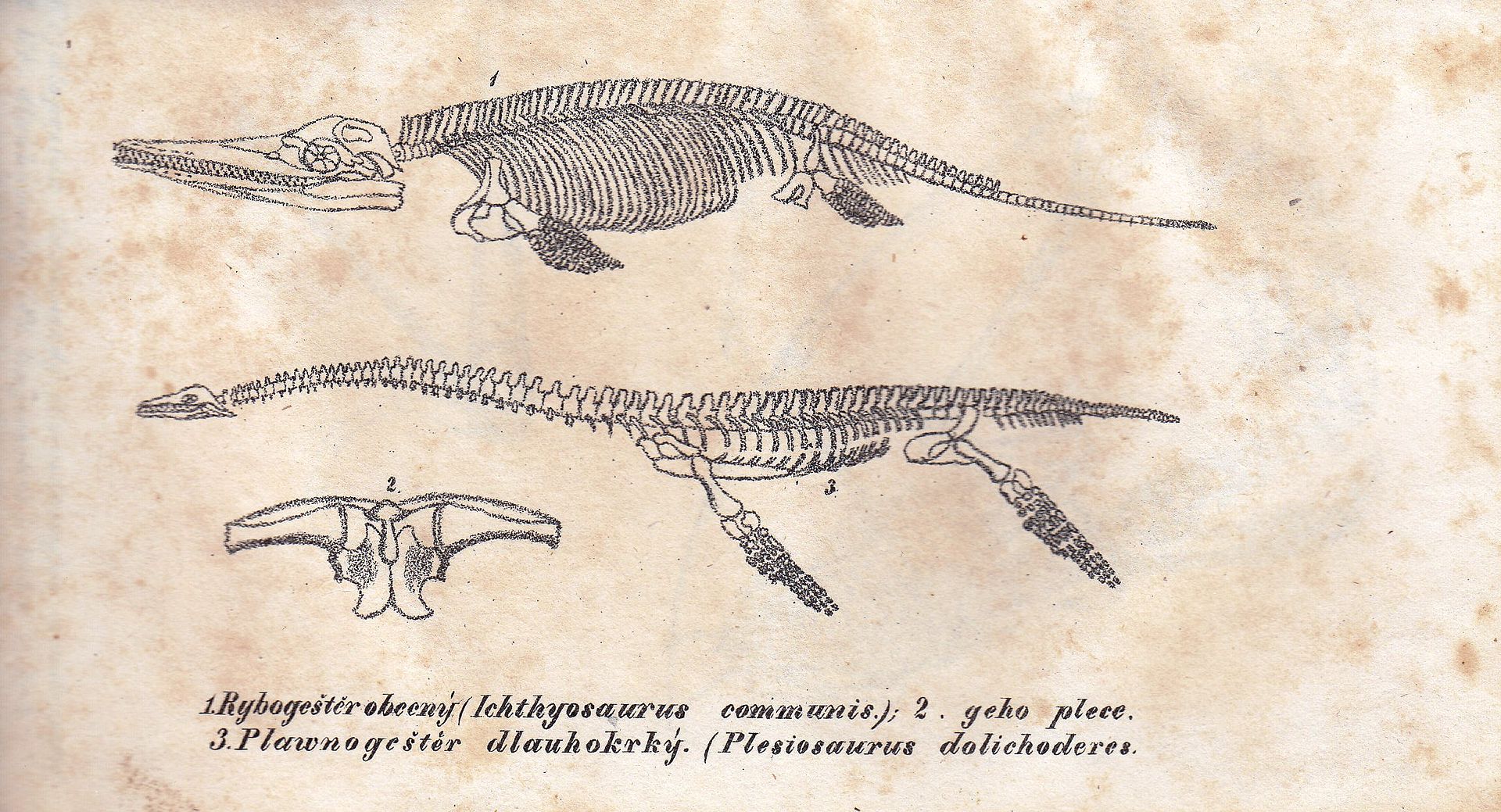

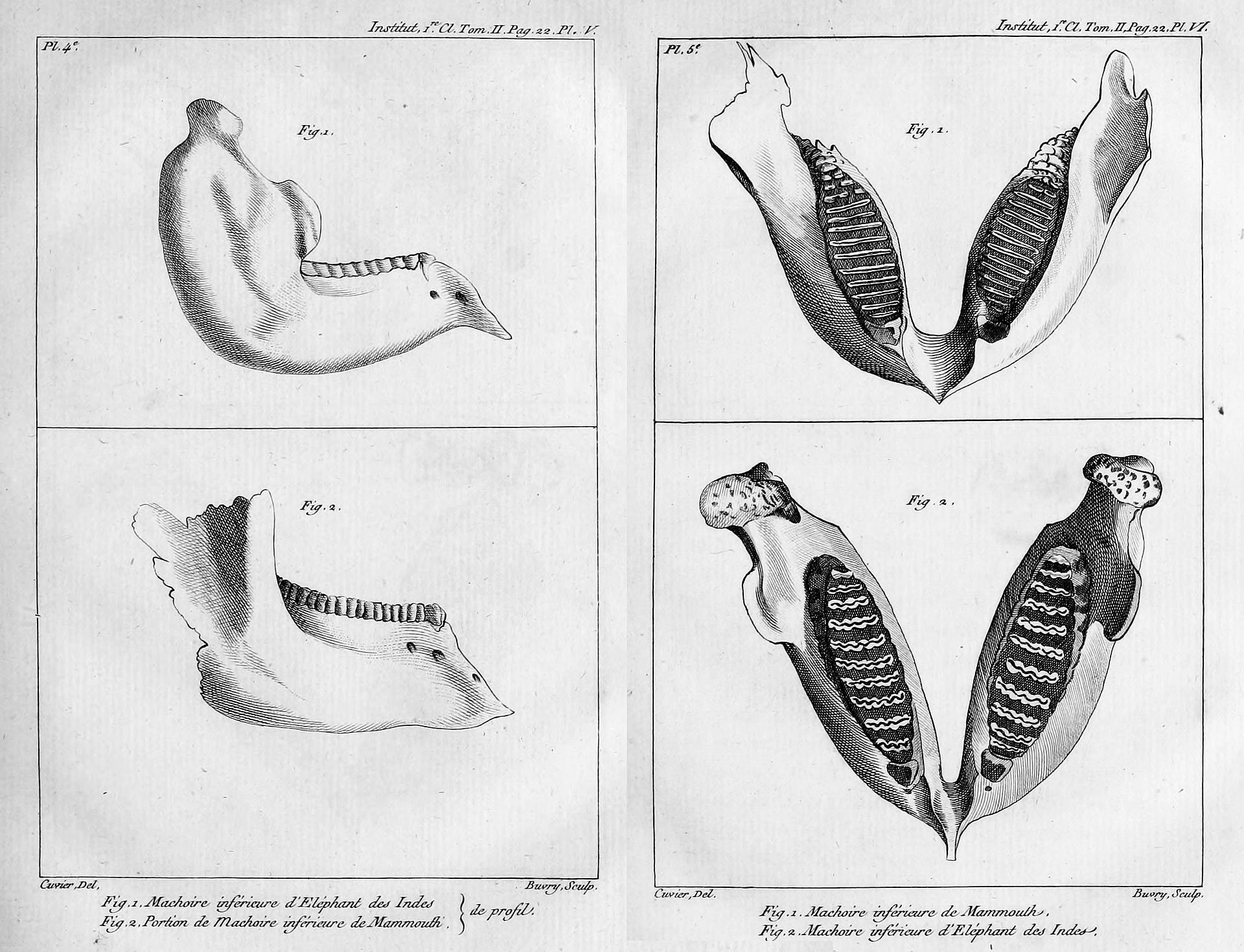

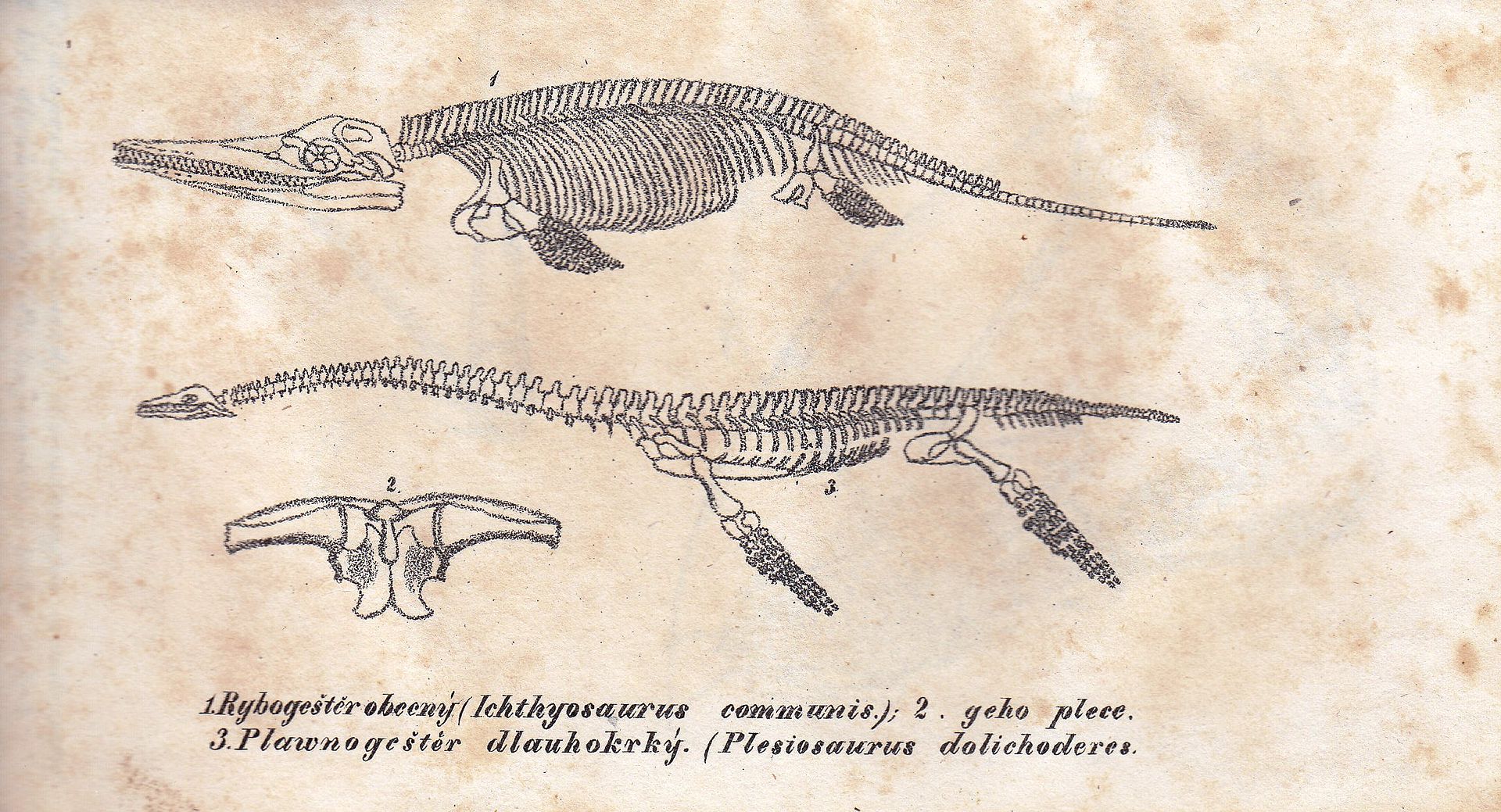

| Scientific ideas and their impact Opposition to evolution Cuvier was critical of theories of evolution, in particular those proposed by his contemporaries Lamarck and Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, which involved the gradual transmutation of one form into another. He repeatedly emphasized that his extensive experience with fossil material indicated one fossil form does not, as a rule, gradually change into a succeeding, distinct fossil form. A deep-rooted source of his opposition to the gradual transformation of species was his goal of creating an accurate taxonomy based on principles of comparative anatomy.[26] Such a project would become impossible if species were mutable, with no clear boundaries between them. According to the University of California Museum of Paleontology, "Cuvier did not believe in organic evolution, for any change in an organism's anatomy would have rendered it unable to survive. He studied the mummified cats and ibises that Geoffroy had brought back from Napoleon's invasion of Egypt, and showed they were no different from their living counterparts; Cuvier used this to support his claim that life forms did not evolve over time."[27][28]  Cuvier with a fish fossil He also observed that Napoleon's expedition to Egypt had retrieved animals mummified thousands of years previously that seemed no different from their modern counterparts.[29] "Certainly", Cuvier wrote, "one cannot detect any greater difference between these creatures and those we see, than between the human mummies and the skeletons of present-day men."[30] Lamarck dismissed this conclusion, arguing that evolution happened much too slowly to be observed over just a few thousand years. Cuvier, however, in turn criticized how Lamarck and other naturalists conveniently introduced hundreds of thousands of years "with a stroke of a pen" to uphold their theory. Instead, he argued that one may judge what a long time would produce only by multiplying what a lesser time produces. Since a lesser time produced no organic changes, neither, he argued, would a much longer time.[31] Moreover, his commitment to the principle of the correlation of parts caused him to doubt that any mechanism could ever gradually modify any part of an animal in isolation from all the other parts (in the way Lamarck proposed), without rendering the animal unable to survive.[32] In his Éloge de M. de Lamarck (Praise for M. de Lamarck),[33][34] Cuvier wrote that Lamarck's theory of evolution rested on two arbitrary suppositions; the one, that it is the seminal vapour which organizes the embryo; the other, that efforts and desires may engender organs. A system established on such foundations may amuse the imagination of a poet; a metaphysician may derive from it an entirely new series of systems; but it cannot for a moment bear the examination of anyone who has dissected a hand, a viscus, or even a feather.[33] Instead, he said, the typical form makes an abrupt appearance in the fossil record, and persists unchanged to the time of its extinction. Cuvier attempted to explain this paleontological phenomenon he envisioned (which would be readdressed more than a century later by "punctuated equilibrium") and to harmonize it with the Bible. He attributed the different time periods he was aware of as intervals between major catastrophes, the last of which is found in Genesis.[35][36] Cuvier's claim that new fossil forms appear abruptly in the geological record and then continue without alteration in overlying strata was used by later critics of evolution to support creationism,[37] to whom the abruptness seemed consistent with special divine creation (although Cuvier's finding that different types made their paleontological debuts in different geological strata clearly did not). The lack of change was consistent with the supposed sacred immutability of "species", but, again, the idea of extinction, of which Cuvier was the great proponent, obviously was not. Many writers have unjustly accused Cuvier of obstinately maintaining that fossil human beings could never be found. In his Essay on the Theory of the Earth, he did say, "no human bones have yet been found among fossil remains", but he made it clear exactly what he meant: "When I assert that human bones have not been hitherto found among extraneous fossils, I must be understood to speak of fossils, or petrifactions, properly so called".[38] Petrified bones, which have had time to mineralize and turn to stone, are typically far older than bones found to that date. Cuvier's point was that all human bones found that he knew of, were of relatively recent age because they had not been petrified and had been found only in superficial strata.[39] He was not dogmatic in this claim, however; when new evidence came to light, he included in a later edition an appendix describing a skeleton that he freely admitted was an "instance of a fossil human petrifaction".[40] The harshness of his criticism and the strength of his reputation, however, continued to discourage naturalists from speculating about the gradual transmutation of species, until Charles Darwin published On the Origin of Species more than two decades after Cuvier's death.[41] Extinction This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (April 2017) (Learn how and when to remove this message)  Georges Cuvier's 1812 skeletal reconstruction of Anoplotherium commune. The stratigraphy and lack of modern analogue in the extinct mammal was proof of extinction and ecological succession. Early in his tenure at the National Museum in Paris, Cuvier published studies of fossil bones in which he argued that they belonged to large, extinct quadrupeds. His first two such publications were those identifying mammoth and mastodon fossils as belonging to extinct species rather than modern elephants and the study in which he identified the Megatherium as a giant, extinct species of sloth.[42] His primary evidence for his identifications of mammoths and mastodons as separate, extinct species was the structure of their jaws and teeth.[43] His primary evidence that the Megatherium fossil had belonged to a massive sloth came from his comparison of its skull with those of extant sloth species.[44] Cuvier wrote of his paleontological method that "the form of the tooth leads to the form of the condyle, that of the scapula to that of the nails, just as an equation of a curve implies all of its properties; and, just as in taking each property separately as the basis of a special equation we are able to return to the original equation and other associated properties, similarly, the nails, the scapula, the condyle, the femur, each separately reveal the tooth or each other; and by beginning from each of them the thoughtful professor of the laws of organic economy can reconstruct the entire animal."[45] However, Cuvier's actual method was heavily dependent on the comparison of fossil specimens with the anatomy of extant species in the necessary context of his vast knowledge of animal anatomy and access to unparalleled natural history collections in Paris.[46] This reality, however, did not prevent the rise of a popular legend that Cuvier could reconstruct the entire bodily structures of extinct animals given only a few fragments of bone.[47] At the time Cuvier presented his 1796 paper on living and fossil elephants, it was still widely believed that no species of animal had ever become extinct. Authorities such as Buffon had claimed that fossils found in Europe of animals such as the woolly rhinoceros and the mammoth were remains of animals still living in the tropics (i.e. rhinoceros and elephants), which had shifted out of Europe and Asia as the earth became cooler. Thereafter, Cuvier performed a pioneering research study on some elephant fossils excavated around Paris. The bones he studied, however, were remarkably different from the bones of elephants currently thriving in India and Africa. This discovery led Cuvier to denounce the idea that fossils came from those that are currently living. The idea that these bones belonged to elephants living – but hiding – somewhere on Earth seemed ridiculous to Cuvier, because it would be nearly impossible to miss them due to their enormous size. The Megatherium provided another compelling data point for this argument. Ultimately, his repeated identification of fossils as belonging to species unknown to man, combined with mineralogical evidence from his stratigraphical studies in Paris, drove Cuvier to the proposition that the abrupt changes the Earth underwent over a long period of time caused some species to go extinct.[48] Cuvier's theory on extinction has met opposition from other notable natural scientists like Darwin and Charles Lyell. Unlike Cuvier, they didn't believe that extinction was a sudden process; they believed that like the Earth, animals collectively undergo gradual change as a species. This differed widely from Cuvier's theory, which seemed to propose that animal extinction was catastrophic. However, Cuvier's theory of extinction is still justified in the case of mass extinctions that occurred in the last 600 million years, when approximately half of all living species went completely extinct within a short geological span of two million years, due in part by volcanic eruptions, asteroids, and rapid fluctuations in sea level. At this time, new species rose and others fell, precipitating the arrival of human beings. Cuvier's early work demonstrated conclusively that extinction was indeed a credible natural global process.[49] Cuvier's thinking on extinctions was influenced by his extensive readings in Greek and Latin literature; he gathered every ancient report known in his day relating to discoveries of petrified bones of remarkable size in the Mediterranean region.[50] Influence on Cuvier's theory of extinction was his collection of specimens from the New World, many of them obtained from Native Americans. He also maintained an archive of Native American observations, legends, and interpretations of immense fossilized skeletal remains, sent to him by informants and friends in the Americas. He was impressed that most of the Native American accounts identified the enormous bones, teeth, and tusks as animals of the deep past that had been destroyed by catastrophe.[51] Catastrophism This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (April 2017) (Learn how and when to remove this message)  These Indian elephant and mammoth jaws were included in 1799 when Cuvier's 1796 paper on living and fossil elephants was printed. Main article: Catastrophism Cuvier came to believe that most, if not all, the animal fossils he examined were remains of species that had become extinct. Near the end of his 1796 paper on living and fossil elephants, he said: All of these facts, consistent among themselves, and not opposed by any report, seem to me to prove the existence of a world previous to ours, destroyed by some kind of catastrophe. Contrary to many natural scientists' beliefs at the time, Cuvier believed that animal extinction was not a product of anthropogenic causes. Instead, he proposed that humans were around long enough to indirectly maintain the fossilized records of ancient Earth. He also attempted to verify the water catastrophe by analyzing records of various cultural backgrounds. Though he found many accounts of the water catastrophe unclear, he did believe that such an event occurred at the brink of human history nonetheless. This led Cuvier to become an active proponent of the geological school of thought called catastrophism, which maintained that many of the geological features of the earth and the history of life could be explained by catastrophic events that had caused the extinction of many species of animals. Over the course of his career, Cuvier came to believe there had not been a single catastrophe, but several, resulting in a succession of different faunas. He wrote about these ideas many times, in particular, he discussed them in great detail in the preliminary discourse (an introduction) to a collection of his papers, Recherches sur les ossements fossiles de quadrupèdes (Researches on quadruped fossil bones), on quadruped fossils published in 1812. Cuvier's own explanation for such a catastrophic event is derived from two different sources, including those from Jean-André Deluc and Déodat de Dolomieu. The former proposed that the continents existing ten millennia ago collapsed, allowing the ocean floors to rise higher than the continental plates and become the continents that now exist today. The latter proposed that a massive tsunami hit the globe, leading to mass extinction. Whatever the case was, he believed that the deluge happened quite recently in human history. In fact, he believed that Earth's existence was limited and not as extended as many natural scientists, like Lamarck, believed it to be. Much of the evidence he used to support his catastrophist theories has been taken from his fossil records. He strongly suggested that the fossils he found were evidence of the world's first reptiles, followed chronologically by mammals and humans. Cuvier didn't wish to delve much into the causation of all the extinction and introduction of new animal species but rather focused on the sequential aspects of animal history on Earth. In a way, his chronological dating of Earth's history somewhat reflected Lamarck's transformationist theories. Cuvier also worked alongside Alexandre Brongniart in analyzing the Parisian rock cycle. Using stratigraphical methods, they were both able to extrapolate key information regarding Earth history from studying these rocks. These rocks contained remnants of molluscs, bones of mammals, and shells. From these findings, Cuvier and Brongniart concluded that many environmental changes occurred in quick catastrophes, though Earth itself was often placid for extended periods of time in between sudden disturbances. The 'Preliminary Discourse' became very well known and, unauthorized translations were made into English, German, and Italian (and in the case of those in English, not entirely accurately). In 1826, Cuvier published a revised version under the name, Discours sur les révolutions de la surface du globe (Discourse on the upheavals of the surface of the globe).[52] After Cuvier's death, the catastrophic school of geological thought lost ground to uniformitarianism, as championed by Charles Lyell and others, which claimed that the geological features of the earth were best explained by currently observable forces, such as erosion and volcanism, acting gradually over an extended period of time. The increasing interest in the topic of mass extinction starting in the late twentieth century, however, has led to a resurgence of interest among historians of science and other scholars in this aspect of Cuvier's work.[53] Stratigraphy Cuvier collaborated for several years with Alexandre Brongniart, an instructor at the Paris mining school, to produce a monograph on the geology of the region around Paris. They published a preliminary version in 1808 and the final version was published in 1811. In this monograph, they identified characteristic fossils of different rock layers that they used to analyze the geological column, the ordered layers of sedimentary rock, of the Paris basin. They concluded that the layers had been laid down over an extended period during which there clearly had been faunal succession and that the area had been submerged under sea water at times and at other times under fresh water. Along with William Smith's work during the same period on a geological map of England, which also used characteristic fossils and the principle of faunal succession to correlate layers of sedimentary rock, the monograph helped establish the scientific discipline of stratigraphy. It was a major development in the history of paleontology and the history of geology.[54] Age of reptiles  Ichthyosaurus and Plesiosaurus from the 1834 Czech edition of Cuvier's Discours sur les revolutions de la surface du globe In 1800 and working only from a drawing, Cuvier was the first to correctly identify in print, a fossil found in Bavaria as a small flying reptile,[55] which he named the Ptero-Dactyle in 1809,[56] (later Latinized as Pterodactylus antiquus)—the first known member of the diverse order of pterosaurs. In 1808 Cuvier identified a fossil found in Maastricht as a giant marine lizard, the first known mosasaur. Cuvier speculated correctly that there had been a time when reptiles rather than mammals had been the dominant fauna.[57] This speculation was confirmed over the two decades following his death by a series of spectacular finds, mostly by English geologists and fossil collectors such as Mary Anning, William Conybeare, William Buckland, and Gideon Mantell, who found and described the first ichthyosaurs, plesiosaurs, and dinosaurs. Principle of the correlation of parts In a 1798 paper on the fossil remains of an animal found in some plaster quarries near Paris, Cuvier states what is known as the principle of the correlation of parts. He writes:[58] If an animal's teeth are such as they must be, in order for it to nourish itself with flesh, we can be sure without further examination that the whole system of its digestive organs is appropriate for that kind of food, and that its whole skeleton and locomotive organs, and even its sense organs, are arranged in such a way as to make it skilful at pursuing and catching its prey. For these relations are the necessary conditions of existence of the animal; if things were not so, it would not be able to subsist. This idea is referred to as Cuvier's principle of correlation of parts, which states that all organs in an animal's body are deeply interdependent. Species' existence relies on the way in which these organs interact. For example, a species whose digestive tract is best suited to digesting flesh but whose body is best suited to foraging for plants cannot survive. Thus in all species, the functional significance of each body part must be correlated to the others, or else the species cannot sustain itself.[59] Applications Cuvier believed that the power of his principle came in part from its ability to aid in the reconstruction of fossils. In most cases, fossils of quadrupeds were not found as complete, assembled skeletons, but rather as scattered pieces that needed to be put together by anatomists. To make matters worse, deposits often contained the fossilized remains of several species of animals mixed together. Anatomists reassembling these skeletons ran the risk of combining remains of different species, producing imaginary composite species. However, by examining the functional purpose of each bone and applying the principle of correlation of parts, Cuvier believed that this problem could be avoided. This principle's ability to aid in the reconstruction of fossils was also helpful to Cuvier's work in providing evidence in favour of extinction. The strongest evidence Cuvier could provide in favour of extinction would be to prove that the fossilized remains of an animal belonged to a species that no longer existed. By applying Cuvier's principle of correlation of parts, it would be easier to verify that a fossilized skeleton had been authentically reconstructed, thus validating any observations drawn from comparing it to skeletons of existing species. In addition to helping anatomists reconstruct fossilized remains, Cuvier believed that his principle also held enormous predictive power. For example, when he discovered a fossil that resembled a marsupial in the gypsum quarries of Montmartre, he correctly predicted that the fossil would contain bones commonly found in marsupials in its pelvis as well.[59] Impact  Line engraving of Cuvier, 1832 Cuvier hoped that his principles of anatomy would provide the law-based framework that would elevate natural history to the truly scientific level occupied by physics and chemistry thanks to the laws established by Isaac Newton (1643 - 1727) and Antoine Lavoisier (1743 - 1794), respectively. He expressed confidence in the introduction to Le Règne Animal that someday anatomy would be expressed as laws as simple, mathematical, and predictive as Newton's laws of physics, and he viewed his principle as an important step in that direction.[60] To him, the predictive capabilities of his principles demonstrated in his prediction of the existence of marsupial pelvic bones in the gypsum quarries of Montmartre demonstrated that these goals were not only in reach, but imminent.[61] The principle of correlation of parts was also Cuvier's way of understanding function in a non-evolutionary context, without invoking a divine creator.[62] In the same 1798 paper on the fossil remains of an animal found in plaster quarries near Paris, Cuvier emphasizes the predictive power of his principle, writing,[58] Today comparative anatomy has reached such a point of perfection that, after inspecting a single bone, one can often determine the class, and sometimes even the genus of the animal to which it belonged, above all if that bone belonged to the head or the limbs ... This is because the number, direction, and shape of the bones that compose each part of an animal's body are always in a necessary relation to all the other parts, in such a way that—up to a point—one can infer the whole from any one of them and vice versa. Though Cuvier believed that his principle's major contribution was that it was a rational, mathematical way to reconstruct fossils and make predictions, in reality, it was difficult for Cuvier to use his principle. The functional significance of many body parts was still unknown at the time, and so relating those body parts to other body parts using Cuvier's principle was impossible. Though Cuvier was able to make accurate predictions about fossil finds, in practice, the accuracy of his predictions came not from application of his principle, but rather from his vast knowledge of comparative anatomy. However, despite Cuvier's exaggerations of the power of his principle, the basic concept is central to comparative anatomy and paleontology.[59] |

科学的思想とその影響 進化論への反対 キュヴィエは進化論、特に同時代のラマルクやジェフロワ・サン=ハイレールが提唱した、ある形から別の形へと徐々に変化していくという進化論に批判的で あった。彼は、化石資料の豊富な経験から、ある化石形態が徐々に別の化石形態に変化することはないことを繰り返し強調した。種が徐々に変化していくことに 反対する彼の根深い根源は、比較解剖学の原則に基づいた正確な分類学を作るという目標であった。カリフォルニア大学古生物学博物館によると、「キュヴィエ は有機的進化を信じていなかった。彼はジョフロワがナポレオンのエジプト侵攻から持ち帰った猫やトキのミイラを研究し、それらが生きているものと何ら変わ らないことを示した。キュヴィエはこのことを利用して、生命体は時間の経過とともに進化しないという主張を支持した」[27][28]。  魚の化石とキュヴィエ キュヴィエはまた、ナポレオンのエジプト遠征隊が数千年前にミイラ化した動物を回収したが、それらは現代のものと何ら変わりがないように見えたと述べてい る[29]。「確かに」、キュヴィエは「これらの生物と我々が見ている生物との間には、人間のミイラと現代人の骨格との間にあるような大きな違いは見いだ せない」と書いている[30]。 ラマルクはこの結論を否定し、進化はわずか数千年の間に観察されるにはあまりにもゆっくり起こりすぎたと主張した。しかしキュヴィエは、ラマルクや他の博 物学者たちが自分たちの説を支持するために、「一筆書きで」何十万年という歳月を都合よく導入したことを批判した。その代わりに彼は、長い時間が何を生み 出すかは、より短い時間が生み出すものを掛け合わせることによってのみ判断できると主張した。さらに、部分の相関性の原理を信奉していた彼は、(ラマルク が提唱したような方法で)他のすべての部分から切り離された状態で、その動物を生存不能にすることなく、どのようなメカニズムでも動物のどの部分でも徐々 に変化させることができることに疑問を抱いていた[32]。 キュヴィエは『ラマルクへの賛辞』(Éloge de M. de Lamarck)の中で、ラマルクの進化論は以下の2つの恣意的な仮定に基づいていると書いている[33][34]。 ひとつは、胚を組織化するのは精液の蒸気であるというものであり、もうひとつは、努力と欲望が器官を生み出すというものである。このような基礎の上に確立 された体系は、詩人の想像力を楽しませるかもしれないし、形而上学者はそこからまったく新しい一連の体系を導き出すかもしれない。 その代わり、典型的な形は化石記録の中に突然現れ、絶滅するまで変わることなく存続するのである。キュヴィエは、彼が思い描いたこの古生物学的現象(これ は100年以上後に「断続平衡」によって再び取り上げられることになる)を説明し、聖書と調和させようとした。彼は、彼が認識していた様々な期間を、創世 記にある最後の大異変の間の間隔であるとした[35][36]。 新しい化石の形態が地質学的記録の中に突然現れ、その後、地層の上で変化することなく継続するというキュヴィエの主張は、後に進化論を批判する人々によっ て、創造論を支持するために利用された[37]。変化のなさは「種」の神聖な不変性と一致していたが、キュヴィエが大推薦者であった絶滅の考え方は明らか にそうではなかった。 多くの作家が、キュヴィエは化石人類は決して見つからないと頑なに主張していると不当に非難している。しかし彼は、「私が、人骨はこれまで人為的な化石の 中には見つかっていないと主張するとき、それは化石、あるいは石化物と呼ばれるものを指していると理解しなければならない」[38]。キュヴィエの主張 は、彼が知る限り発見されたすべての人骨は、石化しておらず、表層の地層からしか発見されていないため、比較的新しい年代のものであるというものであった [39]。しかし、彼はこの主張において独断的であったわけではなく、新たな証拠が明らかになると、後の版には、彼が「化石人骨化石の一例」であると自由 に認めた骨格について記述した付録を付けた[40]。 しかし、彼の批判の厳しさと評判の高さは、チャールズ・ダーウィンがキュヴィエの死後20年以上経って『種の起源』を出版するまで、自然学者が種の漸進的な変化について推測することを思いとどまらせ続けた[41]。 絶滅 このセクションは検証のために追加の引用が必要である。このセクションに信頼できる情報源への引用を追加することで、この記事の改善にご協力いただきた い。ソースのないものは異議申し立てされ、削除される可能性がある。(2017年4月)(このメッセージを削除する方法とタイミングを学ぶ)  ジョルジュ・キュヴィエが1812年に作成したAnoplotherium communeの骨格復元。絶滅した哺乳類の層序と現代の類似種の欠如は、絶滅と生態系の継承を証明するものだった。 キュヴィエはパリ国立博物館に在職していた初期に、化石の骨の研究を発表し、それが絶滅した大型の四足動物のものであると主張した。そのような彼の最初の 2つの出版物は、マンモスとマストドンの化石が現代のゾウではなく絶滅種のものであると同定したものと、メガテリウムを巨大な絶滅種のナマケモノであると 同定した研究であった。 [42]マンモスとマストドンを別個の絶滅種として同定した彼の主な証拠は、その顎と歯の構造であった[43]。メガテリウムの化石が巨大なナマケモノの ものであったという彼の主な証拠は、その頭蓋骨を現存のナマケモノのものと比較したことによる。 キュヴィエは彼の古生物学的方法について、「歯の形は顆の形に、肩甲骨の形は爪の形につながる; 同様に、爪、肩甲骨、顆骨、大腿骨は、それぞれ別々に、歯や他の部位を明らかにする。 「[45] しかし、キュヴィエの実際の方法は、動物の解剖学に関する膨大な知識と、パリにある比類なき博物学コレクションへのアクセスという必要条件のもとで、化石 標本と現存種の解剖学的構造との比較に大きく依存していた[46]。しかし、この現実は、キュヴィエはわずかな骨の断片から絶滅動物の身体構造全体を復元 できるという俗説の台頭を妨げるものではなかった[47]。 キュヴィエが生きたゾウと化石のゾウに関する1796年の論文を発表した当時、絶滅した動物種は存在しないと広く信じられていた。ビュフォンのような権威 者たちは、ヨーロッパで発見されたウーリーサイやマンモスのような動物の化石は、熱帯にまだ生息していた動物(すなわちサイやゾウ)の遺骸であり、地球が 冷え込むにつれてヨーロッパやアジアから移動してきたのだと主張していた。 その後、キュヴィエはパリ近郊で発掘されたゾウの化石について先駆的な研究を行った。しかし、彼が調査したゾウの骨は、現在インドやアフリカで繁栄してい るゾウの骨とは著しく異なっていた。この発見によってキュヴィエは、化石は現生象のものであるという考えを否定するようになった。なぜなら、その巨大さゆ えに見逃すことはほとんど不可能だからである。メガテリウムは、この議論に説得力のある別のデータを提供した。最終的に、彼は化石が人類にとって未知の種 に属するものであることを繰り返し確認し、パリでの地層学的研究から得られた鉱物学的証拠と相まって、キュヴィエは、地球が長い年月をかけて急激な変化を 遂げたために、いくつかの種が絶滅したという命題に突き進んだ[48]。 キュヴィエの絶滅に関する理論は、ダーウィンやチャールズ・ライエルのような他の著名な自然科学者たちから反対を受けた。彼らはキュヴィエとは異なり、絶 滅は突発的なものではなく、地球と同じように動物も種として徐々に変化していくと考えていた。これは、動物の絶滅は破滅的なものであると提唱していたよう なキュヴィエの理論とは大きく異なっていた。 しかし、キュヴィエの絶滅説は、過去6億年の間に起こった大量絶滅の場合には正当化される。この200万年という短い地質学的スパンの間に、火山の噴火や 小惑星、海面の急激な変動などもあって、全生物種の約半数が完全に絶滅したのである。この時、新しい種が増え、他の種が減り、人類の到来を促した。キュ ヴィエの初期の研究は、絶滅が実に信頼できる自然な地球規模のプロセスであることを決定的に証明した[49]。絶滅に関するキュヴィエの考え方は、ギリシ ア語とラテン語の文献を幅広く読んだことに影響された。 キュヴィエの絶滅理論に影響を与えたのは、彼が収集した新世界の標本であり、その多くはアメリカ先住民から入手したものであった。彼はまた、アメリカ大陸 の情報提供者や友人から送られてきた、アメリカ先住民の観察、伝説、巨大な骨格化石の解釈のアーカイブを保管していた。彼は、ネイティブ・アメリカンの証 言のほとんどが、巨大な骨、歯、牙を、大災害によって破壊された深い過去の動物であると同定していることに感銘を受けた[51]。 大災害主義 このセクションには、検証のための追加引用が必要である。このセクションに信頼できる情報源への引用を追加することで、この記事の改善にご協力いただきた い。ソースのないものは異議申し立てされ、削除される可能性がある。(2017年4月)(このメッセージを削除する方法とタイミングを学ぶ)  これらのインドゾウとマンモスの顎は、1799年にキュヴィエの生きたゾウと化石のゾウに関する1796年の論文が印刷された際に含まれていた。 主な記事 天変地異説 キュヴィエは、彼が調査した動物の化石は、すべてではないにせよ、ほとんどが絶滅した種の遺骸であると考えるようになった。生きたゾウと化石のゾウに関する1796年の論文の終わり近くで、彼はこう述べている: これらの事実はすべて、相互に矛盾がなく、どのような報告によっても反対されないので、何らかの大災害によって破壊された、我々の世界以前の世界の存在を証明しているように私には思われる。 当時の多くの自然科学者の考えとは異なり、キュヴィエは動物の絶滅は人為的な原因によるものではないと考えた。それどころか、人類は太古の地球の化石記録 を間接的に維持するのに十分なほど長く存在していたと提唱した。彼はまた、さまざまな文化的背景の記録を分析することによって、水の大災害を検証しようと した。彼は、水の破局に関する多くの記述が不明瞭であることを発見したが、それでも彼は、そのような出来事が人類史の瀬戸際で起こったと信じていた。 このためキュヴィエは、カタストロフィ主義と呼ばれる地質学的な学派の積極的な支持者となった。カタストロフィ主義とは、地球の地質学的特徴や生命の歴史 の多くは、多くの動物種の絶滅を引き起こした破滅的な出来事によって説明できると主張する学派である。キュヴィエはそのキャリアの過程で、大災害は一度だ けでなく、何度も起こり、その結果、さまざまな動物相が次々と変化したと考えるようになった。特に、1812年に出版された四足動物の化石に関する論文集 『Recherches sur les ossements fossiles de quadrupèdes(四足動物の化石の骨に関する研究)』の前説(序論)では、この考えを詳細に論じている。 キュヴィエは、ジャン・アンドレ・ドリュックとデオダ・ド・ドロミューを含む2つの異なる資料から、このような破滅的な出来事に関する独自の説明を導き出 した。前者は、10千年前に存在した大陸が崩壊し、海底が大陸プレートよりも高く隆起して現在の大陸になったと提唱した。後者は、大津波が地球を襲い、大 量絶滅に至ったという説である。いずれにせよ、大洪水が起こったのは人類史上ごく最近のことだと彼は考えていた。実際、彼は地球の存在は限定的であり、ラ マルクのような多くの自然科学者が信じていたほどには広がっていないと考えていた。 彼の破滅主義理論を裏付ける証拠の多くは、化石の記録から得られている。彼が発見した化石は世界最初の爬虫類の証拠であり、年代順に哺乳類、人類と続くと 強く示唆した。キュヴィエは、すべての動物の絶滅と新種の導入の原因についてあまり掘り下げようとはせず、むしろ地球上の動物の歴史の連続的な側面に焦点 を当てた。ある意味で、彼の地球史の年代測定は、ラマルクの変質論的理論をいくらか反映したものであった。 キュヴィエはまた、アレクサンドル・ブロンニャールとともにパリの岩石サイクルの分析に取り組んだ。二人は層序学的手法を用いて、これらの岩石の研究から 地球の歴史に関する重要な情報を推定することができた。これらの岩石には、軟体動物の残骸、哺乳類の骨、貝殻などが含まれていた。これらの発見から、キュ ヴィエとブロングニアールは、多くの環境変化は急激な大災害の中で起こったが、地球自体は突然の擾乱の間に長い期間平穏であることが多かったと結論づけ た。 この「予備講義」は非常に有名になり、英語、ドイツ語、イタリア語に無断翻訳された(英語の場合は完全に正確ではなかった)。1826年、キュヴィエは 『Discours sur les révolutions de la surface du globe(地球表面の隆起に関する考察)』という名前で改訂版を出版した[52]。 キュヴィエの死後、地質学のカタストロフィック学派は、チャールズ・ライエルらによって提唱された均一主義に押され、地質学的特徴は、侵食や火山活動な ど、現在観測可能な力が長期間にわたって徐々に作用することによって最もよく説明されると主張した。しかし、20世紀後半に始まった大量絶滅の話題への関 心の高まりは、科学史家やその他の学者の間で、キュヴィエの研究のこの側面への関心を復活させるきっかけとなった[53]。 層序学 キュヴィエはパリ鉱山学校の教官であったアレクサンドル・ブロンニャールと数年にわたり共同研究を行い、パリ近郊の地質に関するモノグラフを作成した。1808年に予備版が出版され、1811年に最終版が出版された。 このモノグラフの中で、彼らはさまざまな岩層の特徴的な化石を同定し、それをもとにパリ盆地の地質柱状列(堆積岩の秩序だった層)を分析した。その結果、 地層は長い年月をかけて形成されたものであり、その間に動物相の交代があったことは明らかであり、この地域はある時は海水に、またある時は淡水に沈んでい たことが判明した。同時期にウィリアム・スミスがイギリスの地質図を作成したが、この地質図もまた、特徴的な化石と動物相転移の原理を利用して堆積岩の層 を相関させたもので、このモノグラフは層序学という科学分野の確立に貢献した。古生物学の歴史と地質学の歴史における大きな発展であった[54]。 爬虫類の時代  イクチオサウルスとプレシオサウルス(1834年チェコ版『Discours sur les revolutions de la surface du globe』より 1800年、キュヴィエはバイエルンで発見された小型の空飛ぶ爬虫類の化石[55]を初めて活字で正確に同定し、1809年にプテロダクティル (Ptero-Dactyle)と命名した[56](後にプテロダクティルス・アンティークス(Pterodactylus antiquus)とラテン語化)。1808年、キュヴィエはマーストリヒトで発見された化石を巨大な海棲トカゲと同定した。 キュヴィエは、哺乳類よりもむしろ爬虫類が支配的な動物相であった時代があったという正しい推測をした[57]。この推測は、彼の死後20年以上にわたっ て、主にメアリー・アニング、ウィリアム・コニベア、ウィリアム・バックランド、ギデオン・マンテルといったイギリスの地質学者や化石収集家たちによっ て、最初の魚竜、プレシオサウルス、恐竜を発見・記載した一連の目を見張るような発見によって確認された。 部分相関の原理 パリ近郊の石膏採石場から発見された動物の化石に関する1798年の論文で、キュヴィエは部分相関の原理として知られるものを述べている。彼はこう書いている[58]。 ある動物の歯が、その動物が肉で栄養を得るために必要なものであるならば、その消化器官のシステム全体がその種の食物にとって適切であり、その動物の骨格 全体と運動器官、さらには感覚器官までもが、獲物を追いかけて捕らえるのに巧みなように配置されていることは、これ以上調べなくても確かである。もしそう でなければ、動物は生きていくことができない。 この考え方はキュヴィエの部分相関の原理と呼ばれ、動物の体内のすべての器官は相互に深く依存しているとするものである。種の存続は、これらの器官の相互 作用の仕方に依存している。例えば、消化管が肉の消化に最適でも、体が植物の採食に最適な種は生き残れない。このように、すべての種において、身体の各部 分の機能的意義は他の部分と相関していなければならない。 応用 キュヴィエは、彼の原理の威力の一端は、化石の復元を助ける能力にあると考えた。ほとんどの場合、四足動物の化石は完全な骨格として発見されるのではな く、解剖学者によって組み合わされる必要のある散乱した断片として発見された。さらに悪いことに、堆積物には複数の種の動物の化石が混在していることが多 かった。解剖学者がこれらの骨格を組み立て直すと、異なる種の遺骨が組み合わされ、想像上の複合種が生まれる危険性があった。しかし、それぞれの骨の機能 的な目的を調べ、部分の相関性の原理を適用することで、この問題は回避できるとキュヴィエは考えた。 この原理が化石の復元に役立つことは、絶滅を支持する証拠を提供するというキュヴィエの研究にも役立った。キュヴィエが絶滅を支持する最も強力な証拠は、 化石化した動物の遺骸が、もはや存在しない種のものであることを証明することである。キュヴィエの部位相関の原理を応用すれば、化石化した骨格が真正に復 元されたものであることを確認しやすくなり、現存する種の骨格と比較することで得られた観察結果を正当化することができる。 インパクト  キュヴィエの線刻画、1832年 キュヴィエは、アイザック・ニュートン(1643年~1727年)とアントワーヌ・ラヴォアジエ(1743年~1794年)がそれぞれ確立した法則のおか げで、自然史が物理学と化学が占める真に科学的なレベルにまで昇華されるよう、彼の解剖学の原理が法則に基づく枠組みを提供することを期待した。彼はル・ レーニュ動物誌の序文で、いつの日か解剖学はニュートンの物理法則のように単純で数学的で予測可能な法則として表現されるようになるだろうと自信を示して おり、自分の原理をその方向への重要な一歩と見なしていた[60]。彼にとって、モンマルトルの石膏採石場に有袋類の骨盤骨が存在するという予測で示され た自分の原理の予測能力は、これらの目標に手が届くだけでなく差し迫ったものであることを示していた[61]。 部分の相関の原理はまた、神の創造主を呼び出すことなく、非進化的な文脈で機能を理解するためのキュヴィエの方法でもあった[62]。パリ近郊の石膏採石 場で発見された動物の化石に関する同じ1798年の論文の中で、キュヴィエは自身の原理の予測力を強調し、次のように書いている[58]。 今日、比較解剖学は完成の域に達しており、一本の骨を調べただけで、その骨が属する動物の階級、時には属さえも、とりわけその骨が頭部に属するものか四肢 に属するものかを、しばしば決定することができる......。なぜなら、動物の体の各部分を構成する骨の数、方向、形は、常に他のすべての部分と必要な 関係にあり、ある点までは、骨のどれか一つから全体を推測することができ、逆もまたしかりだからである。 キュヴィエは、彼の原理が化石を復元し、予測を立てるための合理的で数学的な方法であることが大きな貢献であると考えていたが、実際には、キュヴィエが彼 の原理を用いることは困難であった。当時はまだ多くの身体部位の機能的意義が不明であったため、キュヴィエの原理を使ってそれらの身体部位を他の身体部位 と関連付けることは不可能であった。キュヴィエは化石の発見について正確な予測を立てることができたが、実際には、彼の予測の正確さは、彼の原理を応用し たものではなく、むしろ比較解剖学に関する膨大な知識によるものであった。しかし、キュヴィエが彼の原理の力を誇張していたにもかかわらず、基本的な概念 は比較解剖学と古生物学の中心となっている[59]。 |

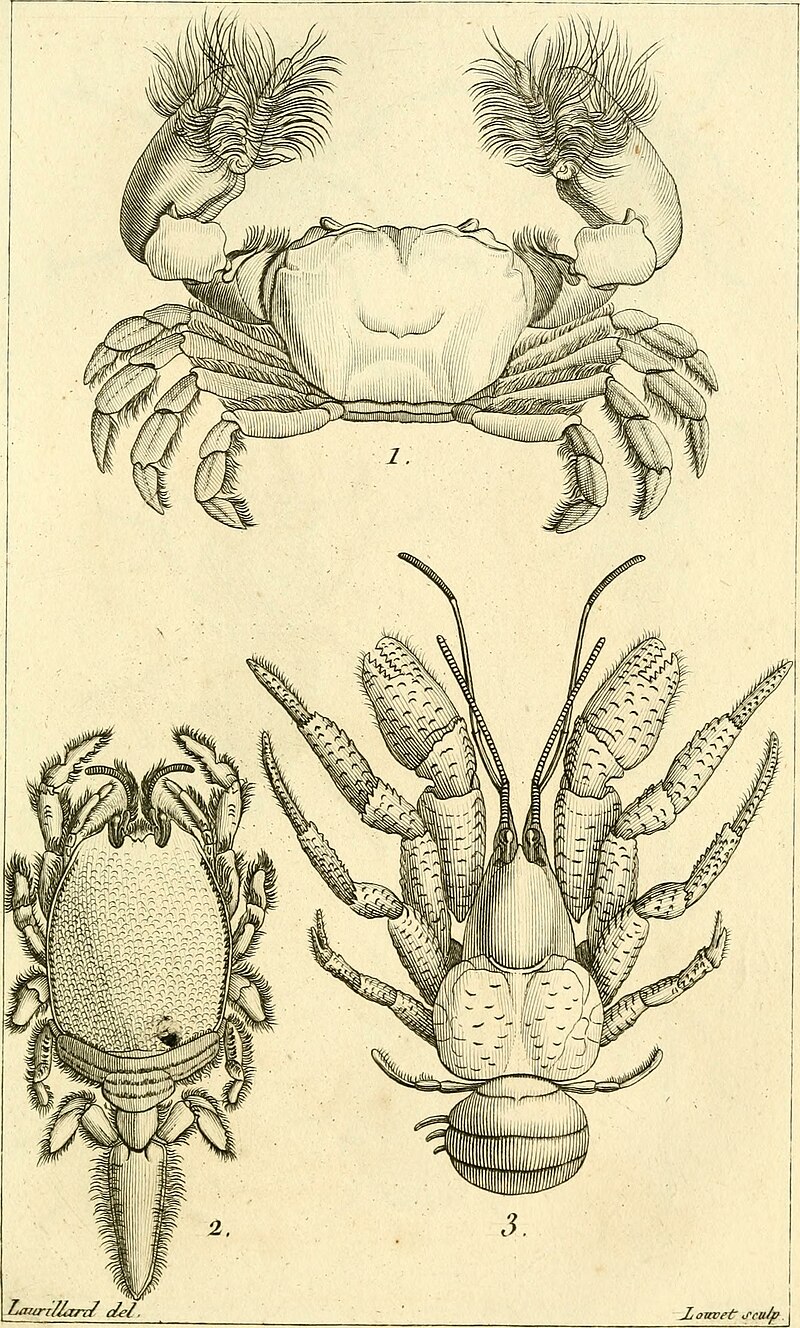

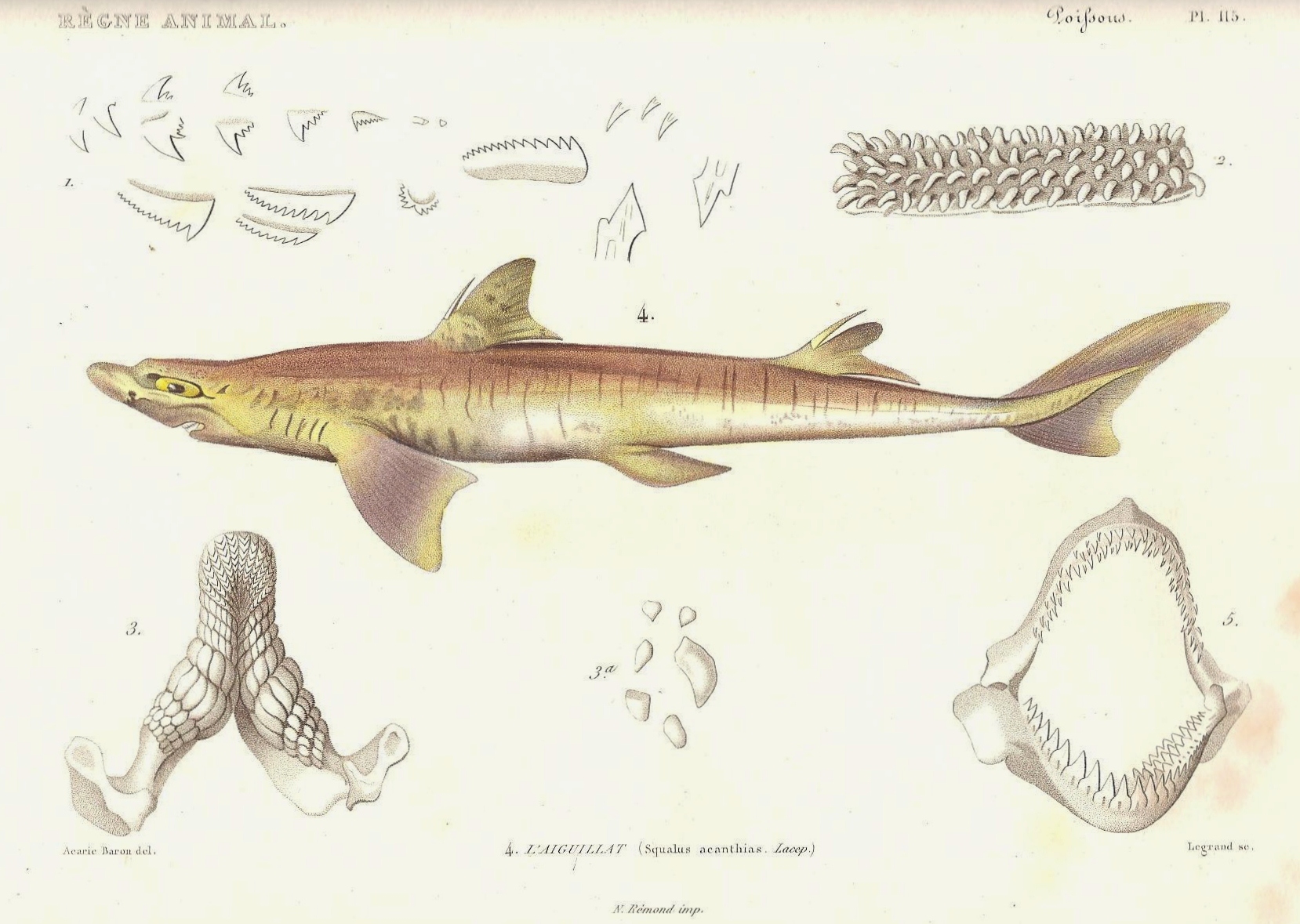

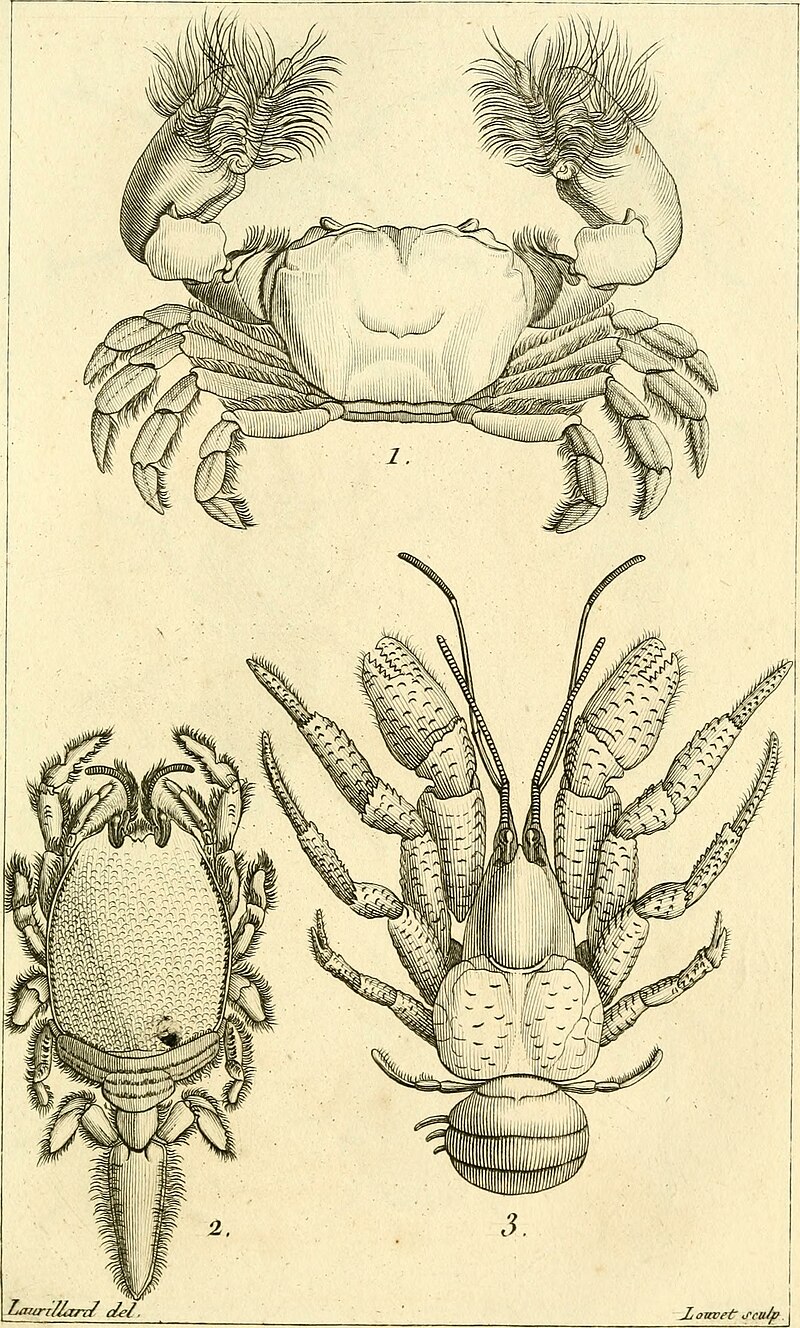

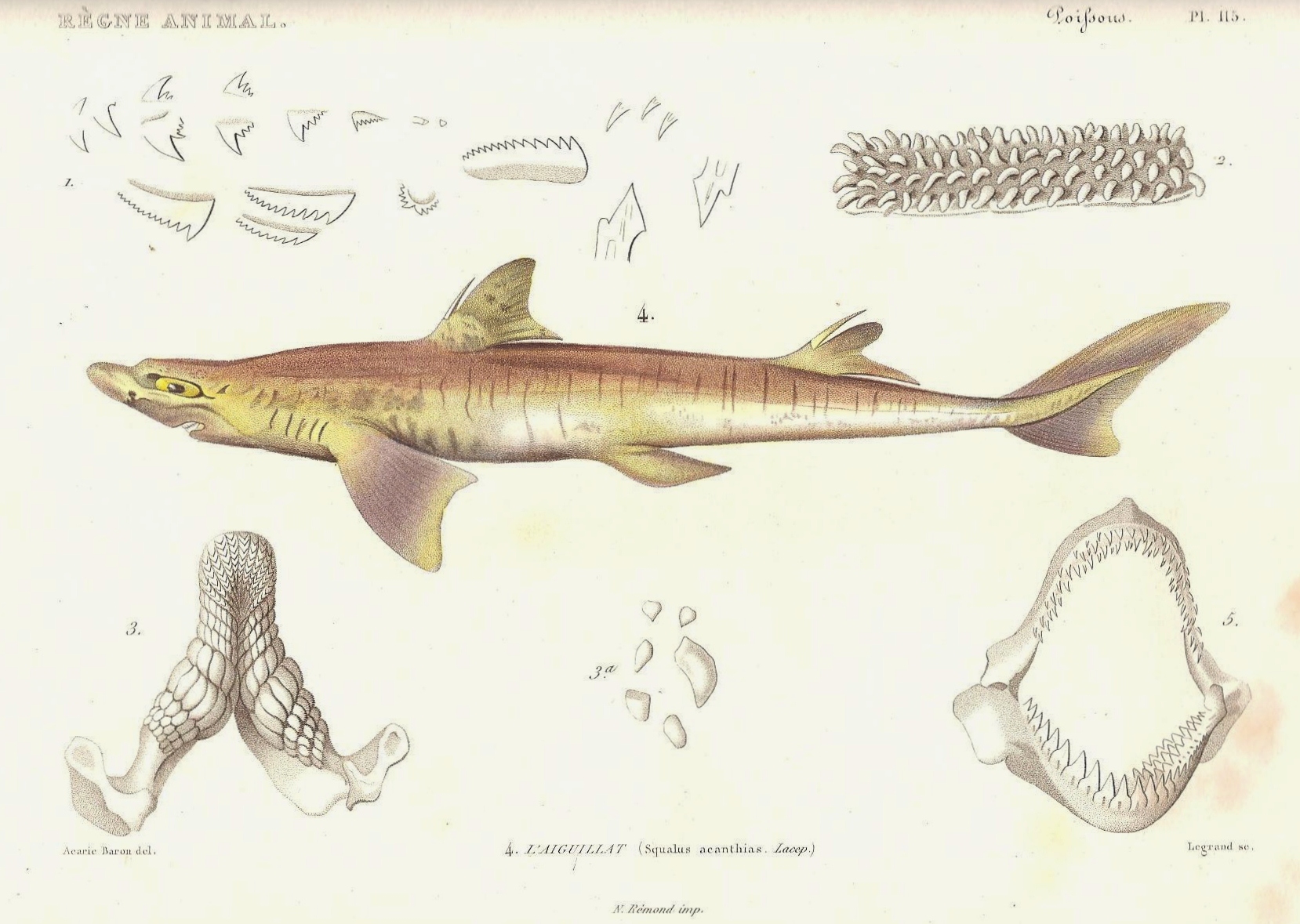

| Scientific work Comparative anatomy and classification  Plate from Le Règne Animal, 1817 edition At the Paris Museum, Cuvier furthered his studies on the anatomical classification of animals. He believed that classification should be based on how organs collectively function, a concept he called functional integration. Cuvier reinforced the idea of subordinating less vital body parts to more critical organ systems as part of anatomical classification. He included these ideas in his 1817 book, The Animal Kingdom. In his anatomical studies, Cuvier believed function played a bigger role than form in the field of taxonomy. His scientific beliefs rested in the idea of the principles of the correlation of parts and of the conditions of existence. The former principle accounts for the connection between organ function and its practical use for an organism to survive. The latter principle emphasizes the animal's physiological function in relation to its surrounding environment. These findings were published in his scientific readings, including Leçons d'anatomie comparée (Lessons on Comparative Anatomy) between 1800 and 1805,[a] and The Animal Kingdom in 1817. Ultimately, Cuvier developed four embranchements, or branches, through which he classified animals based on his taxonomical and anatomical studies. He later performed groundbreaking work in classifying animals in vertebrate and invertebrate groups by subdividing each category. For instance, he proposed that the invertebrates could be segmented into three individual categories, including Mollusca, Radiata, and Articulata. He also articulated that species cannot move across these categories, a theory called transmutation. He reasoned that organisms cannot acquire or change their physical traits over time and still retain optimal survival. As a result, he often conflicted with Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire and Jean-Baptiste Lamarck's theories of transmutation.  Plate from Le Règne Animal, 1828 edition In 1798, Cuvier published his first independent work, the Tableau élémentaire de l'histoire naturelle des animaux, which was an abridgement of his course of lectures at the École du Pantheon and may be regarded as the foundation and first statement of his natural classification of the animal kingdom.[19] Mollusks Cuvier categorized snails, cockles, and cuttlefish into one category he called molluscs (Mollusca), an embranchment. Though he noted how all three of these animals were outwardly different in terms of shell shape and diet, he saw a noticeable pattern pertaining to their overall physical appearance. Cuvier began his intensive studies of molluscs during his time in Normandy – the first time he had ever seen the sea – and his papers on the so-called Mollusca began appearing as early as 1792.[63] However, most of his memoirs on this branch were published in the Annales du museum between 1802 and 1815; they were subsequently collected as Mémoires pour servir à l'histoire et à l'anatomie des mollusques, published in one volume at Paris in 1817.[19] Fish Cuvier's researches on fish, begun in 1801, finally culminated in the publication of the Histoire naturelle des poissons, which contained descriptions of 5,000 species of fishes, and was a joint production with Achille Valenciennes. Cuvier's work on this project extended over the years 1828–1831.[19] Palaeontology and osteology  Plate from Le Règne Animal, 1828 edition In palaeontology, Cuvier published a long list of memoirs, partly relating to the bones of extinct animals, and partly detailing the results of observations on the skeletons of living animals, specially examined with a view toward throwing light upon the structure and affinities of the fossil forms.[19] Among living forms he published papers relating to the osteology of the Rhinoceros indicus, the tapir, Hyrax capensis, the hippopotamus, the sloths, the manatee, etc.[19] He produced an even larger body of work on fossils, dealing with the extinct mammals of the Eocene beds of Montmartre and other localities near Paris, such as the Buttes Chaumont,[64] the fossil species of hippopotamus, Palaeotherium, Anoplotherium, a marsupial (which he called Didelphys gypsorum), the Megalonyx, the Megatherium, the cave-hyena, the pterodactyl, the extinct species of rhinoceros, the cave bear, the mastodon, the extinct species of elephant, fossil species of manatee and seals, fossil forms of crocodilians, chelonians, fish, birds, etc.[19] If his identification of fossil animals was dependent upon comparison with the osteology of extant animals whose anatomy was poorly known, Cuvier would often publish a thorough documentation of the relevant extant species' anatomy before publishing his analyses of the fossil specimens.[65] The department of palaeontology dealing with the Mammalia may be said to have been essentially created and established by Cuvier.[19] The results of Cuvier's principal palaeontological and geological investigations ultimately were given to the world in the form of two separate works: Recherches sur les ossemens fossiles de quadrupèdes (Paris, 1812; later editions in 1821 and 1825); and Discours sur les revolutions de la surface du globe (Paris, 1825).[19] In this latter work he expounded a scientific theory of Catastrophism. The Animal Kingdom (Le Règne Animal) Main article: Le Règne Animal  Plate from Le Règne Animal, 1828 edition Cuvier's most admired work was his Le Règne Animal. It appeared in four octavo volumes in 1817; a second edition in five volumes was brought out in 1829–1830. In this classic work, Cuvier presented the results of his life's research into the structure of living and fossil animals. With the exception of the section on insects, in which he was assisted by his friend Latreille, the whole of the work was his own.[19] It was translated into English many times, often with substantial notes and supplementary material updating the book in accordance with the expansion of knowledge. Racial studies Cuvier was a Protestant and a believer in monogenism, who held that all men descended from the biblical Adam, although his position usually was confused as polygenist. Some writers who have studied his racial work have dubbed his position as "quasi-polygenist", and most of his racial studies have influenced scientific racism. Cuvier believed there were three distinct races: the Caucasian (white), Mongolian (yellow), and the Ethiopian (black). Cuvier claimed that Adam and Eve were Caucasian, the original race of mankind. The other two races originated from survivors escaping in different directions after a major catastrophe hit the earth 5,000 years ago, with those survivors then living in complete isolation from each other.[8][66] Cuvier categorized these divisions he identified into races according to his perception of the beauty or ugliness of their skulls and the quality of their civilizations. Cuvier's racial studies held the supposed features of polygenism, namely fixity of species; limits on environmental influence; unchanging underlying type; anatomical and cranial measurement differences in races; and physical and mental differences between distinct races.[8] Sarah Baartman Alongside other French naturalists, Cuvier subjected Sarah Baartman, a South African Khokhoi woman exhibited in European freak shows as the "Hottentot Venus", to examinations. At the time that Cuvier interacted with Baartman, Baartman's "existence was really quite miserable and extraordinarily poor. Sara was literally [sic] treated like an animal."[67] In 1815, while Baartman was very ill, Cuvier commissioned a nude painting of her. She died shortly afterward, aged 26.[68] Following Baartman's death, Cuvier sought out and received permission to dissect her body, focusing on her genitalia, buttocks and skull shape. In his examination, Cuvier concluded that many of Baartman's features more closely resembled the anatomy of a monkey than a human.[9] Her remains were displayed in the Musée de l’Homme in Paris until 1970, then were put into storage.[69] Her remains were returned to South Africa in 2002.[70] |

科学的研究 比較解剖学と分類  1817年版『Le Règne Animal』より パリ博物館において、キュヴィエは動物の解剖学的分類に関する研究をさらに進めた。彼は、分類は器官が集合的にどのように機能するかに基づいて行われるべ きであると考え、これを機能的統合と呼んだ。キュヴィエは解剖学的分類の一環として、より重要な器官系に、より生命力の弱い身体の部位を従属させるという 考えを強化した。1817年の著書『動物界』には、こうした考え方が盛り込まれている。 解剖学的研究において、キュヴィエは分類学の分野では形態よりも機能が大きな役割を果たすと考えていた。彼の科学的信念は、部分の相関関係の原理と存在条 件の原理の考えに基づいていた。前者の原則は、器官の機能と生物が生存するための実用的な用途との関連を説明するものである。後者の原理は、周囲の環境と の関係における動物の生理的機能を強調するものである。これらの知見は、1800年から1805年にかけての『比較解剖学の授業』(Leçons d'anatomie comparée)[a]、1817年の『動物界』(The Animal Kingdom)などの学術書に発表された。 最終的にキュヴィエは、分類学的・解剖学的研究に基づいて動物を分類するための4つの枝分かれを開発した。その後、彼は動物を脊椎動物と無脊椎動物のグ ループに分類し、それぞれのカテゴリーを細分化するという画期的な研究を行った。例えば、彼は無脊椎動物を軟体動物門、放射動物門、有尾動物門の3つに分 類することを提案した。彼はまた、種はこれらのカテゴリーを越えて移動することはできないと明言した。彼は、生物は時間の経過とともに身体的特徴を獲得し たり変化させたりしても、最適な生存を維持することはできないと推論した。その結果、彼はしばしばジェフロワ・サン=ハイレールやジャン=バティスト・ラ マルクの転変説と対立した。  1828年版『Le Règne Animal』のプレート 1798年、キュヴィエは最初の独立した著作であるTableau élémentaire de l'histoire naturelle des animauxを出版した。これはパンテオン学院での講義を要約したものであり、彼の動物界の自然分類の基礎であり、最初の記述であると考えられる [19]。 軟体動物 キュヴィエはカタツムリ、ゴカイ、イカを軟体動物(Mollusca)と呼ぶ一つのカテゴリーに分類した。彼は、これら3つの動物が殻の形や食性において外見上異なっていることに注目したが、全体的な外見に顕著なパターンを見出した。 キュヴィエはノルマンディー滞在中に軟体動物の集中的な研究を始めたが、彼が初めて海を見たのはこの時であり、いわゆる軟体動物に関する論文は早くも 1792年に掲載され始めた[63]。しかし、この部門に関する彼の回想録のほとんどは1802年から1815年にかけて『Annales du museum』に掲載された。 魚類 1801年に始まったキュヴィエの魚類研究は、最終的に『Histoire naturelle des poissons』として結実した。このプロジェクトにおけるキュヴィエの作業は1828年から1831年にかけて行われた[19]。 古生物学と骨学  1828年版『Le Règne Animal』のプレート 古生物学の分野では、キュヴィエは長い手記のリストを出版した。その一部は絶滅した動物の骨に関するものであり、一部は化石形態の構造と関連性を明らかにする目的で特別に調査された現生動物の骨格に関する観察結果を詳述したものであった[19]。 現生動物のなかでは、サイ・インディカス、バク、ハイラックス・カペンシス、カバ、ナマケモノ、マナティーなどの骨格に関する論文を発表した[19]。 モンマルトルやパリ近郊のビュット・ショーモン[64]などの始新世層の絶滅哺乳類、カバの化石種、パラオテリウム、アノプロテリウム、有袋類(彼はディ デルフィス・ジプソラムと呼んでいた、) メガロニクス、メガテリウム、洞窟ハイエナ、翼竜、サイの絶滅種、ホラアナグマ、マストドン、ゾウの絶滅種、マナティーとアザラシの化石、ワニ類、ケ竜 類、魚類、鳥類の化石などである。 [19]化石動物の同定が、解剖学的な知識が乏しい現存動物の骨学との比較に依存していた場合、キュヴィエは化石標本の分析を発表する前に、しばしば関連 する現存種の解剖学の徹底的な文書を発表していた[65]。哺乳類を扱う古生物学部門は、基本的にキュヴィエによって創設され、確立されたと言えるかもし れない[19]。 キュヴィエの主要な古生物学的・地質学的調査の結果は、最終的に2つの別々の著作の形で世に出た: この後者の著作の中で、彼はカタストロフィ主義の科学的理論を説いた[19]。 動物王国 (Le Règne Animal) 主な記事 レニュ動物誌  ル・レーニュ動物誌』1828年版より キュヴィエの最も称賛された著作は『レニュ動物』である。この著作は1817年に八つ折り4巻で出版され、1829年から1830年にかけて5巻の第2版 が出版された。この古典的著作の中で、キュヴィエは、生きている動物と化石の動物の構造に関する生涯の研究成果を発表した。昆虫の項で友人のラトレイユの 協力を得た以外は、すべてキュヴィエ自身の手によるものであった[19]。この著作は何度も英訳され、しばしば大幅な注釈や補足資料が付され、知識の拡大 に合わせて書物が更新された。 人種学 キュヴィエはプロテスタントであり、すべての人間は聖書のアダムの子孫であるとする一元論(単元論)を信奉していたが、彼の立場は通常多元論者と混同されていた。彼の人種研究を研究した作家の中には、彼の立場を「準ポリジェニスト」と呼ぶ者もおり、彼の人種研究のほとんどは科学人種主義に 影響を与えている。キュヴィエは、コーカソイド(白人)、モンゴル人(黄色人種)、エチオピア人(黒人)の3つの人種が存在すると考えていた。キュヴィエ は、アダムとイブはコーカソイドであり、人類の原種であると主張した。他の2つの人種は、5,000年前に大災害が地球を襲った後、異なる方向に逃れた生 存者から生まれたものであり、それらの生存者はその後、互いに完全に隔離された状態で生活していた[8][66]。 キュヴィエは、頭蓋骨の美しさや醜さ、文明の質の認識に従って、彼が特 定したこれらの区分を人種に分類した。キュヴィエの人種研究は、多遺伝主義の特徴とされるもの、すなわち種の固定性、環境の影響の限界、不変の基礎型、人 種における解剖学的および頭蓋測定の違い、そして別個の人種間の身体的および精神的な違いを保持していた[8]。 8. Jackson, John P.; Weidman, Nadine M. (2005). Race, Racism, and Science: Social Impact and Interaction. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0-8135-3736-8.pp.41-42. 66. Kidd, Colin (2006). The Forging of Races: Race and Scripture in the Protestant Atlantic World, 1600–2000. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-79324-7.p. 28 サラ・バートマン キュヴィエは他のフランス人博物学者とともに、「ホッテントットの ヴィーナス」としてヨーロッパの見世物小屋に展示されていた南アフリカのホコイ族の女性、サラ・バートマンを検査にかけた。キュヴィエがバートマンと交流 した当時、バートマンは「その存在は実に悲惨で、並外れて貧しかった。サラは文字通り動物のように扱われていた」[67] 。1815年、バールトマンが重い病気にかかっていたとき、キュヴィエは彼女のヌード画を依頼した。彼女はその直後、26歳で亡くなった[68]。 バートマンの死後、キュヴィエは彼女の体を解剖する許可を得、性器、臀部、頭蓋骨の形に焦点を当てた。彼女の遺体は1970年までパリの人間博物館に展示され、その後保管された。 彼女の遺体は2002年に南アフリカに返還された[70]。 |

| Taxa described by him See Category:Taxa named by Georges Cuvier Official and public work  Apart from his own original investigations in zoology and paleontology Cuvier carried out a vast amount of work as perpetual secretary of the National Institute, and as an official connected with public education generally; and much of this work appeared ultimately in a published form. Thus, in 1808 he was placed by Napoleon upon the council of the Imperial University, and in this capacity he presided (in the years 1809, 1811, and 1813) over commissions charged to examine the state of the higher educational establishments in the districts beyond the Alps and the Rhine that had been annexed to France, and to report upon the means by which these could be affiliated with the central university. He published three separate reports on this subject.[71] In his capacity, again, of perpetual secretary of the Institute, he not only prepared a number of éloges historiques on deceased members of the Academy of Sciences, but was also the author of a number of reports on the history of the physical and natural sciences, the most important of these being the Rapport historique sur le progrès des sciences physiques depuis 1789, published in 1810.[72] Prior to the fall of Napoleon (1814) he had been admitted to the council of state, and his position remained unaffected by the restoration of the Bourbons. He was elected chancellor of the university, in which capacity he acted as interim president of the council of public instruction, while he also, as a Lutheran, superintended the faculty of Protestant theology. In 1819 he was appointed president of the committee of the interior, an office he retained until his death.[72] In 1826 he was made grand officer of the Legion of Honour; he subsequently was appointed president of the council of state. He served as a member of the Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres from 1830 to his death. A member of the Doctrinaires, he was nominated to the ministry of the interior in the beginning of 1832.[72] Commemorations  Statue of Cuvier by David d'Angers, 1838 Cuvier is commemorated in the naming of several animals; they include Cuvier's beaked whale (which he first thought to be extinct), Cuvier's gazelle, Cuvier's toucan, Cuvier's bichir, Cuvier's dwarf caiman, and Galeocerdo cuvier (tiger shark). Cuvier is commemorated in the scientific name of the following reptiles: Anolis cuvieri (a lizard from Puerto Rico), Bachia cuvieri (a synonym of Bachia alleni), and Oplurus cuvieri.[73] The fish Hepsetus cuvieri, sometimes known as the African pike or Kafue pike characin, which is a predatory freshwater fish found in southern Africa was named after him.[74] There also are some extinct animals named after Cuvier, such as the South American giant sloth Catonyx cuvieri. Cuvier Island in New Zealand was named after Cuvier by D'Urville.[75] The professor of English Wayne Glausser argues at length that the Aubrey-Maturin series of 21 novels (1970–2004) by Patrick O'Brian make the character Stephen Maturin "an advocate of the neo-classical paradigm articulated .. by Georges Cuvier."[76] Cuvier is referenced in Edgar Allan Poe's short story The Murders in the Rue Morgue as having written a description of the orangutan. Arthur Conan Doyle also refers to Cuvier in The Five Orange Pips, in which Sherlock Holmes compares Cuvier's methods to his own. |

キュヴィエが命名した分類群 Category:Georges Cuvierによって命名された分類群」を参照。 公式および公的な作品  キュヴィエは、動物学と古生物学における独自の研究の他に、国民研究所の常任秘書として、また一般的な公教育に携わる役人として、膨大な量の仕事をこな し、これらの仕事の多くは最終的に出版された。1808年、彼はナポレオンによって帝国大学の評議会の一員に任命され、1809年、1811年、1813 年には、フランスに併合されたアルプスおよびライン川以遠の地域の高等教育機関の状況を調査し、これらの教育機関を中央大学と提携させるための方法につい て報告する使命を帯びた委員会を主宰した。彼はこのテーマについて3回に分けて報告書を発表した[71]。 また、研究所の永久秘書として、科学アカデミーの物故会員に関する数多くのエログ史料を作成しただけでなく、物理学と自然科学の歴史に関する数多くの報告 書の著者でもあり、その中で最も重要なものは、1810年に出版された『1789年からの物理学科学の進歩に関する歴史的報告書』である[72]。 ナポレオンが没落する前(1814年)、彼は国家評議会の一員となり、その地位はブルボン家の復活にも影響されることはなかった。彼は大学の総長に選出さ れ、公教育評議会の臨時会長も務め、またルター派としてプロテスタント神学部の監督も務めた。1819年には内務委員会の委員長に任命され、その職を亡く なるまで務めた[72]。 1826年にはレジオン・ドヌール勲章のグランド・オフィサーとなり、その後、国家評議会議長に任命された。1830年から亡くなるまでアカデミー・デ・ ディスクリプション・エ・ベルズ・レトルのメンバーを務めた。ドクトリネールのメンバーであった彼は、1832年の初めに内務省に指名された[72]。 記念  ダヴィッド・ダンジェによるキュヴィエ像、1838年 キュヴィエはいくつかの動物の命名で記念されている。キュヴィエのアカボウクジラ(彼は最初絶滅したと考えていた)、キュヴィエのガゼル、キュヴィエのオ オハシ、キュヴィエのビチル、キュヴィエのドワーフカイマン、Galeocerdo cuvier(イタチザメ)などである。キュビエは以下の爬虫類の学名に記念されている: Anolis cuvieri(プエルトリコ産のトカゲ)、Bachia cuvieri(Bachia alleniのシノニム)、Oplurus cuvieriである[73]。 アフリカ南部に生息する捕食性の淡水魚であるHepsetus cuvieri(アフリカカワカマスまたはカフエカワカマスとして知られることもある)は、彼にちなんで名付けられた[74]。 また、南米の巨大ナマケモノCatonyx cuvieriなど、キュビエにちなんで命名された絶滅動物もいる。 ニュージーランドのキュビエ島は、ダルヴィルによってキュビエにちなんで命名された[75]。 ウェイン・グラウザー英語教授は、パトリック・オブライアンによる21の小説(1970年から2004年)からなるオーブリー・マチュリン・シリーズは、 登場人物のスティーヴン・マチュリンを「ジョルジュ・キュヴィエが明確にした新古典主義のパラダイムを提唱する人物」にしていると長々と論じている [76]。 エドガー・アラン・ポーの短編小説『モルグ街の殺人』では、キュヴィエがオランウータンの記述を書いたとして言及されている。また、アーサー・コナン・ド イルは、シャーロック・ホームズがキュヴィエの方法と自分の方法を比較した『5つのオレンジの種』の中でキュヴィエに言及している。 |

| Works Tableau élémentaire de l'histoire naturelle des animaux, 1797 See also: Category:Taxa named by Georges Cuvier Tableau élémentaire de l'histoire naturelle des animaux (1797–1798) Leçons d'anatomie comparée (5 volumes, 1800–1805) Essais sur la géographie minéralogique des environs de Paris, avec une carte géognostique et des coupes de terrain, with Alexandre Brongniart (1811) Le Règne animal distribué d'après son organisation, pour servir de base à l'histoire naturelle des animaux et d'introduction à l'anatomie comparée (4 volumes, 1817) Recherches sur les ossemens fossiles de quadrupèdes, où l'on rétablit les caractères de plusieurs espèces d'animaux que les révolutions du globe paroissent avoir détruites (4 volumes, 1812) (text in French) 2 3 4 Mémoires pour servir à l'histoire et à l'anatomie des mollusques (1817) Éloges historiques des membres de l'Académie royale des sciences, lus dans les séances de l'Institut royal de France par M. Cuvier (3 volumes, 1819–1827) Vol. 1, Vol. 2, and Vol. 3 Théorie de la terre (1821) --- Essay on the theory of the earth, 1813; 1815, trans. Robert Kerr. Recherches sur les ossemens fossiles, 1821–1823 (5 vols). Discours sur les révolutions de la surface du globe et sur les changements qu'elles ont produits dans le règne animal (1822). New edition: Christian Bourgeois, Paris, 1985. (text in French) Histoire des progrès des sciences naturelles depuis 1789 jusqu'à ce jour (5 volumes, 1826–1836) Histoire naturelle des poissons (11 volumes, 1828–1848), continued by Achille Valenciennes Histoire des sciences naturelles depuis leur origine jusqu'à nos jours, chez tous les peuples connus, professée au Collège de France (5 volumes, 1841–1845), edited, annotated, and published by Magdeleine de Saint-Agit Cuvier's History of the Natural Sciences: twenty-four lessons from Antiquity to the Renaissance [edited and annotated by Theodore W. Pietsch, translated by Abby S. Simpson, foreword by Philippe Taquet], Paris: Publications scientifiques du Muséum national d'Histoire naturelle, 2012, 734 p. (coll. Archives; 16) ISBN 978-2-85653-684-1 Variorum of the works of Georges Cuvier: Preliminary Discourse of the Recherches sur les ossemens fossiles 1812, containing the Memory on the ibis of the ancient Egyptians, and the Discours sur les révolutions de la surface du Globe 1825, containing the Determination of the birds called ibis by the ancient Egyptians[77] Cuvier also collaborated on the Dictionnaire des sciences naturelles (61 volumes, 1816–1845) and on the Biographie universelle (45 volumes, 1843-18??) The standard author abbreviation Cuvier is used to indicate this person as the author when citing a botanical name.[78] |

作品 動物の自然史基本図、1797年 Category:ジョルジュ・キュヴィエが命名した分類群も参照のこと。 動物の自然史の初歩的な表(1797-1798年) 比較解剖学(全5巻、1800-1805年) アレクサンドル・ブロンニャールとの共著『パリ近郊の鉱物学的地理学に関するエッセイ、地理学的地図と地形図を添えて』(1811年) 動物の自然史の基礎と比較解剖学入門のために、その組織に従って分布された動物種(全4巻、1817年) 四足動物の骨格化石に関する研究-地球の変動がもたらしたいくつかの動物の特徴を明らかにする- (全4巻、1812年) (フランス語) 2 3 4 軟体動物の歴史と解剖に役立つ覚え書き (1817) (フランス語) キュヴィエによるフランス王立科学アカデミーの会員による歴史的回顧録(全3巻、1819-1827年)第1巻、第2巻、第3巻 地球の理論 (1821) --- 地球の理論に関する試論、1813年、1815年、ロバート・カー訳。ロバート・カー 化石の研究(1821-1823年、全5巻)。 地球表面の回転とそれが動物にもたらした変化に関する考察(1822年)。新版:クリスチャン・ブルジョワ、パリ、1985年(仏文) 1789年から今日までの自然科学の進歩史(全5巻、1826-1836年) 詩の自然史(全11巻、1828-1848年)、アシーユ・ヴァランシエンヌによって続刊された。 Histoire des sciences naturelles from leur originur jusqu'à nos jours, chez tous les peuples connus, professée au Collège de France (5 volumes, 1841-1845), edited, annotated, and published by Magdeleine de Saint-Agit. Cuvier's History of the Natural Sciences: twenty-four lessons from Antiquity to the Renaissance [edited and annotated by Theodore W. Pietsch, translated by Abby. Pietsch 著、Abby S. Simpson 訳。Simpson 著, Philippe Taquet 序文], Paris: Publications scientifiques du Muséum national d'Histoire naturelle, 2012, 734 p.. (coll. Archives; 16). (coll. Archives; 16) ISBN 978-2-85653-684-1 ジョルジュ・キュヴィエの著作のヴァリオラム:古代エジプト人のトキに関する記憶を含むRecherches sur les ossemens fossiles 1812の予稿集と、古代エジプト人がトキと呼んだ鳥の決定を含むDiscours sur les révolutions de la surface du Globe 1825[77] 。 キュヴィエは『自然科学辞典』(全61巻、1816-1845年)、『普遍生物誌』(全45巻、1843-18?) 植物名を引用する際、この人物が著者であることを示すために、標準的な著者略称としてキュヴィエが用いられる[78]。 |

| Saartjie Baartman, the "Hottentot Venus" whose body Cuvier examined Frédéric Cuvier, also a naturalist, was Georges Cuvier's younger brother. History of paleontology for more on the impact of Cuvier's scientific ideas List of works by James Pradier |

キュヴィエが遺体を調査した「ホッテントットのビーナス」、サートジー・バールトマン 同じく博物学者のフレデリック・キュヴィエはジョルジュ・キュヴィエの弟である。 キュヴィエの科学的思想の影響については、古生物学の歴史を参照のこと。 ジェームズ・プラディエの作品リスト |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Georges_Cuvier |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆