アメリカ先住民の墳墓保護と返還に関する法律

NAGPRA,

Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act

The Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA), Pub. L. 101-601, 25 U.S.C. 3001 et seq., 104 Stat. 3048, is a United States federal law enacted on November 16, 1990. この「アメリカ先住民の墳墓保護と返還に関する法律」の解説は、リンク先のウィキペディア(英語版)に準拠している。 この法律は、連邦政府機関および連邦政府から資金提供を受けている機関 に対して、アメリカ先住民の「文化財」を直系傍系および文化的に提携しているアメリカインディアン部族、アラスカ先住民コミュニティ、ハワイ先住民 の組織に返 還することを義務付けている。文化的遺物には、遺骨、副葬品、聖なるもの、文化的財産となるものなどが含まれる。連邦政府の補助金プログラムは、本国送 還のプロセスを支援し、内務長官は、これに従わない博物館に対して民事罰を科すことができる。 アメリカ先住民の墓の保護と返還に関する法律は、1990年11月16日以降に連邦または部族の土地で発掘または発見された文化財の所有権を定める法律で ある。この法律は、水資源局法に基づき連邦政府から州に譲渡された土地にも適用される。 しかし、この法律の規定は私有地には適用されない。この法律では、ネイティブアメリカンの遺骨と関連する葬祭用具は直系卑属に属するとされている。直系卑 属が特定できない場合、それらの遺骨や物品、関連する葬祭品や神聖な物品、文化財は、遺骨が発見された土地の部族、またはそれらと最も近い関係を持つ部族 に帰属する。この問題は、カリフォルニアほど顕著ではない。多くの小さな部族が認定される前に消滅し、現在でもネイティブアメリカンおよびネイティ ブアメリカンの部族の子孫として連邦政府の認定を受けているのは、ほんの一握りに過ぎないのである。

| Native

American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act The Act requires federal agencies and institutions that receive federal funding[1] to return Native American "cultural items" to lineal descendants and culturally affiliated American Indian tribes, Alaska Native villages, and Native Hawaiian organizations. Cultural items include human remains, funerary objects, sacred objects, and objects of cultural patrimony. A program of federal grants assists in the repatriation process and the Secretary of the Interior may assess civil penalties on museums that fail to comply. |

アメリカ先住民の墳墓保護と返還に関する法律 この法律は、連邦政府機関および連邦政府から資金提供を受けている機関 [1]に対して、アメリカ先住民の「文化財」を直系傍系および文化的に提携しているアメリカインディアン部族、アラスカ先住民コミュニティ、ハワイ先住民 の組織に返 還することを義務付けている。文化的遺物には、遺骨、副葬品、聖なるもの、文化的財産となるものなどが含まれる。連邦政府の補助金プログラムは、本国送 還のプロセスを支援し、内務長官は、これに従わない博物館に対して民事罰を科すことができる。 【現在改定中です】 |

| NAGPRA also establishes

procedures for the inadvertent discovery or planned excavation of

Native American cultural items on federal or tribal lands. While these

provisions do not apply to discoveries or excavations on private or

state lands, the collection provisions of the Act may apply to Native

American cultural items if they come under the control of an

institution that receives federal funding. |

NAGPRAはまた、連邦または部族の土地におけるアメリカ先住民の文

化財の不注意による発見または計画的な発掘のための手続きも定めている。これらの規定は、私有地または州有地での発見または発掘には適用されないが、連邦

資金を受ける機関の管理下にある場合は、同法の収集規定がアメリカ先住民の文化財に適用される場合がある |

| Lastly, NAGPRA makes it a

criminal offense to traffic in Native American human remains without

right of possession or in Native American cultural items obtained in

violation of the Act. Penalties for a first offense may reach 12 months

imprisonment and a $100,000 fine. |

最後に、NAGPRAは、所有権のないアメリカ先住民の人骨や、法に違

反して入手したアメリカ先住民の文化財を取引することを犯罪としている。初犯の場合、12ヶ月の禁固刑と10万ドルの罰金に達する可能性がある。 |

| Background The intent of the NAGPRA legislation is to address long-standing claims by federally recognized tribes for the return of human remains and cultural objects unlawfully obtained from precontact, post-contact, former, and current Native American homelands. Interpretation of human and indigenous rights, prehistoric presence, cultural affiliation with antiquities, and the return of remains and objects can be controversial and contested. It includes provisions that delineate the legal processes by which museums and federal agencies are required to return certain Native American cultural items—human remains, gravesite materials, and other objects of cultural patrimony—to proven lineal descendants, culturally related Native American tribes, and Native Hawaiian groups. Outcomes of NAGPRA repatriation efforts are slow and cumbersome, leading many tribes to spend considerable effort documenting their requests; collections' holders are obliged to inform and engage with tribes whose materials they may possess. NAGPRA was enacted primarily at the insistence and by the direction of members of Native American nations.[2] |

背景 NAGPRA法の趣旨は、アメリカ先住民の先住地、後住地、旧住地、現住地から不法に入手した遺骨と文化財の返還を求める連邦公認部族の長年の訴えに対処 することにある。人権や先住民の権利、先史時代の存在、文化的帰属と古美術品、そして遺骨や文化財の返還に関する解釈は、議論を呼び、争点となることがあ る。NAGPRAには、博物館や連邦機関が、特定のアメリカ先住民の文化財(遺骨、墓の資料、その他の文化遺産の対象物)を、証明された直系卑属、文化的 に関係のあるアメリカ先住民部族、およびハワイ先住民グループに返還しなければならない法的手続きを規定する条項が含まれています。 NAGPRAによる本国への返還の成果は遅々として進まず、多くの部族が要求の文書化に多大な労力を費やしている。コレクション所有者は、所有する可能性 のある資料について部族に伝え、協力する義務がある。NAGPRAは、主にアメリカ先住民の主張と指示によって制定された[2]。 |

| Tribal concerns Tribes had many reasons based in law that made legislation concerning tribal grave protection and repatriation necessary. State Statutory Law: Historically, states only regulated and protected marked graves. Native American graves were often unmarked and did not receive the protection provided by these statutes. Common Law: The colonizing population formed much of the legal system that developed over the course of settling the United States. This law did not often take into account the unique Native American practices concerning graves and other burial practices. It did not account for government actions against Native Americans, such as removal, the relationship that Native Americans as different peoples maintain with their dead, and sacred ideas and myths related to the possession of graves. Equal Protection: Native Americans, as well as others, often found that the remains of Native American graves were treated differently from the dead of other races. First Amendment: As in most racial and social groups, Native American burial practices relate strongly to their religious beliefs and practices. They held that when tribal dead were desecrated, disturbed, or withheld from burial, their religious beliefs and practices are being infringed upon. Religious beliefs and practices are protected by the first amendment. Sovereignty Rights: Native Americans hold unique rights as sovereign bodies, leading to their relations to be controlled by their own laws and customs. The relationship between the people and their dead is an internal relationship, to be understood as under the sovereign jurisdiction of the tribe. Treaty: From the beginning of the U.S. government and tribe relations, the tribe maintained rights unless specifically divested to the U.S. government in a treaty. The U.S. government does not have the right to disturb Native American graves or their dead, because it has not been granted by any treaty. |

部族の懸念 部族には、部族の墓の保護と送還に関する法律を必要とする、法律に基づいた多くの理由があった。 ・州の法定法。歴史的に、州は標識のある墓だけを規制し保護してきた。ネイティブ・アメリカンの墓はしばしば無標であり、これらの法律によって提供される 保護を受けられなかった。 ・慣習法。植民地化した人々は、米国を開拓する過程で発展した法体系の多くを形成した。この法律は、墓やその他の埋葬に関するネイティブ・アメリカン特有 の慣習を考慮に入れていないことがしばしばあった。この法律は、強制退去のようなネイティブ・アメリカンに対する政府の行為、ネイティブ・アメリカンが異 なる民族として維持している死者との関係、そして墓の所有に関連する神聖な観念や神話を考慮に入れていなかった。 ・平等な保護。ネイティブアメリカンやその他の人々は、ネイティブアメリカンの墓の遺骨が他の人種の死者とは異なる扱いを受けていることにしばしば気づい た。 ・憲法修正第一条 ほとんどの人種的、社会的グループと同様に、ネイティブ・アメリカンの埋葬慣習は、彼らの宗教的信念と慣習に強く関連する。彼らは、部族の死者が冒涜さ れ、乱され、あるいは埋葬が差し止められた場合、彼らの宗教的信念と慣習が侵害されていると考えた。宗教的信念と実践は、憲法修正第1条によって保護され ている。 ・主権的権利。アメリカ先住民は主権者として独自の権利を有しており、彼らの関係は彼ら自身の法律と慣習によって管理されることにつながる。人々とその死 者との関係は内部的なものであり、部族の主権的な管轄下にあるものと理解される。 ・条約 米国政府と部族の関係が始まった当初から、部族は、条約で特に米国政府に譲渡されない限り、権利を保持していた。米国政府は、いかなる条約によっても認め られていないため、ネイティブアメリカンの墓やその死者を妨げる権利を有しない。 |

| Description The Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act is a law that establishes the ownership of cultural items excavated or discovered on federal or tribal land after November 16, 1990. The act also applies to land transferred by the federal government to the states under the Water Resources Department Act.[3] However, the provisions of the legislation do not apply to private lands. The Act states that Native American remains and associated funerary objects belong to lineal descendants. If lineal descendants cannot be identified, then those remains and objects, along with associated funerary and sacred objects, and objects of cultural patrimony belong to the tribe on whose lands the remains were found or the tribe having the closest known relationship to them.[3] Tribes find the burden of proof is on them, if it becomes necessary to demonstrate a cultural relationship that may not be well-documented or understood. Nowhere has this issue been more pronounced than in California, where many small bands were extinguished before they could be recognized, and only a handful, even today, have obtained federal recognition as Native Americans and descendants of Native American bands. |

説明 アメリカ先住民の墓の保護と返還に関する法律は、1990年11月16日以降に連邦または部族の土地で発掘または発見された文化財の所有権を定める法律で ある[2]。この法律は、水資源局法に基づき連邦政府から州に譲渡された土地にも適用される[3]。 しかし、この法律の規定は私有地には適用されない。この法律では、ネイティブアメリカンの遺骨と関連する葬祭用具は直系卑属に属するとされている。直系卑 属が特定できない場合、それらの遺骨や物品、関連する葬祭品や神聖な物品、文化財は、遺骨が発見された土地の部族、またはそれらと最も近い関係を持つ部族 に帰属する[3]。この問題は、カリフォルニアほど顕著ではない。多くの小さな部族が認定される前に消滅し、現在でもネイティブアメリカンおよびネイティ ブアメリカンの部族の子孫として連邦政府の認定を受けているのは、ほんの一握りに過ぎないのである。 |

| Congress attempted to "strike a

balance between the interest in scientific examination of skeletal

remains and the recognition that Native Americans, like people from

every culture around the world, have a religious and spiritual

reverence for the remains of their ancestors."[4] The act also requires each federal agency, museum, or institution that receives federal funds to prepare an inventory of remains and funerary objects and a summary of sacred objects, cultural patrimony objects, and unassociated funerary objects. The act provides for repatriation of these items when requested by the appropriate descendant of the tribe. This applies to remains or objects discovered at any time, even before November 16, 1990.[5] Since the legislation passed, the human remains of approximately 32,000 individuals have been returned to their respective tribes. Nearly 670,000 funerary objects, 120,000 unassociated funerary objects, and 3,500 sacred objects have been returned.[5] |

議会は、「骨格標本の科学的検査への関心と、アメリカ先住民が世界中の

あらゆる文化の人々と同様に、祖先の遺骨に対して宗教的・精神的な崇敬を抱いているという認識との間でバランスを取る」ことを試みている[4]。 この法律はまた、連邦資金を受け取る各連邦機関、博物館、または施設が、遺骨と葬送品の目録と、聖なるもの、文化遺産のもの、および関連性のない葬送品の 要約を作成することを要求している。この法律は、部族の適切な子孫から要請があった場合、これらの品目を本国送還することを定めている。これは、1990 年11月16日以前であっても、いつでも発見された遺骨や物品に適用される[5]。 この法律が成立して以来、約32,000人の遺骨がそれぞれの部族に戻されました。670,000近くの葬祭用具、120,000の関連性のない葬祭用 具、および3,500の神聖な物品が返還された[5]。 |

| The statute attempts to mediate

a significant tension that exists between the tribes' communal

interests in the respectful treatment of their deceased ancestors and

related cultural items and the scientists' individual interests in the

study of those same human remains and items. The act divides the

treatment of American Indian human remains, funerary objects, sacred

objects, and objects of cultural patrimony into two basic categories.

Under the inadvertent discovery and planned excavation component of the

act and regulations, if federal officials anticipate that activities on

federal and tribal lands after November 16, 1990 might have an effect

on American Indian burials—or if burials are discovered during such

activities—they must consult with potential lineal descendants or

American Indian tribal officials as part of their compliance

responsibilities. For planned excavations, consultation must occur

during the planning phase of the project. For inadvertent discoveries,

the regulations delineate a set of short deadlines for initiating and

completing consultation. The repatriation provision, unlike the

ownership provision, applies to remains or objects discovered at any

time, even before the effective date of the act, whether or not

discovered on tribal or federal land. The act allows archaeological

teams a short time for analysis before the remains must be returned.

Once it is determined that human remains are American Indian, analysis

can occur only through documented consultation (on federal lands) or

consent (on tribal lands). A criminal provision of the Act prohibits trafficking in Native American human remains, or in Native American "cultural items." Under the inventory and notification provision of the act, federal agencies and institutions that receive federal funds are required to summarize their collections that may contain items subject to NAGPRA. Additionally, federal agencies and institutions must prepare inventories of human remains and funerary objects. Under the act, funerary objects are considered "associated" if they were buried as part of a burial ceremony with a set of human remains still in possession of the federal agency or other institution. "Unassociated" funerary objects are artifacts where human remains were not initially collected by—or were subsequently destroyed, lost, or no longer in possession of—the agency or institution. Consequently, this legislation also applies to many Native American artifacts, especially burial items and religious artifacts. It has necessitated mass cataloguing of the Native American collections in order to identify the living heirs, culturally affiliated Indian tribes, and Native Hawaiian organizations of remains and artifacts. NAGPRA has had a dramatic effect on the day-to-day practice of archaeology and physical anthropology in the United States. In many cases, NAGPRA helped stimulate interactions of archaeologists and museum professionals with Native Americans that were felt to be constructive by all parties. |

こ

の法律は、亡くなった祖先や関連する文化財を丁重に扱うという部族の

共同利益と、同じ人骨や物品を研究するという科学者の個人的利益との間に存在する重大な緊張関係を調停しようとするものである。この法律で

は、アメリカン

インディアンの遺骨、葬祭用具、聖なるもの、文化財の扱いを2つの基本カテゴリーに分類しています。この法律と規則の不注意による発見と計画的な発掘の項

目では、1990年11月16日以降の連邦および部族の土地での活動がアメリカン・インディアンの埋葬に影響を与えるかもしれないと連邦職員が予測した場

合、またはそのような活動中に埋葬が発見された場合、その遵守責任の一部として、潜在的直系卑属またはアメリカ・インディアン部族の関係者と相談しなけれ

ばならない。計画的な発掘の場合、コンサルテーションはプロジェクトの計画段階で行われなければならない。また、不慮の事故による発見については、協議の

開始と完了のための短い期限を定めている。本国送還の規定は、所有権の規定とは異なり、部族や連邦の土地で発見されたか否かに関わらず、この法律の発効日

以前でも、いつでも発見された遺物や物品に適用されます。この法律では、遺骨を返還しなければならない前に、考古学チームが分析のために短期間滞在するこ

とを認めている。遺骨がアメリカン・インディアンであると判断された後は、文書による協議(連邦の土地)または同意(部族の土地)を通じてのみ、分析を行

うことができる。 同法の刑事規定では、アメリカ先住民の遺骨やアメリカ先住民の「文化的 物品」の売買を禁止している。同法の目録および通知規定に基づき、連邦政府機関およ び連邦資金を受ける機関は、NAGPRAの対象となる物品を含む可能性のあるコレクションを要約することが義務付けられている。さらに、連邦政府機関およ び団体は、遺骨および葬祭用具の目録を作成しなければならない。この法律では、葬祭用具は、連邦政府機関またはその他の機関がまだ所有している遺骨と一緒 に埋葬された場合、「関連する」と見なされる。「関連性のない」葬祭品とは、遺骨が当初は連邦機関やその他の機関によって収集されなかったか、あるいはそ の後破壊されたり紛失したり、もはや所有されなくなった遺物を指す。その結果、この法律は、多くのアメリカ先住民の遺物、特に埋葬品や宗教的な遺物にも適 用される。そのため、遺骨や遺物の生前相続人、文化的に提携しているインディアン部族、ハワイ先住民の団体を特定するために、ネイティブアメリカンのコレ クションの大量の目録作成が必要になった。NAGPRAは、米国における考古学と自然人類学の日常的な実践に劇的な影響を及ぼした。多くの場合、 NAGPRAは考古学者や博物館の専門家とネイティブアメリカンとの交流を促進し、すべての関係者が建設的であると感じている。 |

| History Background The late 19th century was one of the most difficult periods in Native American history in regards to the loss of cultural artifacts and land. With the founding of museums and scholarly studies of Native American peoples increasing with the growth of anthropology and archeology as disciplines, private collectors and museums competed to acquire artifacts, which many Native Americans considered ancestral assets, but others sold. This competition existed not only between museums such as the Smithsonian Institution (founded in 1846) and museums associated with universities, but also between museums in the United States and museums in Europe. In the 1880s and 1890s, collecting was done by untrained adventurers. As of the year 1990, federal agencies reported having the remains of 14,500 deceased Natives in their possession, which had accumulated since the late 19th century. Many institutions said they used the remains of Native Americans for anthropological research, to gain more information about humans. At one time, in since discredited comparative racial studies, institutions such as the Army Medical Museum sought to demonstrate racial characteristics to prove the inferiority of Native Americans.[6] |

歴史 背景 19世紀後半は、文化財や土地の喪失という点で、ネイティブアメリカンの歴史において最も困難な時代のひとつであった。博物館が設立され、人類学と考古学 の発展に伴いネイティブ・アメリカンの学術的研究が進む中、多くのネイティブ・アメリカンが先祖代々の財産と見なし、また他の人々が売却した遺物を、個人 の収集家と博物館が競って入手した。この競争は、スミソニアン博物館(1846年設立)や大学付属の博物館だけでなく、アメリカの博物館とヨーロッパの博 物館の間でも行われた。1880年代から1890年代にかけては、収集は訓練を受けていない冒険者たちによって行われていた。19世紀後半から蓄積さ れた遺骨は、1990年の時点で、連邦政府機関が14,500体の死亡した先住民の遺骨を保有していると報告されている。多くの機関が、ネイティブ・アメ リカンの遺骨を人類学の研究に利用し、人間についてより多くの情報を得ようとしたと言っている。一時期、比較人種学が否定された後、陸軍医学博物館のよう な機関では、ネイティブアメリカンの劣等性を証明するために人種的特徴を示そうとしたことがあった[6]。 |

| Maria Pearson Maria Pearson (1932-2003) is often credited with being the earliest catalyst for the passage of NAGPRA legislation; she has been called "the Founding Mother of modern Indian repatriation movement" and the "Rosa Parks of NAGPRA".[7] In the early 1970s, Pearson was appalled that the skeletal remains of Native Americans were treated differently from white remains. Her husband, an engineer with the Iowa Department of Transportation, told her that both Native American and white remains were uncovered during road construction in Glenwood, Iowa. While the remains of 26 white burials were quickly reburied, the remains of a Native American mother and child were sent to a lab for study instead. Pearson protested to Governor Robert D. Ray, finally gaining an audience with him after sitting outside his office in traditional attire. "You can give me back my people's bones and you can quit digging them up", she responded when the governor asked what he could do for her. The ensuing controversy led to the passage of the Iowa Burials Protection Act of 1976, the first legislative act in the United States that specifically protected Native American remains. Emboldened by her success, Pearson went on to lobby national leaders, and her efforts, combined with the work of many other activists, led to the creation of NAGPRA.[7][8] Pearson and other activists were featured in the 1995 BBC documentary Bones of Contention.[9] |

マリア・ピアソン マリア・ピアソンは、NAGPRA法成立の最も初期の触媒であるとしばしば評価されている。彼女は「現代のインディアン送還運動の創始者」、 「NAGPRAのローザ・パークス」と呼ばれている。 [7] 1970年代初期に、ピアソンは、ネイティブアメリカンの骨格が白人とは異なる扱い を受けていることに愕然とした。アイオワ州交通局のエンジニアである彼 女の夫は、アイオワ州グレンウッドでの道路工事中にネイティブ・アメリカンと白人の両方の遺骨が発見されたことを彼女に告げた。26人の白人の埋葬者の遺 骨はすぐに埋め戻されたが、ネイティブ・アメリカンの母子の遺骨は、代わりに研究のために研究所に送られた。ピアソンはロバート・D・レイ知事に抗議し、 伝統的な服装で知事のオフィスの外に座り、ついに知事に謁見することができた。知事が「何かできることはないか」と尋ねると、彼女は「私の仲間の骨を返し てくれ、掘り返すのはやめてくれ」と答えた。この論争は、1976年の「アイオワ州埋葬者保護法」の成立につながった。この法律は、アメリカ国内で初めて ネイティブ・アメリカンの遺骨を特別に保護する立法法であった。 この成功に勇気づけられたピアソンは、国の指導者に働きかけ、彼女の努力と他の多くの活動家の活動が相まって、NAGPRAの創設につながった[7] [8]。ピアソンと他の活動家は、1995年のBBCドキュメンタリー番組「Bones of Contention」で紹介された[9]。 |

| Slack Farm and Dickson Mounds The 1987 looting of a 500-year-old burial mound at the Slack Farm in Kentucky, in which human remains were tossed to the side while relics were stolen, made national news and helped to galvanize popular support for protection of Native American graves.[10][11] Likewise, several protests at the Dickson Mounds site in Illinois, where numerous Indian skeletons were exposed on display, also increased national awareness of the issue.[12] |

スラック・ファームとディクソン墳墓 1987年にケンタッキー州のスラック・ファームで起きた500年前の古墳の略奪事件は、遺骨が投げ捨てられ、遺品が盗まれたことで全国ニュースになり、 ネイティブアメリカンの墓の保護に対する国民の支持を集めることになった[10][11]。 同様に、イリノイ州のディクソン・マウンド遺跡で、多数のインディアン骨格が展示されていたことから、いくつかの抗議行動もこの問題の国民意識を高める きっかけとなった[12]。 |

| Return to the Earth project Return to the Earth is an inter-religious project whose goal is to inter unidentified remains in regional burial sites.[13] Over 110,000 remains that cannot be associated with a particular tribe are held in institutions across the United States, as of 2006.[14] The project seeks to enable a process of reconciliation between Native and non-Native peoples, construct cedar burial boxes, produce burial cloths and fund the repatriation of remains. The first of the burial sites is near the Cheyenne Cultural Center in Clinton, Oklahoma.[14][15] |

大地に還るプロジェクト 2006年現在、特定の部族と関連づけることができない11万体以上の 遺骨がアメリカ国内の施設に保管されている[14]。このプロジェクトは、先住民と 非民族の和解のプロセスを可能にし、杉の埋葬箱を作り、埋葬布を作り、遺骨の本国送還に資金援助することを目的としている。最初の埋葬地はオクラホマ州ク リントンのシャイアン文化センター付近である[14][15]。 |

| Controversial issues A few archeologists are concerned that they are being prevented from studying ancient remains which cannot be traced to any historic tribe. Many of the tribes migrated to their territories at the time of European encounter within 100–500 years from other locations, so their ancestors were not located in the historic territories.[16] Such controversies have repeatedly stalled archaeological investigations, such as in the case of the Spirit Cave mummy; fears have been voiced that an anti-scientific sentiment could well have permeated politics to an extent that scientists might find their work to be continuously barred by Native Americans rights activists.[17] |

論争の的となる問題 少数の考古学者は、歴史上のどの部族にもたどりつけない古代の遺跡の研究を妨げられているのではないかと懸念している。このような論争は、スピリット・ケ イブのミイラの場合のように、考古学的調査を繰り返し停滞させてきた。反科学的感情が政治に浸透し、科学者がネイティブアメリカンの権利活動家から継続的 に仕事を妨害されるかもしれないと懸念されている[17]。 |

| Kennewick Man Compliance with the legislation can be complicated. One example of controversy is that of Kennewick Man, a skeleton found on July 28, 1996 near Kennewick, Washington. The almost complete skeleton was close to 9,000 years old.[18] Ancient remains from North America are rare, making it a valuable scientific discovery.[18][19] The federally recognized Umatilla, Colville, Yakima, and Nez Perce tribes had each claimed Kennewick Man as their ancestor, and sought permission to rebury him. Kennewick, Washington is classified as part of the ancestral land of the Umatilla. Archaeologists said that because of Kennewick Man's great age, there was insufficient evidence to connect him to modern tribes. The great age of the remains makes this discovery scientifically valuable.[20] As archaeologists, forensic specialists, and linguists differed about whether the adult male was of indigenous origin, the standing law, if conclusively found by a preponderance of evidence to be Native American, would give the tribe of the geographic area where he was found a claim to the remains.[21] Anthropologists wanted to preserve and study the remains, however, steps had already been taken to repatriate the Kennewick Man given that he was discovered on federal lands. A lawsuit was filed by Douglas Owsley and Robson Bonnichsen, along with other notable anthropologists, in the hopes of preventing the repatriation of the skeleton. In 2004, the court sided with the plaintiffs' assertion that due to the skeleton's age, there was not enough information available at the time to conclude whether the Kennewick Man had any cultural or genetic ties to any present day Native American tribes, and granted the plaintiffs' request to further study the remains.[18] New evidence could still emerge in defense of tribal claims to ancestry, but emergent evidence may require more sophisticated and precise methods of determining genetic descent, given that there was no cultural evidence accompanying the remains. One tribe claiming ancestry to Kennewick Man offered up a DNA test, and in 2015 it was found that the Kennewick man is "more closely related to modern Native Americans than any other living population." In September 2016, the US House and Senate passed legislation to return the ancient bones to a coalition of Columbia Basin tribes for reburial according to their traditions. The coalition includes the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation, the Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation, the Nez Perce Tribe, the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Reservation, and the Wanapum Band of Priest Rapids. The remains were buried on February 18, 2017, with 200 members of five Columbia Basin tribes, at an undisclosed location in the area.[22] |

ケネ

ウィックマン 法規制の遵守は複雑な場合がある。論争の一例として、1996年7月28日にワシントン州ケネウィック近郊で発見されたケネウィック・マン (Kennewick Man)の骨格がある。北米の古代遺跡は珍しく、科学的にも貴重な発見であった[18][19]。連邦政府が承認したウマティラ、コルヴィル、ヤキマ、ネ ズパース各部族はそれぞれケネウィック・マンを祖先だと主張し、再埋葬する許可を求めていた。ワシントン州ケネウィックは、ウマティラ族の祖先の土地の一 部として分類されている。 考古学者によると、Kennewick Manは非常に古いため、現代の部族と結びつける証拠は不十分である。考古学者、法医学者、言語学者によって、この成人男性が先住民であるかどうかが異な るため、もし圧倒的な証拠によって先住民であると決定的になった場合、発見された地域の部族に遺骨の権利が与えられるという常法がある[21]。 人類学者は遺体を保存し研究したいと願ったが、ケネウィックマンが連邦の土地で発見されたということから既に送還するための措置はとられていた。ダグラ ス・オウスリーとロブソン・ボニクセンは、他の著名な人類学者とともに、骸骨の本国送還を阻止することを目的として訴訟を提起した。2004年、裁判所 は、骨格が古いため、ケネウィックマンが現在のネイティブアメリカンの部族と文化的または遺伝的なつながりを持つかどうかを結論づけるのに十分な情報が当 時はなかったという原告側の主張を支持し、遺骨をさらに研究するという原告側の要求を認めた[18]。 部族の祖先に対する主張を弁護する新しい証拠がまだ出てくる可能性はあるが、遺骨に付随する文化的証拠がなかったことから、新しい証拠には遺伝子を判定す る、より高度で正確な方法が必要かもしれない。 ケネウィックマンの祖先を主張するある部族はDNA鑑定を申し出、2015年にはケネウィックマンが "現存するどの集団よりも現代のネイティブアメリカンに近縁である "ことが明らかになった。2016年9月、米国上下両院は、古代の骨をコロンビア流域の部族の連合に返還し、彼らの伝統に従って再埋葬するための法案を可 決した。この連合には、コルビル居留地の連合部族、ヤカマ民族の連合部族とバンド、ネズパース族、ウマティラ居留地の連合部族、プリーストラピッズのワナ パム・バンドが含まれています。遺骨は2017年2月18日、コロンビア流域の5つの部族の200人のメンバーとともに、その地域の非公開の場所に埋葬さ れた[22]。 |

| International policies The issues of such resources are being addressed by international groups dealing with indigenous rights. For example, in 1995 the United States signed an agreement with El Salvador in order to protect all pre‑Columbian artifacts from leaving the region. Soon after, it signed similar agreements with Canada, Peru, Guatemala, and Mali and demonstrated leadership in implementing the 1970 UNESCO Convention. The UNESCO convention had membership increase to 86 countries by 1997, and 193 by 2007. UNESCO appears to be reducing the illicit antiquities trade. It is not an easy business to track, but the scholar Phyllis Messenger notes that some antiquities traders have written articles denouncing the agreements, which suggests that it is reducing items sold to them.[23] An international predecessor of the UNESCO Convention and NAGPRA is the 1954 Hague Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict.[24] The Hague Convention was the first international convention to focus on preserving cultural heritage from the devastation of war. Looting and destruction of other civilizations have been characteristics of war recorded from the first accounts of all cultures. |

国際的な政策 このような資源の問題は、先住民の権利を扱う国際的な団体によって取り組まれている。例えば、1995年、米国はエルサルバドルと、すべての先史時代の遺 物をこの地域から出さないように保護するための協定を締結した。その後、カナダ、ペルー、グアテマラ、マリとも同様の協定を締結し、1970年のユネスコ 条約の実施にリーダーシップを発揮した。ユネスコ条約は、1997年までに86カ国、2007年までに193カ国に加盟国を増やした。ユネスコは違法な古 美術品売買を減らしているように見える。追跡するのは容易なビジネスではないが、学者のフィリス・メッセンジャーは、一部の古美術商が協定を非難する記事 を書いていることから、彼らに売られる品物を減らしていることが示唆されると指摘している[23]。 ユネスコ条約とNAGPRAの国際的な前身は、武力紛争の際の文化財の保護に関する1954年のハーグ条約である[24]。 ハーグ条約は戦争の荒廃から文化遺産を保護することに焦点を当てた最初の国際条約であった。他の文明の略奪と破壊は、あらゆる文化の最初の記録から記録さ れている戦争の特徴である。 |

| On September 30, 1897,

Lieutenant Robert Peary brought six Inuit from Greenland to the

American Museum of Natural History in New York, at the request of the

anthropologist Franz Boas, in order to "obtain leisurely certain

information which will be of the greatest scientific importance"

regarding Inuit culture.[25] About two weeks after arrival at the

museum, all six of the Inuit became sick with colds and fever. They

began to perform their tribal healing process and were mocked for their

bizarre behavior. These people became a form of entertainment for the

Americans. By November 1, 1897, they were admitted to the Bellevue

Hospital Center with tuberculosis, which they likely had contracted

before their trip. In February, the first Inuk died and shortly after

that two more followed. By the time the sickness had run its course,

two men survived. Minik was adopted by a superintendent of the museum,

while Uissakassak returned to his homeland in Greenland. Later, after

being lied to and being told that his father Qisuk had received a

proper Inuit burial, Minik was shocked to find his father's skeleton on

display in the museum. In 1993 the museum finally agreed to return the four Inuit skeletons to Greenland for proper burial. Representatives of the Museum went to Greenland that year to participate. In contrast to peoples in other areas, some local Inuit thought that the burial was more desired by the Christian representatives of the museum, and that the remains could have just as appropriately been kept in New York.[26] David Hurst Thomas' study of the case shows the complexity of reburial and repatriation cases, and the need for individual approaches to each case by all affected parties.[26] |

1897年9月30日、ロバート・ピアリー中尉は人類学者フランツ・ボ

アズの依頼により、イヌイット文化に関して「科学的に最も重要となるある情報をゆっくりと得る」ためにグリーンランドから6人のイヌイットを

ニューヨーク

のアメリカ自然史博物館に連れてきた[25]。

博物館到着後約2週間、6人は風邪と熱で病気になり、6人全員がインフルエンザにかかった。彼らは部族の治癒プロセスを実行し始め、その奇妙な行動から嘲

笑された。この人たちはアメリカ人にとっての娯楽となった。1897年11月1日、彼らは結核でベルビュー病院センターに収容されたが、おそらく旅行前に

感染していたのだろう。2月には最初のイヌクが死亡し、その直後にさらに2人が死亡した。病気が治る頃には、2人が生き残っていた。ミニックは博物館の管

理人の養子になり、ユイサカサクは故郷のグリーンランドに戻った。その後、父キスクはイヌイットの正式な埋葬を受けたと嘘をつかれたミニックは、博物館に

展示されている父の骸骨を見てショックを受ける。 1993年、博物館はようやく4体のイヌイットの骸骨をグリーンランドに戻し、適切に埋葬することに同意した。この年、博物館の代表者がグリーンランドに 赴き、参加した。他の地域の民族とは対照的に、地元のイヌイットの中には、埋葬はキリスト教徒である博物館の代表者が望むところであり、遺骨はニューヨー クで保管するのが適切であったと考える者もいた[26]。 David Hurst Thomasによるこの事件の研究は、再埋葬と送還の事例の複雑さと、すべての関係者によるそれぞれの事例への個別のアプローチの必要性を示すものである [26]。 |

| Protecting cultural

property In the United States, the Archaeological Resources Protection Act (ARPA) protects archaeological sites on federally owned lands. Privately owned sites are controlled by the owners. In some areas, archaeological foundations or similar organizations buy archaeological sites in order to conserve cultural resources associated with such properties. Other countries may use three basic types of laws to protect cultural remains: - Selective export control laws control the trade of the most important artifacts while still allowing some free trade. Countries that use these laws include Canada, Japan, and the United Kingdom. - Total export restriction laws are used by some countries to enact an embargo and completely shut off export of cultural property. Many Latin American and Mediterranean countries use these laws. - Other countries, such as Mexico, use national ownership laws to declare national ownership for all cultural artifacts. These laws cover control of artifacts that have not been discovered, to try to prevent looting of potential sites before exploration. |

文化財の保護 米国では、連邦政府が所有する土地にある遺跡は、考古学資源保護法(ARPA)により保護されている。私有地の場合は、所有者が管理している。また、地域 によっては、考古学財団などが遺跡を購入し、その遺跡に関連する文化資源を保存しているところもある。 他の国では、文化財を保護するために、3つの基本的なタイプの法律を使うことがある。 - 選択的輸出規制法は、最も重要な文化財の取引を規制する一方で、ある程度の自由貿易を認めている。選択的輸出規制法は、最も重要な文化財の取引を規制する 一方で、ある程度の自由貿易を認める法律である。この法律を採用している国には、カナダ、日本、イギリスがある。 - 全面的輸出制限法は、一部の国が禁輸を実施し、文化財の輸出を完全に遮断するために使用する。多くのラテンアメリカや地中海沿岸の国々がこの法律を用いて いる。 - また、メキシコのように、すべての文化財の国有を宣言する国有法を用いている国もある。この法律では、未発見の文化財を管理することで、遺跡探査前の略奪 を防ごうとしているのである。 |

| https://bit.ly/3evzn6c |

https://www.deepl.com/ja/translator. |

| Maria Darlene

Pearson

or Hai-Mecha Eunka (lit. "Running Moccasins") (July 12, 1932 – May 23,

2003) was an activist who has successfully challenged the legal

treatment of Native American remains. A member of the Turtle Clan of

the Yankton Sioux[1] (which is a federally recognized tribe of Yankton

Dakota), she was one of the primary catalysts for the creation of the

Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA). Her

actions led to her being called "the Founding Mother of the modern

Indian repatriation movement" and "the Rosa Parks of NAGPRA".[2] |

マリア・ダーレン・ピアソンまたはハイメカ・ウンカ(「走るモカシン」

の意)(1932年7月12日 -

2003年5月23日)は、ネイティブアメリカンの遺骨の法的扱いに挑戦し、成功した活動家であった。ヤンクトン・スー族[1](ダコタ州ヤンクトンの連

邦公認部族)のタートル一族の一員であり、アメリカ先住民墓地保護・送還法(NAGPRA)創設の主要な触媒の一人であった。彼女の行動により、「現代の

インディアン送還運動の創始者」、「NAGPRAのローザ・パークス」と呼ばれるようになった[2]。 |

| Activism Maria first became an active advocate for the repatriation of Native American human remains in 1971.[1] At this time, the Iowa Highway Commission uncovered the skeletal remains of 26 European-American pioneers as well as the remains of a Native American woman and her infant child during road construction in Glenwood, Iowa. She learned of this from her husband, John Pearson, who was an engineer for the Iowa State Highway Commission.[1] While the remains of the 26 white settlers were quickly reburied, the remains of a Native American mother and child were sent to the Office of the State Archaeologist in Iowa City for study.[3] Learning of this incident, Maria was appalled that the skeletal remains of Native Americans were treated differently from white remains. Pearson staged a protest in the State Capitol and finally gained an audience with Gov. Robert D. Ray after sitting outside his office in traditional attire. "You can give me back my people's bones and you can quit digging them up" she responded when the governor asked what he could do for her. Maria continued to meet with legislators, archaeologists, anthropologists, physical anthropologists, and other tribal members, which led to the passage of the Iowa Burials Protection Act of 1976,[4] the first legislative act in the U.S. that specifically protected Native American remains. Emboldened by her success, Pearson went on to lobby national leaders, and was one of the catalysts for the creation of NAGPRA.[5][2] Pearson was featured in the 1995 BBC documentary Bones of Contention.[6] Maria was also nominated twice for a Nobel Peace Prize for her substantial contributions toward the protection and repatriation of Native American remains. |

活動 マリアは、1971年にネイティブ・アメリカンの遺骨の本国送還を積極的に提唱するようになった[1]。 その頃、アイオワ州道路委員会が、同州グレンウッドでの道路建設中にヨーロッパ系アメリカ人の開拓者26人の骨格と、ネイティブ・アメリカンの女性とその 子どもの遺体を発見したのである。26人の白人入植者の遺骨はすぐに埋葬されたが、ネイティブアメリカンの母子の遺骨はアイオワシティの州立考古学者に送 られた[3]。 この事件を知ったマリアは、ネイティブアメリカンの骨格が白人とは異なる扱いを受けることに憤慨した。ピアソンは州議会議事堂で抗議活動を行い、伝統的な 服装で知事ロバート・D・レイの部屋の前に座り込み、ついに知事に面会することができた。知事が「何かできることはないか」と尋ねると、彼女は「私の仲間 の骨を返してほしい、掘り返すのはやめてほしい」と答た。マリアはその後も、議員、考古学者、人類学者、身体人類学者、その他の部族メンバーと面会を重 ね、1976年にネイティブ・アメリカンの遺骨を特別に保護する米国初の立法法「アイオワ州埋葬品保護法」を成立させるに至った[4]。この成功に勇気づ けられたピアソンは、国の指導者に働きかけ、NAGPRAの創設の触媒のひとつとなった[5][2] 。ピアソンは1995年のBBCドキュメンタリー番組「Bones of Contention」で取り上げられた[6] また、ネイティブアメリカンの遺体の保護と送還に対する多大な貢献からノーベル平和賞の候補に2度ノミネートされている。 |

| Personal Maria Darlene Pearson (given name Darlene Elvira Drappeaux) was born in Springfield, South Dakota on July 12, 1932 where her mother gave her the Yankton name Hai-Mecha Eunka (translated as "Running Moccasins").[1] She married John Pearson in 1969, and spent most of her adult life in Iowa. Pearson had six children: Robert, Michael, Eldon, Ronald, Richard, and Darlene and 21 grandchildren and 15 great grandchildren. Pearson died in Ames, Iowa May 23, 2003 at the age of 70.[7] |

パーソナル マリア・ダーレン・ピアソン(本名:ダーレン・エルヴィラ・ドラッポー)は1932年7月12日にサウスダコタ州スプリングフィールドで生まれ、母親から ヤンクトン族の名前「ハイメカ・ウンカ(走るモカシン)」を授かった[1]。 1969年にジョン・ピアソンと結婚し、成人後はほとんどアイオワ州で過ごすことになる。ピアソンには6人の子供がいた。ロバート、マイケル、エルドン、 ロナルド、リチャード、ダーレーンの6人の子供と、21人の孫、15人の曾孫がいる。2003年5月23日、アイオワ州エイムズで70歳で死去した [7]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maria_Pearson |

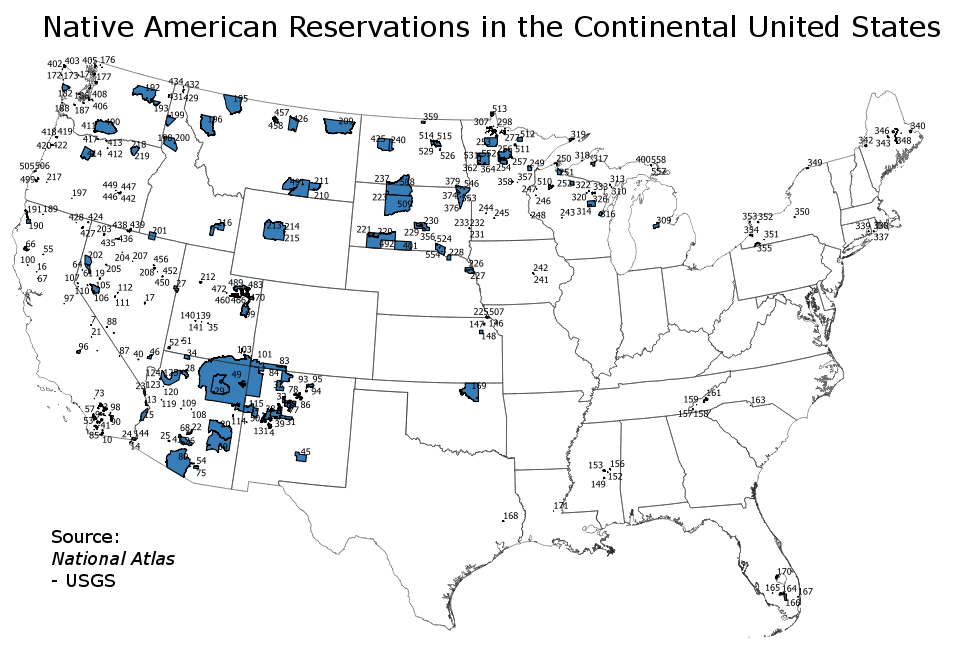

Map of Native American reservations.

●アメリカ合衆国憲法修正第1条(First Amendment to the United States Constitution)

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.

連邦議会は、国教を樹立し、若しくは信教上の自由な

行為を禁止する法律を制定してはならない。また、言論若しくは出版の自由、又は人民が平穏に集会し、また苦痛の救済を求めるため政府に請願する権利を侵す

法律を制定してはならない。

ネイティブ・アメリカン墳墓保護と返還に関する法律

(条文と試訳)

The

Native American

Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA), Pub. L. 101-601,

25

U.S.C. 3001 et seq., 104 Stat. 3048, is a United States federal law

enacted on November 16, 1990.

| Public Law 101-601 101st Congress An Act To provide for the protection of Native American graves, and for other purposes. Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, |

公法101-601 第101議会 法律 アメリカ先住民の墓の保護およびその他の目的を定めること。 アメリカ合衆国議会の上院および下院を代表することにより制定する。 【現在改定中です】 |

| SECTION 1. SHORT TITLE This Act may be cited as the "Native American Graves Protection Repatriation and Repatriation Act". SEC. 2. DEFINITIONS. For purposes of this Act, the term— (1) "burial site" means any natural or prepared physical location, whether originally below, on, or above the surface of note. the earth, into which as a part of the death rite or ceremony of culture, individual human remains are deposited. (2) "cultural affiliation" means that there is a relationship of shared group identity which can be reasonably traced historically or prehistorically between a present day Indian tribe or Native Hawaiian organization and an identifiable earlier group. (3) "cultural items" means human remains and— (A) "associated funerary objects" which shall mean objects that, as a part of the death rite or ceremony of a culture, are reasonably believed to have been placed with individual human remains either at the time of death or later, and both the human remains and associated funerary objects are presently in the possession or control of a Federal agency or museum, except that other items exclusively made for burial purposes or to contain human remains shall be considered as associated funerary objects. (B) "unassociated funerary objects" which shall mean objects that, as a part of the death rite or ceremony of a culture, are reasonably believed to have been placed with individual human remains either at the time of death or later, where the remains are not in the possession or control of the Federal agency or museum and the objects can be identified by a preponderance of the evidence as related to specific individuals or families or to known human remains or, by a preponderance of the evidence, £is having been removed from a specific burial site of an individual culturally affiliated with a particular Indian tribe, (C) "sacred objects" which shall mean specific ceremonial objects which are needed by traditional Native American religious leaders for the practice of traditional Native American religions by their present day adherents, and (D) "cultural patrimony" which shall mean an object having ongoing historical, traditional, or cultural importance central to the Native American group or culture itself, rather than property owned by an individual Native American, and which, therefore, cannot be alienated, appropriated, or conveyed by any individual regardless of whether or not the individual is a member of the Indian tribe or Native Hawaiian organization and such object shall have been considered inalienable by such Native American group at the time the object was separated from such group. |

第1条 表題 本法は、「米国先住民の墓の保護および送還に関する法律」として引用されることがある。 第2条 定義 本法において、以下の用語は、 (1) 「埋葬地」とは、元々地表の下、上、上のいずれであっても、文化の死の儀式または儀式の一部として個々の人間の遺骨が埋葬される、自然または準備された物 理的場所をいう。 (2) 文化的所属(帰属)」とは、現在のインディアン部族またはハワイ先住民の組織と、識別可能な以前の集団との間に、歴史的または先史的に合理的に追跡でき る、集団同一性の共有関係が存在することをいう。 (3)「文化的遺物」とは、人骨および以下のものをいう。 (A) 「関連葬送品」とは、ある文化の死の儀式の一部として、死亡時またはそれ以降に個々の遺骨とともに置かれたと合理的に考えられる物品で、遺骨と関連葬送品 の両方が現在連邦機関または博物館の所有または管理下にあるものをいう。ただし、埋葬目的または遺骨収容目的にのみ作られた他の物品は関連葬送品とみなさ れるものとする。 (B) 「非関連副葬品」とは、ある文化の死の儀式の一部として、死亡時またはそれ以降に個々の遺骨とともに置かれたと合理的に考えられる物品をいう。遺骨が連邦 政府機関または博物館の所有または管理下になく、その物品が特定の個人または家族、もしくは既知の遺骨に関連すると、または特定のインディアン部族に文化 的に帰属する個人の特定の埋葬地から持ち出されたと、証拠の優越によって同定できる場合。 (C) 「神聖な物」とは、伝統的なアメリカ先住民の宗教指導者が、現在の信奉者による伝統的なアメリカ先住民の宗教の実践のために必要とする特定の儀式用具を意 味するものとする。 (D)「文化遺産」とは、個々のアメリカ先住民が所有する財産ではなく、アメリカ先住民の集団または文化そのものにとって継続的な歴史的、伝統的または文 化的重要性を有する物であり、したがって、個人がインディアン部族またはハワイ先住民組織の一員であるかどうかにかかわらず個人が疎外、占有または譲渡で きず、その物体がその集団から分離した時点でそのアメリカ先住民集団によって不可侵とみなされたものでなければならないものとする。 |

| (4) "Federal

agency" means any department, agency, or

instrumentality of the United States. Such term does not

include the Smithsonian Institution. (5) "Federal lands" means any land other than tribal lands which are controlled or owned by the United States, including lands selected by but not yet conveyed to Alaska Native Corporations and groups organized pursuant to the Alsiska Native Claims Settlement Act of 1971. (6) "Hui Malama I Na Kupuna O Hawai'i Nei" means the nonprofit. Native Hawaiian organization incorporated under the laws of the State of Hawaii by that name on April 17, 1989, for the purpose of providing guidance and expertise in decisions dealing with Native Hawaiian cultural issues, particularly burial issues. (7) "Indian tribe" means any tribe, band, nation, or other organized group or community of Indians, including any Alaska Native village (as defined in, or established pursuant to, the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act), which is recognized as eligible for the special programs and services provided by the United States to Indians because of their status as Indians. (8) "museum" means any institution or State or local government agency (including any institution of higher learning) that receives Federal funds and has possession of, or control over. Native American cultural items. Such term does not include the Smithsonian Institution or any other Federal agency. (9) "Native American" means of, or relating to, a tribe, people, or culture that is indigenous to the United States. (10) "Native Hawaiian" means any individual who is a descendant of the aboriginal people who, prior to 1778, occupied and exercised sovereignty in the area that now constitutes the State of Hawaii. (11) "Native Hawaiian organization" means any organization which— (A) serves and represents the interests of Native Hawaiians, (B) has as a primary and stated purpose the provision of services to Native Hawaiians, and (C) has expertise in Native Hawaiian Affairs, and shall include the Office of Hawaiian Affairs and Hui Malama I Na Kupuna O Hawai'i Nei. (12) "Office of Hawaiian Affairs" means the Office of Hawaiian Affairs established by the constitution of the State of Hawaii. (13) "right of possession" means possession obtained with the voluntary consent of an individual or group that had authority of alienation. The original acquisition of a Native American unassociated funerary object, sacred object or object of cultural patrimony from an Indian tribe or Native Hawaiian organization with the voluntary consent of an individual or group with authority to alienate such object is deemed to give right of possession of that object, unless the phrase so defined would, as applied in section 7(c), result in a Fifth Amendment taking by the United States as determined by the United States Claims Court pursuant to 28 U.S.C. 1491 in which event the "right of possession" shall be as provided under otherwise applicable property law. The original acquisition of Native American human remains and associated funerary objects which were excavated, exhumed, or otherwise obtained with full knowledge and consent of the next of kin or the official governing body of the appropriate culturally affiliated Indian tribe or Native Hawaiian organization is deemed to give right of possession to those remains. |

(4)

「連邦政府機関」とは、米国のあらゆる省、機関、または組織をいう。この用語にはスミソニアン協会を含まない。 (5)「連邦土地」とは、米国が管理または所有する部族地以外の土地を意味し、1971年のアルシスカ先住民請求権和解法に従って組織されたアラスカ先住 民の法人およびグループによって選ばれたがまだ譲渡されていない土地も含まれる。 (6) 「Hui Malama I Na Kupuna O Hawai'i Nei」とは、非営利のハワイ先住民の団体をいう。ハワイ先住民の文化問題、特に埋葬の問題を扱う決定において指導と専門知識を提供する目的で、1989 年4月17日にその名でハワイ州の法律に基づいて設立されたハワイ先住民の団体を意味する。 (7) 「インディアン部族」とは、インディアンの部族、バンド、国家、その他の組織された集団または共同体を意味し、(アラスカ先住民請求権和解法に定義され た、またはそれに従って設立された)アラスカ先住民村を含み、インディアンとしての地位により米国がインディアンに提供する特別なプログラムおよびサービ スを受ける資格があると認識されたものである。 (8)「博物館」とは、連邦資金を受け、先住民の文化財を所有または管理している機関または州もしくは地方政府機関(高等教育機関を含む)をいう。アメリ カ先住民の文化的物品を所有または管理している施設、州または地方政府機関(高等教育機関を含む)を意味します。この用語には、スミソニアン博物館および その他の連邦機関は含まれない。 (9)「アメリカ先住民」とは、米国先住民の部族、民族、文化に属する、またはそれらに関連するものをいう。 (10) 「ハワイ先住民」とは、1778年以前に現在のハワイ州を構成する地域を占め、主権を行使していた原住民の子孫である個人をいう。 (11) 「ハワイ先住民の団体」とは、以下を行う団体をいう。 (A)ハワイ先住民の利益を提供し、代表することができる。 (B)ハワイ先住民にサービスを提供することを主な目的としている。 (C) ハワイ先住民の問題に精通している団体で、ハワイ事務局および Hui Malama I Na Kupuna O Hawai'i Nei を含むものとする。 (12) 「ハワイ州事務局」とは、ハワイ州憲法によって設立されたハワイ州事務局をいう。(13)「占有権」とは、疎外権を有する個人または集団の自発的な同意に よって得られた占有をいう。インディアン部族またはハワイ先住民の組織から、アメリカ先住民の関連性のない葬儀用具、聖具、または文化財の対象物を、その 対象物を譲渡する権限を持つ個人またはグループの自発的な同意を得て最初に取得することは、その対象物の所有権を与えるものとみなされる。ただし、このよ うに定義された表現は第7節(c)において適用すると、米国債権裁判所の判断により、28 U. S. C. 1491に従い米国による修正5条の取得に帰結するであろうという例外を除いて、このように定義された場合、所有権に帰結するとみなされる。 ただし、第7(c)節の適用により、合衆国法律集第28編第1491節に従って合衆国請求裁判所の決定するアメリカ合衆国による修正第5条の収奪をもたら す場合には、「所有権」は他に適用される財産法の規定によるものとする。近親者または適切な文化的に関連するインディアン部族またはハワイ先住民組織の公 式統治機関の十分な知識と同意をもって発掘、発掘解除、またはその他の方法で入手されたアメリカ先住民の遺骨および関連葬祭用具の最初の取得は、それらの 遺骨に対する所有権を与えるものとみなされる。 |

| (14) "Secretary" means the

Secretary of the Interior. (15) "tribal land" means— (A) all lands within the exterior boundaries of any Indian reservation; (B) all dependent Indian communities; (C) any lands administered for the benefit of Native Hawaiians pursuant to the Hawaiian Homes Commission Act, 1920, and section 4 of Public Law 86-3. SEC. 3. OWNERSHIP. (a) NATIVE AMERICAN HUMAN REMAINS AND OBJECTS.—The ownership or control of Native American cultural items which are excavated or discovered on Federal or tribal lands after the date of enactment of this Act shall be (with priority given in the order listed)— (1) in the case of Native American human remains and associated funerary objects, in the lineal descendants of the Native American; or (2) in any case in which such lineal descendants cannot be ascertained, and in the case of unassociated funerary objects, sacred objects, and objects of cultural patrimony— (A) in the Indian tribe or Native Hawaiian organization on whose tribal land such objects or remains were discovered; (B) in the Indian tribe or Native Hawaiian organization which has the closest cultural affiliation with such remains or objects and which, upon notice, states a claim for such remains or objects; or (C) if the cultural affiliation of the objects cannot be reasonably ascertained and if the objects were discovered on Federal land that is recognized by a final judgment of the Indian Claims Commission or the United States Court of Claims as the aboriginal land of some Indian tribe— (1) in the Indian tribe that is recognized as aboriginally occupying the area in which the objects were discovered, if upon notice, such tribe states a claim for such remains or objects, or (2) if it can be shown by a preponderance of the evidence that a different tribe has a stronger cultural relationship with the remains or objects than the tribe or organization specified in paragraph (1), in the Indian tribe that has the strongest demonstrated relationship, if upon notice, such tribe states a claim for such remains or objects. (b) UNCLAIMED NATIVE AMERICAN HUMAN REMAINS AND OBRegulations. JECTS.—Native American cultural items not claimed under subsection (a) shall be disposed of in accordance with regulations promulgated by the Secretary in consultation with the review committee established under section 8, Native American groups, representatives of museums and the scientific community. |

(14) 「長官」とは、内務長官をいう。 (15) 「部族の土地」とは、以下を意味する。 (A) インディアン居留地の外側の境界内にあるすべての土地。 (B) すべての従属インディアン共同体。 (C) 1920年ハワイアンホーム委員会法および公法第86-3条第4項に基づきハワイ先住民の利益のために管理されている土地。 第3条 所有権 (a) アメリカ先住民の遺物および物品-この法律の制定日以降に連邦または部族の土地で発掘または発見されたアメリカ先住民の文化的物品の所有権または管理権 は、以下のとおりとする(列記する順序で優先される)。 (1) アメリカ先住民の人骨及び関連葬祭用具の場合、アメリカ先住民の直系卑属に。 (2) その直系卑属が確認できない場合、および関連性のない葬祭用品、聖具、文化財の場合は、以下のとおりとする。 (A) 当該物品または遺骨が発見された部族の土地にあるインディアン部族またはハワイ先住民の組織において。 (B) 当該遺物または物品に最も近い文化的関係を持ち、通知により当該遺物または物品に対する権利を主張するインディアン部族またはハワイ先住民の組織、または (C) 当該文化的関係が、当該遺物または物品に最も近い文化的関係を持ち、通知により当該遺物または物品に対する権利を主張するインディアン部族またはハワイ先 住民の組織、または (C) 対象物の文化的所属が合理的に確認できず、かつ、対象物がインディアン請求委員会または米国請求裁判所の最終判決によりインディアン部族の原住民の土地と 認められた連邦土地で発見された場合、以下の通り。 (1) 発見された地域を原住民として占有していたと認められたインディアン部族が、通知により、その遺骨または物品に対する権利を主張する場合、または (2) (1)で指定された部族または組織よりも、異なる部族が遺骨または物品とより強い文化的関係を持つことが、証拠の優位性によって証明できる場合、最も強い 関係を証明したインディアン(先住民)部族で、その部族が通知により、その遺骨または物品に対する権利を主張する場合。 (b) 非請求のアメリカ先住民の遺骨と物品。第(a)項に基づき請求されなかったアメリカ先住民の文化財は、第8項に基づき設立された審査委員会、アメリカ先住 民のグループ、博物館及び科学界の代表者と協議して長官が発布した規則に従って処分されるものとする。 |

| (c) INTENTIONAL

EXCAVATION AND REMOVAL OF NATIVE AMERICAN

HUMAN REMAINS AND OBJECTS.—The intentional removal from or

excavation of Native American cultural items from Federal or tribal

lands for purposes of discovery, study, or removal of such items is

permitted only if— (1) such items are excavated or removed pursuant to a permit issued under section 4 of the Archaeological Resources Protection Act of 1979 (93 Stat. 721; 16 U.S.C. 470aa et seq.) which shall be consistent with this Act; (2) such items are excavated or removed after consultation with or, in the case of tribal lands, consent of the appropriate (if any) Indian tribe or Native Hawaiian organization; (3) the ownership and right of control of the disposition of such items shall be as provided in subsections (a) and (b); and (4) proof of consultation or consent under paragraph (2) is shown. (d) INADVERTENT DISCOVERY OF NATIVE AMERICAN REMAINS AND OBJECTS.—(1) Any person who knows, or has reason to know, that such person has discovered Native American cultural items on Federal or tribal lands after the date of enactment of this Act shall notify, in writing, the Secretary of the Department, or head of any other agency or instrumentality of the United States, having primary management authority with respect to Federal lands and the appropriate Indian tribe or Native Hawaiian organization with respect to tribal lands, if known or readily ascertainable, and, in the case of lands that have been selected by an Alaska Native Corporation or group organized pursuant to the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act of 1971, the appropriate corporation or group. If the discovery occurred in connection with an activity, including (but not limited to) construction, mining, logging, and agriculture, the person shall cease the activity in the area of the discovery, make a reasonable effort to protect the items discovered before resuming such activity, and provide notice under this subsection. Following the notification under this subsection, and upon certification by the Secretary of the department or the head of any agency or instrumentality of the United States or the appropriate Indian tribe or Native Hawaiian organization that notification has been received, the activity may resume after 30 days of such certification. (2) The disposition of and control over any cultural items excavated or removed under this subsection shall be determined as provided for in this section. (3) If the Secretary of the Interior consents, the responsibilities (in whole or in part) under paragraphs (1) and (2) of the Secretary of any department (other than the Department of the Interior) or the head of any other agency or instrumentality may be delegated to the Secretary with respect to any land managed by such other Secretary or agency head. (e) RELINQUISHMENT.—Nothing in this section shall prevent the governing body of an Indian tribe or Native Hawaiian organization from expressly relinquishing control over any Native American human remains, or title to or control over any funerary object, or sacred object. |

(c)

ネイティブアメリカンの人間の遺物およびオブジェの意図的な発掘および除去-発見、調査、または除去の目的で、連邦または部族の土地からネイティブアメリ

カンの文化財を意図的に除去または発掘することは、以下の場合にのみ許可されている。 (1) 当該品目が、1979年考古資源保護法(93 Stat. 721; 16 U.S.C. 470aa et seq.) の第4節に基づいて発行された許可に従って発掘または除去される。 (2) そのような物品が、部族の土地の場合、該当する(もしあれば)インディアン部族またはハワイ先住民の組織と協議し、またはその同意を得て、発掘または撤去 されること。 (3) 当該物品の処分の所有権および管理権は、(a)項および(b)項に規定されるとおりとする。 (4) (2)に基づく協議または同意の証拠が示されていること。 (d)アメリカ先住民の遺跡および遺物の不用意な発見。 (1) この法律の制定日以降に連邦または部族の土地でアメリカ先住民の文化財を発見したことを知っている、または知る理由がある者は、省長官、または米国の他の 機関または団体の長に書面で通知する。また、1971年アラスカ先住民請求権和解法に従って組織されたアラスカ先住民の法人またはグループによって選定さ れた土地の場合は、その法人またはグループにも通知する。建設、採掘、伐採、および農業を含む(ただしこれらに限定されない)活動に関連して発見された場 合、その者は発見地域での活動を停止し、当該活動を再開する前に発見物を保護する妥当な努力をし、本款に基づく通知を行うものとする。本小節に基づく通知 の後、省長官、米国の機関もしくは団体の長、または該当するインディアン部族もしくはハワイ先住民の組織が通知を受けたことを証明した場合、その証明から 30日後に活動を再開することができる。 (2) 本節に基づき発掘又は除去された文化財の処分及び管理は、本節に定めるところにより決定されるものとする。 (3) 内務長官が同意した場合、(内務省以外の)部局の長官又は他の機関若しくは団体の長の(1)及び(2)に基づく責任の全部又は一部は、当該他の長官又は機 関の長が管理する土地に関して長官に委譲することができる。 (e) 撤去-本節のいかなる規定も、インディアン部族またはハワイ先住民の組織の統治体が、アメリカ先住民の遺骨、または葬祭用具、もしくは神聖物に対する所有 権または管理権を明示的に放棄することを妨げるものではない。 |

| SEC. 4. ILLEGAL

TRAFFICKING. (a) ILLEGAL TRAFFICKING.—Chapter 53 of title 18, United States Code, is amended by adding at the end thereof the following new section: "§ 1170. Illegal Trafficking in Native American Human Remains and Cultural Items "(a) Whoever knowingly sells, purchases, uses for profit, or transports for sale or profit, the human remains of a Native American without the right of possession to those remains as provided in the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act shall be fined in accordance with this title, or imprisoned not more than 12 months, or both, and in the case of a second or subsequent violation, be fined in accordance with this title, or imprisoned not more than 5 years, or both. "(b) Whoever knowingly sells, purchases, uses for profit, or transports for sale or profit any Native American cultural items obtained in violation of the Native American Grave Protection and Repatriation Act shall be fined in accordance with this title, imprisoned not more than one year, or both, and in the case of a second or subsequent violation, be fined in accordance with this title, imprisoned not more than 5 years, or both.". (b) TABLE OF CONTENTS.—The table of contents for chapter 53 of title 18, United States Code, is amended by adding at the end thereof the following new item: "1170. Illegal Trafficking in Native American Human Remains and Cultural Items.". SEC. 5. INVENTORY FOR HUMAN REMAINS AND ASSOCIATED FUNERARY OBJECTS. (a) IN GENERAL.—Each Federal agency and each museum which has possession or control over holdings or collections of Native American human remains and associated funerary objects shall compile an inventory of such items and, to the extent possible based on information possessed by such museum or Federal agency, identify the geographical and cultural affiliation of such item. (b) REQUIREMENTS.—(1) The inventories and identifications required under subsection (a) shall be— (A) completed in consultation with tribal government and Native Hawaiian organization officials and traditional religious leaders; (B) completed by not later than the date that is 5 years after the date of enactment of this Act, and (C) made available both during the time they are being conducted and afterward to a review committee established under section 8. (2) Upon request by an Indian tribe or Native Hawaiian organization which receives or should have received notice, a museum or Federal agency shall supply additional available documentation to supplement the information required by subsection (a) of this section. The term "documentation" means a summary of existing museum or Federal agency records, including inventories or catalogues, relevant studies, or other pertinent data for the limited purpose of determining the geographical origin, cultural affiliation, and basic facts surrounding acquisition and accession of Native American human remains and associated funerary objects subject to this section. Such term does not mean, and this Act shall not be construed to be an authorization for, the initiation of new scientific studies of such remains and associated funerary objects or other means of acquiring or preserving additional scientific information from such remains and objects. |

第4条 違法な売買流通 (a) 違法取引-合衆国法典第18編第53章は、その末尾に以下の新条項を加えることにより改正される。 "§ 1170. 先住民の遺骨および文化的物品における違法取引 "(a) アメリカ先住民の墓の保護と送還に関する法律に規定されたそれらの遺骨に対する所有権のないアメリカ先住民の遺骨を、故意に販売、購入、利益のために使 用、または販売もしくは利益のために輸送した者は、本号に従って罰金、または12カ月以下の懲役、もしくはその両方、また2回目以降の違反の場合は本号に 従って罰金、5年以下の懲役、もしくはその両方が課される。 "(b) アメリカ先住民の墓の保護および送還法に違反して入手したアメリカ先住民の文化的物品を故意に販売、購入、利益のために使用、または販売もしくは利益のた めに輸送した者は、このタイトルに従って罰金、1年以下の懲役、またはその両方、また2度目以降の違反の場合はこのタイトルに従って罰金、5年以下の懲 役、またはその両方とする。". (b) 目次-合衆国法典第18編第53章の目次は、その末尾に以下の新項目を加えることにより修正される。 "1170. 1170. 在米先住民の遺骨および文化財の違法取引 "を追加することにより修正される。 第5条 遺骨および関連葬祭用具の目録 (a)総則——各連邦機関およびアメリカ先住民の遺骨および関連葬祭用具を所有または管理している各博物館は、当該品目の目録を作成し、当該博物館または 連邦機関の保有する情報に基づき可能な範囲で、当該品目の地理的および文化的所属を特定するものとする。 (b)必要要件——(1)第(a)項に基づき必要とされる目録及び識別は、以下の通りでなければならない。 (A) 部族政府及びハワイ先住民の組織の職員並びに伝統的宗教指導者と協議して完成させる。 (B) この法律が制定された日から5年以上経過した日までに完成させる。 (C) 実施中および終了後、第8項に基づき設置された審査委員会が利用できるようにする。 (2) 通知を受け取った、または受け取るべきであったインディアン部族またはハワイ先住民の組織から要請があった場合、博物館または連邦機関は、本節(a)で要 求される情報を補足するために、入手可能な追加の文書を提供するものとする。文書」とは、本節の対象となるアメリカ先住民の遺骨および関連する葬祭用具の 地理的起源、文化的所属、および取得と寄贈にまつわる基本的事実を決定するという限られた目的のための、目録やカタログ、関連研究、または他の関連データ を含む、博物館または連邦機関の既存の記録の要約を意味する。この用語は、当該遺骨および関連葬祭物に対する新たな科学的研究の開始、または当該遺骨およ び物から追加の科学的情報を取得もしくは保存する他の手段を意味せず、また本法はこれを許可するものと解釈してはならない。 |

| (c) EXTENSION OF TIME

FOR INVENTORY.—Any museum which has

made a good faith effort to carry out an inventory and identification

under this section, but which has been unable to complete the

process, may appeal to the Secretary for an extension of the time

requirements set forth in subsection (b)(1)(B). The Secretary may

extend such time requirements for any such museum upon a finding

of good faith effort. An indication of good faith shall include the

development of a plan to carry out the inventory and identification

process. (d) NOTIFICATION.—(1) If the cultural affiliation of any particular Native American human remains or associated funerary objects is determined pursuant to this section, the Federal agency or museum concerned shall, not later than 6 months after the completion of the inventory, notify the affected Indian tribes or Native Hawaiian organizations. (2) The notice required by paragraph (1) shall include information— (A) which identifies each Native American human remains or associated funerary objects and the circumstances surrounding its acquisition; (B) which lists the human remains or associated funerary objects that are clearly identifiable as to tribal origin; and (C) which lists the Native American human remains and associated funerary objects that are not clearly identifiable as being culturally affiliated with that Indian tribe or Native Hawaiian organization, but which, given the totality of circumstances surrounding acquisition of the remains or objects, are determined by a reasonable belief to be remains or objects culturally affiliated with the Indian tribe or Native Hawaiian organization. (3) A copy of each notice provided under paragraph (1) shall be sent to the Secretary who shall publish each notice in the Federal Register. (e) INVENTORY.—For the purposes of this section, the term "inventory" means a simple itemized list that summarizes the information called for by this section. SEC. 6. SUMMARY FOR UNASSOCIATED FUNERARY OBJECTS, SACRED OBJECTS, AND CULTURAL PATRIMONY. (a) IN GENERAL.—Each Federal agency or museum which has possession or control over holdings or collections of Native American unassociated funerary objects, sacred objects, or objects of cultural patrimony shall provide a written summary of such objects based upon available information held by such agency or museum. The summary shall describe the scope of the collection, kinds of objects included, reference to geographical location, means and period of acquisition and cultural affiliation, where readily ascertainable. (b) REQUIREMENTS.—(1) The summary required under subsection (a) shall be— (A) in lieu of an object-by-object inventory; (B) followed by consultation with tribal government and Native Hawaiian organization officials and traditional religious leaders; and |

(c)インベントリー作成のための期間の延長——本節に基づく目録作成

及

び識別を行うために誠実に努力したが、そのプロセスを完了することができなかった博物館は、第(b)(1)(B)項に定める時間の要件の延長を長官に上訴

することができる。)

長官は、誠実に努力したことが認められれば、そのような博物館に対してその時間要件を延長することができる。誠実な努力の表明には、目録作成と識別のプロ

セスを実行するための計画の策定が含まれるものとする。 (d) 通告——(1)本節に従って特定のアメリカ先住民の人骨または関連葬具の文化的所属が決定された場合、当該連邦機関または博物館は、目録作成完了後6ヶ月 以内に、影響を受けるインド部族またはハワイ先住民の団体に通知するものとする。 (2) (1)で要求される通知は、以下の情報を含むものとする。 (A) 各米国先住民の人骨または関連する葬祭用具を特定し、その取得をめぐる状況を示す。 (B)部族の起源が明確に識別できる遺骨または関連葬祭用具を列挙する。 (C)インディアン部族またはハワイ先住民の組織と文化的に関連があると明確に識別できないが、遺骨または物品を取得した状況を総合すると、インディアン 部族またはハワイ先住民の組織と文化的に関連がある遺骨または物品であると合理的に判断されるアメリカ先住民の遺骨および関連する埋葬品をリストアップし ているもの。 (3)第1項に基づき提供された各通知のコピーは、長官に送付され、長官は各通知を連邦官報に掲載するものとする。 (e) インベントリ-本節の目的上、「インベントリ」という用語は、本節で要求される情報を要約した単純な箇条書きのリストを意味する。 第六条 6. 第6項 非関連葬祭用具、聖具、及び文化財に関する要約。 (a) 一般に、アメリカ先住民の関連性のない葬祭用具、聖なる物、あるいは文化的遺産の所蔵またはコレクションを所有または管理している各連邦機関または博物館 は、当該機関または博物館が所有する入手可能な情報に基づき、当該物品の書面による要約を提供するものとする。その概要は、コレクションの範囲、含まれる 物品の種類、地理的位置、取得の手段及び時期、並びに容易に確認できる場合には文化的帰属を記述するものとする。 (1)第(a)項に基づき要求される要約は、以下の通りである。 (A) 対象物ごとの目録の代わりとなるものであること。 (B) 部族政府及びハワイ先住民の組織の職員及び伝統的宗教指導者との協議に従う。 |

| (C) completed by not later

than

the date that is 3 years after

the date of enactment of this Act. (2) Upon request, Indian Tribes and Native Hawaiian organizations shall have access to records, catalogues, relevant studies or other pertinent data for the limited purposes of determining the geographic origin, cultural affiliation, and basic facts surrounding acquisition and accession of Native American objects subject to this section. Such information shall be provided in a reasonable manner to be agreed upon by all parties. SEC. 7. REPATRIATION. (a) REPATRIATION OF NATIVE AMERICAN HUMAN REMAINS AND OBJECTS POSSESSED OR CONTROLLED BY FEDERAL AGENCIES AND MUSEUMS.—(1) If, pursuant to section 5, the cultural affiliation of Native American human remains and associated funerary objects with a particular Indian tribe or Native Hawaiian organization is established, then the Federal agency or museum, upon the request of a known lineal descendant of the Native American or of the tribe or organization and pursuant to subsections (b) and (e) of this section, shall expeditiously return such remains and associated funerary objects. (2) If, pursuant to section 6, the cultural affiliation with a particular Indian tribe or Native Hawaiian organization is shown with respect to unassociated funerary objects, sacred objects or objects of cultural patrimony, then the Federal agency or museum, upon the request of the Indian tribe or Native Hawaiian organization and pursuant to subsections (b), (c) and (e) of this section, shall expeditiously return such objects. (3) The return of cultural items covered by this Act shall be in consultation with the requesting lineal descendant or tribe or organization to determine the place and manner of delivery of such items. (4) Where cultural affiliation of Native American human remains and funerary objects has not been established in an inventory prepared pursuant to section 5, or the summary pursuant to section 6, or where Native American human remains and funerary objects are not included upon any such inventory, then, upon request and pursuant to subsections (b) and (e) and, in the case of unassociated funerary objects, subsection (c), such Native American human remains and funerary objects shall be expeditiously returned where the requesting Indian tribe or Native Hawaiian organization can show cultural affiliation by a preponderance of the evidence based upon geographical, kinship, biological, archaeological, anthropological, linguistic, folkloric, oral traditional, historical, or other relevant information or expert opinion. (5) Upon request and pursuant to subsections (b), (c) and (e), sacred objects and objects of cultural patrimony shall be expeditiously returned where— (A) the requesting party is the direct lineal descendant of an individual who owned the sacred object; (B) the requesting Indian tribe or Native Hawaiian organization can show that the object was owned or controlled by the tribe or organization; or (C) the requesting Indian tribe or Native Hawaiian organization can show that the sacred object was owned or controlled by a member thereof, provided that in the case where a sacred object w£is owned by a member thereof, there are no identifiable lineal descendants of said member or the lineal descendants, upon notice, have failed to make a claim for the object under this Act. |

(C) 本法律制定日から3年以上経過した日までに完了すること。 (2) 要請があれば、インディアン部族およびハワイ先住民の組織は、本節の対象となるアメリカ先住民の物品の地理的起源、文化的所属、および取得と譲受をめぐる 基本事実を決定する限定的な目的のために、記録、目録、関連研究またはその他の関連データにアクセスできるものとする。そのような情報は、すべての当事者 が合意する合理的な方法で提供されなければならない。 第7条 返還 (a) 米国先住民の遺物および連邦政府機関および博物館が所有または管理している物品の再活用。 -(1) 第5項に従い、アメリカ先住民の遺骨および関連葬具が、特定のインディアン部族またはハワイ先住民の組織と文化的に関係があることが判明した場合、連邦機 関または博物館は、アメリカ先住民またはその部族または組織の既知の直系卑属からの要請により、本項第(b)号および第(e)号に基づき、その遺骨および 関連葬具を速やかに返還しなければならない。 (第6項に従い、関連性のない葬祭用具、聖具、または文化財の物品に関して、特定のインディアン部族またはハワイ先住民の組織との文化的関係が示された場 合、連邦機関または博物館は、インディアン部族またはハワイ先住民の組織の要請により、本項第(b)号、(c)号および(e)号に基づき、当該物品を迅速 に返却しなければならない。 (3) 本法律が適用される文化財の返還は、要請を受けた直系卑属又は部族若しくは団体と協議して、当該文化財の引渡場所及び方法を決定するものとする。 (4)第5節に従って作成された目録、または第6節に従って作成された要約において、アメリカ先住民の人骨および葬祭用具の文化的所属が確立されていない 場合、またはアメリカ先住民の人骨および葬祭用具がその目録に含まれていない場合、要請に応じて、第(b) 項および第(e) 項に従って、また未関連葬祭物の場合、第 (c) 項に従って、アメリカ先住民の人骨と葬祭用具の文化的帰属の確認が行われなければならない。(c)項に従って、要請したインディアン部族またはハワイ先住 民の組織が、地理的、血縁的、生物学的、考古学的、人類学的、言語的、民間伝承的、歴史的、またはその他の関連情報もしくは専門家の意見に基づいて、証拠 の優位性により文化的帰属を示すことができる場合、当該アメリカ先住民の遺骨および葬祭用具は迅速に返還されるものとする。 (5) 以下の場合、要請があれば、(b)、(c)および(e)に従って、聖物および文化財は迅速に返還されるものとする。 (A) 要請者が、神聖な物品を所有していた個人の直系卑属である場合。 (B) 要請したインディアン部族またはハワイ先住民の組織が、その物体が部族または組織によって所有または管理されていたことを示すことができる場合。 (C) 要請したインディアン部族またはハワイ先住民の組織が、聖なる物がその構成員によって所有または管理されていたことを示すことができる。ただし、聖なる物 がその構成員によって所有されていた場合、当該構成員の直系卑属が特定できないか、直系卑属が通知を受けて、この法律に基づきその物に対して請求しなかっ た場合でなければならない。 |

| (b) SCIENTIFIC

STUDY.—If the lineal descendant, Indian tribe, or

Native Hawaiian organization requests the return of culturally

affiliated Native American cultural items, the Federal agency or

museum shall expeditiously return such items unless such items are

indispensable for completion of a specific scientific study, the

outcome of which would be of major benefit to the United States. Such

items shall be returned by no later than 90 days after the date on

which the scientific study is completed. (c) STANDARD OF REPATRIATION.—If a known lineal descendant or an Indian tribe or Native Hawaiian organization requests the return of Native American unassociated funerary objects, sacred objects or objects of cultural patrimony pursuant to this Act and presents evidence which, if standing alone before the introduction of evidence to the contrary, would support a finding that the Federal agency or museum did not have the right of possession, then such agency or museum shall return such objects unless it can overcome such inference and prove that it has a right of possession to the objects. (d) SHARING OF INFORMATION BY FEDERAL AGENCIES AND MUSEUMS.—Any Federal agency or museum shall share what information it does possess regarding the object in question with the known lineal descendant, Indian tribe, or Native Hawaiian organization to assist in making a claim under this section. (e) COMPETING CLAIMS.—Where there are multiple requests for repatriation of any cultural item and, after complying with the requirements of this Act, the Federal agency or museum cannot clearly determine which requesting party is the most appropriate claimant, the agency or museum may retain such item until the requesting parties agree upon its disposition or the dispute is otherwise resolved pursuant to the provisions of this Act or by a court of competent jurisdiction. (f) MUSEUM OBLIGATION.—Any museum which repatriates any item in good faith pursuant to this Act shall not be liable for claims by an aggrieved party or for claims of breach of fiduciary duty, public trust, or violations of state law that are inconsistent with the provisions of this Act. SEC. 8. REVIEW COMMITTEE. (a) ESTABLISHMENT.—Within 120 days after the date of enactment of this Act, the Secretary shall establish a committee to monitor and review the implementation of the inventory and identification process and repatriation activities required under sections 5, 6 and 7. (b) MEMBERSHIP.—(1) The Committee established under subsection (a) shall be composed of 7 members, (A) 3 of whom shall be appointed by the Secretary from nominations submitted by Indian tribes. Native Hawaiian organizations, and traditional Native American religious leaders with at least 2 of such persons being traditional Indian religious leaders; (B) 3 of whom shall be appointed by the Secretary from nominations submitted by national museum organizations and scientific organizations; and (C) 1 who shall be appointed by the Secretary from a list of persons developed and consented to by all of the members appointed pursuant to subparagraphs (A) and (B). |

(b)

科学的研究-直系卑属、インディアン部族、またはハワイ先住民の組織が、文化的に関連したアメリカ先住民の文化財の返還を要求した場合、連邦機関または博

物館は、その成果が米国にとって大きな利益となる特定の科学研究の完了に不可欠である場合を除いて、その品目を迅速に返還しなければならない。当該物品

は、科学的研究が完了した日から遅くとも90日以内に返却されなければならない。 (c) 返還の基準-既知の直系卑属またはインディアン部族もしくはハワイ先住民の組織が、この法律に従ってアメリカ先住民の関連性のない葬祭用具、聖具または文 化財の返還を要求し、反対の証拠の提出の前に、単独であれば連邦機関または博物館が所有権を持っていなかったと認めるような証拠を提示した場合、その機関 または博物館は、その推測を覆して物品に対する所有権を持っていると証明できる場合以外は、その物品を返還するものとする。 (d) 連邦政府機関および博物館による情報の共有-連邦政府機関または博物館は、本項に基づく請求を行うのを支援するため、当該物品に関して保有している情報 を、判明している直系卑属、インディアン部族、またはハワイ先住民の組織と共有するものとする。 (e) 相違する請求:文化財の送還について複数の請求があり、この法律の要件に従った後、連邦機関又は博物館が、どの請求者が最も適切な請求者か明確に判断でき ない場合、機関又は博物館は、請求者がその処分について合意するか、この法律の規定又は管轄の裁判所により紛争が解決されるまで、当該品目を保持できるも のとする。 (f) 博物館の責任: この法律に従って誠実に品物を送還した博物館は、被害を受けた当事者による請求、受託者義務違反、公共信託、またはこの法律の規定と矛盾する州法の違反の 請求に対して責任を負わないものとする。 第8条 審査委員会 (a) 設立 - 本法律成立日から120日以内に、長官は第5節、第6節、および第7節に基づき要求される目録作成および識別プロセスならびに本国送還活動の実施を監視お よび審査する委員会を設立するものとする。 (b) 構成 - (1)第(a)項に基づき設立された委員会は、7名の委員で構成される。 (A) そのうちの3名は、インディアン部族から提出された指名の中から長官によって任命されるものとする。(A) 3名は、インディアン部族、ハワイ先住民の組織、およびアメリカ先住民の伝統的な宗教指導者の中から長官が指名し、そのうちの少なくとも2名はインディア ンの伝統的宗教指導者とする。 (B) 国立博物館組織と科学団体から提出された指名のうち、長官が任命する3名。 (C) (A)および(B)に従って任命されたすべての委員が作成し同意した人物リストの中から、長官が任命する1名。 |

| (2) The Secretary may not

appoint Federal officers or employees to

the committee. (3) In the event vacancies shall occur, such vacancies shall be filled by the Secretary in the same manner as the original appointment within 90 days of the occurrence of such vacancy. (4) Members of the committee established under subsection (a) shall serve without pay, but shall be reimbursed at a rate equal to the daily rate for GS-18 of the General Schedule for each day (including travel time) for which the member is actually engaged in committee business. Each member shall receive travel expenses, including per diem in lieu of subsistence, in accordance with sections 5702 and 5703 of title 5, United States Code. (c) RESPONSIBILITIES.—The committee established under subsection (a) shall be responsible for— (1) designating one of the members of the committee as chairman; (2) monitoring the inventory and identification process conducted under sections 5 and 6 to ensure a fair, objective consideration and assessment of all available relevant information and evidence; (3) upon the request of any affected party, reviewing and making findings related to— (A) the identity or cultural affiliation of cultural items, or (B) the return of such items; (4) facilitating the resolution of any disputes among Indian tribes. Native Hawaiian organizations, or lineal descendants and Federal agencies or museums relating to the return of such items including convening the parties to the dispute if deemed desirable; (5) compiling an inventory of culturally unidentifiable human remains that are in the possession or control of each Federal agency and museum and recommending specific actions for developing a process for disposition of such remains; (6) consulting with Indian tribes and Native Hawaiian organizations and museums on matters within the scope of the work of the committee affecting such tribes or organizations; (7) consulting with the Secretary in the development of regulations to carry out this Act; (8) performing such other related functions as the Secretary may assign to the committee; and (9) making recommendations, if appropriate, regarding future care of cultural items which are to be repatriated. (d) Any records and findings made by the review committee pursuant to this Act relating to the identity or cultural affiliation of any cultural items and the return of such items may be admissible in any action brought under section 15 of this Act. (e) RECOMMENDATIONS AND REPORT.—The committee shall make the recommendations under paragraph (c)(5) in consultation with Indian tribes and Native Hawaiian organizations and appropriate scientific and museum groups. (f) ACCESS.—The Secretary shall ensure that the committee established under subsection (a) and the members of the committee have reasonable access to Native American cultural items under review and to associated scientific and historical documents. (g) DUTIES OF SECRETARY.—The Secretary shall— Regulations. (1) establish such rules and regulations for the committee as may be necessary, and (2) provide reasonable administrative and staff support necessary for the deliberations of the committee. |

(2)

長官は、連邦政府役人または職員を委員会に任命することはできない。 (3) 空席が生じた場合、その空席は、その発生から90日以内に、当初の任命と同じ方法で長官によって補充されるものとする。 (4) (a)項の下に設立された委員会の委員は無給で務めるが、委員が実際に委員会業務に従事した各日(移動時間を含む)について、一般予定表の GS-18 の日当と同等の割合で経費を支給されるものとする。各委員は、合衆国法典第5編第5702条及び第5703条に従って、日当を含む旅費を支給されるものと する。 (c) 責任: (a)項の下に設立された委員会は、以下の責任を負うものとする。 (1) 委員会のメンバーの一人を議長に指名すること。 (2) 入手可能なすべての関連情報および証拠の公正かつ客観的な検討および評価を確保するため、第5節および第6節に基づき実施される目録作成および特定過程を 監視すること。 (3) 関係当事者の要請があれば、以下に関連する事項を検討し、所見を述べる。 (A) 文化的遺物の同一性又は文化的所属。 (B) 当該品目の返還 (4) インディアン部族、ハワイ先住民の組織、または直系血族間の紛争を解決する。(4) 望ましいとみなされる場合、紛争当事者の召集を含め、当該品目の返還に関連するインディアン部族、ハワイ先住民の組織、または直系卑属と連邦機関または博 物館との間のあらゆる紛争の解決を促進すること。 (5) 各連邦機関および博物館が所有または管理している文化的に識別できない遺骨の目録を作成し、その遺骨の処分方法を開発するための具体的な行動を勧告するこ と。 (6) 部族または組織に影響を与える委員会の作業範囲内の事柄について、インディアンの部族、ハワイ先住民の組織、および博物館と協議すること。 (7) 本法律を実施するための規則の策定において、長官と協議すること。 (8) 長官が委員会に割り当てることができるその他の関連任務を遂行する。 (9) 必要であれば、本国送還される文化財の将来の管理に関して勧告を行う。 (d) 本法に従い審査委員会が作成した、文化的遺物の識別又は文化的 所属及び当該遺物の返還に関する記録及び所見は、本法第 15 項に基づ く訴訟において認められる可能性がある。 (委員会は、インディアンの部族及びハワイ先住民の団体並びに適切な科学及び博物館団体と協議して、第(c)項(5)に基づく勧告を行うものとする。 (長官は、(a)項の下に設立された委員会及び委員会のメンバーが、審査中のアメリカ先住民の文化財及び関連する科学的及び歴史的文書を適切に入手できる ようにするものとする。 (g)長官の義務-長官は、以下を行う。 (1) 委員会のために必要な規則と規定を制定する。 (2) 委員会の審議に必要な合理的な管理及び職員の支援を行う。 |

| (h) ANNUAL REPORT.—The

committee established under subsection (a) shall

submit an annual report to the Congress on the

progress made, and any barriers encountered, in implementing this

section during the previous year. (i) TERMINATION.—The committee established under subsection (a) shall terminate at the end of the 120-day period beginning on the day the Secretary certifies, in a report submitted to Congress, that the work of the committee has been completed. SEC. 9. PENALTY. (a) PENALTY.—Any museum that fails to comply with the requirements of this Act may be assessed a civil penalty by the Secretary of the Interior pursuant to procedures established by the Secretary through regulation. A penalty assessed under this subsection shall be determined on the record after opportunity for an agency hearing. Each violation under this subsection shall be a separate offense. (b) AMOUNT OF PENALTY.—The amount of a penalty assessed under subsection (a) shall be determined under regulations promulgated pursuant to this Act, taking into account, in addition to other factors— (1) the archaeological, historical, or commercial value of the item involved; (2) the damages suffered, both economic and noneconomic, by an aggrieved party, and (3) the number of violations that have occurred. (c) ACTIONS TO RECOVER PENALTIES.—If any museum fails to pay Courts, an assessment of a civil penalty pursuant to a final order of the Secretary that has been issued under subsection (a) and not appealed or after a final judgment has been rendered on appeal of such order, the Attorney General may institute a civil action in an appropriate district court of the United States to collect the penalty. In such action, the validity and amount of such penalty shall not be subject to review. (d) SUBPOENAS.—In hearings held pursuant to subsection (a), subpoenas may be issued for the attendance and testimony of witnesses and the production of relevant papers, books, and documents. Witnesses so summoned shall be paid the same fees and mileage that are paid to witnesses in the courts of the United States. SEC. 10. GRANTS. (a) INDIAN TRIBES AND NATIVE HAWAIIAN ORGANIZATIONS.—The Secretary is authorized to make grants to Indian tribes and Native Hawaiian organizations for the purpose of assisting such tribes and organizations in the repatriation of Native American cultural items. (b) MUSEUMS.—The Secretary is authorized to make grants to museums for the purpose of assisting the museums in conducting the inventories and identification required under sections 5 and 6. SEC. 11. SAVINGS PROVISIONS. Nothing in this Act shall be construed to— (1) limit the authority of any Federal agency or museum to— (A) return or repatriate Native American cultural items to Indian tribes, Native Hawaiian organizations, or individuals, and |

(h)

年次報告書-(a)項の下に設立された委員会は、前年度における本項の実施の進捗および遭遇した障害に関する年次報告書を議会に提出しなければならない。 (i) 終了-(a)項の下に設立された委員会は、長官が議会に提出する報告書において、委員会の作業が完了したことを証明した日に始まる120日の期間の終了を もって終了する。 第9条 罰則 (a) 罰則: この法律の要件を満たさない博物館は、内務長官が規則で定めた手続きに従って、内務長官から民事罰を課される可能性がある。本項に基づき課される罰金は、 当局による聴聞の機会の後、記録に基づいて決定されるものとする。本項に基づく各違反は個別の違反とする。 (b) 罰金の額-第(a)項に基づき課せられる罰金の額は、他の要素に加え、本法に基づき公布された規則に基づき決定されるものとする。 (1) 関係する品目の考古学的、歴史的、または商業的価値。 (2) 被害を受けた当事者が被った経済的および非経済的な損害。 (3) 発生した違反の数。 (c)罰金回収のための措置: 博物館が、第(a)項に基づき発行され上訴されなかった長官の最終命令に従って、あるいはその命令の上訴に対して最終判決が下された後に、裁判所に民事罰 の査定額を支払わない場合、司法長官は罰金を回収するために米国の該当地方裁判所で民事訴訟を起こすことができる。この訴訟では、当該違約金の有効性およ び金額は審査の対象とはならない。 (d) 召喚令状-第(a)項に従って行われる公聴会では、証人の出席と証言、および関連書類、書籍、文書の提出のために召喚令状を発布することができる。召喚さ れた証人には、米国の裁判所で証人に支払われるのと同じ手数料および走行距離が支払われる。 第10条 補助金 (a) インディアンの部族およびハワイ先住民の団体: 長官は、アメリカ先住民の文化財の本国送還においてかかる部族および団体を支援する目的で、インディアンの部族およびハワイ先住民の団体に補助金を支給す る権限を有する。 (長官は、第5節及び第6節に基づき要求される目録作成及び識別を行う博物館を支援する目的で、博物館に対して補助金を交付する権限を有する。 第11条 財源の確保 本法のいかなる内容も、以下のように解釈されることはない。 (1) 連邦政府機関または博物館の以下の権限を制限するものではない。 (A) アメリカ先住民の文化的物品をインディアン部族、ハワイ先住民の組織、または個人に返還または送還する。 |

| (B) enter into any other

agreement with the consent of

the culturally affiliated tribe or organization as to the

disposition of, or control over, items covered by this Act; (2) delay actions on repatriation requests that are pending on the date of enactment of this Act; (3) deny or otherwise affect access to any court; (4) limit any procedural or substantive right which may otherwise be secured to individuals or Indian tribes or Native Hawaiian organizations; or (5) limit the application of any State or Federal law pertaining to theft or stolen property. SEC. 12. SPECIAL RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN FEDERAL GOVERNMENT AND INDIAN TRIBES. This Act reflects the unique relationship between the Federal Government and Indian tribes and Native Hawaiian organizations and should not be construed to establish a precedent with respect to any other individual, organization or foreign government. SEC. 13. REGULATIONS. The Secretary shall promulgate regulations to carry out this Act within 12 months of enactment. SEC. 14. AUTHORIZATION OF APPROPRIATIONS. There is authorized to be appropriated such sums as may be necessary to carry out this Act. SEC. 15. ENFORCEMENT. The United States district courts shall have jurisdiction over any action brought by any person alleging a violation of this Act and shall have the authority to issue such orders as may be necessary to enforce the provisions of this Act. Approved November 16, 1990. |

(B)