人間の遺骨の返還と再埋葬

Repatriation and reburial of human remains

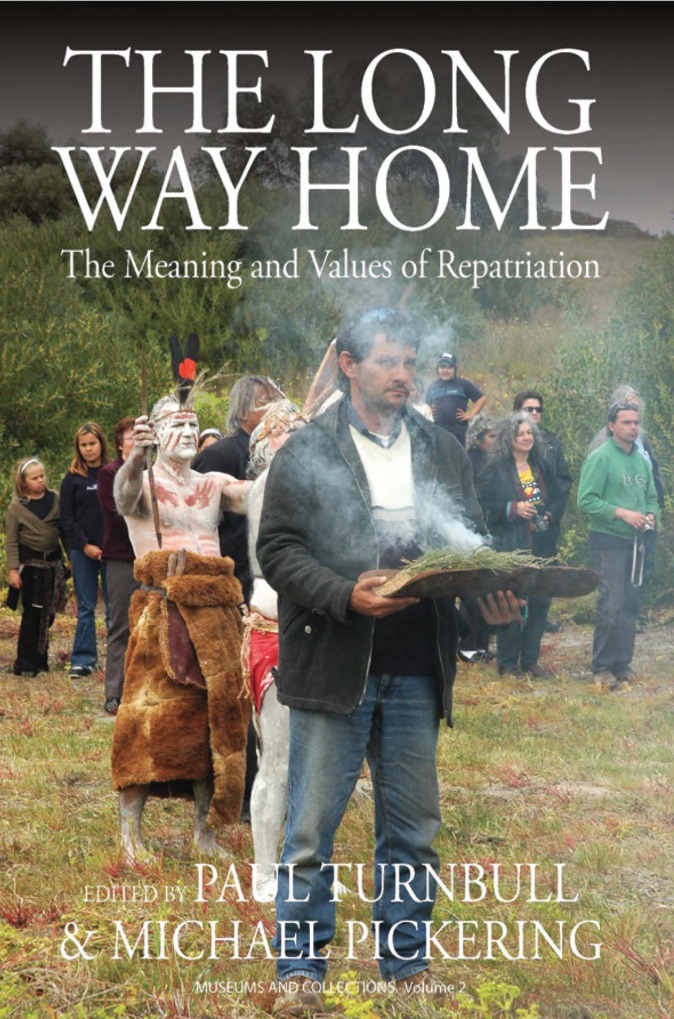

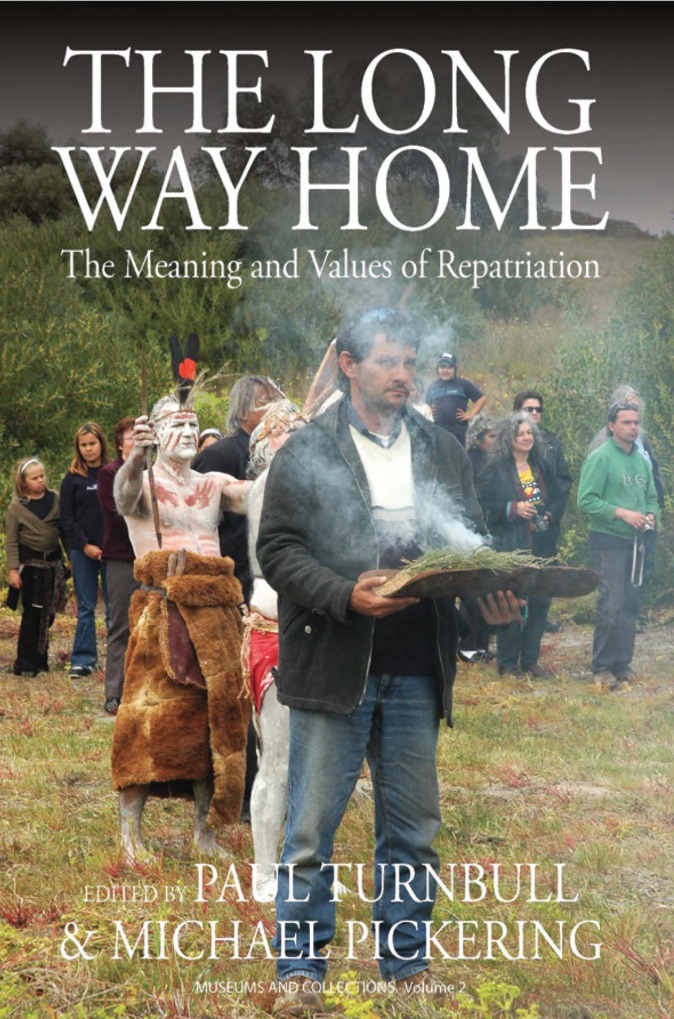

☆ 【この資料の問題点】- Wikipedia 英語からの翻訳;この中の例と見解は、主に英語圏とフランスを扱ったものであり、世界的な見解を示すものではありません。これを改善したり、トークページ で議論したり、あるいは新たに作成することもできます。(2023年1月)★写真は、The long way home : the meanings and values of repatriation / edited by Paul Turnbull and Michael Pickering, Berghahn Books , 2010 . - (Museums and collections)

The

examples and perspective in this deal primarily with the

English-speaking world and France and do not represent a worldwide view

of the subject. You may improve this , discuss the issue on the talk

page, or create a new, as appropriate. (January 2023)

| The repatriation and reburial of human remains is

a current issue in archaeology and museum management on the holding of

human remains. Between the descendant-source community and

anthropologists, there are a variety of opinions on whether or not the

remains should be repatriated. There are numerous case studies across

the globe of human remains that have been or still need to be

repatriated. |

遺骨の返還と改葬は、考古学と博物館管理における遺骨収容の現在の問題である。遺骨を本国へ返還すべきかどうかについては、遺骨収集家や人類学者の間でも様々な意見がある。返還された、あるいは現在も返還が必要な遺骨のケーススタディは世界中に数多くある(→関連ページ「遺骨を使ったDNA研究の倫理」)。 |

| Perspectives The repatriation and reburial of human remains is considered controversial within archaeological ethics.[1] Often, descendants and people from the source community of the remains desire their return.[2][3][4][5] Meanwhile, Anthropologists, scientists who study the remains for research purposes, may have differing opinions. Some anthropologists feel it's necessary to keep the remains in order to improve the field and historical understanding.[6][7] Others feel that repatriation is necessary in order to respect the descendants.[8] Descendant and source community perspective The descendants and source community of the remains commonly advocate for repatriation. This may be due to human rights and spiritual beliefs.[2][3][4] For example, Henry Atkinson of the Yorta Yorta Nation describes the history that motivates this advocacy. He explains that his ancestors were invaded and massacred by the Europeans. After this, their remains were plundered and "collected like one collects stamps."[2] Finally, the ancestors were shipped away as specimen to be studied. This made the Yorta Yorta people feel subhuman—like animals and decorative trinkets. Atkinson explains that repatriation will help to soothe the generational pain that resulted from the massacres and collections.[2] Additionally, there is a repeated theme that descendants have a spiritual connection to their ancestors. Many Indigenous people feel that resting places are sacred and freeing for their ancestors. However, ancestors who are boxed in foreign institutions are trapped and unable to rest. This can cause tremendous distress for their descendants. Some descendants feel that the ancestors can only be free and rest in peace after they are repatriated.[2][3] This is a similar sentiment within Botswana. Connie Rapoo, a Botswana native, explained the importance of ancestors being repatriated. Rapoo explains that people must return to their home for a sense of kinship and belonging.[4] If they're not returned, the ancestors' souls may wander restlessly. They may even transform into evil spirits who haunt the living. They believe repatriation helps to grant peace to both ancestors and descendants.[4] Historical trauma Main article: Historical trauma The argument for repatriation is further complicated by the historical trauma that many Indigenous people experience. Historical trauma refers to the emotional trauma experienced by ancestors that is passed onto generations today. Historically, Indigenous people have experienced massacres and the loss of their children to residential schools. This immense grief is also shared and felt by descendants.[9] Historical trauma is perpetuated by the status of ancestors being boxed away and studied. Some Indigenous people believe that the pain will be alleviated when their ancestors are repatriated and free.[2] Anthropologists' perspective Anthropologists have divided opinions on supporting or rejecting repatriation. Anti-repatriation Some anthropologists feel that repatriation will harm anthropological research and understanding. For example, Elizabeth Weiss and James W. Springer believe that repatriation is the loss of collections, and thereby the "loss of data."[6] This is due to the nature of Western science and epistemology. To improve scientific accuracy, biological anthropologists test new methods and retest old methods on collections. Weiss and Springer describe Indigenous remains as the most abundant and significant resource to the field. They believe that reburial prevents the improvement and legitimacy of anthropological methods.[6] *James W. Springer and Elizabeth Weiss, Repatriation and the Threat to Objective Knowledge, 2021 According to some anthropologists, this in turn prevents many important findings. Studying human remains may reveal information on human pre-history. It helps anthropologists learn how humans evolved and came to be.[7] Additionally, the study of human remains reveals numerous characteristics about ancient populations. It may reveal population's health status, diseases, labor activities, and violence they experienced. Anthropology may identify cultural practices such as the cranial modification. It can also help populations today. Specifically, anthropologists have found signs of early arthritis on ancient remains. They believe this identification is beneficial for the early detection of arthritis in people today.[7] Some anthropologists feel that these discoveries will be lost with the reburial of human remains.[6][7] 6.Weiss, Elizabeth; Springer, James (September 2020). Repatriation and erasing the past. University of Florida Press. pp. 194–210. 7. Landau, Patricia (2000). Mihesuah, Devon (ed.). Repatriation Reader: who owns American Indian remains?. London: University of Nebraska Press. pp. 74–94. 遺骨返還の推進論理 Not all anthropologists are anti-repatriation. Rather, some feel that repatriation is an ethical necessity that the field has been neglecting. Sian Halcrow et al. explains that anthropology has a history of racist double standards.[8] Specifically, White remains within archaeological and disaster cases are reburied in coffins. Meanwhile, Indigenous and non-White remains are infamously boxed and studied. She notes that the unethical sourcing and study of remains without permission is considered a civil rights violation. Halcrow et al. proposes that the repatriation is the bare minimum request to have one's remains treated the same as others.[8] Some anthropologists view repatriation—not as a privilege—but as a human right that had been refused to people of color for too long. They don't view repatriation as the loss or downfall of anthropology. Rather, they feel that repatriation is the start of anthropology moving toward more ethical methods.[8] 8. Halcrow, Siân; Aranui, Amber; Halmhofer, Stephanie; Heppner, Annalisa; Johnson, Norma; Killgrove, Kristina; Schug, Gwen Robbins (26 November 2021). "Moving beyond Weiss and Springer's Repatriation and Erasing the Past: Indigenous values, relationships, and research". International Journal of Cultural Property. 28 (2): 211–220. doi:10.1017/S0940739121000229 |

視点 遺骨の返還や改葬は、考古学の倫理の中でも議論の余地があると考えられている[1]。 多くの場合、遺骨の提供元コミュニティの子孫や人々は、遺骨の返還を望んでいる[2][3][4][5]。 一方、研究目的で遺骨を調査する科学者である人類学者の意見は異なることがある。分野や歴史的理解を深めるために遺骨を保管する必要があると考える人類学 者もいれば[6][7]、子孫を尊重するために返還が必要だと考える人類学者もいる[8]。 子孫とソースコミュニティの視点 遺骨の子孫や提供者コミュニティは、一般的に返還を主張している。例えば、ヨルタヨルタ民族のヘンリー・アトキンソン(Henry Atkinson)は、この擁護の動機となった歴史につ いて述べている[2][3][4]。彼の祖先はヨーロッパ人に侵略され、虐殺された。その後、彼らの遺骨は略奪され、「切手を集めるように収集された」 [2] 。これによってヨルタヨルタ族は、人間以下の動物や装飾品のように感じられるようになった。アトキンソンは、返還は虐殺と収集から生じた世代間の痛みを和 らげるのに役立つと説明する[2]。 さらに、子孫は祖先と精神的なつながりがあるというテーマも繰り返されている。先住民の多くは、先祖にとって安息の地は神聖であり、解放される場所だと感 じている。しかし、外国の施設に閉じ込められた先祖は、閉じ込められ、休むことができない。これは子孫に多大な苦痛を与える。子孫の中には、祖先が自由に なり安らかに眠れるのは、祖先が本国に返還されてからだと感じている人もいる[2][3]。 これはボツワナ国内でも同じような感情である。ボツワナ出身のコニー・ラプーは、祖先が返還されることの重要性を説明した。ラプーは、人々は親族意識と帰 属意識のために故郷に帰らなければならないと説明する[4]。祖先の魂は悪霊となって生者を悩ますことさえある。彼らは、返還は祖先と子孫の両方に平和を 与えるのに役立つと信じている[4](→「ネクロポリティクス」)。 [4]Rapoo, Connie (June 2011). "'Just give us the bones!': theatres of African diasporic returns". Critical Arts. 25 (2): 132–149. doi:10.1080/02560046.2011.569057 歴史的トラウマ(歴史のトラウマ) 主な記事 歴史的トラウマ 返還の議論は、多くの先住民が経験する歴史的トラウマによってさらに複雑になっている。歴史的トラウマとは、祖先が経験した感情的なトラウマが今日の世代 に受け継がれていることを指す。歴史上、先住民族は虐殺を経験し、居住学校で子供たちを失った。この計り知れない悲しみは、子孫も共有し、感じている [9]。歴史的トラウマは、先祖が囲い込まれ、研究されている状態によって永続化されている。先住民の中には、祖先が返還され自由になれば、その痛みは軽 減されると信じている人もいる[2]。 人類学者の視点 返還を支持するか拒否するかについては、人類学者の間でも意見が分かれている。 ☆返還反対派 一部の人類学者は、返還が人類学的研究や理解に害を及ぼすと感じている。例えば、エリザベス・ワイスとジェームズ・W・スプリンガーは、返還はコレクショ ンの喪失であり、それによって「データの喪失」[6]につながると考えている。科学的精度を向上させるために、生物人類学者は新しい方法をテストし、古い 方法をコレクションで再テストする。ワイスとスプリンガーは、先住民の遺骨はこの分野にとって最も豊富で重要な資源であると述べている。彼らは再埋葬が人 類学的手法の改善と正当性を妨げると考えている[6]。 一部の人類学者によると、このことがひいては多くの重要な発見を妨げている。遺骨を研究することで、人類の先史時代に関する情報が明らかになる可能性があ る。人類学者が人類がどのように進化し、どのような存在になったかを知るのに役立つ。[7] さらに、人骨の研究は古代の集団に関する数多くの特徴を明らかにする。人々の健康状態、病気、労働活動、彼らが経験した暴力などが明らかになるかもしれな い。人類学は、頭蓋改造のような文化的慣習を明らかにすることができる。また、人類学は今日の集団にも役立つことがある。具体的には、人類学者は古代の遺 骨から初期の関節炎の兆候を発見している。彼らは、この特定が現代人の関節炎の早期発見に有益であると考えている[7]。 人類学者の中には、こうした発見が遺骨の改葬によって失われるのではないかと感じている者もいる[6][7]。 ★返還賛成派(Pro-Repatriation) すべての人類学者が返還に反対しているわけではない。むしろ、返還は倫理的に必要なことであり、この分野はそれを軽視していると感じている者もいる。シア ン・ハルクロー(Sian Halcrow)らは、人類学には人種差別的なダブルスタンダードの歴史があると説明している[8]。一方、先住民や非白人の遺骨は、悪名高い箱詰めにさ れて研究される。彼女は、許可なく遺骨を調達し研究することは、市民権の侵害であると考えられていると指摘する。ハルクローらは、レパトリエーションは自 分の遺骨を他人と同じように扱ってもらうための最低限の要求であると提唱している[8]。 人類学者の中には、返還を特権としてではなく、あまりにも長い間有色人種に拒否されてきた人権として捉える者もいる。彼らは返還を人類学の損失や没落とは考えていない。むしろ、返還は人類学がより倫理的な方法へと向かうきっかけになると感じている[8]。 |

On

22 October 2017 the Presidio of Monterey hosted tribal nations in a

repatriation and reburial ceremony of Native American remains in the

local cemetery. The remains of 17 Native Americans and over 300

funerary objects discovered between 1910–1985 were laid to rest. On

22 October 2017 the Presidio of Monterey hosted tribal nations in a

repatriation and reburial ceremony of Native American remains in the

local cemetery. The remains of 17 Native Americans and over 300

funerary objects discovered between 1910–1985 were laid to rest. |

2017年10月22日、モントレーのプレシディオは部族国家を主催し、地元の墓地でネイティブ・アメリカンの遺骨の本葬と改葬の儀式を行った。1910年から1985年の間に発見された17人のネイティブ・アメリカンの遺骨と300以上の葬具が安置された。 2017年10月22日、モントレーのプレシディオは部族国家を主催し、地元の墓地でネイティブ・アメリカンの遺骨の本葬と改葬の儀式を行った。1910年から1985年の間に発見された17人のネイティブ・アメリカンの遺骨と300以上の葬具が安置された。 |

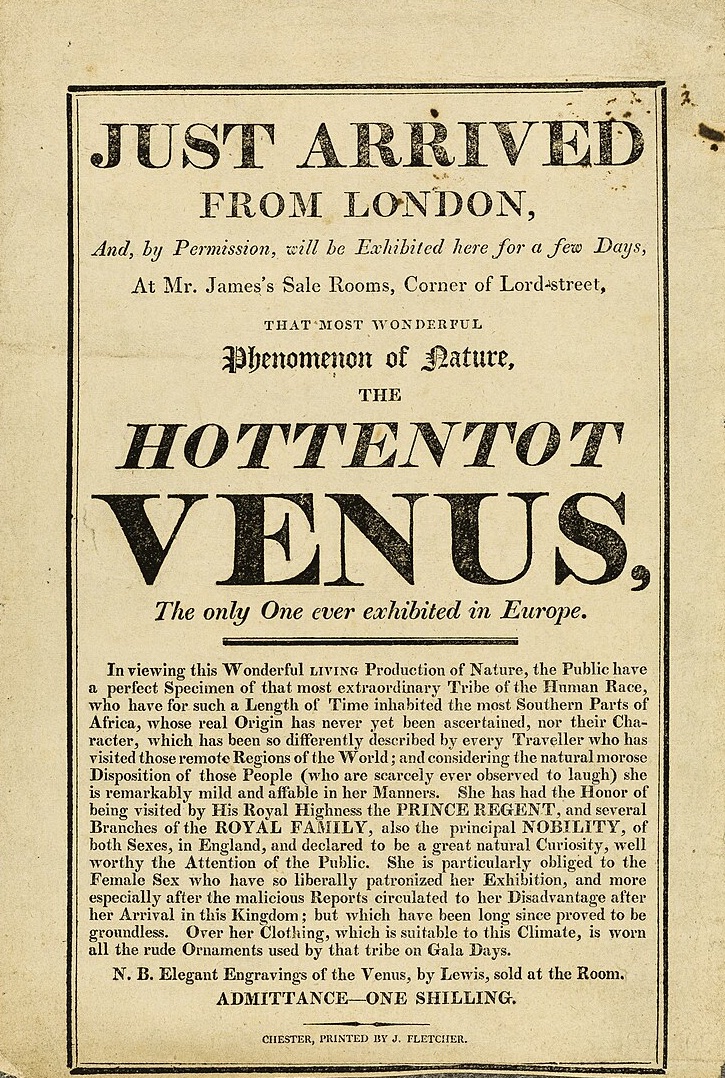

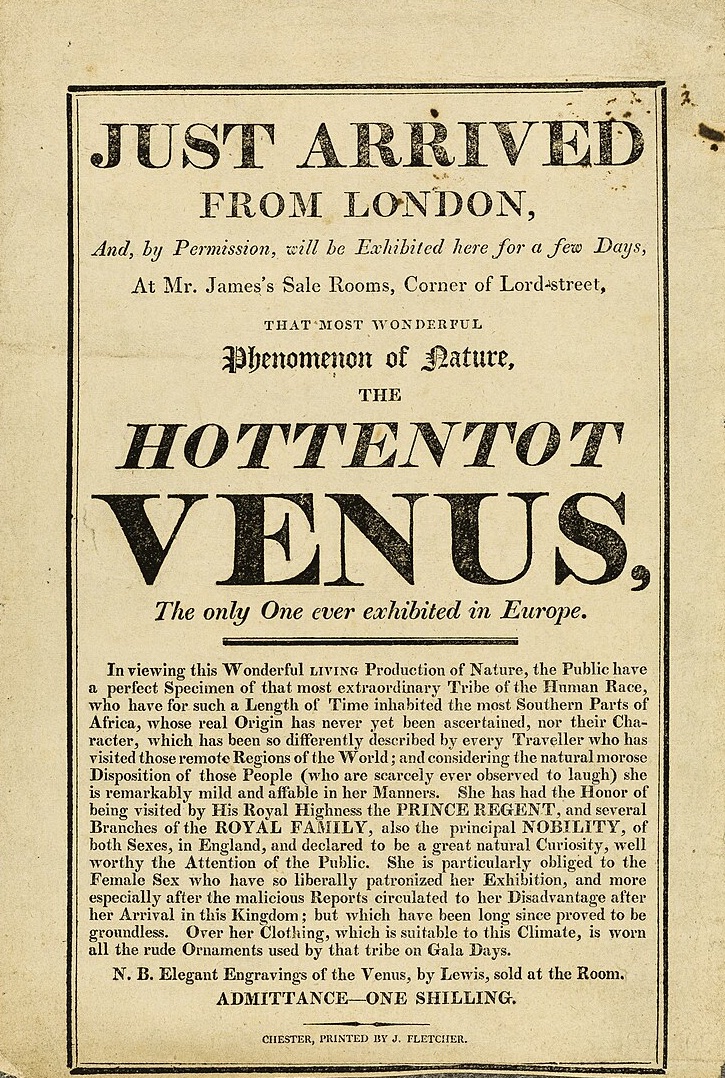

| Health considerations Some of the remains were preserved with pesticides that are now known to be harmful to human health.[10] Case studies Australia Indigenous Australians' remains were removed from graves, burial sites, hospitals, asylums and prisons from the 19th century through to the late 1940s. Most of those which ended up in other countries are in the United Kingdom, with many also in Germany, France and other European countries as well as in the US. Official figures do not reflect the true state of affairs, with many in private collections and small museums. More than 10,000 corpses or part-corpses were probably taken to the UK alone.[11] Australia has no laws directly governing repatriation, but there is a government programme relating to the return of Aboriginal remains, the International Repatriation Program (IRP), administered by the Department of Communications and the Arts. This programme "supports the repatriation of ancestral remains and secret sacred objects to their communities of origin to help promote healing and reconciliation" and assists community representatives work towards repatriation of remains in various ways.[12][11][13] As of April 2019, it was estimated that around 1,500 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander ancestral remains had been returned to Australia in the previous 30 years.[14] The government website showed that over 2,500 ancestral remains had been returned to their community of origin.[12] The Queensland Museum's program of returning and reburying ancestral remains which had been collected by the museum between 1870 and 1970 has been under way since the 1970s.[15] As of November 2018, the museum had the remains of 660 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people stored in their "secret sacred room" on the fifth floor.[16] In March 2019, 37 sets of Australian Aboriginal ancestral remains were set to be returned, after the Natural History Museum in London officially gave back the remains by means of a solemn ceremony. The remains would be looked after by the South Australian Museum and the National Museum of Australia until such time as reburial can take place.[17] In April 2019, work began to return more than 50 ancestral remains from five different German institutes, starting with a ceremony at the Five Continents Museum in Munich.[14] The South Australian Museum reported in April 2019 that it had more than 4,600 Old People in storage, awaiting reburial. Whilst many remains had been shipped overseas by its 1890s director Edward C. Stirling, many more were the result of land clearing, construction projects or members of the public. With a recent change in policy at the museum, a dedicated Repatriation Officer will implement a program of repatriation.[18] In April 2019, the skeletons of 14 Yawuru and Karajarri people which had been sold by a wealthy Broome pastoralist and pearler to a museum in Dresden in 1894 were brought home to Broome, in Western Australia. The remains, which had been stored in the Grassi Museum of Ethnology in Leipzig, showed signs of head wounds and malnutrition, a reflection of the poor conditions endured by Aboriginal people forced to work on the pearling boats in the 19th century. The Yawuru and Karajarri people are still in negotiations with the Natural History Museum in London to enable the release of the skull of the warrior known as Gwarinman.[19] On 1 August 2019, the remains of 11 Kaurna people which had been returned from the UK were laid to rest at a ceremony led by elder Jeffrey Newchurch at Kingston Park Coastal Reserve, south of the city of Adelaide.[20] In March 2020, a documentary titled Returning Our Ancestors was released by the Victorian Aboriginal Heritage Council based on the book Power and the Passion: Our Ancestors Return Home (2010) by Shannon Faulkhead and Uncle Jim Berg,[21] partly narrated by award-winning musician Archie Roach. It was developed primarily as a resource for secondary schools in the state of Victoria, to help develop an understanding of Aboriginal history and culture by explaining the importance of ancestral remains.[22][23] In November 2021, the South Australian Museum apologised to the Kaurna people for having taken their ancestors' remains, and buried 100 of them a new 2 ha (4.9-acre) site at Smithfield Memorial Park, donated by Adelaide Cemeteries. The memorial site is in the shape of the Kaurna shield, to protect the ancestors now buried there.[24] New Zealand Te Papa, the national museum in Wellington was mandated by the government in 2003 to manage the Karanga Aotearoa Repatriation Programme (KARP) to repatriate Māori and Moriori remains (kōiwi tangata). Te Papa researches the provenance of remains and negotiates with overseas institutions for their return. Once returned to New Zealand the remains are not accessioned by Te Papa as the museum arranges their return to their iwi (tribe).[25][26][27] Remains have been repatriated from Argentina, Australia, Austria, Canada, Denmark, France, Germany, Ireland, Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, United States and the United Kingdom.[26][28] Between 2003 and 2015 the return of 355 remains was negotiated by KARP.[26] Heritage New Zealand has a policy on repatriation.[29] In 2018 the Ministry for Culture and Heritage published a report on Human Remains in New Zealand Museums[30] and The New Zealand Repatriation Research Network was established for museums to work together to research the provenance of remains and assist repatriation.[31] Museums Aotearoa adopted a National Repatriation Policy in 2021.[32][33] Canada Main article: Canadian Indian residential school gravesites During the 1800s, Canada established numerous residential schools for Indigenous youth. This was an act of cultural assimilation and genocide where many of the children died and were buried at these schools. In the 21st century, these mass graves are being discovered and repatriated. Two of the most well-known mass graves includes those at the Kamloops Indian Residential School (over 200 Indigenous children buried) and the Saskatchewan Residential School (over 700 Indigenous children buried). Canada is working on searching for and repatriating these graves.[34] France During the French colonization of Algeria, 24 Algerians fought the colonial forces in 1830 and in an 1849 revolt. They were decapitated and their skulls were taken to France as trophies. In 2011, Ali Farid Belkadi, an Algerian historian, discovered the skulls at the Museum of Man in Paris and alerted Algerian authorities that consequently launched the formal repatriation request, the skulls were returned in 2020. Between the remains were those of revolt leader Sheikh Bouzian, who was captured in 1849 by the French, shot and decapitated, and the skull of resistance leader Mohammed Lamjad ben Abdelmalek, also known as Cherif Boubaghla (the man with the mule).[35][36] Germany In 2023 seven German museums and universities returned Māori and Moriori remains to the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa in New Zealand.[37][38] Austria In 2022 the Natural History Museum, Vienna returned the remains of about 64 Māori and Moriori people, collected by Andreas Reischek, to Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa in Wellington, New Zealand.[39][40] Estonia President Konstantin Päts, was imprisoned in the USSR after the Soviet invasion and occupation, where he died in 1956. In 1988, efforts began to locate Päts' remains in Russia. It was discovered that Päts had been granted a formal burial service, fitting of his office, near Kalinin (now Tver). On 22 June 1990, his grave was dug up and the remains were reburied in Tallinn Metsakalmistu cemetery on 21 October 1990.[41][42] In 2011, a commemorative cross was placed in Burashevo village, where Päts was once buried.[43] Ireland The British anthropologist Alfred Cort Haddon removed 13 skulls from a graveyard on Inishmore, and more skulls from Inishbofin, County Galway,[44][45] and a graveyard in Ballinskelligs, County Kerry, as part of the Victorian-era study of "racial types". The skulls are still in storage at Trinity College Dublin and their return to the cemeteries of origin has been requested,[46][44][47] and the board of Trinity College has signalled its willingness to work with islanders to return the remains to the island.[48] On 24 February 2023, Trinity College Dublin confirmed that the human remains, including 13 skulls, in their possession would be returned to Inishbofin.[49] This process is to formally begin in July 2023, with similar repatriation of remains at St. Finian's Bay and Inishmore to be started later in the year.[50] Spain El Negro The name "El Negro" refers to a dead African man who was taxidermized and displayed in the Darder Museum in Banyoles, Spain. His initial grave had been dug up around 1830. He was then taxidermized and dressed up with fur clothing and a spear. "El Negro" was sold to the Darder Museum and on display for over a century. It wasn't until 1992 when Banyoles was hosting the summer Olympics that people complained of the displayed and taxidermized human remains.[5] In 2000, "El Negro" was repatriated to Botswana, which was believed to be his country of origin. Numerous Botswanans had gathered in the airport to greet "El Negro." However, there was controversy in the status and shipment of his remains. First, "El Negro" had arrived in a box, rather than a coffin. Botswanans felt this was dehumanizing. Second, "El Negro" was not returned as the whole body. Rather, only a stripped skull was sent to Botswana. The Spanish had skinned his body, claiming his skin and artifacts to be their property. Numerous Botswanas felt severely disrespected and offended by the objectification of "El Negro."[5][4] United Kingdom The skeleton of the "Irish Giant" Charles Byrne (1761–1783) was on public display in the Hunterian Museum, Glasgow despite it being Byrne's express wish to be buried at sea. Author Hilary Mantel called in 2020 for his remains to be returned to Ireland.[51][52] It was removed from public display as part of redevelopment work in the late 2010s early 2020s although Byrne’s skeleton was retained in the museum collection to allow for future research.[52] Druids The Neo-druidic movement is a modern religion, with some groups originating in the 18th century and others in the 20th century. They are generally inspired by either Victorian-era ideas of the druids of the Iron Age, or later neopagan movements. Some practice ancestor veneration, and because of this may believe that they have a responsibility to care for the ancient dead where they now live. In 2006 Paul Davies requested that the Alexander Keiller Museum in Avebury, Wiltshire rebury their Neolithic human remains, and that storing and displaying them was "immoral and disrespectful".[53] The National Trust refused to allow reburial, but did allow for Neo-druids to perform a healing ritual in the museum.[54][55] The archaeological community has voiced criticism of the Neo-druids, making statements such as "no single modern ethnic group or cult should be allowed to appropriate our ancestors for their own agendas. It is for the international scientific community to curate such remains." An argument proposed by archaeologists is that: "Druids are not the only people who have feelings about human remains... We don't know much about the religious beliefs of these [Prehistoric] people, but know that they wanted to be remembered, their stories, mounds and monuments show this. Their families have long gone, taking all memory with them, and we archaeologists, by bringing them back into the world, are perhaps the nearest they have to kin. We care about them, spending our lives trying to turn their bones back into people... The more we know the better we can remember them. Reburying human remains destroys people and casts them into oblivion: this is at best, misguided, and at worse cruel."[56] Mr. Davies thanked English Heritage for their time and commitment given to the whole process and concluded that the dialogue used within the consultation focussed on museum retention and not reburial as requested.[57]  An ephemera advertising Sarah Baartman as the "Hottentot Venus" for public amusement. Sarah Baartman Main article: Sarah Baartman Sarah Baartman was a Khoikhoi woman from Cape Town, South Africa, in the early 1800s. She was taken to Europe and advertised as a sexual "freak" for entertainment. She was known as the "Hottentot Venus." She died in 1815 and was dissected. Baartman's genitalia, brain, and skeleton were displayed in the Musee de l'Homme in Paris until repatriation to South Africa in 2002.[4] United States Main article: Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act The Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA), passed in 1990, provides a process for museums and federal agencies to return certain cultural items such as human remains, funerary objects, sacred objects, etc. to lineal descendants and culturally affiliated Indian tribes and Native Hawaiian organisations.[58][59][60] Ishi Main article: Ishi Ishi was the last survivor of the Yahi Tribe in the early 1900s. He lived amongst and was studied by anthropologists for the rest of his life. During this time, he would tell stories of his tribe, give archery demonstrations, and be studied on his language. Ishi fell ill and died from tuberculosis in 1916.[61]  Ishi of the Yahi tribe making fire Ishi had explicit wishes to be cremated intact. However, against these wishes, his body underwent an autopsy. His brain was removed and forgotten in a Smithsonian warehouse. Finally, in 2000, Ishi's brain had been found and returned to the Pit River tribe.[61] Kennewick Man Main article: Kennewick Man The Kennewick Man is the name generally given to the skeletal remains of a prehistoric Paleoamerican man found on a bank of the Columbia River in Kennewick, Washington, United States, on 28 July 1996,[62][63] which became the subject of a controversial nine-year court case between the United States Army Corps of Engineers, scientists, the Umatilla people and other Native American tribes who claimed ownership of the remains.[64] The remains of Kennewick Man were finally removed from the Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture on 17 February 2017. The following day, more than 200 members of five Columbia Plateau tribes were present at a burial of the remains.[65] |

健康への配慮 遺体の一部は、現在では人体に有害であることが知られている農薬(殺虫剤)で保存されていた[10]。 ケーススタディ オーストラリア オーストラリア先住民の遺骨は、19世紀から1940年代後半にかけて、墓、埋葬地、病院、精神病院、刑務所から持ち出された。他国に持ち去られた遺骨の 多くは英国にあり、ドイツ、フランス、その他のヨーロッパ諸国、米国にも多数ある。公式の数字は実態を反映しておらず、多くは個人のコレクションや小さな 博物館に収蔵されている。おそらく英国だけでも10,000体以上の死体や死体の一部が持ち去られた[11]。 オーストラリアには本国送還を直接規定する法律はないが、アボリジニの遺骨返還に関連する政府のプログラムとして、通信芸術省が運営する国際本国送還プロ グラム(IRP)がある。このプログラムは、「癒しと和解を促進するために、先祖代々の遺骨や秘蔵の神聖な品々を元のコミュニティへ送還することを支援」 するもので、コミュニティの代表者が様々な方法で遺骨の送還に向けて活動することを支援している[12][11][13]。 2019年4月現在、アボリジニとトレス海峡諸島民の祖先の遺骨は、過去30年間で約1,500体がオーストラリアに返還されたと推定されている [14]。 政府のウェブサイトでは、2,500体以上の祖先の遺骨が出身コミュニティに返還されたことが示されている[12]。 クイーンズランド博物館が1870年から1970年の間に収集した先祖代々の遺骨を返還し、埋葬し直すプログラムは1970年代から行われている [15]。 2018年11月現在、同博物館は5階にある「秘密の神聖な部屋」に660人のアボリジニとトレス海峡諸島民の遺骨を保管している[16]。 2019年3月、ロンドンの自然史博物館が厳粛な儀式によって正式に遺骨を返還した後、37組のオーストラリア・アボリジニの先祖伝来の遺骨が返還される ことが決まった。遺骨は、改葬が可能になるまで、南オーストラリア博物館とオーストラリア国立博物館が管理することになった[17]。 2019年4月、ミュンヘンの五大陸博物館での式典を皮切りに、ドイツの5つの異なる機関から50体以上の先祖の遺骨を返還する作業が始まった[14]。 南オーストラリア博物館は2019年4月、4,600体以上のオールドピープルを保管し、改葬を待っていると報告した。多くの遺骨は1890年代の館長エ ドワード・C・スターリングによって海外に運ばれたものであったが、さらに多くの遺骨が、土地の開墾、建設プロジェクト、または一般市民の手によるもので あった。最近、博物館の方針が変更され、専任のレパトリエーション・オフィサーがレパトリエーション・プログラムを実施することになった[18]。 2019年4月、1894年にブルームの裕福な牧畜民と真珠業者がドレスデンの博物館に売却した14人のヤウルとカラジャリの人々の骸骨が、西オーストラ リア州のブルームに持ち帰られた。ライプチヒのグラッシ民族学博物館に保管されていたその遺骨には、頭部の傷や栄養失調の跡があり、19世紀に真珠採り漁 船で働かされていたアボリジニの劣悪な環境を反映していた。ヤウル族とカラジャリ族は、グワリンマンとして知られる戦士の頭蓋骨を公開できるよう、ロンド ンの自然史博物館と交渉を続けている[19]。 2019年8月1日、英国から返還された11人のカウルナ族の遺骨が、アデレード市の南にあるキングストン・パーク海岸保護区で、長老ジェフリー・ニューチャーチが率いる式典で安置された[20]。 2020年3月、『Returning Our Ancestors』と題されたドキュメンタリーが、『Power and the Passion』という本に基づいてビクトリア州アボリジニ遺産協議会(Victorian Aboriginal Heritage Council)によって公開された: シャノン・フォークヘッドとアンクル・ジム・バーグの著書『Our Ancestors Return Home』(2010年)に基づき、受賞歴のあるミュージシャン、アーチー・ローチがナレーションを担当した[21]。これは主にビクトリア州の中等学校 向けの教材として開発されたもので、祖先の遺骨の重要性を説明することで、アボリジニの歴史と文化に対する理解を深めることを目的としている[22] [23]。 2021年11月、南オーストラリア博物館は、先祖の遺骨を持ち去ったことをカウルナ族に謝罪し、アデレード墓地が寄贈したスミスフィールド・メモリア ル・パークの2ヘクタール(4.9エーカー)の新しい場所に100体の遺骨を埋葬した。記念碑は、現在埋葬されている先祖を守るため、カウルナの盾の形を している[24]。 ニュージーランド ウェリントンにある国立博物館テ・パパは、2003年に政府からマオリとモリオリの遺骨(Kōiwi tangata)を送還するカランガ・アオテアロア・リパトリエーション・プログラム(KARP)の管理を委任された。テ・パパは遺骨の出所を調査し、海 外の機関と遺骨返還の交渉を行っている。ニュージーランドに返還された遺骨は、テパパが収蔵することはなく、博物館がイウィ(部族)への返還を手配する [25][26][27]。アルゼンチン、オーストラリア、オーストリア、カナダ、デンマーク、フランス、ドイツ、アイルランド、オランダ、ノルウェー、 スウェーデン、スイス、アメリカ、イギリスから遺骨が返還されている[26][28]。 ヘリテージ・ニュージーランドは本国送還に関する方針を持っている[29]。2018年、文化遺産省はニュージーランドの博物館における遺骨に関する報告 書を発表し[30]、博物館が協力して遺骨の出所を調査し、本国送還を支援するためにニュージーランド本国送還研究ネットワークが設立された[31]。 ミュージアムズ・アオテアロアは2021年に本国送還方針を採択した[32][33]。 カナダ 主な記事 カナダ・インディアン居住区学校墓地 1800年代、カナダは先住民の青少年のために多数の居住学校を設立した。これは文化的同化と大量虐殺の行為であり、多くの子供たちが死亡し、これらの学 校に埋葬された。21世紀になって、これらの集団墓地が発見され、本国に返還されつつある。最も有名な集団墓地は、カムループス・インディアン・レジデン シャル・スクール(埋葬された先住民の子どもたち200人以上)とサスカチュワン・レジデンシャル・スクール(埋葬された先住民の子どもたち700人以 上)の2つである。カナダはこれらの墓の捜索と送還に取り組んでいる[34]。 フランス フランスのアルジェリア植民地化時代、24人のアルジェリア人が1830年と1849年の反乱で植民地軍と戦った。彼らは首を切られ、頭蓋骨は戦利品とし てフランスに持ち去られた。2011年、アルジェリアの歴史家アリ・ファリド・ベルカディがパリの人間博物館(Musée de l'Homme)で頭蓋骨を発見し、アルジェリア当局に通報し た。遺骨の間には、1849年にフランス軍に捕らえられ、銃で撃たれて首を切られた反乱指導者シェイク・ブジアンのものと、シェリフ・ブバグラ(ラバを連 れた男)としても知られるレジスタンス指導者モハメド・ラムジャド・ベン・アブデルマレクの頭蓋骨があった[35][36]。 ドイツ 2023年、ドイツの7つの博物館と大学がマオリとモリオリの遺骨をニュージーランドのテ・パパ・トンガレワ博物館に返還した[37][38]。 オーストリア 2022年、ウィーンの自然史博物館がアンドレアス・ライシェックが収集したマオリ族とモリオリ族の遺骨約64体をニュージーランドのウェリントンにあるニュージーランド・テ・パパ・トンガレワ博物館に返還した[39][40]。 エストニア コンスタンチン・ペーツ大統領は、ソ連の侵攻と占領の後、ソ連に投獄され、1956年に死去した。1988年、ロシアでペーツの遺骨を探す努力が始まっ た。その結果、ペーツはカリーニン(現トヴェリ)近郊に、彼の事務所にふさわしい正式な埋葬を許可されていたことが判明した。1990年6月22日、彼の 墓が掘り起こされ、遺骨は1990年10月21日にタリン・メツァカルミストゥ墓地に再埋葬された[41][42]。2011年、ペーツがかつて埋葬され たブラシェヴォ村に記念の十字架が設置された[43]。 アイルランド イギリスの人類学者アルフレッド・コート・ハッドンは、ヴィクトリア朝時代の「人種タイプ」の研究の一環として、イニシュモアの墓地から13の頭蓋骨を、 ゴールウェイ州イニシュボフィン[44][45]とケリー州バリンスケリッグスの墓地からさらに多くの頭蓋骨を持ち出した。頭蓋骨は現在もトリニティ・カ レッジ・ダブリンに保管されており、元の墓地への返還が要請されている[46][44][47]。トリニティ・カレッジの理事会は、島民と協力して遺骨を 島に返還する意向を示している[48]。 2023年2月24日、トリニティ・カレッジ・ダブリンは、所有する13体の頭蓋骨を含む遺骨をイニシュボフィンに返還することを確認した[49]。この プロセスは2023年7月に正式に開始され、セント・フィニアンズ・ベイとイニシュモアでも同様の遺骨返還が年内に開始される予定である[50]。 スペイン エル・ネグロ 「エル・ネグロ」とは、剥製にされ、スペインのバニョレスにあるダルデル博物館に展示されていたアフリカ人男性の死体のことである。彼の最初の墓は1830 年頃に掘り起こされた。その後、剥製にされ、毛皮の服と槍で着飾った。「エル・ネグロ」はダルデル博物館に売却され、1世紀以上展示されていた。展示され 剥製にされた人骨に苦情が寄せられたのは、バニョレスで夏季オリンピックが開催された1992年のことだった[5]。 2000年、"エル・ネグロ "は、彼の出身国であると信じられていたボツワナに送還された。多くのボツワナ人が空港に集まり、「エル・ネグロ」を出迎えた。しかし、彼の遺骨の現状と 輸送については論争があった。まず、"エル・ネグロ "は棺ではなく箱に入って到着した。ボツワンの人々は、これは人間性を奪うものだと感じた。第二に、「エル・ニグロ」は遺体ごと返却されなかった。むし ろ、剥ぎ取られた頭蓋骨だけがボツワナに送られた。スペイン人は彼の遺体の皮を剥ぎ、その皮膚と工芸品を自分たちの所有物だと主張したのだ。数多くのボツ ワナ人は、「エル・ニグロ」が客観視されたことで、ひどく軽蔑され、気分を害したと感じた[5][4]。 イギリス アイルランドの巨人」チャールズ・バーン(1761-1783)の骸骨は、バーンが海への埋葬を希望していたにもかかわらず、グラスゴーのハンター博物館 に展示された。作家のヒラリー・マンテルは、2020年に彼の遺骨をアイルランドに返還するよう呼びかけた[51][52]。2010年代後半から 2020年代初頭にかけての再開発工事の一環として公開展示から外されたが、バーン氏の骸骨は将来の研究のために博物館のコレクションとして残された [52]。 ドルイド ネオ・ドルイド運動は現代の宗教であり、18世紀に始まったグループもあれば、20世紀に始まったグループもある。一般的には、鉄器時代のドルイドに対す るヴィクトリア朝時代の思想か、それ以降のネオペイガン運動に触発されている。祖先崇拝を実践している者もおり、そのため、自分たちが今住んでいる場所で 古代の死者をケアする責任があると信じている場合もある。2006年、ポール・デイヴィスはウィルトシャー州エーヴベリーにあるアレクサンダー・キーラー 博物館に対し、新石器時代の人骨を再埋葬するよう要請した。 考古学コミュニティはネオ・ドルイドに対して批判の声を上げており、「現代の単一民族グループやカルトが、自分たちの目的のために先祖を利用することは許されるべきではない。このような遺跡を管理するのは、国際的な科学コミュニティである"。考古学者たちの主張はこうだ: 「ドルイド教徒だけが遺骨に感情を持っているわけではない......。先史時代の)人々の宗教的信条についてはよくわからないが、彼らが記憶されること を望んでいたことは知っている。私たち考古学者は、彼らを再び世に送り出すことで、おそらく彼らに最も近い親族となる。私たちは、彼らの骨を人間に戻すこ とに人生を費やしながら、彼らのことを気にかけている......。知れば知るほど、彼らのことをよりよく思い出すことができる。遺骨を埋葬し直すこと は、人々を破壊し、忘却の彼方へと追いやる。これはよく言っても見当違いであり、悪く言えば残酷である」[56]。 デイヴィス氏は、イングリッシュ・ヘリテージの全プロセスに費やされた時間とコミットメントに感謝し、協議の中で用いられた対話は、博物館の保存に焦点を当てたものであり、要求された埋葬に焦点を当てたものではなかったと結論づけた[57]。  サラ・バートマンを「ホッテントットのヴィーナス」として宣伝し、人々を楽しませたエフェメラ。 サラ・バートマン 主な記事 サラ・バートマン サラ・バートマンは1800年代初頭、南アフリカのケープタウンに住んでいたコイコイの女性である。彼女はヨーロッパに連れて行かれ、娯楽のための性的 「フリーク」として宣伝された。彼女は "ホッテントットのヴィーナス "として知られていた。彼女は1815年に死亡し、解剖された。バートマンの生殖器、脳、骨格は2002年に南アフリカに返還されるまでパリの人間博物館 に展示されていた[4]。 アメリカ 主な記事 アメリカ先住民の墳墓保護と返還に関する法律(NAGPRA) 1990年に成立したアメリカ先住民の墓の保護と本国送還法(NAGPRA)は、博物館や連邦政府機関に対し、遺骨、葬具、聖具などの特定の文化財を直系 子孫や文化的に提携しているインディアンの部族やハワイ先住民の組織に返還する手続きを定めている[58][59][60]。 イシ 主な記事 イシ イシは1900年代初頭のヤヒ族の最後の生き残りである。イシは人類学者たちの間で暮らし、その余生を研究された。この間、彼は自分の部族の話をしたり、 アーチェリーのデモンストレーションをしたり、言語について研究されたりした。イシは病に倒れ、1916年に結核で亡くなった[61]。  火を熾すヤヒ族のイシ イシはそのまま火葬されることを望んでいた。しかし、その希望に反して、彼の遺体は解剖された。脳は摘出され、スミソニアン博物館の倉庫に忘れ去られた。2000年、ついにイシの脳が発見され、ピット・リバー部族(Pit River Tribe)に返還された[61]。 ケネウィック・マン 主な記事 ケネウィック人 ケネウィック・マンまたはエンシェント・ワン[=返還を要求した「ウマティラ・ネイティブ・アメリカン居留区部族連合」の呼称]とは、1996年7月28日にアメリカ合衆国ワシントン州ケネウィックのコロンビア川岸で発見された先史時代の古アメリカ人男性の骸骨に一 般的につけられた名前である[62][63]。この遺骨の所有権を主張するアメリカ合衆国陸軍工兵隊、科学者、ウマティラ族、その他のネイティブ・アメリ カン部族との間で、9年にわたる論争的な裁判の対象となった[64]。 ケネウィックマンの遺骨は2017年2月17日、バーク自然史文化博物館から最終的に搬出された。翌日、コロンビア高原の5部族の200人以上が遺骨の埋葬に立ち会った[65]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Repatriation_and_reburial_of_human_remains |

|

| Kennewick Man or Ancient One[nb

1] was a Paleo-Indian man who lived during the early Holocene, whose

skeletal remains were found washed out on a bank of the Columbia River

in Kennewick, Washington, on July 28, 1996. Radiocarbon tests show the

man lived about 8,400 to 8,690 years Before Present, making his

skeleton one of the most complete ever found this old in the

Americas,[1] and thus of high scientific interest for understanding the

peopling of the Americas.[2][3][nb 2] The discovery precipitated a nearly twenty-year-long dispute. Native American tribes asserted legal rights to rebury the man under the federal Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA), a law that protects Indian remains from disrespectful treatment, such as storage in labs, museums, and private collections.[5] The United States Army Corps of Engineers, which holds jurisdiction over the land where the remains were found, retained legal custody. The science community wished to conduct research on the skeleton and asserted he was only distantly related to today's Native Americans and more closely resembled Polynesian or Southeast Asian peoples, a finding that would exempt the case from NAGPRA. Technology for analyzing ancient DNA had been improving since 1996, and in June 2015, scientists at the University of Copenhagen published a study of Kennewick Man's sequenced genome, which found that Kennewick Man is nested within the diversity of contemporary Native Americans, though he cannot be associated specifically with any particular modern group.[1] In September 2016, the US House and Senate passed legislation to return the remains to a coalition of Columbia basin tribes. Kennewick Man was buried according to Indian traditions on February 18, 2017, with 200 members of five Columbia basin tribes in attendance, at an undisclosed location in the area.[6] Within the scientific community since the 1990s, arguments for a non-Indian ancient history of the Americas, including by ancient peoples from Europe, have been losing ground in the face of ancient DNA analysis.[7] The identification of Kennewick Man as closely related to modern Native Americans symbolically marked the "end of a [supposed] non-Indian ancient North America".[7] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kennewick_Man |

ケネウィック・マンま

たはエンシェント・ワン[nb

1]は完新世初期に生きた古インディアン人で、その骨格は1996年7月28日にワシントン州ケネウィックのコロンビア川岸に流れ着いて発見された。放射

性炭素測定によると、この人物は現在より約8,400年前から8,690年前に生きており、アメリカ大陸でこれほど古い時代に発見されたものとしては最も

完全な骨格のひとつである[1]。 この発見は、20年近くに及ぶ論争を引き起こした。ネイティブ・アメリカンの部族は、連邦法であるアメリカ先住民の墳墓保護と返還に関する法律(NAGPRA) に基づき、インディアンの遺骨を研究所や博物館、個人のコレクションに保管するなどの無礼な扱いから保護する法的権利を主張した[5]。科学界はこの骸骨 の調査を希望し、現在のネイティブ・アメリカンとは遠縁に過ぎず、ポリネシアや東南アジアの人々に近いと主張した。 古代のDNAを分析する技術は1996年以来向上しており、2015年6月にはコペンハーゲン大学の科学者たちがケネウィック・マンのゲノム配列の研究を 発表し、ケネウィック・マンが現代のネイティブ・アメリカンの多様性の中に入れ子状に存在していることを明らかにした。2016年9月、アメリカの上下院 はコロンビア流域の部族連合に遺骨を返還する法案を可決した[1]。ケネウィック・マンは2017年2月18日、コロンビア流域の5部族のメンバー200 人が出席し、その地域の非公開の場所にインディアンの伝統に従って埋葬された。 [6]1990年代以降の科学界では、ヨーロッパからの古代人を含むアメリカ大陸の非インディアン古代史の主張は、古代のDNA分析の前に根拠を失いつつ あった[7]。 ケネウィック・マンが現代のネイティブ・アメリカンに近縁であると特定されたことは、象徴的に「非インディアン古代北米の終焉」を意味した[7]。 |

| Elizabeth Weiss is an American anthropologist. She was a professor of anthropology at San Jose State University. Education In 1996, Weiss received a BA in anthropology from the University of California, Santa Cruz. In 1998, she received a MA in anthropology from California State University, Sacramento. In 2001, she received a PhD from the University of Arkansas in Environmental Dynamics. [1] From 2002 to 2004, Weiss did post-doctoral work at the Canadian Museum of Civilization.[1] Career In 2004, Weiss became a fully tenured professor at San Jose State University.[2] In April 2021, Weiss gave a presentation at the Society for American Archaeology virtual annual meeting titled "Has Creationism Crept Back into Archaeology?" She claimed during the presentation that NAGPRA gives control of scientific research to the religious beliefs of contemporary Native American communities.[3][4] In February 2022, Weiss sued San Jose State officials claiming that they retaliated against her for her views and restricted her from accessing skeletal remains that she was studying.[5][6][7] She is being represented by a lawyer from the Pacific Legal Foundation.[8] In June 2023, Weiss had reached a settlement with San Jose State that allowed her to voluntarily retire with full benefits, effective May 29th, 2024. Due to fears that she may be fired and subsequently lose employment benefits, Weiss accepted a voluntary leave to pursue "more fruitful opportunities".[9][10] She had hoped the lawsuit would pressure the university to reinstate her access to the skeletal remains she had been studying. The judge overseeing the case dismissed her efforts as the Muwekma Ohlone tribe, which the remains belonged to, would have to be involved in the lawsuit. However, due to the tribe's sovereign immunity, it cannot be sued.[11] Personal life Weiss was married to J. Philippe Rushton.[12] She is now married to Nick Pope. Awards and honors In 2019, Weiss received the College of Social Sciences’ Austen D. Warburton Award of Merit for excellence in scholarship.[13][7] Books Reburying the Past: The Effects of Repatriation and Reburial on Scientific Inquiry (Nova Science Publishers, 2008)[14] Bioarchaeological Science: What we have Learned from Human Skeletal Remains (Nova Science Publishers, 2009)[15] Introduction to Human Evolution 2010[16] Paleopathology in Perspective: Bone Health and Disease through Time (Rowman & Littlefield, 2014)[17] Reading the Bones: Activity, Biology, and Culture (University Press of Florida, 2017)[18] with James W. Springer Repatriation and Erasing the Past (University Press of Florida, 2020)[19][20] On the Warpath: My Battles With Indians, Pretendians, and Woke Warriors (Academica Press, 2024)[21] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elizabeth_Weiss |

エリザベス・ワイスはアメリカの人類学者である。サンノゼ州立大学で人類学の教授を務めた。 学歴 1996年、カリフォルニア大学サンタクルーズ校で人類学の学士号を取得。1998年、カリフォルニア州立大学サクラメント校で人類学の修士号を取得。2001年、アーカンソー大学で環境動態学の博士号を取得。[1] 2002年から2004年まで、カナダ文明博物館でポスドクを務めた[1]。 キャリア 2004年、ワイスはサンノゼ州立大学の終身教授となった[2]。 2021年4月、ワイスはアメリカ考古学協会(Society for American Archaeology)の仮想年次総会で 「Has Creationism Crept Back into Archaeology? 」と題する発表を行った。彼女はプレゼンテーションの中で、NAGPRAは現代のネイティブアメリカンのコミュニティの宗教的信念に科学的研究の支配権を 与えると主張した[3][4]。 2022年2月、ワイスはサンノゼ州立大学の職員が彼女の見解に対して報復を行い、彼女が研究していた骨格標本へのアクセスを制限したと主張し、サンノゼ州立大学を訴えた[5][6][7]。 2023年6月、ワイスはサンノゼ州立大学と和解を成立させ、2024年5月29日付で完全な給付金を得て自主退職することを認めた。解雇され、その後雇 用手当を失うかもしれないという懸念から、ワイスは「より実りある機会」を追求するために自主退職を受け入れた[9][10]。彼女は訴訟によって、研究 していた骨格標本へのアクセスを回復するよう大学に圧力をかけることを望んでいた。訴訟を監督する判事は、遺骨が属するムウェクマ・オローン部族が訴訟に 関与しなければならないとして、彼女の努力を退けた。しかし、同部族は主権免責のため、訴えられることはない[11]。 私生活 ワイスはJ・フィリップ・ラシュトンと結婚していた[12]。現在はニック・ポープと結婚している。 受賞歴 2019年、ワイスは優秀な学者に贈られる社会科学大学のオースティン・D・ウォーバートン功労賞を受賞した[13][7]。 著書 Reburying the Past: The Effects of Repatriation and Reburial on Scientific Inquiry』(ノヴァ・サイエンス・パブリッシャーズ、2008年)[14]。 Bioarchaeological Science: What we have Learned from Human Skeletal Remains』(ノヴァ・サイエンス・パブリッシャーズ、2009年)[15]。 人類進化入門 2010[16] Paleopathology in Perspective: Bone Health and Disease through Time (Rowman & Littlefield, 2014)[17] 骨の健康と病気(ローマン&リトルフィールド、2014年 骨を読む: 活動、生物学、文化(フロリダ大学出版、2017年)[18]。 with James W. Springer Repatriation and Erasing the Past(フロリダ大学出版、2020年)[19][20]。 On the Warpath: My Battles With Indians, Pretendians, and Woke Warriors』(アカデミカ出版、2024年)[21]。 |

| Tribal's Sovereign immunity A sovereign state is one that is independent from all other authority, retaining the right and power to regulate its internal affairs without foreign interference. Sovereign immunity is the doctrine that precludes the assertion of a claim against a sovereign without the sovereign's consent. Indian tribes are sovereign entities. The exact nature of tribal sovereignty, however, is not clear. One theory holds that tribal sovereign status is inherent. Tribal sovereignty is not granted to tribes by the United States but rather reserved as inherent in their status as governments predating the formation of the United States. The fact that the colonizing nations and, subsequently, the U.S. government entered into treaties with tribes supports this view. |

部族主権免責 主権国家とは、他のあらゆる権力から独立し、外国の干渉を受けずに内政を規制する権利と権力を保持する国家である。主権免責とは、主権者の同意がない限り、主権者に対する請求の主張を排除する法理である。 インディアンの部族は主権主体である。しかし、部族主権の正確な性質は明確ではない。一説によると、部族の主権は固有のものである。部族の主権は、合衆国 が部族に与えたものではなく、むしろ合衆国成立以前の政府としての地位に固有のものとして留保されている。植民地化した国々、そしてその後アメリカ政府が 部族と条約を結んだという事実は、この説を支持するものである。 |

| The long way home : the meanings and values of repatriation / edited by Paul Turnbull and Michael Pickering, Berghahn Books , 2010 . - (Museums and collections) |

|

| Indigenous peoples have long

sought the return of ancestral human remains and associated artifacts

from western museums and scientific institutions. Since the late 1970s

their efforts have led museum curators and researchers to re-evaluate

their practices and policies in respect to the scientific uses of human

remains. New partnerships have been established between cultural and

scientific institutions and indigenous communities. Human remains and

culturally significant objects have been returned to the care of

indigenous communities, although the fate of bones and burial artifacts

in numerous collections remains unresolved and, in some instances, the

subject of controversy. In this book, leading researchers from a wide

range of disciplines in the humanities and social sciences reflect

critically on the historical, cultural, ethical and scientific

dimensions of repatriation. Through various case studies they consider

the impact of repatriation: what have been the benefits, and in what

ways has repatriation given rise to new problems for indigenous people,

scientists and museum personnel. It features chapters by indigenous

knowledge custodians, who reflect upon recent debates and interaction

between indigenous people and researchers in disciplines with direct

interests in the continued scientific preservation of human remains. In

this book, leading researchers from a wide range of disciplines in the

humanities and social sciences reflect critically on the historical,

cultural, ethical and scientific dimensions of repatriation. Through

various case studies they consider the impact of repatriation: what

have been the benefits, and in what ways has repatriation given rise to

new problems for indigenous people, scientists and museum personnel. It

features chapters by indigenous knowledge custodians, who reflect upon

recent debates and interaction between indigenous people and

researchers in disciplines with direct interests in the continued

scientific preservation of human remains. |

先住民族は長い間、西洋の博物館や科学機関から先祖伝来の人骨や関連遺

物を返還するよう求めてきた。1970年代後半以降、彼らの努力により、博物館の学芸員や研究者は、遺骨の科学的利用に関して、その慣行や方針を再評価す

るようになった。文化・科学機関と先住民コミュニティとの間に新たなパートナーシップが築かれた。遺骨や文化的に重要な遺物は、先住民のコミュニティに返

還されたが、多くのコレクションにある遺骨や埋葬品の運命は未解決のままであり、場合によっては論争の的となっている。本書では、人文・社会科学の幅広い

分野の第一線の研究者たちが、本国送還の歴史的、文化的、倫理的、科学的側面について批判的に考察している。様々なケーススタディを通して、本国送還が先

住民や科学者、博物館職員にどのような利益をもたらし、どのような形で新たな問題を引き起こしているのか、その影響を考察している。本書では、先住民の知

識保持者たちによる章を設け、遺骨の継続的な科学的保存に直接的な関心を持つ専門分野の研究者と先住民との間の最近の議論や交流について考察している。本

書では、人文・社会科学の幅広い分野の第一線の研究者が、本国送還の歴史的、文化的、倫理的、科学的側面について批判的に考察している。様々なケーススタ

ディを通して、本国送還が先住民、科学者、博物館職員にどのような影響を与えたか、どのような利益をもたらしたか、どのような形で新たな問題を引き起こし

たかを考察している。本書では、先住民の知識保持者たちによる章を設け、遺骨の継続的な科学的保存に直接的な関心を持つ専門分野の研究者と先住民との間の

最近の議論や交流について考察している。 |

| Acknowledgements Introduction Paul Turnbull PART I: ANCESTORS, NOT SPECIMENS Chapter 1. The Meanings and Values of Repatriation Henry Atkinson Chapter 2. Repatriating Our Ancestors: Who Will Speak for the Dead? Franchesca Cubillo PART II: REPATRIATION IN LAW AND POLICY Chapter 3. Museums, Ethics and Human Remains in England: Recent Developments and Implications for the Future Liz Bell Chapter 4. Legal Impediments to the Repatriation of Cultural Objects to Indigenous Peoples Kathryn Whitby-Last Chapter 5. Parks Canada's Policies that Guide the Repatriation of Human Remains and Objects Virginia Myles PART III: THE ETHICS AND CULTURAL IMPLICATIONS OF REPATRIATION Chapter 6. What Might an Anthropology of Cultural Property Look Like? Martin Skrydstrup Chapter 7. Repatriation and the Concept of Inalienable Possession Elizabeth Burns Coleman Chapter 8. Consigned to Oblivion: People and Things Forgotten in the Creation of Australia John Morton PART IV: REPATRIATION AND THE HISTORY OF SCIENTIFIC COLLECTING OF INDIGENOUS REMAINS Chapter 9. The Vermillion Accord and the Significance of the History of the Scientific Procurement and Use of Indigenous Australian Bodily Remains Paul Turnbull Chapter 10. Eric Mjoeberg and the Rhetorics of Human Remains Claes Hallgren PART V: MUSEUMS, INDIGENOUS PEOPLES AND REPATRIATION Chapter 11. Scientific Knowledge and Rights in Skeletal Remains - Dilemmas in the Curation of 'Other' People's Bones Howard Morphy Chapter 12. Despatches From The Front Line? Museum Experiences in Applied Repatriation Michael Pickering Chapter 13. 'You Keep It - We are Christians Here': Repatriation of the Secret Sacred Where Indigenous World-views Have Changed Kim Akerman Chapter 14. The First 'Stolen Generations': Repatriation and Reburial in Ngarrindjeri Ruwe (country) Steve Hemming and Chris Wilson Notes on Contributors References Index |

謝辞 はじめに ポール・ターンブル 第一部:標本ではなく祖先 第1章 送還の意味と価値 ヘンリー・アトキンソン 第2章. 先祖を送還する: 誰が死者を代弁するのか?フランチェスカ・キュビロ 第II部 法律と政策における送還 第3章. イギリスにおける博物館、倫理、そして遺骨: イングランドにおける博物館、倫理、遺体:最近の動向と将来への示唆 リズ・ベル 第4章. 先住民への文化財の本国送還における法的障害 キャサリン・ウィットビー=ラスト 第5章. 遺骨と文化財の本国送還を導くパークス・カナダの方針 ヴァージニア・マイルズ 第3部 送還の倫理と文化的意味合い 第6章. 文化財の人類学とはどのようなものか?マーティン・スクライドストラップ 第7章. 本国送還と不可分の所有という概念 エリザベス・バーンズ・コールマン 第8章 忘却の彼方へ: ジョン・モートン 第4部 送還と先住民遺骨の科学的収集の歴史 第9章. ヴァーミリオン協定とオーストラリア先住民の遺骨の科学的収集と利用の歴史の意義 ポール・ターンブル 第10章. エリック・ミョーベリと遺骨の修辞学 Claes Hallgren 第V部 博物館、先住民、そして送還 第11章. 骨格標本における科学的知識と権利-「他者」の骨のキュレーションにおけるジレンマ ハワード・モーフィー 第12章. 最前線からの派遣?応用的レパトリエーションにおける博物館の経験 マイケル・ピッカリング 第13章 あなたが持っていなさい-私たちはここにいるキリスト教徒なのだから」: 先住民の世界観が変化した場所における秘儀の本国送還 キム・アカーマン 第14章. 最初の「盗まれた世代」: ンガリンジェリ・ルウェ(国)における送還と再葬 スティーブ・ヘミングとクリス・ウィルソン 寄稿者ノート 参考文献 索引 |

| https://ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BB11671891 |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆