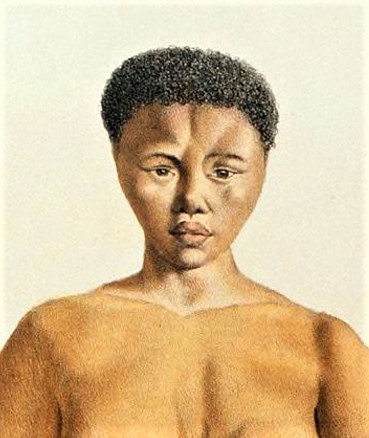

Sarah

Baartman (Afrikaans: [ˈsɑːra ˈbɑːrtman]; c.1789– 29 December 1815),

also spelt Sara, sometimes in the diminutive form Saartje (Afrikaans

pronunciation: [ˈsɑːrtʃi]), or Saartjie, and Bartman, Bartmann, was a

Khoikhoi woman who was exhibited as a freak show attraction in

19th-century Europe under the name Hottentot Venus, a name which was

later attributed to at least one other woman similarly exhibited. The

term "Hottentot" was the colonial-era term for the indigenous Khoekoe

(formerly known as Khoikhoi) people of the southwestern area of Africa.

The women were exhibited for their steatopygic body type uncommon in

Western Europe which not only was perceived as a curiosity at that

time, but became subject of scientific interest, albeit of racist bias

frequently, as well as of erotic projection. However, it has been

suggested by anthropologists that this body type was once more

widespread in humans, based on carvings of idealised female forms

dating to the Paleolithic era collectively known as Venus figurines,

also referred to as Steatopygian Venuses. Sarah

Baartman (Afrikaans: [ˈsɑːra ˈbɑːrtman]; c.1789– 29 December 1815),

also spelt Sara, sometimes in the diminutive form Saartje (Afrikaans

pronunciation: [ˈsɑːrtʃi]), or Saartjie, and Bartman, Bartmann, was a

Khoikhoi woman who was exhibited as a freak show attraction in

19th-century Europe under the name Hottentot Venus, a name which was

later attributed to at least one other woman similarly exhibited. The

term "Hottentot" was the colonial-era term for the indigenous Khoekoe

(formerly known as Khoikhoi) people of the southwestern area of Africa.

The women were exhibited for their steatopygic body type uncommon in

Western Europe which not only was perceived as a curiosity at that

time, but became subject of scientific interest, albeit of racist bias

frequently, as well as of erotic projection. However, it has been

suggested by anthropologists that this body type was once more

widespread in humans, based on carvings of idealised female forms

dating to the Paleolithic era collectively known as Venus figurines,

also referred to as Steatopygian Venuses.

"Venus" is sometimes used to designate representations of the female

body in arts and cultural anthropology, referring to the Roman goddess

of love and fertility. "Hottentot" was the name for the Khoi people,

now usually considered an offensive term. The Sarah Baartman story is

often regarded as the epitome of racist colonial exploitation, and of

the commodification of the dehumanization of black people.[citation

needed]

|

サラ・バートマン(Afrikaans: [ˈra ˁˈbɑ;

c.1789 -

1815年12月29日)※バールトマンとも表記;サラ、時には短縮形のサーティエ(アフリカーンス語の発音:[ˁsɑi])、サーティエ、バートマン、

バートマンとも表記されたコイコイの女性で、19世紀のヨーロッパでホッテントットのヴィーナスと呼ばれ、見世物にされていた。ホッテントット」とは、ア

フリカ南西部の先住民コエコエ(旧名コイコイ)の植民地時代の呼称である。彼女たちは、西ヨーロッパでは珍しいステトピーの体型で展示され、当時は珍しが

られただけでなく、しばしば人種差別的なバイアスがかかるものの、科学的関心の対象となり、またエロティックな投影の対象にもなった。しかし、旧石器時代

の理想的な女性像が彫られたヴィーナスフィギア(Steatopygian

Venuses)とも呼ばれる彫刻から、この体型がかつて人類に広く存在していたことが人類学者によって示唆されている。

「ヴィーナス」は、芸術や文化人類学において、ローマ神話に登場する愛と豊穣の女神を意味し、女性の身体の表現を示すために用いられることがある。

"Hottentot

"はコイ族の名前で、現在では通常、不快な言葉とされている。サラ・バートマンの物語は、人種差別的な植民地搾取、黒人の非人間化の商品化の縮図とみなさ

れることが多い[要出典]。

|

Early life in the Cape Colony

Baartman was born to a Khoekhoe family in the vicinity of the Camdeboo

in what is now the Eastern Cape of South Africa[2][3] (then the Dutch

Cape Colony; a British colony by the time she was an adult). Saartjie

is the diminutive form of Sarah; in Cape Dutch the use of the

diminutive form commonly indicated familiarity, endearment or contempt.

Her birth name is unknown.[4] Her surname has also been spelt Bartman

and Bartmann.[1][2]: 184 Her mother died when she was an infant[5] and

her father was later killed by Bushmen (San people) while driving

cattle.[6]

Baartman spent her childhood and teenage years on Dutch European farms.

She went through puberty rites, and kept the small tortoise shell

necklace, probably given to her by her mother, until her death in

France. In the 1790s, a free black (a designation for individuals of

enslaved descent) trader named Peter Cesars (also recorded as

Caesar[5]) met her and encouraged her to move to Cape Town. Records do

not show whether she was made to leave, went willingly, or was sent by

her family to Cesars. She lived in Cape Town for at least two years

working in households as a washerwoman and a nursemaid, first for Peter

Cesars, then in the house of a Dutch man in Cape Town. She finally

moved to be a wet-nurse in the household of Peter Cesars' brother,

Hendrik Cesars, outside of Cape Town in present day Woodstock.[2][7]

There is evidence that she had two children, though both died as

babies.[2] She had a relationship with a poor Dutch soldier, Hendrik

van Jong, who lived in Hout Bay near Cape Town, but the relationship

ended when his regiment left the Cape.[2]

Hendrik Cesars began to show her at the city hospital in exchange for

cash, where surgeon Alexander Dunlop worked. Dunlop,[8] (sometimes

wrongly cited as William Dunlop[5]), a Scottish military surgeon in the

Cape slave lodge, operated a side business in supplying showmen in

Britain with animal specimens, and suggested she travel to Europe to

make money by exhibiting herself. Baartman refused. Dunlop persisted,

and Baartman said she would not go unless Hendrik Cesars came too. He

also refused, but he finally agreed in 1810 to go to Britain to make

money by putting Baartman on stage. The party left for London in 1810.

It is unknown whether Baartman went willingly or was forced.[2]

Dunlop was the frontman and conspirator behind the plan to exhibit

Baartman. According to a British legal report of 26 November 1810, an

affidavit supplied to the Court of King's Bench from a "Mr. Bullock of

Liverpool Museum" stated: "some months since a Mr. Alexander Dunlop,

who, he believed, was a surgeon in the army, came to him to sell the

skin of a Camelopard, which he had brought from the Cape of Good

Hope.... Some time after, Mr. Dunlop again called on Mr. Bullock, and

told him, that he had then on her way from the Cape, a female

Hottentot, of very singular appearance; that she would make the fortune

of any person who shewed her in London, and that he (Dunlop) was under

an engagement to send her back in two years..."[9] Lord Caledon,

governor of the Cape, gave permission for the trip, but later said

regretted it after he fully learned the purpose of the trip.[10]

|

ケープ植民地での幼少期

バートマンは現在の南アフリカ共和国東ケープ州[2][3](当時はオランダ領ケープ植民地、成人後はイギリス領)のカムデブー近郊でコエホ族の家庭に生

まれた。ケープタッチ語では、親しさ、愛らしさ、軽蔑を表すために小形化することが一般的であった。出生名は不明[4]。姓はバートマン、バートマンとも

表記される[1][2]。 184 幼少時に母親を亡くし[5]、父親はその後、牛の運搬中にブッシュマン(サン族)に殺害された[6]。

バートマンは幼少期から10代をオランダのヨーロッパの農場で過ごす。思春期の儀式を経て、フランスで亡くなるまで、おそらく母親から贈られた小さな亀甲

の首飾りを持ち続けた。1790年代、ピーター・シーザース(シーザー[5]という記録もある)という自由黒人(奴隷の血を引く個人の呼称)の貿易商が彼

女に出会い、ケープタウンに移住するよう勧められる。記録には、彼女が強制的に連れて行かれたのか、自ら進んで行ったのか、それとも家族がシーザーズに送

り届けたのかは記されていない。彼女は少なくとも2年間はケープタウンに住み、最初はピーター・シーザースのもとで、次にケープタウンのオランダ人男性の

家で洗濯婦や保母として働いていた。最終的にはケープタウン郊外の現在のウッドストックにあるピーター・シーザースの弟ヘンドリック・シーザースの家で乳

母として働くようになった[2][7]。 彼女には2人の子供がいたが、いずれも赤ちゃんの時に亡くなっている証拠がある[2]。

ケープタウン近くのハウトベイに住む貧しいオランダ兵ヘンドリック・ファンジョンと関係を持ったが、彼の連隊がケープから離れたため関係は終了している

[2]。

ヘンドリック・セザースは現金と引き換えに彼女を市立病院に案内するようになり、そこには外科医アレクサンダー・ダンロップが勤務していた。ダンロップ

[8](ウィリアム・ダンロップと間違って表記されることもある[5])はケープの奴隷宿のスコットランド人軍医で、イギリスの興行師に動物標本を提供す

るサイドビジネスを行っており、彼女にヨーロッパに行って自分を展示してお金を稼ぐよう勧めた。バートマンはこれを拒否した。ダンロップは粘り強く説得

し、バートマンはヘンドリック・シーザースも来なければ行かない、と言い出した。彼もまた拒否したが、1810年になってようやく、バートマンを舞台にあ

げて金を稼ぐためにイギリスに行くことを承諾した。一行は1810年にロンドンに向けて出発した。バートマンが自ら進んで行ったのか、強制されたのかは不

明である[2]。

ダンロップはバートマン出品計画の表看板であり、共謀者であった。1810年11月26日のイギリスの法律報告によると、「リバプール博物館のブロック

氏」からキングズベンチ裁判所に提出された宣誓供述書には次のように記されている。「数ヶ月前、陸軍の外科医であったと思われるアレキサンダー・ダンロッ

プ氏が、喜望峰から持ち込んだカメレオパールの皮を売りに来た。それからしばらくして、ダンロップ氏は再びブリック氏を呼び、その時、岬から向かっている

途中に、非常に珍しい外見のホッテントットの女性がいること、ロンドンで彼女を見せた者は誰でも幸運になれること、彼(ダンロップ)は彼女を2年後に送り

返す約束になっていることを話した...」[9]

岬の知事のロード・カリドンはこの旅行を許可したが、後に旅行の目的を十分に知って後悔していると語った[10]。

|

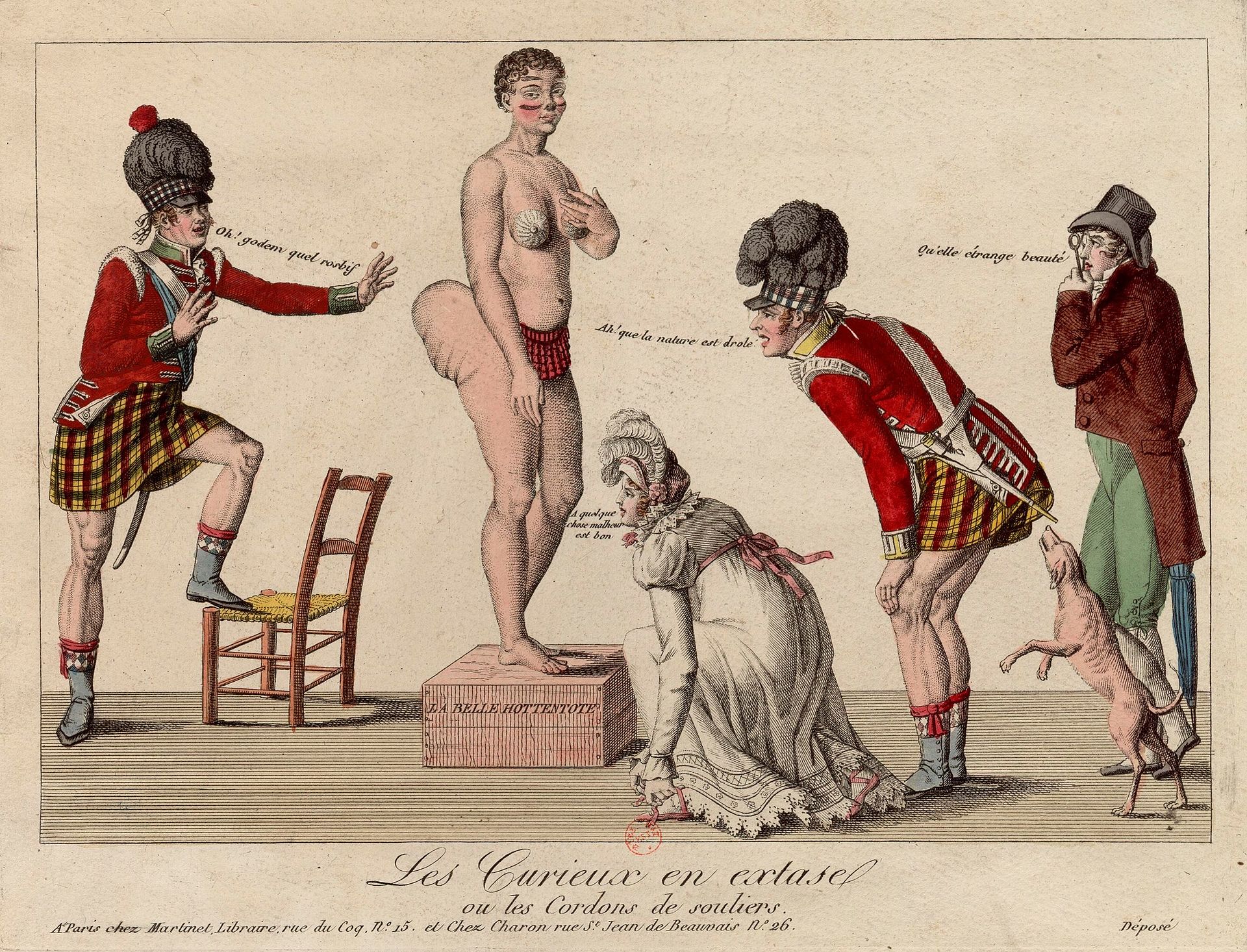

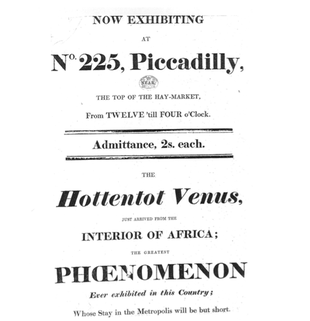

On display in Europe

Hendrik Cesars and Alexander Dunlop brought Baartman to London in

1810.[4] The group lived together in Duke Street, St. James, the most

expensive part of London. In the household were Sarah Baartman, Hendrik

Cesars, Alexander Dunlop, and two African boys, probably brought

illegally by Dunlop from the slave lodge in Cape Town.[2]

Dunlop had to have Baartman exhibited and Cesars was the showman.

Dunlop exhibited Baartman at the Egyptian Room at the London residence

of Thomas Hope at No. 10 Duchess Street, Cavendish Square, London.

Dunlop thought he could make money because of Londoners' lack of

familiarity with Africans and because of Baartman's pejoratively

perceived large buttocks. Crais and Scully say: "People came to see her

because they saw her not as a person but as a pure example of this one

part of the natural world".[2] She became known as the "Hottentot

Venus" (as was at least one other woman, in 1829[11]). A handwritten

note made on an exhibition flyer by someone who saw Baartman in London

in January 1811 indicates curiosity about her origins and probably

reproduced some of the language from the exhibition; thus the following

origin story should be treated with skepticism: "Sartjee is 22 Years

old is 4 feet 10 Inches high, and has (for a Hottentot) a good

capacity. She lived in the occupation of a Cook at the Cape of Good

Hope. Her Country is situated not less than 600 Miles from the Cape,

the Inhabitants of which are rich in Cattle and sell them by barter for

a mere trifle. A Bottle of Brandy, or small roll of Tobacco will

purchase several Sheep – Their principal trade is in Cattle Skins or

Tallow. – Beyond this Nation is an other, of small stature, very subtle

& fierce; the Dutch could not bring them under subjection, and shot

them whenever they found them. 9 Jany, 1811. [H.C.?]"[12] The tradition

of freak shows was well established in Europe at this time, and

historians have argued that this is at first how Baartman was

displayed.[2] Baartman never allowed herself to be exhibited nude,[13]

and an account of her appearance in London in 1810 makes it clear that

she was wearing a garment, albeit a tight-fitting one.[14] She became a

subject of scientific interest, albeit of racist bias frequently, as

well as of erotic projection.[15] She was marketed as the "missing link

between man and beast".[8]

Her exhibition in London just a few years after the passing of the 1807

Slave Trade Act, which abolished the slave trade, created a scandal.

Numerous Britons expressed discontent over a Dutch settler exhibiting

an enslaved woman in the country.[16] A British abolitionist society,

the African Association, conducted a newspaper campaign for her

release. The British abolitionist Zachary Macaulay led the protest,

with Hendrik Cesars protesting in response that Baartman was entitled

to earn her living, stating: "has she not as good a right to exhibit

herself as an Irish Giant or a Dwarf?"[4] Cesars was comparing Baartman

to the contemporary Irish giants Charles Byrne and Patrick Cotter

O'Brien.[17] Macaulay and The African Association took the matter to

court and on 24 November 1810 at the Court of King's Bench the

Attorney-General began the attempt "to give her liberty to say whether

she was exhibited by her own consent." In support he produced two

affidavits in court. The first, from a William Bullock of Liverpool

Museum, was intended to show that Baartman had been brought to Britain

by individuals who referred to her as if she were property. The second,

by the Secretary of the African Association, described the degrading

conditions under which she was exhibited and also gave evidence of

coercion.[14] Baartman was then questioned before an attorney in Dutch,

in which she was fluent, via interpreters.

Historians have subsequently stated doubts on the veracity and

independence of the statement that Baartman then made.[16] She stated

that she in fact was not under restraint, had not been sexually abused

and had come to London on her own free will.[17] She also did not wish

to return to her family and understood perfectly that she was

guaranteed half of the profits. The case was therefore dismissed.[16]

She was questioned for three hours. The statements directly contradict

accounts of her exhibitions made by Zachary Macaulay of the African

Institution and other eyewitnesses.[13] A written contract was

produced,[18] which is considered by some modern commentators to be a

legal subterfuge.[2][4]

The publicity given by the court case increased Baartman's popularity

as an exhibit.[4] She later toured other parts of England and was

exhibited at a fair in Limerick, Ireland in 1812. She also was

exhibited at a fair at Bury St Edmunds in Suffolk.[2] On 1 December

1811 Baartman was baptised at Manchester Cathedral and there is

evidence that she got married on the same day.[19][20]

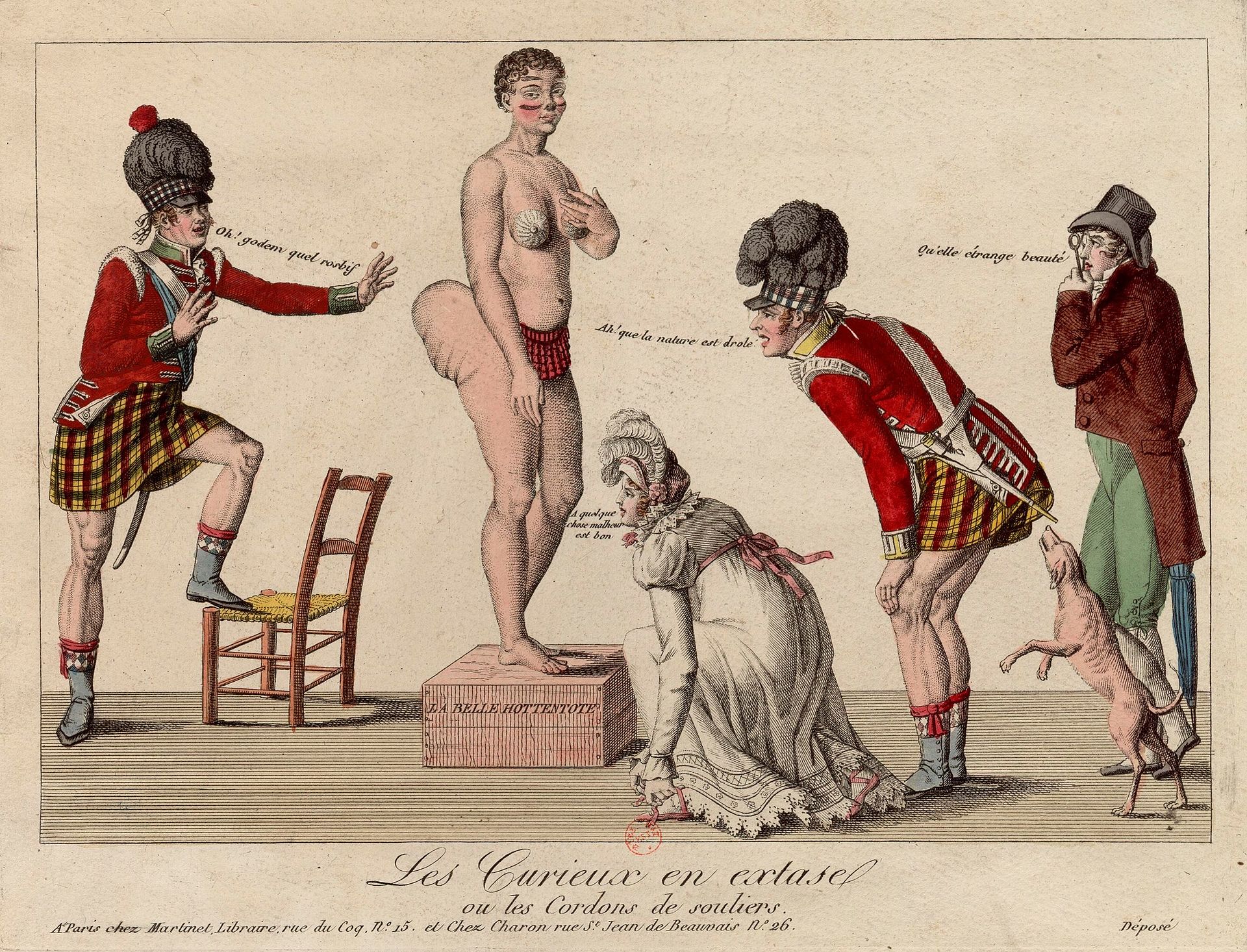

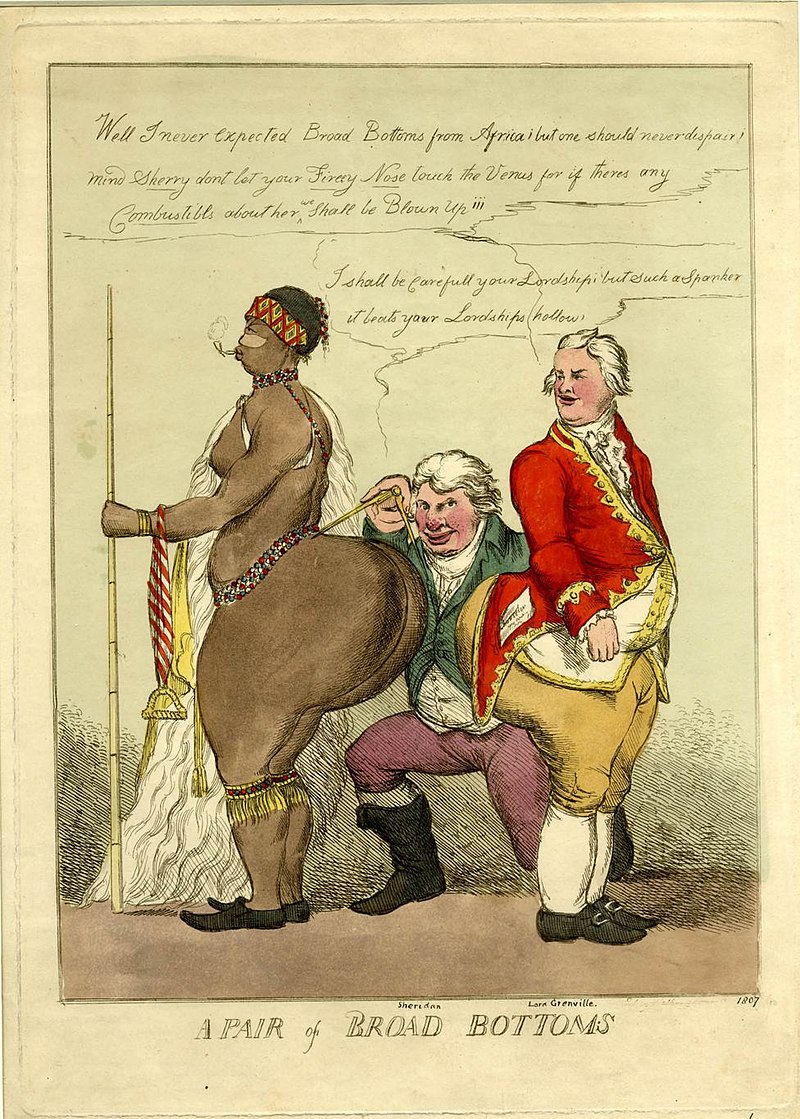

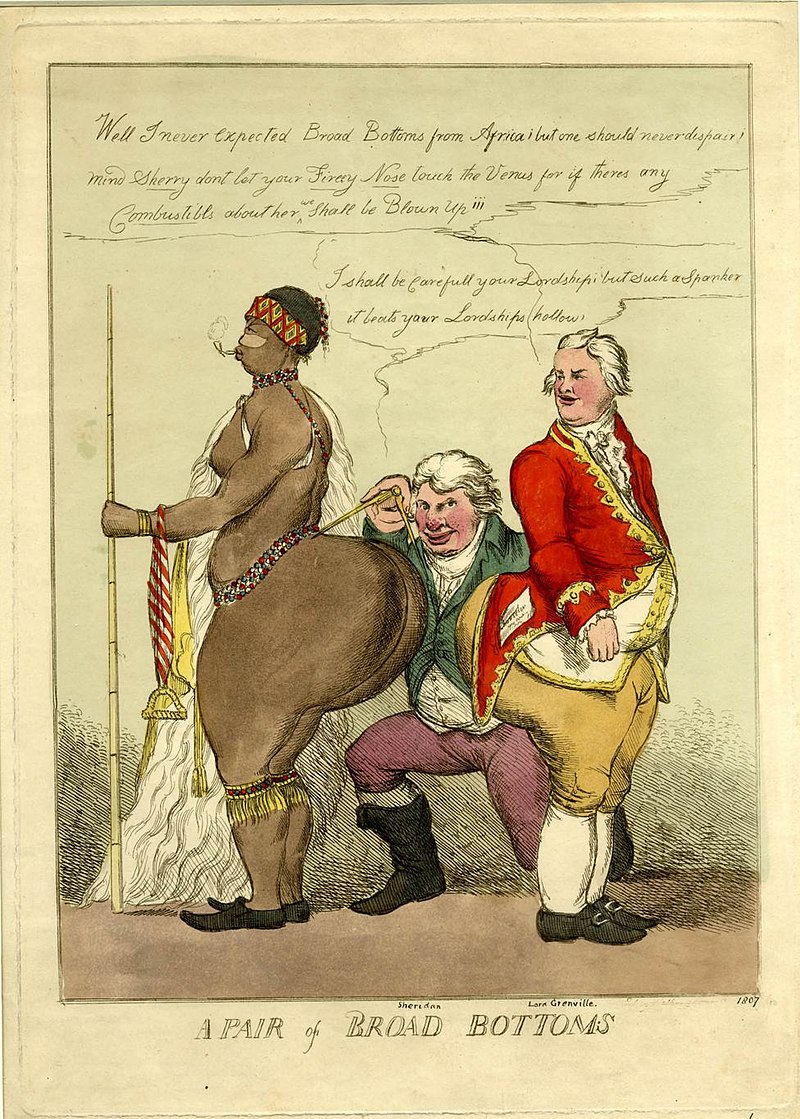

A caricature of Baartman drawn in the early 19th century

|

ヨーロッパでの展示

1810年、ヘンドリック・シーザースとアレクサンダー・ダンロップはバートマンをロンドンに連れてきた[4]。

一行はロンドンで最も高級なセント・ジェームス地区のデューク通りに同居していた。その家にはサラ・バートマン、ヘンドリック・シーザース、アレクサン

ダー・ダンロップ、そしておそらくダンロップがケープタウンの奴隷宿から不法に連れてきたアフリカ人の少年2人が住んでいた[2]。

ダンロップはバートマンを展示する必要があり、シーザースは興行師となった。ダンロップはロンドンのキャベンディッシュ・スクエア、ダッチェス・ストリー

ト10番地のトーマス・ホープの邸宅にあるエジプシャン・ルームでバートマンを展示した。ダンロップは、ロンドン市民がアフリカ人になじみがないことと、

バートマンが侮蔑的に認識されている大きな臀部のために、お金を稼ぐことができると考えたのである。クレイズとスカリーは言う。「彼女は「ホッテントット

のヴィーナス」として知られるようになった(1829年に少なくとももう一人の女性がそうであった[11])。1811年1月にロンドンでバートマンを見

た人が展覧会のチラシに書いた手書きのメモには、彼女の出自についての好奇心が示されており、おそらく展覧会の言葉の一部が再現されている。したがって、

以下の出自の話は懐疑的に扱われるべきである。「Sartjeeは22歳で、身長は4フィート10インチ、(ホッテントットにしては)器量が良い。彼女は

喜望峰で料理人をやっていた。彼女の国は岬から600マイル弱のところにあり、その住民は牛が豊富で、物々交換でほんのわずかな金額で売っている。ブラン

デー1瓶、またはタバコの小巻で、羊数頭を購入することができる。-

この民族の向こうには、小柄で非常に繊細かつ獰猛な別の民族がいる。オランダ人は彼らを服従させることができず、見つけるたびに撃ち殺した。9

Jany, 1811.

[バートマンは裸で展示されることを決して許さなかった[13]。1810年にロンドンに現れた彼女の記録では、ぴったりしたものではあるが衣服を身に着

けていたことが明らかである[14]。 [14]

彼女は、しばしば人種差別的な偏見を持っていたとはいえ、エロティックな投影と同様に科学的な興味の対象となった[15]。

彼女は「人間と獣の間のミッシングリンク」として売り出された[8]。

奴隷貿易を廃止した1807年の奴隷貿易法の成立からわずか数年後にロ

ンドンで行われた彼女の展示はスキャンダルを引き起こした。多くのイギリス人が、オランダ人入植者が国内で奴隷の女性を展示したことに不満を表明した

[16]。

イギリスの奴隷廃止運動団体であるアフリカ協会が、彼女の解放を求める新聞キャンペーンを実施した。イギリスの奴隷廃止論者ザカリー・マコーレーが抗議を

主導し、それに対してヘンドリック・シーザースは、バートマンには生計を立てる権利があると抗議し、次のように述べている[16]。「マコーレーとアフリ

カ協会はこの問題を法廷に持ち込み、1810年11月24日、キングスベンチ法廷で検事総長は「彼女自身の同意によって展示されたのかどうかを語る自由を

与える」試みを開始した[17]。法廷では2つの宣誓供述書が提出された。最初のものはリバプール博物館のウィリアム・ブロックによるもので、バートマン

が彼女を所有物であるかのように言っていた人物によってイギリスに持ち込まれたことを示すためのものであった。その後、バートマンは、通訳を介して、彼女

が堪能であったオランダ語で弁護士の前で尋問を受けることになった[14]。

歴史家はその後、バートマンがその後行った陳述の真実性と独立性に疑念を述べている[16]。

彼女は実際には拘束されておらず、性的虐待も受けておらず、自由意志でロンドンに来たと述べている[17]。また家族の元に戻ることを望まず、利益の半分

を保証されていることを完全に理解していた。そのため、この事件は却下された[16]。彼女は3時間にわたって尋問を受けた。アフリカン・インスティ

テュートのザッカリー・マコーレーや他の目撃者による彼女の展示会の証言と直接的に矛盾する供述をしている[13]。

契約書が作成されたが、これは現代の論者によって法的裏技であると考えられている[18][2][4]。

裁判による宣伝はバートマンの展示品としての人気を高めた[4]。

その後、イングランドの他の地域を巡り、1812年にはアイルランドのリメリックのフェアに展示された。1811年12月1日にはマンチェスター大聖堂で

洗礼を受け、同日に結婚した形跡がある[19][20]。

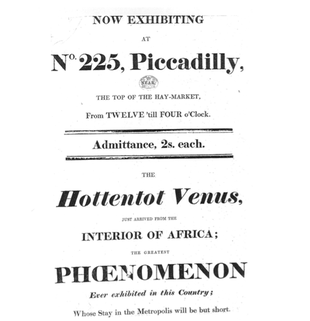

Baartman's exhibition poster in London

|

Later life

A man called Henry Taylor took Baartman to France around September

1814. Taylor then sold her to a man sometimes reported as an animal

trainer, S. Réaux,[21] but whose name was actually Jean Riaux and

belonged to a ballet master who had been deported from the Cape Colony

for seditious behaviour.[5] Riaux exhibited her under more pressured

conditions for 15 months at the Palais Royal in Paris. In France she

was in effect enslaved. In Paris, her exhibition became more clearly

entangled with scientific racism. French scientists were curious about

whether she had the elongated labia which earlier naturalists such as

François Levaillant had purportedly observed in Khoisan at the

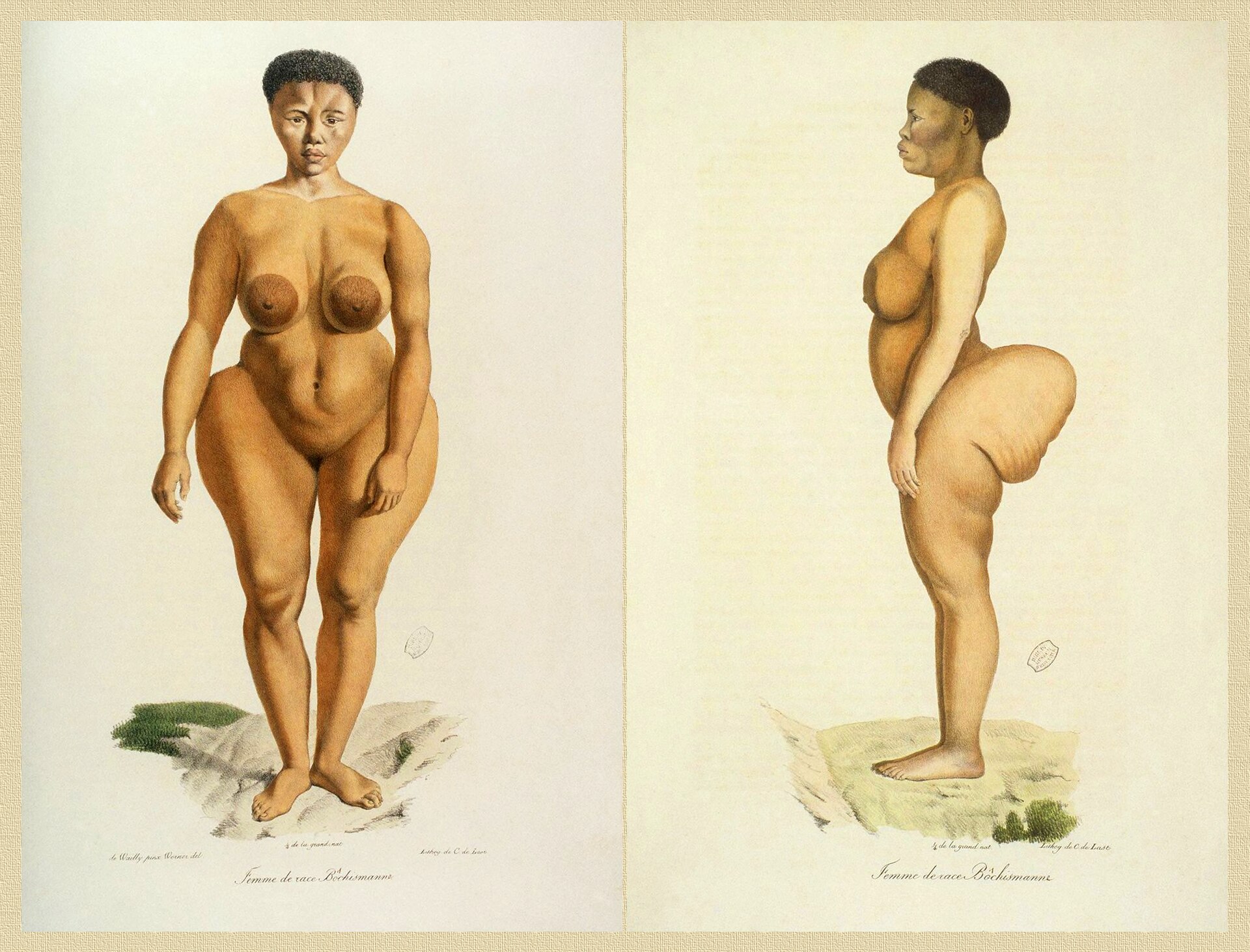

Cape.[21] French naturalists, among them Georges Cuvier, head keeper of

the menagerie at the Muséum national d'Histoire naturelle, and founder

of the discipline of comparative anatomy visited her. She was the

subject of several scientific paintings at the Jardin du Roi, where she

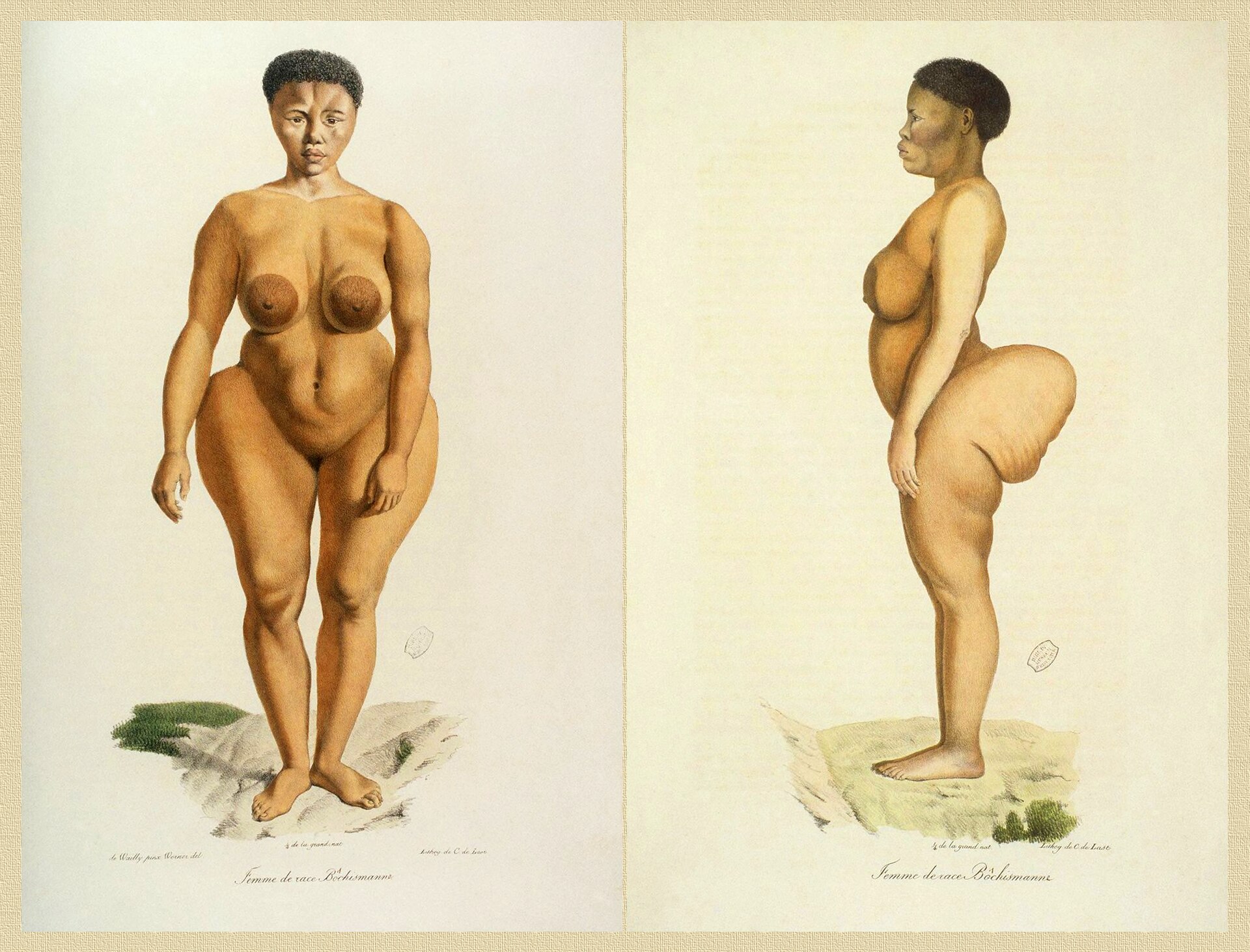

was examined in March 1815: as naturalist Étienne Geoffroy

Saint-Hilaire and Frédéric Cuvier, a younger brother of Georges,

reported: "she was obliging enough to undress and to allow herself to

be painted in the nude". This was not really true: Although by his

standards she appeared to be naked, she wore a small apron-like garment

which concealed her genitalia throughout these sessions, in accordance

with her own cultural norms of modesty.[22] She steadfastly refused to

remove this even when offered money by one of the attending

scientists.[4][2]: 131–134

She was brought out as an exhibit at wealthy people's parties and

private salons.[8] In Paris, Baartman's promoters did not need to

concern themselves with slavery charges. Crais and Scully state: "By

the time she got to Paris, her existence was really quite miserable and

extraordinarily poor. Sara was literally treated like an animal. There

is some evidence to suggest that at one point a collar was placed

around her neck."[2] At the end of her life she was a prostitute, and

penniless.[23][24]

|

その後の人生

1814年9月頃、ヘンリー・テイラーと呼ばれる男がバートマンをフランスに連れて行った。テイラーはその後、動物調教師のS.Réauxと報道されるこ

ともあったが[21]、実際にはJean Riauxといい、扇動的な行動でケープコロニーから追放されたバレエ団の師匠に属していた。

Riauxは15ヶ月間パリのパレ・ロワイヤルでより厳しい条件の下で彼女を展示していた[5]

。フランスでは、彼女は事実上奴隷のようなものであった。パリでは、彼女の展示は、科学的な人種差別とより明確に絡んでいた。フランスの科学者たちは、フ

ランソワ・レヴァイヤンなどの博物学者がケープでコイサンに観察したとされる細長い陰唇が彼女にあるかどうか知りたがった[21]。フランスの博物学者、

中でも国立自然史博物館の動物園長であり比較解剖学の創始者のジョルジュ・キュヴィエは彼女を訪れた。1815年3月、王宮庭園に展示された彼女の絵画

は、自然科学者のエティエンヌ・ジェフロワ・サン・ヒレールとジョルジュの弟であるフレデリック・キュヴィエの報告によるものであった。自然科学者のエチ

エンヌ・ジェフロワ・サン・ヒレールとジョルジュの弟フレデリック・キュヴィエは、「彼女は服を脱ぎ、裸体で描かれることを十分承知していた」と報告して

いる。しかし、これは真実ではない。彼の基準では彼女は裸に見えるが、彼女自身の文化的な慎み深さの規範に従って、セッション中は性器を隠す小さなエプロ

ンのような衣服をしていた[22]。彼女は、出席した科学者の一人がお金を提示しても、これを外すことを頑なに拒否した[4][2]。 131-134

彼女は裕福な人々のパーティーや個人のサロンで展示物として引き出された[8]。パリでは、バートマンのプロモーターは奴隷の罪を気にする必要はなかっ

た。クレイズとスカリーは次のように述べている。「パリに着くまで、彼女の存在は実に惨めで、非常に貧しいものであった。サラは文字通り動物のように扱わ

れていた。ある時、首輪が彼女の首にかけられたことを示唆するいくつかの証拠がある」[2]

生涯の終わりに、彼女は売春婦で、無一文だった[23][24]。

|

Death and aftermath

Baartman died on 29 December 1815 around age 26,[1] of an

undetermined[25] inflammatory ailment, possibly smallpox,[26][27] while

other sources suggest she contracted syphilis,[3] or pneumonia. Cuvier

conducted a dissection but no autopsy to inquire into the reasons for

Baartman's death.[2]

The French anatomist Henri Marie Ducrotay de Blainville published notes

on the dissection in 1816, which were republished by Georges Cuvier in

the Memoires du Museum d'Histoire Naturelle in 1817. Cuvier, who had

met Baartman, notes in his monograph that its subject was an

intelligent woman with an excellent memory, particularly for faces. In

addition to her native tongue, she spoke fluent Dutch, passable

English, and a smattering of French. He describes her shoulders and

back as "graceful", arms "slender", hands and feet as "charming" and

"pretty". He adds she was adept at playing the jew's harp,[28] could

dance according to the traditions of her country, and had a lively

personality.[29] Despite this, Cuvier interpreted her remains, in

accordance with his theories on racial evolution, as evidencing

ape-like traits. He thought her small ears were similar to those of an

orangutan and also compared her vivacity, when alive, to the quickness

of a monkey.[4] He was part of a movement of scientists who were aiming

to codify a hierarchy of races with the white man at the top.[8]

|

死とその余波

1815年12月29日、バートマンは26歳の時に死亡した[1]。原因不明の[25]炎症性疾患、おそらく天然痘[26][27]、他の資料では梅毒、

または肺炎に感染したとされている。キュヴィエはバートマンの死因を調べるために解剖を行ったが、剖検は行わなかった[2]。

フランスの解剖学者アンリ・マリー・デュクロテ・ド・ブランヴィルは1816年に解剖の記録を発表し、ジョルジュ・キュヴィエは1817年に

『Memoires du Museum d'Histoire

Naturelle』に再掲載した。バートマンと面識のあったキュヴィエは、そのモノグラフの中で、解剖対象が知的な女性で、特に顔に関する記憶力に優れ

ていたことを記している。彼女は母国語に加えて、流暢なオランダ語、流暢な英語、そしてフランス語を少し話すことができた。肩と背中は「優美」、腕は

「ほっそり」、手と足は「チャーミング」「かわいい」と書いている。それにもかかわらず、キュヴィエは彼女の遺骨を人種進化論に則って、猿に似た形質を示

すと解釈した[29]。彼は彼女の小さな耳はオランウータンの耳に似ていると考え、また生きている時の活発さを猿の素早さに例えた[4]。

彼は白人を頂点とする人種の階層を成文化しようとする科学者の運動の一員であった[8]。

|

Display of remains

Saint-Hilaire applied on behalf of the Muséum d' Histoire Naturelle to

retain her remains (Cuvier had preserved her brain, genitalia and

skeleton[8]), on the grounds that it was of singular specimen of

humanity and therefore of special scientific interest.[4] The

application was approved and Baartman's skeleton and body cast were

displayed in Muséum d'histoire naturelle d’Angers. Her skull was stolen

in 1827 but returned a few months later. The restored skeleton and

skull continued to arouse the interest of visitors until the remains

were moved to the Musée de l'Homme, when it was founded in 1937, and

continued up until the late 1970s. Her body cast and skeleton stood

side by side and faced away from the viewer which emphasised her

steatopygia (accumulation of fat on the buttocks) while reinforcing

that aspect as the primary interest of her body. The Baartman exhibit

proved popular until it elicited complaints for being a degrading

representation of women. The skeleton was removed in 1974, and the body

cast in 1976.[4]

From the 1940s, there were sporadic calls for the return of her

remains. A poem written in 1978 by South African poet Diana Ferrus,

herself of Khoisan descent, entitled "I've come to take you home",

played a pivotal role in spurring the movement to bring Baartman's

remains back to her birth soil.[3] The case gained world-wide

prominence only after American paleontologist Stephen Jay Gould wrote

The Mismeasure of Man in the 1980s. Mansell Upham, a researcher and

jurist specializing in colonial South African history, also helped spur

the movement to bring Baartman's remains back to South Africa.[2] After

the victory of the African National Congress (ANC) in the 1994 South

African general election, President Nelson Mandela formally requested

that France return the remains. After much legal wrangling and debates

in the French National Assembly, France acceded to the request on 6

March 2002. Her remains were repatriated to her homeland, the Gamtoos

Valley, on 6 May 2002,[30] and they were buried on 9 August 2002 on

Vergaderingskop, a hill in the town of Hankey over 200 years after her

birth.[31]

Baartman became an icon in South Africa as representative of many

aspects of the nation's history. The Saartjie Baartman Centre for Women

and Children,[32] a refuge for survivors of domestic violence, opened

in Cape Town in 1999. South Africa's first offshore environmental

protection vessel, the Sarah Baartman, is also named after her.[33]

On 8 December 2018, the University of Cape Town made the decision to

rename Memorial Hall, at the centre of the campus, to Sarah Baartman

Hall.[34] This follows the earlier removal of "Jameson" from the former

name of the hall.

|

遺骨の展示

サン=ヒレールは自然博物館

に代わり、バートマンの遺骨(キュヴィエは脳、生殖器、骨格を保存していた[8])を、人類で唯一の標本であり、科学的に特別な関心があるとして保存を申

請した[4]。

この申請は認められ、骨格と遺体はアンジェ自然史博物館に展示されることになる。彼女の頭蓋骨は1827年に盗まれたが、数ヵ月後に戻ってきた。復元され

た骨格と頭蓋骨は、1937年に設立された人間博物館に移されるまで、来館者の関心を集め続け、1970年代後半まで展示が続けられた。また、バートマン

の遺体は、遺体と骨格が背中合わせになるように展示され、彼女の脂肪が臀部に蓄積していることを強調し、そのことが彼女の身体への関心事であることを強調

するものであった。バートマンの展示は人気を博したが、女性を卑下する表現であるとの苦情が寄せられた。骨格は1974年に取り除かれ、遺

体は1976年に石膏型取された[4]。

1940年代から、彼女の遺骨の返還を求める声が散見されるようになった。1978年にコイサン族出身の南アフリカの詩人ダイアナ・フェラスが書いた詩

「I've come to take you home」が、バートマンの遺骨を生家に戻す運動に重要な役割を果たした[3]。

この事件が世界的に知られるようになったのは、1980年代にアメリカの古生物学者スティーブン・ジェイ・グールドが「人間の尺度(The

Mismeasure of

Man)」を書いてからであった。1994年の南アフリカ総選挙でアフリカ民族会議(ANC)が勝利すると、ネルソン・マンデラ大統領はフランスに遺骨の

返還を正式に要請した[2]。多くの法的論争とフランス国民議会での議論の後、フランスは2002年3月6日にその要求に応じました。彼女の遺骨は2002年5月6日に彼女の故郷であるガムトゥース・バレーに送還され[30]、

2002年8月9日にハンケイの町の丘、バーガデリングスコップに生後200年以上経ってから埋葬された[31]。(※「フリクワ民族会

議」)

バートマンは、南アフリカの歴史の様々な側面を代表する存在として、南アフリカの象徴となった。1999年、ケープタウンにDV被害者のための避難所

「Saartjie Baartman Centre for Women and

Children」[32]が開設された[33]。南アフリカ初の洋上環境保護船「サラ・バートマン号」も彼女の名前にちなんでいる[33]。

2018年12月8日、ケープタウン大学はキャンパスの中心にあるメモリアルホールをサラ・バートマンホールに改名する決定を下した[34]。

これは、先にホールの旧名から「ジェイムソン」が削除されたことを受けたものである。

|

Symbolism

Sarah Baartman was not the only Khoikhoi to be taken from her homeland.

Her story is sometimes used to illustrate social and political strains,

and through this, some facts have been lost. Dr. Yvette Abrahams,

professor of women and gender studies at the University of the Western

Cape, writes, "we lack academic studies that view Sarah Baartman as

anything other than a symbol. Her story becomes marginalized, as it is

always used to illustrate some other topic." Baartman is used to

represent African discrimination and suffering in the West although

there were many other Khoikhoi people who were taken to Europe.

Historian Neil Parsons writes of two Khoikhoi children 13 and six years

old respectively, who were taken from South Africa and displayed at a

holiday fair in Elberfeld, Prussia, in 1845. Bosjemans, a travelling

show including two Khoikhoi men, women, and a baby, toured Britain,

Ireland, and France from 1846 to 1855. P. T. Barnum's show "Little

People" advertised a 16-year-old Khoikhoi girl named Flora as the

"missing link" and acquired six more Khoikhoi children later.[citation

needed]

Baartman's tale may be better known because she was the first Khoikhoi

taken from her homeland, or because of the extensive exploitation and

examination of her body by scientists such as Georges Cuvier, an

anatomist, and the public as well as the mistreatment she received

during and after her lifetime. She was brought to the West for her

"exaggerated" female form, and the European public developed an

obsession with her reproductive organs. Her body parts were on display

at the Musée de l'Homme for 150 years, sparking awareness and sympathy

in the public eye. Although Baartman was the first Khoikhoi to land in

Europe, much of her story has been lost, and she is defined by her

exploitation in the West.[35]

|

シンボリズム

故郷を追われたコイコイは、サラ・バートマンだけではない。彼女の物語は、社会的、政治的な歪みを説明するために使われることがあり、これを通して、いく

つかの事実が失われてきた。西ケープ大学の女性学・ジェンダー学教授であるイヴェット・アブラハムズ博士は、「サラ・バートマンを象徴以外のものとしてと

らえる学術的な研究が不足している」と書いている。彼女の物語は、常に他のテーマを説明するために使われるため、疎外されてしまうのです」。バートマン

は、西洋におけるアフリカ人の差別と苦しみの象徴として使われているが、ヨーロッパに連れて行かれたコイコイ族は他にもたくさんいた。歴史家のニール・

パーソンズは、1845年にプロイセンのエルバーフェルトで開かれた見本市に、南アフリカから連れて行かれた13歳と6歳のコイコイの子供たちについて書

いている。2人のコイ族の男性、女性、赤ん坊を含む旅芝居「Bosjemans」は、1846年から1855年にかけてイギリス、アイルランド、フランス

を巡業しました。P・T・バーナムのショー「リトル・ピープル」はフローラという16歳のコイコイの少女を「ミッシング・リンク」として宣伝し、その後さ

らに6人のコイコイの子供を獲得した[citation needed]。

バートマンの物語は、彼女が故郷から連れ去られた最初のコイ族であることや、解剖学者ジョルジュ・キュヴィエなどの科学者や一般人による彼女の体の大規模

な搾取と検査、また彼女が生前と生後に受けた虐待のためによく知られているかもしれない。彼女はその「誇張された」女性像のために西洋にもたらされ、ヨー

ロッパの人々は彼女の生殖器官に執着するようになった。彼女の体の一部は150年間、人間博物館に展示され、世間に認識と共感を呼び起こした。バートマン

はヨーロッパに上陸した最初のコイコイ人であったが、彼女の物語の多くは失われ、彼女は西洋での搾取によって定義されている[35]。

|

Her body as a foundation for

scientific racism

Julien-Joseph Virey used Sarah Baartman's published image to validate

racial typologies. In his essay "Dictionnaire des sciences medicales"

(Dictionary of medical sciences), he summarizes the true nature of the

black female within the framework of accepted medical discourse. Virey

focused on identifying her sexual organs as more developed and distinct

in comparison to white female organs. All of his theories regarding

sexual primitivism are influenced and supported by the anatomical

studies and illustrations of Sarah Baartman which were created by

Georges Cuvier.[36]

It has been suggested by anthropologists that this body type was once

more widespread in humans, based on carvings of idealised female forms

dating to the Paleolithic era which are collectively known as Venus

figurines, also referred to as Steatopygian Venuses.[3]

Caricature of Baartman by William Heath (1810).

|

科学的人種差別の基礎となる彼女の身体

ジュリアン=ジョセフ・ヴィレイは、サラ・バートマンの公開された画像を用いて、人種的類型を検証している。彼は『医学辞典』というエッセイの中で、黒人

女性の本質を医学的言説の枠組みの中で要約している。ヴィレは、白人女性の性器に比べ、彼女の性器がより発達し、特徴的であることに注目した。性的原始主

義に関する彼の理論はすべて、ジョルジュ・キュヴィエが作成したサラ・バートマンの解剖学的研究と図版に影響を受け、支持されている[36]。

旧石器時代の理想的な女性の姿の彫刻に基づいて、この体型がかつて人類に広く存在していたことが人類学者によって示唆されており、それらは総称してヴィー

ナスの置物として知られており、ステアトピーのヴィーナスとも呼ばれている[3]。

Image from Volume 2 of Natural History of Mammals (1819).

|

Sexism

From 1814 to 1870, there were at least seven scientific descriptions of

the bodies of black women done in comparative anatomy. Cuvier's

dissection of Baartman helped shape European science. Baartman, along

with several other African women who were dissected, were referred to

as Hottentots, or sometimes Bushwoman. The "savage woman" was seen as

very distinct from the "civilised female" of Europe, thus 19th-century

scientists were fascinated by "the Hottentot Venus". In the 1800s,

people in London were able to pay two shillings apiece to gaze upon her

body. Baartman was considered a freak of nature. For extra pay, one

could even poke her with a stick or finger.

|

性差別

1814年から1870年にかけて、比較解剖学で行われた黒人女性の身体に関する科学的記述は少なくとも7つあった。キュヴィエによるバートマンの解剖

は、ヨーロッパの科学の形成に貢献した。バートマンは、解剖された他の数人のアフリカ人女性とともに、ホッテントット、または時にはブッシュウーマンと呼

ばれた。未開の女性」は、ヨーロッパの「文明化された女性」とは全く異なる存在として捉えられていたため、19世紀の科学者は「ホッテントットのヴィーナ

ス」に魅了されたのである。1800年代には、ロンドンの人々が1人2シリングを支払って彼女の体を眺めることができたという。バートマンは自然界の怪物

と見なされていた。さらにお金を払えば、棒や指で彼女をつつくこともできた。

|

Colonialism

There has been much speculation and study about colonialist influence

that relates to Baartman's name, social status, her illustrated and

performed presentation as the "Hottentot Venus" though considered an

extremely offensive term, and the negotiation for her body's return to

her homeland.[2][4] These components and events in Baartman's life have

been used by activists and theorists to determine the ways in which

19th-century European colonists exercised control and authority over

Khoikhoi people and simultaneously crafted racist and sexist ideologies

about their culture.[16] In addition to this, recent scholars have

begun to analyze the surrounding events leading up to Baartman's return

to her homeland and conclude that it is an expression of recent

contemporary post colonial objectives.[4]

In Janet Shibamoto's book review of Deborah Cameron's book Feminism and

Linguistic Theory, Shibamoto discusses Cameron's study on the

patriarchal context within language, which consequentially influences

the way in which women continue to be contained by or subject to

ideologies created by the patriarchy.[37] Many scholars have presented

information on how Baartman's life was heavily controlled and

manipulated by colonialist and patriarchal language.[2]: 131–134

Baartman grew up on a farm. There is no historical documentation of her

indigenous Khoisan name.[35] She was given the Dutch name "Saartjie" by

Dutch colonists who occupied the land she lived on during her

childhood. According to Clifton Crais and Pamela Scully:

Her first name is the Cape Dutch

form for "Sarah" which marked her as a colonialist's servant. "Saartje"

the diminutive, was also a sign of affection. Encoded in her first name

were the tensions of affection and exploitation. Her surname literally

means "bearded man" in Dutch. It also means uncivilized, uncouth,

barbarous, savage. Saartjie Baartman – the savage servant.[2]: 9

Dutch colonisers also bestowed the term "Hottentot", which is derived

from "hot" and "tot", Dutch approximations of common sounds in the Khoi

language.[38] The Dutch used this word when referencing Khoikhoi people

because of the clicking sounds and staccato pronunciations that

characterise the Khoikhoi language; these components of the Khoikhoi

language were considered strange and "bestial" to Dutch colonisers.[4]

The term was used until the late 20th century, at which point most

people understood its effect as a derogatory term.[39]

Travelogues that circulated in Europe would describe Africa as being

"uncivilised" and lacking regard for religious virtue.[4] Travelogues

and imagery depicting Black women as "sexually primitive" and "savage"

enforced the belief that it was in Africa's best interest to be

colonised by European settlers. Cultural and religious conversion was

considered to be an altruistic act with imperialist undertones;

colonisers believed that they were reforming and correcting Khoisan

culture in the name of the Christian faith and empire.[4] Scholarly

arguments discuss how Baartman's body became a symbolic depiction of

"all African women" as "fierce, savage, naked, and untamable" and

became a crucial role in colonising parts of Africa and shaping

narratives.[40]

During the lengthy negotiation to have Baartman's body returned to her

home country after her death, the assistant curator of the Musée de

l'Homme, Philippe Mennecier, argued against her return, stating: "We

never know what science will be able to tell us in the future. If she

is buried, this chance will be lost ... for us she remains a very

important treasure." According to Sadiah Qureshi, due to the continued

treatment of Baartman's body as a cultural artifact, Philippe

Mennecier's statement is contemporary evidence of the same type of

ideology that surrounded Baartman's body while she was alive in the

18th century.[4]

Sarah Baartman's grave, on a hill overlooking Hankey in the Gamtoos River Valley, Eastern Cape, South Africa

|

植民地主義

バートマンの名前、社会的地位、「ホッテントットのヴィーナス」という極めて不快な言葉でありながらイラストやパフォーマンスで表現したこと、そして彼女

の身体を祖国に返すための交渉に関連する植民地主義の影響については多くの推測や研究がなされてきた[2][4]。

[バートマンの人生におけるこれらの構成要素や出来事は、活動家や理論家によって、19世紀のヨーロッパの植民者がコイコイ族に対して支配と権威を行使

し、同時に彼らの文化について人種差別的、性差別的なイデオロギーを作り上げた方法を決定するために用いられてきた[16]。これに加えて、最近の学者た

ちはバートマンが祖国に戻るまでの周辺の出来事を分析し、それが最近の現代のポスト植民地の目的の表現であると結論付け始めている[4]。

ジャネット柴本はデボラ・キャメロンの著書『フェミニズムと言語理論』の書評の中で、キャメロンの言語内の家父長制的文脈に関する研究を取り上げ、その結

果、女性が家父長制によって作られたイデオロギーに含まれ続ける、あるいは従う方法に影響を与えていると述べている[37]

多くの学者が、バートマンの人生がいかに植民主義者と家父長制的言語によって大きく制御され、操作されていたかを情報として示している[2]: 131-

134

バートマンは農家で育った。彼女の先住民コイサン族の名前に関する歴史的資料はない[35]。

彼女は幼少期に住んでいた土地を占領していたオランダ人入植者によって「サートジィ」というオランダ名を与えられた。クリフトン・クレイスとパメラ・スカ

リーによる。

「彼女のファーストネームは、ケープタッチ語で「サラ」を意味するもの

で、植民地時代の使用人であることを表している。また、「Saartje」という短縮形は、愛情を示すものでもあった。彼女のファーストネームには、愛情

と搾取の緊張関係が内包されている。彼女の苗字は、オランダ語で文字通り「ひげを生やした男」を意味する。また、未開の、野生の、野蛮な、野蛮人という意

味もある。Saartjie Baartman - 野蛮な使用人[2]: 9」

オランダの植民者は「ホッテントット」という言葉も与えた。これは、コイ語の一般的な音をオランダ語で近似した「ホット」と「トット」に由来する

[38]。 [この言葉はコイ語の特徴であるクリック音と澱んだ発音のため、オランダ人がコイ族を指す際に使用された[4]。

ヨーロッパで流布した旅行記はアフリカを「未開」であり宗教的な美徳を無視していると描写していた[4]。黒人女性を「性的に原始的」で「野蛮な」ものと

して描いた旅行記やイメージは、ヨーロッパの入植者によって植民地にされることがアフリカにとって最善の利益であるという確信を強めていた。文化的、宗教

的な転換は、帝国主義的な含みを持つ利他的な行為と考えられていた。植民者はキリスト教の信仰と帝国の名の下にコイサン文化を改革し修正していると信じて

いた[4]。学者たちの議論は、バートマンの身体が「すべてのアフリカ女性」の象徴的描写として「激しく、野蛮で裸で手懐けない」ものになり、アフリカの

一部を植民地にし物語りを形成する重要な役割になっていることを論じている[40]。

バートマンの死後、彼女の遺体を母国に戻すための長い交渉の間、人間博物館の学芸員補佐であるフィリップ・メネシエは彼女の返還に反対し、次のように述べ

た。「科学が将来何を解明してくれるかは分からない。もし彼女が埋もれてしまったら、このチャンスは失われてしまう......私たちにとって、彼女はと

ても重要な宝物であることに変わりはないのです」。サディア・クレシによれば、バートマンの遺体が文化財として扱われ続けていることから、フィリップ・メ

ネシエの発言は、18世紀に生存していたバートマンの遺体を取り巻くのと同じ種類のイデオロギーを現代に伝える証拠である[4]。

南アフリカ、東ケープ州、ガムトゥース川渓谷のハンキーを見下ろす丘にあるサラ・バートマンの墓

|

Traditional iconography of Sarah

Baartman and feminist contemporary art

Many African female diasporic artists have criticised the traditional

iconography of Baartman. According to the studies of contemporary

feminists, traditional iconography and historical illustrations of

Baartman are effective in revealing the ideological representation of

black women in art throughout history. Such studies assess how the

traditional iconography of the black female body was institutionally

and scientifically defined in the 19th century.[36]

Renee Cox, Renée Green, Joyce Scott, Lorna Simpson, Cara Mae Weems and

Deborah Willis are artists who seek to investigate contemporary social

and cultural issues that still surround the African female body. Sander

Gilman, a cultural and literary historian states: "While many groups of

African Blacks were known to Europeans in the 19th century, the

Hottentot remained representative of the essence of the Black,

especially the Black female. Both concepts fulfilled the iconographic

function in the perception and representation of the world."[36] His

article "Black Bodies, White Bodies: Toward an Iconography of Female

Sexuality in the Late Nineteenth Century Art, Medicine and Literature"

traces art historical records of black women in European art, and also

proves that the association of black women with concupiscence within

art history has been illustrated consistently since the beginning of

the Middle Ages.[36]

Lyle Ashton Harris and Renee Valerie Cox worked in collaboration to

produce the photographic piece Hottentot Venus 2000. In this piece,

Harris photographs Victoria Cox who presents herself as Baartman while

wearing large, sculptural, gilded metal breasts and buttocks attached

to her body.[41] According to Deborah Willis, the paraphernalia

attached to Cox's body are markers for the way in which Baartman's

sexual body parts were essential for her constructed role or function

as the "Hottentot Venus". Willis also explains that Cox's side-angle

shot makes reference to the "scientific" traditional propaganda used by

Cuvier and Julian-Joseph Virey, who sourced Baartman's traditional

illustrations and iconography to publish their "scientific"

findings.[41]

Reviewers of Harris and Cox's work have commented that the presence of

"the gaze" in the photograph of Cox presents a critical engagement with

previous traditional imagery of Baartman.[4] bell hooks has elaborated

further on the function of the gaze:

The gaze has been and is a site of resistance for colonized black

people globally. Subordinates in relations of power learn

experientially that there is a critical gaze, one that "looks" to

document, one that is oppositional. In resistance struggle, the power

of the dominated to assert agency by claiming and cultivating

"awareness" politicizes "looking" relations – one learns to look a

certain way in order to resist.[42]

"Permitted" is an installation piece created by Renée Green inspired by

Sarah Baartman. Green created a specific viewing arrangement to

investigate the European perception of the black female body as

"exotic", "bizarre" and "monstrous". Viewers were prompted to step onto

the installed platform which was meant to evoke a stage, where Baartman

may have been exhibited. Green recreates the basic setting of

Baartman's exhibition. At the centre of the platform, which there is a

large image of Baartman, and wooden rulers or slats with an engraved

caption by Francis Galton encouraging viewers to measure Baartman's

buttocks. In the installation there is also a peephole that allows

viewers to see an image of Baartman standing on a crate. According to

Willis, the implication of the peephole, demonstrates how ethnographic

imagery of the black female form in the 19th century functioned as a

form of pornography for Europeans present at Baartmans exhibit.[41]

In her film Reassemblage: From the firelight to the screen, Trinh T.

Minh-ha comments on the ethnocentric bias that the colonisers eye

applies to the naked female form, arguing that this bias causes the

nude female body to be seen as inherently sexually provocative,

promiscuous and pornographic within the context of European or western

culture.[43] Feminist artists are interested in re-representing

Baartman's image, and work to highlight the stereotypes and

ethnocentric bias surrounding the black female body based on art

historical representations and iconography that occurred before, after

and during Baartman's lifetime.[41]

|

サラ・バートマンの伝統的イコノグラフィーとフェミニスト現代美術

多くのアフリカ系女性ディアスポラ人アーティストが、バートマンの伝統的な図像を批判している。現代のフェミニストたちの研究によれば、バートマンの伝統

的な図像や歴史的な図版は、歴史を通じて芸術における黒人女性のイデオロギー的表現を明らかにするのに有効であるという。こうした研究は、黒人女性の身体

の伝統的な図像が19世紀にどのように制度的・科学的に定義されたかを評価するものである[36]。

レニー・コックス、レニー・グリーン、ジョイス・スコット、ローナ・シンプソン、カーラ・メイ・ウィームス、デボラ・ウィリスは、アフリカの女性の身体を

いまだに取り巻く現代の社会的、文化的問題を調査しようとするアーティストたちです[36]。文化・文学史家のサンダー・ギルマン(Sander

Gilman)は次のように述べています。「19世紀にはアフリカの黒人の多くのグループがヨーロッパ人に知られていましたが、ホッテントットは黒人、特

に黒人女性の本質を代表する存在であり続けました。どちらの概念も世界の認識と表現において図像学的な機能を果たしていた」[36]

彼の論文「Black Bodies, White Bodies: Toward an Iconography of Female

Sexuality in the Late 19eenth Century Art, Medicine and

Literature」は、ヨーロッパ美術における黒人女性の美術史的記録を辿り、また美術史の中で黒人女性と禁欲の関連性が中世の初めから一貫して図式

化されていることを証明している[36]。

ライル・アシュトン・ハリスとレニー・ヴァレリー・コックスは共同で写真作品『Hottentot Venus

2000』を制作した。デボラ・ウィリスによれば、コックスの身体に取り付けられた道具類は、バートマンの性的な身体の部分が「ホッテントット・ヴィーナ

ス」としての彼女の構築された役割や機能にとって不可欠であることを示す目印である[41]。またウィリスは、コックスの横からのショットが、キュヴィエ

とジュリアン=ジョセフ・ヴィレイが「科学的」な発見を発表するためにバートマンの伝統的な図版や図像を利用した「科学的」な伝統プロパガンダに言及して

いると説明する[41]。

ハリスとコックスの作品の批評家は、コックスの写真における「まなざし」の存在が、バートマンに関するこれまでの伝統的なイメージとの批判的な関わりを提

示しているとコメントしている[4] ベル・フックスはまなざしの機能に関してさらに詳しく述べている。

まなざしは、世界的に植民地化された黒人の抵抗の場であったし、今もそうである。権力関係にある部下たちは、批判的なまなざし、つまり文書化するために

「見る」まなざし、対立的なまなざしがあることを経験的に学ぶ。抵抗闘争において、支配される側が「意識」を主張し、育てることによって主体性を主張する

力は、「見る」関係を政治化する-人は抵抗するためにある種の見方を学ぶのである[42]。

"Permitted

"はサラ・バートマンに触発されてルネ・グリーンが制作したインスタレーション作品である。グリーンは、黒人の女性の身体が「エキゾチック」、「奇妙」、

「怪物的」であるというヨーロッパ人の知覚を調査するために、特定の鑑賞方法を作り出した。観客は、バートマンが展示されていたと思われる舞台を想起させ

る設置された台に足を踏み入れるよう促されます。グリーンはバートマンの展覧会の基本的なセッティングを再現しています。台の中央にはバートマンの大きな

画像と、フランシス・ゴルトンによるキャプションが刻まれた木の定規やスラットが置かれ、バートマンのお尻を測るように観客に勧めています。また、木箱の

上に立つバートマンの姿を見ることができる覗き穴も設置されている。ウィリスによれば、覗き穴の暗示は、19世紀における黒人の女性の姿の民族誌的イメー

ジが、バートマンの展示会にいたヨーロッパ人にとっていかにポルノの一形態として機能したかを示している[41]。

彼女の映画『Reassemblage: トリン・T・ミンハは、『Reassemblage: From the firelight to the

screen』において、植民地主義者の目が裸の女性の姿に適用するエスノセントリズム的偏見についてコメントし、この偏見によって裸の女性の身体がヨー

ロッパまたは西洋文化の文脈において本質的に性的挑発、乱暴、ポルノとして見られることになると主張している[43]。

[フェミニストのアーティストたちはバートマンのイメージを再表現することに関心を持ち、バートマンの生前、生後、生前に起こった美術史的な表現と図像に

基づき、黒人女性の身体を取り巻くステレオタイプや民族中心的な偏見を強調するために活動している[41]。

|

Media representation and

feminist criticism

In November 2014, Paper Magazine released a cover of Kim Kardashian in

which she was illustrated as balancing a champagne glass on her

extended rear. The cover received much criticism for endorsing "the

exploitation and fetishism of the black female body".[44] The

similarities with the way in which Baartman was represented as the

"Hottentot Venus" during the 19th century have prompted much criticism

and commentary.[45]

According to writer Geneva S. Thomas, anyone that is aware of black

women's history under colonialist influence would consequentially be

aware that Kardashian's photo easily elicits memory regarding the

visual representation of Baartman.[45] The photographer and director of

the photo, Jean-Paul Goude, based the photo on his previous work

"Carolina Beaumont", taken of a nude model in 1976 and published in his

book Jungle Fever.[46]

A People Magazine article in 1979 about his relationship with model

Grace Jones describes Goude in the following statement:

Jean-Paul has been fascinated

with women like Grace since his youth. The son of a French engineer and

an American-born dancer, he grew up in a Paris suburb. From the moment

he saw West Side Story and the Alvin Ailey dance troupe, he found

himself captivated by "ethnic minorities" — black girls, PRs. "I had

jungle fever." He now says, "Blacks are the premise of my work."[47]

Days before the shoot, Goude often worked with his models to find the

best "hyperbolised" position to take his photos. His model and partner,

Grace Jones, would also pose for days prior to finally acquiring the

perfect form. "That's the basis of my entire work," Goude states,

"creating a credible illusion."[46] Similarly, Baartman and other black

female slaves were illustrated and depicted in a specific form to

identify features, which were seen as proof of ideologies regarding

black female primitivism.[36]

The professional background of Goude and the specific posture and

presentation of Kardashian's image in the recreation on the cover of

Paper Magazine has caused feminist critics to comment how the

objectification of the Baartman's body and the ethnographic

representation of her image in 19th-century society presents a

comparable and complementary parallel to how Kardashian is currently

represented in the media.[48]

In response to the November 2014 photograph of Kim Kardashian, Cleuci

de Oliveira published an article on Jezebel titled "Saartjie Baartman:

The Original Bootie Queen", which claims that Baartman was "always an

agent in her own path."[49] Oliveira goes on to assert that Baartman

performed on her own terms and was unwilling to view herself as a tool

for scientific advancement, an object of entertainment, or a pawn of

the state.

Neelika Jayawardane, a literature professor and editor of the website

Africa is a Country,[50] published a response to Oliveira's article.

Jayawardane criticises de Oliveira's work, stating that she "did untold

damage to what the historical record shows about Baartman".[51]

Jayawardane's article is cautious about introducing what she considers

false agency to historical figures such as Baartman.

An article entitled "Body Talk: Feminism, Sexuality and the Body in the

Work of Six African Women Artists", curated by Cameroonian-born Koyo

Kouoh", which mentions Baartman's legacy and its impact on young female

African artists. The work linked to Baartman is meant to reference the

ethnographic exhibits of the 19th century that enslaved Baartman and

displayed her naked body. Artist Valérie Oka's (Untitled, 2015)

rendered a live performance of a black naked woman in a cage with the

door swung open, walking around a sculpture of male genitalia,

repeatedly. Her work was so impactful it led one audience member to

proclaim, "Do we allow this to happen because we are in the white cube,

or are we revolted by it?".[52] Oka's work has been described as 'black

feminist art' where the female body is a site for activism and

expression. The article also mentions other African female icons and

how artists are expressing themselves through performance and

discussion by posing the question "How Does the White Man Represent the

Black Woman?".

Social scientists James McKay and Helen Johnson cited Baartman to fit

newspaper coverage of the African-American tennis players Venus and

Serena Williams within racist trans-historical narratives of

"pornographic eroticism" and "sexual grotesquerie." According to McKay

and Johnson, white male reporters covering the Williams sisters have

fixated upon their on-court fashions and their muscular bodies, while

downplaying their on-court achievements, describing their bodies as

mannish, animalistic, or hyper-sexual, rather than well-developed.

Their victories have been attributed to their supposed natural physical

superiorities, while their defeats have been blamed on their supposed

lack of discipline. This analysis claims that commentary on the size of

Serena's breasts and bottom, in particular, mirrors the spectacle made

of Baartman's body.[53]

|

メディア表現とフェミニズム批判

2014年11月、『ペーパーマガジン』はキム・カーダシアンの表紙を発表し、彼女は伸びた背中でシャンパングラスのバランスを取っているように描かれ

た。この表紙は「黒人女性の身体の搾取とフェティシズム」を是認しているとして多くの批判を受けた[44]。

19世紀にバートマンが「ホッテントットのヴィーナス」として表現された方法との類似性は多くの批判と論評を促した[45]。

作家のジェネーバ・S・トーマスによれば、植民地主義の影響下にある黒人女性の歴史を知っている人なら誰でも、カーダシアンの写真がバートマンの視覚的表

現に関する記憶を容易に引き出すことに結果的に気づくだろう[45]。

この写真の写真家で監督であるジャン=ポール・グードは、1976年にヌードのモデルを撮影し、彼の著書『Jungle

Fever』で発表した前作『Carolina Beaumont』に基づいて写真を制作している[46]。

1979年のピープル誌の記事で、モデルのグレース・ジョーンズとの関係について、グードは次のように記述している。

ジャン=ポールは、若い頃からグレースのような女性に魅了されてきた。フ

ランス人エンジニアとアメリカ生まれのダンサーの息子である彼は、パリ郊外で成長した。ウエストサイドストーリーやアルビン・エイリー舞踊団を見た瞬間か

ら、「少数民族」である黒人女性やPRに心を奪われるようになったのだ。"ジャングル熱

"があったんです。今では「黒人は僕の作品の前提だ」[47]と言っている。

撮影の何日か前に、グードはしばしばモデルと一緒に、彼の写真を撮るのに最も適した「誇張された」位置を探した。彼のモデルでありパートナーであるグレー

ス・ジョーンズも、最終的に完璧なフォームを獲得するために、何日も前からポーズをとっていたそうだ。「それが私の作品全体の基礎である」とグードは述べ

ており、「信頼できる幻想を作り出す」[46]。同様に、バートマンや他の黒人女性奴隷は、黒人女性の原始主義に関する思想の証明と見なされた特徴を識別

するために、特定の形でイラストや絵に描かれた[36]。

グードの専門的な背景とペーパー誌の表紙の再現におけるカーダシアンのイメージの特定の姿勢と提示は、フェミニストの批評家に、バートマンの身体の客観化

と19世紀の社会における彼女のイメージの民族誌的表現が、現在カーダシアンがメディアで表現されている方法といかに比較・補完し合う並列を提示するかを

コメントさせている[48]。

2014年11月のキム・カーダシアンの写真に対して、クレウシ・デ・オリベイラがJezebelで「サーティ・バートマン:オリジナル・ブーティ・ク

イーン」と題する記事を発表し、バートマンが「常に自分の道を進むエージェント」だったと主張している[49]。

オリベイラが続けて、バートマンは自分自身の条件でパフォーマンスを行い、自分自身を科学の発展の道具、娯楽の対象、国家の駒として見ようとしないのであ

る、と主張している。

文学教授でウェブサイト「Africa is a Country」の編集者であるNeelika

Jayawardaneはオリベイラの記事に対する反論を発表している[50]。ジャヤワルダネはデ・オリヴェイラの仕事を批判し、彼女が「バートマンに

ついて歴史的記録が示すものに計り知れないダメージを与えた」と述べている[51]。ジャヤワルダネの記事は、バートマンのような歴史上の人物に彼女が考

える誤った代理性を導入することに慎重である。

Body Talk "と題された記事。カメルーン出身のKoyo Kouohがキュレーションした「Feminism, Sexuality and

the Body in the Work of Six African Women

Artists」で、バートマンの遺産とアフリカの若い女性アーティストへの影響について言及されています。バートマンに関連する作品は、バートマンを奴

隷にし、彼女の裸体を展示した19世紀の民俗学的展示物を参照することを意味しています。アーティストのヴァレリー・オカの作品(Untitled,

2015)は、扉を開けた檻の中で、黒人の裸婦が男性器の彫刻の周りを何度も歩き回るライブパフォーマンスをレンダリングしたものである。彼女の作品は非

常にインパクトがあり、ある観客は「私たちはホワイトキューブにいるからこれを許すのか、それともこれに反乱を起こすのか」と宣言した[52]。

岡の作品は、女性の身体がアクティビズムと表現の場である「ブラックフェミニストアート」として説明されている。この記事は、他のアフリカの女性アイコン

についても言及しており、アーティストたちがパフォーマンスや議論を通じて、「白人はどのように黒人の女性を表現するのか」という問いを投げかけることに

よって、どのように表現しているのかについても触れている。

社会科学者のジェームズ・マッケイとヘレン・ジョンソンは、バートマンを引用して、アフリカ系アメリカ人のテニス選手であるヴィーナスとセリーナ・ウィリ

アムズの新聞報道を、"ポルノ的エロティシズム "と "性的グロテスクさ

"という人種差別を超えた歴史物語の中にはめ込んでいる。マッケイとジョンソンによれば、ウィリアムズ姉妹を取材する白人男性記者たちは、彼女たちのコー

ト上のファッションや筋肉質な肉体に固執する一方で、コート上での成果を軽視し、彼女たちの肉体をよく発達しているというよりも、むしろ男っぽい、動物

的、あるいは超セクシーであると表現してきたのである。また、彼らの勝利は生まれつきの身体的優位に起因し、敗北は鍛錬の欠如に起因するとされてきた。こ

の分析は、特にセリーナの胸と尻の大きさについてのコメントは、バートマンの身体についてなされたスペクタクルを反映していると主張している[53]。

|

Reclaiming the story

In recent years, some black women have found her story to be a source

of empowerment, one that protests the ideals of white mainstream

beauty, as curvaceous bodies are increasingly lauded in popular culture

and mass media.[54]

Paramount Chief Glen Taaibosch, chair of the Gauteng Khoi and San

Council, says that today "we call her our Hottentot Queen" and honour

her.[8]

|

物語を再生する

近年、一部の黒人女性は、大衆文化やマスメディアで曲線美がますます賞賛される中、彼女の物語が白人の主流の美の理想に抗議し、力を与える源であると見な

している[54]。

ハウテン州コイ族・サン族協議会の議長であるパラマウントチーフ、グレン・ターイボッシュは、今日「我々は彼女を我々のホッテントット・クイーンと呼び、

彼女を尊敬している」と述べている[8]。

|

Bibliography

Crais, Clifton & Scully, Pamela (2009). Sara Baartman and the

Hottentot Venus: A Ghost Story and a Biography. Princeton University

Press. ISBN 978-0-691-13580-9.

Gilman, Sander L. (1985). "Black Bodies, White Bodies: Toward an

Iconography of Female Sexuality in Late Nineteenth-Century Art,

Medicine, and Literature". Critical Inquiry. 12 (1): 204–242.

doi:10.1086/448327. JSTOR 1343468. PMID 11616873. S2CID 27830153.

Qureshi, Sadiah (2004). "Displaying Sara Baartman, the 'Hottentot

Venus'" (PDF). History of Science. 42 (2): 233–257.

doi:10.1177/007327530404200204. S2CID 53611448. Archived from the

original (PDF) on 5 January 2012.

Scully, Pamela; Crais, Clifton (2008). "Race and Erasure: Sara Baartman

and Hendrik Cesars in Cape Town and London". Journal of British

Studies. 47 (2): 301–323. doi:10.1086/526552. JSTOR 25482758. S2CID

161966020.

Scully, Pamela (2010). "Peripheral Visions: Heterography and Writing

the Transnational Life of Sara Baartman". In Deacon, Desley; Russell,

Penny; Woollacott, Angela (eds.). Transnational Lives. pp. 27–40.

doi:10.1057/9780230277472_3. ISBN 978-1-349-31578-9.

Willis, Deborah (Ed.) Black Venus 2010: They Called Her 'Hottentot'.

Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press. ISBN 978-1-4399-0205-9.

|

|

|

|

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sarah_Baartman.

|

https://www.deepl.com/ja/translator.

|